Sustainability Week Journal

November 2025

Welcome to the Sustainability Journal, where our school showcases its commitment to improve sustainability and protect the future of our planet. Importantly, as a community we can make a difference through collective action –whether by cutting down on waste, saving resources, or supporting sustainable projects – to help build a sustainable future. I would like to thank all the pupils who have contributed to this journal, offering engaging and encouraging insights by raising awareness and educating others on our shared responsibility in protecting the environment. It’s the small changes that make lasting impacts.

Hermione Everall

Environment Polly

articles

Some Inspiration By Alexander Herratt

Why must we make an effort for sustainability? By Iris Liu

Sustainability is more than responsibility By Daisy Dai

The use of mycelium as sustainable alternatives to traditional materials: By Sasha Sherwin

Sustainable Eating By Joy Guo

Smart Traffic, Sustainable City By Reema Al-Bulushi

Issues of ‘Fake’ Sustainability: how recycling is a get-out-of-jailfree card By Jerin Chong

Why is climate change propaganda becoming less effective in driving action?

By Annie Chen

Staff articles

Beekeeping By Mr Dewhurst

COP30: what is it and why is it important? By Mrs Ellis Analysing Uppingham School’s

By Miss Playle

Alexander Herratt

In more recent years, I’ve noticed that the word “sustainability” gets more and more eye rolls. I don’t blame you; we’ve all heard the same things in the news or in chapel: record high temperatures, rising sea levels, extreme weather — you know the rest.

At school, it can sometimes feel like the things we do to help the environment are pointless. After all, there are billions of people in the world, and only a few hundred of us here at Uppingham. To be honest, that feeling isn’t entirely unreasonable. A shower that’s thirty seconds shorter probably won’t change much when compared to the huge amount of water wasted through countless unnecessary ChatGPT prompts, or the air pollution produced by large corporations every single day.

But that’s not the point! Yes, on our own it’s difficult to make a noticeable difference. However, what truly matters is choosing to play your part. It’s about shifting the culture we live in — buying less, reusing more, and making choices with the environment in mind. Those small actions — turning off lights, taking shorter showers, bringing a reusable water bottle — might seem insignificant. But if everyone does their part, they stop being small.

I once heard someone make a really powerful point: In the past, people lived their lives guided by faith in something greater than themselves. Over time, that guiding force has shifted. Today, many of us act with making money at the centre of our decisions — and it’s hard to say that has done us much good. People need hope and something meaningful to believe in. Now, more than ever, that purpose should be the environment.

I’m not saying this as a political activist or telling you to abandon ambition or stop caring about money. In fact, I believe in working hard and aiming high. But I also believe that success means nothing if it comes at the cost of the place we all live.

This isn’t about taking shorter showers for the sake of it. It’s about shaping a mindset — a way of living that recognises our shared responsibility. If each of us makes small, conscious choices, we build a culture that values the planet as much as progress. And when that culture grows, larger systems and institutions are forced to change with it.

We don’t change the world all at once. We change it by choosing who we want to be — every day. So go out there and do your part.

P.S. And if you’re still not convinced to act more sustainably… I have full confidence that you will the moment you start paying your own bills.

Iris Liu

It’s easy to feel confused about sustainability. We’re told to turn off the lights, give up air conditioning, and, most notoriously, forfeit our plastic straws. I totally understand the annoyance of a paper straw dissolving in your drink. The core problem seems to be that we’re constantly making sacrifices, yet the environment continues to deteriorate. Where is the reward for our effort?

To make matters worse, it feels deeply unfair. While you’re diligently protecting the planet, someone else might be cruising in a gas-guzzling car, air conditioner on full blast, sipping an iced coffee with a plastic straw. It’s discouraging.

However, our world is undergoing a fundamental shift that reframes this entire challenge. We are witnessing the rise of a new value system centred on carbon emissions. The basic idea of “carbon currency” is simple: reducing one ton of carbon dioxide is equal to creating one unit of economic value. In other words, protecting the Earth is becoming synonymous with creating wealth. And money—well, that’s a language everyone understands.

So, the next time you choose to bike instead of drive, remember: every pedal stroke is the sound of coins dropping into your digital wallet.

