The ffiessenge,

University of Richmond

April 1977

Editors: Lynn Vernon

Ann Dickenson

Glenn Court

John Jacobs

Co-Editors:

Melissa McWethy

Colleen Murphy

Debbie David

To the dedicated people who have contributed to this magazine: Thanks. To the non-dedicated people who have contributed to this magazine: Thanks, also. To the dedicated people who have not contributed to this magazine but may , at some time in the natural course of events, have cause or be forced to glance, if only momentarily, at this magazine or some portion thereof : Good Luck. To the dedicated people who will never see this book: Good riddance. To the non-dedicated people who will never see this book or who could care less: Peace.

The Editors

Contents

Danse Macabre

Debbie David

The PoLter's Union Richard Davenport

Pondering on the Life of City Pigeons Leigh Hay

The Crossroads Lurk

Supper's Ready

Fear of Intimacy

October Night

The Wild Swans

Zurich See Joe

Monday Morning Untitled Sisyphus

The Red Shoes

DefiniLions of Poise

Inverness

Untitled lndifference

LamentaLion

Dinner

Rose To AlberL Beguin

Untitled

A

Without Hope

Art Credits

Kathy Edwards

Glenn Court

Terrie Powers

Glenn Court

Betsy Skinner

Glenn Court

Glenn Court

Colleen Murphy

Jim Cumbie

Glenn Court

H. Christie Prince

Ann M. Dickenson

H. Christie Prince

Jill Hanau

Christie Clarke

C. B. Pitchford

Debbie David

Katherine Henry

II. Christie Prince

Glenn Court

SLephen McMasters

J. A. Hanau

Ann Bennighof

Jim Cumbie

Debbie David

Ann Bennighof

Glenn Court

Ralph Porter

Danse Macabre

Even if il rains, the children will go trick-or-Lreating tonight. Draped in sheets and bundled in raincoals which hide their coslumes, The litlle Lols will complain, looking like sluffed versions of their everyday-selves. Running hopefully from door-Lo-door, stopping only Lo retrieve candy Thal falls from overflowing bags or works its way through holes In the bolloms, impish eyes glowing they know ( or pretend Lo know) nolhing Of Lhe Lrue fear of goblins and ghosls.

Perhaps one child will knock on my door and finding Lhat no one answers, Close his bag sadly and wonder al such indifference. He can not know and does not feel Lhe parl of me Lhat is beside him Kissing him softly on the forehead and dropping fortune cookies in his Which read "This is only the beginning." He can nol know thal this is our night, Too, and can not feel how we hold each other at the party, dancing, dancing, Dancing even in spite of rain.

Debbie David

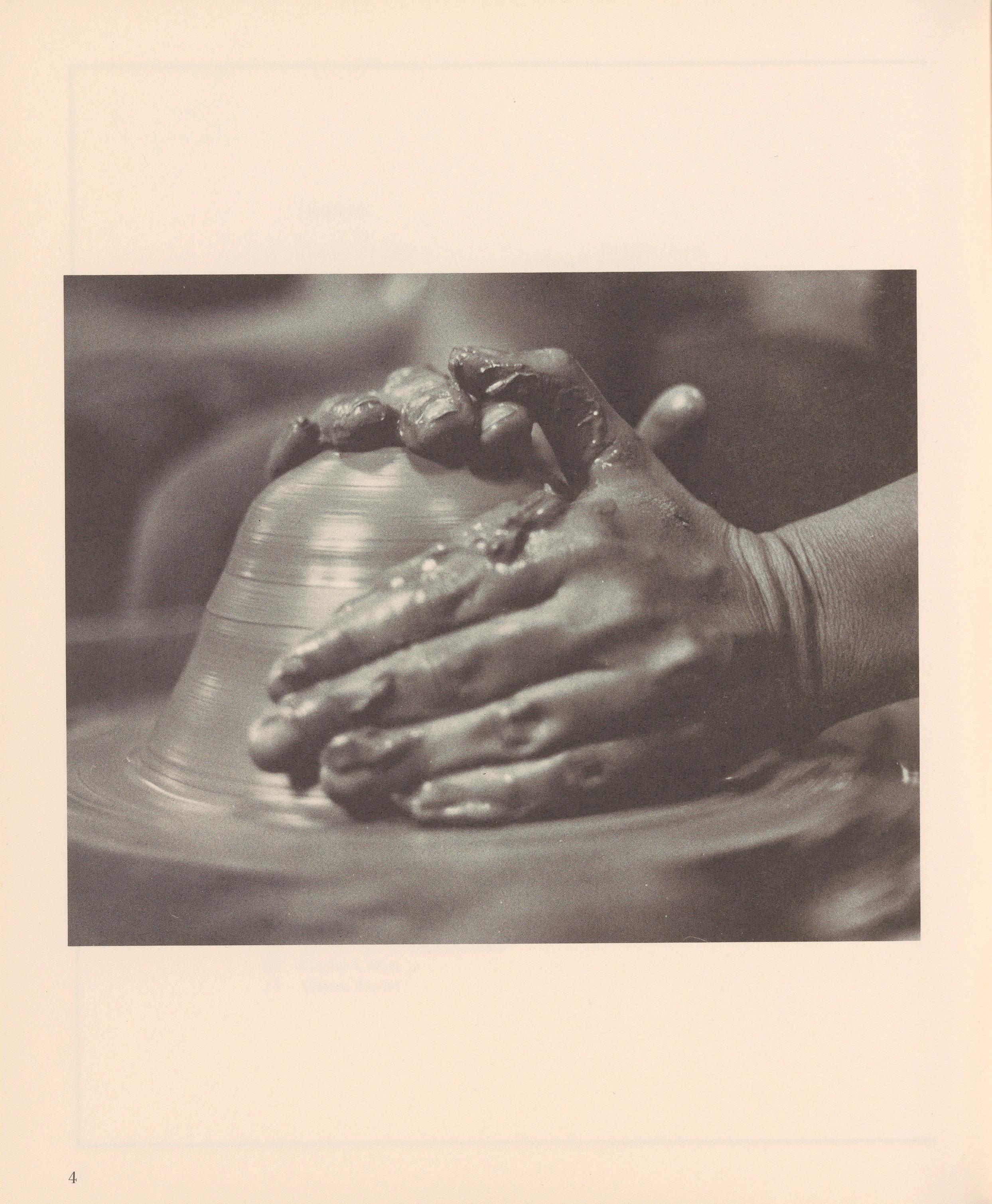

The Potter's Union

Wedge in, curl up, twist back and again, The Potter centers his subject.

