University of Richmond Students Co,rdially Invited to

University of Richmond Students Co,rdially Invited to

(NINTH AND GRACE STllEETS-0PP08ITE CAPITOL SQUARE)

REV. BEVERLEY D . TUCKER, JR., D. D., RECTOR

SUNDAY SERVICES

9 :45 . A. M.-Sunday School

10 :00 A. M.-Bible Classes

11 :00 A. M.-Morning Prayer and Sermon

8 :00 P. M.-Evening Prayer and Sermon

Vested Choir of 40 Voices With the Following Soloists:

Tenor-Joseph Whittemore Soprano-Mrs. Frances W. Reinhart

Bass-Norman Call Alto-Mrs . F. Flaxington Harker F. Flaxington Harker, Director and Organist

• • •

ST•

PAUL'S is the historic "Church of the Confederacy," referred to by Mrs. Jefferson Davis as "The West• minster Abbey of the South." Pews occupied by President Davis and General Robert E. Lee are marked by silver tablets. The memorials to Confederate leaders and others are among the most beautiful in the entire country. A liberal Christian message, for thoughtful and forward-looking young men and women 1s preached from its pulpit.

• • • MAKE THIS YOUR CHURCH HOME WHILE LIVING IN RICHMOND

Prices Arranged from $35 to $50

SPECIAL DISCOUNTS TO STUDENTS

708 East Main Street

1. Richmond College, a College of Liberal Arts for Men.

2. Westhampton College, a College of Liberal Arts for Women.

3. The T. C. Williams School of Law, a Professional School of Law, offering the Degree of LL. B.

4. The Summer School. W. L. Prince, M.A., Director.

W. L. PRINCE, M. A., DEAN

Richmond College for Men is an old and well-endowed College of Liberal Arts, which is recognized everywhere as a Standard American College. Its degrees are accepted at face value in the great graduate and technical schools of America. Its alumni are so widely scattered through the nation that the new graduate immediately joins a large and friendly group of men holding positions of power and influence. The College occupies modern and well-equipped buildings, on a beautiful campus of 150 acres in the western suburbs of Richmond.

MAY

LANSFIELD KELLER, PH. D., DEAN

Westhampton College for Women, co-ordinate with Richmond College for Men, is housed in handsome buildings on a campus of 140 acres, separated from the Richmond College campus by a beautiful lake of about nine acres. All degrees are given by the University of Richmond, and those conferred on women are, in all respects, equivalent to those conferred on men. While the two institutions are co-ordinate, they are not co-educational.

J. H. BARNETT, JR., LL. B., SECRETARY

Three years required for degree of LL. B. in the Morning Division, four years in the Evening Division. Strong faculty of ten professors. Large Library. Moderate Fees. Open to both Men and VJ,;imen. Students who so desire can work their way.

For catalogue, booklet, or views, or other information concerning entrance into any College, address the Dean or Secretary.

F. W. BOATWRIGHT - President

FALL (Poem)

J. W. Kincheloe, Jr. 4 Sketched by Lloyd Caster

"AN' EvEN DE BLUE JAY HAD TO LAUGH" (Short Story), Eugenia Riddick 5

THE VIRTUES OF A CHINA DoG (Essay) . Catherine Branch 11

GOLDEN 90's-PLATINUM 20's (Short Story) . .

GRAYLANDSTREET EAST (Short Story)

Miss VIRGINIA'S KINGDOM (Sketch)

THE UNPARDONABLESm (Translation)

THE FLOATING SPAR (Short Story)

MARSH GAs (Short Story)

No

(Sketch) . .

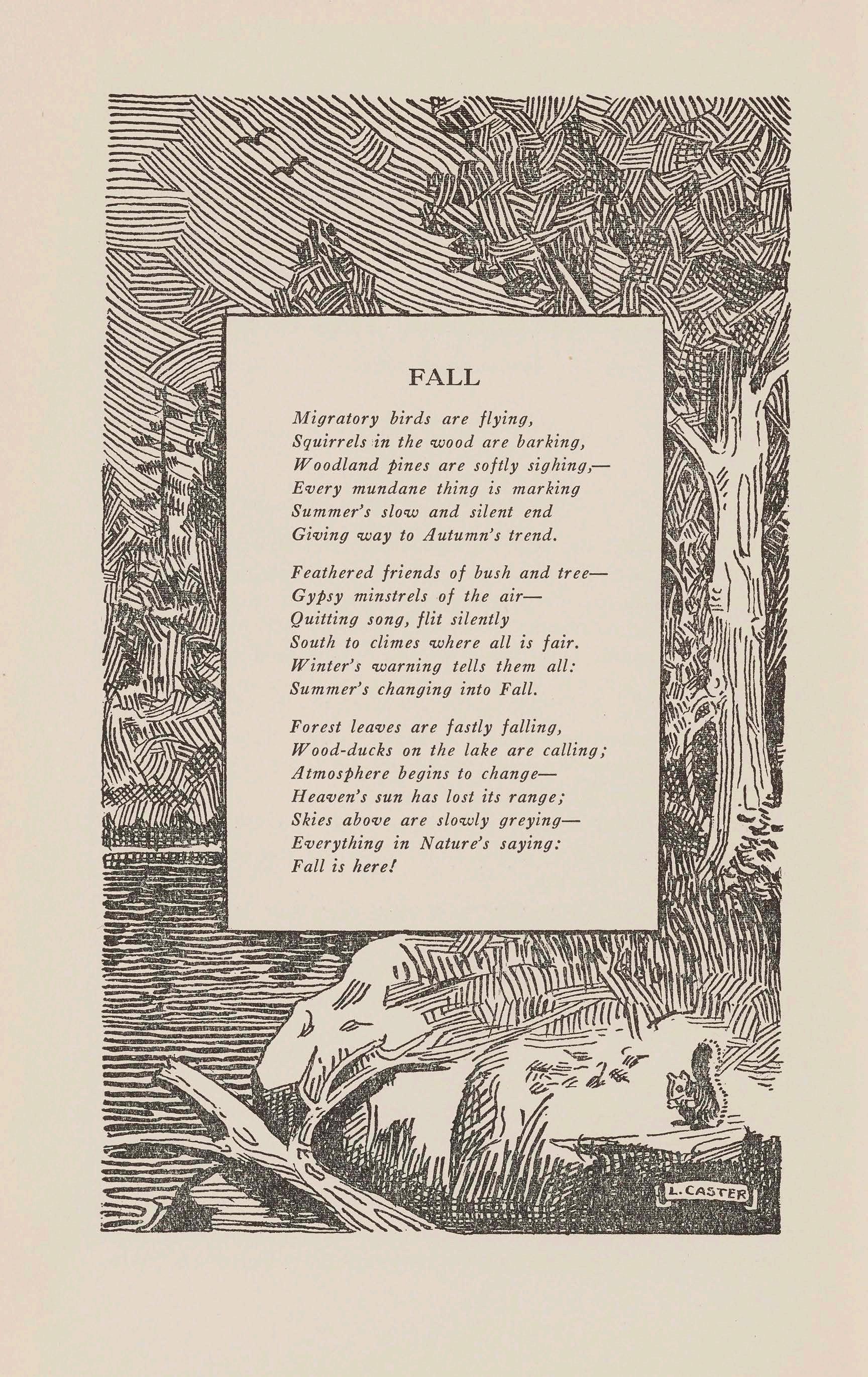

Migratory birds are flying, Squirrels in the wood are barking, Woodland pines are softly sighing,Every mundane thing is marking Summer's slow and silent end Giving way to Autumn's trend.

Feathered friends of bush and treeGypsy minstrels of the airQuitting song, flit silently South to climes where all is fair. Winter's warning tells them all: Summer's changing into Fall.

Forest leaves are fastly falling, Wood-ducks on the lake are calling; Atmosphere begins to changeHeaven's sun has lost its range; Skies above are slowly greyingEverything in Nature's saying: Fall is here!

VoL. LII

NOVEMBER, 1926 No. 1

"Swing low, sweet chariot, A-comin' foh to carry me home; Swing low, sweet chariot, A-comin' foh to carry me home"

came from behind the little log cabin with the white picket fence around it. The voice which rang forth so voluminously was rich and mellow with that deep brown color which can be attained only when an old negro mammy is leaning over her pot, and is as unconsciously blending herself and her spirits in with the hot summer day as the blue jay, who is almost bursting his throat in his attempts to outdo the singer of the melodious refrain. The blue jay had probably just eaten, for he sang with such gusto. These appeared to be Lindy's sentiments, too, for she stopped short in the midst of her melody and said :

"What for you a-settin' dar, Mista Blue Jay? You done et dem eggs out ob dat wren's nest, I bet. Now dar you sets, a-mockin' me like you was a person!"