This isn’t just a theoretical concept; it’s already happening. Singapore has implemented a carbon tax, set at $25 per tonne of CO2 for liable companies. Following Brexit, the UK established its own Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS).

So, the next time you choose to bike instead of drive, remember: every pedal stroke is the sound of coins dropping into your digital wallet.

In summary, we are not merely adjusting our economy; we are rewriting its very purpose. We are transitioning from an era defined by the extraction of resources—by the mining of gold and the drilling of oil—to an era measured by the preservation of our planet. This isn’t a minor policy shift; it is a profound redefinition of value itself, signalling a collective, global determination to forge a future that thrives in balance with nature. This is the new frontier of progress, and by embracing it, we are not just hoping for a sustainable world—we are actively building it.

Daisy Dai

Sustainability is more than a practice –it is a philosophy of balance, a pledge to the future. It is the delicate art of meeting today’s needs without stealing the possibilities of tomorrow. This pursuit weaves together environmental care, social equity, and economic resilience in a fragile yet resilient balance, ensuring that the planet’s resources are used with respect and foresight. Urging us to tread lightly, live consciously and honour the life that surrounds us, it is a call to live responsibly: to reduce waste, to champion ethical production, to preserve energy, and to safeguard the intricate web of life that sustains us. Every decision carries weight: conserving energy, protecting biodiversity, reducing waste and nurturing fairness are no longer choices – they are acts of stewardship. In an era marked by climate change

and dwindling resources, sustainability is not a distant ideal but a vital path forward – our shared commitment to a thriving, enduring world.

Even within the familiar rhythm of daily life at Constables, this vision quietly unfolds. A flick of a switch, turning off lights as we leave a room, becomes an act of conservation, a whisper of energy saved. Typing notes on a computer rather than on paper is a silent salute to forests that continue to breathe. Choosing to walk instead of drive, though small in scale, ripples outward – reducing carbon, reclaiming air, reaffirming connection to place. In our homes, rewearing clothes before washing them saves water and energy, while opening a window to let in fresh air becomes both a breath of health and a gesture toward efficiency.

It is in these moments – seemingly ordinary yet profoundly consequential – that sustainability takes shape. Each of these choices, though simple, forms part of a larger story – a story of awareness, intention, and care.

Sustainability is not confined to grand gestures or sweeping reforms; it lives in the quiet moments of mindfulness that, together, illuminate a future worthy of the generations yet to come. It is a story told not in headlines or statistics, but in gestures: mindful, deliberate and enduring. Through each choice, we weave a legacy, a promise that the earth will endure, vibrant and alive, for generations yet unborn.

Sustainability is more than responsibility – it is reverence and in its quiet embrace, the future begins.

Sasha Sherwin

There are sustainability problems with the traditional materials used in most products: plastics and synthetic fabrics (e.g. polyester and nylon) are made from non-renewable petrochemicals and release greenhouse gases from production and decomposition, since they are not biodegradable. Conventional cotton uses lots of water and pesticide in production; water requires extensive energy to work with and pesticide pollutes water and soil, posing risk to human health.

Mycelium, however, offers us an alternative to this. Mycelium is the vegetative parts of fungus which are made up of hyphae, a highly dense fibrous filament. This contains proteins, glucans (a glucose polymer) and chitin (the lining of a fungal cell wall), which form a highly cross-linked, complex structure; this allows for a high tensile strength, therefore making it useful as a material. The current process for making materials with mycelium involves growing it on a fibrous, organic substrate (which can be made from agricultural byproducts to further utilise waste). The natural growth of the mycelium then creates a network of hyphae, binding the substrate together and providing it with strength. To form a specific shape, it is grown in a mould, then after 1-2 weeks is heated so that the organism is dry and inactive, making the material stable. Some successful applications of the material are fire-retardant material, aesthetics

(fashion and decor), packaging or other flexible, lightweight materials and insulation.

