The MESSENGER

October, 1923

October, 1923

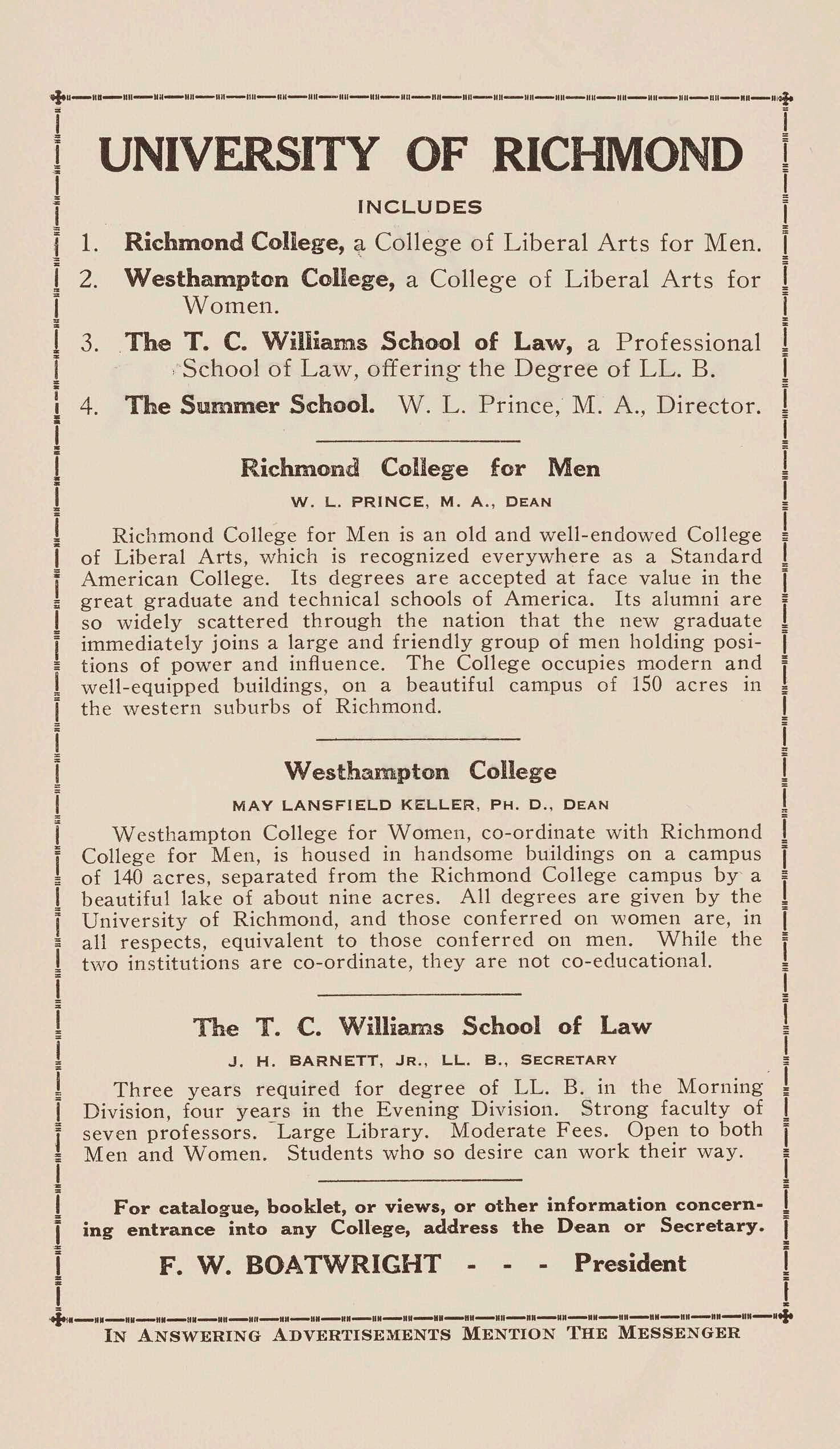

INCLUDES

i 1. Richmond College, <;l,College of Liberal Arts for Men.

2.

3. i i I 4 .

Westhampton College, a College of Liberal Arts for Women.

The T. C. Williams School of Law, a Professional ,School of Law, offering the Degree of LL. B. The Summer School. W. L. Prince, M. A., Director.

W. L. PRINCE, M. A., DEAN

Richmond College for Men is an old and well-endowed Collegeof Liberal Arts, which is recognized everywhere as a Standard =.I American College. Its degrees are accepted at face value in the great graduate and technical schools of America. Its alumni are so widely scattered through the nation that the new graduate immediately joins a large and friendly group of men holding positions of power and influence. The College occupies modern and well-equipped buildings, on a beautiful campus of 150 acres in the western suburbs of Richmond. I

i I MAY LANSFIELD KELLER, PH. D., DEAN I

f Westhampton College for Women, co-ordinate with Richmond !

·.I College for Men, is housed in handsome buildings on a campus I of 140 acres, separated from the Richmond College campus by a I beautiful lake of about nine acres. All degrees are given by the I i University of Richmond, and those conferred on women are, in :_I all respects, equivalent to those conferred on men. While the i two institutions are co-ordinate, they are not co-educational. I I I I i

J, H BARNETT, JR. , LL. B., SECRETARY

Three years required for degree of LL. B. in the Morning • Division , four years in the Evening Division. Strong faculty of seven professors. - Large Library. Moderate Fees. Open to both Men and Women. Students who so desire can work their way.

For catalogue, booklet, or views, or other information concerning entrance into any College, address the Dean or Secretary.

F. W. BOATWRIGHT - President

Session of Thirty-Two Weeks

Excellent equipment; able and progressive faculty; wide range of theological study .

Tuition Free. Expenses Moderate.

Special Financial Aid for Students Requiring Such Assistance. Full Information and Catalogue Upon Request

E. Y. MULLINS, President

LOUISE WILKINSON ________________________________

ELSIE NOLAN _____________________________________Business Manager

DR. KELLER _________________________________________Advisory Editor

DR. LANDRUM ______________________________________Advisory Editor

All contributions should be handed to the department editors or the Editor-in-Chief by the 1st of each month preceding. Business communications and subscriptions should be directed to the Business Manager and Assistant Business Manager, respectively. Address-

Tradition is a most potent factor , in the life of any institution. It is the sense of a foundation in the past no less than of a goal in the future which gives unity to the large body of infinitely varied students brought together in a university. Tradition The Freshman does not become a real part of this and body until he feels the sway of its traditions; the Custom alumnus does not cease to be a part of it until those traditions lose their hold upon him. They constitute the very soul of Alma Mater-the vital, imperishable spirit. As long as tradition remains a thing of spirit and principle, its influence is wholesome. At once an incentive to effort and a standard by which that effort may be judged, is just such a conservative force as is needed in a group susceptible to ever-changing ideas and ideals. Yet, it is elastic enough to permit of gradual change and allow for progress. This is not true when the legacy of the past takes the form of a custom. In that case it becomes a definite, inflexible thing, incapable of expansion in accordance with the growth of the institution. Like the ring upon a child's finger, it may do injury if not removed in time.

We wish by no means to say that all customs are harmful. The majority involve matters of so little consequence that they are in no danger of becoming so. Nor would we advocate, as a safeguard against those few which may be or have been injurious, the abolishing of all the little formalities and observances which add charm to campus Ii£e. Without them college days would be far less colorful and vivid. What we do advocate is a saner attitude toward the subject as a whole . Any custom instituted by one class to fill a need felt at the time may be broken by another class for whom that need no longer exists. It is surely not sacrilege to cast aside an inherited garment which has grown, not only shabby, but painfully inadequate. Let us not allow our reverence for the past to blind us to the demands of the present and of the future.

L. W.

A literary publication often times does not represent the literary attainment of the students of a college or university. In many cases it represents the extraordinary efforts of the second best of the students. In some cases it represents the second best efforts of the best writers of the group. In a surprisingly few cases, and these, it may be said, are exceptionally rare, does the publication represent the best efforts of the best writers. The reasons are distinctively clear ; the results are shockingly disastrous.

The fundamental reason prevalent in most colleges is the fact that there is too much "forced writing." Too much of the "last hour drive" before the publication goes to press. The result of this is cramped articles and badly constructed sentences and paragraphs. The remedy is obvious. More care exercised in the creative process.

Another enemy to good writing, an enemy which saps the very life and energy from literary creation, is plagiarism. In his book, The Book of Plagiarism, George Maurevert states that plagiarism is as old as literature itself, and wherever there have been writers there has been plagiarism or the accusation of that literary or intellectual transgression. Aristophanes accused Euripides of having stolen from Aeschylus. The Roman poets became plagiarists of the Greeks. Vergil is the great plagiarist of Homer. It is well to remember the words of la Mothe le Vayer, who said: "One may rob as the bees do it, without harming anybody, merely sucking honey from the flowers; but robbery in the manner of the ant, which carries away the whole grain, should never be imitated."