Soft hands enter, pulling Lhe mass to symmetry. Dripping waste spills spinning down and dirty.

Still silenl exhale, hearl holding palm pulsing, Charge Lhe body raising slowly upward.

The figures sland tall and pliable, Friclionless, Complement to touch in life Logether.

Richard Davenport

Pondering On The Life Of City Pigeons

I wonder if all the bus fumes they must breathe change their genes so that they all are born with bodies as gray as downtown buildings and wings the color of melted asphalt.

Leigh Hay

The crossroads lurk ominous in the foreground my walk slows the cobblestone and brick pavement changes slowly to hard black concrete The grassy shoulders dissolve replaced by iron guardrails roads-intertwining, progress to straight narrow paths leading to diamonds I close my eyes--timid--and back away

Colleen Murphy

Light.

So this is it, he thought. I'm dead. I have died a mundane death, and here I am, waiting to be judged. This is the Big Cahuna.

He floated in a pink, misty void. There was nary a detail to be seen. All was limbo .

Well, what's the deal? Is St. Peter going to show up or not? For that matter, can I be sure that we're dealing with Christianity here? Maybe Mgubwe the Devil-God will throw me into the pit. No, no, must maintain faith. I'm going home to Jesus.

"Dixon? Walter Dixon?"

The words cut through the mist like a dum-dum bullet through cotton candy; the whole scenario caved in with a shudder. He found himself in an austere room with clean stone walls. Steps led up to a lighter room.

"Walter Dixon?" the voice repeated.

"Right here," the man answered. There was seemingly nothing to do but go up the steps. He did.

Lord, I'm tense, thought Dixon. I might actually go to Hell in a few minutes. Ah well, my time has come. Might just as well face it.

"Hello, young fellow. Have a seat." Dixon was in a bare room with a tiny old man, certainly under four feet in height. The utliness of that man had to be seen to be fully comprehended. His nose was long and thin, with a large wart. It dripped. A long, dirty beard stretched from chin to belly (the girth of which belied the man's height). He walked with a slight limp. Dixon warily made his way to a convenient stool which appeared seemingly from nowhere.

"So you're dead, eh?" the little man said. Dixon nodded. "Yep, you were a plumber, and you got killed in a car accident on Route 32 at 4:55 p.m. on the 14th. Your wife was named Marge, and your kids were Charles and Susan. You were born on August 22, ] 926, in Erie, Pennsylvania. Your first grade teacher was Mrs. Murphy. You see," he winked, "we do know everything."

Dixon nodded, dumbfounded.

"You 're dead , all right. A lead pipe cinch. You've plugged your last leak. You've turned in your wrentches. You 're off to that Great Toilet Bowl in the Sky. Yes-yes! Roses are red, violets are blue, you cashed in your chips on Route 32!" The old gnome doubled over in paroxysma of laughter.

This is insane, thought Dixon. Here I am dead, waiting to be judged by St. Peter so I can find out whether I'm going to Heaven or Hell, and this dinky maniac is spinning 'Roses Are Red" poems. Where's the justice?

Aloud, Dixon ventured, "Pardon me, sir, but could you tell me what the procedure here will be? In my life, I was given to understand that there would be a judgment, and I would maybe to go Heaven--"

"So-ho! You fail to comprehend, my fine-feathered friend! If St. Peter there be, St. Peter is me! You see," and here his cackle dropped to a conspiratorial stage-whisper, "we don't deal with Heaven or Hell here. Judge you we will, yes-yes! But not for that. No-no, ho-ho."

Dixon was getting impatient with such nonsense. "So what's the deal?"

"You 'II be reincarnated!" and the little man positively rolled with laughter. "Now, let us settle this account.

"On the one hand, you were a good Boy Scout."

Dixon stared.

"On the other hand, you were a disrespectful son."

"I don't believe this."

"Ah, but it's true. You were a loving husband, but a remote parent.You did good plumbing work, but you overcharged for it. You were loyal lo your friends, but a crude backstabber to others. Yes indeedy, as we balance the scales of your life, all comes out even "

Dixon held his breath.

" ... except for one thing. June Paciorek."

"Oh my God! You won't hold that against me! I was drunk, and it was only that one time under the back porch!"

"Life is rough, and death is rougher. You did il, so now you pay. Let's see, let's see ... Fruit fly!"

KaZAM!

I don't believe it, he thought. First I'm a plumber. Then some stupid screw runs a red light and kills me. Then, I get juclged by one of the Seven Dwarves. And now

He gingerly tried his wings. They worked, if a little clumsily. It was a problem walking with six legs. Also, his eyes wouldn't focus very well, and he had trouble getting used to wide-range vision. Still, he was able to get himself down into the depths of what seemed to be a crate of oranges.

June Pacorek! He hadn't thought of her in years, and here she'd gotten imprisoned in an insect body. The shock still rolled over him in heavy, palpable waves.

Okay, so this is how it is. Well, at least I can still think rationally. Maybe my best bet is to play it cool in this live, and work my way up on the ladder again. How long does a fruit fly live, anyway? A couple of weeks, maybe? I can stick it out. But fortune was on his side. Instinctively he had crawled towards a bruised and rotting fruit at the top of the crate. "Mon Dieu! Damnez !es insectes!" thundered an unseen voice. For a moment, he was in great, red pain, but soon all was black .

"So-ho, back so soon, eh?'

"Listen, fella, I don't like this system, but I don 't run it. You made me a fruit fly, you should know they don 't live long." In a more collected state of mind, Dixon would have been decidedly less harsh to the man who demonstrably held his

fate in his hands. However, his frustrations were beginning to show.

"Ah-ha! Don't like the system, eh? Well, here's a little secret. There's an alternative, yes -yes!"

Dixon perked up.

"The old Bible technique, you know. Brought in by popular request. You want it?"

"Of course! Why--"

"You've got it!"

KaZam!

It was a vision of lovliness. Dixon was not walking, he was floating. Beneath him was a fluffy swirl of white matter, soft and slightly tickling on his sandallet feet. Warm, golden light diffused everywhere, as did mellow, melodic harp music. How this is more like it, thought Dixon.

"You were a good Christian for many years," said his companion, a tall androgynous being identified only as Adelard. "You have earned your reward. Here is your hapr; now enjoy yourself." The being flew off at great speed.

Dixon strummed his new instrument, amazed at the ease with which he could extract rich chords. Thinking incongrously of the little dwarf, he laughed heartily. Probably some sort of purgatory, he figured. Deciding that he ought to mix with the rest of the population, Dixon struck out in a random direction.

