HANG GLIDING + PARAGLIDING + SPEEDFLYING

Croak & Cluck by Harry Martin

Shortpack HG by Erika Klein

How to grow hang gliding? Design a small packing glider

Satellite Communication by Riley Ferré

Managing device complications while abroad

The Quiet Summiteer by Jack Sheard Solo athlete completes 100-peak climb-and-fly in New Zealand

Walking the Line by Mitch Riley and Bill Belcourt Utah paragliding record flight report | July 6, 2025

2025 Hang Gliding Nationals by Paul Brooke A retrieve driver's experience at Paradise Airsports

Chelan Competitions by Jonathan Hutton; photos by Patrick Penoyar A volunteer's perspective

Thunderstorm Warning by Dennis Pagen Survival of the fastest

X-Alps Rookie by Jared Scheid First time out at the World's Toughest Adventure Race

Armchair SIV by Calef Letorney Modern Collapse Response

HANG GLIDING, PARAGLIDING, AND SPEEDFLYING ARE DANGEROUS ACTIVITES

USHPA recommends new or advancing pilots complete a pilot training program under the direct supervision of a USHPA-certified instructor, using equipment suitable for their level of experience. Many of the articles and photographs in the magazine depict advanced maneuvers being performed by expert pilots. No maneuver should be attempted without appropriate and progressive instruction and experience.

The Elise is a light and compact EN A paraglider, suitable as a first wing after school or for leisure pilots. Offering the highest levels of passive safety with agile and fun handling, it can be your faithful long-term companion to take on your trips, hikes and even cross country flights.

Do you have questions about USHPA policies or programs? Are there topics you’d like to hear more about?

EMAIL US AT: info@ushpa.org

Interested in taking a more active role supporting our national organization? USHPA needs your skills and interest.

VOLUNTEER AT: ushpa.org/volunteer

For other USHPA business +1 719-632-8300 info@ushpa.org

James Bradley, Executive Director

: I'm excited to welcome Point of the Mountain in Utah and Crestline in Southern California back into the fold as USHPA chapters insured by Recreation RRG. These are two of our most important clubs, with large memberships, many visitors, and busy skies. I want to acknowledge the heroic volunteer work of USHPA members involved with the two chapters. Luke Berger and Jamie Sheldon at Crestline, and Chris Santacroce, Bob Janzen, and Bob Black at the Point, have proactively created positive cultural change inside their clubs and improved practices to make them insurable again. Across the table, Tim Sullivan, Tim Herr, Randy Leggett, and Steve Rohrbaugh at Recreation RRG stayed with them until Recreation could approve them for USHPA chapter insurance policies. Both clubs should be able to renew this winter with only ordinary effort. Well done!

ing a new set of rules for drones operating beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS). I’m ensuring that our interests are represented and heard, alongside those of skydivers, powered paragliders, balloonists, the Experimental Aircraft Association, and other airsports groups. I hope we’ll arrive at a requirement for these drones to include “detect and avoid” technology that will be able to “see” all of us. It's helpful that the large commercial interests understand that accidents would be a bad look for them. Even if the drones can see us, I expect to be unnerved when one flies by.

At USHPA, we’ve completed a fouryear strategic plan, starting in 2026, that has been approved by the board. Please have a look at ushpa.org/strategy and share your thoughts and comments with me.

The United States Hang Gliding & Paragliding Association, Inc. (USHPA) is an air sports organization affiliated with the National Aeronautic Association (NAA). The NAA is the official representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), which is the world governing body for sport aviation. The NAA represents the United States at FAI meetings.

The NAA has delegated to USHPA the supervision of FAIrelated hang gliding and paragliding activities, such as record attempts and competition sanctions.

An Amazon delivery drone being piloted remotely using an onboard camera narrowly missed the basket of a hot air balloon in Arizona a couple of months ago. These drones weigh 88 lbs empty and fly at 60 mph. The FAA is develop-

If you know something I need to know, please visit USHPA.org/meetwithjames to book a Zoom with me.

REGION 1 NORTHWEST

REGION 2 CENTRAL WEST Northern

REGION 3 SOUTHWEST

REGION 4 SOUTHEAST

REGION 5 NORTHEAST and INTERNATIONAL

To deliver programs and services that support all our members, foster a community of skilled and knowledgeable pilots, and promote and protect the freedom to fly.

A vibrant free flight community across the United States.

Core values & guiding principles

Celebrate the spirit of discovery and the joy of being in the outdoors.

Support ongoing education, development of skills, and acquiring of the judgment that comes from experience and attention.

Be stewards of our natural places, our flying sites, and the future of our sport.

Act ethically, take 100% ownership, communicate clearly, respond effectively.

Foster a considerate community free from harassment and abuse.

James Bradley Executive Director james@ushpa.org

Charles Allen President president@ushpa.org

Kirby Ryan Vice President vicepresident@ushpa.org

Olga Grunskaya Secretary secretary@ushpa.org

Pam Kinnaird Treasurer treasurer@ushpa.org

Galen Anderson Operations Manager office@ushpa.org

Chris Webster Information Services Manager tech@ushpa.org

Anna Mack Program Manager programs@ushpa.org

Maddie Campbell Membership & Communications Coordinator membership@ushpa.org

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2025)

Kirby Ryan (region 3)

Nelissa Milfeld (region 3)

Pamela Kinnaird (region 2)

Olga Grunskaya (region 5)

Bob Ferris (region 3)

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2026)

Van Spurgeon (region 3)

Charles Allen (region 5)

Nick Greece (region 2)

Stephan Mentler (region 4)

BGD DUAL 3

BGD’s all-new DUAL 3 brings a clean-sheet redesign to its popular pro tandem series, delivering next-level performance, precision, and fun. Three sizes, effortless launch, new trimmers and a smooth relaxed feel, the DUAL 3 performs in harmony with pilot and co-pilot. Lighter than the Dual 2, the glide is better, the climb rate is impressive, and the overall experience is just a joy. Re-engineered trimmers, narrower webbing, with a full 16 cm of direct travel, the DUAL 3 launches effortlessly, climbs in weak thermals, and handles with playful precision. New brake geometry gives just the right amount of feedback and response so it’s intuitive and fun for the pilot while remaining super smooth and relaxing. Schedule a test flight or meet your nearest dealer by visiting flybigskypg.com, exclusive USA importer.

BGD CURE 3 The CURE 3 is the newest cutting-edge, high-performance 2-liner EN-C from BGD. It shares family traits and a design philosophy with the DIVA 2, BASE 3 and BREEZE, which means top-of-class performance combined with excellent passive safety and feeling. It is pure performance and a joy to fly! Fewer lines means less line drag, and the rear-riser steering is light, precise, and direct. The CURE 3 is an unbeatable 2-liner with a high arc, raked wingtips, reflex profile and best of all, winglets! Schedule a test flight or meet your nearest dealer by visiting flybigskypg.com, exclusive USA importer.

BGD BASE 3

Top-of-B-class performance and low-B comfort and stability, this wing is a new design sporting 2.5-line design with a reflex profile, unsheathed aramid lines and winglets! Designed for cross-country pilots who have started flying XC on a low-B and are looking for more performance to push their distances. BASE 3 has some secret ninja skills: it’s slow-speed handling make top-landing a breeze and its super easy to launch in strong winds because it is so pitch stable and does not surge. A responsive and talkative glider, the BASE 3 gives the pilot good feedback at all times. And something new for BGD, the BASE 3 has winglets: a safety feature helping the glider exit smoothly from steep spiral dives. The BASE 3 is a real feel-good glider with excellent glide performance, the tool for pilots to break their personal XC bests while feeling at ease. Schedule a test flight or meet your nearest dealer by visiting flybigskypg.com, exclusive USA importer.

FLYTEC LIVE WIND

SeeYou Navigator just got a major upgrade. Live Wind Measurements are now integrated directly on the moving map. Windspeed is shown numerically adjacent to colored arrows showing direction. The arrow colors also show wind strength categories: GREEN (light), YELLOW (moderate), RED (strong), BLACK (dangerous). Tap any displayed wind arrow for details like gusts, temperature, humidity, and pressure. Wind measurements are automatically merged from various sources, giving you a unified and seamless view, with no manual setup needed. Let the wind work for you with SeeYou Navigator, Oudie N, and Omni. SIM card or cellphone pairing required. For more information: info@flytec.com, +1 800-662-2449.