"Swing low, sweet chariot" once more rang out. Lindy always sang as she washed.

'Way down the street a little old negro man could be seen approaching. He walked with an unusually springy step, and one could safely surmise that he was singing, too. He carried a stick .. but he very seldom used it for anything more helpful than keeping time to his song. As he drew closer Lindy saw him. She gave him no notice save pushing down harder with her big black arms, and saying, apparently to the pot:

"Here comes <lat good-foh-nothin' Tom, a-comin' here atta his dinner at dis time ob day. I'se a great min' to not gib him none."

Tom still came sprightly on, supremely unconscious that he was the cause of the menacing look on Lindy's face. Once more Lindy

addre~sed the pot. (It was the only thing that ever stayed still long enough to hear Lindy through her say) :

"He'll come along here a-tellin' me how hungry he am. I ain't gwine to gib him nary vittal. He am de good-foh-nothin'est husban' I eber had."

"Howdy, Miss Lindy."

Lindy cocked her ears. Could it really be Tom talking like that? Lindy did not deign to answer.

"Nice day, ain't it, Miss Lindy? Is you all gwine to de big meetin' ob de Holy Rollers tonight?"

Lindy could stand it no longer. She withdrew her plump black arms, covered with soapsuds up to the elbow, wiped each one off with her hands, then placed them akimbo on her ample hips. This was a characteristic pose of Lindy's when she was getting ready to deliver an oration against somebody's character. As she stood there with her ten tight plaits standing straight up, and her broad shoulders made all the broader by the position of her arms, Tom thought that everyday Lindy got to looking more and more like a big black cloud, ready to burst itself on any unwary traveler.

"Tom," said Lindy in an inquiring tone, "Hab you done lost de few grains ob sense which de good Lord hab seen fit to gib you? I seen you comin' a-prancin' down de street wid <lat glorinating look on your face. I 'spects you is gettin' ready to tell me you was detained down to de libery stable." ( Lindy summoned all her sarcasm in pronouncing that one word "detained.") Tom always came home late with that word on the tip of his tongue, and it affected Lindy just as a match affects paper; it made her flare up in one flame of wrath.

"Since you mention it, Miss Lindy, I believe I was detained, but not down to de libery stable. Me an' Mista John was habin' a converse about matrimony and sich like. He ask'd me how long me an' you hab been married, an' I said it was nigh onter thirty years, an' he said <lat was too bad."

"How come Mista John say <lat was too bad, ain't I done been your lawful wedded wife £oh thirty years? Tom Casor, you git dot air deverlish look out ob your eyes!" Lindy was becoming disturbed. She felt that Tom was holding something out on her, as it were. She had forgotten the pot of clothes, and even the dinner she was keeping warm for him in the oven. Lindy leaned over and picked up a stick. She began to waddle swiftly to where Tom

was impishly leaning on the white picket fence, holding the stick at a menacing looking angle.

"Look out, Lindy, look out!" yelled Tom, beginning to be a little afraid himself of the turn which things had taken. He did not want to provoke Lindy to blows. "You all ain't got no claim on me no more!" he finished, moving away from the fence. The last sentence stopped Lindy short in her tracks. Tom did have something up his sleeve, and Lindy was determined to force it out of the hole in his elbow.

"What is you talkin' about, us all ain't got no claim on you? Ain't I yo' lawful wedded wife? You comes up here a-callin' me 'Miss Lindy' an' a-prancin' around. You come in dis here yard foh I knocks your head offen your shoulders. Ain't I your lawful wedded wife?" she asked again.

"Well, Miss Lindy, since you mention it, you ain't my lawful wedded wife. Mista John hab jest tol' me that I an' you am not married, an' what am more, we never has been in sich a state!" Tom ejaculated. Lindy's stick remained stalled in mid-air, then slowly it dropped to her side. Tom and she not married ! Why the whole thing was unthinkable. She and Tom had been married for more than thirty years. She could remember now their wedding. It had been in the great bare spot under the biggest oak tree in the yard. Mista John had married them, and all the negroes from her plantation had been there as well as those of Tom's. And the wedding feast had been wonderful. There had been sausage, fried chicken and hard cider enough to feed all General Lee's army.

"Tom, how come we ain't married?" Lindy asked, waking from her reminiscence with a start.

"Just cause it weren't lawful foh Mista John to marry us. We has got to go to town and be married befoh de Justice ob de Peace. Well, good day to you, Miss Lindy!" And Tom started on off.

"But Tom," cried Lindy, "ain't us all gwine to town an' git ourselves married agin? I'll go an' tell Pisle Paul to hitch up de boss an' me an' you'll go into town right now," Lindy said, almost pleadingly.

'Tse sorry, Miss Lindy, but I don' see as how I kin git into town today. I had jest started over to <lat light-skinned gal's house. I'll see youall agin an' talk over <lat little matter."

"Tom, ain't you gonna marry me no more? What foh you gwine over to see <lat yellow-skinned gal foh ?" There was real distress in Lindy's voice.

"Well, I thought I might as well look around £oh I commits myself to matrimony agin." Tom was immensely enjoying his little joke on Lindy, and he hobbled on down the street singing.

Slowly light began to dawn on Lindy. Tom was playing a joke on her. Tom intended to marry her all the time, but he just wanted to frighten her. She would teach him to fool with her. Nobody would have Tom, she was sure, and he was absolutely helpless without her. She would fix him all right.

It was getting rather late in the afternoon. Lindy finished her clothes and hung them out to dry. The sun was just mid-way in the western sky, and Lindy glanced at it with a contemplating eye. It did not take Lindy long to make up her mind, and when once it was made up she stood firmly by her convictions.

Lindy went into the house and took out her best black taffeta. She washed her face and hands, put on her dress, and then dusted an old powder rag over her shining black countenance. Next she undid all ten of her plaits. She combed them and combed them until each strand of her hair glistened and shone. She did not put them back into the ten plaits, but this time she parted her hair in a straight part down the middle, and bringing her short locks straight down on each side, she caught them with two side-combs. Next she took out two gold earrings and put them in her ears. Lindy was dressed in her Sunday best, and Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like Lindy.

Lindy went into the kitchen, picked up a little rocker, and took it out to the porch. She put it down and then sat down in it. She began rocking back and forth, humming to herself.

The sun was away down now. It must be nearly half past four. To the idle passerby Lindy appeared to be a peaceful negro, waiting to go to a funeral, so calm and dressed up she was. Little could one suspect the direful designs going on in Lindy's mind. The sun shone glaringly upon the roof of the "big house." No being was in sight, save one old cow that was grazing on the little plot of grass in front of Lindy's cottage. This was the time of day when all the inhabitants of the "big house" took a nap , and all the negroes were working in the fields. It seemed quite strange to Lindy for her to be rocking on the front porch like she had nothing to do. But still she sat and still she rocked, waiting for something or somebody.

Just then the object of all Lindy's strange doings appeared around the corner. Lindy rocked and hummed with renewed vigor.

She was shrouded in an air of supreme unconcern, and she gave never a glance to the thing appearing around the corner.

As for the thing, he was beginning to feel really apprehensive. What if Lindy was mad with him! He would be in a pretty fix then. Tom hadn't had any dinner, and he was beginning to be a little weary of his joke. There was something the matter with Lindy, for sure. It wasn't usual that she dressed in her Sunday best and sat on the front porch this time of day. Tom cautiously approached the fence, opened the gate and walked in. Lindy saw him and gave him a wide, white-toothed smile. Tom breathed a sigh of relief; Lindy was all right after all; his fears had been ungrounded. She was just dressed up because she was ready to go to town and have the ceremony performed.

"I'll go on 'round to de back an' hitch up Dobbin, Lindy, so as we kin git to town an' back befoh dark," he said.

'Tse sorry, Mista Tom, but I don' see as how I kin git into town wid you today. You see, I'se expectin' company," and again Lindy gave Tom her white-toothed smile.

Tom was visibly taken back. This time Lindy had the upper hand.

"Does you mean to say how you ain't gwine to marry me?" he exclaimed in an incredulous tone.

"O Mista Tom, dat am so sudden!" exclaimed Lindy in a surprised way. "I shore does respect youall askin' me to marry you, but I don' see as how I kin rightfully do it, seeing as how you ain't courted me none!"

"Lindy, what am you talkin' about? Here I is ready to take you in town an' let de Justice ob de Peace join us in holy wedlock £oh eber an' eber. Come on, Lindy!"