Four hours later, he had found no one. Moreover, the white fluf was losing its novelty; that tickling was getting noxious. Plus, the difficulties of focusing in this light made his eyes hurt.

Eight hours later the harp was out of tune.

Dixon was ready to vent his anger, when he finally saw another halo bobbing in the distance. He hurried towards it as quickly as he could. As its wearer came into view, Dixon saw a round, tired-looking woman with glazed eyes and a blank expression. A tarnished harp hung in limp hands.

"Hail, madam!" greeted Dixon.

"Hail?" came the weak answer.

"How are you today?"

"Today?"

"Come, let us strum our harps together."

"Strum? Harp?" For a moment a gleam of terror flashed in her eyes, and her muscles tensed. Then she relaxed again. "Together?" Dixon left, wondering what he was supposed to be doing if no one want to play harp music with him.

As the hours passed the harp got heavier and heavier. It was dreadfully out of tune, and Dixon had worked up some nasty blisters on his fingertips anyway. Nowhere was another soul to be seen.

The full impact of his boredom did not hit him until he realized how long he had gone without so much as thinking a thought. There was nothing to do here, plain and simple. He slammed his harp down into the mist. "Goddammit, I can't take it anymore! This is rediculous! All right, I'll be reincarnated!"

Everything froze.

"Hee-hee, I knew you'd be back, oh yes I did."

Dixon sighed. "Okay, you were right. No need to be vindictive. Just pass your sentence, and let me get on with it."

"They never do like Heaven, do they. So, you 'II be needing a new assignment, all right. Let me see, one two three; got to be fair. There's still June Paciorek, no denying. But, perhaps you've learned something redemptive. Perhaps ..ah yes, a turkey!"

KaZAM!

It could have been worse. The pen was warm, and the food was pretty good once he got over his prejudice Turkeys were sociable, if none too bright; he could have a fairly good time. Plus, the leaves were brown, so Thanksgiving couldn't be too far away. And in his next life ...

Jim Cumbie

Fear of Intimacy

I sit alone in the kitchen of a flimsy apartment building, listening to a stereo, friends having gone to see old Greta Garbo movies at the Biograph theater. The plywood walls vibrate faintly listening also, with, perhaps it is serenity to folk music of ten years past: Peter, Paul, and Mary singing that the day is done.

It is dusk and early January brings snow and bitter cold, winds that lash with harshness -raw and unfamiliar to the quiet of coastal Virginia, where winter usually ambles through chillness and stark rains, out of respect for tradition.

The slender length of the cigarette is burnt, and the smoke dissipates quickly in the still air, losing itself in the wistful and forlorn words of an Irish song written centuries long gone, sung by mellow voices a decade since.

Dimly , reluctant, in a mist of embarrassed memory, comes the late Wednesday afternoon three days past.

Falling voiceless, the eloquent silence of cold whiteness, falling lightly throughout the tedious eight hours of work in a university bookstore, falling from a pale and muted sky the snow cloaks gently white and pure the fragile ice on the river, the barren cold of winter ground.

A nervous fear of intimacy and friendship creates a barrier between the street and the house

Apprehensive emotions idle time

in the cold and wetness of snow. Gloveless fingers fall into the blessedly familiar act of artistic creation -sculpt the snow into the serene, independent lines of feline sagacity, of a cat sitting lifeless and icy on the hood of a snowbound car. The wet cold of snow suddenly, sharply, bites through the suede of tennis shoes into sockless feet.

The door is opened, a vain soothing of apprehension. Discomfort returns with warmth, and coffee steams from dark cups. I find myself retreating on the secure paths of the old stories told so many times before that they are told unconscious of the telling.

Words stumble, and I clutch frantic at the smooth steel railing of easy conversation:

Cardboard boxes, remnants of a moving van, lie cradled in a driveway, nestled and blanketed by the snow, reminding me of a barn-burning fortnight late one summer, when a number of farmers lost entire hay crops, by arson, in smoke and beautiful flame.

The nest I meant, though, was the high one in a distant tree.

A pause, a brief lull, as I continue to stare out the window at the snow falling through the naked trees. I find myself terrified, staring out the window as if it offers the solution of the universe, hoping desperately that conversation will roll,

and flow I sense a vitality, with the grace of tides.

As she mentions the copy of the Bayeaux tapestry hanging on the wall,

a cool purity of beauty akin to Bernini, Donatello, perfection in carven marble. 1 leap off the sofa, startled, and peer for an eternity of seconds at the infinitely small stitches sewn eight hundred years ago , of Norman cavalry figures, and Anglo-Saxon housecarls, wishing that the Viking ships could carry me away. Again, I stare out the window, after a brief glance at the understanding warmth of her dark eyes.

Steadfastly, I refuse to look at her as I speak afraid, perhaps.

Sensitivity and intellect form pure lines of smoothness and grace, sculpt gaunt, with a gentle warmth, the fine bones of her face. All the while I stare embarrassed at the falling snow, glancing occasionally into the warmth of her dark and very human eyes, afraid, perhaps,

to find a denial of simple friendship, a denial I know does not exist, wondering at the persistency of my fear sympathizing, Ill-at -ease, I refuse to look ... timid and fearful, impressed again as by a first visit to a Florentine museum: the awesome yet gentle perfection of Renaissance sculpture.

later in the evening, with the poor souls stranded along roads in snowy ditches, wishing desperately that it were spring and the forsythia were m bloom

October Night

Darkness

on a windy starless night. Embracing my bunched figure

Soothing me with fond memories

While lovers laugh and whisper behind us, Independence and I have our affair.

-H. Christie Prince-

H. Glenn Court

THE WILD SWANS

Seven swans for brothers

What would a girl not do to save seven enchanted brothers?

Would she not wander the world, Balance seven spells by holding her tongue, Knit eleven coats of stinging nettles? Like breathing with broken ribs I knitted with swollen fingers not noticing when my hair was knitted in. Then the king found my hiding place and was bewitched by my golden hair though it stung his hands -he kept touching my hair. He said I would be queen and took me home to bathe my red fingers. But Lhe people found out the king's beloved who knotted grave-weeds and pain into coats that smelt of corpses. Burn, they cried , burn her! I could not speak, mu fingers were too slow. At the very stake I threw the coats over my magical brothers and they were men again. They put out the flames, they untied me. There are no longer seven Magic brothers except the youngest whose coat was not finished. I can only soother my ruined fingers now by stroking the softest down of his one great white wing.

--Ann Marie Dickenson

Zurich See

Lihe plump graceful ladies at a masquerade ball The spinnakers glide past with only the breeze as their escourts .

