Henry Nguyễn Design Editor

Henry is a junior from Bentonville, AR. He is majoring in graphic design with a minor in gender studies and art history. His artistic practice focuses on the expansion of design accessibility to marginalized communities within spaces of entrepreneurship and politics. He has two cats named Hieu and Bao.

Marshall Deree

Visuals Editor

Marshall is a senior from Fayetteville, AR. He is graduating with a B.A. in journalism with a concentration in multimedia storytelling and production. He holds love for photography, traveling, and his cat Cricket. He aims to be a photojournalist.

Emma Bracken

Editor-in-Chief

Emma is a senior from St. Louis, MO. She is graduating with a B.A. in English and a minor in history. Since her sophomore year, she has worked for the magazine. Outside of reading and writing, she enjoys arts and crafts, yoga and watching ocean documentaries.

Addie Jones

Assistant Editor

Addie is a senior, graduating with a B.A. in political science and journalism with minors in gender studies, nonprofit studies and rhetoric writing studies. She is also Chair of Headliners Concert Committee, Copy Editor for the Arkansas Traveler and the Marketing/ PR Officer Democracy Fellows. Outside of campus, she loves all things theater and listening to new album releases.

Mackyna Parsons

Online Content Editor

Mackyna is a senior from Tulsa, OK. She is graduating with a B.A. in journalism, concentrated in multimedia storytelling and production. She works as a Social Media Manager for Student Affairs and helps lead a Life Group at Antioch Community Church. She enjoys kayaking, traveling and hosting.

This is my first print issue being Editor-In-Chief of Hill Magazine. Stepping into this position, I was met with a lot of unknowns and found myself navigating new spaces. This is something we all feel as we try to navigate the ever-changing social and political reality of our world and who we want to be within it.

It is human nature to seek home, belonging and connection. This issue explores different flaws in humanity that tear these things apart, as well as the love and community that help rebuild them. When civil liberties and basic survival are under attack, we can be disconnected from our shared home. Lost on Earth is about finding the people and places that bring you home to yourself, and acknowledging the hardships of those who have been displaced, ostracized or isolated.

I would like to first thank Henry Nguyễn for bringing these abstract ideas into a beautiful spread that represents the heart of all of these pieces. He always led with heart and ambition to make this magazine everything we dreamed of. I would also like to thank Marshall Deree for another semester of leading our photographers and pushing the limits of what we can do with our visuals. He has been a vital member of Hill Magazine for several semesters now, while always bringing fresh ideas and pushing us all to do bigger and better things.

All my thanks to my assistant editor, Addie Jones, for being my righthand man and keeping the ship afloat, all while bringing the most positive attitude and true dedication to journalism. And thank you to Mackyna Parsons for running our website and social media while we focused on print and treating each story with care and compassion. Final thanks to Professor Bret Schulte for constantly pushing us to grow and evolve, as well as being a support system throughout this first print endeavor of mine.

And all my thanks to the readers for picking up this issue and going on this journey with us. We hope you enjoy Lost on Earth and share this moment of connection with us.

Emma Bracken Editor-in-Chief

Johana Vazquez

Isabella Larue

Erin Bailey

Bria Ifland

Nadeshka Melo

Featuring the works of Zach Benson, Evan Meyers, Anna LeRoux, Jill Stone, Karlena Fletcher, Jane Tucker, Michael C. Kiele, Emerson Foster, Rachel Whitten, Minahil Qazi, & Guerin Honeycutt

Artwork by Zach Benson

Short story by Anna LeRoux

Photo series by Evan Meyers

Poem by Jill Stone

Artwork by Karlena Fletcher

Poem by Jane Tucker

Artwork by Michael C. Kiele

Artwork by Emerson Foster

Poem by Rachel Whitten

Uphill Battle to Acceptance by Erin Bailey

Artworks by Minahil Qazi

Artwork by Zach Benson

Grieving the Living by Isabella Larue

By Johana Vazquez

You had no choice but to flee. The country you were born in and grew up in is no longer somewhere you feel safe, and every second you’re there is a gamble with your life. Maybe your country is at war with another, and your childhood home was bombed and destroyed. Maybe your country has been embattled in a civil war spanning years or decades. Perhaps you were targeted, assaulted or almost killed.

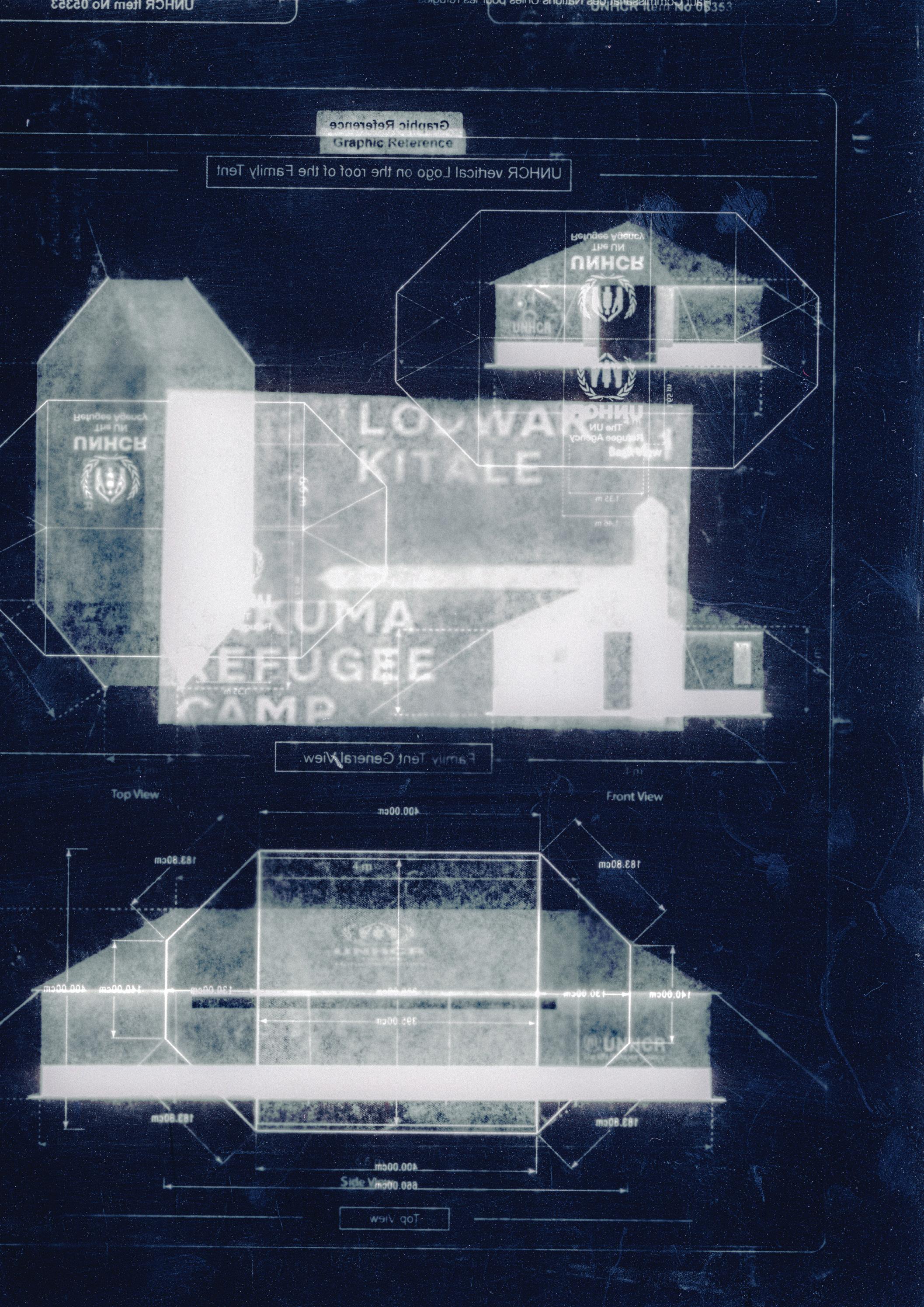

So you flee on foot, by bus, by boat, and you make it to another country. You seek refuge at a United Nations camp and prove you cannot return to your home country based on five grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. You are granted legal status as a refugee and given a tent.

You wait for years (months based on the urgency of your situation). You do interviews and check in with UN officials every few years. You see people come and go from the camps, but most people never leave, and you start to think you won’t either. Then you get news that a country has selected you (because you don’t choose the country) for potential resettlement.

You interview with the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, and once you are approved, you go through additional vetting and background checks. You’re told you leave in two weeks, so you prepare (perhaps borrowing money from the U.S. government for a plane ticket you will have to pay back). You sell your belongings to neighbors. Maybe you sell a small business you started at the camp. Maybe you are prepared to leave family behind or have family in the United States waiting for you.

Then, the day before your flight is supposed to leave, you receive word that the U.S. government canceled your flight, and you won’t be going anywhere. You are back to where you began with no belongings, no country, no home and no hope. In the United States, a resettlement agency was ready to receive you and give you all those things.

In Northwest Arkansas, that agency is Canopy NWA, formed by a group of Arkansans in 2016 to welcome refugees to the region, resettling close to a thousand people in the last nine years. Since January, the agency has expected to receive 200 people who are now barred from entering the country; 68 had flights booked.

