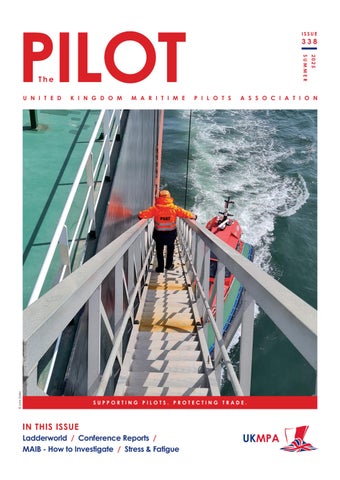

PILOT

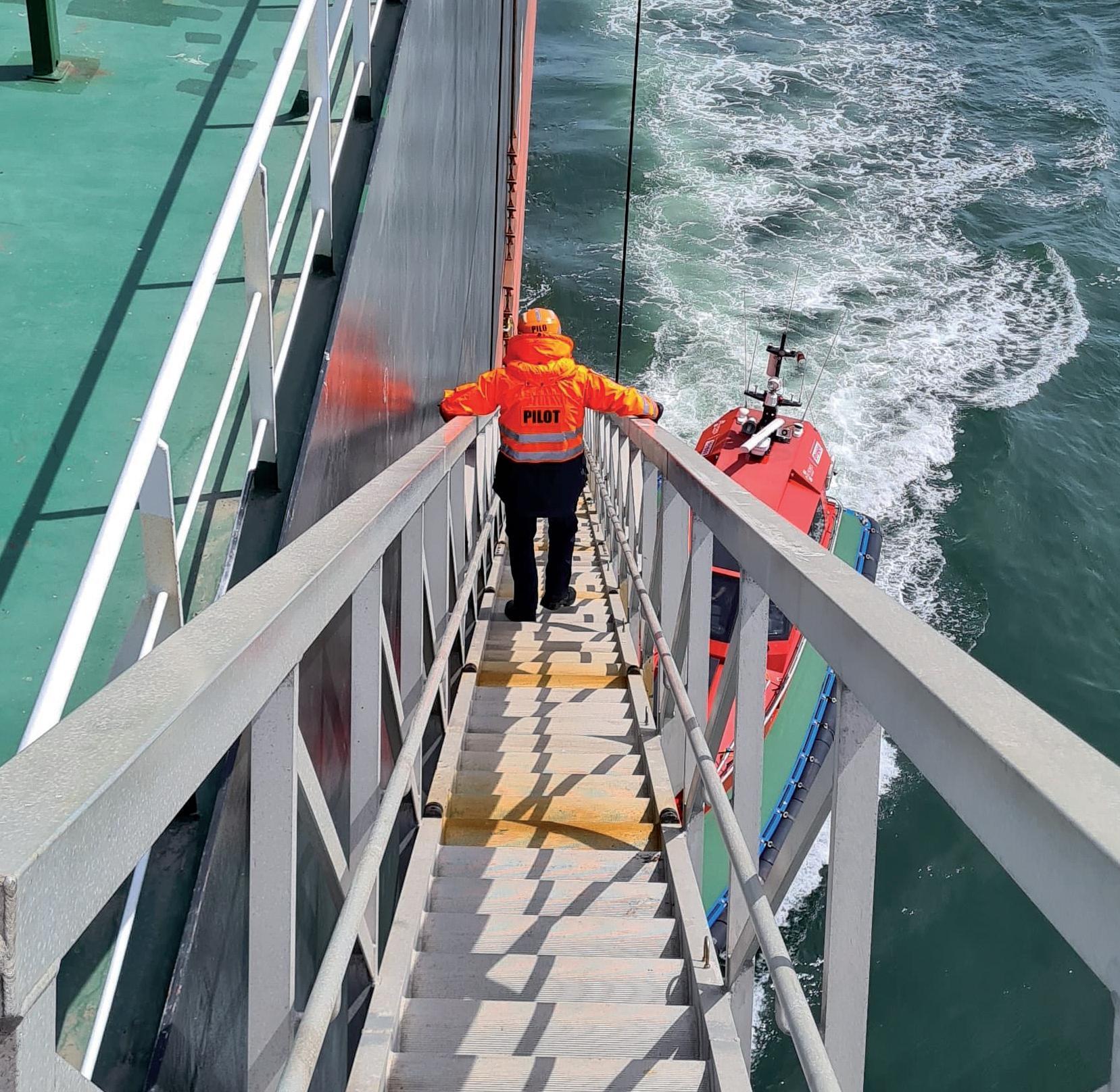

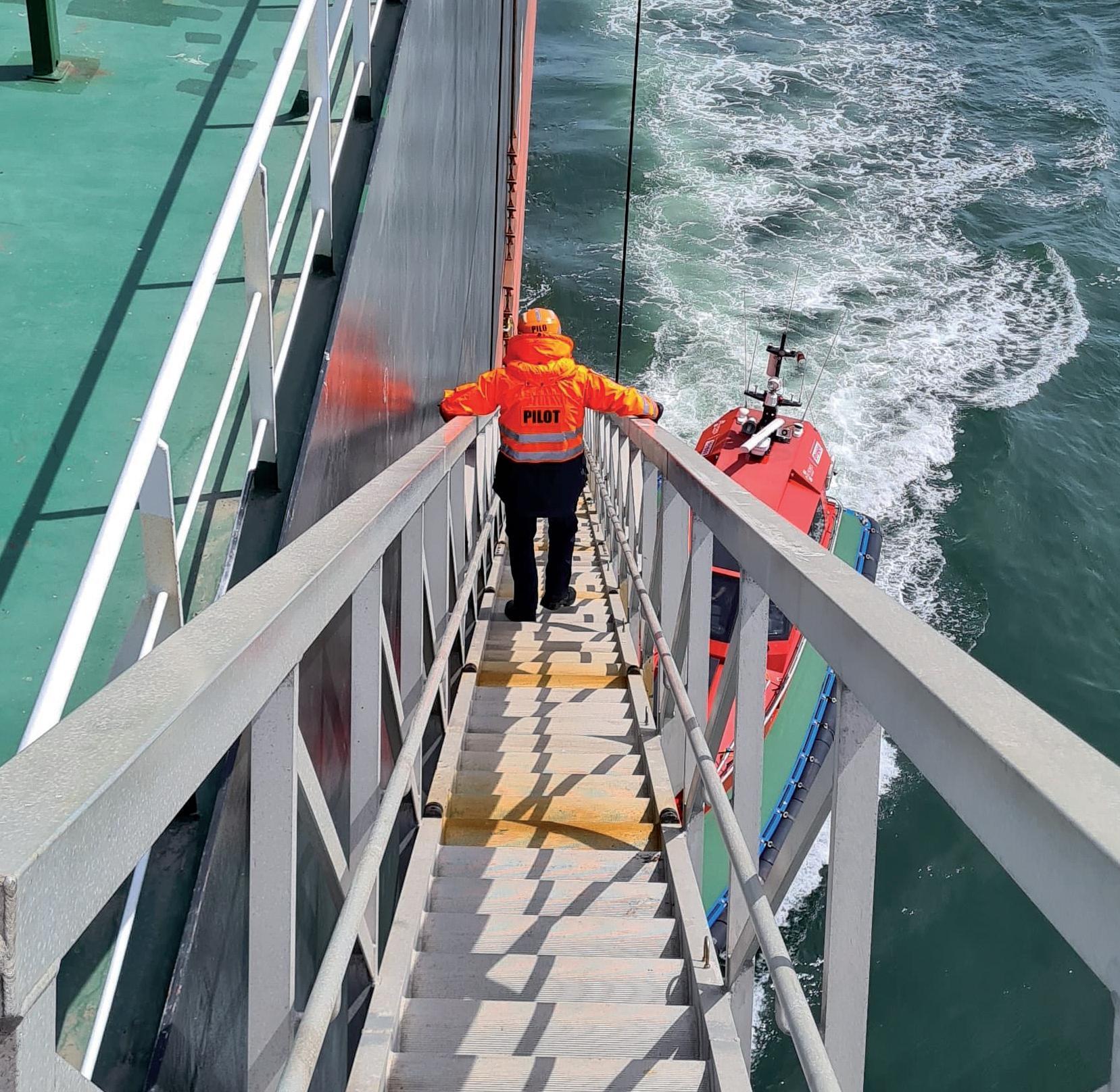

One of the most dangerous aspects of our job as pilots is the boarding and disembarkation to and from vessels. Sadly, it remains a fact that there have been and continue to be pilot fatalities or injuries when joining or leaving vessels.

This edition focuses on pilot boarding and disembarkation, manoverboard recovery, technology and health aspects affecting pilots.

Of course, it is not just pilots who climb pilot ladders. Marine surveyors visiting vessels to undertake their relevant surveys and inspections climb and disembark via the same boarding and landing arrangements as pilots.

I welcome on board Robert Norman, manager at Idwal Surveyors, who gives an insight into his surveyors climbing pilot ladders.

My first experience of pilot ladder climbing was in July 2005, aged 16, when working as a deckhand on board a Humber bunkering tanker barge for a local Hull company. My job was to climb up the ladder and connect the bunkering hose to the manifold. I recall the first time doing this was onboard the bulk carrier Gladstone at Immingham Bulk Terminal. The climb was the best part of 9m with coal dust blowing down on me. This vessel had rounded sheer strakes, and I remember being cautious when reaching for the stanchions to complete the climb; likewise the same applied when disembarking.

