University of Richmond Students Cordially Invited to

University of Richmond Students Cordially Invited to

REV. BEVERLEY D.

SUNDAY SERVICES

9 :45-Bible Classes and Sunday School

11 :00--Morning Prayer and Sermon

8 :15-Evening Prayer and Sermon

Vested Choir of 40 Voices With the Following Soloists:

Tenor-Joseph Whittemore Soprano-Mrs. Frances W. Reinhart Bass-Norman Call Alto-Mrs. F. Flaxington Harker F. Flaxington Harker, Director and Organist

ST.PAUL'S is the historic "Church of the Confederacy," referred to by Mrs. Jefferson Davis as "The Westminster Abbey of the South." , Pews occupied by President Davis and General Robert E. Lee are marked by silver tablets. The memorials to Confederate l~ders and others are among the most beautiful in the entire country.

A liberal Christian message, for thoughtful and forward-looking young men and women 1s preached from its pulpit.

"We, the members of the First Baptist Church of Wartburg, Tenn., desire to express our appreciation for the kindness, liberality and skill of Kellam Hospital, Richmond, Va., shown our beloved Pastor, Rev. I. H. Bee, in the successful cure of that dread disease, cancer, and his restoration to us in perfect health and, we trust, many more years of usefulness.

"And Further, Be it Resolved, That a copy of these resolutions be placed on the records of the church and a copy forwarded to Kellam Hospital.

"Done at regular session of the Church, this 9th day of August, 1925."

CARRIE S. HONEYCUTT, Clerk and Treasurer.

Entirely new suburban home by January, 1926; progressive and orthodox faculty of eminent Christian scholars; comprehensive and practical curriculum; large and world-wide student fellowship; numerous student-served churches; tutition free; financial assistance where needed, and moderate expenses; the Harvard or Johns Hopkins of the theological world.

Twenty-two University of Richmond students last Session. University of Richmond third among 167 schools. University of Richmond men have high rating.

Write E. Y. MULLINS, President

BOULEVARD AND PATTERSON AVENUE Service With a Smile

GOOD THINGS TO EAT AND DRINK

204 NORTH 5TH ST.

FLOWERS FOR EVERY OCCASION

"SAY IT WITH FLOWERS"

TELEPHONE MAD. 215

OPPOSITE MILLER & RHOADS 5TH ST ENTRANCE

Centrally located in the city of Philadelphia, 1812-1814 South Rittenhouse Square. TUITION AND ROOM RENT FREE Opportunities for self-help. Student Loan Fund available. Great libraries and museums in the city available to students.

High Educational Standards. Strong and Scholarly Faculty.

Four Schools: THEOLOGY, including the courses of study usually offered in theological seminaries. MISSIONS. RELIGIOUS EDUCATION. RELIGIOUS MUSIC.

Ten minutes from University of Pennsylvania. Session opens September 21, 1926. Write for new bulletin.

1. Richmond College, a College of Liberal Arts for Men.

2. Westhampton College, a College of Liberal Arts for Women.

3. The T. C. Williams School of Law, a Professional School of Law, offering the Degree of LL. B.

4. The Summer School. W. L. Prince, M.A., Director.

W. L. PRINCE, M. A.,

DEAN

Richmond College for Men is an old and well-endowed College of Liberal Arts, which is recognized everywhere as a Standard American College. Its degrees are accepted at face value in the great graduate and technical schools of America. Its alumni arc so widely scattered through the nation that the new graduate immediately joins a large and friendly group of men holding positions of power and influence. The College occupies modern and well-equipped buildings, on a beautiful campus of 150 acres in the western suburbs of Richmond.

MAY LANSFIELD KELLER, PH. D., DEAN

Westhampton College for Women, co-ordinate with Richmond College for Men, is housed in handsome buildings on a campus of 140 acres, separated from the Richmond College campus by a beautiful lake of about nine acres. All degrees are given by the University of Richmond, and those conferred on women arc; in all respects, equivalent to those conferred on men. While the two institutions are co-ordinate, they are not co-educational.

.J. H. BARNETT, .JR., LL. B., SECRETARY

Three years required for degree of LL. B. in the Morning Division, four years in the Evening Division. Strong faculty of ten professors. Large Library. Moderate Fees. Open to both Men and Vfomen. Students who so desire can work their way.

For catalogue, booklet, or views, or other information concerning entrance into any College, address the Dean or Secretary.

F. W. BOATWRIGHT - President

COPYRIGHT

1926 BY

LESLm L. JONES

MAY-JUNE , 1926

w. E. SLAUGHTER

Painted! . ..

That ' s what you are; Daubed with dazzling hopes, With lustrous promises, With livid power.

A luring beck'ning vampire, Sucking peace from happy souls From lowly hearts. . No! no longer do you charm me, Wrenching joy

From beauty, from love, From dutyNo longer do you lure me With your transitory visions Of a labored life's reward.

Through Contentment's glass I see you As a hypocrite deceitful.

Today caresses me with the fragrance Of present self-satisfaction; Contentment enfolds me In her warm, refreshing bosom.

So, Let me linger o'er the joys The present day can give. Tomorrow comes Then, It will be Today.

Bright, beck ' ning Future, You, too, will be Today. I shall wait No. 7

MARIAN R. MARSH

Young Cuyler slammed the heavy door shut in a last attempt to escape the sound of his mother's impassioned voice as she flung insult after insult steeped in venom at him. He stood beside the closed door for one brief moment, and as. he turned the key that gave him grateful refuge however short, he heard a gasp of enranged surprise followed by retreating indignant footsteps. He exulted in the quiet privacy of his father's spacious library with its row upon row of voluptuously soft-bound volumes. Dad was a good sort anywayqueer and given to strange and inexplicable brooding at times, but a good sort for all that. If he were here now, he would be the last one to sling vile epithets at the name of the girl his son had chosen to make his wife.

"Common ! -no social position ! -beneath you -not fit to be a Cuyler's wife!" As the memory of his mother's words returned, the boy's lip curled and an expression of disgust filled his eyes that were already dark with scorn. "No," he said, half aloud, "you were never more right; she's not fit to be a Cuyler's wife. She's a damned sight too good! Common -ha!" It was laughable. The word might more aptly be used of the whole lot of society in which the Cuylers lived and moved and had their being, that had long since succumbed to ennui with the world in general.

With one slender and almost femininely white hand, he impatiently thrust back the dishevelled mass of blonde locks that clustered about his temples. Strange Dad had offered no advice this morning when he had told him of his intention to marry ! Instead he had merely hesitated uncertainly for a moment, and then without a word, left the room, to return almost immediately. There had been a peculiar expression, almost of embarrassment on his face as he placed in Cuyler's hands a slender volume bound in foreign fashion and said, "You will read it?" And he had added "- alone?" There was no denying it-his father did queer things. And the boy, wondering but secretly pleased that his announcement had caused no greater disturbance, had slipped the strange little book into his pocket and as quickly forgotten about it in the ensuing encounter with his mother.

Now he drew it from its forgotten place in his pocket where it had lain since morning, and curiously began to examine it more closely. Struck with the unusual beauty of the binding, he studied

its queer designing before opening it. "Deucedly pretty," he thought, "costly, too!" The leaves were edged with fine gold and they were of some sort of smooth parchment unknown to the boy. Turning them rapidly, Cuyler was surprised to see that each page was filled with the close writing of his father. "So! Dad had kept a diary." But no -it was more a journal, for the entries were made irregularly and sometimes at long intervals. Opening now to the flyleaf, he was startled by its inscription written in a beautifully quaint but scarcely legible hand :

Like theSilence of sleeping seas, Shadows of dusk-cloaked leas, Beauty that falls from the night's brimming cup, Gardens of faint-hued flowers, Gossamer golden hours, Fleet inward dreaming of hearts lifted upy our friendship to me.

-Quan Lee.

The boy was perplexed; he felt that to read these pages would be to desecrate some exquisite, buried chapter of his father's life. And yet he had not sought to read it; his father had made the request.

At the top of the first page was the inscription: "PRIVATEJouRNALOF ANTONYKENT CUYLER,"and under it these entries:

MAY2, l~I had thought little of the advent of Wu Sin, seller of antiques on Verlaine Way, until today, when I chanced to enter his queer little shop in search of a gift for Vivian's birthday. I was as tired of giving her flowers and candy and jewelry as she must be of receiving them, and I was determined to find something different, if it were no more than an Oriental fan or an image of gilded wood. It must be quefque chose de nouveau! The shop was quiet when I entered, and after walking heavily about for a moment to inform the keeper that he had a customer waiting, I began to examine the curious things that lined the walls of the shop. There was an air of mystery arising from the very exclusiveness, antiquity, and ingenious arrangement of the Chinaman's wares. The walls were hung in tapestries wrought in golds and dull blues and startling greens; incense from grotesque burnished burners filled the air with subtly sweet aromas ; and silk fabrics, fans, coarse articles of pottery, brazen urns, ornaments of finely carved wood, and innumerable jewelled and beaded trinkets completed his store. When I had scarcely begun to examine one treasure, another would catch my eye and demand inspection. In the midst of my gazing, I heard the soft rustling of a silken curtain to the rear of the place, and turning, I beheld the not so much

handsome as majestic figure of Wu Sin. He was tall and slightly made -old, too, I think, though faintly greying hair and a slight infirmity of mien were his onlyi signs of old age. His manner and tone were marked by that imperturbable gravity so characteristic of Orientals; he was both gracious and inscrutable in the search for my gift. We finally settled on a jewelled belt, a rare, exquisite thing that immediately caught my eye.