1-.1.Chri stie Princ e

JOEY

Joey liked to slither when he walked. Every part of his walk, dress and movements were crucially important to his image. His feet seemed to touch the ground a little too far in front of his body forcing him to lean back as he walked. His arms compensated for this by swinging in time with his feet giving him forward momentum. Joey was cool. His Levi's were always just the right shade of faded and his beard always had one day's growth on it. He tried hard to maintain the "rough night" look without ruining his natural handsomeness. Joey's true genius was looking spontaneous after hours of preparation. His real pride and joy was a long thin scar on his right cheek. He liked to run his finger down it as he talked to people. It gave him an air of having really lived. It was because Joey was so cool that he wouldn't cry when his mother died. Instead he hated her.

Joey's father cried. He cried quite a bit, because he had loved his wife. Stan wasn't cool, but he really didn't need to be His wife loved him and made him feel whole. Stan couldn't understand just why his wife should die. It didn't seem like she had had enough time to live. She wasn't very pretty and Stan knew that. She had gotten quite heavy and tired-looking, but Stan had gotten used to her. He missed having her around. Joey couldn't understand that. He wouldn't even let Stan talk about it, so Stan cried instead.

A few days after she died Joey came home from school early and found Stan sitting in the bedroom crying. He was in his work clothes and he was holding her picture. Joey tried to ignore him and went into his room to listen to music. A couple of hours later when Joey came out again he saw that his father was still sitting hunched over her picture, but he had stopped crying. Joey was disgusted. He grabbed his coat and went out to get a beer.

The local bar was Joey's kingdom. All the chicks liked him and all the guys thought he was tough. Joey decided he would get layed so he picked up Trixie on his way over. He didn't really like Trixie but then he really didn't like being layed. It was just a part of being cool. The night went as planned and Joey didn't get in until 2:00. As he stumbled into his room he noticed that Stan's light was still on, and then he passed out.

Joey woke up in a bad mood. He didn't like being hungover. He slowly got himself up and went into the kitchen for some orange juice. From the kitchen he could see Stan. Stan was still sitting as he had been the day before. Joey felt a little sick. He quietly walked over and whispered Stan's name. When Stan still didn't move Joey gave him a nudge and the cold body he felt made him throw up. Stan was dead. Joey stood over Stan for about an hour not moving, and then Joey cried.

Jill Hanau

MONDAY MORNING

Monday morning.

The sink ate my tight conlact lens for breakfast And washed it down with tears of laughter from the faucet.

The mirror just stood there , mocking me, As I pulled the sink's tongue out and peered down its Lhroal hoping it had not yet swallowed.

The water in the hot pot began to bubble with the effort of suppressing its laughter. And my glasses were playing hide-and-seek all alone.

I stood Lhere, blind and defeated, And well reminded that it was Monday mormng.

--Christie Clar/re

Red eyes not open, important nine-thirty class; ten twenty-seven.

--C. B. Pitchford

SISYPHUS

Sisyphus, al the foot of the mountain Your stone is waiting though you Can count your muscles by their aching And your rebellious fingers stiffen At the thought of another haul as you Press them to the stone again, And feel again the places they have Dug out with years of pushing.

Men have said you have no prayer And no thought but pushing ever Enters your mind, but men have Been wrong before. Tell them, Sisyphus, How the stone never falls twice In the same exact place, with what Precision il tumbles always a fraction Of an inch to one side.

Tell them how, eroding with time, The stone gets smaller and smaller And how one day you hope to Carry a minute pebble to the Top of the mountain and build A monument around it. Tell them That you need no sympathy and You are at home on the mountainside.

Classifying all the flowers lakes up Much of your time, and the stone Is only secondary, tell them. But on summer nights I've seen you, Sisyphus, Asleep with your head against the Stone and dreaming that the real Mountain is inside of it, and you Should Le chiseling instead of pushing.

Sisyphus, in those dreams you Realize your only real fear. Your fingers tell the age of Your dreams, and trails of the stone Like radii from the top of the Mountain come down in perfect symmetry. You are too young to begin lo chisel And too old to continue pushing.

ll is not the falling of the stone That troubles you or the pushing That tires you, it is the awful Stillness between pushing and falling When you want to complete the symmetry, But you are afraid that your fingers Will not find their place on the stone again, And you wonder if the place has eroded.

--Debbie David

THE RED SHOES

Your ribs like leather serpents writhe beneath the trunk of your tired, bewildered body. They are hissing softly, wrapping gentle whispers around your lungs.

The muscles of your buttocks have turned to onion lumps; each layer, when peeled a way, reveals another, calloused and smelling of the earthy darkness.

Dance onward little girl -you snatched the greedy magic of those pretty crimson shoes. You believed that happiness was sealed in color -but those burnished flames licked your toes with the crooked tongue of death.

--Katherine Henry

Definitions of Poise

I believe I can give adequate definitions of 'poise' because daahlings I've had to cultivate them for survival. Poise is being able to sit at a table with five Tunisian self-made millionaires in a Paris reslaurant: to be able to sit at the table after an exhausting day around the Louvre, the metro, L 'Opera, the pick-ups, and listen for hours to dynamic French-Arabic business talk of lhe Paris garment district of Tunisian escapes: to be able to sit there and look interested in a dress that is not at all chic and Addidas sneakers, with cropped hair and a growling stomach-BUT to sit there and look interested when YOU DON'T UNDERSTAND ONE WORD ANYONE IS SA YING!

Poise is when five Tunisians, yourself and your brother are sitting in a four seater car and conversation comes to an abrupt halt because they all want to hear you sing-preferably something zippy and with a beat. (Saturday Night and I Ain't Got Nobody would you believe'?)

Poise is being able to sit at a dinner table with six 35 year old Zurich artists who speak minimal English-to sit there with a hopefully unglazed look in your eye after a seven hour train ride from Paris, a swim in Zurich See, and absolutely exhausting.cry and too much wine-But to sit and act as if you understand or are really interested in what's being said (Which I was).

