DESIGNING THE VALLEY

Urban Design in Rural California

Ettore Santi

Foreword by Margaret Crawford

Designing the Valley: Urban Design in Rural California is a publication produced by the Master of Urban Design Program at the University of California, Berkeley. The book is the result of the advanced studio Designing the Valley: a Rural California Studio, created by Margaret Crawford, Scott Elder, and Ettore Santi in Partnership with the Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau, and taught by Ettore Santi in the Fall of 2022. The studio marked the beginning of a longer partnership initiative between UC Berkeley’s Master of Urban Design program and the Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau, with the aim of making a real-world impact in the Salinas Valley.

All rights reserved:

© Texts Ettore Santi and Margaret Crawford

© Images Patricia Cespedes Flores, Jiaxing Cui, Yaoyao Ding, Sen Du, Xuyuan Fan, Yash Gogri, Diego Gonzalez Ramirez, Isha Khan, Byron Li, Rita Ling, Sagarika Nambiar, Srusti Shah, Varun Shah, Freya Tan, Mufeng Yu

© Cover Photo Jiaxing Cui

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

The projects are the result of the Fall 2022 Master of Urban Design Advanced Studio Designing the Valley. To learn more:

Website: https://ced.berkeley.edu/iurd/urban-design

Instagram: @Berkeley_MUD

The studio was sponsored by the Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau and designed in partnership with the Bureau’s Executive Director Craig Kaufman.

Book design by Xuyuan Fan and Yash Gogri

Typeset: Futura Md BT

ISBN 9798853043404

Many observers and practitioners would agree that the field of Urban Design is at a crossroads. Current paradigms, created in the 1970s, have achieved success in upgrading the design and livability of urban cores in Europe, North American, and Asia. But demographic changes, remote work, the growth and influence of cities in the Global South, along with new theoretical constructions such as Planetary Urbanization1 have revealed a global array of new design issues at all scales. Although Urban Design appears to be the only design specialization that has the capacity to take on these new challenges, to do so means redefining what we mean by urban. Geographers and others have identified a host of new spatial configurations such as Desakota regions, Edge Cities, megacities, urban-rural interface, and wildernessurban interface, that demonstrate the increasing blurring of built and natural environments once considered to be distinct. In an informal way, we have seen this new definition of urban design

reflected in recent MUD thesis topics. Students have addressed pressing spatial issues in suburban, exurban, rural, and even wilderness sites, far beyond the city limits. Their projects demanded working at a larger scale and understanding far more complex economic, political, and social conditions than traditional urban sites.

As a result, we were excited when MUD faculty member Scott Elder introduced us to Craig Kaufman, Executive Director of the Salinas Valley Tourism & Visitors Bureau, who he met while working on the Anza National Historic Trail in the area. Craig suggested that the MUD program could take on the Salinas Valley. He described the region as a place with both problems and potentials that could be addressed through design, local economic development, environmental restoration, and housing. The valley, known across the world through the work of John Steinbeck, encapsulates California’s cultural, environmental, and economic histories. As we conducted research and visited the valley, we agreed

1 Brenner, Neil and Christian Schmid, “Planetary Urbanization,” Implosions / Explosions: Toward a Theory of Planetary Urbanization (Berlin: Jovis, 2014).

that it was a location rich with opportunities to reconsider using an expanded set of urban design tools. Scheduling an advanced urban design studio there, we were lucky to have the ideal instructor for this project, Ettore Santi, already at the CED. In addition to being an experienced architect and urban designer, Ettore is also an expert on rural transformation, having completed a PhD dissertation on current efforts to reconfigure agricultural land and villages in the Hunan province of China. He was able to bring his knowledge of how agriculture and urban processes operate globally along with his understanding of the nuances of the local situation to define the studio.

This studio demonstrates another important concern of the MUD program: engaging with real world dynamics and circumstances. Craig connected us with many individuals in the region, ranging from important stakeholders to residents of all kinds. Partnering with local people and groups proved crucial to understanding

how things actually work and established limits to our design imaginations. These connections provided valuable information and ideas not available elsewhere. Craig also pointed out the critical link between low-impact tourism focused on history and culture and funding the area’s muchneeded social services.

Hovering over any university-community partnership is the question: who benefits? Students learn an enormous amount by working with real world situations. But once their class ends, they leave, rarely following through on their proposals. This can leave their local partners wondering what they have gained. In order to avoid this problem, and because we found the Salinas Valley so compelling, local residents so responsive, and working with Craig so productive, we have committed to at least five years more work in the valley. This book represents our initial analysis and concepts. As we continue working, we hope that they will develop into real projects that can be implemented.

This book stems from the idea that narrowly urban design is no longer sustainable or just. Recent planetary changes have brought rural areas to the center of public attention. The outbreak of Covid-19, for example, could not be separated from China’s ongoing restructuring of its food systems. Geopolitical shifts have impacted global supply chains of food and resource extraction, with direct consequences on rural economies. Worldwide, in many rural places, access to land and food systems, water scarcity and pollution, deforestation, and ecotourism developments are posing previously unexplored design challenges. All these transformations demand urban designers to move their thinking beyond cities as the only units of analysis and intervention.

The book seeks to expand urban design’s uniquely creative, cross-disciplinary, and multiscalar approach by connecting it with methods from agronomy, forestry, political

ecology, Indigenous knowledge, literary criticism, culinary cultures, and more. The work presented here is the product of Designing the Valley: A Rural California Studio held at UC Berkeley’s Master of Urban Design in the Fall of 2022. The class led fifteen students from Urban Design, Landscape Architecture, and City and Regional Planning to think beyond traditional taxonomies of urban, suburban, and rural. The projects embrace new frameworks such as planetary urbanism (Brenner and Schmidt, 2015), territorialism (Vigano, 2014), desa-kota region (McGee, 2009), ruralization (Krause, 2013) to think broadly and beyond the spatial binaries of an “urban center” and a “rural periphery.”

Rather than focusing on a neighborhood, a corridor, a waterfront, or other elements of urban morphology, the studio took “the California Valley” as a unit of analysis. The concept and unit of “the Valley” in California has emerged as a specific type

of hinterland urbanism, in which localized land and food economies interact with planetary circuits of agriculture and tourism logistics. Both historically and currently, the Valley is as constitutive of California urbanism as the megaregions of Los Angeles or the San Francisco Bay Area.

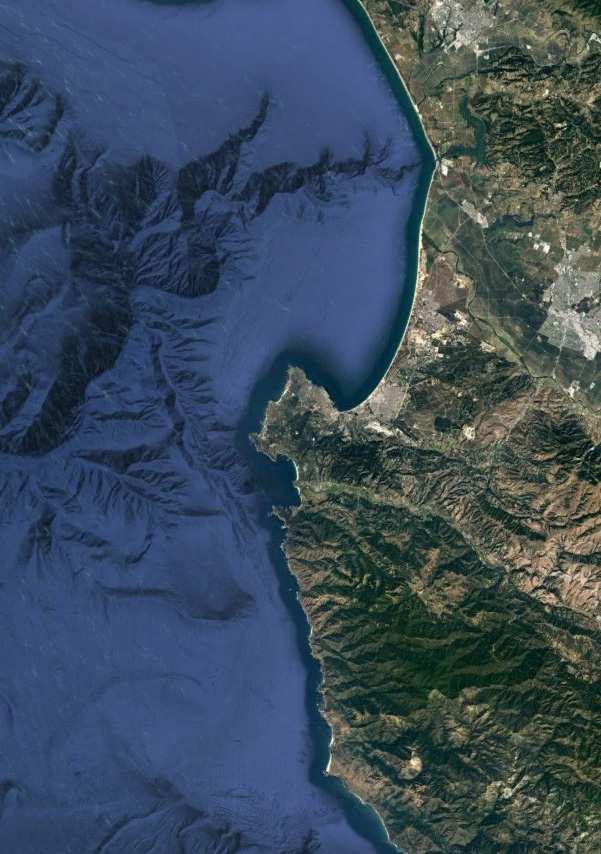

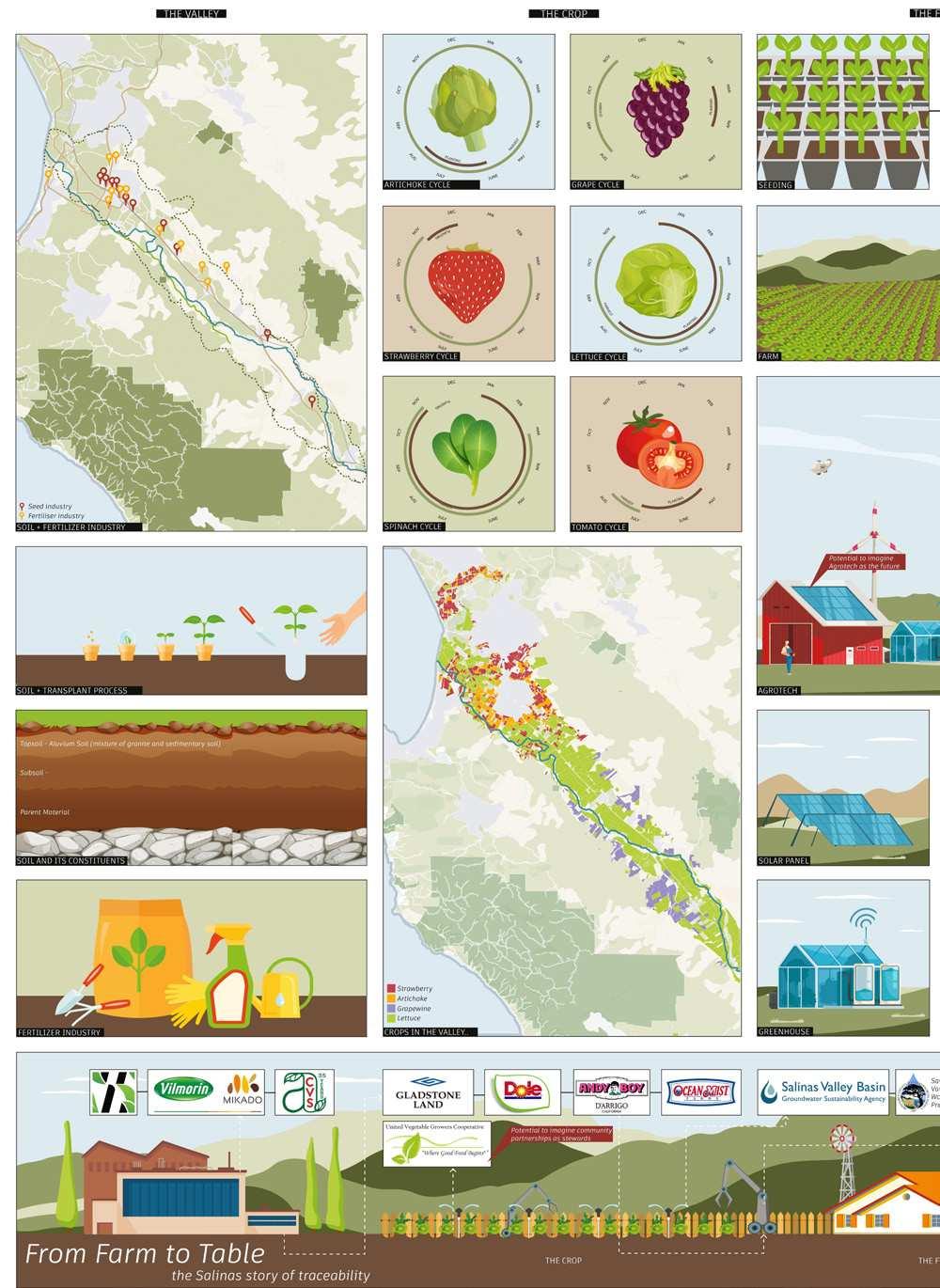

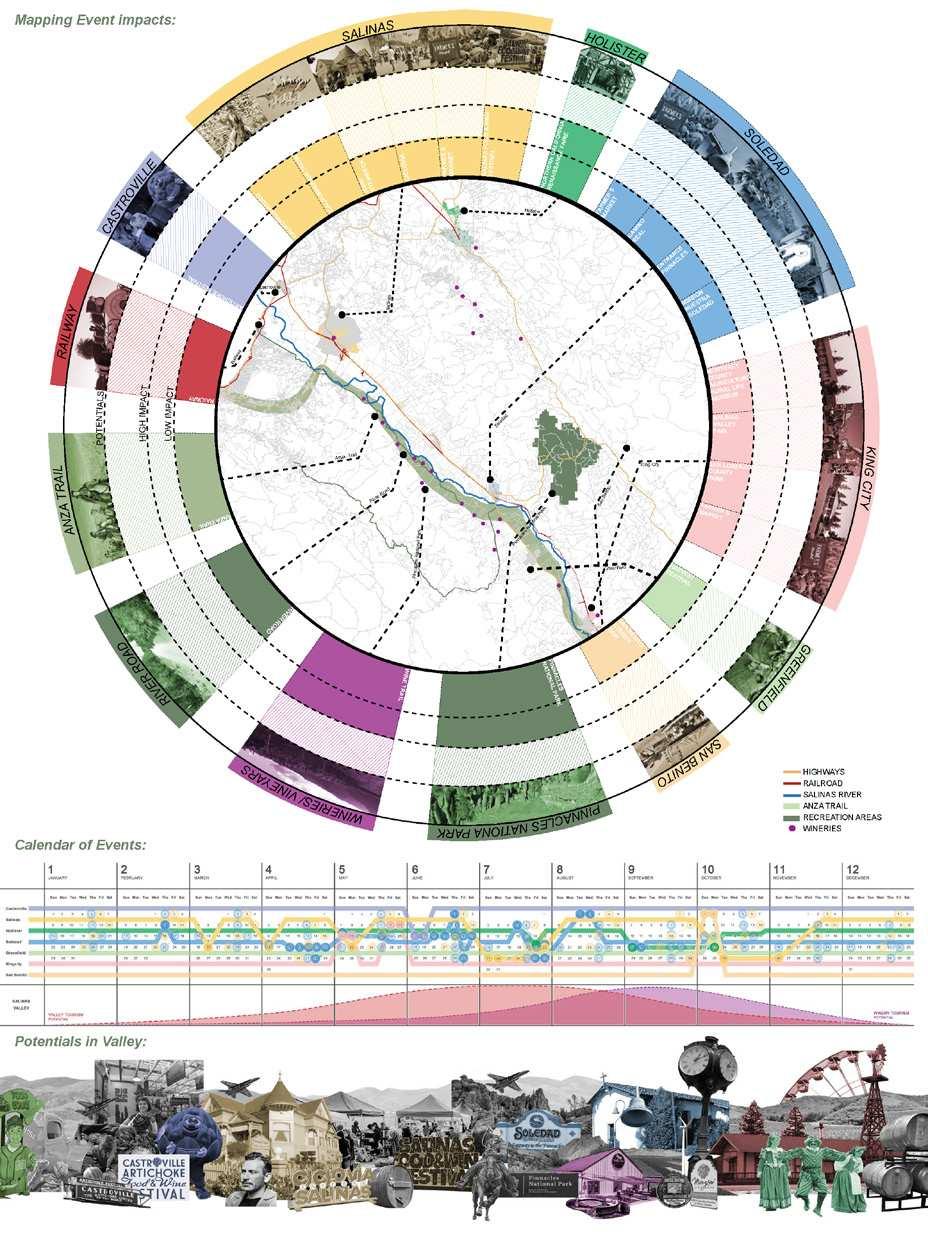

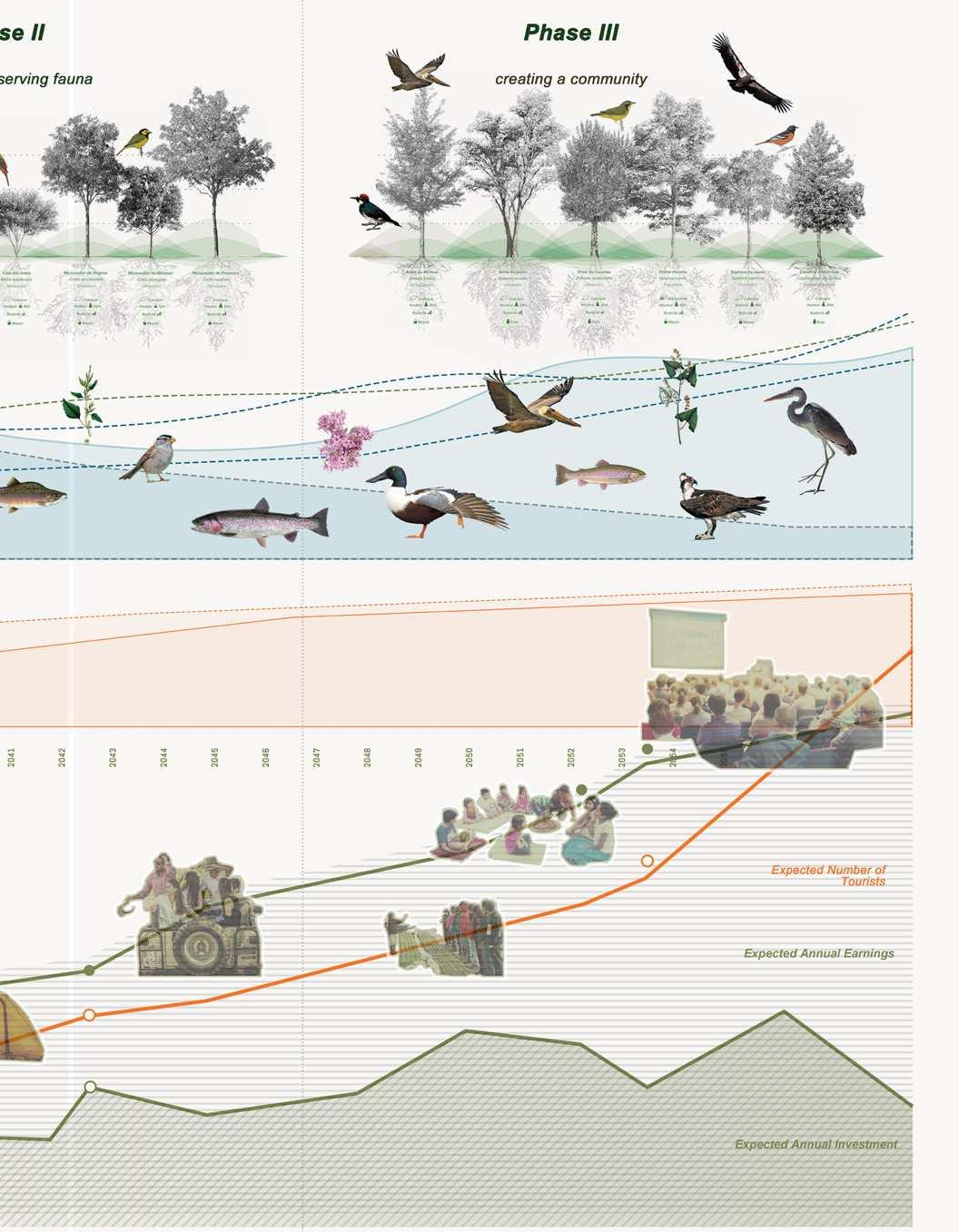

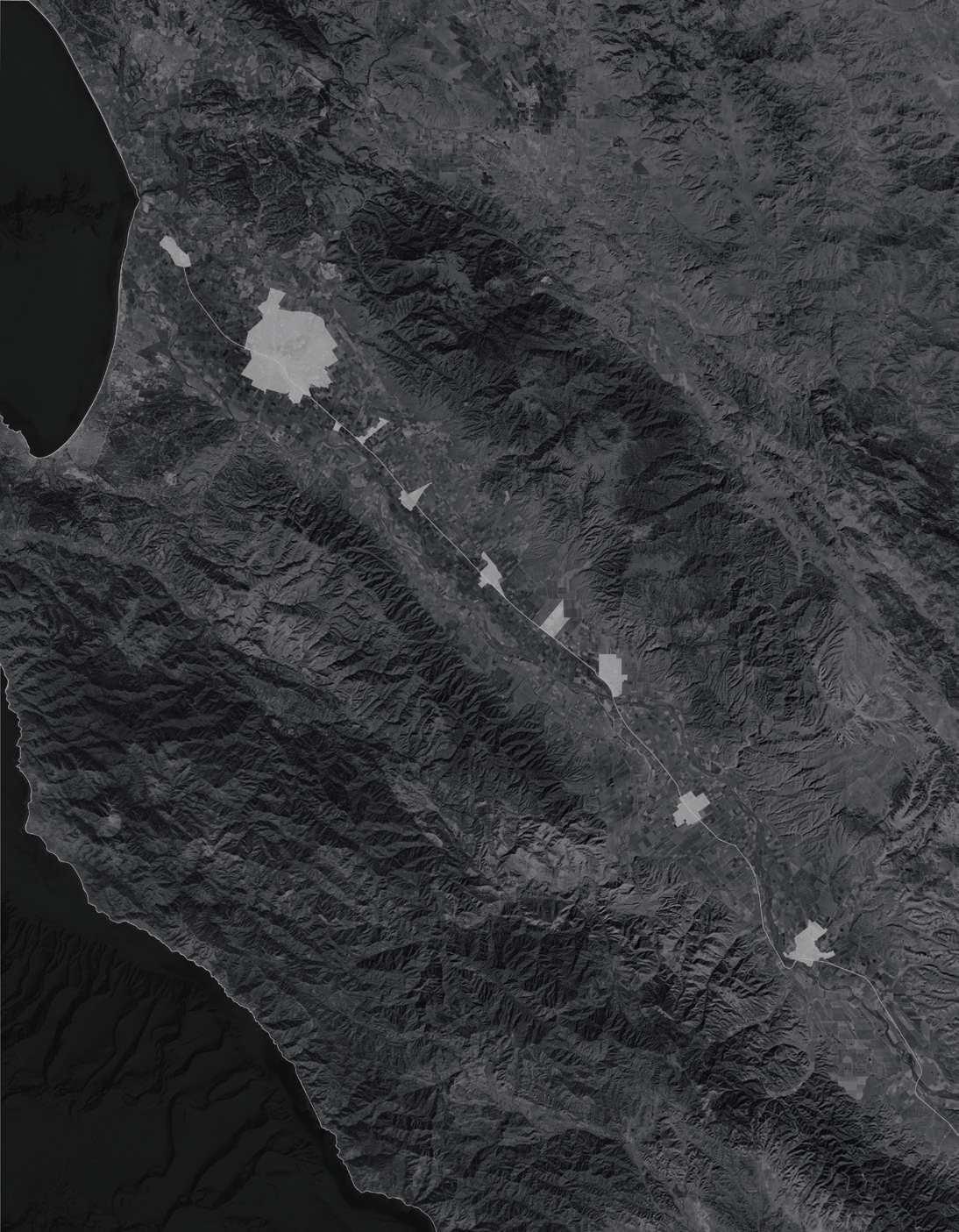

The class focused on the Salinas Valley, also known as “the Salad Bowl of the World” a large lettuce agribusiness node that stretches for 90 miles inland from the Monterey Peninsula. The valley produces about 61% of the leafy greens consumed in the United States and exports its produce to Mexico, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, Hong Kong, Korea, Saudi Arabia, the European Union, and the United Arab Emirates. While less well known than other valleys in California, such as Napa or San Joaquin, the Salinas Valley embodies the same rich environmental and economic histories that define California’s present. Its iconic landscape has inspired artists and writers, including the Nobel laureate John Steinbeck, a native of Salinas.