GIN GTO 3

The new Gin Gliders GTO 3 is an EN-C 2-liner with best in class performance. It comes in six sizes from 60 kg to 130 kg and weighs around 4.4 kg. The aspect ratio is 6.5. It features Gin Wave Leading Edge Technology which increases performance at high angles of attack. This paraglider is available through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

GIN EASINESS 4 The Advance Easiness 4 is a lightweight (2.15 kg) split leg, reversible harness that comes with Edelrid Aura carabiners. It very comfortable and has helmet suspension on the top of the backpack along with velcro on the shoulders for a vario and hook knife. This harness is available through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

GIN VERSO 4 The Gin Gliders Verso 4 is a reversible airbag harness with seat board that comes in five sizes and weighs 3 kg in the medium size. The backpack (70L) is removable and replaceable. The backpack features bottle holders and zippered pockets and the harness is a two buckle arrangement. The Gin Verso 4 is available through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

OZONE ATAK 2 (size L now available) The Ozone Atak 2 was designed for precision speedflying, in the air and on the snow. An innovative leg strap design implements what Ozone refers to as an anti-ball-crusher system, and transitions from seated to standing have never been easier. The harness folds down to a thin and compact wafer for storage in your wingbag or hiking backpack, and in the air the harness has enhanced weight-shift sensitivity for fast turns and snappy barrel rolls. It has an optional lightweight and low pack volume airbag protector, which can be easily installed or removed. www.flyozone.com

OZONE F*RACE 2 (now available in all sizes) The Ozone F*Race 2 is an ultra-lite hike-and-fly competition harness that was designed for the Red Bull X-Alps and tested by Ozone’s most demanding vol-biv adventure pilots. It features an anatomically designed dyneema support structure, low profile inflatable protection with an integrated micro-pump for inflation, an ergonomic front mount reserve, and tons of pockets and storage options for inflight access and vol-biv missions. www.flyozone.com

: Photography, writing, and illustrations are the lifeblood of our publication, as are the contributors who dedicate their time to submitting them. I would like to offer my sincerest apologies to Cherise Tuttle, who was the photographer of our wonderful cover shot for the Summer 2025 issue. Cherise was with John Bartholomew and Kari Castle that day and her photo accidentally got mixed into John's personal shots. Entirely by accident, John submitted it as his own. Cherise, thank you so much for reaching out to let us know about the error.

Mistakes like this may seem small, but miscrediting a piece of work can carry consequences. To overlook a contribution, even inadvertently, risks diminishing both the artist and the trust our community places in this publication.

The reality is that in a world where digital files are quickly transferred from SD cards or phones to shared drives, confusion can occur. This doesn’t excuse the error, but it does highlight the need for better organizational systems to protect everyone involved. In an effort to avoid such situations in the future, I suggest that contributors take a few steps to ensure the integrity of our pages.

• Label your work clearly: Before sharing photos in a group folder, consider changing the file name(s) or updating the metadata to include your name as the photographer.

• Secure permission first: To submit photos that are not your own to accompany a story you wrote, you must have explicit permission from the photographer. This protects you, the publication, and most importantly, the creator whose work you want to feature.

• Ask questions early: When in doubt of ownership, just ask the potential owner(s). Chances are, they will recognize it as theirs.

• Pause when uncertain: If you are still unsure of the ownership of a photo, please do not submit it. The risk of misattribution is too great. These may seem like extra steps when creating and submitting a story, but they are essential to the integrity of our work. At the end of the day, this magazine is a collective effort: writers, photographers, illustrators, designers, and readers all play a role in shaping it. That’s why it is so important that every voice and every image is treated with respect. Cherise, once again, thank you for your grace in bringing this to our attention. And to all our contributors: thank you for entrusting us with your work, issue after issue.

For decades, this magazine has provided the free flight community with a space to share content with fellow pilots, and we look forward to keeping up this tradition with a continued focus on accuracy.

©2024 US HANG GLIDING & PARAGLIDING ASSOC., INC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of USHPA.

POSTMASTER USHPA Pilot ISSN 2689-6052 (USPS 17970) is published quarterly by the United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, Inc., 1685 W. Uintah St., Colorado Springs, CO, 80904 Phone: 719-632-8300 Fax: 719-632-6417 Periodicals Postage Paid in Colorado Springs and additional mailing offices. Send change of address to: USHPA, PO Box 1330, Colorado Springs, CO, 80901-1330. Canadian Return Address: DP Global Mail, 4960-2 Walker Road, Windsor, ON N9A 6J3.

Liz

Dengler

Managing Editor editor@ushpa.org

Julia Knowles

Copy Editor

Greg Gillam

Art Director

WRITERS

Dennis Pagen

Lisa Verzella

Erika Klein

Calef Letorney

Do you have a story idea you would like to pitch? We are always looking for stories.

EMAIL LIZ AT: editor@ushpa.org

Are you ready to contribute a complete story? We are always looking for articles, photography and news.

GET STARTED AT: ushpa.org/contributors

All articles, artwork, photographs as well as ideas for articles, artwork and photographs are submitted pursuant to and are subject to the USHPA Contributor's Agreement , which can be reviewed on the USHPA website or obtained by emailing Liz.

Would you like to run an advertisement ? Great!

CONTACT US AT: advertising@ushpa.org

Klein

: When students arrive for their first hang gliding lesson at our Los Angeles beach site, their first question might be: “Is this dangerous?” (Or, “Where’s the bathroom?”) After a few runs down the hill, they may jump to another puzzling question: “How do you transport one of these?”

We explain they’ll need to mount a rack on their car

to carry their glider. Actually, they’ll probably have to build the rack first, or find a friend who can weld. And don’t forget they’ll need space to store a 17-foot-long glider. (Fingers crossed they have a car. And a garage.)

Navigating these hurdles is more than worth it for the experience of hang gliding, and it’s entirely possible to achieve or to find ways around each of them.

“Hang gliding may never be quite as convenient as paragliding, but what if we had a glider that packed to 5 feet or less to fit easily in a car or plane; SET up in less than 15 minutes?”

social media views that have sparked conversations with pilots and non-pilots around the world, I’m increasingly confident that this would be the most achievable way to help hang gliding thrive.

Everyone has their own thoughts about growing the sport of hang gliding. Ask five hang glider pilots and you’ll get 20 opinions on ways to reverse the sport’s decline, often including reducing insurance and other costs, gaining or regaining site access, and increasing instructor numbers. Though these goals are worth pursuing, they’re extremely difficult (and in some cases impossible) to achieve. They also largely ignore the low student retention rates in the sport.

Creating an efficient small-packing hang glider isn’t easy, but one prominent hang glider designer has assured me that the technology now exists to do it. The main thing we need is a design.

Still, glider transport and storage are notable barriers to entry for new pilots. It can also continue to frustrate experienced pilots trying to figure out rental or transport logistics to fly in other states or countries.

This leads to my main idea for growing the sport: I believe we should create a convenient and effective small-packing hang glider. After 18 years as a hang glider pilot, including as an instructor, former USHPA employee, and content creator with over half a billion

The growth of paragliding has already highlighted the attractiveness of portability and convenience. Hang gliding may never be quite as convenient as paragliding, but what if we had a glider that packed to 5 feet or less to fit easily in a car or plane; set up in less than 15 minutes; had easy handling and similar performance to current recreational wings—and was still a hang glider so had no risk of deflations? Many pilots (both hang glider and paraglider) around the world have told me they’d be interested. I know all of our students would be, too.

Small-packing hang gliders already exist, but I don’t

think they’ve become convenient enough to gain widespread popularity. Hang gliders from German manufacturer Finsterwalder come the closest. However, their 6-foot breakdown size is still relatively large, and many pilots report taking an inconvenient 40 minutes to set them up from the shortpack configuration (compared to around 10-15 minutes for standard hang gliders).

Major hang glider manufacturer Wills Wing also introduced shortpacking on its Falcon 3 beginner/recreational glider, which remains an option on the Falcon 4. I own a shortpack-capable Falcon 4 and love it, but the gliders’ similarly large shortpack size and hourplus shortpacking time make the feature primarily only useful for international travel, with regular/long-packing for everyday use.

