Dear Readers,

With each issue, our thought process is to preserve the art of storytelling in order to keep our cultural history alive and thriving. Each issue serves as a testament to the creativity, and impact of the narratives we share. This spring we are proud to highlight stories that capture the essence of legacy and the transformative power of words—stories that remind us of the importance of both action and expression in shaping the world around us.

We honor the life and contributions of Teresa Price, a steadfast advocate for youth empowerment and education. Her dedication to creating opportunities for the next generation has left an indelible mark, and her story reminds us of the responsibility we all share in lifting as we climb.

We also explore the world of storytelling with Nadirah Muhammad, whose journey as a writer highlights the revolutionary disposition of words. Her reflections on the craft, creativity, and purpose behind writing serve as an inspiration to all who seek to share their truths and shape narratives that matter.

These stories remind us that impact comes in many forms—through action, through words, and through the lives we touch along the way. As always, we invite you to engage, reflect, and continue the conversations that move us forward.

Until next issue,

Sonia Montalvo Editor-in-Chief,

by Sarad Davenport

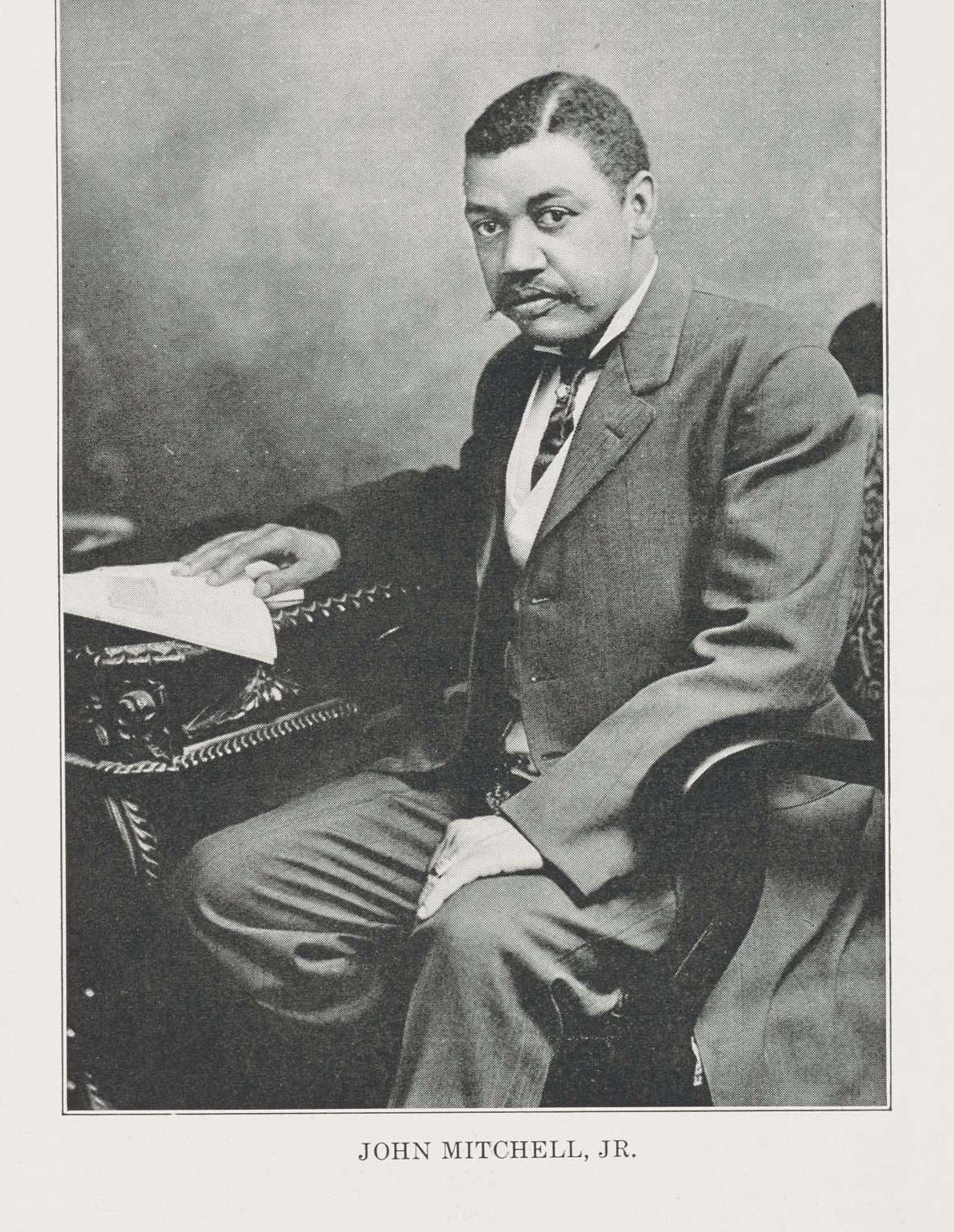

Vinegar Hill Magazine sat down with Nathaniel Shaw, the producing artistic director of the Firehouse Theater, and J. Dontrese Brown of BROWN BAYLOR™, a key collaborator, to discuss an ambitious new project. This initiative aims to bring to life the lesser-known stories of Virginia’s rich and complex history, focusing on the life of John Mitchell Jr. Through a partnership with the Mitchell family and the Richmond Planet Foundation, this project seeks to dramatize these stories for a wider audience. Here is the full conversation, capturing the essence of their vision and the

journey ahead.

Vinegar Hill Magazine: So, Nathaniel and Dontrese. What are you all up to?

Nathaniel Shaw: The Firehouse Theater, where I’m the producing artistic director, has a robust new play initiative. We like to walk that journey alongside a playwright from inception, through development, to world premiere production, and try to build bridges for new plays and new voices even beyond that world premiere. As I was contemplating specific initiatives in relation to

creating new plays, one of the wonderful ways to look at today and this moment we’re living in is to examine our history, especially missing anthologies of that history, missing volumes of the anthology of that history. I found myself in a conversation with the Virginia Museum of History and Culture about the potential in partnering in that effort. Could we find specific missing or lesser-told stories from Virginia’s incredibly rich, complicated, and horrific history? Being so emblematic of American history, the goal is to find those missing stories and dramatize them for larger audiences. Around that time, Dontrese and his partner Hezekiah introduced the Mitchells to me and the story of John Mitchell, Jr. From my perspective, it felt like the ideal way to launch the initiative, telling the lesserknown stories of these heroic acts, of these amazing individuals who fought against oppression and bigotry throughout Virginia’s history.