The final exhortation is that since the literary publication contains the best that is submitted it is necessary that a greater supply be submitted. The best of anything should not be all of it.

J.H.M.

RICHARD ROWLAND, '24

Romain Rolland, in that remarkable epic of youth, Jean Christophe, is known to remark to the extent that "there is an age in life when we must dare to be unjust, when we must make a clean sweep of all admiration and respect got at second hand, and deny everything - truth and untruth - everything which we have not ourselves known for truth."

Frankly, there is something of this same feeling of revolt in the mind of the writer when he considers this science-ridden age. Undoubtedly, ours is an epoch of research and generalization. Everywhere we have pointed out to us the manifold benefits of science and its methods. We cannot escape the significance attaching to it. The aid which this strange genie of accuracy and thoroughness has been in pandering the human desire for physical comfort and ease, is only equalled by the increased need we are developing for the protection of science against the disastrous effects of luxury and indolence. The situation is a paradox. The actual expression of this urge becomes a Frankenstein, constantly turning upon itself to devour at one extreme, while it grows at the other. And there is small chance that we actually advance with such a monster creating and destroying.

Against this all-pervading force I raise a feeble voice, for I am being guilty of awful heresy when I dare to question the scientific method. I can expect little approbation from those who have flocked to the side of utilitarianism and turned to scoff at those who remain beyond.

I do not lament the passing of former ages, nor do I deem them more productive of happiness than this one. For science and the scientific method unquestionably contain indispensable possibilities. The qualities of accuracy, thoroughness, unselfishness, progress, research, and massed knowledge cannot be gainsaid as absolutely necessary attributes for all the physical and perhaps some of the social sciences. Beyond this, there is grave

danger of imposing anything more than the general attitude of science wherein it takes the form of progressiveness, fair-mindedness and knowledge.

The collegiate world has accepted in toto the scientific method, and has ceased to question its plausibility. Like the evolutionary hypothesis, the subtlety of which appeals so strongly to our rational desire for the co-ordination of all knowledge, for cataloguing every possible manifestation of variation and change, and which every branch of learning has appropriated for its own expostulation,the scientific method, I reiterate, has been welcome with open arms and allowed to be the basis for all further endeavor. Open any text-book written within the last twenty years. What do you see? The scientific spirit is assumed as obligatory for any understanding for the subject. History compiles its facts and interprets . them in the name of science; chemistry acclaims its own accomplishments as illustrative of the very nature of science; sociology devotes itself to digging energetically into great masses of data, trying to classify, to catalogue, to graph human phenomena; economics makes an effort to become a formula : all in order to present to reason, cold impassive reason, a guide book of life, a simple and brief direction, and to assign to all human actions , desires, ambitions and manifestations of man's effort toward a control and an identification of himself with his environmenta mere prescription for behavior. Science aims to simplify, to bring out of chaos, to organize and to eliminate-to make all things applicable to rule, and a known rule. And this reduction of complexity is in no wise uncommendable.

In so far as information is concerned, or as the mere accumulation of facts and of classification is directed, the scientific method is by far the most effective one mankind has yet wielded. It has given us the automobile, the incandescent lamp, radio, protection of health, and a countless number of utilitarian advantages; and they are now necessary, they are pleasing to any normal being. But when the scientific method -when science, let us say,exceeds its natural bounds and slips into alien territory, then the result attained is sickeningly ineffectual. My thesis is merely : that science becomes a blatant failure i n the interpretation of

,literature. By literature I mean belles lettres; not circulars on spring styles for men, nor the Einstein Theory of Relativity and its countless explanations; not Henry Crewe's Physics, nor Macpherson and Henderson's General Chemistry; not the Outline of Science, nor Ely's Outlines of Economics; not books of law, nor differential calculus -not these masses of information which are aimed at the dissemination of facts: iron is a metal with an atomic weight of 55.84, the sand flea has a certain number of jaws plus attachments, the single tax has these advantages and these disadvantages, but by literature I mean the Iliad, Othello, Les Miserables, Salammbo, The Red Lily, Lord Jmi, and the endless list of great writing.

To attempt to understand these masterpieces of fine art by means of scientific methods is to prostitute our intellects. To attempt to teach these records of human joys and sorrows with a meterstick and a microscope is a wretched failure in modern pedagogy. And much of the contempt for belles lettres which is extant at this very moment in the workaday world, much of the unpardonable ignorance of college graduates concerning their own literature is due to this bastard offspring of science and fine art. It is a fact to be deplored by every student and lover of literature; it is a danger which professors in English departments will do well to avoid-although, in actuality, they themselves have often been seduced by the pleasing wiles of science. For it is no unworthy consideration that the greatest literature was not assembled in a scientific manner and obviously cannot be dissected or analyzed by any method other than the spirit of that impulse used in its creation. Unfortunately, it seems, students are not as gullible as professors would like to have them. The pedantry of science in literature is not difficult of discernment even in our university.

The actual classroom procedure extends even to the question of parallel reading in literature. When assigned in accord with scientific methods, and when interpretation is demanded by research in the same way, there appears to be a paucity of interest which sours our reaction, and unless we have become pedants at this tender age we say, "This is dry reading." And well it might be so considered. If Hamlet becomes in the classroom a laboratory

for research, isolation and classification of human qualities and motives, it will fail to reach the student. If on the other hand, it is taught in a manner of totality, of subtle feeling, and expression of that strange mixture of emotion and intellect which we call human life; if the ideal is emphasized and not the clothing of the actors or the length of Polonius' beard; if the true discernment of the character Hamlet is attained, and idle discussions concerning his insanity are forgotten, then Hamlet will mean more to students, and I even risk the assertion: that professors may profit.

For we can easily observe that the subject matter of great literature is limitless. And it may not be banal here to remark that there is sociology in Hamlet; also psychology, even chemistry ( the poison - was it not?), even ethics, and so on endlessly. But there is also art, genius -which no classified knowledge has yet succeeded in interpreting, no pedagogue in actually isolating. It is this strange blending of simple constituents and genius which has given eternal value to the work. To dissect is to destroy.

The plea of this article is for common sense in considering the matter. Chemistry concerns itself with pulling down certain compounds and then building them synthetically. The chemist says: "I can now manufacture vanilla with as much ease as nature. The difference is so slight that it is negligible." He has achieved this seeming wonder by analyzing natural vanilla and determining its constituents. Literature cannot be subjected to similar treatment, although the majority of students and professors seem to think so. If it could be, then there would be no trouble in teaching the writing of great literature, and Swinburnes would be as numerous as chemists. For when professors of literature dissect Anatole France's Thais, they may arrive at a prodigious number of observations, even facts -but that is not sufficient; the vital principle, the real artistry is forgotten, and the class is deluded into believing that by using the methods of science, in tearing ,clown a work of art, in dissecting and inspecting the vitals of the mechanism, they are being made to understand literature. Wretched illusion! Little wonder that college professors of English are held in such contempt by writers of literature - and those who strive to appreciate it.

Now it should be manifest that the intelligent interpretation of belles lettres requires a man to be a student of literature for its intrinsic and self-sufficient value. The philologist is no more competent as a specialist to interpret the classes than a chemist. For the latter may understand the elements composing the compounds which form the basis of certain colors used by the painted, but it is obvious that the chemist, in this particular, would not necessarily understand and be capable of pointing out the beauties of a Greuze landscape by discoursing learnedly about the virtues of cobalt. One might just as well assert a policeman to be a competent authority on literary criticism, in so far as he figures extravagantly in some books. We assert that knowledge of a particular subject can only deal directly with the information of literature, which, we are to believe, is the more ephemeral part of it. In support of this reflection we take the liberty of calling to mind the story of Christ, which, while having in actuality many errors of history and science, retains artistic values which preserve for it a lasting and beautiful significance.

The ineffectuality of college courses in writing is not surprising. They neglect the vital need for . real literature: an intelligent knowledge of such a thing which seems to consist of the recognition that behind a story -a plot -a miserable cataloguing of facts -of words and paragraphs -there is a demiurge which can only be understood intuitively -outside -beyond the materialism of science and its methods. For there is one thing relative to the writing of literature which is fairly certain: scientific methods of research in letters will not produce of themselves a work of any artistic value whatever.

In conclusion, literature as such can neither be taught nor written according to the rules of science. When the illusion exists that it can, then art may be found in a catalogue of mill supplies or in a city directory. Science, while supreme in the realm of the knowledge of information , is a sorry spectacle in that of the knowledge of inspiration. Concerning the study of literature, our attempt should be to divorce from our minds the apparent inclination to reduce everything to scientific reason, and to cease expending otherwise valuable energy searching for ulterior motives

and hidden secrets, when a common sense method of study will make for an understanding and a satisfactory return from the perusal of belles lettres.

