SURVIVAL

You never forget your turtle origin story.

Mine began far from the field. I worked for many years in international finance before following my passion for wildlife and conservation. I went back to school, earning graduate degrees in environmental studies and biology, and later taught ecology at York University in Toronto. While working with the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy in Kenya, I helped discover an unknown population of critically endangered Pancake Tortoises (Malacochersus tornieri)—a finding that sparked a new National Recovery and Conservation Action Plan.

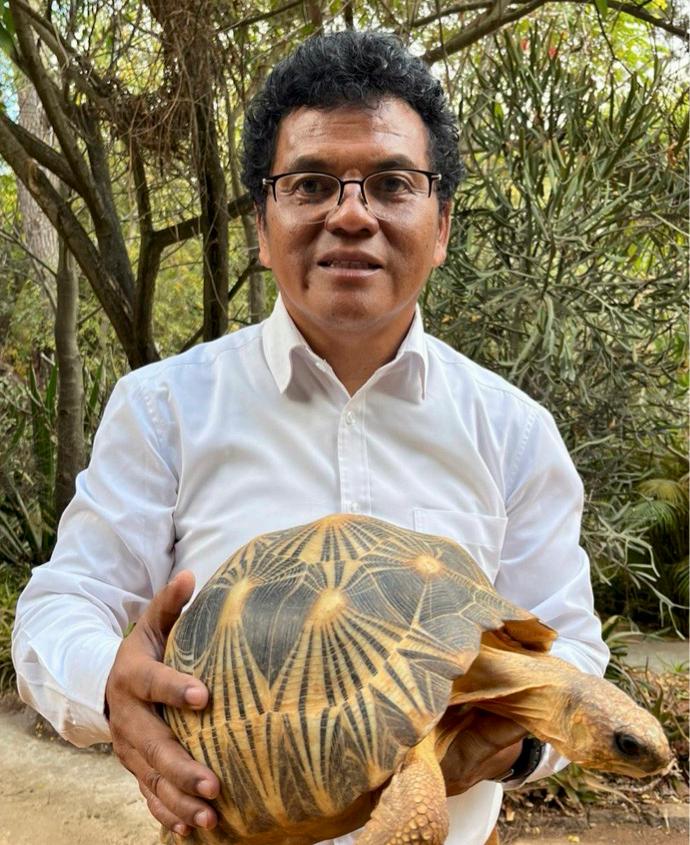

Now in my third year as President and CEO of Turtle

Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux holds a critically endangered Mary River Turtle (Elusor macrurus) during a field survey with one of TSA’s newest partners, the Burnett Mary Regional Group for Natural Resource Management (BMRG), in Australia.

Survival Alliance (TSA), I am honored to welcome you to the 2024–2025 issue of Turtle Survival. This has been a defining period of growth and transformation, expanding our capacity to protect the world’s most vulnerable turtles.

TSA’s global footprint now spans more than 30 countries. You’ll read about intensive head-starting programs for the elusive Asian Giant Softshell Turtle (Pelochelys cantorii) in Cambodia and efforts to solve complex taxonomic puzzles in Central America. Across the globe, our teams continue to innovate and adapt to ensure a future for turtle species everywhere.

When three successive cyclones devastated our Lavavolo Tortoise Center in Madagascar earlier this year, staff and community members fought through chest-high water to save thousands of tortoises. Their story, “Tortoises in the Storm,” embodies courage in crisis and compassion in action.

Their resilience also underscores why we continue to invest in veterinary care, community partnerships, and rapid response capacity. We recognize that lasting success depends on collaboration. Our partnerships with zoos, aquariums, and conservation organizations around the world continue to deepen, creating a global network ready to respond swiftly to emergencies and progress conservation efforts. As natural disasters and wildlife confiscations become more frequent, this shared network has become nothing short of a lifeline for turtles in crisis.

We are also excited to celebrate the launch of Turtle Survival Alliance Canada, a new partner helping to expand global impact for turtle conservation.

The path ahead remains challenging, but courage and collaboration define our journey. I hope you enjoy the stories in this issue and that they inspire you to support, to act, or to add a new chapter to your own turtle origin story.

In conservation,

Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux President and CEO

The Incised Wood Turtle (Rhinoclemmys pulcherimma incisa) is one of the 33 species and subspecies of continental (non-marine) turtles that inhabit Central America.

About the Cover: First described to science 60 years ago, the Narrow-bridged Mud Turtle (Kinosternon angustipons), like many Central American species, remains poorly understood. Almost nothing is known about its wild populations. A recently initiated focus on Central America by the Turtle Survival Alliance and our partners aims to learn more about this and other species so that targeted conservation actions can be developed (see p. 2). Photo: Rio Dante Para

expedition story from Central America’s turtle frontier

No maps. No contacts. No guarantees. In March 2025, a Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA) expedition to Costa Rica began as a true leap of faith, with none of the usual advantages of local data or field connections. What they did have, however, was a clear goal: to unravel taxonomic uncertainties involving some of Central America’s less understood turtles, like the White-throated Mud Turtle (Kinosternon albogulare), White-lipped Mud Turtle (Kinosternon leucostomum), and Western Central American Slider (Trachemys grayi).

The team aimed to capture turtles and collect blood samples for DNA analysis to resolve these uncertainties. The data would help identify distinct lineages, clarify the phylogeny of key turtle groups, confirm species and subspecies boundaries, determine taxonomic status, and reveal ranges and ecological needs—information crucial for targeted and effective conservation efforts.

Costa Rica, like much of Central America, is a land of deep biodiversity, shaped by its position as a bridge between continents. Coastal mangroves, lowland moist forests, tropical dry forests, pine-oak woodlands, and montane cloud forests knit together into a tight mosaic. These habitats, packed into a relatively small land area, have been sculpted by a mountainous volcanic belt running down the spine of the country. Costa Rica alone hosts nine types of continental (non-marine) turtles.

Across the wider region, that diversity expands into a remarkable blend of North and South American lineages, forged during the Great American Biotic Interchange—a major event in Earth’s history when land and freshwater animals migrated between North and South America after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama roughly 3 million years ago. It’s a herpetological paradise and a taxonomic puzzle.

With little more than determination and purpose, the team prepared for whatever the field would throw their way.

Before their boots even touched the ground, the team knew they would need allies. That’s how they found CRWild, a local outfit accustomed to leading tourist expeditions in search of reptiles and amphibians, primarily snakes and frogs. The guides had occasionally seen

turtles on their tours but, in their words, had “never… done anything with turtles,” as tourists had never asked them to. That would soon change.

The team’s first target was the Pacific Coast, a region surprisingly underrepresented in scientific literature, particularly genetic work. The Tárcoles River, a wide, turbulent waterway crawling with crocodiles, seemed like a good starting point. They rented a large boat, loaded it with traps, and set out with a mix of optimism and adrenaline.

The river delivered sights, but not science. “It was very easy to see them in the water and basking,” said Natalia Gallego-García, TSA’s Director of Conservation Genetics, referring to the Western Central American Slider, one of the expedition’s target species. But the Tárcoles is governed by powerful tides. “Usually, when you set traps, you have to leave them in the water for hours before checking them. By the time we came back, the traps were all out of the water.” The attempt ended in complete failure.

That night, deflated, the team checked into a small

From left: A Panamanian Slider (Trachemys grayi panamensis) basks on a log in the Tárcoles River, southwestern Costa Rica; Natalia Gallego-García, Director of Conservation Genetics at the Turtle Survival Alliance, takes a blood sample from a Central American Wood Turtle (Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima manni) with the assistance of César Barrio-Amorós of CRWild.

hotel to regroup. In a twist no one could have predicted, the breakthrough came not from the mighty Tárcoles, but from a tiny pond tucked beside the hotel bathrooms. The hotel grounds featured two small ponds. Eric Munscher, a Natural Resources Program Director for SWCA Environmental Consultants, walked by, squinted into the murky water, and said, “I think we can find a mud turtle here.” And he was right. Within a single night, those little ponds yielded six White-throated Mud Turtles, more turtles than the team had captured in an entire day on the Tárcoles. Even better, the turtles were distinctive. Their little

red snouts earned them the instant nickname “Rudolph.”

Moments like that are why fieldwork in Central America is unlike anywhere else. In just one small country, one can encounter species from two continents, side by side, often sharing the same creeks and ponds. The region is home to 22 species and 11 subspecies of continental turtles across five families. It’s a convergence zone; a living laboratory for evolution. Even within a single species, such as the Whitethroated Mud Turtle, variation can be striking. The red snouts of the individuals the team found in the hotel ponds reflect local genetic influences and remind us that each population has its own unique story.

But that richness is under threat. Nearly one-third of Central America’s turtle species are listed as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. Some, like the Pacific Coast Musk Turtle (Staurotypus salvinii), remain so poorly known that even basic details such as distribution, population size, and life history are shrouded in uncertainty. Others, like the Central American

River Turtle (Dermatemys mawii), have been well studied but remain critically endangered, their numbers slipping away due to overharvest and habitat loss.

