Vol. XCIII, No. 3

University of Richmond

Design by Karen Berndtson

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Dale Pa trick

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

C. W. Bennett

BUSINESS MANAGER

Martha Dorman

LAYO UT EDITOR

Bill Owens

ART CO-EDITORS

Karen Berndtson

Joanne Gill

PROSE EDITOR

Edwin J. C. Sobey

PROSE STAFF

John Helfrich

Shelley Abernathy

Lynne Robertson

POETRY EDITOR

James Bowen

•

•

•••••• John Holmes

• Charles P. Barrett

•••••• Bob Musick

••• Richard Goode

• R. L. Musgrave

Ken Gassman

••••••••••••••• ,Gayle Covey

•••••• Charles P. Barrett

.... James Bowen

••• Robert P. Arthur

POETRY STAFF

Ellen Shuler

CIRCULATION MANAGER

Cathie Angle

TYPISTS

Florence Tompkins

Jane Frazer

Vinnie Richards

ILLUSTRATORS

Joanne Gill

Bill Deel

Karen Berndtson

Richard Hershaft

Published three times annually by University of Richmond Publications , Incorporated. Right is reserved to alter contributions to meet publication requirements All communications should be addressed to THE MESSENGER, Box 42, University of Richmond, Virginia

All love is relative. Man cannot appreciate the presence of love unless he has experienced the absence of it. Patriotism, the love a man holds for a woman, the devotion one feels for his family, all these reach a greater and deeper meaning when the object of love has been denied for a time.

One might describe love as liking more than disliking, caring more than not caring, accepting more than not accepting. It is not a concern for the immediate need but for the ultimate need. Love is complete and total involvement.

If a man is capable of cruelty, he is capable of kindness; he is capable of love. He could not be cruel unless he was, to some extent, involved. Even cruelty entails some form of caring. If one did not care, he would not even bother to be cruel.

The one who truly loves anyone or anything is not afraid to be identified

Four

with it. He is not afraid or embarrassed to say, "this is my home, this is my country, this is my family."

I do not believe that any man can exist without feelings of love. If he shuts himself away from the world, he is, in a sense, indicating an involvement in (a love for, if you will) solitude.

Love may, in its beginnings, be starryeyed, but until it transcends this stage, it will not endure. Love cannot exist apart from reality; for if it is not realistic, if it does not see the flaws in the beloved, it is not love. Love is approached only when one recognizes the flaws and accepts them nonetheless.

Love cannot be defined, for no two people can feel, express, or understand love in the same manner. Thwarted love brings a mixture of feelings. It is the end of an experience, but it is not the end of love. Love, as the saying goes, can always come again, but it will never be exactly the same -just as wonderful, perhaps, but never the same.

The man who sees through the eyes of love sees a world worth living in. He sees hopes worth fulfilling, dreams worth ·dreaming. He possesses joie de vivre.

And so, what is it all about? Countless times through all ages man asks himself the question. Each man puts forth his answer hoping that it will prove acceptable. Who is to say that one is right and the other wrong?

-HOP

The Messenger

I.

After I'm sure

That the Blue and Gray Have stopped arguing, I'll close my eyes. The only burden will be Deciding between the circus And the green forest.

And I'll make my choice Depending on who I'm with, And whether I'm eating Cotton candy or counting blue splotches Painted by infinite leaves.

I won't be home in time for dinner. And if you want to come, You must take your shoes off, • So my friends won't see you coming.

by John Holmes

Your confused sunshine left me kneeling, Trying to befriend the darkened rain.

I can no longer see you, But I can hear you. I can no longer touch you, But I can sense you.

Placing a tear drop on my finger, I will toss it in your direction. And if it comes to rest Upon your unseen face, And saddens your smiling cheek, Then falls into the puddle, (In which you too will kneel) I will be satisfied.

The Messenger

Snow comes soon on the red bones of dawn, and our mourning will whiten to the wan face of our day all the valleys, ribs, and the hills of these events, chilling the love and the sundry of her eyes away.

Somehow the soft felt weather turned from the skies of winter, whitsun, and the praying churches all their leaden hopes and fears, leaving the fraying hair of their God behind, unburned but coming whitely on us and quickly, yet then thru the falling flakes of such unnumbered faith we warred on the lovely deaths and entrances of all her weather born and stormy children, till slowly here fall the shadows, covering and brown on the cold rouge of ground, cumbersome, and heavy over the earth where we fought with our finished ghosts down; we are mingled now, one nation, o beautiful .

Snow comes down on the red bones of dawn, and our mourning whitens to the wan face of our day all the valleys, ribs, and the hills of these events, chilling the love and the sundry of her face away.

- Charles P. Barrett

by Bob Musick

In 1904 at Queens College l> London, Kathleen Beauchamp adopted the nomde-plume, Katherine Mansfield, and launched a literary career which was to be filled with much physical and mental anguish, disappointment, and a degree of success. Although her writings consist of short stories, critical reviews, and some poetry, it was her short stories that established her small but secure position in literature. As her technique developed and her skill matured, she gained the respect of professional writers for the beauty of her tightly-controlled, evocative stories. Though she was influenced to some extent by the writings of Chekov and by her admiration for the Romantics and Shakespeare, the style she developed was uniquely, unimitatively her own. She relied, not upon the truths of science nor technical proficiency to create her stories, but rather upon her intuitive insight, a vision of life.

Her most limpid, imaginative writing and that in which she felt most deeply concerned was written after her beloved brother Chummie died in 1915 while he was engaged in the conflict of World War I. Just days before he left to meet his death, she recorded in her journal a conversation about their child :1ood, revealing their unity of spirit and their shared joy. ''But isn't it extraordinary how deep our happiness was--how positive--deep~ shining, warm. I remember the way we used to look at each other and smile--do you?--sharing a secret ••• What was it?" she wrote. "I think itwas Eight

the family feeling--we were almost like one child. I always see us walking about together with the same eyes, discussing ••••! felt that way again, just now." She was profoundly shocked and deeply moved when the reality of life and death was driven home to her so dynamically by his death. After this, as she related in her journal, she reexamined the direction of her life's effort and reevaluated the criterion she had set for her personal fulfillment. In her grief she pledged herself to his memory in her writing. "My darling, I've got things to do for both of us, and then I will come as quickly as I can. Dearest heart, I know you are there, and I live with you, and I will write for you." Later she wrote, exploring the depths of her sorrow, ''I am just as mu,:;h dead as he is. The present and the future mean nothing to me. I am no longer curious about people; I do not wish to go anywhere; and the only possible value that anything can have for me is that it should put me in mind of something that happened or was when he was alive ••••I feel! have a duty to perform to the lovely time when we were both alive. I want to write about it and he wants me to."

The anguish she suffered began to resolve itself into a search for answers to the questions she put to herself over a mourning period of several months. "Now, really, what is it that I do want to write? I ask myself, Am I less of a writer than I used to be? Is the need to write less urgent?" A reevaluation of

The Messenger

her previous writing in the light of her encounter with the enigma of death led her to write;

Never has my desire (to write) been so ardent. Only the form that I choose has changed utterly. I feel no longer concerned with the same appearances of things. The people who lived or whom I wished to bring into my stories don't interest me any more. The plots of my stories leave me perfectly cold. Granted that these people exist and all the differences, complexities and resolutions are true to them - -why should I write about them? They are not near me. All the false threads that bound me to them are cut away quite.

As a result of this introspection, Miss ' Mansfield resolved to pay a "debt of. love" to '.:ler dear Chummie and to the charming country of New Zealand where they had spent a childhood which now she so frequently relived in her memory. She would write of the people and country of New Zealand. "But all must be told with a sense of mystery, a radiance, an after-glow, because you, my little sun of it, are set. You have dropped over the dazzling brim c,f the world. Now I must play my part." She sought to grasp the most sublime means of expression to convey her feelings and impressions. First she turn,3d to the vessel of poetry but at length she confided to her journal her determination to compose an elegy to her brother "almost certainly in a kind of special prose ... nothing that is not sim:ple, open."

Shortly afterward in February, 1916, the first of the New Zealand stories, "The Aloe," which was the original version of ''Prelude," was written as an initial step toward the payment of her "debt of love.,. From then until her death she continued to write stories of 'Sixty-Seven

her homeland, of which the best known are "Prelude," "At the Bay" and "The Doll• s House.'' But there are many others less complete than these which deal with the subject of New Zealand or with characters whom she had known in her childhood and about whom she wrote either in New Zealand or transposed to an9ther setting.

Through the next seven years until her death, there were other factors, su::;h as her unsatisfactory relationship with J. Middleton Murry and her in,::essant struggle against illness, which affected the style and subject of her writing but none other which could be called the touchstone of her literary career that was Chummie's death. The memory of her brother and the covenant she made with his spirit never forsook her, even in the face of increasing personal difficulties. The task she set for herself and the manner of its completion through Nine

prose was the dominant director of herenergies. Many of the characteristics of her writing, its elliptical quality, the splendid description, and the involvement of the author in the story were evident in her earlier writings. All of these qualities developed with Miss Mansfield's growing maturity as a writer and as a person, hastened, to be sure, by Chummie's death. But the uniqueness of Miss Mansfield's immersion in her writings, her personality pervading each character and her descriptive power permeating each scene, was greatly accentuated by her decision to conceatrate on glowing memories she had of her brother, her family, her country.

