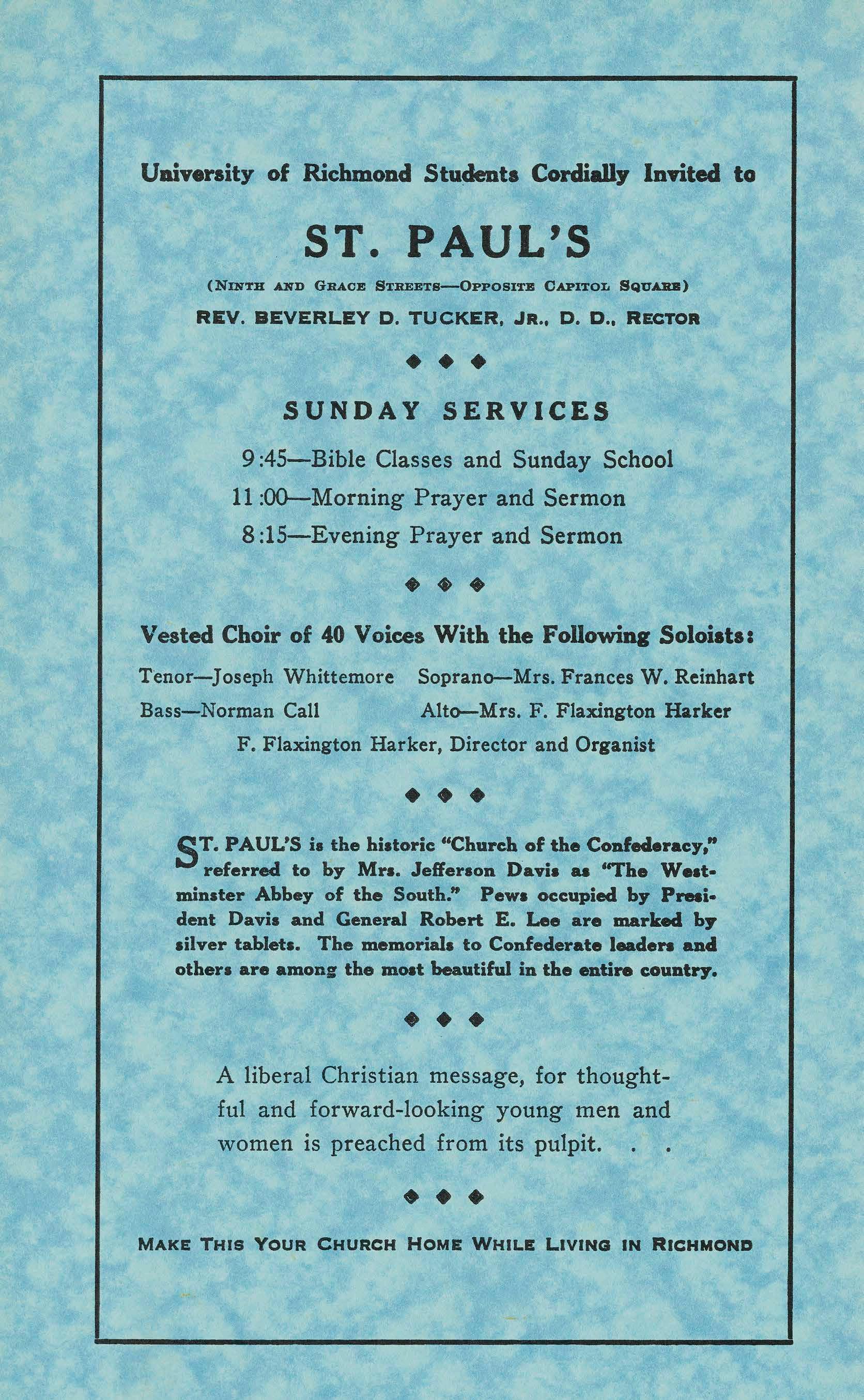

University of Richmond Students Cordially Invited to

University of Richmond Students Cordially Invited to

(NINTH AND GRAOE

REV. BEVERLEY D . TUCKER, JR . , D . D., RECTOR

SUNDAY SERVICES

9 :45-Bible Classes and Sunday School

11 :00-Morning Prayer and Sermon

8 :15-Evening Prayer and Sermon

Vested Choir of 40 Voices With the Following Soloists: Tenor-Joseph Whittemore Soprano-Mrs. Frances W. Reinhart Bass-Norman Call Alto-Mrs. F . Flaxington Harker F . Flaxington Harker, Director and Organist

ST •PAUL'S ia the biatoric "Church of the Confederacy," referred to by Mra. Jefferaon Davia u "The Welt• minster Abbey of the South." Pewa occupied by Presi• dent Davis and General Robert E. Lee are marked by silver tablets. The memorials to Confederate 1-den and others are amonir the moat beautiful in the entire country,

A liberal Christian message, for thoughtful and forward-looking young men and women is preached from its pulpit

"We, the members of the First Baptist Church of Wartburg, Tenn., desire to express our appreciation for the kindness, liberality and skill of Kellam Hospital, Richmond, Va., shown our beloved Pastor, Rev. I. H. Bee, in the successful cure of that dread disease, cancer, and his restoration to us in perfect health and, we trust, many more years of usefulness.

"And Further, Be it Resolved, That a copy of these resolutions be placed on the records of the church and a copy forwarded to Kellam Hospital.

"Done at regular session of the Church, this 9th day of August, 1925."

CARRIES. HONEYCUTT, Clerk and Treasurer

Entirely new suburban home by January, 1926; progressive and orthodox faculty of eminent Christian scholars; comprehensive and practical curriculum; large and world -wide student fellowship; numerous student-served churches; tutition free; financial assistance where needed , and moderate expenses; the Harvard or Johns Hopkins of the theological world.

Twenty-two University of Richmond students last Session. University of Richmond third among 167 schools. University of Richmond men have high rating.

Write E. Y. MULLINS, President

1. Richmond College, a College of Liberal Arts for Men.

2. Westhampton College, a College of Liberal Arts for Women.

3. The T. C. Williama School of Law, a Professional School of Law, offering the Degree of LL. B.

4. The Summer School. W. L. Prince, M.A., Director.

W. L. PRINCE, M. A., DEAN

Richmond College for Men is an old and well-endowed College of Liberal Arts, which is recognized everywhere as a Standard American College. Its degrees are accepted at face value in the great graduate and technical schools of America. Its alumni are so widely scattered through the nation that the new graduate immediately joins a large and friendly group of men holding positions of power and influence. The College occupies modern and well-equipped buildings, on a beautiful campus of 150 acres in the western suburbs of Richmond.

MAY LANSFIELD KELLER, PH. D., DEAN

Westhampton College for Women, co-ordinate with Richmond College for Men, is housed in handsome buildings on a campus of 140 acres, separated from the ·Richmond College campus by a beautiful lake of about nine acres. All degrees are given by the University of Richmond, and those conferred on women are, in all respects, equivalent to those conferred on men. While the two institutions are co-ordinate, they are not co-educational.

J. H. BARNETT, JR., LL. B., SECRETARY

Three years required for degree of LL. B. in the Morning Division, four years in the Evening Division. Strong faculty of ten professors. Large Library. Moderate Fees. Open to both Men and Vfomen. Students who so desire can work their way.

For catalogue, booklet, or views, or other information concerning entrance into any College, addreu the Dean or Secretary.

F. W. BOATWRIGHT - - President

G. CARY WHITE is a Senior in Richmond College, Editor-in-Chief of The Collegian, and leader of our campus communists.

IONE STUESSY, a Senior in Westhampton College, and co-ordinate Editor of , The Collegian, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.

MARY LOUISE McGLOTHLIN, Senior Class, Westhampton College, makes her first appearance in The Messenger this month.

CUTHBERT WHOO SIS is a nom .de plume.

C. H. ROBINSON, a Senior in ·Richmond College, and Vice-President of Student Government, is also a new contributor.

GEORGE REYNOLDS FREEDLEY was graduated from Richmond College in June, 1925. He is a member of the local Chapter of Sigma Upsilon Literary Fraternity.

W . E. SLAUGHTER, Junior Class, Richmond College, 1s Assistant Editor of The Messenger.

ALICE LICHENSTEIN, a Junior m Westhampton College, makes a first bow in this number.

J. MARK LUTZ is a Senior in Richmond College and a former Editor of The Collegian. He is a member of Sigma Upsilon.

J. MOYER MAHANEY, who has published in The Messenger before, has taken an active part in the work of The University Players, and is Manager of Basketball in Richmond College. He is a Senior.

Contest Announcement on Page 41.

The entire contents of this magazine are protected by copyright and must not be reproduced without permission.