“Central America is teeming with life, but the truth is we still don’t fully know where many of its species live or how they’re doing,” said Andrew Walde, TSA’s Senior Director of Conservation and Science. “Without that information, it’s like trying to protect something while blindfolded. Knowing where species live and how their populations are changing is the foundation for effective conservation.”

For the team, the work in Costa Rica is part of a broader strategy by TSA to map, understand, and conserve Central America’s freshwater turtle communities. And that means not just fieldwork, but fieldwork done smartly. Their genetic work relies on strategic sampling. “I get more information by sampling more sites than more individuals per site,” Natalia explained. “Ten to fifteen samples per species at each site gives the best chance of untangling taxonomic knots.”

America is a mosaic of landscapes shaped by a mountainous volcanic belt that runs down the spine of the region.

This geography has created a high diversity of habitats within a relatively small area, allowing for impressive species assemblages. The region and its species have become a focus for the Turtle Survival Alliance and our partners. Today, we have projects in Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico, while we explore opportunities to expand into additional countries in the region. These projects examine how the region’s biogeography has shaped freshwater turtle diversity, identify current knowledge gaps, investigate genetic diversity and lineages, and develop strategies to conserve Central America’s turtle communities. Pictured: Brown Wood

Seven months after the first expedition, a TSA team returned in October for a second trip, focusing inland to chase a particularly elusive species: the Narrow-bridged Mud Turtle (Kinosternon angustipons). Almost nothing is known about the wild populations of this turtle. So much so that Eric said with a laugh, “Good luck finding them.”

The team arrived in the middle of a strange rainy season. They set traps in what looked like ideal habitat— lots of creeks and abundant marshland deep within the tropical forests of the country’s northeast—hoping to capture any species that might be present. They saw a couple of sliders basking, taunting them with their presence. Yet each time the team pulled the traps, they were mostly empty. “It’s extremely frustrating because everything looked fine… we set the traps and basically nothing,” Natalia exclaimed, recalling yet another fruitless check. In the end, they did catch turtles, but far fewer than they had expected.

Exhausted and with fewer genetic samples than anticipated, the team trudged toward La Selva Biological Station, recognized internationally as one of the most productive field stations in the world. There, hope returned. They scouted a small creek near a roadside home, knocked on the door, and were met by an “amazing, sweet, old guy.” He told them, with the casual certainty only locals possess, that the turtles “come every evening,” and that he sees “40, minimum.” As promised, that evening the creek came alive. Within ten minutes, the team had captured twenty enormous Black Wood Turtles (Rhinoclemmys funerea). It was a logistical nightmare, but a good one.

The turtles were too many to process in the field, so the team hauled them back to their cabin, where chaos quickly took over. Black Wood Turtles are “extremely messy.” Overnight, they crawled out of their bins, stomped around the room, and left a trail of mud and poop in their wake.

Their last night brought the team to the location where

Clockwise from left: Despite being well studied and the focus of conservation efforts—primarily in Belize—the Central American River Turtle (Dermatemys mawii) continues to decline; Cataloging more than sixty Black Wood Turtles (Rhinoclemmys funerea) kept the team busy in northeastern Costa Rica; Eduardo Reyes Grajales displays the sharp beak cusps of a Narrow-bridged Musk Turtle (Claudius angustatus), affectionately known as the “vampire musk turtle,” in Chiapas, Mexico.

the Narrow-bridged Mud Turtle was first described. The mood was complicated. “Half of me wanted to trap turtles and half of me didn’t,” Natalia confessed. Success would mean an all-night processing session before heading straight to the airport. The first trap was full of Black Wood Turtles again. They groaned. “We’re not going to sleep because of wood turtles, and there’s no mud turtles.” Trap after trap confirmed their dread—empty, or brimming with the “wrong” species. Then came the last trap. Inside was exactly what they had hoped for: the elusive Narrowbridged Mud Turtle, waiting like a reward after all the mud, the mess, and the mosquitoes. Andrew and Eric jumped up and down, hugging in celebration. For biologists, moments like this are what make it all worth it.

This expedition wasn’t just about collecting samples. It was about building something lasting. The team brought along Emmanuel Bello and Rio Dante Para, two students from local partners Turtle Love and CRWild, to train them in turtle survey techniques. The long-term vision of TSA isn’t to fly into countries, collect data, and leave. “The idea is to build local capacity so that community members can start creating or setting management strategies,” Natalia explained. In a region where conservation capacity is limited, planting that first seed matters. If Emmanuel and Dante continue their work, if CRWild broadens its focus from snakes and frogs to turtles, and if Turtle Love (which focuses on marine turtles) increases its capacity for continental species, the team’s impact will carry on long after they leave.

Central America’s freshwater turtle diversity is both a marvel and a warning. Species like the Pacific Coast Musk Turtle remain ghostlike in the field, known more from anecdotes than from fresh data. Others, like Central American River Turtles, are teetering on the edge despite decades of study. That contrast shapes the team’s field strategy: some species need targeted conservation action, while others still require their basic stories—where they live, how they live, and how many remain. It’s a species-byspecies approach that ensures no turtle is overlooked. When looking back on the first expedition, it isn’t the big boat on the Tárcoles that is remembered most clearly. It’s the little pond behind a hotel bathroom, where a brightnosed mud turtle poked its head above the water and

reminded the team why fieldwork demands both rigor and flexibility. They came to Costa Rica chasing taxonomic mysteries and left with more than just DNA.

This is what turtle conservation looks like on the ground: not polished, not linear, but real. Fieldwork is messy, unpredictable, and sometimes magical. It begins with uncertainty, and sometimes, like in that tiny hotel pond, it delivers surprises that make every failure worthwhile. And somewhere on the Pacific Coast, “Rudolph” still swims in that pond, his red nose peeking through the murky water, a tiny symbol of discovery and the first swell in a wave of conservation TSA envisions spreading across Central America.

Contributors, Interviewees, & Editors (listed alphabetically by last name): Marc DupuisDesormeaux, Elena Duran, Jordan Gray, Natalia GallegoGarcía, Pearson McGovern, Eric Munscher, Samantha Nottingham, and Andrew Walde

Saving Mekong giants before they vanish

Chris Poyser, Head Keeper of the Koh Kong Reptile Conservation Center (KKRCC), found himself standing over a black plastic tub in Koh Kong, Cambodia, peering at a group of hatchlings he had never imagined would arrive. They were Asian Giant Softshell Turtles (Pelochelys cantorii), among the most elusive and imperiled turtles in Asia.

The hatchlings looked otherworldly, their flattened bodies and short snouts giving them the “frog-faced” appearance that earned the species its nickname. “They’re super cute,” Chris admitted with a laugh, “really unique faces, a face only a mother could love sort of deal.”

But the arrival of those babies in 2024 was not the joyful milestone one might expect. It was an act of desperation.

This story begins on the Mekong River, a behemoth of Southeast Asia. In Cambodia, the Mekong spreads into a braided channel—broad, powerful, and turbid, its surface broken by islands and sandbars that rise and vanish with the seasons. Villages along its banks live in rhythm with the water’s moods, and the sandbars are where female Asian Giant Softshell Turtles crawl each dry season to dig shallow nests. In a river so vast, the nests are fleeting, fragile pinpricks of life.

For years, community patrols supported by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WSC), Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA), Mandai Nature, and other partners guarded these nests. It was exhausting work, involving long nights and endless kilometers of shoreline, but the rewards were tangible. In 2021 and 2022, their vigilance paid off: a combined 131 nests were located, yielding 2,488 hatchlings that were released into the wild in jubilant religious community ceremonies. Families gathered on the riverbanks, children splashed in the shallows, Buddhist monks sprinkled holy water on hatchlings, and fishermen who once caught turtles now joined in releasing them. The river seemed alive with hope.

But that moment of stability proved tragically brief. In 2023, the number of protected nests collapsed from 65 the previous year to just 10. The following years brought no recovery—only 11 nests in 2024, and 12 in 2025.

“When we spoke with the nest protectors, they all said it was an increase in poaching,” Chris recalled. “People coming to the river and targeting the turtles.”

Although the Cambodian Fisheries Administration (FiA) has made significant efforts to eradicate poaching through patrols, educational campaigns, and awareness materials, the decline persists due to the vast geographical area of the Mekong and the limited number of law enforcement officers. Fishing descended on the Mekong like a shadow. Long lines bristling with hooks stretched unseen beneath the surface. At night, fishers wielded “cold and hot electrofishing” equipment that sent surges of current through the turbid water, stunning everything in its path. The turtles— large and highly prized—were irresistible targets. As WCS Associate Conservation Herpetologist Steven Platt put it, “The price people are willing to pay has gone through the roof—we really can’t compete.”

