Sp 2024

Spring 2024

Journal of Virginia Journal of International Affairs

Virginia

Table of Contents

Staff

About the Journal

From the Editor

Anna Murray Papers

Competition in Connectivity: Gauging the Impact of US EffortAbroad in Limiting the Use of Huawei Manufactured 5G

Telecommunications Equipment

Ben Makarechian

Securing Stability: Will the Chinese Communist Party Survive the Post-Covid Era?

Michelle Nguyen

“The sun has set behind the hills:” Prominent ShidaiquArtists’Stories

Under the Chinese Communist Party, 1949–1978

Calvin Pan

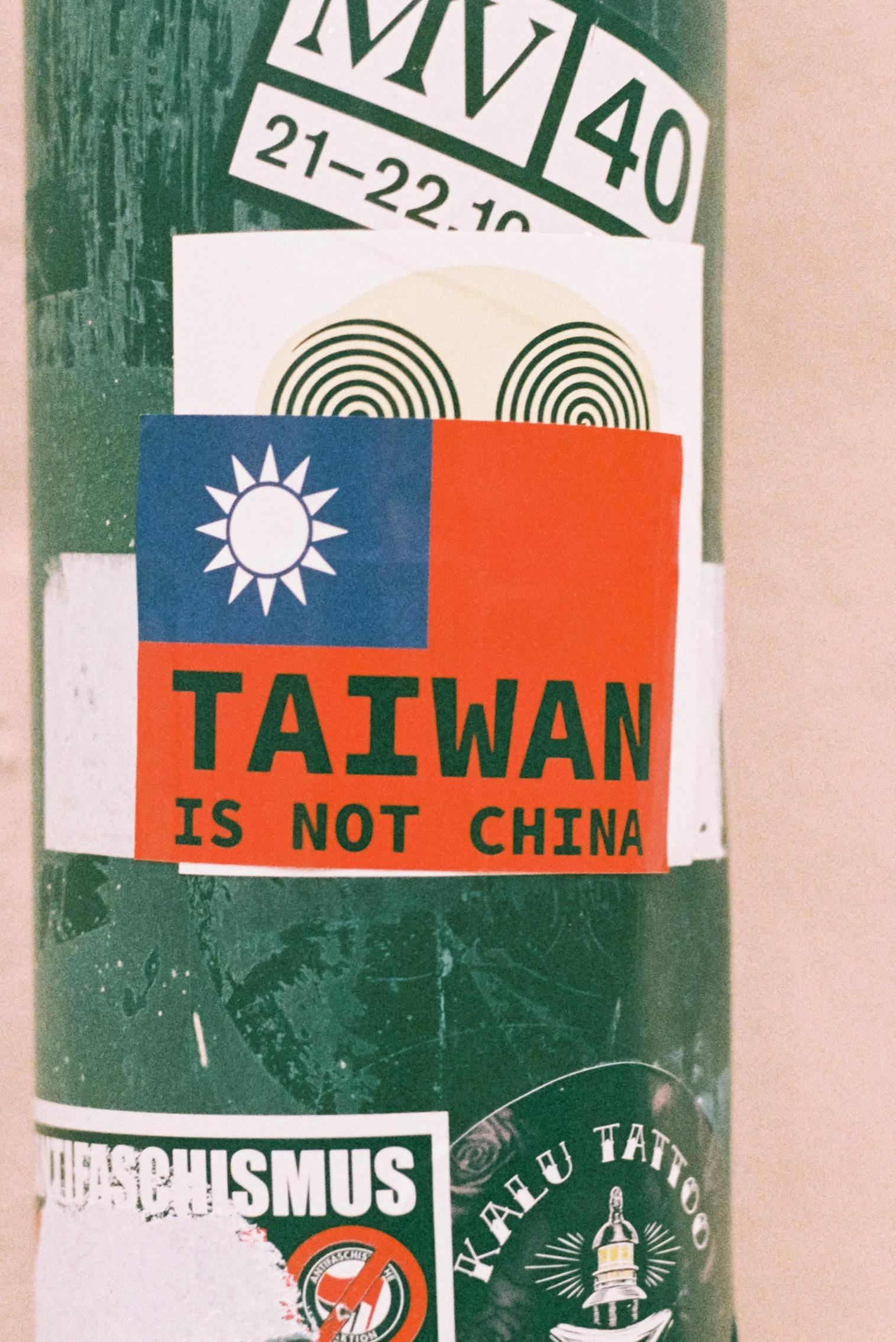

AStable Status Quo: Finding a Solution to the China-Taiwan Conflict

Alex Yang

Op-Eds

Chaos in ECOWAS and Regionalism’s Regression:America’s Role

Wyatt Dayhoff

Indonesia’s Nickel Empire at the Expense of Human Rights

Apal Upadhyaya

Staff

Editor-in-Chief

Managing Editor

Co-Production Chair

Co-Production Chair

Media Manager

Event Coordinator

Staff Editors

Ella Gilmore

Apal Upadhyaya

Anisha Iqbal

Avery Sigler

Wyatt Dayhoff

Nithya Muthukumar

Anna Murray

Victoria Djou

Neha Jagasia

Maggie Meares

Will Hancock

Pratha Purushottam

Michelle Nguyen

DeetyaAdhikari

Brooke Blosser

Emmett O’Brien

Alexander Macturk

Sydney O’Connell

4

About the Journal

The Virginia Journal of InternationalAffairs is the University of Virginia’s preeminent publication for undergraduate research in international relations. The Virginia Journal is developed and distributed by the student-run International Relations Organization of the University of Virginia. The Virginia Journal is one of the only undergraduate research journals for international relations in the country, and aims both to showcase the impressive research conducted by the students at UVAand to spark productive conversation within the University community. The Virginia Journal seeks to foster interest in international issues and promote high quality undergraduate research in foreign affirs. The Journal is available online at vajournalia.org.

Submissions

Interested in submitting to the Virginia Journal? The Journal seeks research papers on current topics in international affairs that are at least ten pages in length. Only undergraduates or recent graduates are eligible to submit.

Contact

Submissions should be sent to vajournalia@gmail.com

5

From the Editor-In-Chief

Dear Reader,

The Spring of 2024 has been a testament to the importance of ties that bind cultures across the globe. The conflicts and tensions seen today preempt a discussion not only of current peace and stability, but also the necessary steps to prevent tensions from erupting in the coming years. This semester’s journal primarily focuses on increasing tensions in EastAsia to present conflicts in the region as a microcosm of some of these ongoing discussions across the globe. Our hope is that, taken together with shorter pieces discussing the future of regional institutions and protections for populations caught in the crosshairs of the balance between economic growth and environmental harm, these lessons can help to inform future approaches to national security threats and spark thought-provoking discussion on multilateral relations. The papers included here discuss topics from the expansion of Huawei to changes and adaptations to protest culture in China, from the future of Taiwanese relations with China to artistic persecution and perseverance during the Cultural Revolution. We hope that these articles not only help to strengthen understanding of these crucial topics, but also spark discussion about the topics and their implications for our connections as a globe. These papers are incredibly insightful works, and I hope you will learn from them as I have over the past couple of months.

6

The production of this journal would not be possible without the collaboration and contribution of many different individuals throughout the production process. The hard work and dedication of the Journal Executive Board over the past few months to plan and produce this final product cannot be overstated. It has been a privilege to work with such a wonderful editorial staff, both on the main papers as well as opinion pieces published on our website and throughout the university community. We as a journal extend our gratitude to the International Relations Organization at UVA for providing the staff with the opportunity to produce such an important publication. I also would like to thank the authors for their contributions to this semester’s publication, as well as the support of UVAfaculty at every turn.

Finally, I would like to thank you, our readers, for taking the time to interact with the works present in this journal and to learn from the students at this university grappling with difficult topics in foreign affairs. I am honored and excited to present this semester’s journal to you.

All the best,

Anna Murray Editor-in-Chief of the Virginia Journal of InternationalAffairs

Anna Murray Editor-in-Chief of the Virginia Journal of InternationalAffairs

7

Papers

Competition in Connectivity: Gauging the Impact of US EffortAbroad in Limiting the Use of Huawei Manufactured 5G Telecommunications Equipment

Ben Makarechian

About theAuthor

Ben Makarechian is a third year student at the University of Virginia’s Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy. He is majoring in Public Policy and International Economics. He is also

11

pursuing a minor in Chinese. Ben’s policy areas of interest consist of CCP economic statecraft policies, cross strait relations, and non-proliferation. He resides in Los Gatos, California and hopes to pursue a career in US national security policy.

Abstract

As developing nations have begun to implement the next generation of cellular telecommunications equipment into their national infrastructure, the United States and the People’s Republic of China have quietly engaged in a diplomatic struggle to control precisely which infrastructure each country adopts. In the US, fears over the national security implications of allies adopting Huawei-provided telecommunications infrastructure led the Trump and Biden Administrations to implement sanctions against Huawei and begin a global campaign of diplomatic pressure. How successful were these actions, however, at limiting the spread of Huawei technology? This article uses an independently created data set cataloging the 5G equipment provider for over 160 countries using over 50 unique sources to compare the rate of Huawei technology adoption before and after landmark US actions against Huawei. This article finds that while US efforts have been effective at decreasing the rate at which countries adopt Huawei technology, its warnings

12

have not been universally heeded by allies or non-allies, indicating potential concerns about the reliability of key security partners.

