Sponge Layer Cake

By Frank Cervarich ) Jr.

Sitwell Fletcher at his rather-too-much desk; scratched sharply his crispy pen across obscure invoices and obsolete triplicate forms. Blue piles, red piles, yellow piles with hill-lets of pink, white, and green sheets mounted orderly before him . He leaned back, taking a smooth, slim cigarillo from his pocket; punching it emphatically into his soft-skinned resolute jaw. Reaching for a match in his vest pocket, he eased his Ben Franklin glasses down his slender sharp nose He replaced them with a squint and a forefinger. The room was steel gray, business-like The steel-hard gray metal of his desk and file cabinets were contentment, horrifyingly so. He stared at his do o r blankly, looked at the wall opposite his cabinets on which he had placed his degree in Chemistry from Pennsylvania State University, as well as his masters from Lehigh University, and plunged down to work in his shirt-sleeves-rolled-up-for-action attitude. The bare wall behind him hung ponderously. The silver chroming on the desk and cabinets shone, demanding note. The void-air, businessworld atmosphere stood like pillars before him. He rubbed his eyes, seeming to be a man who had put in a hard day, possibly an equally hard night.

Caldwell Peyton sauntered into his office to fill it up somewhere with his insolence . Sitwell, hating to be disturbed at work, particularly by Cal Peyton, jerked up his head, scrutinizing . The young-executive-on-his-way-up, complete with Ben Franklin glasses; cigarillo, in the manner of John F. Kennedy; mustache complimented by long-well-groomed hair, the mark of a true cosmopolitan; and well tailored clothes, distinguished citizen that he was. For Cal Peyton to impose his insultingly-impetuous, stocky form before Sith Fletcher was royal impertinence . "Yes?" What can I do for you, Cal?" Sitwell ground out in jagged shop talk, griting into the insulting "yes ."

Cal, not ever ruffled, possibly inspired, grinned. "Fletch, got this hang-up in the lab. What with you being the top dog and all, we decided to consult you before presuming to use our brains to make a decision."

The tip of Sitwell's cigarillo, temptingly wet and alluring, when bit into was sour paste. Coffee grounds of tobacco dissolved in his mouth. Bitter tasting Cal twisted his mouth, destroying his secure pleasure.

Cal on the other side of the desk with his blunt form hunched and swayed from foot to insubordinate grins.

"What's the trouble, Cal? The equipment? Chemicals? What?" Would Cal ever be defensive?

Cal answered slow and unconcerned; his arm bent stiff on Sitwell's desk. Sitwell distinctly wished he were in his native Boston. At home he could anger freely.

"Seems somebody pulled the wrong switch monkeying around. The whole generator's all shot to hell." "Hell" waved Cal's arms in the air and shrugged his face. His shoulders were soft puddles of insolence.

"Hell" rose Sitwell from his desk before he allowed himself to answer. Bluntly he wished Cal would come out into the open. He hated unresolved conflicts; Cal hung on quiet and discouraging. Sitwell wanted to smash Cal's head into the toilet, shouting, "All right, what's your story? Come clean."

"What seems to be the problem, Ed?" Sitwell breezed into the lab toward his right-hand man, Ed Demsey. He asked ignoring Cal's knowledge. He asked even as the wearily grinning Cal shuffled back to his work table.

"Well, Sith, looks like we have a little power trouble. You know what that'd do to the Taylor experiment. We're supposed to have that material ready to program by Monday."

Sitwell nodded wearily. He was running through his mind possible imperfections. If he and Ed could figure the machine out, he sarcastically mused. They couldn't afford to call in repairmen at this stage of the game. "Well, let's you and I see if we can't qualify for an electrician's job. Who knows, if I can figure this thing out I might become a mechanic. Can't beat the. pay," Ed launghed.

Cal watched with an amused smile on his face, an insistant disturbance to Sitwell. Experimental Incorporated would have , enjoyed seeing two of its most highly paid chemists jabbering over wire connections and fuses. Sitwell's face doggedly held a tight-skin grin.

The machine flicked on near closing time. "If we ever have

a lag, we should get that thing fixed "

"If we ever have a break, you better start worrying about another job. Experimental doesn't like idle hands," smiled Sitwell in his be-pleasant-to-employees talk.

Ed laughed; Sitwell lite another cigarillo . He offered Ed one "No thanks Takes more of a man than I am, I suppose, to puff on one of those things ."

. Sitwell puffed, making small talk over Ed's family and children. He was not married. Once he had been engaged; it had never worked out. The smoke in his chest was painful. He wanted to cough.

He ambled back to his office , nodding officially to secretaries and clerks, the machine man. As he entered his office the five o'clock whistle went. He looked at his watch automatically hoping an empty five o'clock hope and sat down to his desk . He still had some work that had to be done . He resumed his pose, with strained intensity; an executive at work .

Into his black hardtopped XKE he slid . The inside shone mahogany panels, leather dash and seat covers. He was still paying for this machine, but he didn't mind . He smartly turned over the engine and flicked on his FM radio . Grinding into first gear he smoothly, majestically, powered off. He lit his third cigarillo of the afternoon.

Traffic zoomed by on the turnpike despite the hour . Richmond, Virginia, was becoming quite a little metropolis. It wasn't Boston but . . Sitwell sat very straight in his bucket seat with his pointed cigarillo straight, perpendicular out from his body He was erect and attentive yet not unnatural, similar to a military school graduate who naturally assumes an attitude of command. His XKE steadily ate up the road . He was a conclusive picture of Amer:.can success, even international success. His hair, his suit, his mustache, his car, his cigarillo, his radio, his job, his education in the North. He gleamed rich-clean pleasure in himself.

A large frame house well over two hundred years old . Wood frame painted white with large blue shutters . Hardwood floors glistening with polish. Silk curtains drapped royally in large blown-glass windows . Williamsburg furniture and Queen Anne accoutriments tastefully filled a two-bedroom home. There was even a large fireplace in the kitchen, brick with swinging steel accessories cleanly painted black . The sun conveniently settled behind this house as Sitwell pulled into the driveway. Brahms was busily wailing on his FM md io . He pulled satisfactorily on his cigarillo. His country home . "Good evening, Edna. How are you tonight?" jauntily asked

Sitwell, posing; passed Edna, the efficient colored housekeeper in the kitchen . He had come in through the garage entrance.