The impact was devastating. Adult females were killed outright. Males disappeared too, leaving behind a population struggling to reproduce. By 2025, infertility plagued 69 percent of the recorded nests. “We’ve just seen a lot of fully infertile nests,” Chris said grimly. “That suggests

females are relying on sperm retention rather than mating with a male within that breeding season.”

For Chanti Gnourn, Mekong Project Manager for WCS Cambodia, who had devoted years to organizing community nest protection and release events, the decline was heartbreaking. Where once villagers gathered in celebration, now there were hardly any hatchlings to release—and even fewer with a chance to survive. The joy of releasing a turtle had been replaced by the grief of explaining to children why the river was suddenly devoid of them. The Mekong, which once embodied abundance, now felt like a place of loss.

Faced with a collapse in natural reproduction, the team, with careful consultations with the FiA, made a drastic deci-

From left: Chanti Gnourn of Wildlife Conservation Society Cambodia (left) and local nest protectors document a freshly laid Asian Giant Softshell Turtle (Pelochelys cantorii) egg clutch; This hatchling Asian Giant Softshell Turtle shows off his frog-like face, the origin of the moniker “frog-faced turtle” for this species.

sion in 2025: every surviving hatchling would be removed from nest protection cages along the Mekong and sent to the KKRCC for “head-starting”—rearing in captivity until large enough to face the gauntlet of predators lurking in the Mekong’s mighty waters.

At first, local officials resisted. They wanted the hatchlings released directly into the river, following tradition. But Chanti lobbied tirelessly, persuading them that survival depended on a new strategy. “I am very happy because we will see the babies grow up,” he said, “and it will be less dangerous for them when we release them back into their natural habitat.”

Yet head-starting Asian Giant Softshell Turtles was no simple task. Few had ever succeeded. “It’s too bad we weren’t thinking about this all along,” Steve admitted. “We wouldn’t be learning on the fly.”

The first trial group of 26 hatchlings in 2024 proved to be a brutal learning curve. When they first arrived, they refused to eat. “It was a trial by fire,” Chris remembered. “We

really had to try a lot of things very quickly—trial and error.” Mortality was high, and few survived.

Chris quickly discovered why the species had stymied others who had tried to raise them in captivity. Unlike many softshell turtles, they refused dead food. They are pure ambush predators, burying themselves in sand and waiting for prey to swim past. “When you look at them from the front, they’re all mouth,” Chris said. “And they wouldn’t touch anything except live fish fry the width of their head.”

But from failure came knowledge. The team secured steady shipments of live giant snakehead fry from fish farms in Phnom Penh. With the right diet, the turtles began to thrive. Their behavior was mesmerizing: they would vanish beneath the sand, invisible, until a flicker of movement betrayed the strike of a lightning-fast head. Only when they surfaced for air—brief, deliberate breaths—did caretakers glimpse them. “They spend pretty much all their time just buried in the sand,” Chris said. “Waiting.”

The plan now is to raise the turtles to “dinner plate size”—

20 to 30 centimeters in carapace length—before release. That will take about two years. In the meantime, the team is expanding facilities, building shallow brick-and-mortar ponds lined with deep sand to accommodate the growing juveniles. Beyond this immediate effort, the vision is even larger: to establish an assurance colony at Koh Kong. If successful, the center could one day hold a breeding population of adults, providing a safeguard against extinction in the wild and a source of hatchlings for future reintroductions.

It is a monumental effort for a monumental species. The Asian Giant Softshell Turtle can grow to over one meter in length, making it one of the largest freshwater turtles in the world. Once widespread, it now teeters on the edge of extinction. The Mekong, vast as it is, may be one of the species’ last strongholds. “This site is critical,” Platt emphasized.

For Chris, the responsibility is daunting but invigorating. “It’s an opportunity to really figure out how to save this critically endangered species,” he reflected. “It’s a big stress and responsibility, but it’s exciting.”

On the Mekong, the patrols continue. Nest protectors still watch the sandbanks, recording temperatures, guarding the few remaining clutches. Some nests are translocated closer to protector huts for safekeeping. But the numbers remain stubbornly low.

Clockwise from top left: Nesting by the Asian Giant Softshell Turtle (Pelochelys cantorii) has dropped precipitously in this area of the Mekong River, from 65 nests in 2022 to an average of 11 today; An adult Asian Giant Softshell, which can grow to over a meter in length, lies on a sandbar of the Mekong River; Asian Giant Softshell Turtles often nest on steep sandbars in what may be one of the species’ last strongholds; Young Asian Giant Softshell Turtles are reared at the Koh Kong Reptile Conservation Center in tubs with a thick layer of sand for burrowing and plants for hiding.

Each surviving hatchling is precious. For hatchlings of this species, time is of the essence: transported by boat, taxi, and truck from the riverbanks to Phnom Penh and finally to Koh Kong, they must move immediately or risk faltering, representing the fragile thread connecting the Mekong’s embattled ecosystem to a possible future.

For Chanti, seeing them survive in captivity brings pride and relief, even if it means foregoing the once-celebrated community release events. “Before, when the hatchlings were released into the Mekong, we didn’t know where they were going, and being so small, it’s very dangerous for them,” he said.

The Asian Giant Softshell Turtle’s fate is far from secure. Its survival hinges on vigilance along the Mekong, strong deterrence against poaching, and the painstaking work of rearing youngsters at Koh Kong. Yet amidst the crisis, there is resolve.

As Alistair Mould, Country Program Director for WCS Cambodia, put it, “The Wildlife Conservation Society team is dedicated to restoring a viable population of Asian Giant Softshell Turtles to their former levels along the Cambodian Mekong. This will be achieved through our long-term commitment to working closely with the Cambodian National Fisheries Administration and Provincial Fisheries Administration Cantonments of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, as well as with indigenous peoples and local communities, to protect their habitats, enforce fisheries laws, combat the trafficking of this species, and improve local livelihoods.”

And in black plastic tubs in Koh Kong, where frog-faced hatchlings lie buried in sand, that fight for survival has already begun.

Contributors, Interviewees, & Editors (listed alphabetically by last name): Elena Duran, Chanti Gnourn, Jordan Gray, Alistair Mould, Samantha Nottingham, Steven Platt, Chris Poyser, Sitha Som, and Andrew Walde

MADAGASCAR

Under siege, human courage and resilience ensures survival for thousands of endangered tortoises

Carrela Anjaramamitiana, Lead Keeper of Turtle Survival Alliance’s Lavavolo Tortoise Center (LTC), awoke to his wife shaking him. Their home was filling with water, and outside, the ground had become a shallow lake. In the darkness, he rushed into the storm, his first thought not of his house or belongings but of the tortoises.

The night before, 1,300 newly confiscated juvenile Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys radiata) had been settled into a shaded pen. Now they bobbed in floodwater, helpless against currents coursing through the compound. With only a handful of keepers and veterinarians present, Carrela waded into the rising water, scooping armfuls of tiny tortoises.

“At that moment, I ran to save the tortoises,” he said. “I knew that in this water they wouldn’t survive.”

It was only the beginning.

The Lavavolo Tortoise Center sits quietly on Madagascar’s southwest coast, tucked between spiny forest and village fields, its expansive enclosures home to some of the rarest animals on Earth. To those who work here, it is more than a conservation facility—it is a fortress of hope, a living ark built to safeguard thousands of critically endangered Radiated and Spider (Pyxis arachnoides) tortoises rescued from poachers. Since its renovation in 2018, following back-to-back confiscations that brought more than 17,000 tortoises into care, Lavavolo has been both sanctuary and battleground, a place where tireless staff and community members fight every day against the tide of extinction.

In January 2025, the tide turned literal. The year began with an unrelenting onslaught of cyclones that tested every person, every wall, and every ounce of resolve within Lavavolo’s gates. In mid-January, Cyclone Dikeledi swept in with pounding rain. At first, staff welcomed the water. In a region starved by drought, rain often meant good fortune, nourishment for crops, and a reprieve from relentless dryness. Yet by dawn, joy turned to alarm. Rising waters surged into homes and enclosures, carrying belongings, furniture, and tortoises alike.

Help arrived in waves. By 8 AM, villagers who had long worked alongside the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA)

TSA Madagascar staff members Hamedisoa (front) and Matahodra carry some of the thousands of tortoises engulfed by flooding to safety.

Clockwise from top left: At Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA)’s Lavavolo Tortoise Center in Madagascar, shade structures that usually provide shelter became both life rafts and drowning risks during flooding episodes; TSA Madagascar staff members carry bins of rescued tortoises through deep water to safety; A Radiated Tortoise (Astrochelys radiata) clings to a piece of damaged shade structure roofing during flooding caused by Tropical Cyclone Dikeledi.

Madagascar team streamed through the gates. They knew the land’s history. Floods had struck decades before, and when word spread that water was rising again, they came without hesitation. What began as a dozen rescuers soon became dozens more, each carrying tortoises to safety while their own homes and livestock lay threatened.

