URJ Uppingham Research Journal Issue 1 April 2024

By

By William McChesney

How is female identity and sexism portrayed

An introduction to superconductivity 4 By Avignon

Increasing Use of Artificial Intelligence in 7 Genomic Medicine for Cancer Care: The Promises and Possible Drawbacks By Summer Jones James Elroy Flecker: Poetry and Personae 13 By Benedict Braddock Resource Utilisation Elasticity Model: 21 How resource utilisation elasticity impacts long-term economic growth

Eliazar Marchenko

did Nazism become so popular by 1933? 33

Index

Lam

By

How

analysis

37

scroll

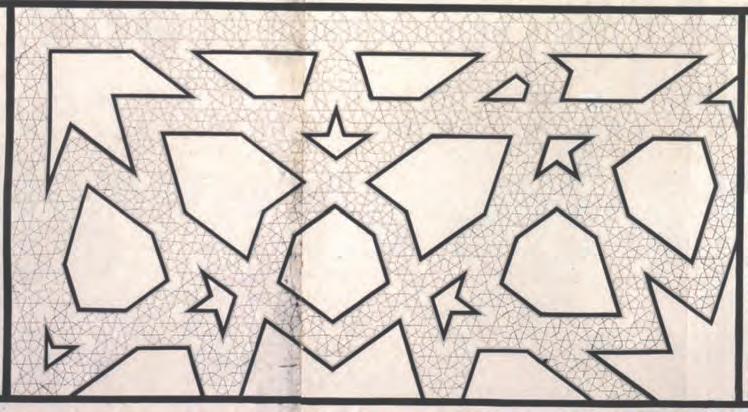

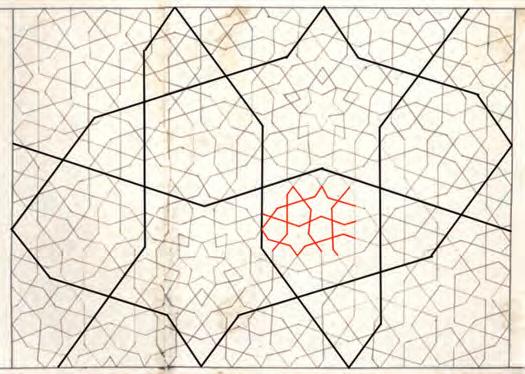

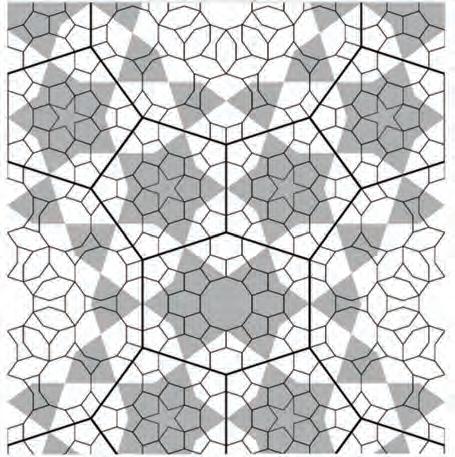

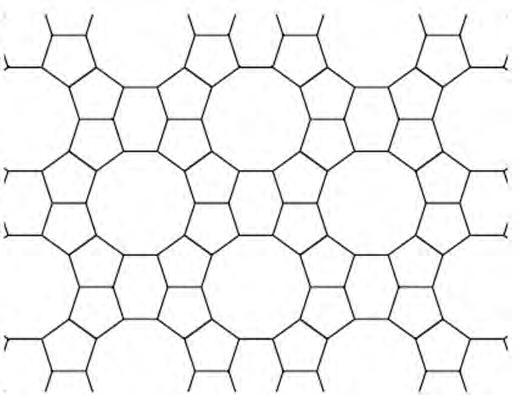

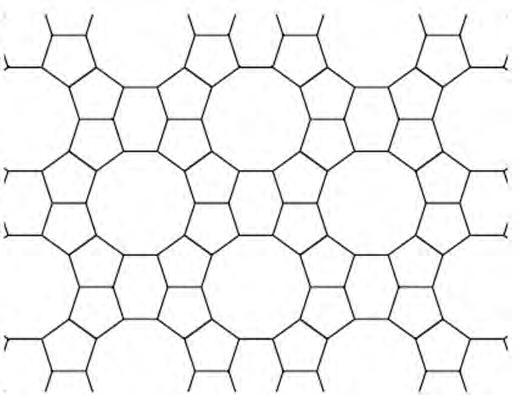

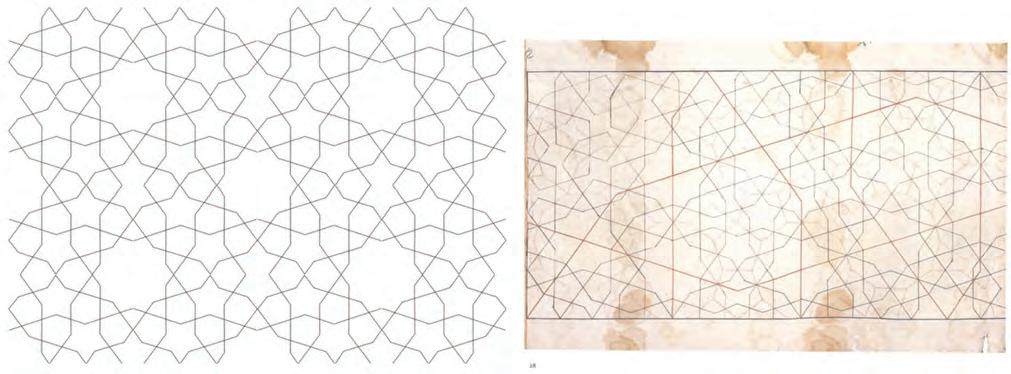

Henry Peech Mathematical

of panel 32 from the

Topkapı

42

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 2

in the Old Testament? By Jasper Blake

Foreword

Welcome to the Uppingham Review Journal, where the curious minds of our generation are leading students’ scholarly discussions, posing exciting problems and offering captivating opinions. We are thrilled to present the first edition of the Uppingham Review Journal: the platform led by high-school students for high-school students to publish the most outstanding works.

In the pages, you will explore science, humanities, arts and technology through the perspectives and ideas of student scholars. Each article, research paper and creative work has been carefully chosen for its quality, originality and impact on its field. These pieces showcase what level of work students can accomplish even at these foundational steps towards higher education.

Uppingham Review-Journal goes beyond being a review journal; it exemplifies how student-scholars can lead, motivate and offer insights to the global academic community. It is the only secondary school student-led academic publication in the country and symbolises student empowerment and intellectual collaboration. Our team of editors, all pupils at Uppingham School, has put in a great deal of effort to carefully curate a collection of the most outstanding papers that not only meet, but surpass ,the standards of academic excellence.

As you explore this edition, we encourage you to recognise the opinions, research and the deep level of exploration that each writer brings to their work. From ground-breaking studies to literary interpretations and from innovative technological advancements to critical analyses of historical events, we showcase the finest achievements in student academic pursuits.

Furthermore, this publication acts as a link that connects student-scholars with the wider academic community, offering a platform for discussion, feedback, and development. We hope that Uppingham Review-Journal will spark a love and interest in learning and exploration in both readers and contributors alike; our goal is to nurture an environment for student research that will thrive in the years to come.

In introducing this edition, I thank our contributors whose commitment and brilliance set a high academic achievement standard. We also express gratitude to the Uppingham staff: tutors, teachers and mentors whose guidance has been vital in turning this vision into reality.

In particular, I would like to acknowledge Mr Addis, who has consistently helped with assessing the works and day-to-day operations of the Journal, providing invaluable knowledge and experience for the Journal.

Eliazar Marchenko Uppingham Review Journal Founder and Head Editor

3 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

An introduction to superconductivity

By Avignon Lam

Abstract

Superconductivity is a promising technology that can have many uses in the future, from medical imaging to transport systems to power transmissions. This paper provides a basic understanding of the mechanisms behind low temperature superconductivity, and its potential applications in a larger scale.

Introduction

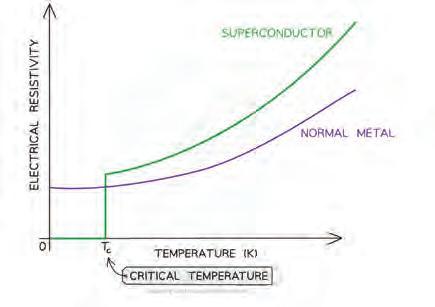

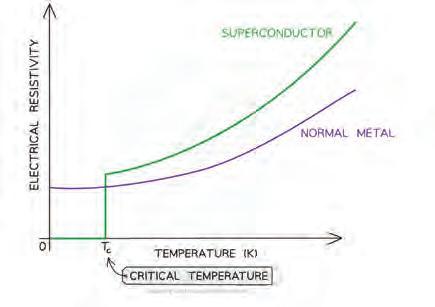

We know that when temperature decreases, resistance decreases as well, and that the relationship between the two can be modelled as linear at room temperatures. However, when temperature further decreases, resistance begins to decrease at a smaller rate, and at very low temperatures it is found that the resistance sharply drops to 0 for certain materials (See Fig 11 ). In fact, Onnes discovered this in 1911 when he cooled liquid helium down to 4.2K2. This is described as superconductivity.

