Dear VH Readers,

Summer is back, and as Vinegar Hill takes a pause for the season, we hope this issue feels just like that for you all—a pause. A moment to sit with the fruits of your labor. To reflect on the work, the weight, and the beauty that’s happening all around us.

In this issue, we hear from Darnell Lamont Walker and a perspective on what it means to be uncompromising in morals—even if it means losing access and position. Through the lens of fictional character Kim Reese of hit TV show Different World, Darnell invites us to consider the cost of integrity, and what it looks like to hold onto your values when the world asks you to let them go.

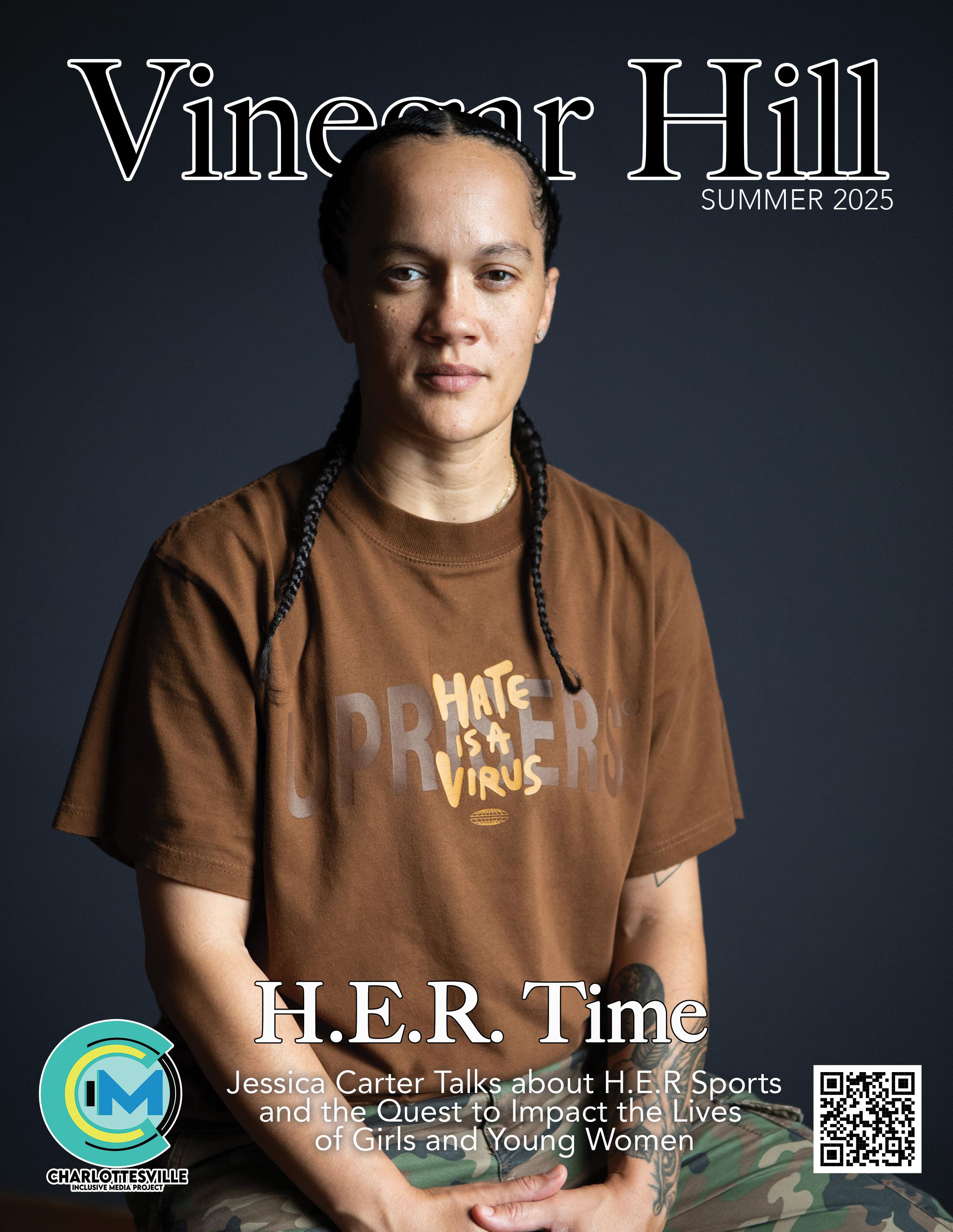

We’re also excited to share the work of Jessica Carter and her platform, HER Sports—created out of the need to amplify women athletes who are too often overlooked. Jessica didn’t wait for someone else to make space. She built it herself, and in doing so, created a space for others to be seen too.

This issue is rooted in acknowledging the kind of work people don’t always clap for. The kind that happens when nobody’s watching. Our hope is that you read these pieces and That take pause for yourself. We hope something in them stays with you.

As we gear up for the Fall season, If you are interested in writing for Vinegar Hill Magazine in the future, please know that we value the work you do and only want to make space for it here. Please send your queries to info@ vinegarhillmagazine.com.

Sonia Montalvo

by Darnell Lamont Walker

(Dedicated to the ones who turned down the money, took the hard road, and never stopped looking in the mirror)

There’s an episode of A Different World that’s tattooed on my memory— stitched into my spine like ancestral wisdom. Kim Reese, pre-med student, daughter of working-class parents, first in her family to chase a dream that big, is offered a scholarship to attend medical school. It’s a lifeline. It’s salvation. It’s everything she’d been working toward.

But there’s a catch.

The company offering the scholarship is deeply invested in apartheid South Africa. Their

money is blood money, plain and simple. Unapologetically. And Kim Reese turns it down.

Let me say that again: Kim Reese, broke, brilliant, and Black, turns down the scholarship. Not because she has a backup plan. Not because she found a loophole or had a quiet sponsor waiting in the wings. But because she couldn’t stomach the thought of building her future off the bones of her people. She says no. Even when some told her the answer should’ve been yes. Even when the math didn’t math. Even when it made no damn sense to anyone but her and her mirror. I was just two days away from my 8th birthday, but that episode changed me. It hit me in a part of myself I didn’t know was listening. That moment lit something in me—a flame I still carry.

After that, I became someone I hadn’t yet met: the person who speaks up. The person who walks out. The person who refuses to just go along.

