PILOT

Supplied globally and to the majority of UK ports. Unlike other marine helmets, the MH4 offers 90 joules all round protection with 100 joules protection to the crown. The Manta has been designed to protect the pilot in the following areas:

• PORTS/QUAYS EN16473 Technical Rescue Helmet – this covers the pilot moving around the quay or the port. It has the same impact

and penetration test as the safety helmet plus it also has chemical, molten metal and electrical protection. It also has a ballistic impact test of 120 metres per second all around the helmet same as safety goggles.

• CLIMBING/BOARDING SHIP EN12492 – this is the climbing standard which gives the Manta it’s climbing approval. In EN16473,

there is also a field of vision test and a 10metre ladder climb test to make sure the helmet can be used while climbing a ladder and there is no restriction to view.

• MARINE OPERATIONS/PILOT BOAT PAS028 Marine Safety Standard – this covers the Manta for all operations on water.

- 100 joules Sides - 90 joules

Welcome to Issue 336 of ‘The Pilot’. I must start by thanking you for the kind feedback received from the last edition, it is greatly appreciated given the numerous hours spent producing the magazine.

The theme of this edition is a split theme between legal and training with some independent content added. It was brought to my attention earlier in the year that the legal aspect of pilotage was due for a refresh for all those within the pilotage industry. The articles serve as a reminder to us of how the fundamentals work and how good practices can assist or go against pilots unless complied with. Of course, we all must be in compliance with the various laws to maintain a high professional standard.

This edition allowed for independent articles from a ship master’s viewpoint of the pilots. I felt it was refreshing to have a master, to which we work with, give their view and highlight the importance of the role we undertake. The second theme of pilot training is one close to me. I have always been a strong believer in comprehensive training to ensure the maximum performance can be achieved. This edition looks at the various ways training is undertaken around the UK districts, which includes articles written by the training providers outlining how their training can assist us pilots and pilot management. Of course, training is not just about navigation. Grant Walkey of Trident Training who provides medical training for pilots and launch crews has written for this edition. It remains a sobering fact that pilots go to work and sometimes do not return. However, if an accident does occur and medical invention can be achieved to save life quickly, it will depend upon the medical training received to try and reach a positive outcome.

The magazine editor’s plans are always changing when obtaining content. I thank graphic designer Tony Fisher at Spectrum Creative, for his excellent standards of graphics and to all those that contributed to the pilot magazine past and present so far.

EDITOR

The next edition, 337, will reach you after November’s UKMPA Conference. If you have not already booked your conference place, please consider it now following the details provided on the conference advert in this edition.

Safe Piloting Matthew Finn editor@ukmpa.org

Web Captain / James Musgrove

April and May have been exceptionally busy with conference engagements. I attended the IMPA Congress in Rotterdam and, shortly after, the EMPA Conference in Antwerp. Additionally, several members participated in the UK Harbour Masters Spring Conference in Edinburgh.

These events provided valuable opportunities to reconnect with colleagues worldwide and discuss various pertinent topics. Following the IMPA Congress, we issued the "Power Limiter Circular," addressing a key issue of interest. The EMPA Conference, held over two days at the impressive Port of Antwerp Administration building, focused primarily on pilot safety, featuring a session with three pilots sharing their survival stories.

Other significant events included the British Tug Association and Port Skills and Safety seminar. A recurring theme across all conferences was

the emphasis on maintaining high standards in pilotage. As an association, we are committed to promoting the highest standards, surpassing the minimum recommendations of IMO A960.

Continuous improvement and skill development, whether through new technology or refining existing practices, are crucial for us as senior marine professionals. With that in mind,I welcome the article on Page 14 which discusses a concept of conduct and suggestions on how this can be managed effectively.

The new Port Marine Safety Code is set to be published soon. Over the past few months, we have actively participated in the working group reviewing the Guide to Good Practice. Both the Code and the Guide serve as essential frameworks for enhancing port safety. Unfortunately, we still observe some ports attempting to weaken Pilotage Exemption

Certificate (PEC) regulations, allowing larger vessels into more confined waters to board a pilot. IMO A960 recommends that pilot boarding areas provide sufficient time and sea room for a safe MPX and boarding process.