Properties of superconductivity

There are a few properties that superconductors exhibit. Firstly, a superconductor placed in a magnetic field will have induced currents that have its own magnetic field. These magnetic fields expel any magnetic flux inside the superconductor, showing what is known as the Meissner effect, which can be shown by the London equations. A common demonstration of the effect is by placing a small superconductor on a magnetic track. The superconductor will then levitate on the track and can move with little resistance to motion.

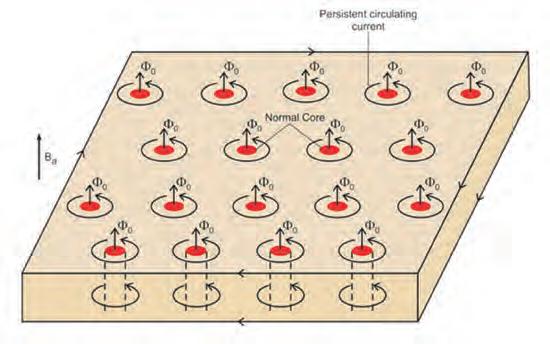

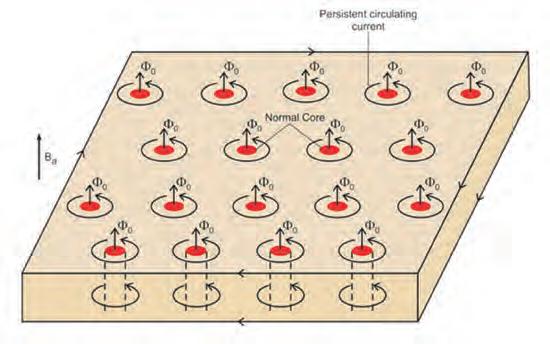

Another property of superconductivity is that when put in a magnetic field (H) of large enough strength (i.e. > Hc, the critical value), superconductivity disappears. This temperature varies with material and is generally higher in Type 2 superconductors than Type 1 superconductors. The difference between the two types is that Type 2 superconductors, can enter a mixed state when the magnetic field strength is between Hc1 and Hc2, where the material remains superconducting mostly but contains holes, often called vortexes, to allow the some of the magnetic field lines to pass through, allowing it to be placed in a magnetic field of larger strength. (Fig 23) 1

4

“Superconductivity (5.2.3) AQA A Level Physics Revision Notes 2017”, Save My Exams

“Further experiments with liquid helium. C. On the change of electric resistance of pure metals at very low temperatures etc. IV. The resistance of pure mercury at helium temperatures”, Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, 1911 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

2

Mechanisms

As for now, the most popular theory of explaining superconductivity is the BCS theory named after the initials of the 3 scientists that proposed the theory. However, the theory only provides an explanation to conventional superconductors with critical temperature lower than 40K, and the exact mechanism behind superconductors with a higher critical temperature is still unknown.

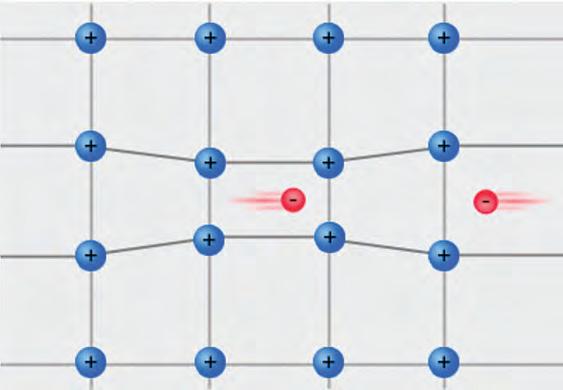

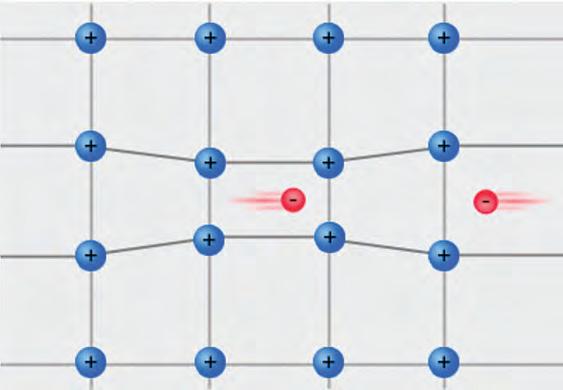

A key part to understanding BCS theory are the Cooper pairs of electrons which can move through the lattice (Fig 34). To put it simply, the formation of cooper pairs occurs due to distortions of the lattice of the material. When an electron moves through the lattice, positively charged ions in the lattice are slightly attracted to the moving electron, creating an area of higher charge density. This area of higher charge density attracts another electron. This results in the 2 electrons becoming bounded with each other. Do note that these “bonds” can have a length of around 30 to 1500Å, and will also have many other electrons between them, hence they are not actually bonds.

Alternatively 5, we can consider two electrons with opposite momentum (and opposite spin) having wavefunctions Ψ1 = ei(kx-wt) and Ψ2 = ei(-kx-wt) where ±k is their momentum. The probability distribution of the superposed electrons, |(Ψ1 +Ψ2) ⁄√2|2, results in a standing wave, hence there are regions of higher electron charge density and regions of lower charge electron density, resulting in the distortion of the lattice as positive ions are more attracted towards regions of high electron charge density.

Now that Cooper pairs are formed we can talk about their quantum properties. The pairs can be treated as a single particle and have an integer spin as opposed to a half integer spin of a single electron, hence they obey Bose-Einstein statistics and can now occupy the same energy level. This is different from normal materials at room temperatures where electrons obey the Pauli exclusion principle and must occupy different energy levels with pairs of opposite spin. The Cooper pairs in the lattice are now said to be in the same quantum state, meaning that each pair must gain equal amounts of momentum in an electric field, and have the same momentum. Hence, breaking just one of the pairs through interacting with the lattice is impossible as that would mean not all the pairs have the same momentum, resulting in no resistance as there is no interaction. However, as temperature rises near the critical temperature, we gain enough energy to break all the pairs, and electrons now interact with the ions in the lattice, causing resistance.

3 “The Phenomenon of Superconductivity and Type II Superconductors”, R.G. Sharma, 2021

4 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cooper_pairs.jpg

5 https://thiscondensedlife.wordpress.com/2015/09/12/draw-me-a-picture-of-a-cooper-pair/

5 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

Applications

There are various fields which can see the applications of superconductors. These applications all use the property of a superconductor that it can have a strong magnetic field, however these applications are currently limited due to the low critical temperature of superconductors, and difficulties of manufacturing strong and resistant superconducting wires that can withstand strong currents or magnetic fields.

Superconductors are often used in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). MRI requires a strong magnetic field in order to align hydrogen nuclei to the field. When the field is disrupted, the protons realign and release specific radio waves, which are detected and can create an image. As a strong magnetic field is required, superconductors such as the common NbTi (Niobium-Titanium), are used in coils around the patient table. These superconductors are surrounded by a coolant such as liquid helium to maintain low temperatures. Although NbTi currently dominates the superconducting technology in MRIs, there is potential usage of MgB2 in situations where a extremely high magnetic field is not required.

Superconductors can also be used in transport, particularly in Maglev trains. These trains require strong magnetic repulsions or attractions to different coils to lift the train up, which a superconductor enables. The trains can than move along the track without friction to the ground, potentially allowing much higher speeds.

Other uses may include particle accelerators where superconductors are used to create strong EM fields, or in power transmission, although the latter is too expensive to be used on a large scale currently. They can also be used in quantum computing where the |0⟩ and |1⟩ states are represented by the ground and excited states of the qubits respectively.

Conclusion

To conclude, superconductors are materials that have no resistance under their respective critical temperatures. This is due to the binding of electrons to form Cooper pairs, which behave like bosons and have the same quantum state, preventing them from interacting with the lattice. Superconductors have many potential applications, such as in MRI, trains, quantum computing, or in particle accelerators.