As continued to grow, so did the flame. I started showing up at school board meetings, demanding a Black History class in our curriculum. When they smiled politely and told us, “maybe next year,” I threatened them with walkouts. They tried to dismiss us. I stared them down. I even brought my mother with me as backup. Eventually, they didn’t just fold—they put me on the board. A teenager. Loud. Relentless. Full of fire.

I started shouting “brick by brick, wall by wall, free Mumia Abu-Jamal!” through the streets of Charlottesville and on Thomas Jefferson’s academic plantation, walking a tightrope between discipline and defiance.

The road didn’t stop there. I was invited to Cuba by my college-aged activist friends to sit with Assata Shakur. I was 16 or 17 and mother said no to the trip, but I continued walking the same path with local activists who taught me how to sharpen my analysis, how to move

with strategy, how to throw a punch without lifting a fist. I protested. I organized. I learned to pick my battles but never my truths.

After college, I turned down job offers that would’ve made my parents proud and my bank account less tragic, because I knew those jobs were built on harm. In college, I watched friends get threatened with suspension and expulsion for what I called “no good reason,” and I jumped in. I got loud. I got disruptive. I made it my business to raise hell when hell was what they gave us.

I’m not romanticizing the struggle. I’m saying it was worth something.

And I wasn’t doing it alone. There were so many of us. A whole damn gaggle. We studied together, skipped class to organize together, nearly got arrested together. We were alive with resistance. We took ourselves seriously and we took each other seriously. Our futures mattered, but not more than our dignity. But something’s shifted. And I’ve been wrestling with it.

The other day, I watched a video of a young Black woman from an HBCU, and she was glowing. Beaming. You would’ve thought she’d won the lottery. She talked about how she’d landed a fellowship at the White House. This White House.

The one currently overseeing genocide, weaponizing borders, and not pretending to give a damn about equality.

She was proud. And I couldn’t blame her for the pride. She’s been told her whole life that’s the pinnacle. That’s the dream. But I looked at her and thought: Kim Reese would never.

Years ago, a former friend posted a smiling selfie with a known figure who’s spent years undermining Black lives. I said something. I couldn’t not. We haven’t spoken since.

Black folks I love, respect, and once marched beside are joining police departments that

brutalized their own cousins, uncles, mamas. Not to dismantle from within. Not to infiltrate and disrupt. Just for the benefits. Just for the steady paycheck. Just for the “respect” and probably for the likes.

And look—I know survival is hard. I know we’re all tired. I know the system is rigged, and for a lot of us, it feels like the only way to win is to play the game. But when did we stop asking whether the game is worth playing?

When did the line we used to draw in the sand get replaced with a brand deal and a good salary?

When did we stop being afraid of mirrors?

Kim Reese would never.

She wouldn’t smile for a photo op with a killer of her kinfolk. She wouldn’t trade her soul for a fellowship. She wouldn’t join a system of oppression and justify it with buzzwords and hashtags. She’d be scared, yes. She’d be unsure. But she’d still say no.

And it’s not about her being fictional. That’s the thing. It wasn’t fiction. Not for those of us who took it to heart. Kim Reese represented a generation of us who believed in something bigger than ourselves.

She reminded us that there’s a difference between being successful and being significant.

We watched her, and we moved differently. We took risks. We

lost jobs. We burned bridges. We made enemies. We called out our own people when they were out of line. And we did it because the fight was real. Because the harm was real. Because our elders taught us, “All skinfolk ain’t kinfolk,” and “freedom ain’t free,” and “don’t let them use your Black face to sell white lies.”

So when I look around today and see folks trading legacy for clout, trading ethics for access, I get worried. I get angry. I get heartbroken.

But I also remember that there are still some of us out here. Holding that fire. Holding the line. Maybe quieter now. Maybe

in different corners. Maybe no longer a gaggle, but still lit.

So this is a call. A reminder. A reclamation.

We don’t all have to say no. But some of us must.

We don’t all have to march. But some of us must.

We don’t all have to sacrifice, but if no one does, then what are we left with?

Kim Reese would never. And once upon a time, neither would we.

But we can still find our way back.

by Sonia Montalvo

In our last issue, writer Nadirah Muhammad published a beautiful piece about the hardships Black women writers face and her love for the art form. Her words have stayed with me, stirring up a mix of emotions for me that I thought I had reckoned with.There’s a portion of her article specifically that makes me ponder on my own journey with writing. In it she states:

“I’ve always loved the feeling of discovering the perfect word to describe a moment in time. The art of finding that word perfectly suited to capturing all the

emotions and weight of a moment is something I deeply value. Like any lover of words, I choose mine carefully and have learned to articulate every syllable to ensure they reflect the power they deserve.”

In my own reflection after sitting with her piece,I’ve come to realize that my relationship with writing and editing has not always been defined by love or passion alone. Here are my thoughts as raw and true as I can muster the courage to share with you.

I have made the very difficult

decision to step down as Editor In Chief of Vinegar Hill Magazine. A lot of tears are being shed even as I write the statement and make it plain. This piece is my last with the platform under this role. This is the fulfillment of my younger dreams personified, so leaving something I prayed for so deeply, doesn’t even feel real. As I transition out of this role, I am conflicted. I grew up thinking that writing and editing were magical jobs to have. I knew in my heart that I would wake up, head into work, enjoy the clicking of computer keyboards, and relish in the taste of long all-nighters to tell the stories that were important to me.

I was secure in the dream I had for myself as a future Journalist and Editor. So secure, in fact, in 2016 I began applying to Journalism programs that I felt aligned with what I wanted. I had previous writing and editing experience with other news sources, so I thought for sure that I was an ideal candidate. Funny enough, I never heard back from any of them.. That was until 2017, I got my acceptance email from Morgan State University’s Journalism program almost a year after I sent in my application. By this time, I had imagined new dreams for my writing and career. I had just selfpublished my first book the year before, and truly I was burned out from trying to make writing work. I thought I loved it, but I didn’t feel like it loved me back. Seeing the acceptance letter again for the sake of this article, almost felt like a punch to the gut with feelings that I thought I buried deep. Something I once wanted, I didn’t feel like it belonged to me anymore. Looking back over it, I don’t think I ever wanted it as badly as I tried to make myself believe. In many ways, my journey with Vinegar Hill became the space where that old dream got a second wind—but in a way that felt authentic to me. I didn’t need an institution to say yes. I had finally gotten what I once waited for. Transparently, That’s what makes leaving this role so hard.