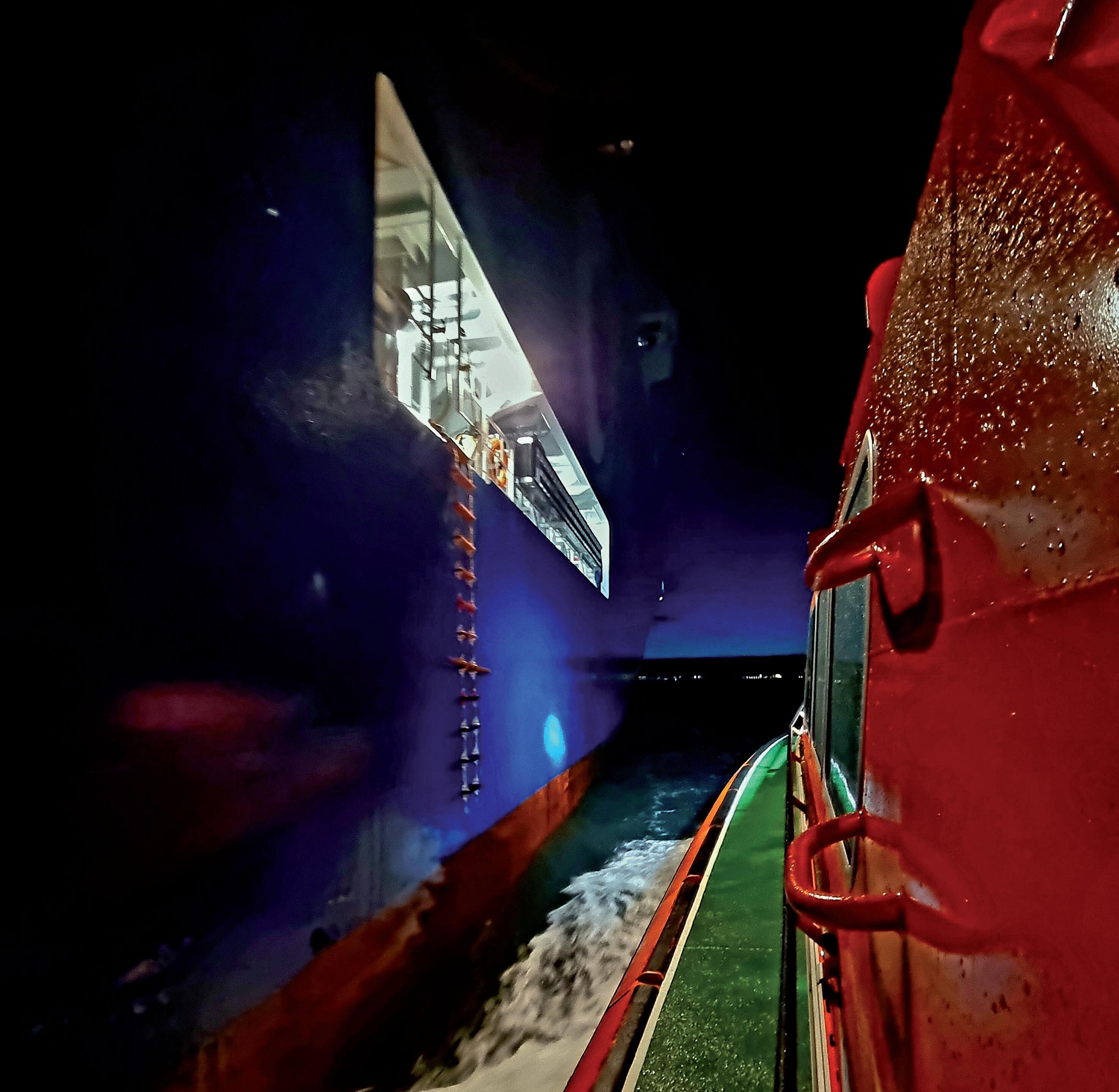

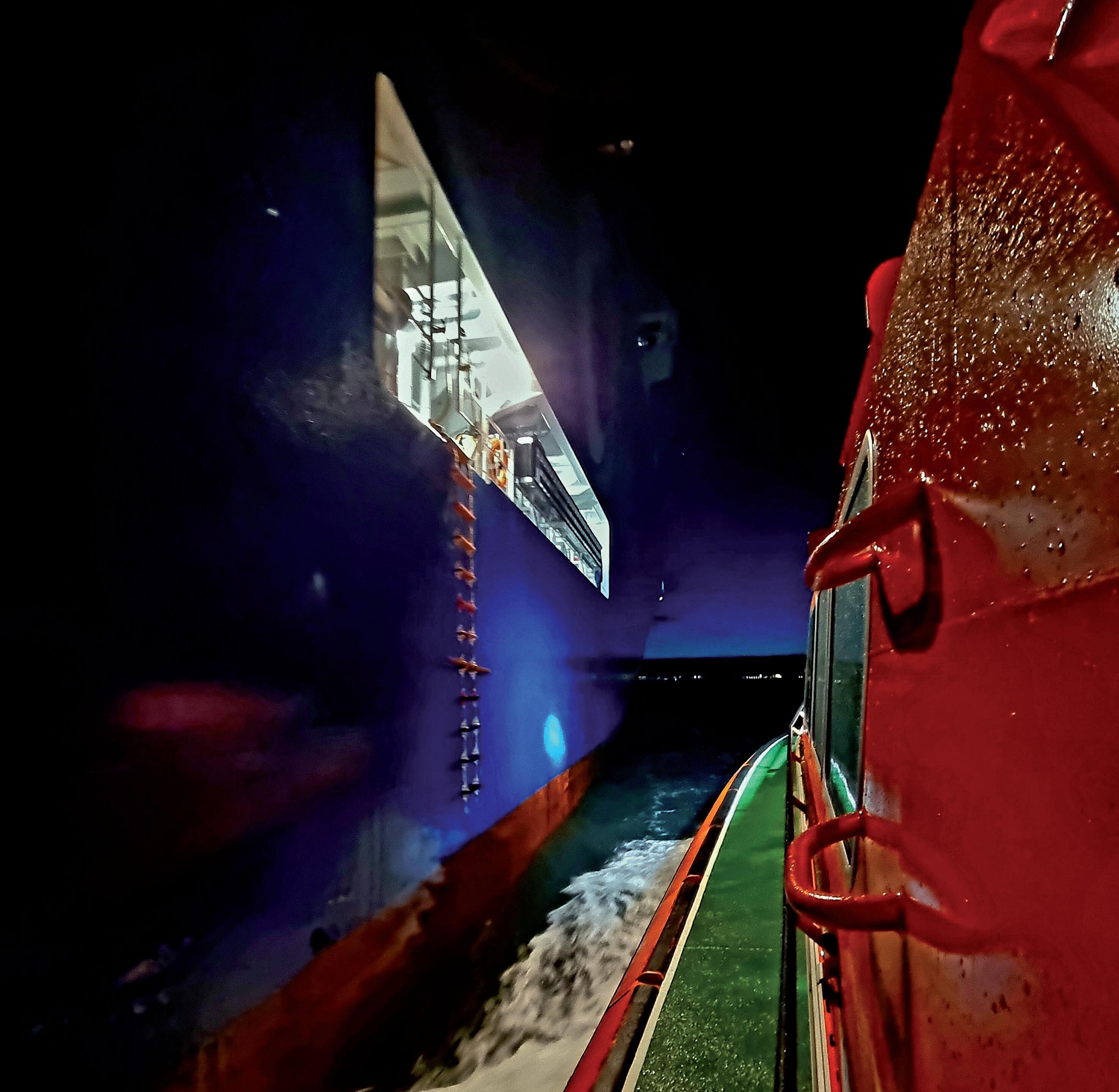

The IMO NCSR 11 meeting marked progress towards amendments to SOLAS regulations V/23 and the mandatory implementation of new performance standards for Pilot Transfer Arrangements. Our Vice Chair, Chris Hoyle, represented us as part of the UK delegation during this significant week. Of significant note is that from 2028 all pilot ladders will have to be replaced 36 months after manufacture or 30 months after installation. I’d like to thank the MCA’s UK Technical Services Navigation team for their continuous engagement.

Our mental health campaign, "Safe Haven," led by James Musgrove, is now supported by the Mental Health Professional Support line provided by the Sailor’s Society. We also offer the Safe Haven Hotline, "Speak with a Fellow Pilot," for confidential support. The importance of having someone to talk to cannot be overstated.

We are looking forward to the 136th UKMPA Conference/AGM in Harrogate from November 19th to 21st, 2024. The conference will focus on "The Pilot-Tug Relationship" and "Pilots: The Value of the Human Element." This is a fantasticopportunity to engage with peers and stakeholders from other districts. Our Conference team lead by Alan Stroud are bringing together what will be a great event full of content and entertainment, I encourage you to book early.

Hywel Pugh / UKMPA Chairman

Chairman Hywel Pugh chairman@ukmpa.org

Vice Chairman Christopher Hoyle vice.chairman@ukmpa.org

Vice Chairman Jason Wiltshire vice.chairman@ukmpa.org

Region 1 Executive Alan Stroud region1@ukmpa.org

Region 2 Executive Chris Grundy region2@ukmpa.org

Region 3 Executive Peter Lightfoot region3@ukmpa.org & Secretary & EMPA VP Peter Lightfoot secretary@ukmpa.org

Region 4 Executive Robert Keir region4@ukmpa.org & Membership Robert Keir membership@ukmpa.org

Region 5 Executive Paul Schoneveld region5@ukmpa.org & IMPA VP Paul Schoneveld paul.schoneveld@ukmpa.org

Region 6 Executive Jason Wiltshire region6@ukmpa.org & Treasurer Jason Wiltshire treasurer@ukmpa.org

Technical & Training Chair John Slater technical@ukmpa.org

Web Captain James Musgrove webcaptain@ukmpa.org

Region 1 Deputy Simon Lockwood deputy1@ukmpa.org

Region 2 Deputy Mike Robarts deputy2@ukmpa.org

Region 3 Deputy Alan Jameson deputy3@ukmpa.org

Region 4 Deputy Ross McCauley deputy4@ukmpa.org

Region 5 Deputy Brent Bolton deputy5@ukmpa.org

Region 6 Deputy Richard Eggleton deputy6@ukmpa.org

Circle Insurance Ian Storm Ian.storm@circleinsurance.co.uk M: 07920 194970

Insurance Queries Claire Johnstone claire.johnstone@circleinsurance.co.uk

Incident Reports Via UKMPA app insurance@ukmpa.org

UNITE Michelle Brider michelle.brider@unitetheunion.org

Web Captain James Musgrove webcaptain@ukmpa.org

Editor Matthew Finn photos@ukmpa.org

Minor incident 0141 249 9914 insurance@ukmpa.org

Major incident 0800 6446 999 insurance@ukmpa.org Incident Reports insurance@ukmpa.org

Mental Health Support

Safe Haven Hotline 0800 433 2163 Visit www.ukmpa.org for further details

Alyn Black Aberdeen

Joseph Day Aberdeen

Jonathan Nicholls Portsmouth

Sean Boyce Milford Haven

Andy Stopford Workington

Karolina Jabrzyk Humber

Joel Robinson Humber

Martin Griffiths Medway

Christopher Lewys Rees South Wales

Tom Imrie Forth

Andrew Blake Dundee

James Kenneth ABP S Wales

Haydn Clarke London

Keith Fuller Tees

Members of the Section Committee have been working hard to secure opportunities for our members from smaller regional ports that often lack the funding of our major portsif you think this applies to you please drop us a few lines at office@UKMPA.org, we would love to hear from you, our conference and other opportunities are just around the corner.

In the world of insurance, compliance is paramount. It serves as the cornerstone for ensuring fairness, transparency, and stability within the industry. Non-compliance, however, can have far-reaching effects, not only on insurers, but also on policyholders and the broader economy. Understanding the implications of non-compliance is crucial for all stakeholders involved.

Non-compliance refers to the failure to adhere to laws, regulations, or industry standards set forth by relevant regulatory bodies. This can encompass various aspects of insurance operations, including underwriting practices, claims handling, financial reporting and consumer protection measures set by the Financial Conduct Authority. When these insurance entities deviate from these prescribed standards, it can lead to a host of negative consequences.

For policyholders, the consequences of non-compliance can be equally severe. Insurance policies are designed to provide financial protection and peace of mind in times of need. However, if a policyholder is found to be non-compliant, it may jeopardise the validity of cover or impede the timely payment of claims. This can leave policyholders vulnerable and exposed to financial hardships, defeating the very purpose of insurance coverage.

In addition, all parties can suffer from reputational damage. As professionals we all rely heavily on trust and credibility to attract and retain relationships. Any perception of misconduct or unethical behaviour can tarnish that reputation, eroding confidence and loyalty. This, in turn, can result in a loss of business opportunities, difficulty in attracting top talent and ultimately, confidence in our chosen profession.

Ian Storm / Circle Insurance

Understanding the Impact of Non-Compliance on Insurance

In the wider insurance sphere, noncompliance can expose insurance companies to legal and regulatory penalties. Regulatory agencies such as the Financial Conduct Authority have the power to impose fines, sanctions, or even revoke permissions for serious violations. These penalties not only have financial implications but also disrupt business operations and undermine organisational stability.

Beyond immediate repercussions, non-compliance can also have longterm financial implications. Insurance companies operate in a complex ecosystem where risks are carefully assessed and priced. Non-compliant practices can distort risk assessments,

leading to inaccurate pricing and underwriting decisions. This can result in inadequate reserves, unexpected losses, and ultimately, financial instability.

In extreme cases, it may even threaten the solvency of an insurance company, exposing the market and the premiums therein.

Moreover, non-compliance can hinder innovation and market competitiveness. In an increasingly digitised and interconnected world, regulatory compliance plays a pivotal role in facilitating technological advancements and market innovations. Companies that fail to comply with regulatory requirements may find themselves unable to adopt new technologies or offer innovative products and services, putting them at a significant disadvantage compared to their compliant counterparts.

Non-compliance poses a substantial risks and consequences for insurance companies, policyholders, and the broader economy. It undermines trust, invites regulatory scrutiny, disrupts financial stability, and stifles innovation. As such, insurance companies must prioritise compliance efforts, invest in robust compliance frameworks, and foster a culture of ethical conduct and accountability. By doing so, they can mitigate risks, enhance their reputation, and uphold the integrity of the insurance industry for the benefit of all stakeholders involved.

If you have any comments on the insurance arrangements or would like to know more about the insurance we provide then you can contact us at insurance@ukmpa.org

By Chris Grundy / PLA Pilot & Region 2 Executive committee member

Robert Keir, Chris Grundy and Ross Macaulay were pleased to represent the UKMPA at the United Kingdom Harbour Masters Association (UKHMA) Spring Conference in Edinburgh. Conference started with an afternoon event which allowed your representatives time to catch up with Harbour Masters from across the country and discuss issues that pilots face across the UK in an open and honest manner. Subjects included 'Pilot Ladder Defects' (PLD's), Towage issues and pilotage representation.

Virginia McVea (CEO MCA) was present and we had a lengthy discussion with her about the key issues facing pilotage at this time, it was made

clear that the UKMPA wished to engage with the MCA at all levels, With this in mind the following day we had a comprehensive discussion with Mike Bunton (MCA, Head of Navigation).

The speaker programs provided an interesting insight into issues facing the industry. Brian Murphy (CEO. Poole Harbour) gave an interesting presentation upon the recent oil spill at Wytch Farm and the resultant response. Graham Grant (Cromarty Firth towage) spoke and the UKMPA has offered to assist in the planned discussions on non routine towage.

Grant Walkey gave a presentation on the IECC Course and Adam Parnell updated delegates on Chirp’s efforts to

improve safety in the industry. The UKMPA has an excellent relationship with these bodies and Hywel Pugh sits on the Maritime Advisory Board for CHIRP.

The MAIB were present and we had a lengthy discussion with Bill Evans, Principle Inspector of Marine Accidents. This provided an excellent opportunity to chat over current items and to try and understand the issues that we collectively face. Co operation during recent investigations has helped foster a good relationship between UKMPA and the MAIB who are keen to work with us and engage at all levels going forward.

All the best Chris

“Pilots perform dynamic risk assessments, making thousands of decisions to execute their professional activities. Pilots assist in maintaining the safe operational integrity of the United Kingdom’s ports and harbours, ensuring they remain free from incidents and pollution. The Port Marine Safety Code exemplifies the industry’s commitment to managing risks around the clock. We are pleased to share a letter from the former Minister for Aviation, Maritime, and Security, Baroness Vere of Norbiton, with the Department for Transport's permission. This letter underscores the industry's responsibilities in ensuring the safe and efficient operation of UK ports and harbours. The UKMPA has collaborated closely with the Department of Transport on updating the PMSC Guide to Good Practice, recognising that pilots are the ultimate users of decisions made by other stakeholders.”

Dear All,

UK ports and good governance

Over the past few decades, Government has worked alongside industry to develop key pieces of guidance that outline non‐statutory responsibilities in order to ensure our ports sector is in the right position to meet and manage challenges safely and successfully. The Government is grateful to the ports industry for keeping the country supplied and open for business and particularly for the hard work the sector undertook during the Coronavirus pandemic.

To ensure that all ports maintain a high standard of governance, the Ports Good Governance Guidance (PGG) was published in March 2018. It provides a comprehensive framework of principles and practices that ports should be following, including the principles of transparency, accountability, and openness. Putting these at the centre of port operations is vital to ensuring that ports operate safely and sustainably over the long term.

We are pleased to say that the majority of port operators in England work hard to follow the relevant aspects of the PGG. However, to ensure the sector maintains its high standards across the board, and to help the minority of ports that may not been able to follow the relevant aspects of government guidance, we are writing out to the industry with a reminder of the value in using these resources. Indeed, although it has been some time since its publication, the PGG remains a helpful and essential document.

It is fundamental that ports and harbours are suitably resourced in terms of both their management, infrastructure and finances. In particular, we would encourage ports to ensure they have a suitably prepared workforce to manage their operations and to properly plan how they manage and safeguard their infrastructure.

For local authority owned ports this can mean sufficiently financing port operations in line with their duties and obligations. This is also true for Trust

Ports, but in addition means getting the suitable skills onto their boards and moving away from the representative model, which the PGG advises against.

Transparency is one of the key principles of good governance for ports. Ports should therefore look to provide clear and accurate non‐commercial information about their activities and operations, including financial and performance reports. We would suggest that where suitable, this information could be made available to all stakeholders, including port users, local communities, and regulatory bodies. Ports should also engage with their stakeholders to ensure that where possible their interests are represented, and where suitable their concerns addressed.

Accountability is an important principle of good governance. Ports should be accountable to their stakeholders, including their boards, management, and employees, as well as regulatory bodies such as the Department for Transport (DfT). Ports should have effective mechanisms in place for monitoring and evaluating their performance, as well as addressing any issues or concerns that arise.

The Port Marine Safety Code is another piece of guidance that has been developed with industry to assist Statutory Harbour Authorities and other marine facilities in discharging their legal powers and duties safely and effectively. It also provides a standard against which the policies, procedures and performance of organisations can be measured. The Code covers a wide range of areas including governance and the role of board members and others, risk assessments, Marine Safety Management Systems, emergency planning, vessel traffic management, and environmental management. We expect all ports to comply with the Code, and to have appropriate measures in place to manage risks and prevent incidents. The Code should be read alongside the companion Guide to Good Practice which provides additional guidance and practical examples to ensure delivery of safe, efficient, and accountable operations based on industry best practice.

Indeed, any statutory harbour authority that did not submit its compliance during the recent PMSC Compliance Exercise should seriously consider why it was unable to do so. Those that have done so are listed here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ port‐marine‐safety‐code‐compliant‐ports/port‐marine‐safety‐code‐compliant‐ports‐list

We are currently working in partnership with industry representatives to review the Code and the Guide to ensure they remain fit for purpose with a view to publishing a new version as soon as possible. It will therefore be important that port operators examine any updates closely.

Universal best practice principles are at the heart of these pieces of guidance. They include:

a) Conflicts of interest: Ports should have robust policies in place to identify and manage conflicts of interest among their board members, management, and employees. This is important to ensure that decisions are made in the best interests of the Port and not influenced by personal interests.

b) Risk management: Ports should have effective systems in place to identify and manage risks associated with their operations. This includes conducting regular risk assessments and implementing appropriate controls to manage these risks.

c) Performance monitoring: Ports should have effective systems in place to monitor and evaluate their performance against their objectives and targets. This includes collecting and analysing data on key performance indicators, such as vessel movements, cargo throughput, and financial performance.

d) Stakeholder engagement: Ports should engage with their stakeholders regularly to ensure that their interests are represented, and their concerns addressed, where possible.

Even though the above‐described guidance documents are not statutory, staying on top of these responsibilities is vital for effective operations. We encourage you to take this letter as a reminder of your duties and responsibilities as a port, use it as an opportunity to review your governance arrangements and take any necessary action to ensure that your port is complying with the guidance. Maintaining high standards for safety and good governance across all ports remains at the forefront of DfT priorities.

If you have found it difficult to interpret or follow any of the recommendations in the Ports Good Governance Guidance, the Port Marine Safety Code or any other relevant guidance, we would be keen to understand why and what challenges you have faced. We want to work with you to ensure all guidance for ports remains fit for purpose.

If you have any questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact my officials. Thank you for your continued hard work to ensure governance and safety standards within the UK ports sector remain high.

Baroness Vere of Norbiton

By Dan Wood / Master Mariner, Ports & Harbours Governance Expert

The tanker Sea Empress, whilst under pilotage, grounded on her approach to Milford Haven on the evening of 15 February 1996. The vessel carried just over 130,000 tonnes of crude oil (MAIB, 1999). The vessel grounded several times during the subsequent emergency and salvage response efforts. It spilt around 72,000 tonnes of cargo and 370 tonnes of heavy fuel oil in the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park marine areas (ITOPF, 2024), which cost £60m in environmental response measures (ITV, 2021).

The Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB), investigated and reported on the incident, identifying 67 key findings and 24 recommendations (MAIB, 1997).

The Department of Transport (DfT) was recommended to implement procedures for monitoring Competent Harbour Authorities (CHAs) regarding pilot standards (MAIB, 1997).

A review of the Pilotage Act, 1987 was undertaken. The review recommended that pilotage services should continue to be provided by CHAs and integrated with safety management systems (SMS) for the harbour and a ‘Marine Operations Code for Ports’ be developed to set a national safety standard (UKG, 1998).

The Port Marine Safety Code (PMSC) was introduced in March 2000 and made mandatory on 1 January 2002 (DfT, 2016). It was supplemented by the ‘Guide to Good Practice on Port Marine Operations’ (GtGP). The latest update is November 2016. A draft document, the ‘Ports & Marine Facilities Safety Code’, is currently out for consultation.

On 9 December 2002, the Secretary of State for Transport stated that out of the 107 CHAs in operation at that time, 89 had issued a statement of compliance in accordance with the PMSC. He further stated that his officials were continuing to correspond with the remaining 18 CHAs that they were reporting ‘that they are in an advanced stage of implementing the PMSC’. (UKG, 2002).

Pilotage is regulated by the Pilotage Act, 1987, but the PMSC reminded CHAs to assess marine risks and the need for pilotage, issue directions, authorise pilots and ensure that pilots were trained.

The PMSC is structured around five key elements: a duty holder accountable for marine safety, a designated person (DP) providing independent assurance to the duty holder, formal risk assessment, a marine SMS (MSMS) to manage risks and consultation with affected stakeholders (DfT, 2016). Pilotage is not regarded as a key measure under the PMSC, but as a ‘Specific Duty and Power’. Chapter 9 of the GtGP provides guidance on pilotage standards.

In July 2007 the DfT in its ‘Ports Review,’ stated that the MCA ‘confirms that all CHAs with significant marine activity have declared their compliance with the Code’ (UKG, 2007)

DfT also committed to revising the GtGP ‘working with stakeholders to specify best practice for the issuing of Pilotage Exemption Certificates (PECs) and to improve the guidance on Formal Risk Assessment. DfT were also considering ‘possible legislative changes to the 1987 Act to modernise the provisions on pilotage powers and improve the control of PECs’ (UKG, 2007).

On 19 December 2007, the tug Flying Phantom was engaged in a towing operation (Red Jasmine under pilotage) in restricted visibility on the River Clyde when she girted and was lost, with three fatalities. The MAIB investigated the incident and highlighted 15 safety issues and made two recommendations directly related to three of the five key elements of the PMSC, the DP, risk assessment and SMS (MAIB, 2008).

The MAIB further highlighted that Clyde pilots had not been involved in marine risk assessment reviews and thus the instructions available to the pilot onboard were ‘ill-defined and vague’. Recommendations relating to pilotage improvement from an incident in 2000 with the same tug were found to have not been implemented fully.

The report further stated that ‘Since the PMSC’s introduction, MAIB has conducted 23 investigations into contacts, collisions and groundings in port waters (out of a total of 44 for this type of accident). Recommendations from these investigations have been aimed at the ports industry, yet it appears that the lessons from an accident at one port are not always being learnt by others.’

On 3 April 2012, the cargo ship Carrier grounded while attempting to depart Raynes Jetty at Llanddulas in deteriorating weather. The vessel was driven onto shore defences, spilt 33,000 litres of gas oil, and declared a constructive total loss. Raynes Jetty was privately owned and not subject to the PMSC, so it did not have adequate marine risk assessments, SMS, or oversight in place (MAIB, 2013).

The MAIB made a single recommendation to the DfT to include non-statutory harbours in the PMSC (MAIB, 2013). Raynes Jetty had been under the CHA for Liverpool until 1988. Pilotage from then on was a voluntary undertaking with Liverpool Pilots providing the service on request.

The MAIB noted that ‘Pilotage was not compulsory for berthing at Raynes Jetty, and the master was understandably keen to avoid the additional costs of hiring a pilot. Had he taken a pilot, or been able to seek advice from a competent harbour authority, it is likely that he would have been advised against putting his vessel alongside until the weather improved.’ (MAIB, 2013).

Between 2010 and 2013 there was much debate regarding the introduction of the Marine Navigation Act, 2013 and its consequences for pilotage standards. The Transport Committee recommended that the MCA conduct eight health checks annually on ports that do not comply with the PMSC and that ports publish accident statistics (UKG, 2013). These requirements did not specify a careful consideration of the changes to pilotage qualifications, certification and PECs.

On 22 August 2016, the ultra-large container vessel, CMA CGM Vasco de Gama, grounded whilst approaching the port of Southampton. The MAIB report highlighted shortcomings in the PMSC audit process relating to pilotage operations. A recommendation was made to the port operator to ‘Conduct a thorough review, through its internal audit process, of the implementation of company procedures for pilotage planning and bridge resource management at all its UK ports.’ (MAIB, 2017).

Thus, several issues surrounding the PMSC and how it interacts with pilotage are still prevalent. These include accountability, risk assessment, integration of pilotage management systems with CHA MSMS, audit of pilot operations and tracking and trending of pilotage incidents to prevent their recurrence.

With crumbling infrastructure in some ports and upgrades in others to facilitate the servicing of giant floating offshore wind structures, coupled with the rapidly changing technological and legislative landscape, the risk profile for ports and pilotage is changing. The current iteration of the PMSC does not include pilotage as one of the ten key measures for marine safety. But pilots remain our key control for protecting national strategic assets and the interests of our island nation.

In 2021 the MAIB published their first study of unsafe pilot ladders. This was in direct response to a huge initiative from the pilotage industry to deal with this high consequence risk. This initiative is ongoing with recent analysis published in 2022. We must publish the same for marine incidents involving pilotage to learn and improve.

In 2026, it will be over 25 years since the introduction of the PMSC. The industry must do more to ensure that the PMSC is effective in addressing the key reason it was introduced i.e. to improve pilotage standards and the management of pilotage operations by CHAs. With the new PMSC currently under review, we must ensure that pilots are given full resources and support to ensure the safety of our critical marine transport nodes. We must reestablish organisational memory from the origins of the PMSC. We must maintain the image and status of our pilots as ‘trustworthiness personified’ (Conrad, 1899).

• DfT (2018). ‘A Guide to Good Practice on Port Marine Operations: Prepared in conjunction with the Port Marine Safety Code 2016’. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5dfcc4a8ed915d1f5dc3d3ad/MCGAPort_Marine_Guide_to_Good_Practice_NEW-links.pdf

• DfT (2022). ‘Ports and Shipping FAQs’. Available at: researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9576/CBP-9576.pdf

• DfT (2016). ‘Port Marine Safety Code’. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/ media/5f63874d8fa8f51069100621/port-marine-safety-code.pdf

• DfT (2007). ‘Ports policy review interim report’. Available at: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20070807211504/http:/www.dft.gov.uk/ pgr/shippingports/ports/portspolicyreview/portspolicyreviewinterimreport [Accessed 24 February 2024]

• HSE (2013). ‘Statistics report for the Ports Industry 2012/13p’. Available at: www.hse.gov.uk/ports/assets/docs/port-industry-statistics-report-2012-13.pdf

• ITF (2013). ‘The reality of assessing accident levels in ports’, Port Technology, Edition 56, pp. 15 – 16. Available at: wpassets.porttechnology.org/wp-content/uploads/ 2019/05/25182039/The_reality_of_assessing_accident_levels_in_ports.pdf

• ITOPF (2024). ‘SEA EMPRESS, Wales, UK, 1996’. Case Study. Available at: www.itopf.org/in-action/case-studies/sea-empress-wales-uk-1996

• ITV, 2021. ‘The Sea Empress: 25 years on since one of the biggest environmental disasters in the UK’. Available at: www.itv.com/news/wales/2021-02-15/the-sea-empress25-years-on-since-one-of-the-biggest-environmental-disasters-in-the-uk

• MAIB (2022). ‘MAIB Annual Report 2021’. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/maib-annual-report-2021

• MAIB (2023). ‘MAIB Annual Report 2022’. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/maib-annual-report-2022

• MAIB (2008). ‘Girting and capsize of tug Flying Phantom while towing bulk carrier Red Jasmine with 1 person injured and loss of 3 lives’. Available at: www.gov.uk/maib-reports/girting-and-capsize-of-tug-flying-phantom-while-towing-bulkcarrier-red-jasmine-on-river-clyde-scotland-resulting-in-1-person-injured-and-loss-of-3-lives

• MAIB (2013). ‘Grounding of general cargo vessel Carrier’. Available at: www.gov.uk/maib-reports/grounding-of-general-cargo-vessel-carrierat-raynes-jetty-in-llanddulas-wales

• MAIB (1997). ‘Grounding of oil tanker Sea Empress and the subsequent salvage operation’. Available at: www.gov.uk/maib-reports/grounding-of-oil-tanker-sea-empress-inthe-approaches-to-milford-haven-wales-and-the-subsequent-salvage-operation

• MAIB (2017). ‘Grounding of the ultra-large container vessel CMA CGM Vasco de Gama’. Available at: www.gov.uk/maib-reports/grounding-of-the-ultra-large-container-vessel-cmacgm-vasco-de-gama

• Transport Committee (2007). ‘Transport - Second Report’. Safety and Employment. Available at: publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200607/cmselect/cmtran/ 61/6102.htm

• Transport Committee (2013). ‘Transport Committee - Ninth Report’. Marine Pilotage. Available at: committees.parliament.uk/work/4838/marine-pilotage/

• UKG, (2009). ‘Marine Accident Investigation Branch (Reports)’. Volume 497: debated on Tuesday 20 October 2009. Available at: hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2009-1020/debates/09102046000002/MarineAccidentInvestigationBranch(Reports)

• UKG (1998). ‘Pilotage Act: Review’. Available at: publications.parliament.uk/pa/ ld199798/ldhansrd/vo980728/text/80728w03.htm

• UKG (2007). ‘Ports policy review interim report’. Available at: webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20070807211504/http://www.dft.gov.uk/ pgr/shippingports/ports/portspolicyreview/portspolicyreviewinterimreport

• UKG (2002). ‘Statutory Harbour Authorities: Transport written question –answered on 9 December 2002.’ Available at: www.theyworkforyou.com/wrans/ ?id=2002-12-09.86092.h

By Captain Keith Mclean

Some of the most highprofile incidents of recent years have involved vessels utilising two pilots:

“Ever Given” in Suez, “CMA CGM Vasco da Gama” in Southampton and “Eagle Otome” in Houston. There were two pilots on the “Dali” when she struck the bridge in Baltimore, albeit one of them was an apprentice. This article discusses the circumstances that warrant the use of additional pilots, the legal background in the UK, the advantages and disadvantages of additional pilots, and the human factors involved. We will also look at pilot training for additional pilot operations.

Section 2 of the Pilotage Act 1987 clearly outlines the general duties of a Competent Harbour Authority (CHA) in respect to pilotage. Each CHA must decide what pilotage services need to be provided. It follows that in some circumstances a CHA may decide that a vessel should embark two, or more, pilots.

Section 15 of the Pilotage Act 1987, which relates to compulsory pilotage, states that a vessel should be “under the pilotage of an authorised pilot accompanied by such an assistant, if any…” The reference to an assistant pilot is important, as it gives the assistant pilot (or Second Pilot – SP) the same limitation of liability under Section 22 of the act as the Lead Pilot (LP).

The Port Marine Safety Code (PMSC) and the associated Guide to Good Practice (GTGP) set out a national standard for every aspect of port marine safety, including pilotage. The Code is not mandatory, but there is a “strong expectation” that all harbour authorities will comply.

Section 4 of the PMSC states that the pilotage services provided by a CHA should be determined by risk assessment. So, it follows that risk assessments may indicate that the carriage of two or more pilots will help to reduce risk to an acceptable level in certain circumstances.

Section 9.5.44 of the GTGP states “Formal risk assessment should be used to identify any circumstances in which more than one pilot would be needed to conduct the navigation of a vessel safely”.

When to use additional pilots?

So, under what circumstances should a CHA consider assigning additional pilots to a vessel? As with many things in pilotage, circumstances will vary from port to port. As a generalisation, where the risk assessment has indicated a “high severity” of an incident and a reasonable degree of likelihood then an additional pilot can be utilised as a measure to help mitigate the risk. Large vessels in relation to the space available, hazardous cargoes, environmental impact, and visibility from the conning position issues would be among the factors to consider.

It may be that the provision of a one pilot can be considered a single barrier that can fail in certain circumstances – perhaps by making an error of judgement, becoming incapacitated or dropping dead on the bridge. I know of at least one pilot who died on the approach to a breakwater port. As all pilots know, the fully functional bridge teams that can seamlessly take over from the pilot remain few and far between.

How does an additional pilot mitigate risk?

The operations performed with additional pilots will be of high criticality. Although the probability of an incident may be low, the large size of the vessels and the associated potential environmental and commercial impact means the criticality of the consequences of an incident can be extreme. Simply having redundancy in the system and the provision of a monitoring role increases the reliability of operations and therefore lowers risk. Throughout the whole operation the second pilot can provide the lead pilot with more information to support their decision making. At times of high stress and workload the SP can reduce the pressure on the LP by dealing with external communications.

As the list of high-profile incidents in the opening paragraph suggest, simply assigning additional pilots to a vessel is not sufficient to remove risk entirely. However, pilotage organisations should have in place clear procedures as to how the additional pilot(s) should be best utilised so they can bring optimal added value to the operation. Pilot organisations using additional pilots should train for multiple pilot operations so that each pilot’s role is clearly understood. On boarding a vessel, the master and bridge team should be briefed during the Master / Pilot Exchange as to the role of each pilot.

Portable Pilot Units (PPUs) are without doubt a useful navigational aid that can enhance the pilot’s situational awareness (SA). However, PPUs also take time to set up and require monitoring that can reduce situational awareness. In many case the SP can be best utilised in a supporting role to deal with the PPU setup, PMX paperwork and external communications thereby decreasing load on the LP and increasing his Situational Awareness (SA).

In the case of the CMA CGM Vasco da Gama grounding the MAIB report says “the duties, responsibilities and expectations of the assistant pilot role” were not documented within the port’s Safety Management System. Ports and pilot organisations should have clear and practical procedures in place for multi pilot operations. Rostering arrangements should clearly show which pilot is the Lead Pilot, and recording is essential to ensure that all pilots are sufficiently experienced in Lead and Second Pilot roles.

Simply putting two or more pilots onboard a vessel does not in itself increase safety, beyond providing a degree of redundancy. It is essential that all pilots engaging in multi pilot operations are appropriately trained, in addition to the normal Bridge Resource Management, in order to extract the greatest added value from additional pilots.

Appropriate training and procedures will vary from port to port. For example, the procedures for a port with pilotage acts of long duration will vary from with short acts of pilotage. Ports with locks require special consideration, and the optimal positioning for the SP will vary from berth to berth.

Marine centred Human Factors training will give pilots an understanding of the Human Factors involved and will help avoid some of the potential pitfalls of dual pilot operations.

IHF were asked to look at the dual pilot operation at a major European oil terminal after a VLCC had made a heavy landing. After IHF consultants had looked at the case and observed operations it was clear that the terminal had no procedures for dual pilot operations. The more senior pilot had insisted that he would act as lead pilot, and there were clear power / distance issues between the pilots. The more junior SP was reluctant to intervene when the speed of approach was clearly too high. Event driven cycles / checkpoints and clear procedures have been introduced at that port.

IHF were asked to run a pilotage and human factors workshop for the Suez Canal pilots after the “Ever Given” incident. The pilots involved in the workshop were trained to work better together, improve bridge team engagement, communication, and better support each other in terms of workload and critical decision making.

Captain Keith McLean is a Chartered Master Mariner. He previously sailed as Master on Suezmax tankers. He has more than 30 years pilotage experience, both in UK and overseas. He is Marine Advisor to IHF Limited (www.ihf.co.uk) and was previously Vice Chairman of the International Standard for Pilotage Organisations.

IHF provide Human Factors training worldwide in multi pilot operations, pilot assessor training and pilotage workshop.

Much has been written on the Master/Pilot relationship in regard to the management of a vessel whilst in a Pilotage area. However, a tension often arises when a Master announces he wishes to manoeuvre his vessel, or the more common “you advise me Pilot”!

This article explores the definition of conduct, the practicalities of the master manoeuvring the vessel, and the framework of how the relationship can be managed. We will also look at the reports that should be made to the Harbour Master or Competent Harbour Authority (CHA) in each respect.

In the UK, under the provisions of the Pilotage Act 1987, the pilot has conduct of the navigation of a vessel.

• Pilotage Act 1987, Sec 31 – “pilot” has the same meaning as in the Merchant Shipping Act 1894 and “pilotage” shall be construed accordingly.

• Merchant Shipping Act 1894, Section 742, states a pilot to be - ”any person not belonging to a ship who has the conduct thereof”.

• The Mickleham (1918). This case considered the meaning of the word “conduct” and concluded that if a ship is to be conducted by a pilot it “does not mean that she is to be navigated under his advice: it means that she must be conducted by him”.

• The Tactician (1971). In this case the judge also considered the meaning of the word “conduct”, and stated: “it is a cardinal principle that the Pilot is in sole charge of the ship, and that all directions as to speed, course, stopping, and reversing, and everything of that land, are for the Pilot”.

By Jason Wiltshire, Alan

Peter Lightfoot

It therefore follows that within the UK, Pilots are not advisors. Advice is defined as a guidance or recommendation offered in regard to prudent future action – it can be accepted or rejected! This is not to say that a Pilot cannot offer advice, an example of this is perhaps recommended moorings for the port stay in view of local weather conditions; but advice does not feature when it comes to the navigation of the vessel in a compulsory pilotage area.

All pilots will be familiar with how different types of vessels need to be conducted within their respective districts. For a coaster, manoeuvring through a lock complex or within a critical approach to a berth or jetty, it may be more effective for the Pilot to be “hands on” – physically manipulating the vessel controls to achieve the desired outcome. For most other vessels, a Pilot will give direct orders

to the Master, bridge team, and tugs, in order to conduct the vessels navigation. Both methods would appear to be compliant with the general theme of conduct in that the Pilot is in sole charge of the navigation and all directions are for the Pilot.

A tension arises when a Master wishes to undertake the manoeuvring of the vessel. It is common to see the small signs on bridges or as a common entry in log books which reads “To Master’s orders and Pilot’s advice (TMOPA)”. Within the UK legal framework this is incorrect, but we can acknowledge that ships operate worldwide in varying legal jurisdictions. I would suggest the meaning of this phrase to be better explained as…

“The Master should assess any instruction given by the Pilot to ensure that if the Pilot’s instruction is carried out, the vessel will be safe”.

On the vessel's bridge, the dynamic between the master and pilot can be best clarified by differentiating between Power and Authority. Power refers to the capability to take action regardless of the propriety of doing so, whereas Authority pertains to the right to act irrespective of the means or capability to carry out the action. While at sea, the master possesses both the power and authority over the ship and its crew. However, upon entering an area of compulsory pilotage, our legal framework dictates that the pilot assumes the authority to conduct the navigation - the vessel's safe movement.

So how do we permit a Master who wishes to manoeuvre a vessel whilst complying with our responsibilities?

We have discussed the method of direct conduct, i.e either physically manoeuvring the vessel or via spoken orders. In each respect, the Pilot makes all directions as to speed & course, according to an agreed passage plan and shared mental model. This common method of direct conduct is best defined as controlling the direction of the vessel, without an intervening factor.

This gives rise to another method, which we can term “Indirect Conduct”. Here, a Master could manoeuvre his vessel, for example from a berth to a lock. A detailed passage plan should be agreed, with the Pilot then setting the parameters in which that vessel remains within a navigationally safe operating profile. Such a profile could feature clearing distances, maximum speeds and zones of heading for approach. It is crucial to also make clear and agree that in the event of non-compliance with the plan, the conduct will switch back to direct. A report should be made to the Harbour Master that the Master is manoeuvring the vessel. Once underway, the Pilot plays an active role to lead the task, whilst the Master performs the manoeuvre within the agreed profile.

Should the vessel stray from the agreed safe operating profile, intervention from the Pilot may be necessary to bring the vessel back on track. A useful acronym to achieve this is PACE (Probe/ Alert/ Challenge/ Emergency), which uses graded assertiveness enabling the Master to pause, consider, and adjust their course of action.

Finally, if the manoeuvre takes the vessel outside of the agreed safe operating profile, the Pilot should then switch to direct conduct, with directions as to speed and course given as normal, and an accompanying report made to the Harbour Master.

There will of course be cases where the Pilot feels that this method of conduct is inappropriate for the specific manoeuvre or transit, in which case this can be discussed and asserted in the planning stage.

We can best define Indirect Conduct as a type of conduct happening in addition to the intended result.

The vast majority of this type of evolution can pass without incident. But what happens if a Master then refuses to comply with Pilot’s orders? Putting aside the obvious danger from such a course of action, it should be borne in mind that Section 15(3) of the Pilotage Act reads, “If the master of a ship navigates the ship in an area and in circumstances in which pilotage is compulsory for it by virtue of a pilotage direction without notifying the competent harbour authority which gave the direction that he proposes to do so, he shall be guilty of an offence…”

It therefore follows that there is a statutory burden on the Master to notify the CHA of their intention to take conduct of the vessel from the Pilot. In a past judicial review concerning the revocation of a Pilot’s authorisation, the Pilot was left open to criticism when he did not make reports to the CHA when he became concerned as to the Masters increasing disregard for the Pilots directions.

Any Pilot would be well advised to make a report to the CHA, both where the Master is manoeuvring the vessel and more importantly, in any circumstance in which either method of conduct is

displaced so that the vessel is no longer under Pilotage, in order to protect his/her own authorisation and position. As a practical matter, the actions to be taken in the event of any differing judgment between a Master and Pilot on potential situations arising that could stand the vessel into danger should be planned and agreed as part of the MPEX. This can include notifying the Master of the reports that need to be made to the CHA in each respect, and performing these accordingly.

A pilot’s delegation of the manoeuvring of the vessel is not an abandonment of conduct, but simply one way of exercising it.

The definitions and practicalities of conduct are of crucial importance. By acknowledging the differences and incorporating them into the MPEX, the navigational safety of the vessel can be preserved at all stages. It is imperative that notifications are made to the Harbour Master both when a Master is manoeuvring the vessel and, in any situation where Pilots orders are disregarded, in order to protect your own authorisation.

The authority to determine the method of conduct for any evolution always rests with the Pilot.

When a ship intends to navigate through an area of compulsory pilotage, it is crucial that the master's power and the pilot's authority align. A mutual agreement between both parties concerning the feasibility of the proposed transit is essential, including any changes in the method of conduct, as neither party can, or should, proceed without the other.

In defining the relationship between a Master and Pilot, (and indeed between a Pilot and their CHA), any alterations to bridge procedures for pilots must be rooted in concepts or principles that are mindful of the realities. Becoming proactive in making such definitions can serve to improve standards and widen the circle of responsibility in assuring safe acts of Pilotage, that support Pilots and protect trade.

By Keith McLean & Neil Clark / Chief Executive Officer at IHF Limited

DUAL PILOT OPERATIONS ARE MUCH MORE COMMON IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION THAN IN MARINE PILOTAGE. INDEED, THEY ARE PRETTY MUCH THE NORM AND HAVE BEEN FOR DECADES. THERE IS MUCH THAT WE AS MARINE PILOTS CAN LEARN FROM OPERATIONS IN THE AVIATION INDUSTRY.

Marine operations by their nature are slow paced for most of the time, and then faster paced during specific crucial moments. There is no need for a high level of communication constantly throughout the whole operation because of the slow nature of changing circumstances. However, no matter how slow, the circumstances are dynamic and therefore constantly evolving. There often isn’t a lot of communication between the two pilots unless there is a specific request being made, or concern being brought up. The approach to communication can easily become mostly reactive ‐ a “no news is good news” policy ‐where the Lead Pilots operate “alone”, and the SP is silently monitoring the activity and will only “jump in” if there is a request or any concern. If no communication is made, the assumption is that everything is good.

Or, during period of low activity, it is easy for the two pilots to be sidetracked into conversation about non‐operational matters, become distracted, and inevitably lose situational awareness. One extreme example is the “Eagle Otome” incident in Port Arthur, Texas (2010). To quote the National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) report : “The second pilot allowed himself to lose situational awareness by reading the newspaper”.

The subsequent collision with a cargo vessel and a barge caused considerable pollution and closed the waterway for five days – and no doubt considerable professional embarrassment to the newspaper reading pilot.

With a reactive approach to communication, there is no way to know throughout the operation if each pilots’ situational awareness is aligned with the actual current status of the dynamic, evolving circumstances and if both pilots are aligned between themselves. In other words, there is no way to know if both their individual and their shared situational awareness is accurate and maintained throughout the whole operation.

An effective way of achieving this, and as practiced in aviation, is by introducing Event Driven Cycles to the operation. Event Driven Cycles are proven methods of ensuring Two Man Operations happen in actuality. It is a simple technique for building and harnessing the good work of competent individuals. The objective with this is to build on the existing competency of the pilots without changing

the nature of the operation or adding more workload like three‐way communications. An Event Driven Cycle approach is, essentially, performing an operation having identified what are the critical events and, before each critical event, introduce a checkpoint. Critical events could be achieving certain speed thresholds, wheel over positions, start and end points, decision making positions or passing certain navigational marks or reporting points. The checkpoint is a short conversation between the pilots to confirm they are both aligned on the current state and on the next step.

This can be easily and effectively done by covering the Past‐Present‐Future questions: “what have we just done?”, “where are we know?”, “what is the next step and how will we do that?” This conversation is also another opportunity for discussing any concerns that exist or may come up moving forward.

It is important to note that the checkpoints are in no way a replacement for the usual open bridge communication, and any remarks and concerns should continue an as‐required basis, at any moment during the operation. It should also not replace the current start of operation briefings, i.e. the pre‐boarding planning between pilots and the Master/Pilot information exchange. These have their individual purposes including the decision to even perform the operation or not and to communicate the details of the procedure to the bridge team. The checkpoints are additional communications points after the start of the operation to align both pilots on the developing situation. It might be that circumstances are unchanged since the briefings and all steps carried out so far

have been as expected, or it might be that some circumstances have changed.

