Wellness Hub

Wellness Hub

Relaunched

Nurturing the heart of veterinary care

IPP ... what?

Introduction to intermittent positive pressure ventilation specifically under anaesthesia

Small animal endoscopy in veterinary nursing: A guide

Levelling up your consulting nurse game

The Official Journal of the Veterinary Nurses Council of Australia Inc. Reg. No. A0031255G ABN 45 288948433 VOL. 30 • NO. 01 • MARCH 2024 THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY NURSES JOURNAL

for vet nurses and technicians

Lauri

Cert

DipTDD, AVN, TAE, DipBus, Dip.Couns, DipBA, DipMgt, Cert IV CAS

Janet Murray

BSc Veterinary Nursing, AssocDegAdult&VocEd, Cert IV TAE, RVN, AVN

Elise MacPherson

Dip VN (GP) & SURG, Dip Lab Technology (Pathology Testing), Cert IV VN, RVN, AVN Jo Hatcher

Dip VN, Cert IV VN, Cert IV TAE, RVN, AVN

Shauna James

Cert IV VN, GradCertCaptVertMgt (CSturt), RVN

VNCA NATIONAL OFFICE

PO Box 7345, Beaumaris VIC 3193

Phone 03 9586 6022

Fax 03 9586 6099

Web www.vnca.asn.au

ADVERTISING

Phone 03 9586 6022

Email vnca@vnca.asn.au

VISION STATEMENT

The VNCA aspires to strengthen the position of Veterinary Nurses as part of the veterinary healthcare profession.

MISSION

The VNCA: Serves and represents all Veterinary Nurses

Protects the professionalism of Veterinary Nurses

Promotes the value of Veterinary Nurses as vital in delivery of quality veterinary care

Advocates for the increased recognition of Veterinary Nurses across Australia

Supports Veterinary Nurses through the provision of continuing education and networking opportunities

Strengthens the position of Veterinary Nurses across the veterinary industry Engages all Veterinary Nurses across the veterinary industry.

01

President’s report

02 Wellness Hub – Nurturing the heart of veterinary care

04

06

AVNAT – Recency of practice demystified: Essential insights for veterinary nurses and technicians

Wellness Hub – Setting your new year workplace goals

08 IPP … what? Introduction to intermittent positive pressure ventilation specifically under anaesthesia

14 Levelling up your consulting nurse game

16 Small animal endoscopy in veterinary nursing: A guide

24 Meet VfCA’s Rural and Regional Program

Case Report – Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint arthrodesis in a warmblood

32

Client fact sheet – Fear and stress-free treats for dogs

34 Member Vitals – Tamaryn Bond and Tarlea Hann

37 Congratulations to our AVNs and

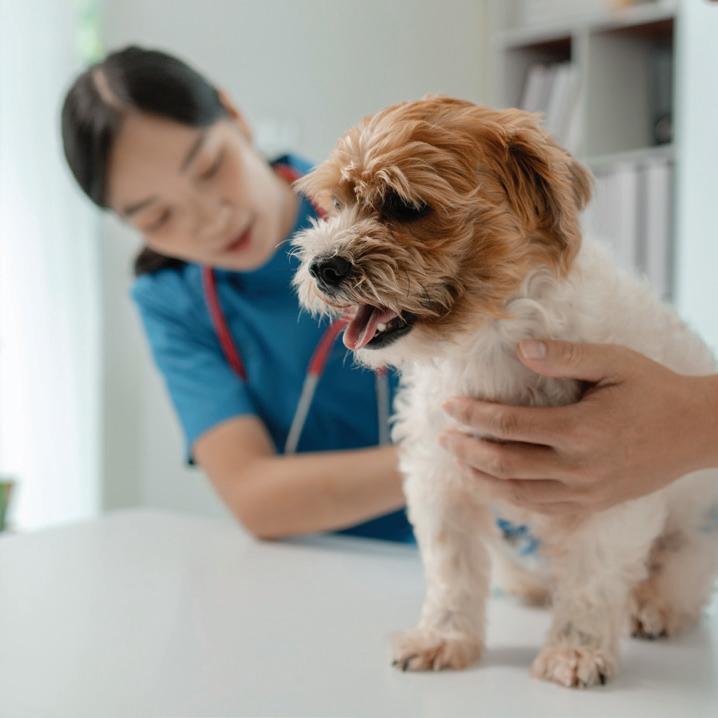

Cover image ©shutterstock/PeopleImages.com - Yuri A CONTENTS Contents VOLUME 30 • NO. 01 • MARCH 2024 NEWS & UPDATES

26

OUR VISION & OUR MISSION 14 08 06 THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY NURSES JOURNAL BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Gary Fitzgerald Vice President Trish Farry Michelle Foxcroft, Anita Parkin, Rebecca Coventry, Asha Yeoman, Samara Blake VNCA MEDIA CHAIR

Murray Email media@vnca.asn.au EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Murray Lauri Steel Elise MacPherson Shauna James REVIEW PANEL

AVNAT registered professionals

Janet

Janet

Steel

IV VN, DipVN (ECC & GP), DipVET,

President’s report

Dear VNCA Members,

I trust this message finds you well. In the busy months since our last AVNJ, our commitment to advancing the veterinary nursing and technician profession has led to significant developments that I am excited to share with you.

OUR COLLABORATION WITH AVBC FOR VN AND VT REGISTRATION

In December, the AVBC convened a workshop, inviting the VNCA and several other stakeholders to establish a pathway towards statutory regulation for veterinary nurses and technicians in Australia. The day saw robust discussions and diverse perspectives from stakeholders.

ANZSCO SUBMISSION – SHAPING THE FUTURE

In December, the VNCA submitted recommendations to the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO). Our proposal suggests future-focused changes, including updates to occupation titles, minimum qualifications, and listed skills. We advocate for recognising advanced practitioners with the addition of an Advanced Veterinary Nurse/Technician category. Additionally, we support elevating Certificate IV in Veterinary Nursing to a diploma level, fostering academic career pathways.

ADVOCATING FOR POSITIVE CHANGE – NSW RADIATION REGULATION FEEDBACK

Our active involvement in shaping the future of our profession was evident when we provided feedback on proposed changes to the NSW Protection from Harmful Radiation Regulation.

Committees, including AVNAT, Professional Advancement, and NSW, collaborated on a detailed submission under the oversight of the Board of Directors. This engagement reflects our commitment to positive change benefiting veterinary nurses and technicians.

NEW MEMBER ASSISTANCE PROGRAM – PRIORITISING WELLBEING

A huge thank you to the Membership Committee for their efforts to produce our most recent member benefit. The VNCA has partnered with Converge International to provide members with access to a highly regarded Employee Assistance Program (referred to as MAP – Member Assistance Program), commencing January 15, emphasising holistic wellbeing. This initiative aims to provide valuable support to our members, contributing to your overall wellbeing.

VNCA/ROYAL CANIN/LINCOLN INSTITUTE PARTNERSHIP –FOSTERING LEADERSHIP

We are thrilled to announce our partnership with Royal Canin and the Lincoln Institute, offering 150 sponsored positions for VNCA members in the ‘Emerging Leaders Course’. Emphasising non-clinical skills development, this initiative seeks to elevate the leadership potential of veterinary nurses and technicians.

STRATEGIC PLANNING FACILITATED SESSION – SHAPING OUR FUTURE JOURNEY

The VNCA Board of Directors participated in a facilitated strategic planning session to meticulously chart our course for the next 3 years. Strategic planning is a pivotal

Gary Fitzgerald VNCA President

Gary Fitzgerald VNCA President

Your involvement and dedication are the driving forces behind these achievements. Together, we are shaping a brighter future for veterinary nursing and technology. Stay tuned for more updates, and I look forward to celebrating further successes with each of you.

step in ensuring our continued success and growth as an association. This process allows us to align our objectives, identify key priorities, and set a clear direction for the VNCA’s future. Stay tuned for more detailed information about the outcomes of this session as we look forward to sharing the exciting developments that will shape our journey ahead.

Your involvement and dedication are the driving forces behind these achievements. Together, we are shaping a brighter future for veterinary nursing and technology. Stay tuned for more updates, and I look forward to celebrating further successes with each of you.

Warm regards

Gary Fitzgerald VNCA President

FROM THE PRESIDENT DIVISION CONTACTS If you would like to attend a divisional committee meeting, it is important that you RSVP. NSW Melissa Shoard E nsw@vnca.asn.au QLD Jade Davies E qld@vnca.asn.au SA Sonia Van De Kamp E sadiv@vnca.asn.au VIC Danielle Gaynor E vic@vnca.asn.au WA Tracey Woods E wadiv@vnca.asn.au DIVISION CONTACTS it March 2024 1

Nurturing the heart of veterinary care

VNCA Wellness Hub relaunch elevates member benefits and workplace wellbeing

In the dynamic world of veterinary care, where compassion meets professionalism, the Veterinary Nurses Council of Australia (VNCA) has taken a giant leap forward with the relaunch of its Wellness Hub. Dedicated to the tireless veterinary nurses and technologists who play a pivotal role in the wellbeing of animals and clients, the revamped Wellness Hub promises a transformative experience that extends beyond individual members to benefit the entire workplace.

A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO PROFESSIONAL WELLBEING

At the core of VNCA’s mission is a commitment to supporting the health and wellbeing of its members. The refreshed Wellness Hub, unveiled as a dynamic space for personal and professional growth, introduces a Member Assistance Program (MAP). This program, developed in partnership with Converge

International, provides comprehensive support to members, acknowledging the unique challenges faced by veterinary professionals.

MEMBER ASSISTANCE PROGRAM (MAP)

The MAP offers a huge range of resources designed to effectively manage both mental and physical health. The program covers a wide range of assistance from career guidance and conflict resolution to nutrition and lifestyle support. VNCA members can gain access to a team of professionals, including organisational psychologists, leadership coaches, and accredited conflict resolution mediators.

The MAP goes beyond the ordinary, offering specialist support for diverse demographics, including First Nations, LGBTQI+, Eldercare, Disability and Carers,

At the core of VNCA’s mission is a commitment to supporting the health and wellbeing of its members.

The refreshed Wellness Hub, unveiled as a dynamic space for personal and professional growth, introduces a Member Assistance Program (MAP).

Student, and Spiritual & Pastoral client needs. This inclusive approach reflects VNCA’s dedication to fostering a workplace culture that respects and supports the diversity within its community.

CONVERGE ONLINE LIBRARY AND WELLNESS APP

In addition to personalised support, members can explore a wealth of resources through the Converge online library. Fact sheets, articles, videos, and animations cover a spectrum of wellbeing topics, empowering members to take control of their health journey.

The award-winning Converge Wellness App further enhances engagement by providing tools, autonomy, self-awareness, and motivation to VNCA members. This initiative aligns with the hub’s commitment to not only address immediate concerns but to empower individuals to proactively manage their wellbeing.

FLOURISH E-MAGAZINE

Stay informed with the latest in health and wellbeing through the Flourish e-magazine. A curated collection of articles and insights from Converge offers valuable perspectives on maintaining a healthy work/life balance.

EDUCATION FOR EVOLUTION

Recognising the ever-evolving landscape of veterinary care, the VNCA continues its commitment to member growth through education and networking opportunities. The education section of the Wellness Hub provides access to ongoing personal and professional development, fostering a culture of continuous learning within the veterinary community.