In progress: New small-packing glider designs

Fortunately, some people share my belief that a convenient, smaller-packing glider is the future of hang gliding and are actively working to make it a reality.

Swiss pilot Florian Kohli began hang gliding in 2023. Living in an apartment and not owning a car at the time, he sought a smaller option than the gliders currently available on the market. After purchasing tubing from Finsterwalder, he created his first model, the TPHG 4.6, which measured just 4.6 feet long when packed. Kohli took the glider to California for its first test flights in November 2024, drawing a crowd of hang glider pilots as well as attracting emails from interested pilots around the world asking about buying the glider.

While the TPHG 4.6 received some criticism online for its not-yet-airworthy design, many praised Kohli’s efforts and willingness to innovate and refine his design. Despite having no formal engineering training, Kohli was excited to apply his inventor’s mind to the process. “Every single thing you think is difficult, someone will find the answer,” he said. “Why won’t you

do the same?”

Ultimately, Kohli’s goal is to develop a DHV-certified version of the TPHG that measures less than 5.7 feet when packed, weighs less than 44 pounds, packs down to a narrow width, and can be set up in under 20 minutes. On his way toward that objective, Kohli hopes to complete the second version of his glider and return to Los Angeles to test it this November (you can find updates on his website: hangglifter.com).

“I would just love to hear people say, ‘I would like to try hang gliding,’” Kohli said.

Australian instructor, top pilot, and hang glider developer Rohan Holtkamp is also working on a new glider design, the Dynamic Soarer, based on the ATOS C rigid wing glider. He has several even more ambitious goals, including: a packing time of under three minutes, a pack length of 5 feet 3 inches, a weight of 36 pounds, L/D of 16:1 or better, stall speed at maximum load less than 20 knots, and instant roll response.

“If you can’t offer compelling sink rate, L/D, stall speed, top speed, landing, handling, glide slope control, or safety improvements over the competition, then the market will not be swayed by a heavier and slower to rig option to a paraglider,” he said.

Holtkamp, who retired from instructing in 2023 to focus on designing the hang glider (as well as manu-

facturing a folding kayak), plans to load test the glider this year. “Hang gliding could blossom with uptake of a wing like the Dynamic Soarer,” he said, “as it addresses most previous barriers and will be very easy for paraglider pilots to adapt to.”

I’m thrilled to see pilots working on designs (if I had any engineering background, I’d join them) and hope more people recognize the potential and continue to drive innovation. So far, most hang glider manufacturers I’ve spoken to remain focused mainly on performance increases. They’re hesitant to commit resources to a new small-packing design because, they say, the market is too small to guarantee a return on their investment. However, this is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

: I encourage you to follow and support the development of new small-packing hang gliders, push for the changes you want to see, and vote with your wallet by contributing to development efforts when available and, ultimately, buying the finished product. Yes, some new designs will be lower-performance recreational gliders, but remember that they can pave the way for higher-performance gliders if they’re successful. Rather than lamenting insurance costs and other issues we likely can’t change, it’s critical to focus on areas we can for the best chance of growing the sport.

: Satellite communication devices have become an essential tool for backcountry expeditions and adventures in remote locations. It is common to see Garmin’s InReach Mini dangling from various pilots’ harnesses as they prepare to launch.

A standard cellphone GPS uses signals from multiple satellites in orbit, calculating the user’s approximate position first based on the time it takes for the GPS receiver to detect the signal from a satellite. The process is then repeated with usually three more satellites, using the intersection of each coverage area to calculate a precise location. Garmin’s GPS devices and other satellite phones are equipped with technology to actively transfer data to satellites in orbit, making them efficient sources of communication in isolated areas. However, their ability to bypass local telecom networks has led many national governments to regard them as security threats.

Out of concern that satellite communication devices could be used for insurgency, espionage, or to bypass censorship, many countries ban or heavily restrict satellite phones and GPS communication devices. Traveling without being aware of such restrictions could result in significant legal penalties and device confiscation.

Anti-terrorism efforts and national security are significant motivating factors in creating bans on satellite devices. For example, Nigeria prohibited the use of satphones in regions prone to conflict after Boko Haram fighters were found using them. Unauthorized sharing of information is also a threat. Satphones operating using the Thuraya network were banned in Libya during the 2011 civil war, and users were arrested as suspected spies. Mobile phones are much easier for government and national security organizations to track, leading to regulatory control requirements and specific licensing for the use of satellite communication devices. In Russia, individuals must pre-register their SIM cards and obtain approval from the communications regulator to enable call tracking and support counter-terrorism efforts.

India is a very popular flying destination, offering the potential for big flights and vol-biv adventures in the Himalayas. It is also one of the countries possessing strict bans and restrictions on GPS devices and satellite communicators, implemented after the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai. Throughout the entire country, it is forbidden to use any device connected to the Iridium (what Garmin uses) and Thuraya networks.

The Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act was passed in 1933, originally referring to radio transmissions. It reads, “Whoever possesses any [wireless telegraphy apparatus, other than a wireless transmitter,] in contravention of the provisions of section 3 shall be punished, in the case of the first offence, with fine which may extend to one hundred rupees, and, in the case of a second or subsequent offence, with fine which may extend to two hundred and fifty rupees.”

Most recently amended by the 2023 Telecommunications Act, all versions prohibit the use of satellite transmission devices without permission from the Department of Communications, which is a significantly difficult task to achieve. An InReach device

uses SMS to connect users to the “outside world,” which is precisely what violates the Telegraphy Act.

The only way to legally use a satellite communication device in India is as a registered expedition company based in the country. A license from the Department of Communication and the Ministry of War is still required, and the complexity of the application process means that only a few large operators can obtain it. Smartwatches and smartphones are allowed since the two-way satellite messaging available in the new iPhones currently only functions in the USA, Mexico, and Canada. According to an article on the topic by ExplorersWeb, a local mountain guide, Sunil Nataraj, "explained that groups such as India’s Mountaineering Federation are trying to make their case. But he believes that mountaineering is not yet powerful enough to change such a well-entrenched policy.”

India is not the only country where such restrictions exist. The accompanying table summarizes all countries where satellite devices are either banned or heavily restricted. Entering any of these countries without being aware of the local laws regarding satellite communication could result in a variety of consequences. You could face monetary fines and significant prison sentences, your device could be confiscated, and you may attract unwanted attention from security services as a suspected unauthorized actor or spy.

Alternative solutions when traveling in such countries include renting a local, licensed satphone within the country or contacting a local guide who possesses a registered device that could be used for emergencies. In countries with less severe restrictions, it may also be possible to use one-way emergency beacons, GPS messengers, HAM radios, or mesh networking devices.

The main takeaway is that it is critical to diligently prepare and research before traveling to any unfamiliar location. If necessary, declare your device at customs to avoid suspicions of smuggling, and have contact information for the appropriate embassy or legal counsel readily available. The proper training of individuals employed by businesses or guiding agencies that operate in such countries is imperative to avoid conflicts in countries with significant risk.

Bangladesh† Banned. No permits or possession

Chad†* Banned. No permits or possession

China* De facto ban unless obtained via state providers

Cuba† Permit required from Ministry of Communications

India†*§ Restricted. License (NOC) required from DoT for Inmarsat only

Libya* Authorities often confiscate devices despite no explicit ban

Myanmar (Burma)* Effectively banned. Only allowed with rarely granted permit

Nigeria¤ Banned in Borno. Legal status unclear nationally and possession risky

North Korea* Banned. No permits or possession.

Pakistan¤ Banned in parts of NW. Use elsewhere may require military approval

Russia* Pre-approval & SIM registration allowed with Roskomnadzor. Foreigners can register for up to 6 months

Sri Lanka* Permit required. License from telecom regulator (TRCSL).

