IOWA VISION

We’ve been looking forward to 2025 for a long time. This is the year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of our department, welcome new faculty members, and see our researchers continue to break new ground on projects focused on AI, inherited eye diseases, and more.

This year we welcomed Drs. Marc Toeteberg-Harms, Tina Hendricks (R ‘24), Tahreem Mir, and Ken Goins to our faculty. Dr. Hendricks finished her residency at Iowa in June of 2024 before seeking new educational opportunities in Africa and South Dakota. In her return she joined our comprehensive and cataract service. Dr. Toeteberg-Harms relocated to Iowa City from his role as Associate Professor for the Department of Ophthalmology and James and Jean Culver Vision Discovery Institute at Augusta University in Augusta, GA. Prior to his faculty position at Augusta, Dr. Toeteberg served as Director of the Glaucoma Service and Director of Inpatient Ophthalmology for University Hospital Zurich in Switzerland. After completing his residency training in Germany and Switzerland, Dr. Toeteberg completed fellowship training in Boston, MA and Cleveland, OH. Dr. Mir, the newest member of our retina service, joined us after completing her residency at the Yale School of Medicine and a vitreoretinal surgery fellowship at Vanderbilt University. She also completed a post-doctoral research fellowship at the Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital, where she served as Associate Director of the Retinal Imaging Research and Reading Center. Ken Goins returns to Iowa City as a Clinical Professor. Dr. Goins previously worked in the department from 2003 to 2018 in roles including Associate Professor, co-medical director, and director for the cornea service. Prior to his time at Iowa, Dr. Goins worked at the University of Chicago Hospitals and Clinics and Southeastern Eye Clinic. From 2018 to present, he has remained a Professor Emeritus for our department while he also worked as a Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology for the University of Kansas Medical Center.

This past year was a landmark for breakthroughs in ophthalmology research. Our department has been at the forefront of several transformative advancements. Notably, our researchers contributed to groundbreaking

studies in corneal endothelial disease and diabetic macular edema, and they used artificial intelligence to identify patterns in retinal layers, analyze retina texture, and diagnose eye disease. There were also advances in understanding genetic mutations in inherited eye diseases. We conducted clinical trials in cornea, retina, and thyroid eye disease. This research is pushing the boundaries of science and shaping the future of eye care.

Our commitment to advocacy was highlighted at the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Mid-Year Forum in Washington, D.C. Our residents, serving as “Advocacy Ambassadors,” had the privilege of meeting with key policymakers to discuss critical issues affecting our field. It was particularly inspiring to see Dr. Aaron Dotson (R24) recognized for his outstanding work in promoting diversity and inclusion.

After almost two decades serving as the head of the department, I’ve decided it’s time for me to transition out of that role. The University has started the search process for my successor, and I’ll remain as head until that person has taken over. I’ve been a faculty member here for 37 years and that will continue, as I plan to remain on faculty even after transitioning out of my role as head. There are too many people and memories from my time at Iowa to mention here but it’s safe to say that I feel extremely grateful to have been able to serve the department alongside amazing physicians and friends.

As we look forward, we remain committed to our mission of excellence in patient care, research, and education. I am confident that with the continued support of our alumni, we will achieve even greater heights. Your contributions and engagement are invaluable to our success, and I encourage you to stay connected with us.

Thank you for your unwavering support and dedication to the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. Together, we are making a difference in the lives of countless individuals.

Keith D. Carter, MD Chair and Department Executive Officer Lillian C. O’Brien and

Dr. C.S. O’Brien

Chair in Ophthalmology

BY MATT BROWNING

In the dynamic world of ophthalmology, Dr. Elaine Binkley stands out as both a skilled clinician and a pioneering researcher. An associate professor at the University of Iowa, she specializes in retinal diseases and ocular oncology—two complex and rapidly evolving areas where her work is already transforming patient care.

Dr. Binkley’s expertise in ocular oncology, particularly in treating eye cancers such as ocular melanoma, sets her apart. She utilizes advanced techniques like brachytherapy and vitreoretinal surgery to tackle these challenging conditions. Her recent retrospective study on postoperative echography emphasizes the need to adapt radiation treatment plans based on changes in tumor size and position due to edema or hemorrhage.

“Like many centers, we found that echography helps us localize the plaque that delivers radiation and align it properly during surgery,” Dr. Binkley explains. “But then we realized that for some patients, the tumor can shift slightly after plaque placement—meaning they may not be getting the intended radiation dose. That insight led us to start adjusting treatment accordingly.”

This refinement has led to more precise treatment, improving long-term outcomes and patient safety. Dr. Binkley’s work in this area reflects her commitment to both clinical precision and continuous improvement.

Beyond ocular oncology, Dr. Binkley plays a key role in advancing retinal disease research. As the site principal investigator for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research (DRCR) Network’s Protocol AL, she leads the largest nationwide study of radiation retinopathy in

patients treated for uveal melanoma since the landmark Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study.

These trials are exploring new therapies to prevent vision loss caused by radiation treatment. Her work is part of a larger shift toward evidence-based, personalized care in ophthalmology—targeting therapies to the specific biological and clinical profiles of patients.

She collaborates with top institutions and researchers nationwide, magnifying the impact of her findings. Her focus on the molecular and genetic mechanisms of retinal and oncologic eye conditions is helping shape a future where treatments are more targeted and effective.

Dr. Binkley’s contributions have not gone unnoticed. She was awarded a $1.3 million research grant from the Gilbert Family Foundation for her studies related to neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), a genetic disorder that can lead to tumors involving the eye and nervous system. This grant supports her ongoing investigation into better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for patients with NF1-related vision issues. She has also been honored by her patients. Named among the top 10% of providers in the Patient’s Choice Awards, Dr. Binkley’s compassionate approach has earned her a strong reputation not only for innovation, but for human-centered care.

As retina fellowship director at the University of Iowa, Dr. Binkley is shaping the next generation of specialists. Under her leadership, the program has become one of the few to offer direct hands-on training in both retina and ocular oncology. “Since I’ve been on faculty, we’ve trained three vitreoretinal surgery fellows who also now

practice ocular oncology,” she says. “Our fellowship gives them early and immersive exposure to treating complex conditions like ocular tumors, which most retina programs don’t offer.”

By integrating oncology into retina training, Dr. Binkley ensures that more clinicians are equipped to provide comprehensive, cutting-edge care in these overlapping disciplines.

Dr. Binkley’s approach to research is deeply rooted in her clinical experience. “I love my research projects because they are directly connected to the patients I care for,” she says. “They’re an extension of clinical care—helping to find better ways to treat blinding and life-threatening conditions.”

She uses state-of-the-art imaging and surgical techniques to enhance both diagnosis and treatment. Her research frequently stems from real-world questions that arise

during patient care—driving a cycle of inquiry, innovation, and improved outcomes.

Her attention to detail and empathy are hallmarks of her patient care. Whether in the operating room or the lab, Dr. Binkley is committed to improving quality of life for people facing serious vision challenges.

Still early in her career, Dr. Elaine Binkley has already made significant contributions to the fields of retinal disease and ocular oncology. Her blend of scientific rigor, innovative thinking, and compassionate care marks her as a rising leader in ophthalmology.

As new technologies and therapies continue to evolve, Dr. Binkley’s work is shaping how complex eye diseases are understood and treated—both today and in the future. Her vision is clear: deliver better outcomes, develop smarter treatments, and train the next generation to do the same.

BY MATT BROWNING

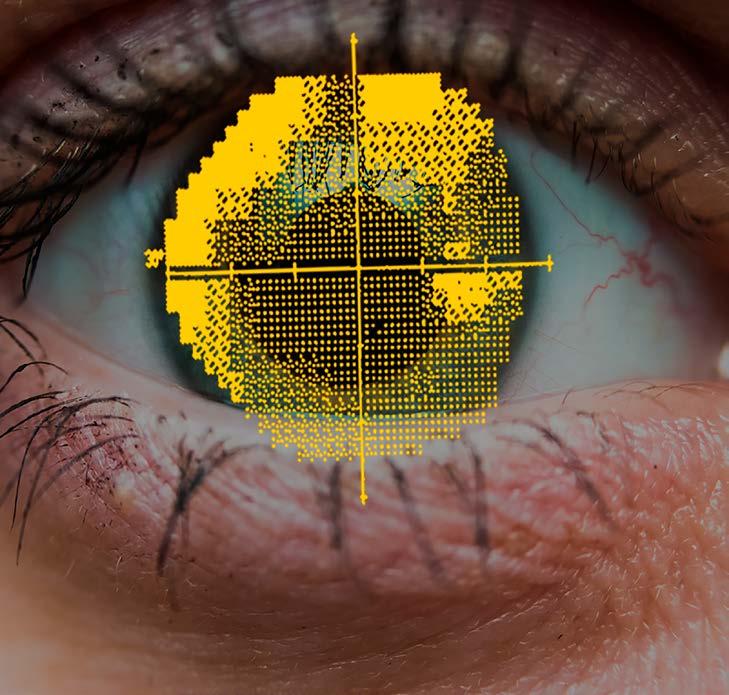

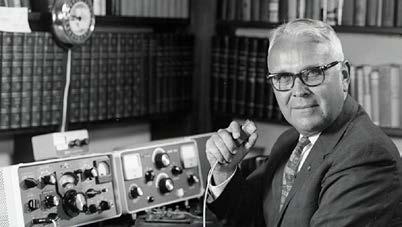

Imagine a world where cutting-edge technology helps doctors diagnose diseases faster, more accurately, and without requiring an in-person visit. Thanks to artificial intelligence (AI), that future is rapidly becoming a reality. Leading this charge is Dr. Michael Abràmoff, an ophthalmologist and computer scientist at the University of Iowa (UI), whose groundbreaking work is transforming healthcare accessibility.

