CALIBRE12 .1 Thenew J12inexclusive blue ceramic, designed andassembled by theCHA NELManufacture CA LIBR E12.1self-windingmovement, chronometer-certified by theCOSC. SwissOfficial ChronometerTesting Institute.

CALIBRE12 .1 Thenew J12inexclusive blue ceramic, designed andassembled by theCHA NELManufacture CA LIBR E12.1self-windingmovement, chronometer-certified by theCOSC. SwissOfficial ChronometerTesting Institute.

THIS TIME OF YEAR IS ALWAYS ESPECIALLY ENJOYABLE AT GOODWOOD, when the spring flowers, trees and hedgerows on the Estate first burst into life (you can read all about the mysteries and rituals of hawthorn on p26). Of course it’s also the time when we are preparing for Members’ Meeting, which will once again kick off the historic racing season in style (p30), and finalising plans for Goodwoof, our annual celebration in May of all things canine, which has fast become one of the best-loved fixtures in our calendar. This year, dachshunds will be enjoying their moment in the sun, while the popular Barkitecture competition returns, with Kevin McCloud once again taking charge of the judging. Read how seriously he takes his duties on p18. We also talk to five well-known dog lovers about the lessons their dogs have taught them (p58).

In May we will celebrate the opening of the Goodwood Art Foundation, a major creative development for the Estate, which we have been working on for many years. We are thrilled that the Foundation’s first show will feature new work from Rachel Whiteread, in both the outside spaces and indoor pavilions. You can read all about the Foundation on p50 and we very much hope as many of you as possible will come along to share the opportunity to enjoy world-class art in the heart of the South Downs.

Elsewhere in the issue we meet disco queen and regular Goodwood guest Sophie Ellis-Bextor (p40), we share new insights into the psychology of speed (p64), and discover why eating well can make us happier (p92). And last but definitely not least, we look at what makes a truly memorable party (p76). We’ve hosted many of them at Goodwood over the past 300 years, so we have some secrets to share.

I very much hope to welcome you to Goodwood soon.

Emily Maitlis

Award-winning journalist and broadcaster – and now host of chart-topping podcast The News Agents – Emily relies on her trusty whippet, Moody, as a running companion to help her unwind after work. She is one of the high-profile dog owners who share what their canine companions bring to their lives, on page 58.

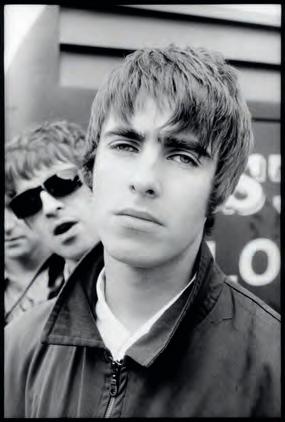

Marek Kohn

Brighton-based author and journalist Marek often writes on the interplay between scientific understanding and social norms. For this issue, he takes a deep dive into what happens to the human body when we travel at speed. Marek’s book Dope Girls has recently been adapted into a major drama series for the BBC.

One of the UK’s best-loved writers on mental health – his books include Reasons to Stay Alive and The Midnight Library – Matt is another contributor to our feature in praise of dogs (ahead of Goodwoof 2025, Goodwood’s celebration of all things canine). He reveals how his Labrador, Bruce, helped him recover from depression.

An art writer who contributes to titles including Apollo and the Financial Times, for this issue

Emma talks with celebrated artist Rachel Whiteread as part of her feature on a major new launch: the Goodwood Art Foundation. Read about the opening exhibition from Whiteread, and more about the foundation, on page 50.

Rebecca Seal

Can eating particular foods boost our mood and enhance our mental health? In search of sound scientific thinking and advice, journalist and author Rebecca speaks to Goodwood’s gut health expert Stephanie Moore, on page 92. Rebecca’s latest book is Be Bad, Better: How Not Trying So Hard Will Set You Free (Souvenir Press).

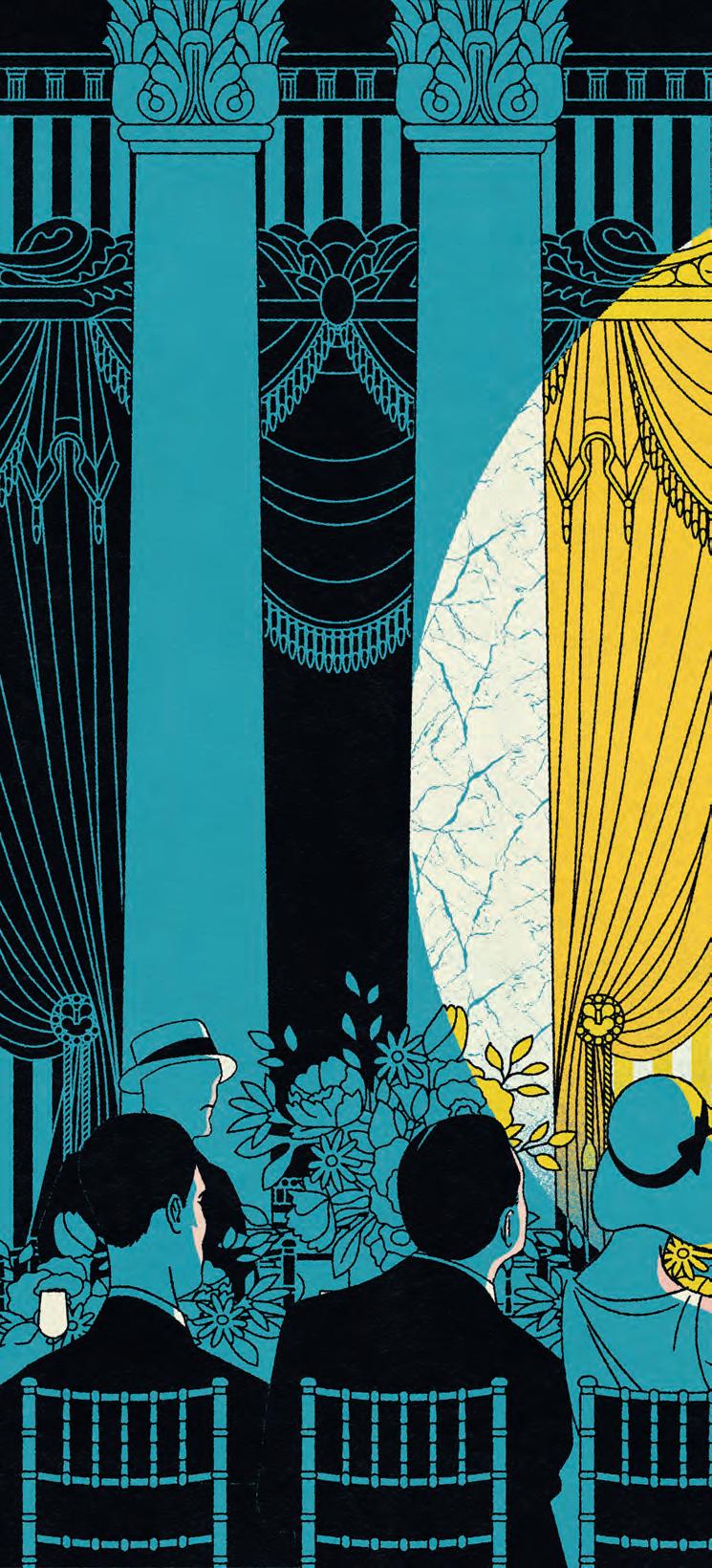

The illustrator of our feature on extraordinary parties at Goodwood, on page 76, Timba is a multi-disciplinary graphic artist. He describes his work as “often characterised by a sense of nostalgia and childhood memories” and has created imagery for Little White Lies, Disney, ESPN, Mr Porter, Nike, Wired and many others.

Editor

Sophy Grimshaw

Art director

Vanessa Arnaud

Editorial directors

James Collard

Gill Morgan

Creative director

Sara Redhead

Sub-editor

Damon Syson

Picture editor

Sharon Martins

Project director

Sarah Glyde

Goodwood content director

Will Kinsman

Goodwood managing editor

Jennie Gott

Goodwood junior picture editor

Max Carter

For all advertising and editorial queries, please contact Goodwood via magazine@goodwood.com

Goodwood Magazine is published on behalf of The Goodwood Estate Company Ltd, Chichester, West Sussex PO18 0PX, by Uncommonly Ltd, 30-32 Tabard Street, London, SE1 4JU. For enquiries regarding Uncommonly, contact Sarah Glyde: sarah@uncommonly.co.uk

© Copyright 2025 Uncommonly Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission from the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure the

of the

contained in this publication, the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors it may contain.

WE DEVELOP DOPAMINE BY ENGINEERING HIGH-PERFORMANCE CARS. THIS ONE COMES WITH THE FULL POWER OF 585 HORSES.

AS WE BELIEVE IN TRUE DEDICATION, WE ALSO ADHERE TO A SPECIAL PHILOSOPHY: “ONE MAN, ONE ENGINE.” THAT MEANS THE AMG COMBUSTION ENGINE IS BUILT BY ONE PERSON PUTTING THEIR WHOLE HEART INTO IT.

FOR YOU TO FEEL ALIVE.

BECAUSE IT’S MERCEDES-AMG.

BOOK YOUR EXTENDED TEST DRIVE* TODAY AT MERCEDES-BENZ.CO.UK

Official government consumption for the Mercedes-AMG SL 63 4MATIC+ combined: 21.1-21.2 (mpg) 13.4-13.3 (l/100km) CO2 emissions 303305g/km. Figures shown may include options not available in the UK. For comparison purposes only. Real world figures may differ. Figures may vary according to factors such as driving styles, environmental conditions, road conditions and accessories fitted. Further information about the test used can be found at www.mercedes-benz.co.uk/WLTP. Correct as of print, 02/25. *T&Cs apply. Extended test drives, subject to availability, 25+.

