Hospital Eyes New Beds for Youth

By BRETT YATES

BENNINGTON – Vermont could have ten to 12 new inpatient psychiatric beds for adolescents by 2024 if a proposal by Southwestern Vermont Medical Center comes to fruition.

Direct input from psychiatric survivors or family members has yet to be brought into discussion on the idea, and some have questions about whether it is an appropriate plan.

Hospital officials have stressed the uncertain nature of the plan thus far. The first step will be a feasibility study, which was scheduled to begin by late fall and is due for completion by March 31.

SVMC has targeted a 4,500-square-foot area within its main hospital building in Bennington for a potential renovation that would create a private room for each patient, as well as an “education space” for schoolwork and a common area for “visits with family, peers and support persons.”

Its preliminary cost calculation for the project estimates a price tag as high $10.425 million from pre-construction to launch.

Prolonged delays in emergency departments across the state for kids awaiting inpatient psychiatric placements — sometimes for a week or more — led the Department of Mental Health to issue a request for proposals for a new highacuity pediatric psychiatric unit last January.

It called for “up to 10 beds” to supplement Vermont’s only children’s psych ward at the Brattleboro Retreat.

But DMH initially received just one response, which the University of Vermont Medical Center subsequently withdrew, citing a budgetary shortfall.

DMH reissued the request for proposals in June, and this time, SVMC decided to throw its hat in the ring. “The first time they offered the RFP, we started to pull together a proposal and really started looking at this and realized that it was just really a significant lift for SVMC,” Director of Planning James Trimarchi recalled.

By BRETT YATES

An increased regulatory focus on removing psychiatric inpatients’ opportunities for selfharm has led Vermont’s hospitals to make major changes to improve safety. But according to psychiatric survivors, some of these changes have yielded unintended consequences in how supportive the units feel.

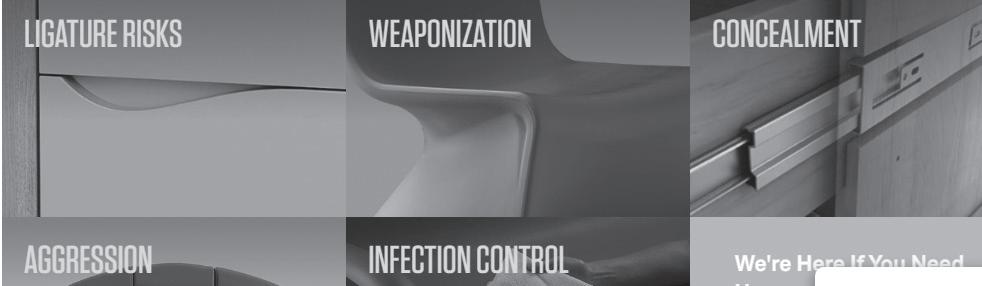

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services defines a “ligature risk” as “anything which could be used to attach a cord, rope, or other material for the purpose of hanging or strangulation.”

Possible ligature points, per CMS, include “shower rails, coat hooks, pipes, and radiators,” among other common objects.

Hospitals offering psychiatric care can achieve regulatory compliance by removing such objects or, when removal may not be possible, by restricting patient access to spaces that contain them.

By some accounts, this effort has had the side effect of creating a less hospitable and less free environment in psychiatric units.

After several earlier stays, a psychiatric inpatient returned this fall to Central Vermont

Medical Center. She noticed a number of differences. In the past, by her recollection, patients had enjoyed unsupervised use of the laundry facilities.

Now, they had to ask staff to unlock the

“When the proposal that they did receive got withdrawn,” Trimarchi continued, “they

(AdobeStock) (Continued on

Does Safety Hurt More Than Help?

staff looked on. The unit’s microwave had also disappeared, and patients had lost access to hot water for tea.

Under CMS rules, hospital patients have “the right to receive care in a safe environment.” The agency’s interpretive guidelines specify that this requirement intends to protect “the patient’s emotional health and safety as well as his/her physical safety.” Sometimes, however, these paired promises appear to come into conflict with one another.

laundry room each time they wanted to wash, dry, or retrieve their clothes.

The same locked area of the psychiatric unit also contained books, puzzles, and an exercise bike, as well as a small, semi-enclosed terrace that patients used to be able to visit as they pleased.

Now, however, staff had to bring books out to them, and the terrace was off-limits all day except for an hour, during which patients would crowd together for a few breaths of fresh air as

“How can you feel comfortable enough to start healing if you feel that you can’t do things for yourself, and you have to feel you’re bothering someone to do something simple?” the CVMC patient asked. Understaffing had compounded the problem. Overburdened workers could still be “pretty accommodating if people were patient,” but the patient also reported an instance in which one staffer became “very annoyed” by a request for assistance. An encounter of this kind “really impacts the way you feel about yourself,” the patient said.

officials attributed most of the changes experienced by the Central Vermont (Continued on

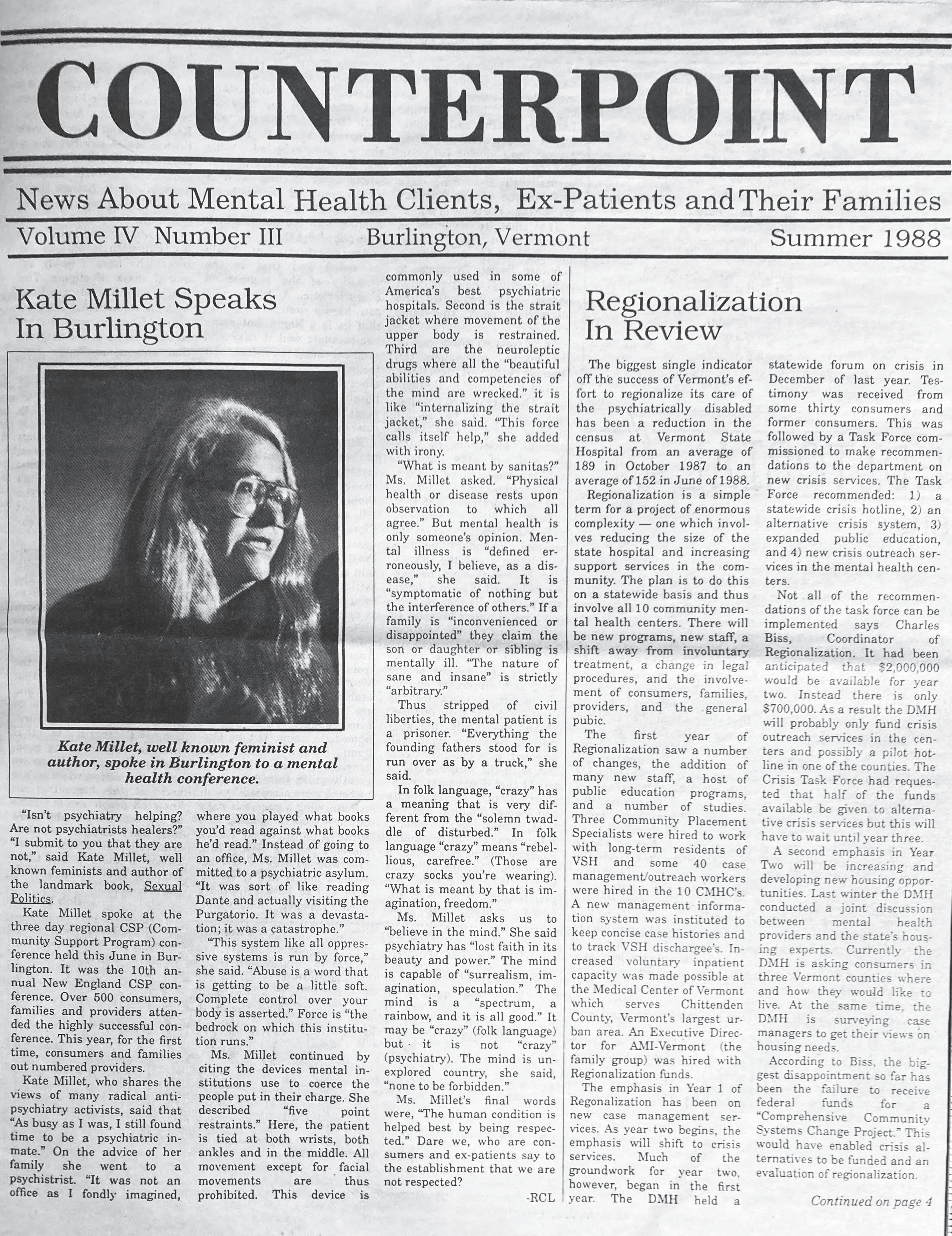

NEWS, COMMENTARY, AND ARTS BY PSYCHIATRIC SURVIVORS, MENTAL HEALTH PEERS, AND OUR FAMILIES VOL. XXXVII NO. 3 • FROM THE HILLS OF VERMONT • SINCE 1985 • WINTER, 2022 22 Out of the Darkness Walk 12 The Arts 8 Telepsych May Expand in EDs

“We didn’t submit a proposal in that first round, but we had good conversation with the

Department of Mental Health about a kind of shared vision of what the need is in the community and what we might be able to do.

page 3)

page

Hospital

4)

The federal CMS guidelines say hospitals are supposed to protect “the patient’s emotional health and safety as well as his/her physical safety.”

VERMONT PSYCHIATRIC SURVIVORS BOARD

A membership organization providing peer support, out reach, advocacy and education. Board meets monthly. For information call 802-775-6834 or email info@vermont psychiatricsurvivors.org.

COUNTERPOINT EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

The editorial advisory board for the Vermont Psychiatric Survivors newspaper can always use help! Assists with poli cy, editing and brainstorming on topics for articles. Contact counterpoint@vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org

ALYSSUM Peer crisis respite. To serve on board, call 802-767-6000 or write to information@alyssum.org

DISABILITY RIGHTS

VERMONT PAIMI COUNCIL

Protection and advocacy for individuals with mental ill ness. Call 1-800-834-7890.

DISABILITY RIGHTS VERMONT

Advocacy in dealing with abuse, neglect or other rights violations by a hospital, care home, or community mental health agency. 141 Main St, Suite 7, Montpelier VT 05602; 800-834-7890. disabilityrightsvt.org

VERMONT CENTER FOR INDEPENDENT LIVING

Peer services and advocacy for persons with disabilities. 800-639-1522. vcil.org

HEALTH CARE ADVOCATE To report problems with any health insurance or Medicaid/Medicare issues in Vermont 800-917-7787 or 802-241-1102. vtlawhelp.org/health

VERMONT CLIENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM

Rights when dealing with service organizations such as Vocational Rehabilitation. Box 1367, Burlington VT 05402; 800-747-5022.

NAMI-VT

Family and peer support services, 802-876-7949 x101 or 800-639-6480; 600 Blair Park Road, Suite 301, Williston VT 05495; www.namitvt.org; info@namivt.org

ADULT PROGRAM STANDING COMMITTEE

Advises the Commissioner of Mental Health on the adult mental health system. The committee is the official body for review of and recommendations for redesignation of community mental health programs (designated agencies) and monitors other aspects of the system. Members are persons with lived mental health experience, family mem bers, and professionals. Meets monthly on 2nd Monday, noon-3 p.m. Check DMH website www.mentalhealth.ver mont.gov or call-in number. For further information, con tact member Daniel Towle (dantowle@comcast.net) or the DMH quality team at Eva.Dayon@vermont.gov

LOCAL PROGRAM STANDING COMMITTEES

Advisory groups, required for every community mental health center. For membership or participation, contact your local agency for information (listings on back page.)