"Why, Mista Tom, I ain't gwine to marry you widout any courtin'. Don' you reckolect as how you used to come to see me o' nights, an' bring me candy an' flowers while I was a-makin' up my mind to marry you?" Tom nodded in dumb assent. "Well, I'se jest as undecided now as I was then."

"Lindy, does you mean I is got to come to see you and court you jest like I done thirty years ago?" asked Tom unbelievingly, "befoh youall will marry me?"

"Dem's my sen'iments perzactly, Mista Tom."

It seemed to Tom that his little joke had been strangely enough turned on him. He was game, however, and solemnly asked, "Will you keep company wid me tonight?"

Lindy smiled her gracious smile and said, "Yas, Mista Tom." Tom lifted his hat and walked off. Lindy went into the house. * * * * * * *

It was eight o'clock and a full moon two weeks after Tom had told Lindy they were riot married. Down the road came the clatter of horse's hoofs. As the buggy approached the little log cabin, surrounded by a white picket fence, the horse slowed down of its own accord. It was right that he should have, for being a bright horse he could easily catch on to a thing after he had done it over and over again every night for two weeks.

"Whoa, Dobbin!" cried a negro voice, and out of the buggy stepped a little old negro man. In one hand he carried a brown paper bag which contained five sticks of pepperment candy. In the other he carried a stick.

He walked quickly up the path and knocked on the door.

"Come in!" said another negro voice.

He walked in and held out the bag to a fat negro woman, saying, almost in the same breath, "Miss Lindy, will you marry me?"

At last fortune had smiled.

"Oh, Mista Tom, I'm sure as how I'll bP. both delighted an' p1eased. Dis am so sudden!"

And even the blue jay sitting on the white picket fence had to laugh.

Open sesame Into the library of life; I loiter in the alcove, Perplexed, Move slowly to the next And loiter there.

Another comes in Straight through the corridor To his destination, Pulls down a book Selected in premeditation.

No one can deny it; he is really hideously ugly. In all my Iife I have seen him in but one position, with but one expression on his face-a fierce expression of superiority, especially over innocent and gentle kittens which found warmth on my hearth, an expression conveyed largely through his bulging blue eyes. His body is made of brown china, his head of brown and white mottled ware, and he boasts white ears. His general appearance resembles that of a bull dog more than any other species. Vercingetorix-he never answered to a name until I began my study of Caesar-rests in a three-quarter canine position on one end of my bedroom mantel, keeping close watch on the time indicated by the alarm clock on the opposite end, which he faces.

The china dog was acquired by my grandmother at the period when every lady thought it the height of fashion to own as many useless objects as possible. I can well imagine that during one phase of his dog's life, he occupied the place of honor on one side of the carved, rosewood etagere and gazed hungrily at the stuffed woodfinch directly opposite in a glass case.

I opened my long friendship with the china dog by rescuing him from a basket of old junk, being carried downstairs by my Mammy Susan for a rummage sale. For years he had lain packed away in a box of straw in the farthest corner of the attic.

"Sho', chile, you kin hav' 'im," said Mammy in reply to my demand. "Don't see what yo' wants wid 'im, do'," she went on. "Wid dem develish lookin' eyes of his'n, wouldn't no nigger buy 'im. Looks too much like er evil spirit fit to conjure."

And so, the china dog came to live in my room. For two years, until I was ten, he served me as a door-prop. I used to fancy that he was a terrible monster whom I held under a magic spell and compelled to guard the entrance to my palace of <;!reams. Sometimes it was a veritable fairyland he watched over, for I was a rather imaginative child, and was fond of enacting in my own room stories of fairies, giants, princesses, and magic. Always the china dog, that was to be given the atrocious name of Vercingetorix, did his duty by the door, silent, stolid, with the almost savage expression in his glassy eyes.

There came a time when the ambition of my young life was attained. Wearing a white crepe paper dress decorated with silver

stars, and holding my head high with a crown of silver paper, I acted the part of queen of the fairies in a "Fantasy of Flowers." Returning home after my first and last appearance as an actress, I could hardly get enough of looking at myself in the long mirror. "How beautiful, how really fairy-like the crown and starry dress make me," I reflected. Turning finally from the image in the glass my eyes met first the sight of the brown china dog.

"Oh, you hideous, terrible, horrible old monster," I remember saying, "Now that I am the fairy queen, I will free you from the magic spell."

That night I slept with the china dog in my arms, and from that time looked upon him as a real friend. Following the lifting of his magic spell, he was promoted to his present position on the mantel.

It is my experience that a china dog is satisfactory in every respect. Vercingetorix has indeed been my confidant. I have told him my trials and struggles in school, have entrusted to him my likes and dislikes for certain persons; always he maintains strict silence, and gives me a sense of privacy between two. Of ten, in a fit of loneliness, I take Vercingetorix from his place and whisper confidingly in his ear. Generally, the fierce look in his china blue eyes makes me forget everything else, even wonder if there isn't a gleam of kindness lurking behind them.

Then, too, a china dog is most satisfactorily petted. Never does he come in with muddy feet and soil your clothes. He will sit quite still and let you stroke his head. Moreover, Vercingetorix is not greedy. In fact, he possesses all the virtues of a perfect dog except for the expression in his eyes; this is perhaps caused by too much restraint on his natural desire to hunt and kill.

For eight years, the china dog watched over me, night and day; ever watchful, ever awake, ever ready to respond to any mood. Now, he watches over an empty room and each day accumulates a thicker coat of dust.

M. E. K.

Beneath the sophisticated flare of her hat and the jaunty impudence of one ear-pearl she raised troubled eyes.

"But, Bill, you will forget-you know you will!"

His clothes were the last word in what the college men will wear for fall, and his shoulders slouched in a most debonair droop, but his voice was low and husky when he answered.

"Lony, hush! It hurts for you to talk like that-you can't mean the things you say-you know you don't mean them. You know how much I care for you-why in the world don't you trust me?"

The long topless roadster was parked in the darkness outside the station, and Lony was fumbling with a traveling coat as she answered.

"Oh Bill, the way I do want to trust you-Lord, how I want to believe in you. If I just didn't know you so well-but I understand you so terribly well, honey. Why, you don't want me to take you seriously-it would scare you to death."

For reply the boy slipped an arm about her slim shoulders and drew her to him.

"Lony, why should I lie to you? Why would I have wanted so many dates if I hadn't loved you-why, you've meant everything to me these months. Lony, I swear I love you, and your going away can't change a thing. I'll always love you, always . . ."

Lony drew a deep breath; ended it with a quick little, "Oh, well," and stood up in the roadster. Her dark traveling dress fitted perfectly, and ended at her silk-covered knees. Dizzy-heeled alligatorskin slippers bore her slender weight, and from a square bag to match she drew a dorine and flippantly rouged her lips. Sophisticatedyes, certaintly Lony Lou was sophisticated. Her lips were vivid now, but the boy saw through the dusk that the piquant bow was trembling.

"Bill, you're just like all the other wise old boys today-you've been precious to me; you hand out a perfect line; you swear you love me, but I'm afraid of you, Bill. I know you don't mean a word you say. . . . Oh, well, let's go! How long before my train time?"

The long line of Bill's chin tightened. He pulled Lony down beside him.

"Lony, listen to me! It's awful for you to feel this way about me. I can't let you go away feeling so. Why, you must think I'm shallow and just a fool."

"Oh, no, Bill; but can't you see how I £eel? Why you have other dates; you drink after I ask you to slow up. Life's just a joke to you; I'm just a good-time pal-and when we're each off at college again, some other good-time pal will take my place. That's the terrible part about these happy-go-lucky play-days of today. All of us love Ii£e-love it, and today we play with it. And we play with love; so that when we do stumble on real love we can't find the faith and confidence that true love needs-we're just afraid to trust any one-we can't trust a soul, Bill!"

Lony made emphatic dots on the windshield with her lip stick as she talked.

Bill adjusted the tie which matched his plaid sox, gave an absentminded twitch to his fraternity pin, and lit a cigarette.

"Sit down, Lony !" he ordered from the corner of his mouth.

Lony Lou pulled at the side of her flippant little hat, caught back a sigh, and dropped beside him in the seat. ·

Bill tapped the steering wheel with his cigarette.

"Lony, listen. You're right-people's can't trust each other today. When I see an attractive girl like you, I'm afraid to fall-afraid because I couldn't trust you out of sight."

He flicked away his cigarette and caught up one of her fingers as he went on.

"The wise things you say may be true, but they're probably soft talk; the kisses you give me may be sweet, but they may be just as sweet tomorrow night for someone else. Lony, every boy who's played about a bit, and has known good times and girls, is afraid to love the girl of today-she's played, too, you see."

