Medicalsocietieshavebeenaroundforcenturies,and theycontinuetoplayanimportantroleinthehealthcare industrytoday.Thesesocietiesprovideaplatformfor physicianstonetwork,shareknowledge,andlearnfrom eachother.Whiletherearemanydifferentmedical societiesatthenationalandinternationallevels,it's equallyimportantforphysicianstoconsiderjoiningtheir localmedicalsociety.Inthisarticle,we'llexplorewhya physicianshouldjointheirlocalmedicalsociety.

Oneoftheprimarybenefitsofjoiningalocalmedicalsocietyistheopportunitytonetworkwithotherphysicians andhealthcareprofessionalsinthearea.Thesesocietiesoftenhostevents,suchasconferences,seminars,and workshops,wherememberscanmeetandsharetheirexperiences.Networkingcanhelpphysiciansbuild relationshipswithcolleagues,whichcanleadtoreferrals,collaborations,andevenjobopportunities.Byjoininga localmedicalsociety,physicianscanestablishthemselvesasactivemembersofthehealthcarecommunityintheir area,whichcanenhancetheirreputationandcredibility.

Medicalknowledgeandpracticesareconstantlyevolving,andit'sessentialforphysicianstostayup-to-datewith thelatestdevelopmentsintheirfield.Localmedicalsocietiesoftenoffercontinuingeducationprograms,which provideopportunitiesforphysicianstolearnnewtechniques,technologies,andtreatments.Theseprogramscan helpphysiciansimprovetheirclinicalskillsandstayinformedaboutemergingtrendsintheirspecialty.Inaddition, continuingeducationcreditsareoftenrequiredforlicensureandboardcertification,sojoiningalocalmedical societycanhelpphysiciansfulfilltheserequirements.

Localmedicalsocietiesalsoplayanimportantroleinadvocatingforphysiciansandtheirpatients.Thesesocieties worktoinfluencehealthcarepolicyatthelocal,state,andnationallevels,advocatingforissuesthataffect physiciansandtheirpatients.Byjoiningalocalmedicalsociety,physicianscanhaveavoiceintheseadvocacy effortsandhelpshapehealthcarepolicyintheircommunity.Inaddition,localmedicalsocietiescanprovidea platformforphysicianstoadvocateforissuesthatareimportanttothem,suchasaccesstocare,patientsafety,and medicalliabilityreform.

Localmedicalsocietiesalsoofferopportunitiesforphysicianstodeveloptheirleadershipskills.Manysocieties haveleadershippositions,suchascommitteechairs,boardmembers,andofficers,whichprovideopportunitiesfor physicianstotakeonleadershiprolesandmakeadifferenceintheircommunity.Servingina leadershiprolecanhelpphysiciansbuildtheirprofessionalnetwork,enhancetheircommunicationskills,and developtheirstrategicthinkingabilities.

Finally,joiningalocalmedicalsocietycanprovidephysicianswithasenseofcamaraderieandsupport. Physicianscanoftenfeelisolatedintheirpractice,andjoiningamedicalsocietycanhelpthemconnect withlike-mindedindividualswhosharetheirpassionformedicine.Thesesocietiescanprovideaforum forphysicianstodiscusschallengestheyarefacing,shareexperiences,andprovidesupporttoone another.

Inconclusion,joiningalocalmedicalsocietycanprovidephysicianswithnumerousbenefits,including networkingopportunities,continuingeducation,advocacyandpolicyinfluence,leadershipopportunities, andcamaraderieandsupport.Byjoiningalocalmedicalsociety,physicianscanenhancetheir professionaldevelopmentandmakeapositiveimpactontheircommunity.

Warmly,

J. Richard Rhodes, MDAt night, emergency departments across the country are filled with persons suffering the adverse effects of drug abuse or actively experiencing an overdose. Unfortunately, these patients have become little more than routine, especially in America’s urban healthcare facilities.According to the Centers for Disease Control, in 2020 alone, more than 93,000 individuals died from drug overdoses—an increase of over 30% from the prior year. Three-quarters of these deaths were due to opioid overdose, rather than from prescription medicationsoralcohol.Itisspeculatedthatthis increase is an effect of the isolation and stress that many endured throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this figure serves to highlightanequallygrimtruth:theresourcesto treat substance abuse disorder patients are simply not there. Because of this paucity, preventable deaths from a treatable disease take the lives of tens of thousands of Americanseachyear.

During the year and a half that Joseph worked in an emergency department, he saw many complex patients, but there was one who particularly affected him. Upon arrival at the ER one day, Joseph came face-to-face with a patient on the brink of death. This young woman was progressing through an overdose on opioids before his eyes, with her chest remaining frozen still and the color drained fromherface.

lifesaving power of Narcan.As the following hours ticked by, the young woman whose death he had nearly witnessed slowly recovered and was back on herfeetbeforethedaywasover.

Months later, and without another visit from this patient, it was discovered that she was homeless. Despite her trying circumstances, she had sought rehabilitation and, with time, was able to overcome her addiction. Joseph’s account provides just one tale among many as to why education about addiction and increasing the use and availability of Narcan is necessary if we are to provide substance use disorder patients the chance at life they deserve. Truly, this medication has the power to keep familieswhole,livesintact,andgravesempty.

Within minutes of his first visitation, this patient was given the lifesaving medication Narcan, and immediately regained consciousness and the ability to breathe. In this singledramaticepisode,Josephlearnedofthe

Through various social and medical measures, patients like this one could also overcome their addictiontoopioids.Onewaytohelpthosefighting addiction is to increase the availability of Narcan and to take a community-based approach to fight opioid addiction. A study in Pittsburgh performed by Dotson et. al (2018) implemented several social interventions in the interest of discovering which were most effective at reducing the mortality of opioid overdoses. The study found that increasing the distribution of Narcan in pharmacies and allowing it to be dispensed without a prescription, in conjunction with bystander training on recognizing the signs of opioid overdose and the use of Narcan, significantly reduced opioid overdose deaths. This model is both applicable and readily implemented in many other communities in this country and could serve as a model across the state of Florida. Emily and Joseph are active in several student organizations that are working toward expanding the availability of Naloxone with the hope to save numerous lives across the state of Florida.

Paul M. Graham, M.D.According to the American Cancer Society, skin cancer is by far the most common type of cancer worldwide. Non-melanoma skin cancer accounts for approximately 3million cases in the United States eachyear withtheincidence continuing toclimb. Approximately1out ofevery 3cancers diagnosed worldwideisaskincancer.Additionally,1outofevery5Americanswill develop a skin cancer during their lifetime. The two most commontypes of non-melanoma skin caner arebasal cell carcinoma (BCC)andsquamous cell carcinoma (SCC).Basal cell carcinomaaccounts for approximately 80%of all non-melanoma skin cancer diagnoses. Chronic sun exposure is the single most important cause of all forms of skin cancer with damage oftenoccurring during childhood and adolescence years in those who practice poor sun protection habits.

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer worldwide, occurring primarilyin fair-skinned individuals with a history of sun exposure. Risk factors include numerous blistering sunburns, immunosuppression, family history of BCC, and a history of radiation exposure. Basal cell carcinoma develops from cells contained withinthe bottom layer of the epidermis called the basal layer. Fortunately, theyare often slow-growing with a very lowrate of cancer cell spread (metastasis) outside the primary site of occurrence. It is very importantto have all BCCs treated to preventlocal surroundingskindestructionifleftuntreated.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) isthesecond most common form of skin cancer worldwide.The majority of SCCs develop in individualswith a history of chronicsun exposure. The closer to the equator one lives, the more likely that individual willdevelop SCC. The immune system also plays an important role in the development of SCC. Those that are immunosuppressed or on immunosuppressive medication have a significantly higher risk of developing SCCs. Certain high-risk types of thehuman papillomavirus (HPV) may also play a role in SCC development. This type of skin cancer develops from cells that make up the bulkof the epidermis. Squamous cell carcinomahasaslightlyhigherriskduetoitsabilitytospreadintobloodvesselsandnerves.Itisforthisreasonwhy theyshouldbeproperlytreatedearlyon.

Numerous treatment options exist for these non-melanoma skin cancers, including the use of topical immune system modifyingmedications (5-flurouracil, imiquimod, ingenol mebutate), cryotherapy (freezing), electrodessication and curettage(“scraping and burning”), surgical excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. After beingdiagnosed with a non-melanoma skin cancer, your physician will determine the besttreatment option based on the lesion size, type, location, and aggressiveness of the skin cancer. Some skin cancers have small “roots” that may extend deeper in the skin, beyond what we can see on the biopsy. Intheseinstances,surgicalinterventionisneededtocompletelyremovethe skincancer.