Most pilots join and leave via pilot launches. Our job would be impossible were it not for the skilful and professional conduct of pilot launch crews. This edition includes a pilot launch coxswain’s viewpoint from two senior launch coxswains at the Bristol Port Company.

In the event of a pilot going into the water, the magazine looks at the various man-overboard techniques used to rescue a pilot. Recovery technology is advancing all the time: this has been demonstrated at Milford Haven with the introduction of Zelim’s recovery rotating platform. Scott Tonks from Zelim presented this at the 2024 UKMPA conference in Harrogate and I am pleased to welcome Scott to this edition with his recovery article.

Last year’s UKMPA conference also included a presentation on AI and how this new technology is affecting the marine industry. Patrick Galvin from EMPA provides an interesting insight into this new, evolving industry.

As your editor I am always looking to include pilot health-related articles to the magazine and increase health awareness for those working in the pilotage industry. Associate professor Luana Main from Deakin University in Australia, who presented at the Australian Conference in 2023, has kindly written an article on stress, fatigue and how these factors affect a pilot’s job performance.

Thank you for reading Issue 338.

As winter’s storms fade and summer’s calm settles, the UK’s ports remain the lifeblood of our nation, handling 95% of UK trade by volume through perpetual effort. This resilience is built on the trust and commitment of maritime professionals – none more so than pilots.

To become a pilot is to embrace a calling defined by a commitment to dealing with the unpredictability of the environment, operations and resources. It demands years of training, continuous learning and the courage to make thousands of safety-critical –occasionally unpopular – decisions under pressure. Once aboard, pilots are entrusted with safeguarding vessels, cargo and the vital infrastructure of our ports and waterways. This trust is not given lightly. It is earned through skill, independent thinking and a dedication to getting it right when getting it wrong is not an option.

Trust is the cornerstone of our profession. Strong trust fosters open communication, enabling pilots to report issues candidly and providing port authorities with critical insights. The result? Fewer incidents, safer operations and greater productivity. Weak trust, by contrast, obscures risk and undermines progress. Pilots bridge this gap, acting as the vital link between ship and shore, ensuring our ports remain safe and efficient in an ever-changing maritime landscape.

Recent events, such as the incident involving Solong and Stena Immaculate, underscore the strength of our port systems. The swift response from tug operators was exemplary, preventing a potentially catastrophic outcome. As Chair, I am proud to now serve as an ex-officio advisory member to the executive committee of the British Tugowners Association (BTA), strengthening our partnership with the BTA and the UK Chamber of Shipping. Together, we advance the critical work of pilots, tugs and their crews – unsung

heroes who facilitate billions in trade and protect our coasts, often as first responders.

Tugs and pilots share a bond of mutual trust, essential to national maritime safety and security.

My thanks go to the UKMPA team for their continuous commitment to UK plc and to editor Matt Finn for delivering another exceptional issue of The Pilot.

As pilots, we have the warrant of public trust – and we deliver.

Christopher F Hoyle / UKMPA Chairman

Chairman Christopher Hoyle chairman@ukmpa.org

Vice Chairman Jason Wiltshire vice.chairman@ukmpa.org

Region 1 Executive Alan Stroud region1@ukmpa.org

Region 2 Executive Chris Grundy region2@ukmpa.org

Region 3 Executive Peter Lightfoot region3@ukmpa.org

Region 4 Executive Robert Keir region4@ukmpa.org

Region 5 Executive Neville Dring region5@ukmpa.org

Region 6 Executive James Musgrove region6@ukmpa.org

Treasurer Alan Stroud treasurer@ukmpa.org

Secretary & EMPA VP Peter Lightfoot secretary@ukmpa.org

Membership Robert Keir membership@ukmpa.org

Technical & Training Chair John Slater technical@ukmpa.org

Web Captain James Musgrove webcaptain@ukmpa.org

Region 1 Deputy Simon Lockwood deputy1@ukmpa.org

Region 2 Deputy Mike Robarts deputy2@ukmpa.org

Region 3 Deputy Alan Jameson deputy3@ukmpa.org

Region 4 Deputy Ross McCauley deputy4@ukmpa.org

Region 5 Deputy Paul Schoneveld deputy5@ukmpa.org

Region 6 Deputy Matthew Finn deputy6@ukmpa.org

Circle Insurance Ian Storm Ian.storm@circleinsurance.co.uk M: 07920 194970

Insurance Queries Claire Johnstone claire.johnstone@circleinsurance.co.uk

Incident Reports Via UKMPA app insurance@ukmpa.org

UNITE Maria Ball maria.ball@unitetheunion.org

Web Captain James Musgrove webcaptain@ukmpa.org

Editor Matthew Finn photos@ukmpa.org

Mental Health James Musgrove region6@ukmpa.org

IMPA VP Paul Schoneveld paul.schoneveld@ukmpa.org

Minor incident 0141 249 9914 insurance@ukmpa.org

Major incident 0800 6446 999 insurance@ukmpa.org

Incident Reports insurance@ukmpa.org

Mental Health Support

Safe Haven Hotline 0800 433 2163 Visit www.ukmpa.org for further details

Luis Martinez Iturbe London

Johnny Cowie London

William Hatch London

Rajwinder Singh Kandola London

Michail Kapellos London

Jake Bryan London

Dan Thompson London

Neil Topping London

Glenn Higgenbotham Tees

Bryon O’Hanlon Troon

Steff Wilkinson Humber

Matthew Maclntosh Humber

Samuel Turner ABP S/Wales

James Gillespie Belfast

Jake Hall Heysham

Ian Harrison Lowestoft

Oystein Hoyvag Portland

Maciej Miszcuk Harwich

Trevor Dann Crouch

Eric Wiseman Peterhead

Darren Steele Belfast

James Adock Humber

Retired

Gavin Hoe-Richardson Liverpool

Edwin Lyon D-Sea Pilot

Chris Thomas Liverpool

Graeme Hutchinson Forth

Rory Jackson Southampton

Every day, pilots across the UK navigate challenging decisions, intricate vessel manoeuvres, and everchanging conditions. Before they even reach the bridge, pilots face some of their most challenging decisions when boarding and disembarking via pilot ladders. Sometimes even the most experienced pilots can find themselves in situations where things go wrong – fast.

The Health & Safety at Work Act 1974 places a legal duty upon employers – and by extension, port operators and vessel owners – to ensure, as far as is reasonably practicable, the Health & Safety of all workers and others affected by their operations.

The updated Port & Marine Facilities Code reinforces this obligation by requiring harbour authorities to implement a safety management system and appoint a designated person to provide assurance of compliance. Failure to do so can result in prosecution and fines.

These instruments of legislation are there to protect the safety of all pilots, employed or self-employed.

Poor pilot ladders can cause injuries and other human costs. In one case, a pilot descending a ladder that had been incorrectly rigged stepped down to the pilot launch just as the ladder shifted unexpectedly, causing the pilot to fall and sustain significant injuries. Despite the clear failure in the rigging, the pilot’s legal claim was reduced because the court ruled there had been contributory negligence on the pilot’s part. This underlines a critical truth: even when you are not at fault, the legal system may not offer full protection.

By Ian Storm / Circle Insurance

Insurance can provide legal support, financial cover and peace of mind in the event of incidents.

Our unique combination of covers, developed between Circle and UKMPA, can provide you with cover for:

• Legal representation in personal injury and liability claims (legal defence)

• Income protection during recovery (personal accident – weekly cover)

• Capital benefits in the event of life-altering injuries (personal accident – capital cover)

The case mentioned is not an outlier and shows that, no matter how experienced or cautious, we can all be vulnerable to the unseen. Over many years, Circle Insurance Services has supported many pilots in managing the legal process and mitigating their financial loss. Without our support, some pilots would have been left in a far more precarious position, and we are proud to support pilots in all aspects of their important role. However, insurance is not a substitute for vigilance or safety, and there is a responsibility to remain watchful when boarding and disembarking.

Please remember to report unsafe ladders in the UKMPA app because port operators and ship operators must uphold their legal duties under the Port & Marine Facilities Code and the Health & Safety at Work Act. Where ladders are not fit for purpose, we urge members to refuse to board rather than have blame (contributory negligence) assigned to them and any claims payment reduced.

As ever, we urge all members to review their current coverage to ensure that it meets their needs. If you are unsure, you can contact any of the team at Circle Insurance Services and we will be happy to help.

The UKMPA Chair Chris Hoyle and the Region 4 (Scotland) executive officer Bob Keir attended and spoke at the recent UK Harbour Masters’ Association spring seminar in Edinburgh on 1 and 2 April on behalf of the UKMPA.

As ever, this was a very well organised event full of learning points from throughout the industry. Much of the subject matter is of particular local interest to Scotland, with many of the smaller Scottish ports being represented in addition to the major players from around the UK.

It was pleasing to see seven UKMPA members in attendance, some of whom hold joint UKMPA/UKHMA membership as part of dual roles in their ports. This was Paul Brooks’ last Edinburgh seminar as UKHMA president, and he carried on the tradition he introduced where he encourages attendees to join him on a walk up Arthur’s Seat on the morning before day two of the seminar to blow the cobwebs away. Paul will step down as president in June to be replaced by Alan McPherson of the Forth. Paul has always made the UKMPA representatives very welcome at his conferences and seminars and I am sure Alan will continue this hospitality and the Arthur’s Seat morning walk next year.