"Everything's fine, Mr . Fletcher. I fixed for three like you said. The Williams' are still coming aren't they?" She asked from her well knowing eyes, tinged with an indescribable Negro face .

Sitwell nodded, looking through some mail left by the post. " Yes We'll have drinks in the parlour before we eat. Oh, and see that there's no vinegar in anything . Mrs. Williams has that allergy if you'll remember ." With this Sitwell chuckled in their private joke over Mrs. Williams, hopefully embarrassed before those that knew him too well. Edna, still viewing the eruption of Mrs . Williams on that particular night, laughed for Mr Fletcher .

"Yes sir, I'll see to it," she giggled .

Sitwell nodded, leaving the room. Edna had little or no accent supposedly common to Southern Negroes. Another time, honored legend smashed. He wandered into the den and mixed himself a drink, then went upstairs to wash up for his guests , trying not to begin to wonder what he was thinking

"Vivian, charming as ever," slightly too energetically spoke to Sitwell as he pointed himself toward the bar to mix his third drink . "As my delightful mother often said, 'The woman who looks charming to a man before dinner, directly that is, is either superior or engaged in an affair with the beholder.' I believe that is how she put it. My father never commented, of course. He elucidated on Wordsworth and Coleridge for some reason."

Vivian Williams tithered in a large loving seat , drawing up her delicate arms in modesty. "Sith, you are such a tem:e I can't see how your employers allow such a flatterer to remain hidden behind test-tubes and paper reports . They really are losing quite a delightful chance for appealing to the feminine market, if there is such for them ."

Sitwell stared out at Vivian, his near-forty companion still hanging onto her girlish figure probably through painful dieting and excruciating exercises Sitwell almost smirked as he pictured Vivian straining over sit-ups and push-ups. Jeffrey Williams leaned ponderously against the mantle before the fireplace, holding a drink before him His huge frame, much like the football player's body he had used in college, bulged, temptingly gutty. Sitwell could feel Jeffrey's weight and height shadowing him across the room . They formed a pleasant triangle . The fire cheered the atmosphere delicately . Sitwell's well-proportioned physique glowed with the warm settling of fire-drinks .

"I always have wondered whether you really do work as a chemist, Sith . I always picture you pulling up some archeo..:

logical discovery in Southern Rhodesia or some place that proves man had handmade artifacts sixty million years ago or whatever. Are you sure you're not pulling our legs?" asked the red, puffed cheeks of Jeffrey across the room .

Sitwell smiled at his two admirers whom he had asked in to keep him company. He did tire of them quickly, but they were constant and so faithful. He laughed for them and prepared one of his charming repartees. "Father often urged me to take up the . study of Biogeography. I have never failed to be amused at his incongrous hittings upon flat statements of logic He described to me most vividly several times the delight in tracing the path of the horse around the world, of following the sycamore in fossils. It appeared to me to be some strange form of art, maybe nature's expression. Maybe just to have sport with us, nature scratched etchings in rock and coal that resembled plants, forna et flora." With this Sitwell waved his drink in the air. His elbow was resting on the arm of a tall, straight-backed chair. He sat poised and sauve in his home surroundings

He mixed another drink and sat down

"You can eat whenever you've a m ind to, " announced Edna.

"Shall we remove to repass," waved Sitwell as he came from the bar with a straight Scotch and ice, the glass half full. The Williams' formed themselves in, surrounded by the sweeping-arm invitation of their clever child, Sitwell They had no children of their own. Vivian often worried over the welfare of young Sitwell. There were afternoons when Sitwell would bare his chest to her; these were the days she most enjoyed. Jeffrey swayed in his big man walk into the small dining area, seeming to emanate destruction for the cherry wood dining table at every step. They settled themselves over their eight o'clock meal.

Sitwell caught Edna 's eye before she left the room . He asked quietly, "Some dinner music and the scotch, please, Edna ."

Edna nodded and waddled out of the room, disgust mounting. Mr. and Mrs Williams exchanged concerned glances. Sitwell was a nice boy, but he did drink . Mozart came through the chambered speakers into the dining room, milling and swaying. Sitwell smiled in approval, downing his scotch. Edna came in with the now half-full bottle. "Thank you, Edna ."

"Sith, don't you ever consider getting married?" asked Mrs. Williams innocently as the meal settled down . "I mean, you seem to have about everything that a man could want except a mate to please him. Haven't you ever considered marriage?"

Sitwell raised his glass presumably to the glory of womanhood, their stick-togetherness or some other quality innate. Once, my charming belle of the Southern fields Once , my elegant flower of lily fields Once , my julepy-spiced one. Once I was engaged."

There was an expectant look on Vivian's face . "Was she not worth your charm? "

"She was , my dear. She was worth m y charm and more She was the pearl of quality She was the flawless diamond She was the emerald so radiant that others appeared as stones ."

"Oh, Sith You and you flowery speech What happened?" asked Mrs . Williams curious, enchanted by the radiance of young Sitwell .

"She, my dear Vivian, still waits. Yes, that's right. I suppose I could call her this moment and marry her this weekend. She's still in Philadelphia unmarried. It is rather a shame to let such a captivating women go to waste ."

"Why haven 't you called," bluntly asked Jeffrey, leaning over a forkful of asparagus hollandaise

"I wonder . I wonder, I reach for that phone often. I consider the process . I am not sure what holds me back. I fear

partially that I might destroy her by captivity She's a very delicate hothouse bud . She would die in most climates. She requires careful attention. I do not wish to be the death of so pure and unmatched a specimen of sensitivity . I would rather crush out my own life than see her ruined by some inadvertent blunder on my part, some idiotic mistake that I make in all good faith. Yes, I still consider mating with her. There is a membranous link between us that defies definition. We will never be able to love another person in just the same fashion . I often wonder, my dear friends, just why it is that I have never married the sweet, the fair, Ellen . For that is her name I wonder often." With this Sitwell gave a sad smile to his friends from his filmy brown eyes full of some bubbling fire, awkwardly resembling flirtation.

"Oh Sith , that's a lovely expression of your emotion . You really should set down some of your thoughts. I know that you could sell if you only put your mind to it. He's so sensitive isn't he, Jeff?"

"Yes, my dear, of course . Young Sith has quite a talent with words, especially in bachnallian ." With this Jeffrey masticated a heavy morsel of the steak covered with mushrooms and wine sauce. Sith's eyes were dulled and vague now This scene before him would not reveal emotion . He had to approximate.

