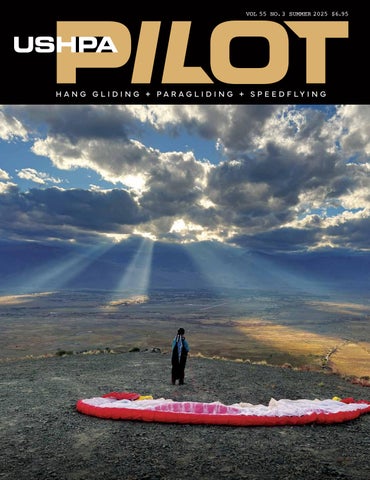

HANG GLIDING + PARAGLIDING + SPEEDFLYING

USHPA Awards by Cathleen O’Connell

An important tool for the community

Hyner View’s 50th Anniversary by Brian Vant-Hull Celebrating our unique history

Armchair SIV by Calef Letorney What the flap?!

Magic Land by Jeffrey Packard

A festival of flight down under

Building Bump Tolerance by Arjun Heimsath

Re-Winging It by Erika Klein

Six paraglider pilots’ journey into hang gliding

Ladies Unite In Santa Barbara by Liza Verzella

Partners With “The Bear” by Dave Embertson Free flight at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore

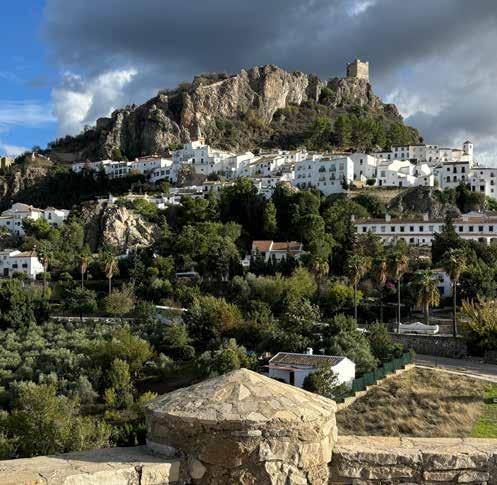

Work From “Home” by Lucas Soler Testing Algodonales as a remote work and flying hub

Lessons From Valle by Jeff St. Aubin Big air, big consequences at El Péñon Classic

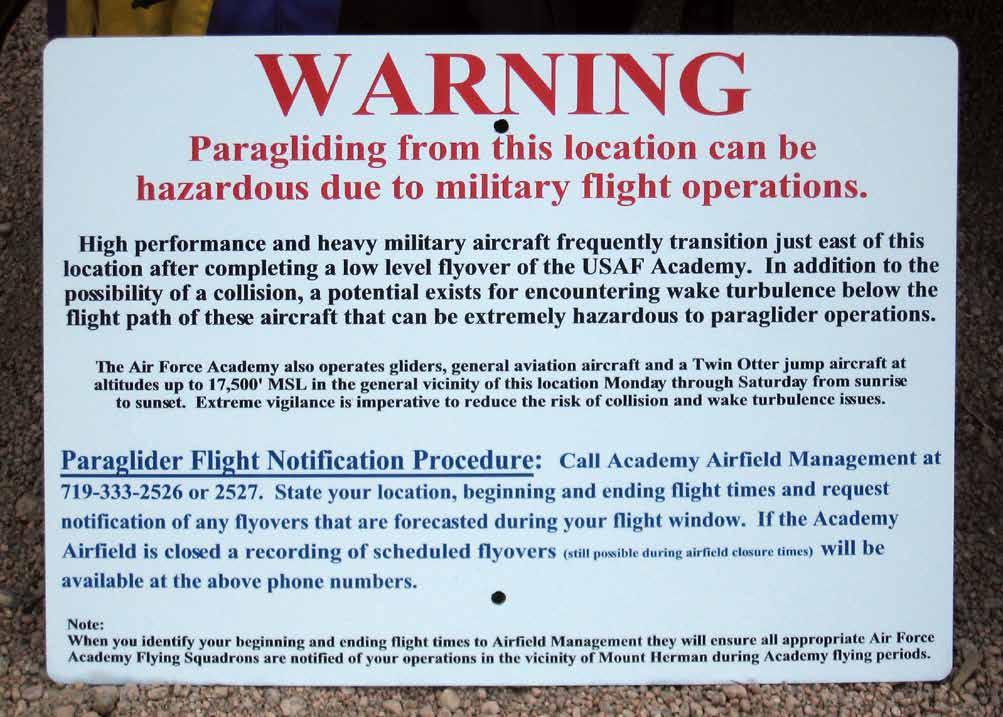

Deconfliction: What Is It? by Martin Palmaz

Flying: The Supreme Meditation by Sofía Puerta Webber

HANG GLIDING, PARAGLIDING & SPEEDFLYING ARE DANGEROUS ACTIVITES

USHPA recommends new or advancing pilots complete a pilot training program under the direct supervision of a USHPA-certified instructor, using equipment suitable for their level of experience. Many of the articles and photographs in the magazine depict advanced maneuvers being performed by expert pilots. No maneuver should be attempted without appropriate and progressive instruction and experience.

The series for the perfect start to paragliding. Choose between two versions: the robust classic and a light DLS version with more performance from 3.6 kg. Flying fun and feeling great in the air are guaranteed with the ALPHA.

Distributor: super yinc.com, info@super yinc.com, 801-255-9595

Do you have questions about USHPA policies or programs? Are there topics you’d like to hear more about?

EMAIL US AT: info@ushpa.org

Interested in taking a more active role supporting our national organization? USHPA needs your skills and interest.

VOLUNTEER AT: ushpa.org/volunteer

For other USHPA business +1 719-632-8300 info@ushpa.org

James Bradley, Executive Director

: In 2005, USHPA’s mission was written: “To grow the membership.” Not surprisingly, it didn’t create growth. That’s because growth isn’t a mission— it’s a byproduct. It emerges when we do the right things well and inspire people.

Imagine if Steve Jobs had declared Apple’s mission “to make money” instead of “to make tools for the mind that advance humankind.” Do you think we’d still be hearing about Apple today?

Steve’s mission aimed boldly at creating value. At USHPA, we’re working to do exactly that—create value for our members. Even more than attracting new pilots, we want to do better at keeping the ones we have. To this end, we’re determined to create a more responsive and supportive association for you than ever, and a stronger national community.

reduce the overwhelm factor of new students on the hill, and they’re really excited about it.

The P2 course, which will complement on-hill training, is in the works. H1 and S1 development will start soon. We aim to have P1-P4, H1-H2, and S1-S2 courses done in time for the 2026 flying season. After pilot training we will add instructor training, including a course on running a flight school.

If it feels like a new day at USHPA, I hope you’ll spread the word. If you know someone who let their membership lapse, I hope you’ll invite them back. We have a lot of work ahead and we’re stronger with everyone on board. You can find our current mission at ushpa.org/about.

The United States Hang Gliding & Paragliding Association, Inc. (USHPA) is an air sports organization affiliated with the National Aeronautic Association (NAA). The NAA is the official US representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), which is the world governing body for sport aviation. The NAA represents the United States at FAI meetings.

The NAA has delegated to USHPA the supervision of FAIrelated hang gliding and paragliding activities, such as record attempts and competition sanctions.

One exciting piece of this is our pilot training curriculum development. As I write, we’ve completed version 1 of USHPA’s first-ever online course, a ground school and theory course for the P1 rating, with an accompanying exam. It’s hosted on our new Learning Management System (LMS), and it’s being tested by a few instructors and students. Senior instructors say this course will

If today’s USHPA doesn’t feel worthy of your support, I’d like to know why. Drop me a note at james@ushpa.org, or go to USHPA.org/meetwithjames to book a meeting. I look forward to speaking with you.

In order to provide an up-to-date event list, USHPA Pilot no longer prints events in the quarterly magazine. Please scan the QR code at left to go straight to the list, or visit the USHPA website at: ushpa.org/calendar

REGION 1 NORTHWEST Alaska Hawaii Iowa Idaho Minnesota Montana North Dakota

Nebraska Oregon South Dakota

Washington Wyoming

REGION 2 CENTRAL WEST

Northern California

Nevada Utah

REGION 3 SOUTHWEST

Southern California Arizona

Colorado

New Mexico

REGION 4 SOUTHEAST Alabama Arkansas

District of Columbia Florida Georgia Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Missouri Mississippi

North Carolina

Oklahoma

South Carolina

Tennessee

Texas West Virginia Virginia

REGION 5 NORTHEAST and INTERNATIONAL

Connecticut

Delaware Illinois Indiana Massachusetts Maryland Maine

Michigan

New Hampshire

New York

New Jersey

Ohio

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

Vermont Wisconsin

To deliver programs and services that support all our members, foster a community of skilled and knowledgeable pilots, and promote and protect the freedom to fly.

A vibrant free flight community across the United States.

Celebrate the spirit of discovery and the joy of being in the outdoors.

Support ongoing education, development of skills, and acquiring of the judgment that comes from experience and attention.

Be stewards of our natural places, our flying sites, and the future of our sport.

Act ethically, take 100% ownership, communicate clearly, respond effectively.

