Bulpadok 2024

Photo by Ellie Wang

The Bulpadok Journal of Arts and Literature

A collection of Academic & artistic endeavours

The Bulpadok team and its contributors acknowledge and pay respect to the Traditional Owners of the land on which this journal was created, the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung peoples of the Kulin Nation. We acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded, and that we live and work on stolen land. The Bulpadok is committed to reconciliation.

Zara Blake

Sophie Clarke May Ding

Roy McNab

Patrick Morgan

List of Contributors

Grace Charles-Jones

Asher Goddard

Evie Grace

Lilias Smart

Forrest Wilkes

Grace Koczkar

Editor-in-Chief

Roy McNab

Grace Koczkar

Publisher

E-Plot Printing Solutions

Thank

Chloe Baird

Ellyne Chin

Jo Edselius

Asher Goddard

Matilda Wise

Alicia Xu

Lee Zhuang

Designer

May Ding

Letter

From

Roy McNab

Editor-in-chief

In the movie Dead Poets Society, one of my favourites, a tweedcoated Mr. Keating says that art sustains us, it’s what we live for. My life has been informed by a love for the arts, whether it was my grandparents’ shelves stacked with books, playing Bruno in a production of The Witches in Year Seven, hitting the pots and pans in a rock and roll band, or even stopping to gaze at some famous artwork that’s so grand yet arcane. All these things sustain me. So, the opportunity to be a chief editor of the Bulpadok magazine, a magazine that celebrates the academic and artistic feats of Trinitarians, felt like the genuine propulsion into the best forms of selfexpression.

Editors

The

Art has the unique capacity to both excite and deepen our understanding. In the 31st edition of the Bulpadok, Trinitarians wrote about who they are, who they were, where they come from, the issues pushing against us today; they mixed the real and the abstract with photographs and illustrations. We ought to take pride in the fact that we can create. It must be a comforting thought for Old Trinitarians from the ‘90s, knowing that their short stories and essays are still exhibited to be read in the Trinitania section of the Leeper Library, an enduring affirmation of their art. And that will our art one day, still on show after decades passed. This quote from a Creative writing lecture has always stuck with me: “Even if all you do is write a few scribbles in your notebook at 2 a.m., you are still a writer.” We are all artists: the recipe of your family’s spag-bol, a longcrafted birthday message, smashing cutlery like drumsticks – it’s all art!

I would like to thank the Bulpadok committee for their support during our Old JCR meetings and their helping source all the great material you’re about to see. In particular I would like to thank my co-editor Grace Koczkar and the chief designer May Ding, for their ceaseless work and undying ambition to ensure we can best celebrate the artistic endeavours that encapsulate Trinity.

I hope you enjoy this edition of the Bulpadok, and may your artistry never cease!

Grace Koczkar

Editor-in-chief

The 2024 Bulpadok Journal of Arts and Literature is a collection of the incredible artistic talents of members of the Trinity community. Whether through writing, photography, music, paint, or ceramics, each piece in this edition reflects the wonderful varying artistic mediums and expressions of the individuals who have kindly volunteered their work to be featured. The amazing hardworking contributions of everyone to this edition have been a testament to how important the expression of art, passion, and creativity is. Thank you to everyone who has volunteered their creative pieces and time to this edition, particularly I want to thank co-editor Roy McNab who has put in so much time and effort in creating the 2024 Bulpadok and ensuring that it represents the fantastic diverse artistic endeavours of the Trinity community. I hope you enjoy reading the edition as much as I have enjoyed collaborating with everyone on this project. Thank you!

Working on the Bulpadok has introduced me to many talented and passionate individuals, who are not afraid to share a piece of their own world through art and literature, to find resonance with others. With global issues such as climate change and gender inequality, it is those creators who work tirelessly to bring awareness and advocacy to inspire us. Their work also deepened my appreciation of everyday: ceramic, nature, college, music, and deep thoughts, which is why the design for each person is different: I wanted to create something to represent everyone, out of the feeling and interpretation I have for their works. Like all creators, I found joy in the process of crafting this magazine, and was proud to take part in capturing a piece of Trinity’s creative era. Hope you love these works as much as I do.