The class took its shape by collaborating with a community partner, the Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau, and its Executive Director Craig Kaufman. This partnership enabled students to undertake extensive field trips to the Salinas Valley. During these immersive field experiences, students connected and exchanged information with relevant actors such as landowners, growers, government agencies, NGOs, farmworkers, and more. They initially defined their own sites in

relation to these political-ecological milieus and associated regional and transnational systems.

Throughout this consistent engagement, we tested a design approach that is simultaneously territorial and situated. Strategies operate at the very large scale that characterizes rural space. Yet they engage with many place-specific conditions that change dramatically across space, defined by varying geologies, land use patterns, politics and economies, and historical conditions. As a result, each project contemplates a unitary territorial strategy composed of a large number of design parts, all of which can be flexibly readapted to the changing site conditions.

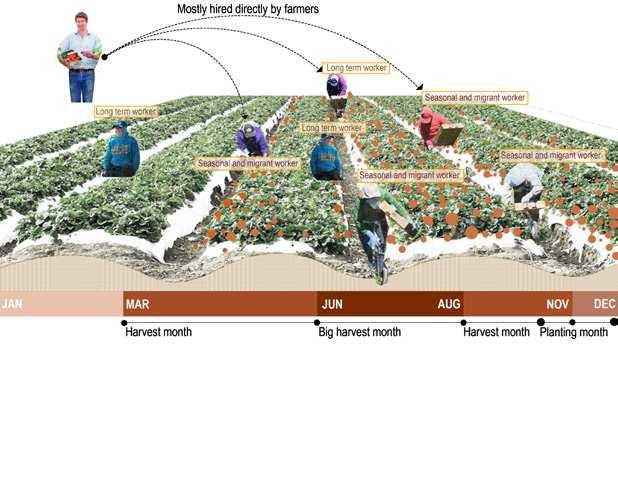

This immersive approach exposed students to some crucial design challenges posed by the Salinas Valley and its ongoing transformations. These changes include the expansion of agrotourism and territorial branding, increasing complexity of food systems, water scarcity and ecological change, Indigenous politics, homelessness, and seasonal immigrant farm labor. Students took on challenging questions associated with Valley urbanism, such as: what does it mean to design at the territorial scale? Can the life cycle of a crop affect the way we organize and experience space? Do endangered fishes, birds, insects constitute a public, and can their space also accommodate others such as human tourists?

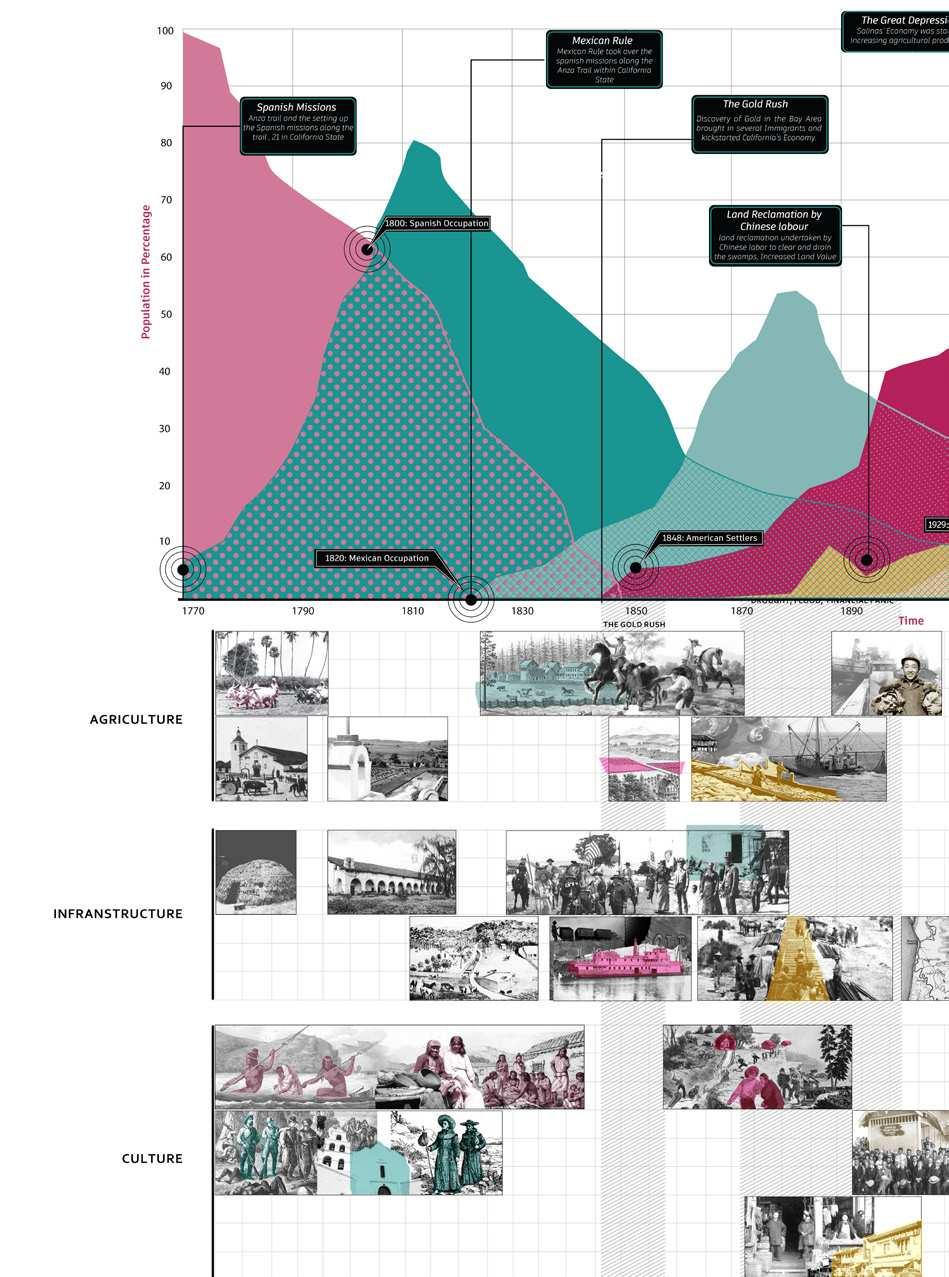

Unlike other rural areas across the world, which typically changed over time from feudal land systems to family farming or cash cropping, and then, more recently, to intensive corporate agriculture, California agriculture largely skipped over these intermediate steps. For millennia, California was inhabited by nomadic Native populations who did not rely on agriculture. The post-18th Century waves of colonial settlements, from the Spanish missionaries to the Mexican rancheros (the “Dons”), to the settlers moving from the East, imported commercial farming. Crops served as commodities to be sold for profit on the regional and national markets, making rural California a pioneer of modern agribusiness. In the 20th Century, California agriculture has yielded a large array of fruits and vegetables, all of which, once shipped via railroads, contributed to shaping the dietary habits of the entire country. Today, the encounter of industrial farming, logistics, agro-biotechnologies, tourism, and nature itself– with its unique climatic and geological conditions, has generated a peculiar and productive “urban” condition that arguably bears no equals on the planet.

This commercial aspect of California agriculture is now changing. In addition to corporate agribusiness, the past few decades saw the emergence of the leisure industry. Places like the Napa Valley became known for their wine production, attracting tourists from every corner of the planet. Through campaigns of “territorial branding,” local governments and grower organizations discursively tied their regional environment to the high quality of their crops. This strategy aimed at attracting visitors who were interested in experiencing the produce, the landscape, and an imaginary of rural gentility. As California Valleys tried to diversify their brands (Napa and Sonoma went for wine, San Joaquin specialized in walnuts, almonds, and tomatoes, Salinas is focusing on lettuce), their environments have responded to accommodate new activities such as food tourism, nature exploration, and “glamping,” all of which further blur the categories of metropolitan, urban, and rural.

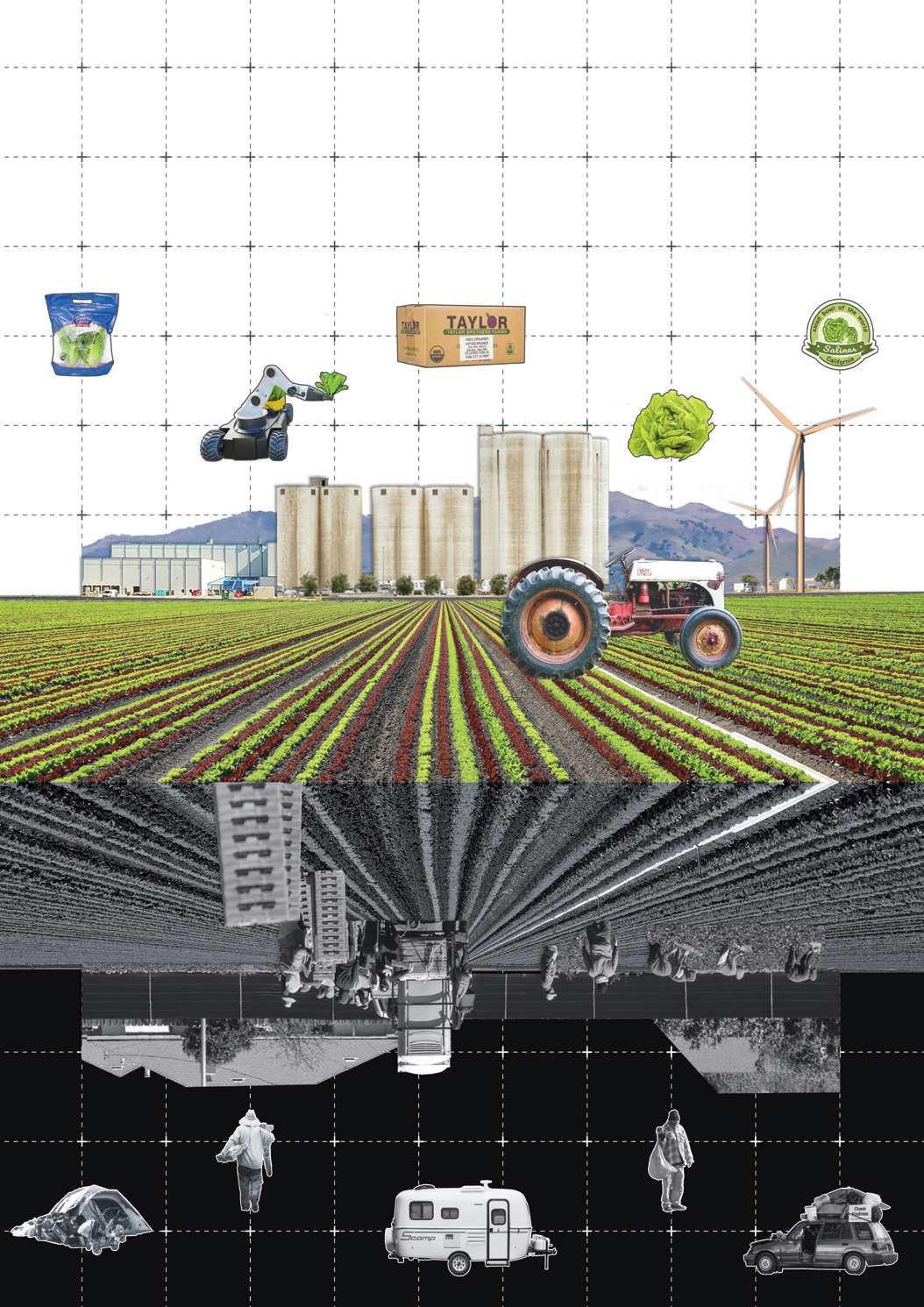

The Salinas Valley presented us with a peculiar angle to study and address these dynamics. Unlike the vast territory of the Central Valley, the Salinas Valley is a narrow 90-mile long canyon shaped by the freshwater streams descending from the Gabilan Range and the Carmel and Big Sur hills into the Salinas River. The Valley is a hospitable and fertile region. Its abundance of water and the mild climate made it first the home of the native Te’po’ta’ahl tribes– named by settlers Salinians, and later to Spanish missionaries, Mexican landlords (or Californios), until its formal annexation to the US in 1847. Its proximity to Monterey’s port, the state’s first capital and an early global trade node, made the Valley one of the earliest agricultural regions in the American West to interface with global supply chains. Over the decades, the Valley hosted many waves of immigrant labor, from Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino workers to the more recent wave of Mexican immigrants that started with the Bracero Program of the 1940-50s.

While the Salinas Valley has long been

part of the world systems comprising globalization, the “worlding” of the Valley is now expanding to new sectors. The recent upgrade of Pinnacles National Park (previously classified only as a National Monument) combined with the ongoing plans to create a National Heritage Area around the Monterey Bay Area, along with local efforts for territorial branding, may soon connect the Valley to regional and global tourist flows. While these dynamics offer rich economic opportunities, they also present tensions; the Salinas Valley is not immune from the problems affecting California at large, including a housing crisis, homelessness, conflicts across racial and class lines, and even risk of epidemics and pathogen outbreaks (e.g. escherichia coli in lettuce). Whether or not these changes will happen, what forms they will take, and who will benefit from them, is yet to be determined. Our studio sought to intervene in this state of transition, deploying design tools to catalyze forces already in place, test unexpected synergies, and advance new visions for the Salinas Valley and its inhabitants.

Making urban design “go rural” required us to reinvent design tools and methods beyond canonical approaches. The first step required reimaging representation. How do we represent the rural? The countryside is often rendered quantitatively and abstractedly, either through GIS maps or via color-coded charts of soil quality, land ownership, farm productivity, etc. In this studio, we investigated different visual languages to capture the evershifting materiality of land and nature, the operational complexity of its multiscalar logistics, and the embodied experience of this environment. Students researched topics that interested them among the many historical, socio-cultural, economic, technological, and environmental questions posed by the Salinas Valley. They summarized their findings through powerful

graphics that narrated their own story of the subjects that they analyzed. Students used a multimedia approach, experimenting with collage, comics, film, rendering, and more. This form of representation was key for the projects to reach a broader audience than that of design experts. Visuals became public images, as students created visual narratives that were compelling, engaging, and complex, yet widely understandable.

After an initial exploration and a long field trip to the Salinas Valley, students worked on their site construction. This exercise led them to define the main argument about their site, a claim that guided them to define their design.

After gathering knowledge about the Salinas Valley, students asked: what are the intellectual, geographical, historical

boundaries of their design inquiry? What are the socio-ecological processes at play, and where do they span across time and space? What is their original site thesis in relation to this inquiry, and what design direction does their argument lead? Each group identified and mapped the actors and networks involved, and the space in which they operated. These included private or government institutions, local organizations, seed types, plants, animals, soil conditions, (bio)technologies, circuits of knowledge, and more.

to define their own territorial strategy. This was perhaps the key step of the design studio as it defined the character of each intervention, and clarified what each project was doing. The first question was always an issue of scale. At the rural scale, everything is stretched. We explored how urban design strategies need to be crafted at the territorial scale. We understood territory as a governed space upon which different agencies, institutions, human and more-than-human forms of power operate. In order to be a territory, a space does not need to be unitary or consolidated.

be described as rambling, multi-pointed, dispersed, scattered, wide-spread, uneven, heterogeneous, etc. In spite of the unique characters of each strategy, they all shared some core elements. All strategies were:

Territorial: strategies operated all across the Valley. They sought to build synergies among many public and private partners across municipal jurisdictions.

Low-impact: each strategy’s impact on the ground was minimized. They tried to leverage what already exists by adding

Flexible: Not everything presented in the strategy needed to happen, or at least not immediately. Parts could be crossed out, readapted, relocated, rescheduled etc., so as to give our partners the ability to readapt each project to the local contingencies

Justice-oriented: all projects sought to leverage many assets in the Valley to redistribute their benefits mostly to the disadvantaged and struggling, particularly precariously housed populations, farmworkers, and Indigenous groups.

Given this stretched condition of design strategies, each group formulated a large array of design interventions that acknowledged the scale of the Valley. Students proposed as many designs as their territorial strategy demanded. These interventions were conceived to be as individual as they were interdependent. Most importantly, they relied on a variety of tools that collectively expanded the spectrum of techniques available for urban designers. These included:

(1) canonical urban design tools: architectural: programs / buildings / forms landscape: systems / ecologies / flows policies: guidelines / organizations / norms

(2) other design tools, such as: geo / biological long section (territorial) studies agronomic / horticultural / botanical biochemical archeological hydrological

(3) non-typical design tools, such as: culinary mediatic/communicational Indigenous systems of knowledge literary histories

Finally, and not less importantly, students designed their narrative. They reconsidered their project holistically, and inscribed it into an overarching and persuasive narrative to engage their audience. This exercise unified all the design products created across the semester, including research, site construction, design graphics, and future possibilities. Students were encouraged to be experimental and to think broadly. At this stage, they asked: what kinds of creative maps, renderings, collages, videos, VR tools, conceptual/ interactive physical models, or else, would be required to convey the design message? And what should their visual language be? They worked with complexities and contradictions, juxtaposing the logical with the surprising, the predetermined with the defamiliarized, and the rational with the poetic. The results were largely outside of the vocabulary of typical urban design projects that we are used to seeing, both in the academy and in the industry.

Salinas

Big Sur

Watsonville

Castroville

Monterey

Carmel-By-The-Sea

Carmel Valley

Big Sur

Watsonville

Castroville

Monterey

Carmel-By-The-Sea

Carmel Valley

San Juan Batista Hollister

Salinas

Spreckles

Chualar

Gonzales

Soledad

Pinnacles

National Park

Greenfield King City

San Juan Batista Hollister

Salinas

Spreckles

Chualar

Gonzales

Soledad

Pinnacles

National Park

Greenfield King City

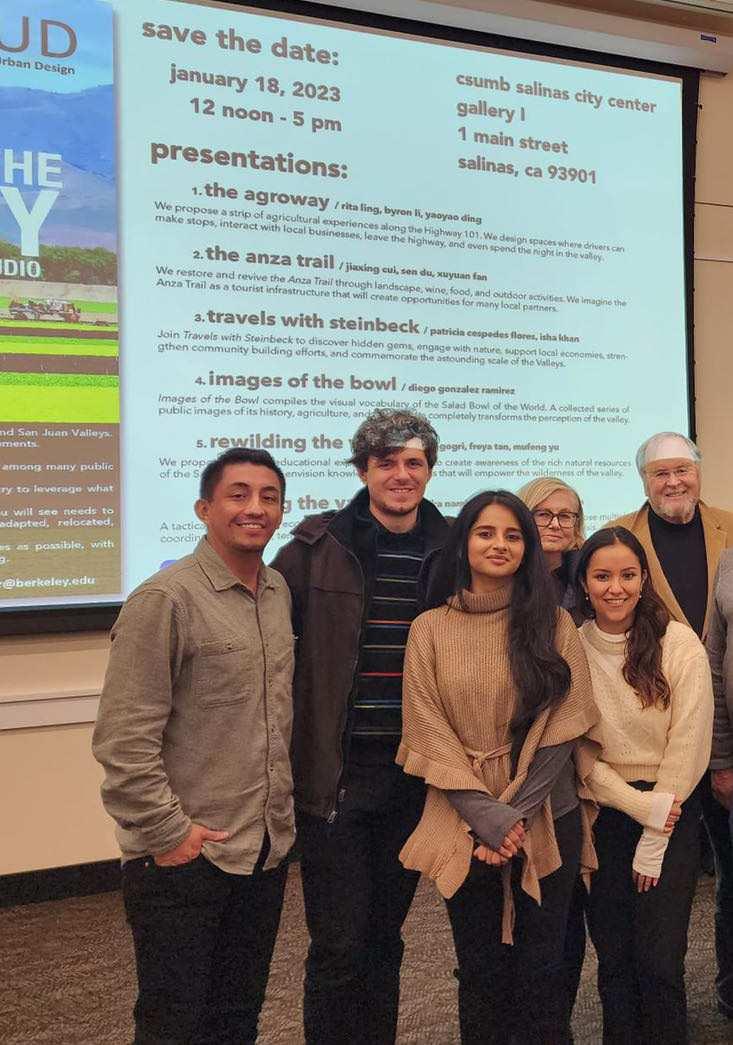

The book is the result of the advanced studio, Designing the Valley: a Rural California Studio, created by Margaret Crawford, Scott Elder, and Ettore Santi in partnership with the Salinas Valley Tourism and Visitors Bureau, and its Executive Director Craig Kaufman. The studio marked the beginning of a longer partnership initiative between UC Berkeley’s Master of Urban Design program and the Visitors Bureau, with the aim of making a real-world impact in the Salinas Valley and surrounding areas.

This partnership enabled the situated design approach of this studio. Designing the countryside requires us to move beyond abstract analyses and get “down to earth,” jumping into the reality of the actors,

politics, and materials that co-produce the region. Students continually engaged with local actors, residents, and experts who offered their feedback throughout the development of the projects. This increased the quality and reliability of design outcomes, as well as pushing the boundaries of what the urban design field can be. As part of this immersive approach, we encouraged students to think of themselves as real stakeholders in the Valley. Working with local organizations, they assisted and tried to persuade local actors to make decisions. To do this, they mobilized the action tools of design representation, which we tested into new visual languages, storytelling formats, and persuasion strategies.

At the beginning of the semester, the students embarked on a research trip lasting five days, exploring the Salinas Valley. Craig informed them about the efforts of the NGO to promote the region and boost tourism, aiming to generate more revenue for essential social services in the area. Students visited the valley multiple times, first on their own and then guided by local stakeholders, including the Monterey County Farm Bureau staff, the National Steinbeck Center, the National Park Service, local planners as well as farmers and historians specializing in local and Indigenous history. These individuals were the community members with whom the students collaborated to develop

projects that showcased the unique aspects of the Salinas Valley.