Contacts 16

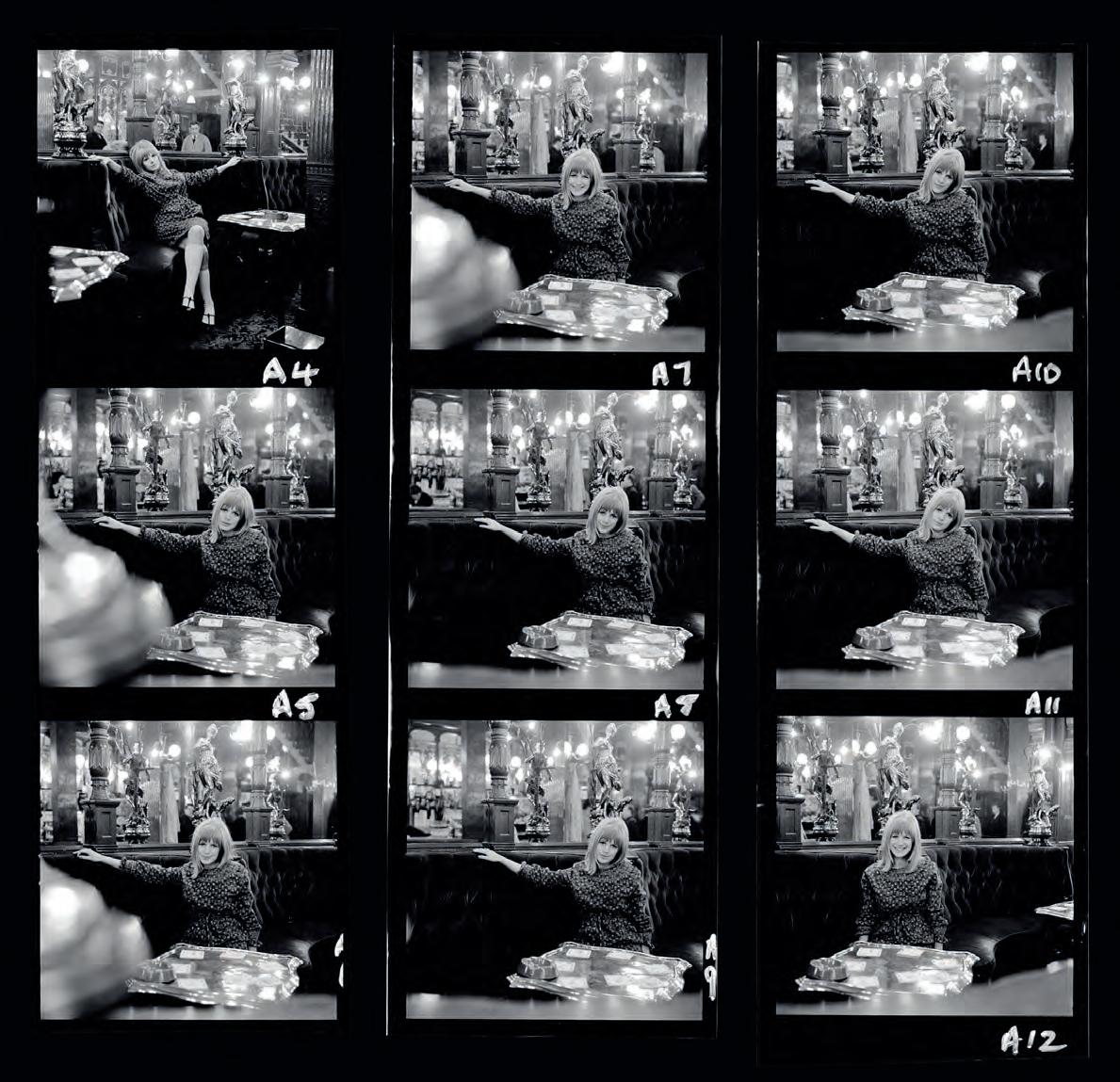

Gered Mankowitz, Marianne Faithfull, 1964

In the doghouse 18

Barkitecture at Goodwoof 2025

Personal best 21

Cycling glory could be yours

Perfect scents 22

Goodwood’s fragrant new candles

The long and the short of it 24

In praise of the dachshund

Bringing in the May 26

Hawthorn’s pagan power

Cool Britannia 28

The Britain in Pictures book series

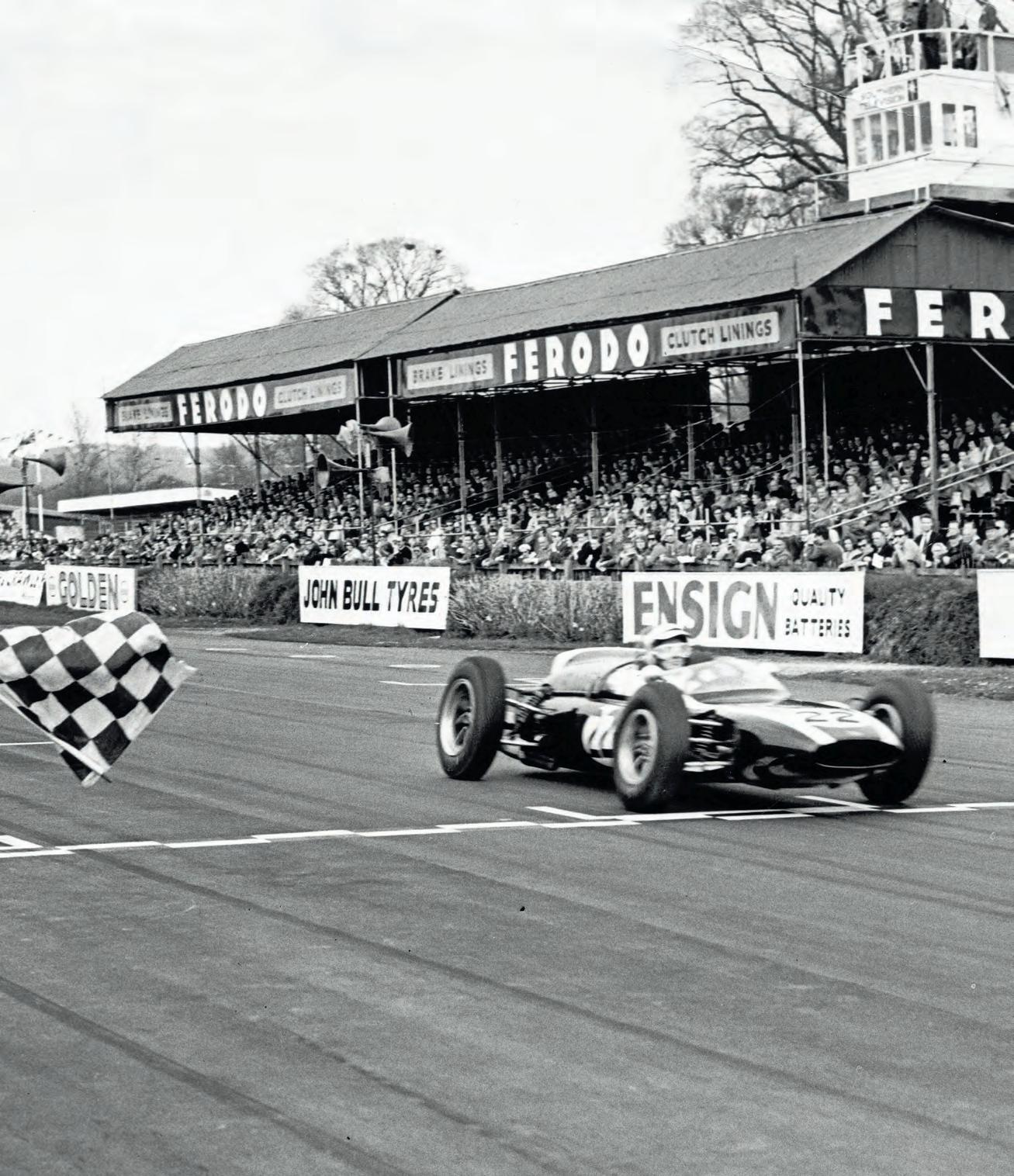

Glory days 30

Recalling Goodwood’s F1 history

China syndrome 32

Rural-themed crockery

There’s nothing like a dome 35

Goodwood House renovations

Eating for victory 36

VE Day memories, 80 years on

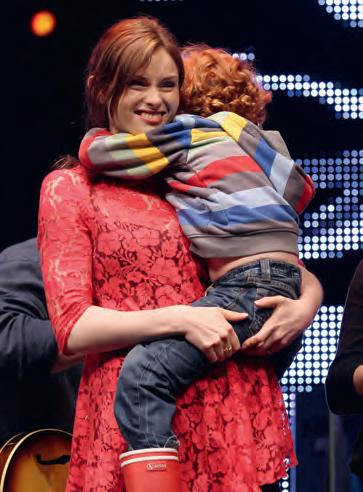

“I’ve done so many festivals and shows where I’ve been like, ‘Can anybody hold the baby while I sing?’”

Knowing she’s on the road to something amazing :

Mastercard is proud to champion women in motorsport, celebrating the heroes of today and inspiring the trailblazers of tomorrow.

Detail from Rachel Whiteread’s Detached 2, 2012

“SEEING A GREAT PIECE OF ART CAN TAKE YOU FROM ONE PLACE TO ANOTHER,” says the celebrated British artist Rachel Whiteread. “It can enhance daily life, reflect our times and, in that sense, change the way you think and are.” Whiteread is perhaps best known for her casting technique, through which she creates new sculptural artworks that in some way record or respond to existing objects or spaces. In the words of Whiteread’s gallery, Gagosian, “Through casting, she frees her subject matter – from beds, tables and boxes to water towers and entire houses – from practical use, suggesting a new permanence, imbued with memory.”

The detail seen on our cover is from the artwork Detached 2, 2012.

An eponymous Rachel Whiteread show leads the programme at the Goodwood Art Foundation, a major new arts venue set in the grounds of the Goodwood Estate. Visitors will be able to see a new, site-specific sculpture by Whiteread, as well as some of her previous work, and that of other international contemporary artists.