It would be the very essence of conceit and vanity to anticipate any change in the methods adopted by our elders-who, they say, are wiser than we; for they will continue to exalt science, the artificial, the superficial - and delude themselves into believing that they interpret literature.

Science has run amuck.

C. N. SNEAD

Silvery hang the clouds at eventide, Filt'ring floods of sunbe0ms streaming gold; Coo,l blue specks of heaven dot the wide And vaulted aerial real in outline bold. The gathering clouds obscure the paling blue, Low rumbling thunder heralds th ' approaching storm; A billion swishing raindrops beating through, Create torrential rivulets in foam. Then from the dew-kist earth aromas rise, To rapturously refresh all living things ; 'Tis said its incense travels to the skies, And then returns again on liquid wings.

I looked into your heart today; Scarce can my soul believe the things I saw. My mind repents, my eyes rebel today Against my penitential mind, because of what I saw.

I looked into your heart today; A pure and spotless, wondrous heart I believed Once, and now I touched the things today With trembling fingers, and I repent because I believed.

Yes, I looked into your heart today; I saw a story written there, and I perceived There was another story written on your face today, So different from the hewrt story that I perceived.

Today, I looked into your heart; today I looked into your face, and I know I am deceived. The sunshine of my soul has fled today;

A paltry fear camps 'round my heart, because I am deceived.

I looked into a world of hearts today; I !oohed into a world of faces, and I see That eyes and smiles, and what you say today, And what you thin!?, and feel must agree with what I see. -R.C.E.

MARGARET HARLAN, '26

Gregory Hobday kept a book shop on Way Street, a street which in the clays of Hobday, Sr., was the busiest street of the town, along which the best stores flourished, and over whose cobble-stones rumbled the first horseless carriage. Long ago the best stores had left Way Street, and moved to more fashionable districts, to be succeeded by second-rate groceries and meat shops Respectable stores had drawn in their long-respected signs to be replaced by three glistening balls. In the midst of this, Hobday's book shop remained unchanged. Its customers were people who knew it; book lovers who came to find an old copy of a loved author. But the street paid little attention to it or to its owner. The neighboring people entered it only when compelled to ask for change or to collect their small bills. As Mrs. O'Flarrety, who lived upstairs, remarked to her neighbor, "It ain't even decent alive. All the books what ain't dead and buried in their own dust turns up their noses at yer \to tell you yer ain't in yer proper atmosphere."

The merchants of the street coveted the book shop. It was a corner shop and a fine location for a grocery or a pawn shop. Mr. Malory, the neighborhood butcher, had tried for years to persuade Hobday to sell it, but the old man was deaf to all offers.

Gregory Hobday was as old and deserted as his store . Time had left him there, surrounded by strange neighbors who puzzled him. He wondered at their scorn and disregard for his books. He saw them pass the racks of books, his most tempting ones, which he placed in stalls outside the shop; saw them pass by with uninterested, unheeding eyes, only to enter the next corner drug store and emerge with gay-covered magazines. In late afternoons, when the sun's last light invaded the dusty interior of the shop, and glowed softly on dull gilt edges of the old books, he would stand by the door, a wistful look in his faded blue eyes, dreaming of days when well-dressed men in high silk hats, resting their canes

on their arms, stopped to regard the contents of the stall, and finger through volumes of Thackeray and Dickens; when small boys, rolling hoops along the walk, would stand on tipetoe to look over the edge of the stalls, almost awed at the spread of so much knowledge. Then Gregory Hobday would arouse himself from his dreaming to chase away some freckled-faced little Irishman, who delighted to torment old Hobday, by pretending to snatch up a book.

In the back of the store hung a faded brown curtain, partitioning off a small room. In this were his desk, with its cumbersome old account books, an oil stove, and a small iron bed. In one corner stood a locked cabinet, the contents of which were a subject of much speculation to the neighbors of the street who had ventured into the back room of Hobday's shop. Some said it contained money, the hoard of a miserly old man. Others declared that it could hold nothing but bills. However, it did contain only the dust of dreams and the relics of never accomplished ambition; a stack of music books, yellow backed compositions; a paint box of twisted, half-used tubes; a portfolio of sketches and half-finished drawings; and a handful of brushes standing in a grey stone jar. Against the cab inet leaned a dust-covered violin case.

The old cabinet held, close locked, the secret of Hobday's one time dreams. When he was young, his parents, believing him endowed with great talent for the violin, gave him many lessons. All went well for a time, while the novelty of playing held his interest. \i\Then he tired of the work of practicing, they blamed it on his youth, and hoped that, when he was older, ambition would arouse love for the work of it. There was, however, something in his character which kept him from the routine and real work which would have made him famous.

His music master, unwilling to give up such a promising pupil, tried to help Hobday master himself. Then one day the teacher called the young man to him and said, "Hobday, you just haven't it in you. You could be a great violinist; you have the talent, but there is something in you that keeps you from real work.

You are lazy, Hobday, downright lazy, and it's no use to teach you any more."

So his ambition to be a great violinist had ended. He tried painting, but there again he met the obstacle of work. He wanted to compose; knew that he could compose, but he seemed unable to stick to the technical study. There was a piece which ran through his mind, a piece he knew would be great if he could but put it on paper or play it. He was unable ever to draw it from his mind, although it followed him all his life. Somehow he felt that some day he should play it, but it was always just beyond his reach, always too faint to become anything real. And so it lived in his brain, a thing to torment' him and remind him of ambitions never fulfilled. Then when his father died, Hobday took over the book shop and found, in the books he loved, some small content.

Even old Hobday could not have told how the youngest O'Flarrety invaded the dusty shop and conquered the heart of the lonely old man. One afternoon as he stood behind the counter, he felt the timid pulling of a hand at his coat sleeve. Annoyed, he looked down into the bright blue eyes of a ridiculously small boy, who raising himself on his toes, leaned over the counter, one hand cupped to his mouth, the other pointing over his shoulder at the back room of the store.

"I seen it," he said, "when I peeked in your window. May I look at it, Mr. Hobday?"

Strange as it was, he knew what the boy meant, and wondering that he should do so, he led the little fellow to the back room and unlocked the violin case. He had not seen his fiddle since the day he had closed it up after his last lesson, twenty years ago. He wiped the dust from the golden brown back, and tuned up the two remaining strings. Hardly heeding the boy, he began to play. The notes, from his time-rusted fingers, were quavering threads of sound , but to Patrick O'Flarrety they were true music. Then, when the boy cried, "Lemme, lemme try it," Hobday put the violin under his chin, placed the small fingers on the keyboard, and with his hand on the boy's, guided the bow across the strings.

After this first meeting, Patrick hurried to old H9bday's shop every day, when school was out, to play the violin and listen to

the old man's stories of music and its masters. Hobday opened bis cabinet and took out the yellow-backed books.

Patrick seemed to have a great love for the violin, and with it, the capacity to work, which Hobday had never had. Encouraged by his teacher, he progressed rapidly.

"Fight yourself, fight yourself hard. Don't let anything get the better of what you want to do," Hobday would tell the boy, bringing his fist down on his desk to emphasize the words.

Patrick, seated at his feet, would clench his small fist and pound it down upon his knee. "Fight yourself, fight yourself hard," he would repeat.

One day, during a lesson, the man and the boy beheld the angry figure of Mrs. O'Flarrety in the doorway. With eyes ablaze, she raged at them.

"An' this is where the little scoundrel has been hiding himself, when he ought to be running me errands? Playing the fiddle is he? Well, we'll see."

Now, if ever, thought Hobday, he must plead for the boy's future.

"Mrs. O'Flarrety," he said, "your son has much talent, I believe, and he knows how to work at practicing. Madam, I beg that you allow him to receive what little instruction I am able to give him. Who knows but that he may have the making of a great musician?"

"Great musician, is it? The only music he'll ever make is with hitting the pipes with a hammer, like the respectable plumber his father is."

She snatched the violin from Patrick's hands, and raised it to strike it against the bookshelf. Hobday pointed his finger at the astonished woman, strange fierceness in his eyes. Mrs. O'Flarrety regarded him with mouth open, holding the fiddle above her head.

"Madam," he said, "the masters of ages are looking down ·upon you. Immortal ghosts of players deplore your act. The spirits of music are watching you with horror. Madam, you will put that violin down gently."

Dumbfounded, Mrs. O'Flarrety put the fiddle clown upon the ~bed and hurried out of the shop.

The next day, in order to overcome the opposition of the boy's parents, he offered to employ Patrick, as an errand boy, an unneeded office, but a good excuse for lessons in the back room. Mrs. O'Flarrety explained it to her neighbor. "Faith an' it makes me tremble to see me boy with the raving idiot, but, Mrs. Malory, as I've said before, two dollars is two dollars."