As I turned to leave the shop, a second rustling of the curtain made me glance back. And framed against the silken background was as real a vision of sublimity as I ever hope to behold this side the Glittering Gate -a slight girl clad in an Oriental tunic embroidered in startling shades. I was rude enough to stare, and in that moment I had an unforgettable impression of her small, dark beauty, full red lips, and the dimples of a laughing, yet pensive mouth. A Chinese, with that face? Impossible! The mystery of her presence in Wu Sin's house enthralls me; it would be fascinating to solve it. Ah! but I am forgetting -Vivian !

MAY 15, 1900-I had almost forgotten the incident at Wu Sin's, so busy have I been with my work and the making of final plans for the house that the good pater is building as a wedding gift for Vivian and me. The contractor promises to have it all complete by early fall. And the wedding will be in October. But to go back, Vivian asked me to go with her this noon to Wu Sin's to purchase a particular piece of tapestry that had caught her fancy as it hung in the window yesterday. We went and after a moment of waiting the curtains parted, and not Wu Sin, but the girl entered. Naturally she made no sign of recognition, but in a quiet and courteous voice asked what we wished . As she showed us the tapestry, I was rude enough to stare a second time, and I found her even more lovely than before. Her teeth were small and even; her skin faintly golden in hue with the delicate coloring of a rose; and her eyes as darkly blue as a wood violet. There was charm and poise enough in her manner to convince me of one thing -her's is no common lineage, whatever her race ! I don't know whether Vivian perceived my ·undue interest in the girl or not; I only know that she hurried me away before I could show her any of the things that I had found so rare. And for a woman, she was uncommonly quiet all the way home!

MAY 30, 1900-Vivian and I rode over to the site where the foundation for our house is already being laid. Vivian acts so strangely whenever I venture a remark about our future happiness; she always silences me with something about being sentimental. I 'Wish she were less cold.

JUNE 1, 1900-Curious thing! I was walking past the little shop today when the door opened and Wu Sin motioned to me to enter. Surprised, I followed him in, through the curtains at the back, and on till we came to a porch opening out onto a small courtyard arched

over with numberless interlacing boughs. There were flowering shrubs in porcelain vases, strange caged birds on gilded wooden stands grotesquely carved, and exotic mats and silken cushions on the stone floor. The girl whom Wu Sin called Quan Lee was seated, embroidering golden dragons against a fabric of blue. Wu Sin explained that knowing my interest in old and beautiful things, he wished to show me some of his latest acquisitions. Quan Lee embroidered and said little, but once or twice when I looked her way I surprised her own covert sideways glance. Once our glances met and unless I am mistaken, a slight red tinged the golden hue of her cheek. I know that she smiled ever so faintly, and as I smiled back, I think she must have read in my eyes the tribute they sought to pay her beauty. As I write, the memory of her moves me strangely; the charm that emanates from her even insensibly steals over me, in spite of myself and-Vivian! Wu Sin asks me to return, but I don't know -I don't know. I don't know if I dare!

JuLY 10, 1900-As I re-read the concluding words of the above I wonder that I could stop with so paltry a description of Quan Lee. Since that day when I saw her first, I have become a frequent visitor at Wu Sin's shop. He is a queer being; at once gracious, suave, smiling, and - impenetrable. He seeks my advice on all occasions, and yet, I could swear he does it only to make opportunities for me to be with Quan Lee. But he tells me nothing of her, and when I venture some query as to her relation to him, or to her total lack of Chinese characteristics, he merely studies me in a strange fashion, smiles more strangely still, and-changes the subject. If I only knew ! But surely he will tell me.

And Quan Lee! She seems no longer to fear me, for she has lost almost all of her former shyness in my presence. She talks to me as she embroiders, of the Orient, and so vivid is her describing that I can close my eyes and feel the fragrant south winds that she tells of; see her bright robed figures reclining on cushioned barks that glide always softly over lazy blue waters; live on her islands topped with mountains that rise boldly from the sea. When she stops and I open my eyes, it is only to be enthralled again, this time, by a small hand that can charm one with its mere toying with a fan or an embroidery needle. Today she shyly gave me a small journal that Wu Sin found in his endless wanderings. It is a costly, beautiful thing, and I shall transfer my entries here to its smooth pages with utmost care lest I should spoil any part of it.

Vivian has been gone to their summer place for more than two weeks. She writes that she will be gone a month longer before she returns to make her final preparations for our wedding. Wedding! The word strikes a chill dread into my heart. I love her still, but I never thought her so artificial and cold till now. I gloried in the credit she would do me as a wife, until now, but I think I overlooked

a chief er thing -happiness ! If only Quan Lee had never come ! Or if she only were not in Wu Sin's -house! But conjecture is dangerous!

JULY 26, 1900-I dreamed last night of Quan Lee, a strange disturbing dream that has troubled me ever since I awoke.

Vivian writes that she is anxious to be back doing some of the endless things that have to be done. Was man ever more miserable than Antony Cuyler ? I actually grow cold at the thought of this marriage that has been the hope of both our families since Vivian and I were children. Oh, just to get away; to know that she has no Chinese blood in her veins. But even if I knew -would I dare to make the break-now? My heart is heavy, for I know that I would not.

AUGUST2, 1900-Vivian returns tomorrow! And there must be an end to this seeing Quan Lee, whose very sight is like a cool luxuriant breath from far away lands. I have never so much as touched her; love has not even been mentioned. And yet I feel as guilty and miserable as a cur. I feel that she is aware of the attraction she holds for me. And something unfathomable in her eyes, recently clouded over as if tears arose to them and yet remained unshed, insensibly tells me that she is neither as carefree nor happy as she was that day when I first caught a glimpse of her against dull silken curtains. She is still gay, my little Quan Lee, but she is also sad. Once I spoke to her recently and she made no answer ; her eyes seemed turned upon some inward dreaming.

AUGUST25, 1900-The announcements are out and the house is all complete. Decorators and furnishers and upholsterers are there at all hours working their wonders of modern beauty. But even as I look and nod approval and force a smile at Vivian's exclamations of delight, my eyes play cruel tricks on me, and I am seeing instead a small courtyard roofed over with interlacing boughs; flowering shrubs in porcelain vases, strange caged birds on gilded wooden stands; and seated on a painted floor mat, a girl in a bright silken tunic, embroidering a pattern of dragons against a fabric of blue. I met her and Wu Sin on the streets today and they were both dressed for travel. I stopped, and they spoke to me as usual except for a new shade of reserve in their manner. But as they passed on, she turned and smiled, an unforgettable smile. I wondered if they could be going away for long; but I soon came to the shop and found it empty. A "For Rent" sign hung on the door!

SEPTEMBER30, 1900-The sky outside is dark with rain clouds, and I can scarcely see through my window for the steady downpour that veils my sight. Already the streets are everywhere filled with great pools of water. And this voice of the elements is wholly in keeping with my feelings which are as leaden as the sky outside. I

received a letter today from Wu Sin which I shall paste here, for it explains itself. It gave no address and the postmark was indistinguishable.

September 25, 1900.

The name of Cuyler is old, lad; that of Quan Lee dates with the centuries. The Cuyler blood is proud; but royal is the blood that flows through Quan Lee's veins.

Once in my travels in search of rare and beautiful things, I befriended an exiled and dying prince. He left me to care for his daughter, then a child of twelve, whom I have called Quan Lee. His one plea was that I should never take her back to her native land, but help her instead to find happiness in a freer country. I vowed and Wu Sin will keep his vow. Once he thought that she had found it-he knows now that it is waiting ahead somewhere for her.

It is not hard to recognize a jewel rightly labelled, lad. Only a master knows it out of setting!

WU SIN.

The darkness comes quickly, and the rain outside has slacked to a steady drizzle. My room is shadowy and I can scarce see to write in this pallid light. From somewhere - from nowhere there come endless pictures, glimpses of dreams I have sought to forget. Now it is a slight girl clad in an Oriental tunic framed against a dull background of silk; now it is Quan Lee seated on a painted floor mat, embroidering a pattern of dragons - gold dragons -against a fabric of blue. And always the subtly sweet aroma of burning incense steals over me, enveloping my senses like a mesh. God ! And I am to be married - tomorrow !

