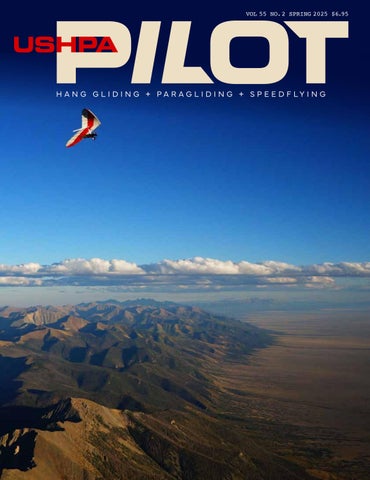

HANG GLIDING + PARAGLIDING + SPEEDFLYING

Cover Photo by Josiah Stephens A lucky pilot skying out near Villa Grove, Colorado.

Cover Photo by Josiah Stephens A lucky pilot skying out near Villa Grove, Colorado.

Association 6 Editor 8 Briefs 9 Ratings 62

USHPA Awards by Liz Dengler 10

Honoring the 2024 receipients

Accident Review Committee submission by Chris Mann 16

Preflight, preflight, PREFLIGHT!

Colombia Páramos by Riley Ferré 20

Exploring new hike-and-fly missions

Community Builders by Lindsey Ripa Burns 26

What it takes to throw a fly-in

Trip to Villa Grove by Jeff St. Aubin 32

A bi-wingal pilot explores a Colorado gem

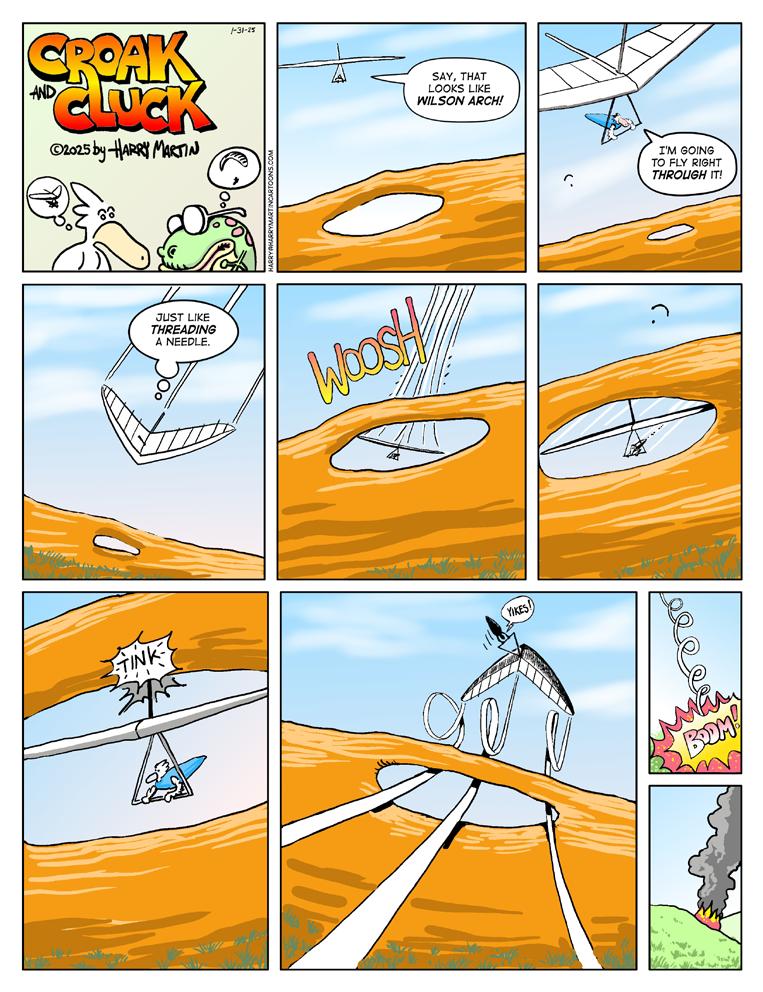

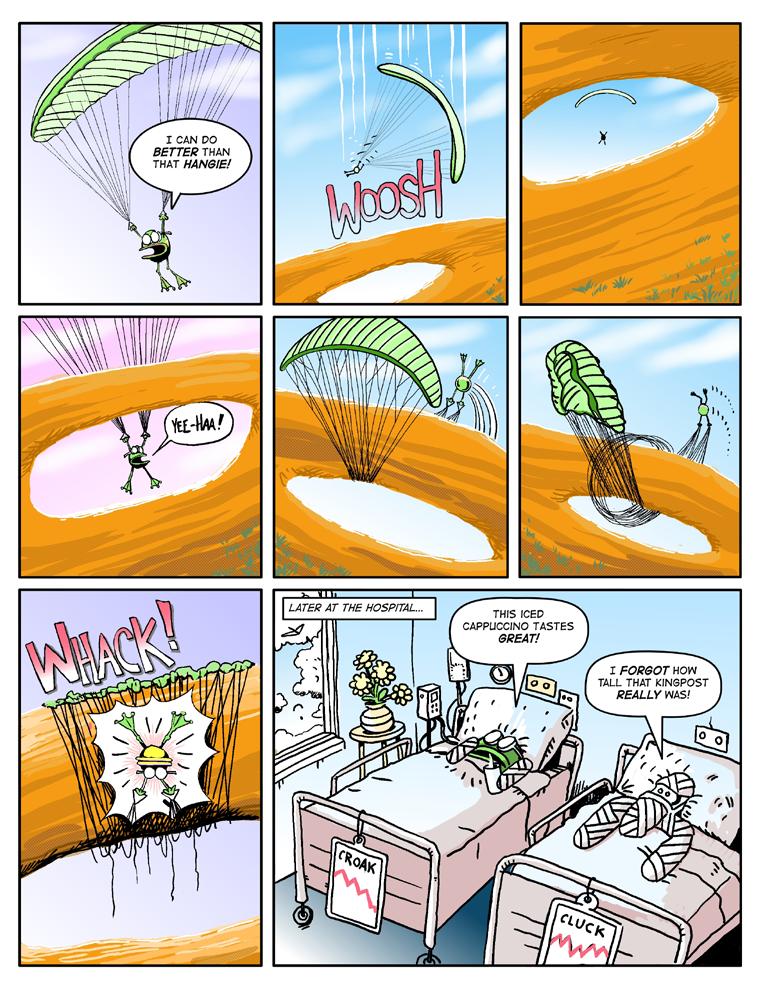

Croak & Cluck cartoon centerspread by Harry Martin

Ice Lake by Arias Anderson 40

A Colorado speedflying mission

Windy Kiting Skills by Brian Petersen (with Erika Klein and Heather Harston) 46

Common windy kiting mistakes and tips for fixing them

Reviewing the Rapido 3X by Calvin Freeman 52

A versatile speedwing for advanced pilots

NorCal Cross Country League 2024 by Jugdeep Agarwal 56

Updates and results

Mistakes and Miracles by Dan Corley 58

HANG GLIDING, PARAGLIDING, AND SPEEDFLYING ARE DANGEROUS ACTIVITES

USHPA recommends new or advancing pilots complete a pilot training program under the direct supervision of a USHPAcertified instructor, using equipment suitable for their level of experience. Many of the articles and photographs in the magazine depict advanced maneuvers being performed by expert pilots. No maneuver should be attempted without appropriate and progressive instruction and experience.

©2024 US HANG GLIDING & PARAGLIDING ASSOC., INC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of USHPA.

POSTMASTER USHPA Pilot ISSN 2689-6052 (USPS 17970) is published quarterly by the United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, Inc., 1685 W. Uintah St., Colorado Springs, CO, 80904 Phone: 719-632-8300 Fax: 719-632-6417 Periodicals

Postage Paid in Colorado Springs and additional mailing offices. Send change of address to: USHPA, PO Box 1330, Colorado Springs, CO, 80901-1330. Canadian Return Address: DP Global Mail, 4960-2 Walker Road, Windsor, ON N9A 6J3.

Versatile by design www.nova.eu/ion-7

Do you have questions about USHPA policies or programs? Are there topics you’d like to hear more about?

EMAIL US AT: info@ushpa.org

Interested in taking a more active role supporting our national organization? USHPA needs your skills and interest.

VOLUNTEER AT: ushpa.org/volunteer

For other USHPA business +1 719-632-8300 info@ushpa.org

James Bradley, Executive Director

: Flying is magical, wondrous, and gives us so much. With good instruction, a conservative attitude, and an ordinary amount of luck, we can fly for decades without a serious mishap. Maybe.

We can mitigate the likelihood of a flying mishap by keeping more margin than we think we need, in every situation. Stay more in front of the ridge, farther from the big cloud, closer to the field, higher above the side valley, farther from the rock face, more aware of the valley wind, more ready to use the reserve, more willing to land in the safer place—or even not launch that day. Make extra margin part of your flying temperament and you'll need less luck. You might also find it doesn't diminish your enjoyment.

though it too goes out of date: cloudbasemayhem.com/insurance. If you're going to Switzerland, be sure and join Rega, which will cover your emergency helicopter ride: rega.ch/en

Please don’t fly without health insurance.

: You’ve probably heard dues are going up, for the first time in nine years, on April 2. If you Google “inflation calculator”, you’ll find the new pilot dues match 2016's in real dollars. It’s just another frustrating effect of inflation.