VoL. LI

COPYBIGBT

1926

BT LESLIE L. JONES

Time , I am tired of you,

Tired of your endless tramp, your footsore march ; Tired of your endless footsteps, marching, marching , To the lash of belting, the whirr of machinery, Nine long . . • hours

Time, I am tired of you, Even your cool grey walk at dusk With rapid pace past long gaunt rows Of sombre houses, Sad with the tragic story of the poor.

Tired of you, Time, old tempter, Bringing the moon In the spring, Mocking , fleeting, tender, Flooding the backyards of the world with mystic beauty, Ragged little yards with crooked smiles

Tired of you, Time, Taking the moon, the stars, the sky, Wrapping them in the dull grey dawn .

Tired of you with your weary whistle In the silence of the daybreak.

Tired

Tired of you for your nine long hours Your fleeting little bribes of beauty. No. 5

loNE STUESSY

I would pay a tribute to my mother. It is not a tribute of filial affection, nor one of reverence, nor yet one of gratitude for maternal self-sacrifice. It is rather the expression from one woman to another of real admiration and honest wonder at the woman that she is and the mother that she has become.

My mother dominates our family, not because of her position as legal guardian of her six "infants" and consequently her hold upon the purse, nor yet because of any feeling of filial duty that we have towards her. Her preeminence is due entirely to her superiority of attractiveness and of ingenuity. To begin with, mother is larger physically than any of her daughters and she is better looking. Many mothers, and I say it with all due reverence, are content to allow their youthful beauty to become only a memory as they live in that of their daughters. But we are very proud that our mother has retained an interest in herself. We are proud that her clothes are more costly than ours. We are proud of her beautiful hair, and we share her jealousy when some careless observer declares that one of us has mother's hair, for we have not, and we know it.

We girls have learned that our mother is very attractive to menall men, both old and young. What more desirable quality could there be than this in a mother of girls? Few mothers can advise their superior flapper off spring as to how to treat their gentleman friends and have their words eagerly accepted. But we listen and if worse comes to worst, mother is called in to settle any trouble that has got beyond our depth. Yes, indeed, mother is very attractive to men. A woman, whom her husband calls cold, yet who can for eighteen years hold that husband to the passionate devotion of betrothal days, such a woman must indeed be attractive. Mother has a genuine liking for men together with infinite tact in handling them, a rather valuable quality, to be sure, in a widow with six children. I am reminded of the day that we moved. In addition to our whole family, Mother had secured the services of two colored girls and a moving van with three men. Nevertheless, nlthough they knew that Mother was far more capable than they of handling the situation, her two brothers-in-law both left their own work absolutely alone for the whole day and insisted upon actually working all day to help Mother get moved. At the end of the day, when Mother laughed and said

that two brothers-in-law were almost equal to one husband, they felt amply repaid.

I have seen Mother leave her baking on Saturday afternoon to talk for hours with an enthusiastic young friend of ours about the respective merits of Grade A and Grade B plumbing fixtures. And I have seen her successfully hide her yawns at midnight after a four-hour discussion of life in Porto Rico or the fascination of various biological phenomena. The strange part to me is that Mother always knows something about whatever topic they choose.

Is it worth-while for a busy woman to devote so much of her time to just being nice to men folks, especially when that woman has no earthly desire for a man for herself? In a mother of girls, there could be nothing more worth-while. I remember that I was once very much surprised to learn that I was the only one of a group of girls who told her mother everything. I couldn't understand why girls didn't take advantage of their mother's interest and experience and get her to advise them, instead of blundering on alone. Perhaps today, there are a few details that I have never mentioned to my mother, from mere reticence, but from the casual remarks that she makes occasionally, I know that she knows exactly what has happened because it has . happened thousands of times before. Mother is never shocked and she never asks questions. Perhaps this is why not only her own daughters, but many other girls who visit us go to her room at night when they return from their dates or parties, and tell her of the things that have happened. Many unvoiced questions are answered in that quiet hour, and many a young heart, troubled with the problems of life, is comforted. Mother seldom reveals any of her own romance, but as we are of one flesh, we know, even as she knows, that our problems and reactions are the same. Mother has the wonderful courage to remain silent while her daughters fight out their own distinies, standing ready to aid them only when they call upon her. And through this tactful reticence, yet thorough understanding, our Mother has became the real mother of many girls besides her own. It costs a few hours' sleep, perhaps, to have to wait until every girl is safely in, but she has the surety that she can trust her own daughters whether it be two o'clock in the morning or ten-thirty o'clock in the evening.

My mother maintains the right of developing her own personality and she is ready to grant to her daughters the same privilege. We are free to choose whatever life we will, no matter what her own ambitions for us may have been. The money that was saved for a

post graduate course is cheerfully used to fill the hope chest. For after all, that is the real result of having had such a mother. Her daughters can conceive of no higher position in life than to be such a wife and such a mother. She has made our home the pattern from which five new homes will some day be cut.

A mother of girls I have called her, because she has so eminently fulfilled all the needs of her daughters. If any man doubt her success, let him remember that no artist, however wonderful, can bring perfection from faulty material. No one who knows her can deny this tribute save perhaps one. Sammy, the eight-year-old brother, vigorously protests that his mother is a boy's mother because she always knows just what he likes. And no doubt he, too, is right.

GEORGE REYNOLDS FREEDLEY

All my life I've looked at Life Through a dirty window pane. I've always wanted to raise the sash But somehow or other I never havePerhaps it's nailed.

MARY LOUISE MCGLOTHLIN

All day long the little girl's nose had been wrinkled by the most delightful anticipation. She had valiantly tried to smooth it into an everyday, decorous feature, but then she would remember again, and her nose would shape itself into soft, pink wrinkles. The classroom glowed with a sort of roseate haze, and the little girl smiled so beatifically at the teacher that the instructor feared the little girl was ill. The figures on the board did a prim dance before the eyes of the little girl as she thought of her secret. The little boy had accosted her bruskly as the lines passed in the yard. It was only a hoarse whisper, but pregnant with joy for the little girl.

"Say, I want ter see you after school. Hear! I got somethin' for you!"

The most entrancing conjectures floated before the dreamy eyes of the little girl. "Would it be a diamond necklace all sparkly like the teardrops that she had once seen on mother's face? Or would it be a big stick of candy, all gayly striped with red and white, like the pole before the barber's shop. Maybe it was a lovely flower with pinky petals and a smell like freshly bathed babies." At the possibility of a flower the nose wrinkled even more. The little girl carefully counted on her small, pink hands, the minutes she would still have to wait.

"Five, ten, . . and maybe a teeny wee bit longer." The little girl wasn't quite sure.

The minutes ticked slowly by, and at last the little girl was slipping her arms into her warm little jacket. The matter of fact lines began to move out the door. She lingered behind the other sturdy little figures, and waited impatiently at the corner of the yard. The sunshine was very warm and soft on her uplifted face, and the vagrant wind caught with playful fingers at her short pleated skirt.

The little boy strolled across the playground most deliberately, and stopped with legs widespread before the little girl. Perhaps the wondering happiness in her face made him pause. The little girl smiled up at him and whispered very humbly, "Well?"

The little boy stared a moment, then with a curious half-grin, commanded abruptly, "Shut your eyes tight, and hold out your hands."

There was a breathless moment of waiting. Then something soft and cold was plumped into her outstretched hands. She heard scampering footsteps. Then she opened her blue eyes and looked at the gift in her hands. A small, dead mouse with disconsolate, drooping tail, ruffled gray fur and drooling mouth! The little girl stared. Her eyes widened until they ached with the pain of comprehending. Then without a single cry she dropped the mouse to the hard pavement and walked sturdily away. Her face was very white and still. The wind blew suddenly cold. She buttoned her jacket closer . The sun was behind a gray cloud with a trailing wisp of gray like the tail of a forlorn mouse.

The impeccable butler cleared the table with the skill of a noiseless automatum. When the door had closed on well-oiled hinges behind his retiring form, the man leaned back into the deep comfort of the chair, and blew contented smoke rings into the air. The girl stared moodly into the warmth of the fire. The room behind them was filled with soft shadows that retreated and advanced like well-drilled battalions. The Man was very content to relax and be amiable after his hearty meal. The Girl stirred restlessly. Her face was strained and bore a look which may only be described as bound. One imagined that the emotions of many years had been carefully controlled beneath that sensitive face, and that the pent up flood was becoming unbearably strong. Even now the waves of the flood sent ripples to the surface, as warnings of a deeper more powerful under current. One prayed not to be present at the denouement. The Girl gazed almost appealingly at her companion, but quickly flushed and again probed the depths of the fire.

