RICK HUDSON AND RICK HILLS FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK

RICK HUDSON AND RICK HILLS FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK

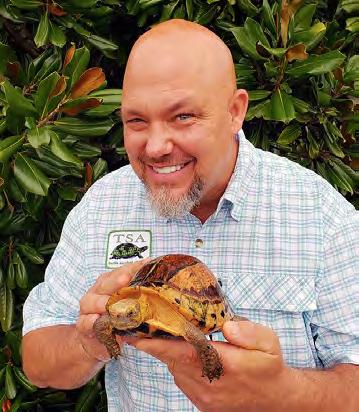

How many guys named “Rick H” does on organization need? For the TSA the answer is two. In August, Rick Hills took over as CEO/Executive Director, assuming management of the day-to-day operations of the TSA, with Rick Hudson staying on as President of the Board. Both Ricks are focused on fundraising. Hills has moved to Charleston, South Carolina, where he is overseeing both our three-person staff of Jan Holloway, Jordan Gray, and Emily Kiefner in our new office, opened in 2018, and our five-person staff at our Turtle Survival Center (TSC) in nearby Cross.

Hills is negotiating a steep learning curve, as he works to understand the complexities and the myriad of personalities that make up an organization global in scope. There are a lot of moving pieces within the TSA and many of us juggle many responsibilities

with a lot of balls in the air at any given time of day.

The transition to Charleston has been years in the making. Since we opened the TSC, we have been cognizant of the need to make ourselves better known in the greater Charleston community. We believe there is great fundraising potential in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. The TSC represents our greatest asset in terms of bringing what we do globally home to local people. One of Rick Hills’ most important goals is to guide that process and to ensure that the TSA name is as familiar to South Carolinians, indeed lay people everywhere, as it is to turtle conservationists and enthusiasts around the world.

The Lowcountry citizenry is environmentally aware. It appreciates the region’s natural beauty and its gorgeous coastline. Many

different volunteer groups are involved in nest watch and health monitoring activities for the different species of sea turtles of the region. The South Carolina Aquarium has a world-renowned facility that cares for injured sea turtles and the TSC is fortunate enough to get to share their amazing veterinary services. Our hope is to expand on the existing local sea turtles awareness by introducing people to the work done locally and globally at the TSC.

One of Hills’ happiest discoveries has been how receptive Lowcountry people are to the TSA and to the presence of the TSC. “I didn’t know that!” is a regular, pleasantly surprised reaction to a description of our work. The challenge ahead is to translate that receptiveness into support for the TSA’s programs, one Hills is excited to tackle head-on.

BOARD MEMBERS

Andre Daneault

William Dennler

Susie Ellis, PhD

Michael Fouraker

Tim Gregory, PhD

Brian Horne, PhD

Rick Hudson, President

John Iverson, PhD

Patricia Koval, LLD, Chair

Dwight Lawson, PhD, Vice-President

Kim Lovich

Lonnie McCaskill

John Mitchell

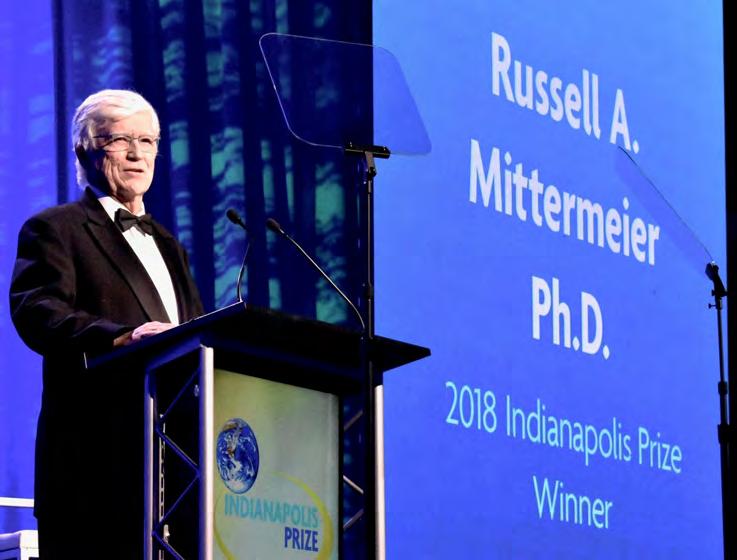

Russ Mittermeier

Hugh Quinn, PhD

Anders Rhodin, MD

Walter Sedgwick

Frank Slavens

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Richard M. Hills

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

Andrew Walde

ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF

Jordan Gray

David Hedrick

Jan Holloway

Emily Kiefner

TURTLE SURVIVAL CENTER STAFF

Carol Alvarez, RMA, NCPT

Clinton Doak

John Greene

Cris Hagen

Nathan Haislip, MS

RANGE COUNTRY PROGRAM LEADERS

German Forero-Medina, PhD

Kalyar Platt, PhD

Herilala Randriamahazo, PhD

Shailendra Singh, PhD

(Cover Story)

– Bangladesh (Batagur Baska Project)

– Myanmar

– Indonesia (Sumatra)

– Indonesia (Sulawesi)

– Vietnam (Rafetus swinhoei)

– China 49 – Belize

– Colombia 56 – Cambodia

– Behler Award

– Indianapolis Prize

– Member Spotlights

– Outreach 75 – Donor Recognition

3 – Partners 5 – TSA Partner News

– TSA Europe

– Brewery Partnerships

– theTurtleRoom

ABOUT THE COVER: The TSA and our partners were overwhelmed with Radiated Tortoise (Astrochelys radiata) confiscations in Madagascar in 2018, but we rose to the challenge. Massive rescue efforts presented all hands on deck response. By year’s end we had triaged and provided long-term care for nearly 18,000 of these iconic tortoises. As a result, new partnerships were formed, existing ones strengthened, and an enhanced facility brought to life in Lavavolo. Needless to say, the trajectory for this species’ wild survival in Madagascar presents a grim future. This species faces functional extinction in the wild in the next 20 years unless the all-out assault on the tortoise and its habitat is stopped. To save this species from becoming the next on a long list of those that have disappeared from their native land, a full-scale, multi-national conservation initiative must be taken on their behalf. The time is now. See full story pp.19 PHOTO CREDIT: MARK LEWANDOWSKI

Jan Holloway is originally from Pulaski, a small town in upstate New York near Lake Ontario, and has been a lover of all animals since a very young age. Her true passion was horses though, which led her to earning her AAS in Equine Studies from Cazenovia College, NY before continuing her education, earning her BA in English, Creative Writing. After graduating in 1988, she moved to South Carolina to take a position as the Breeding Manager at a large Saddlebred horse farm outside of Columbia, SC. She later explored other career fields including Sales/Marketing and Print Media and Publishing. Most recently, before accepting her position as Administrative Coordinator at the Turtle Survival Alliance in December 2017, she was the Activity Coordinator at another local non-profit agency for nearly five years. She has always been a reptile enthusiast, and bearded dragons, aquatic turtles, and non-venomous snakes have been among her most recent pets. Jan also currently serves as Secretary.

Another Upstate New York native, John joined the TSA in March 2018 as our newest Chelonian Keeper. Beginning with turtles found in ponds near his house at the age of 5, John has held a lifelong fascination with chelonians. This fascination led to honing his skills in turtle husbandry, to which he has dedicated the last 43 years of his life. Prior to his employment by the TSA however, chelonian keeping and their conservation was a hobby. After attending Florida State University, John moved to Southern California where he entered the professional construction sector. The trade skills acquired in this sector significantly add to our ability to expand the Turtle Survival Center’s infrastructure and animal care apparatuses and mechanisms. While John has a strong interest in all genera of chelonians, the Asian box turtles of the genus Cuora are his favorite, with a particular interest in the Southern Vietnam Box Turtle (Cuora picturata).

Emily Joined the TSA in September 2018 as Administrative Assistant. No stranger to the South Carolina Lowcountry, Emily has lived Charleston for the last ten years where she has worked as a Program and Administrative Assistant and Office Manager for various establishments. Prior to relocating to the Lowcountry, she lived in numerous states and countries abroad, including England and Germany. A graduate of Dickinson College in Pennsylvania with a dual-degree in International Business and Management, and German Studies, she later obtained her Paralegal Degree here in Charleston. When she is not working toward our commitment of “zero turtle extinctions,” Emily loves to travel, play tennis, and ride horses. Her diverse background and work experience has enabled her to quickly fill her role at the TSA.