Sudan* Strictly controlled. Approval & license from telecom authority. Must declare device on visa application

South Sudan* Permit and device registration with government required. Prior coordination advised

Ethiopia* Permit required. Written permission from Ministry of Communication/IT before import

Turkmenistan* Banned. No legal use. Strict enforcement and search are common

Mauritius* Restricted. License required from ICT Authority

Thailand* Restricted. Personal radio/sat devices need NBTC license

Vietnam¤ Restricted. Government permission required to import/use. Zero tolerance

Iran* No explicit ban but high risk. Devices often confiscated

Syria¤ War conditions. Likely treated as illegal for civilians

Oman¤ Requires import permits for radio devices

Nicaragua¤ Reports of ban due to regime security

* Confiscation

† Arrest/imprisonment § Fines

¤ Variable or unknown

1,600 kilometers travelled on foot

145,000 meters climbed

84 flights (including 60 from summits) 5 top landings on summits

solo adventure (and doesn't care whether you know about it or not)

: If it’s not on social media, did it really happen?

The modern adventure industry emphasizes personal branding and visibility, so why would any outdoor adventurer so much as swing their ice-axe without a “content strategy?” Or, worse, forget to take their camera out?

Nathan Longhurst, 24, completed a four-month campaign in the austral summer of 2024-2025 to summit every peak on The New Zealand Alpine Club’s 100 Greatest Peaks list. His feat was quicker than the only other completion time by 29 years and 8 months. Behind his long blond hair, beard, and weathered cheeks, Nathan comes across as a quiet, contemplative person who would rather be out on his next trip than talking about the last one.

“[Making content] is not my forte. My forte is running around by myself in the mountains,” he says. “It’s difficult for me to be out there, capturing content, while staying immersed in that personal experience,” he continues. “For a long time, it was quite hard for me to turn the camera on and not have it pull me out of this flow state.”

Nathan is an experienced trail runner, rock climber, ice climber, skier, and alpinist. He set the record for being the youngest person at 21 years old to complete the Bulger List (the highest 100 peaks in Washington), and he was the first person to bag all 247 peaks in the Sierra Peaks Section List within a calendar year.

But he has only recently added “pilot” to his list of

abilities. He started paragliding only 15 months before his trip to New Zealand, forming the idea and planning just two months before summiting the first peak. Adding flight to his skill set opened up new possibilities. One of his supporters, Jason Hardrath, described his use of a paraglider in this adventure climb-and-fly setting as “game-changing.” Nathan didn’t wait long to put his new skill to use: “I pretty much started the first peak straight from the airport,” he said.

The New Zealand Alpine Club’s list of 100 Great Peaks includes everything from Aoraki (Mount Cook) to remote technical summits like Jagged Peak in the Arrowsmith Range. The list was compiled in 1991 to celebrate the club’s 100th anniversary and aimed to encourage climbers to try a range of peaks of varying difficulty. New Zealand climber Don French became the first person to complete the list in February 2021 in a pursuit that spanned three decades. Nathan would attempt to link all these peaks throughout a four-month campaign. And he saw paragliding as a way to make that happen.

Nathan visited New Zealand for the first time in March 2024. “I just absolutely fell in love with the mountains,” Nathan said. “I was super impressed by the combination of relatively easy access, but big mountain feel with remote and rugged mountain terrain.” This was a combination he hadn’t really experienced much in the lower 48.

“The terrain is incredible for flying,” he said. “It’s true alpine terrain with big glaciers and ice falls; really

complex, interesting, and steep terrain.” Many summits are technically challenging from all approaches and lack easy routes to the summit. In Nathan’s eyes, this made them appealing for both pure alpinism and paragliding.

“From the climb-and-fly perspective, I think it’s some of the best terrain in the world,” he said. “Many of the approaches didn’t even have trails; they were either just bushwhacking or scrambling up a river bed.”

Nathan made it clear his achievement won’t officially count as a record* for completing the list, but that was never the point for him.

*Technically, Nathan didn't adhere to the rules over where each ascent should start. His use of a paraglider meant he could launch from one peak and land some way up on the next one. There was also at least one peak where he tagged the highest point, but the list states a sub-peak as the official summit. Though this aspect was frustrating, he still considers himself to have reached all 100 summits.

The 100 Peaks would be a serious undertaking for any experienced pilot, so it was surprising to hear that Nathan took up flying only 15 months before attempting the first peak on the list. “I will say there is no substitute for experience,” he said. “But in terms of having flown for a year, I’m quite proud of the amount of time and the number of flights that I put in.”

In his first year of flying, Nathan did almost 1,000 flights and “probably around 300 hours” of flying time.

“I was basically living in my van at the flight park near the local soaring site in Salt Lake City, Utah, and flying there just about every day,” he said. The nomadic lifestyle and seasonal work as a trail-running guide allowed him to chase flyable conditions.

It’s important to have equipment you can rely on, and for Nathan, simplicity is important—as is weight. He opted to use trail running shoes as much as possible, adding microspikes when he had to scramble up a glacier. His wing choice also called for something lightweight, but still had to be fun.

“I’ve mostly been flying my Nova Bantam,” he said. “I enjoy it quite a lot. It’s a really fun and dynamic wing to fly while still coming in a really lightweight package. It’s easy to launch even in higher winds.”

Unfortunately, midway through the trip, he snagged some lines during a launch from a rocky site, and the resulting damage put the Bantam out of commission. His aim to complete the whole project before the winter snow arrived appeared to be in jeopardy. It took the generosity of a local pilot to get the project

His progression included a month in Lauterbrunnen, Switzerland, “just doing a ton of laps” and time in the eastern Sierra doing technical climb-and-fly work. Even so, Nathan didn’t undergo any specific training in preparation for this project. “A lot of the flying I was doing before New Zealand did prepare me quite well,” he said. “But it wasn’t deliberate training.”

back on track, and it wasn’t long before Nathan had the ultralight Dudek Run-and-Fly as a replacement.

The technical challenges of New Zealand’s conditions became apparent immediately. Nathan described starting a crucial climb at 2 a.m. to catch optimal flying conditions, including a 2,500-meter vertical route on Sefton with “pretty sustained technical climbing for that whole length,” followed by a flight off the summit.

“My window for optimal flying conditions off the top of Sefton over to Footstool, and then off Footstool back down to the valley, was relatively short,” Nathan said. “I was expecting some stronger wind from behind by the middle of the day—similar to the Foehn in the Alps.” But he was able to make the flights before the wind took over for the day.

Nathan’s longest continuous link-up covered 23 peaks over 11 days and required helicopter resupply drops at mountain huts. “I planned this link-up and it felt like a total pipe dream,” he said. All the conditions would have to come together for him to have a chance. Which wasn’t exactly how it happened. “I did have four storm days,” Nathan said. “Sitting in huts, listening to the weather shake the walls.” He credited the New Zealand hut system as being an integral part of making this project possible.

In between storms, there was beautiful weather and clear skies. “I was able to do this really incredible, aesthetic movement through the central part of the range; through the highest peaks there, flying off these beautiful, technical summits. In a couple of cases, actually landing directly on some of these summits, which was spectacular,” he said.

Flying added a layer of complexity to Nathan’s decision-making. “My options are I can either downclimb this mountain, which can have its own hazards, be really complex, and take hours, or I can fly off,” he says. “If I’m able to safely launch, I’ll be back in my car in 10 minutes—but that has its own set of risks, especially if the conditions are anything less than ideal.”

Carrying a wing also fundamentally changed Na-

than’s experience of the summits. “Another by-product of having the wing is, as you arrive on a summit, it’s hard to just look at the views,” he said. He became “instantly hyper-aware” of everything related to flying—wind direction, wind speed, possible launch direction, and cloud development. “I’d try to take a moment to look around, but for the most part, on any day I was considering flying, as soon as I was on top, I was immediately in the mode of analyzing flying conditions.”

Being pulled out of the experience had been Nathan’s main reason for shunning the use of cameras while on a trip. Now, the very thing that would open up new experiences was threatening his engagement, too. But he found another way: “The moments of seeing and appreciating the natural beauty around me were actually while I was moving up. While I was climbing,” he said. “I like to set big goals and dedicate myself to them,” he said. “I find a lot of flow and a lot of gratification in solo travel. I’m much more centered and in tune with the mountains when I am by myself.”

Don French, 66, is the only other person known to have completed the 100 Peaks list. He has been an avid climber for most of his life. Nathan had a meal with Don, and the two shared adventure stories, with Don giving the benefit of his years of experience. Don became impressed by Nathan’s strategic use of flight.