In the writings of the post-Chummie era of her Jif e, Miss Mansfield exhibited the twofold search for fulfillment which she was experiencing as a person. In her quest for the essence of herself as a woman and as a writer, she involved herself deeply in attempts to find both. This quality of immersion or total involvement characterized both her everyday life and the world she created through her writing. She sought to express herself through her relationship to Murry, a relationship in which she had hoped to fulfill herself as a woman and a wife. This proved impossible due to the incompatibility of the ego-centric, neurotic Murry and the ill, self-doubting Katherine. Even then she was never removed from living, as she called it, "the detail of life, the life of life." From her childhood she had shown an acute perception and an appreciation for the moments of life which she experienced fully. She wrote to one of her closest confidantes, Lady Ottoline Morrell, in 1919 and described a moment of extreme empathy in which she had experienced life and . tried to convey the breathless beauty of it.

On Bank Holiday, mingling with the crowd I saw a magnificent

sailor outside a public house. He was a cripple; his legs were crushed, but his head was beautiful--youthful and proud. On his bare chest two seagulls fighting were tattood in red and blue. And he seemed to lift himself--above the crowd, above the tumbling wave of people and he sang: "Heart of mine, Summer is waning."

Oh, Heavens, I shall never forget how he looked and how he sang. This is one of the things one will always remember. It clutched my heart. It flies on the wind today -- one of those voices, you know, crying above the talk and the laughter and the dust and the toys to sell. Life is wonderful wonderful bittersweet, an anguish and a joy-and oh! I do not want to be resigned--[ want to drink deeply-deeply. Shall I ever be able to express it?

Miss Mansfield's sensitive nature would engage her even in the most mundane matters. The hardships of illness and the unhappiness of a spasmodic love affair preyed upon her mind and sharpened her perception of the beauty and sordidness of living. In a letter to Lady Ottoline she confided just after a depressing encounter with one of the servants, ''I feel so much more sensitive to everything than I used to be--to people good or bad, to ugliness or beautiful things. Nowadays when I catch a glimpse of Beauty--! weep--yes, really weep. It is too much to be borne--an::l if I feel wickedness--it hurts so unbearably that I get really ill. It is dreadful to be so exposed--but what can one do?"

There was seldom a time when she completely ceased to feel the harmony and the beauty of her surroundings. She would always drink deeply of ''these

The Messenger

days (on which) oae is tired with bliss." Her involvem~mt in life was co:istant, always searching for a completeness for herself. She lived the moments but looked for the overall pattern of her existence which would unify those moments. She sought fulfillment in marriage, she sought it in health after she had lost hers, she sought it later through selfexamination. But she never lost her wondering appreciation of the momentary beauty in nature. She wrote to Dorothy Brett late in her life, "I wanted to wish you joy. I can in spite of everything in life. I can and by that I don't mean that it's any desperate difficulty. No, let us rejoice." Near the end of her life she experienced a revulsion for her life and her work, engendered by the agony of her illness and the distrust of her personal universe. But from this abyss of lost faith she emerged Beeking a fresh beginning, a regeneration of the spirit. Only months before her death she recorded the gist of a conversation she had had with a friend.

I began telling him how dissatisfied I was with the idea that Life must be a lesser thing than we were capable of imagining it to be .... One heard, one thought one heard, the cry that began to echo in one's own being: "I have missed it,· I have given up .... If this is all, then Life is not worth living.

But I know it is not all .... Take the case of Katherine Mansfield. She has led, ever since she can remember, a very typically false life. Yet through · it all, there have been moments, instants, gleams, when she felt the possibility of something quite other.

The involvement Miss Mansfield had with life was transmitt e d naturall y to he r

'Sixty-Se ve n

fiction. She immersed herself , ·iii her effort to describe life as she saw it with a vision of childhood, perceptive with fresh, candid associations. She put herself emotionally into the creation of characters and scenes from real-life models. Late in 1921, after completing "At the Bay," another of the installments she paid on her "debt of love" to Chummie, she wrote to Dorothy Brett: ''It is as good as I can do, and all my heart and soul is in it, every single bit. It is so strange to bring the dead to life again. There's my Grandmother •••there stalks my uncle •••• You are not dead my darlings. All is remembered. I bow down to you. I efface myself so that you may live again through me in your richness and beauty. And_ . one feels possessed."

The characters who peopled the world of her fiction are marked by her touch. They appear as she observed them with the frankness of a child. She delved into the inner consciousness of her main characters and through them made oblique revelations.

Miss Mansfield put her personality and vitality for life into her characters, attributing to them the qualities which caused her to absorb the beauty and the ugliness of life so completely. Her best creations, animated by her nervous energy, breathed reality.

But Miss Mansfield's immersion in a story went even deeper than just into the characters. She employed her talents . to create a scene, a moment, an atmosphere. She strove to become a part of nature in setting a mood for a scene. Either through direct but fresh and imaginative description or through oblique, elliptical suggestion, she evoked a tangible impression. A striking example of her ability to capture the precise mood of a moment is preserved in a letter to Dorothy Brett. She wrote describing the end of a fruitless day: ''N ,Jw a pale sun like a half-sucked p e pp e rmint is mdtin g in th e sky." With Eleven

her intense awareness of and empathy with the moods of nature she combined the ability for selecting just the right word to convey an impression. Even the sm,,.llest phrases help to evoke the mood.

In her journal she tried to express by an allusion to Dickens, the perfectio:i of immersion, an unpremeditated oneness, she was seeking in her writing. "There are moments when Dick~ns is possessed by this power of writing: he is carried away. That is bliss. It certainly is not shared by writers today. The death of Cheedle: dawn falling upon the edge of night. One realizes exactly the mood of the writer and how he wrote, as it were, for himself, but it was not his will. He was falling dawn, and he was the physician going to the Bar."

Katherine Mansfield's immersive nature is remarkable too in that during a period of increasing ill health near the end of her life, she channelled her energies into stringent self-examination. It was during a period of her life in which the physical pains of tuberculosis, rheumatism, pleurisy, and the emotional need for an understanding mate deprived her of her creative drive. She immersed herself in her own personality with no outlet in writing. She scrutinized her life and her work intensely in this depressed, corrosive condition. In her earlier days of professional writing. she had been well able to distinguish her optimum from her minimi.lm efforts. But in her state of desperate soul-searching she would slip off into periods of black despair in which she doubted the value of any of her writing. Completely lost in herself she wrote to Lady Ottoline Morrell: ''(There) is a state of mind I know so terribly well--That regret for what one has not seen and felt--for what has passed by--unheeded. Life is only given once and then I waste it." She castigated herself for failing--in living and in writing. But at length, out of this introspection came courage to hope for health to continue writing and Twelve

to place her work again in perspective. She arrived at the conclusion that spiritual development was the real criterion for achieving health and fulfillment. ''I am sure that meditation is the cure for the sickness of my mind i.e. its lack of control. I have a terribly sensitive mind which receive_s every impression and that is the reason why I am so carried away and borne under." Only months before her death she wrote, "It's only now I am beginning to see again and to recognize the beauty of the world."

In the closing entry of her journal she recorded what she wanted of life and of health. It summed up the deep, romantic love and involvement she felt for life in general and for her writing in particular and is a fitting conclusion to her life's story.

By health I mean the power to live a full, adult, living, breathing life in close contact with what I love the earth and the wonders thereof--the sea the sun .... I want by understanding myself to understand others. I want to become all that I am capable of becoming so that I may be ... a child of the sun .... And out of this (involvement in life) I want to be writing. (Though I may write about cabmen. That's no matter.)

But warm, eager, living life-to be rooted in life-- to learn, to deisre, to know, to feel, to think, to act. That is what I want. And nothing less. This is what I must try for .... Now that I have wrestled with it .... I feel happy--deep down. All is well.

Above the phlox touch and green of our lying down falls the wing trembled song of anguish, and from within the willow branch of april comes the swallow sound, stirred fearful by the invasion of our yearning, and as we huddled warm, shallow amid the wild softness and fields, the spring wanderings of our dreams opened full within the sun blush of color and sky, · and while the whisper hollow of our reverie broke upon the leaf bright innocence of the hillsides, the wilderness fell silent, hushed by the unsung flutter of wings rushing upward, beyond the lost moment of our desire.

- Richard Goode

by R. L. Musgrave

Mrs. Jones rose from her seat in the rear of the courtroom as her namt! was called by the prosecuting attorney. She moved forward up the aisle slowly, warily, keeping watch over the crowd gathered for the big trial. She walked upright, perhaps a little too proudly, but with an inner anxiety about all the spectators, whose persistent, penetrating stares met her eyes like some evil, indefinable malignancy reaching out for her. What did they want of her?

Flashbulbs periodically illuminated her face like small streaks of lightning, giving her visage a bleached, stark whiteness for a split second. Her features were angular, at odds with each other. The lines of her nose, chin, and cheekbones seemed to collide unexpectedly somewhere near the center of her face. She felt crowded, smothered by all the strange bodies, the congregated masses; she was not used to crowds, and began to wonder if she should really be going through with this. It was her duty. She had witnessed a crime, and was in court now to tell what she had seen ••• the knife was raised •••one of them screamed •••then everything had been still, and the overhead light in her office dangled above her head, glaring silently, as she saw the man turn and run away. The phone •••the police •••

Someone was helping her onto the stand. A Bible was held out to her, and the man holding it said, ''Do you swear that the testimony you are about to give

Fourteen

is the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?"

"I do."

The man then said, •'State your name."

Mrs. Jones paused, as if awakening from a day dream, then said calmly, "Josephine Ellsworth Jones."

The man said, "Be seated, please," and walked away with the Bible.