PEER WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE

Webpage provides an up-to-date account of statewide peer training and registration information as well as updates about its progress and efforts. www.pathwaysvermont. org/what-we-do/statewide-peer-workforce-resources/

MADFREEDOM

MadFreedom is a human and civil rights membership organization whose mission is to secure political power to end discrimination and oppression of people based on perceived mental state. See more at madfreedom.org

MENTAL HEALTH LAW PROJECT

Representation for rights when facing commitment to a psychiatric hospital. 802-241-3222.

ADULT PROTECTIVE SERVICES

Reporting of abuse, neglect or exploitation of vulnerable adults, 800-564-1612; also to report violations at hospi tals/nursing homes through Licensing and Protection at (802) 871-3317

Hospital Advisory

CENTRAL VERMONT MEDICAL CENTER NEWLY forming. Contact counterpoint@ vermontpychiatricsurvivors.org for more information and meeting schedule.

VERMONT PSYCHIATRIC CARE HOSPITAL Advisory Steering Committee, Berlin, check DMH website for dates at www.mentalhealth.vermont.gov

RUTLAND REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER Community Advisory Committee, fourth Mondays, noon, call 802-747-6295 or email lcathcart@rrmc.org

UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT MEDICAL CENTER Program Quality Committee, third Tuesdays, 9-10 a.m., for information call 802-847-4560.

BRATTLEBORO RETREAT

Consumer Advisory Council, fourth Tuesdays, 12-1:30 p.m., contact Director of Patient Advocacy and Consumer Affairs at 802-258-6118 for meeting information.

Trainings and Conferences

PEER WEBINARS

Doors to WellBeing hosts monthly one-hour webinars for peer programs on every last Tuesday of the month. For more information and to register, https://www.doorstowellbeing.org/webinars

MENTAL HEALTH ADVOCACY DAY

A “save the date alert” has been posted for January 30, 2023 for the annual Mental Health Advocacy Day traditionally held at the state capital building. It will continue this year in its interim virtual format.

PEERPOCALYPSE

The Mental Health & Addiction Association of Oregon has announced a “save the date” for the tenth annual Peerpocalypse conference May 8-11, 2023. More information will follow on the conference web page at www.mhaoforegon.org/peerpocalypse when the date is nearer.

PEER WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE

See page 8 for details on three new training offerings through Pathways Vermont.

VT Psychiatric Survivors, 128 Merchants Row Suite 606, Rutland, VT 05701

Phone: (802) 775-6834

email: counterpoint@ vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org

MISSION STATEMENT:

Counterpoint is a voice for news and the arts by psychiatric survivors, ex-patients, and consumers of mental health services, and our families and friends.

Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved FOUNDING EDITOR

Robert Crosby Loomis (1943-1994)

EDITORIAL BOARD

Kara Greenblott, Zachary Hughes, Sara Neller, Laura Shanks, Dan Towle

The Editorial Board reviews editorial policy and all ma terials in each issue of Counterpoint. Review does not necessarily imply support or agreement with any posi tions or opinions.

PUBLISHER

Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, Inc.

The publisher has supervisory authority over all aspects of Counterpoint editing and publishing.

EDITOR

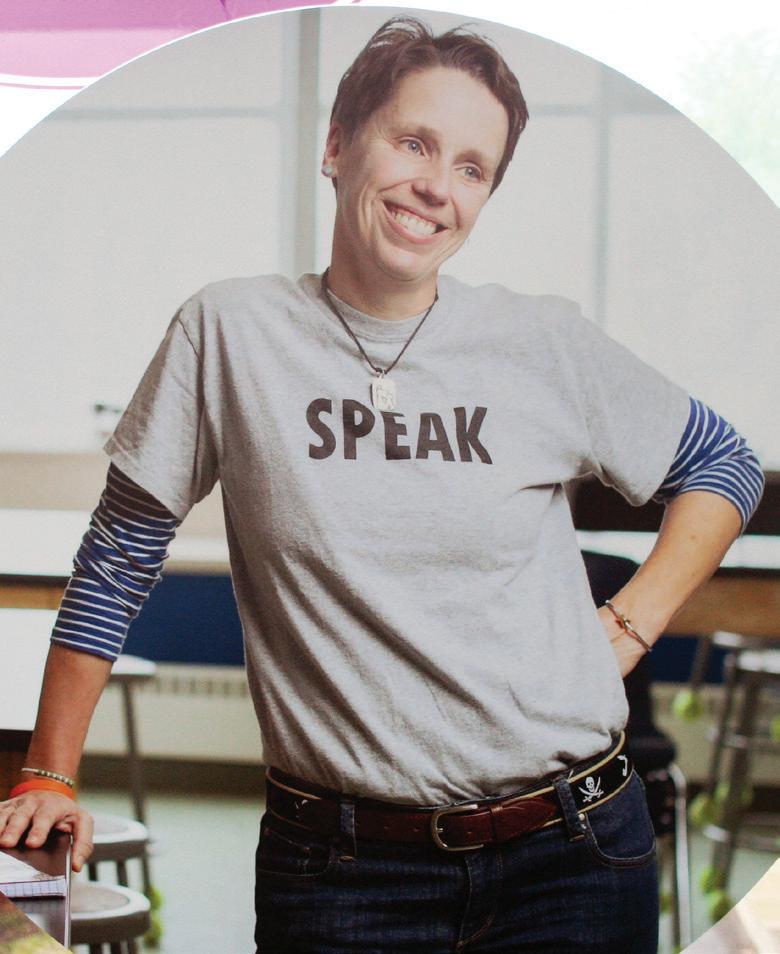

Anne B. Donahue

Brett Yates, Co-Editor

Opinions expressed by columnists and writers reflect the opinion of their authors and should not be taken as the position of Counterpoint

Counterpoint is funded by the freedom-loving people of Vermont through their Department of Mental Health. Financial support does not imply support, agree ment or endorsement of any of the positions or opinions in this newspaper; DMH does not interfere with editorial con tent.

Counterpoint is published by Vermont Psychiatric Survivors three times a year, distributed free of charge through out Vermont, and also available by mail subscription. Vermont Psychiatric Survivors is an independent, statewide mutual support and civil rights advocacy organization run by and for psychiatric survivors. The mission of Vermont Psychiatric Sur vivors is to provide advocacy and mutual support that seeks to end psychiatric coercion, oppression and discrimination.

Counterpoint does not use pseudonyms in its reporting without stating that a pseudonym is being used and without an explanation for why the person’s identity is not being disclosed. Counterpoint does not use anonymous sources under any circumstances.

Checks

Send to: Counterpoint, Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, 128 Merchants Row, Suite 606, Rutland, VT 05701

Access Counterpoint online at www.vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org

Fall 2018

2 c Enclosed is $10 for 3 issues (1 year). c I can’t afford it right now, but please sign me up (VT only). c Please use this extra donation to help in your work. (Our thanks!)

or money orders

made

should be

payable to “Vermont Psychiatric Survivors.”

Don’t Miss Out on a Counterpoint! Peer Leadership and Advocacy

NAME: ADDRESS: CITY • STATE • ZIP Mail delivery straight to your home — be the first to get it, never miss an issue.

Advocacy Organizations Department of Mental Health 802-241-0090 www.mentalhealth.vermont.gov For DMH meetings, go to web site and choose “more” at the bottom of the “Upcoming Events” column. ADDRESS: 280 State Drive NOB 2 North Waterbury, VT 05671-2010

