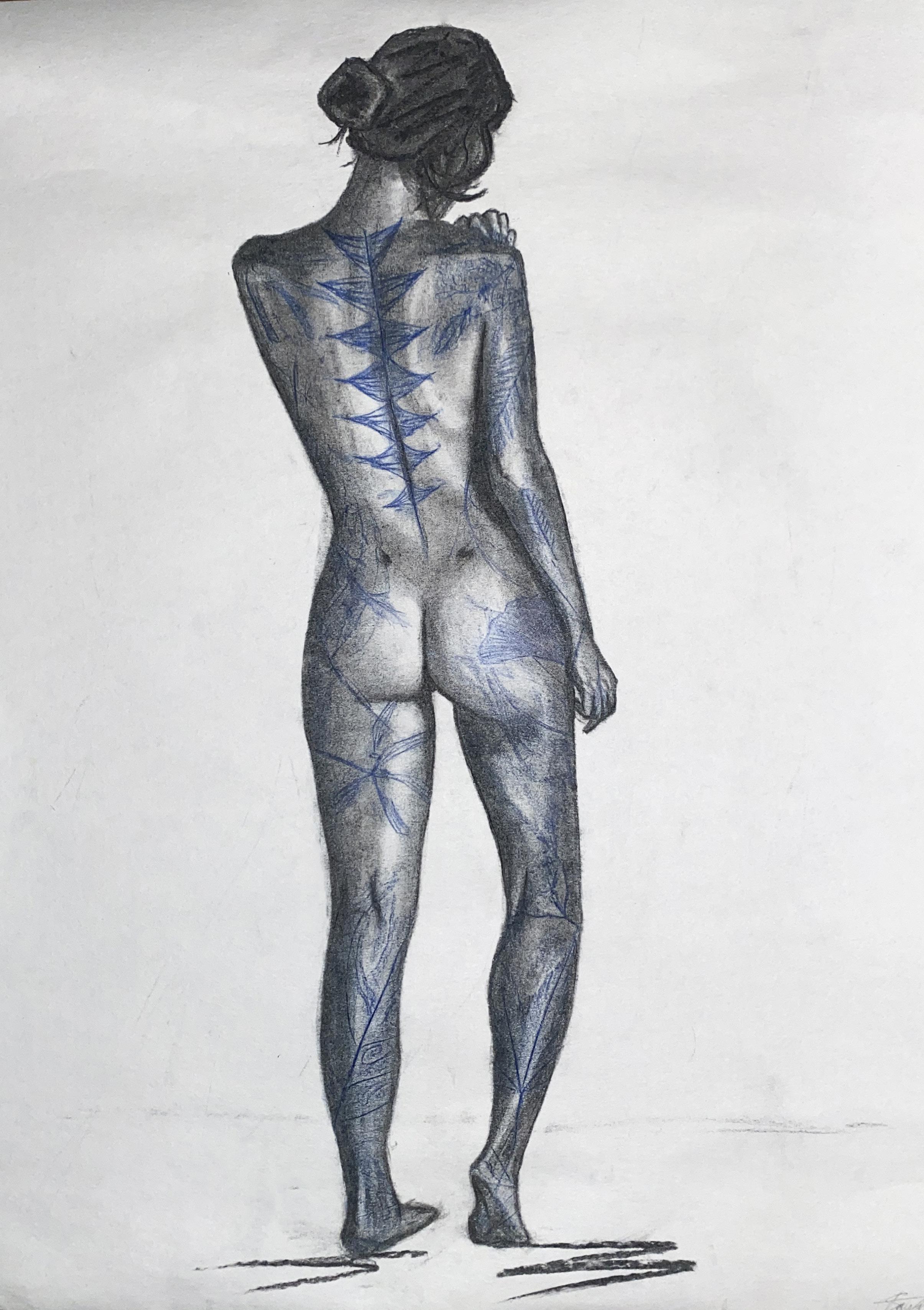

Cover artwork by Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Cover artwork by Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Cover artwork by Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Cover artwork by Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Supported by Trinity College

100 Royal Parade Parkville, VIC 3052

Australia

Harriet Grummet Editor PublisherAll rights reserved. No part of this publication, including artworks, may be reproduced. The views expressed in the Bulpadok are those of the respective contributors.