Mrs. Jones took her seat, and now surveyed the courtroom from this different angle. There was the crowd out there, and the jury over here on the left, and the judge ••••She looked upward, to her right, at the ominous figure in black who was to preside over this horrible affair. He was justice incarnate, an irreproachable symbol of right. Mrs. Jones felt a closeness to what he symbolized, a kinship with the forces of good. She was comforted in her prescience that right would overcome, and the defendant would be brought to his just reward. And there was the prosecutor's table in front of her, and the defendant's table over to her right •••the man who •••horrible look in his eye when he brought that knife down. What kind of man, to kill two little girls? Urchins, to be sure, but they were human, too. Something more than meets the eye. See the nervous look on his face •••what can be going through his mind? Horrible place to have to work anyway. Maybe now the docks would be safer. None of this would have happened if her husband hadn't died and left her in need of more , support. Nice people to

The Messenger

work for, though, but in a warehouse office, on the docks. Why did she have to be the one to see it happen? Mrs. Jones again felt uneasy at the gaze of the spectators •••vicious people •••like the Roman crowds, out for the slaughter ••• Pluto let his eyes roam over the group of spectators. He squirmed slightly in the defendant's chair, aware of the animosity in the crowd. He didn't like the idea of all those people at his trial. He knew it could hurt his case. He'd seen it happen before to other guys. First they cause a ruckus, and next thing you know the jury's right along with them, until everybody's convinced you're guilty.

He looked carefully at the woman on the witness stand. She seemed to radiate a kind of coldness, a ruthless disregard for anyone but herself. She was the one •••those cops sure surprisedmewhen they grabbed me •••"Pluto Brown? You're under arrest for murder." I kepttelling them they had the wrong guy, but you

know cops; once they get started, you can't argue with them. Best thing is just let them get their kicks until you can get a good lawyer. And it's really not too bad with this new system •••Treat you with kid gloves when they arrest you, tell you all that stuff about constitutional rights, even hired me a lawyer free before they'd ask me any questions. Stupid alibi, I guess •••don 't even know if the lawyer believes me. Maybe that's why he doesn't want me to testify •••afraid what the prosecutor can do on the crossexamination. But I bet I'd fool him. I'd show that other guy he can't make a fool of me. After all, the only thing I have to do is just stick to the truth. So maybe I didn't show up for work that night, and maybe they did happen to catch me down on the docks •••but that was hours later. Nah, they'd never believe that I just was walking around that night, not doing anything. Pretty stupid alibi. But that's just it:-it's too stupid to be made up. Now, if I had wanted to make up a good alibi,

I sure as hell could've done better than that. They have to see that. It's so ridiculous, it has to be true. Nah, that prosecutor couldn't get to me on crossexamination •••after all, I'm no cheap crook ••• sure, I know about those other times, but that's been years •••kid stuff like stealing cars; just for joyrides, and after all, there wasn't any real harm done. Besides, the cops had me cold on those raps; caught me red-handed. This thing is different. This time I got nothing to hide •••

" •••to hide the knife in the water. I saw him do that. He threw it way out in the water. Then he looked around and started running along the docks.''

The prosecutor stepped closer to Mrs. Jones as he spoke. "Now, Mrs. Jones, are you sure you got a good look at the killer before he ran away?"

Mrs. Jones smiled confidently. "He was only as far away from m,e as the defendant is now."

'' And do you see the killer present in the courtroom today?"

"Yes sir, I do.''

'' And is he the defendant, Pluto Brown?"

"Yes sir, he is."

Mrs. Jones heard the murmur rise among the spectators, and swell into a full tide of noise, pun~tuated by the relentless pounding of the judge's gavel, and the cries of ''Order I Order in the court!" Mrs. Jones could not bear the noise. She was not used to all this commotion. It was like the night they had taken her to the police station after she saw the murder •••she had thought she would tell them what she had seen, and what the man looked like, and then they would let her go home, but •••three hours; three hours she had spent, late at night, all alone with the police •••the dreadful people she had to look at •••common thieves, alcoholics, prostitutes, horrible people. It was such a cold and dirty place •••the lights were dim, the rooms were untidy and old. The police them-

selves were not much better. Ever since her husband had died she had been afraid of being alone in places like that. After all, she was a lady. All those people stared at her as if she were some kind of freak or something. There was no decency to be found. She could think only of getting out of there, escaping the endless interviews and waiting, sitting in different rooms telling the story to so many different policemen, detectives, patrolmen, plainclothesmen •••she just wanted to get out. And then finally they had shown her the book of photographs of former crimj_nals and she had picked out his face immediately. No doubt about it. That face was engraved on her memory for life, and she could never forget it. The police had reassured her; they knew the man •••couple months ago •••unusual rape case; released for lack of evidence •••it all fit •••they were about to let her go home. Finally, at last, she would be able to breathe again the fresh, peaceful air of the sane world. They would let her know if they caught him and when to come to court. But even in · blessing her with freedom they were curt and disrespectful to her. They hardly noticed her after she identified the picture; all they could think about was finding him and arresting him. The police moved about her in the tiny room, each handling some different aspect of the organization of the search. At last someone said to her, as if brushing her off, "Oh, Mrs. Jones, you can go hom,e now if you wish. The desk sergeant will arrange a ride for you." Then back to work, as if she had never been there.

"Now, Mrs. Jones, let's go back to that night again for just a moment," said the prosecutor as he paced slowly in front of the judge's bench. "What did you do as soon as you saw the killer run away?"

"I called the police and told them what I had seen, and told them to send an ambulance for the two girls.''

"And when the police arrived, did

The Messenger

they take you to headquarters and ask you to identify the killer's picture?"

''Oh, yes, I picked his picture out right away. I just knew it was the man, and especially after the police told me that he had been questioned about a rape a couple of months ago •••then I just knew •••"

"Objection!" came the defense lawyer's voice. "The witness is volunteering information, and, in addition, is speaking from hearsay. If counsel wishes to introduce this point, he should have an officer of the law testify to it."

''Objection sustained. Strike the witness's last statem -::mt from the record," said the judge.

Mrs. Jones noticed that the prosecutor was staring at her reproachfully. He had warned her before the trial about volunteering information, and about just answering the questions as he asked them. But it was too late now. The crowd of spectators was buzzing again and had to be brought to order once more.

Pluto sank further in his chair. There they go again. Why don't they just kick out all those people and have just the jujge and the jury and then maybe we could stick to the facts •••never thought they'd bring up that about the rape •••nah, no reason to worry about that; they couldn't even hold me on that charge ••• just circumstantial evidence, like they say •••same as now. They don't really have any evidence in this case, except for this meddling woman up there •••look at her. Must think she's some kind of queen or something. What in hell would make a woman do something like this? I mean, I got nothing against her •••I never did her any harm •••why is she meddling in something like this? Does sh,e really think that I could kill two little girls like that? •••such soft little bodies, that long soft hair that children have .•• they were unspoiled little ••• no, they were inhabitants of the docks. Doubt if they were unspoiled after all ••• but still, those soft baby faces. Saw their

'S i xty-S e ve n

faces •••saw the picture in the paper. They brought it to me down at headquarters. Dirty cops laughing at me. "Do you feel proud about this, Pluto? Do you get a kick out of. this kind of thing? You're lucky, Pluto ••• if the Supreme Court weren't watching, I'd belt you one now, just on general principles" •••wiseacre detectives •••! never did them any harm. What does this woman have against me, to come down here and put the finger on me in front of all these people •••sornebody paying her off? Nah, I got no enemies with that kind of money. Nah, she's probably just one of these civic-minded do-gooders. Public duty and all that. Wouldn't mind it so much except they're fooling around with me and the electric chair. Oh well, even if everything goes wrong and they find me guilty somehow, the lawyer says there are all kinds of appeals we can make, all the way up to the Supreme Court. That's funny. Never pictured old Pluto Brown up before the Supreme Court. Wonder if you call those guys ''your honor" or what. They probably have something higher to call them •••God, this is bad, just sitting here like this for hours while all these people who don't really know a damn thing get up and point the finger at old Pluto ••• getting hungry •••wonder if they'll let me eat lunch soon •••what tirn •:: is it anyway?

"And what · time was all this?" the prosecutor asked Mrs. Jones.

''Well, let's see •••I remember it was ten minutes to ten when I called the police from my office, and it was a few hours before I left the police station to go home. I got home about one-thirty in the morning."

"Thank you very much, Mrs. Jones. Cross-examine?"

The defense lawyer came forward slowly, deliberately, and walked toward Mrs. Jones. She felt her body tighten and brace itself, as if the oncoming verbal barrage were to be physical as well. She would not let herself be made a fool of in front of all these people. She

S e venteen

had come here to tell her story, and she was going to stick to it. She would not let any fancy-talking lawyer twist her words around •••no, not after what she had had to go through •••she had come a long way with this, and it had been a hard road, a hard road indeed for a lady; and she was not about to have it turn out to be all in vain •••this criminal must be brought to justice ••. after all, she was only doing her duty to the public •••the sam,3 any self-respecting citizen would do. After all, we should all take a little civic pride •••there could be no future hope for justice unless we do this.

"Mrs. Jones, as you know, in a murder case such as this, the defendant must be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt," the defense lawyer was saying. "Now you have testified that you identified Pluto Brown's picture within only a few minutes after the police showed you the book of photographs. Don't you think this a little unusual, shall we say?"

"Not really," answered Mrs. Jones confidently. ''It just shows how certain I was about the killer's identity."

'' And are you still just as sure about your identification?"

M:rs. Jones looked puzzled.

"What do you mean, sir?"