During these multiple trips, each group developed close exchanges with one or more select stakeholders with which they developed their own strategy and designs. This was a way to deepen students’ understanding of local politics and dynamics in place, while also avoiding alienating local actors from the design process. The resulting six projects tackled various issues such as fair economic development, environmental rehabilitation, activation of public spaces, housing, community unity, and the utilization of education to involve people in the valley:

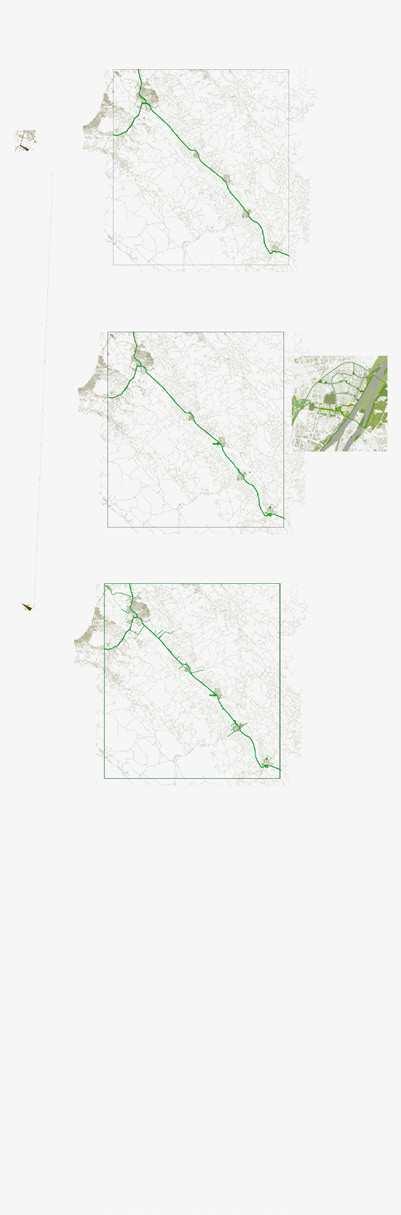

1.The Agroway, by Rita Ling, Byron Li, Yaoyao Ding. The strategy proposes a strip of agricultural experiences along Highway 101, with spaces where drivers can make stops, interact with local businesses, leave the highway, and even spend the night in the Valley.

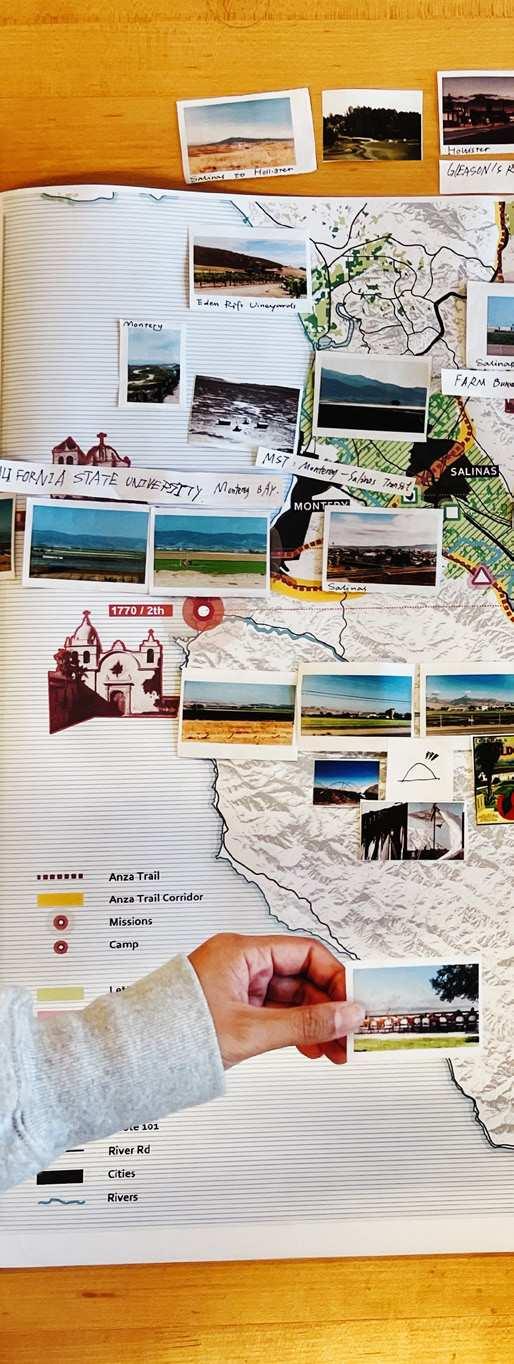

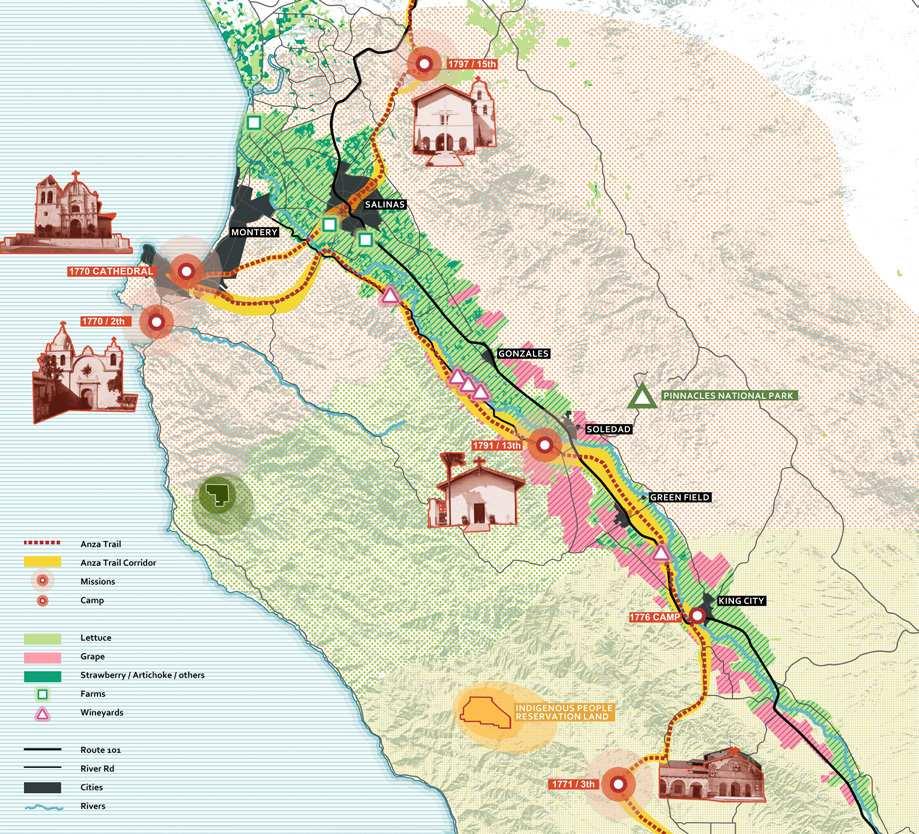

2.The Anza Trail, by Jiaxing Cui, Sen Du, Xuyuan Fan. This is a strategy to restore and revive the Anza Trail through landscape, wine, food, and outdoor activities. Students imagined the Anza Trail as a tourist infrastructure that reveals the Indigenous histories of the Valley, while offering many opportunities to tribal members and small businesses in Salinas.

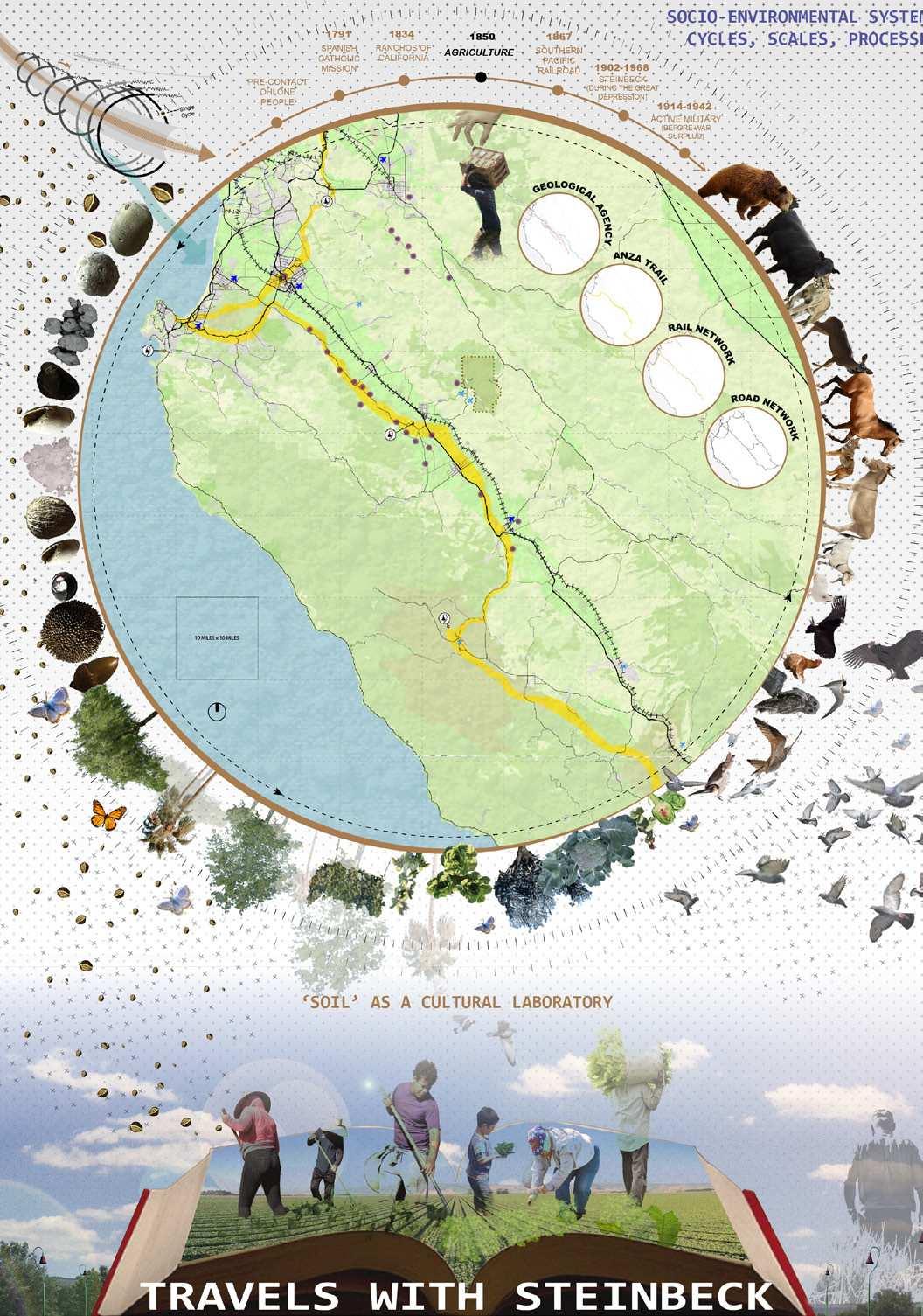

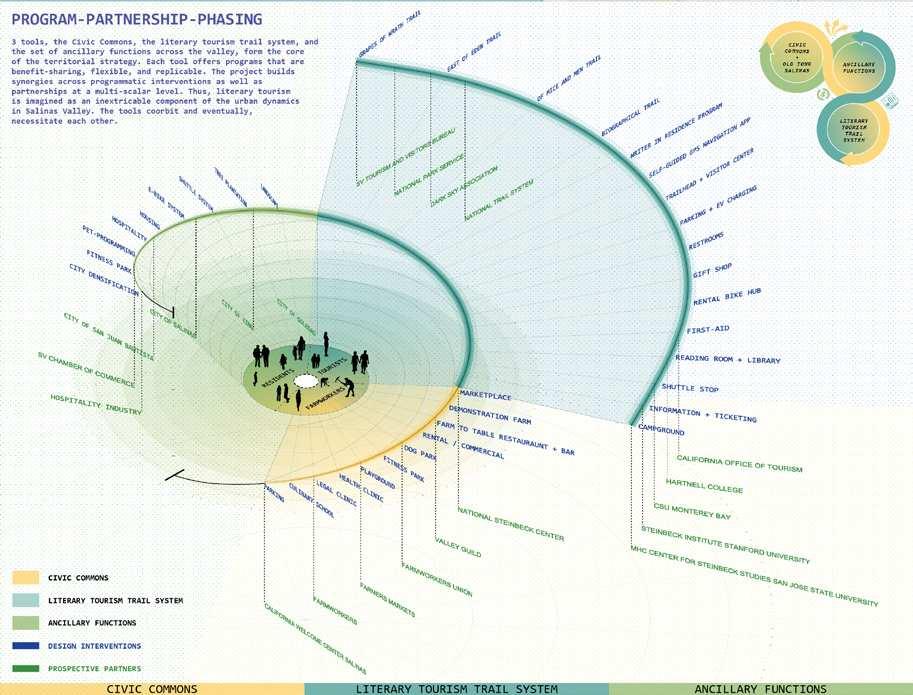

3.Travels with Steinbeck, by Patricia Cespedes Flores, Isha Khan. Travels with Steinbeck is a literary tourism program based on the novels of John Steibeck. The strategy leads to discovering hidden gems, engaging with nature, supporting local economies, strengthening community building efforts, and admiring the astounding scale of the Valleys.

4. Images of the Bowl, by Diego Gonzalez Ramirez. This strategy compiles the visual vocabulary of the “Salad Bowl of the World.” A collected series of public images of its history, agriculture, and architecture located in key sites across the Valley redefines the aesthetics and uses of many public areas. Together, these public images completely transform the perception of the Valley.

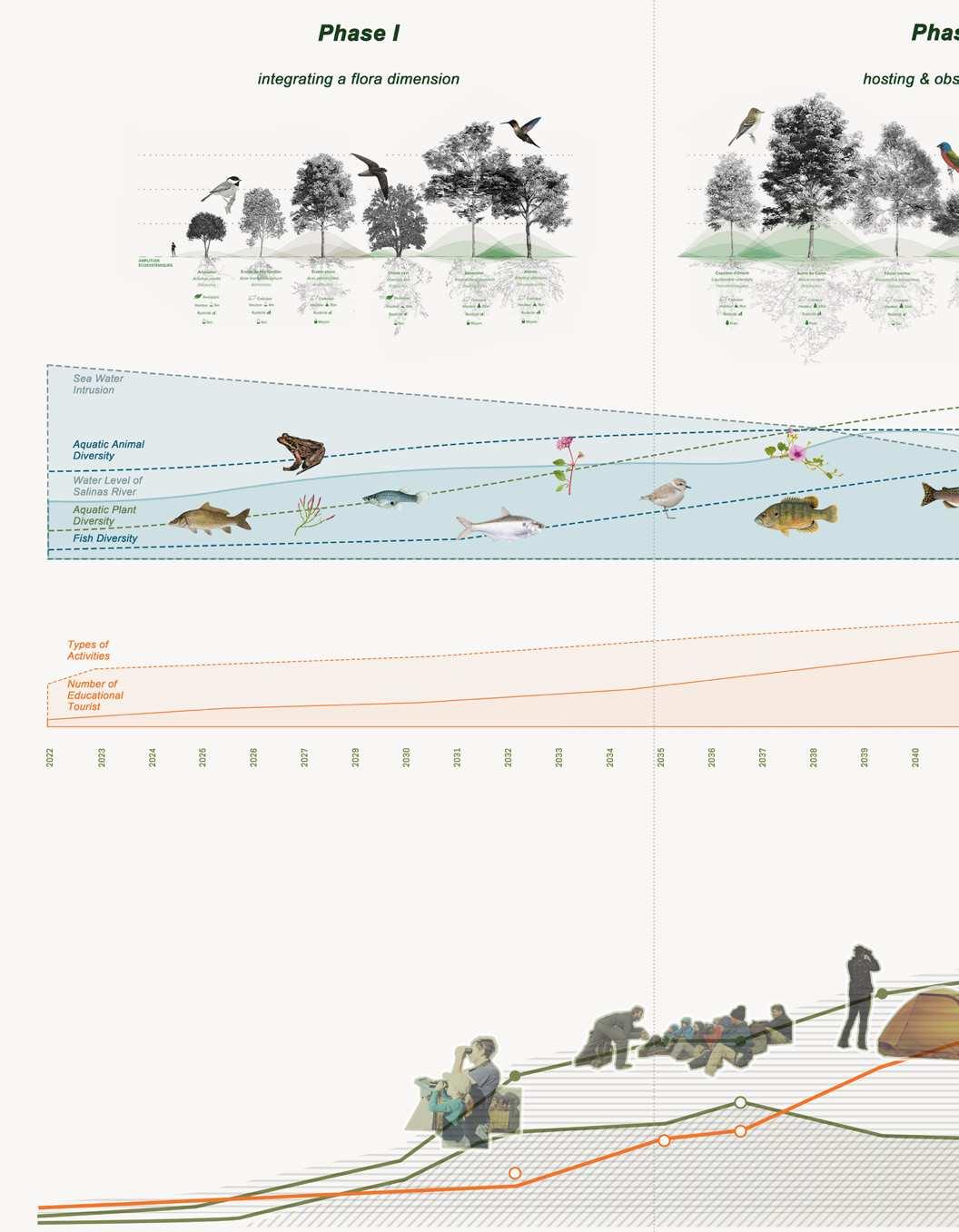

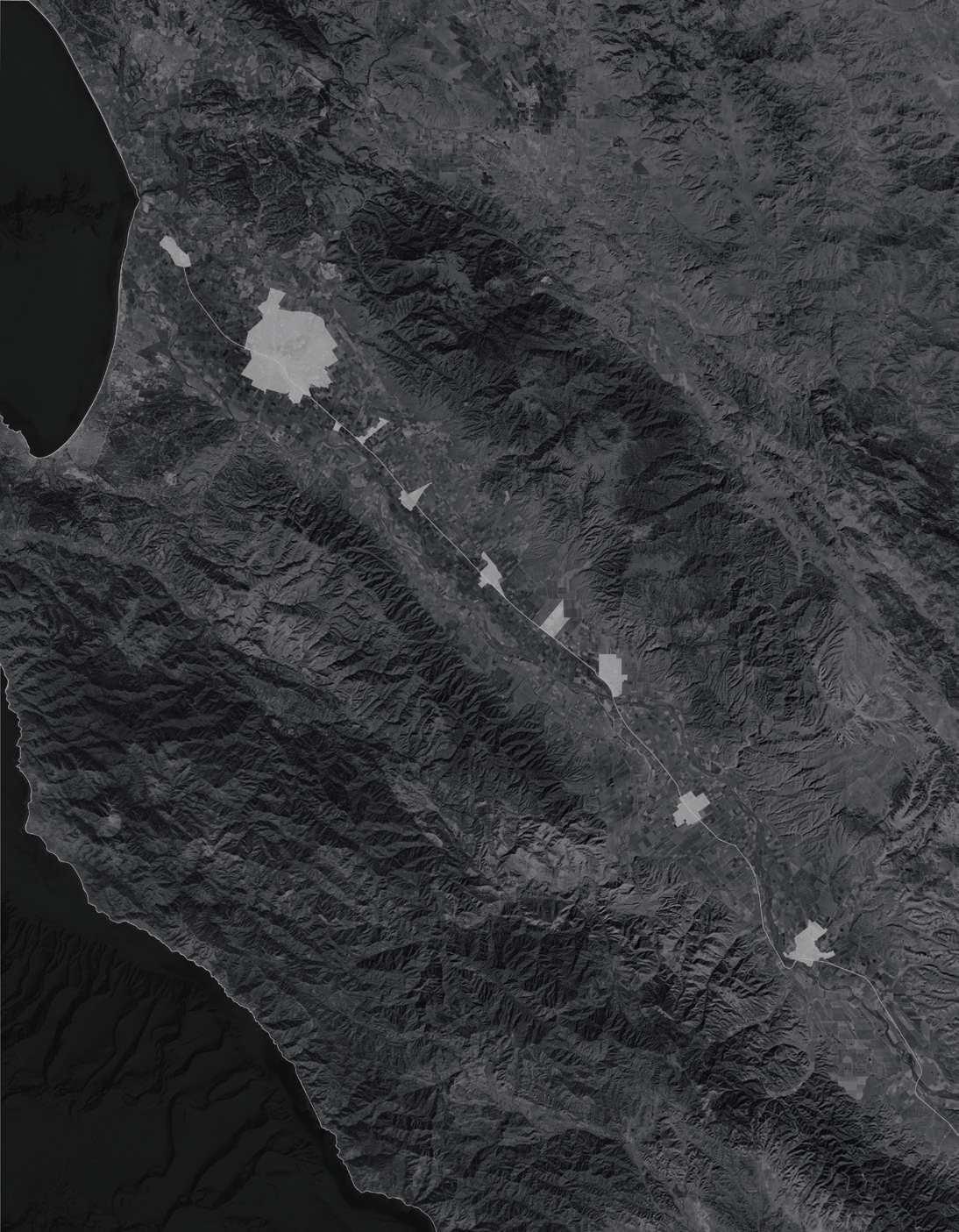

5.Rewilding the Valley, by Yash Gogri, Freya Tan, Mufeng Yu. This strategy proposes different educational experiences that aim to create awareness of the rich natural resources of the Salinas Valley. Combining education, recreation, and ecology, all projects envision knowledge productions that will empower human and nonhuman inhabitants of the Valley.

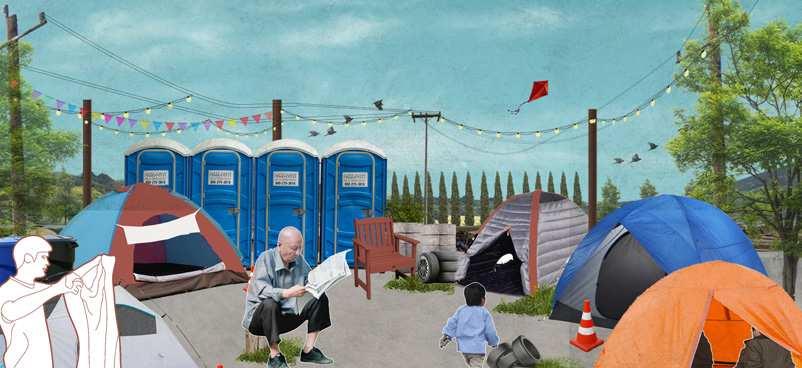

6.Housing the Valley, by Sagarika Nambiar, Srusti Shah, Varun Shah. This is a tactical approach to reconfigure housing using different degrees of temporariness. The strategy proposes multiple, coordinated, low-cost, temporary solutions that intervene holistically in the valley’s housing crisis.