As the water rose, priorities sharpened. TSA Madagascar’s Director, Hery Lova Razafimamonjiraibe, who was in meetings in Fort-Dauphin, coordinated from hundreds of miles away. He urged staff to keep tortoises on elevated ground and to safeguard government records—hardcopy documents that legally recognized custody of each confiscated animal. His instructions balanced the urgency of animal care with the legal responsibilities of a nation fighting the illegal wildlife trade.

“The first thing I asked for was accurate information from the team,” Hery recalled. “What was the level of the water? Which enclosures were flooded? How many tortoises were inside them? What was the condition of the staff housing? How was the health of the staff, and how much drinking water did they have? I asked many questions to gather as much information as possible to make the necessary decisions.”

Meanwhile, TSA Veterinary Assistant Rindra Navalona Rakotobe, who goes by Navalona, along with seven veterinary students from the University of Antananarivo endured a grueling two-day journey: first by rental cars from the capital to Tuléar, then by speedboat across the rough seas of the Mozambique Channel from Tuléar to Anakao, and finally by rugged car ride over cyclone-damaged roads to Itampolo, the nearest town to Lavavolo. Laden with heavy veterinary supplies, they arrived to find the center still half-drowned.

The storm ended, but the flood did not. For four days, water lingered like a siege, seeping through soil and saturating every structure. When the ground finally dried, staff, volunteers, and citizens counted losses, repaired pens, and began feeding and treating thousands of tortoises. The aftermath was staggering: about 8,000 tortoises required treatment or preventative care for pneumonia caused by the cold floodwaters. Each needed five antibiotic injections administered every 48 hours. To track treatments, staff used paint markers to mark tortoises’ carapaces with X’s, O’s, and lines.

As they worked beneath the warmth of the Madagascan sun, the horizon darkened again. Seeing a new cyclone, Elvis, on the radar, Dr. Tsanta Fiderana Rakotonanahary, TSA Madagascar’s Head of Veterinary Support, urged, “Take a rest, because it’s going to hit hard again. Take a rest, get your strength again, because we need to face this situation again. You need to eat well, sleep well, because we don’t have the right to be sick.”

Just twelve days after Dikeledi, Cyclone Elvis struck.

Stronger than the first, it sent water levels climbing higher still, submerging areas thought safe and forcing new evacuations. This time the team was better prepared. They had warned nearby communities, cleared enclosures, and raised supplies. But Elvis surpassed expectations. Floodwaters reached more than two meters, swamping ground once considered high. Motorcycles, engines, even furniture stowed in Lavavolo village fell victim to the rising surge.

Community members bore their own losses—homes collapsed, livestock disappeared into flood currents— yet they stayed, side by side with TSA staff. Together they hauled literal tons of prickly pear cactus, chopping, carrying, and preparing it as feed when natural forage was lost. What might have been a disaster became solidarity. They ate meals as a family, received small stipends and rice in return, and found dignity in the collective mission.

The respite was short. By early February, Cyclone Honde barreled toward the region. This third assault dwarfed the rest. Winds tore at structures, and torrents rose above three

meters, overtopping Lavavolo’s walls and pushing tortoises beyond the compound’s boundaries. For the first time, staff evacuated completely, leaving gendarmes to guard the site while they sheltered in Itampolo and nearby villages. When they returned by pirogue—the traditional wooden canoe—they found devastation. Buildings stood like islands in a lake, walls overwhelmed, enclosures unrecognizable. Dozens of tortoises floated outside the compound, marked only by painted carapace IDs that identified them as Lavavolo residents.

It was a nightmare scene, yet the response was resolute. The devastation at Lavavolo made immediate transfers impossible. Roads had been ripped apart, bridges collapsed, and what is normally a six-hour journey to the TSA’s Tortoise Conservation Center (TCC) in Tsihombe stretched into a grueling two-day ordeal once routes were finally passable weeks later. Only then could staff and partners move roughly 5,000 tortoises to the safety of TCC, where sturdier facilities and higher ground offered a more secure future.

Those that remained at Lavavolo were consolidated onto elevated, rockier terrain. Old pens in low-lying areas were abandoned, shaded structures rebuilt, and new water systems installed. The floods reshaped Lavavolo, limiting TSA’s ability to utilize the basin’s flatter terrain, but allowing keepers to manage fewer enclosures and monitor the tortoises more closely.

This turning point also underscored the importance of Turtle Survival Alliance’s wider network across Madagascar. The organization manages or co-manages 14 sites nationwide, 12 of them in the South within the natural range of Radiated and Spider tortoises. These sites span long-term care facilities, triage centers, community-protected forests, and reserves and protected areas. At the center of this network is the TCC, established in 2015, which has become the lynchpin of TSA’s program in the South and the heart of its Confiscation to Reintroduction Strategy. Today, it is home to well over 15,000 tortoises. In the wake of Lavavolo’s flooding, the move to TCC was not just a relocation of animals—it

was a demonstration of how a national strategy, built over years, allows for resilience in the face of disaster.

For Dr. Rakotonanahary, coordinating the veterinary response from the capital, the floods underscored the importance of both medical triage and human resilience. Veterinary teams worked in rotations. They prioritized large tortoises first, whose weight made them vulnerable to entrapment, and attended to smaller individuals when energy flagged. They planned for food shortages, secured water from distant wells when local supplies were compromised, and maintained morale through constant communication and psychological support. Without teamwork, the crisis might have been insurmountable.

“We were all really stressed,” Dr. Rakotonanahary recalled. “But we managed to get through it because of teamwork and good communication. We supported each other very, very much. Providing mental support to the team on the ground was my first priority.”

Carrela and his team carried the weight of daily labor.

From left: Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA) staff, volunteers, and community members move tortoises to higher, safer ground after the TSA’s Lavavolo Tortoise Center (LTC) was flooded by Tropical Cyclone Dikeledi; Veterinarians and veterinary students from the University of Antananarivo’s Department of Veterinary Sciences and Medicine treat the 11,000+ tortoises at the TSA’s LTC.

They waded through chest-high water. They sorted tortoises by size once safety allowed and rebuilt enclosures stone by stone. They hired local men and women who had lost livelihoods in the storm, providing income through reconstruction work. What began as crisis relief became employment, empowering communities to recover their homes while also restoring the center. Reflecting on the intensity of their work, Carrela said,

“The work for us is not just work; it really touches us. When tortoises have problems, they don’t need motivation. I just tell the team, ‘Guys, we have to do this.’”

His words capture the heart of the team’s dedication,

driven not by duty alone but by care, urgency, and shared purpose.

Hery’s leadership remained constant throughout. Though physically distant, he provided direction, secured resources, and linked the ground team with global networks. “We had to communicate constantly. So, I was available 24 hours, seven days a week. And not only me, but all the staff here in Tana. And I’m really thankful to the team on site because they were able to be resilient,” said Hery.

Turtle Survival Alliance wasted no time in rallying support. Within days of the first cyclone, the organization issued a press release and shared the unfolding crisis with its global community, while major outlets including the Associated Press and Mongabay carried the story to an even wider audience. In total, nearly 40 news outlets shared the story, amplifying the urgent call for help. At the same time, TSA leadership made direct appeals. At the Association of Zoos & Aquariums’ Directors’ meeting in January, photos of the devastation were shown to colleagues one by one, spark-

Clockwise from top left: In June, 2025, 5,000 tortoises were transferred from Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA)’s Lavavolo Tortoise Center (LTC) to TSA’s Tortoise Conservation Center, the lynchpin of our program in the South; After cyclones devastated the LTC, new elevated facilities were under construction on higher ground by mid-2025; Community members brought and prepared thousands of kilograms of cactus for the tortoises at the LTC, providing essential food for those affected by the flooding.

ing urgent conversations about how to help. The response was extraordinary. Partners, donors, and institutions around the globe immediately pitched in, offering emergency funds, supplies, and expertise. What began as a desperate appeal quickly grew into a lifeline, ensuring that Lavavolo’s staff and tortoises and the local community were not left to weather the disaster alone.

The team’s courage became legendary. Dr. Rakotonanahary was “really proud” of her staff, who “never abandoned, they never complained.” Navalona spoke of their “good vibe” and “strong connectivity,” describing them as “a small family.” Hery called them “resilient” and “incredible,” recalling the sight of staff smiling, holding tortoises in floodwater. Carrela praised Tongasoa, Head of Keepers, who entered the floodwaters despite not knowing how to swim—a risk shared by many of the other volunteers and keepers. At times forced to push through chest-high currents, he helped move tortoises to higher ground. His determination to act in the face of personal danger stood out as an exceptional example of courage and commitment.

By midyear, the center had stabilized. Enclosures were safer, routines restored, and tortoises steadily recovering. The ordeal had cost dearly, but it also reaffirmed Lavavolo’s purpose. Following the storms, the team rebuilt the perimeter wall and began new construction for the office, staff housing, and other key infrastructure, all placed on higher ground that had stayed dry through successive cyclones. Once it became clear which paddocks lay within the flood basin, they expanded the facilities onto higher, safer terrain. To make this possible, the regional manager brought together community members and local authorities, culminating in a traditional ceremony that secured a safer future for both the tortoises and their caretakers.