Bob Sanguinetti, CEO of Aberdeen Harbour, gave a presentation on the new harbour to the south of the existing harbour, which has been called South Harbour. He went through the construction phase, costs and a bit on the challenges for pilots using the new port with much bigger ships than they have been used to.

Ron Bailey, interim Harbour Master Ardersier, gave a presentation on the new port there – he stepped down the day before the seminar and becomes Designated Person.

He has been replaced by UKMPA member Donald MacKenzie, who has moved there from Cromarty. Donald will be HM at the new port and will also fill in as pilot as and when required. It is a CHA and has been granted pilotage powers by the Scottish government.

Kevin Clancy, partner at Shepherd & Wedderburn Solicitors, gave a legally based presentation. Kevin has a double life as a Scottish Football League referee, handling big games like Rangers v Celtic.

Alex McIntosh, head of marine on the Clyde, former Aberdeen HM and Clyde pilot, gave a very personal and interesting account of her journey from single mum at 18 while a first-year cadet and how she continued despite the challenges.

Fraser Wallace, Head of Harbours at Calmac, gave an overview of the Calmac operation, its vessels and 26 harbours and 2,000 employees, and explained how Calmac is often the subject of bad press, whether justified or not.

Todd Charles Schuett from Kongsberg gave a presentation on a Smart Port software product, mainly the sharing of data between ship and shore and the benefits. One benefit would be steaming at economical speed during the voyage – greener and cheaper.

An expert panel discussed pilotage, tug use and safety, in which Chris Hoyle and Bob Keir were the panel experts alongside Stephen Packer of Targe Towing. Alan McPherson, Chief Harbour Master, Forth, was the panel moderator. This was a very good session with plenty of delegate participation and questions.

David Dawkins, Deputy HM, Orkney, gave a presentation on another new port development – five new berths or extensions in Scapa Flow with a large amount of new quay space being proposed for cruise ships, rigs and offshore support.

William Heaps, consultant at Marico, gave a presentation on Safety Management systems and auditing.

Mark Ashley Miller sailed round the UK and Ireland coasts over four years and met every HM in the UK (256) and visited every port (310). He did a similar presentation three years ago but has now written a book, Harbours and their Masters. This was an interesting and amusing presentation. If anyone wants to buy the book, it is available to order now via Fernhurst Books or Amazon: use code UKHMA for a 30% discount, which I’m sure he won’t mind us sharing with UKMPA members. Mark has raised £30,000 for the Sailors’ Society to date and book proceeds are also going there.

Big thanks to Martin Willis and Judy Turley for organising these excellent events and for extending their hospitality to UKMPA members.

Robert Keir / Region 4 Executive / Membership Secretary

By Alan Stroud – UKMPA Treasurer

This year’s AMPI Conference was a professionally run event, with Continuing Professional Development (CPD) certificates offered to all participants ensuring strong engagement throughout. Despite the vast area AMPI covers, the shared goal of raising pilotage standards was tangible, leaving many, including myself, impressed by the level of professionalism and collaboration across the Australasian region.

A standout feature was the high-level co-operation between AMPI and NZMPA, bolstered by a tour of the Cairns port and its advanced VTS, capable of controlling multiple zones and relocating operations during emergencies – an impressive demonstration of resilience.

Opening keynote: lessons from near misses

Angus Mitchell, chief commissioner of the ATSB, opened with an in-depth review of the Rosco Poplar near-miss. His address focused on the validity of current check pilot systems and underscored the importance of contingency training and consistent certification standards.

Coastal and reef pilotage

Highlights included Capt Vikram Hede’s history and breakdown of Great Barrier Reef pilotage – where job durations can reach 45 hours –and Capt Warwick Conlin’s insights

into Barrier Reef cruise ship pilotage, remaining on board and adding to the passenger experience.

Captains Peter Listrup and Trond Kildal from Cairns presented on safely when accommodating increasingly large cruise ships. Their focus on ship-specific wind thresholds and bridge teamwork offered a refreshing take on safety and adaptability. Capt Carl Robins added a UK perspective, detailing Southampton’s cruise pilotage complexities.

Mental health and peer support

Psychologist Keith McGregor captivated the room with practical methods to reframe stress and foster resilience. His session, along with contributions from Revd Canon Garry Dodd and leadership coach Mark Le Busque, brought valuable non-maritime perspectives, reinforcing the need for holistic support systems in our profession.

Critical incident response

Capt John Barker shared Auckland’s proactive ‘Project Valentine’ initiative –simulating incidents to pre-emptively

improve SOPs. Dr Phil Thompson’s analysis of the Dali–Baltimore bridge allision added weight to arguments for enhanced escort towage, while Wendy Sullivan addressed tailored first aid training for maritime settings.

Safe pilot transfer – a call to action

NZMPA’s Capt Steve Banks delivered an emotive presentation on pilot transfer fatalities, shifting focus to unsafe practices and the need for better recovery gear. His data-driven approach, supported by Capt Pasi Paldanius’ account of the Finnpilot rollover, underscored the urgency for reform. I took the opportunity to describe the UK’s immediate emergency care course, developed in partnership with the UKMPA, highlighting some key personal experiences to underscore the necessity of this training for all involved in the boarding and landing process.

Competency and check pilot systems

Sessions led by AMC Search and Capt Matt Shirley explored advanced approaches to check pilot independence. Using biometric data such as eye-tracking and stress response,

AMC’s tools show promise for recruitment and assessment. Capt Shirley emphasised the value of independent group audits to combat operational drift.

Rounding off, MSQ’s Kell Dillon spoke on Queensland’s emergency response and pilotage strategy and meteorologist Thomas Hough offered a timely seasonal forecast, while Alison Cusac, known locally as ‘The Shipping Lawyer’, delivered a motivating closing address.

The AMPI 2025 conference not only delivered on professional development but offered real opportunities for collaboration and innovation. Its balance of technical, operational and human-focused content was a benchmark for similar events –and one I hope we continue to draw inspiration from.

By Arie Palmers / Maritime pilot at Netherlands Loodswezen & pilot ladder expert

It has been a while since the UKMPA published something in its magazine on the wonderful world of pilot ladders, so it is time for a small update on recent events and mishaps written from my side. I’ll leave the explanation of new rules, etc, to my good friend Kevin Vallance to prevent us talking about the same topic. At the moment of writing, the 2025 IMPA safety campaign is about to start. My tally is over 50% non-compliance year after year and I really wonder what the new results for this year will be.

As you might know, I was one of the people involved in the workgroups to develop a brand-new pilot ladder poster as well as a thorough revision of the regulations. I’m glad to notice that more captains and shipowners reach out to me with questions regarding their PTAs (Pilots Transfer Arrangements) and how they can make them compliant. You’ll find the before-and-after pictures here. After all, it is more than ladders; it is the complete pilot transfer arrangement that has to be compliant. Stanchions are an oft-overlooked item that pilots do not complain about, despite the fact that faulty stanchions were the root cause of

several accidents, including a fatal one that occurred in Sandy Hook a few years ago when a pilot dropped to his death due to faulty stanchions. Please check the stanchions and have them rectified! It’s a small job for a welder to get it compliant and therefore safe to use –something the pilot before you didn’t care enough about to get it fixed. Don’t be the pilot before you! Make it safe for yourself and the people that will need to use it after you. You might even save someone’s life, if not your own.

It has been proven that the EMPASafe app has stirred things up quite a bit: more and more pilots are using this way of reporting and I have received quite a few notifications from your side of the pond that a vessel with deficiencies is coming our way. We are therefore warned and take extra care when we approach that vessel. The app has recently been updated and has more and better features now – thank you EMPA for looking after the community. After all, the app is made by pilots, for pilots, to help each other to keep coming home vertically instead of horizontally. The last thing you want is to end up as a statistic.

As I am writing this article, I am on my way back to the Netherlands after attending the TUMPA (Turkish Maritime Pilots Association) conference where I was given the opportunity to talk a bit on ladders and of course interact with a lot of TUMPA members and the sponsors who made the event possible. Over the past years, TUMPA has lost a few pilots because of bad PTAs, so they are very serious on this topic and collectively do not accept below-standard setups.

Pilots, however, are reluctant to report any defects despite the fact that it is mandatory by law. We can also identify this lack of reporting in the annual number of reports in the IMPA campaign: on average around 5,000 reports in two weeks worldwide, not much at all but nevertheless the average non-compliance plus the total body count was reason enough for the IMO to review. We can only hope that the new poster and regulations will improve the unacceptable situation we are currently living in. Even if I were wrong with my tally (for the sake of conversation let’s assume that) and the IMPA non-compliance rate of 20% on average is correct, basically nothing has changed over the years.

Thank the entity you believe in that nuclear power plants or even British Rail have better scores.

Being confronted with a dodgy setup means the entire chain has failed: construction, approval, certification, maintenance, audits, vetting, port state control, surveys and whatnot have completely failed from start to finish, resulting in a pilot being confronted with a dangerous ladder. The fact that the situation doesn’t change much ‘noncompliance-wise’ is because pilots are also mutually responsible for this problem, besides a lot of other causes: we are hesitant, complacent – yes maybe even lazy or self-satisfied – and do no report.

Facts you don’t report are set aside: the least you can do is solve the problem by interacting with the parties involved. But for me it is absolutely no problem to shake the tree with all involved stakeholders sitting on the branches of that tree.

