Guidelines for Historic Structures

Design

Adopted June 8,2022

Washington County,Maryland

Acknowledgements

Historic District Commission:

Gregory Smith, Chair

Lloyd Yavener, Vice Chair

Ann Aldrich

Vernell Doyle

Kourtney Lowery

Michael Lushbaugh

Edith Wallace

Jeffrey A. Cline (BOCC Representative)

Special Acknowledgements:

The Maryland Historical Trust

Preservation Maryland

Washington County Historical Trust (WCHT)

Clear Spring Historical Association (CSHA)

Former Historic District Commission Members:

Robert Bowman II

Thomas G. Clemens

Kurt Cushwa

Michael Gehr

Chris Horst

Sandra D. Izer

Gary W. Rohrer

Charles R. Stewart

Merry Stinson

Christine Toms

Carla Viar

David Wiles

County Staff:

Jill Baker, AICP, Director, Department of Planning & Zoning

Debra Eckard, Administrative Assistant, Department of Planning & Zoning

Meghan Jenkins, GISP, GIS Coordinator/HDC Staff person, Department of Planning & Zoning

Stephen Goodrich, AICP, Former Director, Department of Planning & Zoning

Wyatt Stitely, Comprehensive Planner, Department of Planning & Zoning

Cover Photos (Clockwise)

Burnside Bridge, Plumb Grove

Mansion, Church of the Brethren, Antietam Observation Tower

Adopted: June 8, 2022

ii Historic Structures

Table of Contents

Purpose of the Design Guidelines

Historic District Commission

Certified Local Government

National Register of Historic Places and Section 106 Review

HDC Review Areas

Historic Rural Villages (Historic Communities)

Antietam Overlay

Historic Preservation Overlay

Tax Credits

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties

What’s Historic?

Significance

Integrity

Application Requirements

Evaluation Process

Demolition

Demolition Permit Evaluation

Demolition Permit Review

Failure to Comply or Willful Disregard

Demolition Permit Application

Requirements

Ordinary Maintenance

A Short History of Washington County

Architectural Styles of Washington County

Vernacular Forms 18th-19th Century

Georgian

Federal

Greek Revival

Italianate/Italian Villa

Second Empire

Queen Anne and Other Victorian Styles

Colonial Revival

Classical Revival

Twentieth Century

Mill Complexes

Common Accessory Structures

Commercial Buildings 1890-1930

Commercial Buildings Post 1930

Gas Stations

Ecclesiastical Architecture

Schoolhouses

Historic Markers

Standards for Review

Standards for Rehabilitation

Design Guidelines iii

Table of Contents (continued)

Guidelines

Setting and Site

Viewsheds

Site and Landscape Design Features

Landforms, Plantings and Landscapes

Fence and Walls

Circulation Systems

Patios, Decks, and Other Site

Features

Archaeological Resources

Cemeteries

Existing Accessory Buildings

Rehabilitation of Existing Buildings

Building Exteriors

Masonry

Additions to Historic Buildings

New Construction and Accessory

Buildings

Site and Building Lights

Signs

Solar and Other New Technologies for Environmental Sustainability

Solar Green Roofs

Wind Turbines

Hazard Mitigation

iv Historic Structures

Wood Entrances Windows Roofs Porches

Design Guidelines v

This page is intentionally left blank

These design guidelines are a set of guiding principles that establish a basis for the Historic District Commission’s (HDC) recommendations, approval, or denial of applications. The HDC uses these Guidelines and the Secretary of Interior’ s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties to determine if proposed work is appropriate for properties that fall under its review. Maryland Land Use Code S8.1018.501 and Article 20 of the Washington County Zoning Ordinance require the HDC to base its decisions on these documents. Conformance with the Secretary’s Standards is also a condition of the County’s Certified Local Government status, a program administered by the National Park Service (NPS) and Maryland Historical Trust (MHT), which is the state’s federally designated State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO).

These guidelines provide guidance for the protection and enhancement of significant historic structures, sites, and districts. Additionally, the guidelines define the appropriateness of requested exterior changes to existing historic structures and the approval of harmonious new construction within historic districts with attention to scale, massing, proportion, materials, and height.

Purpose of the Design Guidelines

Design Guidelines 1

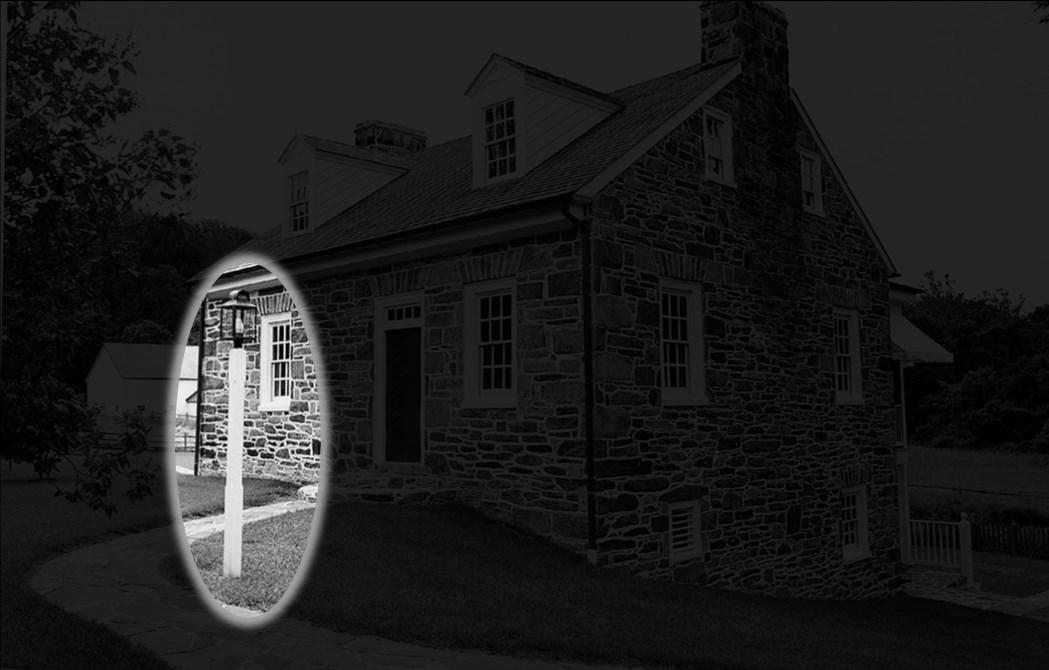

Mong-Linger Farm, Spring House, WA-IV-004

Historic District Commission

The Historic District Commission (HDC) was created in 1986 and its duties and powers are largely housed in the Zoning Ordinance for Washington County. The HDC is responsible for reviewing applications which are affected by select Rural Villages in the County (see Rural Villages Inventory), the Antietam Overlay 1 or Antietam Overlay 2 (AO) zoning districts, and the Historic Preservation (HP) zoning overlay. In addition, applications affecting properties on the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties (MIHP) are also reviewed. The HDC makes recommendations regarding legislation, applications for zoning text or map amendments, special exceptions, variances, site plans, subdivisions or other proposals affecting historic preservation or historic resources. Other duties of the HDC include:

• Recommend programs and legislation to the Board of County Commissioners and Planning Commission to encourage historic preservation

• Serve as a clearing house for information, provide educational materials and information to the public and undertake activities that advance the goals of historic preservation

• Development of additional duties and standards. For example, criteria to be used in the review of building permit applications

• Prepare, adopt, publish and amend additional guidelines to provide adequate review materials for applications including HP and building permits

• Oversee maintenance and updating of the inventory of Washington County Historic Sites

2 Historic Structures

Bank Barn, Rufus Wilson Complex, WA-V-074

Certified Local Government

The State of Maryland has a total of 24 counties, of which, eleven are Certified Local Governments (CLG) having a special commitment to historic preservation. Washington County is one of the few western counties designated as a CLG. The County obtained the designation in August of 1991. While the Certified Local Government program is a Federal-State-local partnership administered through Maryland Historical Trust (MHT), it is mentioned here because the Historic District Commission (HDC) acts as the required qualified historic preservation commission for the program.

Benefits of becoming a CLG include: eligibility to compete for funds to conduct projects that promote preservation, CLG sub-grant funds, ability to participate in the CLG Educations Set Aside Program, formal participation in the National Register nomination process, annual performance evaluations, and priority technical assistance. Being designated as a CLG means that the County is recognized by the National Park Service as being able to participate in the national policy of preservation.

National Register of Historic Places and Section 106 Review

The National Register is a tool that is used to document historic resources that are significant to the Nation and worthy of preservation. The National Register does not have regulatory power but it does provide a process for additional review for resource impact when Federal or State funding or permitting is involved in a project. It also provides access to Federal tax credits to incentivize rehabilitation projects. Because the HDC is a CLG, they are part of the review and coordination process for National Register nominations in the County.

Section 106, part of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, review occurs when any Federal or State funding or permitting is involved in a project that affects a National Register resource or a resource eligible for the National Register. In many cases properties identified on the MIHP may trigger at least an initial review for Section 106. Any project which has the potential to trigger this review should contact the Maryland Historical Trust (MHT) prior to application at the County to ensure the Section 106 process has been initiated. This opens up a consultation with Federal, State and local government (HDC), as well as the public, about views and concerns for the project. The review usually results in agreements and plans to mitigate the impacts on historic resources.