The Turtle Survival Alliance is proud to acknowledge the following organizations that make our work possible. The organizations listed here provide a range of services supporting our mission, including guidance, networking, strategic planning, funding, husbandry, rescue, animal management, marketing and public relations, field research, logistical and technical support, salaried positions, and other resources.

This year the TSA welcomed Brian D. Horne, PhD, to our Board of Directors while bidding farewell to Colin Poole and Jim Breheny, all of whom represent the Wildlife Conservation Society. Both Colin and Jim have been strong supporters of the TSA since its inception, and we thank them for their years of service toward our mission. Likewise, Brian has also been heavily involved with the TSA since its early days, serving as an active member of TSA’s leadership committees for many years. With a focus on the turtles of Southeast Asia, Brian brings a wealth of knowledge regarding their status and conservation and will greatly bolster our influence in the region.

Brian has held a life-long love for reptiles. It all began with his first pet snake at the age of 4, and he has provided care for “herps” ever since. In pursuing his interest in herpetology, Brian attended Virginia Tech, where undergraduate mentor, Dr. Robin Andrews, encouraged him to explore reptile natural history. Later in his undergraduate career, he would become a student researcher under Dr. Carola Haas, performing field work with Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) in southwestern Virginia.

Following undergrad, Brian earned his Master of Science, studying nesting behavior of the Yellow-blotched Map Turtle (Graptemys flavimaculata), under Dr. Richard A. Seigel. Continuing his advanced education, Brian joined Dr. Willem Roosenburg’s lab at Ohio University in pursuit of a PhD and, at the encouragement of Dr. Richard Vogt, studied the White-lipped Mud Turtles (Kinosternon leucostomum) of southern Mexico, creating a predictive model for embryonic diapause in this species. Upon completing his dissertation, Brian accepted a postdoc position at the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research, where his focus centered on developing a conservation program for the Red-crowned Roofed Turtle (Batagur kachuga) in India. This work would become the genesis of the TSA’s India program.

Currently, Brian is the Coordinator of Freshwater Turtle and Tortoise Conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) where he oversees programs across the globe, with a notable emphasis in Southeast Asia and Latin America. In this role, Brian continues to integrate field research and animal husbandry to advance the conservation of the world’s most endangered chelonians, with the ultimate goal of restoring species to their full ecological function across their former range. He sees the key to success lying in a better understanding of reintroduction biology, and working with countries to protect their species from habitat loss and illicit trade.

“Zero turtle extinctions in the 21st century” – a bold pledge by an emboldened group of chelonian conservationists. The Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA) is in its 17th year of this commitment to the tortoise and freshwater turtle species of the six continents on which they reside. Created in 2001 in response to “The Asian Turtle Crisis,” the title given to the rampant and unsustainable harvest of Asian turtles, the TSA has since expanded to create a global chelonian conservation network.

During its first four years, the TSA operated as a task force for the IUCN’s (World Conservation Union) Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (TFTSG). In 2005, the TSA sought an independent 501(c)

(3) nonprofit status, with a home base at the Fort Worth Zoo, Texas. As the TSA’s global reach grew, so did its need for restructuring, and a Board of Directors was instituted in 2009. With this growth also came the need for the construction of a facility to house and provide assurance colonies for some of the world’s most endangered species of chelonians. Thus, the Turtle Survival Center, now home to 700 specimens, was created in the backwoods of coastal South Carolina.

The Turtle Survival Alliance continues to be a global force in the effort to provide dynamic in situ and ex situ conservation initiatives including breeding programs, assurance colonies, and management plans; field research and culturally sensitive

conservation initiatives; hands on, readable, and viewable public outreach; and sharing information, techniques, and communication throughout the chelonian conservation community. Through working collaborations with zoos, aquariums, universities, private turtle enthusiasts, veterinarians, government agencies, and conservation organizations, the TSA is widely recognized as a catalyst for turtle conservation, with a reputation for swift and decisive action.

As anthropogenic threats such as habitat loss, poaching, and pollution continue to wreak havoc on turtle and tortoise populations worldwide, the TSA is committed, now more than ever, to fight for the preservation of these animals.

Anders G.J. Rhodin1,2, Hugh R. Quinn1, Russell A. Mittermeier1,2, Nicolas

Last year, the Turtle Conservation Fund (TCF) and the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund (MBZ) each marked significant milestones in reaching the one-million-dollar mark for dedicated turtle and tortoise conservation funding. Both funds have continued their loyalty to turtle and tortoise conservation support over the past year. One of the recent projects supported by both funds has now had some very welcome results: the rediscovery of a nearly extinct species, the Nubian Flapshell Turtle (Cyclanorbis elegans), along the White Nile in South Sudan.

This large softshell species has been assessed by the IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group to be one of the most critically endangered turtles in the world, literally teetering on the brink of extinction. There have been no sightings of any animals in the wild for several decades, and the only known captive died in a private U.S. collection in 2012. The historic distribution of the species was in the SubSaharan Sahel region, in a series of apparently disjunct populations extending from Ghana to South Sudan, but with no current evidence of persistence in most of its range. Several focused field surveys over the years by Luca Luiselli and associates in Togo, Ghana, and Nigeria, and supported by TCF and MBZ, as well as others, have provided only negative results—no Nubian Flapshell Turtles were discovered.

Raising hopes of rediscovery, support from TCF to Patrick Baker in 2014 resulted in preliminary interview reports of the possible continued presence of C. elegans in South Sudan, however, no animals were found (though descriptions by local fishermen were quite precise). Further support to pursue these

preliminary reports, as well as to collect data on the distribution and abundance of other turtle species in South Sudan, was provided to Luiselli and colleagues Gift Simon Demaya and Tomas Diagne by both TCF and MBZ again in 2017. The local South Sudan team also included John Sebit Benansio and Thomas Francis Lado from the University of Juba.

Field work by this team in South Sudan has now confirmed the continued survival of a small population of C. elegans in the White Nile (and records of 9 other turtle and tortoise species). The hopeful news of rediscovery of this nearly extinct species must be tempered by the fact that this remnant population is under severe threat from local exploitation and consumption as well as habitat loss. Continued exploitation of this population is sure to continue unless new protective measures are initiated.

The creation of a novel protected area for the section of the White Nile in which they inhabit is being considered in conjunction with the Government of South Sudan and with the support of Rainforest Trust. Furthermore, Luiselli is pursuing additional survey work to establish size and density of the population and to document habitat

preferences. Establishing a captive breeding program in South Sudan and perhaps elsewhere also needs to be considered.

The TCF was founded in 2002 by the IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, Turtle Survival Alliance, and Conservation International. Through August 2018 it has provided funding for 250 projects focused on turtles and tortoises, at an average of $4,352 per project, for a total disbursement of $1,088,000.

The MBZ was founded in 2008 by His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, and through September 2018 has provided a total of about $17.5 million in grants to 1800+ projects. Of these, 111 projects have focused on turtles and tortoises, at an average of $9,910 per project, for a total turtle disbursement of $1,100,000.

Both TCF and MBZ greatly value the support of the turtle conservation community in our efforts and we are honored and pleased to be able to provide as much support as we do for so many of the critically important front-line and on-the-ground efforts on behalf of global turtle conservation. By continuing to expand and grow our capacity for providing support, we hope to make an increasingly important impact on all turtle conservation efforts. Please consider submitting your grant proposals to us for consideration at www.turtleconservationfund.org and www.speciesconservation.org.

Acknowledgements: 1Turtle Conservation Fund; 2Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund

Jeffrey E. Lovich, Joshua R. Ennen, Mickey Agha, and J. Whitfield Gibbons

Throughout our careers, now spanning more than 100 cumulative years, people consistently ask us the same questions when they find out we are conducting research on turtles: 1) why do you study turtles, and 2) why are turtles important? It is often easiest to put on our “scientist hats” and tell them that doing so provides important information to resource managers to recover or

better conserve turtle populations. If that doesn’t satisfy them, we sometimes turn to a long list of turtle superlatives including statements like, turtles are in a lineage that is over 200 million years old, they survived the extinction of the dinosaurs, many species have embryonic sex determined by incubation temperature, females can store viable sperm for years, or other captivating

facts about turtles. Some people walk away satisfied while others remain mystified by our fascination with turtles.