The United States Hang Gliding & Paragliding Association, Inc. (USHPA) is an air sports organization affiliated with the National Aeronautic Association (NAA). The NAA is the official representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), which is the world governing body for sport aviation. The NAA represents the United States at FAI meetings.

The NAA has delegated to USHPA the supervision of FAIrelated hang gliding and paragliding activities, such as record attempts and competition sanctions.

We can mitigate the consequences of a flying mishap by having health insurance. If people depend on you financially, consider also life insurance. Check your policies for aviation or adventure sports exclusions. If you're going abroad, make sure your insurance covers you there. Consider adding air ambulance repatriation, which will bring you back to a hospital near home. The insurance isn’t costly, the air ambulance is, and you don’t want to be stuck in a foreign hospital for months. USHPA partner MedJet offers USHPA members a discount: medjet.com/USHPA. If you want to add SAR and medical, be aware that policies and pricing change constantly. Cloudbase Mayhem has a webpage that can help,

: As a USHPA member, you're part of, and providing crucial support for, the only national organization in the U.S. that works every day to maintain and improve your flying experience and opportunities. You’re helping to build and support a vibrant national community of free flyers.

To this very end, we’re hard at work on several initiatives. I invite you to check out the strategic plan: go to USHPA.org/about and click the strategy link. Then send me your thoughts at james@USHPA.org

You also get a long list of member benefits, which you can see at USHPA.org/benefits.

: Do you have an experience, a frustration, or an idea you think I should know about? Please go to USHPA.org/meetwithjames. I look forward to speaking with you.

REGION 1

South Dakota

Washington Wyoming

REGION 2 CENTRAL WEST

REGION 3 SOUTHWEST Southern California Arizona Colorado New

REGION 4 SOUTHEAST Alabama

To deliver programs and services that support all our members, foster a community of skilled and knowledgeable pilots, and promote and protect the freedom to fly.

A vibrant free flight community across the United States.

Core values & guiding principles

Celebrate the spirit of discovery and the joy of being in the outdoors.

Support ongoing education, development of skills, and acquiring of the judgment that comes from experience and attention.

James Bradley Executive Director james@ushpa.org

Charles Allen President president@ushpa.org

Kirby Ryan Vice President vicepresident@ushpa.org

Olga Grunskaya Secretary secretary@ushpa.org

Pam Kinnaird Treasurer treasurer@ushpa.org

Galen Anderson Operations Manager office@ushpa.org

Chris Webster Information Services Manager tech@ushpa.org

Anna Mack Program Manager programs@ushpa.org

Maddie Campbell Membership & Communications Coordinator membership@ushpa.org

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2025)

REGION 5

Be stewards of our natural places, our flying sites, and the future of our sport.

Act ethically, take 100% ownership, communicate clearly, respond effectively.

Foster a considerate community free from harassment and abuse.

Kirby Ryan (region 3)

Nelissa Milfeld (region 3)

Pamela Kinnaird (region 2)

Olga Grunskaya (region 5)

Bob Ferris (region 3)

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2026)

Van Spurgeon (region 3)

Charles Allen (region 5)

Nick Greece (region 2)

Stephan Mentler (region 4)

Liz Dengler

Managing Editor editor@ushpa.org

Julia Knowles

Copy Editor

Greg Gillam Art Director

WRITERS

Dennis Pagen

Lisa Verzella

Erika Klein

Julia Knowles

Do you have a story idea you would like to pitch? We are always looking for stories.

EMAIL LIZ AT: editor@ushpa.org

Are you ready to contribute a complete story? We are always looking for articles, photography and news.

GET STARTED AT: ushpa.org/contributors

All articles, artwork, photographs as well as ideas for articles, artwork and photographs are submitted pursuant to and are subject to the USHPA Contributor's Agreement , which can be reviewed on the USHPA website or obtained by emailing Liz.

Would you like to run an advertisement ? Great!

CONTACT US AT: advertising@ushpa.org

: One of the benefits of your USHPA membership is this magazine, which gives back to the community in a few ways. Besides highlighting the stories of our members in this publication, we also pay our published contributors. We’re always on the lookout for stories from our members. Travel, tips, hang gliding stories, home site reports, the mental game, gear reviews, and more! Whatever you’re excited to share with the community, we probably have a home for it. Send a pitch my way: editor@ushpa.org

In this issue, pilots share compelling pieces covering a wide range of topics. We start by honoring the 2024 USHPA award recipients. Each year, USHPA issues awards and commendations to members who make contributions to our sport, often recognized by their peers. These pages contain some touching quotes from nominators, and they’re worth a read. As you read through the awards list, consider nominating someone for 2025!

Two brave members have come forward with articles about their accidents. One was fueled by complacency and failure to complete a full preflight check. The other resulted from a healthy dose of hopium and trying to force a flight in inappropriate conditions. We applaud both pilots for sharing their stories, which helps promote a culture of openness and safety across our community."

Three members discuss their travel experiences on missions to explore new places. From a hang glider’s first

time to the legendary Villa Grove, Colorado, to hike-and-fly treks of Colombia’s remote gems, to a backpacking mission to speedfly over the stunning Ice Lake in Colorado, these authors do a masterful job crafting their tales. I’m certainly excited to start planning my own summer adventures!

Intermission is provided by the delightful Croak and Cluck—darlings and misfits of the hang gliding and paragliding world. Flip to the centerfold to chuckle at their misadventures.

A gear review of a newly-beloved speedwing for advanced pilots keeps potential buyers in the know; tips for kiting in high wind from experts at the Point of the Mountain, Utah, can prepare members for when conditions start to pump up. Both stories showcase great photos that capture the essence of each story.

The last two articles focus on running events and supporting the community. You will find an expert recap of the Northern California leagues (something I wish we had where I live) and a thoughtful breakdown of what it takes to plan and run a fly-in.

Enjoy the issue. With the sheer diversity of experiences and perspectives packed into these pages, you may have to read it twice!

NOVA BION 3

The BION 3 is aimed at professional tandem pilots. It features an easy takeoff along with great turning characteristics. It’s 40.68m with a weight range from 110 to 220kg. The BION 3 certifies EN-B and weighs 6.8kg. It comes in three colors and is available through Super Fly with your choice of bags. www. superflyinc.com +1 801-255-9595 or your local dealer.

The legendary SIGMA is born again with the SIGMA DLS (EN-C). The redesigned internal structure is still durable but light (3.7kg). Features include Nitinol mini-ribs to maintain leading edge shape at speed and the pitch control system, which keeps a clean profile when C-inputs are given. It comes in five sizes, from 57 to 128kg, at an aspect ratio of 6.1. It comes with a COMPRESSBAG DLS but also comes with the pilot’s choice of concertina, light rucksack, normal rucksack, or fast-packing bag. Available through Super Fly: www.superflyinc.com +1 801-255-9595 or your local dealer.

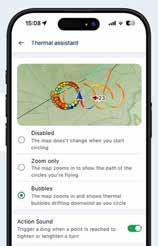

Naviter is introducing SeeYou Navigator 3.2. featuring an improved Thermal Assistant with Thermal Bubbles that provide a more intuitive thermal detection to help you climb faster. Fine-tune your navigation display with a configurable snail trail length. Also included in v3.2 is an upgraded FAI triangle assistant that ensures precision when completing your tasks. Plus, a new wind calculation algorithm delivers more accurate real-time data for better decision-making. This update also includes crucial bug fixes, ensuring smoother, more reliable performance. Available now for your Oudie N, Omni, iPhone, or Android. For more info: www.flytec.com | info@ flytec.com | +1 800-662-2449

ATAK 2

The Atak 2 harness is a purpose-built speedflying harness designed by top pilots to meet the unique needs of the sport. It combines multi-season versatility with a lightweight, compact, and durable design. The Atak 2 is suitable for all levels, from new pilots to expert speed riders. It is optimized for comfort and precision while kiting or riding in upright positions, offering ultra-smooth transitions from standing to sitting. www.flyozone.com

The Camino 2 is easy to launch, has smooth handling, and best-in-class 2-liner performance. It has an aspect ratio of 6.3 and features the wave leading edge, which provides better stability at speed. It is light and compact and can be packed in a compress bag. The Camino 2 only weighs 3.9kg in the medium size. It is available in five sizes from 60 to 125kg. Available through Super Fly: www.superflyinc.com +1 801-255-9595 or your local dealer.

The latest in the LIGHTNESS series harness has slightly better comfort, handling, and looks while preserving all the great LIGHTNESS 3 qualities. It has 35% more storage, a new cockpit design, and it comes with a hook knife, windshield, and LIGHTPACK DLS. It comes in three sizes and accommodates pilots from 155 to 200cm. It weighs 3.47kg in the medium size. Available through Super Fly: www.superflyinc.com +1 801-255-9595 or your local dealer.

: Each year, USHPA honors exemplary pilots and community members with the USHPA awards. These themed awards and commendations show our appreciation for those who have contributed significantly to the free flight community.