The repeated cyclones transformed TSA Madagascar’s approach. The team developed emergency protocols for disasters ranging from floods to fires, trained veterinary students as a rapid-response force, and furthered their investment in community-based livelihoods.

The TSA’s Lavavolo Tortoise Center holds a unique place in conservation not because it has avoided hardship, but because it has faced it head-on. From responding to massive confiscations to devastating cyclones, its staff, veteri-

narians, and community partners have weathered trials few could imagine. Their story is not simply one of survival. It is one of adaptation, innovation, and unwavering commitment to a future where Madagascar’s tortoises roam freely once more.

Through disaster and recovery, the Lavavolo Tortoise Center has proven more than a sanctuary for tortoises. It is a beacon of resilience—for wildlife and for the Malagasy communities who stand shoulder to shoulder with them.

In every rescued tortoise, every painstakingly rebuilt enclosure, and every release back to the wild, the legacy of Lavavolo is written. It is the story of a small corner of Madagascar carrying the weight of a global treasure, and refusing, even in the face of floodwaters, to let it wash away.

Contributors, Interviewees, & Editors (listed alphabetically by last name): Carrela Anjaramamitiana, Marc Dupuis-Desormeaux, Elena Duran, Jordan Gray, Samantha Nottingham, Navalona Rakatobe, Tsanta Fiderana Rakotonanahary, Hery Lova Razafimamonjiraibe, and Andrew Walde

Thank you to the Lavavolo Tortoise Center Keepers & community members of Itampolo who were interviewed for this piece:

Keepers: Tongasoa, Sylvestre, Fitahia, Matahodra, Hamedisoa, Julmen, Vagnomana, and Vorirene

Community members: Niavindraza, Faleandraza, Jean, Evitsike, and Ongibaky

UNITED STATES

Within fragmented wetlands, orangecheeked turtles fight for survival

The itching was relentless. A scaly, oozing rash spread across my arms and beneath my armpits, defying every anti-itch cream and forcing me into long-sleeve synthetic shirts for two weeks. It felt like greyscale from Game of Thrones. “This too shall pass” was my only comfort. It did—but not before leaving scars, now faded, though the memory remains sharp. And that is where the real story begins.

On Monday, May 12, fellow turtle biologist Eric Munscher and I, Jordan Gray, fetched Joe Pignatelli, Project Leader of the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA)’s Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) U.S. Field Project, from Newark Liberty International Airport. In collaboration with Brian Zarate, a biologist with New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection – Fish and Wildlife (NJDEP), the three of us had traveled to this part of the country for one purpose: to survey for this beautiful, cryptic, and critically endangered species.

For turtle enthusiasts, the tiny Bog Turtle inspires awe. Their mahogany shells contrast with brilliant orange, red, yellow, and occasionally white blotches on the sides of their heads—a flash of color that betrays their secretive nature. Protecting these elusive turtles demands active, intensive conservation efforts.

Native to the Eastern United States, the Bog Turtle ranges from northeast Georgia to Massachusetts and western New York. Its populations exist in two disjunct management units, northern and southern, separated by roughly 270 miles (436 km). Despite its name, the species inhabits stream-, spring-, and seep-fed fens, sedge meadows, sphagnum bogs, marshes, and open shrubby swamps. All of these habitats are highly imperiled, fragmented, and isolated, the primary reason for which the Bog Turtle is considered Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. New Jersey still holds some of the strongest populations, even though it is the nation’s most densely populated state.

The following morning, overcast, with a light mist in the air, Eric, Joe, and I met with seasoned Bog and Wood (Glyptemys insculpta) turtle NJDEP field biologist, Jim Angley, and a group of other surveyors for what one could only describe as a “Bog Turtle Blitz.” Nearly two dozen field biologists gathered at a well-studied site to search for these elusive turtles. One could liken it to an Easter Egg hunt.

And, much like Easter Egg hunts that occur across suburbia of the cultural West, the search for this turtle was not amidst romantic vistas of wetlands and woodlands.

Roads, subdivisions, and even meticulously groomed athletic fields pressed hard against the edges of the site. And those were just the obvious intrusions. Roughly a third of the wetland was smothered by Common Reed, or Phragmites, a towering invasive grass. Its dense stands choke out native vegetation, alter hydrology, and erase the open, sunny patches Bog Turtles need. Like so many other wetlands in the species’ northern range, this once-pristine valley had been reduced to fragments, an all-too-familiar story for the Bog Turtle.

And yet, there they still were. A population clinging to life against all odds. In less than an hour, the group had turned up 17 Bog Turtles, living proof that when we protect and manage habitats, turtles can do what they do best: survive. For a species so often defined by decline, that morning’s tally was a reminder of why we search and why protecting even the smallest patches of wetlands matters.

Clockwise from top left: Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) prefer open, sunlit wetlands with dense vegetation and shallow rivulets; Juvenile Bog Turtles often display bright, contrasting colors and distinct growth rings on their shells; This juvenile Bog Turtle was discovered hiding within the safety of a poison sumac mound, one of the most toxic plants in the United States.

The next day’s conditions were cool and rainy—far from ideal for finding Bog Turtles, which prefer warmer, sunnier weather. According to Gary Standard, our radio-telemetry technician and experienced Bog Turtle surveyor, such weather makes spotting them especially challenging. But having flown from different parts of the country for this survey, we weren’t about to let a little rain slow us down. That morning, we set out for TSA’s primary Bog Turtle site without delay.

“Got a male!” exclaimed Joe, before Gary had even unpacked the radio telemetry equipment. That’s how Bog Turtle surveys go: a blend of experience, grueling searches on foot, or on hands and knees, and, often, sheer luck. In spite of the conditions, the turtle was active among the tussock sedge and sphagnum moss right beside the boulder we had chosen as our “home base” for the morning’s survey. Fortunately, Joe’s seasoned eye and ingrained search image of a Bog Turtle allowed him to spot it before it vanished into the mucky abyss.

This adult male was already familiar to Joe and Gary, recognized by the v-shaped notches in its shell. More telling was the small radio transmitter fixed to its carapace, marking it as one of the turtles under study. By chance, it had been lurking at the base of “our boulder,” and Gary’s receiver would no doubt have detected it soon.

Our radio telemetry project is revealing how two groups of Bog Turtles share a connected wetland, yet remain separated by a small forest—a “barrier” of sorts. One turtle’s movements suggest it could cross if the barrier were managed, offering insight into how connectivity might be supported for these elusive turtles.

Beyond tracking movement, nest monitoring has become a key goal of the project, providing a direct measure of conservation impact. In three years of telemetry work, the team has found only two nests, both of which failed— one likely destroyed by a Black Bear, whose size and rolling habits can easily flatten a nest, and the other eaten before hatching, though the culprit remains unknown. Protecting nests here could allow more hatchlings to survive, tipping the scales for this fragile population.

Even with intensive searching through steady rainfall, only one additional male was located, and only with the aid of the radio receiver, underscoring how elusive these turtles can be. The weather also hindered our progress,

drenching our equipment and adding to the challenges we’d faced all day.

As we left the site, one could only wonder about its longterm prospects. With relatively few turtles but sufficient habitat, and a subadult last documented in 2023, would it recover without human intervention? Such intervention would most often take the form of habitat maintenance and restoration, including periodic removal of successive woody vegetation, nest detection and caging, and predator exclusion measures. These methods have greatly increased Bog Turtle populations in other areas. The question remains: will they work here?

Pondering these questions, we set off for our next site not far away.

We pulled up at an iron gate off a semi-rural road on state protected land. The woodland was dense here. The rain had softened, light enough to barely feel, and though it was still heavily overcast, there was a different aura about this place. Walking down a well-worn trail past large granite outcroppings, we descended into a natural bowl in the landscape. Bending low, we slipped beneath another gate, this one woven from spiny vegetation. Then, looking up, we saw it. Beautiful and unmistakable. This is what Bog Turtle habitat is supposed to look like.

Shallow rivulets wound their way through large, vibrant clumps of skunk cabbage. Bright green sphagnum moss carpeted the bases of thick tussock sedges, their blades rising in dense, brilliant green tufts. Young leafy growth was pushing from the branches of red maple and dogwood, while soft fiddleheads and the unfurling fronds of sensitive fern were everywhere. The whole place was alive, surging with spring green. Amid all this life stood the native poison sumac, one of the most toxic plants in the United States. It was a reminder that beauty in these wetlands, and finding Bog Turtles, often comes with a price.

“Be careful,” Joe warned, “you do not want to touch that stuff, even the branches.” Just then, Eric exclaimed, “Found one!” and reached down by the base of a sumac root mound. It was an adult male. Without hesitation, I got on the ground and thrust my arm into the cavernous mound, hoping the turtle might have a friend nearby.