The boy breathed heavily; there was no doubt in his mind now. Placing the slender volume on the table, he unlocked the door noiselessly, and as quietly slipped from the house.

That evening a telegram came to the Cuyler mansion, containing just three words :

ANTONY KENT CUYLER, JR.

Mrs. Cuyler made no sound, but her husband as he gently laid her on the chesterfield and rang for restoratives, smiled ever so faintly. Perhaps-from the memory of gold dragons - his eyes were strangely bright.

J. MARK LUTZ

Lanice is the wonder of a stark tree against a hon-fire of clouds ....

Too cerebral to be beautiful in the usual sense, there is a look about Lanice as of a live seed untouched as yet by rain and sun. . . . but Lanice is never the same two days in succession, people say.

neither is the sky answer .... . winds the sea, you

Like the higher of the species, Lanice has been long in growing up, but now something is stirring within. Lanice wants to create, but is impotent . . . the rain and sun of experience have not brought about germination. . . .

On one side of Lanice is necessity, on the other fear for the future . . . both shading Lanice from rain and sun.

Between fear and the future Lanice will have life pressed out, and will be as dusty as are other dried flowers.

There is no look of repentance in the eyes of the old man. He sits by the fire and smokes, puffing out his cheeks, occasionally grunting as his hands, with their raised surfaces like a relief map, takes a poker to mend the fire. . . .

The old man has gone against the counsel of everyone who should know what is good for him, and he has failed as they predicted, and their superiority would be confirmed if he would but show repentance ....

. . . I took advice before and failed, he says . . . there is some satisfaction in failing for yourself.

Although Evadne should be a mother to many men she has borne only one . . . one on whom she breathes the love that should be divided with dozens. . . .

She is a tiger cat watching her brood; quick to scent a danger; quicker to sense a slight. Her jealous love has succeeded in killing the one thing she loved, for she has squeezed the breath from the body of her child when the_ father reached out his hand. . . .

Tearless, unrealizing, she sits there hugging her dead child. Already the infant is cold in death. Only a short time now and the nearness of death will cast dark shadows across the pallid, pinched little face. . . .

Lad minces in his walk. Lad likes perfume. Lad has a face as rose-like as that of a girl. . . .

Because his father never seemed to like him Lad has clung to his mother with a love that is rare . . . and for her he will be good ....

Some day Lad will realize that all his books have not told him that you cannot change a weed into a flower with another name.

Delyne is the sea pulled by the moon.

Her moods are as changing as an unfolding flower of the night, while she loves as casually as a breeze from her south in a rose garden . . . and as carelessly for consequences. . . .

Delyne sits by the road and watches for a lover who is always just out of sight. She finds many whom she thinks is the awaited one, but she learns her mistake soon . . and they call her inconstant. . . •

WARREN A. McN EILL

I sing the praise of bygone days When the hearts of men were young; Of ages flown when love was known And supremely ruled on earth; When vows were said and tears were shed As langorous lovers clung.

I sing the praise of bygone days When each heart was filled with mirth; When maids were shy and hopes rose high At each smile or sigh or glance; When failure meant but deep content, Since to dreams it gave new birth.

I sing the praise of bygone days When men trusted sword and lance ; When, finding zest in beauty's quest And without a thought of gain Each one was keen to serve his queen And but laughed at each mischance.

I sing the praise of bygone days ; Of Romance's early reign.

BY ONE OF 'EM *

In one of the recent divorce trials the woman was reported to have said: "I once went with a Harvard man, but he seemed refined." That conjunction "but" raises the query, Could a Harvard man be anything but refined?

The mighty name of Harvard stretches a subtle influence into the furthest educational back-washes of the republic, and conjures respect among the most non-intellectual of the bourgeoisie. Hard-headed business men like the sound of the word in their mouths; flappers at tacky house parties quail before the information, "I go to Harvard"; penniless "English majors" of denominational junior colleges have suppressed desires to "do research" in Cambridge; in fine, the mighty intellectual arbiter of the East, squatting like some hindoo idol over dingy decaying Cambridge, transcends its sanctuary, the Yard, and spreads its magic name into every corner of the fortyeight sovereign states.

Part and parcel with the reputation of this ancient seat of learning, there is the expression which may be met with widely: "The Harvard Man."

Who is this Harvard man? Society items in metropolitan newspapers bear reference to the approaching marriage of some unknown woman to an equally unknown male, "a Harvard man." A bootlegger (high class!) is arrested: "a Harvard man." A great lawyer dies: "he was a Harvard man." A street-masher is apprehended: "he was a Harvard man."

Aside from the seven or eight thousand students attending the various schools of Harvard, there are 44,000 of the Harvard men extant at the moment. Our population is saturated with them: one trips over their feet in theatre aisles, jostles them in the subway, runs them down with one's car, and yet, is seldom the wiser.

We have heard all our lives of this creature of the gods. Just what is he, after all? What distinguishes him from the honored graduate of the I. C. S, (Scranton) or of the Barber College?

Despite the fact that for the price of tuition one may acquire the appelation in question, there should, in all justice, be some standard, some description, some characterization of this Harvard man. From

* Five Richmond College men are now attending Harvard.

postulates usually accepted by parents whose sons may go to college, I hope to present illustrations of this protege of old John Harvard so that the public may know him when he appears. The reader will be able no doubt to draw from these illustrations a portrait somewhere correct. The writer reserves his personal mental picture of the Harvard man.

The Harvard man is handsome. This is a quality unwittingly assumed by the majority of people to whom Harvard is remote. And yet is the Harvard man the near-sighted, shabbily dressed, roundshouldered, rat-faced graduate student with a battered brief case dangling from his hand, and with a goose-look on his empty countenance?-this greatest of Freud's arguments for the inferiority complex? -this future professor? Is he the tall, high-headed, welldressed law student on whose wide chest there tumbles the Phi Beta Kappa key? Is he the mature-featured, raccoon-skin coated undergraduate driving to the Yard in a topless Marmon? Is he the bashful, retiring negro, of varying shades of color, who is silent and unassuming, yet who makes the Southern student nervous in the restaurants and on the subway? Is he the slant-eyed Chinese who is not sensitive to his language being overheard in public and who sits in his library stall ten and twelve hours a day? Is he the thin, well-dressed, loud-voiced, unsensitive student with Semitic features? Is he the bald-headed, middle-aged, high school principal making a last dash ( ?) at the "doctorate" before he returns to his ignominy in secondary education? Is he the burnt-cork complexioned Hindoo, who speaks perfect English and wears his native hat? Is he the blond Frenchman who is mistaken for a Teuton and a Scandanavian?

The Harvard man is handsome, no doubt; but the weak-chinned undergraduates with the rubber stamp features of those in our Northern metropolises is predominant. The sons of those I-forget-howmany manufacturers who read the Literary Digest "for their mind's culture" have no more distinctiveness in looks than have the clothes they wear: the same in Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco. The wide-trousers, blazer, sport hat type is in slight evidence at Harvard. For with his top coat collar up and his hat brim down, the Harvard undergraduate lounges from the Yard to the Square; when he has passed, we forget his face as we do the faces of the multitudes we pass on Broadway. But he is none the less "a Harvard man."

An undergraduate, tall and skeleton thin, with rimless pince-nez and a C. Chaplin mustache, emerges from the sacred Yard. His

head covering is a low crown derby which is too large; his top coat encloses his narrow chest in a double-breasted coachmanlike garment, and his spindlelegs are thrust into elephantine goloshes flapping freely with his awkward gait. . . . The Harvard man is handsome !

The Harvard man is well-mannered. We shall make no attempt to define a gentleman. The term generally presupposes self-restraint and the absence of annoyance to the comfort and good taste of one's fellows. But the Harvard man must be a gentleman, having attended a school so thoroughly saturated with gentility and high-hatted intelligence. His etiquette comes to mind in the picture of undergraduates drunk and noisy on the trolley cars, -entertaining the passengers with stupid antics; or the same undergraduates now sober in the classrooms muttering under their breaths concerning the professor: "Listen to that -----fool !"

It is a matter of no great importance that men to whom one has been formally introduced never speak to one afterwards. But those same individuals, should you be the first to finish an examination in the room where they are, will reward your alacrity by stamping their feet thunderingly upon the floor in sneering tribute to your good fortune and in hope for your resultant humiliation. . . . The Sophomore Class of Harvard, reeking and creaking with traditions, concludes its annual evening smoker in the living room of the Harvard Union by pelting each other barbarously with doughnuts, much to the annoyance and danger of anyone passing in the lower halls. . . . What if a student must be reprimanded by the authorities for refusing to allow his room to be cleaned, and for living in dirt and disorder and carelessness to the extent of setting fire to the rubbish in his room and having his laundry consumed. What if1 he seeks his clothing on the floor under the furniture, and treads upon his fur coat ( a popular sign of opulence) when he crosses his room? Surely it is not for us to censure a man's private manners. This is a day of personal ethics. It is no concern of ours that a student in a restaurant cleans his teeth with a napkin; but we are reminded that the Harvard man is well-mannered, and that it is more difficult to eat as a gentleman than to speak as one.