Chris Santacroce

Presidential Citation

From 2024 USHPA President Bill Hughes: Though USHPA is professionally managed by a small handful of dedicated employees, it relies heavily on pilot and instructor volunteers who give up significant chunks

balanced perspective to many of the tough subjects we tackle. As an administrator, instructor, tandem pilot, and school operator, Chris understands the demands placed on each group. However, he also sees things from the FAA/USHPA perspective of what is required to safeguard the future of free flight in the U.S. He was instrumental in the insurance transition, and last year he helped us craft important messaging to drive cultural change after some issues with waiver compliance that had the potential to jeopardize our tandem exemption.

Please join me in congratulating Chris on the award

L to R: Chris Santacroce (Presidential Citation), Larry Smith (Exceptional Service), David Blacklock (Paragliding Instructor).

of their personal time to further USHPA’s mission and to protect and grow free flight for all of us.

Few people in USHPA’s history have done as much to grow the sport or contributed as much as a volunteer as 2024’s Presidential Citation Award winner, Chris Santacroce. He has long been a driving force in training and certification and increasing pilot safety. He has been central to our efforts to collect data, analyze, and report on accidents. He’s also contributed significantly to setting standards and guidelines for tandem flights and tandem instructor appointments. Last year, Chris was chair or co-chair of three different USHPA committees. He brings a unique and

and thanking him for his ongoing work to support USHPA’s mission. Chris is a role model for what a member of the USHPA community can be.

This award recognizes any member or non-member’s outstanding service to USHPA during the year. An individual may receive this only once, and in 2024, the Awards Committee recognized Larry Smith. Larry has been an integral part of the free flight community for many years. Steward of the legendary site at Villa Grove in Colorado, Larry has gone above

and beyond to ensure its access. Hosting annual organized events, casual fly-ins, and a revolving door of visitors, Larry has introduced numerous pilots to flying in this area. Nominators were quick to mention his helpful nature and willingness to host groups at his property (adjacent to the LZ) during flying events. Thank you, Larry, for your care and attention in keeping Villa Grove an amazing site for hang glider and paraglider pilots alike.

Paragliding Instructor of the Year

With an overwhelming number of nominations, David Blacklock has been awarded Paragliding Instructor of the Year. His students have universally noted his kind, patient, and calm demeanor. “With his patience, supportive nature, and willingness to go the extra mile, David possesses a rare combination of qualities that make him an outstanding paragliding instructor,” said one nominator. “He is not only a skilled pilot with a deep understanding of the sport, but also a gifted teacher who can convey that knowledge effectively.”

Another nominator commented, “Dave combines keen perception and a watchful eye with a willingness not only to meet students at their current level of participation and understanding, but also to adapt to their particular learning style and method of engagement.”

Dave also seems to have a knack for teaching through stories and humor, as numerous former students commented on his ability to inject humor or personal anecdotes into their lessons. “He is a gifted storyteller who never fails to inspire new students or put a smile on the face of a pilot frustrated or embarrassed by that last flight,” offered one pilot. It’s clear this award is well-deserved. Congratulations, David!

Brady Mickelson, Jens Bracht, Barry Barr, Tyler Lee, and Dan Homes

Best Promotional Film

This award is granted to the filmmaker(s) whose work is judged best by the Awards Committee after considering aesthetics, originality, and a positive portrayal of the sport. In 2024, the recipient was the KAVU short film: “Forever Busy Livin’. ”

One nominator described the film as “…a touching short about two of the kindest and longest-enduring people in our sport.” C.J. and George Sturtevant have been USHPA members for more than 43 years! “KAVU, a Seattle-based clothing company, made a heartwarming feature about our O.G. royal couple of free flight,” another commented. “The film deftly highlights their deeply entrenched love of each other and their shared thirst for adventure by highlighting their incredible journey across the world over the last four decades under hang gliders and paragliders.

The film sweetly shows a life well lived and how the beat still plays on for two amazing members of our organization.”

The leader behind the movie, Brady Mickelson, had this to say about filming the project: “It was incredibly fun hanging out with C.J. and George for four days. They made us dinner from their garden, C.J. baked some killer macarons, and we learned the term MUSTGOS (aka: leftovers or food in the fridge that needs to be eaten).” He continued, “I also want to give a shout-out to the KAVU crew for investing in storytelling and letting me run with it. It’s pretty rare these days for companies to do this. Big love to Barry, Dan, and Tyler.”

When I reached out to C.J. to get her take on the film, she had this to say:

When Nick [Greece] first told us that KAVU wanted to do a short documentary about us, we were puzzled: Why us? I’m not typically comfortable being the center of attention. But Nick assured us it would be fun. So, in September of 2023, two young men and all their video-making gear showed up on our doorstep, and indeed, the fun began. We dug through and told the stories behind decades-old flying photos and slides. We drove and biked to paraglider sites and pickleball courts while Brady and Jens filmed. They chatted with and filmed our friends and neighbors. And then they left, and we still had no clear idea when we’d see a finished product, but Nick was right: The process was great fun!

It wasn’t until we were on a paragliding trip in Mexico and a paraglider pilot working on her computer in the LZ where we were packing up kept looking

over at us, then back at her computer, then back at us, hollered over, “Are you C.J. and George?” that we finally saw the video. And it blew us away! Brady and Jens took all those bits and pieces, images and chats, and turned them into this amazing portrayal of our lives together. We still have no idea why KAVU chose to sponsor the creation of a video about us, but we’re grateful to them, Nick, Brady, and Jens for this beautifully crafted story.

For those of us who have watched the film and heard the legendary tales, we know why they chose C.J. and George. Your lives together and paragliding careers are an inspiration to all of us, and we thank you for letting your story be told. You can watch “Forever Busy Livin’ ” on KAVU’s website here: adventure.kavu.com/cj-forever-busy-livin or via YouTube: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifWS5SIpycM

Finding a mentor can be a challenge to those new to the sport. Luckily, the pilots of Ellenville, New York, are never at a loss, thanks to Rick Fitzpatrick. “He is incredibly generous with his time with me, and took me under his wing in a way that I hadn’t experienced since my youth,” said one nominator. Rick is quick to donate his knowledge to local pilots and visitors alike, and is always generous with his time to ensure safe flights and good experiences. “Both days that I flew Ellenville, Rick spent the whole day on the mountain, waiting until the evening when the wind calmed down enough to launch. He didn’t fly either of these days but was completely happy to advise and

Richard Fitzpatrick

years of flying experience, graciously helping both new and experienced pilots reach their goals. This eagerness to share his local flying site and his knowledge is a huge boost to the sport of hang gliding,” said another pilot. Rick goes above and beyond to support the growing community of pilots. Another nominator mentioned, “Rick came to Ellenville in 2020 and tirelessly helped at launch and picked students up from the LZ to let them get multiple sled rides until they were ready for soarable air.” Rick continues to support and mentor pilots as they progress in the sport. Numerous pilots owe at least some of their progression to him. Thank you for all you do for the community!

Philippe Renaudin is an enthusiastic teacher, dedicated mentor, and devoted pilot. He is an integral part of the free flight community. He always ensures his students are prepared, and safety is his priority. One nominator commented, “With over three decades of experience since 1990, he has trained countless individuals, fostering a strong community of skilled paragliders. His leadership in founding the first paragliding club on Long Island in [the early 2000s] shows his commitment to expanding and promoting the sport, creating a lasting impact on the paragliding community.”

Many others were quick to speak to Phillippe’s dedication to teaching students. “Phil teaches with gen-

MAKE YOUR NOMINATION AT: ushpa.org/awards

NOMINATIONS ARE DUE OCTOBER 1.

PRESIDENTIAL CITATION - USHPA's highest award.

ROB KELLS MEMORIAL AWARD - Recognizes a pilot, group, chapter or other entity that has provided continuous service, over a period of 15 years or more.

USHPA EXCEPTIONAL SERVICE AWARD - Outstanding service to the association by any member or non-member.

NAA SAFETY AWARD - The NAA presents this award to an individual, recommended by USHPA, who has promoted safety.

FAI HANG GLIDING DIPLOMA - For outstanding contribution by initiative, work, or leadership in flight achievement.

FAI PEPE LOPES MEDAL - For outstanding contributions to sportsmanship or international understanding.

CHAPTER OF THE YEAR - For conducting successful programs that reflect positively upon the chapter and the sport.

NEWSLETTER/WEBSITE OF THE YEAR (print or webbased).

INSTRUCTOR OF THE YEAR AWARD - Nominations should include letters of support from three students and the local Regional Director. One award per sport per year may be given.

RECOGNITION FOR SPECIAL CONTRIBUTION - For volunteer work by non-members and organizations.

COMMENDATIONS - For USHPA members who have contributed to hang gliding and/or paragliding on a volunteer basis.

BETTINA GRAY AWARD - For the photographer whose work (three examples needed for review) is judged best by the committee in aesthetics, originality, and a positive portrayal.

BEST PROMOTIONAL FILM - For the videographer whose work is judged best by the committee in consideration of aesthetics, originality, and a positive portrayal.

uine enthusiasm and great care for his students. He emphasizes safety and solid skills and is a pleasure to be around,” another offered. Thank you, Philippe, for your dedication and service to the sport.

The Hudson Valley Free Flyers Club leadership has worked incredibly hard to support their community of pilots at the Ellenville Flight Park. Together, they endeavored to purchase the Ellenville Flight Park from its private landowner. Though the sale eventu-

ally halted (due to an unanticipated decision by the landowner), the team worked tirelessly for months to the brink of success. The nominator stated, “Their work established a model for similar efforts to secure flying sites.”