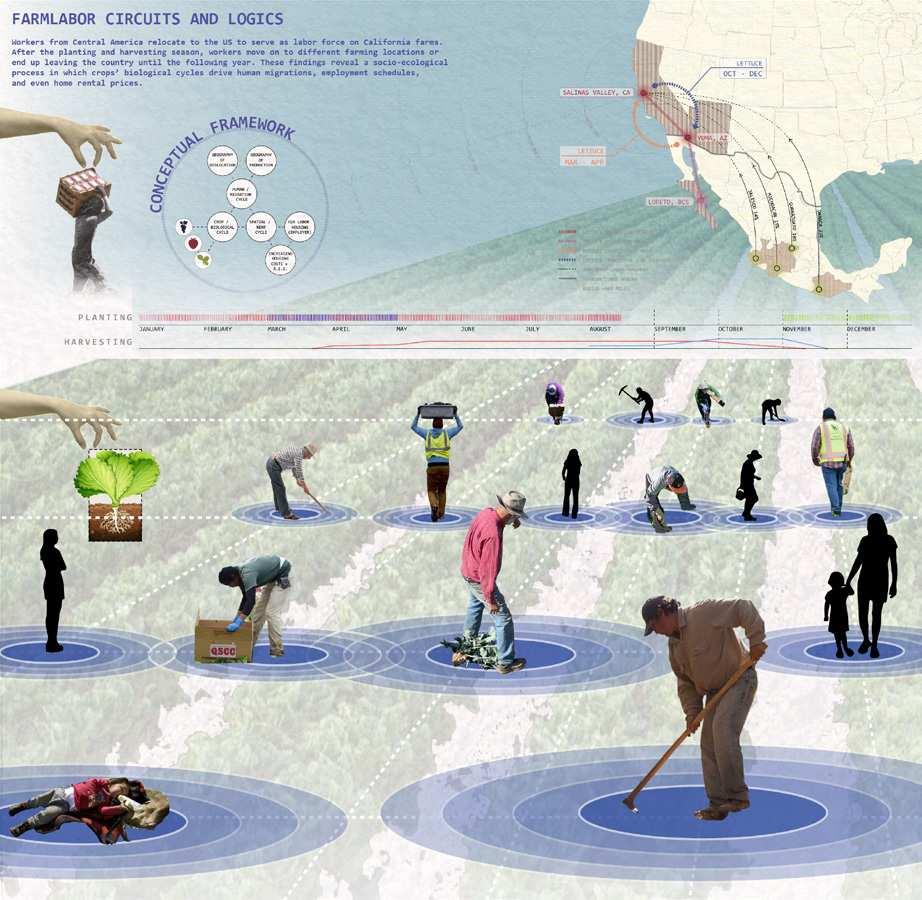

is a person who: during the preceding 12 months, worked at least an aggregate of 25 or more days or parts of days in which some work was performed in farm work; earned at least half of his or her earned income from farm work; not employed in farm work year-round by the same employer

is a seasonal farmworker who has to travel to do the farm work and is unable to return to their residence within the same day

LETTUCE PRODUCTION NETWORK

LETTUCE PRODUCTION NETWORK

LETTUCE TRANSITION - MAIN

LETTUCE TRANSITION - AS REQUIRED

IMMIGRANT LABOR MOVEMENT

TRANSNATIONAL BORDER

RADIUS +500 MILES

Crops Loop H-2A seasonal field laborers working with contractors travel between differnet crops and farms

Credits - Yaoyao Ding, Jiaxing Cui and Yash Deepak Gogri

Credits - Mufeng Yu, Byron Li and Varun Shah

“Comprehensive implementation of Agrotech products in the industry will not happen without a qualified workforce. Although the education and training of a tech savvy workforce will happen over time, we need to rely heavily on teaching and train ing today’s students and current workforce. That effort needs to be more strategic and Executive Director of the NGO Salinas Valley

“We have an abundance of natural land scapes found in the Salinas, San Juan and San Antonio Valleys, not to mention two National Park Service assets in our region — Pinnacles and the Juan Bautista De Anza Historic Trail. Leveraging these two assets’ ties together taps into the economic tourism activity that is already found on the coastal

“The survey asked farm workers if they would prefer to have a permanent residence in Mon terey or Santa Cruz County, if available. Some said they would prefer it. The wish to live in a better location under more comfortable condi tions, close to work and opportunity, was the overwhelming sentiment that came through in the responses.”

“Light that escapes into the sky is detrimental to experiencing clear dark skies in urbanized areas. I was able to illustrate the vastness of options that may be available if Pinnacles were to capitalize on this opportunity of becoming a dark sky hotspot. I believe that dark sky tours could become larger scale community events that could be explored in and around campsites, as well.”

“I wish that accessibility and connectivity were more developed both inside and to the park. The parks do get a lot of wildlife that traverse them on a regular basis - mountain lions and coyotes are the most popular. On occasions we also have birds and reptiles. Maybe if there was public transit available, more people would want to visit them here.”

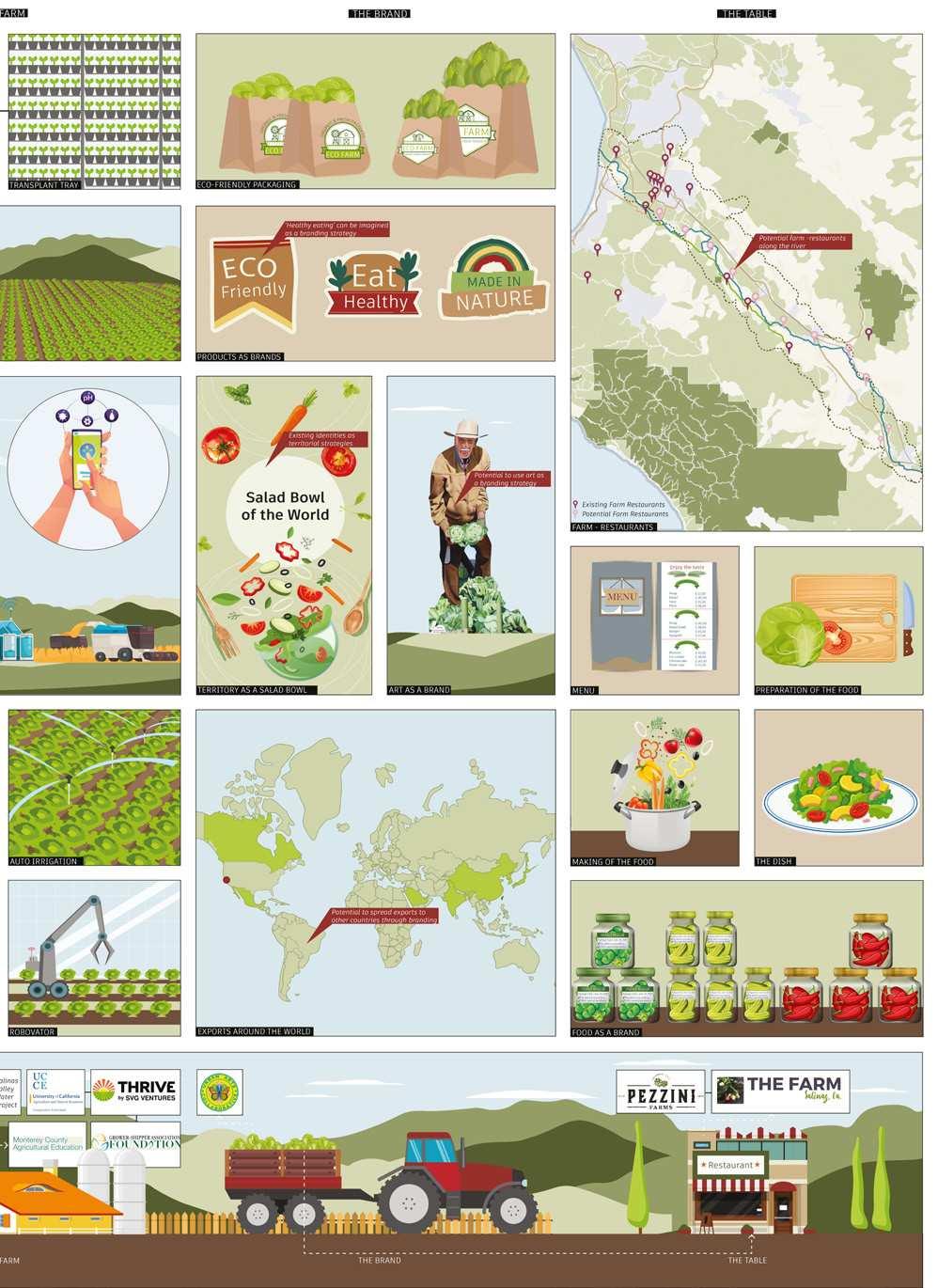

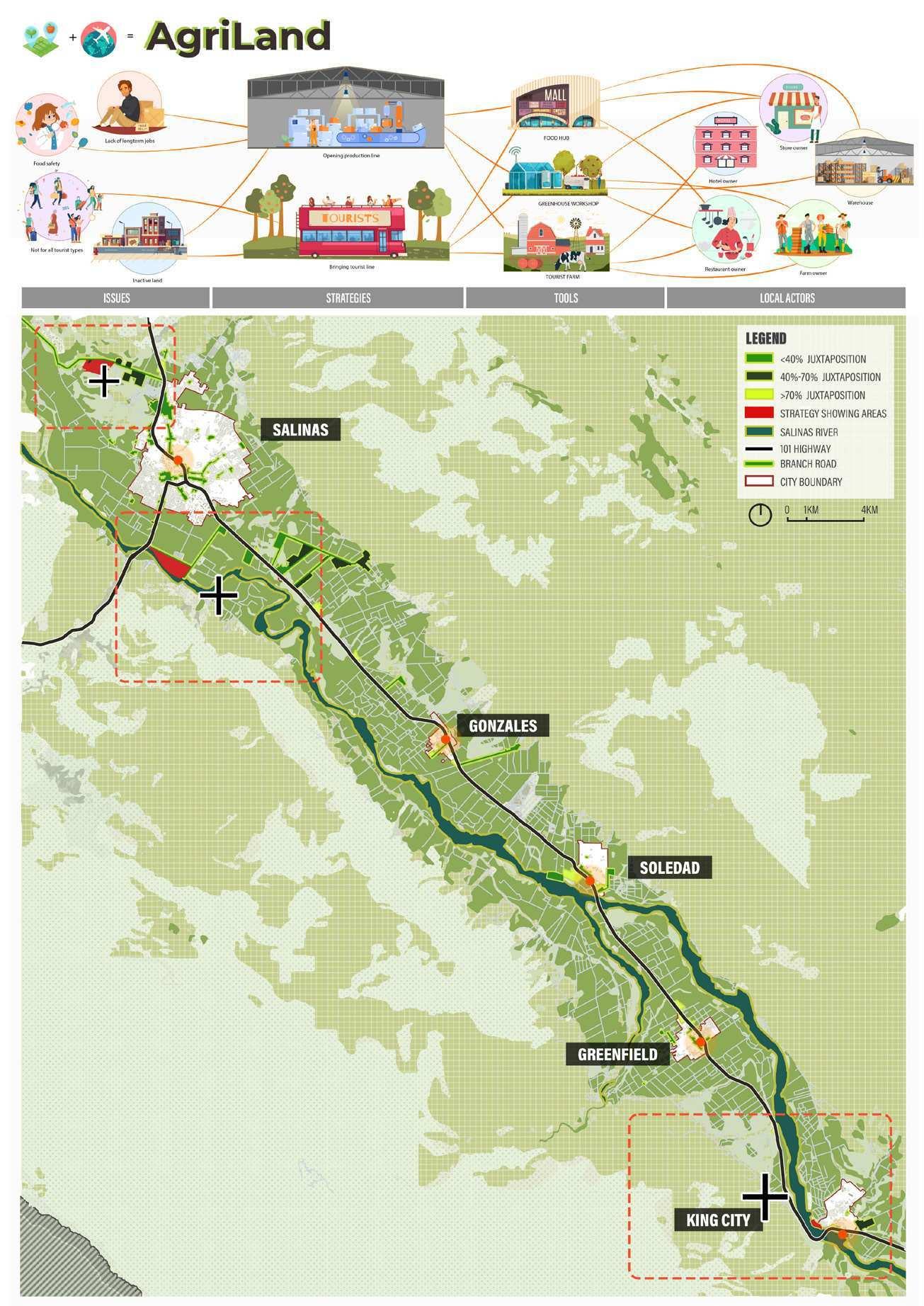

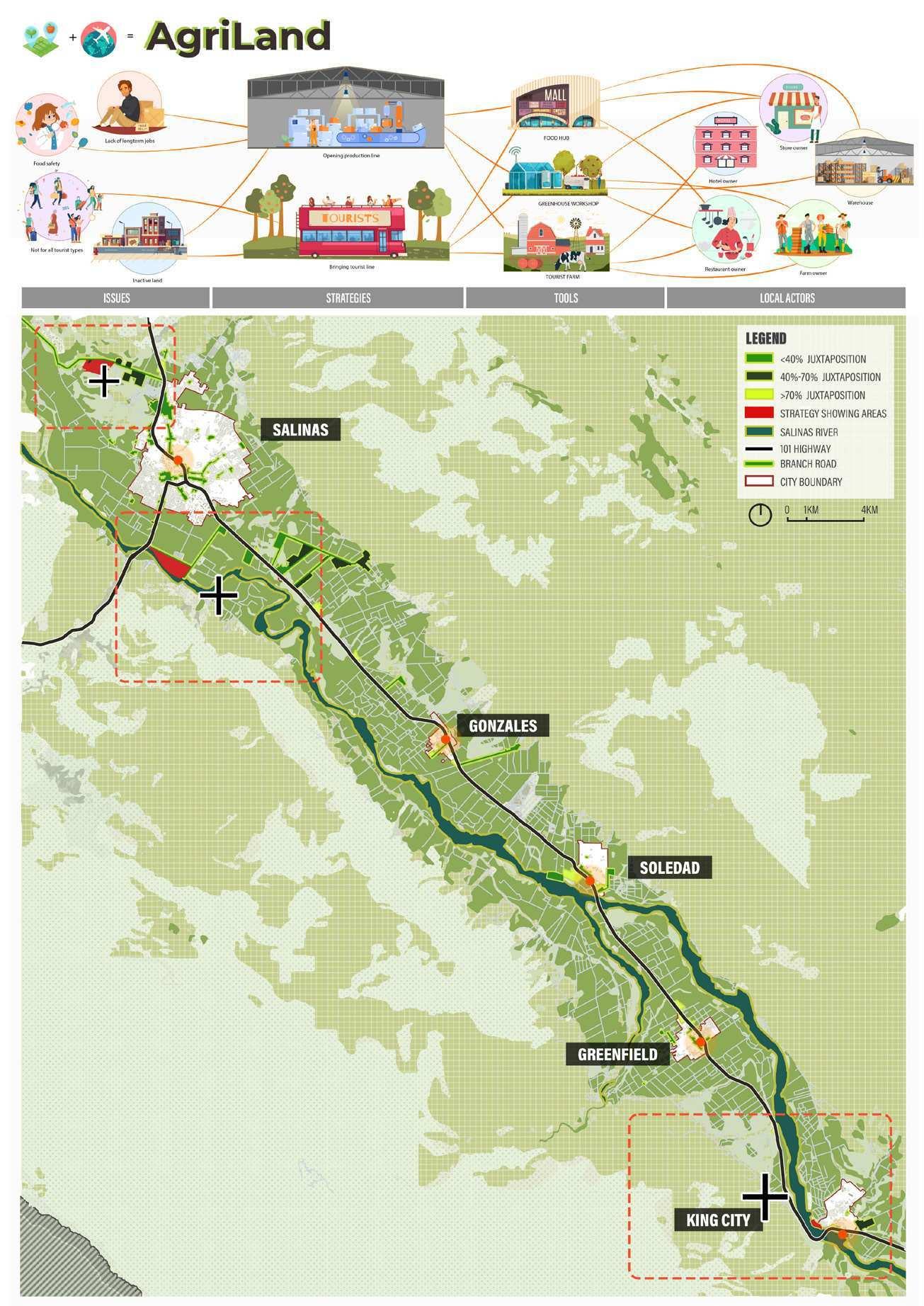

The Agroway seeks to make visible the agricultural processing that takes place in the Valley, often locked inside black-boxes and is often invisible to outsiders. Rita Ling, Yaoyao Ding, and Byron Li envisioned a series of nodes along Highway 101 where travelers can make stops and explore the Valley’s food operations. Their project aims to increase public awareness of the labor, technology, and capital involved in the food we receive on our table every day, while also raising appreciation for the region’s rich environment.

The proposed nodes create a range of opportunities for visitors and local small businesses, including farm and ranch visits and workshops held in greenhouses. The project includes the creation of a food hub modeled after the popular Eataly concept, but focusing on showcasing the unique local agricultural products. The hub would feature a grocery store, restaurants, and kitchens, along with demonstration farms that allow visitors to interact with the production process. Overall, the strategy reconceives this segment of the H-101 into an agro-experiential highway, which would support the local economy and foster a deeper appreciation for the work and dedication of the Valley’s agricultural labor.

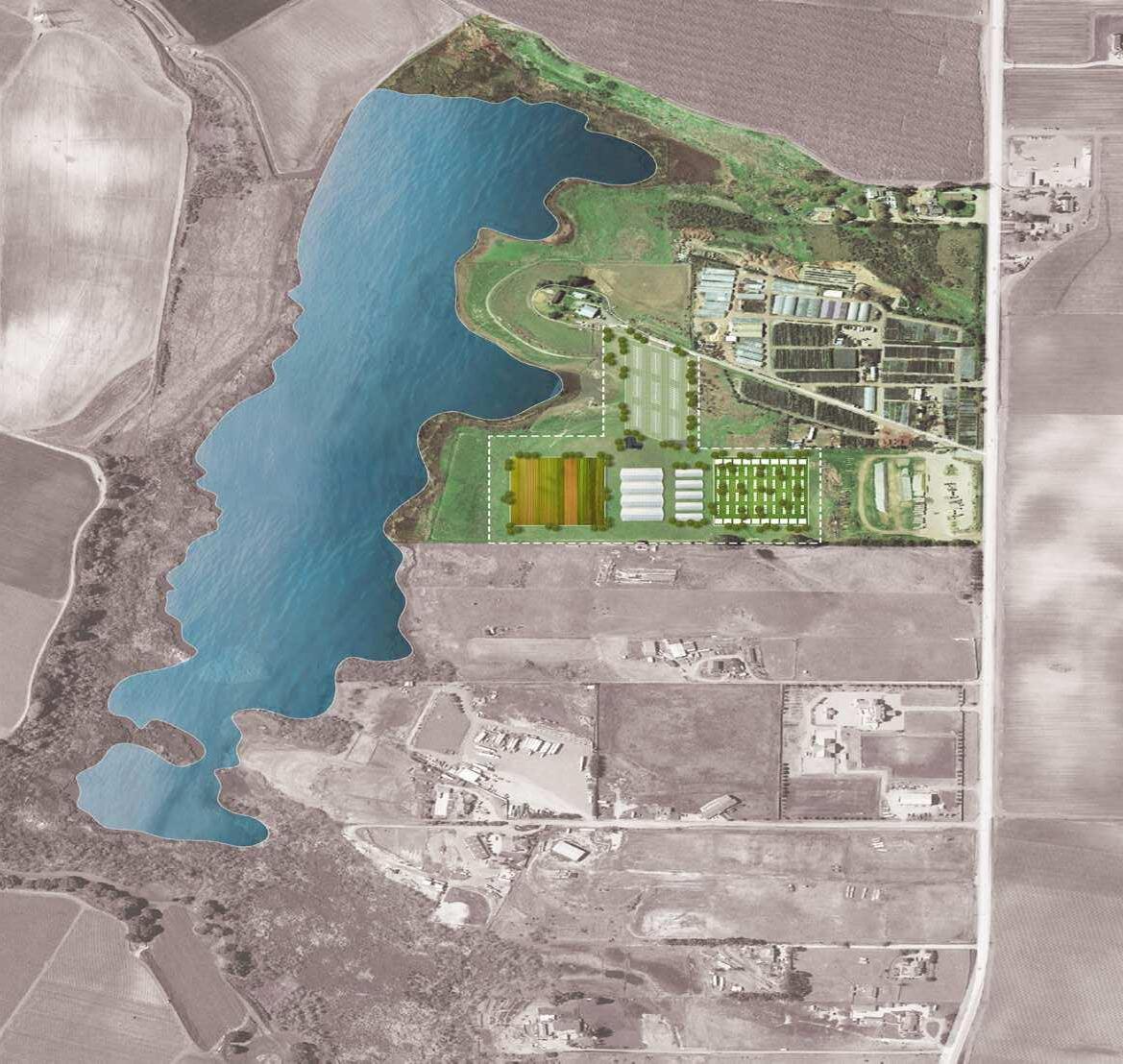

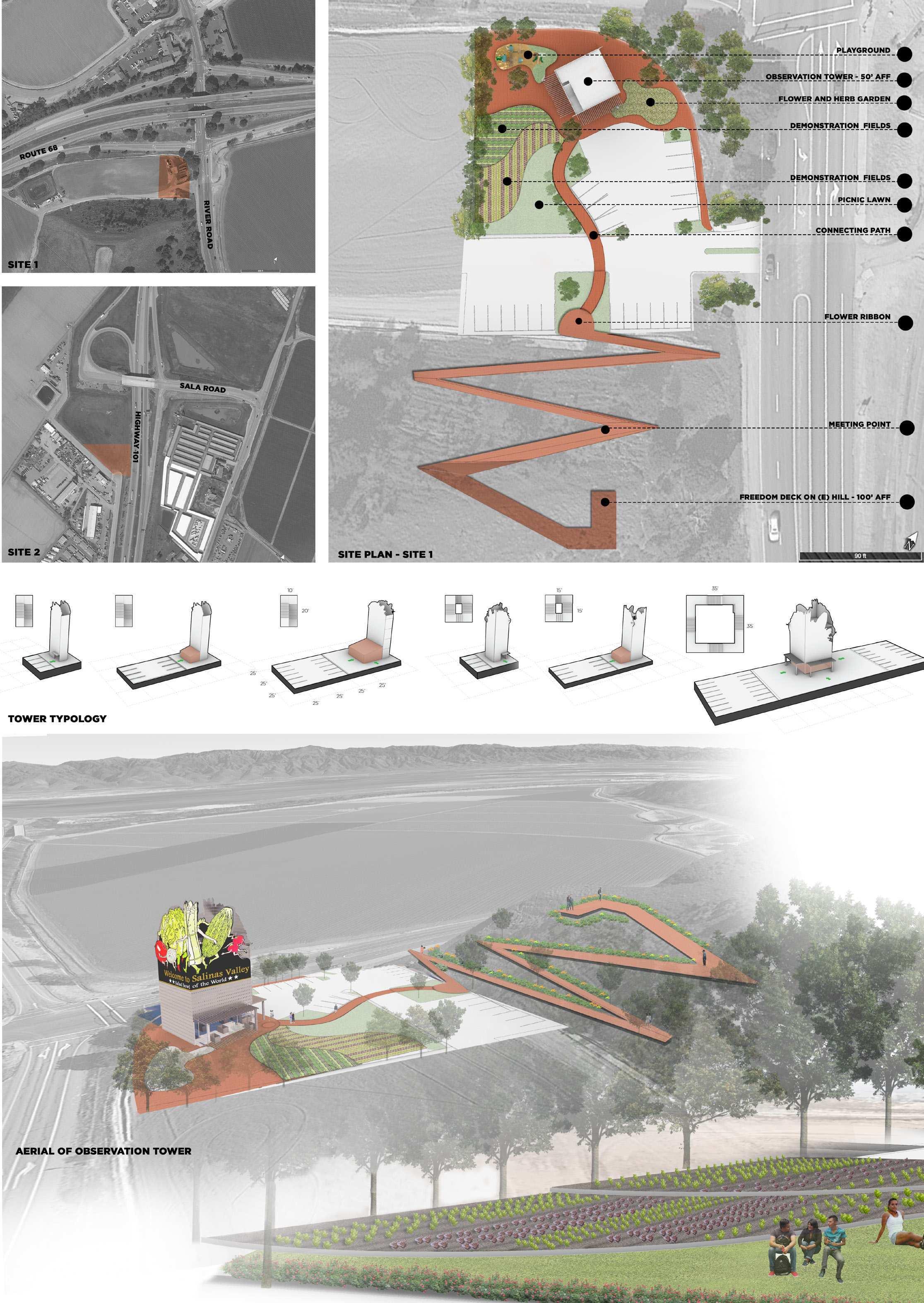

Thousands of cars drive through the Salinas Valley every day, but they hardly make stops. The strategy seeks to bring together the flow of cars crossing the Valley with the food production flows happening in the Valley. For doing that, the three major nodes are: a food hub, located at the headquarter of Tanimura & Antle agribusiness, in the adjacent to Spreckels Sugar Factory; a greenhouse workshop located at the Lakeside Nursery, in north Salinas; and a Ranch Hotel and public park located at the San Lorenzo County Park in King City. These three major nodes can catalyze further economic activities (vending, food trucks, hospitality) along the 101 corridor.