Foster a considerate community free from harassment and abuse.

James Bradley Executive Director james@ushpa.org

Charles Allen President president@ushpa.org

Kirby Ryan Vice President vicepresident@ushpa.org

Olga Grunskaya Secretary secretary@ushpa.org

Pam Kinnaird Treasurer treasurer@ushpa.org

Galen Anderson Operations Manager office@ushpa.org

Chris Webster Information Services Manager tech@ushpa.org

Anna Mack Program Manager programs@ushpa.org

Maddie Campbell Membership & Communications Coordinator membership@ushpa.org

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2025)

Kirby Ryan (region 3)

Nelissa Milfeld (region 3)

Pamela Kinnaird (region 2)

Olga Grunskaya (region 1)

Bob Ferris (region 3)

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2026)

Van Spurgeon (region 3)

Charles Allen (region 5)

Nick Greece (region 2)

Stephan Mentler (region 4)

FLYTEC WORLDWIDE OBSTACLE WARNING Imagine having an extra pair of eagle eyes with you on your flight, scanning for hazards like power lines and cable cars, that can show you nearby obstacles and warn you when you are on a collision approach. Naviter is pleased to announce that this feature is now available worldwide in SeeYou Navigator running on Oudie N/N+, Omni, and smartphones. Nearby threats are highlighted in red on the flight map, providing crucial time to alter flight path. Tap on displayed obstacles for detailed info and the ability to customize warnings, empowering you to make informed decisions and fly safer. Download selected areas for offline use, and let Oudie N/N+, Omni, and SeeYou Navigator help you spot and avoid obstacles. For more information: info@flytec.com | +1 800-662-2449

LEVEL FUZE

The FUZE parakite wing offers a fresh approach to parakite soaring with a solid design, progressive safety, and exhilarating flight, featuring a noticeably steeper and faster profile than existing parakites. Enjoy intuitive handling with a consistent increase in pressure throughout the brake range for precise control and feedback. The predictable and progressive stall point enhances piloting confidence. Durable materials are used throughout with reinforced leading edge and wingtips, while the simple risers include a “Dive blocker” system. Feel the immediate and precise roll response—the signature “Level Touch.” www.levelwings.com

LEVEL FLAME 2

The FLAME 2 wing keeps the innovative, accessible, and playful spirit of its iconic first version, offering access to miniwing flight and pure speedflying for all. Its new profile provides better exploitation of flight angles, the redesigned air intake optimizes internal pressure, and the redesigned arc improves the overall efficiency of the wing. The mini-ribs on the trailing edge increase speed and performance while going further in responsiveness, dive, and precision. The wing features a 10cm trimmer range on all sizes, which gives a feeling of two different gliders in one. Highlights include intuitive launch behavior for high summits, soaring, and everything in between, and reduced weight for faster, easier launches, and lower pack volume. www.levelwings.com

The FLEX, EN-A paraglider, is for first flights to first cross-country epics. The Flex is safe, returns to stable flight alone after each maneuver, and reacts gradually to the pilot’s actions on the handles. The long brake travel allows for fine and efficient turning while remaining precise, with a high tolerance for imprecise inputs. Inflations are gentle, and the wing stops naturally above the pilot without effort. Three color options, four weight options, and the iconic Level Wings bird design. www.levelwings.com

The square reserve’s increased stability, combined with the Angel SQ’s excellent sink rate, makes it a higher-performance reserve than traditional rounds. The Angel SQ has a relatively large surface area yet is very light in weight, giving exceptional sink rate and stability performance with fast opening times. Now the line has expanded with the Angel SQ 180, which is designed for pilots with an all-up weight of less than 180kg (including paramotor and light tandem use). The Angel SQ and the ultra-light SQ Pro range are in stock now in most sizes. www.flyozone.com

2 The Swiftmax 2 is our high-performance tandem glider designed for XC pleasure flights and professional tandem flying. Based on the world record-holding Swiftmax, this new generation pushes the performance envelope even further whilst improving safety, comfort, ease of use, and longevity. The new version incorporates winglets to improve roll stability and reduce parasitic movements, enhancing comfort for both pilot and passenger. It maintains a semi-lightweight construction for easy everyday use but has been reinforced in critical areas to improve durability and longevity. The glider has improved performance with a lower EN-B certification and a wider certified weight range from 120 to 230 kg. The new design also incorporates rollercam trimmers and 20mm risers. It is already holding several world triangle distance and speed records. www.flyozone.com

The new ALPHA 8 takes the classic entry-level wing to the next level in terms of performance and passive safety. The ALPHA series stands out with its clear line setup and col-

or-coded risers and brake handles, making ground handling especially intuitive. The wing launches effortlessly and is exceptionally easy to fly, thanks to its balanced pitch and roll behaviour. Other key qualities include long brake travel, a smoother ride in turbulence, and a great sink rate for an EN-A level glider. Last but not least, the handling is dynamic and fun. It comes in five sizes with a weight range starting at 50 and going all the way up to 145 kg. Medium size weighs 4.5 kg and 4.15 kg in the DLS version. This paraglider is available in both versions through Super Fly, Inc., with your choice of bags: www.superflyinc.com, +1 801255-9595, or your local dealer.

4 Mini is a tool for professional tandem pilots to expand their mode of operation. It makes it easier for light pilots to fly with light passengers. In addition, it also offers greater mar-

gins when faced with valley winds or stronger breezes. Both sizes still maintain the excellent sink rate and ease of launch/landing that make the Fuse the best-selling tandem. The Fuse Mini comes in 32m and 38m and still carries EN-B certification. The glider weight is 6.5 kg (in the 38m), and it comes in one color only (the 32 is red and the 38 is turquoise). Custom colors are possible with an extended delivery time and a surcharge. This paraglider is available through Super Fly, Inc., with your choice of bags: www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-2559595, or your local dealer.

The EN-C cross-country paraglider VORTEX is a well-balanced and light two-liner with 65 cells and an aspect ratio of 6.1. Weights start at 3.3 kg for the size XS, and it is available in four

sizes from 60 to 110 kg. It is made from Dominico 20D (35g) on the leading edge and Dominico 10D (26g) on the rest of the upper and lower surface. Internals are Porcher Skytex 32 hard and ultra-light Porcher Skytex 27. The Vortex has Height-Adjustable B-Handles (HAB-Handles); they are made of carbon and can be height-adjusted to five levels. This is a perfect first lightweight 2-line C for any qualified pilot. Still, the speed and glide will let you keep up with almost any glider in the category. It comes in one color, white. This paraglider is available through Super Fly, Inc., with your choice of bags: www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-2559595, or your local dealer.

Liz Dengler

Managing Editor editor@ushpa.org

Julia Knowles

Copy Editor

Greg Gillam Art Director

WRITERS

Dennis Pagen

Lisa Verzella

Erika Klein

Julia Knowles

Do you have a story idea you would like to pitch? We are always looking for stories.

EMAIL LIZ AT: editor@ushpa.org

Are you ready to contribute a complete story? We are always looking for articles, photography and news.

GET STARTED AT: ushpa.org/contributors

All articles, artwork, photographs as well as ideas for articles, artwork and photographs are submitted pursuant to and are subject to the USHPA Contributor's Agreement , which can be reviewed on the USHPA website or obtained by emailing Liz.

Would you like to run an advertisement ? Great!

CONTACT US AT: advertising@ushpa.org

: We have a jam-packed magazine in store for readers this issue. From technical and mental discussions to travel tales to site management, our writers have covered it all.

First, USHPA reminds members to nominate top-notch individuals in their flying community for the annual USHPA awards. By recognizing and lifting up the pillars of our community, we can continue to improve our flying sites and experiences.

There is plenty to learn about right here on our home turf. A ladies’ fly-in in California demonstrates how easy it is to support one another. In Pennsylvania, Hyner View’s 50th Anniversary Fly-in reminds us how long some sites have been available to us, and of the many tales that span its rich history. Often, we take for granted our opportunities to fly in the U.S., but the story from Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore shows us of the considerable work that goes into maintaining relationships and flying privileges at our local sites. In that vein, open communication about other air traffic around any flying site is essential, and sites like Mt. Herman embrace deconfliction to keep everyone safe.

EDUCATION Learning in our sports comes in many forms. This issue covers technical advice, as seen in the Armchair SIV, as well as mental or emotional

aspects, as represented in Building Bump Tolerance and The Supreme Meditation. All approaches to learning require small steps, take practice, and, most importantly, patience with ourselves and our egos as we develop the skills we need to fly well. We also find an engaging tale about paragliders, after years in the sport, taking up hang gliding as a new way to enjoy free flight! Your flying skills might translate more easily than you expect!

TRAVEL We fly around the world in this issue: participating in hang gliding competitions in Mexico, testing a remote work-and-flying lifestyle in Spain, and attending speedwing fly-ins in New Zealand. These travelers give readers a glimpse into the flying opportunities in the far reaches of the globe.

: We received a lot of great feedback from readers about our last couple of issues. I love hearing that you’re enjoying the magazine, and I want to ensure we continue to improve it by featuring stories you’d like to see. We’ve set up a super short and easy feedback questionnaire so you can let us know how we can improve your reading experience. It’s only three questions long and should take you less than five minutes. Scan the QR code and let us know!