Design Guidelines 3

HDC Reviews

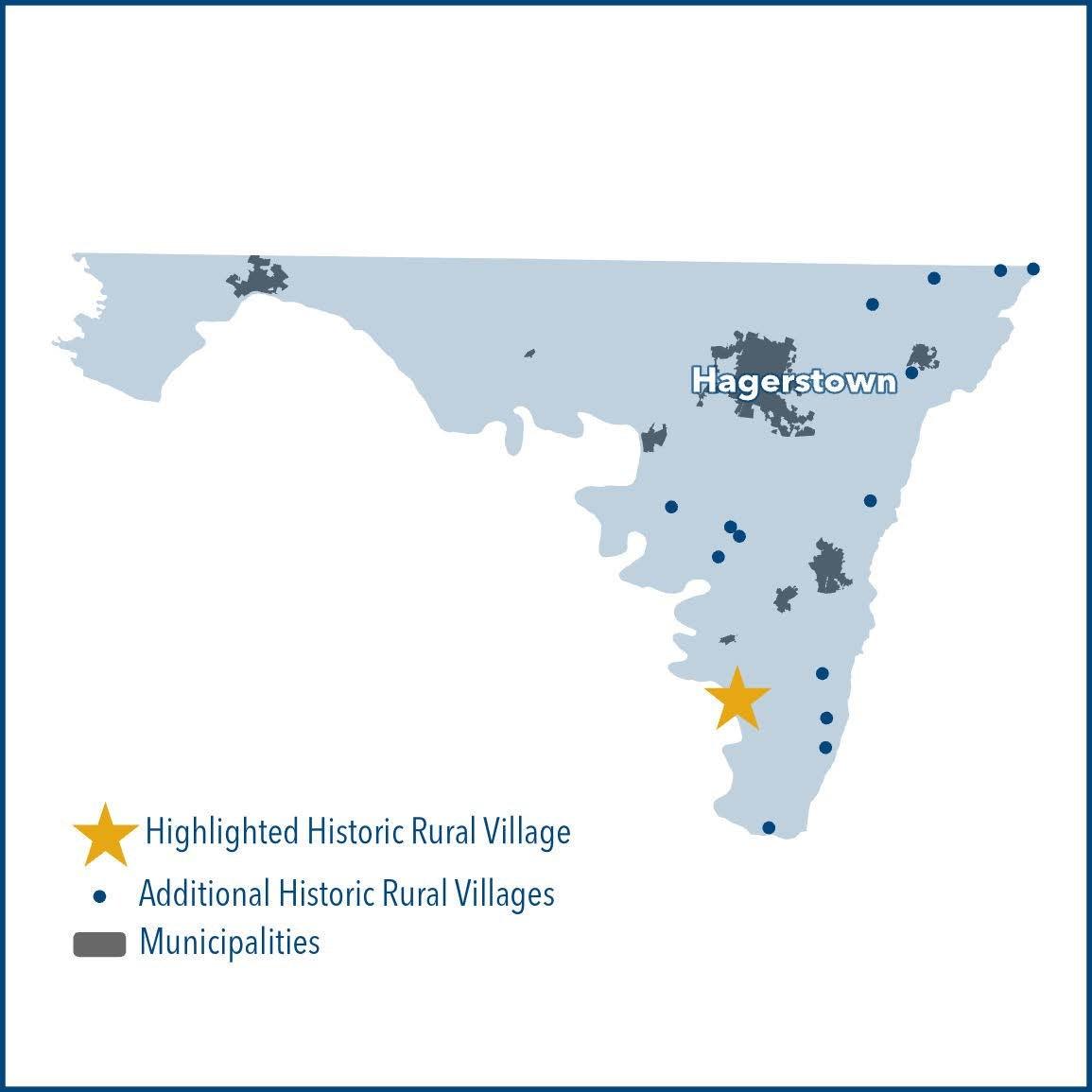

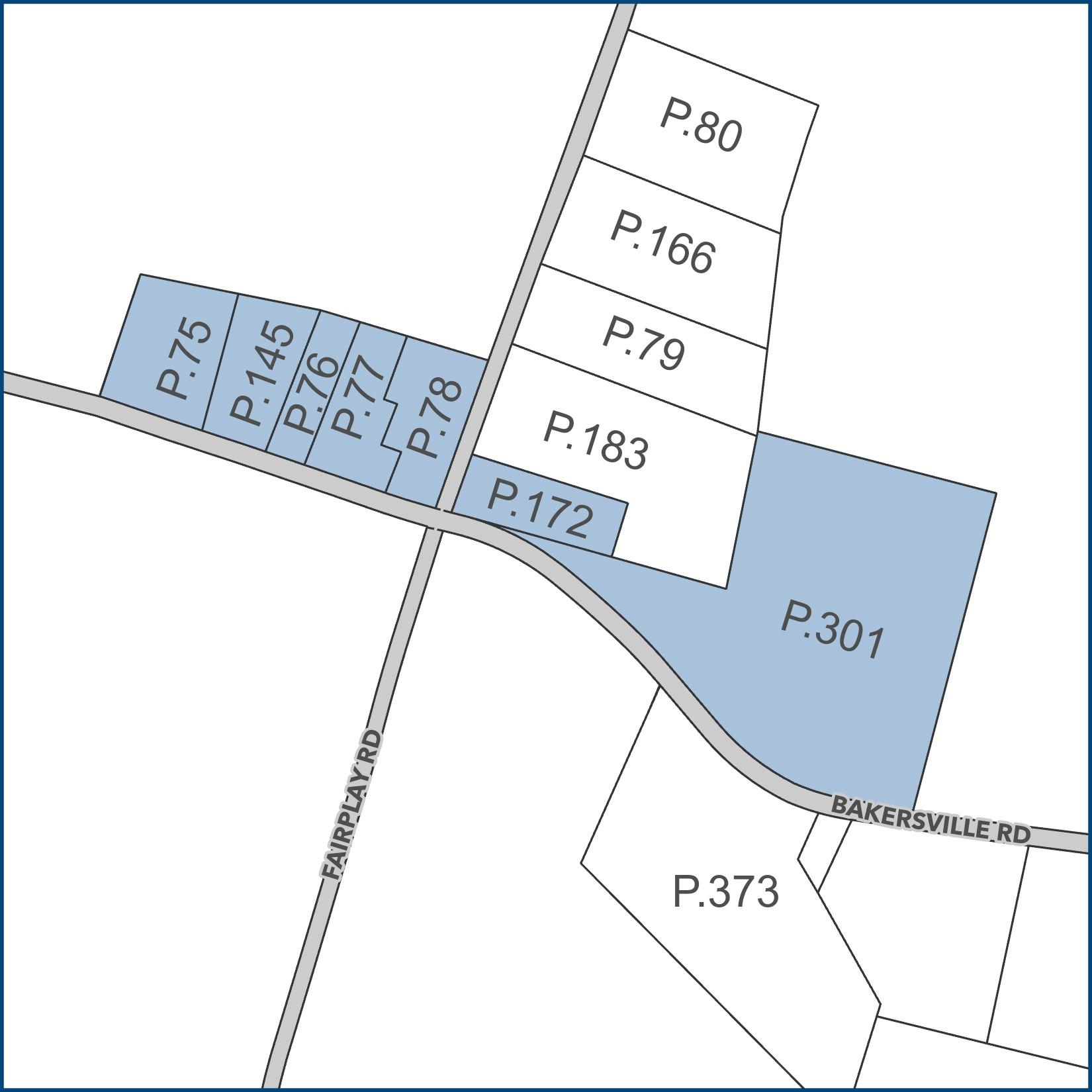

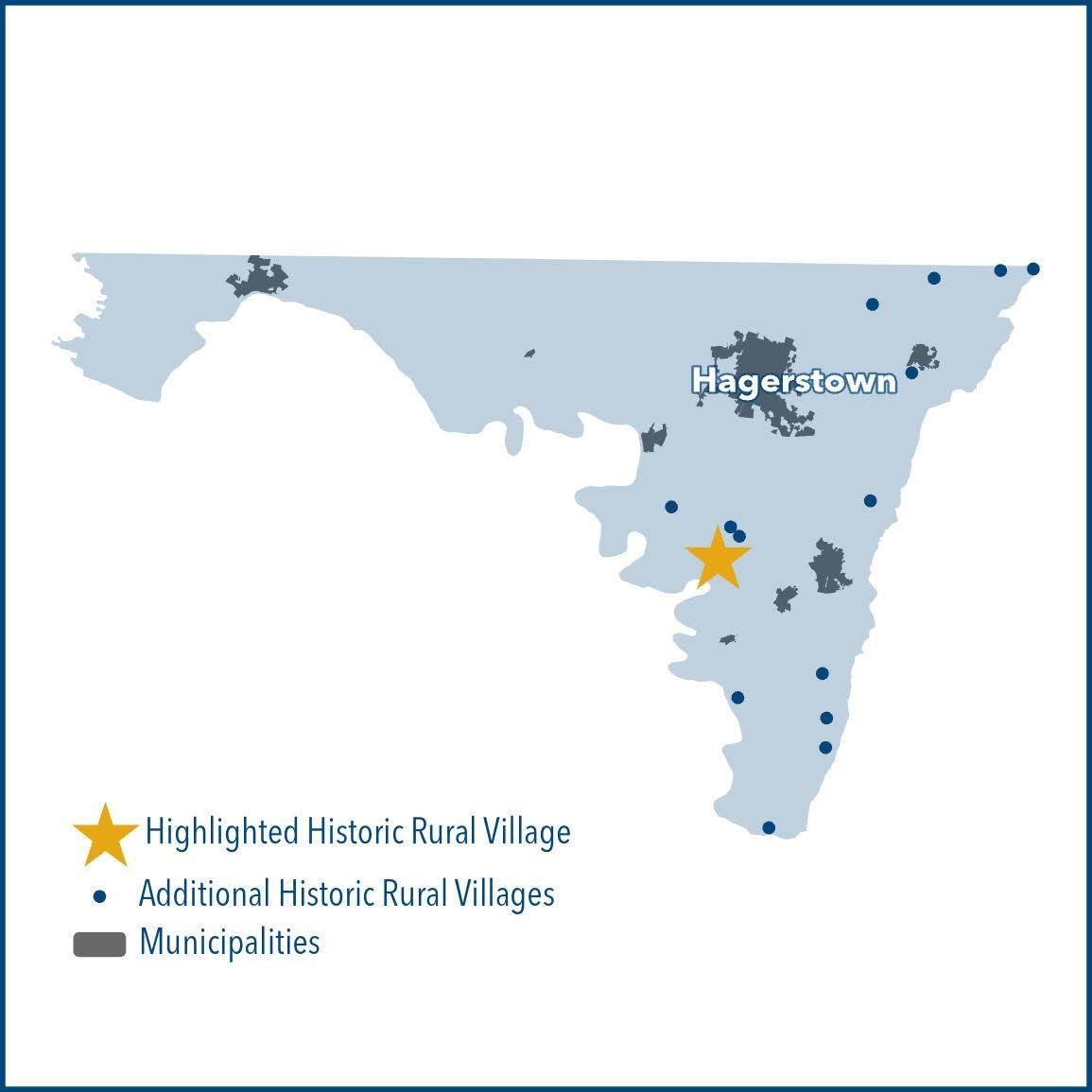

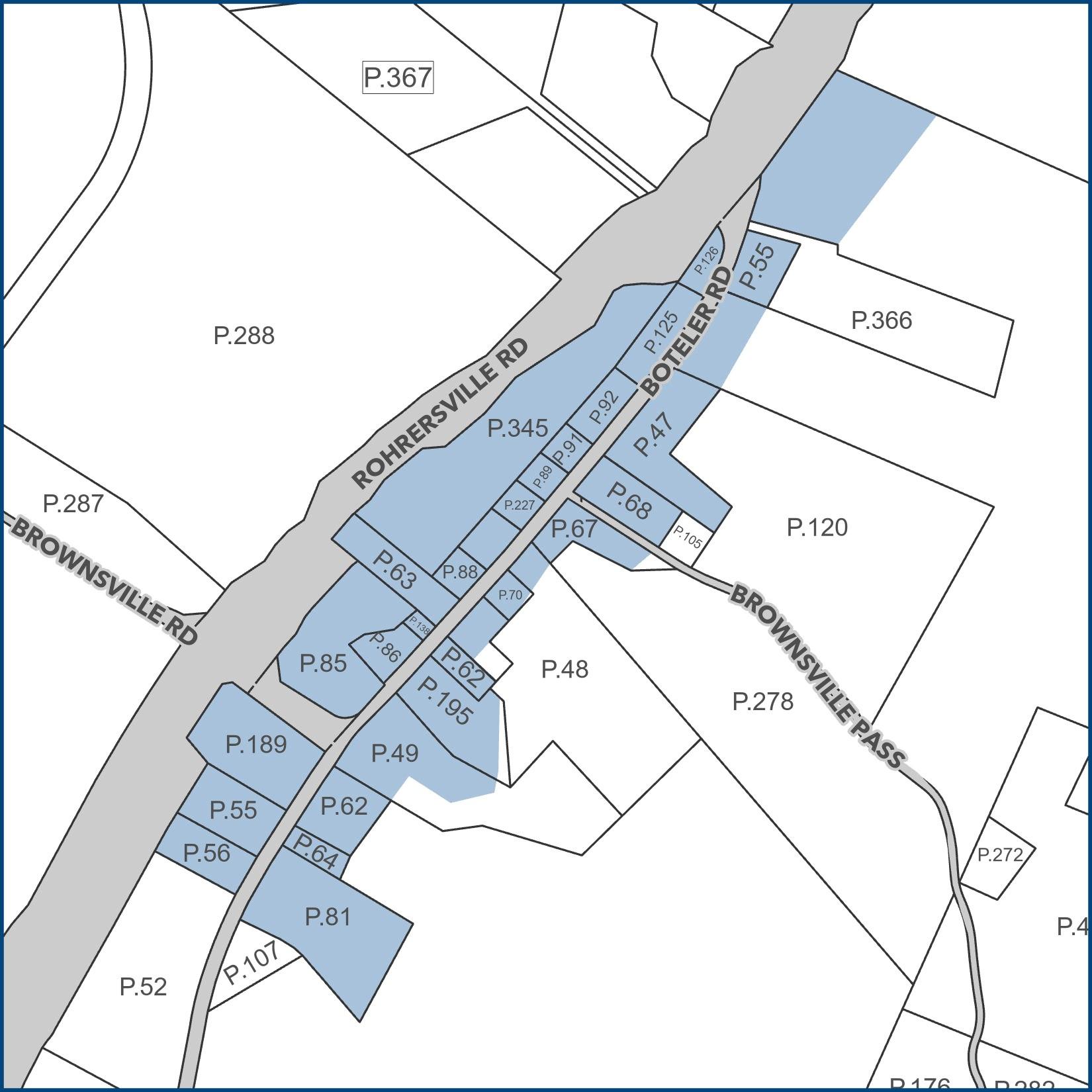

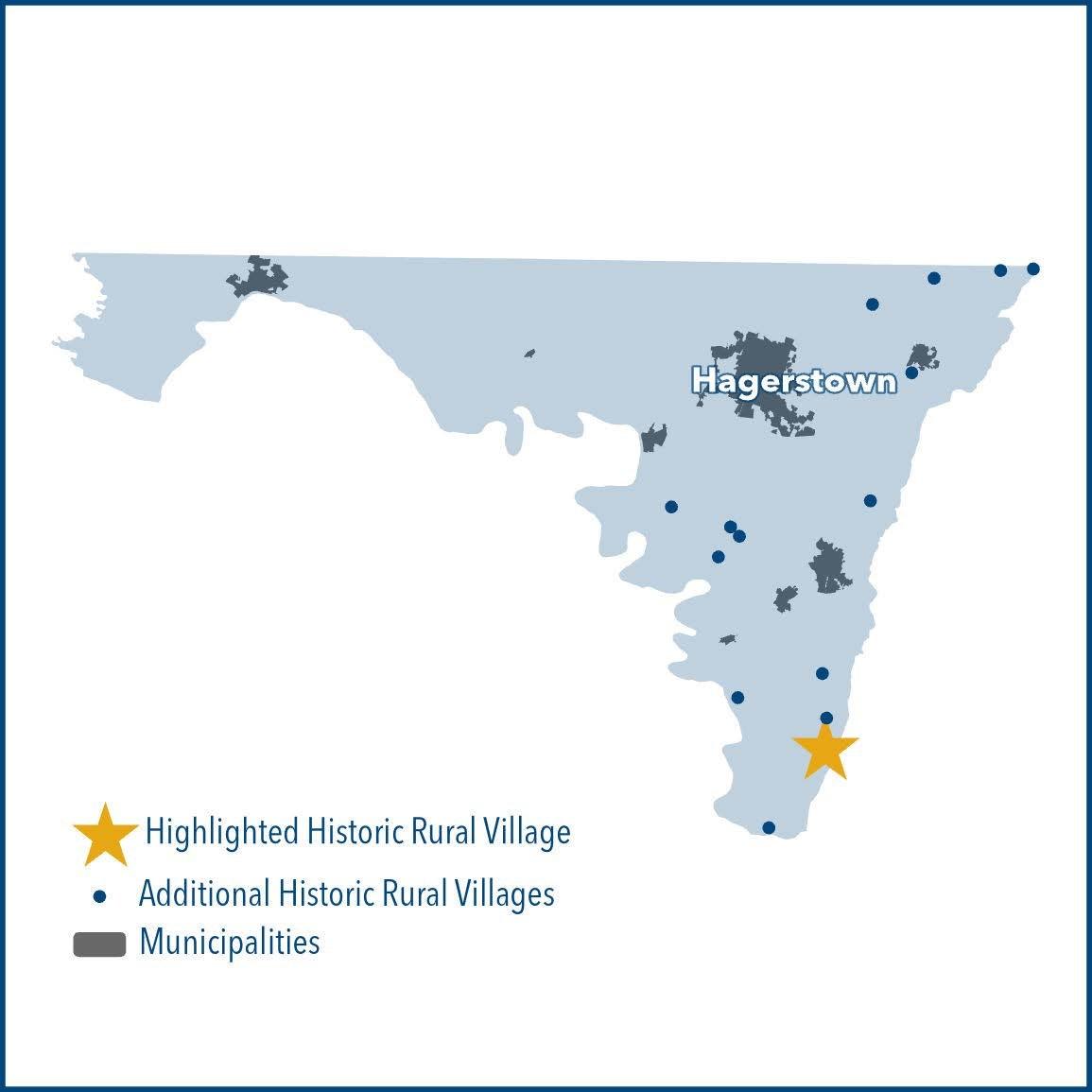

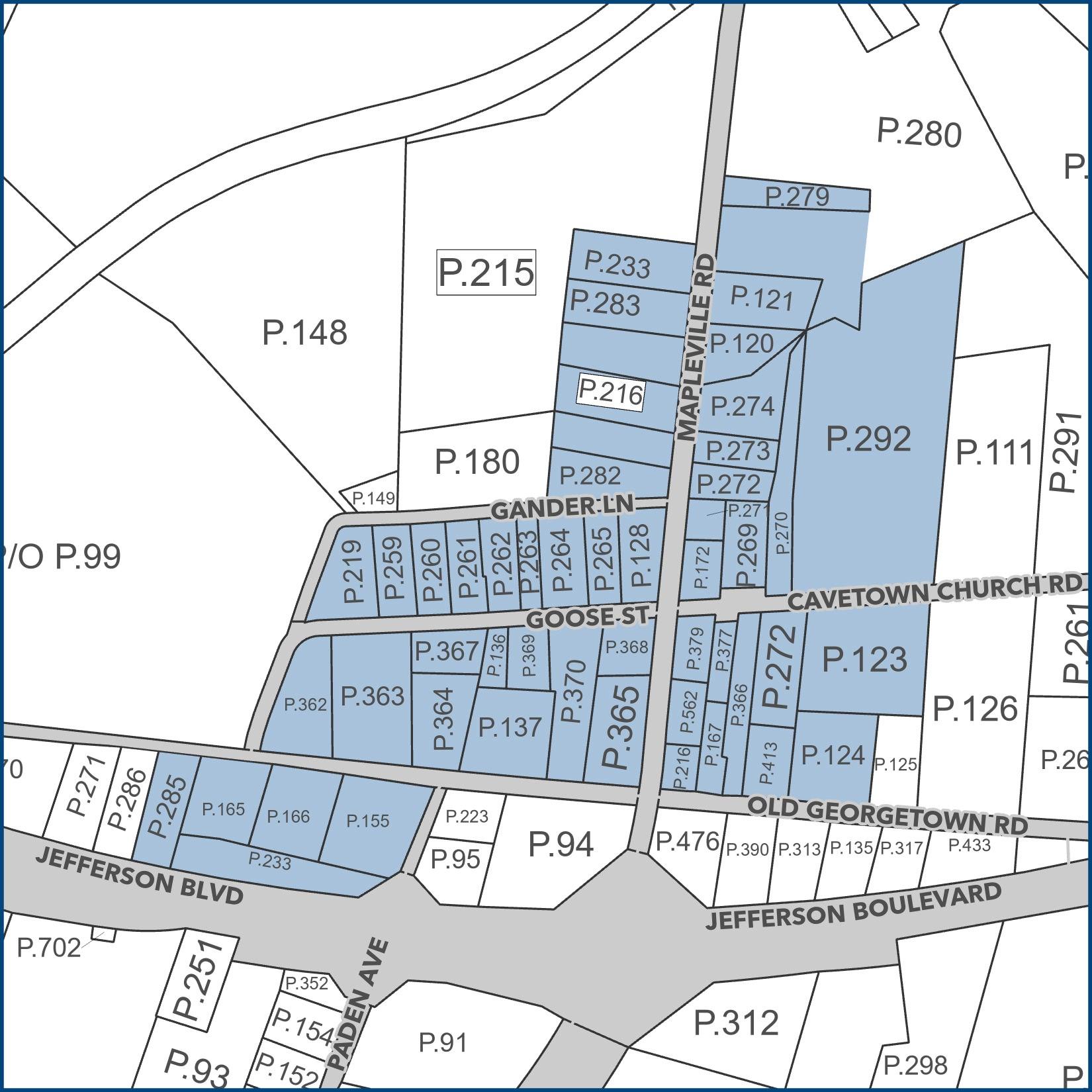

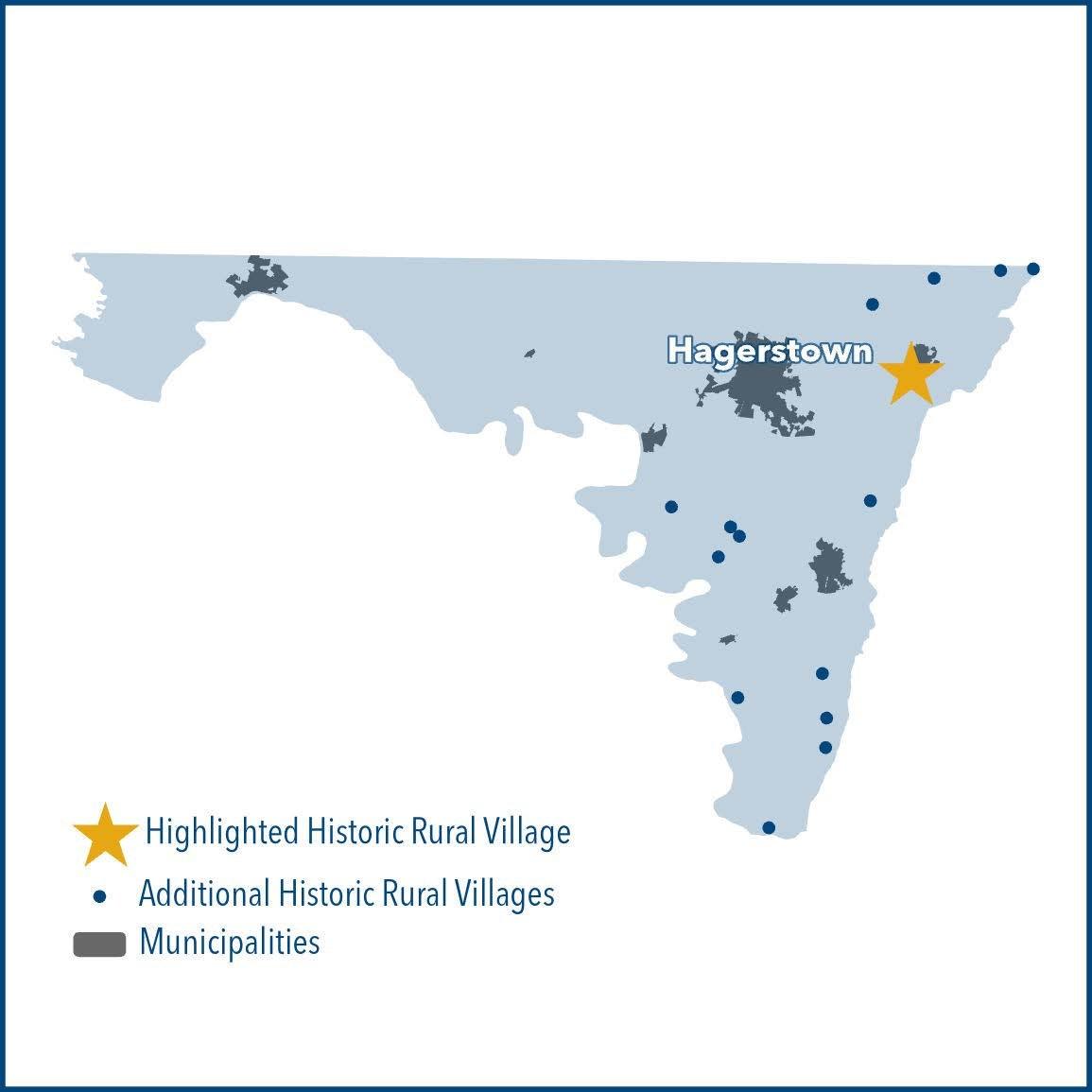

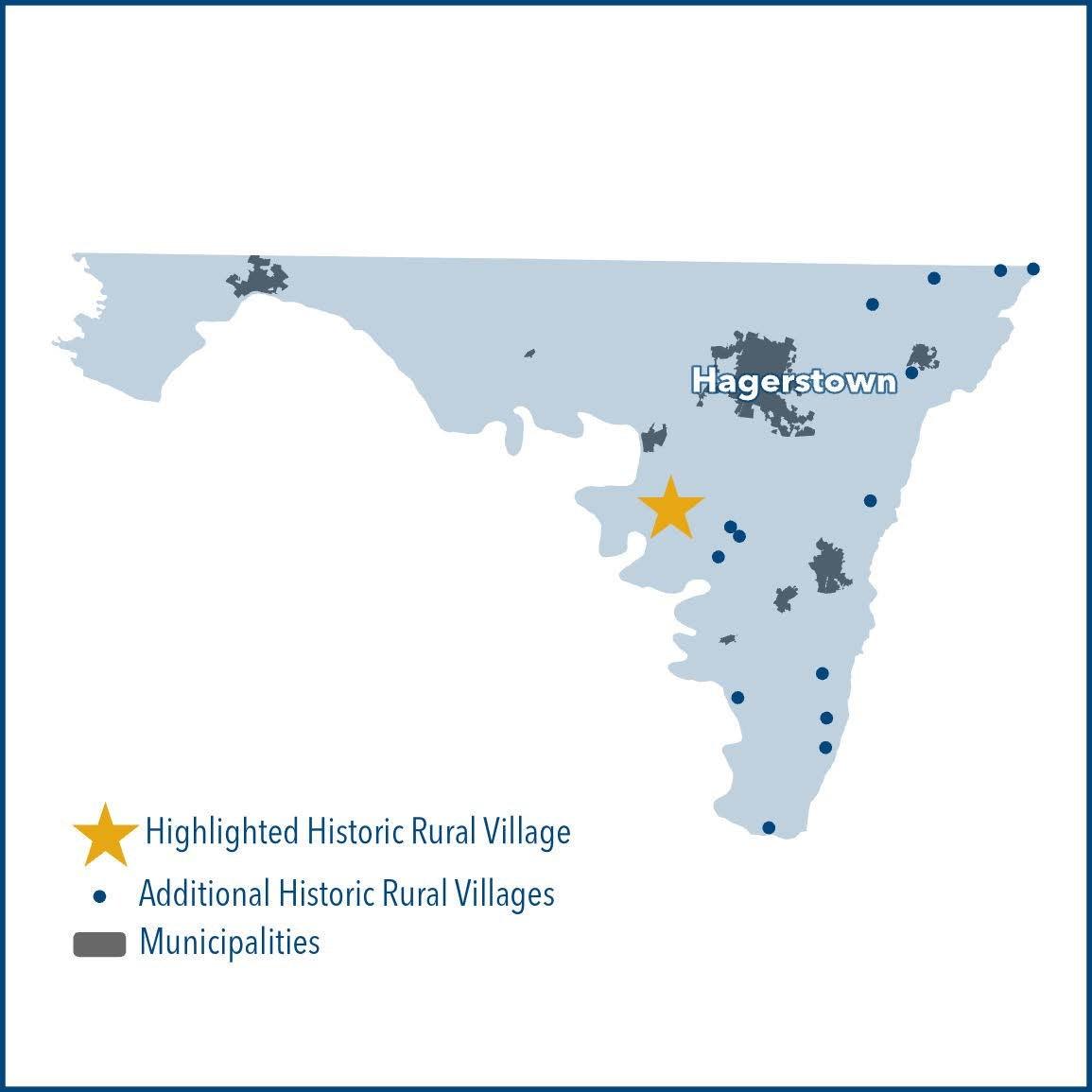

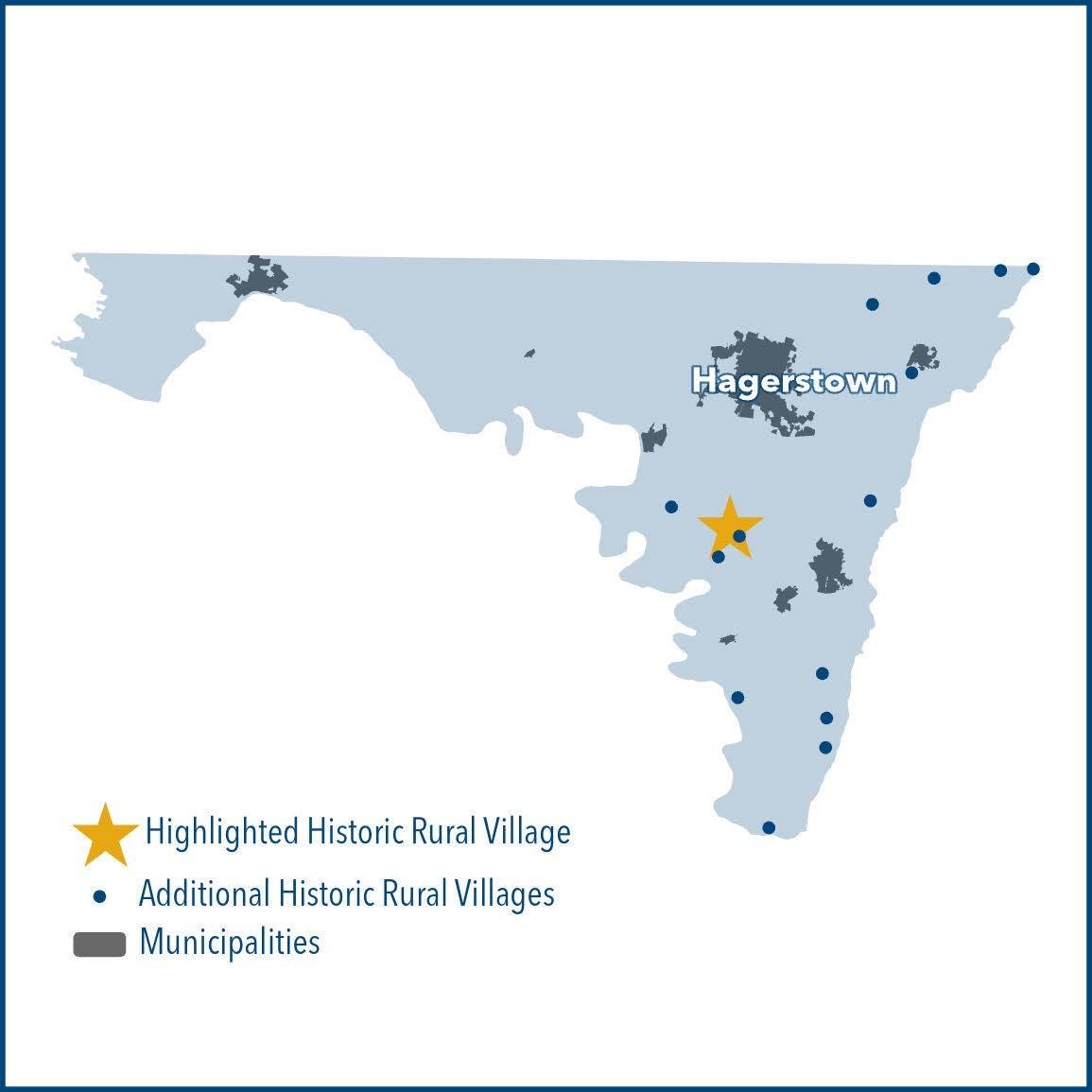