Sure enough, my fingers brushed against it, the unmistakable feel of a shell to a turtle biologist. Pulling it out, we saw a gorgeous, unmarked subadult. Its temporal head patches were large and tangerine orange, and its shell bore the lightbrown striations and distinct growth rings of a young animal. We were ecstatic. This discovery gave us the inspiration and motivation to search even more thoroughly in the area, hoping to find additional turtles hidden within the habitat.

As Joe expressed, “That is definitely something that happens with Bog Turtle surveys. Even in sites where you know that they’re there, that you’ve personally found them in before, you can lose steam if you haven’t found one. Then, you or someone else finds one, and automatically that adrenaline rush comes in, you get your second wind, and you’re

From left: Joe Pignatelli, Project Leader for Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA)’s Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii) U.S. Field Project, prepares to catalog a newly discovered adult male; Joe Pignatelli (Puget Sound Energy/TSA), Eric Munscher (SWCA Environmental Consultants/ TSA), Jim Angley (New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection), and Jordan Gray (TSA); Marking and cataloging Bog Turtles is key to monitoring populations over time; Active, intensive research and conservation efforts are essential for the survival of Bog Turtles, such as this newly discovered adult male.

completely reinvigorated.” The adrenaline rush of finding those two turtles pushed us forward.

Over the next hour, we found several more Bog Turtles, adults and unmarked subadults alike, as we reluctantly “noodled” through bases of poison sumac. Even in this well-studied wetland, their presence reminded us how cryptic the species can be. The unmarked subadults confirmed successful reproduction, showing that this lush, densely vegetated habitat continues to support new generations of Bog Turtles. This is how it should be, and for other populations, that is how it can be once more.

Surveying Bog Turtles is a blend of perseverance, patience, and occasional serendipity. From the relentless itch of poison sumac to hours spent crawling through mucky wetlands, every step demands dedication. Yet the rewards are tangible—the flash of tangerine head patches, the feel of a tiny shell, and the thrill of discovering subadults. Each turtle

reminds us that, despite habitat fragmentation, invasive species, and relentless development, life endures when people like Joe, Gary, Brian, and Jim, along with organizations and agencies, work together to protect these fragile wetlands.

Bog Turtle conservation is as much about hope as biology. Protecting nests, maintaining habitat, and removing invasive plants are actions that can ripple through a population, giving this species a chance to survive and thrive. Seeing these turtles in healthy wetlands reminds us that, with continued care and effort, a future can be restored for populations across the landscape. And that’s our goal.

Contributors, Interviewees, & Editors (listed alphabetically by last name): Elena Duran, Jordan Gray, Eric Munscher, Samantha Nottingham, Joe Pignatelli, Andrew Walde, and Brian Zarate

KENYA

A

tiny tortoise sparks a big conservation story in northern Kenya

by KEVIN GEPFORD

On a rocky outcrop overlooking the plains stretching north beyond the boundaries of Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, a group of Lewa staff and I came to survey the area where its Pancake Tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri) story began. Although this ledge of Precambrian rock has been combed over several times before, the team hoped to find more. Sumpere Toki, Lewa’s tortoise hero and one of its longest-serving employees, gave a shout from below. He held in his gentle hands a little unmarked tortoise that he’d retrieved from its rough crevice. In 2019, Sumpere discovered Lewa’s first two tortoises very near here, an area known locally as Dadaboi, establishing the reserve’s importance as a tortoise conservation site. “Those two brought a lot of curiosity,” Sumpere told me. “Everyone was interested to know how far they can spread.”

The discovery changed everything, starting with reshaping the map of their range. Nearly a thousand individuals have been found across northern Kenya, including 150 on Lewa. And now, six years later, a new National Recovery and Conservation Action Plan has made the Pancake Tortoise a state-level conservation priority. It’s listed as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Near where Sumpere stood, veterinarian Meshak Kibiwot measured a second tortoise with his calipers then set it on the scale—it weighed less than a can of soda. The animal sensed opportunity. With three quick waggles of its feet, it flipped over and scrambled toward its crevice.

Mercy Kinya, a herpetofauna and hydrology researcher, intercepted. Meshak injected a PIT tag into the tortoise’s rear leg cavity, then returned it to Mercy—she was ready to notch the edge of its shell with a file. She worked carefully. When the notches met her standards, she opened a small bottle of animal-safe hot pink fingernail polish and daubed the notched scutes to help make the tortoise visible even deep inside a crevice.

The tortoise looked abraded as if by sandpaper from a life lived between rough stones. Tawny slash-marks on the scutes of its carapace echoed the shape of its long claws. It was slightly larger than my palm and slightly thicker than its name might suggest—more like a short stack of pancakes.

Clockwise from top left: Timothy Kaaria and Mercy Kinya begin their intake process for a newly found Pancake Tortoise (Malacochersus tornieri) at Nanapa Community Conservancy; Francis Kobia shows rangers from Lekurruki Conservancy how tortoises are measured; The Lewa team discovered ten tortoises living under a single boulder at Nanapa Community Conservancy—helping extend their documented range in Kenya’s Northern Rangelands.

In Swahili, they’re called kobe kama chapati after the round chewy flatbread served with almost every meal. Mercy placed it in a bucket and poured in an inch and a half of water. The tortoise plunged in its head—neck pumping with great greedy swallows for nearly a minute.

“We were so thrilled to see the government recognize this effort and transform it into a national agenda,” Dominic Maringa told me. He’s Lewa’s head of conservation and wildlife. “Lewa started this journey simply to identify and secure an easily overlooked species within its boundaries. The recovery plan marks a meaningful shift by bringing the Pancake Tortoise into the national spotlight. It feels incredibly uplifting.” He added, “Focusing national investment on them signals a significant shift toward more inclusive and thoughtful conservation practices. It sends a strong message that all wildlife has value—and that true conservation considers entire ecosystems.”

Lewa Wildlife Conservancy occupies 250 square kilometers (97 square miles) on the northern flank of glacier-streaked Mount Kenya, rising almost on the equator. Greenhouses dot the slopes above here, where rich volcanic soils feed Kenya’s booming flower industry. Lewa serves as a gateway to the Mount Kenya ecosystem, linked by a corridor and a highway underpass for wildlife to move freely from savanna into montane forest.

Lewa’s conservation story began in the 1980s with black rhinos. Over time, its mission expanded to encompass the neighboring communities. It now partners with them to support education, healthcare, and sustainable livelihoods. Lewa has also taken the lead with conservation workshops and training in these conservancies. One of its partners, Oldonyiro Conservancy, lies just beyond Lewa’s northern border—where Samburu pastoralism stretches across a sweep of arid rangeland. Both conservancies are part of the Northern Rangelands Trust network—a mosaic of community-owned lands managed for conservation and livelihoods, and protected from development like commercial agriculture and mining. “These communities

play a central role by helping to support conservation efforts on the ground,” said Dominic. “Their knowledge of the land and endemic species, combined with active involvement, makes them key partners in ensuring longterm success.” Tomorrow we will visit Oldonyiro.

Before dawn, our team loaded into two trucks and headed north past Isiolo, then turned west. The pavement gave way to brick, then gravel, then dirt—passing some rocky cliffs rising above the acacias and over a narrow bridge, then climbing past some crumbly red anthills to a series of low Maasai homes along a ridge. After three hours we reached Oldonyiro, where a dozen rangers in green fatigues waited. Many had the open-lobed ears traditional among the Samburu. One ranger sported a beaded bracelet. Several carried rifles. They gathered under the shade of an open shelter as Jacob Ngwava from the National Museums of Kenya led a presentation introducing them to the idea of tortoises as a conservation priority. Jacob later told me that many of them may have walked this landscape their entire lives without ever seeing a tortoise.

After lunch, we drove to a never-surveyed outcrop that had clear tortoise potential. Ninety-five percent of Pancake Tortoise habitat and populations occur outside for-

mal Wildlife Protected Areas. Although wild populations in southern Kenya through Tanzania and into northern Zambia have been decimated by poaching and intensive slash-and-burn agriculture, here their numbers are believed to be stable. “This area is in pretty good condition,” Jacob told me. “There hasn’t been a lot of disturbance from livestock.” The tortoises had left us a sign: The base of a massive slab of quartz-veined granite was scattered with dry dung—crumbly, brown pellets about the size of a pencil cut into pieces. A cloud moved in overhead, casting the rocks and people and trees into shadowless light.

Francis Kobia, also a member of Lewa’s team, joined Sumpere in the search. They pointed their flashlights into a crevice under the slab. Francis flashed a smile of triumph and dropped to his stomach. He slipped in a long wire with a hook like a coat hanger. It made quick scraping sounds as he worked to loosen a tortoise’s grip without harming its soft body. But the tortoise had different plans. It held fast with strong claws, and did a push-up—pressing up against the roof of the crevice. Francis nudged his hook behind the tortoise. It caught, and he made a series of swift pulls, spinning the tortoise down faster than it could claw back up. He grabbed it and passed it to the intake team, which had set up a base on top of the slab to process them. Tortoises started coming out, one after the next. Within minutes, the men retrieved six tortoises, and they kept going until we had a trundle of ten—eight females and two males. This was a large colony—a great discovery.