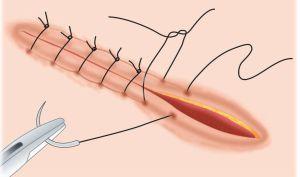

Mohs micrographic surgery provides a highly specialized and effective treatment option in patients with qualifying skincancers.Thisprocedurehasa97-99%curerate,which is superior to manycancer treatments in medicine. Mohs micrographic surgery was developed in 1938 by Dr. Frederick Mohs, a surgery professor at the University of Wisconsin. With this specialized procedure, the skin cancer is conservatively removed while simultaneouslyattempting to preservenormal skin. The removed portion of theskinis then carefully mapped, color-coded, and prepared for examination under the microscope, which all takes place withinthesameday.

The Mohs surgeon will meticulously examinethe tissue specimen and determine if any residual skin cancer is present. If residual tumor is found, the Mohs surgeon will only go back to that specific location to remove another small portion of tissue. One of the most important aspects of Mohs microscopic surgery is the ability to examine approximately100%of the skin margins under the microscope, ensuring that all of theskin cancer is completely removed prior to closingthesurgicalwound.

In contrast, a conventionalsurgical excision requiresseveral days for both tissue processing and microscopic examinationby a trained dermatopathologist. During this process, only approximately 1%of the skin margins are examined. This small percentage of examined skinmay contribute to a higher rate of recurrence if adequate surgical margins are not taken at the time of the surgery. In the event that more skin cancer cells are found in the examined skin,thesurgeonwillthereforehavetoperformasecondsurgicalexcisiontocompletelyremovetheresidualtumor.

∙ Largeskincancersonthehead andneck

∙ Skincancersinareaswhere preservationofnormalskinis vital

∙ Face,scalp,neck,nose, ear,eyelids,lips,hands, andgenitalia

∙ Sitesofhightumorrecurrence andriskoftumorspread

∙ Recurrentskincancers

∙ Aggressiveskincancers

Mohs micrographic surgery involves a series of stages consisting of the surgical excision followed by immediate microscopic examination of the tissue. TheMohs surgeon is focusedon removingthe least amount of tissue, while still providing adequate surgical margins to completely removethe skin cancer. Initially, it is not possible to know the final sizeof the surgical wound. This is often dependent on the number of stages that are required to completely remove the skin cancer cells. For reference,approximately50%ofallMohsmicrographicsurgery

cases require at least 2 stages for complete skin cancer clearance.After all theskin cancer cells are removed, the Mohs surgeon will surgically close the wound and the procedure will becomplete. Some wounds may be too large for simple closure and willrequire a skin graftor flap. In this case, the Mohs surgeon will design a closure that willpreserve the skin’s function and movement, while reducing the appearance of the scar. Stay tunedforafuturearticleonskingraftsandflapsusedinwoundclosure.

FollowingMohs micrographic surgery, it is recommended to minimize strenuous activity to reduce tension on the wound and decrease the risk of bleeding from blood pressure elevation. Pain is usually minimal butTylenol may be taken for discomfort. Suture removal time canvary depending on the location of the surgical wound,ranging from 5-14 days. Keep in mind that it often takes 12months for the surgical wound to regain similar strength of the surrounding skin. Surgical site redness may take up to 6 weeks to fade.The appearance of the scarwillfade over time, but incasesof elevated (hypertrophic or keloidal)scars, steroid injections may be used to assist inflattening. Various options exist for the treatment of noticeable scars including resurfacing lasersandmicroneedlingifthecosmeticresultisunacceptable.

AdvantagesofMohsMicrographicSurgery

∙ Highestcurerateofalltreatmentproceduresforskin cancer

∙ Preservationofnormalskin,allowingfora goodcosmeticoutcome,whilereducingthe appearanceofthesurgicalscar

∙ Lowassociatedriskwithlocalanesthesia(numbing)in anoutpatientsetting

References:

1. James,WilliamD,DirkM.Elston,TimothyG.Berger,andGeorgeC.Andrews. Andrews’Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology.London:Saunders/Elsevier,2011.Print.

2. http://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/skin-cancer-non-melanoma/statistics

3. http://www.dermatology.ucsf.edu/skincancer/mohs.aspx

4. http://www.who.int/uv/health/uv_health2/en/index1.html

5. http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/mohs-overview

PhotoCredit:Onlinedermclinic.com,UCHospitals, Drugs.com,WebMD.com,Healthwise,OnSurg.com, MDpulp.com,FDA.govFlorida State University Department of Behavioral Sciences and Social Medicine

ACTS2 Project:African-AmericanAlzheimer’s CaregiverTraining and Support

TheACTS2 Project meets the needs of distressed caregivers of older adults with dementia.The program offers faith-integrated, skills-training and support over toll-free telephone to African-American dementia caregivers residing in Florida.ACTS2 also conducts a robust outreach effort to raise awareness about dementia through social media and community-based presentations (reaching over 7,000 annually), while also providing no-fee, telephone-based consultations and community referrals to caregivers and other stakeholders across Florida and the U.S.

Research has found manyAfrican-American adults do not participate in social service programs outside their culture and community. In addition, financial challenges and limited transportation options to get to appointments prevent caregivers from accessing help.To overcome these barriers, ACTS 2 has successfully trained 23African-American faith community workers (lay pastoral care facilitators) to deliver faith-integrated, skills-building and support sessions (a 12-part series ranging from relaxation training integrated with prayer and meditation to problem-solving through goal setting). Over 150 family caregivers have enrolled in the 12-sessionACTS2 program over the past 4 years. Caregivers reported:

significant improvement in health and emotional well-being

significant improvement in self-identified caregiving and self-care problems

· strong bonds between caregivers and lay facilitators who offer ongoing support

· very positive perceptions of the usefulness of the program

The U.S. Health Resources and ServicesAdministration Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program, Florida State Primitive Baptist Convention, WinterFall Night of Giving, Joseph G. Markoly Foundation, Synovus Corporation, Florida State University College of Medicine, and private donors provide financial support to theACTS2 Project.

Ifyouweretoaskmeto lay in a recliner for four hourscoveredin a mountain of blankets and read my favorite book, I would probably say yes. Ofcourse!Whodoesnotwant4hoursto relax in a recliner? But there’s a catch isn’t there? This recliner comes with kidneyfailure,itrequiresvascularsurgery to create an arteriovenous access, it comes with a machine that filters your blood500ml/minforthreetofourhours. A recliner that makes you feel tired instead of rested and cold instead of warm. It is an extra trip you will have to make3timesaweek;youmayevenneed to cancel your lunch date and take time offwork.

I replayed our visit when I met you at thehospital.Walkinginyourroomatthe crack of dawn with my papers and some notes I scribbled down from your chart. I was in a rush to report to my attending nearlytrippingovermyselfineveryroom. However, I saved your place for last. A fewminutesgoby,asIstandoutsideyour door; I re read my bulleted notes. 58-year-old female with a history of chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension; hospital day three. Consult to nephrology should have been made earlier, if not for a possible congestive heart failure exacerbation. Yourcreatinehadjumpedfrom2to5and your electrolytes were less than ideal. Yourkidneyfunctionbarelyhangingonat 17.Iforcedmybestsmileandopenedthe door. “Hello Mrs. K! I am a medical student working with the nephrologist today. Can I talk with you about your kidneys?” I started. Excitement in your eyes I later learned you were a teacher. You came to the hospital with difficulty breathinganddizziness,andthiswasn’t

the first time. You recollected the struggles you had this past year in and out of the hospital for complications of both your heart and the diabetes. Unfortunately, this time it took a larger tollonyourkidneys.

Going back in the room my preceptor and I had only one plan: dialysis or no dialysis. She looked tired and weighed down, held up only by the hope of her husband and daughter next to her. This retired teacher almost took the words from us, she knew the options. She had been seeing nephrology for years and hoped her kidney function would eventually turn around, but always knew the inevitable. Her husband braced her fortheimpactofthenews.Mrs.KIthink weshouldtalkaboutdialysis andnowI can’tforgetyou.