Visitors can download an app that geolocates the different attractions along the agroway. In addition to the three main nodes, all businesses partaking in the Agroway project can be visible on the App. In this sense, the Agroway turns into an infrastructure that connects drivers to local businesses in both physical and virtual space.

Spreckels Sugar Factory, now Tanimura & Antle Headquarter

Lakeside Nursery

San Lorenzo County Park King City, CA

A portion of empty land inside the headquarter of Tanimura & Antle Inc. in Spreckels is designated as the Food Hub. The hub is accessible from Spreckels Avenue, a beautiful tree-lined road that offers a perfect entry point into the Valley. Beyond Highway 101, this site is also connected with Highway 68. This location makes the hub very suitable to attract residents of Monterey and the Peninsula into the Valley. This building integrates local organic produce markets with kitchens and restaurants distributed on three floors. The outdoor space is a demonstration farm, a large publicly-accessible cultivated area where visitors can pick produce or make a stop for eating.

The Lakeside Nursery in northern Salinas is an example of a local production and warehouse business to be transformed into a larger tourist attractor. Empty land in the nursery is set to accommodate new interactive exhibition greenhouses, where tourists can learn about the food processing in the Salinas Valley, participate in growing procedures and remotely monitor the growth of their crops through an app. Greenhouses may showcase processes around lettuce, strawberries, mushrooms, and more. A set of workstations are made available for visitors, schools, and large groups to take farming and cooking classes. The area also features a demonstration farm and a marketplace.

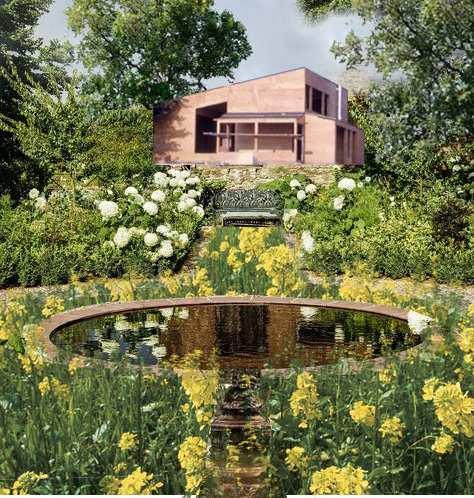

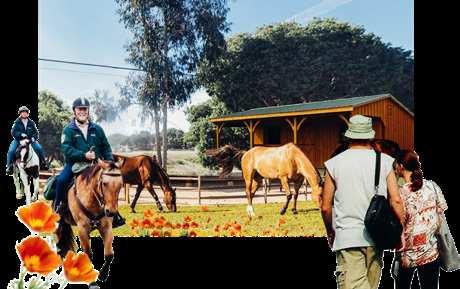

The County-owned San Lorenzo park in King City will accommodate a ranch resort. This node integrates different forms of low-impact hospitality (suites, rooms, log cabins, glamping, RV, and camping) with a horse ranch, animal enclosures, ponds, restaurants, shops, and a farmers’ market. The resort is directly linked to the hiking trails crossing the Salinas River, thus offering many opportunities for outdoor recreation. Most importantly, the resort maintains the public nature of the park by leaving its open areas accessible to the public. The resort is low-impact and reversible. All hotel facilities are designed to be easily removable (using prefabricated wood cabin units) and set to maximize the use of underground utilities already available in the park.

Juaxing Cui, Sen Du, and Xuyuan Fan’s project centered around the historic Anza Trail, a route established in 1775-1776 by Spanish commander Juan Bautista de Anza to extend Spain’s influence to what is now the Bay Area. The Anza expedition largely followed trails already used by Indigenous groups inhabiting the Salinas Valley. Today, the Anza Trail is largely invisible.

The project brings the Anza Trail back to life by marking it with native wildflowers such as California poppies. Native plants are a way to reclaim the Trail’s belonging to Indigenous tribes. The team’s proposal also incorporates two land restitution strategies for sites that were important to the Esselen Tribe of Monterey County. To further enrich visitors’ experience, the project includes open-air museums to be curated by Indigenous groups, food stops, and craft markets at the various missions along the trail. The Trail also connects with nearby wineries to generate outdoor recreational activities. This allows visitors to immerse themselves in the history and natural beauty of the Valley, experience the products of its land, and learn about the Indigenous past that underpins its present-day outlook. The project serves as an example of a sustainable and justice-oriented tourism model that benefits visitors, tribal groups, local businesses, and residents.

Fragmented history and historic landmarks remain on the Anza trail. These precious clues tell the complex history of California, from indigenous tribes to various stages of colonization. With the funding from National Park Service and the fame of the Anza trail, we will embrace this plurality and fragmentation by offering a variety of experiences and perspectives within a unitary consolidated trail. At the same time, we are also trying to repair the harm colonialism has done on indigenous people.

A Big Effort from NPS Already Exists

A Widely Known Anza Trail Story

Strategies

Potentials Challenges

Potentials Challenges

Fragmented Historical Information

Objective

Objective

Strategies

Mark The Trail through Native Flowers

A Widely Known Anza Trail Story

Fragmented Historical Information

Complexity of History

Partnership

Land Restitution for Native People

Land Restitution for Indigenous People

Complexity of History

Activate Missions and Overlay Indigenous Elements

Activate Missions & Overlay Indigenous Elements

Cooperate with Various Levels of Businesses

Cooperate with Various Levels of Businesses

ESSELEN TRIBE SALINAN TRIBE

Missions Foundation TIER II Cities in Salinas Valley TIER III Partnership Private Organization/ Company TIER VI TIER I National Park Service Native Tribes

The primary component of the strategy is the consolidation of the original trail by marking its sediments with native plants. These flowers not only enhance the landscape experience but also communicate the belonging of the Anza trail to the native tribes.

Mission will serve as a main showcase of Indigenous histories. In partnership with the Missions foundations, Mission Soledad, and Mission San Antonio de Padua, the project reclaims new exhibition areas to be curated by the Valley tribes, which will showcase the Natives’ perspective of the Valley’s history. This project works in tandem with two landback strategies on the Santa Lucia Range.

Restoring the quadrangle courtyard with VR Educational Garden

A segment of the Anza Trail is now River Road, a scenic roadway adjacent to wineries and ranches. River Road offers unique elevated views of the Salinas Valley’s landscape. The strategy connects wineries on River Road to the Anza Trail program. Wineries can host glamping sites, food trucks for tasting events, shows and festivals. A new art studio can work in partnership with Salinas artists and galleries in the Carmer to further connect the Anza Trail to the Peninsula tourism.

The Anza Trail is first and foremost an experiential project that offers visitors multiple transportation options to explore the Valley, including cars, bikes, hiking trails, and horses. The strategy includes two horse stations at the beginning and the end of the existing San Juan Bautista de Anza hiking trail. Horse stations will activate the connection between Salinas and San Juan Bautista, bringing visitors to experience the Mission San Juan Bautista, also known as the Mission of Music.

Isha Khan and Patricia Flores proposed a literary tourism strategy. Their vision aims to establish pathways connecting towns in the Valley with significant locations mentioned in Steinbeck’s novels.

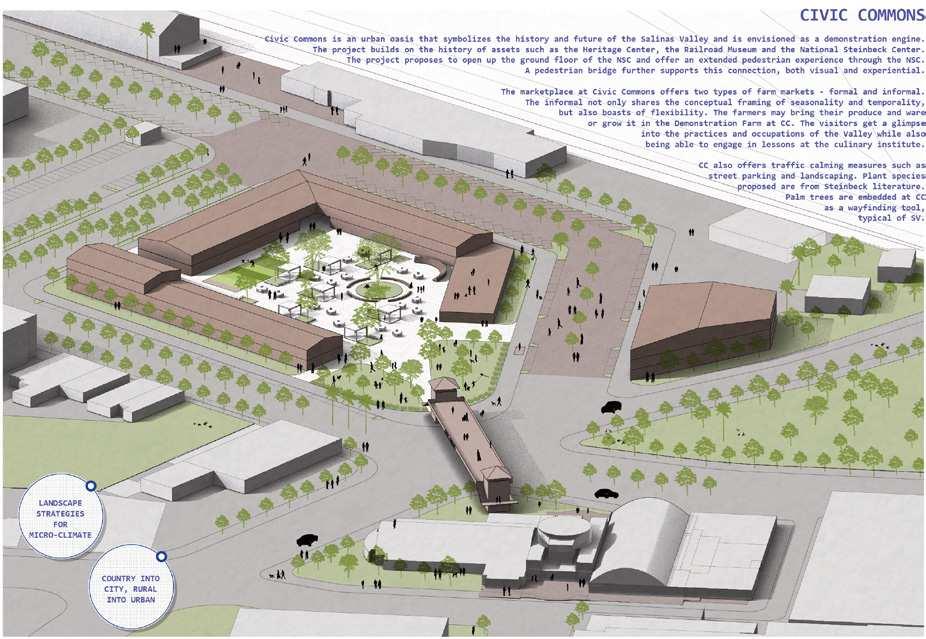

The project draws inspiration from Steinbeck’s ability to portray the lives of Valley residents, particularly farmworkers and immigrants, through trails themed around Steinbeck novels and infused with immersive experiences. The trail system also revitalizes underutilized areas in the Valley’s downtowns, such as a large parking lot located in the heart of Salinas. Students redesigned this empty space into a “Civic Commons”, a marketplace where locals, including farmworkers, can sell goods and access essential legal and healthcare services.

“Travels with Steinbeck” incorporates new campgrounds at Pinnacles National Park to observe the night sky away from light pollution of lower lands. The trails enable people to engage with the landscape and culture by immersing themselves into its smell, sounds, and tastes. All the literary tourism experiences offered by “Travels with Steinbeck” are designed to foster opportunities for locals’ engagement and economic benefits.

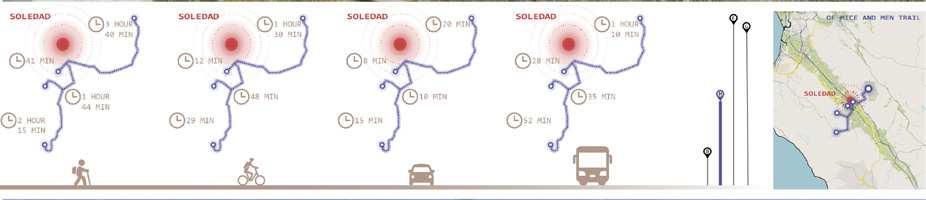

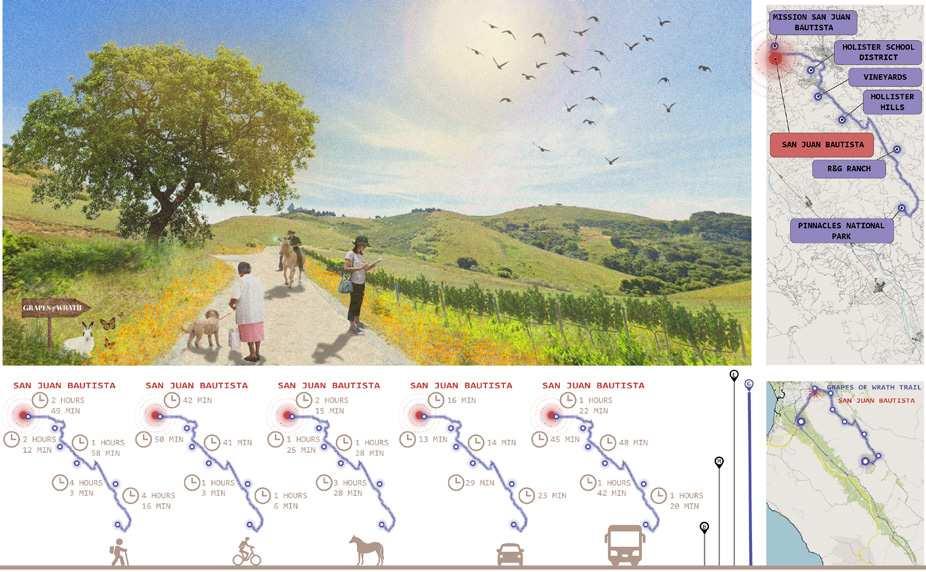

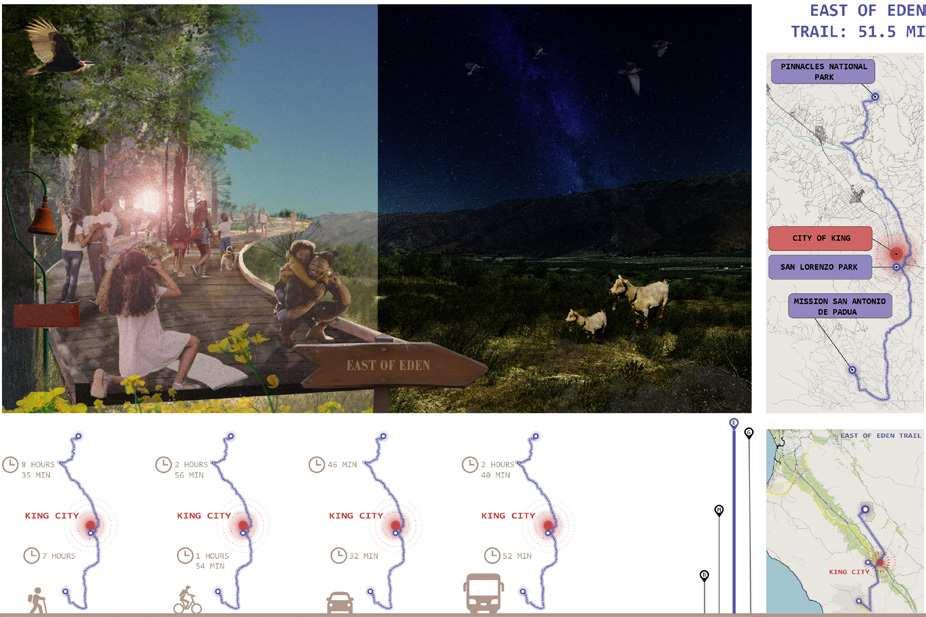

The territorial strategy identifies a network of cross-Valley trails designed around the places mentioned in John Steinbeck’s novels. Three trails are inspired by major works of Steinbeck (East of Eden, Of Mice and Men, and Grapes of Wrath), and one trail is inspired to Steibeck’s own life story. The trails are anchored to three downtown reactivation projects in Salinas, Soledad, and King City.

Civic Commons occupies a portion of the Salinas Amtrak Station Parking lot and Heritage Park. The lot was designed in anticipation of the (now suppressed) high-speed railway station.

Civic Commons will welcome visitors entering the valley via Amtrak. It will offer a marketplace and basic services for immigrant farmworkers and the unhoused population.

The “Of Mice and Men” literary trail connects Paraiso Springs, a unique vista point and outdoor thermal site, with Pinnacles National Park. The trail crosses some places where the story of George Milton and Lennie Small unfolded, particularly Arroyo Seco and Soledad. It also elicits broader reflections on the complex relations between the human and the natural world

Route Map

Observation Point

The East of Eden and Grapes of Wrath trail link Mission San Antonio de Padua, King City, Pinnacles National Park, and San Juan Bautista through a variety of historical and ecological experiences inspired by Steinbeck’s work. The trails expose visitors to the diverse natural cycles at multiple scales, from the cycles of crops to those of human migrations, from the changes of seasons to the rotations of planets– to be observed during Dark Sky Tours at Pinnacles