Lony nodded sadly. "Yes, and when you say you love me, and always will, you say it so fluently that I know you've said it so often before that you're in perfect practice."

"Yes, but Lony Lou." Bill turned her towards him. "Even though I am the boy of today, although I do play with love, and don't trust you, I'm not a coward, and I am sincere. I have fallen for you, and you can kick me to India, but I'll always love you, always."

"Oh, Bill !"

"Kiss me, Lony Lou."

Sophisticated hat and jaunty collar forgotten, Lony Lou was in his arms.

"Oh, Bill, I want to love you so completely-playing all the time is so dam' tiresome. Bill, I want to be true to you . . ."

"And, Lony, there isn't any other girl in the world who interests me now. Lord, to think you really love me. Oh Lony "

The train's last whistle was dying away as a long roadster rolled away from the station. Pensively the driver guided its dark length down the main street and on into the residential section. For a long while after he stopped it in the driveway he sat staring at the headlights cutting the autumn gloom. At length he drew a deep breath, switched off the lights, and stepped over the low door. On the way to his room he stopped by his father's door.

"I'm taking the big car tonight, Dad. I've got a date with a girl who wants to drag along another couple."

In a crowded sorority room a telephone rang.

"Who do you want-oh, Lony Lou? Sorry, she isn't here now. Oh, just a moment, here she is now. Phone, Lony."

Lony crossed slim silk knees, pushed back a big hat, and caught up the telephone.

"Yes?"

The girl standing beside her whispered quickly, "It's Jake Spar, Lony-he's red hot-don't make a date with him-honey, he drinks like a hound and he really is wild, Ellen says."

Lony Lou was smiling sweetly.

"Awfully afraid not, Jake-wait a second, though, will you?"

One hand over the phone she asked, "Did that letter come for me today?"

"No, it hasn't come yet; but Lony !"

To the phone again Lony smiled sweetly. "After all, Jake, I believe I can make it-party sounds good to me-nine-thirty, thennice going-good bye !"

FRANCES ANDERSON

Gray land Street is a street of smells: pungent smells of cooking; cloying throat-filling fumes of exhaust gas from the huge, lumbering busses; sometimes in the spring scents of roses and honeysuckle, and always in the fall the adventurous odor of burning leaves and wood fires. Truly Grayland Street is a place to use your nose instead of ears or eyes.

But one odor that never floated up Grayland Street, never could have reached Grayland Street, in the mid-western city of Browntown, Illinois, was the hot, fervid incense of the East, the musty smell of the Bagdad bazaars, of sandalwood, of eastern perfumes, of adventure.

For Margie Hammond, however, the combined odor of Grayland Street seemed the odor of the Bagdad market, and the smell of the melting tar pavement was that of the burning white sands of the desert. For Margie attended the movies, and Margie read books, and Margie was a dreamer. Yet she was not a person with whom one would associate romance. Romance and Margie were different. Margie was fat, forty, red-haired, and mild-eyed; Margie was poor, uneducated, and dull; in short, Margie was commonplace. But nevertheless Margie had her dreams.

She did not see the stream of touring cars that flowed so restlessly all day up the street. Instead they were the caravans of the East, trains of camels loaded high with wicker baskets, ridden by Arabs garbed in gaudy silks and gaily hued turbans. The brick parched houses that lined the street were not shelters of brick and mortar to Margie, but rug-hung shops of Bagdad, shops of polished brass work where the workingmen's tiny hammers filled the air with an eager sound; the sound of the horses hoofs of the movie sheiks as they galloped in the moonlight. Or maybe they were shops of sweet meats; or she pictured them as they were so temptingly displayed in carved boxes, delicacies of nuts and figs, marvelous food. And again, the houses were even shops of the pawn-brokers, where the wizened owners kept beautiful jewels in their dusty stores. They were lovely stones for which men had died-a dagger thrust in the dark, a cry-and this. Oh it was a beautiful wo rld filled with the glamour of the East, that breathed the perfumed odor of the bazaars, and that fed upon the stuffed dainties fit for sultans. It was a world peopled with dark handsome Arabs and veiled women, among whom

Margie the fair-haired English girl, the slender, beautiful English girl, was a goddess to be worshipped.

Yet sometimes Margie wished she wasn't so much of a goddess; she wanted the handsome bus driver to speak to her and overcome the barrier between them. For Margie had become infatuated with a bus driver and found an answer to her worship in his eyes. She built around him a wonderful romance-the romance she had seen so of ten upon the screen. This one was hers and it would come true. In the meantime Grayland Street was transformed and Margie with it.

And then one day Gray land Street conquered the Bagdad Bazaar; the gasoline fumes overcame the eastern incense. The jerking line of automobiles replaced the slow, rhythmical procession of camels and yellow busses were yellow busses and not Arab steeds. That day Margie woke up.

The day had started out most gloriously. The boarders had returned from a trip and given Margie five dollars for a presentfive lovely dollars she didn't have to give to Papa, five dollars for her own. Margie hadn't hesitated as to what she would buy with it. In Walker's window there was a beautiful wide-brimmed pink hat, the kind the flappers were wearing, the kind the tall, fair-haired English girls were wearing. Now she could have it. Now it was hers.

The saleslady assured her it was becoming.

"All the other young girls are wearing them, dearie. You'll like it, I know."

Oh, Margie knew she would like it, but would her Maybe today she could get on his bus. Maybe today he would speak to her. Maybe-Oh! World of stored up maybes, why did they have to rise to haunt her again! Well, anyway, maybe.

It was late afternoon when Margie returned. She had been to a movie and had lived the story on the screen. Only she was more beautiful than the heroine, and the bus driver more handsome than a thousand heroes. And now she was on his bus, the front seat behind him. A fat man was reading his paper beside her, unconcious of the bus driver. The car slowed past the terminal and another driver hopped on. He stood beside Phillipe, for so Margie called her hero, and began to talk. Margie could hear them distinctly.

"Lo Pete, how's tricks? Had any fun today? Seen your fat crush any?"

And he: "Naw, I ain't seen her. Hope the old lady ain't croaked on my hands. Don't know how the kids ud get along without her. Li'l Pete comes a-runnin' to me every evening. 'Daddy, daddy, tell me about the fat lady. What did the fat lady do to-day?' And even Mary says to me, 'Law, Pete, you'll make me die laffing at the way you do your eyes. You oughta go in the movies,' she says."

Oh, how awful Margie felt! Had Phillipe a wife, children, and a crazy fat woman in love with him? Oh well, he'd have to leave them all. She, Margie, would be his inspiration. And thus, until she forgot her corner and the sight of her house reminded her.

Joe and Pete were still talking. "There's her house now, but I don't see her nowhere. Guess she done croaked, et herself to death, I guess. Well-that joke's over. Poor old lady."

The bell rang faintly and the bus lumbered to a stop. Margie arose and tottered to the door. How glad she was the hat had a wide, floppy brim; he couldn't see her face. But even the hat could not keep the mockingly solicitous voice from her ear: "Stand aside, Joe, and let the fat lady pass. Guess I've got a weakness for fat ladies, eh?"

To L---

R.B.c.

Lithe and slender, beautiful-thee, As we danced so closely clinging, Swayed by music, souls a singing Love with every rhythm mingling.

Warm and tender, passionate-thee, As we drank the kisses burning Hot, yet silver'd with a yearning For a love that vows no turning.

JEAN MACCARTY

"Well?" questioned Miss Virginia's voice on the telephone. "Miss Virginia, this is Nancy."

"Why, do you know, I was just thinking of you at that moment. I heard something very nice about you today."

You had a nice warm feeling after this characteristic announcement from Miss Virginia You marveled every time you called her or met her how she could have been thinking about you just the minute before, but it was too flattering to question. Miss Virginia had a way of making everyone feel that she was vitally interested in them.

When you first entered her school you were sent to sit in the swing on the rose-covered front porch, or to observe the shape of the leaves of a certain tree in a corner of the yard, until Miss Virginia could see you and talk over the things which interested you. For hours and hours you dangled your legs from the swing, and tried to converse with a rather lumpish girl beside you, who was waiting, too. She was an "old" girl, but she was not in the least communicative. Out in the yard as many as seven girls walked about linked arm in arm. In some parts of the yard you might see a whole class loitering in a group. Class spirit is rampant at Miss Virginia's, but it is not something which is called by any name and talked about, and kept alive by noisy rallies. It is rather felt by each girl, and exists because of the friendliness of each girl for each other girl, and a devotion of the class individually and en masse to Miss Virginia. You had plenty of time to observe the beauty of the yard, the thick old oak trees which shaded most of the yard, the flowers, the wellkept hedge. But this yard was to mean far more to you after a few months spent with Miss Virginia. No longer would you speak of the "flowers" in the yard, but of the "scarlet sage" and the "blue ageratum."