The leadership team included Wayne Neckles, Brian Herbert, Shani Schechter, Brian Vant-Hull, Kenneth Foldvary, James Donovan, Michael Strother, Tony Davis, Jane Lenard, and Paul Voight. The team raised all necessary funds for the purchase and maintenance of the property, kept the community well-informed throughout the process, worked with additional entities such as state and town officials to ensure an efficient process, and, after the sale setback, continued to look beyond Ellenville to consider other sites in the region that could be opened or preserved.

“USHPA members should commend this team of leaders for their innovation, inspiration, unified effort, and engagement of the Ellenville hang gliding and paragliding community in a noble cause,” a nominator stated,

I couldn’t have said it better myself. We thank each of you for your incredible efforts and for sharing your enthusiasm.

Get the gear that fuels your passion at discounted prices.

Your Pilot or Instructor USHPA membership automatically qualifies you to join. Simply scan the code to get started.

Unlock up to 60% o on top outdoor brands

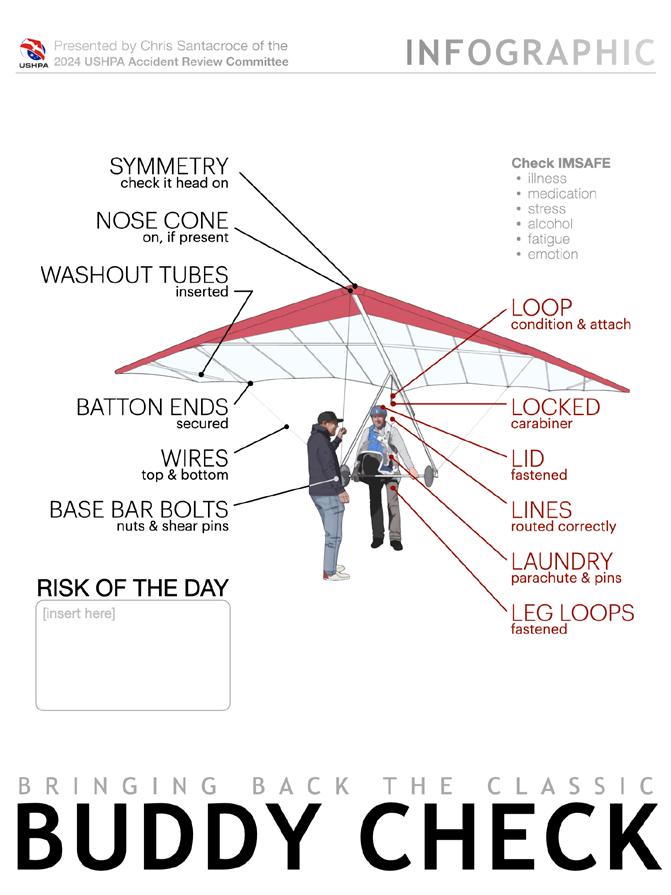

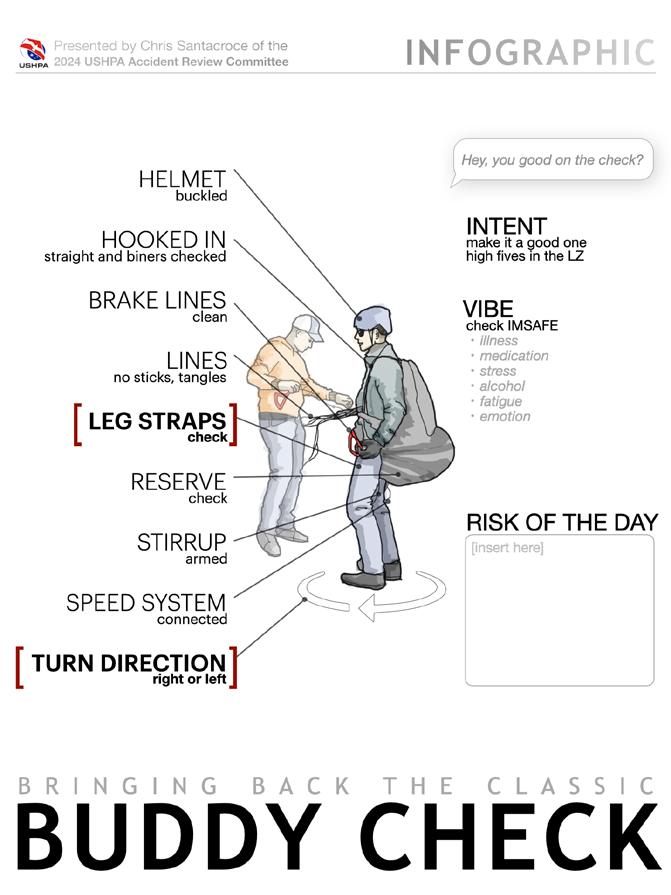

So that others may learn from his mistakes, P4 pilot Chris Mann has shared the following incident.

Years flying: 3

Flight hours: 360

Thermal flight hours: 300+

Wing: BGD Lynx 2

Harness: Air Design Sock SL

Location: Big Walker, Virginia

Date: Oct 8, 2024 @ 1:30 p.m.

WX: Light meteo winds with thermals, 5-8 mph

: Recently, I went to fly at a new site with pilots I had never flown with before. I was the last of three to launch, rushed but confident. After bringing up my wing and kiting for a few seconds, I turned and launched.

A second or two after getting into my pod, I felt and heard a pop and immediately noticed my right riser floating in the air above my head, brake toggle still in my hand.

My immediate thought was, “I need to crash back into the hill.” In the milliseconds that followed, I noticed no significant change in my flight path, though I’m sure there was some. Within a second or two, I started turning to the left. I’m assuming this probably was not due to any input from me but simply what a wing connected via only one riser does naturally. I came down onto the hill approximately 20 feet below where I had launched,

through a briar patch and onto a large rock. The impact burst the harness’s airbag. I was fortunate to walk away with only a busted lip and an extremely sore tailbone.

I believe I failed to fully close the soft link that holds the riser to the harness. The events suggest it was partially closed, as the riser stayed attached while kiting and immediately after launch for a few seconds. The risers were attached to the harness in the reverse launch position. After placing the right riser on the right soft link, I immediately moved on to place the left riser on the left soft link. I believe I failed to go back and fully close the right soft link.

A lackadaisical and overconfident approach to the day, brought about by having flown about 50 hours over the previous month at much more challenging launches and in more challenging conditions.

• Radio chat while setting up to launch.

• Chatting with spectators while setting up to launch.

• A lack of currency with this harness, which I hadn’t used in a couple of weeks.

• Long driving days on the days immediately prior.

• Pressure to get in the air to chase others.

• Soft links have no self-closure, as seen with carabiners.

Images show the varieties of soft links. If you choose to use them, make sure you know their lifespan, limits, and how to properly secure them.

1. Preflight check, preflight check, preflight check! My normal preflight check goes from patting my bottom to ensure protection is inflated, then checking helmet strap, chest strap, leg loops, riser connection, and reserve. To assure a successful check, maintain a “sterile cockpit” while doing preflight checks and preparing to launch. If preflight is interrupted, start over.

2. Attach risers to the harness using auto-closing and locking carabiners. I don’t feel the minimal weight savings of soft links are worth the risk.

3. Take every launch and flight seriously.

In recent years, our culture has encouraged us to be self-reliant and do systematic preflight checks each time we fly. Alas, preflight errors do occur. In most cases, the story is that the pilot DID do a preflight

but that something happened along the way. This is why buddy checks are so essential and have been a critical cornerstone of our culture since the infancy of our sport.

None of us can be 100% on our preflights 100% of the time. Statistically, our odds of missing an item go way down when we bring in another set of eyes. Some oversight from a different vantage point can often help to spot one or two things that have been overlooked. Sometimes, it’s as simple as zipping up an open pocket. Other times, the buddy can find something out of place that can literally save the day.

Thanks for being a good flying buddy to all of your friends. Decades into your flying experience, you can take a huge sense of pride in having been a good buddy.

by Riley Ferré

: For years now, Colombia has served as one of my home bases. I first arrived in 2022 to study abroad, with little knowledge about the country other than its exceptional paragliding conditions. I flew more than I studied and fell in love with the culture and its abundant energy, the mountains, and the tropical sky. During the peak flying season, I work as a cross-country tour guide. I have had countless opportunities to immerse myself in the country, its people, and its landscape during the off-season as well. There is so much more to Colombia than most people are exposed to throughout the three-month paragliding season. The Andes of Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador are the only mountains with the unique el páramo ecosystem, which can be found between 3,000 and 4,500 meters above sea level. Los páramos are extremely important ecologically, consisting of abundant water, golden mosses, and a magical plant called el Frailejón which

only grows about one centimeter per year. Every time I hike up to a páramo, I am awestruck by the magic of this ecosystem, which is easy to compare to a fairyland.

From October to December 2024, I was fortunate enough to hike and fly from several of Colombia’s páramos from which only a handful of pilots had launched previously. I am a competition pilot and consistently fly throughout the year. This diligence allows me to embark on flying adventures that demand a higher skill level. I would only encourage pilots to commit to such plans once they are confident in their physical and mental strength as both an athlete and a pilot.