"You are very kind," she spoke evenly between tight lips, "To have me here tonight, to give me one last glimpse of luxury before I begin to try to exist on my own meagre earnings. I "

"But, Natalie, don't you understand that that isn't at all necessary." He spoke more slowly. He realized that it was a very delicate situation. My entire wealth is at your disposal. You know I w ant to lend you all you need. You can cancel the debt, since you so insist, when the dividends from that land in South America begin to come in."

The Girl laughed abruptly. It was a very sudden, startling laugh that shattered the well-bred quiet of the room. One wondered how such a depth of bitterness could be enclosed in only a laugh. It was

almost a torn sob. When the man had first begun to speak her eyes had shone for a moment as warm as the fire-light, but as he continued the dreariness of burnt out, deserted hearts seemed to fill her eyes. She made a weary, little movement with her hand a futile, hopeless little gesture.

"Please," she requested bitterly, "don't insult my intelligence by alluding to those lands in South America. You and I both know that they are but a fairy tale to save my self-respect." He attempted to interrupt.

"No, don't stop me. You have been most kind in settling father's debts after his rather cowardly exit from this world. I hope he is happy in the next."

She went on with only the slightest flicker of emotion.

"I am deeply grateful to you, because without you I would possibly have followed father in a few days. The rage and despair of those numerous creditors would have seeped into my very soul like some poisonous liquid. I pray some day I will be able to repay you-at least in part."

She waved aside his protesting hand. A dreary half smile-then she continued.

"I never dreamed anyone could live so sumptuously on absolutely nothing. And I-I was helpless, ignorant. Now I am helpless, ignorant and alone."

The silence fell like a stifling blanket over them. The Man was frankly puzzled.

"But, Natalie," he protested, "you have innumerable friends, old tried friends who love you. And as I said, what I have is "

She silenced him with a look.

"Can't you understand that I want something more, something on which I may depend." Her level glance only partially hid the "little girl" appeal in her eyes. But the Man gazed in the fire.

"We must all lose our loved ones," he said gently and slightly embarrassed.

"I know," the Girl returned. "We also lose other, more precious things."

The Man was deeply bewildered. Suddenly, with a smile, he drew from his pocket a pink bit of paper and attempted to slip it into the girl's hand. With a bitter, broken cry she tore it into fragments and

scattered them m the flames. When she faced her companion her eyes were like blue rivers which slowly emptied themselves within her, leaving only cracked, drained riverbeds. The potent flood within her had suddenly and irrevocably ebbed back into the sources of her being. Her eyes were set in an enormous quietness.

"You see," she concluded with a terrible calmness, "we either lose or never find the most precious things in life. Please call a cab for me. And goodbye. You have been very kind."

C. H. ROBINSON

Youth, Alert upon a corner, Wanting to enter into the life Of every woman passing by, Yet going to his rooms and Reading the American Magazine.

CUTHBERT w HOOSIS

I awoke early that morning. In fact I always awake early in the city, especially the first night. Just before dawn milk wagons chip the silence-clipclop, clipclop, clipclop . . . a long procession of them right out of the dairy, their horses' hooves beating crisp tattoos upon the asphalt-clipclop, clipclop, clipclop. Beneath my window they separate, one going southward, another northward, another straight on into the east-dipclop, clipclop, clipclop.

And then the trolley cars. The hotel where I am staying stands on a street into which the car-barns, far to the west, empty their restless, flat-wheeled charges-clang, clang, clang, brrrumpp, brrrumpp, brrrumpp . . . whole battalions of them, racing noisly through the dusk seeking their proper routes-clang, clang, clang, brrrumpp, brrrumpp. . They too, separate beneath my window, north, east, south. Metal switch sticks ring sharply against' steel rails, and to weary patrolmen, awaiting the dawn, it is a welcome sound.

I stretch myself luxuriously beneath the covers and gaze lazily at the large square of blue-black sky framed by the southern window. A gentle spring breeze steals over the house-tops and into my room. . it is April, and one has youth. Life is sweet . sweet.

I stretch myself luxuriously and gaze up at the large square of blue-black sky. Pleasantly, my thoughts drift . drift. Drift leisurely, futilely. The play last night . Elaine . . . the long ride into the country . . . home . . Avallon-Avallon, the little village where one is not 'roused by milk carts or surface cars. It is the blackbirds who sound reveille in A vallon. In April they fill the old oak trees, and their shrill pipings mingle curiously with the bu .shed caress of wind and pine tree . . . the spring wind and the pine trees of A vallon. A vallon. I do not regret Ava!lon. Elaine sleeps just down the corridor, and at nine o'clock I shall breakfast with Elaine. It is April, and one has Youth. . Imperceptibly the patch of blue-black sky becomes brighter . brighter, softer, fainter. A truck or two rumbles down the street . . a few motor cars . . . newsboys . from out the tower of a nearby church, the sudden peal of a bellthe Angelus. It is six o'clock.

The Angelus rings and it is six o'clock. Newsboys. Rumbling motor busses, horns, sirens. The patch of blue-black sky becomes

light blue, clear blue the daintiest, frailest, so£test sort of blue with handsfuls of flitting, white clouds. From far away, a factory whistle. Another. Another. A chorus of factory whistles. It is seven o'clock.

I threw back the covers and get up. I go to the window and look out look far away across the roofed prairie which is a city. It is April, and one has Youth. Li£e is sweet, and clean, and fresh.

Above me are blue sky and white clouds. Below are steel and stone and asphalt. And up out of the street rises a building, a tall building, a church. A church building, whose walls are huge blocks of dirty grey granite, stands straight up before me, looks me bitterly in the eye. It is April, and one has Youth . . A dull, grey church looks me bitterly in the eye.

Its walls are huge blocks of rough grey granite. Its roof leaps to an acute peak high above the surrounding buildings. Angles, corners, points. There is nothing smooth about this building, nothing soft, nothing round In truth, a gloomy pile with its roof, its somber roof, thrusting its hideous edge up after the clouds the frail, fairy clouds, all contour, and down, and velvet striving to pierce their softness-like the dull blade of a rusty axe against the white throat of a pretty woman.

A mournful tableau. One wonders one begins to wonder if there may not be some connection between this architectural harshness and those minds which dwell therein whether each sharp angle of the material building may not be matched by some narrow creed in the spiritual structure. One wonders.

A black bulletin board stands near the door of the church, and neat, white letters appear thereon:

MY GRACE Is SuFFICIENT FOR THEE

Cor. II :12-9

"My grace is sufficient for thee." I wonder. It is April and I have Youth and I wonder . Those slender, pale girls walking rapidly down the hill to the factories which lie just beyond the church will "grace" repay them for the nine hours of tobacco dust and fumes, for the nerve-destroying clatter of belts and pulleys and insane machinery? For the dark, back rooms in lodging houses? For the loneliness?

And I wonder, too, if these find "grace" sufficient: the children of the East Side, and those of the Carolina cotton mills ; the Armenians, the millions of surplus women in Europe who will never know the arms of a lover.

It is April, and I have Youth. Life is sweet for some. There are blue skies, and white clouds. There are gentle spring breezes. And there are bromides, and there are platitudes and there are lies.

Slowly I turn from the window. A bit of the granite bitterness creeps into my heart. Creeps into my heart . and out again. And pity comes. Pity. For it is April, and I have Youth.

Perhaps, I murmur to myself, as the ~arm, voluptuous fingers of the shower-bath enfold me, perhaps when_winter comes, and Youth no longer companions me, perhaps then I shall find "grace" sufficient perhaps then, I shall even desire a few harmless lies to comfort my cooling blood.

But now it is April, and I have Youth .Youth, and Elaine.

C. H. ROBINSON

Far be it from me to draw conclusions about higher education. In fact I break down and confess that colleges are the stuff, and they are hereby awarded a set of four-brake ear-rings and all that, an' all that, an' all 'at. Fathers, send us the raw material; mothers, we crave your bouncing baby boys !

But, then, again, on the other hand, Russell Frazier met his downfall, and college and women did it. The onward march of this ambitious son of nature toward membership in the select group of literati and intelligentsia was thwarted by fate in the form of a gushing young demoiselle, who thanked God every night for having sent into the world the rah-rah boys with their never-ending supply of lucre.

Having thus rambled on for a pair of paragraphs, I now make bold to announce my intentions for the next half hour. Friends, Romans, and basketball fans, draw up your chairs and you shall hear of the decline and fall of one Russell Frazier, and how his dream for the cognomen Bach. of Arts was nipped in the proverbial bud. There, I've told you, and don't accuse me of holding out on you.