He poured himself another drink . Was this his fifth or sixth? The bottle was less than a quarter full. He never remembered consumption of alcohol.

The meal consumed, they sat around the table over creme de menthe. Sitwell spoke "I recall a charming account of Albert Einstein when he was young It seems that he was a rather neglected youth. No one paid much attention to him. He was considered a dull child. He never spoke much He was constantly in his room alone . He cared little for dress His hair and body were often unkempt. One day he went to school. As with every day, the students taunted him . He ignored them as usual. They did such things as trip him and generally harass him You know how young children are, quite heartless, you understand, despite what is popularly believed about them . I should know . Einstein was failing math I imagine everyone knows that. Our answer today in all our wisdom was that he was bored. The story to prove this is what I'm trying to tell. It seems he was sitting there one day in class and the teacher called on him to work a problem on the board that they were supposed to have done just prior, by the teacher's request. Usually Einstein watched the rest work This time the teacher noticed him bent

intently over his work, so she called on him to see what he had been doing; having never reached him before, she wondered naturally. She wondered many things, as we can well imagine She was probably surprised to see that he even comprehended her question . She was probably wondering if he could wield a pen . One can imag ine the smugness of the teacher calling young Einstein to that board . Einstein, ignoring both the whispers of his classmates and the curiousity of the teacher, went to the board without a word He scribbled some figures, a few equations, and an answer up . Everyone watched and then watched some more . You see the figures and formulas were incomprehensible to all of them including the teacher. She scowled Einstein for his foolish attempt to trick her and the class. Einstein sat down. The truth, the tale tells us, is that the problem was correct with Einstein's variations Can one imagine oneself in that position, frowned on by foolish mases . I like to enjoy what I read, and this story amused me greatly I think it could be employed as a fairy-tale in the future to remonstrate fools and churls."

Mr. and Mrs. Williams smiled indulgently . Mr. Williams nodded at Mrs . Williams "Shall we go into the parlor?" spoke Sitwell cheerfully before they could act . The two sheepishly followed poor young Sitwell .

As Sitwell was seemingly organizing himself for another soliloquy, the front doorbell rang. Edna came in. All turned expectantly to see behind Edna a young man of about twenty come into the room . He was a comely youth, somewhat effeminate, with black curly hair and pale complexion . His clothes were exhibitionistic . He waddled slightly as he walked. He murmured as he came in, "Hi, Sith . I thought I'd drop by. It is all right? I'm not intruding, I hope," he spoke as he walked to the center of the room, seemingly headed into the fireplace at the opposite side of the room from whence he entered. Sitwell stopped him with, "No, dear boy. You have interrupted nothing."

Mr. and Mrs. Williams rose weakly . "We were just saying how we must go. Sith, it was a delightful dinner. Jeffrey has to be on the plane bright and early tomorrow. You understand? "

"Of course So glad you could come " Sitwell escorted the Williams' out as the young man daintily settled himself into a chair near the fire and wantonly looked out through a black window.

"Who were those dreadful people, Sith, friends of yours? " sneeringly asked the young man . Sitwell parried "Where have you come from, Charles? Can I mix you a drink?"

"Please," delicately ennunciated Charles, pulling the house cat into his lap to pat.

Music changed conclusively from Bach's Brandenburg Concertos to the Rolling Stones as Sitwell left the room for another bottle of scotch. Satwell came back in, wearing a sport coat and an ascot. He found Charles still perched in his chair by the fire, hypnotically looking into that fire . The fur on the cat did rise. Charles turned his eyes sparkling to meet the Loretta Youngentrance of Sitwell.

"Your fire is so charming," commented Cha rles through the d in and the blare of the Stones .

"Yes," answered Sitwell rather slyly as he seated himself gracefully across the room. He dragged now on a large cigarillo, freshly lit. They sat in silence before the firestones conflict, lost in their own schizophrenia.

The music played. It rocked and tumbled into the jiggers of the transformed night. The soaring, splitting side of Sitwell jelled itself into unconformed errosion He h ad no reason to

let himself be. He was only sitting out his term . His head felt largely large, and he tilted it down towards the ground. In his hand was a drink. It was so pleasantly heavy in his hand. He let his wrist sink and felt the weight. This reminded him His father, his father.

" Charles, never allow yourself to be shoved under in this

mass hysteria of non-being. Never show through as the fool that masses are. Let your mind receive the words of Wordsworth in his early career. Let your soul take in the words of his wisdom to your heart. Don't ever let anyone subjugate you to their tyranny. Give up. Give up, but not in the sense of a concession. Leave the masses and their foolhardy verdicts of wrongs or of rights. Can't you see that you must become a human in the vastness of releasing yourself. If you can release yourself into the formless and bountiful eternal, then, then, and then only will you become, a person, a human that should be allowed to live. You will only begin to live by giving up, but not giving up. Do you understand that Charles?"

Charles pleasantly looked into the fire and did not comment. Sitwell was part of the loud background music that blared through the chamber speakers. He was so pleasant to be around. Sitwell never asked much of you. Sometimes a kiss, occasionally to spend the night. All Sitwell ever did was fall asleep deep in his drugged life of the beyond human. He was really an amazing person. Charles knew he vrould never meet anyone like him again and did not care to.

"If you will only make the logical connection of Wordsworth, of Stevenson even, to the Oriental religion of the I Ching or Zen Buddhistic cults then you will understand what it was that these two men were trying to say If you will only try to follow them closely and then allow yourself to become what they are. If you will only struggle and give into all the life that is theirs then you will at last become a human. Don't you want to become a human? The greatest achievement of man is to become a civilized man. Civilized is a term that few people comprehend. To be civilized is to be truly humanitarian, not in the sickly, missionary attitude that is so often filled with your own egotism, but in the sense of really caring. Christ understood. He was a Zen person. The idea is to become a Christ. Don't mess around with this becoming Christ-like idea. Let yourself fall all the way into the only experience in your life that is worth the time or the effort to attempt. Don't get hung up on foolish worldly desires. Let yourself go and then roam in the air. It won't be easy. And the harder you strain with your mind the further you will get into true understanding of your faith. If you will only let yourself go. Become the pilgrim on his way to find the Holy Grail. The Holy Grail is your redemption. The Golden Bough rings its alarms all through your ears and you must hear." Sitwell was out of his seat now walking towards Charles with a fierce look in his eyes. There was no recognition. He saw no one. He was blindly trying to fall into his hope . "You must open

you eyes." He grabbed Charles by the arms and shook him violently. Then in horror he let go of the boy who was beginning to become indignant, no longer indulgent to Sitwellian life Sitwell sat, and rose immediately. He went into the kitchen, looking for he was not sure what. The music jived and hipped over the pipes, bouncing from wall to chair . Sitwell was lost somewhere in the middle of the motion in the music. He was set free in the horror of losing no commitment. He wanted to find. He heard from the parlor .

