Dear StayFresh Readers,

Welcome to another exciting issue of StayFresh Magazine! In this edition, we bring you stories of innovation, heritage, and self-reliance, highlighting individuals and initiatives that are making a significant impact.

Our features include an inspiring look at Chris Gaither, a master sommelier who is dedicated to making the world of wine more accessible to everyone. Learn about his journey, his role as Director of Education at the Blackowned Brown Estate in Napa Valley, and his restaurant Ungrafted, which he co-founded with his wife.

We also delve into sustainable living with Nivek Anderson-Brown, a homesteader who, along with her husband, has embraced a life of self-sufficiency at Leaf & Bean Farm in South Central Virginia. Discover how she leverages 21st-century technology to share traditional practices and offers classes on gardening, fermentation, and more.

In “The Rundown,” we provide snapshots of sustainability efforts worldwide. This includes Farm Fresh 24/7, an app launched by Damien Lieggi and Lawrence “NatureBoy” Seals to connect people with local produce and reduce dependence on corporatized food systems. We also explore the stunning art installations of Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, who creates masterpieces from recycled materials. Finally, learn about Payton McGriff’s organization, SHE (Style Her Empowered), which designs adjustable school uniforms for girls in places like Togo, West Africa, addressing barriers to education access and promoting reuse.

Lastly, Philip Cobbs shares a deeply personal reflection on Buck Island, a now-vanished Black community in Albemarle County, Virginia, where he grew up. His poignant essay explores the importance of ancestral land, the legacy of slavery, and the dream of equality that lived in this historic place.

We hope these stories inspire and inform you, encouraging a deeper appreciation for our communities, our planet, and our shared history.

Sincerely, The StayFresh Magazine Team

by Phillip Cobbs | Photo by Kori Price

There was a time when I would have perceived being told, “Stay in your place” as insulting.

But the descendants of ancestral land carry the burden of trying to understand its true value. For African Americans, this can lead to a deeper appreciation for who they are and why.

Only by staying in my place could I have experienced and learned what I did. It has given me a perspective I would not have if I had spent my life someplace else. I fortunately was given the opportunity to write about my place, Buck Island, and it opened a window of understanding I never expected.

The community of Buck Island, 10 miles southeast of Charlottesville in Albemarle County, is where I grew up in the 1960s. It now only exists in the minds of its descendants. It is a vague memory of those who

knew it. Those of us who remember can reminisce about past times and confirm whether those memories are real or figments of our imagination. For me embarking on that journey of confirming has been eye opening.

Last October, I visited my only brother, Peter Cobbs III, in Los Angeles. We recollected what growing up was like for each of us, and we had some similar memories of Buck Island but our five year age gap made our experiences quite different. On that trip, we connected with our cousin, Barry Jones, who grew up in New York and visited Buck Island in the summer as a child in the 1950s. He recalled an experience that remains etched in his memory. An Elder took him to a “special place” on the property, near the Rivanna River. Barry described the spot as being shady and removed. There, this Elder showed him what remained of enslaved quarters. In the

“The descendants of ancestral land carry the burden of trying to understand its true value. For African Americans, this can lead to a deeper appreciation for who they are and why,” writes Philip Cobbs. Kori Price/Charlottesville Tomorrow

center stood a whipping post. Barry still remembers touching it and how eerie it felt.

That confirmed my understanding of the land was real. I had written that the “low grounds” of Buck Island, in the fertile floodplain of the river, had once been the realm of slaves.

Why did the Elder feel it was important to show Barry the enslaved dwellings?

I don’t think it was to frighten him. Rather, I believe it was to connect him to the past.

The Buck Island community had preserved the whipping post and the memories of this spot, for a reason. I believe it was a part of the past the family recognized as being important, important enough to not be forgotten. While those quarters may not have housed any of our family members, there were enslaved people held there. Our family has roots that are entangled in slavery. We experienced what it was like to witness our people being beaten and whipped and that has left

This story was published as a part of Charlottesville Inclusive Media’s First Person Charlottesville project. Have a story to tell?

a deep impression etched in our conscience.

Dr. Sarah Garland Boyd Jones, who was born at Buck Island and became the first African American female doctor in Virginia, worked tirelessly to care for people in Richmond. She was driven harder than the horses that pulled her carriage on daily rounds. There are conflicting accounts on the cause of her untimely death in 1905, before she turned 40. But her descendants might surmise that the gruelling work might have been the real cause.