''I mean that there is still not the slightest doubt in your mind that you haven't identified the wrong man?"

There was a long pause. M.rs. Jones looked around the courtroom. She began to feel closed in again •••all the bodies ••• the crowd of people •••why wouldn't they just let her go home?

She cleared her throat and said, ''Not the slightest doubt whatever. He's the one who killed those little girls."

The way she delivered this line set the spectators to murmuring again. Mrs. Jones noticed the defendant's face. It was tormented as he looked behind him at the crowd. It was evident that he had not slept well for some time. He had that worn and haggard look of all prisoners, which made him loo!<:even more

positively guilty. It was a criminal's face ••. Mrs. Jones had always noticed this characteristic of certain faces. The criminal always had a sort of otherworld look about him •••high foreheads ••• oversized ears •••small eyes •••mangled noses •••and there was always something on one side of their faces that made their bisymmetrical appearance faulty. Pluto Brown's jaw seemed to droop more on the left side than the right. His was a perfect example of the archetypal, m1.sformed criminal face •.• oh, thank heavens •.•now they were releasing her, telling her she could return to her seat. She was filled with a sense of relief. She rose majestically to go back to the gallery. The judge's words soothed her as he said, "The witness is excused."

Pluto did not excuse her. How could anyone excuse a bitch like that for putting the finger on an innocent man? This damn lawyer they appointed me hasn't done too much either •••let her go right through his fingers without challenging what she had said at all. Oh God, what can I do now? This stupid jury is really going to give it to me. They're going to believe the whole prosecution case against me •••that bit about Ruby telling me to get out of her apartment didn't help any either •••easy to see how a guy could get thrown out by his girl and then go rape somebody. If Ruby hadn't been such a bitch about the whole thing, none of this would have ever happened. But I would have to leave there and go for a walk down on the docks to think things over. Boy, she must hate me almost as much as that Jones lady to tell the police about our quarrel. Maybe she really believes I did it, too •••well, just goes to show, you can't trust anybody •••you'd think your own girl friend would have a little more faith in you •••

''The little faith we now have would be betrayed, and another criminal would go free. This man's history is known to you," the prosecutor continued, ''and there can be no doubt that he did, indeed,

The Messenger

commit this murder •••"

Mrs. Jones sat in the rear of the courtroom now, her ordeal finished. She listened attentively as the prosecutor gave his summation to the jury. He was eloquent in his plea for justice. Mrs. Jones agreed with him completely. Piling evidence on evidence, he went through the case painstakingly, reviewing everything of importance to help the memory of the jurors. Mrs. Jones, though she was physically reft of all emotion since finishing her testimony, knew that she would be unable to sleep tonight if the defendant went free. She was silently egging on the prosecutor in his exhortation; she was rooting for justice, after all. Anyone with any conscience would have done the same thing •••That horrible, glaring light overhead in the office ••• wonder that he hadn't seen her looking out at him •••just a pause to go to the water fountain, and then a look out through the blinds into the gathering darkness along the piers •••the water lapping softly at the pilings •••then the scuffling noises •••three figures, but only one standing, the flash of the knife in the darkness •••raised high on its perch at the end of the man's arm •••brought down with horrible swiftness, again, and again, and ••.Nol Oh my God, please stop screaming •••what am I seeing? What is that man •••stops, looks into the water, lifts his arm and throws the knife, flashing1 falling, far, far out into the river. Stops again, looks: silence, deathly silence; looks all around •••the light ••• swinging on the chain overhead •••should I cut it out? Does he see it? Is he looking this way? His face •••running now, hear his feet striking the planks of the docks, growing fainter as he runs ••• Oh my God ••• Oh my God •••

"OI1 my God, that's a barefaced lie!" shouted Pluto, jumping to his feet and pounding the table in front of him. He was trying to tell them that he hadn't done it; he had to make them see that ••• but the baliff's men were tugging athim,

'Sixty-Seven

dragging him down into the seat once again •••the long wait •••the jury is leaving now •••I sure hope they think twice before they say I'm guilty. How can they think that I would do something like this? I mean, I may be bad, but I would have to be insane to rape and kill two little girls like that •••am I insane? If not, then how did I get into this mess in the first place? Oh, God, why don't they come back? They've been in there for two hours already ••• maybe that means they're having trouble deciding •••

Don't know why they should have any trouble, when they know he's guilty •••! hope they send him to the electric chair •••too bad they can't hang, draw, and quarter him, or at least fix it so he could die slowly. He deserves it •••scum and filth I've had to put up with •••I at least hope they don't have any trouble deciding he's guilty.

Oh God, here they come •••this is where I really get it ••.I can tell by their faces they think I'm guilty •••none of them will look at me straight •••come on, you bastards, look at me •••are you afraid to look at the man you judged guilty?

Their faces look as if they're going to let him go free. Of all the •••it's obvious that he's guilty •••that would really be a miscarriage of justice. Maybe they just found him guilty but recommended mercy. There's certainly no reason for mercy in this case •••cold-blooded •••I wouldn't be afraid to have him killed •••

Don't have me killed •••! want to live ••• just like you •••my body and my mind are both fighting for survival •••please let me live •••

Thumbs down •••take him to the electric chair •••never to see the light of day again •••

''M:ister Foreman, have you reached a verdict? "

