C0 "' 'Cb

University of Richmond

poetry and prose

Twilight KMen EbeJr.t

Summertide KMen EbeJr.t Unlv-:rsil'/•·,Rlchmoif~ .

Al ice in Wal lyland (an essay) TamaJtaS:tan1-ey

Bad Scene Chw CleMy

Untitled, Ward of Whom? AU,,u.,onBlake

In Nirvana, The 11 Successful 11 AU,,u.,onBlake

It Was May, Wired TamaAaStan1-ey

Genesis John Light crystal] ine images Amy ViWUQh

An End to Something (a short story) Je66 BeAgen

Tribute Amy VietJuQh

Cloudb .urst GnaQeM. ViUbeJr.to a wor l d wi thou t Gneg Hudoon

Close to Home SU6an SQhonbeAgen

Reflections on Mothers Chenyl R. Gibby

Oceanic Lifecycles Sue SwaVL6on

As She Spoke MMk Simenfy

Journal Entry Sue SwaVL6on

Violet Golden A.W. Payne

For Ginger Vaniille Ru.th PanteA

For James Vaniille Ru.th PanteA

I'm No Dummy, I Just Deliver (an essay) Julia G. ZimmeAman

Ode No. 3 Randy KeMhneA

Havens (a short story) Cnaig Bnown

Notes on Contributors

art and photography

Edith Clay Camp "Eiff and Shini"

Julia G. Zimmerman

Ercle Herbert

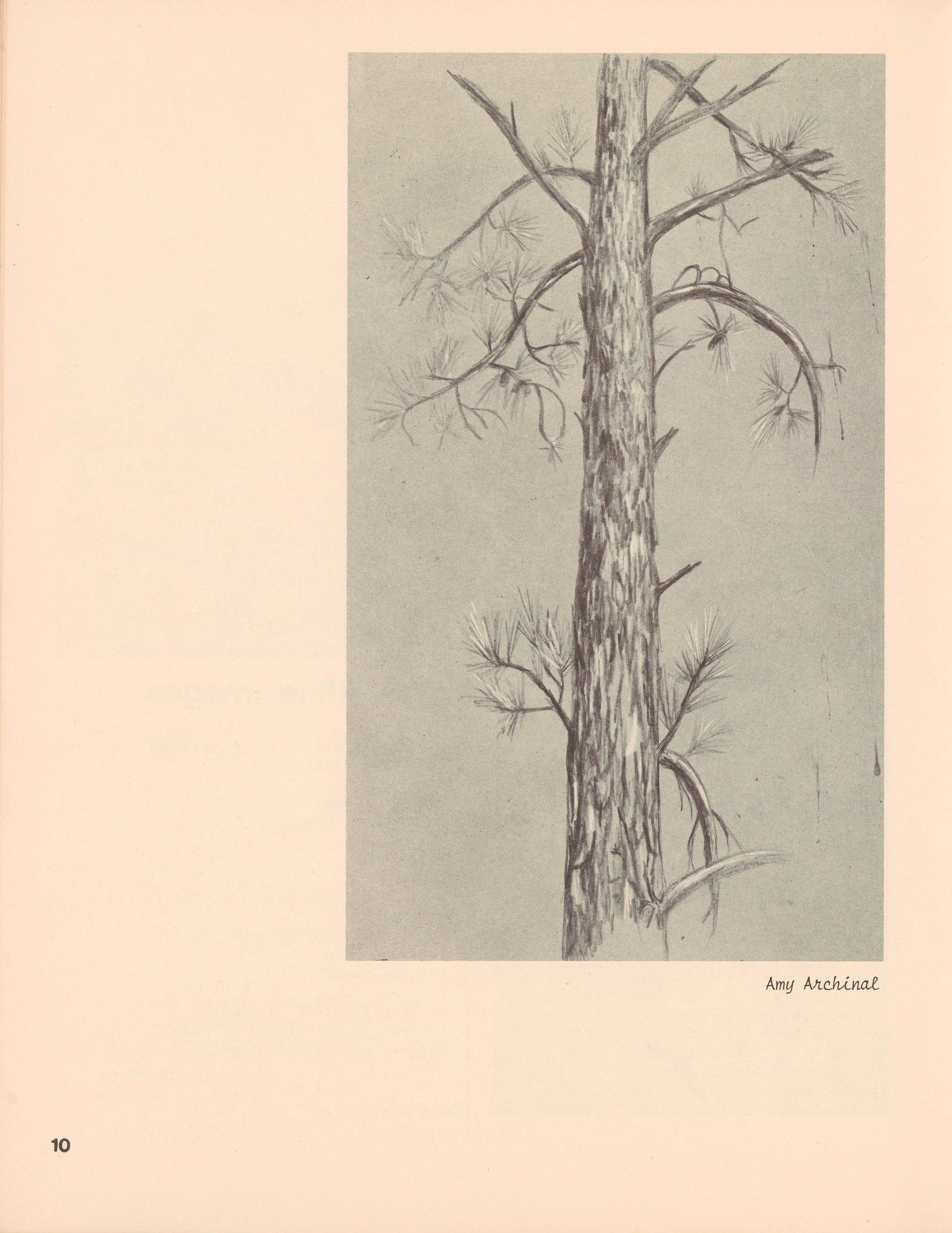

Amy Archinal

Konrad Berk

Celia Naranjo "NMWJ.>U6"

Pete Warren

S. W. Crowe 11 "Young Gazudingl.>"

Amy Archinal

Julia G. Zimmerman

Gwenny So "The Moon Lady"

Amy Archinal

Jan Griffin

Demetrios Mavroudis

Twilight

Twilight approaches stealthily as he 1 ingers on Horizons of untravelled passages, suspended Upon fragile, timeless threads.

Strength wanes from his frail body as the sea recedes Darkness draws near, cold and silent; swirling, Lucid forms drift before him now, and Children spinning round in glee Are woven in the tapestry.

He conjures days of youth, sunlit

Animated figures entwining yarns from the past

Long obscured by time, yet now

Starkly arrayed on veined 1 ids.

Gauzy figments weave through his mind's hollows ...

Green echoes of laughter, fireflies dotting balmy Nights 1 ike tiny sparks, and her in white Summer cotton, a silhouette against the blazing sunset ..•

Shadows lengthen outside the cottage

Recalling previous afternoons of deeply gathering dusk--though Not these opaque blues--they had been Liquid amber then.

The curtains drawn, winter's hour nears

Evening passages.

Crimson fire engulfs his soul, gnarled

Hands contract

Anticipating,

Fear dissolving, dissipating.

Whirling fog enshrouds, disguising thresholds

Infinitely drifting

Deeper, cascading

Black and white converge.

Sea spray, velvet ashes, misty mornings

Fade to pallid gray eternally

Flowing silent streams,

Naked reflections unravelled into

The final act, Ni ghtfa 11.