The reimagining of my life didn’t allow writing to take front and center as it once did. I had moved on to taking youth development more seriously and moved across the country to teach. For the sake of this article, I went back to look at my application essay. It’s heartbreaking to admit that I can realize even in the essay, I was laying the foundation for the feelings I have about writing and editing today. In it, I stated:

“Journalism is my passion simply because it gives the space to make the narratives that go unnoticed, front and center. These truths live under fabricated and calculated lies. Good journalism is, if nothing else, there to slap its readers in the face with the truth. In any aspect of writing, being a truth seeker is my Mission.” I was not excited about Journalism or writing; for me, it was simply about the urgency of the narratives.”

For some time, I’ve felt guilty about these feelings. I pondered on if they’ve made me an ideal candidate to take the helm as Editor of such a sacred publication like Vinegar Hill Magazine. I now know it has been my questioning, my care, and my willingness to listen that have helped me carry the role with honesty. Not always perfectly, but definitely with intention.

Over the last year and a half what I have enjoyed most in this role was hearing the experiences of others. There is great necessity in building community through experience. Something about connecting with others through their lived and written experiences, somehow deepens the understanding —of ourselves, of each other, and of the world.” It’s why we as humans love hearing about favorite celebs, or even why salacious hearsay is appealing to some. Connectedness helps us to understand little by little. I’ve sat in the living rooms of community legends, in conference rooms with political candidates, in book stores with musical talents and the common thread for me or rather what kept me tied to the work, was my own was my desire to understand and my self-imposed obligation to seek and tell their truths, We lose a great amount of history when we allow the stories of those around us to go unwritten. It was never about the love of writing, it was about the responsibility that comes with it.

This time with the publication has taught me two things that I’d wish to share with you before I step down from my position.

Every time you see an article pop up on our site, or in a print issue, please understand our writers are doing the very best at taking record of the past and present, and condensing it into 1,200 words or less. It’s one of the most heartbreaking parts of this work and most Journalists will tell you the same. Picking apart something so layered and alive into something brief and readable for the short attention span of society. We carry the heavy and real weight of commemorating people’s truths, and knowing that no word count will ever truly convey the magic in what they shared in totality Behind each piece are countless hours and sometimes days of listening, transcribing, fact-checking, editing, and doubting if we’ve given it all we can. Any Journalist or media professional will tell you that we often ask ourselves whether we’ve done justice to the people who trusted us with what they’ve shared, and whether we’ve captured the fullness of what they gave us. The cuts we make are painful, and once released to you, you have the luxury of never worrying about that. I urge you, after you read any

article, to do more research on what’s being shared. Treat them the same way you would something you’re passionate about. Continue to learn all you can about what is being shared with you. Continue to help us keep it alive.

2. Listening is a radical act

I’ve learned that listening is a form of genuine care. It’s how we validate those around us. It is how we value the spaces we inhabit. A universal truth is that we all only want to be heard. I’ve come to understand that listening is not just about gathering quotes; it’s about being present. So much of my work with Vinegar Hill Magazine has reminded me that being an ear to someone’s or something’s truth is its kind of gift, and it’s the type of gift that gives to the listener and the speaker. It’s easy to think that listening only requires the listener to be quiet, but that couldn’t be the farthest from the truth. Listening is an obligation to be open and patient with what is being shared. One may not always agree with what they are listening to, but there’s always something to be taken from what you’ve heard. It could be a new perspective or even just the reminder that someone’s truth exists alongside your own. Listening, when done with intention, is an act of protest. It says, Though I don’t have all the answers, I’m committed to learning. In a world full of noise, choosing to listen to those around us is one of the most generous things we can do for one another.

While I will no longer serve at the helm of this publication, I will always be a writer. It is mandatory work. This will not be the last you see of me but I’ve made peace with the fact that it will not be in the same ways. Revising your dream doesn’t mean giving it up in its entirety. It means giving space for it to grow in other ways.

Thank you Vinegar Hill executive staff andreadership for allowing me to be a part of you during my time here. Thank you for welcoming me into this community and letting me share in retelling the narratives we hold dear in this area. I am excited to share with you in the future, as writing will always be a part of me. Whether this work is a passion or a necessity, it is real.

by Sarad Davenport | Photos by Kristin Finn

You know that feeling of being so in tune with something, it feels like therapy? For Jessica Carter, that’s sports. It’s her sanctuary, her outlet, her passion. And it’s the driving force behind HER Sports, an organization celebrating its five-year anniversary of empowering women and girls through athletics and community.

Jessica’s story is one of fierce dedication, not just to the game, but to the next generation. As the co-owner of a mental health therapeutic service business and a dedicated caregiver for her mom, Jessica wears many hats. But right now, her main focus is on pushing HER Sports to new heights, culminating in a big anniversary event that aims to bring the whole community together.

From Country Girl to Court Leader: The Early Spark

Jessica’s athletic journey started in the red dirt roads of Fluvanna, Virginia. “I’m from the country,” she laughs, explaining how her parents and relatives encouraged her and her cousins to be outside, active, and, often, a little dirty. With a basketball court in the yard thanks to her uncles, and a dad who worked on trucks, Jessica’s early years were filled with outdoor play.

Her first love wasn’t even basketball – it was baseball. A natural left-handed pitcher, Jessica played with all boys, a common theme in her early athletic life. “I was always that type of girl that wanted to get dirty,” she recalls. Her parents even incentivized her pitching prowess, giving her 25 cents for every strike she threw. She remembers leaving the field with bags full of quarters, sometimes upwards of $5.

“Baseball was my love at first,” she shares, even admitting she always wanted to play shortstop because

that’s “where all the balls go” and you “gotta be quick with your hands.” This early immersion in competitive, often male-dominated environments, instilled a deep-seated competitive spirit in Jessica.

When she transitioned to Charlottesville City schools in fifth grade, basketball took center stage. She began playing AAU for Coach Brooks with the Mt. Zion Lady Cavaliers. This experience provided a foundational sisterhood and rigorous training. “Remember coach picking us up and then creating a sisterhood because the majority of a lot of the women around here were, were under him,” she recalls of her time with Coach

Brooks, also noting that he “made us go to church” and sing in the choir, adding a unique dimension to their team bond. Playing with boys continued, shaping her mindset on the court. “I think I came out the womb competitive,” she muses, humbly adding that she always wanted to be the best version of herself. When boys “played soft” with me, she’d get mad. It was an instinct. She knew they would make her better.