For more on the Goodwood Art Foundation, and to hear from Rachel herself, turn to page 50

Noted: people, objects, news and ideas, from the folkloric significance of hawthorn and a speed-cycling challenge to the irresistible charm of the dachshund

WORDS BY SOPHY GRIMSHAW

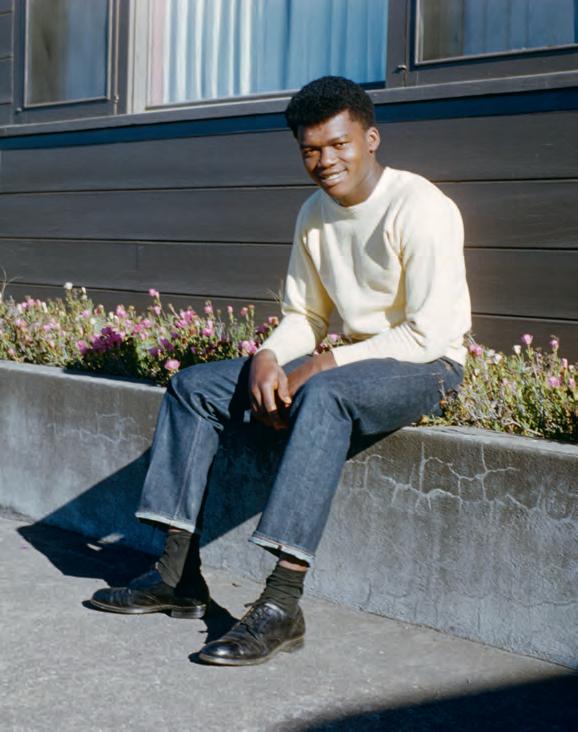

Legendary rock photographer Gered Mankowitz on shooting an almost unknown Marianne Faithfull in a London pub

Gered Mankowitz was in the early days of his photography career in 1964 when some friends, the musical duo Chad & Jeremy, introduced him to a fellow singer they had met on a TV show, Marianne Faithfull.

At the time, Faithfull – who died in January – had one single to her name, As Tears Go By, but she had not yet released her debut album or begun her high-profile relationship with Mick Jagger.

“She was beautiful, funny, bright and clever, and I asked her immediately if I could take some photos of her,” says Mankowitz. It was the start of a working relationship that would see him capture several seminal images of the singer, some of the most iconic of which were taken in a pub, the Salisbury, in London’s Covent Garden.

“I thought this pub might make a fantastic location for her, so we went over there one morning,” Mankowitz recalls. “The landlord had no objections to us taking some photographs, and I just used the available light. We chose this corner because it encapsulated the pub so perfectly. I liked seeing the guys in the background, who just happened to be in there having a pint, but Decca Records didn’t like them being in it. They later chose a different photo of mine, also taken during this session, as her album cover [for Come My Way]. But in my

favourite photo of these she has her arms open and is unsmiling. It’s intriguing. There’s an innocent sexuality to it; she looks welcoming, as though you might be able to come and say hello to her. It was only really when I had an exhibition of my work, in 1981, that I was able to draw people’s attention to it.”

Of his photography career in general, Mankowitz says: “I was interested in the viewer having a sense of contact with the person, whether it’s Kate Bush, the Rolling Stones or Jimi Hendrix. They’re the hero of the shot and, in a way, I shouldn’t intrude.” He describes this image of Faithfull as “important to me on many levels. Because of my photos of Marianne, her manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, became aware of me, and I was also able to photograph the Rolling Stones.”

How will he remember her? “She was so clever and well-read and became just an extraordinary artist. We had a 60-year friendship, last speaking just before Christmas 2024. But I think I’ll always remember her as that bright and beautiful friend that I met in the 1960s. I remember sitting in the pub with her, and laughing.”

Purchase a print of Gered Mankowitz’s image of Marianne Faithfull, or his contact sheet, at iconicimages.net

WORDS BY ALEX MOORE

Goodwoof’s Barkitecture sees renowned studios vying for top-dog status with spectacular kennel designs

For the fourth edition of Barkitecture, Goodwoof’s star-studded kennel design competition, the brief “From Nature; For Nature” was given to entrants. “Personally, I’m interpreting that as the ways dogs experience the natural world,” explains Kevin McCloud, the face of Channel 4’s Grand Designs, who will once again lead the competition’s judging panel. “But because dogs are so sophisticated, it’s about how they interpret the natural world for us. How do we see the world through their eyes, and how can that enrich the relationship?”

Let’s call it a loose brief, one that should allow the teams plenty of wiggle room. Among the roster of globally renowned studios taking part this year will be LA-based SOM Architects, award-winning Sussex firm Randell Design Group, and the Earl of Snowdon (known professionally as David Linley), with Wales-based Hall + Bednarczyk returning for a fourth time. Past entrants have included Foster + Partners, Grimshaw, and Birds Portchmouth Russum Architects, who won in 2022.

“Historically, entrants rise spectacularly to the brief and treat it like a really serious project, as if it were a concert hall,” says McCloud. “I love the dedication and the quality of the finished samples, which are subsequently sold at auction [for charity]. Many of those kennels from previous years are still being used, which is testament to their longevity and the care and the craftsmanship with which they’re made.”

So what will the judges (among whom will be a number of discerning dogs, brought in especially) be looking for? “Well, I’d like to say one that automatically looks like it’s appropriate for a dog, but that’s not always the case,” says McCloud. “Some look more sculptural, and yet the dogs can really relate. Gianni Botsford won in 2023 with the most beautiful abstract design. Ultimately it’s about how dogs respond, so in a way that becomes a sort of self-fulfilling aspect of the exhibit.”

See the 2025 Barkitecture designs at Goodwoof, 17-18 May. Tickets are available at goodwood.com

Mpg (l/100km) (weighted combined): 141.2 to 166.2. CO₂ emissions (weighted): 3945 g/km. Electric energy consumption (weighted combined): 25.7 to 27.6 kWh/100Km (N.Comp). Equivalent all electric range: 37 to 41 miles. These figures were obtained using a combination of battery power and fuel. The BMW M5 Touring is a plugin hybrid vehicle requiring mains electricity for charging. Figures shown are for comparability purposes. Only compare fuel consumption, CO₂ and electric range figures with other cars tested to the same technical procedures. These figures may not reflect real life driving results, which will depend upon a number of factors including, accessories fitted (postregistration), variations in weather, driving styles, fuel type and vehicle load.

WORDS BY ALEX MOORE

Want to be a record-breaker on two wheels? Then aim for the Fastest Known Time on an obscure route

In June 2025, former professional cyclist Molly Weaver will attempt to break the world record for the fastest circumnavigation of the UK coastline by bike. If all goes to plan, she’ll cycle an average of 370km every day for three weeks, shaving a day off the current record set by Nick Sanders in 1984. That’s the same Nick Sanders MBE who has circumnavigated the world 11 times, eight of those on a motorcycle, and who in 2005 broke his own record, taking just 19 days and four hours (averaging around 1,600km a day) to make a lap of the planet – on a Yamaha R1.

Being the fastest is probably something that appeals to every semi-serious cyclist, but for most of us, it’s just not within our abilities to achieve such greatness. Unless, of course, you focus your attention on slightly more obscure routes, like the 338km Badger Divide between Inverness and Glasgow, or the 155km South Downs Way (Classic Route) from Eastbourne to Winchester. The latter record, incidentally, is held by social entrepreneur Mike Ellicock, who completed the journey in six hours and 51 minutes. How do we know? Because Ellicock captured his ride on Strava and has since

logged it as a Fastest Known Time (FKT) on a dedicated website-cum-leaderboard presided over by Weaver.

“I have a difficult relationship with racing,” says Weaver, who currently holds eight FKTs, including the legendary Lakeland 200, arguably the toughest mountain bike route in the UK. “But for some reason I’ve found that attempting to break records has only ever been fun. Perhaps it’s the lack of external pressure.”

Weaver is far from alone in preferring to race the clock over picking off the peloton. Indeed, the time trial format became hugely popular during lockdown, when traditional racing was put on hold, and has shown no signs of slowing down since. Thousands of cyclists around the UK now compete for FKTs on hundreds of established routes. The only rules: you have to ride solo and the route must be further than 150km, 20 per cent of which is unpaved. To submit a time, cyclists should send in the log from their bike computer or GPS tracker and Weaver and the team will endeavour to validate the attempt. All being well, you’ll have bagged yourself a world record, albeit one that Guinness probably wouldn’t get out of bed for.

WORDS BY GILL MORGAN

Acclaimed chandler Rachel Vosper has teamed up with Goodwood to create two evocative new candles inspired by the Estate’s flora

As job titles go, “chandler” has a whiff of the medieval about it. But in fact, the art of candle making has had a revival in recent years and Rachel Vosper, who has created two candles for Goodwood, is at the forefront of the trend.

Vosper discovered her calling on a beach in Barbados two decades ago, when she had a chance meeting with a candle maker. She visited his studio the next day, and was captivated. Today at her store in Belgravia, she specialises in creating bespoke, hand-poured candles that magically evoke the essence of a person or place.

Vosper’s enthusiasm for her craft bubbles over as she explains this mysterious process: “I always start by asking people to describe their favourite smells,” she explains. “Anything from a parent’s cologne to a memorable holiday destination. It often releases a complex mix of emotions and nostalgia.” Using a fragrance wheel to explore the different scents with the client, Vosper gradually builds up the fragrance, layering and balancing the base notes –those heady scents like cedarwood, patchouli, white musk and bergamot – with more tempered middle notes and finally lighter, more floral, top notes.

And what of the Goodwood candles? “My main feeling was that I wanted to do the Estate justice,” she says, describing her research trip to Goodwood last spring to seek inspiration for

the unique scented candles she has created in collaboration with the Duchess of Richmond. “It’s an extraordinary place,” she continues. “There were so many elements to encapsulate. It was a joy to work with the Duchess, who has such a deep knowledge of the Estate – and of fragrance.”

The two resulting candles – called White Flowers and Woodland – are inspired by the flora of Goodwood. Unsurprisingly, given the glorious Cedars of Lebanon that have graced the parkland for almost 300 years, cedarwood is a key base note in each. White Flowers takes inspiration from the scents of spring, when the first blooms at Goodwood burst into life, including the famous white magnolias that lend their name to the Magnolia Cup ladies-only charity race. Woodland, meanwhile, is an earthier fragrance, inspired by the opposite end of the season.

Fragrance is a highly subjective field and Vosper is illuminating on the subject of how we experience scents in an entirely individual way, influenced by a heady mix of memory, emotion and body chemistry. The olfactory equivalent of Proust’s madeleine, a scent can evoke a particular time and place in a way that no words can. Vosper’s great skill is being able to help transport us there.

