Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire Recovery & Resilience Plan

For Mora and San Miguel Counties, NM

For Mora and San Miguel Counties, NM

On behalf of the Capstone Masters of Community and Regional Planning students we would like to thank Erin Callahan, our Instructor of Record, and Michaele Pride and Catherine Harris, our professors, for their guidance in creating this plan. We benefited greatly from the ideas and designs shared with us by our fellow students in the Design and Planning Assistance Center (DPAC) Mora and San Miguel Fire Resilience Studio.

A special thanks to community members and local professionals who have shared their wealth of knowledge with the DPAC studio this semester. The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire and Flood Resiliency Plan was made possible with their expertise and ongoing guidance.

About the Authors:

At the University of New Mexico (UNM), seven graduating Master’s of Community and Regional Planning (MCRP) students participated in a 2023 Design and Planning and Assistance Center (DPAC) studio to create a resiliency plan for Western Mora and San Miguel Counties as their Capstone project. The DPAC studio facilitated several participatory community engagement events and sought to connect the students with affected residents. The students researched the impacted area and the communities affected by fires and flooding, crafting this multi-scale regional resilience plan based on their findings. Several iterations of recommendations were made and presented to reviewers before completing the final plan. The plan is limited in scope by the capacity of the student planners who worked on it, though they made their most diligent efforts.

Kyla Danforth

Karina Rodgers

John Sandlin

Ayonitoluwa Oyenuga

Vidal Gonzales

Tina Ruiz

Helen Ganahl

Figure 1: Pendaries

Figure 2: New Mexico Context Map

Figure 3: Where people live in Impacted Area

Figure 4: Map of Impacted Area

Figure 5: Provinces of New Mexico

Figure 6: Southern Rockies Ecoregion, Sangre de Cristo Mountains

Figure 7: Ecoregions of New Mexico

Figure 8: Natural Fire Cycle

Figure 9: Observed and Projected Temperature Change, New Mexico

Figure 10: Summer Monsoon, Eastern New Mexico

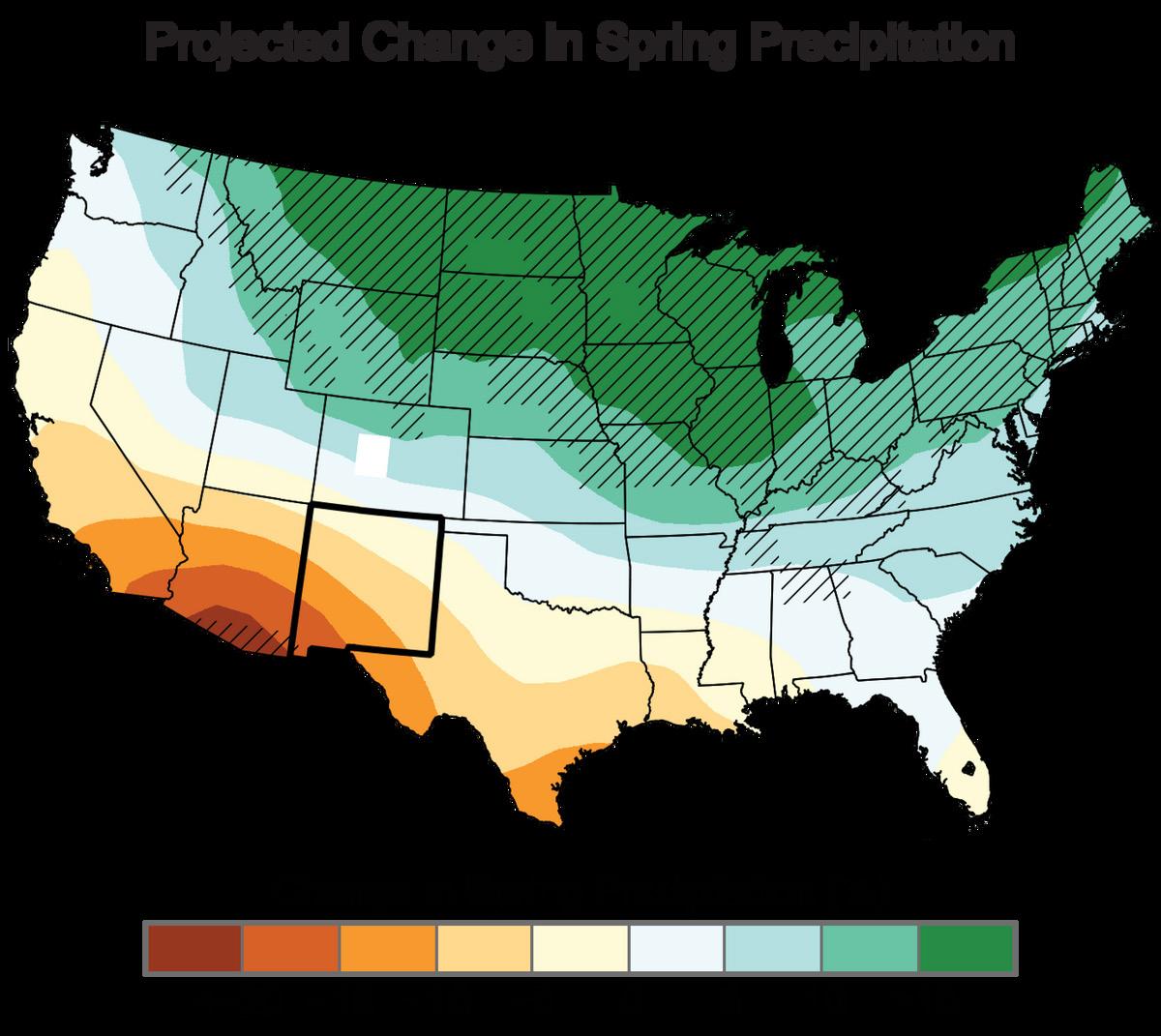

Figure 11: Projected Change in Spring Precipitation (Drop in precipitation for New Mexico)

Figure 12: Low water levels in Storrie Lake, NM, 2012

Figure 13: Historic Pecos Pueblo

Figure 14: Prescribed Burn in Santa Clara Pueblo

Figure 15: San Rafael Church, La Cueva, New Mexico

Figure 16: American Progress (1872) by John Gast

Figure 17: Fire suppression in the Lassen National Forest, 1927

Figure 18: Firefighter lighting spot fires during a prescribed burn

Figure 19: Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire Timeline

Figure 20: Hermits’ Peak/Calf Canyon Fire burn scar

Figure 21: Fire on a ridge above Holman, NM

Figure 22: Post-fire flooding, Rociada, NM

Figure 23: Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Emergency Response Timeline

Figure 24: Map of Affected Areas and Entities

Figure 25: A watershed

Figure 26: Ponderosa Pines damaged by Bark Beetle

Figure 27: Pre- and Post-Fire Watershed Function

Figure 28: Peak to Valley Watershed Restoration Model

Figure 29: Santa Clara Watershed Restoration Workers

Figure 30: Fire Impacted Watersheds (HUC10)

Figure 31: Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Burn Scar Debris Flow Potential during a 1” of rain per 15 minutes storm event

Figure 32 Stakeholders within a Watershed

Figure 33: Watershed Restoration Community Engagement Model

Figure 34: Wicker Weir

Figure 35: Zuni Bowl

Figure 36: Log Filter Dam

Figure 37: Bottomless Culvert

Figure 38: One Rock Dam

Figure 39: Contour Log Felling

Figure 40: Watershed Restoration Funding Opportunities

Figure 41: Mora County Commissioner surveying damage left by fire and stormwater flooding

Figure 42: Second grade students from Mora Independent Schools reseeding a local ranch impacted

Figure 43: Population of San Miguel County (U.S. Census Bureau [1], 2021)

Figure 44: Population of Mora County (U.S. Census Bureau [2], 2021)

Figure 45: Population of the City of Las Vegas (U.S. Census Bureau [3], 2021)

Figure 46: Race and Ethnicity of San Miguel County (U.S. Census Bureau [4], 2021)

Figure 47: Race and Ethnicity of Moral County (U.S. Census Bureau [5], 2021)

Figure 48: Race and Ethnicity of the City of Las Vegas (U.S. Census Bureau [6], 2021)

Figure 49: Languages Spoken in San Miguel County (U.S. Census Bureau [7], 2021)

Figure 50: Languages Spoken in Mora County (U.S. Census Bureau [8], 2021)

Figure 51: Languages Spoken in the City of Las Vegas (U.S. Census Bureau [9], 2021)

Figure 52: Worker Classes in San Miguel and Mora County (U.S. Census Bureau [10], 2021)

Figure 53: Workforce Industries in San Miguel and Mora County (U.S. Census Bureau [11], 2021)

Figure 54: Occupancy Status in Las Vegas City, Mora and San Miguel Counties (U.S. Census Bureau [12], 2021)

Figure 55: Year Structure Built in Mora County, NM (U.S. Census Bureau [13], 2021)

Figure 56: Year Structure Built in Las Vegas, NM (U.S. Census Bureau [14], 2021)

Figure 57: Year Structure Built in San Miguel County, NM (U.S. Census Bureau [15], 2021)