Bibliography

Brian Skinner, This Condensed Life. “Draw me a picture of a Cooper Pair”

https://thiscondensedlife.wordpress.com/2015/09/12/draw-me-a-picture-of-a-cooperpair/#:~:text=In%20a%20Cooper%20pair%2C%20two,carry%20electric%20current%20without%20 dissipation

Explainthatstuff. “Superconductors”

https://www.explainthatstuff.com/superconductors.html

University of Cambridge. “Lectures on Superconductivity”

https://www.ascg.msm.cam.ac.uk/lectures/

University of Cambridge. “Superconductivity (All content)”

https://www.doitpoms.ac.uk/tlplib/superconductivity/printall.php

6 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

Increasing Use of Artificial Intelligence in Genomic Medicine for Cancer Care: The Promises and Possible Drawbacks

By Summer Jones

1. Abstract

This article explores how artificial intelligence (AI) is currently being used in genomic medicine. It examines the role of AI and how it can be used to evolve and improve medicine as a whole and discusses whether or not we should integrate it more into healthcare by evaluating its benefits and potential challenges. It explores the social, logistical, ethical, and other factors that can be considered when considering how AI can be used to benefit genomic medicine.

2. Introduction

Medicine is an ever-evolving discipline that demands new and innovative ideas in order to save as many lives as possible. Cancer is a disease that remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, killing approximately 10 million in 2020 alone. (1) Thus, the discussion of artificial intelligence (AI) regarding cancer treatments is becoming increasingly prominent in the medical field. It seems almost inevitable that AI will eventually become standard across all modern medical specialities in healthcare, with more than $1 billion in venture capital investment being received by global healthcare big data analytics companies in the first nine months of 2017 as stated by Merck Capital. (2) However, many are divided in their beliefs of how much of a role AI should have in our future. Individuals may question whether the potential drawbacks that AI creates may outweigh its possible benefits as suggested in a lot of mainstream media. Therefore, we are left with a fundamental question: Should AI be used in genomic medicine for cancer care?

3. Artificial Intelligence: What is it?

AI is a combination of sophisticated technological advances, encompassing a series of algorithms combined with theories that enable it to carry out tasks that typically require ‘human’ intelligence. Our perception of AI varies greatly. Some may consider AI in terms of science fiction, envisioning a dystopianesc future as seen in Blade Runner or Star Trek, whereas others may instead associate it with medical diagnosis (3) or radiotherapy. Similar to other industries, the field of medicine is embracing AI to surpass the limitations of human capabilities. The Cambridge Dictionary defines AI as (4) ‘the study and development of computer systems that do jobs that previously needed human intelligence.’ So, to put it plainly, artificial intelligence is a broad term that could be interpreted as the use of robots to carry out tasks in the place of humans. Artificial Intelligence in medicine intends to improve and save the lives of many by achieving greater success (in terms of precision and speed among other skills) than humans can independently.

4. The Current and Future Use of AI in Genomic Medicine for Cancer Care

Current AI techniques and models vary largely due to the number of different companies that claim them. (5) However, a standard computer-based model commonly used is Machine Learning (ML) - it comprehends patterns in an overall volume of information to construct classification and prediction models derived from the training data. It was first termed by Arthur Samuel in 1959 and since then has evolved greatly.(6) It can be used to create and develop individual treatments for patients, assist doctors in learning what to prescribe and predict the potential future of a patient’s medical journey.(7) It uses a system where it is trained, as perhaps a human would, where it will be punished for bad performances and rewarded for good performances. This feedback system reinforces its learning over time which helps it make models that can be used to then perform complex tasks. The Machine Learning will process data from a number of sources (biological, clinical, environmental, and experimental) through formatting, cleaning, scaling, normalization, unsupervised learning, and deep learning. (8) This creates models that are generated using Machine Learning algorithms (Model training and Evaluation). After model development and selection, diagnostic results can be predicted and thus provide medical advice. Therefore, it could be suggested that Machine Learning is significant in changing how the healthcare system works. It can help to make diagnoses and prescriptions of drugs and also reduce the risk of clinical

7 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

errors for cancer patients. This could mean that doctors, among other individuals in the medical system, have more time to help a greater amount of cancer patients or reduce the risk of ‘burnout’ and so allow them to work more efficiently and devote more time to other features of patient care. (9)

Omics technologies aim to detect genomics in a specific biological sample and can be combined with AI to enable the study of complex biological systems. This has allowed the identification of disease biomarkers (using omics data) that can then lead to a simplification of a patient cohort categorization and can give preliminary diagnostic data to enhance the management of cancer patients and minimise high-risk emergencies in patients. Oncology itself relies on a history of evidence of past patient data which forms the basis for the creation of scoring systems. These, in turn, lead to the implementation of cancer risk assessment and disease diagnosis. (10) Using traditional approaches, it is almost impossible to understand the innumerable number of environmental and genetic factors relevant to specific cancers. However, AI allows for comprehension of this web of interactions as it can interpret the inconceivable magnitude and high dimensionality (11) of such data. Therefore, it is vital to use AI in a way that allows for an accurate understanding of a person’s cancer status.

AI techniques like deep learning technology (DELT, a subset of machine learning) can be used to identify and classify different tumours. (12) It can be used in cancer prognosis in combination with genomic data and uses methods that have been successful in predicting patient survival times, improve the function of gene editing tools and predict how certain types of cancer will progress in a patient. In recent years, DELT has continued to evolve extensively due to advances in learning algorithms, ever-increasing data availability and increasing computing power. AI-based models are now typical as part of breast cancer imaging. In August 2023, a Swedish study found that the utilization of AI software to interpret mammograms (an X-ray picture of the breast) resulted in the detection of 20% more cancers when compared to the conventional double reading approach by two radiologists. Additionally, the use of AI did not cause an increase in false positives. (13) This study provides an example of how AI can be used to diagnose cancer at its early stages of development. Consequentially, more patients can be cured of cancer and thus the economic, personal, and societal costs of cancer care are reduced. More time can be spent devoted to enhancing cancer care itself. For example, doctors could potentially develop more personalised care and support planning for patients.

The integration of ML and genomics data can help to diagnose cancer subtypes, understand cancerdriven genes better, and discover new markers and drug targets. These features can ultimately pave the way for customised approaches and treatments for individual patients. For instance, in 2021, Xingze Wang developed a deep network model (LungDIG) that can diagnose lung cancer subtypes by mixing imagegenomics data and hybrid deep networks that have achieved ‘not only a higher accuracy for cancer subtype diagnosis than state-of-the-art methods but also has a high authenticity and good interpretability.’(14) Moreover, AI is also being used in combination with liquid biopsy to identify signatures of colorectal malignancies (CRC, the second most frequently diagnosed type of cancer). (15) Machine learning techniques are being used to find the primary kind of cancer from a liquid biopsy. This is significant because early detection of CRC can have a huge impact in decreasing mortality and current methods like histopathological analysis of tumour tissue and colonoscopy are limited in success and no longer sufficient in capturing ‘the complex relationships between biomarkers and cancer subtype heterogeneity’ (16) Another current use of AI is demonstrated through a company named Freenom which uses AI to screen for cancer by analysing a person’s blood sample. It has raised over $100 million from investors and its test is being used by leading healthcare providers. (17) Evidently, there are a series of examples over recent years that demonstrate the potential of AI in combination with genomic data in improving diagnosis over a broad range of cancer types.

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 8

The integration of CRISPR with artificial intelligence is also a promising area for enhancing cancer therapeutics. ML tools and DL models can help the CRISPR-Cas9 system to have higher-precision target predictions. MDL-based algorithms have significantly improved the system’s efficacy concerning the reduced off-target effects which is a crucial factor in expanding their application in clinical therapeutics. As the list of new algorithms continues to evolve, the CRISPR-Cas9 system is expected to improve its increased on-target activity with corresponding minimum off-target effects, which will ultimately be crucial in its future clinical and therapeutic applications. (18) CRISPR technology itself can be used to modify immune cells and so make them more powerful in preventing the development of cancer and can alter DNA nucleotides (to prevent harmful mutations) through ‘cutting’ certain genes and replacing them with the correct versions. This is done to control and avert the process of carcinogenesis. (19) As CRISPR is still a new technology, any additions like AI are vital in improving its use in the future and determining how it can be used in relation to cancer care.

Moreover, AI algorithms can help analyse errors in prescriptions made by doctors. A study from John Hopkin’s patient safety experts claimed that medical error accounts for close to 250,000 people per year in the USA alone, therefore being the third leading cause of death in 2016. (20) ML models analyse historic electronic health records (a stored collection of patient-related information, that has been adopted in routine practice as genomic medicine has advanced) and then compare new prescriptions against this information. Any current prescriptions which differ from the typical patterns get flagged and enable doctors to take note of them and, if necessary, review and adjust them. An example of the success of AI being used in this way can be found in Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s use of an ML-powered system that serves this purpose. Over the course of a year, the system identified a total of 10,668 potential errors, with an impressive 79% being clinically valuable. In consequence, the hospital was able to save $1.3 million in healthcare-related expenses and enabled the improvement of quality of care by preventing drug overdosing and health risks. (21) VAIPE (a system developed by the research team at Vin Uni-Illinois Smart Health Centre and partners) is another example of an AI algorithm that uses graph neural networks and contrastive learning to warn users of medical errors when detecting prescription drugs. Dr Hieu, co-leader of the project, claimed, “The accuracy of these algorithms is completely superior to existing traditional methods.”

