The Official Journal of the Veterinary Nurses Council of Australia Inc. Reg. No. A0031255G ABN 45 288948433 VOL. 29 • NO. 3 • SEPTEMBER 2023 THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY NURSES JOURNAL Just breathe: Mechanical ventilation for small animals Principles of community-centred veterinary care Common presentations of avian emergencies Get ready to celebrate Veterinary Nurse & Technician Awareness Week Thefuture is in yourhand s AWARENESS WEEK VET NURSE & VET NURSE & TECHNICIAN TECHNICIAN 9-13 Oct o ber 2023

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President Gary Fizgerald

Vice President Trish Farry

Michelle Foxcroft, Anita Parkin, Rebecca Coventry, Asha Yeoman, Samara Blake, Tayla Atkinson

VNCA MEDIA CHAIR

Janet Murray

Email media@vnca.asn.au

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Janet Murray

Lauri Steel

Elise MacPherson

Shauna James

REVIEW PANEL

Lauri Steel

Cert IV VN, DipVN (ECC & GP), DipVET, DipTDD, AVN, TAE, DipBus, Dip.Couns, DipBA, DipMgt, Cert IV CAS

Janet Murray

BSc Veterinary Nursing, AssocDegAdult&VocEd, Cert IV TAE, RVN, AVN

Elise MacPherson

Dip VN (GP) & SURG, Dip Lab Technology (Pathology Testing), Cert IV VN, RVN, AVN

Jo Hatcher

Dip VN, Cert IV VN, Cert IV TAE, RVN, AVN

Shauna James Cert IV VN, GradCertCaptVertMgt (CSturt), RVN

VNCA NATIONAL OFFICE

PO Box 7345, Beaumaris VIC 3193

Phone 03 9586 6022

Fax 03 9586 6099

Web www.vnca.asn.au

ADVERTISING

Phone 03 9586 6022

Email vnca@vnca.asn.au

VISION STATEMENT

The VNCA aspires to strengthen the position of Veterinary Nurses as part of the veterinary healthcare profession.

MISSION

The VNCA: Serves and represents all Veterinary Nurses Protects the professionalism of Veterinary Nurses

Promotes the value of Veterinary Nurses as vital in delivery of quality veterinary care Advocates for the increased recognition of Veterinary Nurses across Australia

Supports Veterinary Nurses through the provision of continuing education and networking opportunities

Strengthens the position of Veterinary Nurses across the veterinary industry Engages all Veterinary Nurses across the veterinary industry.

Cover image ©getty images/skynesher CONTENTS Contents VOLUME 29 • NO. 3 • SEPTEMBER 2023 NEWS & UPDATES 01 President’s report 02 VNCA joins forces with Vets for Climate Action 03 AVNAT Registration Scheme sees surge in registrations; moves closer to national recognition 04 Get ready to celebrate Veterinary Nurse & Technician Awareness Week 06 Just breathe – Mechanical ventilation for small animals 12 Principles of community-centred veterinary care 16 Common presentations of avian emergencies

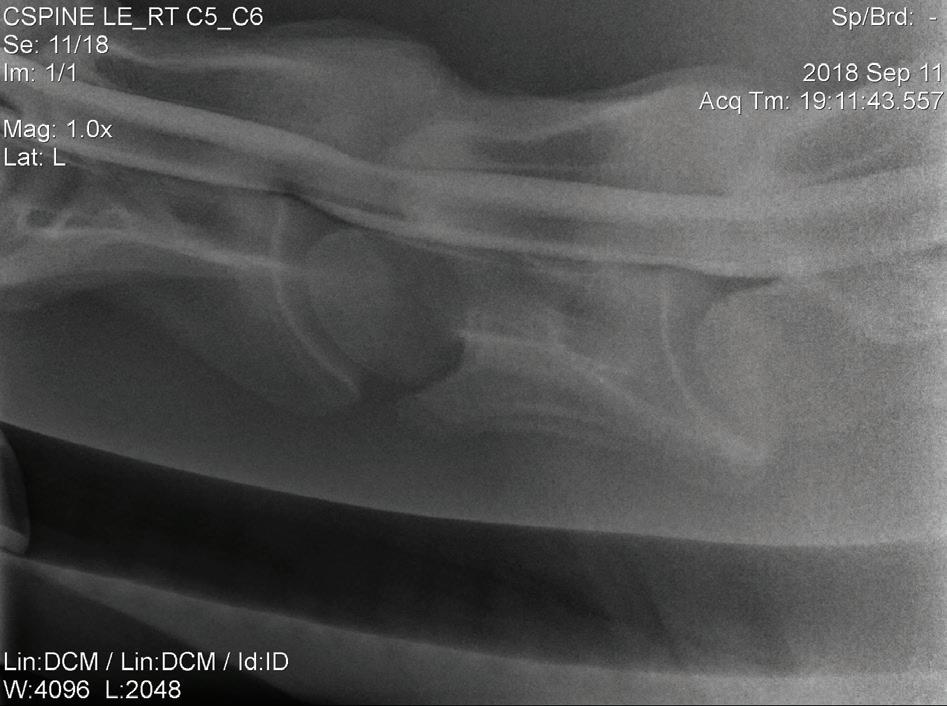

Case Report – Warmblood with cervical vertebral myelopathy (Wobbler syndrome) 30 Anaesthetic monitoring 34 Client fact sheet – How to tell if your pet is in pain 36 VNCA HR Advisory Service – Flexible working arrangements 38 A brief history of VfCA 39 Member Vitals – Iffy Glendinning

Congratulations to our AVNS

Congratulations to our AVNAT registered professionals

VISION & OUR MISSION 30 12

24

40

41

OUR

THE AUSTRALIAN VETERINARY NURSES JOURNAL

President’s report

Ihope this message finds you well, energised, and passionate about the year ahead. As spring approaches, so does an increase in caseload, particularly with anticipated snake envenomation and tick paralysis cases as the weather gets warmer. Let’s remember the importance of open communication with colleagues, friends, and family. We’re all in this together. The upcoming RUOK day on 14 September reminds us to ask, ‘Are you okay?’ and have meaningful conversations.

In October, we have an important week to look forward to – the Veterinary Nurse and Technician Awareness Week (9–13 October). It’s a time to acknowledge and thank each of you for your incredible contributions as part of the one healthcare team. The theme for this week is ‘The Future is in Your Hands’, which resonates with the VNCA’s initiatives this year. Our continuous efforts towards protection of title, national registration, and regulation of veterinary nurses and

technicians will undoubtedly shape the future of the veterinary industry.

Since the last AVNJ issue, the Australasian Veterinary Boards Council (AVBC) and the VNCA collaborated in Melbourne to advance regulation and title protection for veterinary nurses and technologists across Australia. Our board of directors remain committed to progressing this agenda and address it regularly in our meetings.

July witnessed the New South Wales parliament launching an inquiry into the veterinary workforce shortage. Our submission, primarily addressing the role and challenges faced by veterinary nurses, aimed to spotlight the indispensable role we play within the veterinary healthcare team. Recommendations encompassed solutions to the challenges voiced by our members – skills utilisation, remuneration, workloads, attrition rates, and wellbeing for veterinary nurses and technicians.

Our continuous efforts towards protection of title, national registration, and regulation of veterinary nurses and technicians will undoubtedly shape the future of the veterinary industry.

Gary Fitzgerald VNCA President

In the days prior to writing this, I have been invited to represent the VNCA’s submission and present evidence at the NSW parliament hearing in Sydney. This opportunity to address challenges and suggest solutions is both exhilarating and nerve-wracking. Reflecting on past reports, it’s clear that veterinary practices across the nation have struggled with staffing shortages and increased workloads for many years. Change is imperative, and the NSW parliament’s involvement signifies their engagement to find appropriate solutions. The phrase ‘The Future is in Your Hands’ rings truer now more than ever.

Lastly, we have a chance to acknowledge those who consistently go above and beyond. Nominations for the Veterinary Nurse or Technician of the Year Award, as well as Student Veterinary Nurse and Technician of the Year, are now open and will close on Friday 15 September.

I wish you all the best in the upcoming months and eagerly await posts showcasing your team’s recognition and celebration of your contributions as vet nurses and techs.

Thank you

Gary Fitzgerald VNCA President

FROM THE PRESIDENT September 2023 1

VNCA SUPPORTERS 2023 VET NURSE/TECHNICIAN OF THE YEAR SUPPORTER PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT SUPPORTER

VNCA joins forces with Vets for Climate Action

New partnership aims to drive environmental sustainability and animal welfare advocacy

In an exciting development for the veterinary community and the broader cause of environmental stewardship, Vets for Climate Action (VfCA) and the Veterinary Nurses Council of Australia (VNCA) recently entered into a partnership agreement. This collaboration marks a significant step forward in advancing the shared mission of both organisations – to promote responsible environmental practices within the veterinary field while ensuring the wellbeing of animals.