Russell was my roommate, which is another way of saying that for six weeks I purchased neither tooth-paste, shaving cream, aqua velva, nor necque-tie. Being a loyal sophomore and a faithful member of the Ministerial Association, I felt backward about revealing to this young offspring of nature the manifold ramifications of college life when he put in his appearance September last. Instead I freely dispensed fatherly advice and warned him about gold-diggers, etc., etc., etc.

So diligent was I in seeing to it that he got started right that I soon won his confidence. Before the first week was over he had shown me pictures of his family for nine generations back and told me every piece of gossip that had ever been concocted around his natal camping grounds. Why, without any introduction at all, I could have gone up to any person in his home town and told him everything that had ever happened to him. Ezra Wharton, for example. I'd have slapped him on the back and said, "Ez, Ole B'y, has your prancing, prowling Ford broken down lately and left you stranded with the school teacher out back of Si Morris' river farm?"

Oh Lord! I never heard so much gossip since John died. For two weeks my life was a perfect torment. Now, don't get the idea

that Rus was a bad sort. In fact, you had to like the boy. If I had been a girl I would have told you about nine paragraphs back about his wonderful curly hair, manly figure, et cafeteria, but envy prohibits me from saying more than that Rus "was a combination and a form indeed where every god did seem to set his seal to give the world assurance of a man."

Now, as I was saying, at the end of about two weeks of this I decided that something had to be done, and then is where fate said "step right up and call me ole reliable, here's your solution."

B. Y. P. U. socials are usually very nice. I've been a party to some forty-seven and am no worse for same. In fact, I know of no indoor sport safer than a B. Y~ P. U. social. So when, on Thursday, two weeks after school opened, I was notified that a social was to be negotiated by one of the B. Y. P. U.'s in town I knew straightway that fate was smiling on me. I dashed in and notified Rus that he was about to make his debut and to put on his other clean shirt and follow me to the high lights.

All of us historians now agree that that was step number one in the downfall of Russell Frazier.

But, as I was about to say, we went to this affair and it was one of the most typical shags at which I ever chirped present. Long about 10 :00 o'clock, after I had introduced Rus to all the girls I knew and some tie-score and ten that I didn't know, I was over in one corner peacefully trying to whistle after having devoured about seventeen dry crackers. I was putting across a rather successful performance and was about to drift over to where a group of gushing young America was trying to see how much ice cream they could melt when I realized that I hadn't seen Rus for quite a spell. However, I had no idea that anything could happen to anyone at such an affair so I continued my rounds, and it was not until the shag was breaking up that I got uneasy about the old lady.

After quizzing nearly everyone in the place I found one blushing damsel who was willing to confess that she saw Helen Lawrence go off with a tall, handsome sort of chap about two hours back. That was all I needed.

If the preacher had been in sight I would have gotten him to turn the social into a prayer meeting, but there being no Pollyanna in sight I did the next best thing and sallied forth to school and put a picture of the old lady's mother on his desk before tapping, likewise rapping, also slapping the portals of dreamland.

Next morning I awoke, as usual, about class time and while arranging myself in my nether garments I noticed that Rus had failed to put in an appearance during the night. Holy smokes ! What could have happened to the lad?

I didn't say a word to a soul but kept my eyes open and along about chapel time my visual purple functioned to the extent of revealing one Russel Frazier strolling along toward ye student shoppe.

"Why you wild and reckless prodigal son," I casually remarked. "That's a nice way to treat a friend. Run off and leave me without even kissing me good night, and then not reporting until I'm about to get out a search warrant for you. And that's not all. Art cognizant, lad, that of all grasping, clutching, perfidious, dangerous gold-diggers that ever played on innocence, Helen Lawrence wins the pasteboard alarm clock? Even you.r best friends won't tell you, but you stand about as much chance of achieving prominence with Helen as a new scratch on a seven-year-old Chevrolet. Why in the Hell didn't you tell me what your intentions were? Didn't you know that it wasn't good form to be running amuck with anybody you happen to meet?"

"But we just drove around to her home to dance awhile, and were coming straight back, only. "

"Yes, that's just it, only you didn't know Helen Lawrence. I tell you, lad, she's no one for an innocent freshman to be seen with. Without her every drug store and dance hall in the city would go out of business. Of course, you seemed good rushing material, and before you knew what it was all about you were wearing the pledge pin of the 'Throw Me A Worm, I'm A Fish Fraternity.'"

However, one of my failings is my tender heart, so I eased out of this tirade with a warning against more dates with friend Helen.

"Don't let this girl string you, Rus. She has more fraternity pins than Balfour. She doesn't know the meaning of the word mercy. Well, that's that, let's drift over to the shop and drink a tonic to the health of Mollie, the girl back home."

I gave the matter no further consideration, but bless me! if that crook didn't have a date with Helen Lawrence that very night ! He claimed that she called him up and he couldn't get out of it.

What's more, I'm a knock-kneed tadpole if he didn't miss the last car three nights in succession. I never saw the like since John died !

In ten days Rus was the dancingest fool that ever writhed. Fiftytwo steps of the Charleston held no terrors for him. He had more

slides than an educated trombone. Furthermore, not being satisfied with my supply of necque-ties he began to ransack the whole dorm. Then he took to borrowing money. In ten days my outlay of sheckles was so meagre that I seriously considered opening up a shoeshinparlor, for ladies only, in order to add dimension to bosillo.

Higher education Hell ! Russell Frazier learned more from one date with Helen Lawrence than he could have scooped up in a classroom in eight, or than Adam Smythe could have figured out by 6644 A.D. I felt completely outclassed. Instead of giving out fatherly advice, I had to huddle myself over in a corner and listen to him rave about that rip-rearing knock 'em down and drag 'em out orchestra at the winter garden, those big red roses painted on knees (not the bee's), the cute little fl.ask he got from Ebberhardt's, why the deuce the doctor wouldn't put out more sick excuses, and how in Hell was he to get more money out of the old man !

That kept up for over three weeks, which is decidedly too long for an ordinary crush to last. In fact, I have always had a sneaking notion that the guy who made that wise crack about "absence makes the heart grow fonder" knew more about women than any man since Kipling. But Rus didn't give that omen a chance to do it's stuff, and I collided head-on with the conclusion that indirectly I was the cause of afl this draw-back on education and was morally obligated to emancipate Rus from the fangs of Helen Lawrence. Therefore, I set my medulla oblongata, corpus collosum and various other portions of my mental paraphrenalia into action to devise a devise.

The Prince ( I had started calling Rus that), had never been able to see why 1 should have such a grudge against Helen, being as I only knew her by reputation. I confessed that all along and, furthermore, vowed a vow that I had no desire to know more of her. This got him hot as a dozen red heads, and that's where the devise I had been looking for popped into view.

The Pot and Kettle Club, of which Helen was the steam, was going to give a shag Friday night, and the Prince had been practicing his slides all week in preparation for same. Now he up and heaves at my feet the demand that I go along with him and Helen and in order not to be a wall-flower that I drag Helen's seventeen-year-old sister, Edna. Can you beat that?

I refused steadily for two days, and then like grabbing a forward pass from the dark ramparts of nothingness, I jumped up, shouted, and before I knew it a touchdown had been done !

Well, as I was about to say, I finally gave in, and Edna was notified that her debut was to be committed. The Prince warned Helen that she was to pass in review and to be on her f's and n's, so to speak. And likewise, on our side of the line of battle preparations were far from neglected.

The Prince appointed himself chairman of the committee on preservation of worship at the shrine of Bacchus, and when Friday finally persuaded Father Time to let it arrive I never saw two sponges more anxious to get soaked.

You might not believe it, but Helen and her kid sister drove out for us in their car, which was a fine car and could have passed for an armored car, so well was it provided with curtains. We were all pepped up from the start and I expected a memorable evening.

To add to my joy I won the toss, and elected that Edna and myself should arrange ourselves on the back seat. With a thick coating of introductory jargon and a liberal outlay of wise-cracks, which I have neither the space nor the heart to repeat, we ambled along. By a unanimuos vote of those voting ( I refrained from expressing my sentiments), it was decided that we should not pay our visit to the Pot and Kettle Club until later in the evening, so away drove friend Helen, who gave about as much attention to driving as a professor does to preparing his lectures. However, I was feeling too good to get scared and burrowed down into about seven car robes. One can pick up several good points in seventeen years and Edna was as bad as I had expected. She even went so far as to let me hold her hand, whereupon I instructed the Prince to keep his rye to himself as I was sufficiently drunk with emotion. I always did like to nestle down on the rear seat of a big car and sing, so I struck up the popular air, "I called for milk and got coffee," the girls joining in on the eighth chorus. We got along fine, and it was about eleven bells before we favored the Club with our presence.