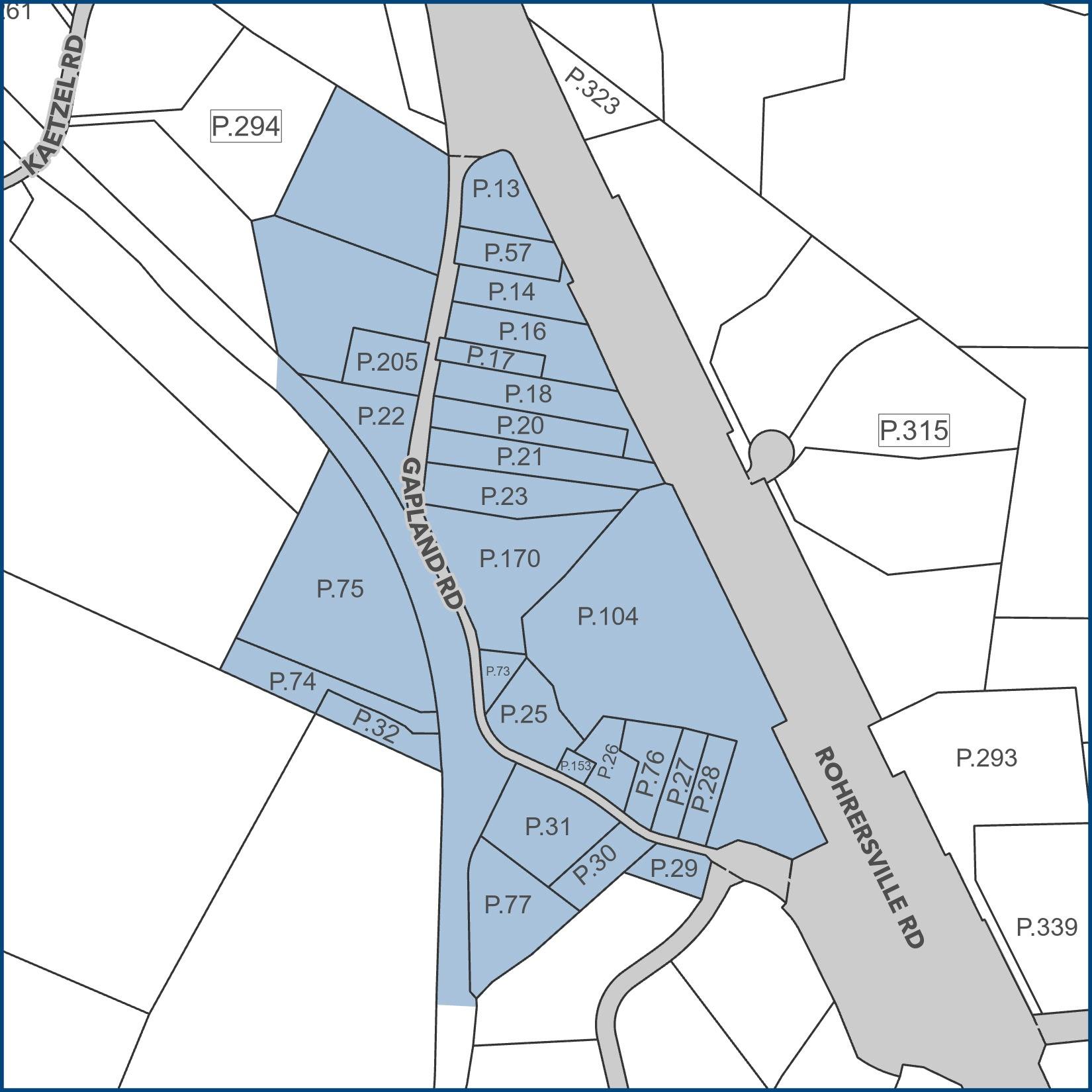

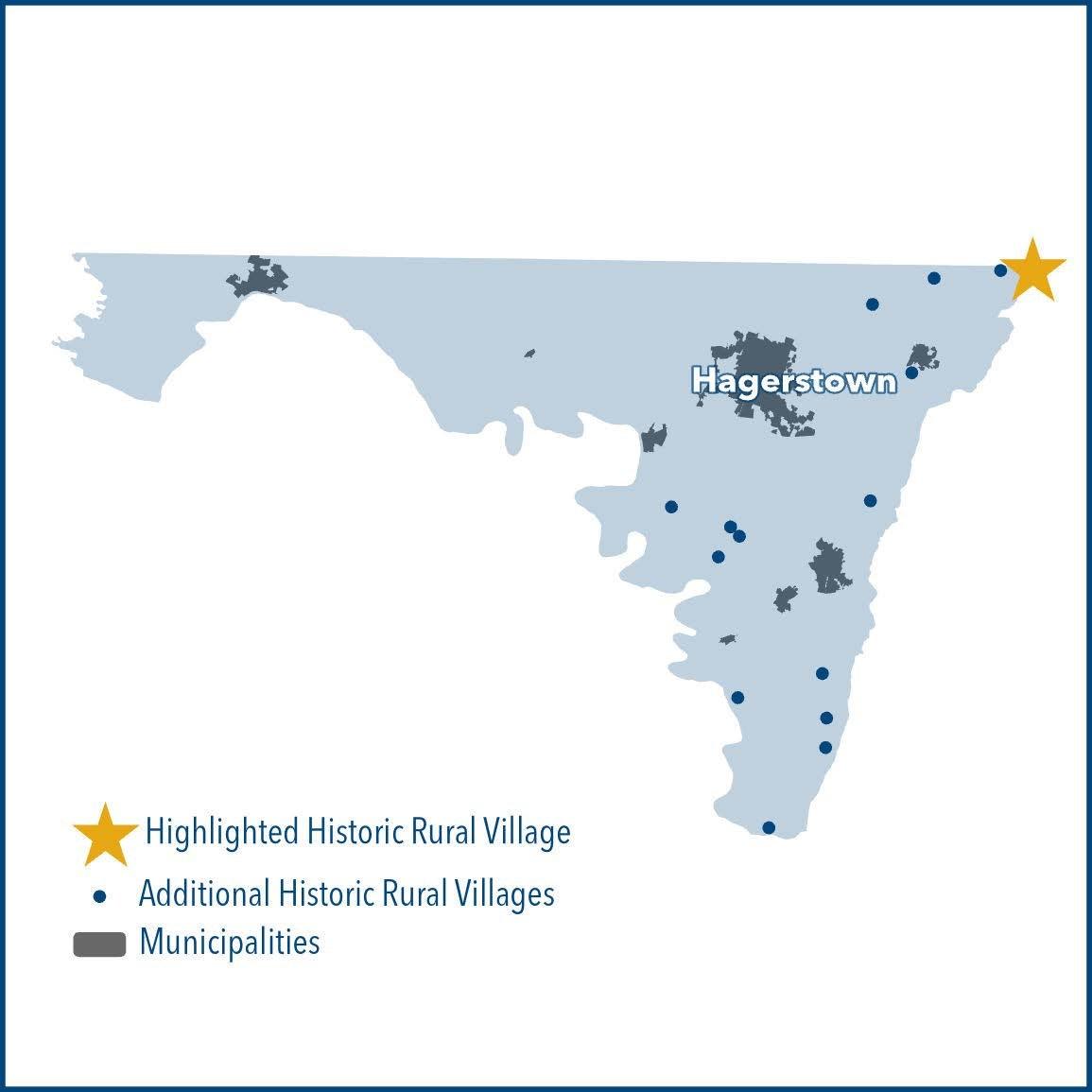

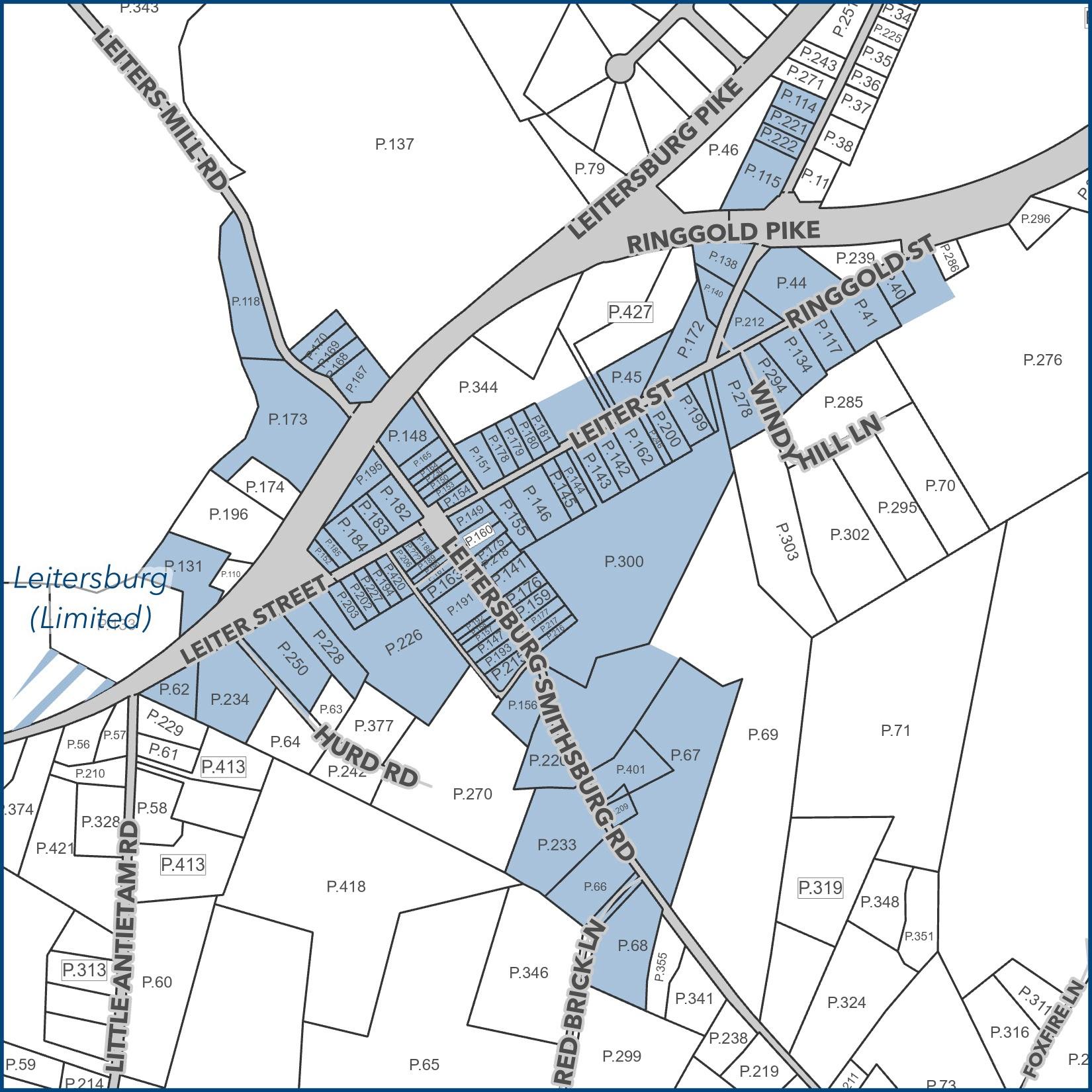

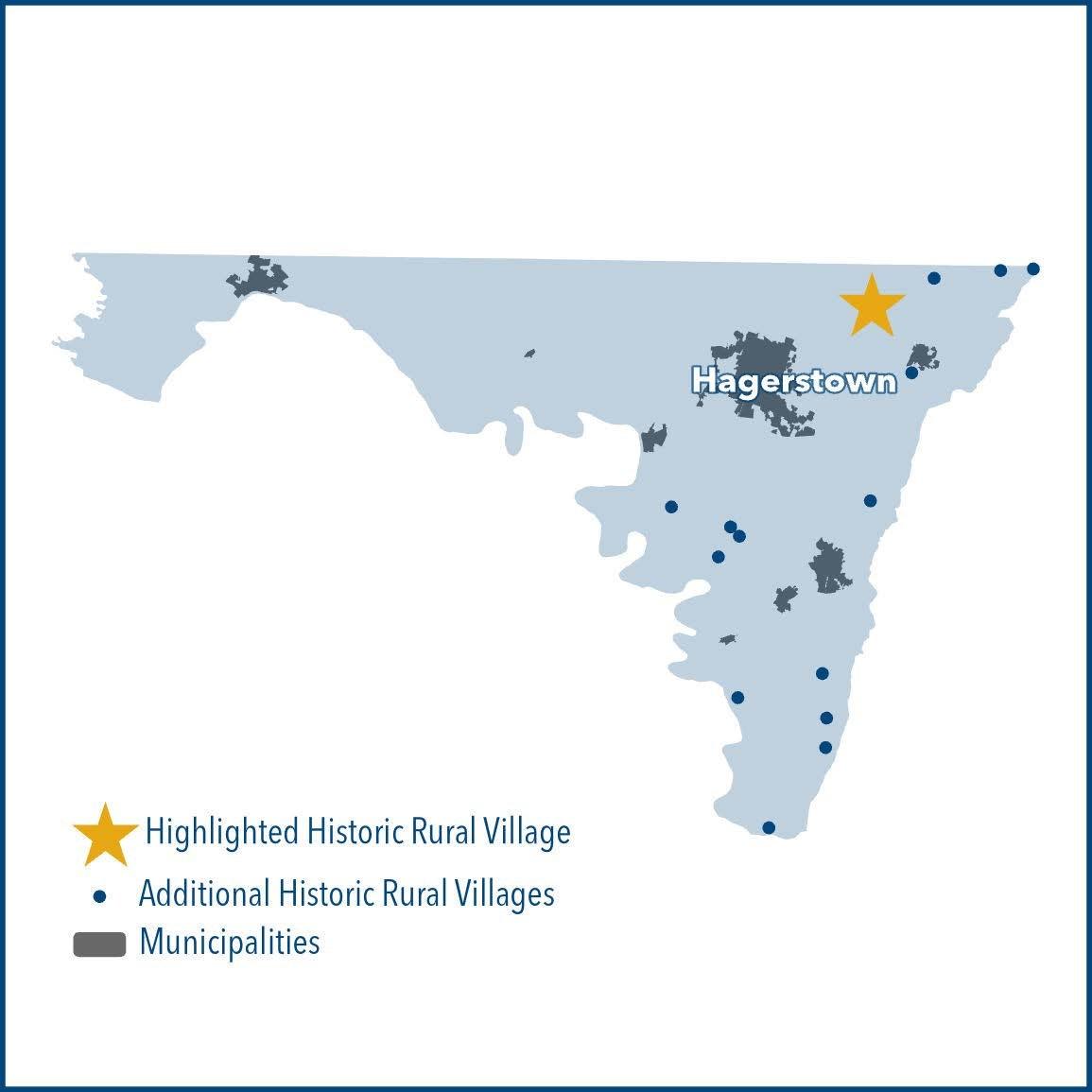

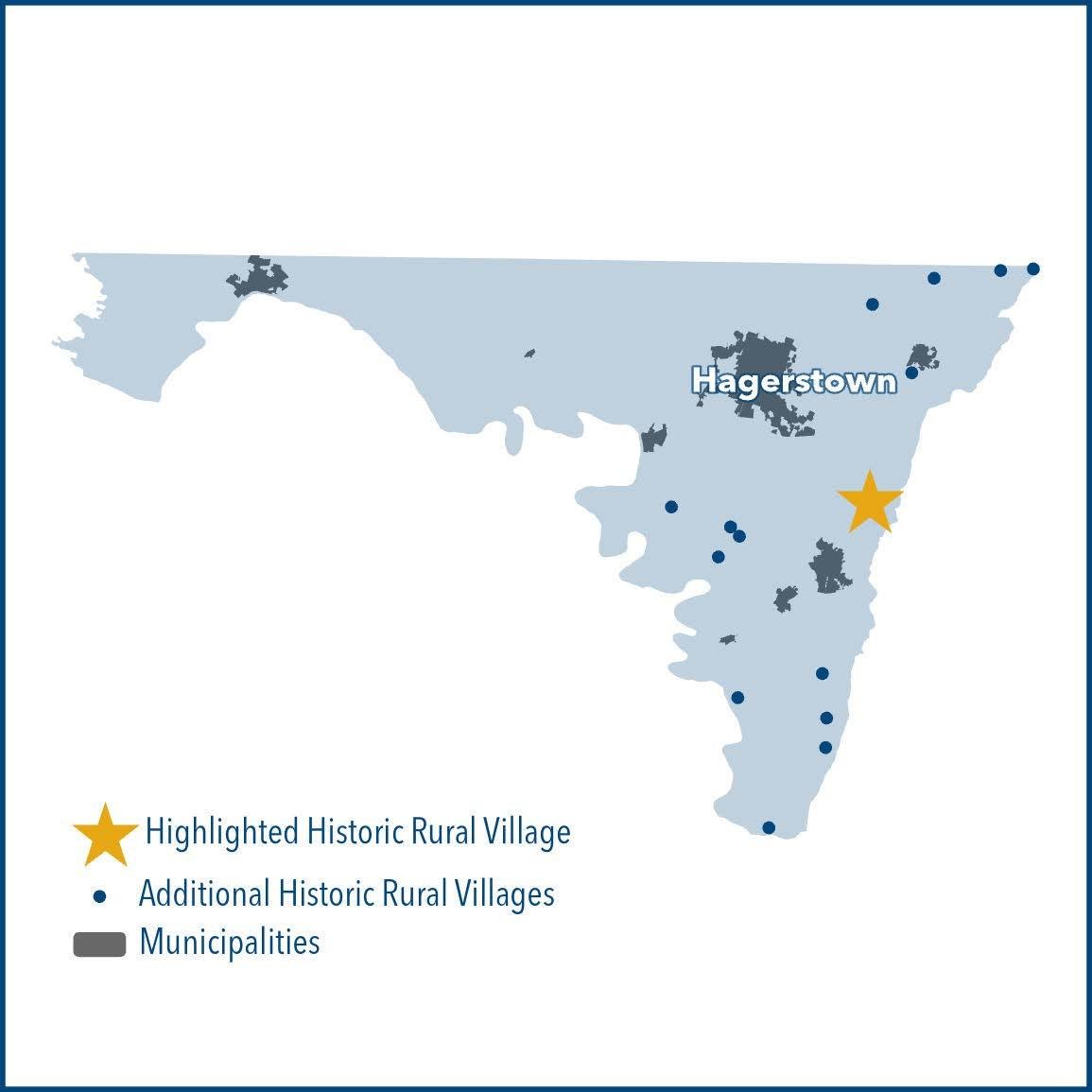

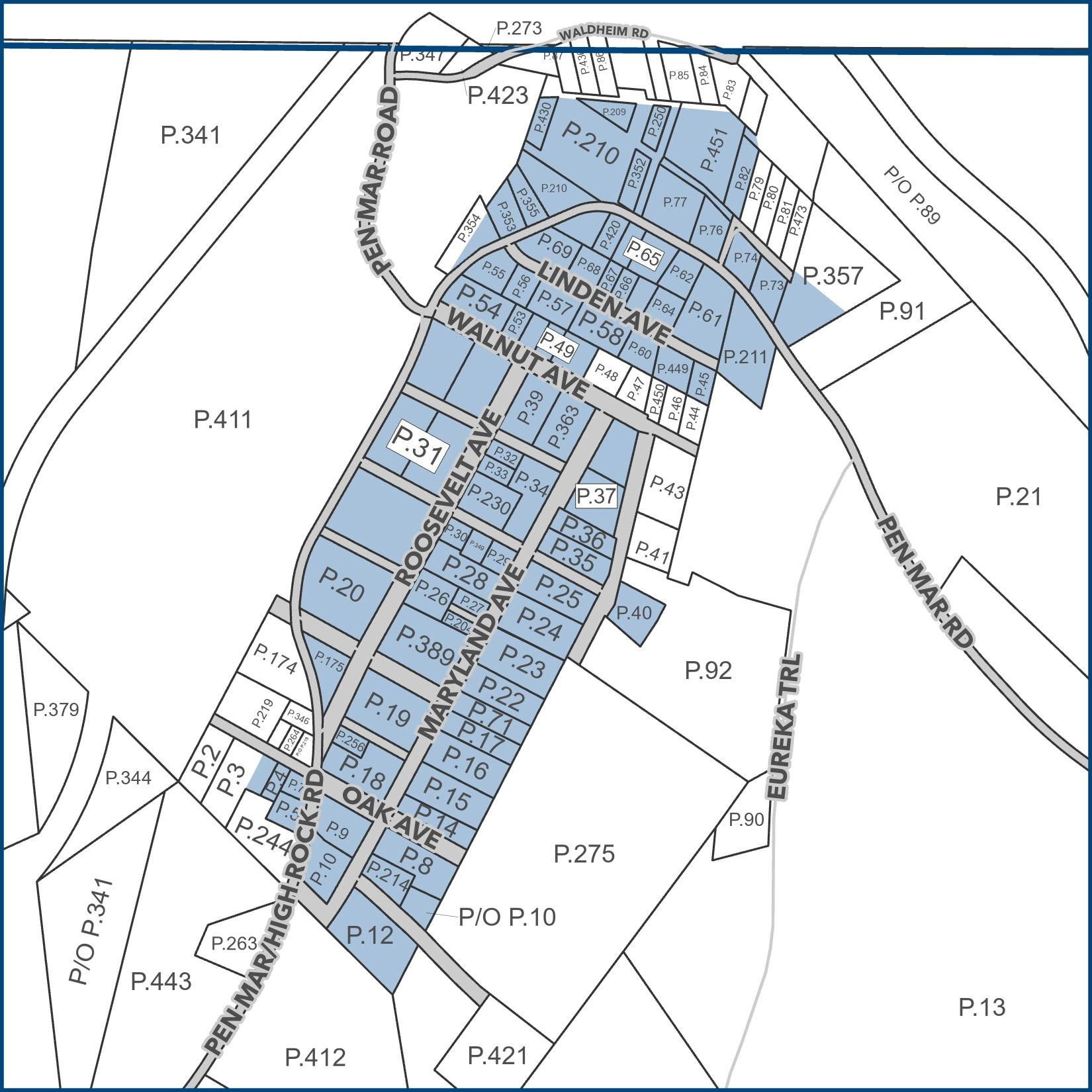

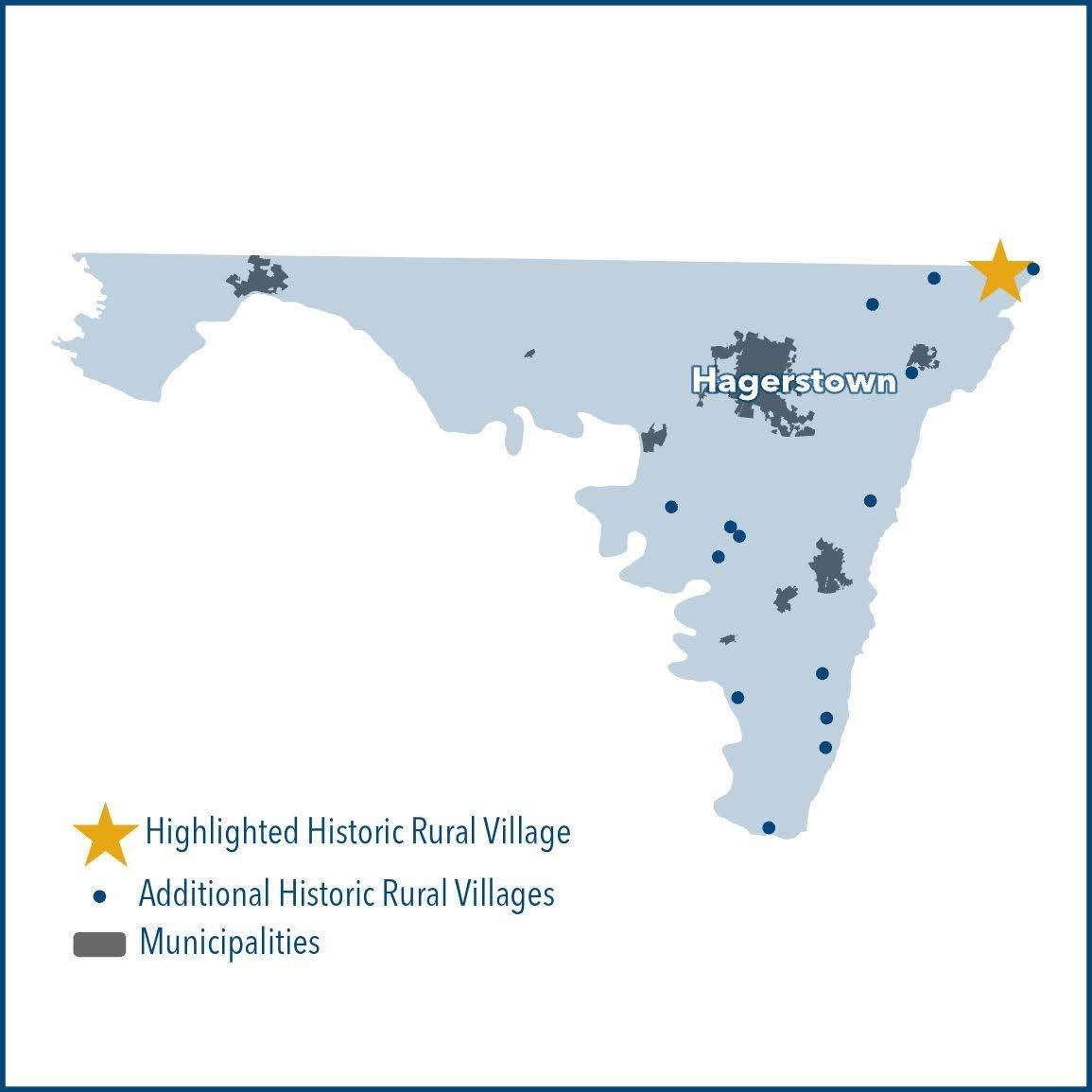

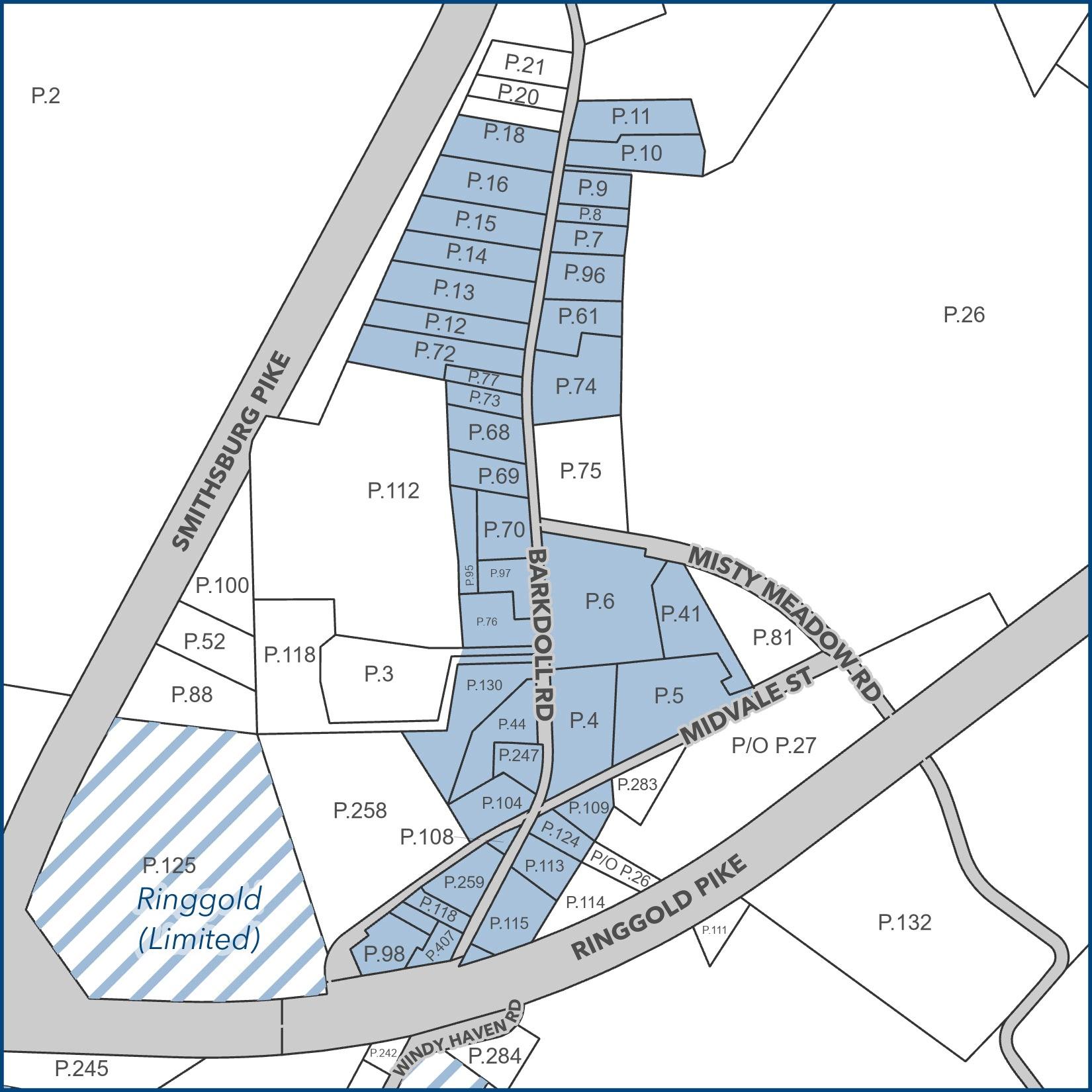

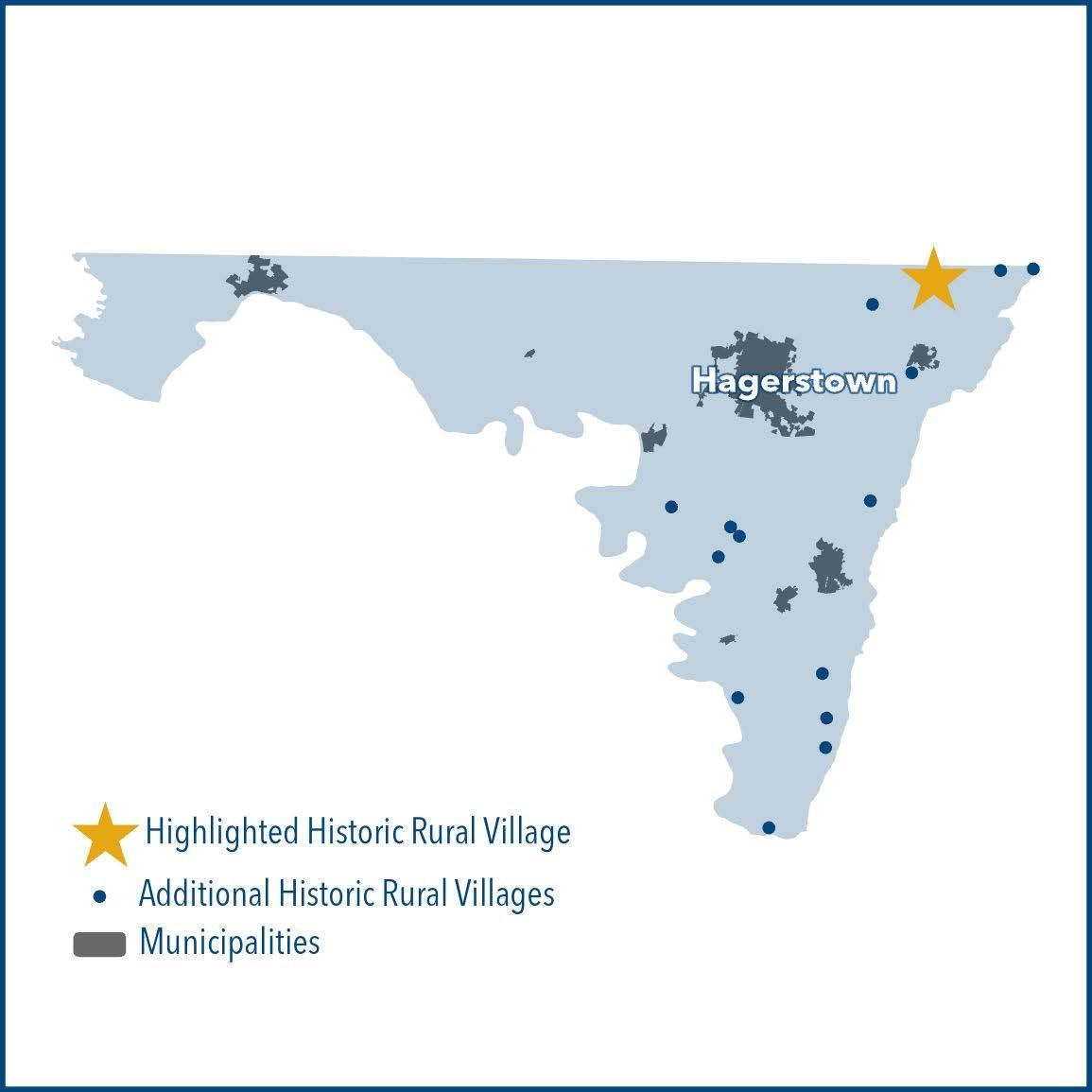

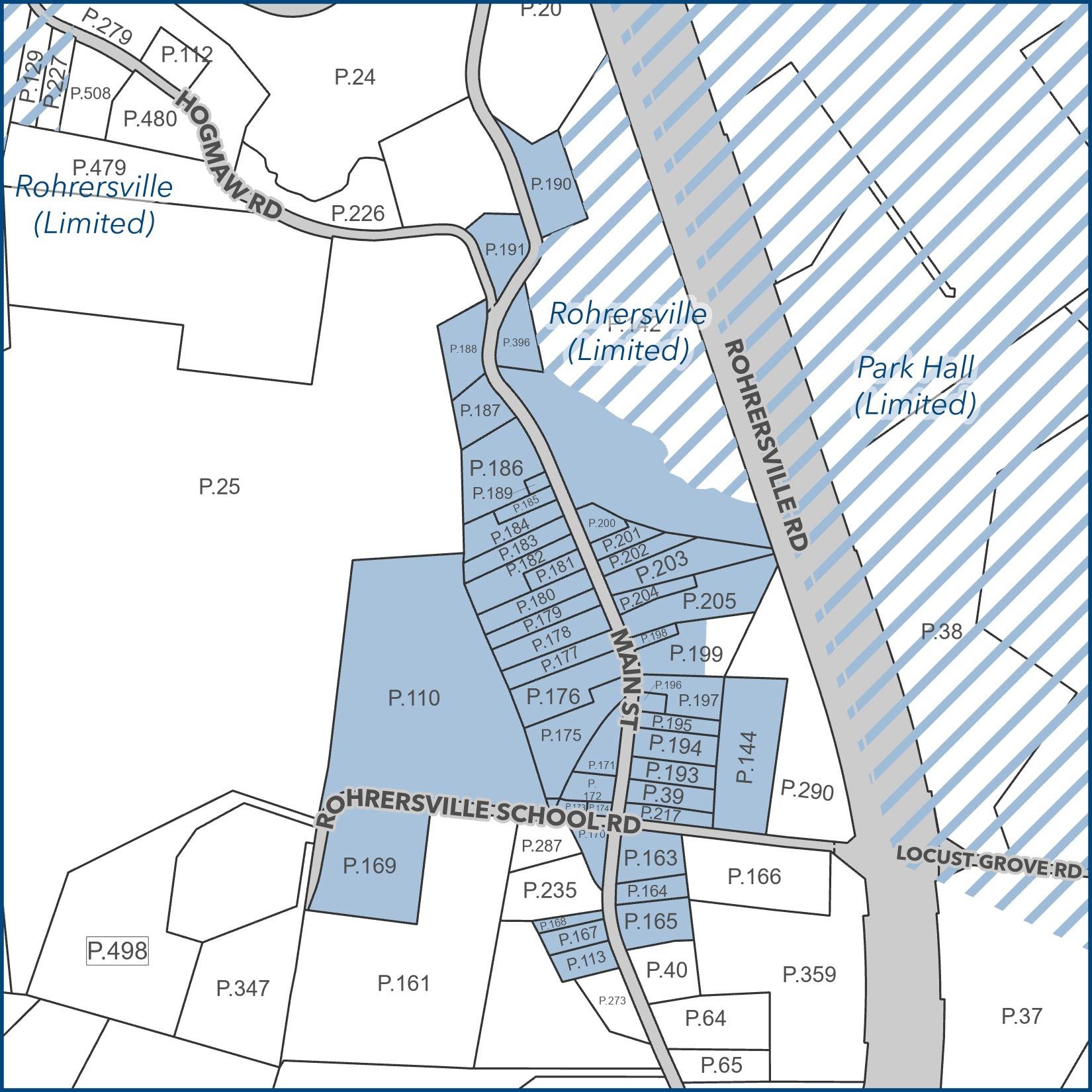