The next years were happy ones for Hobday, and for the boy, filled with promises of success. Patrick's interest in his music seemed only to be strengthened by time. The clay soon came when Hobday was no longer able to teach the boy from his scanty knowledge. Knowing that the boy's parents would not, and could not pay for his further instruction. Hobday mortgagee! the shop for half its value and sent Patrick to the best master in the city. He would pay the mortgage off somehow, he thought, but with the scant profits of the shop, he was able only to provide for his living needs, and keep up the interest.

So Patrick grew up, having his one ambition : to be a great violinist, and coming, each day, nearer and nearer his dream.

One day, when he was eighteen, he hurried to Hobday, from a lesson, eyes sparkling. There was a wonderful violin that his teacher had shown him, an instrument with a golden voice, a rare : fiddle from Italy. And he could have it for two thousand dollars. Patrick could hardly be blamed. When Hobday paid for his. lessons, he lied to the boy, telling him that he had money enough. To Patrick a storekeeper meant a prosperous man. And Old Hobday had no family to care for. Furthermore, neighborhood gossip said that the old man was a miser with stacks of gold hidden in the back room. Only the butcher knew the truth and guarded the secret. Therefore, Patrick received the man's aid, . and was truly grateful, expecting, of course, one clay to repay him ..

So Patrick got the prized violin, and put Hobday's old fiddle back in the corner by the cabinet, where it remained untouched. And Hobday went to the butcher one night and mortgaged the , shop for its full value.

Two years later, came the fulfillment of the boy's dream, a, concert, in the presence of the foremost critics. Hobday's joy in the boy's success was clouded only by the fact that he was:

finding it impossible to pay the interest on the mortgage. The butcher had threatened to foreclose. If he could only put it off until after the boy's concert, it would not matter so much then. Patrick should have nothing to mar the perfection of his triumph. He begged the butcher to put it off until the clay after the concert. The butcher consented, for the store was his, he knew. A few clays would make little difference.

The concert was all the old man and Patrick had hoped for. Hobday sat through with happy content. When it was over, he did not go to the stage to speak to Patrick. He would not embarrass him by protruding his rusty figure into the group of smart musicians which surrounded the young man.

With tired steps, Hobday dragged his way home. Only a few lights remained in the street. Dark store fronts gazed blankly at him. Ahead, the thin spire of a church cut the moon in two. He felt very old and very lonely, yet) his heart warmed to a small glow of content. So little Patrick, his pupil, had won his success, had reached the top. It seemed only yesterday that the boy sat at his feet, his chin in his hands, his eager bright eyes following every movement of his teacher. How well he remembered th e boy as he struck his small clenched fist down upon his knee, echoing Hobday's words, "Fight yourself, fight yourself hard. Don't let anything get the better of what you want to ,do." Patrick had won his fight against himself, had clone what he , old Hobday, had failed to do.

He reached the shop and, by the pale bluish street light on the corner, took the large rusted key from his pocket and fitted it to the lock. Longingly he gazed at the front shop, bathed in the moonlight. Tomorrow it would all be changed. Carrots and onions would fill the stalls. Flies would crawl over them. And through the old green door would come smells of sawdu st and fish.

The door bell jangled sleepily as he went inside. He groped his way to the back room and lighted the lamp on his desk. There were final accounts to settle and books to be balanced for the last time. He drew up his chair and opened the heavy ledgers. His mind wandered far from the book. The long columns of figures

would not stay still. They became notes and ran up and down a scale, so he could not add them. He pushed back the book and raised his eyes to rest them. The notes still danced before him , left the pages for the dark shadows of the room. They grew , expanded, took forms and became little devils. They began to laugh, they danced, they perched upon the bookshelves. One had the face of his old music master, and leered at him out of the gloom.

"Hal! Ha! Hobday, you were going to be great, weren't you ? But you failed. Something got you, got you and strangled you , Hobday. It was your self, your own lazy self, Hobday, that you couldn't conquer. You're a failure, a failure. It got the best of your dreams, didn't it? You were going to compose. How about that piece, Hobday? Never could play it, could you? You're old. Pretty soon you'll die, Hobday, and you'll never hear it. It will die with your brain and rot with your brain. And even your soul won't hear it. Ha! Ha! The great man that was to have been. He died, and left an old wreck of dreams, with a book shop in place of fame. And tomorrow you'll lose that too. What will you do then ?"

The old man buried his face in his hands to hide the dancing figures. Why did they all laugh, a hideous, mocking laugh? To balance his books he must add up figures, but they bothered him , dazed him. Unwilling he raised his eyes again to the top of th e bookshelf. The music master had disappeared. In his place, the puffy face of the butcher leered down at him.

"Tomorrow, Hobday, you know the mortgage is due. You won't pay it , you can'tr pay it; can you, Hobday? Of course, not . The shop will be mine, old Hobday, mine to hang with strings o f sausages and fat steaks. I'll tear down your bookshelves, and throw your books into the street. And I'll cover the floor with sawdust, Hobday, nice fresh, yellow sawdust. The bell will jangle all day. Or maybe I'll take it down. It's old fashioned, you know, Hobday. Your father's book shop, a meat store, a smelly , bloody meat store. You couldn't even keep that. It's gone where everything that you have ever attempted has gone - into a failure . A failure, Hobday, like yourself. You couldn't hold out, couldn 't

keep it. Something got you. Your self, your own lazy self. What are you going to do after tomorrow, Hobday? Where are you going? There is nothing you can do. Take your violin, Hobday, take it out in the street and play it. Play on the corner to the people who pass by. They will hate you because you get in their way. In the houses, sick people, and tired people, will curse you for keeping away their sleep. You will play street tunes, soundless bits of crazy music. Ha! Ha! Gregory Hobday playing street tunes instead of your composition. The hand which was to have swayed audiences will be stretched out for pennies. You'll have to have something to gather the pennies in, Hobday. Take your brush jar. It's just the thing. Throw away the brushes, brushes which were to have painted your masterpieces, and hold out the jar for children and pitying ladies to drop their pennies in. Ha! Ha! Gregory Hobday, a failure."

Unsteadily, the old man rose and paced the small room, his eyes closed, hands tight over his ears, trying to shut out the voices and the faces. Their laughter grew louder and more hateful. He could see their hideous faces through his hands. They pressed closer about him, smothering him.

Then his song came to his mind, faint at first, but with a steady, soothing sound. As it grew louder, the laughter of his failures seemed to fade. He felt that he must play it. It never had been so clear, so real. If he could play it, the faces would go, and the voices be drowned in its sweetness. He knew he could play it . He would show the faces that he was not all failure. Then, in his triumph, he would laugh at them.

Then Hobday took the violin from the case and began to play, first the practice scales, then the childish pieces he had first learned, then the few great works he had mastered. Out of his mind, at last , it came, the dream of his life, and formed itself on the strings. First, it was indistinct, lost in all the failures he had made. Then it grew stronger, firmer, now a thin thread of melody , then again , a great rush of melting chords. It was all he had dreamed it would be; a group of girls and boys dancing on the village green , in the twilight; the vesper song of nuns in a convent; the marching song of a mighty army; and the soft sweet playing of a blind

fiddler at a country inn. He played his life out in the piece, his hopes, his failures, and his dreams. Always he had known that it would end in ~ e long chord, beginning low on G string, and rising to one perfect note, high on E.

The theme was almost played out now, out of his mind and into his soul. The voices had almost ceased. The faces were barely visible. He reached the last chord, beginning in a low note on G string, like the wind in pine trees , then rising, swelling , triumphant . He reached the E string, and with peace in his eyes , slid his fingers up, up for the last perfect note.

Then the tiny wire string snapped. And the old man slipped to the floor, the violin crashing to pieces against the bookshelf.

J. MARK LUTZ

Forsooth, woman's faithfulness, like her virtue, 1s largely a matter of man's own imagining.

And it so happened that there once lived a rich young ruler exceedingly blessed of the gods, fair of limb and mind, who had as yet not crossed the threshold of love into that realm of true knowledge.

His gold and precious stones formed a mighty mound to the honor of the frugality of his forefathers, and his fame spread throughout the land and even beyond the borders thereof.

It so happened that there were many maidens who came to the royal courtyard daily and formed a mighty throng, seeking to become the chosen one of the king.

"Praise be to Allah, the Compassionate, Oh Commander of the faithful, there awaits in the courtyard a mighty throng of virgins, each seeking the supreme honor of being selected for your royal couch," quoth the lord high chamberlain of the realm.

"Imp of misery, seek out the fairest three of the throng and bring them unto me, for then will I select she who shall be mine," the young monarch replied.