We understand the cost of laboring to achieve a goal that is not obtainable within our lifetime. Still we must strive to carry on the legacy that we inherited.

The place in Richmond where Sarah was laid to rest is now denoted by a simple grave marker in the long neglected Evergreen Cemetery. Fortunately she is well remembered, not only because of the statue of her that was put up in the Virginia Women’s Monument in 2022, but throughout Richmond. Last year, there was a successful campaign to save the building that once housed the Richmond Community Hospital, which she helped found on the campus of Virginia Union University. I think Sarah would have been pleased to know her labor was not in vain.

I knew my mother gave birth to me at Buck Island. A Charlottesville Black physician, Dr. Garrett was there, but doctors who looked like him could not practice at the University of

Virginia hospital. He made a house call early in the morning to attend to my mother’s delivery. During my visit to Los Angeles, I asked my brother Peter what he remembered of that day. He recalled it as one of his happiest and saddest days. He was happy to have a new baby brother and he was sad to lose a baby sister.

I knew my twin sister had died at birth, but I’d never talked with him about it before. He described accompanying our father to the family cemetery on top of a nearby hill, where they buried my sister. I pictured my 5-year-old brother watching the sister he had only known about for hours, being buried. That was the first time I knew where she was interred and it was comforting to know she was resting in the same place as our mother and father.

I didn’t attend Spring Hill Baptist Church, but I knew it was once the center of Buck Island community life, where joyous homecomings and

ruckus revivals were held. My mother was born across Thomas Jefferson Parkway from the church in 1920, and was the secretary there in her youth. The church still owns an acre of land that my grandfather gave them. Albemarle County currently taxes the church more for that acre than the total it taxes for the adjacent 13 acres, according to county records. The beleaguered trustees and leaders of the historic church of which I am a part of, recognize the building is in dire need of repair and are considering selling that acre because otherwise they will have to continue paying the county real estate tax.

Buck Island was once a thriving Black community and it’s an example of countless Black communities throughout the county and country. I recently attended a gathering in Brown’s Cove, a community in the western part of Albemarle County, and there I met Eursaline Inge. I found out her father, Pete Jones, a former leader of that Black community, was a relative who came from Buck Island.

Why is it important for me to remember Buck Island?

Looking back at my life, I now see how my appreciation for my own history developed. It was, in some ways, through the times I did leave Buck Island. I fortunately had parents who valued travel. One of the earliest trips I remember is driving through the deep south to New Orleans. I still recollect pulling into gas stations and being refused service. It was the summer of 1963, the year

of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

From New Orleans we flew to Mérida, Mexico. Traveling by bus and train, we visited many places including Mexico City, Acapulco and even Cancún which was still a small fishing village. My mother later reminded me that during the trip I talked about how much I missed Buck Island. Don’t get me wrong, I loved the experience, but it made me appreciate my home even more than I had before.

Within the boundaries of the place I call Buck Island, an important part of American history unfolded. There, people attempted to live out the creed of freedom upon which this country

was created. While those attempts were not perfect — and could be viewed as failures because the Buck Island I remember no longer exists — I am a product of those efforts.

Every community is unique and recognizing what makes it so can take time. It took me most of my life to understand what was unique about Buck Island. Thomas Jefferson penned eloquent words about equality, and from my home in Buck Island today, I can see Monticello. But I experienced a different version of equality, Dr. King’s dream of equality, at Buck Island.

Unfortunately, the Buck Island I knew as a child is gone, but I am determined to keep that memory alive on all the land where it once was.

by Katrina L. Spencer

There are fewer than 300 master sommeliers in the world, according to the Court of Master Sommeliers Americas. The certification this institution grants, providing recognition to people in the beverage industry, is the most esteemed and competitive of those available. About ten percent of master sommeliers are women. Fewer than five of master sommeliers are Black. Chris Gaither is one of them.

This historically black college grad started his post-secondary studies at Atlanta’s Morehouse College, the institution par excellence for Black men in the United States. At that time, as a Spanish major, he didn’t know that he’d become a leading mover, shaker and

oenophile -- a lover of wine. But life sometimes brings surprises. He worked in restaurants then and was encouraged to learn more about the age-old, fermented drink.

“I became one of the most knowledgeable people on staff,”

Gaither said.