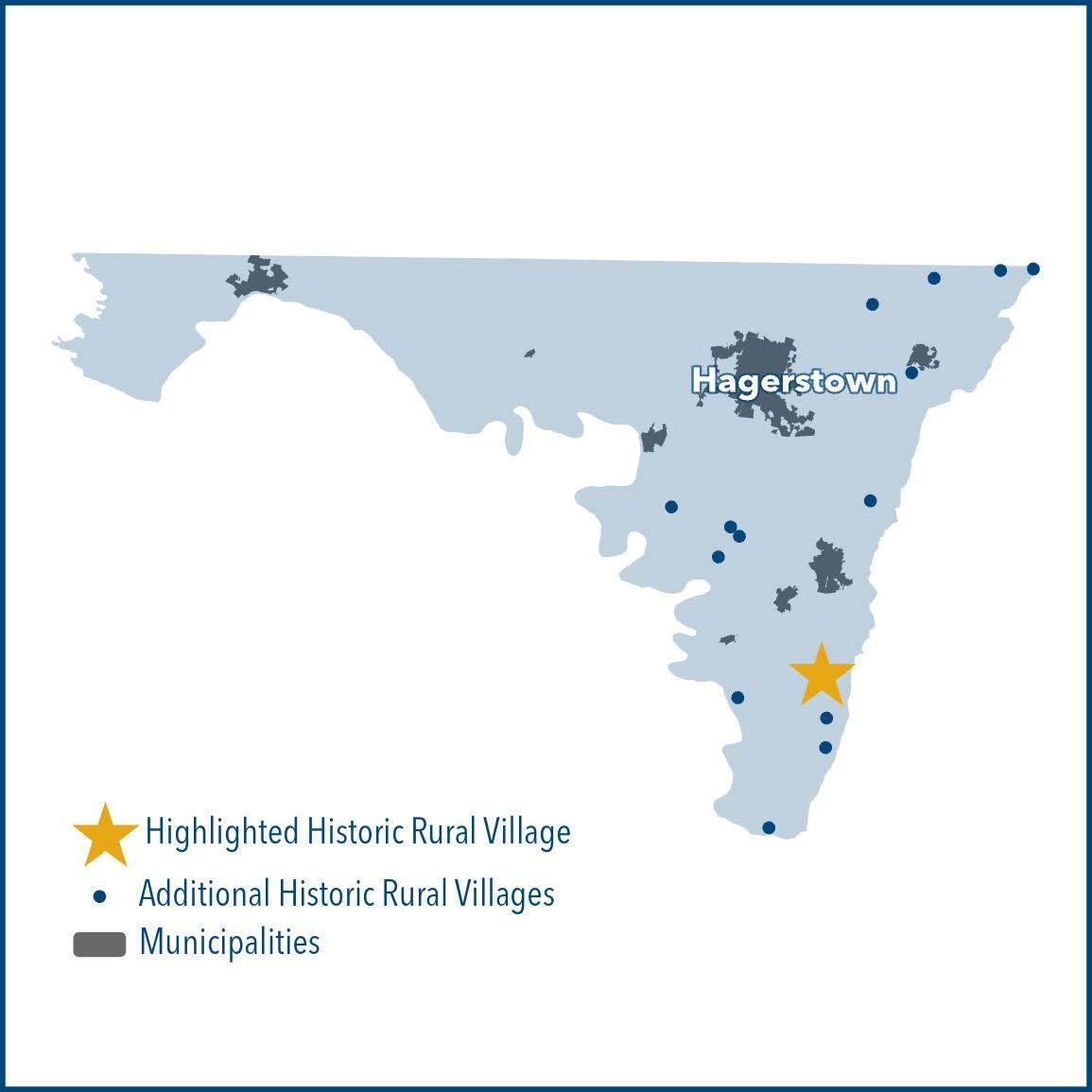

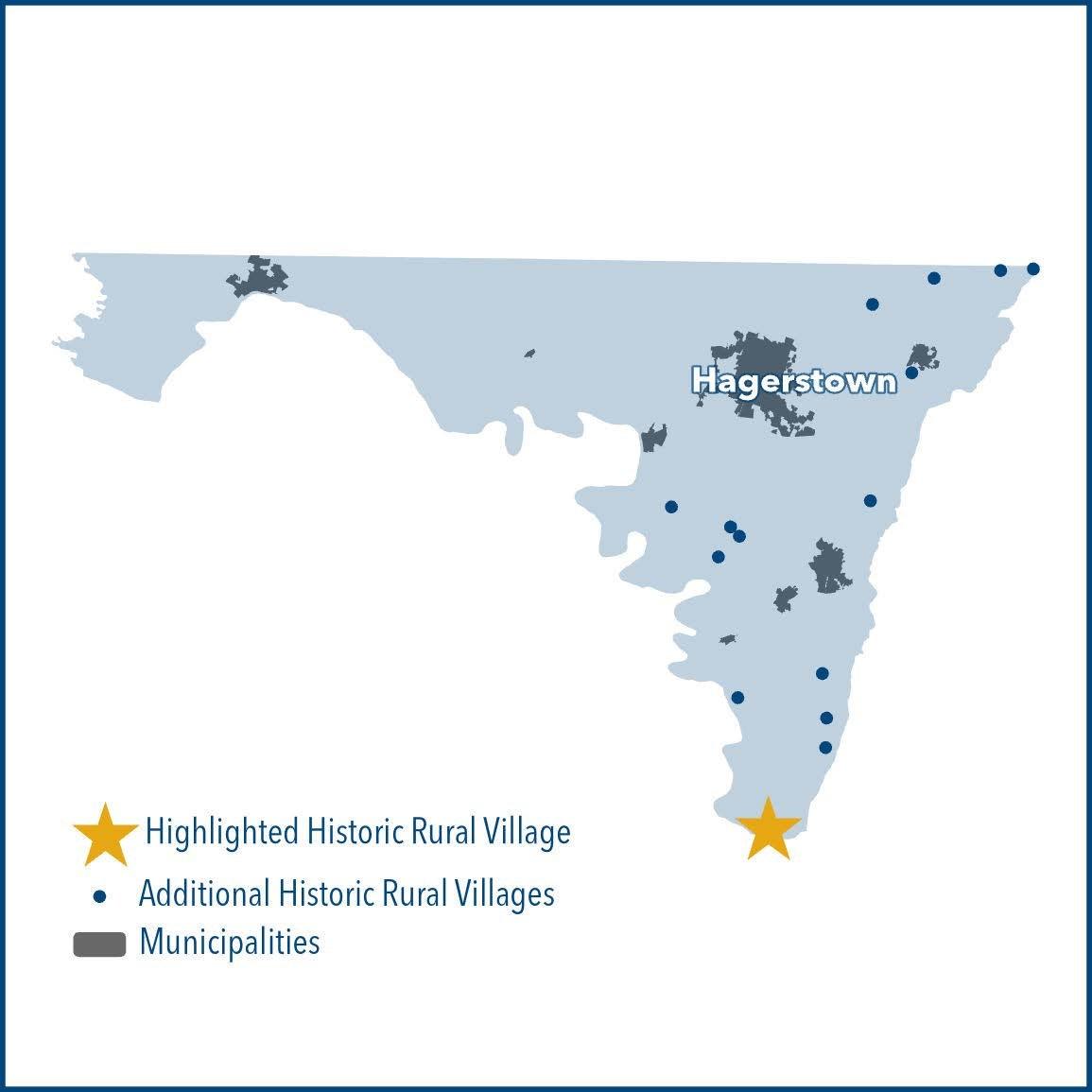

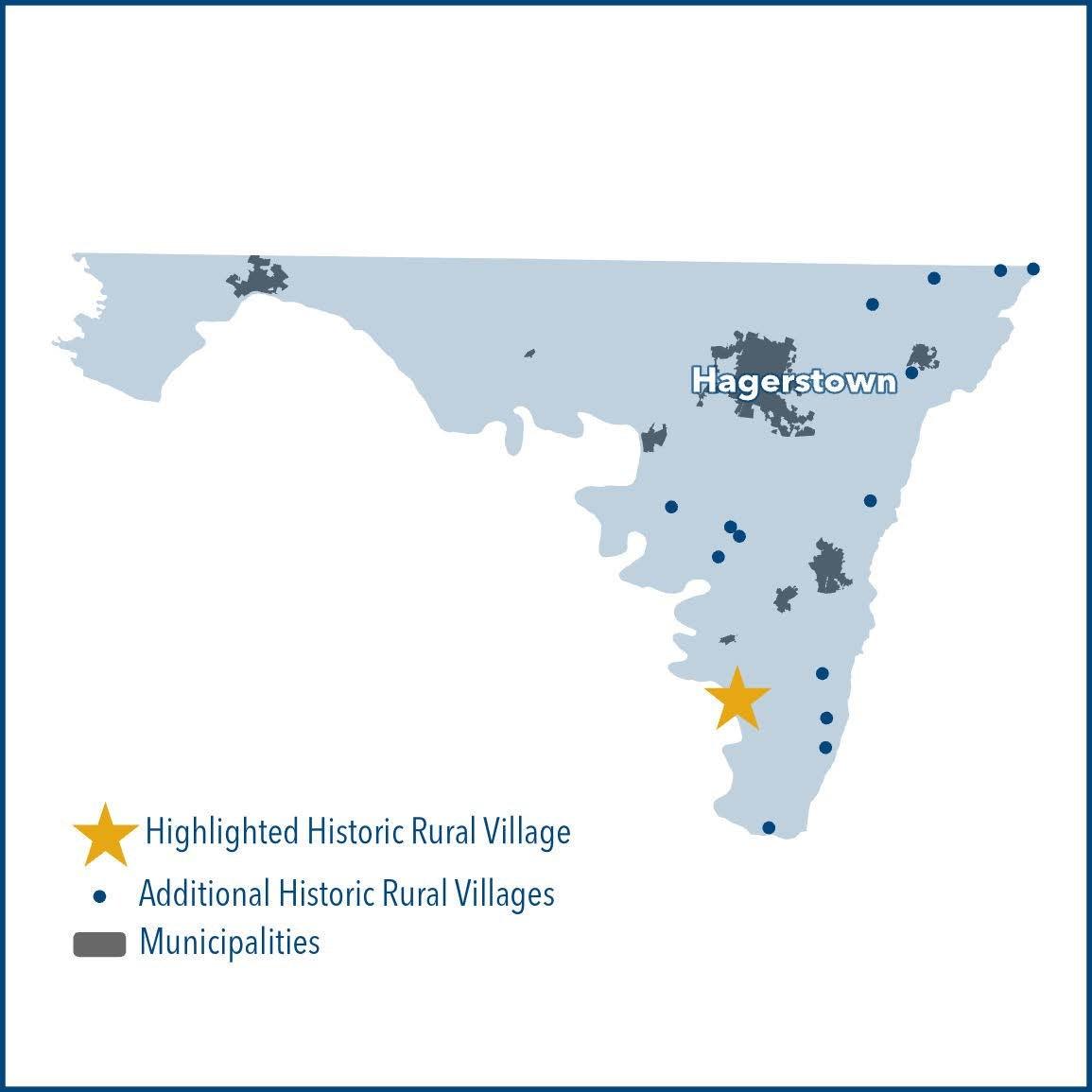

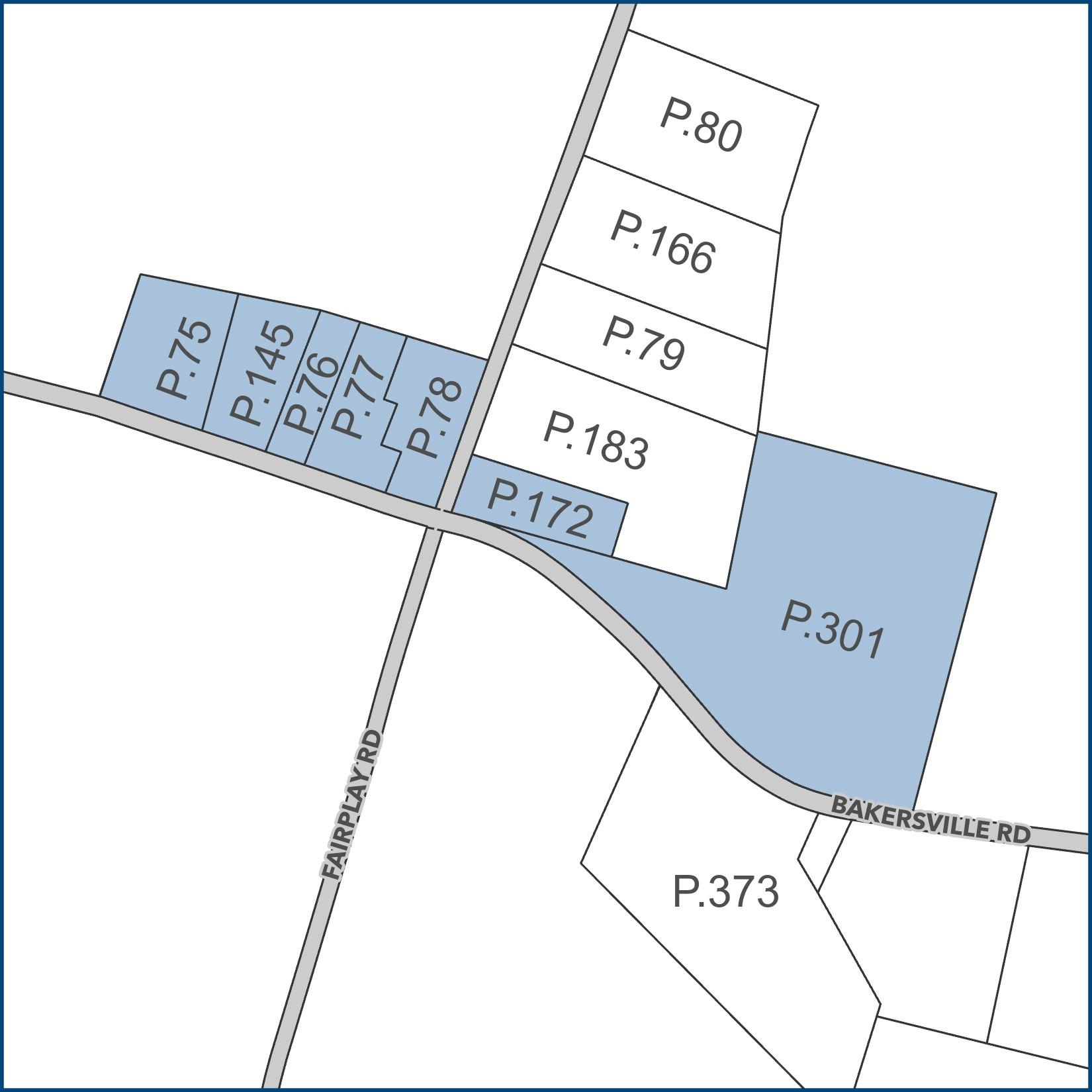

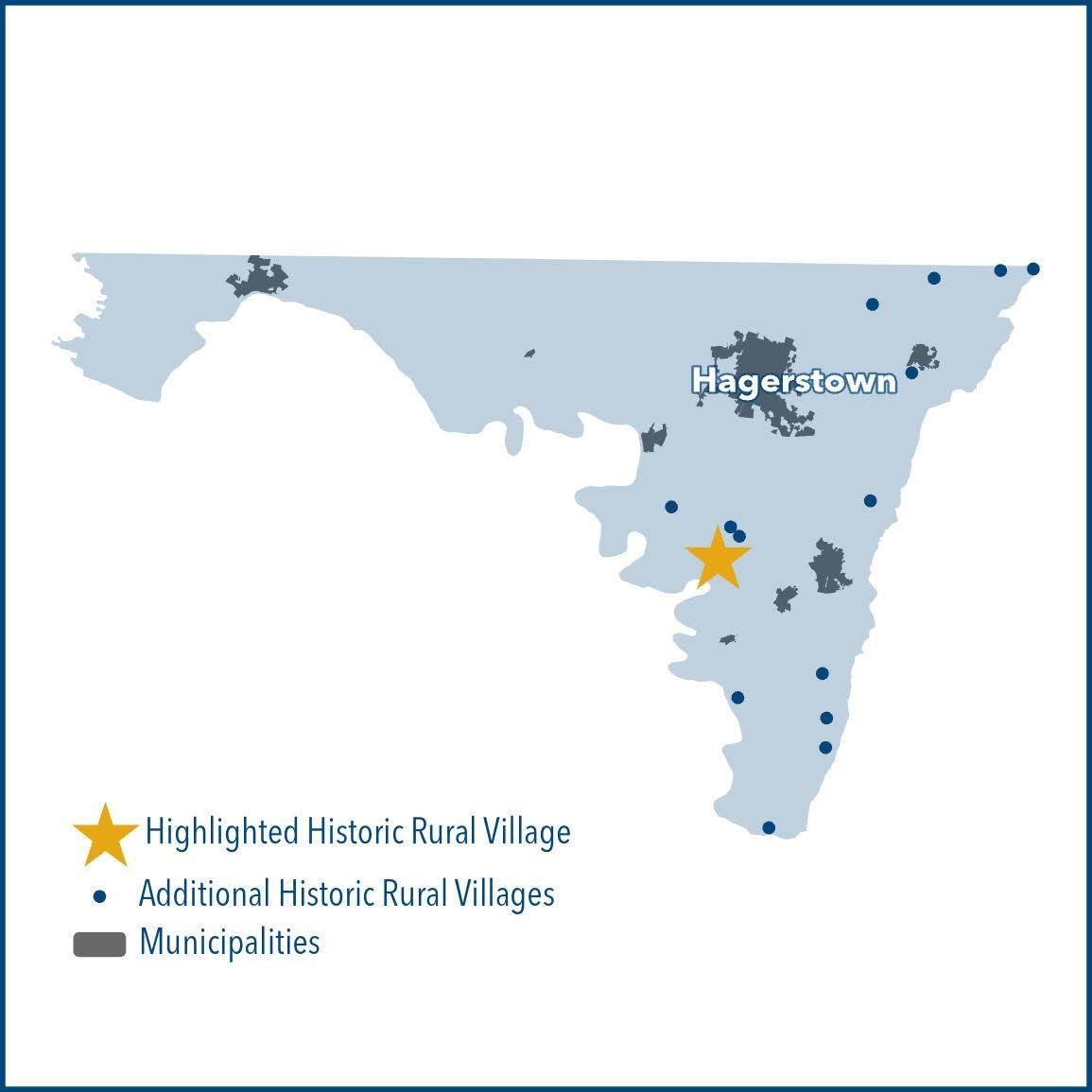

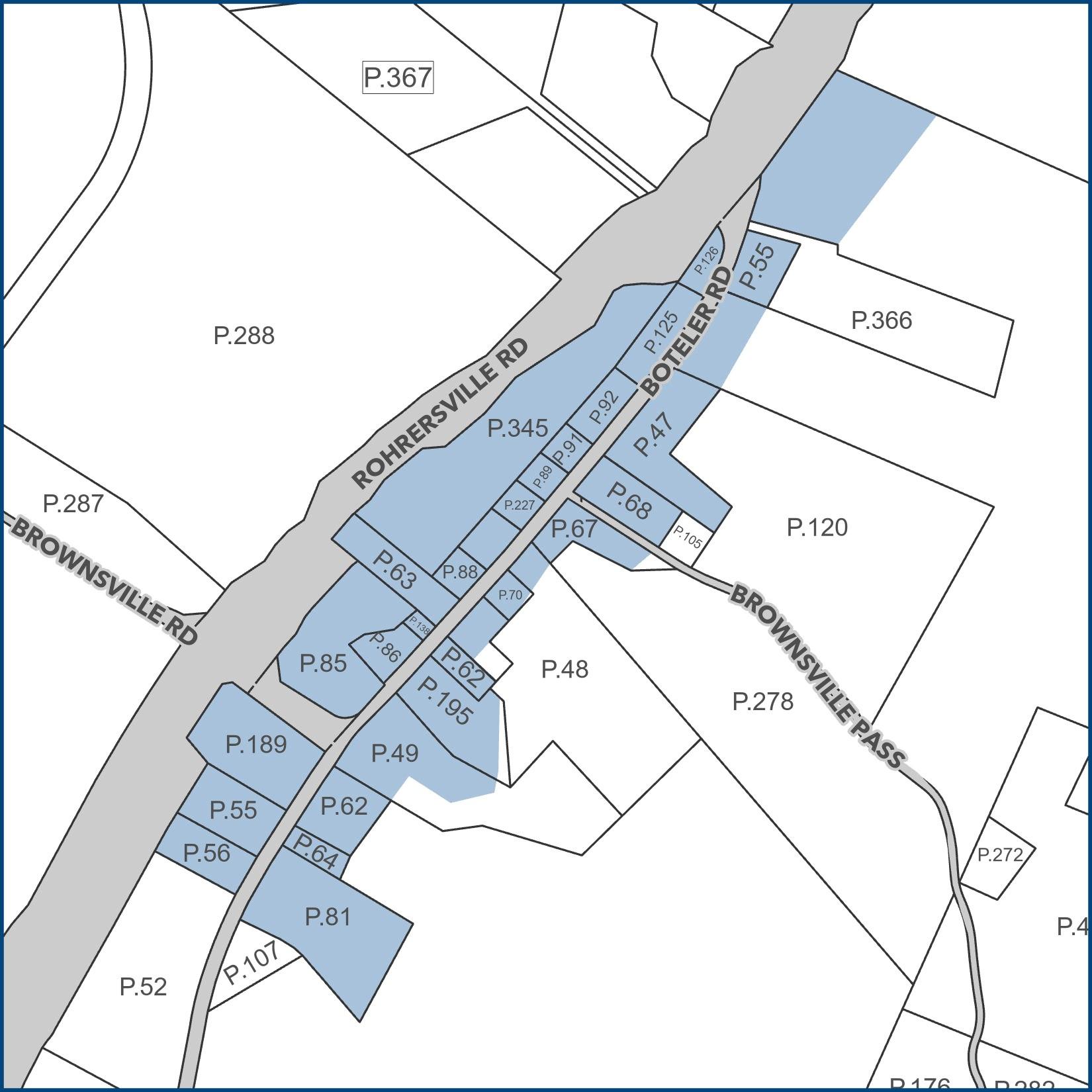

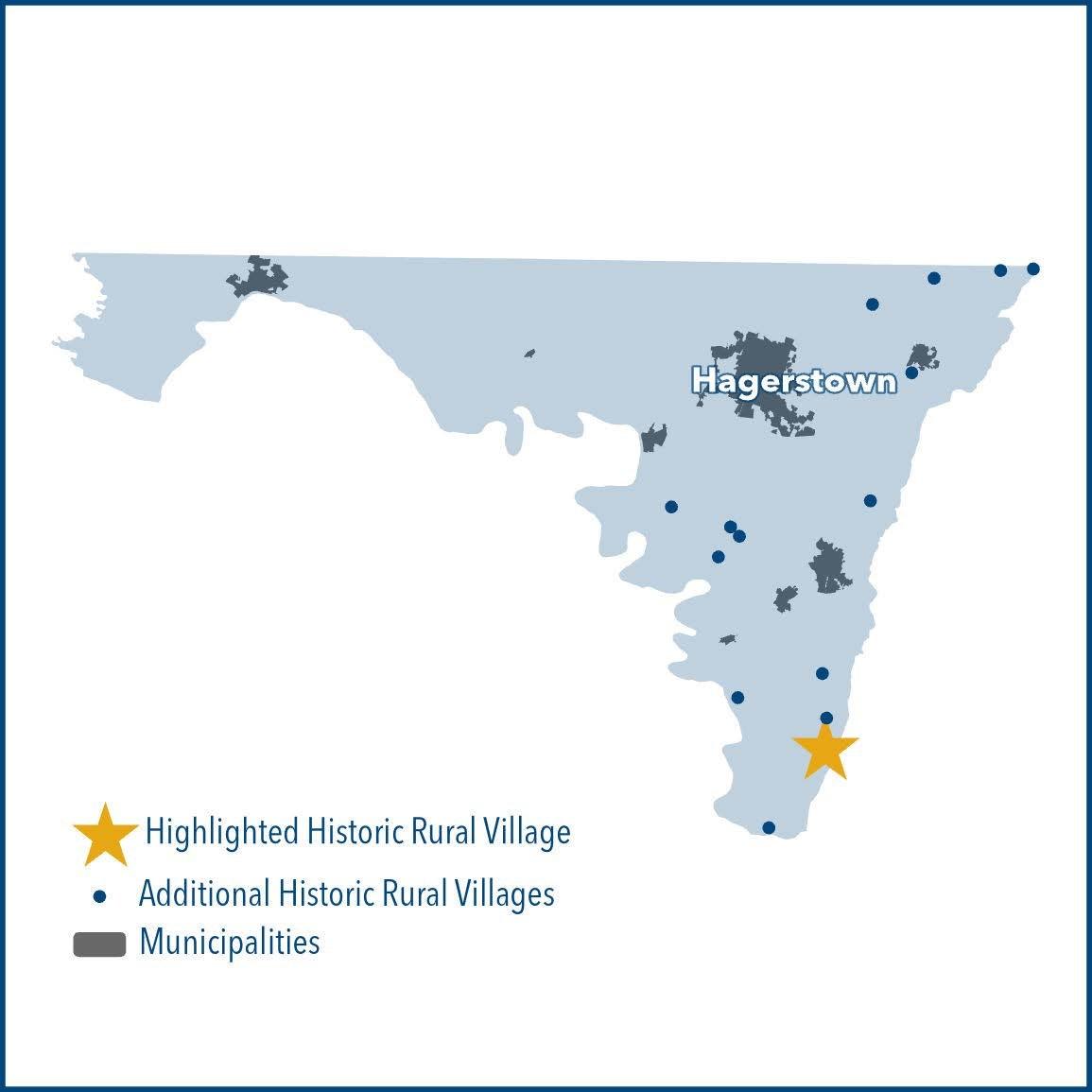

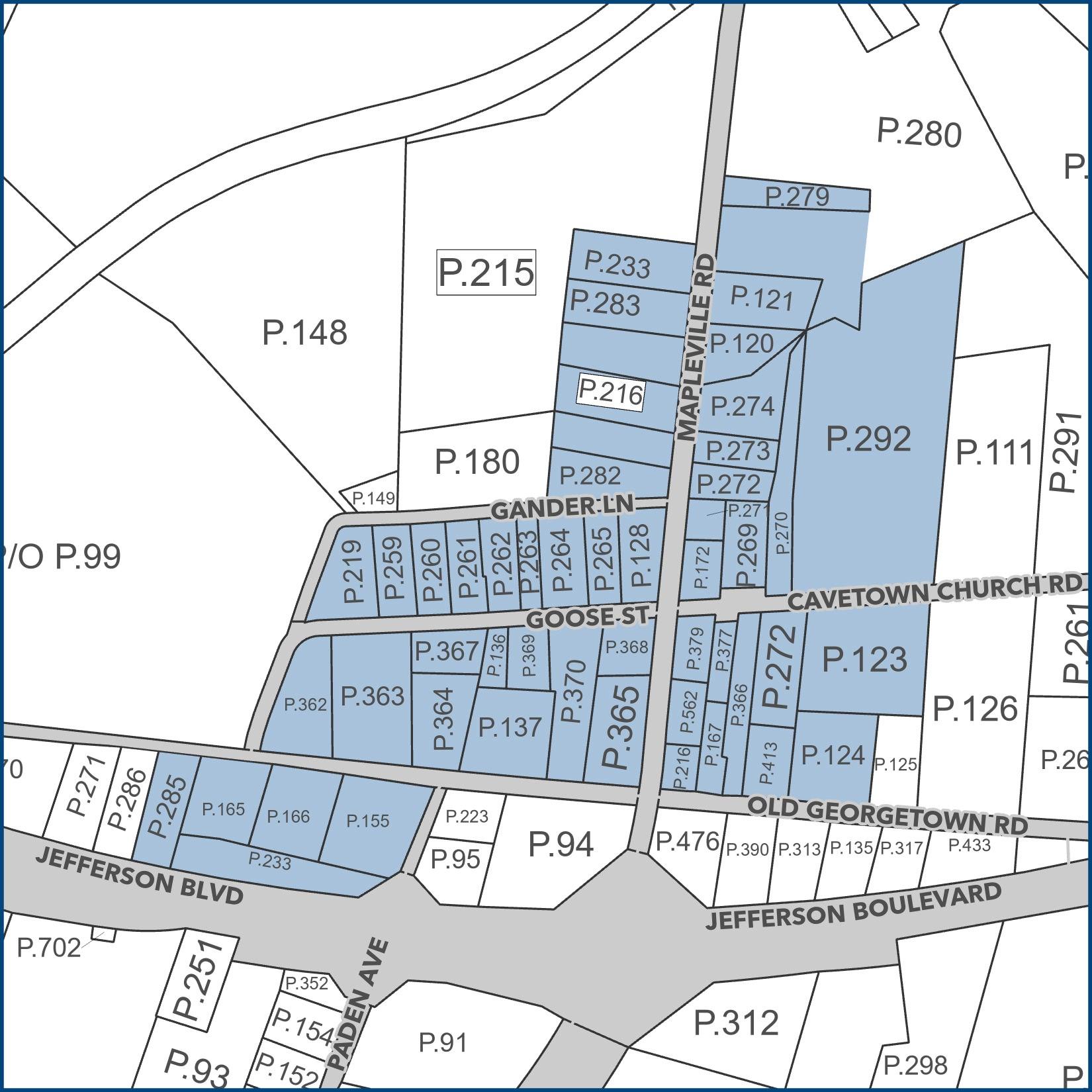

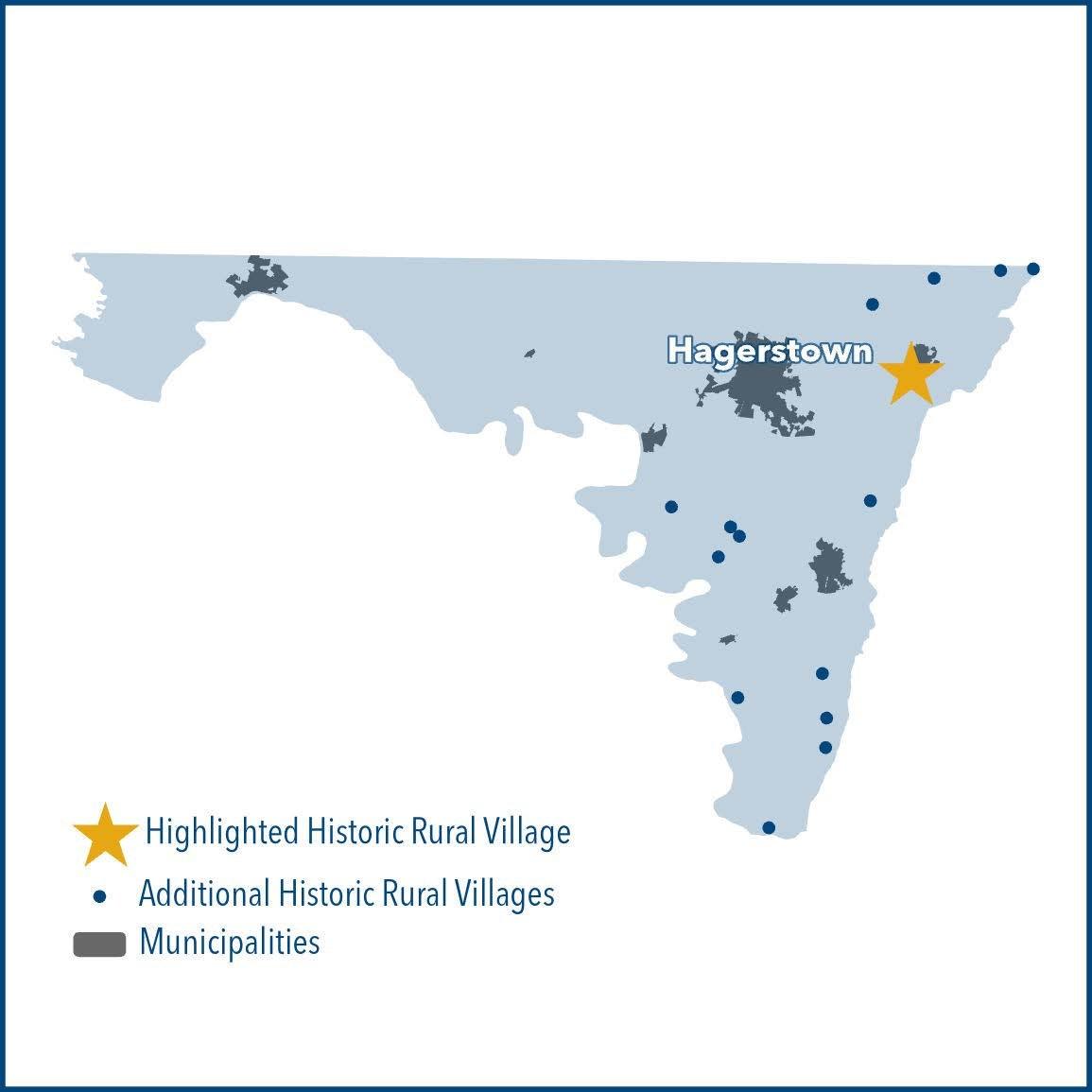