''We have, your honor.••

Nineteen

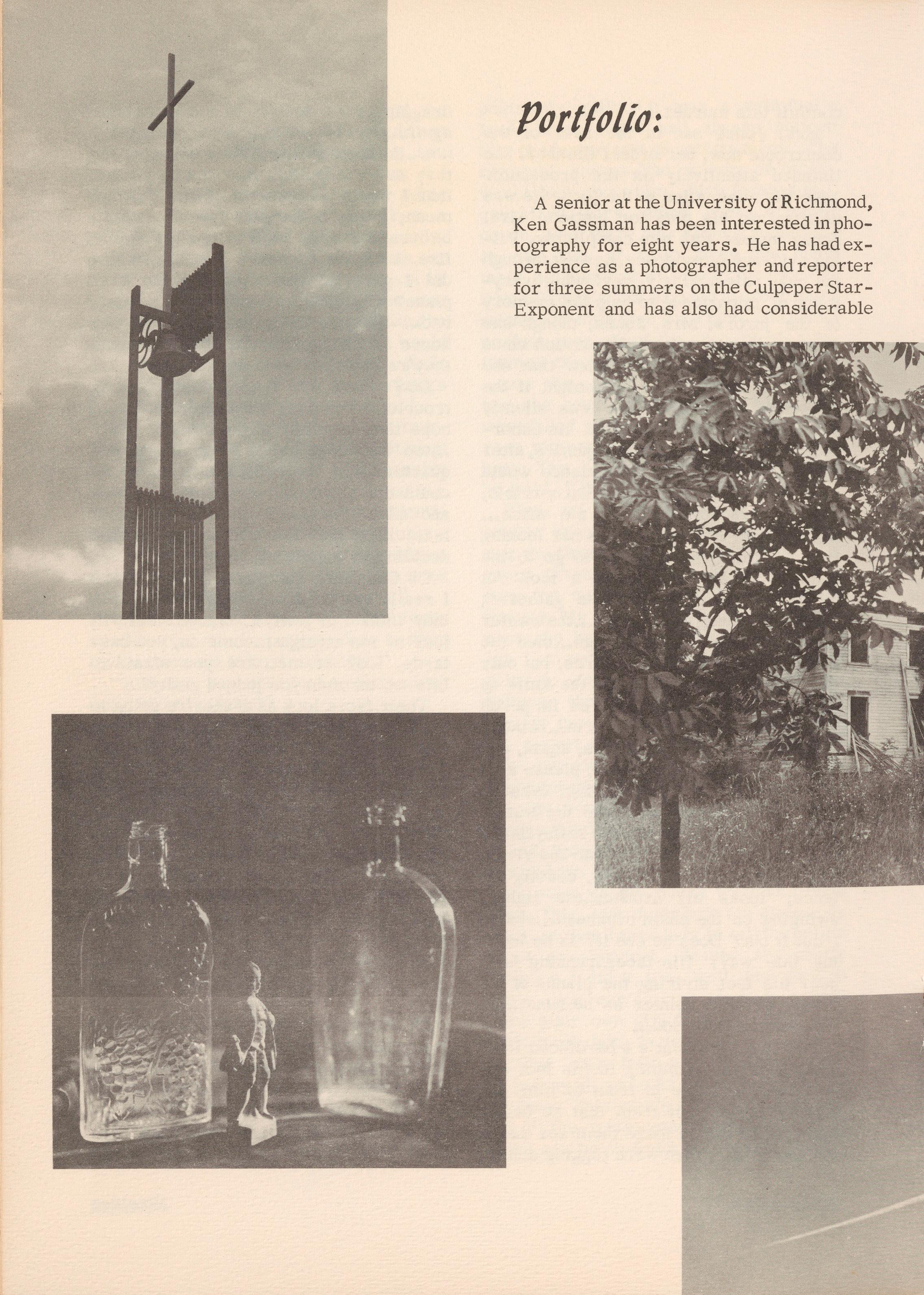

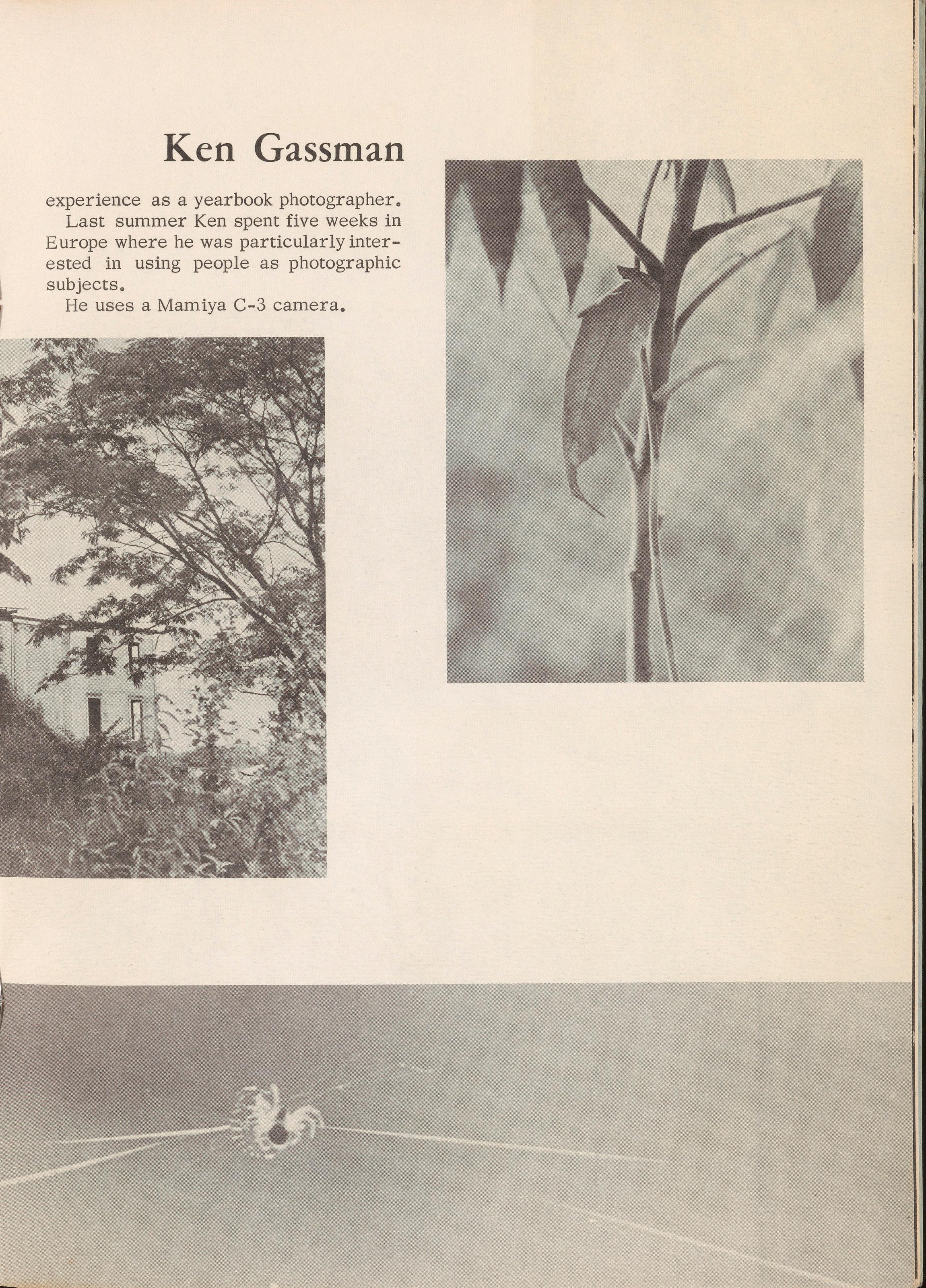

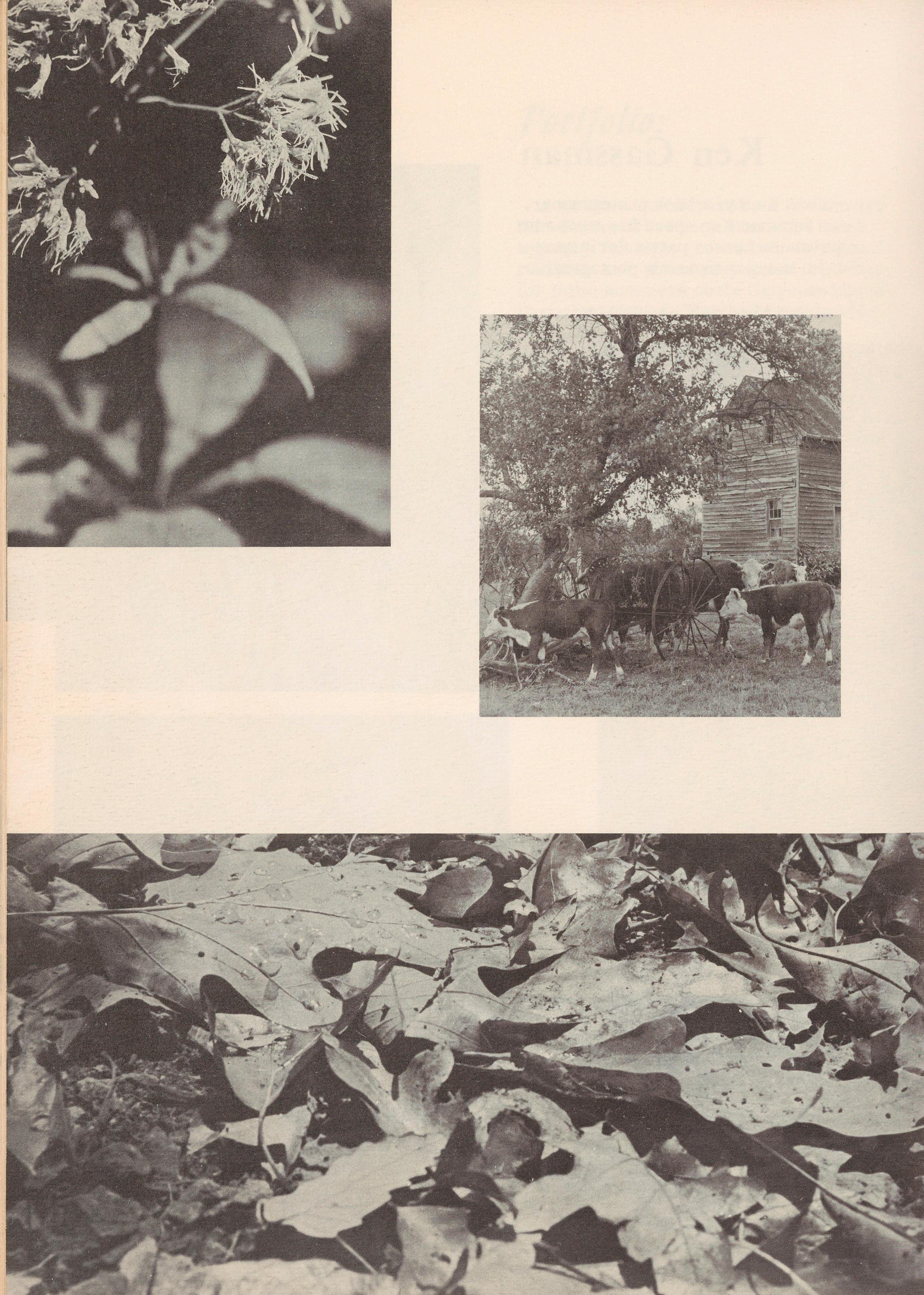

A senior at the University of Richmond, Ken Gassman has been interested in photography for eight years. He has had experience as a photographer and reporter for three summers on the Culpeper StarExponent and has also had considerable

experience as a yearbook photographer. Last summer Ken spent five weeks in Europe where he was particularly interested in using people as photographic subjects.

He uses a Mamiya C-3 camera.

by Gayle Covey

Immaturity is youth and youth is immaturity. Immaturity is basically growing to understanding: The climax is realization; the denouement is maturity.

Immaturity is falling in like instead of in love. It's holding hands and kissing and at the sam= time realizing that all will melt with the noon day sun. It's a toobig masculine ring on a too-small feminine finger.

Immaturity is the feeling that it's always too late. It's lying when a lie is convenient and later, weeping. It's tears over foolish acts and words that can never be done or said over. It's wishing to relive a special moment--a moment when a word of encouragement may have inspired the downcast; a moment when opportunity offered itself; a moment when a head held high would have been a source of strength.

Immaturity is an episode in the superlative. Each event is the most important; each desire is the most urgent; and each hurt is the most painful.

Imm:1turity is a leather bound volume of one's own poems, titled in script on

Twenty-Four

the first page. It is a collection of introspective essays that are despairing and · irrational, yet strangely perceptive.

Imm:1turity is doubting. It m.ingles the disbelief in the Suprem= and His frightening closeness. It's wondering if there is such a place as Hell, such an emotion as love, such a thing as me soul.

Immaturity is the vagu=n•~ss of the past, the startling awareness of the present, the unrealism of the future. It's forgetting yesterday, living for today, and being unconcerned about to;norrow. It's being from day to day--each day a separate unit to h= lived and then b;,iried in the serenity of night.

Immaturity is conforming to being an individual. It is learning to live by one's own soul, singing one's own song, dreaming one's own dream, hoping one's own hope, praying one's own prayer.

I, then, am the embodiment of immaturity. My beliefs are as modulating as my moods, as illusive as my aspirations, as unstable as my actions. My restless body houses a restless soul in se!lrch of realization of the Divine, in

The Messenger

search of connection with the Universal.

Maturity will end the search, will enable my reaching hand to grasp. Until then, I stake all belief, all faith, in my power to eventually achieve understanding. By acquiring firm belief in myself and my judgment, my shaky belief in the Deity will be valid and sure when it jells into conviction.