A company that specialises in this is Mycotech Lab: they aim to create a portfolio of different building materials using fungus in their product, MycoTile. In order to suit insulation the fluffy, spongy texture is retained, but can be made more compact for fibreboard or strawboard, or even be pressed harder to make brick. Since conventional building materials like concrete and petroleum-based products are high emitters of greenhouse gases, using mycelium instead decreases this substantially, especially since, at the end of a building’s life, it can simply be composted. Mycelium is biodegradable, requires low-energy in production and revalues agricultural waste, overall contributing to a significantly lower carbon footprint. Also, due to the diversity of fungal species and types of substrate available there are lots of unique characteristics that could be utilised, promising vast possibilities for the use of mycelium for materials in the future.

Sustainable eating habits include choosing foods that support both human health and environmental well being, while remaining affordable. To achieve sustainable diets, it is important to think about where our food comes from and how it is produced.

Meat consumption has a major impact on the environment and is one of the biggest causes of environmental damage today. Producing meat uses large amounts of land, water, and animal feed, which puts a lot of pressure on natural resources. For instance, producing 1 kg of beef requires on average 15,415 litres of water. Producing meat also creates a lot of greenhouse gases, such as methane and carbon dioxide, that contribute to global warming. In many parts of the world, forests are cut down to make space for cattle farming or to grow animal feed, leading to habitat loss and reduced biodiversity. Because of these effects, eating less meat or choosing more sustainable food options can greatly help protect the planet.

Diets rich in plant-based foods, such as fruits, vegetables, legumes (pea family), nuts, and whole grains support health, and are linked to lower risks of chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure and cancer. Plant based diets provide important nutrients the body needs, including

protein, healthy fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. They also tend to contain more fibre and beneficial plant compounds known as phytonutrients. Studies from institutions such as Oxford and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine found that shifting toward sustainable diets can cut environmental impacts by up to 25–30% and often lower food costs, particularly when meat consumption is reduced. However, people who follow a vegan diet may need to take certain

supplements (especially vitamin B12) to make sure they get all the nutrients necessary for good health.

Other than focusing on a more plant-based diet, there are other ways to eat sustainably as well. Growing your own food allows you to control what you consume and reduces the carbon footprint from transportation.

Choosing seasonal or locally sourced produce supports local farmers and cuts down on emissions caused by long distance shipping. Additionally, avoiding plastic packaging helps minimise plastic waste and pollution. By combining these habits, you contribute to a healthier planet and promote a more environmentally friendly food system.

Reema Al-Bulushi

Growing up in the heavily congested city of Muscat, commuting to and from school was always a pain in the back, literally because of how often I found myself sitting stuck in traffic. Recently, I was given the opportunity to research a topic of my interest and develop an innovation for it. I chose to dive into finding an approach that optimises traffic management in Muscat.

Initially, I thought the problem could be solved simply by expanding the roads to reduce congestion, but it turns out I was way off the mark. While researching and comparing Muscat’s situation with different cities, I realised that the root of congestion is not necessarily in the increasing number of cars on narrow roads, but in the very foundation of Muscat’s traffic infrastructure. I asked the city’s traffic department if they had a central system that used collected data to improve traffic operations. To my surprise, they didn’t, and seemed confused by the question. They explained that they only collect data from radars and store it without doing anything further with it, which made it clear to me why the traffic congestion in the city was not improving.

That is when I realised what my innovation would be. It would have a gradual yet powerful effect for longterm sustainability and improvement. This is where my knowledge in technology came in. After writing a 1,500 word literature review and comparative analysis, I developed a solution specifically tailored to the city’s traffic challenges. I thought of a Smart Traffic Management System

(STMS) that analyses traffic patterns, identifies underused roads, and proposes new routes to balance the load across the road network. The innovation lies in the addition of artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML) models! ML models are employed to predict future traffic patterns and provide actionable recommendations for long-term improvement. I believe this approach addresses gaps in the transportation infrastructure by maximizing the efficiency of existing roads, further reducing the immediate need for large-scale overhauls.

Of course, I had to test my theory out by coding an ML model prototype. I fed the model with real traffic data gathered by Muscat’s current radars and got promising results. There was a clear correlation between traffic levels at different times in the day, and the model also accurately predicted short-term traffic patterns. This helped me to evaluate the feasibility and adaptability of implementing STMS in Muscat.

I believe it is sustainable because STMS uses real-time data from radars to monitor congestion, propose development plans, and integrate public transportation. Its implementation would be costeffective, relying on existing monitoring infrastructure rather than requiring new equipment. Most importantly, reducing congestion means fewer idling vehicles and, therefore, lower greenhouse gas emissions; contributing to a cleaner, more sustainable urban environment.