“I think everybody is in awe,” Don said. “I’m seeing the cunning that he’s using.” He described how New Zealand is “famous” for its loose rock, making for “scary climbs” and dangerous river crossings. “[Nathan] climbed a subsidiary mountain, flew into the head of the glacier, then did his climb out!” Don said with admiration, explaining how this approach avoided dangerous climbing sections. “There’s a very big river called the Landsborough, which is really, really remote,” Don said, “and he flew across the river to do the river crossing. So, if you’re by yourself and flying with a wing, it just eliminates that risk issue. So, yeah: in awe of his cunning.”

Nathan is a climber, trail runner, and ultra-runner who has also become a pilot. His rapid progression

on the summit of Mt.

after

BOTTOM Nathan on the summit of Mt. Tasman, after a traverse from Mt. Haast, moments before flying off and top landing on Torres Peak. Aoraki/Mt. Cook in the background.

by Nathan Longhurst

from zero to flying from technical peaks in extreme terrain demonstrates both the accessibility of our sport and its game-changing potential for mountain athletes.

“It’s ridiculously, absurdly fun,” Nathan said. “Flying introduces this whole new dynamic element into my movement through the mountains. It has created a whole new layer of looking at terrain. You’re climbing mountains, but how do you move between these mountains efficiently, using a wing? Where can you launch and where can you land? And how can you maybe bypass difficult sections of travel, difficult glacier crossings, or river crossings, or avoid really long and dangerous descents? This climb-and-fly style has presented this whole new dimension and challenge,” he concluded.

Coming into the landing field from his 100th peak, Nathan was met by elated supporters, friends, and family. Since that moment, he has been asked to share his story with many people. The attention was alien and overwhelming. A culture shock. His reality had been so solitary for so long.

“NATHAN's rapid progression from zero to flying from technical peaks in extreme terrain demonstrates both the accessibility of our sport and its game-changing potential for mountain athletes.”

During our interview, it often felt like he always had one eye looking out the window. The end of the project was the end of it. With an eye drawn to the outdoors, Nathan seemed to have already moved on and was probably planning his next big project.

by Mitch Riley and Bill Belcourt

Utah paragliding record flight report | July 6, 2025

At the time of writing, this flight secured the Utah free flight record. Flights like this are variable and require the full skill set of very advanced pilots. Their decisions and conditions encountered are not to be taken lightly.

[BILL] Big XC flights in the Mountain West can be complicated. Wind direction and strength can vary significantly along the route. You can traverse multiple mountain ranges with different magnitudes of cloud development and turbulence. You might fly days and/or parts of the route that are “on the margins.” Essentially, “on the margins” means the edge of what

is reasonable and relatively safe. There can be magic on the edge, but slipping off to the wrong side is a real possibility.

To play the edge, you need to understand the risks and be at peace with all possible outcomes. This was one of those days. We had to adapt and improvise, unless it became obvious that we had to land to avoid a gust front. Fortunately, that point never came. We got to play the edge, following that shifting line until

the sun set. It was glorious. We weren’t out there just flying distance; we were exploring a line through the sky, fueled by different factors at different points in the day. Some clouds we ran from; others we ran towards. We refined our position, and we walked the line. I am sure we made plenty of mistakes en route and had to draw on a lot of past experiences, but ultimately, we got to where we needed to be in the sky to fly the length of the day.

[MITCH] On the evening of July 5, I met Bill at his house to refill my oxygen bottle and discuss the forecast and flight plan. The forecast was for top of lift to be well above our 18,000-foot limit, with patchy overdevelopment on the route, plenty of west wind up high, and reasonable winds on the surface. Bill pointed out the areas with potential “outflow” and how we might fly around it if the overdevelopment got as bad as forecasted. We planned a flight with two waypoints: Jupiter Peak as our starting point, and Laramie, Wyoming, as our goal. A 500 km flight center-punching the Uintah Mountains on a day with proper wind and a chance of overdevelopment—it was a classic Belcourt plan, and I was happy to be along for the ride. After getting an above-the-green fill on my O2 bottle, I went home, had a good dinner, and went to sleep early. I woke up bright and early and made a coffee as I prepared an ice bath. Starting the day with a cold plunge forces my mind to get used to persevering through hardship, my metabolism to fire up, and my energy reserves to stay higher throughout the day. A long day of cross-country paragliding is a test of endurance as much as it is a test of skill. Many pilots can fly well for a couple of hours; keeping a comp wing efficiently flying throughout an entire day in big conditions is a whole different ballgame. In the ice bath, I calmed my breathing and focused on my goal for the day. My goal was not to break the Utah free flight record, or to fly 500 km. My goal was to land at sunset with Bill Belcourt. Bill has been a legend of free flight since well before I started flying. He has been a mentor, friend, and confidant of mine for over a decade. At 61 years old, Bill is charging harder than any U.S. long-distance or competition pilot. I was quite

sure that if I flew with Bill all day long, we would have an incredible experience and fly pretty darn far.

On takeoff, we found light wind, cycles coming up the hill, and a clear blue sky in all directions. Jupiter Peak sits at 9,950 feet ASL, on the east (typically lee) side of the Wasatch. Nearby is a convergence of three of the main Wasatch Canyons: Big Cottonwood, Little Cottonwood, and American Fork. Oftentimes, the first cloud of the day in the Wasatch forms somewhere above this convergence of the canyons.

Eventually, the SLC crew made it up to join us. Bill mentioned that the morning forecast was showing more overdevelopment and, therefore, a higher likelihood of outflow. The general feeling was, “Let’s see what the day gives us.”

11:00 a.m. Jupiter Peak

[MITCH] A visiting P3 launched, marking some lift as the first cloud formed above the meeting of the canyons. Soon, I was suited up and launched into a sturdy cycle and a great climb. As I rode the thermal up through 12,000 feet, I saw Bill launch. I quickly made it to cloudbase at 14,000 feet, more than 2,000 feet lower than we had forecasted.

The air was smooth as I waited up there for Bill. Arash, Matt, Ben, Lisa, and others were also climbing up. Soon enough, Bill and I were gliding over my home of Park City. The Park City area is convergence central. The Weber River flows north out of the northwest side of the Uintas towards Morgan, then through the Wasatch to Ogden. The Provo River flows south from the southwest side of the Uintas toward Heber, then through the Wasatch to Provo. Additionally, west of Park City is the densest part of

the Wasatch Mountains, featuring large west-facing slopes that heat up and block any west wind until late in the afternoon.

The trick for our first move was to find that convergence, and I think we did. The glide was great, with occasional light lift. At times, it felt like the best lift line occupied just seven cells of my glider. When I felt it move left or right on my glider, I would adjust my heading to get it back to the middle. Bill came on the radio with multiple “radio checks,” all of which I responded to—it was obvious he could not hear me. We needed to arrive as high as possible for our next climb, and we were gliding to lower terrain—and likely into a more stable airmass—so we flew at trim speed, occasionally slowing our gliders with brakes when in light lift.

[BILL] I radio checked on launch and could hear my transmission on the radios around me. I assumed it was all good. What I didn’t realize was that I could not hear anyone through my speaker mic. I eventually figured that out after Mitch flew close to me and yelled over that he could hear me on the radio. I unplugged the mic and could then monitor trans-

missions, but the radio, being inside the Submarine harness, made it too difficult to transmit unless absolutely necessary. Turns out we didn’t need to discuss much.

12:03 p.m. 18 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] We found a climb over the hills to the north of the Browns Canyon Road. It was a weak, snakey climb that we desperately needed to cross Rockport Reservoir and progress into the Uintas. Next, we were on a typical line for entering the Unitas: Big Piney Ridge. As we reached higher terrain, the thermals remained challenging and weak. Soon, Bill and I were down in the upper Weber Canyon, frisbeeing downwind in crappy, stable thermals, working hard to find the right climb to get us back in the game. My mind was awash with thoughts about how the Uintas were too stable and windy, that we would need a whole lot more altitude to ensure that we wouldn’t land in a high, rocky pine forest miles away from any roads.