After years of study and an internship at world-class restaurant destination the French Laundry in Northern California, the trajectory of his career took hold. Gaither is not only an expert

Chris Gaither and his wife, Rebecca Fineman, pose for a photo with their children at their restaurant and bottle shop, Ungrafted. Hundreds of wine selections and new American cuisine are served there in San Francisco, California. Photo credit: Zha Zha Liang

on wine, sake, vermouth and cider, he’s also the director of education at Brown Estate. Brown is the first and only Black-owned estate winery in Napa Valley, the United States’ best known region for wine culture. There he trains staff who work in tasting rooms, preparing them to introduce the vineyard’s products to guests. He travels, too, dozens of times a year, marketing, including at his alma mater.

Part of his ethos is making wine more approachable to a broad variety of people, a trend that appears to be gaining traction and popularity in the industry. Certain myths abouts wine can be intimidating to newcomers. For example, much media coverage would suggest that wine is strictly European, that it’s exorbitantly expensive by default and that enjoying it is for a narrow sliver of the global population. Gaither is here to disassemble those myths.

“You don’t have to be a wine specialist to appreciate wine,” Gaither said.

On brand with the educator he is, Gaither cited a variety of ventures led by people of color who have broken ground in the field. Theopolis Vineyards, Maison Noir Wines, the McBride Sisters, J. Moss Wines, Vision Cellars and Dwayne Wade have all captured his attention. He can also rattle off specialized resources in the digital realm, like the well respected GuildSomm reference guide, that help consumers, too -- especially newcomers -- to navigate the world of wine, making it more accessible.

The book and web site Wine Folly, for example, touts itself as a master guide to wine. Online, the site is masterfully illustrated with captivating infographics that make learning fun and engaging. Its A-Z guide includes descriptions of a wide selection of grapes, ranging from Greece’s Agiorgitiko to Austria’s Zweigelt, and the regions highlighted where grapes are grown are as familiar as Idaho and as respected as Bordeaux.

British wine critic Jancis Robinson’s writing, he said, educates the general public about wine, too. Her site includes nearly 300,000 wine reviews, robust glossaries of wine-related terminologies, maps, travel diaries, book reviews, a podcast and commentary on a unique event titled Vin & Hip-Hop, or Wine & Hip-Hop, hosted in Burgundy. Robinson’s is one of the most respected names in the industry globally, which has led to her offering tips to the queen of England!

The Kachet Life, was a third site Gaither shared. It features the lifestyle-based blog and podcast of wine enthusiast Kachet Jackson Bell, a Black woman. Jackson Bell writes, “I believe you can be both the muse and the CEO of your life.” Her site shows the ways in which she is artistic and creative, but also business-minded and intentional about what she

consumes and curates. As much as subscribers should expect to learn about wine through Jackson Bell, they should also expect wine pairings, exercise tips and travel reflections.

Gaither’s ambitions to reach people don’t end there. Along with his wife, Rebecca Fineman, also a master sommelier, the two have founded the restaurant and bottleshop Ungrafted in the Dogpatch neighborhood of San Francisco, open since 2018. At the family-friendly establishment, you can choose from 700 wine selections to drink, 250 retail selections to purchase and order za’atar pull-apart bread, fried chicken over polenta or steak frites. Gaither’s engagement in the field is only limited by imagination, which continues to grow.

by Sarad Davenport | Photos by Kori Price

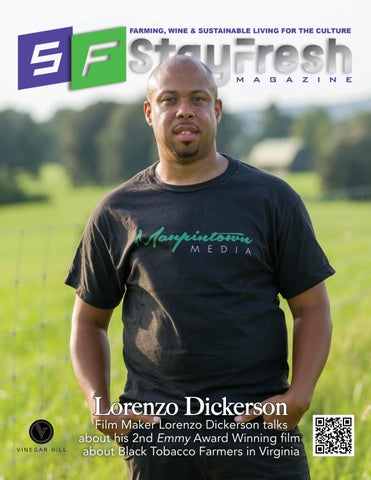

In a world that often rushes forward, filmmaker Lorenzo Dickerson is steadfastly looking back, unearthing the rich, untold narratives of rural Black communities and bringing them to the forefront. Fresh off his second regional Emmy win for the documentary short Cash Crop, Dickerson is not just a filmmaker; he’s a preservationist, a storyteller, and a champion of the values that define a generation.