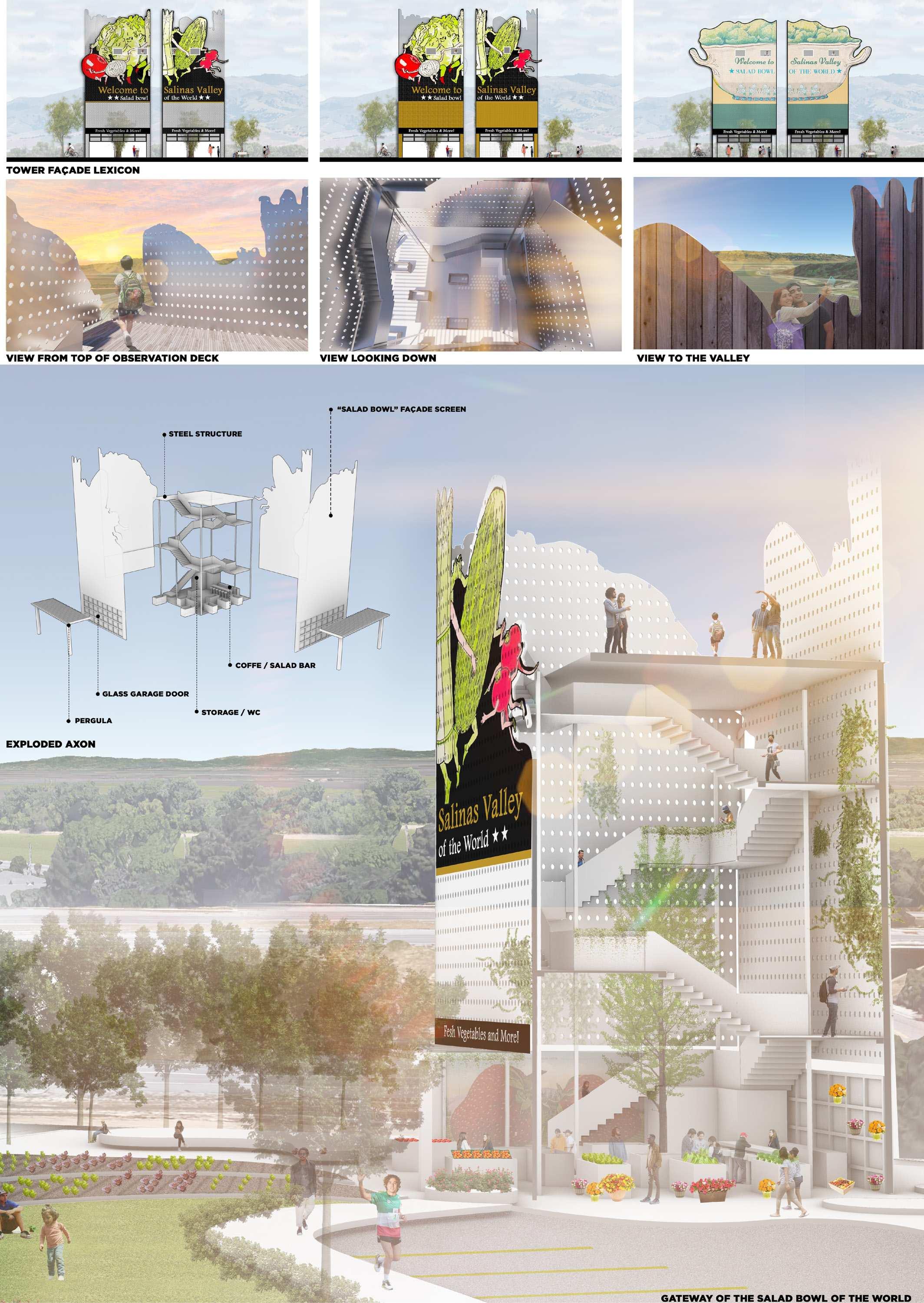

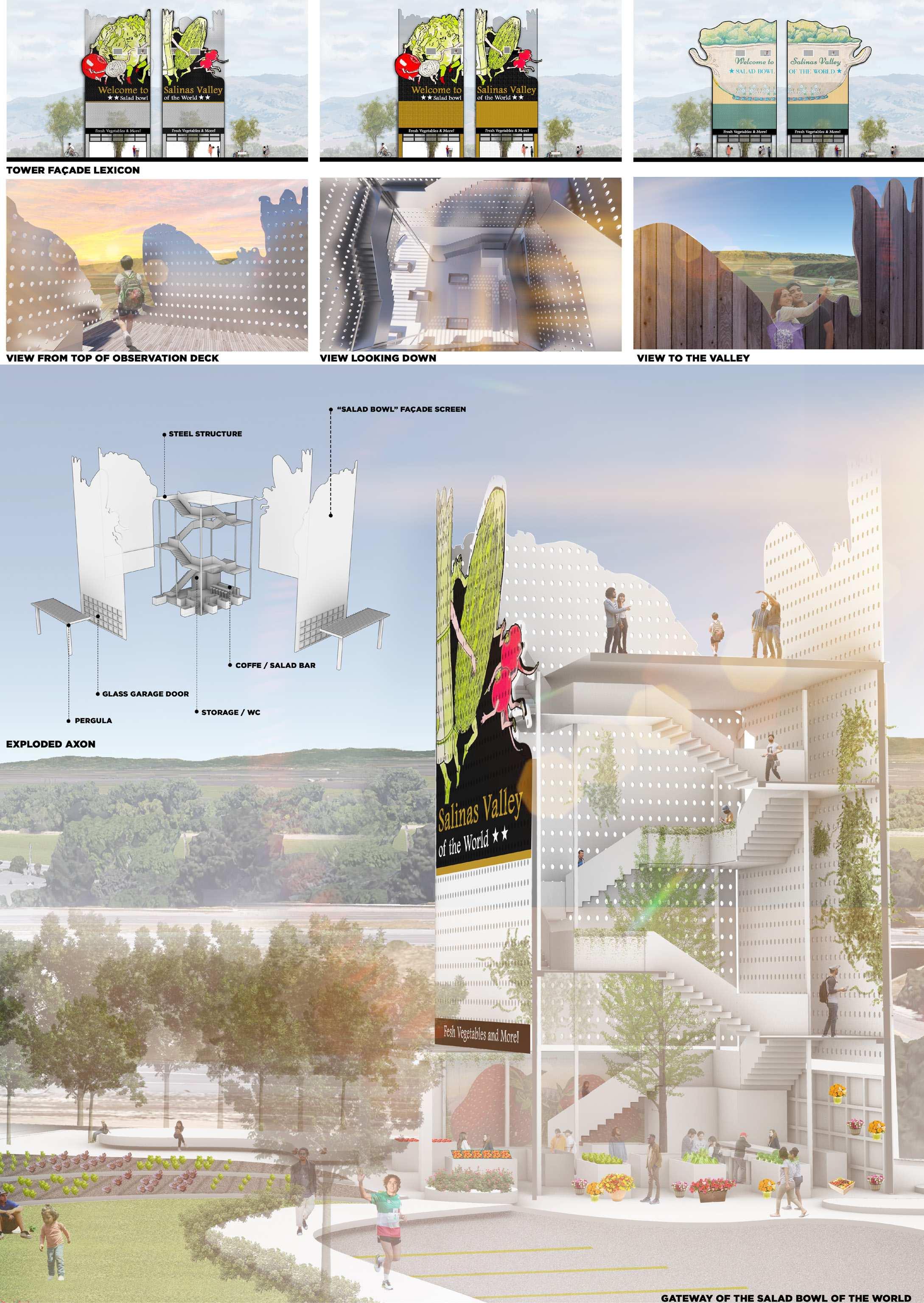

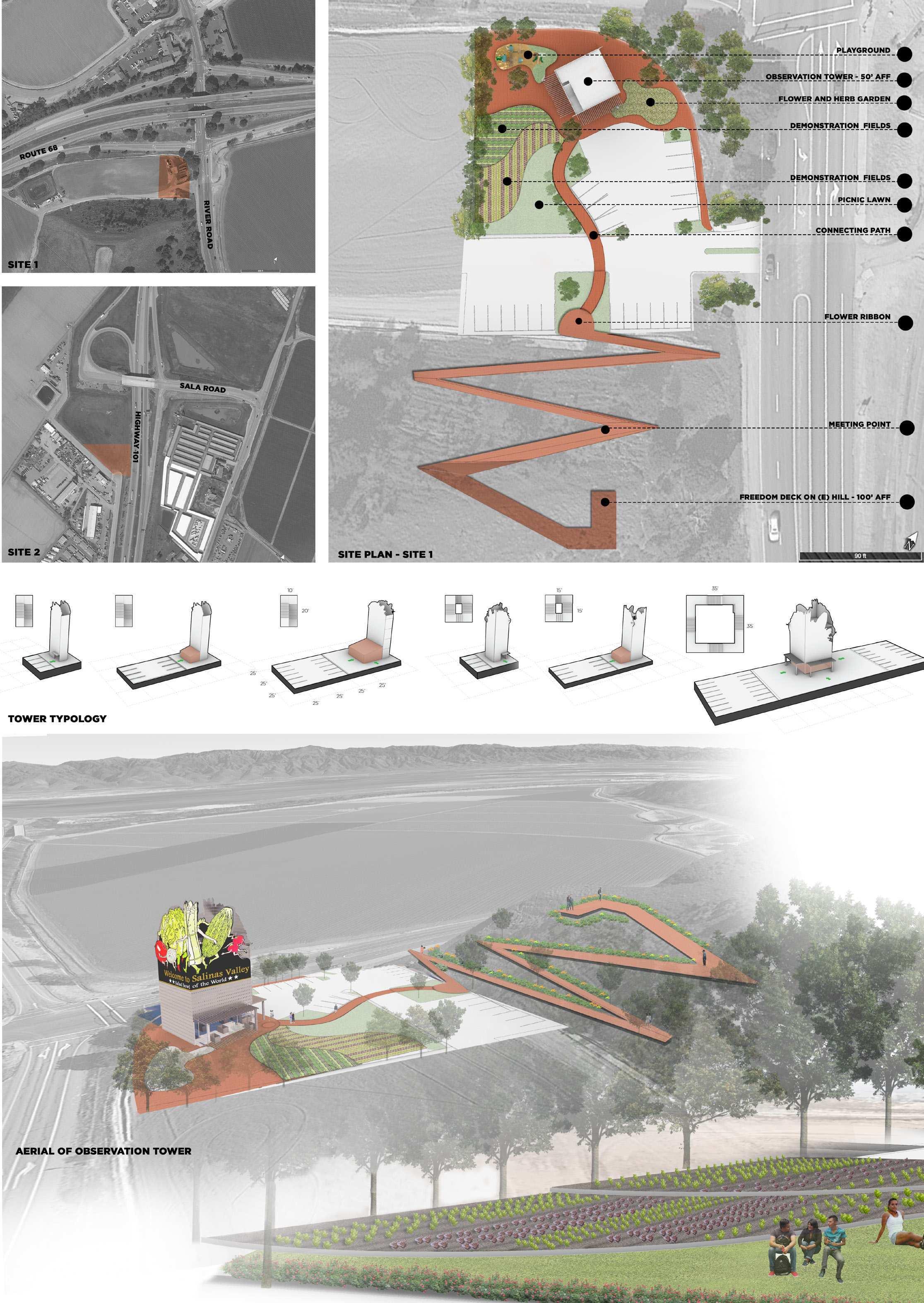

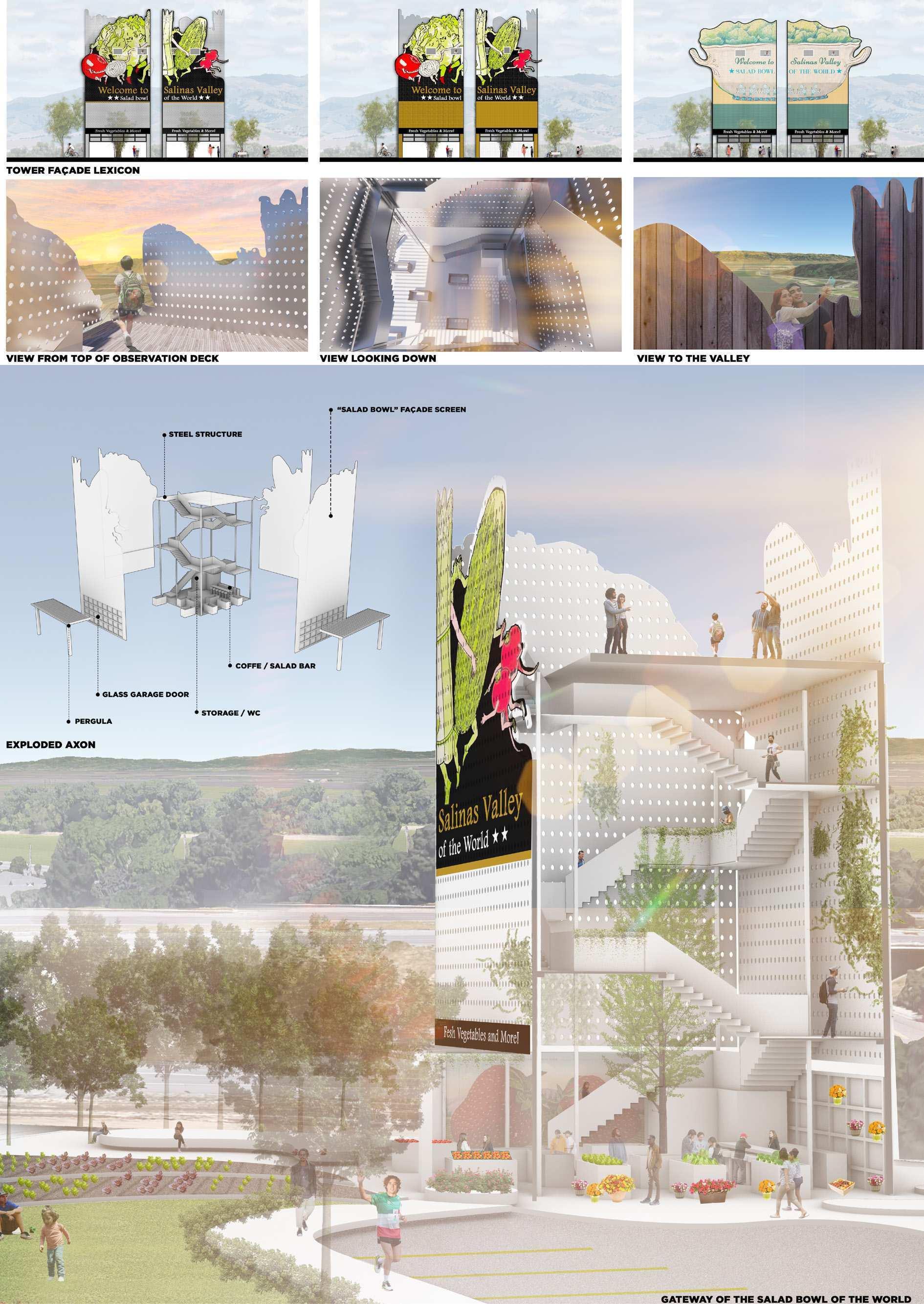

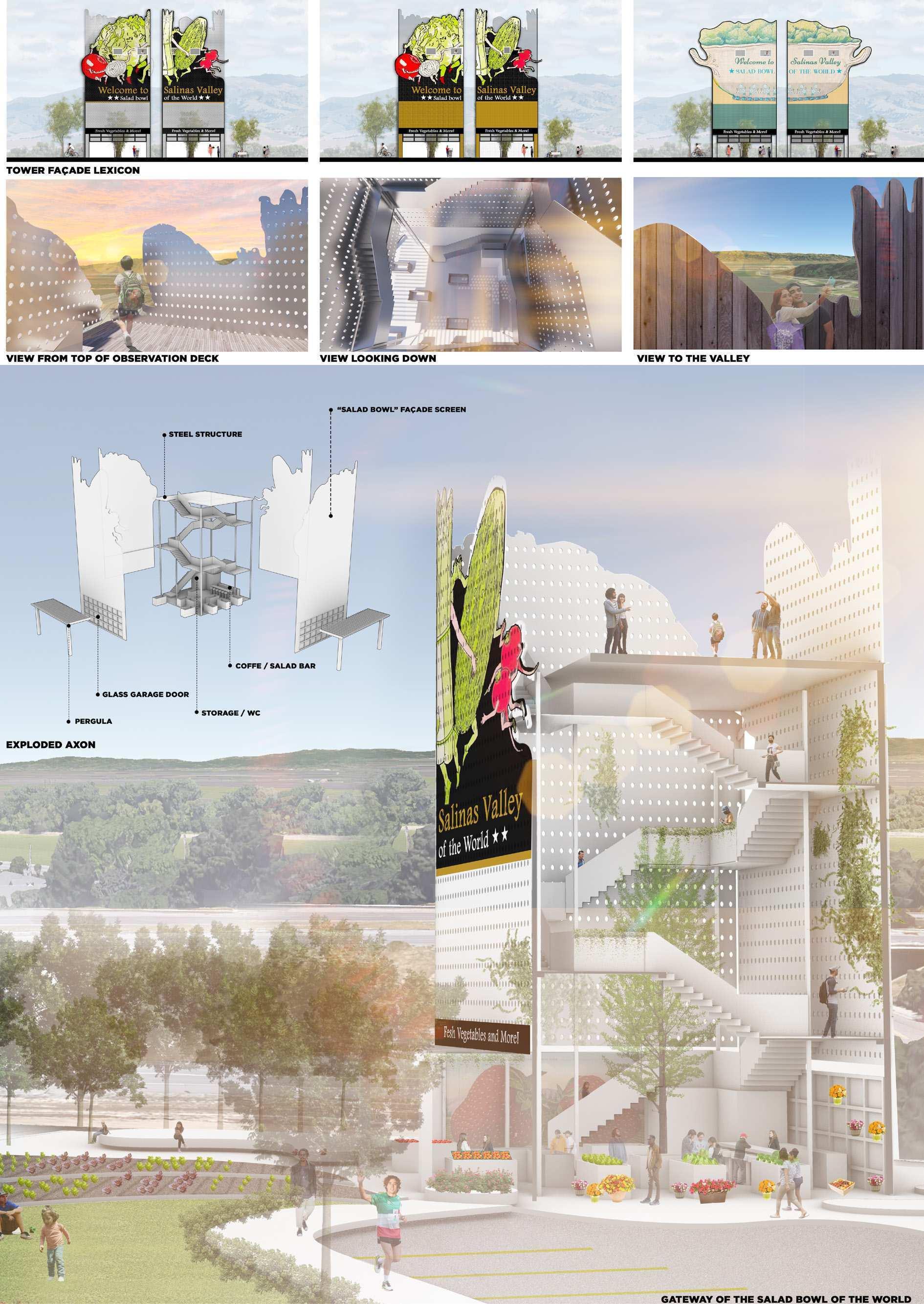

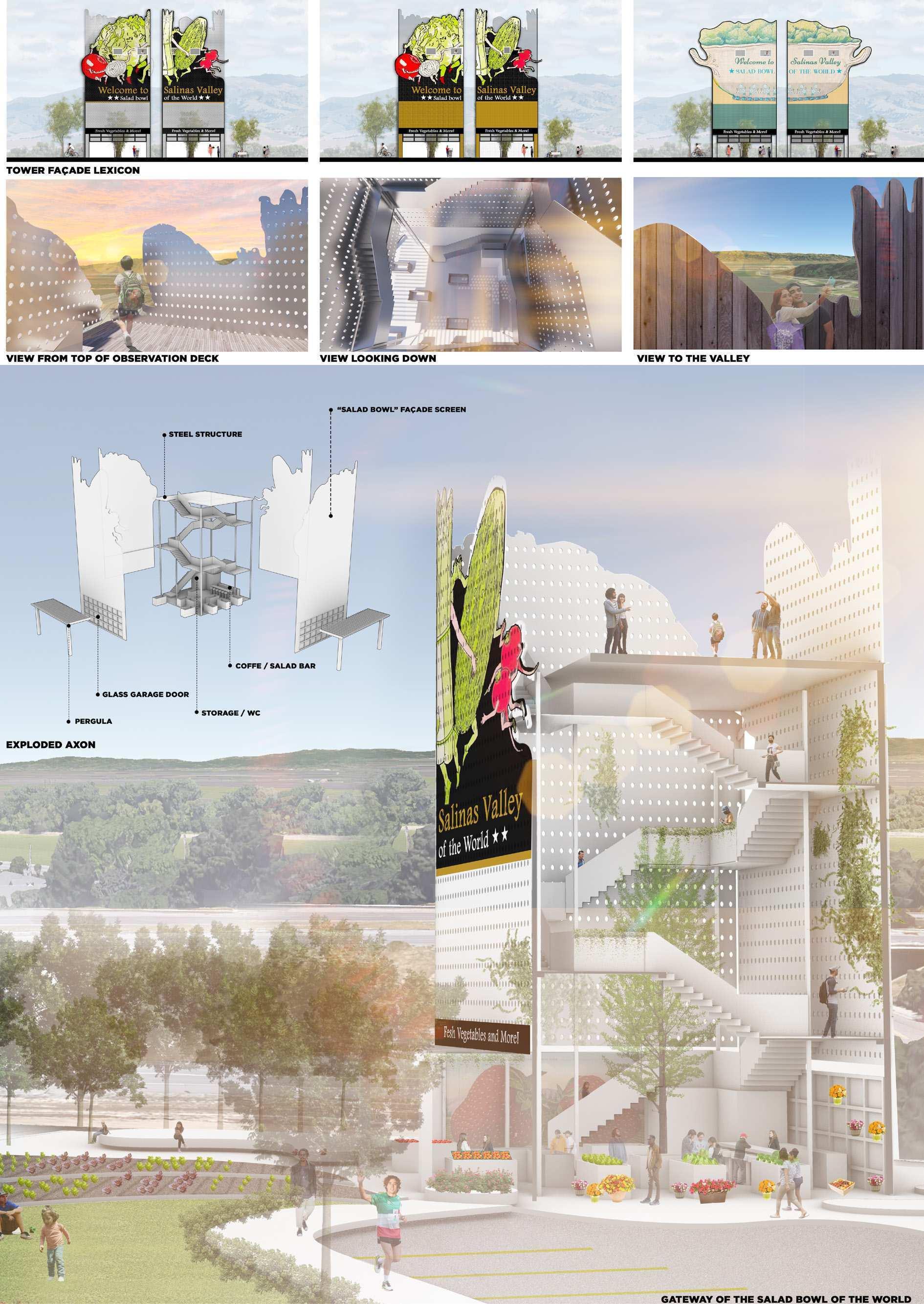

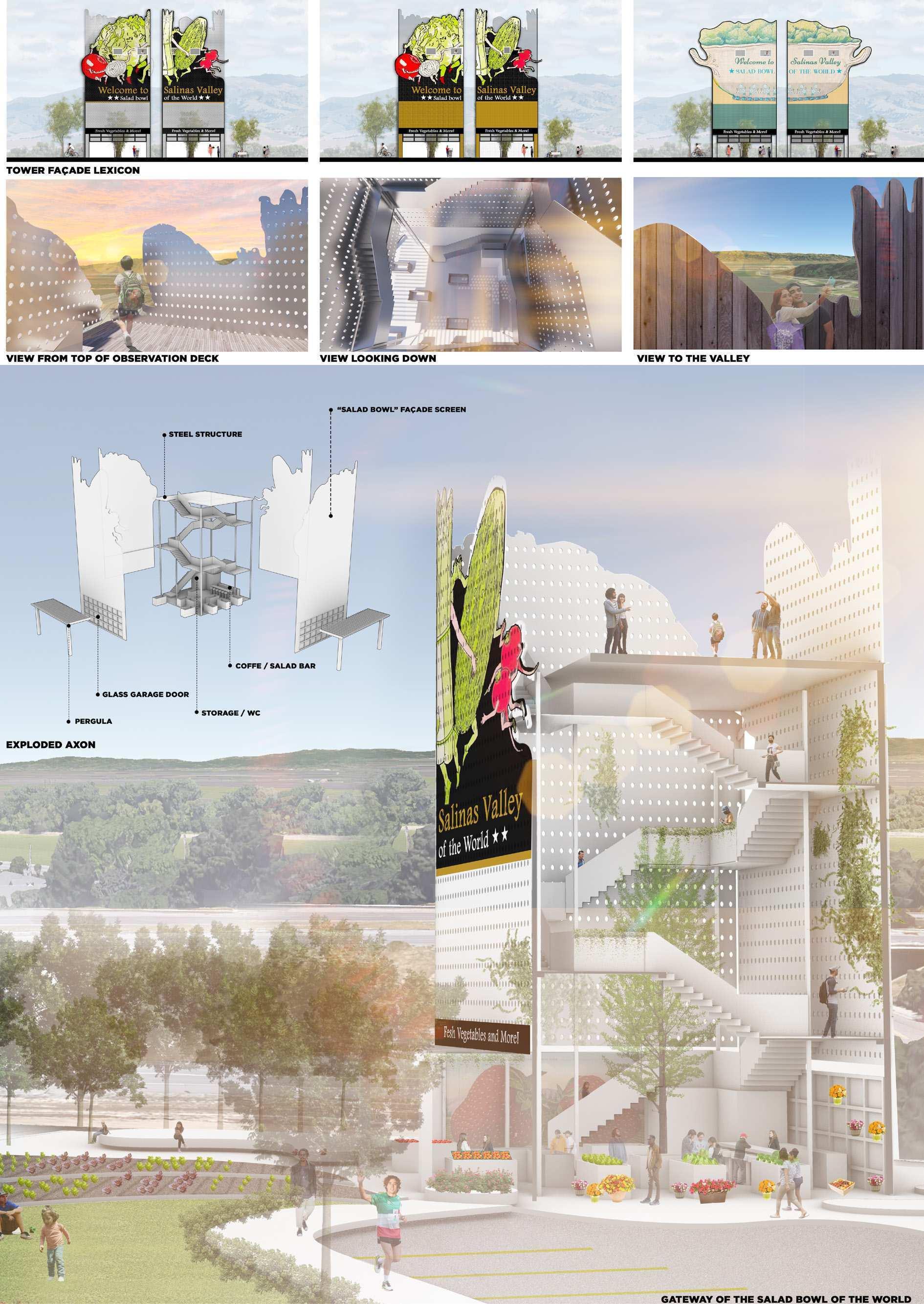

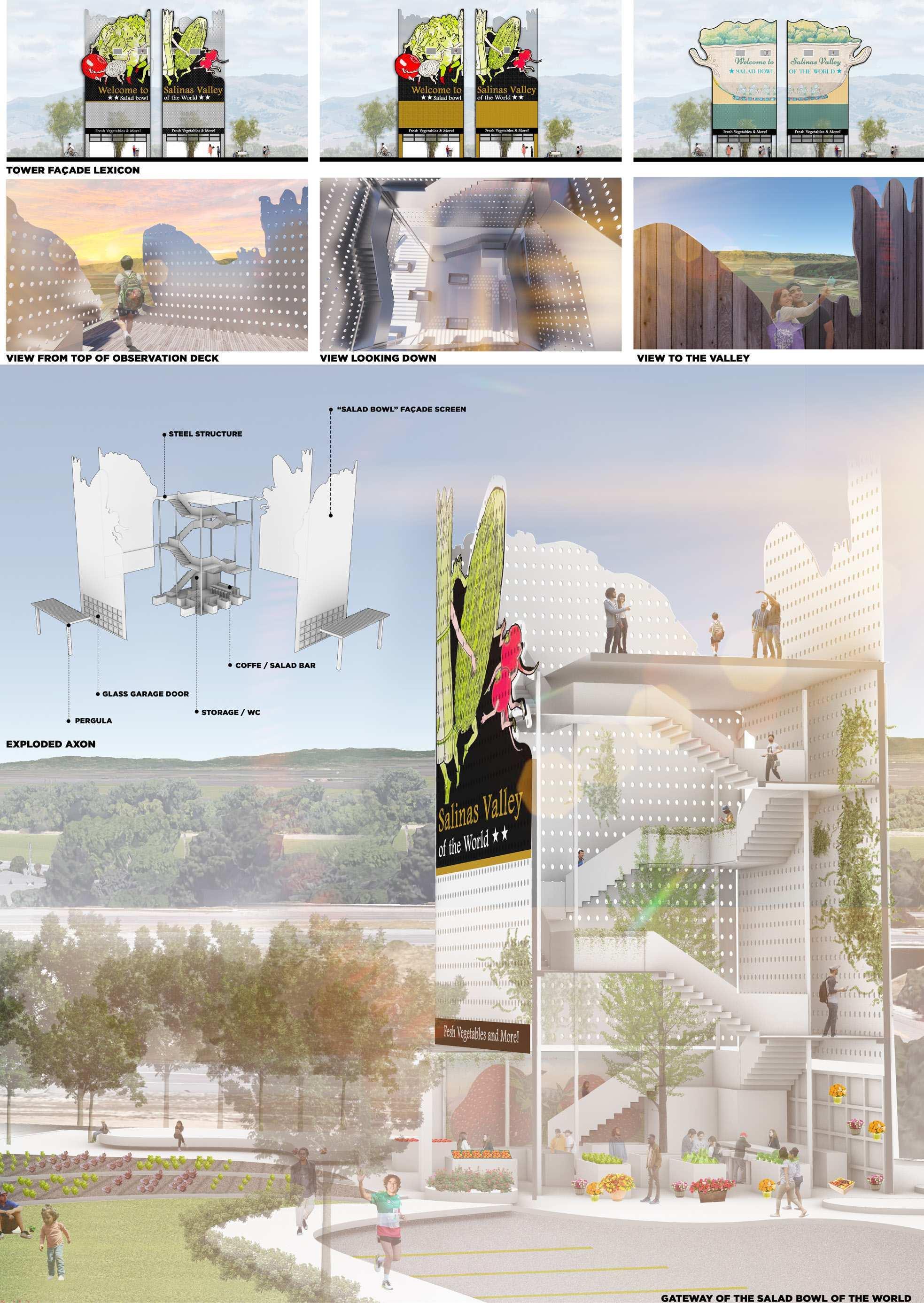

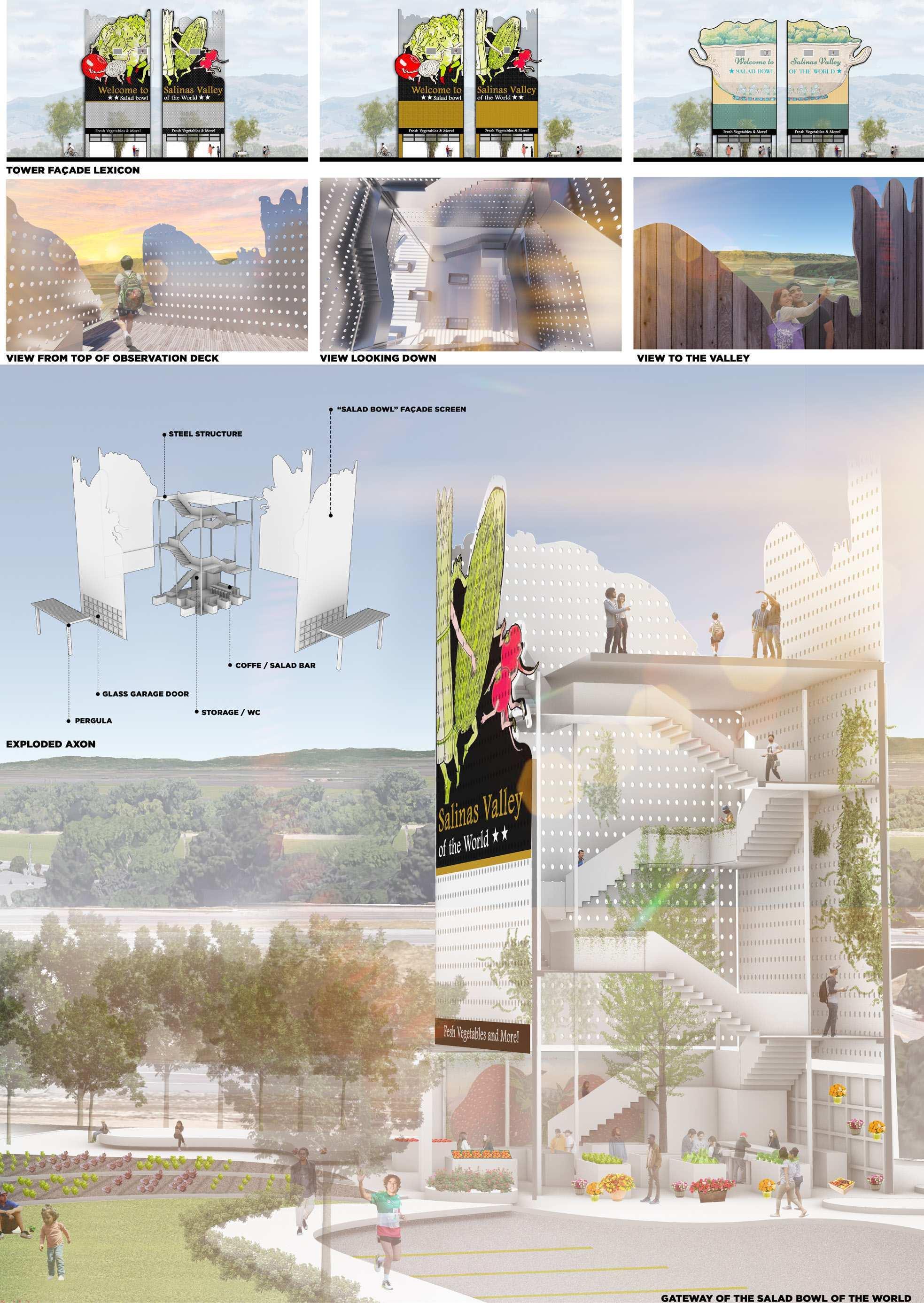

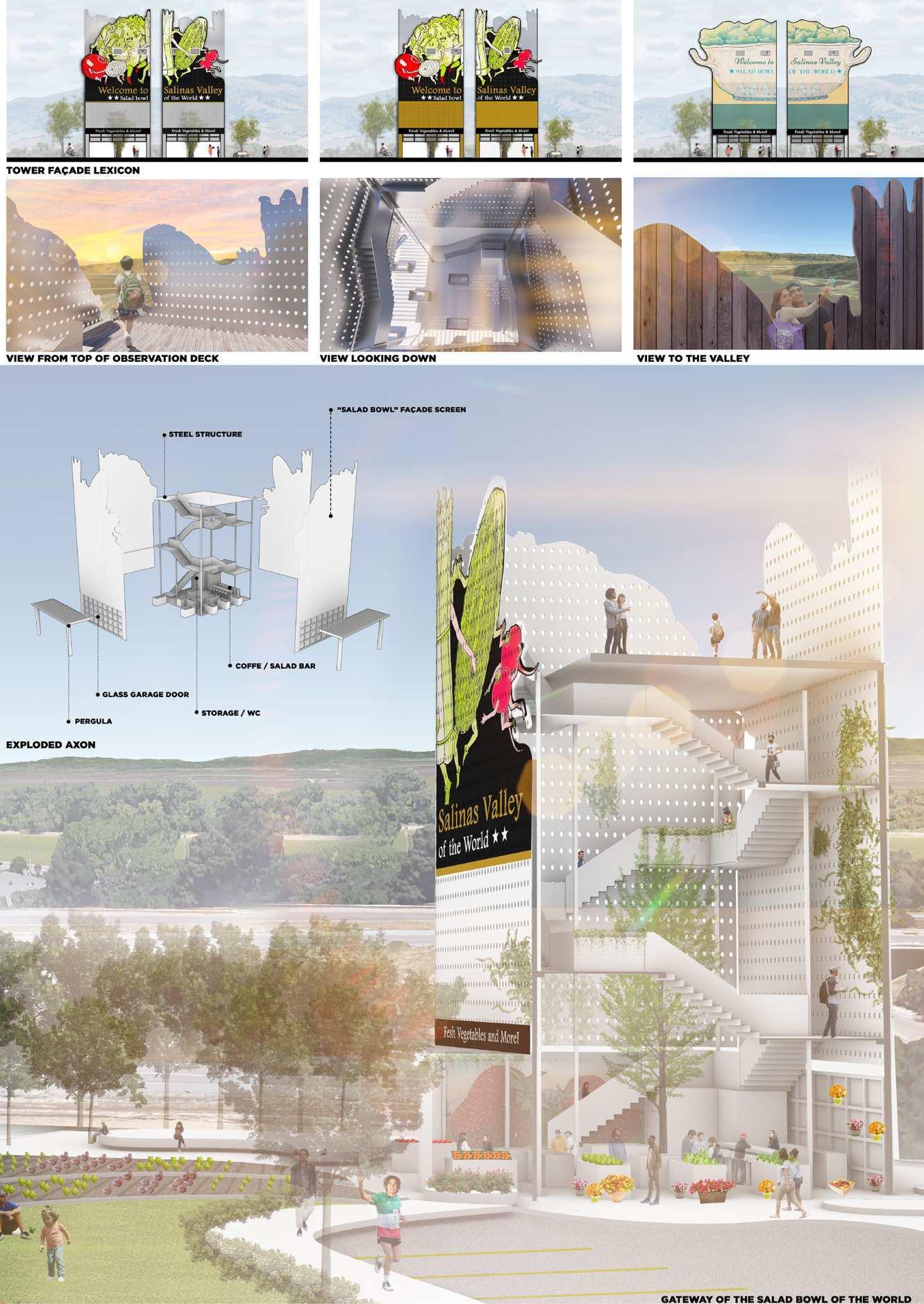

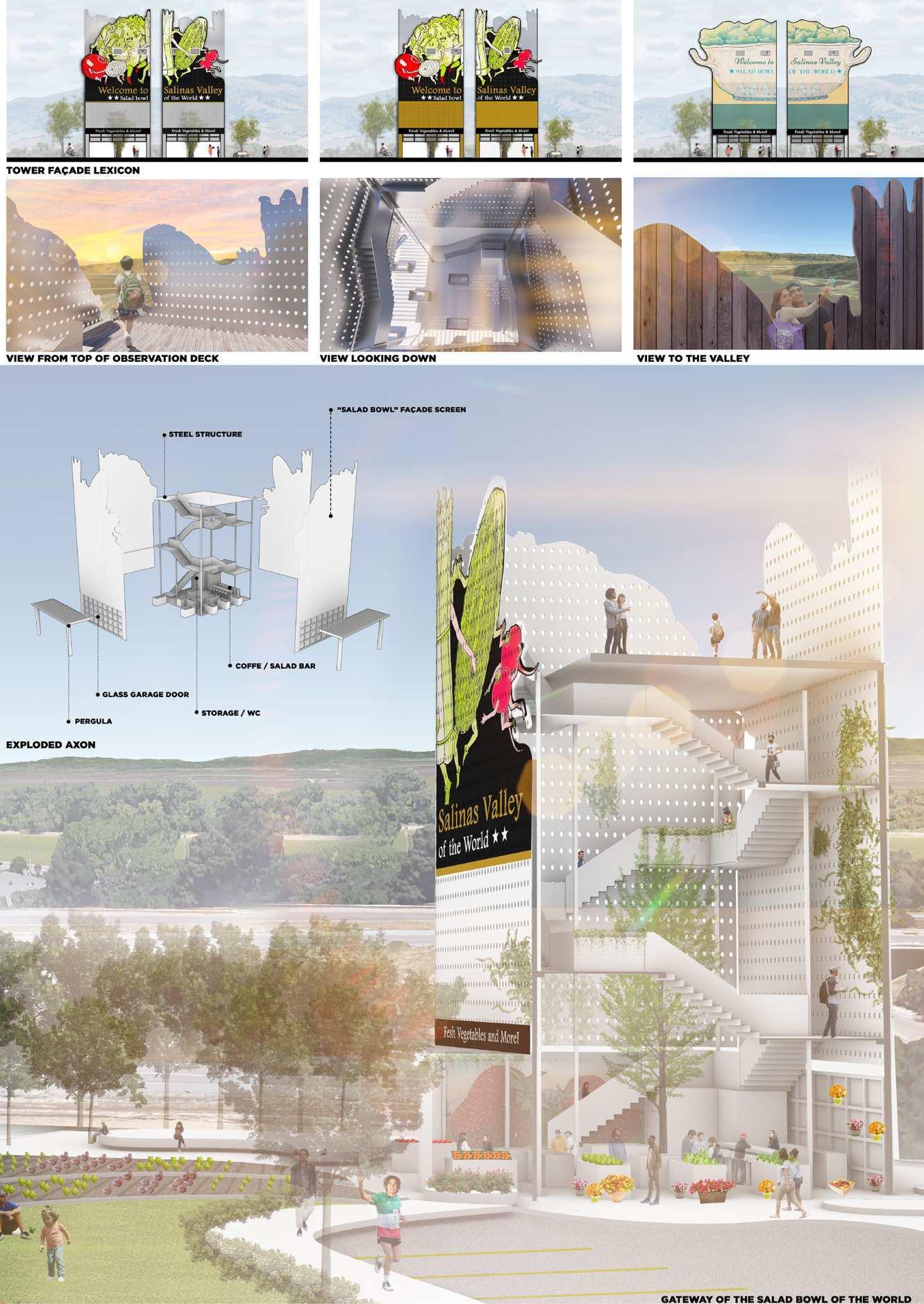

Diego Gonzalez Ramirez’s project “Images of the Bowl” offers a billboard-led strategy. He gathered and analyzed various images representing the Valley’s landscape, including its vernacular architecture, lettuce-filled fields, agribusiness advertising graphics, and Mexican textile arts. By distilling the visual language unique to the region, Gonzalez Ramirez proposed a collection of billboards, mural paintings, and public images that would effectively capture the distinct identity of the “Salad Bowl of the World.” These public images of Salinas’ history, agriculture, art and architecture are located in key sites across the Valley to redefine the aesthetics and uses of many public areas.

The central piece of the project is an observation tower designed to offer visitors a different visual perspective of the Valley’s iconic landscape. In addition to its role as an observation point, the tower serves as a food stand, where local growers can sell their produce to visitors. The tower also acts as a “gateway” billboard, signaling the entry point to the Salinas Valley. Together with other public images composing this strategy, the observation tower radically transforms the experience and perception of the Valley.

Mural paintings can transform anonymous elements into landmarks. These include the Taylor Farms processing plant’s tower or the empty brick wall of the National Steinbeck Center. Soledad downtown serves as a gateway town to Pinnacles National Park, but currently this is not visible. A new billboard intervention on the anonymous Pinnacles Visitor Center and Soledad Downtown will visualize the town’s gateway function, and be visible to travelers on Highway 101.

The observation tower integrates different functions into one single intervention: offering a vista point to tourists, providing a farm stand space for local vendors, and marking the entrance to the Salinas Valley. The tower is a prefabricated steel structure that could be easily located at multiple entry points in the Valley. Visuals and silhouette are inspired by early 20th Century advertising images created from Salinas growers.