May Ding

CONTENT pt1 pt2 CERAMICS

Zara Blake

MUSIC PAINTING

May Ding, Above the Cloud

Roy McNab, Flavour

PHOTOGRAPHY

Sophie Clarke

Patrick Morgan

ESSAY

Grace Charles-Jones, Topic of National Importance: The Implementation of Nuclear Energy in Australia is not the Solution to the Climate Crisis

Lilias Smart, How are the language features of non-fiction used in Half the Sky to give voice to women facing oppression in developing countries?

POEM

Asher Goddard, Kauri Tree

Evie Grace, There was a blackbird in the road

Forrest Wilkes, Moonscape

SHORT STORY

Grace Koczkar, Milk

Art pt1

by Sophie Clarke

Photos

A collection of Moments

Patrick

Photo by

Morgan

Topic of National Importance

The Implementation of Nuclear Energy in Australia is not the Solution to the Climate Crisis

by: Grace Charles-Jones

Winner: Franc Carse Essay Prize

Introduction

In Australian politics and the media, nuclear energy is being presented as a viable alternative to renewable energy. This is not the case. Nuclear power is complex, costly, requires decades to establish; and will fail to replace fossil fuels within the sufficient time required to address global warming and climate change. The production of energy is essential to the modern world and facilitates the transport, livelihood, and sustenance of billions of people. Since the industrial revolution, concern surrounding the excessive burning of fossil fuels and the race to establish and commercialize low-carbon energy generation has become one of the most pertinent issues of this century.

The Brundtland Report of 1987 defines sustainable development as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Brundtland, 1987). Though outdated, the report highlights a fundamental concept in this current energy transition phase. In the debate regarding the introduction of nuclear energy to Australia, careful consideration of the tradeoff between present energy requirements and a sustainable future is key. Whilst nuclear offers a lower-carbon solution to the climate crisis, renewable energy sources such as solar power, wind, geothermal, hydroelectricity and battery storage are the epitome of sustainable development.

There is no existing legislation or regulatory framework for nuclear energy in Australia. Its introduction would function as a diversion of momentum from renewable expansion that is already established and able to provide greater economic opportunity and no waste. The implementation of nuclear power into Australia comes at an immense price both at initial build and throughout its operation (CSIRO, 2024). This cost is not helped by the requirement for uranium which is a finite resource at the

mercy of market fluctuation. And especially with the introduction of battery energy storage systems as a mainstream technology, the cost of renewable energy is by far the most economically viable option. Furthermore, the time required to manufacture a nuclear plant is on average 15 times longer than what is necessary to construct a wind farm (Ritchie, 2023). And problems associated with nuclear energy extend beyond its lengthy construction timeframes. Decaying radioactive waste will remain a problem for thousands of years. This waste is not only unsavory, but a potential hazard to human health and environmental quality. While nuclear power leaves a lasting footprint, renewable energy sources utilize the very fabrics of our planet in a symbiotic partnership between the elements and human necessity. Nuclear energy is a disruptive distraction that will derail the progress of renewable energy to sustainably tackle climate change.

Nuclear Energy and its History

Nuclear energy has been providing our planet with light and warmth since its inception (Ferguson, 2011). Extreme heat and pressure deep inside the sun allow the fusion of Hydrogen atoms to form Helium. This process releases energy which is emitted via the surface of the sun (Ferguson, 2011). Nuclear energy can also be created by fissionwhen unstable heavy atoms split. The first human controlled nuclear fission occured in 1942 and utilized ‘slow’ neutrons in a chain reaction of a uranium isotope (Brooke et. al, 2014). According to the World Nuclear Association, nuclear power now provides 10% of the Earth’s energy from 440 power reactors and is the second largest source of low carbon power. Countries including Canada, the USA, France, Russia and China are leading pioneers in the expansion and development of commercial Nuclear power (World Nuclear Association, 2024). Nuclear energy provides one solution to a reduction in extreme atmospheric CO2 levels caused predominantly by the burning of fossil fuels at unprecedented and unsustainable rates.