Jessica’s high school years at Charlottesville High School (CHS) under Coach Harry Terrell were legendary. She humbly played JV her freshman year, recognizing the abundance of talent on varsity. “I just knew I wasn’t going to get any playing time because, you know, we had Kandi, Shenika, it was Crystal, it was so many people on that team.” She used her time on JV to become a better leader and refine her skills. Her sophomore year, everything clicked. The team went an incredible 28-0 and won the state championship. Jessica’s role was clear: “come off the bench and be that spark, be a...second string point guard” to Kandi and Shenika. She excelled, contributing significantly to their championship run. Over her entire high school career playing varsity, she estimates only losing “about three to four games.” CHS basketball was more than just wins; it was a culture. “The cheerleaders, how the crowd came out, the orange floor,” she recalls, emphasizing that “nobody could ever take that from us.” They were, in her opinion, “by far the best girls basketball program in the state, hands down.”

One particularly memorable moment highlights the unique environment they navigated. A local newspaper article, penned by a Western coach who was also her gym teacher, referred to them as “a bunch of thugs.” Jessica will never forget it. “Now looking back, that really showed me the dynamic in how people viewed basketball. And I think that’s what sparked us. That’s what kept us together.” It cemented her lifelong pride in being “orange and black till I die.” She believes the CHS program produced “powerful women” whose strength still shows today.

Jessica’s college journey took an unexpected turn. During her senior year of high school, she tore her ACL while playing against Fluvanna High School. Despite continued play “being hard headed, being competitive,” the injury impacted her college offers. She had hoped to go to an HBCU like Morgan State, but her options dwindled.

Mary Baldwin, a D3 all-girls school in Virginia, kept calling. “I never thought I was going to go to D3 and the all-girls school,” she admits, having envisioned a different “college experience for basketball.” The gym wasn’t what she expected, and initially, she felt a strong desire to quit. “I called my mom and crying because I wanted like, I was so ready to quit.” Her confidence was shaken, especially due to her knee injury, which led her to play without a brace her freshman year. But a turning point came her sophomore year. She started putting in the work, staying in the gym, and getting her teammates

to join her. Her dedication didn’t go unnoticed. A teammate approached her and declared, “Oh, you’re the new point guard.” Just like that, Jessica embraced her new role as a scorer, something that hadn’t been her primary focus in high school where she was surrounded by other “beasts.”

She led Mary Baldwin to new heights, breaking records and retiring with an incredible 1956 points, just shy of 2000. She was an All-American D3 player and even had

the chance to play against Kristi Toliver after graduating. Despite not pursuing professional basketball due to life hitting her hard, including her mom getting sick, Jessica looks back on her Mary Baldwin experience with deep appreciation. She graduated with a bachelor’s in sociology, and the “extension of sisterhood” and the close-knit community she found there made it a truly valuable journey. “God put this in my life for a reason,” she reflects.

Jessica’s commitment to community work began in college, volunteering at the Virginia School of Deaf and Blind. Her heart was always with “the misunderstood.” After graduating, she spent 15 years serving the community in various capacities – working in women’s prisons, detention centers, group homes, and mental health schools. She was constantly looking for ways to make a difference.

The spark for HER Sports ignited while she was coaching at Buford Middle School. She saw a critical need for outside activities for girls, recognizing the “huge drop off” in female athletic participation. She knew firsthand the positive impact sports had on her life and countless other women in Charlottesville, whose stories often mirrored those of the girls she was working with.

She had a “core group of the misunderstood,” girls with “terrible attitudes” who wouldn’t have been playing if she wasn’t their coach. Working with them solidified her desire to create something more. The parents of her middle school and travel teams also pushed her, seeing the benefit of extracurricular activities. Jessica

wanted HER Sports to be more than just basketball, incorporating the mental health aspect that was her professional background and personal experience.

When COVID-19 hit, she started small workshops, solidifying the need for an organization like HER Sports. Her research as a case manager for Region Ten confirmed that nothing similar existed. “I wasn’t going to reinvent the wheel,” she explains. Instead, HER Sports became a “mirror of what I’ve had” – an organization built on sisterhood, mentorship, and providing an outlet. The authenticity she brings, she says, comes from these experiences and the relationships she’s built over the years in Charlottesville and within the industry. It’s about “just paying it forward.”

The HER Sports Awards is the cornerstone event for the organization, now in its fourth year. Originally a gala, it has evolved to focus more on its core mission: bringing the community together to celebrate, empower, and educate young girls and women in sports. It’s a movement to invest in women and girls’ sports, and the awards aim to unite Charlottesville, Monticello,

Albemarle, and Western high schools in one building.

This year’s event at the Paramount aims to be more comprehensive, incorporating elements like “tunnel fit,” where girls express themselves through pre-game fashion, and music that not only inspires women in sports but also addresses critical community issues like gun violence and youth suicide.

Jessica’s call to action for the community is simple yet profound: “Unity is community.” She believes that instead of just talking about the need for unity, “we really just got to be about it.” She urges people to set aside egos and pride. “It’s so much that we can offer, but we’re offering too much, but too little production. It’s too, too little results because everybody is spread out instead of coming together.”

She’s not saying HER Sports is the only answer, but rather that it can be a vital part of a larger, unified effort. “Everybody who’s trying to serve youth, her sports can be a part of it, too, because we serve girls. And not only that, we have young men that volunteer.”

Her heartfelt plea is for people to “just be in the building and show support.” Learn about HER Sports, see how you can get involved, and understand the profound impact they are having. She particularly acknowledges the strong support from men in the community.

Tickets for the HER Sports Awards are affordable ($15 for students, $25 for adults, with VIP options available). Every dollar raised goes directly back to the kids, funding programs and supporting a new scholarship fund in honor of Edward Brooks. This fund will provide sponsorships for athletes, athletic programs, and girls who can’t afford sporting gear or participation fees.

Jessica’s work doesn’t go unnoticed. Her dedication is making a tangible difference in the lives of young

girls and women. She emphasizes the importance of checking in on one another, especially those who appear strong. “We all are out here trying to make a difference, but we do face our own struggles. And just a simple hello, checking in will be will be great for you.”