In general, STMS is a data-driven, adaptable approach to optimise traffic management; it is the foundation of every single traffic operation that can be carried out. It lays the groundwork for sustainable growth by ensuring that Muscat’s transportation network evolves in parallel with its urban growth.

recycling is a ‘get-out-of-jail-free’

Jerin Chong

The decaying state of our planet was and is still a rising concern, but nature only has one part to play in this. Burning fossil fuels, air and water pollution, resource depletion, deforestation, biodiversity loss are some of the largest current threats to Earth’s habitable state and all have one common cause: humans. To expel some of the guilt that comes with actively fuelling climate change, large companies and corporations are starting to promote cleaner habits such as recycling their products or using paper rather than plastic straws (#SaveTheTurtles, right?).

Campaigns such as Fridays for Future, the Priceless Planet Coalition, and even Mr. Beast’s #TeamTrees or #TeamSeas initiative all recognise the dire need for change and are trying to educate today’s generation about these issues that have and will stain our page in history. These activist movements are mostly done through peaceful protests or uploaded on social media platforms, encouraging us to donate and like to “plant a tree”!

However, these strategies might be having the opposite effect on the wider population, perhaps even subconsciously instilling a mindset that introduces the single-action bias; this is a concept where taking one initial, manageable action to address a complex problem, in this case climate change, creates a sense of accomplishment so large it reduces the individuals’ drive to engage further with more impactful efforts.

In studies done by UNICEF and WHO, it is proven that humans tend to feel overwhelmed by big, global crises outside our individual reach; our stress response system may become overactivated and the sheer volume of

chronic stressors can accumulate to the point where individuals feel a sense of allostatic load. With a problem as present and looming as climate change, the cognitive dissonance between our values of “I care about the planet” (however superficial they may be) and the alarming reality becomes clear as day. Performing a simple, tangible action like dumping garbage in a green trash can rather than a black one can reduce the disharmony within our minds, almost like it tells us that we’ve done our part – even if we only did it once.

After performing this one good deed, our mind gathers credits, of sorts, that we then feel right to “spend” on inaction or even contradictory behaviours; this is known as moral licensing. From this, the cleaner habits we adopt become a token that protects our identity and secures us a spot on the “correct” side of the issue, disregarding future need for further, more serious engagement. Changing one’s incandescent light bulb to LED strips does not secure an image of an ethical person and is not an indicator to ignore energy consumption elsewhere.

The danger of the single-action bias lies not within the single action itself, but the false sense of security they curate. It draws people towards actions because of their convenience and makes systemic, more impactful solutions seem like just too much effort. This confuses activity with impact, and it falls straight into the system resistant to fundamental change. Corporations enthusiastically promoting consumer-level actions shift the burden of responsibility from producers to individuals, deflecting and ensuring the focus remains on minor behavioural adjustments rather than the root issues of production and

consumption. Furthermore, the single action neutralises the emotions –outrage, discomfort, guilt – essential for substantive activism, discarding the future possibilities of movement.

As a society, we must reframe our definition of taking responsibility. Recognising the bias is crucial, and we must start seeing action as not a single checkbox but rather a continuous path of stacking commitments; from the first act stems the second, and from symbolic action, such as using a reusable bottle, comes behavioural changes and community advocacy. If people start viewing this road as something achievable, something in reach, we can start shifting towards political engagement aimed at civic reform.

If people start embracing the discomfort of confronting climate change and perhaps their own actions that have previously fuelled it, we will realise that meaningful change is not convenient and in fact requires the time, effort, and sacrifice of guilty pleasures.

Without a mental shift, we remain on the path towards an uninhabitable Earth.

Annie Chen

In recent years, climate change has always been the topic that stayed at the top of the list of themes that are being discussed. From school debate contests and Model United Nations (MUN) topics to long chats at the dinner table between relatives, climate change has become a mantra theme that rings in the back of everyone’s heads. The message is clear and direct: the planet is in crisis because of human activity, and urgent changes need to be taken into action. Yet despite the escalating stakes, a sense of fatigue and even the mere agreement from the public due to the remoteness of this cause is set in among everyone. This particular propaganda is becoming increasingly less effective in driving action.