Rachel Vosper’s candles are available at the Goodwood Shop, Goodwood Motor Circuit and online via goodwood.com/shop

WORDS BY DAMON SYSON

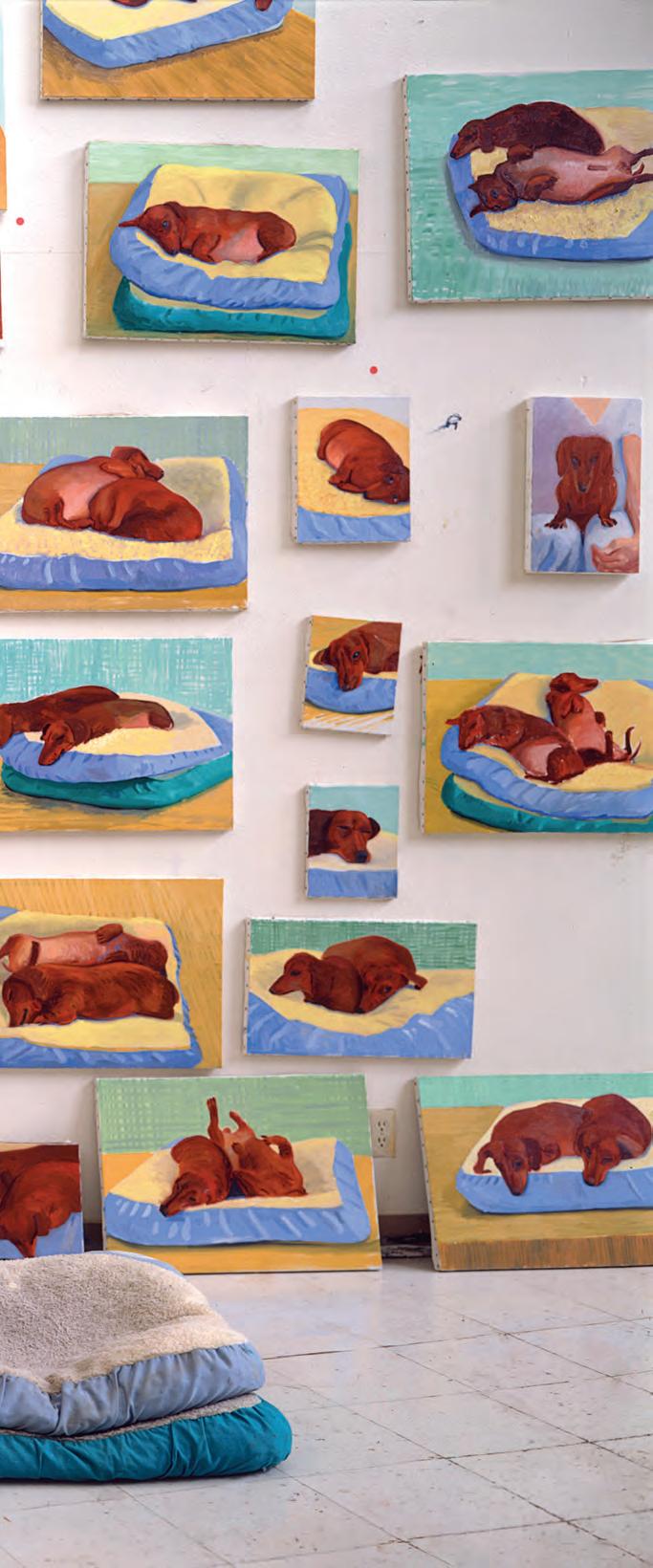

With dachshunds taking centre stage at Goodwoof 2025, we trace the breed’s enduring appeal, from its badgerhunting origins to inspiring celebrated artists such as Andy Warhol and David Hockney

As any owner of a dachshund will tell you, what this short-legged, longbodied canine lacks in stature, it more than makes up for in personality. Famed for its bravery, energetic temperament and unexpectedly deep bark, the so-called sausage dog (or wiener dog in the US) currently ranks fourth in the list of most commonly owned breeds in the UK.

And its popularity is growing. In recent years, the dachshund’s expressive eyes and oversized ears – not to mention a surprising air of imperiousness – have made it a big hit on Instagram. Dachshunds also seem blissfully unaware of their diminutive size, as attested by TikTok star Bosco (@boscoandhisbigstick) whose clips pull in up to 50 million views.

Originating in Germany during the 18th century, the dachshund (translation: “badger dog”) was bred to flush out burrow-dwelling prey, its slim form giving it access to subterranean spaces other hounds couldn’t reach. Today, the breed comes in two sizes, miniature (weighing 5kg or less) and standard (usually 9-12kg), and with three types of coat: smooth-haired, wire-haired and long-haired.

If you happen to own a dachshund, you’re in stellar company, joining a list that features JFK, Audrey Hepburn, Jack Nicholson, Marlon Brando and Marilyn Monroe. Current devotees include Nicole Kidman, Dita Von Teese and pop icon Adele, who has a dachshund named Louis Armstrong. Dachshunds have also served as canine muses to some of the world’s most famous artists. David Hockney, for example, painted hundreds of portraits of his two sausage dogs, Stanley and Boodgie, including many of them in his 1998 book, David Hockney’s Dog Days.

Andy Warhol was another notable fan. In 1973 he purchased a smooth-haired dachshund puppy whom he named Archie. The A-list hound accompanied Warhol everywhere – including restaurants, where he would be hidden under a napkin – and he was a regular at legendary nightclub Studio 54. Warhol later acquired another dachshund, Amos, to provide companionship for Archie, and the pair were immortalised in his 1976 series of artworks inspired by cats and dogs.

Another artist who fell hard for the charms of these cylindrical pooches was Pablo Picasso, whose regular companion, Lump (named after the German word for “rascal”), was a dachshund owned by American photographer David Douglas Duncan. Lump stayed with Picasso for six years at his villa in Provence, and featured in several of his works, including no fewer than 15 of the artist’s 44 studies of Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas. In 2006, Duncan published a book of photographs entitled Picasso & Lump: A Dachshund’s Odyssey.

Yet despite this breed’s celebrity fans and undoubted allure, it does carry two caveats. Dachshunds have a one in five chance of developing intervertebral disc disease (IVDD), which can result in paralysis. They are also notoriously stubborn, though bizarrely this only tends to endear them more to their owners. As dachshund-lover EB White, author of Charlotte’s Web, put it: “Of all the dogs whom I have served, I’ve never known one who understood so much of what I say or held it in such deep contempt.”

WORDS BY MARK HOOPER

As its distinctive blossom begins to appear once more in our hedgerows, we examine the folkloric myths and pagan significance of the hawthorn

A frequent sight in rural parts of the UK, including the Goodwood Estate, the distinctive white – and sometimes pink – blossom of the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) traditionally heralds the arrival of spring.

Around 200 species of Crataegus have been identified, and can be grown as hedges, shrubs or trees. They provide a rich habitat for wildlife, with a bountiful supply of nectar in the flowers, while their autumnal berries are a source of food for birds. They’re not bad for humans, either: for centuries, the tangy, nutrientfilled hawthorn berry has been used as a herbal remedy for ailments such as migraines, high blood pressure, heart disease, digestive problems and insomnia. This is largely due to the antioxidants the berries contain, but also because of a longheld superstition that the hawthorn will bring luck in love, as well as wealth and happiness.

Because it usually flowers around May Day (although sometimes blossom can appear as early as April or as late as June), the hawthorn is associated with many springtime celebrations. Hawthorns (from the Anglo-Saxon “Hagedorn” or “hedge thorn”) were used as the original maypoles, with their flowers woven into spring garlands, crowns and wreaths during rituals to celebrate the pagan festival of Beltane.

As a symbol of nature’s rebirth and of fertility, the hawthorn has also been used for centuries to decorate thresholds – although superstition sometimes holds that it can bring bad luck if it is brought inside the house, with many during the plague likening the plant’s distinctive smell to that of death. This is most likely because the organic compound trimethylamine is found both in hawthorn blossom and decaying tissue (it’s also the cause of the pungent odour given off by fish).

Hawthorn has proved consistently useful in hedges to mark the edge of a landholding; the thorns provide protection both physical (from cattle) and metaphysical (from spirits). In some traditions it was also thought to mark the threshold to the Otherworld of faeries and – blending pagan and Christian traditions – it can often be found in churchyards, and is sometimes said to have been used in Christ’s crown of thorns. So think twice before chopping down a hawthorn, as ancient wisdom warns that this is sure to bring bad luck. Just ask the Roundhead who cut down the Holy Thorn of Glastonbury on the orders of Oliver Cromwell – and was immediately blinded by one of its tiny flying spikes.

WORDS BY GILL MORGAN

Conceived as an exercise in patriotic wartime propaganda, the Britain in Pictures series is now catnip for design-lovers

They say don’t judge a book by its cover, but for many collectors of the increasingly coveted 132-book series Britain in Pictures a moreish array of gorgeous complementary colours – are one of the most alluring things about them.

The series, published by Collins between 1941 and 1950, was the brainchild of Hilda Matheson, who was hired to undertake “special work” at the Ministry of Information during World War II. As part of a propaganda drive, she came up with the idea of commissioning leading thinkers of the day to write on aspects of British culture in order to raise national pride. And what writers she found. The roll call of names authoring these short guides is extraordinary, from George Orwell (The British People and Vita Sackville-West (English Country Houses (British Dramatists, no 32) and Cecil Beaton (British Photographers

Not that everyone leapt at the opportunity: Virginia Woolf wrote to a friend, “She asked me to write some damned book for some damned series. It was to be patriotic; at the same time intellectual; also badly paid.”

Conceived to be accessible, affordable and readable, the word length was short – essays were 12,000 words – and each volume elegantly slim at just 48 pages. Titles were grouped into nine main subject areas: history, literature, science, society, topography, arts and crafts, education and religion, medicine and engineering, and sport and natural history.

But it is surely those covers that make so many of us yearn to add just one or two more to our collections, mixing as they do a palette of striking shades with distinctive, characterful typography and simple line-drawings. The overall effect is beguiling: clearly vintage but deeply appealing to a contemporary eye. From striking pinks (English Children Flowers in Britain, no 65) to chalky blue (English Education green (English Letter Writers, no 81) and moleskin brown ( no 130), the colour palette could vie with Farrow & Ball’s chart as aesthetic catnip for design-lovers. The real joy comes when a decent number are displayed together, a gorgeous tile effect of bibliographic beauty.

As they were published in such high numbers, the volumes are easily found in second-hand bookshops, charity shops and online vintage sellers such as Abe Books, usually for around £10 each, although rarer editions or sought-after names can reach closer to £200. Complete collections can fetch thousands. Weaver Antiques, in Rogate, West Sussex, has some lovely examples, which owner Gary Shepherd explains came from the collection of renowned artist and critic Adrian Stokes. He confirms the enduring enthusiasm for the books.