Meeting Dates and Membership Information for Boards, Committees and Conferences

Peer Organizations State Committees

-

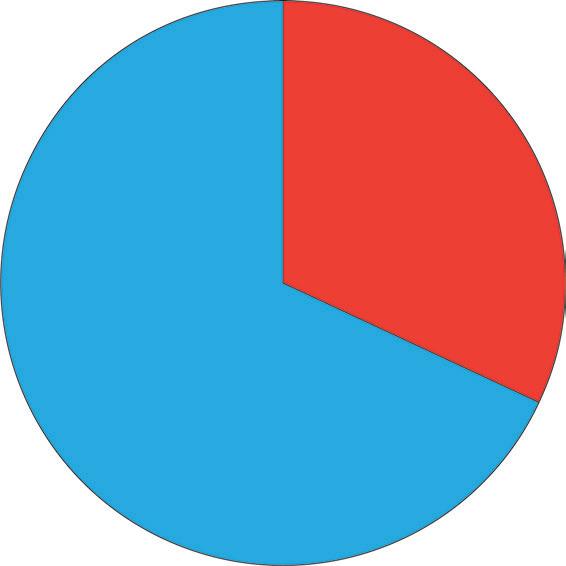

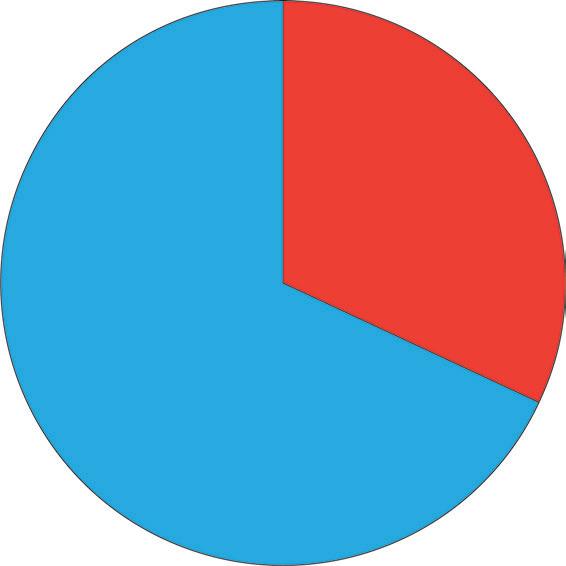

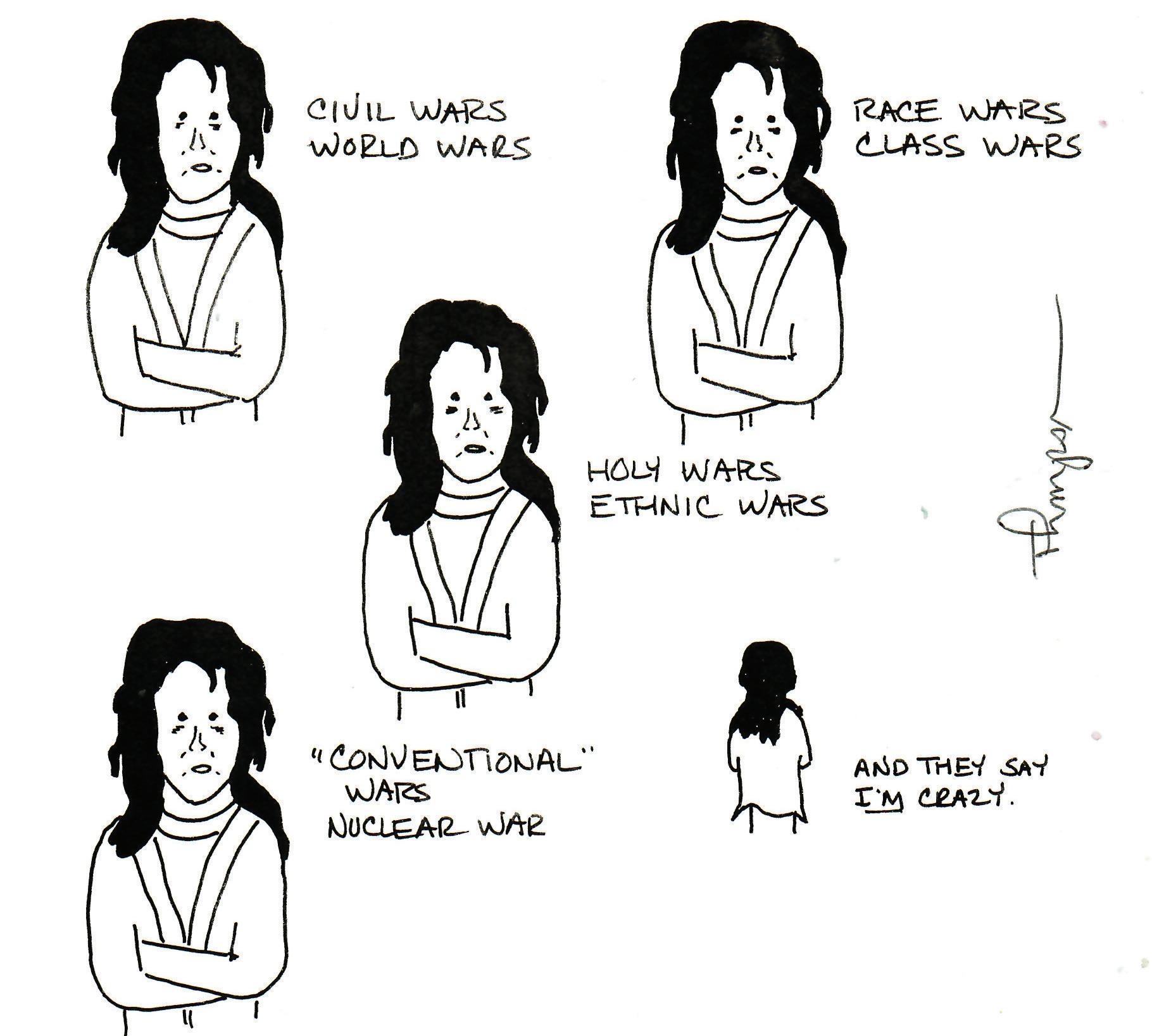

Counterpoint Opinion Poll

Do safety features to prevent self-harm in hospital psych units make them feel like a less healing environment?

Fall Poll Results:

The Small Number Responding Support a Separate Forensic Facility

RUTLAND – Of a total of only 25 responses to Counterpoint’s fall poll question, about two-thirds supported creation of a separate hospital for patients who are involved with the criminal justice system.

In Vermont – unlike most states – such forensic patients are held in facilities which also have individuals who are being held based on being perceived as a danger to self or others, but not accused of a crime.

“Too many people with psych Dx are grouped with real, criminally insane sociopaths who prey on us,” one person wrote in the comments section. “They carry on their deadly routines in hospital. Which makes recovery from a suicidal, depressive, or hallucinatory episode

all that much harder. Being housed together also reinforces stigma and unfounded stereotypes.”

The poll was open to anyone who accesses it through Counterpoint or other Vermont Psychiatric Survivor links which do not distinguish whether responses are coming from psych survivors, families or other members of the public. The number of replies make the results particularly random, rather than an indicator of general opinion.

One of the comments suggested that some individuals may not have understood the question. “I believe we do [need a forensic hospital] because without one where are people of Vermont supposed to go to get the mental health they need to get so that they can start to

feel better?” they wrote. “Without the help for mental health and [from] VPS I feel and know that I would probably not be around or in the state of Vermont.” The writer urged services “for the homeless, mental health and [such as] VPS.”

One person’s thoughts included a message to potential forensic patients based upon her own experiences. It is printed in full on page 17 as a commentary.

HOSPITAL EYES NEW

BEDS

FOR YOUTH • Continued from page 1 reached back out to us and they said, ‘Is there a possibility that we could do a joint feasibility study and see whether or not this makes sense?’”

SVMC signed a contract for $25,000 with DMH in late October to examine the statewide demand for inpatient psychiatric beds for children between the ages of 12 and 17, and the potential cost of construction and operations at SVMC. The contract commits DMH to “share perspective and concerns from other Vermont agencies and departments in order to ensure that collateral impacts are considered in the design of the unit and its operations.”

SWMC is also required to “obtain feedback on the design and operations from [United Counselling Services, Bennington’s community mental health center], mental health advocacy organization such as Disability Rights Vermont and persons with lived experience.”

However, the resulting report, which must include “reflective anticipated impact on state agencies and departments,” does not require any similar assessment of impact on children and families.

Trimarchi, the SWMC planning director, said they’ll solicit input from “organizations that can speak to lived experience, to make sure that we have the design right and the model right and the programming right.”

“We haven’t had the kickoff for the feasibility study, so there has been no firm commitment to engage any specific group. What I can tell you is we will engage groups,” he clarified.

The contract doesn’t compel SVMC to build the unit.

“We’re a medical facility, not historically

an inpatient psychiatric facility,” Trimarchi acknowledged. “We’re exploring the idea.”

In doing so, SVMC expects to get a better understanding of several potential roadblocks.

“There’s a lot of challenges from the space constraints, from the regulatory constraints,” Trimarchi noted. “There’s staffing challenges, in terms of recruitment of the right providers to staff it... If we’re going to do this, we want to do this right, and the right way to do it is traumainformed, in the least restrictive way,” he said.

proposal, but to the extent it’s constructing another locked facility to serve youth, I think that that might be not what Vermont really needs right now,” she commented. “There needs to be a lot more work done in Vermont to provide better, proactive, and progressive treatment options in the communities.”

Counterpoint asked DMH whether any input was solicited from psychiatric survivors in the lead-up to or writing of the request for proposals for this or other new projects it is pursuing.

A spokesperson said that the state “made a reasonable assumption that some peer communities and providers may likely be bidders” on the projects, and allowing direct participation in drafting an RPF would exclude them from bidding.

But soliciting input and questions has been a consistent part of all the planning, DMH said, including through the adult and children’s mental health standing committees.

Vermont Psychiatric Survivors Executive Director Karim Chapman expressed hope that VPS could offer peer support at the facility if SVMC’s proposal pans out.

“For various reasons, such as liability issues, VPS traditionally hasn’t had a history of doing that kind of work with adolescents,” he said. “I would love to see VPS in a position where we are supporting young people.”

Disability Rights Vermont Executive Director Lindsey Owen’s first reaction to SVMC’s plan was unenthusiastic.

“I haven’t had a chance to look at that exact

“Many stakeholders, including peers, have identified the need for expanding the options for care offered in a diversity of settings, rather than relying on the Brattleboro Retreat,” it said in a written response. The RFP was developed “to gauge the interest and feasibility” for an increase in child and adolescent inpatient beds and if it goes forward, “it will begin the process of diversifying available choices for care.”

The DMH statement said that with the feasibility report from SWMC, it “anticipates being able to work collaboratively to develop a project plan that best meets the needs of Vermonters, which will include stakeholder engagement at that time.”

Fall 2018 NEWS . 3 Winter 2022

Results of the poll will be published in the next issue of Counterpoint. OR by going to www.vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org/counterpoint/

QUESTION:

VOTE by scanning this onto your mobile phone: 8 responses “NO” 16 responses “YES”

(by Graham Ruttan, Unsplash)

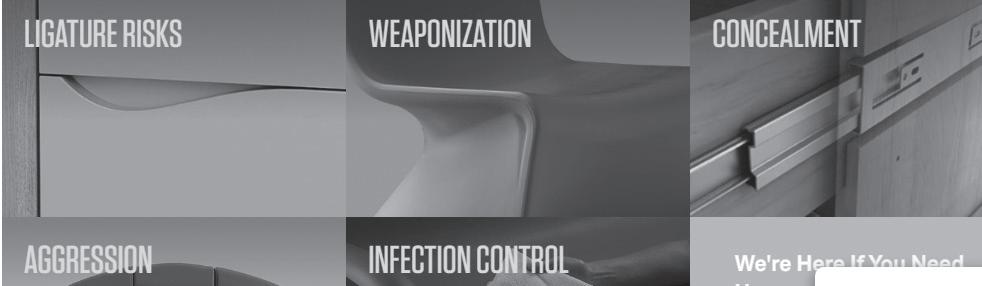

PHYSICAL SAFETY MANDATES

Medical Center patient directly to new ligature risk requirements. They pointed to stricter inspections by surveyors from the Joint Commission, the organization that accredits US hospitals. In 2019, the Joint Commission revised its “national patient safety goals” for suicide prevention, following a 2017 decision by CMS to prioritize ligature risk within its own regulatory framework.

“There were reports of increased amounts of inpatient deaths on psychiatric units,” Dr. Robert Althoff, the chair of psychiatry at the University of Vermont Health Network, recalled.

“That then translated into surveys that specifically looked at what are opportunities on inpatient psychiatric units for people to hurt themselves.”

Althoff mentioned that the University of Vermont Medical Center had needed to buy new, safer beds for inpatient psychiatry, in addition to addressing smaller items like door handles and shower bars.

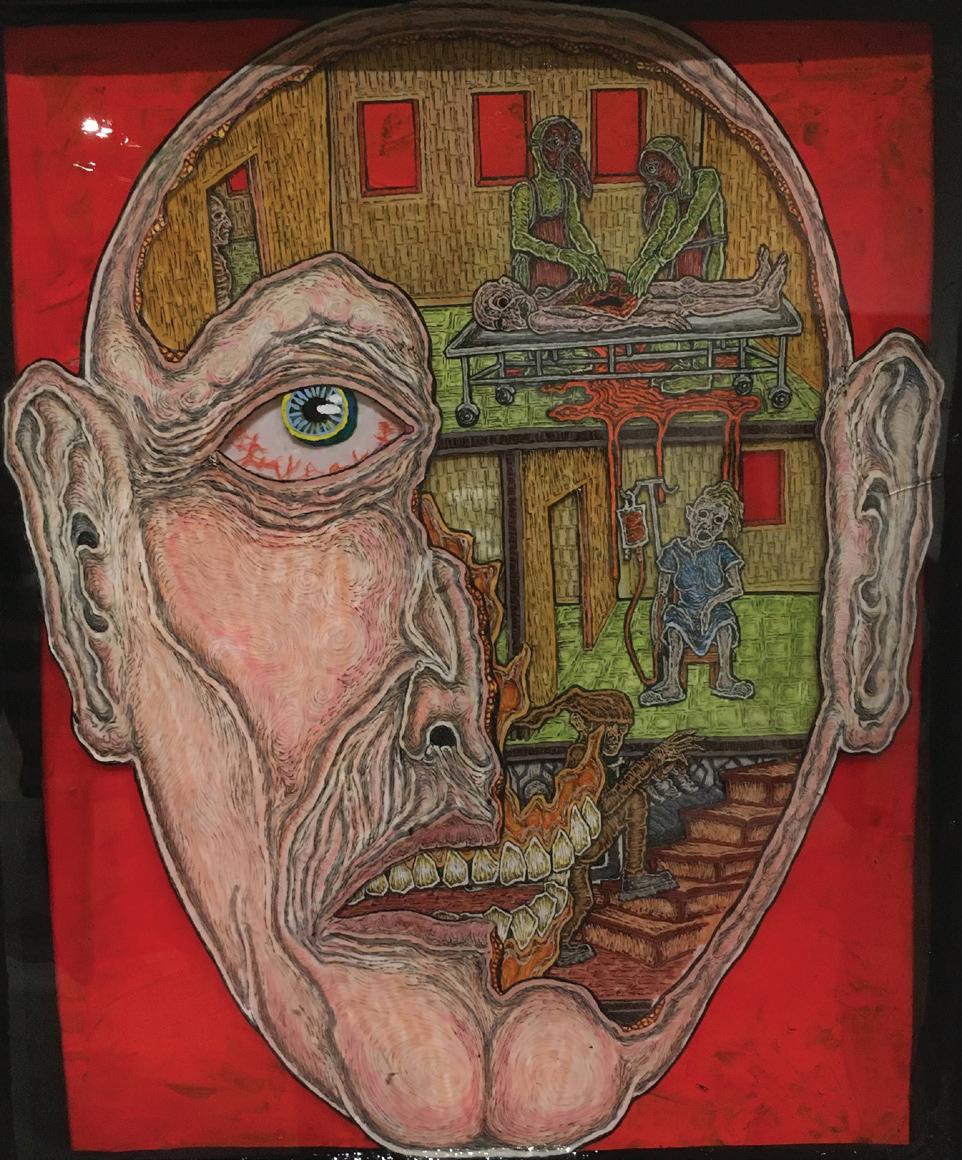

Those beds, which replaced previously approved “psych-safe” beds, are single piece plastic molded units with a mattress on top. UVMMC solicited input from its patient advisory committee in its attempt to select ones that felt least institutional.

