The University of Arkansas’ award-winning student-run magazine presents

The University of Arkansas’ award-winning student-run magazine presents

We would like to give a huge thanks to our wonderful writers and photographers who helped us make this dream come alive....

Poem by Bailey Wheeler

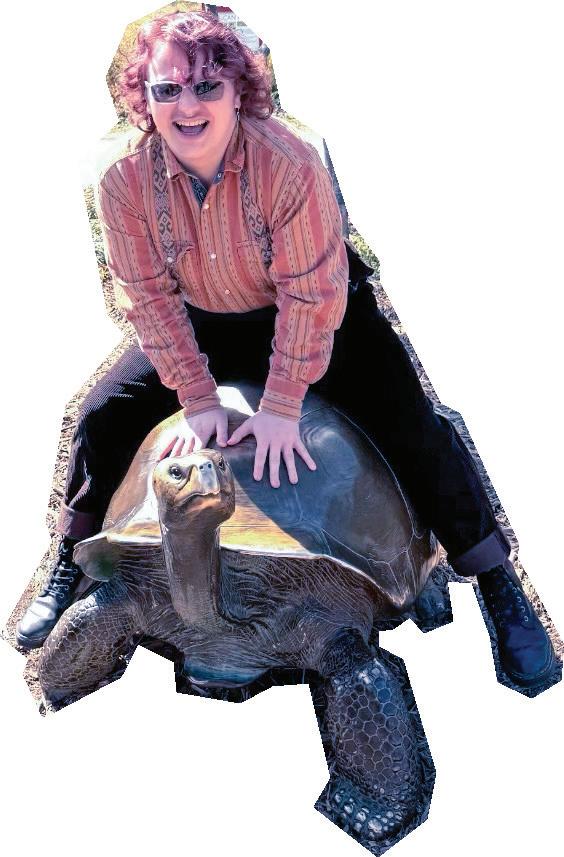

Photo by Ally Eckels

By Emma Bracken

Time Floats

Poem by Baleigh Laughard

Photo by Evan Meyers

Degrees & Diamond Rings

By Ella Karoline Hendricks

Midnight Surgery

Photo by Etta Salzman

Childhood Memorial

Poem by Juno Myers

Photo by Fiona Scoggan Beyond

By Natalie Murphy & Ashton York Consequences

Short story by Adam Lorio Photo by Henry Nguyen

Sunlight: bright and cold

Tough like hair gel, Second-hand love.

The Mother of my father, And, Mother of my Father (the one with the angel).

Standing in storms: To wait for the yellow bus Or

Stomp around in mushy wet oil stained puddles (under the parking lot overhang and behind the corn fields).

Its heavy like car keys, Like holding in tears.

Sweet like crying at the gas station.

By Emma Bracken

Photos by Marshall Deree

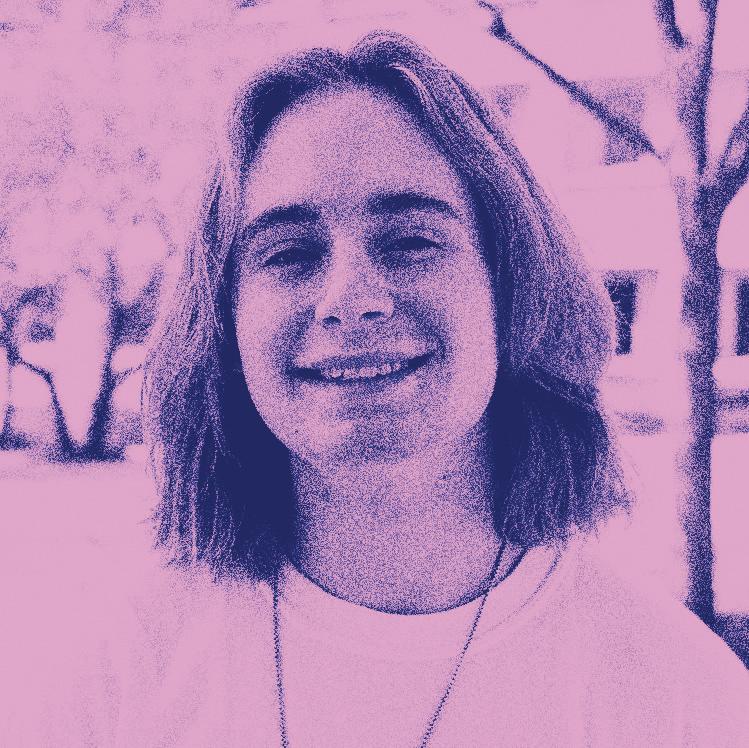

Sophie Trist’s most common dreams are what she describes as a cycle of sleep-induced confusion. She starts suddenly awake, trying to make sense of whatever dreamscape she was falling off or running from, before once again losing sense of the world around her. The world feels unsteady and slow, and the clear consciousness of morning seems to still be out of reach. It is in this movement that she realizes she is still dreaming, repeating the cycle until somewhere along the way, she does actually wake up to face the day. Getting up, the day ahead of Trist will carry on much like any regular college student—eating breakfast, going to class and working on assignments—but her disability sets apart her waking life from most. She is blind.

Sighted people often wonder about the dreams of blind people, and how the nonvisual world can translate into tangible dreamscapes. For Trist, being blind may make her dreams slightly different from the ones many of us are familiar with, but they reflect her physical reality just as all of ours do. As a graduate student and instructor here at the University of Arkansas, Trist’s

dreams often recount classroom scenarios and deadlines. Alongside the typical school-related stress dreams, such as taking an exam you are unprepared for or showing up late, Trist has other obstacles that others may never consider. She noted that one dream she has had is showing up to teach and having no braille materials for the lesson.

Many of us have similar or identical types of dreams, though we don’t know why, exactly. There is something about our dreams that seem to be universal. Though sleep and rest are an inevitable and relatable part of human life, they look different for everyone, especially those with physical disabilities. Conversations surrounding sleep can also bring forth an array of prodding questions and misunderstandings. As Trist navigates the world of academia and

Sleep is a profoundly unique and yet wholly relatable human experience. One aspect of human sleep that seems to be universal is our tendency to dream. For reasons still largely unknown to us, our minds create worlds of their own

“When I dream, I dream the same way that I experience this world, which is mainly

as our bodies lay still. Dreams, though sometimes wild and nonsensical, can manifest into what we think about and hope for during the day. Throughout the entire etymological history of the word “dream,” these different definitions have been intertwined.

It seems that both when sleeping and awake, humans are predisposed to aspiration and optimism. It is an inherent side-effect of our intelligence, a desire to plan for and ruminate about what the future could look like. We dream, both when asleep or awake, about the places we want to go, the love we wish to find, or the problems we know we are soon going to have to confront and solve.

Much like the physicality of sleep, the way that people go about setting goals and finding avenues to achieve them is complex and colorful across the board. There is no one road to success, and even if there were, it is important for us to remember the varying levels of access we were born into. People are born with different physical abilities as much as we are born with different interests or personality traits.

In the realm of sleep, people with certain disabilities, such as visual impairment, are the subject of questioning and misunderstandings from

able-bodied people. Trist explained that she is often asked if she and other blind people sleep with their eyes closed. Trist explained that this sort of question has no answer, because the spectrum of experiences in the blind community is so wide. Trist, who has been blind since birth and has prosthetic eyes, notes that she does not close them when sleeping.