2 March 2024 WELLNESS HUB

Wellness Hub

for vet nurses and technicians

RESOURCES FOR A BALANCED WORKPLACE

The VNCA understands the pivotal role workplace environments play in the wellbeing of its members. With a focus on promoting mentally healthy workplaces, the resources section of the Wellness Hub offers a curated list of free and accessible resources. Advocating for individual wellbeing not only benefits the members but contributes to animal welfare, staff productivity, and retention.

WITH THANKS TO WELLNESS HUB SPONSORS

None of this would be possible without the generous support of the Wellness Hub sponsors. The VNCA extends its gratitude to gold sponsor Royal Canin and silver sponsors Hill’s Pet Nutrition and VetPay for their unwavering commitment to advancing the wellbeing of veterinary nurses and technologists in Australia.

The relaunched VNCA Wellness Hub marks a significant milestone in the journey towards holistic wellbeing for veterinary nurses and technologists in Australia. By prioritising the health and happiness of its members, the VNCA sets a benchmark for workplace wellbeing in the veterinary care sector, reinforcing its commitment to excellence in every aspect of veterinary nursing and technology.

Sponsorship opportunities

We invite you to consider a partnership with the VNCA by becoming a Wellness Hub sponsor as we endeavour to make a meaningful impact on the community of veterinary nurses and technologists across Australia. Our sponsorship packages are thoughtfully crafted to align with the goals of your organisation, and they offer varying levels of support.

We encourage you to reach out to us to receive a comprehensive copy of

our sponsorship prospectus and to initiate a discussion regarding potential sponsorship opportunities.

Contact Information

Phone: 03 9586 6022

Email: admin@vnca.asn.au

We look forward to the opportunity to discuss how your organisation can contribute to and benefit from our mission to enhance the wellbeing of veterinary professionals in Australia.

March 2024 3 WELLNESS HUB

©gettyimages/AnnaStills

Quality practice through standards and learning

Recency of practice demystified: Essential insights for veterinary nurses and technicians

WORKING TOWARDS FORMAL REGISTRATION OF VETERINARY NURSES AND TECHNICIANS

In December, VNCA and AVNAT representatives attended a meeting hosted by the Australasian Veterinary Boards Council (AVBC) to work on the path forward to formal regulation of veterinary nurses and technicians in Australia. The meeting was attended by various veterinary surgeon board registrars, the AVA and veterinarians in practice. It was pleasing to once again see the positivity in the room for the registration of veterinary nurses and technicians and this is another step along the pathway to national registration. Discussions have also occurred with the South Australian Veterinary Surgeons Board as they work on developing the veterinary practice regulations for the state.

WHAT IS RECENCY OF PRACTICE AND HOW DO I SHOW EVIDENCE OF THIS?

A common question asked of the AVNAT Regulatory Council is what is recency of practice and how do I show evidence of this if I have not been working in a clinical setting in the last 12 months?

To be eligible for registration in the AVNAT Registration Scheme, veterinary nurses with an Australian Certificate IV in Veterinary Nursing qualification (or equivalent), an Associate Degree or Bachelor of Veterinary Nursing, and veterinary technicians with an approved Bachelor of Veterinary Technology qualification (or equivalent) who are currently practising in the profession are eligible to apply for registration.

Importantly, the definition of ‘practice’ in the AVNAT Framework and Policies includes any role in which the individual uses their skills and knowledge as a practitioner in their profession. Practice includes the direct provision of services to patients and the use of professional knowledge and/or skill in a direct clinical or non-clinical way. This includes non-direct relationships with patients such as working in management, administration, education, research, advisory, regulatory or policy development roles and any other role that impacts the safe, effective delivery of veterinary nursing and related services.

As such, individuals employed in veterinary practices, animal welfare organisations, research and teaching institutions, appropriate government bodies or related

It was pleasing to once again see the positivity in the room for the registration of veterinary nurses and technicians and this is another step along the pathway to national registration.

4 March 2024 NEWS

©shutterstock/David Herraez Calzada

employment, and in veterinary nutrition and pharmaceutical companies, are all eligible to be registered under the AVNAT Registration Scheme. There is no requirement to be working purely in a veterinary practice to be registered; however, you are required to provide details of your employment in the last 12 months. The current industry, regulatory and legal framework in Australia precludes self-employed (independent) veterinary nurses and veterinary technicians from being registered under the AVNAT Registration Scheme. This position will not change until mandatory registration is more widely implemented in Australia.

To show recent practice, registered individuals must demonstrate completion of at least 1000 hours of practice in the preceding five years, with not more than two consecutive years out of practice. The recency of practice for periods of less than five years can be demonstrated by the completion of at least 200 hours of practice within each of the last three consecutive years AND no more than two consecutive years out of practice. Those individuals who may have taken a career break due, for example, to maternity/paternity leave of more than two years, are subject to the AVNAT Return to Practice policy.

Completion of annual continuing professional development (CPD) requirements does not constitute recent practice. Recent practice requires showing active use of knowledge and skills relevant to the profession in a professional practice setting.

Other methods of demonstrating recency of practice include:

• completion of case studies or logbooks that clearly demonstrate that you have undertaken tasks such as surgical and medical nursing in a veterinary workplace setting

• research or a workplace study undertaken to demonstrate you have applied time and effort into seeking continuous improvement in a veterinary workplace setting

• resources developed for the workplace such as policies, procedures and training materials.

For more information, please refer to the AVNAT Framework and Policies on the VNCA website.

View AVNAT Framework and Policies here

AVNAT registration for the 2024/2025 cycle

There are only 4 months left before it is time to renew your AVNAT registration as the AVNAT registration year runs from 1 July to 30 June each year. So, it’s best to start to get yourself organised now!

Apart from the financial aspect (i.e. paying the renewal fee), the renewal process involves three key elements:

1. Meeting your continuing professional development (CPD) requirements

2. Preparing a career plan for the coming financial year

3. Confirming your compliance with the mandatory declarations. Meeting your CPD requirements is often the area that strikes terror into the hearts of vet nurses and technicians when they think they won’t have enough CPD points. Fear not, the situation is never as dire as you think –you just need to understand what, when and how you are going to meet your target. For more information, visit the Renewal Hub.

March 2024 5 NEWS

TO BE UPDATED

2024 VET NURSE/TECHNICIAN OF THE YEAR SUPPORTER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT SUPPORTER

VNCA SUPPORTERS

Setting your new year workplace goals

The New Year is officially here, and as everyone slowly filters back into the workplace after the summer holidays, it’s natural to start rethinking about your professional goals as reality starts to kick in.

While we all love the allure of a fresh start, we also know that good intentions can get lost in the shuffle of our busy everyday lives. Achieving goals and New Year’s resolutions in the workplace can be especially difficult without forming a plan and strategy to tackle them. So, here are five tips to make this the year you achieve some of your workplace goals!

Take some time to reflect

Before you make any goals, take a step back and review what you actually want to achieve in the short and long-term. Are these the same as last year? If not, why do you think that’s the case? Articulate your

aspirations — whatever they may be! The key reason why it’s important to do this is because it’s hard to stick to resolution if your heart’s not in it.

When you commit to making a change, you need to make sure that your actions align with your core values. One exercise that can help you decipher what you want your future to look like is asking:

What am I doing?

• Who am I working for?

• How do I feel?

Be honest in your assessment. If you’re not, it will be harder to inspire yourself to make the necessary changes that are in line with your goals.

Focus on smaller goals

At the start of a New Year, it’s so easy to get caught up in the euphoria of a new start. As a result, it’s common to make sweeping generalised goals without knowing how to achieve them. While it’s okay to set big, long-term targets, your next step should be breaking it up into small, realistic objectives. If your goal is to achieve a promotion, for example, you could set smaller goals like talking to your manager or relevant professional about it, taking the time to produce more accurate work, or researching how others have been successful in your organisation or industry.

... it’s common to make sweeping generalised goals without knowing how to achieve them. While it’s okay to set big, longterm targets, your next step should be breaking it up into small, realistic objectives.

6 March 2024

WELLNESS HUB ©shutterstock/PeopleImages.comYuri A

It can be helpful to map out a timeline of when and how you want to make strides towards your career aim. Prioritising one or two action items to work on every quarter can also help you meet your ultimate goal. Don’t be afraid to ask for honest feedback. Many people wait until an end-of-year evaluation to seek out feedback, but it can be more productive to ask regularly throughout the year.

Increase your knowledge

No one knows everything, but there are always ways to improve yourself, and this is especially true in your professional career. Identify one or two actions you can take, like an industry meeting you can attend or regularly reading publications that will offer insight about the future. You could also take a course to learn or improve a skill that’s useful in your current position, or that will help you get the next one.

Nurture your workplace relationships

If you enjoy your working environment, you’re more likely to be more effective and productive in your job. In fact, regardless of the industry, positive workplace relationships are one of the most important factors in your career success. Make a habit of learning the preferences of others and you will have better relationships at work. Improving your workplace relationships might mean taking the time to understand your boss’s

One of the most important things to keep in mind about professional resolutions is that they don’t have to be intimidating. Your goal is often not something far off or unobtainable. You’re simply resolving to change something, right now. Don’t worry too much about the future. Just focus on the progress you can make right now.

personality and communication style to better interact with them professionally. Master the art of managing up, down and across in all your workplace relationships.

Stay on track and keep at it! So, you’ve set yourself up for success. How do you make sure you actually get there? There are a few easy ways to help you stay motivated along the process. The first is to develop a habit. If your goal is to improve your communication, perhaps implementing a time every week where you get together with your team or manager to discuss what you’ve done or what you have in the pipeline can help make this action more natural to you.

It can also be beneficial to share your professional goal(s) with a trusted friend or co-worker and aim to reach them together.

You can create a shared Google Doc with your chosen person where you write down your goals, deadlines, plans and other thoughts or schedule a monthly check-in to update each other on your progress. Another tactic is using rewards. If you reach one of your goals, or micro-goals, treat yourself to something you really enjoy, whether that’s a meal out with your partner, a special bottle of wine or champagne, or expensive chocolates. The reward will help your desire to reach your next goal.