©2024 US HANG GLIDING & PARAGLIDING ASSOC., INC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of USHPA.

POSTMASTER USHPA Pilot ISSN 2689-6052 (USPS 17970) is published quarterly by the United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, Inc., 1685 W. Uintah St., Colorado Springs, CO, 80904 Phone: 719-632-8300 Fax: 719-632-6417 Periodicals Postage Paid in Colorado Springs and additional mailing offices. Send change of address to: USHPA, PO Box 1330, Colorado Springs, CO, 80901-1330. Canadian Return Address: DP Global Mail, 4960-2 Walker Road, Windsor, ON N9A 6J3.

MAKE YOUR NOMINATION AT: ushpa.org/awards

NOMINATIONS ARE DUE OCTOBER 1.

PRESIDENTIAL CITATION - USHPA's highest award.

ROB KELLS MEMORIAL AWARD - Recognizes a pilot, group, chapter or other entity that has provided continuous service, over a period of 15 years or more.

USHPA EXCEPTIONAL SERVICE AWARD - Outstanding service to the association by any member or non-member.

NAA SAFETY AWARD - The NAA presents this award to an individual, recommended by USHPA, who has promoted safety.

FAI HANG GLIDING DIPLOMA - For outstanding contribution by initiative, work, or leadership in flight achievement.

FAI PEPE LOPES MEDAL - For outstanding contributions to sportsmanship or international understanding.

CHAPTER OF THE YEAR - For conducting successful programs that reflect positively upon the chapter and the sport.

NEWSLETTER/WEBSITE OF THE YEAR (print or webbased).

INSTRUCTOR OF THE YEAR AWARD - Nominations should include letters of support from three students and the local Regional Director. One award per sport per year may be given.

RECOGNITION FOR SPECIAL CONTRIBUTION - For volunteer work by non-members and organizations.

COMMENDATIONS - For USHPA members who have contributed to hang gliding and/or paragliding on a volunteer basis.

BETTINA GRAY AWARD - For the photographer whose work (three examples needed for review) is judged best by the committee in aesthetics, originality, and a positive portrayal.

BEST PROMOTIONAL FILM - For the videographer whose work is judged best by the committee in consideration of aesthetics, originality, and a positive portrayal.

: Everyone knows a pilot, instructor, landowner, driver, club officer, rescuer, or mentor (either an individual or team of people) who step up substantially to ensure the accessibility, safety, or enjoyment of free flight. The USHPA awards are an excellent tool to acknowledge their efforts publicly. In this way, not only do we collectively recognize their contributions, but we also may positively reinforce the inclination of others to amplify their own efforts to serve free flight.

I've used the awards for recognition several times, and you can too. It is important to get efforts that support free flight in front of the committee via the this simple process:

1. Collect identifying information about the nominee(s). This can be found on the website at ushpa.org/awards

2. Select an appropriate award as listed on the website.

3. Complete the nomination form, describing contributions you believe USHPA should applaud, and submit.

Making a case for the nomination doesn't have to be a complicated. A few simple sentences will suffice, writing as if you are waiting on launch and telling someone about what the nominee has done that impressed you. Simple, economic language is best.

Telling the awards committee the story of how an individual or team stepped up to benefit others will make a powerful case. You don’t have to decide if your nomination is award-worthy. The USHPA committee will do so if you put the nomination in front of them for consideration.

Let’s use the USHPA Awards program to its full potential and ensure the light of community-wide appreciation shines on those we see giving a bit extra on behalf of free flight. We all will benefit.

Nominate today. Nominate often. Scan the QR code to begin.

Get the gear that fuels your passion at discounted prices.

Your Pilot or Instructor USHPA membership automatically qualifies you to join. Simply scan the code to get started.

Unlock up to 60% o on top outdoor brands

: It was in February of 1975 that a group of pilots who had been flying the ski slopes in Central Pennsylvania (what is now Tussey Mountain Ski Area) came to check out the Hyner View scenic overlook on a tip from Judy Hildebrand (before she was flying). The group pushed a couple of picnic tables up to the wall of the overlook to create a makeshift ramp so they could launch. Dennis Pagen got the spotlight as the first in the group to launch, “probably because I was the stupidest,” he says. The pilots landed directly out front—across the railroad tracks from our present LZ. Word traveled fast, and the next day a group from Philadelphia came up, found the picnic tables still in place, and flew. An iconic site was born.

Inevitably, a ranger caught the pilots in the act and put a stop to their flying fantasies. In response, the pioneers were first put in touch with the Renovo Tourist Bureau, eventually working their way to the upper echelons of the Pennsylvania Park Service. Initially tentative, the pilots were pleasantly surprised at the enthusiastic reception they received from an agency eager to sponsor a noninvasive activity that would attract visitors (and hence funding).

The next step was securing a permanent LZ. Across the river from launch was an abandoned grass airfield

owned by the Conti family, who operated a bar at the end of the field. They had a friend living on-site who was happy to mow the field, and they allowed camping with easy access to the river. These arrangements were all rolled into the bargain for a very reasonable annual fee (originally free), thus giving birth to a relationship that lasted nearly 40 years.

A great launch with a 150-degree directional window, landing where you camp, a bar you can stumble home from without even needing to check for traffic—is it any wonder Hyner drew people from a 300+ mile radius?

In its heyday in the 80s and 90s, a Hyner summer weekend would draw 200 people, with tents and campfires lining both sides of the LZ and continuing back into the woods. You could spend the whole night wandering from fire to fire, each with a different personality. It was not unheard of for die-hard partiers to see the sunrise.

The phrase “a boo-waa day” was born at Hyner during the 1978 Nationals. In the days before towing, Hyner was an ideal choice for a competition, and everyone came. The Cleveland boys brought a van with only two discernible gears: the low gear would let out a low “booo” which then shifted into high “WAAA!”

So a day featuring weather propitious enough to fire up the van became known as “a boo-waa day.” Though the phrase originated at Hyner, as far as we know, the first exultation of “Boo-waa!” in flight occurred near Blacksburg, Virginia, attributed to Randy Newberry. Now it belongs to the ages.

That van was also a fearsome presence in the bottle rocket wars that raged over the years. People started firing rockets from campfire to campfire, but when the van pulled up and the door rolled back, everyone knew to dive for cover. And then there was the fire jumping, which evolved from the stupid (jump over the fire) to irresistibly stupider (“I bet you can’t jump over that fire while naked”), and a Hyner tradition was born. It developed into an almost programmatic item of the Hyner experience, culminating with 13 naked couples jumping hand-in-hand in 2003.

The “drag races” started in the mid-90s. On some Fourth of July weekend, a group of semi-sheepish contestants emerged from their tents in full regalia—heels, fishnet stockings, makeup—and proceeded to the windsock to start a footrace. Word got around and everyone came to watch; it was a hit. Over the years, the drag races grew to over 20 contestants, categorized

into flats and heels, with the local community showing up to enjoy the show. The tradition continued into the early 2000s.

I made my first appearance at Hyner in the late 90s as an H2 during the heyday of the drag races, knowing nothing of the shenanigans. I had just finished setting up my tent and noticed some folks setting up another tent in the middle of the field, which seemed a strange choice. It was an old army tent with a roof and sides; acetylene gas was quietly being generated inside. Suddenly, a couple of bottle rockets flew towards the lightly closed door, the tent glowed orange, and it jumped 10 feet in the air. I realized I had walked into the Burning Man of the Pennsylvania Wilds.

Sadly, so many of the wonderful characters who helped create the special Hyner magic are no longer with us. But the memories are strong, and you can still hear the stories from Dennis Pagen, Bob Beck, and others. Some of the craziness still endures, even though Hyner LZ has moved from private to state property, dampening the wildness a bit. That move is a story worth telling.

The Conti family owned the original LZ, but when the patriarch died and the kids moved away, there

was an opening. A local real estate speculator gained one-third ownership, which wasn’t enough to give him control, but enough to raise the antennae of the previous Hyner president, Shawn MacDuff. MacDuff researched our new owner and saw the profit motive would spell our eventual doom. But a property across the river was to become available, adjacent to where the first flights off Hyner had landed. In a masterstroke of political maneuvering, Shawn convinced the Nature Conservancy to buy the property and turn it over to the local Forest Service for management. The covenant was that the land would be available for pilots to land, and even camp, in perpetuity. Free flight at Hyner was secure, but the script had to play out. The Forest Service cleared and leveled an LZ for us, seeded it, and commenced mowing.

For years, nothing happened with our old LZ. Eventually, the remaining Conti family wanted out, and when they sold, it was time for us to move to the new LZ, which the Forest Service had been patiently holding for us. After we mowed a starter campground on the new land, the Forest Service graciously agreed to clear brush from a forested portion to make a pleasant shady campground, which we’ve continued to landscape lovingly. They maintain the LZ; we maintain the campground. So far, it’s been a match made in heaven, for they get sent usage fees from the state and appre-

ciate how carefully we maintain the land. That move was eight years ago.