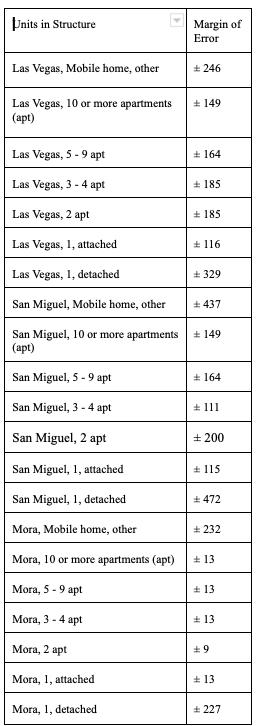

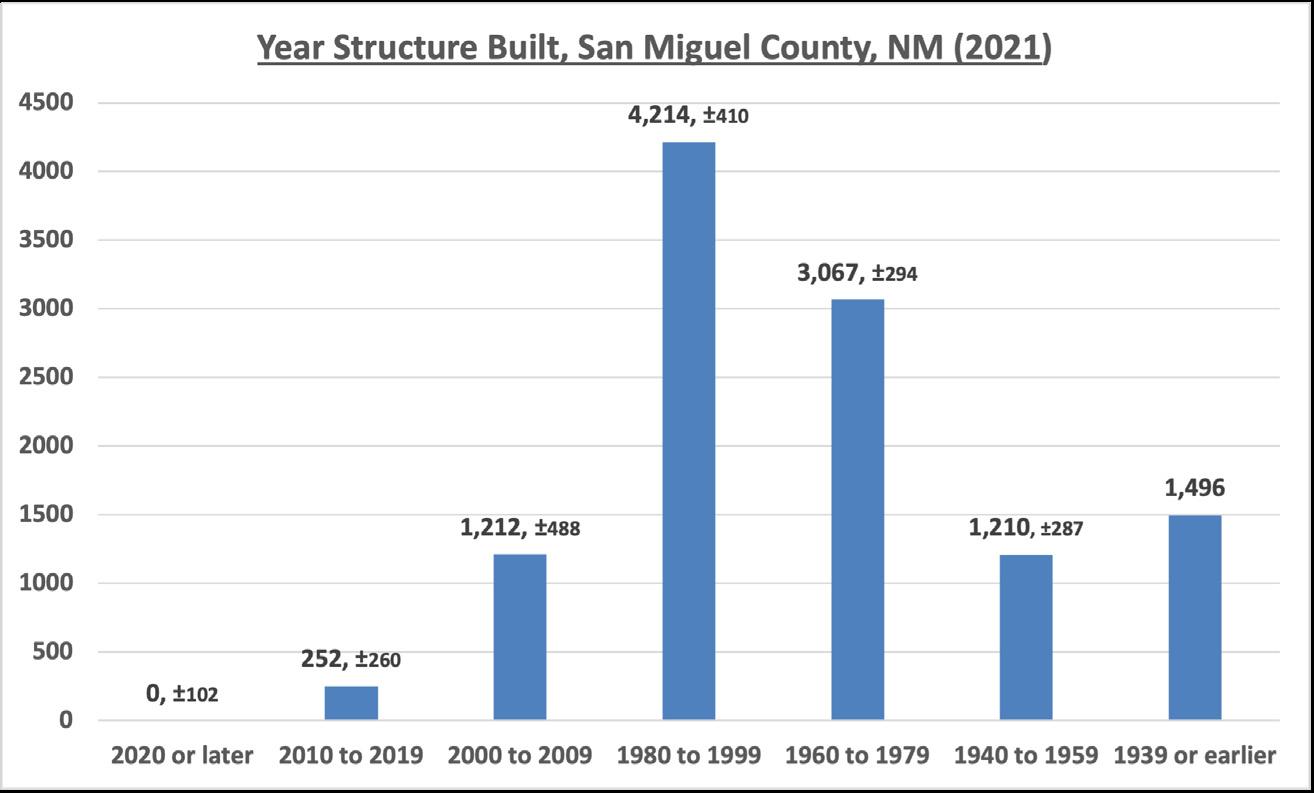

Figure 58: Units in Structure in Las Vegas City, Mora and San Miguel Counties (U.S. Census Bureau [16], 2021)

Figure 59: Smoke next to house

Figure 60: “The San Miguel Sheriff’s Office confirmed nearly 350 homes have been destroyed”

Figure 61: Permit-Ready One Bedroom Plan

Figure 62: Co-housing site plan and perspective

Figure 63: “How does the AHA work?”

Figure 64: Render of rural house

Figure 65: Santa Fe WUI Classifications Map

Figure 66: 1891 railway map with Central-Northeastern NM area encircled, and rail accessible urban centers underlined.

Figure 67: General Sales Tax/GRT is NM largest revenue source

Figure 68: Variance of GRT for Municipalities and Counties

Figure 69: County Road in Mora

Figure 70: Types of Partnerships

Figure 71: Water Treatment Plant

Figure 72: Food Accessibility within 20 miles (rural location)

Figure 73: Damaged Acequia

Figure 74: Acequieros Working The Land Category – “Planting garlic in mixed, irrigated plot of fruit trees and herbs”

Figure 75: Hillside Erosion Control Section

Figure 76: Stormwater Retention

ACIDF - Acequia Community Infrastructure Ditch Fund

ACS - American Community Survey

ADUs - Accessory Dwelling Units

AMI - Area Median Income

CLG - Certified Local Government

CWPP - Community Wildfire Protections Program

DHSEM - Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management

DPAC - Design and Planning Assistance Center

DOI - Department of Interior

ENMRD – Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department (New Mexico)

EPA - Environmental Protection Agency

FEMA - Federal Emergency Management Agency

GRT - Gross Receipts Tax

HPCC- Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon

NEPA - National Environmental Policy Act

NMDHSEM - New Mexico Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management

NMED - New Mexico Environmental Department

NM-FPTF - New Mexico Fure Planning Task Force

NMMFA - New Mexico Mortgage Finance Authority

NCNMEDD - North Central New Mexico Economic Development District

MCRP - Master of Community and Regional Planning

MFA - Mortgage Finance Authority

MDWCA - Mutual Domestic Water Consumer Associations

RFP - Request for proposal

RCAC - Rural Community Assistance Corporation

RIP - Rural Infrastructure Program

RPN - Rural Partners Network

UNM - University of New Mexico

USDA - United States Department of Agriculture

USFS - United States Forest Service

WUI - Wildland Urban Interface

“the Plan” - Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire recovery Resilience Plan

“the Impacted Area” - Western Mora and San Miguel Counties

“

DPAC Planning Team” - Master’s of Community and Regional Planning Students, Plan Authors

In April 2022, the Northern New Mexico Counties of Mora and San Miguel experienced the largest wildfire in New Mexico history. Ignited by two merged U.S. Forest Service prescribed burns, the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire raged for over three months, resulting in over 300,000 acres of forest and agricultural lands burned.

Since August 2022, an ongoing recovery effort that crosses all facets of daily life has consumed communities in Western Mora and San Miguel counties. To contribute to these efforts, the University of New Mexico (UNM) 2023 Design and Planning and Assistance Center (DPAC) studio invited a small group of Master of Community and Regional Planning (MCRP) graduate students, referred to in this plan as the “DPAC Planning Team,” to develop the following Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire and Flood Resiliency Plan for their Capstone project.

This plan presents a wealth of background information on population demographics, natural systems, fire

management practices, and human history. The DPAC Planning Team tailors resilience-increasing recommendations to the region’s environmental and population contexts. Each topic area discusses the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire and the associated flooding’s catastrophic impact on the region, referred to as the “impacted area.” It is noted throughout the plan that some impacts were of direct consequence, while others exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities.

Drawing on their findings, the DPAC Planning Team identifies critical areas to direct recovery and resiliency efforts: Housing, Economy, Watershed, Infrastructure, and Food Systems. The DPAC Planning Team hopes that the opportunities identified in the plan, bounded by the scope of the semester-long class, will engage readers across communities, associations, and agencies, sparking conversation and contributing tangibly to community recovery efforts.

OPPORTUNITIES INCLUDE:

Housing Opportunities:

Historic Preservation & Adaptive Reuse

- Explore hybrid preservation and adaptive reuse to adapt historic and abandoned structures to meet community and economic development needs.

Bulk Building Permits

- Enable a faster permitting process with permit-ready building plans for multiple pre-approved house sizes and designs.

Zoning Alterations in Las Vegas City, San Miguel County

- Generate flexible space while maintaining the city’s regional character, and encouraging intergenerational living arrangements, and increasing the availability of livework spaces.

Affordable Housing Act Mortgage Finance Authority

compliant plans and ordinances for San Miguel and Mora Counties.

- Creation of donation-enabling affordable housing plans and accompanying ordinances by local government.

Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Zoning

- Implement WUI-specific codes on a county level to create defensible spaces and fuel breaks, reduce fuel loads, and improve fire resiliency.

Economic Opportunities:

Gross Receipts Tax (GRT)

- Increase the number of businesses generating revenue, to boost the local tax base and increase governmental capacity to implement programming.

Film Industry

- Increase film production by working with the NM Economic Development Department Film Credit Unit to maximize tax incentive programs and create local workforce opportunities.

Agricultural Practices

- Implement recommendations in the NM Agricultural Resiliency Plan to support current and future farmers by conserving wildlife habitat and water supplies, provide training resources, brand NM grown products, and improve infrastructure to reduce waste and increase composting.

Watershed Opportunities:

Peak to Valley Watershed Restoration Technique

- Begin restoration work in the higher elevations and work downstream to reduce stormwater runoff velocity and increase the resilience of downstream communities.

- Organize all stakeholders within the watershed to create a community-driven watershed restoration plan through the facilitation of a third-party planning and engineering firm.