ThedoctorandItoldyouweneededto prepare for dialysis. We explained the twotypes,andyouchosetherecliner.Are you scared for your arteriovenous fistula surgery? Are you worried this is the end stage of life and not just end stage renal disease? Unfortunately, I don’t need to ask,theanswersarewrittenonyourface, as your eyes gaze down and up to your family.Thelightinyourfacegoesdimand with it the hope in your heart. Did you wonder how this happened? Did you have any regrets? Can you handle the stigma of other’s opinions on your lifestyle choices? You have slowly declined for months now in and out of the hospital. It is difficult for me to imagine what you have experienced in your life with diabetes, heart failure and now kidney failure. I’ve never watched my blood sugar, had my legs swell twice the size, struggled to walk to the bathroom,orlaidinahospitalbedasyou have. I have nothing more to say but stand in the silence. The guilt inside me still lingers after we left you there. An interactionIhopetoneverforgetbecause I know you won’t. I changed your life by puttingyouinthat

chair; and I hope if it was me, I would havethecouragetositinthatrecliner. IwishIcouldmeetyouagain.Iwonderif you are doing better now. Was your central venous port put in with care? How was the first time in the recliner? Were you able to schedule for a fistula? But no that is where it ended. I have watched many times the delivery of devastatingnewsinmypatients,butuntil thisoneIhadneverdoneitmyself.Ithink we often forget our own mortality, even when we know the inevitable will happen. Many patients struggle with chronic disease; some carrying more mortalitythanothers.Inthemedicalfield we often see the disease process and stages, but never encompass the full picture of the chronic disease. The physical and emotional injuries our patientsmustendure.

Throughout my time in nephrology, I spent six weeks driving to multiple dialysis clinics. Sometimes 3 in one day. I spent countless hours with my preceptor flipping through papers analyzing and developing treatment plans and checking potassium and calcium over and over. I examined patients sitting in those recliners. I wonder is there anything we can do different to ease this burden for you?

Astaticvoiceon the intercom shouted, “We have a nursing home resident found unresponsive. Asystole on arrival. CPR started immediately. ETA 10 minutes.” Everyone around me quickly jumped into action to prepare. The afternoon had been slow in the emergency department, and the whole team was excited to jump into actiontoprepareforthearrivalofa

critical patient. It was my first day as a medical student in the emergency department. I had not yet figured out how I could best help the team in moments of chaos. Everyone seemed to havetheirnicheinthesescenarios,andit felt like I might disrupt the intricate flow ofthedepartmentwithanywrongturn.I tried my best to be present but also stay out of the way. However, it seemed like everywhere I turned to get out of the wayputmeinthewayofsomeoneelse.

With the blink of an eye, EMS was rollinginthebay.Ourpatientwasalready attached to the Lifeline Arm. Her eyes were wide open and fixed towards the ceiling. Her skin was leathery and gray. She had a single drop of blood falling fromthecornerofhermouth.Thethrust ofthecompressionswastheonlycatalyst causingthebloodtoslidedownherchin. Therestofherbodywascompletelystill. Shelookedalmostdoll-like.Itwashardto believe that she had been alive earlier thatday.

After an initial assessment, she was pronounced dead. Our team crowded around her lifeless body and took a moment of silence. With nearly no informationaboutthepatient,wehadto relyonherbodytotellherstory.Looking at her, I assumed she must have been olderthanmygrandparents.Herhairwas sparse and unkempt. She looked emaciated.

After further examination, the picture becamemoresinister.Itwasevidentthat shehadnotbeenabletocareforherself. HermusclesweresoatrophicthatIcould not imagine her body giving her the strength to move even the smallest of muscles. She looked like she had been sitting in the same soiled bottoms for days. Sores filled her backside. She had evidently been severely neglected at the place she entrusted to keep her safe. I was shocked by her condition. My preceptorexplainedtomethatitwasnot uncommon to have a patient brought in fromanursinghomeinsuchadeplorable condition. Much of the staff in nursing homes work tirelessly every week to treat patients as best they can. But budgetcutsandstaffingshortagescause

the patients to suffer the most. My perspective shifted. I could not be angry at the nursing home staff for failing this patient. The problem lies in the medical system at large. How can we as a society let our elders suffer in their time of greatest need? There is not a single person or group to blame. Our national medical system fails this vulnerable populationeveryday.

Ithinkofthispatientquiteoften.Inthe emergency department, we must report the ill-treatment of elderly adults in nursing homes. We hope the complaint findsitselfintherighthandsandpositive changes soon follow. But change is a long,slowprocess.Wehavethegreatest impact on our patients when we treat themwiththeutmostrespectwhenthey come through our doors. Even if our patienthaspassedbeforetheyarrive,we can help bring them peace. We can observe a moment of silence for the deceased. We can change their bedding, clean them up, and designate a quiet, dark room for their bodies to lie while waiting for family or the coroner to arrive. These small notions of respect quicklybecomeapartofourroutineona busy day in the emergency department. However, it is important to do our due diligence for our patients and resist the temptation to go through the motions without thinking of the deeper meaning of our actions. Even with a patient who wasmistreatedbywayofafaultysystem in the final years of their lives, we have an obligation to create a sense of peace and dignity for our patients as their lives cometoaclose.

While physicians in other specialties may not interact with patients in this samecapacity,itisstillvitaltoremember ourroleasaphysician.Wemaynotknow all of the hardships our patients face in their daily lives. However, we have an opportunity to create a safe haven for our patients by advocating for them and treatingthemwithrespect.

6 Weeks

by Alyssa FerlinKnock,knock.Afresh third-year medical student enters the room. It’s the last week of her first rotation. She dawns bright green OR scrubs and a white coat with pockets that are visibly packed with papers, a small book, multiple pens, a mini spiralized notebook, and granola bars,whicharenecessarysinceshenever knows when her next meal will be given the chaos that is general surgery. The room is tiny but pretty standard for a doctor’s office. There’s an exam table, 2 chairs, a rolling stool, a sink, and a desk connected to the wall. There are no computers in the room. She notices the rather pregnant woman sitting in the chairnexttothepatient.Theirhandsare interlocked.Beforeaskingaboutonsetof symptoms and where it hurts and what makesitbetterandwhatmakesitworse, she learns a lot about the couple. They are expecting not only their third child but their third girl. She is due 10 weeks from now. He works in security just down the road. He likes to fish. His youngest daughter likes to fish with him, but his oldest daughter wants nothing of the sort. They’ve been married for 10 years. They love their life. They smile big and they smile often. He’s here because ofasmalllumpinhisgroinarea.Ahernia perhaps? He casually mentions a history of melanoma. A 32-year-old with a historyofmelanoma?

He’s rather unconcerned about the history of melanoma. He was cleared a few years ago. He’s young, in-shape, and healthy. Life got busy so follow up with his oncologist wasn’t necessarily a priority.Butthislumppoppedup.It’snot painful; a little bothersome perhaps, and he just wanted to get it checked out. On their way out of the room, there are handshakes, head nods, smiles, laughs anda“takecare,youtwo.”

The third-year medical student goes about her life. The patients she thought aboutdailyandcaredfordeeplyoverthe

past several weeks, she’ll probably never seeagain.6weekshavepassedsinceshe met the kind couple in the tiny clinic room for a lump in the groin. Her white coat pockets aren’t quite as full these days, and the green surgery scrubs have beenexchangedforaslickblackscrubset more commonly worn by the internists. At the computers in the doctor’s lounge, she notices a familiar name on the patient list. She reads the notes in his chart like a story book. She’s stunned. Metastatic melanoma. Everywhere. A 32-year-oldguywhowashealthy6weeks agoandexpectinghisthirdchildisinthe intensive care unit. And he’s dying, quickly.

Thethird-yearmedicalstudentwalksup thestairs.Shethinks,whatdoyousayto someone who was seemingly fine 6 weeks ago but is now a frail, dying version of who they once were? The gameplan:getin,giveyourcondolences, chat if they want but keep it short if not, do your physical exam, and be on your way.ButwhentheICUdoorsopen,sheis met with his two young daughters being ushered down the hallway by a nurse. Sheismetwiththeshrillcryandscreams of a 36-week pregnant woman, who just 6weeksagowassmilingeartoearbutis now watching her husband take his last breaths, entirely helpless. 6 weeks ago, sheandherhusbandcrackedjokesabout the cost of the three weddings they’d be paying for 20 years down the road. 6 weeksago,therewereonlysmilesandno tears.6weeksago,lifewasnormal.But6 weekshavepassed.

The third-year medical student feels tears coming on. She is unsure what is allowedinamomentlikethis.Isitbadto cry?Isitokayforhertofeelpainlikethis for people she barely knows? How does she push these feelings aside so she can go see the next patient on her list with a smileonherface?

That night she drives home in silence. She weeps. She weeps for the young wife,whojust6weeksagodidn’thaveto plantogothroughchildbirthwithouther husband by her side. She weeps for the little girls, who just 6 weeks ago were playingoutsidewiththeirdadwithouta

careintheworld.Sheweepsforthebaby girl, who will never get to meet her dad. She weeps for the man, who is now at rest,whofoughtsohardtomakeittohis third daughter’s birth so he could hold herjustonce.