Competition in Connectivity: Gauging the Impact of US Effort

Abroad in Limiting the Use of Huawei Manufactured 5G Telecommunications Equipment Introduction

The rise of China as a great power in the late 2010s has had far reaching implications for the US-led global order in place since the end of the Cold War. In response to China’s rapidly increasing global political influence, the United States, under both the Trump and Biden administrations, has shifted from an anti-terror, Middle East focused foreign policy to one that gives increasing priority to strategic, economic and geopolitical competition with China. An early battleground emerging from the intensifying struggle for international influence between the two powers is 5G equipment vendor choice for national, next-generation cellular networks. Huawei, a Chinese firm with suspected ties to the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has become a global leader in the provision of 5G systems and equipment, toting cheaper and more efficient technology than its competitors (Balding 1). Huawei’s cheaper systems are already popular in many parts ofAfrica, and now the company

13

has been increasing its share of the 5G communication equipment market in Europe. Fears over the CCP’s ability to use Huawei’s technology to gather sensitive national security information from the countries it has partnered with have ledAmerican officials to place increasingly severe restrictions on the company’s ability to do business in the US and obtainAmerican-made technological components. While the sanctioning campaign has been effective domestically, it has had mixed results at limiting Huawei’s expansion abroad, leading the US to rely on its influence as the West’s dominant power to convince countries to heed its warnings about the dangers of Huawei’s network expansion.

This paper aims to examine the success of the US’international efforts at limiting the growing influence of the CCP through the spread of Huawei’s 5G communication equipment. First, it will provide background on the international 5G telecommunications equipment market, establish the legitimacy of accusations made about Huawei’s ties to the CCP, and detail the extent of the US’ diplomatic action to limit global adoption of Huawei provided infrastructure. Second, it will detail the experimental methods and data sets used to test the hypothesis that the US’current efforts have been unsuccessful at decreasing Huawei’s market share of 5G communications networks. Lastly, the analysis will explore

14

the implications of the results for the present level of US influence across both allied and non-allied nations. Huawei’s presence in American allied countries represents a small foothold for the CCP in its effort to increase its global influence. The US must ensure that the measures it is currently taking are sufficient to preserve its global hegemony.

Background

The fifth generation technology standard for cellular networks, commonly known as 5G, represents the most substantial improvement in wireless communication since the technology’s inception.Along with fast speeds, the new standard boasts greater connectivity capacity, making 5G networks especially suitable for the group of connected devices known as the Internet of Things.

Despite 5G’s obvious advantages, rollouts of the technology have been slow and costly, partially due to the current structure of the 5G equipment market (Ayyagari and Gröne, 2022). Because of the complexity of the equipment needed to establish a 5G communications network, only three firms are currently able to offer 5G infrastructure at competitive prices: Sweden’s Ericsson, Finland’s Nokia, and China’s Huawei. Currently, Huawei enjoys a clear advantage in marketing its equipment and dominance in the Chinese

15

telecommunications market due in large part to subsidies and direct funding from the Chinese government. Meeting China’s demand for telecommunications equipment has allowed Huawei to operate at economies of scale unmatched by its competitors, giving it the ability to undercut market prices (Kaska et al, 2019).

Allowing foreign companies to establish 5G infrastructure has national security implications no matter the vendor’s country of origin, but unique characteristics of Huawei’s ownership structure and the laws it is forced to comply with make its provision of critical infrastructure an especially concerning national security threat. The high cost of 5G infrastructure as well as differences in equipment architecture between vendors make any potential “roll backs” extremely costly and time consuming, effectively locking a country in with one vendor until the world moves to the next generation of telecommunications technology.Additionally, the growing network of interconnected devices expected to be facilitated by 5G networks increases the scope of potential cyber attacks and blurs the line between vital core and periphery edge networks (Mohan 449). In addition to the cyber security risk factors inherent to 5G technology, Huawei manufactured equipment presents additional risks for the national security of its customers.All Chinese companies are subject to the CCP’s increasingly stringent

16

National Intelligence Cyber Security laws, which are both ambiguous in their scope and exact requirements. For example, article 7 of China’s National Intelligence Law states that “[a]ny organization and citizen shall, in accordance with the law, support, provide assistance, and cooperate in national intelligence work, and guard the secrecy of any national intelligence work that they are aware of ,” but it is unclear what the definition of “national intelligence work” is or what actions “providing assistance” entails (Hoffman and Kania). In addition to being subject to the CCP’s influence and ambiguous laws, the specifics of Huawei’s ownership structure are also unclear. While Huawei defines itself as employee (i.e privately) owned, research by Balding and Clark has shown that employees do not own any portion of the company, as the “stock” they are given as compensation is merely part of a profit-sharing incentive program, giving the holder no voting power within the company. Instead, Balding and Clark find that over 98% of Huawei is owned by an organization called “Huawei Holding Trade Union Committee,” which itself has an unclear ownership structure. Because other Trade Union Committees are frequently heavily influenced by CCP officials, it is reasonable to assume that the same is true of Huawei (Balding and Clark, 2019). Huawei’s subjection to Chinese laws and the potential for it to be effectively acting as an arm of the CCP abroad combined with the far reaching, long term impli-

17

cations of 5G infrastructure vulnerabilities should make customers of the Chinese company particularly concerned for the safety of nationally sensitive information.

Due to the established threat presented by Huawei’s provision of 5G telecommunications equipment, the United States has adopted a substantial regime of sanctions and trade restrictions while simultaneously pressuring allies to exclude Huawei from their 5G development plans. The US has taken action against Huawei since as recently as 2008, when the US government blocked the Huawei-financed purchase of Santa Clara-based telecommunications equipment company 3com through regulatory scrutiny.An open letter from Huawei to the US government in 2011 calling for its “fair treatment” prompted a full investigation into its classification as a security threat.After a year of review, however, the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence maintained that Huawei was untrustworthy, and urgedAmerican companies to “remain vigilant” towards its activities (Tang 4563 - 4564). The most severe domestic action taken against Huawei occurred in 2019, when the Department of Commerce added Huawei to its Entity List, which initiates a sanction requiringAmerican companies to obtain licenses before being allowed to export US manufactured technology to Huawei, while also effectively banning the domestic use of its

18

equipment. Congress is currently considering legislation to publicize license applications and acceptances in order to further ensure thatAmerican firms cannot provide Huawei with technologies that may contribute to its current technological advantage (Gallagher, 2022). The US’actions proved effective, as Huawei has definitively stopped its efforts to enter the US consumer market.

Abroad, the US’s efforts have been more reliant on political pressure than on legislation. Its first international move against Huawei is marked by the creation of the so-called Prague Proposals after the Prague 5G Security Conference in March 2019. The conference, attended by 30 countries consisting of NATO members and global US allies, discussed national security considerations countries should make when choosing 5G telecommunications equipment vendors, with special emphasis on vendors that could be influenced by foreign governments (US Embassy Prague, 2019).

The US continued its opposition of Huawei in 2020 by establishing the so called “Clean Network,” a group of over 30 countries that “addresses the long-term threat to data privacy, security, human rights and principled collaboration posed to the free world from authoritarian malign actors” (State Department 2020). While both the creation of the Prague Proposals and the establishment of the Clean Network are evidence of the US government’s recognition

19

of Huawei as a threat to geo-political influence, it has become clear that these measures may not have been effective, as countries involved in booth agreements went on to ignore the non-binding agreements in their 5G network implementation. Currently, the US relies primarily on using diplomatic pressure to convince countries to sign Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) regarding 5G implementation policies. These non-binding agreements build on the framework developed in Prague and outlined in the Clean Network to further restrict Huawei’s expansion. These MOUs often formally establish a country’s commitment to developing a “clean network” that cannot be influenced by authoritarian actors, language which is effectively equivalent to committing to avoid entering a deal awarding a Chinese telecommunications equipment vendor the right to provide national 5G infrastructure (Olteanu 43).

Data and Methods

Currently, the conflict between the US and China revolves around the contracts awarded by either national governments or prominent, national telecommunications companies to provide 5G infrastructure. The US aims to limit the amount of nations that choose Huawei as their vendor for 5G equipment, as doing so will limit the scope of the CCP’s intelligence access and its ability to

20

leverage its influence over the critical infrastructure of US allies if a conflict breaks out. These contracts can be used as a means to measure the effectiveness ofAmerican efforts to limit Huawei’s expansion. In 2019, the United State’s tenor on Huawei developed 5G equipment decidedly changed, marked by the US’most extreme domestic action, adding Huawei to the DOC Entity List, and its first concrete international action, the establishment of the Prague Proposals. If analysis of Huawei’s international contracts reveals a steep decline in deals with governments and prominent telecommunications vendors after 2019, then it can also determine that the diplomatic urging of the US alone can sufficiently influence the governments of the world at large to stay away from Huawei-produced technologies. If the volume of contracts awarding Huawei the right to provide national 5G networks increases or remains at the same level after 2019, we can determine that the US’current policy is failing to limit growing Chinese influence and further action must be taken.