: Now, for Hyner’s 50th anniversary, we want to show off our mountain, new LZ, and camping area (with a river for swimming directly across the neighborhood road). The official celebration is planned for the weekend of Labor Day 2025, but if you can’t make it, we’ll also be gathering over the July 4th weekend, and you are welcome to join us.

What can you expect when you come? Let’s start with the flying experience. The launch is a scenic overlook, which means it’s wide open. It’s a popular tourist site mainly due to the flying, so you are on stage from glider setup to launch: you may as well enjoy the attention. The main launch is a steep slope with WNW to NNW directions available. There’s also a west ramp launch for hang glider pilots.

Paraglider pilots who don’t feel comfortable with the steep slope have a grass pad and gentler slope available for W to SW winds. The LZ is a 3:1 glide and plenty large for experienced pilots, though new H2s will need to practice setting up approaches over a larger field before coming to Hyner. Those from the west who have never flown around trees may feel it’s a bit tight. Paragliders should not have any landing issues. Without a long ridge, you may be scratching for

thermals during many flights. But when Hyner turns on, it’s an unbeatable experience with a river valley as your playground. Even if conditions don’t seem favorable, Hyner is steep enough to get off in light winds from most directions. If you don’t get up, the sled ride from 1,300 feet AGL is beautiful, with plenty of time to check out the river and nearby ridges. On many mornings, the river valley will fill with clouds, with launch poking out above. If winds are not suitable for Hyner, we have sites for the east, north, and southeast within two hours’ drive.

We charge $50 for a tent or camper, regardless of how many are in it (family-friendly), though if a second pilot is included, it’s an extra $25. The flying fee is a monthly membership good for the entire calendar month. Portapots will be on site, the river is available for washing, or you can drive five minutes up the road to a campground and slip them a few dollars for running water and a hot shower. We will cater a dinner on Saturday night during the Labor Day celebration, which is included in the fee. For those interested, a history of Hyner PDF is being compiled by Aron Lantz.

The LZ is not suitable for spot landing contests, and the landscape is too forested for cross country flights (though there have been a dozen over the decades by brave and talented souls). But we may feature a duration contest for fun, with plans to recreate the pilon contest of the 1978 Nationals. And you don’t want to miss the campfires.

Look us up on www.hynerclub.com. Fly-in information is posted and will increase in detail as the date approaches. Our detailed site guide is available for those who register, though you may have to email us to request it.

Hyner is rich in the history of our sport, with incredible views and experiences. Nothing would make us happier than to welcome you to what many of us consider to be our second home.

This article could not have been written without the invaluable input of Dennis Pagen, Bob Beck, Shawn MacDuff, and Aron Lantz. This story has been edited for length. The full-length article and more can be found at the anniversary website: http://www.hynerclub.com/hyner50th.html

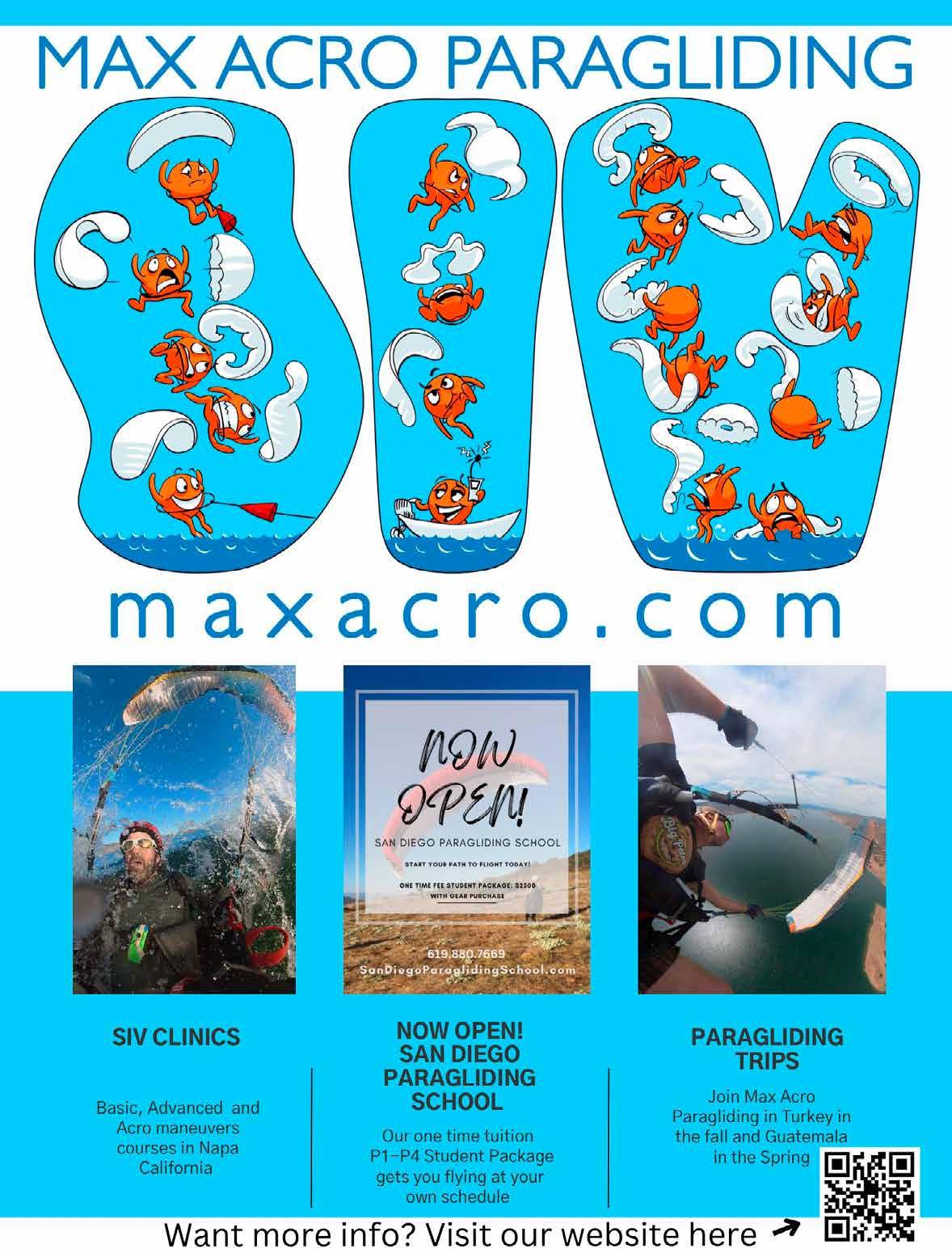

Calef Letorney

Calef Letorney is a USHPA Advanced Instructor who has been teaching SIV since 2017.

: Sage advice is ignored by many, especially while top landing. Flapping—a series of deep brake inputs to create a more vertical descent—is both an effective landing technique and a leading cause of accidents. The platitude “know your stall point” is meaningful, yet it is an incredibly dangerous oversimplification that invites tragedy. In this Armchair SIV, we will discuss the dangers of flapping, techniques for the desired outcome, and the complexity presented by unknown variables before concluding with some simple rules to maximize safety when using this inherently unsafe technique. There’s

significant conflicting advice surrounding flapping techniques, and even more misunderstanding; so, let’s delve into this black art.

“Don’t flap: it’s dangerous!”

This subject is top of mind for me after recently spiraling down to avoid a rescue helicopter after a P4 pilot attempted to flap into a thermic landing zone. The ensuing stall from approximately 60 feet resulted in a loss of consciousness for several minutes, a compound wrist fracture, and a pelvis fracture. Years ago at this same site, I witnessed a master pilot inadvertently spin and then stall while flapping in a top landing, earning a lifetime membership to the Broken Vertebrae Club. There are countless similar stories. Why do we keep flapping, and what can we do to avoid these injuries?

First, let’s discuss the abstinence method. Analogous to unintended teen pregnancy, the only 100% effective way to avoid injury from flapping is to completely avoid the risky behavior. If you master landing approaches, there’s rarely a reason to flap. And if you do find yourself going long on landing, there are almost always alternatives. But as you might expect, preaching abstinence is not particularly effective because, in the moment, flapping seems safer and more convenient than alternatives such as choosing to land in a tree or hiking back up to your car. What follows is a frank conversation about this explicitly dangerous technique because “just don’t do it” isn’t working.

Learn and apply these concepts at your own risk!

If you’re going to flap, do it right. We’re looking for fairly rapid, purposeful, deep brake pumps to bring the glider right to the edge of stall (or actually stalling), immediately followed by a quick hands-up to prevent the glider deformation of a full stall. The

depth, timing, and frequency of the hand pumps can vary based on many factors (wing, weight, pilot preference, etc.). Still, we achieve the desired descent by flirting with stall, which can happen unexpectedly early, making all flapping inherently dangerous.

The safest way to learn to descend by flapping is first to learn your stall point while reverse kiting in various wind conditions. Looking up at the wing, rapidly apply full brakes. When the glider deforms to stall, immediately put your hands up to keep the wing overhead.

The next step is to repeat this exercise forward kiting, not looking at the wing and flapping based on feel. Judging our own ability is particularly difficult when learning a new skill: You might demonstrate and discuss the technique with a mentor or instructor before you practice flapping in flight.

