PILOT

Conference & Port Reports / Canal Pilotage & Towage / Fatigue, Are You Aware? / What Makes Human Factors? /

Conference & Port Reports / Canal Pilotage & Towage / Fatigue, Are You Aware? / What Makes Human Factors? /

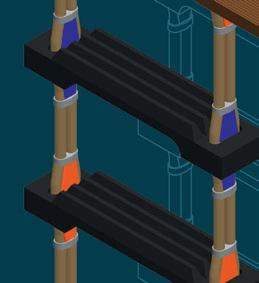

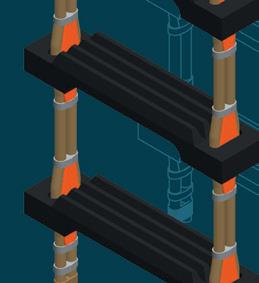

oun all r helmets of UK po Supplied

POR • protect TheMa otectipr

R

o a has been designed t nt

own. o the cr on t ection with 100 joules ot d pr ers 90 joules f s, Unlikeothermarine ts or o the majority globally and t theMH4of A

Technica S EN16473 Y RTS/QU eas wing ar ollo the pilot in the f

th Hltthi

thep pilot the p Resc Ithasthesameimpact It has the same impact por y or ound the qua ving ar mo

ARDING A •

ety goggle sameassaf ound the second all ar est of 120 met impact t It also has otpr moltenmetalandelec helmet plus it also has ationtesta and penetr l s: ection.

thisisthec EN12492

w. o vie ction t

ers the v cue Helmet – this co t. oval limbing appr s c it’ es t h giv d whic standar – this is the c In EN16473, a the Mant

s on w

e bing a ladder and ther thehelmetcanbeused metreladderclimbtestto

oafieldofvisiontest PERA TBO

CLIMBING/BO operations ve – thisco Ma AS028 A MARINEO • estric is no r limb while c makesure anda10m thereisals limbing GSHIP es e helmet es per tr a ballistic ctrical chemical, asthesafety P sonwater rstheMantaforall andard ety St arineSaf

AT TIONS/PILO T

First, I would like to thank Alan Stroud for his dedicated time and effort on arranging the UKMPA conference in Harrogate last November. The conference delivered high-standard presentations from excellent speakers, some of whom have written articles for this edition. The UKMPA would again like to thank those who attended and spoke at the event.

Second, I would like to congratulate the following: Chris Hoyle for his promotion to UKMPA Chairman, Jason Wiltshire for his promotion to Vice Chairman and Alan Stroud to Treasurer. Also, congratulations to Neville Dring and James Musgrove who have become Region 5 & 6 representatives respectively.

Thank you to the outgoing chairman Hywel Pugh for his dedicated service to the UK pilotage Industry. Hywel is a fountain of pilotage knowledge and has represented the UKMPA exceptionally well over the years.

The theme for this edition is tugs and towage along with human factors in our industry. The magazine has not covered towage within pilotage in great detail for many years. I felt it was time to look closer at this aspect of our industry, coinciding with the 2024 UKMPA conference theme.

The theme of the magazine also coincides with the release of the MAIB report on the tragic Biter accident. On a personal note, I have been fortunate to work alongside some excellent tug crews and masters in my career; one was when I was working with a Hull company taking a project cargo all the way inland to Gainsborough in 2020. The unique skills when using conventional towage were clearly demonstrated by the experience of the tug crews.

Questions do arise regarding the use of these types of tug, the training of tug crews, pilots and when to make fast the tug. However it also has to be remembered the type of ports which require these unique size and type of tugs.

This edition has articles from the MCA about the need to report pilot ladder defects, fatigue management and Goodchild, the launch manufacturer explaining launch specifications.

Reporting of defective pilot ladders remains vital in maintaining the safety of pilots. The Maritime & Coastguard Agency clearly outlines this in this magazine. In a future edition, I plan to cover the latest pilot ladder developments.

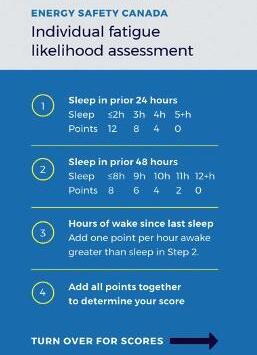

I welcome Claire Pekcan to this edition. Claire made an excellent presentation at the EMPA conference in Antwerp and again at the last UKMPA conference on fatigue management. Pilots who are fatigued are a danger to themselves and to others. There are many reasons for this and these are highlighted in this edition.

John Slater, who has spent considerable time and effort writing his article on climb zone criteria, appears in the membership section. John is passionate about this matter and one of the reasons for appearing in this edition is for readers to have a closer understanding of the mindset of climbing ladders. This matter is very much up for future discussion in the interests of future safety.

I thank James Musgrove for his updated article about mental health. His dedication to this service is exemplary and all pilots should be aware of this important service at their disposal.

Congratulations to Hywel Pugh and James Musgrove on receiving their service awards at the UKMPA conference last November.

Thank you for reading. Safe piloting and thank you once again to all those of

Matthew Finn / Editor UKMPA

It has continued to be a busy year since my last report, culminating with the 136th AGM and conference in Harrogate, which was a resounding success. Conference is always an opportunity to engage with the membership and this conference saw several members attend conference for the first time. The feedback was very good and I would encourage all to attend where possible.

The shipping minister was unable to attend in person but did send a video message where he highlighted our importance to the UK’s economy and future growth. Thank you to all the sponsors, exhibitors and speakers for their support.

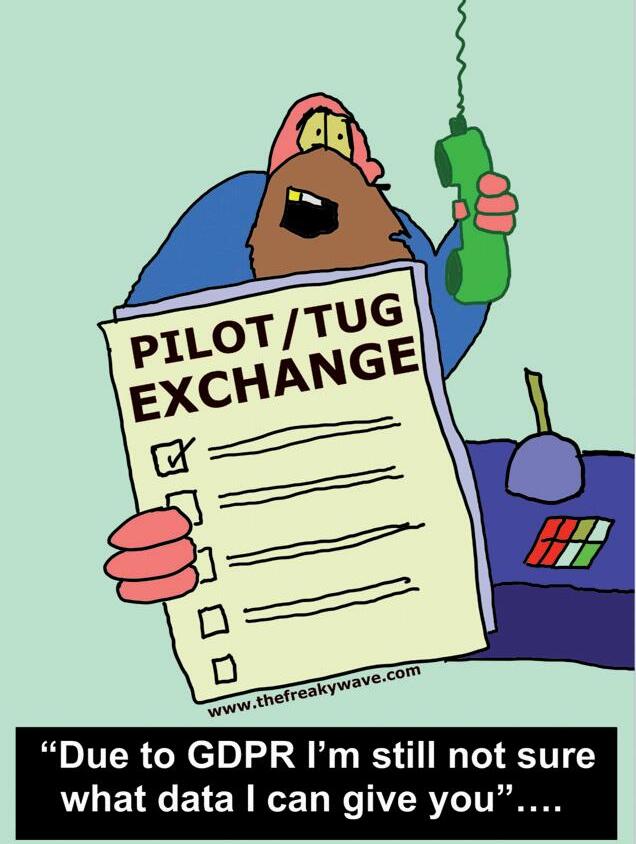

The MAIB has released the report into the girting of the tug Biter. I hope you have all read it. It highlights that we sometimes operate within very small margins. The UKMPA in partnership with BTA/UKHMA/BPA and the Workboat Association has been asked to develop guidance for inclusion in the Port Marine Safety Code’s Guide to Good Practice and other appropriate publications that emphasise the importance of conducting a pilot/tug exchange, in addition to the master/pilot exchange, to ensure that the pilot, bridge team and tug crew have a common understanding of the intended arrival or departure manoeuvre, the potential hazards and their respective roles in managing them.

The new pilot ladder performance standards are progressing well through the various committee stages at the IMO and we have been receiving regular updates from IMPA. The next step is adopting the amendments in June 2025 to allow entry into force on 1 January 2028.

EMPA is holding its next conference in Krakow Poland, next year. EMPA has also launched the EMPAsafe app for reporting defects.

Engagement with stakeholders has been good in the past few months, with members of the executive attending various meetings, conferences and seminars. These are, to name a few, MCA, IMO, DfT, UKMPG, BPA, BTA and the Chamber of Shipping.

Our very own James Musgrove –Tees Bay pilot and now a member of the executive – attended and spoke on the Safe Haven project at the AMPI Conference in Papua New Guinea.

It has been over three years since I took up the role of chairman. I stood down at the conference in Harrogate and handed over to Capt Chris Hoyle. It has been an honour and a privilege to chair the UKMPA. I would like to thank the executive for all their support and wise counsel; for the families of the executive it is always difficult balancing the workload and I really appreciate the time they have given to me. So, I wish Chris and the executive a bright future as I step back into the ranks of the membership.

Hywel J Pugh

THANK YOU

TO THE EXECUTIVE FOR YOUR SUPPORT DURING MY TENURE AS UKMPA CHAIRMAN, IT HAS BEEN AN HONOUR

Awarm welcome to 2025. Exhausted but satisfied after a hugely successful AGM and conference in Harrogate, your volunteers at the UKMPA have taken some welldeserved downtime over the holiday period to recharge with family and friends.

We say a fond farewell to our outgoing Chair, Hywel Pugh, and extend our gratitude to his 14 years of selfless dedication to our profession.

I was honoured to be elected as Chair in Harrogate and as such I have taken some time to reflect on the UKMPA’s progress over the past few years. With our membership numbers at a record high, and with increasing interest from wider stakeholders, I am proud to say our recognition and engagement across the industry is stronger than ever. It is through this strong engagement that we can continue to deliver on our mission of supporting pilots and protecting trade.

Within our own ports sector there is no more stable occupation than maritime pilots retaining that essential specific expert knowledge. The ever-increasing demand for the expert knowledge that maritime pilots possess reiterates the recognition of their ability to maintain the integrity of the ‘last blue mile’.

It is crucial that continuity, and the collaboration between pilots and industry, is maintained so that we can support the profession, keep our shores and infrastructure free from pollution and damage and support the end goal of protecting our vital seaborne trade flowing as an island nation.

In a short time the UKMPA has been able to deliver many successes, notably our mental health support and industry engagement programmes. As we move into to 2025, we will strive to maintain a stable and engaged association to benefit both our members and the continued success of the ports and maritime sector, recognising that we should always seek to improve on best practice and not acquiesce.

Your UKMPA committee will look forward to supporting the membership and acting as a vital conduit with its partners and wider stakeholder group to ensure the success and strength of shipping and ports. After our hugely successful debut in 2023, we look forward again to taking part in London International Shipping Week (LISW), partnering with Maritime London to highlight the critical work of pilots to the wider industry.

Before I sign off, I would like to welcome Jason Wiltshire CMMar (Bristol) as our new Vice-Chair, who now takes responsibility for running our association’s day-to-day activities. Jason has spent the past eight years as our diligent and respected treasurer and clearly brings a wealth of experience to his new role. The Treasury is now under the care of Alan Stroud (Medway). Adding to the Executive is always an exciting time and I would like to welcome two new board members: Neville Dring (Liverpool) and James Musgrove (Tees).