The third-year medical student learns that it is okay to feel pain for those she hascaredfor.Shelearnsthatmedicineis not always about curing and fixing people. And she learns, most importantly, that the heart of medicine lies not in the science, but in the human-to-human bond that is formed betweentwopeople.

Itwasthethirdweek of my neurology rotation around 10 in the morning when my attending and I werefinishingourmorningroundsinthe community hospital. As we filed through the long fluorescent-lit, vinyl-lined hallways, we were urgently paged for a consultation on a patient post-cardiac arrest. With haste, we logged into the nearest computer to learn more about ournewpatient.

On one hand, a thorough review of his chart revealed an average 54-year-old with an uneventful health history until beset by a heart attack early that morning. On another hand, the scans of his brain showed the extensive devastation that his brain endured while only being without oxygen for a few minutes.Hewasseverelybraindamaged, but I retained a small glimmer of hope that our physical exam would elicit something positive, some sign of consciousawareness.

Following my physicians lead, we marchedintothathospitalroomtofindit filled with this patient’s family. We learned about the events preceding this hospitalization and conducted our usual neurologic exam. As we proceeded throughit,wetestedhisvision,reflexes,

ability to follow commands, and tone of his muscle. Every stimulation was met with no response. My physician stood facing the family, offering a gentle and comfortinghand,andgavethenewsthat no one ever wishes to hear, that their lovedonewouldnotrecover.

We shared the images of his brain, and explained the disease process that their love one succumbed to in their current state. The physician assured the family that he did not suffer. He wasn’t brain dead, but brain damaged. In a sense, he neitherexistedwiththelivingnoramong thedead.Hisdamagewassevereenough that he would never awaken, but he could remain alive with the appropriate medicalcare.Hisfamilywasperplexedat this thought, to which my physician followedwithhispreferredanalogy,“The lightsareon,butnoone’shome.”Thisis a phrase that everyone easily understands,aphrasethatwillstickwith methroughtherestofmycareer.Asthe words left my attending’s mouth, I witnessed a unified epiphany spread amongst the family about their loved one’s condition and the realization that big decisions would have to be made in thedaystocome.

As I left that room with tears streaming down my face, I now saw life through a new lens. In all my prior brain injured patients, “The lights were on, and someone was home.” This phrase gave the family hope for recovery and that their loved one was still in their physical body. But this was the first time that it wasn’tthecase.Ireflectedonhowweall experience loss and share this as a core human experience. I have experienced loss myself and know of its pain and devastation.Thisexperienceofdelivering bad news showed me what it means to be human, and the heartbreak experienced by families receiving the worstnews.Wealwaystalkaboutputting the needs of our patients first, but what happens when our patients can’t make decisions for themselves? What about theneedsoftheirfamilies?

As a future physician, I will have many roles.Iwillwalkthelinebetweenlifeand death.Iwillbetheretosupport both my

best and worst times of their life. In medicine, we are always strapped for time, but I hope we all remember to support and listen to the families of our patients. They are the advocates of our patients, and deserve our time and respect to make informed decisions. There is something special about being heard, and we as physicians are sometimes a family’s only source of knowledge about what is happening. I hopewealllearnhowtoexplaincomplex diseases and tests in a way that anyone can understand. As physicians, we spend more than a decade developing our knowledgeandexpertise,anditwouldbe a waste to not have the capability to share this information in manageable pieces.

Ultimately, our patient was disconnected from life support, had his organs procured to give life to another, and was allowed to peacefully pass on. Despite their heartbreak, our patient’s family expressed their gratitude to my physician for the time he spent with them and the knowledge shared. They were able to process what had happened, understand their options, and make those hard decisions that no one ever wishes to make. They were able to givetheirlovedoneadeathwithdignity, andtheyfoundcomfortinthis.

If anything, my short four weeks in neurology, eight months into my clinical rotations,gavememoreappreciationfor life than any other experience in medical school. It gave me a more profound perspective on the fragile line between life and death, and furthermore, to take nothing for granted. My physician demonstrated extraordinary empathy and compassion to every one of his patients and their families, he took the time to have difficult conversations, and he endowed in me the understanding thatwordscanheal.

ItwasSpringof

I was in my junior year at UF taking a course called Introduction to Medical Professions II, a course that allows undergraduate studentstolearnaboutthevariousfields of medicine and shadow physicians at Shands Hospital. I followed my resident physician into the patient’s room where we were met by a seemingly healthy, jovial man in his early 60s, Mr. Seto. He had severe squamous cell carcinoma of thetongueandmouth.Hewasscheduled tohaveamandibularreconstructionwith afibularfreeflaplaterthatmorning.Ifelt sad for the patient for being inflicted by this disease but was excited at the same time about being able to watch the surgeonshealhisaffliction. Thesurgery was long and arduous and took several hours, but ultimately went smoothly. I distinctly remember how grateful the patient’s family was as my preceptor explainedthegoodnewstothem.

LittlehadIknownwouldIseethesame patient four years later during my third yearofmedicalschoolaspartofthecare team. I was on the second week of my internalmedicinerotationwhenIwalked into the room to find Mr. Seto, the same patient I had seen four years earlier for his mandibular reconstruction. I remembered him instantly. However, rather than speaking to the same healthy-appearing, jovial man that I had metfouryearsearlier,Iwasspeakingtoa cachectic, severely ill individual who was barely able to speak a single sentence. As I asked him what brought him in, he merely stated “it’s . leaking again .” as he pointed toward his abdomen. I was barely able to understand what he said but lifted his gown up to find a gastrostomy tube placed with gastric secretions covering his abdomen, slowly eating away at his epidermis. I asked him how long this has beengoingonfor,

whichhereplied,“aweek.”Irealizedthis patientwasgoingtobefarmorecomplex than I initially anticipated and decided to tackle his unchanged G-tube dressings first. The nurses were busy, so I decided tochangethedressingsmyselfasIwould be able to collect additional history from Mr.Seto.Itwasstillincrediblydifficultfor me to understand him, but it got easier the longer I talked to him. During this, I learned that despite the attempts by the surgeons, his oral cancer had metastasized to several parts of his body includinghisesophagusandlarynxwhich endedupaffectinghisspeech.

Iwasdevastated.IperceivedMr.Setoto be my ‘first patient.’ I had scrubbed in, assisted with the procedure, and stood bytheattending’ssideasheexplainedto thefamilythatthesurgerywasasuccess.

I wondered how this could have happened, and whether the surgery failed. I later learned that he had a 40 pack-year smoking history. While he had quit smoking after his mandibular reconstruction, it was too little too late andthecancermetastasized.

I rounded on Mr. Seto every morning. This was my first time being able to followthesamepatientformultipledays at a time. As the weeks went by, I got to know him quite well. I learned that he lovedworkinginhisgardenandwasabig Nascarfan.Ilearnedabouthisfamily;he has a wife, kids, and grandchildren. Medical school ethics taught me: They are people first then patients. It wasn’t until taking care of Mr. Seto that I had actually felt this notion. I had been working in the healthcare environment for9monthsandwasbeginningtoforget that patients were not just patients, but ratherpeoplewhobecomeill.Iknewthis conceptintheorybutwasnotapplyingit to my practice. Having met him four yearspriorandgettingtoknowhisfamily and hobbies, I realized that this was an incrediblyhumanizingexperience.

As time went on Mr. Seto’s condition continued to deteriorate. The surgeons and gastroenterologists were unable to seal the tube. His metastatic disease was progressing rapidly in severity. TPN was initiatedashewasnolongerableto

tolerate nutrition via the G tube. By the end of the week, he was on dialysis. My preceptorandIinformedthepatientthat his prognosis appeared to be extremely poor.MypreceptoraskedMr.Setotocall his family so he can inform them of the situation.Iquicklyrealizedthattherewas a significant chance of my ‘first patient’ dying before I had even finished medical school. I was overcome with emotion as the empathy and compassion I felt toward Mr. Seto overwhelmed me. I constantly thought about Mr. Seto, and how his condition affected those around him. I began to apply a similar sense of empathy and compassion toward my other patients. I began thinking about their emotions, fears and how their affliction affected their friends and family.