Sumpere is proud that his first find became the start of something bigger. “Those first two were a game-changer. Nobody thought it would lead to such a big thing that would be adopted across the country.” He wants to push the work even further. “What we need is a massive survey in these conservancies, to determine the full extent and population of this species in northern Kenya.”

Dominic sees the recovery plan as key. “In ten or twenty years,” he said, “I want to tell the story of how Kenya made a bold commitment to protect even the most vulnerable species and their habitats, leading to a thriving tortoise population that’s no longer threatened and has been removed from the IUCN endangered list.”

About the Author: Kevin Gepford is a science journalist who writes about conservation and endangered species. In his forthcoming book, he travels to the front lines of tortoise conservation—from the Galápagos Islands and Aldabra Atoll to Madagascar, Bangladesh, the Mojave Desert, and beyond—connecting global efforts to save these remarkable creatures. His reporting blends fieldwork, science, and travelogue to show how species survival depends on human action.

Clockwise from left: Sumpere Toki helped discover the first colony of Pancake Tortoises (Malacochersus tornieri) at Lewa; Mercy Kinya daubs a splotch of non-toxic fingernail polish above the tortoise’s freshly filed notch; A ranger looks north toward the rangelands from Dadaboi, the rocky outcropping where Lewa’s first Pancake Tortoise colony was discovered.

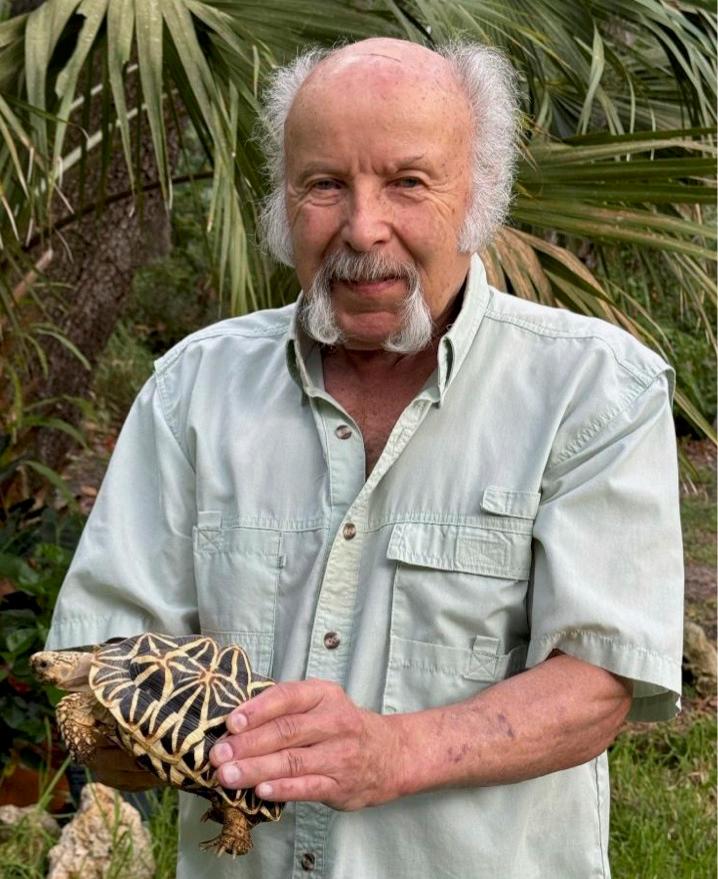

by J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS, JOSH ENNEN, AND MICKEY AGHA

The 19th annual Behler Turtle Conservation Award in 2024 celebrated and honored Jeffrey E. Lovich. Jeff was born in Virginia, and spent many happy childhood hours in regional wetlands catching frogs and turtles, including a large Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) that his mother immediately made him return. His favorite place was his grandparents’ farm in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania where his father would take him on nature walks. On one of those walks, they found a Red-spotted Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens), further cementing Jeff’s interest in amphibians and reptiles. In light of his fascination with reptiles and amphibians, his mother bought him Zim & Smith’s Reptiles and

Amphibians, his first book on herpetology. He still has that well-worn book.

As a young student, Jeff had a consuming passion for wild things and wild places. Early experiences with Eastern Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina) brought home by his father provided inspiration, and in middle school, science teachers encouraged his interest in science. Jeff’s main hobbies as a teenager were backpacking and fishing, especially in pursuit of native Brook Trout, and he came perilously close to becoming an ichthyologist!

Jeff attended college at George Mason University as a biology major, and knew that he liked animals (not cell biology or genetics!) and wanted to work outdoors. Serendip-

itously, Carl Ernst, the renowned turtle biologist, was one of his professors. Carl took him under his guidance and Jeff started to study turtles in earnest and earned an MS in biology with Carl as his major advisor. Carl then encouraged Jeff to pursue a PhD under Whit Gibbons at the University of Georgia (UGA) and Jeff convinced Whit to take him on even though Whit was just starting a sabbatical at the Smithsonian. While Jeff was at UGA’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory (SREL) in South Carolina, he met Justin Congdon, who became an influential member of his graduate committee. Jeff studied sexual size dimorphism in turtles for his dissertation, and participated in ecological and life history studies on turtles at SREL, taking the lead on several research projects.

Jeff’s first job as a herpetologist was as a technician at the Smithsonian. He later worked as a Wildlife Biologist for the Bureau of Land Management and the National Biological Service. He became Director of the Western Ecological Science Center of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and then Chief of the Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center of the USGS, and finally Research Ecologist with the Southwest Biological Science Center of the USGS in Flagstaff, Arizona—ironically, a place too high and cold for turtles—and retired from that position in 2024.

Jeff has published on ecology and taxonomy of turtles and other wildlife for over 40 years, resulting in over 200 publications and five books. He co-authored two editions

of books on turtles of the United States and Canada with Carl Ernst, and a book on turtles of the world with Whit Gibbons. Jeff has described and named four turtle taxa, including three in the U.S. and one in Japan, naming two in honor of his mentors—Escambia Map Turtle (Graptemys ernsti) and Pascagoula Map Turtle (Graptemys gibbonsi). Jeff’s studies have taken him across the U.S., as well as to Ethiopia, Morocco, Japan, and the Galápagos, but most of his research was and remains in the deserts of California. He has been a Fulbright Scholar in Morocco and an elected Fellow of the Linnean Society of London. Jeff is a member of the IUCN SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, and has served on the editorial review board of Chelonian Conservation and Biology since its inception, and is currently one of its main editors.

Jeff’s continuing research centers on turtle ecology, including the impacts of utility-scale wind and solar energy development on wildlife and their habitats, especially Desert Tortoises (Gopherus agassizii) and Southwestern Pond Turtles (Actinemys pallida) struggling to survive in arid, human-impacted environments in the Mojave Desert.

Jeff takes pride in being a positive influence on early-career turtle research scientists and aficionados. Take a trip out into the desert with him to track a tortoise and one is transported into a field classroom filled with adventure, wildlife education, and long-lasting memories. For Jeff, finding a tortoise hidden in its native habitat is akin to discovering a lion in the brush of the Serengeti. A high-level excitement ensues, along with careful observations, handling, and care to not overly disturb the animal.

His influence on turtle ecology and conservation has extended to a diverse network of individuals who have had the honor of working with him throughout his prestigious career, including collaborators that he has either employed, guided, encouraged, or empowered towards successful scientific research careers. He often notes that the most rewarding part of his career has been mentoring others to help them achieve their career goals in science. The ripple effect of Jeff’s mentoring of younger turtle biologists over the years has been exemplary.

Collectively, Jeff’s efforts have promoted a better understanding of turtles at all levels from scientists to the general public, not only in North America but worldwide. His professional accomplishments with turtles through his numerous high-impact publications are well known to any turtle researcher anywhere. Few ecologists have had such far-reaching influence on promoting turtles both to the scientific community as well as to conservationists worldwide. Jeff wants his work to inspire others to study and conserve turtles, and because of his dedication to achieving that goal, his legacy and influence will certainly continue for a long time.

Recognizing Lifetime Achievements: Pat Koval, Herilala Randriamahazo, Elliott Jacobson, and Terry Graham

by

ANDERS G.J. RHODIN, RICK HUDSON, PETER PAUL VAN DIJK, ANDREW D. WALDE, AND VIVIAN P. PÁEZ

The Pritchard Turtle Conservation Lifetime Achievement Awards honor older or retired later-career individuals who have made major and significant contributions to the turtle conservation and biology community. The awards are based on open community nominations and final selection by the Behler/Pritchard Award Committee. The following individuals were selected and honored in 2024.