"It was a strange place," you mused, as you dangled your legs and observed the impenetrable girl beside you. "You had seen the efficient, breezy principal, who had a pleasant voice and manner. She had welcomed you to the school, and told you about the nice hot lunches you could get every day at the cafeteria. She also told you that you would be very much interested in the bracing games of basketball which she and the athletic instructor would teach you to play. It would also be splendid for you to ride with her and

the girls. She concluded by telling you the hour when you could go home in the afternoons. All this, and yet, it had done you no good. Evidently, the title 'principal' signified little in this school. It was for an audience with Miss Virginia that you waited."

Directly a girl came to you with the announcement that Miss Virginia awaited you in the conservatory. You walked round the corner of the porch and met Miss Virginia at the door of the conservatory. She led you into the yard. Round and round the yard you followed the little old lady as she talked, with her arms folded on her breast.

"Now, my dear," she would say, "Spanish is a very interesting subject, but you can't study Spanish all the time. I see that you would naturally be interested in it since you have just come from a city in which you hear it spoken a great deal. -You don't care for mathematics. Well, you'll find Bessie an excellent teacher. Don't distress yourself about mathematics. Perhaps you can write. Bring your notebook out to me. You know you must write about the things you have seen and done. -Have you read 'Henry Esmond'? -Yes, yes, that's good. We'll study that a great deal this winter. -Shelley ?-yes? You like Shelley? -Ah! No indeed, I can't see why any nice girl should want to go to a university. It's a very foolish notion. You'll forget it. What should you do when you got there? Of course, the University of Virginia is the foremost university in America. -We shall see about Radcliffe or Bryn Mawr. -Did you see the sunset from your window yesterday afternoon? Unusually beautiful, wasn't it? Now, my dear, you may go home on the car with Margaret Grant, an exceedingly fine girl."

And so ended your first day at school. Where were you? What had you accomplished? Where was your schedule of hours and rooms? What were you to do tomorrow. -Wait-drift.

S~veral weeks passed. You went to almost any class during these weeks. At any time Miss Virginia might come in and take you out to another class. In fact, you were never quite "settled" at Miss Virginia's. But it was the eight hours a week spent in Miss Virginia's English class which really mattered. The other teachers were all delightful, charming, cultured, and capable women, but you really can't get a distinct picture of them when you think of Miss Virginia. The Junior Class, of which you were a member, consisted of about fifteen girls. The class was a brilliant one. Almost every girl in it wrote well, was widely read, and traveled. Miss Virginia sat at her round, carved mahogany table on a high

box. The table was placed by the conservatory door. The English period was often a succession of conferences of individual members of the class with Miss Virginia in the conservatory or in strolls about the grounds. When she talked to us she usually stood up. When she read to us she sat down. You can never forget how very old and white she looked as she sat on her high box with rows of books on the table in front of her. Her silvery hair, faultlessly groomed, made no contrast with her pale face. Her features were aristocratic-a beautifully chiselled nose, pale lips. The part of her face which comes to you whenever you think of her in the still of a summer night or at any time when quiet reigns, is her eyes,strange, amber eyes, which at times looked like pools of velvet, at other times burned and glowed like coals in the darkness. These eyes exercised the weird fascination of a snake's eyes on a bird. After she had read "Christabel" to you in her mellow voice, you recoiled from her eyes-they were those of the Lady Geraldine. They drew you, and yet repelled you. Round her snowy throat was tightly clasped a heavy chain of woven gold. Heavy gold bracelets bound her wrists. Her black silk dress was relieved by a collar of exquisite cream lace.

Miss Virginia's English class never palled. Each day brought forth new books, poems, themes, current events, observations, criticisms. Miss Virginia strove to teach her class English history, English literature, and the correct pronunciation of French. At times she was systematic and gave us the kings of England during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in succession. Her landmark and ours, in the matter of kings, was "James the first, the wisest fool in Christendom," as she reiterated. As for Shelley and Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge-we never exhausted them. Hardly two weeks passed that we didn't write a theme on one of them or a comparison between two of them. How exhilarating it was to be summoned to the telephone in your house about 11 o'clock of a winter evening to hear Miss Virginia saying in her vibrant voice, "I'm very well pleased with your compositionn on Wordsworth's 'Intimations!' I really believe you're getting the thought." ( Miss Virginia never thought of calling anybody before 11 or 12 o'clock of an evening.) When we weren't studying Keats and Shelley or "Henry Esmond," we were memorizing Burke's "Speech on Conciliation." Oh! the hours spent on Burke! Often Miss Virginia walked out of the room while she was in the middle of a sentence. She reappeared again as suddenly. When you were in another class Miss Virginia might appear in the room. She looked all about her.

Everyone remained standing until she turned her back and walked out without a word.

Miss Virginia desired us to have an appreciation and evaluation of people, poetry, and "minute details" in writing. To cultivate the first she gave us, in an inimicable manner, intimate glimpses of famous people. She was humorous and satirical at once. To cultivate a love of poetry she had us read, study, memorize, and write about it. Her great dictum in the art of writing was "give specific details. Name the color and the shape." She once sent us out into the yard to make a list of as many different kinds of trees, flowers, birds, shrubs, and angles of shadows as we saw there. We then culled the details, organized them and wrote descriptive essays.

"Well" queried Miss Virginia's voice on the telephone.

"Miss Virginia, this is Nancy."

"Dear Nancy, I was just thinking of you. I shall decide on the best college for you. Don't you worry. In the meantime, I shall think of the best books for you to read this summer."

Dear friend, weep not for dust enearthed here; For that same clay which was my flesh and blood Was but an anchor of an infinite soul Which now perceives that longed for scope that earth denied.

ELAINE CLARE

The following translation of Canto XXXV of Dante's "Inferno" was made from a manuscript recently discovered in the library of a Capuchin monastery situated some four leagues south of Florence, Italy. This is the famous "missing canto," to which many references may be found in commentaries on "The Divine Comedy." The XXXIV Canto-Cary's translation-closes in this manner:

"We climbed, he first, I following his steps, Till on our view the beautiful lights of Heaven Dawned through a circular opening in the cave: Thence issuing we again beheld the stars."

"And now," said my Master and Guide, "We come to the last of the punishments, the sternest of all judgments."

"Here?" I marveled aloud. "Surely not here. Surely this must be Paradise!"

Below us-for we stood upon a high place-stretchecl a landscape of surpassing beauty. More truly it was an enchanted garden. A series of enchanted gardens. Lovely rolling lawns, lovely, smooth, level lawns lay here and there, broidered with trees, and hedges, and shrubs of ineffable delicacy and form. Fountains played in the open spaces . . . gleamed in the liquid light of a large, white moon which had just begun to climb the eastern sky, half-hidden by a tall, strange tree. . . . In the shadows of shrubs and low, round trees, statues of nymphs, and fauns, and goddesses glistened with a pale warmth. White marble benches lurked near hedgerows, and on each bench was a girl and a boy. Other boys and girls danced rhythmically, with unimaginable grace, across the long, sweeping lawns. And from hidden places came music . . . waltzes of breath-taking beauty . . . waltzes of tear-bringing tenderness. And on the benches each lass lay close in the strong, young arms of her lad, and the moon climbed higher, and higher, and I thought I would have fainted from the sheer loveliness of it all.

"Punishment?" I murmured. "Surely not here. Surely this must be Paradise."

"It is Hell," said Virgil, and he led me closer to the edge of the high place upon which we stood, and his hand pointed downward. . . . There, in the shadow of the high place, between us and the lovely, sweeping lawns, sat row after row of people. They were most of them women. All of them were virgins, and none of them was less than forty years old. Each sat rigidly in a straight, small

chair, and the eyes of each were fixed unblinkingly upon the scene which lay before us. . . . And the music came floating across to us, painfully sweet . . . and the frocks of the girls clung close to their straight, young limbs, or whirled in the rhythm of the waltz, and I could have wept for the loveliness of it all. But the faces of the persons below us, the erect, rigid persons below us, those faces were unsmiling.

"Each of these," continued my mentor, "has committed the unpardonable sin. And here must they sit for eternity, and cannot ever look away from the hateful scene before them."

"Hateful?" I protested.