“Any flat surface had to have something that was diagonal, so that a ligature would slide off of it rather than wrap around it,” he recounted. “Things that may have met the standard 10 years ago now don’t meet the standards.”

“I can imagine, having talked to people, that it would feel like it’s a more sterile environment – that it’s just a plainer environment than you would want, that it could not feel as friendly,” Althoff acknowledged.

Dr. Conor Carpenter, the medical director for inpatient psychiatry at CVMC, told a similar story about the Joint Commission surveys.

“Their reviewers are not unaware that things that they may ask in terms of creating safe environments have a trade-off for a therapeutic environment. Yet they make it clear that their priority is in safety, and we do the best we can to work with that and maintain as therapeutic an environment as we can here,” he said.

New ligature safety standards aren’t the only changes that have taken place in psychiatric units over the years. Since 2020, COVID-19 precautions have periodically limited visitors and, at times, confined patients to plastic “anterooms.” Before that, health and sanitation standards had already evolved, such as favoring surfaces that don’t allow liquids to soak in.

“You don’t want rugs because they collect pathogens or whatever you want to call it,” said a former UVMMC inpatient, whose most recent stay, in 2020, brought back memories of a “dramatically more homey” environment at the same hospital during earlier hospitalizations between 1999 and 2004, with comfortable couches and available snacks.

“If you restrict food, you’re less likely to have

• Continued from page 1

food scattered around, so you’re not going to have germs from this food that gets spilled,” he elaborated. “It’s a progression, I think, that’s been happening for a while.”

A patient who had been hospitalized at CVMC in the 1980s found herself at the same facility again this August. In the old days, she had passed the time by making mosaic tile hot plates and had sometimes received permission to leave the hospital temporarily.

But this year, she found no arts-and-crafts program inside the psychiatric unit, which she couldn’t exit until her discharge.

Two patient representatives at Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, Grace Walter and Laura Shanks, relayed comparable anecdotes from clients in inpatient settings.

Walter described a Vermont Psychiatric Care Hospital patient who “has been in the psychiatric system for a long time” and “enjoyed collecting leaves or flowers and hanging them on his walls or door” after time in the yard. More recently, however, the patient was “told he wasn’t allowed.”

Shanks brought up an inpatient at UVMMC who, at the start of her third stay this year at the facility, discovered suddenly that she would not be able to bring her wedding band or other small personal items that “provide therapeutic support” into the psychiatric unit with her.

“It didn’t make sense. To me, those don’t pose a risk of harm,” Shanks said.

A third VPS patient representative, Nate Lulek, offered a happier picture of Rutland Regional Medical Center, which, starting in 2019, spent more than $4 million to redesign its psychiatric unit to “correct risks of self-harm.”

Lulek’s account suggested that, by reconstructing the unit from top to bottom, RRMC had managed to provide ligature safeguards without adding restrictions upon patient movement, resulting in few complaints.

He also praised efforts to offset the sterility of the ligature-resistant environment.

“They had artists go up and do murals in common areas. Each one of the rooms are single, and they have artwork from local artists, so that it gives it less of an institutional feel, to a certain extent.”

A patient comment supported what Lulek said. “When I was in RRMC in August 2021, it was not oppressive, but freeing, and health restoring,” she said.

But Lulek noted in November that RRMC was due for a survey by the Joint Commission, which must reaccredit hospitals every three years. “RRMC got notified, I think, last month,” he said. “And who knows if there’s going to be any more stuff thrown on that now has to be done?”

A 2019 report by the National Association

for Behavioral Healthcare estimated that, nationwide, hospitals had to spend $880 million annually in order to comply with ligature risk regulations that could be “unpredictable” and “inconsistent.”

The report recommended reforms such as “a more evidence-based approach to ligature-risk review,” whereby regulators would not demand modifications without “a compelling empirical basis.”

According to NABH President Shawn Coughlin, the report made an impact.

“We were able, in working with CMS, to get some clarifications and some standardization that we had hoped for,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean that Joint Commission surveyors have necessarily altered their judgments yet.

“It absolutely does take time to filter down through the various survey processes, and there probably will always continue to be various interpretations by surveyors,” Coughlin surmised. “Obviously, we’d like to see them be in lockstep.”

In 2018, an article in the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety debunked the commonly cited statistic that the United States sees 1,500 inpatient suicides annually. In fact, the researchers found that the number was closer to 50 or 60.

“There’s so few incidences of people committing suicide in hospitals,” a patient told Counterpoint.

“We’re spending a lot of money to avoid a very, very rare event. And that’s money that could otherwise have been spent someplace else and could have affected lives and reduced suicides in a different way.”

In 2018, Counterpoint reported on a change at the Brattleboro Retreat that required bathrooms to be locked, meaning that patients had to find a staff person to unlock one any time they needed to use the facilities.

The Retreat attributed the change to its own assessment of safety needs, and said there were no alternative measures that would keep patients safe.

”Being denied autonomy over one’s basic bodily functions – being made to ask permission to relieve oneself – is... demeaning and humiliating...” said Calvin Moen, a patient representative from Vermont Psychiatric Survivors at that time.

VPS called it an “affront to patient dignity” and said that patients found it “dehumanizing and degrading.”

The Retreat did not respond to requests by Counterpoint for comments for the current article.

Editor’s note: psychiatric survivors interviewed for this story asked not to be identified by name to protect their privacy.

Fall 2018 NEWS 4 Winter 2022

(by Kateryna4, Unsplash)

An advertisement for psychiatric furniture displays the selling features being highlighted.

New Legislative Agenda Unclear

by BRETT YATES

MONTPELIER – With at least 47 new faces entering the Vermont House of Representatives and nine freshman senators, the 2023-2024 legislative biennium looks more than usual like a blank canvas. Mental health advocates will be watching closely to see how it fills up.

The governor typically submits his executive budget recommendations about two weeks after the start of the session. At that point, legislators –and the public – will hear about the Department of Mental Health’s funding priorities for fiscal year 2024, which begins in July of 2023.

Among potential areas for attention, DMH policy director Nicole DiStasio pointed to workforce shortages “at all levels of service delivery, particularly for psychiatry;” the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, where efforts to increase in-state call center capacity continue; and mobile crisis response services.

Mobile Crisis Units

Following the start of a pilot program for a youth-oriented mobile crisis team in Rutland, the legislature instructed DMH last spring to develop a model for statewide mobile services. DMH issued a request on Nov. 1 for proposals from “qualified providers that could include, but are not limited to, Vermont Department of Mental Health Designated and Specialized Service Agencies.”

The vendor or vendors will provide “rapid

community crisis response, screening and assessment, stabilization and de-escalation services, coordination with and referrals to health, social, other services and supports, and follow-up services as needed” to Vermonters of all ages.

DMH will consider “a range of staffing models,” though the RFP notes that “best practices include incorporating trained peers.”

A report on the Rutland pilot is due to arrive on legislators’ desks by Jan. 15. DMH sees mobile crisis services as one way to keep Vermonters with mental health needs out of emergency departments.

Blueprint for Health Expansion?

According to Senator Ginny Lyons, the presumptive chair of the Senate Committee on Health and Welfare, mobile crisis teams won’t be enough on their own to solve the problem.

Lyons praised the Vermont Blueprint for Health, a healthcare reform initiative that has supported several programs for “whole-person care” since 2006, calling it “a model for the country,” but said that it could do more for mental health.

“I’ve been in conversation with folks about expanding Blueprint to cover mental health,” she revealed, “so that we have in place comprehensive primary care for folks with mental health needs and make it as important as any other area of primary care.”

An upcoming report by the state’s Mental

Health Integration Council, also due by Jan. 15, could offer related recommendations.

Forensic Hospital Discussion

The intersection of criminal justice and mental health is likely to be a major topic among legislators. A Forensic Working Group studied the issue for a year and will soon issue a report of its own, but philosophical divisions appeared to prevent its members from arriving at a unified recommendation for how Vermont’s psychiatric facilities should deal with patients who’ve faced criminal charges.

“They didn’t provide any resolution to that issue. It just threw it back on our table,” Lyons said. Lyons anticipates working on a bill that would propose a forensic hospital – a locked facility that would treat arrestees deemed incompetent to stand trial or adjudicated not guilty by reason of insanity.

By Lyons’s account, it could also house some convicted criminals who have mental health needs. “The thinking is, well, we need to have something for people who have committed these crimes,” she said. “I don’t want to put them in Corrections, but how do we handle this? That continues to be a huge question. And so having a secure facility is the direction, I think, that some folks are going.”

“Right now, there are funds for a facility,” she added.

Urgent Care Options Are Underway

by BRETT YATES

BURLINGTON – The Department of Mental Health is actively looking to relieve Vermont’s overburdened emergency departments by expanding other options for care during mental health crises. There has not yet been any direct involvement by psychiatric survivors about specific criteria that should be included.

The Howard Center, Chittenden County’s community mental health center, has one idea. It has already been under development and a spokesperson said it would be seeking broader input, but not until its proposal is further along.

DMH issued a request for proposals for new urgent care services from qualified Medicaid providers in October. The document listed four potential models: a hospital-based “EmPATH” program (Emergency Psychiatric Assessment, Treatment & Healing); a “Living Room”-style crisis center with peer support; a “PUC” (Psychiatric Urgent Care) clinic; and a “CAHOOTS” (Crisis Assistance Health Out On The Streets) mobile response team.

There was no requirement for those who submit proposals in response to DMH to solicit input from the survivor community about their intended urgent care model.

Furthermore, the request for proposals appears to bypass the efforts of peer groups to develop peer respite programs that might provide crisis support options in similar ways.

Last year, the effort by four peer-affiliated organizations to propose that model failed to gain funding by the legislature. DMH said that the new programs described by the RFP were all based on a special federal funding opportunity, so they can only be developed by organizations that can receive Medicaid funds.

“Peer respites are not eligible for enhanced

funding because services are not billable to Medicaid,” DMH said. Peer support staff are not certified in Vermont, which is a barrier to that funding.

Howard Center Has Possible Plan

Before the RFP’s release, the Howard Center had already begun working to develop a plan for an urgent care clinic for mental health needs in Burlington. Initial conversations included potential partnerships with the University of Vermont Medical Center and the Community Health Center of Burlington.

According to Howard Center Chief Client Services Officer Catherine Simonson, it would operate much like an urgent care clinic for physical injuries and illnesses. “For instance, if you sprain your ankle,” Simonson said, “that doesn’t necessarily mean you have to go to the emergency department, but you need attention. You can’t wait till your doctor’s office opens up.”

The clinic would be open to the public, with no appointments needed, for about 12 hours a day. Clients would not be able to stay overnight, but Simonson envisions that those in need of additional stabilization would return the next day for a follow-up.