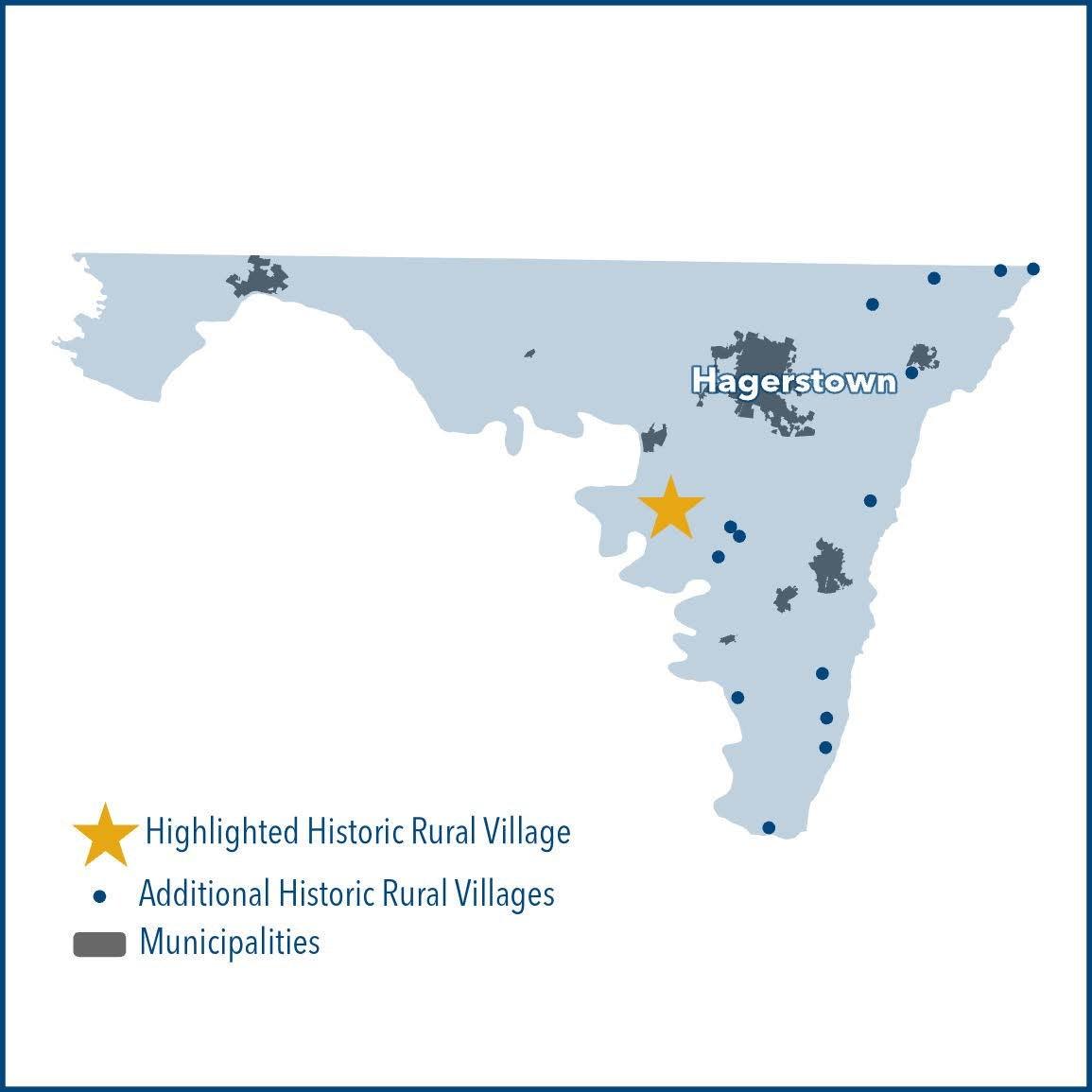

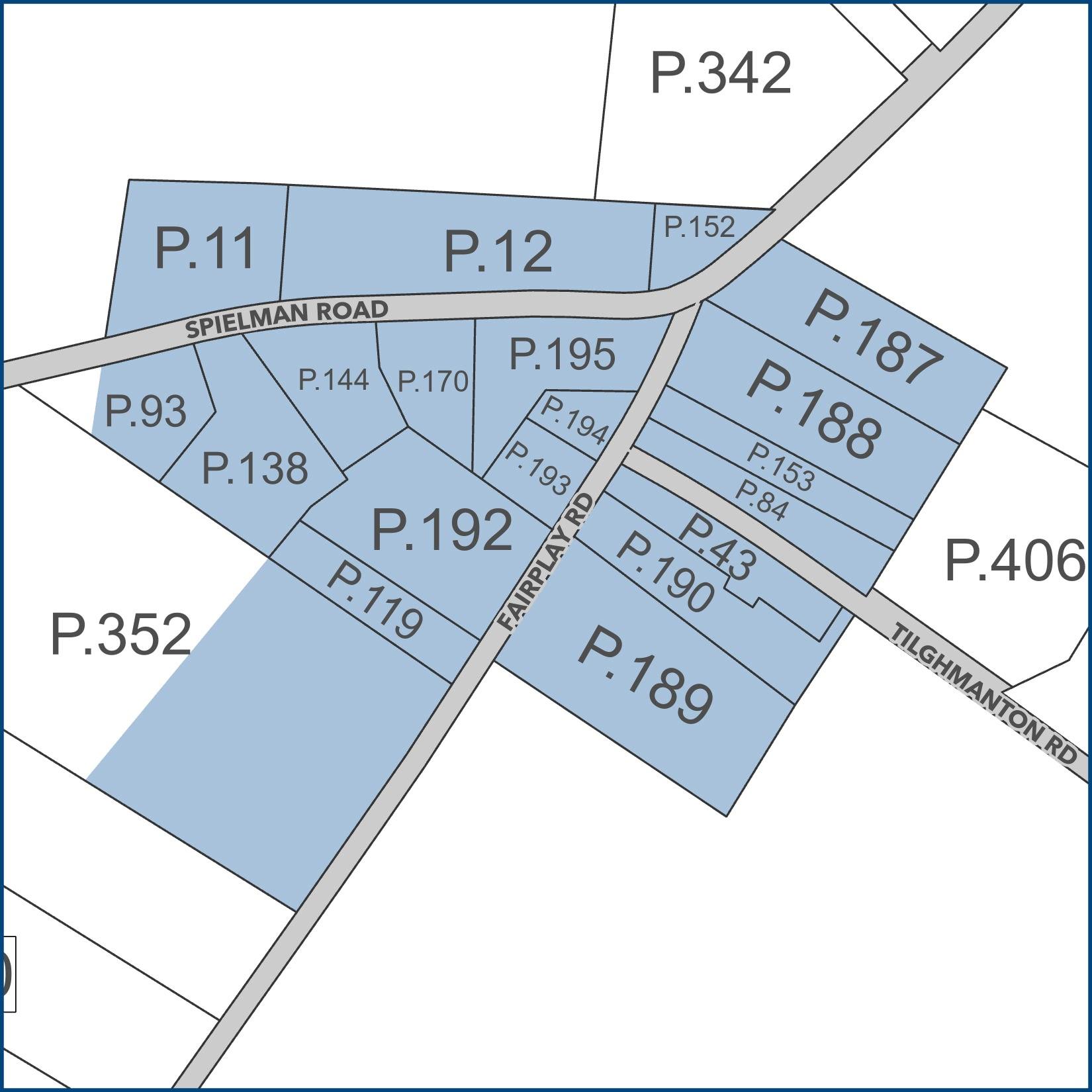

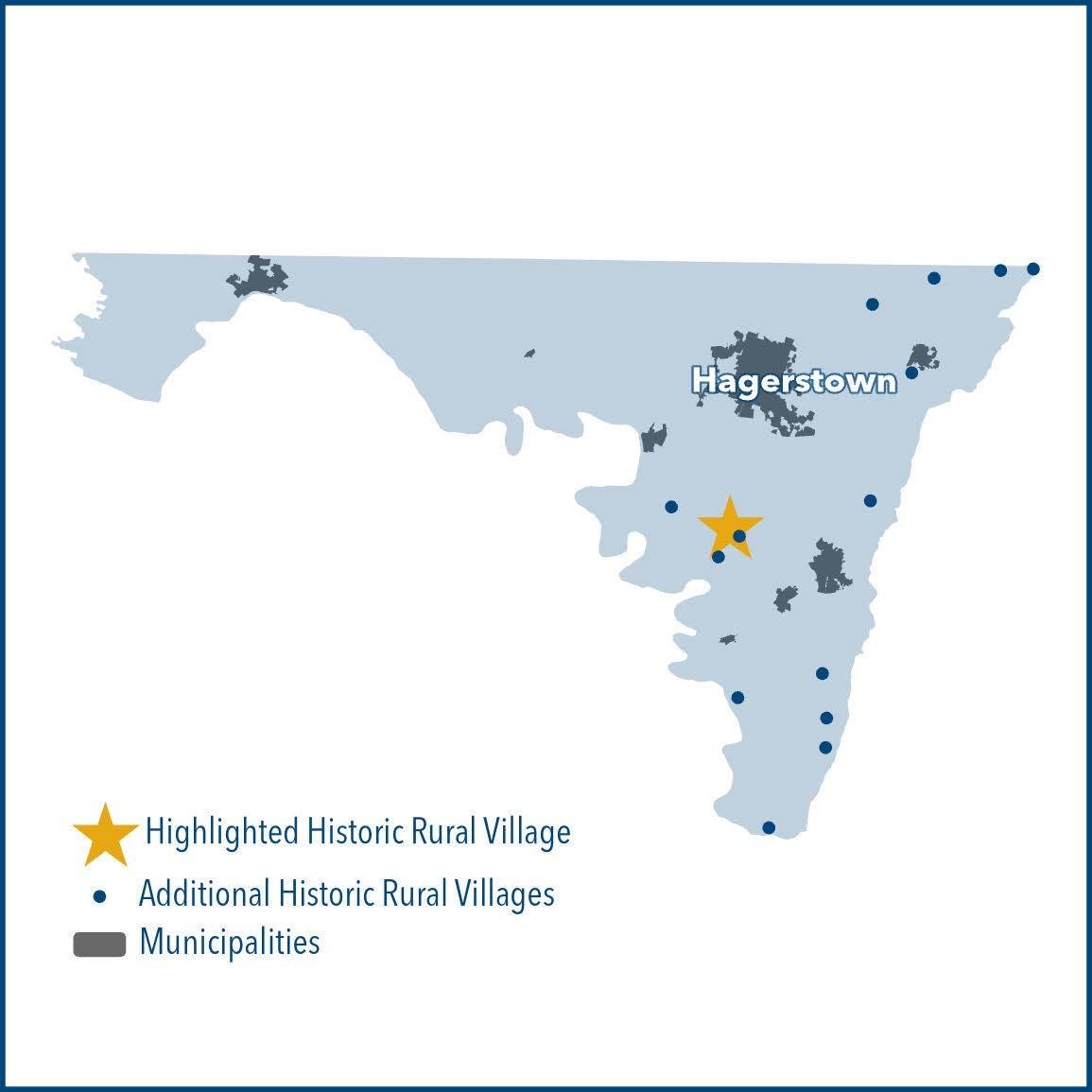

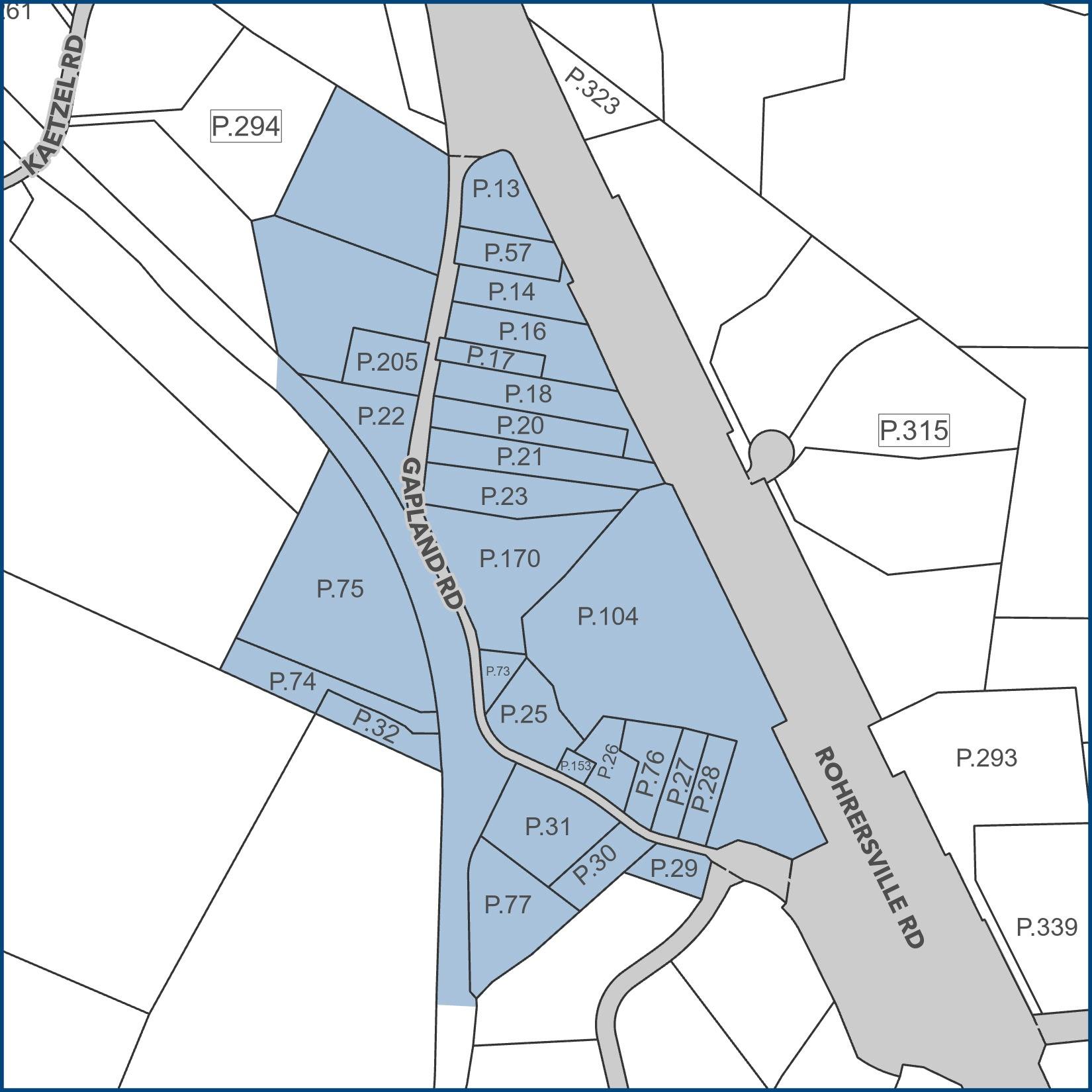

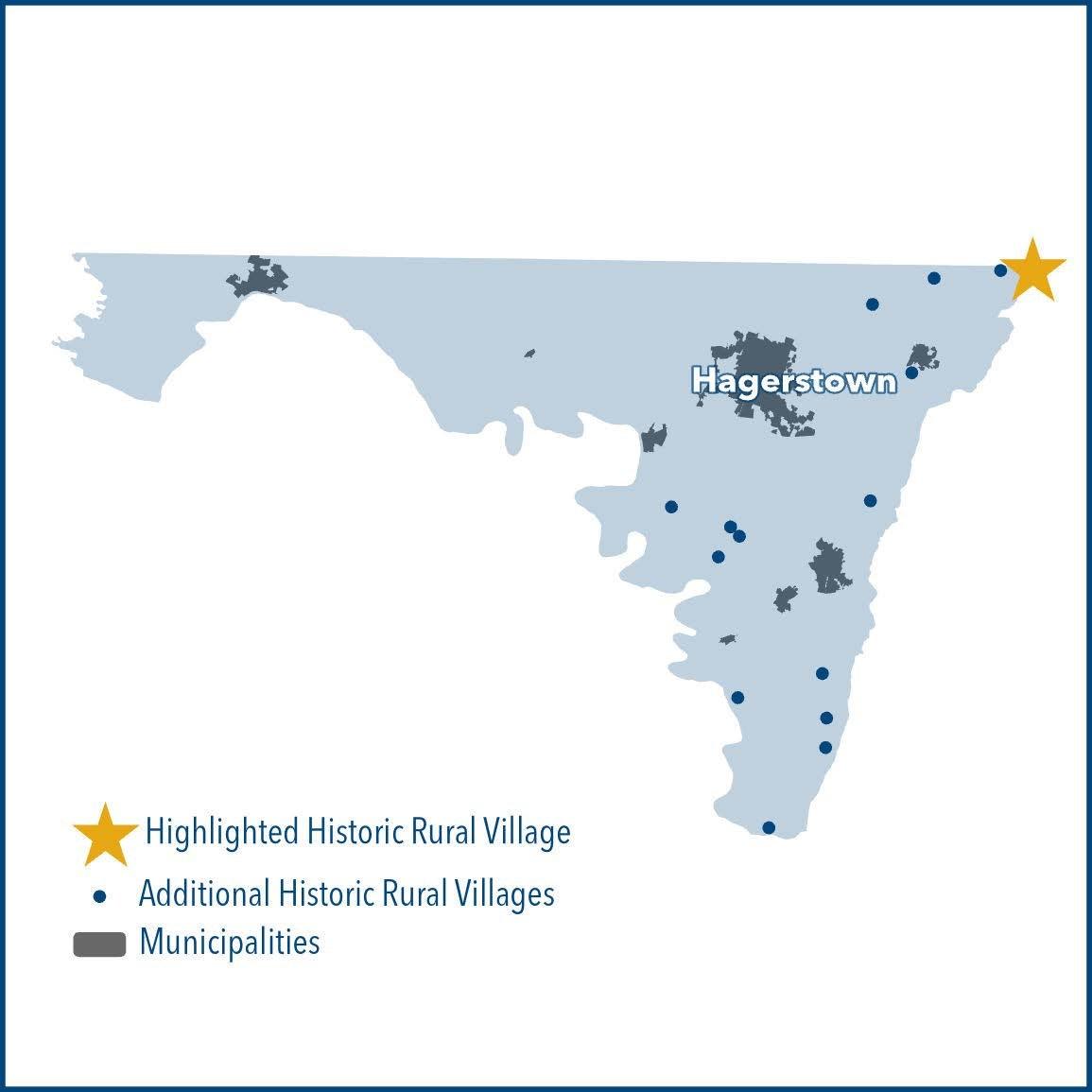

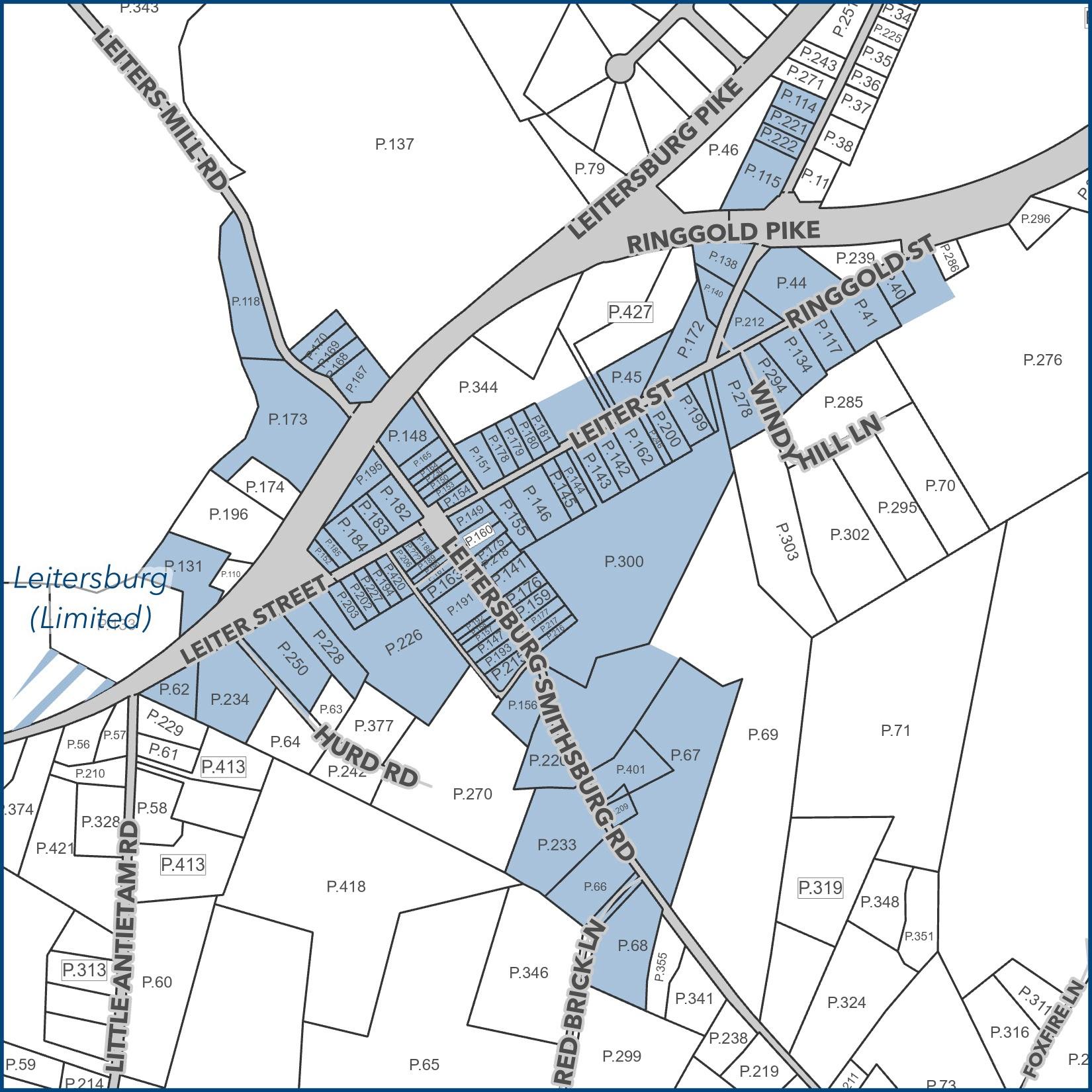

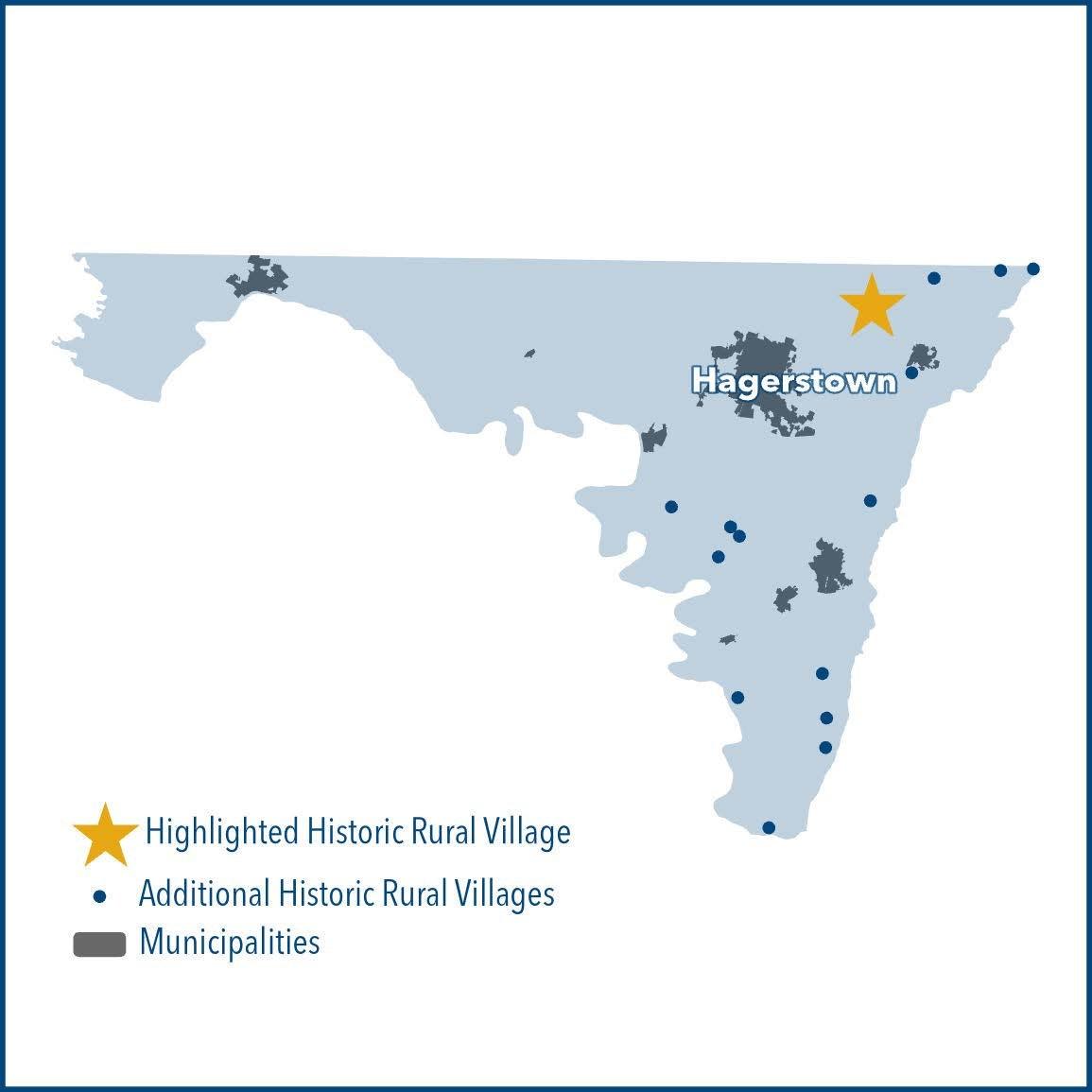

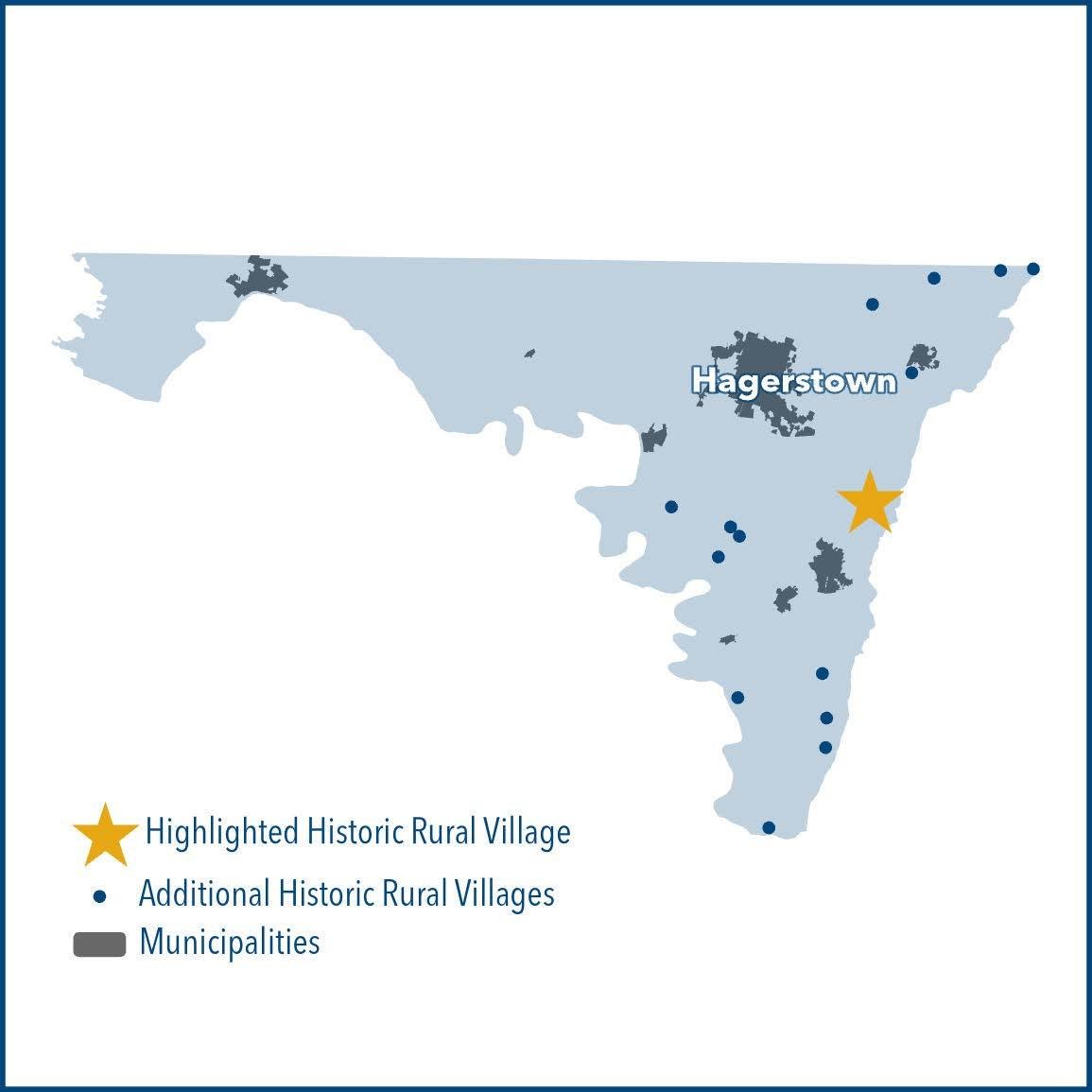

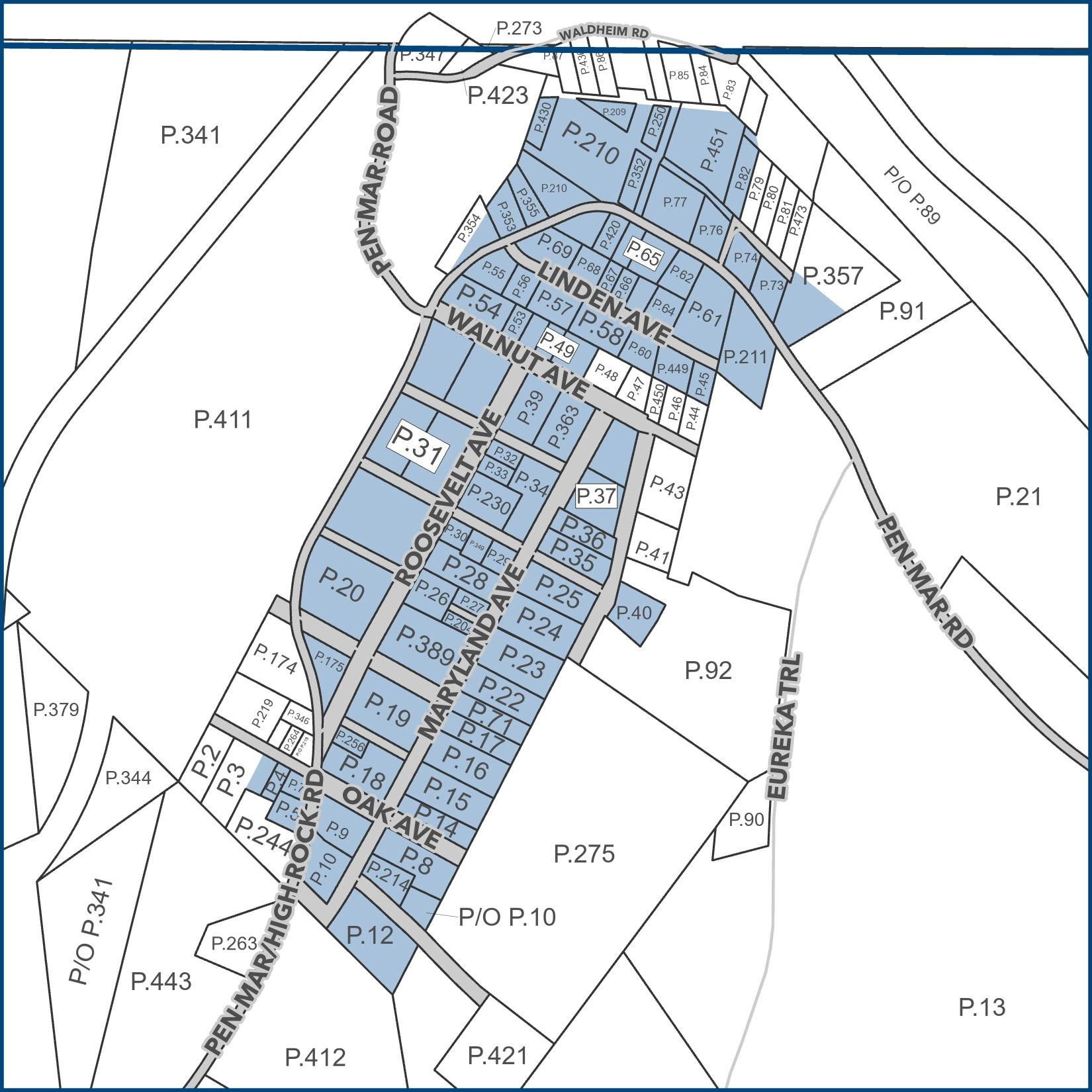

Historic Rural Villages (Historic Communities)