The next and more consequential step is to practice in laminar ridge lift, flapping just a few feet off the ground. In this semi-controlled environment, you can do deep pumps and experience the stall point repeatedly. Master instructor Chris Santacroce reminds us that what’s below you matters, so it’s best to practice above soft sand or snow. If you choose to learn over a firm surface (like at the Point of the Mountain, Utah), you might get banged up. Be careful not to apply these skills to too many different situations, as the stall point changes dramatically and will catch you off guard.

“How do you know you’re approaching a stall?”

This is a bit of a trick question. The most reliable way to identify an impending stall is to watch the shape of the wing. During SIV, we teach pilots to watch the glider throughout the stall. The shape and movement of the wing will tell you everything, but when we’re flapping in a top landing, it’s nearly impossible (and certainly not advisable) to stare up at the wing, so visual cues are not helpful while flapping during a landing attempt. We must rely on feel and experience.

Many will argue the signs of an impending stall are

easy to feel; I find it’s not so simple. Yes, the brakes get harder, but that’s uselessly early, way before stall. The remaining pre-stall indicators we feel are often wing-specific, subtle, and unreliable, as they can change dramatically depending on the underlying conditions.

What about the obvious feedback of brake lines going slack, getting yanked backwards, and feeling weightless? Those all happen post-stall, after your goose is cooked. The takeaway is that, contrary to improving safety, learning the feel of your stall point can embolden pilots to flap in situations dramatically different than the practice environment, and the consequences can prove disastrous.

The challenge is that the hand position of a para-

glider’s stall point changes with the underlying variables. The term “stall point” itself is misleading as it implies a single location, but in reality, there is perhaps a two-foot range of brake positions at which a stall might occur. A few of the underlying variables that change stall point location include: air density, glider design, wing loading, whether you are standing on the ground with a partially-loaded glider, state of glider (dry, wet, sand or snow inside, porous, or out of trim), vectors of pilot and glider movement, and changes in the vector of air movement.

Wings are agnostic to the movement of a homogeneous air mass. Your glider will fly a normal glide ratio and sink rate through the air; it’s our movement in relation to the ground that changes. Still, the turbulent air we fly in is often anything but homogenous. Rapid changes in air movement momentarily affect our angle of attack until the new airmass overcomes the inertia from our movement through the previous airmass.

Turbulence, especially mechanical and thermal, creates the most dramatic instantaneous change to the brake position at which our gliders will stall. Given all this uncertainty, I argue that instead of “know your stall point,” we are better served by “know that you don’t know your stall point”. Regardless of practice, our stall point in that moment remains a mystery that necessitates ample margin for error.

In strong turbulence, stalls can occur with just a few inches of brakes applied. This was recently illustrated to me when a student asked for my analysis of his big collapse video. I watched the video and quickly paused to comment, “This is a stall; there was no collapse. Look at the tips blowing forward: this only happens when the glider stalls and flies backwards.” He was in disbelief, arguing he could not have stalled as he was hardly pulling the brakes. I asked another SIV instructor who provided the same analysis.

The student then recounted the intense turbulence that preceded the stall, and we had a great conversation about the factors that change the hand position, which may cause a paraglider to stall. Later, the pilot sheepishly admitted that two other instructors had

Factors Look out for these things that can surprise you while flapping.

• Changing your glider: your new glider may stall very differently

• Changing your harness, especially with differing carabiner height

• Turbulence

• Wrap vs. no wrap

• Big winter gloves, especially with wraps

• Wing loading: the smaller the load on a particular wing, the smaller the usable brake range

• Change in density altitude

• Condition of wing: trim and porosity. Gliders can go out of trim and stall earlier. We’ve seen brake lines shrink five inches just from kiting in the morning dew

The list goes on and on. Use your imagination and keep an ample safety margin.

identified the incident as a stall. He was shopping for an instructor to support his collapse theory, perhaps to avoid accepting that a modern EN-B paraglider can stall when normal brake inputs are applied to abnormal situations.

Expert paraglider and aerospace engineer Jason Wallace explained it best: “Aerodynamically, stall comes primarily from wing angle of attack and airspeed. Hand position only influences those variables.” If turbulence and/or other factors have created an abnormally high angle of attack, any amount of brake input only puts us closer to stall. Fortunately, this student stalled with ample altitude, and the recovery of his wing was uneventful. Conversely, flapping does not provide this safety margin: we’re flirting with stalls very close to the hard stuff.

Never flap higher than the height at which you’re willing to stall and fall from.

Prepare to PLF with your feet down and extra forward-lean BEFORE flapping. Your acceptable

stall height should assume a feet-first landing, but stalls yank us backwards. This makes it challenging to land feet-first even when starting from an upright position (and seemingly impossible from a seated position). Landing on your back from just a few feet can be disastrous, so don’t be lazy: lean extra far forward before flapping. Bonus: the additional drag from an upright posture reduces glide ratio and helps our goal of landing shorter.

: The above rules are only as good as our consistency of adherence to them. The false imperative of “needing” to top land leads us astray as we overestimate our flapping abilities and underappreciate the likelihood and severity of adverse outcomes. Indeed, this past season I made precisely this mistake. “Needing” to top land to help novices launch, I set up a fine approach at my home site only to find thermic lift on final. Fearing I’d not get a second chance, I decided to break my rules and force it in. Being dramatically too high inspires the most aggressive

of flapping, and my wing horseshoed into a stall at about 30 feet up. With hands up and a double dose of patience, I prevented the worst outcomes, falling vertically until the glider dove. The ensuing recovery arc worked out perfectly for a smooth top landing that earned applause from the onlookers. Feeling like an absolute idiot, I owned my mistake lest anybody attempt to emulate this reckless behavior. I noted this incident in my logbook and reflected on how, even 20 years into my paragliding career, I still occasionally make serious errors.

My thoughts on this controversial and divisive topic continue to evolve because, like much of paragliding technique, there are no measurably correct answers. With so much uncertainty surrounding this topic, many pilots and instructors will have different opinions. Disagreement on these concepts is great because it’s the discussion that matters most as we work together to move this topic from taboo to a known, discussed, and calculated risk.

Soft landings!

: The enveloping roar of our helicopter sank into a silence pierced only by the shrill echoing calls of a half-dozen kea. These cheeky mountain parrots are a curious bunch—four of them were pecking at my shoes, whilst behind me, several more had a go at my backpack as I awaited the arrival of another load of speedflying pilots.

I was a long way from my newly adopted home of Boulder, Colorado. Even at this alpine altitude, the air felt thick and humid in comparison. What could pull me from my mountain paradise, where spring skiing was well underway? Beyond the joy of reconnecting with old friends, I was eager to reunite with the community of human-powered flight advocates and enthusiasts who’d helped shape my passion for these sports. It had been nearly two years since I broke my ankle on a bad landing, and I was keen to get back up into the mountains where it all began. My first adventure with human-powered flight took place when a friend offered to take me on a tandem flight from the top of Mount Plenty in the Arthur’s Pass region of New Zealand’s South Island. Returning to the birthplace of my pursuit of flight, and doing it alongside familiar faces, felt like the perfect way to leap back in after my injury.

After narrowly missing the Magic Land festival by just a week during my last visit to New Zealand, and hearing dozens of flying friends saying how much fun they had, I was determined to join the crew for the next time around. This annual gathering, dreamt up by epic adventure couple Dan Pugsley and Vicki Zadrozny, lasts for a whole week, with Acrofest qualifying rounds, sky diving and speedflying boogies. Hike-and-fly missions started on Monday and continued through Thursday, when the festival site officially opened to the public and the food trucks and music performances joined

the mix. With a full roster of adventure-sports events planned each day and a mix of music and performances planned for after the sun went down, Magic Land promised heaps of fun, excitement, and good old-fashioned merriment.

I serendipitously found myself between apartments in March and April of 2024, and I packed up to attend the events. With my overstuffed bag of flying gear and two smaller bags for camera gear and clothes, I was off on another adventure. Landing in Christchurch after a full night’s sleep, I was ready for action; the weather, however, was not. The next day, after meeting up with a few friends, I quickly found myself at Taylor’s Mistake, one of New Zealand’s most popular flying sites and the place I first learned to fly.

Wanting to get a few flights under my belt before heading down to Wanaka for the speedflying boogies, I had driven to Taylor’s for some soaring on the big wing and, once the wind died down, a few sledders on my speedwing. I also went on a mission up Mount Plenty with my mate Matt, who had been there for my first tandem flight as well as when I broke my ankle. It was a beautiful morning hike straight up the mountain, and it took a bit of exploration to find a takeoff with the wind in our faces.

After getting this last flight under my belt, I was ready to set off south, winding through the stunning landscapes of the South Island. I stopped near Twizel, where the skydiving boogie was taking place, but in the morning, the pitter-patter of raindrops on my rooftop tent encouraged me to continue driving south towards Wanaka. The next morning, I was picked up shortly after 5 a.m. by Mal Haskins, who was in charge of organizing the speedflying boogie out of the Mount Cook Airport. Driving mostly in the dark, we finally arrived

around 7 a.m. and found the parking lot already full of fellow speedfliers, their petite backpacks lying in little piles around the vehicles.