The Howard Center aims to find a communitybased site for the program in the vicinity of UVMMC, which would allow staff to easily refer patients to the emergency department if they meet criteria for hospitalization.

“Right now, for Howard Center, we don’t have a building set up such that there’s a lot of space for walk-ins,” Simonson observed.

The Howard Center already has a mobile response team for mental health emergencies, but Simonson believes that a brick-and-mortar clinic would provide a valuable supplement.

“It’s recognizing that many people in our community are choosing either not to wait for mobile outreach, or they want a place to go,” she said. “They don’t want somebody coming to their home or to wherever they are.”

DMH initially took part in discussions about the idea with the Howard Center and its partners but later assumed the role of a neutral party as it prepared to evaluate responses to the request for proposals. “Once an RFP is issued, they can’t be a part of any planning,” Simonson noted.

Pathways Vermont, Burlington’s peerled specialized service agency, joined later conversations. In Simonson’s vision, peers from Pathways and from the Howard Center’s own peer support team would join mental health clinicians, crisis workers, case managers, administrative staff, and a medical provider in a “multidisciplinary approach.”

“Our hope with the urgent care center is that it will be staffed such that people are not having to wait a long time to get their needs met and to be able to see somebody,” Simonson added.

Patients, she said, would enjoy a “calmer, trauma-informed” environment with “a little bit more personal space” than they’d find in an ED.

Simonson pledged that the Howard Center would solicit broader input on the plan upon securing a location and a contract with DMH. This would include consulting the Howard’s Center Community Advocacy Network Standing Committee and holding forums “for folks who identify as psychiatric survivors and other groups.”

“The fact that we haven’t done it yet is not so much not seeing the value in that, but feeling like we need to be further along, because there’s still a lot of work to be done,” Simonson explained.

DMH’s deadline for proposals was Nov. 14.

NEWS . 5 Fall 2018 NEWS Winter 2022 5

Conflict of Interest?

State Lags on Requirement To Divide Case Management from Services

By BRETT YATES

MONTPELIER – In 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued new regulations intended to protect Medicaid beneficiaries who receive care outside of institutional settings.

Vermont is still playing catch-up, which is frustrating advocates who have worried for years about a conflict of interest between agency case managers and the services their clients are eligible to receive.

A category of programs called “homeand community-based services” accounts for about $115 billion in annual Medicaid spending nationally.

In Vermont, under the administration of the Department of Mental Health and the Department of Disabilities, Aging, and Independent Living, they have five names: Choices for Care, Community Rehabilitation and Treatment, Developmental Disabilities Services Program, Intensive Home- and Community-Based Services, and Traumatic Brain Injury Program.

Through home- and community-based services, the state’s community mental health centers and specialized service agencies deliver care to Vermonters with psychiatric diagnoses and developmental and intellectual disabilities. But before they do, for each client, they perform an assessment of needs and design a plan to address them.

According to CMS, its new regulations require that part of the process to start taking place under a different roof. Under the updated rules, in order to avoid conflicts of interest, case managers cannot work for the same agency tasked with delivering the package of services that they’ve coordinated.

The federal regulators say that this revision relieves case managers of “possible pressure to steer the individual to their own organization.” They should instead offer clients “full freedom of choice of types of supports and services and individual providers” and be prepared to tackle “problems related to outcomes and quality,” which, as CMS points out, can be hard to do if the problems owe to “the performance of coworkers and colleagues within the same agency.”

This summer, CMS approved Vermont’s application for a five-year extension on its Global Commitment to Health waiver, the agreement that governs the state’s Medicaid program. In doing so, it conditioned that agreement upon Vermont’s willingness to enter compliance with its conflict-of-interest rules. Once CMS has okayed the state’s plan, it will appear within the waiver, on page 250, as Attachment Q.

So far, the page sits blank. Last December, the Vermont Agency of Human Services proposed a five-year transition to conflict-free case management, as it’s called, but CMS rejected it and demanded a three-year timeline.

It hasn’t yet approved Vermont’s hastened corrective action plan, originally scheduled to begin its stakeholder engagement phase this past September with the assembly of an advisory committee of “consumers, providers, families, guardians, advocates, and other groups.”

But the state has continued to get ready. In November, AHS executed a contract for technical assistance. A long process of analysis will precede the actual implementation of the

new system of case management, set to begin in 2025. A new stakeholder engagement plan is also being developed, and the process will begin after the plan is finalized, AHS indicated.

to tell them that,” she observed. Most states have already fully adopted conflict-free case management, but Vermont officials were initially reluctant to disentangle their “vertically integrated system,” as Murphy called it.

“We are by far the farthest behind,” she said. In her view, the creation of an “ombuds office” will be a key reform. The ombuds would investigate complaints by individuals who receive home- and community-based services.

An option the state could pursue to meet the federal requirements would be to contract with an organization to provide mandatory conflict-free case management throughout Vermont, or it could require each agency to find a third-party case management service of its own choosing.

The agencies themselves could provide reciprocal case management in one another’s geographic catchment areas, or some could transition exclusively to case management with others functioning exclusively as service providers.

Other states offer examples, but so far, no one knows what will happen here.

That has made some people nervous, including Rutland Mental Health Services CEO Dick Courcelle. “We’re still trying to understand what this really means because, in some cases, it makes no sense,” he opined.

Until recently, Vermont hoped to achieve conflict-of-interest compliance simply by offering Medicaid beneficiaries the option of receiving case management separately from the provision of their home- and community-based services, but CMS let the state know last year that simply providing clients with an option wasn’t good enough.

The Vermont Center for Independent Living has been a longtime advocate for a move to conflict-free case management.

“It’s about people truly understanding all their different choices, and I think that we have had a history in Vermont where people aren’t always given all the information,” said Sarah Launderville, VCIL’s executive director.

“It’s not like the federal government said, ‘Here’s a new rule we want to see.’ It was people with disabilities nationally coming together and saying, ‘We want to see this happen,’” she added.

Kirsten Murphy, the executive director of the Vermont Developmental Disabilities Council, also expressed support for the change to address the conflicts of interest that she said do exist in Vermont’s system of care.

“People don’t have to receive their services from their regionally designated agency, but sometimes they don’t learn about that because it’s not in the interest of their regional agency

“Consider you’re going to your doctor, and your doctor diagnoses you with type-two diabetes, but your doctor says, ‘I am diagnosing you with diabetes, and we need to manage that diabetes. However, I cannot be the one to do that, so I’m going to refer you to someone else for your care.’ That’s sort of what this is.”

By Courcelle’s judgment, the service provider is in a better position than a third party to design a plan of care because the service provider knows “what can be delivered, what’s available, and how to arrange those services.”

He also wondered where funding for case management contractors would come from and whether cash-strapped community mental health centers would suffer financially under the new arrangement.

“You’re dealing with a system that is fragile and has been fragile for many years due to chronic underfunding,” he commented. “My assumption is that this is a zero-sum game. If the money has to go somewhere, it’s going to have to come from somewhere.”

Courcelle pointed out that Vermont’s community mental health centers don’t operate on a fee-for-service basis, so they don’t have an incentive to load up clients with unnecessary services.

“But the federal government tends to like a one-size-fits-all approach,” he said.

Eating Disorders Treatment Input Sought

WATERBURY — The Department of Mental Health has announced that it is seeking public input on eating disorder treatment in Vermont.

An eating disorders work group, chaired by the department, is seeking comment from those who are struggling with eating disorders or those who have had problems in finding care for themselves or others. Suggestions are being solicited for improving treatment options, and input will be shared with state health care

providers, lawmakers, and school systems to help to build a better system of care, DMH said. Further information, is at mentalhealth.vermont. gov/about-us/boards-and-committees/eatingdisorders-workgroup

Those interested in sharing their experiences or recommendations can address them to: AHS.DMHCommunications@vermont.gov. All communications will remain confidential unless unless permission to use a name is provided.

NEWS 6 Fall 2018 NEWS 6 Winter 2022

“It’s about people truly understanding all their different choices, and I think that we have had a history in Vermont where people aren’t always given all the information.”

(by Jason Wong, Unsplash)

Town Says Plan To Replace Woodside Mislabels Youth Violence as a Disability

By BRETT YATES

WATERBURY – A growing preference for community-based care for justice-involved youth led the state to close the scandal-plagued Woodside Juvenile Rehabilitation Center in Essex more than two years ago.

Since then, the Agency of Human Services has struggled to find a new setting for juvenile offenders who are deemed to need a locked facility and mental health support.

“I’m as frustrated as you,” Secretary of Human Services Jenney Samuelson told lawmakers at a meeting of the Joint Legislative Justice Oversight Committee this fall.

A plan to open such a facility in the small town of Newbury has ended up in a legal debate as to whether the small but growing number of youths who have been alleged to have committed violent acts should be categorized as having a disability.

That category would bypass restrictions in a town’s zoning laws, but the town has declared its opposition to what it has called “the notion that any juvenile who commits a crime is, by default, mentally disabled.”

The case has ended up in Environmental Court, which found that the program did qualify as a group home for persons with disabilities. The town declared that it would file an appeal.

Since 2020, Vermont has sent children charged with delinquent or criminal acts across state lines to the Sununu Youth Center, but amid indictments against staff for physical and sexual abuse, the New Hampshire legislature ordered its closure in 2023.

A recent VTDigger report revealed that nine minors have spent time in Vermont’s adult jails.

Last year, Newbury’s land use authority rejected an application by a state-contracted nonprofit for the construction of a “residential treatment facility” with six beds for justiceinvolved adolescents on the outskirts of the village of Wells River.

The local zoning dispute has drawn into question the nature of the proposed program in Newbury and appears to have revealed the need for an additional facility elsewhere to fulfill the former’s original purpose: to replace Woodside.

Since 1984, the state’s Department for Children and Families, which is under the Agency of Human Services, had operated Woodside as a juvenile detention center. In 2011, the state added psychiatrists to the staff and, partly in order to draw federal funding through Medicaid, relabeled it a treatment facility.

In 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services rejected the reclassification, deeming Woodside’s so-called patients to be “inmates” instead, meaning the program was not eligible for federal funds.

In 2020, the legislature instructed AHS to submit “a long-term plan for Vermont youths

who are in the custody of [the state], are adjudicated or charged with a delinquent or criminal act, and who require secure placement.”

It called for a “physically secure” program with a “no eject/no reject” policy, meaning any

maintaining a clear distinction between mental health treatment and criminal detention.

Conflating them “doesn’t help the situation at all,” he commented. “That’s a bad mix.”

Jessica Kell, the director of the Child, Youth and Family Services Division at Washington County Mental Health Services, criticized a “fragmented” system that, for reasons of zoning or funding, requires children to demonstrate that they fulfill specific criteria before they can receive care.

“These kids need help, and there is no way of getting it when we can’t agree on who is responsible for it,” Kell said.

The starting point should not be to “define by law what they need,” but instead, for a clinical process of diagnosing what is needed to get underway even as the help is occurring.

child in need of the program had to be admitted.

A property was identified in Newbury, to be operated by Becket, a New Hampshire-based nonprofit.

State law requires a “residential care home or group home” which serves eight or fewer “persons with a disability” to be considered in the same way as a single-family home for zoning purposes.

The Newbury Development Review Board ruled that, as a proposed replacement for Woodside, it was not a residential care home or group home, but rather a “high-security detention facility,” just as CMS had determined regarding Woodside.

The board cited plans for a 12-foot fence and 24-hour infrared video cameras throughout the site. The board then rejected the application under its zoning bylaws.

The Environmental Court sided with the state, saying that “DCF anticipates the individuals who will be served at the facility to have disabilities or disorders (mental, social-emotional, developmental, etc.) or need assessments for such based on their behaviors and needs at time of presentation.”

