Battle Erupts on Hotel Evictions

by ANNE DONAHUE

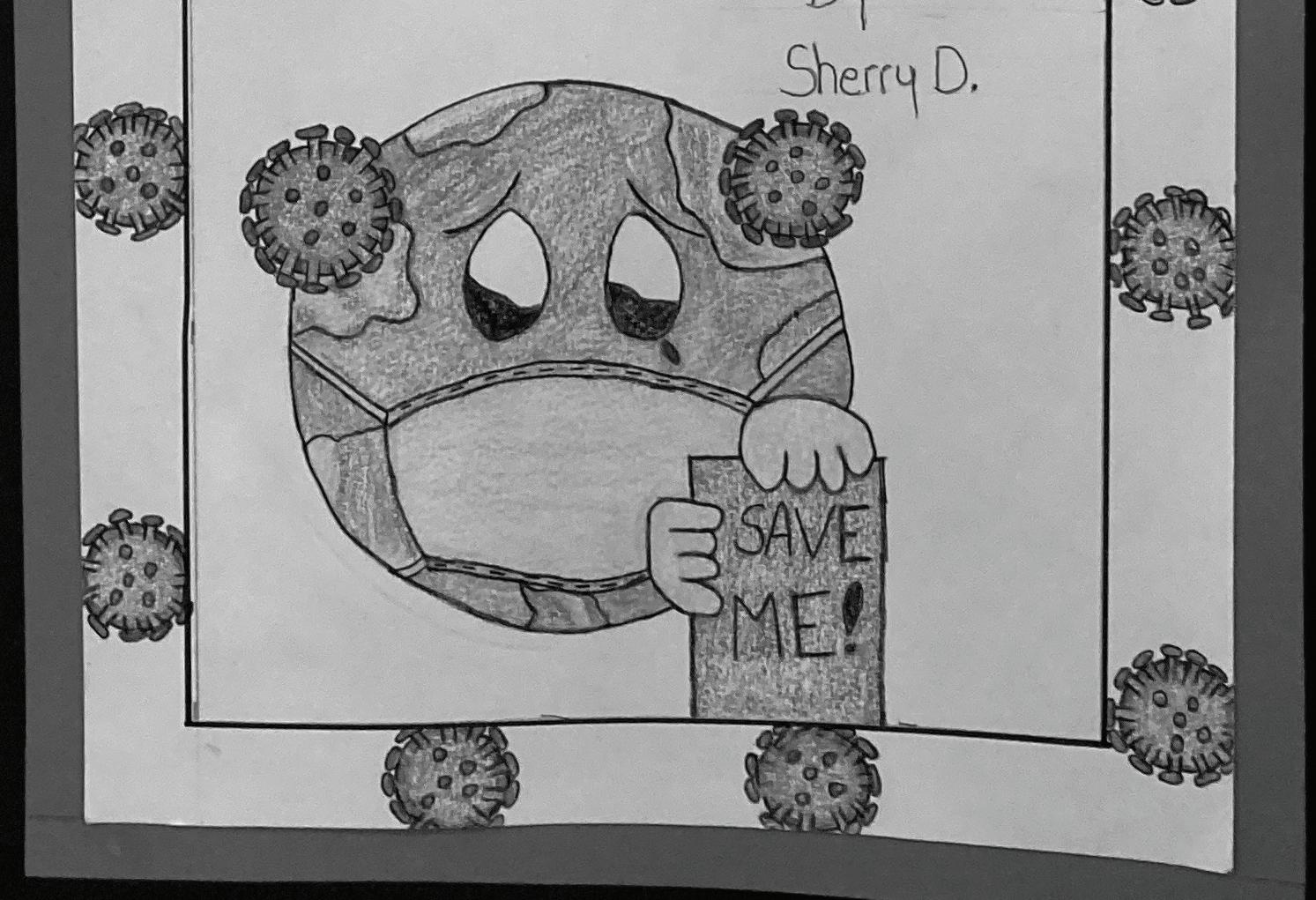

MONTPELIER – Some 2,800 individuals, including children, who have been housed at hotels during the COVID pandemic face losing shelter by July 1, leading to a contentious political battle over the state’s budget and its responsibility to keep a safety net in place.

In late May, the administration announced new steps to make the transition less abrupt, and

on May 30, the Vermont Legal Aid announced a lawsuit to attempt to block the evictions. Those actions leave many individuals with uncertainty about what may happen, and when.

A single mother with two children living in a hotel in Berlin, who identifies as a person who has experienced mental health challenges, has taken a leading role in gathering testimonials and sending them to legislators from others around the state feeling desperation about imminent homelessness.

“Many people are going to die, including myself and children,” Rebecca Duprey wrote. “Do people’s lives really mean that little to you? Continuing to fund housing while creating permanent housing will save

lives.” Duprey is one of five hotel residents named as class action representatives in the Legal Aid lawsuit.

The prospect of a massive surge of unsheltered Vermonters drove a group of legislators in the House to vote against the state’s budget for the coming year based on its failure to extend the emergency hotel program until alternative housing is found for current residents.

That could set up a further showdown if those legislators block a veto override vote on June 20. They wanted more money allocated to keep the motel program open until alternatives are in place, but the governor vetoed the budget saying it already spent too much, resulting in new taxes.

People with psychiatric disabilities are among those now facing a return to homelessness and some advocates have said that among the repercussions will be an increase in emergency room use. “They’re getting dumped, and [being told] ‘where you fall is where you fall,’” said Vermont Psychiatric Survivor Executive Director Walt Wade. VPS has been sending outreach staff

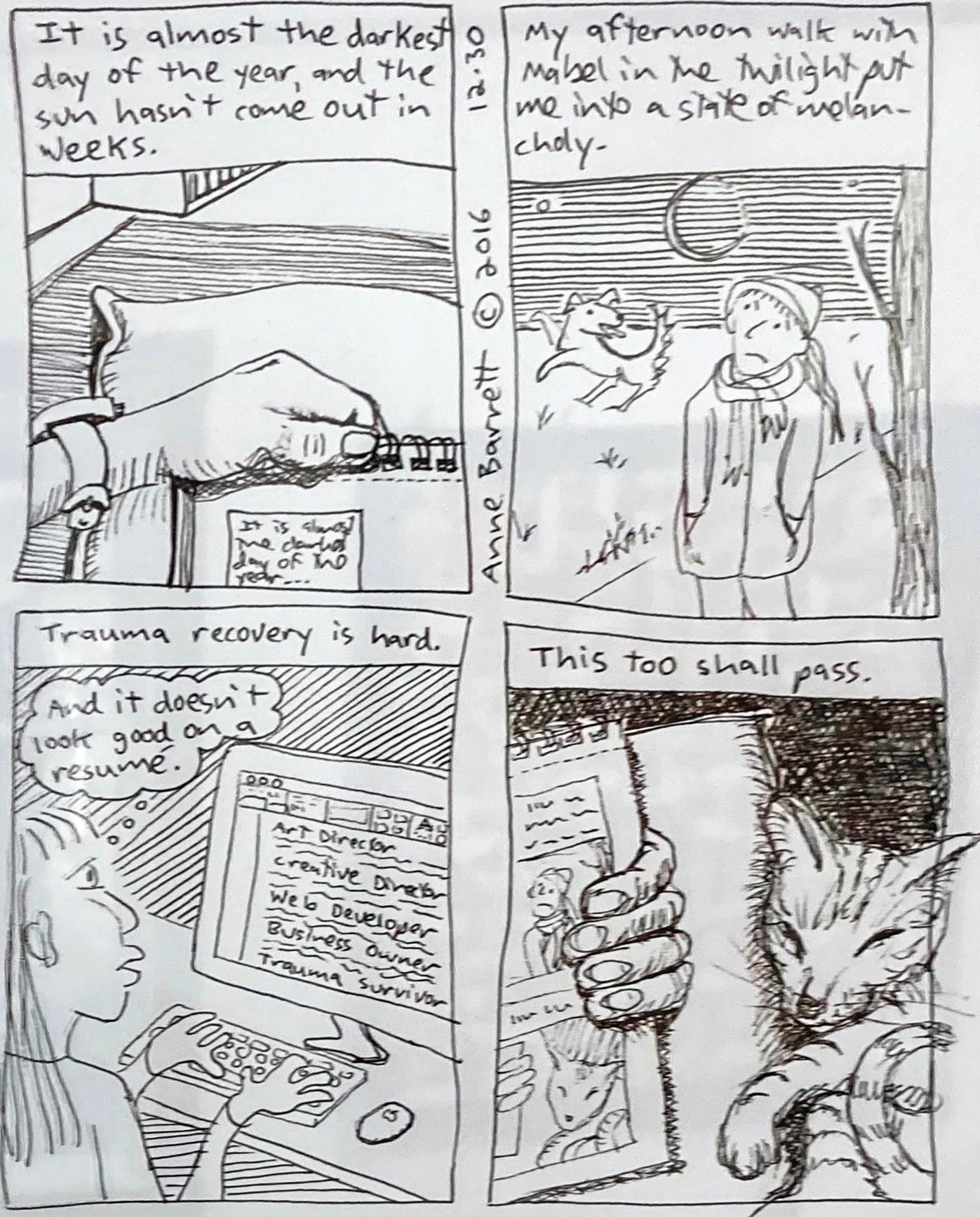

‘I’ve Got To Walk the Walk’

by ANNE DONAHUE

news, she is the consummate professional: composed, articulate, relaxed.

That reflects a large part of how she sees herself. As her high school’s class valedictorian and someone who “strives for perfection,” she said she was “taught as a woman and as a professional that [one] can be branded as weak or sensitive or outof-control” if feelings are exposed.

Guessferd knew the experience of being branded, because she was hospitalized several times in her high school and college years, diagnosed with PTSD and anxiety and living through wearing “the scarlet letter” as she walked through the hallways with her head down.

“I knew that everyone knew,” she said.

By 2018, with help from a course of dialectical behavioral therapy in college, Guessferd had pulled away from her symptoms and had entered the world of broadcast journalism, living her dream to be a writer and “tell people’s stories.”

Then COVID hit. Guessferd found herself reporting on how others were experiencing the pandemic but keeping her own challenges siloed away and wondering, “was I the only person to struggle?”

She found herself deeply depressed and unmotivated and felt she had lost the love of her job.

“Rock bottom is such a lonely place,” she reflected in her interview with Counterpoint. “At the end of the day, it’s you and yourself.”

Finally, one day, she walked into her boss’ office to say, “I can’t do this. I need help.”

She felt like a failure and was terrified she was going to ruin her reputation.

Instead, her supervisor offered her the potential of taking time off under the federal medical leave act, telling her it was “an option that you have a right to.”

That had never occurred to her.

“You think of a physical, debilitating condition” as the basis for a medical leave, Guessferd said, but that’s a misconception. The support from her work environment “was truly the cornerstone” for recovery.

She kept doubting the validity of taking the

(Continued on page 4)

BURLINGTON – When Christina Guessferd takes to the air as co-anchor on the WCAX nightly

NEWS, COMMENTARY, AND ARTS BY PSYCHIATRIC SURVIVORS, MENTAL HEALTH PEERS, AND OUR FAMILIES VOL. XXXVIII NO. 1 • FROM THE HILLS OF VERMONT • SINCE 1985 • SUMMER 2023 22 Editor Says Farewell 14 The Arts 5

VPS

New

Executive Director

Christina Guessferd, WCAX Reporter and Producer

(Photo by Anne Donahue)

Vermont Psychiatric Survivors Board Vice-President Zachary Hughes testifies before the House Judiciary Committee in April.

(Photo by Anne Donahue) (Continued on page 27)

Peer Leadership and Advocacy

Meeting Dates and Membership Information for Boards, Committees and Conferences

Peer Organizations State Committees

VERMONT PSYCHIATRIC SURVIVORS BOARD

A membership organization providing peer support, outreach, advocacy and education. Board meets monthly. For information call 802-775-6834 or email info@vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org.

COUNTERPOINT EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

The editorial advisory board for the Vermont Psychiatric Survivors newspaper can always use help! Assists with policy, editing and brainstorming on topics for articles. Contact counterpoint@vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org

ALYSSUM Peer crisis respite. To serve on board, call 802-767-6000 or write to information@alyssum.org

DISABILITY RIGHTS VERMONT PAIMI COUNCIL

Protection and advocacy for individuals with mental illness. Call 1-800-834-7890.

ADULT PROGRAM STANDING COMMITTEE

Advises the Commissioner of Mental Health on the adult mental health system. The committee is the official body for review of and recommendations for redesignation of community mental health programs (designated agencies) and monitors other aspects of the system. Members are persons with lived mental health experience, family members, and professionals. Meets monthly on 2nd Monday, noon-3 p.m. Check DMH website www.mentalhealth.vermont.gov or call-in number. For further information, contact member Daniel Towle (dantowle@comcast.net) or the DMH quality team at Eva.Dayon@vermont.gov

LOCAL PROGRAM STANDING COMMITTEES

Advisory groups, required for every community mental health center. For membership or participation, contact your local agency for information (listings on back page.)

Advocacy Organizations

DISABILITY RIGHTS VERMONT

Advocacy in dealing with abuse, neglect or other rights violations by a hospital, care home, or community mental health agency. 141 Main St, Suite 7, Montpelier VT 05602; 800-834-7890. disabilityrightsvt.org

VERMONT CENTER FOR INDEPENDENT LIVING

Peer services and advocacy for persons with disabilities. 800-639-1522. vcil.org

HEALTH CARE ADVOCATE To report problems with any health insurance or Medicaid/Medicare issues in Vermont 800-917-7787 or 802-241-1102. vtlawhelp.org/health

VERMONT CLIENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM

Rights when dealing with service organizations such as Vocational Rehabilitation. Box 1367, Burlington VT 05402; 800-747-5022.

NAMI-VT

Family and peer support services, 802-876-7949 x101 or 800-639-6480; 600 Blair Park Road, Suite 301, Williston VT 05495; www.namitvt.org; info@namivt.org

PEER WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE

Webpage provides an up-to-date account of statewide peer training and registration information as well as updates about its progress and efforts. www.pathwaysvermont. org/what-we-do/statewide-peer-workforce-resources/ MADFREEDOM

MadFreedom is a human and civil rights membership organization whose mission is to secure political power to end discrimination and oppression of people based on perceived mental state. See more at madfreedom.org

MENTAL HEALTH LAW PROJECT

Representation for rights when facing commitment to a psychiatric hospital. 802-241-3222.

ADULT PROTECTIVE SERVICES

Reporting of abuse, neglect or exploitation of vulnerable adults, 800-564-1612; also to report violations at hospitals/nursing homes through Licensing and Protection at (802) 871-3317

Hospital Advisory

VERMONT PSYCHIATRIC CARE HOSPITAL

Advisory Steering Committee, Berlin, check DMH website for dates at www.mentalhealth.vermont.gov

RUTLAND REGIONAL MEDICAL CENTER

Community Advisory Committee, fourth Mondays, noon, call 802-747-6295 or email lcathcart@rrmc.org

UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT MEDICAL CENTER

Program Quality Committee, third Tuesdays, 9-10 a.m., for information call 802-847-4560.

ACTIVE MINDS CONFERENCE

BRATTLEBORO RETREAT

Consumer Advisory Council, fourth Tuesdays, 12-1:30 p.m., contact Director of Patient Advocacy and Consumer Affairs at 802-258-6118 for meeting information.

CENTRAL VERMONT MEDICAL CENTER NEWLY forming. Contact counterpoint@vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org for more information. Every other month, 4th Tues, 11-12.

Conferences

Calling it “the nation’s leading mental health conference for young adults,” Active Minds will host its 2023 conference in Washington, D.C., July 7-8. For more information go to: www.activeminds.org/programs/national-conference-2023/speakers/

ABCT 2023 CONFERENCE

The Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT) 2023 conference will be held November 16-19 in Seattle. Its theme is “Cultivating Joy with CBT [Cognitive Behavioral Therapy].” For more information, go to: www.abct.org/convention-ce/

NARPA 2023 CONFERENCE

The 2023 conference of the National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy (NARPA) will be held in New Orleans September 6-9. For more information, go to: narpa. org/conferences/narpa-2023/ Conference Keynoters include Ira Burnim, J.D., Director, Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law; David Cohen, Ph.D., Professor and Associate Dean, Luskin School of Social Work, UCLA; Working for Racial Justice and Equity: panel presentation led by Kwamena Blankson, J.D., NARPA President; Innovative Non-Police Responses in Crisis Situations, group presentation; Robert Dinerstein, J.D., American University Washington College of Law, Annual updates on recent cases affecting disability rights/mental health law.

VT Psychiatric Survivors, 128 Merchants Row Suite 606, Rutland, VT 05701

Phone: (802) 775-6834

email: counterpoint@ vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org

MISSION STATEMENT:

Counterpoint is a voice for news and the arts by psychiatric survivors, ex-patients, and consumers of mental health services, and our families and friends.

Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved

FOUNDING EDITOR

Robert Crosby Loomis (1943-1994)

EDITORIAL BOARD

Kara Greenblott, Zachary Hughes, Joanne Desany, Sara Neller, Laura Shanks

The Editorial Board reviews editorial policy and all materials in each issue of Counterpoint. Review does not necessarily imply support or agreement with any positions or opinions.

PUBLISHER

Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, Inc.

The publisher has supervisory authority over all aspects of Counterpoint editing and publishing.

EDITOR

Anne B. Donahue

Brett Yates, Co-Editor

Opinions expressed by columnists and writers reflect the opinion of their authors and should not be taken as the position of Counterpoint

Counterpoint is funded by the freedom-loving people of Vermont through their Department of Mental Health. Financial support does not imply support, agreement or endorsement of any of the positions or opinions in this newspaper; DMH does not interfere with editorial content.

Counterpoint is published by Vermont Psychiatric Survivors three times a year, distributed free of charge throughout Vermont, and also available by mail subscription. Vermont Psychiatric Survivors is an independent, statewide mutual support and civil rights advocacy organization run by and for psychiatric survivors. The mission of Vermont Psychiatric Survivors is to provide advocacy and mutual support that seeks to end psychiatric coercion, oppression and discrimination. Counterpoint does not use pseudonyms in its reporting without stating that a pseudonym is being used and without an explanation for why the person’s identity is not being disclosed. Counterpoint does not use anonymous sources under any circumstances.

Department of Mental Health

802-241-0090

www.mentalhealth.vermont.gov

For DMH meetings, go to web site and choose “more” at the bottom of the “Upcoming Events” column.

ADDRESS: 280 State Drive NOB 2 North Waterbury, VT 05671-2010

c Enclosed is $10 for 3 issues (1 year).

c I can’t afford it right now, but please sign me up (VT only).

c Please use this extra donation to help in your work. (Our thanks!)

Checks or money orders should be made payable to “Vermont Psychiatric Survivors.” Send to: Counterpoint, Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, 128 Merchants Row, Suite 606, Rutland, VT 05701

Access Counterpoint online at www.vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org

Fall 2018

2

Don’t Miss Out on a Counterpoint!

NAME ADDRESS CITY • STATE • ZIP Mail delivery straight to your home — be the first to get it, never miss an issue.

-

VERMONT MAD PRIDE is a march and celebration organized by psychiatric survivors, consumers, mad people, and folks the world has labeled “mentally ill.”

MAD PRIDE is about shedding shame, challenging discrimination, advocating for rights, affirming mad identities, remembering and participating in mad history, and having fun. Our lives and contributions are valuable and need celebration!

DATE: July 15, 2023

TIME: 1 PM - March 2-4 PM - Program

LOCATION: Battery Park

Burlington, VT

SPEAKERS (TO DATE):

ROUTE: Assemble at Hood Plant parking lot on King Street, between S. Winooski Avenue and Church Street and march to Battery Park.

PROGRAM: Spoken word, music, speeches, and more; Food and commemorative T-shirts provided

For more information: info@madpridevermont.org

Fall 2018 NEWS . 3 Summer 2023

Sera Davidow Director, Wildflower Alliance Bob Whitaker Author, Mad in America

Wilda L White Founder, MadFreedom

I’VE GOT TO WALK THE WALK • Continued from page 1 time for something that no one could see. “You can feel a lot of shame. It’s misplaced shame.”

It was her colleagues who told her, “You deserve it, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.”

And it was the company’s Human Resources department that focused on what their employee needed, and why.

“What do you need from us?” they asked; “Take what you need.”

Going to her boss was really hard, she said. “It was scary.”

She feared the response would be, “you’re fired.” But Guessferd now reflects that “if that was how they handled it, I wouldn’t want to work here.”

She took 12 weeks off in all, six to center herself while on a waiting list for treatment, and then an intensive six-week course of DBT.

She was encouraged by her therapist, who told her, “What you need is more than what I can give,” and she recognized that she had lost what she had gained in the DBT skills she had learned in college.

“I was not exercising that muscle,” she said. She needed to “give myself the grace to take a breather and not feel I failed.”

Did she feel labeled by taking that time, as she had in her school years?

“At first, I did,” Guessferd said. But then she decided to write a public tweet to share her experience. She opened it by saying, “You may not have seen me on air” recently.

As a long-time mental health advocate, Guessferd said she recognized that “if I’m going to talk the talk, I’ve got to walk the walk.”

She believes in living with transparency, and if she expects others to ask for help, “I can do my part to let them know they are not the only one” by making her story public. Just because “you view the world a little differently” shouldn’t be a basis for discrimination, she said.

One of her transformational moments was when she started the DBT and, as she poured her heart out, received the advice that she should reconsider her diagnosis.

She looked at the list of symptoms for borderline personality disorder and found it resonated. “I have never felt so seen,” she said. It was “a day and a moment that I’ll never forget” because recognizing a diagnosis takes its power away. Rather than controlling her, she sees it as just one part of who she is.

The “white noise” may still be in her brain, causing “shame – guilt – fear – doubt,” and while “you can’t silence those thoughts,” you can analyze their validity. When her brain is leading her toward catastrophic symptoms, like “I’m blowing up my life,” she has learned to say, “I see you. Now go away.”

Guessferd said she has “learned to embrace and celebrate my mental illness and consider it my superpower,” because the so-called negative traits are also “part of what makes me, me.”

That is someone who is empathetic, compassionate, and fiercely loyal, with strong convictions, and who takes accountability for herself, she said.

Her ongoing challenge is making the

distinction between “who’s Christina the human being” and “who’s Christina the journalist,” telling the stories of other people without “losing my identity in the process.”

She “doesn’t want to sacrifice professionalism” by bringing her personal feelings or her own strong personal convictions into stories and needs to “navigate a career with the traits of myself that can be to my detriment,” she said. She fears that recognizing her “me” could influence her perspectives as a journalist, yet, “you can’t ignore what you are feeling.”

care of yourself” and be able to communicate one’s needs to others. Guessferd said that she works on how to “balance the formula” between therapy, medication and taking that time needed for self-care. She said she’s “baking with [that] recipe every day.”

Mental health also requires having empathy for others and understanding that every person is carrying their own story. It means needing to see that “everyone’s doing the best they can.”

Classmates who were mean to her in high school and college days, calling her “crazy” and “psycho” were too young to “have that wisdom to understand.”

It was her boss who told her she didn’t need to make that sacrifice, she just needed to “respect every other opinion out there” as well. He told her, “I never want to stifle that creativity” that makes her so good at what she does, Guessferd said.

Guessferd believes that her journey also taught her employer “the urgency of every employee taking care of themself.”

Putting oneself out publicly as a journalist makes one subject to criticism, so taking care of employees is crucial, she said.

It is a trend she sees starting in the larger society, as companies experiment with ideas on how to support their employees and begin to recognize that doing the best for one’s employees is also “doing what is best for the business.”

Guessferd said she has come to recognize that living with an illness is okay; it “makes you who you are. You can walk tall.” Developing the tools to do so can be painful, because one must “dig deep into the place you didn’t want to go.”

Instead of putting bandaids on a wound, it requires “cleaning out the wound – that’s painful,” she said. She remembers “being so scared of how much it’s going to hurt.” But in pulling away the bandaid, she said she found herself. It enables one “to be able to thrive as opposed to just surviving.”

“My job for my health is to make sure I have those tools” and to recognize that mental health requires that “you must carve out time to take

After one college episode in which she took off from the school and was picked up by ambulance to be taken to the hospital, the school conditioned her pending study abroad application on her taking DBT – which was highly positive for her.

But it also meant she was rejected by many friends who said, “I can’t deal with you anymore.” In the future, “I would hope they would ask questions instead of judging.”

Only two classmates were willing to ignore her “rumored reputation” and “would not let that taint their view of me.” They helped change her life and they remain best friends.

Guessferd said her experience with discrimination shows it can frequently be subtle: a doctor dismissing concerns about medication side effects, or family members saying someone is spoiled.

“It’s ingrained in us, that the pain of breaking a bone is more real.”

But she sees hope in the way society is talking more about mental health and with the help of science, the impact of mental health on physical health is being recognized.

Guessferd’s plea to others now is that if someone in their life is struggling, “Don’t just say you support them. Prove it.”

“Practice compassion, because if you practice judgment, it will escalate,” while compassion “will stay with you forever.”

Treat them “not with pity but as a human being,” she said. “You don’t have to talk with them about it,” Guessferd said. “Just be there.”

She likened it to holding one’s arms open and saying, “You don’t have to come in here, but you can if you like.”

Fall 2018 NEWS 4 Summer 2023

When her brain is leading her toward catastrophic symptoms, like “I’m blowing up my life,” she has learned to say, “I see you. Now go away.”

Christina Guessferd on a nightly news edition on WCAX in Burlington.

Counterpoint has a public comment section online! You can respond to any of our articles on our Wordpress at www.vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org/counterpoint-articles/ !!!!!! WOW! Did you know?

(Photo by Anne Donahue)

ED Looks To Increase Advocacy

by ANNE DONAHUIE

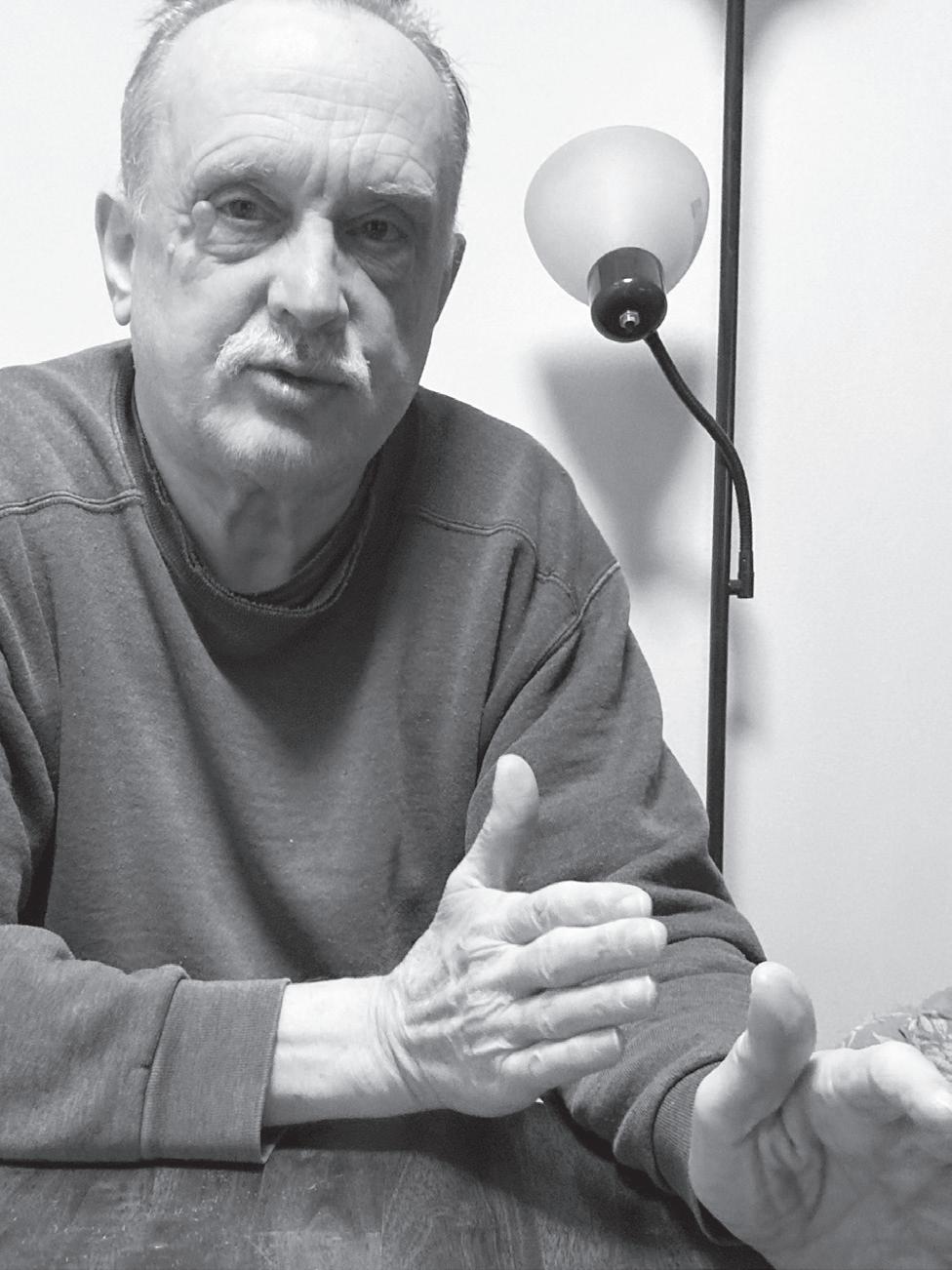

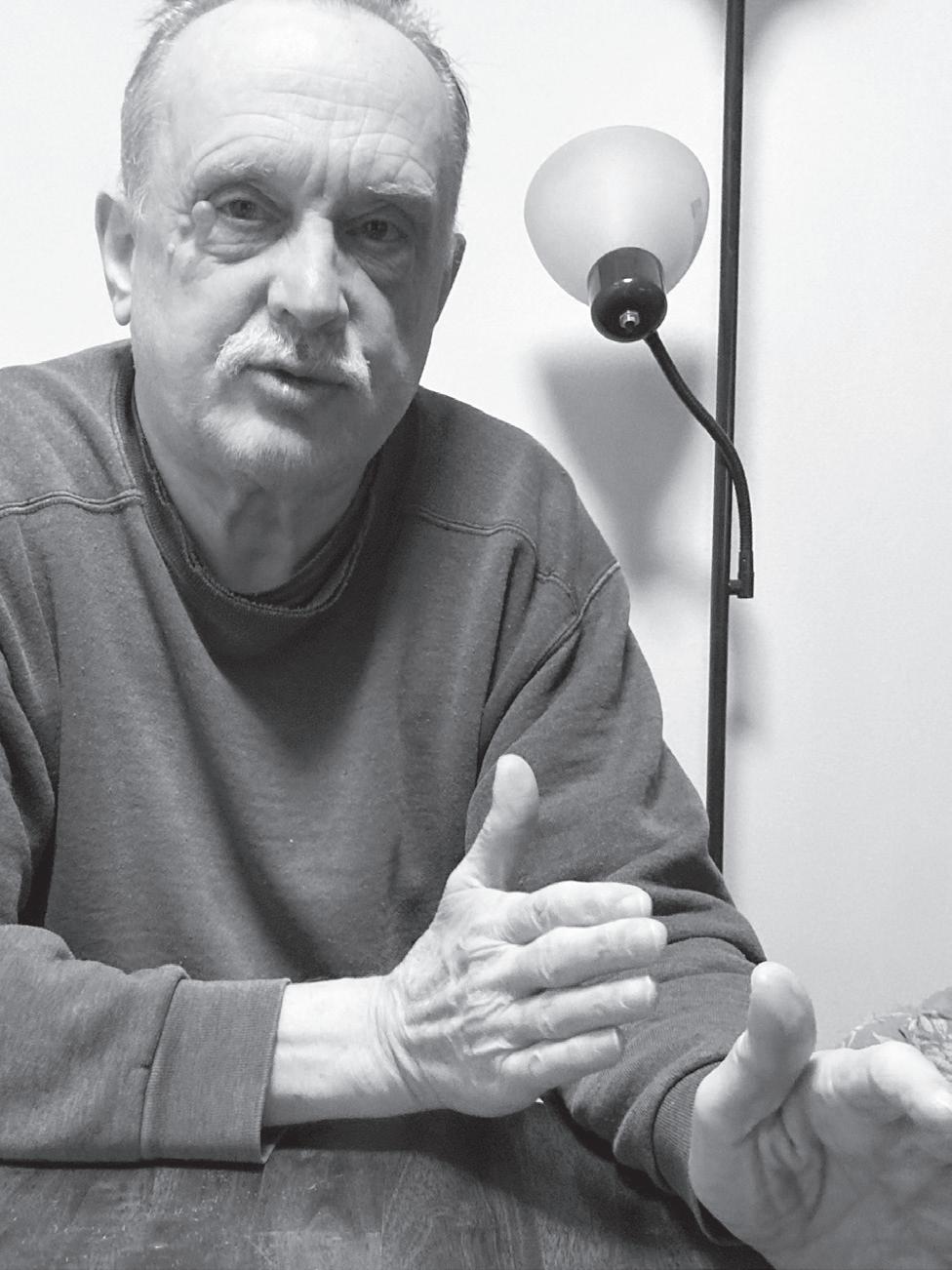

RUTLAND – Walt Wade, a longtime advocate for youth and those with addictions who joined Vermont Psychiatric Survivors in 2020, has been named its new Executive Director.

He said his vision is “making VPS the agency that it should be” that “advocates [for] and protects people who can’t help themselves right now.”

“I remember being there,” he told Counterpoint. Counterpoint is published by VPS.

Wade identifies as a survivor who has been “through a whole life and all phases of addiction.”

There was a time in his life that he said he didn’t care about anyone else.

It was on March 12, 1982 that a moment in time changed his life. He went to drink at his usual bar and saw three men sitting at the same three seats where they sat every single day.

“Wow, that’s going to be me.”

He called the AA hotline. He is now 41 years sober. At the same time, he went from “taking advantage of everybody” to becoming “driven to help other people.”

“It was so strange to me,” he said.

Since then, he and his wife have been foster parents for some 40 years and adopted four of the teens who were in their care.

One of them died three years ago of an overdose, bringing the addiction crisis home once again.

Foster care started when he was asked to “do a favor” and take in a youth in crisis who needed a place for the weekend. Seven months later, he was still there.

“Our house was wild,” with as many as seven teenage boys living there at one time in a crisis placement. The youngest was nine, and he was one of the boys that Wade and his wife, Mary, adopted at age 13.

For 19 years, Wade worked for Rutland High School as the in-house suspension supervisor –a job he said he loved. “It was all the kids who acted like me” when he was younger, he said.

Meanwhile, he got his bachelor’s degree in human services.

In 2020, two weeks before the COVID pandemic closed down the state, Wade started a new job as the peer support outreach coordinator at VPS. Because everything changed with COVID, and hospitals were no longer accessible for offering peer support, the position lost its clear focus.

“COVID kind of changed what we did,” he said. Wade ended up taking on assorted roles helping with the VPS community links project in Rutland and with supporting individuals staying in the emergency hotel program.

“It has been eye-opening,” he said. “The thing I found… we had many, many people that were going to get left out” once the emergency ended. The resources now available don’t match with the needs of those who will be losing their hotel placements when the budget ends on July 1.

That crisis will require agencies around the state to work together to build a stronger system, and Wade wants VPS to become an active part of collaboration.

He wants to “show them that I care what we do as an agency and as a state… advocating for people in the state who are having a hard time.”

He told her how proud he was of her, and she started crying. “No one’s ever told me they were proud of me,” she said.

The challenges are harder when also dealing with the stigmatization of people with mental health diagnoses, Wade said, and he wants to make people more aware of those obstacles. VPS has an opportunity to make a difference for them, he added.

The staff at VPS all “know what it’s like to feel hopeless [and] looked at like ‘less than.’”

“It just kills me to see someone doing so well” and then see symptoms “kick up” but being unable to get help because of waiting lists.

Wade said it used to take several calls to connect someone with help, but now, even after eight or nine calls or more, he might still be unable to find the right services.

VPS is now getting back into hospital units to offer peer representative support, and there’s a lot of need to rebuild relationships, Wade noted. Staff have changed on both sides, and many of the nursing staff are “travelers,” meaning they are hired under temporary contracts.

“They have no clue” what VPS patient representatives are, he added.

VPS needs to rebuild its advocacy role as well, Wade said.

“We need to be in the middle of it,” he said. “You may help one person,” but that means there are likely 100 more facing the same challenges.

Wade said that includes being a voice in the legislature. The VPS board vice president, Zachary Hughes, began testifying this spring on critical rights issues.

An example Wade pointed to was a bill that would allow people who are waiting for care in an emergency department to be arrested if they get out-of-control.

“Nobody deserves to [go to] work and get hit and spit at,” he acknowledged, but people in a mental health crisis “are not their real selves” and “we’re punishing them.”

Wade pointed to one of the personal experiences he had doing outreach in being able to see what is possible.

Through another contact, he learned about a young woman who was sleeping in her car with her 5- and 7-year-old daughters in November. She was too afraid to ask for help out of fear that the Department of Children and Families would take the girls away from her.

Wade told her, “If you let me help you, they’re not going to take your kids.” He got her into a hotel, and she was able to find part-time work.

“She’s an excellent, excellent mother,” he said. “I believe she’s going to make it.”

He wants VPS to advocate “where people with mental health [labels] are getting shortchanged.” If the legislature “is making a law that hurts people, how is that ever right?”

He wants VPS to be an agency that “helps make laws that help” instead.

“People shouldn’t be punished for having a mental illness,” he noted.

Another example is the number of additional locked beds being added to the system, including plans for a new forensic unit.

That kind of planning is “probably because it’s easier” than building a stronger system of community supports, he reflected.

But, “how does it help?”

VPS Blocks Change to Law on Consent

MONTPELIER – A move to allow an advance directive to be explained remotely instead of in person was dropped by a legislative committee after testimony by Vermont Psychiatric Survivors.

The legislation addressed a type of advance directive that allows a person to lock themselves into a decision and forgo the right to object to a treatment if they are later found incompetent. Otherwise, laws require a court hearing to impose involuntary treatments.

The bill in the House Human Services Committee would have made permanent the current COVID exception, allowing remote witnessing for regular advance directive.

It proposed for the first time that the special “Ulysses clause” to allow treatment over objections – which requires added protection for witnesses and assurances that the person understands the decision – could be completed remotely as well.

Zachary Hughes, vice president of the board of VPS, said that the decision that is being made in those cases is so important, the in-person requirement should remain.

“It’s handing over power,” he said. “It’s about power. It’s about trust.”

The committee’s chair, Rep. Theresa Wood, responded by saying that his testimony was an example of how sometimes “a few short minutes

and a few short words can change one’s mind.”

She and some other members of the committee had expressed potential openness to make the change.

Immediately after Hughes’ testimony, Wood polled the committee, and the proposal was unanimously removed from the bill.

The Ulysses clause can be used by anyone writing an advance directive, but has generally been focused on being available to persons with a diagnosis of mental illness who might want to ensure they can receive a treatment in the future despite objecting after being found not competent to make a decision.

The bill is now in the Senate.

NEWS . 5 Fall 2018 NEWS Summer 2023 5

Walt Wade

His vision is “making VPS the agency that it should be” that “advocates [for] and protects people who can’t help themselves right now; where people with mental health [labels] are getting shortchanged.”

State Expands Urgent Care Sites

by BRETT YATES

WATERBURY — Projects intended to keep Vermonters out of emergency departments during mental health crises are coming to nearly every part of the state.

Of the 12 submissions generated last year by the Department of Mental Health’s request for proposals for mental health urgent care services, eight will receive funding, including seven brand-new programs.

Iterations of three different models of crisis care will move forward: psychiatric urgent care clinics (“PUC” or “PUCK”), community crisis centers (“Living Room”), and crisis response teams (“CAHOOTS”).

Using time-limited federal dollars, DMH has awarded grants to six of Vermont’s community mental health centers – Counseling Service of Addison County, Washington County Mental Health Services, Health Care & Rehabilitation Services of Southeastern Vermont, Lamoille County Mental Health Services, United Counseling Service, and Howard Center – and to the Burlington Police Department.

There is no clear plan yet as to how the programs will be sustained after the two-year federal grants expire in 2025.

CAHOOTS Model

Per city documents, BPD’s CAHOOTS-style crisis team will allow mental health clinicians and EMTs to “intervene in crisis situations where armed law enforcement is not necessary.”

Burlington allocated $400,000 for the program in its municipal budget for fiscal year 2023 and subsequently applied to DMH for funds to cover the difference between that sum and the estimated annual cost, between $800,000 and $950,000 in total.

The concept comes from Eugene, Oregon, which called it Crisis Assistance Helping Out On the Streets. Now labeled “Burlington CARES,” the model does not involve peers.

“After this two years, the city intends to fund this on their own, so we kept the model as it was as a whole,” DMH Deputy Commissioner Allison Krompf said.

Last year, the city’s plan included references to “qualified mental health professionals empowered to require emergency evaluations,” which serve to begin the process of involuntary hospitalization. At the time, Burlington expected to contract Howard Center, which employs QMHPs, to run the program. More recently, however, the city decided to manage the program in-house instead. That led DMH to “go back” and look at the proposal again, Krompf related.

“We want the person who’s responding to know what the threshold is for involuntary hospitalization, but we are not going so far now as to say that... they on their own could go out to the community and involuntarily hospitalize somebody,” she clarified. “So we did [tell] the Burlington PD that we wouldn’t authorize them in this program to be doing that.”

Urgent Care Model

PUC stands for Psychiatric Urgent Care, and PUCK stands for Psychiatric Urgent Care for Kids. These programs provide assessments by Masters-level clinicians, crisis de-escalation, and access to psychiatric consultation, according to Krompf. They can also

treat co-occurring medical needs of mild to moderate severity. Despite the model’s “clinical” focus, it “still comes with a space that’s much more well suited for people in a mental health crisis” than an emergency room, Krompf said.

DMH “has asked and required that there be peer supports” at each clinic, she noted, and those accepting pediatric patients will have “sensory spaces.”

“If you have a child or even an adolescent who’s really having a difficult time, putting them in a space where they can’t touch anything, and if they do, they can get in trouble… it’s just really tough,” Krompf said.

Pathways Vermont submitted a response to DMH to create a peer-run respite center but Krompf said that it didn’t meet the federal criteria for funding.

“We are really interested in finding a way to move that forward. We couldn’t use this bucket of money,” she said.

Living Room Model

The Living Room model, coming to Addison County and Washington County, intends to create a warm, homelike environment for patients. In DMH’s vision, this works to promote “autonomy, respect, hope, empowerment, and social inclusion.”

DMH said launch dates may vary by program.

UCS has run a PUCK clinic in Bennington since 2019. Its DMH grant will support the hiring of full-time staff and expanded operating hours, including evenings and possibly Saturdays, likely by July or sooner, per UCS.

According to UCS Executive Director Lorna Mattern, PUCK has “decreased emergency room utilization for children between 33% and 40%” in its catchment area.

“When kids would get picked up, often from school, by the police, they didn’t have anywhere else to go, and so they would often, if not always, end up in the emergency department. And I think what PUCK showed the state and funders and others is that we can create alternatives,” Mattern said.

“We can provide trauma-informed, familyfriendly, kid-friendly environments and still respond to a mental health crisis and help stabilize and keep them in the community.”

Howard Center’s PUC clinic in Burlington will serve adults only.

Krompf characterized the proposal as a collaboration that also included the University of Vermont Medical Center and the Community Health Centers of Burlington.

The University of Vermont Health Network is expected to be contributing about $8 million toward three years of operating costs and the initial space renovations to fill a funding gap beyond the DMH grant.

That money is part of a proposal for reuse of reserved funds that still needs approval by the Green Mountain Care Board. According to a submission by the health network, the DMH grant covers only $1.6 million over two years, while three years of operating costs will total about $7.65 million.

Psychiatrists and peers will work together in what Krompf called a “multidisciplinary team approach” for “person-centered care.”

“When someone enters that space, there isn’t some prescription of, ‘Oh, you get exactly this,’” she described. “There’s a peer involvement that says, ‘What are you looking for? What are your goals, and how can we support you?’”

Launch dates for the new urgent care services may vary by program.

“Each proposal has a different timeline,” Krompf told the House Committee on Health Care in May.

“But the money that we have to spend on this needs to be expended by 2025. So, if that gives you an indication – we aren’t looking for a twoyears-out implementation. These are things that had dates within six months, nine months.”

Anticipating a future need for state dollars, legislators asked whether DMH had a plan in mind for how to pay for the programs in the long term.

Krompf told them that “the leaders on this, in terms of funding, are well aware that they’re putting things in motion to serve the population for mental health urgent care that don’t have sustainable funding, and I do think some of this is going to be a need for CMS and Medicaid to acknowledge that.” But “Medicaid can’t pay for all services for everyone,” she added.

Northeast Kingdom Human Services’ project did not qualify for the special federal funding because it proposed to offer patient stays longer than 24 hours, so DMH asked the legislature for an allocation from the state’s general fund.

Its proposed Front Porch Crisis Care treatment center will offer four to six crisis beds in the region of the state that has fewer than any other. Stays will range from two to ten days.

For same-day services, NKHS Executive Director Kelsey Stavseth described a plan that would incorporate aspects of both PUC(K) and the Living Room, with “access to nursing, psychiatric, and medication management services” on a “walk-in” basis within a “therapeutic environment” featuring peer support.

NKHS will need to buy a new building to house the program, which it will develop in a phased approach that will, however, allow some components to start up within its existing facilities.

Stavseth noted in February that a realtor had already identified some potential candidates for a new property, which, “for staffing access,” would preferably lie within the I-91 corridor, no more than an hour’s drive for patients from Orleans, Essex, or Caledonia County.

NEWS 6 Fall 2018 NEWS 6 Summer 2023

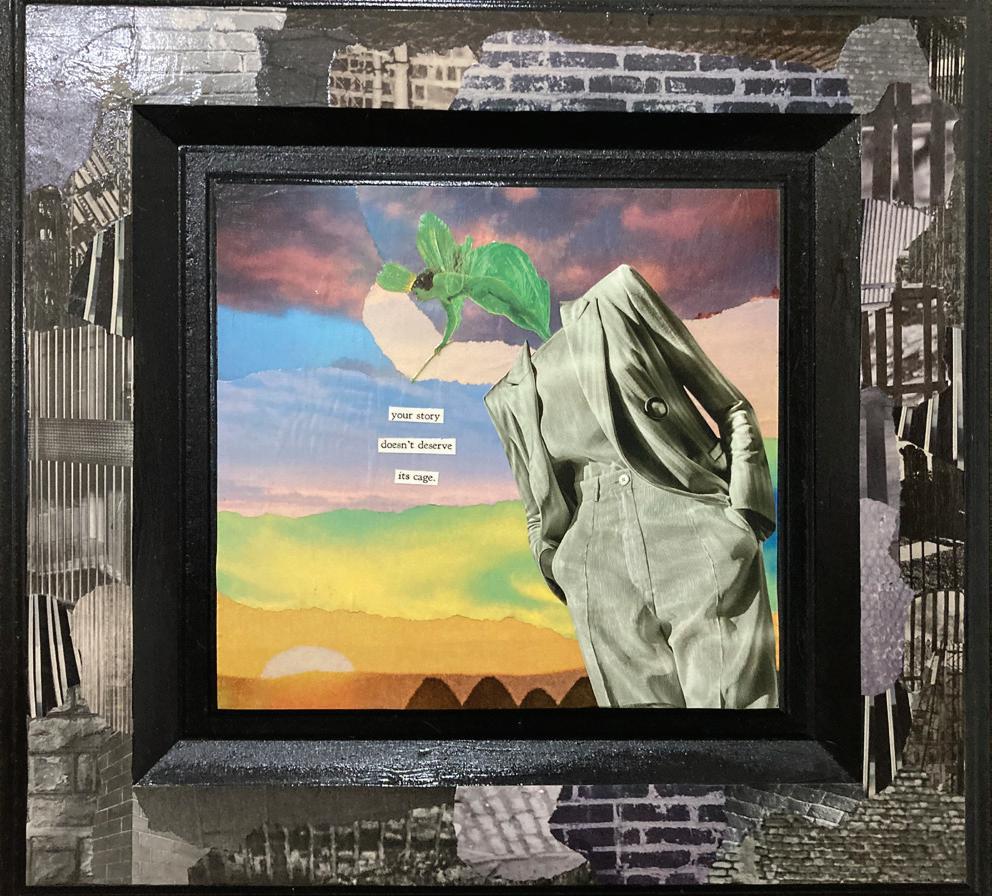

(Photo by Nik Shuliahin, Unsplash)

Mobile Crisis To Go Statewide

by BRETT YATES

WATERBURY – The Vermont Department of Mental Health expects to launch a unified statewide mobile crisis response service this year. It follows a 13-month pilot program in Rutland which had to limit operations due to challenges recruiting workforce.

DMH selected Healthcare & Rehabilitation Services, the community mental health center for Windham and Windsor counties, as its vendor. HCRS will subcontract Vermont’s nine other community mental health centers, creating a unified system for the entire state.

Deputy Commissioner Allison Krompf told legislators that “the go-live date is set for Sept. 1,” but HCRS leadership was not clear whether that would be possible. Contract negotiations between DMH and HCRS have not yet concluded.

Last year, the legislature mandated that the mobile crisis response program incorporate peer support workers.

“Having people with lived experience being able to be deployed is a really important theme as we roll this out,” Chief Operating Officer Anne Bilodeau said.

According to DMH, each two-person mobile response team will have at least one clinician. A peer can fill the other role but, by HCRS’s account, may not always do so. “It will be flexible,” Karabakakis said. “In many cases, the response will be based on what the family or what the individual needs. Oftentimes they might be working with a case manager who really knows the individual, who really knows the family, and they might be that second person.”

In testimony before the House Committee on Health Care, Rutland Mental Health Services Director of Emergency Services Loree Zeif

wondered where the needed employees would come from. “While I support this two-person initiative,” she said, “I cannot imagine how we will staff it.”

Zeif suggested that it would “cost many more

request for proposals last year that offered a maximum of five DMH contracts to serve 10 catchment areas throughout Vermont. Its executives characterized the proposal as a statewide collaboration.

“There were other options, like maybe taking regional approaches, but I think in the end we all agreed that, if we worked together, HCRS would be the lead,” Karabakakis said. “I met with all the executive directors for many hours to really sort of flesh this out.”

times what the state has anticipated to provide the level of service we’re looking at.”

In May, the legislature allocated $422,812 to fund four new positions within DMH to oversee the program, which is intended to reduce strain on emergency departments by sending mental health workers into homes and communities at callers’ request.

“We’re hopeful” about the timeline, HCRS Executive Director George Karabakakis told Counterpoint. “If we really want to operationalize this and make this happen in a successful way, we need to have that date reflect the reality of what’s on the ground, so we’re in the process of discussing that.”

“I would just say that there is a lot of complexity to creating a statewide initiative that involves saving lives in crisis situations,” Bilodeau added. “And we want to be particularly thoughtful and caring to make sure that everyone has the staffing that they need and those staff are trained and that we have the right protocols in place.”

HCRS submitted the only response to a

Each of Vermont’s community mental health centers already offers emergency services, for which DMH data indicates rising demand. But capacity varies, and in DMH’s telling, none can currently provide mobile outreach at all times. The new program will standardize practices in accordance with requirements set by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which include an obligation for 24/7/365 readiness. Special CMS funding will help bolster the program for a three-year start-up period.

“You shouldn’t have to worry about which [community mental health center] it’s attached to. It’s just mobile crisis response,” Krompf said. “And at some point, it may be able to be dispatched through 988, which would even provide a centralized number.”

Per a DMH report, the youth-oriented pilot by RMHS “experienced significant workforce challenges,” reducing operations to 40 hours a week. “It’s clear to us that there’s a vacancy issue in existing programming,” Krompf told Counterpoint. “It’s clear to us that any expansion will also have to manage the fact that there’s a staffing crisis. So the hopeful news is that not all of this has to be brand new. There’s ways to take existing resources and leverage them.”

‘Soft Restraints’ Required of Police

by BRETT YATES

by BRETT YATES

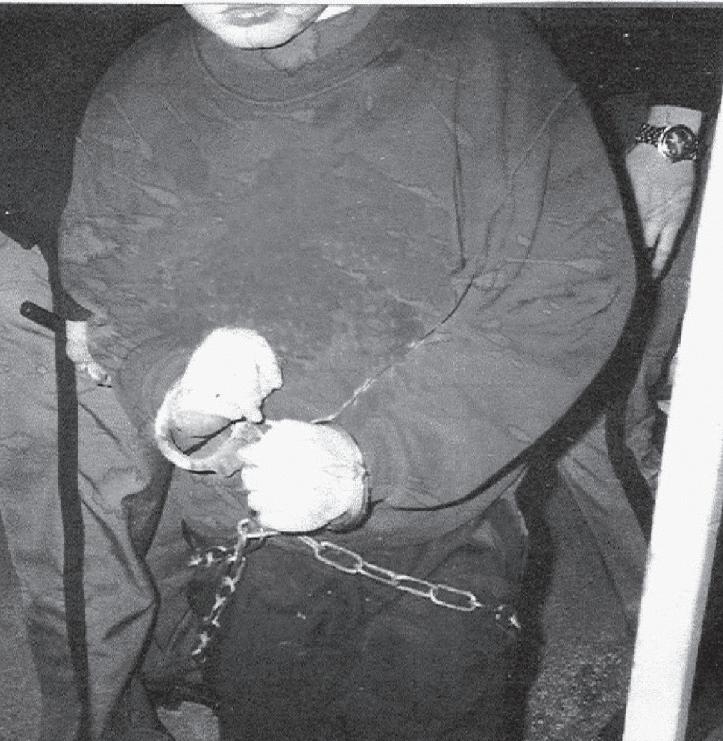

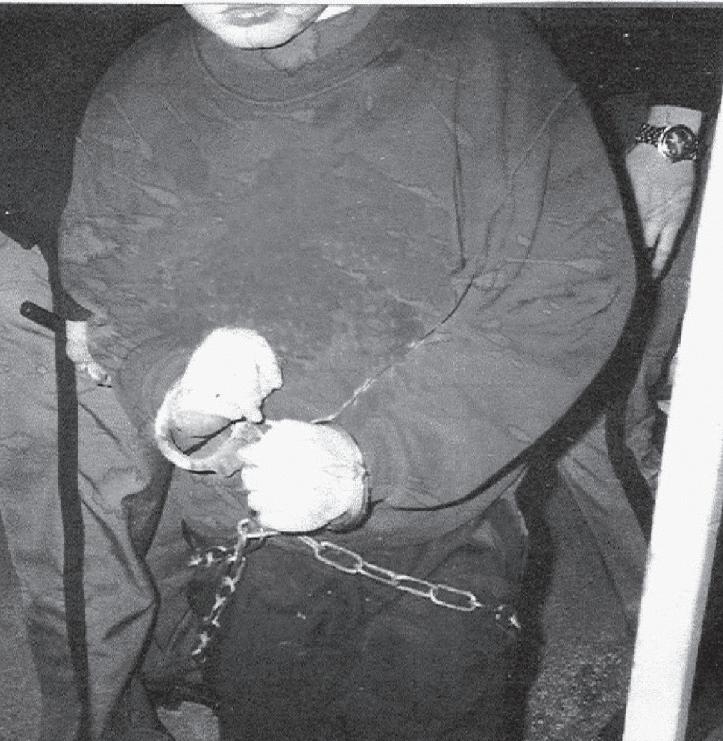

MONTPELIER – Starting in July, police cruisers throughout Vermont will have to carry “soft restraints” for transporting individuals after responding to a mental health crisis.

These devices, with fabric resembling that of a seat belt, will offer an alternative to “mechanical restraints” such as metal handcuffs. A new law specifies that officers will use soft restraints “as a first option” for these passengers when restraint is deemed necessary for safety.

The requirements also extend the same criteria that have been in effect for sheriff transports since 2005 to all law enforcement. Those include avoiding physical and psychological trauma, respecting privacy, and using means that are the least restrictive necessary for the safety of the patient. That 2005 law was passed as a result of advocacy by Vermont Psychiatric Survivors after hearing from the parent of a young boy who was taken to the Brattleboro Retreat by sheriffs in wrist, ankle and waist shackles.

The overall new bill focused on the transportation of individuals who have been taken into the temporary custody of law enforcement based upon a finding that the person presents an “immediate risk of serious injury to self or others.”

The legislation made several other changes to the procedures by which a person can be brought unwillingly to healthcare facilities for an emergency examination to be hospitalized against a person’s will. Sen. Ginny Lyons introduced the bill following several months of

meetings organized last year by Vermont Care Partners, the umbrella organization for the state’s community mental health centers.

The workgroup, which included representation by Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, examined the statutes that govern involuntary interventions during apparent mental health crises that take place outside of medical settings.

In the absence of a physician who would certify the need to hold the individual in advance of potential inpatient admission, a Superior Court judge’s warrant is the alternative authority.

State law previously allowed a police officer or a mental health professional to take a community member into custody and transport them to a hospital only if such a warrant was granted. The revisions to the law will now allow the forced transport to take place as soon as the warrant is applied for.

Lawmakers added language drafted by Jack McCullough of Vermont Legal Aid’s Mental Health Law Project. He described a growing problem of judges permitting involuntary interventions based on inaccurate secondhand information. Warrant applications must now rely on the applicant’s own observations unless accompanied by a signed statement of facts from another source.

Through the bill, Vermont Care Partners said it hoped to shift more of the responsibility for the warrant and court-ordered transport onto police officers specifically, citing fears of physical harm among its agencies’ clinicians and resulting workforce recruitment challenges. According to

Brandi Littlefield, the Howard Center’s assistant director of First Call for Chittenden County, the desired change would resolve delays in “access to hospital care as a result of confusion of who will provide the emergency transport.”

In the final legislation, only law enforcement can take individuals into custody for mental health reasons without a physician’s certificate. A mental health professional can still provide transportation to them “if clinically appropriate,” but not by court order.

NEWS . 7 Fall 2018

NEWS Summer 2023 NEWS Summer 2023 7

This photo of a 10-year-old boy (taken by his father) being led into the Brattleboro Retreat by sheriff’s officers in 2004 led to the first change in law to begin eliminating such practices. (Photoshop used to remove identifiers on sweatshirt.)

One director said she supported the approach, but “I cannot imagine how we will staff it.”

Peer Certification Plan Funded

by BRETT YATES

MONTPELIER – The Vermont Department of Mental Health’s new budget includes funds for a “Peer Supports Credentialing Program.”

DMH requested an allocation of $187,500 from the state’s general fund to cover half of the projected cost of its startup and its first year of operations, based on the expectation that federal Medicaid dollars would pay for the remainder.

“The bulk of that money would actually go towards training,” Director of Adult Services Patricia Singer told the House Committee on Health Care. “We hope to train up to 60 folks in the first year.”

According to Singer, the program will target adult mental health peers exclusively, despite “some overlap” between their work and that of peer recovery coaches, who offer support for substance use conditions.

MadFreedom founder Wilda White, who testified alongside Singer, noted that the budget would support “the very basics of a certification program,” which she envisioned would someday offer additional credentials for mental health subspecialties such as geriatric support, forensic support, and peer supervision.

“That’s a ways off,” White predicted.

Most U.S. states have already established official certification processes for peers, which can make their services eligible for Medicaid reimbursement. Last year, after Vermont’s legislature failed to pass a bill to implement such a system, DMH – with the urging of the peerled organizations who’d drafted the legislation – determined to proceed through internal rule-

making. First, the department issued a $30,000 grant to Pathways Vermont’s Peer Workforce Development Initiative, which subcontracted Wilda White Consulting to host stakeholder meetings for a potential certification program. This spring, White completed a report with recommendations for DMH.

DMH does not have a specific timeline for a decision to accept or reject those recommendations, according to Deputy Commissioner Allison Krompf.

White’s report distinguishes between “assessment-based” and “professional” certification programs. The former would certify peers on the basis of their performance during a training period, while the latter would

require an additional body to administer a test following the training. According to the report, the input received by White over the course of six public sessions, which 77 individuals attended, demonstrated a consensus in favor of a professional program.

The report calls for DMH to contract a peerrun organization for each of three central tasks: to screen candidates for eligibility to enroll in peer support training (on the basis, for instance, of testimony of “lived experience”); to develop and administer a training curriculum; and, in tandem with the Office of Professional Regulation, to issue credentials. A single vendor would handle the training statewide and could potentially take on the contract for screening as well. The endorsed screening standards would not disqualify applicants on the basis of their education or their state of residence. A criminal history would not bar them automatically.

The report also includes a draft of a Medicaid state plan amendment. Peer supporters employed by Medicaid-enrolled providers would practice under its guidelines, serving clients “who have a mental health or substance use condition and who have peer support included as a component of their person-centered, wellness plan, which serves as the plan of care.”

Once DMH has affirmed or rejected the report’s policy recommendations, the Peer Workforce Development Initiative will move on to what it calls “phase two” of its “work plan,” which will include helping to draft requests for proposals from peer-run entities for DMH’s possible use.

Gun Restrictions Focus on Suicide

by BRETT YATES

by BRETT YATES

MONTPELIER – A bill described as intending to protect Vermonters at risk of suicide by boosting safety through restrictions on gun owners and purchasers passed the legislature this spring. It awaits action from the governor.

Rep. Alyssa Black introduced “An act relating to implementing mechanisms to reduce suicide” in February. All three of its “mechanisms” related to firearms: their acquisition, possession, and storage.

The legislation cited Vermont’s 142 suicides in 2021, of which 83 (or 58%) used guns. These suicides accounted for 89% of Vermont’s deaths by firearm that year. Black’s son died by suicide in 2018 shortly after buying a gun.

Black suggested that Vermont’s troubling suicide rate – about 45% higher than the national average in 2021 – is owed to its high rate of gun ownership. Suicide attempts by other means are far less likely to achieve a lethal outcome.

“The rates of suicide in states with high gun ownership [are] double what it is in states with low gun ownership,” Black told fellow legislators. “And the interesting part is, when you look at the number of firearm suicides between the two groupings of states, they are dramatically different – when you look at suicides by all other methods, they are equal.”

First, the bill would require gun owners whose households include children or persons prohibited from possessing firearms to keep their guns locked and stored separately from their ammunition.

Second, it would extend the right to file a petition for an “extreme risk protection order” to the person’s household and family members. Such orders, if granted by a judge, can force a

potentially dangerous person to relinquish their legally purchased firearms. Currently, only a state’s attorney or the Attorney General can file the petition.

Finally, the bill would impose a waiting period for gun buyers, except at gun shows. A licensed dealer would transfer the firearm 72 hours after its purchase.

amount of time, they are less likely to have a mental health diagnosis, they’re less likely to be involved in the mental health system, and they’re less likely to have made a prior suicide attempt.”

Much of the debate about the bill centered on its constitutionality. But Rep. Anne Donahue, who proposed a strike-all amendment in March, questioned the likely efficacy of its provisions in a state with “a large amount of gun ownership.”

Donahue pointed to what she saw as a lack of available data on relevant details of Vermont’s suicides, such as how long before the incident each victim had acquired their weapon and whether it was stored in a safe or unsafe manner at the time. She entreated the legislature to mandate a study before moving forward.

In testimony before the House Committee on Judiciary, Dr. Rebecca Bell, a pediatrician at the University of Vermont Children’s Hospital, represented the Vermont Medical Society and the Vermont chapter of American Academy of Pediatrics, both of which supported the bill. She emphasized what she regarded as the particularly spontaneous nature of suicides by firearm.

“When researchers look at people who have attempted suicide with a firearm versus other methods, what they find – and this is true when I look at my cases in Vermont of young people – is… that those who choose a firearm are doing so more impulsively than those who choose another method,” she said.

“So they’ve thought about it for a shorter amount of time, they planned for it for a shorter

“My hunch is that there might be a case to be made for safe storage, but I don’t think we know that,” Donahue said. “I think the 72-hour hold, given the circumstances of our state, is extremely unlikely to do anything significant. But I could be wrong.” The amendment failed.

“If H. 230 is postponed for one more year and one extra person dies that wouldn’t have had to die – we’re not willing to put it off,” Black said.

A subsequent attempt to modify the bill to add police officers but to delete the addition of family and household members from among the groups able to initiate extreme risk protection order petitions also failed.

NEWS . 8 Fall 2018 NEWS Summer 2023 8

“The rates of suicide in states with high gun ownership [are] double what it is in states with low gun ownership.”

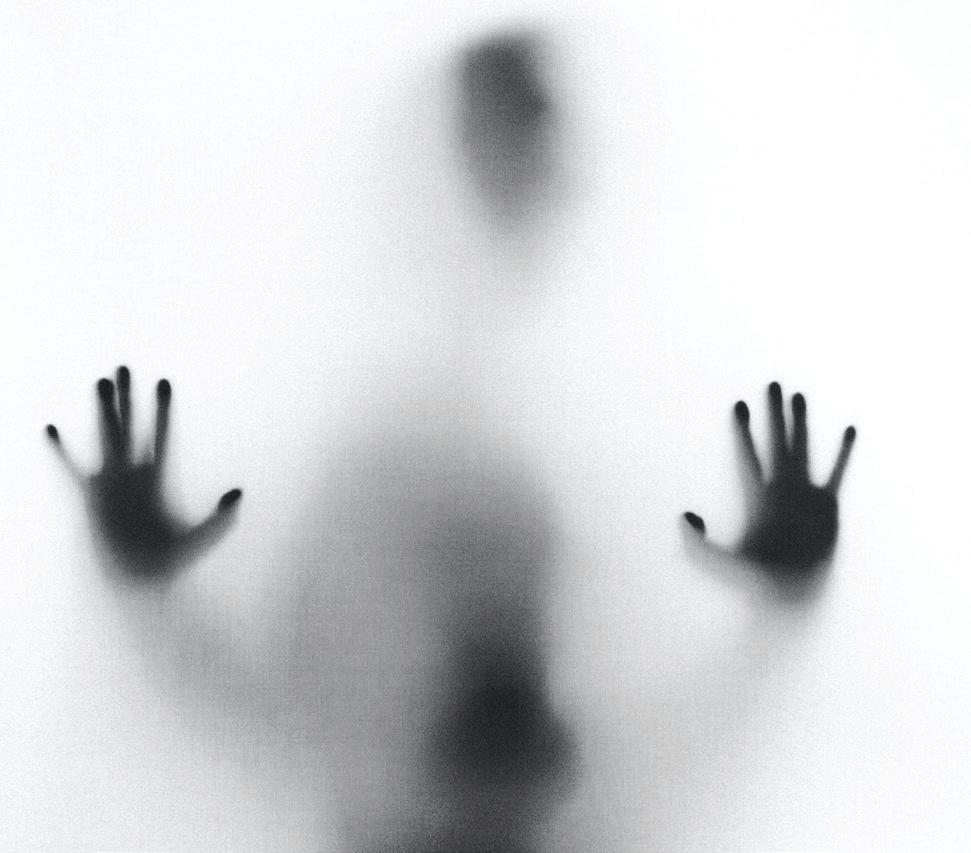

(Photo by Kateryna, Unsplash)

New Law Allows Arrests in EDs

by BRETT YATES

MONTPELIER – Arrests by law enforcement may become a more common sight in Vermont’s emergency departments. Owing to a change in law, police can arrest and remove hospital patients or visitors for certain misdemeanors without a warrant even if an officer was not present to witness it – something they cannot do now.

Advocates who opposed the change cited fears that it would serve to criminalize mental health crises. That led legislators to shrink the scope of the bill, which originally applied to all healthcare settings.

The bill was also narrowed to ensure that no patient could be arrested and removed from the hospital if they had not been evaluated yet, were not in stable condition, or were waiting for an inpatient admission.

Zachary Hughes, the vice president of the board at Vermont Psychiatric Survivors, voiced opposition to increasing the number of arrests in hospitals. “I think a citation is maybe less traumatic than an arrest,” he observed. “You may be deterring people from the hospital.”

Hughes encouraged legislators to consider ways of calming emergency room patients before violence occurs.

“I think there are times when you can involve the peer population, who can provide support while the person is in waiting mode, depending on how acute the situation is,” he said.

In order to make an arrest without first obtaining a warrant from a judge, police must have “probable cause” to believe that a crime has taken place.

On this basis, an officer can arrest a felony suspect even without witnessing the incident directly, but in the case of a misdemeanor, an officer arriving after the incident occurred, can only take the accused party into custody if the alleged offense appears on a list of 17 crimes in current law. The bill added three more to protect healthcare workers in hospitals and for emergency service responders, targeting assaults, threats, and disorderly conduct in those settings.

Before voting in favor of the bill, the House Committee on Judiciary added a requirement that the Vermont Program for Quality in Health

Care compile a report examining how adequate training and sufficient staffing levels, among other possible improvements that would not involve police, may support safer hospitals. The legislature will receive it next January.

The Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems pushed for the bill. Nurses, doctors, and paramedics appeared before the legislature to describe what they said was an increasingly dangerous working environment, particularly in understaffed emergency departments, and a sense of having little recourse for burnout-inducing harms endured on the job.

at hospitals. “If we’re talking about a person who’s brought to a hospital, there’s typically a reason why,” said DPS Deputy Commissioner Daniel Batsie.

“They’re having a psychiatric breakdown, they’re having a medical condition, they’re having something that has brought them there for evaluation or treatment.”

Colonel Matt Birmingham of the Vermont State Police conjectured that such an arrestee would likely return to the same hospital after their arraignment.

“I would find it to be challenging, if not impossible, for a judge to impose conditions of release that they’re not allowed to go to an emergency room,” Birmingham said, “because that’s probably illegal.”

Jack McCullough from Vermont Legal Aid’s Mental Health Law Project doubted whether the bill would make healthcare workers safer.

“I have never once in my 20 years thought about leaving emergency medicine,” said Jill Maynard, a nursing director at Southwestern Vermont Medical Center. “However, over the past 12 months, I ponder leaving the ED and, on the most difficult days, leaving the profession altogether.”

Recalling incidents of spitting, hair-pulling, sexual harassment, and death threats, Maynard reported that she’d been “made to feel guilty for calling the police” or had been told that “the patient had a mental health diagnosis –therefore, they would not be held responsible for their actions.”

Alison Davis, a medical director at Rutland Regional Medical Center, shared a secondhand account: “One night, a female staff member had a urinal thrown at her and was then punched in the side of the head by a patient. That patient remained in the ED that night, awaiting bed placement, but the following day was reported by staff to be bragging about ‘hitting that broad’ and asking staff, ‘This is Vermont: what are they going to do?’”

Representatives from the Vermont Department of Public Safety expressed concerns, especially from the standpoint of legal liability, about the possibility of interrupting crucial care

“While superficially appealing, nothing in this bill provides an opportunity to interrupt, cease or prevent a crime when it is happening – everything in this bill is about responding to a criminal act after it has occurred,” he said.

Washington County Mental Health Services Executive Director Mary Moulton testified about the need for “upstream services” that would reduce burdens on emergency departments.

Speaking as an advocate, Rep. Anne Donahue criticized committee discussions for the “degree of the focus on mental health” despite reports of increases in violent behavior among Americans irrespective of any psychiatric diagnosis.

She said that the bill “could end up being a highly disproportionately used tool, driven in part by implicit bias” against psychiatric patients.

Sen. Dick Sears, who introduced the bill, stressed during the Senate hearings what he saw as an imperative to give officers a stronger signal to intervene in attacks upon healthcare workers.

The Vermont Rules of Criminal Procedure similarly single out “assault against a family member, or against a household member” among the misdemeanors for which officers can make immediate arrests without seeing them firsthand. “The goal was to put together legislation that would mirror what we do with domestic violence right now,” Sears said.

Fall 2018 NEWS . 9 Summer 2023

Counterpoint Opinion Poll If you threaten ED staff while in a mental health crisis, should you be arrested for a crime? Results of the poll will be published in the next issue of Counterpoint. OR by going to www.vermontpsychiatricsurvivors.org/counterpoint/ QUESTION: VOTE by scanning this onto your mobile phone: Current law permits a citation, but not an arrest, for misdemeanors.

Feasibility Study Failed To Include Required Input from Advocates

Youth Inpatient Unit Is Funded

by BRETT YATES

BENNINGTON – The state legislature budgeted $9.225 million in fiscal year 2024 for the construction of an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit at Southwestern Vermont Medical Center, indicating its approval of the project.

The Department of Mental Health told legislators that the plan was moving forward to develop a 12-bed unit. The recently completed feasibility study “suggests the need for more than

not reach out to any other groups during the preparation of the feasibility study, Director of Planning James Trimarchi acknowledged.

“There has been no public input to the process at this point,” said Trimarchi, who characterized the feasibility study as a technical procedure carried out via spreadsheets and diagrams.

Trimarchi noted that SVMC’s Board of Directors hasn’t yet reviewed the results.

Part of the feasibility study was a “demand analysis,” which sought to quantify Vermont’s need for additional adolescent inpatient beds. One model used figures from Massachusetts, which has 38.4 beds per 100,000 kids. The same rate, transposed to Vermont, would yield a total of 18.5 youth beds.

12” such beds in addition to the existing 10 to 14 beds at the Brattleboro Retreat, DMH reported.

However, according to SVMC Director of Planning James Trimarchi, the final status of the proposal remains uncertain until the hospital Board of Directors decides whether to move forward, which is not expected to occur before August or September.

That would be a delay of three or more months from the original timeline, which he attributed to uncertainty surrounding the legislature’s appropriations bill.

The feasibility study – which Trimarchi said was still a draft – reported that “clinical experience, anecdotal information, and state reports indicate that a crisis exists in access” to adolescent inpatient care but that no “structured data is available to accurately calculate the number of additional beds needed in Vermont,” which “could be zero to12.”

“The real answer is that we don't know,” Trimarchi said.

DMH initially requested an allocation for the project in January during the annual budget adjustment, stressing a need to “reduce the number of youth waiting in an emergency department” and to serve “individuals who are currently denied admission at the Brattleboro Retreat due to medical needs that cannot be managed in a non-medical hospital setting.”

But legislators waited until spring, when SVMC had completed the initial feasibility study, to approve the funds.

The study identifies a former area for medical records within the hospital as a suitable site for the unit. The document’s schematic shows 12 bedrooms, as well as a dining room, two social rooms, a consult room, and a seclusion suite, as well as access to an outdoor area.

DMH had contracted SVMC to perform the feasibility study in October. The contract included a requirement to “obtain feedback on the design and operations from the local Designated Agency, mental health advocacy organization[s] such as Disability Rights Vermont and persons with lived experience.”