Southeast Elevation

Northwest Elevation

Southeast Elevation

Northwest Elevation

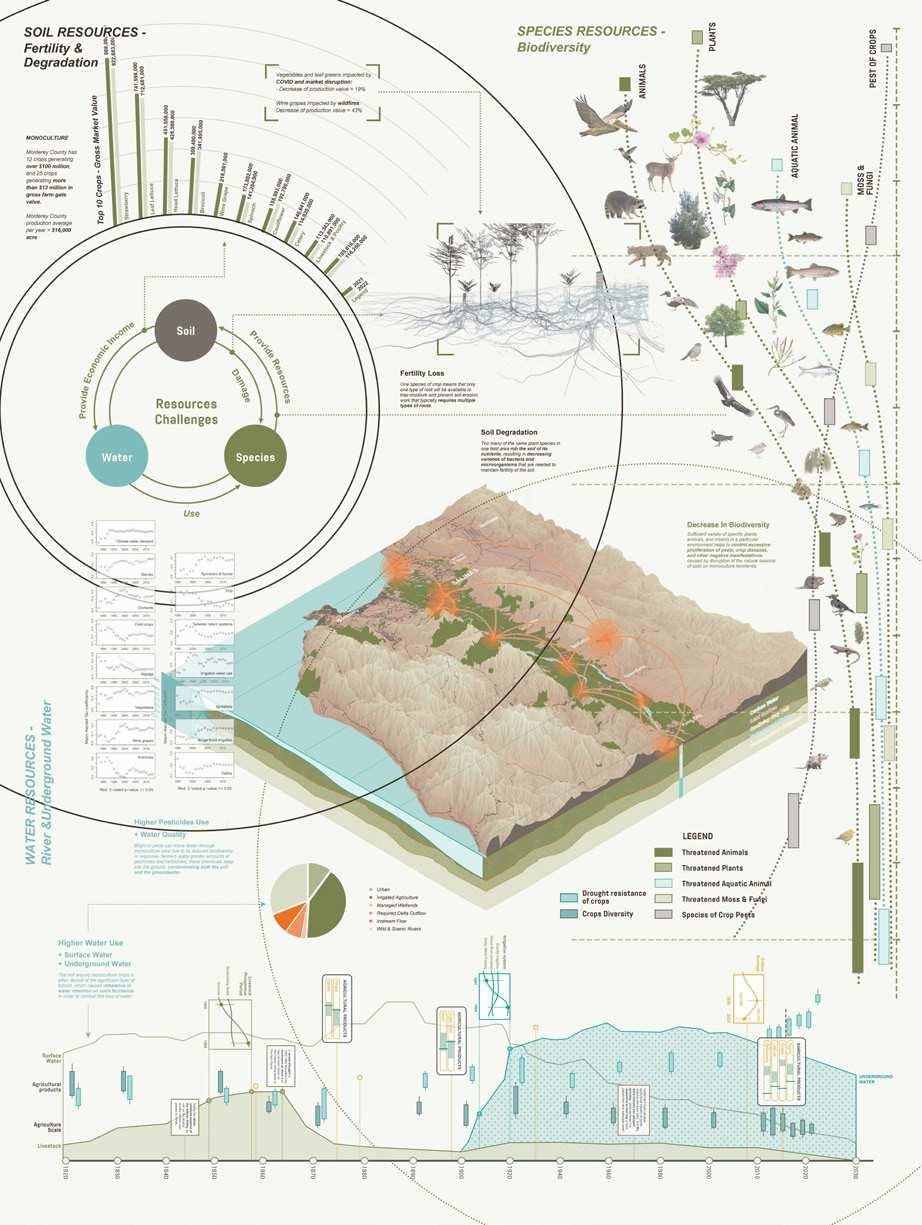

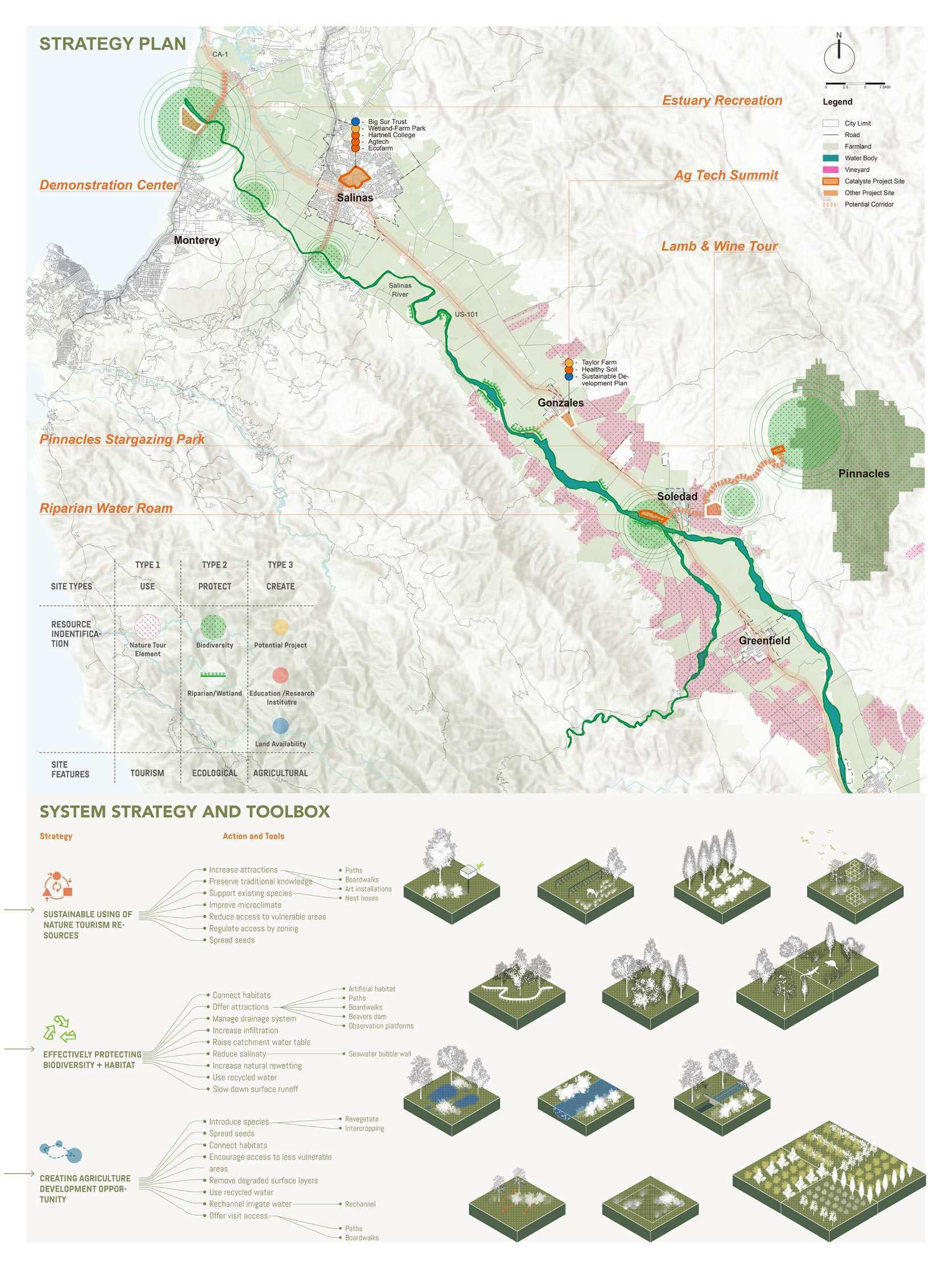

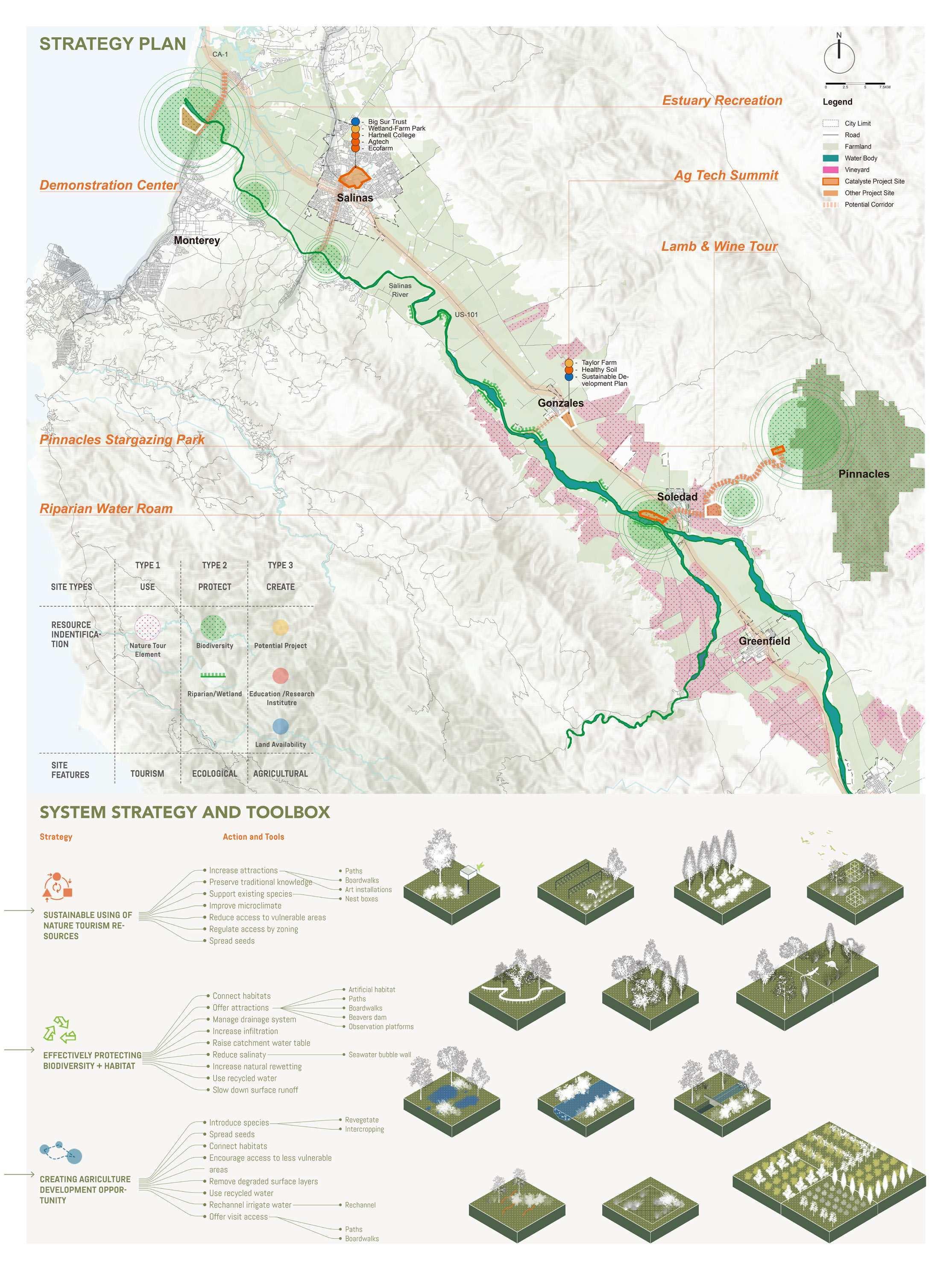

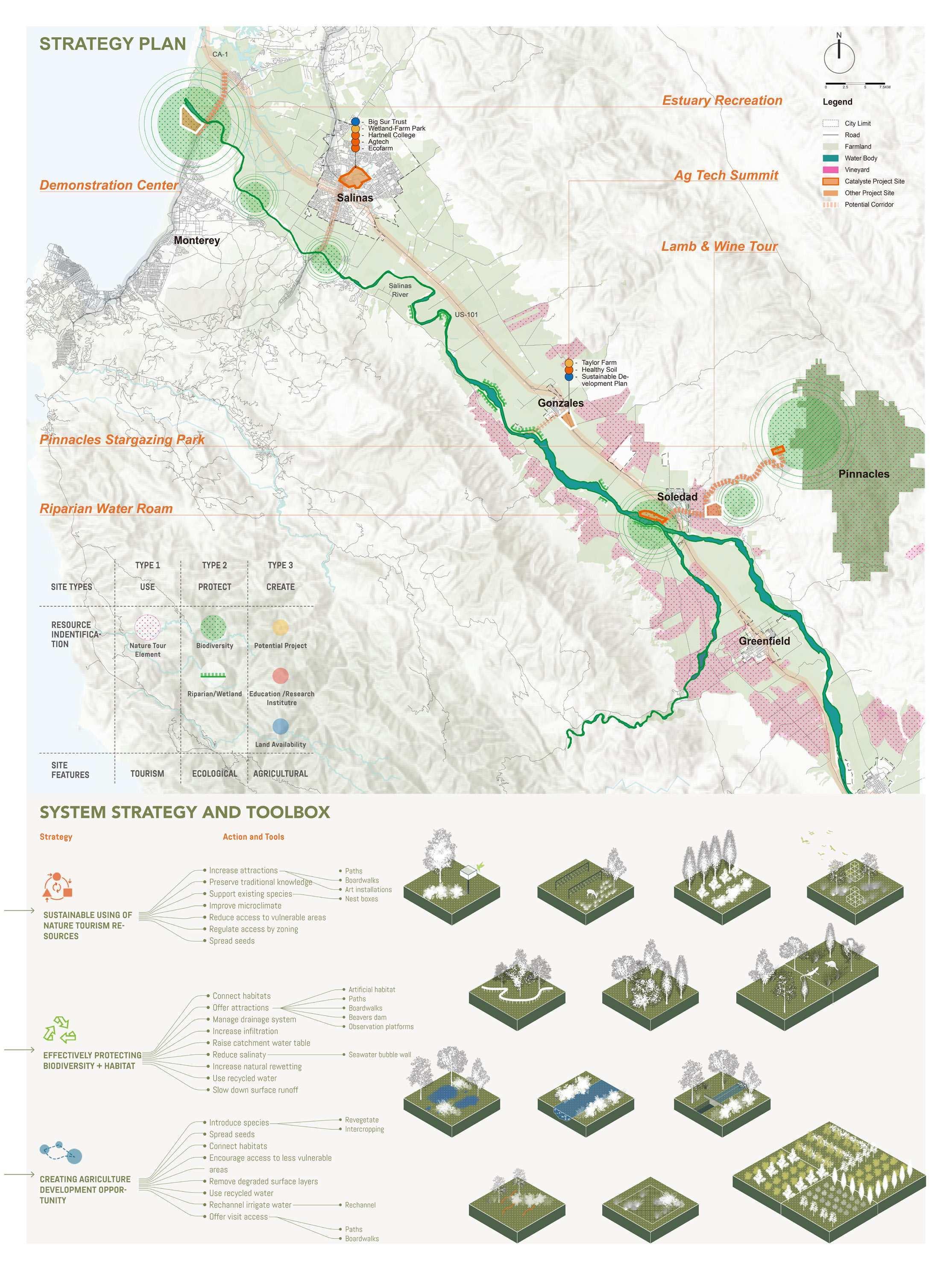

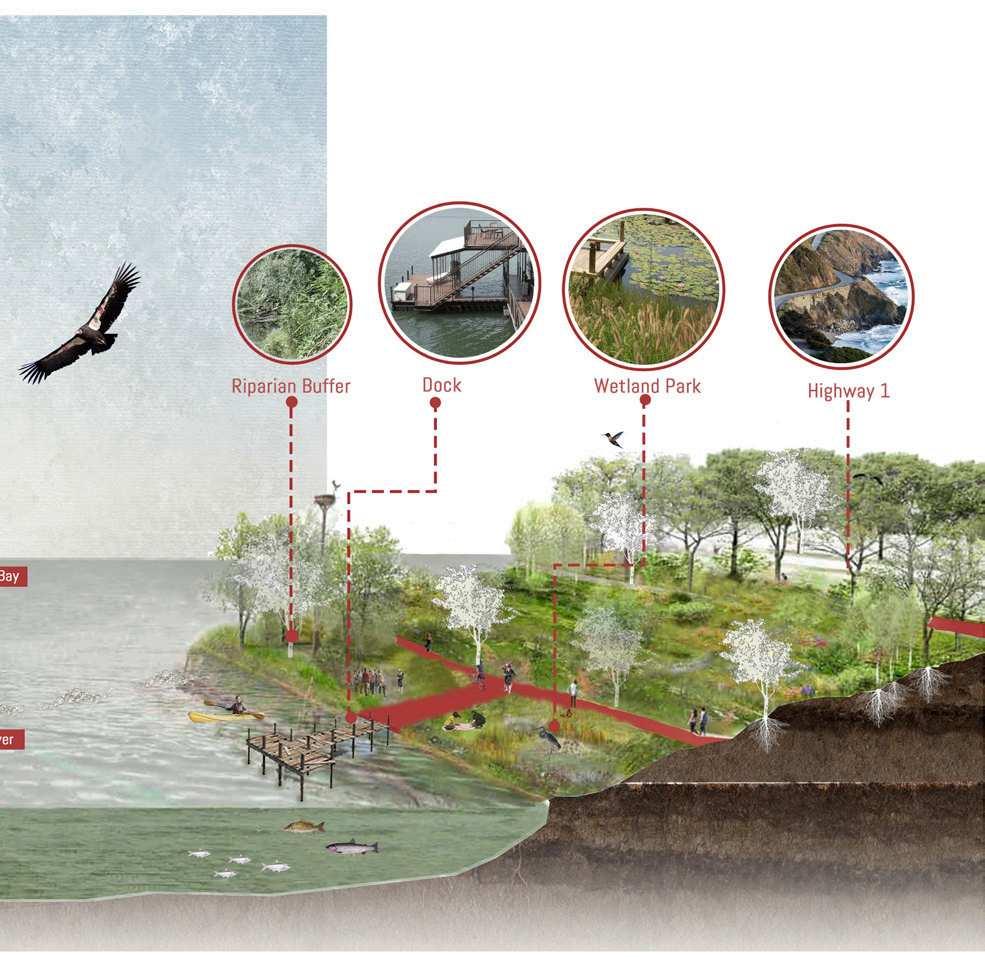

Mufeng Yu, Freya Tan, and Yash Deepak Gorgi‘s project started from their analysis of the ways agribusiness operations had transformed the once diverse ecosystems of the Salinas Valley. In their research, they identified that these operations had impacted the region‘s wildlife and reduced biodiversity. To address these issues, the team designed a network of catalyzing pilot projects to revive ecology, promote knowledge, highlight and redistribute natural resources, and attract tourists to the area. The goal was to shift the identity of the Salinas Valley to become an alternative model of agriculture: economically diverse, ecologically sustainable, and breeding innovation at the intersection of ecology and technology.

The team‘s plan involves six pilot interventions, including the regeneration of the estuary where the Salinas River meets Monterey Bay to revitalize the lost biodiversity in the area. They also propose transforming a flood inundation zone in Salinas into a biodiversity park that would demonstrate different farming techniques. Other programs include creating educational programs for local communities to promote environmental stewardship and building a network of hiking and biking trails that would allow visitors to explore the region‘s diverse habitats. By bringing together situated technical solutions with broader political and pedagogical projects, the sites seek to promote the cultural shift necessary to sustain responsible models of agriculture in the Salinas Valley.

Over time, due to unmonitored extraction by the agriculture industries has tipped the balance scale over leading to drying up of the Salinas river. Due to reduction in the existing water table, it has allowed for salt water intrusion at the bay, which has led to loss of high levels of biodiversity and making it flood prone

The design framework involves intervening in six different sites across the valley to promote envrionmental awareness, coexistence of natural and man made ecosystems and promote tourism. The six sites include - The estuary, The Big sur Land Trust park, City of Gonzales, River Intrersection at Soledad, The Vineyards and finally the Pinnacles National Park.

The design strategy uses a toolkit of technical and social solutions that are implemented in different scales across the valley. The solutions are mainly focused on 3 impacts - Promoting sustainable use of natural resources in the valley, protection of existing natural flora and fauna and creative resilient system of agricultural development in the valley. The solutions range from creating non intrusive paths , trails and boardwalks that allow the ecosystem to thrive and yet bring people to these attractions. On the other side of the spectrum the solutions also include creating smaller dams that channel the water efficiently and increase surface area for ground water recharge Policy solutions of innovative farming methods that are less harmful to the ecosystem around are also implemented in strategic sites.

The wetland park and demonstration area is a center of the whole education system, which include a wetland park going to built by Big Sur land Trust, a demonstration area for farmers and farm owners, but with main focus on students and children both from salinas and other areas, where they can experience,the wetland park and observe the resilient mechanisms in place, engage in wildlife watching and track the inward migration of fauna into the valley.

At the intersection of Soledad and river,the point where the river diverges.The proposed diversion facility by the project aims to maximise surface reduce its support on underground surface water can change the microclimate in biodiversity and can allow for temporary camps during the summers. enviosned as a rich ecological zone.

and Arroyo Seco diverges.The Salinas water water retention to underground water. retaining microclimate bring glamping and summers. This is zone.

The pinnacles national park which by itself is a great tourist attraction and allows for a unique way to experience nature. but in order to provide for create the dark sky experience, one must reduce the dust and light pollution and that’s emitted into the sky to allow for more days to be “star gazing days” leading to greater economic return and to reduce the dust pollution it’s vital to keep the water system in check to reduce the loose soil being emitted into the atmosphere

“Every year, 371,262,000 pounds of fruits and vegetables are exported to other countries.”

“From drones in the fields to robots packing lettuce, farms are getting smarter – and Salinas is ripe with opportunity for investment in agtech.”

“Salinas Valley boasts an $8 billion agriculture industry and is home to agricultural giants such as Driscoll’s, Dole and Taylor Farms to name a few.”

“It’s a passion for us because you’re a steward of the land and take care of it…,” Bunn said, “and we hope to pass it on to the next generation.”

“Salinas is famous as the Salad Bowl of the World for agriculture and our fresh, home-grown produce is available internationally.”

“If everyone has that idea of not my neighborhood, then we’ll never have the services for the unhoused.”

“Due to the seasonality of the agriculture industry, Salinas’ unemployment rate often exceeds 10 percent in the winter.”

“Many are overpaying for their housing, living in squalid, substandard homes and/ or doubling and tripling up with other households in overcrowded conditions.”

“These are people who are feeding the world. They shouldn’t be sleeping in their cars.”

“Thousands of people come, and there’s very little empty space for them to live.”

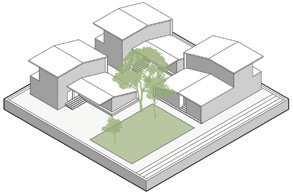

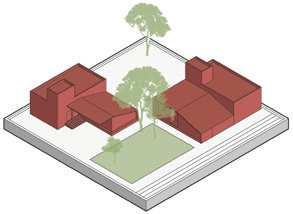

Sagarika Nambiar, Srusti Shah, and Varun Shah’s project addresses the need for housing and social support for the Valley’s largely migrant workforce by exploring how tax revenue from other ecotourism programs could be utilized to address these needs. Students analyzed the economic, ecological, and land-use changes that had enabled the Valley to become known as the “Salad Bowl of the World.” The team recognized the issue of housing scarcity being a troubled mirror to the abundance of produce provided by the land.

The strategy entails site-specific, flexible, low-cost housing solutions of varying degrees of permanence that could adapt to the cyclical nature of production in the valley. Their proposal includes linking the development of various housing typologies with a land banking system, creating financial strategies to help provide multiple housing options for workers. Overall, the project aims to foster more equitable models of housing development that take into account the needs of the valley’s diverse population.

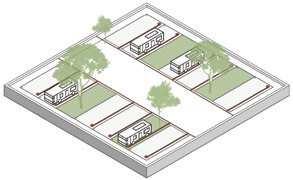

Housing scarcity in the Salinas Valley is a product of the high price of its productive land. The prevalence of agribusiness land uses has limited availability of housing land. This strategy has mapped all unused public and private land parcels existing throughout the Salinas Valley and collected them into a single database. Parcels are very different in their ownership status, location, infrastructural and utility supply, proximity to urban centers, etc. The strategy offers potential developers (agribusiness, landlords, community development, government agencies, NGOs, and faithbased organizations) an array of six different affordable housing investment

typologies, to be selected based on the land conditions, the budgetary constraints, and other factors. By looking at housing problems holistically, this strategy leverages both public and private actors and assets to elicit a constellation of small-scale, flexible, diversified housing interventions.

Ownership: Universities / FBOs

Identifying the site wrt the land bank

Providing services: portable toilets

Providing security: lighting

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership:

Ownership: Universities / FBOs

Salinas

Providing infrastructure: charging points

Ownership:

Identifying parking lots

Providing services: toilet block

Providing security: lighting

Providing security: society office

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership: Universities / FBOs

Ownership: Agribusinesses

electricity

Identifying the site wrt the land bank

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership: Private landowners

Providing services: water, sewage,

Placing trailers while creating green spaces

Ownership: Nonprofits

Making of the trailer park community

Plan of the Trailer Park, King City // Ownership: Privately Owned

Ownership: Universities / FBOs

Ownership: Public Land

Identifying the site wrt the land bank & transporting modules

Ownership: Non profits

Ownership: Non profits

Providing security: society office

Providing community gathering spaces

Providing services: water, sewage, electricity

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Private landowners

Plan of the Modular Housing Scheme, Soledad // Ownership: Privately Owned

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Public Land

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership: Nonprofits

Identifying existing services: water, sewage, electricity

Placing tiny homes in clusters

Providing community gathering spaces

Ownership: Agribusiness

Repeating units to form a cluster

Ownership: Agribusinesses

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Private landowners

Ownership: Private landowners

Plan of the Tiny Village, near Salinas //

Plan of the Tiny Village, near Salinas //

Unhoused, 39

‘My family used to be concerned with safety in the past. However, with the faith organisation being involved, we dont have to worry anymore!

Unhoused, 24

‘It was so easy to get our trailers and park them here! The site is clean, has good facilities and social spaces!

Suffiecient basic facilties like toilets, showers and security that the institution provides have helped reduce our apprehensions at night.

‘There were so many configurations to choose from! The facilities like the creche, garden, community kitchen etc, make our daily lives way more convenient!’

‘We initially lived in a 1BHK home. But as our family grew, it was super convenient to have another bedroom plugged into our existing unit.’

Student, 19

Farmworker, 42

The studio was an exploration into how to expand the limits and scope of urban design and relocate it outside of what we commonly define as cities. This was largely a leap in the dark. It required more than redeploying existing urban design techniques to rural towns and farming fields. It forced us to think: how can we establish a relationship with the environment that is not extractive? From an urban design perspective, encountering the rural means embracing a complex interdisciplinary field of inquiry that pushes us beyond the city as the only unit of analysis and intervention. By doing so, we needed to redirect design thinking towards other systems of knowledge, such as agronomy, forestry, political ecology, but also Indigenous and situated knowledge, and food cultures.

As the Master of Urban Design’s engagement with the Salinas Valley continues, more of these hybridation are to come. While this book is being written, the Salinas Valley initiative at UC Berkeley’s Master of Urban Design has raised further funding for moving the projects initiated in the studio into their feasibility stage. We hope that our efforts will serve as inspiration for other designers dealing with the complex social and ecological networks shaping rural space.

Ultimately, “going rural” could be seen as a means of self-critique in the spatial design fields; as a way for interrogating the very structures of knowledge upon which we have constructed our discipline. The rural forces continually ask: What is the urban? What is design? When we think we know the answers to these questions, at that very moment, it may be time to think again.

Margaret Crawford holds degrees in Architectural History, Housing and, Urban Planning. Before coming to Berkeley, Crawford chaired the History, Theory, and Humanities program at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles and, from 2000-2009, was Professor of Urban Design and Planning Theory at the Harvard GSD, teaching history and design workshops and studios. Her scholarly work includes Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The History of American Company Towns, The Car and the City: The Automobile, the Built Environment and Daily Urban Life and two editions of Everyday Urbanism, along with numerous articles and book chapters on immigrant spatial practices, shopping malls, public space, and other issues in the American built environment. In 2008, Doug Kelbaugh called Everyday Urbanism “one of the 3 leading paradigms today in urban design.” Since 2003, Crawford has been investigating the effects of rapid physical and social changes on villages in China’s Pearl River Delta. She recently co-edited Critical Texts in Chinese Urbanization, a four- volume collection of English-language studies of Chinese urban development. She is currently working on regional design projects in the Salinas Valley.

Scott Elder is an urban designer and researcher with degrees from University of Oregon, Columbia University, and University of California, Berkeley. After starting a career in corporate urban design and real estate consulting, Scott returned to academia compelled by his interest in landscape-driven concepts and the territorial scale. He has subsequently worked for the U.S. National Park Service in heritage trail planning, projects spanning from urban to wilderness, bringing these concepts back into the classroom together with discourses on American urbanism.

Ettore Santi is an architect and urban designer with a Ph.D. in Architectural History and Theory. He holds degrees from Milan Polytechnic, Tongji University, Shanghai, and University of California, Berkeley. His work on planeatry rural transformations blends design thinking with concepts from rural geography, agrarian history, and the environmental humanities. He has conducted research on agrarian change in rural villages in Hunan province of China. He has worked as a designer and consultants on urban and rural projects in Italy, China, and the United States.

ISBN 9798853043404

“Not everyone is lucky enough to be born in Salinas. But for those of us lucky enough to pay a visit, chances are we’ll never look at a head of lettuce the same way again.”

-- John Steinbeck