Now, I was not dispensing hokum just now when I said that I had a plan. I would have told you about it sooner only I was afraid that it might leak out before I had a chance to work it. Mr. Bok had a plan some time ago, but of all plans ever planned, mine was the best plan, and I had no sooner seen Helen than I began its application. In outline it was this : Rus was crazy over the dame . the best way to cure him was to have her turn him down flat . knowing Helen's rep that could be done . the dance of the Pot

and Kettle Club was an ideal place for her to throw him I was willing to make the sacrifice and run off with Helen thus leaving Rus deserted by the girl he was crazy over he would get hot and never speak to her again I'd withdraw and all would be over. Selah! (Never mind laughing at this plan. It may sound simple, but I got kick galore out of it.)

Now when I eased out the information about six minutes ago that Helen was the steam of the Pot and Kettle Club, I didn't mean that she was too hot for the rest of the kettle and withdraw into the elite vapor class. Far from it. That Club was no cool joint, take it from one who was warmed. It was on the third floor of Liggett's Drug Co., and was barricaded with hose in case the dance got too hot and started a fire. Services were held last week in memory of the last sober cop who presented himself at the place. The Venus Five furnished music for all dances, liquor for intermission five dollars extra per.

When we put our heads inside the door I came near fainting. God! what an orchestra! The trombonist was up on top of the piano using his slide as a cue to drive an electric light bulb into the corner pocket. The wielder of traps was crawling around over the floor looking for his drum and keeping time by smacking flies, nails, or aged gum. The violinist, not to be outdone, had doffed coat and put on a derby and was astradle two chairs showing Kreisler how it ought to be done. Last, but not least, the sax tormentor was crawling over the piano chasing the trombonist, in the mean time giving off ( wave length 347) an exhibition of step number 36,½ of the Charleston as it is done in the cabarets of Port Said.

The only completely sober man in the place was the guy who demanded four dollars from us as we entered, and he was slightly off. "vVhoopee," yelled Helen, "I want to d-a-n-c-e !" "Woman," I says, "come hither and be satisfied." So saying off we glided to the tune of "Somebody Stole My Gal," and the Prince was minus a girl. He finally collected himself to the extent of becoming half owner in the concern: "Edna and Rus, Dancers."

Well, Helen was popular as the devil and Rus didn't have the opportunity of showing the multitudes that he and Helen Lawrence danced well together. God ! That woman could dance and she sure exhibited her talents.

Intermission came about twenty minutes after we arrived and with all the skill of a barber shaving, for the 100,000th time I got

Helen out of the place, argued her into leaving Rus and Edna to shift for themselves and away we drove in her car. Thus far my plan was working.

We were gone one-half hour by Western Union time. Eighteen minutes of that time I used to sell myself as a desirable young gentleman who knew considerable and just loved to waste his money on flappers. Four minutes of that time was allotted to heaving compliments at the feet of fair Helen, and six minutes I listened to what she had to say on the subject. Now the other two minutes Well, as I was about to say, when we put in our second appearance at the Pot and Kettle Club, we found neither the Prince nor sister Edna, so we warmed up to the tune of the popular air : "Does the Spearmint Lose Its Flavor On the Bedpost Overnight?" After the encore, which I danced with Mary Christmas, I caught sight of Rus coming straight on from the southeast aperature of the building, the captain of a reeling craft. He recognized me and figured out that if I was there then Helen must be around somewhere, so he staggered away to find her. Well, altogether he might have taken eleven steps with Helen before some happy soul tapped ( also rapped and likewise slapped) him on the shoulder and said, "Whoopee, I'm a puff of steam, let's evaporate!"

Now you'll have to go to the Associated Press records for the complete account of what happened at that dance. Those who attended called it "the meanest struggle of the year." During the following two weeks the membership of the Pot and Kettle Club increased some 100 per cent even though the toll of dues was raised. Writing the event up in my diary I just left a big blank and wrote across the page the follownig wise-crack from Shagspare :

"Come and Charleston as you go On my corn bespeckled toe, And as we pass out in the morn, Say, 'brother, didn't we turn 'em on?'"

The Prince made a perfect fool of himself. Helen was completely disgusted with him. Finally when the orchestra played the famous "trio" song ( "Trio clock in the morning"), she even ref used to dance it with him, and in a few minutes we began the journey home with Helen Lawrence, Edna Lawrence and yours truly on the front seat and a blank rear seat. Even so!

I stayed in town that night and it was around twelve bells when I planked foot on the campus next morning. I drihed on down to

the room, and I break down and con£ess I was not greatly surprised when I found that the Prince had not been in at all the night before. In fact, he didn't show up all day. Naturally I was up in the air as to his whereabouts but had no way of trying to find him, since his circle of .friends in town was rather limited. I hoped for the best and waited for nature to take her course.

Well, Tuesday morning was just the same as Monday morning except for the fact that I arrived at all classes on time and likewise went to chapel-a remarkable triumph of my better self. Returning to the room at 12 :10, I found that Rus had been there during my absence and, believe it or not, removed all of his belongings! Yes sir, not a thing was left but my bed, desk, wastebasket, whiskbroom, and ash tray. Being sort of dazed I eased over to sit on the corner of my desk and saw a note there, with the old lady's congomen signed on the clotted line. The note ran :

"DEAR OLD LADY : I belonged on the farm all along, and now I know it. I'm through with college, woman-everything. But, for God's sake don't let Helen Lawrence make a fool out of you like she did me. RUSSELL."

On the desk also was a copy of the telegram he had sent to his folks back at home. That ran:

"Kill fatted calf ; meet me tonight; through with college. YOUR SON."

P. S.: I forgot to say that that very night Helen called me up and asked me to come around as she wanted to talk to me ! Now, I ask you!

GEORGE REYNOLDS FREEDLEY

With a dash, a flare Of vivid red hair 'Neath a jaunty hat, And a jargon pat,

Is the painted jade, No longer a maid, But a gay rich thing, Who used to sing-

"What does it matter 'Bout au damn chatter Of virtue and that, When you have a new hat,

A flair, a voice bold In ways love is sold, And you are so young, A leader among

Those artists and all, Who sleep in the hall ? Oh, t' hell with preachers, Narrow-faced teachers.

I am what I am, And don't give a damn." So endeth the plaint Of no would-be-saint.

MARGARET HARLAN

The child Sybil sat before the great loom. It was hot in the factory and her head ached with dull throbs. If she could but creep inside of her head, she was sure that she would be able to hear it pounding like the machinery. If only it would ache with the same rhythm as the great engines-it wouldn't hurt her so much then-her head would become a part of the throbbing heart of the factory. How she hated the heart of the factory. When she went home in the summer dusk or winter darkness she heard it-all the way-always throbbing, ever pulsing with sickening beats that followed her, no matter how far she walked. Sometimes she ran along the road with her hands pressed over her ears, but she could feel the pulsing through her body. After she had rushed into the house, hoping to escape, it had followed her, followed her even in her sleep from which she often sprang in screams at the even throbbing, throbbing of the factory wheels.

Besides the throbbin,g, other things troubled Sybil, things too heavy for her ten years. Strange thoughts rushed through her mind which was working too fast, too furious, it seemed, for her head. It seemed to be running up large hills and down, until she panted for breathyet kept on further, faster. Sometimes it met its own thoughts, at others it seemed to hold more than one thought, trying to keep both in check, as a man who drove two horses which pulled in different directions.

This morning she had been dizzy, so dizzy that her mother had timidly asked the father whether Sybil ought not stay at home. But he had said that it was lack of air, and made her walk the two miles to the factory instead of riding perched up behind Joseph on the grey horse Peter. Now her head was quite clear-much too clear. She wondered what would happen if it beat much faster. If she failed to stop it, it might run too far away from her. She felt that it was already going too fast to tell her hands clearly what to do. Yet she remembered to keep the strip of cloth going into the machine in a straight stream, to guide it evenly into the sharp teeth which reached out to sieze it, and to keep her hands far enough away from the whirling rollers.

All the while her mind was running on, on, up this hill, down the next, the steady stream of cloth oozed out of the loom above her,

through her hands, on into the teeth of the machine in front of her. The cloth was hot and clung to her fingers. Its coarsness scratched against her wrists.

She let her eyes wander towards the window at her right and to the scene outside. It was a clear day of late spring. The air outside would be warm and soft, not stiffling hot as it was within. She seldom looked out of the window. Twice she had been caught at it, reprimanded the first time, the second she had been placed at a machine in a dark corner until she could learn to pay close attention to her work. Now she was back at the place near the window. This morning she could not keep her eyes from the sight of the sparse wood in which the factory was set. Not more than a hundred yards from the window was a small clump of willows bordering a small stream which ran in a shallow cascade down a few scattered rocks. Feeling the hardness of the seat, Sybil imagined beneath her body the softness of the silky grass which grew on the banks; breathing the dust-laden air of the factory, she could taste the sweet warmth of the spring midday.