Just like the widely known story from Aesop’s Fables, ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf,’ constant alarm can desensitize the audience that receives it, which acts as a major factor that decreases the effectiveness of climate change propaganda. When an anesthetic is used too often, or when every weather event is portrayed as an unprecedented catastrophe, it all leads to redefining the sense of ‘urgency’ as enfeebled and weakened. This repeated and persistent ringing at the back of our heads about climate change and its long stagnation has subconsciously redefined the evaluation of its priority, gradually becoming accustomed to and accepted by the public, and no longer triggering guilt towards the actual cause. The definition of ‘propaganda’ and ‘alarmism’ then becomes weaponized to confuse the public. The term “propaganda” is strategically used by opponents to frame climate communication as manipulative,

exaggerated, and untrustworthy. On the other hand legitimate calls for urgent action are dismissed as “alarmism” designed to scare people into accepting economic sacrifice.

Climate change presents several challenges for the public due to its complexity and cognitive overload, and the mismatch in scale between the daily life of the public and the global scale problem of climate change. Most people concentrate their attention on their daily life, which leads to an increase of one degree Celsius in global average temperature over decades, being far less significant and tangible than the daily worries of the public, such as unexpected rain. The sensory and experiential inaccessibility to the actual significance of this causes a sense of distance and the idea “this is none of my business” against climate change. For many people, climate change remains a complicated, slow-moving crisis. If considered, climate change not only refers to the effect of carbon dioxide, but it is also a cascade of interconnected effects from ocean acidification, glacier melt, jet stream disruptions, biodiversity loss, and agricultural shifts. As a citizen realizes their meager strength to contribute to the global change the sense of responsibility the ambition to contribute to the revolution thins down and drifts away from one’s life.

In my opinion, perhaps the most significant factor that dims climate change propaganda is the intense politicization of the issue. Due to the popularization of

streaming media such as Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, acknowledging and supporting climate change policy has been dramatized to become a litmus test for political identity, subtly changing the scientific opinion of one into tribal allegiance and proposing uselessly ineffective arguments. When climate change becomes tied to identity, the public stops evaluating information based on its factual merit and instead starts evaluating it based on whether it aligns with their group’s beliefs.

Despite the increasingly ineffective message of traditional climate change urges, it does not mean the cause has thinned down in any way but indicates the terms of communication and propaganda must evolve as time goes. I believe the solution to change is making the issue local and personal, focusing on tangible co-benefits like cleaner air, energy independence, and green job creation, and telling a story of opportunity and innovation rather than just painting doom. To drive action, we must move beyond simply sounding the alarm and start painting a picture of a future worth fighting for.

Mr Dewhurst

As many of you are aware, Uppingham has a small apiary perched on top of the Science School, and along with a small group of pupils and Mrs Wilding, I am the school beekeeper. They are quiet now, and each colony is down to a couple of thousand bees, but they don’t hibernate; until the temperate rises above about 12 degrees, they live off the honey they have stored away in their hive, which is why it is so important that we don’t just take it all.

Once it starts getting warmer, and plants start flowering, you will start to see bees out foraging for nectar to make honey from, and pollen to feed the baby bees with. But they have a much greater importance than that; the honeybee is a ‘keystone species’, a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance.

Bees (and there are about 270 species of bee in the UK, of which 24 are bumble bees, and only one is the honeybee) are a key pollinator and pollinators support the reproduction of 80% of the world’s flowering plants: essentially, without pollinators, the rest of the natural order starts to collapse. Honeybees are responsible for around $30 billion a year in crops – without bees we could lose the plants they pollinate, all the animals that eat those plants, and all the animals that eat them.