Analysis of Huawei’s 5G contracts is based partially on David Sack’s 2021 research with the Council on Foreign Relations. In his research, Sacks compiled a list of every country’s official position on use of Huawei’s 5G technology. Sacks identified 73 countries who had plans to develop 5G technology in 2021. He la-

21

beled an additional 106 countries as “not yet considering 5G,” but provided information about those countries’past business dealings with Huawei or any general statements made by their leaders about national relationships with Huawei or the CCP. Figure 1 shows a map indicating the different stances of countries on the use of Huawei’s 5G network equipment based on Sacks’s research.

This study focused on expanding and updating Sacks’s data set to reflect 5G’s rapid adoption throughout Europe and the developing world between 2021 and the end of 2023. In order to determine the country’s stance on 5G, I conducted internet searches for news articles and official announcements about contracts with Huawei or competing 5G infrastructure firms. The same five searches were conducted for every country missing from Sack’s original 2021 data set in order to maintain consistency and objectivity.

The first search conducted was “[Country name] 5G infrastructure vendor” in order to find any major headlines that had emerged about the country’s 5G infrastructure choice since 2021. The next three searches conducted were “[country name] [equipment vendor name] 5G,” where [equipment vendor name] was either Huawei, Eriksson, or Nokia. These three searches aimed to find any official announcements coming from the vendor themselves. The final search was “[country name] Huawei ban.” The goal of this search

22

was to find any headlines about Huawei bans being considered or enacted by the country in question. Conducting these searches yielded data for the 5G equipment vendors for 48 of the 105 additional countries. For countries not considering building national 5G infrastructure systems, searches for government contracts granting Huawei the right to provide non-5G equipment or infrastructure, such as fiber optic cables and smart city technology, were conducted. This analysis provided data for 43 additional countries. 14 additional countries from Sack’s 2021 analysis were excluded from the final data set either because they had not made significant investments in internet infrastructure or there was no evidence indicating that they had any kind of national relationship with Huawei. For each observation, the year of publication for the source article was recorded so the 5G equipment vendor decisions could be compared across time. The final data set included information on the 5G infrastructure decisions or the status of the relationship with Huawei for 164 unique countries and gathered information from 51 individual sources. The most commonly cited sources were international telecommunications news website CommsUpdate, international news agency Reuters, and each equipment vendor’s corporate website.Atable with the complete data set can be found in the linked Excel file on the sheet labeled “Table 5.”

23

Because the search results showed that many countries are currently in different stages of the process of choosing a 5G vendor and implementing 5G infrastructure, and that many countries had bans and restrictions varying in their levels of severity, some generalizations had to be made in order for the data to be interpretable. To generalize each country’s 5G policy, observations were divided into two groups: “not likely to use Huawei 5G equipment” and “Already using or likely to use Huawei 5G equipment.” The first group includes countries that have enacted bans on Huawei’s telecommunications equipment, have significant restrictions on Huawei’s equipment, have already awarded a contract to an alternative telecommunications equipment vendor (Nokia or Ericsson), or have signed an MOU with the United States committing to providing a clean network. The latter group includes countries that have already implemented Huawei’s 5G telecommunications infrastructure, committed or expressed desire to have Huawei build national 5G telecommunications infrastructure, or have had a large telecommunications network provider sign a deal with Huawei to jointly develop 5G infrastructure within their borders.

For countries not yet considering 5G infrastructure, the group includes countries that have made substantial investments in non-5G, Huawei supplied telecommunications or internet infrastructure. In order to test whether the US’allies are more receptive to its warn-

24

ings about Huawei’s 5G telecommunications equipment, I divided the sample into US allies and non-allies to analyze the difference in their response to the US’anti-Huawei rhetoric at the end of 2019.

In this analysis, the designation of “ally” was given to the 47 countries who are either NATO members or listed by the US as Major Non-NATOAllies.

While the new data set is a successful expansion of Sack’s 2021 work, it is difficult to actually test this study’s hypothesis due to the absence of a control for countries that had close working relationships with Huawei prior to 2019. This limitation is partially due the increased degree of difficulty finding news articles from prior to 2019 and partially due to the lack of transparency in national vendor choice before the politicization of the issue by the United States (Strand, 2022). The current data set also fails to control for exogenous factors such as regional vendor availability and budgeted spending on 5G infrastructure. In the future, it also may be useful to control whether a country’s government signs a contract allowing Huawei to provide 5G telecommunications equipment for 5G infrastructure or whether a country’s leading wireless network provider works in tandem with Huawei to develop 5G technology. This difference is important because some governments may have limited input over 5G equipment vendor decisions

25

if they leave the choice up to wireless network providers. Compiling two observations for each country, one from 2019 and one from 2023, would control for countries that built 5G infrastructure with Huawei equipment or signed contracts with Huawei before the US began its international Clean Network campaign at the end of 2019. This method would also track countries that changed their telecommunications vendor in response to US rhetoric, which would be a strong indication of receptiveness toAmerican demands due to the substantial costs of the infrastructure “rollbacks” associated with switching equipment vendors.

Results

The first analysis considered all 164 countries in the data set. Before 2019, 70 countries were placed in the “already using or likely to use Huawei 5G equipment” category while 12 countries were placed in the “not likely to use Huawei 5G equipment” category.After 2019, 34 countries were categorized as already using or likely to use Huawei 5G equipment and 45 countries were categorized as not likely to use Huawei 5G equipment, indicating a substantial increase in the rate of adoption of technology from Nokia and Ericsson as well as the rate of global bans or restrictions against Huawei. Breaking countries down into allies and non-allies

26

revealed that most of the countries taking measures to limit the likelihood of Huawei technology use after 2019 were US allies. Of the 45 countries taking action making them unlikely to use Huawei technology after 2019, 26 were US allies. US allies were also much less likely to adopt Huawei technology after 2019, as only 7 of the 34 total countries adopting Huawei technology after the increase in US anti-Huawei rhetoric were US allies. US diplomatic pressure was less effective at preventing non-allies from turning to Huawei to provide their telecommunications infrastructure, as the majority of non-allies making decisions about national telecommunications infrastructure after 2019 made deals with Huawei. The results of this analysis are displayed in graphs one and two below and tables one and two in the appendix.

“Breaking countries down into allies and non-allies revealed that most of the countries taking measures to limit the likelihood of Huawei technology use after 2019 were US allies”

27

Asecond analysis considering only countries developing or currently possessing national 5G infrastructure was conducted to ensure that trends are not being distorted by the 43 countries that only had their relationship with Huawei analyzed. Trends emerging in the analysis of all 164 countries were largely reflected in the analysis of the subset of 121 countries with some discernible position on 5G infrastructure. To highlight, there was a sharp decrease in the rate at which countries adopted Huawei’s 5G telecommunications equipment after 2019, with the majority of countries making decisions about 5G infrastructure taking action to make it difficult for Huawei to play a role in the national 5G network. Just as in the first analysis, a country’s receptiveness to US rhetoric depended highly on whether or not the country was a US ally. The vast majority of countries using alternate 5G equipment vendors or implementing bans on Huawei equipment were US allies, while the majority of non-allies making 5G infrastructure decisions after 2019 chose to use Huawei equipment. The second analysis is illustrated in tables three and four and graphs three and four, all of which are included in the appendix.

Discussion

The results of the analysis indicate a distinct increase after

28

2019 in the number of countries taking measures to limit the likelihood of Huawei technology use. However, the scope of the decline is by no means all encompassing, and indicates areas where either US influence is declining or Chinese influence is rising due to its increased global outreach. The analysis shows that countries who are not formal allies with the US are much less receptive to its diplomatic pressure against Huawei equipment. Large nations with developing economies in the Middle East and LatinAmerica, such as SaudiArabia, Iran, Oman,Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela, were the most likely to adopt Huawei 5G technology, possibly indicating the desire of growing economies to prioritize development and a place on the cutting edge of mobile technology over strengthened geopolitical relations with the US. Many of these countries are involved in China’s ongoing Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an international infrastructure development program that aims to expand Chinese influence through increased financial and economic engagement with emerging market countries. Participation in the BRI, and acceptance of the large public loans from Chinese banks and companies characteristic of the program, provides further indication that these countries may be looking to move away from the US-led global order.

29

“Large nations with developing economies in the Middle East and LatinAmerica, such as SaudiArabia, Iran, Oman, Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela, were the most likely to adopt Huawei 5G technology, possibly indicating the desire of growing economies to prioritize development and a place on the cutting edge of mobile technology over strengthened geopolitical relations with the US”

The US’minimal influence over the equipment vendor decisions of non-allies is also visible inAfrica. Huawei already enjoys huge influence in the world’s least developed countries due to its long history of providing cheap telecommunications infrastructure inAfrica. The analysis shows that the US’change in rhetoric

30

had little effect onAfrican countries’telecommunication equipment vendor decisions. ManyAfrican countries’previous relationship with Huawei as an equipment vendor carried over to the new generation of equipment, and those not yet considering 5G, such as Ghana and Guinea, continued to make large investments in infrastructure reliant on Huawei technology after 2019. The economic difficulties manyAfrican countries face, combined with Nokia and Ericsson’s history of neglecting theAfrican market, make their selection of Huawei as a telecommunications equipment vendor more likely due to practicality than intentional disregard ofAmerican pressure. Thus, while Huawei’s dominance may not indicate decliningAmerican influence inAfrica, it certainly is an indicator of China’s increasing influence in the region.