There are certainly other reasons why people study or conserve turtles. Some simply like turtles, perhaps because of a memorable childhood experience with these marvelous creatures. Others study turtles to learn how to better conserve them since

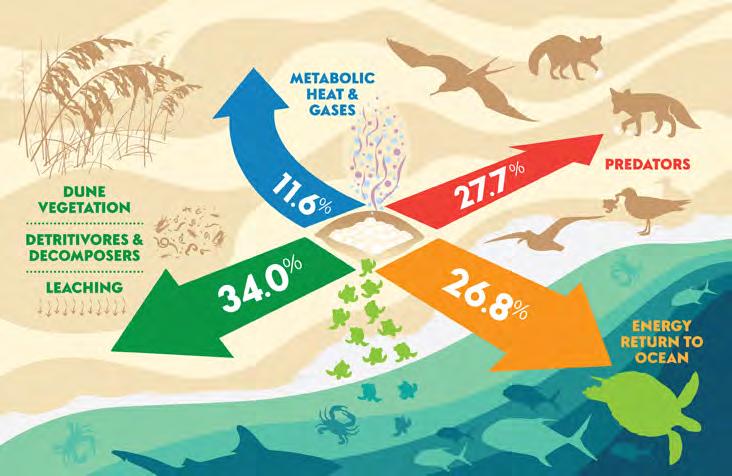

almost 60% of the world’s 357 turtle species are threatened or have become extinct since the year 1500. Moral, esthetic, or legal arguments are additional rationales given by some for protecting turtles. Turtles are remarkable and beautiful animals, and some are protected as threatened or endangered species under penalty of law. In addition, turtles have value to humans culturally, as a food resource, via tourism value (e.g., Galápagos Islands), and increasingly as pets. In a recent article (Lovich, J.E., J.R. Ennen, M. Agha, and J.W. Gibbons. 2018. Where have all the turtles gone, and why does it matter? BioScience.), we provide a new paradigm by assessing the ecological value of turtles.

Ecological value can be defined as the worth attributed to a plant or animal in terms of their benefits to the environment. Think of the ecological value of trees to us as an example. By maintaining healthy forests, we get access to economically important products like wood and paper. Turtles also have value to the ecosystems they occupy, including to humans who share those same environments in many cases. In our BioScience article, we bring attention to the global plight of turtles and identify what we will lose from an ecological

perspective as populations continue to decline and species disappear.

Before humans caused widespread declines of turtle populations, due primarily to overharvest and habitat destruction, turtles often occurred in very large numbers and had high biomass in the various ecosystems they occupied. As a result, they made valuable contributions to soil processes, mineral, nutrient and energy cycling, scavenging of carrion, and seed dispersal and germination enhancement of various plants. For example, many turtles propagate plants across the landscape by eating and defecating seeds that remain viable after passing through their digestive tracts. Aquatic turtles transport seeds of plants such as water lilies. Box turtles and tortoises disperse the seeds of numerous terrestrial plants. In addition, some tortoises dig burrows that turn over the soil, making minerals and nutrients available to other animals and plants. In addition, those same burrows provide shelter for hundreds of other commensal species, many of which cannot dig burrows by themselves. Other turtles are important scavengers that keep waterways cleaned of dead aquatic organisms including fish. Turtles

are even being used to restore degraded ecosystems in places like the Galápagos Islands where their numbers were greatly reduced over time. As turtle populations continue to decline worldwide, these known ecological roles are greatly diminished with incompletely-known consequences for ecosystem health and the survival of other species, especially those that have commensal relationships with turtles.

A fundamental question is, why is public awareness of declining turtle populations and the importance of healthy turtle populations lagging relative to other charismatic species? There are three possible explanations. First, reptiles are generally not as well-liked as mammals and birds by the public. However, turtles are the only reptiles that are generally admired and even elevated as cultural icons (e.g., the fable of The Tortoise and the Hare, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles). Second, shifting baselines obscure what has been lost in the past. People born into a world with few turtles accept that as a new norm. Third, is what we call the “perception of persistence.” Since many turtle species can live a long time, populations that are not reproductively viable can consist of surviving adults that persist for decades before they too eventually die, with no recruitment of juveniles for the future.

Many turtle populations continue to slide toward extinction around the world and the ecological consequences are still not fully understood. It would be a sad world indeed without turtles, the only animals that ever lived with their shoulders and hips inside the rib cage. They are arguably nature’s greatest success story, having outlived the dinosaurs by a wide margin. Will they outlive us?

Contact: Jeffrey Lovich, U.S. Geological Survey, Southwest Biological Science Center, 2255 N. Gemini Drive, MS-9394, Flagstaff, AZ 86001-1600, USA; [ jeffrey_ lovich@usgs.gov]

Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) in the disjunct southern portion of their range exist in idyllic mountain fens, seeps, and wet meadows. Since the arrival of Europeans, approximately 90% of these rare habitats have been destroyed. Despite this significant habitat loss, the southern population network has historically been considered a stronghold for Bog Turtles. The viability of the populations that make up this network is likely critical to long-term survival of the species.

Unfortunately, the demographic characteristics of our most intensively studied sites

Mike Knoerr and Dr. Cassie Dresser

in North Carolina (NC) and Tennessee (TN) suggest population-level declines. For example, annual adult survival for these NC populations is low (0.86 – 0.94, Tutterow et al. 2017) when compared to northern Bog Turtle populations and other turtle species. Egg and juvenile survival can be low as well given field observations and skewed age class distributions. These populations are often dominated by old turtles with few/ no juveniles observed in recent decades. Although an aging demographic is characteristic of most sites, high egg survival (>50% annually) and a high proportion of juveniles

(>40% of encounters) have been observed in two stable NC populations. Analysis suggests that high survival at the beginning stages of life contributes to the stability and growth of these populations.

Although we have made strides in understanding drivers of decline, the mechanism(s) behind these demographic trends are not fully understood. At Bern Tryon’s TN site, where the entire known population is comprised of captive-bred, head started, and wild raised adult turtles, wild recruitment has not been observed, despite nearly 30 years of trans-

location efforts. At some of the “aging” NC sites, catastrophic nest predation, particularly by human-subsidized mesopredators, has been documented in recent years. Based on current trends, some NC populations may be experiencing 6-10% annual decline and the TN population may face extinction without continued stocking efforts. While vital rates certainly fluctuate in any given year, multiple decades of encounter data suggest that it is improbable for these declining populations to stabilize on their own.

With a handful of questions and objectives in mind (and support by the TSA’s Bern Tryon Grant), we (Dr. Cassie Dresser at Michigan State and Mike Knoerr in Clemson University’s Barrett Lab) joined forces to better understand drivers of recruitment failure and to implement applied management. Cassie spent the summer working in Bern Tryon’s TN site, the same site where she had spent years studying the population as part of her PhD dissertation. Accompanied by her undergraduate research assistant, Sarah Klein, and supported by Zoo Knoxville staff, they set out to find and track gravid turtles in order to locate their nests. To assess drivers of nest fate, a subset of nests was protected with predator excluder cages, while others were left undisturbed. Furthermore, nests were monitored using wildlife cameras to identify potential nest predators and inform future predator management. Mike and his technician Cody Davis spent most of their season working with two “aging” populations in NC (with additional support from the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and NC-The Nature Conservancy). Their goal was to assess the effectiveness of in situ recruitment augmentation and habitat restoration at increasing survival and populationlevel stability. This field work included: caging nests with excluders, building solar-powered electric fences around core nesting areas, mesopredator trapping, and

hydrological/vegetative restoration.

Preliminary observations at Bern Tryon’s TN site differ from those made in NC. While most female turtles of adequate size and health in NC become gravid annually (>90%), <50% of the females monitored at Bern’s site became gravid in 2018, a trend observed across multiple field seasons. Why comparatively fewer females produce eggs here has yet to be determined. As of this writing, four eggs from the five nests monitored have hatched. The remaining eggs have either not yet hatched or appear infertile. We anticipate that these data and the questions they generate will help us better assess whether Bern’s population has the capacity to become self-sustaining long term.

In NC, 27 nests were found across three sites. Results from the management efforts look promising as predation, the primary driver of failure in 2016/2017, was reduced to nearly zero. Photos and video suggest that the electric fences and nest cages were effective at excluding a multitude of predators. Gravid turtles successfully nested in areas cleared of woody vegetation. Egg survival was fairly high (64%)

with 65 hatchlings having been marked and released. This is likely the largest cohort of hatchlings to survive in decades. Many of these hatchlings have since been observed active in newly inundated areas created via hydrological restoration efforts.

Bog Turtles offer a unique challenge to those dedicated to saving them. While facing the acute problems inherent in avoiding extirpation, we have arrived at a place where we must consider pragmatic and imperfect solutions. In best case scenarios, research and management efforts like these implemented in TN and NC may help stabilize populations. In precipitously declining populations, they may be only stop-gap measures that boost turtle numbers and buy us more time. Regardless, we have more turtles today than we did earlier this spring. That is a start.