In 2018, Dr. Abràmoff founded Digital Diagnostics, a UI spinoff company that made history by securing the FDA’s first-ever approval for an AI system capable of independently diagnosing disease. This revolutionary tool detects diabetic retinopathy—one of the leading causes of vision loss—without the need for a physician’s input. According to a recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine, this AI-powered diagnostic system is now the fastest-growing medical AI procedure in the world, giving patients faster, more efficient access to critical care.

Dr. Abràmoff’s vision extends far beyond diabetic retinopathy. As a UI professor and executive chairman of Digital Diagnostics, he is pushing the boundaries of AIdriven healthcare, exploring its potential to detect other diseases, including glaucoma, and conditions outside of ophthalmology.

But his research isn’t just about expanding AI’s diagnostic capabilities—it’s about changing how healthcare operates. He has been at the forefront of investigating AI’s ability to boost productivity and promote health equity, two areas that have historically lacked real-world scientific data. In a landmark randomized controlled trial, published in Nature Digital MeDiciNe, Dr. Abràmoff and his team provided the first evidence of AI’s impact on efficiency across industries— not just in healthcare. Their study revealed that retinal doctors using Digital Diagnostics’ autonomous AI system, LumineticsCore, completed 39.5% more patient encounters per hour compared to traditional methods. This breakthrough underscores how AI can alleviate physician workload while improving patient outcomes.

One of the most promising aspects of AI in medicine is its potential to close long-standing healthcare gaps. A recent study co-authored by Dr. Abràmoff, published in Nature Communications, found that Black youths with diabetes received eye exams at the same rate as their white counterparts when LumineticsCore was utilized. This finding is significant—it suggests that AI can help eliminate disparities in access to essential medical screenings. By delivering instant diagnoses, AI ensures that patients receive timely follow-up care, increasing the likelihood that they will return for future treatments and reducing the risk of preventable complications.

Dr. Abràmoff sees AI not just as a tool for improving productivity but as a force for democratizing healthcare. By leveraging autonomous AI, he believes healthcare systems can dramatically reduce costs while expanding access. For example, AI-driven diabetic eye exams could lower costs by two-thirds, making critical screenings more affordable and accessible to underserved populations.

To illustrate AI’s transformative power, Dr. Abràmoff draws a compelling parallel to the agricultural revolution. “A century ago, food shortages and famine were common, but mechanization and automation made food affordable and widely available,” he explains. “Today, AI has the potential to do the same for healthcare—making highquality medical care accessible to all, just as automation did for farming. Iowa, with its John Deere combines running autonomously, is a prime example of productivity in agriculture. I want that same level of efficiency in healthcare, where no one has to worry about getting the care they need.”

Dr. Michael Abràmoff’s pioneering efforts in AI are reshaping the landscape of modern healthcare. By integrating AI into medical diagnostics, he is paving the way for a system that is more efficient, equitable, and accessible to millions worldwide. His work is not just an innovation—it’s a movement that could redefine how healthcare is delivered for generations to come.

Dr. Yehudit Brody (Neuro-Ophthalmology) San Francisco, California

Dr. Rupak Bhuyan (Retina)

Private Practice (Lancaster Retina Specialists), Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Dr. Lindsay Chun (Neuro-Ophthalmology) Los Angeles, California

Dr. Farzad Jamshidi (Retina)

Faculty, Pittsburgh Medical Center Vision Institute, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Dr. Christian Mays (Glaucoma)

Private Practice (The Eye Guys), Augusta, Georgia

Dr. Marina Peskina (Cornea)

Private Practice (Eastern Maine Eye Associates), Bangor, Maine

Dr. Margaret Strampe (Pediatric Ophthalmology)

Private Practice (St. Paul Eye Clinic), St. Paul, Minnesota

Dr. Kyle Green (Surgical Retina)

Residency: University of Rochester, Flaum Eye Institute, Rochester, New York

Dr. Taariq Mohammed (Surgical Retina)

Residency: University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, Maryland

Dr. Jaffer Naqvi (Nuero-Ophthalmology)

Residency: Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brooke University

Dr. Rupin Parikh (Oculoplastics)

Residency: Dean Mcgee Eye Institute, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Dr. Nicole Somani (Surgical Retina)

Residency: Baylor College of Medicine, Cullen Eye Institute, Houston

Dr. Lupe Torres (Cornea)

Residency: UTHealth Houston McGovern Medical School, Ruiz Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Houston

Dr. Richard Yi (Surgical Retina)

Residency: Prisma Health/University of South Carolina School of Medicine Columbia, Columbia, South Carolina

Dr. Andrew Zolot (Glaucoma)

Residency: Rush Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Rachel Chu (Cornea)

Residency: University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas

Dr. Kathy Dong (Oculoplastics) Residency: Glick Eye Institute, Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana

Dr. Justin Grassmeyer (Surgical Retina) Residency: Casey Eye Institute, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon

Dr. Saloni Kapoor (Surgical Retina) Residency: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Dr. Nicole Mattson (Glaucoma) Residency: University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Dr. Valencia Potter (Ophthalmic Genetics) Residency: Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio

Dr. Aaron Dotson Cornea Fellowship, University of California San Francisco

Dr. Andrew Goldstein Private Practice (Shepard Eye Center), Santa Maria, California

Dr. Tina Hendricks Faculty, University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology

Dr. Mahsaw Mansoor Medical Retina Fellowship, University of Michigan

Dr. Sean Rodriguez Vitreoretinal Disease and Surgery Fellowship, University of Colorado

Dr. Noor-Us-Sabah Ahmad MD, King Edward Medical University

Dr. Ella Gehrke

MD, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine

Dr. Nicolas Heckenlaible MD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Dr. Thomas Meram

MD, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine

Dr. Peter Sanchez MD, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine

Dr. Lauren Tomlinson MD, Albany Medical College

Dr. Erin Capper

MD, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine

Dr. Caitlin Hackl MD, University of Texas Galveston

Dr. Emma Hartness

MD, University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine

Dr. Meghan Hunt MD, University of Texas Houston

Dr. Alina Husain MD, Weill Cornell Medical College

Dr. Reiker Ricks MD, University of Utah School of Medicine

The P. J. Leinfelder award was inaugurated in 1982 by alumni who wished to pay tribute to Dr. Leinfelder—scholar, teacher, and physician. Dr. Leinfelder served on the staff of the Department of Ophthalmology from 1936 to 1978. A faculty committee presents awards each year to the resident and fellow physicians who have made significant contributions in preparing and delivering seminars.

Resident Winner: Joanna Silverman, MD “Is Suction-based Tectonic Stabilization Protective Against Endothelial Loss?”

Fellow Winner: Margaret Strampe, MD “Quality of Life Improves After Strabismus Surgery”

BY BEN PARTRIDGE

By collaborating with international institutions, supporting student-led initiatives, and launching innovative programs for doctors from developing nations, the University of Iowa’s (UI) Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences is enhancing eye care access and quality for underserved populations worldwide, including in its own backyard.

Under the leadership of Dr. Kanwal Matharu, co-director of UI Global Eye, the department is forging connections with institutions across the globe, including a collaboration with India’s prestigious LV Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI). This initiative has provided transformative experiences for medical students like Aditya Somisetty

After a month of hospital volunteering in Cuenca, Ecuador, UI medical student Brian Young found inspiration at the breathtaking Quilotoa Volcano Lake

“My time at LVPEI was a turning point in my journey toward global ophthalmology, showcasing the transformative power of low-cost, innovative solutions for preventable eye diseases in underserved communities,” said Somisetty, a second-year medical student. “Observing how a quick, reproducible procedure can profoundly enhance a patient’s life, especially in resource-limited areas, underscored the field’s unique potential.”