To believe in myself, I must first be aware of my reality. I may choose my sentiments, aversions, and prejudices but I may not be deluded--! may not pervert, ignore, or desecrate those things which exist within myself.

My self-portrait is shaped by a progression of loves.

I have loved first my teachers, for their devoted errors. Their minds, juxtaposed against mine, trying to establish a basis quickly beneath my ideas, are behind me, are waiting for the results: the extent of failure.

Among this group are my parents. They, like everyone, are waiting for the culmination of the ritual. The theme of the song will be revealed only in the last note--in the finality they, like each of us, cannot live to hear. And so they are waiting now for the minor revelations: The graduations, the marriages, the children. But not, of course, quietly.

Wiihin my family, I have loved my sister. Because one must love one's sister, in :ier failures and sometimes successes, in her strength, in her blindness, in her successful em ,?.rgence from foolish, foolish youth.

Writers--there are many I have loved. There is Maugham, whose Phillip is enslaved, and who seems to understand, I think, that Mildred is in a greater, more inescapable bondage. Earlier I loved Margaret Mitchell, who wrote a single book with the flair for a series of shoddy volumes. Shakespeare, because he let Ophelia drown, and left us with the image of her thrashing m·,dly about with lilies. Steinbeck, because he presented life in the garish light of suffering.

'Sixty-S e ven

And I loved Ayn Rand, partly, or perhaps principally, because she was the thing to love that year.

I have loved folksingers, In and Out, ethnic and pseudo. They are so wealthy in their dishonesty, so deep in their simplicity, so much smarter than we are, whatever they sing.

I have loved so many boys, and some men, because they have called or spoken or smiled at me. And some of them have asked for more. That is a question each must ask oneself. And those who cannot understand the answer? I have loved them too, for their dedication, for their simplicity. But we parted because of Mother, Se venteen magazine, Ann Landers, and the innate morality within me. One love almost endured my demands for perfection. Now I glimpse the possibility of mature love -sacrificing one's entity for a greater whole: Blending of souls, mingling of minds, striving towards worthiness.

I have been befriended and have reciprocated or subtly, tactfully sent my regrets. I have loved those with whom I shared experiences, ideas, and aspirations; those with whom I enjoyed the communion of intellect; those who cared enough to probe; __those with whom I laughed, cried, and empathized; those who accepted me.

The hard lines of living and the blackness of dying I have loved. These rules, these barely sketched directions, have given and taken away, and because they are there, I love them.

There is, nowhere in this partial, unsteady portrait, any semblance of logic, any explanation, any order of existence. And that, in life, is why I love.

In my immaturity, I believe my character--my reality--is reflected by my capacity to love. If, in truth, God is love, this is valid and significant: Love engenders my first glimpse of the Supreme and it is, ultimately, the only link between heaven and earth, between Him and

D

Twenty-Five

Strong birch branch

you hear in the singing sound of wind your own unspeakable name, touched with love on the curling strands of supple golden bark,·

You are nested in by feathered hearts, and you affirm from the crushing blood of the earth and the withered God aloft, the birds of your own swift paradise

Then stand in bending wind a curving bone of God's contention-hand honed in his loving main burned from moon to the sun and the west-wild wind--

And turn to him alone, shifting down your rigid limbs and arching loose your hair, you wear an ashen powder tonight in his ancient chamber bed,·

Soft birch branch

you hear in the sighing braille of the wind your own whispered name, touched with love on the fraying strands of frail white bark.

-

Charles P. Barrett

'Sixty-Seven

One passed under the sun With a faint smell of perfume, Without notice, and was gone.

Deep within the shifting springs Of thought, a rustle of waters Betrayed him to himself.

The magic was momentary, But the waters were revealed In their fiercest fullness By the lingering sweet scent.

So too, in the clear night air, When the great king was walking In the silence of his chamber,

Surveying the silence Of his holy kingdom,

And saw the dark woman bathing Below in her green garden, Did the waters rustle.

- James Bowen

Twenty-Seven

by Robert P. Arthur

We were on a manhunt, looking for a killer.

All through the hunt nature had seemed to me convoluted, twisted out of perspective, as if the universe were twisted taut, like damp wrung-out clothes. Every bud, every stem seemed grotesque in beauty or grotesque in sickness. And through it all there was the glare, celestial, yet uncertain, of refracted light that wound itself around branches, shimmered off the white underside of aspen leayes ..•• It was Colby •••• Colby who made it that way.

All about there was a horrible stillness, a vague presentiment that the inexplicable would become concrete. It was as if the little leaves had lapped up all sound, as I imagined little black tongues of toad-like creatures lap up water.

Colby silently handed me a can of brown bread. To thank him, I waved my hand weakly, then began eating with relish •••• but warily. The first morsel seasoned my hunger, made me careless, and I foolishly ate with abandon, laying my rifle on the glistening wet grass so that the sharp green blades poked like spires through the trigger hoJ,ising. The trigger itself would be wet and slippery. Colby cast a cold eye.

Then suddenly there were birds screaming in the sky, so thick overhead that it seemed a thundershower was upon us; it had rained all morning and now in

Twenty-Eight

the afternoon, the wild black birds were drying their wings by beating them in the sun ••or had something disturbed them? But careless of my surroundings, I plucked the bread from the can and thrust it into my mouth.

I wasn't afraid for I felt with disgust that Colby, clad in a red and white hunting ja ,::ket of coarse wool, was not so careless as ! throughout the meal he had kept his finger on his trigger and now his eyes focused on the immense wall of black pines that rose before us like a dark granite bluff.

"Could it be he?"

Colby flattened out on the grass and calmly motioned for m,3 to do the same,.

"Yes.''

''But how?" I asked, scrambling down beside him and leveling my rifle on the long lines of pines that stood up in stark relief against th ,e sky, stiffly, like the black plum3s on a nin •::!teenth century hearse.

"Listen to the dogs.''

I held my breath till I thought my chest would split; the fierce baying of the hounds floating malignantly through the shadows had gotten closer; black and devilish, the yelps were still far away but they were now audible and unpleasantly thrilling.

''He's traveling in an arc," Colby whispered, "a wide sweeping arc that's swept back into the county. He might come right at us."

The Messenger

"We'll kill him, kill him!" I exclaimed. A sudden rage came over me; boiling over, it spilled out into Colby's ear. My words were filled with the blackest hatred, but Colby didn't seem to notice ••••• He gave m~ merely a glance, the certain look that I detested with all my soul.

''Why not?" I exclaimed, ''Why not? I'm a poet, Colby, .· I feel things very deeply."

He shrugged.

''He killed a little girl, Colby, a little girl •••molested her too. We mustn't forget that."

"He'll be stopped," muttered Colby calmly, giving m~ another of those hateful glances.

''We've got to shoot him down like a dog Colby, like a dog." Tears of frustration jerked from my eyes. ''He never gave anyone else a chance/' I said too loudly, "he's mad, like a dog. I'm going to cut him in half •••"

Colby's eyes scanned the trees; he put a blade of the wet grass in his mouth and chewed it carefully.

"He's got a twelve gauge."

"I don't care, I just don't care."

Colby put his - finger to his lips, "shhhhh."

I knew then that I never should have · gone out with Colby, never should have jumped to his side when the townspeople had lined up and decided to go out in pairs. I never should have gone out with the rear guard which was established in case the killer should circle. I should have chosen another partner and followed the dogs, for being in the rear guard meant that I would have to wait in the black pines with a person like Colby.

At any rate, I shouldn't have gonewith Colby. Hadn't I learned in the seven years I had been his neighbor that I couldn't stand his prolonged company?

. We had already been in the woods thirty hours together •••thirty unbearable hours and twenty of them had been spent in the rain so that m y clothes were already

Thirty

soggy and heavy, wet and clinging. How did I ever expect to bear his glances? What strange magnetism ~ould he have had for me so that when the townspeople paired off, I lept to his side?

"Why did I go with you?" I muttered. Colby looked at me. "Because you couldn't help it.''

The woods had become silent; the birds had passed. The air seemed charged with the last wave-like vibrations of their cries; the hounds in the distance had inexplicably ceased their baying. My hands ached for a tighter grip on the slippery wet stock, and my heart cried out to explode the barrel; my eye slid along the death-like gray.

Then faintly there was a movement, almost imperceivable, emanating from a patch of wild thorny vines of rose that made a dazzling green and red fence in the midst of a cluster of drooping black pines; there was a rustle as if the underbrush was palpitating.

"Hold your fire/' said Colby.

The blast rocked me back so that I seemed to snap at the waist; Roman candles went off in my head with such fury that my eardrums seemed to split, and by the light of their flares, I perceived my barrel smoking.

There was a large billow of smoke at first, but in an instant, it was a thin steady steam like the curling wisp from a cigarette.

"I can't!" I exclaimed, after the action. ''It happened too fast; I didn't have time to see."

Colby said nothing, but climbed to his feet, shouldering his weapon and gazing before him at the black pines ahead. In the afternoon light, he seemed a gray statue, a chunk of granite in a checkered woolen jacket.

I put my hands to my eyes to shut out the sight, but my traitorous fingers parted, forcing upon me the dreaded sight. A black and white spotted dog savagely snapped at the blood on his shoulder, then with a few quick bounds

The Messenger

and a weak plaintive howl, flopped forward on the wet grass. His eyes were glazed, his mouth was open, and a rivulet of blood poured without force from his throat.

"It could have been he!" I cried, "It could have been."