While the analysis found the US’Clean Network to be effective at preventing its smaller, European allies from choosing Huawei to provide 5G telecommunications equipment, some of staunchest allies, both European and non-European, still chose to build 5G networks using Huawei-supplied equipment. Ireland, Iceland, the Philippines, and Pakistan all ignored US warnings and continued to implement Huawei’s telecommunications equipment after 2019. These countries’decisions may be the clearest indication of the global power structure shifting towards multi-polarity,

31

as they indicate openness to working relationships with Chinese companies and governments for the foreseeable future, even as the US begins to sever ties and look elsewhere for trade and business partnerships.

Interestingly, the results of this analysis of 5G telecommunications equipment vendor choices closely parallel the Atlantic Council’s 2021 report by Moyer et. al., which analyzes the scope of the US and China’s global influence. Moyer and his team measure the US and China’s influence using the Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity (FBIC) Index, a metric that measures a combination of the frequency with which countries interact and the dependance one country has on another. Their analysis focused on comparing the amount of countries where the US had the highest FBIC and the amount of countries where China had the highest FBIC, and examining changes in each country’s top influencer between 2000 and 2020. Their report found that while the US did not lose its influence in many countries between 2000 and 2020, the number of countries China had high influence over increased drastically over the same period, as it replaced former colonial powers such as France and the UK as the country with the highest FBIC in many developing nations due to its outreach through the BRI (Moyer et. al. 2021). Telecommunications equipment choices of

32

countries before and after 2019 exhibit a similar pattern to the one found in Moyer’s work. The US’allies largely heed its warnings about the cyber security threat posed by using Huawei’s 5G equipment, but the breadth of its message is limited by the economically favorable relationship with China many developing countries are beginning to establish. Therefore, 5G telecommunications equipment vendor choice, especially in the US-allied countries that chose to implement Huawei’s equipment, may be a leading indicator of who a nation is most influenced by. This means we can expect to see countries like the Philippines and Pakistan continue to develop their relationship with China in the coming years, despite officially being US allies.

It is important to note that the limitations of this data set, mainly its failure to control for countries that already had Huawei equipment before 2019 and its failure to address exogenous factors such as equipment price and regional vendor availability, may decrease the accuracy of its findings. However, the data is robust enough to provide a broad overview of the global influence of the US and China through the lens of global 5G equipment vendor selection.

33

Conclusion

Analyzing the 5G telecommunications equipment vendor selections of different countries before and after the US increased its diplomatic pressure to reject Huawei’s 5G equipment in 2019 revealed that while US efforts have been effective at decreasing the rate at which countries adopt Huawei technology, its warnings have not been universally heeded by allies or non-allies. The limitations of the data set prevent us from fully rejecting the hypothesis that US diplomatic action has been ineffective at decreasing Huawei’s share of the 5G telecommunication equipment market, but we can be reasonably confident that the growing number of countries adopting bans on Huawei or signing contracts with alternative equipment providers will curb Huawei’s market dominance when it comes time to implement future generations of telecommunication equipment. The fact that certain US allies have chosen to allow Huawei to build their 5G networks should be concerning toAmerican policy makers from both a security and geopolitical perspective. If conflict erupts, taking precautions to ensure secure communications with an ally using a Huawei-built 5G network could significantly hinderAmerican intelligence and military response.Additionally, adverse 5G equipment vendor decisions of US allies could hint that they are considering exploring the benefits

34

of increasing economic and geopolitical relations with China and the CCP. The decision of a select group of US allies to implement Huawei’s 5G equipment shows that staying inAmerican favor is no longer the first priority for countries trying to further their interests on the world stage. In order to ensure the cooperation of allies moving forward, the United States could introduce binding treaties committing countries to banning Huawei manufactured equipment or move to sanction countries that choose to implement Huawei’s systems.As the world around us becomes increasingly connected, we must remain vigilant about who controls the technologies we rely on.

“In order to ensure the cooperation of allies moving forward, the United States could introduce binding treaties committing countries to banning Huawei manufactured equipment or move to sanction countries that choose to implement Huawei’s systems”

35

36 Appendix Table 1 Before 2019 After 2019 Investing in Huawei Technology (Any Kind) 7034 Huawei Bans or Adopting Other 5G Infrastructure 1245 Table 2 Before2019 After 2019 Allies NonAllies Allies NonAllies Investing in Huawei Technology (Any Kind) 1060727 Huawei Bans or Adopting Other 5G Infrastructure 392619 Table 3 Before 2019 After 2019 Countries with Huawei 5G3031 Huawei Bans or Adopting Other 5G Infrastructure 1245

Table 4

Before2019 After 2019

37

Allies Non-Allies Allies Non-Allies Countries with Huawei 5G 922723 Huawei Bans or Adopting Other 5G Infrastructure 392619

Bibliography

The data set used in this paper can be accessed using this link:

https://tinyurl.com/huawei5Gdata.

Ayyagari, Deepak, and Florian Gröne. “The State of 5G: Capturing More Value from Telecoms’Connectivity Services.” PwC, 2022.

https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/tmt/ telecommunications/ the-state-of-5G-capturing-more-value.html.

Balding, Christopher, and Donald C. Clarke. “Who Owns Huawei?” SSRN Electronic Journal,April 17, 2019. https://doi. org/10.2139/ssrn.3372669.

Cave, Daniel Et al. Mapping China’s Tech Giants. Canberra, Australia.Australian Strategic Policy Institute.April 2019. https:// www.aspi.org.au/report/mapping-chinas-tech-giants. Hoffman, Samantha. “Huawei and theAmbiguity of China’s Intelligence and Counter-Espionage Laws.” The Strategist, September 12, 2018. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/huawei- and-the-ambiguity-of-chinas-intelligence-and-counter-espionage-laws/.

39

Kaska, Kadri, Beckvard, Henrik and Minárik, Tomáš. Huawei, 5G and China as a Security Threat. Tallinn, Estonia. The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. 2019.

Gallagher, Jill C. “U.S. Restrictions on Huawei Technologies: National Security, Foreign ...” Congressional Research Service, January 5, 2022.

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/ R47012/2.

Mohan, Jaya Preethi, Niroop Sugunaraj, and Prakash Ranganathan.

“Cyber Security Threats for 5G Networks.” 2022 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (eIT), 2022.

https://doi.org/10.1109/eit53891.2022.9813965.

Morris, David. 2023 “The Huawei battleground:Acritical case of political risk in the new global power contest” Wirtschaft und Management 30, Moyer, Jonathan D., Collin J. Meisel,Austin S. Matthews, David K. Bohl, and Matthew J. Burrows. Rep. China-US Competition,

40

Measuring Global Influence. TheAtlantic Council , 2021. Olteanu, Mihai. “The Sino-American Competition on the 5G Technological Field.” Perspective Politice 15, no. 1–2 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.25019/perspol/22.15.3.

Sacks, David. “China’s Huawei Is Winning the 5G Race. Here’s What the United States Should Do to Respond.” Council on Foreign Relations, March 29, 2021. https://www.cfr.org/blog/china-huawei-5g.

State Department Staff. “The Clean Network .” U.S. Department of State, January 17, 2020. https://2017-2021.state.gov/the-cleannetwork/.

Strand, John. “The market for 5G RAN in Europe: Share of Chinese and non-Chinese vendors in 31 European countries.” Strand Consulting 2022.

Tang, Min. 2020. “Huawei Versus the United States? The Geopolitics of Exterritorial Internet Infrastructure.” International Journal

41

Of Communication, 14, 22. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/ view/12624/3204.

U.S. Embassy Prague. “The United StatesApplauds the Czech Republic for Hosting the Prague 5G Security Conference.” U.S. Embassy in The Czech Republic, May 6, 2019. https://cz.usembassy.gov/the-united-states-applauds-the-czech-republic-for-hostingthe-prague-5g-security-conference/.

42

Securing Stability: Will the Chinese Communist Party Survive in the Post-Covid Era?

Michelle Nguyen

About theAuthor

Michelle Nguyen is a second-year student pursuing a Bachelor ofArts in Government.Aside from writing for the Virginia Journal of InternationalAffairs, she is involved in the Multilingual Outreach Volunteer Effort and the Global Inquirer Podcast.After completing her undergraduate studies, she hopes to pursue a legal career and further explore the complex relationship between citizens and political institutions.