President Smith, of Washington and Lee, recently declared that a man's ability to get on with his associates was as just a criterion for college entrance as high grades : Is he neat? Is he clean? Is his behaviour gentlemanly? Dr. Smith's questions should be asked at Harvard. The apparent tradition of the superior intelligences in

New England is that when winter comes, one should keep warm at all expense : hence, no ventilation in trolley cars, theatres, classrooms, or public buildings. Arthur Brisbane's identification of progress with the phenomenon of ten million bath tubs in the United States is consoling in its implications. But one begins to think that Puritan New England did not get its share. Alas for the necessity in classrooms of moving one's seat repeatedly to escape the presence of some splendidly dressed Harvard man whom Brisbane's "progress" . has not reached. The "backward South," we see, hasn't caught up with all the methods of the North!

Harvard's manners quickly become those of the foreign student. A high caste Hindoo shakes hands with one of his fell ow countrymen and later says to his occidental friends: "In India I could na' do that. He is lower than I; if I shake his hand, I mus' go take a bath ; but here where wood-choppers become president we have democracy." When asked whether his democratized manners would be understood in India, he said : "Oh, no ! They would not receive me : I am western civilization." But he is a Harvard man : he understands our manners even if he secretly laughs at his expedient use of them.

Finally, the Harvard man is intellectual. Considering the reputed "commercial value" of the Harvard degree and the pre-eminence of its professors, one needs hardly, question. the supreme intellectualism of its students. Harvard is like some magic pitcher, a fountain overflowing with sparkling gems of knowledge: a royal road to erudition. And students sit, rapt in the brilliance of their instructors, learning rare and potent beauties of ancient lore. Who can deny that the Harvard man is intellectual? Who can doubt that the Harvard man is no little knowing in this complex world? And upon this point we recall the Harvard College graduate, a member of Phi Beta Kappa, a student in the Law School, who recently was surprised to learn that there was such a thing as venereal disease. Another, likewise a member of Phi Beta Kappa and a third year law student, was wondering whether a girl's "I shall be glad to see you," as a response to his request for a second engagement, contained expressed hope for his stifled sex urge. What if a Harvard senior, an applicant for the cum laude graduation honors, should come to the graduate of a small Southern college for information on how to write a paper which would satisfy the requirements of his candidacy? We may not question the intelligence of a student who memorized

the vocabulary of an old French text-book, or who annotated William Congreve's plays and made complete "corrections" of the dramatist's errors in grammar; but what should we say of that otherwise sane fellowship-holder, and future government professor, who, having finished his lunch, eats a cold baked Irish potato and two crackers left by some former patron of the restaurant, with the observation that he "hates to see food wasted!"

Three Harvard undergraduates were watching a mediocre production of shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra. The following conversation issued from them: "Shaw is like these people who read The America n Mercury and The Nation - sophomores who never go up, exponents of a smart-aleck philosophy which can explain and answer everything." "Yes," was his companions' weak rejoiner. "But, listen, listen," said the first as his friends threatened to descend from the intellectual pinnacle to which he had lifted them, "such people don't know that the essential nature of reality is a paradox." An awed silence followed his remark, the platitude paraded by; his companions were prostrated, speechless. And for the benefit of his neighbors , this Harvard man announced at the conclusion of the play: "That's the best revue I've seen this year." . . . George Pierce Baker has gone to Yale : yet dramatic criticism at Harvard is as subtle as ever. . . . . The Harvard man is nothing if not intellectual. There are those who say he is not intellectual.

There is no gainsaying the ancient honor for the Harvard man; for he is handsome, well-mannered, and most excellently intellectual.

This play makes no pretense of being original work. Those readers who know John Davidson will recognize his poetry all through it, changed in places, to be sure, and interspersed with my own, but, none the less, unmistakably his. I have here attempted to draw a picture, in his own words, of that tragic young man who died, I think because he lacked a sense of humor.

The first scene is laid in Scotland during the latter part of last century; a country where, Davidson says, "A creed could kill" and where "Time stood still and change made holiday"; a country of Presbyterian zeal and ugly narrowness, where the young poet found but little of that beauty that he craved, and none of the tolerance which later proved itself necessary to his existence.

As the curtain rises two men are seen in a little room furnished in the best Scotch Presbyterian style. The older man seems even more austere than the room furnishings; stern as only a Scotchman can be stern The young man looks half-afraid, but determined to see it through. Both are muffled up as if they had just come in. The poet addresses his father:

POET: Father, I could not stay. I will not worship A God who rules like a tyrant, by fear!

FATHER: My son, the longest life must end. Die Unbelieving, an'd in endless woe you must Believe in death throughout eternity.

POET: I shall consider no "shalt not," and nor Man's "must." \Vhy can I not be let alone?

FATHER: But, son, your promise to your mother. It Eased her broken heart before she died. You Killed her, you're killing me: is it not sin Enough my poor unheeding willful boy?

POET: Aye, my promise, wrung from me when she \Yas dying, because you said my unbelief in her Dull God was killing her! A dreadful death To die believing in so dull a God, A useless Hell, a jewel-huckster's Heaven!

FATHER: Yes, son, it was your unbelief killed her.

PoET:

JOHN DAVIDSON

No, father, 'twas her savage creed that killed. And I will have no kind of creed at all. Henceforth I shall be God ; for consciousness Is God: I suffer; I am God: this Self, That all the universe combines to quell, Is greater than the universe; and I Am that I am. To think and not be God?It cannot be! Lo! I shall spread the news, And gather to myself a band of Gods And out of chaos make the world again. Behold, my father! We, who heretofore, Fearful and weak, deep-dyed in Stygian creeds Against the shafts of pain and woe, have walked

The throbbing earth, most vulnearble still In every pore and nerve; we, trembling things, Who but an hour ago with awe beheld A shaven pate mutter a Latin spell

Over a biscuit; we, even we, are Gods ! Nothing beneath, about us, nor above Is higher than ourselves, we are supreme !

FATHER: The unpardonable sin of Lucifer, To make himself God's equal! Now, my son, Let me curse God and go to Hell for you! I cannot face your mother, you unsaved! If my eternal death could but requite Your sin -perform the perfect will of GodAmen. I come, Lord Jesus. If his sin Be not to death, save him, Lord. Heaven opens !

The old man slumps down in his chair. The young man goes to hi·m, touches his head, knee.ls beside him, takes his hand and then lets it fall limp. He buries his face in his hands and sobs:

POET: Again your awful creed has taken life! My father, may you both be kinder now.

The curtain rises revealing a rocky cliff beyond which the surf can be heard roaring and the waves breaking on the rocks. It is

twilight. The poet stands looking out to sea. After a brief silence the poet speaks:

POET: I am not old enough to die, and yet I am too young to walk the world. Oh, fool, to think that far away from home I'd find the world was beautiful and free!

0 idle dream : thought of a child. How unintelligent, how blind I am ! How vain! Am I a God? a mole, a worm!

An engine frail, of brittle bones conjoined; With tissue packed; with nerves, transmitting force; And driven by water, thick and colored red : That may for some few pence a day be lured In thousands to be shot at! Oh, a God, That lies and steals and murders! Such a God, Passionate, dissolute, incontinent!

A God that starves in thousands, and ashamed, Or shameless in the workhouse lurks; that sweats In mines and foundries! An enchanted God, Whose nostrils in a palace breathes perfume, Whose cracking shoulders hold the palace up, ·whose shoeless feet are rotting in the mire!

A God who said a little while ago, "I'll have no creed"; and of his Godhood straight Patched up a creed unwittingly -with which He went and killed his father. Subtle lie That tempts our weakness always; magical, And magically changed to suit the time !

A God who cannot face the world and live; Who looked for beauty and could find but lies. Ah, world! would my eyes had seen you ere My dreams of beauty wrought to make you fine. I thought to lead a mighty band of Gods And out of chaos make the world again; I leave a world with which I could not copeOh, Lord, forgive this, my futility. Farewell, oh world of creed and filthy lies!

There is silence for a moment. Then the poet hurls himself over the cl•ff. For a brief space there is no sound but the beating of the surf as the curtain slowly falls.

C. L. DODDS

(Lmoleum

Cut by S. Warren Chappell)

Europe, to mr notion, isn't such a bad place to spend a vacation, and it becomes rather irksome to hear so many American invaders, lately arrived from Podunk Center, Kansas, and until recently able to converse only on the yield of wheat and the month's churning, get all worked up over the poor service at Ciro's, take exception to the left-of-way traffic rules of London, find fault with the color of Veronese's paintings, or see nothing but crude amateur touches to Notre Dame.