Ka1te.nEbe.Jt;t

Summertide

Honeysuckle vines

Languidly trail perfumed nectar, Heady elixir courses through Entangled veins; Your presence ebbs and flows As the tide, waves of Sultry summer heat envelop in Primal rapture. Silently you came, Relentlessly, as those first Heated days of the season.

Ka1te.11Ebvz;t

Alice in Wallyland

It is tough to live as a writer, a worker of words, in a land that adores manipulating numbers. By walking around with a Notion Anthology, I demand misunderstanding. For instance, I have noticed that I have the sadistic habit of letting my companions read my work. I practically beg them to abandon their Macroeconomics for a moment and read my words. Why? Either I am sure that my stuff will benefit them greatly, hence to forego the opportunity would be 1 ike slapping Confucius in the face, or I am attempting to prove that while they are creating monetary empires, I am not just scribbling in a corner. Yes, while they sweat over their calculators, I labor over the right verb.

But the most interesting study unfolds when the actual act is performed, the reading of my writing. It begins with the victims physically scanning my work. For a moment they feign awe, then say (much too loudly), "This is good. 11

Once realizing how banal that sounded, they say (much too softly), 11 1 don 1 t really understand line five or the fourth comma.11 I think they say this for two reasons: one, to prove they actually did read it and two, to estab1 ish the fact that they are liberal when faced with the arts.

I can hear them now, 11 So why not humor the kid and her typewriter? 11 or, 11 lt takes all kinds, snicker, snicker. 11 Well, anyway, I try to satisfy their dubious appetites for understanding with an explanation. But a moment after I say, 11Th is means that ... , 11 I stop and blurt out much too harshly, 11 lt can mean whatever you want it to mean. There is no Right Answer. 11 I notice a brief twinkle in their eyes, as if they found out they really don 1 t need an eraser. However, instead of exhilaration, they feel tricked and turn back to words that contain no mystery and many wrong answers.

Ta.ma.JutStanle.y

Bad Scene a poetic jest in three parts

Indignon quidquam nepnehendi, non ql.,l,,UlCJl.M~e CompMUwnill.epideve pu.tetwr., ~ed ql.,l,,Ulnupen. --Horace, AM PoWQa 76-77

Ciaou!

--Ernest Hemingway

I •Gathering Storm

Victorian scalpels driven snickersnack among our forest: Thinning out, throwing out, wasting out. Christian thimble. Fernsehen short-sighted idolater. Thou bespeaketh thy bespeech to all, Do you not, machete man, From your high tower, Usurping your power?

I saw them leave chrome brackets in the street. Smash. Ah. We knew what it was. It was one of us, the car towed away backwards, A lifeless body with arms passing last. His throat was cut by polyester halos-Sweeney Todd among the nightingales-The snakey blade slithering midst the druids, We who make artful pottery from the clay of love, We who have sailed the world, beheld its wonders. There is no place 1 ike Eden.

11.Armageddon

Invaded? What? must have been sleeping! They have cleared our homeland for their condominiums of narrowness. Welcome, Dr. Johnson. Hope you have a nice stay.

My face drops off. Can stand ... no longer ..• 0, the holly! the holly! This life no longer jolly!

Ill. Elegy

My fellow bards, our reservation of wooded lands is gone, Acquired by Rev. Chivington.

Whiskey-lover Tim Finnegan, bereft of spirits, forever dead. We no longer rejoice. Metaphysicality grounded. We are done. Walden drained. It was a thorough job.

And what say those halo men? T.S.

It is a bad scene. A bummer for the druids, mean.

Edi;th Clay Camp Ch!u-6 Cle.My

Four Poems

Legs, belly, bikini

Bare bone s 1 i m

Diet starving spa aerobics

Anorexic social skeletons (or cultural corpses?)

Ward of Whom?

He looked like he was sitting, But he had no choice Because he had no legs.

A fat skateboard supported him. He moved from time to time so he Could keep his mangy coat from under its wheels.

His eyes rolled, and he rubbed his sandpaper chin. "Buy comb!" he shouted. "Buy comb!" He raised his black-toothed offerings. ''Buy comb! 11

He existed as his own family.

The Media called him a 11 streetperson."1 1

The Government told him to get a job.

So he sold combs.

Nickels gathered in a nearby can: a sacrament to his efforts. At night he wheeled his skateboard to a nearby poolroom.

Those were his days. "Buy comb, 11 his vocabulary.

The Media called him a 11streetperson. 11 The Government told him to get a job.

In Nirvana

Tangible serenity

Lounging in the sun

Blissfully aware Of an adored presence.

Realizing that fantasies Do not have to be And love is real

Safely within the extraneous particles Of everyday life That were an initial attraction, Still noticed, still alluring, But not the core.

The «success·ful»

Busy, busy performances Actors With no Soul

Financially sneering From the heights of spiritual emptiness And basic ignorance.

Their hollow mastery of form Part of a shallow image And a mockery of Art.

Vanished, in a millenium, Expelled from th~ universe Except, perhaps, for a pathetic re i nca rnat ion.

Al-U..l, on. Bla.k.e.

It was May

It was May and yes finally you wanted me-porchlight fumble of the keys then waves blended the colors flesh algae blue remember the fridge hum on denim pants sandals dangling on New England decor white ceiling and hair ribbons you smiled cascading to the carpet. I kept looking around to get it right: next to the coffee table Your gold necklace arms around my waist. Your mouth was a fern I wanted to touch but even in the dream everytime I came to the place that was you changed to air and I whispered Adam.

TamaJta.S.tan£e,y

Wired

It's been coming on for a long time; my clock blinks 5.184.000.000 minutes-starting with batteries to waddle my duck and never stops ... fluorescent suns, hi-fi roosters, pinball smiles •.. I find no recreation in this modern recreating-to plug and unplug my existence. I am drained so I get on the wire to Mr. President and ask him to buy General Electric a contraceptive so they will quit f------with my head.

Tama/taS.tan£e,y

Ju.i.ia..G. ZhnmeJmJan

Genesis

Among the lights of night and the still of truth, somewhere in the middle of the blue expanse within the realm of God and limitless perfection, a poison is sown. The first and only mistake. It clings and scrapes in its effort for 1 ife choking the good as it tramples wisdom with ignorance so crude and barbaric. Yet it hangs to the creation of itself managing to eat and suck, parasitic to all. And from the quagmire within the beauty the beast slouches and trudges to expand, to grow with strength and appetite. The deity convulses and writhes in anger caused by a fear of which none of the new, only the One could conceive. The results far too extreme. Its cry is deep: The passing of time, Growth of ignorance. Creation of conceit, mistrust and hate lust and sin pain and sadness.

John Ught

crystalline images

crystal, glass. a looking glass: a mirror. a mirror image: reflection in glass, c rys ta 1 , reflecting.

the smiles, the laughter, the tears. the tears: feel the pain, but never again feel the pain return; never

we, the crystalline images, reflect in eternity 1 s mirror. (are we worth reflection?)