Article written and produced by Wellness Hub Member Assistance Provider Converge

converginternational.com.au

Learn new animal care skills in days or weeks A TAFE NSW short course is a great way to upskill and gain the skills you need quickly. Nurture your career and enrol in a specialised short course today. RTO 90003 | CRICOS 00591E | HEP PRV12049 tafensw.edu.au/short-courses March 2024 7

WELLNESS HUB

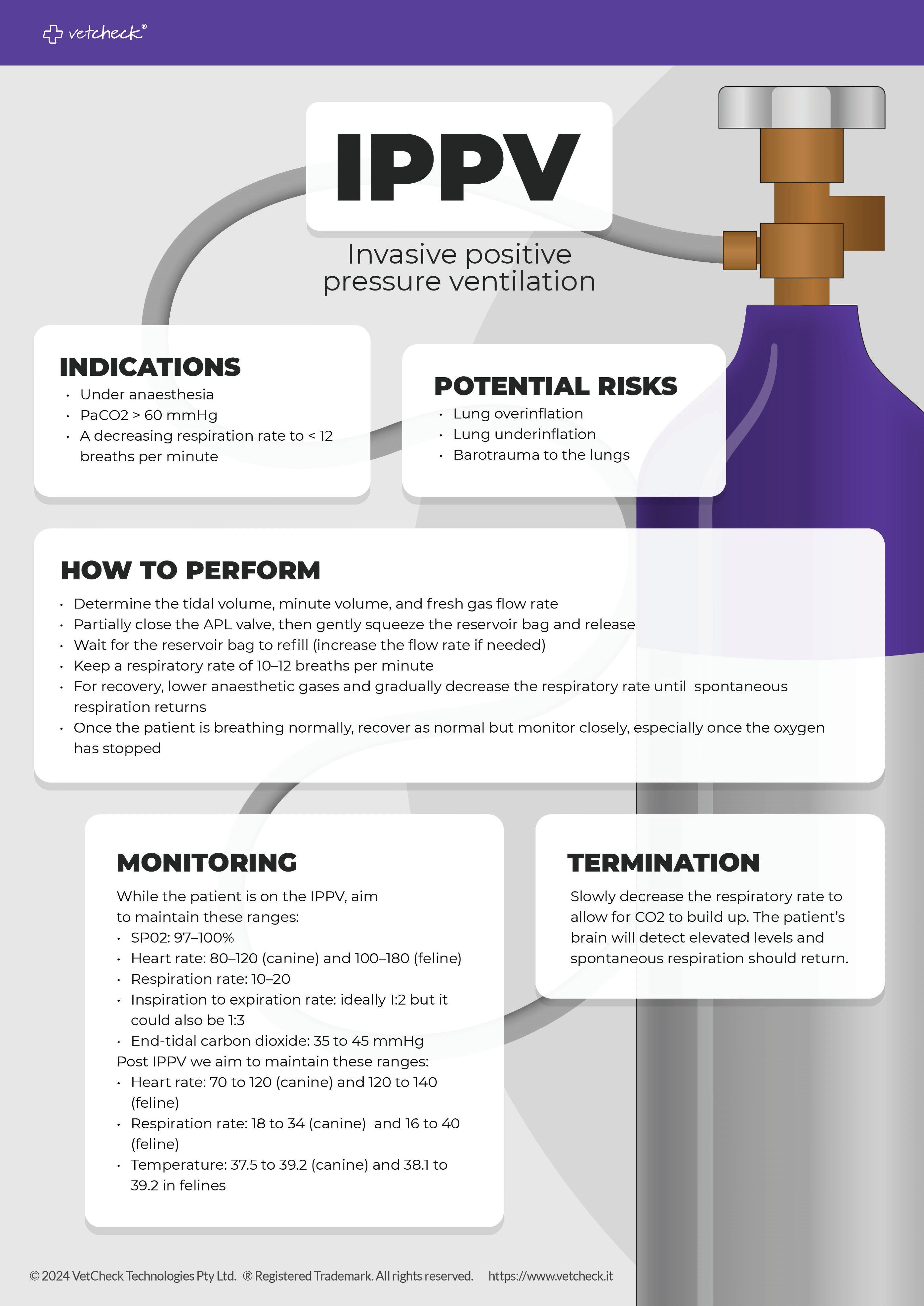

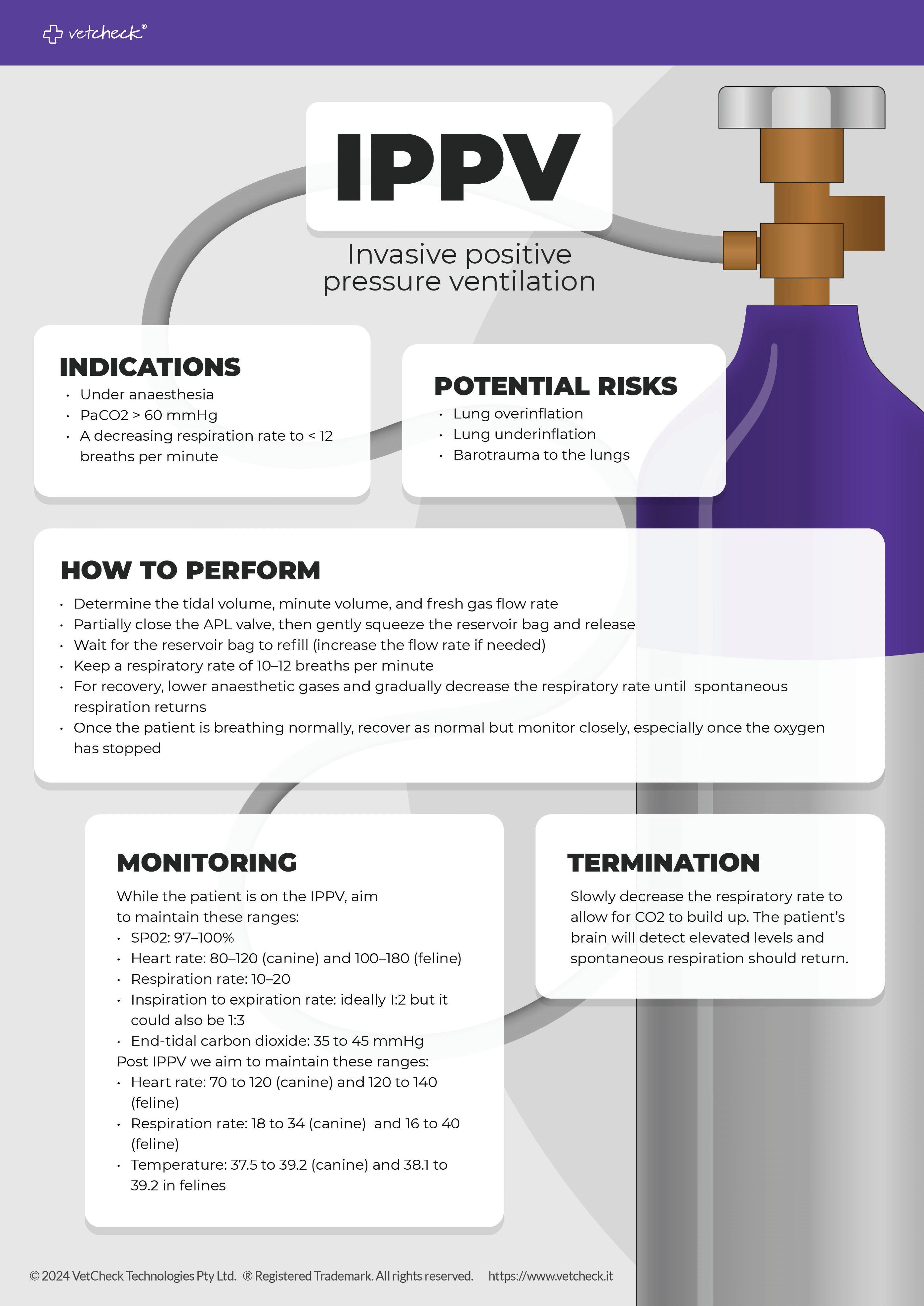

IPP … what? Introduction to intermittent positive pressure ventilation specifically under anaesthesia

by Samantha Dhatt

DipVN ECC, Dip Ldrshp & Mgt, Cert IV VN, VTS ECC, RVN

The administration and monitoring of anaesthesia for surgical procedures can be a complex process that requires knowledge, technical skills, awareness, critical thinking, and a level head.

A thorough understanding of normal and abnormal vital signs/physiology and patients’ conditions, the principles of anaesthesia and anaesthetic depth, and the ability to ask questions regarding a patient’s condition are the most important factors in monitoring anaesthesia safely.

INTERMITTENT POSITIVE PRESSURE VENTILATION (IPPV)

Positive pressure that is maintained only during inspiration (manual or mechanical).

POSITIVE END-EXPIRATORY PRESSURE VENTILATION (PEEP)

Positive pressure that is maintained within the lungs at the end of expiration (not covered).

WHEN WOULD PPV BE INDICATED?

Positive pressure ventilation is indicated when a patient cannot ventilate adequately. This is defined as a PaC02 (partial pressure of carbon dioxide) of > 60 mmHg (normal 35–45 mmHg).

1. Thoracic surgery

2. Hypoventilation

3. Apnoea/respiratory arrest

4. Cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation

5. Anaesthesia

6. Neurological alterations affecting CNS

7. Toxins

8. Snake envenomation

9. Pulmonary parenchymal disease –causing impaired gas exchange

WHEN WOULD PPV BE INDICATED DURING ANAESTHESIA?

• To manage post-induction apnoea

• To manage respiratory arrest

• To manage hypoventilation/ hyperventilation

• To manage hypocapnia/hypercapnia

• In circumstances where ventilation is compromised (diaphragmatic hernia, pleural space disease, gastric dilation and volvulus)

• In open chest/thoracotomy surgeries During cardiopulmonary cerebral arrest

• In circumstances where inflated chest radiographs or CTs are required

WAYS TO PROVIDE POSITIVE PRESSURE VENTILATION – USING HANDS OR A MECHANICAL VENTILATOR

1. Anaesthetic circuit

2. Anaesthetic ventilators – are a good way of providing mechanical ventilation to surgical patients. Anaesthetic ventilators are not used for long-term ventilation due to the limited modes; the delivery of 100% oxygen does not allow for a fraction of inspired oxygen to be adjusted, and no humidification systems. Using a mechanical ventilator for anaesthesia has both pros and cons (discussed later)

3. Ambu bag (not covered)

4. ICU ventilators (not covered)

AIMS OF IPPV (ANAESTHESIA)

1. To deliver appropriate amounts of oxygen to patients to maintain normal oxygen gas exchange

2. To remove appropriate levels of carbon dioxide from the patients to maintain normal blood gas levels

3. To maintain the appropriate depth of anaesthesia by delivery of consistently low levels of gaseous anaesthetic

IPPV or ‘squeezing the bag’ may seem like a benign procedure but can have catastrophic consequences if not performed correctly. Nurses monitoring anaesthesia ideally should be trained and deemed competent in both the technical and theoretical aspects of IPPV to minimise the chances of complications.

DEFINITIONS (OXFORD DICTIONARY)

Lungs – each of the pair of organs situated within the ribcage, consisting of elastic sacs with branching passages into which air is drawn, so that oxygen can pass into the blood and carbon dioxide be removed.

Pleural pressure – is the pressure surrounding the lung, within the pleural space.

Intrapulmonary pressure – intra-alveolar pressure is the pressure of the air within the alveoli, which changes during the different phases of breathing.

Intercostal muscles – the intercostal muscles are a group of muscles found between the ribs that are responsible for helping form and maintain the cavity produced by the ribs. The muscles assist with expansion and contraction during breathing.

Ribs – each of a series of slender curved bones articulated in pairs to the spine (12 pairs in humans), protecting the thoracic cavity and its organs. The ribs help in the expansion and contraction of the thoracic cavity and protect the lungs and heart.

Diaphragm – a dome-shaped muscular partition separating the thorax from the

8 March 2024 CLINICAL

AVN and AVNAT

Continuing Professional Development

A thorough understanding of normal and abnormal vital signs/ physiology and patients’ conditions, the principles of anaesthesia and anaesthetic depth, and the ability to ask questions regarding a patient’s condition are the most important factors in monitoring anaesthesia safely.

abdomen in mammals. It plays a major role in breathing.

Tidal volume – the air that moves in or out of the lungs with each breath.

Atmospheric pressure – is the force exerted on a surface by the air above it as gravity pulls it to Earth. Atmospheric pressure is commonly measured with a barometer. Measured in cm of H20.