Contact: Mike Knoerr, Clemson University, School of Agriculture, Forest, and Environmental Sciences, 244 Lehotsky Hall, Clemson, SC 29634 [mike.knoerr@ gmail.com]; Cassie Dresser, Michigan State University, Lyman Briggs College, 919 E Shaw Ln, East Lansing, MI 48825 [cdbriggs@msu.edu]

Cris Hagen, Nathan Haislip, Carol Alvarez, Clinton Doak, and John Greene

The Turtle Survival Center (TSC) had its best year yet for egg production. Over 400 eggs from 21 species were laid in 2018. Eggs were divided between three different incubators at temperatures of 78° F (25.5° C), 82° F (27.7° C), and 85° F (29.4° C) for different temperature sex determination among the species. This was the first year that the TSC successfully hatched the Sulawesi Forest Turtle (Leucocephalon yuwonoi) and the Asian Black Giant Tortoise (Manouria emys phayrei). Other species that reproduced at the TSC this year include Yellowheaded Box Turtles (Cuora aurocapitata), Chinese Box Turtles (Cuora flavomarginata), Indochinese Box Turtles (Cuora galbinifrons), McCord’s Box Turtles (Cuora mccordi), Southern Vietnam Box Turtles (Cuora picturata), Ryukyu Black-breasted Leaf Turtles (Geoemyda japonica), Spiny Hill Turtles (Heosemys spinosa), Sulawesi Tortoises (Indotestudo forstenii), Vietnamese Pond Turtles (Mauremys annamensis), Red-necked Pond Turtles (Mauremys nigricans), and Beale’s Eyed Turtles (Sacalia bealei). For the fourth year in a row, Big-headed Turtles (Platysternon megacephalum) have reproduced at the TSC, for a grand total of 30 offspring. Outside of the TSC, Zhou’s Box Turtle (Cuora zhoui) reproduced in the U.S. for the first time since 2015. The two C. zhoui hatchlings are the first offspring produced from a male imported from the Munster Zoo in Germany last year as part of an international bloodline exchange.

Contact: Cris Hagen, Turtle Survival Alliance, 1030 Jenkins Road, Suite D, Charleston, SC 29407, USA [chagen@turtlesurvival.org]

During the first week of 2018 an extremely rare weather event occurred in Charleston, SC blanketing the region with 5-6 inches of snow for nearly a week before it all melted. The outdoor residents at the Turtle Survival Center remained dormant either underwater in ponds or under piles of mulch and leaves on land during this winter anomaly. PHOTO CREDIT: CRIS HAGEN

This year marks the 5-year anniversary of the Turtle Survival Center (TSC). Thinking back to its humble beginnings and the 2013 TSC article in the TSA magazine, it’s been amazing to witness the growth and transformation that has taken place. The TSC started with a staff of one, quickly growing to four during the first few months of operation, and currently maintains five full-time employees. The living collection has grown

from about 300 individuals in the first year to around 700 individuals, representing 29 species. During the first five years of construction, seven separate facilities have been built, as well as renovations to existing facilities, for a current total of more than 400 enclosures for turtles and tortoises. The initial construction phase of the TSC is nearly completed. However, the continued growth of the Center to meet animal man-

agement needs of the institutional collection plan will require another phase of construction over the next decade. This will include new utilities, facilities, and a few hundred more enclosures.

As the years go by and turtle residents of the TSC become more acclimated to their environment, reproduction increases. While

time and acclimation are likely to be the most prominent factors for an increase in egg production, some changes in husbandry and diet over the past year may also be important contributing factors. This year was a record year for reproduction at the TSC. More than 400 eggs from 21 species were produced, compared to only 160 eggs from 18 species in 2016 and 125 eggs from 15 species in 2017. The priority species chosen for captive management at the TSC are thriving and reproducing exponentially, a testament to the knowledge and dedication of the staff.

Time, some enclosure modifications, diet additions, and probably several other factors have led to this year’s record-breaking reproduction. Examples of recent husbandry changes include: many turtles now have their own individual enclosures instead of being housed in pairs or small groups, and

males and females are only put together for mating encounters at appropriate times. This greatly reduces stress and injury from intraspecific aggression and constant mating attempts when housed together year-round. Additionally, since the wild diet of many species kept at the TSC is largely unknown, a wide variety of commercially available and cultivated food items are regularly being added to the diet mix in an attempt to provide the most complete diet possible. Furthermore, a regular vitamin/calcium supplement routine began in 2017. With regard to young specimens, hatchling Big-headed Turtles (Platysternon megacephalum) are now on a filtered recirculating system featuring spray bars to help simulate the flowing water of a stream habitat. This has been observed to aid in the proper shedding of their scutes.

One of the only known genetically unrep-

resented wild-caught pairs of Rote Island Snake-necked Turtles (Chelodina mccordi) in the U.S. resides at the TSC. The female has been in captivity since 1999 and has been without a mate for the majority of that time. The male was in a similar situation and was obtained in 2017. This year, the female produced a total of 23 eggs. One egg partially developed, yet failed to hatch. However, this is a good sign that this pair is becoming reproductively active again after nearly 20 years of solitary captive existence. Hopefully this pair will be producing many offspring in the future and adding a new bloodline to the U.S. captive population. With only 154 individuals in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) managed studbook, many of which are related, a new genetic line will be an important addition for captive conservation efforts.

In October 2017, the TSC began the process of applying to become a certified related facility of the AZA. After a lengthy application preparation and submission process, an onsite inspection was conducted in June 2018. The AZA accreditation hearing was held in Seattle, WA on 23 September 2018 and there the TSA/TSC was granted certified related facility status. The certification will open doors for additional funding possibilities, provide eligibility for specific conservation awards, allow TSA staff to be studbook keepers, and will hold the TSC to a high standard of animal care. The AZA inspection team was very impressed with the TSC, including the institutional collection plan and operating procedures, demonstrating that the TSC staff have always held a high standard of animal care.

Contact: Cris Hagen, Turtle Survival Alliance, 1030 Jenkins Road, Suite D, Charleston, SC 29407, USA [chagen@ turtlesurvival.org]

The island of Sulawesi, in the Indonesian archipelago, is known to have two endemic species of turtles, the Sulawesi Forest Turtle (Leucocephalon yuwonoi) and the Forsten’s Tortoise (Indotestudo forstenii). Both species have proved challenging to successfully breed in captivity. These species are tropical and can mate and produce eggs any month of the year in the captive setting. At the Turtle Survival Center (TSC), both species are housed in the tropical Sulawesi Greenhouse. The breeding season is structured to coincide with winter months, as this is the off-season for many of the TSC’s other temperate and subtropical species. Mating events are brief, with animals paired for only a short time to allow copulation and prevent any unnecessary aggression. Throughout the year, we house both

species individually or, in rare cases, two female Forsten’s Tortoises in a larger enclosure, to limit these antagonistic interactions.

There are approximately 160 Forsten’s Tortoises spread amongst 29 institutions in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) Studbook, with nearly one fourth of that total living at the TSC. The TSC has maintained a population of Forsten’s Tortoises since 2013, however, we have had low reproductive output. They receive a varied diet that includes a variety of vegetables and some fruit. In 2017, vitamin/mineral supplements and cuttlebone were regularly added to all turtle diets. Prior to this, supplements and cuttlebone were sporadic. During the 2017/2018 breed-

ing season, Forsten’s Tortoises were paired the same as they have been in years past, however egg production increased dramatically. We saw a more than threefold increase in egg production for the 2018 egg-laying season (23 eggs) when compared to the 2016 egg-laying season (seven eggs). We hypothesize that some of the observed increase in reproductive output could be correlated to acclimation time since moving to a new environment at the TSC. However, we would expect to see a somewhat gradual increase as individual animals “come online,” whereas production increased by 228%, suggesting that husbandry changes may have contributed to the increase in egg production.

For the Sulawesi Forest Turtle (Leucocepha-

lon yuwonoi), major husbandry changes were implemented this year. Initially, these animals were housed in medium Waterland Tubs with a shallow water area, however, keepers noticed that animals were struggling to come onto land to feed, which may also have restricted their ability to nest. After a brief pilot study in 2017, we decided to deepen the water for all individuals and provide rocks, which aid the turtles in climbing the ramps and offer perches in the deeper water. For the 2017/2018 winter breeding season, animals were paired similarly to the previous breeding season except we extended the time-frame to approximately twice as long (six months versus three months).