Techniques and Technologies for Watershed Restoration

- Implement Zuni bowls, one rock dams, wicker weirs, log filter dams, bottomless culverts, and contour log felling in order to slow water, decrease erosion, improve ecosystems, and increase water seepage into the ground.

Infrastructure Opportunities: Water Partnerships

Outdoor Recreation

- Work with the NM Outdoor Recreation Division to jumpstart community investments in outdoor recreation businesses, infrastructure, and conservation efforts.

- Improve technical, managerial, and financial capacity of water systems. Identify potential partners with whom to build capacity and generate solutions via Mutual Aid Agreements, Memorandums of Understandings, and shared technical knowledge.

Mitigate Flood Risks

- Install river and lake jettys or breakwaters to divert debris, along with water quality sensors; Invest in permanent water treatment plant; extend well casings; upgrade intake screen to minimize blockages.

Increase Broadband Access

- Apply for ReConnect Loan and Grant Program funding.

Food Systems Opportunities: Community Engagement Model

-Educate and organize volunteers, repair acequias, and prepare for potential future disasters.

Disaster-Relief Fund for Acequias

- Provide a funding source that does not require locally matching funds. Allowing for quicker implementation and remediation.

Acequia Stormwater Retention Design

Design strategy to filter and mitigate the intensity of stormwater runoffs intercepting it with detention basins where water is slowed and phyto-remediated before absorption into the soil rather than contaminating the acequia water.

This resilience plan, to be referred to throughout as “the plan,” addresses two overlapping concerns:

1) Vulnerabilities in Western Mora and San Miguel Counties before The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire.

2) Issues explicitly caused or exacerbated by the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire in the impacted area of Western Mora and San Miguel Counties.

In the plan, the University of New Mexico Master’s of Community and Regional Planning (MCRP) Capstone Design and Planning Assistance Center (DPAC) students address obstacles to recovery in the impacted area, identify the regional need for climate resilience, and propose recommendations. The plan seeks to understand existing communities in the impacted area and respond to community needs on several scales while building resilience.

This plan defines resilience as: “The ability of human and non-human systems to react, respond, and adapt to change in a way that strengthens future generations and cycles” (Design and Planning Assistance Center, 2023).

Considering the unique culture and history of the impacted area, the plan offers recommendations to increase community resilience to future disasters. It explains current regulatory processes to the best of the DPAC Planning Team’s capabilities.

“Resilience is the ability of human and nonhuman systems to react, respond, and adapt to change in a way that strengthens future generations and cycles” (Design and Planning Assistance Center, 2023).

The geology of the impacted area is dominated by the southernmost portion of the greater Rocky Mountain Province, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. These mountains were created by the folding and faulting of the North American continent approximately 80 to 55 million years ago (Northrup & Read, 1996). The region was subsequently scoured by Pleistocene ice age glaciers (21,000 years ago) producing the peaks and valleys that we see today (Leonard et al., 2023). As the glaciers receded and the climate warmed, forests grew on the mountain slopes and grasslands in the valley bottoms.

Moving from west to east, the high peaks of the Sangre de Cristo mountains transition to the Basin and Range Province and finally to the Great Plains region (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d.). The area is drained by two major river systems, the Pecos and Canadian, whose smaller tributaries, the Gallinas and Mora rivers, will factor into this plan.

Ecoregions are a system for defining areas of ecosystem similarity that can be divided into different levels of spatial hierarchy.

The impacted area is dominated by two ecoregions: the Southern Rockies and the Southwestern Tablelands. Steep and rugged mountains characterize the Southern Rockies ecoregion. The high-elevation ecoregion has alpine characteristics, while the mid-elevations transition from coniferous Ponderosa Pine, Douglas Fir, and Aspen forests to Pinyon Pine, Juniper, and Oak. Lower elevations are dominated by grass and shrub vegetation. The Southwestern Tablelands consist of mesas, canyons, and badlands supporting grasslands and semiarid rangeland transitioning from juniper and scrub oak along the higher-elevation flanks (Omernik, 2000).

Ecoregions are a system for defining areas of ecosystem similarity that can be divided into different levels of spatial hierarchy.Figure 7: Ecoregions of New Mexico Image Credit: https://gaftp.epa.gov/EPADataCommons/ORD/Ecoregions/nm/nm_pg_3.pdf

Fire is an important component of the regional natural systems. For millennia, ecosystems have relied on cyclical patterns of disruption and recovery, and fire is considered a “keystone process” in driving those cycles (Defenders of Wildlife, 2020). Many of the ecosystems that are present in the impacted area are fire-adapted. Ponderosa pine forests rely on low-intensity fires naturally occurring on a 5–25-year cycle to burn forest ground litter and create open space between trees.

In addition, periodic higher-intensity fires burned smaller trees and shrubs, leaving the larger-diameter trees intact, allowing for the open-canopy characteristics that spur the growth of grasses and forbs on the forest floor (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2023).

The climate in Northern New Mexico is greatly influenced by mountainous terrain; temperatures decrease by 3 degrees with every 1,000 feet of elevation increase. The mean annual temperature for the northern mountains and valleys is around 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Average maximum temperatures hover in the upper 70s but clear skies and low humidity cause daytime temperatures to fluctuate an average of 25-35 degrees between daily high and low temperatures. In the winter, average daytime temperatures hover in the 30s.

Precipitation in the northern mountains can average around 20 inches a year, falling mainly during the monsoonal rains of July and August. Average annual snowfall can range from 100-300 inches depending on elevation. Heavy rainfall over a short period can lead to significant runoff resulting in flash flooding. In addition, snowmelt may cause streams and rivers to swell and exceed the flood stage (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, n.d.).

Over the past century, temperatures in New Mexico have risen over 2 degrees Fahrenheit, with the last decade being the warmest on record. Climate projections indicate that annual average temperatures will increase, spring precipitation will decrease, there will be less snowpack, winters will be shorter, and severe droughts will become more intense (Frankson & Kunkel, 2022).

During a DPAC field trip to Holman, NM to observe damaged and flooded acequia systems, local resident Gilbert Quintana noted that “the winds never used to be this bad” (G. Quintana, personal communication, March 3, 2023). There is a debate across the climate change fields on whether winds are increasing or decreasing, but a recent study indicates that average wind speeds across the globe, including North America, have increased from 7 mph to 7.4 mph (Harvey, 2019).

Besides warming temperatures, “Climate Chaos” is characterized by sudden, unpredictable, severe, and catastrophic storms. As normal climate patterns are disrupted, it is not uncommon to see a large portion of the average yearly precipitation occur in just one season, or even in one severe storm event. Although not directly indicated in the climate trend data for New Mexico as of 2021, the 2022 monsoon season in the impacted area produced an unprecedented number of record rainfall events.

In fact, on August 20th, 4-9 inches of rain fell on the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon burn scar, resulting in catastrophic flooding in downstream communities (Hergert et al., 2022).

A hotter, drier climate is already impacting the region, threatening human health, farming, grazing, and infrastructure. The chances of severe dust storms and catastrophic wildfires will continue to increase.

https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/las-vegas-area-irrigators-ask-court-to-intervene-indam-project/article_168a8598-8f5e-5098-be9e-606a161ffdf8.html

Spanish Conquistadors in search of gold first visited Pecos Pueblo in 1540 during Francisco Vazquez de Coronado’s expedition. In 1583 Spanish Missionaries were assigned to Pecos Pueblo; by 1680 the Pueblos revolted against Spanish rule, gaining 12 years of freedom from Spain. In 1692, the Spanish reconquered New Mexico with the help of Pecos Pueblo and other indigenous allies. Due to increased hostilities between enemy tribes and disease, the people of Pecos Pueblo abandoned their village by 1838 and moved into presentday Jemez Pueblo (Sturtevant, 1988; Dozier, 1983).

The impacted area was home to hunter-gather groups from approximately 18,000 years ago to 500 A.D (U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d.). In the 1100s, ancestors of the future Pecos Pueblo residents occupied what we now call the Pecos Valley. Construction of the Pecos Pueblo began in the 1300s, resulting in a large multistoried village by 1450. The people of Pecos Pueblo farmed, hunted, gathered, and traded for necessities. The location of their village in a Sangre de Cristo mountain pass enabled it to become a center for trade among the plain’s tribes and the pueblos in the Rio Grande Valley (Sturtevant, 1988; Dozier, 1983).

Indigenous people of the southwest managed North American landscapes for an estimated 18,000 years (U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d.). In the Americas, Indigenous people utilized fire as a forest and grassland management tool to enhance the growth of food and utility plants (Wagtendonk, 2007). In the southwest, Puebloan Indigenous People combined frequent small fires and selective logging to enhance ecosystems and maintain a healthy fuel load in the forests.

At the time of Spanish contact, the Puebloan people understood how to manage their forests, sustainably utilizing its resources, and enhancing it through various techniques and technologies such as check dams and Zuni bowls, still used today in watershed restoration and improvement projects (Kapoor, 2017). When Spain and Mexico colonized the southwest, the incoming residents adopted these indigenous practices, managing the forests of their communal lands to benefit their communities.

HUMAN HISTORY

In 1794, Spanish settlers began moving east from Santa Fe toward Pecos Pueblo and established the first land grant community of San Miguel del Bado. Land grant economies were based on farming, hunting, trading, ranching, and harvesting from the landscape. Descendants of the San Miguel del Bado Grant and other Spanish/Mexican settlers utilized San Miguel del Bado as a point of departure to establish further land grants, such as the Anton Chico Grant, Tecolote Grant, and Town of Las Vegas Grant. Mexican independence from Spain in 1821 led to political shifts in New Mexico and the reshuffling of power relations between the tribes and Hispanic communities (Dozier, 1983). The Town of Las Vegas Grant was formally created in 1835, making it a Mexican Era land grant not permanently settled until 1838 due to increasing military raids by the Comanche and Apache (Arellano & Vigil, 1985). The Santa Fe Trail opened in 1821, and, due to their proximity to the trail, these communities became an important part of trade between Mexico and the United States (Sturtevant, 1988).