Lorenzo Dickerson, a selfdescribed “rural guy from Virginia,” finds his deepest inspiration in the very soil his parents and grandparents tilled. “Anytime I’m back in that space, that’s just, you know, where I feel

the most comfortable, where I get inspiration,” he shared. His latest project, Cash Crop, is a testament to this connection. The film, a collaboration with Reel South, PBS North Carolina, VPM, and Black Public Media, delves into the world of tobacco farming in Lunenburg County, Virginia, through the eyes of Cecil Shell, a man whose family has farmed the same land for three generations.

Dickerson’s profound connection to rural life stems from his childhood. As an only child, he spent countless hours with the elders of his community—his grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-aunts and uncles.

“I was definitely that kid that was on his bike all day long,” he reminisced, recalling how his grandmother would have to call a cousin’s house to ensure he came in before dark. These years were filled with listening to stories and asking questions, an experience that laid the groundwork for his filmmaking career. “Really the work that I do now, a lot of it is really me kind of chasing down those pieces of stories that I heard as a child and wanting to learn more and fill in the blanks,” Dickerson explained.

For Dickerson, storytelling is the height of expression, especially for the Black community. He believes that without it, “we run the risk

of losing the values that came out of the community.” He holds his grandparents’ generation in high esteem, recognizing their distinct way of life and the lessons they imparted. He fondly recounted how his grandfather, after church, would remove his suit jacket, put on a bucket hat, and cut the grass, still impeccably dressed. Or how his mother would take his dress shirts to his grandmother to be perfectly pressed. These memories speak to a generation that epitomized patience, selfdiscipline, and an enduring resilience—values Dickerson feels are increasingly vital today.

The genesis of Cash Crop was a journey back to his rural roots. After his first Emmy-winning film, Raised/Razed, which focused on Charlottesville, Dickerson was keen to explore rural Virginia. Seven years ago, he obtained a list of African-American farmers in the state. Though initially sidetracked by other projects, he revisited the list. One farmer had moved, but the other, Mr. Cecil

Shell, proved to be an invaluable connection.

“Mr. Shell reminds me so much of him,” Dickerson said, speaking of his late father, also named Lorenzo. The shared mannerisms, similar sayings, and even their mutual love for tinkering with old muscle cars forged an immediate and deep bond. This personal connection infused the project with an added layer of meaning for Dickerson.

Cash Crop tackles the complex intersection of tradition and progress in Lunenburg County. The film highlights the struggle of tobacco farmers like Mr. Shell, who are committed to preserving their legacy, against the backdrop of burgeoning solar farms. These farms, attracted by cheap, flat land, offer an alternative income for landowners but threaten the long-standing agricultural traditions and the very fabric of the local economy. “The main conflict is the solar facilities coming in and one, changing the way of the economy of the

county,” Dickerson noted, “but then also losing the potential to lose that tradition of tobacco farming.”

Winning his second regional Emmy was a moment of great pride for Dickerson, particularly because his 10-year-old son was by his side. Unlike his first win, when he was unaware of the intricate Emmy process, this time, Dickerson understood the magnitude. Yet, with more films in his category, his confidence wavered. “My 10-year-old was like, ‘You got it. We got it.’ He was not wavering at all,” Dickerson recounted, smiling. “So it was really cool for like, I don’t know, like to lean into his confidence in that moment.” Seeing his son walk up with him to accept the award was “probably my favorite of the evening.”

Dickerson’s approach to fatherhood mirrors his artistic philosophy: deeply rooted in instilling confidence and embracing the values passed down through generations. “I love being a dad,” he affirmed, explaining how he prioritizes picking up his children from school, cherishing those moments. His primary goal is to ensure his sons are “confident Black boys in this world.” This conviction comes directly from his own father, Boo, who was “the most confident person I’ve ever met in my life.” His father’s unwavering belief that

“everything always works out for old Boo” is a mantra Dickerson strives to pass on to his boys.

After living in Raleigh-Durham and Maryland, Lorenzo and his family returned to Charlottesville in 2015 when his wife pursued her doctorate at UVA. This return home felt like fate. “I just feel like we’re supposed to be here,” he recalled telling his wife. “We’re supposed to be here back home for some reason.” It was around this time that he began his filmmaking journey. Now, residing near his in-laws, his children walk to their grandparents’ house, mirroring his own rural upbringing. This deep connection to his community, his family,

and his roots continues to fuel his remarkable storytelling.