“I don’t expect people, especially young people, to know a lot about blindness,” Trist said. “I know that I’m probably the first blind person that you’ve had an extended interaction with. A lot of things I will take on good faith, people just don’t know and are asking in the spirit of curiosity.”

Another phenomenon of human perception is the idea of colors and the distinct possibility that we could all perceive them differently. For the visually impaired, particularly those who are entirely blind, color is another source of questioning from sighted people.

Trist said.

Trist explained that color to her is more of a concept that is intertwined with the emotional and cultural context of the words we use to describe them. For example, green inspires ideas of growth and rejuvenation, blue generates the feel of water and calmness, and red is hot and passionate. Without a visual frame of reference for understanding color, Trist connects the same connotations that we all do when it comes to defining color.

“When I dream, I dream the same way that I experience this world, which is mainly sound, touch and words,” Trist said. “So I don’t dream in color because my brain was never wired to have that kind of input.”

Though the visual experience is different, Trist explained that her dreams are not much different from anyone else’s. They are often confusing or nonsensical, where details shift and slide without reason. She also experiences the same type of first-day-of-school anxiety dreams and other typical nightmares.

As a creative person studying fiction writing, Trist is also able to use her dreams as a source of creativity when it comes to her work. Sometimes, the ideas that float through her mind at night can be grounds for a great fiction piece.

“I have had moments where a dream, by an indirect process, has been incorporated in a story or provided a kernel of inspiration,” Trist said.

Though our sleep patterns and dream types may look different, Trist explained that our takeaways from dreams are often very similar. It is important for us to learn about the ways that people are similar to us despite our differences, and understand the varying experiences of human life all around us. Blind people are often the target of ignorance when it comes to sleep and dreaming. It is possible that this lack of understanding could manifest into disbelief or doubt when it comes to aspirational success as well.

When it comes to dreams, the sort that are scribbled into notebook margins or pasted onto a vision board, we all have different approaches to goal-setting. Some of us want rigid structure and an idealized list of steps to achieving

our goals, while others would rather have their goals in the back of their minds as they allow life to naturally progress them forward. Dreams are at the center of our lives and experiences, both in terms of when we sleep and as we plan for our futures.

“I think that it’s interesting that dreams refer to both of these things, because I think they spring from similar parts of your mind,” Trist said. “When you’re asleep, your mind comes up with all of these wacky scenarios. But aspirations, at least for me, also come from a place of imagination.”

Trist explained that her aspirations stem from ideas of what she could be and what the world could be, both stemming from creativity and journeys we take through our own imaginations. Whether or not these things are happening consciously seems not so important. Because our experiences of both types of dreaming appear so intertwined, our misconceptions and judgments surrounding them are often as well. The experience of having a disability, as Trist explained, is wildly complex and differs from person to person immeasurably.

According to the World Health Organization, about 16% of the world’s population have physical disabilities. This is a wide spectrum of different experiences, from deafness to arthritis to cerebral palsy. There is no monolithic experience of disability, as there are so many ways our abilities are varied and fit into the categories we have created to better understand them. However, people with any type of disability can relate in the fact that the world is built inherently for the able-bodied, and oftentimes they are expected to keep up without assistance or accessibility measures.

Our fast-paced world is not designed for differences in ability and pace or carving space for accessibility. Our society is built on competition, and those with disabilities are often left behind rather than uplifted. In a collegiate environment, there can be a lot of pressure and standards to live up to. Just the act of being a student seems reliant on the similar sort of competition and overworking culture of our economic system.

Trist uses braille materials to work with the virtual classroom structure we have in place on campus, but the possibility of not having access to those resources has manifested into a nightmare for her. Beyond braille for the visually impaired, it is crucial to have a variety of accessibility measures in place across campus to allow students and staff of all abilities to succeed.

There is some effort on behalf of the university to create accommodating spaces for those with disabilities. Elaine Belcher, associate director of administrative services at the Center for Educational Access, works with students to accommodate their needs through a variety of programs and services. Belcher shared that according to the National Center for Education Statistics, around 21% of undergraduate students reported having a disability.

There is a clear need for resources such as the CEA across all educational institutes in the country, but there is also always room for improvement in our larger community, and even in our interpersonal relationships. Given that the NCES statistics only account for reported cases of disabilities, and the CEA can only provide for students who reach out for help, there is an entire population of people struggling but

keep silent about it due to the stigmatized relationship with physical health we uphold in America.

As students work toward achieving their goals and dreams on campus, the CEA provides avenues to help lead students with disabilities along that path. Belcher encourages students to reach out to the CEA even if they are not sure if they qualify for accommodations. The definition of a disability, because of its complexity, can often be warped or narrowed. But when it comes to accessing dreams, and finding ways to mold them into reality, sometimes challenging the structure you are stuck in is an important first step.

The world of course is not always willing to form itself around an individual’s needs. This sort of rhetoric is sometimes perpetuated against accommodation efforts. People demand others to fit themselves into some semblance of what we define as the status quo, even if it is physically impossible for some. The fallacy of this type of logic is that physical disabilities are not a one-in-a-million experience but nearly one in four. In order for us to uphold values of success, aspirations and making our way in the world, creating accessible pathways is a necessity.

Nena Chadwick, president of the National Federation of the Blind Arkansas, explained the necessity of organizations such as hers to not only support the blind population of the region but also educate its sighted community. As someone who experienced going blind later in life rather than being born without sight, she understands the differing levels of understanding and acceptance when it comes to blindness. A large part of making that progress is understanding that everyone’s abilities and understandings of the world are different.

“We make sure that we meet them where they are at, not where we think they should be,” Chadwick said.

Chadwick explained that dreams represent finding ways to do all of the same things that sighted people can do, even if they look different.

“Dreams are having the freedom of being independent and not having to struggle with barriers such as the websites that are not accessible, or taking care of our health with medical devices that are not set up for the blind,” Chadwick said.

“Dreams are having the freedom of being independent and not having to struggle with barriers such as the websites that are not accessible, or taking care of our health with medical devices that are not set up for the blind,”

Accommodations are necessary in order to allow our community to thrive, and give equal opportunity and assistance to the disabled population. Everyone regardless of ability shares the need to sleep, and in that experience our minds conjure up the dreams that fuel our thoughts and aspirations during the daytime. The difference in the manifestation of those dreams into reality and where we are able to go once we wake up, and how easy it is to navigate the complex world we live in. The dreams of disabled people are equally as bright, expansive and realistic, if we can create an accessible and open community. For Trist, one way of shaping the community into a more accessible space is by writing disabled characters into her fiction and finding ways to create representation for disabled people to feel seen, and for able-bodied people to learn about their experiences.

If someone were to paint a picture of the dreams of our community, there would be more colors than anyone would be able to process. Regrowth, peace and intensity, all mix together and help us understand not just what we all are aspiring toward but what we need. In examining the similarities and differences in our abilities and desires, it becomes increasingly clear that there is value in that natural born curiosity instilled in us all, stirring empathy within. Understanding each other is the first step to providing for each other, the birthplace of dreams that inspire creativity for everyone to work towards a better, more accessible community together. ***

there you drift away iridescent and full weightless and important mere seconds old.

lived quicker than you could die, captured recklessly. the sky a relentless fire, and the ground a crowd of blades. that laughter, the Pillar, keeps separate the Weight.

one second left, goodbyes unsaid, a burst that screams: this is where we end. Four seconds i lived, Four seconds you watched, quicker lived than died, pop. the memory an Afterthought.