ATMOSPHERIC PRESSURE IN RELATION TO BREATHING

Atmospheric pressure is 760 mmHg. The pressure in the lungs (intrapulmonary pressure) is equal to atmospheric pressure. Air (gases) moves along a pressure gradient from high pressure to low pressure. Hence, air will only move into the lungs when the intrapulmonary pressure drops or becomes more negative.

PHYSIOLOGY

The breathing cycle involves air going into the lungs during inspiration and air leaving the lungs during expiration. During a cycle, there are both pressure and volume changes.

There are three phases of a breath cycle:

1. Rest – where there is no airflow

2. Inspiration – where air enters

3. Expiration – where air leaves

INSPIRATION – ACTIVE

The intercostal muscles and the diaphragm are the two most important muscles/organs in normal respiration. Then you have the two most important pressures: atmospheric pressure and intrapulmonary pressure – both 760 mmHg. They are balanced; there is a difference of 0.

During inspiration, the diaphragm contracts and moves down, and the intercostal muscles contract, expanding and raising the rib cage. This allows the intrapleural volume to increase, resulting in the intrapulmonary pressure decreasing to approximately 759 mmHg (in relation to atmospheric pressure this is -1 mmHg). Allowing air to move into the lungs.

EXPIRATION – PASSIVE

The diaphragm relaxes and moves back to its original place. The intercostal muscles relax resulting in a decrease in the thoracic cavity. This causes the intrapulmonary volume to decrease, causing an increase in pulmonary pressure to 761 mmHg (+1 mmHg). Gases will move out from the lungs into the air (outside) down its pressure gradient.

POSITIVE PRESSURE VENTILATION

Two different types of positive pressure ventilation:

1. Positive pressure ventilation (PPV)

2. Positive end-expiratory pressure ventilation (PEEP) (not covered)

INSPIRATION – POSITIVE PRESSURE

Air is pumped into the alveoli (via an endotracheal tube); alveoli pressure becomes much more positive, causing gas exchange. This causes the diaphragm to passively descend and the lungs/chest to passively expand as you are forcefully pushing air into the lungs.

March 2024 9 CLINICAL

Continued next page ©shutterstock/Anamaria Mejia

IPP … what? Introduction to intermittent positive pressure ventilation specifically under anaesthesia

Continued from previous page

EXPIRATION – POSITIVE PRESSURE

The forceful push of air is released, driving gas inside the ventilator housing (outside the bellows) or reservoir bag to be exhausted into the atmosphere.

This causes elastic recoil of the diaphragm resulting in it returning to its original place. The chest cavity decreases and results in an intrapulmonary pressure difference of -1 mmHg resulting in air moving out of the lungs.

CHANGES IN PHYSIOLOGY

Positive pressure ventilation is changing the normal physiology of the body, and this can have profound consequences on all the systems of the body (including cardiac, renal, gastric, nutritional, neurological and neuromuscular).

The main cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological physiological consequences relating to an anaesthetic ventilator can include:

hypotension (low blood pressure)

• reduced cardiac output (cardiac output is the amount of blood the heart pumps in one minute, and it is dependent on the heart rate and stroke volume)

• decreased lung volume

• hypercapnia (elevated carbon dioxide level)

• hypocapnia (decreased carbon dioxide level)

Positive pressure ventilation can reduce cardiac output, which can result in hypotension. The increased intrathoracic pressure decreases venous return and right heart filling, which may reduce cardiac output. This occurs when inspiration is too long, and/or expiration is too short, and respectively when inspiratory pressure is too high.

Positive pressure ventilation may also increase pulmonary vascular resistance. The alveolar pressure is increased, which has a constricting effect on the pulmonary vasculature. This results in a decrease in blood flow to the lungs, and inadequate exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. When the inspiratory pressure is too high, the pulmonary vascular collapses. When the inspiratory pressure is too low, the alveoli collapse.

A decreased lung volume occurs when the tidal volume is too low, resulting in the collapse of the alveoli and occurs when an inadequate minute volume (minute volume is the tidal volume x the respiratory rate) is set.

The potential cerebral effects of positive pressure ventilation on an anaesthetic ventilator are related to the variations in carbon dioxide levels which directly affect blood flow to the brain. Carbon dioxide levels are measured using a capnograph (ETC02), which can effectively be controlled by altering the respiratory rate and tidal volume. ETC02 is the most accurate noninvasive method of determining if a patient is ventilating appropriately.

Hypoventilation causes an increase in ETCO2, generally with the patient not ventilating enough to remove carbon dioxide due to being in a deep anaesthetic plane. This leads to vasodilation, respiratory acidosis and increased blood flow to the brain.

Hyperventilation causes a decrease in ETCO2, with too much carbon dioxide being removed. This leads to vasoconstriction, respiratory alkalosis and decreased blood flow to the brain. Oxygen delivery to the tissues is reduced and brain damage can result.

DANGERS OF IPPV (ANAESTHESIA)

1. – Overinflation

– Initially, there may be no obvious signs of injury

– Traumatic lung injury from overdistension results in an inflammatory response

– Reduction in lung function

– Reduced cardiac output resulting in hypotension

– Excessive respiration rate resulting in hypocapnia

2. – Underinflation

– Failure to deliver appropriate amounts of oxygen (patient becomes hypoxaemic)

– Failure to deliver anaesthetic agent (light patient or patient wakes up)

– Failure to remove appropriate carbon dioxide (patient becomes hypercapnic)

3. – Consistency (manual vs mechanical)

– Ventilated patients reach the anaesthetic surgical plane more quickly compared to spontaneous breathing

ANAESTHETIC CIRCUITS

Typically, in general practice, IPPV under anaesthesia is performed using a t-piece or circle circuit.

T-PIECE

– Gas flow is controlled by pressure

– A high fresh gas flow is typically used

– The fresh gas flow flushes out the waste gas and carbon dioxide

– Difficult to reintroduce waste gas to the patient

HOW TO PERFORM IPPV USING T-PIECE

1. Occlude the end of the reservoir bag or close the valve.

2. Allow gas to fill the bag.

3. Squeeze the bag to inflate the chest (squeezing the bag will forcefully push fresh gas and inhalation anaesthetic into the patient).

4. Release the bag or open the valve and allow the patient to exhale (when the valve is released the incoming high FGF rates ensure the exhaled gas goes out via the expiratory limb of the circuit).

5. Repeat.

HOW TO PERFORM IPPV USING A CIRCLE CIRCUIT

1. Much safer than using a reservoir bag on the expiratory circuit (t-piece or bain).

2. Circle circuit has its own valves; inspiration and expiration valve and pop-off valve.

3. Close the pop-off valve.

4. Squeeze the reservoir bag (this forces fresh gas and inhalation anaesthetic to the patient, no carbon dioxide).

5. Release the reservoir bag (this allows waste gas to go into the circle).

6. You can give several breaths before opening the valve (and refilling with fresh gas).

10 March 2024 CLINICAL

WHAT RATES/VALUES DO WE NEED TO KNOW?

1. Target ventilation pressures are not related to weight or volume (you will only know the pressures reached during IPPV if you have a manometer attached to the anaesthetic machine).

– Generally, pressures of 10–20 cm H20 will adequately ventilate patients

– Cat: 10–14 cm H20

– Small dog: 10–14 cm H20

– Medium dog: 15–20 cm H20

– Giant dog: 18–25 cm H20

2. If you do not have a manometer to measure the pressure, the lungs should be inflated by approximately ⅓. You must be actively watching the patient’s chest when performing IPPV. Start with small squeezes of the reservoir bag and increase slowly to a point of obtaining a ‘normal’ chest movement for your patient (each patient will be different depending on the species, size and chest conformation), and maintain normocapnia.

ANAESTHETIC VENTILATORS

History

One of the earliest mechanical ventilators in human use was the Drinker respirator (or ‘iron lung’), which was developed during the polio epidemic in the 1920s. The ventilator, however, worked using a negative pressure gradient. The machine created a sub atmospheric pressure around the thorax, expanding it and causing air to be drawn into the lungs by a negative pressure gradient. The first positive pressure ventilator was invented by John Emerson in 1949 and is the preferred method of ventilation.

Anaesthetic ventilators play a vital role in anaesthesia and have different requirements than those of an ICU ventilator. The anaesthetic ventilator (including bellows) is used in combination with a circle system, adjustable airway pressure limiting valve (mechanical or digital), entrance for fresh gas, entrance for an anaesthetic inhalation agent, scavenge system, and carbon dioxide absorber.

BENEFITS OF USING AN ANAESTHETIC VENTILATOR VS HAND VENTILATING

• Maintains constant and consistent ventilation

• Optimises the delivery of inhalation anaesthetic

• Frees up the anaesthetist

• More labour efficient

AIM: The goal when using an anaesthesia ventilator is to maintain physiologic homeostasis.

TYPES OF VENTILATORS

There are 3 types of positive pressure ventilators used in veterinary medicine.

1. Volume: volume cycled; pressure limited = volume is set but once a pressure limit is reached no more volume is delivered

2. Pressure: pressure cycled; volume limited = pressure is set but once the volume limit is reached the ventilator ends the breath even if the pressure was not reached

3. Time cycled: fixed inspiratory time is set (not covered)

The most common type of anaesthetic ventilator is the volume cycled, pressure limited.

WHAT RATES/VALUES DO WE NEED TO KNOW

1. Respiratory rate (RR)

a. Breaths per minute

b. Initial: 8–12 bpm

c. Adjustments 6–15 bpm generally

2. Tidal volume (TV)

a. Amount of air/oxygen delivered in one breath

b. Initial: 10–12 ml/kg

c. Adjustments: 8–14 ml/kg

3. Minute volume (MV)

a. Amount of air/oxygen delivered in one minute

b. MV = TV x RR

c. 150–250 ml/kg/min

4. Inspiratory:expiratory ration (I:E)

a. Ratio of inspiratory to expiratory time

b. Ideal: 1:2, 1:3

c. Inspiration approx. 1 second

5. Peak inspiratory pressure (PIP)/pressure limit

a. The highest airway pressure applied to the lungs during inhalation

b. Generally, pressures of 10–20 cm H20 will adequately ventilate patients

c. Cat: 10–14 cm H20

d. Small dog: 10–14 cm H20

e. Medium dog: 15–20 cm H20

f. Giant dog: 18–25 cm H20

PERFORMED WITH THE CIRCLE CIRCUIT

1. Leak test the anaesthetic machine as per normal

2. Select the correct size bellows

– Paediatric for TV < 250 ml generally

3. Depending on the type of ventilator either:

– Flip the lever ‘ventilator’ and attach the ventilator hose (if not already connected)

– Remove the reservoir bag and replace it with the ventilator hose

– Close the pop-off valve

– Attach the scavenge hose (if not already connected)

– Check all hoses and connections are correct

4. Leak test the ventilator (you should have already leak tested the anaesthetic machine)

– Essential that you know there are no leaks in the systems before placing an animal on the machine)

5. Remove the ETC02 sensor (if you have one available) and hold a finger over the Y-piece of the circuit or use a reservoir bag in place of it.