45

Abstract

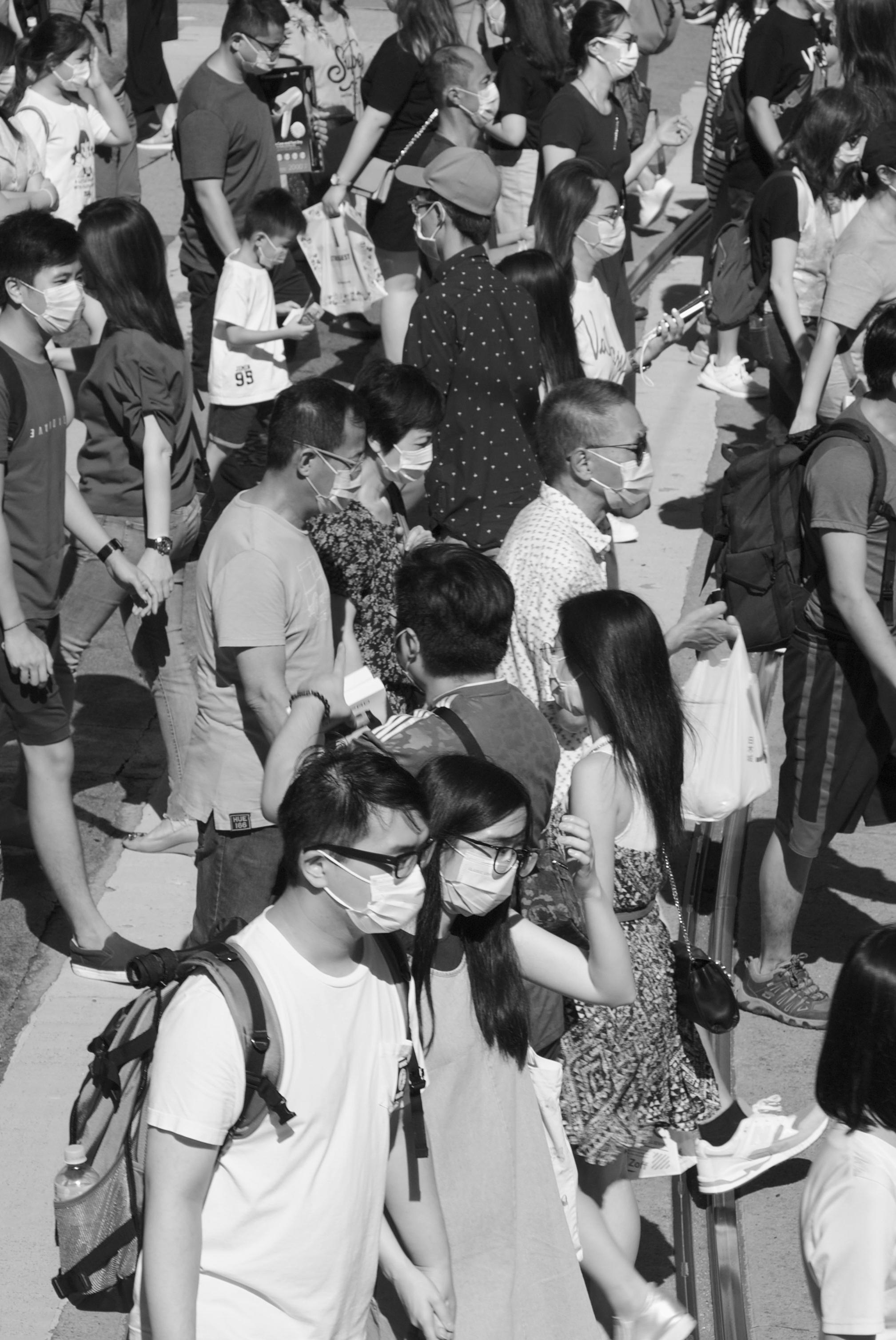

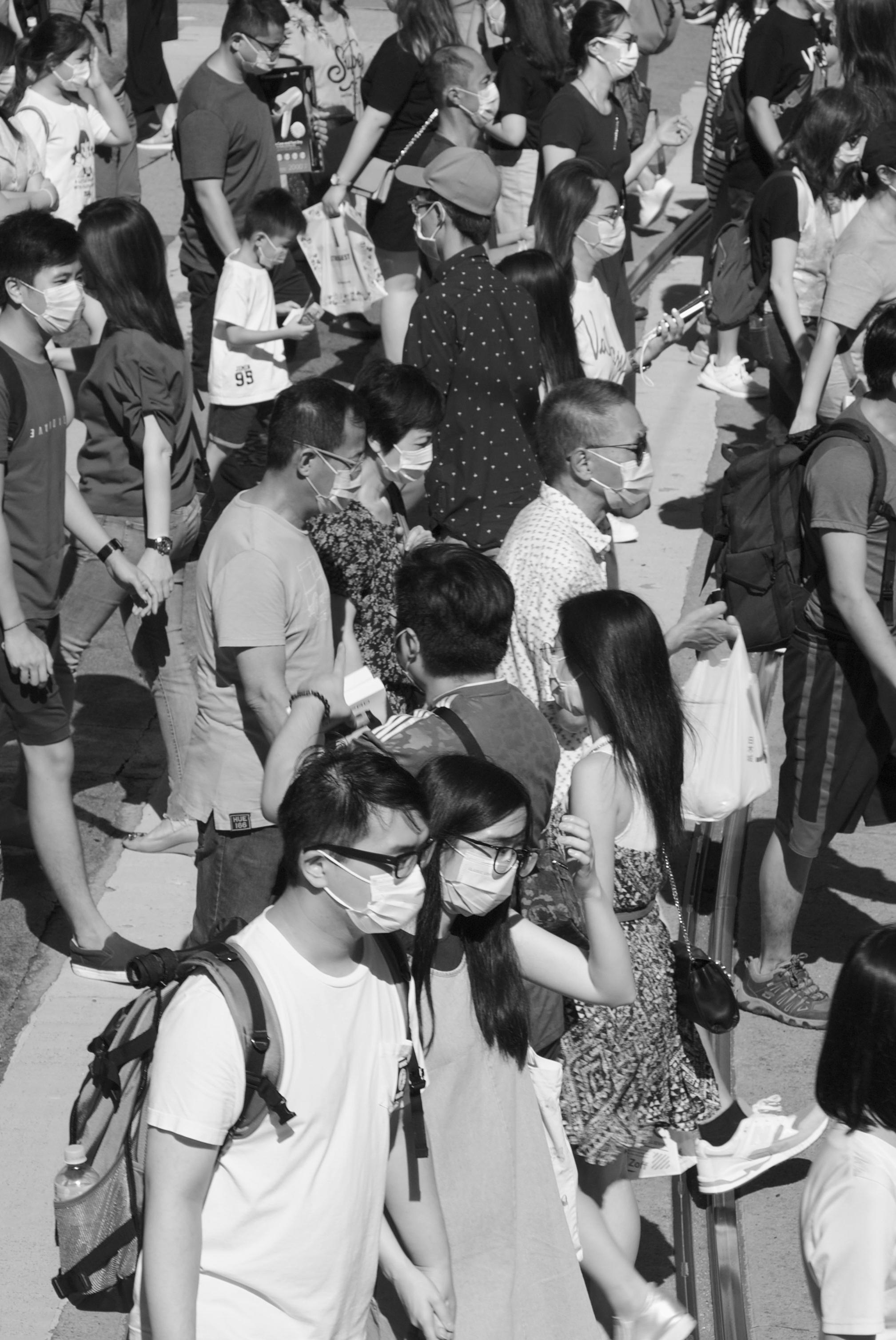

Political protests are often viewed as challenges that threaten the stability of the ruling regime. In certain contexts, however, political protests instead serve as a mechanism to alleviate tensions between citizens and their government. In the People’s Republic of China, political protests enable citizens to communicate their grievances to the Chinese Communist Party, strengthening the Party’s grip on power. This paper seeks to address the sources of stability of the Chinese party-state, as well as explore the implications of the Zero COVID policy on regime stability. It begins by examining the tradition of rules consciousness, which underlies the paradoxical nature of political protests in China. It then analyzes how the CCP manipulates a federalist governmental structure to preserve legitimacy and evaluates the implicit social contract between citizens to explain acquiescence to the governing regime. This paper concludes with an analysis of how COVID-19 protests differ from previous political demonstrations in China and thus pose a distinctive threat to the party-state.

46

Securing Stability: Will the Chinese Communist Party Survive in the Post-Covid Era?

I. Introduction

“The discrepancy between political protests and regime support is one of the central paradoxes of contemporary Chinese politics”’(Dickson, Shen, and Yan 2017). The unprecedented economic reforms of the post-Mao era have induced numerous conflicts between citizens and the government. From 1993 to 2005, the magnitude of popular protests increased tenfold (Cai 2008). Common causes of protests include economic inequality, forced displacement in exchange for low compensation, and environmental pollution brought about by industrialization and urbanization. Dramatic increases in civil unrest are often believed to erode state legitimacy and lead to political liberalization, yet no such bottom-up transformation has occurred in China.

Three core components enable the coexistence of civil unrest and political stability in Chinese society. First, a tradition of rules consciousness permeates Chinese political culture. In protesting, citizens intend to promote their interests rather than challenge the party-state. The regime sustains this culture by implementing a

47

decentralized government structure. Second, the regime deliberately generates a local legitimacy deficit, which increases support of the central government to the detriment of local institutions. Third, the implicit social contract between the party-state and its citizens contributes to the regime’s resilience, such that citizens are willing to offer political acquiescence in exchange for economic prosperity.Although the Chinese party-state has survived many instances of popular revolt, the protests against the Zero COVID policy pose a distinct challenge to the authoritarian regime, as they undermine these core tenets. Protests against pandemic restrictions break from the pattern of rules consciousness; such demonstrations target both local officials and the central government. The decline in individual income has thus shattered the social contract which has long served as a stabilizing force in state society interactions.