Amy Vie;tJuc.h

E1td.e. He.Jtbe.Jtt

An End to Something

The boy leaned heavily against the trunk of the oak. He looked out over the salt marsh stretching from the bottom of the ridge to the distant river. A pair of black ducks warily circled a small pothole, and not 1 iking the looks of things, quickly flew towards the river and became dark specks on the horizon. Stretching his legs out on the dry leaves, the boy leaned his head back against the rough grain of the tree and gazed upward, through the bare and twisted branches at the sullen winter sky. Everything was still. The air was crisp and laden with the sweet smell of the marsh.

He was tal 1 and lanky and wore old blue jeans and worn leather hunting boots. The chamois shirt hung loosely on his muscular frame and was hurriedly rolled up at the sleeves. A grey wool watch cap restrained a bush of curly black hair which burgeoned out around his ears and neck. His features were sharp, with the exception of his eyes, soft and grey, quick, piercing, and capable of great emotion. He came here often, although not as much as he used to, to think about things Now he thought about going back to school for the second semester: the small dorm room, the hall bath and his roommate, who was from the city. He didn't really want to go back, but he knew he would. It would be hard--he used to like school, but things were different now.

The boy was disturbec by the long rasping cry of a redtail hawk soaring on stiff wings over the marsh. The bird

showed up conspicuously against the dark sky as it circled, hunting for an unwary bobwhite quail or cottontail along the perimeter of the marsh. The boy watched the hawk for a long time, and for a fleeting moment, he too was soaring, free and wild, high above the trees. Then, as suddenly as it had appeared, the hawk sailed out of sight further along the ridge. He sat for a while longer and then rose slowly and began the trek back to the house.

He walked up the slate path to the front door of the ranch-style house. The house was big and there were two cars and a pickup truck in the driveway. Smoke curled out of the rough brick chimney. It was dinner time so the boy figured his father would be home by now. He opened the door and walked down the hall to the rear of the house. His father sat in a large, leather easy chair with his feet resting on the hearth. A pipe sat rigidly between his teeth, and the evening paper rested on his lap. The man's bright blue eyes stood out against his weathered skin. His hair was thick and beginning to grey. ''Hey son.''

''Hey''

He walked over and eased himself onto the couch opposite his father.

"Where've you been? Your mother didn't know if you'd be back in time for dinner."

"Just out for a walk. I went down to the west marsh."

11 Did you see any ducks? 11

11Just a couple. I don't think thev,'ve come down yet. It hasn't been too cold. Maybe by the ti me the season ro 11s a round. 11

11I sure as he 11 hope so. I to 1d a bunch of the fellas that we'd take them opening day. I promised them we'd shoot a few. 11

The man tossed the paper onto the floor and settled deeper into the overstuffed chair. He gazed intently at his son.

11 ls there anything bothering you, Josh? 11

11No, not real ly. 11

11You don't seem yourself lately. 11

11 Real ly, everything's okay. I'm just. .. just a little tired--that's all. 11

11Have you seen Karen s i nee you I ve been home? 11

11 No, I 1ve been sort of busy. 11

The boy avoided his father's scrutiny and his eyes wandered about the room.

11You know if you need someone to ta 1k to ... 11

11Yeah, I know. I think I'm going to wash up for dinner. 11

The boy began to stand up, but the man stopped him.

11Hey, son ... 11

11Yeah. 11

Their eyes met.

11 Never mind. 11

The boy began to walk down the corridor toward the bathroom. The man leaned forward in the chair and strained his voice ...

"You had better turn in early tonight. In case you've forgotten, deer season opens tomorrow. The usual crowd is coming. I Ill wake you . 11

The boy responded without turning his head.

11Okay. 11

He disappeared down the hal 1.

The man sat pensively for a moment and drew on his pipe. He wondered what was bothering the boy. He sat for a moment longer and then continued with the front page.

That night Josh lay in bed unable to sleep. The alarm clock purred softly on the nightstand. It was pitch black and the bov thouoht he had never se e n such a dark

night. He thought about Karen and wished she were with him. He didn't know when it had started to go bad, but it had. Once it started there was nothing anyone could do--he knew that now. He remembered their last weekend at school.

They had lain in bed, her head resting heavily on his chest, her thick auburn hair lying loose and wild. She was tal 1, almost too tall, and one of her tawny legs was thrown languidly over his own. Her breath came softly, and she was warm and smelled sweet. Josh pulled her closer and she sighed contently. He had never been happier. She lifted her head and kissed him softly.

11Why don't you stay until Monday?"

11 You know I can't. 11

She looked up at him and smiled. He knew she couldn't. She had to go back to school, but he always asked jokingly and half-expectantly.

11Why not? 11

11 You know I would if I could. 11

11We1ll go up to the mountains--the leaves will be changing."

11I can I t! 11

11 1 111 get a hotel room with a double bed. 11

11Oh, shut up. 11

They laughed and she gazed up at him.

11 1 love you, you know that. 11

The boy_paused for a moment and then replied in a half-whisper.

"Yeah, but it's not good to say it too often. 11

"What did you say? 11

11 1 said it's not good to say it too often. 11

11Why not? 11

11 1 don't know. I guess as soon as yo11 start talking about something, it goes wrong. It's sort of like counting on something and not getting it. Sometimes I think things go wrong because you're so sure about how they 111 turn out. 11

11 1 know what you mean. Don't worry, I won I t 1et i t change. 11

"Yeah, all right, but let's not talk about it anyway. 11

"Sure if that's how you want it. just want you to be happy, but I love you anyway. 11

11Me too. 11

She had slept, but the boy had lain

awake thinking. He had tried to think that it would be like without her. The thought had scared him and he had decided not to think about it.

Now it was a reality. He knew it couldn't go back to being what it was. He wished now that he had told her that he l o ve d he r . I n h i s own way he had t r i e d , but she had needed more. She had needed someone to hold her hand and buy her flowers. She needed someone to stand up and yell to the whole goddamn world that they were in love. Now the loneliness grew inside him until he thought he could stand it no longer. In the dark, his eyes filled with tears.

He was awakened by a gentle nudge on his shoulder. His father stood next to the bed.

"Come on. It's time to get up. 11

The man walked softly out of the room. The boy rolled out of bed and pulled on longjohns and thick, wool hunting pants. He hated the cold of the morning. The clock next to the bed read five o'clock.

Josh walked out of his room, past the bedrooms of his brothers and mother and sister. He tried to be quiet and carried his boots so as not to make too much noise. Before he reached the kitchen, he could smell the coffee. His father already had breakfast waiting, and the boy ate hungrily.

"Hurry up, there's already some people down at the barn. 11

The boy wolfed down his food and then hurriedly laced his boots. The man slipped into a heavy down parka that had been hanging on a peg by the back door. The boy donned a down vest. He flicked off the kitchen light, and the two opened the door and stepped outside. The freezing air was a shock. It was a clear night, and the sky was full of stars. They strode down the hill behind the house towards the old barn. The boy suddenly remembered,

11 Did you put the guns in the truck?"

The man responded with a nod. Already there were six mud-splattered pickups in front of the barn. A dozen men ' stood patiently against the trucks, talking in low voices with their hands crammed into the pockets of their hunting

coats to ward off the bitter cold.