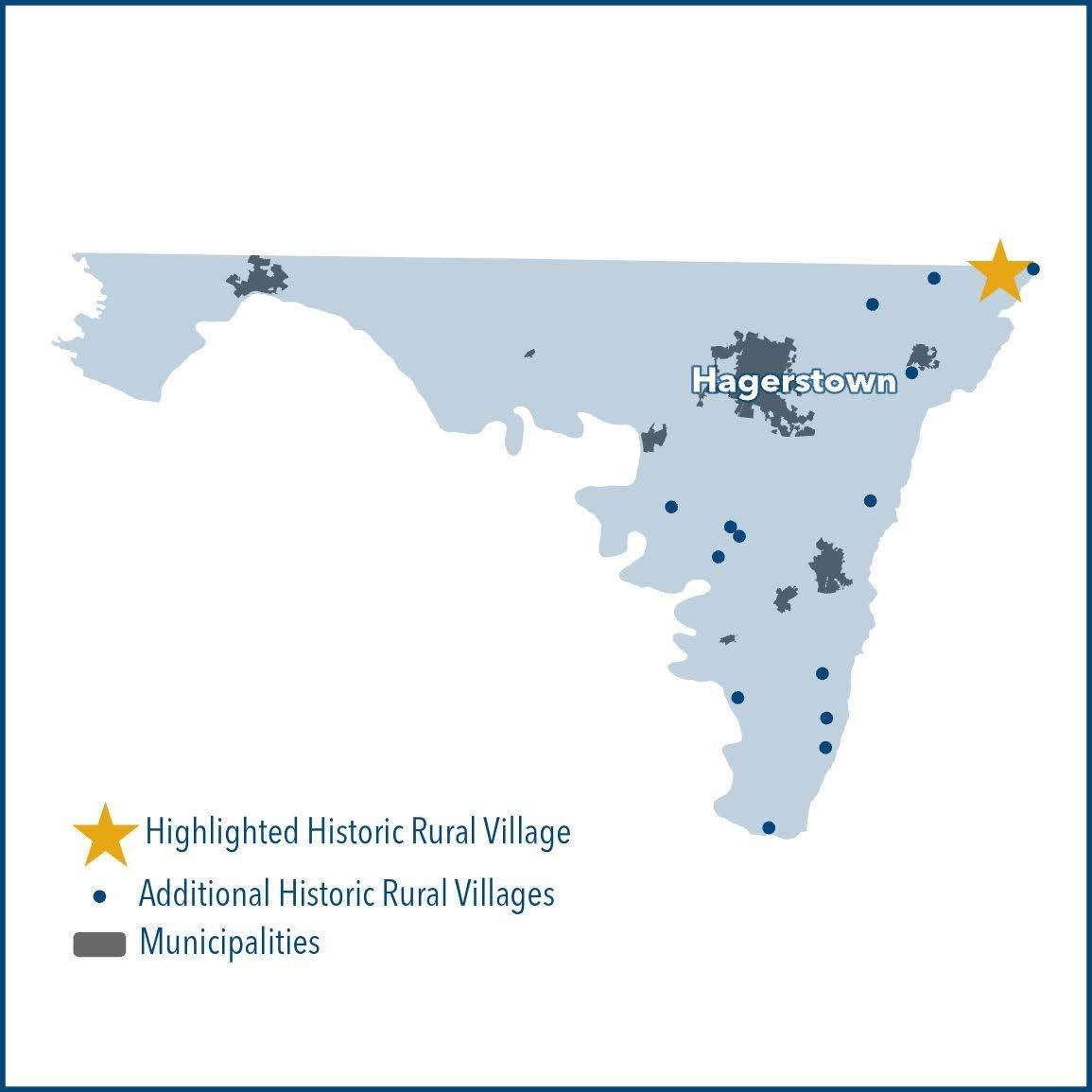

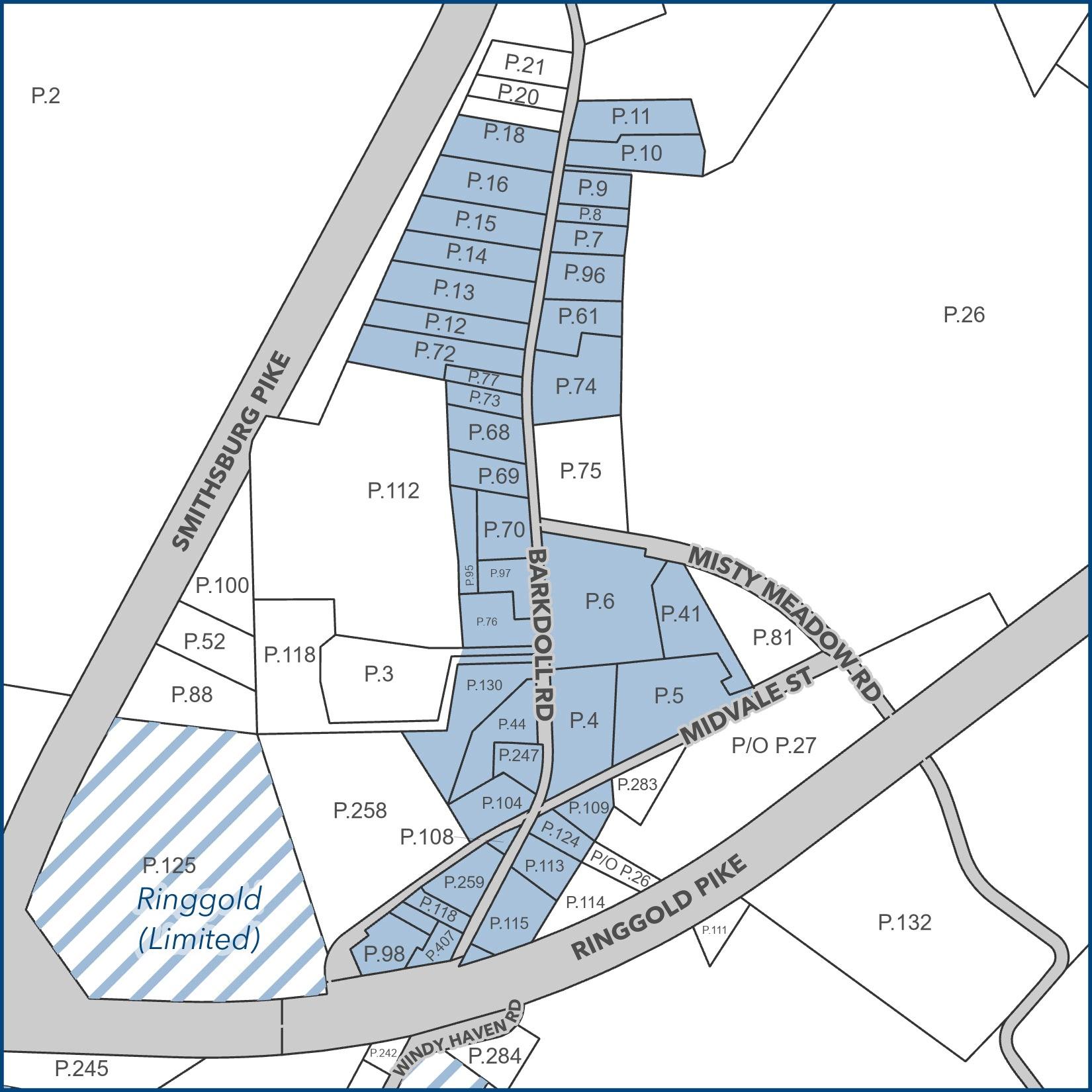

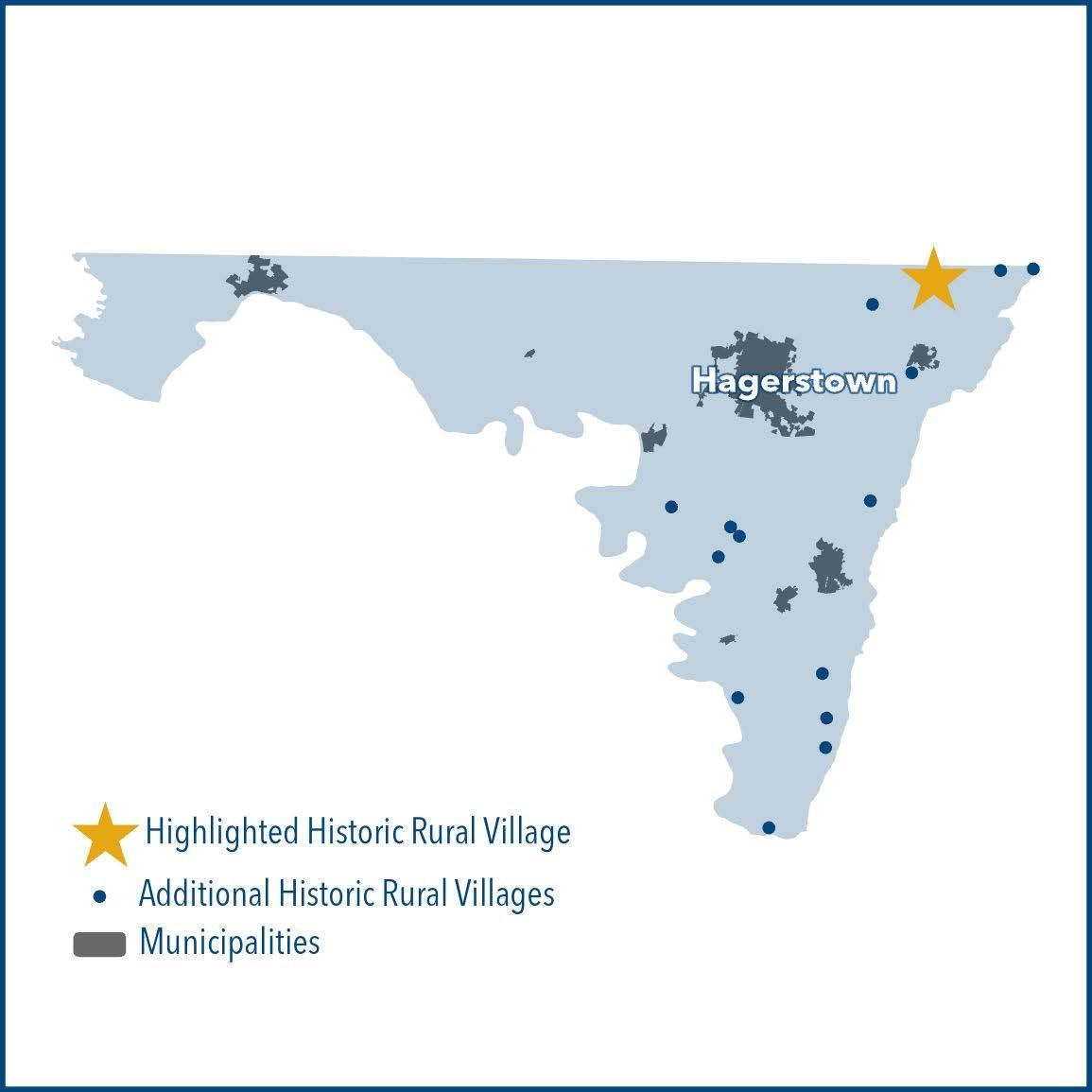

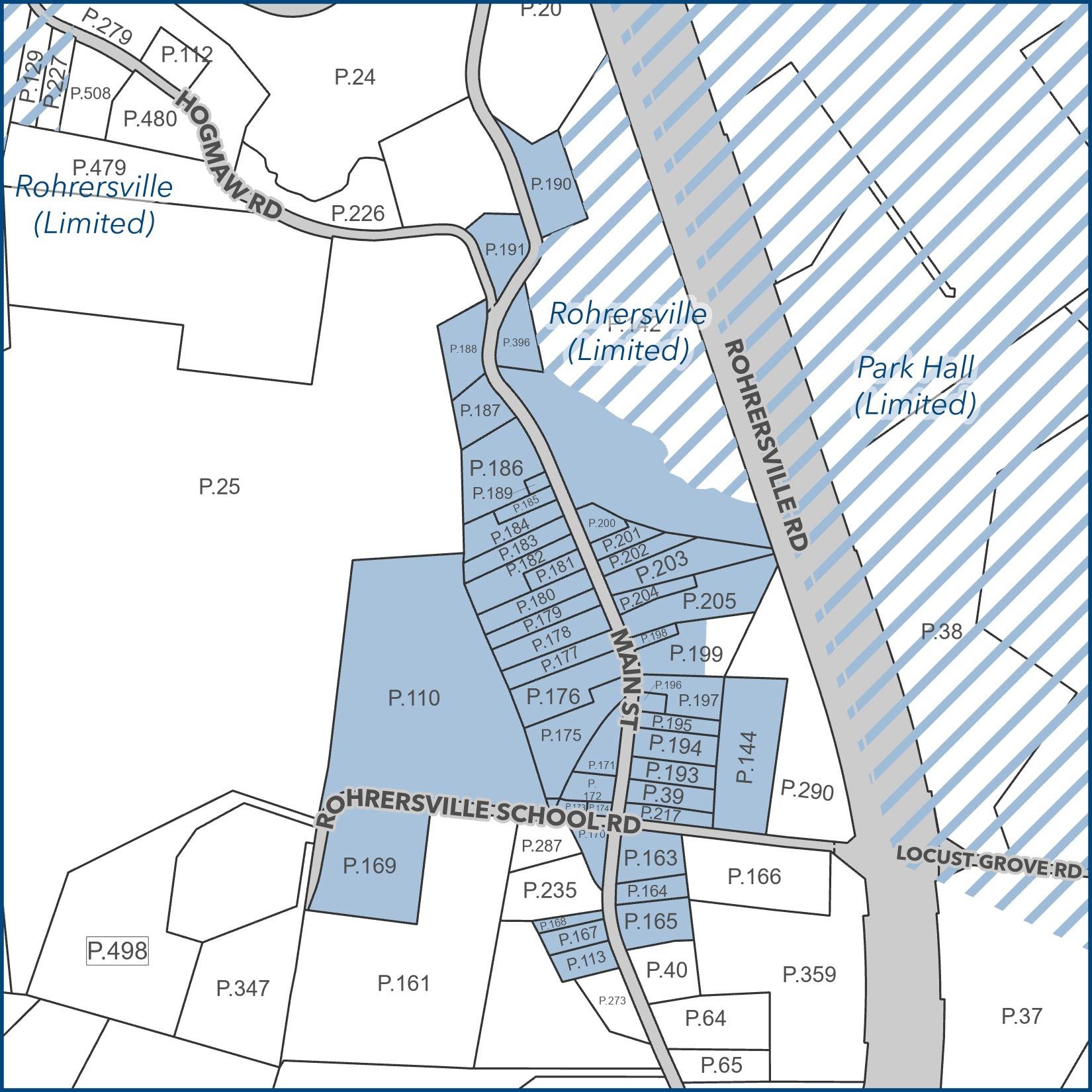

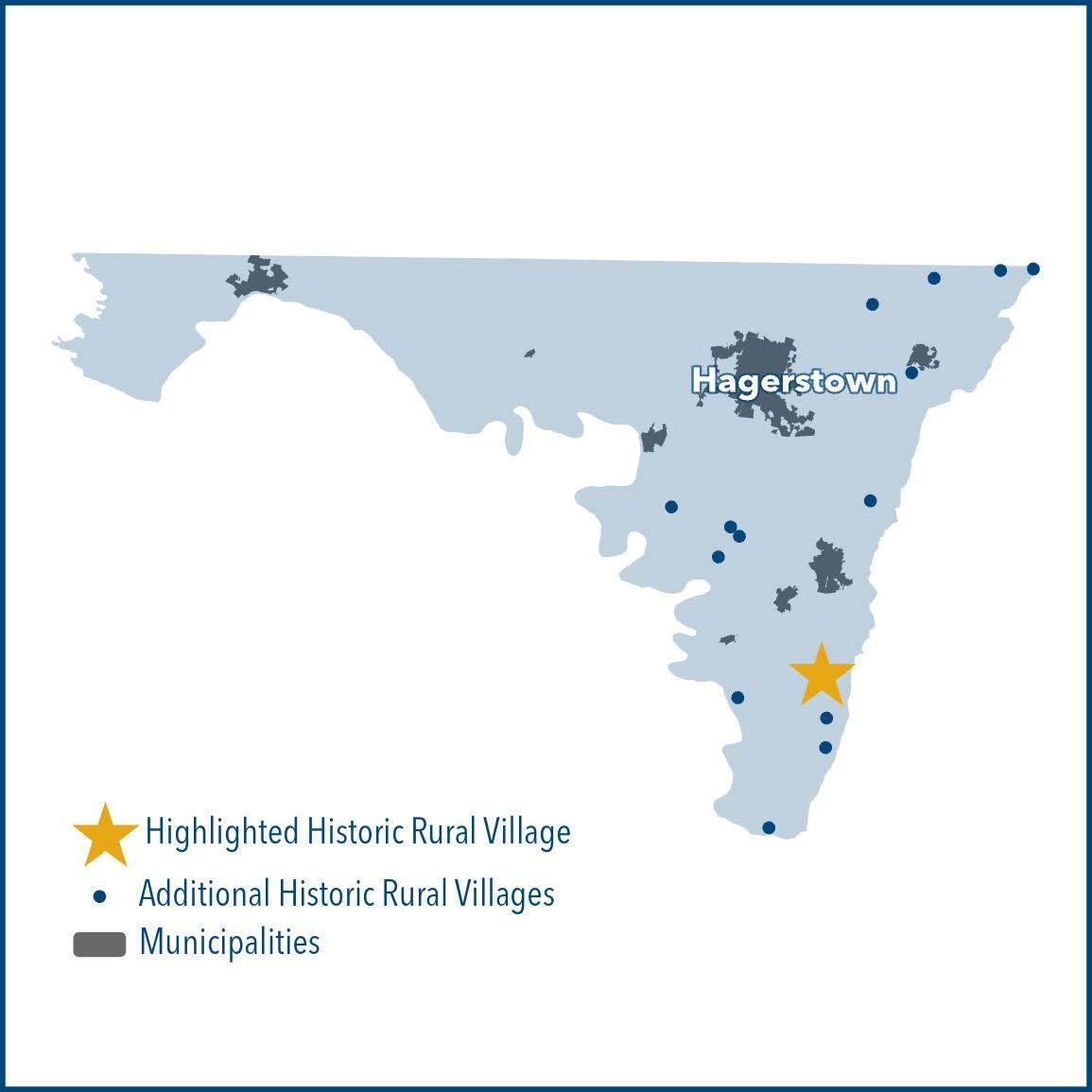

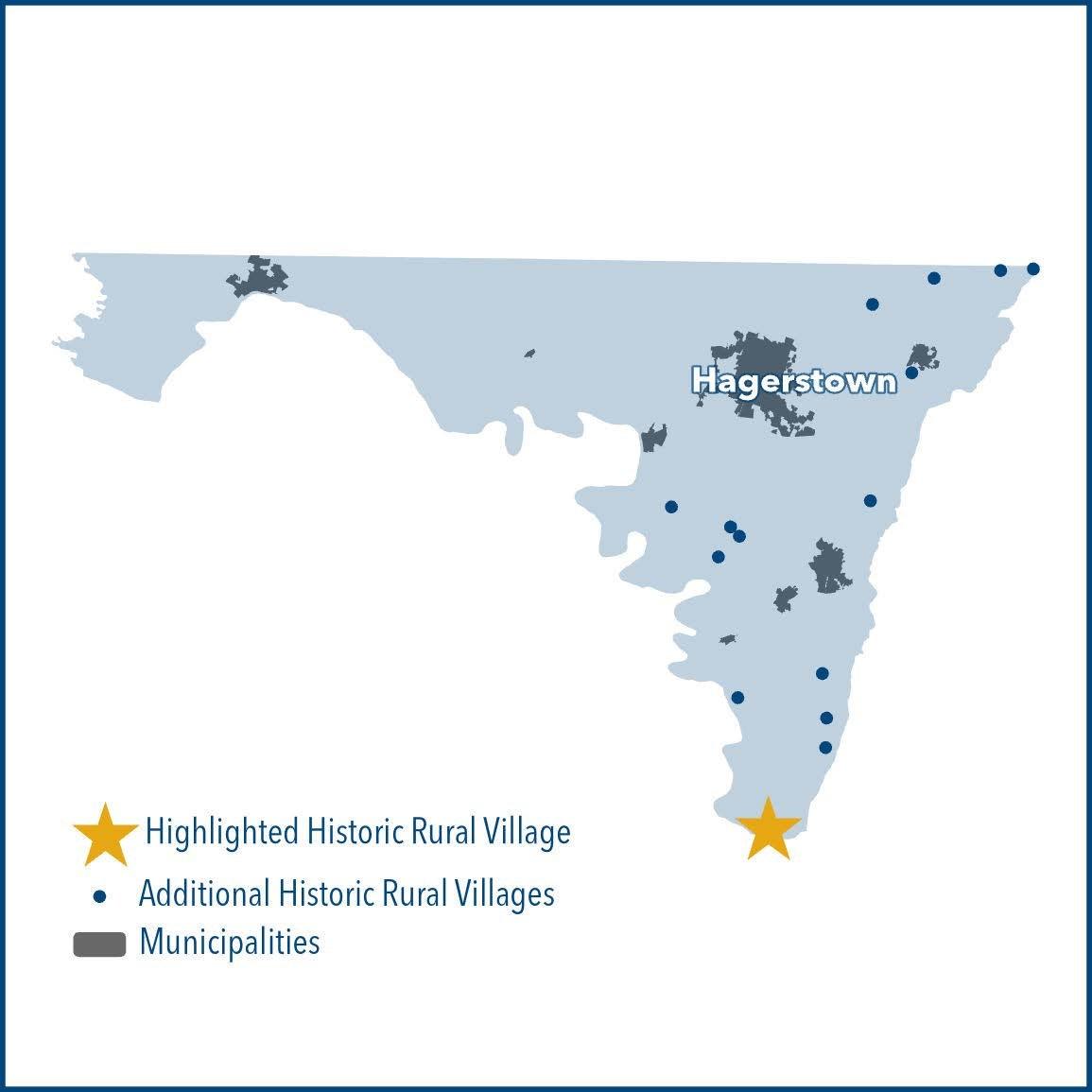

The County’s unincorporated Rural Villages are often strongly related to industry, transportation or migration. The County has a zoning classification of Rural Village; but, it is important to note that Historic Rural Villages do not always coincide with this zoning designation. Once an Historic Rural Village is surveyed by MHT or the County, the individual resources identified would henceforth have to undergo review by the HDC if any exterior changes are to be made.

Those properties individually listed on the MIHP within the Rural Village Zoning designation would also have HDC review of applications. Lastly, new construction in County surveyed Historic Rural Villages which have been adopted would also be reviewed by the HDC.

View Interactive Mapping

4 Historic Structures

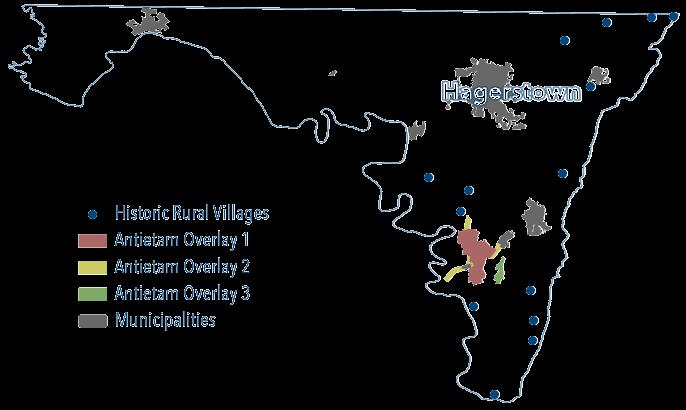

Map of the Historic Rural Villages and Antietam Overlay Areas

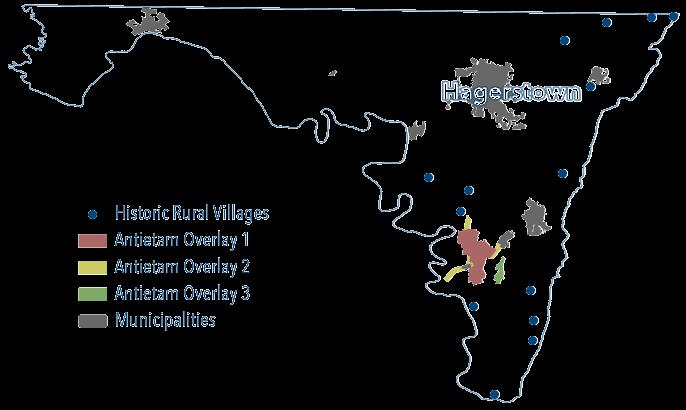

Antietam Overlay

The protection of scenic vistas, especially those associated with small towns and villages, is important to historic resource protection. Deteriorated vistas can detract from the context of historic resources and also reduce the goal of immersion that heritage tourism strives to achieve. Washington County has numerous examples of historic and cultural landscapes, such as the Rural Villages. Currently, the County has adopted only one land management regulation specifically targeted at preserving the context of the Antietam National Battlefield. The Antietam Overlay zoning district protects viewsheds around the Antietam National Battlefield and its approaches with additional levels of review.

There are three distinct subareas that are defined in the Antietam Overlay zoning district. Overlay Area 1 (AO1) encompasses the Battlefield proper and a buffer surrounding the Federally owned land. In this area, the exterior appearance of all uses are subject to HDC review. Overlay Area 2 (AO2) consists of the approach areas to the Battlefield along major transportation corridors. The AO2 area requires applications involving the exterior appearance of all commercial and non-residential uses, excluding farm structures, to include HDC review. The final area, Overlay Area 3 (AO3), pertains to the Red Hill middle ground viewshed from the Battlefield. This area was designated with assistance from the National Park Service via a technical study entitled “Analysis of the Visible Landscape: Antietam” published in April 1988. Regulations in this area limit the amount of tree cutting allowed on specific areas of Red Hill. Applications in the AO3 area, unless individually listed on the MIHP, are not reviewed by the HDC.

Design Guidelines 5

Additional Tax Credit Resources

Secretary of Interior Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties

MHT Tax Credits

County Tax Credit Resources

County Tax Credit Ordinance

County Tax Credit Application

Section 20.6, Washington County Zoning Ordinance

United States Internal Revenue

Service, Publication 530, Tax Information for Homeowners

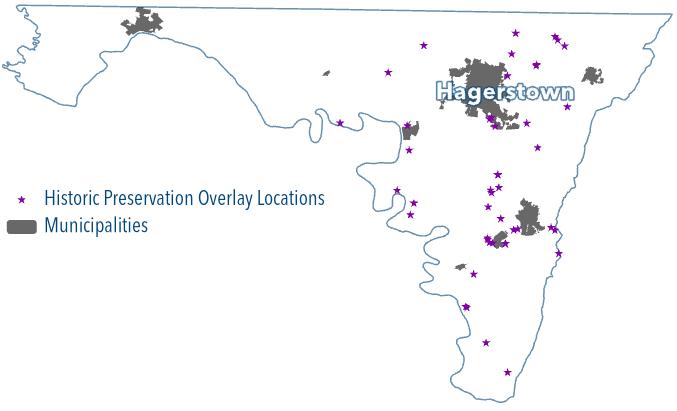

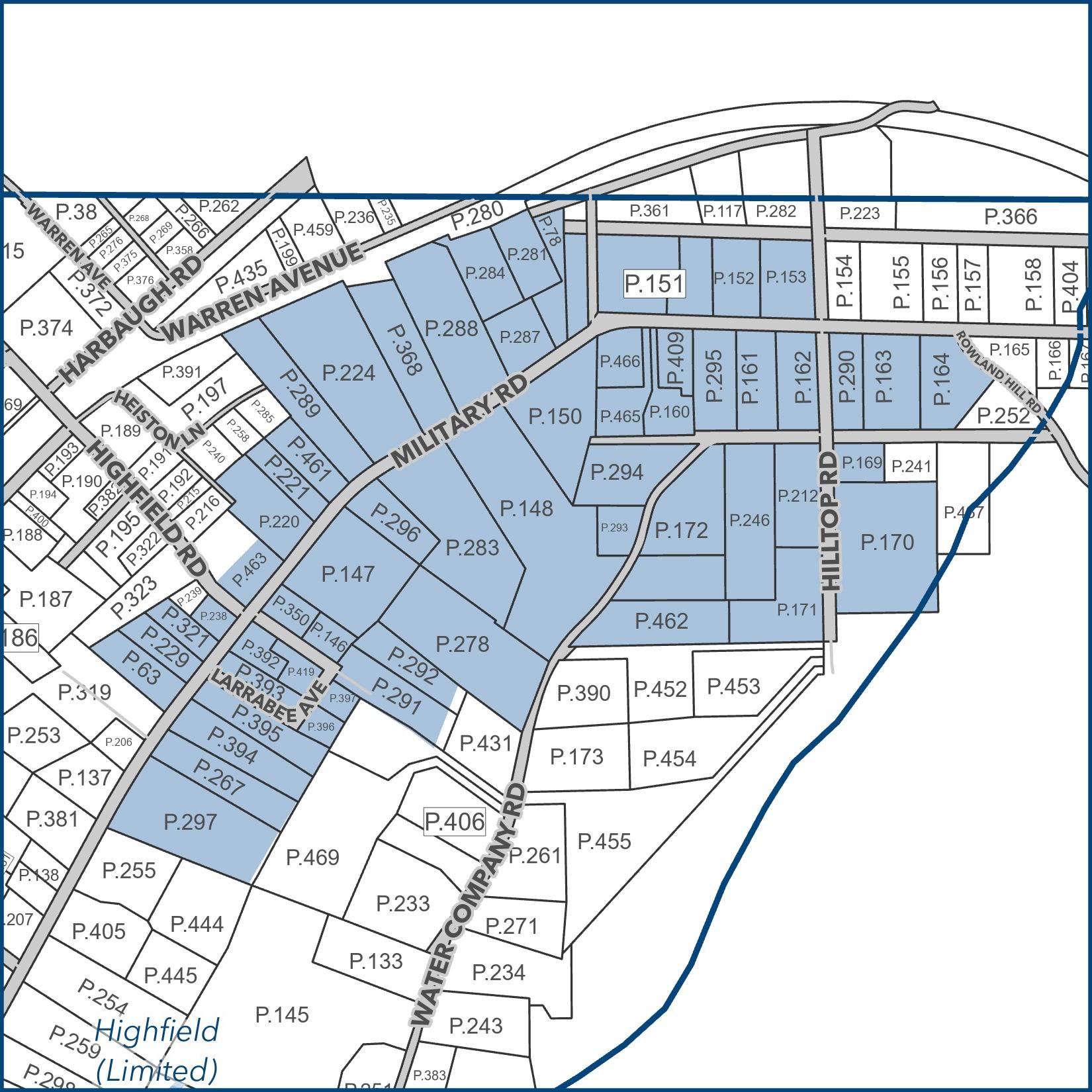

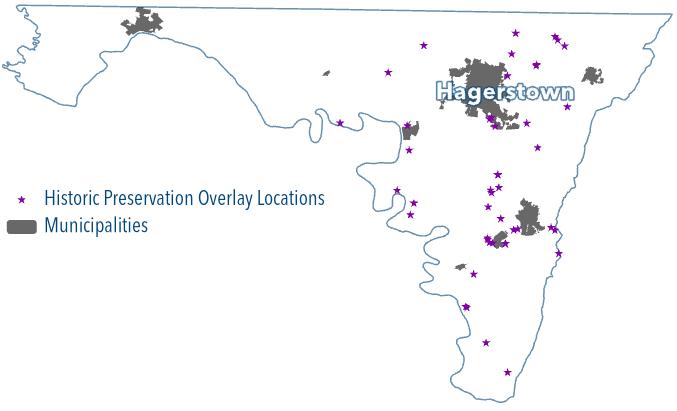

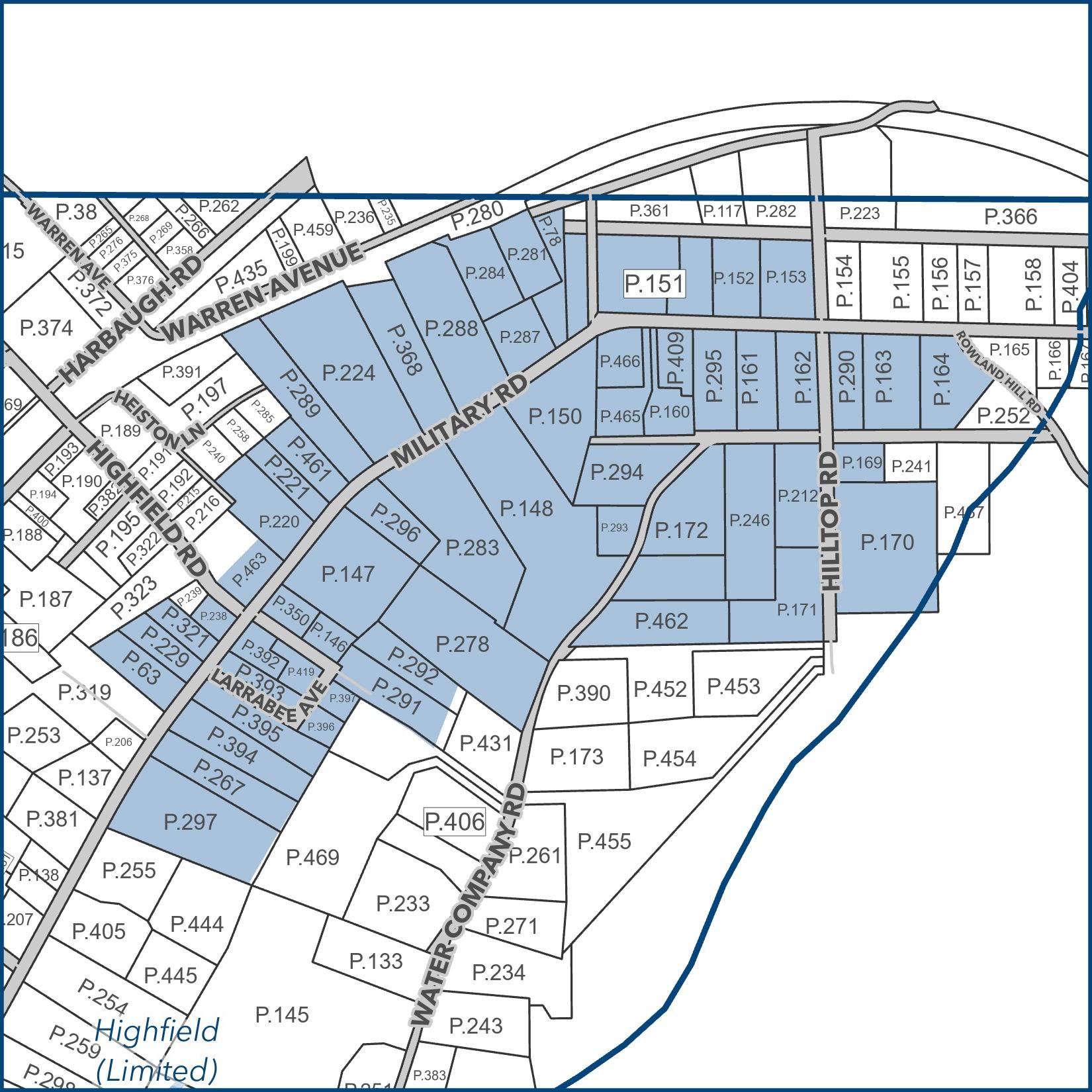

Historic Preservation Overlay

The purpose of the Historic Preservation zoning overlay district is to provide a mechanism for the protection, enhancement and perpetuation of historic and cultural resources. It is an overlay zone meant to enhance, not substitute, for the existing zoning designation, that regulates land use. The presence of the overlay on a property indicates there is a historic or cultural resource that has significance to the heritage of Washington County. This overlay must be in place on a property to be eligible for County tax credits. Once in place, the HP Overlay provides continued opportunities for County tax credits as well as providing review authority for new construction or modification of existing structures’ exteriors on the property. The HDC reviews all applications for the HP Overlay and any applications containing HP Overlay. There are currently more than 40 HP overlay areas within the County. The intention of the Overlay, as listed in the zoning ordinance, is as follows:

• Safeguard the heritage of Washington County as embodied and reflected in such structures, sites and districts;

• Stabilize and improve property values of such structures, sites, and districts and in Washington County generally;

• Foster civic pride in the beauty and noble accomplishments of the past;

• Strengthen the economy of the County; and

• Promote the preservation and appreciation of historic structures, sites and districts for the education and welfare of the residents of Washington County.

Tax Credits

One of Washington County’s main tools used to promote historic preservation since 1990 is the tax credits for the restoration and rehabilitation of exteriors on historic structures. These credits are applied for prior to work starting, to determine if the property is in the HP Overlay or Antietam Overlay 1 or 2 zoning areas. If the property is not in an existing area the HP Overlay must be applied prior to application for the tax credit. This overlay is added through the rezoning process. Once the property is in an eligible area, credits of up to 10% of the total amount spent on preservation are available from the County if the owner follows the Secretary of Interior Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. The HDC reviews applications for tax credits against eligible items in the Zoning Ordinance Section 20.6 or improvements as described by the US Internal Revenue Service. The owner can also apply for State and Federal tax credits up to 20% through the Maryland Historical Trust, which is a separate application process.

6 Historic Structures

7

Antietam Iron Works Bridge (SHA W5731), WA-II-033

Map of the Historic Preservation (HP) Zoning Overlays View Interactive Mapping

Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties

The primary repository for resource identification and documentation is the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties (MIHP). The Inventory was created by the Maryland Historical Trust (MHT) shortly after its creation in 1961. The inventory includes the nationally listed resources mentioned previously as well as those added by State and local efforts. The County, with grant assistance from the State, has been adding resources to the MIHP since the 1970’s. The County currently does not maintain its own inventory of historic or cultural resources. The properties fall into the categories of Buildings, Districts, Objects, Sites or Structures. The HDC reviews impacts to all resource categories listed but primarily reviews permits and plans affecting buildings on the Inventory.

What’s Historic?

Historic resources have factors which are used to evaluate and prioritize them. Typically, to be included on the National Register, a resource must be at least 50 years old. Age of the resource is simply one component to be considered.

Significance

Resources can have local, state or national significance. Typically, there is a period of significance which can be anywhere from a thousand years to a few days depending on the events the resource may be associated with. Significance is the importance of a property to the history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, or culture of a community. Significance is achieved by association with a set of criteria:

Criteria A

That are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history; or

Criteria B That are associated with the lives of significant persons in our past; or

Criteria C

Criteria D

That embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or

That have yielded or may be likely to yield information important in history or pre-history.

8 Historic Structures

Design space, structure, and style of a property. This includes such elements as: organization of space, proportion, scale, technology, ornamentation, and materials.

Materials

Workmanship

Feeling

Association

Materials are the physical elements that were combined or deposited during a particular period of time and in a particular pattern or configuration to form an historic property.

Workmanship is the physical evidence of the crafts of a particular culture or people during any given period in history.

Feeling is a property's expression of the aesthetic or historic sense of a particular period of time.

Association is the direct link between an important historic event or person and an historic property.

Design Guidelines 9

Sign, Rufus Wilson Store, WA-V-074

These guidelines will provide assurance to property owners that their application review will be based on clear and consistent standards. These guidelines are also designed to be flexible and interpreted to accommodate each request as it is measured against the unique circumstances of each application, existing historic structures, and the proposed activities.

In the event of a conflict between state laws and the County’s ordinances and policies or these Design Guidelines, the HDC will consult with the County Attorney’s Office.

Application Requirements

The HDC makes prompt and proper decisions to issue a Certificate of Appropriateness or comments in support or not in support of applications when it has sufficient information to determine all aspects of a design proposal. The applicant bears the responsibility for ensuring that all applications are complete and on time.

The Historic District Commission hosts a public meeting on the first Wednesday of each month. Applicants must submit their detailed application at least ten (10) business days before the meeting to be included on the agenda.

The following information is determined to be the minimum acceptable to accompany an application for review by the HDC.

1. Scale drawings and pictures of the existing buildings showing their current condition. *All photographs must be in color and have excellent clarity; digital format is preferred.

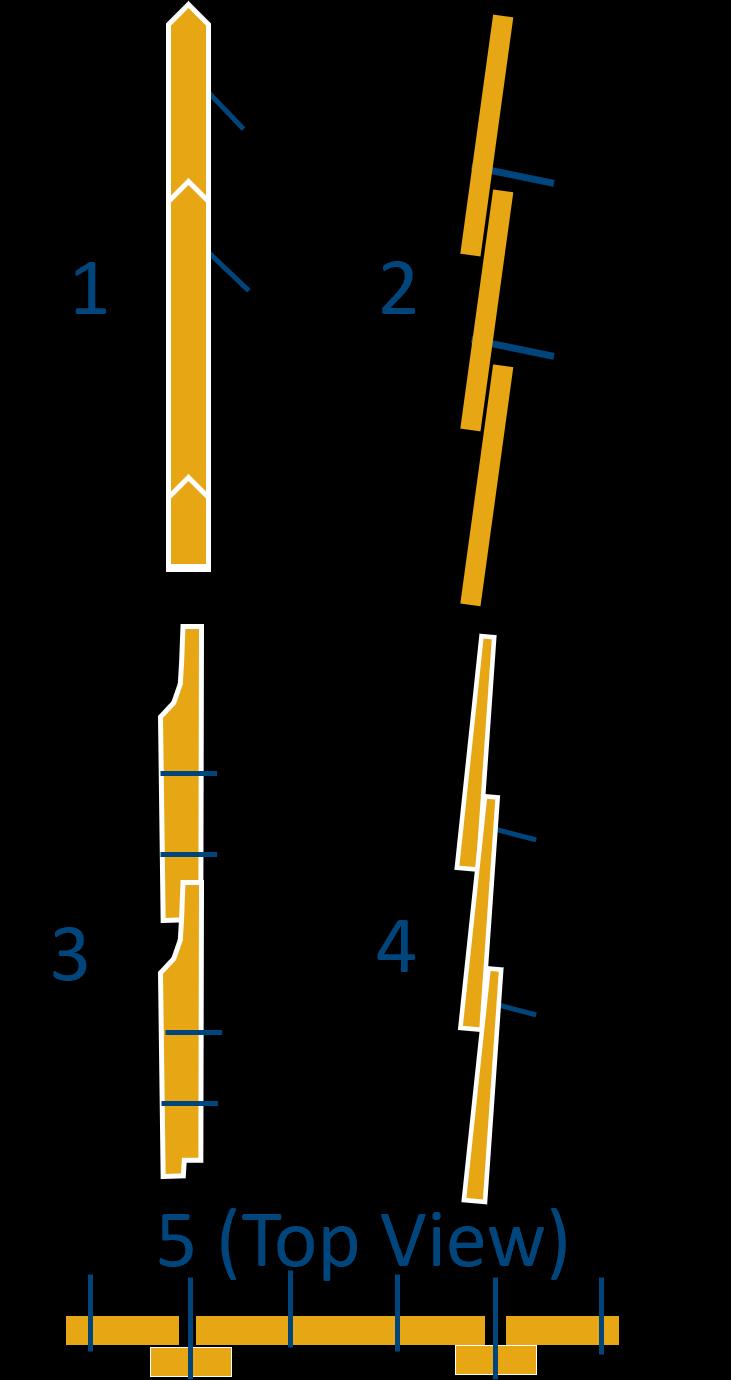

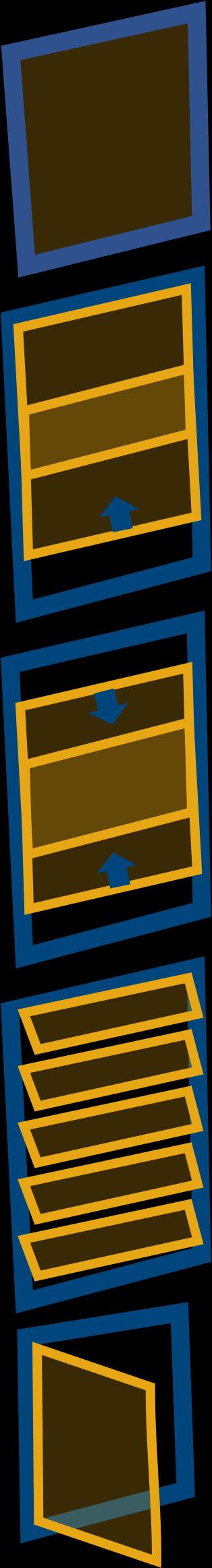

2. A scale drawing of the proposed changes to the existing building or the new construction, showing all affected sides of the structure. The drawings should identify all new materials and show the actual design of a treatment rather than descriptions in words alone. Dimensions should be provided.

3. A scale drawing of the property showing the location of the existing buildings on the site and the location of the building additions or new construction. The relationship to public road and other points of access shall also be shown. The relationship of other buildings in the same or adjacent historic districts should be shown.

4. Sufficient information to determine the appearance of new exterior materials either in the form of manufacturer’s publications or samples. Photographs are especially helpful.

10 Historic Structures

5. See demolition section for additional application requirements specific to that application type.

Applications that require HDC reviews resulting in a Certificate of Appropriateness that are approved, approved with conditions or disapproved include:

1. Design review for construction within a Historic Rural Village or Antietam Overlay

2. Design review for construction within a Historic Preservation District

3. Demolition permit review for all structures within a Historic Preservation District or contributing structures within the Antietam Overlay

4. Determination for the issuance of County property tax credits for properties in the Historic Preservation District, Antietam Overlay, or National Register District within a municipality with a Historic District Commission

Applications that require HDC reviews resulting in comments in support or not in support for the application include:

1. Design review for construction within a Rural Village zoning designation for a property containing resources on the MIHP

2. Demolition permit applications for structures identified on the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties that are outside the review areas listed above

3. Zoning text, zoning map amendments, special exceptions and variances, site plans, cell towers, and subdivision applications that affect historic structures or zones

The HDC does not review permit applications for construction under 100 sq ft in the Antietam Overlay or Rural Village zoning designations. Agricultural building permits also are not reviewed in those areas. The HDC does not review applications for interior changes but will provide consultation if requested. The information listed above is specific to the application review of the Historic District Commission. Additional submittal requirements may be necessary. Applicants should contact the Division of Permits and Inspections to determine those requirements. All applications, excluding Historic Preservation Tax Credit, are currently made through the Division of Permits and Inspections.

Did you remember?

Check for State or Federal Funding/Permitting and apply to MHT if needed

Check for MIHP or HDC Review Area Information

Check building permit or plan requirements

Check additional HDC application requirements based on review type Review the Design Guidelines for the work proposed

Design Guidelines 11

Evaluation Process

The Commission shall consider only exterior features of a structure that would affect the historic, archeological, or architectural significance of the site or structure, any portion of which is visible or intended to be visible from a public way. It does not consider any interior arrangements, although interior changes may still be subject to building permit procedures. The Commission renders a decision on a completed application within 45 days of receipt of the completed application. Failure to act within the specified time period shall be considered an approval of the application by the Commission. The 45-day review period may be extended upon agreement by the Commission and the applicant.

1. The application shall be approved by the Commission if it is consistent with the following criteria:

A. The proposal does not substantially alter the exterior features of the structure.

B. The proposal is compatible in character and nature with the historical, cultural, architectural, or archeological features of the site, structure, or district and would not be detrimental to achievement of the purposes of Article 20 of the County Zoning Ordinance.

C. The proposal would enhance or aid in the protection, preservation and public or private utilization of the site or structure, in a manner compatible with its historical, archeological, architectural, or cultural value.

D. The proposal is necessary so that unsafe conditions or health hazards are remedied.

E. The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation and Guidelines for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings and subsequent revisions are to be used as guidance only and are not to be considered mandatory.

2. In reviewing the plans for any such construction or change, the Commission shall give consideration to and not disapprove an application except with respect to the factors specified below.

1. The historic or architectural value and significance of the site or structure and its relationship to the historic or architectural value and significance of the surrounding area.

2. The relationship of the exterior architectural features of the structure to the remainder of the structure and to the surrounding area.

12 Historic Structures

3. The general compatibility of exterior design, scale, proportion, arrangement, texture, and materials proposed to be used.

4. Any other factors, including aesthetic factors, that the Commission deems to be pertinent.

3. The Commission shall be strict in its judgment of plans for those structures, sites, or districts deemed to be valuable according to studies performed for districts of historic or architectural value. The Commission shall be lenient in its judgment of plans involving new construction, unless such plans would seriously impair the historic or architectural value of surrounding structures.

For Rural Villages, additional review criteria for applications are listed in Architectural Review of the Zoning Ordinance and include:

1. The exterior appearance of existing structures in the Rural Village, including materials, style, arrangement of doors and windows, mass, height and number of stories, roof style and pitch, proportion.

2. Building Size and Orientation

3. Landscaping

4. Signage

5. Lighting

6. Setbacks

7. Accessory structures

Design Guidelines 13

Click

to View Document

Demolition

Washington County encourages the retention of significant buildings, structures, sites, objects, or other historic resources within the County. Given the irreversible nature of demolition, full deliberation of all alternatives before action is essential.

Additional Resources:

Preservation Brief #31 Mothballing of Historical Buildings

Demolition Permit Evaluation

In considering a request for a Certificate of Appropriateness or comment to demolish a structure, the Commission will weigh the criteria listed in the Evaluation Process previously discussed.

Demolition Permit Review

Demolition review is a legal tool that provides the Historic District Commission with the means to ensure that potentially significant buildings and structures are not demolished without notice and review. This process creates a safety net for historic resources to ensure that buildings and structures worthy of preservation are not inadvertently demolished.

Demolition review does not always prevent the demolition of historically significant buildings or structures. Rather, as the name suggests, it allows for review of applications for demolition permits for a specific period to assess a building’s historical significance.

If the applicant or the HDC requests additional guidance regarding the property to determine significance or documentation status, the Maryland Historical Trust may be contacted to assess a to-be-demolished structure. The Maryland Historical Trust does not have a formal role in regulating or reviewing local demolitions but will act as a technical resource as needed.

Failure to Comply or Willful Disregard

Failure to comply or disregarding these policies will result in applicable fines being administered.

The Historic District Commission will review demolition permits for structures 400 square feet or greater or if partial demolition is proposed in coordination with new construction or additions. Reviewable structures are on the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties (MIHP), within the Historic Preservation Zoning Overlay, Antietam Overlay 1 or 2 or are greater than 50 years old in a Historic Rural Village.

14 Historic Structures

Demolition Permit Application Requirements

The following demolition permit application requirements are in addition to the Application Requirements listed previously for the Historic District Commission. Demolition permits that involve multiple structures, such as a farmstead or site, should include documentation that will enable full review of all involved structures.

The demolition permit number, provided after permit application with Division of Permits and Inspections, must accompany the demolition application materials listed below. Materials for HDC review may be submitted digitally to the Department of Planning & Zoning at askplanning@washco-md.net once the permit application has been filed. Applicants may be required to provide additional materials to other reviewing agencies.

A. Written description and history of the building or structure to be demolished.

B. Detailed drawings, such as construction or trim details.

C. Floor plan for each floor level, drawn to approximate scale or fully dimensioned.

D. Applicant’s plan for the recycling of waste generated.

E. A report analyzing the demolition alternatives and mitigation (listed in descending order of preference) as to their feasibility. The report shall consist of thorough, deliberative analyses of each of the alternatives, explaining why each alternative is or is not feasible. Additional photographs should be provided in support of the analysis. In cases where a permit may involve multiple structures, each structure must have its alternatives documented.

F. A site plan illustrating any proposed development or introduction of plantings following demolition (if applicable).

The HDC highly encourages the early review and involvement of the Maryland Historical Trust (MHT), using their Project Review Form. The instances where MHT should be consulted include buildings, sites, and projects that involve State or Federal funding or may require state or federal permits; for example, a state highways entrance permit. This review will ensure that the Section 106 process, if needed, is at least started before the HDC reviews a demolition permit. This process allows for greater consulting party input.

The HDC may request additional information from the applicant following the review and discussion of the application. Additional information ensures that the structure has been fully documented before a Certificate of Appropriateness or support of a demolition permit occurs. This documentation could include supporting documents from licensed professionals such as an architect, engineer, or restoration specialists.

Demolition Alternatives

Redesigning the project to avoid any impact to the structure or its setting;

Incorporating the structures into the overall design of the project;

Converting the structure into another use (adaptive reuse);

Relocating the structure on the property;

Relocating the structure to another property;

Demolition Mitigation

Documenting the structure as a whole and its individual architectural features in photographs, drawings, and/or text. This documentation should follow the Standards and Guidelines for Architectural and Historical Investigations in Maryland and be completed by a professional as listed in those Standards;

Salvaging from the structure historically significant architectural features and building materials.

Design Guidelines 15

Preferred Less Preferred

Initial Process for demo (Applicant)

Open Maryland Historical Trust (MHT) Project Review if applica-

Consider demolition alternatives and gather documentation which supports those alternatives’ feasibility

Apply for demolition permit with Division of Permits and Inspections AFTER any applicable Site Plan, Grading or Subdivision review is completed.

Supply required documents and demolition permit specific required documents to HDC Staff at time of demolition permit application.

Review Process for demo (HDC)

Complete demolition permit applications will be distributed for review by the HDC at next meeting date. Permit is shared with additional interested historic partnerships for comment. If MHT Project Review is applicable review will not be scheduled until MHT initial review is complete.

HDC Meeting Process for demo (HDC and Applicant)

HDC discusses provided application information and any qualified professional documentation with the applicant. Demolition alternative information will be reviewed extensively. Note: No public comment is taken. This is not a hearing.

HDC Recommendation

HDC will make motion in support or not in support of the demolition permit.

Support

If the HDC supports the demolition permit, a letter stating support will be attached to the application with reasoning and the application will need no further HDC review.

Not in Support

If HDC is not in support of the permit, the permit and all review information will be forwarded to the Planning Commission to be scheduled at their next available meeting date for their determination of support. Planning Commission may provide additional alternatives to the applicant that are available from the subdivision or site plan perspective to minimize impacts to historic resources.

16 Historic Structures

Ordinary Maintenance

Maintenance of all structures, historic or otherwise, is strongly encouraged. Routine maintenance of buildings in the historic preservation zone, rural villages, or properties listed on the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties may not require review or approval by the Historic District Commission, a Certificate of Appropriateness, or a building permit. However, it is strongly recommended that the customer reach out to the Historic District Commission prior to starting work if there are questions regarding a project on a historic structure. The Historic District Commission is a resource for proper treatments and can assist in determining if the changes are within the scope of ordinary maintenance. Ordinary or routine maintenance is work that does not alter the exterior features of a Historic Site or contributing structure. Key exterior features, including roof materials, doors, windows, moldings, are discussed later in detail in these guidelines.

Ordinary maintenance can include activities to prevent or correct deterioration, decay. or damage to a structure or any part thereof as long as repairs or replacement are of like material and design. Nothing in these guidelines shall be construed to prevent ordinary maintenance or repair that does not involve a change of design, material, or of the outward appearance of a building.

While the repair of an individual pane of glass in a window may be considered maintenance, the restoration of windows, or other exterior elements, as part of an overall home improvement project may be considered for tax credits. The HDC reviews applications for tax credits against eligible items in the Zoning Ordinance Section 20.6 or improvements as described by the US Internal Revenue Service. It is important to reach out to the HDC or staff to determine if a project may qualify for tax credits.

Additional Resources:

Preservation Brief #3 Improving Energy Efficiency in Historic Buildings

Preservation Brief #39 Holding the Line: Controlling Unwanted Moisture in Historic Buildings

Preservation Brief #47 Maintaining the Exterior of Small and Medium Size Historic Buildings

Publication 530, Tax Information for Homeowners, United States Internal Revenue Service

Washington County Zoning Ordinance, Section 20.6

Design Guidelines 17

A Short History of Washington County

The first European settlers who arrived in Lord Baltimore’s colony of Maryland in 1634 were mostly English Catholics. It took another 100 years before the first land patent was issued in what is now Washington County. While some of those applying for the earliest patents in our county were of English descent, it was the German Protestants emigrating south out of Pennsylvania who would have the greatest impact on the landscape and architecture. Settlers such as Jonathan Hager, Hagerstown’s namesake, and other skilled Germans decidedly had the largest impact of transforming a wilderness landscape into neat, productive farms and towns. The architecture in both their homes and agricultural buildings reflects their Dutch, German, Swiss, Italian, Bohemian, and English heritage. With the farming of vast acreages, surviving outbuildings and deed references provide evidence that large landowners in the County owned slaves or indentured servants to tend to their land. As a result, there are examples of institutional buildings such as schools to support the African American community as well as vernacular structures which were later homes to the freed.

As the transportation routes of the rivers, canals, and roads to the area improved, an even larger mix of ethnic groups came to the area. The legacy of these settlers and their descendants is a diverse accumulation of architectural styles and construction methods that make Washington County a unique and special place. The German’s fondness for usage of the most readily available building material, native limestone, is reflected in the stone houses, barns, and bridges that are still evident in our community. Surviving also, are the English brick and log structures. Along the National Road and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, many highstyle, large, brick and frame buildings appeared, reflecting the financial prosperity there. Other humbler structures were built elsewhere, representing the more common agricultural settlements. Fortunately, many of the older buildings of our early days remain. The purpose of these Guidelines is to assist those who wish to preserve and restore these defining aspects of our culture.

18 Historic Structures

Design Guidelines 19

013

Sunshine

Hill,

WA-VI

Old Forge Farm, Surveyor’s Last Shift, WA-I-054

Valentia, WA-I-231

Stone Hill, WA-II-403

Photo Credit (All Photos): WCHT

This page is intentionally left blank

Whether magnificently restored or lovingly maintained, the historic properties that dot Washington County’s rural roads and rolling hills are fine adornments in the rich tapestry comprising Maryland’s diverse history.

Washington County contains examples of a wide variety of eighteenth, nineteenth, and early-twentieth-century residential and commercial architecture, including Federal, Greek Revival, Italianate, Second Empire, Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, and Neoclassical Revival styles.

Very rarely are buildings academic, textbook examples of their particular style; rather most are vernacular interpretations of high-style architecture. The original design includes numerous modifications. Through their decorative detailing, these vernacular buildings reflect the influences of popular styles.

The character-defining elements that define a building’s style are particularly important to preserve and should receive special consideration in planning for maintenance or rehabilitation e.g. siding, windows, doors and roofs. The following descriptions and illustrations provide an introduction to the historical background and distinguishing features of the architectural styles commonly represented throughout Washington County.

Architectural Styles of Washington County

Design Guidelines 21

Keewaydin, Mt. Angelwood, WA-IV-089 Photo Credit: WCHT

The term vernacular (or folk) architecture generally refers to buildings not planned by an architect but based upon regional traditions, the materials at hand, and some expedience.

Vernacular Forms 18th—19th Century

The earliest houses in Washington County do not fit easily into any particular category, but they can be grouped by several identifying features that reflect the changes in eighteenth and nineteenth-century rural domestic architecture.

Character-Defining Elements

1730 to 1760

• Stone, log, or log-encased clapboard over a rough-stone foundation

• Constructed over a spring

• 1 to 1 ½ or 2 stories

• Steeply pitched roofs

• Large central chimneys

• Very small window openings

• Batten doors

• Puncheon logs and rocks as insulation between the basement and first floor

1760 to 1790

• Stone, log, or log-encased clapboard over a stone foundation

• Usually 2 stories

• Jack arches over windows

• Gable-end chimneys

• More refined cut stones, quoined corners

• Mid-century structures reflect a variety of styles, dependent on the ethnicity of the builder

22 Historic Structures

Kammerer House, WA-I-013

David’s Friendship, WA-I-388

1790 to 1820

• Stone, brick, clapboard

• One to two stories

• Often with two front doors

• Segmented arches above windows

• Gable-end chimneys

1820 to 1860

• Stone, brick, clapboard

• One to two stories

• Plain lintel above windows

Design Guidelines 23

Scratch Ankle Farm, WA-II-084

Brightwood, WA-I-216

Photo Credits: WCHT and Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties (MIHP), Maryland Historical Trust

Georgian – 1720 to 1840

Georgian architecture developed in England out of the Classical Revival which dominated Europe during the Renaissance and Enlightenment. The Georgian style’s name comes from the successive rulers of Great Britain, King George I through King George IV, who ruled England while Georgian architecture was popular. Georgian architecture became unpopular in the United States at the time of the Revolutionary War as American architects wished to separate their style from British influence.

• Simple 1-2 story box, 2 rooms deep, using strict symmetrical arrangements

• Panel front door centered, topped with rectangular windows (in door or as a transom) and capped with an elaborate crown/entablature supported by decorative pilasters

• Cornice embellished with decorative moldings, usually dentil work

• Multi-pane windows are never paired, and fenestrations are arranged symmetrically (whether vertical or horizontal), usually 5 across

• Roof: 40% are side gabled; 25% gambrel; 25% hipped

• Chimneys on both sides of the home

• A portico in the middle of the roof with a window in the middle is more common with postGeorgian styles

• Small 6-paned sash windows and/or dormer windows in the upper floors, primarily used for servants’ quarters.