The view looking up towards Mount Blackburn, our intended drop-off destination, was picturesque. However, the peak was completely enshrouded in clouds. The first crew went up in the helicopter, reporting beautiful views but no break in the clouds. The crew of seasoned locals was confident that the sun would break through and we would be clear to fly before the thermals began. As the waiting continued, crews drifted off to find other hike-and-fly destinations. However, as this would be my first ever flight in a helicopter, I was keen to stay and roll the dice.

My patience paid off. I went up with the first crew and did my best to capture the experience on film whilst my jaw lay squarely on the floor. I’ve flown hundreds of times under my own propulsion, but sitting in the passenger seat of this whirling beast of a machine was unlike anything I’d yet experienced. If my sensory organs weren’t already overloaded, the view of the ragged mountainside colliding with the vibrant colors of Gorilla Stream as it joined the Tasman River was simply stunning.

The machine (how the crew referred to the helicopter) swayed back and forth like a pendulum suspended by a tree limb in the wind, and before I knew it, we had set down on that little mound of crushed rock. It felt like a place one would only hover over for a SAR mission, not some place where we’d set down to drop off a dozen or so speedwing pilots. The engine kept spinning, a

caustic assault on my ears, as the rotors fought to keep us stationary while we all shuffled out.

As the helicopter disappeared around a ridge, a silence set in as one can only experience on mountaintops. The world around me dropped off in all directions, and I had to catch myself to keep from stumbling down the side of this very steep mountain. There was little margin for error on this quite committing takeoff, and I was glad to have listened to my instincts to bring my camera bag instead of my flying kit on this round.

The pilots took off one after the other—due to the steepness of the takeoff, they were airborne in just a couple of steps. Everyone was keen for a second round, so when the heli dropped off the next crew, I jumped back onboard for a ride to the landing zone near the mouth of the Gorilla Stream to capture the tail ends of their flights.

With two rounds of flights complete, the crew headed back towards Wanaka for a solid meal and a good night’s sleep, with hopes of a second day of heli-adventures on the cards for the next morning. In the morning, there were five full loads of pilots queued up for the adventure at 7:30 a.m. I traded my camera bag for the speedwing, this time intent on flying down with that first load.

The views from atop Coromandel Peak were breathtaking as the group of primarily speedflying pilots unloaded from the heli. One after another, they lined up along the ridge, watching with excitement as the seasoned heli pilot dove down over the ridge on a trajectory similar to one of the speedwings themselves. As the final load emptied, the thunderous assault of the rotors calmed, and silence blanketed us once again. It was now our turn to fly down that same couloir, with nothing but the sound of our whistling wings and whoops and hollers as we carved our way down the mountain. After this exhilarating start, the rest of the day was spent at the local paragliding spot, Treble Cone (TC).

The next day was rainy and proved to be a good rest day, and even hike-and-fly adventures out of town ended in hikes back down. The evening treated participants to film screenings, including one by Rick Neeves about

last year’s Magic Land, as well as a touching film called Being Human, about the loss of a pilot and his partner’s determination to fulfill their dream of performing aerial silks from a tandem paraglider. There was also a chat with prominent mountaineer and pilot Nathan Longhurst about his recent accomplishment of climbing and flying the 100 tallest peaks in New Zealand in just 103 days. The night was capped off with music and dancing for those looking to extend their merriment until the wee hours.

On Friday morning, the first official day of the festival, I decided to link up with my old mate, Jamie, and head out for a few laps at TC on my speedwing along with another group of keen pilots. Some of them had been training with Jamie at his speedflying school (Jamie’s

Speedfly School) all week, so while I was shaking off the cobwebs, everyone else was positively ripping. However, I quickly found my groove. For the first time in nearly two years, I broke through the fear and moved beyond my deep, intentional breathing at landing. Finally, I let out a yelp of joy upon touchdown! The fear I’d felt since my accident a couple of years ago had finally been replaced by joy, and a grand smile broke across my face. I was back!

After seven laps at TC, I was ready to go back to camp. Upon my arrival at the camping area, I found most of the level and lake-view spots already filled with tents and vehicles, so I was off on the hunt for a new level spot before the sun went down. The evening was filled with tales of the day’s events. Stories ranged from

A group of cheeky Kea, New Zealand’s indigenous mountain parrot, atop Mount Blackburn, playfully distract me while another two sneakily attempt to open my backpack behind me.

a HUGE New Zealand flag unfurled behind a skydiver to paramotor candy drops to the first of two XC workshops.

As the sun set, artists performed a series of aerial silk demonstrations right outside the main tent. The performances highlighted their strength and beauty, which was balanced perfectly by the golden glow of the setting sun. A host of DJs and performers shut down the night. What energy hadn’t been spent earlier that day was completely consumed on the dance floor. Needless to say, sleep came easily that night.

On Saturday morning, more than 60 people gathered near the main tent, ready for the mandatory helicopter briefing. In perfect time, as the briefing ended, the unmistakable roar of an approaching heli broke the stillness of the morning mountain air. Twelve heli-loads later, 60 pilots were joined by at least another 15 who

had hiked the steep, unmarked path to the top. As best we could manage, we pilots gathered on the peak for a quick photo, then dispersed to lay their wings out on the numerous takeoffs.

Several speedflyers had each thrown $10 into the pot to see who could land on the raft by the beach. I didn’t see who made it, but I did see a lot of splashes from a distance. I opted for a safe and dry landing on the LZ, but not before snapping some photos of the wet wing graveyard for all that went in the drink.

Once everyone had had their opportunity to attempt the raft landing, seasoned pilot Jamie Lee set up to perform a swoop and a ground loop above the lake, with the goal of landing on the raft after the maneuver. The crowd was in awe as his wing screamed towards the water. He abruptly climbed back in the air and rotated fully in a ground loop before coming back down close

top left Group of pilots gathered atop Coromandel Peak before the Magic Land Fly In.

top right Jamie Lee lands on the raft after a swooping ground loop above the lake on Glendhu Bay.

middle left The crowd watches from the beach as people fall, fly, and maneuver in the sky above them at Glendhu Bay.

middle right Paragliding pilots taking off from Coromandel Peak above Wanaka Lake.

bottom left Karolina Sikora performing on the trapeze at Magic Land.

bottom center Prue Beams beaming after an awesome morning lap of Treble Cone on her speedwing.

bottom right Silver Beats plays a laser harp at Magic Land Festival.

bottom lower right Gordie Oliver (of Buttermere Bash in the UK), Alan Swann, Dan Pugsley, Cindy Swann, and Vicki Zadrozny at the closing night party at Magic Land 2025.

enough to tap his heels on the water. With what seemed like nowhere near enough speed, he somehow managed to glide all the way to the raft, fully stalling to bring his butt into contact with the edge, then bouncing up and collecting his wing before it could get wet. His bounding heel clicks with wing bundled safely in hand sent the crowd off into a second cacophony of cheers.

BASE jumpers followed, dropping from tandem paragliders above the lake, many of them also attempting the raft. With wild accuracy, wingsuiter Boris Adamov, roared through the sky above the lake, deploying his chute and then dropping ever so elegantly onto the middle of the raft.

Stefani Henderson danced thousands of feet in the air on her aerial silks beneath the tandem canopy of Andres Contreras. The performance concluded with Andres dropping her elegantly on the raft, and then cheekily dragging her into the water to roaring applause.

The Acrofest finals concluded the events over the water that day with infinity tumbles, helis, and SATs, all with attempted wingtip drags and landings on the raft.

Adequately drenched in both water and sun, the merry festival goers meandered back up the shore to the

main tent, where a silk aerialist once again took to the stage. As the setting sun cast a golden light, the music cranked up a notch and the costumes came out to party. Live acts mixed with DJ sets, and laser lights lit up the night sky. I crawled into bed shortly after midnight, but stories of others painted a picture of wonderfully wild festivities into the wee hours of the next morning. Designed as an opportunity for adventure sports lovers to get together and cross-pollinate, Magic Land was a success. Pugsley and Zadrozny managed a tight ship full of fun and adventure. Even with so many enthusiasts in the air and many more on the ground enjoying the action and party, the event went off without any major incidents, and everyone left eager for the next festival. In keeping with a general theme of leaving the place better than we found it, Leave No Trace was the name of the game, and the space was improved by several generous native tree planting worker bees leading up to the festival.

To find out more about the next festival in March 2027 (plenty of time to make plans), check out the Magic Land website: https://www.magiclandfestival. com/ and follow along with the action on Instagram at @magicland_adventuresportsfest.

“The meaning of life is to find your gift. The purpose of life is to give it away.” – Pablo Picasso

: During the last two weeks of December 2024, we had one tragic fatality and three serious accidents within our club, the Arizona Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association. The fatality was heartbreaking and sent shockwaves through our community. When it happened, I was in Brazil, pushing my thermaling and XC flying limits. The accidents drove me to reflect upon my progression as a paraglider pilot and more deeply consider the challenges and rewards of the sport.

I love facing these challenges in this relatively new passion of mine, and I want to keep improving in the aspects that are difficult for me. However, I continue to face a small problem: I hate bumps. In the aftermath of the accidents in my community, I keep thinking about this. How do I deal with my fear of bumps?