It's queer how even good Americans, who have done their duty and have seen America first, roam about the contingent guided by Thomas Cook or his ever-present son, because their knowledge of continental languages can be summed up with "quanto costa," "combien," and "wie viel," comparing each building on which they carve their initials, with the First Methodist Church of Lake Crystal, and each monument of Angelo or Rodin with the one erected to the heroes of Rice County who fell in the Spanish-American War.

When a newly-knickered tourist, fresh from Rotary, steps off the boat at Cherbourg or Southampton, where all conventional tourists land, he seems to have lugged along with him everything he had previously possessed except sincerity and consideration -and then we wonder at Europe's opinion of us. It's something of a lack of respect of youth for age, perhaps. Recall the voyager from Jersey City who said, "Humph! I don't see so many wonderful things abroad. If America was as old as Europe, I bet she'd have things just as old." Deep, that!

Embarrassment approaching shame was mine atop the Wimbley bus in London, when a lady, who had proved most pleasant on shipboard - a college graduate who had been yearning for the culture the old world could afford her, remarkably ignorant of weather difficulties on the island - spoke in a shrill Connecticut voice of the miserably dirty appearance of all the public buildings she had seen. The queen mother's palace was a "mess," Hyde Park "wasn't in it" with the Bronx Zoo, Brooklyn Bridge "had it all over" Tower Bridge. Even Kew Gardens failed to please her. About us sat justly indignant Britishers.

The prize of them all was the man we nick-named Bozo, owner, according to information tendered two minutes after he approached us, of a chain of luncheonettes in our metropolis. He was going to fly all over Europe, he said, while his shrinking wife sank back in deeper silence among the hotel cushions. "You could get a better idea of the country and not have to mingle with the natives." He did fly from Croyden Field, out of London, to Ostend and ran along the aisle of the plane like the proverbial two-year-old, and tried, on a self-invited visit to the pilot, to persuade the latter to do some "stunts." We caught him down from the clouds later, however, on the Rhine trip, or rather he caught us, for he saw us first. The trip was boring him. "Why I thought this might be like the Grand Canyon of the Colorado -it's not even like the Palisades!" Wouldn't he have been pleased had they been? The only really worthwhile happiness he experienced on the river came when he hired one of the German waiters (who spoke English) for work in one of his luncheonettes.

So the vacationist, like 0. Henry's rubber-necker, scrambles across the Atlantic, parades through London Tower, brawls about Zelli's at Montmartre, covers the Alps with paper bags, makes himself a nuisance at Mc;mte Carlo or a spectacle at the Lido, shows his ignorance by claiming the Gothic experiment of Notre Dame has not the graceful lines St. John's the Divine will possess when various creeded men have subscribed enough to finish it. He swarms with hundreds of his compatriots in upon Sunday services at San Marco, stumbles over kneeling worshippers or priests performing their rites, takes snapshots, and climbs high on the grill-work to see "what's going on" before the altar tomb. One be-spectacled American doing intensive traveling took his bicycle into the church with him. What he was doing with a bicycle in Venice he alone knew. This shrine of St. Mark, to the casual traveler, is an Oriental sideshow of a three-ring circus. Nothing is sacred to him. Nothing pleases him.

But once back in the States, what a difference! He has borrowed travel books on the return trip, and has at his tongue's end the names of localities, famous men, paintings and operas. For years those less fortunate townsmen hear of Soho, Rigi, Folies-Bergeres, Brunelleschi, Uffizi, Neckar, Campo Santo, The Mall, Victor Emanuel, Duval's, astronomical clocks. With continued reading, knowledge of many of the places visited grows, so that by the time he has mellowed with age, his memories of his visit to

Europe mellow, and he is able to inspire youth to go forth, be bored, and return to "high-hat" the grocer next door.

Let's go abroad next summer, but may we find room for reason and sincerity, for consideration and politeness, when we fill our trunks full of meat juice, knickers, binoculars, steamer rugs, and playing cards, and return with not only Roman stripe scarves, a copy of La Vie Parisienne, hotel stickers and nineteen strings of Venetian beads, but with a contented glow in our hearts of being natives of a youthful state which has inherited much from Europe and can still learn much.

M.W.H.

There are Grey days, May days, Then there are the Pay days, Gay days, Everything -a-gag days, Dog days, Mad days, Sad days, Always April Fool's days, School days, Dear-old-golden-rule-days, Cool days, Once-a-year-birthdays, Mirth days, Rash days, Ash days, When-everything-goes-wrong days, Long days, Oh-we'll-do-it-one-days, Sun days, When all is done, the Last days, Past days.

ELINOR U. PHYSIOC

When he was sixteen Godfrey Lewis first realized that he was not like the others. A trivial occurrence had first revealed the fact to him. The class-room had been still except for the clear tones of the school mistress who was reading the class a stirring account of the French revolution. Godfrey leaned forward, visualizing the dramatic scene between Marat and Charlotte Corday. The hysteria of that distant scene seemed real -present -to him. The teacher stopped, glowing with youthful interest. She was a pretty thing, fresh from college and eager to "inspire." Godfrey quickly began a rapid fire of comment in response to her questions concerning his appreciation of the reading, he was excited and flushed over his mental picture of blood-stained streets and the howling French mob. While the teacher explained something to him, Godfrey heard one girl say to another: "a pink satin trimmed with crystal beads." His blood boiled. The variance of thought seemed desecration to him. But he looked about the room. The rest of the class weren't in France. Sara Wills was writing notes to Buck Edwards. "Hungry" Camp was examining a cut finger. Mary Allison was making signs to Maud Cary. They were in the Lewis Creek High School, and simply aching to get out. Godfrey withdrew into himself -he guessed he was a fool anyhow.

Godfrey had started the custom of walking home with the teacher, after the others had departed. Miss Allan was interested in him. She told him about college, the courses she had taken under a real Frenchman, and she described France as she had seen it on a summer's tour. It was she who taught Godfrey his song. It was the song of the French peasant maid which ends:

"He is my love, Give him to me; I have his heart , My heart has he. "

that he especially loved. In the dim, cool parlor of her boarding house, he would lean upon his hands as he watched her sing, and listen to her lyric voice, dreaming of green fields in French pastures where he would be the shepherd and she the shepherdess. The song became his motif . . . a sort of symbol of his ideal existence, of

the perfect moment which he hoped to find. One night, at a party, Godfrey was in high good humor. No one danced more violently or sang more lustily than he. Someone said, "Miss Allan is going to get married soon. She got her ring last night." Godfrey stumbled. The girls and boys laughed maliciously knowing how the shot had hit its mark. He never knew how he got away. Soon, he was almost running to Miss Allan's. He paused at the gate; Miss Allan was smgmg, as she had never sung for him:

"I have his heart, My heart has he."

Choking, the boy turned away and wandered disconsolately down the road. The hour he passed afterward was a dark anguished one. His futile unrecognized love for her was ended in a tearing disappointment - one of the many in his life. He sat for a long time -at the spring, with his head in his hands - thinking.

Godfrey was twenty when he astounded the village again. The people he knew dubbed him "serious minded," and he hated it. He strove to keep up with the frivolous crowd, who, with popularity as their standard, lived their lives through with minds full of automobiles, parties, scandals, dollars and cents.

At this time, Jim Leslie, a young surveyor who was boarding at the Lewis's was Godfrey's best friend. From this man, Godfrey received a new and devastating thought of religion. It came to him one Sunday as he occupied the family pew with his mother. Some words of Jim's ran through his mind as the Rev. Mr .Smith expounded the reasons for missions.

"Have you your own religion or has some one made one for you?"

Godfrey moved uncomfortably. A heritage of his birth and environment tried to make him feel sacrilegious. He thought, "What is my religion anyway?" He looked about the church with eyes that saw reality for the first time. Sarah Wills was writing in her hymn-book. Buck Edwards was looking at it from the corner of his eye. Mary Allison and Maud Cary, dressed in their best, were pondering on what to wear to a dance Monday night. "Hungry" Camp was fast asleep.

Rev. Mr. Smith had his own way of preaching. At high points of his sermon, he would hollow like a wounded bull, but when he felt that he must put it over, he would come to the front of the

chancel and whisper to the stolid congregation with tears in his eyes, "Oh, my brethren, consider the sin of the Koreans! They have never known Jesus." Godfrey stared. He felt awake. He looked about him suddenly. This wasn't Korea, but did he or anyone else there know Jesus? Not one -not one of the crowd was thinking of Jesus. Old Mr. Edwards was asleep. He hadn't thought of Jesus as a kind and loving man, nor of His philosophy of love in his life. Jesus was the name used by pastors to put over prayers to God. Torn with a new emotion, Godfrey got up and left the church. Again, he went to the spring and rested his face in his hands. The still quiet, the restful calm came to his soul. He tried to pray, but he didn't know what to pray about. The song came to his memory, "I have his heart; my heart has he." "Yes," thought the boy, "I want God and myself to be like that." Religion had meant that particular church and preacher to him before, but now he couldn't go back there. He shuddered at it again-"they don't know Jesus." He'd have to go to hell, he supposed. He rose wearily, and, trying to shut away blasphemous thoughts from his questioning mind, went home.