A child came in view, a girl of Sybil's age, pushing a bicycle at her side. Sybil knew that she had ridden up the hill to the factory willows. Sybil turned her eyes-she dared look no longer-and fixed her attention upon the cloth which poured down from the loom into the machine, scratching through her hands.

When she looked again the child had seated herself beside the water and was smiling with content into the stream. She might sit there thought Sybil, as long as she wished, in the soft greeness of grass. The child reached her hand towards the water and dabbled her fingers in the stream. How cool it was, how pleasant! She dipped both hands into the water, cupped them, and lifted them full to her forehead. A slight shiver of joy passed through Sybil as she fancied the delight of that coolness against her own throbbing head. Again she felt the sticky coarseness of the cloth brushling through her fingers. If she were only that child!

Perhaps she was. Could it be that she had come up the hill and seated herself under the willows? Could it be that she had been watching herself? It was queer, but it seemed to be true. Overhead the willows whispered, and the slim grass caressed her bare feet. She leaned above the stream and reached her hand into the water. How cool it was, how sweet ! She stretched the other hand into the stream and the stream slipped through her fingers. She leaned farther above the water, until its coolness almost touched her face. But

the stream was not satisfied with her fingers, it drew her arms on also-up to their elbows-while the coolness rushed over her arms. Now she would cup her hands and bring them up to her throbbing forehead. She tried to pull them from the stream, but they would not be loosened. Her head throbbed and she could not raise her hands to comfort it. Suddenly the stream became hot, stiffling, and her arms throbbed with her head-with her heart-with her whole body, and the engines-pounding, burning, throbbing.

Somewhere in the distance she thought that a woman screamed. The pulsing of her head and arms grew fainter. Then the engines ceased their pounding, the heart of the factory stood still.

G. CARY WHITE

Your beauty is a lily, A soft lily, a fragrant lily, Soft as the summer night, Fragrant as summer incense.

Bending in the breeze, tender, quiet; A breeze you do not understand.

How many dark souls, Ploughed with suffering In a steel mill, Have made the soil rich Where you flower.

Always the winds Are not so kind.

-"that's for remembrance"

The following translation from Catullus was made by Walter Jorgenson Young ('07), and first appeared in The Messenger for April, 1906

Let us live, my Leshia, and love. As for gossip of the sages old, Not a whit for all their squibbs care we. Suns may set, but they shall rise again, We-when once our light so brief doth fade, One eternal sleep our night hath made

w. E. SLAUGHTER

The first rays of the hot oriental sun had just glanced from the peak of yonder distant mountain as J ezza waved goodbye to his mother standing in the doorway of their rough shack; then he turned and pranced gaily down the dry, dusty road that ran from the little town of Bethsaida, in Galilee, and followed along beside the lazy Jordan River as it wound its sluggish course on the way to the Sea of Galilee. The boy was very happy that morning, carefree and jubilant. For the first time in his young ten years his mother had given him a whole day of unrestrained freedom. A whole day! No scolding, no punishing, no mother's eyes to watch hi s ever y movement , no continued warnings to keep away from the leper colony . Gee! he wanted to see that place, so of ten had he been warned to keep away from it. Well, today he knew what he would do, and he lifted his long, slender new fishing rod from his shoulder and silentl y praised his father's workmanship. He knew what he would do: he would go where his father had been fishing. He broke into a whistle as he stopped to pick up a lucky-stone. When he reached the first turn in the road and stopped to look back, there stood his mother in the doorway, watching him. She waved to him and he replied. He felt in his sack to be sure she had not forgotten a lunch. Yes, there were some barley loaves in there. He turned lightly toward Joppa , where he knew his father often went to work in the fishing boats.

It was still early when he reached the crude little wharf. Over on one edge sat a figure he instantly recognized. It was Mark, the little crippled orphan who often came to Bethsaida to beg. He liked Mark; he pitied him, too, pitied him because he had to crawl wherever he went on account of his useless little leg. J ezza was glad that Mark was there. They greeted each other and sat side by side. Out upon the quiet waters were many little fishing boats. In one of these J ezza knew his father was working, but, as hard as he looked, he could not recognize him. He baited his pin and with feet dangling over the edge of the wharf, he cast his line.

Minutes rolled into hours. The Oriental is very patient, but J ezza had become very restless for he had caught only two fish. And how small they were ! He had been tempted to throw them back into the water. But, no, he would take them home to give his mother. She would be proud of him and tell him what a good boy he was and what

a good fisherman he would be, like his father. So they sat there, munching on the barley loaves.

When J ezza looked again out toward the fishing boats he noticed a sudden stir of excitement among them. . All began quickly to come in toward the town. Ahead of them glided a smaller boat in which were a lot of strangers, he knew by their garb. The boy dropped his pole and ran over to where the boat would land, but suddenly turned and ran back to his comrade who had begun crawling after him. Lifting his arm over a shoulder so that Mark could stand beside him, Jezza watched the strangers as they jumped out of the boat on to the sandy shore and began to climb the gentle slope beside the little pier.

The little group came down the road and approached the boys. One, who seemed to be the leader, and was taller than the others and whose garments were cleaner, J ezza noticed, stopped when he came to them. He noticed the sad look that had moulded itself upon Mark's face from his years of helplessness, and patted him on the head. That was not unusual-everyone stopped to speak to Mark. But when The Man, in a few kind words, told the cripple to stand up, J ezza was amazed. He looked down at the little limb that was bent and deformed, and, lo, it was as straight and strong as his own!

The fishing boats had all landed and men were hurrying up the hill after the strangers, who had moved on. J ezza called to his father in the crowd and ran to meet him.

"Of a certainty, he is the one," his father remarked to himself in an awed whisper, as his son repeated over and over again the stranger's kind words. "Come, son, we must follow him."

Over on a grassy knoll the little group had stopped. A great multitude of people had gathered around them, and as the father and son toiled up the slope with the many others they heard marvelous tales of this man's healing powers and great knowledge. Everyone was excited. Everyone was talking in wonderment. Presently The Man stood up and the noisy throng became instantly quiet. What an appeal there was in his tone as he spoke, what power in his words ! They listened and wondered for a long time.

What a crowd it was that had assembled there! J ezza looked around him. Men, women, children and even babies were there, some lying prone upon the grass, some sitting in groups, little family groups. Over on the horizon he could see the sun dropping down behind the distant clouds.

He turned toward the speaker. He had finished and several of his companions were walking among the people as though searching

for something. One approached them and greeted Jezza's father familiarly. He asked if either of them had anything to eat, as "The Master" wanted it. J ezza's face brightened and he eagerly reached into his little sack and pulled out the remnants of his lunch. There were just five little loaves left. As he handed them to the man one of the little fish fell to the ground. The man wanted the fish too. So J ezza gave him that and the other. Just little fish they were, what did he want them for, he mused. The rolls and two fish were given to The Teacher who called for two baskets that an old woman sitting near had beside her. In one he deposited the rolls, and in the other he placed the fish. The rest of The Man's companions returned from their search and were unable to find anything.

As the curious crowd watched, The Man stood, raised his face to the darkening sky and spoke softly. Then, reaching into the baskets, he began to give to his astonished companions armsfull of large fish and rolls and told them to distribute these among the hungry people. Jezza's eyes were wide with amazement. The multitude was silently wondering.

Over to his left the Father heard several groups in excited conversation, and, taking J ezza by the hand, he strolled over to them.

"Let us take him and crown him as our ruler," one was saying as they drew nearer.

"We will not have to work for food nor labor for taxes, for. lo! has he not supplied us all from nothing?"

The group grew larger and all were eager to go to the Teacher and make him their king. What a mighty people they would be! They could conquer all nations with The Man's mighty power, and would have a Ii£e of ease and plenty. With a shout, they set out for the group of strangers.

But they had gone. The companions of the Teacher were already pushing out from shore in their little boat, but the Teacher was not with them. - He had completely disappeared, yet no one had seen him leave.

The shades of dusk had been gathering for an hour before the crowd began to leave the knoll, to break up and flow in all directions toward many homes. Jezza caught his father's hand. He was tired and wanted to go home.

"We will go back to Bethsaida and tell Mother and the people there about this great man," the father said kindly.

The boy was glad and he wanted to see his mother. He would tell her about the good time he had that day, and about how her rolls and his little fish were changed into thousands. And he would tell her about little Mark. She would be surprised, like his father had been. She would be proud of him and would kiss him, he mused, as he tagged along at his father's side.

ALICE LICHENSTEIN

If you knew how you are adored I wonder what you would think.