11 How are you boys doing?" His father's voice boomed. They walked up to the group and shook hands with everyone. There were a bunch of doctor friends of his father and several others Josh didn't recognize. Jack Davidson, who lived on the next farm over, walked up and slapped Josh on the back. The boy responded with a fleeting smile and a quick handshake.

11 How I re yo u do i n g , Jo s h ? 11

"Okay and yourself?"

11 1 can't complain. We had a good crop this year. How's school coming?"

"Okay, I guess. 11

"Looks like we're going to have fine weather today. 11

11 Yeah. 11

They stood for a moment, nervously sh uff l i ng their feet. Josh I s eyes wande red.

11 Wel l, say 'hello' to everyone for me. I hope you get one today. 11

"Sure Josh. 11

Davidson walked over and began talking to Josh's father in a loud voice. He wondered what was bothering the boy. Josh took several steps and sat huddled on the tailgate of the nearest pickup

in the perimeter of the 1 ight shed by the glaring head] ights. He pulled himself deeper into the heavy coat. The now loud laughter from the group of men seemed miles away.

Two more trucks pulled up and four men stepped out. From the rear of one of the trucks, dogs whined anxiously from their kennel boxes. His father began:

11 l 1 m glad to see that y'all could make it th is morning. We've got right many here, so we' 11 have to spread out pretty well. I figure we'll Just do it 1 ike we did last year. Johnny, you and Sam take the dogs up to the north ridge and let them run at about six o'clock. Everyone else take the same stand as you did last time. I've hunted with each of you many times, but be careful. Be sure of your target before you squeeze the trigger, and no one is to leave his stand and go wandering about. I think that's about all. Good luck. Let's get going, the sun's starting to come up. 11

There was a murmur of approval from the crowd, and the hunters piled into three of the trucks and began the trip to the other side of the farm.

The man and the boy walked back to the house and followed the others in their own truck. They were silent as they rocked down the muddy road. The boy felt the excitement beginning to grow. He loved opening day. The truck rolled to a stop next to a densely wooded ridge. A cornfield stretched out to the left.

11 1 1 l l pick you up at noon. 11

The boy hopped out and walked around to the rear of the truck and uncased his shotgun. He stuffed a half-dozen shells in the pocket of his vest and, waving to his father, began the walk to his stand. He paused for a moment and watched the 1 ights of the pickup fade in the darkness. The boy picked his way through the dense brush up the ridge. He came to the top of the rise and walked about a hundred yards back in the woods to where the brush began to thin. He sat down at the base of a sapling pine and pulled on a pair of gloves. Below him a small drainage stream ran from the cornfield. The woods rose up steeply to another ridge opposite him. The sky had begun to 1 ighten, but it was stil 1 too dark to see well. Josh slipped two shells into the magazine of the worn short-bar14

reled pumpgun. He chambered one and slipped another into the magazine. He checked to be sure the safety was on. He pulled his knees up to his chest and rested the gun between them. Now, he waited and thought the inevitable. He had decided. Sometimes you just had to leave things behind no matter how much it hurt. He remembered the night he graduated from high school. He had been sad that it was over and yet excited about the prospect of going to college. He knew he would never see many of the friends he had spent all those years with again. He hadn't known if he and Karen would even last through college, but that was al 1 he had to cling to. Now, that too was slipping away. It was spoiled now, and he resolved not to get in a rut. Once you were in a rut, it was hard to get out. The forest grew lighter, and suddenly the yells of the hounds echoed through the trees. Although he was no longer cold, a shiver ran up his spine. He clenched the gun tighter and partially opened the chamber to be sure it was loaded. The baying of the hounds grew still fainter as they circled around along the edge of the marsh. Two quick shots and then a third travelled crisply across the cornfield on the bitter morning air. Josh wondered if they had scored. It was full light now, and the ridge was bathed in sunlight and shadow. The baying of the hounds began again and grew progressively closer. Soon they were no more than three ridges off. The boy peered anxiously in the direction of the hounds' now frantic yelping. He could see nothing through the densely wooded forest. Suddenly, a slight motion caught his eye. Fifty yards down the drainage creek something had moved. Still, the boy could discern no shape. The cover along the creek was very thick. From nowhere a tawny image materialized. The doe seemed merely an apparition in the shadows of the forest. The animal cautiously stepped into the open. The boy clicked the safety off and slowly raised the gun to his shoulder. Seeing some motion, the doe started and bolted up the ridge opposite the boy. He fired quickly and felt the s 1ug strike home wi th a so 1 id 11 thwack. 11 The animal faltered but continued to struggle up the ridge. Suddenly, she collapsed and rolled clumsily down the ridge

and came to rest with a dull thud at the edge of the creek. The boy paused for a moment and then rose and picked his way down the ridge. The animal lay with her long thin legs buckled underneath. Her head was twisted backwards, and a stream of crimson blood ran from her nose onto the dry winter leaves. The boy stared at the deer for a long time and then kneeling, ran a gentle hand across the animal's s 1eek hair. It was over. The winter sun illuminated the ridge and brightened the thick undergrowth below.

1 enn BeJz.geJl.

Tribute

Morning sun shone on; the blood-stained blossoms lay tattered. Misty futures locked eternally with irretrievable keys Nature's theatre presents her stark realities.

Deepest dusk is shattered by an anachronistic sun Of Life, yet thunder rocks the sky: a storm, a fear-filled nausea. Winter observes, not loosing his reign; Spring battles insistently from within Chaos wreaks her vengeance with Her watch and no humility. And simultaneously, Screechingly, untimely Death arrives To bring the tiny lives to eternity The blood-stained blossoms lay tattered

Amy Vie.W.c.h

Cloudburst

I float on the polar breeze. Mountains of ice crash ... the sky is falling. Waltzing the thin 1 ine of reality, We are walking, have drowned in my hunger. We have been driven beneath The icy crust

You sought to raise me above. can neither dissolve the gravity of silence, Nor shatter the vacuum of vast expanse. I rest in the coolness of your arms, Longing to release the emptiness.

G~ace,M. VJU.be,Jz.:to

a world without

an echo in the dark, like a flash of lightning before the storm whose thunder is felt--not heard, a gentle sobbing as the warm winds scowl across the parched earth now thirsty for the rain. a leaf-bare tree stands against the sky outlined by a light which quickly fades--above the clouds, the jagged boughs 1 erratic gestures point, to and fro as the wind whips about the tossing 1 imbs. as the drumming din of distant thunder --1 ike cannon bursts pervades the darkness, a soaring eagle tossed about like a leaf aloft the gusts alights upon a branch searching for shelter. the clouds are ash and smoke-refuse from the world that floats like clouds but gives no rain. the 1 ightning is from distant fires where war-torn cities 1 ie in waste beneath the darkness. the eagle sits upon the tree who knows no refuge and has no prey-in a world beneath the smoke.