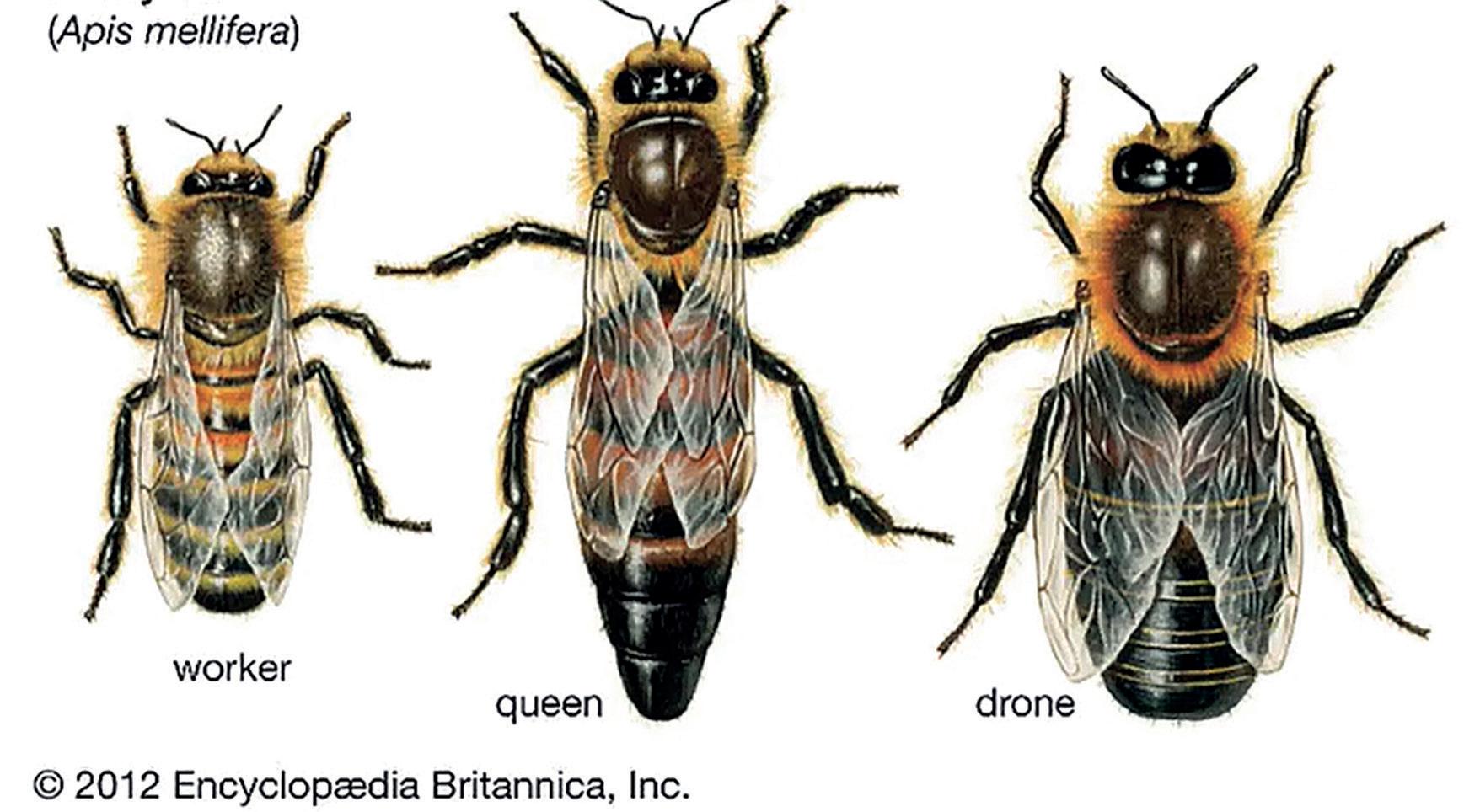

In brief, there are three types of bee in each colony: the queen who lays eggs to create the other two types, the drones (male bees) and the workers (female bees).

The queen bee lays about 2,000 eggs each day between April and September, and without her a colony simply cannot survive. She is of course where we get the expression ‘queen bee’, stereotyped in the media as beautiful, charismatic and manipulative. But in the colony she is far from that: she does get fed, cleaned and looked after by the worker bees, but the moment she is of no use – and her only use is laying eggs – they raise a new queen, launch a coup and it’s all over for her. She either sets off with a swarm to set up a new colony, or the new queen kills her.

After that she starts to visit flowers within around a 2-mile radius: pollinating them while they collect pollen, nectar and water for the hive. During the summer that is about 5 weeks of hard work before she dies.