By Ella Karoline Hendricks

Julianna and Matthew Breazeale kiss on the steps of Old Main. The couple got married in August 2024, while still studying at the University of Arkansas. Photo by Keely Loney

Julianna Breazeale has always dreamt of finding love. She grew up dreaming of romantic, classic love. She wasn’t the type to dream of her wedding day, instead, she dreamt of the life it would bring. White picket fences, shiny diamond rings, a beautiful family of her own. Topped off with a handsome, supportive, loving partner to be with her every step of the way. Julianna Breazeale knew she would find it—and fight for it.

“I always knew I would get married young,” Breazeale said. “I have always been mature from a young age. I never cared to go into the crazy dating scene and I wasn’t willing to date anyone I wouldn’t marry.”

And true to her word, Breazeale got married on Aug. 11, 2024, to her husband, Matthew, while they were both in school at the University of Arkansas. Between juggling school work, wedding planning and their social lives, the couple faced the possibility of judgment and the question of the realities of a wedding, like scheduling and financial constraints.

“Because we are so young, the challenges were not between us, but more like us against the world,” Breazeale said.

But those uncertainties and fears pale in the light of love.

Breazeale experienced the joy of finding love at a young age. The couple were 15 and 16 when they met in Spanish class their sophomore and junior year of high school in September of 2020 and have been together for five years now. Breazeale describes her relationship as natural and healthy. As a match of two personalities and souls who want the same thing, she said.

In the South, marriage is almost seen as the next step in a young woman’s life. Traditionalists cite it as a key developmental phase, an item to be ticked off a checklist. Adolescence, prom, high school, marriage, kids. And in the state of Arkansas, many hold these ideas close, often in the name of Christian values. These beliefs extend far, even to the state’s flagship university.

College and marriage are not as mutually exclusive as they once appeared. The converging ideas of the progressive nature of university combined with the traditional viewpoints on love, marriage and family has led to an interesting phenomenon: the concept of a “Ring by Spring” campus.

While marriage rates are on the decline, a number of students at the University of Arkansas still dream of getting married during or right after graduating college.

“It was that we felt lucky enough to find our person for life, and then why hold off on that?”

Megan Papageorgiou said.

Most well known at religious schools such as Brigham Young University and Baylor University, a “Ring by Spring” campus is a college campus that has a large number of students getting engaged while still in school or shortly thereafter. At these schools, the campus culture lends itself to marriage, or at least the societal acceptance of young marriage and engagements.

Yet, according to the US Census, Arkansas has one of the highest divorce rates in the country, averaging at 11.09 when the national average is 7.1 per 1,000 women aged 15 and older in 2022.

And on the whole, marriage rates are declining. According to Pew Research Center, “ among adults between the ages of 18 and 29, just 16% are married, compared with a majority (57%) of adults over the age of 30.”

Everyday U of A students defy the odds for the chance at love, despite the fact that marriage as a whole is on the decline and many people believe young marriage is more likely to end in divorce. Instead, the “Ring by Spring” phenomenon takes hold.

This idea is not foreign in other parts of the country and has been a part of American culture ever since women have stepped on college campuses—girls going to college to get their “MRS degree.” This idea is a more traditional view that is not as common in modern day, but in some majors – namely “pink collar” majors such as education, nursing, and liberal arts–the stereotype persists. It is a joke that undermines the intellectual value of the degree and degrades the woman from a person seeking intellectual betterment to simply searching for a romantic partner.

In a “Ring by Spring” campus, this is not contained to specific majors, instead young marriage is seen throughout the campus. Even so, this idea of a “Ring by Spring” campus is more common in the South than in different parts of the nation. It begs the question: What pushes these couples to get engaged at such a young age?

Breazeale has never once doubted her decision to get married before her or her husband’s college graduation. Instead, they have embraced married college life together.

“Being in the Bible Belt,” Breazeale said, “there’s a lot of individuals who have values on marriage and just getting married young, versus in the North, where that’s not as a big a push. So I do think this is more of a place you’d see it than if you went anywhere North.”

Laying out in Old Main, over cups of coffee or even overheard in sorority dining rooms—talks of marriage and engagement are abuzz on the U of A campus. Girls discussing potential bridesmaids and creating Pinterest boards full of dresses and rings. Some take it as a far off exercise, a bridge to be crossed in many years, while others look to the near future.

Recently engaged and in the depths of wedding planning is Megan Papageorgiou, a junior at the U of A who is planning on getting her masters and becoming a child-centered play therapist. Papageorgiou has been with her partner for almost two years and is looking forward to their upcoming summer wedding set at a beautiful local church.

“We met through our parents at church,” Papagoriou said. “His grandparents were leading a small group that my parents joined, and they wanted me to meet him because he’s two years older, and he was already at the U of A, so they just wanted me to have a familiar face.”

They hit it off instantly and the pair were inseparable after their first date, texting nonstop and seeing one another almost daily. They started dating and got engaged exactly one year later.

“I do think that marriage is more common in the South, but I know personally, I would want to be engaged to him wherever we lived,” Papageorgiou said. “If we lived in New York and happened to me, or were raised there, I just know that this would have happened no matter where.”

Outside opinions and values can be influential in relationships, especially if the couple is close to their family. Both Papageorgiou and Breazeale said their families were very supportive of their engagements, and both women said their families did not pressure them in any way.

Papageorgiou and her fiance both come from Christian families and hold their faith very strongly in everyday life. However, it is not the driving factor in her engagement. Instead, the love they have for one another,

guided by their faith, led them to get engaged at a young age.

“It wasn’t like we’re getting married young because in our religious group everyone gets married young,” Papageorgiou said. “It was that we felt lucky enough to find our person for life, and then why hold off on that?”

There is a link between religion and marriage. According to Pew Research Center, Evangelical Protestants are the most concerned about the effects of the decline of marriage rates in the United States, with 55% saying that fewer people getting married will have a negative impact on the future.

God acts as the guiding force in Breazeale’s relationship, she said. Both Breazeale and her husband have been deeply involved in the Christian church since childhood and have put God at the forefront of their thoughts.

“I was 16 years old, and we were praying over our relationship and asking for the Lord’s blessing, valuing the way He says to do relationships,” Breazeale said. “And I think we’re just evidence that it works because we did our best to do the things that He told us to do, and He’s really blessed us for it.”

Religion is a major factor in many people’s identities, and it plays heavily into relationships when a person’s morals and ethics are built by their religion. Church is a place many people find community in and often form friendships and relationships with like-minded people. Many share this dream of getting married and settling down early, with ideas being repeated and normalized in these circles. On the opposite side of societal acceptance is social ostracization, as often occurs in the case of purity culture.

Purity culture often shames the members who participat-

ing in sexual acts before marriage and idealizes those who stay “pure,” as in sexually inactive before marriage.

In Christian culture, it is emphasized that both parties remain sexually inactive with each other until marriage, as it is viewed as a Holy sacrament. This, colloquially known as purity culture, has traditionally fallen more so on women as opposed to men. Some view it as backward while others hold it very personally.

Breazeale and her husband chose to wait for marriage, but Breazeale said she believes there is some harm in what the Church has put out in terms of purity culture.

“(The church) has hurt women in the process of trying to invent purity,” Breazeale began. “It really upset me as I realized the culture around the concept. When I was younger, I read a book and had a good conversation with my mom about purity. It’s not about a girl being a perfect virgin and instead on a relationship with Jesus. There are benefits to waiting till marriage, it’s not easy and doesn’t look the same for every couple. There are really good physical, emotional and spiritual benefits for waiting for marriage, and there should be no shame around making mistakes and learning as you go.”

Purity culture has a foothold in Arkansas society, yet it also contrasts pretty heavily to mainstream college bar and hookup culture. Saving yourself for marriage is a personal choice, but it can also be difficult to be around others who do not share your beliefs.

“I would say it’s pretty unique to campus culture—lots of people would question me on it,” Breazeale said. “It blew their minds.

People assume that we had no physical connections, but we were still intimate and knew each other well.”

Breazeale hasn’t had quite the typical college experience and said with being in a serious relationship, college life has looked a little different—maybe a bit more contained, while still enjoying her youth.

“Those typical college experiences—sorority, functions, parties—are not mutually exclusive to being single,” she said. “I guess just as a Christian in general, I have a different balance of fun and what people consider fun. I’m not attracted to super high, fast life but insead having fun in moderation. Just more contained and respectful. We still like to do things but stick with people that know us.”

When prompted about if campus culture influenced them in any way, Breazeale said, “(Engagement in college) is very rare. I don’t think there’s many. I think we’re a smaller population, a more group. I think since we go to a big SEC school, the culture is more like young party life. So being married in college is kind of shocking to most people I tell, but everyone who I know on campus is extremely accepting.”

It’s important to note that for Breazeale, being married hasn’t made her lose any independence in her morals or beliefs. “My beliefs and my morals are who I am to

my core,” Breazeale said. “They would still be there if I wasn’t married. I would still act and behave in the same ways. Instead, I think marriage has elevated and made my experience even better — whether that’s having a study partner or walking me out the door before an exam. I haven’t changed for it, but instead, it has made me better.”

But for some on campus, marriage is not in the immediate post-grad cards. Isabella Galloway has been with her high school sweetheart for almost five years now.

“We actually met around COVID,” Galloway said. “So he literally just slid into my DM and texted me: ‘I think you’re really pretty.’ And we just kept talking. It was March or April of 2020, and whenever we could finally go back outside, we met up.”

Galloway, a college sophomore majoring in chemical engineering, and her partner have been long distance through their college years. Long distance can be very difficult for couples, especially at a young age. Galloway’s boyfriend attends Louisiana Tech, but she chose to attend the U of A as she earned several scholarships for her degree.

Long distance can be difficult with communication, as it can be hard to convey feelings and meaning clearly. Yet, the distance has not lessened their relationship, merely presented some challenges.

“I would say (the relationship is) very supportive,” Galloway said. “And I would say it’s really easy to be honest.”

Galloway and her partner have communicated expectations of one another and have practiced the art of long distance. They aren’t the type of couple to get upset at smaller things, or hiccups in communication, instead maintaining a strong relationship built on trust and healthy expectations.

Galloway has no immediate plans for engagement or marriage, instead is enjoying her relationship with her boyfriend in its current label. Galloway treasures the ease in which her relationship holds—for the pair, they are happily content with being there for one another. They are not in any rush to tie the knot, instead trusting their relationship will pass over into that next phase of life.

Modern ideas of marriage are changing. No longer is the expectation of young women to be married directly after college. Many young women enjoy the season of singleness in their lives, using this time for self-development and growth. Every year, it becomes more and more acceptable for women to delay partnerships, engagements, and marriage. For some, marriage is not a necessary part of a fulfilled, successful life.

That is the beauty of this day and age, each person chooses what is best for them at that moment. Whether that be marriage, motherhood, partnership, or existing as an individual, everyone is entitled to their own ideal of happiness.

Galloway is looking forward to this unknown chapter of her life, full of wonderful, exciting possibilities. Papageorgiou is currently busy planning her wedding for this upcoming summer, sending pretty personalized invitations out to her friends and family, with white dress shopping and bridesmaid proposals. And Breazeale is enjoying her life as a newlywed in her last years of college, taking in all of the changes that come with this new distinction. Living with her husband and building the life they have always dreamed of, Breazeale experiencing the joy of her life-long plans finally coming to fruition.

“I always knew I was gonna be a wife,” Breazeale said. “But it wasn’t my biggest dream. I wanted to be Matt’s wife. That connection that I always dreamt of—finding the one, right person—I knew he was out there and I found him.”

Regardless if the University of Arkansas campus is a “Ring by Spring” school or not, at the core of these relationships, seems to be true love and happiness. Young, full, inviting adoration that deserves to be celebrated. It is not every day we find the love of our lives and who can blame them for catching it and holding on tight? ***

“Midnight

The repeated remembrance of memories taints my dreams. It’s a strange happiness that swells in my bosom, wrapping my chest in its insincere embrace. It is a comfort, this misremembering. I can smell it in the air when the seasons change, reminders that I see the corpse of my childhood through a lens of rose: The soft hush of the water singing its lullaby, lulling me to sleep by the riverbed; Tiny feet pattering (or stomping, as the bugs tell me now) among meadows, building flower crowns and fairy huts;

The wrinkled palm of a relative long gone grasping tiny fingers, pulling me away from the pickup truck going lightning-fast on careful dirt roads, my ensuing giggle, her gentle sigh. Oh, what I wouldn’t give to enter this dream state again.

My heart weeps to think of hearing the mourning dove coo without the stain of remembrance, of looking up at the sky and feeling the wind whipping my cheeks for the first time, of feeling the scraping of tree bark against my still paper-smooth skin. I want to feel what it is to be alive as the soul of my six-year-old self:

Innocent, unaware, and full of awe.

By Natalie Murphy & Ashton York

NLocal Vignettes of the American Dream

orthwest Arkansas has become a melting pot over the last three decades. With the accompaniment of three Fortune 500 companies shuffling in workers daily and the University of Arkansas’ enrollment rates increasing every year, the local growth will only continue—as will the dreams of success in its confines.

The region has come to share the ethos of the American Dream. Known as the “Land of Opportunity,” Arkansas has a rich history full of the success stories of immigrants, students, teachers, philanthropists, business owners, and the list is destined to continue.

Karla Cruz, Nick Addison and Eric Howerton are three locals pursuing their own dreams and ideas of success in the region. Each from a different background, with different experiences and stories to tell, they were all asked the same question: How attainable is the American Dream in Northwest Arkansas? The following recounts their personal experiences living in the region and whether they see the American Dream in their daily lives.

¡échale ganas!

Give it all you got!

Those were the words Karla Cruz’s parents said to her when she Facetimed them, sharing the news that she had gotten a job offer. It was the morning of Nov. 4, 2024. They were the first people she had told, reassuring them everything would be okay.

It had been six months of exhausting job hunting and interviewing when she accepted the position to be a senior analyst at the Sam’s Club Home Office in Bentonville. Relief washed over her as she realized the search was finally over.

Truthfully, Cruz had felt nowhere near confident about how her first interview with the company had gone, surprised to have even made the second round, she said.

She had been running late to the first interview, almost going to the wrong building, and her flustered state was getting the best of her while answering questions. The whole experience felt like a blur, she said, but despite it all, the company had seen something in her. By the final round of interviews, Cruz felt confident she would get the job.

Receiving the offer felt like she had just achieved the big goal she had been working toward for the last five years.

But it was more than that. She knew what it meant to her family, having immigrated from Mexico to Northwest Arkansas in the ‘90s to have access to these opportunities.

On the call with her parents right after receiving the news, it felt like everyone could finally breathe. It was a nice feeling to tell them, she said, but it also felt different from past accomplishments. While it was theirs to celebrate, it was hers to have.

It had felt different when she graduated with her bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Arkansas. Despite her hard work to attain a full-ride as a first-genera - tion student, she knew she was com- pleting the dream her mom set aside three decades ago to move to the United States. As the oldest daughter in her family, Cruz said she approached success with her mom and the things she never got to do in mind.

“I think that when I graduated, the first thing I told my mom was, ‘This was for you. So whatever’s next is mine,’” Cruz said.

“It felt like it was my mom’s dream, too,” she continued. “It felt almost like it was hers a little bit more than it was mine, and everything that’s next is fully my own, and I think we both accept that.”

When Cruz received her master’s degree at the University of Arkansas the next year, it was hers: her decision, her hard work and her perseverance. No one had pushed her to pursue grad school; she had even told her parents for a time she wasn’t going to apply.

Her decision to apply to grad school and the senior analyst position had been her choice. It was her individualism, a trait she believes is unique to the United States. What Cruz describes is the exact ethos of the American Dream—the opportunity to carve your own path toward success and a better life.

“It’s weird because obviously I grew up in American culture, and American culture is very independent and individualistic, and I love that about the United States, I think that’s great,” Cruz said. “But I also grew up in Mexican culture, where I think it’s less individualistic. It’s much more focused on the collective, on the we, on the community.”

ly for that side of her community, and with the recent legislation targeting them, her empathy only extends further.

“While I feel very grateful for the opportunities that I have that my parents didn’t and that my parents specifically wanted me to have,” Cruz said, “I also think it’s important to understand the systemic issues that immigrants face and that even children of immigrants face because they look different than what this ‘American’ should look like, so it honestly makes me very sad to think about.”

The day after Cruz got the news of her job offer, her celebration quickly turned to grieving for the future. It was Election Day, and by nighttime, her focus had shifted toward the Hispanic community as President Donald Trump led in the polls.

law enforcement enter churches, schools, hospitals and weddings to make arrests, leaving undocumented individuals, including children, vulnerable.

Even scarier for Cruz is the president’s yearning to end birthright citizenship. While his order has been met with strong legal pushback from 22 states thus far, if put into law, this would impact the future children born of immigrants on American soil. In doing so, it would be unraveling the 14th Amendment and its nearly 160-year-long history.

This understanding is a complexity many children of immigrants understand, and it is seen throughout Cruz’s life. She has roots in both cultures, but in relation to her identity, she said she is “neither here nor there,” not one culture more than the other.

While Cruz said she does not truly know what it feels like to be an immigrant, she still acknowledges the hardships those like her family have to go through along their journey to gaining citizenship and the persistence of discrimination that often follows. She feels deep-

During his last term, Trump used immigration as a political scapegoat. As he continued his campaign for the 2024 election, he showed no signs of easing up on this stance.

Trump’s reelection was hard for Cruz to accept. She still doesn’t know if she fully has, she said. Following his inauguration, she was shocked at how quickly his administration took action, specifically on the undocumented population. Just in his first week in office, he signed 10 executive orders on immigration.

Cruz was especially upset when Trump revoked a policy first enacted in 2011 that prohibited Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Patrol officers from making arrests in “sensitive spaces.” This now lets

“That really upset me because I just felt like they are just targeting everyone right now,” Cruz said. “It really scares me that they want to hold children accountable for something that they really have no say in, like a 5-year-old who was brought over here undocumented. Their home is here, not there. And for (Trump’s administration), I feel like these decisions are made without any sort of empathy.”

As Cruz may have recently gotten a taste of the American Dream, many others in the United States and Northwest Arkansas are having it stripped from them.

“It’s very difficult to reach your full potential when there’s hostility wherever you are, whether that’s in your community or culture,” Cruz said. “And I think from when I was younger to now, I’ve always had a very defiant view, I would say, of the American Dream because I don’t always think that people are treated here the way that they should be.”

The concept of the American Dream suggests equal opportunity for all, yet the diverse identities and experiences of those pursuing it may reflect otherwise. Although Cruz has found success in Northwest Arkansas, she acknowledges she is likely the exception and not the rule.

As she navigates this chapter of her life with a new job and entering a presidential term, she feels uncertain as she looks to the future but will continue to give it all she’s got. While she has gratitude for the opportunities the region and country have provided for her, she only hopes it can be extended more kindly and freely to others.

“I think if I were to redirect the American Dream outside of success from culture,” Cruz said, “it would be to inspire and uplift others into achieving their dreams as well. In the American Dream, it is very, very emphasized of your success—your individualism and how you are going to make things better for yourself. But I think it would be good for people to redirect their energies into helping others. Whether that’s your community, whether it’s a community you’re not familiar with—taking what you have, the talents that you have, and helping and uplifting others.”

Karla Cruz stands with her parents outside of Bud Walton Arena, following her graduation from the University of Arkansas in 2023. Cruz, who went on to graduate with her master’s in 2024, was a first-generation student and recently received a job working at the Sam’s Club Home Office in Bentonville.

The American Dream has long been a symbol of hope in the United States, but what does it truly mean? The answer, it seems, depends on who you ask.

“At least originally, this idea of liberty and democracy—that’s the American dream,” said Nick Addison, a senior at the University of Arkansas.

“But

at the same time, being a queer person living in America, it’s hard to do simple things like starting a family, getting married, changing legal documents and accessing medical care that is necessary for me.”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the American Dream as “the idea that every citizen of the United States should have an equal opportunity to achieve success and prosperity through hard work, determination, and initiative.” But how level is the playing field when reaching the American Dream?

Race, class, gender and sexual orientation, identities in their own right, all play a role in one’s ability to attain the American Dream, despite the common claim that this dream is for everyone.

Addison has mixed feelings about life as a queer, transgender man in the U.S. He said he feels lucky to have a great community around him in Northwest Arkansas, but it is difficult to be a queer person in America right now due to the uncertainty of new legislation. As an English education major, the ever-changing school legislation may determine a large part of where his career goes after graduation.

The idea of the American Dream has changed with each generation, and during the Cold War, it became an argument for consumer capitalism, according to historian Sarah Churchwell. While its weight shifts and citizens have given the term

new meaning over the years, this idea of material success is why most picture the American Dream as gaining wealth and career accolades.

With the American Dream, some may imagine 1950s suburban America, populated by stay-athome moms and fathers who spend all day at work. Others may envision their arrival in a new country, a land full of new opportunity and hope. But perhaps the perspective of the American dream is a mindset, ever-shifting to meet the needs to keep individuals alive and persevering.

“In my mind, the American Dream is just about getting to the top of whatever career you’re in and pushing that narrative,” Addison said. “But for me, if I was defining my own American Dream, it lines up more with just doing the most good I can; making a positive impact on the people around me, and

advocating for a better country than the state it’s in right now.”