The VNCA and VfCA’s alliance is embedded in their collective commitment to addressing the pressing issue of climate change and its impact on animals, ecosystems, and the veterinary sector as a whole. With a strong focus on sustainability and holistic animal care, this partnership is poised to bring about meaningful change.

Both parties are enthusiastic about the prospects of this collaboration and are

dedicated to progress in the field of climate action and animal care. As a partner, VfCA will offer VNCA members a host of valuable services aimed at fostering knowledge, engagement, and action towards a more sustainable future. These offerings include microlearning sessions, dedicated webinars, lectures at the 30th VNCA Conference, and informative articles in the Australian Veterinary Nurse Journal (AVNJ) centred around climate care, as well as exclusive discounts to VNCA members attending VfCA’s educational webinars, seminars, and climate care programs.

VfCA’s flagship initiative, the Climate Care Program, is set to play a pivotal role in this partnership. The program, developed collaboratively by veterinarians, vet nurses, educators, and researchers, comprises a comprehensive, online 6-module course designed to guide veterinary practices through step-by-step

processes to enhance their environmental sustainability. By focusing on areas such as energy and water conservation, waste reduction, chemical use reduction, and fostering a culture of sustainability, the program not only benefits the environment but also supports increased profitability for practices. This program’s self-paced nature ensures that even busy veterinary practices can effectively implement the recommended changes.

As the VNCA and VfCA join hands to address the pivotal issue of climate change, they are demonstrating that collective efforts within the veterinary field can create a powerful impact on both animal welfare and global sustainability. With the implementation of the Climate Care Program and the wide array of resources offered to VNCA members, this partnership will engage our community through key initiatives that support a more resilient and responsible future.

NEWS 2 September 2023

DIVISION CONTACTS If you would like to attend a divisional committee meeting, it is important that you RSVP. NSW Melissa Shoard E nsw@vnca.asn.au QLD Jade Davies E qld@vnca.asn.au SA Sonia Van De Kamp E sadiv@vnca.asn.au VIC Danielle Gaynor E vic@vnca.asn.au WA Tracey Woods E wadiv@vnca.asn.au DIVISION CONTACTS it

Quality practice through standards and learning

AVNAT Registration Scheme sees surge in registrations; moves closer to national recognition

We have now entered our fifth registration and CPD cycle since the launch of the AVNAT Registration Scheme in 2019. In the last few months, there has been an increase in the number of veterinary nurses and technicians becoming registered, which shows the level of commitment and dedication to your profession and brings us another step closer to becoming a recognised true profession.

The AVNAT Regulatory Council, along with the VNCA Board and Professional Advancement Committee, have been working closely in the last few months with the Australasian Veterinary Board Council (AVBC) on the progression towards national mandatory regulation across Australia.

In May, representatives from the AVNAT Regulatory Committee, the Professional Advancement Committee and the VNCA Board, attended a meeting with the AVBC along with the chairs and registrars from all Australian state veterinary surgeons’ boards and from New Zealand. The day was dedicated to discussion on how national registration of veterinary nurses and technicians could be developed. While there are still some challenges in changes to legislation for this to occur, those who attended agreed this is a step that is vital for the future of the veterinary profession.

Also in May, Jo (the chair of the AVNAT Regulatory Council) was invited to speak at the AVA conference by the

Veterinary Business Group of the AVA. Jo spoke in the ‘State of the Market’ panel and in a lecture on registration of veterinary nurses and technicians and the AVNAT Registration Scheme. Both sessions were well attended and again there was positive support for registration.

The AVNAT Committee has now commenced the process of conducting the audit for the 2022/2023 cycle of registration and CPD. Audits

spent or planned to spend more than 12 months away from work, then you would be subject to the Return to Practice Policy conditions. For more information on this policy, please visit the VNCA website under AVNAT policies and framework. To apply for a career break, please complete the online form on the VNCA website under the renewal hub.

Are you interested in becoming registered

NEWS

September 2023 3

©getty images/Antonio_Diaz

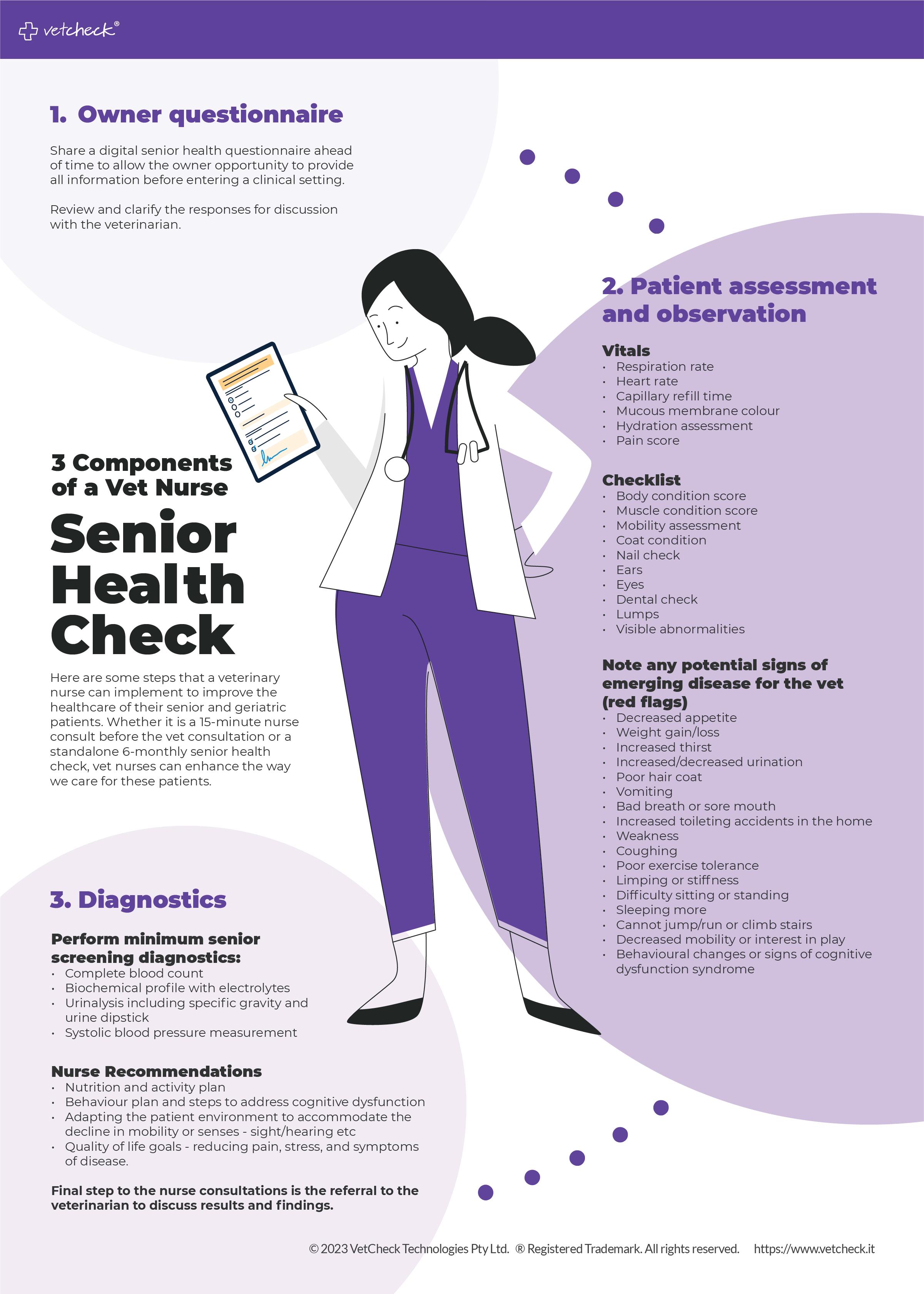

Get ready to celebrate Veterinary Nurse & Technician Awareness Week

As October draws near, veterinary nurses and technicians across Australia are gearing up for an exciting week dedicated to raising awareness about their vital contribution to the animal healthcare industry.

From Monday 9 October to Friday

13 October, Vet Nurse & Technician Awareness Week will shine a spotlight on you – who are often the unsung heroes within the veterinary healthcare team.

The theme for this year’s awareness week is ‘The future is in your hands’. This powerful theme aims to empower veterinary nurses and technicians with essential messages about accountability, self-management, education, skill utilisation, profession advocacy, and goal setting. Throughout the week, daily themes will be unveiled, and these will be reinforced through various communication channels. A daily online micro-learning unit will be made available for our community.