If 011 knew that all my love is condensed into one cup for you-

one enormous cup with depth unknown, filled with purest love, sparkling ruby, from my longing heart.

Many seek a soothing draught in vain;

I preserve it pure and untouched for you alone.

Though you may never know, my heart will drain into that cup drop by drop until I die.

J. MARK LUTZ

Well, if that isn't the funniest thing city paper it says that J eb Tide killed his wife she was a bad woman. here in the all because

It's so strange for Jeb to have objected that . when his mother was bad, too, . to a thing like even if no one ever knew exactly what she had done.

. Everybody said J eb would come to some terrible end, but he didn't seem like the kind of boy who would kill. Why, he was timid at school; . . that is, at first then he got sullen and quiet when he found we wouldn't have anything to do with him . . he was just like something driven m a corner . and striking out at anything in sight.

Not that he had anything to protect himself against, for every one was kind enough to him, . even if we couldn't go with him, . because his mother and father did not live together . and the older folks shook their heads about him and said they suspected things we didn't understand then

In the early mornings as we ran up the road to school and tried to skate on the frozen mirrors of ice in the ruts of the road, J eb used to follow along . eagerly, at first, like he was trying to catch up, when he knew . somewhat sad and apart.

Coming home in the evenings, when we stopped to shake the gold-balled persimmon trees, he would stand off in the distance looking shy, like he wanted to be with us, . but one day some of the older boys saw him and chased him, shouting ugly names, . . and they caught him when he slipped on the glassy pine needles. . Then J eb fought until Tom hit him with a stone and knocked him senseless to keep him from beating all the boys.

. He had such a . . . temper . . J eb once beat old man Silas' boy when he said something about Jeb's home. . . . No one blamed J eb much for that, except that he had no right to not like anything any one chose to say to him . with him coming from such folks.

After he saw that he couldn't go with us in the grammar grades, Jeb gave up any plans of going to high school . and he quit when his mother died. . They say there wasn't a soul at the funeral except J eb. . . Perhaps that is one reason why he left town shortly after the funeral.

. Jeb must have drifted around a bit before going to Smithville, because it was some time later when he was doing fine there that Mag Oliver visited in that town. . . Even some of the best people of Smithville were surprised when she told them about Jeb's mother. . . . Of course, they had to leave him alone after they knew, . and it wasn't long before he drifted on some say because he lost his job after what Mag told.

It was about ten years later that Tom met J eb in the city . and found him about to marry a pretty girl who worked in the same store he did. . J eb was doing fine and the girl seemed glad to be marrying him . .for a good reason, as he found out . . . because she was a bad lot herself.

Some say she fooled Jeb good, . . . but he couldn't have expected a really good woman to marry him . . . and she wasn't much, or she wouldn't have had anything to do with J eb after what Tom told her . . she even said she wasn't any better than Jeb's mother, and she was glad to know about Jeb, so that if he ever said anything about her past she'd have something to say back. . . . . . Just what happened after they married I don't know, . except what the paper says here about Jeb's killing her, and he gave as his reason that she was the wrong sort, . although to our way of thinking he shouldn't have married any one . . . with his kind of people. .

. Well, the paper says the jury seems against him and people are tired of so much murdering on such excuses which is right . . for J eb didn't have any right to get mad about anything like that . . . with his mother.

J. MOYER MAHANEY

The sun was well up when I returned from my morning walk to the village of clay huts, whitewashed and silvery in spite of increasing heat. The activities of the early hours had subsided, giving place to the usual characteristic tendencies-sleeping and snoring in what little shade could be found. Indeed, what else could one do in a region just south of the Rio Grande! Work was well-nigh impossible in either the merciless sun or the scant shade. The natives, who had long since become acclimated to it, slept in doorways or in rudely constructed hammocks of flax and hemp, beneath dull green trees which vainly attempted to halt the sun's down-pouring rays. Mongrels lay in shady nooks and crevices, oblivious to all things, in their imitation of shiftless masters.

As I neared my own hut, a nameless, uncontrollable fear took hold of me, and I wondered no little if Montrose would be improving, as the old doctor from El Dora, almost fifteen miles distant, had promised yesterday. Or was it a promise? I believe it was more an intimation which guarded an unexpressed fear. I had met Montrose at the Philadelphia Art Exhibition two years previous, and his frank seriousness and undeniable talent had impressed me so much that I had asked him to return to Mexico with me for a year. He had no sooner settled down to real work in a new country than he fell into love, into inescapable love with Rivera, a native girl, and very pretty, even beautiful. Despite protests, and even threats from his mother, he had married her, only to be cut off from a meager but entirely useful allowance. Now, with a young wife and three-months-old boy to provide for, he was seriously ill with the dreaded Mexican fever. As I neared the cottage I was met by the young mother.

"He-he ask for you," she faltered when I reached the door. In her arms she held her young child, and as she spoke she pressed its tiny form nervously against her own brown, sun-burnt body.

I entered the hut hesitatingly and studied intently for a fleeting moment the faded body lying on the skin-draped wicker couch, and covered by a rumpled mosquito netting. Those eyes of blue, so magnetic when first we met in a far-away exhibition room, were now encased in dark, circled sockets. The cheeks, burnt to a tan by hot sun-rays, were hollow, and the skin was drawn tightly over the cheekbones, giving them an Indian-like appearance. His body impressed

me as being in a state of utter exhaustion and complete surrender to that which is commonly called Fate.

"My friend (he had always called me that), do not send any word-for the present-to the States of my sickness. It-it's no use, you know, for she broke-she broke off all ties-long time ago. And," he looked with a sickened longing toward the young mother and child, "I want-I want to die here-here with Rivera." He let his arm fall feebly around the shoulders of his young wife as she knelt beside his couch.

"You are all right, old man," I tried as best I could to encourage him, though I knew full well that my very voice betrayed me. "The doctor still has hopes that-."

"Oh, I think I know all about-that," he interrupted. "But I-well, I know what I feel. It's-it's hard to breathe-now, my friend." He motioned to Rivera, "May I have some water, dear?"

Rivera brought some water in a native jar that was colored with splashes of purple and red-her poor endeavor to imitate Montrose. It was cool water from a near-by spring, and as I stood there watching him drink it eagerly, his breathing became more even. In a moment, however, the cooling effect was gone, and it became once more quick and laborious. The color, too, had left his face and neck, making them pallid and lifeless. I could stand no more, so I moved slowly away and attempted to busy myself with other things. It was a vain attempt, however, for my mind returned again and again to the near-by couch.

While the apparent longness of the day bore oppressively upon me, my mind would not cease to torment itself with divers thoughts ; the inevitableness of death hung like some hungry, zealous nemesis over the small house, and my nameless fear found only small relief in that ancient formula-the Iron Hand of Fate. It was well past noon when the doctor arrived. His visit was as short and futile as it was regular, and when he left he gave us no spark of encouragement, no ray of hope whatsoever. "Hot-house plant," he told me, in a whisper, as I helped him mount; "he lacks reserve strength."

Later I was sitting in the doorway watching the doctor and his horse sink gradually from view over the distant mounds. Rivera sat near the couch on my three-legged stool, caressing the sleeping boy as she hummed some strange and wierd Mexican tune. Suddenly the sound of a dull cough reached my senses, followed by an audible silence. Rivera had ceased her song; and with tense body she gazed at me out of wild, questioning eyes. I, too, was dumb, paralized with

newly confirmed fears, so that I could only gaze at her speechless. But I saw neither her nor the couch, but instead, some blurred, indistinguishable object on the wall beyond.

It was Rivera who finally broke the silence. She almost dropped the child into its ill-made crib of reeds, and ran to the couch whereon lay the still form of Montrose Lagarre. In vain she shook it, caressed it, called aloud to it. "Montrose, my Montrose, answer me, Montrose! It is your own Rivera." But only the steady humming of tropical insects answered her as she fell with outstretche<l arms across the inert body. The jar of cool water, overturned, emptied its contents on the damp dirt floor, and the shining water ran questioningly hither and thither, to rest finally in dark, still pools.

It was the first day I had tried to work since Montrose had fallen sick, almost three months past. I sketched slowly, deliberately, and also a little nervously-sometimes not at all. My mind frequently wandered back to those days when we had painted together, Montrose and I, and told jokes and stories about our adventures, and talked about our most secret ambitions. But I was alone again, with his easel leaning against the house near-by, where the sun's rays, piercing a faded tree, drew fantastic shapes upon it. I lived in heavy lonesomeness, and the monotony of it weighed on my soul, imprisoning my every thought in its iron vault. Montrose would be with me no more; I felt as if half of me were dead.