"To them," said Virgil. And over the long, sweet lawns danced Youth, and fireflies danced with them. Music of painful beauty stole through the hedgerows. "They said to the world," he continued, "that they loved young people, for once they were persons of authority. Thy once held power over the lives of Youth, and over the happiness of Youth. But they, themselves, had never known the arms of a lover . . . they had never kissed a man in the shadow of a tall, green hedge . . . or else, they had forgotten. And so, in their hearts, they hated Youth, and the foolish lovely, little pleasures of Youth. And large white moons put rage into their thin breasts-and envy. And so they bound Youth with petty tyrannies, and futile, needless rules. And they laughed, in their hearts, when they saw the hurt, wondering faces of Youth. And now they must sit here forever and look unceasingly upon Youth . . . upon the Youth they envied and hated. For that is the greatest of all sins, that is the unpardonable sin . . . to hate Youth when you have passed forty."

And so saying, he took me by the hand and led me from off this high place, and away from that lovely land where the strong, slender bodies of Youth danced with unimaginable grace across the long, moon-kissed lawns.

HELEN COVEY

When the taxi passed those familiar three bumps in succession, Gene knew that he was only one block away from home. He hoped vaguely that Mother would be feeling better; it was beginning to be fearfully inconvenient, not having her at his side. Two whole weeks .... It was time now for him to begin learning how to manage without her. But no, not that! He preferred to say that it was time for her to have recovered enough to resume her duties.

The taxi slowed up; the driver jerked open the door. "This is the number," he stated impersonally.

Gene paused on the step and extended his hand gropingly for assistance. "Would you mind, if you ple<!se-all the way up the door."

The taxi driver took his arm. "This is a kind of bad place on a dark night like this-rough like-ain't it?"

Gene hesitated for an instant and hated himself for doing so. Why should he feel embarrassed? "It isn't that," he replied quietly, "but I am blind."

"Zat so? I was thinking you were the soberest man I ever seen that had to be helped to his house."

Gene felt the pity in the man's voice and shrank from it. He despised pity; it made him too painfully conscious of his misfortune. For that very reason he found it difficult to meet people. If it weren't for Mother he probably would never go out; she insisted on his having a change from his still home, and even taxed her strength taking long walks with him because he would not go alone. Her pity was different from other people's; it comforted instead of hurting. . . .

The taxi driver was speaking: "Must be expecting you. Lights all burning."

Ah, Mother was better, then, and out of bed. Otherwise she and the neighbor who was sitting with her until Gene should come home would not have needed the lights.

They reached the front steps, and Gene was suddenly at ease. "I can manage very nicely from here, I believe. You were paid at the club? Thanks for your help."

"Yes, sir," replied the driver; "don't mention it," and his footsteps hustled down the cement walk. Then the motor hummed

smoothly for a minute, grew fainter, and the sound died completely as the taxi turned a corner. That was how things happened with him, Gene reflected; if there was ever a friendly encounter, all traces died away in a short while like the sound of the receding motor. And he was always left quite alone, with just Mother.

He entered the house quietly. "Mother!" was his first thought, his first utterance. The call brought no answer . Didn't that man say all the lights were burning? Light was hard for Gene to imagine, for his enveloping darkness was so profound. He called again, louder: "I say, Mother!"

A door opened-her bedroom door, it sounded like-and someone descended the stairs with slow heavy step.

"Mother?" Gene turned his sightless face toward the stairway, hoping for her, yet doubting the step.

"This ain't yo' ma.,. Certainly not; the voice was too harsh, and she wouldn't have used those words.

"Oh, yes-Mrs. Carpenter , I had forgotten that you were taking care of her while I was out." Gene tried to keep the disappointment out of his voice. "How is she now?"

Mrs. Carpenter took up her story with the pleasure that many people feel at telling bad news. She talked with more animation than Gene had ever noticed in her before. "To tell the truth, she's right smart worse . She's been sufferin' something terrible with them heart pains. She tells me tonight when · I come in, that they been gettin' worse steady for four da~s."

Gene started to ask to see his mother, but the old woman disregarded him and continued. "So I says to her, 'I'm gonna call a doctor,' I says, 'I ain't gonna set here an' see you suffer. An' I'm not gonna have anybody say that you was worse because I wouldn't call a doctor!' So I went an' called Dr. Carmichael, an' he called Dr. McBride, an' they're up there now givin' her a epidemic or somethin'."

"Mother sick enough for two doctors? Mrs. Carpenter, I can't see how this could have developed so suddenly."

The neighbor's voice, high and shrill with excitement, took on the tone of pity that stabbed Gene whenever he encountered it. "That's just the trouble, as I says to Dr. Carmichael a little while ago. You couldn ' t see how much she's been agonizin', an' o' course, she wouldn't tell you. I says to them I thought it was you comin' m, and they say you stay down here quiet like, till they call you."

Mrs. Carpenter began creaking back upstairs again. Gene wanted to know more, to go upstairs to his mother, but was too greatly agitated to know what to say. "Is she very sick?" he faltered.

The old woman paused, and her voice came to him from almost the top of the stairs. It was like the off-stage voice in plays. "Sure, she's mighty low. But don't you worry, because there's two of the best doctors there is workin' on her. I'll let you know anything that happens."

She slowly finished her ascent. The bedroom door opened and a multitude of little muffled sounds slipped out. Then the door closed, and Gene was alone again.

He groped for a chair and sat down heavily, dropping his hat carelessly to the floor, holding his cane. He did not even remove his gloves. The darkness that had enveloped him for six years became haunted with a whirl of bitter memories and menacing fears. Yes, everything was in a whirl, unreal-his past, his plans for the future, his beliefs. He was clearly conscious and sure of only two things: the bedroom upstairs where two doctors and a sick woman and an excited neighbor made little muffled sounds; and himself, maimed and helpless and dependent, and in utter darkness.

His anxiety sharpened his insight, and he began to perceive hitherto unnnoticed items in his memories of former times. Mother had always been suffering, more or less, since he'd been blind. When the ambulance had brought him home six years ago with his head swathed in bandages, she had moaned once, ever so softly. Then she had said, "Why, Gene, son, I'm so glad to have you home again! You don't know how I've missed you." And she had kissed his chin, the only unbandaged part of his face. After that moment he had never heard her even sigh.

After a few months of his new life of darkness, he had realized that their funds must be shrinking, but he hadn't had to worry. His conscience had hurt just a little, because he had neglected to be more thoughtful of his widowed mother's future while he could have provided for her. But she had shouldered the responsibility. One afternoon she told him that she was making Mrs. Henderson's children's fall clothes.

"You mean that you are taking in sewing, as old Mrs. Carpenter would say?" Gene was overcome with shame at the prospect of being supported by his mother.

She answered as calmly as if this day did not mark a turning point in her heretofore work-free existence. "Yes, that's it, I

suppose. It gives me something to do with my hands while I am talking to you. And besides, it allows us a few little luxuries that we might not have without it."

"But, Mother," Gene protested, "sewing by hand-isn't that dishearteningly slow? You must have a machine."

"No, Gene, that isn't necessary. The exertion of operating a machine would be bad for my heart. This is a very good arrangement."

Consequently he had not worried. Now for the first time he thought of the eye strain she had borne, the long hours she had worked to finish some garment and buy music for him with her pay. And this for six years. . .

About that music, too; it must have been endless trouble for her. When he had no longer been able to read music he had despaired of ever playing again. Thoughts of the piano in the midst of that fine orchestra which was no longer his, tantalized him almost beyond endurance.

Then Mother had selected a Victrola record-Massenet's Elegie had been that first one-and played it over and over for him until his groping fingers could duplicate it on the piano. That had opened fascinating vistas for him, and by constant practice with Mother always there to help, he had acquired a very creditable repertoire.

For over a year he had been giving solo concerts. But he never played in public unless it was absolutely necessary to relieve the grave financial situation; he hated to meet people and feel their pity. But it had been necessary often enough ;Mother's sewing was inadequate regardless of how hard she worked. Why, just very recently he had reached home after a concert at the club, where he appeared regularly, and had found her still sewing far after midnight.

"I just thought it would be better for me to finish this before I go to bed," she explained.

And the next morning she had not been well enough to leave her bed, nor the next day. She was still there, suffering terribly. And he had never guessed it.

Gene had depended so entirely on Mother, and he had been so efficiently cared for that he had never dreamed of her having any physical weakness. She had walked with him, worked indefatigably at his music with him, and had sewed for hours and hours to provide for him; and of course he had thought her the incarnation of strength. Moreover, she had read to him, talked to him, kept him entertained-in fact, she had just chummed with him and kept alive

his social nature, which had been threatened with total extinction by his supersensitive attitude toward every one he met. Mother had been both a support and a stimulus. Without her-well, that was simply out of the question, for without Mother there was nothing for Gene but outer darkness.