Notwithstanding, Australia’s nuclear ban since 1998 has prevented the establishment of domestic nuclear infrastructure. Recent political debate has resparked discussion surrounding the introduction of nuclear power to Australia’s shores. The Liberal and National Parties have hinted at plans to deliver plants as a top priority (Parkinson, 2024). In a recent ‘Coalition Senator’s Dissenting Report’ Australia’s current nuclear ban is described as “an accident waiting to happen” (Environment and Communications Legislation Committee, 2024). This demonstrates the highly topical nature of this paper that will evaluate whether nuclear energy in Australia is economically viable,

cost and time effective, and if waste can be managed appropriately. Nuclear power has had no part in Australia’s past and it does not belong in our future.

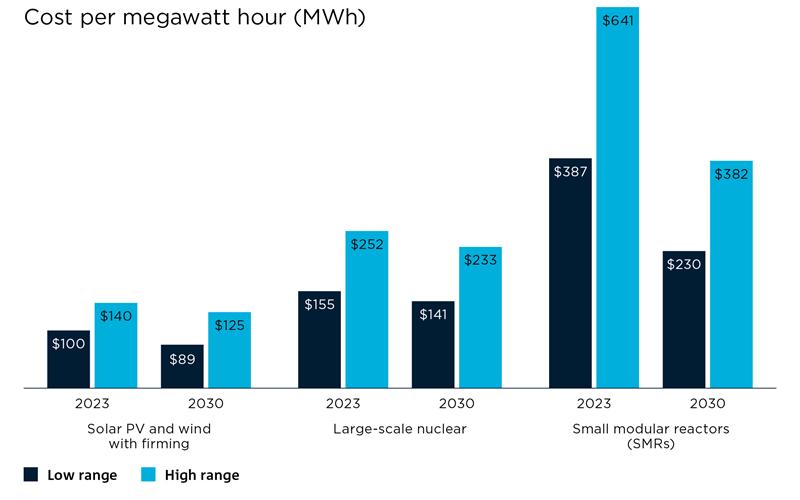

COSTS

Whilst nuclear is a large provider of power for a vast number of aforementioned nations, in Australia, there is no existing legislation, regulatory framework, facilities or infrastructure supporting nuclear power. The comparison of foreign costs to projects in Australia is complicated by differing costs of labour, national standards and workforce expertise (CSIRO, 2023). The latest GenCost 2023-24 report conducted a levelized cost of electricity analysis to calculate a tangible cost over the life of the asset including initial costs, maintenance and ongoing operation. Figure 1. below illustrates the findings that renewables remain the lowest cost newbuild electricity technology (GenCost, 2023).

Figure 1. visualises a lower predicted value and an upper predicted value for the cost per megawatt hour of electricity generated by solar/ wind (far left), large scale nuclear (middle) and SMRs (far right). Demonstrating a clear cost advantage for renewables. Source: CSIRO, 2024

The time and cost estimates for large-scale nuclear projects, akin to South Korea’s nuclear system, will be severely impacted by first-time, first of type, project challenges. (CSIRO, 2023). It is estimated that nuclear power in Australia would be at least 10-15 per cent more expensive compared to the United States, due to a lack of “nuclear power experience, physical or regulatory infrastructure” (McNeil, 2007). Furthermore, nuclear power invokes a host of ‘non-climate’ costs. These include costs associated with the extraction and transport of uranium, water use and waste disposal (McNeil, 2007). Uranium market prices tend to be highly volatile. And on a longer time scale, with the depletion of cheap and more accessible deposits, the costs of uranium production will grow to increase market prices (Mirkhusenav et. al, 2023). Despite the fact that Uranium is found in abundance in Australia, (i.e. there is direct

flow from the mine site to the nuclear plants) uranium is still a finite resource that exists in the context of variable market value and economic fluctuation (MacDonald, 2003). Therefore, the cost of mining, transportation and workforce will always cost more than the wind blowing or the sun shining.