Hispanic settlers moved into the Mora area in the early 1800s, and the Mora Land Grant was formally established in 1835. The Mora Land Grant officially had three communities: the Plazas of Valle de Abajo, Santa Gertrudis, and San Antonio. In 1846, The United States Army arrived in New Mexico and by 1848 the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed to end the MexicanAmerican War. At this point in time, many Americans started moving into these areas and established settlements, towns, or ranches (Arellano & Vigil, 1985; Ebright, 2008; Shadow & Rodrìguez-Shadow, 1995).

In order to execute the treaty obligations of the United States (U.S.) after the Mexican-American War (18461848), Congress created the Survey General Process (1854-1891) and the Court of Private Land Claims (18911904). These processes resulted in many land grants receiving land patents from the U.S. General Land Office. In the eyes of the U.S. government, the U.S. had fulfilled its treaty obligations. Conversely, the political and civil rights of land grants were not upheld as political entities of the prior sovereign, a violation of treaty obligations. After the issuing of land patents, many land grants were partitioned off in partition suits by lawyers and other prominent individuals involved in the adjudication of the land patents. In other cases, land grants were subdivided and sold as a means of obtaining money to pay land taxes or through questionable back-door dealings by the land grant’s board of trustees (Ebright, 2008). Land grants today are governed by various New Mexico State Statutes under Chapter 49 (Chapter 49, 1978). In San Miguel and Mora County, there are the community sub-grants and land grants of the Town of Las Vegas, the Mora Land Grant, Los Vigiles, Lower Gallinas, San Geronimo, and San Augustine.

In 1912, New Mexico became the 47th state. This meant yet another change in governmental jurisdiction and subsequent land use protocols. In 1908, the United States Forest Service (USFS) designated the 1.5 million acre Carson National Forest, and in 1915, the 1.6 million acre Santa Fe National Forest (USFS Santa Fe, n.d.). Management of newly formed national forests was shaped by the settler-colonial philosophy of total fire suppression to protect natural resources and neighboring private property (Norgaard, 2022). The USFS national forest designation determined allowable uses within the impacted area, with little consideration for residents with thousands of years of proven practices.

hotter and drier conditions and stressed by competition for nutrients, light, and water, are vulnerable to pests and disease (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2023). The goal of returning the forest to an open canopy system with a cleared understory is achieved through thinning and prescribed burning. Unfortunately, some of these prescriptive interventions are met with the unpredictable nature of climate change-driven weather events and the failure of colonial systems and unwieldy bureaucracies to nimbly navigate a changing climate, as was the case with the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire.

service-fire-suppression/

Modern fire management approaches within the National Forest Service are changing as the peril of forests ripe for catastrophic fire is realized. Fire suppression created dense and congested forests full of combustible fuel sources. Large conifers, subject to

On April 6, 2022, USFS personnel in the Pecos/Las Vegas Ranger District of the Santa Fe National Forest initiated the Las Dispensas prescribed burn. High winds picked up later that afternoon, carrying embers outside of the project boundary and causing several spot fires. This led to its designation as the Hermit’s Peak Wildfire, named after the nearby mountain peak. By April 19th, the fire had consumed 7,573 acres of forest and was considered 81% contained (InciWeb, 2022).

Earlier, on April 9, a second fire had ignited to the west of the Hermit’s Peak Fire due to the reignition of leftover burn piles from a January USFS-prescribed burn. It was named the Calf Canyon Fire, and by April 21, it escaped fire containment lines, burned 123 acres, and was 0% contained (Gabbert, 2022).

On April 22, a red flag warning was issued by the National Weather Service, warning of “extreme, dangerous, and dire” weather conditions (Hergert et al., 2022a). Winds gusting between 60-75 mph accelerated the two fires

and within 24 hours they merged into one, growing from a combined 7,573 acres to 42,341 acres with 0% containment (Hergert et al., 2022a). Over the next few months, driven by extreme winds, the combined fire grew an average of 10,000 acres per day. On August 21st it was declared 100% contained. Having burned a total of 341,471 acres, the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire was the largest in New Mexico history and the largest for the contiguous United States in 2022 (Pratt, 2022). Of the total lands destroyed, 58% were private, and 41% were federal. 903 structures were burned, including approximately 300 houses (American Rivers, 2023), or, according to another source, 430 houses (Lohman, 2023).

An unprecedented amount of rain fell on the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon burn area during the 2022 monsoon season causing dozens of flash floods across the region over the course of the summer. The National Weather

Service issued 82 flash flood warnings, recorded 43 flash flood days, and cataloged 58 flash flood reports (New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute, 2023). According to a KOAT Action 7 News report, ranch owners Frankie and Geri Herrera’s property was hit with 22 flash floods after the fire (Lenninger, 2023). The resulting damage affected private landowners, roads and bridges, water treatment systems, acequias, and riverine ecosystems. As temperatures warm up in the spring and snowmelt increases, runoff will pose a new threat to downstream communities and systems. Post-fire flooding can continue for 3-5 years after a highintensity fire. Building resilience in affected communities is of the utmost importance.

A healthy watershed acts like a sponge, absorbing rainfall and snowmelt to release it slowly, in a controlled fashion. Streams run clear and cold as forests filter and cool water running downhill. In a watershed, all surface water flows to a single outlet point. When rain falls, or snow melts, that surface water flows into a stream, a creek, a river, and eventually into a larger body of water. In addition to surface water, groundwater is part of the watershed. Surface water soaks into the ground (known as infiltration) to create groundwater, which can be imagined as underground rivers flowing downstream towards an underground lake (aquifer). When full and healthy, they release spring water, which adds to surface water. Springs are important for watersheds to maintain surface water during dry seasons and drought.

sub-regions known as HUCs, or hydrologic unit codes. HUC 2 refers to a region, HUC 4 a subregion, HUC 6 a basin, HUC 8 a subbasin, HUC 10 a watershed, and HUC 12 a subwatershed (U.S. Geological Survey, 2022). For the purposes of this plan, when we speak of a watershed, we are referring to the HUC 10 watershed scale, which spans an area of approximately 40,000-250,000 acres.

Watersheds are divided into larger regions and smaller

Climate change-driven drought has severely impaired healthy watershed function by decreasing the amount of annual precipitation and leaving dry forests vulnerable to pests like the bark beetle. Higher temperatures cause snowpacks to evaporate into the atmosphere or to melt before infiltrating the ground, resulting in downstream flooding. Additionally, increasing intensity and severity of storm events drop significant amounts of precipitation in shorter durations. Unable to absorb the deluge, watersheds shed the runoff, ultimately decreasing groundwater recharge, affecting surface water levels during the dry season, and lowering spring output.

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire damaged an already fragile watershed, turning it from a sponge into a spillway. As a result of the fire, tree canopy was lost, herbaceous ground cover was destroyed, and scorched soils could not absorb storm runoff, resulting

in catastrophic downstream flooding and debris flows. Houses were flooded, acequias were choked, and roads and bridges were washed out. New Mexico’s municipal water supply reservoir in Las Vegas was contaminated with unfilterable ashy sediment (Nielsen, 2022).

https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r3/forest-grasslandhealth/ insects-diseases/?cid=STELPRDB5228457

The fire and subsequent watershed degradation impacted federal, state, county, municipal, and private lands. Considering that a watershed may span the geographic bounds of several entities, a coordinated approach to restoration must be considered. Time is critical; watershed restoration is an important first step toward recovery and resilience.

https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/fire-hydrology-data-viz-story-carousel

To achieve watershed restoration, it is recommended that a Peak to Valley Watershed Restoration technique be implemented through multi-stakeholder cooperation, coordination, and community engagement. By beginning restoration work in the higher elevations and working downstream, stormwater runoff velocity is reduced, increasing the resilience of downstream interventions and communities. This technique was used in the Santa Clara Creek watershed in response to the 2011 Los Conchas Fire that burned 150,000 acres in the Jemez Mountains. Partnering with FEMA and several other stakeholders like the US Forest Service, National Park Service, US Army Corps of Engineers, New Mexico Department of Homeland Security, and many others, Santa Clara Pueblo embarked on a topdown watershed-scale restoration project. Starting

at higher elevations, working downhill, using on-site materials, bio-engineering (engineering with nature and natural materials), reforesting with native species, and implementing long-term monitoring and adaptive management, the Pueblo has improved its resilience against future flooding (Altmann, n.d.).

Cross-agency collaboration and coordination formed the watershed restoration framework that led to this promising successful practice. Similar measures should be implemented in the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire region.

Since the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire impacted such a large geographic area (see Figure 27 for fire impacted watersheds), watershed restoration can be daunting. In total, nine separate watersheds were impacted. It is recommended that watershed restoration be prioritized by high debris flow potential due to burn severity (see Figure 31 for post-fire debris flow likelihood). The headwaters of the Santa Clara Watershed has been selected as an example, but this framework can be applied to any impacted watershed. Many areas within the Gallinas Watershed have a moderate to high debris flow potential. Additionally, the Rio Gallinas was declared one of America’s most endangered rivers by the American Rivers organization due to climate change, and outdated forest and watershed management practices (American Rivers, 2023). Figure 32 demonstrates the diverse stakeholdership that exists within the Gallinas Watershed. It serves as an example of collaboration and community engagement that should be conducted to prepare a watershed restoration plan.

https://quizlet.com/344860366/ river-environments-characteristics-of-the-drainage-basin-gcseccea-geography-diagram/

PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

The DPAC Planning Team recommends enacting this model to create a watershed restoration plan and bring together diverse watershed stakeholders in creating a restoration plan that aims to heal the land, heal the people, and build trust among stakeholders.

The first step in the proposed Watershed Restoration Community Engagement Model is to have the US Forest Service and local non-profits (such as the Hermit’s Peak Watershed Alliance or the New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute) organize all stakeholders within the watershed to create prerequisite unifying goals and objectives of a watershed restoration plan.

Next, all stakeholders should work to create a request for proposal (RFP) based on these unifying principles to hire a third-party planning and engineering firm to create the watershed restoration plan.

The RFP process review committee should be composed of watershed stakeholders and unifying community leaders so that the needs of all the stakeholders are upheld during the firm’s hiring process. The review committee should work to hire a planning and engineering firm that will uphold all of the needs of the stakeholders, facilitate meetings fairly, build trust among all stakeholders, and guide the planning process based on equitable planning principles. This will ensure that all stakeholders are given equal footing and no single stakeholder is given elevated status, such as the US Forest Service.

After hiring the firm is an appropriate time to host the all-stakeholder kickoff meeting. At this meeting, all stakeholders can come together to create a vision for the plan, create focus groups, and solidify unifying goals and objectives of the plan. These principles will guide the rest of the planning process. The next step of this model is the focus group meetings. During these meetings these groups will identify specific needs/goals and propose possible interventions on their site(s) of concern.

After this step, the all-stakeholder follow-up meeting will take place. At this meeting every focus group will discuss their proposed ideas/interventions and collect comments, feedback, and suggestions. There is a feedback loop into the previous focus group meetings section, so they can address feedback and adjust their interventions accordingly. This feedback loop will continue as often as possible until satisfactory interventions and ideas are met. The planning/ engineering firm will write the draft plan after completing

the feedback loop step.

After the draft plan is complete, only the section of the plan that concerns public lands (such as the US Forest Service) should be put out for public comment. Since the plan will concern many private lands, those portions do not require public comment. At this same time, the agencies required to conduct a National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) assessment shall do so. After receiving comments, the public land agencies and the third-party firm shall address the comments.

Next, the third-party firm should re-draft the plan according to the plan’s vision, unifying goals, and the requirements of the public land agencies. The new draft shall be sent out for review to all watershed stakeholders. The third-party firm should work to organize an all-party stakeholder approval meeting to discuss the draft plan, approve the plan, or suggest the third-party firm make final edits. Finally, the plan shall be approved by the various government entities (as per their requirements) and all parties shall work towards the plan’s implementation.

This section will discuss watershed restoration techniques and technologies that can be implemented at different scales. Many of these techniques and technologies can be implemented on private property, land grants, and federal lands. These interventions are meant to slow water, decrease erosion, improve ecosystems, and increase water seepage into the ground, thereby supporting a resilient landscape that can withstand the impacts of climate change.

Wicker weirs are dams that are placed in a waterway or arroyo to decrease erosion. To build a wicker weir, drive wooden stakes across the waterway and then weave tree limbs, willows, or any other similar material perpendicular to the flow of water (Zeedyk et al., 2009).

Image Credit: https://quiviracoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/An-Introduction-to-Erosion-Control.pdf

Zuni bowls are a headcut erosion intervention rock structure that prevent headcuts from moving up a waterway. To build a Zuni bowl, choose a headcut and trim it back to create a bowl-like form that slopes around 70 degrees. Then, place smaller or flatter rocks below where the pour-over will be, and stack medium to large rocks at the spillway of the bowl to create the pour-over. Next, stack medium to large rocks around and up the bowl to meet the top of the headcut. Lastly, create a one rock dam below the Zuni bowl to slow the water down and to create another pool in between the one-rock dam and the pour-over (Maestas et al., 2018).

Image Credit: https://www.milkwood.net/2011/11/04/making-a-zuni-bowl-let-the-water-do-the-work/

Log filter dams work to stabilize heavily eroded hillsides by catching debris and sediment while slowing water down to decrease water erosion. To build a log filter dam, place a large log perpendicular to the flow of water in a waterway and anchor it into the ground. Next, stack logs at about a 70-45 degree angle along this large log and anchor them into the ground as best as possible. Lastly, place medium to large rocks along the base of these angled logs on the upslope side (Altmann, n.d.).

Bottomless culverts can be installed where previous bridges or traditional culverts were. Bottomless culverts allow for an increased flood capacity and allow for natural stream function to occur (such as fish passage). Santa Clara Pueblo has installed many of these bottomless culverts after the flooding of the Santa Clara Canyon in the aftermath of the Las Conchas Fire, while providing adequate fish habitat under the bottomless culverts. This allows fish to congregate under the bridge on hot summer days, which is important with the increasing impacts of climate change (Altmann, n.d.).

One rock dams are rock structures, about one rock in height, that help slow water down to decrease the erosion process. The first step in creating a one rock dam is to build a footer for the splash apron on the downstream side of the structure. Next, tightly fit medium to large rocks together to make a uniform surface. Lastly, extend the rocks onto the banks so that the water does not flow around the dam but over it (Maestas et al., 2018).

Contour log felling is an effective way to slow down the effects of water erosion. Dead trees on a hillside can be downed and pinned in place laterally. Pinning is not necessary but helps to secure logs in place and reduce the total amount of downhill debris. This method is highly effective, has a low cost, and is not labor intensive (After Wildfire, n.d.).

Utilizing a Peak to Valley Watershed Restoration approach, the following implementation timeline should be used to create a watershed restoration plan. In the short term, the US Forest Service and non-profit organizations should organize the stakeholders of the watershed and implement the Watershed Restoration Community Engagement Model to draft the watershed restoration plan. The plan shall be drafted and approved by the various entities involved. In the midterm, the plan and its interventions shall be implemented. In the long term, these interventions shall be monitored, maintained, and re-designed as necessary.

According to FEMA’s HPCC Wildfire FAQ Website, FEMA will only cover the “Cost of reforestation or revegetation not covered by any other federal program” (FEMA, 2023). This implies that other funding sources should be sought out in the order to fund restoration work. Below is a table of funding sources available to the diverse stakeholders that may be present in a degraded watershed.

The difficult Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fire and flood recovery process has taken a toll on residents. Many are frustrated with FEMA after experiencing difficulties navigating bureaucratic channels to receive economic relief and housing support (Chacon, 2022). This frustration has exacerbated the lack of trust in FEMA and government officials in communities throughout the two counties.

“It’s more than just a fire that’s burning trees and burning homes. It’s also burning into our souls.” - Susan Vigil, Mora County resident quoted in Chaco, 2023.

The complete disruption of people’s lives caused by the flooding and fires on traditional ways of life cannot be overstated. Many impacted residents lost livestock directly to the fire or to the loss of grazing lands that previously sustained their herds (McKay, 2023). Others relied on the now burned landscape for informal income, like tree harvesting and hunting. As mentioned earlier, numerous residents lost their homes and, with them, invaluable sentimental possessions (Hampton, 2023). Washed-out roadways and damaged infrastructure prohibit others from accessing their lands (McKay, 2023). All of this has had serious mental health impacts. Studies have shown that direct exposure to large-scale fires significantly increased the risk for mental health disorders, particularly for PTSD and depression. If left untreated, these disorders have long-term impacts (Williamson, 2022).

Residents of the impacted area have reflected on and shared issues sleeping, experiencing fear of rain, fear of leaving their homes, and fear of never being able to return to their lands (McKay, 2023). Mental health resources are available to residents affected by the fire and flooding. FEMA is offering reimbursement to residents who seek treatment between April 6, 2022, and April 6, 2024 (FEMA, 2022). In addition, there are treatment services through New Mexico Highlands University Counseling, Latino Behavioral Health Equity, HELP New Mexico, Community Behavioral Health Action Team, and more.

“It’s more than just a fire that’s burning trees and burning homes. It’s also burning into our souls.” - Susan Vigil, Mora County resident quoted in Chacon, 2023.

In Mora County, the Mora Independent School District is helping their students cope with the aftermath of the fires by reseeding the forest of a local ranch. Through this program they teach children how wildfires work, refamiliarizing children with the landscape, and giving them an opportunity to help with recovery, as well as hope for the future (Matusek, 2023). Community healing and education programs such as this one can be a great tool to address trauma and fear that is felt by residents. Community physical and mental health is a central component to maintaining resiliency and should be prioritized in community recovery efforts.

www.csmonitor.com/USA/Education/2023/0127/First-fire-then-floods.-How-a-school-district-helps-students-recover

In 2021, the total estimated population of San Miguel County was 27,357; its largest city, Las Vegas, had a population of 13,247. Neighboring Mora County had a population of 4,232. All three places declined in population from 2010 to 2021 with San Miguel County losing the most significant number of people at an estimated decline of 1,964. These populations are projected to continue declining (Legislative Finance Committee, 2021; Northern New Mexico Development District, 2021).