The court noted testimony of the operator’s intention to transfer youths who do not meet the criteria for a “mental health disability” to a “more appropriate treatment setting” following such assessments.

Declaring their intention to file an appeal, municipal officials emphasized what they still regarded as the project’s primary aim as a lock-up: “It’s clear that the proposed facility is a detention center first and any mental health services they offer are secondary.”

In an interview with Counterpoint, Vermont Psychiatric Survivors Executive Director Karim Chapman stressed the importance of

Kell said that isn’t a quick process or just a matter of an assessment at an intake – it needs to happen by allowing the professionals who are licensed by the state to be given the space to do their jobs.

Disability Rights Vermont Executive Director Lindsey Owen has also followed the saga in Newbury.

“I would like to be able to take the state for its word that, if somebody goes to that program and does not have a diagnosis that would be appropriate for that setting, they would find an alternative and appropriate placement for that child,” she said.

“I think Disability Rights Vermont’s position is really not so much the legal status of the kids that are there,” Owen continued, “but really just making sure that those children are being served in the best way possible and in a therapeutic setting.”

To Owen, the biggest impediment is the location. “The grocery stores are at least 20 minutes away,” she described. “If the goal in the long run is to successfully rehabilitate and reintegrate these children into communities, it’s questionable how that’s going to happen in such an isolated rural environment.”

At the Oct. 25 meeting of the Joint Legislative Justice Committee, Samuelson said that placement in Newbury would depend upon a clinical determination of eligibility for care. “The provider makes the decisions about who is admitted,” she said.

That would leave unmet the need for the program that was originally described as required to replace Woodside: one that must admit and hold any juvenile deemed in need of a locked facility. According to AHS, the solution will take place in two steps: the establishment of a short-term detention center, followed by the development of a long-term one.

Samuelson pledged to return to the committee at its December 12 meeting with more information.

Peer Workforce Training Sessions Offered

Vermont’s Peer Workforce Development Initiative has announced several upcoming free training opportunities. For more information on any of these three, including how to register, contact training@ pathwaysvermont.org

Intentional Peer Support Core Training will be starting Monday, January 23 via Zoom on Mondays and Wednesdays for 10 half days. There is a $100 fee for IPS Core materials.

Mad Movement Histories will be April 4 and 6, 12:30 - 4:30 p.m. each day. It will explore mad movement histories through themes of

resistance to oppression and building alternative supports, and through lenses of racial, disability, economic, and gender justice.

Harm Reduction Approach to Psychiatric Drugs will be May 2 and 4, 12:30 - 4:30 p.m. each day. “As peer support workers, we are sometimes discouraged from having conversations about psychiatric drugs and are encouraged to leave it to the medical professionals. This two-day participatory workshop introduces a model for thinking about psych drugs as neither good nor bad, but as chemicals that can have benefits and also come with risks,” PWDI said.

NEWS . 7 Fall 2018 NEWS Winter 2022

(AdobeStock)

Telepsych May Expand in EDs

By BRETT YATES

A one-year federally funded project aims to help expand telehealth-based psychiatric assessments to emergency departments across the state.

Thanks to an earmark secured by Senator Patrick Leahy, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration sent $901,123 in congressionally directed spending to the Vermont Program for Quality in Healthcare in September. VPQHC, a nonprofit established by the state legislature, will build what’s it calling a Vermont Emergency Telepsychiatry Network to support coordination among hospitals, prepare medical and administrative staff, look for ways to access long-term funding, and evaluate outcomes.

“The problem we’re trying to solve is that Vermonters, adults and youth and children, are waiting a long time in emergency departments. They’re having mental health and psychiatric needs that are unmet,” said Quality Improvement Specialist Ali Johnson, the project lead.

Earlier this year, with the help of the Northeast Telehealth Resource Center, VPQHC used a philanthropic donation to research existing emergency telepsychiatry practices in Vermont’s hospitals.

“We found that some of them had it, and some of them didn’t,” Johnson recounted. “The ones who didn’t, some of them don’t want it; some of them do want it.”

During VPQHC’s needs assessment, the organization reached out to “all kinds of stakeholders,” as Johnson put it, including Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, with the intention, ultimately, of assembling an advisory board. The board, once it comes together, will meet monthly to make recommendations over the course of the project.

“There will be some psychiatrists on that board. We also will include people from governmental agencies like the Department of Mental Health and Medicaid. We will include, hopefully, people with lived experience,” Johnson said. “People who are receiving services are one of the key sectors of this coalition we’re trying to build.”

She also cited an expected board seat for Disability Rights Vermont. VPQHC may “look into stipends” to promote participation.

Johnson described emergency telepsychiatry as a “consentbased” service. The choice to wait for an assessment by an in-person provider will remain available for both voluntary and involuntary patients, she said. Telepsychiatry has expanded globally since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Increased need and workforce shortages, especially acute in rural areas, both appear to have played a role.

“There is some good evidence that telepsychiatry can be effective in working with people,” observed Kevin Martone, board president of the National Association for Rural Mental Health. “But you don’t just want to default to it as a cost-saving measure.”

Martone noted that emergency departments that replace in-person physicians with

best environment that they can,” Martone said.

Johnson said that, “We’re hoping to learn best practice from the hospitals that already do this, turn that into training for the newcomers to telepsychiatry, and also buy equipment and services for hospitals that might already have telepsychiatry in place or are trying to build it.”

Trainings will cover big-picture topics such as, in Johnson’s words, “Is this evidence-based? Is this a good idea?” in addition to nuts-and-bolts details related to electronic health records and insurance. Other sessions will focus on “traumainformed care and thinking about Englishlanguage learners and people with disabilities.”

Among the hospitals that don’t already have telepsychiatry, VPQHC will pick two – a “midsize hospital” and a smaller “critical access hospital,” both yet to be named – for “demonstration projects.” A portion of the SAMSHA funding will pay for these institutions to hire emergency telepsychiatry vendors vetted by the Northeast Telehealth Resource Center.

telepsychiatrists will have to rely on the rest of their staff – including social workers, peer supporters, and nurses – to provide a stabilizing human presence for patients in crisis. “If the clinical assessment to make a determination about inpatient care needs to be done by a psychiatrist and they don’t have that and they need to consult with someone [virtually], the other folks on that team need to really be trained on engagement and be warm and welcoming and all of those things to try to create at least the

According to Johnson, the “midsize hospital” intends to contract a Vermont-based treatment center that specializes in children and adolescent psychiatry. The other contract could go to an instate or out-of-state vendor.

“We’ve modeled our project on some work that’s been really great in North Carolina, and one of the ways they show their impact is in overturned involuntary commitments. And telepsychiatry is used in that process,” Johnson added.

Peer Certification Efforts Continue

By BRETT YATES

After a bill that would have created a statewide certification program for peer support workers in Vermont failed in the legislature last spring, advocates continued to pursue the idea.

“When they kind of shut it down, the peer movement, in their own way, went back to the drawing board: OK, we’ve got to come at it a different way. Let’s try to redefine what we’re trying to say,” Vermont Psychiatric Survivors Executive Director Karim Chapman said.

Vermont is one of only four states that does not have a mental health peer certification process.

The Department of Mental Health issued a $30,000 grant to Pathways Vermont, which operates the state’s Peer Workforce Development Initiative, to pay for a series of meetings that would seek to resolve “key issues and risks” associated with peer certification by soliciting stakeholder input. Pathways subcontracted Wilda L. White Consulting, a firm owned and operated by the founder of the nonprofit MadFreedom.

Over the course of six Zoom sessions hosted

by White this fall, peers and others discussed various potential forms of certification and certifying bodies, eligibility requirements and training focuses, as well as how the mental health continuum of care would incorporate certified peers. After each session, White distributed a survey to gather more detail from participants. DMH will review responses.

“Part of my job here is to submit a report,” White explained at the final meeting. “And in that report, it should contain a recommended design of a statewide peer support worker certification program, include a summary of items that need resolution, and then create a work plan of what are the next steps and how will we get that done.”

She explained that phase two of the process will be “convening a smaller group, still with broad stakeholder representation, to finalize where we go from here, so we can move into certification and move into implementation of a certification program.”

DMH intends to make use of this work, according to Director of Policy Nicole DiStasio.

“The Department expects to have a

recommendation from the stakeholder workgroup that will inform the next steps for this critical work,” she said.

Last spring, after the legislature had stripped the funding from the peer certification bill drafted by Vermont’s peer-led organizations, those same organizations sent a letter to ask lawmakers to allow them to “work cooperatively with DMH to develop and implement a statewide peer certification program outside of the legislative process.”

But Vermont’s precise path to peer certification, if it happens, is not yet certain. Senator Ginny Lyons, the presumptive chair of the Senate Committee on Health and Welfare, mentioned her awareness of ongoing discussions involving the Office of Professional Regulation and the Secretary of State’s office as well as DMH and peers.

“Do we need to do anything legislatively, except maybe rubber-stamp what’s happened or make some tweaks to what they’re proposing?” Lyons wondered. ““I will be catching up with that. I would like to bring them into committee and have that conversation.”

NEWS . 8 Fall 2018 NEWS Winter 2022 8

(AbobeStock)

The pilot program for telehealth services for those in a psychiatric crisis will be “consent-based,” the organization said.

Group Joins Battle for Parity

‘Inseparable’ Seeks Recognition of Mind-Body Interconnection

By ANNE DONAHUE

PORTLAND, OR – A new, national organization has been formed with a stated purpose to press state and federal policymakers to recognize that “health of the body is inseparable from health of the mind.”

The organization – named Inseparable – was founded in 2020 with the purpose of “creating a movement” to demand and win policy changes that improve care for all Americans, according to Angela Kimball, Senior Vice President of Advocacy and Public Policy.

‘Lived Experience’

Kimball said in an interview that its leadership includes psychiatric survivors along with family members of people labeled with mental illness and mental health professionals.

Kimball cited the organization’s Vice President of Partnership, Keris Myrick, as evidence of its commitment to keep its mission “grounded in people with lived experience.”

Myrick’s background as a psychiatric survivor includes serving on the board of the National Association of Peer Supporters and as a CoEditor of the Journal of Psychiatric Services “Lived Experience and Leadership” column. She was also a past director of the Office of Consumer Affairs for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Initiative with Legislators

Kimball said while hosting a booth at this year’s annual convention of the National Council of State Legislators, staff from Inseparable discovered an “upswell of interest” among legislators about addressing mental health challenges in their states.

“They were hungry for resources,” she said.

As a result, Inseparable began a new initiative this fall to develop a coalition of legislators across state lines and across political parties to help advance the states’ mental health priorities.

The founder and president, Bill Smith, has a career in campaign management, messaging research and communications, and movement

building and lead national efforts on marriage equality. It was the loss of a family member to suicide that led Smith to create Inseparable, Kimball said. The organization is taking “an issue-oriented campaign approach” to its efforts, and is not trying to replicate others who do broad based advocacy, she said.

Organizational Priorities

The Inseparable web site identifies its three immediate priorities for policy action as:

1. Eliminate the gap between the number of people who need help and the people who get help.

2. Ensure every school has services to provide for the health and well-being of all students.

3. Stop criminalizing mental illness and expand crisis response.

The web site stresses the universality of mental health issues, and says it “fights for a future where mental health policy, no longer an

911 can too often turn a crisis into tragedy like in the Daniel Prude case.” Prude died after being physically restrained by Rochester, New York police officers while experiencing a mental health crisis in 2020.

“We’ve been focusing the conversation on how to really build a fully equipped crisis response system, but we’re still worried about it because the system’s not fully ready for it,” Smith said in a blog post.