Amazingly a single bee will create about 1/12th of a teaspoon of honey in her lifetime, and for one colony to make a 1lb jar of honey will take around 2 million flower visits.

Then there are the worker bees: between 5 and 80 thousand of them depending on the time of year. Each worker bee has a defined series of jobs as she gets older within the colony – a couple of weeks doing jobs around the hive, tending the queen, feeding the larvae and moving food and stores around the hive, then a few days on sentry duty, protecting the entrance of the hive from wasps, raiding bees, and other predators.

Meanwhile the drones have only one job: to mate with new queens that are setting up their own colony. Other than that, he does not contribute (he doesn’t even have a sting) and he dies immediately after mating. And if he never mates then he is expelled from the colony in winter to save stores and dies anyway.

So this summer, if you have the time, ask a beekeeper if you can sit near a hive and watch them work: it is enormously relaxing and truly uplifting.

Mrs Ellis

This year, Uppingham’s Sustainability Week is running at the same time as COP30. COP30 is the 30th meeting of the Conference of the Parties, a group of countries who signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992. There has been a COP meeting every year since 1995, except for 2020. It has led to global agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

The Kyoto Protocol was adopted at COP3 in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan, and came into force in 2005. It required countries to commit to a reduction in their emissions of greenhouse gases including carbon dioxide and methane. It recognised that more developed countries had a greater historical contribution to emissions and consequently assigned them greater responsibilities, but it also allowed ‘emissions trading’ between countries. The protocol has faced criticism for its limited scope (only developed countries had legally binding targets, so countries such as India and China were excluded), but it laid the groundwork for future agreements and proved that international cooperation was feasible.

The Paris Agreement was adopted at COP21 in 2015 in Paris, France. It introduced specific goals to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with aim to limit this increase to 1.5°C. It requires countries to submit plans, called Nationally Determined Contributions (NSCs), to reduce emissions every five

years. Currently, the NDCs are not sufficient to meet the 1.5°C target, but the agreement also established a more transparent framework for reporting actions and progress.

COP30 is a deadline for the next cycle of NDCs to be submitted, and there is hope that they will be more ambitious than in previous years. These annual meetings are high profile diplomatic gatherings, but they are also the engine of global climate governance. COP provides an annual platform for nations to reflect on their progress, strengthen commitments, and collaborate on innovative solutions. With the urgency of the climate crisis growing and the 1.5°C target slipping further from reach (the general consensus amongst scientists is that the opportunity to reach it has now been missed), COP30 is an opportunity to reset global ambition and accelerate the transition to low-carbon economies. The decisions made in the coming years will shape the future of our planet and ensure that sustainability is not just a goal, but a shared responsibility.

Miss Playle

Climate change is one of the world’s most significant environmental challenges with global consequences, including increased frequency of extreme weather events, droughts, floods, and loss of biodiversity. Human activities such as burning fuels for heating, producing electricity, and powering vehicles all release greenhouse gasses, a key driver of climate change. Greenhouse gasses from different sources can be converted to one measurable unit, tCO2e (tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent), and quantified in a ‘ carbon footprint’.

Uppingham School’s baseline carbon footprint was set using data from the 2022-2023 academic year, this was calculated at 2,971 tCO2e. From this baseline figure, Uppingham School Trustees approved a target to reach Net Zero Carbon by 2050. To support reaching this future target we have set two interim targets in 2030 and 2040.

Achieving Net Zero Carbon means reducing our carbon footprint as much as possible, then offsetting any residual, unavoidable emissions by removing an equivalent quantity of carbon from the atmosphere through tree planting or other activities.

In the 2024-2025 academic year we reduced our annual carbon footprint from the baseline by 122 tCO2e to a total of 2,849 tCO2e.