[BILL] I was hoping we would see more clouds popping earlier along a more direct line towards I-80 and Fort Bridger, but it was just blue. That, combined

with scrappy weak climbs that didn’t even go to 13,000 feet, made me want to keep to the terrain. Weber Canyon was the most conservative route choice, as it leads directly to the north slope of the Uinta Mountains. The Uintas were forecasted to overdevelop (OD), and conditions were clearly heading that way. Weber Canyon should have been cracking. It wasn’t—climbs were weak, wind-shredded, and didn’t go very high. The few clouds that were starting to pop around us dissipated. It felt stable, while a few miles to our east, it was booming. I couldn’t imagine it was better further north, where the terrain was lower and flatter. I felt we were in the best place, but it was still tough. Matt marked a good climb that at least allowed us to move along and be low in the wind somewhere else.

1:44 p.m. 50 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] I looked at our progress: 2 hours 40 minutes flown and only 50 km from takeoff—this was not a big day. As we slowly soared mountain faces and drifted back in weak, punchy thermals, Matt Weiseth came in underneath us and eventually found a ripping strong thermal out in the valley. He alerted us to it on the radio, and we were able to climb up to 14,000 feet and dive into the Uintas.

The next couple of climbs and glides in the Uintas were ferocious. It took constant attention to keep the glider open. Matt came on the radio, saying he had had enough and flew out to a landing. The clouds on our side of the crest were joining together and starting to fall out. Outflow was imminent, and we needed to do something. We started running to the north, trying to maintain as much altitude as possible while also getting as far away from the potential outflow as possible.

All of our communication was sublingual; when I saw Bill point towards a forming cloud, I joined him. When he saw my choice of a more northerly line to escape the overdevelopment, he would join me. Arash came on the radio saying, “I’m coming down under reserve, my glider went absolutely nuts.” I remember thinking, “That makes sense, this air is crazy.” I relayed the message to our driver and asked Arash to check in when he had landed safely, and he eventually did. This part of the day was powerful to say the least.

[BILL] It felt to me that we were on the edge of two

air masses: the more stable one, which was crushing the lift and compressing the wind, and the airmass going big over the Unitas. It was no surprise that it was turbulent in this zone. You know it’s bad when you don’t even want to turn in the lift—I was flying squares in the worst of it. Once we got through that area, the lift became more organized, and I tried to relax as I climbed to base, looking at the OD to the south for half of every turn. I told myself not to worry: we’d be mashing bar to the north soon.

3:30 p.m. 127 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] Bill and I got separated. We were both at cloudbase, I led out, and the OD was still raging behind us. I fell into a horrendous sink line and found myself low, hot, and struggling to control the glider in an edgy little ripper. Then I saw Bill at cloud base, passing 7,000 feet over me, heading further north and running further away from the development. Half of every circle, I was staring at this black mass of rain and wondering when the outflow was going to show itself. I wanted to leave the climb and run, but I knew I had to concentrate on gaining altitude and therefore increasing my options.

For the next hour, the stress got to me. Fatigue from the turbulence, running from the possible outflow, and getting low and hot had me climbing badly, gliding badly, and considering landing. Eventually, I found myself in a nice, smooth 3 m/s climb to cloudbase and noticed that the rain was too far away to worry about. Just like that, the stress lifted, and I was mentally back in the game. My next mission was to find Bill, and I was quite certain he was in front of me. I’d have to fly fast, and fly well, to meet back up.

Eric Konold, our retrieve driver, came on the radio to check in. I told him Bill’s radio was not working, and asked him where Bill’s last inReach message was. “East of Green River,” came Erik’s reply. “Excellent, I am almost at Green River,” I said. Five minutes later, I saw Bill about 3 km in front of me and at my altitude. “I have Bill in sight,” I said on the radio. After a couple of thermals, Bill and I were reunited.

[BILL] I heard that transmission and Mitch’s next one saying he had me in sight. I couldn’t see him, but I

slowed down to make it easier for him to catch up with me. It didn’t take long. We were back together at Rock Springs, in a much better place in the sky after battling for the last 4.5 hours to get there.

5:30 p.m. 221 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] My previous fatigue and stress vanished. I was back to flying well, thinking clearly, and having a blast. Bill and I shared big, strong, and relatively smooth thermals with spectacular views of the Flaming Gorge and the desert plain of Wyoming. Our glides became buoyant with a great tailwind. At onethird speed bar, we were traveling 80 km/h over the ground. Ahead, we could see the Jim Bridger power station, evaporation pond, and dry lake bed. Occasionally, a massive dust devil would rise off the dry lake bed, composed of white dust and minerals.

6:10 p.m. 256 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] We were on one such buoyant glide, with a blue hole ahead, when I got a great line and Bill got a terrible one. He couldn’t find my lift seam and was quickly thousands of feet below. I made three turns in a strong climb, and he didn’t find it. Suddenly, Bill made an abrupt north turn, towards clouds and the Jim Bridger dry lake. I elected to continue on course, and keep an eye on Bill. I turned in every piece of light lift, keeping it nice and slow so that Bill could join once he got up. I saw Bill get lower and lower, flying further and further north. His yellow glider and harness were lit up in the evening sun, and I eventually saw him catch a strong climb.

[BILL] I got a bad line and we were headed into a blue hole, so I took a hard left and headed north to

the closest cloud near the Jim Bridger power station. It was pretty sinky until I was properly under the cloud, and I still didn’t find lift. I headed downwind to the massive smokestack and black coal fields adjacent to the plant, figuring it was bound to work. I found a strong, narrow ripper that sucked in a cloud of dry lakebed dust that got me back in the game. I ended up on a parallel line to the north of Mitch at a similar altitude. We met in the middle, and this was the last time we would be separated.

7:00 p.m. 290 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] The blue hole we had previously worried about turned into a sky of glass-off cumulus, with rain and virga to our south, and its associated cold outflow, providing enough instability to give us big areas of 1.5 m/s lift. After eight hours of full-on fero-

cious flying, the battle of the day was over; we were now flying in the reward part of the day. Smooth air, incredible scenery, and a great friend to share it all with—it doesn’t get much better. I got out my camera and started taking photos and video; it was too beautiful not to. At this point in a long day, you never know which thermal is going to be your last, so speed to fly is all about maintaining as much altitude as possible. We still had a tailwind of over 30 km/h, and were making great progress. I wasn’t thinking about any record or even the distance from takeoff; my main goal was still to land at sunset with Bill.

8:15 p.m. 350 km from Jupiter

[BILL] We had found the perfect seam of buoyant air

“Let’s see what the day gives us.”

for what seemed like the final glide of the day. But, as luck would have it, we got one more climb to nearly cloudbase after 8 p.m. As we climbed, the light and our position were unreal. The gliders and harnesses were glowing like they had lights inside them. The sky was as dramatic as can be, with clouds dropping out and a rainbow as we turned on the edge of the line. Mitch was right there, and we were hooting and hollering at each other. I would say it was unbelievable, but Mitch took pictures!

8:20 p.m. 362 km from Jupiter

[BILL] It was looking like a storybook ending for the day, but Mother Nature gave us one last reminder of the forces we had been playing with for most of the day. We got a little too south of the ideal line and into the downflow from the clouds dropping out. The clouds looked just as good as the ones that produced our last climb and great glides. Our ground speed didn’t change much, but the sink and turbulence were bad for a good few minutes until we adjusted our line to the north. We got back on the better line for the final glide and a smooth landing.

[MITCH] We went on a glorious final glide: smooth buoyant air, jaw-dropping views, and success on the horizon. I followed Bill so that I could continue to take photos and video. We were gliding at trim, making 70 km/h over the ground when suddenly I saw

Bill’s yellow Enzo start to buckle, pitch, and shake. I quickly put my phone (camera) down and prepared for the beating. It was just that—I had to use full brake authority to prevent collapses, while dealing with unpreventable dramatic yaw movements. After a few minutes of Kung Fu fighting and a lot of altitude loss, we were back on our magnificent, buoyant sunset glide. We were gliding over the first paved road we had seen in hours. Branching off from this paved road was a wide gravel road that pointed directly downwind.