GJte.gHud6on

Ce,U,a.NaJLa.njo

Close to Home

I never saw death coming but how could I? no one let on, especially you never a look or a word to give me a hint business as usual damn it I never got a chance to say goodbye I can't even remember the last time I saw you

Maybe it's best that I wasn't around for death only for your life sitting on your knee thinking time would never run out you made it seem so-and part of me stil 1 believes in monkey-doodles and disappearing pennies

SM a.n Sc.honbe.Jtge.Jt

Reflections on Mothers

In her dressing room nothing is changed. Grey-white hairs cling to her brush; Drops of water still slide in the sink.

Golden, her hand mirror reflected her youth. Thick, black curls, firm taut skin, Fat, laughing babies cooing and chortling.

The tarnished mirror pee 1 i ng s i 1ve r. Hidden safe by older bosoms and rustling skirts, The place of precious things among the legacy of cherished mothers.

Antiqued histories. Umbilical connections to women with legends and stories and strength. Secrets of continuance, a vote for fertility.

CheJr..ylR. Gibby

Amy Mc.Unal.

Oceanic Lifecycles

Oshshsh ..• ..• Un breezes

Pound the waves Of ecstasy

In surges, Capping the white fervor Of peaked enthusiasmUntil Crashshsh!

The excitement breaks, And all must start anew In this methodic kingdom Of life.

S u.e.Swa.n6on

As She Spoke

The bonfire threw her shadow on the sand as if we stood upon a rug of antique Asian or1g1n.

The flamel ight penetrated the darkness beneath her pale brow and flashed, flickered brightly in the hopeful chandelier gleam of her eyes.

As she spoke, a mahogany mixture of youthful optimism and fetal existential ism panelled her voice.

And as her words entered my head, the silence created by the sound of the sea rose and withdrew, leaving a cold 1 iving room of middle-class despair.

G. Zimmvuna.n

Jul.ia.

MaJtliSime.Illy

Journal Entry

What do I want from 1 ife?

I wish I knew. Happiness, I guess. If only I knew what would make me happy ...

Everyone is so uptight today. I wish I could understand what makes them unhappy.

Why couldn't everyone just take 1 ife as it comes

Instead of making tragedies of frivolity?

People are too competitive--too selfish; I think that's part of it.

Maybe they're happier being unhappy, Worrying about the miniscule

To make themselves seem benevolent. Martyrdom rules many lives.

If only people would take the time to think about what they already have going for them ...

Maybe then they'd find peace and not have to dream the ludicrous things they do. But then again, who defines happiness? Those who never get discouraged from reaching their dreams?

Realistically though, how often do these dreams find reality?

Not too. Life's funny that way. Those who want something the most never seem to get it.

Maybe there's a moral in there somewhere: Maybe we should quit wanting. It does become a disease at times, most of the time actually.

I think Thoreau said it best:

11A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone. 11

It's true, the less we need to be happy, The happier we are.

We should be content with 1 ife's Si mp1i Ci ty, But that was forgotten years ago when man became Ambitious and impatient. People take things for granted too much-Like their friends and family, Like the beauty of nature.

When was the last time you told your best friend ,

Or even your brother, that you love him?

Then again, when was the last time you took a walk outside--

Without any destination--

To appreciate God's creations?

It doesn't matter if it's overcast, for rain is beautiful too.

It's sad that we forget these things. If society weren't so time-oriented, maybe we'd discover

The meaning of e;te.Jtnal happiness.

Now, that would make me very happy.

Violet Golden

Violet's firm shell rocks in Rhythm's clockwork Of mind and soul.

Her pacing movement--always a step ahead and Two behind.

Rays of crimson-gold and blinking Brilliance Hide the facial tone and lines. A secret message slides from a pulsating mouth-Hungry, passionate days come slower. And sheets of air clap an echo of forgotten Thoughts.

Now the vibrant beauty is Nature's past. The structured cylinder stick now prancing into Eden, silver apple in hand.

A.W.Pa.yne.

For Ginger

I watch your dark face and curved eyes as you cut apples, oranges and bananas into inch-pieces for our dessert. I am reminded that we have come through.

Lived a floor apart in a women's dorm, joked that our feet had worn a path down the stairs between our rooms. Shared tentative secrets about the

two versions of the same man we had chosen to love.

The next year we spoke again of our mirrored 1ives. I would pick up the phone and you would already be there, although it hadn't rung. On the Jewish New Year I baked a round challah for continuing 1 ife. You gave me a red paper packet with a penny inside to start my Chinese New Year with luck. You taught me Chinese proverbs paralleling my Yiddish ones.

We have reached dessert. There is nothing we can't share. You toss in strawberries, leaving them whole. And we sit down, to eat.

Va.nie.Ue.Ru.th Pa.nteJt

For James

When you brought me back to a playground we climbed the steel sculptures and I felt that old fear of being up high with my legs dang] ing

How funny for two children to hug at the top. I saw my past again yesterday and from this distance the ugly features were exaggerated as in a circus mirror.

The swings were too low. The weekend with my two childhood friends brought everyone into question, even you. In spite of only knowing you a few months we swung in synchrony as if we always had.

The walk back was flat. The hills are behind me now. The present is the playground, the road and you.

I'm No Dummy, I Just Deliver

It's 11:15 as I pull my car to the front of Marsh Hall. I check my orders, unload several pies out of my portable pizza oven and then, before entering the dorm, safeguard my car against any hungry, empty-pocketed, devious, alcohol-ridden Richmond College boys.

From a third-floor window a voice shouts, "Yeah, rah, the pizza's here ... and it's about time, you dawdling idiot. 11 With that, I enter the dorm and slalom my way around empty Domino's boxes and torn-down election posters to get to room 244, my first delivery.

Knock, knock. 11Who is it? 11a voice asks. "It's the Domino's delivery man, 11 I reply. The door opens. 11 But you're not a man?" he says in confusion, (and who says RC boys aren't intelligent?) 11And neither are you, 11 I feel like saying, but don't. _ Instead, I give him a pie and a smile and then hint around for a tip. 11 Yeah, 11 I say, 11 1 took this delivery job so I can fly home to see my dying mother. 11

11 Oh, yeah?" he says, 11We11, 1et me give you a tip--don't fly TWA, their rates are higher. 11 He snickers and then shuts the door. Money I need, that I don't.

I pick up my pride and remaining pizzas, and leave the dorm. Outside, find several RC boys hovering around my car, drooling on the windows. Immediately I throw one of the empty pizza boxes into the street to distract the boys as I sneak into my car and drive off to my next delivery, the Mods.

The front door to Mod 7 is open, so casually strol 1 in and yel 1, "Anyone order pizza?" No response. I yell again. Finally, the music is turned down and a voice ye 11s back, 11 No one I s home. Go away. 11

"But didn't you order a pizza?" I yell. No reponse. So I yell again. Finally, a door opens and a face appears through the smoke. 11Oh yeah, I guess we did, 11 the face says and then asks, 11 how much do you charge for bounced checks?"