And so that’s what we’ve been up to. We’ve been partnering closely with the Mitchell family, the descendants of John Mitchell Jr., and their foundation, the Richmond Planet Foundation. It was a no-brainer to bring on BROWN BAYLOR™ to do all of the brand design and elevation and to help us build relationships in the community. We’re working closely with the Virginia Museum of History and Culture from a research perspective, and we’ve just commissioned what I would consider to be a nationally emergent playwright. I think we’ve caught a real star on the

rise in a woman named Kristen Adele Calhoun, who we will bring to Richmond from March 18th through 25th to start her research journey, building a relationship with the Mitchell family and our network of partners to bring this story to life. We hope to develop this play over the course of a couple of years and premiere it. Our ideal time to premiere it would be in the spring of 2027.

Vinegar Hill Magazine: Great, great. Give me a little context. I’m already interested. My questions are bubbling up. Without giving away any of the artistic direction, give a little context on the Richmond Planet and the Mitchell family. Either of you can tackle that or both of you can tackle that.

J. Dontrese Brown: Hezekiyah

Baylor of BROWN BAYLOR™, I don’t know if you know, he’s got lineage to the John Mitchell Jr. family. So this is something that has always been important to us. We did feature a huge part of Hidden in Plain Sight Richmond, dedicated to John Mitchell

Jr. We had insights from the John Mitchell family. He’s from Richmond, and he did more than just a newspaper. He was the voice of Black Americans. He was the fighter. He had the resiliency and determination to do what is right. He hurled the thunderbolt of truth, which is one of my

favorite statements from him. He showed how important it was to give more of yourself to the betterment of everyone else. And really being able to fight in a time frame where someone like him, it was a lot. Some of the narratives and the stories that I’m sure will come to light through Kristen are

hard to believe. During that time, he had the audacity to step in and fight for what was right. That’s what he was doing. He was giving voice to the voiceless. He was really showing us, from a Black American standpoint and from an American standpoint, let me just say it that way.

What can be done when you believe in something that is right and you have the will and power to do that? The why is because of how he gave a perspective from the Black people and the Black voices here in our city, the capital of the Confederacy at the time. We need to own that and appreciate that. There’s so much more about him, just hearing the stories of scenarios of riding horses across Virginia to support a young Black man accused of addressing a white woman out of character and his fight to get on horseback and ride across the state. We had a conversation the other day, and we were all, you know, with the new playwright and everybody, we were just all chatting and, John Mitchell and Ida were on the phone and Hezekiyah was there and they were like, so, give us some things about like, what did he do? How did he do it? How did he walk through the city? How did he do this? They were just giving some things. Hezekiyah said, yeah. And he had a.38 on his hip. Like the dude was strapped and ready to go. Don’t come at me the wrong way. I’m fighting in the right of justice, and I’m going to do it by whatever means necessary, to quote the late, great Malcolm X as well.

So it was the inspiration that he provided. Another question we asked was, as we develop our narratives and our story, is why this moment? Look at our world today. We’re still fighting the same battles. We’re still fighting the same conversations. Now, are we going to be the heroes that we seek in regard to standing up

in the fight of justice and what’s right? Or are we going to step back in the shadows and let all of these things happen, right? The last thing we talk about is, why is this important to us, to me, to you, our communities? Because it uplifts everybody. It allows us to own who we are and have confidence in our voices to make positive change. The unique thing I like about this whole thing, as we talk about the partnership with Firehouse, and Nathaniel, Kristen, Katrina, and his whole team, and the Brown Baylor team, and everybody, is what experience can we make with this narrative that people walk away inspired to make impactful change, whatever that impactful change may be. But understanding how someone, just a local Richmonder, decided to make impactful change. So that’s how I would begin to answer that question. I’ll leave it to Nathaniel to see if he wants to add any other context.

Nathaniel Shaw: I think you got it. It’s that last piece that feels most critical to me when choosing to tell a story. It’s one thing to just do a bio play of somebody from history. But why? What do we hope for? What do we hope the outcome or impact is? I think to tell the story of a man who, in those circumstances at that time, facing the threats and the danger that he faced to do the bold things that he did through the Richmond Planet and of his own accord, I think it can inspire us today to stand up against the machinery and the difficulties that we feel when we see injustices in the world. So I think leaning into that as a why is a wonderful thing.

J. Dontrese Brown: Yeah. And just rolling off of the Super Bowl (and Kendrick Lamar’s performance), I’m sure, Nathaniel, from an artistic standpoint, your mind had to be like, holy cow. For someone that’s like us, that looks like us on a stage to fight against the conversation of empowerment, the criminal justice system, the disrespect of women, artistic voices and empowerment, the society and how it’s divided. Racism. When you look at it from that standpoint and you’re on that platform, we want people to walk away with that feeling like, Holy cow! Look at all these symbolisms and metaphors and things that are important, but also who he was. What he ate and when he ate and how he slept and his family relations. What was the city of Richmond like when he was here, and what was he doing? Who did he hang out with? Who did he go grab a beer with? We’re excited for that too. Coming off of Sunday and having a platform of someone who is leveraging their voice to stand up in the face of justice, however they decide to do it through whichever channel they use. This was hip hop. Artistic performance, all of that involved. It was pretty powerful.

Vinegar Hill Magazine: Yeah. I have a related question. Maybe Nathaniel, you can start off, the choice of application to have this conversation through theater. Why theatre? Why do you think that theatre is a methodology to address some of these issues, to give historical context, to tell stories? Why theatre?

Nathaniel Shaw: I’m a theatre person, so maybe my opinion is a little biased, but I have yet to experience a more powerful medium than theatre when you’re telling something of great import and you want to impact change. For a couple of reasons. One, especially in a smaller venue like the Firehouse Theatre, you are literally breathing the same air as the people going through the trials and tribulations that are being portrayed on the stage. You’re in that same space. There is an intimacy and immediacy in theater that I don’t think can be duplicated on a screen as powerful as filmmaking is. And I deeply admire filmmaking. So that’s certainly one aspect, that intimacy and immediacy. I also love the fact that with live theater, people have to gather together to hear the story. It’s one thing to sit in one’s living

room by themselves, experiencing a story. It’s quite another thing to bring the rich and complicated diversity of our community into the same building, to share these transformational stories together. That communal sharing of an impactful story like this is something that can only be done in a live performing arts setting.

a fan.

J. Dontrese Brown: I couldn’t have said it better myself. That’s why the partnership with Nathaniel and leveraging the theater is so tremendous. For me, art is art for art’s sake. But it’s also important because art, theater, and creativity give you a platform to express a lot of different things in a lot of different ways because it allows people to take it in the way that they feel is appropriate for them, and then walk away with something. The exciting thing is, as we talked about, Nathaniel and our teams together collectively, what is that experience like? The immersiveness of it, bringing people together in that one space to breathe and feel what’s going on and exclude all the outside noise and be able to focus on this, but not only be a participant as a viewer, but be a participant in the narrative that’s being told.