Either way, the checkpoint is the platform that will align both pilots on the current status, prediction of future states, and how to perform and adapt, if necessary, the next steps. It creates the opportunity to proactively take action and avoids the possibility of more drastic corrective actions further down the line.

Furthermore, checkpoints are observable actions which allow the benefits of such approach to become apparent to any organisation that is commercially funding the activity and it also instils confidence to the bridge team witnessing/participating in the operation. This may sound like a subtle change but there can be a big difference in performance.

Just as valuable as the briefing and the checkpoints is de‐briefing at the end of an operation. Debriefing is definitely a valuable practice that is recommended but does not routinely happen in pilotage if the operation goes to plan. The de‐briefing is an opportunity for the two pilots to reflect on the completed operation and assess how the operation went, regardless of whether it was successful or not.

“Was there anything that could or should have occurred differently? Was there anything unexpected that they had to deal with? Did they deal with it in the best way? Why was it unexpected? Could it have been foreseen? If so, what led the pilots to not notice or take action sooner?”

The de‐briefing can address these topics and as an outcome, produce lessons learned can be shared with other pilots to contribute to competency, development, and incident prevention.

By Simon Lockwood / ABP Southampton Pilot

Looking out over the East Channel of Cork Harbour from Rams Head on a clear day with a moderate but noticeable breeze running we wait in anticipation for the demonstration of the EF-12 Workboat.

Courtesy of Artemis Technologies, Chris Hoyle, Alan Stroud and myself are here to experience the demonstration of the 100% electric active foiling workboat. Built on the experience of the Americas Cup team, Artemis Technologies have designed, developed, built and are now showcasing the result of their plunge into the commercial workboat industry. Their aim is to bring in a range of commercial vessels including passenger ferries of varying size and pilot launches.

Having watched the EF-12 pass, we return to the Royal Cork yacht club to board the vessel and see her in action. Inside, limited controls but plenty of electronics being used for measuring and diagnostics. At the wheel, a number of coloured buttons perhaps resembling a PlayStation controller. Apparently this is to engage and disengage “flight mode” and to manually adjust the foil.

As we go out to the East Channel entrance, the launch almost unnoticeably rises up and we are seemingly skimming the surface of the waves, dead upright, no rolling or pitching. The noise only a gentle whining from the battery powered motor.

It would be an anticlimax for anyone anticipating the thrill of a boat ride (various dignitaries have been visitors to Artemis at their home in the Titanic Quarter, Belfast including two recent Prime Ministers) but for anyone who’s been hammering through 3m+ seas in a hot, noisy and smelly launch for an hour to get out to a ship, this seems positively luxurious.

For a real sense of the difference, we stop, pass over onto the support rib that’s been shadowing us and watch from there as the EF-12 repeats the demo. This time the difference is stark as we bounce along taking the waves whilst the EF-12 rises elegantly out of the water. The range stated at up to 50nm at 25 knots is impressive for an all-electric vessel but may push the limits for any port with a long run out and something that may challenge a port with multiple boardings and landings in one trip. However, with the ability to transit at up to 28 knots and charge to 15nm range in 15 minutes or fully in around 1 hour via the fast charge system, it is conceivable that ports with short runs out and enough time between jobs to allow for recharging may be eyeing this up for their future needs. Artemis are also developing hybrid range extenders but believe the majority of ports will be able to operate on 100% electric.

In terms of performance in rough weather, assurances were given of performance in 4.18m seas during the Guinness world record crossing from Northern Ireland to Scotland as well as recent client demonstrations with Scandinavian pilots which saw 50 knot winds while maintain 22 knots cruise speed This is something we looked forward to experiencing ourselves in Cork but will have to wait for another opportunity in less favourable conditions to test fully.

Artemis have commenced the build process of the EF-12 Pilot Boat, the first customer deliveries are scheduled for late summer 2025.

By Tony Anderton / Associate Lecturer at Timsbury

Since my retirement from pilotage in Bristol in 2019, I was fortunate enough to become an Associate Lecturer in ship handling at Warsash Maritime School, part of Solent University, Southampton, UK where I am based at Timsbury Lake supporting the full-time staff. Most of us are either working or retired UK pilots and will be familiar faces in the UKMPA world. The ports we have worked at include Southampton, Portsmouth, Weymouth, Bristol, and London. Between us, there is a vast range of experience on all types of vessels and in most types of ports, from open water terminals to locked in systems and rivers with the usual British weather to boot as well as the challenging tides to be found around our waters.

When Matt asked me to draft this article, I thought I risked preaching to the converted, but to those who have still yet to come to the UK’s manned model training centre at Timsbury, what is all the fuss about? It is a place where all new pilots want to come and when they do, I am sure that in addition to having a constructive week in a beautiful environment doing what they love, they take more than enhanced knowledge and experience away with them. Our delegates benefit not only from doing the manoeuvres but also from exploring and discussing ship handling in the classroom. Our courses are intense, we warn students on day one that at the end of each day they will be dog-tired, but it does not seem to stop them discovering the delights of Romsey. All those manoeuvres, done outside and hopefully in British weather, as well as thinking about all the theory that is passed on in the classroom.

“WHEN MATT ASKED ME TO DRAFT THIS ARTICLE, I THOUGHT I RISKED PREACHING TO THE CONVERTED”.

Have sympathy for our international fellow professionals who are jet lagged as well, fortunately they survive and after a hard Monday they are fully functioning. The life of a pilot prepares them for days and nights of disturbed work-life balance after all!

An uninitiated visitor at our 10-acre facility near Romsey, Southampton will see grown men and women riding around a lake on miniature ships. As we know, they are honing a unique set of skills all pilots and ship handlers need to manage the world’s largest vessels in the confined waters of their ports. Limited by both geography and depth, the conditions they practice in on the lake makes the training here as realistic as possible using the range of 1:25 scale models of tankers, bulk carriers, container ships, ferries, and tugs.

For the newly authorised, the backbone of all our ship handling courses is lectures on all aspects of ship handling theory, leading to the practical side of developing slow speed control and honing situational awareness. More experienced pilots will want to push their abilities and work at extremes of the operational window. The lake area is shallow in most parts, ably simulating the effects of low under keel clearance. We also take time to discuss and practice emergency procedures. The courses offered are varied according to customer requirements, the core offering is a 4.5-day Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA)approved course that meets the needs of most attendees. For more senior pilots, an advanced version tailored to the individual or their sponsor’s need.

Other courses are on offer and indeed, we can tailor a course to meet most needs. It truly is an international clientele that join us, from the US and Canada, West Africa, and Europe as well as Asia and the Middle East.

There are 22 berths, buoyed channels, a lock, and space to practice each manoeuvre. Each model has one student acting as pilot, with the second acting as Mate/engineer- each pairing has a lecturer with them critiquing the manoeuvre as well as passing on valuable knowledge and experience.

I attended a manned model ship handling course twice in my career and I carried with me that knowledge and experience I picked up during those visits. It is a powerful thing to know that potentially, you are enabling a successful career. Why does the course complement ‘in district training’ so well?

A new pilot coming into pilotage will get whatever training his district has to offer, and we all know that varies greatly. Here at Warsash, we take a pilot, assess his or her skills and over the course of the week try to make them a better pilot than when they arrived. The scaling effect of a 1/25th model allows for many manoeuvres to be conducted and it is not unusual to do 40-50 ‘jobs’ in the week. Everything happens five times faster.

We start with familiarisation on the models and the lake itself. It only takes a short while to get used to the scaling factor of the models, so by the end of the morning, or certainly at the end of day one, students can conduct manoeuvres to a reasonable level of success. Port and starboard side berthing, with stopping and turning typically take up most of day one.

The first lecture will be on principles of ship handling, including Pivot point, stopping and turning. More presentations through the week usually include, ‘the effect of wind,’ bow thruster, interaction, and the use of tugs. We also cover manoeuvring podded vessels, as well as talking about emergency procedures.

As the week progresses, following on from the daily lectures we build in practical demonstrations of the subject theory and put it into practice, reinforcing a key learning element of the course.

The complexity of the tasks increases based on each student’s capability. Some individuals, move on quickly, others need more time with various aspects of ship handling.

The lecturers observe and analyse each manoeuvre from the jetty or a dinghy, offering constructive advice and feedback after each task. Time is available to give both the pilot and mate the opportunity to discuss the manoeuvre.

The benefit of the scaling factor allows for repetitions of a job if required, but by the latter half of the week we see greater finesse and precision.

By Thursday afternoon of a typical course, with the syllabus covered, we have time to allow students to return to any ships or manoeuvres they would like to repeat. Friday morning is similar, and it is important not to leave early! If, as an attendee, you have a certain manoeuvre you would like to try, please speak up. Current generators and tugs are available to ensure that conditions on the lake are as realistic as possible.