-H. Christie Prince

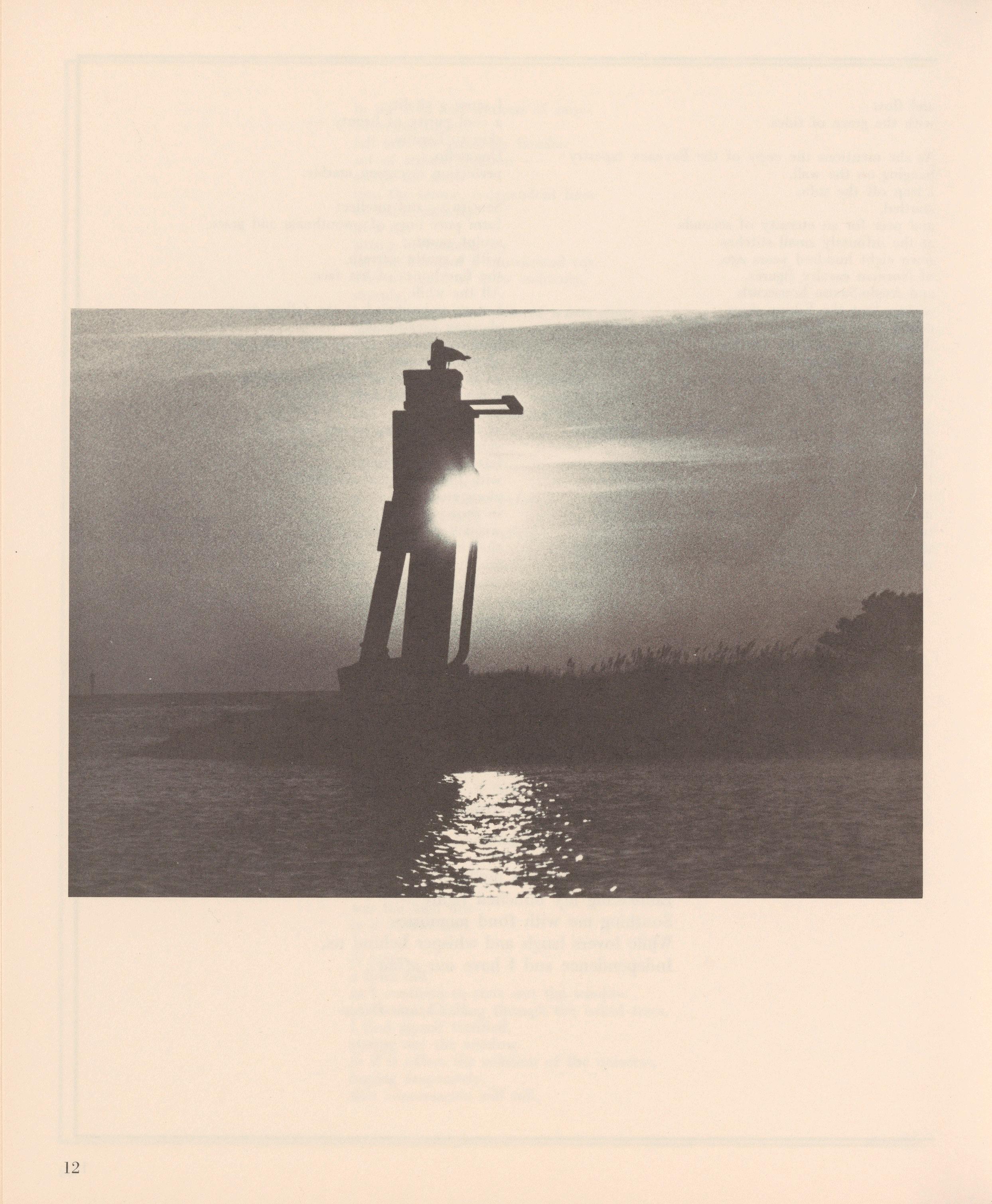

On Leaving Inverness at Dusk

Smoke curls ethereal, dissipating in the stillness, whispering voiceless in the stale air of a second-class British Rail compartment.

Waiting, claustrophobic, I gaze blankly and nauseated as the harsh rhythm of the train rolls jolting and unceasing.

Tracks stretch endless, implacable, inexorable, through the wild impervious grass of Scottish lowlands. Steel burns steel in harsh solitude, over rough lushness of Celtic hills and ravaged moors, through the sluggish blackness of industrial night.

Waiting, in silent frustration, I sit cramped in the mustiness, waiting, perhaps for the winter sun and bitter cold to move through the smudged window grime, a window permanently fastened a window perhaps like the murky bitterness of lukewarm coffee sitting on tables with cigarette stubs and ashes, reminding one that after the party are the empty bottles and sticky glasses.

Outside the train, the sleeping lull of bitter cold purges.

I recall a lyrical essay on leaving Prague by train: smog and filth receding, leaving something, perhaps light, about to break through.

Glenn Court

Keeping himself busy he walks slowly across the room, To re-adjust his pictures on the wall, And put his pencils back in the proper can. It kills time,

He says to himself in a frozen breath, Turning away from the desk to sit in his rocker. Rocking back and forth, hours a day, It kills time.

He goes to his small kitchen and pours out Another can of pork and beans, Heats it, Eats it, and belches softly as he says to himself in a whisper, so he won't disturb the cobwebs in the dinette, It kills time.

He goes into the bedroom and shucks off his ratty corduroys, Brushes his teeth, Puts on his flannel pajamas, Falls in bed, Turns the cap on the bottle, And kills himself

Stephen McMasters

Indifference

He looked up at me and said "Why?"

I said, "because."

He asked me, "Did I love him?"

I said, "Of course." He smiled.

I smiled back. He was there. I was here. I walked, he followed. He died, I read about it in the newspaper.

].A. Hanau

Lamentation

This is the city of charred remains (search her squares to see if you can find a man-)

The sound of wailing over the plain quivers echoed in the gut-strings behind the eyes of agony.

The cut stone cisterns that we hewed out are poisoned with the dust of death. The adders inhabit the crumbling remains these are the adders that cannot be charmed these are the adders that feed on the dust.

(-and what of the fountain spring, lively and cool and what of the sun in the jungle pool?)

The desert jungle women rise weary and late, wear tinkling gold anklets and bracelets and crescents carefully applying bright henna to hair, painting the eyelids with ochre and sootthese empty hollows once were their eyes. They wrap their hips with filthy rag skirts and go forth to seek water (the cisterns are poisoned) and to seek men, and to seek bread.

They wait for a visitation of quail, of turtledoves, swallows, and cranes in their season; the fowlers however with insidious nets basket the birds.

The women have nothing to give to the children but anklets and bracelets and crescents of gold. Gold powdered in water is unhealthy for children; if you feed them gold powdered in dust , they will die.

(hear them cry as the children die the sound of loud lamentation in Ramah Rachel refusing to be consoled)

A sorrowing sweltering sky enfolds the land with a shrill overwhelming cry. In the shadowed city the adders hide burrowing surreptitious holes.

(-where are the souls of the dead men? -lapping the sterile sand.)

Sudden and deep the thunder spoke the brass bowl broke slashing and soaking the dead earth, filling the hollows, purifying the stagnant pools collecting in the broken cisterns' mire, coming to one with the ancient pool

(-and the lotos rose, quietly, quietly, and the surfaced glittered out of heart of fire.)