He left his chair restlessly and sat on the stairs, anxious for news from the bedroom. Was that a hurrying of footsteps up there? He hoped that it would mean a change for the better in his mother's condition.

He had let her work too hard, forgetting the limitations of her aging physique. Hereafter he would comb the city for opportunities to give concerts, much as he hated to do it; he would keep himself continually busy and relieve her from her financial worries, at any rate. He appreciated Mother now. He knew that she had been the floating spar to which he, a drowning man, had clung blindly; and he was now being frightened when that spar, overburdened with his weight, threatened to sink. He would make life so easy for her now!

The bedroom door opened, and the stairs began to creak with the descent of Mrs. Carpenter, probably.

Gene became strangely happy. This would surely mean that Mother was better and that he could see her. He would tell her of his good resolutions, and that would help her recuperate. And then, when she was entirely well-he thought of an old fairy story phrase to apply to their future: "And they lived happily ever after."

He was decidedly cheerful as he called up to Mrs. Carpenter, "May I come up to see her now? I have something to tell her!"

The old woman's voice shook sanctimoniously, and was vibrant with the tone of pity so repugnant to him. "Sh, man," she quavered, "be quiet. Yo' ma's been took."

And thus Gene learned that the floating spar had sunk.

The man, tall and gaunt, floundered through mire knee-deep. He might have walked along the highway where the earth was firm and level, but furtively he avoided the road and plunged through the depths of the leprous swamp, where creeping and crawling things abound. On and on he trudged, occasionally breaking into a tired little run when he came upon a stretch of dry ground. All the while he held close and tried to silence the chinking of a heavy bag which he carried beneath his coat. Hour after hour the man struggled forward with eyes distended in wildest terror. The sun sank, night fell, the fresh green of the little spring leaves became leaden gray, and the tangled vines and serried underbrush, dim in the noon of day, assumed a Stygian blackness. The man pressed on like a hunted creature, bruising his feet on stones and tearing his legs among thorns. His eyelids, long propped with terror, now began to droop-to close. The hurried footsteps lagged, knees bent, arms hung limply at side, breath came huskily in gasps. Painfully he dragged forward ever more slowly. At last, at the top of a small hillock-a sharp intake of breath, a stifled groan, and the man fell in a sodden heap on the cool, moist turf. * * * * * * *

Embers still glowed among the charred logs which had burned untended since morning. It was already dark outside, and the effect of the dull, red sparks was curious. The table cast a ludicrous shadow all over the wall. Overturned chairs projected long, black lines across the rough board floor. The sharp angles of the rustic furniture, the crazy umbral arabesques, the crimson gloom lent' the cabin the appearance of a torture chamber. Nor was the torture chamber without its victim, for, stretched full length on the rude floor, lay the stark form of a man. He seemed to be lying there laughing almost, for the corners of his mouth were twisted into an odd grin. His lips were slightly apart like those of a living man, but his mouth was full of clotted blood. The cause of his death was apparent; the handle of a large butcher knife projected from his breast. Blood had flowed freely from the knife-handle to the floor and had seeped through the cracks between the warped planks, but now only dry, brown stains were left. The man's head lay

against a leg of the table upon which rested a small empty box and a few scattered coins. The door was closed but not bolted.

Dawn! Atop a small hillock a lean, gaunt figure lay prostrate. The figure stirred. Long arms writhed and trembled, unshaved jowls quivered. Cold sweat bathed the forehead of the sleeping man. His sunken eyes opened and rolled about in abject terror. Broad shoulders quaked, and the man sat up. He leaped to his feet, glanced wildly about, clapped his hand over a bag at his waist-a bag which persistently jingled-and darted off through the underbrush and into the stagnant pools beyond.

Blindly the man fled away from hideous dreams and more hideous thoughts. He tried not to think, but his will quailed before unbidden memories that flooded his brain; an elder brother, a quarrel over the inheritance, a struggle, a convenient butcher knife, a quick thrust, and his brother had lain quivering at his feet. He had died, but not before he had uttered a fearful cry that must have thundered through the cracks of the cabin and flooded heaven and hell with its venom:

"God ! You've killed me, you Cain!"

With the curse of the dead man in his ears, he had broken open his brother's strong box, emptied the contents into a bag, and bound the bag to his waist where it now jingled, a constant reminder.

"God ! You've killed me, you Cain !"

And, memory-tortured beyond endurance, the man ran headlong into briars that the cruel thorns might tear his flesh and make him forget for a moment.

Would the logs never burn out? They still glowed, though, the sun had risen on a new day.

The face of the corpse was illumined by the cold, gray light which streamed through the east window.

When the man, near mad with horror, had first left the rude log cabin, he was too terror-stricken to decide in which direction to travel. He had wandered aimlessly about until his burning brain had cooled enough to admit sane thought; then he had at once decided upon his destination : the city with its thousand hiding places and its million

souls to hide among. Thenceforth, he had traveled constantly cityward, swerving from his course only to avoid the road which he dreaded as he did the hand of the law which he had transgressed.

Fear of justice which must long ere now have discovered his repulsive crime, fear of determined men, fear of keen-scented dogs, whose breath he often fancied he felt on his back, spurred him on when all his being cried out from fatigue, and hunger, and exposure. Sometimes as he labored forward a mocking voice from within held discourse with him :

"So this is the man who flees to the city to forget and be forgotten! This is the man who runs away to the city with his murdered brother's ducats jingling at his waist! Splendid! In the city he will be safe, for there the law will be unable to discover him in the midst of so many. There he will cast off the past like a soiled garment and live in the future on his murdered brother's money. 0 most excellent future! He will become wealthy, and honored, ay, and beloved for his goodness and uprightness. But can he ever forget the body on the floor with the butcher knife in its vitals-with its mouth full of clotted blood?"

And the man distinctly heard a hard, crisp laugh which he could have sworn was his brother's. The voice continued:

"Go on, you wretch, go on to the city where you can lose your identity, and prosper, and gain the acclaim of the world! They will praise you extravagantly, no doubt. But their applause will mean nothing to you, for, when you are most honored, you shall hear my curses ringing in your ears. You may deceive the world, but you cannot deceive yourself, for I shall stick by your side and curse you until you lie stark and cold with me, you Cain!"

The man did not slacken his pace, but beads of perspiration dropped from his forehead.

The last spark died out on the hearth.

The dead man lay undisturbed, but the grin on his face seemed broader and more malicious.

Another night spent in the swamp, another breathless day of floundering and wading and the man stood on the brink of a swift river. The river was all that lay between him and the city, but rivers must be crossed. A bridge there was indeed, but that route

was barred to him, for here, thought he, the law, grim and watchful, must by now be awaiting the murderer.

The man paced about on the bank. From time to time he paused to gaze at the stacks and piers of the city or the water rushing past him. His heel grated on something hard. He looked. A mussel ! Food ! An hour he spent searching for shellfish, breaking them on stones, and swallowing them greedily, for it was his third day without nourishment.

This strange, barbaric repast finished, the man resumed his pacing. He must cross, that was certain, for thus he was losing valuable time. How to gain the opposite bank without crossing the bridge ! He was a good swimmer, but the stream was dangerously swift-and cold, for it was yet early spring. A raft would not be difficult. He could bind logs together with vines, but that would take time. He must hurry.

The man decided. He doffed his heavy coat, and, removing his shoes, tied them to his belt by their cords. The heavy money-bag he carefully balanced with the shoes. A moment he paused, then waded into the chilling flood. His body sank out of view as he walked forward. At length his feet left the bottom, and he swam out into the current.

The current was brisk and handled the man roughly, but he was a strong swimmer and managed to make progress. As he neared the middle, the stream became swifter, and the water roared and howled about his ears as it carried him far down the river and away from the city. The swimmer could see that some four miles below him the banks closely approached each other. He hoped to reach the opposite side before he was carried to that point, for he realized the fact that so swift a current in a wide river must assume the speed of a torrent when pressed for space. He exerted every iota of what strength was left him to accomplish his object. He drew himself across the deluge with great sweeps of his long arms. He was crossing the middle of the stream when his face became livid, his arms curled tightly against his breast, his legs became rigidly stiff, and he went bobbing down the river like a cork. The unfortunate wretch groaned amidst the swirl of waters. He had entered the stream too soon after eating the shellfish, and his muscles were contracted into a horrible cramp.