When I returned Monday morning, I was greeted by some of his family members who had flown in from various partsoftheUS.Tomysurprise,oneofhis daughters had recognized me from before.Onphysicalexam,Ifoundthathe was disconnected from his IVs, dehydrated, had fallen out of bed, developed a sacral decubitus ulcer, and his abdomen was soaked by gastric secretions from the leaky G tube. I was overcome with frustration that he was not being cared for appropriately. I had never felt anger that a patient was being uncared for until this time. I quickly found the nurse and helped apply dressings and reconnect his IVs. I stood there and made sure everything on my list was done as I texted my preceptor asking to increase his pain medications andorderanairbed.Onmywayout,the patient’sfamilythankedmeforbeing too attentive. I thought: I guess I have been extra attentive to Mr. Seto However, I realized that because I had begun to feel compassionate and empathetic toward this patient, I was being more thorough and ultimately providingbettercare.

I began applying the same values towardmyotherpatients.Iremembered: They are people first then patients. I realized that I must never lose touch of thesevaluesandthatImustfeel

compassion and empathy for all my patients. Compassion can be defined as: a deep response to the suffering of another. Caring for Mr. Seto emphasized that medicine is both a science and an art. He taught me that compassion is a critical part of the art of healing. True healing must involve empathy and compassion, and I realized that I must keep these values for the rest of my career. Before he was discharged, his family divulged to my preceptor that “I was one of the providers to care for Mr. Seto at Halifax.” Upon further introspection, I realized that this patient hadfinallytaughtmethe art ofmedicine.

Scanning my eyes downthelaundry list of patients’ names androom numbers, I was filled with anticipation and anxiety as I was told that we were expected to makeroundsonthefortypatientsonour daily census. This was my first day as a third-year medical student starting on inpatient internal medicine, and I was terrified. My preceptor ran down the list with his fingers and then used his black pentoindicatewhichpatientshewanted me to “claim,” as if they were commodities. After reading the short blurb explaining each patient’s chief complaint,hestoppedatonepatientand said, “Oh this will be a good one for you to see; you’ll see this diagnosis all the time on inpatient.” After reviewing my patient’s chart, I learned that she was a 51-year-oldfemalewhopresentedtothe emergency room complaining of sharp abdominal pain in the midepigastric region as well as nausea, vomiting, and signs of dehydration. Due to the state of her dehydration, continuous vomiting, andabdominalpain,shewasadmittedto theinpatientfloor,whereshereceivedIV fluids,andmoretestswereordered. Walkingintothepatient’sroomhavinga generalsenseofwhat’sgoingon,I

they are in the hospital. Upon initial observation, I notice an obese female who appears her stated age sitting up in bed in acute distress with a green vomiting bag in hand connected to multiple IV’s and monitoring systems. “I’m in a lot of pain and I can’t keep anything down,” my patient said. Using theCLCscriptinmyhead,Istartedasking the “focused problem” questions and learned that she rated the “sharp” pain an 8/10 and that she had a similar episode approximately 1.5 years ago, where she stayed in the hospital for 2.5 weeks with three days in the ICU. “I’m scared,”mypatientsaidasshelookedme intheeye,“Idon’twanttohavetogoto the ICU again.” I looked at her and said, “We are going to do everything in our power to try to prevent that from happening,” having no idea if we can preventthatfromhappening.

AfterIlefttheroom,Iwenttogocheck on my patient’s labs. She had a WBC of 14.5, calcium of 6.6, glucose of 330, lipase of 333, total cholesterol of 397, and triglyceride level of 7,534. I reported myfindingstomypreceptorincludingthe updated labs, and he said, “Just as I suspected, acute pancreatitis.” We kept her on IV fluids, nothing by mouth, morphine for pain, and anti-emetics. I came back the next morning to check on my patient to see if anything improved. She said her pain had decreased to a 6/10 but she was still vomiting most of the night. On the third day of her inpatientstay,Iwenttocheckonher,and instead of only talking about her symptoms, she started to confide in me. “I’masinglemom,andI’mreallyworried about my kids. I just want to go home to themandmakesurethey’reok.”Isaidin reply, “First, we have to make sure that you are ok before you can go and help them, but it’s normal to feel this way.” This was the first statement I made where I felt confident in what I said was true. She reluctantly nodded and started blaming herself for why she was in the hospitalinthefirstplace.“Iknowmydiet isn’t the best,” she said, “and I could exercisemore.”Althoughthese

statements were true, now was not the time for her to start getting more depressedandanxiousabouthercurrent hospital stay. I tried to navigate the conversation away from her blaming herself and towards using this as motivationtoputherhealthfirstinorder to be there for her kids. She seemed receptive to my feedback and appreciativeofthetimeIspenttalkingto herlikeanotherhumanbeinginsteadofa labvalue.

On the sixth day of checking in on her and learning that she was still nauseous with a few vomiting episodes, my preceptorstartedtolosehispatienceand accuse other diagnoses that she had for why she was still in the hospital. “It’s all heranxiety;it’sallinherhead,”hesaid.I then rounded on my patient with my preceptor and could tell how overwhelmed he was with his growing patient list and how he was ready to discharge my patient no matter how she felt. On paper, my patient was getting better, but in person, she was still vomiting, unable to keep most food down, and not physically ready to be discharged.

When I went back to check on my patient before I headed home for the night,Icouldtellthatshewasaffectedby my preceptor’s reaction earlier that morning. “I don’t mean to be a burden, but I don’t think I’m ready to go home just yet.” I knew from what I had seen throughout the week and after my conversationswithher,mypatientwould notbeinthehospitalifshedidn’thaveto be. “I know you don’t,” I told her, again confident in my statement. I felt incredibly sad that my patient felt like a nuisance for trying to heal in a place designated to help those suffering. My experience led me to realize though that if the people assigned to help you are overcomebytheirownstrugglesandthe medicalsystemcontinuesinthedirection of putting profits over patients, it makes it much harder to fully invest one’s energy into helping those who need them. I hope in my future practice that I continuetolistentomypatients,evenon thesixthday,becauseIknowhow

terrifyingitcanfeeltobeinthehospital, evenwhenyou’renotthepatient.

Growingup in Ithaca, a small town in upstate New York knownbest for being home of the prestigious Cornell University, I found myself always longing to leave. As a kid, I’ve always had a natural talent for buildingthings,usingmyhands,andonly looked forward to shop class in junior high. I certainly never dreamed of workinginconstructionwhenIwasakid, but it was a job that suited me and paid well enough to support an 18-year-old withachildontheway.Iknewthatonce I found out I was going to be a father, moreschoolingwasnotanoptionforme. I quickly joined the field of construction the day after I graduated high school because I made my mother a promise that she was still going to have a child with a high school diploma. For the next 3 decades of my life, I witnessed a field that changed tremendously with enforcements of regulations and safety requirements that made me question whether my own health was ever impacted as a construction worker. Nevertheless, I was proud to say I had a hand in building a large majority of the homes and office retail space in upstate New York during a hard-working career lasting just over 30 years. While I’m proud of the career I left behind, retiring at 52 was certainly not what I expected tooccur,either.

Over the last decade of my career, I transitioned to a pure supervisory role. My managers helped me save face and told my coworkers it was because they neededmeasasitesupervisor;however, everyone knew later in my career that I wasn’tquitetheworkerIwasonce.Iwas never an athletic guy and I certainly neverexercised,butIdidn’tthinkIwould tire so easily in my late-40s. Often, my guyswouldseemehavetotakeabreak

and fall short of breath. Having never smokedadayinmylife,Ijustassumedit was the physicality of the job taking its toll on me. It wasn’t until I retired that I truly felt like my body was giving out on me. Persistent cough spells lasting minutes at a time followed by gasping breathsforairwerealltoofrequentofan occurrence. Although I knew something waswrong,IpusheditoffforyearsuntilI achieved the second greatest accomplishment of my life, becoming a grandfather.

Shortly after having my son, his mother andIwerenotabletoseeeyetoeyeand grewapart.Mygreatestregretinlifewas not spending enough time with my son. I’ve missed baseball games, birthday parties, and taking him to school on many mornings all so I could provide as best as possible. I was never a rich man, but I made sure my son always had enough to be comfortable. Fortunately, mysonwasabletodomanythingsthatI couldn’t. First and foremost, he received acollegedegree.Healsoworkedhardto make his relationship work with his wife, whom he met at college. His success as an engineer afforded him a lifestyle that allowed him to comfortably have a child inhislate20s.HemoveddowntoFlorida to be closer to his wife’s family and they extendedtheinvitetome.Ifiguredsince heistheonlyfamilymemberIspeakto;a change of scenery may not be a bad thing. Shortly after, my grandson came into this world. I knew that there was now another life to live for and that my healthshouldbeprioritized.