6. Fill the bellows:

– Use the oxygen flush – The bellows should remain at the top and filled

– Most common source of a leak is the housing if not placed on correctly

7. Set the pressure relief valve (depending on what type of ventilator you have will depend on if this is done manually or automatically calculated via the system interface of the ventilator)

– Generally, pressures of 10–20 cm H20 will adequately ventilate patients

Continued next page

March 2024 11 CLINICAL

Continued from previous page

– Cat: 10–14 cm H20

– Small dog: 10–14 cm H20

– Medium dog: 15–20 cm H20

– Giant dog: 18–25 cm H20

– This valve will open when the pre-set pressure is reached within the circuit

8. The manometer is used to evaluate the pressure within the circuit

CONNECTING THE PATIENT TO THE VENTILATOR

1. Double-check all connections and settings

2. Fill the bellows to the top before turning on the ventilator (this gives some oxygen to the bellows once the patient is initially attached)

3. Turn on the ventilator

4. Connect the patient to the circle system

5. Initially keep the FGF high so the bellows fill to the top (this may take several breaths; once filled the FGF rates can be set to normal)

6. Do NOT use the oxygen flush once the patient is attached

7. If the bellows are not rising to the top, there is a leak (most leaks are due to an insufficiently inflated ET t ube cuff)

8. Read the TV at the top of the white discs (or the system interface)

9. Adjust the TV as required by using either the inspiratory flow knob or the system interface

10. Watch the patient on inspiration: – Should look like a ‘normal’ breath for that individual patient

Monitoring specific to anaesthetic ventilators includes:

Normal values/rates/description

Oxygen saturation (Sp02)

Heart rate (HR)

• Normal SpO2: 97–100%

• The patient’s SpO2 is the percentage of oxygensaturated haemoglobin and indicates how well the lungs are delivering oxygen to the blood

• The pulse oximeter measures both SpO2 and heart rate and is monitored continuously

• Normal – canine: 80–120 bpm

• Normal – feline: 100–180 bpm

• Bradycardia (low heart rate) may indicate excessive anaesthetic depth or a response to vagal stimulation (HR < 80 in dogs and < 100 in cats should be reported to the supervising veterinarian or technician for evaluation

• Tachycardia (high heart rate) may indicate light plane of anaesthesia/inappropriate response to surgical stimulus, from an inadequate anaesthetic level

Respiratory rate and depth (RR)

• Normal RR: 10–20 breaths/minute

• Normal inspiration lasts 1–1.5 seconds and expiration lasts 2–3 seconds (a ratio of 1:2)

• Basic respiratory monitoring is based on clinical observations

• Chest excursions should be assessed with both spontaneous respiration and IPPV and should be a depth of ⅓ of the chest cavity

• Breathing should be smooth and regular, with thoracic and diaphragmatic components

• Advanced respiratory monitoring can be done using a capnograph

• Hypoventilation can be a result of increased anaesthetic depth (patient is too deep)

• Hyperventilation can be a result of inadequate anaesthetic depth (patient is light)

11. Check the pressure gauge to see what the pressure is reaching with each breath

– If pressure is too high the pressure valve will open (some make an audible noise)

– Double-check the TV value – Increase the inspiratory flow?

12. The pressure gauge should go to 0 +/- 2 cm H20 on expiration

MONITORING

The monitoring of the anaesthetised patient is a continual process and parameters should be monitored every 5 minutes. Monitoring patients on an anaesthetic ventilator is aimed at maintaining physiologic homeostasis and monitoring and responding to trends.

Specific to ventilator

• No changes to normal rates/values should be observed provided patient is oxygenating normally

• Heart rate trends should consistently be monitored when using an anaesthetic ventilator to assist in determining depth of anaesthesia (patients on a ventilator generally require less anaesthetic to maintain an appropriate level of anaesthesia)

• Both bradycardia and tachycardia can be a result of physiological changes to the patient

• Trends more important than values

• Inspiratory to expiratory ratio should remain the same at 1:2

• Respiratory rate will be determined by the level of end-tidal carbon dioxide

• Generally, start 8–12 bpm (increase only when required to maintain carbon dioxide levels)

• Monitor anaesthetic ventilator settings vs actual RR; if the RR is higher than the settings the patient may be bucking the ventilator (check anaesthetic depth and adjust accordingly)

12 March 2024 CLINICAL

End-tidal carbon dioxide (ETC02)

Normal values/rates/description

Normal 35–45 mmHg

• Measured by a capnograph

• End-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) is the level of carbon dioxide that is released at the end of an exhaled breath and is one of the best non-invasive ways to monitor a patient’s ventilation status under anaesthesia

• Characteristics of a normal capnograph waveform include:

– waveform starts at zero and returns to zero – the amplitude of the waveform depends on the ETC02 concentration – the width of the waveform relates to the expiratory time – each waveform has 4 phases

Specific to ventilator

Use the ventilator settings (tidal volume and respiration rate) to assist in maintaining the patient’s ETC02 to normal values

• Hypercapnia (elevated ETC02) is directly related to hypoventilation. Treatment is focused on treating the cause:

– check anaesthetic depth (generally the patient is too deep)

– reduce anaesthetic administration

– ensure fresh gas flow is adequate; increase if metabolic rate is increased

– increase RR rate on the ventilator

– check TV and minute volume rates

Hypocapnia (reduced ETC02) is directly related to hyperventilation. Treatment is focused on treating the cause:

– check anaesthetic depth (generally patient is too light)

– increase anaesthetic

– check temperature

– check cuff is still inflated (deflated cuff will result in a low ETC02 when on a ventilator due to the forceful push of gases)

– check perfusion parameters

Arterial blood pressure (non-invasive)

Depth of anaesthesia

Normal BP: 120/80 mm Hg (80–120 mmHg systolic, 60–100 mmHg diastolic)

• Normal mean arterial pressure between 70–90 mmHg

• BP may be measured in a variety of ways including Doppler or automated oscillometer devices

• The most common cause of hypotension is excessive anaesthetic depth

• Other causes include hypovolemia due to intraoperative bleeding or preoperative dehydration, hypothermia or hypoxia

Hypotension – Check anaesthetic depth (generally the patient is too deep)

• Due to changes in normal physiology of positive pressure ventilation, hypotension may be a result – reduce the tidal volume (to increase cardiac output)

• Ventilated patients reach anaesthetic surgical plane more quickly and thus checking of anaesthetic depth is a priority when on an anaesthetic ventilator

• Generally, a reduced concentration of inhalation is required

WEANING BACK TO SPONTANEOUS BREATHING

1. Using mechanical ventilation

– Anaesthetic ventilators do not allow for efficient weaning, so this is performed by changing your settings

– Gradually decrease the RR to 5 bpm – ETC02 will increase = lightened anaesthetic depth

– Patient will attempt to take spontaneous breaths

– Take off ventilator by reverting to a manual system

2. Using manual ventilation

– Revert to a manual IPPV system

– Attach reservoir bag or switch toggle from ventilator to reservoir bag function

– Open pop-off valve

– Attach scavenge

– Manually ventilate using PPV until the patient breathes well on their own – Wait 20–30 seconds before giving a breath to enable the ETC02 to build

References

JM Burkitt Creedon and H Davis. Advanced monitoring and procedures for small animal emergency and critical care. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

DC Silverstein, K Hopper. Small animal critical care medicine. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2023.

Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia. 5th ed of Lumb and Jones; KA Grimm et al. editors. 2015.