The lord high chamberlain bowed with true oriental courtesy, but his heart was heavy, for he knew that the young sovereign was to come to grief and that there was no such thing as true beauty among womankind.

But being a sagacious and faithful lord high chamberlain he went out unto the mighty throng, and after three days and three nights of prayerful selection he returned unto his king and said:

"Most just of the just, highest of the high, three maidens await within the royal rooms. Three of the most priceless jewels of the land have been chosen for your approval. Behold, here they are."

But the king was exceedingly vexed, for each of the three maidens was equally lovely to behold. From their ivory-tipped

feet to their ebony-glossed hair they were of marvelous smoothness. And the three showed their charms before the king and made loud cries to him of their great love and the empyrean joys that would be his did he but have the excellent wisdom to select her.

"Ulcerous growth on a toad, it is too hard on me to pick from these three she whom I will crown with my love. They are all of the same fairness. But I cannot take them all unto my bed, for I have sworn a mighty oath, even that by the beard of my fathers, that I would only cherish one flower in my heart. Select the finest bloom from the posey. Each doth protest that she love me better than life itself."

Being exceedingly wise the lord high chamberlain hid a smile, for in those days to smile at the whim of a king was death.

"Most illustrious potentate, it is only by your aid that I can accomplish that great task which you have set out for me, that of culling a blossom for your regard," answered the lord high chamberlain.

Upon the word of the king that he would be obedient unto the word of the lord high chamberlain the chamberlain banished all from the chamber of the king. He had brought unto the chamber rich trappings, much fine gold and wonderful jewels of the size of huge eggs that glistened and gathered in the light, giving it back in manifold colors.

Now when this was done he caused the king to stain his royal robe with the blood of a lamb that had eaten of the tender grass beside the brook and told the king that he must fall upon his couch even as though he were slain.

Whereupon this being accomplished the lord high chamberlain threw open the doors and appeared before the three maidens, each preening herself for the regard of the sovereign.

"Gravid with grief is the day," wailed the chamberlain, so loudly that even doves on the roof were troubled.

"Why is there such sorrow?" asked the maidens as one, crowding forward to see inside the chamber of the king.

"Our royal master has slain himself, oh woe be mine. He could not select the fairest from among you wretched wenches .

Loving you all he has had these priceless gems heaped here to go to her who could be so assuaged. She who loved him unto death can join him there on his couch."

But the three maidens being true women passed their lover without a sigh and fell to quarreling among themselves over the treasures heaped in great blue and gold and red and orange in the corner of the chamber.

Whereupon the king arose in wrath and directed that they be torn asunder, for he was still a gentle king and did not wish to prolong their lives.

And Scheheoazade perceived the dawn of day and ceased saying her permitted say.

J. B. HANCOCK

It was a quiet morning. Jim Hall was walking briskly along a path that led up into the hills. From his lips there sounded a cheery whistle, and if one had been there to see, he would have sworn that Jim was engaged. His whole air belied the fact, for in truth, he actually was. And what is more, Jim wa s engaged to a beautiful, well, the most beautiful girl in the world.

As he strode rapidly along, breathing the fre sh morning air into his lung s, and with his arms swinging clock-like fashion, Jim was seeing a vision of her as she told him goodbye when he had started on his last year's vacation in the hills. "I'll be waiting for you, Jim," she had told him, "and you must not forget me while you are away." Yes, all that had taken place one long year ago, and now Jim found himself back in the mountains again with only a very pleasant memory, for the only girl v,as back in college and he was impatiently doing the waiting.

Jim smiled at the recollection. Others had said she would forget him, but he knew better. Katherine loved him too much for that, and besides, well, she was simply n ot that kind of a gid. At such a thought Jim burst forth into singing and began to walk rapidly towards a high peak that seemed too difficult for anyone to climb unless he was stimulated to unusual effort by some extraordinary trick of mind. But there was another reason why Jim chose this difficult piece of mountain climbing; he wanted to be alone witb n ot hing but the thoughts of Katherine and the still air and the m ountain scenery. However, when he ha d climbed to the top of the peak Jim saw something unexpected. A man was there. His back was turned to Jim, and he was sitting almost motionless, with head bowed and resting in his hands. Evidently he had not even heard Jim's approach, for he did not move.

"Hello!" shouted Jim. Slowly the man turned around, but ,d id not seem disturbed or even surprised at the approach of another individual so early in the morning, and on the top of the most

.,.,,!,

inaccessible peak in the vicinity ~ Aj/ flie • light f e11 more directly on the man's face Jim observed a youthful appear;rnc_e under the camouflage of premature age. His dress w~s of tflJ oett~r .sort, and his bearing gave evidence of a man of tulture. ii,,

The man did not speak. This perplexed Jim, 1for he immediately perceived that the stranger was in some kind of trouble. Slowly Jim approached him, wondering just what he ought to say. Jim pitied a man in trouble, and could see no reason why anyone should be long faced on such a fine morning as that was. Certainly there was nothing in his own heart to cause even uneasiness. In fact, he had never seen the world seem so bright. Ah, Katherine! When he thought of her and knew that she was his only, there was actually a reason why the man in front of him should feel blue and discouraged! A smile of pity passed over his face as he walked up to the stranger and laid a hand on his shoulder.

"Something troubling you, old man?" he said patronizingly. A sigh escaped the lips of the one in distress.

"Oh," he replied, evidently glad to take someone into his confidence, "just a girl, that's all."

Poor fellow, mused Jim, as he walked a few steps away and sat down. He must get the man to tell his troubles. Maybe he could help him. Again Jim thought of Katherine; such a pity this man did not have a girl like her; a real girl.

"She didn't kick you?" Jim finally began.

"Oh, no," replied the stranger, "it's -it's - kind of hard to explain. But if you do not mind, I will tell you." He smiled half cynically. "Yo see it's this way: I have promised to marry a wonderful girl when college closes next June, but as time draws near , I find that I am not able financially to make good that promise." He halted. "And if I tell her," he continued, "I am afraid she will not understand."

A girl like Katherine Norris would understand, thought Jim. "Surely she will understand!" Jim encouraged. "She must understand."

The man said nothing, but looked out across the hills. Early morning was fast passing into the brighter light of day. Golden rays of sunshine streamed across the intervening valleys, and the green foliage of trees, responding to the urge of spring, swayed lightly in the morning breeze. Jim and the stranger rose simultaneously to their feet.

"Give her a chance, old man," said Jim, as he extended his hand to say goodbye. "Tell her the whole affair, then don't worry about the girl."

"I'll do it," said the stranger; "I'll take you at your word. She shall know all." He hesitated a second. "But Katherine is such an unsuspecting creature ; so trusting and expectant." He was meditative. "It will be hard to disappoint Katherine Norris."

Jim was sure he saw a flash of lightning, and he could feel the thunder in his very soul. His hands fell limp by his sides, and for a moment it semecl to him that the sun was going down instead of up. As a matter of fact, he thought it had set. The stranger walked away. Jim sauntered wildly, blindly toward the edge of the steep mountain. For a moment it seemed he would go over. He never saw anything that looked more inviting than the deep valley below. But he didn't jump. "Darn her," he said audibly, and as he strode off clown the mountain he lit a cigarette and began puffing it vigorously.

Off in the secluclecl recesses of the mountain side a typical native peered with wide eyes clown the valley.

"Say, Mammay," he called to the old woman near by. "Thar comes that railroad you been heered tell about lately. Don't you see the smoke puffing from 'at steam engin' down in the valley?"

JUDSON EVANS, JR.

Nobody ever really knew whether Ione's hair was naturally that color or was henna dyed. At the country club in the city she was staying over during spring holidays, the ladies of the sideline battalion cast a unanimous ballot in favor of the henna, but Don Warner, looking the field over, was more interested in the great, big blue eyes than anything he had seen since the last lucky 75 on a mathematics exam.

When a girl has been cooped up in a seminary for several months, she should naturally have a less jaded countenance on a dance floor than the all-year-round flappers who never miss a struggle as long as there is a saxophone left to moan out the sad refrain of "Sittin' on the inside -lookin' at the outside -waitin' for the evening mail." Hence Don smiled a somewhat cynical smile when he heard the tender inuendoes about the brevity of Ione's dress.

It is not to be presumed that Donald was susceptible to every drooping eyelash that went merrily swishing near his cheek. He frequently took thought on the classic motto: Be dumb, little girl, and let who will be clever," and among the flappers exercised the caution which comes from shattered romances. Ione's hair was bobbed and shingled up the back and her soft brown eyes sparkled, somewhat differently, Don admitted.

Her "you know I adore to dance with you -you're the smoothest dancer on the floor. Maybe it 's 'cause you're tall, etc.," sounded like syndicated material, but somehow he felt that Nemesis had stacked the cards on him by failing to allow them to meet before intermission. One never can do well in a race unless he starts from scratch was the reflection.