Vinegar Hill Magazine: I can feel you speaking from your heart, and I’m going to I want to get a little bit more to the tactical, what you can share at this point about the ideas of how the Richmond Planet might manifest itself in the final product. If there’s anything you can share. And then if you know, Mr. Mitchell’s family dynamic. So that’s interesting to me, around press and how that might manifest itself in the work of some of the ideation that you all might be having at this point? And also family.

Nathaniel Shaw: Dontrese might be able to speak to this better. If I miss anything, let me know. It’s hard to anticipate today exactly how it’s going to manifest in the play. John Mitchell, the living John Mitchell, who’s a part of this project and a part of the Richmond Planet Foundation, he often says you can drop a needle on the record of John Mitchell Jr.’s life anywhere on his life, and you’re going to find a dramatic story. So it’s hard to know exactly what the playwright is going to be most inspired to talk about from John Mitchell Jr.’s incredible life. We

have made it an important part of the piece that the legacy and impact of the Richmond Planet be a part of this play. The importance of journalism has come up in many conversations. Especially the kind of journalism necessary then that actually stood up and stopped or fought against, most specifically, the lynchings that were happening across the South postReconstruction, in this period of American history where things kind of drop off a little bit and most Americans don’t know, kind of from Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement, we don’t really know that story and that chapter. That’s a significant period that I’m talking about, that we don’t have a deep enough understanding of.

So thank God some people like John Mitchell and the Richmond Planet and other Black newspapers across America were speaking up and fighting back. Exactly how it’s going to play into the story, I don’t yet know. To your other question. Dontrese, if you want to elaborate, please do. I think the Mitchell family may be the most important ingredient of this research period. It’s one thing for Kristen to sit in a library and read a few books about John Mitchell Jr., or go to the Virginia Library and pore over the microfiche or whatever form it’s in today of the Richmond Planet record, which she will do and which will be very valuable to the work. But to be able to sit with the Mitchell family and their extended network of people who have ties and relationships and connections to those ancestors, and to be able to commune with them and talk about, and get a feel for what the man might have been like through his ancestors, through his descendants, I think will bring a level of personalization and intimacy to the work that you don’t often get when you’re doing a biographical play or film.

J. Dontrese Brown: I think you’re absolutely right. Nathaniel, you hit it on the head. I think our golden nugget is the John Mitchell family. Our week of research with Christine here is going to be extremely powerful. The family is going to collect members of the family for her to sit with and hear these narratives. It’s going to be unbelievable. The way the newspaper will tie in, of course, it’s the anchor. It’s what everyone knows about John Mitchell Jr. from a high level standpoint. But he also had a clothing shop. He was also in love with map making. There

are some things that we don’t know about in as much detail. The reason why I say that is because it humanizes him a little bit more, it shows some of the other things that he loved to do. So, when Kristen gets here and she’s able to, I mean, we have access to the complete digital database of all the Richmond Planets right at our fingertips. But when she gets here and she’s able to put her fingers on the original newspapers, that’s one thing that’s really going to be powerful.

And then to sit with the family and talk about and hear all these other things is going to be critically important. So, I’m kind of like Nathaniel. It’s like we have some ideas. But until Kristen gets here, until all the minds get together, we’re thinking of some fundraising events and how we can tie some things into it based on whatever we start to uncover. To make these a bit more intentional about who he is and what he’s about. We don’t know that yet. We have ideas, and it just gets us when we sit in the room or on a Zoom and we start talking, it’s just like, oh, oh, oh and this, oh, and this and this and this. So until we’re able, the week that she’s here is going to be extremely important for us and for her to understand who Richmond is and who John Mitchell is and his family. Then she’ll take that and be able to begin to frame how she feels the best way to tell this narrative.

Vinegar Hill Magazine: What do you want the public to know now? What is the call to action? What do you want people to do at this juncture?

Nathaniel: I’ll start off. I think that these kinds of things. I’m going to be expansive in these kinds of things. A nonprofit theater that wants to tell these kinds of stories, to see these stories actually coming to life within a community and then having a life beyond that community. This only happens if enough people who care about that story being amplified and elevated get involved, participate, and invest, and that might be through a ticket purchase, or it may just be through attending a reading of the show, or it may be more. From a Firehouse perspective, anyone excited about learning more about the John Mitchell, Jr. Project, anyone who thinks that they might like to support the project, anyone who would like to attend an event associated with the John Mitchell, Jr. Project

should reach out to us. That can be sent to info at Firehouse Theater or you can call us at (804) 355-2001. I’d be very happy to hear from anyone in the community, this community or beyond, who is excited about what we’re trying to do and is interested in participating and joining us in some way on this journey.

J. Dontrese Brown: I’ll just add, of course, Nathaniel is in the same mindset as I am. As a nonprofit, it takes support to get something like this off the ground. Any contribution, no matter how big or small, is important to us. Any contribution around the communication of this thing is important, no matter how big or how small. What I would suggest from a creative standpoint, adding on to what Nathaniel said, is watch us. Watch us look at this small spark of what we thought could be something that led to an introduction to Nathaniel that led to the idea of this play. That led to signing one of the most up-andcoming playwrights that galvanized a small organization of community members that believe in this thing as we walk through this and bring it to fruition. So just watch because a lot of times folks have these ideas in their mind and yeah, it sounds like a corny idea or no one’s going to believe in this idea or who’s going to want to support it until you put it out in the universe. And then you realize that this is something that Nathaniel is excited about. And then we have a connection to the John Mitchell family. And then things start to churn and it’s like, okay, then what’s the next and the next and the next. So just watch us and watch how we build the momentum and then participate. Don’t just sit back. Act, join and contribute as we go along this journey. You will see how powerful one little spark of an idea, just as John Mitchell did and led, could change the dynamics of our community that empowers other individuals to believe that they can do this thing too.

Vinegar Hill Magazine: Great. Well, I just want

to thank you all for sharing this with me. I already feel empowered. I feel empowered, like when you said that he had a clothing shop, I was like, oh, even our publication has a merch component.

The conversation with Dontrese and Nathaniel reveals a passionate and collaborative effort to bring the story of John Mitchell Jr. to life through theater. This project not only aims to highlight the historical significance of Mitchell’s work but also seeks to inspire contemporary audiences to engage with issues of justice and empowerment. As the project unfolds, Vinegar Hill Magazine will continue to follow and support this journey, inviting the community to participate and witness the transformative power of storytelling.