The Cost of Upgrading Renewables for Full Reliance

The transition to renewables has been hampered by intermittency issues.

Wind and solar are not available around the clock or in all weathers (Prakash, 2023).

Nuclear power does not share this problem. Fossil fuels such as coal or natural gas are often cited as “baseload power” sources which are constant, purportedly reliable and able to provide power where renewables cannot. The integration of renewable energy sources in combination with fossil fuel energy can cause instability in the electrical grid leading to voltage fluctuation, reverse power flow or even collapse (Datta et. al, 2020). The devastating effects of fossil fuel burning on atmospheric composition removes this as an option and places pressure on the transition to fully independent renewable energy systems. To mitigate this, a battery energy storage system or BESS can enhance the operational flexibility of renewable energy.

Energy storage technologies have existed for 150 years and are rapid and used at all voltage levels. Though recent advancements in battery technology including lithium-ion batteries facilitate the large-scale application of this technology (Datta et. al, 2020) in order to phase out baseload power sources. The commercialization of these higher density, large scale batteries facilitates the transition to totally renewable energy and negates intermittency issues. Additionally, the cost of a kilowatt-hour of battery storage has fallen by 99% over the last 30 years. This is assisted by the cost of solar cells plummeting as the technology has become mainstream (Martin, 2024). South Australia, for example, is on track to meet its goal of 100% renewably produced energy by 2027 (Energy & Mining, 2024) and BESS is predicted to continue rapid expansion. The commercialisation of BESS removes this hurdle from renewable energy usage. The technology is readily available and far more cost efficient to implement than a nuclear plant from scratch. And not only can batteries make renewables accessible round the clock, they are also significantly faster to establish than nuclear power.

Construction Timeline

Solar and wind farms are substantially quicker and less complex to construct than nuclear power plants. The speed in construction and operation is crucial to address climate change and global warming. Installed solar capacity has expanded tenfold in the past decade and the next tenfold increase is projected to occur in less time than the construction of one nuclear reactor (Martin, 2024). What the International Energy Agency forecast would take 20-years, occurred in only 6-years, illustrating the unprecedented exponential growth of these renewable installations. Furthermore, the abundance of lithium, nickel and cobalt found in Australia is ideal for efficient battery development (Martin, 2024).

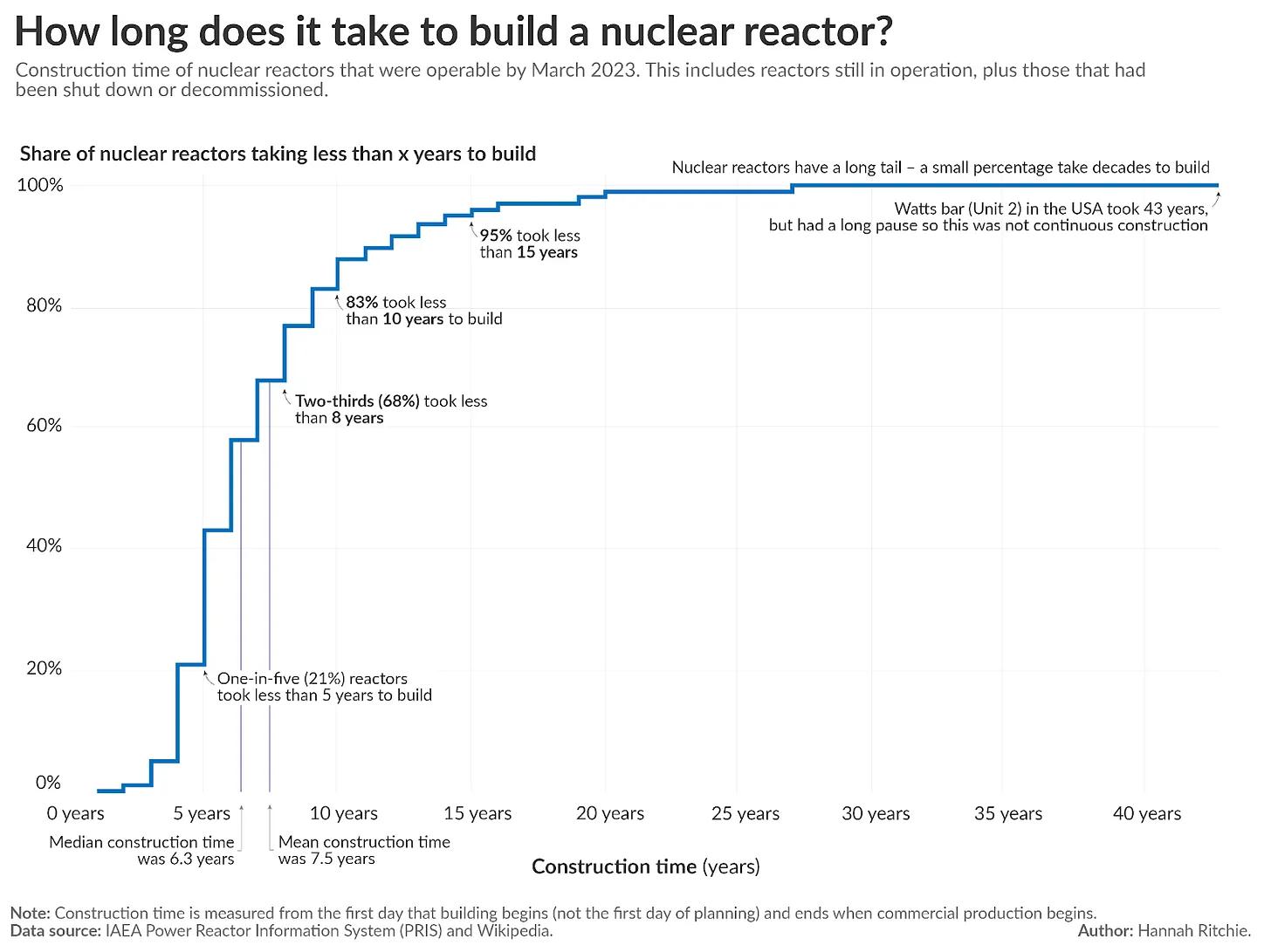

On average, the time to complete construction on a nuclear power plant is 6-8 years excluding planning and permission periods. Figure 2. also outlines the small percentage of reactors that end up taking decades to build (Ritchie, 2023).

Figure 2. shows a mean construction duration of 7.5 years for nuclear reactor construction from the first day of building, 1 in 5 reactors having taken 5 years or less and a ‘long tail’ in which a small percentage take more than 15 years to complete. Source: Ritchie, 2023

The US energy department planned the development of 8 reactors between 2010-2017. However, this timeline was impacted when the first license to build was not approved until 2012 illustrating the prominence of delays common to nuclear construction (Ferguson, 2011). The head of Australian Energy Regulator Clare Savage stated that “just writing a regulatory framework for nuclear would take eight years” (Parkinson, 2024). In contrast, wind farms take 6 months to assemble (Moses, 2019). Making the establishment of wind energy 15 times faster to implement than nuclear.

To combat this extensive construction duration, the concept of small modular

reactors were introduced as a compact and time efficient alternative to large reactors. The US department of energy claimed the SMRs are far faster to construct and due to their modular nature, are better at balancing power supply and demand (Lyman, 2024). In practice, SMRs are no more economical, safer or efficient than large-scale reactors (Lyman, 2024). The SMR project established in the United States in 2015 was canceled in 2023 following a 56% increase in reported costs (CSIRO, 2024). Likewise, the French nuclear giant EdF also canceled SMR plans for the same reason. Reliance on this untested technology is unnecessary. Renewables are already established, cheaper and faster to build.