Ann Bennighof

DINNER

What am I doing here? I am fully thirty years of age, yet I have never learned to refuse these idle invitations. But Elizabeth insisted, and there she is clear across the room, while 1 am alone with

" ... Helen of Troy. Zeus! Not even Homer himself had the skill to evoke the image of this woman. There she sits beside me, flanked by brave Agamemnon, and she is to the others in the room as the full moon is to the spark of iron on stone. Truly, I think that the launching of one Lhousand ships was a miserly act in light of those wondrous features."

Lord, I've been dreaming again. Did this woman say something about the soup? Yes, it's good, it's fine; just spout an automatic response. This is why I hate social gatherings at private waterholes. I am invariably stuck with some plump matron who wanLs to make small talk. No wonder the human race is going to hell in a handbasket, when all the great minds of the age are assaulted by drivel from all sides. Gad, there she goes again! Yes, it was good. IL was terrific. IL was superb. Anything to silence you.

Ah, here comes an en tree. Perhaps she will receive a triple helping which might possibly fill her mouth and keep it shut. We are served, and it is fish ...

" ... from Lhc waist down. From the waist up, I see the most magnificently proportioned human bodies my eyes have ever beheld. Their faint greenish cast merely accentuates the volumptuous curves of Lhe females, the hardened thews of the males. With eyes of clearest amber, they waLch me as 1 watch them. And suddenly, 1 realize that they cannot live out of water. Soon Lhey will die, and it will be Lragic."

Hmm. I have Lhe distinct feeling thaL the woman on my right asked me a question. FurLhermore, I am fairly certain that I answered it. Did I say, "I like fish"? Did I ask if she likes fish'? Does iL malter? She does have a decidedly bemused look on her face; I hope I wasn't babbling.

Except now I will have to babble, because she is interrogating me about my culinary preferences. Yes, I like cucumbers. Yes, I like potatoes. Do you like potatoes? You don't ...

" Bu L lad, we haven't had a drop of rain these seven years. The barley won't grow, the kine are dying and it's getling hard to find clean drinking water. All we have left is potatoes, lad, and you say you don'L like them?"

She's staring. Now she asks (again) about cucumbers. Sure, I like cucumbers. Still.

l see Elizabeth gaily chatting with the gentlemen on her right. At the moment I am Lhoroughly galled by Lhe realization that my own sister is comporting herself in the same manner as this dinosaur beside me. In facL, I am quite angry. Must all women be brainless? Is Lhere no hope? I believe I will relieve my aggression by assaulting this fish. With uncharacteristic savagery, I thrust my gleaming knife deep in its vitals ...

" ... Lord Rast steps back, astonishedmenL written on his face. With three strokes faster than his eyes can follow, I have knocked his epee from his hand, cut his purse from his belt, and flung said purse to a comely maiden at the table. Rast runs out of the room in disgrace. Honor satisfied, I return to my meal. An awe-stricken serving-boy offers me wine, but I refuse it. I am mindful that the cowardly Rast and his associates will be preparing an ambush, and I musL needs keep me wits about me."

No, I don't think I'll have any of this wine either. Of course, it is too late to be concerned about ambushes; this woman has already mauled me tonight. But wait, it isn't Loo late to save the rest of the evening. Where did I read that article? Yes, I remember now. After the meat dish, I can rid myself of her. I must be careful not to be overanxious and rush through Lhe meat; Elizabeth would never let me hear the end of it. Ah, here's the salad. Now I spring the trap. The history of nutrition is a fascinating topic, but women cannot abide it. Yes, it's working; she does not want to hear it. 0 merciful heavens, is it possible? Could it be? Yes, she is Lurning to that beefy lout to her right? At last, I am undisturbed ...

" ... There is no breeze. The pennants droop in the humid air. Yet I remain rigid as iron. l close my helmet visor, lower my lance, and charge."

Jim Cumbie

To Albert Beguin

Sometimes words must wait oulside on the doorstep silent the clumsy shoes that broughl me to this luminous place.

Ann Bennighof

Rose

Rose slands in front of the mirror

Out of habil, no longer bothering lo look

How her hand paints her lips

Thal shade of red which she is known by. She drinks black coffee feeling

Thal nothing will ever wake her up And bu llons the house coat

That she wears oul of modesly

Even though no one is there. The morning paper has nothing lo inleresl

Her, the comics flashier lhan even her Clothes, and the obituaries not Printing how long she has kepl alive

The passions of dead men. She goes lo lhe window and parting

The curlains, she counts the four floors

Down to lhe children in lhe streel

And wonders if they see her as she Sees herself, jumping from lhal window

A hundred times a day and sealing lhe Wooden walls back to the top, Doing it again and again,

Or if just one might see her slanding On the ledge and suddenly ex lending wmgs In flight.

Debbie Darid

The subtle minutes of time and madness that wax and wane with the effortless grace of the moon have gently forever obliterated the tragic futility of a youthful despair that sat for years like some silver shilling, some British coin, heavy and useless on a bare table in the hills of South Carolina.

What is left of that weak and pleading sadness is only an aesthetic merit, and poitnant but fading memories of London's gray rains.

I need no longer fear the aged contentment of those small New Jersey towns that lid in the arm of an Atlantic cape, passively receptive to breezes that blow from the sea, rolling salt and moisture down the silent breadty of Victorian streets.

Faintly weary of this bitter winter I sit alone in an echoing farmhouse, gazing at burning logs and thinking of spring and summerwhose lush green cool and shade shall sway silent and seductive over memories of ice and snow and Handel's water music, but whose sun shall never glimmer so strong and piercing as it does in this January sunset over the frozen waters of rivers and iceglossed snow.

Glenn Court

A Life Without Hope

He stood alone against the cold. Around him a sea of snow rolled and dipped until it broke upon a pine forest. Clinging white crystals drifted past his face, catching hold of his bushy red beard and making him appear older than he was. His face resembled a mountain carved by time and the elements; his eyes were two glossy black stones left by a glacier ages in the past. Encased in a huge coat made of bear skin he .could easily have been mistaken for the creature at a distance: more than once such a mistake had almost proved fatal. There was no sound, save that of the wind sliding through the forest and the thump of individual flakes against the knee-deep snow ocean. The quiet roar was almost deafening. Exhaled breath hung frozen in midair before falling with the snow and diffusing into the white sea. Ahead of him lay a rugged mountain chain thrusting up through the clouds where its peaks were shrouded in a gray-white void. Night was fast approaching; the pale light of day was dissolving into darkness. From behind, the direction of the forest, came the rhythmic vrunch, crunch, crunching of boots in the snow.