The syllabus we follow is MCA accredited, and you will take home a certificate, but I would say the content of each course is tailored to the needs of each student. Some struggle for the first couple of days with speed control, others get it right in an hour or two. Whoever we have, and whatever their

needs, we always aim to give those who join us our best efforts, even down to offering personal support if a pilot turns up with a problem they are having in district. With the range of models and berths we have, it is easy to design something to simulate whatever issue is troubling them. I have rigged floating modular docks and current generators to simulate Los Angeles, Vancouver finger jetties, Gladstone lock in Liverpool for ebb approaches as well as Immingham on the Humber.

Going forward, Warsash Maritime School will continue to develop new courses and the range of models and facilities at Timsbury.

To this end, we will soon have a twin podded container/ passenger ship model, and in the classroom, we will have ‘SAMMON’ Fast Time Simulator from Innovative Ship Simulation Gmbh, which will be a valuable training and planning aid enabling students to see the effects of the application of manoeuvring tools on a ship’s position and speed, as well as the effect of wind and current.

What do we as pilots take away from the course? Our delegates will have reinforced their detailed knowledge of the principles of ship handling, as well as practised many manoeuvres hopefully with an eclectic group of colleagues where shared experiences enhance the week, both in the classroom and after hours. I am confident they will carry this experience and knowledge for their whole careers. The more senior pilots use the course as part of their continued professional development, and occasionally arrive with a ‘wish list’ of manoeuvres to try out.

As a former student, and now Associate Lecturer, I can agree with everyone I have heard say “It’s probably, the best course I’ve ever been on,” it is nice to be able to say we hear that quite a lot!

Piloting skill like yours doesn’t come from nowhere. It takes time, experience, and ongoing practice – a commitment to continuous professional development.

Warsash Maritime School’s simulation centre and manned model ship-handling centre offer the perfect way to keep your skills sharp, combining world-renowned training with a realistic, safe and controlled piloting environment.

• Our ship-handling centre is unique in the UK, and one of just a few worldwide.

• Scaled models of real single, twin-screw and azimuth drive propulsion ships, replicating the hydrodynamics and handling characteristics of an actual class of vessel.

• Buoyed channels, a four-mile scale-length canal, turning basins and 21 flexible berths for any ship-handling scenario.

• Radio-controlled tugs, jack-up oil rig and portable current generators for specialist training.

• Dedicated twin-screw course for superyachts.

• Seven full-mission linkable bridge simulators, with digital twinning.

Find out more at maritime.solent.ac.uk/ship-handling

By Dr Mark McBride, Group Manager, Ships and Dredging, HR Wallingford

With continuing enhancements in computing technology, ship and tug navigation simulators are becoming more and more accurate and realistic. This allows them to play a vital role contributing to the safety of port operations through, for example:

• Pilot and tug master training as part of their continual professional development, along with providing a safe environment in which to practice and develop the response to emergency scenarios

• Simulation based training can be widened to include all of those involved in the operations, such as Harbour Masters and VTS operators

• Assess the impact of changes in ship sizes and/or their design on operational safety, and in the evaluation of the navigational aspects of port development

• Allowing pilots and tug masters to become familiar with new ship sizes and port developments before having to do it in reality

• Investigating the causes of ship and tug related incidents and near misses in ports, and examining possible mitigation measures to reduce risk

• Assisting with assessing the aptitude and attitude in the pilot selection process as part of the recruitment process

• Providing a tool to help accelerate the training of new pilots and to help build their confidence, noting that simulation training should only be used to supplement onboard training time.

HR Wallingford has been developing and using navigation simulation for over 35 years to evaluate the impact of new ships in ports or terminals, in terms of their manoeuvrability, environmental limits and towage requirements. This process continues to improve due to high quality modelling and enhancements in the visual scene display.

The 11 full mission simulators that HR Wallingford operate in their state‐of‐the‐art Ship Simulation Centres, located in Wallingford in the UK and Fremantle in Western Australia, combine hydraulic modelling research, vessel manoeuvring models, and expert experience from naval architects, master mariners, engineers, mathematicians and scientists.

Each simulator has a full 360 degree field of view and replicates a ship or tug's bridge in real time, representing spatial and temporal vessel behaviours. A high quality visual scene is key to a credible training scenario, as a pilot needs to be able to see a range of accurate and realistic visual cues to be able to carry out an exercise realistically. Sophisticated numerical models of the wind, waves and currents are also included to provide representative environmental forces, which are also integrated into the visual scene for increased realism.

It is essential in training that pilots and tug masters learn on realistic, high quality models of their actual port, and with ships and tugs that are representative. The quality of the simulation combined with the bespoke facilities that are specifically designed for the simulation of

pilotage, have been key to its success as a training tool. If maritime pilots and tug masters are operating in a port that they know well, their confidence is boosted by seeing that the simulator correctly replicates existing navigation conditions and the layout of the port.

The simulators can be run individually or can be integrated and used simultaneously, allowing interactions between a ship and a number of tugs, with large vessel simulations routinely supported by up to four separate tug bridge simulators, each operated by an individual tug master. This allows for a joined‐up approach as team training contributes to port safety, allowing pilots and tug masters to share each others’ experience and knowledge.

The simulators can be used to help assess particular situations or to develop the best methods to handle ships. This also can be used to assist in determining the limiting conditions in which a ship can enter and leave a port safely. The simulator can help a pilot and tug master understand, quantify, and use the sometimes very large hydrodynamic forces acting on vessels to their advantage. In addition, simulations can help contribute to risk assessments for the port authority and ship operators/owners.

Simulators are now widely employed in pilot and tug master training for learning different manoeuvring techniques, moving up class and refresher

courses. Pilots can use simulators to practice high risk manoeuvres in complex areas, such as navigating in difficult conditions, to gain confidence and reduce the risk of accidents. Simulators can also be used to create weather conditions, such as squalls, which otherwise may not occur regularly, yet require specific expertise.

A key aspect of the simulator training is the ability to try, fail, learn, and try again, without any negative repercussions and in a completely confidential environment. Pilots complete a simulation scenario which allows individuals to assess themselves and identify areas for improvement, as well as providing a catalyst for round‐table discussion and constructive feedback based on the port’s best practices. In this way it is also possible to develop procedures in the simulator in combination with practical experience that can then be put into practice on the water.

On completion of each simulation run, the team gathers to debrief and discuss, using an on‐screen playback of the session. Within minutes the system can be reset to run another simulation.

When examining port and terminal designs, it is important that the simulation models can be altered quickly to allow potential changes to the layout to be modelled and assessed efficiently. In‐built flexibility also makes it possible to tailor scenarios to the specific training needs of the pilots and tug masters.

In our Ship Simulation Centres, we have personnel available to discuss and make modifications of all aspects as required. By having simulation teams in both the UK and Australia, we can make more complex changes overnight, if required.

While hydraulic modelling capabilities and ship handling models are essential to ship simulation work, having a comprehensive support team makes a real difference. In our Ship Simulation Centres, for example, we draw on an expert team of experienced maritime engineers, master mariners, pilots, tug masters, naval architects, scientists and software modelling experts, all underpinned by HR Wallingford’s broader maritime and coastal engineering research and consultancy capabilities.

When used appropriately, simulators are now essential tools for effective pilot and tug master training, allowing a safe training environment in which to explore a range of possible scenarios. Looking ahead it is expected that simulators will continue to improve, with ship and tug manoeuvring models becoming more and more sophisticated, and with further advances in the detail of visual scenes. So their effectiveness in the training pilots and tug masters will continue to improve, with every step forward contributing to ensuring safer navigation in ports.

For HR Wallingford, recent upgrades offer the potential to develop bespoke simulator training environments more quickly than before, and without the need for significant investment from the client. Working in partnership with the industry allows successes to be shared making simulation an essential tool to train the navigation team.

Author bio

Dr Mark McBride has more than 35 years’ experience in port and maritime design related work. He is responsible for all HR Wallingford’s studies relating to ship motion and offshore applications, including vessel manoeuvring, ship mooring and port/terminal operations. He has a degree in naval architecture and a doctorate in port operations simulation, and has managed a wide range of ship and offshore related projects. He regularly chairs and participates in PIANC, SIGTTO and British Standards Working Groups.

bio

HR Wallingford is an independent engineering and environmental hydraulics research and consultancy organisation. We create smart, data-centric solutions for the natural and built environments to help the world understand the influence and changing impact of water. We deliver practical solutions to complex water-related challenges faced by our international clients. In addition to our Ship Simulation Centres, our facilities include state of the art physical modelling laboratories, a full range of numerical modelling tools and, enthusiastic people with world-renowned skills and expertise. A dynamic research programme underpins all that we do.

By Dr Mark McBride, Group Manager, Ships and Dredging, HR Wallingford

By Captain Matthew Easton / MNM CMMar FNI

The vast number of acts of pilotage conducted on a daily basis around the world are concluded satisfactorily with little, if any, analysis of the performance of all those parties involved and how effective the communication was between everyone.