Lorenzo’s work is a powerful reminder that the most compelling stories often lie closest to home, waiting to be uncovered and shared. His dedication to preserving Black narratives and celebrating the resilience of his community makes him an invaluable voice and a true inspiration.

by Katrina L. Spencer

When Nivek AndersonBrown and her husband decided to commit to the homesteading lifestyle all the way, she said there were field mice the size of cats that rose up out of the land to avoid the rumble of their bush hog lawn mower. They spooked her, but she wasn’t to be dissuaded. Since then, she’s gotten to know all types of local critters: foxes, raccoons, deer, wild turkeys, guineas, a baby bear, groundhogs, moles, beavers, owls, snakes, salamanders, toads, spiders and ticks!

Worn by the hustle and bustle of corporate America, the two, Nivek (nuh-VEEK) and her husband, who she lovingly calls “Mister,” headed

for the country in South Central Virginia. There they took on the labor of love in establishing Leaf & Bean Farm, a home built on productive land and the site of her entrepreneurial business as a social-media based influencer. You can find her and the true tales and teachings of their lifestyle on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube.

“I’m the hardest working woman you know,” Anderson-Brown said.

Between planting, pruning, harvesting, canning, powdering, pickling, fermenting, drying, freezing, photographing, filming, editing, recruiting brand deals and loving her family, her hands are full, and she may in fact win that title. She practices traditions

that have been in many American families for generations and uses 21st technologies to reintroduce them to worldwide audiences.

“For all my life, there was some type of growing going on,” Anderson-Brown said.

Her work with plant life started at home and she associates her relationship to the flora with spirituality and medicine.

“I consider myself a conjuring woman,” she said.

She and her mother are herbalists and avid users of home remedies. She takes purple dead nettle, for example, to ward off allergic reactions, and apple cider vinegar

every day. What she doesn’t know from home training, she gains from “YouTube University,” she said, taking an active interest in her continued education and being hands-on in her approach. The bumpy patches she has encountered could be the most lesson-rich moments of her journey.

“I’ve got failures for days,” Anderson-Brown said.

Her first two flocks of chickens were killed by raccoons and foxes, she said, when she and her husband didn’t realize the level of security they needed to protect them. It took her a year to establish a sourdough starter, she

said. And once, she took a fall of over four feet that sent her to the hospital.

“Don’t confuse my joy for ease,” she said. “It ain’t easy. But I love it.”

The trials and the errors all contribute to what she calls the

“ever-learning process.”

“Even the hard stuff is fun,” she said.

Her countless wins, however, are not to be ignored. Among them, to name just a small portion, are her beef tallow and frankincense eye serum, powdered aloe vera, collagen soups, dandelion wine that “tastes like sunshine,” she said, floral bath salts, wild rose rosé, pine cone syrup, homemade throat lozenges and more. In an age of dependence on the grocery industrial complex, the proportion of her self-reliance is uncanny.

Anderson-Brown points out that the systems many depend on have certain fragilities and vulnerabilities to them. If any part of the process is interrupted in developing quality crops that are transported to stores, all can fall apart. By that logic, homesteading is not a quirky hobby meant to impress social media followers. Rather, it’s a survival skill. For Anderson-Brown, it’s not a question of if the systems we know will crumple and fail; it’s a question of when.

“If you don’t do it willingly,” Anderson-Brown said of homesteading, “you are going to find yourself in a position to do it unwillingly.”

But before you pack up your things and purchase a plot of land in the southern backwoods, know that this homesteading disciple believes that this lifestyle can take place in spaces that aren’t rural.

“Homesteading is a verb,” she said. “You can be homesteading anywhere.”

Homesteading doesn’t have to be a complex system of cans, jars and drying racks, ducks, goats and chickens, hoes, yokes and scythes. It can be herbs, she said, steeped in water on the window sill or baking one’s own bread or making one’s own yogurt. There are many ways to incorporate the ethos of self-reliance into one’s life in all types of spaces at all types of scales.

Anderson-Brown teaches classes online for anyone worldwide wanting to pick up skills in gardening, fermentation, canning, breadmaking and more. You can launch your journey with her by visiting www.leafandbeanfarm. com or get introduced to her work via TikTok lives on Sundays.

In the homesteading influencer landscape, Anderson-Brown appreciates a less stylized aesthetic that reflects the work of living on a farm. Sometimes that includes dirt, spills, stains and interruptions caused by humans or other animals she loves. Her work reflects realism, inclusion and history. And in terms of community, she looks forward to the establishment of conferences that embrace Black homesteaders and other people of color.