On every mission, I was accompanied by one of Colombia’s best-known hike-and-fly pilots, Alex Villa. Alex has pioneered most of the country’s routes and is a trained mountain guide. Hiking and mountaineering are not as developed in Colombia as in Europe or the United States, requiring proper preparation and the company of an experienced guide. It is strongly recommended that you seek local advice if you plan a trek into Colombia’s mountains.

Our first adventure took us to El Cerro San Nicolás, located in Los Farallones del Citará in the Antioquia region. The hike up this mountain was challenging, especially when carrying packs full of gear to spend a night at the top and fly down the following morning. The trail was incredibly steep and included several passes that required the assistance of ropes and tree roots. It would be best described as a climb or scramble rather than a hike.

Leaving at 9:00 a.m., we hiked about seven kilometers, climbing 2,168 meters. We pitched our tent at 3,830 meters, just below the summit. After about 7.5

“There

is nothing quite like using one’s physical strength and experience flying to reach distant paradises and descend amongst the clouds.”

hours of challenging yet stunning trekking through the jungle, we arrived just as the sun was setting and enjoyed a breathtaking view from above the clouds. We collected water from the leaves of bromeliads for drinking and food preparation.

One of the defining characteristics of the páramo ecosystem is that the weather drastically changes within minutes. It can be sunny and blue one minute, then cloudy and windy the next. It rained throughout the night on San Nicolás and continued until 10:00 a.m. the following day. We were considering staying another night on top when the rain finally stopped and we felt a calmer wind cycle through. We immediately packed up camp and headed toward our planned launch. We decided to launch from just below the summit, as it was already late in the morning, and we knew that cycles would be too strong for a safe launch from the top.

I prepared my kit, consisting of AirDesign’s 14-meter UFO and Slip harness, on the lee side of the launch where I was protected from the stronger cycles. After patiently waiting for a launchable window, I was rewarded with one of the most beautiful flights of my life. I flew above the morning layer of clouds to where they

ended at the start of the valley. My glide was perfect. Soaring alongside dense jungle and majestic waterfalls, I felt incredibly alive.

Alex and I landed safely where we had parked the truck the previous morning, with huge grins spanning our wind-beaten faces. The family who lives on the farm where we parked greeted us with a delicious home-cooked Colombian lunch. They asked us a handful of questions regarding our journey, as they have lived at the base of the mountain for years but have never had the opportunity to reach its summit.

Before starting the road trip home, we shared coffee with one of the original mountain guides of Cerro San Nicolás. He had climbed the mountain about 100 times. He can no longer summit, as the descent is too hard on his back, but he smiled upon hearing of the possibility of descent using a lightweight tandem paraglider in the future!

About a month later, Alex and I hiked El Páramo del Sol, the highest mountain in Antioquia at 4,080 meters. This hike was less steep yet longer than the scramble up to Cerro San Nicolás. The 15 kilometer trail, which

starts outside the town of Urrao, winds through the jungle and up to magical valleys full of Frailejones, some of which are over 100 years old.

We pitched the tent at the trailhead and slept for about four hours before hiking through the night. We decided to hike in the dark to avoid carrying camping gear to the top, planning to arrive at the summit at sunrise.

We started hiking around 11:00 p.m. and summited around 5:00 a.m., just before sunrise. Walking during the night is a different experience. There is nothing to look at except the small area lit by headlamp, and I entered a flow state previously unfamiliar to me. I relaxed into my thoughts and the movement of my body. The six-hour trek felt like three.

After we enjoyed the sunrise, the wind started to blow in nicely. We took advantage of the window and launched early. It had rained heavily during the previous days, and we decided not to risk waiting as we did not want to hike down. We found a patch on the windward side clear of Frailejones and prepared to launch. By around 7:00 a.m., we were airborne, experiencing the inexplicable sensation of flying after an intense physical effort. There was a thin cloud layer above the valley at an altitude that granted us plenty of time to

descend through the soft morning clouds and find a safe spot to land in the agricultural town of Urrao. We touched ground alongside a herd of curious cows, packed up, and celebrated over eggs, arepas, and coffee with the local friend who retrieved us. Giddy with adrenaline, we continued discussing the adventure throughout the drive home. We recounted to each other the thoughts that flowed through our minds while hiking in the dark, expressing how much we both enjoyed our first time trekking through the night. Finding a good partner for these big missions is essential, as the company makes or breaks the entire experience. Neither Alex nor I like to chat while hiking; we prefer the meditation that comes with being silent. We would rather listen to the wind, the birds, and the rustling of the leaves than talk for talking’s sake. We pull each other up mountains with our energy, and we know the silence will be broken when necessary.

The weeks between each big mission consisted of nonstop training, including trail running, strength training, and relatively small hike-and-fly routes. I live in the mountains above Medellin, just an hour-anda-half hike from a small launch at about 3,200 meters. On some mornings, we would train by hiking to the launch with lightweight kits and flying down to land

just below the house. The breakfast and coffee afterward never tasted so good!

After all the necessary training and preparation, the final mission of 2024 was the biggest, most challenging, and most inspiring. El Nevado del Tolima, a volcano in El Parque Nacional Natural Los Nevados, is among Colombia’s ten highest peaks, towering at 5,215 meters. The summit is a glacier composed of 69 million cubic meters of ice, a number that is rapidly decreasing due to the warming climate.

Our first day on the mountain involved 24 kilometers of hiking and 1,770 meters of ascent to the base camp of Arenales. Initially, we planned to sleep at a refuge at 4,000 meters, where there is a natural hot spring. However, due to our quick pace, we arrived at Los Termales del Cañon at 2:00 p.m. and decided to take advantage of the remaining daylight, continuing on higher.

The next morning, we broke camp at 2:00 a.m. and headed for the summit, carrying ropes, harnesses, ice axes, and crampons. The trek from base camp consisted of technical rocky sections and about one hour of hiking on the glacier. While hiking on the glacier, we were properly equipped with ice gear and connected with about 12 meters of rope between us, mitigating the risk of falling into a crevasse. On the way up, we

passed signs marking previous extents of the glacier, further dramatizing humans’ impact on this ecosystem.

We summited too fast for our own good, reaching the top at 5:00 a.m. It was still dark, and we were forced to wait about one and a half hours for the sun to rise and a launch window to open. We waited on top, constantly moving our bodies and walking in circles to fight off the bone-chilling cold. This was the most challenging part of the whole journey. My eyelashes were frozen and frost lined my pants and jacket.

The wind on the summit was not too strong, but the cycles were not consistently coming up from one direction. We carried our gear from one side of the glacier to the other, working to find the safest place to launch. Just as we thought we would have to hike down, the cycles began to consistently blow in from where we had initially planned to launch. Before every hike and fly mission, preparation includes studying maps and creating descent plans A, B, and C, as you never really know what conditions you will face. We had waypoints marked on our devices indicating safe places to land and offline maps downloaded on our watches and phones to ensure safe navigation.

I took advantage of the window, inflated my wing, and successfully launched, becoming the first woman to fly from El Nevado de Tolima. Launching from this altitude was distinct due to the thin air: I had to use

the entire length of the glacier for my feet to leave the ice and my muscles to relax into the harness. The whole way down, until my boots met the soft earth again, I gawked at the wild beauty of where I was.

Alex had to wait another 20 minutes for an adequate cycle but was soon able to follow me via paraglider. Once airborne, strong winds limited our reach, and we could only fly out about 6 kilometers. This left us with a 12-kilometer hike back to the trailhead. By the time we made it to the Jeep that would drive us to town, my legs were aching and my shoulders were numb, but my heart was full and my mind was clear.

These two days were some of the most physically demanding days of my life. From the high altitude to the distance to the 20-kilogram pack on my back, this adventure required every ounce of energy I had to give. It also provided me with another opportunity to meditate on the vastness of Mother Nature and observe her power. I am consistently motivated to embark on missions such as this due to my recognition of the importance of deeply connecting with the natural world. For me, it is intense meditation and is a connection only attainable in the places that are most difficult to access.

There is nothing quite like using one’s physical strength and experience flying to reach distant paradises and descend amongst the clouds. It is pure, liberating, and fueling. These missions would not have been possible had I not trained constantly during the time between. I continue to be amazed by all that my body is capable of. It inspires me to keep pushing and learning while I am still strong enough to do so.

: After this amazing season, I look forward to planning more hike-and-fly journeys in Colombia as there is still so much to explore. The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range, located alongside Colombia’s Caribbean coast, holds the country’s highest peak, Pico Colon. This group of mountains is extremely sacred to the various Indigenous communities that rely on them, and possesses an energy that I will not even attempt to describe with words. Travelers must receive permission from the designated Indigenous groups

whose territory will be a part of any journey through these mountains, whether flying or not. I have only stared at them endlessly from the beach below. It is a goal of mine to be one of the first women to descend from their ice-capped peaks beneath the canopy of my paraglider.

These adventures would not have been possible without an immense respect for La Pachamama. The elements are strong and have a power that must be honored. Yet, we humans are a part of nature. There is a constant exchange of energy between us and our surroundings, which can be recognized with enough awareness. Every day, I thank La Pachamama for her protection and for allowing me to enjoy and learn from her entire force.