“The conversation has really been around the three-digit number [988], not around the full crisis response system,” he said.

Focus on Parity

In terms of parity, the organization says on its web site that federal legislation for equal health coverage “was never properly enforced, as states are responsible for their own implementation.”

As a result, it “has left too many without the care they’re entitled to... Closing the treatment gap and increasing access to care includes addressing affordability, expanding insurance coverage, integrating mental health into primary care, and building a much bigger, culturally and linguistically competent

bodies. Each affects the other — just like us. Together, we are inseparable.”

The organization’s web site says that it can “feel overwhelming to experience the broken pieces of our system and frustrating to not see this crisis prioritized by our elected officials.

“The shared trauma brought on by the pandemic, a national reckoning around systemic racism, the threats of the climate crisis, and our broken approach to mental health have all laid bare the need for change.”

View on Crisis System

Inseparable’s priority on ending the criminalization of mental illness includes “working with mental health and criminal justice reform advocates to build and expand a robust crisis response system that prioritizes health and well-being,” it says, “because calling

RESEARCH REVIEWS IMPACTS OF BIAS

Two new reports have discussed the impact of bias on health equity and on research.

The first study, reported on in the Key Update from the Mental Health Consumer’s Self-Help Clearinghouse, is titled The Economic Burden of Mental Health Inequities in the United States.

“For the first time,” Daniel E. Dawes JD, was quoted as saying, “there is tangible evidence demonstrating how decades of systemic health inequities have yielded significantly worse outcomes for racial and ethnic minoritized, marginalized, and under-resourced populations.” In the study, the Satcher Health Leadership Institute reported on a four-year period (2016-2020) when, at minimum, nearly

117,000 lives and approximately $278 billion could have been saved. The free, 62-page study is available for download at satcherinstitute. org/research/ebmhi/

In a second recent report, The University of Vermont’s fall magazine summarized research that says the new scientific field measuring nature’s effect on human well being has “a diversity problem that threatens its ability to make universal scientific claims.”

The report is titled, “Nature Helps Mental Health, Research Says – but Only for Rich, White People?” The field in psychology and environmental science “has produced numerous important studies detailing the benefits of

The web site lists the organization’s values as: Caring – We can better care for each other by demanding a mental health policy that better cares for us.

Unity – The health of our minds cannot be separated from the health of our bodies, and we cannot be separated from each other on this issue.

Progress – We are moved by our hearts, but act with our minds, deploying skill, strategy, and innovative tactics to ensure we don’t just fight, but win.

Power – Together, we have the power to lift each other up. Together, we are a force. A force for help. A force for hope. A force for healing.

Relentless Hope – We harness our hurting for healing, to fight for a world we believe is possible: one with the mental health support we all need to thrive.

nature, forests and parks on human wellbeing and mental health, including happiness, depression and anxiety,” the article said.

But analysis of the research by UVM found that study participants were overwhelmingly white and that BIPOC communities were strongly underrepresented.

“This narrow sample of humanity makes it difficult for the field to credibly make universal scientific claims,” the magazine said that the UVM researchers reported.

The impact of research that discriminates has been one of the issues that gained public awareness after COVID, which impacted the BIPOC community more severely.

Fall 2018 NEWS . 9 Winter 2022

(AbobeStock)

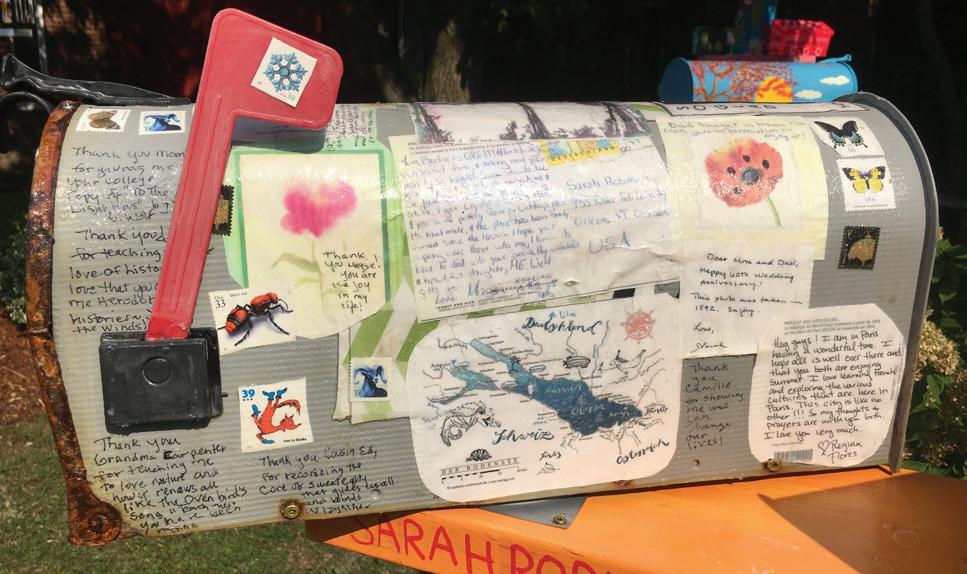

by SARAH ROBINSON

by ADAM FORGUITES

by RAGHAD AMJED

by VESNA DYE

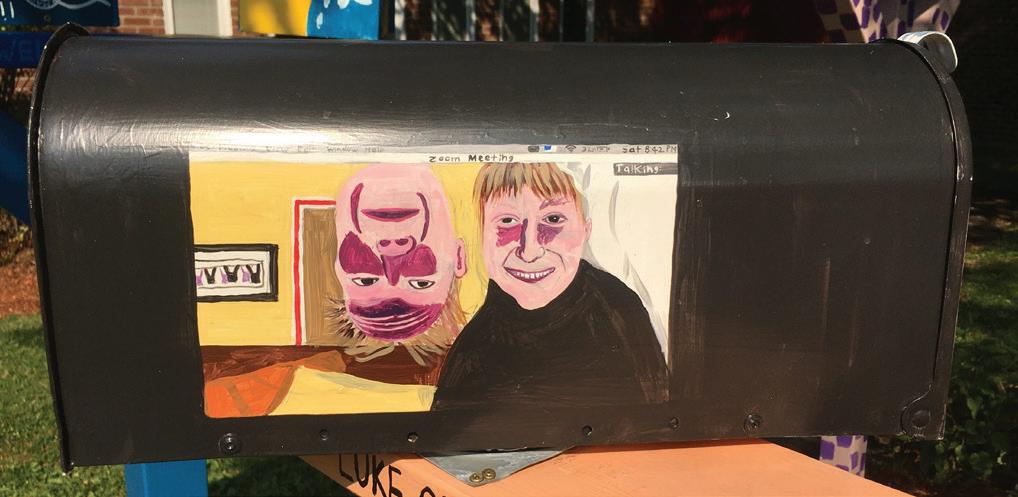

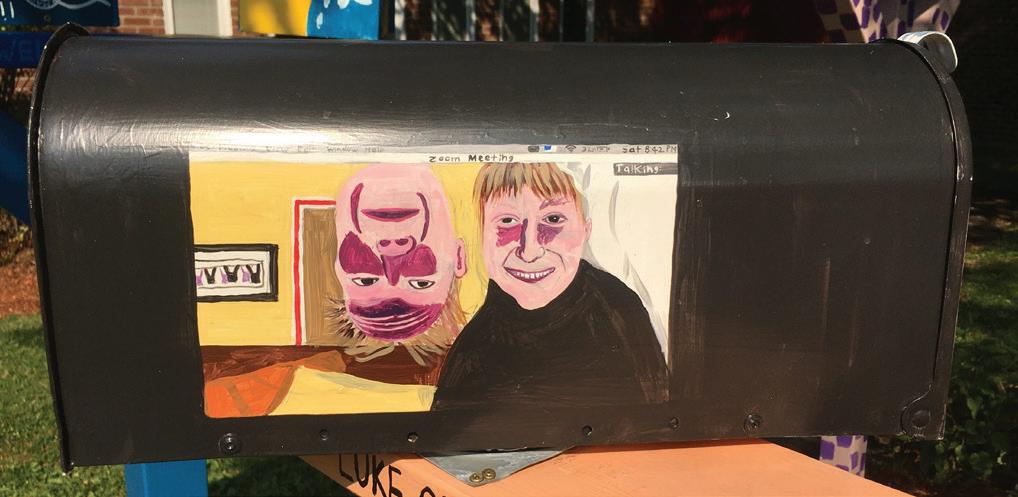

by LUKE CARLSON

Artists Wow Burlington in 2 Exhibitions

By BRETT YATES

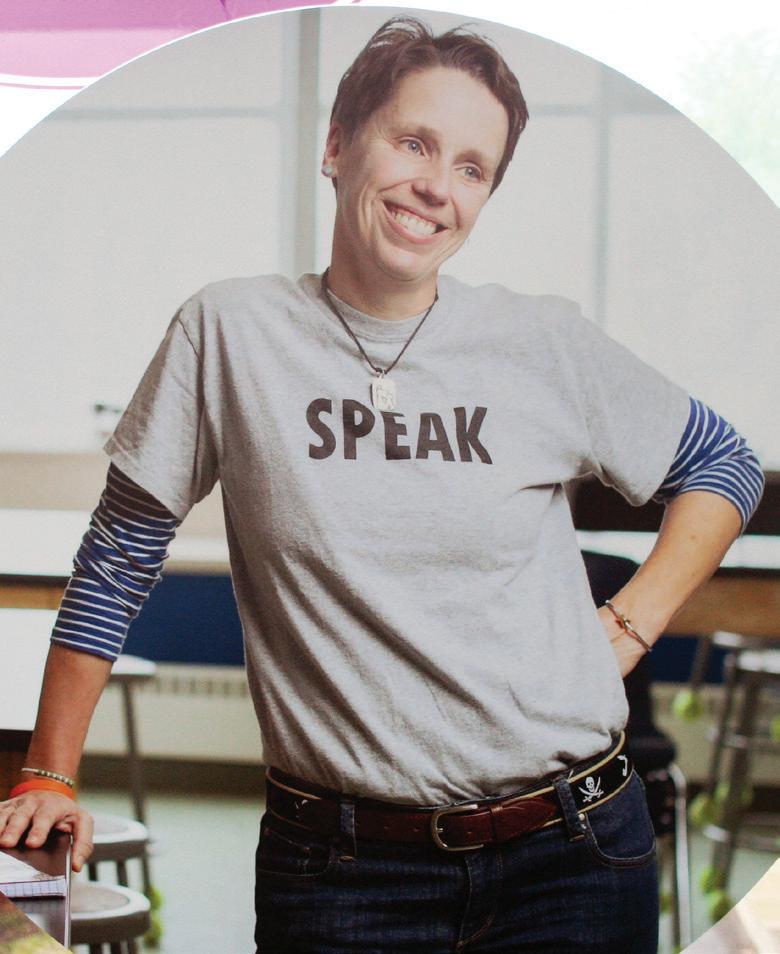

By BRETT YATES

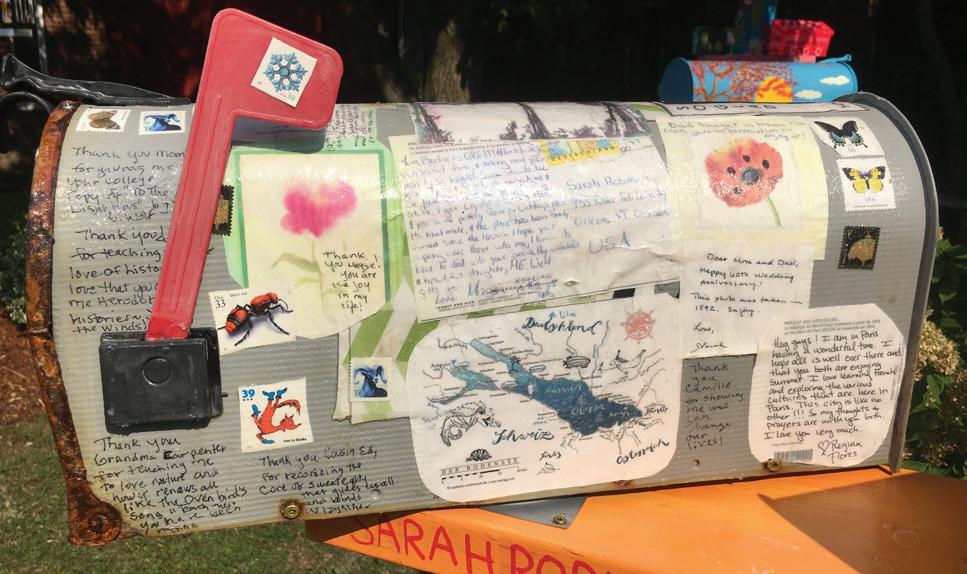

Does anyone write old-fashioned letters anymore? In front of the Howard Center at 300 Flynn Avenue in Burlington, a collection of 13 decorated mailboxes pays tribute to the history of the United States Postal Service and to the human bonds forged over centuries by handwritten communication.