As the week draws to a close, veterinary nurses and technicians are invited to celebrate their achievements and dedication on Veterinary Nurses & Technicians Appreciation Day. The day will be filled with festivities and gratitude, honouring the contribution of our

exceptional community. On this day, the efforts and dedication of these professionals will be acknowledged and celebrated. Undoubtedly, a highlight of the week will be the announcement of the winners of the prestigious 2023 Veterinary Nurse/ Technician and Student Veterinary Nurse/Technician of the Year awards, proudly sponsored by Hill’s and Boehringer Ingelheim.

To further amplify the awareness campaign, various downloadable resources will be released in the lead-up to the Vet Nurse & Technician Awareness Week. These resources are aimed at helping participants bring awareness to their roles, celebrate the week in their workplaces, and participate in exciting initiatives, including a competition centred around the theme ‘The future is in your hands’.

HELP US TO RAISE THE PROFILE OF THE WORK THAT WE DO …

The veterinary community is encouraged to follow the Veterinary Nurses Council of Australia (VNCA)

on social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram to stay updated with the latest developments. Additionally, they can download social media tiles, add their photos, and share empowering statements using hashtags like #VNTAW23, #myVNCA, and #TheFutureIsInYourHands.

The Vet Nurse & Technician Awareness Week 2023 promises to be a dynamic and inspiring event, fostering a sense of unity, celebration, and professional growth among veterinary nurses and technicians nationwide.

AWARENESS WEEK VET NURSE & TECHNICIAN VET NURSE & TECHNICIAN

The future is in your hands

NEWS 4 September 2023

VNTOY Awards are proudly sponsored by

9-13 October 2023

Dive into the exciting week ahead!

With Veterinary Nurse & Technician Awareness Week 2023 just around the corner, it’s time to gear up for a week filled with empowerment, education, celebration, and camaraderie.

Mark your calendars and get ready to make the most out of this fantastic opportunity to connect with peers, learn, and contribute to the growth of your profession. Here’s a sneak peek into the planned schedule for each day of the week, so you can start planning your participation now:

DAY 1: Accountability

Kickoff Speaker: Amy Newfield

On the first day, embrace the theme of accountability. Tune in to Amy Newfield’s anticipated talk, where she will inspire you to take ownership of your personal and professional development. The day’s focus will be on how each individual can contribute to their growth by being accountable for their journey.

DAY 2: Self-management

Speaker: Erica Honey

Erica Honey will lead the discussions on self-management. Learn how to set meaningful goals and devise effective plans to ensure your success. This day is all about fostering a proactive approach to your career, allowing you to shape your path with purpose and clarity.

As you prepare for this transformative week, make sure to pencil in the schedule, participate in the planned activities, and engage with the speakers and events. Keep an eye out for updates, resources, and engaging content leading up to the Veterinary Nurse & Technician Awareness Week. Get ready to embrace the theme 'The future is in your hands' and be a part of this enriching experience that celebrates, educates, and empowers veterinary nurses and technicians across Australia.

DAY 3: Education & Utilisation

Speaker: Suzie Mclean

Suzie Mclean’s insights will guide you through the realm of education and skill utilisation. Discover how to build confidence in your abilities and commit to continuous learning for career growth. This day will empower you to harness the power of knowledge and put your skills to effective use.

DAY 4: Advocacy

Keynote Speaker: Patricia Clarke

Advocacy takes centre stage on Day 4. Patricia Clarke’s potential talk will highlight the significance of your role and how you can promote the importance of the veterinary nursing and technician profession. Learn to advocate for both yourself and your profession, acknowledging the valuable contributions you make.

DAY 5: Celebrating Your Success

Celebrate with VNCA: Announcing Vet Nurse/ Technician of the Year Awards

The week concludes on an exhilarating note. Join the Veterinary Nurses Council of Australia (VNCA) in celebrating your achievements and dedication. The highly anticipated moment arrives as the Vet Nurse/Technician of the Year and Student Vet Nurse/Technician of the Year awards, sponsored by Hills and Boehringer Ingelheim, are announced. The celebration continues as the VNCA takes time to reflect on the organisation’s accomplishments over the past year.

NEWS September 2023 5

Just breathe

Mechanical ventilation for small animals

by Asha Yeoman Cert IV VN DipVN (ECC) RVN AVN

Mechanical ventilation is positive pressure ventilation (PPV) provided by a specialised unit designed to maintain the respiratory functions of a patient who is unable to adequately breathe to sustain life without assistance. There are many circumstances in which a patient may require mechanical ventilatory support and the prognosis will vary according to the individual patient’s conditions and underlying pathology. One retrospective study (Hopper et al., 2007) found that patients receiving mechanical ventilation for pulmonary disease had a survival to discharge rate of 22%, whereas patients with hypoventilation were documented with a 39% survival to discharge.

INDICATIONS FOR MECHANICAL VENTILATION

There are three primary indicators to support the implementation of mechanical ventilation.

Spontaneous ventilation involves a delicate balance of muscular contraction and relaxation, energy expenditure and pressure gradients.

Inhalation is an active process, whereby the thoracic cavity expands in size by contractions of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles.

Severe hypoxaemia

Oxygenation status is assessed by measurement of the partial pressure of oxygen in an arterial blood sample (PaO2). Hypoxaemia is defined as a PaO2 of < 80 mmHg, while a PaO2 of < 60 mmHg is considered severe hypoxaemia. Ideally, PaO2 is measured using an arterial blood sample in a blood gases analyser. If this is not available, pulse oximetry may be used but is less accurate and less reliable. An SpO2 reading via pulse oximetry of 90% is equivalent to approximately 60 mmHg PaO2. Potential causes of severe hypoxaemia may include pulmonary parenchymal disease, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, diffusion defects, and conditions such as ARDS and smoke inhalation.

Severe hypercapnia

Hypercapnia is defined as a partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) of > 50 mmHg. Severe hypercapnia is a PCO2 of > 60 mmHg. Hypercapnia may be caused by dead space ventilation, increased carbon dioxide production, and various conditions or events such as neurological disorders, airway obstruction, toxicosis, and pleural space conditions, amongst many other potential causes.

Severely increased respiratory effort or risk of respiratory fatigue

Patients who are utilising excessive stores of energy to maintain spontaneous ventilation and are subjectively deemed at risk to be unable to maintain such increased effort, may require mechanical ventilation to support their respiratory function.

RESPIRATORY PHYSIOLOGY

Spontaneous ventilation involves a delicate balance of muscular contraction and relaxation, energy expenditure and pressure gradients. Inhalation is an active process, whereby the thoracic cavity expands in size by contractions of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles. This expansion creates a negative pressure system, and therefore a pressure gradient resulting in air flow between the low pressure space (the airway opening) and the high pressure space (the lungs). Conversely, exhalation is a passive process in which the contracted muscles relax and allow the thoracic cavity to reduce to its original size, expelling the air flow.

The efficacy of spontaneous ventilation not only relies on the effectiveness of the above systems utilised in inhalation and exhalation, but the adequate inflation of the lungs, which is dependent on two aspects –compliance and resistance – which are two factors to consider when selecting appropriate mechanical ventilation settings. Pulmonary compliance is a measure of the lung’s elasticity or expandability and refers to the lung’s ability to stretch and expand. Variables that may impact pulmonary compliance include the elasticity of connective tissues, surface tension, and the position of the patient, as well as pathological conditions such as pneumonia, emphysema, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Airway resistance refers to the resistance of the respiratory tract to air flow along the pressure gradient

6 September 2023 CLINICAL

during both inhalation and exhalation, noting that resistance can differ in inhalation compared to exhalation. This resistance is dependent on the length and diameter of the airway as well as the viscosity and density of the gases (Hagen-Poiseuille equation) and can be affected by changes in such.

During mechanical ventilation there are 4 types of breaths a patient may take. Spontaneous breaths are those that are initiated and undertaken solely by the patient without intervention or support by the ventilator. If a spontaneous breath is initiated by the patient but subsequently supported with air flow from the ventilator, it is deemed a supported breath. Breaths that are initiated and controlled entirely by the ventilator without patient effort are termed mandatory breaths, and breaths that are produced in part or in full by the ventilator are assisted breaths. A breath can be further categorised into four phases: initiation of inspiration, inspiration, end of inspiration, and expiration.

The aim of mechanical ventilation is to provide respiratory support

targeted to the patient’s specific needs, considering how and why the patient’s physiological respiratory function is impaired and what method of support is required to supplement that function. This is addressed by implementing targeted modes and settings designed to support volume, pressure, flow or timing – or a combination of any/all of those factors – according to the impairments identified and support required to sustain adequate respiratory function.

PRIMARY CONTROL VARIABLES

Volume control ventilation

In volume control ventilation, the operator can determine the tidal volume to be delivered by the ventilator over a set period. As such, the volume and flow are controlled and remain consistent, whilst the pressure is determined by the outcomes of the set tidal volume in conjunction with the patient’s pulmonary compliance.

Pressure control ventilation

In pressure control ventilation, the operator can determine a set airway pressure to be delivered over a set period. As the delivered pressure is

fixed and consistent, the resulting tidal volume and air flow will be determined by the patient’s pulmonary compliance and airway resistance.