This extension allowed us to gain more breeding data and better detect if there were any peaks in egg production. Eggs were laid between April-October at the TSC with peaks in June and July (five and four eggs respectively). The lowest months of egg production were September and October with one egg produced each month. Prior to 2018, less than 12 eggs had been produced since 2013. We observed a 700% increase in egg production in 2018 compared to 2017, with 17 eggs produced. The majority of these eggs were produced from animals brought to the TSC in 2013.

This year saw the production of the first captive-hatched Sulawesi Forest Turtles at

the TSC. The first hatchling was found in March from an egg that was most likely laid sometime in October 2017 from a female that has laid non-viable eggs for over a decade. On June 1st the same female laid another egg that was collected and placed in an incubator at 26° C (78° F). This second hatchling emerged after 5 1/2 months of incubation. Time, husbandry changes, diet additions, and extended breeding periods all likely played key roles in making 2018 such a successful year.

Contact: Nathan Haislip, Turtle Survival Alliance, 1030 Jenkins Road, Suite D, Charleston, SC 29407, USA [nhaislip@ turtlesurvival.org]

Deadline for Summer 2019 internship application is February 28th.

Deadline for Fall 2019 internship application is May 31st.

Start Date can vary based on availability after May 1st and August 1st.

The Chelonian Internship Program is perfect for undergraduates and graduate students who plan to pursue a career in conservation and captive management of turtles and tortoises.

Key Benefits:

• Gain hands-on experience with the day to day operations of a chelonian conservation center.

• Build husbandry skills for ex situ conservation for some of the most endangered chelonians in the world.

• Develop basic veterinary care techniques as they apply to captive chelonian husbandry.

For more information including responsibilities, expectations, qualifications, costs, and how to apply contact Clint Doak at cdoak@turtlesurvival.org.

Cris Hagen, Nathan Haislip, Carol Alvarez, Clinton Doak, and John Greene

ing all 8 adult females in the collection. The adults arrived in different groups during 2014, 2015, and 2017. Double clutching, and in one case triple clutching, was documented in 5 females. There was a 45% hatch rate and eggs were incubated at various temperatures to produce both sexes. To our knowledge, this is the most captive bred C. picturata produced worldwide in a single breeding season at any one location.

The Southern Vietnam Box Turtle (Cuora picturata) was described in 1998 and for many years was known only from trade specimens until the first scientific documentation in the wild occurred in 2011. Originally recognized as a subspecies of the Indochinese Box Turtle (Cuora galbinfrons), further molecular research elevated C. picturata to full species status in 2003. They have been commercially collected and observed in the international food and pet trades since at least the early 1990’s.

This species has generally been considered difficult to breed in captivity with limited, yet steady success among a handful of turtle specialists worldwide. The Turtle Survival Center (TSC) is the only institution in the U.S. known to have successfully bred them.

This has been a banner year for C. picturata propagation at the TSC. Prior to 2018, a total of 8 C. picturata eggs were produced, resulting in a single hatchling. During the 2018 reproductive cycle, February to June, a total of 20 eggs were produced represent-

TSC staff collect data on eggs (measurements, developmental stages, temperature for sex determination, incubation durations, etc.), as well as life history information in regards to growth and maintenance of hatchlings and juveniles. Preliminary data, from a sample size of only two, suggests that C. picturata may grow and mature at a faster rate than its closest relatives C. galbinifrons and Bourret’s Box Turtle (Cuora bourreti) when raised under similar conditions.

“The future is in your hands.” An oftrepeated statement in speeches to young audiences meant to inspire them, this statement, unfortunately, is often an absolvement of responsibility of the current generation, and bestowment of burden upon those of the future. We currently face a worldwide biodiversity crisis that will not be solved in a single generation alone. It is paramount for current leaders in biodiversity conser-

vation and research to foster involvement and encourage younger generations to both appreciate and take an interest in the world around them. In essence, we must champion our children and their children to not only carry our torch, but to light the path for others, promoting the understanding that wildlife conservation is not a whim. Rather, it should be an intrinsic part of who we are as human beings. After all, children are

naturally inquisitive, and it is said that scientists are kids that never stopped exploring.

It’s been clinically proven that fostering cognitive abilities, creativity, problem-solving skills, physical health, social relationships, self-discipline, and stress reduction enhance children’s growth and development. The environment for fostering these can be found all around you; in back yards, in neighbor-

hoods, in parks—it’s called nature! Conservationists need to find ways to move and empower younger generations to explore and protect the natural world. An emerging environmentalist sees the natural world not as a resource, but a delicate web of which we are just one part, and deserving of our utmost respect and care—a line of argument that is particularly appealing to young people. We must teach our children to live and learn as part of nature, not apart from it. What does it take to get today’s young people excited about environmental conservation? How do we harness their energy, creativity, and desire to take part in conservation efforts? The Turtle Survival Alliance’s North American Freshwater Turtle Research Group (TSANAFTRG) believes it should begin with hands-on work in an outdoor setting, giving them real-world experiences that boost their interest and enthusiasm for the natural world. If we show kids the value of research and conservation, while having fun doing it, then maybe we can persuade some to become conservationists themselves. We have been fortunate to have a large group of young volunteers assisting with our research in Florida and Texas over the years, ranging in age from 8 to a 17-year-old high school senior. They are future conservationists and researchers; they are the future of TSA-NAFTRG.

Herein we focus on several of these young volunteers’ experiences to gather a better understanding of what young people find important and how they see themselves being able to participate in conservation efforts.

Michael Skibsted: I began volunteering with the TSA in late 2016, however, I had known about the TSA long before I learned I could join it! Unlike most, I first experienced the wonder of turtles through books. Living in California, I didn’t have much access to them in the wild. As I began to delve deeper into chelonian literature, I began to learn about the dire situation they face. Moreover, I realized that it was largely due to human related actions. Once I fully grasped this, I became restless and

yearned for more than books; I began to search for opportunities. Surprisingly, as a 4th grader (back in 2013) there weren’t many opportunities to help the world’s turtles. This all changed three years later when I got involved with TSANAFTRG, assisting with field studies at their Comal Springs research site. Through the TSA, I have really gotten a grasp on what conservation means, and the feelings that accompany it. Many people associate the term with working to protect an already threatened animal. Through TSA-NAFTRG I have realized that this interpretation is far from the truth. Conservation is simply working to conserve something that you love and, in return, receiving a feeling of great accomplishment that you have played a part in prolonging its survival.

Being 14 years of age, I have a different perspective than most. I believe anyone with a passion, no matter the age, has the power to change the field they work in and do great things for the animal they are working to save. If the passion is there, nothing can stop an individual from doing great things. I believe that incorporating more young people who truly radiate passion for the

field of conservation would benefit the future of conservation as a whole.

Madeleine Morrison: When I first began working with the group, I honestly didn’t understand the importance of the group’s research for conservation. In fact, I didn’t really know why they were doing their research—I was just happy to get to work with and learn about turtles. All of this changed, however, once I learned more about the organization. I now realize that one of the most important things scientists can do to protect a species is to learn everything they can about it. This information (mostly collected through field research) is paramount for learning the most efficient and effective ways to tailor conservation towards any specific species or organism. This is a powerful piece of information for me to have learned at such a young age, as it has truly changed the perspective that I approach my academics with. Additionally, performing species investigations with TSA-NAFTRG has heightened my appreciation of nature in all its complexities, and has therefore made me even more passionate about conservation. I cannot stress enough the importance of allowing people to have this realization at a young age.

Tristan and Hailey Munscher: Both Tristan and Hailey Munscher have grown up with turtle research and conservation through their father Eric Munscher’s role within the TSA. One might think that being around such work on a constant basis would potentially dissuade them from wanting to participate. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Tristan and Hailey have taken to turtle research in their own way. Tristan (12)joined the TSA-NAFTRG team at Bull Creek in May and was able to capture 102 turtles on his own, a full third of the captured turtles that weekend. Hailey (9) has taken a shine to Alligator Snapping Turtles (Macrochelys temminckii) and joins her father on every trapping session there is. Both children understand the importance of turtle conservation and have a natural love and appreciation for the animals. Last year they devised a bait study for a local bayou in order to see if they could capture county record Common Musk Turtles (Sternotherus-odoratus) in Harris and Montgomery counties, Texas. They were successful and now have a distribution note in Herpetological Review

There are ever increasing numbers of conservation groups, including some state programs, who are creating programs geared toward younger generations. A few good examples of how conservation groups can enlist the help of younger generations and in so doing create a lasting impression on them are:

• Green Hour Program: The National Wildlife Federation’s Green Hour program is designed to encourage parents, schools, childcare centers, park agencies, camps, grandparents, and others to adopt a goal dedicating an hour of time per day for children to play and learn about nature in the outdoors.