The village was in an uproar in 1917. Godfrey, with twenty of his schoolmates, was going to war, leaving their farms and frivolities. Godfrey was twenty-three. He had not been able to go to college because of his father's ill health and consequent poverty.

When all the other boys were breaking their hearts over leaving home, Godfrey's heart beat high with hope. Paris . . .Paris . . . Versailles . . . he would see those famous scenes again -in reality, not in dreams. All his hopes were centered upon speedily being sent abroad.

At Camp Custis, Godfrey was summoned before his lieutenant. "Private Lewis, you are to be permanently detailed to this commissary department. You are to report there at once."

Godfrey reeled. France was forever to be a dream. His soul cried to God to grant him one hope of happiness. However, he was a soldier. He saluted and departed. Night after night he would lie in his bunk asking for France, though in the morning he would rise to begin once more his prosaic task of dispensing leggings, caps and uniforms to luckier mortals than he, soon to be fighting in his longedfor land. Thus, Godfrey knew the war. He thought himself immune to further disappointment after this.

In 1919 Godfrey married Lyn Cary, a sister of a former schoolmate, who had helped to cheer him during his weary training. After the dust and grind of army life, quiet evenings in a fire-lit parlor seemed most desirable to him. Lyn had a plaintive voice and learned "his" song to please him. Godfrey would listen, propping his chin in his palms, and the promise of such a life-long serenity made him drift quietly into marriage.

Godfrey and Lyn stood near the rail of their honeymoon ship bearing them to Havana. They watched the sun set, and Godfrey's heart leaped wildly as Lyn began to hum softly, "I have his heart , my heart has he" - ever so softly. He was terribly happy almost in anguish, he clasped to his heart one moment, for which he had waited all his life.

"My sweetheart," he murmured enraptured. "Let's never go back there. I want a new world with you."

Lyn turned her brown eyes upon him in amazement.

"Why, Godfrey, I just can't wait to get home and see what everybody'll say!"

Then, again, Godfrey knew disappointment.

Chloe fell in love with a choir boy at St. John's when she was thirteen. She and Stella, her bosom companion, had gone to "Stella's church," and there, Chloe, among candles and Easter lilies had her first experience of childish love. She could not see him often. Her parents did not approve of any deviation from their straight Presbyterian path. Chloe soon recovered from the love affair, but in the cathedral she had learned to love the solemnity of ritual and the beauty of holiness. Finally, she rebelled. "Mother, I am sixteen, and I know my own mind. I can't go to a church with an electric sign hanging out in front, like a movie. My God isn't there." And she never went to any church. "I don't know what I want," she would say.

The Williams were not devout, merely conventional. The suburban town in which they lived was only a half hour's ride from New York. The family reflected its spirit of "every man for himself"; money was the main requisite to them for a happy and serene life. Chloe early discovered that inspiration was not to be found at home. Her earliest refuge was her friend, Stella. Stella

Lockwood, a few years older than Chloe, was a tall, blonde. Her sophistication and independence drew Chloe into an adoration which lasted through Chloe's girlhood. She often told Chloe that ideali sm was ridiculous, and that she would never submit to the illusions of love if it should interfere with her career.

In high school Chloe became acquainted with a woman who was to influence the rest of her life. Madame Bondelier had spent her youth in Paris, and, in her middle-age, had been hired by the state to teach future New York merchants and housewives French grammar and translation. Madame liked Chloe.

"You are a Frenchwoman, mon ange ," she told her. "Your dark eyes and hair tres chic." Chloe was striking-looking, supple bodied as a statue by Brenda Putman.

Chloe loved to go to Madame's rooms, where the open grate and grand piano seemed to evoke expression of her inner self.

"Ma , cheri e, this song will delight you," cried Madame one evening. "I thought of you and your ideal of whom you've told me." And Madame played the shepherd's song and sang in her foreign . voice.

"Oh, it is he!" cried Chloe. "I can see him as you sing."

When Chloe was finishing high school, the war broke out. Chloe's desires for freedom beat about her soul like the wings of a startled bird. But, an untrained woman was fit for home duty only, and Chloe was a canteen worker in her home railroad station. The ceaseless stream of trains bearing youthful sacrifice to unused ideals made her life torture at times, but all was finally swallowed up in war.

Mr. Williams was not averse to adding to his Lank account even in the crisis , and the armistice found the family nearly millionaires. Chloe was now a beautiful woman who knew how to use the money to set her off to advantage. Stella was established in her career and her apartment on \ iVashington Square. Chloe loved her friend and envied her independence. Stella was the secretary to Mr. Eugene Harrison, a young Wall Street wizard. Then she met Angelo Morato. Angelo Morato, a typical Italian, fulfilled Chloe's dreams of an ideal lover. Instead of taking her to a musical comedy when she craved John Barrymore, he would quietly reserve seats to see the famous actor. Afterward , he would imitate in almost perfecti on of

detail Barrymore's love-making. Angelo loved music, and Chloe's starved soul enveloped him like a cloud.

Then, one day, Chloe, bored with her daily routine, came to New York unexpectedly to visit Stella. She had determined to accept Angelo. She loved him. The tinkle of a piano reached her ears as she approached the apartment. "I have his heart, my heart has he." Angelo playing for her ! Chloe, flushed and brillianteyed, softly opened the door. The music had ceased . . . for Stella, lying in Angelo's arms, was being covered with his kisses.

Chloe was twenty-seven when she married 'Gene Harrison. He did not bore her. She did not expect even that from life . . . she could not be bored, for she was interested in nothing. Eugene was a successful business man who needed a beautiful wife

The night she married 'Gene they stood upon the veranda of their hotel in the moonlight. "Oh, tell me if you e'er should meet him -a shepherd lad so true and fair," came the music from the palm garden.

Chloe felt dead inside. This was what happened to you then. This was what life had promised to her. "Oh, God!"

'Gene saw her expression. "What's the matter, dear? Aren't you happy?"

"Oh . . yes," said Chloe.

Chloe answered the phone with a petulant frown. If 'Gene were going to be late again, she was going to be cross.

"Hello," she jerked out the word as she snatched up the receiver. A pause.

"My dear, I can't see how you can expect me to get in there in time for dinner. It's 6 o'clock."

Another pause.

"But look at the weather. It's terrible. It seems to me you have a lot to do to ask me to come all that way to meet a couple of hicks from Lewis Creek." She glanced miserably at the comfortable sofa she had just left. It was comfortable. 'Gene had put his foot down concerning a room furnished with antiques. Nothing unsubstantial was to find room in his house.

"Very well, meet me at the Thirty-third Street entrance."

Godfrey Lewis in his hotel room in New York conversed with his wife .

"Lyn, honey, Mr. Harrison has asked us to dine with him and his wife at the Lorraine. He is a nice man, and he did me pretty on this deal. We must go."

Mrs. Lewis smiled at her husband.

"How about us dining with the Harrisons? I know Liz will simply die!" She was already beginning preparations by screwing her short, blonde hair up in a knot, and cn.vering her face with cold cream. Godfrey threw himself down on a divan and, murmuring "yes" occasionally to Lyn's questions regardless of their import, began his survey of the newspaper.

When the time came for them to leave, Godfrey had to admit that Lyn looked as well as he had ever seen her. Dressed in a brown lace dinner frock, her hair seemed more golden, her eyes browner than usual. Lyn was only twenty-eight he remembered with an involuntary glance at the mirror. The grey at his temples shocked him. He had not known how middle-aged he looked.

Eugene Harrison and his wife met them in the lobby of the Lorraine . His easy manner and smooth management made the Lewises admire him and put them on agreeable terms immediately. They were soon established in a place near the dance floor. It was not until the second course arrived that Godfrey had an opportunity to observe Mrs. Harrison.

Chloe was distinctly bored. The Lewises seemed to be of a type 'Gene often had to deal with, in a business way, wealthy farmers from some outlandish place. After eliminating Lyn as a possible affinity for 'Gene, he had grown fond of younger women lately, she turned her attention to the music. The Lorraine was featuring a famous classical-jazz exponent-and their music was rather good.

'Gene and Lyn soon danced off, leaving Godfrey and Chloe alone. Godfrey although he felt that nothing could interest his hostess, was compelled to talk.

"Mrs. Harrison, have you ever been South?" he asked, smiling at her.

"Only Palm Beach," she replied, noticing for the first time his steel-grey eyes and brown skin. His hair was tinged with grey at the temples, but was still brown and thick. He was massively built, but not clumsy.

"Then, you don't know Virginia?"

"Scarcely, I have passed through there."

"It's a great state," he said enthusiastically.