VENTILATORY MODES

Continuous mandatory ventilation

Continuous mandatory ventilation (CMV) is a mode in which the ventilator delivers exclusively mandatory breaths, at a determined pressure or tidal volume, set at a time-triggered frequency. This mode is utilised in patients who are unable to initiate or deliver any spontaneous breaths, or patients who require specifically titrated respiratory support and spontaneous breaths are not appropriate.

Assist control ventilation

Similar to CMV, assist control ventilation (AC) delivers mandatory breaths at a determined pressure or tidal volume; however, these are set with a minimum respiratory rate and can be time-triggered or patienttriggered by allowing the patient to initiate a breath that is then delivered by the ventilator.

©shutterstock/unoL September 2023 7 CLINICAL Continued next page

Just breathe: Mechanical ventilation for small animals

Synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation

In synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV), the number of mandatory breaths is set and delivered by the ventilator, but the patient can perform spontaneous breaths in between. The ventilator will synchronise the mechanically delivered breaths with the patient’s breaths to avoid breath stacking, but only the mandatory breaths can be controlled by rate. The patient’s breaths are not controlled and therefore there is no maximum respiratory rate in this setting.

Continuous positive airway pressure

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a mode of continuous spontaneous ventilation; in this mode, the patient determines the timing and volume of spontaneous breaths independently initiated, whilst the ventilator provides a consistent positive airway pressure throughout the breath cycle. This supports the patient’s spontaneous breaths and is often used as a ‘weaning’ mode as the characteristics of the respiratory function are evaluated by the ventilator and will alert if inadequate.

Pressure support

Similar to CPAP, pressure support (PS) provides a continuous positive baseline airway pressure during the inspiration phase of the breath cycle, to aid in reducing airway resistance that may impact the patient initiating adequate spontaneous breaths. This mode is often used in conjunction with another simultaneously, such as CPAP or SIMV.

VENTILATOR SETTINGS

Within the selected modes of ventilation there are settings that contribute variable factors to address the patient’s specific support needs. Typically, these settings can be estimated utilising generalised factors and then adjusted according to the monitoring data produced during ventilation by both the ventilator and the patient. Pulmonary compliance and airway resistance are the primary factors to consider when selecting setting parameters.

Trigger variable

This parameter determines the trigger to initiate a mandatory breath; typically, it may be time whereby it determines the period of time that it delivers a mandatory controlled breath if the patient does not initiate a spontaneous breath. The trigger variable may also be pressure or flow sensitive.

Respiratory rate (RR) & I:E ratio

The respiratory rate can be set to a specific factor or by adjusting other variables such as minute ventilation, inspiratory time or expiratory time. While respiratory rates should factor the patient’s specific needs, they are typically set at 10–20 bpm.

The ratio of inspiration to expiration can be set specifically by the operator or calculated by the ventilator. Typically, this is set to 1:2 to ensure full expiration prior to the next inspiration.

Note: If respiratory rates are increased, the expiratory time should be decreased. The I:E ratio should not increase more than 1:1 to avoid intrinsic peep.

Inspiratory time and flow rate

Inspiratory time is typically set for one second but may be reduced if the patient is set to an increased respiratory rate. In VC modes, the flow rate can be set instead of inspiratory time; the faster the flow rate is set the quicker the breath is delivered. Flow rates are typically 40 L/min–80 L/min according to the patient’s needs.

©getty images/Alexandr Lebedko 8 September 2023 CLINICAL Continued from previous page

Consistent monitoring and intensive nursing care should facilitate rapid identification of complications that may occur during the provision of mechanical ventilation.

Tidal volume (TV)

A normal TV in healthy small animals is typically 10–15 ml/kg. In VC ventilation, often the TV is set to 6–8 ml/kg to avoid overdistension causing barotrauma in compromised lungs. The TV can be further increased if deemed insufficient for the patient’s needs, but typically is not set above 10 ml/kg.

Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

PEEP maintains pressure in the airways during exhalation and prevents full exhalation occurring. This results in the lungs remaining consistently semiinflated, which helps keep open alveoli that may have collapsed. Note: PEEP increases peak airway pressure and can potentially contribute to barotrauma. It also maintains an increased intrathoracic pressure, which could compromise venous return abilities.

MONITORING

Intensive monitoring is a core component of providing critical level care to patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Ideally, a ventilated patient will receive 1:1 nursing care with a dedicated nurse to facilitate continuity of care and increase the potential for minor changes in condition to be identified early and addressed efficiently. Vital parameters should be assessed and recorded frequently to monitor trends, along with recording ventilator settings and patient data output to correlate findings and identify the potential requirement for adjustments. Parameters that should be regularly assessed may include:

• electrocardiography

• blood pressure

• capnography

• pulse oximetry

• body temperature

• heart rate

• mucous membrane colour and capillary refill time

• fluid intake vs output

• arterial blood gas values.

Recorded data should include nursing considerations provided, types of fluid and volumes, nutritional input, medications administered, sedative or anaesthetic agents utilised and volumes, and maintenance/ placement of all indwelling catheters or tubes.

COMMON COMPLICATIONS ENCOUNTERED DURING VENTILATION

Consistent monitoring and intensive nursing care should facilitate rapid identification of complications that may occur during the provision of mechanical ventilation. These complications may be the result of fluctuating ventilator setting requirements, patient condition changes, environmental changes or equipment dysfunction. Complications that may be encountered include:

Hypoxaemia and oxygen desaturations

Hypoxaemia and oxygen desaturations may occur either acutely or gradually. An acute desaturation can indicate a sudden dramatic decrease in pulmonary function, such as a pneumothorax, or externally to the patient by equipment malfunction, lack of oxygen supply or disconnected circuitry. A gradual desaturation can indicate a progressive decrease in pulmonary function, such as the development of pneumonia, ARDS, or barotrauma. It may also suggest the potential for a circuitry leak or failing oxygen supply.

Troubleshooting would include confirming placement of monitoring equipment to ensure validity of results, assessing the circuitry for leaks or displacement and ensuring the adequate delivery of oxygen supply. The degree of hypoxaemia should be confirmed utilising arterial blood gas analysis and the patient assessed for potentially developing pulmonary conditions.

Hypotension

Positive pressure ventilation can lead to increased intrathoracic

pressure, which in turn can result in reduced venous return. High PEEP levels cause positive intrathoracic pressures during exhalation, which may further compromise venous return, also leading to or exacerbating hypotension. Hypotension may also be caused by hypovolaemia, cardiopulmonary disease, and resultant effects of medications administered.

Troubleshooting may include confirming placement of monitoring equipment and assessing the blood pressure cuffs for air leaks. Hypotension should be measured, and values confirmed utilising either an invasive blood pressure analysis method or an ultrasonic Doppler. If hypovolaemia is suspected, the fluid therapy plan prescribed may require adjustments. A medication review may be required to ensure the hypotension is not secondary to medical therapy or sedative/anaesthetic agents being utilised.

Hypercapnia

Hypercapnia may be noted as acute or gradual onset; however, typically the underlying causes are the same simply in varying severity. The source of hypercapnia is usually derived from either the patient end or the machine end of the ventilator system; causes within the patient may include pneumothorax, increased pulmonary dead space such as barotrauma, or an endotracheal tube obstruction or dislodgement. Ventilator equipmentrelated causes may include increased equipment dead space such as excess circuitry and/or connections, incorrect assembly of the ventilator circuit, or inadequate ventilatory mode and/or settings.

To troubleshoot a hypercapnic event, it is recommended to thoroughly evaluate the equipment and circuitry to confirm adequate and reasonable volumes and flow, consider suctioning or replacing the endotracheal tube and perform air leak and oxygen supply assessments. Blood gas

September 2023 9 CLINICAL Continued next page

Just breathe: Mechanical ventilation for small animals

analysis is beneficial to determine the validity of true hypercapnia, and the patient should be assessed for the development of pulmonary conditions.

Air leaks and air flow obstructions

Most ventilator machines will alert the operator to a detected air leak, or air flow obstruction noted whilst delivering breaths. An air leak is often attributed to disconnected or damaged circuitry or endotracheal tubes, whereas an air flow obstruction could indicate a physical obstruction within the circuitry or endotracheal tube, or progressive pulmonary disease causing increased airway resistance.

Troubleshooting an air leak or air flow obstruction is by similar methods to above: thoroughly evaluating the integrity of the equipment and circuitry, assessing for obstructions, and examining the patient for development or progression of pulmonary conditions.

NURSING CARE

Intensive level nursing care is a critical aspect in maintaining patient wellbeing and preventing complications during the provision of mechanical ventilation. Ventilated patients will be under sedation and therefore recumbent and unable to address their bodily functions or protective needs.