“The meaning of life is to find your gift. The purpose of life is to give it away.” – Pablo Picasso

: I have always enjoyed a good scheme—the more actionable version of a daydream. In the early days of my flying career, eager to solidify my footing in the paragliding community, I hatched a scheme to bring together the ladies of free flight to create connections and bring a little celebratory flair to the get-together. The inaugural Swifts Fly-In was hosted in Villa Grove, Colorado in 2019. Since then, I have hosted an additional four ladies’ fly-ins, and have twice hosted the largest free flight event in the country—the Red Rocks Fall Fly-In. Hosting all of these events has revealed to me that community bonding is a foundational skill we may not consider as necessary as kiting or forecasting, but we should. We pilots tend to pride ourselves on independence and self-reliance. After all, we are 100% responsible for our decisions when we fly. While that is all well and good, we bolster our longevity in the sport when we have a supportive community with whom to celebrate and commiserate. When I reflect on my happi-

est flying days, my friends are just as much a part of the memory as the sound of my vario.

If you have ever been to the Red Rocks Fall Fly-In, you’ll know the landing zone can be an electric and boisterous atmosphere full of pilots regaling each other with the highs and lows (both literally and figuratively) of their flights. I have met pilots simply by walking over to a recognizable wing and harness and high-fiving over a shared thermal. I do not know every pilot, but I know we all share a love of the sky, and there’s a special kinship between us all who do this wacky sport. Have you ever tried to relate the experience of circling at cloudbase to your coworkers at the water cooler or been met with bemused confusion at your explanation of how we don’t quite “jump” off the mountain? The chance to gather and share experiences and stories with our fellow pilots is a real gift. All this is to say that we all have a role in our community. I know that one of you is like me: You’re a schemer, a doer; you excel at tying a vision together and executing it. You want to fill a need within your local club for increased connection. You want to democratize our collective knowledge so that we all

become better and safer pilots. If you are reading this and feel a call to give back but are overwhelmed with the “how,” read on.

The first thing to consider when throwing your event is the location. Are you familiar with the nuances of the local weather enough to confidently give weather briefings? If not, can you outsource this task to a knowledgeable local pilot?

Depending on the size of your event, does the landing zone have enough room to safely accommodate multiple pilots landing at once? What additional visual aids could be necessary (e.g., wind socks, streamers, etc.)? Is the launch large enough to accommodate at least a few pilots at a time? Is there a safe space for pilots to prepare for flight away from the main launch zone? Plan these zones before the event and give a proper site introduction to relate this information to pilots.

You will likely need to charge money to offset the cost of throwing the event. I have thrown small grassroots events out of my backyard and now have hosted the largest free flight event in the country multiple times. There is an endless possibility of things on which to spend money, but common expenses will be insurance, permit fees, high visibility vests, a microphone, t-shirts or other swag, food, trash service, porta-potties, and website fees. Optional expenses could include emergency service standby and compensation for your core team.

A small event, such as a weekend fly-in with a barbeque, T-shirts, insurance, and permits, can cost as little as $1,500. However, an event as large as the Red Rocks Fall Fly-In costs around $25,000.

Throwing an event is not a one-person job. I am guilty of taking on more than I should and burning myself out, and I highly recommend delegating to save your sanity. A small event can be handled with

an event coordinator, a safety coordinator, and a vehicle coordinator. In this scenario, imagine the event coordinator as the face of the event who coordinates with local agencies, applies for insurance, provides official communication to participants, collects fees and waivers, executes the daily schedule, and has the authority to close launch or call off flights for the day. The safety coordinator is responsible for keeping the launch safe and efficient, providing insight into the daily weather forecast, relaying pertinent information to the event coordinator, and communicating with emergency response personnel in the event of an incident. The driver coordinator organizes shuttle

trips to launch, and coordinates retrieves if the event offers this service.

The larger the event, the more critical it is to have co-coordinators and a volunteer coordinator if your team of volunteers is large enough.

Volunteers are the lifeblood of a fly-in. They will point pilots in the right direction, help with registration, fluff wings on launch, move chairs, pick up food, unbox T-shirts, drive to launch, or drive retrieve. A good volunteer is worth their weight in gold, and you should set aside a portion of your budget to reward them. I like to ask mine for their favorite drinks and snacks to keep on hand. Make sure event participants know who your volunteers are and thank them daily.

Consider whether your location requires permits. For Red Rocks, we have a permit from the National Forest Service to conduct an event on their land. Don’t be discouraged if you face this hiccup—the paperwork can be easy. In our case, the Forest Service only requires a tally of total pilots per day during the event with an associated fee. In Monroe, the city owns our landing zone. We have an excellent relationship with the city, which simply needs timely notification of our event schedule. Please contact your local club officers to see what relationships exist with the landowners of your launch and landing zones. Using existing relationships when contacting government agencies or private landowners is best.

Speaking of local relationships, consider attending a city council meeting in the town where you plan to host an event. A face-to-face conversation is irreplaceable when explaining the nuances of a paragliding event. For Red Rocks, I attend three city council meetings a year—one to share the event schedule, describing each event and how it will affect the city; one just before the September season to solidify how we and the city will work together; and one after the events to report back on how it all went. By being upfront on every step, I can assure the town that we are working with their best interests in mind.

Some points of discussion at the meetings are messaging residents about keeping vehicles away from the landing zone, coordinating on dumpsters and traffic near the landing zone, placing extra streamers and windsocks, and creating a plan of action for emergencies. I call the sheriff’s office and contact the local head of Search and Rescue prior to the event to brief them on our activities.

In addition to the city council, consider contacting a local city or county tourism office member. Free flight lends itself to splashy content for these agencies, and you may be able to get some freebies through the relationships between your tourism office and local businesses.

Finally, consider including local businesses in your event. The coffee shop, the pastry store, the taco truck, and the pizza joint could all be

eager for a slice of the pie. Not only does this help the community feel involved, but it also helps spread the word about free flight to those who have not yet been exposed to the sport. Your goal is to create a positive association with free flight within the local community.

The Red Rocks Fall Fly-In supports local businesses by including chosen vendors in our coupon book, which each participant gets in their registration bag. The coupons are the result of a handshake deal with the owner of a restaurant to provide a free meal to a pilot at a subsidized price that CUASA will reimburse after the event. It is a great way to direct event participants’ money into the hands of local business owners. It cannot be understated how important these relationships are to the favorable viewing of pilots in the community.

Insurance

Love it or hate it, someone is likely going to require insurance to rubber stamp your event. You will also want peace of mind knowing that your personal

assets are protected in the event of an incident. If you are wondering if your event requires insurance, USHPA has a handy document on their “ACE Accreditation Application” page that spells out what requires insurance.

Insurance processing can take time. Submit your request at least three months before your event. The bright-line test that will likely require you to

have insurance is charging fees above the cost of general membership to your local chapter. For example, a chapter-sponsored barbeque after a normal day of flying is not going to require insurance. The Red Rocks Fall Fly-In charges an entry fee, so we must have insurance. Once you have determined that you need insurance, follow these steps:

1. Apply for Ace Accreditation on USHPA’s website. You need to provide the name of the event, a sponsorship letter from your local chapter, and some basic information like who the event coordinators will be, whether there will be instruction or towing involved, and whether you are seeking $500,000 or $1 million in insurance (some landowners require $1 million or more).

2. Receive your approved application for ACE Accreditation.

3. Receive your application for insurance with the Recreation Risk Retention Group (RRRG). To complete this application, you will need the coordinates of all launches and landing to be insured, the names of the private landowners or agencies of launch and landing zones, and a risk mitigation plan. The risk mitigation plan is a document that explains any risk during the event and your plan to mitigate it. For example, a general risk at the Red Rocks Fly-In is the remoteness of our terrain. We mitigate this risk by requiring a satellite communicator. You will also be asked how you plan to mitigate risk at any approved launch or landing zone. For example, Cove launch has power lines that run down the spine of the northwest aspect. This risk is mitigated by having the launch director point them out during a site briefing on launch.

4. Submit your insurance application with the attached risk mitigation plan via the RRRG portal and make corrections as necessary based on their comments.

5. Receive your approved application from RRRG, which includes Certificates of Insurance for each landowner and a waiver for your participants to sign. Participants at an RRRG-insured event must be active members of USHPA.

After determining your entry fees, clearly communicate to the public what the cost includes. Also, make it clear that participants must be current USHPA members and

members of your local club to participate. User-friendly websites like WordPress can help you build a page to advertise and collect applications or fees for your event. Reach out to your local club and see whether they are open to hosting your event on their website platform to utilize existing resources. I suggest establishing a cancellation and refund policy upfront, as it is common for pilots to contact you with requests for refunds due to life circumstances, injury, etc.

While I won’t tell you how to run your fly-in, I strongly suggest one piece of advice: Go into the event, repeat the mantra, “Flexibility is the best ability.” Things will go wrong. Your driver may cancel at the last minute, your club truck could break down, a volunteer may quit midweek, the weather could be unconducive to flying, and the show must go on. Just like in rock climbing, redundancy is the name of the game. Try to have extra drivers and volunteers to prepare for the inevitable day when something doesn’t go according to plan. Here in Monroe, we

deal with wild shifts in weather, so in the past, our backup plans have included speaker events, a tutorial on how to use XC Skies, a paragliding gear swap, reserve repacks, and ground handling practice in the landing zone. All that matters is that you try—we all know the weather is never a sure bet.