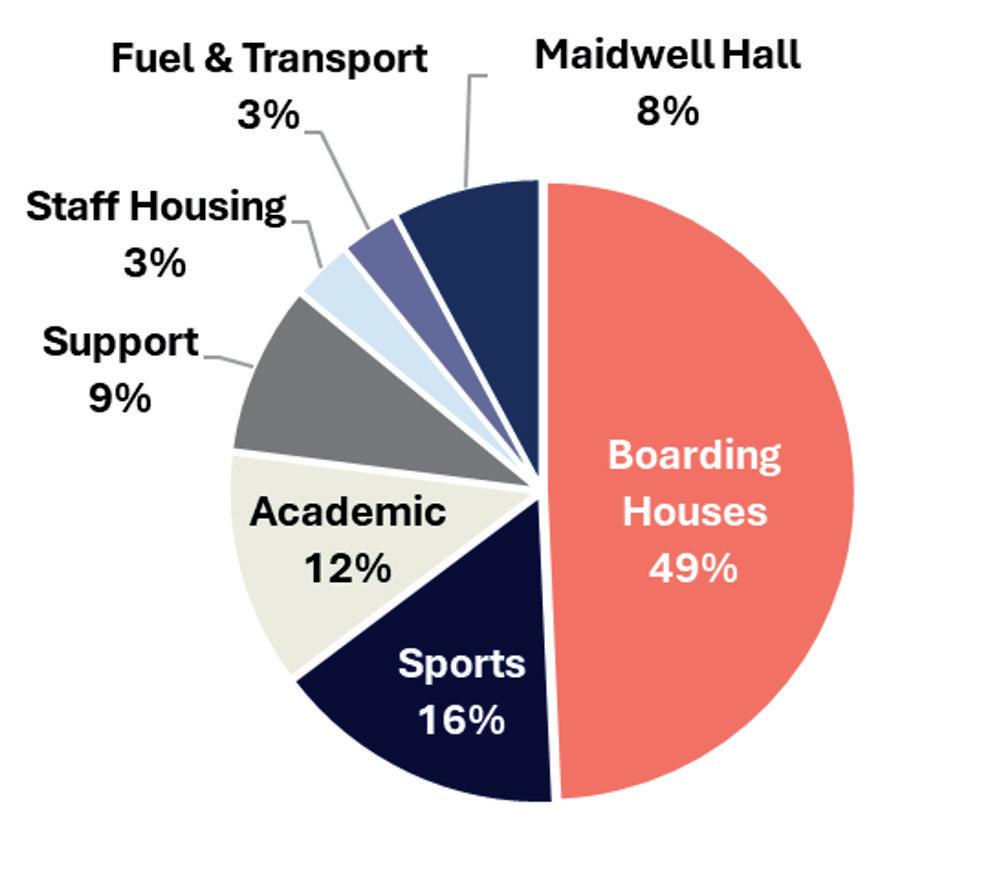

Our footprint in the 2024-2025 academic year was made up of the following categories:

Gas consumption, predominantly due to gas heating systems, makes up the largest proportion of Uppingham School’s carbon footprint.

To reach Net Zero Carbon by 2050 we will need to minimise our reliance on natural gas for heating. This will be carried out in two phases;

Making our heating systems as efficient as possible by minimising the kWh of gas burned whilst maintaining the same heat output. This can be completed by reducing heat loss through improved insulation within buildings. Improving heating controls to ensure systems only run when they are needed, not over-heating buildings and ramping down systems when the properties are empty.

Decarbonising our heating by switching to electrically powered systems such as air source heat pumps.

Air source heat pumps work like a reverse refrigerator, using the air from outside, absorbing any heat in the air using a refrigerant, compressing the gas that is formed to increase the temperature even more, then using the heat to run the heating system. Switching from gas to electrically powered heating systems will

significantly reduce Uppingham School’s carbon footprint, although a lot of work is required to make our buildings ready for the transition. Per unit, electricity is much more expensive than gas, so the systems need to work very efficiently to be financially viable. They generally produce lower levels of heat than gas systems, so buildings with air source heating must be very thermally efficient so heat is not lost through uninsulated roofs or single glazed windows.

Electrically powered heating will reduce our carbon footprint as the ‘carbon intensity’ of electricity can vary significantly depending on how the electricity is made. Power stations that produce electricity from burning coal or gas have a much higher carbon intensity that nuclear or renewable sources such as solar and wind. As the UK electricity grid increases the proportion of total power coming from renewable sources, the carbon intensity reduces.

In the future, we will also investigate options to install our own renewable electricity supplies such as solar photovoltaic panels and storing this home-made electricity inside battery banks to be available when most needed within our buildings.