II. The Tradition of Rules Consciousness

The Chinese people adhere to a deep-rooted tradition of rules consciousness; protestors express their discontent while simultaneously acknowledging the authority of the party-state. Protestors are careful to prove their loyalty to the central government by petitioning for redress of grievances within the state-es-

48

tablished legal framework. This tradition can be traced back to the imperial era when rural peasants petitioned for lower taxes.After these petitions proved futile, the peasants demonstrated en masse on the streets and looted the local yamens. Still, the difference was shown to the central government. Protestors prevented the looting from reaching the emperor’s treasury and designated a select group to protect his financial assets (Perry 2016). This tradition continued during the economic reforms of the post-Mao period. In the late 1980s, local governments increased tax rates to offset the revenue losses caused by decollectivization. Villagers initiated protests by filing letters of complaint, in which they denounced local officials and cited the specific regulations these authorities violated. However, most letters did not challenge the legitimacy of central authorities or the policies they passed. Only after their petitions were disregarded did the protestors engage in violent acts, such as arson and the killing of local officials (Perry 2016).

III. The Benefits of Chinese Federalism

Authoritarian governments possess two major tools to manage popular resistance: repression and concession. When faced with large numbers of protests, authoritarian governments cannot dismiss repression as a viable re-

49

sponse. However, overreliance on repression may antagonize apolitical citizens and potential supporters of the party-state. Moreover, excessive repression insulates regimes from the grievances of citizens, fuels resentment, and undermines the state’s legitimacy. Unconditional concessions are often interpreted as indications of state weakness and thus provoke greater resistance. Therefore, authoritarian governments must balance repression and concessions in order to maintain social stability.Adecentralized governmental structure enables the Chinese party-state to utilize repressive tactics while minimizing harm to the regime’s legitimacy. This structure also allows the regime to grant concessions without undermining state strength. In this system, high-level officials grant autonomy to, but also impose restraints on, local authorities to handle social unrest. This divided system creates differing incentive structures for the central and local governments. The central government holds greater interest in maintaining the regime’s legitimacy, compelling it to be more tolerant of protests. The local government, in contrast, prioritizes social stability. This is because in response to increasing social unrest during the late 1990s, the central government required the provincial government to enact reforms. The cadre evalu-

50

ation system was then amended to include stringent social stability targets to be met by local authorities (Heurlin 2016). Local governments face a lower cost for, and are thus more likely to use, tactics of repression.

“Adecentralized governmental structure enables the Chinese party-state to utilize repressive tactics while minimizing harm to the regime’s legitimacy. This structure also allows the regime to grant concessions without undermining state strength.”

In addition, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) purposefully manipulates the decentralized government structure to produce a local legitimacy deficit. Chinese citizens report a 16% higher level of trust and support in the central government compared to the local government (Dickson, Shen, and Yan 2017). By

51

delegating responsibilities of managing social unrest to local governments, the central government deflects the blame for mishandling of grievances. Interventions by the central government—in the form of granting concessions and implementing policy changes—enhance the party-state’s image.

This strategy of deflection is evident through the central government’s response to a 2004 protest in Hanyuan.As part of a dam development project, the government seized farmland and homes.Approximately 100,000 peasants had petitioned local authorities for higher compensation but were unsuccessful in their attempts. These peasants then staged an occupation of the construction site to halt the project. The local government deployed upwards of 10,000 soldiers and 1,500 police officers to restore order. Violent confrontations ensued, resulting in the deaths of villagers and police officers. To appease the protestors, the provincial government pledged to increase compensation and to relocate the homes of the peasants. The central government detained several senior county officials, including the deputy city mayor, on charges of corruption (Cai 2008).Although expanding infrastructure is a key component of the central state’s agenda, it was able to avoid blaming its policies by allowing local authorities to handle the immediate aftermath.

52

IV. The Implicit Social Contract

The expansion of the middle class often results in democratic transitions. Societies with a dominant middle class have a more equal distribution of socioeconomic resources, leading to a more balanced distribution of political resources. Moreover, many members of the middle class earn their income through business ownership. They thus demand rule of law to constrain state power and protect their assets, resulting in implementation of a democratic system (Lu 2005). Despite the growth of the Chinese middle class since the 1970s, the Chinese Communist Party has maintained its grasp on power.

The implicit social contract between the regime and its citizens serves as a source of stability for the Chinese party-state. Citizens acquiesce to authoritarian political governance in exchange for economic prosperity.Amultivariable analysis of regime support in urban China found that pocketbook factors indicating personal prosperity, specifically the rise of individual income, is statistically significantly and positively associated with support of both the central and local governments. Contrary to conventional wisdom, sociotropic factors that suggest aggregate

53

economic growth, such as increased per capita GDP, do not correspond to greater support for central or local institutions (Dickson, Shen, and Yan 2017).

This contract especially influences the middle class’s support for democratization. Survey research by Jie Chen and Chunlong Lu in cities across China regarding support for democratic institutions indicated a negative and statistically significant correlation between economic satisfaction and support for democratization. This correlation was stronger among middle-class individuals than working-class individuals (Chen and Lu 2011). The relationship indicates that the greater citizens’satisfaction with their economic circumstances, the higher their support for the ruling party-state. Furthermore, the support of Chinese citizens will continue even in the face of a declining economy, as long as individual incomes are unaffected.

V. The Distinctive Challenge COVID-19 Poses to Regime Stability

In late December 2019, Dr. Li Wenliang issued warnings regarding the novel coronavirus in an online chat forum. Local authorities forced Li to disavow his claims and censored the information he disseminated.Afterwards, Li contracted COVID-19 and

54

died, catalyzing criticism of the party-state. In order to quell doubts about the effectiveness of its governance system, the CCP implemented the Zero COVID policy. The party enacted strict measures to contain the spread of the virus, including prolonged lockdowns of major cities and large-scale COVID testing.

By March 2020, new cases ceased to emerge in China. The seeming success of China’s public health policies enabled the party-state to revise the narrative of the outbreak. Originally, it seemed as if the party-state was willing to forfeit lives to preserve its own image. The unyielding COVID-19 policies proved that the party-state would sacrifice anything, including a growing economy, to protect the life of the common people. The policy also demonstrated the advantages of an authoritarian system in dealing with a public health crisis. Chinese leaders framed the failure of the United States, India, and Brazil to contain the virus as an indication of the deficiencies of liberal democracy. “Some may object that this [low number of COVID-19 deaths in China] was because China restricted freedoms more than ‘democracies,’… But what kind of democracy would sacrifice millions of lives for some individuals’freedom not to wear masks?” (Mark and Schuman 2022). The Zero COVID policy seemed to prove the superiority of the Chinese party-state, bolstering support for the regime.

55

“The COVID measures that were once hailed as the saving grace of the people’s health now seemed unreasonable”

However, the Chinese people became weary after enduring two years of draconian pandemic restrictions. Citizens were prevented from earning income to support their families. They constantly feared the prospect of being forced into quarantine facilities. Tensions escalated when lockdown measures prohibited citizens from entering grocery stores. The Chinese people faced starvation when the state delayed food deliveries to individuals’ homes. The COVID measures that were once hailed as the saving grace of the people’s health now seemed unreasonable.

Protests against the Zero COVID policy initially followed the pattern of rules consciousness rooted in Chinese history. Demonstrations were confined and directed grievances towards local authorities. In mid-2022, protests called attention to the harm pandemic restrictions had caused to citizens’livelihoods. In Guangzhou, migrant workers demolished barriers established to prohibit entry into their stores. In Zhengzhou, Foxconn factory em-

56

ployees walked out in protest of delayed bonuses and the contaminated environment of quarantine dormitories.

However, protests began to deviate from the pattern of rules consciousness in November 2022. These demonstrations spread across regions and the public expressed anti-regime sentiments. During the White Paper protests, citizens took to the streets to demonstrate against pandemic barriers, which prevented emergency services from extinguishing a fire in a building of Urumqi and ultimately resulted in the death of ten civilians.

Protestors displayed blank sheets of printer paper, representing their loss of civil liberties. These demonstrations escalated over the span of two days and became the largest anti-regime protest in China since the Tiananmen Square Movement. The White Paper protests are significant as they broke the psychological barrier the Chinese party-state had carefully constructed. Up until these demonstrations, public expressions of anti-regime sentiments were unthinkable. Protestors now view the state as the source of their grievances, rather than the problem solver.

To reduce social unrest, the Chinese party-state utilized repressive tactics. Local authorities analyzed cell phone data to apprehend protestors, interrogating them about their organizing methods. The CCP’s successful repression of protests came at a high

57

cost, as it reduced the elevated confidence the Chinese citizens placed in their authoritarian system. In turn, this impaired the trustbased arrangement that dominates governance in China. The CCP has established two opposing systems of repression to maintain social stability.Acoercive and surveillance-based system is implemented in Hong Kong, Tibet, and Xinjiang. In all other regions of China, the CCP utilizes a trust-based model. This trust-based system of governance was vital to the implementation of the Zero COVID policy. Residents’committees mobilized civil servants, party cadres, and unpaid volunteers to convince fellow citizens to comply with rigid lockdown measures and submit to frequent testing. This system deteriorated as the pandemic progressed.As the Omicron variant spread, the local government was forced to hire more pandemic workers, many of whom held no ties to the communities where they were employed. These new workers were less successful in compelling citizens to abide by COVID restrictions. Local governments were then forced to hire security guards who used violent tactics to coerce citizens to comply. Shocking videos published online exposed security guards beating elderly citizens to enforce restrictions, provoking public outrage.