Jessica Carter is not just building an organization; she’s building a legacy of empowerment, unity, and unwavering support, one powerful woman and one determined girl at a time.

by Leslie M.Scott-Jones

Sinners is a supernatural horror film produced, written, and directed by Ryan Coogler, best known for the Black Panther film series. The film is set in 1932 in the Mississippi Delta, and follows the story of a family of three young Black men, and stars Michael B. Jordan, Delroy Lindo, Wunmi Mosaku, Miles Caton, and Jayme Lawson. The film has been heralded as an artistic masterpiece for its complex and layered story. It is also important because, due to Coogler’s bargaining power, and the attachment of star Michael B. Jordan to the project, he was able to secure ownership (owning the film after 25 years), final dollar

gross (a cut of the gross profit), and final cut privilege (final say in how the film is put together). This is a deal that no Black director has ever received from a major studio. To date, it has grossed over $250 million in the U.S. and Canada and over $80 million elsewhere, bringing its total to over $338 million worldwide. No one can argue the fact that the film is a success, no matter which ruler you use. I would argue that even if you are not a horror movie fan, you should see this movie, and there are several reasons.

Placing the story squarely in the Jim Crow Era allowed Coogler to create an instant nostalgic memory for Black folk and speak

to the way the quest for the American dream has worked on Black folk, and particularly how we are barred from achieving it and why. For instance, the wooden nickel (IYKYK) emphasizes how even post-emancipation Black people were kept poor by being paid in plantation currency, rather than real money. This practice ensured they would never make enough to leave or own anything of their own. Academics and historians Jemar Tisby and Keisha N. Blain created and published a reading list on the African American Intellectual History Society’s website, which “delves into the multifaceted historical, cultural, and social contexts depicted in the film,

providing audiences with a deeper understanding of its layered narratives.” It covers historical context, African American spirituality, Blues and its origins, Black art and poetry of the era, and books detailing the Great Migration, the Great Depression, as well as gender dynamics, Black people in the military, and early civil rights struggles. The “syllabus” also gives insight into vampire lore, other educational resources, websites, music, films, and series to watch, if you like the genre.

If you liked the feel of The Color Purple, then this visual

landscape is right up your alley. Visualizing for us the plight of a sharecropping family from the beginning of a day until the end brings up memories of grandparents or perhaps greatgrandparents on farms not too far outside of the city we call home. Many of us can relate to the plight of the preacher’s kid, who just wants to play music and the pull of a life spent on a stage instead of in a field. Some of us had grandmothers who were the women everyone went to if something was ailing them, or who packed a bag and went house to house healing people with roots, herbs, and poultices. These

are things our DNA carries, that makes us feel comfortable and understood in ways only another Black person would understand. It is Coogler’s gift to us, dealing out this shorthand in overt visuals and partly covert languages spoken in hushed tones and veiled gestures, reminiscent of cornrows that told us how to get free.

The title of the film isn’t the only thing layered about this story. It is a horror film, dealing with vampires that terrorize the opening night of a juke joint owned by the twin brothers, Smoke and Stack, played by Michael B. Jordan. This film

speaks directly to our history as Black folk in this country, in the deliberate choice to make the vampires white and Irish. It mirrors the relationship between these two communities. Relating specifically to Charlottesville’s Vinegar Hill neighborhood, where there was a significant Irish population, the two communities lived together peacefully. As the Irish were thought of as lower on the totem created by white society than Black folk, we became friends. As they became recognized as being white, and their societal status began to improve, they left Black and indigenous folk behind for greener pastures. We see that echoed in the plot of the film, as the Irish vampire tempts the Black folk, speaking of how the oppression they face is the same, and joining them would mean solidarity and survival. When, in fact, joining them means eternal damnation. It takes a special kind of genius to equate vampirism with supremacist culture. Turning it into a literal virus that infects you and twists your soul. I found it particularly important that the indigenous people were the ones hunting the vampire and tried to warn everyone of the danger. Just as in the annals of history, they were ignored and dismissed. There are multiple sins committed in the film. Lying, cheating, and murder, to name a few. There are multiple parallels between the lives of the brothers that add to the layering of this story. Smoke fell in love with a healer/conjure woman, and they had a baby that died. Stack, the more flashy of the brothers, fell in love with a woman who could pass for white, whom he left so she could have an easier life as a white woman. Both of these women demand the truth from the brothers before they agree to help them with the joint. They each demand that love be declared

for them. It can’t be emphasized enough that finally, there is a love story between the charismatic, sexy Black leading man and a full-figured, dark-skinned Black woman who does not commoditize or denigrate herself to achieve her goals. She stands in her truth and her power and firmly says what she will and will not allow with grace and love. I’m here for all of that.

Finally, as an artist, the most wonderful thing about this movie is how Coogler managed to bring Afrofuturism into the mix yet again during the dance sequence in the juke joint. As we weave through the dance floor, we see and hear glimpses of past and future rhythms, dances, fashions, and lives. Through this magical sequence, we are reminded that all the music we listen to today came from rhythms created by Black people. We are reminded that every trend in fashion has been heavily influenced by the particular swag of Black folk. This reminder is bittersweet because we know that even though our purchasing power totals over a trillion dollars annually, we hold only 3% of the nation’s wealth. We are reminded that they love our rhythm and hate our blues. Once again, the nostalgia hits you, and like our ancestors did before us, we make a way outta no way and laugh, sing, and dance because aint no use cryin over spilt milk. You may find yourself, as I did, laughing through the tears of the familiar realization of how amazing we are as a people.

I’m not necessarily a horror fan. I am a huge Blerd, and a fan of Coogler, which is why I went to see this movie, and it did not disappoint. Even if you don’t like horror, you’ll like this. The biggest sin you could commit is to miss it.

by Kishara Griffin

There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

I’ve heard this scripture frequently spoken in the pulpit as a call to set aside cultural and gender disparities, to collectively strive for equal contributions and oneness as the church reflects God’s vision. Unfortunately, the teachings have often been used to encourage the body of Christ to take on a color-blind identity and accept gender/sex prejudices to conform to an imagined ideal image. Such messages eventually required marginalized people to forfeit more and more aspects of their social identity to conform to Paul’s demands for oneness. Together with this message, pastors highlighted the call to establish an intimate personal relationship with Christ. If you grew up in the Black church or attended services in the late 2000s, I would not be surprised if, like me, you struggled to

internalize these messages – and often left church with a sense of inadequacy, humiliation, and alienation from the faith and your creator. It might even be possible that these messages left you immobilized and apathetic to suffering within our communities and the larger world. Why: the question then becomes how does one develop personal intimacy with God when they are actively peeling pieces of their identity away to fit within church culture?