While SVMC maintains regular contact with United Counseling Service, Bennington County’s “designated agency” for mental health, it did

The Chair of the House Health Care Committee, Rep. Lori Houghton, appeared to believe the commitment to the site was more definite when she said on the House floor on May 12 that SVMC will be beginning the Certificate of Need process this summer to get approval for the project from the Green Mountain Care Board. Based on testimony by DMH to the committee earlier that week, “The intent by the Department of Mental Health... is for the beds to be placed at Southwestern Medical Center,” Houghton said.

In a timeline presentation to the committee, Commissioner Emily Hawes showed a graph from the SVMC feasibility report based upon Board approval by May and the Green Mountain Care Board application to be filed by June, which could not actually occur until after the SVMC approval.

Meanwhile, a “queuing theory model” – based on Vermont Association of Hospitals and Health Systems data suggesting that 48 adolescents per quarter need inpatient care, with an average length of stay of 15 days – seemed to indicate that Vermont should have 12 or more youth beds.

Trimarchi views a model developed by the American Psychiatric Association in 2022 as the most accurate for calculating demand . He pointed to its consideration of “more than 40” factors, including the availability of communitybased resources. But by his account, Vermont hasn’t yet aggregated all the information needed to use it.

And even if it did, that information could shift at any time. Demand could change if, all of a sudden, there is an investment in equal resources dedicated to building out outpatient services,” Trimarchi posited. “I have very little sense that the calculation of demand can even be done sensibly.”

Still, for him, the need to “do something” remains apparent. The current thinking is, let's build this 12-bed unit. If it eliminates the languishing in the emergency departments,” Trimarchi theorized, “then we know we've met demand. Until we do, we just gotta keep building these things.”

DMH Deputy Commissioner Allison Krompf told Counterpoint that she believes there is a consensus on the need for it. “I think the question mark still is, can an organization in this climate right now stand up a new wing of a facility, build staff? I would imagine any organization is not going to feel extremely definitive.”

Some legislators and advocates, however, have both questioned whether Bennington is the right place to do it. “I’m just wondering if there are any other potential places that are further north,” Sen. Ginny Lyons said.

The SVMC feasibility study referenced the same question, asking, “Should new beds be created in southern Vermont since the current beds are also in southern Vermont at the Brattleboro Retreat (Vermonter’s expectation that care resources, particularly those funded by the state, are nearby and equitably located.)”

Trimarchi indicated that the hospital would begin to survey advocates and community members after the Board approval in late summer.

“We're a long ways to ‘yes’ on this thing,” he observed. “So if we decide to proceed, the input from the public will be critical because that's where we will share with them the block diagram and say, ‘Does this layout for individuals with lived experience make sense?’”

The feasibility contract ended on March 31. But Trimarchi emphasized in May that the study was “not technically done. It’s still in draft phase.”

“I haven't received input from the Department of Mental Health yet,” he said. “If they come back and say, ‘Hey, we gotta share this with the disability rights group to have their input before we can close the book on it,’ then let's do that.”

“Additional [requests for proposals] must be requested and ways found to help other institutions, such as the UVM Medical Center, meet the requirements of those RFPs,” NAMIVermont Board President Charles R. Siler urged in written testimony.

SVMC was the sole respondent to the second issuance of DMH’s RFP last year. The University of Vermont Medical Center initially threw its hat in the ring before withdrawing its plan on account of financial difficulties.

If the project moves forward at SVMC, it will aim for a launch date in December 2024. The projected annual cost of operations will exceed $7 million. It would likely require Medicaid to subsidize the costs as a result of private insurers’ tendency to under-reimburse inpatient psychiatric services. “The initial goal, although unlikely, would be to achieve reimbursement parity across payers,” the feasibility study said.

NEWS 10 Fall 2018 NEWS 10 Summer 2023 NEWS Summer 2023

“Demand [for beds] could change if, all of a sudden, there is an investment in equal resources dedicated to building out outpatient services... I have very little sense that the calculation of demand can even be done sensibly.”

Southwestern Vermont Medical Center in Bennington. The inpatient unit would be created through rehabilitation of the wing at the far right. (Photo courtesy SVMC)

Forensic Unit Gets Green Light

by BRETT YATES

MONTPELIER – A years-long legislative effort to create a separate forensic mental health system culminated in the passage of a law that will, by next summer, turn the four and five-bed units of the Vermont Psychiatric Care Hospital into a locked “therapeutic community residence” that will allow the use of restraint and seclusion for psychiatric patients being held based upon criminal charges.

Most U.S. states already have separate psychiatric facilities for defendants deemed incompetent to stand trial or found not guilty by reason of insanity. But until now, Vermont’s system of care has not distinguished between such patients and those involuntarily committed by civil courts.

The new law stipulates that two units at VPCH, a locked, 25-bed, state-owned hospital in Berlin, will serve as the “initial” site for segregated forensic treatment, seeming to imply the eventual construction of an all-new facility.

But Deputy Commissioner of Mental Health Allison Krompf said the Department has no such plan. She said the intent was to grant flexibility in case the VPCH conversion falls through.

“There was no sort of, ‘We’re gonna start here and then in three years plan to move it somewhere else,’” she said.

In order to change uses, VPCH will receive a new license from the state to treat justiceinvolved patients on court orders of nonhospitalization (restrictions outside a hospital.) This changeover – which was exempted from requiring a Certificate of Need from the Green Mountain Care Board – will result in a loss of nine high-security, “level-one” inpatient beds when they become forensic beds instead.

But as part of addressing a patient population committed based on allegations of violent offenses, the new law requires the Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living to modify its licensing and operating regulations to create a new category of “residential” treatment

that will have permission to use emergency restraint and seclusion and administer courtordered drugs.

In 2021, psychiatric survivors campaigned successfully against a plan by the Department of Mental Health to use restraint and seclusion at its new locked residence in Essex, which belongs to a category of 24 facilities statewide that have never legally deployed such practices.

The forensic facility at VPCH will be the first.

Vermont Psychiatric

defendant’s mental state at the moment of the alleged offense, that of competency addresses their ongoing ability or inability to stand trial.

Under the new law, DMH-appointed psychologists – not just psychiatrists, as before – will be eligible to evaluate defendants for competency during a one-year trial period.

The original bill instructed DMH and DAIL to develop a plan for a treatment program specifically aimed at restoring someone’s competency to stand trial, but the final legislation instead mandated a report from the departments “on whether a plan for a competency restoration program should be adopted in Vermont.”

Zachary Hughes, the vice president of Vermont Psychiatric Survivors’ board of directors, offered testimony on both bills. He urged legislators to remember that, once a doctor has judged a defendant incompetent to stand trial or a court has found them not guilty by reason of insanity, “this isn’t a criminal situation anymore.”

Over recent years, Vermont police have attributed a handful of high-profile crimes, including the murder of a young woman in Bennington in early 2021, to perpetrators with psychiatric diagnoses. In their aftermath, victims’ families have pushed legislators to address public safety concerns.

Two years ago, at the legislature’s demand, DMH convened a workgroup for the purpose of developing a plan to remedy “any gaps in the current mental health and criminal justice system structure.” But its diverse membership, which included both psychiatric survivors and crime victims, failed to reach a consensus.

This year, lawmakers moved forward to modify laws that govern competency exams and insanity defenses in Vermont’s criminal courts, as well as authorizing the new facility.

While the question of sanity addresses a

He also encouraged them to “keep politics out” of their decision-making, and to consider making more investments in voluntary mental health programs before building a forensic facility. “You may not need it if we can get more community services rolling,” he said.

The Senate version of the bill set criteria for admissions (and for expedited admissions) at forensic facilities that included not just individuals in DMH custody but also those in DAIL custody based upon being “persons with an intellectual disability” who, according to a civil court, had committed violent acts. They have received care only in community placements since the Brandon Training School closed in 1993.

Testimony by Green Mountain Self-Advocates and Disability Rights Vermont, among others, protested the plan. The legislature ultimately created a workgroup to assess specifically “whether a forensic level of care is needed for individuals with intellectual disabilities.” A report is due by Dec. 1.

DMH Head Ruled in Contempt of Court

BURLINGTON – A Superior Court found the Commissioner of the Department of Mental Health, Emily Hawes, in contempt of court in May for what it described as “knowingly and willingly disobeying the Court’s order” for an updated psychological evaluation of a defendant’s competency to stand trial.

Judge Alison Sheppard Arms of the Chittenden Criminal Division will fine Hawes, in her role as commissioner, $3,000 if DMH does not act to comply with the order.

DMH’s communications director, Alexandra Frantz, said that DMH had not initially received a “clear directive to complete the evaluation” last

November, and once it understood the order, it placed the individual on the current wait list.

According to the court decision, DMH had asserted that it was only under a statutory obligation to perform one evaluation per defendant.

Arms said DMH used “nonsensical assertions and nonexistent legal grounds” to defend against its “continued obstruction of the criminal justice process.”

Frantz noted that DMH has had a significant backlog of evaluation cases, made worse by the COVID pandemic, that has caused waits of up to a year. She said DMH hopes that some of

the issues raised by the case will be addressed through S. 91, a bill passed by the legislature this year revising laws on forensic evaluations and now awaiting signature by the governor.

The legislature rejected language from DMH to no longer require it to provide further evaluations once there was an initial finding of competency, but did add a required showing of a change in circumstances before a new evaluation can be ordered in such cases. It allows, for a oneyear trial period, forensic psychologists as well as psychiatrists to conduct evaluations. It also allows a warrant to be issued if a defendant fails to appear for a scheduled evaluation.

Mental Health Budget Upped by 4.63%

MONTPELIER – The Department of Mental Health’s budget for next year was increased by 4.63%, or slightly more than $14 million, including funding added by the legislature.

There were no funds added to expand peer-led programs.

The DMH budget proposal was for slightly more than a $7 million increase to contribute to an expansion of the Blueprint for Health program, to add four staff positions to oversee a new statewide mobile crisis response system, for new urgent care programs, and for funding a

peer certification program (see articles on pages 6 through 8 about those programs.)

However, it included no increase in that base budget for community mental health centers, which advocates testified would result in a cut to community services because of inflationary pressures and the number of vacant staff positions at current salary scales. The legislature added a five percent increase for community mental health centers and a new staff position for quality oversight staff. The final budget brought the total DMH budget from last year’s $303,469,211 to a

new $317,528,698. The Blueprint expansion is a two-year pilot project intended to help primary care doctors in addressing patients who have both mental health and substance use diagnoses. It will expand a program called “Hub and Spoke” that currently focuses only on opioid addictions. The pilot will increase staff for existing Community Health Teams embedded in primary care, “who will help with screenings for social determinants of health, referrals and care coordination,” testified Jessa Barnard of the Vermont Medical Society.

NEWS . 11 Summer 2023