"Hey Hawk!"

The voice belonged to the owner of the approaching boots. Hawk did not move; he kept his gaze fized at the sky. In another moment there was someone at his side.

"You won't do any watching tonight with the storm Hawk. I don't even see why you waste your time. No one's ever going to find us."

"They 'II come."

"That's what you've been telling us for years and we're still as marooned as we ever were. Did you realize we've been on this planet twenty years come next week? Twenty years! Think of it!"

"Twenty years is a long time."

"It sure as hell is! I frankly have my doubts that we 'II see twenty-one."

"Come on, let's go inside."

Hawk watched as Palmer struggled through the drifts back to the forest. Could it really have been twenty years? Palmer's hair had turned white long ago and his shoulders had slumped. He was wearing that same old parka randomly covered with odd patches and on his left breast was the faded emblem of the Federation. There weren't very many others left anymore and most of those were old and tired; there were few children.

"We brought in your telescope," Palmer called over his shoulder.

Hawk could see the cave entrance just ahead. It had been modified when they first arrived and now had a steel wall with viewing ports and an old air lock door from the ship. Its snow covering reminded him of melted sugar on a hot Danish sweet roll. Snow. Had there ever been a time on this planet without snow? As he entered the door he could feel a wall of warm air sting life back into his face.

Inside was a large room with rock walls. Several passageways had been cut into the cave leading off to a honeycomb of chambers. There had been a time when

everyone had his own private little cave, a little comfort on a savage planet until they were picked up by another ship. But another ship never came ... now just a handful of dwellings were occupied. In the center of the room was the communal fire, the center of their dying culture; the place where they first did their cooking before the kitchens were built, the place where they held meetings, where friendships were made, where love was whispered, where memories were endured. The fire was slowly burning out. Fire light was their only illumination in the great room at night; there was something warmer, more human about a fire than with the artificial-light panels. Hawk walked over to the fire and took off his gloves; he could feel life flow from the fire into his hands. He flexed his fingers and rubbed his palms together.

From across the room came a young girl. Young girl? It was Helen, she was almost twenty now, almost as old as their ordeal. It would probably be more appropriate to call her a young woman, a beautiful young woman. She had short dark hair and a shapely mouth that always wore a trace of a smile. Her eyes were soft velve-brown; they used to sparkle when she talked, but not anymore.

"Hawk," she said quietly, "my father would like to see you; it's very important."

Her father was the Captain, their leader. The Captain was old, a fading reminder of a distant, faraway past and to some the symbol of a fruitless struggle.

"Tell him I'll be there in a minute."

From somewhere waybdown by his feet he could feel a little hand tugging at his pants legs; there was a motley group of children staring up at him.

"Tell us a story, tell us about when we first came here," asked a little boy with blond hair and a runny nose.

Hawk smiled and bent down, "O.K. Rufo, I'll tell you all about it, but you 'II have to wait until after dinner."

"Will you tell us all about the space ships and the war and the giant bears and why we call you Hawk?"

"Right after dinner."

"You promise?"

"Yes, I promise."

"You won't forget?"

At that moment one child's mother approached, "You children run off and play, stop bothering Hawk." With that the children scattered like a pregnant dandelion before the wind. The woman, Catherine, moved in closer to Hawk. They were about the same age, Catherine being somewhat younger, but she hardly looked as though she was out of her twenties.

"They like hearing the story come from you so much more than listening to the tape library," she said with that bewitching smile of hers. She watched him with seductive green eyes that made Hawk feel uneasy. "My husband has been gone a long time; it's good to have a father figure around for my son."

"A father figure?, she means to make me his father," he thought. "Still, it might not be so bad." He had been

married once, long ago, in the beginning. What was her name? Sharon? So long ago, almost eighteen years. They were both so young and alive; there was still hope of rescue and a strong will to survive. He was glad that she didn't live to see that spirit wither in the snow.

"If you step into my kitchen, I'll fix you some coffee," Catherine said.

"No, I've got to see the Captain, but thank you anyway," he said. The huntress would stalk him quietly and try again.

Hawk entered one of the passages. The bare rock walls arched over his head giving him the feeling that he was back on the ship again. Light panels smiled down from above with their cold impersonal illuminations; occasionally the passages were carpeted. The doors to individual dwellings were recessed into the walls; usually they were left open since the heating unit for the complex kept all living parts of the caves at the same temperature. The caves were warm, each like a lighted womb. There were not so many open doors now; most of the dwellings stood frozen and empty far off in darkness. The settlement at first had been a sprawling little community, but as time passed it resembled a pond drying up; its edges crept in toward the center , leaving the outerhomes silent and barren. Ahead was the Captain's door, closed and in shadows. Hawk tooks a deep breath and exhaled, then gave the door three sharp knocks .

Helen let him into the room. The miniature cavern was dimly lit by several orange-yellow glowing spheres; Hawk could sense a heavy emotional drain as he passed through the entrance. Through a smaller doorway on the right he could hear a weak call.

"Hawk, is that you?"

"Yes sir," he answered as he entered.

Before him lay an old, old man imprisoned in his bed by failinghealth; near the prisoner stood another glowing sphere, perceptibly fading. Helen entered silently behind Hawk and sat down in the shadows to listen.

The Captain looked at the big man in the bear skin and produced a weak smile, "Going native, eh?"

Hawk managed a slight smile also, "That's what anthropologists are for; that's why every major space vessel was required to carry an anthropologist."

The Captain lost his smile among the sour wrinkles of his face. He was old for this planet; no one else was as old as the Captain. His skin was dark and withered; it stuck to his bones tracing every detail of his skeleton. He reminded Hawk of the mummies of Earth, dessicated, wrapped in sheets and surrounded by canopic jars. The Captain spoke again.

"There were four hundred and thirty-seven of the six-hundred-man crew that survived the battle and all of those landed safely on the planet At first we were alive, we could survive because we knew that we would soon be rescued. We lost few in those early years."

Hawk thought again of Sharon and how she had looked lying in the snow pale and frozen. There were tiny flakes dotting her face and her eyes were closed as if she were only resting beneath the trees for a little while; that had been less than two years after they had arrived. The Captain resumed,

"I watched our spirit begin to drop after seven, eight , and nine years passed, and I saw it disappear that tenth winter when fifty of us died. There are only about fifty-five

of us left now from the original crew and another twenty of our descendents. Hawk, I'm old, too old, and my hope is gone now too. Fleet Command might think thatour shop was lost with all hands, perhaps it was; but there is something else to think about. "Our side may have lost the war. It is possible that another ship may not pass this way for several thousand years."