Nathaniel Shaw is the Producing Artistic Director for the Firehouse Theatre. He was the Founding Artistic Director for The New Theatre, served as Artistic Director for Virginia Repertory Theatre, and was the founding Artistic Director for The Active Theater (NYC). He was the inaugural New Play Development Director for Glass Half Full Productions, Tony and Olivier Award Winning Producers of Betrayal and was an Associate Choreographer for Once, supervising both the Broadway production and the First National Tour.

J. Dontrese Brown is a passionate leader committed to empowering others, especially youth. With expertise in brand design, creative strategy, and leadership, he inspires excellence through respect, integrity, and empowerment. A sought-after speaker, he serves on numerous boards, including CRRHS, The O’Brien Foundation, and BridgePark RVA. His impressive background includes leadership roles at AIGA and degrees from Georgetown College, Morehead State University, and Savannah College of Art & Design.

by Nadirah Muhammad | Photos by Kori Price

Ihave always been a storyteller, an observer, a feeler. I have always been soft and sensitive, attuned to the vibrations of nature’s gentle rhythm, constantly trying to find the right words that fit these big feelings. Writing gave me a place to unapologetically release these all-toobig emotions, and the more words I learned, the more opportunity I had to give depth and breadth to this stream of consciousness that only grew stronger over time. I’ve always loved the feeling of discovering the perfect word to describe a moment in time. The art of finding that word perfectly suited to capturing all the emotions and weight of a moment is something I deeply value. Like any lover of words, I choose mine carefully and have learned to articulate every syllable to ensure they reflect the power they deserve.

But in doing so, I noticed a striking difference in how my words were received. When those around me were considered introspective, reflective, and precocious, I was labeled judgmental, pretentious. We limit Black women by asking them to limit their vocabularies, and, in turn, their voices.

I fell in love with the written word because it was one of the only places where I felt heard. A pen and paper was my canvas, a place where my thoughts, emotions, and observations could exist without judgment or limitation. But today, when books by Black authors and beyond are being banned, efforts to increase inclusivity are being dismantled, and the U.S. Department of Education reports that 85% of Black students lack proficiency in reading skills, writing becomes not just a passion but a necessity. It is imperative now more than ever to preserve the power of the written word.

While exact figures vary, estimates suggest that only around 5-7% of published authors in the US are Black, and an even smaller percentage of those are Black women. So small, in fact, that after searching various sources, I still could not determine an exact percentage. This statistic speaks volumes about the severe lack of representation and the invisibility of Black women’s voices in literature and writing.

Some of my earliest memories are intertwined with lines from my favorite books. Some of my earliest answers to the age-old question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” were writer, poet, storyteller. But I couldn’t understand why that answer was often met with puzzled looks and dismissive comments. Why is it so hard for people to accept Black women as writers?

As Black women, we are not given the luxury of the perceived quietness and gentleness that is often associated with the writer’s aesthetic. Society brands us as loud, abrasive, the direct antithesis to the “writer’s cliché” of the soft-spoken, introspective intellectual. Challenging these narratives is an uphill battle.

In fact, working my way through the writing world has often felt like scaling a mountain with all the right tools but a steeper trek. Every milestone is met with resistance; every accomplishment is shadowed by claims that it was earned through affirmative action, not merit. Constantly doubted, yet forced to prove my worth and exceed all expectations, I am reminded that this struggle is one that many Black women face every day.

My heart breaks for little Black girls whose dreams are crushed by strangers who limit them based on preconceived notions of who they are and what they can become. It’s far too common for people to say,

“You can’t be a writer,” or “You can’t be successful in that field.”

In the words of the great Toni Morrison, “If there is a book that you want to read and it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” In this time of the “death of DEI,” we must write. In a time where it is urgent to preserve the art of the written word and encourage diverse voices in a field that is currently under attack, we must write. In an education where the first Black female author I read wasn’t until I completed my own capstone curriculum, I must write.

I write for young me. I write for those yearning for stories untold. I write because I believe in a calling to do so, and I hope I can encourage others to do the same.

At any given moment on any given day, you’ll find me with my journal either in hand or carefully perched just an arm’s length away. Lovingly tucked in a nearby bag, along with an embarrassing amount of my favorite pens in the accompanying pocket, my journal waits for a fleeting but never far moment of inspiration to call it into action. My iPhone Notes app has never known peace, always at hand for me to transcribe the lines of poetry that come to me on a morning walk or over a cup of coffee.

But being a Black woman writer in today’s society adds an extra layer of complexity to every intersection of my identity. Finding a voice in this world—that I recently overheard someone call “the death of DEI”—has become increasingly challenging. As I reflected on those words, I realized that while writing is my safe haven, my opportunity to understand the world around me at my own pace with pen and paper, it’s also a battleground, especially for Black women. Writing has always been my weapon of choice, but this fight for recognition and space isn’t easy, especially in a time when diversity programs are disappearing, and the need for us to find our voices has never been more urgent.

by Corey E. Carter

Corey E. Carter is an educator with over twenty years of experience. His career has included teaching in inner-city and suburban schools, while his leadership experience has included work with the District of Columbia Public Charter School Board, Maya Angelou Public Charter School, and Prince George’s County Public Schools, the 18th largest school district in the U.S. He is a graduate of Albemarle High School and Virginia State University.

Interestingly enough, it’s 2025, and as Black Americans we find ourselves at the crossroads of yet another flashpoint in American history. Sometimes I wonder if there’s ever been a time where we haven’t been at the crossroads. This time, the stakes are as high as they’ve ever been. The shift toward what feels like a revival of McCarthyism—embodied in the new education policy from the Trump administration—presents significant challenges. The effort to erase “indoctrination” in American schools, under the guise of preventing balanced instruction, is gaining ground. It’s becoming a revisionist agenda through a controversial and powerful executive order about K-12 education. While it’s not hard to spot the many inconsistencies in the language of the order, what’s difficult is turning lemons into lemonade. Still, I have faith because I come from a people who have done far more than survive America’s convulsive tango dance with liberty and injustice.

Having been a product of the public school system—one that I believe had many strengths, though not without its flaws—I have concerns about the application of this radical right-wing agenda. However, my experience in the world of school choice—having worked with one of the nation’s largest and most progressive charter school authorizers, and later serving as a charter school administrator for a particularly challenging student population—gives me a different perspective. In light of this, I see an opportunity within the “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling” executive order.

Propaganda, fake news, and half-truths aside, there’s one aspect of President Trump’s education platform that I can support: increasing opportunities for school choice and directing funding to support that initiative. In a time when the ground under our children’s education is increasingly unstable, and the ultimate aim of those promoting a more disillusioned product in the name of avoiding “indoctrination” is becoming clearer, we have an opportunity to “seize the time” and innovate.