I communicated directly with one manufacturer, who of course stated that his ladder met all requirements and was class-approved (where have I heard that before?). I contacted class recently (an IACS member) and showed them that the specific ladder was below any acceptable standard. After nine months of absolute silence I contacted the classification society again and they told me that the manufacturer had been visited and all problems were resolved. Why do I have a gut feeling there still might be issues? When I see a similar ladder in front of me, I can do nothing else than turn the vessel away. It is important to keep the problems where they belong, after all. The moment I set foot on a dangerous system, the ownership of the problem suddenly changes from the vessel to me, and I like to keep away from problems I do not wish to own.

The pilot before me – I cannot state this often enough – obviously had no problem at all with a dangerous ladder. Again, complacency, laziness and maybe even fatigue mean we have given up on this. If so, there will never be any improvement.

As long as we as a brotherhood do not stick together, the problem will not go away: accepting belowstandard setups will teach the crew that not following the requirements is also okay. It is a downhill slope. As admins of the #Dangerousladders page, we sometimes say to each other: if every member’s partner would be on the page, the problem would be solved tomorrow.

Please, Dear all, stay awake, stay ready for action and, most of all, stay safe.

On average, Idwal boards around 10 vessels every day. These inspections are carried out across the globe, from maritime hubs like Singapore and Amsterdam right through to smaller ports in all corners of the globe. Boarding is carried out while the vessel is alongside or during its stay at anchor. Our records indicate that boarding the vessel is the second most common safety issue reported.

The issues encountered range from gangways and accommodation ladders not being landed properly on the quayside to another surveyor being presented with a 12m-long rope ladder to climb. Unsafe and unorthodox boarding arrangements are not uncommon, particularly when boarding from sea side.

About 15% of Idwal inspections are carried out while the vessel is at anchor. This introduces a different set of challenges. The vessel may have been at anchor for an extended period of time, the Master is rarely on the bridge overseeing the surveyor’s boarding

and crew are regularly not standing by at the ladder. The surveyor is left in a difficult position as they try to establish contact with the vessel, often out of phone signal range and with transfer crew keen to get back to base as soon as possible. Ensuring that surveyors have the tools to support them in these situations is vital.

Idwal has in place a 24/7 phone line to assist surveyors. Surveyors are also required to wear PPE that is in good condition and maintained according to manufacturer guidance. However, the best tool that we can provide to surveyors is to support a change in mindset by avoiding taking the risk in the first place.

Sadly, many surveyors have a mentality of proceeding against their better judgement when faced with an unsafe situation for fear of not getting paid. This dangerous behaviour must be stopped. Over the past couple of years, I have devoted considerable energy to broadcasting a clear and concise message to surveyors: do not proceed if it is unsafe to do so. To achieve this, we have delivered seminars, published

safety circulars and made certain that our guidance is clear and universal. Under no circumstances should anyone’s safety be compromised.

The mindset is changing. But the need for change does not stop with the surveyor. I have also run educational sessions for office colleagues who have not worked at sea so that they can understand the realities of boarding a vessel in a port or conducting an enclosed-space entry. And we have implemented a clear requirement for clients to ensure safe means of access for our surveyors. After all, the vessel’s obligations to provide a safe means of boarding are not diminished under any circumstances.

The task remains ongoing. As I sit in my office overlooking Cardiff docks, it is easy to think that we have done all we can. While I would love that sense of satisfaction in a job well done, I think it is far from the reality. With the variety of surveyors, ports, vessels and circumstances that we encounter on a daily basis, the work to ensure that surveyors are properly equipped to know how to respond to unsafe situations and to ensure that the industry recognises and appreciates the challenges faced by surveyors will remain a key priority not just for surveying companies like Idwal, but for the wider maritime industry as a whole.

By Robert Parker-Norman Head of Surveyor Management, Idwal

By Kevin

Amendments to Solas Regulation V/23 were approved at the IMO Maritime Safety Committee session MSC 109 in December 2024. This was the culmination of a longdrawn-out process dating back over a decade.

When the new regulation comes into force, it will close a number of anomalies that have crept in over time. It is beyond the scope of a short magazine article like this to identify all the changes, but by focusing on one tragic, avoidable accident that occurred because stakeholders were not complying with the regulation in either spirit or intention, it is hoped that readers will be inspired to explore the full content of the new regulation and make reference to:

It has been acknowledged for a number of years that there were fundamental problems, in effect loopholes, within Regulation V/23, which came into force in July 2012. It required a fatal accident in December 2019 before the attention of the IMO was finally alerted by IMPA to two particularly serious issues. This finally prompted a full-scale review and revision of the regulation.

WHEN THE NEW REGULATION COMES INTO FORCE, IT WILL CLOSE A NUMBER OF ANOMALIES THAT HAVE CREPT IN OVER TIME.

On 30 December 2019, while embarking a container vessel at the Sandy Hook Pilot Station, Captain Dennis Sherwood fatally fell from a combination laddertrapdoor arrangement.

The arrangement had the pilot ladder suspended from the bottom of the accommodation ladder’s lower platform, requiring a degree of acrobatics when transitioning from the pilot ladder to the accommodation ladder. Captain Sherwood had difficulty during the transition and he fell to his death.

On 17 January 2020, I boarded the vessel involved in the fatal accident while it was alongside at Newark, New Jersey, as a member of the team employed by the US Super Lawyer representing Captain Sherwood’s estate. The photo opposite was taken during that visit.

This type of construction is not unusual, despite a definite statement in IMO Resolution A.1045 that in this situation, i.e. a trapdoor arrangement, “the pilot ladder should extend above the lower platform to the height of the handrail and remain in alignment with and against the ship’s side”.

The first loophole exploited in this situation was that the content of IMO Resolution A.1045 and the content of ISO Standard 799 remain only footnotes to the regulation. As such, many flag state authorities are of the opinion that they are only recommendations and cannot be legally enforced.

It is shocking to discover that the need for the pilot ladder in a trapdoor arrangement to extend to the height of the handrail was first mentioned in Resolution A.426, which was adopted in November 1979, a full 40 years before the death of Captain Sherwood.

THE TRAGIC DEATH OF CAPTAIN SHERWOOD WAS A MAJOR CATALYST FOR THE REVISION OF SOLAS V / 23, WITH THE INDUSTRY FINALLY ACKNOWLEDGING LONGSTANDING LOOPHOLES.

The revised version of Regulation V/23 contains, as a mandatory performance standard, the requirement that for combination ladder-trapdoor arrangements, ‘the highest step of the pilot ladder is at least 2m above the platform and is secured to pad eyes on the inboard side of the frame so that it rests firmly against the side of the ship’.

Another loophole of regulation V/23, which was exploited by shipbuilders, classification societies and ship operators, was the use of so called ‘grandfather rights’. It was argued that because the vessel concerned (and its 12 sister ships) were constructed before Resolution A.1045 was adopted in 2011, the vessel did not have to comply with the content. This interpretation omitted to acknowledge that the previous resolutions applying to pilot transfer arrangements – A.889 from 1999, A.667 from 1989 and the previously mentioned A.426 from 1979 – all contain the same recommendation that “the pilot ladder should extend above the lower platform to the height of the handrail and remain in alignment with and against the ship’s side”.

When adopted, the new Regulation V/23 will eventually remove this loophole, although not finally and completely until January 2030. However, it is hoped that, encouraged by the IMO Marine Safety Committee, flag state authorities will require ships to comply before January 2028.

By Dominique Vaugrenard, Pilot on the Seine River, Port of Rouen

My name is Dominique.

I am 54 years old and have been a pilot on the Seine River since 2005, guiding vessels safely into and out of the Port of Rouen. With over 20 years of experience, including four years as a senior pilot in charge of traffic co‐ordination, I am deeply familiar with the procedures, challenges and responsibilities of this critical role. But on 22 April 2021, a routine transfer operation turned into a traumatic accident – one that not only affected my health and career but also sparked a conversation on the safety of pilot transfers in France.

That evening, the Van Star, a Panamax tramp vessel measuring 190 metres in length and 32 metres in beam, 6.5 metres draught, was sailing up the Seine River towards Rouen to load scrap metal. It was arriving in ballast from Terneuzen, Netherlands. During the transit, a changeover from the second to a third pilot was scheduled at kilometre point 256 in the port of Rouen. This third pilot – me – was to complete the final manoeuvring phase and berth the vessel.

At approximately 9:40 pm, the launch Oceanite left its berth to transfer me to the Van Star. At 9:46 pm, in early night conditions, we approached the starboard side of the vessel where a combination ladder had been deployed.

A

This setup, involving both an accommodation ladder and a pilot ladder, is common when the vessel’s freeboard exceeds 9 metres. Unfortunately, the configuration that evening would prove to be dangerously flawed.

The platform of the accommodation ladder had been positioned too high, covering the pilot ladder, obstructing the forward rope that I needed to grip with my right hand. This rope was essential for maintaining balance and advancing safely up the ladder. I was forced to shift my body weight while holding on with only my left hand. At the same time, my feet were placed on a repaired pilot ladder step that was thicker but less stable than the others. Suddenly, I lost my grip and fell 4.5 metres onto the hard deck of the launch vessel below.

Injuries, investigation and critical failures:

The fall resulted in four significant fractures – my left wrist, elbow, scapula and ankle were all injured, with two requiring surgeries. I was evacuated to Rouen Hospital, where I remained for several days before beginning a lengthy rehabilitation. Due to the strain on hospitals during the Covid‐19 pandemic, access to operating rooms was delayed, further complicating my recovery.