"The dog must have lost the scent, then wandered back here/' Colby said to him self, striding forward.

''How could I have known?" I said, following quickly on his heels. ''It could have been the killer. It could have very easily been the killer, you've got to admit that."

The wet grass seemed to surrender beneath Colby's boots.

"For God's sake, Colby.''

Colby turned, and then he gave me that look •••Oh how I dispised it; it made me look into myself. How often he had looked at me like that. For seven long years, or maybe more -anyway, ever since I had known him, he had ruined my plans with that look. I seemed to swallow my heart as I turned my eyes away and down.

There was no disapproval in Colby's eyes; how I wish there had been. But rather, his face was a mask of quiet, serene understanding. There was no blame, no disgust, but there was no pity either; no sorrow, no hurt, no sym:_:>athy, no surprise •••••••he wasn't cold, but he wasn't warm; he was like a man calmly com~ing his hair -he was like my father.

''I couldn't help it Colby."

He nodded.

"Damn it, I couldn't.''

He smiled faintly, "You don't have to explain," he said, and then thoughtfully, ''Things like this happen."

Colby walked on; never before had I so yearned to blurt out the news about myself and his dear wife Nora ••••but I again, though the yearning seemed to tear at my breast with sharp jagged pincers, became as mute as a church, the force remaining latent inside me like

'Sixty-Seven

the steam of a hot-lidded cauldron. He passed by the blood spot on the green without glancing down, then stomped through a yellow outcropping of cornflowers. With a gesture of his hand, he led me at last to a vantage point in the strip of field that revealed the outer line of black pines. They swerved for miles, and then on the blue horizon., skidded into the sky. There he stopped ••••pensive.

He waited.

I wrung my hands in despair and frustration; he had no right to treat me this way; I had never pretended to be an expert in woodlore. No, I had never admitted that hunting repulsed me. I had come to the township to write •••••for no other reason •••••! wanted to set down in my poetry the beauty of the woods., the marvelous colors, the sweet sounds and smells, for I had always felt a mystic deepness about nature that made my mind take flight and sing. I wanted to capture its soul •••••but always, always, . Colby was there, destroying, destroying ••.• Even now I would have turned back, charged back to my home to rid myself of him., but I could never have gotten back alone, and seeing Colby standing there in the midst of cornflowers, gray arid impressive, like a sententious Buddha, made me realize anew -I couldn't ever hope to get back alone. For Colby was a community man. All the answers for him were cut and dried. He was stern, practical •••the type of man every man needs to help him find his way back to a place.

His calm profile cut a shadow out of the setting sun.

Then we walked on. Colby spoke without emotion, ''We have to go to Bideller."

"But why?" I said, then I wrung my hands and muttered too faintly to be heard, "About killing that dog, Colby ••• I don't think •••••I'm not supposed to be •••"

Colby paid no attention; his thoughts seemed to be deep in the darkness of the pines.

Thirty-One

"He's circled back," he said, as if to himself; as if I weren't to hear, "so we know he's headed east. If he were coming straight at us or if he were coming from there," Colby pointed to the north with his rifle, ''the dog would have been downwind and would have scented him. As it is, he must be south of here, which means he'll have to cross the river, and its too wide to cross except at Bideller.,.,

"Yes, of course," I said, "of course."

But Colby was unmoved by my effusion; without acknowledging my comment, he strode to the south down an invisible but predestined path. He walked on faster than I could walk and I caught mysel:.: taking two strides to his one, half skipping across the wet grass like a boy. Between tears for the dog and outrage engendered by Colby, I scarcely knew how to behave.

I hated to feel weak and helpless, and my mind was crawling with bitter thoughts. In my stupor, I failed to notice that the brush was alive.

A bobolink, brown like a squirrel, was matted against an assemblage of fallen logs until we approached; then detecting us, the spring wraith, with a ho a rse strained cry, spread his wings and disappeared upward in a frenzied spiral of white and brown feathers. So startled was I, the bird having shot close by my head, that I fell back emitting an involuntary shout of surprise.

But it was not until three or four steps later that Colby bothered to look up at all, and then it was only to cheek the . position of the sun.

His mottled coat then moved on a pace, seeming to vanish through the ring of black pines. I stumbled forward, banging my shins on a rotted stump, before I again caught a panicked glance of his woolen red-checked form disappearing in the woods that enclosed us •••I followed ••••no longer dreading.

I tried to keep my laughter quiet so Colby wouldn't hear; so great was the

Thirty-Two

task that I was forced to hold my sides. He was threading his way through a thicket ahead; the noise he made was like that of an elephant rising from the rushes. On the other hand, I was quiet. My feline movements were inaudible even to the man who walked a few paces in front of me.

The dark wood was alive with a scintilating beauty; through the uppermost branches of pine, blackbirds were pieces of coal against the face of the sun, and the smell of pines, thick like musk, and sweet like perfume, highlighted little eyelike flashes of red blossoms that peeked at us through the dark. Somewhere in the distance that the thick trees made farther, a thrush warbled sweetly to its lover, and faintly singing, rising and falling, there was the sound of water. No light invaded our sanctuary; the light was forced away by the pines' joined hands, the winds' blowing of needles.

This darkness had the effect of making me see matters better and I concluded this; the essential difference between Cofoy and myself was that he was not a poet, and that I undeniably was and never wished to be anything else. I said to his red-checked back while disengaging my coat from a bush or briars, "I say Colby, how goes the business? Doing well I hope.''

He might have been surprised, but he wasn't.

"Yes," he answered. ''You ought to know, you work there."

"That's wonderful, of course," I said. ''Everybody's buying rifles I guess."

"You sell a few rifles."

"Shells too eh, I suppose."

"Yes, shells too."

"Ha," I murmured, under my breath.

The essence of the thing was clear; Colby was clearly not a poet whereas I was, to be sure. Witness his failure to be moved by the sudden thrilling, daring flight of the squirrel-colored bobolink, The Messenger

that zipped like a bullet through the brush and near his head. I, of course., being the poet, was filled with ecstasy by its wild careening flight upward, and then by its gay., powerful loops in the blue sky above the pines •••but Colby felt nothing, nothing. As to nature., he was dead, like my father. I had him there and the knowledge, now certain, of his insufficiency, heartened me considerably as I clum;_:>edalong behind him in a jagged, rutted trail.

It was probably this insufficiency in him that had endeared me to his wife. She appreciated my poem;;; when I read them before the fire •••she wanted me for my verse. But he •••••he responded by silently knocking the ashes from his pipe and looking at me with that gaze I so despised, that horrible understanding mixed with indifference that, without accusation., seemed to tell me that I was in the country because I could not impress anyone but rustics -an atrocious lie. If I had meant to impress, would I have ever become a clerk in Colby's store, would I have accepted food from his hands?

Witness also Colby's behavior when I killed the dog. Had he cried out, had he mourned? No, emphatically no. Were not my reactions superior? The dog's death seemed to carve a hole in my soul., a great gaping hole that only can be cut into the hearts of poets, never in the hearts of lesser men. Did taking food from Colby then make me his inferior? •••no, once again emphatically. He was like my father •••healthy., depended upon, successful in his community. But were either of them ;;)Oets? Ha I I hitched up my pants and listened to the birds as I walked. They seemed to tell me secrets about the woods; there were gulls there that whispered darkly of the strangeness of the sea. Robins and wrens., finches and linnets in many colored humorous garments, chatted gaily into my ears, and my eyes became cloudy as if a mist was before them.

'Sixty-Seven

could give myself freely to the birds. How many men in the world there are who know nothing of this glory, or of this sacrifice? I resolved then never again to turn away from Colby's stare. I marked well how difficult it was for him to walk in foe woods quietly, while I could creep quietly enough ••• It was as if I belonged in the woods and he did not. It made me chuckle to think that if I stealthily crept away, he would suddenly find himself abandoned and unable to find his way back to town. I could vividly picture him lost in a maze of pines.

This reflection boosted me co:isiderably, so much so that I felt somewhat taller than I had a moment before and I strove to catch up with Colby so that we w91:1ld be walking breast to breast with our shoulders aligned. Debouching from a maze of Ellum, charred ashen timber from a fire in the fall, we broke into a little dell whose circle was split in two by a stream of cold blue water that gushed steadily, almost merrily., from the southernmost end of a distant thicket of wild hedge, which was, by the way, shrouded with vines, and currycombed by the water's blue veined pattern of rivulets. The wind was bracing, al~ost cold; foolish thrush and seven colored linnets, still unaware of our presence, sang in warbles beyond the woodgate., and I for one, strode about feeling very much better.

We stopped for a while and rested beneath the aspen that roughly marked the center of the dell; cornflowers dotted the wet grass about it and there was the heavy smell of invisible lilac.

It seemed a pity that this was lost on Colby.

He slumped down under the aspen, resting a back that should have been weary from its labors. I was too excited for such sloth. Scarcely able to contain myself, I walked back and forth impatiently rubbing my hands together.

''Beautiful, eh Colby?"

Thirty-Three

"Yes, it's beautiful."

"Ha," I said to myself, continuing my pacing, "Do you truly find .it so?"

From the corner of my eyes I shot him a rapid glance and then off into the wood as if I were lost in contemplation, divorced from the figure in the redchecked coat.

"Yes, I do," he said.

"Of course," I smiled, "I don't suppose that you find anything else here, something intangible which is impossibl<:; to define in any save a mystic sense.''

Receiving no answer, I turned about and found that Colby was scarcely attentive; the contents of his knapsack were spread out before him and he was slowly twisting the aluminum lid of his thermos bottle. His cup was upright waiting to receive the brownness of coffee.