For other Black people who do similar work, Anderson-Brown points to Upendo States Farm that offers a glamping (think camping plus glamour) experience and the GrounEd Group that also aspires to teaching self-reliance.

With all the richness in Anderson-Brown’s world, she feels no lack.

“We live a life of abundance,” she said. “I’m not missing out on anything.”

A woman in Atlanta, Georgia, shows off the plant-based bounty she has collected from a Farm Fresh 24/7 initiative.

by Katrina L. Spencer

Welcome back to The Rundown where we provide you with snapshots of sustainability efforts happening in your backyard, around the world and in digital spaces. This season we highlight works that support an ethos of interdependent communities, artistic expression and the education of girls. Since we saw you last, what sustainability measures have caught your eye? Have you adopted any new sustainability practices? Write us at vinegarhillmag@gmail.com with “sustainability” in the regards line to share about worthwhile sustainability projects you have

seen or adopted. Here are our three below.

Tech: Farm Fresh 24/7

In 2018, Damien Lieggi and Lawrence “NatureBoy” Seals launched an app, Farm Fresh 24/7, meant to help the public divest from big box grocery stores. Their aim has been to encourage people to look to each other as resources, reducing their dependence on corporatized food systems, and to promote “community over capitalism,” Seals said.

The Farm Fresh 24/7 app connects people with goods, products

or surplus to others who are interested in them, all based on regional proximity, and it’s free to use. Many local gardeners, growers, makers, producers and bakers are looking to sell or may yield more edible goods than they can use in one go. This technology helps to avoid waste, establish community and, importantly, prompts users with knowledge of growing and making to teach others how to do so as well.

I opened the app and my mouth started to water. It’s like having a farmer’s market on your phone! The app featured pictures of vegetables, baked goods, fish and more in my area that were

An infographic displays all the ways users can interact with the Farm Fresh 24/7 app, buying, selling and bartering. Photo provided by Lawrence “NatureBoy” Seals

available for sale or bartering, but there were plants, herbs, spices, syrups, eggs and jam, too! With 100,000 downloads and counting, the app is active. The creators are looking for investors to further develop what they have put into place. Find out more on Facebook or Instagram.

This West African artist’s productions sell for millions of dollars at auction via Sotheby’s, and per his signature artistic flair, they are made by using recycled materials. El Anatsui is from Ghana, though most of his work has taken place in Nigeria, and some of his large and best known art installations tend to look like shiny, metal blankets made of aluminum bottle caps, finely knit together with copper wire. They are rich in texture, suggesting movement even when immobile, and generously blooming in color, begging to be touched. They can be found all over the world in museum collections and warp the mind when considering that art so impressive came from what we typically consider discarded refuse. Aside from reflecting a strong value for sustainability and a creative mentality for innovation, El Anatsui’s works are also ambitious in scale: taller than a man in height and spanning the considerable expanses of walls in width. “Seepage,” for example, housed at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, is over 10 feet tall and over 16 feet wide. Zoom in on either side of “Seepage” by visiting the museum’s website or follow @elanatsui.art on

Instagram for more.

Global: Uniforms

If you wore a school uniform growing up or your children do now, then this sustainability effort will hit close to home. As children

grow every year, new clothing is needed for them to wear while they pursue their education. The price of said clothing in some places, however, may be a barrier to education access. This is the problem that captured and held creator Payton McGriff’s attention. While this concern is less prominent stateside, it’s more pressing in some places, one being Togo in West Africa. McGriff, then, with much community aid, problem-solved and created a garment for girls to wear that can be adjusted in size as they grow and later recycled for other uses. CNN reports that the uniforms created by McGriff’s organization, SHE, Style Her Empowered, can be

adjusted using cords and used for six different sizes. When the wearer outgrows the garment, younger girls can use it or transform the fabric into menstrual products. The innovative approach has created jobs for women, shown a route to reducing textile use and promoted reuse. See more on Facebook, Instagram or LinkedIn.

You created the perfect business cards and you have more orders than you can handle, so what’s next? As your business banking partner, we’re here to find solutions that will work for you.

Business Banking

Business Loans | Free Business Checking* | Remote Deposit Capture Treasury Management | Credit Cards

*$100 to open | No minimum balance requirement. No monthly maintenance fee, but other fees can apply. Please refer to the Fee Schedule.