I quoted Picasso above because I love the idea that the purpose of each of our gifts is to share it. My gift happens to be logistics, and I am sure someone else out there has a similar gift to give to their community. If you are not one to throw an event, be an enthusiastic participant and realize that these events do not happen without your commitment. While we all like to chase good weather, planning an event where everyone signs up three days beforehand is impossible. If you want to see more fly-ins happen, commit to attending, hopefully flying, and definitely strengthening your bonds with fellow pilots. If this article inspired you, please feel free to contact me at lindseyripaburns@gmail.com. I would be happy to help answer questions to get your event off the ground.

Blue Skies!

Jeff St. Aubin

: Labor Day marks the annual migration of Lookout Mountain pilots from Tennessee and North Georgia to Villa Grove, Colorado, seeking big air and stunning glass-offs. Oxygen systems are dusted off, long johns and ski suits are brought out of hibernation, and the rigs are piled high with all the camping gear and toys needed to live off the grid for a few weeks in the high desert.

Villa Grove is a spectacular site known to hang glider pilots nationwide. With stunning views all around, launch sits at 9,760 feet and faces southwest on the edge of a bowl below the 12,461-foot Galena Peak. The site is about a third of the way up the Sangre de Cristo Range. Several 14ers rise up to the south on the way toward Great Sand Dunes National Park, with the impressive Blanca Peak (the 4th highest mountain in Colorado) looming in the distance.

Getting up and out at Villa is not a gimme. If you’re not going up right off of launch, the move is to cross the gully to your left and work the triangular slope at the northern edge of Hayden Pass. If you strike out

there, it’s time to head out to the LZ by Larry’s and hope you have enough altitude to hook something popping off of the valley floor, which sits at 8,000 feet. This move seems to work reliably, but it can be pretty spooky scratching low over such a slanted alluvial plain. Turning on the upwind edge of a thermal allows for around 200 feet of clearance. But cranking around while hoping to not fall out the back side, the ground looms, and that clearance seems to disappear. With only cactus, sage, and rocks to judge your altitude, things can look deceiving. Sinking out before the reasonably flat field by Larry’s, you may find yourself in a never-ending ground effect, skimming over rocks and spiky vegetation as the ground drops away just enough to match your glide angle. At some point, you just have to commit, power flare, and hope you don’t get intimate with a cactus.

On my first flight at Villa, I launched a bit early and hit nary a bump but easily made it to the LZ on my Gecko. All good, mission accomplished; a safe launch and landing is all I ever ask for when flying a new site.

I radioed my friend Christina Williams, who was on launch with her paraglider, letting her know the air was still smooth. If she launched ASAP, she could probably get in another paragliding lap as it was still before 11:00 a.m. It was her first time flying out West, and I had been vocal about the dangers of the high-desert, big-mountain air, but as they say, we don’t know what we don’t know. As I finished breaking down, the longtime Aspen pilot I was chatting with casually said, “Oh look! They’re doing aerobatics!” I looked up, and my heart jumped to my throat. “That’s not on purpose!” I said and rushed to the radio.

Conditions on launch had changed after I landed: draw from strong thermals began to generate some tailwind cycles. Keen to get in a second flight and encouraged by my earlier report of smooth conditions and the advice of a local pilot who said it looked good (which it did for them), Christina waited for a cycle to blow in and launched. But now it was pushing 11:30 a.m., and the air was active. About 500 feet over the valley floor, she hit an absolute ripper of a thermal that threw her around like a rag doll. The glider went behind her, below her face, to the left, to the right, and back again. It was terrifying to watch, and it felt like it went on for far too long. I only had a few hours of paragliding experience and didn’t know what to say to her. Thankfully, someone wiser and calmer came on the radio and helped Christina make the right decisions. She managed to keep the wing open; by flying back towards the range, she escaped the brute of a thermal and was safely on the ground as quickly as she could descend. Back on terra firma, redlining on adrenaline, Christina was very thankful to be unscathed and appreciative of the free lesson. She was now more motivated to improve her skills and confidence in the air.

It is difficult to communicate just how powerful the air can be to the uninitiated. I love big air in big mountains—in my hang glider. Cranking into a 1,500+ fpm

climb in my flexwing gets me giggling with glee, but the thought of encountering the tumbling edge of such a beast in my paraglider gives me cold sweats and weak knees. Kudos to the paraglider pilots who got off Villa early that day and made it down the range to the sand dunes and beyond. The pilots making peak-season big mountain flights in paragliders are Jedis. But also, have you considered hang gliding?

: The next day, I missed out on a dose of flying adventure as I had to drive back and forth to Denver to pick up my dad, Richard, whom I had recruited to come out for the week as a retrieve driver. For some reason, I usually feel more calm and collected flying XC with my dad driving retrieve; I probably feel more confident that I won’t make stupid decisions in front of him. This was his fourth time getting dragged across the continent to chase us sky addicts, so he knew the ropes. The forecast predicted it to blow east, so the plan was to fly the Whale. This 12,100-foot peak at the

northwest end of the valley is accessed via a gnarly 4x4 approach. On our way back to Villa, I got a call that one of our group was missing. He had gone over the back, he was flying without an InReach, and no one had been able to reach him by phone. My heart sank; over the following hours, all I felt was anxiety and dread about the fate of my friend. Why didn’t he have an InReach? He was one of our group’s more accomplished XC pilots and should have known better. Luckily, there are only happy endings in this story.

Flying his paraglider down a cloud street past Bonanza, the pilot got pinned low and had to make an emergency landing in an avalanche chute. Bruised and battered but otherwise uninjured, he hiked down until he found a trail that led to a road. After another four or five miles of walking, he found a gate where, lo and behold, his girlfriend had just arrived, having followed his last reported location on XCTrack. As they rolled up to camp that evening, we were all ecstatic to see him in one piece, albeit quite humbled. Despite his misadventure, none of us would best his distance on this trip.

Many pilots climbed to over 17,000 feet that day and were able to fly back to camp. It proved to be the best flying day of the trip as well as one of the most dynamic. Even before our friend went missing, there had already been plenty of excitement. There was a blown

launch, a blown tire on the descent, and a couple of hard landings, one resulting in a decidedly U-shaped basetube. Thankfully, there were no more than bruised egos.

Our group learned some lessons on this day alone. You can get away with diving into the control frame when launching from Lookout’s very forgiving ramp, but this technique is slightly less desirable when launching on a flat slope above 12,000 feet. Additionally, be prepared to acquire some Rocky Mountain pinstripes on whatever 4x4 you bring. Seriously consider upgrading to properly knobby off-road tires if making the trip to Villa, as none of the approaches to

merino with oxygen flowing, hooked in, and ready to go. I am somewhat notorious for launching first, as I would rather sweat it out on launch with an empty sky in front of me, patiently waiting for signs that tell me to go, than wait in line to hustle off into a crowded arena already full of pilots vying for only so much lift. There are a healthy number of streamers crisscrossing the face below launch, so it is easy to map the thermals and their approach.

A nice cycle rolled through and I launched. We were warned not to turn 360s right off of launch, so I worked a few figure 8s to no avail and then hightailed

it across the gully to that primo southwest face at the edge of Hayden Pass. I connected with something weak and gained a meager hundred feet. Rego, another pilot on our trip, launched and tried to join the pitiful climb, but it fizzled out as we scratched up the shallow slope. We both pushed out toward the road to gain more clearance, and I connected with some more measly bubbles. I worked them as I watched Rego glide out toward the LZ. The climb never consolidated as I skimmed the terrain as far back as I felt comfortable. I pushed out toward the road once again when—BOOM—I hit it. Cranking and banking, I held on for three thousand feet and topped out the thermal at 12,000 feet nearly half an hour after launching. Still below the top of Galena Peak to my east, I decided to turn south and explore downrange.

After crossing Hayden Pass, it took a little bit of time to connect with another tight bullet ride. I bailed from the climb at 11,500 feet and kept pushing south, deciding to stick to the front range and just go for distance rather than trying to get back onto the upper ridge line. There was a light easterly forecast at altitude, and I figured things would only get more gnarly the higher I got. I headed south, and I eventually arrived above the bat caves (a pair of gaping voids in the orange rock) at 10,000 feet. I circled their openings, marveling at my vantage point above a few hikers, and eventually connected with another ride up to 11,500 feet. Pushing south another couple of spines, I found one more climb. By this time, my whole body was ach-

ing, and I was starting to feel the ground suck. I had noticed a nice landing spot relatively free of cactus back by the bat caves. Feeling rather jubilant after a smooth touchdown into the wind, I found I could barely lift my arms to unhook from my glider. My body was totally exhausted! I had only flown for an hour and a half and made it a mere 14 miles down the range, but it was one of the most rewarding and physically demanding flights I have had: every climb was a battle, and the best anyone else got that day was an extended sledder.