Ocular care

As a ventilated patient is under sedation, they are unable to protect the surfaces of their eye via blinking, which results in an increased risk of ulceration. Protective measures should be implemented by way of instilling topical lubrication into the eye to prevent dryness. It is important to note that in feline patients, recent studies (Eördögh et al., 2016) have documented that irritation can occur through use of ointment style ocular preparations, and so it is recommended to utilise liquid drops or gel-based lubricants in these patients. Topical lubrication should be administered every 2–4 hours. In addition, fluorescein staining should occur every 24 hours to assess for the

development of corneal ulceration so appropriate treatment can commence if necessary.

Oral care

Due to lack of movement, potentially abnormal saliva production, and absence of swallowing reflex, the patient is at increased risk of both oral/lingual drying and pooling of secretions. Oral care techniques should be performed every 4 hours and include gently cleansing the oral cavity with 0.05% chlorhexidine solution to reduce bacterial presence before thoroughly suctioning to remove excess secretions and debris. To prevent lingual drying, the tongue should be positioned within the mouth as best as possible, and a glycerine solution can be applied. Bruising, pressure sores and pressure necrosis are an increased risk due to lack of movement and tissues pressing; this can be minimised by frequent repositioning of equipment such as pulse oximetry probes and endotracheal tube ties, adjusting the tongue position away from the teeth, and utilising cushioning devices to reduce the pressure of the endotracheal tube against the surfaces of the mouth.

Airway maintenance

When intubating the patient for mechanical ventilation, a sterile endotracheal (ET) tube should be used to minimise the risk of bacterial contamination. It is broadly recommended to perform suctioning procedures in the ET tube, typically every 4 hours; however, some literature has suggested suctioning is only necessary when excess secretions or obstructions are suspected. The ET tube should be removed and replaced with a new sterile ET tube to minimise risk of secretions building and potential bacterial contamination. Humidification of the airway can be achieved by utilising heat and moisture exchange (HME) filters, and heated water humidifiers.

Toileting

The ventilated patient is at risk of skin irritation caused by pooling secretions

of urine or faeces, or overdistension from retention of these within their urinary bladder or bowel. The urinary bladder should be assessed for size and tension, and manually expressed at 4 to 6-hour intervals, as required. Alternatively, an indwelling urinary catheter with a closed collection system can be aseptically placed to ensure hygienic collection of urine and avoid potential scalding and associated skin inflammation or infection. If an indwelling urinary catheter is placed, this should be maintained with consistent catheter care protocols every 4–6 hours, such as cleaning with an 0.05% chlorhexidine solution to reduce the risk of bacterial contamination. Patients with or without an indwelling urinary catheter should have appropriate bedding and toileting pads placed underneath them to avoid contamination of the bedding and patient by leaked secretions.

Urine, whether collected by expression or within a closed collection system, should be measured and recorded as output in order to effectively calculate the fluid balances of the patient. This is typically recorded in a ml/kg/hr format.

Faeces should be collected and appropriate hygienic care provided to the patient’s anal region. Emollient creams may be applied if required to protect and soothe skin from inflammation and scalding.

Recumbent care

Pressure ulcers, tissue necrosis, peripheral oedema, and muscular atrophy can occur in patients with prolonged recumbency.

10 September 2023 CLINICAL Continued from previous page

Mechanical ventilation is a complex procedure provided to critical patients, with extensive aspects of care to be considered.

The recumbent patient should be rotated every 4 hours, alternating between sternal, left lateral, and right lateral recumbency. In some patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, lateral recumbency may not be appropriate due to individual needs and ability for thoracic expansion; in these patients it is recommended to maintain their cranial end in sternal recumbency and alternate their hind limbs between left and right lateral placement. Gentle passive range of motion exercises should be performed in conjunction with the regular rotation of the patient to assist in preventing muscular atrophy.

The patient’s bedding should also be considered to ensure adequate padding under all body surfaces. In large breed dogs, and patients predisposed to or with pre-existing joint disease, the bedding provided should include adequate support and positioning of the joints.

Reduction of stimuli

External stimuli, including light and

sound, may result in the need for increased sedative or anaesthetic agents. Implementation of barrier measures to reduce these stimuli sources may be warranted and may include placement of cotton balls or swabs within the patient’s ears and the use of a covering material such as a mask over the eyes. Barrier measures implemented should be recorded on the patient chart and changed at regular intervals to prevent contamination.

CONCLUSION

Mechanical ventilation is a complex procedure provided to critical patients, with extensive aspects of care to be considered. The veterinary nurse or technician providing this care should have adequate understanding of the variables and supportive requirements involved in order to contribute to improved patient outcomes.

References

American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC). AARC clinical practice guidelines.

Unlock boundless opportunities with AVNJ advertising!

Are you seeking to connect, collaborate, and conquer the veterinary industry? Look no further!

Elevate your brand's presence and seize the chance to mingle with top-tier professionals in the field. The Australian Veterinary Nurses Journal (AVNJ) is your gateway to unrivaled networking and relationshipbuilding opportunities.

Why choose AVNJ?

• 25+ years of industry trust and respect

• Exclusive readership of veterinary nurses and technicians

• National exposure through electronic and hard copy distribution

• Quarterly powerhouse of expertise in full-colour vibrance

Your brand deserves a spotlight that shines from coast to coast. Don't miss your chance to access

Endotracheal suctioning of mechanically ventilated patients with artificial airways. Respiratory Care 2010;55:758–764.

Boller M & Fletcher DJ. Post-cardiac arrest care. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K (eds.) Small animal critical care medicine. 2014:17–25. St Louis: Elsevier. Edwards Z, Annamaraju P. Physiology, lung compliance. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan.

Eördögh R, Schwendenwein I, Tichy A, Loncaric I, Nell B. Clinical effect of four different ointment bases on healthy cat eyes. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul;19 Suppl 1:4–12.

Epstein S. Care of the ventilator patient. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K (eds.). Small animal critical care medicine. pp. 185–190. St Louis: Elsevier.

Hopper K, Haskins SC, Kass PH et al. Indication, management, and outcome of long-term positive-pressure ventilation in dogs and cats: 148 cases (1990–2001). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2007;230:64–75.

Mellema MS. Ventilator waveforms. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K (eds.). Small animal critical care medicine. 2014:166–172. St Louis: Elsevier.

Peche N, Köstlin R, Reese S, Pieper K. Postanaesthetic tear production and ocular irritation in cats. Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 2015;43(2):75–82.

Silverstein DC and Hopper K. Small animal critical care medicine. 2014. 2nd ed. St Louis: Elsevier.

Yagi K. Mechanical ventilation. In Veterinary technician’s manual for small animal emergency and critical care. CL Norkus (ed.). 2018.

a multitude of marketing avenues and amplify your visibility on a national scale.

Dive into the world of limitless potential today!

Scan the QR code or visit www.vnca.asn.

au to unveil a realm of possibilities.

September 2023 11 CLINICAL

Principles of communitycentred veterinary care

What can veterinary nurse/technology students and graduates learn from these principles to create inclusive veterinary practices?

by Courtnay L Baskerville Cert II EqStudies BBiomedSc (Hons) PhD GCertHE

ABSTRACT

Traditionally, education in veterinary nursing has largely focused on the required technical skills with a strong foundation of clinical knowledge. However, with the development and implementation of well-defined day one competencies (DOC) by the VNCA now encompassing communication skills, significant emphasis has been placed on the development of nontechnical capabilities for all veterinary nursing/technology (VN/VT) students. These DOCs essentially require VN/ VTs to reflect deeply – for example, when communicating effectively and expressing appropriate empathy, VN/ VTs must have some awareness of the complex social inequalities that many clients face when accessing veterinary care so that they can holistically support a client through challenging situations.

There has been much consideration of community-based veterinary medicine in the last few years, which largely focuses on the role of veterinarians delivering services to vulnerable community members. It could be argued, however, that there has been little consideration of the role VN/VTs can play here more broadly, and while these opportunities begin to emerge, the aim of this evidencebased, short communication is to consider social determinants of health and complex barriers that many clients face when accessing veterinary care and consider the role of practising VN/VTs in creating inclusive veterinary practices.

INTRODUCTION

In 2018, the Access to Veterinary Care Coalition commissioned a national study in the US to better understand the barriers to veterinary care. Here, it was found that in the previous 2 years, 28% of respondents had experienced a barrier to veterinary care and the primary barrier was financial (Wiltzius et al., 2018). To the author’s knowledge, similar studies have yet to be performed in Australia, but it is reasonable to consider that the current economic landscape of Australia will also likely be impacting access to veterinary care for Australian pet owners. As global events continue to impact households, concepts of accessible veterinary care, founded on the principles of primary healthcare (PHC) and social models of health are now being explored with urgency, as stakeholder groups and the larger veterinary industry work together to curb this emerging critical animal welfare issue. It could be argued, however, that there has been little consideration of the role VN/VTs can play here more broadly.