58

“Protestors now view the state as the source of their grievances, rather than the problem solver”

The widespread protests led the Chinese Communist Party to completely reverse its Zero COVID Policy.Although this measure was successful in decreasing the number of protests, new forms of social contention have emerged. For instance, in Nanjing, young adults honored the statue of Sun Yat-sen with flowers as a demonstration of their disapproval of the Chinese Communist Party. Such acts of social contention reveal citizens’declining trust in the party state’s capacity to fulfill the implicit social contract. COVID lockdowns have reduced individual incomes, yet the party-state still demands unquestioned compliance. The Chinese economy has suffered downturns before, such as the large increase in unemployment rates due to state-owned enterprise reforms and the 2008 global financial crisis. Post-COVID economic recovery will prove more difficult. China’s annual economic growth rate has decreased from approximately 11 percent to 3 percent, making the effects of unemployment and reduced income more impactful.

Moreover, The Zero COVID policy has reduced the level

59

of citizen buy-in required for the trust-based model of governance. Initially, citizens were willing to abide by strict Zero COVID guidelines, as they believed the policies protected lives. As the pandemic persisted, citizens saw a decline in their quality of living and began defying public health policies. The aftermath of the Zero COVID policy may create a dilemma that gradually deteriorates the resilience of the regime. In order to enforce future policies on a less compliant citizenry, the state must utilize more coercive methods. Excessive use of repressive tactics, however, may undermine the legitimacy of the regime.

It should be noted that tactics of repression were effective in restabilizing the Chinese party-state following the Tiananmen Square movement. Eyewitness accounts report soldiers unleashing gunfire and teargas upon the protestors, as well as tanks crushing the demonstrators to death (Calhoun 1989). These assaults were followed by a state-sponsored campaign of intimidation in which criminal courts severely punished alleged rebels. However, the context of the suppression of the Tiananmen Square movement differs from that of the Zero COVID policy. China enjoyed a robust economy during this period. Economic reforms implemented under Deng Xiaoping had improved the standards of living for numerous citizens, such that the Chinese

60

people saw their individual incomes rise with state-sponsored wage increases. The private sector manufactured a consistent output of consumer goods. The household responsibility system increased the earnings of rural peasants. In this prosperous economic climate, citizens were more willing to overlook the regime’s actions (Baum 1992). The post-COVID economic conditions of China are less conducive to such a reaction.

“Four decades after China’s opening up and reform, it seems as if social mobility has hit a ceiling”

The Chinese party-state will face greater challenges in repairing the implicit social contract with its citizens. The Zero COVID policy has had a detrimental impact on the Chinese economy. Four decades after China’s opening up and reform, it seems as if social mobility has hit a ceiling. The economy is stagnating, and unemployment rates have reached upwards of 30 percent in cities (Ong 2023). The Chinese economy seemed to recover from its pandemic policies; its economic growth rate decreased to 2.2 percent in 2020 but increased to 8 percent in 2021. However, pocketbook factors are more determinative of regime

61

support than sociotropic factors. Zero Covid policies have severely damaged factors related to individual income, specifically the growth of small businesses. In 2020, approximately 6 million new enterprises registered whereas 4.5 million unregistered. This trend worsened in 2021: roughly 1 million small enterprises formed whereas 4.4 million unregistered. This is particularly devastating to ordinary citizens, as small businesses generate 80% of urban jobs in China (Mark and Schuman 2022). The state must enact reforms to increase individual economic prosperity— rather than solely focusing on macroeconomic growth—to preserve the regime’s resilience.

However, a similarity that both the Chinese people living during the Tiananmen Square movement and Zero COVID policy protest share is the memory of the Cultural Revolution. During the Tiananmen Square massacre, this memory created a fear of chaos, which diminished popular support for the protests. Survivors of the Cultural Revolution were haunted by the deaths, torture, suicides, and destruction of homes they witnessed. Victims also lost trust in their social networks, as citizens were encouraged to turn in individuals of a landowning background (Thurston 1984). The Chinese people pass down memories of the Cultural Revolution within their families, such that younger generations in

62

China continue to prioritize political and social stability. Chinese citizens report corruption and stability as the top issues requiring reform (Le andAlon 2004). It is likely that the Chinese party-state will exploit this fear of chaos to preserve the regime’s survival in the aftermath of the Zero COVID policy.

VI. Conclusion

The Chinese party-state has survived due to a historical tradition of rules consciousness, a decentralized governance system, and the continued fulfillment of the implicit social contract with its citizens. The tradition of rules consciousness dictates that protestors express their grievances, while also demonstrating their loyalty to the state. Protests often include petitions filed according to state-sanctioned procedures. Rather than challenging the authority of the party state, protestors call upon the regime to fulfill its promises. The Chinese federalist system also serves as a source of political stability. The structure allows the state to balance repression and concession as methods of enforcement. Moreover, the state intentionally produces a local legitimacy deficit in order to increase support of the central government. Finally, the social contract that forms the basis of state-society interactions contributes to the regime’s resilience. Citizens are willing to acquiesce to the party-state in exchange for greater economic opportunities.

63

These fundamental tenets have enabled the Chinese party-state to survive numerous protests. The COVID-19 pandemic poses a substantial challenge to the resilience of the regime, as it undermines these core elements. Chinese citizens hold the central government responsible for draconian pandemic measures, leading them to deviate from the tradition of rules consciousness. Unlike previous protests, the Chinese party-state cannot simply deflect blame onto local governments. Most importantly, the Zero COVID policy has damaged the social contract between the state and its citizens. The Chinese people are no longer willing to abide by pandemic restrictions, which both deprive them of their civil liberties and harm their economic prosperity. In order to ensure its survival, the Chinese party-state will attempt to implement reforms that repairs these fragmented fundamental tenets. The success of the central government in doing so remains to be seen.

64

Bibliography

Baum, Richard. “Political stability in post-Deng China: problems and prospects.” Asian Survey 32, no. 6 (1992): 491-505.

Cai, Yongshun. “Power Structure and Regime Resilience: Contentious Politics in China.” British Journal of Political Science 38, no. 3 (2008): 411–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27568354. Calhoun, Craig. “Revolution and repression in Tiananmen Square.” Society 26, no. 6 (1989): 21-38.

Chen, Jie, and Chunlong Lu. “Democratization and the Middle Class in China: The Middle Class’sAttitudes toward Democracy.” Political Research Quarterly 64, no. 3 (2011): 705–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23056386.

Dickson, Bruce J., Mingming Shen, and Jie Yan. “Generating Regime Support in Contemporary China: Legitimation and the Local Legitimacy Deficit.” Modern China 43, no. 2 (2017): 123–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44505164.

Heurlin, Christopher. 2016. “Disruptive Tactics and Buying Stability in Local Government Responsiveness.” Responsive Authoritarianism in China: Land, Protests, and Policy Making.

67

Cambridge University Press. pp 54-89.

Le Lu, and IlanAlon. “Analysis of the Changing Trends inAttitudes and Values of the Chinese: The Case of Shanghai’s Young & Educated.” Journal of International and Area Studies 11, no. 2 (2004): 67–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43111449.

Lu, Chunglong. “Middle Class and Democracy: Structural Linkage.” International Review of Modern Sociology 31, no. 2 (2005): 157–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41421642.

Mark, Jeremy, and Michael Schuman. “The Party Wins.” China’s Faltering “Zero COVID” Policy: Politics in Command, Economy in Reverse. Atlantic Council, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/ resrep41248.4.

Ong, Lynette H. “The CCP after the Zero-Covid Fail.” Journal of Democracy 34, no. 2 (2023): 32-46.

Perry, Elizabeth. 2010.“Popular Protest in China: Playing by the Rules,” in China Today, China Tomorrow edited by Joseph Fewsmith (Routledge), Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Thurston,Anne F. “Victims of China’s Cultural Revolution: The Invisible Wounds: Part I.” Pacific Affairs 57, no. 4 (1984): 599620.

68

“The

sun has set behind the hills:”

Prominent Shidaiqu Artists’Stories

Under the Chinese Communist Party, 1949–1978

Calvin Pan About theAuthor

Calvin Pan is a first-year UVAstudent from McLean, Virginia, majoring in ForeignAffairs and minoring in Data Science and French. Having lived in China for half his life, Calvin is immensely interested in Chinese history and China-US relations. He’s also an avid jazz pianist, playing in a small jazz group at UVAin addition to a funk rock band (favorite pianist: Bill Evans). Calvin is currently working on another research project about Tibetan Buddhism

71

in Taiwan. Outside of writing, Calvin is the Treasurer of UVA’s International Relations Organization, the parent organization of the Journal. Calvin also is a trial counselor with the University Judiciary Committee, and loves to run/hike/bike/do anything outdoorsy!

Abstract

The shidaiqu tradition was a style of music that emerged in China’s cosmopolitan port cities and fused Western musical conventions and jazz vocabulary with Chinese lyrics and instrumentation, becoming wildly popular in China from the 1920s-1950s. Shidaiqu was particularly reviled by the Communist Party as being decadently capitalist and insufficiently nationalist, and as a result, its practitioners were ostracized and often treated severely once it came to power. This paper uses a number of Chinese primary and secondary sources in translation to, for the first time in English, piece together the stories of three shidaiqu practitioners (Li Jinhui, He Lüting, and Zhou Xuan) in a narrative format. Those stories are often forgotten in both China and the wider world, but still hold critical importance in explaining the nature of the Communist Party’s earliest years of rule.

72

“The sun has set behind the hills:” Prominent Shidaiqu Artists’Stories Under the Chinese Communist Party, 1949–1978

Introduction

If you flipped open a copy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s official state newspaper, the People’s Daily, any time during the 1950s, chances are that you’d see language like the following: “Used to corrupt and anesthetize the fighting will of the people.” “It only serves the depraved bourgeoisie, Western slave masters, and Chinese traitors employed by the enemy” (Xu, 1958). “Vulgar and ugly” (People’s Daily Commentator, 1958). The CCP was attacking one of its greatest enemies with those harsh words: not opium, or drinking, not even Chiang Kai-Shek, but rather, a far more sinister foe—popular music.

After its 1949 victory in the Chinese Civil War, the CCP systematically repressed non-revolutionary popular music, or shidaiqu, as part of itsAnti-Rightist campaigns aimed at restructuring society. Labeling it “yellow music” – and thereby painting it as an ideological enemy associated with Western constructs of decadence, pornography, and capitalism – the Communist Party succeeded in nearly eradicating the once

73

wildly-popular art form.Over the course of this violent crackdown, thousands of composers and singers associated with the pop music industry were labeled as enemies of the state and either persecuted or made to flee China, while others strategically moved to producing state-sanctioned “red music” instead (Mittler, 1997).This essay aims to chronicle the stories of three notable figures in the shidaiqu world who experienced this suppression first-hand, countering the underrepresentation of individual artists’stories in the field of Chinese pop culture studies. In doing so, it also endeavors to restore an oft-forgotten sense of agency to those musicians’stories by highlighting their individual decisions and actions in responding to a brutal regime.

Historical Context

Historical context—both immediate to the 1940s and 1950s and a longer culmination of historical trends—illuminates the CCP’s decision to brutally repress shidaiqu artists. After the death of the Qing Emperor Qianlong in 1796, heralding the end of China’s last true golden age, the Chinese state entered a steady decline. Defeat at the hands of the British in the First Opium War in 1839 signaled the start of a “century of humiliation,” during which military and economic stagnation,

74

as well as an increasingly corrupt state, led China to suffer disasters like the Taiping Rebellion. This left the nation vulnerable to embarrassments like the loss of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, allowing Western empires to carve out treaty ports—most notably the city of Shanghai—and zones of influence from the nation. Eventually, this downward spiral sparked the 1911 Xinhai Revolution.Angered by the imperial government’s lackluster efforts at reform, millions of Chinese, led by a Western-educated elite and Westernized regiments of the Qing Army, overthrew the Qing Dynasty—a movement which would also spur a mass drive to modernize Chinese art and culture in the May 4th Movement. The dream of a resurgent modern China was never realized, however, as a rift between rival governments established by the two leaders of the Revolution, Yuan Shikai and Sun Yat-sen, eventually spiraled in 1916 into a decade-long Warlord Era with various generals battling for power.

In 1928, the nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) under Chiang Kai-Shek reunified the nation under a government based in the city of Nanjing, ushering in an era of relative stability. At the same time, the Communist Party (CCP) emerged as a contender, with Mao Zedong eventually becoming the leader. Originally the KMT’s left wing until its members were brutal-

75

ly massacred by the KMT, the CCP started waging a guerilla civil war against the KMT. Many Chinese artists during this time oriented their work towards making political statements in support of either side, with shidaiqu musicians generally being more in support of the KMT (Wilson Lewis et.al, 2023).

This low-intensity civil war would be put on hold with the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1937, starting the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), which saw the KMT and CCP join forces in a Chinese United Front.Art in China during this period shifted overwhelmingly to mass nationalist art that aimed to inspire the Chinese populace in its war effort, and shidaiqu artists were criticized for not devoting themselves to this cause. Following the defeat of Japan in the Second World War (of which the Second Sino-Japanese War had become a theater), the CCP and KMT renewed their civil war. Initial KMT victories were quickly reversed due to the Soviet Union providing the nascent CCP with large amounts of material aid and much greater support amongst a Chinese populace who saw the KMT as elitist. By 1949, the CCP had conquered most of mainland China, declaring a new People’s Republic of China (PRC) and pushing the KMT to relocate the island of Taiwan. It then undertook a series of ill-fated mass campaigns to restructure the Chinese nation under Mao Zedong’s model of

76

agrarian socialism—most notably theAnti-Rightist Campaign (1957–59), Great Leap Forward (1958–62), and Cultural Revolution (1966–76)—leading to the deaths of millions through purges and famines caused by economic mismanagement. The party especially targeted artists and the intelligentsia during this period, as they were viewed as agents of reactionary thought. Following the death of Mao Zedong, reforms by his successors (most notably Deng Xiaoping) would see the PRC undertake programs of limited economic liberalization and reversing its stringent focus on ideological purity, leading it to experience rapid economic growth and allowing it to finally reemerge into a leading role on the world stage in the 21st century (Wilson Lewis et.al, 2023).

It was in this tumultuous political environment that shidaiqu emerged. China’s gradual decline on the world stage had spurred many Chinese intellectuals to advocate for the adoption of Western thought in many areas, including culture, believing that those ideas were the key to China’s reclaiming the title of a modern global power. In the aftermath of the Xinhai Revolution, those sentiments culminated in the May 4th Movement. Originating in 1919 through student protests against Western powers unilaterally ceding the province of Shandong to Japan in the Treaty of Versailles, the movement

77

eventually transformed into a nationalist anti-elite movement calling for the rapid transformation of all Chinese culture and society (Encylopaedia Britannica, 2019).At the forefront of the May 4th Movement were musicians who sought to revolutionize and “modernize’’Chinese popular music. In the Western concession cities of China, particularly Shanghai—which, as cultural crossroads between “East” and “West,” represented the perfect environment for their fusionist endeavors—those artists labored to combine traditional folk music withAmerican jazz and Hollywood film music (“时代曲 (Shidaiqu/Shanghainese jazz),”, 2022).Eventually, they created a new genre, shidaiqu.

Li Jinhui is widely regarded as the first artist and father of this new music, composing pieces such as “毛毛雨” (“Drizzle”) that featured a traditional pentatonic folk melody combined with Western instrumentation, exemplifying the fusion-based nature of the genre (Jones, 2023). In the relative stability of the Nanjing Decade, new imported technologies such as radios and record players allowed for the mass dissemination of shidaiqu. This newfound popularity led to infrastructure springing up to support the burgeoning art form, such as record companies like Shanghai Pathé Records, and training grounds for new artists like Li Jinhui’s Bright Moon Song and Dance Troupe. Shidaiqu’s ties to Shanghai’s growing film industry also bolstered

78

its influence, with immensely successful movies like 馬路天 使 (Street Angels) featuring soundtracks by notable composers like He Luting and offering promising stars like Zhou Xuan a path to fame in both the film and music worlds (Lun Chun et.al, 2015).

By the early 1940s, shidaiqu had become an integral part of the cultural fabric of China, with famous musicians playing to packed dance halls (NPR, 2014).Yet, political realities, both global and domestic, saw the genre increasingly come under attack as useless.As Dale Wilson states in his review of Andrew F. Jones’2001 book, Yellow Music: Media Culture and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age, Japan’s 1931 invasion of Manchuria prompted those in both leftist and rightist circles to consider “urgent [political] issues of the day, such as modernity, gender, class, and a politics of national salvation” in evaluating music (Wilson, 2001).Due to not focusing on any of those issues, and rather on themes of love and beauty, shidaiqu came to be condemned as “yellow,” a color often associated with pornography and decadence in Chinese culture. This criticism was heightened by shidaiqu’s marked contrast with qunzhong yinyue, a form of leftist mass music that was concurrently popular with shidaiqu and was oriented around those political themes (Wilson, 2001).

79

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, shidaiqu also became negatively associated with occupying Japanese authorities, as the art form flourished in the city of Shanghai while it was under Japanese rule (Wilson, 2001).All this led the Nanjing KMT government to suppress shidaiqu starting in 1947 as part of a broader nationwide campaign against vice, particularly the cabarets often associated with the music. Though this crackdown was largely successful in most of China, musicians alongside entertainment industry workers in Shanghai protested in a “Dancers’Uprising,” wuchao, on January 31, 1948—an effort that, alongside other organized resistance, was enough to persuade the Nanjing government to reverse its crackdown (Field, 2010).When the CCP came to power after the Chinese Civil War, they similarly took a stance against shidaiqu and other forms of Westernized and non-revolutionary “bourgeoisie” art, viewing music as “one of the battlegrounds for Mao’s revolutionary ideology” (Parham, 2014).Learning from the mistakes of the KMT government, the CCP initially took a gradual approach towards the eradication of shidaiqu, forming a number of pro-government musicians’unions to generate support among musicians, and slowly phasing out shidaiqu from radio- and record-based distribution while providing alternative employment to now-jobless industry workers (Jones

80