"I shall stay in this house always," Rivera stood in the low door and spoke slowly, very slowly, as she looked toward me. "Because my Montrose lived here, and-because we lived here. No?" As she stood in the open doorway, the rays of the morning sun, forcing their way through shade trees overhead, fell full upon her. "Yes," I said to myself, "she is beautiful; Monty was right-she 1s near perfect."

"Yes, RiveriJ.," I replied to her question, while I paused in my work and looked toward her, "you may stay here as long as you wish." She seemed relieved at my answer, for later I heard her humming a tune as she went, baby in arms, to lay fresh desert flowers on the new grave ·wherein slept Montrose, laid there with many blessings by the kind village priest.

LESLIE L. JONES ------ Editor-in-Chief Assistant Editor

w. E. SLAUGHTER--- -

M. s . SHOCKLEY -

C. B. H. PHILLIPS

w. R. VAIDEN --

JAMES H. GORDON- Assistant Editor Business Manager - Assistant Business Manager - Assistant Business Manager

MARGARETHARLAN------ Editor-in-Chief

JEAN MAcCARTY - - - -- - Assistant Editor

ALIS LOEHR ----- Business Manager

GREYROBINSON - - - Assistant Business Manager

THE MESSENGER is publishedeverymonthfrom Novemberto June inclusive by the studentsof TheUniversityof Richmond . Contributionsare welcomedfromall members of the studentbodyand iromthe alumni.Manuscriptsnot foundavailableior publication will be returned . Subscriptionrates are TwoDollarsper year; singlecopiesTwenty-Five Cents . All businesscommunicationsshouldbe addressedto the BusinessManagers . (Enteredas secondclassmatterin the postofficeat The Universityof Richmond.)

The December number of THE MESSENGERcontained a short story, in the French, by Louis Carpeaux . For the best translation of this story executed by any student of Richmond or Westhampton Colleges, the editors offered a prize "imported direct from Paris and suitably inscribed."

This contest closed on February 10th, and the ten manuscripts submitted were immediately turned over to the judges for careful consideration. The judges were Prof. C. L. Dodds, Richmond College; Prof. William M. Jones, Richmond College; Miss Grace Landrum, Westhampton College; Miss Virginia Withers, Westhampton College.

The manuscripts, signed with noms de plume ( the authors being unknown to the judges), were read and rated independently by each judge, who then submitted a list giving his or her first, second and third choices. The story translated by Mr. Elmer B. Potter, Freshman Class of Richmond College, received three first choices and one second choice. Mr. Potter, therefore, is hereby declared winner of THE MESSENGER'Sfirst translation contest.

Mr. Donald DeVilbiss, Senior, Richmond College, received second honors, with one first choice, one second choice, and one third choice, while Miss Jean MacCarty and Miss Elizabeth Jones, both of Westhampton College, each received one second and one third choice. Mr. Cyril Myers, of Richmond College, received one third choice.

The staff takes this opportunity of thanking all those who have contributed to the success of this attempt to stimulate literary interest on the campus-the students who so enthusiastically responded, and the faculty members who so kindly read and judged the manuscripts.

Mr. Potter's translation will be published in the April issue of THE MESSENGER.

Now that the translators have said their say, and bowed themselves gracefully from the scene, we will ring up the curtain on the playwrights. In conjunction with the University Players, The Messenger hereby announces a contest in which the field of effort will be confined to one-act plays. For the best one-act play submitted to the Editors not later than May 1st, 1926, a prize will be given by this magazine. In addition to this, the University Players will produce the winning play some time before Commencement of this year. The judges in the contest will be:

Miss Emily Brown, Dramatic Coach.

Mrs. Ralph Chappell, Westhampton College.

Mr. C. L. Dodds, Richmond College.

Manuscripts must be signed with a nom de plume, and accompanied by a sealed envelope containing the real name of the author.

There is no limit to the number of plays which may be submitted by any one person. The only requirement being that all contestants be students in the University of Richmond. Members of the University Players are equally eligible to compete.

This is the first contest of the kind which has been held at the University of Richmond. It is hoped that local dramatists, or would be dramatists, get quickly busy and make this venture as successful as was the recent translation contest.

STUART McGUIRE, M. D., -- President

New College Building, Completely Equipped and Modern Laboratories, Extensive Dispensary Service. Hospital Facilities Furnish 400 Clinical Beds; Individual Instruction; Experienced Faculty; Practical Curriculum. Eighty-Seventh Session Opens September, 1925

For Catalogue or lnformatfon, Address

J. R. McCAULEY,Secretary 1150 East Clay Street RICHMOND, VA.

WHEN you order flowers from this good Flower Shop you get the utmost in service that modern facilities and careful attention to details can produce. Mail or telephone orders receive the same attention that you would get if you came personally to the store

COMETOATHLETICHEADQUARTERS!

IMPROVE your game! Whatever the sport, SPALDING equipment will give you the greatest possible aid. Correctly designed and of the finest materials, you take no chances with a "Spalding."

We have represented the Liverpool & London and Globe Insurance Co., Ltd., for more than fifty years.

Mfg. by THE BAUGHMAN STATIONERY CO.

Wholesale School Supplies

THE MOST MAGNIFICENT HOTEL IN THE SOUTH

European Plan

For Visiting Parents and Friends to Stop

Every Comfort for the Tourist

Every Convenience for the Traveling Man

LEADING -LARGEST-OLDEST OPTIC.AL HOUSE SOUTH

Main and Eighth Streets 223 East Broad Street

KODAK FILMS DEVELOPED FREE When Purchased of Us and Prints Are Ordered

MAIL ORDERS GIVEN PROMPT ATTENTION

Boulevard and Grove Avenue

9 :00 A. M.-BIBLE SCHOOL

11 :00 A. M.-PUBLIC WORSHIP

7 :00 P. M.-B. Y. P. U.

8 :00 P. M.-PUBLIC WORSHIP WEDNESDAY

8:00 P. M.-Mm-WEEK SERVICE

w. w. WEEKS, MINISTER

Are used in Kroog's (formerly Abrams') Cakes to give it that delicious homemade flavor and golden color. Demand the genuine of your dealer-if he doesn't handle Kroog's (formerly Abrams') Cakes, phone us.

EDWIN A. ALDERMAN, President

THE TRAINING GROUND OF ALL THE PEOPLE

Departments represented: The College, Graduate Studies, Education, Engineering, Law, Medicine, The Summer Quarter. Also Degree Courses in Fine Arts, Architecture, Business and Commerce. Tuition in Academic Departments free to Virginians. All expenses reduced to a minimum. Loan funds available for men and women. Address

THE REGISTRAR, University, Va.

IMPORTED

Brass, Cloisonne , Chinese Vases , Silk Gauze Lanterns Atlantic Hand Dipped Candles, Novelties

104 East Grace Street Madison 2570

Tuition and room rent free. Scholarships available to approved students. Seminary within 13 miles of Philadelphia. Metropolitan advantages. Seminary's relations to University of Pennsylvania warrant offer of the following courses:

1. Regular Courses for Preachers and Pastors. Seminary. Degree of B. D. or Diploma.

2. Training for Community Service. Seminary and University. Degrees of B. D. and A. M.

3. Training for Advanced Scholarship. Seminary and University. Degree of Th. M. at Seminary, or Ph. D. at University.

MILTON G. EVANS, LLD., President, Cheater, Pa.

ROYAL TYPEWRITERS FOR RENT Special Rates to Students

Will enjoy "browsing" in our store; there is no obligation to make a purchase; you are welcome here at all times .

DON'T JUST SAY

SOLD OVER THE ENTIRE SOUTH

Manufactured by Southern Dairies, Inc.

-and we will restore it completely to its original appearance. It's surprising how thoroughly we clean old hats. That's why we say "Save your old hat."

Bring us your last season's hat and we will remodel it to the new styles - at small cost. New models to try on and select from.

Convenient

Representative DAN BEGOR

Especially Invited to

CORNER BROAD AND TwELFTH STREETS

REV. GEO. W. McDANIEL, D. D., Pa1tor

Church Services: Preaching Sundays 11 :00 A. M. and 8 :00 P. M. Prayer Meeting Wednesday 8 :15 P. M.

Sunday School: Meets at 9 :30 A. M. Baraca, Philathea and other organized Bible Classes.

B. Y. P. U.'s: Meet at 7 :00 P. M. Sundays. Fellowship Union meets in Baraca Room. Fidelity meets in Sunday School Auditorium ; Loyalty meets in Church Parlor.

•cOME THOU WITH US AND WE WILL DO THEE GOODn

THE BOYS' MEETING PLACE, AS WELL AS THE OLD GRADS RICHMOND HOME.

BROAD STREET AT EIGHTH