Don was sadly replacing his scarf in the cloak room, following that last dance to a jazz arrangement of Tosti's "Goodbye" and the fragrance of one of Coty's famous concoctions, which bobbed-

haired damsels place behind their ears for one reason or another, lingered on his coat lapels. Yes, it was tough break in the gamenot meeting Ione before.

"Hello," called a so£t Southern voice to the unsuspecting young man. "It looks like my date has passed me up. Isn't that tragic? But you'll take me home, won't you?"

Ione was looking around just outside the dressing room and incidentally applying the final touches of dorine and lip rouge. Don felt hope returning. Stock in life took a jump.

"Dearheart, I won't do anything but take you home if I can shake yon elusive shiek, who must be seeking you. He's sure to find you and blast my hopes, but say, how about tearing down the main drag tomorrow afternoon and indulging in a 'dope' at N unnally's soft drink emporium?"

"You waste no time, do you, old dear? But since you're so masterful and all that, why I suppose I'll have to come down at 3 :30. Oh! There he comes. I enjoyed dancing with you, oh, just lots. Don't forget tomorrow. Bye-" II

In many cities there is one drug store which is distinguished as the headquarters for the "cake eater" and "N unnally's cowboy" species ever on the alert for the passing flaps. Don did not linger long in front of Nunnally's before - he was cheered by the sight of Ione, clad in a new spring suit and the usual accoutrements. The other curbstone cooties backed up and cast critical eyes over the damsel and a questioning glance at Don. After the formality of greeting and apology for being late they parked at one of the glass covered tables.

"Who are all those cookie nibblers out front?"

"Oh, they're some of the leading citizens recuperating from arduous studies at college."

"Poor dears, they remind me of the good old song." She sings very softly:

"He's a curbstone cootie - Mama's pride and beautyThey call him 'Jelly Bean'; He parts his hair in the middle, and plasters it down And rolls his jelly roll until his sweetie is found. Now the girls don't deny itHe's simply a riot-you know what I mean! He doesn't care for Bevo, beer or wineHe has to have his ice-cream soda all the _time, For he's a curbstone cootie, Mama's pride and beauty, They call him 'Jelly Bean.' "

She smiled one of those enigmatic smiles which have interested me since a certain tragic incident in a very famous apple orchard.

"That's good, dear heart, and I notice that you speak with the soft Alabama tones and I was all prepared for a Pennsylvania gold digger masquerading as a mountain wildflower come to gladden hearts in the forlorn and backward Southland. Where are you from?"

"\,Vell, if you demand history. I live in Mississippi-on the Gulf. And I mean on it. Why, at night the moon comes up over the water and shines right up Beach Street into my house. You just ought to see it!"

For some reason Donald thrilled to this and responded: "Say no more, my soul's joy. You're the true Ione."

"I ain't nobody else but Ione!"

They had intended, of course, going to the movies to watch Rodolph shiek the women for a few rounds, for ordinarily there is little else to do. But somehow, for reasons which he did not formulate in detail, Don was seized with the orthodox mad desire to do something different.

"Can't we think of something besides a movie? Is there no yearning to rise above the rabble? Ione, can't I find something of the Carol Endicott urge on our Main Street? Isn't there something-"

"Oh, there are lots of things and places for little boys like you, but you see we have rules at our school and I'm one of those conscientious girls -you know, student committee persuasion - and I couldn't think of breaking a rule. It hurts my conscience somethin' terrible and I know that you wouldn't have a little girl forget all she has heard about the ideal of service and lose her moral ascendency and all that sort of thing? You couldn't bear to do that, now could you?"

"Who, me? Why I don't any more mind than if you were one of those terrible girls who play around and just don't even care about rules - you know one of the 'I couldn't help it' girls."

"Oh, well, if I were that kind of girl, where could we go. That is, what could we do?"

"Ah! Something desperate! Something wild, like the Gayety burlesque - unconventional, but, of course, nice. I might suggest, if you were a true soul mate, that we dash out into God's open spaces and witness the blossoming of May flowers - seek the fastnesses of nature - the wonderment of the great outdoors - dogwood blossoms, babbling brooks. In fine, that we go to walk."

"Fine line! Hold it!"

Donald was forced to go through the business of looking hurt over the implication that he was not sincere and serious and numerous other things which the situation seemed to demand.

"Woman, don't trifle with my youthful affections! That's not a line. I'm serious-minded, and don't ever toy with a seriousminded man."

"I would, fair one, that you come out of the adamantine flapper armor and forget that you've been everywhere and seen everything. If it will do any good I am willing to say 'we seem to have met before, to have known each other always, etc.,' for, I am told, that is the proper thing to say."

"\!\Thy, of course, I place you. You're Mr. Addison Sims, of Seattle. No, I'm wrong. You're my Antony and it was in Egypt that our astral selves last met. When I was Cleo did I say 'My Antony' soulfully, like that?"

"You did not! In fact, you trifled with me, as you're trifling now and caused him to lose a cattle and lots of sleep, as well as my reputation. Don't you remember? I said, 'I have done my military work ill-I have clone this thing-well! I have stabbed myself! I am dying, Egypt! Dying-"

"Oh, Charmian, trot out the aspics. I fain would d ie!''

Pansies bloom early and beautifully in Hollywood Cemetery -in a certain historic city, and as they walked along Ione and Don realized that it was spring outside, that the world was beautiful .and that birds were singing. It has been recorded how such realizations cause unrest in the soul.

It was one of those afternoon when thoughts of Indian summer, .and visions of nymphs rally 'round a fountain nestled in flowers, flood the mind. Sweet thoughts of twilight entered Don's mind. World weary rouge that he was. He was weakening. Perhaps. ,after all, there were damsels sweet and understanding who could dispel that "utter agony of empty arms."

In a cemetery the tendency is to pause and ponder. But since the faint perfume was wafted from the henna bobbed locks it is no wonder that, philosopher though he was, Don kissed her lightly upon the right cheek approximately seven-eighths of an inch from the corner of a Cupid's bow mouth. He forget to be a sophisticate.

"Again it is appropriate to say, My Antony, that you waste no time."

"That's a fine sort of a come-back! Just when I was thinking that you were the true Etarre the ageless, and wondering just what it was Paris said to Helen on such occasions, why you step down out of the mist of romance and say what a fine man Menelaus was - or almost that. Have you no dreams?"

As strange as it may seem, the transition from the flapper to an exponent of the late Regina Victoria is slight. Somebody had touched that spark of imagination in Ione which caused the tiniest •o f tears to roll down a little powder lane.

"Oh, I'm so sorry. I thought you wanted me to be hard 'n' modern and everything. You don't know how I want to hear you say those dreamy things that little girls love. I've been so disappointed in things and I didn't want ever to show it. You'll think I'm awfully dumb by being silly like this, but I can't help it. I thought you were just hard and clever and you're nice and imaginative. It is so pretty here with all the flowers and I feel like a lonely little girl and want to cry on your shoulder."

It was Nietzche who said: "That which, in spite of fear, excites one's sympathy for the dangerous and beautiful cat, 'woman,' is that she seems more afflicted, more vulnerable, more necessitous of love and more condemned to disillusionment than any other creature."

The strongest man had his Delilah and "the wisest man amang them a', he dearly loved the lassies, O." It is not recorded what was said or sung unto Samson's ear, but Don \,\Tarner heard the tragic story of Bessie, who "like all good girls now Bessie just had to fall. And that ain't all, 'cause Bessie couldn't help it -any more than you or I could."

"\,Von't you let me be your little dream girl so that I can come to you and tell you what a darling boy you are?" A few moments before that would never have happened, but the only certain thing in life and in cemeteries is that you never can tell about such matters.

"You've been quite the nicest boy I ever saw and I don't feel a Lit world weary. Because I'll never see you again -and because you seem to know anyway -I'll tell you that secretely in my heart of hearts I still hope to meet Prince Charming. And he'll look like you! But don't you ever say I said so, for I'll frost up and deny it as being sickly sentimentality unworthy of a modern woman in search of a career. And you know what our parents might say."

"Oh, they'd tell us a story about Little Rollo in the good old days. We have one consolation, these will be the 'good old days' a few years from now."

"Here we are in an unconventional place -almost happy in thinking that we were made for each other and we may be in love. At any rate you're the sweetest girl I ever saw and I wish I could park here on this bench until Venus rises to blink down at us. Thank the Lord there are no old women anxious to insert a little scandal into our rather funereal setting."

"It is the darlingest place and I adore to be with you."

By the tones of their voices shall ye know them -the grating, rasping of those unfortunates who are never good for being righteous:

"You ought to be ashamed! Right here on the public highway! I'll hev you t' know this is a respectable neighborhood. We don't allow none o' that lyin' around here in that young feller's arms!