I still remember the deafening, ringing tone I heard from my ears and the sensation of my stomach dropping when the word “mesothelioma” came out of my doctor’s mouth. This was only a condition I had heard of on TV commercials and never expected to see anyone with it in person, let alone be diagnosed with it. When I received the diagnosis, I was devastated––I couldn't bear the thought of my life ending like this. I first thought of the new life I wished to have in Florida, finally being able to be a part of my grandson’s life. Afterhearingmanynumbersand

I figured it was best to just be present with my family. I’ve accepted that my time will come, just like everyone else. Althoughmyconditionworemedownto thepointwhereIlost40poundsandwas coughing up blood almost monthly, I knewtherewasstillmoreoflifetoenjoy. However, when lumps of tumor starting to poke out of my rib cage and raise my skin, I quickly felt that it would be difficulttoenjoylifeincomfort.Thepain of taking a simple breath would send a shockwave throughout all of my body thatwasunbearable.

On my 58th birthday, almost one year ago, I watched my grandson play soccer for the first time. It took all of my strength to ignore the constant chest pain I was having or the lack of sleep catchinguptomeasIwasunabletorest while I was chronically aching. Previous doctorshavetriedtomanagemypainby theguidelinestheyweretaught.Theydid notlistentomeasapersonandwentby what protocol told them to. When I told them that the pain of a t-shirt rubbing against the lumps of tumor protruding through my skin felt like an 18-wheeler crashingintomyribcage,theystatedthat anymorepainmedicationsissomethingI would have to see a pain specialist for. Painspecialistsrecommendedallsortsof surgicalinterventionsandlong-termpain pumps. I felt that undergoing surgery would probably be something I’d never wake up from and turned to a new doctortoseeiftherewashope.

Mynewfamilydoctoristhefirsthuman I’ve seen cry when I described the pain I went through on a daily basis. He was able to provide me with medication that allowed me to live a comfortable life. He trusts me enough to use these pain medications responsibly and aimed to relievemeofmyburden.Iamfinallyable to sleep and spend the remaining time I have with my grandson in comfort. He later introduced me to the idea of hospice, and it frightened me, however his explanation of what services may be provided to me to keep me in comfort were encouraging. For the first time in mylife,Ilookforwardtomymonthly

visits with my doctor. He is not a doctor who looks back at my previous life choices and tries to pinpoint what may havecausedmycondition.Hefocuseson howIcanbeabletomaximizemyquality of life. It brings me joy to see how he is sharing his empathic qualities to his students and is helping create a generationofnewdoctorsthatwillfocus onthepatient.

I was the eagereyed, hopeful future surgeon walking into my first third-year rotation with the notoriously toughest surgeons at my campus.Ihadnoideawhattoexpectand held my reservations as to any prior judgement that was bestowed in my mind. As the day progressed, I continued to become more comfortable in working with and around my preceptors. Nearing the end of the day, our final case was with SJ. He is middle aged man with a long-standing history of Crohn’s disease in which he had previously been treated with an extensive bowel resection some 20+ years prior leaving him with an ileostomy. His complaint was that the past few weeks he has noticed some “painandslowingoftheflowthroughthe ileostomysite.”

I follow my preceptor into the pre-op holding area and see a pensive man surrounded by his wife and daughter. Theyalllookanxious,includingSJ,whois unsure what this process will hold. My preceptor explains to them what he believes is happening based on the imaging and the conservative steps surgically to be made today. SJ agrees to thisplan.AsthesurgeonandIgobackto prep, I rattle off my questions about his thoughts of potential outcomes and subsequent adverse events that may ensue.However,allIcanthinkofarethe anxiousfacesthatwerestoodwaiting

with baited breath at what the surgeon wasgoingtosay,allwhiletheirfacesheld complete confidence in his plan. The surgery proceeded without issues and the minor dilation we enacted at the ileostomyorificewasthebestfirststepto resolving his issue. The next morning as I am rounding, I stop by to check in on SJ. His wife was patiently waiting at the bedside watching him as he slept. In an effortnottodisturbhimatthemoment,I spoke to SJ’s wife about how he was overnight and delve into deeper subjects onhispasthistoryandhowhehasended up in this predicament. Through the few minutesIspokewithher,Icouldfeelher anxiety lifting as she had a voice in that momenttoexpressherconcerns.Igently awaken SJ to do a brief physical exam including checking his ileostomy site while asking some questions. No issues werepresentonmyexamandIexplained I would return later with the surgeon. A few hours pass and we return to the roomasateam.Thesurgeonexplainshis procedureandrationaleandinformsSJif he can eat and have reasonable flow at the ileostomy, discharge is an option. Later in the day, we return and find SJ withgreatflowanddischargehimhome.

A brisk few days pass on the surgery service. As I log into the computer and check my preceptor’s list of patients, I notice a familiar name, SJ. How was SJ back in the hospital? We sent him home and he was doing fine, I thought to myself.AsIproceedthroughmyrounds,I stopbyhisroom,andtomysurpriseheis up at the early hour. I begin to inquire about what’s brought him back in. The soft-spokenSJexplainstheprogresswhile in the hospital but the weakness and the continued issues of blockage at the ileostomy he had at home again. I knew as the surgical team we were going to have to try again. We returned to the operating room again trying with our most conservative treatment of a more extensive dilation with the intent of keeping him a few extra inpatient hospital days to ensure a proper recovery.AsIroundedthenextfewdays, SJandIbegantobondwhilehewas

awake in those early morning hours. I provided a reassuring smile and ensured he was comfortable while maintaining a jovial relationship with him for the times whenhiswifeordaughterweren’tthere. His symptoms resolved during the hospital stay and he was recovering well from the surgery so he was discharged. This was the first patient relationship I had built as a third-year medical student withoneofmypatients.Iwasabletosee the care and compassion I could build just over a few days and how this impactedbydesiretocontinuetosoothe the patients with whom I was on the treatmentteamwith.

Adaypassed,noSJ.Anotherday,noSJ. A week passed, no SJ. I was beginning to miss our comforting conversations of my experiencesstartingmyclinicalrotations. But I also understood, not seeing him back was for the best. Another week passes and my preceptor received a page from the ED: “Patient with an ileostomy complaining of bowel obstruction.” My heart was gutted as I knew the sweet and kind SJ was back at thehospital.

The outlook now entailed a more extensive open surgery since the prior twoyieldednopositivelong-termresults. My expectations were that the kind, caring family members of SJ would begin to turn on the surgery team as it now seemed he was in a perpetual cycle in and out of the hospital. However, his wasn’ttheresponsewereceived.Coming to speak with them in the pre-op, while mildly agitated, they were still extremely grateful for the efforts so far in trying to postpone the major open abdominal surgery. With a reassuring nod to his family, I ensured he would be in good hands. A small tear fell from his wife’s eye as she nodded in reciprocation as he wasbeingwheeledback.

Over the next two weeks, SJ remained on our patient list as his hospital course was complicated with prolonged antibiotic regimens, postoperative bowel rest, and electrolyte abnormalities. Through that time, I ensured I left home a few minutes early to have some extra timetotalkwithSJ.Wecontinuedto

build the bond as I wanted to make his hospitalstayjusta littlebitbetter.

My time on the surgery rotation was coming to an end and yet SJ was still sitting, waiting, and hoping his hospital course would come to a close soon. On myfinalday,Iwalkedintohaveourfinal chat. I thanked him for being so reassuringtomyinitialclinicalexperience and so positive about the entirety of the situation he was in. I thanked him for comforting me and expressed how unfortunate it was that we had to meet thisparticularway.SJgesturedformeto take a seat on the foot of his bed. He grasped my hand and said, “Thank you. Thankyouforspendingthetimewithme and my family. As a father myself, I can only imagine the pleasure your parents have to call you their son. You are going to make a wonderful physician.” Tears were rolling down his face as I knew this hospital course was one of the toughest battles he faced. I thanked him, received ahugfromhiswifeandexitedtheroom.I held those words as I walked down the hallway, holding back my own tears, as not only was I grateful for spending the extra time with SJ but also to be in a position to make an impact in the way I had. I knew from this experience that no matter what is happening in your life or how busy it is on your day, those few extra minutes to connect will mean the most.

Itwasapproximately 7:05amwhen I and the rest of the day team huddled in the nurse’s station receiving sign-out. Overnight, the pediatric emergency department received an 11-year-old female in status asthmaticus. With proper execution of thestatusasthmaticusprotocol,thenight team was able to drastically improve her conditionandshewas

reportedly “looking pretty good” by morning rounds. When we walked into the room to meet and assess her, we notedminimalworkbreathing,saturating around 97% on high flow oxygen, diffuse but mild wheezing on auscultation. To a layman, she looked like a normal kid resting in bed; to a medical professional, shehadcheateddeath.