Mora County and San Miguel County have an aging population that younger generations will not replace at a similar rate (U.S. Census Bureau [1], 2021; U.S. Census Bureau [2], 2021; U.S. Census Bureau [3], 2021). In 2021, Mora’s population was nearly its lowest since the Census was first administered in the 1860s (U.S. Census, 2021). Data available on population and housing supply is

affected by including the eastern halves of Mora and San Miguel counties in the information collected in the impacted area.

The City of Las Vegas has a large young adult population (15 to 24 years old), most likely due to the colleges and universities located there. Many students will leave the Las Vegas/San Miguel County area after graduating from higher education and will not join the local workforce. This region is generally suffering from an out-migration of working-aged people seeking higherpaying jobs and living opportunities to urban centers (such as New Mexico’s largest city, Albuquerque).

Percent Margin of Error Range per Age/Sex Category: 0.5% - 3.7%

Estimated Total Population (2021): 4,232

Percent Margin of Error Range per Age/Sex Category: 0.9% - 2.9%

Estimated Total Population (2021): 13,247

In 2021, San Miguel County, the City of Las Vegas, and Mora County had similar racial and ethnic makeup. All three places and their populations had a high percentage of people who self-identified as White, ranging from 56.9% to 58.5% of the total population. The next major race group was the “Some other race” category, ranging from 23.4% to 29% of the total population. The third largest racial group in these areas were the people that identified as being of “Two or more races.”

There is a large Hispanic/Latino population in these areas. Still, because the US Census Bureau does not consider Hispanic/Latino a race but an ethnicity, these people identify under the racial category that “fits them the best” (U.S. Census Bureau [7], 2021). Historically, Hispanic/Latino people have suffered discrimination, leading many to identify as White to escape that

discrimination (Pérez et al., 2008; Gómez, 2018). In all three locations, the percentage of Hispanic/Latino identifying people ranged from 77.9% to 83.1% of the total population (U.S. Census Bureau [4], 2021; U.S. Census Bureau [5], 2021; U.S. Census Bureau [6], 2021).

LANGUAGES SPOKEN

Margin

Margin

The speaking populations (5 years and older) in San Miguel County, the City of Las Vegas, and Mora County had a significant number of Spanish speakers in 2021. (U.S. Census Bureau [8], 2021; U.S. Census Bureau [9], 2021; U.S. Census Bureau [10], 2021).

Spanish is the most common language spoken and should be accounted for when conducting any type of public relations or form completion.

Populations in San Miguel and Mora County tend to be older, with most people aged 50 and over. Notably, in Mora County, 61% of the population 16 years and older does not participate in the labor force. Similarly in San Miguel County, 52% of the population is not in the labor force, compared to New Mexico where only 43% of the total population is not in the labor force. In Mora County, nearly 3% of workers are classified as unpaid family workers, possibly due to family agricultural practices.

The largest economic industry in San Miguel and Mora County is education, healthcare, and social assistance. Two large institutions are housed in Las Vegas; the NM Behavioral Health Institute and NM Highlands University (U.S. Census Bureau [11], 2021).

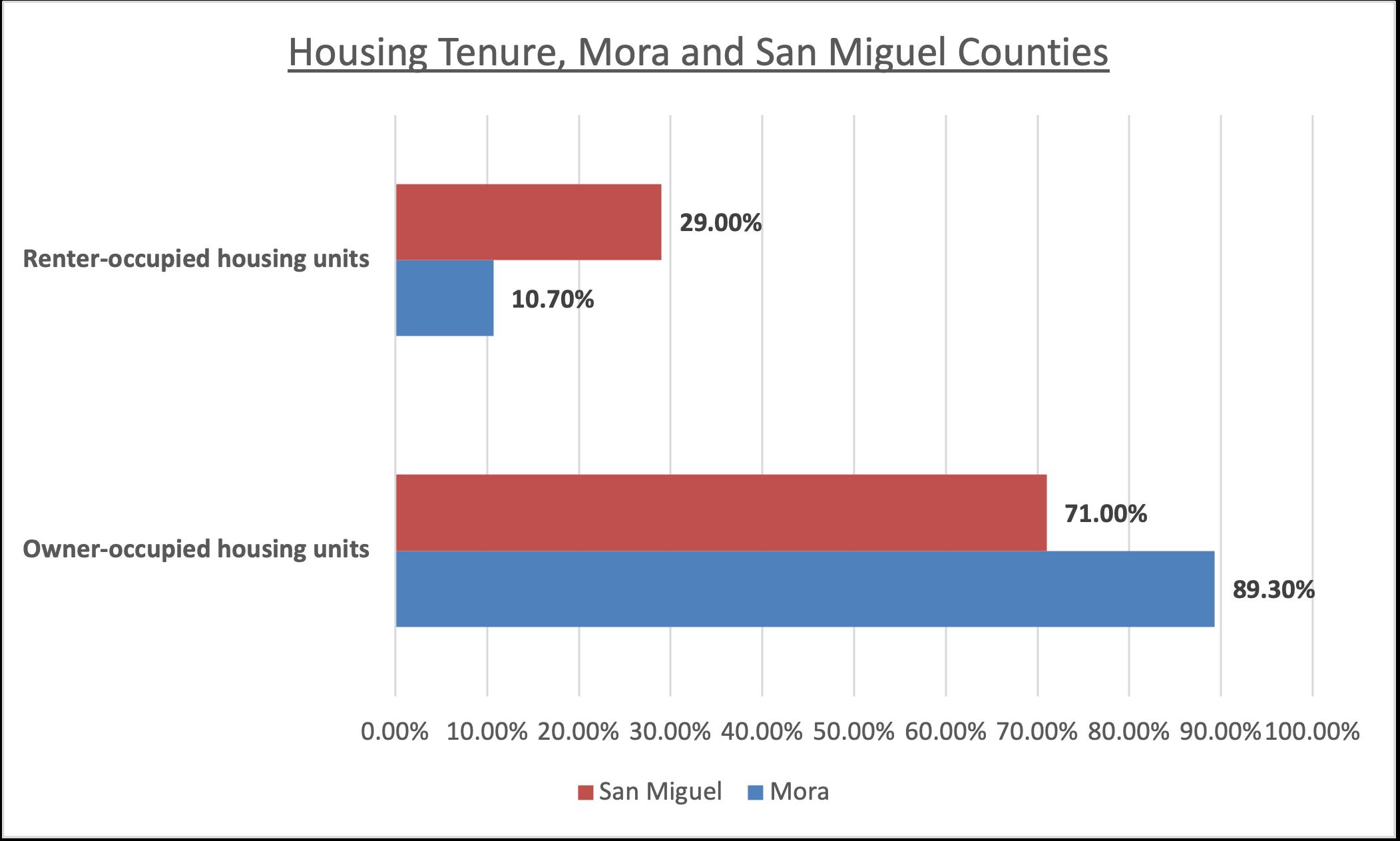

Nationally, the United States is experiencing a multifaceted housing crisis compounded by high inflation and a federal minimum wage that has been stagnant since 2009. Pre-fire housing in Mora and San Miguel Counties was inadequate to meet population needs because of increasingly high housing costs. Data from the New Mexico Mortgage Finance Authority’s “2022 New Mexico Housing Strategy” indicates that rent increases between 2010 and 2019 far outpaced Area Median Income (AMI) growth in all but two New Mexico counties. In Mora County, AMI increased by less than 10%, while rent increased by nearly 30%; In San Miguel County, AMI increased by less than 10%, while rents increased by approximately 15% (MFA, 2022, p. 4).

Housing in the impacted area is further constrained by strained supply chains, small tax bases, and limited housing developers in rural areas. Anecdotally, the impacted area has a workforce housing shortage, and community partners in western Mora and San Miguel Counties have expressed concern over inadequate housing. Based on a windshield survey conducted by the DPAC Planning team in Holman, Mora, Rociada, and Las Vegas, numerous houses in the impacted area appear unsuitable for providing safe and dignified shelter. Many of these houses appear vacant, and ownership may be unclear.

Over the past decade, minimal new housing has been developed in the impacted area. An aging housing supply generally has fewer retrofits, making it less resilient as the climate changes. Older housing is potentially less appropriate for increasingly in-demand livework space, especially in slightly more urban areas like Las Vegas. It might also not meet the needs of an aging population or family arrangements that are other than the nuclear family arrangement.

According to the data, one residence has been built in Mora since 2010; a notably large margin of error accompanies this estimate.

1,061 built between 1980 and 1999 (U.S. Census, ACS 2021 S2504)

In San Miguel County, only 252 units were built after 2010, while 1,496 are from 1939 or earlier and 4,214 were built from 1980 -1999.

In addition to hiring locally in the impacted area, the community will need housing for the workers employed to construct future development in the area. At present, a high proportion of the housing in the impacted area is comprised of mobile homes and manufactured housing, which is limited in its value retention and ability to remain structurally sound over the years. However, pre-built housing presents a plus in that it is easier and quicker to acquire, which is important in an area impacted by natural disaster.

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fire and floods caused the loss of 166 houses as of April 2022 (Davis & Reed Jr, 2022); by August 2022, approximately 430 were burned or compromised (Lohman, 2023). It was extremely difficult for many of the displaced residents to establish temporary housing after losing their homes. After the fire, there was an “analysis showing there was just one rental apartment available in Mora and San Miguel counties” (Lohman, 2023). As has been established, the impacted area is low-income, and in some cases, the families in residence go back to the establishment of Mexican land grants in the 1830s, if not earlier (Lohman, 2023). Their displacement threatens an entire way of life. In the unique New Mexican cultural context, FEMA aid to rebuild is difficult to obtain. Some homeowners do not have property deeds, as their homes and land were passed down over the generations in an informal and familial manner. Aid is slow to be dispersed while alternate forms of property determination are decided on. It is difficult to quantify the value of homes and lands

that go back generations. Some Mora and San Miguel County residents are still living in FEMA flood trailers or Albuquerque motels (Mckay, 2023; Myscofski, 2023). “As of April 19, just 13 of the 140 eligible households had received FEMA housing. Only two of them are on their own land.” (Lohman, 2023).

Although Northern New Mexico is unique in character, across the U.S., there are more people living in the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) than ever, which, with the threat posed by extreme weather events, is more dangerous than ever (Read and Mowry, 2018). From 1990 to 2010, the housing density in forested lands “increased in area by 33 percent (from 581,000 to 770,000 km2, an area larger than the state of Texas). Additionally, the number of housing units in the WUI grew by 41 percent (from 30.8 million to 43.4 million homes), with dwellings in the WUI accounting for 43 percent of new home construction over this period. (Radeloff et al., 2018).” (Read and Mowry, 2018, p. 2).

Image Credit: Unsplash/Mike Newby, https://newmexicosun.com/ stories/626038937-it-looked-like-a-war-zone-mora-county-re-

San Miguel and Mora Counties have diverse, culturally rich histories that hold the potential for preservation and adaptive reuse projects. In the post-fire recovery process, historic preservation and adaptive reuse are a tool to build economic development and housing capacity. The City of Las Vegas has a well-established historic preservation program that has aided its economy by drawing tourists and creating spaces to hold public events. Las Vegas is registered as a Certified Local Government (CLG) within the state of New Mexico, which means the city implements preservation ordinances (NMHD:CLG, n.d.). Las Vegas’ preservation ordinance has a Cultural Historic Overlay Districts Zone that protects and monitors the use and rehabilitation of historic structures and sites within its boundaries (City of Las Vegas, 2005).

Different levels of government can apply for CLG status in the state, thereby gaining access to federal funding and paving a path toward a planned historic preservation program. Residents and city governments are able to receive tax credits from the State Tax Incentive program for resources that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) (Historic Preservation Division & CLG Program, 2022). These resources can include housing and structures that are intended for commercial use. Both San Miguel and Mora counties have established historic resources listed on the NRHP and can utilize CLG status, and tax credits, to help address economic and housing needs.

Adaptive reuse is defined as reusing an existing building for a purpose other than it was originally designed (Prosoco, 2022). Adaptive reuse can be utilized to adapt historic or abandoned buildings to current community

needs. In the impacted area, housing is the most pressing identified post-fire need. In Albuquerque, the New Mexico Mortgage Finance Authority (MFA) has launched a program called “NM Affordable Futures.” This program highlights the need to preserve affordable housing units in the city and, when appropriate, implement adaptive reuse a means to do so (NM Affordable Futures, n.d.). Among San Miguel County leaders, there is a desire to take a hybrid approach to preservation and community development. Adaptive reuse is a recommended practice for addressing housing and economic concerns, from creating multi-family and affordable housing, developing more emergency shelters and communal spaces, and further building community capacity and resilience. There are currently many grant opportunities to explore through non-profits like the National Trust for Historic Preservation for community-based preservation and adaptive reuse projects, especially in rural areas and for communities recovering from natural disasters (Grant Programs, n.d.).

Recommendations for historic preservation and adaptive reuse can be enacted on a short to long-range timescale. Implementation can begin at any time and is flexible. Phase one of implementation is short-range and involves inventorying of historic resources, and vacant or unused structures. Phase two comprises of applying to opportunities for financial assistance, such as state tax credits or grants through non-profits. Depending on capacity, this can be carried out on a mid-range scale. Phase three carries out planned and funded projects, either on a mid to long-range scale, based on the project.

Bulk building permits for permit-ready plans eases and accelerates the homebuilding process. Pre-approved plans in multiple sizes and designs, such as freestanding houses, multiplexes, and accessory dwelling units, could streamline rebuilding in approved areas and even incentivize new homeownership in the impacted area. While developers have teams to support them, it is harder for individual homeowners to afford and navigate the permitting process. Bulk building permits with preapproved up-to-code house designs could ease

the homebuilding process for non-developers and potentially speed up workforce housing development.

If adopted as an ADU design such as the Permit Ready ADU policy implemented by the city of Sacramento (City of Sacramento, 2022), the designs could be useful for creating intergenerational and non-traditional housing by placing more housing on previously single-family lots. Zoning changes would need to accompany this in some areas.

Bulk Permitting for pre-approved housing plans can be enacted on a short to mid-range timescale, dependent on city and contractor capacity. The permits speed up home-building on the home-buyers end, but must be pre-approved by the county. Once a licensed architect or contractor has submitted the plans to the county for approval, they can be permit-ready. Additionally, if the housing form deviates from what is allowed in current zones, zoning changes would need to accompany the permits.

There are existing opportunities to create affordable housing in the city of Las Vegas because of the city’s Affordable Housing Act (AHA)-compliant Affordable Housing Plan. However, there are also more land use zoning restrictions within the city than in the rest of San Miguel County. Outdated zoning imposes a rigid and ultimately unhelpful urban form. Zoning reform, mentioned in the Las Vegas 2020 Comprehensive plan (p. 91). Zoning changes in Las Vegas should strive to generate flexible space while maintaining the area’s regional character, and should encourage intergenerational and novel living arrangements, increasing the availability of live-work spaces.

Elmo Baca, member of the San Miguel Long Term Recovery Group, owner of Las Vegas’ Indigo Theater, and Las Vegas Community Foundation Board Chair noted that around the historic Las Vegas Plaza there is utilization of live-work space with storefronts below and housing above. This multi-housing model could be expanded beyond the plaza to accommodate

changing workforce needs and preferances for shorter commutes. Increasing density in the city by removing single-family zones is being explored by cities across the U.S. An example city closer to the size of Las Vegas than some is Walla Walla, Washington, population 33,000, a city that made significant zoning changes, such as “the consolidation of single-family zoning into a single lowdensity zoning type, a wider variety of allowed uses in the lower density zone, a reduction of residential parking requirements, and more flexible accessory dwelling unit regulations” (Fesler, 2021).

In the Case of Las Vegas, plan recommendations include:

-Practice gentle density. Berg & Houseal (2023) cite a study by Daniel Kuhlmann that makes associations between increased property values and comprehensive plan changes that propose density increases.

-Allow duplexes and accessory dwelling units by right in single-family residential zones.

-Create and allow missing middle housing such as quadplexes, mansion apartments, and cooperative housing.

See Figure 62 for an example co-housing design by UNM DPAC architecture student Jing Qin.

Las Vegas with enought city government capacity, can implement zoning reform on a short timescale. A zoning overhaul is mentioned in the Las Vegas 2020 Comprehensive Plan, indicating existing interest in utilizing zoning changes as a tool to promote density and affordability. Additionally, there are many precedents for zoning reform across the country.

In New Mexico, the state anti-donation clause prohibits government contributions to “any person, association, or corporation” (New Mexico Finance Authority Oversight Committee, 2022). This prevents local municipalities from donating land or providing resources or funding to affordable housing. To enable the government’s legal donation of resources to affordable housing creation, the New Mexico legislature passed the Affordable Housing Act (AHA) in 2004.

The AHA requires that the local government create an affordable housing plan and an accompanying ordinance in order to contribute resources to affordable housing. Both the plan and the ordinance must be approved by the Mortgage Finance Authority (MFA). The MFA is a “quasi-governmental” organization that partners with municipalities, non-profits, for-profits, and other entities to increase housing access for low- and moderate-income renters and homeowners (MFA, n.d.). The MFA assists its partners in navigating AHA requirements. Once an ordinance is in place, donating bodies and allowable donations include:

For under-resourced county governments, creating and passing an AHA plan and ordinance will not materialize resources. It does legalize and facilitate the transfer of already existing resources. Similar to the watershed community engagement model proposed in this plan, a catalyst might be necessary. In the AHA, there are requirements for maintaining an affordability period; according to the National Association of Counties, County Commissioners can manage housing projects in all New Mexico Counties. For San Miguel or Mora County to manage a pilot housing project would require capacity building and adequate staff within the county. To the knowledge of the DPAC Planning Team, Habitat for Humanity is the only nonprofit developer working in the impacted area. There is a need for affordable housing oriented-developers in the impacted area.

Utilizing the approach laid out on the MFA website (MFA, n.d.), phase one of the AHA should be implemented in a short- to mid-range timescale, dependent on county capacity. Phase one is the initial phase wherein the counties draft the Affordable Housing Plans and Ordinances, the MFA approves the drafts, and the County passes them. In phase two, the government identifies a “qualified grantee” and in phase three, the affordable housing donation is made. The timeline for these actions is dependent on the existence of a qualified grantee and funds, land or another form of qualified donation, and could take place over a short, mid, or long-range timescale.

As wildfires become less of a seasonal occurrence and more of a year-round problem, it is important to consider how communities are developed in relation to their environment. Wildlife Urban Interface (WUI) is defined by the United States Fire Administration as, “an area where human development meets or intermingles with undeveloped wildlands and vegetative fuels.” There are two types of WUI: intermix and interface. Intermix is when development is interspersed with wildland vegetation, such as forested areas. Interface is development borders but is not interspersed with wildland vegetation. This can appear as a clear edge between wildlands and WUI development. As climate change exacerbates environmental conditions, development within the WUI faces increased risks from wildfires (U.S. Fire Administration, 2022).