•National Recreation and ParkAssociation: Wildlife Explorers Program (5-10); Nature Tykes (3-6)

•Pennsylvania Department of Conservation

Tabitha Hootman has been involved in the Turtle Survival Alliance – North American Freshwater Turtle Research Group’s (TSA – NAFTRG) turtle population studies in Florida for 14 years. Currently, Tabitha is a graduate student in Jacksonville University’s (JU) Marine Science Master’s Program. She is teamed with JU and TSA-NAFTRG to complete her thesis: Movement Patterns of Peninsula Cooter (Pseudemys peninsularis) and Florida Red-bellied Cooter (Pseudemys nelsoni) Found in Wekiwa Springs, Florida. The study stemmed from observations noted in our long-term population study at Wekiwa Springs State Park (WSSP). Over the years, the team would notice individuals leaving the sample area and then reappearing years later, sometimes in what seemed like groups. Originally, these observations were thought to be attributed to sampling bias, but as the data set grew, and other springs were added, it was noted there was movement into and out of the spring. The team would catch turtles at Kelly Park, approximately 14 km upriver, that were originally caught at WSSP, and vice versa.

In July 2018, 48 turtles from the sample area were outfitted with radio transmitters. Additionally, four turtles were outfitted with GPS data loggers. Starting on 4 August 2018, Tabitha has tracked these turtles every weekend. She covers about 48 km while tracking their movements and logging locations into a handheld GPS unit. She will continue to track the turtles for one full year. At the end of the year, Tabitha expects to discover the extent of the turtles’ movements and assess their migratory nature from her observations so that we can better understand how far they travel, or if they leave the area for any period of time.

This study is the first of its kind to track the movements and migration patterns of both freshwater turtles. Little information exists concerning the habitat requirements and movement patterns of the Peninsula Cooter and Florida Red-bellied Turtle. The data acquired will provide vital information, elucidating habitat preferences and critical habitats required to maintain these populations.

and Natural Resources (Good Natured)

• National Park Service Junior Ranger Program (https://www.nps.gov/kids/jrRangers.cfm)

As conservation stewards, we must further empower and cultivate younger generations with

the aim that they can stand up together with us and say, “The future of wildlife is in our hands.”

Contact: Eric Munscher, SWCA Environmental Consultants, 10245 West Little York, Houston, Texas, USA [emunscher@swca.com]

2018 was to become an unforgettable year for TSA Madagascar, unfortunately for many of the wrong reasons. Tortoise confiscations continued to mount, and dominated program activities for the third year straight—punctuated by the largest tortoise seizure on record. Over 10,000 Radiated Tortoises (Astochelys radiata) were seized in Toliara (Tuléar) in April, the magnitude of which rocked both the global conser-

vation community as well as Malagasy authorities. In the words of an ambassador at the U.S. Embassy in Antananarivo, “This one crossed the line.”

Officers and first responders from the Ministry of Environment, Ecology, and Forests (MEEF/Atsimo-Andrefana region) were shocked by the horror of so many sick and dying tortoises, and faced innumerable challenges in moving and caring for them.

Fortunately, a tortoise center in nearby Ifaty – SOPTOM’s Village des Tortues – was available to receive the tortoises. TSA Madagascar rapidly responded by sending in a vet team led by Dr. Ny Aina Tiana Rakotoarisoa (TSA) and colleagues from Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and the veterinary school in Antananarivo. For the first 10 days, this small team worked tirelessly to save tortoises suffering from starvation, dehydration, and

neglect at the hands of cruel and greedy wildlife traffickers.

Meanwhile, at TSA headquarters, this became an all hands on deck moment and we immediately began mobilizing all available resources. By April 21st, the first wave of U.S. responders — Team Radiata 1 — had arrived in Madagascar, with staff representing TSA, Bronx Zoo/WCS, Oklahoma City, Dallas, Knoxville, and Hogle Zoos, and led by Dr. Bonnie Raphael. Armed with nearly 590 kilograms (1300 lbs.) of veterinary supplies, Team 1 continued the tasks of tortoise triage and determining which tortoises were strong enough to be moved to a permanent facility. The team was divided upon arrival, with some staying in Ifaty to treat tortoises and others going south to Lavavolo to prepare the existing tortoise center for A LOT of new arrivals. Prior to this time, the facility in Lavavolo was no more than a walled enclosure with no infrastructure for the people caring for tortoises. Due to an overwhelming response from the U.S. zoo and aquarium community, the TSA was able to deploy another six teams of wildlife warriors over the course of three months, consisting of vet techs, keepers, construction and maintenance workers, as well as some of the leading chelonian veterinarians in the world. Together these men and women — 75 in total — endured long hours and hardships, bonding together under harsh conditions and limited resources, to save nearly 10,000 Radiated Tortoises AND build a functioning tortoise center in a remote and isolated area of southwest Madagascar. It was one of TSA’s finest moments, illustrating our ability to deploy resources rapidly and effectively in times of crisis.

The TSA prides itself on being able to respond in these kinds of situations, but it must be noted that our job was made easier by the amazing outpouring of financial support from the global turtle conservation community. Over 70 organizations stepped up in this time of need, 45 of them

Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) institutions, along with over 500 individual donors. While the number of donors and dollars raised is impressive and illustrates the generosity of our community in times of crisis, the brutal fact is that TSA Madagascar is now caring for over 23,000 tortoises spread over six centers. The financial impact of maintaining this many tortoises is considerable, and diverts resources from other important aspects of our organization. Our long term goal at the TSA is for zero turtle extinctions and, in order for this to become a reality, harsher punishments for poachers need to be established. Organized poaching syndicates must understand that there will be consequences for such griev-ous offenses. If not, the future of the Radi-ated Tortoise in the wild is doomed.

In a year that saw a publication describing the rapid extinction of the last wild populations of Ploughshare Tortoises (Astrochelys

yniphora), we must realize that we are on a similar trajectory with A. radiata and ask ourselves if we will allow this to happen on our watch.At the time of this writing, the three primary perpetrators of the Radiated Tortoise smuggling ring were recently given six years in prison and fines of $30,000, the most severe sentence ever handed down for poaching in Madagascar. However, this verdict is being appealed and we anxiously await the final word. It is important that this conviction and harsh penalty be upheld in order to send a strong signal to poachers, else this case will have been in vain. Without dogged persistence and enforcement, we could be writing the epitaph for this species in the not-too-distant future.

The TCC welcomesAndrew Leith, our first Peace Corp volunteer, who comes to us with a background in agriculture.Aside from im-

proving our vegetable garden, he is charged with working with the local communities and training them on improved agriculture techniques, enabling them to produce more food, as well as creating a source of revenue when they sell surplus produce to the TCC for tortoise food. On the construction front, we just broke ground on a new ultra-secure facility for our group of young Ploughshare Tortoises. As part of this project, and in keeping with our goal of improved security at the TCC, we will soon be bringing a greatly expanded solar power system to the Center. This will allow for a high-tech security system for our A. yniphora that is specifically designed to keep them safe. In addition to a range of other security measures, we are also finalizing plans for a sturdier and more predator proof perimeter fence to surround the 12-hectare core area. Finally, our new Community Outreach Center (COC) is taking shape and Phase 1 is nearing completion. Funds for the next two phases are secured, all supported through Utah’s Hogle Zoo. True to the vision of Christina Castellano, the COC will, once completed, have space for special community events, provide opportunities for education and outreach activities, offer comfortable accommodations for visiting scientists, donors and guests, and create a welcoming environment to the five local communities that, together, provided TSA with the land for the TCC (over 90 hectares total). In addition, a water collection cistern will provide much-needed water to these impoverished communities, which endure extreme hardships during the ever-worsening drought conditions in the south.

The tortoise poaching crisis is getting worse and, thusly, our concerns for the safety of the staff and tortoises at our Centers are increasing. To ensure that our security guards are better prepared to deal with potential threats, we have contracted with a leading global security solutions group, G4S. In July, staff from the TCC and LTC traveled to Ampanihy

for three days of intensive training. Soon, G4S will make site visits to both Centers to make recommendations for improving security measures and to train staff in their specific work environments. Maintaining good relations with the local communities is integral to our security plans as they are our first line of defense against poachers.