Back in 1993, when I was a senior at Virginia State University, I was the Managing Editor of The Virginia Statesman, the student publication. I had

the privilege of attending a lecture by the powerful Kwame Ture. After his inspiring talk, I was fortunate to speak with him for about ten minutes. I asked him what I should do to help my people. His initial response was, “Organize!” For those ten minutes, he schooled me on the importance of organization, mobilization, and institution-building in our communities.

What’s the connection? We need safe spaces for our communities—places where our children can learn not only about the beauty of America’s promises but also about the ugliness of its broken ones. They need educational environments that cultivate their gifts while dismantling the prisonto-playground pipeline. The president’s initiative could provide the resources for wise educators to create such environments.

Charter schools are neither new nor free from controversy, but they offer amazing possibilities. When the officials in my hometown of Charlottesville, VA, responded to Brown v. Board of Education with Massive Resistance (essentially saying, “If you make us integrate, we’ll shut the schools down”), Black families took the education of their children into their own hands—into basements, churches, and community spaces. When our ancestors were denied the right to read and write, the boldest among them took the responsibility of education into their own hands. The examples of success that emerge from institutions we create ourselves, when we own the responsibility, are unparalleled.

In the words of Booker T. Washington, “Drop your buckets where you are.” In the words of Dr. Carter G. Woodson, “Re-educate.” In the example of the Black Panthers, initiate programs. And, as Kwame Ture commanded me, organize. If school choice is going to expand, we should make lemonade and build our own schools. If we are concerned that this Executive Order will lead to a less wellrounded, non-objective, colonizer-minded product, we should build our own schools. The pathway is there, the resources are there, and the promise is there.

by Dionna L. Mann

I was on the phone with Mrs. Olivia (Ferguson) McQueen (1942-), the granddaughter of Dr. George Rutherford Ferguson (1877-1933) who was an African American physician in Charlottesville long before integration.

“Have you spoken with Teresa Walker Price?” Mrs. McQueen asked regarding my attempt to learn more about some photographs I wanted to use in an author’s note that would appear in my traditionally published debut novel for young readers Mama’s Chicken and Dumplings, then in the final stages of editing.

Out of embarrassment I paused. I had to admit I hadn’t heard of Mrs. Teresa (Jackson) Walker-Price.

“She’s as old as the hills,” I remember Mrs. McQueen saying. “Try calling her.”

I wondered: why hadn’t I come across the name “Teresa WalkerPrice” while doing research about Vinegar Hill, a once thriving African American commercial and residential neighborhood of Charlottesville that is the setting of Mama’s Chicken and Dumplings? After all, I had been digging and digging with

madness and discovering and uncovering facts about Vinegar Hill and the larger African American community of Charlottesville for many moons to get the details inside my novel correct.

And yet, there it was: a missed primary resource—a breathing, flesh-and-blood one, and her name was Teresa (sounds like Tuh-ress-uh and not Tuh-ree-suh). Naturally, the moment I got off the phone with Mrs. McQueen, I searched the Internet. Who was Teresa WalkerPrice?

Soon I discovered that Mrs. WalkerPrice had familial roots woven into Charlottesville’s African American history and stretching back to Monticello, the hilltop home of Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States. And the most incredible thing? Mrs. Walker-Price, whom I now know as Miss Teresa, was born in 1925, the same year as my ten-year-old main character, Allie! Mrs. McQueen was right! I needed to speak with her!

I wondered, though, if Miss Teresa would remember being ten years old in 1935—walking the streets of Charlottesville, shopping the stores on West Main Street, visiting Mr. Inge’s Grocery to buy penny candy? Would she remember details about attending Jefferson School, my main character’s school, and be able to supply me with the answers to questions I still had despite my research? Most importantly, would she be able to tell me more about Dr. Edward Stratton, Jr., the physician who served the African American community in 1935 whose name I’d borrowed for a doctor mentioned in my novel.

I clicked an online telephone book and searched for her. As I dialed the number, I could feel my heart tap dancing.

“Hello?” A strong yet elderly woman’s voice answered—clear, warm, kind.

“Mrs. Jackson Walker-Price?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. “Who is this?” I introduced myself, and explained the purpose of my call.

She laughed her beautiful, unforgettable laugh. “I thought you were one of those people trying to sell me something.”

I laughed, too. “Not me,” I said. “I promise.”

And so, our phone conversation ensued—easy as instant pudding— smooth, sweet, uplifting to the

soul. Her recollections were crisp. Her humor was delightful. Her stories made my heart soar, my brain happy-tingle, my inside-tears flow. I was reliving history, the kind my parents and grandparents might have experienced, simply by listening to someone who had lived it, someone who remembered it, someone willing to share it. My missed research hole was being filled!

“Come by and see me anytime,” Miss Teresa said as our conversation wound up.

“Really?” I asked. “Anytime?” “Anytime.”

And so, a few weeks later, I took her up on the offer.

I drove down Miss Teresa’s narrow street—the same width it had been since the early days of Charlottesville, parked, walked up

Teresa Walker-Price, 98 years old, speaking with Dionna Mann about the real Dr. Stratton.

the steps to her brick home onto a fine porch, and knocked. Miss Teresa’s daughter-in-law opened the door, and invited me in. Miss Teresa, being 97 years old at the time, was descending her stairs in a mechanical chair. She was as beautiful as her laugh. Her short gray hair her crown. Her blue eyes her jewels. Her peachy tan skin her satin robe. She rose from her throne.

“Hello, Mrs. Walker Jackson Price,” I said. “I’m Dionna Mann, the author of that children’s book that takes place in 1935 Vinegar Hill. We spoke on the phone.”

“Yes, of course!” she said. “Come in, and sit with me.”

I walked behind her, past her piano lined with photographs, through her tidy living room, and into a sitting room with walls graced by her son Franklin’s pencil, ink and charcoal sketches. She settled into a chair surround by piles of books

and magazines, all of which had pages turned out, or bookmarks inserted to indicate where she’d stopped reading. A wall with inset bookshelves with barely any space stood ready to accept more from her read collection. Miss Teresa’s sitting room was a true sign that she had spent many years as a school librarian, and the obvious subject of her interest was African American history.

A dignified bust of a contemplative Black man sculpted by her son Henderson Day “Bo” Walker, Jr. peered in my direction. Mind your manners, it seemed to say. This is my Mama you’re talking to.

I sat up straighter. “Do you prefer that I call you ‘Mrs. Jackson Walker Price, or…’”

“My friends call me Miss Teresa.”

“May I call you Miss Teresa?”

“That’s what I meant,” she said, then laughed again. “So, what do you want to know.”

Where to start?

I pulled a photograph up on my phone. I believed it to be of Dr. Stratton but wasn’t sure, so I handed the phone to Miss Teresa.

“Is this Dr. Edward Stratton who was a physician here in the 30s?” I asked.