The department’s global efforts also extend to Africa, where medical students like Brian Young are engaging in cutting-edge research on conditions like juvenile glaucoma. Working alongside faculty mentors Dr. John Fingert and Dr. Olusola Olawoye, Young sees great value in the department’s international collaborations.

“Borders are just lines in the sand, and countless people need our help right now,” said Young, a secondyear medical student. “There’s a place for you in this community, and no matter how you choose to contribute, you’ll find many people eager to support you.”

Young also emphasizes the importance of local-global ophthalmology through his volunteer work with local underserved communities. “Patients receive care through several outreach clinics, including the University of Iowa Mobile Clinic, KidSight, Operation Hawkeyesight, and the Free Eye Clinic. These organizations provide services including free surgery, medical devices, exams, medication, and follow-up to individuals. Volunteering at these locations, and being able to speak Spanish, has deepened my understanding of healthcare disparities in other countries and strengthened my passion to make a difference abroad. Though the world is vast, I have found that I can effect global change right here in Iowa.”

Dr. Kanwal Matharu, who joined the department in 2023 as an assistant professor and member of the Cornea Service, brings a wealth of experience in global ophthalmology. After completing his medical education and training at McGovern Medical School, Baylor’s Cullen Eye Institute, and fellowships at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Stanford University, Dr. Matharu has been instrumental in expanding UI’s global eye care initiatives.

Dr. Matharu has a strong background in global eye care, having completed a global ophthalmology fellowship this past year at Stanford and working with the Himalayan Cataract Project, a major nonprofit in the field. “Since I’ve been at Iowa, I keep pinching myself because in a very neat and tidy way, all the different things I’ve been studying are coming to fruition and coming together in synergistic ways,” said Matharu.

Dr. Matharu emphasizes the importance of building relationships with local communities to create sustainable eye care systems, as well as the critical role of education.

“In academia, there are three parts: direct patient care, research, and education. What I saw during my global ophthalmology fellowship was the global yearning for more education, and Iowa has been one of the best educational institutions—not only for ophthalmology but also in terms of our eye banking and just the ethos here— it’s second to none.”

Dr. Matharu envisions Iowa becoming a global leader in ophthalmology over the next two decades, beginning with establishing the university as a training hub for physicians from low- and middle-income countries. His long-term strategy involves building partnerships with institutions in developing regions to strengthen local care standards and create a replicable model for global eye care programs. The department’s reputation has already opened doors. “Because of Iowa’s prestige in ophthalmology, we were invited to participate in the Global Ophthalmology Consortium,” said Matharu. “Though we’re just starting to organize our international efforts, we’re already engaging at the national level.”

“The goal is to develop solutions that resonate within each community, whether in India or rural Iowa,” said Somisetty. “True change in healthcare arises from addressing barriers to access and empowering local providers.”

For the University of Iowa, this work underscores its commitment to global health and education, demonstrating the far-reaching benefits of academic and medical collaboration. UI’s International Programs office plays a crucial role in facilitating these global partnerships, assisting with Memorandums of Understanding and other agreements.

“International Programs is pleased to support the work of the Department of Ophthalmology, which has a strong record of global engagement,” said Russell Ganim, associate provost and dean of International Programs. “One of our chief goals is to facilitate connections within the data science community, enhancing clinical practice and research to develop innovative solutions that transform lives.”

The University of Iowa’s Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences is transforming global healthcare— one patient at a time. By connecting across borders and empowering local communities, they’re turning medical treatment into a human mission.

“Ophthalmology captivated me with its capacity for immediate, life-changing impact,” said Somisetty. “These experiences [in India] reminded me that while ophthalmology can be highly technical, it remains deeply human.”

BY BRIANNE ROE, RN, MSN, OPHTHALMOLOGY NURSING SUPERVISOR

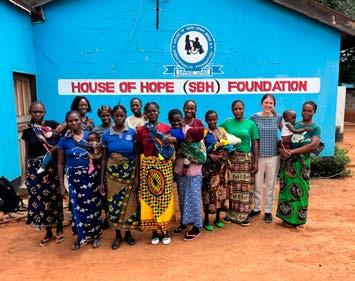

As part of a Carver College of Medicine delegation, Dr. Kanwal Matharu and I recently traveled to Zambia, where we met with leaders from UIHC, International Vision Volunteers, and Hilary Twiggs from Orbis. One of the most impactful stops on our trip was the House of Hope, a transformative organization focused on children with hydrocephalus and spina bifida.

Founded nearly a decade ago with the help of Dr. Rebecca Reynolds (Neurosurgery), the House of Hope combats the deep-rooted stigma surrounding these conditions. In parts of Africa, such diagnoses are tragically linked to beliefs in witchcraft—leading, in some cases, to infanticide. The House of Hope offers an alternative: education, medical support, and empowerment for families.

They provide safe housing, coordinate hospital visits, and teach parents how to care for their children. One inspiring initiative teaches families how to grow and cook nutrientrich food, helping sustain their children’s health. Perhaps most powerfully, mothers are encouraged to become advocates—returning to their villages to raise awareness and break the cycle of stigma.

Dr. Reynolds, former Dean, Brooks Jackson, and University Teaching Hospital (UTH) staff are now exploring ways to integrate ophthalmic care into the House’s services. Since hydrocephalus often affects the optic nerve, early eye assessments could be life changing. We’re working toward equipping the facility with a dedicated exam room and essential tools for immediate eye evaluations.

During our visit, we also toured eye clinics at UTH and Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital. We met with leaders who voiced an urgent need for better training in pediatric ophthalmology, nursing curriculum, instrument care, and RetCam use. Dr. Matharu led a hands-on wet lab for second-year students, who were eager and incredibly appreciative.

We saw firsthand the challenges: overcrowded clinics, paper records, and sweltering rooms with no air circulation. One patient—a 24-year-old woman—needed bilateral corneal transplants after a severe infection. But without eye banks or trained corneal surgeons, treatment options remain heartbreakingly limited. Cultural beliefs

This trip was a powerful reminder of the impact of partnership, education, and community-led care. There’s still much to be done— but hope is growing.

BRIANNE ROE, RN, MSN, OPHTHALMOLOGY NURSING SUPERVISOR

around organ donation compound the issue, creating a severe tissue shortage.

Sterilization practices also differ. Instruments are soaked in chlorine, washed, rinsed, and then run through a small sterilizer—before being placed unwrapped in open trays for reuse. It’s a system born of necessity, but one that highlights the need for improved infrastructure and training.

Finally, we visited the Orbis Zambia office, where the team shared their incredible 15-year journey advancing eye care in the region. I’ll be collaborating with them to develop subspecialty curriculum for their Cybersight platform— bringing high-quality education to remote providers around the world.

This trip was a powerful reminder of the impact of partnership, education, and community-led care. There’s still much to be done—but hope is growing.

BELOW: Rebecca Reynolds and house of hope women.

BOTTOM: The Orbis Group.

Researchers Dr. Arlene Drack, Dr. Alina Dumitrescu, Dr. Ian Han, and Dr. Stephen Russell are pioneering treatments for rare inherited eye diseases such as achromatopsia, albinism, Bardet-Biedl Syndrome, Batten’s disease, Leber’s congenital amaurosis, retinitis pigmentosa, and X-linked retinoschisis. Their work spans from preclinical studies to human trials, offering hope for patients with these challenging conditions.

The department’s translational science efforts are uncovering the genetic underpinnings of eye diseases. Dr. Oliver Gramlich is investigating the role of cholesterol in optic neuritis in multiple sclerosis, while Dr. Markus Kuehn is exploring T-cell mediated damage to retinal ganglion cells in glaucoma.

Under the leadership of Dr. Edwin Stone, the Institute of Vision Research is delving into the genetics of ocular diseases. Dr. Stone focuses on genetic mutations in inherited eye diseases, Dr. John Fingert uses stem cell-derived cells to study glaucoma genetics, and Dr. Robert Mullins examines the pathophysiology of macular degeneration through genetic analysis. Dr. Seongjin Seo is developing gene therapy for inherited eye diseases, and Dr. Budd Tucker is researching ways to halt age-related macular degeneration through targeted gene therapy.

Dr. Mark Greiner, working with UI Associate Vice President for Research Dr. Aliasger Salem and Dr. Sara Thomasy, Professor of Surgical and Radical Sciences at UC Davis, are elucidating the mechanism of ferroptosis in the cornea and tests the efficacy of a novel, pathway-specific drug therapy combatting ferroptosis using Fuchs cell and animal models.

The University of Iowa’s Ophthalmology Department is at the forefront of groundbreaking research and clinical trials, leveraging the latest advancements in artificial intelligence and computer-aided morphological studies to revolutionize eye care.

The department continues to push the boundaries of vision science, offering new hope and improved outcomes for patients worldwide.

chael Abrámoff has teamed up with Dr.