The field of genomics is rapidly evolving and ultimately transformative- it is becoming increasingly clear how intertwined this field of medicine and AI are becoming. The future of AI in genomics is promising and is estimated to be worth $47.6 billion by 2025. Over the next few years, engineers are researching how ML can be used with nanotechnology to improve medicine delivery and ultimately how AI can be integrated across the healthcare system. The application of AI in healthcare as a whole has the potential to manage some of the supply-and-demand challenges, such as long waiting times, limited resources, and overwhelmed healthcare professionals, faced by the NHS. It is projected that by the year 2030, the world will have 18 million fewer healthcare professionals whilst the gap between supply and demand will continue to escalate for staff employed by NHS trusts and potentially increase to almost 250,000 full-time equivalent posts. (22) With these factors, aging populations and the rising burden of chronic diseases, AI may appear to be the only viable solution in the future of medicine.

5. The Problems of the Combination of Artificial Intelligence in Genomic Medicine for Cancer Care

Whilst AI has already proven to be useful in genomic medicine e it is likely that as it advances further several ethical, medical, and technological challenges will be confronted. Like all disciplines, AI has its limitations.

9 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

One crucial concern is that of the patient’s privacy. Many of the emerging AI companies are controlled by private entities outside of the NHS (23), which could lead to such corporations having a greater role in protecting and using patient health information. This information is typically highly sensitive and revealing about patients and their families, therefore it may cause great stress to the public if public bodies are able to obtain their information without their direct knowledge. For instance, a survey conducted among a sample of four thousand American adults revealed that only a mere 11% were willing to share health data with tech companies in stark contrast to 72% with physicians, and only 31% were ‘somewhat confident’ in tech companies’ data security. Clearly, there is a struggle between the need for technology like ML that needs data in order to work accurately and the actual desire of the public to share their own genomic and health information. This could cause more stress to patients (such as those in cancer care) and create a sense of unease, which is ultimately opposed to the effect that the healthcare system wants to have on its nation.

In spite of the fact that many patients have a willingness to believe in AI-based diagnosis itself, many tend to more frequently trust doctors when the AI-based diagnosis differs from that of the doctors. (24) Ergo, it could be suggested that AI should remain as a tool to extend human capabilities rather than to replace them. Therefore, it is important to have experienced and knowledgeable professionals who can interpret the results from AI and make decisions based on them, as often AI is described as ‘black box’ (‘a system that produces an output without justification’). (25) Moreover, there is a potential issue with AI using incorrect data. There is a possibility that inaccurate or even incomplete data could be used in AI algorithms and thus cause inaccurate diagnoses or treatments for cancer patients. AI may even perpetuate existing inequalities in healthcare (if limited in its database), so, it must be emphasised that diverse and representative datasets are used to prevent inaccurate conclusions. AI also presents economic challenges. These issues primarily stem from the high computational costs associated with AI algorithms and the significant resources necessary (like ‘high-performance computing and large data storage capabilities’).

6. Conclusion

As evident from the great variety of applications of AI in genomic medicine for cancer care, it is clear that there are many advantages and promising ways we can use AI both now and in the future in healthcare. It is undeniable that there are some challenges in the current AI technology, however, there is no reason to suggest that we should not continue to improve and find ways to integrate AI into the medical industry. We should embrace that AI will become increasingly prominent in the future of all industries, and so be prepared to tackle the ethical issues that will arise with its adoption into modern society. AI algorithms have already proven to improve cancer care across a broad range of studies and will undeniably further medical progress.

References

(1) Cancer Research UK, (2022), Worldwide Cancer Statistics [Available from: rb.gy/gnw1c]

(2) G eorge Morrisey, (2018), Will artificial Intelligence eventually replace Cancer geneticists? [Available from: https://shorturl.at/eCKY3]

(3) The Medical Portal, (n.d.), AI In Medicine [Available from: rb.gy/bl8oa]

(4) Cambridge Dictionary, (n.d.), Meaning of Artificial Intelligence [Available from: rb.gy/hpb8o]

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 10

(5) Jia Xu, Pengwei Yang, Shang Xue, Bhuvan Sharma, Marta Sanchez-Martin, Fang Wang, Kirk A. Beaty, Elinor Dehan, Baiju Parikh, (22 January, 2019), Translating cancer genomics into precision medicine with artificial intelligence: applications, challenges and future perspectives [Available from: rb.gy/23xt1]

(6) Wikip edia, (6th October, 2023), Machine Learning [Available from: rb.gy/6v02s]

(7) Sudeep Srivastava, (September 29, 2023), The Future of Patient Care: AI in Healthcare [Available from: https://shorturl.at/anDKP ]

(8) Sameer Quazi, (15 June, 2022), Artificial Intelligence and machine learning in precision and genomic medicine [Available from: https://shorturl.at/lTX01 ]

(9) Jia Xu, Pengwei Yang, Shang Xue, Bhuvan Sharma, Marta Sanchez-Martin, Fang Wang, Kirk A. Beaty, Elinor Dehan, Baiju Parikh, (22 January, 2019), Translating cancer genomics into precision medicine with artificial intelligence: applications, challenges and future perspectives [Available from: rb.gy/23xt1]

(10) Jacob T Shreve, Sadia A. Khanani, MD, and Tufia C. Haddad, (2022), Artificial Intelligence in Oncology: Current Capabilities, Future Opportunities, and Ethical Considerations [Available from: https://shorturl.at/moJS1 ]

(11) Minhyeok Lee, (July, 2023), Deep Learning Techniques with Genomic Data in Cancer Prognosis: A Comprehensive Review of the 2021-2023 Literature [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10376033/]

(12) Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union, (21 May, 2021), Background Note on Unlocking the Potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Cancer Research and Care [Available from: rb.gy/a4oue]

(13) Jamie DePolo, (August 3, 2023), AI-Supported mammogram Reading Detects 20% More Cancers [Available from: https://www.breastcancer.org/research-news/ai-mammogram-reading]

(14) Xingze Wang, Guoxian Yu, Zhongmin Yan, Lin Wan, Wei Wang, Lizhen Cui Cui Lizhen, (December, 2021), Lung Cancer Subtype Diagnosis by Fusing Image- genomics Data and Hybrid Deep Networks [Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34855599/]

(15) Octav Ginghina, Ariana Hudita et al., (March 8, 2022), Liquid Biopsy and Artificial Intelligence as Tools to Detect Signatures of Colorectal Malignancies: A Modern Approach in Patient’s Stratification [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8959149/ ]

(16) Linjing Liu, Xing jian Chen et al., (June 30, 2021), Machine Learning Protocols in Early Cancer Detection Based on Liquid Biopsy: A Survey [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8308091/ ]

(17) Arkadiusz Skuza, (July 9, 2022), AI and Genomics: A Profitable Advancement for the Healthcare Industr y [Available from: rb.gy/m2xrm ]

(18) Ajaz A . Bhat, Sabah Nisar at al., (18 November, 2022), Integration of CRISPR/ Cas9 with artificial intelligence for improved cancer therapeutics [ Available from: rb.gy/0j540]

11 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

(19) Rob Stein, (December 13, 2022), CRISPR gene-editing may boost cancer immunotherapy, new study finds [Available from: rb.gy/9wg6h]

(20) Michael Daniel, (May 3, 2016), Study Suggests Medical Errors Now Third Leading Cause of Death in the U.S. [Available from: rb.gy/yk4lt]

(21) Sudeep Srivastava, (September 29, 2023), The Future of Patient Care: AI in Healthcare [Available from: https://shorturl.at/anDKP ]

(22) Junaid Bajwa, Usman Munir, Aditya Nori, Bryan Williams, (2021), Artificial Intelligence in healthcare transforming the practice of medicine

[Available from: https://www.rcpjournals.org/content/futurehosp/8/2/e188.full.pdf]

(23) Blake Murdoch, (15 September, 2021), Privacy and aritifical intelligence: challenges for protecting health information in a new era

[Available from: https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12910-021-00687-3]

(24) Lushun Jiang, Zhe Wu et al., (March, 2021), Opportunities and challenges of artificial intelligence in the medical field: current application, emerging problems and problem-solving strategies [Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8165857/]

(25) Saravanan Sampoornam Pape Reddy, Delfin Lovelina Francis at al., (2023), Artificial Intelligence in the G enomics Era: A Blessing or a Curse? [Available from: https://shorturl.at/lIXZ0]

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 12

James Elroy Flecker: Poetry and Personae

By Benedict Braddock

James Elroy Flecker, of course, is relevant to Uppinghamians as the poet and OU for whom our senior literary society is named; moreover, he is relevant to the author personally not only as an Uppinghamian but also as a Decanian, both attending Dean Close School in Cheltenham before coming here; indeed, the library at Dean Close is called the “Flecker Library” to this day. But Flecker also has a broader significance as one of the central figures in pre-First World War 20th century poetry, forging a strongly individual and often visionary voice out of threads as disparate as the Parnassian movement in France and the contemporaneous Georgians in England, the poetries of the Classical world and of Central Asia, often all viewed through the lens of his own upbringing, which instilled in him both a religious impulse and a sense of “home” to which Flecker often returns. As he matured as a poet, Flecker seems to have adopted three central literary “personae” - Flecker the Headmaster’s Son, Flecker the Visionary, and Flecker the Romantic, which lend character to his work in often quite unexpected ways through an inventive use of poetic diction and imagery, and a seamless blurring of distinct influences.