More specifically, I fear the invisible forces in the air that make my wing “thwap,” “thump,” “rustle,” “flap flap” or potentially fold mysteriously in half and send me into an autorotation. I don’t like bumps in airplanes either, especially when I look out the window and see the wing wobbling and down. I really don’t.

Unfortunately, when I learned to fly nearly four years ago, I also learned that paragliding in Arizona comes with bumps—a lot of them. Even a supposedly simple beginner flight off Merriam Crater near Flagstaff, Arizona, can put me in a 1,000 fpm thermal right into the zone of thwumping and thwapping I dislike. The first time I hit that turbulence, it was all big ears and speed bar to get out of it; this only incurred the laughter and admonishment of more experienced pilots watching me fly away from lift. Years later, I now love thermals and that feeling of smoothly turning in circles, getting right into the thwapping and thumping zone. I’m finally comfortable enough to push it a bit so that my wing tips chatter now and again. I’m also learning that the bumps are not only about the invisible forces of the air but also about my skills as a pilot. It helps to meet

more experienced pilots who dislike bumps and feel precisely the way I do about these invisible forces abusing our wings. They also point out that the fear diminishes with experience. Everyone says, “You’ve got to build bump tolerance.”

Part of the magic of this sport is that I’m continually learning. I love it more and more as I improve my skills. The mistakes I make are challenges for me to work through rather than indictments of my abilities as a pilot. I know I can fly, and sometimes I even fly well. I feel excited rather than scared by the challenges I continue working through. Though there have been plenty of experiences, one particular flight in Arizona earlier in my career exemplifies my gradual

“mistakes I make are challenges for me to work through rather than indictments of my abilities as a pilot.”

building of bump tolerance.

Mingus Mountain has a spectacular launch with almost 4,000 feet of relief between the launch and the LZ. Back then, I’d already flown from Mingus half a dozen times or so but hadn’t had the kind of stellar thermal flight folks talk about, probably because I was actively avoiding such a flight. I knew I hated bumps, and Mingus has a reputation for rough air.

That day, I launched into an elevator ride straight up at about 800 fpm and then headed left to the house thermal. Instead of cutting and running by pushing straight out and hoping that I could get out of that scary ride, I let it take me up and turned relatively smoothly in it. When I got into the thwapping and thumping space, though I wasn’t thrilled, I stuck with it.

I tried to relax and breathe deeply, remembered lessons I’d learned in my SIV courses. Most importantly, I saw my friends flying above and around me and not spontaneously falling from the air. I turned and got to the top of the lift and cruised back and forth for a while. I was elated and realized I’d crossed a serious threshold in my flying comfort. Upon landing, the first thing I exclaimed was, “I’m building bump tolerance!”

The author unpacking at launch, in Sapairanga, Brazil. Photo by Ederson

I still don’t like bumps, but I’ve learned I can fly through them without serious repercussions. My fear of bumps has diminished gradually, and I’m trying to trust the active piloting skills I have acquired. In Brazil, the thermals were mild compared to Arizona or Utah, and I found myself in this blissful state of understanding of what thermal flying is “supposed to” feel like. Of course, the Brazilian air doesn’t always stay free of bumps, just like the Colombian or French air I’ve flown. But these relatively gentle experiences have helped me gradually build my bump tolerance. Upon returning from each destination, I find I can fly higher and further in the Arizona air. I am beginning to comprehend that it simply takes time—hours in the air and on the ground kiting—to build the muscle memory and nerve responses that enable me to effectively fly through bumpy air without fear. My SIV experiences have also helped immensely. Beyond building the skills necessary to handle the kind of aerial disaster that we all fear most, SIVs have helped me understand the fundamental stability of my wing. Of course, I still struggle at times. Even just late last year, I found myself pitching and rolling in some tough air above Monroe Peak in Monroe, Utah. I inevitably pushed out, hoping desperately for some calmer air. Despite not hanging with it that day, I reminded myself, “I’m building bump tolerance.” And it’s true: I am. My mind knows that I’m safest in the air, especially up high, but it takes time for this rational knowledge to become an emotional understanding that allows the joy of flight to flow through the bumps. With each flight, I build this tolerance. Whenever I use my rational brain to keep going and overcome my emotional instinct to turn and flee, I feel like I’m progressing. Alas, accidents do happen in this sport. Thankfully, our club is very open about sharing information so we can all learn and grow as pilots. Some can be tragic, but they all lead to reflection about this sport that we love. For me, that reflection yields an understanding that with more time and gradual progression, I will significantly expand the joy that I find in free flight.

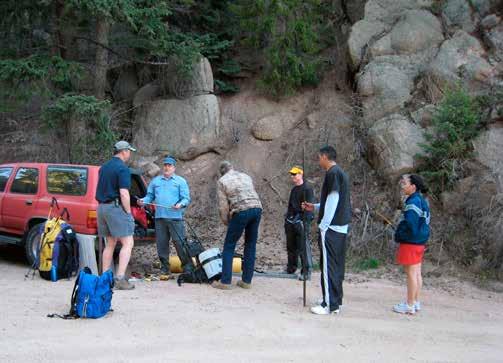

: No one, even the most committed hang glider pilot, would argue if I said that paragliding is more convenient than hang gliding. So I was surprised one afternoon in the LZ when a pilot told me he’d recently returned to hang gliding after decades away because he found paragliding to be, in his words, more limiting.

A wing that you can throw in a backpack sounds like the most limitless way to fly, but it turns out that quite a few paraglider pilots have their reasons for picking up or returning to hang gliding. I spoke with six of these pilots: John Bartholomew (the pilot in the LZ), Chris Gulden, Bonita Hobson, Jarred Bonaparte, Reavis Sutphin-Gray, and Chris Santacroce.

Will the next one be you?

I already paraglide; why would I want to hang glide? Jarred Bonaparte has thousands of hours on paragliders after flying them since 2013.

But the Northern California pilot wanted to fly hang gliders for high-wind days, big-mountain air, and XC flights. “I just thought to myself, there’s less to be concerned with in a hang glider when I’m flying in nasty, turbulent air,” said Bonaparte, who did a training hill lesson a few years ago and is now an H3. “That’s my next step: pushing the thermal flying well beyond what I am currently comfortable with on a paraglider.”

He added that hang gliders are, simply, fun. “It feels more like you’re flying your body than a paraglider does,” Bonaparte said. “When I fly my paraglider, I feel like I’m flying with the birds, but when I fly my hang glider, I feel like I am a bird.”

Chris Gulden, an instructor with Eagle Paragliding in Santa Barbara, California, who started hang gliding

in 2023 on the same hill where he teaches paragliding, agreed. “Because your center of gravity is closer to the wing on a hang glider, I would say the sensation of flying a hang glider can feel more dynamic and fun than it is on a paraglider,” Gulden said.

John Bartholomew, a Southern California pilot who flew hang gliders in the 80s before moving to powered aircraft, started paragliding a few years ago and has

met many of his goals. “With paragliding, I’m where I want to be: I’m flying a two-liner and I can get big flights if it’s a good day,” he said. But while paragliding in the Owens Valley last year, Bartholomew had a realization. “The whole time I was flying, I was like, ‘I just wish I was in a hang glider,’” he recalled. He bought a used hang glider for $1,500 and has been flying regularly ever since, aiming to cover more ground, fly faster, and have improved handling in turbulence.

Windy and turbulent XC flying, especially in the Owens, has also drawn other paraglider pilots to the speed and rigid structure of hang gliders. On a summer 2020 trip to the Owens, Reavis Sutphin-Gray found himself driving more for his hang gliding friends than doing his own flying. A few months later, he began taking hang gliding lessons. Now on an intermediate hang glider, he plans to choose the wing for windy ridge soaring days and, eventually, for flying big-mountain convergence lines and long routes in the Owens. “I hope to use the performance of a hang glider to map out difficult sections of routes that I’ve been attempting on paragliders,” he said.

Gulden shared a similar story. “There are a lot of days out there in the desert or in the Owens where I just wouldn’t want to be flying a paraglider, and that made hang gliding a natural progression for the types of sites, conditions, and times of year that I wanted to continue to fly,” he said.

Adding the wing type also opens up the option of fly-

ing hang glider-only launches like Yosemite in California and Makapu’u in Hawaii, a goal for several pilots I spoke to. But when it comes down to it, it’s simply a way to help you fly in a wide range of conditions.

“I’ve always said, ‘I don’t care how I’m in the air, as long as I’m in the air,’” said Bonita Hobson, a tandem paragliding instructor with Sky Ride Paragliding in Northern California who earned her H3 in 2022 alongside Bonaparte, her partner.

How hard is it to learn? Chris Santacroce, a former Red Bull athlete and owner of Super Fly Paragliding in Utah, regularly introduces paraglider pilots to hang gliding at the Point of the Mountain. Santacroce picked up hang gliding shortly after he learned to

“hang gliding is probably easier than you think, especially coming from paragliding–but don’t neglect the basics.”

paraglide in the 90s and says that 80% of their skills transfer. “You did all the work for paragliding, and then you didn’t know it, but it turns out that you’re also perfectly tuned for hang gliding,” he said.