• Larger windows with 9 or 12 panes on the main floors

24 Historic Structures

Design Guidelines 25

Daniel Donnelly House, WA-II-417

Photo Credit: Paula Stoner Dickey, MIHP

Ditto Knolls, WA-II-093

Photo Credit: WCHT

Hitt-Cost House, WA-II-252

Photo Credit: WCHT

Federal – 1780 to 1840

Houses of the Federal period, constructed during the first years of the new republic, retained the general form of their Georgian predecessors, but were characterized by more delicate decorative detailing that often incorporated elements derived from early Greek and Roman design.

• Fanlight over door (almost always rounded, rarely squared), sidelights

• Classical/Greek detailing of entryway, Palladian windows, balustrades, oval/ circular

• Rooms in some high-style examples

• Fenestration is symmetrical as Georgian style.

• Double-hung sash windows for first time (Georgian also)

26 Historic Structures

Woburn Manor, WA-II-458

Ferry Hill, WA-II-035

Rose Hill, WA-I-374

Photo Credits: WCHT

Greek Revival – circa

1830 to 1860

The Greek Revival style spread rapidly across America between 1830 and 1850. Two factors helped increase the style’s popularity. Archaeological excavations during this period increased public awareness of ancient Greece, and citizens of the new American republic sympathized with modern Greece’ s involvement in its war for independence (1821-30).

• Low-pitched gable, hipped or shed roof; gable may face front

• Portico or recessed entrance; pilasters, square posts, or classical columns

• Entrance with transom and sidelights

• Broad frieze below cornice, sometimes with rectangular attic windows

• Trim incorporates geometrical forms, “bull’ s eye” and foliated motifs

Design Guidelines 27

Plumb Grove Mansion, WA-V-015

Italianate/Italian

Villa – circa 1830 to 1880

The Italianate style developed as part of the Picturesque movement which was a reaction against classical formality. The style has two basic forms. Italianate buildings based on Renaissance models are rectangular in plan with symmetrical façades, whereas the “Italian Village” type is based on the designs of rural farmhouses in Italy and are characterized by an asymmetrical L-shaped or T-shaped floor plan with a tall tower.

• Low-pitched gable or hipped roof (attached buildings may have shed roofs)

• Eave cornice with decorative brackets

• Walls are given a smooth finish; finely coursed brickwork with narrow mortar joints is typical; cut stone and stucco were also used

• Enriched detailing such as string courses and quoins

• Tall, narrow windows, often with roundarched heads

• Windows may have elaborate frames, hoods, bracketed lintels, or pediments

• Porch or arcade may span the façade, or a small portico may define the entrance

28 Historic Structures

Streetscape in Williamsport, WA-WIL-025, WA-WIL-026 & WA-WIL-027

Second Empire – circa

1860 to 1890

The Second Empire style is most readily recognized by the characteristic mansard roof; a hipped roof of double pitch. The lower slopes of the roof, just above the building walls, are steeply pitched to create a usable upper story lighted by dormer windows. This roof form is named for the seventeenth-century French architect François Mansart. The style became popular in France during the Second Empire (185270) and spread to the United States in the 1860’s.

• Generally symmetrical, rectangular in plan and 2 ½ stories high

• May have a projecting entrance mansard roof, usually covered in slate; sometimes slates of various shapes and colors are used to create intricate patterns

• Lower slopes of roof may be straight, convex, or concave; windows may be topped with semicircular or segmental arches and often have bold molded heads

Design Guidelines 29

Rufus Wilson Complex, WA-V-074

Queen Anne and other Victorian Styles – circa 18801910

The Queen Anne style is derived from medieval English architectural forms.

• Asymmetrical plan and massing

• Variety of surface treatments, textures, and colors

• Elaborate decorative trim, shingles and brickwork

• Irregular roof line with multiple steep gables

• Conical-roofed tower at corner

• Façade may have various projecting bays

• Row houses often have second-story oriel windows

• Porch may span façade, sometimes wraps around corner of building

• Double-hung windows often have multiple small lights in upper sash; sometimes forming a border around a single large pane. These small lights may be either clear or include colored stainedglass windows and transoms

Historic Structures

Eby House, WA-I-328

Colonial Revival – circa 1876-1920

The American Centennial of 1876 prompted a revival of interest in the nation’s heritage. As a result, architects began to study the building forms and detailing of the Colonial period. The return to these historical precedents was partly a reaction against the unrestrained exuberance that characterized Victorian era design. Colonial Revival buildings often combine turn-of-the century building forms with decorative elements derived from eighteenth-century architecture. This detailing is often over-scaled and sometimes incorporates features of the Queen Anne style, whose period of popularity overlapped that of the Colonial Revival.

• Generally symmetrical façade, 2 or 2-1/2 story height

• Gabled, hipped or gambrel roof form

• Masonry or frame construction

• Brick may be laid in Flemish bond pattern

• Frame buildings covered with wood siding in bevel profile, or with wood shingles

• Multi-pane sash windows

• Porches may have heavy tapered columns and balustrades with square or turned balusters

• Entrance located in the center of the façade, with transom and sidelights

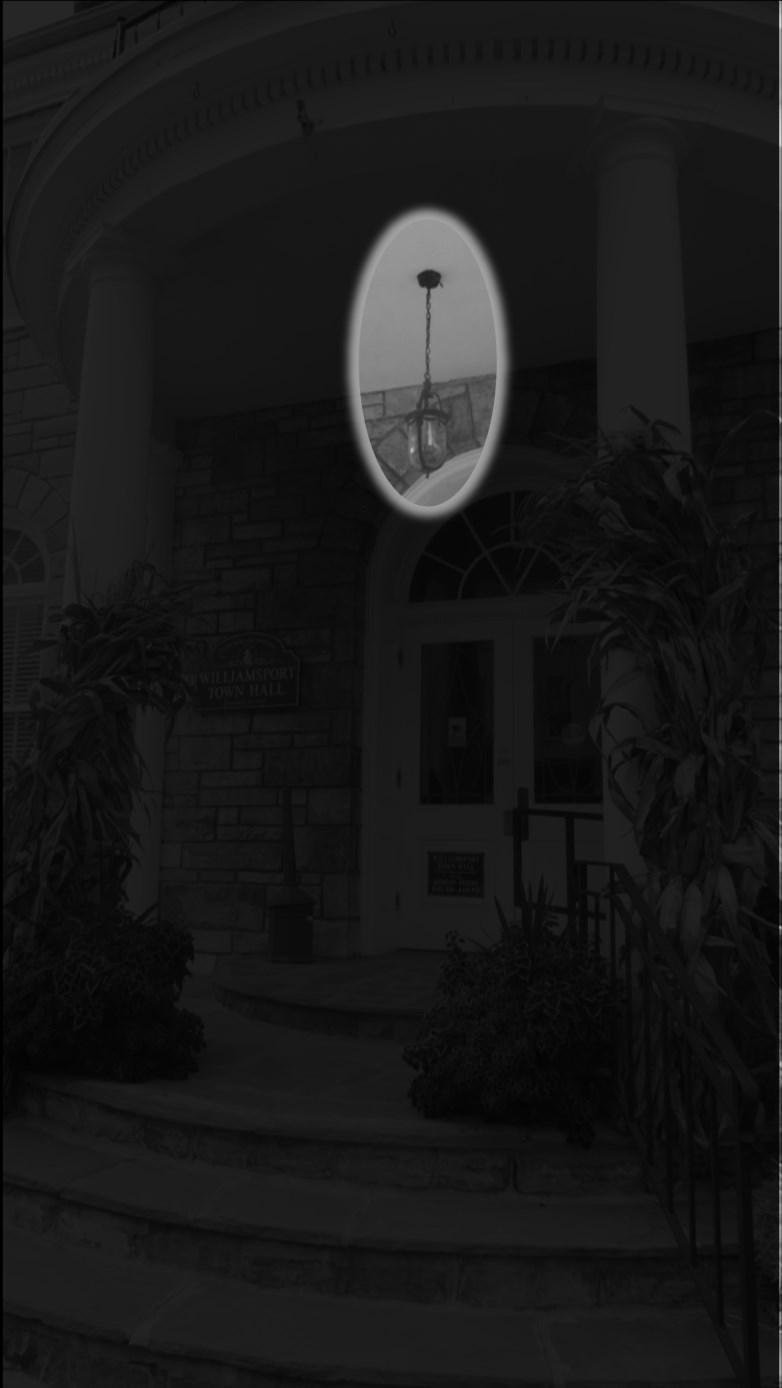

Classical Revival – circa 1900-1920

Developed in America in the first quarter of the twentieth century, this style was popular for public and commercial buildings; its monumentality was frequently used in the construction of bank buildings. The Neoclassical Revival employed features from Greek antiquity such as Ionic and Corinthian columns and pedimented porticoes to embellish balanced, regular compositions. Wall surfaces were smooth and often were finished in fine materials such as marble.

• Classical Greek and Roman architectural elements: columns, round arches, heavy entablatures, often with elaborate detail

• Symmetry in plans, use of wings or corner pavilions

• Used for government and civic buildings; common for banks

Design Guidelines 31

WA-II-385, Shepherdstown Pike, Sharpsburg

WA-HAN-055, West Main St., Hancock

Twentieth Century 1900-1950

The modern styles of architecture are a result of America’s efforts to design inexpensive housing that was eye-pleasing and functional, but could be built quickly to keep up with the fast-paced effects of the industrial revolution. Builders stopped constructing elaborate Victorian styles in favor of homes that were compact, economical, and informal.

A predominant architectural style of Washington County in the twentieth century, the American Foursquare, is known by a variety of terms. These include box house, a cube, a double cube, or a square type American house. The style first appeared about 1890 and remained popular well into the 1930s. The American Foursquare lent itself to endless variations and finish details by individual buyers.

Bungalows, often associated with the Craftsman Style, are characteristically smaller houses. These structures were predominantly built after 1905. Construction of the style began in California, the state where the architects most associated with the Craftsman style, Greene and Green, were based. This style of house was frequently found in pattern books for purchase. Some were even offered as complete packages including materials to be built on site.

Ranch style houses, also known as the American ranch, California ranch, rambler, or rancher, is another of the domestic architectural styles that has now aged sufficiently to have become of interest. First built in the 1920s, the ranch style was extremely popular among the booming post-war middle class of the 1940s to 1970s. The ranch house is noted for its long, close-tothe-ground profile, and minimal use of exterior and interior decoration.

32 Historic Structures

Foursquare

• Simple floor plan

• Boxy, cubic shape

• Full width front porch with columnar supports and wide stairs

• Offset front entry in an otherwise symmetrical façade

• 2 to 2 ½ stories

• Pyramidal, hipped roof, often with wide eaves

• Large central dormer

• Large single light windows in front, otherwise double hung

• Incorporated design elements from other contemporaneous styles, but usually in simple applications

Bungalow

• Low-pitched, gabled roof (front, side or cross gabled roof)

• Wide overhanging eaves

• Exposed rafters under eaves

• Decorative brackets (knee braces or corbels)

• Front corner porches under roofline

• Tapered or squared columns supporting roof or porch

• 4 over 1 or 6 over 1 sash windows

• Hand-crafted stone or woodwork

Ranch Style

• Single story

• Horizontal, rambling layout: long, narrow and low to the ground

• Rectangular, L-shaped or U-shaped design

• Open floor plans

• Low pitched rooflines with wide eaves, often hipped or gabled

• Attached garage or carports

• Large windows and sliding glass doors

Design Guidelines 33

Maugansville, WA-I-804

Bungalow, 1400 Block of Sharpsburg Pike, Hagerstown

Ranch, Benny Drive, Hagerstown

Mill Complexes

Washington County has a rich history in agriculture and forestry. These industries required local mills to process timber and grain products into commodities for locals. Many larger creeks in the County, such as Beaver Creek and Antietam Creek, provided the water power necessary for locals to construct the dams, races, and sluice boxes that ensured those waters were harnessed effectively. There are mills scattered along waterways throughout the County. Early mills were of log construction. Remaining mills are predominantly limestone construction. The mills contain additional features such as water wheels and milling machinery including millstones. Support buildings associated with storage of the raw or processed materials are common. The homes of the operators or owners are also part of the complex. Communities frequently sprang up directly adjacent to these complexes. Many mills are associated with early large landowners of the County. There are approximately 50 sites associated with mills on the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties in the County.

• Masonry exterior

• 2-4 stories

• Built into the bank of water source

• Rectangular shape for Mill

• Gable roof

• Wood shingle or metal roof

• Windows along all façades of varying fenestration

• Support buildings

• Stream engineering including races, sluices and dams

34 Historic Structures

Design Guidelines 35

Doub’s Mill; Newcomer’s Mill, WA-II-090

Photo Credit: WCHT

Rose’s Mill, Pleasant Grove Mills, WA-I-413

Common Accessory Structures—Pre 1930

Many structures within the County are part of a complex of buildings, all of which contribute to the history of the County and site. These structures create a historic landscape. They are often of similar construction to the main structure on the property, but they could have been built before or after the main structure depending on the development of the complex.

Bank Barn

These 2-story structures are built into a hill or bank with the lower level being equipped for housing animals while the upper levels are used for storage. The second floor is often extended, or cantilevered, over the first providing shelter for animals. Columns or posts may support the overhangs. Barns can be constructed of masonry or wood. The narrow-end side walls are frequently brick or stone with openings for ventilation. The openings form a decorative pattern. In some cases the barn may include distinctive paint colors such as red or white. Sign painters used the large exterior wall spaces for design advertisements. Cupolas and weather vanes are often present in varying number and configurations.

Spring House

These structures are typically single story or two story masonry construction. They are varying sizes in the County from small 1-room buildings to larger multi room buildings. They were built over a spring on the farm complex and were used for the protection of the water source and for refrigeration. Location of the house and barn in relation to the spring would be an important component in the landscape of the complex. They were often distanced from animal husbandry buildings to protect the water source.

36 Historic Structures

Bank Barn at WA-II-286

-IV-004

Mong-Linger Farm, Spring House, WA

Summer Kitchen

These single-story structures were usually built directly behind a main house in a building complex. They were constructed of various materials including log and stone, but generally had a large stone fireplace on the narrow-end side wall. They had 1 to 2 bays of windows with a single entry door. Summer kitchens were for cooking and canning during the summer months to keep the heat from the fireplace out of the main house. In some cases these structures are now attached to the main structure of the complex through enclosure or breezeways.

Smokehouse

These were typically single-story structures of masonry (stone or brick). Structures could also be made from frame, log or a combination. Gabled roofs were predominant, but there are examples of pyramidal roofs in the County. These were used for the preparation and preservation of food. To contain the smoke being used for preservation, they would typically have a single door with no chimney or windows . Hardware for hanging or laying meats to dry may still be present in the structures. They were usually sited near the house and may have been close to the summer kitchen.

Stone wall and Stone Fence - 1750-1850

Stone walls in the County are typically cut stone laid with mortar and topped with either angular or flat stone. These are prominent features around ecclesiastical sites. Often visible from the right-of-way and adding to the rural landscape are stone fences, which are fieldstone, typically flat, laid without mortar. They are frequently found along property lines or dividing pasture and croplands in the rural areas. Each of these are often several courses in height making them at least 3 feet high.

Design Guidelines 37

Stone Fence along Dam #4 Rd, WA

-II-275

Stone Walls at St Marks , WA-II-024

Summer Kitchen-Plumb Grove, WA-V-015

Photo Credit: CSHA

Smokehouse, Oak Springs Farm, WA-V-093

Photo Credit: CSHA

Commercial Buildings – 1890 to 1930

Commercial buildings dating from 1890 to 1930 are distinguished by large windows arranged in groups on their façades. Developed in Chicago in the 1890s, this style drew upon the structural innovation of steel-frame construction, which enabled much larger window openings than were possible with traditional bearing wall masonry. Beginning in the 1870s, molded, glazed terra cotta became a popular substitute for carved stone. It was used extensively to finish commercial building façades in the early twentieth century. Terra cotta was popular at this time because it could be used to mimic much costlier stone such as marble and granite.

• Vertical emphasis, typically 2-4 stories in height

• Flat roofs

• Masonry wall surfaces

• Three-part windows or projecting bay windows

• Decorative cornices

• Steel and beam construction

• Ground floor storefronts

Commercial Buildings – Post 1930

Art deco

• Sharp edge, linear appearance

• Smooth wall surface usually stucco

• Geometric forms, zigzags and chevrons or stylized motifs on the façade

• Low relief decorative panels

• Towers and vertical elements

• Strips of windows with decorative panels

• Stepped or set back front façade

• Fluting around doors and windows

38 Historic Structures

Williamsport Barbershop, WA-WIL-020

Professional Arts Building

WA-HAG-057

Gas Stations—Post

1910

• Varied exterior materials including frame, rusticated concrete block, and stucco

• Historicized roofs, matching borrowed architectural style or flat roofs with very low slope

• Borrowed architectural styles to blend to surrounding neighborhood

• Box-Type Stations, which can be in the Art Moderne style

• Multi-use, structures that can include convenience store, restaurants or car repair garages attached

• Service bays

• Attached or detached canopies being flat or stylized

• Gas pumps that could be covered by canopies directly adjacent to structure or very close to a road right-of-way

• Signage indicating name or services

• Associated outbuildings (e.g., car washes, garages, storage sheds)

Additional Resources

Preservation Brief #46 The Preservation and Reuse of Historic Gas Stations

Design Guidelines 39

Himes General Store, Weverton Road, WA-III-031

Gas Station, Southeast corner of Wilson Blvd. and S. Potomac St., Hagerstown

Ecclesiastical Architecture

Ecclesiastical architecture was dramatically influenced by English architect James Barr’ s Anglican Church Architecture. It was first published in 1842 and was dedicated to the Oxford Society for Promoting the Study of Gothic Architecture. A second edition followed in 1843, and a third, in 1846

• Simple one storied, gable roofed structures

• Masonry structure walls

• Gothic or Romanesque revival architectural characteristics including pointed arch windows, which may include tracery and doors with transoms

• Single or double entrance doors

• Steeples, towers with bells

• Varied sash configurations but may include decorative stained glass in multiple bays

• Outbuildings, adjacent cemeteries, and structures such as stone walls may contribute to landscape and be similarly styled

40 Historic Structures

Tolson’s Chapel, WA-II-202

Church of the Brethren, WA-II170

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, WA-III-012 Manor

Schoolhouses

Early twentieth century schoolhouses in Washington County tended to be one room, single-story structures. The exterior materials of the school houses varied with wood, brick and stone being common. The building shape is usually rectangular or square and often includes a gable end roof with prominent front entrances. Several bays of windows allowed adequate lighting of the classroom. The buildings may also include a bell or belfry top. There are many surviving school houses in the County that have been repurposed into uses such as community buildings, museums, or commercial businesses.

Historic Markers

Washington County is bordered on the north by one of the most famous boundaries in the United States, the Mason-Dixon Line. Settling a property dispute between the Penns of Pennsylvania and the Calverts of Maryland, these mile markers were decorated and placed at one mile intervals along what is now the northern State Line of Maryland. These markers are large blocks of limestone with engravings on each State’s side. The historical significance of these mile markers and the line they mark spans from colonial times through the Civil War.

The National Road, or Old National Pike as it’s also known, has historical markers along the north side of its length. The State of Maryland owns the stones as they reside in the right-ofway. The first stone was placed at the Baltimore Courthouse; they continue along the route throughout the County at one mile intervals. These are much smaller than the Mason-Dixon markers. They are engraved on the side facing the road indicating the distance to “B” or Baltimore. These stones are also varying in their material. Some are limestone; some are quartzite. These stones and other historic markers are often on the National Register and should never be moved, stabilized, or otherwise altered without the express consent and supervision of the Maryland Historical Trust.

Design Guidelines 41

Wilson School, WA-V-007

National Road Mile Marker, WA-II-728

This page is intentionally left blank

42 Historic Structures

Standards for Review

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for Preserving, Rehabilitating, Restoring & Reconstructing Historic Buildings provides an explanation of treatments for historic properties and their respective standards and guidelines. The Standards were originally developed in 1976 and have had subsequent updates. The HDC will use the most recent edition published by the National Park Service in conjunction with the Washington County Historic Guidelines for review. The Standards were originally developed to ensure that properties receiving federal funding or federal tax benefits have a consistent review. They are written to apply to a wide variety of resource types and have found wide use at the Federal, State and Local levels as a basis for design guidelines.

Design Guidelines 43

Barn at the Dennis Farm, WA-V-025

Photo Credit: CSHA

Four treatment types are described in the Secretary of Interiors (SOI) Standards: Preservation, Restoration, Reconstruction, and Rehabilitation.

Preservation is the maintenance and repair of existing historic materials or preservation of the structure in its current form with little or no replacement or new addition.

Restoration aims to return a building to a specific time period, acknowledging the need to remove changes since that time and recreate previous aspects that have been removed.

Reconstruction re-creates vanished or non-surviving portions of a property for interpretive purposes.

While these three treatments may be applied at the owner’s request during HDC review, The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation are the basis of the Washington County Historic Design Guidelines.

Standards for Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is defined by the SOI as the act or process of making possible an efficient compatible use for a property through repair, alterations, and additions, while preserving those portions or features that convey its historical, cultural, or architectural values (36 CFR 68.2(b)). The Standards are as follows:

1. A property will be used as it was historically or be given a new use that requires minimal change to its distinctive materials, features, spaces, and spatial relationships.

2. The historic character of a property will be retained and preserved. The removal of distinctive materials or alteration of features, spaces, and spatial relationships that characterize a property will be avoided.

3. Each property will be recognized as a physical record of its time, place, and use. Changes that create a false sense of historical development, such as adding conjectural features or elements from other historic properties, will not be undertaken.

4. Changes to a property that have acquired historic significance in their own right will be retained and preserved.

5. Distinctive materials, features, finishes, and construction techniques or examples of craftsmanship that characterize a property will be preserved.

44 Historic Structures

6. Deteriorated historic features will be repaired rather than replaced. Where the severity of deterioration requires replacement of a distinctive feature, the new feature will match the old in design, color, texture and, where possible, materials. Replacement of missing features will be substantiated by documentary and physical evidence.

7. Chemical or physical treatments, if appropriate, will be undertaken using the gentlest means possible. Treatments that cause damage to historic materials will not be used.

8. Archeological resources will be protected and preserved in place. If such resources must be disturbed, mitigation measures will be undertaken.

9. New additions, exterior alterations, or related new construction will not destroy historic materials, features, and spatial relationships that characterize the property. The new work will be differentiated from the old and will be compatible with the historic materials, features, size, scale and proportion, and massing to protect the integrity of the property and its environment.

10.New additions and adjacent or related new construction will be undertaken in such a manner that, if removed in the future, the essential form and integrity of the historic property and its environment would be unimpaired.

These Standards are the underlying basis of the SOI guidelines which provide explanations that are applicable to a wide range of projects. The County’s Design Guidelines are meant to supplement and further provide local examples.

Design Guidelines 45

This page is intentionally left blank

46 Historic Structures

These Design Guidelines are made available to assist owners of historic buildings in understanding how historic preservation policies affect their plans to maintain, preserve, or enhance their properties. The information provided is intended to assist with planning and implementing projects in a way that is mindful of the historic nature of both the property being reviewed and its surroundings.

If appropriate, the Historic District Commission may reference specific treatment guidelines from The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation that may not be listed in this document either due to summarization or update to the Secretary’ s documentation. References to appropriate documentation will be made in any Certificate of Appropriateness that is issued. It is recommended that the Guidelines included be consulted before application with the appropriate County agency or before applying for a Certificate of Appropriateness with the Historic District Commission.

Design Guidelines 47 Guidelines

Gum Tree Farm, WA-II-371

These guidelines acknowledge that buildings have been and will be altered over time. They are not meant to discourage change but rather to encourage compatible and sensitive change to the site and existing buildings. It is important to note that the Commission is first and foremost a resource and can provide consultation regarding proposed changes before work has begun or applications for permits have been made. In fact, this is preferred, especially in cases where Local, State, or Federal tax credits may be sought.

Several key themes to the guidelines should be considered no matter the topic discussed. They include:

1. Identify, retain, and preserve features that are important in defining the overall historic character of the building or site. If repair or replacement is necessary, use materials that match the original as closely as possible. The Commission can help to identify key site and building features, which is the first priority before standards and guidelines can be applied.

2. Protect and Maintain features by practicing routine maintenance and ensuring site protection through documentation of the resource and consideration of resource details such as proper drainage around the site and its resources.

3. Repair or replace damaged or missing units using materials that match the original as closely as possible. If a feature is missing, it should be replaced based on documentary or photographic evidence. If no evidence of the design of the feature exists, a new design compatible with similar details existing on the building or site as well as the overall character of the building or site should be used.

Setting and Site

One of the seven considerations for resource integrity for National Register consideration is setting. Setting is the large scale physical environment of a historic property. The setting extends beyond the features directly on a parcel and can involve the greater surrounding landscape. The relationship of buildings to each other, setbacks, fence patterns, views, circulation systems, and landscaping all contribute to the setting. The building site consists of a historic building or buildings, structures, and associated landscape features and their relationship within a designed or legally-defined parcel of land. A site may be significant in its own right or because of its association with the historic building or buildings. The Zoning Ordinance has an additional definition for the term site, which includes the physical as well as the visual elements. (Washington County, Maryland, 2021, p. 190)

48 Historic Structures Themes: Identify Retain Preserve

Viewsheds

The views to and from historic resources, districts, or rural communities contribute significantly to their character. Viewsheds can be large in scale, such as the viewshed around the Antietam National Battlefield or smaller such as the view from a window or fixed point around a historic structure. The Zoning Ordinance has measures in place, such as the Antietam Overlay and Historic Preservation Overlay, which offer protection to viewsheds around identified resources. But it’s important to acknowledge the varying scale of viewsheds and impact their integrity can have on the context of the resources in the County.

Site and Landscape Design Features

Landforms, Plantings, and Landscapes

Landforms include, but are not limited to, terraces, berms, and grading on a site. Trees, hedgerows, shrubs, cultivated fields, and formal and informal gardens are among the historic plantings and landscapes that are important historic features in Washington County. Along with landforms and features, they provide some of the greatest impact on the setting for many of the historic resources in the County. Unlike most materials used in historic buildings and structures, plantings and landscapes are subject to change from season to season and from year to year. Mature plantings often set the context of both public and private spaces in historic structures.

Fences and Walls

Throughout the County a variety of fences and walls mark property boundaries, confining livestock, protecting crop fields, and providing security and privacy. The materials and construction range from metal to stone to wood; however, stacked or mortared limestone or wood are the most common. Stylistically, the design of fences and walls is often related to the principal structures on the property. Distinctive gates and corner posts are also distinguishing features of many historic fences and walls.

Design Guidelines 49 Protect Maintain Repair Replace

-II-170 Looking North toward WA-II-184

Manor Church of the Brethren, WA

Circulation Systems (Driveways, Walkways, and Parking Areas)

Circulation systems serve the purpose of allowing movement of pedestrians and vehicles into and around historic resources. The materials, extent, and pattern of these systems can vary dramatically between urban, suburban, and rural settings. More urban or suburban settings tend to include short, straight, paved concrete or asphalt driveways. Sidewalks and walkways are variable in material, as well, but usually parallel the streets and are separated from private walks by a step or change in grade. Buildings in these areas are typically facing the street. Parking areas are either on-street or in asphalt parking lots. The more rural systems tend to include long, curved driveways with a gravel base. The rural systems also sometimes include gateposts flanking the entry to the drive and trees to either side of the driveway. Walkways constructed of gravel, concrete, brick, or stone are still found in the rural area often linking formal or informal parking areas, gardens, or entrances to the building.

Guidelines For Existing Setting and Site

1. Features should not be moved or relocated, nor should circulation routes be interrupted.

2. Spatial relationships between buildings on sites should be maintained.

3. If possible, intrusions into viewsheds should be removed or masked with appropriate vegetation.

4. Existing plantings should be maintained by fertilizing, pruning, treating for disease, or in other appropriate ways. If replacement due to deterioration or disease is necessary, it should be a plant of similar size and texture. Use of native species of plants is encouraged when appropriate. Invasive species should be avoided or removed if possible. The Commission recommends referencing the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MDDNR) or United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) invasive species information when considering changes to plants.

5. Maintain major patterns of vegetation in working landscapes.

6. Any changes made to features surrounding a historic resource should be compatible with the existing. An archaeological assessment should be done before making any changes.

7. Disturbance to the earth and terrain should be minimized, especially around building foundations.

8. Maintain proper site drainage to prevent water damage.

9. See also Key Themes. (p.48)

50 Historic Structures Themes: Identify Retain Preserve

Walkway, Plumb Grove, WA-V-015

Guidelines for Proposed Setting and Site

The guidelines for existing site details should be consulted in addition to those below.

1. Select new plantings and design changes to landscapes adjacent to historic properties to be compatible with the existing. Locate new plantings so that they maintain or enhance the property’s historic character and its context.

2. Consideration as to whether, at maturity, plantings will affect building systems, such as gutters, foundations, should be given in design.

3. The location of new site features, including fences, walls, parking, should be compatible with the overall character of the historic resource and its landscape. Review of the proposed design will include materials, height, configuration, scale, and details.

4. Consider screening parking areas or other added site features when appropriate and feasible.

5. Existing historic circulation patterns should be considered foremost in the design and the location of new parking areas. They should not be within the primary viewshed of a historic resource or landscape.

6. Access points for vehicles or pedestrians to parking areas should minimize impacts on the historic landscape and its rhythm through use of rear parking and alley access where feasible.

7. See also Key Themes. (p.48)

Additional Resources:

Preservation Brief #36 Protecting Cultural Landscapes: Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes

Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties and Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes

MD DNR Invasive Species Information https://dnr.maryland.gov/Invasives

USDA Invasive Species Information https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/

Design Guidelines 51 Protect Maintain Repair Replace

Patios, Decks, and Other Site Features