Like human nursing in medicine, the veterinary nurse/veterinary technician/technologist (VN/VT) remit in clinical practice is wide and varied and absolutely vital to upholding high standards of patient care. VN/VTs are regularly charged with highly specialised tasks such as documenting and administering controlled and cytotoxic drugs; operating radiography equipment, overseeing complicated patient care and monitoring anaesthesia; developing clinic protocols and

standard operating procedures and ensuring the safe storage, handling and disposal of hazardous chemicals (Harvey, Ladyman, & Farnworth, 2014). As we unpack the remit of VN/VTs, it is clear that the contributions of VN/ VTs in clinical practice have played heavily in shaping modern veterinary medicine and veterinary patient care. While the industry works to clarify and bolster the practice of veterinary nursing in Australia and worldwide, the technical aspects of nursing are often the defining characteristic of a VN/VT (Orpet & Jeffery, 2022). It has been noted that clarifying these technical aspects of veterinary nursing is vital for the larger veterinary industry so that VN/VTs may practise to their full capabilities in clinical practice (VN Futures Report, 2016). While these initiatives aim to enhance professional satisfaction and curb the ‘dissatisfaction crisis’ that has been outlined previously (Rumple, 2021), it will likely also enhance society’s understanding of the role of VN/VTs (Davidson, 2017).

VN/VTs should anticipate that like human nursing, the profession of veterinary nursing will likely be required to meet complex societal expectations, and with the implementation of well-defined day one competencies (DOC) by the VNCA now encompassing communication skills, significant emphasis has been placed on the development of non-technical capabilities for VN/ VT students. These DOCs essentially require VN/VTs to reflect deeply –for example, when communicating, effectively expressing appropriate

12 September 2023 CLINICAL

empathy, VN/VTs must have some awareness of the complex social inequalities that many clients face when accessing veterinary care so that they can holistically support a client through challenging situations. It is, therefore, vitally important for VN/VTs to continue to explore the community landscape VN/ VTs operate in, notably regarding accessible and inclusive veterinary care. The aim of this evidence-based, short communication is to consider social determinants of health and complex barriers that many clients face when accessing veterinary care and consider the role of practising VN/ VTs in creating inclusive veterinary practices.

COMMUNITY-BASED VETERINARY MEDICINE

In the human healthcare sector, the area of medicine which is concerned with the health of a community is often referred to as PHC. Here, PHC is an approach which aims to strengthen health systems, bringing healthcare closer to communities in a whole of society approach (WHO, 2023). According to the World

Health Organisation (WHO), PHC is fundamentally grounded in the premise that all people have the right to achieve high levels of health (WHO, 2023) and it is recognised that when PHC is accessed early and consistently, there are associated benefits including improved patient outcomes and reduced health inequalities (Smolowitz et al., 2015). In 1998, WHO identified social determinants of health (SDH) which can influence health in positive and negative ways. These include: income and social protection, systemic and long-term structural conflict, social inclusion and non-discrimination, accessible education and access to affordable health services of good quality (WHO, 2023). Recent research exploring the parallel impact of SDH on animal health found that, not surprisingly, the SDH can and do impact the social determinants of animal health (SDAH) and an animal’s general health status (Card, Epp & Lem, 2018). Overall access to veterinary healthcare, continuity of veterinary care and voluntary preventive health screening for companion animals have been recognised as SDAH and

The aim of this evidencebased, short communication is to consider social determinants of health and complex barriers that many clients face when accessing veterinary care and consider the role of practising VN/VTs in creating inclusive veterinary practices.

these may be further impacted if a person is experiencing one or more SDH (Card, Epp & Lem, 2018).

Different terms in veterinary medicine have been used to describe veterinary care founded on the principles of PHC and social models of health, including community-focused veterinary care and veterinary community medicine. Authors of a large systematic review of veterinary care for underserved communities have recommended the term ‘Community-Based Veterinary

Continued next page ©shutterstock/SeventyFour September 2023 13 CLINICAL

Principles of community-centred veterinary care

Continued from previous page

Care’ (CBVC) to describe interventions and clinics addressing underserved animal populations at the community level (this term will be adopted here) (LaVallee, Mueller, & McCobb, 2017). In practice, principles of CBVC may be offered through exploring incremental or spectrum of care options with clients. The scholarship of spectrum of care suggests that with limited information, clients and veterinary professionals can equate expensive treatment/diagnostics with superior veterinary care (Stull et al., 2018). Yet, the provision of veterinary services will often be influenced by many factors, including principles of best practice or ‘gold standards’, practice goals and values, clinic resources, the knowledge and skills of the veterinarian, as well as the owners’ goals, values, resources and knowledge (Stull et al., 2018). Stull et al. (2018) conclude that providing a continuum of acceptable care that is both evidence-based and client responsive is the cornerstone of the principles of spectrum of care; however, the greatest challenge is perhaps influencing veterinarians and motivating behavioural change. The concepts of CBVC were largely considered ‘hidden curriculum’ in veterinary education where lessons, values or insights are passed on to students, formally or informally and sometimes, purposefully, or not

(Whitcomb, 2014). Today, servicelearning experiences, where studentrun veterinary clinics offering low cost veterinary care are beginning to emerge in the US as part of the embedded veterinary curriculum and the clinical rotation experience. According to current research, after veterinary students attended the service-learning experiences during CBVC clinic rotations, students reported that they were significantly more confident in managing cases where there were barriers to care (King et al., 2021). Further, a study of fourth-year veterinary medicine students found that purposeful information raising awareness about accessible veterinary care enhanced students’ understanding of barriers to veterinary care and students’ opinions of incremental care and/or spectrum of care options were more favourable (Hoffman, Spencer & Makolinski, 2021). Students recognised that regardless of whether they were intending to practise in CBVC, an awareness of care barriers and confidently managing cases where barriers were apparent, was important to gain a broader understanding of diverse communities to meet the needs of all clients (King et al., 2021).

It is clear that these outcomes are relevant to VN/VTs in practice too. In the human healthcare sector, nurses

have historically played strong roles in community care as district or visiting nurses. While the evolution of veterinary nursing/technology has been largely hospital-based care, there are many areas where principles of PHC nursing could be modelled and adapted to a clinical setting. For example, adding CBVC practices to the ever-expanding veterinary nursing consult portfolio. However, to do this VN/VTs will need to be ready to critically evaluate assumptions, values and/or beliefs of accessible veterinary care and who has a right to access this care. In doing this, VN/VTs can lead initiatives by exploring SDAH and CBVC needs through community engagement, applying spectrum of care principles and revising terminology and communications with colleagues and owners around ‘gold standard’ care, and importantly, identifying and removing barriers to care that may have been unknowingly constructed.

In conclusion, accessible veterinary care is a critical animal welfare issue and while veterinary education is working to curb this through the implementation of purposefully curated CBVC curriculum, VN/VTs can also equip themselves and lead CBVC initiatives in the clinic and the community.

References available on request.

14 September 2023 CLINICAL

Learn new animal care skills in days or weeks. Nurture your career with a range of specialised short courses. + Caring for Native Wildlife in a Clinical Environment + Advanced Anaesthesia for Veterinary Nurses + Natural Therapies for Animals - Massage RTO 90003 | CRICOS 00591E | HEP PRV12049 tafensw.edu.au/short-courses

CELEBRATING GROWTH INSPIRING EXCELLENCE

17-19 April 2024

Adelaide Convention Centre

THE VNCA CONFERENCE COMMITTEE WARMLY INVITES YOU TO SUBMIT AN ABSTRACT FOR CONSIDERATION TO PRESENT AT THE 30TH VNCA CONFERENCE.

Your commitment to sharing your knowledge and expertise is paramount to the success of VNCA conferences. We understand the dedication it takes to craft and submit an abstract, and your willingness to contribute to the advancement of the veterinary nursing field is deeply appreciated.

CALL FOR ABSTRACT SUBMISSIONS CLOSING SOON

Don’t miss this unique chance to come together to commemorate 30 years of VNCA conferences with colleagues from around the country and beyond.

Scan the QR code below to visit the website and submit your abstract NOW!

SPONSORSHIP AND EXHIBITION PROSPECTUS NOW AVAILABLE

Over the past three decades, the VNCA Conference has been a beacon of knowledge sharing, professional development, and camaraderie for veterinary nurses and technicians from around Australia, and beyond. The 2024 conference promises to be even more remarkable as we commemorate our 30th anniversary and continue to advance

PRINCIPAL PARTNERS

the field of veterinary nursing. We invite you to be part of these celebrations – which we anticipate could be bigger and bolder than the previous 29 years!

You will need to get in fast – there are a few exclusive options to choose from and these will sell fast!