In 2013, I embarked on a personal journey to make sense of the disconnect I was experiencing between my relationship with Christ and Sunday preachings. I felt led by the Holy Spirit to quit reading my Bible in isolation, and instead attended services and Bible

studies. During that time I invested my time in reading books to explore Black church history- and the relationship between blackness and Christianity. This was the first time I had explored Christianity through a black-centered, historical and social justice perspective, and it opened my eyes to the black church’s positive accomplishments – as well as prompted me to examine its deeply broken institutional and cultural dynamics.

I did, and still do, venerate the Black church as the epicenter of black resilience in the face of slavery, Jim Crow, and the impacts of poverty before, during, and after the crack epidemic. Nonetheless, I saw the black church as the epicenter of anti-blackness, replicating white power systems that promote sexism, racism, homophobia, and capitalism. Knowing that the Black church has served both these roles was the primary reason why it was difficult for a person like me to get closer to Christ. As a black woman, a sexual being, an advocate who rejects the notion of respectability politics, and a person who disagrees with using others as a vehicle for economic advancement, I began seeing church culture as a mirror of all the things I identified as oppressive.

As police killings of unarmed Black people in the United States became more widespread in 2014, the impacts of racism became more tangible to me. I pledged to be an advocate for change, and I set out to focus on what I believed Christ would do. In the pursuit of antiracism and justice, I connected with a community of people of color outside of the church. To navigate this community, I had to grasp the value of collaborating with those whose identities differed from mine. I found myself yearning to demonstrate compassion, knowledge, wisdom, and humility as I organized around issues impacting BIPOC communities. I wanted to reflect Christ without subjecting individuals or groups with oppressed identities to harm or erasure. As I began to move with purpose inside the organizing community, I found I needed to undo the various forms of repressive practices I had acquired in the church. Being able to have tough conversations with the people I was collaborating with and learning how to show up with care and consideration moved me forward in my commitment to the principles of justice and even closer to God as I leaned on the spirit for direction. Taking a stand against injustices while placing my body and social privileges at risk helped me finally understand what Paul meant in Galatians 3:28. Finally I knew that

the people who were placed in my life truly reflected true unity in efforts to promote justice and social change, which more accurately portrayed the Church than any edifice could. For me, moving out of the church was an act of worship— an effort to honor God in spirit, reflect Christ in non-conventional ways, and apply biblical principles to life beyond the mirrored white power structures that reinforce our oppression. I saw it as a pathway to true spiritual growth.

At the time of moving through this experience, I recognized I wasn’t the only person who felt this way. I noticed Young black Christians like me were looking for something real and seeking spiritual spaces that are free from oppression and spoke to relevant Black struggles. I came to see Paul’s call for unity as a beautiful concept of spiritual oneness within the faith. However, I also noticed how some preachers misused this concept, emphasizing unity while avoiding or ignoring the need to engage with cultural differences and the lived experiences of marginalized communities within the body of Christ. I recognized through my experiences that in order to move towards that unity we must join in the lives of those who are most marginalized, and in doing so, to witness societal change through the demonstration of the biblical fruits of the spirit. I learned we can not ask our people to strive towards unity and intimacy with Christ without allowing our people to “authentically exist”- PeriodT!

by Aran Shetterly

“Cast down your bucket where you are.”—Booker T. Washington

As I pull into my hotel in Pulaski, a train rumbles through the center of town, heading west with a long, colorful load of double stacked shipping containers. Its thunder and whistle, held in by a beautiful brim of mountains, briefly fills this Southwest Virginia town. And then it’s gone and everything seems strangely quiet, as in the aftermath of a fire that’s consumed a building, when the roar and hiss have abated and all that remains is memory, ashes, and an uncertain future. One’s

ears recalibrate and Peak Creek’s light, burbling music returns. Then the low swoosh of a car rolling past abandoned, 20th century industrial buildings, whisking someone to work, school, church or on an errand to the Dollar General.

The fire metaphor in my introduction of the town is intentional. I’d been lured the two-and-half hours from Charlottesville, along Interstates 64 and 81, and down the Valley of