1. Biographical sketch

Herman Elroy Flecker, as he was named at birth, was born on November 5, 1884 in Lewisham; his father William was a failed mathematician turned Anglican priest who, in 1886, made the decision to take his wife Sarah and two-year-old son across the country to become the first headmaster of Dean Close School in Cheltenham, where Flecker was raised and later educated. He spent his sixth form years, however, here at Uppingham, where he garnered a bad reputation for his lack of punctuality and general slovenliness, although rigorous training in Greek and Latin composition instilled in him a strong and lasting interest in the Classics; indeed, the first poems of which he was proud, published among the “Juvenilia” in his Collected Works, were a set of translations of Catullus. After Uppingham, Flecker studied at Trinity College, Oxford, where he adopted the name “James” and became close friends with Arthur Waley, later to become a leading orientalist and sinologist, and John Beazley, who would go on to be a noted archaeologist and art historian. While at Oxford, Flecker became greatly influenced by the last flowering of the Aesthetic movement there, which valued “art for art’s sake”, under the tutelage of John Addington Symonds; Flecker later stated that he wrote “with the single intention of creating beauty”1, and though he is often associated with the Georgian movement, his work, fortunately, does not possess the same pastoral lifelessness and diluted middlebrow conventionality that tends to characterise that particular school, but instead shows the influence of both Aestheticism and the French school of Parnassianism, which relied on clarity and simplicity for its emotive force. After graduating with a third in Greats, he trained as an interpreter in Persian and Arabic at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge; it was during this period that his first collection of poems was published, The Bridge of Fire, in 1907.

In 1910 he briefly joined the consular service, serving as an interpreter in Constantinople, Smyrna and Beirut, but was forced to resign having been diagnosed with tuberculosis later that same year. Fortunately the experience had not been in vain; his time in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East inspired poems in the collection The Golden Journey to Samarkand, published in 1913, which was followed a year later by a novel, The King of Alsander; moreover, he had met Helle Skiadaressi that same year on a ship bound for Athens; they were married in 1911. Sadly, however, Flecker’s tuberculosis gradually became more intense, and he spent his last two years in various sanatoria in Switzerland, dying at Davos on January 3, 1915, at the age of thirty; on his death, he was described in perhaps justifiably hyperbolic terms as “unquestionably the greatest premature loss that English literature has suffered since the death of Keats”2. He was buried at Bouncer’s Lane Cemetery in Cheltenham in critical high regard but in relative public obscurity; however, the publication and staging of his verse play Hassan in 1922 made him a betterknown figure than he had been in his life and established him in the national consciousness as an important figure in early 20th century literature.

1 (Ward 1928, p175); cf. J. C. Squire’s introduction to The Collected Poems of James Elroy Flecker (1916).

2 (Macdonald, 1924)

13 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

2. Flecker the Headmaster’s Son

Arguably, the first Flecker “persona” to emerge was that of Flecker, the Headmaster’s Son. Growing from infancy to adulthood in a school environment where strict discipline had to be followed at all times had an essentially threefold effect on Flecker’s creative output: firstly, the regular chapel services he had to attend for long periods on Sundays and also during the week instilled in him a strong religious impulse; secondly, being tied so closely to an institution that encouraged competition both internally and with other schools fostered a strong sense of identity and the value of “home”; thirdly, the privileged but also socially vulnerable position he held as the son of the headmaster brought about a sense of isolation and loneliness, and having to prove himself on his own terms. This may explain his impatience to excel in Greek and Latin translation, but more importantly this combination of conflicting factors created an internal tension in Flecker to which he would return in his poems throughout his life. For example, in the early poem From Grenoble Flecker states an initial desire to experience the world in its fullness which is replaced by a yearning to return to his natural domain:

Now have I seen, in Graisivaudan’s vale,

The fruits which dangle and the vines that trail,

The p oplars standing up in the bright blue air,

The silver turmoil of the broad Isere

And sheer pale cliffs that wait through Earth’s long noon

Till the round Sun be colder than the Moon.

Mine b e the ancient song of Travellers:

I hate this glittering land where nothing stirs: I would go back, for I would see again Mountains less vast, a less abundant plain,

The Northern Cliffs clean-swept with driven foam,

And the rose-garden of my gracious home.3

The image of the “rose-garden” probably came from the garden of flowers that Sarah Flecker had cultivated at Dean Close, and which the young Flecker must have explored for hours as a child. Flecker also drew on his experiences of summer holidays at the Dorset seaside town of Southbourne in the poem ‘Brumana’, written in April 1913, when Flecker was wracked with tuberculosis and, according to Heather Walker, “the heat was intolerable and on doctor’s advice…[Flecker’s Greek wife, Helle Skiadaressi] took her husband up to Brumana on Mount Lebanon [where they were staying] in the hope that the cool mountain air would aid his recovery”4. Flecker became productive yet yearned to go back to England, a feeling that was heightened by the sight of pines near the place he was staying, which reminded him of the ones he had seen at Southbourne as a child. It was said that the boy Flecker preferred to wander alone at Southbourne, but the freedom he lacked at Dean Close may not have left him with much choice. The reference to the “chosen tree” in Brumana may also have meant that he had a set path at Southbourne and a particular arbour he returned to time after time because it afforded him a certain sense of security:

3 (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 29)

4 (Walker 2006, 512)

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 14

Oh shall I never never be home again?

Meadows of England shining in the rain

Spread wide your daisied lawns: your ramparts green

With briar fortify, with blossom screen

Till my far morning – and O streams that slow

And pure and deep through plains and playlands go,

For me your love and all your kingcups store,

And – dark militia of the southern shore,

Old fragrant friends – preserve me the last lines

Of that long saga which you sung me, pines,

When, lonely b oy, beneath the chosen tree

I listened, with my eyes upon the sea.5

Interestingly, the outbreak of the First World War in July 1914 caused the outcomes of his Headmaster’s Son persona to come full circle; what had been a difficult, conflicted, and deeply personal element of his poetic voice now found a new purpose as a means of expressing a sense of patriotism; his home was now not limited to the confines of the Dean Close rose-garden, but could be extended to include the whole of Great Britain. This new mode was expressed in one of Flecker’s final poems, The Burial in England, which finished in 1914 but was not published until February 1915, two months after the poet’s death. It contrasts the burial of the dead in England with the quick but much less friendly doom that awaited the soldiers killed in France in the early stages of the war, and is similar in tone to Rupert Brooke’s “The Soldier”; indeed, the two poems share remarkably similar original titles – Flecker’s was originally called “The Speech of the Grand Recruiter”, Brooke’s simply “The Recruiter”. The outbreak of war also caused a shift in Flecker’s poetic vision from optimism to the view stated by Hassan in Flecker’s long verse drama of the same name: “poetry is a princely diversion, but for us, it is a deliverance from Hell”⁶; nonetheless, in The Burial in England, Flecker’s assuredness of diction and the integrity of his earliest motivations stand as firm as ever:

These then we honour: these in fragrant earth

Of their own country in great peace forget

Death’s lion-roar and gust of nostril-flame Breathing souls across to the Evening Shore.