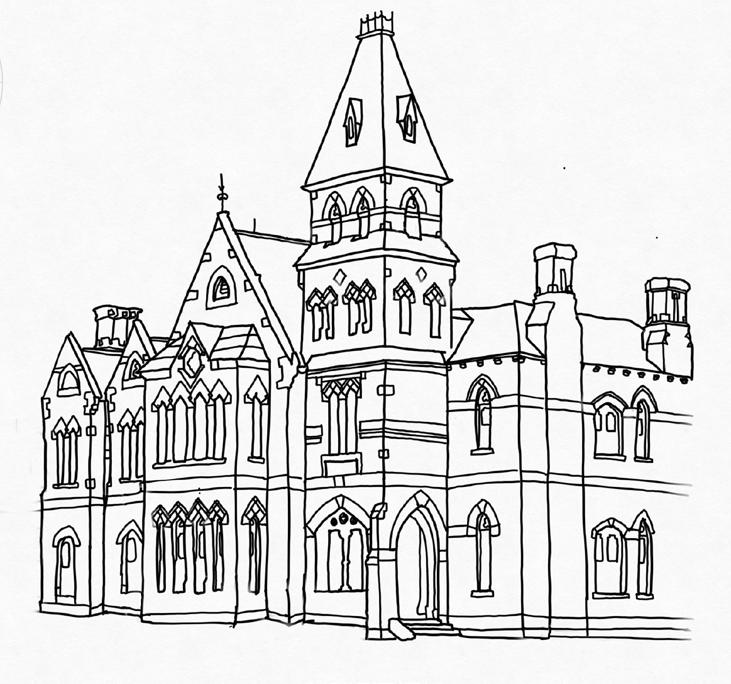

Sketch of Bishops by Willow Plex

Space must be cruel.

A world that has never known anything but darkness and silence, who does nothing but steal anyone brave enough to be curious, must be cruel. It is the only plausible explanation when Space plucks out our heroes – our brothers and sisters, leaves them wandering aimlessly, mindlessly with blown out pupils and the last taste of vitality curdling on their tongue.

But we seem to forget that everyone, even Space, is lonely.

Space has been here longer than anyone.

It must have been millennia upon millennia ago when she woke up to an eternal stretch of pitch-black darkness. She felt the same as anyone as she blinked slowly and surely, waiting for pinpricks of light to shine themselves through. They never did.

Frightened by the glaring darkness, she tried to scream, for someone to hear her cries, for someone to find her. But the boundless edge of the blackness swallowed her pleas and no one heard her. The sound never ricocheted back. The sound waves disappeared like they had never existed in the first place.

Like anyone, she grew used to the solitude. And patience always pays off, in the end. Or so they say. the end. Or so

Some million years after she was born, came stars, little masses of gas that pressed together too enthusiastically that they exploded in an inferno, the resulting light filtering through the interstices of her darkness. After the stars came planets, clumps of rock that bred their own species of life, and spontaneous combustion to make what earthlings would come to know as the Sun.

Good things do not always come to those who wait; she realised this with a hard and brutal slap to the face as the obscure expanse of oblivion slowly filled itself up with celestial bodies one hydrogen atom at a time.

Because even then, no one cared to pay attention to her, not when planets had their moons and the Sun could talk to other stars that burned brighter than he did, millions of light years away. Somewhere, between the eruptions of supernovae and black holes, Space learnt that loneliness is synonymous with a darkness that bleeds with light.

A couple of years down the line, and Space would come to remember the day vividly, the first rocket interrupted the silent darkness. With the large cylinders of fortified titanium – like spurious comets – came humans, made of oxygen and carbon and other cheap elements of life.

But, she was drawn to them. Curiosity coursed through her veins as she arched to catch a shy glimpse at them, for once, grateful for the shadows that shielded her from vision. The humans, bulked up in gleaming ivory suits, moved in the strangest ways. They were unlike any orbit she had witnessed before in all her years of existing. She smelt their ragged breaths of fear and anxiety, of adrenaline and audacity.

Let her tell you this: curiosity never did

It should not come as such a surprise that Space looked at herself, at the darkness littered with ignorant lights and silent chatter, and decided life would be better if it could be a little like the fleeting ones on Earth.

Eons old and infinite years to age, she dreamt of becoming human. Young and terribly naïve, she thought that the mores humans she pocketed, the more human she would become herself. Naturally, happiness would fall in line.