"Tell me about it," Chloe said, half-listening to him, and merely responding to him for politeness sake. So he told her of his native town, he talked of his life there and his business. ' But as he talked he seemed to transform himself to Chloe. From the commonplace words he had intended to utter, he changed to a description of the old Georgian homes and their inhabitants, their lives and characters, and he found her laughing heartily over a recent quarrel between Mr. Smith and Aunt Lulu Cary. Chloe was moved by his deep voice, was forced to listen, to concentrate on what he said, and to share his mood. Chloe was tired, her dark eyes seemed unusually piercing and her face almost pallid. Godfrey had never seen a woman like her -nor had she ever seen a man who had so interested her since Angelo Morato.

"Oh, I am sorry. I didn't mean to bore you like this," he murmured, as he realized that the dancers were returning, and ready to leave. Chloe gasped. She had not realized time nor situation. All that he had said seemed new - vital. To meet a person interested in people for themselves, to know a man who loved his neighbors, and laughed at their little souls cynically withal. .

They went to see "George Cotes Dollies." 'Gene enjoyed Lyn's fresh, unbiased comments, Chloe was strangely quiet, Godfrey amused. They danced afterward at a roof garden. 'Gene had gone to pay the check and Lyn was in the coatroom, while Godfrey and Chloe waited at the elevator. An orchestra was playing in the mezzanine. At the beginning of a number, a strange sensation seized their hearts.

"Oh tell me if ere you meet him," Godfrey met Chloe's eyes. "He is my love, give him to me; I have his heart, my heart has he," whispered the violin. The remembrance of years of futility swept over them as they gazed - caught by a terrible sweetness of almost tortuous bliss. "She understands," thought Godfrey. "He knows," thought Chloe. The music died away at last. Chloe was pale, fainting. Godfrey, shaking uncontrollably, his lips. white.

'Gene and Lyn came. They took the elevator. They said, "Good-bye."

"Gee," said Lyn, pulling her hair to the top of her head and plastering a blob of cold cream on her noise. "I had a good time, didn't you?"

Godfrey leaned on his hands, he hardly heard her. "Yes . . . " said he .

WARREN A. MCNEILL

"BeUerophon, however, was so affected by the gentleness of his aspect and by the thought of the free life which Pegasus had hereto! ore lived that he could not bear to keep him a prisoner, if he really desired his liberty.

"Obeying this generou,5 impulse, he slipped the enchanted bridle off the head of Pegasus, and took the bit from his mouth.

"'Leave me, Pegasus,' said he. 'Either leave me or love me.'

"In an instant, the winged horse shot almost out of sight , soaring upward from the summit of M aunt Helicon. Being long after sunset it was now twilight on the mountain top, and dusky evening over all the country round about. But Pegasus filew so high that he overtook the departed day, and was bathed in the upper radiance of the sun."

At this point John Morris stopped reading and laid aside his well-worn copy of "The Wonder Book." His eyes, he found, had grown a bit dim. Perhaps it was the slanting rays of the setting sun streaming through the windows of his study that made them feel misty -yes, it must be that. For surely no man of thirty could give any other logical excuse -one which his neighbors would understand -for having his eyes grow dim while reading a story intended primarily for children.

And yet, he reflected, it was queer. For, although it was true that he usually re-read the tale of the Chimaera at about this hour and the failing light might cause his eyes to smart at one time as well as another, it was always at this point in the story that this experience came to him.

Holding the closed book in his hand, John Morris gave himself over to reflections. He began to wonder if Hawthorne had indeed written this tale for children. Was it not intended rather for those of the perception which in childhood we all have but in later years are so apt to lose?

John Morris thought of his childhood and of the bright dreams of his youth -those winged steeds of desire on which he too had flown to Mount Helicon and had gone to the fountain of Pyrene to quench his thirst with that crystal liquid which sustains the muses.

He thought of those fair creatures through whose aid he too had slain the fierce Chimaeras which go about devastating the world of dreams with the hideous breath of reality.

Wreathing in and out among these thoughts there eddied and swirled the memory of certain faces and forms reminiscent of girls he had known and, after a fashion, had loved.

Gradually they became more distinct until they seemed to resolve themselves into two faces alone. In one he saw sympathy and understanding, companionship and friendliness, encouragement and devotion.

But, in the other, was revealed the wild and untamed fire of ambition, unquenched aspirations toward a romantic ideal and that which makes a man worship and follow after the unttainable until such time as he may die and, perhaps, approach that unsullied goal.

Bellerephon, on the mountain top, looked into the eyes of Pegasus and saw the decision required of him. Possession was possible under the spell of the enchanted bridle. Pegasus could ht. his, if he willed it so, but-at what a price! To confine to earth a creature destined to soar above the clouds; to sully unmarred hoofs with the dust of common highways; to break the divine spirit with perpetual restraint -that was to leave Pegasus bridled.

But to bid farewell to all that was tangible in this perfect experience; to see the winged steed bound away from earth and become but a glittering speck, eventually vanishing in the glow of the setting sun, to return no more, save only on the wings of memory -that was to loose Pegasus.

John Morris had felt that idealization and understanding must be mutually exclusive; that a choice 'must be made between them. To turn tq th~ one face was, it seemed, to accept reality with all its earthly attributes; to gain a companion at the price of a dream; to win satisfaction by the loss of eternal aspiration toward perfection, indeed -to bridle Pegasus.

Turning to the other face meant bidding farewell to hopes and plans; to lose that material center about which dreams revolved; to live in the joys of memory and to seek everywhere for that which no man ever has found this side of the bounds of the tangible -that was to loose Pegasus.

Now, however, John Morris saw neither the one face nor the other, but he looked into the mystic and troubling eyes of Pegasus. He felt the tug of the winged steed at the halter of circumstance.

Slender fingers passed gently through John Morris' hair and he turned to kiss a delicately shaped wrist that slipped down over his, shoulder as he moved to one side of his morris chair. Drawing the slender form into his embrace, he snapped on a light at his elbow, then handed her the book. Soothingly the mellow tones of her voice sank into his soul as she read the ending of the story.

"So he slipped the enchanted bridle from the head of the marvelous steed.

"'Be free, forevermore, my Pegasus!' cried he, with a shade of sadness in his tone. 'Be as free as thou art fleet!'

"But Pegasus rested his head on Bellerophon' s shoulder, and would not be persuaded to take flight."

GEORGE REYNOLDS FREEDLEY

God peered over the edge of the marble rampart and saw the broken down stoops of the negro huts

cluttered about the sewerage stream

A strange creature, God. What?

C. L. DODDS

(Linoleum Cut by S.

Warren Chappell)