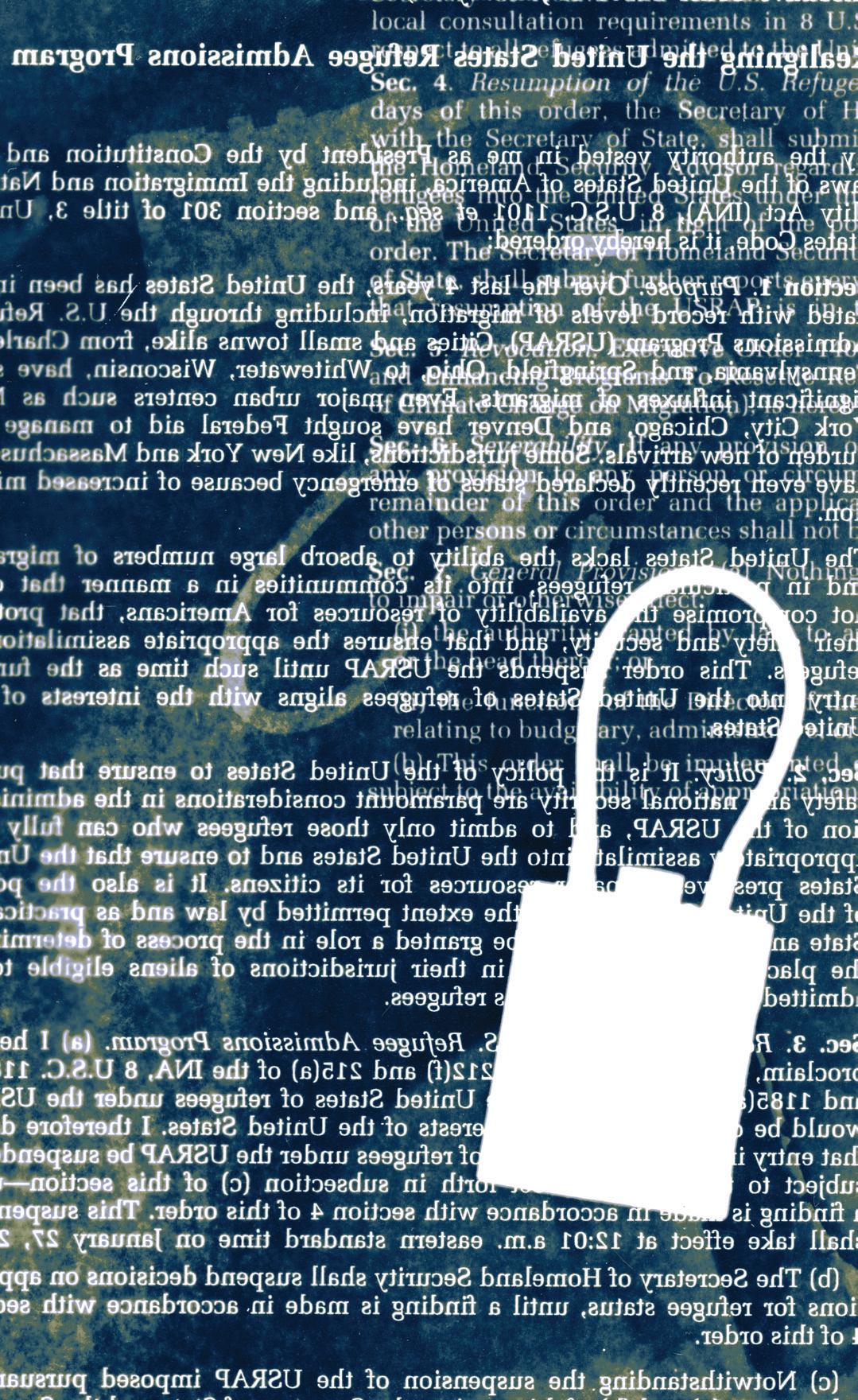

Refugees stopped coming shortly after President Donald Trump signed an executive order on Inauguration Day to suspend the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, enacted by Congress in 1980 to limit and surveil the admission of refugees. Before the halt, the maximum number of refugees that could be resettled through USRAP in 2025 was 125,000. The executive order claimed to suspend the program to “realign” it to serve U.S. interests. Two days later, the State Department canceled flights for refugees already vetted and approved for travel.

Resettlement agencies and individuals are challenging Trump’s executive order and decision to freeze millions of federal dollars for refugee resettlement in Pacito vs. Trump, an ongoing class action suit. This is the longest and most comprehensive suspension of the program to date.

Canopy’s Executive Director Joanna Krause said the agency has lost a portion of its federal funding after USRAP’s sus-

pension—going from 70% of its budget earlier this year to 55% in October. She said they expect federal support to decrease drastically next year. Canopy is relying more on community donations and grants to serve its clients in the area.

Krause said donations were crucial post-January to house, clothe and feed newly arrived families. The last refugee family they received arrived January 17th.

“I am continuously impressed and grateful for the hundreds of people who came forward and made donations, whether they were large or small,” Krause said.

Krause explained that the agency will continue to help 750 individuals who arrived within the last five years through their “Long Welcome” program with immigration services, after-school/summer programs for children, healthcare navigation and employment guidance.

Canopy is very protective of its clients, rarely connecting them with the media. The agency employs a few former refugees, and their stories and journey to the United States mirror those of nearly 3 million refugees seeking resettlement in 2025, according to the UNHCR.

Photos by Bria Ifland

The Canopy NWA office in Fayetteville, Arkansas, is an unassuming building on Wedington Avenue tucked behind a Casey’s Gas Station. On April 3, the office was a little busier than usual as members of the public visited for NWA Gives Day, a day devoted to raising donations for non-profits in the region. People stopped by for drop-in sessions to hear about Canopy’s work, employees were planning social media videos, and clients came to support and meet with their case managers.

There was an unspoken urgency to raise their goal of $35,000 this year. Layoffs had already begun within the agency; resettlement agencies were struggling nationwide as the pause on federal funds continued.

The action of the day was in the background for Saratiel Mugisha, who sat at his desk in a warmly lit room, making calls to clients. As a case manager, Mugisha helps clients find housing and jobs, enroll their children in school, guide them on how to get documents like an ID or Social Security card and take them to medical appointments.

Mugisha, 35, does for them what someone once did for him when he arrived at the Canopy office as a refugee from Rwanda in December 2021. He began working as a case manager almost a year later due to his proficiency in three languages: English, Kinyarwandan and Swahili.

Although born in Rwanda, Mugisha spent most of his life in a Kenyan refugee camp. His family had fled the violence of the Rwandan civil war and genocide in the early 1990s. If he could describe life in the camp in one word, it would be insecurity.

People die from malnutrition, women get sexually assaulted, and help from the police comes with a price. In 2018, Mugisha opened a bar that was vandalized, and he began to receive threats. He was granted resettlement on an individual case, separate from his family, who continue to live in the camp.

Before the halt on refugee admissions, Mugisha expected to manage a couple of incoming refugees who would have reunited with family in the area.

“We had promised their family that they were going to be with them,” Mugisha said.

“We are going to help their family be here, give them the services they deserve, but now we can’t.”

He said everyone involved is stressed and unable to do anything about it. He understands the mental toll of clinging to the hope of a fresh start.

Rwanda has a complicated history with ethnic disputes that have divided the country for centuries, worsening after Belgium replaced Germany as Rwanda’s colonizer in 1916.

Belgium’s 30 years of colonial rule racialized the country’s three ethnic groups—the Tutsi, Hutu, and Rwa—and the identities that were once fluid in practice became rigid through the use of ID cards, according to a resource guide from the University of Minnesota. Tutsis were the local elite until the Belgians left the Hutus, the ethnic majority, in power after Rwanda gained independence in 1962.

Hutu leaders at the time portrayed the Tutsi as outsiders, according to The Brussels Times. More than 300,000 Tutsi were driven out of the nation, exiles who would

return as members of a rebel guerrilla group in 1990.

Tensions amounted to a civil war, and then to a genocide that ended in 1994. Mugisha was just a child during this time and didn't talk much about the politics in Rwanda in the 1990s. However, the world was stunned when, in a time span of 100 days between April and July, the genocide resulted in the deaths of nearly a million ethnic Tutsi and moderate Hutus. It is regarded as one of the worst genocides in modern history.

The country has tried to work towards peace and a unified Rwandan identity since then, adopting in 2003 an official policy of "ethnic nonrecognition," which included removing ethnic labels from ID cards and textbooks, according to an article from Princeton University's Journal of Public and International Affairs.

Born in 1990, Mugisha, like many babies in Rwanda, was given a unique name. There are no surnames or family names that each generation passes down. In Kinyarwandan, the language predominantly spoken in Rwanda, “Saratiel” means shining like a star or being rich, and “Mugisha” means blessing. He was the fifth child out of eight and the second of only two boys.

Mugisha and his family are Hutus. He said his family lived a peaceful life in Bugesera before the genocide. His father owned a shop selling farming tools. The rising violence in the country led Mugisha's family to leave their home. They went to a camp for displaced Rwandans, where they lived for three years. Once they arrived, Mugisha and his siblings were separated from their parents.

After on-and-off imprisonment, his mother returned to them, but his father did not. He was accused of supporting Huthu extremists, which Mugisha said was not true.

The federal refugee resettlement program began when Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980 in response to an influx of Vietnamese refugees after the Vietnam War. Before then, refugee resettlement was largely ad hoc, with legislation responding to specific crises like those following World War II, when the United States admitted more than 350,000 Europeans.

The Refugee Act established a standardized system for vetting and resettling a maximum number of refugees every year. The annual admissions figures, set by the president to establish the number of refugees allowed into the country the following year, have ranged from a high of 207,116 in 1980 to a low of 15,000 in 2021 under Trump’s first presidential term.

Trump officials have yet to set a number this year, ignoring the deadline on Sept. 30 and further halting the program. News reports indicate that the administration is considering a new record-low cap of 7,500 refugees for 2026. The plan would reportedly reserve the majority of those slots for white South Africans of Afrikaner ethnicity, a change from a system that typically prioritizes those most at risk of persecution, regardless of their race and language.

Trump alleges the small population is being persecuted by their Black-led government and their land is being seized, which the South African government has repeatedly denied.

The federal program has resettled more than 3 million refugees since 1980 and has been suspended only two other times. The first time was for several months after the 9/11 attacks, by the Bush administration. In 2017, Trump enacted a travel ban and barred the entry of people from seven Muslim-majority countries, suspending the refugee resettlement program for 120 days.

“We have a lot of data that shows this program is run effectively and that it’s beneficial to the states and communities,” Krause said. Between 2005 and 2019, refugees contributed $123.8 billion more than they cost in government expenditures, at both the federal and state levels, according to a 2024 study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Krause said apart from economics, the difference that refugees make in their community is immeasurable, but just as real.

In partnership with Canopy, the Ozark Literacy Council teaches refugees English in classes it offers to the wider community. Jackie Hernandez, the Welcoming Manager, said the refugees and immigrants they teach cultivate a friendly atmosphere even with all the adversity they face.

Hernandez said one of their star pupils is a woman, a refugee from Afghanistan, who arrived completely illiterate. She was pretty shy at first, but very eager to learn. Within a span of six weeks, she had gone from knowing nothing to writing and speaking English at a kindergarten level.

Without his father, Mugisha’s mother decided to flee with her children from Rwanda in 1999. Nine-year-old Mugisha slept hidden in the hills during the ten days it took to walk to Tanzania, a neighboring large country in the Great Lakes region of East Africa. There they lived in a camp for a month before they were informed the camp would soon be evacuated and all Rwandans would be sent back.

With the little money she had, Mugisha’s mother paid for bus tickets, and they landed at a refugee camp on the outskirts of Kakuma, Kenya. The camp was established by UNHCR, the United Nations’ refugee agency, in 1992 after the arrival of the “Lost Boys of Sudan,” referring to the thousands of children who were displaced or orphaned during the Second Sudanese Civil War.

The camp welcomed Ethiopians that same year who fled their country following the fall of the Ethiopian government. And then came the Somalians, who were experiencing high insecurity and civil strife. Rwandans were among the newer arrivals in a growing, diversifying community. The camp is currently one of the largest in the world, housing more than 300,000 people, and it is under governmental plans to evolve into a city.

Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia continue to be among the top six countries in Africa facing displacement crises due to civil wars or Islamic insurgencies. War in Sudan displaced a total of 14.3 million people—a third of the nation’s population—by the end of 2024. Most displaced people remain within their own countries, but many have crossed borders as refugees or asylum seekers.

As they were being registered, Mugisha’s mother asked for her husband, and they hoped he had somehow made it out of Rwanda. After mentioning his name, they found him in the system. His father had arrived three years prior, and it took four months to be reunited with him. The camp was so large, and it was a challenge to track down where he was living.

Reunited, his family settled into the provided tents with blankets, cooking pots and some food to cook. They met with U.N. officials and pleaded their case. Mugisha’s family was granted refugee status in 2000, which sparked hope that it would not be long until they found a home elsewhere. But as the months and years dragged on, and as their tent home became two decent-sized buildings made of iron sheets, and as Mugisha became a young teenager and then a man, that spark waned.

“And they came to realize,

their home.”

Mid-afternoon on NWA Gives Day, Mugisha received a call from his wife, who called to say goodnight. She lives in Nairobi, Kenya, where they met while he attended Zetech University. The couple, forced by the long distance between them, have roughly three daily routine calls: in the afternoon here when it is bedtime for her, at his bedtime when it is morning for her and sometimes in between. They started dating shortly after he arrived in the U.S. and married last year in a Nairobi church when he returned to Kenya. He hopes to bring her to the U.S. one day.

After the call, Mugisha got out of his seat to stop a woman who walked past the door wearing a long black winter coat with a fur-lined hood. The woman, Jeannette, walked in with a crooked smile and freely gave everyone hugs. A long-time client at Canopy, she is a fellow refugee from Rwanda and a single mother in the U.S. with her husband in Africa.

She had recently attained U.S. citizenship and Mugisha congratulated her. Refugees in the U.S. are generally eligible for permanent residency after one year and can apply for citizenship five years after receiving their green card.

As they spoke in Kinyarwanda, the conversation filled the room and their words bounced in a quick, unpredictable rhythm. Mugisha conducted the music, speaking with his hands and, at times, playing with the pen on his desk.

“Abana banyu bameze bawe?” He asked her in Kinyarwanda, "How are your children?”

“They’re older and in school,” she said. “That’s why you don’t see me as stressed as before.”

Mugisha chuckled, “Ah yes, that was a rough time.”

Photos by Bria Ifland

Her small joke could be heard in the way she spoke it. Kinyarwanda, unlike Swahili, is a tonal language and fluctuates—the pitch of a word can change its meaning.

They alternated asking each other about their significant others in Africa, wondering when they would see them again. Behind them, Canopy employees walked past the door, guiding visitors into the building. By the end of the day, they had raised a little over $34,000.

In “Bouquet of Raising Hands” I am seeking to describe the relationship between both fighting against and relenting to a struggle, specifically for me it is surrounding the struggle to fit into my own skin as a queer person as I was growing up. From a young age I had queer thoughts and feeling, and as I continued to develop I found myself in varying stages of both embracing myself as a queer person and vehemently fighting against it. In this work, I represent my childhood development as a house plant, but this plant is made of arms and hands that are growing and trying to leave the pot. Each hand is in a different state of struggle, ranging from grasping and pulling, to a resigned limpness. I am using these hands to depict this struggle, where I am repressing my identity and refusing to accept and love myself for who I am. I often found myself either ready to embrace myself or realizing that I would never be able to be myself due to my home environment. These surroundings are echoed by the area encompassing the plant. The plant sits in a decorative pot, atop a decorative doily, in a standard suburban style room and features. I often attribute my struggles to accept my identity to my time growing up in a conservative neighborhood, where I often heard about how wrong it was to feel the way I felt in private. This setting is meant to invoke the aesthetics of that neighborhood.

E A T W H A T Y O U L O V E ,

L O V E W H E R E I T ’ S F R O M

From traditional to lactose-free varieties, dairy provides great nutrition while supporting local communities. With 94% of US dairy farms being family owned, choosing dairy means giving back to the farmers who make it possible.

by Evan Meyers

The forest was a false cathedral, its limbs creaking like old bones, and the wind whispered threats through hollow trunks.

The fox prowled the edges of the clearing, eyes lit like dimmed lanterns, teeth ground down. Hunger hummed beneath its ribs, yet it did not strike the fledgling shaking in the brambles. Instead, it nudged the creature toward a shelter, guiding it through a path where claws and talons might overlook. To do so was perilous. The fox risked exposure, risked hunger, and yet the impulse persisted; a dangerous mercy, older than reason.

Above, crows organized in an ink spilled across the sky. When one blighted, another swooped near, pressing its shadow close, shielding the fallen. An eagle hovered, talons gleaming, waiting for weakness; an opportunistic hunter.

In that moment, the birds’ insistence on one another showed a human truth: to aid another is to risk oneself, to place kinship above safety, to defy nature.

The cages of men were different. Eagles circled endlessly behind iron; fledglings shivered on fractured, thin branches. The impulse to shield another, to bear risk for the sake of kin, had been hollowed out, replaced with rules and spectacles and accusations to the unfamiliar based on a false fear of depleting resources.

Outside the branches and bramble, barred like cages, the wild persisted. Even when teeth flashed and hunger clawed at their own marrow, the fox pressed the fledgling into shadow. They defied the unspoken law that demanded self-interest, that whispered all who are different are threat. And in that defiance, the forest murmured truths humans too often forget.

Have you heard that living is just letting leaves grow out from under your nail beds? Because I remember how it feels to sprout from the ground. But even when I was so young, I was talking, though they could not hear me. And moving, though you may not have noticed.

I will always be green, and sugary, becoming pollen that runs into the road, leaking sap from punctures in my skin–so that caterpillars will often find me. We understand each other–I think. They smell like chlorophyll to me, the caterpillars.

But we’re both used to being picked or plucked by little girls named Melba who live in Montgomery–Louisiana that is. Because living is just waiting on someone to die. Melba can’t die–I think. How can she when she fills up the sky above me? She blocks out the sun.

If she presses me in a bible, maybe I won’t have to wrinkle up and die.

While bloody bones–I’ve heard them rattle around in the loft of the barn–but I was not born there. I wouldn’t choose that for myself. Life itself is not a choice, as is the hot wasp sting that is puberty–and then death.

But right now, I’m as dead as Chinese tallow, which I thought was oh so hard to kill.

A

poem by Jill Stone

Karlena Fletcher, Innocence, 2024. Oil on canvas, 30x36 in.

I planned this painting with the intention of capturing my memory of the specific grass from one of my childhood backyards. However, the more I tried to home in on specificity, the more idealized and generalized the image in my mind became. All I could envision was the must lush, most green, not-too-tall and not-too-short, softest bed of grass. I realized that to little children, grass is neither fescue nor Bermuda, it does not need to be watered and weeded. Grass is simply the backdrop of our play and curiosity; it is the insurance of a good time to be had. It is only when we grow up that grass becomes a time-sucking, environment-damaging, never-ending chore. To take grass for granted is proof of innocence, and to remember it vibrantly green is evidence that we were well-loved in childhood. As I painted each blade, I mourned that I spent childhood waiting to grow up, only to spend my adulthood wishing I was still that safe, fearless, wonderstruck kid.

To Fayetteville resident Emma Claire Nelson, home is everything. When her home is stable, she feels it, too. When her home is filled with pieces of her life, such as her art, posters, plants,and two cats, she feels comfortable and one with the space she has chosen for herself. When her apartment, Flats on Hill, was bought out from under her by the University of Arkansas, awaiting to be bulldozed and replaced with student housing with no date in sight, she did not believe it.

Erica McIntosh, Nelson’s roommate, was told by an old friend that their month-to-month apartment was marked as “sold” on the online realty application Zillow with no prior notice in December 2024. This was her sixth move in five years in the fast-growing city, and it felt like the city only wanted to spit her out.

Living there had been a dream for both Nelson and McIntosh. Nelson said it should be a historic site with the way it was built because of its unique build with an emphasis on organic material, tree shading and a flat roof, culture poured out from every orifice in a neighborhood surrounded by cookie-cutter complexes, like The Atmosphere and Cardinal apartments. Flats on Hill are all steel and brick with sliding doors and vast windows for every room. Small rocks lined the outdoor area, with wooden railings against scenic pathways.

The two cried for hours upon learning their dream home was taken from them without so much as an email or letter in their mailbox. Nelson mourned the home she fell in love with alongside her friend, but what scared her more was the ultimate question of where they were supposed to go next. She was unsure if she could continue to be tossed around from place to place for another five years.

The city of Fayetteville is the second-fastest-growing city in Arkansas, largely due to the UofA at the epicenter of the bustling town. The City Council voted unanimously in April 2024 to declare a housing crisis in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It reflects a larger issue of the country having an across-the-board emergency for homeowners and renters. This is telling of the hundreds of people in the city with a lack of renters’ rights. Additionally, across the country, 70% of all extremely low-income families

pay more than half their income on rent, and only 1 in 4 impoverished families who need assistance for housing receive it, leaving over 580,000 Americans homeless any night. It is a nuanced issue and the key to eradicating generational poverty, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

As a solution to citizens feeling unheard amid this evolving crisis, former Mayor Jordan created a housing crisis task force, a collaborative committee to recommend ways to approach the housing insecurity problems and increase the housing supply in June 2024. The group meets publicly on the third Wednesday of every month to hear the community’s concerns and questions.

Bo Diamond, task force member and managing partner and co-founder of real estate firm Caisson Capital Partners, is intent on making more affordable housing through his role in the task force and his real estate position, specifically for essential workers. Diamond said the issue begins with the unique situation Fayetteville finds itself in, which is one so largely based around a hefty university. The problem lies in balancing the needs of the

political and social interactions of student housing and the other real estate markets that exist within the city, so to him, fighting against the development is not an effective solution.

Fayetteville’s housing report from 2023 highlights the demand in the city for a place to live and how staggering it is, especially when it comes to the average rental costs and the monthly income for citizens of the growing city. Of the 18,535 households in Fayetteville earning less than $50,000 yearly, 72.8% are financially burdened by housing costs. To fully relieve these financially bur-

dened households, Fayetteville will need to build 6,000 housing units below $875 per month and almost 5,500 new units below $500 per month. Consistently, from 2019 to 2023, the number of new housing units, from single-family to multi-family, has never exceeded 1,400.

“I think that many people who have been here for longer see Fayetteville as something completely separate from Springdale and Rogers and Bentonville, and I think that’s also shortsighted,” Diamond said. “We have to work within the broader context of Northwest Arkansas.”

Diamond discussed that the task force is in the process of brainstorming and trying to work within the city’s system to reach members of the city council to make them palatable. He agrees that they do not have that much power, but a group of professionals who are in the space, so that they understand the problem well, yet without the ability of a politician. Nelson and McIntosh’s lease was supposed to end in July 2025, but they only found out about this student housing project in January, after a year of it already being in the works. It cost $3,400 total to break their lease and move out for the two of

them, which meant they both needed to come up with $1,700 each, fast.

Nelson did not have this kind of money, nor the time to figure out how to get it or find new housing. She works five days a week at two jobs, a restaurant and a boutique, and is a part-time graphic design student on the other two days at the university. The panic set in, and she was forced to seek outside financial help as the reality of the situation began to settle: come up with the money or stay in the complex set for demolition.

“I feel like I work an adequate amount, enough to have some money, but I just don’t,” Nelson said while folding her arms across her chest and adjusting the towel wrapped around her short, blonde hair, looking askance. “I can’t possibly afford what people are asking.”

Nelson went to her family, who had limited financial means, for money. Her parents help with her rent and car payments as needed, but with four children, their money is spread thin.

To take care of the rest, Nelson reached out for a grant from FayIRA, Fayetteville Independent Restaurant Alliance, an organization that provides financial relief for hospitality workers across the city.

72.8%

Emily Tripplet, a friend of Nelson’s and a longtime member of FayIRA, is an Arkansas native and a bartender at “Fayetteville Taco and Tamale” who moved to Fayetteville in 2016 with her own share of housing problems and abrupt relocations. While living here, she has seen her apartment situation and the city she’s called home for nine years now go from bad to worse, as well as watching her friends and family around her struggle with issues of rising rent and predatory landlords.

“They want those people that have unmaxed-outable gold American Express cards because those people are more likely to pay it than me, a bartender, like what name do I have?” Tripplet said. “What accolades do I have?”

Tripplet lives with her boyfriend, Charlie Jones, a musician, in a unique situation where they do house and yard work for the older couple. The landlords pay them hourly for it and knock off the money from their rent, making it more affordable for the working couple. Even with this better home, she is still in a precarious situation with older landlords.

“So the odds of them giving it over to God knows who is really scary, but I just pray that they hold onto it as long as they can,” she said with a frown.

Despite the development of the housing crisis task force, the locals have grown restless at the city’s reaction to the insecurities. Many have banded together to give monetary support through FayIRA, people like Nelson, and the community-based organizations to bring some recognition and pool together resources to fight it, like the Arkansas Renters Union has done more than the city.

The rise of these associations proves the camaraderie in the area amidst widespread financial turmoil for the Fayetteville population and also the gravity of how no one seems to be on their side.

Arkansas Renters United is a statewide organization with the mission to give renters in the area a voice and fight for fair landlord-tenant laws to give renters protections. The state has no laws

households in earning less than are burdened by 72.8% in less than

to protect renters, so this group meets to rectify these issues through community mobilization and speaking out against abusive landlords. The activism group is led by Billy Cook, who has run for State Representative of District 19, a known public servant and community organizer intent on fighting for renters and representing an economy for working people, not the wealthy few.

Cook spoke at length during the Arkansas Renter’s United meeting, getting everyone up to speed on the gathering’s proceedings of future events and what their group means to accomplish. Cook gave the floor to the members surrounding him, who ranged from a man in old-fashioned suspenders who had been homeless for years from a housing crisis to an elderly landlord to young environmental activists in the area. Anyone renting in the state is eligible to join the group and attend the meetings for the non-profit. Nothing in the space was ultimately one-sided, and it only solidified how complex the issue of housing is, with no simple solution.

Yannik Dwyer, a prominent member of the ARU and freelance landscaper, has come to realize that there is no real leadership in her eyes.

Dwyer discussed how the city of Fayetteville spends exuberant amounts of money but rarely on affordable housing for the community. The city of Fayetteville spent $17 million on a parking garage and over $30 million on the new Ramble Arts program, a new gathering space in downtown Fayetteville. The money is funneled into enterprises focused on attracting new people to the city, not taking care of the thousands who already reside here in unsafe or insecure housing.

Between 2019 and 2024, the City of Fayetteville granted around $1.5 million in financial support to non-profit organizations that focus on sheltering the city’s unhoused population and $1.63 million in Arkansas Rescue Plan Act funding to nonprofits geared toward at-risk individuals in the city. The 71B Rezoning project is a plan to increase the amount of affordable housing in the 71B corridor, and in fall 2023, the city passed the project, which said they would consider rezoning property along the city’s central corridor.

Dwyer spoke at length about the housing crisis, starting with the complaints from the citizens about homelessness in the area. Dwyer said he hears talk about it, framed as a huge crisis, and yet, none of the housing crisis task forces’ 25 action points were that the city should build housing.

Dwyer ascribes the issue to the lack of affordable housing in the city. The housing she sees is primarily luxury and too expensive for the average citizen to afford, so it creates an influx of buying property out from under people to develop costly student housing and not to the benefit of the community, which Nelson fell victim to herself.

Over the last 20 years, growth in Fayetteville’s median house cost has outpaced the increase in median household income. Median house value grew by 275%, while median household income increased only 64%. The average salary of a Fayetteville resident is $57,176. Of the nearly 18,582 Fayetteville households making less than $50,000 annually in 2023, about 15,000 or 79.7% were cost-burdened by housing costs, which is an increase from 72.8% in 2022. In this group, six times the number of cost-burdened households lived in rental housing than in owner-occupied housing, according to the 2025 Fayetteville Housing Assessment by the City of Fayetteville.

“You need to show leadership,” Dwyer declared. “Nobody else will do it for you.”

Nelson is trying to do just that, but moving from home to home with little to no permanence has taken a toll on her mental and physical health. Nelson suffers from the autoimmune disorder, Ulcerative Colitis, which is a chronic inflammatory bowel dis-

“My home become It’s become advantage strangers

ease (IBD) that causes abnormal reactions in a person’s immune system and ulcers on the inner lining of the large intestine.

She often deals with extreme nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fatigue. It is hard for her to develop an appetite and keep down food or water, so she drops weight rapidly and dangerously. She dropped down to 112 pounds from 130 in less than a month. As a result, Nelson frequently visits the hospital because of malnutrition. Every year, she has had to move; she’s worked two jobs at the same time out of necessity, which poses a struggle amid her bouts of pain and health scares, taking a toll on her body from the stress and physical labor that it takes to relocate.

home has no longer become my safe space… become a monetary advantage for strangers in Texas.”

Nelson has moved all of her things by herself on multiple occasions, with the added challenge of pets, wondering where they were going to go in the meantime. Every eight weeks, Nelson must get infusions to remain healthy, and whenever she does not receive these treatments regularly, she gets very sick and needs immediate hospitalization.

“In a world of chaos, my home is my safe space.” Nelson yawned, evidently tired from a day of moving. She looked around at the boxes, apologizing for the mess on the floor.

“My home has no longer become my safe space…It’s become a monetary advantage for strangers in Texas,” Nelson said.

Carter Rideout, another Arkansas native and full-time worker at a local thrift store, “Cheap Thrills,” believes the same thing since coming to Fayetteville in September 2022.

Rideout lived with their sister and their sister’s fiancé when they first moved here for around six months while looking for a place of their own because of how limited their options were. The place Rideout finally found felt too good to be true, just under $800 for a two-bedroom townhouse by themself. The owner, to them, felt “sleazy,” never really fixing anything in their place that was broken, despite saying he would.

A little over a year went by when the owner sold the homes to a corporate property management company that raised Rideout’s rent almost immediately. The only thing protecting Rideout’s financial security was the fact that their apartment was not yet renovated, keeping the com-

pany from raising the rent an exorbitant amount. The company wreaked havoc on the property before selling the complex to another corporate real estate entity that still owns the row of homes.

Longtime owners were being evicted from their houses, treated as expendable, and tossed out without a second thought. A neighbor two townhouses down from Rideout knocked on their home one night, having never spoken to Rideout before. The neighbor informed Rideout about a note he saw on his door, telling him that he needed to move out by the end of the month because the new owners had sold his unit without telling him. The stranger simply wanted to let Rideout know in case the same thing happened to them, a courtesy that the realty corporation did not want to extend.

At the end of January, Rideout came home from work on the very same note, and they had to vacate the unit by the end of February. A practice Rideout described as “Morally just? No, but legal, perhaps.”

“I love my space so much…” Rideout said. “My home base is so important to me. So, it’s sad that it felt too good to be true and that it was kind of ripped out from under me.”

As Nelson sat there in her new home, arms wrapped around herself comfortably in her pajamas and skincare, she concluded that despite finding a new place, she still was not secure.

Nelson and McIntosh’s new home was a “dream come true,” but it came with its downsides. A common thread with her various residences is that compromises always had to be made. The house does not have a washer, dryer, dishwasher, or garbage disposal, not even an oven.

When it came to her housing situation, everything else in her life was constantly affected, from her work to her well-being to her performance in school. She works for two local businesses, one of which is currently closed and set to reopen later in the month, which puts a strain on her to make sure the small businesses run smoothly. When Nelson is worried about

money and affording rent, other responsibilities fall to the wayside. With no work, she struggles to afford rent and when she’s working both jobs, she doesn’t have time to tend to her commitments. Nelson also faces the challenge of school on top of every commitment, and it has caused her grades to slip, her grades suddenly dropping from an A to a C and tanking all at once.

“When I move, something has to give, and it’s usually something crucial,” she said grimly. “I really can’t afford to f--- up, but it happens anyway.”

Nelson’s story, along with many of her friends and colleagues, still exists in a precarious situation, all of whom exist in fear of whether they will be blindsided once again by a corporation or landlord who controls their home and their fates. With organizations such as Arkansas Renter’s United uplifting the community and FayIRA supporting its workers, the crisis seems less daunting for the people in their spheres.

but they don’t know how it leaves stripes, slicing through half-open blinds, across my mother’s face in her dead father’s room.

No one mentions the way it burns through the wild thorn-bitten blackberries, leaving them warm and hummingbird small for tiny grasping hands.

They forget the sun-stale chlorine in public pools and the searing concrete where we sprawled our soaking legs, the way water reflected in blue eyes and full cheeks, and how we didn’t mind staying out longer because her baby face still looked young.

They never write of the sleeping heat of a stalled car, hands lazily drooping out the open window, the melting hum of a grocery store parking lot and the forgetting that this minute only happens once.

No one talks about the marriage of sun and water and the icy freeze of the spring down the road where mothers still doze in lawn chairs and neighbors shriek and squirm at a crawdad’s pinch.

They leave out the ache of scraped knees and black asphalt streets; the smell of warm dirt, the fading memory of grandmother’s carpet. Ripping up grass and four-leaf clover and burying the dead lizard we found in the yard.

They can’t remember those summers the way I can. The sun feels the same today as it did before I knew how bad it could get. The pool is closed and we’re grown. It feels the same if nothing else does.

As a human in these unsettled times, I find solace in the creation of art. My work, titled REFUGE, is an expression of a secure yet imaginary environment where I am protected by the joy of the things I find precious. Surrounding this bubble is the uncertain and somewhat menacing world which cannot be ignored. The balance of light and darkness alludes to the cycle of energies that make up the universe.

Dawn. Orange sun, rising, wheels peeling out, kissing the curb, black tire tracks melting earnestly beneath summer’s yellow hues streaming, streaming through cracked windshield, legs burning against pocked leather seats, singing loudly to the radio, as if discovering my voice for the first time, winding, winding down backcountry roads, lost in the wilderness, admiring Aladdin, rolling over hills through dusk. Bumping along dirt roads, growing old, adding years to my days, adding gas to my tank, finding and losing my way among the etchings of white cliffs, engulfed in the scent of pine needles, the whisper of aspens, losing and finding my way, crying, crying, mourning the end of the long drive, celebrating the fulfillment of the journey, palms resting against hard rock, feet planted in the riverbed, delivering me to the mountaintop where I will discover God, watching the orange sun, rising. Dawn.

Rachel Whitten

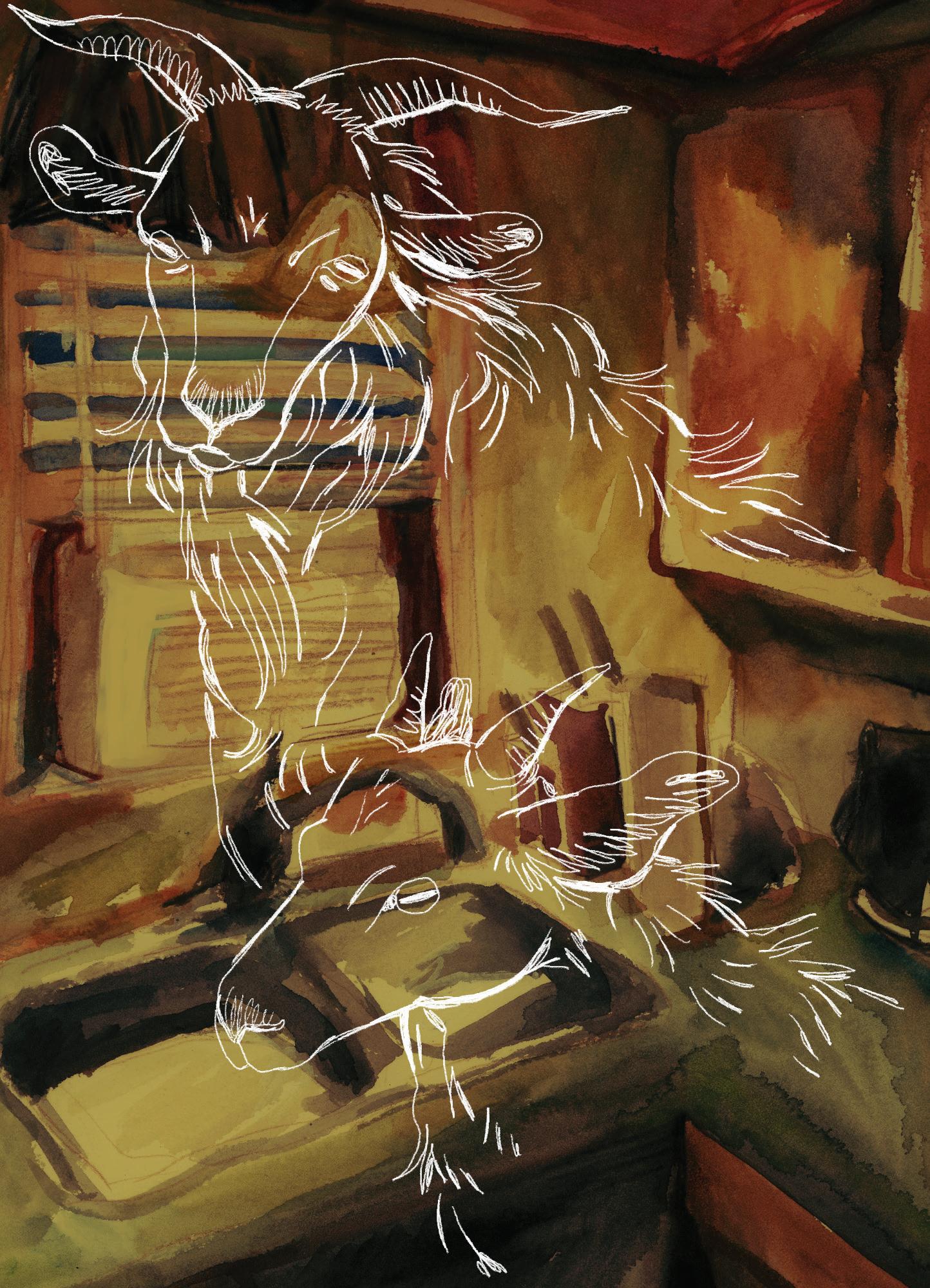

Emma’s Goats is a piece on my (step) sister’s grief and her means of coping after the recent passing of her father Jim over the summer. Emma and Jim were close, and I always admired the bond they had together as she was raised in rural Arkansas. Although I didn’t have Emma in my life until I was fourteen, I lived that life of hers vicariously through visits to the farm and stories of the animals she grew up with—even her giving me the honor of preserving the skull of her childhood goat when the time came. When Jim passed, I saw Emma in this quiet state of mourning I have never observed in her, let alone anyone. A few days after the news, I remember getting the message that she bought four new goats for her father's land. Grief is something one wrestles with in their own way and is up to the beholder what to do with that; in Emma’s case being manifesting it into the connection with the farmland and its animals. This piece of Jim's farmhouse kitchen with her new goats illuminated over is a homage to all the wild animals she grew up with and how they will continue to remain as something so familiar to her.

By Erin Bailey

He hadn’t realized that he presented differently than others. He had never really thought about it, he just dressed how he wanted. This was until he made friends with a group of his classmates that used they/them pronouns when referring to him.

Arleaux Afton was 15 at the time. He remembers how comforting it was to be assumed as something other than what he was assigned to at birth. This was the first time he started to question his gender.

After a lot of time and thought, he came out to himself for the first time as trans-masculine. He knew he wanted to tell his parents next, but it was easier said than done. Too nervous to come out face-to-face,

Afton started by texting his dad. His dad took it well and was very accepting. His mother, however, wouldn’t take it well.

“When I came out to my mom, she said a lot of hurtful things, like, ‘But you still like wearing dresses,’ ‘But you never showed the stuff when you were a kid,’ ‘I know you so well. You’re not a guy,” Afton said. “I have a really hard time confronting

people, and so I just swallowed it and said ‘yeah’.”

Due to his mother’s reaction, Afton decided not to tell anyone else about him being transgender.

“It was really hard because throughout the years my mom would say, ‘Oh well, it’s not that hard to accept your child,’” Afton said. “And I’m like, then why couldn’t you?”

While Afton today has built a

community that embraces who he is, the uphill battle to acceptance is still ongoing.

On President Donald Trump’s first day back in office, he issued an executive order declaring that only two sexes will be recognized by the United States and that they are assigned at conception and cannot be changed.

“We’re being erased,” Afton said. “They’re trying to write us out of a lot of laws and out of the websites that were for us.”

Just over a month ago, a page on the State Department’s website providing information

for “LGBTQI Travelers” was changed to only address “LGB Travelers.”

Another page on the State Department web page that used to provide “Resources for LGBTQI+ Prospective Adoptive Parents” now says “LGB Prospective Adoptive Parents.” The Social Security Administration, an independent federal agency, also has made changes to remove the mention of transgender people and intersex people. A page formerly called, “Social Security for LGBTQI+ People” has now been updated to “LGBQ People.”

Other web pages mentioning the LGBTQ+ community have been removed as well. Such as, a page on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website about tobacco use among LGBTQ+ people, on the Justice Department information about LGBTQ+ working group, and on the website for the Labor Department a page dedicated to the Commerce Department’s LGBTQ+ program and resources about avoiding discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Afton moved out of his parents’ house when he was 19 and started working for Chartwells, the University of Arkansas food court, in 2021. He quickly noticed that one of his shift leads, Percy Parker, wore a pronoun pin with his uniform. Afton said that seeing Parker wear his identity so proudly encouraged him to wear one too, and he came out as nonbinary to his coworkers. He said it was easier than before because no one at work knew him personally.

“When Percy had asked me, ‘Oh, do you want to go by a different name?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, I want to go by Jack,” Afton said. “And so, they were able to reprint my name tag and everything.”

Afton first went by Jack as suggested to him by a friend who was also questioning their gender. The name wouldn’t stick around for long, however.

Afton’s parents often came to the Union food court to eat lunch as his mother used to work for the university and really enjoyed the food. It was unlike any other day until his mother noticed his name tag. Rather than it saying the name she had known him by, it said Jack. Puzzled, she

called attention to it, sending panic down Afton’s back.

“She kind of just saw it,” Afton said. “And she was like ‘Jack? Okay,’ And didn’t really say anything more on it. Eventually, we were talking about it, and she was like, ‘It feels a little bit hurtful that I had to learn this way, that you’re trans’ and I was like it was just easier for me to come out to people that didn’t know me. She eventually was, like, you know, I’ll accept you.”

Afton said it was a bit easier after that. She wanted to pick out a new name for him because she said Jack didn’t suit him. Things settled down for them and eventually, Afton became more confident and started using he/him pronouns and shifting toward more masculine things. Around this time, he also changed his name again to Arlo. This time, when he told his mother that he was changing his name, she was much more accepting. Although, she did suggest he change the spelling to the Cajun spelling “Arleaux,” and the name stuck.

The Trevor Project conducted a survey in 2023 examining U.S. adults’ perspectives surrounding issues that impact LGBTQ+ youth. Through a national sample of 2,200 U.S. adults, they found that the majority (54%) of adults would be comfortable with their child if they came out as LGBTQ+, and 57% would be comfortable if their child started using gender-neutral pronouns. They also found that 69% agree that the parents—not politicians, should have the ultimate say over whether their child received transgender medical care or not.

However, not everyone has the same experience with their family, and discrimination looks differently for everyone. In 2013, Percy Parker had just transferred to Rogers High School from Benton County School of Arts and quickly found himself in a dilemma. The GSA (Gay Straight Alliance) met in his homeroom, leaving him with two options: join the club or find another one. While the second option may seem simple, it would require him to first get up from his desk, walk to another room and interact with new people. To him the answer seemed obvious. Without hesitation or much thought into what the GSA was, he joined.

His laziness would change his life forever.

When Parker first joined the club as a freshman, he had never heard of being queer or transgender, let alone met anyone who identified as such.

“As a young kid, I didn’t really understand what being gay was either,” Parker said, chuckling. “In middle school I had a crush on a guy, who apparently was gay, but I had no idea. I was just like, ‘Why can’t he just like me?’ not understanding that’s not how being gay works.”

Through the GSA club, Parker learned a lot about queer culture. Parker remembers the club hosted a transgender guest speaker and that was the first transgender person he had met. As he learned about other people’s experiences, he also came to terms that he was queer, too. At the time, he was not sure exactly what that meant to him. It would not be until his freshman year of college in 2017 that he would discover that he was transgender as well.

He started by telling his roommates who were very accepting of his transition. He then started to tell his classmates. Similar to Afton, he said it was easier to come out to people who didn’t know him. Lastly, he told his family. His sister was the only person who was actively supportive.

“She was really accepting,” Parker said. “She’s like, ‘Okay, what are your new names? I promise I’ll try to get your pronouns correct,’ and she’s been really good about it, even when I’ve changed my name a couple of times.”

When Parker was able to get his name legally changed, he sent a text message out to his family in a group chat. He said that his sister-in-law and step-mother said “congratulations” and that his brother and dad didn’t say anything. Then, even after that, his father still refers to him by his deadname and incorrect pronouns. Parker said he has since cut contact with his father.

Parker has a medical condition that prevents him from using testosterone to transition. He said that for him, getting to use his preferred name and pronouns mean a lot to him and that being able to get his name legally changed helped him feel more like himself.

“I finally feel more like me and people can’t call me that other name now because that’s not me anymore,” Parker said. “So, it just felt really free and I was really excited. I was so happy and I immediately texted everybody I knew and was like, ‘Hey, oh, my God, my name change finally went through,’ and everybody’s been really happy for me, for the most part.”

It’s been four years since they first met. Afton said that Parker was the one who first helped him accept who he is. Still to this day, the two continue to support each other—now as husbands.

“One of the best things is finding a group of people that are very supportive,”Afton said. ‘They don’t have to be your family or your current friends, but finding an LGBT space, even online, is always great. I was always online talking with people and because they didn’t know me, I didn’t know them, we could just be whoever we wanted to be...”

“...It was freeing.”

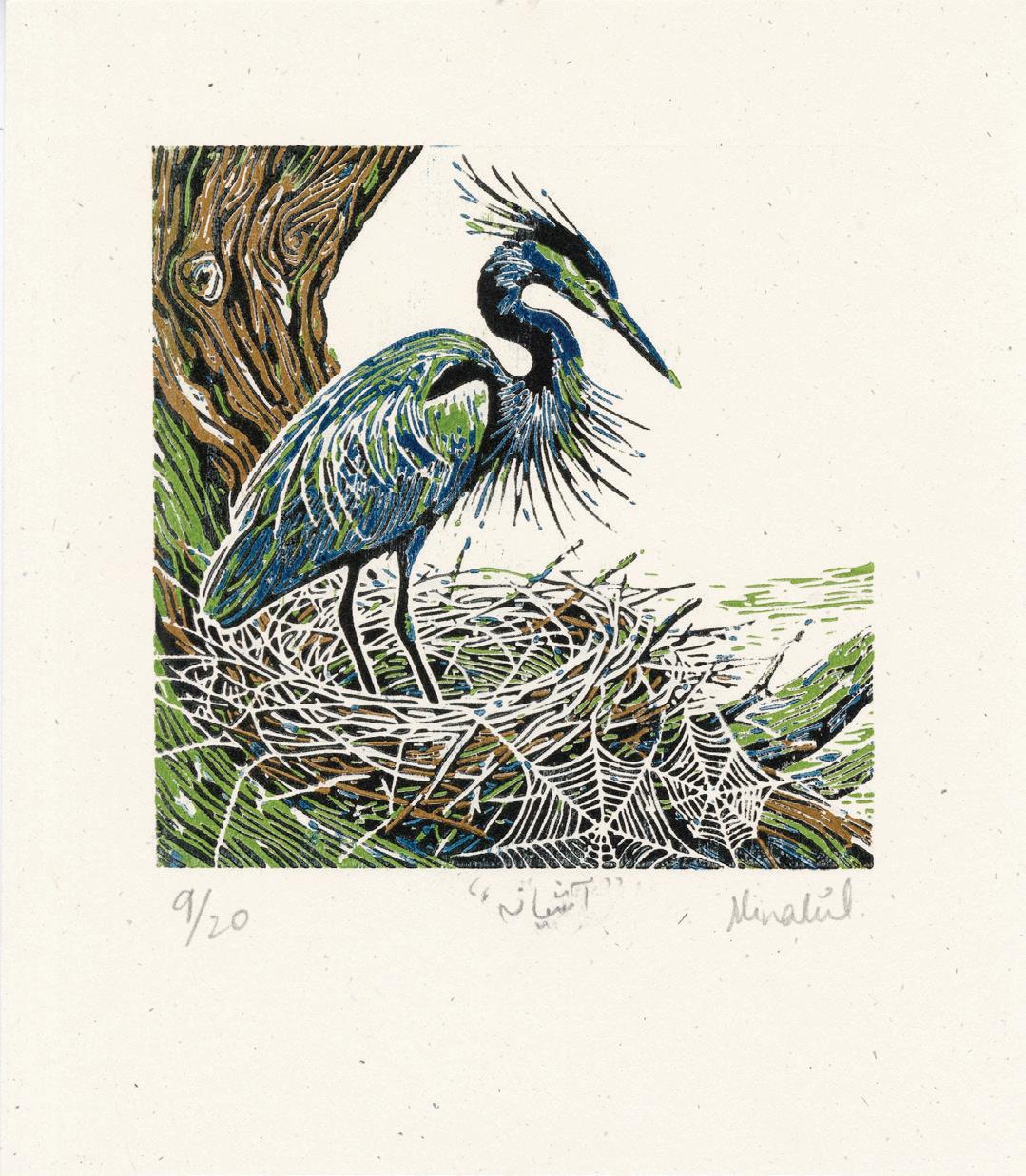

Minahil Qazi, ﺁشيانه (Home), 2024. 6 screens woodcut, 6x7 in.

“ﺁشيانه (Home)” explores the interconnectedness between humans, animals, and nature, symbolizing Earth as a shared sanctuary. The blue heron, its nest, spider webs, and trees represent the delicate balance of ecosystems, while the concept of "home" underscores the need for collective responsibility in maintaining environmental cleanliness. By protecting nature, we protect ourselves, fostering a safe and nurturing habitat for all living beings. The work highlights the reciprocity between care for the environment and human well-being.

“

Minahil Qazi, ﺁزادی (Freedom), 2024. Relief, 14x18 in.

(Freedom)” envisions a world where living without fear is a profound blessing, often unrecognized or unattainable. The artwork parallels personal liberty and environmental harmony, suggesting that a clean, utopian environment may seem unattainable but can be approached through small, meaningful contributions. It highlights the ripple effect of individual actions in nurturing the ecosystem, fostering a sense of collective responsibility and hope for a freer, healthier world.

Minahil Qazi, بگلا (Blue Heron), 2024. Intaglio, 8x22 in.

“بگلا (Blue Heron)” reflects the intricate interconnectedness of life within nature. The piece symbolizes the cyclical relationship between living beings and their environment through an intaglio composition of the blue heron, its nest, and a tree layered back-to-back. This arrangement emphasizes harmony, coexistence, and the inseparable bond shared by all elements of the natural world. It invites viewers to recognize and respect this interconnectedness to foster balance and sustainability.

In “I Don’t Want to Bloom Yet” I illustrate the sinking feeling of coming out as a queer man, and the idea that to finally come out is to bloom fully but is also to relent control and face the of loss of lifelong connections. I often use a shower or bathroom scene as a way to describe the feeling of uncleanliness that I experienced growing up queer in a predominantly conservative environment. The hand coming out of the overflowing tub is of a figure resigned to being submerged, and with it follows a blooming flower, a night blooming cactus (specific genus being the epiphyllum oxypetalum). This particular flower is a cactus bloom, a bloom that occurs only at night and often only once a year; however, this bloom can also occur if the plant itself is in a critical condition or close to death. A short-lived moment of beauty, one that signifies the end of a cycle or the beginning of a drastic change. This sentiment mirrors my thoughts on coming out as being a chance to finally be myself with those I love, while also being an event that could shake the foundations of my relationships with those closest to me.

The first time I learned my father wasn’t ever going to get better was in November 2016, when he kidnapped me and my siblings, stuck in his hotel room until late into the evening.

It was Thanksgiving, and it was my dad’s turn to have the three of us. As divorced parents with joint custody and visitation rights, they would trade off every holiday and every weekend. It would adjust occasionally because of my parents’ schedules. Still, more often than not, it would be my father who skipped visitation or denied us on holidays because he was “busy.”

Sometimes, he would forget us—me, my younger sister, Emma, and my younger brother, Russ—or come so late to pick us up at our after-school daycare in elementary school that it would go into the night. As a result, my mother would have to pay extra fees to the school for watching us longer. Even as a kid, I knew what it meant. He had other, more important plans.

That Thanksgiving, nine years ago, my father refused to take us home, saying his brother was coming to visit, but our uncle never showed. We weren’t fed all day, and instead, he sat us down at the table, ranting for around two hours before taking all three of our phones so we couldn’t call our mother. It was a television stand because we were living out of a hotel room for a few weeks at that time. He often had trouble paying for rent in the various houses and apartments we lived in.

I remember feeling like I was never going to see our mother again. From a young age, I called upon her for a lot of support, and she would often calm my anxiety, especially when it related to my father.

But that Thanksgiving night, my dad ripped that avenue away.

Growing up, my father’s motto was always: “What happens in this house, stays in this house.”

My dad would often get like this—red-faced, manic, and wildly flailing around—while he would rant, letting whoever he would direct his anger toward know why they were wrong and he was right. Later in the night, he finally took us back to our mother after she threatened to call the police if he didn’t return us.

The unspoken agreement between my siblings and me that we would keep our dad’s secrets finally lifted that night when we arrived safely back to our mother, and the three of us told her everything that happened. This was one of the last times we saw him outside of a court-mandated therapy session, and one month later, my mother filed an emergency motion to suspend visitation in December 2016.

I am using pseudonyms for many people in the story, including my father. I have not spoken to him in seven years because he lost custody of my siblings and me on account of emotional abuse, a charge almost impossible to prove, coupled with a restraining order. Thanksgiving 2016 was used as evidence for this: a night of manipulation, fear, isolation and unadulterated rage.

Parental substance misuse has an overwhelming impact on the well-being of their children. Between 2015 and 2019, more than 2 million children lived with a parent with a substance abuse disorder. These parents suffering from addiction are less likely to effectively take on a parental role for their child. What follows is an onslaught of loss, conflict, violence or abuse, and children taking on the role of guardian for their own parents.

According to a KFF poll, United States drug overdose deaths are at an all-time high, as many are feeling the impacts across the country, with two-thirds saying a family member or themselves have been addicted to drugs or alcohol, experienced a drug overdose or experienced homelessness due to addiction. Three in 10 U.S. adults have been addicted to opioids, prescription painkillers or illegal substances such as heroin.

As someone with a father who suffered from addiction during my childhood, I have learned from a young age to

be quiet about his unseemly habits or erratic behavior and the effects he had on my siblings, my mother and me. I decided to not be quiet anymore and go to an Al-Anon meeting, a group for the families of people who suffer from addiction for the first time. When I arrived at the “Alano Club,” a few people stood outside smoking a cigarette and chatting before their respective meetings. It was set in an old church with posters of Bible quotes on the white walls.

While pouring myself coffee, a man told me where I could find the room specifically for Al-Anon, taking it upon himself to welcome me to the space. I was overwhelmed. I didn’t know there was even something like this for families and not just communities to help the users get sober. I sat in the meeting for a little over an hour, where the entire session was dedicated to making any newcomers feel comfortable, like me. Everyone went around the room to share their stories and what this group has meant to them for 20+ years, with most of the room being at least past their 50s.

I was pleasantly surprised at how warm and inviting AlAnon was. Despite the feeling of raw vulnerability with people I had never met, I felt understood in a way people don’t often understand me and my relationship with my dad. I didn’t feel alone with that anxiety. The people in the room met me with murmurs of agreement and words of encouragement when I spoke. I said things I had never said aloud before, shaking in my seat as I accounted only vague details of my father’s addiction and abuse. I talked about how it felt like I was grieving my dad, despite him still being alive, and it feels like I’m mourning the father and childhood I could have had if he was sober. Would he still be in my life? How differently would I have turned out if I grew up with a father who didn’t suffer from addiction?

Growing up, I found myself wishing my parents never met. For my siblings’ sake, my sake and, most of all, my mother’s sake. I watched the way he hurt my mother constantly, screaming at her in locked rooms, slamming her against cabinets, spending her money on his vices and hurling insults at her over phone calls. I saw the pain he caused both when he was around and long after he was gone. Before meeting, the two of them had drastically different upbringings, ones that clashed when it

Photo by Guerin Honeycutt

came to their values. My mom grew up in a traditional, conservative, Christian home in Green Forest, Arkansas, in a very sheltered environment.

My dad, on the other hand, grew up in Tampa, Florida, with an older brother and a twin brother. The three of them were frequently in and out of trouble, raised by a single mom because their dad left when they were born. My dad and his brothers were usually babysat by their family dog and left to their own devices. My father would tell me growing up that his dad abandoning them

left deep, emotional scars, and it encouraged him to be a better father to my siblings and me. He promised he would never leave us, too.

When he turned 12, his dad returned, but he was in and out of his life, causing constant instability in his home. He was the life of the party, like he always was, courting attention wherever he went. She had never heard someone sing like that before, and she was instantly drawn in. They were engaged within six months. Her memories from their time together, as well as mine, are murky, so some details are missing.

David Russ, my great-uncle and a licensed psychologist, is a founding partner of Carolinas Counseling Group in Charlotte, North Carolina and focuses on severe anxiety disorders in adolescents. He is a co-creator of a treatment program for anxious children called “Turnaround: Turning Fear into Freedom.” He turned it into a book, chock full of metaphors like comparing emotions to a rollercoaster stopping on an incline and never knowing when it would fall.

For many children of addicts, there are countless unknowns, and they don’t have the language to articulate their experiences. So, as a child, it became one of my favorite books that helped me understand my anxiety and other upsetting emotions exacerbated by my father.

Russ said that after traumatic experiences, namely from childhood through the lens of someone now in adulthood, people will not remember the categories and reference points that existed at the time of the event.

A traumatized person is left asking themselves why they did something or why they did not know how to do something. Developmentally, one couldn’t understand what was happening to them until much later as a means of self-protection. People’s brains favor remembering danger as a means of survival.

People will not think about traumatic events for years before they suddenly come back, frequently with no warning. Anything recurring and problematic leaves its mark, such as a loved one’s addiction, on the lives of the family members.

“Like when you’re anxious, it’s just you and the bear,” Russ told me. “You don’t care what kind of trees you’re running through; you don’t care about world hunger or the stock market, it is you and the bear.”

Things that impair the front of the brain, “the caveman part,” also impair one’s survival instincts and impulse control. It is the alarm portion, which makes it more automatic, so if it is flooded or impaired by substances, your available IQ drops. People begin to rant, bombarded by anger, and say things without thinking. Without the substance, one’s brain would likely prevent the person from committing a volatile or thoughtless act.

This explanation brought to mind the nights when my father would spend hours ranting. The rants ranged from blaming my siblings and me about the bad day he was having to paranoid ramblings that I couldn’t keep track of. The drug-induced neurosis.

My sister, Emma, remembers that the most: how much he talked. She would sit there and count down the seconds to distract herself, watching the clock, and doing the math. My sister said the numbers made sense when other parts of our lives did not. When she counted, she found that some of the rants would be up to five or seven hours. If either of us spoke, they would go on for longer.

“Addiction creates a lot more uncertainty and insecurity,” Russ explained. “It’s almost like you can be dealing with the same person, but the sober person is one thing and the person under the influence is a whole different thing.”

Before my dad’s opioid addiction, my mom and dad got married in 1999, before my mom graduated from Drury University in

Missouri in 2000. My dad was working for the Holland Railroad Company at the time, where he would weld the track and lay it. They were long-distance because of the travel he had to do for his job, but they made it work. My mom told me about his accident at her work when he was sitting in a high rail truck, a vehicle that can drive both on and off the railroad track, when a runaway rail car started sliding down the track, where he couldn’t jump out or back up. The rail cars were supposed to have air brakes that could engage at any time to stop them, but they were faulty, a condition the company was aware of but neglected to address.

The car hit him enough to injure his spine with three herniated and ruptured discs, in need of a spinal neck fusion, which limits one’s ability to move their neck from side to side. He left the company on disability, where he later developed arachnoiditis, a rare spinal inflammation and pain disorder. He didn’t work for another ten years.

His addiction started while being treated for his disorder. My dad called one of the nurses who treated him and complained that his prescribed pain medication wasn’t working anymore. They explained it was because he was addicted to them, and he asked for another medication that would work again.

“And it was like this total acknowledgment of ‘yeah we know you’re addicted to this opioid…’” my mom said. “They gave him something stronger.”

During this time of doctor’s visits and pain prescriptions, he went from taking Tylenol 3, an opioid and a combination of codeine and acetaminophen, now discontinued due to the risk of liver damage, to OxyContin, a highly addictive pain medication.

After his treatment was over and he began recovery in physical therapy, his addiction was starting to take its toll on both him and my mother. The two of them decided to move to an apartment together in Little Rock, Arkansas, before he proceeded to take the down payment for the apartment and gamble it away at a casino.

“I remember the first time he started taking [Adderall], he was like… slack-jawed and just completely stoned out of his mind on it.” “But he had

She was forced to borrow money from her parents, which always felt like the worst-case scenario for her, as someone who could consistently take care of herself. Now, she was taking care of her husband. Six months into their marriage, after the accident, her panic attacks began.

Over 10 months, he spent over $50,000 on drugs. Opioids quickly escalated to various, stronger pills to fentanyl popsicles and regular use of cocaine that he also began to sell. My dad’s doctor had fired him as a patient because he was intimidating him into giving him Adderall that not covered by insurance. He also escorted him out of numerous emergency rooms for faking injury to score more painkillers.

“I remember the first time he started taking it, he was like…slack-jawed and just completely stoned out of his mind on it,” my mom said. “But he had no pain.”

David is a former drug user and the product of generational addiction, the child of an addict with a brother and a sister, both meth users, who are still deep in drug use themselves.

In 2008, David, 19 at the time, worked at a restaurant in his hometown with friends from college and high school who were taking opiates. This was his first introduction. This was at the height of the opioid epidemic. That year, drug overdoses in the U.S. caused 36,450 deaths.

He started taking OxyContin and feeling sick afterward because he was starting to wake up in the morning feeling very ill. He began to figure out that, after taking the drug again, he would feel better, and that’s where the dependence began. He was surrounded by friends who were all in active addiction, and it led to a tailspin for him.

OxyContin was the kind of drug that would wear off after 24 hours, which is when he would start to feel withdrawal. With heroin, on the other hand, he started to feel unwell every 6 to 8 hours. No one had any idea he was knee deep in addiction while juggling two jobs, an active social life, and to everyone else, nothing was wrong. That was the scary part. In 2023, around 54.2 million people 12 and older needed treatment for a substance use disorder, but only 23% received it.

by

The financial burden of his addiction began to take a toll on both him and his loved ones when he started to run out of money. He began stealing from his family to pawn off items like a camera from his niece and money from his mother’s purse.

“Every dollar I had went toward my habit,” David recalled. An addict will do it out of fear in the moment, then the reality will settle in when the drugs wear off, and they are only left with deep regret. It was then that he started to realize he needed a change.

When it came to my dad, everything moved so quickly, and my mom was always in survival mode. His accident, as well as the subsequent failure of his medical professionals who initially fed his addiction, was the first instance in a long battle of my father’s drug habits, financial strain and abuse toward my mother, being dragged along at his whim in her fruitless efforts to save him.

Erin is someone who has also seen the effects firsthand from her alcoholic father, who also abused narcotics, among various others, still unknown to her. It was harder to hide the excessive drinking, but he was discreet with his pills of choice to her and her twin sister. She recalled the first time she realized her father’s addiction went further than alcohol when she was 17.

When she got her wisdom teeth removed, she was prescribed oxycodone, a strong opioid, and her mother immediately told her to make sure she hid it and that her father did not come into her room without giving her an explanation, which was odd to her as a young adult who only viewed the pill as something to treat pain. It resonated with her in that moment that her father had a problem.

In April 2024, at the time of the one-in-a-lifetime solar eclipse, Erin’s father worked on a passion project over the span of months to throw an eclipse festival. It was a whole affair with a huge stage, friends, and family from all over, music, food trucks and cabins for everyone to stay in for the night.

That night, Erin sat out on the porch with her mom, sipping wine and talking under the stars after a long day. He came out on the porch, the physical embodiment of a dark cloud over their conversation before he pulled out his balloon and inhaled next to them.

Their talking wavered, and when he spoke, the gas would warp his voice. It was low and warbling, blissed out and leaning back in his chair while Erin and her mom tried to carry on as if everything was fine.

Before she fell asleep, Erin cried in bed with a dark, looming feeling that something horrible was about to happen to her or her family.

“I just had this feeling that was the last conversation I would have with my dad…” Erin said. “And in three weeks, he was dead.”

Her father passed away late April after overdosing on the combined toxic effects of oxycodone, clonazepam (an anti-anxiety medication) and trazodone (an antidepressant), with a glass of wine, after years of on-and-off use.

The anniversary of her father’s death is at the end of April. She spends the day with loved ones, a necessary focus on community in a time of ongoing grief.

When she had been around him, she remembers an immense wash of shame, that gnawing ache in her stomach. It wasn’t quite pity, but a sense of deep sadness, the equivalent of watching a car barreling toward a wall at full speed, where the watcher can do nothing but stand and scream for them to slam the brakes. Erin’s family is now left with thousands of dollars of debt from both his habits and the destruction they have caused, including over five cars totaled within the span of a few years.

To me, one of the scariest parts of addiction is the generational cycle, from one user to their descendants; it becomes embedded into their DNA. Genetics are responsible for almost 50% of the risk for drug and alcohol dependence. The other factors are environmental, such as exposure to a parent’s drug use have a higher probability of behavioral problems for the children of addicts, frequently leading to experimenting with substances.

For me, I’ll never know if my dad got sober. After my parents divorced in 2010, my mother started seeing a therapist and was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, generalized mood disorder, panic disorder, ADHD, PTSD and battered-wife syndrome, with my father at the root of them all. I started seeing a therapist at 12 years old, where my siblings and I were diagnosed with PTSD, depression, generalized anxiety disorder and ADHD, all of which stem from our time with my father, too.