Addison’s motivation to have a positive impact on society is due in part to his negative experiences. In the past, he has had coworkers and peers pry him, asking personal and uncomfortable questions about his identity, simply because he was the only queer person they knew.

While he was working minimum-wage jobs and just trying to collect a paycheck, he was faced with uneducated conversations about how some people thought “transness was caused by air pollution.”

He said these types of ideas were voiced regularly in his Oklahoma hometown, and having to navigate the everyday harassment at work was frustrating because it was not what he was there to do. Addison was not there to educate people on his identity.

Addison also said he feels like his current career path is at risk because some politicians do not think trans people should be teachers or be around children at all. He has already faced rules that make him feel uneasy while student teaching.

shown him that there are many additional challenges people have to face in order to achieve the American Dream.

“You expect me to live a life that has this mobility,” Addison said, “but if I can’t even do things like get treatments correctly or talk to a doctor that understands me, how am I supposed to achieve that American Dream?

“(The American Dream) is just about, ‘How can I make my life the best it can be with the situation that I’m in?’” Addison said. “Also, just dreaming of making America a place where I do want to live and I do feel like I can thrive.”

“There’s legislation in place in Arkansas that requires me to do things that I know are, at the very least, traumatizing and would have been really dangerous for me if they happened to me,” he said. “I’m having to do that to my students.”

He feels as though many setbacks and forces are working against him when it should not have to be so difficult, he said. Furthermore, he said this experience has

“It just doesn’t really feel like it is for me,” Addison continued. “The general voice doesn’t feel like it wants to support the true democracy, liberty, life, the pursuit of happiness.”

In a nation built on individualism and differences, there is a certain beauty in choosing how one decides to measure success and prosperity. In many queer-specific spaces in Northwest Arkansas and across the South, there is a sense of community that many individuals cannot find elsewhere.

Addison often sees how American policies and society treat trans citizens. Not only does he face these issues himself, but he has several friends who deal with similar struggles. This appears to greatly impact their view of the American Dream.

“I think a lot of (the transgender community’s) dreams for our futures are related to our transition and just making ourselves more comfortable,” Addison said. “It feels like there’s more of a focus on, ‘How can I live my most authentic, happy self?’ rather than, ‘How can I commit so hard to something where I get outward success?’ like the traditional American Dream is. It’s more about internal gratification.”

Arkansas native Eric Howerton was born and raised in Jonesboro and moved to Northwest Arkansas around the year 2000 to be a newspaper photographer. Since then, Howerton has built his career on a foundation of strong relationships and persistence, starting multiple local businesses on his own.

Howerton graduated from Arkansas State University with a degree in photojournalism. He then wanted a location change, primarily so he could start a magazine called Get Outside, which focused on outdoor Arkansas.

At 22 years old, after working for the newspaper, Howerton was waiting tables at Olive Garden in the evenings to support his magazine during the day. He later helped other magazine publishers to design and lay out their productions. “I realized while I was doing the magazine, the advertisers could not create good artwork to put in the magazine,” he said. “And I was like, ‘So, this is a freaking problem.’ So, I started helping them.”

Howerton said creating his own magazine was pure chaos. He saw the beauty of the Arkansas outdoors and felt there was a story to be told, and the magazine became his first of many projects.

Howerton currently owns Doing Business in Bentonville, a media company for Walmart suppliers, PodcastVideos.com, a podcast

studio in Rogers, and more. He has a shared podcast with Mark Zweig called “Big Talk About Small Business,” where the two entrepreneurs discuss their experience working with local businesses and strategies.

While some may want to start a business with the idea of getting rich, Howerton said he is motivated to simply provide services that can fix others’ problems.

“I see (the business industry) as there’s a problem,” Howerton said. “I can see it clearly. I see the possibility of fixing it. It might as well be me because no one else is getting off their ass to take care of the problem.”

He said he does not believe there is such a thing as a good or bad climate for the market. There will always be a need for services and products, no matter how advanced or in-advanced society is, he said. The economy is a “chaotic system of itself,” and nobody can predict what it is going to do next.

“We’re always thinking that money is just deserving of certain people, certain classes, certain education,” Howerton said. “That’s all bull crap. If

you really look at the American Dream—American history—American entrepreneurship is the dream. That’s where it starts. An individual sees a market need, goes and fulfills that market need, and is relentless to making sure that gets done; they push through the hardships and work their living faces off until it becomes true.”

Howerton said U.S. laws are structured to allow new entrepreneurs to start a business without having much money beforehand. Investors can pull together money to allow the entity to be born. If the company loses a large amount of money, not every single person involved is liable for the whole amount, he said.

He also said the fact that small business owners get to keep most of the profit is a huge benefit of living in America.

“You have the freedom to earn money, but you still have to pay your taxes,” Howerton said. “You give back to the government, so it can continue to do its thing and function and operate, but I think it’s a fairly decent tax rate in comparison to other countries (where) you only get to keep 30% of what money you earn.

“That money is just a sign of the bartering system that is set up,” he continued. “If I have more money, then I can buy more things, give more things back and build more things.”

Howerton sees the American Dream as the freedom to create his own path to success and the ability to earn. His idea consists of small entrepreneurs creating their own businesses without being hindered by their religion, race, gender or anything else. He said it is the ability to earn money for oneself, solve problems, progress and contribute back to society.

“You’re designed to struggle,” Howerton said.

“Struggle is the honor, contributing back to society until the day you die.”

No matter the perspective, navigating success in the U.S. requires significant determination and resilience. It inspires a deeper look at what the American Dream represents to each of us and how we can pursue success in our own ways. ***

Short story by Adam Lorio

It’s been four years that I have been isolated in this wood. Time has numbed my conscience, methodically whittling me into the diminished thing I am today. Time...I hardly remember the man at which It began to chisel away four years ago. I hear a sparrow in the distance–I usually hear the sparrow at this time of the day; I rarely see it. It’s days like these–warm and bright, a joyful call in the distance that I must be sharper than ever. I must not become relaxed in the false security that warmth brings.

I know it is Wednesday, and I know it is spring. I know little else than survival. I always loved spring, but here in this forest spring is... confused. The blossoms transform the trees into a flurry of white, a blinding omen of what lies ahead: winter. Winter terrifies me–Time has ensured I think this way especially here where it is so lonesome, so cold, and always it has been so unknown. At least it will be peaceful...

A twig breaks. It was not a deer, not a bear, surely not any type of animal. Am I alone? Is there another man in this isolated place? Yes, surely yes. It is not cold, but I begin to shiver. I sense there is a breath much stiller than my own. Surely there is another man, but with what intent? Surely he is here to kill, to kill me. Surely. I take cover in a bush and stare into the open space in search of my unknown assailant. I sit for what feels like hours. Perhaps it is.

The thought of the man I used to be creeps into my brain. If it were he who was stranded here, he would be dead by now. In most ways, he already is...

Photo by Henry Nguyen

I push the thought away, a necessary skill. I must remain detached from thoughts that will distract me from survival. I think of the enemy. As I search for a sign of his existence, I become angry that he will not show himself, the coward. I am too angry. I’m a fool! Anger clouds judgment; judgment is survival.

I know this, but still, I foolishly choose to shout at him. I shout again and again, each call growing increasingly desperate. I am lonely. The anger resonates within me, burning with such a passion that I have no choice but to shout again. I realize I’m nearly begging him to show himself. I continue to shout anyway. Where is this coward? He must have gone by now. A tear might have formed in my eye. What has Time done to me?

Snap. I hear another twig! This time much louder and more violent than before. Any wish for my friend to show himself vanishes instantly. I remind myself of the danger the presence of such a foe produces. Surely he has merely been waiting for his chance to kill me. I let the adrenaline take over my body as I escape with anacquired, animalistic fury through the thickest of the forest. Based on nothing but instinct, I dive into the brook that silently drifts through the wood.

I stay underwater until I begin to spasm. At last I give myself the liberty to breathe, and I gasp as I burst out of the slow-moving current. I slowly lift my head to glance upstream towards the blindingly bright glare of the trees. Is it time? I chuckle as I tell myself they are blossoms, but surely it is snow. Surely it must be winter.

“I swear I told you that,” a sentence I have said countless times in conversation with friends and family. I say it with conviction, racking my brain to when the discussion was held. Only later do I realize in reality the conversation did not happen. Lucid dreams have often left me fully convinced that I have participated in entire discussions due to their vividity. Similarly, there are moments where “I swear I did that,” echoes in my mind, only for me to realize later I had dreamt my actions and my brain had temporarily stored them as the memory of actually doing them.

By Anna LeRoux

by Erika Fredricks

My personal lucid dream experiences often include extensions of conversations or interactions I have had with people, which is what makes them so easily become a memory. Especially if I have been replaying an experience in my mind, I can almost guarantee I am gonna dream about it later. I rarely have dreams that are fantastical or that I have complete control over,and often it sometimes takes me a while to figure out I am dreaming. Once I come to the conclusion that I am dreaming, it is easiest just to let it happen because if I try to wake myself up it can cause sleep paralysis, which is a disgusting feeling.

These experiences have made me wonder about the nature of consciousness itself. If I can be aware enough to control a dream while still asleep, what does that say about our normal waking consciousness? Perhaps our everyday awareness exists on a spectrum rather than as a simple on-and-off switch.

Dreams have always captivated humanity, from the sensation of floating effortlessly through space to the familiarity of childhood memories resurfacing. They seem to tap into our deepest emotions, desires and fears. For centuries, the meaning of dreams has been the subject of speculation and intrigue, from the worship of Morpheus, the Greek God of Dreams, to the theories of Sigmund Freud. But what if these nightly experiences serve a deeper purpose? What if they actively shape how we solve problems, fuel creativity or even influence our most important decisions?

For some, lucid dreaming—the state where the sleeper becomes aware they are dreaming and, in varying degrees, can influence their dream—has been reported to have a profound impact on people’s daily lives and creative processes.

In my experience, when I am deeply stressed by a creative block my brain turns to lucid dreaming. if I have been stressed about a creative block enough it is possible my dream will try to fix it. However, attempting to utilize complete control over my dreams in these situations leaves me feeling less rested because I was never fully able to “shut my brain off”. The absence of regulation is part of what confuses me throughout my day —blurring the line between what I actually did and what my mind may have fabricated.I can usually rely on lucid dreams to give me a constant sense of deja vu throughout my week.

From a scientific perspective, dreams are far more than mere random brain activity during sleep. While much of the dream world remains mysterious, the growing body of research into sleep, lucid dreaming and brain science sheds light on how these surreal experiences shape our waking lives.

We spend about one-third of our lives asleep, and during this time, our brains are far from dormant. As we sleep, our brains cycle through different stages of sleep, including the well-known REM (rapid eye movement) phase, when most vivid dreaming occurs. During REM, the brain is almost as active as it is when we are awake, processing memories, consolidating information and making connections between seemingly unrelated ideas. This stage of sleep is when we are most likely to experience lucid dreams, though not everyone has.

According to the Clinical Neuroscience of Lucid Dreaming from the Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews journal, “A recent meta-analysis on the prevalence of spontaneous LD estimates that 53 % of peo- ple have experienced it once, while 23 % can be considered regular lucid dreamers.” Additionally, this journal describes lucid dreaming as a “learnable ability”, which begs the question how much control we have over our brains in dreams.

These statistics reveal something fascinating about human consciousness. With over half of people experiencing lucid dreaming at least once, it appears to be a natural potential of the human mind rather than an anomaly. Yet the drop between one-time experiences and regular occurrences from 53% to 23% suggests mastering this state requires more than just natural ability according to the journal.

Like meditation or emotional regulation, it seems we can develop greater control over our sleeping consciousness through practice. Just as playing an instrument or speaking a new language requires consistent practice, maintaining the ability to lucid dream demands consistency. It seems our consciousness is not just something that happens to us, it is something we can actively shape even in our sleep.

It took me a long time to figure out I was a lucid dreamer. It was not something I was familiar with nor something I had ever tried to practice. Once I discovered that it was irregular for people to be able to wake

themselves up or influence their thoughts while dreaming, I became curious and started looking into what could be my cause. While I can fully shape my dreams, it usually only happens at the very beginning or end of the dream, and is easiest if it is the topic of something I have spent the day thinking or stressing over. If I did not remember going to bed, lucid dreaming can leave me feeling like I never slept at all.

Sleep scientists have long been interested in the link between dreaming and memory. From the perspective of Dr. Angel Houts, a psychology professor at the University of Arkansas, dreams, particularly lucid dreams, can provide valuable insights into how the brain processes memories and solves problems. In lucid dreams, the dreamer is aware they are dreaming and, in some cases, can exert control over the dream’s direction. This semi-conscious state presents a unique opportunity for researchers to observe how the brain operates between wakefulness and sleep.

“Studying lucid dreaming can give us insights into how the brain handles memory

and problem-solving,” Dr. Houts said. “Since you’re partially awake in lucid dreams, it’s like observing the brain working in a hybrid state between dreaming and wakefulness. This could help researchers understand how we organize and retrieve memories and how creative problem-solving might happen without the usual constraints of waking life.”

“This process is very fulfilling to me because I often create pieces I would’ve never made without the idea coming to me in a dream.” said Abbie Ahlbrandt, a freshman and artist at the U of A.

Freud, in his work “The Interpretation of Dreams (1900),” said dreams are the “royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” Although he did not specifically address lucid dreaming, as the term was only first coined by Frederik van Eden in 1913, he did theorize there was a direct link between the unconscious mind and dreams that may present a deeper understanding of a person’s psyche.

In some ways, lucid dreaming takes Freud’s theory a step further by offering a glimpse into the complex levels of consciousness at the same time.

One of the most intriguing aspects of lucid dreaming is the hybrid nature of the experience. The conscious and unconscious minds seem to coexist in a fluid, overlapping space where you can observe your subconscious thoughts while still maintaining some level of control. This gives rise to the potential for introspection and self-awareness.

According to Dr. Houts, lucid dreaming can be understood as a kind of “conversation” between conscious awareness and unconscious processes. In lucid dreams,

said. “You’re conscious, but the brain is still in a dream state. It’s a unique experience where you can observe your un- conscious mind at work while still hav- ing some control over it.”

This intersec- tion of awareness and un- awareness suggests that lucid dreaming could be more than just an odd experience, it could be a vital part of how we understand ourselves and how we process emotions, desires, and conflicts that we may not confront directly in waking life. Lucid dreaming may also be a way for us to confront unresolved issues or serve as an emotional outlet for the things that our conscious mind suppresses.

It’s no secret that many of the world’s most groundbreaking ideas have come to people in their sleep. Albert Einstein reportedly visualized the theory of relativity after a vivid dream. The famous chemist August Kekulé came up with the structure of the benzene molecule after dreaming of a snake biting its own tail. The connection between dreaming and creativity is well-documented, and modern science is beginning to uncover how dreams might unlock the door to creativity and problem-solving.

“Dreams have a lot to do with my creative process, even though I don’t dream often,” said Emelia Roy, a sophomore pre-graphic design student at the U of A. “My dreams are often in nature,and I channel that heavily in my art.”

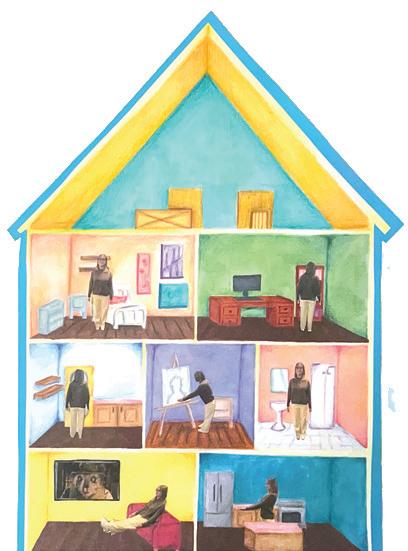

Deree

Abbie Ahlbrandt, a University of Arkansas art student, begins a new painting, backdropped by her painting “Self-Portrait 2.” Ahlbrandt often uses her vivid dreams as inspiration while creating.

the dreamer is aware that they are dreaming while the brain is still engaged in unconscious, automatic functions. This dynamic can offer clues about how we become self-aware, how our unconscious mind informs our waking reality and how different levels of consciousness overlap.

“Lucid dreaming lets us peek into this dialogue between what we know and what we don’t know,” Dr. Houts

Dr. Houts said that lucid dreaming could provide insights into how we solve problems without the mental constraints we experience

when awake. By becoming aware of the dream state, we free ourselves from the rigid boundaries of logic and the limitations of waking reality, potentially unlocking new, innovative ways to approach a problem.

“Lucid dreaming allows us to break free of the usual constraints,” Dr. Houts said. “In the dream state, there’s no distinction between what’s possible and what’s not, so the mind can explore ideas without the usual judgments or limitations.”

person dreams about may be vastly different from someone else’s experience. Additionally, as anyone who has tried to recall their dreams knows, details often fade quickly. This makes it difficult for researchers to gather consistent data from a large group of individuals.

and the media until I was discussing poor sleep with someone who had them.

“Why don’t you just change the scene or wake yourself up?” I thought unknowingly due to my ability to control aspects of my dreams have almost always helped me avoid nightmares entirely.

This has profound implications for how we approach creativity, innovation and even therapeutic techniques. Lucid dreams could serve as a rehearsal space, where we can experiment with ideas and experiences without the fear of failure or consequence. Whether it’s artists looking for new ways to express themselves, inventors seeking novel solutions or scientists struggling to crack complex problems, lucid dreams offer a place to think freely, untethered from reality’s rules.

“There have been many times where I get vivid imagery of objects or ideas in my head while I’m sleeping, and when I wake up I record whatever I can remember,” said Ahlbrandt “Afterwards, when I have time, I go back and create what I saw during my dreams into paintings.”

As compelling as the science of lucid dreaming is, studying dreams presents unique challenges. Dreams are subjective experiences—what one

as using sleep labs to monitor brain activity, employing brain imaging techniques and encouraging participants to keep dream journals. These tools help scientists collect data and track patterns in dream behavior, but the inherent subjectivity of dreams remains a significant hurdle.

Despite these challenges, the study of lucid dreams offers a unique opportunity to understand consciousness, memory and creativity. Since lucid dreaming allows us to be both aware of and immersed in the dream state, it provides a rare glimpse into how the brain processes information, creates new ideas, and bridges the conscious and unconscious worlds.

For example, “My personal art involves watercolor florals, and many scenes I paint have either been from my dreams or based on the composition of places in my dreams.” said Roy.

It is important to continue discussing dreams since they are so dependent on the person. Personally, I was not aware that nightmares and night terrors were normal until an embarrassingly old age. I thought they were dramatized in film

The way lucid dreams affect my sleep quality has made me think more deeply about the trade-offs between dream control and rest. While I appreciate being able to steer away from unpleasant dreams or explore more deeply the things I imagine awake, there’s definitely a cost. Those mornings after intense lucid dreams often leave me feeling like I’ve been solving complex puzzles all night instead of truly sleeping. It’s as if my brain never fully disconnected from consciousness, keeping one foot in the waking world and the other in dreamland.

This is because lucid dreaming prevents me from reaching deep REM sleep, the restorative stage of the sleep cycle. While the dream may feel vivid and real, it comes at the cost of feeling less rested upon waking. If there was more open discussion, people may find how unique their individual brains are. Continuous research on dreams is a social necessity to ensure people have a more empathetic understanding to them and each other.

Dreams have long been recognized as culturally significant, with many societies attributing

spiritual or mystical meaning to dreams. From the ancient Egyptians, who believed dreams were messages from the gods, to modern-day therapists using dreams to help patients uncover hidden emotional truths, dreams have played an essential role in human culture.

In ancient Greek mythology, Morpheus, the god of dreams, was believed to have the power to appear in the dreams of humans, often taking different forms to communicate messages or reveal truths from the subconscious. As one of the Oneiroi, the personifications of dreams, Morpheus influenced not only the dream world but also how dreams were perceived as powerful, sometimes prophetic experiences.

Dr. Houts suggests that it might be worthwhile to continue exploring how different cultures interpret and experience lucid dreams. While lu-

possible or normal.

This might explain why so many societies have treated dreams with such reverence, because they represent one of the few truly universal human experiences.

Perhaps this is why dreams have endured as a subject of fascination despite our increasingly technological world. They remain one of the few experiences that technology can’t fully capture or explain, a nightly reminder that there are still mysteries in being human.

Dreams are more than fleeting mental snapshots. They offer a window into the workings of our unconscious mind, shedding light on how we process emotions, memories and problems. Lucid dreaming, in particular, has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of creativity, problem-solving and the nature of consciousness itself.

is a phenomenon that can be found across many societies, the way it is understood and approached may vary significantly based on cultural beliefs and traditions.

“Cultural differences could influence how we experience and interpret lucid dreams,” Dr. Houts explained. “In some cultures, dreams might be seen as an extension of spiritual experiences, while in others, they might be understood in more psychological or neurological terms.”

Sometimes it’s as if dreams are a kind of cultural reset button, stripping away our learned assumptions about what’s

“I have also had dreams that push me to create art, such as ones where I’m showcasing my work in exhibits,” Ahlbrandt said. “This encourages me to keep going, knowing that it could one day come true.”

Lucid dreaming has always influenced people and I am no exception. While dreaming, not just lucid, has sparked creativity and problem-solving, it is always interesting to see the way reality and the surreality of dreaming uniquely influences people. Our daily lives bleed into our dreams and vice versa. As research dreams grows, I hope more people can appreciate the profound uniqueness of their minds and the expression of that within dreams.***