"Colby," I said, "people like myself, at times, can appear to be very strange, for example, at this moment I am exceedingly grieved by the death of a mangy hound. These woods, this water; these flowers and their delicious smells, seem to indicate to me that nature and its creatures blend together in a lasting harmony that I disrupted by an infernal shot. Do you see what I mean?

''They are beautiful," Colby answer .ed quietly, putting the coffee to his lips.

Something jerked inside of me, "That's why I hated to kill the dog. Do you see that. You don't, do you •••it surprised you extremely?"

"You didn't know it was a dog."

"Of course, I didn't!" I cried, unable to keep my arm from making a gesture revealing agitation. "But it's not that which matters. What really counts is that •••that •••that ••••"

"That the dog is dead," said Colby.

"Yes, yes, yes," I shouted, "what really counts is that one of the vital parts has been destroyed, not by nature but by mechanics ••can 't you see that a vital link has been broken? Doesn't the

Thirty-Four

beauty of the woods reveal the tragedy •• hasn't the essence of communion vanished?"

''We could have used the dog to track down the killer,'' said Colby.

"Oh damn it, Colby." With the stock of my rifle I slashed a white leaf from the aspen, "I'm a different sort of man," I cried, flinging my rifle to the ground with all my strength. "I'm a sensitive man and I believe in my feelings. May the world forever damn those who don't."

I was aware of hot tears streaming down my face, and I turned away from the threatening figure slouched against the tree, calmly sipping his coffee from a plastic cup.

"You think I'm a comedown from my father, don't you, Colby?"

Colby said nothing.

''Don't you?'' I repeated.

"You look foolish hopping around," he said.

I shook my head without turning around. "Colby," I said, "there's something about you ••I don't know what it is exactly, but you make me want to go head first into the trunk of the largest tree I can find.''

"Well," said Colby, "I know that's true, but standing around here talking about it is not getting us any closer to the killer, is it?''

"No.''

"Let's get a move on then.''

Colby got to his feet stiffly and moved away from the tree carrying his rifle at port arms so that the wooded stock seemed a thick limb extending from a red and white checked trunk.

'' All right," I muttered, still bristling with indignation. As I stooped to pick up my rifle by the barrel, I was especially angry, for my retrieving the weapon brought me a sudden sense of humiliation, it was as if I were a ch~ld, shamefully picking up a toy I has hastily and foolishly thrown away; if Nora has be.en present, I would have hid my face.

The Messenger

I was again a number of steps behind Colby. Now on his feet, he seemed like liquid sliding down the green slope, a mechanical soldier perfectly adapted to his game. He reached the stream and cleared it with an effortless bound, a movement that suggested to me those abstract statues designed to capture grace, and I was suddenly once again the noisy one. In a matter of seconds, I seemed to have lost my sense of balance, and what is more, my sense of direction ••••for I could have sworii we were headed north, an impression that was immediately corrected when I glanced at the sun and determined Colby, as usual, to be right •••he was like my father in that.

We entered into our second ring of pines; I had the impression that we were passing through concentric circles; things seemed to be spinning about; the woods, the hedges, the flowers, the grass, high at the dell's edge, seemed to be part of a moving ring spinning_. swirling, to its eruption at a distant vertex.

It was darker than ever in the woods, possibly darker than an open field at night. The branches overhead were woven together heavy and dark, black threads stretched taut above us so that the sky seemed not to be the sky, but rather a massive horizontal loom supporting a fabric with silvery glitters. But I knew those glitters to be something other than they seemed, they were afternoon stars.

Their faint light shone only on Colby's red-checked coat as it slithered in and then out of my vision.

"Colby:• I said, "You won't tell your wife, Nora, about my shooting that dog, will you?"

''My wife?" replied Colby nonchalantly, stepping high to avoid the gray briars that opposed him. "She's more your wife.''

It was as if a branch of pine struck me in the face. In my surprise, I almost dropped my rifle, but Colby walked on .

'Sixty-Seven

with no more concern than if he had remuked on the weather.

''Colby," I said, ''What can you mean by that?"

His answer was dry, "She's mere like you than me."

"But man, you support her."

"So I do," he remarked, and then flatly added_. "I support you too."

The color rose quickly into my cheeks; the rage inside· me blossomed like a flower and tendrils seemed to creep into my arms and legs, making me stiff all over. I would have shouted had not Colby suddenly stopped and motioned for me to do the same. "Quiet," he whispered, and then he froze.

In the sudden stillness a wail could be heard in the distance. It was faint but distinct; it continued for an agonizing moment and then quite suddenly broke off, leaving the woods in a death-like quiet.

"He's killed the lead dog," muttered Colby. "He '11 be running for Bideller."

I felt ice water streaming from my face. Suddenly and inexplicably, I felt weak all over and I slumped down to the ground letting my rifle fall from my hands. My scene went unnoticed_. for Colby was calmly checking his cartridges. I groaned, almost inaudibly, but Colby heard; his cold frayed eyes made m,~ shiver as he turned to discover me seated on a mound of dry needles.

"Are you surprised now?" I said meekly.

Colby cocked his rifle ~9mplacently, "Why should I be surprised?JJ

"Not even by the question?"

"No."

"Haven't you ever been afraid before?"

Colby looked at the sun and then at his watch. "It'll be.dusk in twenty minutes, he'll hit Bideller in about twenty-five. We ought to be there in ten_. that is, if we trot once we reach the river. If we don't run, he'll make the crossing before we get there."

Thirty-Five

"Colby," I cried, once again too loudly, ''I •m not going. I won't kill a man, I will not be responsible for the death of a man, or a dog, or a flower. I am a poet Colby, a fell victim of my finer feelings. I love this Colby." I indicated with sweeping gestures, the woods, the briars, the brush wedded together about: me. "Nothing can make me kill a fellow creature. I don't expect you to understand. The bobolink told me not to and I certainly won't do it.

Colby's look was blank.

"You don't understand, do you?"

Colby plucked a leaf and putting it in his mouth, began to chew slowly. My dread was doubled for something about his eyes told me he understood all too well the swirling cycle of my emotions. He gave the impression that he himself had gone through it, or I should say around it, and then at last outgrown it. As for myself, I refused to see it.

"I •m a poet,,. I muttered.

"Yes," he said.

''Does it surprise you?"

Colby looked at his watch, ''We've lost five minutes."

''I don't care," I shouted, "I won't have him killed! I'm a lover of God; I'll warn him, I swear I will, if I have to."

"We'd better be going."

"Will you give me quiet •••quiet, quiet, quiet, quiet."

"We have to kill this fellow:•

''I won't be a party to revenge.•'

"No revenge. We have to kill him or he '11 kill again.''

''Look Colby, I can talk with my hands if I have to." I threw my hands at the sky. I cried, "Think, Colby, think! Why did this fellow kill. He killed because he had to. He looked at the world and it wasn't right, and he made a new one where killing was right. You know this is true, you've known it all along. Damn it, Colby, this fellow's a poet!"

Colby cocked his rifle; the harsh metallic click was like the single beat of a drum. Colby's words were flat.

Thirty-Six

"He '11 kill again if we don't kill him!•

As if struck in the face, I screamed, "I won't have it that way, I won't! Both of my fists struck the ground, and I rolled on the ground in pain.

But Colby wasn't there to bear witness; it took me several moments to realize that his red-checked coat had disappeared in the foliage as if the dimly perceived majestic green curtain had prematurely closed behind him. Beyond the emerald scrim, I could hear him thrashing. There was the sound of closes being torn apart, the dull thud of rotten limbs breaking, the hollow tread of heavy boots as they beat a winding path to the river.

In the darkness, I becam,e afraid.

"Colby," I called. There was no answer. It was like the many times I had called after my father. The wind started up and faintly whistled~ the needles began to sway in the uppermost branches. Through a gap in the open ceiling, I saw that the sun had gone and the sky was no longer blue, but rather, washed in dying colors, the mostprominent being gray.

There was the dreary sound of an owl., and then I heard the baying of a dog. I scrambled to my feet and ran. Gasping for breath, tripping and falling, I ran blindly through the woods, following Colby through the web of pine in a jagged line past brush and rocks., and through a black glade that seemed to seal off the way I had come.

At last I reached the river, but he was still ahead of me; in the distance, I could see his rosy figure against a backdrop of water stream:i.ng in a long curve back into the pines on a far horizon. He was running at an even pace, never breaking stride.

He was strong and lithe as a deer.

"Colby," I called, but he failed to check his pace. He flitted in and out of the falling darkness, but when the land rose, I could see his red form outlined against the dark green of the far bank.,

The Messenger

and I strove to reach the point where he had last appeared.

''Colby,'' I called, but my voice seemed taken by my exhaustion. It was too weak to be heard and rather like a whine inside my soul. Still carrying my rifle before me, I pressed in hard with my elbows at the pain that grew in my sides till it seemed a fire raged there. I fought for air and slapped at my legs to drive away the rubbery numbness, but still Colby gained ground. The twenty minutes it took to reach Bideller seemed like hours, but at last the tail end of the river narrowed and became a stream, and I could dimly see in the encroaching dark, the old wooden bridge that marked the northern .boundary of Bideller.

Colby was stretched out in the undergrowth on the southern side of the bridge and I flung myself down beside him.

''Thank God l" I exclaimed.

Colby ignored me.

"I couldn't let you face this alone.,, Colby nodded; machine-like, his eyes roved over the steep far bank.

"He'll use the bridge," I said.