2024 CONFERENCE KEY DATES

Tuesday 19 September 2023

Abstracts submissions close

Thursday 19 October 2023

Presenter notifications

Wednesday 29 November 2023

Program launch and registration opens

Wednesday 6 March 2024

Early Bird registration closes

Tuesday 16 April 2024

Pre-conference masterclasses and President’s Welcome Drinks

17–19 April 2024

30th VNCA Conference

VNCA Conference

WWW.VNCA.ASN.AU SCAN THE QR CODE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE 30TH VNCA CONFERENCE

Common presentations of avian emergencies

by Rebecca de Gier VTS (Exotic Companion Animal), BAppSc (Wildlife Biology and Animal Production), Dip General Practice, Cert IV Vet Nurse, RVN, ALS Certified (RECOVER)

INTRODUCTION

According to our understanding of avian patients, the majority of the health issues that bring them to the veterinary clinic should be considered a medical emergency. Our treatment of these animals is crucial and can mean the difference between life and death, as the mortality rate in exotic animal emergency medicine is high. Avian patients require prompt veterinary attention, and proper first aid and emergency care can help stabilise their condition and increase the chances of a successful outcome. Emergency care involves expertly applying treatment techniques in response to injury or sudden illness, with the goal of preserving life, preventing further deterioration, and facilitating recovery.

©getty images/skynesher

16 September 2023

CLINICAL

RECEPTION

Assessing the severity of a patient’s condition over the phone can be challenging, but if the owner is calling with concerns about their pet, the recommendations from the consultation are crucial. To gather information, staff handling the calls can ask questions, such as the species and gender of the animal, its age, the symptoms, and any medication used. Keep in mind that exotic animals are skilled at hiding signs of illness, so by the time the owner realises their animal is sick, it is often in a serious and urgent state.

It is important for all staff to feel confident in their ability to evaluate a patient and plan for when and who should see them. This is the purpose of triage, which is a process of classifying patients based on the urgency of their situation, and reassessing as needed. This requires training, and the nurses must be competent, qualified, and experienced in handling emergency situations, as well as knowledgeable about emergency procedures. Most importantly, the veterinarian needs to trust the veterinary nurse or technician to determine the order in which patients are seen.

TYPES OF EMERGENCIES

HISTORY TAKING

Many avian patients are known to conceal signs of illness, and some species have limited daily interaction with their owners. Gathering information during a consultation or physical examination, or even handling the pet, can quickly worsen its condition.

It is essential to obtain a comprehensive medical history as many of the medical issues experienced by avian patients are often related to their living conditions and diet. The medical history may be taken after the pet has been rushed into the treatment room or in the consultation room with both the patient and the owner present.

A thorough physical examination can provide a significant amount of information, but valuable diagnostic insights can also be gained from a detailed history and an assessment of the pet’s environment or cage. Observing the patient visually can also be informative, and it is important to be mindful of the pet’s strength and avoid causing stress during manual restraint.

To effectively diagnose abnormal conditions, it is important to first

understand what is normal for the species. With over 200 different species of avian pets, each animal can present differently. Doing research to understand what is normal for the species before the consultation can help you identify subtle signs of illness before it’s too late.

HANDLING OF SICK PATIENTS

The examination of avian patients is similar to that of other species, but it’s crucial to gather as much information as possible from the patient’s history and visual examination before the physical exam. Allowing the pet to acclimatise for 5–10 minutes before the exam can reveal clinical signs that may have been missed and reduce stress on the patient. Before conducting the physical exam, ensure you have all necessary equipment and the room is secure. Avoid trying new techniques on sick or weakened patients as it can worsen their condition quickly. Before the exam, additional heat, a quiet environment, oxygen, and fluid therapy may be required to stabilise the patient. The handling of sick birds should be done with their medical condition in mind and may involve multiple procedures over several sessions or all at once, depending on the veterinarian’s direction. To be cautious when handling a sick bird, watch for signs such as open-mouthed breathing, weakness, dazed behaviour, and a weak grip, which indicate the patient is not coping and should be placed back in its cage for recovery. In some cases, the bird may require oxygen therapy.

A couple of important safe patient handling points to note:

• Birds do not have a diaphragm, so rely on the movement of their skeletal muscles to pass air around their body into their lungs and air sacs, so when handling ensure that the keel can move freely.

• If a patient presents with a fracture, that limb will continue to be painful

Anything not listed above

Triage classification Description Example First priority Life-threatening Treatment must be initiated within seconds to minutes Bring immediately to the treatment room

mentation,

of

Urgent Currently

priority Patient stable Pressing problem that is non-critical Treatment initiated within hours

lacerations, history of but not currently vomiting and/or diarrhoea, etc.

priority Patient completely stable Needs evaluation, but not urgently

Major bleeding, breathing problems, altered

shock, history

toxin ingestion, etc. Second priority

stable, but may become 1st priority patient, need to be reassessed, or have treatment initiated within minutes to hours History of major trauma, history of unsuccessful urination, repeated vomiting, or diarrhoea, etc. Third

Fever,

Fourth

September 2023 17 CLINICAL Continued next page

Common presentations of avian emergencies

until the fracture is stabilised and when you are handling these animals ensure that the injured limb is not placed in an unnatural position that will be causing neurons to be firing and increasing catecholamine release.

AVIAN SUPPORTIVE CARE

Nutritional support

Food is crucial in emergency situations involving birds, as they quickly deplete their glycogen stores. A sick or injured bird may stop eating, causing its condition to rapidly worsen. You can try enticing the bird to eat by offering a variety of foods that match their normal diet as much as possible. If your clinic often sees birds, it is advisable to have a range of food options, including:

• pelleted diets in different brands and sizes, appropriate for the species

• seeds for budgies and finches, and for larger parrots, pigeons, poultry, and waterfowl • lorikeet mix, in dry powder form or watered down to a syrup consistency • nut mixes for parrots as treats following treatment • frozen vegetables, in sizes suitable for smaller parrots or poultry and larger parrots

• chick starter and hen layer pellets, offered dry for poultry and submerged in water for waterfowl • Formulated mixes for omnivores or granivores, which can be mixed with commercial pet food or sprinkled on vegetables • Whole prey items such as mice and rats, for raptors and other species that form casts.

Additionally, you must consider the type of food and water bowls the animals will need to consume their food. Different bird species have different preferences, such as shallow plates for pigeons and doves, the ability to submerge their full beaks into wet lorikeet mix for lorikeets and being able to fit their head into the bowl for parrots. Some birds, particularly wild ones, may not know how to eat from bowls, so scatter feeding may be necessary.

In cases where a bird is not eating on its own, has lost weight, or has an

injury that prevents it from eating, crop feeding may be necessary. The crop volume of a parrot is around 3–5% of its body weight. The diameter of the crop needle should be appropriate for the patient’s oesophagus, and its length should reach the crop, located at the thoracic inlet. A red rubber tube and a 60 ml catheter tip syringe can be used for poultry or large macaws. The crop feeding formula should be mixed with hot or warm water to a pancake-like consistency. Before feeding, it is important to check that the temperature of the formula is between 38°C and 40°C to avoid crop stasis or burns. The bird should be adequately hydrated before starting the feeding process, as dehydration can slow down crop emptying.

When birds regurgitate, they shake their heads from side to side, and it is important to never hold them, as this can cause aspiration. After regurgitation, it is important to monitor the bird’s respiratory rate and effort and clear any food materials from the glottis using a cotton-tipped swab if necessary.

Warming

Birds consume a large amount of energy to maintain their body temperature and sick or injured birds can quickly become hypothermic. This rapid metabolic rate makes small birds particularly susceptible to hypothermia. To keep these birds warm, a heat lamp or brooder should be used. If a bird is cold, it will ruffle its feathers, tuck its head behind its wing and close its eyes. Thus, it is crucial to have a source of heat available for sick birds. The ideal setup is a hospital incubator or brooder that provides controlled heat and humidity.

When using a heat lamp for recumbent birds, a minimum gap of 30 cm should be maintained between the bird and the heat lamp to prevent overheating. Observe the bird for signs of heat stress, such as open beak breathing, and adjust the heat lamp as necessary. Be cautious of overheating, which can be indicated

Food is crucial in emergency situations involving birds, as they quickly deplete their glycogen stores. A sick or injured bird may stop eating, causing its condition to rapidly worsen. You can try enticing the bird to eat by offering a variety of foods that match their normal diet as much as possible.

by flat feathers, outstretched wings, and open mouth breathing. It is especially important to use caution in overweight birds.

For patients that require a brooder, it is advised to use the following temperatures:

• Neonate with no feathers – 32–34˚C

• Ducklings – 30˚C if BAR, 32˚C if QAR or dull, heat lamp and hotties if in a cage

• Adult/fully feathered birds that are critically unwell – 30˚C

• Adult/fully feathered birds that are mildly unwell – 28˚C.