The outdoor installation, titled Connections, opened to the public on Sept. 10 during Burlington’s South End Art Hop, an annual three-day festival, with members of the Howard Center Arts Collective uncovering their veiled works one by one before a crowd.

It was one of two major fall events for the arts program. Call and Response is an exhibition hosted by the Fleming Museum. (See article below.)

The Arts Collective describes itself as “an alternative arts program for people who have lived experience with mental health and/ or substance use challenges” and includes Howard Center clients, staffers, and unaffiliated community members.

“Our mission is really to create opportunities

to make art together, to share our art with one another and learn from one another – and then also to exhibit our work to the community,” Arts Collective Coordinator Kara Greenblott said. Connections casts a skeptical eye upon the dominance of email, Facebook, and Twitter today. An introductory statement by artist Sarah Robinson, read aloud at the opening, criticized the “fractured” thought processes of the internet era and the “reduced services” and slowed delivery times at USPS.

According to Eryn Sheehan, the group’s studio manager, the project that would become Connections began in 2020, when the Arts Collective started to solicit donations of old mailboxes. “We posted on Front Porch Forum and different places around town. And then we’ve been painting them and working on this exact project since spring,” she recounted.

Each mailbox sits on a six-foot post, sunk into concrete. Sheehan expects the installation to withstand Vermont’s winter weather and to last for one and a half to two years in the Howard’s meditation garden. The painted mailboxes display both abstract and figurative designs.

Sheehan, who joined the Arts Collective four and a half years ago as a Howard Center client, pointed to the “little musical symbols” on her mailbox, noting that she had drawn inspiration from what she called “the music of the spheres” – the sounds that she can hear “coming from trees and different celestial bodies.”

A newer member, Vesna Dye, joined the collective after hearing about Connections at Pathways Vermont. “I’m not much of an artist, but I said I’ll do it because I love the post office, and I’m writing hundreds of letters everywhere in the world,” she explained. Dye borrowed her mailbox design from a “thinking of you” card that she received shortly after signing up for the project. Raised in Croatia, Dye lived in Canada and California before moving to Vermont and, by her account, relies on letters, cards, and packages to stay close to family members and friends.

“I only write short emails,” Dye related. “The letters are, I think, much more personal. They’re much more creative – you can say more. I have this nice paper that I like to get, and then a nice card, and I’m hoping people are saving this.”

Second Project Debuts at Fleming Museum

By BRETT YATES

BURLINGTON – A temporary exhibition at the University of Vermont’s Fleming Museum of Art dives deep into its archives and comes up with something new. Call and Response: Personal Reflections on the Fleming Collection

opened on Sept. 13 and features 16 members of the Howard Center Arts Collective. Call and Response found inspiration in paintings and objects as old as the 17th century. Each new work reshapes an artistic vision from the past.

Manager of Collections and Exhibitions Margaret Tamulonis pointed out that the Fleming’s first director, Henry Perkins, was a leaders in eugenics in the early 1900’s. Eugenics supported sterilization of people who were deemed unfit to have children, including those with psychiatric disabilities. She described the show as part of an ongoing process of “examining and reckoning” with the museum’s historically exclusionary practices.

Curator of Education and Public Programs Alice Boone noted the impact that the show had already had upon visitors. “I brought the psychiatry medical students into this space, and [it] was so affecting for them that the professor who I work with actually brought his entire department back, and we spent about an hour and a half talking in that space,” she told the artists at an opening reception. “What they all came to was this sense that they were really transformed by

NEWS 10 Fall 2018 The Arts 10 Winter 2022

Saint Man of Peace (2022) by AMJED JUMAA

seeing your art and really transformed into thinking about the ways that they need to do their work differently.”

(2022)

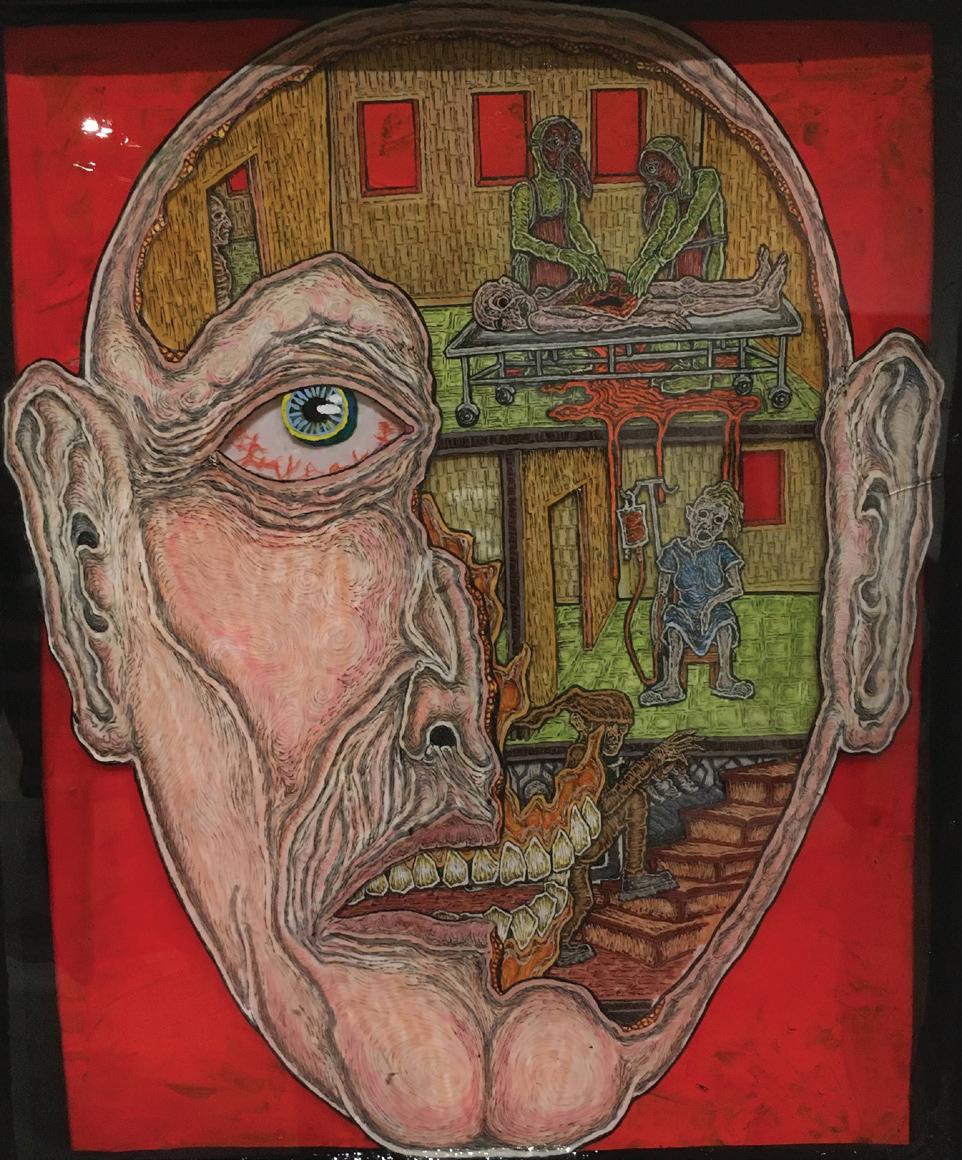

Progression

of Modern Medicine

by THOMAS G. STETSON

Founding Director To Step Down

By BRETT YATES

ROCHESTER – The peer-run respite Alyssum announced this summer that after 11 years, the organization’s founding director, Gloria van den Berg, had made plans to step down.

Alyssum held an open house at its homelike, rural property in the White River Valley on Sept. 16. Former guests, employees, peer leaders, and state officials gathered to celebrate van den Berg’s accomplishments with live music, lunch, and a bonfire.

Alyssum’s two crisis beds, funded by the Vermont Department of Mental Health, have offered a voluntary, non-clinical alternative to psychiatric hospitalization since 2011, when it became the state’s first (and, to date, only) peer-run respite. According to a directory maintained by the National Empowerment Center, such facilities exist in only 13 states.

“She’s just been a tremendous asset to Vermont,” DMH Adult Services Director Patricia Singer said of van den Berg. “Alyssum models a tremendous peer support model. I think it shows how good respite care can really be beneficial to people who are in distress.”

Van den Berg noted that as far back as 2019, she’d formulated a “five-year plan” for “stepping away from mental health.” Since then, “a lot of things happened” in her personal life.

“My daughter had cancer. We had Covid. My sons all moved back home,” she recounted. “And I found myself having a really hard time with cold weather, probably as a result of my age. And so, in the big Covid transition, you have to make sense out of this somehow. I wound up purchasing a house in Florida.”

Van den Berg’s sons will inherit the working farm that she operated for three decades on a hillside down the road from Alyssum. She has given up full-time Vermont residency, following a switch to telework during the pandemic. An earlier transition to “collaborative management” at Alyssum had already reduced her on-premises role.

“It happened when our house manager left about three years ago. We decided not to hire another house manager and to sort of distribute the house manager’s responsibilities amongst staff,” she remembered. “It’s a very well thoughtout structure that we operate under. The great benefit of where Alyssum is at now is that the staff can collaboratively manage the day-to-day program.”

From Florida, van den Berg continues to oversee Alyssum’s budget and financial reporting, to apply for grants (most recently, for a new kitchen), and to participate in Vermont’s “statewide stuff,” like the ongoing effort to design a peer certification program.

She expects her exit to take place “within the time frame, probably, that I was thinking of.”

“The board really felt that they wanted a director who was in residence in the state,” she observed. “I would be remote eight, nine months out of the year. They want something more

than that. So, it was kind of a push-me-pull-me situation with the board.”

As of September, Alyssum’s board of directors hadn’t yet initiated a formal search for van den Berg’s replacement. No one knows exactly how long it will take once it begins.

According to longtime board member Marty Roberts, who had scheduled her own retirement for Oct. 1 this year, the position could possibly become a part-time role, leaving “more funding for the staff.”

Before Alyssum’s founding, Roberts joined a working group assembled by Vermont Psychiatric Survivors and tasked by DMH to help replace services at the Vermont State Hospital, then still operational, by creating a peer-run program.