8:48 p.m. 387 km from Jupiter

[MITCH] We followed this gravel road until 20 feet above the ground, then simultaneously turned base to final and landed together after spending over nine and a half hours in the air. It was three minutes after sunset, the sky was ablaze in yellows, reds, and oranges, and Bill and I shared a heartfelt hug. I don’t have words to describe the joy, satisfaction, and camaraderie I felt at that moment. We packed up our gliders, and Erik soon appeared in Bill’s truck to take us home. [BILL] Landing right next to Mitch after nearly 10 hours of high-drama flying where we worked together, stuck with each other, and shared in those amazing moments in the final hours was incredible. This one is going to be hard to beat!

Get the gear that fuels your passion at discounted prices.

Your Pilot or Instructor USHPA membership automatically qualifies you to join. Simply scan the code to get started.

Unlock up to 60% o on top outdoor brands

: Are you familiar with the concept of naïveté? Years ago, when I saw a documentary about Tiki Mashy visiting Wallaby Ranch. I remember thinking, “Wallabies? Why go all the way to Australia?” Really.

These days, as an H2 novice, I assumed that a flatland national hang gliding competition would be a straightforward undertaking. That was another grand example of naïveté. I spent a week as a volunteer retrieval driver to determine what is essential to host an event like the 2025 Hang Gliding Nationals—my time there quickly dispelled my misconceptions.

Paradise Airsports at Wilotree Park in Groveland, Florida, has north-south and east-west grass runways, a layout that can accommodate any wind shifts that occur on any given day. The convivial clubhouse offers a large-screen TV, comfortable, air-conditioned rooms for rent, and shared bathroom and kitchen facilities. The office is located on the ground floor, under a porch roof where pilot briefings (and potluck suppers!) are held.

I learned that organizing these events requires a significant amount of personal time away from one’s family. I began to realize that a common thread among the leaders in the hang gliding community is ongoing generosity. I saw examples of this generosity repeated throughout my week.

Victoria Nelson supervises and manages all aspects of the air sports. She schedules the aerotows for visitors who want to experience free flight in a hang glider and collects and records all the registration fees. She is also part of the launch crew that ensures all pilots are safely in the air within the launch window. She seems to do three or four things all at once.

Eric Williams is one of the co-owners of Wilotree Park, which encompasses Paradise Airsports. He is the event host, safety director, rescue coordinator, and medical coordinator. Additionally, he is a long-time instructor and often pilots tandem discovery flights. One of his many jobs is community relations. Though central Florida seems to be under assault by massive development, Wilotree Park is still surrounded by fields full of cows and horses (expensive animals owned by

sensitive ranchers). As is common in competitions, not all pilots will make goal for the day, instead making unplanned landings in these same fields. Pilots receive a “Do Not Land” list at the very first briefing. In the event of a rancher getting ruffled, Williams makes every attempt to see that nothing was damaged and no animals were traumatized. He takes his job as a good neighbor very seriously.

All of our endeavors require organization. Stephan Mentler is a co-organizer of the meet along with Eric Williams. Mentler, a long-time pilot who has been flying since 2004, is also USHPA director of Region 4, which encompasses fifteen states and the District of Columbia. He has organized four events and competed in several dozen, including the 2014 World Hang Gliding Championship in Annecy, France. As the organizer, before the competition, he sent a message to all the pilots asking them to download the Volandoo app so that they could keep a record of their tracks. He also plans and manages the budget.

The Meet Director, Jamie Shelden, is an experienced pilot who has competed internationally. Her administrative work for the Commission Internationale de Vol Libre (CIVL) spans seven years, including roles as a steward, jury member, and lecturer at a jury and steward training seminar in Budva, Montenegro—and now as a Meet Director.

The Director’s job involves a multitude of responsibilities. She coordinates with all committees, including safety, scoring, launch, and weather updates. She is integral to determining daily tasks and ensuring adherence to the FAI’s rules and regulations. Shelden was also part of the launch crew that staged launch carts, alerted pilots in the queue, and even brought water to waiting pilots who were sweltering in their pod harnesses in the 90° Florida heat. Shelden came to Florida from her home in Watsonville, California, to direct both this and the Bobby Bailey Memorial. She took time away from her law practice to do so—again, I see a demonstration of an unselfish love of the sport. A good day of flying starts with being dropped into a nice thermal, and a good tug pilot will do precisely that. Jim Prahl, Derreck Turner, and Mick Howard are all tug pilots and hang glider pilots. Turner and Howard also competed in this National event. The three of them were integral to the event’s success, as they successfully got all competing pilots airborne within the launch window.

Davis Straub is a competitive pilot, maintains and edits “The Oz Report,” and has served as a Meet Director for the 2013 World Championship in Forbes, Australia. During Nationals, he prepared and delivered the morning weather briefings, posting screenshots from the NOAA website on WhatsApp to give pilots a glimpse of the flying conditions they could expect. Because of Straub’s briefings, I began to see the im-

portance of micrometeorology and started correlating the weather abstract with what I was seeing in the sky. Although I was still learning about various aspects of weather to understand his briefings, it seemed that the task finishers had an excellent and almost visceral knowledge of thermaling and weather.

The first task was cancelled due to thunderstorms that were forecast to develop while pilots were in the air. All parties were set up and ready to launch, but the members of the safety committee had to make a decision that was sure to disappoint. However, as always, safety was the determining factor.

On the second day, the pilot briefing was scheduled for 11 a.m. Tasks for Open Class and Sports Class were posted, along with the day’s launch order, and Straub provided the weather brief. As a retrieve driver, I had the Life360 app loaded onto my phone and Volandoo on my iPad. With Life360, I could create a group with only the pilots for whom I was driving. Tap the pilot’s picture and then tap “get directions”, and it would lead me to the pilot’s location—it was an essential tool to find and retrieve the pilot.

Volandoo helped me keep track of all pilots while they were in the air. If any of the pilots in my group showed a constant loss of altitude, I assumed that they were preparing to land, and I got ready to mark the location. Volandoo displays task cylinders, and if you tap

one of the hang glider icons, it will display the pilot’s name and track. Below the graphics, the text displays the name, altitude, speed, vario up or down, distance covered, distance to goal, time in the air, and type of hang glider flown.

As a pretty new H2, before this competition, I had no idea what CAPE stood for, what a task cylinder is, what either Life360 or Volandoo were, or what the phrase “made goal” meant. Each day brought an avalanche of information that I tried to absorb. It was a fun ride!

Days three, four, and five continued with flyable weather. The launches were high-charged, choreographed, and brought non-stop action. For a brief moment, Paradise became the world’s busiest airport. As the launch window approached, pilots brought

their gliders to a staging area. There would be three or four pilots lined up on launch carts, ready to be towed. The launch crew checked over every pilot and glider. When the pilot was ready, the signal was given, and the tug pilot applied full power. Almost as soon as the pilot released the cart, someone would drive out with a gas-powered Gator to retrieve it. At the same time, the launch crew would move the next pilot into position while the next tug taxied out to its spot. If a pilot landed and needed a “relight”, there was someone in another Gator ready with a launch cart to tow them back to position. The launch crew was well-practiced, and the event depended heavily on these dedicated volunteers for success.

On the third day, neither of my pilots made goal. I tracked them via Volandoo and then used the Life360 app to locate them on the ground. They were both a short drive south of Wilotree and within minutes of each other. They had wisely landed inside fenced fields, without cattle, close to the road. Radios, WhatsApp, and cell phone messaging made communication and

pick-up a breeze.

The final day of the event was not flyable, and pilots were alerted via WhatsApp. An awards dinner was held that night, but unfortunately, I was unable to attend. A pilot from Portland, Oregon, had asked for a ride to Orlando airport, and we had to leave Paradise by 11 a.m.; departure from Paradise was necessary.

: The week left me astonished at the depth and breadth of the experience and knowledge of all of the people involved in producing the 2025 Nationals at Paradise Airsports. If you’re a novice pilot and want to see firsthand what’s possible in this sport, find an event and volunteer. You will see an array of gliders, harnesses, equipment, and styles that you wouldn’t usually see as a student, and you’ll witness world-class pilots competing with one another. Listening to the informal post-flight commentary in itself is worth its weight in gold. The experience boosted my desire to be part of this small but generous community tremendously, and I’m happy that I did it.

by Jonathan Hutton

photos by Patrick Penoyar

: The state of Washington is divided by mountains. The route to Chelan from the west requires crossing the Cascades, transitioning from lush lowlands and coasts to the sharp, arid desert. The town is a popular destination for tourists, with vineyards and campgrounds scattered throughout the landscape surrounding a deep-water lake. Unlike tourists, pilots come primarily for the Butte and the energetic lift of midday thermals, which fuels two paragliding competitions: the Ozone

Chelan Open and the U.S. Open of Paragliding. Word has traveled far about the Chelan comps and the experience of volunteering at them. There is lore and mythology: stories of mishaps and mixups, ill-conceived meal plans, and hijinks with ambitiously inexperienced pilots. Wise volunteers know this is not a vacation. We go to work, but we know there will be rewards too: flying, learning, and reveling in this improbable sport. The roster of volunteers this year included a mix

Out of the starting gates pilots work their way to the first turnpoint.

of first-timers and veterans, brand-new and experienced pilots, couples, individuals with white-collar jobs, and free-spirited adventurers who live in vans.

I arrived at camp in the afternoon, days before the main event, in a rental van stuffed with camping gear, my flying kit, and a small PA system. A triad of pine trees near the property’s edge was my living room for the two weeks of competitions, shading me from the midday sun. My coffee station was primitive but more than adequate—packets of Starbucks instant and a butane camp stove. As a volunteer, I began each morning the same way: coffee, yoga, work assignments, meeting prep, and then breakfast.

“Do you think…today…we’ll get a chance to fly?” a volunteer asked me. I couldn’t make any promises, but I knew that yes, we would fly. Sled rides from the Butte to the park, as well as early morning ridge soaring, could be possible for volunteers. However, this was not our primary purpose: we were there to support and enable others to fly, making the event possible through our effort and focus.

This year, we implemented changes for volunteers based on lessons learned from 2024, including an upgraded shower, rules on charging personal devices, an application process, and a volunteer guidebook. Start to finish, our circus of activity is a DIY effort, built on donated time and talent.

Our first comp day was a bit rocky, which isn’t a surprise. The rhythm and feel for what needs to happen and when is not yet reflexive, but we expected the next day to be easier. Matty Senior, the event director, reminded everyone why they were there: flying the Butte is a perk, but not a guarantee. Our attention and priority must be on supporting our competitors. As the morning meeting continued and I welcomed the newly-arriving volunteers, the next cascade began. Vans departed, with comp pilots piling in to head up the craggy, pitted path to launch (calling it a road is too generous a term). Two vehicles had already made it up the Butte early, where volunteers had set up tents, tables, flags, and water stations.

As vans departed to load up with pilots and climb the Butte, the task committee met to brainstorm around the picnic table. I watched the vans move on my laptop

screen, each one equipped with a GPS tracker. I only half-listened to the task discussion because several people have messaged me about a van that inexplicably went up to launch with no passengers. Mistakes like this will happen, and we plan around them in real-time, gracefully. We laughed about it later.

For the first-time volunteer, being at Chalan is an initiation and a trial: your bandwidth will be tested, as will your ability to take instruction. All around is material for overwhelm—vans full of people, chatter, an ever-evolving list of to-dos, and narrow windows of time to complete them. At launch, a gaggle will coalesce overhead; but we, the vol-

teers, must redirect our focus to the wing on the ground in front of us.

On a typical morning, I arrive at launch around 9:45 with the safety team and a few other volunteers and free-fliers. Volunteers readied themselves for morning sled rides to the riverside Chelan Falls Park, and I was their retrieve driver. In first gear, I drove down the Butte, rewarded with a moment alone. The volunteers packed their wings in haste under a row of shade trees before we returned just in time for the launch window, as wind techs showed everyone where lift could be found. Competitors began moving faster than a shuffle, readied kits, and pulled buffs over their faces. It’s tough to know how they are feeling when their eyes are the only clue.

Clipboard in hand, I made note of where my retrieve drivers were. Some of them would need to depart asap; others would leave later on, once the line of pilots in the queue had reduced by half. Glid-

ers launched in a panoramic vista, one after the other, with intention and usually without incident, although a few wings needed to be carefully excised from sagebrush. Several comp pilots thanked us directly as we laid out their wings across tarp or dusty gravel. You are so welcome. Helping in this way was a joy; witnessing this scene and being part of an event of this scale was a privilege.

A friend of mine once told me that paragliding saved his life. I wonder how many of these pilots, competitors, and volunteers feel this same reverence for the sky, for our ability to fly in it, and for the ways that you cannot

help but change once you begin.

Once all of the drivers had departed, only a few free flyers remained, preparing themselves for launch in stronger winds. A small team of volunteers worked together to clean up the launch before departing for the day. Back at camp, a few drivers waited on standby, while some had already departed, en route to staging areas to pick up pilots who had sunk out. With the morning chaos handled, I could sometimes take a brief rest in a hammock before lunch.

In the afternoon, our drivers returned, full of stories, effervescent. They told us about challenging retrieves,

working in concert with pilots who became their navigators, sweaty celebrations, and detours. Like the comp pilots, they accomplished something important. The pride was tangible: we all contributed what we could to make this work, supporting each other with acts of service each day that felt necessary, because they were.

The next day, we found ourselves back at launch, but the wind was cold, whipping across our faces. Of course, I forgot my puffy. The comp was nearly over, and I found myself wishing for a rest day to pause the constant, unrelenting movement. The task was canceled, and I was overwhelmed with relief. Several volunteers organized a trip to a nearby beachfront park. A slackline was strung up between two trees, and paddle boards were inflated with wheezy hand pumps. I rested on my back, above the water, staring at the wisps of cotton cloud. I am so fortunate to be here.

As we neared the end of the second comp, morale was high. The team knew what was expected and sprang into action unprompted. We had practiced this routine every day, rotating people into different roles, balancing the workload, and maintaining our little village in

the grass. Of course, there were snafus and outbursts, disappointments, and miscommunications—but we navigated them, adjusted, and learned.

The closing ceremony was its own event within an event, but my capacity to plan and delegate had been worn down by sun, dust, and uneven ground. Doing this was its own form of endurance race, and I was not sure how much further I could go. Matty asked me for the list of people returning rental vans, which I produced after leafing through stacks of dog-eared notes.

I skipped the dance party; my energy was gone. I’d run as far as I could, and besides, there was a rental van to drive to the airport the next day. Volunteers had already departed, wishing us well in our group chat and expressing their gratitude for the experience and the time we spent together. We did something remarkable, and next year will be even better.

This story is adapted from a chapter in the author's new book, Unflappable: Soaring Beyond a Diagnosis, available now. Find out more at unflappable.blog

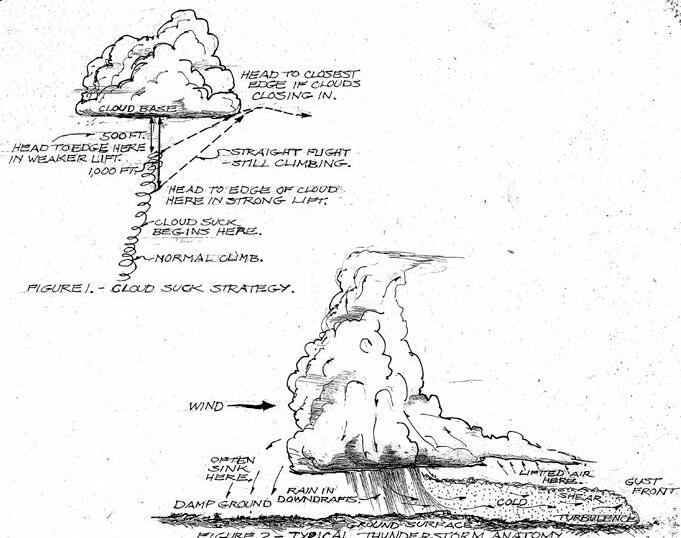

Dennis Pagen

: After 50 years of writing for this publication, attempting not to repeat myself, I have come to realize that some topics need repeating and some dead equines must be beaten. One such topic is thunderstorm lore—judging, avoiding, and escaping these aerial beasts. At least two recent events where pilots were sucked up to over 24,000 feet in thunderstorms have prompted this revisit for safety’s sake. Fortunately, both pilots survived with harrowing tales to tell; however, we are aware of other incidents that didn’t end so well.