Dr. Miachael Abràmoff has teamed up with Dr. Friedman at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Institute and Digital Diagnostics, backed by a CDC grant, to tackle barriers in glaucoma treatment. Their innovative approach aims to enhance early detection and intervention.

Dr. Elliott Sohn and Dr. Milan Sonka from the College of Engineering are utilizing AI to identify patterns in retinal layers, predicting the effectiveness of anti-VEGF treatments for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). This collaboration promises more personalized and effective treatment plans for patients.

Dr. Mark Greiner is working with Evolucare, a French company, to develop objective measures for assessing the progression of Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. This research could lead to earlier, less invasive treatments, potentially reducing the need for corneal transplants.

At the VA Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Vision Loss, Dr. Matthew Harper and Dr. Mona Garvin are using AI to analyze retina texture, providing insights into the severity of traumatic brain injuries and the progression of glaucoma.

Dr. Budd Tucker, working with Drs. Robert Mullins and Edwin Stone and Dr. Kimerly Powell of OSU, is developing an AI-guided approach to facilitating high-throughput automated manufacturing of clinical grade photoreceptor cell therapeutics.

The department hosts numerous clinical trials aimed at treating various eye diseases:

Cornea:

• DEKS Trial: Investigates the impact of donor diabetes on endothelial loss post-DMEK surgery (NIH-sponsored).

• DTX Study: A natural history study of Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (funded by Design Therapeutics).

• PUTT Trial: Examines an experimental treatment for acanthamoeba (NIH-sponsored, led by UCSF).

Retina:

• DRCR Retina Workshop: Tests injections and implants for radiation retinopathy (NIHsponsored).

• NAC Attack: Evaluates N-Acetylcysteine for retinitis pigmentosa (NIH and Johns Hopkinssponsored).

• SPARK Trial: Follows patients receiving SPARK THERAPEUTICS’ experimental injection for RPEmutation eye disease (industry-sponsored).

• Hyperion tests the capacity of Sepofarsen to reduce the effects of Lebers’ Congenital Amaurosis.

Thyroid Eye Disease: treatment.

• Upcoming trials include new treatments for XLRS, Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis, and innovative glaucoma devices. The department is also collaborating with industry partners to enhance diagnostic tools for uveal melanoma and create a registry for inherited eye disease patients.

Glaucoma:

• The Elios and IStar trials both test the effects of minimally invasive surgical devices on lowering intraocular pressure for glaucoma patients.

BY MATT BROWNING

In the field of ophthalmology, few challenges are as daunting as preventing cell death in the cornea. Dr. Mark Greiner and his team at the University of Iowa are at the forefront of this battle, pioneering research that could revolutionize the treatment of corneal diseases. Their focus is on using ubiquinol, a powerful antioxidant, to prevent cell death in the cornea, potentially eliminating the need for corneal transplants in many patients.

The cornea, the clear front part of the eye, relies on a layer of cells called corneal endothelial cells to stay transparent. These cells do not regenerate, making them vulnerable to damage from various sources, including sunlight, inherited diseases, and trauma. When these cells die, the cornea becomes cloudy, leading to vision loss. Traditionally, the only solution has been corneal transplantation.

Dr. Greiner explains, “These corneal endothelial cells don’t repair themselves. They don’t divide. They can get injured easily. They never turn over, which means that they’re constantly exposed to ultraviolet rays in sunlight, various diseases, and other factors that can cause damage.”

At the Iowa Lions Eye Bank, Greg Schmidt, who was the lead processing technician when Dr. Greiner first joined the faculty at Iowa in 2012, started to notice that some of the corneal tissue they were recovering and hoping to use for transplant surgeries were tearing.

Schmidt didn’t just accept these results; he wanted to know why this was happening, so he took a step back and started looking at the donor medical histories for the corneal tissues that were tearing and were unusable.

“He found a large number of those tissues that tore came from donors that had diabetes,” said Greiner. “As the Associate Medical Director at the time, I heard this and said, ‘We’re gonna study this.’ And that’s exactly what we did. We found that tissue from diabetic donors had a greater chance of tearing.”

Through studying the tissue of diabetic donors, the team realized that corneal endothelial cells in general were extremely sensitive to oxygen and that this played a role in the death of those cells. Greiner and his team started asking questions. “Jess Skeie along with our research scientist at the time looked at the results and said, ‘If we’ve got oxygen sensitive cells, shouldn’t we be looking at keeping these cells healthier by minimizing the impact of high oxygen on those cells?” Greiner said.

The Greiner lab’s research has uncovered that ubiquinol, the active form of Coenzyme Q10, can significantly reduce oxidative stress in corneal cells. Oxidative stress is a major factor in cell death, and by mitigating this stress, ubiquinol helps maintain the health and function of corneal endothelial cells. This discovery is particularly promising for patients with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy, a common condition that affects millions worldwide and is characterized by oxidative damage.

“Ubiquinol is an antioxidant that can restore normal levels of mitochondrial function,” says Dr. Greiner. “By adding ubiquinol to the storage media for donor corneal tissue, we found that it could improve the tissue’s health. However, the challenge was its instability in liquid form.” Before they could translate this finding to patients and diseases like Fuchs dystrophy, Greiner needed to address this tricky formulation problem.

The Greiner lab team recognized that ubiquinol’s instability in liquid form posed a challenge that required thinking outside their skillset. In a move that he credits as a “total game changer,” Dr. Greiner reached out for help to Dr. Ali Salem from the College of Pharmacy and the current Associate Vice President for Research. The two

researchers struck up a collaboration and friendship that took Dr. Greiner’s work to the next level. Together, the Greiner and Salem labs developed a stable, soluble form of ubiquinol that can be used in various liquid formulations, including eye drops.

This breakthrough means that instead of using the ubiquinol solution exclusively in cornea storage media and relying solely on surgical interventions to treat corneal diseases, patients could potentially use a ubiquinol solution as a topically applied eye drop to maintain the health of their corneal endothelial cells. This non-invasive approach could prevent the progression of diseases like Fuchs dystrophy, reducing the need for corneal transplant surgery all together.

Dr. Greiner’s research is supported by a dedicated and talented team. At the core is Dr. Jessica Skeie, the Senior Research Scientist. Dr. Skeie has been with the University of Iowa’s ophthalmology department for over 20 years. She began her journey as a bioengineering student, later switching to cell biology for her PhD. Her extensive experience and expertise are invaluable to the lab’s success.

“Jess [Skeie] is absolutely essential to our team,” says Dr. Greiner. “She has been in ophthalmology longer than anyone in my lab and brings a wealth of knowledge and experience.”

Greg Schmidt, the director of research and business development for the Iowa Lions Eye Bank, has played an outsized role in helping create the Greiner lab, as well as challenging Greiner to ask the big questions. “Greg helped found the lab and encourage me from the beginning to dream bigger than what we initially set out to achieve.” Greiner added, “Greg’s technical expertise in handling corneal tissues have been essential in establishing several techniques that have made our research possible.” As mentioned previously, it was also Schmidt who first started to notice the fragility of some cornea transplant tissue from diabetic donors that eventually set Greiner on his current course of research.

“Dr. Mark Greiner” continues on page 22

A visual field test is a measurement of the area where objects can be seen in the peripheral vision when someone focuses on a central point. Visual field testing is one way to measure how much vision a person has in either eye, and how much vision loss may have occurred over time. Because of this a series of visual field tests can identify patterns and the process of change one’s vision has undergone. In this way, visual fields can be essential for clinicians in identifying vision problems early on or for helping researchers understand the effect a certain therapy has on one’s vision.

BY MATT BROWNING

While the staff at the Iowa Visual Field Reading Center (IVFRC) might not work directly with patients, they’re having a huge impact on new and developing therapies for patients across the country. At its core, the IVFRC specializes in the meticulous assessment of visual fields— an essential component in diagnosing and managing a spectrum of ocular conditions, from glaucoma to neurological disorders affecting vision. Michael Wall, MD, director of the IVFRC, emphasized that their commitment to accuracy is paramount to the reputation the center has developed across the country. “We first use a digital checking method to evaluate a visual field in order to make sure the right test was given, the pupil size is appropriate, among many other things. A score out of 100 is provided by this digital tool based on how clean the results of the visual field test file are” Wall said. “But then we have two independent readers analyze the results to look for errors called perimetric artifacts that interfere with analysis. If those readers independently agree, we go with that result. If they don’t agree, a third independent reader is brought in until a consensus is achieved.” While it might seem tedious at points, it’s a process that produces the most accurate results—and accuracy is what has helped build the international reputation of the IVFRC. Wall said “Our job is to give the research sponsor the cleanest data possible.” Wall stressed that the iVFRC assists sponsors in clinical trials all the way from developing the study protocol to obtaining clean results, to performing visual field analysis and aiding in the study’s statistical analysis.