Around 10 AM, the patient’s mother, who spent the night at the hospital, notified the nurse that she wanted to take her child home now that she was feeling better. The nurse rushed back to the station to convey to the rest of the medical team how this “ghetto mom” couldn’t understand that her child was only appearing well due to the steroids, albuterol, and oxygen being provided to her. The mother, however, was adamant that the child was fine and she simply needed a refill of her albuterol inhaler beforeshetookthepatienthome.Outof concern for the wellbeing of the child, the attending physician decided to call DCF in an effort to overrule the desire of the mother to take the child home against medical advice. I remember feelingsotornasthephysicianmadethe call; I understood that the doctors and nurses believed a discharge was not in the child’s best interest, and even considered it to be child neglect. However, involving DCF was an overstep of parental authority in medical decision makinglikeIhadneverwitnessedbefore. Ultimately, DCF denied the physician’s request for required the patient to remain in the hospital as her condition was now stable and seemingly no longer life-threatening. The medical team was furious. They proceeded to tell the mother they would call the police if she tried to take her daughter home. As one would imagine, the mom did not take these statements and threats very well, and this conversation quickly turned combative.

When the doctors and nurses walked out,Istayedinthepatient’sroomtotalk to the mom alone. With a calmer voice and kinder words than had previously been hurled at her, I tried to explain the severityofthesituationtothemomand

why the patient needed to stay in the hospital. It was during this conversation that the mom disclosed to me that she hassixotherkidswithnosupportsystem and needed to leave so she could take care of her other children. She felt like shehadnochoice.Thiswasaperspective ofthecasethatthedoctorsandstaffdid not know and maybe did not care to know. They just felt like she was an “ignorantmom”notdoingwhatwasbest for their child. Despite our conversation, the mother eventually collected the patient’s belongings and took her home. None of the medical team, including myself, was surprised when the patient’s sats dropped to 83% as soon as the little girl took the nasal cannula out of her nose.Mybiggestfearforthepatientwas that she would decompensate later that dayandenduprightbackinourcare.

This situation was difficult for me as someone who tries to always see both sides of an argument. I certainly understood the medical reason for why the patient needed to remain in the hospital; it was clear that the patient’s status improvement was due to the medications and care that were being provided for her in the hospital. However,partofmewantedtosidewith the mother as well. I believe this cognitive dissonance originated because the medical team did not try to understand the mom’s motivations or understanding. They just saw her as a senseless woman and later joked about herhavingmorekidsthanshecouldtake care of when they found out the real reason behind wanting to take the patient home. But in my time with her, I wasabletoseeherasahuman,makinga difficultdecision,wantingtodowhatwas best for her kids. This situation reminds me that while I will advocate for my patients, I will do it with humanity, empathy, and understanding. We are seeing our patients and their families in some of their most stressful moments, and we owe it to them to meet them with genuine care and respect. While advocating for our pediatric patients can sometimes require DCF involvement, I willalwaysremembertoinvestigatethe

situation to the best of my ability and refrain from making character judgements without gathering all the information.

Dr.ViktorE. Frankl was an Austrian psychiatrist, and he wrote that there are three aspects of human existencethatareinevitable–pain,guilt, and death. Yet his books ask that we declare optimism in the face of this tragedy hecallsit“tragicoptimism.”

For a number of the patients I met in the hospital and clinic this past year, it was clear to see that they were encountering some or all of the parts of this triad. In the face of their tragedies, I witnessed a wide range of responses. Somecourageous,someoptimistic,some melancholy, terrified, depressed, angry, resigned, etc. Often it was a mix. But I saw that people have the ability to find meaning despite their tragedy and I strongly believe that the role of the medical person in this case is to help facilitate this in each patient. From my own personal experience of death and dying,itisultimatelytheresponsibilityof theindividualtofindtheoptimisminthe face of tragedy. And the optimism only can come from finding meaning, and no one else can do that task for you. But! I think this task is something facilitated by the heart and soul of a person and therefore the physician, by being loving and tender to the patient, may help create that freedom in the soul that enables a person to seek the meaning. AndI’veheardtheseconclusionsinsome patients: great deeds they did, people they loved, and trials which they had gone through with dignity and courage. Thesewonderfulthingsstoredupintheir lives like treasures, which cannot be lost anddonotfadeaway.

Oneday,Imetapatientintheclinic.I

walked in the room, and he was sitting hunched forward with his hands on the bench and had the thousand-yard stare I had become very familiar with. I smiled and introduced myself; he scrunched a quick smile and then back to the weary gaze.Hewasonly67yearsoldbutlooked much older and had a strong New York accent.Hewasthinandhadwire-framed glasses over a weathered tan face with grey hair that flowed out from the sides of his head; he kind of looked like Doc Brown. I decided to do more of an open, no-agenda type interview since the visit didn’t include a specific, acute problem. He had worked for a record company for decades in New York City before moving toFloridawithhiswife.Hehadlivedabit on the wild side throughout his life; was very politically active and outspoken during the ‘70s and had led many demonstrations during college. The nature of his career included lots of drug use, and of course, rock and roll. He was basically healthy since birth: never significantly sick throughout his life and always active. Yoga was a big part of his lifeforseveraldecadeswhichwasoneof his favorite hobbies and accomplishments.

When he hit age 50, he was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and received successful treatment for it. But a decade later, was diagnosed with scleroderma and then amyloidosis. His trips to Mayo Clinic ended with the conclusion that although symptoms could be targeted, there was nothing real that could be done for the diseases themselves. He explains to me now – “I am not interested in going back to Mayo I want to focus on living the bestlifeIcanforthetimeIhaveleftand that’sit.”Itisclearhehurts.Hewalkslike apersoninpainandhebreatheswithhis eyes open and closed randomly, like a person in pain. He has oxygen at home andmovesfromroomtoroomonaline. “Enough length,” he explains, “to make my big trip each day.” He means the trip from the living room to his office where hiscomputerissetupforZoomcallseach day.Hestillworksandisabletodosoas afree-floatingheadonZoom.He

explains, “when you work like that, no one knows you look like a tired old bird and that you’re sick…there’s no context soit’snicetojustworkandnothavethat surrounding you. Plus, I work with a bunchofyoungkidsnowandIthinkthey think of me as some grandfather to them but it works out; it’s a nice relationship.Ilovemywork.”

Myeyesshiftdownatsomepoint,andI see Elvis Costello on the faded old gray t-shirthe’swearing.“ElvisCostello!”Isay. He looks down and smiles, “Oh yea, I’ve seen him too many times to count he’s justspectacular,Iwaskindaaroadie.”I’m excited.“YouknowoneyearIlistenedto his album with Burt Bacharach almost everyday?”Isaid.PaintedfromMemory, he says with a wide grin. “Yes!” And we dive into the world of music. We go through the songs in the album and talk about its genius and then we’re talking about other artists and we’re on the same exact musical wavelength as time soars past us; he throws out a favorite line and I counter with another line. We laugh and we just smile ear to ear we’re talking about Joni Mitchell and how he, if stranded on an island, would choose to take Court and Spark with him, and I said I might take Bruce Hornsby’s Hot House, and he almost jumpsupwithexcitementforthatalbum too and pretty soon in my smiling I notice my eyes feel a little wet and I feel that heaviness on my chest that is a dull type of devastation because I can hate the nature of that inevitable triad, “pain, guilt,anddeath.”Whenthepatientison the table, I am auscultating and I can’t help but look at him as he sits there and imagine his younger self, pain-free and doingyogaoratanElvisCostelloconcert. AsIpercusshisabdomenandpalpatehis posterior tibial pulses, I feel a sort of communion with my new friend; it’s bittersweet. He laughs as I am looking in his ear and I ask what is funny. He says, “You know I haven’t talked about music like that in a while, what a pleasant morning.” I wholeheartedly agree. The visit comes to end as I jot a note or two down. I notice he wipes a couple tears awayas

he is sitting back on the bench, looking out the window. A bit later when he leaves the office, we both turn to meet again before he rounds the corner, and we shake hands to say goodbye. He is beaming and I feel a sort of love in my heart for this patient, that love that comes from fellowship with another humanbeing.

Of all the things we do in a day; all the things we pine over, worry about, or strive for…I believe these loving encounters with patients is what seems to really matter. Thinking back to Dr. Frankl’s philosophy, I know that if even little acts or expressions of compassion can be exchanged, it brings the human spirit to a place a little less vulnerable to despair. It is my privilege to be able to take care of patients and love them throughthisuniquefellowship.