But then, as she snatched the ambitious explorers when they ventured out, one tentative footstep at a time, she watched them retaliate with terror and anger and misery. Estranged from a world they knew, they became mirror images of the prison they were stranded within.

She began to watch that planet, Earth, ‘humans’ lived, and she welled up with feelings that she had never experienced before, despite the way all the planets and stars ignored her. In watching Earth, and in being curious, she also learnt what it meant to be envious.

If there is anything that humans are known for, it is their emotions. It is their drive – the way they surround themselves with family and friends. It is the way they lift one another up and sacrifice themselves so someone else can dare to dream of a warmer tomorrow.

In the end, she wanted desperately to help them, but she could not. They had long drowned in her vacuum of hydrogen and desolation, asphyxiated cold bodies reduced to mere bones clothed by a thin layer of hollowed skin.

It is such a tragedy that lessons are only learnt too late.

Only hundreds of silenced hearts and blue-blooded organs later did Space comprehend the crime she had unwittingly, but willingly, committed. Only then did she vow never to steal another human again. She would not force her own sadness onto someone else. Just because her boat was capsizing, it did not mean others had to drown with her.

For someone who had spent an eternity in the darkness and would know nothing of a future without, she would not make someone else suffer her same demise. She would not make astronauts lonely the way she was.

She is made of constellations and galaxies, of planets and moons.

She is built up by bones of loneliness and skins of yearning.

She is Space, and she dreams of being loved.

Mother Sanders’ Lemons

Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Mother Sanders’ Lemons

Sophia Gawan-Taylor

¿Piensas que es posible que una academia puede regular un idioma?

La Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española (ASALE) es la entidad que regular y unificar el idioma español por todos los países hispanohablantes.

Lenguaje inclusivo es cuando sustantivos colectivos/pronombres evitan el género así que toda la gente es incluida. “Existe la discriminación hacia la mujer” a resulta de la lengua patriarcal. Por otro lado, el lenguaje inclusivo aumenta la visibilidad de las mujeres.

La Real Academia Española (RAE) (1713) fue la primera Academia de ASALE. Declaran que, en situaciones del plural, el masculino debe utilizarse (también para referirse a las mujeres). Sin embargo, aunque no es gramaticalmente correcto, muchos hispanohablantes usan una @ en lugar de la ‘a’ o ‘o’ para representar ambos géneros en la misma

Do you think it’s possible for an organisation to ‘regulate’ a language?

The Association of Academies of the Spanish Language (ASALE) is an entity that regulates and unifies the Spanish language for all Spanish-speaking countries.

Inclusive language is when collective nouns/pronouns avoid gender so that all people are included. Discrimination towards women is a consequence of patriarchal language. Inclusive language, on the other hand, increases the visibility of women.

The Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) (1713) was the first academy in the ASALE. They declare that in plural phrases, the masculine should be utilised (even when referring to women). However, even though it is not grammatically correct, many Spanish-speakers use an @ instead of the ‘a’ [feminine marker] or the ‘o’ [masculine marker] to represent both genders in

palabra. Latinx es un término para personas no binarios de Latinoamérica. La ‘x’ funciona para “acabar con la definición binaria”. La ‘x’ y la @ funciona bien en el lenguaje escrito, pero son difíciles para pronunciar. Luego, gente en Argentina, Chile, México y Puerto Rico, usa la letra ‘e’.

the same word. Latinx is a term for non-binary people in Latin American. The ‘x’ functions to ‘remove the binary distinction’ altogether. The ‘x’ and the @ work well in written language but are difficult to pronounce. Therefore, people in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Puerto Rico use the letter ‘e’.

La RAE actualiza un manual, Libro de estilo de la lengua española, cada año para ‘muestra la evolución’ de español. El año pasado, la palabra ‘coronavirus’ agregó. No obstante, la RAE todavía no incluía el uso de la ‘e’ como una manera para neutralizar lengua.

¿Porque la RAE no acepta nuevos pronombres/palabras sin género? ¿Es sexista o sola obstinada?

The RAE update a manual, Spanish Language Style Book, every year ‘to show the evolution’ of Spanish. Last year, the word ‘coronavirus’ was added. However, the RAE still has not included the use of ‘e’ as a way of neutralizing language.

Why can’t the RAE accept new pronouns/un-gendered words? Is it sexist or just stubborn?

I’d be bulbous and distended Like my mother’s big toe Lips dripping with acid

Thick-ankled thick-tongued

Cantankerous and glowing

Some faceless man would see you come out Bluefaced and slimy, you Looking at me little oracle

Little alien indented head

Would i love you As a mother should ? fragile and unmarked as you are

You know more about living Before we give you words fresh out the ether

I wanna absorb it all & you you you

We must imagine

We must imagine

Sisyphus is happy

In the small worlds

A chunk of fried chicken A drive in the rain

I find you in the strings like filaments Stretching from muscle to bone

Crackling in the bottom of the saucepan

Eyes like holograms, watch me in overlays

Watch the rock roll back down down down The sunny hill

I top up my myki again Bathe myself like a good child

Heart pumping molasses

It gets heavy sometimes

Harriet Grummet

Clarkes Resident

Evelyn Carapetis

Clarkes Resident

Evelyn Carapetis

I’m forever grateful to my Anglo Australian Father and my Malaysian Indonesian Mother for showing me that inter-racial/religious relationships are possible. Thank you for teaching me that the hue of the heart, not the skin, is of the highest importance.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen racism against Asian people surge worldwide, as well as a collective reassessment of racial identity following the recent Anti-Asian Hate protests; I’ve often been thinking about what it means to be of mixed-race. When people ask me, “where are you from?”; it is usually answered with “it’s a long story” or more bluntly, “I’m a mutt.” I know many others will share this feeling, where giving a short and simple reply is often more accessible and less fraught with racial anxiety.

Despite the multiracial population growing three times faster than the world’s population as a whole (Pew Research Centre, 2015), there is still a severe paucity of research for the under-represented group, especially given the complexity of what it means to be multiracial. In 2018, 32% of registered marriages were of partners born in different countries, compared to 18% in 2006 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2018). My own mixed-race experience has pushed me to examine the nuanced realities of multiracial issues like the “But what are you really?” question, being ‘white passing’ and the black/white racial dichotomy. This discourse, of course, does not encompass the array of other mixed-race experiences. Nevertheless, I believe that

whether you are mixed race or not, we can all relate to identity estrangement in various forms.

Both out of personal curiosity, and so we would have a quick reply to the dreaded “But what are you really?” paragon, my brother and I split $110 to surrender our spit into a test tube to investigate what exactly we were, as our parents were not so sure either. Acknowledging the numerous inaccuracies involved with DNA ethnicity test estimates, privacy concerns, and the lack of sequencing in Eastern human DNA. Our mutt-blood allegedly consisted of 22% Malaysian, 7% Indonesian, 7% Thai, 7% Filipino, 3% Cambodian, 2% Vietnamese, 2% Japanese, 33% Irish, 12% Scottish, 3% English, and 2% Welsh. This large jigsaw of European-Asian ethnicities only made answering the original question even more complex. As well as bringing up issues of how do I present myself, how do I frame my identity, and does this make me less Malaysian or Anglo-Australian? It created this dilated ethnic limbo, that if one was not simply here or there, then one was nowhere.

Focault (1991) argues that genealogies require us to consider histories of the present,

not in a search for an origin or linear trajectory that led us to the now. The historical antagonism to mixedness is well documented; such examples are the miscegenation 1 laws in the Jim Crow system in the U.S. (Romano, 2003) and the Aborigines Protection Act 1869 (Ellinghaus, 2001), which restricted marriage between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Yet, the central concerns within contemporary discussions often still hold echoes of colonial ideologies. My parents were accepted and blessed from both of their families, despite coming from different cultural and religious backgrounds (Muslim and Christian), and proceeded to have two marriages: a traditional Akad Nikah (Malay wedding ceremony) and a Western wedding. However, just one generation before them, there was even Anglo-Australian disapproval regarding marriage between members of different denominations of Christianity, let alone members of other religions and races. Still in contemporary society, regardless of where I was in the world, my parents’ relationship was perturbed with notions that my father had ‘saved’ my mother from her impoverished village and that I was living proof of Asian fetishisation and ‘romantic colonialism’. This only accentuates some individual’s uneasiness surrounding interracial relationships.

Additionally, there is a presence of mix-race erasure in media and lexicon used. Both Barack Obama (44 th U.S. president) and Meghan Markle (Duchess of Sussex), are mixed-race; however, they are hegemonically seen solely as black people despite being partially white. In this way, they’re denied their mixed-race identity in preference of a more readily accepted mono race. Furthermore, children of transracial placements suffer name-calling such as ‘Bounty Bar’ and ‘coconut’, which were and still are pejorative terms to describe black people raised by white middle-class families who took on the

values that they had been brought up in (Suki Ali, 2020). Thus, suffering a lack of belonging and authentication from both their white and black communities.

Being‘Whitepassing’inaCOVIDage

In 2020, I was told by my mother over a call that I was “lucky that I looked more white,” because I would not have to suffer as much anti-Asian harassment as others. This was right after I had told her that two University of Melbourne international students had been subject to a racist attack in April 2020, where two women yelled “coronavirus” and that “they didn’t belong here” (Woolley, 2020). I knew that she only had my safety in mind but hearing her say that if one ‘passes’ for white; then one is subject to less harassment, abuse, and racism, filled me with heartache. With a heavy heart, I admitted that I was ‘lucky’ that my race is ambiguous. I’ve been mistakenly identified as Chinese, Korean, Brazilian, Spanish, Italian, ‘just white’, or ‘spicy white.’ However, I’m lucky to have a white-sounding surname to put on my CV and that I (mostly) don’t worry whether the shape of my eyes makes others treat me differently. Although, it was still a common stance that white people would see me as Asian, and Asian people would see me as white or orang putih celup, which translates to a ‘white person dipped in local sauce’. Not fitting into a particular phenotype made it feel as if there was no space to belong, and invalidated speaking on POC issues because I was ‘white passing’. Attempting to navigate the twisted strands of acceptance and assimilation made it only more difficult against the broader backdrop of Asian violence and hate.

Alongside the various complexities, conflicts and innate contradictions, being multiracial comes with unique pleasures and benefits of being exposed to multiple cultures. I’m lucky and proud of my mixed heritage; I have grown up in the Australian suburbs, and in

my kampong (Malaysian Village), I have been to both a mosque and a church. I can learn more about the world and hear more stories from my Atok and Matok (Malaysian Grandparents) and Gran and Grandpa. Some celebrate the benefit of being able to flit between cultures while embracing both. Others have the inherent strain of not being in one placeof being from neither here nor there; tugged between one identity and the other.

The sustained and damaging black/white racial dichotomy is a systemic contention that often fails to be recognized. For decades in the mainstream press, coverage on the topic of multiracialism and the mixed-race experience has failed to consider the matter in all of its rich complexity and nuance. Even in institutional frameworks, like at university, the hegemonic rhetoric surrounding race is allocated into two categories: “white” versus “POC;” an extension of the black/white paradigm. Furthermore, in government censuses and medical forms, having to tick the “other” box for the demographic information can be alienating. Race exists on a continuum of greys, and being mixed is to be caught in the middle of the paradigm, not knowing where to belong or how to identify ourselves. The binary structure itself underpins most models of difference and discrimination and doesn’t allow for a genealogical plurality. I argue that this dichotomy is problematic as it doesn’t allow those of mixed-race to occupy two identities simultaneously, reconciling the differences and carving out a space to exist between the binary.

In closing, navigating mixed-race identity through a racially charged landscape is complex and full of innate contradictions. To be at peace with one’s ethnic identity requires the suturing of the psychic and discursive in their constitution, whilst fully and unambiguously acknowledging all facets of

one’s plurality. Although I sit uneasily at the corner of two colliding cultures, I am proud of the unique and prickly parts of my mixedrace. Although the terrain of identity is difficult to traverse, no one should be made to feel like they must collect disparate fragments of individual cultures in order to feel enough white, enough black, or enough Asian. My lived experiences of being mixed-race and challenging notions of “Butwhatareyou really?,” being white-passing during COVID, and detrimental racial dichotomies is not synonymous with everyone. However, I hope that there will be some elements from this discourse that will resonate with you. In the storm of straddling different worlds, there exists a clarity of who we are and a calmness that grounds us when we finally find that airy, weightless space inbetween.

RejectingtheBlack/WhiteRacialDichotomy

RejectingtheBlack/WhiteRacialDichotomy

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (28 November 2017). Increase in marriages for Australians born overseas. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/3310.0Media%20Release12016

Ellinghaus, K. (2001). Regulating koori marriages: The 1886 Victorian Aborigines protection act. Journal of Australian Studies, 25(67), 22-29. htt ps://10.1080/14443050109387635

Focault, M. (1991). Discipline and Punish. Penguin.

Ali, S. (2020). Mixed-Race, Post-Race: Gender, New Ethnicities and Cultural Practices. Routledge.

Woolley, S. (2020). Coronavirus: University of Melbourne international students assaulted in unprovoked racist attack. 7 news. https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/ health-wellbeing/coronavirus-university-of-melbourne-international-students-assaulted-in-unprovoked-racist-attack-c-983675

Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Sophia Gawan-Taylor

Sometimes the shifting sands of my mind terrifies me. The topography changes, I lose my sense of direction And forget who and where I am.

But then again, As thought and epiphanies fall away from me I remember Arcadia’s train, And that everything will be fine.

After all, If the realisation was really that important It will come back to me.

It is the memories that get lost, the memories I mourn for Forgotten, until dimly recalled by some strange reminder, Some strange time later.

Tin-tinted pattering of rain on the roof wakes you quietly in the dripping early hours of some lilac-skied morning sporadic, soothing, beating out the pulse of the world in a steady trickle that cradles you through your dormant half-sleep.

With too much time in these moments haunted shadows linger and leave you in your laments, walking through the mirrors of your mind where you might hope to leave them behind.

This fear of loneliness which you’ve carried so long like a well-worn stone in your pocket, like a long-known friend, it isn’t resolved by staying with someone you feel lonely with. It just denies real company.

The Beat Generation tramping the blind-ended streets, voyeuristic, crowded, diaphanous people. Close-packed windows telling of close-packed lives. The sonderous cacophony of individuals all vying for their own pursuits, in mad-hattered fervour and restless-souled beating, down they tread, along paths of destiny, heads held low against the wild winds of chance, and all the while, denying in futility their own getting-old. Each and everyone convinced, convicted, constitutionally inclined to their own supreme individuality.

You are so trapped, transfixed by the image of yourself, a victim, that you can’t see the axe you wield in your hand and the doors, hearts and hair you tear with your axen tantrums of victimhood.

And still I’ll lie here smoking my Macbeth quotes and tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow restful as anything the seasons dance in their cyclical exchange, my teeth grow long but nothing really changes.

It’s for you and He I wandered for tracking the dusty plains of the Nullarbor all these long years. In truth, never sure where I was really going, but always sure I was getting there.

And now that I’ve arrived in that place that isn’t I’ll lie there, rest my weary head smoking my Macbeth quotes

and contemplating an existence that was simply so that it could be not.

In 2021, the E.R. White Committee chose to purchase an outdoor sculptural piece by Australian artist Lachlan Ross, titled United. United is a bold and simple piece, comprising of three chain links symbolising Trinity College, and commissioned to complement and celebrate the modern architecture of the new Dorothy building. The contrasting colours and textures of stainless steel and corten steel are symbolic of the diversity and unity found in our college community, which brings together students from so many different backgrounds and experiences. The corten steel has a rusty finish, which will naturally weather and oxidise over time. It will slowly change in colour and texture without requiring any maintenance.

The reason our Committee felt so strongly about this piece is its themes of strength, unity and reconnection. Although we live in an increasingly “connected” world in the age of the internet, all students in 2020 suffered from physical separation and the fragmentation of our community due to Covid-19. For us, United was a celebration of our reconnection and reunion this year. We see it as a symbol of hope for the strength of our interpersonal connections, which have weathered a period of such great uncertainty. We hope that this is a message which will resonate with everyone, and remind future generations of students about the power and fortitude of the friendships and community found at Trinity.

- E. R. White Committee 2021

President - Evie Davidson

Secretary - Cassie Lew Fatt

Treasurer - Hugo Hart

Committee Members - Millie a’Beckett, Zoe Gillies, Charley Woodcock

Love Letter no. 348

Willow Plex

We acknowledge and pay respect to the traditional custodians of the land on which the Bulpadok was printed and conceptualised, the Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung people of the Kulin nation.

We acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded and that we live and work on stolen lands.