Pat Koval, a Canadian lawyer by profession, has had a passionate interest in turtles since childhood. Since the 1980s, she has been a convener, dedicated supporter, and material contributor of resources for global turtle conservation. Pat initially joined the Board of Reptile Breeding Foundation, a former Canadian organization committed to developing

captive assurance colonies. She joined the Board of World Wildlife Fund Canada and served for 12 years, including as its Chair, ensuring that turtles were always on the agenda for policy and funding purposes. She was also Board Cochair of the Ontario Turtle Conservation Center. Pat has also contributed professional, legal, and other resources to the turtle conservation work of other organizations, including Wildlife Preservation Canada, World Animal Protection, Chelonian Research Institute, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Rainforest Trust. Pat’s most significant and passionate involvement and commitment has been to the Turtle Survival Alliance (TSA). She accepted an invitation to join its Board after attending an Annual Symposium, and she and her husband Alan helped TSA acquire and build its Turtle Survival Center. She became TSA’s Board Chair in 2014 and has since worked with its dedicated staff and other Board members to transition TSA through challenges and emerging opportunities.

Herilala Randriamahazo is a Malagasy wildlife conservationist and recently retired Senior Technical Advisor of Turtle Survival Alliance Madagascar. He earned a PhD from the University of Kyoto, Japan, and began his conservation work with the UK-based Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust in Madagascar, focusing on the ecology and conservation of the Flat-tailed Tortoise (Pyxis planicauda) in Kirindy, Menabe Region. He moved on to work on conservation and trade issues for Malagasy tortoises, sea turtles, and freshwater turtles for the U.S.-based Wildlife Conservation Society. He helped organize several workshops focused on Malagasy

turtles and tortoises: a Conservation Assessment and Management Plan workshop in 2001, a Population and Habitat Viability Analysis workshop in 2005, and an IUCN SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (TFTSG) Red Listing workshop in 2008. He also participated in the development of a National Turtle and Tortoise Conservation Strategy Plan for Madagascar in 2011. He joined TSA Madagascar in 2010 as a Senior Technical Advisor and provided leadership in governmental relationships, CITES turtle listing and trade issues, and oversaw TSA’s role in confiscations, rescue care, and repatriation of poached Radiated Tortoises (Astrochelys Radiata) and Spider Tortoises (Pyxis arachnoides) in southern Madagascar. He was also appointed a Regional Vice-Chair for Madagascar by the TFTSG.

Elliott Jacobson was born in Brooklyn, New York, received a BS from Brooklyn College, City University of New York, an MS in snake physiology at New Mexico State University, and a DVM and PhD at the University of Missouri. He was a wildlife veterinarian for the state of Maryland, 1975–1977, and a resident in Wildlife and Laboratory Animal Medicine at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, 1977–1979, after which he was appointed Assistant Professor and helped develop the Zoological Medicine Service. He is a Diplomate of the American College of Zoological Medicine and became full Professor in 1989. Over the last 40-some years, he has worked on health problems of a wide variety of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. His laboratory specialized in infectious diseases of reptiles including the development of serologic assays and molec-

ular diagnostic assays used to determine exposure to and infection with certain pathogens. He has authored or coauthored 292 refereed scientific papers, 52 chapters in texts, edited or co-edited six books, and served as an investigator on 83 funded projects since 1978. He is now retired from the University of Florida and is Professor Emeritus of Zoological Medicine.

Terry Graham has studied turtles for many decades with an emphasis on species in the northeastern United States. His research on the disjunct northern population of the Red-bellied Turtle (Pseudemys rubriventris) in Massachusetts led to its federal listing as Endangered. Working to protect this endangered population, Terry started the first nest caging and hatchling headstarting program in the U.S., a protocol eventually adopted worldwide. His doctoral dissertation focused on the effects of acclimation temperature and photoperiod on locomotor rhythms and temperature selection in a group of southern New England freshwater turtles. Terry took up scuba diving to allow him to work with turtles under the ice, first the Red-bellied Turtle in Massachusetts and finally the Northern Map Turtle (Graptemys geographica) in northern Vermont. He always tried to add to our knowledge of the status of threatened freshwater turtles, much of which contributed to his productivity as a Professor of Biology at Worcester State College, where he worked for 33 years. Sabbatical leaves over that span also enabled him to research and publish on the terrestrial navigation of the Eastern Long-necked Turtle (Chelodina longicollis). He is now retired and lives with his wife Cindy on a farm in Vermont.

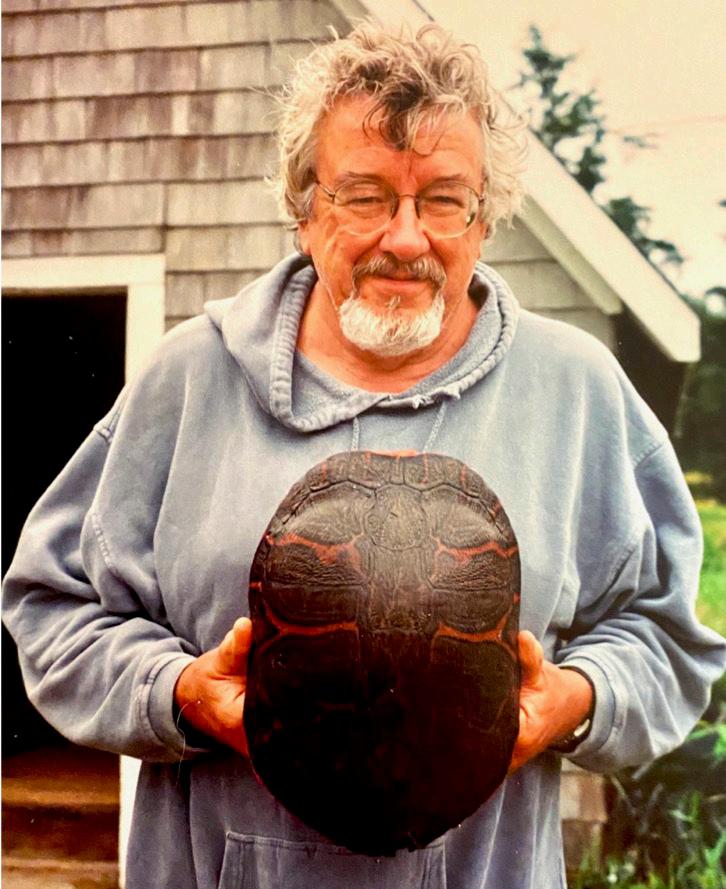

From left: Arthur with a Suwannee Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys suwanniensis) on the Suwannee River, Florida, while attending a previous TSA/ TFTSG annual symposium; Arthur in the field in Papua New Guinea working with the Piku Team (now Piku Biodiversity Network).

by MICHAEL B. THOMSON, DEBORAH S. BOWER, AND ANDERS G.J. RHODIN

The 20th annual Behler Turtle Conservation Award in 2025 honored and celebrated Arthur Georges for his research in wildlife conservation and turtle recovery efforts.

Growing up near Brisbane, Australia, Arthur spent his early years on a rural property surrounded by a range of reptile and amphibian-friendly habitats. He spent much of that time searching for frogs and reptiles, to the consternation of his parents, as many were quite venomous. His interests extended well into his teens; an older cousin had a large collection of turtles, so Arthur asked his father to build him a pond, and he was ultimately proud to have more pet turtles than any other kid in the area.

Arthur was a quiet child, a dreamer who did poorly at most subjects in school, and was hopeless at sports. He was fortunate to be given a book, A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle, by his uncle visiting from America. This introduction to science fiction was transformational; it led to others by Robert A. Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke (who he met in Sri Lanka as a teenager), and Isaac Asimov. Asimov was a prolific writer of science texts and popular accounts which the young Arthur devoured—by the age of 14, he decided to be a scientist.

He completed a degree in mathematics and physics at the University of Queensland. His fascination with nature, reptiles, and turtles, was regarded more as a hobby. How-

ever, this changed when his father and Canadian physicist Harry Messel arranged for him to participate on a crocodile research project in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. This was herpetology at its best and opened his eyes to the idea that herpetology could be a career. On the one hand, he could be a mathematician in a desk job; on the other hand, he could follow an exciting career in the outdoors following a passion that had consumed him from a young age. Slam dunk decision.

After he finished his math degree, he did an extra year of zoology and enrolled in an honours year in reptile physiology. When in Arnhem Land, he had met Grahame Webb who led the crocodile program and who had worked on thermoregulation in reptiles. The evening discussions were inspiring, and Arthur chose to do his honours research on head-body thermal gradients in reptiles. He went on to a PhD in zoology working on the freshwater turtles of Fraser Island in Queensland. There he met and was inspired by both John Legler and Peter Pritchard. He teamed up with Peter Baverstock and Mark Adams to complement morphological taxonomy with molecular systematics, and with John Cann, who generously shared his exceptional knowledge of freshwater turtles and their diversity to guide field sampling—work that continues to this day.