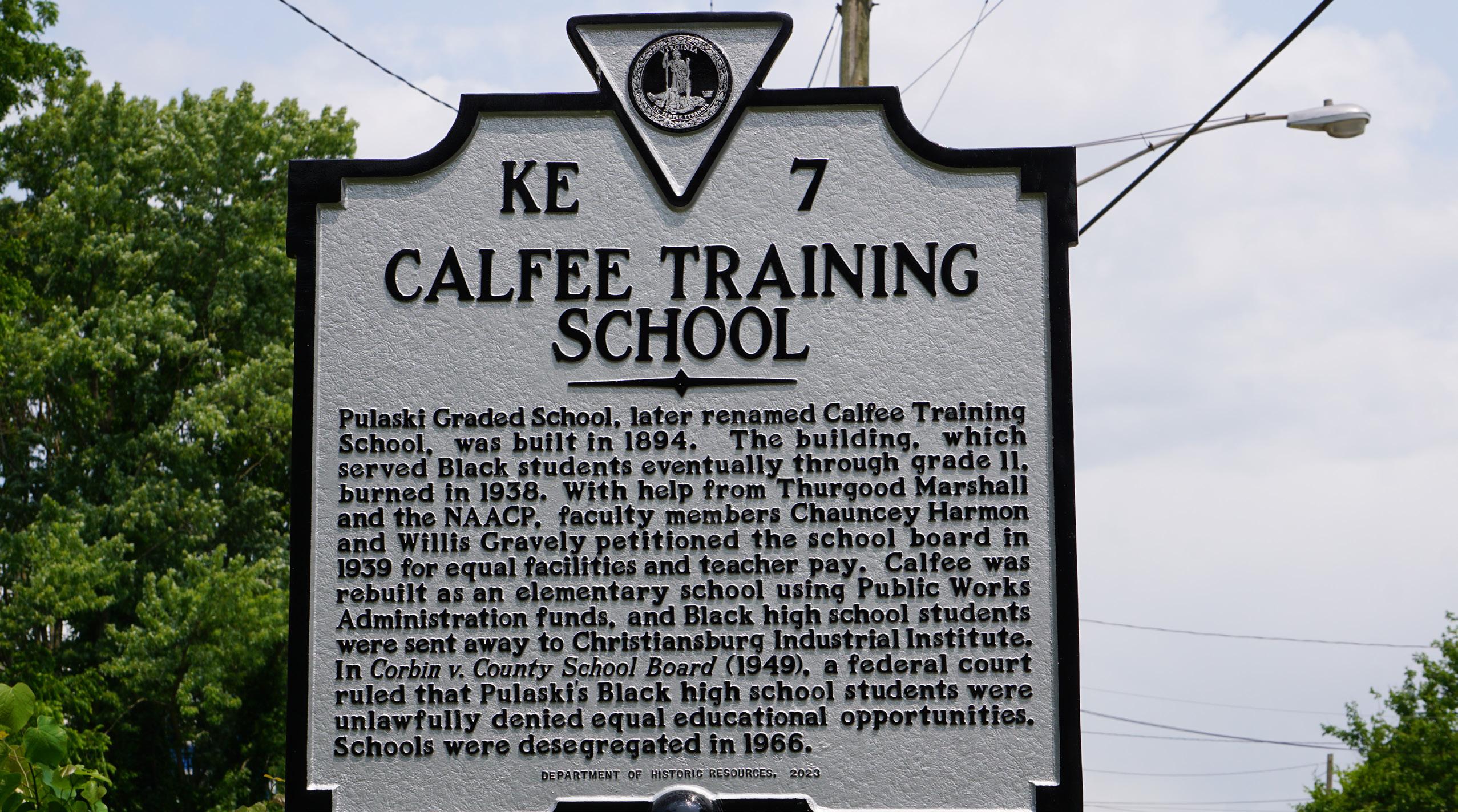

Virginia by the planned unveiling of a quilt, stitched together not only with thread, but with history, love, and vision. And the story of the quilt begins with a fire that engulfed Pulaski’s rickety, segregated Calfee Training School late on November 10, 1938, and burned into the wee hours of November 11. No one seems to know if the fire was an accident or set intentionally. They do know, however, that the fire department which was across the street didn’t respond for two hours.

You could say, too, that this journey of remembering begins with Dr. N. Wayne Tripp’s 1995 dissertation, Chauncey Depew Harmon, Senior: a case study in leadership for educational opportunity and equality in Pulaski, Virginia, that rescued and documented the history of that fire and the efforts of Pulaski’s brave Black citizens to insist on equality in their schools during the Jim Crow period of legalized segregation. The late Congressman and Civil Rights leader John Lewis said that “Democracy is not a state. It is an act.” History, too, is an act; it’s an act, such as a dissertation, a

song, or a quilt, of organizing and transmitting memory. It binds life’s fragments into knowledge that can pass from one generation to the next, informing our choices as citizens.

In 2018, Jill Williams together with Dr. Michael “Mickey” Hickman and other alums of the Calfee Training School began a project to guide Pulaski’s community in reimagining what the empty, crumbling space that had once been a source of both community conflict and pride could be today. The vision that emerged attracted partners and funding.

Today, Williams is the Executive Director of the Calfee Community and Cultural Center, created to “[revitalize] the legacy of the historic Calfee Training School by serving our community’s present needs in order to create a stronger future”. Those needs include a childcare center and programs to address food insecurity, mental health issues, and continuing education.

“Recent generations in Pulaski have forgotten that slavery and Jim Crow reached into these Appalachian hills and valleys,” says Williams. “Virginia textbooks,” she continues, “focus

primarily on the large plantations of the state’s fertile lowlands.” Questions, therefore, about why, historically, some thirty percent of the population in Pulaski was African American go unasked and unanswered.

Growing up in Pulaski, Williams had never heard about the history of the Calfee Training School fire and its connection to the struggle for Black liberation. When she and the Board Members discussed it, they saw an opportunity to recover and celebrate the local history of Black resistance to inequality. They knew that America’s racial history continued

to affect their lives; the school board, board of supervisors, and city council in Pulaski are all white today and the local community has documented racial disparities in policing and school punishments. Williams and the Calfee board believe this local history represents a way to teach citizens, and especially young people, not only job skills, but the importance – and power – of civic engagement, how knowing local history can help a community understand where today’s inequities and injustices come from and provide the tools and courage to address them.

“Something’s happening in Pulaski”

Dr. Tripp’s dissertation tells us that in 1938, twenty-five-year-old Chauncey Harmon was the newly appointed principal of the Calfee school when it burned. The local kid had left Pulaski to be educated at the prestigious Tuskegee Institute in Alabama before returning home as a young man ready to make his mark. In May 1938, Harmon attended a teacher conference where the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) issued a call for Virginia teachers willing to make a legal stand against unequal school facilities attended by Black children and pay for Black teachers. Harmon was already rallying support for the NAACP’s legal fight when the fire destroyed Pulaski’s Black school. As he hurried to find classroom space in local churches for some 250 displaced students, he worked with NAACP lawyers to petition the Pulaski County School Board for a better, 11-room school and

fair salary adjustments for Calfee’s teachers.

In 1939, the School Board, despite pressure from the NAACP and the Black press, rebuffed the community demands. They tabled the discussion of teacher pay and agreed to build an eightroom school that would cost 35,000 dollars (even as they approved a new, 54,000-dollar gymnasium for the local white elementary school), while offering to bus students who desired an education beyond the seventhgrade to the Christiansburg Industrial Institute in the next county, nearly thirty miles away on country roads. The all-white school board also eliminated the jobs of Chauncey Harmon and another teacher active in the push for equality.

Over the next decade, as the NAACP ramped up its legal struggle against inequality in education, parents in Pulaski were growing tired and frustrated by the time their children spent traveling back and forth to Christiansburg. Those wasted hours kept the commuting students from participating in extracurricular activities or staying late to study in the library.

In 1947, a prominent local doctor, P. C. Corbin, working with renowned Civil Rights lawyers from Richmond, Oliver Hill and Spotswood Robinson, sued the Pulaski County School Board for failing to provide equal educational opportunities to his son, Mahatma. 23 families joined him, representing 54 children. In

May 1949, a district court judge dismissed Dr. Corbin’s suit. Six months later, however, the federal Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals with jurisdiction from Maryland to South Carolina found that African American students did indeed face discrimination because of unequal educational resources and facilities, as well as the interminable bus rides.

After more than a decade of taking a dangerous public stand against inequality, Pulaski’s Black community and a team of relentless and brilliant lawyers had won in court. Neither Pulaski County nor the State of Virginia, however, intended to honor the federal court’s decision. In her illuminating book, We Face the Dawn, on Lawyers Hill and Robinson’s fight against Jim Crow, Margaret Edds writes, “Like every other court mandate growing out of the Virginia school equalization campaign, the Fourth Circuit ruling would prove easier to issue than to enforce.”