Before the IVFRC opened their doors in 2008, there was only one other visual field reading center in the country, which was at UC Davis. The IVFRC was the brainchild of Chris A. Johnson, PhD, DSc and Michael Wall, MD, who had a history of collaboration and a passion for creating accurate visual fields readings that could be used by researchers and clinicians alike. As the IVFRC ramped up, Trina Eden, COA was hired to manage many of the day to day logistics and help train research sites to accurately produce visual field results. When asked about Trina’s role at the IVFRC, Dr. Wall said, “she’s a vital part of our reading center. She takes care of all the nuts and bolts of the daily activities. When we start a study, Trina helps us develop the study protocol and then certifies all the perimetrists in the study and makes sure those collecting the visual field results know how to give the test properly. So she spends a lot of time teaching and making sure these people understand the proper technique to doing a visual field.”

While most of the IVFRC’s work is for researchers, Dr. Wall thinks it is also a valuable tool for clinicians to use directly. “We could, in addition to helping with clinical trials, we can also help clinical practices. Ophthalmologists really depend on this sort of data to make informed decisions, and analyzing visual fields gets pretty complicated, because there’s so many different statistics. Part of our job is training, and I think we could really help offices by training their technicians in the same way we train them for a clinical trial.”

As the IVFRC continued to grow, around 2018 they retained the services of Bio::Neos, an informatics and software development group, to design, implement and maintain a secure web site and database management system. This partnership allows the IVFRC to provide a paperless means of allowing clinicians and researchers to transmit data securely over the internet and to communicate and transmit information to Data Coordinating Centers.

With nearly all of the visual field data being processed digitally, this work seems like it would fit well with some of the pattern recognition A.I. is able to do. While Dr. Wall sees this as a direction they are headed, there is still plenty of work to be done in order to create A.I. that can produce

results with the same level of accuracy. “You know, AI is great, but, you know, it’s not the gold standard, and for what we do, the gold standard is anexperienced visual field reader analyzing the visual field patterns. But since we have so much clean data, we’re using some of that to train A.I. to help recognize these patterns.”

As one of the most notable visual field reading centers in the nation, the IVFRC continues to develop new services and abilities in reading visual fields. In addition to analyzing visual field results, the IVFRC also works to train, certify and monitor technicians and other clinical personnel for clinical trials, develop new analysis and interpretation tools for visual field assessment and validate new visual function test procedures.

Publication highlights in 2024

112

180

10,913

2024 CITATIONS OF FACULTY PUBLICATIONS FROM ANY YEAR

2024 faculty publication that has been the most highly cited: Wolf R.M., Channa R., Liu T.Y.A., Zehra A., Bromberger L., Patel D., Abràmoff M.D.,et al. Autonomous artificial intelligence increases screening and follow-up for diabetic retinopathy in youth: the ACCESS randomized control trial. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):421. Epub 20240111. doi: DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-44676-z. PubMed PMID: PMID: 38212308; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCID: PMC10784572.

“Image processing with imageJ” published in 2004 by Abramoff M.D., Magalhaes P.J., Ram S.J.,

Our top five most cited articles in 2024:

“Image processing with imageJ” by Abràmoff M.D., Magalhaes P.J., Ram S.J.

“Ridge-based vessel segmentation in color images of the retina” by Russell S., Bennett J.,Wellman J.A., Chung D.C., Yu Z.-F., Tillman A., Wittes J., Pappas J., Elci O., McCague S., Cross D., Marshall K.A., Walshire J., Kehoe T.L., Reichert H., Davis M., Raffini L., George L.A., Hudson F.P., Dingfield L., Zhu X., Haller J.A., Sohn E.H., Mahajan V.B., Pfeifer W.,Weckmann M., Johnson C., Gewaily D., Drack A., Stone E., Wachtel K., Simonelli F., LeroyB.P., Wright J.F., High K.A., Maguire A.M.

”Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber’s congenital amaurosis” by Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN Jr, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, Banfi S, Marshall KA, Testa F, Surace EM, Rossi S, Lyubarsky A, Arruda VR, Konkle B, Stone E, Sun J, Jacobs J, Dell’Osso L, Hertle R, Ma JX, Redmond TM, Zhu X, Hauck B, Zelenaia O, Shindler KS, Maguire MG, Wright JF, Volpe NJ, McDonnell JW, Auricchio A, High KA, Bennett J.

“A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/ CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration” by Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Hardisty LI, Hageman JL, Stockman HA, Borchardt JD, Gehrs KM, Smith RJ, Silvestri G, Russell SR, Klaver CC, Barbazetto I, Chang S, Yannuzzi LA, Barile GR, Merriam JC, Smith RT, Olsh AK, Bergeron J, Zernant J, Merriam JE, Gold B, Dean M, Allikmets R.

”Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences” by Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, Wagner L, Shenmen CM, Schuler GD, Altschul SF, Zeeberg B, Buetow KH, Schaefer CF, Bhat NK, Hopkins RF, Jordan H, Moore T, Max SI, Wang J, Hsieh F, Diatchenko L, Marusina K, Farmer AA, Rubin GM, Hong L, Stapleton M, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Casavant TL, Scheetz TE, Brownstein MJ, Usdin TB, Toshiyuki S, Carninci P, Prange C, Raha SS, Loquellano NA, Peters GJ, Abramson RD, Mullahy SJ, Bosak SA, McEwan PJ, McKernan KJ, Malek JA, Gunaratne PH, Richards S, Worley KC, Hale S, Garcia AM, Gay LJ, Hulyk SW, Villalon DK, Muzny DM, Sodergren EJ, Lu X, Gibbs RA, Fahey J, Helton E, Ketteman M, Madan A, Rodrigues S, Sanchez A, Whiting M, Madan A, Young AC, Shevchenko Y, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Touchman JW, Green ED, Dickson MC, Rodriguez AC, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Butterfield YS, Krzywinski MI, Skalska U, Smailus DE, Schnerch A, Schein JE, Jones SJ, Marra MA; Mammalian Gene Collection Program Team.

“Dr. Mark Greiner” continues from page 17

The team also includes two outstanding research assistants, Hanna Shevalye and Tim Eggleston Hanna, who joined the lab from the VA, is known for her exceptional imaging skills, producing high-quality scientific images that are crucial for this research. Tim, a seasoned research associate with over 20 years at the University, excels in protein identification, contributing significantly to the lab’s projects.

“Hanna and Tim are my go-to people for hands-on bench work,” Dr. Greiner notes. “Their expertise and dedication are critical to our research.”

Additionally, the lab benefits from a cadre of students from the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, the Carver College of Medicine, and the College of Pharmacy. These students, ranging from undergraduates and medical students to PhDs and postdoctoral fellows, contribute to various projects and gain invaluable experience in the process. Most of them have gone on to successful careers in ophthalmology and fields related to the research done in the Greiner lab.

The Greiner lab’s work has been significantly supported by philanthropic donations. Early funding from grateful patients enabled the initial research that led to these breakthroughs. Philanthropy continues to play a crucial role, filling gaps where federal funding falls short and allowing the lab to pursue innovative ideas without administrative hindrances.

“Philanthropy is why I’m here talking to you about this wonderful project,” says Dr. Greiner. “It opened the door and let us go to town with our work. It continues to sustain our efforts and is vital for our research.”

Philanthropic support has been particularly essential for funding the personnel who make up Dr. Greiner’s team. “Two-thirds of my budget is for our personnel, and not for my time or for the experiments,” Dr. Greiner explains. “It is the people in my lab who really need the support. Philanthropy helps us pay for these world-class researchers who are essential to our success.”

The journey from discovery to clinical application is long and requires substantial resources. Continued support from donors is essential to advance this promising and impactful research. One of the reasons private donors have funded this research in the Greiner lab in the past is because of the huge potential of this research to treat virtually any eye disease where cells are dying because of the effects of oxidative damage. By investing in Dr. Greiner’s work, these philanthropists feel like they can help bring new treatments to patients and prevent vision loss for millions across the globe.

Dr. Greiner emphasizes, “There is no source of funding that is too small or too big to make this research go forward. Philanthropy helps us in so many ways, from jump-starting new ideas to filling the gaps where federal funds fall short.”

Dr. Mark Greiner’s research on ubiquinol represents a beacon of hope for those suffering from corneal diseases. With the continued support of philanthropy, his team can push the boundaries of medical science and improve the quality of life for countless individuals. This groundbreaking work not only highlights the potential of ubiquinol in preventing cell death in the cornea but also underscores the critical role that philanthropy plays in advancing medical research.