The second day of my general surgery rotationwaspacked fullof patients and procedures. After a long day, I was just about to leave late in the evening when there was a page from the emergency room describing a young man in cardiac arrestthatneededanemergencysurgical consult. I was offered to leave since it was getting late, but a hurricane was quicklyapproachingourarea,soIwanted tolearnallthatIcouldwiththetimethat I had. Little did I know the impact this man would have on me and my medical career. When I walked down for the consult, I thought to myself how crazy it was that this man was only a few years older than me. How could he possibly be a victim of cardiac arrest? When the surgeon and I arrived at his room, chaos hadalreadyensued.

Once the patient was stabilized and intubated, the surgeon told me I would be placing his femoral catheter. I was ecstatic to take the lead on the procedure,butverynervousforapoor

outcome. I had never seen a catheter placementbefore.Heguidedmethrough the procedure. I worked carefully, and successfully placed the catheter. I felt so proud of myself for completing my first procedure, while also thankful to this man for affording me the opportunity to learnanewskill.

The next morning when I rounded on him, he was rapidly decompensating. He had no kidney function, and the femoral catheter had blown. Another catheter wasplacedontheothersideofhisgroin, but it was only a matter of time before that one would blow too. A few days after his admission, the decision was made to start a central venous catheter. The surgeon instructed me that I would be performing this procedure, and I was even more nervous than the first time. I had never seen a catheter placed in the neck before, and there is little margin of error when directing a needle into the jugular vein. I kept my hands steady and focused on the instructions being delivered to me. After the successful completion of this procedure, I tore my gown off, and thought again to myself howthankfulIwastobeabletolearnoff ofthispatient.

I rounded on this patient in the ICU every morning and every evening. After his first week in the ICU, his parents began to come sit with him during the day.Wechattedabouthislifebeforethis horrific event. Learning his story made me realize this patient has a whole life outside of these walls, and although I have never seen him awake or communicating, he had two small children at home that had no idea what he was going through. His parents told me of how the patient’s brother died on a skiing trip 10 years ago, and how the patient never recovered. He struggled with depression and alcohol for majority of his adult years after that incident, and now here he was laying in the hospital bed,unconsciouslyfightingforhislife.

After the second week he was in the ICU, he was not turning the corner. His kidney function had not resumed, so he still required frequent hemodialysis. He wasonaventilator,withnumerous

medications all looming over his hospital bed.Afterseveralfailedextubationtrials, the decision was made to give him a tracheostomy tube. This time, the procedure felt different. He was no longera“cardiacarrestinbed3.”Hewas a son, a father, a brother. He was Michael.

After three weeks in the ICU, there was little to no improvement. When I would round on him in the quiet mornings, I would note the beads of sweat dripping down his face. I noticed how much weight he had lost since his admission. A face that was once full of life, now pale and without adipose tissue. I began to wonder if he was going to make it throughthis.Hisfamilyhungphotosona bulletinboardinhisroom,illustratingthe life he had before he was confined to thesefourwalls.Ilookedatthephotoof him with his four-year-old daughter, which was attached to a drawing labeled “feel better daddy, I miss you.” I hoped witheverypartofmybodythathewould pullthroughforthislittlegirl.

A month after admission, his kidney function started to rise. He had finally startedturningthecorner.Hewasawake and able to move his extremities, although he was not alert or oriented. Many thought he had suffered brain damagefromtheincident,andmaybehe wouldneverbethesameMichaelhewas before. How terrible it would be for the familytomournthelossofamanwhois still alive. I continued to root for Michael’s success and I kept my hopes high.

Gradually day by day he improved. I bonded with the family over how far he had come. Eventually, he began to communicate and walk with assistance. Bythelastweekofmyrotation,wewere discharging him from our service. The family had gotten him a spot at a rehabilitation facility in town that would work with him further. I could not help but think what a miracle this has been. Although I only played a small role in his overall care, I was so proud to be part of the team that helped save his life. Every patienthasastoryoutsideofourhospital walls,andthisexperience

illuminated the importance of understanding our patients as people, ratherthanjust“thepatientwithcardiac arrest.”

Caringforthispatientgavemea“why.”I found a love for critical care medicine through this experience, because although there are many poor outcomes in situations like his, recoveries like this make it worth it. This experience ignited apassioninmetowanttointerveneand do all that I can do for critically ill patients,justtohavetheopportunityfor another patient to improve like he did. Watching him recover every day for over amonthwasmorerewardingthanIcould have imagined. I enjoyed learning more abouthim,andamthankfulIwasableto careforhimontheworstdaysofhislife. He may not remember me in his story, butIwilltrulyneverforgethiminmine.

I walk into our patient’sroominthe emergency department and see a young26-year-oldfemalesittingupinthe bed. She is drinking a soda and eating gummy bears. She smiles and waves at me and asks how my day is going. It struck me as surprising that someone with her diagnosis was still this upbeat and bright. She had come to the emergency room thinking she only had a cold with a cough and increasing fatigue, only to find out she had acute myeloid leukemia. I come in to gather her history aswegetreadytoadmither.Weprepare her for her bone marrow biopsy and for induction of chemotherapy. As medical students we learn so much from our patients,abouthowtotalkwithpatients, theirdiseaseprocess,andsomuchmore. However, I had no idea just how much I wouldlearnfromthisyounggirlwhohad just been diagnosed with this serious disease.

This26-year-oldfullofresiliencehadthe resultsofherbonemarrowbiopsyreturn that confirmed the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia. She was started on induction chemotherapy with daunorubicin and cytarabine. As she was receivingherchemotherapyIwouldgoin and check on her every day. Every morning when I walked in the room I heard, “there’s my buddy.” I would see how she was feeling and one day she disclosedtomethathermotherhadjust passed away last week. She further discussedwithmethatshewashopingto makeitoutofthehospitalintimeforher funeral next week. I was shocked. This girl who had just been handed this diagnosis and lost her closest family member still greeted everyday with a smile and always made sure she asked how I was doing. This patient’s resilience and selflessness left a lasting impression on me. She taught me that you never truly know what is fully going on in a patient’s life. As a physician, we can always make an effort to show our patients the utmost compassion and to be patient with them. As I moved forward in my medical school journey after this encounter I always kept her in mind.WheneverIhadadifficultpatientI always reminded myself that I do not know fully what this patient is going through. I always made sure to stop and maintain my patience, keep a calm demeanor no matter the situation, and aboveallexhibitempathy.

Everythinghappenedsofasttogivethis 26-year-old the best chance possible at life. As the days continue to pass by, we continue monitor her labs. We notice that her red blood cells and platelet levels are dropping due to the chemotherapy. We begin to discuss transfusion with the patient, and we find out she is unwilling to accept blood due toherreligion.Thiswasnotdocumented and was not discussed ahead of the induction chemotherapy. This posed a dilemma. The chemotherapy she is receiving will cause her to have pancytopenia. She would most likely not make it through the chemotherapy regimenwithoutthetransfusions.We

discussed with her the risks and benefits of the transfusions, however, she opted to continue without them. We gave her alternative means to increase her red blood cell and platelet counts. However, this was not enough, and her numbers were continuing to drop. We sat down and talked with the patient, and we found out the reason that she did not wantthetransfusion.Shestatedthatshe, in fact, wanted the transfusion, but was fearful of what her community would thinkofher.Wediscussedwithherthatit is completely her decision and no one else’s. She eventually opts to undergo transfusionandthehospitalworkedwith her so her community would not find out.Thisexhibitedtometheimportance ofpatientautonomy.

It is of utmost importance for a patient to retain their autonomy in the hospital. This is yet another quality that this patient left a permanent imprint in my life that I carry with me with every patientinteraction.Ittaughtmetonever make assumptions. It was assumed since she did not have another member of her religious community with her, which is usuallythecase,thatshewasnotpartof this specific community that did not allow blood transfusions. However, this assumption should not have been made and should have been explicitly asked. It also taught me to always clearly explain everything to the patient and make it clear that any decision about their healthcare is nobody else’s choice but theirs, such as what was done with this patient. The original decision to not receive the blood transfusion was out of fear and not her own decision. However, after explaining autonomy to the patient shemadethedecisionthatshewanted.

NoweverypatientroomIwalkintoIsee this 26-year-old girl smiling. I take the lessons that she taught me into every patient interaction. I take with me the lessons of humanism in medicine that I learned from her, to always exhibit empathy,andthatitisimportanttolisten tothewholestorybehindeverypatient.I alwaysmakesuretonotonlyaskabouta patient’s symptoms or disease, but their personallifeaswell.ImakesureItake