And which titles, you may wonder, were the bestsellers of their day, as Britain faced existential threat? Barry Windeatt, keeper of rare books at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, which has its own collection of BIPs, feels there are salutary lessons to be found in those circulation figures. “By a wide margin it was The Birds of Britain, although Life Among the English, Wild Flowers in Britain and The English Poets were the next bestselling titles,” he writes in his blog. A cheering thought, perhaps, that as bombs rained down, the great British public were brushing up on their twitching skills.

WORDS BY DOUG NYE

Formula 1 history was made at Goodwood between 1949 and 1965 with a series of unforgettable races

After its inauguration in September 1948, the Goodwood Motor Circuit became the British venue for a series of high-profile international motor races. While it never aspired to hosting a Formula 1 World Championshipstatus British Grand Prix, the annual Easter Monday meeting on the circuit, from 1949-65, always included a formal Formula 1 race.

The first, on 18 April 1949, was dominated by Derbyshire haulier and pig farmer Reg Parnell; he drove an exotic, freshly imported Maserati 4CLT/48 and won comfortably. Roll on another year, Easter 1950, and “Uncle Reg” won again for Maserati. Argentine muscle-man José Froilán González was the champion at Easter 1952, but the 1954 meeting saw Parnell’s victorious return, this time in his private Formula 1 Ferrari 625.

Into 1955, Goodwood’s Glover Trophy F1 series began, backed by oil man Dan Glover. The inaugural race was won by Roy Salvadori in the Gilby Engineering-entered Maserati 250F, while the following year, Stirling Moss’s Maserati would take Glover Trophy honours, beating Salvadori in a sister car. In 1957, an extraordinary race saw young newcomer Stuart LewisEvans win in the cash-strapped Connaught team’s unpainted entry.

In 1960, in another memorable F1 race at Goodwood, Colin Chapman of Team Lotus saw his extrovert No 1 driver, Innes Ireland, claim the Glover Trophy. The motorsport landscape was about to change though, as a new 1.5-litre Formula 1 took effect, from 1961 to 1965. These were the years that saw ex-motorcyclist John Surtees win the 1961 Glover Trophy in a private “Lowline” Cooper from Graham Hill’s BRM-Climax, though Innes Ireland would win the Glover Trophy again in 1963, in a Lotus-BRM 24.

The era of F1 races at Goodwood would soon be drawing to a close, but there was time in 1964 for World Champion Jim Clark to win hands-down for Lotus, and once more on Easter Monday 1965, in what would be the last F1 feature race. For the circuit’s final year of frontline operation, 1966, the Easter Monday feature race would be run for less-fleet Formula 2 cars. The motor circuit would soon enter its long slumber, from 1966 to 1998, but, for a time, some extraordinary F1 history had been created right here in Sussex. This year’s Festival of Speed, 10-13 July 2025, will be taken over by the world’s largest celebration of 75 years of the Formula 1 World Championship

WORDS BY GILL MORGAN

A curated display of vintage crockery depicting country pursuits and rural scenes is a great way to give your interior the personal touch

After years of stark minimalist lines and fade-to-beige blandness, the characterful, layered interior style termed “maximalist” has made a triumphant comeback – indeed, interiors bible Architectural Digest has declared “immersive interiors” and “real personality” two of their key trends for 2025. Nowhere, perhaps, is this look exemplified to more charming effect than in the British country house, with its familiar tropes of squishably inviting sofas and chairs, elegantly patterned wallpapers and fabrics, book-lined walls and that crucial ingredient: charming mismatched china.

Cindy Leveson, the interior designer behind so many of Goodwood’s renovations, admits that tracking down lovely pieces of original china is “a bit of an obsession. I’m always looking – on eBay, at salerooms and at vintage shops.” Her tip is to land on a theme that is relevant to the house or its occupant and build a collection around that. “It really helps to pull it all together and tell a story,” she says. “So in Hound Lodge, because of the history and original purpose of the building, all the china I bought was related to horses, dogs, hunting and country pursuits. It’s niche, but it works.”

Luckily for Leveson, such “sporting” or country pursuits china was produced in huge quantities in the Victorian era. The leader in the field was porcelain maker Spode, founded in Staffordshire by Josiah Spode in the late 18th century. Hunting scenes abounded, with other makers such as Crown Staffordshire producing similar collections.

Elsewhere on the Estate, Leveson has leant into other themes with her collecting bug. At Farmer, Butcher, Chef, the objects displayed connect to farming and rural life, while her recent renovation of the Goodwood Cottages – four charming holiday properties, which are available for rental stays – includes flower- and fruit-decorated plates evoking the quintessential rural cottage garden. “Much of this china would have been made for display, not eating off. The Victorians were great at this fanciful stuff. It’s a cost-effective way of adding interest to an interior: each piece is a one-off, so it makes a room feel individual and adds character.”

So take another look at that box of granny’s china in the attic; it might be just the thing for a stylish upgrade of your kitchen walls.

Welcome to the future: Your Al and your data, working together in real time as a sovereign platform-anywhere, anytime, any way you need it. Welcome to EDB Postgres® Al

WORDS BY JAMES COLLARD

Work is underway to restore the iconic copper domes that give Goodwood House its distinctive silhouette

“A major character-defining feature” is how the architect Ptolemy Dean described the four copper domes sitting atop the facade of Goodwood House in his “heritage statement”. This was written several years ago now, in support of the Goodwood Estate’s application to restore the domes – a process that got underway in late 2024. It is being done in such a manner that they will continue to look just as they always have, oxidised into that distinctive bluey-green colour. The restoration’s project manager, Patrick Pica, is surely not being hyperbolic when he describes this as “an iconic project for Goodwood”.

The domes and the cylindrical towers they crown were first added in the early 1800s as part of the ambitious extension of James Wyatt’s enlargement scheme, which transformed what had been a much smaller hunting lodge into a grand neoclassical country house deemed more worthy of the Dukes of Richmond. Visually, they pull the long facade together, with Dean likening them to the hinges of the doors on a vintage motor car – as if Wyatt had seen a vision of a future in which this pastoral setting would occasionally roar to the sound of motorsport.

The current restoration is almost certainly not the first, as the typical shelf-life of a copper roof is around a century. But while there’s no record of any previous repairs, today’s makeover began with “building a business case for it”, followed by Dean’s heritage statement, a condition report, and consultation with the Georgian Group, which said the proposals struck “a sensible balance between maintaining visual integrity and taking advantage of technical progress”.

And all this before the plans had even received the approval of Historic England. “After years of planning, it’s wonderful to have started work,” says Pica – one dome at a time, partly to husband resources, partly to avoid key moments such as Festival of Speed. But like a mechanic looking under the bonnet of a car that’s in for repairs, the restorers got more than they bargained for with the first dome. When the scaffolding went up and the cladding was removed – revealing a layer of horsehair and wooden boards, and below them, the rafters supporting each dome – all of the rafters turned out to be rotten. Recreating 73 rafters, no two identical, could surely be described as a labour of love, as well as of painstaking craftsmanship, but once done, the domes of that iconic roofscape should be good for another century or more.

WORDS BY JAMES COLLARD

Eighty years on from the original Victory in Europe Day, 2025’s Goodwood Revival will honour this joyful occasion

By day on VE Day in 1945, street parties were taking place everywhere in Sussex, from Chichester to Shoreham, where, astonishingly, the red flag of our Soviet allies would be raised above the Town Hall. By night, the grown-ups took to dancing – and very possibly more – while bonfires lit up the skies right across the Downs. At Southwick, Hitler was burned in effigy, a “guy” having been styled up as the Führer (who had killed himself a few days earlier) complete with uniform and an arm raised in the Nazi salute. For most children, though, it would have been the food, pooled from long-held reserves in the nation’s pantries and dished up at those street parties, that would surely have struck a chord. “Is peace like this every day?” one child is said to have asked, observing the cake, lemonade and ice cream being served. Things would continue to be scarce, of course. The war with Japan would carry on for several more months, and rationing continued well into the 1950s, by which time Europe would be divided by the Iron Curtain. But this day – 8 May 1945 – wasn’t the time for nuanced thoughts about a problematic future. It was the moment for celebrations.

The West Sussex County Records Office contains a trove of fascinating wartime photographs, many taken by gifted local photographers: barbed-wire defences and guns on the beach; child evacuees looking forlorn upon their arrival from London; rehearsals for air raids or gas attacks; teenagers posing beside a downed Luftwaffe plane; the D-Day armada sailing past on its way to Normandy in 1944. But here, the photographer’s lens captures a moment of pure joy, long-awaited, hard-won, and to be savoured – along with all that ice cream. VE Day will be celebrated at this year’s Goodwood Revival, 12-14 September 2025

Strategic financing solutions for fine art and automobiles

Access up to $250 million backed by the value of your collection

Visit sothebys.com/sfs to learn more and connect with a specialist

Timeless design that beats with an electric heart. The one you adore, now with even more to love .

The all-electric Macan.

Tales worth telling, from hosting the perfect party to the valuable life lessons we learn from our canine friends.

Plus: The Goodwood Interview with Sophie Ellis-Bextor

“I’ve done so many festivals and shows where I’ve been like, ‘Can anybody hold the baby while I sing?’”

Sophie Ellis-Bextor may have won our hearts during lockdown with her regular Friday night “Kitchen Disco”, but she could never have predicted what was in store four years later. The mother-of-five sits down with Julia Llewellyn Smith to discuss family life, nostalgia and how Saltburn changed her life

Sophie Ellis-Bextor couldn’t have ended 2024 more triumphantly. In the hour surrounding midnight, her New Year’s Eve Disco was broadcast on BBC1, featuring the singer performing a medley of disco bangers and greatest hits, before leading a chorus of Auld Lang Syne as Big Ben chimed. She was accompanied by a band that included her younger brother Jackson on drums and her husband Richard Jones, a founding member of rock/pop group the Feeling, on bass.

With the BBC show pre-recorded, Ellis-Bextor was in fact in New York City for New Year’s Eve, where she could be seen live on TV performing her hit Murder on the Dancefloor from Times Square in front of a huge crowd, as part of the city’s pre-countdown entertainment (alongside TLC, the Jonas Brothers and Carrie Underwood). “Those two gigs were pretty epic,” she says with a grin, sitting in a café around the corner from her home in Chiswick, west London. “And also quite funny because my relationship with the New Year is a bit mixed; I’ve had some good ones and some terrible ones. So, in a selfish way, to have my own lovely plan for the night was really cool.”