: The next few days offered meager soaring opportunities due to high winds or overdevelopment, but we made the most of it. Brian Morris stopped by on his way to Utah, keen to get in some high-altitude conditioning before participating in the X-Red Rocks. He convinced Christina and me to go with him on our first hike-and-fly mission. After her rodeo ride and my midday thrashing on the hang glider, neither of us wanted much to do with midday desert air on our paragliders. So we set off before the heat kicked in and tasted the morning’s first few bubbles. It was entirely satisfying and sold me on hike-and-fly as a complete experience without any need to have an extended flight. That evening, we made the trek out to Anne’s, a remote site halfway between Villa and Gunnison that, in the right conditions, can be a playground for ridge soaring, top landing, and hike-and-fly training. The site sits at just under 10,000 feet and offers only 700 feet of altitude to play with. We were a bit crestfallen to find that regional high clouds had shut down the forecasted wind, and we could only get a few paraglider sledders before sunset.

If you’ve ever booked a flying trip to almost anywhere but Valle de Bravo, then you know there are going to be days you can’t fly, so you’d better come prepared—and prepared we were! Christina, Doug, and Eric brought their dirt bikes and ripped around the surrounding area in every spare moment they had. Neil and I went

on epic gravel bicycle rides, braving venturi winds and dodging looming storm cells. The mornings offered hike-and-fly laps, and we squeezed in brief thermal flights before the skies darkened. Afternoon hot spring sojourns let us escape the fine desert dust that otherwise pervaded our existence.

Mark, Dalton, Parking Lot John, Rego, my dad, and Josiah all checked out the Great Sand Dunes National Park, Crestone’s spiritual tourism attractions, and even went on a gem-hunting trip. We all got a lot of entertainment heading into Salida to watch Eric surf the standing wave on the Arkansas River and catch some live music. After a week of high winds and overdevelopment, our numbers started to dwindle, but a few of us stuck around as we could see on the horizon the golden forecast we had all been waiting for: a blue, blown-out day with winds dropping into the low 20s towards sunset—the perfect forecast for a Villa glassoff!

Since I began flying, I have been regaled with tales of legendary Villa Grove glass-offs: flying straight into the valley and getting to above 16,000 feet without a turn, and 100-mile flights to the sand dunes and back as fast as your glider can go. While that Friday the 13th didn’t give us much more than 14,000 feet and no one made it to the sand dunes, cruising over the alpine lakes atop Bushnell Peak and soaring until sunset with my pals was pure bliss and made all the waiting worthwhile. The evening glass-off was my first big mountain flight on my T2C. I had waited to take it out as I was leery of landing my new-to-me topless hang glider at high altitude in switchy midday desert conditions. However, that one flight convinced me that a topless hang glider is truly the machine of choice for big mountain flying. The ability to easily cruise with 60+ mph airspeed makes 30 mph venturis a nonissue, and the amount of ground you can cover in such a machine is astounding. Floating across the valley over the highway in the buoyant golden hour conditions, I likely could have

made it over to Whale, but I wanted to get down while the wind was still blowing on the ground for a smooth touchdown.

Over the week, we watched the aspens start to change color before our eyes. One morning, there was a single patch of yellow on a faraway slope. The following morning, two; and by noon that day, it had grown to three or four. Frost began to form on our tents each morning, and we knew it was only a matter of time before camping in the San Luis Valley became an exercise in frigid masochism. Thankfully, the skies delivered us a final day of puffy cumulus, light winds, and the opportunity to soar the Sangre de Cristo Range to our heart’s content, cruising thousands of feet above the peaks. Once you broke 13,000 feet that day, things went nuclear.

Twirling on a wing tip—“churning the butter,” as they say—my vario was pegged, making sounds you never hear east of the Mississippi. Grateful to be back on my Gecko, which at this point seemed an intuitive exten sion of myself, I let the turbulence buck me about as I carved around, seeking out the rocketing core with the

stupidest grin on my face. Few things in life compare to such sensations. In such booming mountain conditions, I sincerely believe a hang glider is the best tool for the job. Seeing quadruple-digit climb rates only had me drooling for more.

Villa Grove is the real deal. Sure, just surviving in the San Luis Valley day after day is a challenge, but watching the sun light up the valley in the morning, and the stars gleam into existence each evening makes the searing heat, frosty nights, howling winds, and constant dust worth it. If you decide to venture into the heart of the Colorado Rockies, come prepared and bring your A-game, as peak season high-desert conditions are no joke. Every launch and landing at altitude requires skill and confidence to avoid a face full of cacti. When you’re trying to squeeze in flights between pockets of overdevelopment, you need to keep your eye on the sky and be aware of how conditions are changing. Most importantly, though, bring some good friends, your

: Years ago, I saw photos on a friend’s Instagram of a beautiful Colorado high alpine lake that was glacial blue and another with clear waters featuring shades of blue and green, with an island in the middle, surrounded by high peaks. It was one of the most stunning locations I had ever seen. It inspired me, and I knew I had to visit. But life gets busy, and I mostly forgot about it.

Fast forward a decade, and I was reminded that I wanted to see Ice Lake and this beautiful area when I decided to make the trek from Utah to New Mexico for a friend’s wedding; it would only be a short detour into the zone! Now, as a pilot, I had dreams of flying this spot as well, with the specific goal of flying over the lake and foot-dragging the deep blue water at 12,000 feet. What a dream landing area!

I started to look at logistics: Could it be done? You can fly off any mountain assuming you have light enough winds, a good place to set up and launch your wing, and a suitable landing area. After a deep dive into Google Earth and FatMaps (RIP), I found that the area had the correct launch and landing requirements. I plugged that location data into XC Skies and took a moderately in-depth look at the forecasts. Unfortunately, it didn’t look good for the first half of the trip—high winds paired with low pressure/instability and thunderstorms made the area unflyable.

However, there seemed to be a consensus that the winds would significantly lighten up on my way back, with winds projected to be from the SSW at about 8 mph at 12,000 feet and 13 mph at 14,000 feet. I located a potential launch area from a 13,000-foot peak directly over Ice Lake, facing south. The grassy shoreline landing zones also seemed possible. It was finally time to head up to Ice Lake basin to escape the city and get some much-needed nature.

Because this location was so beautiful, I didn’t necessarily need to fly there; I just wanted to see it in person. This was no easy feat, considering it was

Launching with the gorgeous Ice Lake below.

an 8.3-mile round trip hike with about 2,800 feet of elevation gain just to reach the lake/landing area.

However, I was bringing a very lightweight kit: a Level Wings Flame 9m light wing and a Kortel Krueyer 3 lightweight harness, which I mainly use for speedriding missions due to its low pack volume.

If the flying didn’t work out, I had backup plans in place that included a lot of other gear (an FPV drone for cinematic flying, a wetsuit, an ultralight tent, and backpacking gear). Plus, one cow-spotted wiener dog named Zetsu and my girlfriend Ariel, who has been flying paragliders for a few years now.

Based on prior experience, I knew flying deep in a mountain range as dynamic as the San Juans is tricky. As beautiful as the mountains are, they are equally complex, especially how wind and thermals mix to create unstable conditions. You really need to be on your A-game with forecasting in these environments, especially if you’re pursuing flight.

On the evening of August 25, we drove into the San Juans via Highway 550 on the tail end of a massive thunderstorm. We pulled over and waited for it to continue tracking northbound. Once it passed, the views opened up to reveal high, snow-capped mountain peaks as we drove toward the Ice Lake trailhead. The sun was setting, and we were euphoric about the surrounding landscapes. It felt like being in the Alps! The setting sun painted the gorgeous peaks outside Silverton in alpenglow, igniting our imagination. As paragliding and speedflying pilots, we look for flying lines everywhere, and rediscovering this range inspired creativity and energy about what’s possible in this world.

We ended up at the Ice Lake trailhead in the pitch black, and a storm developed, bringing more precipitation. We got some sleep and started hiking the next morning around 6:30 a.m. Once again, post-storm, the clouds broke apart, and we made our way up past creeks and waterfalls, quickly climbing in elevation. We were already above 10,000 feet, and the landscape was epic.

About 1,000 feet below the Ice Lake basin, we reached a clear creek rushing with enough power that we spent more than 10 minutes looking for a safe crossing. I’m usually quick to find a way to navigate tricky creek crossings, but this one was particularly challenging. Eventually, we found one segment that looked possible. I assisted Zetsu across, then Ariel.

When we topped out at the basin, we were greeted with the most beautiful high alpine lake I have ever seen. It glowed beneath the broken clouds, sections of sunlight revealing a bright blue color with hints of emerald, absolutely confirming that our effort was worth it. We set up camp on the north side of the lake, which was the best-looking option for a landing area. This spot would be amazing to fly over. Unfortunately, it was not the primary beach/grass landing zone I had scoped out on Google Earth. The other one was less of a glide, and the terrain was a bit more uneven, but it would still make for a suitable bailout landing zone if needed.

After setting up camp, I quickly configured my small hike-and-fly pack and set off for the south-facing peak towering above Ice Lake. It was clear from the start that I would need a good glide ratio to make the landing area; I needed to glide over the blue Ice Lake itself to reach the shoreline. As I took the ridgeline up, I quickly broke the 13,000-foot mark, and the air felt thin. It was later in the morning than I had wanted, and the only thing keeping the thermals at bay

Coming in over Ice Lake with speed.