Josh Lucas (University of Central Oklahoma and OKC Zoo), in pursuit of his MS degree with financial support provided by Oklahoma City Zoo, and the TSA, are partnering to pioneer a reintroduction strategy for confiscated Radiated Tortoises. This strategy will entail an extensive investigative effort over a minimum of two years, and the results will have the potential to shape how we manage reintroductions in the future. Since it is highly likely that tortoises will continue to be confiscated, it’s im-

portant that we develop and implement an effective system that protects, monitors, and stewards these animals back into the wild.

Our strategy focuses on evaluating three key components: 1) community engagement 2) habitat condition and 3) poacher accessibility. Also, a combination of intense groundtruthing, GIS mapping, and a multitude of follow up surveys will allow us to key in on sites with the highest potential for success. Local community involvement and engagement is certainly the most important aspect of this project and, ultimately, our success will depend upon the willingness of local people to protect the tortoises. To help us better understand the needs, traditions, and perceptions of local communities, we are supporting a study by Naomi Ploos van Amstel, a Dutch MS student who is conducting a broad social survey, the results of which will impact not only site selection but how we incentivize those communities selected.

Once sites are selected, we will employ a soft release strategy to encourage site fidelity, the inclination of the tortoises to remain in the general vicinity where released. The goal is to establish large (~ 1- 2 hectares depending on number and size of tortoises) pre-release enclosures in each site selected, allowing tortoises to acclimate to their new surroundings over a period of one year. Once the enclosure walls are removed, the tortoises will be officially released and allowed to move where they choose. We will continue to monitor the health, movements, and survival of the tortoises via annual population assessment surveys.

As previously stated, reintroduction of the tortoises into their natural habitat is a multifaceted task that will require the collaboration of many people. Josh will be relying on, and working across, different scientific disciplines with local TSA staff and biologists who possess the skill and resolve to move this project ahead. Josh’s role will be to coordinate the efforts of this team from abroad, then spend summers in Madagascar pulling the various components together.

In Josh’s words: “The time to save Radiated Tortoises is NOW. No longer do we have the luxury of sitting idly by and hoping for the best. They are vanishing right before our eyes. The 10,000 are but a fraction of what disappears annually from Madagascar’s spiny forests. TSA has stepped up in a colossal way to be a force for change in the future of this species, and I am honored to be a part of this effort. By stepping into the role of Reintroduction Project Manager I am committed to use the wide array of resources at my disposal to make this project a conservation success.”

ENFORCEMENT MORE IMPORTANT NOW THAN EVER

Obviously, we cannot catch all tortoise poachers, but we must maintain vigilant and continue to apprehend and jail them as a strong, visible reminder that poaching has

• Arnaud Miarison has been hired as Lead Keeper for the Lavavolo Tortoise Center and is responsible for management of a staff of 12 keepers and security guards, as well as the procurement of food, water and supplies. Arnaud also provides oversight of TSA’s rescue centers at Betioky and Ampanihy, is well versed in farming techniques, and has installed gardens throughout the LTC that will help sustain the Center during times of drought. Arnaud comes to us from AVSF, a French veterinary support organization for livestock.

• Hanta Rasoanaivo is the new Finance Manager for TSA Madagascar and is in charge of all aspects of accounting, as well as other senior administrative duties for the office. Hanta graduated from the University of Antananarivo with a degree in law and economic studies and has 25 years of experience in finance management including managing a World Bank project.

• Christel Griffioen is the newly appointed Director of Tortoise Conservation for the Tandroy Region. Christel hails from the Netherlands and comes to us after a stint at the Angkor Center for Conservation and Biodiversity in Cambodia where her passion for chelonians became clear. She has over 15 years working experience with a diversity of species in zoos and wildlife rescue centers throughout Europe and the Middle East. Christel became enamored with Madagascar while spending three weeks helping with the big tortoise rescue earlier this year, and in September assumed the duties of managing the Tortoise Conservation Center. She oversees a staff of 14, including keepers and security guards, and will play a key role in overseeing construction and the myriad field expeditions necessary for developing reintroduction plans.

• Josh Lucas is currently the Lead Keeper of Herpetology at the OKC Zoo and was recently awarded the title of AZA Hero for his passion and devotion to reptile and amphibian conservation. He brings a diverse background of conservation experience into his new role with the TSA as the Reintroduction Project Manager for Radiated Tortoises in Madagascar.

serious consequences. This important aspect of the TSA program has not been well funded for several years, but in 2019 we hope to change that. Our Enforcement Officer, Sylvain Mahazotahy, will resume his important role in applying the dina (a taboo-based social by-law that punishes communities that tolerate poaching activity) throughout the Tandroy region. Further west, in the Atsimo-Andrefana region, the TSA established an emergency response fund that would allow DREEF officials to travel and investigate reports of poaching activity. We believe there is a critical threshold that enforcement must commit to; stay above it and we will maintain some wild tortoise populations, fall below it and we lose this war.

Radiated Tortoises are not the only species impacted by the illegal trade. Due to confiscations over the years we have acquired hundreds of Spider Tortoises (Pyxis arachnoides) that now represent the founders for our assurance colonies. When we conceptualized the TCC, we had plans to manage only a small colony of the Southern Spider Tortoises (P. a. oblonga), the most endangered and range restricted of the three subspecies. The TCC is located within good oblonga habitat, and a small wild population exists within the confines of the Center, so this was a logical decision. Today, though, we have a captive population numbering 130 animals and a new management facility is being built, funded by our strong partner Zoo Knoxville. Eggs are already incubating in situ and the future for these tortoises is looking brighter. In addition to this success at the TTC, we have a nucleus of 120 Common Spider Tortoises (P. a. arachnoides), at the LTC near Itampolo where hatchlings are already being found. Like the TCC, the LTC is located within good Pyxis habitat so success is predictable. Finally, we also have a group of over 100 of the Northern Spider Tortoises (P. a. brygooi), located in two of the rescue centers. We have not decided whether to maintain this group or not but, to date, we have been unable to identify a local

partner with the capacity to help repatriate them to a protected area within their range.

Acknowledgements: For ongoing programmatic support we thank the following: Utah’s Hogle Zoo, Gregory Family Charitable Fund, Nature’s Own, Owen Griffiths/Francois Leguat Ltd., Zoo Knoxville, Columbus Zoo, LA Zoo, The Marjean and Richard Brooks Family Fund, Radiated Tortoise SSP, AZA Radiated Tortoise SAFE program. We would like to thank

all of the numerous zoos, aquariums, non-profit, NGO’s, governmental agencies, and individual donors that provided personnel, equipment, and financial support for our rescue efforts on behalf of confiscated tortoises this year. A special thanks goes to the Wildlife Conservation Society/Bronx Zoo for their exemplary contribution during the April crisis.

Contact: Rick Hudson, Turtle Survival Alliance, 1030 Jenkins Rd. Ste. D, Charleston, SC, USA 29407 [rhudson@turtlesurvival.org]

When April’s record shattering Radiated Tortoise confiscation first took place, I was sent on behalf of the Oklahoma City Zoo to provide aid. At the time I didn’t quite understand what this would entail, but I knew that I had a passion for these animals and wanted to do everything that I could to help. I am privileged to have been a part of the very first team on the ground, now known as Team Radiata 1. We all stepped off of the plane with an overwhelming eagerness to get started, but that initial enthusiasm descended into a tangle of anxiety and head strong determination upon arrival on the scene.

My recollection of day one is still vivid in my mind and I won’t soon forget seeing some 10,000 critically endangered tortoises clustered together en masse. Many were weak, dehydrated, and malnourished. My role was split into two phases; the first involved participation in immediate triage and hydration work at the center in Ifaty. The second saw me travel much further south, to TSA’s new facility in Lavavolo. It was here that I witnessed TSA’s incredible resolve to include local communities in tortoise conservation. The first thing we did was petition the village elder to use sacred land in order to protect these tortoises (I say “we” but really I just sat back in amazement as the process unfolded; Herilala Randriamahazo is the true champion of this effort).

I was one of two Team Radiata 1 members to see the Lavavolo site in its earliest stages. Now, I am the only one to have returned to the site since the confiscation took place so I have a unique perspective on the exponential progression of this place in just five months. When we first arrived at Lavavolo the only thing separating the tortoise site from the wilds of southern Madagascar was a 12-18” rock barrier that circled the perimeter of the tortoise habitat. That is all that was there; no construction had taken place yet but rocks had been dug up from

surrounding areas, standing upright, partially in the ground, enclosing what would later become a an advanced tortoise rescue facility.