\i\Thy don't you say something?"

Poor old soul! Perhaps if you worked all day in a hosiery mill you could not know Pan if he played on his pipes all day and tossed rose petals to the ground.

"Why don't you say something?"

Don had hurtled back from Olympus and he did say something. He said: "Oh, hell !" -inelegant, but expressive.

Ione of the henna bob tossed her head, applied a Dorine and was back to civilization.

"Ugh," she shuddered, "imagine being old and ugly!"

And as they strolled down the driveway, defying Mrs. Grundy as her rasping voice was drowned by the crickets, as they tuned their orchestra and played for youth and flowers and the month of May.

I could not keep the things I saw; They said they were not niine; The beauty of the twilight scene, The morning's glow divine.

They said I had no right to talie

The poet's golden words; The ·woven whispers of the ·winds; The love songs of the birds.

They said I had no right to drink From the fountain of your eyes

The greatest gift the whole world gives; The love that never dies.

But others could not take from me

The power to take all these Safe with me wheresoever I go; They are my memories.

-J. W. C.

HELEN McCONNELL, '26

The wind groaned and howled on the rugged mountain top. It came rushing up the north side, gaining in fury, until it reached Squire Bayer's rambling farmhouse on the highest level, spent it s strength on the old place, and then contented, slowly died as it descended to the little homes hidden in the deep valleys below. The usual smoky-white fog which arises in the West Virginia hills at nightfall was dispelled by its mighty gusts into deep shadowy hollows and inaccessible nooks. The sky gave evidence of the continuous blow, as low heavy clouds, sinister black bodies, passing swiftly over it, now concealed entirely, now revealed, a vague blurred moon. On the morrow in its wake the wind would leave overturned chicken coops, unhinged barn doors, and a scattering of all objects which happened to have been in its widespread path. As no one seemed to show his appreciation of its strong blasts by venturing forth, it tried to get into the creaking old farmhouse, an uninvited, a disturbingly unwelcome guest. It pounded on Squire Bayer's heavy brown doors, threatened the shivering panes with a shattering destruction, attempted to raise on high the low roof, and came down the spacious chimney carrying a swirling volume of soot with it, and blowing the fire in wild fantastic flames.

Before this fire, the lamplight making his friendly face ruddier than ever, sat ' Squire Bayer. Every few seconds he shook his large head and scraped his contented feet on the fender in mild repro val of a too extravagant item in The Rickerville Herald. As a result of his more vigorous nods, his gold-rimmed spectacles fell , from time to time, to his expansive lap. After each of their mishaps he replaced them very ruminatively on his nose, turned his gaze to the steady old clock over the mantel, then successively to all of the objects around the dimly lighted walls of the room until his gaze rested on his wife Josie. Josie presented the appearance of the wife of a prosperous farmer and justice of the peace.

She was a stout, comfortable-looking figure setting in her dee p arm chair. Accompanying the rhythmically moving rockers of h er chair could be heard the habitual squeak of two dry floor board s. She nodded and started there by the fire, in accordance with th e mood of the wind outside.

Suddenly and simultaneously with a renewed onrush of th e wind a pounding on the door was heard.

"What might that be, Jim?" asked Josie, starting from a pleasant dream.

Old Squire Bayer put clown The Rickerville Herald, slowl y removed his spectacles, and walked with a heavy tread to the sturd y oak door. When unbolted, it flew back like a released trap. Th e wind rushed in and rattled the dried palm leaves stuck over a picture of three hallowed saints. On the doorstep stood a neig hbor, Sam Kern, who lived clown the mountain towards Jerry 's Run . The broad brim of his slouch hat was beating against his neck and face, and his coat was pulled close around his throa t. But at his side stood a shivering half-clothed figure, a boy of abo ut fifteen, who kept edging closer and closer to the friendly lig ht within.

"Wal, what be you adoin' up hyar , neigh bor, at sech a infern al hour?" said the Squire. "\i\Talk in , walk in . And who's the lad ye got with ye; be he one of the mountain bo y s?"

"Speak up, boy," said Sam Kern, looking like a wise ow l. "T ell him every thing ye told me. But, hyar , Squire, maybe y e'd be tte r warm his innards with a little vittels , and maybe ye'd bett er put him close to that thar fire. Might help to loosen his tongu e. I'll be a-tellin' ye what I know. Wal, I was a-comin' from a fea st down to John Graver's when I run into that thar lad. I was awhistlin' and watchin' the moon runnin' behind the clouds, wh en I seen him just a-flyin' down by Dry Crick. I begun a-yellin' at him, but he run the faster. I finally cot up with 'im. He wa s a-shakin' like them ash trees by the crick. I says, 'Boy, what th e h-are ye a runnin' from?' " Here Sam Kern stopped and turne d to the boy and said, "Boy, git up hyar and tell 'em what ye hav e

been through this night. By jimmy, there's a-goin' to be a-hangin' 'fore daybreak."

"Wait, Sam," said Josie . "The poor lad ain't had his fill yet, and he ain't warm." The truth was the boy couldn't eat and couldn't get warm.

" 1Nhat ye mean by a hangin' , Sam," said the Squire, knocking his corn cob pipe on the fenders.

"I mean that I - we mountain fellows - is a-goin' to hang old Martin Bracker 'fore this hyar night's past. I been a-tellin' ye he was the devil, I been a-tellin' ye. Why he looks like the old boy. Them wrinkles ain't thar on his mug fer nuthin'. They're streaks of the devil in the honery cuss, and"-

"Stop screaming, Sam, we ain't dee£. That old man, he ain't done nobody harm. Don't ye be a listenin' to folks roundabouts," interrupted the Squire.

"Plague take the old cuss. I say he ain't nuthin' but the devil. What about that thar hair on his head? Don't it grow in two stiff tufts like the devil's horns? Ain't it so, boy?" This to the boy by the fire.

"Wait a minute, now, Sam," said the Squire. "Ye can't be a-hangin' the old man fer his looks, ye know."

"Huh!"

"Just 'cause old Martin outbid ye on them heifers, don't ye be a-holdin' a grudge a'gin' him."

"Me a-holdin' a grudge fer that, huh! Ask the boys 'round hyar did I have to give 'em up 'less I wanted. Huh! He could have 'em. They ain't no good no how. And whar's that kidnapped boy he used to have down yonder a drudgin' fer him?"

"Be ye a-talkin' about his adopted boy? Why, he went to that thar oil State, Texas," said the Squire.

"Yes, he did. Ask this hyar boy. Hurry up, boy, and get your tongue loosened. Y e'll hear a plenty tonight. How about them thar screams the folks 'round hyar have been a-hearin'screams of that murdered boy? I tell ye, the Mills boys heered

'em one night and one of them very boys broke his leg the next day. Fell out of an apple tree."

"Must have been a-stealin' ap--"

"What? And this hyar boy seen , he seen -come on, boy , tell h im what ye seen this night. There'll be a-hangin'."

"Yes, sir, yes, sir. I'll begin from the first. I live down to R ickerville , and some of the fellers down that away said they bet I wouldn't come home with old Martin and spend the night. The y called me 'skeered cat, skeered cat, skeered cat , af eered of old Martin , poor old toothless Martin Bracker; ye can't be a revenue officer ' cause ye're a-skeered to go with him! Go home and git your sister's apron, skeered cat!' "

"Wal, git along, boy," said Sam.

"S o, when I seen old Martin a-comin' out of Ricker's Supply Company, I says, 'Mr. Bracker, kin I ride home with ye and spend tonight with ye?' He let me, and I got on his three-legged mule with him, and we come up the mountain road to his place on the southside. Wal, come supper time, we all set down and begun eatin' stale biscuits and cold beets. After supper him and his wife set down aside the fire; he lit his black pipe, and I saw him a-mutterin' ' tween his old snags. I couldn't hyar nuthin', though. "

" U h -huh , a mutterin' evil charms 'tween his old snags ," broke in Sam.

"Bish up, Sam," said the Squire "Let the boy git on."

"Wal, in a spell he says, 'Boy, go up to the loft. Thar's a soft bed up thar for ye and in the mornin' I'll wake ye and take ye back to town.' "

"Boy, ye'd never opened them eyes ag'in' if-" began Sam.

"So I dumb the ladder to the loft and dumb in a feather bed 'bout as high as this hyar desk top.''

"Wonder them feathers didn't smother ye. I'll git the boy s and we'll hang him 'fore day, and-"

"Wal, I went to sleep. I wasn't afeered and I thought I' d laugh at the fellers down to Riverville, but-" Here the boy choked.

"Go on, go on," yelled Sam.