Immediately after the incident, the French Marine Casualty Investigation Office (BEAmer) launched an inquiry into the causes and circumstances. Their investigation uncovered a disturbing number of safety violations and oversights.

Among the findings were:

• The accommodation ladder platform was incorrectly positioned, obstructing access to the pilot ladder’s forward rope.

• The platform had not been secured properly to the ship’s hull – a key safety measure that was entirely omitted.

• One of the stanchions meant to support the pilot ladder was missing.

• The step I fell from was a replacement step – installed correctly in theory, but with different thickness and spacing, which introduced a subtle instability.

• Most critically, the ladder was visually inspected by me in near‐darkness, without any effective lighting or briefing before the transfer. I noticed the problem too late – by the time I realised the rope was inaccessible, I had already lost balance.

• The investigation further suggested that the accommodation ladder may have been slightly raised between the second and third pilot boarding, which was likely the reason the platform came to obstruct the rope. This subtile change – lifting the platform by only a few dozen centimetres – made the forward rope unreachable and ultimately led to my fall.

The road to recovery: physical and psychological healing: Recovering from the accident required immense physical and mental endurance. After one and a half months of immobilisation with a cast on my ankle and an external fixator on my left wrist, I began intensive daily physiotherapy. For over three months, I engaged in sport and rehabilitation sessions every day to rebuild the strength and stability needed to resume climbing ladders.

But the physical pain was not the only challenge. Emotionally, the experience was deeply traumatic – not only for me but also for my colleagues. Some were shaken by the severity of my injuries, particularly the visible hardware that held my wrist together. One of them, remembering another tragic case involving a pilot crushed between a launch and a vessel, described feeling deeply disturbed by the risks we all take for granted.

Initially, I was hesitant to seek psychological support. It wasn’t until my occupational doctor recommended it during my post‐accident evaluation that I considered reaching out to CRAPEM – the French Seafarers’ Psychotrauma Support Centre in Saint‐Nazaire. With regular phone calls from a compassionate professional named Madame Benoît, I was able to process the emotional weight of the accident. Her support was instrumental in helping me rebuild the confidence to return to work and face pilot ladders again without fear.

Due to the seriousness of the accident, many didn’t believe that I returned to active duty just 146 days after the accident, on 15 September 2021. It was a personal goal, a symbolic milestone and a statement that I would not let this accident define the remainder of my career.

Lessons learned & the need for change: What followed was not just a personal recovery but a movement toward systemic improvement. The French Federation of Maritime Pilots (FFPM), in collaboration with my colleague Thomas Levillain, produced a powerful safety video using real images from our accidents to highlight the risks pilots face daily.

This video www.youtube.com/watch? v=U2DRLX7dyS8 became a training tool, designed to shock viewers into recognising the gravity of even minor oversights.

The Seine Pilot Station also introduced training sessions for launch crews, held off Le Havre at sea. Rouen’s pilots organised ‘Skipper‐Pilot Navigation Meetings’ to review procedures and encourage communication. A local notice to masters was issued to all ships arriving in Rouen, outlining best practices and highlighting the proper rigging of combination ladders.

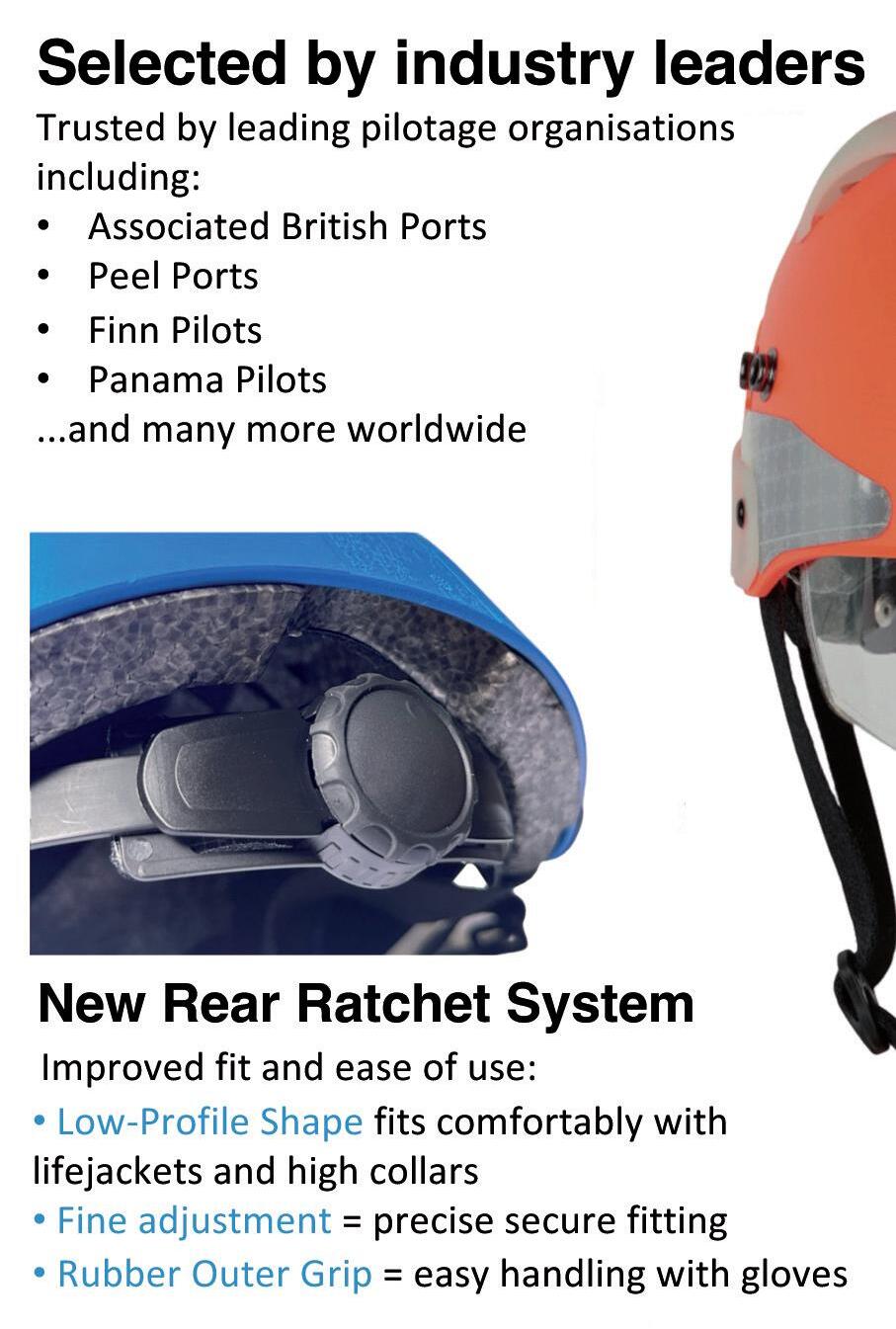

The importance of wearing a helmet was further emphasised – a logical and necessary safety measure, given the height from which a fall can occur and the numerous obstacles on the deck of the launch that pose significant risks in the event of an accident.

Yet despite these efforts, BEAmer noted in its report that incident feedback remains inconsistent across French pilot stations. Many pilots do not report near misses or non‐compliant arrangements, often due to time pressure or a belief that nothing will change. That should be improved. Pilot ladder safety is a chain – each link representing ship design, regulation, crew training, industry standards and onboard procedures. When even one link breaks, lives are at stake.

Even ship design needs scrutiny. On Van Star, the gangway was located dangerously close to the stern and propeller, increasing the risk should a pilot fall into the water. In my case, the launch didn’t have time to move clear. A fall into the water could have been just as dangerous – or even fatal.

Four years later: lasting impact and final reflections: Now, four years on, I continue to live with the long‐term consequences of that night. The injuries I sustained have resulted in arthritis and reduced mobility, particularly in my ankle. I used to be an avid runner –but that’s no longer possible because of the chronic pain.

While new warnings, standards and regulations have since been introduced to enhance the safety of pilot ladders, it’s clear that many of these systems still fall short of compliance. Often, this is due to a lack of awareness among crews about the critical importance of maintaining this equipment in perfect working order – putting the lives and health of pilots at risk.

Though such accidents are rare, their consequences can be severe – and the lessons they teach are universal. They serve as a stark reminder that pilot transfers, though seemingly routine, are among the most hazardous operations in maritime navigation. Every shipowner, captain, deck crew member and port authority shares a responsibility to ensure that these transfers are carried out safely, in full compliance with regulations and with a clear understanding of the risks involved.

I am deeply grateful to everyone who supported my recovery – my family, my colleagues, Madame Benoît at CRAPEM and the dedicated medical professionals who helped me heal. Thanks to them, I was able to move forward. But my commitment remains firm: no pilot should ever have to endure a fall like mine.

Thank you for your attention. Let us always remember that safety – like trust – is built one step at a time.

By Joris J. Stuip / PTR Holland

PTR Holland has been producing high-quality pilot ladders since the 1960s. We have always prided ourselves on the quality of our product, the service we offer and our commitment to making pilot transfer as safe as possible. All our ladders are manufactured in-house at our four production facilities in Rotterdam,

Houston, Singapore and Newcastle, UK.

Our network allows us to distribute our ladders and equipment quickly to the global maritime industry.