You can help support the Greiner Lab’s work! Contact Matt Kuster to learn more about ways you can be a part of this groundbreaking research:

To learn more about how philanthropic support helps advance the work of the University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences and UI Institute for Vision Research, please contact:

Matt Kuster

$16,431,253

Executive Director of Development matt.kuster@foriowa.org 319-467-3720

Katie Sturgell Senior Director of Development katie.sturgell@foriowa.org 319-467-3756

Frank Descourouez

Associate Director of Development frank@foriowa.org 319-467-3672

Jedd Spidell

Assistant Director of Development jedd.spidell@foriowa.org 319-467-3342

The University of Iowa Center for Advancement P.O. Box 4550 Iowa City, IA 52244-4550

319-335-3305 or 800-648-6973

The UI acknowledges the University of Iowa Center for Advancement as the preferred channel for private contributions that benefit all areas of the university. For more information or to donate in support of the eye program, visit the secure website at Givetoiowa.org/eye

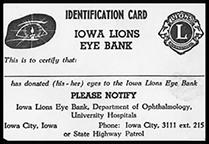

BY FRANCIE WILLIAMSON

This year marks a milestone worth celebrating: on September 13, 2025, the Iowa Lions Eye Bank (ILEB) turns 70! For seven decades, ILEB has been at the forefront of restoring sight and preventing blindness through groundbreaking work in corneal transplantation. None of this would be possible without the dedicated network of ophthalmologists, healthcare professionals, and donors who have shared in the mission of giving the gift of sight.

As we approach this landmark anniversary, we’re taking time to reflect on the trailblazers who built the foundation, the professionals and researchers who continue to push boundaries, and the donors and families who make every transplant possible.

To kick off the celebration, you’re invited to a familyfriendly evening at Big Grove Brewery in Iowa City on Thursday, June 12, from 6:00 to 9:00 p.m., during the

annual Iowa Eye conference. Get ready for some fun with a purpose! Step into the shoes of someone living with Fuchs Dystrophy — a condition that often leads to corneal transplants — by wearing special simulation glasses. Then test your skills in unique games like “Mystery Spin,” “Blind Slide,” and “Cornea-Hole.” Compete for prizes and learn more about ILEB’s latest breakthroughs in transplantation, research, and public education from our passionate staff.

Mark your calendars! A major anniversary celebration is planned for Saturday, September 13, from 2:00 to 5:00 p.m. in Iowa City. Stay tuned to our website, social media, and email newsletter for event details as the big day approaches.

We’re also thrilled to unveil a bold new initiative: an educational exhibit that tells the story of ILEB — our roots, our impact, and the life-changing power of eye donation. This exhibit will be located at the Eye Bank itself, but we’re also designing portable sections that can travel across Iowa to educate communities statewide.

As we celebrate 70 years of transforming lives through sight restoration, we know that our success is a reflection of an entire community working together. With your continued support, we can raise awareness, advance research, and bring hope to even more Iowans in the years ahead. Help us continue this legacy. Contribute to ILEB’s anniversary-year initiatives and ongoing projects at: https:// iowalionseyebank.org/contribute

Together, let’s make the next 70 years even brighter.

When Greg Schmidt arrived in Pondicherry in mid-November of 2024, he was greeted with a banana leaf on his door, welcoming him to the city in southeastern India.

Schmidt, director of research and business development at Iowa Lions Eye Bank, traveled to Pondicherry with Dr. Kanwal Singh Matharu, assistant professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences at the University of Iowa, to visit Aravind Eye Hospital and their eye bank.

“We were able to identify two immediate things the eye bank could implement that had a direct impact on their ability to better utilize transplantable tissue,” Schmidt says.

During his visit to Pondicherry, Schmidt says he was able to watch the Aravind eye bank staff process tissue. He also led training on processing tissue for Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty (DMEK) for the hospital’s cornea fellows.

In the operating room, Schmidt also conducted training on Descement Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK).

“They wear 3D glasses to watch the (monitor), so they can better observe and experience the depth perception of the procedure,” Schmidt says.

After the visit to Pondicherry, Schmidt and Matharu flew to New Delhi to tour Dr. Shroff’s Charity Eye Hospital. While there, they were able to meet Lemlem Ayele, director of the Eye Bank of Ethiopia, who also happened to be visiting.

At Schroff’s, Schmidt met with Dr. Shalinder Sabherwal, director of public health and projects-SCEH Network, who visited Iowa Lions Eye Bank in September 2023. He also conducted DMEK training with some of the fellows at Shroff’s.

Matharu gave Dr. Virender Singh Sangwan, a surgeon at Shroff’s, an Iowa Hawkeye-themed tie, which Sangwan said drew many compliments.

This was the second international trip that Schmidt took in 2024. In January 2024, he traveled to the small African nation of Eswatini with Dr. Matthew Ward and visited the Miracle Campus of the Luke Commission.

Iowa Lions Eye Bank has long been involved in international eye care, including collaborations with surgeons and eye banks overseas. For more information on working with Iowa Lions Eye Bank, email Greg Schmidt at info@iowalionseyebank.org.

Lisa

Medical Student Award for Faculty Teaching -

Resident Award for Fellow Teaching - Rupin Parikh, MD

Dr. Lee Alward Award for Teaching Excellence - Alina Dumitrescu, MD, FACS

Dr. Elaine Binkley was promoted from Assistant Professor to Associate Professor with tenure.

Dr. Mark Greiner was promoted from Associate Professor to Professor and became the Beulah and Florence Usher Chair in Cornea/External Disease.

Dr. Ian Han was named Judith (Gardner) and Donald H. Beisner, M.D. Professor in Vitreoretinal Diseases and Surgery.

Dr. Vera Howe was promoted from Clinical Assistant Professor to Clinical Associate Professor.

Dr. Christopher Sales achieved tenure as Associate Professor.

Dr. Elliott Sohn was promoted from Associate Professor to Professor, as well as an Endowed Chair in Diabetic Retinopathy Research.

Dr. Andrew Pouw was selected to be a member of the Epic Ophthalmology Steering Board. The Ophthalmology Steering Board is working to define the gold standard for EHR use in their specialty. Drawing from their varied practice expertise and Epic experiences, the board will review existing configurations and build on them to improve Ophthalmologists’ quality of care and productivity. He was also awarded Digital Innovator award at Real World Ophthalmology Conference 2024 for “creativity and leadership in leveraging digital technologies to advance the field of ophthalmology”

Dr. Mark Greiner received $2,846,242 as part of a five-year National Institute of Health grant in hopes of creating eye drops that help keep cells in the cornea working well and improve the quality of life by preventing the need for corneal transplant surgery for people with Fuchs endothelialcorneal dystrophy. Dr. Greiner was also the recipient of the AAO Senior Achievement Award–which recognizes individuals for their contributions to the Academy, its scientific and educational programs, and to ophthalmology.

Retina fellow, Taariq Mohammed, was recently awarded a Graduate Medical Education Innovation grant for his project “Digital Indirect Ophthalmoscopy” from the GME office.

Dr. Randy Kardon was this year’s William F. Hoyt Lecturer at the AAO Annual Meeting in Chicago. Dr. Kardon’s talk, “Ophthalmology in the Blink of an Eye!” explains how we can utilize the blink response to various sensory stimuli to diagnose and monitor treatment.

Each year, University of Iowa Health Care recognizes providers as Patient’s Choice Awardees for their excellence in patient experience. The awardees are selected based on patient responses. Only UIHC providers with an aggregate score in the top 10% nationally were recognized.

• Dr. Eliane Binkley

• Dr. H. Culver Boldt

• Dr. Ian Han

• Dr. Pavlina Kemp

• Dr. Andrew Pouw

• Dr. Stephen Russell

• Dr. Edwin Stone

• Dr. Mark Wilkinson ai

1. Mike Edrington and Dr. Jonathan Russell were featured on the cover of July’s Ophthalmology Retina Journal! “MIDD with Outer Retinal and RPE Atrophy” by Michael Edrington and Jonathan F. Russell, MD, PhD was the third-place winner in the Fundus Photo Wide Angle category at the Ophthalmic Photographers’ Society 2023 Scientific Exhibition.

2. Michael Edrington and Dr. Jonathan Russell were featured on the July/August cover of Ophthalmology Glaucoma. Image by Michael Edrington, Photographer, and Jonathan F. Russell, MD, PhD was the third-place winner in the UltraWidefield Imaging category at the Ophthalmic Photographers’ Society 2023 Scientific Exhibition.

3. Meghan Menzel, CRA and Dr. Jonathan Russell were featured on the August cover of Ophthalmology Retina. The image by Meghan Menzel, CRA and Jonathan F. Russell, MD, PhD was the Honorable Mention winner in the Color Fundus Wide Angle category at the Ophthalmic Photographers’ Society 2023 Scientific Exhibition.

4. Michael Edrington and Dr. Ian Han have an image featured on the cover of September’s Ophthalmology Retina! The image by Michael Edrington, Photographer and Ian Han, MD was the first-place winner in theUltra-Widefield Imaging category at the Ophthalmic Photographers’ Society 2023 Scientific Exhibition.