"I don't know what time hit was, but all of a sudden I woke up, and I felt like I'd a-been havin' a night mare. It seemed like I was a-dreamin' that I was the kidnapped boy, and I was a-feelin' old Martin's hands a clutchin' fer my throat, and I felt the blood a-gurglin' in my throat like I was a-chokin'. I was about to puH the covers over my head when I heered a scream, like the one I had tried to make when old Martin was a-grabbin' at my throat in the dream. I jumped under the covers. I know now 'twas the murdered boy and he must a-been choken by old Martin. He ain't went to no Texas. He's murdered, I tell ye. I counted them screams, and they was about nine or ten of 'em."

"Ain't I told ye, Squire! Ain't all the boys been a-tellin' ye!" burst in Sam. "It's the murdered boy. Gone to Texas, huh! Ain't the Mills boys, ain't old man Ball, ain't Maria Kittege heared them screams afore! It's the murdered boy! We'll hang that old devil, Martin Bracker afore tomorrer."

"Calm down, Sam. Let's git on with the story," said the Squire, a little disturbed by his neighbor's vehemence.

The boy began once again. "After them screams I lay there a-shakin'. I felt my blood all a-runnin' in different directions and a-bumpin' into itself. My heart begun a-poundin' like the blacksmith's hammer down to RickerviIIe. It was about to explode. I stuck my head under the covers; I thought I was asmotherin' in them feathers. In a spell I set up in that old bed. I seen all sorts of black spirits a-jumpin' around that room. I stuck one foot on them splintery floor boards. I seen out the loft window that thar was an old drain pipe down the side of the window. I was a-crossin' to git down it, when by h-! the devil stopped me. He was a-goin' to git me, I tell ye, he was a-goin' to git me."

"Stop your shivering an' a-screamin', lad," broke in the old Squire. "Here, Sam, let's push his couch closer to the fire."

"He was a-goin' to git me. I run and jumped in that smothering bed and I thought I'd die. Oh, my God! He was a-goin• to git me, I tell ye. That old shack was a rumbling. Somewhar down stairs I heard old Martin a-yellin'. I cakerlate he was a-

talkin' to the devil. I couldn't move, I tried to git up, I wanted to run, but my legs had a ton on top of 'em! I couldn't move! I could feel the sweat a-oozin' out of me like, Oh, my God, likeand my strength was a-goin' with it! I was smothered in the feathers of that bed! But that ain't all!"

"Do ye hear the boy, Squire?" broke in Sam. "Git on, lad."

"Ye know that old devil had a closet up thar in that loft. I seen it afore I went to bed, but I didn't look inside of it. Suddenly I heared the door creak and it flew ' open. I noticed fe r the first time that the wind was a-blowin'. In that thar black hole a pit of black hell, was - was - "

"Was what, boy?" said the old Squire in a low voice.

"Was the devil's fiery hand. It was a-goin' to git me. It was a-pointin' at me, I tell ye. I seen it. It was curved; it wa s ready to catch me, choke me, and burn me with its fire! As I looked at them greedy fingers I felt a burnin' on my throat. I could feel them fiery fingers on it. It got dry from the searin ' heat of 'em. My mouth opened to keep me from chokin' M y tongue fell from the roof of my mouth, where it had been aclingin' for hours. My head jerked, my eyes got cemented in one spot. They couldn't move, I tell ye. They kept a starin' at that horrible flamin' hand of death, that I could feel on my throat. My legs become stiff and straight like they was broke. I wa s a-tryin' not to drown in them smotherin' feathers, and all th e time I was a-watchin' the devil's hand in that black hole. It s heat was a touchin' my throat! It was a-comin' ! The wind blew ; I heered it like a deaf man whose ears have been opened. Th e door of the closet slammed. That hand was out of sight, and then , thank God, the strength come back to my dumb limbs and head . I jumped out of that thar infernal hollow I'd worn in that bed , run to the window, slid down that pipe, and-"

The boy fell over on the old couch, on which he had been sitting. Ready Josie - she had raised ten children - heated him .some warm milk on the hearth fire and poured it down hi s clenched teeth. From exhaustion he fell into a deep sleep. Sam jumped up and clapped his hands.

"You see, Squire, we've got to git old Martin. Come on, git your lantern. We'll git all the boys 'round hyar and go after old Martin. We'll hang him to that thar old shady walnut tree outside his shack. It's crooked and dark like him. Come on, here! I'll get my coat. Pull on yours and let's hurry. It's a-comin' to twelve o'clock and we'll hang him 'fore mornin'. Why don't you move? Ain't you a-goin', Squire?"

The Squire looked at Sam and replied with infuriating serenity. "Calm down, Sam, ye don't want to make a mistake. I tell ye something's wrong. The old man ain't got the devil's power; no mortal bein' is. He ain't harmful. Let's wait till mornin' to go down yonder. Ain't no use a-skeering the old man's wits out of 'im. Ef yo~ git the crowd outi ye'll do something ye'll regret."

"What's the matter, Squire? You ain't afeered? I'm not af eered. I'll go. I'll go, ef I have to go and hang him myself! I ain't afeered of man or devil even ef ye are."

"Wal, keep calm, keep calm. Ef ye must go down yonder tonight I'll go along, that is ef just us two goes. I figger we can do it all, at least all that is to be done down yonder. Ain't no use takin' the whole confounded universe agin one poor old man. Let's be on our way."

"Oh no, Squire, oh no. I'll git the boys. It's better. I ain't afeered, ye know, but it's safer, and it would seem more lawful and just to let all the fellows in on it. They'd hold a big grudge agin me ef I didn't invite 'em to old Martin's hangin'."

Old Squire Bayer put on his coat and slouch hit, buckled his hob-nail boots, and after filling two lanterns, started towards the door in silence. But before leaving he whispered a few words to Josie, who was watching the now peacefully sleeping boy on the couch.

"Take keer of the boy, Josie. Somethin' unnatural has skeered him, I calculate. Guess ·I'll have to go along with this hyar fool, seein' as he aims to git all his gang together. Maybe I kin keep 'em from harmin' old man Bracker, the pack of dirty hounds."

The Squire and Sam labored along the water-broken roads of the mountain, the one in angry silence, the other in a mad glee. Occasionally they put their lanterns down to pull their coats,

which slashed their legs, closer, and to brace themselves against th e fierce onrush of the wind. Over open spaces, through woode d valleys, they made a complete circuit of the mountain top until they had gathered about twenty men , some of whom were mere boys, some fathers, and some grandfathers. This procedure took about one hour. The whole group with the exception of the old Squire were wildly indicating their coming action s against old Martin. Some of them had their blunder buses, "ready to dro p the old man dead in his tracks if he tried any of his devil's tricks ." They were an unruly group of sturdy, suspicious mountaineer s whose cunning in matters of agriculture and cattle raising didn 't extend to things which aroused their superstition. The talking s of the folks round about, the tales about old Martin , and finall y the episode of the night had stirred up their childish, barbarou s minds to a cry for the blood of the old man. The Squire persistently entreated them to turn back until they should think bette r, but in vain. They cried, "Afeered, afeered, the Squire's afeered , the Justice of the Peace is afeered; let's call a new election, boys. Old Squire Bayers af eered !" The Squire did not notice thei r taunts, but with angry steps followed the childishly gleeful crowd . When they came in view of the shack of old Martin, the march lost some of its alacrity due to each member's premeditated slowing down, "so as to talk to one of the fellers towards the rear. " When they saw the thick walnut tree as black as a stagnant tarn on a cloudy night, they remembered one of the stock tales. Under this very tree the blazing hand of the devil had been seen. But courage rose ·with the thought of their numbers, and 'one membe r suggested that they knock the door down. The Squire protested , entreated and threatened in vain.

"All together, boys," someone cried, and the old door vainly . threatened for years by mountain winds ; fell at tJ-ie onrush o f twenty bulky mountaineers. They rushed in pell-mell, inflamed with their success at the door, and snatched old Martin out of bed. The old man, shivering and shaking in the cold wind which came through the barrierless entrance, jumped up and down in his excitement, anger and perplexity, accompanied by the loud guffaws of the mountaineers.

"Show us the devil's hand," cried one. "Show us the devil's hand," reiterated the others. "Come on, ye'il go up to that thar closet in that thar loft, and ye'll show us, you devil. Come on h b h . " yar, men ; gra 1m.

At this moment the Squire advanced and attempted to explain to the old man the cause of the visit of the crowd. The old man opened his mouth in amazement "Screams, devil's rumbling, devil's hand, did I heer ye right, stranger?" said old Martin, stupefaction written in every feature of his face, even to his wrinkles.

Again the crowd yelled, "Show us the hand, old devil; ye murdered the boy. Now call up the devil. We'll git ye and him, too, and ·we're a-goin' to hang ye on your old tree yonder. Ye'll be a-chokin' soon like the murdered boy. And with this hard blow tonight ye'll rear in all directions like a weather wane."