So on over these the flowers of our hill-sides

Shall wake and wave and nod beneath the bee

And whisp er love to Zephyr year on year,

Till the red war gleam like a dim red rose

Lost in the garden of the Songs of Time.⁷

3. Flecker the Visionary

In spite of the turn in tone necessitated by the outbreak of the First World War, throughout his poetic career, Flecker also cultivated a persona as a Visionary. Poems such as “To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence”, possibly Flecker’s best-known work today, express notes of pessimism comingled with a more assertive sense of optimism that often looks far into the future while bearing in mind the weight of historical precedent. This perceptive dichotomy is perhaps most clearly distinguished in two poems, “A New Year’s Carol” and “Prayer”, both written in January 1906, the beginning of Flecker’s last year at Oxford. The titular generic designation “carol” in the former poem has important implications. In the

5 (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 179)

⁶ (Flecker 1922, ‘Hassan’, 84)

⁷ (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 236)

15 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

Oxford Book of Carols, Percy Dearmer describes carols as “songs with a religious impulse, which are simple, hilarious, popular, and modern. They are generally spontaneous and direct in expression…the typical carol gives voice to the common emotions of healthy people in a language that can be understood and music that can be shared by all”⁸. Certainly Flecker’s use of the stable, “measured swing” of the rhymed quatrain form and direct poetic diction convey these attributes; more importantly, however, the substance of Flecker’s poem, like, the carol form and the concept of “New Year” itself, looks thematically both to the past and future. Indeed, Flecker’s ABBA rhyme scheme could recall Tennyson’s use of the same pattern made famous by his In Memoriam, which similarly faces tonally in two directions, moving from “despair to happiness” via “individual, historical and natural pasts” and “Christian pronouncements”⁹.

Awake, awake! The world is young, For all its weary years of thought: The starkest fights must still be fought, The most surprising songs be sung.

And those who have no other Gods

May still behold, if they bestir, The windy amphitheatre

Where dawn the timeless periods.

Then hear the shouting-voice of men

Magniloquently rise and ring: Their flashing eyes and measured swing

Prove that the world is young again.

O stubborn arms of rosy youth, Break down your other Gods, and turn To where her dauntless eyeballs burn,— The silent pools of Light and Truth.10

Prayer, by contrast, is more sober and much less idealistic in tone:

Let me not know how sins and sorrows glide

Along the sombre city of our rage, Or why the sons of men are heavy-eyed.

Let me not know, except from printed page, The pain of litter love, of baffled pride, Or sickness shadowing with a long presage.

Let me not know, since happy some have died

Quickly in youth or quietly in age,

How faint, how loud the bravest hearts have cried.11

⁸ (Dearmer et al. 1928, v)

⁹ (Kozicki 1977, 673)

10 (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 27)

11 (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 70)

16

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 16

The stable quatrains of A New Year’s Day Carol contrast strongly with Prayer’s use of terza rima, an interweaving form which creates a sense of echo and perhaps nervous expectation. Although both poems begin with imperatives, A New Year’s Day Carol’s apostrophic opening ‘Awake, awake!’ is far more emphatic than the repeated 1st person singular form with which Prayer begins: “Let me not know…”, which also establishes an apophatic language of denial and a desire for ignorance that is at odds with the optimism of “Light and Truth” in the former poem. There, the speaker seems aware of the burden of intellectual history and exhaustion of the “weary years of thought” yet succeeds in articulating a sense of purpose and newfound confidence in the reliability of poetic form. Flecker re-enforces this idea through the broader imagery of Classical antecedents represented by the “windy amphitheatre” and also by bringing in the visual aesthetic of printed poetry; the “silent pools” at the end of a New Year’s Day Carol perhaps suggest the text of a poem, ensconced in white space, like droplets or leaves upon the pool of the page. “Prayer” does not trade in this “starkest fight” of language; instead, Flecker uses subtle paradox and irony, for example, in the last line – “how faint, how loud the bravest hearts have cried”, perhaps heralding prophetically the fragmentation and scepticism pervasive to post-World War One Modernist literature.

4. Flecker the Romantic

The last of Flecker’s three central persona to develop was that of Flecker the Romantic. Flecker’s disciplined upbringing promoted Victorian values of fortitude and restraint over public displays of overt emotion, and so it is perhaps unsurprising that when Flecker’s own romantic experiences in the more liberal circles he moved in at Oxford are presented in his earlier works, they are generally elaborated as furtive subtexts, buried beneath a normative, if rather insipid, veneer. Thus an unknowingly appreciative public audience could be maintained while close friends could procure their own pleasures and meanings. For example, in the brief early poem entitled Song, dated March 1904, a farewell addressed to an ostensibly female love disguises a refer parting between Flecker and John Beazley before the return to Oxford:

Not the night of her wild hair

Nor the remembrance of her eyes

Leave me in so deep despair

As her echoing good-byes.

Swift musicians of the air

Still repeat those idle sighs

And their violins prepare Newer deeper melodies.

Although the path between appearance and reality had to be tacitly navigated at Oxford, Flecker’s experiences at Cambridge were altogether more highly strung; the milieu Flecker moved intended to be far more unabashed in its beliefs. Rupert Brooke, for example, with whom Flecker frequently dined, attracted both by his good looks and their mutual passion for Swinburne and East Asian poetry, maintained a loyal circle of intimates, both men and women; Brooke was also a member of a Cambridge society called the Apostles, for whom homosexuality, it was said, was an open and blatant creed12 Members were chosen for their good looks and family background, with intellectual powers as a secondary condition. On a political level, the Fabian Society pursued the cause of socialism unrepentantly. Flecker’s inability to relax his deep-seated repressive characteristics is reflected by the pervasiveness of elements of regret and isolation in his poems written around this period; for example, The Ballad of Camden Town,

12 (Deacon 1986, 55); for a comprehensive view of the relationship between this and the contemporary literary milieu in Cambridge see also (Taddeo 1997)

17 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

written in January 1909, presents a fictional relationship between a speaker and a woman called Maisie, who leaves the speaker when he is ill, recalling the disintegrating relationship between Flecker and Beazley; in both instances, one in the partnership had to creep away and leave the other not able to explain fully the reason why. The Ballad of Camden Town is also pervaded by a semantic field of emptiness; the room the speaker and Maisie share is described as

A b ed, a chest, a faded mat And broken chairs a few, Were all we had to grace our flat In Hazel Avenue.13

The room in this flat is more like the sickrooms of his experience, or the sanatorium of a school, or the cheap Continental hotel rooms Flecker shared with John Beazley, perhaps suggesting a pretended grandeur amid an undesired sexual sterility. Flecker would return to these images in later poems, such as In Hospital, when, suffering from the full effects of tuberculosis, these same themes of isolation and distress would recur:

Would I might lie like this, without the pain, For seven years — as one with snowy hair, Who in the high tower dreams his dying reign —

Lie here and watch the walls — how grey and bare, The metal b ed-post, the uncoloured screen, The mat, the jug, the cupb oard, and the chair;

And served by an old woman, calm and clean, Her misted face familiar, yet unknown, Who comes in silence, and departs unseen,

And with no other visit, lie alone, Nor stir, except I had my food to find In that dull b owl Diogenes might own.14

In contrast to these two turbulent periods, the years Flecker served as an interpreter in the Eastern Mediterranean represented something of a golden age for both his love life and his romantic poetic persona. On an Athens-bound ship in 1910, he met Helle Skiadaressi; the two were married rather uneventfully in May of the next year, but the period around their honeymoon for Flecker was marked by an extraordinary bout of happy productivity. In February 1911, he composed his Epithalamion, extolling, through classical allusions to Thetis, Triton, Peleus and Aphrodite, the “joyous beauty”15 of married life, and in July he wrote another classically-inspired poem, In Phaeacia, which recalls much of the imagery of Flecker’s earlier works, while also reflecting Flecker’s love of the olive trees of Corfu and above all the garden where he spent so much time.

13 (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 100)

14 (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 194)

15 (Walker 2006, 457)

18

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 18

Had I that haze of streaming blue, That sea below, the summer faced, I’d work and weave a dress for you And kneel to clasp it round your waist, And broider with those burning right Threads of the Sun across the sea, And blind it with the silver light That wavers in the olive tree. 16

A mere year on, however, the mood seems to have shifted somewhat; another poem, written for Helle’s birthday, entitled The Old Ships, also mentions Phaeacia, but the underlying message seems to be “Helle should be content with the beauty of Corfu and what Flecker thought was ‘the time and the place and the loved one together’”17. In other words, Flecker the romantic remained as precarious and as complex as ever.

5. Conclusion

To conclude therefore, in spite of his short life and limited public recognition, the poetry of James Elroy Flecker, crafted through the guises of several interlocking personae, yields a complex, unpredictable, yet profoundly fascinating voice. From the multifaceted desires of the Headmaster’s Son, drawn both to the security of “home”, whether intimate or national, and to the companionship of others, to the young visionary, holding both history and possibility in a single instance, and the maturing romantic, beset by dualities of frustration and contentment, appearance and reality, and repression and expression, Flecker invites us to engage with his epoch in a powerfully sensitive and sensual manner, that our pilgrimage, in some of Flecker’s most famous words, may indeed be beguiled, and that we too “shall go always a little further”:

it may b e

Beyond the last blue mountain barred with snow, Across that angry or that glimmering sea, but surely we are brave, Who take the golden road to Samarkand.18

1⁶ (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 166)

1⁷ (Walker 2006, 494); though see also (Symonds & Ellis 1975, 130)

1⁸ (Flecker 1946, ‘Collected Poems’, 148)

19 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

Bibliography

Deacon, R. (1986) The Cambridge Apostles: A history of Cambridge University’s élite intellectual secret society. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux.