March 2024 13 CLINICAL

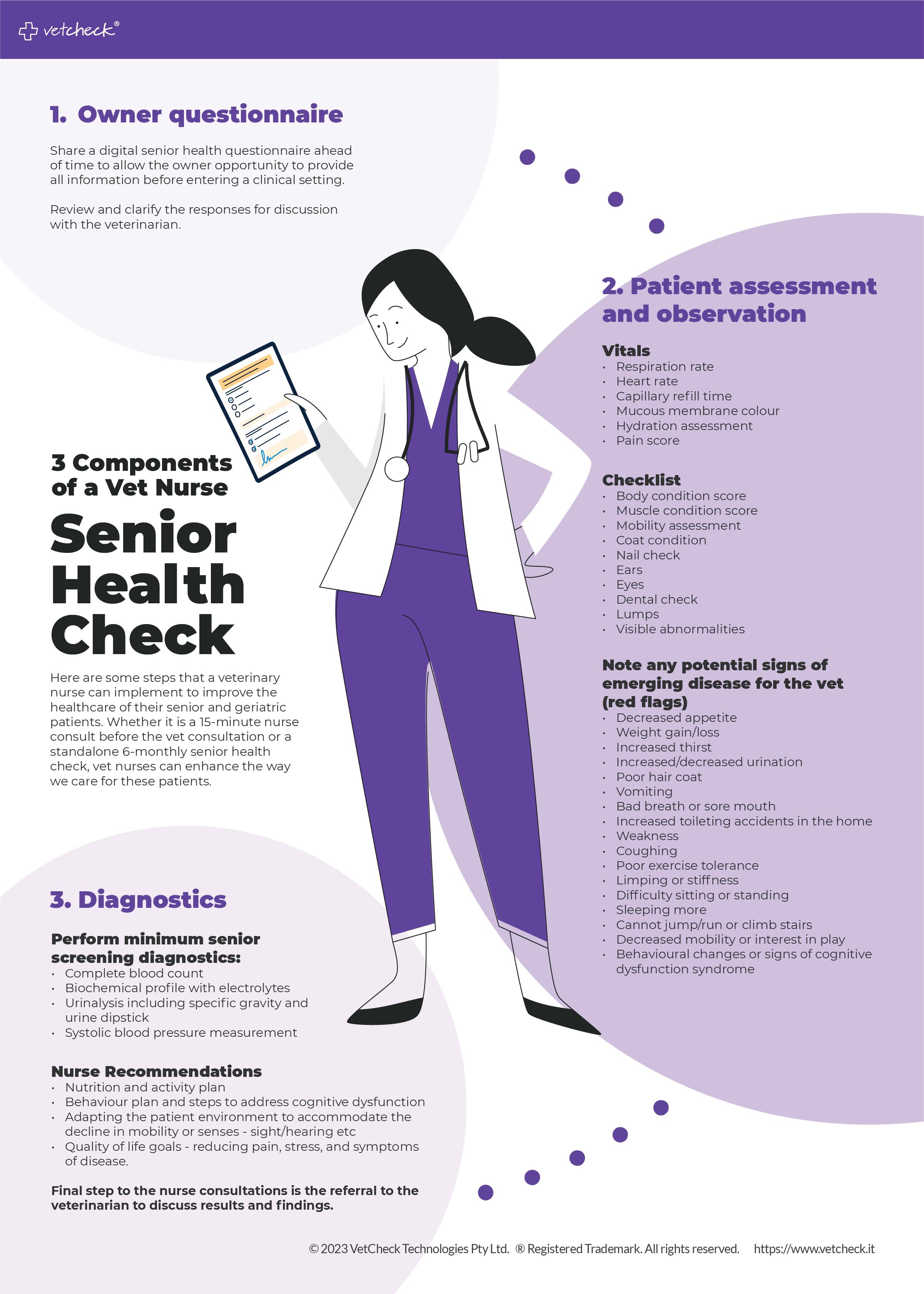

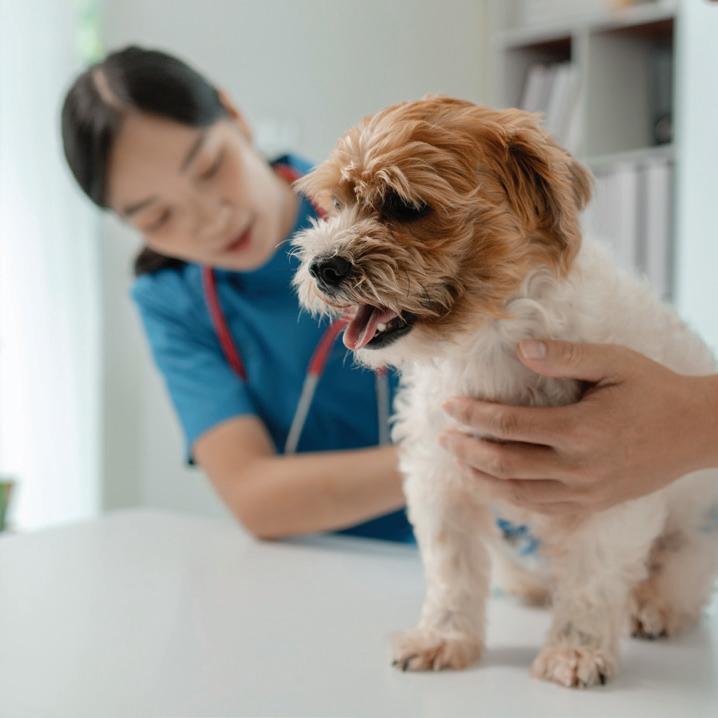

Levelling up your consulting nurse game

by Kim Healy VTS(Nutrition), FFCP(Veterinary), RVN, AVN

It’s no secret that clinics are getting busier, staff are getting more burnt out and job advertisements are staying posted for far longer than we ever thought possible. With no end in sight for the vet shortage and simply training more is not the answer, we are seeing so many qualified and skilled nurses leave the industry for good. We are working harder than we ever have for arguably less job satisfaction, more frustration, and comparatively low wages. For this reason, the average nurse walks away after 5 years and most never look back. So how do we fix this? We adapt, we change our roles, and we change our expectations – and this is where the consulting nurse role slots in quite nicely.

Becoming a consulting nurse can be challenging but highly rewarding. This role should be reserved for highly skilled nurses who are confident in their ability and knowledge. Presently a number of clinics refer to a consulting nurse as one who assists the vet, cleans the rooms postconsult, and performs services such as anal glands, nail trims and minor injections. In my opinion, this is not a consulting vet nurse role and I do feel these types of ‘consults’ seriously devalue our skill and knowledge.

STARTING OUT

If you feel like consulting might be for you but you are unsure where to start, consider team consulting. This consulting style has been implemented by several clinics that

have seen the value and better utilisation of their staff. Team consulting generally involves the nurse starting the consulting process by identifying the reason for the visit and history taking. Depending on clinic protocols, the nurse may then perform a clinical exam, record vitals and flag any deviation from normal. Some clinics do reserve this as a vet job, so role clarification for team consulting is imperative. At this point, the nurse will either move on to another consult or will stay and write the clinical notes for the consulting vet. This is a crucial and incredibly important step in learning consulting skills: watching how others speak with clients, presenting information and understanding body language. The feedback I have had from various nurses is they either lack the confidence to speak with clients or do not see the value in themselves performing such a role. Once they have the opportunity to stand in on routine consults, the mystery of what happens behind closed doors is lifted and instead of thinking ‘I’m not good enough’, their mindset shifts to ‘I could do that’.

SKILLS OF A CONSULTING NURSE

Being a consulting nurse is not a role that everyone is suitable for and that’s okay! One of the biggest mistakes a practice can make is putting people in roles they are not comfortable doing and may not have been employed to do. This ultimately leads to the failure of the role. As this is still an evolving area of practice, don’t be

Team consulting generally involves the nurse starting the consulting process by identifying the reason for the visit and history taking. Depending on clinic protocols, the nurse may then perform a clinical exam, record vitals and flag any deviation from normal.

surprised if you need to prove yourself. This is not a negative point, as this shows you’re confident to work on your own and provide the correct information. This may sound counterintuitive but you also need to prove you can ‘tap out’. You need to know when you have reached your limitations and say no; this will increase trust between yourself and other co-workers. It is very easy to get caught up in being a yes man and wanting to take up as many opportunities as you can, but this is where mistakes happen and this can be detrimental to the patient, client and co-workers. Remember, as there is currently no mandatory registration, our actions fall under the supervising vet, which is why trust between the 2 parties is so incredibly paramount.

Along with recognition of limitations, these attributes make for an excellent consulting nurse:

• Personable and approachable

• Empathetic and supportive

• Keen to learn

• Attention to detail

• Excellent communication skills

• Confidence! Confidence! Confidence!

TYPES OF CONSULTATIONS

The types of consultations you can perform will ultimately depend on your practice and your relationships with the vet team. My advice is to play to your strengths and focus on your area of interest first. It’s likely that you will immediately have more confidence in this type of consult because you already have extra knowledge to deliver the information and answer questions.

Some examples of consults:

• Nutrition, including food trials, supplements, weight loss and general health

Ear revisits, with associated cytology and examination of ears

Juvenile checks

14 March 2024 CLINICAL

• Behaviour plans

• Chronic disease management, such as kidney disease, diabetes, thyroid or cardiac

• Six-monthly senior checks, including geriatric rehab

• Exotic husbandry.

Every consult that you perform can free up a spot for a sick animal. How many times have you seen short revisits booked but needed to turn away a sick patient?

We want to work smarter, not harder! Nurse consultations are NOT free of charge. For years we have had this blanket rule of ‘It’s free to see a nurse’. Why? Is our time not valuable? Do we not have a specific skill set that should be valued? Do we not invest both time and financially into ourselves? When looking at performing anal glands, for example, that is a skill and we bill for that, but we do not bill for the time. When was the last time you had an anal gland expression and were not asked ‘How can I prevent this?’ – and you gave advice. Value your time and value your skill; that is why clients are coming to you.

Every consult that you perform can free up a spot for a sick animal. How many times have you seen short revisits booked but needed to turn away a sick patient?

IMPLEMENTING NURSE CONSULTATIONS

The first step is to identify how nurse consults will benefit the practice. Look at the current staffing situation; is one nurse able to dedicate themselves to consulting for a full day or even half a day? Perhaps the clinic is consistently down a vet, or the consulting vet is consistently running behind and feels overwhelmed. Looking at team consulting may be a good avenue to start down.

Some

benefits to present to employers:

• Increased financial revenue

• More clients through the door = more regular visits

• Decreased workload for vets, especially when short-staffed

• Increased job satisfaction leading to

better staff retention

More vet availability for higher revenue consults

• Utilisation of skills

• Be considered an industry leader. Team meetings to discuss who wishes to be involved and who doesn’t are also important. Hearing from the vets and what would help them out should certainly be considered. Once you become established as a consulting nurse, it is worth keeping track of your figures. There were some days I would have a higher spend per consult than the vets! This type of information can be used at annual reviews and when negotiating a pay rise. The consulting nurse skill set is in high demand in several progressive practices, so if this type of role is something you wish to establish yourself in, the sky is the limit!

March 2024 15 CLINICAL

©shutterstock/Pickadook

Small animal endoscopy in veterinary nursing: A guide

by Animal Industries Resource Centre Team

Endoscopy is a crucial diagnostic and therapeutic tool in veterinary medicine, allowing visual examination of internal organs and body parts without invasive surgery.

Since its inception in the early 19th century, endoscopy has revolutionised veterinary diagnostics and treatment. The skill and knowledge of veterinary nurses are pivotal to the success of endoscopic procedures, ensuring the safety and comfort of the patient throughout the process.

UNDERSTANDING ENDOSCOPY

Endoscopy involves the use of an endoscope (a rigid or flexible optical instrument equipped with a light source) to conduct a detailed visual examination of the body’s internal organs and structures.

The roots of this technology trace back to 1806. The first documented instance of thoracoscopy, an endoscopic procedure examining the chest cavity, occurred in 1912. Since then, the evolution of endoscopy has been remarkable, particularly with the integration of internal light sources, enhancing visibility and diagnostic accuracy.

Endoscopic procedures have numerous benefits, primarily due to their minimally invasive nature. They tend to involve shorter recovery times, reduced risk of infections, and less postoperative discomfort for the patient. The direct visualisation capability of endoscopy enables accurate and immediate diagnosis, swift and precise treatment decisions, and allows for

immediate interventions like biopsy and the retrieval of ingested foreign objects.

However, despite its numerous advantages, endoscopy does come with certain limitations. The procedure needs specialised equipment and a high level of expertise and training. The physical dimensions and design of the endoscope can restrict its application, as certain body areas may be inaccessible or unsuitable for examination with the available endoscopic equipment. The initial cost of acquiring high quality endoscopic systems and the ongoing maintenance they require represent a significant investment.

16 March 2024 CLINICAL

©shutterstock/Lebedko Inna

Additionally, while complications are relatively infrequent, the potential risks associated with sedation or anaesthesia, as well as the procedure itself, must be carefully considered and managed.

TYPES OF ENDOSCOPES

There are various types of endoscopes, each designed for specific diagnostic and therapeutic needs. Primarily, endoscopes are categorised into 2 main types: rigid and flexible.