Chau Pham, MD, FACS was inducted as a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) during the ACS Clinical Congress 2024 in San Francisco. ACS Fellowship is granted to physicians who devote their practice entirely to surgical services and who agree to practice in accordance with the College’s professional and ethical standards. Surgeons voluntarily submit applications for Fellowship, thereby inviting an evaluation of their practice by their peers. In evaluating the eligibility of Fellowship applicants, the College investigates each applicant’s entire surgical practice.

Wanda Pfeifer, MME, CO, COMT presented this year’s Richard G. Scobee Memorial Lecturer at the AACO Annual Meeting in Chicago. Wanda’s talk was titled, “Astigmatism and Amblyopia— Who is at Risk?”. The Richard G. Scobee Memorial Lecture is an invited lecture delivered by an orthoptist selected for outstanding scientific contributions to the field of orthoptics through novel research, publications, and presentations.She also received an Honor Award and was recognized by the AAPOS for her dedication and service.

Erin Shriver, MD, FACS, received the Women in Ophthalmology (WIO) Recognition of Service Award at AAO 2024! The Recognition of Service Award is given to WIO members who have made a significant impact on the organization through volunteer leadership.

Dr. Elaine Binkley presented multiple talks and served as a panelist at the biennial conference of the International Society of Ocular Oncology (ISOO) in Goa, India. The ISOO is a leading non-profit organization dedicated to the practice of ocular oncology and brings together experts from all over the world. During the meeting, Dr. Binkley shared her experience on a variety of topics, including novel therapies for Von HippelLindau disease, choroidal metastases in the era of targeted systemic cancer therapy, and vitrectomy with membrane peeling in a patient with leukemia. She was also selected as a new member of The Macula Society for the class of 2025. The Macula Society is one of the leading retina organizations worldwide, bringing together a “Who’s Who” of leaders in our field. Obtaining membership is a very competitive process. By selecting Dr. Binkley as a new member,the society acknowledges her “extensive contribution to retinal literature” as per the organization’s high standards.

Dr. Elliott Sohn was named an Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Silver Fellow. The title of ARVO Fellow is an honor established to recognize current ARVO members for their individual accomplishments, leadership and contributions to the Association.

Dr. Seongjin Seo was awarded the Blind Children’s Center (BCC) 2024 research grant. The focus of Dr. Seo’s research is the development of mutationindependent, generic gene therapy vectors to treat CEP290-associated Leber Congenital Amaurosis (CEP290LCA). Receiving this grant from the BCC provides a crucial opportunity to push the boundaries of gene therapy,” shared Dr. Seo. “With this support, we are one step closer to developing effective treatments that could transform the future for children with visual impairments.”

Mike Edrington received his Certified Retinal Angiographer (CRA) certification from the Ophthalmic Photographers’ Society! CRA Certification requires submission of work examples that meet established standards as well as successful completion of a written examination.

Castle Connolly Top Doctors represent the top 7% of all U.S. practicing physicians. “These individuals are peernominated and thoroughly vetted by a physician-led research team. These doctors are best-in-class healthcare providers, embodying excellence in clinical care as well as interpersonal skills.”

• Dr. H. Culver Boldt

• Dr. Keith Carter

• Dr. Arlene Drack

• Dr. Jaclyn Haugsdal

• Dr. Randy Kardon

• Dr. Thomas Oetting

• Dr. Stephen Russell

• Dr. Erin Shriver

• Dr. Edwin Stone

Dr. Arlene Drack presented the Distinguished Bryan Research Lecture at Duke University and was the invited speaker for Retina Symposium in honor of Gerald Fishman, MD at the University of Chicago.

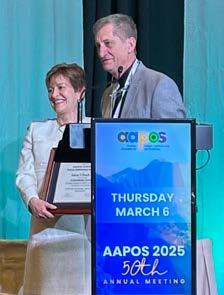

She also received the Costenbader Award and was invited to give the Costenbader Lecture at the 2025 AAPOS conference. This was the first time an Iowa faculty member won the award since Bill Scott in 1994.

Dr. Marcus Noyes was named the 2024 Fellowship Chair for the Scleral Lens Society.

Dr. Edwin Stone was the recipient of the 2025 Helen Keller Prize for Vision Research.

Dr. Kanwal Matharu received funding from the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board for a future project in Egypt.

Dr. Robert Mullins was named Treasurer for the International Society for Eye Research (ISER) in January 2025.

Dr. Michael Wall and Dr. John Fingert were named Carver College of Medicine Impact Scholars. Impact Scholars are selected based on the number of research papers a faculty member has published, and the papers’ impact as determined by how many times they have been cited by other scientists and scholars in subsequent research articles.

Dr. Marc Toeteberg-Harms was invited to give the Henry and Sylvia Yaschik Lectureship in Ophthalmology at the Medical University of South Carolina. His lecture was titled “Is there still a need for trabeculectomies in the modern surgical glaucoma armamentarium?”

Dr. Bill Scott was honored as the Presidential Guest of Honor at the 50th American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS) meeting.

Drs. Bernardo Bach (former postdoctoral scholar), Edward Linton and Elliott Sohn won the Roberto Abdalla Moura Award for the best experimental free paper. Dr. Bach presented the paper at the annual BRAVS Retina meeting in Brazil.

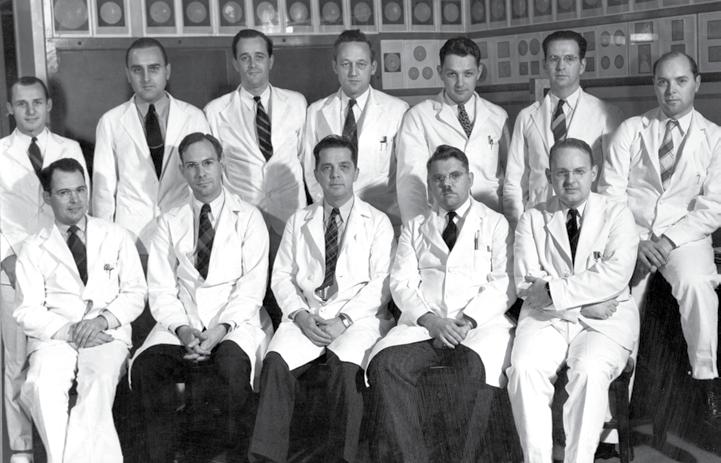

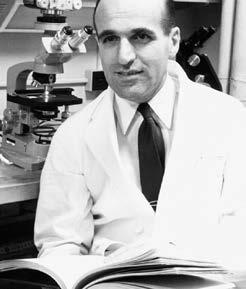

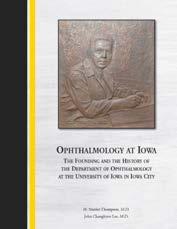

Dr. Cecil Starling O’Brien grew up and graduated from high school, college (Central Normal College) and medical school (Indiana University) in the state of Indiana. The academic path Dr. O’Brien took wasn’t entirely new to him. His father, William O’Brien, was a doctor who started a medical practice in Danville, Indiana. In 1912, as the eye, ear, nose and throat department in Iowa City continued to grow, the elder O’Brien sold his general medical practice in Danville and began post-graduate studies focused on eye, ear, nose and throat. For three years he studied under some of the world’s top experts in New York and London. When he returned to Indiana in 1915, he opened a new medical practice with a focus on the eye. This is the world Cecil S. O’Brien entered as he left medical school.

The younger O’Brien followed in his father’s footsteps by getting his medical degree. But his path to becoming the first head of the ophthalmology department at the University of Iowa required some more experience that he couldn’t have foreseen. After completing his medical internship at Deaconess Hospital in Indianapolis, Indiana, Dr. Cecil O’Brien joined the military from 1914 to 1920. As part of his military duty in the Navy, Dr. O’Brien spent two and a half years working at various hospitals in China, along the Yangtze River. This time would begin O’Brien’s lifelong appreciation of the people of this region. O’Brien’s military service continued to develop him as a physician.

O’Brien was a strict disciplinarian and was said to have run his department like the Marine Corps. Residents were expected to be present and on time wearing a tie and a clean white coat regardless of outside factors such as their own weddings, floods, or department parties the night before.

His field experience with neurosurgery built his interest in neurology and between 1927 and 1929 he popularized the O’Brien facial never anesthesia block, better known as an “O’Brien Anesthesia.”

It was during a stint serving in the eye clinic at the League Island Hospital in Philadelphia from 19191920 that O’Brien decided to pursue a career in ophthalmology. After leaving the Navy, O’Brien enrolled in the Postgraduate School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania where he completed two four-month long courses in ophthalmology, before completing a 18-month residency at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. In 1922 O’Brien was certified by the American Board for Ophthalmic Examinations and spent two years practicing ophthalmology in Toledo, Ohio.

