Fall 2021

Editor-in-Chief

Co-Managing Editor

Co-Managing Editor

C0-Production Chair

Co- Production Chair

Media Manager

Event Coordinator

Special Projects

Emily Ma

Maya Nir

Sukanya Barman

Nicole Luz

Aria Zareibidgoli

Priya Viswanathan

Akshi Kalavakonda

Manaal Khwaja

Editing Staff

Lara Arif

Victoria Djou

Anna Heetderks

Sarah Liu

Jack Massingill

Carina Ritcheson

Sagarika Shiehn

Addie Simkin

Elisabeth Tamte

Nick Wells

The Virginia Journal of International Affairs is the University of Virginia’s preeminent publication for undergraduate research in international relations. The Virginia Journal is developed and distributed by the studentrun International Relations Organization of the University of Virginia. The Virginia Journal is one of the only undergraduate research journals for international relations in the country, and aims both to showcase the impressive research conducted by the students at UVA and to spark productive conversation within the University community. The Virginia Journal seeks to foster interest in international issues and promote high quality undergraduate research in foreign affairs. The Journal is available online at vajournalia.org.

Interested in submitting to the Virginia Journal? The Journal seeks research papers on current topics in international affairs that are at least ten pages in length. Only undergraduates or recent graduates are eligible to submit. Submissions should be sent to vajournalia@gmail.com.

Please direct all comments to vajournalia@gmail.com

Our contemporary era is increasingly characterized by an interconnected and interdependent global landscape. The growing complexity of many global issues today has only made it more critical for us to understand the changing political, economic, and social forces within and between countries. At the University of Virginia, we are fortunate to have a wealth of undergraduate expertise in and passion for international affairs.

This latest edition of the Virginia Journal highlights a diverse range of research areas including the growing danger that China’s influence poses to global democracy, discrepancies in women’s healthcare in rural India, the influence of language variation on countries’ risk for civil war, the challenges and opportunities of supranationalism, and Indian agricultural policy’s implications for economic development.

While the Virginia Journal has undergone a number of changes in its almost two decades of publication, its core spirit remains the same. The Journal aims to provide student perspectives in the field of foreign affairs in order to spark intellectual curiosity and promote open discourse. I believe that this semester’s papers truly meet and exceed that goal. It is my hope that readers will walk away with new insights on these thought-provoking topics.

The Virginia Journal would not be possible without the dedication, and support of many individuals in the UVA community. Producing the Journal is truly a collaborative effort every semester. This semester, in particular, marked our first return to in-person operations after a year and a half of being entirely virtual. The success of this edition can be attributed to the hard work of the Journal’s executive board and editorial staff; it has been a privilege to work with such a wonderful team. I would also like to thank all of the authors for their contribution as well as recognize UVA faculty for their support. Additionally, I would like to express my deep gratitude for the International Relations Organization’s ongoing partnership with the Journal.

Lastly, thank you to all of our readers. I am incredibly excited and honored to present the following research papers. Please take this opportunity to enjoy and reflect on the critical work of these undergraduate scholars.

Sincerely,

Emily L. Ma Editor-in-Chief

Emily L. Ma Editor-in-Chief

Morgan Meyer is a current Second year student at the University of Virginia hoping to double major in Global Studies: Security and Justice and Art History, with a minor in Physics. Her academic research areas of interest include the impact of development on human rights, as well as the intersection of poverty, labor struggles, and incarceration within our increasingly interconnected world. At UVa, Morgan is involved in sustainability work with the dining halls, the Washington Literary and Debate Society, and writes as a freelancer for the Women's Center magazine, Iris. Following her graduation from the University, Morgan hopes to attend law school and continue her work with incarcerated people outside of Oklahoma.

I am happy to see that Morgan Meyer’s paper on India’s agricultural development strategy was accepted for publication by the Virginia Journal of International Affairs. Ms Meyer’s article developed from the papers she did for my Spring 2021 class on the politics and political economy of development. In this class I encourage students to write a first draft early in the semester and then revise in reaction to comments from the TA and myself. Ms Meyer assiduously used office hours in pursuit of both data sources and possible angles of attack on the issue of why conflicts around agricultural policy existed and what their consequences might be. Ms. Meyer wrote a very strong first paper and an even stronger revision. The version for publication in this journal reflects those strengths: a brief but pointed consideration of how India’s colonial history shaped today’s conflicts, postIndependence political structures and economic policies, and then a detailed dive into the big policies affecting India’s agricultural sector and how different interest groups line up around those policies. Several of my students have published in the Virginia Journal of International Affairs and I am pleased to

see Ms Meyer joining their company.

Mark Schwartz Dept of PoliticsUniversity of Virginia

In June of 2020, the Indian Standing Committee on Agriculture issued three emergency ordinances that would later be heard and approved in India’s bicameral legislature. These ordinances intended to introduce new support for India’s small farmers, enabling them to engage in high-value business with multinational corporations and enterprises. However, the 2020 Farm Bills were met with massive resistance on the part of Indian farmers. Over multiple months, in the midst of a viral pandemic impacting India’s economy and citizens, farmers from across the nation gathered in one of the world’s largest protests to date, with hundreds of thousands of people converging on the nation’s capital. This research seeks to evaluate those ordinances in the context of India’s agricultural economic development over time, while focusing on the actual language and protections offered by the legislation. In evaluating these laws, this research hopes to draw new conclusions regarding the priorities of the Modi government, and where to go from here following the stalemate between the government and farmers.

Introduction

India is a country with many challenging natural characteristics that contribute to its developmental struggle. Traditionally, development takes place through the process of raising cropped areas and yields to increase agricultural exports. The funds received from increased agricultural production typically lead to industrial investments, thus resulting in specialized economies of scale. However, India was unable to follow this traditional process, resulting in economic stagnation. India’s complete developmental history is expansive; the totality could not be expressed properly in a discussion of this length. Instead, this analysis will aim to examine a broad history of Indian agricultural development to ascertain a nuanced understanding of the issues impacting the sector to this day. Analysis of this developmental history will determine the effectiveness of the controversial

2020 Agricultural Reform bills that sparked ongoing protests across the nation.

To comprehend the full impact of the legislation enacted in the summer of 2020, it is important to understand the developmental and economic factors that led to it. In the 1890s, most other tropical countries were growing at a rate on par with the capital giants of the world in Europe, at about thirty four percent, as opposed to India’s five percent (Lidman, Domrese 1970). These tropical nations experienced prosperity and growth because they exported countless valuable commodities, initially in agriculture, to build up their status in the global economy and begin the process of development and industrialization. However, much of this great agricultural growth occurred due to the seizure and subsequent cropping of available land, which India lacked. India’s massive population had already seized and cultivated most available land, and a majority of this land was dedicated to food and subsistence crops, not high-value crops for exports (Lidman, Domrese 1970). Inadequate rainfall and unpredictable monsoon seasons contributed to the exhaustion of India’s land while forcing slow development due to starvation. Over the period of 1891-1914, two of eight year-long famines killed over ten million Indians combined (Lidman, Domrese 1970). This contributed more to delay in entering the global market. Incredibly low specialization—even into 1912—was the result of anxiety about food supply, rainfall, and epidemics.

During the beginning of the twentieth century, however, Indian development made a strong attempt to catch up with its tropical compatriots. In fact, in the year 1913, the total value of manufacturing exports from tropical countries comprised 270 million dollars, and over half of those exports came from India (Lidman, Domrese 1970). With the rise in trade came the rise in demand for shipping and packing materials. Indian manufacturers gained ground during this period because of the many cotton and jute manufacturers that developed in response to this demand (Lidman, Domrese 1970). Comparing the successes of Indian industry and export of mineral resources to tropical growth rates at the time, the country measures up quite well (Lidman, Domrese 1970). The primary issue in India’s economic development lies, therefore, in agriculture, and by extension water and land

scarcity, inadequate state building due to imperialism, security and financial struggles, and inefficient land policy.

When considering the issue of water and land scarcity, it is vital to remember that the best way to increase India’s low yield per acre and manage their land is through widespread, well-maintained irrigation and agricultural innovations and improvements, both of which require a valuable resource: water (Lidman, Domrese 1970). India has dealt with a wide variety of water scarcity problems over the course of its development, but initially, the catalyst of its struggles was the uneven and inconsistent distribution of rainfall throughout the tropical nation. Even today, about sixty-five percent of India’s population lives in rural areas, which are economically dependent on agricultural trade and production (Bhattacharya, Patel 2021). Extensive research, published as recently as 2019, on the distributional impact of weather on rural populations concluded that poor farming populations suffer the greatest losses as a result of reduced water availability (Sedova, Kalkuhl 2019). Most rural areas in India received, on average, less than thirty inches of rainfall per year during initial development, and this issue has only worsened with massive population growth, environmental degradation, and poor agricultural practices (Sedova, Kalkuhl 2019). Even when statistics indicate that certain areas of the country received a considerable amount of rainfall, this must be understood in the context of India’s weather patterns. Usually, this seemingly large amount of rainfall is concentrated within the months of the monsoon season. As a result, the majority of the Indian subcontinent is a dry zone, and has implemented rainwater harvesting systems in the present day to better store rainwater for months of drought (Kumar 2019). However, even these rainwater harvesting systems have the potential to cause trouble. For example, due to inadequate maintenance of these systems by the state government of Tamil Nadu, farmers and residents suffered a severe dry spell in 2016 despite the fact that they had been racked by monsoons the previous year (Sedova, Kalkuhl 2019). Without water, it becomes nearly impossible for a country to develop on par with the rest of the world. Without sufficient irrigation, many profitable crops cannot be exported, drying up funding for increased development and technological improvements.

An analysis of Indian development in the late nineteenth and earlier

twentieth centuries by Lidman becomes relevant once more in the face of water scarcity. In his research, Lidman maintains his argument that had the government invested more and earlier in irrigation, the “whole tempo of Indian economic change” would have been different (Lidman, Domrese 1970). This is not a new idea, but it begs the question: why didn’t India invest in irrigation earlier?

The answer is a complicated one, involving inadequate state-building along with security and monetary struggles. Predation strangled India’s economic development, with the imperial British government commanding the country until 1947 (Arora 2013). Taxes were not low during this period, but the colonial administration of Great Britain rarely allowed Indians to hold high-level positions, and the vast majority of decisions made by the English during this time centered almost exclusively on British interests, not those of Indian development. The proceeds from taxation were spent to an “excessive and unfair extent” on British civil administrators and the standing British army, where many of the officers were Englishmen, and Indian subjects were foot soldiers for the UK in conflicts across the globe (Lidman, Domrese 1970). The Indian population’s desire to escape the caste system, famine, and disease made them particularly vulnerable to manipulation on the part of the colonizers.

Following the British regime’s exit from the country, India split into India and Pakistan in the Partition. This divide came about due to the dominant religious differences between Islamic Pakistan and Hindu India (Arora 2013). After the Partition, Indian agricultural development focused on improving food security to prevent famine and raising yields per acre to increase agricultural output until the Green Revolution (Arora 2013). The Green Revolution led to innovations in Indian farming, with the country achieving self-sufficiency in food-grains and extensive backwards and forwards linkages in the fertilizer, seeds, and farm machinery industries (Arora 2013). While this was certainly progress, it is important to note that the benefits of the Green Revolution were felt in already-irrigated regions that grew wheat and rice. These crops constituted India’s most important

agricultural exports at the time, making agricultural improvements smoother, but this concentrated the wealth in the more prosperous areas of the country (Arora 2013). This uneven growth caused greater socioeconomic disparities, already heightened due to the caste system.

From 1980 to 1991, after the Green Revolution, agriculture policy focused primarily on extending the aforementioned benefits of the Green Revolution to more crops and land areas, as well as the diversification of the country’s exports (Arora 2013). This diversification was geared towards higher value commodities: milk, fish, poultry, vegetables, and fruit (Arora 2013). India also worked to increase yields per acre by using higher yielding varieties (HYVs) of seeds. The table below depicts the massive increase in HYVcropped area over time.

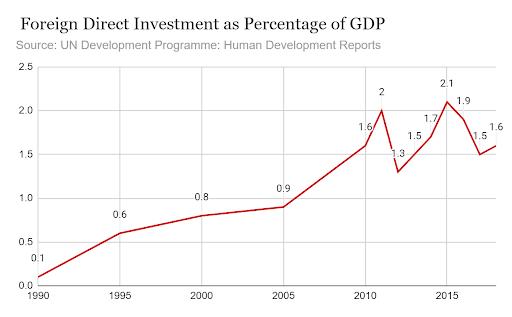

In 1991, economic reforms ushered in the liberalization of Indian agriculture due to increased globalization. In particular, they aimed to “improve the functioning of markets, reduc[e] excessive legislation, and liberaliz[e] agricultural trade” (Arora 2013). The 1991 reforms led to a decrease in public investment in agriculture, paving the way for increased foreign direct investment. The table below portrays change in foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP over time; the late 1990s and early 2000s experienced a massive surge in foreign direct investment to continue economic growth.

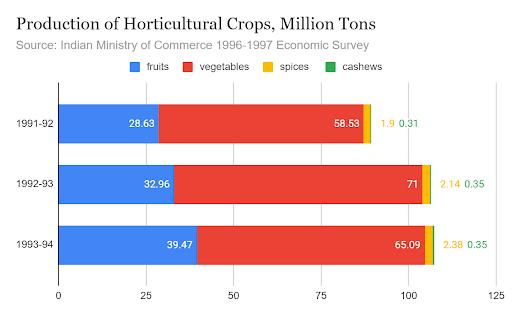

This era also led to higher production of important horticultural crops, particularly fruits, vegetables, and spices, as evidenced by the table below. This increased diversification is crucial for industrialization and development.

Included here are data depicting the considerable growth of those aforementioned diversified horticultural crops: fruits, vegetables, and spices.

In 2000, the government of India established the nation’s first ever comprehensive agricultural policy statement, the National Agricultural Policy (NAP) (Arora 2013). In this statement, the government made a clear commitment to developmental growth with equitable distribution. In acknowledging this commitment to Indian citizens, the government simultaneously recognized its responsibility of balancing economic growth with the rights and quality of life of its most vulnerable citizens. This is the reality for a late developer in the modern world of media and protest -countries late to industrialization do not have the luxury of developing on the backs of subjugated peoples.

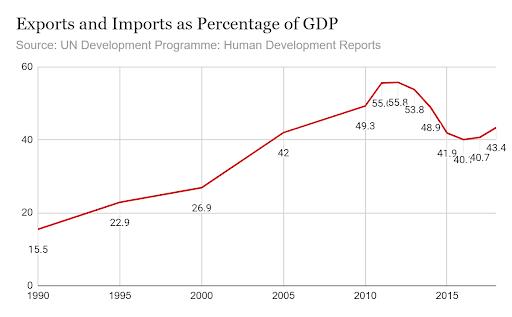

Lastly, before delving into the modern policy issues at hand, it is prudent to provide more economic context to this discussion in terms of exports and imports as a percentage of GDP through discussion of the table below.

The results of hundreds of years of Indian history coalesce in the graph above. The benefits of the 1991 economic reforms are displayed in the rising importance of exports that came with the rising foreign direct investment. Exposure and entry into the market is clearly a beneficial venture in the system of global capitalism, but, as can be seen in this graph, the greatest improvements from the 1991 reform did not manifest for ten to fifteen years after their codification. There exists an opportunity to learn from India’s agricultural history to inform alterations of the 2020 bills that sparked protest; the government should encourage gradual entry into the market while mitigating severe risks for farmers to incentivize economic participation.

Before proceeding to the discussion of the 2020 Agricultural reform bills, it is necessary to discuss a previously neglected aspect of Indian agricultural price policy: the Minimum Support Price, or MSP. This policy is a price floor maintained by the government for twenty three commodities, first instituted in the 1960s (Narayanan 2020). In layman’s terms, MSP is the price the government commits to for the purchase of agricultural goods from farmers if the market price drops below the government’s established minimum support price. By protecting struggling farmers from risk, the

government incentivizes participation in the market. The resulting economic change leads to a rise in agricultural income, protection of small farmers from risk, and increased market participation (Arora 2013). Though not mentioned in the reform bills in question, the support has become a point of focus for protestors, who have called for the MSP’s continuity to be codified into law.

Agricultural development is still an integral struggle in India. The farmers of the country have yet to grow globally competitive, and many state policies have been implemented in congruence with the liberalizing policies of the 1990s. The Agricultural Acts of 2020, better known as the Farm Bills, exemplify this continuation of India’s agricultural policies. On June 5, 2020, the Standing Committee on Agriculture issued these policies as emergency ordinances to be heard later in India’s bicameral parliament (Narayanan 2020). The bills were officially passed in September of 2020, first in the Lok Sabha (House of the People) and then in the Rajya Sabha (Council of the State), with the President Ram Nath Kouhd giving his approval on September 24 (Narayanan 2020). When the ordinances were initially issued, farmers protested in Punjab and Haryana. Following the codification of the bills into law, these protests erupted, with 200,00 to 300,000 farmers from Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and many other states camping out on the highway to the capital, Delhi, in protest (Narayanan 2020). This rapid call to action is even more impressive when one considers that the protests were in November 2020, in the midst of a harsh winter and the COVID-19 pandemic. Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India, repeatedly came forward in support of these laws, arguing on multiple occasions that the bills were intended for the benefit of the farmer, specifically the peasant farmer (Serhan 2020). Modi frames the farmers as ignorant, and some far-right supporters portray the protestors as “leftist anti-nationals” (Serhan 2020). Further, a senior member of Modi’s party, the BJP, claimed the farmers were Khalistanis, a heavy implication considering the large Sikh population in Punjab (Serhan 2020). By echoing the Sikh separatist movement, the BJP member harkens back to Modi’s own divisive, populist campaign and politics. Clearly, the Farm Bills merit discussion and evaluation, contrary to the picture painted by high ranking government officials.

The legislation also merits discussion because of its magnitude: fifty nine percent of the working population of India occupies the agriculture sector. While the sector contributes only around twenty three percent of the country’s GDP, according to the UN, “about seventy percent of its rural households still depend primarily on agriculture for their livelihood, with eighty two percent of farmers being small and marginal” (UN 2018). Agriculture in India is massive, both in its importance to the people of India and in terms of landmass -- India is the seventh largest country in the world, with an area of 3.288 million square kilometers (UN 2018). As mentioned previously, a large percentage of the agricultural workforce consists of small and marginal farmers, whose farms take up less than two hectares of land. Small farmers face even greater challenges due to their economic status and typically rural area. They do not receive the advantages of investment, irrigation, and crop management that larger farms do. Furthermore, small farmers find it difficult to take out a loan due to their minimal economic history, hindering their business prospects. As a farmer in India, little incentive for competitive growth exists and no strong mechanisms spur economic development. India needs agricultural policy reform to better promote economic development and serve the farm laborer population, but the government’s June 2020 economic reform bills caters instead to the interests of international buyers of agricultural commodities.

ThereexistsanopportunitytolearnfromIndia’sagriculturalhistorytoinformalterations ofthe2020billsthatsparkedprotest;thegovernmentshouldencouragegradualentryinto themarketwhilemitigatingsevererisksfor farmerstoincentivizeeconomicparticipation.

The first of these reforms is the “Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act.” This act allows farmers to trade outside of mandis, state operated agricultural trading markets, and permits electronic trading and e-commerce. The act also prohibits state governments

from levying market fees or taxes for any of the aforementioned commerce (Government of India 2020). While this legislation seems innocuous at first glance, many farmers worry that the third provision will lead to a decline in agricultural funding, and therefore the funding of mandis (Narayanan 2020). Without mandis, MSP will no longer be relevant, since it relies on state funding. Without state regulation of trade between farmers and firms, there also exists a high potential for exploitation, which will be further explored during discussion of the second act. When trade moves out of mandis and MSP becomes a memory, small, rural farmers will have no choice but to go into business with global corporations, with little to no option or incentive to sell to a domestic market (Narayanan 2020). The second act provides a framework for this business.

The “Farmers’ Empowerment and Protection Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act” purports to provide a legal framework for farmers to enter into contract farming with buyers. Contract farming describes an agreement between firm and farmer regarding pricing and quantity of the agricultural commodity in question (Bhattacharya 2021). Further, this “framework” has been criticized; according to research done by a fellow of the International Food Policy Institute in New Delhi, “virtually no rules exist for this new space” (Narayanan 2020). Nothing in the policy ensures competition or the absence of collusion, and the policy does not require either party to record or document transactions, defeating the purpose of contract farming (Narayanan 2020). These deficiencies are compounded by the fact that small Indian farmers are not equipped to engage in contract negotiations with international trading partners. This does not degenerate the intelligence of farmers or the respectability of farm work, but critiques the lack of government support to provide better educational programs and aid in contract negotiations. Further,

“Farmer disenchantment with agribusiness comes not some much from their ignorance of lucrative possibilities but from their underwhelming experience in engaging with large corporations” (Narayanan 2020).

Not only do farmers have minimal experience and exposure to large corporations, the experiences they have had or have heard of have been

overwhelmingly negative. As recently as 2019, PepsiCo sued multiple Gujarati farmers for using their patented potato seeds, and this case made international news (Narayanan 2020). High-profile interactions such as this contribute to a sense of distaste and discomfort towards cooperation with large agribusiness.

The second act requires specific evaluation of its dispute mechanism. Though the Indian government has touted the legislation’s fair and efficient framework for dispute resolution, many Indian citizens have critiqued these claims. If a farmer wanted to file a dispute after experiencing exploitation at the hands of a buyer, they must file that dispute with the Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM) assigned that responsibility. SDMs are notoriously known for their corruption and inefficiency, sardonically described as the pinnacles of bureaucracy. Waiting for this dispute to be resolved could take weeks, months, or even years, and the law does not permit farmers to file a lawsuit in Civil Court against the buyer (Narayanan 2020). The third agricultural reform in question exacerbates the financial strain and risks for small farmers associated with the first two acts.

The Essential Commodities Act of 2020 is an amendment to the previous ECA. The ECA lists “essential commodities” that the government does not legally permit to be hoarded in order to manipulate the market price of the commodity in question. In the height of the COVID-19 pandemic—June to late September 2020— the BJP government elected to remove foodstuffs like cereals, pulses, potatoes, onions, edible oilseeds, and oils from the list of commodities protected by the act, stating that it would only intervene in extreme cases (Government of India 2020). The government will only intervene in the price manipulation of these foodstuffs if a nonperishable commodity’s price rises by more than fifty percent, and if a perishable commodity’s price rises by over 100 percent, or doubles. Permitting the stockpiling of essential foods, especially during a pandemic, will inevitably lead to rises in market prices, multiplying the financial strain felt by peasant farmers and encouraging the development of pseudo-monopolies.

Most agree that change is necessary to spur greater economic growth

in agriculture and encourage entry into the global market. However, these bills will lead to premature entry of farmers into the market by design, leaving seventy percent of the country’s livelihoods at the behest of international firms. Change is necessary, but there must be an equilibrium between economic growth and the safety and prosperity of the country’s citizens. The Indian government must ask a crucial question: what push towards growth serves Indian farmers best? A variety of policy issues can be combated to better the gradual entry of small Indian agriculture into the global marketplace.

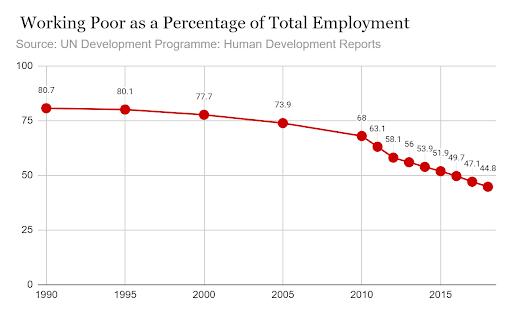

Poverty is widespread in India, with 21.9 percent of the population living below the national poverty line (UN 2018). While India has made significant strides, reducing their percentage of working poor from 80.7 percent in 1990 to 42.4 percent of the workforce, a large portion of the population continues to make less than or equal to PPP$3.20 per day (UN 2018).

Poverty reduces the likelihood of a farmer to take economic risks and invest in high yielding, high value crops, because the focus instead must be on avoiding disease and preventing starvation just to stay alive. Poverty impacts rural agricultural laborers far more than non-farm laborers because agricultural income has not risen with income in other sectors. A 2019 analysis of agricultural wages in India demonstrates that farm wages rise with a rise in non-farm wages, irrigation, and rural literacy (Kumar, Anwer 2020). Policy attempting to concentrate investment, perhaps through state-operated

banks, in irrigation and job training/education is necessary to achieve greater economic security.

During months of protests, farmers have called on the Indian government to write MSP into law, affording financial security and protection to farmers. The government has responded numerous times, claiming that they will not end MSP. In fact, on September 20, 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi posted a tweet, saying, among other things, that the “system of MSP will remain” (Modi 2020). Despite this, the farmers’ worries are not unfounded. For nearly eight months, the government categorically refused to codify MSP into law, raising suspicions. After all, if MSP is to remain, what is the harm in enacting legislation that ensures that after Modi’s departure? Arguably, MSP is more necessary in an international context, as global markets are far more turbulent than domestic markets.

With regards to contract farming with firms, there must be a welldefined and well-regulated framework wherein the government will oversee and monitor contract farming deals presented by buyers according to specified minimum and maximum prices to limit exploitation. This number can be generated in a manner similar to the current generation of MSP values.

To engage in appropriate dispute resolution, there must be a truly effective and efficient mechanism in place with adherence to the policy discussed in the Agreements subsection. The state should make it permissible to file a claim in civil court against exploitative buyers, and provide legal aid if possible. Reducing adherence to corrupt SDMs is key in offering a fair remediation system.

Long-term, sustainable growth requires not only an investment in infrastructure, industry, and agriculture, but also an investment in India’s people. Emergency ordinances rushed through parliament with little debate do not serve the needs of India’s farmers. Legislation that caters almost

exclusively to the ambitions and business interest of wealthy multinational and transnational corporations does not serve the needs of India’s farmers. With a population highly vulnerable to economic exploitation by international actors, these agricultural “reforms” create a perfect recipe for twenty first century predation of the working class.

Arora, V.P.S. “Agricultural Policies in India: Retrospect and Prospect.” Agricultural Economics Research Review. December 2013.

“Agriculture: Production Performance 1995-1999.” 1995, 1996, 1997, and 1998 Economic Surveys. Ministry of Finance. Government of India.

Bhattacharya, Subhendu, and Utsavi Patel. “Farmers’ Agitation in India Due to the Audacious Farm Bills of 2020.” International Journal of Research in Engineering, Vol 4. Jan 2021.

“Exports and Imports (% of GDP): India.”United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Reports. 1990-Present.

“Human Development Indicators: India.” United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Reports. 1990-Present.

Kumar, Rajiv. “Composite Water Management Index.” National Institution for Transforming India. August 2019.

Kumar, Sant, and Md Ejaz Anwer, et al. “Agricultural Wages in India: Trends and Determinants.” Agricultural Economics Research Review, Vol 33. 2020.

Lidman, Russell, and Robert I Domrese. “Tropical Development 1880-1913: India.” Northwestern University Press. 1970.

Modi, Narendra. Twitter Post. September 20, 2020. 5:59 AM.

Narayanan, Sudha. “Understanding Farmer Protests in India.” Academics Stand Against Poverty, Vol 1. 2020.

P, Shinoj, and V.C Mathur. “Comparative Advantage of India in Agricultural Exports vis-a-vis Asia: A Post-reforms Analysis.” Agricultural Economics Research Review, Vol 21. Jan-June 2008.

Sedova, Barbara, and Matthias Kalkuhl, et al. “Distributional Impacts of Weather and Climate in Rural India.” Economics of Disasters and Climate Change. December 5, 2019.

Serhan, Yasmeen. “Where Nationalism Has No Answers.” The Atlantic December 21, 2020.

Singh, Santosh K., and Mark Rosmann. “Government of India Issues Three Ordinances Ushering In Major Agricultural Market Reforms.” US Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. June 29, 2020.

Venkatesh, P. “Recent Trends in Rural Employment and Wages in India: Has the Growth Benefited the Agricultural Labours?” Agricultural Economics Research Review, Vol 26. 2013.

Matt Heller is a fourth year undergraduate in the University of Virginia’s Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy, double majoring in public policy and history. Matt is originally from Glen Rock, New Jersey before he came down to Charlottesville for school. He’s interested in foreign policy topics such as democratic backsliding, great power competition, and national security. Outside of academics, Matt is involved in the International Relations Organization, Model UN at UVA, the University Guide Service, and he writes for the Cavalier Daily.

I am delighted to see that Matthew Heller’s paper “Beijing's Threat to Global Democracy" has been selected for publication in the Virginia Journal of International Affairs. Mr. Heller’s article began as an assignment in a Spring 2021 seminar that I co-teach with Professor Larry Sabato, along with a related internship with the UVA Center for Politics that same semester. The specific assignment for the students was to identify at least one contemporary problem that they believe poses the most significant threat to the health of democracy.

As part of the assignment, I asked students not simply to observe the problem they identify, but to dig deeper and cover what they feel are the likely causes, why it persists and identify potential solutions.

From the title, it’s clear that Mr. Heller didn’t choose one of the more conventional—and typically domestic-focused—responses to the assignment. He reached much further, which was the first aspect of his work that impressed me. Second, I remind my students often that it’s easy be a critique, and thus it is the latter half of the assignment that often poses the biggest challenge for students. As you will read, Mr. Heller handled both parts with equal measures of academic rigor and thoughtful reflection.

Finally, if I may, Mr. Heller’s work serves as a testament that he is a

true leader and a rising star, unafraid to tackle tough challenges, even one as large and daunting as “fixing democracy”. I am not an expert on U.S. China relations, but my background in American politics suggests to me that if democratic societies are to tackle the myriad problems facing this system of governance, it will require sustained effort and robust thought on many fronts - and not just by today’s leaders, but tomorrow’s as well. Mr. Heller models that exact behavior in this thoughtful piece.

Kenneth S. Stroupe, Jr. Associate Director Chief of Staff University of Virginia Center for PoliticsAll over the world democracies have come under assault fromby autocratic forces. Democratic norms like free expression and the peaceful transition of power are being eroded, and a number of once-robust democracies have since backslid. Chief among these autocratic forces leading the attack on democracy has been the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party, who have both actively and passively marketed their model of governance as a contrast to the global democratic order. The paper discusses how China’s authoritarian model is structured, what steps China has taken to export it abroad to disrupt democratic norms in general, and ultimately what policies can be taken by the United States can pursue to rebut this grave threat. Thise paper makes the argument that China’s threat to democracy can be met through increased multilateralism, strengthened international institutions, and continued support for the free-flow of information.

The state of global democracy today is deeply troubling. According to the Global Democracy Index, a ranking developed by The Economist based on electoral processes, government functionality, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties, less than half of the world’s population lives in some sort of democracy, and fewer than one in ten people lives in a full democracy (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021). The year 2020

was particularly challenging for global democracy, as a number of oncefunctioning democracies backslid into autocracy. More worrisome was that even the United States, once a bastion of global democracy, was relegated to the status of a “flawed democracy,” on account of declining public trust in American democratic institutions, which have struggled with delivering policy for the American people (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021).

Within this context, autocracy has been surging globally, particularly as nations where some democratic norms previously existed, have transitioned toward autocracy(Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021). Among these increasingly autocratic countries, one in particular stands out: the People’s Republic of China. China’s autocratic tendencies were on display during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when draconian lockdowns, government censorship, and a pervasive surveillance state were highly effective both at exacerbating and then stopping a pandemic in its tracks. While China’s means to this end were worrisome from the perspective of a citizen, from a government’s perspective, China’s response to the pandemic demonstrated the brutal efficiency of their authoritarian model of governance -- and it soon became the envy of many would-be autocrats globally.

For democracy, however, the threat of China’s autocratic model of governance is grave, and poses a major threat to democratic governance globally. As China’s model demonstrates success while democratic nations falter, the institution of democracy itself faces an international referendum on its continued existence. In this paper, I will discuss China’s authoritarianism, how China is exporting its governance model, and American policies that can be taken to uphold democratic norms and rebut China’s autocracy. I will ultimately argue that democracy can be saved through increased multilateralism, strengthened global institutions, and support for the continued free-flow of information.

At the turn of the 21st century few thought that China, a nominally communist state that was quickly embracing the free market and joining democratic global institutions like the World Trade Organization, would remain an autocracy for long. In the early 2000s, many assumed that China would simply follow the trend of Western nations where economic progress came in tandem with civil and social liberalization. Today, China has

achieved the largest reduction of poverty in world history. Yet the political liberalization that would lend itself to democracy is still missing, and there is no indication it will ever emerge (Mitter and Johnson, 2021).

In retrospect, the Tiananmen Square Incident of 1989, when the Chinese military used tanks to fire on pro-democracy protesters, foreshadowed what was to come. In the 21st century, China has developed a technologically sophisticated censorship regime that restricts the press, and punishes dissent from individuals on social media using a social credit system that creatively curtails the right to free expression. Neither is there any ability to participate in democratic governance, as most policies are centrally made by a small group of party leaders led by President Xi Xinping, who has installed himself as a dictator for life (Gueorguiev, 2019). Moreover, China has recently promoted Han-Chinese ethnic nationalism, which has gone so far as to justify the mass-internment of the ethnic-minority Uighurs in the largest persecution of a religious minority since the Holocaust (BBC, 2021).

Despite these gross abrogations of their rights in favor of autocracy, the Chinese people are happy with the system in place for one reason: it has spurred economic prosperity and created social stability. As one paper from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace explained, China’s middle class has “willingly accepted authoritarian rule in exchange for getting rich,” (Link and Kurlantzik, 2009). Simply, despite the repression of their individual liberties and disenfranchisement, many Chinese citizens support their government because it has skillfully managed the economy over the years. Especially following its success fighting against the COVID-19, the popularity of China’s ruling regime has soared, and the vast majority of Chinese people support their government despite its autocratic nature (Roberts, 2021).

The success of China’s stability-for-liberty tradeoff has been noted internationally, where global leaders respect the model’s effectiveness at delivering policy and popularity with those it governs. This poses a strong contrast to Western democracies, many of which have descended into polarization and political tumult that has bucked the steady hands of establishment leaders. Ian Bremmer, a scholar of global democracy, recently noted that “many governments...around the world see China as a source of security, stability, and opportunity while Europe and America represent political dysfunction and public disgust with government” (Bremmer, 2019).

Given this, it is troubling for the sake of democracy that international leaders are turning to the China-model as a source of inspiration, instead of aspiring to democratic governance. What is more troubling is that China has recently begun to play an active role in exporting its autocratic model abroad to other countries.

One of the main principles of the Chinese autocratic model has been reliance on a technologically sophisticated surveillance state. The Chinese government employs artificial intelligence to surveil its citizens, going through their social media posts, accessing medical records, tracking their locations with facial recognition, and even utilizing government-run DNA repositories. It is a system that is inherently anti-democratic, denying citizens their rights to privacy and making them wary of expressing dissent. It is also a system that China is actively exporting to other nations, such as Malaysia, Egypt, Serbia, Sri Lanka, Kenya, and many others (Andersen, 2020). Chinese companies, most of which are tightly controlled by the state, routinely sell advanced surveillance systems to foreign governments with the intention for them to be used to restrict the rights of citizens. The Chinese government has even provided direct training to over thirty-six foreign governments on how to construct similar surveillance states (Radu, 2018). Of those a number are democratic countries, and China’s exported surveillance technology will help undermine those democratic norms. Nations such as the Philippines and South Africa that have existent democratic institutions are beginning to deprive their citizens of basic civil liberties as those governments impose a Chinese-style surveillance state on their people -- clamping down on dissent, and weakening local democratic norms in the process. The resultant backsliding of those democracies into autocracies is an explicit intention of China’s policies to sell these surveillance systems internationally, as it benefits China politically to establish new autocratic allies and diminish free expression rights abroad that could otherwise disseminate criticism of the Chinese government (Scott and George, 2020).

Recently, China has become something of an international cheerleader for autocracy, as Beijing has flexed its soft power to promote its model of governance as inherently superior to the liberal models of Europe and the United States. This has come in the form of assistance to would-

be dictators seeking to undermine democracy in their home countries. For example, in Uganda in 2019, Chinese-sponsored companies assisted the ruling political party in surveilling and repressing an opposing political party to win an election (Parkinson et al, 2019). Moreover, the Chinese Communist Party has a robust outreach program that has facilitated thousands of direct contacts with foreign political parties over the past decade; these contacts primarily target vulnerable democracies in Asia, Latin America, and Africa (Hackensch and Bader, 2020). One study analyzing these contacts found that they have tangibly contributed to authoritarian diffusion, and benefit China in recruiting allies abroad to undermine existing global institutions and foreign democracies in general (Hackensch and Bader, 2020).

But China’s promulgation of autocracy is not confined to voluntary assistance for aspiring autocrats; China is actively involved in using its economic leverage to co-opt foreign leaders and pressure countries into abandoning democratic principles. The chief economic weapon in China’s arsenal is its “Belt and Road Initiative,” a foreign-direct-investment scheme that invests in infrastructure projects around the world. Recipient countries from this initiative, however, often end up saddled with unsustainable debt and onerous contractual terms that result in local governments becoming de facto vassals of China (International Republican Institute, 2019). The consequences of this economic subjugation have been terrible for democracy. In Hungary, for example, Chinese government-backed investment has been directly linked to corruption by Prime Minister Viktor Orban, whose increased censorship of Hungarian journalists and autocratic power-grabs have been supported by his Chinese benefactors (IRI, 2019).

Not even robust democracies are immune to China’s anti-democratic influence. Take Australia, for example. It is a full democracy according to the Democracy Index, but is heavily connected to China economically. China takes advantage of these close economic ties to exert influence on Australian political elites, using both legal and illegal means to influence politicians with gifts and campaign contributions to condition support for Chinese interests in quid-pro-quo arrangements (IRI, 2019). This illustrates China’s exploitation of the democratic process itself to further its anti-democratic goals, which is also demonstrated by Chinese state-agents’ purchases of Australian media entities in order to produce more content that is favorable toward Beijing (Lee, 2021).

Fortunately, Australia’s democratic institutions have so far resisted the democratic backsliding caused by Chinese influence that other nations have suffered. Australia has passed campaign finance transparency laws in recent years to counter China’s cooptation tactics, and independent Australian media have led the charge in calling out Chinese propaganda that would otherwise remain hidden (IRI, 2019). It is unclear, however, if Australian democratic institutions will be able to resist these incursions forever, as a growing percentage of the Australian population has come to explicitly prefer autocracy over democracy (Lowy Institute, 2020). Especially following responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, many Australians have expressed admiration for the effectiveness of China’s authoritarian policies, and have come to perceive “checks, balances, and rights...to be obstacles to solutions rather than inalienable principles.” (Lee, 2021).

Many democracies have also struggled with China’s censorship of multinational companies seeking to do business in China, which results in restrictions on free speech in countries beyond Beijing’s borders. Such was the case when American news anchors on ESPN were recently forbidden from discussing pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong after China threatened to ban ESPN from its domestic market over the anchors’ exercising their rights to free expression (Osburn, 2019). Incidents like this pose a major challenge to democracies because governments react by restricting anti-democratic actions because of economic pressure imposed by China. Unfortunately, without active intervention from democratic countries to block this, capitalism creates incentives for companies to concede to China’s autocratic demands in order to continue to profit off of their large and growing market of consumers.

The same issue occurs when it comes to Chinese state-owned companies intervening directly in media companies in democratic nations to impose censorship and control information. One scholar focused on China called this process the “outsourcing of censorship,” and observed how Chinese companies invested heavily in media companies in democratic nations like Taiwan, and used those investments as a reward or punishment to condition favorable coverage of China (Huang, 2017). As a consequence, free citizens of democratic countries have seen a degradation of the free press as companies become dependent on Chinese state-backed investment to turn a profit -directly undermining a key pillar of an effective democracy.

Ultimately, China’s greatest means for the export of autocracy is the juxtaposition of their model of governance against Western-style democracies. As China’s economy grows and inevitably ascends to become the largest in the world, democratic countries have struggled economically, with democracy directly to blame for policy blunders like trade wars and stymied social investment that China has managed to avoid. A 2009 report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace speculated that the appeal of China’s autocratic model “abroad will depend in large part on how the Chinese economy weathers the global downturn,” and it is abundantly clear that in 2021, China’s model has proven successful at securing economic prosperity for the Chinese people (Link and Kurlantzick, 2009). But as democratic nations consider how to rebuff the material threat that China poses to their democracies, they must first prioritize ensuring that their own governments are successful. After all, democracy cannot survive if it cannot produce stable governance: if it yields nothing but polarization and strife, there is little to distinguish nominal democracy from autocracy by other means. That said, there are actionable policies that global democracies ought to take to counter China.

China’s export of autocracy is heavily dependent on the ability of the Chinese government to control political narratives through censorship and disinformation that it spreads abroad, particularly through social media. This has posed a challenge for democratic countries where media is an independent enterprise, and governments have few tools at their disposal to rein in media companies when they cater to Chinese demands to censor stories or face retaliation. This needs to change, however, as independent media is the most effective tool to rebuff China’s autocratic advances, as was demonstrated by the successes of Australian media in calling out Chinese incursions on their democracy (IRI, 2019). Democratic governments thus ought to do more to protect independent journalism, and block Chinese acquisitions of media companies to prevent co-option by the Chinese government. Further, transparency requirements ought to be strengthened, requiring disclosures of Chinese investment in media, advertisement buys, and political campaign contributions to ensure that the public can discover any China-related corruption undermining democratic processes (Cook and

Boyajian, 2019).

Secondly, democratic countries will need to do more to counter Chinese foreign direct investment which so often results in the abetting of anti-democratic elements of recipient countries. Nations such as the United States have a major role to play here, and ought to increase their provision of foreign aid through the US International Development Finance Corporation to better counter the Belt and Road Initiative. Moreover, democracies ought to better leverage global democratic institutions such as the World bank and IMF to provide aid to other democracies, loosening standards for fiscal responsibility to instead prioritize democracy-development in recipient countries (IRI, 2019). These measures will allow global democracies to serve as effective partners to each other, mutually strengthening their economies in order to ensure that all countries have better development partners to turn to than China.

Finally, democratic countries will need to commit to engaging in multilateralism, and strengthening the global democratic institutions that have been slowly degrading in recent years. For the United States in particular, this means securing bipartisan commitment to engage the international community in the fields of human rights and support for civil society. This will require the United States to return to ratifying treaties in the Senate and minimizing the number of executive agreements entered into by presidents on the basis of their political authority; this will reduce diplomatic whiplash between administrations by forcing foreign policy to be bipartisan and less reversible than it is today. An increase in the number of treaties the United States enters will ensure it is a more reliable diplomatic partner, improving its global reputation as a multilateral actor.

Once the United States has affirmed its commitment to the global democratic order, it will need to lead the reform and improvement of the institutions meant to uphold global democracy. A major priority to this end should be the removal of China and other autocratic nations like Venezuela

Afterall,democracycannotsurviveifitcannot producestablegovernance:ifityieldsnothingbut polarizationandstrife,thereislittletodistinguish nominaldemocracyfromautocracybyothermeans.

and Libya from the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC): a body that a country like China lacks the legitimacy to sit on. This can take the form of reforming the membership process so that it is tied to average scores across a number of human rights indices, instead of an open nomination system that holds the door open for autocracies to shape the global human rights conversation (Piccone, 2021). By removing human rights-abusing countries from the UNHRC, the UN will better be able to set the global human rights agenda and make policies that can properly enforce democratic norms within the international community.

It is clear that global democracy is under threat from the People’s Republic of China. The Chinese autocratic model, which uses advanced surveillance to restrict the free expression of citizens already kept out of the governing process, is posed for export to vulnerable democracies around the world, which will only worsen an already-grim state of global democracy. China benefits from degradation of democratic values, its foreign policy benefits from the creation of autocratic allies, and its domestic position is strengthened when censorship and repression become the global norm so as not to remind its own people what their lack of democracy represents. Given China’s activities promoting and pushing their model of governance, all democratic nations ought to be concerned about this challenge, and ought to work to combat China’s efforts to attack the institutions of democracy. This will not be easy to accomplish. China’s autocratic model benefits as China’s economy continues to grow, and as democratic countries continue to struggle against polarization and economic populism, Chinesestyle autocracy will only look better by comparison. Democratic countries must put petty differences aside if they are to achieve the political unity necessary to counter the threat to democracy that Beijing poses. It is not an extraordinary leap to imagine increased international development, commitments to free expression, and affirmations of international institutions. Such was the norm during the Cold War when democracy was last under threat by totalitarianism, and so it must be again today. One can be confident that democracy can overcome these struggles, but it will require effort and perseverance to ensure that democracy as an institution survives this threat and continues for decades to come.

Andersen, Ross. 2020. “The Panopticon Is Already Here.” The Atlantic.

Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/ archive/2020/09/china-ai-surveillance/614197/.

BBC. 2021. “Who Are the Uighurs and Why Is China Being Accused of Genocide?” Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/ world-asia-china-22278037.

Bremmer, Ian. 2019. “China-Style Authoritarian Rule Advances Even as Democracy Fights Back.” Nikkei Asia. Accessed May 4, 2021.

https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/China-style-authoritarian-ruleadvances-even-as-democracy-fights-back.

Cook, Sarah and Annie Boyajian. 2019. “How the US Government Can Counter China’s Growing Media Influence.” TheHill. Accessed May 5, 2021. https://thehill.com/opinion/civil-rights/446998-how-theus-government-can-counter-chinas-growing-media-influence.

Gueorguiev, Dimitar. 2019. “Analysis | Mike Bloomberg Said China Isn’t a Dictatorship. Is He Right?” Washington Post. Accessed May 3, 2021.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/12/04/michaelbloomberg-said-china-isnt-dictatorship-is-he-right/.

Hackenesch, Christine, and Julia Bader. 2020. “The Struggle for Minds and Influence: The Chinese Communist Party’s Global Outreach.”

International Studies Quarterly 64(3): 723–33.

Huang, Jaw-Nian. “The China Factor in Taiwan’s Media: Outsourcing Chinese Censorship Abroad.” China Perspectives 3 no. 111:27-36.

International Republican Institute. 2019. “Chinese Malign Influence and the Corrosion of Democracy: An Assessment of Chinese Interference in Thirteen Key Countries.” Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.iri. org/sites/default/files/chinese_malign_influence_report.pdf.

Joe Parkinson, Nicholas Bariyo, and Josh Chin. 2019. “Huawei Technicians Helped African Governments Spy on Political Opponents.” Wall Street Journal. Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ huawei-technicians-helped-african-governments-spy-on-politicalopponents-11565793017.

Kurlantzick, Josh, and Perry Link. 2009. “China’s Modern Authoritarianism.”

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Accessed May 3, 2021.

https://carnegieendowment.org/2009/05/25/china-s-modern-

authoritarianism-pub-23158.

Lee, John. 2021. “The Risks to Australia’s Democracy.” Brookings. Accessed May 4, 2021.

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-risks-toaustralias-democracy/.

Lowy Institute. 2020. “Lowy Institute Poll 2020: Democracy.” Accessed May 4, 2021. https://poll.lowyinstitute.org/charts/democracy/.

Mitter, Rana, and Elsbeth Johnson. 2021. “What the West Gets Wrong About China.” Harvard Business Review. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://hbr. org/2021/05/what-the-west-gets-wrong-about-china.

Osburn, Madeline. 2019. “14 Times U.S. Companies Self-Censored Or Apologized To Appease China.” The Federalist. Accessed May 5, 2021.

https://thefederalist.com/2019/10/10/14-times-american-companiesself-censored-or-apologized-to-appease-communist-china/.

Piccone, Ted. 2021. “UN Human Rights Council: As the US Returns, It Will Have to Deal with China and Its Friends.” Brookings. Accessed May 5, 2021.

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/02/25/ un-human-rights-council-as-the-us-returns-it-will-have-to-dealwith-china-and-its-friends/.

Radu, Sintia. “China Is Teaching Other Governments Its Online Censorship, Surveillance Model.” US News & World Report. Accessed May 4, 2021.

//www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2018-11-01/chinaexpands-its-surveillance-model-by-training-other-governments.

Roberts, Dexter Tiff. 2021. “How Much Support Does the Chinese Communist Party Really Have?” Atlantic Council. Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/howmuch-support-does-the-chinese-communist-party-really-have/.

Scott, Caitlin Dearing and Adam George. 2020. “As China Promotes Authoritarian Model, the Resilience of Its Democratic Targets Is Key.” Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.justsecurity.org/73925/ as-china-promotes-authoritarian-model-the-resilience-of-itsdemocratic-targets-is-key/.

Alex Sarchet is a third-year from Virginia Beach at the University of Virginia, majoring in Foreign Affairs and Linguistics and minoring in French. While this is his first time researching language-caused conflicts, he is interested in conducting further research on the topic as he continues his studies at UVA. In addition to submitting to the Virginia Journal of International Affairs, he is involved with the International Relations Organization through the Model UN Travel Team and the VAMUN Secretariat, as well as being one of the social chairs. When not focusing on his studies or on IR-related activities, he enjoys reading, cinema, and fencing.

This paper examines how language diversity, when isolated as an independent variable, correlates with a country's state of civil war. Of course, in reality, civil wars are caused by and remain ongoing as a result of many complex and interrelated variables. However, as civil war is a result of irreconcilable differences between different groups of people, this paper argues that the linguistic nature of a country can be a predictor of conflict escalating past simple localized violence. The author of this paper analyzes data concerning official and de facto language as well as all living languages used in a country. Then, the author produces data on the amount of civil wars in each country of the world since the end of WWII and the amount of days each country has spent since then in a state of civil war. Using these data, the

author produces ratios of a civil war variable to a language variable in order to see if language diversity correlates with likelihood and duration of civil wars. It is hypothesized in the paper that in countries with a ratio below the world average ratio, language played a major role in its civil war nature. If the ratio is above the world average, then its civil war(s) were likely a result of different issues of which language was not a strong contributor. In the end, the author concludes that there is enough evidence of correlation between language diversity and civil war, but not enough so that it can be used alone as a reliable metric for predicting a country's chances of breaking out into civil war. However, it is proposed that in highly linguistically diverse countries, elevating a language to the official or de facto level can mitigate the chances of civil war.

While analysts have conducted many studies on how ethnic and religious differences affect the likelihood of civil wars breaking out, not as many have looked at linguistic diversity as a correlative factor of civil wars. One article (Bormann et al., 2015) compares linguistic differences to religious differences in influencing rebel activity, and states that language might be a bigger cause of intrastate conflict than religion; however, the data are inconclusive on which has a greater effect, language or religion--they often contribute to civil conflict simultaneously, and it is hard to isolate them for study. Another article discusses how the 22 official languages of India--and its many minority languages--influence the politics of the country and clash with the prominent Hindi and English in the national sphere of influence (Singh & Dhussa, 2020). The Indian government allows official provincial languages to be the primary languages taught in provincial schools, so while Hindi and English dominate at a national level, language conflict is mitigated through this type of appeasement. Most other governments do not grant their minority languages such distinctions. Nelde (2017) discusses current issues in researching language contact and conflict and proposes new methods of studying and resolving these conflicts.

Nelde’s article goes further: In countries where one language is dominant, particularly in former imperial colonies which predominantly speak such languages as English, French, or Portuguese, the dominant language takes center stage in national government. As a side effect, minority languages tend to be deemphasized and only used in cultural and

interpersonal settings, leaving speakers of those languages who do not also speak the dominant language at a massive disadvantage. Minority languagespeakers have reduced social and political mobility (Nelde 2017). This is a language conflict in its most basic form, and it can lead to more drastic conflicts like civil wars if left unresolved. Often, the flames of intrastate conflict are stoked by politicians and economic leaders who use language conflict as a surface-level explanation for civil strife, eliminating the need to address deeply-rooted social and economic issues. Thus, language conflict is used as an excuse to dismiss those with less social mobility and to stop them from advancing, maintaining a status quo. Nelde proposes solutions to conflicts such as those in Canada (between English- and French-speakers) or Belgium (between Flemish- and French-speakers), including giving speakers of minority languages “more rights and opportunities for development,” which in turn reduce the likelihood of minority language speakers taking up opposing ideological positions (Nelde 2017).

My hypothesis in this study is that countries with greater internal linguistic diversity will have a greater likelihood of experiencing a civil war as the disparity between the handful of official and de facto languages and the raw number of languages in use potentially leads to resentment among minority groups. This diversity will also lead to longer wars on average.

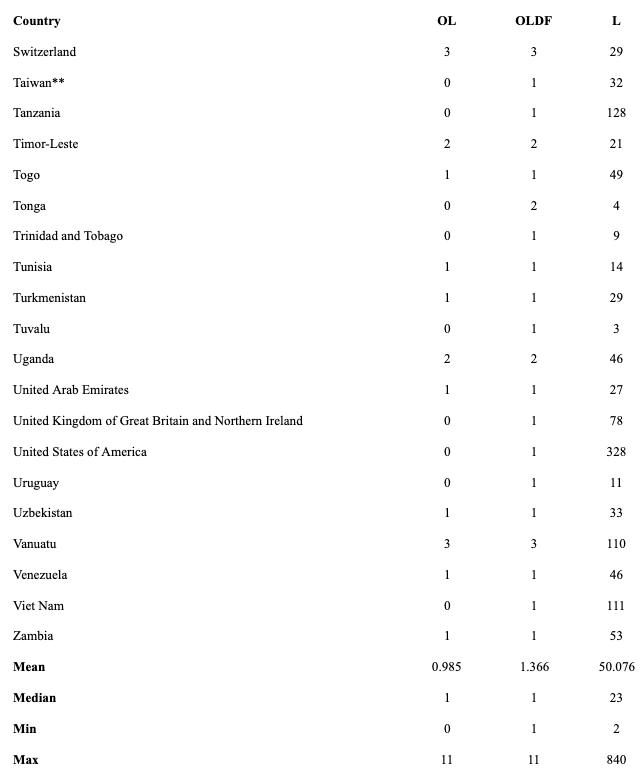

Although studies such as these cover language involvement in conflict well, I wanted to have a more robust, overarching study. I could not find a simple source that gave raw numbers as data, so I compiled one myself. For the language aspect, I use one data set for official languages as dictated by each country's constitution, one data set for all official and national de facto languages, and one for all languages, as listed by Ethnologue. This should provide something to compare official languages to actual linguistic diversity. For my sample set, I used the full list of United Nations member states, the two UN observer states, and Kosovo and Taiwan, given that Kosovo and Taiwan are two states which are both generally considered sovereign and are not members of the United Nations. I originally planned on cross-referencing this list of countries with the CIA World Factbook's list of languages spoken in each country. At first glance, this list appears to distinguish official languages from de facto and minority languages. However, it is often

inconsistent with the linguistic data it presents. For instance (CIA, n.d.):

Burma

Burmese (official)

Canada

English (official) 58.7%, French (official) 22%, Punjabi 1.4%, Italian 1.3%, Spanish 1.3%, German 1.3%, Cantonese 1.2%, Tagalog 1.2%, Arabic 1.1%, other 10.5% (2011 est.)

These two examples are egregiously oversimplified. In the Burma entry, the CIA only lists one language, whereas the country actually boasts 128 languages in use (Ethnologue, n.d.). In the case of Canada, the CIA includes minority languages spoken by immigrants, but no indigenous languages, of which Canada has many. Since nationally-affiliated resources provided such incomplete and inconsistent data, I used the more reliable Ethnologue instead. Ethnologue is additionally useful because it classifies every language used in a country by its status. For instance, I considered all “Statutory National” languages and working languages as “Official Languages” (OL). I combined “De Facto National” languages and working languages with OL to create an OLDF category, which is a more accurate metric of what languages a country's government uses. This is because Ethnologue only looks at constitutions and not at other legislation that would establish an official language, so OL alone would be unrepresentative of the official languages each government uses. Finally, I summed the raw count of living established and unestablished languages to simply “Languages” (L). These are the languages with a substantial number of speakers in a given country-in other words, it does not include immigrant languages spoken by a mere handful of people, but it does include languages spoken by a few hundred or more immigrants. This data set includes sign languages, which have a far less likely probability of leading to conflict than spoken languages. However, the number of sign languages per country is small enough to have only a negligible effect on the data. I counted creoles and pidgins as languages, as well as several substantially distinct dialects (i.e., the Arabic and Chinese dialects) and foreign and immigrant languages, like English in the postcolonial world. Every country on my list had linguistic data on Ethnologue, save Kosovo, which I found elsewhere to have at least seven languages spoken in sizable amounts (Be in Kosovo n.d.). If any languages are currently extinct, they do not show up in the data, even if they were still living

at some point during the range of years this study observed.

For civil war data, I tried avoiding Wikipedia as much as I could, but I was not satisfied with other sources that didn't have the data I wanted all in one place. I used the article “List of civil wars,” pulling information on every civil war, substantial insurgency, and crisis from 1945 to present for a total of 86 cases. One data set is the raw number of civil wars that the observed countries have experienced in those 76 years (CW). The other data set is the number of days that those countries were in a state of civil war or crisis (DCW), expressed as a ratio of that number of days to the number of days since the end of WWII; from September 2, 1945, to May 14, 2021, this totals to 27,649 days, including both start and end dates. I used May 14, 2021 as the end date of the civil wars that were still ongoing at the time of the study. In cases of more than one civil war occuring at once within the same country, I did not count duplicate days to reflect the simultaneous conflicts. Rather, I considered the number of days a country was in any state of civil war.

With these four data sets, I took the following ratios for each country: CW/OLDF; DCW/OLDF; CW/L; DCW/L. The greater the language diversity or the lower frequency of civil wars, the lower the ratios will be. A smaller ratio suggests that language might have been a greater causal factor in the conflict.

Separate spreadsheets were created, listing all countries, all countries by continent, countries that had experienced a civil war since 1945, and countries that had not. I associated historical data with countries that exist today. Often, this was the same country that experienced the historical civil war, as in the case of the Guatemalan Civil War. In some cases, like the various Sudanese civil wars or the Yugoslav Wars, the country no longer exists in the same form it did at the time, so I attributed the same data to each country that developed within the former borders — like North Sudan and South Sudan. I likewise considered language data with present borders in mind.

I took the average of each data column and compared each country to these averages. I hypothesized that if a country's ratios are below the averages, then that could be an indication of correlation between language diversity and likelihood of civil war for that country, or of the longevity of civil war for that country. In countries with above-average ratios, language is likely not a major factor in civil conflict, and those countries rather tend

to descend into civil war in spite of linguistic homogeneity. I did not expect there to be much correlation since this study excludes other interrelated factors of civil war such as ethnicity, religion, and politics, but I hoped to uncover something noteworthy. I expected to find that a greater number of spoken languages is an indicator of civil war and a longer length of time spent in a state of civil war.

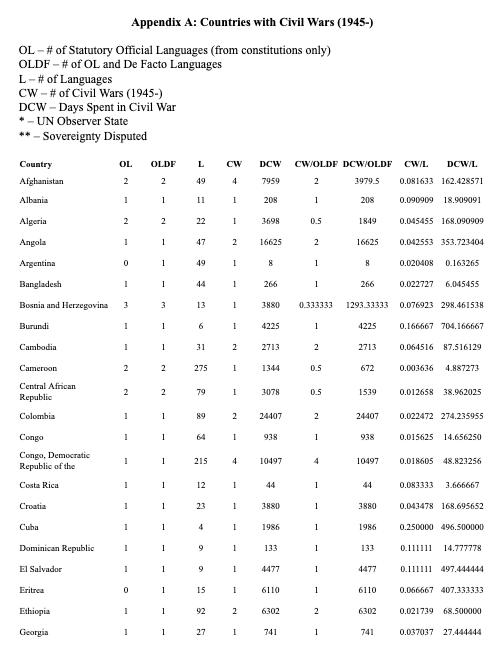

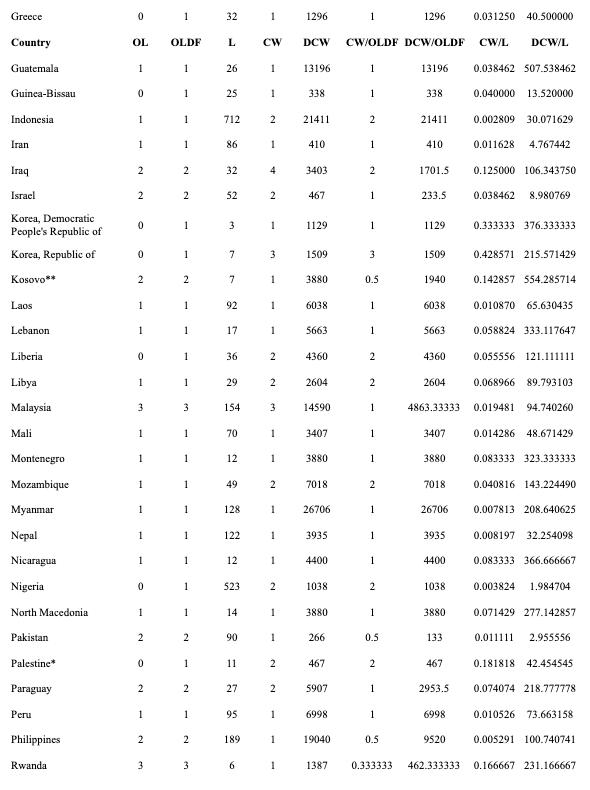

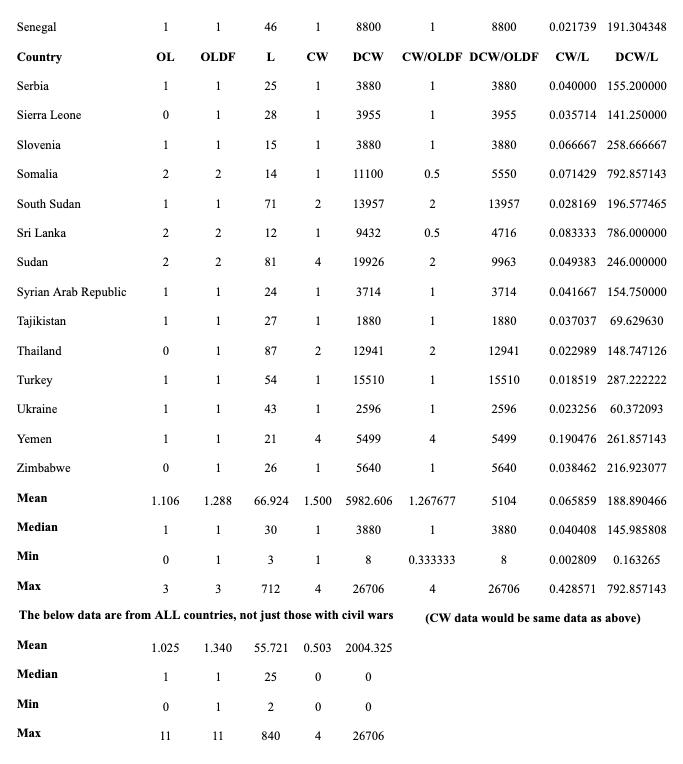

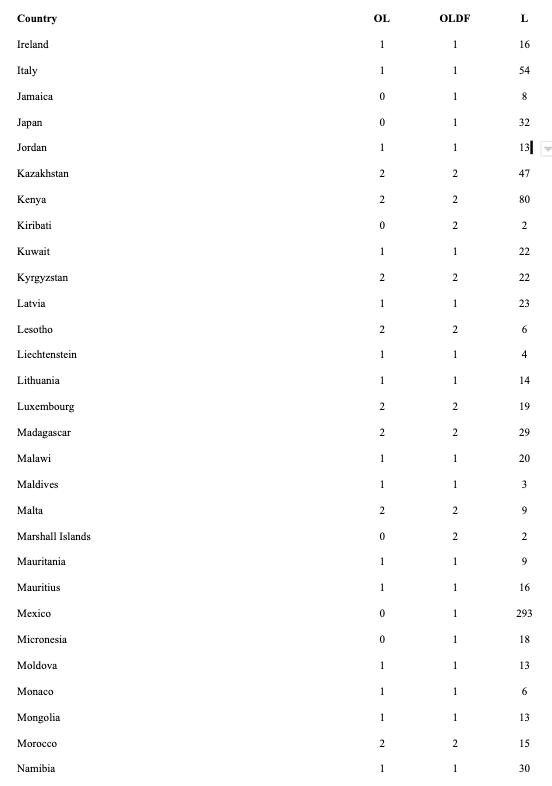

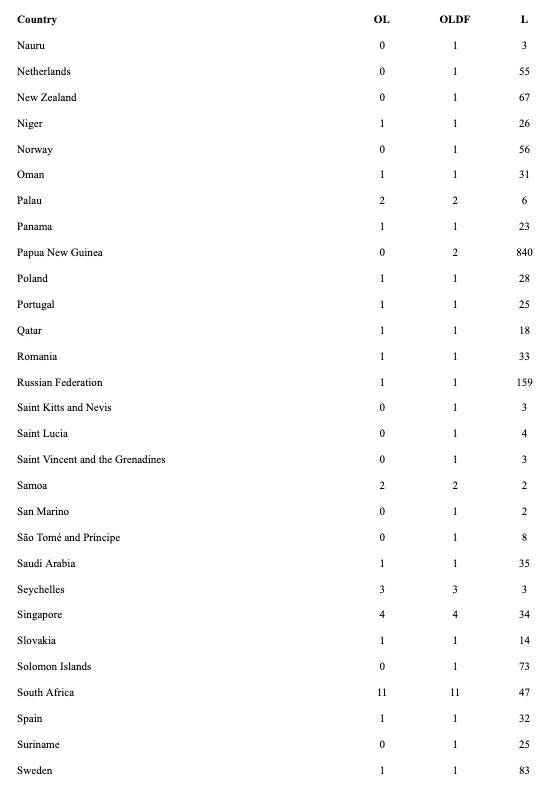

Appendix A shows data for the 66 modern-day countries in the sample that experienced a civil war since 1945. Appendix B shows data for the other 131 modern-day countries in the sample that have not undergone a civil war since 1945. Appendix B excludes data on civil wars, as each country would have a value of 0 in every column. It is provided here as a comparison to the language data in Appendix A.

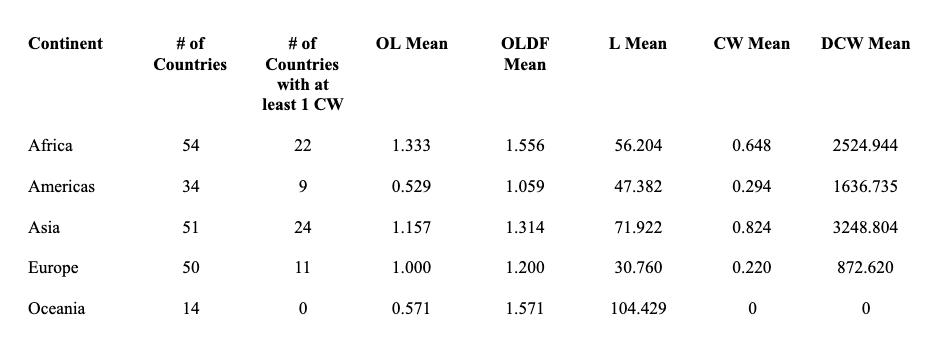

I also considered further breaking down data by individual continents; those data are summarized below. (There is some overlap between continents due to circumstances like Cyprus being part of both Africa and Europe.)

Of the three language-related data sets, L is perhaps the most relevant, as most countries fall between 0-4 OL and 1-4 OLDF (South Africa is an interesting outlier with 11 OL and 11 OLDF). L ranges from 2 languages to 840, making it the most useful metric for linguistic diversity. While OLDF is also important, there is relatively little diversity among countries’ OLDF numbers; very few countries have more than 2 OLDF.

Still, the CW mean seems to correlate to all three language data sets, broken down by continent. Oceania is the clear outlier. L is at its greatest in Oceania, far superseding any other continent, but none of the 14

countries of Oceania have had a civil war in the last 76 years. This discredits my hypothesis that a greater L alone yields a greater likelihood of civil war erupting. Nonetheless, Africa and Asia have a greater L than the Americas or Europe, as well as a greater CW mean. Thus, we can conclude that Oceania is an outlier. One potential explanation for this discrepancy is that the physical restrictions of island nations lead people of Oceania to settle civil differences without warfare; however, nearby island countries in Asia, specifically Indonesia and Malaysia, have each been in some state of civil war for over half of the 76-year observation range. So, on the mainland and in some island nations, a raw number of spoken languages can be an indicator of one or more civil wars breaking out.

Appendix A reflects some of the aforementioned ratios in even more detail. These individual countries’ ratios help us to determine whether a country has experienced one or more civil wars as a result of language or other, unrelated factors. Consider the examples of Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Philippines, and Yemen. Afghanistan has experienced four CWs, totalling 7,959 days spent in a state of CW. Its ratios of CW to both OLDF and L are above the world average, so we can say that Afghanistan’s language diversity did not correlate to its number of CWs; however, its DCW ratios are below the world average, suggesting that language diversity did correlate to the longevity of its CWs. Still, because the majority of the ratios were not below average and did not suggest a language diversity-civil war correlation, we can safely conclude that language has not played an active role in Afghanistan's civil wars.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is very linguistically diverse, yet it only has one official language. Thus, it turns out to be above average in the ratios involving its OLDF, but it is well below average in the ratios involving its L. Because the DRC is a large country, it is possible that CWs have broken out because the widespread speakers of different languages across the country harbored resentment for the government’s favor of one language over the rest. The CW/L ratios suggest this likelihood.

The civil conflict in the Philippines, ongoing for 19,040 days since 1969, causes the Philippines to be above the world average in the CW/ OLDF column only, implying that with a greater number of official and de facto languages, language would have had a greater effect on the conflict in the Philippines. On the other hand, the other ratios are below average, suggesting a stronger correlation between language diversity and CW and DCW.

Yemen has had four CWs since 1945, and is above the average across all four ratios. Because it has such a low amount of language diversity, Yemen represents an exception to the trend where high language diversity correlates to civil conflict. Direct comparison of across-the-board averages between Appendices A and B support the hypothesis. On average, countries with at least one civil war have 1.288 official or de facto languages and 66.924 languages of any status. In contrast, countries without any civil wars have 1.366 official or de facto languages and 50.076 languages of any status. In other words, greater linguistic diversity--especially a diversity of languages which are not officially recognized by national governments-- correlates positively with the likelihood of a civil war taking place. In countries without civil wars, there tend to be more official or de facto languages, suggesting that perhaps by elevating the national status of one or more languages, the mitigation of a civil war can be achieved. One final statistic solidifies this theory’s plausibility: On average, OLDFs represent 6.6% of a CW country's languages while in non-CW countries, that number is 13.6% (and the total world average comes out to 11.3%).