“I was surprised at how easy it was,” said Sutphin-Gray, who soloed a hang glider off the mountain after only a few days on the training hill, later flying for three hours on his first hang gliding thermalling flight. “A lot of my paragliding experience translated to understanding thermals and launch cycles, and most of the learning focused on the differences in the controls and the behavior of the aircraft.”

Skills like ridge soaring and landing approaches also felt familiar on a hang glider, according to the pilots I spoke to. Still, a few things might be tricky for some people. “The biggest thing that I would do, even though [my instructor] warned me not to, was

cross-controlling and leaning my body weight to try to steer like you would with a paraglider,” said Gulden. “That was a challenge that was fairly easily overcome after a couple of days of working on it, because all those mechanical things are usually fixable.”

A few pilots noted that although learning to paraglide tends to be easier than hang gliding initially, that advantage quickly subsides. “I think mastering paragliding is radically more [difficult] than mastering hang gliding,” said Bartholomew.

On hang gliders, “there are these axes of control, and once you understand what each one does, you can quickly figure out how to make the glider do what you want,” Bonaparte explained. “Versus on a paraglider, you’re dealing with a pendulum and there’s a less controllable aspect…you have to figure that out before you can progress with a lot of things.”

So, hang gliding is probably easier than you think, especially coming from paragliding—but don’t neglect the basics. “It might be easy for a paraglider to think that they can skip steps because they already know the air,” Hobson observed. “But my advice would be not to skip those fundamentals….so you don’t get scared or hurt.”

Still, have fun. “Get excited because you’ve been training your whole life for this,” said Santacroce. “Get ready for some things to come really easily.”

But hang glider landings seem scary.

“Everyone expresses how fearful they are of landing when they watch hang gliders, and it’s very different than paragliders, but still it’s very manageable,” said Bartholomew. “I’ve had some crazy rough landings paragliding too.”

“Just like anything else, practice makes better,” Gulden said. “You see a lot of pilots out there who nail their landing on a hang glider every single time,” he continued. “If you’re dedicating as much time at the training hill on a hang glider as when you were learning to fly a paraglider, your landings will be just fine.”

For Hobson, landing with energy when speedflying and powered paragliding transitioned naturally to hang gliding. “So I was landing [my hang glider] with a lot of speed from the beginning, and that was just really fun for me,” she said.

Bonaparte agreed. “To me, the landing of a hang glider, in terms of speed perception and flare timing, is very similar to a speedwing,” he said. While he said he’s still working to perfect his flare timing on no-wind hang glider landings, Bonaparte noted that conditions make a difference. “I have found across the couple hundred flights that I have that when you do have just a little bit of wind, 5 miles an hour, it’s actually very easy to land a hang glider,” he said.

Don’t hang gliders take an hour to set up?

(No.) Though it can be slow your first few times, it can go pretty quickly with practice. “The more you do it, the faster it is,” said Hobson. “I’ve watched experienced pilots put the whole thing together in nine minutes flat.”

“I’m not going to say that it’s just as convenient as a paraglider, but it’s not that inconvenient,” Bonapar-

Jarred Bonaparte ground handling (kiting) before launching at Fort Funston in Northern California.

te said. “In full transparency, there have been times where…it takes me as long to untwist my risers as it does to set up a hang glider.”

For Gulden, “Given how persnickety I am when I fold up my paraglider, if I’m current on both aircraft, it probably doesn’t take me any longer to break down a hang glider than it does to fold up a paraglider.” And since he prefers to arrive at launch early anyway, he said the slightly longer setup time with a hang glider didn’t change anything for him.

Transportation is more complicated, but the pilots I spoke to said it was worth it to expand their flying options. “Transport is a paragliding win, but as soon as a vehicle is set up [with a rack] to handle hang gliders, it’s not that big of a deal,” said Bartholomew.

For some paraglider pilots, flying a hang glider doesn’t even change their XC transportation plans.

“Flying a lot of remote areas, I’m just not the type of person who wants to rely on hitchhiking…so we’re hiring a driver for a big paragliding flight most of the time anyway,” said Gulden. “That said, I know some hang glider pilots who will stash their glider on the

side of the road and then just go back for it later, so there are workarounds.”

Which wing type is safer? As with paragliding, hang gliding can be as safe as you make it, and there are pros and cons to both wing types. The advantages of hang gliding include the ability to fly in stronger conditions, essentially no risk of collapse in the air, and an external frame that can help absorb the impact in the event of a hard landing or crash, among other benefits.

Like paragliding, hang gliding has come a long way since its early days. “I was around in the late 70s when people were just dying right and left in hang gliding… but the modern single-surface hang glider is so much safer than anything flown back in those days,” said Bartholomew. “Personally, I think hang gliding’s one of the safest avenues. A paraglider on a big day can just go away, no matter who you are.” He added that the reserve throws he’s seen most likely would not have happened on hang gliders, where most pilots never need to use their reserve throughout their en-

tire flying career.

Several pilots noted that hang gliders can give you less to worry about in the air. “For me mentally, there’s less of a workload on a rigid wing,” said Bonaparte. “I don’t really ever think about my controls when I’m hang gliding, whereas with paragliding, I think about it a lot, especially if I’m taking big hits or collapses,” Bartholomew added.

Flying either wing involves risks, and the pilots emphasized the need for maintaining currency on both wing types. “I think it’s important to…put in some months or some really consistent time to get mastery,” Santacroce advised. Whether on hang gliders or paragliders, he said, “If people just dabble, then if they take big breaks, when they come back to it, they might not quite have what they need depending on the moment.”

Why try something new? “Treat yourself,” said Santacroce. “Get ready to be really happy that you just tried some other form of free flight, and you might find renewed enthusiasm for foot-launch flying.”

While there are risks involved with learning a new wing type, they may balance out or even outweigh your risks as an intermediate or advanced pilot. “A lot

of people, if they’re going to be in paragliding for a while, are probably going to ramp it up as time goes on—do more cross country, fly a bit more aggressively,” Santacroce explained. “And if you switch to a different aircraft, then you can just fly at the beginner level for a handful of years, the intermediate level for a handful of years, and you’ll fill another 10 years without having to up the intensity and the risk.”

The pilots I spoke to have found learning to hang glide both fun and rewarding. “It was cool to be a beginner again,” said Sutphin-Gray. “I got to a point in paragliding where the gains in skill and performance were incremental, so it was exciting to be on the steep part of the learning curve with the hang glider, having the perspective of thousands of paragliding hours.”

“When I’m on my paraglider, it’s like I need to be doing something, whether that’s going somewhere or doing aerobatics, because just floating in my paraglider doesn’t really bring me joy at the moment,” said Bonaparte. “It may just be the stage I’m at in my hang gliding experience, but I find myself enjoying just being in the air.”

“And,” he added, “it’s silly fun flying like Superman.”

: As the fall winds down, most pilots living in the four-seasonal areas of the U.S. dream of one last bout of warmth, sunshine, and good flying before the winter sets in. These ingredients all came together this past November in southern California at the 4th annual Santa Barbara Fly-In for Female, Trans, and Non-Bi-

by Liza Verzella

nary Pilots, attended by nearly four dozen hang glider and paraglider pilots along with a supporting entourage of mentors, safety crew, organizers, and volunteers.

This event (and its three predecessors), was organized and mentored by veteran paraglider pilot Sarah

Lockwood. Lockwood’s concept for this gathering is “to create a safe and supportive space for pilots to expand their skills, build community, and connect with mentors.” As an attendee and mentor, I can firmly attest that these goals were well achieved, all within the realm of unadulterated fun.

One might ask: why do we need a separate event just for the ladies? What is the importance of such a gathering, and why do we need to dedicate resources to increasing the number of women pilots? Don’t we already live in a fair society where everyone receives equal treatment?

Based on a recent survey sent out to female pilots by the USHPA Women’s Committee (see Julia Knowles’s article “Calling all USHPA Female Pilots” in the Oct-

All we need is a hacky sack. From L to R, mentors Lisa, Kari, and Summer find the joy in para-waiting.

Dec 2024 issue of USHPA Pilot), the clear answer is no, we’re not there yet. Comments from more than 250 pilots who completed the survey show a large percentage have experienced discrimination or poor treatment at flying sites. Knowles notes in her article, “While respondents generally feel supported, over 60% reported experiencing and/or observing sexism (both overt and subtle) or microaggressions within the flying community.”

One example of this type of discrimination happened on the second day of the Santa Barbara event, when a male pilot on launch loudly interfered during a well-handled textbook emergency response situation by calling the event organizer “emotional and overreactive” while she was on the radio coordinating with Search and Rescue. These impactful comments were not only infuriating to the organizer but also a dangerous impediment to the emergency at hand. (Said pilot later apologized to the entire group in the LZ for his interference and expressed his lapse in judgment.)

The Lady Birds gatherings are just one example of concerted efforts to shift this tide.

Knowles continues, “An overwhelming positive theme that arose from the survey was the value of women-specific spaces. From fly-ins to group chats to clinics and beyond, these environments allow female-identifying pilots to learn with a (female) cohort.” Another survey result showed that participants were much more likely to attend a female-specific event, including fly-ins as well as ground handling, thermalling, and beginner XC clinics.