He leaves and then returns with a sixpack and two friends. "Would you take a couple of beers instead of a check?" he asks. 11 Sure, 11 I say as I sit down and take a sip, 11 l 1m no dummy, I just del iver. 11

]ilia G. ZimmeJunan

Ode No.3

We used to walk hand in hand. Braving it--Together. But you left me one day ...

I stood and watched as you crumbled under the force of some Grea te r Power .

My Defender, my Guardian. Left me to face life's storms alone, and unprotected. Oh, how I needed you!

Damn umbrella.

Randy S. KeMhneJt

Havens

I knew winter had arrived when I awoke to see frost on my bedroom window. My father bellowed from downstairs, 11 ••• so, get up! We're leaving in a half-hour. 11 I mumbled something incoherent and rolled over. I was experiencing what appears to be, each time it occurs, the worst hangover in my life. Oh, how I wanted to be back at school and pull the old "throw the pillow over the head" trick and try again 1ater. Kind of 1i ke the ground hog waiting for winter to be gone. I tried it anyway. I dreamed of when my older brothers and sisters and I had to fight for the shower every morning. Now their rooms were always empty when I was home. There was no reason for me to get up.

I awoke again and raised my head from below the pillows. Spring hadn't arrived, and the aches had not gone. It was the moans of my father ascending the stairs which shot me from beneath my warm haven into the co 1d air. I was dizzy. The trophies and posters of my past became a blur.

My chest ached. was realizing the pain my father endures with every step of his arthitic knees. Doctors say he has a few years before his realm of mobility is dependent upon a wheelchair. They say his cartilage is 1 ike the end of a broomstick. I have never cared to think about it. I always wanted him to be the bull he always

had been.

The bedroom door flew open. There he stood with a will I believed I could never possess. Al 1 I could say was, 11 1'm up, Dad! I'm up. 11 He glared and growled in a tone that always made me tremble, "Come here, Adam.11 I obeyed.

"You smell like a goddamn brewery. You came home last night stumbling and-and fumbling all through the kitchen and then up to your bedroom." I stared at his narrowed eyes; his lips were tight and expressed each word, not loudly, but firmly and quite clearly, "As of now, you might never drive my car again!" He paused for what was to be the last of it. ''You cou 1d have k i 11ed somebody ... you are grounded!" I hadn't heard that in years. "For how long?" s 1i pped from my mouth. He gripped my arms with his massive hands and shook me.

"For how long! For as long as I see fit, goddamnit! 11 he retorted from his stern, contorted face. "How can you possibly ask such a question?" Now I was in for it. "Your mother asked you very nicely to return home early from the reunion with your high school buddies for just one night so we could get up early and see her mother," he crisply blazed.

11 1 know, Dad... I know, 11 was my weak response. I couldn't take any more. His voice raged, "You don't know, Adam!" He

continue'd, "You damn well could have ki 1led someone ... 11 I was aware of the dangers, I just didn't seem to think it would ever happen to me. For a moment I stopped hearing him and only saw his full, firm, angry face. His grip tightened. 11 ••• your mother is very upset ... this may be the last time you see your grandmother."

All of this hurt me. Tears formed in my eyes. It transformed my guilt into anger. Somehow I wanted him to hit me. wanted to strike him, something, someone! I knocked his arms and pushed him away, yelling out, "Okay, okay ... okay! 11 I couldn't look into his black eyes.

He pointed at me and returned to the clear, firm voice, "You get your butt in the shower, dressed, and downstairs in ten minutes, or you'll be in more trouble than you've ever imagined!" As he hobbled down the steps, I rushed into the shower. After shaving and dressing, I descended the steps and rushed through the well-decorated foyer into the kitchen.

I was greeted by the front page of the Ne,wYohk Time/2, the clanging of my mother cleaning the pans and dishes, and a plate of cold, coagulated scrambled eggs. I couldn't stand the depressing front-page news that wavered between my father and myself. The eggs were a perfect punishment for my body. I passed, dropping the fork onto the plate.

The Time/2was folded. My father and I exchanged glances. His eyes were wide, his face stern. "Not hungry, Adam?" He knew the answer. "Are you ready to go then?"

"Yes sir, 11 I replied, not even considering a chuckle for his dry, jabbing wit. Dad rose and stiffly walked to the foyer closet for our jackets. I followed suit by delivering the plate of eggs to the sink. My mother slipped her wedding ring back onto her finger and removed her full apron to reveal a black corduroy jacket and skirt with a white, frilly blouse. Her hair was done conservatively. Her eyes shocked me, so filled with tears and yet still able to twinkle enough to say that she loved me. My father returned with our jackets; he wore black, I wore tan.

Dad found an empty beer can on the floor of the car, cursed, then pulled out of the driveway and onward to where my

last grandparent lay. The drive took a while, allowing for thoughts to spin through my head. I wished that my brothers and sisters were going with us so that we could be a family again. It had been four years since we had all been together. Our family was diffused across the country. One in Arizona, two in Chicago, another in California. It was a phenomenon of our culture. Instant communication! Just pick up a phone every traditional holiday. There is no such thing as "the next best thing to being there." My college textbooks elicited what I knew; the family, the main institution of society, was being transformed, destroyed! Oh, how I wished I could pull out my trusty com~unicator like they do on Sta.ILThek and say ''S ' pock, beam my brothers and si~ters and nephews to Philadelphia."

I attempted to ease the tension of the drive by asking piercing questions 1 ike, "How is Cyndy enjoying her new job in Ca1 i forn i a? 11 ••• 11How 1 s the weather been?" I avoided politics, religion, and my academics for fear of agitating the already hostile environment. My greatest breakthrough came when I asked my father what he thought of the Philadelphia Eagles' chances of making it to the Super Bowl. He responded, 11They 1 ve lost their last three and must beat Dallas next week ... ," then changed the radio station. So much for my d ry wi t .

The massive front lawn and huge stone gateways of the Greenhaven Nursing Home came into view. My father drove the car up the long drive and parked in front. He got out, closed the door, and waited for us. My mother turned to me and reached her hand out which I received and needed, "Adam, your father cannot handle seeing my mother like this. He has been through it enough. He does n I t need to again. 11 She paused. I was saddened by this.

"Your grandmother is very thin. If you can believe it, she only weighs seventyfive pounds. She is unable to remember or communicate. 1--1 just wanted you to know. 11 I was aghast at this. I could not imagine my grandmother this way. I didn't want to. We stepped out to the cool fresh air. The day was warming a bit.

Greenhaven Nursing Home was designed to please those who visited but not those who existed there, waiting to die. The

main building of the nursing home was from an old hotel which had closed down some time ago. It was a private institution now, taking up the slack in home health care and cutting the presence of family love. Large, green awnings shielded the white front from its eastward heading. A long narrow addition had been constructed perpendicular to the main building, out of view of .the front.