Sourcing the best materials

Our ladder production starts with sourcing the finest components. The international standard for pilot ladder construction (ISO 799) is very specific on the components

used in the production of ladders. The side ropes are made from Grade 1 mildew-resistant manila rope meeting ISO 1181:2004 requirements. This is one of the highest-quality manila rope grades available and it is selected for its strength, resistance to salt water and resistance to UV degradation. The steps are constructed from ethically sourced, FSC-approved hardwood forests,

giving a robust, knot-free step designed to withstand the marine environment, and our rubber steps are reinforced with a steel bar to ensure they can stand up to repeated impacts with the pilot boat. Finally all the chocks and clamps are manufactured at our Rotterdam facility. PTR developed the H-Clamp seizing method in the 1980s and we still manufacture these unique, high-quality fixings in-house to ensure their quality.

Production depends on the type of ladder we are producing. While we do still offer our clients the traditional hand-seized ladder option, this timeintensive method now only accounts for a dwindling proportion of our output. The H-Clamp has proven to be a firstrate method of ladder production,

giving a long, maintenance-free service life. Prior to producing a ladder, the steps are laid out with the uppermost step and lowermost spreader already fitted with the ladder’s unique ID plate. Our ladders are constructed on long manufacturing track tables designed for this unique purpose. Working in teams on either side of the track tables, the steps and spreaders are laid out and the manila rope is threaded through each one. Next, the chocks are added and the steps set out at the correct distance. The team then work from one end of the ladder, inserting the clamps, ensuring the chocks are firmly against the step and then tightening the clamps using a hydraulic press that applies just enough pressure to ensure the clamp is secure without damaging the ropes. Finally, the thimble is added to the top of the ladder and is clamped or spliced in position.

Our teams have become masters of this process and we can now produce a pilot ladder in a few minutes rather than a few hours. This means we can produce ladders to the customer’s exact requirements and our global distribution network can get a ladder to a ship as quickly as possible. This allows PTR to

produce over 300,000 metres of pilot ladders a year: enough to stretch from Rotterdam to London. Our ladders represent the ethos of the company, offering the best quality, and this is reflected in our certifications. Our products are backed by DNV’s exacting requirements and meet Solas and ISO Standards as well as the relevant MED, MCA & USCG standards.

PTR’s commitment to pilot safety goes way beyond our ladders’ quality. We constantly innovate to drive the industry forward. Our QR code system allows ships to register their ladders on our blockchain database, which can be accessed and reviewed by pilots and Port State Control officials to ensure a ladder is genuine. We regularly sponsor pilot association events, safety initiatives and industry forums to help improve standards, and we are constantly looking at designing products to further enhance pilot ladder safety. Our simple aim is to ensure that the undeniably dangerous act of pilot transfer is as safe as possible for the end user.

PTR HOLLAND HAS BEEN PRODUCING HIGH-QUALITY PILOT LADDERS SINCE THE 1960S.

The Energy Skills Centre at Lowestoft today provides specialist training to a wide variety of clients, from the traditional oil and gas sectors to the emerging clean energy industry.

The facility established itself at its current site in 1985 when it moved from the fishing school located in an old church near Ness point. The new facility was constructed in partnership with Shell UK and for many years served not only the offshore oil and gas industries but the US military and delivered the oneday Sea Survival Course for merchant seafarers and the recreational sailing sector. More recently, the centre has expanded and now incorporates a dedicated climbing facility serving the needs of the offshore wind industry.

Some years ago, we received an enquiry from surveyors associated with the STS sector. The coast of North Suffolk is an established area for these operations, requiring a ladder training course. As a result of this, we developed

a pool session, which was attached to a one-day sea survival course. The session was primarily aimed at giving the delegates an insight into what they might expect when boarding a vessel and at what point they might consider saying ‘no’.

After some time, I thought that the course we were running might be adapted to the marine pilotage sector and by happy coincidence we were approached by Peel Ports, looking to find a facility close to Great Yarmouth that they might use for pilot ladder training. We already had an environment tank/pool where we could provide waves, wind and rain effects, but we needed to fabricate a small structure so that we could provide a flat surface for the ladder to rest against.

We also needed to order an approved pilot ladder for our purposes.

A PTR Holland subsidiary based in Wallsend was excellent and within 10 days and at a very competitive price they delivered our 4.5-metre ladder.

Then came the task of putting the course content together. I thought that it would be best to split the day into three key areas.

The first part of the day is spent looking at the legislative framework around the transfer arrangement. I must be completely honest here: it was only when I started looking at this that I became aware of how little I had really known before. Secondly, we move to the climbing hall where we are assisted by the climbing instructors from Norfolk and Suffolk fire brigade. Initially we only had access to a seven-metre fixed vertical ladder and, while not in any way like what we climb as pilots, it provided a useful snapshot into the differing approach used by emerging industries such as the offshore wind sector and brought into relief the challenges and hazards that pilots face. More recently, we have completed the installation of a nine-metre-plus pilot ladder, which delegates are able to climb (with fall arrest attached).

Interestingly, the nine metres of ladder look far more ominous when placed in a land-based environment. The fire service climbing instructors were a little surprised to find that we climb this regularly as part of our job. We then move over to the environment tank. We know that we cannot ever replicate a true boarding and landing situation; however, by using our small aluminium skiff and the features of the tank, i.e. waves, wind and rain in semi darkness, we are able to create an atmosphere with the potential to get people’s adrenaline running and raise their heart rate.

Safety of our delegates is paramount and for this reason we always have two lifeguards, myself and a pool supervisor, present. We ask that attendees come with the PPE that they would normally wear at work and we run through the correct fitting and use of that equipment. Generally, seeing it inflate and support them in the moments after they enter the water is a tremendously effective affirmation of the trust they place in their equipment, whether it be a dedicated pilot coat with integrated life jacket or a separate life jacket.

After the pool session, we head

for a debrief and look at recent casualty reports related to pilot transfer, finishing with a Q&A session. We have now run ten of these courses and I believe we are finessing it a little each time to ensure that we offer the best possible experience for the delegates. In future, we are hoping to offer the course as an add-on for participants wanting to undertake a basic sea survival course, possibly over 1½ days, should there be interest in that.

By Simon Browne / Managing Director, Apoio Marine

IMPA was at the forefront of the work at IMO to finalise draft amendments to Solas regulation V/23 and a new mandatory performance standard for pilot transfer arrangements. This work was completed in June 2024 and, importantly, approved by the Maritime Safety Committee of the IMO in December 2024.

IMPA is now preparing for the final part of the IMO process, which will be the adoption of the amendments to Solas in June 2025 so that they can enter into force on 1 January 2028. The prospect of a coherent, mandatory regime for pilot transfer arrangements on both Solas and non-Solas ships, regardless of when they were constructed, represents the most significant development for the personal safety of pilots in decades.

The IMPA Executive and Secretariat are grateful to those pilots’ organisations, including UKMPA, that were active on the delegations of member states throughout this process. The synergy with the IMPA delegation has been highly effective.

As part of the process, revised ladder poster illustrations will also be approved and circulated by IMO. The IMO supports IMPA by translating the poster into the official languages of the IMO. IMPA will have a new area of the website dedicated to providing information and guidance on best practices for rigging pilot transfer arrangements.

Early implementation of the amendments is also being pursued as a direct result of the data collected from pilots worldwide during the IMPA safety survey. IMPA continues to evolve the application used during the survey and welcomes user feedback.

AN UPDATE ON IMPA’S WORK PROMOTING THE SAFETY OF PILOTS AND THE PURPOSE OF PILOTAGE

IMPA will co-convene with France and the ISO Working Group to review and revise ISO 799 so that it is well placed to support the implementation of the new Solas requirements ahead of 2028. This work will kick off in July 2025.

Promoting the purpose of pilotage

In August 2024, IMPA kicked off its international study on remote pilotage. The study is designed to establish an authoritative, comprehensive, sciencebased framework that empowers pilots’ organisations and competent authorities to make informed, risk-based decisions about remote pilotage based on their national circumstances. The study is not intended to promote or denigrate remote pilotage.

The study is being delivered through a partnership between IMPA, the National Centre of Expertise on Marine Pilotage (Canada) and the Canadian Coast Guard. It responds to an increasing number and variety of individuals and groups discussing remote pilotage.

The study is at the technology readiness assessment stage, which is being supported by technical expertise from Lloyd’s Register and involves two potential systems that may be able to

help IMPA understand and explore the risk, opportunities and pre-requisites of remote pilotage. The results and the next steps for the study will be published later this year.

Part of the study deals with pilotage as a complex system. It will use expertise from the University of York to help us model pilotage and provide tools to help pilots’ organisations and competent authorities understand the sensitivity of pilotage as a complex system to regulatory, operational and technological changes. This is essential to protect the effectiveness of pilotage as a public service: a x528 reduction in risk (TEMS, 2022) and an incident rate of less than one very serious maritime casualty for every 10 million acts of pilotage (IMPA, IMO GISIS).

IMPA has been monitoring the work of the IMO on a comprehensive review of the STCW Convention and is pleased to report that the risk of pilots being affected is very low. This is important as standardisation of pilot training and certification beyond the recommendations of IMO resolution A.960(27).

The association remains fully engaged in the IMO’s work developing a non-mandatory Code for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS). It ensures that navigation-related expertise is available to the groups developing the code and that nothing within the code could negatively affect pilotage systems and the effectiveness of pilotage as a public service. Our next objective is to ensure that the framework for an experience-building phase effectively broadens and deepens the collective understanding of the risk and consequences of large MASS.