The New Mexico Fire Planning Task Force (NM-FPTF) identifies WUI zones and communities most at risk from wildfires and develops codes and ordinances to further reduce threats, encouraging counties and communities to adopt these codes (EMNRD, 2022). Throughout the years, NM-FPTF has overseen the creation of Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPP). In New Mexico, the majority of counties have implemented CWPPs, including San Miguel and Mora counties. Both counties have identified and ranked communities by high risk, moderate risk, and low risk. The plans make recommendations for these communities as well as county-wide actions to create fuel breaks, defensible spaces, and reduce fuel loads (Anchor Point Group, 2018; The Forest Stewards Guild, 2019).

Both identify the need for improved evacuation routes, infrastructure, and fire-resilient building materials for homes and other structures. The Mora County CWPP cites that WUI-specific codes and ordinances be adopted and integrated for future development in the county.An example of a WUI code can be seen in the City of Santa Fe’s Escarpment Overlay District. In order to protect foothills and viewsheds in WUI zones, the overlay district sets a series of standards that properties and new development must follow. These standards often supersede the underlying base standards in a zoning district. The overlay district standards include fuel thinning and utilizing low burn risk vegetation in its landscaping. The district limits development given that the city has

to approve new developments as well as oversee the construction process. By limiting development in this wildland urban interface area, the chances of wildfire decreases. The city reports that having the overlay zone educates residents on WUI and good fire mitigation practices (Headwaters Economics, 2016).

The plan recommends that Mora and San Miguel Counties move forward with adopting WUI codes and ordinances on a county level and implement overlay zones. Taking these actions will increase the awareness of residents as well as increase resiliency for future fire events.

San Miguel and Mora Counties have already identified WUI zones and written CWPP’s with their own recommendations, so phase one could be enacted be on a short-range timescale implementing WUI-specific ordinances. Phase two involves educating communities and encouraging them to adopt community-specific ordinances to improve fire mitigation. Depending on community and county capacity, this work can be implemented on a mid to long-range scale.

Prior to the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fires, the communities within the boundaries of Mora and San Miguel counties had long sustained populations under a diverse economic system. The northeast region of New Mexico has a rich economic history, from Indigenous trade commerce based on ecological resources to colonized commerce under Spanish and later Mexican government rule.

More recently, the railway ushered in an expanding economy that thrived on shipping, tourism, and trade. The change in railway infrastructure, and subsequent employment, made Las Vegas the fastest-growing city in the Rocky Mountain West by the late 1800s. During

this time the city developed into a cultural hub of hotels, saloons, and dance halls; albeit divided by the ‘old town’ plaza Spanish architecture and the ‘new town’ Jeffersonian grid. This was the modern economic picture until the 1950s when I-25 was built, allowing potential visitors to pass through the area without stopping, thus crippling economic traction (Visit Las Vegas, NM). Within Mora County, substantive food systems have long contributed to a barter economic system, one that relied on abundant natural resources. Catastrophic fires and flooding amidst a changing climate further threaten the economic capacities of people who have thrived on diverse, small-scale, informal economies.

Economic development initiatives can occur at the municipal, county, and state levels. The key economic development groups in San Miguel and Mora counties are the New Mexico Main Street programs, County Planning and Zoning Departments, and the City Community Development Department. A consistent, strong tax base is key to building local government capacity, allowing departments to participate more actively in economic initiatives like purchasing homes for historic preservation.

Within New Mexico, businesses generate sales tax that boosts the local tax base. In the business community, this is known as Gross Receipts Tax (GRT), which in New Mexico is the bulk (36%) of the state’s revenue (New Mexico Voices for Children, 2021). Typically, GRT is passed directly to the consumer in the material cost of items. Thus, if the counties of Mora and San Miguel can increase their tax base through GRT this can increase their governmental capacity to have a larger workforce and stronger programming. GRT rates vary across municipalities and counties.

Figure 68 lists GRT rates for January-June 2023 (NM Taxation and Revenue Department n.d.). Note that higher GRT rates are in municipal areas, thus focusing business development in these regions will generate more GRT. Additionally, the UNM Bureau of Business & Economic Research estimates that Las Vegas-based businesses account for about 80% of the San Miguel county’s GRT (Mitchel, 2010).

Building economic resilience requires building a reliable economic base for people vulnerable to climate changecaused disruption in their daily lives. Additionally, economic development requires intergovernmental collaboration and community outreach. Within the impacted area, diverse economic drivers form the base upon which current assets are built. Within the region, there are assets that can strengthen the economic areas of agriculture, film, outdoor recreation, entrepreneurial initiatives, and mutual/informal sharing practices. Below are state and regional entities with targeted economic development strategies that recognize economic assets within Mora and San Miguel County. Additionally, the state Agricultural Resiliency Plan is discussed as a key resource for growing agricultural practices in a changing climate.

New Mexico Economic Development Department (NMEDD) is the statewide entity striving to increase

economic opportunities for New Mexicans. To identify appropriate priorities, the NMEDD compiles a strategic plan that focuses on key work for each of their programs. Within the 2021 EDD Strategic Plan, Empower & Collaborate: NM Economic Path Forward, recommendations are made to focus on growing the economy in a few key industries (Stephen et al., 2021). Two of those key industries that are feasible in Mora and Las Vegas counties are outdoor recreation and film.

Outdoor Recreation is a growing industry in New Mexico, in part due to the bounty of wide-open natural spaces, which draw residents and visitors alike. The rural mountainous landscapes of Mora and San Miguel County are an ample opportunity for outdoor recreation. Popular outdoor activities that the area could offer to visitors are climbing, hiking, camping, fishing, off-road driving, snow sports, and horseback riding. To support outdoor recreation as an economic development tool,

the NMEDD created the Outdoor Recreation Division (ORD) to work with rural communities in developing outdoor recreation as an economic sector. The ORD jumpstarts community investments in outdoor recreation businesses, infrastructure, and conservation efforts. This is a recommended resource for individuals or businesses interested in expanding outdoor recreation economic opportunities in the region (Stephen et al., 2021).

Film is also a growing industry throughout the state and as an industry is eligible for multiple tax incentive programs. Filming in the regions of San Miguel and Mora County have roots going back to 1913 when the productions of silent westerns. Since then, more notable titles have been filmed there, including Easy Rider (1969), Red Dawn (1984), and the popular series Longmire (20112013) (Filming Location Matching). The film industry can create a range of jobs including production, casting, set costumer, electrician, art coordinator, photographer, stunt coordinator, and even drivers (Crew Calls). Additionally, the film industry can support the utilization of numerous historical sites and buildings that are unique to the area’s architecture.

North Central New Mexico Economic Development District (NCNMEDD) is the regional Council of Governments for the following northern counties: Santa Fe, Rio Arriba, Taos, Colfax, Mora, San Miguel, Los Alamos, and Mora Counties. The main purpose of the NCNMEDD is to assist local governments with community and economic development projects by offering planning tools and technical assistance for regional development of comprehensive economic plans. This support is important to enhance local small business initiatives.

Within the San Miguel and Mora County regions, climate change is impacting centuries old agricultural practices that have sustained generations of families. An example of this is how acequias have become non-operational following the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire. These acequias are vital for agricultural practices, which are now threatened by fire and flooding disasters. In San Miguel and Mora County there are about 1,870 farms. However in Mora county the average net farm income is higher, $9,256 compared San Miguel’s negative $1,156 in net farm income. Thus economically speaking, Mora County has more capacity to develop the agricultural industry.

It is important to note that agricultural production is not solely an economic means to make money, it is also a tool for subsistence living. In this form, agriculture takes on a mutualistic relationship, whereas the market is cooperatively managed as a common group based on mutual arrangements (Lloveras et al., 2020). In a mutual economy, workers directly control the means of production and exchange without relinquishing profit to a central authority. Within the regions of Mora and San Miguel County this may be practiced in communal sharing of products achieved through means of hunting, farming, and ranching. The New Mexico Agricultural Resiliency Plan supports this practice through recommendations to conserve wildlife habitat and water supplies that are detrimental to agricultural practices. Additionally the plan recommends resources and training to develop the next generation of farmers, branding on New Mexico grown products, and improving infrastructure to reduce waste and increase composting practices (NM First & NMSU, 2017).

The timeline for economic development activities will operate on a short, mid, and long-term range. Short term activities will need to focus on environmental remediation and prevention of further social disparities; such as getting people housed and ensuring basic needs are taken care of, such as access to clean water. Mid-term activities should focus on economic development in a few key industries. This can occur by identifying current capacities to scale up the industries of agriculture, film, outdoor recreation, entrepreneurial initiatives, and mutual/informal sharing practices. Once people are operating at a sustained economic capacity, the region can focus on establishing a long-term economic base for communities to withstand a changing environment. Long term outcomes are possible with an equal part focus on social determinants of health (chronic disease, access to healthcare services, behavioral health prevention and treatment), and building a sustainable tax base driven by local economic industries that represent the diverse geographic history that has sustained an array of communities for centuries.

Pre-fire vulnerabilities were hotter, drier weather, and extensive drought due to climate change. Both counties already operated with limited water supply, storage inadequacies, and consumption restrictions. The fires and flooding caused ash and debris contamination of the rivers and wells and significant damage to the existing water infrastructure. The infrastructure was inadequate to treat the contaminated rivers, which led to a threat of no drinking water in the City of Las Vegas. In both communities, concerns about contaminants in the surface and drinking water of private and small water systems were raised in the aftermath of the floods and fires.