The current carried the man too rapidly for him to sink. The agony he suffered could not prevent his thinking, and he dully realized that he was approaching the straits he had sought to escape. Hope le£t the wretch, and at once he became calm. He fully resigned

himself to death, and for the first time in three days the dying cry of his brother grew faint in his ears.

"God ! You've killed me, you Cain !"

The rapids ! Great rocks seemed to rise before the man and rush past him as he was swept with sickening speed into the cataract. Down he plunged to the very bottom of the river where for a few seconds he was spun like a top and then shot again to the surface. The current bore him rapidly down the stream. Rocks lined the banks. The stream itself twisted into a whirlpool. The mad waters hurried the little man on between the Pillars of Hercules and toward the double horror-Scylla and Charybdis! Charybdis won, and the man whirled into the vortex and spun-and spun. Two great forces acted on his little body: the centripetal force of the giant eddy and the centrifugal force of his body's weight. The man sped round a.nd round the great circle, sometimes approaching the center, oftener approaching the circumference. The centrifugal force was victorious, and the tiny form whirled ever nearer the rim of the vortex.

Just as the drawn figure reached the outer edge, a singular thing took place. The frenzied waters spun the man like a pinwheel for a few moments and then shot him away on a tangent with the velocity of a projectile. The speeding body churned the water into foam as it sped diagonally across the current and into a small indentation in the river's bank.

Such indentations or inlets are quite common adjacent to the great, swift river, for the constant whirls and eddies bore the shore line like augers. Strangely, the water in this particular cove into which the spirit of the river chose to toss the unfortunate was quite calm and undisturbed. So little did it mingle with the stream that it had actually grown stagnant. Its banks were lined with reeds.

Now the cramped form, no longer held at the surface by the speed of the river, began very slowly to sink, drawn under by the weight of the money bag at its waist. Down, down into the cool, dark depths the man sank. Life had not quite deserted his body, for as he touched the bottom his fingers clutched in the soft mud, and it oozed between his fingers. He lay very still after that. A few large bubbles rose slowly through the stagnant water and burst among the reeds. Marsh gas ! * * * * * * *

Would no one ever break the silence of the death chamber? Three days had passed and the corpse had begun to rot, but even in decay the swarthy brows seemed arched in triumph.

w. E. SLAUGHTER

It was late in the evening of what had been a burning June day. The sullen clouds hung oppressively low and leaden, and like a pall enshrouded all the land. As I looked out of the open windows of the fast Electric Express train, while the rushing summer air fanned my sweaty face, it seemed that, in the woods we were passing, every leaf drooped in sadness or in fear. The hazy grayness smothered every sound save the rumbling of the wheels. The awesomeness of the charged atmosphere discouraged any voluntary sound from nature outside. The birds with their frolic had departed, leaving slinking, frightened creatures cowering in fearful expectancy. Within me, as I noted all this, there came a strange feeling, indefinable, except that it seemed like a forewarning of some impending disaster.

Even as I looked, the stillness of the fields was broken by a blinding flash and a crashing roar that seemed to burst my eardrums, and the floodgates of heaven were opened and the world became submerged in a summer shower. Around me windows were quickly lowered and every eye for a moment was turned to the sheets of rain, shutting off from us like a curtain the comforting view of the passmg scenery. We rumbled swiftly onward.

Our train of three large and fast electric coaches was crowded to capacity with merry and excited people of all kinds and classes on their way from Baltimore to the graduation festivities at the Naval Academy. Pretty white arms, dresses of every color, jewelry and flirting eyes sparkled beneath the brilliant illumination of the car. Peals of laughter rang out in the merry chatter. Everyone was gay and all formality or social position was forgotten in a time like this when a general purpose was with all.

From my front seat, where I could look out through the cab window of the motorman's operating room, I preceded the heavy train as it smashed its way through the blinding rain. It was like diving into muddy water-it was like falling blindfolded from a building. I thrilled at the novelty of it. I marveled at the daring of the gray-haired motorman who had the throttle wide open and was seated contentedly upon his high stool, eyes staring ahead into the wall of water. The powerful headlight became a candle against the heavy storm. Its strong ray seemed to hit the liquid barrier and bounce back upon us. I turned around to look at the frolicking

passengers who would soon be with their sons, brothers or friends at Annapolis.

When I again looked at the rails through the cab window we were rounding a curve. As I watched I saw to our right a faint glimmer of light which grew brighter and larger as we sped onward. Suddenly our motorman jumped from his stool and I saw him quickly turn off the power. His face was ashen and strange as he applied his brakes with one hand and opened the door that separated us to yell a warning. What he shouted no one knew. It all happened so quickly. For a moment everything became quiet-everyone was in a stupor. I, myself, was paralized with fright and stood hypnotized with fear staring at the approaching light which grew stronger, brighter, larger and larger . . . the crash ! All was black.

How long it had been before I opened my eyes I do not know. I was in darkness and lying down uncomfortably across a hard and narrow something. A leg pained me dreadfully-one, I didn't know which. Then I noticed that my head hurt, too. I tasted blood on my lips and a sickening feeling came over me and I screamed. I tried to move and found that my body was pinned down by an object dark and heavy-and suddenly I realized what had happened. The thought frightened me and I began to cry for help. But my throat was dry and I choked over the sound I feebly made and lay quiet. I could discern nothing in the darkness as I painfully turned my bursting head. Out of this blackness as I lay there came all kinds of horrifying sounds. Behind me I heard an agonizing moan which was stifled almost immediately by a piercing shriek, and the death sigh of some unfortunate victim. A woman was hysterically screaming somewhere near me, and my blood curdled. From away back came the mournful voice of a man calling for a woman. I attempted again to yell, possibly to comfort my senses. This time I succeeded in making a noise and a warm body beside me moved slightly and moaned, "0 -oh God! Where am I?" It was terrible and weird, and I closed my eyes and waited for help.

It seemed years before, over me, I heard the sound of heavy pounding and the splintering of wood. Presently, the top gave way, and as the blade of an axe crashed through the opening, I saw, far above, bright stars twinkling in a cloudless sky The hole was cut larger, a man's head was stuck through, and a tiny thread of light like a gimlet bored its way through the blackness . As the rescuer crawled through I called to him and watched that slender ray of hope as it roamed here and there around the wreckage. In that brief moment

I worshipped it. Hysterically I called to it, spoke to it, and I gave a funny little laugh when it suddenly found my face. A great weight was raised from my body, numbed from pain. I was tenderly lifted and carried out into the warm night air. Once outside the wreckage I was placed carefully down in a lot of mud and wet. An old negro woman came over and, speaking softly, comfortingly (oh! what beautiful music it was to me), washed and bandaged my aching head.

Lying on my back, I stared up at the illumined heavens and started as I recollected the heavy storm of awhile ago. The contrast shocked me: the merriment and the storm ; the sickening cries I now heard and the virgin sweetness of the quiet, clear heavens with every star in its place; while over my shoulder I saw the big moon smiling at the routed storm clouds which were swiftly fleeing across the distant hills in a long train of blackness.

I turned my head toward the wreckage. It was ghastly in the moonlight. One car had telescoped the front car of the train that had hit us. Broken pieces of glass were scattered all around and sparkling like the stars above them. Seats and other objects were lying all about. From the the mass of debris came touching wails, groaning, crying, and sounds from the rescuers as they chopped their way in. From down the road came the clang of a siren and an ambulance came to a quick stop. Three bloody bodies that had been lying near were carefully and quietly lifted and placed in the machine, which immediately rushed away. Automobiles began to come in now and were used to rush the slightly injured to nearby homes or to Annapolis, seven miles away.

When they took me later from the scene of the sad accident and placed me upon a wonderfully comfortable bed it all seemed unreal and I feel asleep from exhaustion and nervousness.

Campus dramatics have received a decided check with the graduation of several loyal workers who gave their talent and time with enthusiasm during the four years of their college careers to develop and firmly establish the University Players.

This year, under the leadership of Lydia Hatfield and Charles McDaniel, a valiant effort must be made to rally round and preserve the standard set last year. Miss Emily Brown, with customary faith in latent talent, again holds the fore as dramatic coach, thus the prospect pleases.

A full program of three one-act plays and one long play is planned. A spring tour in Virginia is rumored, and also a work shop for original plays.

It is lamentable that the course in dramatics for credit is still an unfulfilled dream. The beginning of a splendid spirit was shown in the first presentation of original plays on the campus last spring. However, at this time, there is no prospect of a follow-up by the budding geniuses hereabouts.

By receiving college credit for dramatic work, talent in all branches of the subject would be developed. Life is too full of required work for the average student to "waste" much time on acting or writing. In this manner originality is left to bloom unseen and the divine spark definitely quenched.