IMPA is active in the IMOGender Network and is pleased to inform you that Captain Jo Clark, president of the Australian Maritime Institute, represented maritime pilots during a symposium at the IMO celebrating International Day for Women in Maritime.

The IMPA secretary general, the IMO secretary general and secretariat and colleagues from other industry organisations took part in the assessment panel to make recommendations for the IMO’s Honours for Exceptional Bravery at Sea.

IMPA maintains a close working relationship with the International Organization for Marine Aids to Navigation, participating in its VTS and Digital Technology Committees. The primary objective of this work is to contribute constructively to developing IALA instruments and ensure that IALA’s work does not have a negative impact on pilots and pilotage. A recent example is avoiding premature guidance to coastal authorities, recommending that they change pilotage regulations to enable MASS.

IMPA expects to make a significant announcement in 2025 about our contribution to promoting maritime careers and excellence in maritime training, alongside hosting an inaugural members’ forum and working group in the second half of the year to bring our membership closer to the work of the association.

Planning is also underway for the XXVII Congress in Indonesia, 23–28 August 2026. The registration and accommodation website are expected to go live in June. The IMPA Congress is an integral part of the association’s mission as it provides a platform for pilots worldwide to share knowledge, experience and expertise.

Finally, IMPA will continue to support members who ask for assistance dealing with national challenges.

By Paul Schoneveld / IMPA Representative & Liverpool Pilot

By Scott Tonks, Patrik Wheater & Andy Tipping - Zelim executive team

Boarding a vessel via a pilot ladder is a high-risk operation with potentially tragic results for those falling into the water. A new technology from Edinburgh-based Zelim, however, could mean the difference between life and death.

While safety procedures and training have improved, pilots continue to face significant dangers during vessel transfers. Falls and Man Overboard incidents continue to occur, often in challenging weather conditions where traditional recovery methods struggle to be effective. Indeed, several cases have shown the lack of a rapid and effective recovery has been a key factor affecting the safe rescue of people from the water.

More recently a pilot fell while boarding the ro-ro Finnhawk at the entrance to the Humber Estuary. The MAIB’s interim report noted that the pilot vessel’s crew were unable to raise the pilot vessel’s recovery platform and recover the injured pilot on to its deck.

Zelim’s Swift Man Overboard (MOB) rapid recovery system has been designed specifically to address these challenges head-on. The system is based on a rapid recovery conveyor mounted to a vessel’s stern or side. When deployed, it extends into the water and activates an electric motorised belt, using traction to pull casualties on board in seconds. Unlike traditional methods, it requires no manual lifting and can recover both conscious and unconscious individuals without requiring rescuers to enter the water.

Recognising its potential, Milford Haven Port Authority (MHPA) installed Swift on its 19m pilot boat, Picton, for trials in heavy sea conditions. The system was tested in 2.5m swells, but MHPA,

operating in one of the highest sea states of any port authority globally, has since pushed the system even further. Trials have taken place in 3m swells – the most extreme conditions Swift has faced so far.

During comparative trials offshore Ramsgate, traditional MOB rescue methods took over nine minutes (with multiple failed attempts) to recover a casualty, while Swift completed the task in just 28 seconds.

At the time, UK MHPA pilot Jamie Furlong said, “With the unique and demanding environmental conditions experienced in Milford Haven port, pilot safety and exposure time in the water during Man Overboard occurrences are critical. The opportunity to see the Zelim Swift system at work, with its potential application for our operation, was excellent. The system enables timely extraction of a casualty from the water, allied with an easy deployment system.”

John Warneford, Assistant Harbourmaster at MHPA, echoed similar sentiments. “The design and operation of the system present advantages in reducing potential further injury to personnel being recovered, particularly when recovering in a swell.”

Given the success of the trials, MHPA plans to equip three of its pilot boats with the system and integrate it into new state-of-the-art heavy-weather pilot vessels designed for extreme conditions. Indeed, MHPA’s decision to adopt Swift has drawn interest from other ports and harbours around the world.

On the back of the positive feedback from MHPA about the system’s reliability, for instance, a South American pilot boat operator ordered the technology, which is currently being installed on their pilot cutter. It has also undergone extensive trials aboard Artemis Technologies’ electric foiling

workboat Pioneer of Belfast, the success of which demonstrated its capability to rapidly recover individuals from the water without the need for the vessel to come to a complete stop – a critical feature for high-speed operations.

Speaking in August 2024, Artemis Technologies’ technical director Romain Ingouf stated, “It was good to see another system in operation to compare with the traditional Man Overboard recovery systems used on many vessels for overboard retrieval … We want to provide our customers with a range of effective options.”

Meanwhile, Singapore’s Changi Airport, recognising the importance of waterborne rescue capabilities for aviation safety, has installed Swift on its new high-speed rescue vessel. Given the airport’s proximity to the Johor and Singapore Straits, rapid recovery systems are a critical element of emergency preparedness. During trials, Swift recovered multiple casualties one after the other, significantly reducing rescuer fatigue and the risk of injuries to rescuers. Other airports with runways close to water have expressed interest in the system.

Time is the most critical element in any MOB incident. Even though pilots will be wearing lifejackets, cold-water shock, injury and water inhalation in rough seas can result in fatalities. And while traditional retrieval methods, such as the use of a hydraulic platform – the most widely used option across the pilot boat industry – are effective, they are safe to use in only relatively calm seas as they can pose a risk to the person in water as the vessel heaves, pitches and rolls.

Even when a casualty is reached, lifting waterlogged conscious and unconscious individuals onto a vessel’s deck remains a significant challenge. Swift eliminates these concerns by providing an automated, high-speed retrieval method that operates effectively in adverse weather.

Lloyd’s Register type approval has confirmed Swift’s compliance with Solas regulations, clearing the way for widespread adoption. The system integrates seamlessly with a vessel’s power supply, requires only a single day of operator training and has a load capacity allowing for the simultaneous retrieval of two casualties.

Increasingly, industry leaders are recognising Swift as a potential standard for pilot boat safety. The UK Maritime Pilots’ Association (UKMPA) has highlighted the necessity of improved MOB retrieval systems and best practice for recovery. Zelim’s success at MHPA and other locations provides strong evidence of its viability as a preferred solution. As Swift continues to gain traction, it will undoubtedly save lives where every second counts.

Zelim was founded in 2017 with a mission to transform search and rescue operations through technology-driven solutions. The company, based in Edinburgh, was established by former mariners and rescue professionals who had firsthand experience with the difficulties of Man-Overboard recoveries.

Zelim’s CEO and founder, Sam Mayall, a former seagoing navigating officer, was personally involved in a response to a man overboard incident where shipmates lost their lives as they could not be rescued. This experience drove him and cofounder Doug Lothian to develop solutions that could significantly improve response times and increase survival rates.

Zelim has gone on to develop other life-saving technologies, including an AI-based ManOverboard detection and tracking system called ZOE, and a ManOverboard fast rescue vessel called Guardian.

Since its formation, the company has expanded into the USA with the appointment of former US Coast Guard Commander Matthew Mitchell as director of Search and Rescue.

UK pilots and launch crews complete Man Overboard (MOB) and launch familiarisation training in line with the requirements of their respective CHAs (Competent Harbour Authorities). How does that training relate to the reality of recovering a person in the water (PIW)?

Training – competency vs currency RNLI stations train on average once a week. Like many rescue services, the RNLI uses a competency‐based framework to ensure crews remain competent and, more importantly, current at identified tasks. Competency training focuses on building practical skills and knowledge, assessed through practical evaluations and assessments. Currency training involves updating and refreshing existing knowledge and skills to maintain proficiency.

Maintaining proficiency is achieved by completing specific exercises over a set period of time. Currency training is designed to prevent the scenario of an experienced coxswain always helming the boat during recovery drills. While they have the knowledge to operate the recovery system, when did they last physically perform that evolution?

As I experienced more incidents involving a PIW, I was able to identify any shortcomings or gaps in my training and

incorporate real‐world scenarios into training sessions. Something as simple as losing an engine or a main communication set failure may not seem significant during training, but were it to happen on the day then that previous training and experience may kick in. I say may kick in, because we do not know how an individual will behave in an emergency. On a pilot launch, the potential for heightened stress levels and possible personal or family connections among those involved should be acknowledged.

How we trained

Effective training necessitates exercises conducted across a range of environmental conditions, using and becoming familiar with relevant Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs).

A consistent application of SOPs creates a unified approach across crews that rotate and mix. Often, the first crew

through the door will respond to a PIW incident, so the training sessions must ensure that crews rotate.

For pilot launch crews, rota constraints, etc, mean that a crew may work together who have not completed a drill together before. In this instance, having a standardised approach to training and methods may be beneficial.

Typical training exercises would encompass:

• Comprehensive pre‐launch briefings and checks

• Realistic communication scenarios

• Effective delegation of roles

• Responses to simulated equipment failures

• On‐scene briefing detailing the recovery plan and subsequent casualty care considerations

Finally, a post‐exercise debrief that encourages honest and critical evaluation is crucial for identifying areas for improvement and equipment deficiencies.

The recovery – the reality Recovering a PIW is seldom a textbook operation.

Complications can include a despondent casualty, various types of flotation equipment or none, and clothing or lack thereof. Even a dog might be thrown in to the mix.

Responding to a call for a PIW is a dynamic event. For some crew, it may be their first time, and as a coxswain/helm you will have to manage not only the situation but them too.