By the end of 1924, O’Brien had married Mary Gray and they had a daughter named Patricia. O’Brien was becoming a much sought-after ophthalmologist and nearly accepted an appointment at Tulane University in New Orleans to work with Dr. Marcus Feingold. He instead moved his young family back to his home state of Indiana where he opened a private practice in Indianapolis and was appointed clinical assistant in ophthalmology at Indiana University.

During O’Brien’s time in the Navy until he arrived in Iowa City in 1925, there were major changes taking place at the State University of Iowa Medical College. New departments within the medical college we create, there was talk of building a new hospital and medical college on the west bank of the Iowa River. Ophthalmology was on its way to becoming its own department, which would report to the dean, as opposed to the head of surgery.

For more on Iowa Ophthalmology before 1925, scan this code:

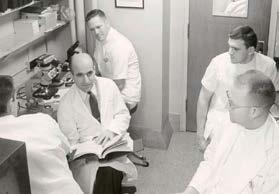

Dr. O’Brien had definite ideas about how to teach ophthalmology and wanted his program to be one of the very best. He structured the program so that each resident was trained thoroughly with a gradually increasing sequence of responsibilities. Lectures in the basic sciences of pathology, histology, pharmacology and optics were given every afternoon. First year residents were put to work doing complete ocular examinations (mostly on university students) including refractions and some visual fields. Later in the first year they began to do simple surgery of the extraocular muscles, enucleations, and some lid procedures to learn the mechanics and fundamentals of ophthalmic surgery. They began cataract surgery in the second year. Research was encouraged, but it was not permitted to interfere with patient care.

In 1927 Dr. O’Brien chose Merle Taylor from Oregon as his first resident before the new University Hospital was built. A new resident was selected every six months and rotated through the program. Dr. O’Brien felt that if he selected residents from different states, Iowa’s reputation in ophthalmology would spread far and wide. This philosophy produced many department chairmen including James H. Allen (Tulane University), Alson E. Braley (New York University and later University of Iowa), Kenneth C. Swan (University of Oregon), Thomas D. Duane (Wills Eye Hospital), Philip P. Ellis (University of Colorado), Phillips L. Thygeson (Director of the Proctor Foundation at the University of California, San Francisco).

O’Brien was a strict disciplinarian and was said to have run his department like the Marine Corps. The residents respected and adhered to the policies and routines established by Dr. O’Brien. Residents were expected to be present and on time wearing a tie and a clean white coat regardless of outside factors such as their own weddings, floods, or department parties the night before. First year residents were required to live in the hospital (that’s why they were called “residents” after all). If a resident wished to be married and wanted to stay in the program, he needed to have O’Brien’s—generally reluctant—approval.

Many of his former residents mentioned in interviews that they had concerns as new residents about having to work with O’Brien, but all were quick to say that their fears soon resolved into respect for his knowledge and for his determination to train residents well.

Daily routines were established and very strictly followed. Many of these routines are still practiced today at the University and many are carried on at other academic facilities influenced by Iowa. Morning rounds began at 8:00 a.m. sharp, seven days a week, even on Sunday. Patients were brought into the clinic for these rounds. Everyone then had the opportunity to see all the interesting patients and discuss the problematic cases. When Dr. O’Brien asked a question, the resident was expected to provide an answer complete with a reason or explanation. Following the presentation of cases in the clinic, the residents

followed O’Brien to the ward to examine the post-operative patients that were still confined to bed. On Sundays, a paper was given by one of the residents. During the week, daily lectures were given promptly at 4:00 p.m. in the lecture room. If clinic patients were not finished in time for the lecture, the patient was asked to wait until after the lecture. The lecture topics were chosen by Dr. O’Brien, but the lectures were given by the faculty.

Dr. O’Brien supported and encouraged his residents, yet he demanded perfection. He was himself a facile surgeon and he would not tolerate work below his standards. Residents began by helping Dr. O’Brien in the operating room, first as a surgical assistant and then, on all except private patients, doing increasing amounts of the operation. They were expected to have read up on the procedure and to be alert enough to be helpful and to be cool enough to withstand sharp orders and reprimands.

O’Brien was a strong, forceful disciplinarian. Dr. Otis Lee (resident, 1941-1944) remembered Dr. O’Brien’s method of discipline. “He gave me hell during practically every surgery. Finally I said, ‘Dr. O’Brien, I thought I was doing everything you wanted me to do. Why do you still give me hell?’ Dr. O’Brien replied with a characteristically rough compliment, ‘Otis, I just want to remind you that it costs me a lot of effort to give you hell. So if I chew you out, it is because I think you are worth the investment.’ “

1928

The seven story, 900-bed General Hospital opens, greatly increasing clinical teaching opportunities for students and trainees.

When not in the clinic, Dr. O’Brien was gracious, friendly, and helpful. He hosted parties for the residents and faculty at his home in the country every week or two. Although these parties lasted until late at night, the residents and faculty were expected to report on time for morning rounds the following day.

*This sketch of Dr C.S. O’Brien and the residency program was adapted from a paper by Drs. John C. Lee and H. Stanley Thompson published in Documenta Ophthalmologica 94: 161-178, Jan 1997 and read at the tenth annual meeting of the Cogan Ophthalmic History Society, Philadelphia College of Physicians, March 8 and 9, 1997.

For more on Iowa Ophthalmology 1925 to 1934, scan this code:

The University of Iowa’s Department of Ophthalmology saw remarkable advancements from 1935 to 1944, largely due to the visionary leadership of Dr. Cecil Starling O’Brien. Appointed in 1925, Dr. O’Brien’s tenure was marked by significant strides in both clinical practice and research. By 1937, his efforts were recognized nationally when he was elected as a director of the American Board of Ophthalmology. This period was crucial in establishing the department’s reputation for excellence in ophthalmic education and patient care.

One of the key developments during this time was the recruitment of talented individuals who would contribute to the department’s growth. In 1937, Lee Allen was hired to draw the fundus of the eye, and under Dr. O’Brien’s mentorship, he developed innovative photographic and gonioscopic techniques that were widely published.

Additionally, Dr. O’Brien brought in Peter Salit, a biochemist with a keen interest in cataract formation, and Phillips Thygeson, who specialized in the microbiology of the eye. These hires significantly bolstered the department’s research capabilities and clinical expertise.

The physical infrastructure of the department also saw notable improvements. Initially housed on the second floor of the new general hospital built in 1928, the department quickly outgrew its space. By 1946, plans for expansion were underway, and by 1949, the department moved into a newly remodeled and expanded area. This new space included a modern clinic area with advanced equipment, which greatly enhanced the department’s ability to provide high-quality patient care and training.

Dr. O’Brien was also instrumental in shaping the educational framework of the department. He established a rigorous training program for residents, emphasizing both basic and clinical sciences of ophthalmology. Morning rounds, a tradition he started, became a cornerstone of the department’s educational program and continue to be an integral part of the training process. This structured approach ensured that residents received comprehensive education and hands-on experience, laying a strong foundation for their future careers.

By the end of this era, the University of Iowa’s Department of Ophthalmology had firmly established itself as a leader in the field. The advancements made during these years not only enhanced the department’s reputation but also contributed significantly to the broader field of ophthalmology. Dr. O’Brien’s leadership and vision were pivotal in transforming the department into a center of excellence that continues to thrive today.

For more on Iowa Ophthalmology 1935 to 1944, scan this code:

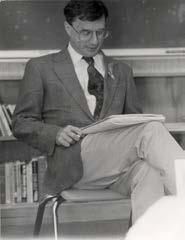

Lee Allen, born Edwin Lee Allen in 1910 in Muscatine, Iowa, was a multifaceted artist whose contributions spanned from regionalist painting to groundbreaking work in medical illustration. His journey as an artist began under the tutelage of notable figures like Grant Wood and Diego Rivera, but it was his tenure at the University of Iowa’s Department of Ophthalmology that truly set him apart in the medical community.

Allen’s early years were marked by a deep engagement with the arts. After graduating from East High School in Des Moines in 1928, he studied at the Cumming School of Art and later at the University of Iowa. His artistic journey took a significant turn when he worked with Grant Wood on various public art projects, including murals funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). This period honed his skills in mural painting and introduced him to the fresco medium, which he studied further under Diego Rivera in Mexico in 1935.

In 1937, Allen accepted a position as a medical illustrator at the University of Iowa’s College of Medicine, Department of Ophthalmology. This role would define his career for the next 39 years. His work involved creating detailed illustrations of the eye’s anatomy and various ophthalmic conditions, which were crucial for medical education and research.

Allen’s contributions to ophthalmology were not limited to illustration. He was instrumental in developing several photographic and gonioscopic techniques that enhanced the field’s diagnostic capabilities.His meticulous

illustrations and photographs were published in numerous ophthalmic journals, making complex concepts more accessible to both students and practitioners.

Allen’s influence on modern ophthalmology is profound and multifaceted. Here are some key areas where his contributions have had a lasting impact: