On the cover

In March, a crowd gathered in Flaum Atrium for the announcement of NCI Cancer Center designation for Wilmot Cancer Institute, putting it in the top 4 percent of the 1,500 cancer centers in the country.

POINT OF VIEW

On the cover

In March, a crowd gathered in Flaum Atrium for the announcement of NCI Cancer Center designation for Wilmot Cancer Institute, putting it in the top 4 percent of the 1,500 cancer centers in the country.

In May, the School of Medicine and Dentistry held its graduation ceremony in Kodak Hall at Eastman Theatre in downtown Rochester, and some students also attended the University-wide ceremony on River Campus. Here, SMD graduates stand to be recognized during the conferring of degrees.

David Linehan, MD

CEO, University of Rochester Medical Center

Dean, School of Medicine and Dentistry

Senior Vice President for Health Sciences

The word “care” is in the name of the field we work in, but think for a moment about the

different meanings of that word.

Yes, we deliver healthcare to help people live their healthiest lives. But before that can happen, we need people who care enough to make a difference. When you do, you’re willing to put in the work no matter how challenging it gets.

It’s that kind of caring that fueled Wilmot Cancer Institute’s decade-long quest to gain coveted NCI Cancer Designation. When this major achievement was announced in March, it put Wilmot in the top 4 percent of the 1,500 cancer centers in the country. In this issue of Rochester Medicine, SMD alumni and others share their experiences at other NCI cancer centers, explaining the unparalleled benefits ahead for our researchers, clinicians, and patients.

You’ll also read about an SMD alum who is changing how we help parents who experience a child born still. Heather Florescue’s heartfelt care for her OB-GYN patients led her to go beyond the conventional wisdom of what people need in those circumstances. She didn’t realize how innovative her approach was until someone pointed it out. Her discovery of a better way to help is now gaining national attention.

These stories represent opposite ends of the spectrum: research into fundamental science and the healing connection between clinician and patient. What they have in common is a level of dedication that can lead to great things.

I hope these stories inspire you and remind you of what can be achieved when people aim to be ever better, no matter how much time and energy it might take.

What do you think?

Rochester Medicine welcomes letters from readers. The editor reserves the right to select letters for publication and to edit for style and space. Brief letters are encouraged.

RochesterMedicineMagazine@urmc.rochester.edu

Read more Rochester Medicine RochesterMedicine.urmc.edu

Submit Class Notes RochesterMedicineMagazine@urmc.rochester.edu

Write to Us

Rochester Medicine magazine University of Rochester Medical Center 601 Elmwood Avenue Box 643

Rochester, New York 14642

by Leslie White

UR Medicine’s Strong Memorial Hospital recently provided its 1,000th heart pump for patients with advanced heart failure. The University of Rochester Medical Center joins a small and elite group—including Duke, Emory, Texas Heart Institute, Columbia, and Cleveland Clinic—to reach this milestone.

UR Medicine has a long history of using left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) for patients waiting for a heart transplant or as a permanent solution for patients ineligible for transplant. It is one of the highest-volume centers for LVAD use in the nation.

With this expertise, our clinicians’ research and insights have supported manufacturers’ efforts to improve pump design. LVADs are now standard therapy, along with medication and transplantation, for heart failure, said Jeffrey Alexis, MD, medical director of the LVAD program.

In 2018, UR Medicine cardiac surgeons pioneered a less-invasive technique for implanting the HeartMate 3 LVAD. Using this approach, surgeons can affix the device to the heart via two small incisions, eliminating the need to open the sternum. A year later, the procedure earned FDA approval. Research has shown that this “sternal sparing” method brings faster healing and recovery.

“Our national leadership in this sternal-sparing surgery put the spotlight on our LVAD program and our successes,” said cardiac surgeon Bartholomew Simon (MD ’15, Res ’22), surgical director of Heart Transplantation and LVAD.

The evolution of LVADs has dramatically improved outcomes. Twenty years ago, the devices were much heavier, and survival rates were fewer than two years. The current HeartMate II and HeartMate 3 pumps, made by Abbott, are significantly smaller and lighter—and more effective.

With 24 years of experience, UR Medicine’s team uses its expertise to determine which patients will benefit from an LVAD. Notably, one UR Medicine patient has lived with the pump for nearly 14 years.

by Kelsie Smith-Hayduk

It makes us cringe—the sound of two helmets smashing during a football game, a player down on the field. But what about all the other hits to the head—like the impact with the ground during a tackle, or a player heading a soccer ball? What do these less-dramatic hits mean for long-term brain health?

Jeff Bazarian (’87 MD, Res ’90, MPH ’02), URMC professor of Emergency Medicine and Neurology, has transformed what we know about concussions throughout his research career. He believes these repeated hits are a silent danger, sometimes without symptoms to warn of a growing injury. When a person’s occupation or activity exposes them to repeated head hits, they can experience subtle declines in neurologic function, such as balance, eye movements, and quick decision making.

Long term, these repeated head hits may contribute to serious neurodegenerative diseases or disorders. But, unlike with concussions, there is no standard of care to track, prevent, or treat these hits.

“We’re trying to determine if we can detect and mitigate the acute effects of exposure to repetitive head hits on the brain,” said Bazarian. “Do these hits alter neurologic function in a way we can pick up using objective measures suitable for use in low-resource environments like battlefields and athletic fields? If so, what can be done to return neurologic function back to baseline as quickly as possible?”

Bazarian recently received a $6.3-million grant from the Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (ARMY MRAA) to lead a four-year, multi-pronged, multi-site study to answer these questions.

Four institutions will track college athletes for this study: male football players and female soccer players from the University of Rochester, University of Buffalo, Indiana University, and The Citadel military college in South Carolina.

Special sensors will track the number of head hits and magnitude, including direction and force. Brain proteins in the blood will be measured before and after games. Previous research has shown that the brain protein GFAP is elevated after a single football game and that elevation is related to head hits.

Participants will also complete tests before and after some games during the season.

Researchers anticipate finding subtle abnormalities in athletes’ performance on these tests, but none can currently be used as a diagnostic tool in the clinic. “A soccer or football player can go through a whole season of repeated head hits and have no symptoms and a normal physical exam. But we hypothesize that one of these tests, or a combination of them, will be a little bit abnormal,” said Bazarian, “and that these abnormalities will correlate with head hit exposure and with neurologic injury in our reference standard—changes in structure of the retina of the eye.”

Researchers aim to see this change in the brain using optical coherence tomography (OCT) to create pictures of the back of the eye. Bazarian and retina expert Steven Silverstein, PhD, professor of Psychiatry, Center for Visual Science, Neuroscience, and Ophthalmology, have already used this technique to measure the number of head hits some football players have had during a season and to correlate them to changes to their retinas.

At the end of the football and soccer seasons, researchers will split the athletes with evidence of clinically silent neurologic abnormalities into two groups. One group will rest for two weeks. The other will be treated with a daily aerobic exercise for 20 to 30 minutes—the current standard of care for a concussion. Researchers anticipate that more subjects in the aerobic exercise group will have improvements in neurologic function than in the rest group.

But what about during the season? Is there a threshold of head hits that a player can sustain and stay healthy, or is it more about the interval of time between hits? Using a soccer ball heading machine, researchers will closely monitor participants who head the ball in sessions every day and compare those who have days off between heading sessions.

“The question is, if we put some time between these sessions of head hits, does that reduce the impact of these head hits on these subtle neurologic changes,” said Bazarian. “We think it probably will.”

Researchers will also investigate whether there is a threshold for how many head hits the brain can sustain before abnormalities appear. Using an animal model, study co-investigators at Boston Children’s Hospital will try to understand if there is a safe threshold or if all hits are harmful.

by Kelsie Smith-Hayduk

Tapping a pen, shaking a leg, twirling hair—repetitive, self-stimulatory movements, known as stimming, are commonplace. For people with autism, stimming can include movements like flicking fingers or rocking back and forth; these are believed to be mechanisms used to deal with overwhelming sensory environments, regulate emotions, or express joy. But stimming is not well understood. And it can escalate and lead to serious injuries.

It’s a difficult behavior to study, especially when the movements involve self-harm. But University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry researchers have found an approach to pave the way.

“By better understanding how the brain processes different types of touch, we hope to someday work toward more healthy outlets of expression to avoid self-injury,” said Emily Isenstein (PhD ’24), Medical Scientist Training Program trainee at SMD and first author of a study in NeuroImage that provides new clues into how people with autism process touch.

Researchers created realistic sensory experiences for active touch (reaching and touching) and passive touch (being

touched). A virtual-reality headset simulated visual movement, while a vibrating finger clip replicated touch. Using EEG, researchers measured the brain responses of 30 neurotypical adults and 29 adults with autism as they participated in active and passive touch tasks.

As expected, the researchers found that the neurotypical group had a smaller response in a brain signal to active touch when compared to passive touch—evidence that the brain does not use as many resources when it controls touch and knows what to expect. However, in a surprising finding, the group with autism showed little variation in brain response to the two types of touch. Both were more in line with the neurotypical group’s brain response to passive touch, suggesting that in autism, the brain may have trouble distinguishing between active and passive inputs.

“This could be a clue that people with autism may have difficulty predicting the consequences of their actions, which could be what leads to repetitive behavior or stimming,” said Isenstein. “The more we learn about how benign, active, tactile sensations like stimming are processed, the closer we will be to understanding self-injurious behavior.”

by Susanne Pallo

AI mental health apps, ranging from mood trackers to chatbots that mimic human therapists, are proliferating. While they may offer a cheap and accessible way to fill the gaps in our system, there are ethical concerns about overreliance on AI for mental healthcare, especially for children.

Most AI mental health apps are unregulated and designed for adults, but there’s a growing conversation about using them for children. Bryanna Moore, PhD, assistant professor of Health Humanities and Bioethics at URMC, wants to make sure these conversations include ethical considerations.

“No one is talking about what is different about kids—how their minds work, how they’re embedded within their family unit, how their decision-making is different,” says Moore, who shared these concerns in a recent commentary in the Journal of Pediatrics. “Children are particularly vulnerable.”

In fact, AI mental health chatbots could impair children’s social development. Evidence shows that children believe robots have “moral standing and mental life,” which raises concerns that children, especially young ones, could become attached to chatbots at the expense of building healthy relationships with people.

Pediatric therapists don’t treat children in isolation. They observe a child’s family and social relationships to ensure the child’s safety and to include family members in the process. AI chatbots don’t have access to this important contextual

information and can miss opportunities to intervene when a child is in danger.

AI chatbots—and AI systems in general—also tend to worsen existing health inequities.

“AI is only as good as the data it’s trained on. To build a system that works for everyone, you need to use data that represents everyone,” said commentary coauthor Jonathan Herington, PhD, assistant professor in the departments of Philosophy and of Health Humanities and Bioethics.

“Children from lower-income families may be unable to afford human-to-human therapy and thus come to rely on these AI chatbots in place of human-to-human therapy,” said Herington. “AI chatbots may become valuable tools but should never replace human therapy.”

Going forward, the team hopes to explore how developers incorporate ethical or safety considerations into the development process.

by Leslie White

New National Institutes of Health R38 grant funding will expand research opportunities for URMC residents in Medicine, Pediatrics, Medicine-Pediatrics, and Dermatology.

The $2.1 million award from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) aims to train a diverse pool of physician-scientists to lead the development, implementation, and evaluation of new approaches to diagnose, treat, and prevent autoimmune, allergic, inflammatory, and infectious diseases across all ages.

According to principal investigator Jennifer Anolik (PhD ’94, MD ’96, Res ’97, Flw ’01), chief of Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology, the training will be implemented through a newly created program: ROChester Stimulating Access to Research during Residency (ROC StARR) Health and Immune Function Across the Lifespan.

“This will be a highly competitive program that supports in-depth research experiences to clinicians early in their careers,” Anolik said.

The program provides one to two years of mentored research training designed to ready residents for continued study throughout their careers. A major goal is to recruit and retain a pool of clinician-investigators with both the clinical and research experience to perform high-impact biomedical research.

Anolik and collaborators across the institution are fast-tracking this program. Each year, up to four residents from Medicine, Pediatrics, Medicine-Pediatrics, and Dermatology will be selected. They will focus on one of three pillars: translational bench science, clinical research and trials, or health equity research and implementation science.

This initiative complements existing training along the physician-scientist continuum at URMC, including a highly successful Medical Scientist Training Program for medical students and the Rochester Early-Stage Investigator Network (RESIN). It is the University’s first R38 program,

filling an important gap in recruiting physicians into research during residency.

The NIH launched its Stimulating Access to Research in Residency initiative in 2017 to help mitigate a shortage of physicianscientists nationwide. It provides financial support for medical residents so they can dedicate up to two years for research.

Selected residents will engage in a mentoring program tailored to their skill level and growth, with protected research blocks during their residency program and an additional year focused on research guided by a team of 35 multidisciplinary faculty preceptors.

Research pillar leads include Laurie Steiner, MD, of Pediatrics, and Ben Korman, MD, of Medicine; Angela Branche, MD (Res ’01, Flw ’04), David Dobrzynski, MD, of Medicine, and Julie Ryan Wolf, PhD (MPH ’07), of Dermatology; and Edith Williams, MS, PhD, of Public Health and Medicine, and Cynthia Rand, MD, MPH, of Pediatrics.

Selected R38 Scholars are later eligible for early-career development awards through the NIH’s prestigious K38 program.

The multidisciplinary training program is led by co-PIs Anolik and Kirsi Jarvinen-Seppo, MD, PhD, chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, along with: Candace Gildner (PhD ’11, MD ’12), director of the Pediatric Residency Research Track; Amy Blatt (Res ’07), director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program; Erica Miller (Res ’15, Flw ’18), director of the Med-Peds Residency Program; Caren Gellin (Res ’07), director of the Pediatric Residency Program; and Mary Gail Mercurio (MD ’90), director of the Dermatology Residency Program.

An internal advisory committee is comprised of Richard Insel, MD, of Pediatrics; Karen Wilson (MPH ’95, MD ’04, Res ’07, Flw ’09), vice chair of Research Pediatrics and co-director of Clinical & Translational Science Institute; Stephen Hammes, MD, PhD, chief of Endocrinology and executive vice chair of Medicine; and Lisa Beck, MD (Res ’87), of Dermatology.

NEUROSCIENCE

by Kelsie Smith-Hayduk

“A number one concern for parents of children and teenagers is how much screen time and how much gaming is enough gaming and how to figure out where to draw the line,” said John Foxe, PhD, director of the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester and co-author of a study in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions that discovered a key marker in the brain of teens who develop gaming addiction symptoms. “These data begin to give us some answers.”

Researchers looked at data collected from 6,143 identified video game users, ages 10–15, over four years. In the first year, researchers took brain scans using fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) as participants completed the task of pushing a button fast enough to receive a $5 reward. Researchers had the same participants answer video-game addiction questionnaires over the next three years.

Participants with more symptoms of gaming addiction over time showed lower brain activity in the region involved in decision-making and reward-processing during the initial brain scan four years earlier.

Previous research in adults has provided similar insight, showing that this blunted response to reward anticipation is associated with higher symptoms of gaming addiction. It suggests that reduced sensitivity to rewards, in particular non-gaming rewards, may play a role in problematic gaming.

“Gaming itself is not unhealthy, but there is a line, and our study clearly shows that some people are more susceptible to symptoms of gaming addiction than others,” said Daniel Lopez (PhD ’23), a postdoctoral fellow at the Developmental Brain Imaging Lab at Oregon Health & Science University

and first author of the study. “We want to know the right balance between healthy gaming and unhealthy gaming, and this research starts to point us in the direction of the neural markers we can use to help us identify who might be at risk of unhealthy gaming behaviors.”

The data used came from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, launched in 2015, which is following a cohort of 11,878 children from pre-adolescence to adulthood in order to create baseline standards of brain development. The open-source data model has allowed researchers nationwide to shed light on facets of social, emotional, cognitive, and physical development.

The University of Rochester joined the study in 2017 and is one of 21 sites collecting this data. Ed Freedman, PhD, professor of Neuroscience at the University and co-principal investigator of the University study site, led this recent research on gaming.

“The large data set that contains this understudied developmental window is transforming recommendations for everything from sleep to screen time. And now we have specific brain regions that are associated with gaming addiction in teens,” Freedman said. “This allows us to ask other questions that may help us understand if there are ways to identify at-risk kids.”

“We’re very proud that this Rochester cohort is a part of this national and international dialogue around adolescent health,” said Foxe, who is also a co-PI on the ABCD Study in Rochester. “We have already seen how this data, including the data gathered here from our community, is having a major impact on policy across the world.”

by Emily Boynton

Gene therapy can effectively treat various diseases, but for some debilitating conditions like muscular dystrophies there is a big problem: size. The genes that are dysfunctional in muscular dystrophies are often extremely large, and current delivery methods can’t courier such substantial genetic loads into the body.

The relatively new technology “StitchR” overcomes this obstacle by delivering two halves of a gene separately; once in a cell, both DNA segments generate messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that join seamlessly together.

Research published in the journal Science showed how StitchR—short for “stitch RNA”—restored expression of large therapeutic muscle proteins to normal levels in two different animal models of muscular dystrophy. StitchR enabled expression of the protein Dysferlin, which is lacking in individuals with limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B/R2, as well as the protein Dystrophin, which is absent in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy is the most common early-onset form of muscular dystrophy, and many who have it become wheelchair-bound in their teens and die in their 20s. People with limb girdle muscular dystrophy experience weakness and wasting in the shoulder, hip, and thigh muscles and often have difficulty standing, moving, and doing everyday tasks.

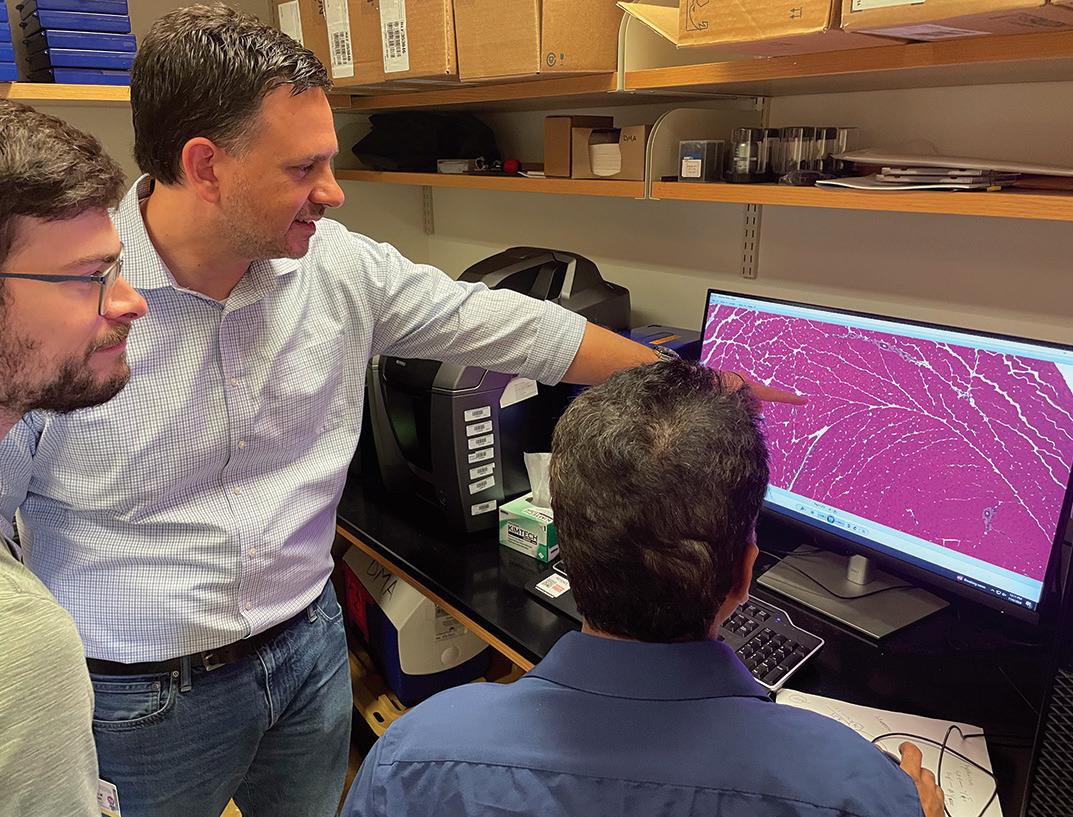

“Gene therapy is a powerful tool for delivering a healthy gene copy back to a patient’s cells to correct genetic diseases, but the vectors used to deliver this information are small, which has so far precluded their use for treating a whole host of diseases caused by mutations in large genes,” said Douglas M. Anderson, PhD, lead study author and assistant professor of Medicine in the Aab Cardiovascular Research Institute at the School of Medicine and Dentistry. “Instead of delivering the full gene in a single vector, which isn’t possible, we’ve developed an efficient dual vector system where two halves of a gene are delivered separately but come together to reconstitute the large mRNA in the affected tissues.”

The technology first arose from a serendipitous observation made in the lab several years ago—that when two separate mRNAs were cut by small RNA sequences called ribozymes, they became seamlessly joined and translated into full-length protein. The team found that when ribozymes cleave or cut RNA, they leave ends that are recognized by a natural repair pathway.

“Similar to when CRISPR enzymes are used to cut DNA, the CRISPR enzymes are just the scissors, and it’s a cell’s natural repair enzymes that glue the DNA back together,” Anderson explained. “We think something similar is happening here, but for RNA.”

The lab optimized efficiency of the process (more than 900-fold from their initial experiments) and adapted the technology into a powerful gene-delivery mechanism.

The research team, including co-first author Sean Lindley, who recently received his PhD from the Anderson lab, found that the stitched mRNAs appear to behave essentially the same way as their natural full-length counterparts.

According to Anderson, who is also a member of the University of Rochester Center for RNA Biology, “StitchR is really plug and play at this point. The sequence requirements for StitchR are minimal, and we’ve now tested this with many different genes and sequences.”

Another feature of this technology is that only the full-length protein is produced. “Other dual vector approaches have been in development for decades but have been plagued by lack of efficiency and the production of less than full-length products,” said Anderson. “With StitchR and other tools, we are working towards treatments for some of the most debilitating genetic diseases on the planet, many of which have no current treatments or cures.”

by Scott Hesel

UR Medicine’s Golisano Children’s Hospital has received a multi-million-dollar grant to lead a first-of-its-kind study comparing the effectiveness of treatments for sickle cell disease. The aim is to help families make more informed treatment decisions for children of different ages and at various disease stages.

The project will compare two treatment options:

• Human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched bone marrow transplantation, a treatment that cures sickle cell disease.

• Disease-modifying therapies, such as blood transfusions and Hydroxyurea, which help control symptoms, including pain, but do not cure the disease.

The study, funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), will recruit 480 children, adolescents, and young adult patients.

“This large sample size will allow us to thoroughly compare the two treatments and assess how they impact quality of life,” said John Horan (Res ’96, Flw ’97, ’00, MPH ’03), the study’s lead investigator and a professor in the division of Hematology and Oncology.

The findings will help families make choices based on the relative risks and benefits of each treatment. While an HLA-matched bone marrow transplant offers a potential cure,

John Horan (Res ’96, Flw ’97, ’00, MPH ’03)

it requires a genetic match—most often from a sibling—and carries a very small risk of death. Additionally, transplant recipients can develop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), where the donor’s immune cells attack the recipient’s body.

Disease-modifying therapies are the alternative to a transplant. Treatments like blood transfusions and Hydroxyurea (a chemotherapy drug) help manage symptoms, severe pain being the most common. Pain occurs when sickled blood cells block blood vessels. These episodes are often compared to the intense pain of a heart attack.

“This study will allow us to look at specific subgroups of patients,” Horan said. “A three-year-old who hasn’t experienced significant complications will have different treatment needs compared to a 19-year-old with multiple health issues. This research will help determine which treatment path makes the most sense, based on a combination of factors.”

Horan is a co-founder of STAR (Sickle Cell Transplant Advocacy & Research Alliance), a nonprofit organization formed by pediatric hematologists and stem cell transplant experts to improve the lives of children with sickle cell disease through blood and marrow transplants.

“We have 25 to 30 centers involved in this study,” said Horan. “We’re hopeful that it will provide critical answers to families across the country who are managing sickle cell disease.”

By Sydney Burrows

Caroline and Ryan Caufield with their second child, Keagan. Caroline holds a Molly Bear, made by a nonprofit as a reminder of a stillborn child. Each bear weighs exactly the birth weight of the child. Caroline says it helps keep their first child, Kiera, close to them.

The day before Caroline and Ryan Caufield were due to have their first child, they learned their baby had no heartbeat. It was 2022, and because of COVID restrictions, it was the first time Ryan had been able to attend an ultrasound with Caroline.

The next day, the Caufields were directed to Highland Hospital’s bereavement suite, where OB-GYN Heather Florescue (BA ’00, MD ’04, Res ’08) walked them through every step of the delivery and beyond.

Caroline remembers how Florescue introduced herself: “I’m Heather. I’m really sorry we have to meet this way, but you’re stuck with me now for the rest of your life. I specialize in this, and I’m going to get you through it.”

Florescue, whose practice became part of URMC in December 2024, supported the Caufields throughout the birth of their daughter, Kiera, and also checked in the day after, on her day off. She continued to call every few days once the couple went home, and she was their provider throughout the pregnancy and birth of their second child, Keagan.

Florescue’s support during Kiera’s birth included doing whatever it took to give the Caufields what they needed.

“Heather made sure our family met Kiera, despite COVID restrictions at the time. And that’s how she is in all of this. She’s a bulldog,” Caroline said, laughing. “She isn’t going to let anyone stand in the way of her patients’ best interest.”

She’s also gaining a national reputation for the work she’s doing. Some of her novel techniques to help families have spread to other hospitals in Rochester and throughout the country. She has teamed up with a national nonprofit and with other experts to establish a residency education program, filling an important gap that benefits doctors and patients alike.

It’s vital work because so much about the aftermath of stillbirth is counterintuitive. Many people assume that parents want to forget the loss as soon as possible and not be reminded even years later, but the opposite is often true.

Florescue learned mostly from experience—and from the moment someone pointed out that what she was doing was far from typical.

In 2018, a longtime obstetrics patient said, “You need to teach the Heather way.” When Florescue asked what she meant, the patient explained that Florescue’s ability to connect with her patients and their families, and the empathetic support system she has developed, is not common.

Before that moment, Florescue had never considered that her way of caring for patients who had experienced loss was exceptional.

Florescue encourages her patients to call whenever they have a question or even an inkling that something might not be right during pregnancy, no matter the time of day. When a patient needs to sit in silence, she waits until they’re ready to talk, then lends a listening ear.

The bereavement room at Highland Hospital contains helpful items, including one of the library carts that Florescue originated.

Caring for her patients, she quickly learned to encourage women to listen to their bodies rather than friends and family. Despite best intentions, loved ones often use their own experiences with pregnancy to affect their advice.

“Tragedy, unfortunately, can happen if worries are dismissed,” said Florescue. “If someone you love says, ‘I’m worried about my baby,’ tell them to call their doctor.”

After further investigating patient care for loss families, Florescue quickly saw a gap in medical education. She set out to teach the next generation of doctors as much as she could from her experiences.

Her research on stillbirth education led her to the Star Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit that offers support and resources to families who experience stillbirth, infant loss, and miscarriage.

Lindsey Wimmer founded Star Legacy after her son, Garrett, was stillborn in 2004. She wanted to raise awareness and offer the kind of support that she had sought during her experience.

“Because of my medical background as a nurse practitioner, I was shocked that I knew so little about stillbirth and that the numbers were so significant,” said Wimmer. According to the CDC, roughly 1 in 175 babies are stillborn in the United States every year. “We decided to honor our son by supporting research. That grew into expanding into the education pieces as well.”

The education aspect of Star Legacy especially interested Florescue. She registered to attend a conference in 2019. It was the

foundation’s largest annual event, yet Florescue realized she was one of only a few medical providers—and the only OB-GYN—in attendance.

“That snowballed my desire to educate and teach how to take care of loss families,” said Florescue, who is now on the medical advisory board of Star Legacy.

Wimmer said, “We meet a lot of physicians who are kind and willing to listen, but Heather was willing to take it a step further. She recognized she had an opportunity to change how care is done in her own practice and in the greater community.”

Knowledge, not concern, was the missing piece. “Even though empathy is there, there’s a disconnect between the provider and the patient,” Florescue explained. “The thought is to give patients privacy and space … which is the exact opposite of what we should be doing. I set on a quest to tell people what they think is wrong is right.”

Her quest led Florescue to first create a “tip book” with suggestions for residents and providers who care for pregnant patients. It begins with two simple suggestions:

1. “I am so sorry. Your baby has died.” Say this, sit with the patient, and just be.

2. Don’t discuss next steps unless asked. Then, just take things one step at a time.

As she promised, Florescue has stayed in close touch with the Caufields.

Ponnila Marinescu (MD ’11, Flw ’21) co-developed the Perinatal Loss Simulation training for residents.

The tip book continues with short and simple directions to help guide providers through conversations with their patients. Even for medical professionals, infant loss can feel taboo to talk about. But speaking about a lost child can help greatly with the healing process.

Parents want to know that someone else will remember their baby, which is why Florescue encourages loved ones to recognize birthdays, verbalize the child’s name, and even ask to see photos in order to give support. “It’s important to show the parents that they are not fully responsible for the legacy of their child,” she emphasized.

In addition to using these tips at Rochester-area hospitals and during a virtual session with a New York City hospital, Florescue has distributed her booklet to people all over the country.

She also worked alongside Wimmer and Star Legacy in starting a residency education program, which kicked off with a half-day simulation event in January 2024 at the School of Medicine & Dentistry. While building the programming, Florescue and Wimmer connected with high-risk OB-GYN specialist Ponnila Marinescu (MD ’11, Flw ’21), who was doing her own work in perinatal loss at URMC.

Marinescu lost her baby, Mila, in February 2020. As she was making her way through this experience, Marinescu discovered the same gap in medical education that Florescue had noticed. She also saw a lack of support for loss families after parents leave the hospital.

This discovery led Marinescu to create an outpatient perinatal loss program at Strong Memorial Hospital. The clinic offers follow-up care to families for up to a year after they experience their loss.

When Marinescu connected with Florescue, her mission for stillbirth care expanded to include medical education. “Most of my work before I met Heather was patient-related care,” said Marinescu. “But working with her has given wings to my internal goals of teaching this to residents.”

Together, Marinescu, Wimmer, and Florescue created the programming for the Residency Perinatal Loss Simulation. It included a panel with former patients of Florescue who shared their personal stories of experiencing stillbirth. Residents also worked through simulations of patients experiencing loss, which is critical because people can react to the experience in different ways.

“I want there to be providers who understand and feel empowered to use the right language when they’re talking to their patients,” Marinescu said. “These families are enduring the worst experience of their lives. Whatever kindness we can share with them will make that experience more compassionate and meaningful.”

The program was just the first step of the trio’s plan. With funding and further research, they’re hoping to expand the reach of their educational programming to residencies across the country.

Another important part of their work is tending to the emotional needs of residents. Marinescu and Florescue have started offering safe-space meetings for residents in Rochester. Every other month, one of them opens their home to residents for an evening.

“It’s a space to be vulnerable, and it changes the residents’ perception of what their own biases and feelings are,” said Marinescu. “It helps them realize that those feelings are real and need to be felt, grieved, and processed, but those feelings do not need to burden them in an unhealthy way.”

Those feelings can include guilt, sadness, frustration, and grief. To offer further support, Florescue will reach out directly to a resident if she knows a patient of theirs has experienced infant loss.

“It’s very lonely when you deliver a baby who has died,” Florescue said. In obstetrics, a provider may have to go from one room, comforting a family who has lost their child, to another, delivering a healthy baby with parents who are overjoyed. “We have to do that in a five-minute stretch, and we can’t let our emotions get the better of us.”

By providing residents with formal education and space to reflect, Florescue and Marinescu hope to help keep future providers working within patient care. “There’s a high rate of burnout for physicians regardless of the circumstance,” Marinescu explained. “But when you don’t give them the tools to approach these clinical cases in the most optimized way, the impact is even more significant.”

Hope can come from the work itself. Florescue points to research showing that doing something altruistic related to your job—like staying in parents’ lives indefinitely—actually decreases your

chance of burnout. “It’s one reason I’m still here while some colleagues aren’t. Don’t get me wrong: I have burnout sometimes. But I’m going to keep doing this.”

Through her extended care for patients, Florescue saw that loss families often find that the experience of making memories can help make a tragic day feel a little less so.

Before connecting with Florescue and Wimmer, Marinescu was unfamiliar with the idea of memory making, which involves creating experiences with your child before saying goodbye. This can range from reading them a book to singing a lullaby or taking photos and videos together.

It can seem logical for healthcare professionals to hurry up and go through the required steps, assuming that the sooner the family can move on, the better off they are. But the opposite is often true. “Taking the time to read your baby a story or do the handprints and footprints is so important,” Wimmer said. “Those moments are going to determine how the family views what has happened to them.”

According to Florescue, “You can never make too many memories. Some dads have questioned, ‘You want me to bathe her? You want me to dress her?’ But then they come around, and they’re holding the baby and watching football.”

Residents gathering in the home of Heather Florescue (BA ’00, MD ’04, Res ’08), far left, for the support group she runs with Ponnila Marinescu (MD ’11, Flw ’21), third from right; residents pictured (from left) are Savannah Kaszubinski, Pivi Vijayakumar, Olivia Rombold, Grace Narlock, and Allison Guarin.

(back row, from left) Nicole Collins, mom of Asher (in front row) and his twin, William, who was born still; Star Legacy Western NY Chair Christina Fedczuk, mom of Vincent, who was born still; Jennifer Chappell, mom of Cooper, who was born still; OB/GYN Jillian Babu (Res ’12); and Florescue joined F.F. Thompson RNs for a library cart dropoff.

Florescue started a library-cart program in hospitals to give parents the experience of reading to their child. The idea had come to her years before, when caring for a loss family. Designated library carts have now been implemented in every hospital in the Rochester region—13 in all—and in multiple hospitals across the country.

“It’s such a natural act to read to your child,” said Florescue. “You’re not only saying goodbye; you’re also saying hello.”

After reading to their baby, families can choose a book or two to bring home from the hospital. There’s a place for a dedication, where they can write their child’s name in a space labeled “This book belongs to ———”.

Using the library cart can help validate the experience of bringing a child into the world. It’s a form of recognition that they are parents.

“It’s always going to be tragic and awful, but it can also be beautiful,” said Wimmer. “A family may be able to say, ‘I didn’t get to raise my daughter, but I got to read her my favorite bedtime story or wrap her in my grandmother’s blanket.’”

For the Caufields, memory making was a big part of their daughter’s story. Florescue encouraged Caroline and Ryan to take photos and videos, read to Kiera, watch their favorite sport with her, and have family members hold her.

It helped guide them through the day. “In that situation, you don’t know what to do,” said Ryan. “The pictures and videos we have are our only memories. So having those to look back on is really nice.”

“We got to spend 24 precious hours with her, trying to make a lifetime of memories,” said Caroline. “It was the most beautiful, precious 24 hours and we are lucky to have gotten that with her.”

Feeling Florescue’s support and the serenity of the bereavement room added to making the day as positive as it could be.

“Everything they did in that room did help with the experience,” said Caroline. “I always tell my friends and family that even though it was a sad experience, my labor and delivery with Kiera was beautiful.” RM

When Florescue was a child, every playdate would lead to her favorite toy—a medical kit—so she could pretend she was a doctor. As she grew older, she found that she loved babysitting and being around children, making pediatrics seem like a natural choice.

While studying at the School of Medicine & Dentistry, Florescue found that obstetrics was a better fit than pediatrics. As a medical student, she cared for a mother of twins throughout labor, talking with her for hours. She connected so deeply that the patient requested Florescue specifically to aid in her delivery, during which one of the twins did not survive.

This kind of bedside manner came naturally to Florescue. She honed her medical skills and patient care throughout her medical education, which she completed in its entirety at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Florescue, who is the mother of triplets, credits the way she interacts with patients largely to the unique simulation program offered at Rochester and learning “the Rochester way” of collaborative care.

For a century, the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry has been at the forefront of discovery—advancing cures, educating future leaders in medicine, and shaping modern care through the biopsychosocial model.

This fall, join us at Meliora Weekend as we look back on our legacy and ahead to our bold next chapter. Enjoy nostalgic reunions, dynamic research talks, and special centennial events—plus unforgettable entertainment and so much more. Registration opens this summer. Learn more at rochester.edu/melioraweekend

SEPTEMBER 18-21, 2025

#melioraweekend

by Sandra Parker

Of the half million or so words in the unabridged dictionary, few are more frightening than this one: Cancer

According to paleontological studies, the disease plagued even the earliest life forms. Egyptian mummies show evidence of tumors, which ancient physicians tried to burn away with a heated “drill,” though they noted that the disease was otherwise untreatable and incurable.

Cancer was at times blamed on demonic possession, pagan worship, black magic, and the alignment of celestial bodies. Treatments such as strapping a live, plucked chicken to the diseased area were at least semi-practical compared to another remedy requiring powder from the horn of a unicorn.

Modern investigations into cures are far more complicated—and promising—than capturing a unicorn. URMC and the Wilmot Cancer Institute have long used a painstaking approach to destroy the link between the words fear and cancer. On March 19, 2025, after nine years of restructuring and expansion, the University of Rochester announced that Wilmot had earned designation by the National Cancer Institute as the nation’s 73rd NCI cancer center, putting it in the top 4 percent of the 1,500 cancer centers in the United States.

This achievement is itself a unicorn—a rare accomplishment earned by just a handful of applicants per decade.

“This is really the beginning of us entering the world of elite cancer centers, and that gives us amazing opportunities to continue to grow at this time when the field is flourishing in research discovery,” says Wilmot Director Jonathan W. Friedberg, MD, MMSc. “Our patients deserve the best outcomes—this designation is a return on investment of the University’s commitment.”

It is expected to substantially improve Wilmot’s ability to garner research dollars, recruit scientists and clinicians, and expand the volume of clinical trials to relieve the cancer burden among the three million residents in UR Medicine’s catchment area.

The accomplishment, which took the better part of a decade to achieve, “gave our investigators, clinicians, and patients hope and optimism that we are going to continue to move forward doing

this important work,” says Friedberg, who adds that he is already focused on the future.

People involved in the process and those who have experience at NCI centers say the designation opens doors in expected and less-expected ways. In multiple realms—from research to recruiting, from halo effects to new community connections—URMC and Wilmot can expect to advance into a new level of results and possibilities.

The designation’s greatest benefit comes from the prestige, says B. Mark Evers, MD, director of the University of Kentucky’s Markey Cancer Center and chair of Wilmot’s external advisory board.

“At Markey, we have seen great things happen: Recruitment picked up, philanthropic giving increased, and our patient volume doubled in the 10 years since designation,” says Evers, who led Markey through initial designation and the next level, comprehensive status.

URMC CEO and SMD Dean David Linehan, MD, points out that the University already had an impressive record: It contributed significantly to two of the five most important advances in cancer research in the past 50 years, an “astounding” fact.

John DiPersio (MD/PhD ’80), who served on the Wilmot external advisory board for the NCI work, is director of the Center for Gene and Cellular Immunotherapy at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and was deputy director of that university’s Siteman Cancer Center when it achieved initial and then comprehensive status. The formula for moving forward, DiPersio says, is to focus on more: more institutional investment, grant applications, cutting-edge and transdisciplinary research, community

engagement, educational programs, buildings, and institutes. Strengthening population sciences is also critical.

Although NCI designation as an elite cancer center was the goal, Friedberg points out that the most important aspect has been boosting Wilmot’s ability to provide extraordinary care to patients with cancer.

“It’s been incredibly rewarding to do this work, both at the physician level taking care of patients, which is still my number one passion, and seeing patients thriving today that I knew 10 or 15 years ago wouldn’t even be alive [without] the improvements we’ve made,” Friedberg says.

But amid the fanfare, those in the know are quick to point out that the real work begins now. Here’s how.

NCI designation is primarily a research award, called a Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG). Wilmot has received the first installment of a renewable $10 million grant that is doled out over five years. The grant also dedicates resources for the education and training of future cancer researchers, clinical trial development, and community outreach.

Just as important is the opportunity to apply for many other research grants available only to NCI centers.

Wilmot’s research programs include more than 100 scientists who work across three broad areas: cancer prevention and control; cancer microenvironment; and cancer genetics, epigenetics, and metabolism.

One of the major goals for the near future is the creation of a new research building. Most of the existing research labs were built 25 years ago, and while some new ones were built in the Wilmot expansion, the building is primarily dedicated to clinical space. Wilmot also will be “reimagining” existing labs, Friedberg says.

“No longer is everything done with a human doing pipetting. You’re looking at these massive databases and manipulating them. So we need laboratory space that is in concert with the times.”

“Research is a big investment with big returns,” says Hartmut “Hucky” Land, PhD, deputy director of Wilmot. “Every pill is based on many years of research involving hundreds of people, with important initial discoveries frequently happening as a complete surprise.”

Gaining NCI designation is part of those big returns. “Patients understand that the top cancer centers have NCI designation,” says Land. “It gives them confidence.”

Foundational research by URMC scientists was instrumental in developing the HPV vaccine— the first cancer vaccine—which has been 90 percent effective in preventing cervical cancer. Gary R. Morrow, PhD (MS ’87) led groundbreaking URMC studies in developing anti-nausea drugs to help patients tolerate chemotherapy.

Wilmot has had many other successes, including launching the region’s first CAR T-cell program for lymphoma, building one of the largest blood and marrow transplant programs in Upstate New York, achieving a top 10 percent national ranking for fewest complications and surgical-site infections for the complex Whipple procedure, and increasing the quality of and participation in clinical trials.

Although cancer centers must adhere to rigid NCI requirements, each center eventually distinguishes itself due to faculty expertise, the needs of the catchment area, and the overall vision of the institution.

As the late legendary oncologist Joseph V. Simone once said, “If you’ve seen one cancer center, you’ve seen one cancer center.”

URMC and Wilmot already occupy a unique niche among cancer centers with investigations into RNA biology, immunologic sciences, and geriatric oncology.

Friedberg’s vision is for Wilmot to become a leader in Developmental Therapeutics, turning scientific discoveries into treatments more quickly. Wilmot is working to fund specialized laboratories for Developmental Therapeutics and to recruit someone to lead the program, which would speed new cancer therapies through first-in-human clinical trials.

In addition to new discoveries, the designation will aid development of “supportive care treatments to ensure that patients do not suffer unnecessarily from the toxic therapies used to treat cancer, and that they are able to recover and live full, enjoyable lives for many years to come,” says Karen M. Mustian, PhD (MPH ’09), Wilmot’s associate director of Population Science and co-leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control Research program.

Rebecca Porter (PhD ’11, MD ’13), a gynecologic medical oncologist and researcher at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, says she typically looks to NCI centers when patients seen in consultation ask for treatment locations closer to home, given that this typically means access to early-phase clinical trials. The focus on lab-based research and translating this to clinical trials "brings the care to the next level, from bench to bedside.”

Thomas J. Lynch Jr., MD, president and director of Fred Hutchison Cancer Center in Seattle and a member of Wilmot’s external advisory board, says URMC’s medium size is an advantage: It will aid collaboration because people are more likely to encounter each other and talk about projects, he says. “This accomplishment by Jonathan Friedberg, David Linehan, and the leadership is truly remarkable and recognizes the long and consistent contribution that the University of Rochester and Strong Memorial Hospital have made to cancer in the United States.”

Lynch is known as a distinguished scientist who 50 years ago coined what is now the motto for Fred Hutch research: “Fearless science is humanity at its best.”

“Designation is a magnet for recruitment; you need it to be competitive to attract the best scientists,” DiPersio says.

“It’s not so much the designation,” Lynch adds, “as what the designation reflects: that the entire medical center has committed to cancer as one of its most important parts.” He expects that Wilmot will further distinguish itself from other cancer centers through recruitment.

Paula Vertino, PhD, a professor of cancer genomics, associate director for basic research at Wilmot and senior associate dean, says her belief that Wilmot would attain NCI status was a factor in her decision to accept a position here in 2018. She came from Emory University’s Winship Cancer Institute, where she had helped lead that program to NCI designation.

To recruits, designation means that there is a deep and long-term commitment to funding research.

“Everyone wants to be at the top of their field, so designation will definitely help in faculty recruitment and in retention,” says Eric A. Singer (Flw ’07, Res ’09), chief of the Division of Urologic Oncology at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Cancer care is like major league baseball,” DiPersio says. “Suddenly

those people will consider you if you are an NCI center. It entices people because you have met the bar. And once you field a team, you can’t ignore your farm team system, or your team will go down the tubes.”

Recruitment begets recruitment. According to NCI cancer center directors, as more jobs are created at Wilmot, there will be a positive effect on the local economy. Evers says that for every job created at Markey, one job was also added locally.

One of the NCI’s new requirements is to engage with the community and ensure that all of the cancer center work reflects the voices and needs of all communities. For patients, designation means that they can be confident about being treated by doctors and researchers who specialize in their type of cancer and can offer cutting-edge treatments not available elsewhere.

“It’s important to go to a place where it’s not just ‘one size fits all,’ but where your treatment plan is going to be tailored to not only your specific medical needs but also your personal goals in light of this new medical challenge,” Singer says.

Wilmot has already established 13 care locations in the primarily rural 27-county catchment area of three million residents, reflecting the fact that some patients don’t have a reliable car, gas money, or time off from work to travel to Rochester. Some in rural communities also fear trying to navigate in the city.

With a new data-mapping tool, Wilmot ventured deeper into the community to gauge the rate of cancer in various populations and to understand barriers to preventing and treating cancer.

“Even though I had done this before, at URMC we were engaged in the community at a level I hadn’t experienced before,” Vertino says. “I gained a new perspective from engaging with the community in the very early stages of the scientific process because it revealed new understandings … about what is important to them. It was bidirectional and eye-opening.”

NCI cancer center directors say that Wilmot will need to continue to expand its community efforts in seeking the next level of designation, comprehensive status. One of the requirements for the higher status is to demonstrate how well the institution is affecting the community’s cancer burden.

One of Friedberg’s immediate goals is to expand Wilmot’s expertise in clinical trials, and he’s confident that Wilmot will become a leader in them. “The expertise, the novelty of the trials, the types of studies that we’re going to be able to perform—and the discoveries that are coming from here—all are going to have a major impact on our patients.”

Evers says that patient volume doubled in 10 years since Markey’s designation, adding that “Wilmot needs to be ready for an onslaught of patients as well as more interest from medical students and faculty. A rising tide floats all boats.” Cancer center directors say that Wilmot can expect a “halo effect” as a result of this new status: As more patients seek cancer care at Wilmot because outcomes are generally better at NCI centers, other areas such as orthopaedics and cardiology also will likely see an increase in patients.

The multi-year process to gain NCI designation grew out of the high incidence of some cancers in Central and Western New York and Wilmot’s desire to expand to meet the need.

When Friedberg was named Wilmot’s director in 2013, the topic of designation was broached but not as a requirement, although it was part of the 10-year strategic plan drawn up in 2008. URMC had held the NCI designation from 1975 to 1999. Since then it had been discussed continually, but not undertaken.

In 2016, Friedberg convened some faculty, staff, and University leaders to debate whether Wilmot should pursue designation. The group’s answer was an emphatic “Yes.”

Step one: Persuade the NCI to accept the application.

Friedberg presented two main reasons. First, Rochester is committed to serving residents in 27 counties in Central and Western New York, which have extremely high rates of cancer, particularly in urban centers and rural areas. The catchment area covers a region larger than the states of New Hampshire and Vermont combined. Approximately 30% of residents live in rural areas, and 17% are over the age of 65.

The team’s new data-mapping tool found the lung cancer rate was 20% above the U.S. average, and nine of the top 10 types of cancer were found to have elevated incidence among the three million residents. If the catchment area were a state, it would have the second-highest cancer rate, behind only Kentucky.

Second, Wilmot has broad expertise in cancer and aging and is one of the few centers with significant depth in the fundamental science underlying geriatric oncology.

Evers, external advisory board chair, says the board was concerned that the NCI wouldn’t see the need for another cancer center in New York state. There were already five comprehensive centers, a clinical cancer center, and a lab center in the state. But Roswell Park in Buffalo is the only one outside of New York City. Evers says that Friedberg clearly demonstrated the specific needs in the Wilmot catchment area.

After the NCI allowed the application to go forward, Friedberg had to navigate a labyrinth of changing requirements. The team involved more than 300 people throughout the cancer center, including clinicians, nurses, faculty, researchers, staff, inpatient and outpatient teams, and clinical trial coordinators.

By all accounts, Friedberg supplied the exceptional leadership and vision needed for such a massive undertaking. Most impressive, his colleagues say, is the creation of a structure of collaboration and outreach that propelled the institution to a higher level of performance. Lynch calls Friedberg “a master at making the teams work well.”

In addition to many small changes, the team instituted major changes:

• restructured Wilmot’s organization to increase interdepartmental collaboration

• boosted fundraising and doubled research funding

• hired 30 researchers and clinicians

• increased clinical trials and participants

• increased number of care locations to 13

• launched a community-engagement program to address disparities in patient access to treatment

• built a new educational and training program

Nationally, less than 3% of cancer patients enroll in clinical trials. Wilmot created more sophisticated and complex trials and increased the number of participants to 12% overall and up to 20% for some blood cancer trials.

Restructuring departments to meet NCI’s stringent research standards meant reorganizing leadership roles and creating additional infrastructure for intra-programmatic collaboration across 20 academic departments and 30 clinical specialties.

“It took time for appreciation of the common goal,” Friedberg says. “We had to get all of the people rowing in the same direction.”

But before the boat could move forward, everyone had to get on board.

Moving from a silo-type operation to a collaborative one has been “miraculous,” says Supriya G. Mohile, MD, director of the Geriatric Oncology Research Clinic and co-program leader of the Cancer Control and Supportive Care Program.

“We’re connected. I feel part of this mission,” Mohile says. “Dr. Friedberg listened and supported us with feedback. He created this culture in which we were empowered to organize our efforts to bring people together from around the institution.”

Friedberg says he enticed researchers from other departments to begin doing cancer research, basically “adopting” them.

“The NCI template forced challenging conversations and changes,” Friedberg says. “The end result is a product that’s much more nimble at conducting research, much more attractive at recruiting the greatest investigators, much more available to patients as far as clinical trials. And it has really forced some institutional commitment and investment that wouldn’t have happened if we didn’t have this template from NCI.”

The lengthy designation process strengthened URMC’s well-known reputation for collaboration and collegiality. Longtime employees found that the process deepened that reputation, while new recruits noted that the reputation was well earned.

“Team science is a hallmark of Wilmot Cancer Institute and the University of Rochester Medical Center, bringing together doctors and scientists to answer the unmet needs of our patients by improving patient care with research,” says Linehan.

After five years of change, Wilmot submitted its 1,100-page application. The first response from the NCI in 2022 was to ask for additional progress. Vertino, who served for six years on the committee writing evaluations of NCI applicants, found that her experience helped provide context throughout the years-long process.

Wilmot made more changes and resubmitted the application, now at 1,300 pages. The official designation notice arrived in March 2025. Friedberg credits the University for its support and funding, the external advisory board for its advice, and the team at URMC for its dedication to the goal.

“I can’t emphasize how much better we are today than 10 years ago,” Friedberg says. “We had a lot of the raw ingredients in place but were missing the organizational capabilities that the NIH expects. I think we have the full package now to put us in the handful of centers with the expertise to rapidly translate discoveries into patient cures.”

Cancer is, unfortunately, a common condition, Friedberg notes. People know that it “steals people from their lives.” While cancer remains a scary word, the tie between it and the word “cure” continues to strengthen.

Cancer research and prevention require a long view. Friedberg points out that the disease was once considered a secret shame, even after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the National Cancer Act of 1937 to create the NCI and even after philanthropist Mary Lasky pushed President Richard M. Nixon to sign the second Act in 1971. Then, in 1974, former First Lady Betty Ford broke the silence when she announced that she had breast cancer, which invigorated efforts into cancer research and screening.

Today, NCI designation has certainly invigorated Wilmot and URMC.

“We are making tremendous progress,” Friedberg says, “and that progress is directly tied to the work of NIH and NCI and our cancer centers. I think that’s the piece people need to hear: The decades-long investment in research is really paying off.” RM

The Class of ’62 Auditorium at the School of Medicine and Dentistry buzzed with excitement and emotion on March 21. At noon, medical students in Rochester and nationwide opened the envelopes that would point the way to their futures as residents.

“Match Day is a significant milestone in every physician’s journey— it marks the beginning of a new chapter of their career and is the culmination of years of hard work,” said David R. Lambert, MD, senior associate dean for Medical School Education. “We are honored to see many graduates choosing to continue their training with us and equally proud of those venturing nationwide with the excellence of a University of Rochester education.”

David Linehan, MD, CEO of URMC and dean of SMD, spoke to the variety of opportunities for students to continue learning.

“Our medical students’ journey at the University of Rochester is enriched not only by the rigorous academic curriculum, but also by involvement in research, impactful volunteer and community service, varied elective pathways, and transformative international experiences. These experiences have honed their critical thinking, empathy, and adaptability, preparing them to meet the challenges of modern medicine with a compassionate and innovative spirit.”

Of the Class of 2025 who will be pursuing residency training, 26 students will stay at URMC for their training or are returning after an internship elsewhere. Most are staying in New York State (38), followed by Massachusetts (10), California (7), Ohio (6), and Pennsylvania (5). The remainder will train in 16 other states.

University of Rochester students pursuing residency training were placed in 29 different specialties. The largest concentrations are in internal medicine, followed by equal numbers in anesthesiology, diagnostic radiology, and general surgery, then family medicine, psychiatry, and emergency medicine.

The 183 new residents who matched with the University of Rochester Medical Center begin their training in Rochester this summer.

by Scott Hesel

Newly named chief of Neonatology, Hitesh Deshmukh, MD, PhD, brings renowned experience in studying immune development in babies. A leading expert in neonatology, his career spans multiple continents. Deshmukh earned his medical degree at the University of Mumbai, completed fellowships at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Duke University, and went on to serve as director of the Center for Perinatal Immunity at the University of Cincinnati— one of the nation’s top pediatric institutions.

Throughout most of his career, Deshmukh has maintained a close connection to both Golisano Children’s Hospital and the region at large, which ultimately drove his decision to join GCH. Years of collaboration with pediatrics researchers at GCH left a lasting impression on him.

“I’ve always appreciated URMC’s strong research emphasis, which is rare among institutions,” Deshmukh said. “And I’m inspired by Dr. Jill Halterman’s vision for expanding research in pediatrics.”

Upstate and Western New York also hold personal significance. During his residency at the State University of New York at Buffalo, he met his wife—who was pursuing her MBA—and proposed to her on Seneca Lake.

“As an immigrant, there are only so many places where you truly feel at home,” he said. “This region helped me find my footing.”

Deshmukh discovered his passion for neonatology in his third year of medical school. Initially considering a surgical career, his perspective changed after attending a session on surfactant therapy led by neonatologists from across the country.

Surfactant derived from lung secretions expands the lungs and helps premature babies breathe. Developed at the University of Rochester, along with several other institutions, surfactant was introduced in the 1990s and has saved countless lives.

“Witnessing the impact of surfactant shaped my identity,” he said. “I decided then to become a physician-scientist.”

Deshmukh has published 58 papers, with 1,561 citations. His research has frequently involved collaborations with GCH faculty, including Kristin Scheible (MD ’04, Res ’07, Flw ’10); Gloria Pryhuber, MD; and Thomas Mariani, PhD

“Hitesh has been at the forefront of translational research in neonatal microbiome-immunologic interactions,” said Scheible. “This is a challenging and competitive field, and he has made groundbreaking contributions.”

These collaborations reinforced his interest in joining URMC, and Deshmukh is looking forward to building on the strong foundation that outgoing chief Carl D’Angio (Flw ’94) built during his nearly 10 years leading the division. The division has been ranked among the nation’s best by U.S. News & World Report for five of the past seven years.

Hitesh

Deshmukh, MD, PhD

Deshmukh said his goals include expanding the division’s clinical research footprint, reestablishing its NIH Neonatal Research Network Center designation, and developing a training program in neonatal immunology for physician-scientists. Clinically, he aims to reduce Rochester’s infant mortality rate to align with national averages.

“This effort will need community engagement,” he said. “We’ll extend beyond the neonatal unit to partner with local organizations.”

For Deshmukh, clinical care and research are deeply connected.

“It’s easy to forget that 20 years ago, the primary goal was simply keeping preterm infants alive,” he said. “We’ve since learned that some early treatments—like steroids and antibiotics—can have unintended long-term consequences. The goal now is to move beyond general clinical tools and embrace precision medicine, understanding the genetic factors that influence treatment responses.”

Deshmukh’s current research includes examining the impact of antibiotics on the microbiome and investigating whether probiotics could serve as an alternative. Additionally, he plans to lead studies on the long-term outcomes of preterm infants, particularly concerning conditions like COPD and asthma.

“Dr. Deshmukh’s expertise, vision, and commitment to translational research make him an ideal leader for our division,” said Jill Halterman (MD ’94, Res ’98, MPH ’01), chair of the Department of Pediatrics and Physician-in-Chief of GCH. “His work will not only advance neonatal care at GCH but also drive meaningful change in the field at large.”

by Emily Boynton

Eric J. Wagner, PhD (BS ’97), professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the School of Medicine and Dentistry, was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the world’s largest general scientific society and publisher of the journal Science

Wagner was selected for his contributions to the fields of molecular biology and biochemistry, particularly his research uncovering how human cells regulate the production of RNA from genes and how disruptions in this process lead to cancer and intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Election as an AAAS Fellow is a lifetime honor within the scientific community. Wagner, co-director of the University of Rochester Center for RNA Biology, is one of 471 scientists, engineers, and innovators who were selected for the 2024 Fellow class for their scientifically and socially distinguished achievements throughout their careers.

“Eric is a card-carrying RNA biologist and powerhouse of technological developments whose work is increasing our understanding of the causes of neuroblastoma and other devastating brain disorders in children,” said Lynne E. Maquat, PhD, founding director of the University of Rochester Center for RNA Biology and the J. Lowell Orbison Endowed Chair and Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the School of Medicine and Dentistry. “We’re extremely fortunate that we were able to recruit Eric back to Rochester as a co-director of both our RNA Center and our newly acquired NYS Center of Excellence in RNA Research and Therapeutics. I couldn’t ask for a more competent and engaged colleague to help further grow our strength in RNA research.”

Wagner received his undergraduate degree from the University of Rochester, followed by a PhD from Duke University. He conducted his postdoctoral work at the University of North Carolina, went on to run his own lab at the University of Texas-Houston and then at the University of Texas Medical Branch-Galveston, and

Eric J. Wagner, PhD (BS ’97) with lab members.

returned to Rochester in 2021 to join the Center for RNA Biology.

Among Wagner’s most well-known research is his work on the Integrator complex, which regulates gene expression in all our cells by helping to manage RNA production. When Integrator was discovered in 2005, Wagner’s lab was one of very few to study it.

Things changed in 2014 when he published a paper showing that Integrator is all over the genome. His work made people realize how fundamental the complex is to gene expression, and many other labs started to work on it.

Over the past decade, Wagner’s team has found that changes to Integrator impact cancer cell growth and neurological development, making it a promising treatment target for neuroblastoma and rare conditions like BRAT-associated brain disorders, which can cause cognitive impairment and seizures in children.

Also a member of the Wilmot Cancer Institute’s Genetics, Epigenetics and Metabolism research program, Wagner was among a small group of scientists who found that the length of RNA is crucial to cancer cells’ ability to divide.

Although Wagner and others are still conducting fundamental research to

understand all the mechanisms at play, this work is making its way into the field of diagnostics as scientists begin to look at the length of RNAs in tumors to determine where they fall on the spectrum of benign to malignant.

“In addition to being a leader in the ever-expanding field of RNA biology, Eric is also a wonderful mentor to many young scientists training in biochemistry, molecular and cellular biology, and cancer,” said Steve Dewhurst, PhD, vice president for research at the University of Rochester. “His knowledge, passion for his work, and dedication to promoting science and the promise it holds for patients and society as a whole make him extremely deserving of this honor.”

Starting his scientific career as an undergraduate at the University of Rochester and now receiving this award as a faculty member holds special meaning for Wagner.

“I’m honored to be elected as an AAAS fellow, but this is far from an individual accomplishment,” he said. “It reflects the aggregate work of all the talented and committed students and postdocs who I’ve had the privilege of working with over the past 17 years. Their research, and the research that’s being done across the broader scientific community, is so important and has a real impact on people’s lives.”

by Leslie White

Internationally renowned physician-scientist Jennifer Anolik (PhD ’94, MD ’96, Res ’97, Flw ’01) was named chief of the Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology (AIR) division in the Department of Medicine, after serving as interim chief since 2021.

Anolik is one of the pioneers in the use of B cell depletion for the therapy of autoimmune diseases and investigation of its effects on patients’ immune function in lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. Her research has established B cell-targeted therapies as a major advance in the field of immunologic disease. She also led groundbreaking studies using tonsil and bone marrow biopsy as a means of probing immune dysregulation in autoimmune diseases.

A faculty member for 22 years, Anolik also serves as associate chair for research in the Department of Medicine; professor of Medicine, Pathology, and Microbiology and Immunology; and director of the Internal Medicine Physician Scientist Training Program.

Under Anolik’s leadership, URMC was one of 11 research groups across the country chosen by the NIH to join the NIH Accelerating Medicines Partnership in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Lupus Network in 2014, and again in 2022—with extension to psoriatic arthritis and Sjogren’s disease. This consortium is developing new treatments using state-of-the-art, single-cell analytic approaches for patients with autoimmune diseases.

Anolik says this bench-to-bedside-and-back approach exemplifies her research program and “will be a critical strategy to promoting clinical and research excellence and vibrant educational programs in AIR in the years to come.”

Anolik plans to bolster SMD’s already robust allergy and rheumatology fellowship programs and is exploring ways to restructure and tailor the programs to support different career paths. “Among my biggest goals are to build on our very strong research capabilities and support medical research across the spectrum of residents to fellows, physicians, and faculty,” she said.

Anolik noted that the new ROC StARR program—ROChester Stimulating Access to Research in Residency Health and Immune Function Across the Lifespan—is a key part of this effort. A collaboration with the departments of Medicine, Pediatrics, and Dermatology, this program is designed to help recruit and retain individuals interested in pursuing careers as physician-investigators.

“I am delighted that Jen has agreed to continue leading our AIR division as chief,” said Ruth O’Regan, MD, chair of Medicine. “The division is in great hands under her leadership and will continue to benefit from her experience and expertise as a clinician, educator, and researcher.”

by Emily Boynton