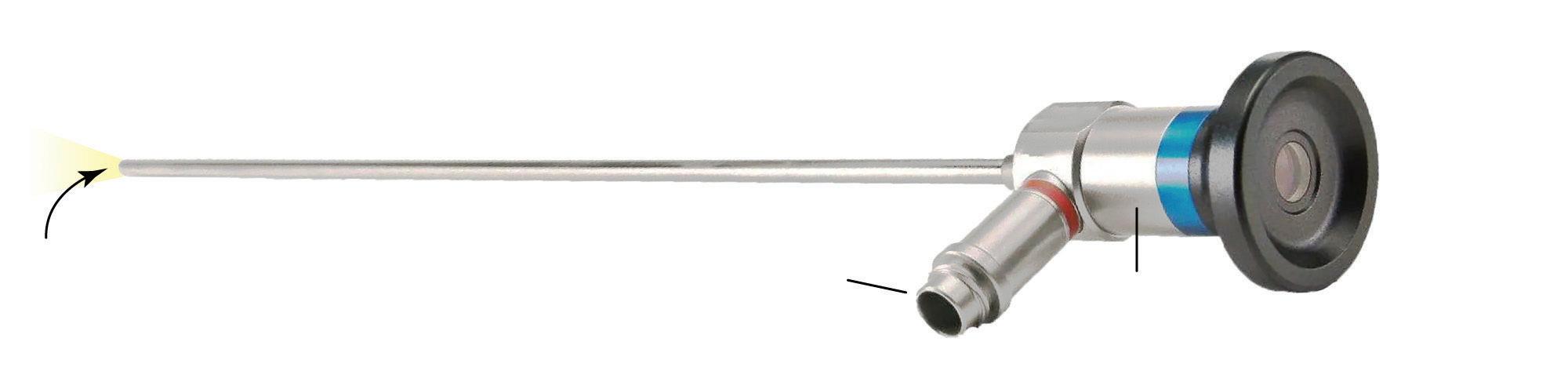

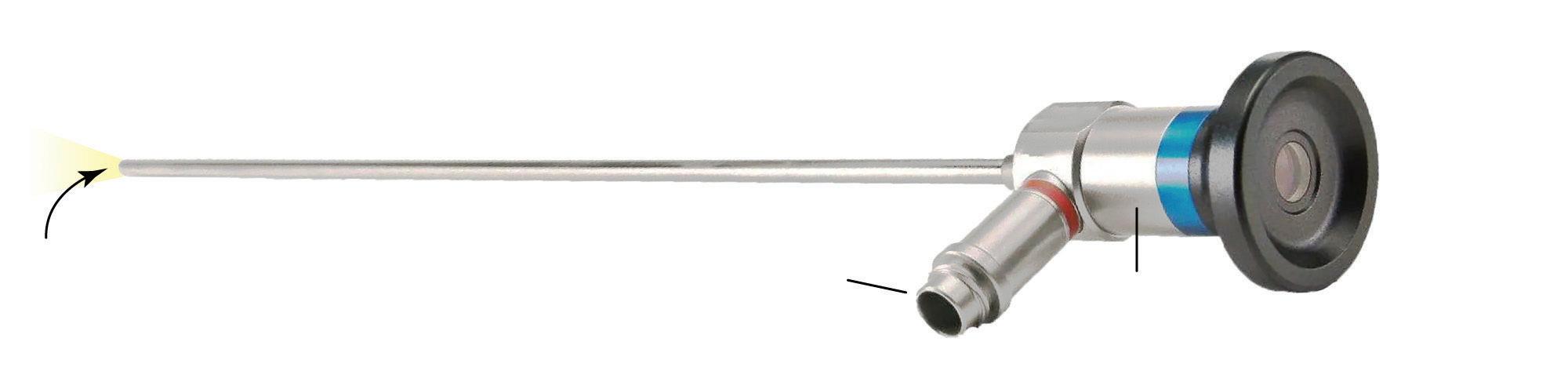

Rigid endoscopes

Rigid endoscopes, known for their durability and relatively lower cost, are predominantly used in procedures where the area of interest is directly accessible. These endoscopes consist of a solid tube equipped with a light source and an eyepiece or camera at one end, providing a clear view of the internal structures. The design variations in rigid endoscopes cater to different applications, including otoscopy for ear examinations, arthroscopy for joint inspections, and laparoscopy for abdominal or pelvic cavity examinations. Their robust construction allows for the attachment of additional instruments, such as biopsy forceps or suction channels, enhancing their functionality in various surgical procedures.

Parts of the rigid endoscope

Eyepiece

The eyepiece is the part of the endoscope through which the clinician views the internal images captured by the objective lens. It often contains additional lenses to magnify the image for detailed observation. The clarity and precision of the eyepiece are crucial for accurate diagnostics and successful procedures.

Light guide adaptor

The light guide adaptor transmits light from the external source into the endoscope. It ensures that the area under examination is well-illuminated, providing a clear and vivid visual field.

Endoscopic procedures have numerous benefits, primarily due to their minimally invasive nature. They tend to involve shorter recovery times, reduced risk of infections, and less postoperative discomfort for the patient.

Insertion tube

The insertion tube is the part of the endoscope that is introduced into the patient’s body. It houses the optical fibres or camera system, light fibres, and in some models, channels for instruments or fluid passage. The rigidity of the insertion tube varies slightly according to its purpose and the specific area it is designed to explore.

Objective lens

The objective lens is located at the distal end of the endoscope and is responsible for capturing the images of the internal structures. It is a crucial component, as the quality of the images obtained during the endoscopic procedure directly depends on the clarity and precision of the objective lens. The lens must be meticulously maintained and handled to ensure optimal performance and accurate diagnostics.

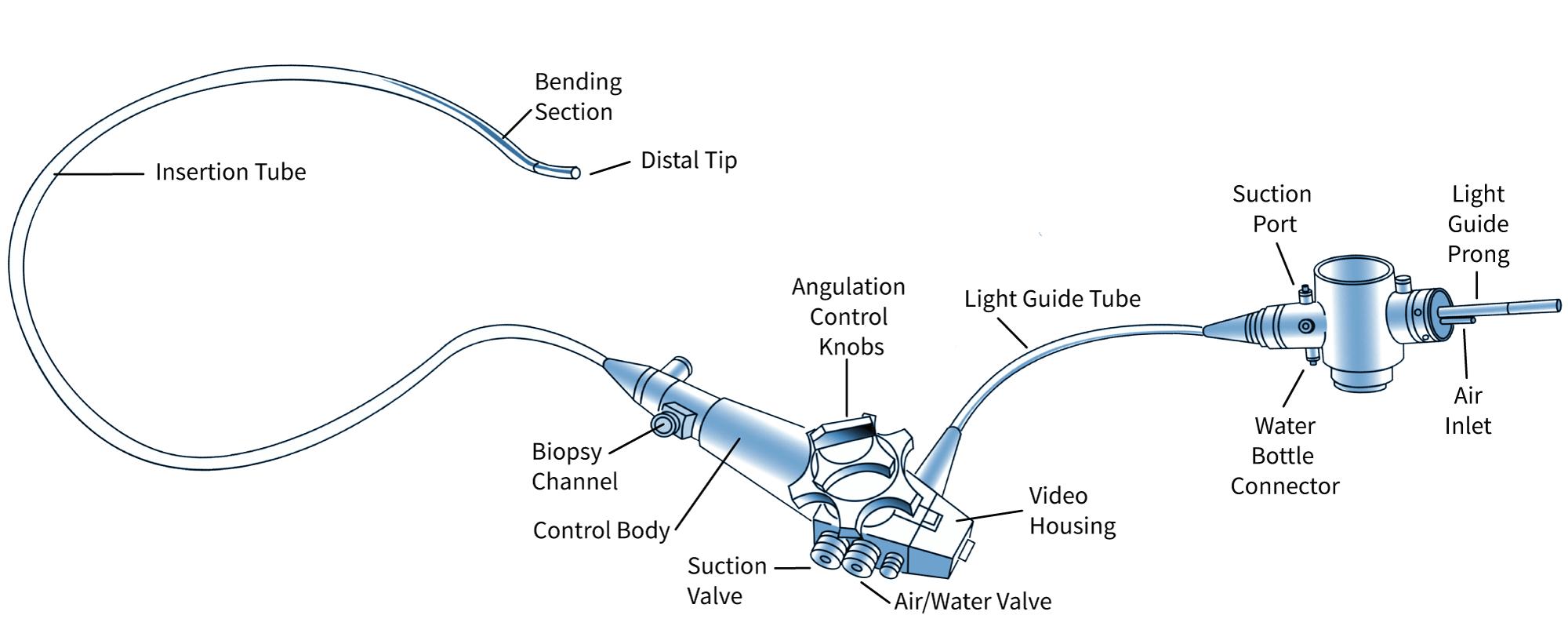

FLEXIBLE ENDOSCOPES

Flexible endoscopes are characterised by their adaptability and intricate design, allowing access to convoluted and delicate internal pathways. These endoscopes utilise a flexible insertion tube containing fibreoptic bundles or a video camera at the distal end, transmitting high quality images to an eyepiece or a digital monitor. The flexibility of these endoscopes makes them indispensable for gastrointestinal procedures like gastroscopy and colonoscopy, as well as respiratory examinations through bronchoscopy. The intricate design includes channels for air,

water, and surgical instruments, facilitating tasks such as biopsy, foreign body retrieval, or stenosis dilation.

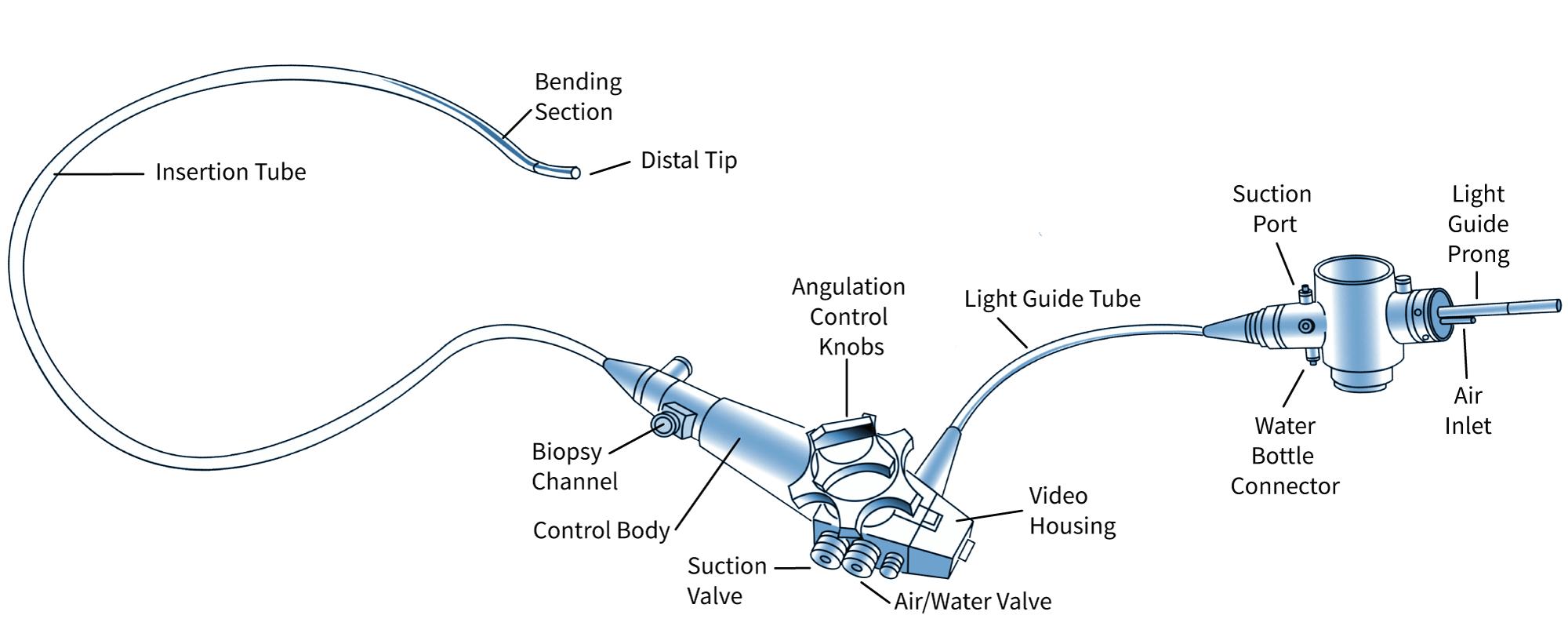

Parts of the flexible endoscope Insertion tube

The insertion tube stands as the backbone of the flexible endoscope, its design varying to meet the diverse requirements of veterinary examinations. Attributes such as length, diameter, stiffness, and tip flexibility are meticulously calibrated to navigate different anatomical structures. Within this tube, the light source and camera or fibreoptic bundles are housed, alongside air and water conduits, crucial for maintaining clarity and facilitating precise manoeuvres during examinations. Additionally, channels within the tube are designed to accommodate specialised instruments and facilitate biopsy collection, significantly enhancing the scope of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. The delicate nature of the insertion tube, however, necessitates cautious handling to avoid damage, underscoring the importance of gentle navigation and protection against external pressures.

Distal tip

The distal tip of the endoscope, housing the objective lenses or CCD chip, is the focal point of the examination, casting light on the internal structures under scrutiny. This tip is adeptly illuminated and designed for intricate manoeuvring, Continued next page

Objective

Insertion tube

Light guide adaptor

Marking ring

March 2024 17 CLINICAL

Eyepiece

Main parts of the rigid endoscope

Small animal endoscopy in veterinary nursing: A guide

Continued from previous page

allowing endoscopists to navigate complex anatomical landscapes and ensure comprehensive exploration. The precision with which the distal tip can be navigated ensures that every examination is thorough and captures clear, detailed visual data from the internal examination site.