It was hard to imagine back then, but amazingly the rescue site has been transformed entirely and the hard work of the local community and Teams Radiata 2-7 is not lost on me in any way. When we first arrived, we had no access to water and had to send a driver at least twice daily with 4-6 empty barrels to fill up at the nearest well which was half an hour away. Nonetheless we pushed on. It wasn’t until our last hour on the ground that a truck loaded with construction supplies finally arrived. By the end of my time in Lavavolo, we had divided the rocky perimeter into quadrants for different sized tortoises and we devotedly watered and fed some 1,800 tortoises that had arrived from Ifaty. Longer-term facilities were built at the site as time went on, and members of later waves may recall watching the start of a vet clinic, storage shed, and food prep area going up.

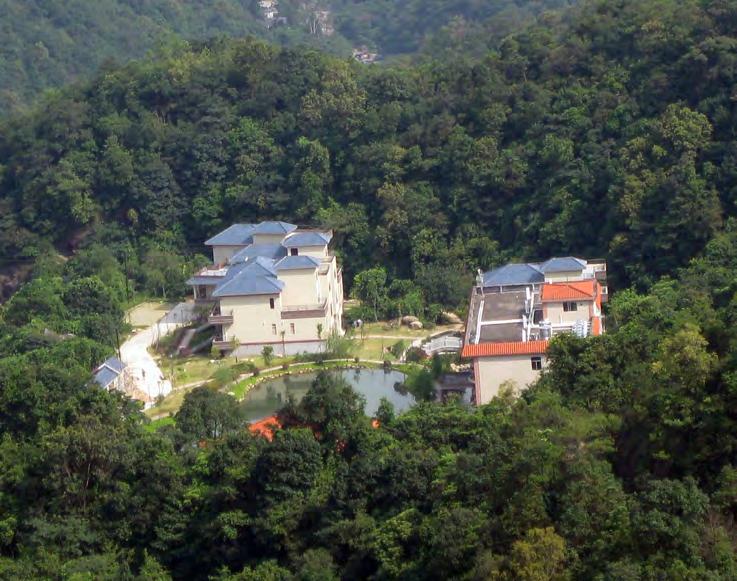

Now, five months later, the Lavavolo Tortoise Center is beaming with life and fortitude, standing as a beacon of light for Radiated Tortoise conservation. Well- constructed rock walls

topped with security wire contain 9,925 tortoises, 8,900 from the Tuléar confiscation and 1,025 from previous seizures. Fourteen staff members manage this Center, including six security guards and six keepers. That equivocates to 1,650 tortoises per keeper. The vet clinic has been completed, and an immaculate food prep kitchen sits adjacent to a large room for receiving food, much of which is grown by the local people and purchased by TSA. The facility now has adequate water storage and it’s easier to keep the tortoise water bowls full and clean. All of the surviving confiscated tortoises have been transferred and are recovering from this horrific confiscation better than we expected.

On my latest visit, I found primarily brighteyed tortoises with good weights, clear eyes, and mouths stuffed with food. Simply thinking about them has me smiling from ear to ear as I write. These tortoises are in capable hands and are undoubtedly going to thrive in their temporary captivity until we can guide them back into the wild where they belong.

Contact: Josh Lucas, Oklahoma Zoo and Botanical Garden, 2101 NE 50th St, Oklahoma City, OK, USA 73111 [jlucas@ okczoo.org]

Bonnie L. Raphael, DVM

As word of the large confiscation of Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) reached veterinarians, procedures for dealing with the anticipated medical problems were initiated. Based on previous confiscations, estimates of the supplies needed were made and distributed to TSA members, zoos, and aquariums.

We knew we could expect stress related illness and depending on how long the tortoises had been held in captivity, and the conditions in which they had been kept, nutritional disorders could also be anticipated.

We knew that the TSA’s Malagasy veterinary team had been providing excellent emer-

gency care with scarce resources, and that supplies were desperately needed. Donations of approximately 590 kilograms (1300 lbs.) of medical supplies were carried to Madagascar with the first wave of responders until conditions on the ground could be assessed.

In the first wave of ex-pat responders were 2 clinical veterinarians and a veterinary pathologist from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). Once we arrived on site we were able to provide immediate assistance to the Malagasy veterinarians. Dr. Conley, the pathologist, set up a post-mortem area and began necropsy examinations on dead

tortoises. In addition to photographing, measuring, and examining each tortoise, hundreds of samples were collected from these cases for further examination such as histopathology and molecular analysis (PCR). Due to limited laboratory facilities in Madagascar the samples were designated for export to WCS in New York City.

Remarkably, a large majority of the tortoises were in fair condition. After being soaked in water and being fed daily, many of them rebounded quickly from their initial lassitude. Approximately 10% of them showed signs of moderate to severe illness requiring

medical treatment with fluids, vitamins, antibiotics, and analgesics. Most of the ill ones were emaciated from chronic malnutrition resulting in softening shells, and about 25% of the sick ones had severe inflammation of the mouth. There was concern that the mouth lesions could have been caused by viral infections such as herpesvirus, picornavirus, or bacterial or parasitic infections (Mycoplasma or intranuclear coccidia). During the first month of intensive treatment the medical case load was reduced from 1,000 animals to approximately 200. Very few new cases developed after medical care was begun.

In order to import the tissue samples into the USA, permits from both the Madagascar government and the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) are required. Thanks to special attention by the Malagasy authorities, the registrar at the WCS and the USFWS, an emergency import permit was issued. All of the samples arrived safely at the WCS by mid-June and when Disney’s Animal Kingdom provided funding, the processing and testing all the samples was able to start in a timely manner.

The samples were sent to multiple labs in the US. In addition to microscopic examination of all tissues (histopathology) by 5 pathologists, testing included PCR for herpesviruses, ranaviruses, adenoviruses, intranuclear coccidian, and Mycoplasma species. In addition to those, a subset was tested for tortoise picornavirus (Rafivirus) and for Reptilian orthoreovirus. All tested samples were negative for all pathogens. Finally, to understand if pathogens may already be present in the wild, samples that had been collected across the Radiated Tortoise’s range in Madagascar in 2010 were also tested. Those samples, too, tested negative.

Lesions related to long-term starvation were the most consistent findings in the tortoise mortalities. There was complete lack of fat stores at necropsy. Abnormal findings such as heart, kidney, or vascular disease were

not seen. Additionally, a large number of tortoises had soft shells. This is consistent with lack of normal levels of calcium, phosphorus, or vitamin D in the diet and lack of access to sunlight, or underlying kidney disease. One of the most striking findings seen at necropsy was severe irritation of the mouth (stomatitis) in many of the cases. Testing has eliminated the most common infectious causes of stomatitis and indicated that bacterial infections were a secondary process, likely occurring opportunistically after a primary insult. Parasites were present in a large percentage of cases, but neither parasites nor intramuscular parasites were associated with disease and were considered incidental.

In summary, most of the lesions seen in the tortoises from the confiscation were consistent with suboptimal nutrition and/ or husbandry. The result of all of the histopathology and PCR testing have not uncovered any infectious disease in these confiscated tortoises. Combined with the advanced laboratory testing, we believe that these confiscated tortoises do not present a disease threat to free ranging wild tortoises.

Although the results of the testing from the April confiscation weren’t completed until November, they are and will be important for future plans for the tortoises now housed at the Lavavolo Tortoise Center. Furthermore, the results informed treatment for the year’s second large confiscation that occurred in late October, by providing information regarding the most likely or unlikely causes of clinical signs in the tortoises.

A special acknowledgment goes out to Disney’s Animal Kingdom, without whose generosity and willingness to immediately provide funding, the medical testing could not have been done. Thanks to all the veterinarians and veterinary technicians that donated their time and expertise, the many husbandry persons and interested volunteers, and all the institutional support for responding to this crisis and helping to assure that most of the animals have been placed in a secure facility for long-term recuperation.

Contact: Bonnie L. Raphael [bonnielrahzv@gmail.com]

Scott Trageser

Each year, Bangladesh becomes more unpredictable; it’s the nature of the beast. This is a country where just a few decades ago, over 80% of the population was suffering from extreme poverty, but in 2024 it is predicted that poverty will be eliminated amongst its population of 166 million. This is a country of change, and the Creative Conservation Alliance (CCA) is a part of that change.

Our work focuses on the most remote region of the country, the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). This region, in southeastern Bangla-