"Sitwell, let's go for a ride. It would be so lovely, don't you think?"

"Why yes, Charles. That's a purely delightful idea ." They both stumbled out to the car, leaving the lights on and the record player going. Sitwell plopped himself in behind his car wheel . He imagined himself floating on a cloud to liberation. He wanted so to open up.

The drive in silence in the dark night was only penetrated by the humming motor and the A .M. which Charles had switched on. There was no communication . The two followed their own pursuits in vague desolution.

The car rumbled, the car roared; it tore down through the town. Stop-lights were assaulted, and lights were captured with the sure precision of the auto . However, the occupants of the car were far from the precision in this precision automobile. As with all humans, the objects of their own creation, being the result of the rarity of analytical and pure thinking, are more pure and good than the human can ever hope to be . Who runs as well as his own car? Who never falls enough in love with his car not to speak to it at one time or another? There is a certain envy, a certain rapport, between the car and its occupant.

Sitwell sat bespectacled behind his car-wheel staring out of the window, a great fog before him . Machinery and complexity confused and threatened him from every side even as he knew that he was on the "in" track of the mechanism of machinery . He was busily trying to keep his blearing eyes on the road, inverting to his mind violently. The act of driving was salvation; it gave him something to do. He had to have something to occupy his mind, else he would diffuse, dissolve . Into his mind, words so like his father's came, so like words that always had some secret terror for him . He tried to block out his excellent memory . He did not want to hear his father's favorite poem now, but it began to slip into his consciousness, to plague his mind and not give it respite until the verse had gone through him. He had to say, remember, the sense of that poem . That damn poem of Wordsworth should never have been writ-

ten. It is a scourge to men like myself. It is the fool utterance of a non-realistic person. But even as he said these words Sitwell knew that he was indeed, in truth the most idealistic person he knew. He knew only himself anyway. "Intimations of Immortality", go out from me. I just want to be a businessman. The horror of such lines as "Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:", "the grave ... a place of thought where we in waiting lie;" "Blank misgivings of a Creature/Moving about in worlds not realized . . . Are yet a master-light of all our seeing;" buried him. He recalled, recalled from the dead youth of college days a belief in becoming a Christ. He drove his car, taking long drinks of sherry, hopeful protection. The car weaved and circled, wandered and glided toward what positions Sitwell did not know. The car-his life. He did not know where he was going, could not allow himself to start to find out where he was going safely in his safe position. The security that he had formed for himself had closed out the possibility that he had dreamed of, the idea that in material ease he could, at his leisure, perform the task of accumulating that knowledge which would compel him to new vistas of insight. He could, it was true, read, often finding obscure and clever statements. He could con-

sider roads on which he could move. He had a chance to think about every possible way of motion that he could go in. But, but, but, but, but, but, but he could not stay in this position and find out for himself what he wanted most-was there a working way of discovering life? Was his existence of material, social and egotistic advancement the only path left open for man to follow? He did not know. He wished he had the nerve to find out. He took another long swallow from his sherry and poked it at Charles . Conversation was what he needed now; life was what he desired. He moved his car for " Ed's", local hangout for Charles people. He could avoid himself in this confusion. He could drink. He could, lastly, only hear the blaring noises of records, voices, vague impressions, sensations, some words coming from his foreign mouth, some observation he would think possibly sage, an impressionistic drunk life . He could sleep drugged and dead until tomorrow and until the next morrow or the next morrow . He took another long swallow from his sherry. He found the bottle mysteriously empty and covetously accused Charles of sneaking.

" I was not sneaking. You drank most of that yourself . I don't see how you can still stand up, Sith. Why don't you cut down on your drinking?" asked the impertinent and narrow Charles.

Sitwell smiled and patted Charles on the cheek; what a fool. " Shall we visit 'Ed's'? Its always best to run in near closing time. We might find a party . Something might be going on."

" That sounds like a splendid idea, although I wish you wouldn't drink anymore tonight. You've had too much already, don't you think?" Charles was hung up and put up and shut up and closed up and a lost account. Sitwell didn't bother to look his way. Why do I waste my time on such drivel? he thought carelessly.

The door, behind which colored lights glowed, opened . Into the misty smoke of modern confusion raced the body of Sitwell; followed twitchingly by the already comfortably occupied Charles. He bouldered over a mass of bodies that congregated around the bar and shot to a table near at hand. He sat and shouted . "A large draft please " Sandy, the nice bartender, nodded confidentially to his steady customer . Everyone tiredly watched Sitwell drink again. They waited for him to say something, for his words to again start to flow. "Amusing", "original" and "poetic" were words describing his delirium . He was hailed the only gleeman in the United States. Sitwell was not in the mood to amuse, in fact could not really see nor care about beings on the outside of him, even as he called and shouted to

them. He was well inside his shell, hopelessly waving to other people well over and above him. He was on a cliff before a large cataract in the earth's surface on which cataract he wished to place his life. Across the cataract he saw a multitude of scorners and half-hearted participants in his own very personal expression of himself . He suddenly feared to tum around and find that the hot wind on his neck was that of a throbbing multitude. Now, above all, he wished for Wordsworth to come save him. He wanted to jump into the individual oblivion of identification with an ultimate . He would wonder at the world. Suddenly he was talking, standing and walking in the bar . Charles idlly talked to one of his friends, only occasionally looking up to Sitwell. Everyone knew that Sitwell was in his own hang up , his own jag, when drunk.

"Listen to me Let me tell you of the night. Yes, I have learned of that night too , and have lived it. Barnes knew she had no concession rights on that commodity . I know of the dark night of man's life . I know of the sunken horror of all men's lives and the secret longings in all their perversity to become . We all feel this There is no one who, when he is facing himself in h is own right mind, will not know this . Yes ; you may laugh now, you may cry-it is all the same We must become . We must act . There is no time now to hesitate Before the time is too late, act or we must start again Do you wish to live another life of boredom? If you do not start acting, start thinking. You will have hell . Yes you will have the hell of life perpetual if you will not start. I cannot make you act. I know that. You must act for yourselves. I must act for myself . By our own analytical act of selfishness, we will find the greatest harmony the world has ever known. You may scoff. We must start sometime . Are men of the world to be always correct? Are they to be always the true sophisticates-knowers of truth-in their belief that man will never changes?" Sitwell wheeled about. He jerked up his head , smashed into someone at the bar who promptly turned and took hold of his private parts in affirmation, and then was rallied out of the bar on the arms of a heavy-armed barkeeper and the laughter of happy people, sick in contentment.

There was no one. There was nowhere. There was nothing. And from this Sitwell knew he had to make life . He had to form, from this mess, substance, his existence. He had to make himself a person, whatever that was . He reached into his glove compartment to drink There was a pint, dissipated and wasted . He drank it off; he drove. He wheeled his car in and through. He circled. He was dizzy. He forgot where he had been, when he had arrived, what he had come from, who he was going to.

In one moment he would suddenly recall a partial phrase, in the next he could find himself looking out the window. He knew no time He felt no movement. He tried to calculate not at all. He sloshed and motivated . He wondered and hoped. He related and promptly remembered a dictionary of useless facts . He knew not where he was. In his head he must have read the solution before He had taken in so many words. Some combination of them must have some clue for him? There must be some cong lomeration of words, no matter how foolish, that would suit him The vestments of conformity and maturity fell from him, and he was stripped to naked embarrassment. He did not know what to do with himself . He did not want to dress now. He could not dress ever , he knew now There was no safety behind fashion . There was no protection in the calming balms of primary needs . He m ust decide what he was now. Was it true that man, devoid

of his environment and outward relation to connection, was nothing? He felt it not so in this moment and then forgot why he felt not. "God is dead. Drive he said ." It that true Larner? There was no need of proof or supposition There was no need of order or clarity . There was no need to be understood He wanted to understand now. He wanted so fearfully to know what he was that all conventions and orderly, labored, slow walks in the direction of purpose were of no use . He must now know. He felt life within the grasp of his tongue. He tried to speak and found lisps, slurrs. He shuttered at his manly weakness. He wanted to retch in his own no-being. Even as he knew, he found no peace . Sitwell Fletcher even with his environmental and social security had no feeling of being. He was non-related to any being. He was moving towards, maybe possibly reuniting with other men. He could not know. He did know that he was shakingly cool , that he was drunkenly hot, that he was uproariously sick, that he was insanely happy . He turned into a Hot Shoppes for something to eat .

On the sidewalk of the Hot Shoppes stood Cal Peyton. Cal, looking at Sitwell pull up, was postured just as he slumped at the office. He appeared to have been standing in that position, in that place, looking at the spot where Sith would pull in for some long time. It was as if he had known that Sith would pull in now and had waited there. He was a delegated agent of some higher authority that for the life of himself Sith could not name. Cal terrified him He looked out from his cloud and there materialized Cal for some reason. He could not make out any objects around him, but he did see Cal standing there It was the only form he knew. He was ordained to see that figure. It must be so. He stepped out of his car and charged at Cal. There had to be some answer if he saw Cal. Cal must have it.

Cal smiled in his slumped attitude . He seemed to have already calculated the weight of the invisible pillar against which he should be leaning . He was cockily formed to his shaping silhouette .

Sith was on him "Hi," was all he could burst out within his radiant smile, light of hope in all things to come.

Cal smoothed himself up. He seemed to have come to the moment he had been waiting for. He drove in the words that he had on his mind . "That lady just made a most amusing comment about you ."

Sith whirled around What lady? Somewhere in the area before him was a white dressed form moving towards the door . In the blurry haze before him he saw a form move and wondered what she was. Said something about him? How could anyone? He looked at Cal inquiringly, who having lost his attitude of the office, was now the prophet with all the good news , cloaked in dark clouds of misgiving and discomfort.

Cal merely smiled again and spoke . "She called you a beatnik ."

Beatnik! Large galloping legs tromped in the empty space between the void body and his way. Shaving shoulders cut into the air crisp and awake. Biting hard insides clinched onto the preforming necessity of man. Sitwell beared down on the lady . Reaction formed without throught was a true self He was speaking now down the lady's neck with Cal following behind, smiling. Sith was bursting forth with his anger, his impatience, his pride, his hope, his indignity, his self, his display . "I am a graduate of Pennsylvania State University. I took my master's degree at Lehigh. My family came to this country in 1786. I work for Experiment Incorporated as head chemist. I have a home valued at $30,000 I own an XKE. I am planning on doing a

doctorate paper for Harvard University-and I am not a beatnik," breathed Sitwell down the lady's neck. On his face was a smile which would have cut into the heart of any person telling them or the pain, the insult, that he had incurred, demanding that he be recognized, telling the world, I refuse to be insulted, discarded with a foolish phrase, that he was not one to be categorized lightly and thrown away, that he was a person, that he was. He was the insane, eye-beaming-light, purposeful maniac that one day discovers a theory man applauds. He was the man who one day ends in the local sanitarium. He was the Dynamic.

The squat Jewish woman turned, understanding that these words were directed at her. She saw then this human. She blushed and fumbled out, "I am sorry."

Sitwell went to his seat without a change of his crucifying smile. He was crucified, the woman had accomplished this. He smiled and the cracks of despair hung through. He was hanging onto his smile as the last strong courageous affirmation of humankind. He was defending his person. He was ecstatic. He was vibrant. He was human.

Cal sat across from him. He was still smiling, but now with approbation. Everything was in the open. There was no need to lie. "You see Fletch, there is no way to escape. You must go out and find your own way."

"And she is wearing that horribly dated dress. Rayon went out with the fifties."

Cal tried. "Forget her Fletch. Forget that fools like that exist. Don't you see that you were made for better things than to be involved with fools like that? Just forget her. Go on to the creation that is the real you. Can't you see that now you can cleanly break with life and go? You have been given the gift of power and response. You have been given a coersive event to react against. You can now live. Don't you see?"

"And that ghastly white. Those vulgar flower decorations on white. God!"

"Listen to me, Fletcher. Sitwell, listen. God, have you lost your mind? Have I wasted my time? There always seemed some hope around you. Listen to me. Don't you see that now is your chance to really be the poetic person you are? Shape up. Order some food and settle down. Begin to really think."

"And look at the tacky coat she's wearing. And that husband of hers. He stoops to that cunt's whims with his very . shoulders. God!"

Cal looked out the window. He wanted to jump through. What was the use? He smiled now a third smile. Man's variety of displaying emotions was limited. Cal regretted this and re-

membered two paintings, one of passion in love and one o f passionate religion, both by Corregio . He slimmed his smile . The true discerner is one who can successfully define what each shade of gray represents between the white and the black He lit a cigarette and blew it out at Sitwell.

They went out to the car together, but it did no good S itwell slumped down behind his car wheel. Cal waved goodbye to him . Sitwell revived, waved back. He had a cheery smile on his face. His cheeks were rosy. His hair looked healthy . He was shiny and clean . He was back in the sway of life He w a s sparked up

Cal wanted to be sick . He did not care to smile as he felt his face assumed a slouch-weary grin. He calculated how many cigarettes he would smoke in his life, and walked away He saw Sitwell lighting a cigarillo as he roared off changing rythmically from one forward speed to the next. There was an insistent surge of power und e r the frightening force of the hood

On the Passing of Summer

While the tide tumbled aimlessly about, And the shore, mocked by a million fluid mouths, Radiated its own scorched worth; the palms, Making unrehearsed innuendos to the passing birds, Wove a whisper of tomorrow.

Into the coming night, or out of the passing day, Whichever bears the greater strength of truth, The crimson sun bloated itself into oblivion, And still the breezes blew.

I stepped onto the virgin beach, and found my name, Being murmmured among the sighing grasses. I wet my feet, and, as I watched the washing foam And the glistening sand, met my creator face to face.

Still, above me, the palms waved langorously In the air, as if to beckon me into their fold, Or into the day that was. I resisted their calling, And walked further along the beach.

Thoughts of my yesterdays fell upon me, As I walked, and, somehow. I taught myself To remember only to continue my paths along The sea-encased finger of beach.

Into the very waves I threw myself, and _ Still there was no reply, save the tumid reply Of sea-things, that glowed as they showed To only me that they knew my name.

I cried my name into the wind, saying, "I am the son of Man," and still, below My harsh garbellings, the grasses and weeds Insisted that they alone knew me.

Wet with the tears of eternity, again, I heard the palms above me sighing, and Laughing with the warm night in some secret jest .

I forgot my yesterdays; forgot the lessons Of the world, and again heard my name, Being called out in the grasses, as I thought To leave the sea-breeze and the night .

Again, 0 . once again, the palms fluttered Above me, and seemed to scorn me. I gazed Upward, into the breeze, the night, and Into the flowing trees, and, as I could Remember the sea with its mysterious sea-things ; As I could remember the very thrilling and Powerful grasses, with my name upon their Reedy lips, I knew that time itself has passed From out my heart. I had loved, and known my creator.

-Robert M. Miskimon, Jr.

Remember?

What is memory

But old footprints

By a secret thinking place?

And yet t feel compelled

To dance once more

The minuet of times gone by.

Hear, oh, do you hear

The sombre harpsicorded fugue?

Frozen rhythm

Repeated , repeated

Dance , dance.

The pati'erns of my sadness come back to haunt me

As Rave/le's "Bolero"

Repeated, repeated.

What is memory

But fresh teardrops in the dust

By a secret thinking place?

Full Grown

The beauty of the soul

Calls out to me in the sunlight.

My love is as the warmth of a gray kitten

Winding obout my bare legs .

My tears as droplets from

A ;ust bathed baby on his mother's skirt.

I long to hug the green earth

As a woman hugs her soldier-lover by the train .

A girl-child plays in the chicken-wired, Fenced-in garden of infancy,

Not tall enough in the toe-scuffed, patent-leather shoes to reach the latch that lets in the beauty.

But suddenly with one great swing of the see-saw

A baby vanishes

A young woman is a butterfly,

Drying her just-unfolded wings.

-Carol Silver

I Wait

I wait for love

With all the expectations Of a piece of bubblegum That's never been popped.

fragment

Part of me is dying as we bury the remnant of an almost communion

The golden tree Now shades the grass As we did once Vibrant and vivid Glittering with sunlight

Reflecting in eyes

Gay reawakening With soft anticipation Of gold to come

Still golden Now

The grass below Turns patterned As we turned Smiling

-Sarah Gilliam

-Carol Silver

Tanka

Cockroach on the floor. Grinning at his secret joy, Kneels a gentle boy. Quietly he shuts the door, Soft he steps upon his toy.

-Robert M. Miskimon

And You Stand Silent

As if from a deep, Empty hole, The sounds of laughter Echo and rise. And you stand silent Wanting someone to hear Your tears.

The laughter rips deep gashes In your sadness. And clutching the gaping wounds, You search for seclusion to bleed Alone.

-Richard Goode

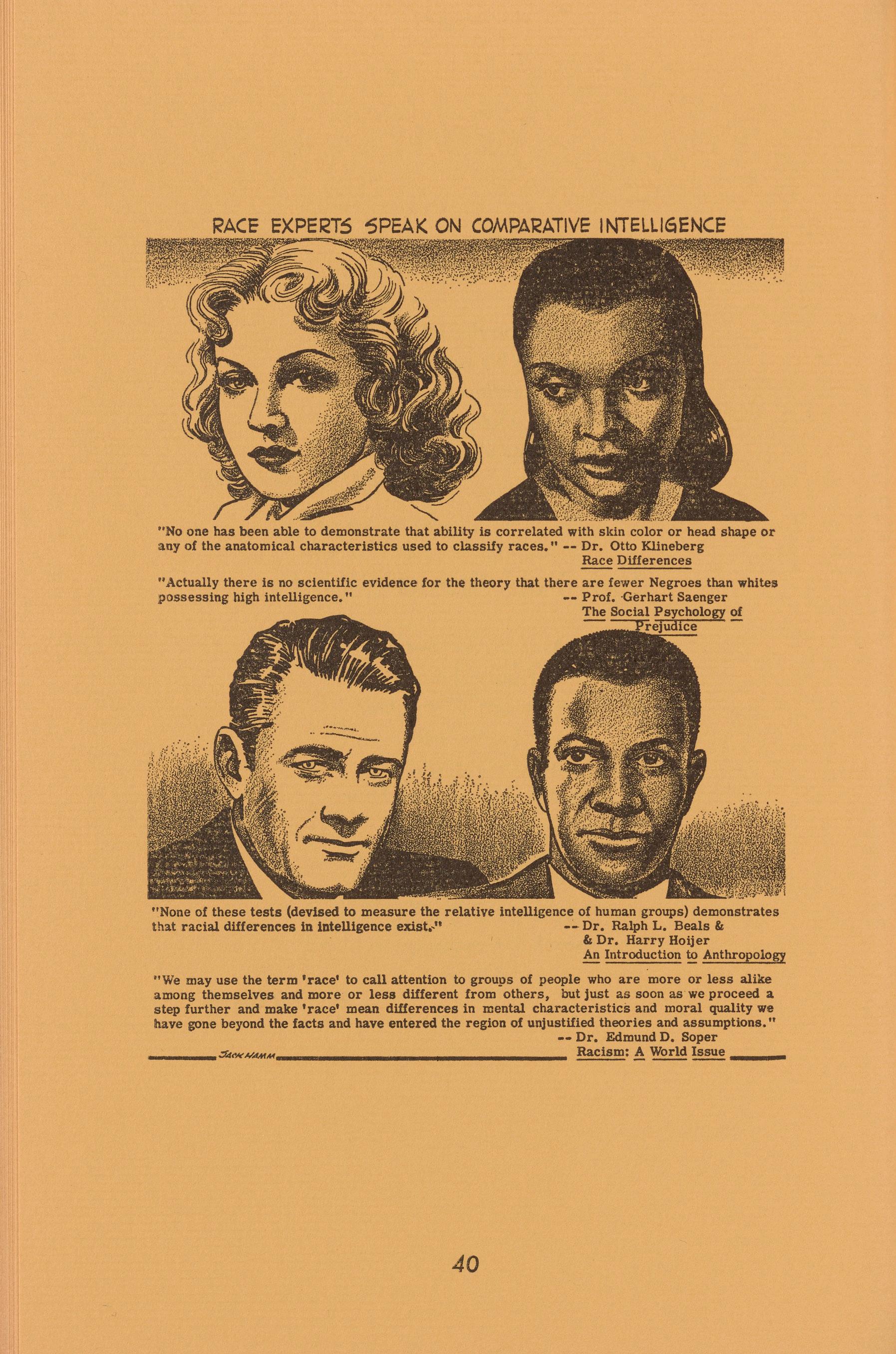

RACE EXPERTS-SPEAKON COMPAlcATIVEINTELLIGENCE

"No one has been able to demonstrate that ability Is correlated with skin color or head shape or any of the anatomical characteristics used to classify races." --Dr. Otto Klineberg Race Differences

"Actually there is no scientific evidence for the theory that there are fewer Negroes than whites possessing high intelligence."

--Prof. ·Gerhart Saenger

The Social Psychology of - rejudice

"None of these tests (devised to measure the relative Intelligence of human groups) demonstrates that racial differences in intelligence exist.-"

·Dr. Ralph L. Beals & & Dr. Harry Hoijer An Introduction Anthropology

"We may use the term •race' to call attention to groups of people who are more or less alike among themselves and more or less different from others, but just as soon as we proceed a step further and make 'race' mean differences In mental characteristics and moral quality we have gone beyond the facts and have entered the region of unjustified theories and assumptions."

--Dr. Edmund D. Soper ____ .,i;,.,.,..,...,M__________________ Racism:~ World Issue_

Apnlngynf a wraitnr

ilnutaua

I am of college age . I am writing this because I want to show what's wrong with me . It seems that millions twice my age have said what is wrong with me ; and millions more my own age have nodded in agreement.

I've no claim to be an American-beyond birthright. But, having been born here, I learned the American way from parents and associates, the same as a Frenchman, Lithuanian, Oriental, or Russian would deal with their own residences .

My family emmigrated from Europe after the Civil War, and they settled in the West. The law didn't bother them greatly until they made a dustbowl out of themselves. They felt F. D. R. was a saint, and they derived their concepts of American democracy from a combination of their own personalities and the stimulus-response patterns of the Great Depression and World War II.

The government helps them, so they'll help the government. If President Johnson, my parents said, wants to black out the Northeast to see whether the citizens of Boston will cut each other's throats , that is vital to security . The government gave them protection from complete collapse in the 30's, from Hitler 1n the 40's, and it has given them protection from the Commies ever since .

I can, then , lay no claim to the heritage of speculation that our founders instituted . At the same time that Jefferson was saying that Americans should tolerate diversity of opinion , reason being in a position of freedom towards combatting error, my forefathers were in the grip of a much older culture. If a man did not share your opinion , there was something wrong with him This was not something that one only felt underneath in his ego; it was something that a person took for his outward creed . I do not think that they could conceive of the mechanics of a larger group of people than themselves .

My mind, then, tends toward more basic items than political theory . I view the world in terms of what has tangibly helped and hindered myself , just as my father and his. I have also inherited my family's religion. They pray for better things . I'm not so sure There are many things that seem right-because they are better things-which are sins .

I cannot, then, accept dogma-unless I personally see its logic. Perhaps you would call me a Doubting Thomas. I think that I learned this approach in school. I have been learning since I learned to read.

I learned a combination of facts and observations. I think the product of this is occasionally somewhat slanted. I am guilty of didacticism for the good of my sanity. There are certain facts that I have deduced, then, which seem basic. I have been taught increasingly as I approached maturity that to learn and not to apply makes education useless.

So I have applied what I deduce to the world as I see it, and have derived a philosophy of life. First of all, a human being is a living animal. Secondly, a human being is an animal with at least enough intelligence to resolve that he has come to a conclusion about something. I think this much can be allowed h~m. Thirdly, he supposedly can differentiate between more things that are similar than lower animals can, there being no higher.

When analyzing, I learned that I should start with the most unadorned root. The above, then, is the most pessimistic argument I can think of. If we wish to be more liberal, and say categorically such things as men definitely can differentiate between many diverse things-far more than any other animalthe logic of this essay should work even better.

So man is an animal, and what does this mean? It means that he behaves as an animal-and he can't help it. He has drives--of anger, of sex, of hunger, and of all the etcetras. How is he different than an animal? There are at least two schools of thought on that. Either he has a higher nature, in conflict with his animal instincts, or he has the ability to express his animal instincts in more sophisticated ways. I hold to the latter view by force of pessimistic habit. But if man is indeed in possession of a higher nature, the logic of this discussion might even prove more telling.

Either way, man has an animal instinct. And what does this. mean? It means that, in order, he wants to live, to have pleasure, and to be comfortable. I separate the last two for semantical reasons, because I know of those who are most uncomfortable in their pursuit and attainment of pleasure.

But, perhaps there are only two: to live, and to be comfortable. Under the second category are such clauses as "life as is worth living"-whereupon, some might ultimately deduce este man become instinct, in kindrence with the rest of naturethe will to live.

So what, then? Well, a tiger kills game because she requires meat rather than grass. Being a tiger, she has a requirement for meat. If she were human, we might say she had a "taste" for it. Tiger cubs perform a ritual of ferocity, because these traits will be useful to them when they are grown .

On the other hand, an antelope runs to avoid death, by the claw of a predator . It is in possession of this response because it is basically not a predator Its talent is for running. Also, in response to perhaps the law which separates one body from another in space, animals must fight enemies, because they must assert themselves to come out ahead . An animal does not say " excuse me ." If an animal w ishes to survive, he should try to get first choice .

Nature, then, gives animals very interesting responses. They seem to attack only when they detect the possibility of success ; they hide, or run away, when they know they will fail at agression. I learned these things from the literature that men have provided me. Men have taught me all that I know, including some things that go against these tenes.

The latter usually happens when a man will seek to apply human objecives to a non-human subject. In Faulkner's The Bear, for instance, we have in a dog named "Lion" a ferocity that makes him continue when the odds are in disfavor. He has size and strength for success against any dog, and his spirit makes him a threat to a bear much larger than he.

The bear received a human name-"Old Ben"-because he seemed to possess human cunning and strength that excites human admiration. Because everyone seems to use dogs in Mississippi for everything, the protagonists had used many in their efforts to corner and kill the bear But they could never find one equal to the task .

Their dogs would yelp with a human quality of desparation, when they were on "Old Ben's" trail. The dogs, being animals, knew that they were outmatched, but not enough to do more than run smack into the holocaust that would tear them to pieces . The sentiment of the narrator seems to go against them They seem to possess a defect that makes them despicable.

An idea of the nature of their despicable quality is discovered through comparison, when one among their number shows itself to possess courage . It is too small to show the slightest injury to the bear, but it is too dedicated to decry its own fate as it journeys toward self-destruction. Faulkner saved the noble creature embarrassment by pulling it from the ranks, for a wise hunter among the hunters of the story realized that

the courage of such a pipsqu e ak could do no more than reduce the population of courageous dogs . It would be like the cop who fires his 32 at Godzilla .

Then at last came "Lion." Lion was a dog that had been left to shift for himself . He was fierce because he could rely on no one living to obtain sustainance. He had no master, though because of chance, rather than personal conviction . The hunters found him as he found the hunters He killed a colt, and a Negro trapped him .

Lion would bite the hand that fed him, but the Negro talked him out of it. The man did not train him, but rather worked out a partnership . The man would make Lion's sustainance easier to come by, if Lion would work for the hunters. The hunters didn't wish to destroy Lion's ferocity . Rather , they wanted to use it.

Now considering the three types of dogs listed, Lion has top priority. We liked him because he had, not courage as much as talent. He had a fair idea that he could win , even against a bear; because Old Ben was fired, while Lion was spirited. Secondly, there was the hound that was brave but too small. The hunters were affectionate with him, but they knew he was useless . He had not the necessary strength-only courage, he was not adequate . Finally, there were, again, the hounds that mbaned their own fate as they marched into battle

So we consider, perhaps, the latter group despicable, as Falkner seems to . But why? Because they didn't measure up? Of course!-for strength is a marked criterion of magnificance. Now consider this Had the latter turned from Old Ben's claws and run away, is there not a thinking person in the world that would think them better for it? But they couldn't do that; after all, they are only dogs.

If you are observant, you might see by now what I am about. I am trying to show why I am a traitor. I simply have no talent for war; I consider myself as more than a dog; and I don't wish to be reduced to one unless it is absolutely necessary .

I would not be effective at killing . I am small and slow . My eyesight is bad, even with glasses. But merely significant, I am unfortunately in possession of imagination, something that is hopefully and apparently absent in the military Imagination makes me put myself in the other person's shoes A good soldier does not bind an enemy's wounds . A enemy will remember the pain you have inflicted before the comfort you have

rendered him. If he survives, he will only hit you harder next time . Arguments, then, are increasingly utilitarian-such as : "we fight to preserve ourselves individually, of necessity acting as a social unit." By the most moral line of thought however, I ask if selfishness is any worse a sin than suicide . Not having the knack for war, I think it would be better for me to run than to yelp toward destruction without showing the least resistance. My life is more important than any nation's, for in war I should be a certain casualty I have noticed that ceremonies honoring the dead are most enjoyed by those who survive.

Are there any situations in which I might fight? · Yes, when a person is seriously wronged with whom I might identify . It might be a loved one whom I see injured; or any human being with whom I could replace myself and feel his helplessnesi;;. Then tendency might be called love. Or perhaps it is only the desire to keep friends around because they give me enjoyment. In either case, I think it is peculiarly human . However, these are not the arguments as to why I am forced to fight that have been presented to me . I have seen instead, a rash of veterans from other wars, who tell me that because they fought it is therefore my obligation to fight also I have heard the arguments of generals who take their profession with the seriousness of blind men. I have heard countless politicians foam at the mouth, thinking that because they use noble words like "commitments", "respsonsibilities", "honor " , "pride", that they are expressing noble thoughts.

Even if by some miracle the State Department would clarify its stand to such an extent that I could see clearly a personal cause in all the global expressions of human imperfection known as the Cold War, I would be obliged to fight independently of the miriads of men that would be fighting the war for the wrong reason.

The traditional call to war seems strangely to me like the bellowing of an ox. One is exerted to masculinity, (etc .); to me , war should beckon with a soft voice and with tears . It is a call to destruction, to death . To me, if I should fight, I should have to fight alone. And I would surely die .

There are some in the world who think that bravado is a necessity in life . Perhaps this is so; but I ask you if there is more courage in walking with tears to the gallows, or in wrestling with the headman's axe .

You might say that there are too many of us, who in the face of an emergency, would question rather than unite. I'll agree with you . But show me the error of my ways.