Air insufflation pump

The air insufflation pump introduces air under mild pressure into the examination area to enhance visibility. This gentle insufflation expands the area being examined, providing a clearer view, and facilitating a more detailed and accurate examination. Carefully controlled introduction of air is crucial for maintaining the balance between visibility and patient comfort.

Water and suction systems

The water and suction systems are designed to maintain the clarity of the objective lens and manage the examination environment. Water, stored in a dedicated bottle attached to the light source or cart, is directed across the objective lens to remove any obstructions to clarity, ensuring that the visual field remains unimpeded throughout the procedure. The suction system complements this by removing fluids or air present at the distal tip, ensuring that the examination area is kept clear for the most precise observational conditions.

Handpiece

The handpiece of the endoscope is ergonomically designed, offering the endoscopist intuitive control over the device’s various functions. Positioned to be held in the left hand, it provides control over the up/down and right/left angulation knobs and locks, as well as the air/water and suction valves. Additionally, the handpiece houses the eyepiece or control buttons for video scopes, along with the focusing ring, ensuring that every adjustment and control is within easy reach. The biopsy/accessory channel also features here, making the handpiece a central hub for managing the functions of the endoscope during examinations.

TYPES OF ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES

Endoscopy encompasses a diverse array of procedures, each tailored to examine and treat specific parts of the body. From gastroscopy providing insights into stomach health, to auroscopy dedicated to ear examinations, endoscopy spans a broad spectrum of applications.

GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Gastrointestinal endoscopy provides a non-invasive way to visually examine the interior of the gastrointestinal tract. This type of endoscopy encompasses several procedures, each tailored to specific sections of the gastrointestinal system.

Oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (OGD) allows for the detailed inspection of the oesophagus, stomach, and the beginning of the small intestine, making it crucial for diagnosing conditions like gastritis, ulcers, or tumours.

Colonoscopy focuses on the lower GI tract, offering insights into the health of the colon and the distal part of the small intestine. It is used to detect mucosal irregularities, polyps, and areas of inflammation or bleeding.

Beyond diagnosis, gastrointestinal endoscopy plays a significant role in therapeutic interventions, such as the removal of ingested foreign objects, polyp excision, and the collection of biopsy samples for histopathological examination.

The indications for gastrointestinal endoscopy are diverse. For animals presenting with symptoms such as chronic vomiting, diarrhoea, unexplained weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding, endoscopy offers a direct way to investigate the underlying causes. It’s particularly useful in cases where noninvasive imaging techniques, such as X-rays or ultrasound, fail to provide definitive answers. The ability to perform targeted biopsies during the procedure allows for the precise identification of conditions like inflammatory bowel disease or gastrointestinal cancers. In emergency

18 March 2024 CLINICAL

parts of the flexible endoscope

Main

TERM AREA(S) EXAMINED USES

Gastroscopy Stomach

Gastroduodenoscopy Upper GI tract (stomach, duodenum)

Enteroscopy Small intestine

Colonoscopy Lower GI tract (colon, distal small intestine)

Rhinoscopy Nasal passages

Diagnosing and treating conditions like ulcers, tumours, and inflammation

Examining and treating diseases in the stomach and beginning of the small intestine

Diagnosing issues in the small intestine such as inflammation, bleeding, or blockages

Examining the colon for polyps, cancer, and areas of inflammation or bleeding

Investigating causes of nasal discharge, bleeding, or obstruction

Bronchoscopy Lower airways (trachea, bronchi) Diagnosing and treating conditions in the airways like chronic cough or tumours

Cystoscopy Bladder

Arthroscopy Interior of a joint

Examining the bladder for stones, tumours, or inflammation

Diagnosing and treating joint diseases and injuries

Laparoscopy Abdominal or pelvic cavity Performing minimally invasive surgeries in the abdomen or pelvis

Urethrocystoscopy Urogenital tract and bladder

Thoracoscopy Thorax (chest cavity)

Examining and treating diseases in the urogenital tract and bladder

Inspecting the chest cavity for conditions like pleural effusion or tumours

Auroscopy Ear Diagnosing and treating ear conditions such as infections, blockages, or tumours

situations where an animal has ingested a foreign object, endoscopy can often be a lifesaving procedure, enabling the removal of the object without the need for invasive surgery.

RESPIRATORY ENDOSCOPY

Respiratory endoscopy is a pivotal diagnostic and therapeutic tool, particularly for conditions affecting the lower airways and lungs.

Bronchoscopy involves the insertion of a flexible endoscope into the trachea and bronchial tree, allowing veterinarians to visually inspect the airways for abnormalities. This procedure is invaluable for investigating persistent coughs, wheezing, shortness of breath, or haemoptysis. Bronchoscopy facilitates the direct observation of the mucosal surfaces, the detection of foreign bodies, the collection of biopsy samples, and even the removal of obstructive material or masses. For conditions like chronic bronchitis, pneumonia, or lung tumours, bronchoscopy offers critical insights that guide diagnosis and treatment.

Bronchoalveolar lavage, a procedure often performed during bronchoscopy, allows for the collection of cells and fluids from the lower respiratory tract, providing material

for cytological examination and culture, thereby aiding in the diagnosis of infections, inflammation, or neoplastic diseases.

The indications for respiratory endoscopy are diverse and cater to a range of respiratory conditions. For animals presenting with clinical signs such as chronic cough, unexplained respiratory distress, or suspected inhalation of foreign objects, respiratory endoscopy offers a minimally invasive yet highly effective diagnostic approach. It’s particularly beneficial when conventional imaging methods, such as radiography or computed tomography, cannot fully elucidate the nature or severity of the condition. In addition to its diagnostic capabilities, respiratory endoscopy can be a life-saving therapeutic intervention, especially in cases involving airway obstruction due to foreign bodies or excessive mucus accumulation.

EQUIPMENT PREPARATION

Before any endoscope procedure is performed the following procedures should be performed to ensure it is in working order.

Inspection of the insertion tube

Ensure the insertion tube is free from irregularities by visual inspection and tactile

examination. Look for dents or protrusions, maintaining the tube’s integrity.

Inspection of the bending mechanism

Check the bending mechanism using angulation knobs, ensuring smooth movement in all directions. Confirm that the knobs move freely and that the tube tip stabilises properly.

Inspection of the optical system

Clean lens surfaces with 70% alcohol and a gauze swab. Assess image clarity and check for broken fibres or black dots, indicating potential damage. Perform white balance for video scopes as needed.

General inspection

Ensure proper light output and check eyepiece contact pins. Clean any deposits and inspect all parts for signs of wear or damage.

Leakage testing

Conduct routine leakage tests to prevent fluid ingress, which could lead to significant damage. Follow the manufacturer’s guidelines strictly to avoid inadvertent damage.

Assemble endoscope

Choose the appropriate endoscope size and type. Connect to the light source,

Continued next page

March 2024 19 CLINICAL

Table 1: Summary of the different types of endoscopic procedures, the specific areas of the body they examine, and their primary uses

Small animal endoscopy in veterinary nursing: A guide

Continued from previous page

video processor, suction device, and water reservoir. Ensure functionality of the suction and flushing apparatus, air insufflation, and image quality. Assemble any additional equipment required for the procedure.

PATIENT PREPARATION AND CONSIDERATION

Diligent patient and equipment preparation and consideration ensure the success and safety of endoscopic procedures in veterinary practice.

The typical process includes:

conducting a thorough pre-procedure assessment to:

– review the patient’s medical history

– perform a comprehensive physical examination

– complete pre-anaesthetic blood work – identify underlying conditions affecting the procedure or anaesthesia choice

– anticipate potential complications

– formulate a tailored anaesthetic protocol

• tailoring anaesthesia protocols and monitoring to:

– consider patient’s age, breed, underlying health conditions, procedure nature – ensure comfort and immobility during procedure

– minimise stress and prevent pain – monitor vital parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation)

– address adverse reactions or vagal responses promptly

– choose anaesthetic agents and plan for smooth induction, maintenance, recovery

• ensuring proper positioning and handling by:

– adhering to correct positioning (e.g. left lateral recumbency for upper GI procedures, sternal recumbency for respiratory endoscopy)

– ensuring optimal access and patient safety

– providing best visualisation and accessibility

– minimising risk of injury or discomfort.

The veterinary team’s careful handling and support during the procedure contribute to the patient’s stability and the overall success of the endoscopy.

GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES

Endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract always requires the patient to be heavily sedated or anaesthetised. Therefore, any clinic policies regarding pre-anaesthetic patient preparation (e.g. fasting) will apply.

Essential steps and considerations involved in this preparation

• Fasting: It’s crucial to enforce a fasting period before the procedure to ensure that the stomach and upper intestinal tract are empty. Typically, the fasting period might last for 12 to 24 hours, depending on the species and the specific instructions of the veterinarian.

• Bowel preparation: This is also required for lower gastrointestinal procedures. This can be achieved through the administration of enemas and/or oral purgatives. The specific agents and the frequency of administration should be decided by the veterinarian.

• Pre-procedural assessment: A thorough physical examination and review of the patient’s medical history are vital to identify any potential risks or contraindications for endoscopy. Laboratory tests such as complete blood count, serum biochemical profile, and urinalysis may be advisable to evaluate the patient’s health status.

Pre-medication: Pre-medication with sedatives or analgesics can aid in the smooth induction and maintenance of anaesthesia. Additionally, anticholinergic drugs may be used to decrease salivary secretions which could obscure the endoscopic view.

• Anaesthesia: Administering appropriate anaesthesia is vital for the comfort and immobility of the animal during the procedure. The anaesthetic protocol should be tailored to the individual patient, taking into account factors such as age, breed, and health status.

The patient is typically positioned in left lateral recumbency for upper gastrointestinal tract evaluation. The exception to this is if the endoscope is being used to assist in the correct placement of a gastroscopy tube. In this case, the animal is usually placed in the right lateral recumbency.

For all upper gastrointestinal tract procedures (where the endoscope is passed orally) the patient should have a mouth gag applied. This ensures that the animal does not bite down and damage the insertion tube of the endoscope.

The anaesthetic nurse should use standard monitoring procedures that would be carried out on all patients undergoing a general anaesthetic. In addition, it is important to be aware that gastrointestinal endoscopy can induce vagal responses (i.e. hypotension and bradycardia). While monitoring, the nurse must ensure that the stomach does not become overinflated and if so the endoscopist must be alerted.

RESPIRATORY ENDOSCOPIC PROCEDURES

Lungs/airway

Urethra

NB

Bronchoscopy typically necessitates general anaesthesia to ensure the animal remains still and comfortable throughout the examination.

20 March 2024 CLINICAL

PROCEDURE POSITION

gastrointestinal tract (gastroduodenoscopy) Left lateral recumbency

gastrointestinal (colonoscopy) Left lateral recumbency

Upper

Lower

(tracheobronchoscopy) Sternal recumbency

(rhinoscopy) Sternal recumbency

Nose/pharynx

(esp. male dogs) (urethroscopy) Lateral recumbency

Table 2: Typical positioning for flexible endoscopy