Adrenaline affects us all differently: some crew may go quiet while others will be trying to do everything. I can recall twice having to tell one crew member to sit down on approach to a casualty.

Communication overload with helmet‐based communication sets combining internal crew chat with external VHF transmissions can present a significant challenge and stress. As a helm, you find yourself in the position of trying to helm the boat, manage and keep your crew safe, and process updates from the Coastguard, all while attempting to locate and recover a casualty. All this time one must not forget that the primary responsibility remains the safety of the crew. The last thing needed is a crew member to inadvertently end up in the water too.

Equipment – considerations and limitations

Equipment available for PIW recovery varies greatly between the commercial and rescue sector. Pilot launches, for example, can be crewed with a minimum of two persons as per MGN 50. © Eddie

Avoiding a discussion on crewing levels, it is undeniable the recovery equipment on board the launch is pivotal to the success of the recovery.

RNLI inshore lifeboats with their low freeboard rely on manual recovery techniques. Being crewed with three or four makes manual recovery the quickest and most effective option. Boat design is also a factor, with limited storage space for recovery equipment.

Crew would kneel down, keeping a hand for themselves and using foot loops (if fitted) to pull the casualty over the side of the boat. Should conditions allow, the sponsons could be deflated to lower the freeboard further.

All‐weather or offshore lifeboats may employ a manual davit system, scramble nets or daughter craft. Often operating with a crew of between five and eight, they can quite easily adapt to the situation.

Contingency planning – multiagency search and rescue Rarely does a lifeboat have the PIW sighted from the beginning. There is usually an element of search‐and‐locate that forms part of the rescue. Tasking information from HMCG is passed in a standardised format, with search patterns set by the co‐ordinating station or guided by local knowledge of the rescue asset.

Lifeboats often train with flank stations, Coastguard teams and Fire & Rescue services. Having an understanding of the capability of local assets through training sessions is essential for contingency planning. For example, one should know which asset in the local area is the fastest or can access the most suitable casualty landing location. This would include helicopters and a knowledge of their response times. A simple training session with a lifeboat could involve a walk around the pilot launch, gathering an appreciation for the layout and the recovery system used. This demonstrates to lifeboat crews how the recovery system is operated and identifies scenarios or ways in which the lifeboat could help in an emergency situation: for example transferring crew members to assist with casualty care. Discussing or practising this beforehand only stands to benefit on the day.

On a final note, while I have referred to RNLI lifeboats, I wish to recognise the work of the independent lifeboats across the UK. I have not commented on them purely as I don’t know how each independent station operates.

MOB by Mike Stannard (former RNLI Helm &

present Liverpool Pilot)

I’ve been fortunate throughout my career to experience pilot boat operations at a range of ports across the UK, from Littlehampton and Shoreham on the South Coast to Liverpool and Heysham in the Northwest, and now here in Harwich. In every location, I’ve been consistently impressed by the professionalism, dedication and conduct of the teams who deliver pilot vessel

operations. Their commitment to safety, precision and teamwork plays a critical role in supporting safe navigation in UK waters, often in challenging conditions and with minimal public recognition. It’s a vital service that underpins the smooth functioning of our maritime infrastructure.

At Harwich Haven Authority, a primary focus for our team is to deliver customer‐focused, safe, sustainable and efficient

marine operations, 24/7. The professionalism and safety of our marine operations are very much led from the front by the skill and dedication of our launch crews. As harbour master, =I see first‐hand the pivotal role these individuals play in ensuring the safe and efficient transfer of pilots to and from vessels navigating one of the UK’s busiest deepwater harbours. Behind every

successful pilotage operation is a crew who have been trained, equipped and trusted.

Our launch crews are the front line of safety. That’s why we invest heavily in their training and development from day one. We are very focused on bringing new talent into the industry and promoting careers within the maritime sector. As a trust port, we are committed to playing a positive role in our local communities, so we are always keen to offer employment opportunities to people living within our area of jurisdiction.

Many of our launch crew members begin their careers through our marine apprenticeship scheme. This two‐year, structured, Level 3 apprenticeship programme is delivered with training provider SeaRegs and not only provides a solid foundation in seamanship, navigation and operational safety, but also supports each apprentice through to a commercially endorsed RYA Yachtmaster Offshore Certificate.

After completing their apprenticeship,

team members can progress to the role of assistant coxswain, as positions become available. This stage focuses on building further experience and developing detailed local knowledge. With continued training and time on the water, the final step is promotion to coxswain. Depending on prior experience, the full progression from new entrant to coxswain typically takes around three years.

But training doesn’t stop with certification. Continuing Professional Development (CPD) is embedded into our operational ethos. From on‐the‐job learning to external specialist courses, our crew are constantly expanding their knowledge. It’s a dynamic career path with real growth, both in terms of responsibility and capability.

As an example of this, we are currently training experienced members of our Marine Support Team to achieve the MCA Master 200 certification. To enhance the crew’s situational awareness and decision‐making, we have taken an innovative step

by sending launch crews to our simulator course at HR Wallingford. Here, they participate in realistic ship simulations alongside pilots, tug masters and VTS officers, building a richer understanding of how their role fits into the broader navigational safety and traffic management picture.

This holistic training helps our launch crews appreciate the complexity of large‐vessel manoeuvring and the inter‐dependent nature of every maritime role, from the bridge of a Megamax containership to the helm of an ASD tug and to the VTS console. The feedback from both the crews and their counterparts in these sessions has been outstanding, with stronger communication and mutual respect evident in day‐to‐day operations.

Safety is not a checkbox; at HHA, it’s a culture. Our commitment goes beyond basic requirements, reinforcing a culture where safety and preparedness are at the heart of daily operations. We place a strong emphasis on maintaining high standards of medical readiness across our marine operations, and I’m hugely supportive when it comes to medical training.

Refresher medical training is routinely undertaken by both our pilot launch crews and pilots. This ensures our teams remain confident and capable of delivering immediate, effective care in emergency situations, whether at sea or ashore. Our crews also participate in regular emergency drills, including Man Overboard (MOB) procedures. These drills are more than compliance; they are about building muscle memory and confidence in high‐stakes scenarios. MOB drills are run in various conditions to replicate real‐life challenges and to maximise the collective learning experience. We have an in‐house first aid instructor to lead scenario‐based drills.

Pilot transfer safety is an area of continual scrutiny and improvement. We are proactive in our engagement with industry best practice. One innovative safety solution has been to equip all our pilot launches with pilot bag baskets on the foredeck. These enable the safe and secure transfer of the pilot’s gear at this critical moment, and without the worry of losing a PPU into the drink. The baskets were designed by our in‐house marine engineering team and then, following a trial period on one launch, further baskets were fabricated by a local company for retrofitting to the rest of our fleet.

It is HHA policy for pilots not to carry their own bags when climbing pilot ladders: all ships are asked to provide a heaving line to haul or lower bags. We also require our crews and pilots to undertake dedicated Pilot Transfer Training provided by East Coast College in Lowestoft. This ensures that all crew members are thoroughly familiar with ladder rigging standards (as per Solas requirements), transfer protocols and how to identify non‐compliance when arriving alongside vessels.

Hadrian’s rail systems are fitted to all HHA pilot launches, providing a secure means of clipping when required. Although I am generally in support of clipping on, following assessment and consultation with our guidance and in alignment with national guidance, our current risk assessment and operating procedure does not mandate for HHA pilots to use the system: it remains available should they choose to do so. All pilot launch crew are required to clip on when moving forward on deck to assist pilots. This approach ensures a high standard of safety during transfers while allowing pilots the flexibility to assess conditions and use the system at their discretion.

As the harbour grows in complexity, draughts increase and ship sizes continue to grow, the need for a highly capable and adaptable pilot launch service will only increase. We are committed to keeping our operations at the cutting edge of safety and technology.

As part of our commitment to innovation and sustainability, we are working in partnership with motorsport technology innovator Purple Sector on the SEAS (Smart Efficient Automated Scheduling) project. Supported by the Department for Transport’s Smart Shipping Acceleration Fund, this feasibility study focuses on the optimisation of pilot launch operations. By applying motorsport‐derived concepts, SEAS aims to enhance scheduling efficiency, reduce carbon emissions and lower operational costs.

This work is closely integrated with a bespoke Digital Twin platform, enabling detailed modelling of future pilot launch power chains, including alternative fuel and propulsion options such as hybrid, electric, methanol and hydrogen technologies. The insights gained will inform our long‐term strategy for sustainable vessel operations, ensuring we continue to reduce emissions on our journey to achieve Carbon Net Zero by 2035.

We see our whole team as part of a larger maritime partnership that includes pilots, tug operators, ships crews and masters, as well as VTS professionals. Each one is a cog in a well‐oiled machine but it is the human element that ensures it all works. Whether it is simulation‐based learning, new equipment or advanced training pathways, our mariners will continue to lead by example in supporting the people who make maritime safety happen every day.

In short, I am proud of UK launch crews, not just for the work they do but for the high standards they set. They are not only a vital part of our present but central to the UK ports and harbours vision for the future of safe and efficient marine operations.

By William Barker, Harbour Master (Marine Director), Harwich Haven Authority

By Senior Launch Coxswains Andy Lucas & Sam Williams

Nestled in most commercial harbours there usually lives a small vessel with a big responsibility. It doesn’t carry cargo or paying passengers but it helps keep global trade moving.