I would like to express our sincere thanks for the work of all our volunteers on the Board and those that stand by as deputies and work on our Technical & Training Committee. To commit family and leisure time as volunteers, working to support fellow pilots and influence the broader industry, shows a strong moral fabric. Our volunteers give up their time because they feel they can make a difference, and I have the utmost respect for this. In signing off, I would like to also pass a special thanks to those colleagues in the districts of our volunteers who support their peers in this priceless work.

Yours Aye

Christopher F Hoyle / UKMPA Chairman

In the insurance industry, effective communication can be challenging. From navigating the complexities of policy wordings to the relatively recent shift towards underwriters working remotely, the industry has a unfair reputation of muddying the waters, despite billions being paid in claims annually.

A broker’s job is to bridge these channels and overcome this unwanted reputation by mastering the oftenforgotten skill of interpreting policy wordings, building strong personal relationships with underwriters and communicating with their policyholders effectively. We rely on these skills and experiences to maximise value for our clients. Similarly, your role as a maritime pilot is critical. You ensure the safe navigation of extremely large ships through narrow, sometimes hazardous waterways. Pilots must continuously develop essential skills and strategies for effective communication, especially in challenging circumstances, to benefit their ‘customers’.

While we all agree on the vital role of a pilot, we have witnessed pilot skills questioned by crew members, leading to communication breakdowns that can result in near misses, collisions or injuries.

Successful passage requires pilots to bridge communication gaps among various crew members, minimising the risk of incidents. Pilots must also co-ordinate with port authorities, harbour masters and tug operators to ensure a perfectly synchronised operation. So, how can we learn from these interactions to keep improving?

To facilitate effective communication, the IMO has developed Standard Marine Communication Phrases, which help ease language barriers and reduce misunderstandings. In our own roles, we must ensure that we are:

• Accurate and concise in our communications.

• Assertive but not overbearing to prevent hierarchical structures from stifling information flow.

• Open to information flow in both directions to support effective decision-making.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we must learn to listen actively. Many of us have been guilty of making assumptions based on limited information, only to discover there was more to learn. I continuously encourage my colleagues to listen more and speak less. I’ve learned the most about our clients when I’ve allowed them to speak, rather than filling every pause in our conversation.

With all this in mind, I’d like to address Circle’s communication with you, the pilots. There seems to be some confusion around why you need insurance to be a member and vice versa. We place this insurance on behalf of the UKMPA membership with two guiding principles: it must be costeffective and it must respond promptly when called upon.

We administer approximately 75 incident reports annually, most of which require minimal intervention. However, in those cases where significant assistance is required, pilots have consistently expressed gratitude for the support we provide during difficult times.

If you’re uncertain about the need for insurance, please take the time to fully read the Frequently Asked Questions document we have prepared, which is also available online at the UKMPA site. If questions remain, don’t hesitate to reach out to either Roger Darkins or me. We’re happy to discuss cover details and share real examples you may find relevant. As a team we are always here to help. We’re at your side so please communicate with us effectively and politely.

Ian Storm / Circle Insurance

Chairman Christopher Hoyle chairman@ukmpa.org

Vice Chairman Jason Wiltshire vice.chairman@ukmpa.org

Region 1 Executive Alan Stroud region1@ukmpa.org

Region 2 Executive Chris Grundy region2@ukmpa.org

Region 3 Executive Peter Lightfoot region3@ukmpa.org

Region 4 Executive Robert Keir region4@ukmpa.org

Region 5 Executive Neville Dring region5@ukmpa.org

Region 6 Executive James Musgrove region6@ukmpa.org

Treasurer Alan Stroud treasurer@ukmpa.org

Secretary & EMPA VP Peter Lightfoot secretary@ukmpa.org

Membership Robert Keir membership@ukmpa.org

Mental Health James Musgrove region6@ukmpa.org

IMPA VP Paul Schoneveld paul.schoneveld@ukmpa.org

“The Pilot” Editor Matthew Finn Editor@ukmpa.org

Technical & Training Chair John Slater technical@ukmpa.org

Web Captain James Musgrove webcaptain@ukmpa.org

Region 1 Deputy Simon Lockwood deputy1@ukmpa.org

Region 2 Deputy Mike Robarts deputy2@ukmpa.org

Region 3 Deputy Alan Jameson deputy3@ukmpa.org

Region 4 Deputy Ross McCauley deputy4@ukmpa.org

Region 5 Deputy Paul Schoneveld deputy5@ukmpa.org

Region 6 Deputy Matthew Finn deputy6@ukmpa.org

Circle Insurance Ian Storm Ian.storm@circleinsurance.co.uk M: 07920 194970

Insurance Queries Claire Johnstone claire.johnstone@circleinsurance.co.uk

Incident Reports Via UKMPA app insurance@ukmpa.org

UNITE Maria Ball maria.ball@unitetheunion.org

Web Captain James Musgrove webcaptain@ukmpa.org

Editor Matthew Finn photos@ukmpa.org

Minor incident 0141 249 9914 insurance@ukmpa.org

Major incident 0800 6446 999 insurance@ukmpa.org Incident Reports insurance@ukmpa.org

Safe Haven Hotline 0800 433 2163 Visit www.ukmpa.org for further details

Tony Fisher –01480 495848 / 07703 279214 –tony@spectrumcreative.co.uk

Sergio Panzini London

Daniel Tolley London

Patrick Kelly London

James Terry London

Caroline Palmer London

Leuan Clark South Wales

Asley Williams Southampton

Rob Hugh Southampton

Daniel Stevens Plymouth

Leslie Maines Tyne

Michael Lynch Workington

Jaimie Fisher Humber

Michael Paterson Associate

Dean Stores Associate

Thursday 1st May 2025

Lee-on-the-Solent Golf Club

We are very pleased to receive continued sponsorship from Ben Huggins and the team at Svitzer Marine Limited, for the 3rd Golf Day in support of the Cachalots Captains charity which for 2025 is Solent Dolphin. www.solentdolphin.co.uk

To book your place, contact - Bruce Thomas bruce.cachalotsgolf@gmail.com

20.11.24

By James Foster / Class 1 Pilot, London Medway / Secretary of the Medway Pilot’s Association

The 136th UKMPA conference was held in the heart of UK’s Historical Turkish Bath and spa town of Harrogate in North Yorkshire. The venue was the grand Victorian 137 guestroom of The Old Swan Hotel.

Having spent the day travelling, five Medway Pilots’ and I experienced heavy snow on the roads, coupled with train and transport delays. It was idyllic and comforting to be greeted by a warm log-burning fire, surrounded by cosy Victorian period features, on such a cold winter’s night.

The evening started with the Chairman’s Reception at the Sun Pavillion, which held a perfect backdrop overlooking the wintery valley and gardens. It was an ideal time to greet face’s old and new, in not only pilotage, but the whole Marine Environment. The current chairman Hywel Pugh, gave a warm welcome and introduction to what was going to be an enjoyable couple of days. In total, the conference consisted of 126 delegates, 16 exhibitors and 17 speakers.

The morning of Day 1 consisted of the UKMPA section committee, giving members’ presentations and reports on current affairs. This included where the association is currently standing and the direction the association is taking. It all appeared positive feedback, and there have also been some internal position changes. I join along with all the members in congratulating them on their current achievements. An official article detailing committee matters will be published shortly.

It was reassuring that the UKMPA has an array of professional associates and contacts to support pilots as part of their membership package.

Day 1 started with Mike Paterson (MD, Svitzer UK) and Scott Baker (head of marine standards at Svitzer) both giving valuable presentations, which included a brief history of Svitzer from its roots and up to what it does and how it partners worldwide. Svitzer operates in over 142 ports worldwide, covering over 137,000 towage jobs, which equates to one towage job every 4 minutes. I’m sure you would agree that these are impressive figures.

One of the interesting reports that was dissected in Scott Baker’s presentation was that of an unfortunate incident involving a conventional tug (the Gray Test) and a feeder container ship in a UK port that nearly resulted in the capsize of the Gray Test tug.

The next presentation was from John McCorquodale of the MAIB, who shared an MAIB report on the unfortunate Biter incident on the Clyde. The sad incident resulted in the loss of two experienced seafarers’ lives. It was almost unbelievable that that it took a mere 10 seconds for the Biter tug to capsize and, just like most incidents, it was never one element that contributed but several. In this case, 14 contributory factors were identified. It puts into perspective just how much towage operations and pilotage continue to be hazardous tasks for seafarers and pilots.

I would highly recommend reading the presentations on both incidents, along with the MAIB report, which the

UKMPA has published on its website. No matter how experienced pilots become, reading about past incidents and taking note of the lessons learnt reminds us all of the dangers involved and of the evolution of safe operating practices that both tugs and ships can employ to minimise certain risks.

Mike Kane, Parliamentary Minister for the Department of Transport (DFT), presented a personal video to the attendees on future developments involving de-carbonisation and how its policy will unlock investments and further growth of the UK economy. It was reassuring to see and hear that the UKMPA and DFT have a good professional relationship, given the fact he had a clear understanding of the important role that pilots have and how they contribute to the economy.

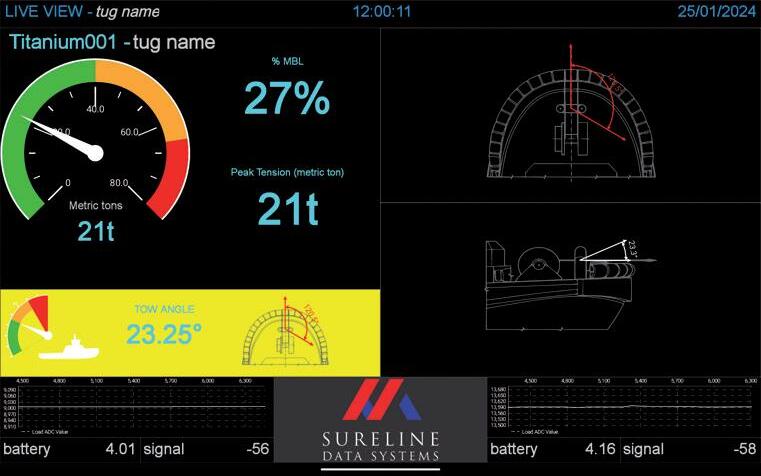

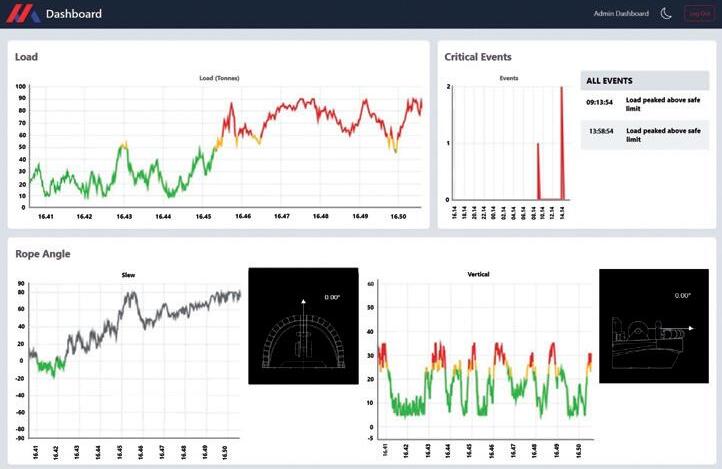

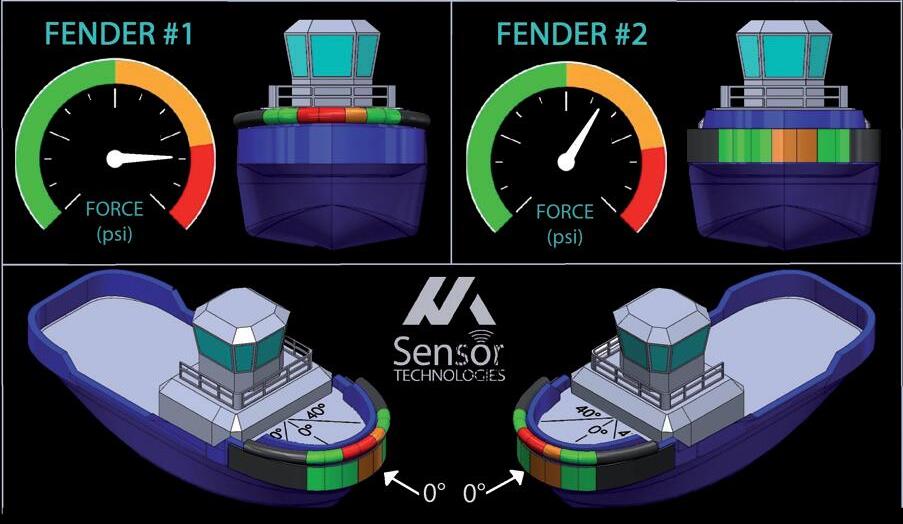

There were four memorable presentations involving new technology, aimed directly at pilotage. The first by Peter Farthing of Sensor Technologies showcased ‘Sureline’ a rope monitoring system that gives tug masters and pilots real-time data on tug lines and mooring ropes. It is able to record and transmit the line tension.

The company’s developments are expanding, which would enable it to use this technology to inform ships and ports with accurate real-time data, the forces applied to fenders and forces applied to vessels and with tugs pushing alongside.

Scott Tonks of Zelim showcased the company’s new technology for Maritime Search and Rescue. 40% of manoverboard (MOB) incidents are reported to be fatal (MAIB) and Zelim has

developed a system that employs Artificial Intelligence in the identification and tracking of MOB casualties. This, coupled with its ‘Swift Rescue Conveyor’, was fascinating to see, whereby something that looked relatively simple and cost-effective could retrieve MOB casualties from the water so effectively and quickly. So it’s no surprise that various workboats are ditching their rescue lines, tripod set-up and means of recovery lifts in favour of this excellent piece of minimalistic and effective lifesaving equipment.

The closure of Day 1 resulted in some refreshments, while patiently waiting to see if any of the attendees had won any of the raffle prizes. Most of us had our eyes on winning the Port and Ship Lego City Box set – oh well, better luck for me next time. But happy building to the lucky pilot who won. However, the raffle and auction raised an impressive amount for the Sailors’ Society charity.

The evening held at the Royal Baths Chinese restaurant gave ample time to socialise, discuss the various presentations of the day and catch up with old and new acquaintances. Although there were many legendary and experienced individuals present, it was great to see new up and upcoming attendees, reflecting a change of generations in our respective pilotage districts.

Day 2 continued on the theme of new technology, with John Cumming of Artemis presenting the latest in pilot boat technology. Hybrid and fully electric hydrofoil pilot boats demonstrated how personnel could be transported at 25-30kt speeds in three-metre seas, in complete comfort, reducing any impact from waves while emitting zero emissions and ensuring sustainability. It was a great insight into what can be achieved today in the marine world. I’m all for a comfortable, seasickness-free feeling of transport

Dr Clare Pekcan gave a first-class, medically proven presentation on the causes and consequences of fatigue in our roles as pilots and what we can do to help. Repeated sleep deprivation has some serious health issues and risks while engaging in pilotage acts but also before and after the job. Clare’s presentation is on the UKMPA website and I strongly encourage pilots to read and familiarise themselves with the content.

It's impossible to go through every presentation and mention all the speakers, as quite frankly, I would be writing a novel on the two-day experience. But that is what I would call it, an experience, and one I would encourage people to attend in the future.

For myself, what stuck out at this conference, compared with others, was the subject and content of the presentations. All of the speakers were confident, enthusiastic and extremely knowledgeable, covering current hot topics in our maritime world, be it, pilotage incidents, best practice, new guidance, fatigue, new technology or how artificial technology could influence the maritime industry and society (thanks to Patrick Galvin of Shannon Pilots for the thought-provoking presentation on Artificial Intelligence).

Iwould like to say a big thank you to all the speakers and attendees for making the 136th UKMPA conference a triumph. And, finally, congratulations to Alan Stroud (treasurer UKMPA /Medway), who spent considerable time organising this successful conference.

The third International Maritime Human Factors Symposium (IMHFS) was held at the IMO Headquarters in London, and I was privileged to attend as a representative of the UKMPA’s Technical and Training Committee, alongside James Musgrove from the Section Committee. The event brought together approximately 160 participants, featuring 47 high-quality presentations across 12 expert panel sessions over two days. The attendees comprised both academics and industry professionals. Key figures included the Chief

Inspector of the MAIB as well as lead representatives from CHIRP Maritime, the International Chamber of Shipping, the MCA, Inmarsat, the Seafarers’ Charity, and the Nautical Institute, which co-hosted the event with the University of Strathclyde.

A significant focus was placed on decarbonisation, with it becoming clear that there is no single, definitive solution regarding which ‘alternative fuel’ is the most viable. One of the more unusual and potentially controversial options discussed was nuclear power. A presentation was delivered by a

company claiming to have developed a reactor that is safe, insurable and efficient, and does not produce nuclear waste.

One of the main concerns, however, centred on the shortage of trained seafarers and how the industry will address the training needs for these new power systems.

Many of the presentations explored the role of AI, autonomy, and emerging technologies, particularly in terms of reducing the human element in maritime operations. Discussions also revolved around how autonomous vessels would interact with the existing COLREGs. One particularly impactful presentation highlighted the importance of mental wellness. The speaker shared a deeply personal and emotional account of a tragic tanker explosion that led to a catastrophic fire on his vessel. Through his experience, he underscored the long-lasting effects of trauma on mental health, stressing that mental health challenges can persist for years, even with professional support.

The MAIB provided insightful statistics on the most common types of accident, while CHIRP emphasised the critical importance of incident reporting. They also highlighted the ongoing issues caused by the lack of a global reporting network and the insufficient number of near-miss reports, which limit the industry'’s ability to learn from such incidents.

The symposium provided a wealth of valuable insights. James and I made every effort to engage with the wider audience and convey the unique perspective and concerns of pilots within the maritime sector.

By Jon Smith / UKMPA Technical & Training Committee

24

The UKMPA Executive are delighted with the attendance of the 2024 Conference and would like to express our sincere gratitude to the organising team, speakers, delegates and sponsors for making the 136th conference in Harrogate, such a great success.

Special thanks to Chevron, our headline Sponsor

THANK YOU!

The EMPA Board convened its most recent face-to-face meeting in Brussels on the 1st and 2nd of October. In addition to this, the Board continues to meet regularly via monthly Teams calls. This report highlights key discussions from the October meeting not covered in the EMPA newsletter, along with updates from various EMPA subcommittees and other relevant topics affecting European maritime pilotage.

In Germany, due to a declining number of applicants from the traditional recruitment route, the German Pilots have commenced their own in-house training.

Applicants will have an equivalent Officer Of The Watch certificate before starting a more extensive training scheme in their respective ports. Most of the current applicants will become pilots before their 30th birthday. The scheme will eventually cover the seven pilotage areas and, although the entry requirements will be lesser, the training will be more extensive to cover the shortfall in experience. Other European countries are also experiencing difficulties in recruiting suitably qualified

officers from the traditional route, so it will be interesting to see how the German model progresses.

In Spain, environmental group Oceancare has advocated for a speed limit of 10 knots for vessels in the waters around Barcelona, Valencia and the Balearic Islands to protect migrating whales and dolphins. According to Oceancare, ships traveling above 10 knots pose a much higher risk of lethal collisions with marine mammals, despite the fact that the probability of such collisions remains low. Oceancare’s data suggests that in 2023, 80% of ships in the northwestern Mediterranean exceeded this speed threshold.

The proposal has led to discussions within the Spanish government regarding the possibility of introducing mandatory speed limits in the region. This is a significant development for the maritime sector, as it highlights the growing intersection between environmental concerns and maritime operations.

There are two EMPA sub-committees. The Technical and Training and the Deep-Sea Pilots sub-committees.

Miguel Castro, who chairs the T&TC recently, attended the Remote Pilotage Days in Helsinki in September.

From an EMPA perspective, we do not like the term Remote Pilotage as we feel that Pilotage only refers to the physical presence of a pilot on the bridge of a ship. We see many of the proposals currently being put forward as enhanced VTS, but that is a whole other debate.

The meeting was well attended by pilots from around the world as well as government officials and industry developers. The main countries looking to introduce remote pilotage are Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Singapore. All currently have projects ongoing with enhanced technology onboard vessels. These include cameras, iPad and even using drones. It should be mentioned that most of these projects are related to fairways, channels and approaches to ports and not to actual docking manoeuvres, however, there have been many challenges detected in implementation so far.

You may ask why these countries are driving this. The reasons given include the following points, increased safety, the safety of crew and pilots in bad weather conditions, emission reductions and cost reductions. Also mentioned on several occasions was a lack of new pilots, with the German training programme mentioned several times. The T&TC in conjunction with Amura has also been working hard in developing the new EMPAsafe app, which went live in October. Our UKMPA app will integrate with EMPAsafe so members do not need to take any action, but I must mention the many hours of work done by our own T&TC committee and extend our thanks to John Slater and his team for their efforts so far.

Those of you who attended last year’s UKMPA conference in London may recall me mentioning the concerns raised by the UK and other European deep-sea pilots. They reported that several deep-sea pilots were operating out of Cherbourg and selling their services as marine advisors to some of the major shipping companies despite being uncertified.

Following reviews of our EMPA recommendations on deep -sea pilotage and in response to concerns raised, we issued a position paper on deep-sea pilotage at our conference in Antwerp (May 2024).

This was sent to all relevant stakeholders around Europe. In that document we recommended that:

“The North Sea-adjoining countries re-form the North Sea Pilotage Commission or an alternative committee to work together for the improvement of DSP services in the Channel and North Sea areas, and to maintain the highest level of professional qualification and certification of DSP.”

Here I must thank Kim Sykes, a DSP and member of the Elder Brethren of Trinity House Newcastle, for acting quickly to re-form this committee. Kim organised the first in-person meeting of the NEDSPA to be held for many years.

Erik Daleg (EMPA president) and I attended in person, and we were joined by over 25 other delegates at Trinity House in Newcastle. The delegates represented the main DSP providers as well as UK, German and Dutch government officials, the three UK Trinity Houses responsible for authorising DSPs and representatives from Nautilus, the Honourable Company of Master Mariners and the North Standard P&I Club.

We discussed several options to highlight the need for properly certified pilots and how to counter the use of non-certified pilots using the recommendations laid out under MGN506(M) and IMO 1080(A).

Carien Droppers, a co-ordinating specialist advisor from the Netherlands, presented insights into how Dutch authorities manage the growing network of wind farms in the North Sea and how they identify the need for DSPs to mitigate risks in these increasingly congested waters.

This meeting was a significant step in maintaining high standards for deep-sea pilotage and will be repeated annually, with the next meeting set to take place at Hull Trinity House in 2025.

It is worth mentioning that the deep-sea pilotage companies here in the UK maintain the highest standards and in fact their current recruitment entry criteria are much higher than many UK ports. Most deep-sea pilots are former ship masters with at least three years’ command experience who undergo an extensive training period before being certified by Trinity House.

Those who attended this years UKMPA conference in Harrogate will recall that I had hoped this year’s EMPA conference would go ahead as planned in Batumi Georgia. Unfortunately, due to the worsening political situation in the country and the ongoing political issues in the region the EMPA board have decided to cancel the EMPA conference in Georgia.

This decision was made following close communication with our member associations and major conference stakeholders. We hope that Georgia will be able to host in the future once the political and global politics in the region are resolved.

Following several excellent alternative applications the EMPA board have decided to hold this year’s conference in Poland. The venue city will be Krakow with conference being held from the 27th-30th of May. Full details will be published on the EMPA website once finalised.

By Peter Lightfoot Vice President - EMPA

By Captain James Musgrove

Our ‘Safe Haven’ initiative has continued to grow. Pilot wellness is crucial to ensuring the safe and efficient operation of vessels, particularly in challenging conditions. Our support services have gained recognition not only domestically but are now inspiring organisations worldwide to prioritise mental health and break down the stigma surrounding it.

I’m pleased to report that, over the past year and a half, there has been a 10% increase in the number of members utilising our ‘Safe Haven’ services to support their wellbeing during difficult times. This underscores the vital importance of mental health support and reassures our members that help is available when they need it most.

In October, we took an important step forward by launching the UK’s first Pilot Wellness Coaching Programme, made possible through our partnership with the Sailors’ Society charity. This programme is not designed for counselling but is aimed at individuals seeking to enhance their overall wellbeing. All sessions are completely free and confidential, and are conducted one‐on‐one with our dedicated wellness coach, Daniel Taljard.

A holistic approach to wellness

Well‐being is a cornerstone of success, both on the job and in personal life. The UKMPA’s Wellness Coaching Programme focuses on nurturing the whole individual, addressing five key dimensions of personal well‐being: physical, emotional, social, intellectual and spiritual health. By guiding members through strategies and practices designed to improve each area, the programme ensures that participants lead balanced, fulfilling lives. The emphasis on holistic wellness is more than just physical health – it’s about fostering resilience, reducing stress and cultivating a sustainable lifestyle that supports long‐term success both on and off the water.

As maritime pilots, leadership is a crucial part of daily life. The Wellness Coaching Programme goes beyond personal wellbeing by also addressing professional development. Through specialised coaching sessions, members gain valuable leadership and management skills, enhancing their ability to lead teams, handle complex challenges and navigate their careers to the next level. These skills are essential in an industry where effective decision‐making, communication and crisis management make all the difference.

Personal growth through proven coaching techniques

Personal growth is at the heart of the UKMPA Wellness Coaching Programme. Built on well‐established psychological principles, the coaching model empowers participants to set meaningful, actionable goals and achieve them. Whether it’s improving work‐life balance, advancing in the maritime field or overcoming personal obstacles, the programme helps members foster self‐awareness and cultivate a mindset for lasting growth and success.

Tailored coaching to fit your needs

One of the key features of the UKMPA Wellness Coaching Programme is its flexibility. Recognising that every individual has unique challenges and goals, the programme offers tailored support that fits diverse needs. Whether a member is seeking a one‐time session to address a specific issue or prefers ongoing coaching to support sustained progress, the programme can be customised to suit the pace and objectives of the individual. This adaptability ensures that the support provided is relevant and effective, regardless of where the member is in their personal or professional journey.

Crisis support when you need it most In the demanding world of maritime pilots, moments of crisis can arise unexpectedly. The UKMPA Wellness Coaching Programme acknowledges this by offering critical crisis support.

In situations where immediate intervention is needed, trained coaches are equipped to connect members with the Sailors’ Society Crisis Team. This support system ensures that members facing urgent issues receive timely assistance, providing them with the resources and guidance to navigate through difficult times.

The UKMPA Wellness Coaching Programme is a significant milestone for maritime pilots in the UK. By addressing the interconnected aspects of personal wellness, career development and crisis support, it equips members with the tools needed to thrive in all areas of life.

With the UKMPA’s commitment to wellbeing and professional growth, members now have an invaluable resource to support their journey towards a healthier, more fulfilling career in the maritime industry. Whether you're looking to improve your personal wellness, develop leadership skills or need support in a challenging moment, the Wellness Coaching Programme is here to guide you every step of the way.

The UKMPA is dedicated to eliminating the stigma surrounding mental health. Our 'Safe Haven' initiative in partnership with the 'Sailors' Society' has been a resounding success, and we remain committed to highlighting this critical issue to support our members during challenging times. We will continue to enhance our support services and elevate the standards of wellbeing for marine pilots, always prioritising their wellness and safety at the core of our mission.

I am delighted to share that at our conference and AGM, our members, delegates, stakeholders, sponsors and speakers generously raised an incredible £2,400 for our partner charity, the Sailors’ Society. A heartfelt thank you to everyone for your kind donations. Every penny raised will go directly towards supporting the invaluable services provided to our members.

Scan the QR code to access the members' area for any enquiries related to our pilot wellness programme.

Mental health professional support service – Call : 020 4577 4313 Safe haven hotline – speak with a fellow pilot – let’s talk Call : 0800 433 2163

By Kerrie Forster / Workboat Association Chief Executive Officer

Within the past 24 months, I have been involved in post-incident proceedings involving pilots and workboat interactions. The workboat industry and the pilot service working closely together, can help to minimise the number of dangerous and fatal incidents in this important port service sector.

Factors involved in those incidents include:

1) Vessel design

Modern tugs are designed to remain extremely stable and stiff throughout their towing work. The tug’s buoyancy is not comprised as it is designed to return quickly to the upright position once the tipping forces are removed. The acting forces applied by the tow are positioned on board in places that contribute the least tipping forces and the most opposing force.

Older tugs, not necessarily designed directly for ship’s towage work, have different properties. They are often built with a soft curve and so a more traditional hull shape, mixed with the alternative, more traditional placement of the towing apparatus and forces. Often, they are single - or twin-propeller driven with a hull design focused on longitudinal efficiency and primarily in the forward direction.

Sadly, it is a fact speed does kill. The greater the speed, the greater the energy mass, the greater the pressure on the tug and associated towing apparatus and the greater the towing risk. The construction and material of any piece of towing equipment that is subject to such pressure is tested for its maximum working load.

For example, each tug along with its towing apparatus and tow line are tested to their maximum working load. The above information may, however, be used in contrary form. The bollard pull of a tug (the Safe Working Load or SWL) is often used to highlight a tug’s ability, not its weakness. A procurement team will look at the SWL of a tug and use that information as a comparison index to judge that vessel against another.

I would like to ask the following:

• How many pilots’ passage plans have the SWL of the tug(s) detailed on them?

• How many plans have the speed at which the ship will make the working load of the tow rise above the SWL under force?

As users and operators, we use that data to create a risk-assessed Safe Working Limit for the conditions. This enables us to make dynamic operational decisions knowing the maximum safe towline limits. It has to remembered that ‘safe working load’ and ‘maximum load’ are different. The tug and its associated equipment tire with age, the propulsion and engines will not be as powerful as when built.

Towing apparatus will require replacing throughout its lifetime, so the safe working load and maximum load of the tug will change (positively or negatively) based on the variables related to the technical condition of the vessel and its equipment. As a consequence, if the tug changes characteristics then the tow will also change.

How many times have you chosen to look away or chosen not to get involved when something unsafe is happening?

At no point should anyone find themselves unable to speak up if they see something going wrong and stop the job. If you are not happy to commit to the job or see something going wrong, stop the job. Do not wait for an accident to occur.

The training requirements for workboats and tugs have gone through big changes in the past 24 months. The introduction of Workboat Code 3 has been one of those catalysts, along with the current revision of STCW that is taking place at the IMO. Digitalisation, new technology and simulation continue to be some of the key considerations for updates. As of the end of 2024, and depending on the size and operation of the vessel you are going to command, there are three main routes to gaining your certificate(s) of competence (CoCs) and becoming a Master of a workboat or tug.

A. Having served deep sea and holding your full STCW Master certificate(s)

B. Workboat-specific routes

C. Tug-specific routes

Option B requires you to meet the requirements of the Workboat Code. This was re-published as Edition 3 in December 2023. All crew have until 12 December 2028 to comply with

the new edition of the code and some may be required to comply earlier depending on the certificate date of the vessel. Many training requirements will become mandatory from 13 December 2026.

Briefly speaking, a Master of a Workboat Code 3 vessel requires the following:

1. A CoC, depending on operating area and tonnage of vessel, such as:

• STCW Master 200 < unlimited

• RYA/MCA Yachtmaster (any variation)

• MCA Boatmasters’ Licence

• RYA/MCA Powerboat Advanced

• Certificate of competency for appropriate area issued by Competent Authority

• RYA/MCA Powerboat Level 2

• RYA/MCA Day Skipper

• Local Authority Licence for appropriate area

2. Sea Survival training

3. First Aid training

4. Firefighting training

5. GMDSS or Radio Operator licence

6. Radar training (if Radar is fitted)

7. Stability training (if the vessel is required to have a stability information book)

8. Electronic Chart System training (if ECS is fitted)

9. ECDIS training (if ECDIS is fitted)

10. Basic food hygiene training (if preparing food)

11. Dangerous Goods training (if vessel is certified to carry DG)

12. Lithium-ion Battery training (if Li batteries are fitted)

13. MGO transfertraining (if performing MGO transfer)

14. General vessel familiarisation training

Option C) is to complete a MCA Tug COC, either 500gt or 3,000gt (following a more conventional, college-based approach)

1. Complete the required tug service

2. Complete the MCA-approved Training Record Book Level 4

3. GMDSS Operator’s Certificate

4. Medical Care (STCW A-VI/4-2)

5. Pass the required MSQ units (Master 500gt Tug) Vessel navigation and tides Unit 11

• Ship Construction Unit 37

• Chart-work and tides Unit 41

• Contribute to stability and watertight integrity Unit 43

• Control tug operations Unit 44

• Control vessel anchoring mooring and securing operations Unit 46

• Interpret Meteorology in the near coastal area Unit 48

• Provide Fire Fighting response on board a vessel Unit 59

• Provide Medical First Aid on board a vessel Unit 60

• Take charge of a watch in the near coastal area Unit 63

• Respond to navigational emergencies Unit 62

• Control Marine Radar and Automatic Identification systems Unit 88

• Control Marine Electronic Navigation Systems Unit 89

• Control Electronic Chart Display Information Systems (ECDIS) Unit 90

• Control Bridge Resources Unit 91

• Direct Tug operations Unit 47

• Manoeuvre a tug Unit 55

6. Hold an OOW (Tug) less than 500gt CoC

7. Pass oral N (T) – Master (Tug) less than 500gt near coastal, or

8. Pass the required additional MSQ units on top of Master 500gt Tug (Master 3,000gt tug)

• Manage personnel on board a vessel UNIT 51

• Manage Vessel navigation UNIT 52

• Manage vessel maintenance UNIT 53

• Manage vessel operations UNIT 54

• Take charge of medical care on board a vessel UNIT 66

9. Navigation Aids, Equipment and Simulator Training (NAEST) Management for <3,000gt Tug

10. Pass oral P (T) – Master (Tug) less than 3,000 GT near-coastal

As shown in the training requirements, the Master (Tug) route includes many tug-specific modules. It also incorporates relevant experience (sea time on Tugs) and the completion of a training record book.

All of these specifically evidence and nurture the candidate’s understanding of tug-specific operations and scenarios.

The training under Workboat Code 3 does not, so the MCA has an additional voluntary training requirement: the ‘Voluntary Towing Endorsement’. This endorsement can be added to any regular CoC but endorses the holder to evidence their understanding of tug-specific operations and scenarios.

This includes the following:

• A minimum relevant experience (sea time on tugs)

• A focus on any of: General Towage, Sea Towage, Ship Assist Towage

• The completion of a VTE Training Record Book

• A practical assessment

The practical assessment covers the areas of the tug-specific MSQ units but in an on board and live setting. This can be more suitable for the style of learning or assessment that some candidates excel in.

The downside is that it is not mandatory. Although 190 VTE certificates have been awarded since the first successful candidate in 2014, there remain many practising tug operators without tug-specific training or assessment.

The Workboat Association has noted this and we are doing things to correct it. Together with the industry and led by the MCA, we recently reviewed the Port Marine Safety Code guidance. One of the biggest chapters to be updated relates to the management and safety of small harbour craft (Tugs and Workboats). Another way we are bridging the gap is the development of training for those vessels engaged in towage that are not contracted as ‘tugs’: for example, vessels that perform a one-off tow to move a floating object or vessel around a harbour or loch or a workboat that could tow but the crew are not often contracted to do so.

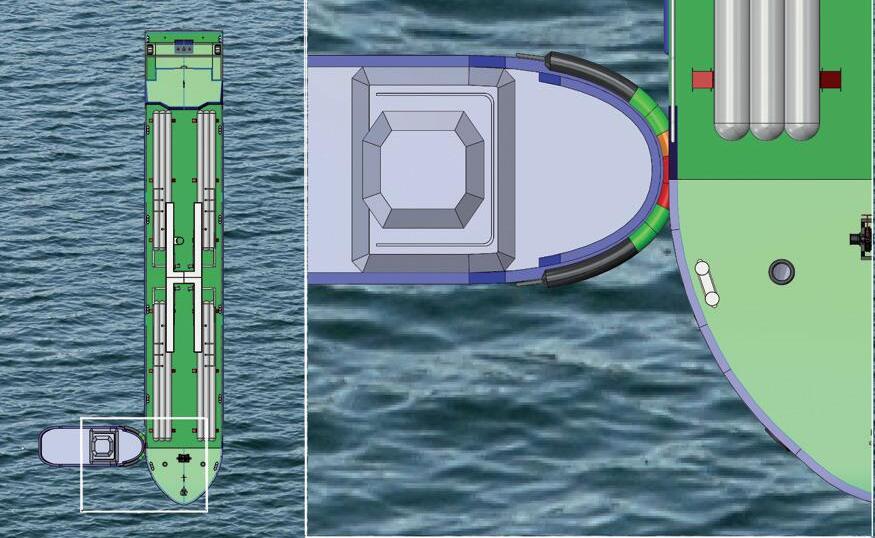

By Edward Pentney / Class 1 Manchester Ship Canal Pilot

The four Victory Class tugs were built between 1973 and 1976 by James W. Cook and Co. in Wivenhoe, Essex. They are the last purpose-built tugs for the Manchester Ship Canal and when they entered service, they replaced early twin-screw designs dating from the 1940s. They joined the Manchester Ship Canal Company’s fleet of approximately 12 working traffic tugs and were based at Runcorn. They are very similar in mechanical design and outward appearance to the older Sovereign Class tugs that entered service in 1956. In the 1980s, Peel bought the Manchester Ship Canal Company and all its assets, including the tugs. By this time, traffic in the upper reaches was in steep decline and the old Manchester Docks had closed completely in 1982. Peel closed the yard at Runcorn and rationalised the tug fleet to just four vessels, these being the Victory Class. They would now be based at Eastham, where they remain to this day. Trade has since been concentrated in the lower reaches, primarily serving the oil refinery at Stanlow and dry bulk trades to Ellesmere Port and Runcorn. © John Eyres

In 1989, the Carmet Tug Company took over the crewing and management of the tugs, although Peel retained ownership of these critical assets. Carmet continues to operate the tugs and is currently the sole contractor for towage on the canal. All four of the tugs – MSC Victory, MSC Viking, MSC Viceroy and MSC Volant – remain in serviceable condition, although spare parts must now be custom-built. They typically operate in pairs, with two tugs working for a week, before spending the following week on standby duties only.

Tug Specifications

The tugs are conventional twin-screw designs, and do not have bow thrusters or winches. They are fitted with twin Allen 640bhp diesel engines for a total of 1,280bhp and a maximum bollard pull of 16 tonnes when towing over the stern. When towing over the bow, only 10-11 tonnes of bollard pull is available. Their chief advantage is their shallow draught of around 3.5 metres, which permits them to get very close to the canal bank. This is often required both on transit and during swinging manoeuvres at Stanlow and Runcorn.

The tugs measure 28.6m LOA by 7.8m beam. The propellors are fixed, four-bladed and measure 2,310mm in diameter – clutched in with conventional gearboxes. Towage is achieved via a 28mm steel wire, secured on mooring bitts (forward) or a towing hook (aft). The hook has a quick-release mechanism built in so the wire can be released quickly under tension if required. As no winch is fitted, the length of the towing wire cannot be adjusted but it is also possible to rig a towing ‘bridle’, which will be discussed below.

The basic requirements for towage date back to the earliest days of the canal in the 1890s and are based on the experience of the first pilots. Any vessel of 113m LOA (370 feet) or greater must take two tugs for the entirety of its transit, regardless of manoeuvring characteristics. Due to the narrow width of the main channel – 36 metres – the tugs are an additional safety measure and can assist with correcting the vessel’s desired centre position should it find itself closer to one bank than the other.

Smaller vessels also require tugs to run astern, which is regularly done between Stanlow and Ince – a distance just over half a mile. Some LPG tankers that visit Stanlow do not have bow thrusters and in these cases the head tug is used to control the bow when swinging and running astern. In other cases, a pilot may simply decide that a smaller vessel below the required parameters may require a stern tug if it is heavily laden, has poor astern power or suffers from extreme transverse thrust when astern movements are given.

The main drawback of the tugs is their lack of power when handling the largest vessels on the canal. The larger tankers (150m LOA x 23m beam x 8m draught) that visit Stanlow are often fitted with air-start main engines and fixed-pitched propellors, giving a ‘dead slow ahead’ speed of 5-6 knots. When slowing down prior to berthing, swinging or entering Eastham Lock, the stern tug is positioned bow-to-stern and thus only has a maximum of 10-11 tonnes bollard pull available. In these cases, the main engine of the piloted vessel must be stopped at least once so that the stern tug can achieve enough ‘grip’ to slow the vessel. CPP vessels are much easier to slow down as the pitch can be fine-tuned to achieve minimum steering speed.

When swinging inbound at Stanlow, the vessel almost always swings bow to port, with the stern of the ship staying in the main channel. The stern tug first slows the vessel down but must then transfer its wire from the forward bitts to the aftertowing hook. This is done by hand by the tug’s crew and is the most critical moment of the operation. It may take up to one minute to transfer the wire and during this time large ahead or astern movements should be avoided on the piloted vessel’s engine / pitch.

When departing Stanlow, the vessel must usually swing bow to port. The stern tug in this case makes fast stern-to-stern with the wire made fast on the after towing hook. Once the piloted vessel has completed its swing, the stern tug must be let go before any significant headway is gained. If the tug is towed stern-to-stern by the piloted vessel above 2 knots, it will be susceptible to girting. Once it has been let go, it will turn around and make fast bow-to-stern for the remainder of the transit to Eastham Lock.

Normal towing arrangements make use of a single towing wire passed through the fore or aft centre leads of the piloted vessel. However, on heavily laden vessels, a ‘bridle’ may also be employed –with two wires sent through both the port and starboard leads. This is especially useful for dead towage, which happens occasionally when a vessel loses propulsion. A gob rope is often used when towing over the stern. During a swing, the head tug remains fast and will push with its stern to assist the often-underpowered bow thruster, assuming one is fitted. Likewise, the tug can also check the swing towards the end of the manoeuvre.

The primary risk to the tugs is that of girting – which is why gob ropes are employed when towing over the stern. Quick-release mechanisms are also fitted to the towing hooks for use in emergencies. It is normal for the pilots to communicate frequently with the tugs, especially when large ahead or astern movements are required on the main engine. The piloted vessel must also avoid towing the aft tug stern-to-stern under all circumstances.

Fresh winds can severely hamper towing operations, more so than with a modern ASD or tractor tug. They do not have bow thrusters and can struggle in a strong cross wind, which means that

unwanted weight must be applied to the towing wire for them to maintain their position. The transfer by hand of the towing wire from fore-to-aft of the stern tug when starting a swing presents a risk of loseing control. The tugs cannot change their position nearly as quickly as an ASD or Voith-Schneider design.

Another risk is that of a wire parting, which fortunately is a rare occurrence. Spare wires are carried on board and can be rigged quickly by the tug’s crew. To summarise, the tugs are more vulnerable than modern ASD or tractor varieties and clear communication between the pilot and tug master is essential. Before any manoeuvre is undertaken, the pilot will confirm the exact details, whether a swing is involved and the destination berth.

Trainee pilots must complete several trips on the tugs during manoeuvres so that they get a good idea of the operations from the tug’s perspective. Wooden model boards are also used to teach and assess pilots moving through the classes –Class 2 is the level when working with tugs becomes more commonplace on the canal. There are no simulators or electronic training aids because of the unique nature of the canal.

Perhaps the best training comes from doing the jobs under supervision of a Class 1 pilot. Vessels over 112m LOA must carry an ‘assistant pilot’ whose job it is to hand-steer the vessel on transit. The assistant pilot is often of a more junior class and, when he is close to moving up a class, he can perform the manoeuvre himself under the watchful eye of the Class 1 pilot. Roughly one third of the vessels on the canal carry an assistant pilot so this is an excellent way to gain experience for junior colleagues.

In summary, I enjoy working with these tugs as I believe they are unique for a major port in the UK, with similar designs elsewhere being phased out in the 1990s. They are now 50 years old and are expected to be the mainstay of our towage for many years to come. The tug masters have decades of experience between them and as pilots we have developed an excellent working relationship with them.

By Captain Henk Hensen / FNI

Tug power has increased considerably over recent decades. Today, some ship handling tugs have a bollard pull of more than 100 tonnes. In addition, high tug power can be installed in ever smaller compact hulls. As a consequence, the composition of tug fleets is changing and, increasingly, pilots are complaining about the absence of the smaller tugs that are needed to handle smaller ships in a smooth, safe and efficient way.

Change in tug fleet composition

The increase in maximum tug power is a consequence of the need to assist and escort very large tankers, bulk carriers and gas carriers, while the latest container carriers have such a large windage that much tug power is needed in case of strong winds. While in previous years, a fleet of conventional tugs would be made up of less powerful tugs than today, it would also – importantly here – include a number of smaller tugs to assist smaller vessels. For the purposes of this article, we will assume that a ‘modern’ tug fleet consists of azimuth stern drive (ASD) tugs, although the discussion that follows applies to most other tugs with azimuth thrusters as well, such as azimuth tractor drive (ATD) tugs. ‘Small or medium‐sized ships’ refers to vessels up to about 160 metres in length. Let us take the tug fleet of the port of Rotterdam as an example. Before the arrival of modern tugs with greater power in around 1980, there were five classes of tug in the Eastern part of the port, with an additional class in the Western part of the port.

Present situation

With a tug fleet consisting solely of modern, powerful ASD tugs, it is frequently the case that these powerful tugs also have to handle smaller ships. Even when the tug is not equipped with slipping clutches, an experienced tug master can manoeuvre these modern tugs very gently. This is a prerequisite when handling smaller and light ships, otherwise the ship manoeuvres may be spoiled. Proper training is therefore essential – but there are other consequences of the use of large and powerful tugs to handle small and medium‐sized ships, which will be discussed below.

Response time

In the Western part of the port where the largest deep‐draught tankers and bulk carriers berth, stronger tugs were available: 6 x 30 tonnes, 4 x 35 tonnes and 2 x 40 tonnes bollard‐pull Voith Schneider tugs.

It is amazing how small tugs handled large ships. For instance, tugs of only 600 hp were assigned to ships of over 200 metres in length, if in combination with one 900 hp tug. Even with the relatively small difference in tug power across the tug fleet, small ships were handled by the smaller tugs and larger ships by the more powerful tugs.

Short response times are an important factor in the smooth handling of small and medium‐sized vessels. This is one of the reasons why smaller tugs are preferred. Tugs with a high bollard pull regularly have to operate with reduced power to avoid overloading the ship’s deck equipment due to high forces in the tow line. This is often needed when handling large ships but always for smaller ships. See Figure 1, where an ASD tug with a bollard pull of 80 tonnes is assisting a relatively small vessel with deck equipment with an estimated Safe Working Load (SWL) of around 30 tonnes. This needs the powerful tug to reduce its pulling power by more than 60 per cent – although reduced power can also be used in combination with tension control on the towing winch, if tugs are equipped with it. The reduced power will lengthen response times. Today’s small ASD tugs are much more powerful than the old ones listed in the table left, with a bollard pull of, let us say, 20 tonnes. The Safe Working Load of deck equipment of ships up to approximately 160 metres is around 30–45 tonnes. In other words, a smaller tug will not need to reduce its power to keep ship bollards and fairleads intact.

It can therefore be expected that small tugs will be able to react considerably faster than large, powerful tugs when assisting smaller vessels. Another reason for that is that tug masters of powerful tugs have to apply the high power carefully, which is less of a concern for smaller tugs.

Another important aspect is the availability of slipping clutches (also called speed modulating clutches) and controllable‐pitch propellers. If an ASD tug is equipped with slipping clutches, it can regulate propeller rpm stepless to zero or from zero up.

When decreasing speed to a minimum, the thrusters stay in the same position (as shown in Figure 4, overleaf), while propellor rpm is decreased gradually till the required speed has been achieved. If a tug equipped with controllable‐pitch propellers decreases speed, rpm or propellor pitch is regulated in such a way that the required minimum speed will be achieved.

A tug that is not equipped with slipping clutches or controllable‐pitch propellers manoeuvres differently. This is shown in Figure 3, where an ASD tug without slipping clutches is approaching a ship that has some headway. During the approach the thrusters remain clutched in and propeller rpm is at its minimum. To reduce speed further, the thrusters are set at an angle. Finally, the thrusters are set almost perpendicular to match the speed of the ship (see Fig 3). Steering is still possible by setting one thruster somewhat ahead and the other somewhat astern. At the final approach (Fig 3), the propeller wash is hitting the ship’s hull –this is clearly visible in Figure 1. Especially with a light ship, this can disturb the planned manoeuvre.

The strength of the effect depends on whether the tug has high‐ or medium‐speed engines. The effect is greatest with high‐speed engines, and of course high power. An example:

RPM (engine) Min Max

Medium‐speed engine 250 1200

High‐speed engine 500 1800

Assuming propeller rpm at maximum speed is 200, propeller rpm at minimum speed with the same reduction is then: Medium speed engine (reduction i = 6): 250/6 = 41.6 rpm. High‐speed engine (reduction i = 9): 500/9 = 55 rpm.

If we take an ASD tug of 70 tonnes bollard pull with a high‐speed engine, towing force at idle speed is then: 552/2002 x 70 = 5.3 tonnes, which means 2.6 tonnes for each thruster. This is the same as a class A or B tug of the type mentioned above pushing with half power against the ship hull. Furthermore, depending on the angle of inflow, the propeller wash may create an area of low pressure along the port side aft of the ship, pushing the stern to port. All are unwanted influences on the ship. The effect of lower‐powered tugs will be proportionally less. For example, a small, low‐powered tug of 20 tonnes will create a side wash force of, in this case, only about 0.7 tonnes. It can be concluded that, for handling small or medium‐sized ships, less powerful tugs are needed, preferably equipped with slipping clutches.

If the assisting tugs are towing on a line, for instance one at the centre lead forward and one at the centre lead aft, they can give steering assistance or control the ship’s speed. They are not in contact with the ship and how they operate depends on the tug master’s experience. Do these tugs have an effect on the manoeuvring of the tanker? This may well be the case –although again, the extent of the effect will depend on the size of the tugs in relation to the size and displacement of the tanker. When tugs towing on a line operate with utmost care, there will be no problems. But it may happen that for some reason the tug makes an uncontrolled movement, causing the line to tighten. This may result in unwanted movement of the ship, for instance a speed increase or a course change.

The tugs can also operate with the push‐pull method. In that case, when the ship is approaching the berth, the tugs are usually made fast and are lying alongside as shown in Figure 4, above. In this situation, the tugs may hinder course‐keeping or delay course changes. For instance, when making a turn to starboard the forward tug has to move with the ship and the aft tug has to be pushed away, causing a lower rate of turn. The effect will be even more pronounced if the towline of the forward tug is coming tight. In addition, when the tugs shown in Figure 4 are proceeding with the ship under an angle, hydrodynamic effects will play a role and will also affect ship’s course‐keeping ability or course changes. Skegs underneath the tugs will increase this effect.

The larger and more powerful the tugs, or the smaller the ship’s draught, the larger the disturbing effect can be.

Let us have a look at the impact of tug size, in this case displacement. A tanker of 145 metres has an estimated displacement when loaded about 27,000 tonnes; when ballasted approximately 17,500 tonnes. Large ASD tugs such as the Damen ASD 3212 have a displacement of 800 tonnes. With two tugs, as in Figure 4, this is a total of 1,600 tonnes. In case of a ballasted ship, almost 9% of the ship’s displacement is hanging alongside. Where smaller tugs are used, for instance the ASD 1810, it is only 3%. That is three times better.

In other words, the impact of the larger tug on the ship is three times higher than that of the smaller type of tug, assuming the same approach speed. This applies to situations as discussed where the tug comes, or lies, alongside a ship and when towing on a line. The higher power of the larger tug may even worsen the situation. So, again, smaller tugs are preferred for handling small and medium‐sized vessels.

Due to the high power installed in present tugs, stability – which was already an important concern for tugs – has become even more important. To increase stability, tugs with azimuth thrusters have become wider. However, such wide tugs have become course unstable as a result. It is a risky situation for a tug when operating close to a ship having headway and coming under the influence of interaction effects. It requires a tug master to be attentive because frequent steering actions are needed, particularly for the more course‐unstable widerbodied tugs. A moment of inattention from the tug master may bring the tug in contact with the ship. Near the bow of the ship this can become catastrophic for the tug and problematic for the ship, while contact at other locations may disturb the ship’s manoeuvre or cause damage to the ship unless the tug is equipped with good fendering. Again, the smaller the tug, the smaller the disturbing effect on the ship, and the lower the ship’s speed, the lower the risks.

This again shows how important it is that tug masters have a good practical training.

Height

Another point is the height of the tug’s bow. The bow of a large tug pushing at the side of a small ship may be too high for it, or may damage the ship’s railing (see Figure 5).

What has to be done?

It has already been shown how important tug master training is. Proper ship handling with tugs requires thorough training by qualified instructors and optimal communication and cooperation with the pilot. Some of the negative effects of large tugs assisting small or medium‐sized ships can be prevented or minimised through good training, but certainly not all. At the same time, if either training or communication is lacking, the negative effects of handling small ships with large tugs will increase considerably. ‘Big is Better’ is certainly not true when it comes to tug assistance for small and medium‐sized ships. Such ships should not be handled by large, powerful tugs, such as today’s ASD and ATD tugs or similar of 40–100+ tonnes bollard pull, because of the risks outlined above, especially when thorough training of tug masters is lacking.

Ships up to approximately 160 metres in length should ideally be handled by more suitable tugs, smaller and less powerful, and preferably having speed modulating clutches or controllable‐pitch propellers. These tugs are also less costly to purchase, and the cost of fuel and maintenance is lower.

A trend of building smaller ASD tugs can already be observed in the Netherlands, France and some other countries. These tugs have enough bollard pull to handle the ships in question safely. Of course, the economic viability of developing a fleet including smaller, less powerful tugs depends on the number of small and medium‐sized ships that call at the port. The more smaller and medium‐sized ships that call at the port, and the more frequently such ships use tugs, the larger the possibilities for smaller and less powerful tugs.

THANKS TO: THE NAUTICAL INSTITUE

This article was previously published in Seaways and now re-published in the Pilot magazine, with the permission of The Nautical Institute.

By Brendan Smoker & Andy Read

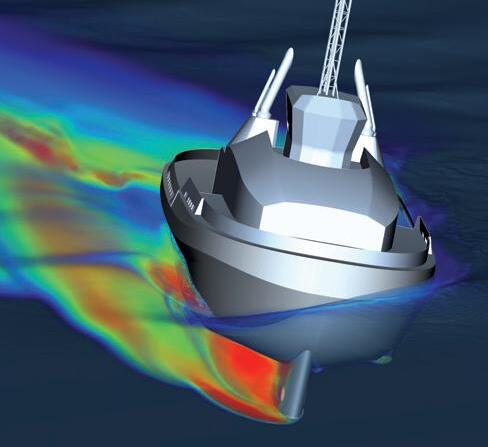

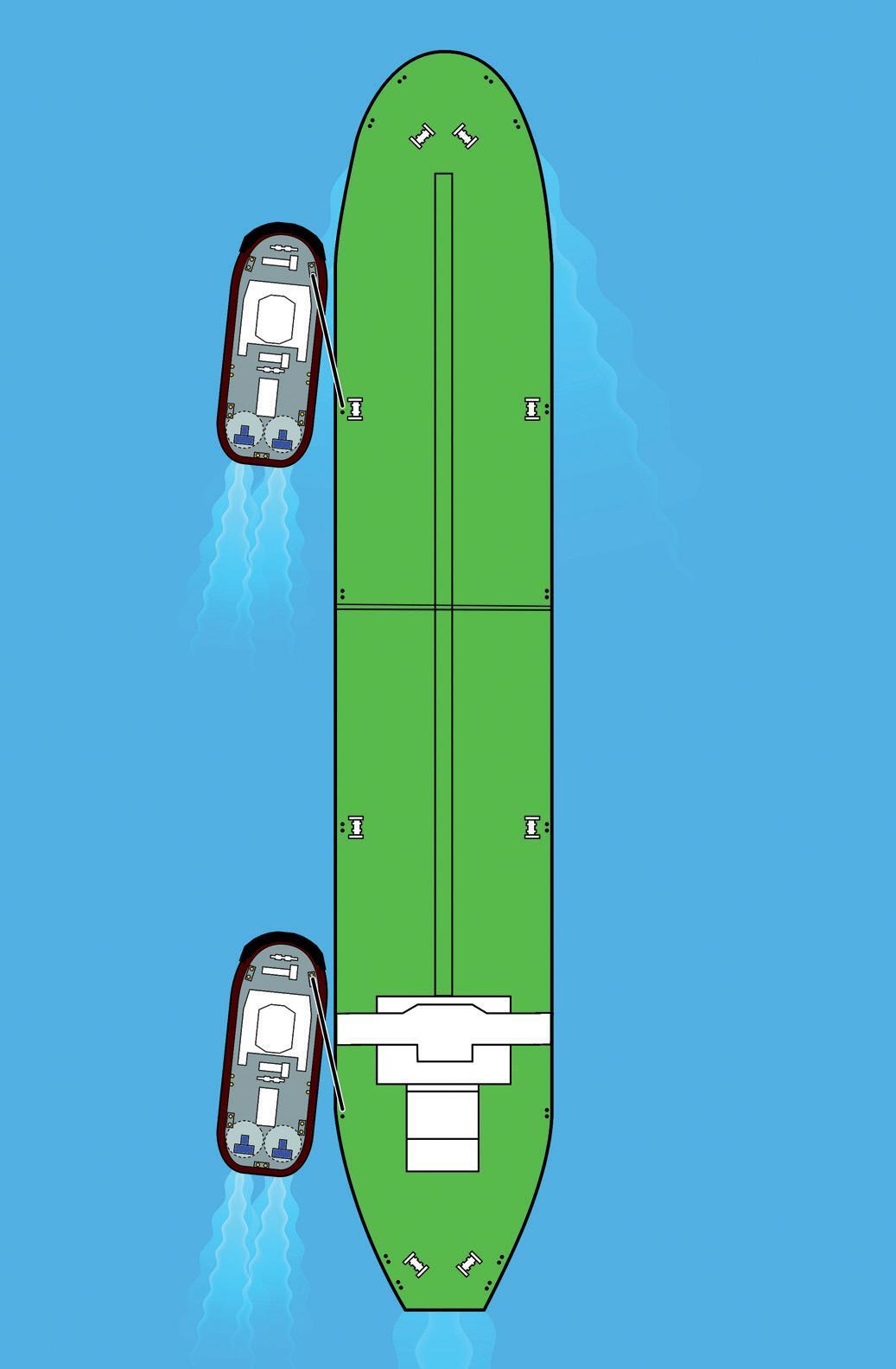

When some readers think of escort towage, they may recall those wellknown images of tugs heeled over to extreme angles, decks immersed, wondering if at some point the tug will capsize. Towage industry leaders would like to think things have come a long way since then, namely in the improved capability of modern escort tugs along with training and competence of those they employ on the controls.

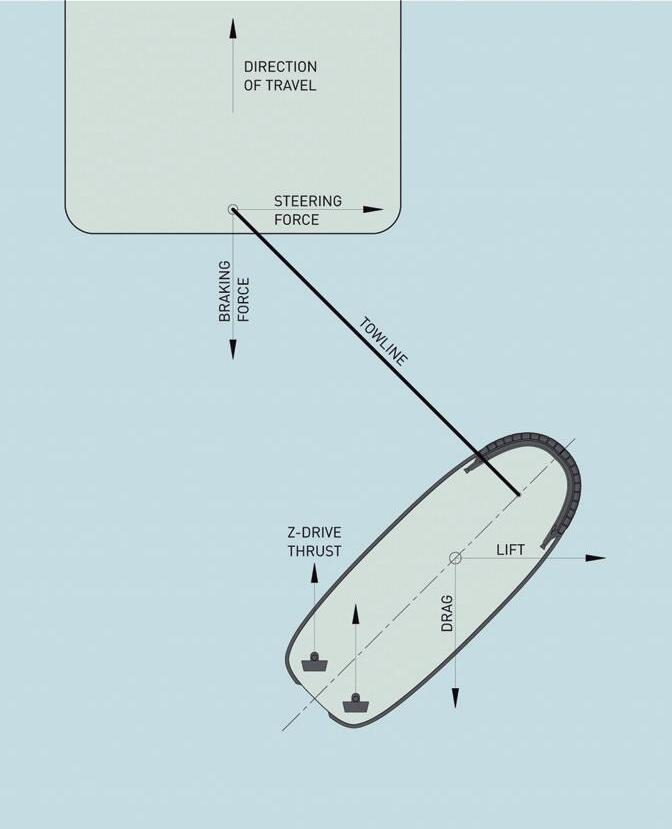

What constitutes an escort tug is often misunderstood. In many cases, people assume that any tug connected to a moving ship is escorting, but this is not the case. In situations where the tug is not imparting any force on the ship and the speed of the connected vessels is less than 6 knots, this situation is properly defined as a ship-assist mode. To be truly considered escort- capable, a tug must

be able to safely and effectively provide steering or braking forces via a towline to the ship at speeds greater than 6 knots. This is typically done in an indirect towing mode, utilising a combination of hydrodynamic lift and drag from the hull and skeg providing towline tension and thrust from the drives to maintain position.

The justification for escort towage has always been a ‘sensitive’ control measure for harbour authorities, weighing the balance between protecting the local environment, port interests and operational necessity against the commercial sensitivities of ever-rising port costs to shipping lines.

When assessing the requirement and parameters for escort towage, harbour authorities should engage with their towage providers (and tug masters) and ask, “What is it we want the tugs to do and what is the added margin of safety that they will provide?” Clarify expectations, limitations and suitability of assets available for the task.

With a clear understanding of escorting speeds, rates of turn and localised requirements from the trials team (pilots) to support this process, effective research and development through simulation, modelling and trials have proven a critical process when validating performance data.

The design of an escort tug is a balancing act between various competing features. The most appropriate tugs result from clearly defined operational requirements, such as, the maximum-rated escort speed (typically 8 or 10 knots), and the maximum steering and braking performance. It is also worth defining if the tug is to operate in calm or heavy weather and if it will be a dual-purpose tug used for both ship-assist and escort duties.

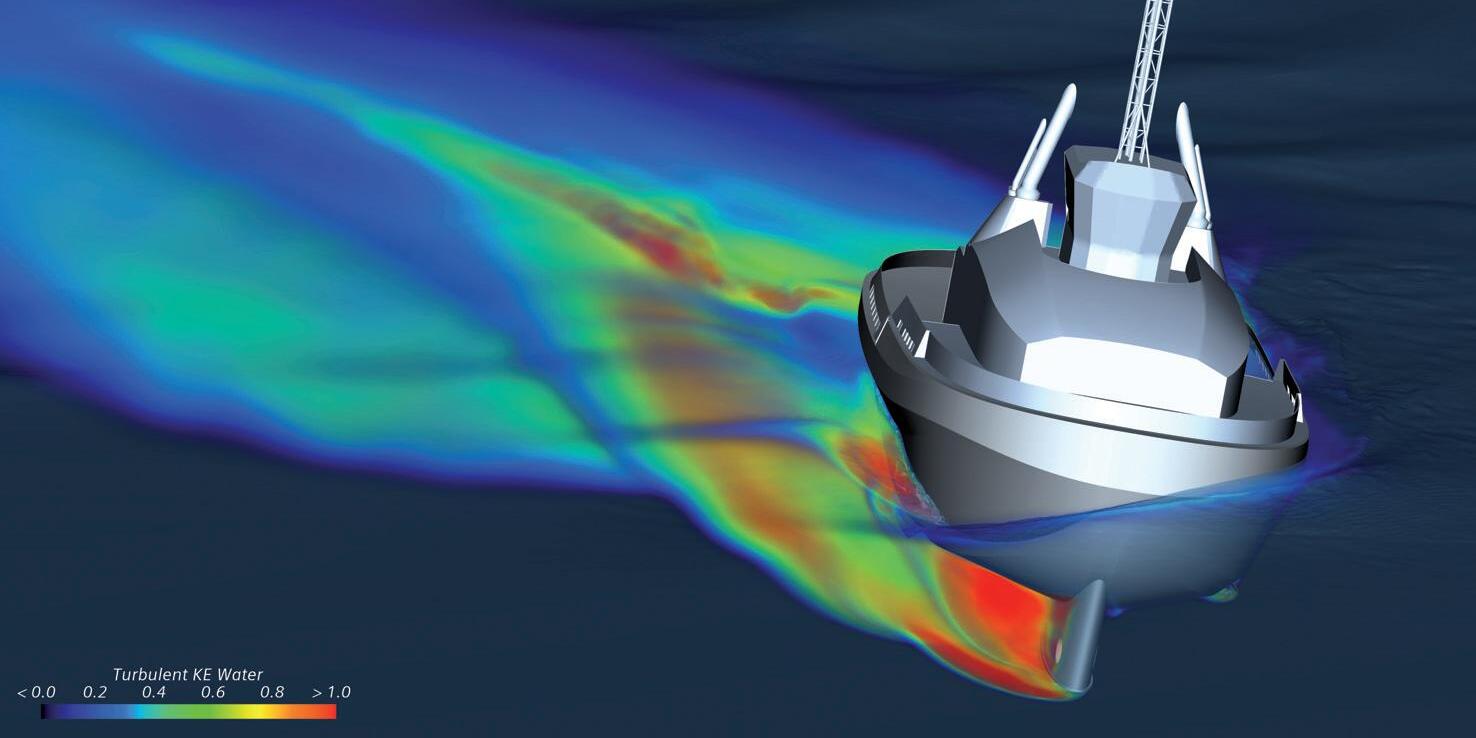

The starting point is typically a proven escort tug 'platform', but with hull dimensions adjusted to provide the stability needed to counteract the expected escort forces. With the centerline skeg being so critical in the generation of escort forces, its shape, size and location are carefully analyzed in CFD or scale model testing. The working deck is carefully laid out so that the escort towline staple is positioned optimally, and is visible to the tug captain.

The longitudinal position of the staple needs to be carefully studied. Too far forward and the tug will not generate the full escort capability of the hull and too far aft and the tug may not be 'fail safe' in the event of a propulsion failure.

Towage operators have made significant investments in fleet renewals to provide high-quality (and appropriate) assets within the ports where they operate. With the significant variety in escort tug requirements, naturally there is also a wide range of escort tug capabilities. Therefore, it is critical for both the tug master and ship pilot to understand the escort performance and limitations of each escort tug on the job.

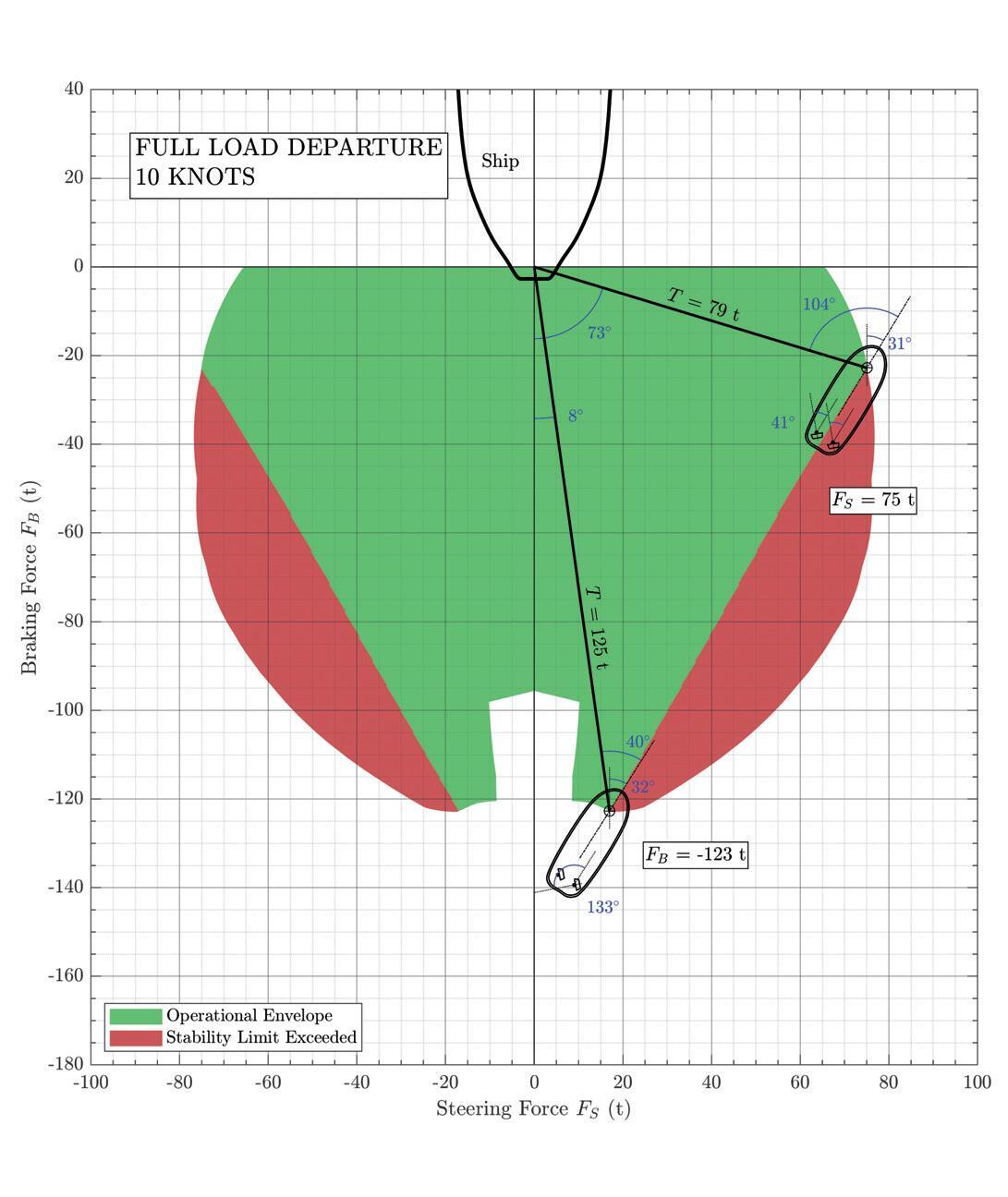

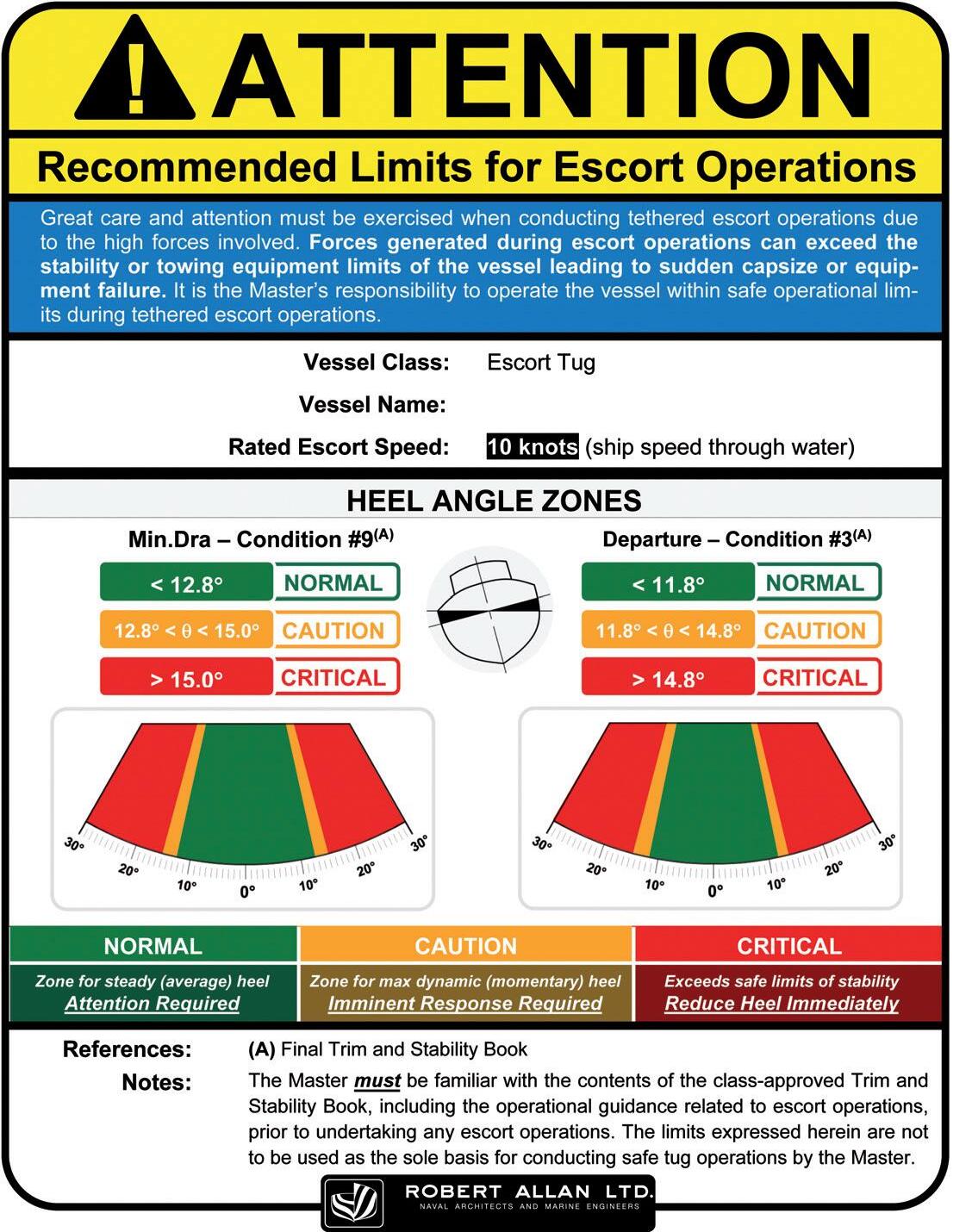

The escort butterfly diagram below shows the performance envelope of the particular tug when tethered in the center lead aft position at the indicated speed and loading condition. The green region indicates the steering and

braking forces the tug can achieve at heel angles equal or less than the class heel angle limit. The red region, if shown, indicates forces the tug can generate but at a heel angle greater than allowable by class.

It is the job of the tug master to adjust position throughout the escort operation to maximise potential and thus effectiveness of the tug during the assist phase.

The four key characteristics of an escort tug are:

• The rated escort speed (typically 8 or 10 knots)

• The maximum steering and braking performance (typically shown in an escort performance butterfly diagram)

• The maximum allowable heel angle while conducting indirect escort

• The Towing System Load Rating (TSLR) that dictates the maximum towline tensions for each wrap angle zone

The rated escort speed, maximum allowable heel angle and TSLR are defined in the Escort Placard, included in the official tug stability book. The placard is meant to be posted in

the wheelhouse to ensure the master is aware of the tug stability and towing equipment strength limits while escorting. The size and position of the skeg, coupled with the hydrodynamic characteristics of

the hull, have a significant effect on the amount of steering and braking force that the tug can generate. It must also have sufficient propulsive thrust to enable proper positioning at all required speeds. With regard to safety, there are several aspects to consider: primarily stability and towing equipment.

The tug must have enough reserve stability in this dynamic situation to properly counteract the extremely high heeling moment that is generated in extreme escort situations. Additionally, all the towing equipment – winch, line and staple, etc – must be engineered for the intended service. For winches, this may include an active payout and retrieval system to prevent slack lines and shock loads that may occur as the tug manoeuvres or moves in heavy seas.

With all towage operations, the exchange between pilot and tug master is a fundamental process to ensure the safe execution of the act. Control of speed throughout the passage is critical to ensuring the safety of the operation. Escort tugs running at their upper escort speed of 10 knots only have limited power reserves to keep pace with the assisted vessel and to manoeuvre into an assist position. It is vital (but sometimes forgotten) to consider the high lateral speeds generated aft as a large vessel rounds a turn. To maintain optimal position, balancing the yaw angle due to the ahead and athwartship speed components can be a challenge for even the most experienced tug master. Because of the high forces involved, selecting appropriately rated deck

fittings is important and the additional loading forces that can be caused by the angle of the towline towards the lead need to be considered. For example, a tug towing on a towline with an angle up to 45° to the vessel, can generate 140% of its bollard pull force on the deck fitting. Pilots should be aware of and communicate any limitations or restrictions these fittings may pose to the escort operation.