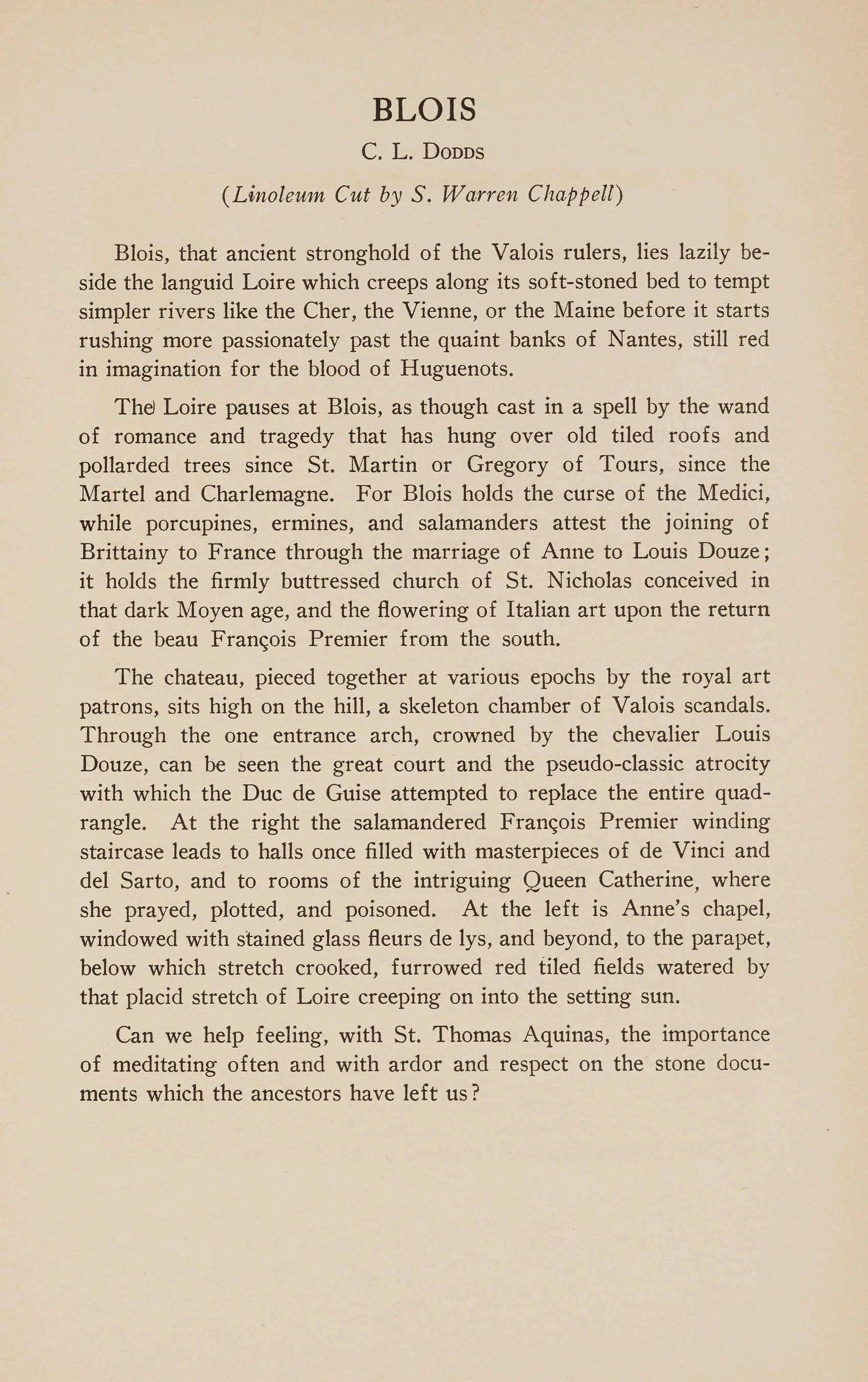

Blois, that ancient stronghold of the Valois rulers, lies lazily beside the languid Loire which creeps along its soft-stoned bed to tempt simpler rivers like the Cher, the Vienne, or the Maine before it starts rushing more passionately past the quaint banks of Nantes, still red in imagination for the blood of Huguenots.

Thel Loire pauses at Blois, as though cast in a spell by the wand of romance and tragedy that has hung over old tiled roofs and pollarded trees since St. Martin or Gregory of Tours, since the Martel and Charlemagne. For Blois holds the curse of the Medici, while porcupines, ermines, and salamanders attest the joining of Brittainy to France through the marriage of Anne to Louis Douze; it holds the firmly buttressed church of St. Nicholas conceived in that dark Moyen age, and the flowering of Italian art upon the return of the beau Frarn;ois Premier from the south.

The chateau, pieced together at various epochs by the royal art patrons, sits high on the hill, a skeleton chamber of Valois scandals. Through the one entrance arch, crowned by the chevalier Louis Douze, can be seen the great court and the pseudo-classic atrocity with which the Due de Guise attempted to replace the entire quadrangle. At the right the salamandered Frarn;ois Premier winding staircase leads to halls once filled with masterpieces of de Vinci and del Sarto, and to rooms of the intriguing Queen Catherine, where she prayed, plotted, and poisoned. At the left is Anne's chapel, windowed with stained glass fleurs de lys, and beyond, to the parapet, below which stretch crooked, furrowed red tiled fields watered by that placid stretch of Loire creeping on into the setting sun.

Can we help feeling, with St. Thomas Aquinas, the importance of meditating often and with ardor and respect on the stone documents which the ancestors have left us?

Men are like matches .. Matches strewn recklessly Upon the table top Left there By indolent Card players.

Long Slender Square shaped Dirty matches With red tips Thumbed By dirty fingers.

Men are like matches Matches strewn recklessly Upon the floor Dropped there By careless Smokers.

Some are remnants Charred . . useless remnants Having served their purpose forgotten . . .

Others are unburnt matches Having flickered For a breath

Then . sputtered out Matches never used . . . neglected

Men are like matches Matches cast aside In the whirl of life

Waiting . waiting To be swept out.

FRANCIS N. TAYLOR

Bud O'Toole hunched his shoulders and slumped heavily against the brick wall behind him. He scowled. It was now five minutes after three and no Solomon. Already the night was beginning to pale in the east, while the lamp posts slowly separating themselves from the surrounding shadows were taking on their usual hard straight lines. The fiery tip of his cigarette stood out in the gloom like a miniature signal ; it faded and glowed. His heart was beating like that, in spurts. He looked up. A dark form was rounding the corner, seeming to crouch as it hurried along the pavement, noiselessly, furtively seeking the shadows like an owl sailing through the forest in search of prey. Bud's foot slid to the ground, his "smoke" described a fiery semi-circle to land with a little shower of sparks just over the curb stone.

"Time you was comin'," he growled. It was his way of passing off the inevitable.

"Couldn't help it, Buddy, but I got 'em." The newcomer's voice rasped, having a tendency to run off into a plaintive whine. The voluminous coat that reached up and around the lower part of his face in great, greasy folds looked like the shadow of one of the tall shrubs that he had whisked up from the ground and cast hurriedly over his frame.

"How's her eyes, Sol, can she last 'till morning?" Anxiety was in the voice. He clutched his companion by the elbow. The face thrust forward seemed pale and drawn in the dim light.

"Yes, she will hold out. The doctor, the big man at Stuart's, will do it in the morning if -I have the jack." He glanced quickly down the walk. "Come on, the bulls are due in ten minutes."

The pair slunk off. Only a dull clank as of iron against iron gave any hint of a moving presence as they made their way down the darkened path. One block ahead and two to the left. They stopped. The smaller man grasped the other's arm. Stealthily he peered up and down the tree-bordered avenue. The well-kept shrubs and hedges that lined the walks were examined hurriedly. Without a word he was over the fence. "Three minutes, Bud. See that window? I'll do it there. Then it's fifty-fifty, and for me the gal's eyes is saved." He look;ed up into his companion's face. "Keep a

sharp lookout, Buddy; she'd die if they got me." He was gone. Sixty seconds later Bud heard the window squeak softly as it slid upward ; he did not see the small black shadow as it climbed over the sill.

It was so quiet. Chilly, too. He tried vainly to button the threadbare coat closer about his neck. ". . . An' for me the gal's eyes is saved." He smiled. Old Solomon and his Mary. Funny how he had first met Mary. Midnight, softly raining, she had been walking alone in the business section. She had smiled and waited for him on the next corner. Funny, he thought, but he sure did like Mary. No, he did not love her. Bud did not love anybody. He was hard. A cop had told him that once; there was no room for love in a heart like his. But Mary should not go blind, not just for the lack of money. Old Sol would attend to that. Bud n;membered once a long time ago, before the war, Sol and he . . .

A hand grasped him firmly by the shoulder. He jumped. His fingers flew instinctively _to his hip. "That's all right, Buddy, it's me." The whining tones were like music to his ears. "I did it. Nine hundred flat, and fifty-fifty mind, as soon as we reach the alley." Once more they melted into the shadows. Stealing across shadowy lawns, sneaking through private driveways, risking every minute the staccato challenge of some night watcher. Slowly they reached the poorer section of the city. At last the great black mouth of an alley opened before them. They dived in. Half hidden from the hazy light of the dirty street, Old Sol drew the roll of notes from the cavernous folds of his great coat. "Fifty-fifty, mind ye, and mine is for the girl." Even here the wheedling drone of his daily trade was evident. Perhaps he had fifty-fiftied before.

The boy watched silently as the old Jew counted the bills into two piles. He glanced quickly at the old man's face. "Wait, damn it, I don't want the stuff; take it all to her." The Jew was surprised. He muttered something; it might have been protest - it probably was not, but the half audible syllables were lost as Bud stepped from the sheltering darkness. He stopped short, glanced sharply to the right and broke into a run down the opposite side of the street, pulling his cap well over his eyes with the same motion. Another second and a giant form was framed in the mouth of the alleyway. A pocket torch flared its inquisitive eye into the heavy gloom and a gruff voice commanded Solomon to crawl out. The hand was not gentle that dragged the piteously pleading Jew from the inadequate shelter of dirty rags and boxes.

"What you got?" The rough hand of the "blue-coat" was not to be denied; the bills forced from the paralyzed hand of the little old man fell to the ground in a fluttering shower.

"Huh," the bulky officer stooped to gather in his spoil. "Huh," the heavy fingers crumpled the paper. "You stole this, you little rat, and single-handed, too; you'll get yours!"

The Sunday morning Times contained a short article at the bottom of the sixteenth page:

" . . . one, Solomon Engelstein, has been sentenced to ten years at hard labor for burglary on the night of Thursday last. The name of the wealthy prosecutor may not be disclosed. The matter is being hushed up generally."

There was no mention of a Mary Solomon who had lost forever the sight of her eyes on Friday last. Such things are not mentioned in the Times.

A gob rolls by armed with a girl, a bedizened hoyden, with jaws moving rhythmically. The blond young giant thinks he is having a hell of a good time. Perhaps he isHow do we know?

SIROCCO. By George Reynolds Freedley. Published privately. Richmond, Virginia 75c.