We climbed up the worn stone steps and entered through two magnificent bronzeencased glass doors. Grand, gold-framed mirrors, massive windows, paintings, and couches lined the walls. Each was an illusion of perhaps a grander past. The air was stagnant and dusty.

Beautiful, healthy plants were on several tables and windowsills. Oriental rugs centered the lobby as well as the other adjoining rooms to the left and right. My mother walked to the reception desk. The original mail slots were still there behind the counter and receptionist, worn smooth by years of courteous exchanges of keys and messages. Most were empty. There no longer was a need for keys. No residents were going to leave alive.

Dad seated himself in a chair by the window, reading the Tlme-6. Sunlight created an awning of streaks barely shining over the top of the paper. Dust floated suspended in air. There was little current to transport the captive particles to resting spots upon the relics of a brighter past. This image remains vivid to me: how my father fidgeted as the dust did, never stable, not belonging to the nursing home.

I stood glancing about the home wondering how many have been coaxed into the elegant foyer knowing they will only leave through the back door in a plastic bag. How many knew that the spacious hotel rooms would encase them in sunlight and beautiful views for as long as their health would hold. Then, it was a systematic assembly line. No bed was to be empty. How wondrous is this business of dying~

A doctor came to the reception desk and spoke with my mother. She bowed her head and quietly cried about what she already knew. Two elderly women seated themselves in the adjoining sitting room and knitted. They were dressed in relics which matched the surroundings but seemed to hang awkwardly. Almost as absurdly as

when my sister, Cyndy, played ''grown up'' and put on my mother's clothes. It was just a matter of time, and their conservative wardrobes would be traded in for bedgowns.

My mind flooded with memories of coming to Greenhaven to see my grandmother the past four years. Once knitting, waiting for us .•. with a walker ... to a wbeelcha1r ... then to a hospital bed in the infirmary .... When I was eighteen, we entered her room to find her seated in a wheelchair. I was depressed. I took her into the hallway, propped her up on two wheels, and played the Infirmary 500, racing down the emaculate tiled floors. She raved; she laughed and shook with excitement. Nurses came running. It was the last time I saw her show any joy.

I have maybe six vague memories of a proud woman who gave me tips on how to tie my shoes, multiply, and fish. I will never fully know her, a person as important to me as the sun and equally taken for granted. She faded more gently and rel inquishingly than the setting sun. Never again shall she softly read a story and caress my forehead as I fall intoworriless sleep. I wanted to strike out against someone or to run into the light of the sun, to cry, to play, to be away from the realization that my life was changing.

My mother walked towards us. My father folded his paper and struggled to his feet. He hugged my mother; they turned to me, "Adam, would you come with me to see my mother?" Tears formed in my mother's eyes. I turned in a daze and followed her, not looking back to see my crippled father. My brothers or sisters should be here. I needed them. My parents needed them.

Momgrasped my arm and led me through the door which opened to the medical wing. Metal memorials were mounted on the white wal'ls, "In beloved memory of. ... " It smelled of Lysol and something else. It was a bad blend. My throat constricted; my heart pounded. We passed through another door, extraordinarily wide, for mobile beds. We entered the second to last stop before death. Wide, brown doors were propped open. Elderly women were sitting up in raised hospital beds gazing at television or into space or out the narrow windows. Plants and flowers were wilted on

every sill. The sun didn 1t seem to shine on this side of the nursing home.

I counted the doors to Grandma 1s room. Automatically, I started to walk in. Someone e1se was in her bed. My nephews 1 finger paintings and drawings were gone. The family pictures and cards were gone. I was disgusted. I looked at my mother, 11Where is she? 11 I was scared.

11 Grandma 1s been placed in the terminal wing, 11 spoke my mother in a soft, firm voice. My head began to spin. She embraced my arm and led me further down the sterile hallway. 11 My mother is dying, Adam... I need you to be with me, 11 she whispered. I thought of my father, our fight, and the pain he must be feeling. We went through another door. Written above it was 11 TERMINALWARD. 11 I was disgusted by the bluntness of the sign. The air, the Lysol, the stench was stronger. I gasped. My mother stopped us and spoke in a penetrating voice, 11Adam, you are old enough to handle this. You must. I need you. 11 There was a deadening pause. 11 1 need you to see her, for one day it will be me and your father ... and later .... '' She caressed my hair and face with her warm, gentle hands and revealed a trembling smile. Her thoughts were so painful. glanced about at everything, sheets in hampers, nurses in vile, dingy medical gowns, and bright fluorescent lights. There was no sunshine. This was the true Greenhaven. The final efficient preparation for death. A sort of gradual genocide. Two rows of glass cubicles with curtains partly drawn. Doors were propped open. In one of these, my grandmother lay dying. The woman who taught children as a profession, as a way of life. A strongwilled soul who endured the Great Depression by sharing. An experience that I will only be able to read about in a text of written words. Words which never could convey more than statistics.

A nurse with a pale face and dark, buggy eyes came to us and whispered, 11 Can help you? 11 I wondered what Life was like for her. It wasn 1t her that I hated. My mother couldn 1t speak. I withheld my loathing for this death haven, 11 Mrs. Gardiner, please. 11 The nurse directed us towards the glass cubicle and pointed inward. My mother let go of my arm and

entered. The room was dark and windowless. I saw a barely living skeleton, motionless. This was my defiled grandmother. Tubes ran into her nose and arms, wires were taped to her neck waiting for another heart to stop. This once strong body barely raised the sterile, white covers from the bed. There was no humaneness in this. Skin stretched so thin that the veins and bones were barely contained. There was no muscular form. Drugged and strapped, this body waited for soil, for worms, for escape. My mother gently sat down beside her. I seated myself on the other side. I must have looked as offended as I felt. My mother touched my shoulder for a moment. 11 Remember her as she was, Adam, not as she is now.••. 11 Her voice faded; her hands clasped my grandmother 1s hand, and I did so also. The hand, once so delicately refined, was chilled and bony. We sat for some time staring at the deteriorating, heavenward face. The eyes were dull. The muscleless face was unable to close its own eyelids. A filmy excretion oozed from the sockets and dripped down to the pillow. Were they tears of loneliness or of waiting?

I couldn 1t stand the silence. Finally, my mother leaned forward and spoke, 11 Mother •.. Mother ... it 1s your daughter and your grandson, Adam... Mother, we love you ... you were the most beautiful mother anyone could hope for. 11 The cold, clammy hands jerked then released. My mother cried out, 11 0h, Mother, I 1m sorry •.. ! 11

I heard myself talking. 11 You were the greatest grandmother, 11 I started to choke. I wanted to tell her about school, about the weather, about the Eaql.es. I couldn 1t say anymore. My mother spoke between sobs. 11 0h, mother ... we love you so much ... 11

A gurgling came from the gaping, toothless mouth. A doctor came into the dark room; he stood until my mother could raise her head to him.

111 1m sorry ... 11 Those words 1 ingered in the stench of the air. How many times did he say that a year? I didn't even know him. He came over and forced the eyelids of my grandmother 1s body closed. At last, ~he was free to be with God in heaven or away from this hel 1. The doctor looked at me in a way of saying I should

help my mother ... it would be best if we left. Best for whom, I wondered.