Of the BBC show, she says, “Being given a gig like that was such an honour, probably one of the highlights of my career. My husband and I put so much care into every detail surrounding it. We wanted to make sure people watching at home were given something escapist and fun and celebratory, so they felt a bit of optimism. I had some really sweet messages from people who weren’t part of a big gathering that night – some from people who were in hospital, another from a woman looking after her 90-year-old mother, who was up and dancing for the first time in ages.”

After this, the New York gig felt “like a glass of fizzy champagne to pop the cork on 2025”. It was still a big moment as until 2024, despite her 28-year UK career, Ellis-Bextor was unknown in the US. “I’d never even done a radio interview there,” she says. But suddenly, in January 2024, her deadpan voice was on repeat, coast-to-coast, after Murder – a song she co-wrote with Gregg Alexander in 2001 – went viral thanks to the memorable closing scene of Emerald Fennell’s black comedy Saltburn. The film’s star, Barry Keoghan, dances to the tune, completely naked, while moving through a series of empty rooms in the film’s eponymous stately home.

Keoghan’s dance became a TikTok sensation. “It has an evil triumph to it that ties in perfectly with the lyrics,” she laughs, approvingly. The song soared to number two in the UK Singles Chart, her first top-ten hit since 2007, and also into the US Billboard Hot 100 – her first-ever appearance on that chart.

“It was an exceptional experience; I never thought I’d be lucky enough to have this viral resurgence,” she says. “I was excited to be part of the film, and I liked it, but of course I didn’t know it was going to go crazy.”

Aged 45, and the mother of five sons, aged between 20 and six, EllisBextor ended up performing 110 gigs in 2024. “I’d had a really busy 2023 and the plan was for a slightly more measured 2024, but after Saltburn, every gap in the diary was full – and I loved it. I definitely have a lot of energy. I always like to make myself very busy, to use that energy up.” And 2024 was certainly a year when she managed to do that. She made her live US TV debut singing on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, before embarking on her first-ever headlining tour in the USA. Murder also led to her singing at the Baftas, popping up during DJ Peggy Gou’s headlining Glastonbury set, sold-out tours of Europe and Australia, and a performance at the Royal Variety Show in front of King Charles.

“It was an extraordinary thing to happen at this stage of my career, and I seized every opportunity with both hands,” she nods “Normally, successes aren’t about high-fiving and toasting each other, they’re more about a stepping stone to something else – like, my single’s done well so I might now tour, and if the tour does well, I might get to record an album. Whereas when an old song you’ve got a really good relationship with is having a moment, you can just make the very most of it.”

This twist was just the latest of many in the singer’s rollercoaster career. The daughter of film producer Robin Bextor and Janet Ellis, now a novelist but formerly a Blue Peter presenter, she grew up in west London, close to her current home, and attended a prestigious local girls’ private school. Her mother Janet was reportedly fired from Blue Peter for the perceived scandal, at the time, of being pregnant as an unmarried woman (though she has since denied this, insisting she left of her own accord).

Having started singing with indie band theaudience in her teens, EllisBextor was the only girl in her year not to go to university. “I signed a record deal in May, sat my A-levels in June and moved out of the family home at the end of July,” she says. The band had a couple of top-ten hits and she was convinced she was on her way, only for them to be dropped by their record label two years later. “I thought I was a has-been at 20,” she says. “But although that wasn’t a nice thing to go through, I don’t think I would have appreciated what came after as much without it.”

She was considering returning to her studies when Italian DJ Spiller asked her to sing over his dance track Groovejet (If This Ain’t Love). The genre was totally different to her prior indie style, but she “was intrigued and wanted to do it”. Unconvinced by her choice, Ellis-Bextor’s manager dropped her, only to see the song make worldwide headlines when it beat Victoria Beckham’s debut solo single to number one. In 2015, the song was announced as the best-selling vinyl single of the millennium.

“Groovejet changed my life,” she says. “It was more significant than anything else I’ve done, not just because it was a success, which gave me back my day job and got me my solo career, but because it taught me about instinct. I did it because it was a breath of fresh air, and I followed my nose, and that’s the way I’ve worked ever since.”

Yet another curveball followed when, at the peak of this newfound stardom, aged 25, just six weeks after she started going out with Jones, EllisBextor became pregnant with their son Sonny. Many couples would have been rocked by the discovery, but they were unfazed. “I’d always wanted to be a young mum, so even though a baby was a surprise, it made sense.”

Combining motherhood with being a pop star is quite a challenge, but one she met with characteristic calm. “There were a lot of positives about it. A baby made me work with more clarity, because if I was going to be away from him, I wanted to be sure that time was accounted for, so I cut out a lot of stuff and focused more. It sharpened my ambition, too, because suddenly there was a line in the sand between this and the life I’d had before. We were at point zero and it was like, ‘Let’s go and get some things achieved, so I have something going on for myself as well as being a mum.’”

“It was an extraordinary thing to happen at this stage of my career, and I seized every opportunity”

Ellis-Bextor and Jones married the following year and went on to have four more sons. “The biggest shift was from no children to one,” she shrugs. “By the time you get further down the line, you just get on with it.”

She has combined wrangling family life with gigging all over the world. “The longest I’ve ever been away for was three and a half weeks, and that was hard. I’m normally someone who takes the latest-possible flight out and the first-possible flight home to be with them.”

The singer adds that she once “did” Australia in two days – playing Sydney and Melbourne on consecutive nights, before flying home again –a feat rendered even more impressive by the fact that she brought her then 16-week-old baby along, with no nanny. “The clubs were full of friendly drag queens and one lovely woman who worked backstage said, ‘I used to be a nanny,’ so I just got her to hold him for the half-hour I was performing. I’ve done so many festivals and shows where I’ve been like, ‘Can anybody hold the baby while I sing?’”

Over the years, she has toured with everyone from George Michael to the reformed Take That. She also reached the final of 2013’s Strictly Come Dancing (“I found that very nerve-wracking, but on the positive side, nothing will ever be so scary again!”) and in 2021 she raised more than £1 million for Children in Need by completing a 24-hour danceathon. “Totally ridiculous,” she says, “but you get such a high at the end.”

Ellis-Bextor has also performed at Goodwood, most recently in 2023, at the annual Raceweek Regency Ball. “Everyone there was having a brilliant time – quite raucous,” she recalls. “I think when people make the effort to properly dress up, they really go for it.” As an avid fan of charity, vintage and second-hand shops (“I always check out the local ones when I’m touring”), today she’s dressed head-to-toe in eBay finds, including a multicoloured fake-fur coat. Another fond memory is of performing at

“Vintage at Goodwood” back in 2010. As part of a celebration of British creativity from 1940 to 1980, pop legend Sandie Shaw oversaw “Reclaim the Song”, in which female singers performed numbers that were originally written and sung by men. “I sang Squeeze’s Up the Junction. That was pretty special,” says Ellis-Bextor.

Yet probably the most meaningful gigs of her career were her “Kitchen Discos”, broadcast live from her house every Friday evening throughout the Covid lockdowns. Audiences worldwide tuned in for a fix of escapist joy as the singer, dressed in showgirl outfits, belted out upbeat hits while various children boogied around her under a mirror ball.

“I started them for a very selfish reason, just needing to lift myself out of what I was dealing with – home-schooling, barking at the kids while doing another load of washing, no work, heavy news on the radio, all manner of stress,” she recalls. “But for this half-hour on Fridays we could just stop everything else, play the music nice and loud, get the disco lights on and have the kids jumping around. Afterwards, Richard would make a cocktail, we’d have some nice food and it would be like, ‘Great, we made it through another week.’ We were just having fun, but silliness can be underrated.”

For now, Ellis-Bextor is mainly holed up in her home recording studio making a new album, before heading off on her largest-ever European tour. “Who knows what will happen next?” she says cheerfully, grey eyes glinting in anticipation. What’s certain is that she’ll never tire of singing Groovejet and Murder. “There’s no nostalgia because every time I sing those songs in a new place, engaging with new people, new layers of memories are added. I feel they’re as full of vitality now as they ever were.”

Sophie Ellis-Bextor tours the UK in May and June 2025, including her biggest London headline show to date, at Royal Albert Hall on 12 June

Ingenieur Automatic 40, Ref. 3289

You don’t have to be an engineer to appreciate the virtues of this watch. The Ingenieur Automatic 40 with a blue grid-patterned dial revisits the bold aesthetic codes of Gérald Genta’s Ingenieur SL from the 1970s, pairing them with outstanding ergonomics and a finishing that is perfected down to the tiniest detail. In the best tradition of engineering, a soft-iron inner case protects the IWC-manufactured 32111 calibre with five-day power reserve from the effects of magnetic fields. IWC. Engineered.

With works by international artists displayed in a stunningly reimagined setting on the Goodwood Estate, the launch of the Goodwood Art Foundation in May 2025 marks the opening of a major new arts destination. Emma Crichton-Miller hears from the people who made it happen, including exhibiting artist Rachel Whiteread

Opening its doors in May 2025, the Goodwood Art Foundation marks a significant new chapter for Goodwood’s 21st-century legacy. The not-for-profit Foundation will provide world-class exhibition programming, with Dame Rachel Whiteread the first artist to be given a headline show here (more on which shortly). Beyond its stellar contemporary art credentials, the creation of the Foundation also encompasses the complete re-landscaping of 70 acres of woodland and meadow, and the launch of an ambitious arts education programme. Its pillars are, simply stated, “art, environment, education”.

Some of the new works that will be seen here, by Whiteread and other artists, are semi-permanent – as part of an annual exhibition programme. The landscaping, overseen by renowned landscape designer Dan Pearson and based around the concept of providing 24 seasonal “moments” each year, will evolve and unfold, continually revealing itself anew.

“It has been a pleasure to be involved,” says Whiteread. “It was more about me reacting to the place than trying to find a place to put something. Goodwood has the extraordinary Festival of Speed, and the house is beautiful; it’s a really interesting place. The landscape renovation came first, an incredibly complex thing to do. It’s very beautifully thought-out in terms of the seasons and which colours you see.”

The Goodwood Art Foundation is a major new addition to the Estate and represents a distinct move towards championing contemporary art. But it’s also a continuation of Goodwood’s long connection with the arts. As the Duke of Richmond and Gordon explained to an audience at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, on the occasion of the launch of the Foundation, Goodwood has long been “a dramatic setting for one of Britain’s most significant private art collections, assembled by the various Dukes over the past 300 years”.