There was, however, a detail that would prove valuable to the NAACP’s ongoing legal campaigns to dismantle Jim Crow in education. The district judge who’d originally dismissed the 1947 case noted that rural white schools weren’t on the same level as the schools in the county’s towns, writing that “no two schools are ever precisely equal.” Edds reports that Spottswood Robinson responded astutely to the judge’s decision, noting that “The significant consideration is that while some white high school pupils may, all Negro high school pupils must, be subjected to such

hardships and inconveniences.” (emphasis added).

This exchange between the judge and Spottswood Robinson helped spark a shift in the NAACP’s legal strategy. After the Corbin v. Pulaski County School Board case, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund stopped fighting for the equalization of segregated

education and started working to desegregate public schools across the South and the Nation. It’s said that two years later, Lawyers Hill and Robinson were on their way to Pulaski to organize a desegregation case, when they learned that Barbara Johns had led a student walkout of the R. R. Moten High School in Farmville. The lawyers rerouted and a Farmville student, rather than a

student in Pulaski, would join the Brown v Board of Education case and the 1954, history-altering Supreme Court decision against segregation.

When Williams approached a local quilting group with an idea for a fabric testament to the 1947 suit, several women agreed to take up the challenge of rendering Pulaski’s history in art.

Interestingly, the active quilters in the area are mostly white. Though many had social connections to members of the Black families involved in the lawsuit, none had “any idea these families went through what they went through,” says Jenny Shepherd. “I didn’t even know about the lawsuit and now I do,” says Rebecca Miller Ferrell. “We were told,” continues Ferrell, “that the slave

ladies [made quilts] for their slave owners. And that makes me feel very special to be able to [make a quilt] for a Black group. It makes me feel important to help them get their history out.” The silence around the case, however, wasn’t only in the white community.

The current chair of the NAACP’s National Board of Directors,

Leon Russell, is from Pulaski and attended the Calfee Training School as a boy in the 1950s and 60s. He has returned to speak at the May 31 gala event where the 23 families and 54 children who joined the Corbin case are to be honored and the quilt unveiled. “No one talked about [the 1949 case],” he says, and his eyes fill, briefly, with tears as he remembers the good things and the hard things about growing up in Pulaski. Until recently, he hadn’t even known about the suit, or that his grandfather and uncle were part of it. When he learned that “a group of people” from his hometown, “motivated by what they saw as discrimination and for their children and future children” had stood up even though doing so carried “risk that could get you killed or fired” and done so in collaboration with the NAACP, the organization he’d worked with for decades, he’d felt exalted. It

was a remarkable convergence in a life committed to civil and human rights in the United States and around the world. “You can’t talk about Pulaski without talking about this history,” he says. “This is what makes this country.” One thing you learn from it, he adds, is that “you don’t have to be Jesse Jackson to be a successful advocate.”

But why the silence? Was it frustration at the fact that the 1949 legal victory didn’t really change anything? Or, maybe, selfpreservation? Was it not wanting to burden Pulanski’s Black children with the pain of history as Jim Crow ground slowly to an end in Virginia? Perhaps folks didn’t want to trouble relationships with white neighbors, like Mrs. Smith with whom Russell’s grandmother made apple butter. Or maybe it takes an outsider, like Dr. Tripp, to point out that your history

matters. Likely it was some combination of these and the fact that life, after the fire’s out and the lawsuit ends, keeps running down the track, leaving little time to dwell on the past.

As 250 white and Black people filter into the event space at the New River Community College in Pulaski County to embrace their shared history. They pause before the king-size quilt, suspended from a clothing rack. Rich in orange and purple and pale yellow, it looks like a gorgeous scrapbook assembled from 23 panels, one for each of the families involved in the Corbin suit. The family names–

Dyer, Peoples, Slaughter, Smith, Truehart, etc. – are spelled out and joined with symbols of family strength and love.

In a town where visible public nostalgia includes an anonymous Confederate statue and a giant painted billboard advertising 5-cent Coca-Cola, this quilt is a new and innovative monument: It’s mobile, personal, and more intent on improving the present and future than glorifying an unrecoverable past.

The evening’s MC is Calfee Center board president, Mickey Hickman. No one loves Pulaski and the history of its Black community more than Hickman. He can show you where the pool hall and the

barbershop were, the best hills for sledding, the Dew Drop Inn, and Juicies, the nightspot where folks went to dance. He’ll explain the intentional interruption of Jackson Avenue that begins in a white neighborhood, dead ends, and then picks up again with the same name in a black neighborhood. A talented athlete, he loves to point out the field where Black boys and white boys played football and baseball, sometimes together. At the gala the memories flow and people are honored, including the remarkable former Calfee Training School teacher, Dorothy Deberry Venable, who at 94, seems like she’d be ready to jump right back into a second-grade classroom tomorrow. Appalachian

storyteller and musician Aristotle Jones sings a rousing tribute to the 23/54 who “risked it all to bring their case.” NAACP Chair Russell challenges the audience not to be content that the quilt has documented their history, but to use it “as a steppingstone” and to stay focused on “where you will take this county and the nation.” The energy in the room is high, inspired, and inspiring.

Leaving the auditorium, I catch the last moments of a sunset flaming deep orange and fire red from behind a silhouetted copse of trees. It looks like nature’s

version of the quilt. Watching the light fade to dark, Jill Williams’ remarks that evening come back to me: “We are living in a time when there’s real pressure to whitewash our nation’s history—especially the painful parts about slavery, segregation, and oppression. And while I understand the impulse to shield children from pain, the danger is this: when we don’t teach the hard history, we also don’t get to teach about the everyday heroes who resisted it. And without those stories—stories that are relatable and rooted in community—how do we inspire the next generation

of leaders? How do we build a better future?”

The next morning, as I drive the winding Dora Highway out of Pulaski, I pass a small church. The marquee reads “Home of the free, because of the brave.” I doubt the pastor was reflecting on the local Black community’s ongoing freedom struggle when he chose those words, but I am.

For more information about the Calfee Center and the 23/54 Quilt visit: https://calfeeccc.org/

You created the perfect business cards and you have more orders than you can handle, so what’s next? As your business banking partner, we’re here to find solutions that will work for you.

Business Banking

Business Loans | Free Business Checking* | Remote Deposit Capture Treasury Management | Credit Cards

*$100 to open | No minimum balance requirement. No monthly maintenance fee, but other fees can apply. Please refer to the Fee Schedule.