“Oh, yes! That’s Dr. Stratton, all right!” she said.

My research was confirmed!

“Did you know him?”

“Know him?” she said. “He ate supper with my family.” She gestured toward her neat-as-a-pin kitchen.

I pulled in closer. “Right here in this house?”

“Oh, yes. Right here. Until his wife came.”

“And he practiced at…” I searched my notes for the location of his practice as it was listed in the 1934 Hill’s Charlottesville City Directory. Only then did I realize that Miss Teresa’s address (with an ½ added) was the same as Dr. Stratton’s practice!

“My father fixed up the basement so he could have a nice place to see his patients.”

I took a closer look at the walls inside Miss Teresa’s home. It was the place where history happened! “What was he like?”

Miss Teresa eyes lit up as she shared how Dr. Stratton was approachable, warm and kind. She shared how she would ride along with him when he treated patients in their country homes. She was about ten then, the same age as my main character. “I was his goddaughter,” she said. “He was my buddy.”

Miss Teresa painted a scene of 1935 Charlottesville that I never would

have been able to envision inside UVa’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collection Library. Her recollections were as clear as a hot summer day without humidity, and I loved the crystal-clear view.

Since my first in-person visit with Miss Teresa, I’ve been privileged to sit with her several more times. Each occasion I’ve learned something new. Sometimes it’s about growing up in Charlottesville during the 30s. Sometimes, it’s about Miss Teresa’s family’s history. Sometimes it’s about life or people in general. But every time, I felt what it means to have someone from an older generation extend her hand to someone of a younger generation. Come on in, out of the cold. Sit for a while, and get yourself warm. Thank you, Miss Teresa, for warming me, and allowing your story to be a chapter in mine.

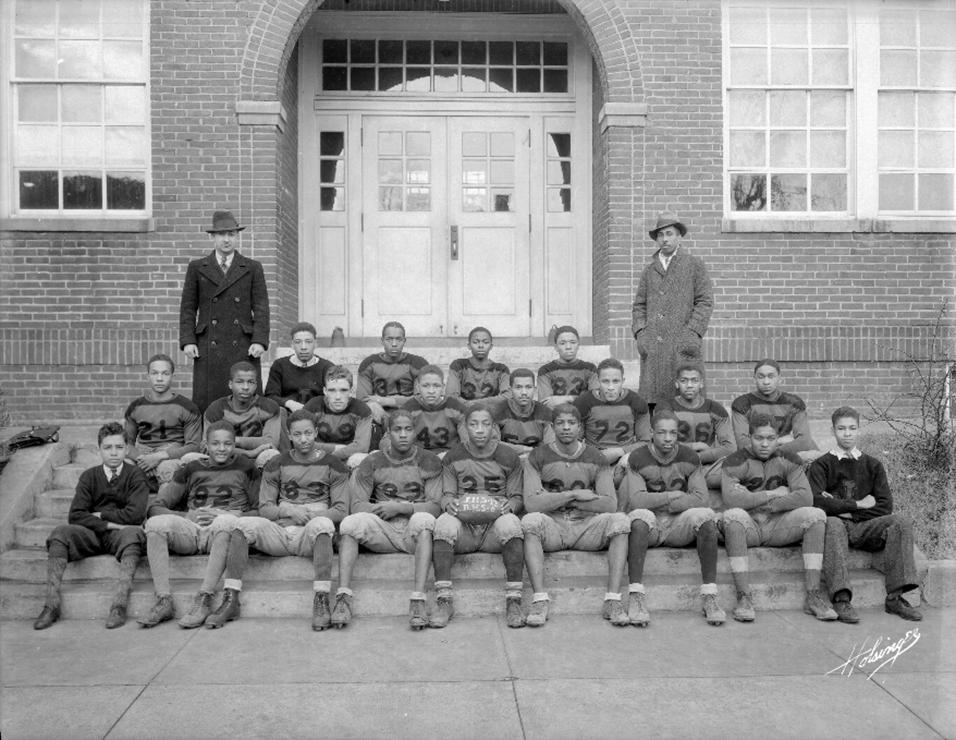

Optional sidebar: Miss Teresa was born to Tessie and William E. Jackson, Jr. (18881972). Her father became locally known as “Billpost” Jackson because of his billboard advertising business. Miss Teresa’s grandmother was Nannie Cox Jackson, an intrepid and beloved domestic science teacher at Jefferson School who generously supported the school’s football team and city lunch program. After Miss Teresa graduated high school from Jefferson School in 1942, she attended Hampton Institute. After passing her final exams, she returned to Charlotteville to teach. She and her first husband, Henderson Day Walker, Sr. had two sons who both became well-respected visual artists. Miss Teresa taught business and typing at Jackson P. Burley High School, and later became certified in library science, and after integration taught at Lane High School. In 2019, Mrs. Walker-Price was awarded a Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Award. She will be 100-years-young on December 14, 2025.

Bio: Dionna L. Mann is the author of Mama’s Chicken and Dumplings, a West Main Street adventure in which Alexandra Lewis

determines to take her life from broken to perfect, one jar of chicken and dumplings at a time. If only Mama will cooperate. Published by Margaret Ferguson Books, an imprint of Holiday House, August 6, 2024, Mama’s Chicken and Dumplings is a Junior Library Guild Gold Selection. Find out more about Dionna online at dionnalmann.com.

by Tracy Howard-Gough| Marley Nichelle

December in Ghana is more than just a season—it’s a homecoming. Every year, African-Americans from all over the world return to West Africa, seeking connection, celebration, and a deeper understanding of our heritage. I was one of them. But this trip was different. I wasn’t just visiting; I was shedding, stripping away the layers of my outside world to fully immerse myself—physically, emotionally, and spiritually—into the place where I felt most like me. A Black woman.

The moment it all changed for me was at the Atlantic Ocean.

I stood at the shoreline, feeling the warm Ghanaian sun on my skin, the same sun that once touched the faces of my ancestors. The waves called to me, whispering a truth I had always known but never fully embraced. I removed all of my clothing, letting go of everything— expectations, burdens, the weight of being “othered” in spaces not built for me. As I stepped into the water, the coolness wrapped around me, a baptism of sorts. Was this the same water that carried my ancestors away centuries ago? Was this the same ocean that bore witness to both their suffering and their strength? The thought sent

a shiver through me, but instead of fear, I felt power. I was here. We were still here. And despite everything, we rise.

Amidst the beauty of reconnection, there were also moments of dissonance. One of the most unexpected realizations was that the journey was not entirely shaped by those with a shared ancestral connection. How could we, as descendants returning to the lands of our ancestors, find our story framed by perspectives that felt distant from our own experience? It was a powerful reminder that even in the search for belonging, questions of voice, agency, and access still linger.

But this experience was not just about struggle—it was about reclamation. It was about understanding that my personal journey, my challenges, my resilience, are all threads in a much larger tapestry. Ghana showed me that my culture, my essence, my being had roots in a place that had faced unfathomable adversity, yet still thrived. And in that, I found strength.

During the pandemic I went on my first trip with the Charlottesville Winneba Foundation. In 2024 I joined as an individual contributor to the Foundation’s board, through Knot Broken where I serve as a co founder. Knot Broken serves as an organization that supports Black women in navigating community resources. Our mission is to empower Black women by providing them with accessible information, education, and connections to critical community services, enabling them to effectively address their needs and overcome systemic barriers within the local area. in 2025 Knot Broken will partner with the Charlottesville Winneba Foundation to sponsor a delegation of youth for their December trip.

That strength led me back.I knew that if given the chance, that I wanted to work together with the

delegation to create a space of equity and representation. In December 2024, I returned to Africa—but this time, I wasn’t just a traveler. I coled the first Black-led delegation through the Charlottesville/ Winneba foundation, ensuring that our voices, our perspectives, and our experiences were centered in the journey home. To guide others in fully immersing themselves in the land, the culture, and the spirit of Africa was an honor and a responsibility I carried with pride. To my fellow African-Americans: if you ever get the chance, please come home. Walk the streets where our ancestors once walked. Taste the food, hear the music, feel the land beneath your feet. Stand in the ocean and let it remind you of where you come from. When you do, you will understand—our history is painful, but our existence is proof of our power.

No matter where we go in the world, Africa is always within us.

by Sonia Montalvo

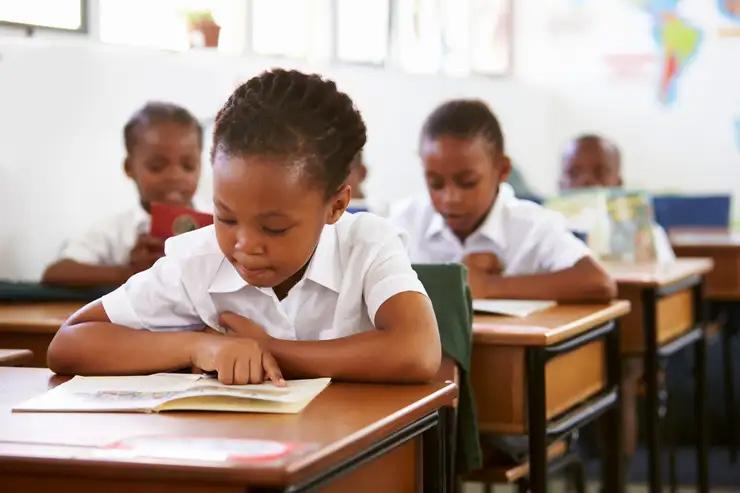

The problem with today’s youth is…

Not a damn thing honestly. Our youth, the next generation of leaders, thinkers, and doers have actually never been the problem. It boils down to the issues they face daily and the lack of resources to assist them where problems actually exist. Working with youth wasn’t something I ever really had an interest in early on. But looking back at a 12 plus year career of working with young people aged 8-22 years old, I’ve learned some things. I, like so many others, thought, “Kids are just bad, and they don’t have any direction.” It wasn’t until I started working within our communities, getting to know families, spending time at their dinner

tables, in the schools, and everywhere in between that I realized that we can never label our youth as “bad” when there are so many systems and factors that that have a hand in how they are growing and maturing.

How easy has it been for us to put the blame on children without doing a deep dive into systems that shape their behavior? In no way am I seeking to bash individuals or entities but rather provide an alternative perspective on how our structures—educational, social, and economic— influence young people and how they navigate the world. By shifting our focus from blame to understanding, we can begin to address the root causes rather than just the symptoms

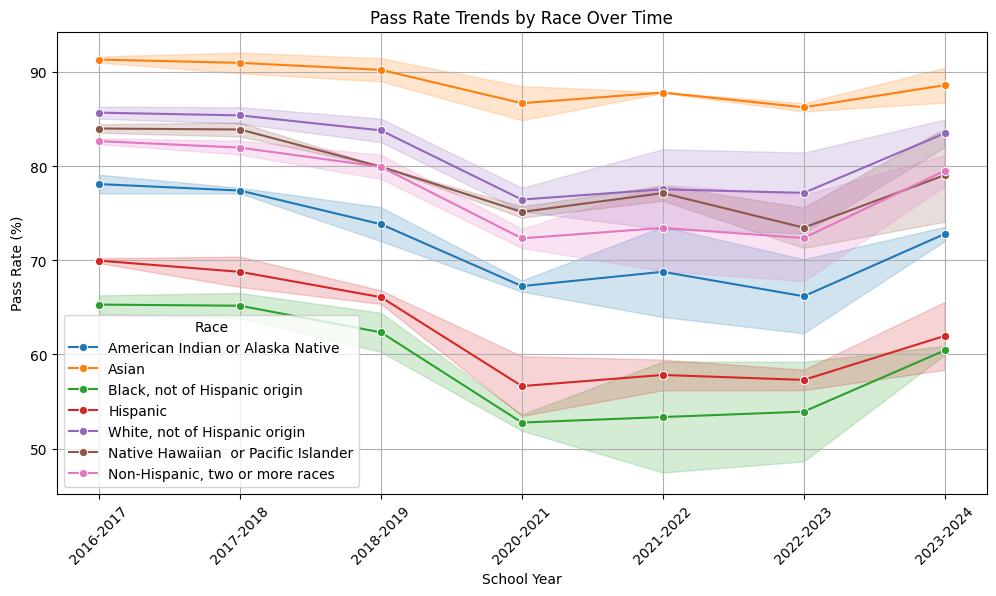

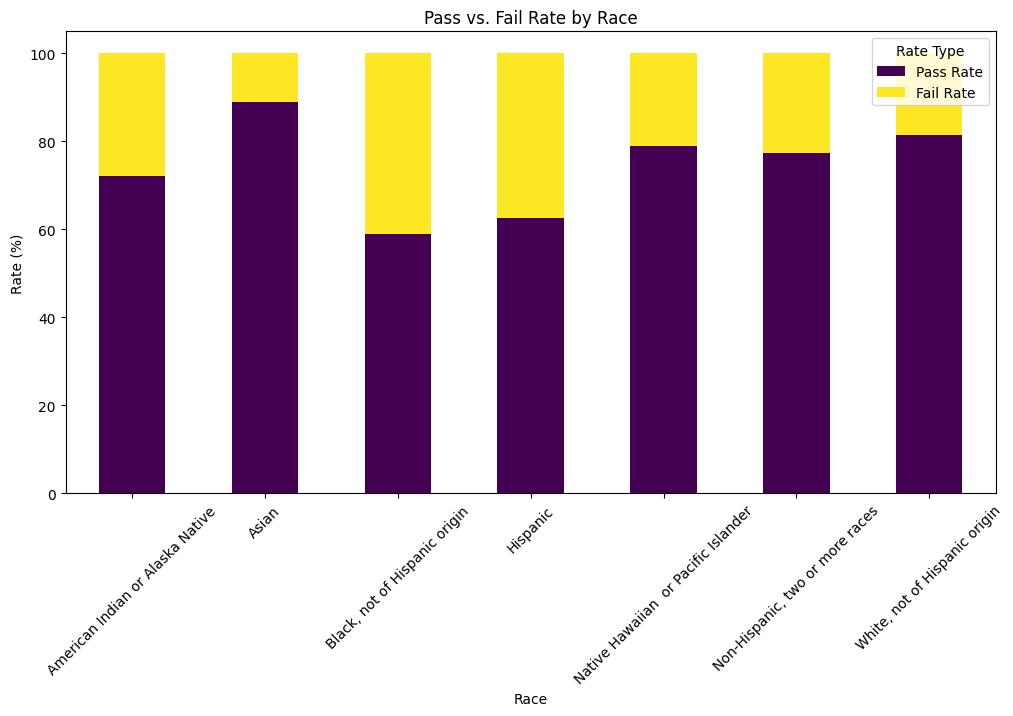

Source: Virginia Department of Education. Test Results Build-A-Table. https://p1pe.doe.virginia.gov/apex_captcha/home. do?apexTypeId=306. Graphs by DSID.

Let’s take into consideration that the later half of Gen Z (2006-2010) and all of Gen Alpha (2010-present) are growing up in a world that I, my peers, our elders, and our predecessors have never known.While some elements may feel familiar to our upbringing, today’s young people are navigating an entirely different landscape. While some youth and young adult experiences remain universal—like identity development, peer pressure, family dynamics, and the desire for independence-we know that the familiar coupled with the uncharted territory of today’s society, does not make the experience any easier for them. If we truly seek to understand the existing hardships of growing up, we can’t look to our previous understanding of our lived experiences. That world is gone. The current political climate, the consistent growth of achievement gaps present in education, the influx of digital misinformation, the rapid evolution of technology, constant exposure to crises through social media, and the lack of mental health resources—all of these factors have created an environment unlike anything we experienced.Let’s also note that the more marginalized the group, the more exacerbated these issues become for them.

As it relates to education, In 2018, when I founded The Girls Are Alwrite, I saw firsthand the disparities in reading and writing proficiency among students of color. The 2016-2017 Virginia Standards of Learning (SOL) test scores revealed a 67% pass rate in reading and 65% in writing for Black students. For Hispanic students, the rates were slightly higher at 71% for reading and 70% for writing. In contrast, their white counterparts had an 86% pass rate in reading and 85% in writing, while Asian students scored 91% and 92%, respectively.

Seven years later, following the life altering events of COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to virtual learning, rising incarceration rates, political unrest, racial tensions, schools reopening for in person learning, consistent decreases in school funding, and the banning of books, these gaps have widened. The 2023-2024 SOL results show an even sharper decline for Black and Hispanic students—Black students now have a 60% pass rate in reading and 61% in writing, while Hispanic students have dropped to 59% in reading and 66% in writing.

While White and Asian students also saw slight

declines, their pass rates remain significantly higher. White students scored 82% in reading and 85% in writing, while Asian students scored 87% and 90%.

As someone passionate about Youth Development, I see how today’s students navigate a digital landscape they’ve turned to for solace. Social media plays a major role in shaping their identities and relationships, all while they face the pressures of academics and the challenges of America’s economic and environmental instability.” Social Platforms, while widely accepted and utilized as a tool to connect with and educate the masses, have also been an aiding accomplice in some of the issues our youth face. In 2023 The Pew Research Center shared their findings from research on Teens and Social Media usage. Findings show that 95% of teens 13-17 use YouTube, TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat. The American Psychological Association reports that most teens spend 4.8 hours a day on social platforms. Youth of today spend almost as much time if not more in digital communities they’ve found or created as they do at school or at home. It’s important to acknowledge the significant influence it has on their

development, self-perception, and interactions with the world around them.

The truth of the matter is that youth are only products of the environment that the adults around them create, uphold and foster. Whether it be home, school, or through the influence of social media, how these children and young adults show up in the world falls back on the direct responsibility of us as the village. Our attitudes, resources, and structures we put in place shape their opportunities, behaviors, and overall development. If we don’t show up in the giving spirit of our time, knowledge, wisdom, and resources, then can we truly point the finger at them being the problem? I encourage you to ask yourself, ‘Am I truly doing all I can as a member of my community to show up in a young person’s life?’ If the answer is no, I implore you to get involved. No longer can we paint youth as the “problem” if we aren’t willing to do all that is within our power to create some solutions. Our presence in the lives of young people is no longer optional. It’s imperative if we want to see them continue to grow. The youth were never the problem. It’s us.

Source: Virginia Department of Education. Test Results Build-A-Table. https://p1pe.doe.virginia.gov/apex_captcha/home.do?apexTypeId=306. Graphs by DSID.

-4 Print full-page ad (full color)

-Online banner ads (see sizes on page 4) full color- these rotate online and can be switched out throughout the month

-4 printed magazine copies

-Total cost for the year $908.00

-4 Print half-page ad (full color)

-Online banner ads (see sizes on page 4) full color - these rotate online and can be switched out throughout the month

-4 printed magazine copies

-Total cost for the year $628.00

-4 Print 1/4 page ad (full color)

-Online banner ads (see sizes on page 4) full color- these rotate online and can be switched out throughout the month

-4 printed magazine copies

-Total cost for the year $508.00

-Sponsorship Section $5,000.00 (annual)

-Home page pop-up $1,000 00 (monthly)

-Video News Post (appears in line with articles) $150.00 (monthly)

-Social Media (FaceBook, Instagram, & Twitter) $75.00 (monthly)

-Newsletter/Email Campaign (1-3 weekly) $75.00 (monthly)

-YouTube Page $75.00 (monthly)

-Online Banners $150 00 (monthly)

2 Mock ups

2 Revisions

You created the perfect business cards and you have more orders than you can handle, so what’s next? As your business banking partner, we’re here to find solutions that will work for you.

Business Banking

Business Loans | Free Business Checking* | Remote Deposit Capture Treasury Management | Credit Cards

*$100 to open | No minimum balance requirement. No monthly maintenance fee, but other fees can apply. Please refer to the Fee Schedule.