The Foundation invited curator Ann Gallagher, previously Director of Collections, British Art, at Tate, to devise a programme of art exhibitions both inside the new galleries and set within the landscape. “It’s a very exciting prospect to have an entirely new art foundation in the Sussex landscape,” she says. “From the outset, the ambition was for the programme to be contemporary, international and of the highest quality.”

The idea for the Goodwood Art Foundation was born following the closure of the Cass Sculpture Foundation in 2020. The brainchild of businessman Wilfred Cass and his wife Jeanette, this commissioning notfor-profit had leased 23 acres of land on the Goodwood Estate since 1992, drawing visitors to view monumental sculptures by a range of contemporary artists in the leafy Sussex landscape. Rather than opting to simply revive

“It’s a very exciting prospect to have an entirely new art foundation in the Sussex landscape”

that idea in-house, however, the Duke decided to expand its ambition. The Director of the Goodwood Art Foundation, Richard Grindy, says of the brief he was given, “It’s not a case of: ‘It would be nice to have a foundation here,’ but rather: ‘How do we build the best foundation in the world?’”

It makes sense, when you look at the history of the arts here. The second Duke of Richmond was a noted patron of Canaletto, while the third Duke of Richmond commissioned paintings from George Stubbs and built a sculpture gallery at Richmond House in London. The current Duke, a photographer and collector of photographs, has overseen the restoration of Goodwood’s magnificent interiors and an extensive rehang of its Old Master painting collections.

With the Goodwood Art Foundation, the Estate can offer art patronage on a significant scale for a modern era, complementing what is already one of the most significant private art collections in England, at Goodwood House. Gallagher has experience of sculpture parks internationally, through her previous roles. At Goodwood, she says, “rather than placing works in an existing landscape, what we have wanted to achieve is a journey through landscape to experience art. Sometimes the landscape will be free of artworks, and sometimes the designers have worked with the positions of sculpture. Landscape and sculpture have been thought about as one.”

Together with Grindy and the landscaping team, Gallagher devised an

annual programme of art in the landscape, anchored by a solo exhibition by a leading international artist. The setting artists respond to is the work of Pearson, the renowned British horticulturalist and landscape designer. “He’s considered one of the best in the world, with his naturalistic planting,” says Grindy. “He truly understands sustainability and biodiversity, and thinks of seasons in terms of the changes you might see over a two-week period, not just over a period of months.”

Some 25 acres of adjacent ancient woodland have been incorporated into the Art Foundation site, while some farmers’ fields to the south of the original site have become wildflower meadows. There are fantastic views to the sea. Yet all of this is contained within a large flint wall, to demarcate and protect this reimagined territory.

The buildings originally designed for the Cass Sculpture Foundation by architect Craig Downie have been restored and repurposed, bringing them up to the standard of museum exhibition spaces. Studio Downie Architects has created the striking new café – sympathetic to the original designs. “You’re literally in a glass box that’s been cantilevered out in the woodland,” explains Grindy. “It’s a beautiful space.”

When it came to the artists, the first choice was, in a sense, easy, although few curators could have delivered it. Gallagher has worked with Dame Rachel Whiteread since Whiteread became the first woman to have

a solo show in the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997. She curated Whiteread’s Tate retrospective in 2017 and is currently working on the catalogue resumé of her sculpture. “Ann and I have a longstanding professional relationship, but we’re also very good friends,” says Whiteread. “It’s nice to work with someone you have that collegiate attitude with.”

Whiteread is known for her poignant, resonant casts, in materials such as resin or concrete, of negative spaces – whether beneath a chair, within a hot water bottle, or the entire interior of a building. Her most famous monumental projects have been in urban landscapes, including House in 1993, a pale ghost of a building holding the memory of its lost East End inhabitants, for which she was awarded the Turner Prize. But Whiteread has also created a series of “shy sculptures” in more hidden-away, natural contexts, such as a boathouse cast in situ by a fjord in Norway, and the quiet, Thoreau-inspired Cabin on Governors Island in New York Harbor.

“What I try to do with these works is to find something that is historic to the area, that people have always seen, and then it’s about making the solid ghost of it,” Whiteread says. For this inaugural solo show at Goodwood, she will exhibit a new large cast architectural piece in the landscape. “It’s nice to think of having a permanent work there [at Goodwood],” she says, “and of it being the beginnings of a new sculpture park. As the place matures, and as

the new landscaping develops and grows and becomes its own thing, it will look really terrific and will, I hope, become a real landmark for the South. The North has the Yorkshire Sculpture Park; down south we don’t have so much. So this is a good start, because so much large-scale sculpture can’t be seen in galleries, it needs to be seen outside.”

Within the two galleries in the main pavilion at the Goodwood Art Foundation, there will be further sculpture by Whiteread, including a recent masterpiece, Doppelgänger, a shockingly burst-open, dilapidated shed, invaded by a branch, which Whiteread built rather than cast, using found wood and metal, in 2020/21.

But perhaps the most radical feature of this solo presentation is a display of photographs by Whiteread; an aspect of her way of working that she has rarely shared before. “I’m hoping the audience will be surprised – the things I take are just happenstance things you see in the street, something that’s slightly different from normal. I always have my eye out for them. I just jump out of the car and take a photograph, which is something my mother always used to do. I treat photography like drawing: a way of worrying through the making of something,” she explains. “It helps me.”

Gallagher is delighted to be able to showcase the photography by Whiteread, which, until now, has always been “a private part of her work;

“Large-scale sculpture can’t be seen in galleries, it needs to be seen outside”

“We wanted to provide a learning programme that was not just about art and design in the curriculum, but also about stepping into the natural world”

nevertheless it seems a central part of her practice”. Through the new landscape, Gallagher has placed significant works by a range of other artists. The Foundation has secured the right to construct a Magic Square by the Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980). A leading figure in the Tropicália movement in Brazil, he was also an exponent of Neo-Concretism and environmental art. One of a series of outdoor sculptures that he designed but which were not completed during his lifetime, this will be the first Magic Square constructed in Europe.

Gallagher has also chosen work by Turner Prize-winning British artists Veronica Ryan and Susan Philipsz, with whom she has worked closely over many years. “Sound-art works, film and performance, as well as sculpture, will be very much part of the programme,” she explains. For Gallagher, the treat for visitors is the opportunity to encounter significant artworks in a relaxed setting. “It’s particularly nice for people to see art as something they can take in slowly as they walk through landscape.”

Crucially, children are set to be among those people engaging with the Goodwood Art Foundation. The arts education expert Sally Bacon, previously the long-time director of the Clore Duffield Foundation for UK arts charities, is overseeing the education programme. “We wanted to break down barriers,” Bacon says, “and make the Foundation’s art activities and creative resources easily accessible and free, to reach the children and

young people who would benefit most: schools and groups that do not have the resources to pay for such visits, who have the fewest opportunities, or who have the most complex needs.”

For the many children who are set to experience the Goodwood Art Foundation, there are age-appropriate opportunities for art-making and critical thinking. “We wanted to provide a learning programme that was not just about art and design in the curriculum – although it’s also that – but also about stepping into the natural world,” says Bacon. “Experiencing art in a beautiful setting, thinking about what art is and can be, and enabling children to express themselves through art, and express their opinions about art.” Whiteread approves. “They are really wanting to give back to the community,” she says. “It’s a great new education facility.”

Ultimately, the Duke of Richmond and Gordon says, the doors should open in May 2025 to a new British arts institution that fosters wellbeing and creativity for people of all ages, “through engagement with art, and connectedness with nature”. Both are long traditions at Goodwood. But with its innovative new architecture and landscaping, and by taking a significant new step into the world of contemporary art, the Goodwood Art Foundation also marks the start of a new era.

Discover more and plan your visit at goodwoodartfoundation.org

The right kit transforms your time outdoors into moments you'll never want to forget. Tried and tested by guides who live for the elements, choosing good-quality kit is an investment in yourself. For yourself.

Dog owners in the public eye reveal to Sophy Grimshaw how canine family-members have changed their lives for the better

“Dogs have lived with people for tens of thousands of years; we have evolved as species together,” says vet Christopher Little, author of The Dog Care Handbook “There are hard-nosed scientific studies that have demonstrated the benefits of owning a dog. For instance, when you stroke a dog you’ve developed a bond with, your own blood pressure and heart rate fall, and there is evidence that beneficial hormone changes emerge in both dogs and owners as their relationship develops.”

It seems that canine companionship could actually extend your lifespan. “Folk who own pet dogs make fewer visits to see their doctors and take more frequent exercise than those who don’t,” Little explains, “especially exercise in green spaces, which has its own health benefits.”

Beyond the outdoor exercise routine and reassuringly non-judgemental company of pets, another proven benefit of being part of the canine ownership club is that our dogs often bring us, indirectly, more meaningful contact with other people. “Dog owners are much more likely to talk to other people when they’re out with the dog,” says Little, “and those conversations tend to be longer and more complex.”

In myriad ways, spending time with a dog is simply good for us (and dogs can do pretty well out of the arrangement, too). Here, some high-profile dog owners reflect on the different ways their canine companions have improved their lives.

Discover the joy of dogs at Goodwoof, a one-of-a-kind festival for canines and those who love them, at Goodwood, 17-18 May 2025. Tickets can be purchased at goodwood.com

Nikki

Tibbles, founder, Wild at Heart florist

I’ve rarely lived a day of my life without a dog by my side, and my dogs have taught me the meaning of true love. It’s unconditional love that they give us. When you love a dog and give it a sense of a safe home, with a routine, trust and respect, you get back everything you put in, and more.

Ten years ago, I set up the Wild at Heart Foundation to help care for stray dogs internationally. Every time I travelled for work, or on holiday, I was taking stray dogs to the vet and trying to get them some help; establishing the foundation has been a way to do that on a bigger scale. We prioritise welfare, such as food and flea treatments, and sterilisation. It costs $25 to sterilise a dog in Mexico, for example, which then prevents thousands more stray dogs from ever being born. I have my father to thank for always having animals in my life. He would bring stray dogs home and he allowed me to do the same. In the morning, my parents would often find me sleeping downstairs with my dogs.

Today I have five dogs, and there’s comfort in always having one at my feet as I work at my desk, or padding up the stairs with me. Ronnie is my oldest: a huge, partially deaf Carpathian

Shepherd, rescued from Romania. I do love a big dog. My dogs Ruby and Rita were stray dogs in Puerto Rico; there are currently some 650,000 strays there. Rita is the most adorable dog; her tail is always wagging and if I wake up in the night she’s right there with me. In summer, she’s up early trying to eat the windfall pears or apples.