11 In a minute, 11 I whispered, wanting to lash out. We sat there for a while, then I went to my mother. I grasped her by the shoulders; her body trembled. She wept softly. 11 Mom, let 1 s take a walk outs i de . 1 1 She rose sh a k i l y .

All the doors of the glass cubicles were closed. Probably standard procedure for the systematic removal of a body. The nearest exit was at the other end of this horrifying death ward. I opened it to a setting sun. My eyes and lungs expanded to the fresh air. I led my weeping mother away from the obtrusive assembly line out into the grass and trees. We said nothing. We just strolled away. We stopped at a bench and rested before the fading sun. 11 Could you get your father, Adam? I just want to sit here for a while, 11 my mother requested. I didn 1 t want to go back in there, ever. But I didn 1 t want my father to remain. I walked around the back of the nursing home and watched the medical wing and the sun disappear, blocked by the illustrious

front bu i l d i ng . rose, startled, 11 Grandma I s touched my arm.

I walked to my father. staring. dead,i 1 I blurted out.

11Thank you for being there. 11 He He We returned to my mother, his wife. My father hobbled, shifting his weight with every painful step and using my shoulder as a crutch. The three of us sat on that bench until the sun had gone to shine upon the other parts of the world. I knew I would see it again tomorrow, but the radiant lady who touched and spoke kindly with others would rise only into my memories. She died defiled and encased in a sterile stench. I wonder if this will happen to my parents and to myself, with a family scattered about the earth. Those left behind experiencing their elders• or siblings• deaths through a telephone. Shall we be locked up in magnificent illusions like Greenhaven until we gradually deteriorate, never to tell the advice or last words about the life we tasted?

Notes on Contributors

Amy R. A~eluna.i..,a senior, is a painter and sculptor when in the manic state, art direc- tor of The Me/2~eng~when in the depressive mode. She has an affinity for armadillos, violets and bluegrass.

Je66 B~g~ is a Richmond College senior with plans to attend medical school in 1 83. His interests are hunting, fishing arid karate.

KoMad B~k, a senior majoring in education and sociology, has free-lanced for the Colorado College Publishing House, The Col- legian and The Web.

A~on Blake writes.

Cnaig Bnown, RC 1994, is a closet writer who enjoys creating memories, daydreaming and having cool water sprinkled all over his body. He plans to grab a bottle and a bible if a nuclear holocaust unright- fu 11y occurs

Eclu:hClay Camp, from Frankl in, Virginia, is a senior. She employs her time creating sculptural pots and etching portraits of her adopted 11 kids. 11

Ch~ Cleany, a senior majoring in English, received the National Council of Teachers of English Award for Outstanding Writing and the International Thespian Society Award for Outstanding Playwrighting. A contributor to last year's Me/2~eng~, Chris is currently writing a play.

S.W. C~oweff is something of a mystery to the folks at The Me/2~eng~.

Gnaee M. ViLibeJUo, a freshman, plans to major in biology. She has been published in the literary magazine of Marymount High School, PegMU6, of which she was an editor. Writing poetry grew out of her songwriting talent.

Kanen EbeJU is a junior majoring in English and art.

Enefe HenbeJUsays he is an ill iterate Richmond College junior, who wisely traded pen for camera. A resident of the Eastern Shore of Virginia majoring in biology, he plans to be the first Med. school acceptee with a 2.6 average.

Gneg Hu~on is a Richmond College sopho- more whose work has previously graced the pages of The Me/2~engen.

Randy KeMhn~, an undeclared freshman, is from New Jersey and proud of it.

John Light, a first-year student at T.C. Williams School of Law, was published in The Me/2~engenand The Fo~h VimeMion during his undergraduate years at UR.

Vemevuo~ Mav~oufu, associate professor of sculpture at UR, has recently been introduced to photography as an extension of his art.

Celia Nananjo, of Boykins, VA, is a senior majoring in English and studio arts. Her artwork has been displayed in the Walter Cecil Rawls Library and Museum in Court- land, VA, and in the student shows in the Modlin Fine Arts Center.

VanieUe R~h Pa~~, a first-year law student at T.C. Wil Iiams and a graduate of Cornell University, has a male secretary.

AndnewPayne, a Richmond College freshman, enjoys occasional experiments in poetry. He intends to major in biology and increase his literary productivity in the future.

SU6anSehonbeng~, a junior majoring in accounting, makes her literary debut in this issue of The Me/2~engen.

MankSimwy, an English and journal ism major, is interested in poetry as a means of personal satisfaction and relaxation.

A staff writer for The Collegian this year, he has been chosen copy editor for 1982-83.

Chenyl R. Gibby, a junior majoring in French TamanaStanley is an English and Education and _English, has been published in the Pewten major. Rev~ewand intends to pursue a literary career.

Jan G~66in appears in The Me/2~enge~for the third time this issue. She is a junior majoring in English, who has sold portraits and shown her work locally. (continued, p.32)

Sue Swan.oon, who will be leaving UR next year in pursuit of better things, is an English and journal ism major. She plans to further her writing career in inspirational Southern California.

Pete WaJUtenis a senior majoring in mathematics. He has never had his work pub1 ished before, and says "Birds are fun to watch. I like to etch them, too."

EcLLtoIL - in - c.hie 6: A~~oua;te EciLtolL: Au V,{,fLec;to1L:

BU6in~~ ManageJL:

Capy EciLtolL:

P1Loc.U1Lement:

Pubuwy:

Sta.66:

Lisa Campbell

Claire Yancey

Amy Arch i na l

Leigh Hogan

Nina I nsa rd i

Mindee Pizer

Mar j or i e Ir v i ng

Lynn Aldredge

A11 i son Blake

Courtney Carpenter

Karen Ebert

Lyn Harper

Diane Hotchkiss

Sue Swanson

Edie Thornton

Alden Tucker

Many, many than/u to ill who helped mak,e thM ue a 6 The Messenger a ~uc_c_~~. A ~pec,,i,a.,tthank, you go~ to the R,i,c_hmondCollege Student GovelLnment M~o~on 601Lthw good-na;tuJLed pa;t;__enc.e,M well M 6inanua1.. ~uppou. OUIL othelL bene6ac.toM, W~thampton College, E. ClaibolLne Robin.o Sc.hool 06 BU6in~~, T.C. Sc.hool 06 Law and the UniveMli!f 06 Ric.hmond BoMd 06 Pubuc.ation.o, ~o d~elLve a ~inc.e!Le "than/u • " FolLthw ,t_;__me,talent and exbta hlndn~~, we explL~~ ouJLapplLeuation to VIL. Steven BMza, Steve NMh, Thom GuaJLniefL,{,,Max V t and oUfL pfL,{,nteJL,Vietz PIL~~ , Inc.. Enjoy!

--The Editors

Copyright 1982 University of Richmond. Printed by DIETZ PRESS, INC.