Dearmer, P., Williams, V.R. and Shaw, M. (1928)

The Oxford Book of Carols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flecker, J.E. (1922) Hassan: the story of Hassan of Bagdad and how he came to make the golden journey to Samarkand: a play in five acts. London: William Heinemann.

Flecker, J.E. (1946) The Collected Poems of James Elroy Flecker: With an introduction by John Squire Edited by J. Squire. London: Secker and Warburg.

Kozicki, H. (1977) ‘“Meaning” in Tennyson’s In Memoriam’, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 17(4), p. 673. doi:10.2307/450315.

Macdonald, A. (1924) ‘James Elroy Flecker’, Fortnightly Review

Symonds, J.A. and Ellis, H. (1975) Sexual inversion. New York: Arno Press.

Taddeo, J.A. (1997) ‘Plato’s Apostles: Edwardian Cambridge and the “New Style of Love”’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, 8(2), pp. 196–228.

Walker, H. (2006) Roses and rain: A biography of James Elroy Flecker. Ely: Melrose Books.

Ward, A.C. (1928) Twentieth Century English Literature. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. (E.L.B.S. ‘English Library’ series).

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 20

Resource Utilisation Elasticity Model: How resource utilisation elasticity impacts longterm economic growth

By Eliazar Marchenko

Abstract

Economics is a science of decision-making. This paper introduces the Resource Utilisation Elasticity (RUE) theory, which improves the current sustainability decision-making process, allowing decisionmakers to use the minimum necessary data to arrive at the current level of long-run economic equilibrium through analysis of the economy’s resource utilisation elasticity. Resource Utilisation Elasticity (RUE) is the measure of an economy’s ability to adapt its resource use for sustainable growth in response to changes in resource availability and technological innovation. This model reflects a general relationship between resource utilisation elasticity and the level of long-run equilibrium, allowing for a more effective decision-making process. This paper explains the relationship between resource utilisation elasticity and long-term economic output in a non-linear manner, exploring a more realistic logarithmic approach. This model reflects the dynamism of resource utilisation in the economy and how it impacts long-term economic growth. Through this approach, the model poses an alternative lens to view policy interventions and resource utilisation, allowing for a more informed and effective decision-making process, leading to both better sustainability and long-run economic growth.

Introduction

Economics has been, traditionally, a science of decision-making, making the best economists, those who can make effective and efficient decisions with minimum available data. Therefore, the most effective economic theories are the ones that reflect the current economic landscape with minimum necessary data, allowing for more effective and informed decisions to be made. Building on this perspective, the RUE theory is a general framework that allows for a quicker and more efficient decision-making process to be carried out. The RUE theory allows for complex economic dynamics to be simplified into a more manageable and predictable curve, providing an explicit view of resource allocation dynamics in the modern complex resource utilisation systems. The RUE model allows both the benefits of specificity and speed.

The RUE theory is significant because it relies on a long-term approach to sustainability, unlike the other models, which simply consider resources as a backdrop for economic agents’ activities.1 The RUE theory prioritises resource utilisation effectiveness and provides a dynamic framework for decision-makers to understand how variations in resource utilisation may impact long-term economic output. By using a more dynamic, sigmoidal curve function, the RUE curve captures the dynamic relationship between phases of resource utilisation (inelastic, unit elastic and elastic) and their corresponding economic outcomes. 2

Modern economies face the realities of increasingly diminishing resources, environmental degradation and increasing search for green-energy technologies. Thus, there is an urgent need for an economic framework that goes beyond traditional, linear theories, and approaches resource allocation in a more dynamic, and, thus, effective manner. The RUE fills this gap by offering a flexible, dynamic curve that considers both resource allocation efficiency and macroeconomic environmental constraints.

This paper adds to the existing body of literature by emphasising the importance of resource elasticity in shaping long-term economic equilibrium. Thus, offering a unique perspective on the sustainability of long-term economic growth. The RUE model provides policymakers and economists with an opportunity to reevaluate their long-term objectives for policy in a time characterised by environmental issues and the pursuit of sustainable development paths.

1 Daly, H.E. & Farley, J., 2011. Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications. Island Press.

2 Romer, D. (2011). Advanced Macroeconomics. McGraw-Hill.

21 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

Theoretical Framework

1. Conceptual Underpinnings

The RUE theory presents an economy as a dynamic entity with subject to resource constraints because the modern economies are subject to resource constraints, which not only limits the maximum output, but also means that there is a non-linear relationship between resource inputs and outputs. In contrast to conventional models, which frequently assume constant returns to scale or concentrate only on labour and capital factors of production as simple inputs, the RUE model includes resource elasticity as a key factor affecting economic equilibrium. The RUE theory attempts to reflect this case of resource elasticity, which includes labour, capital, and land (natural resources), being elastic by nature and the evolving changes to it with the growth of an economy.3

2. Mathematical Representation

The RUE theory is reflected by a logarithmic function that reflects the relationship between resource utilisation elasticity and economic equilibrium. This relationship is formalised as follows:

EERGDP = A

1

Where EERGDP is the economic equilibrium level of real GDP at a given resource elasticity; A reflects the maximum output achievable; k is the parameter determining the steepness of the curve, reflecting how quickly an economy transitions from one phase to another; p is the resource utilisation elasticity; p0 is the mid-point of the curve where the economy exhibits unit elasticity.

3 Pindyck, R. S., & Rubinfeld, D. L. (2018). Microeconomics. Pearson.

+

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 22

e-k(p-p0)

3. Curve Dynamics and Influencing Factors

There are several factors that influence the position and progression of an economy through the RUE curve; some of the factors are presented below.

• Technological advancements are the main factor that would directly influence resource utilisation elasticity. Advances in technology can increase efficiency and productivity, thereby increasing A and adjusting p0. Thus, technological progress provides increased production capabilities, moving an economy along the RUE curve.

• Policy intervention from the government may influence the progression of the economy through the RUE curve, as any economic policy, environmental and social. Changes to policies can have a significant impact on k, the determinant of steepness. Although, the effective policies can facilitate quicker and smoother transitions.

• Global and environmental factors have significant impacts on individual economics, as the global economic trends, trade dynamics and environmental changes can lead to fluctuations in GDP and long-term output of the economy, impacting the extent of resource utilisation efficiency, r, leading to changes in the position of the economy along the RUE curve.

4. Assumptions

The RUE model posits that economies operate with varying degrees of elasticity, at different stages of economic development. In the early, inelastic, phases, resources are utilised in a way that’s not responsive to increases in inputs; thus, for higher resource input, there is less than a proportional output of production in the long-run, meaning that the output doesn’t increase as much as the inputs do. As economies progress and develop, they reach a unit elastic stage where inputs and outputs move in proportion to each other; thus, proportional output is produced as to input. In later stages of economic development, resources are utilised in a more responsive and elastic manner, meaning that for a decreased amount of resource inputs, there is a proportionally larger output of production in the longrun. This allows economies to achieve larger proportional increases in output, for each unit of input.

The RUE model has several key assumptions that should be taken into account to outline the scope of the theory. Primarily, the model has the assumption of homogeneity of resources; thus, their transfer between different applications in an economy will have no opportunity cost. This assumption allows the model to focus directly on the relationship between the elasticity of resource utilisation in the economy and its level of real output. Secondly, the theory has the standard economics assumption of rationality of economic agents, which allows for a more smooth transition between different phases of elasticity of resource utilisation, meaning that the economic agents will behave more predictably and cohesively, allowing for the model to more directly focus on the long-term real output of the economy. The theory also assumes that there is a continuous, smooth transition between the different levels of elasticity in resource utilisation, focusing on the long-term economic output, disregarding the short-term fluctuations and external shocks; thus, these external, temporary shocks are not taken into account in the model. Finally, the model operates under the assumption of full employment of the economy, with no spare capacity, and, thus, all resources are being actively utilised, which allows for the model to focus solely on the effect of changing elasticity on the long-term real output of the economy. Thus, resource allocation dynamics are not taken into account in the model.

The focus of the model on the long-term perspective, in this theory, reflects the theory’s goal of creating a comprehensive framework for understanding how resources are used in a dynamic economy, and what their impact on real economic output is in the long-term. These basic assumptions, together, determine

23 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

the extent and scope to which the RUE theory can be used, outlining the situations where it is expected to provide insights and guidance for policymaking.

5. Empirical implications

Most modern economic theories accept that there are significant implications of resource utilisation efficiency on policy design; however, the RUE theory proposes that the relationship between resource utilisation elasticity and long-term economic output is non-linear. It’s clear that most economies with higher levels of resource utilisation elasticity, thus efficiency, will have a higher development level due to their both technological and labour quality, allowing their resources to be better employed in a dynamic economy. Therefore, in economies with a higher level of resource utilisation efficiency, the theory suggests taking a slower and long-term approach to technology may, in other words, a more sustainable approach to technology, be beneficial, as unsustainable technology may lead to a sooner approach of the resource limit in the short-term if the new technologies require higher usage of resources, they may cause an economic downturn and recession.4 Therefore, it is crucial for developed economies to accurately assess their level of resource utilisation efficiency and the sustainability of their technologies to avoid approaching resource limitation bottlenecks at an accelerating rate of resource utilisation and unsustainable technologies as this may cause production at an unsustainable level, leading to significant economic setbacks. In contrast, in economies with a lower resource utilisation efficiency level, policymakers may focus on the development of all technologies, though still giving preference to those more sustainable, which would allow for an accelerated level of resource utilisation elasticity, allowing for more rapid economic development which will then, in the long-run, foster improvements in the more sustainable technologies. Therefore, developed economies should focus on the promotion of only sustainable technologies to improve both their short-term and long-term sustainability of economic output, while less developed economies should focus on a general level of promotion of technological advancement, which will foster more sustainable solutions in the future as they go further along the resource utilisation elasticity path.

Thus, the RUE model suggests that to tackle the issue of inefficient resource utilisation in economies characterised by low resource utilisation elasticity, such as economies with highly inelastic to unit elastic resource utilisation, policymakers can consider implementing strategies that foster investment in infrastructure and education, for example, investing in the development and improvement of infrastructure such as roads, bridges and utilities. These improvements and advancements provide a more long-term approach to technological development and are arguably more sustainable for long-term economic development rather than larger top-down projects often promoted by the Western countries in their “aid” provisions. These advancements enhance the effectiveness of resource allocation by reducing transportation expenses and increasing overall productivity, allowing for a smooth transition between the different levels of resource utilisation elasticity, leading to sustained and sustainable economic growth, which is imperative in the modern global economy. Additionally, promoting research and development by providing grants, tax incentives or fostering partnerships between the public and private sectors can drive progress that enhances resource utilisation efficiency; this approach is significant as it aims to enhance the long-term productive capacity of the economy and transition towards a flexible and adaptable economic system, which is crucial in the future development of these economies, towards higher levels of output and income.

4 Stern, N. (2007). The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge University Press.

5 Sachs, J. D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 24

6. Policy relevance

Hence, policymakers can use the RUE theory to analyse the long-term impact of their technological advancements’ decisions and their programmes aimed at technological development; through this analysis, the long-term policy can be pivoted and improved by aiming at more bottom-up technology development across all regions to encourage even and, thus, more sustainable development.5 By following the RUE theory, they can determine the path towards higher levels of resource utilisation elasticity; improve the ecological stance of their regions, by and prevent resource bottlenecks from occurring in the short term as the economy progresses through different resource usage levels. The RUE theory encourages policymakers to monitor the levels of resource utilisation elasticity to both model the future progression of the economy and to identify the potential improvements in the economy to promote a sustainable growth approach, as different growth paths are characterised through various stages of elasticity.

These approaches to long-term development allow for a smoother, and more coherent transition from different stages of resource utilisation elasticity, and thus, a lower chance of quick economic output boom with a subsequent downturn, but rather, a more consistent, long-term growth in output. For instance, policies that promote investment in essential industries, create an atmosphere that is more favourable for firms and business development, which can be done through tax breaks for capital-intensive enterprises, removal of excessive regulation and subsidies can all serve to promote capital accumulation. Additionally, the policymakers should focus on infrastructure development, which can entail large public-sector investments, such as in energy, transportation, or communication networks, which would improve resource utilisation elasticity and, in addition, act as the foundations for more sustainable, sustained economic growth. Additionally, in terms of modern economies’ development, a particular emphasis should be placed on educational programs that develop the future labour force’s IT and digital skills; as for modern economies with the current emphasis on the development of these sectors, the labour force possessing such skills will be valuable in the long-run. The strategies suggested by the RUE theory, for the growth of economies with limited resource utiliasation elasticity, are crucial for addressing both short-term challenges faced by low elasticity economies and long term issues. They aim to foster development that aligns with the RUE theory’s emphasis on economies and efficient resource utilisation.

The RUE theory’s focus on sustainability revolves around shifting towards a higher usage of green energy resources across the whole economy. A good example of such strategy for long-term sustainable development through increasing resource utilisation elasticity could be Finland and its “circular economy” model. The circular economy model, in particular, provides a valuable insight into potential long-term economies’ dynamics; as more and more economies approach a higher level of development, a higher level of resource conservation and re-utilisation will be essential in improving resource utilisation elasticity even further, thus, allowing for sustained economic growth in the long-run. It’s not a policy change; it’s a complete reimagining of how we approach energy and resource utilisation. By moving away from non-renewable energy sources and embracing sustainable alternatives, we can not only, make a significant positive impact on the environment, but we can also develop conservation strategies which would allow for higher resource utilisation efficiency, allowing for a smooth economic progression and development. This transition is more than simply adopting green technologies; it involves completely reshaping our understanding of energy and resource conservation, for example, a similar shift can be seen in Spain’s growing sustainable energy sector, through investments in solar farms and promoting the use of green power, Spain is not only reducing its carbon footprint but also creating an industry that is both sustainable and future-proof.

The RUE theory takes technological advancement and innovation at its core, as new technology drives innovation and develops a higher level of resource utilisation efficiency through higher levels of productivity.

5 Sachs, J. D. (2015). The Age of Sustainable Development. Columbia University Press.

25 Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1

It is generally accepted that policy frameworks should rapidly establish environments for research and development. However, the RUE theory poses a significant emphasis on a need for, perhaps, slow but methodical and sustained implementation of the new technologies to avoid creating inflationary pressures on the economy by raising the level of GDP unsustainably; thus some recent European top-down strategies in developing countries would be considered unsustainable by the theory. However, the theory does generally accept that technological advancements and improvements are the essential drivers of sustainable economic growth. Supporting high-tech industries through incentives, such as subsidies and tax breaks, and fostering an entrepreneurial ecosystem are the key strategies to maintain and enhance resource utilisation elasticity levels in both the short and long term. Such strategies would allow for a longer-term outlook on the economy and would improve the level of resource utilisation efficiency in phases of adoption of such programs rather than in a dangerous, inflationary manner as sometimes proposed. The model also acknowledges that policies focused on innovation lead to increased output while facilitating sustainable resource utilisation through efficient production methods and sustainable practices. The main idea, in terms of technological progress, would be that at the later stages of economic development, when the economy approaches full capacity, it is significant that increasing technological levels would have an exponentially increasing effect, while land/natural resources may be depleting; thus, it’s vital to differentiate towards more sustainable technologies, as higher resource intensity technologies would rather create inflationary pressures if other resources become constrained, causing an economic downturn; while more sustainable technologies will allow for higher resource elasticity allowing for a longer span of the diminishing resources.

The RUE model emphasises the need for an alignment of fiscal and monetary policies to ensure optimal resource utilisation elasticity levels. It suggests that fiscal policies should prioritise investments in sectors that promote resource efficiency. This can include providing subsidies for technologies, funding infrastructure projects that encourage efficient resource use and supporting educational programs that align with the demands of a modern economy. On the monetary policy side, the model proposes that central banks and monetary authorities should consider adjusting interest rates and liquidity provisions to support these efforts. This may involve utilising monetary policy tools to encourage investment in industries focused on resource efficiency or stabilising macroeconomic conditions for sustainable growth. The impact of the RUE model extends beyond singular economies, affecting global trade and global economic collaboration. The model advocates for trade policies that facilitate the exchange of technology and skills, thereby enhancing resource utilisation elasticity. It emphasises the importance of cooperation in establishing ecological regulation and standards and promoting joint technological initiatives.

Essentially, the RUE model offers policymakers a framework to develop long-run, sustainable economic strategies, covering a range of areas such as labour policies, environmental initiatives and technological interventions. The main goal of applying the model is not to solely promote growth and development using the concept of improving resource utilisation efficiency in a linear manner; however, to make decisions accordingly to the stage of development of the economy and ensure a responsible and efficient use of resources to then promote long-term development and economic growth.

7. Extensions and limitations

Although the RUE theory has some significant policy and empirical implications and provides an important, novel lens for developing the long-term development of economies, like any theory, it has several drawbacks and significant limitations, which can be expanded upon in the future. Primarily, the theory assumes homogeneity of all resources, which is not true in reality, and thus, the theory does not take the opportunity cost of switching different resources across various economic sectors across applications. Therefore, a possible expansion of the theory could be in developing a more general framework that would include the opportunity cost of reallocating resources and their various applications across the economy. Although it is

Uppingham Research Journal – Issue 1 26