Helping dogs to escape suffering has been incredibly meaningful for me. My dog Zita was rescued from China, where she was kept at a slaughterhouse, tied up on a 12-inch chain. Leo was rescued from Greece, and had been badly abused. He’s still very shy around other dogs, but is now able to run free in the field behind my house. He’s becoming more trusting.

In this country we have a strong tradition of charities that help dogs, but since the Covid-19 pandemic, when many people rushed into dog ownership, there are some five million dogs in the UK that need rehoming. I would urge anyone who wants a dog to consider a rescue dog. Once you find the right dog for you, there really is no other love like it.

To find out more about Nikki Tibbles’ foundation to help stray dogs, which is also the charity partner for Goodwoof 2025, visit wildatheartfoundation.org,

“There’s comfort in always having a dog at my feet as I work at my desk”

“ANIMALS HELP US FEEL THE UNIVERSAL”

Matt Haig, author

Three years ago, Bruce arrived into our lives. I was in the middle of a massive relapse of depression. I couldn’t work; could hardly leave the house; couldn’t do a social media post. I was lost. I’d had to turn down lots of work, and had burnt bridges.

I quit drinking, got a therapist, a psychiatrist and all the King’s horses to put me back together again. I didn’t write for ages. I even turned down a big award – pretty much the only one I’d ever been offered. I’d had a bit of a strange year. The Midnight Library became massive in America, but that did nothing except make me realise I definitely didn’t want to be a famous author, because of all that came with it. I carried on because I felt I had to. For my partner, Andrea. For the kids. And I’d stupidly written a book called Reasons to Stay Alive so I felt I had to do that or it would send a bad signal. I was trapped.

Then Bruce came along. And that meant I had to get out of the house. And for hours. Walking all around Brighton. He is a happy dog. He even breathes happily. And the happiness, the sense of play, the mad enthusiasm and comedy behaviour slowly rubs off. It’s like I was miserable lyrics and he was a really infectious bassline, and so eventually the song became happy. We were New Order, basically. Animals help us feel the universal. They let us step out of the toxic concerns of humans. Big dogs are so much better than big awards, they really are. Friends are important. Especially when they are dogs.

The 10th anniversary edition of “Reasons to Stay Alive” is out now. Matt Haig’s latest novel, “The Life Impossible”, is also in shops now

“Moody has been portrayed in movies and TV dramas”

“WE TAKE OUR CUES FROM OUR PETS”

Emily

Maitlis, broadcaster

Moody is 12 years old now, an old dog. But when he first came to us he immediately filled the gaps between the things that we as a family were feeling, but couldn’t always say out loud. When the boys had had a bad day at school, they would head straight for the dog. It was often a sign for me that things weren’t great. And Moody was often an opener for a conversation. “You’ll never guess what Moods got up to today,” usually led onto the things they had faced, teachers had said, friends had done.

There’s something about a dog’s long, deep sighs when you tickle their ears – that sense of peace descending, the shutting of the front door for a night in. A heavy, immovable lump on the sofa slows down everyone else, looking to de-stress after a manic day. We take our cues from our pets. I love an exhausted dog, because it normally means that we’ve both run hard, ended up with bramble cuts and muddy shins, and have come home to collapse with the release that comes post-exercise. I equally love the look Moods and I give each other – simultaneously – when it’s raining hard and we both can’t bear to look outside; the mutual relief of quiet defeat.

My friend Bridget describes how her cat, Jetski, knows by sniffing her face whether or not she’s going out for the night. She can detect the difference between fresh make-up and cool moisturiser, and she sulks if it’s the former, purrs if it’s the latter. If she’s in, Bridget lights the fire, pops the cat on her lap, and pours herself a glass of wine (“I bring the bottle over so I don’t disturb the cat,” she once told me. I laughed, and said, “You tell yourself whatever you need to…”).

Moody has been portrayed in movies and TV dramas. He’s been in Tatler and The Times. He’s fantastically photogenic. But what few people realise is, he’s also hugely manipulative. He knows exactly how to tap into each family-member’s weakness, how to command just the amount of attention he needs to keep himself well-fed but not overly pampered. He doesn’t really like attention, or affection. Which is, honestly, quite weird for us. But possibly a valuable lesson in over-mothering. Learning how not to pet your pet too much has been a lesson in itself.

Emily Maitlis presents The News Agents podcast on Global

“DOGS MAKE US BETTER HUMAN BEINGS”

Clare Balding, broadcaster

Dogs prioritise a short list of things in life: food, sleep, exercise and love. If those are the four pillars of your life, you’re actually doing rather well – so dogs are pretty smart.

My wife and I relished having Archie, a Tibetan Terrier, rule our lives for 15 and a half years. He was terrific. He could be quite territorial, but he was so affectionate. Archie gave us both a strict routine to our day. I’m writing a book at the moment, so some days I might not go outside until 2pm. That would never have happened with Archie. He also gave us a friendship network in London that was truly diverse, because your dog makes friends, and then you make friends with their owners. That’s part of the joy that a dog brings to your life – the way they encourage you to get out and explore and meet people.

From the time I was a baby, we had dogs. I swear I spent more time with my mum’s first boxer, Candy, than I did with my parents. She looked after me, and took her responsibility seriously. Having grown up with dogs, it was a big deal to me that my wife Alice and I should have a dog – I didn’t think our family was complete without one. Saying goodbye to Archie, in 2020, was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. I haven’t felt ready to have another dog since, but we are about to move out of London, and once we’re settled in our new home, I’m beginning to feel that we might finally be ready to welcome another dog.

People say that we domesticated dogs. I think the reverse is true. I think they’ve domesticated us. I think they make us better human beings.

Clare will be at Goodwoof, in the Literary Corner, with her book “Isle of Dogs” (chapter 11 is all about Goodwoof )

“SOPHIE DOES NOT LEAVE ME A LOT OF TIME FOR WORRYING ABOUT PARKINSON’S”

Rory Cellan-Jones, author

In a way, my first experience of Sophie was that she let me down. For more than a year, she wouldn’t come for a walk. With my old dog, Cabbage, a walk before 7am was a key part of the morning routine. A dog is a really good reason for getting going, and then sometimes you find that you keep going for the rest of the day.

Exercise is vital when you have Parkinson’s, which I was diagnosed with in 2019. I’ve become a lot less mobile since I developed the condition. So when my wife Diane and I arranged to rehome a Romanian rescue dog, those long walks were what I was expecting and looking forward to. Sophie was originally called “Seven”, but I changed her name when she arrived to live with us as a puppy, just before Christmas 2022. I imagined us in the park and I didn’t want to yell “Seven!” I thought it would make me sound like a judge on Strictly, shouting a score. In fact, I spent a year waiting for her to have the confidence to come out with me for a walk at all. It’s only now, after a lot of specialist attention and help, that she does feel able to.

We’ve worked to improve Sophie’s confidence so that she’s no longer too afraid to even come out from behind the couch. Along the way, I’ve found that I’ve needed to concentrate on her problems, not mine, asking myself, “Why has she been so frightened, and what can we do to help her?” It’s been a kind of psychodrama. So Sophie has been a distraction, but in the best way. I even ended up writing a book about her; I never dreamed I would write a book about a dog! Everywhere I go now, people ask me about Sophie, and that simply does not leave me with an awful lot of time for worrying about Parkinson’s. Rory Cellan-Jones’ book, “Sophie from Romania”, is out now

“He gave us a friendship network in London that was truly diverse”

Official retailer of the world’s most desirable cars and Britain’s leading luxury motor group

Scientists still don’t fully understand what makes travelling very fast – or watching others doing it – such a seductive experience. Marek Kohn looks at the neural and physiological systems behind our need for speed, and discovers that it might not be thrills we seek, but “flow”

peed is such a compelling sensation that it only has to be seen in order to be felt. You don’t need to feel the acceleration that Andy Wallace, Bugatti’s official driver, felt as he set a new speed record last November in an open-top Mistral. It’s enough to watch the video shot over his shoulder, showing the track streaming underneath the car and the flurry of digits on the speed indicator as they mount up to show that the Mistral has reached 450kph (the final confirmed figure is 453.9kph, or 282mph, a world record for a car without a roof). Speed demands our attention and triggers our nervous systems, even if we ourselves are stationary.

Intuitively, this seems like an effect that people have always experienced, from the pits of their stomachs to their heads. It would surely always have been in their survival interests, long before horses were tamed and wheels invented, since fast movement would so often have been a source of danger or a response to it, as well as a vital factor in hunts for food. Speed has certainly been the basis of spectator sports since the horse and chariot races of the ancient Olympic Games in Greece, and doubtless long before.

These days, the mechanical successors of those races are based on precision engineering, mathematics, physics and computing power, as Andy Wallace’s account of his job impressively illustrates. Yet the body of organised knowledge about the systems that make cars go very fast is not matched by a corresponding body of knowledge about the neural and

physiological systems that respond to speed. We can easily identify the pang in the stomach and the pulse of excitement, or alarm, as signals arising from the body’s adrenaline-releasing “fight-or-flight” response. But that doesn’t tell us very much about why some people seek such sensations, and find them pleasurable, while others shy away from them. Nor does it tell us much about how people process speed when they are used to it. The brain in the racing driver’s seat may be operating very differently from the brain in the passenger seat.

Part of the reason for this imbalance in knowledge is that questions about which chemicals do what in which neural pathways are not yet settled. In particular, pleasure is still something of a mystery – though that’s not the impression given by popular references to dopamine, one of the substances that carry signals between nerve cells, as a “pleasure chemical”.

‘“Dopamine responds to rewarding stimuli, so if you taste something nice and sweet, for example, dopamine is released,” says Ciara McCabe, Professor of Neuroscience, Psychopharmacology and Mental Health at the University of Reading. “But it’s more than that.”

She explains that it is involved in processes that direct attention towards potential rewards, such as food, water and sex: “It heightens perception and focuses attention toward the particular sights, sounds, and smells associated with these rewards.” Neuroscientists have moved away from seeing dopamine as a source of pleasure in itself, like a drug, to viewing it as a source of the desire for pleasure. It produces wanting rather than liking; the latter may arise from circuits that use the brain’s natural opioids. Dopamine certainly fits the bill as the chemical messenger that keeps us checking our phones, in constant search of likes and similar rewards, but its role in the experience of speed is less obvious.