Fluid therapy

Fluid intake is very important as sick or injured birds can rapidly become dehydrated and will always present as a percentage dehydrated. When avian patients are dehydrated, there is concern about poor tissue profusion and selecting the correct fluid type is equally important.

Crystalloid fluids

Crystalloid solutions, including normal saline and Hartmann’s, are balanced salt solutions that are widely used and freely pass through capillary walls. They remain in the bloodstream for a shorter period, typically 30 to 60 minutes, compared to colloids. Crystalloid fluid resuscitation can replenish fluid volume lost from the bloodstream and attract extracellular

Continued from previous page

18 September 2023 CLINICAL

water due to osmotic pressure. However, crystalloids with lower sodium concentrations distribute more evenly throughout the body, while higher sodium concentrations are more effective as plasma expanders.

Crystalloid therapy, however, can negatively impact microcirculatory blood flow and oxygenation in shock cases, leading to hypoxia even after resuscitation. Additionally, excessive use of crystalloid solutions can cause peripheral and pulmonary oedema and should therefore not be used in patients with heart disease.

Colloid fluids

Commonly used colloid solutions include Hetastarch and Plasmalyte. Unlike crystalloids, colloids are better at maintaining circulatory volume because their larger molecules stay in the blood vessels for a longer time, resulting in an increase in osmotic pressure. The proteins also draw water from the cells into the bloodstream. However, excessive use of colloids can cause cells to become dehydrated over time due to the loss of too much water. Colloids are effective in keeping blood volume stable. For birds needing hydration support, treatment can involve either intravenous or subcutaneous administration of warmed Hartmann’s solution.

Sites of fluid therapy administration include subcutaneous fluids in the inner inguinal membrane and intravenous fluid therapy via the jugular vein, medial metatarsal and basilic veins.

• Maintenance support: 5% body weight subcutaneously (SC) q12

• Correcting mild deficit or dealing with a bird that will not self-drink: 10% body weight SC q12

• Significantly dehydrated, primary renal dysfunction, or heavy metal toxicosis: 10% body weight SC q8

• Do not exceed the 30% body weight total daily amount to prevent fluid overload.

Hospital cage setup

To minimise stress for a sick or injured bird in hospital care, it’s important to provide a peaceful environment. A separate ward away from dogs, cats, reptiles, and birds of prey is recommended. The bird should be kept in a quiet, dark area to help it stay calm, and handling should be limited to essential times only. Additionally, the cage should block the view of other animals, and the bird may benefit from a covered area for added security.

For bedding, use newspaper or absorbent pads. Ensure the bird has access to water, food, and a perch if necessary. In special cases, such as a recumbent bird in need of support or

a geriatric bird needing joint support, a towel or cloth bedding can be used, but only after being rolled into a donut or folded into thick layers.

It’s important to weigh the patient at the same time every day, before administering any food or medication, using the same scale. In certain situations, the patient may need to be quarantined, requiring the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and following proper cleaning and disinfecting protocols to protect other animals, staff, and yourself in the event of zoonotic diseases.

COMMON MEDICATIONS

Depending on the patient’s condition, medications can help with the recovery of a patient. We can look at providing adequate pain relief so that the patient is comfortable to move around, eat and display normal behaviours. Be sure to consider the selection of medications, as some choices will rule out the use of other drugs.

Selecting the route of administration can also be determined by the patient’s condition and access to possible indwelling catheters and IV lines.

Some medications can be given orally, so if the patient is being tube fed, the medications can be added to the slurry and given directly into the crop. Other routes of administration are IM and SQ injections. Be aware of the pharmacology and toxicology of the chosen medications to ensure that they will work as intended.

Common opioids used in birds are:

• Methadone/Morphine – 1 mg/kg IM q 6–12 hr

• Fentanyl – 6–20 mcg/kg/hr

• Butorphanol – 1 to 4 mg/kg IM q 1 to 3 hours

• 50 to 80 mcg/kg/min IV CRI (with 2 mg/kg loading dosage)

• Most used opioid in birds

• For severe injuries such as

Continued next page

September 2023 19 CLINICAL

©getty images/skynesher

Common presentations of avian emergencies

fractures, burns and beak traumas, give 4 mg/kg

• For moderate pain, such as being egg bound or traumatic events (e.g. hit by car) that has not produced fractures, give 2 mg/kg

• Monitor for sedative effects

• Buprenorphine – Suggested dosage – 0.1 to 0.6 mg/kg IM/PO q 12 hours

• Tramadol – 10–30 mg/kg IM, PO q 12 hours

• Questionable bioavailability among species

• To be used in conjunction with meloxicam.

NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUGS

Used to relieve musculoskeletal and visceral pain. Effective for both acute and chronic pain.

• Carprofen – 1 to 4 mg/kg PO, SQ, or IM q 12 to 24 hours for less than 7 days

• Meloxicam – 1.0 mg/kg IM/IV q 12 OR 1.5 mg/kg PO q 12

• Only give in euhydrated patients or patients on fluid therapy

• Appropriate for soft tissue trauma

• Can be used in conjunction with butorphanol and tramadol

• Available in liquid form at 1.5 mg/ ml and 0.50 mg/ml. Injectable 5 mg/ml.

The recognition of pain, the assessment of the condition or injury and the treatment choice are important to the advancement of avian medicine. It is important that veterinary professionals understand and recognise signs of pain in their patient and address it appropriately. Through better understanding and early recognition, pain can be appropriately treated in the avian patient.

COMMON AVIAN PRESENTATIONS

Crop stasis

Crop stasis is a common issue where the crop doesn’t empty efficiently, leading to regurgitation or passive expulsion of food from the mouth, oesophagus, and crop, which can result in aspiration. Poor husbandry is a common cause of crop stasis in hand-raised chicks. Other causes include:

• poor hygiene

• incorrect formula temperature or consistency

• overfilling the crop

• antibiotic administration

• crop burn

• ingestion of foreign material

• diseases of the lower gastrointestinal tract

• heavy metal toxicity.

Before handling the bird, you may observe signs of repeated regurgitation, such as dried food on the feathers, especially on top of the head. Crop stasis is also linked to anorexia, dehydration, depression, and a distended crop that has a sour odour from bacterial or fungal overgrowth.

Diagnosis is made through physical examination, palpation of the crop, cytology and/or culture of the crop contents, radiology, and a full blood profile. Treatment may involve emptying the crop, then providing supportive care in the form of nutrition, heating, and fluid therapy. After the bird is warmed and hydrated, small amounts of diluted liquid diet can be given via tube feeding. If the crop empties well, and the bird does not regurgitate, the volume and concentration of the liquid diet can be gradually increased. If gastrointestinal obstruction has been ruled out, motility stimulants may also be administered.

Broken blood feather

When a bird’s blood feather is broken, the feather shaft functions like a straw, causing the vessels to bleed for a prolonged period due to capillary action.

A bird suffering from anaemia may exhibit signs of weakness, leading to collapse and tachypnoea or tachycardia. Blood feathers can become broken as a result of traumatic events such as falling, having too small a cage, flapping wings, or an animal attack.

If the bleeding has stopped or is minimal, place the bird in a darkened and quiet incubator to minimise stress and lower blood pressure. Observe the bird periodically. If the bleeding continues, apply digital pressure until it stops, and provide analgesia as the area is sensitive. Once the bleeding

Continued from previous page

©getty images/dardespot 20 September 2023 CLINICAL

has stopped, the feather can be allowed to grow out, but it should be trimmed to reduce the risk of further trauma or pain.

If the bird’s condition permits, the feather can be removed under general anaesthesia by grasping it at its base with a haemostat and pulling it in the direction of growth, supporting the surrounding skin and applying pressure if the follicle continues to bleed. Ensure that the pulp has been completely removed from the base of the feather, which should have a rounded and bulging appearance. In case of severe bleeding, administer warmed fluids or a blood transfusion. Monitor the haematocrit as needed and provide ongoing supportive care until the bird’s condition improves.

Leg band constrictions

Leg identification bands on birds, which are put on chicks when they are young or before they are sold, are becoming less necessary with the increasing use of microchipping. All leg rings on pet birds must be frequently examined to ensure they do not cause discomfort or problems with fit.

Leg bands may become tight as a result of the bird’s growth, self-inflicted damage from trying to remove the band, or if the leg gets caught on cage furnishings. The bird may experience sudden lameness, swelling of the affected limb and digits, or trauma to the leg from using its beak to remove the constriction.

Since birds have delicate, brittle bones, it’s crucial to remove tight leg bands under general anaesthesia. Stainless steel bands can be particularly difficult to cut, so a super fine diamond bur or a Dremel tool (or a high speed dental handpiece) is recommended. There’s a risk of toxic shock syndrome where trapped, contaminated blood in the affected limb may flood back to the heart, causing cardiac arrest. Close monitoring, analgesia, and fluid support should be provided both during and after the procedure.

Reproductive disorders – dystocia

Reproductive disorders in birds can