Hawk died a little as he watched his leader crack and crumble into dust.

"Don't think that way Captain, don't lose hope; it's the only thing that will keep us alive. You 're sliding like the others, don't let go!"

"It's too late for me Hawk; I won't make it through the winter. I'm putting you in charge now. You 're the only one of use left who really believes someone will come looking for us. You are going to have to convince the others to keep on going or you 'II be the last survivor. The Captain paused a moment to collect his thoughts. "The power supply will last another twenty years without any trouble. We have fresh water to last us as long as we wish, but you 'II have to watch the food supply." The Captain glanced at a dark form hidden in shadow, his daughter. "Come a little closer Hawk." Hawk knelt down to listen to words meant for his ears alone.

"Hawk, I don't think I'm going to make it through the night. When I die Helen will be alone . I want you to take care of her. You 're the closest friend she's ever had. You are like an uncle or an older brother to her ..promise me you 'II take care of her." There was a tension in the Captain's face, his last traces of energy.

"I'll take care of her Captain." The old man relaxed and closed his eyes.

"Goodby Captain," Hawk whispered.

Hawk look over to a quiet form clothed in darkness, Helen. He had known her all her life. Years ago she had been an ugly little baby, the first born of the colony. There were few births in those early years when rescue was just around the corner. When she was small, he used to make toys for her and occasionally take her out to play in the snow. He could still remember the two-headed snowman they built when she was seven. As she got older he was her best friend; she would come to him to talk, everyone else being too old or too young or too something else. She had come to him when her mother had died five years before, and she would come to him again when her father died. She was a beautiful young woman, so much as Sharon had been; he could see similarities between the two. Similarities ... there would soon be a great similarity between Helen and himself; they would both be alone. He suddenly realized an aching emptiness and a sympathetic desire to grab her in his arms like a child to comfort and protect her. As she walked into the light, pale liquid shadows slithered across her in silent animation. Helen put her arms around him and placed herhead on his shoulder. Hawk held her close, "He's asleep," he said and rubbed her soothingly. Feeling her soft warm body beneath his fingers, he found it difficult to suppress sensual thoughts and replace them with something more appropriate. They stayed there together for a few moments. She had inherited such a tragic lonely life; he had to keep her alive, give her something to live for ...he had to give everyone something to live for. Hawk could see that she was tired and upset, "Let's get you some dinner and then you can lie down and rest," he said.

They had a quiet dinner together and afterwards

Hawk made sure that she went to sleep. He left to keep his appointment with Rufo and the others around the fire.

They sat around the circle of light, ten little sets of ears listening to Hawk tell his stories. The fire was low and, except for the center of the room, the cave was dark, hiding an older audience who already knew the stories from experience. He told of great planets and war; a religious crusade that swept across half a galazy. He told of how their ship, a battle cruser, had been attacked; the fight was brief, but it began a week-long running battle that took them to the edge of an unknown star system, ending in a showdown. Each ship was alone against the other, alone and far, far away from civilization, alone and far, far away from wives and lovers and children and trees and grass and flowers ... and life. Two great dragons breathing fire and death, impatient to draw blood, the ships tore at each other. At first the defensive shields held out, but soon they weakened and each scratch, each tear, each sting could be felt. Then they ripped huge gaping wounds in each other that bled a corpuscle al a time. There were long streams of dead corpuscles, dead humans £loathing through space, their bodies turned inside out by the vacuum, no longer human. Their ship finally dealt a death blow; the enemy ship was killed. Gutted, its black insides hung out like the other dead things that surrounded it. They searched the wreckage for survivors; they found none; survivors are never found in space after a battle.

Victory had not been cheap: one hundred and sixty-three had died and the ship was damaged beyond repair. They found this planet, the only one in the system that could support life, in case they had to abandon their shop. They turned on their distress signal and waited. After several months it became apparent that the ship's orbit would decay and the remaining survivors would plunge to a firy death in the planet's atmosphere. Work was begun immediately to build a home on the planet where they could wait to be rescued. The ship was cannibalized and all usable parts were salvaged. When death did come to the wounded warrior, it consumed barely a skeleton.

Life began anew on the planet. It was cold, bitter cold, deadly cold. There was no way that a village of houses would survive, so they burrowed underground. With entrails from the ship they made a subterranean city with all the conforts of civilization. And then they waited, and waited, and waited ...The distress signal had been screaming for help

for twenty years and no one listened, no one heard, no one answered ...And how did Hawk get his name? From watching, every nigh l with his telescope, every day in the forest. He saw everything: "eyes like a hawk." And the giant bears?

It's getting late children; come to bed," said one of the parents. "You can hear about the giant bears some other time." Slowly amid groans and shuffling feet the cave emptied.

Hawk sat alone looking into the fire, watching it die out slowly. Helen's approach was almost silent. He felt her tense grip on his shoulder. She was trembling.

"He's dead," she whispered.

Hawk turned and put his arms aroundher. "All right, all we can do for him now is to bury him."

They returned to her dwelling where they bathed the dead Captain and clothed him in his old dress uniform with its medals and ribbons, those that marked the seventy years of his life. They took him back into the depths of the cavern, back into the place where nobody ever went, where it was always frozen, back with the others. The Captain seems very light to Hawk; it was almost as if he were carrying a sack full of bones instead of a person. They entered the tomb. Around them were most of the dead of the past twenty years waiting to be returned to their home planet for burial. Waiting silently against walls, silently in rows, silently in death for someone to come and bring them back to wives and lovers and children and trees and grass and flowers ...Somewhere hidden in darkness among the dead was Sharon, still unchanged from the last time Hawk saw her frozen in the snow, still asleep, sleeping with everyone else, forgotten but not gone. He returned with Helen to the fireplace where they sat alone together watching the fire fall asleep.

"We have each other," he whispered, "and that will keep us alive."

They were silent for a while and listened to the fire twist and crack and burn.

"Do you really think anyone will come for us?" she asked.

"They 'II come," he said as he placed another log on the fire. The flame brightened and grew. He crossed the cave to one of the viewing ports. The clouds had passed and above were a million stars. Anyone of them could be a spaceship on its way to rescue the survivors.

Ralph Porter

"Let me advise you to study Greek, Mr. Undershaft. Greek scholars are privileged men. Few of them know Greek; and none of them know anything else; but their position is unchallengeable. Other languages are the qualifications of waiters and commercial travellers: Greek is to a man of position what the hallmark is to silver. "

George Bernard Shaw: Major Barbara