Waste Management and Contamination Risk

The Three-Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima disasters have majorly shaped public opinion on the safety of nuclear power (Bird et. al, 2014). However, with modern safety precautions and management, nuclear power is considered to be a safe method of energy production. Nevertheless, the utilization of radioactive elements, the generation of nuclear energy and the transport of radioactive waste presents significant risk. This accumulation of wastes leads to concentrations of pollutants that degrade environmental quality (Prakash, 2023). More than a quarter million metric tonnes of highly radioactive nuclear waste is dumped in storage near nuclear plants worldwide (Jacoby, 2020). Despite the amount of nuclear projects globally, the method of storage and disposal of nuclear waste is still widely debated. In many cases, waste remains in containers temporarily prior to permanent disposal; however, containers are known to leak these contaminants (Prakash, 2023). Proposed solutions include releasing waste into space, or more realistically, burial in deep rock formations in the Earth’s crust (Lindblom et. al, 1982). With any solution, there is always a degree of risk. For example, an intense earthquake could crack an old pool housing radioactive fuel rods (Hileman, 1982). Why should Australia take this risk and commit to complex and expensive waste management schemes? The aforementioned Brundtland report cites the requirement to meet the needs of the present without compromising future generations. Nuclear waste storage has the potential to inflict significant burden on future generations and this does not lend itself to sustainability.

Additionally, there is a possibility of nuclear plant workers being exposed to unnatural and harmful levels of radiation. Ionizing radiation occurs through spontaneous decay of unstable isotopes that are produced in nuclear reactors (NCI, 2022). Ionizing radiation can cause radiation sickness, cardiovascular disease, cataracts and genetic mutation causing cancers. Arguably, urban air pollution caused predominantly by the burning of fossil fuels, particularly coal, claims around 7 million lives annually. Meaning that under regular operation conditions, waste associated with coal and natural gas is far more harmful to humans than nuclear (Wilkerson, 2016). In terms of renewable energy generation, there is potential for people to fall off roofs installing panels, airborne fragments of broken windmill blades striking unfortunate bystanders and risks associated with the very large material requirements associated with this energy source (Bezdek, 1993). Though these hazards and dangers are common to all infrastructure projects and are not unique to renewable energy production. And whilst solar has been responsible for several deaths per megawatt per year of operation (Bezdek, 1993), the potential maximum deaths caused directly by renewables is dwarfed by the deaths that would occur in a large nuclear accident which cannot be predicted.

Nuclear and the Risk Society

This nexus between nuclear energy and green growth is discussed by Beck who defines the ‘risk society’. He argues that modern science and technological developments have birthed a risk society in which the ultimate aspirations of creating wealth have been overtaken by the production of risk (Beck, 1988). Where we once had an industrial revolution concerned with acquiring wealth and efficiency, we now have the quest for safety.

He argues that risks in a ‘risk society’ are odorless like radioactive wastethis is accompanied by a degree of anxiety. Reflexive modernity describes how risk is constantly in the making and in our risk society, we dwell on the uncertainty of the hazards around us (Beck, 1998). In the question of nuclear development in Australia, understanding our risk society is beneficial in evaluating whether nuclear is worthwhile in the long term or negatively contributing to risk and public anxiety. Sustainable development contains inherent risk due to the nature of novelty and the unknown. However, nuclear power introduces an unnecessary higher level of uncertainty not evident in renewable energy production. Epitomized by the transport of nuclear waste through civilian neighborhoods-this induces public anxiety and is entirely avoidable through the maintenance of the nuclear ban.

Conclusion

Solving the global climate crisis has evolved from discussing what to do, to how to do it. It is clear that fossil fuels are unsustainably contributing to global warming and a shift to cleaner forms of energy generation is paramount. For Australia, there is a clear path towards a clean energy future. A mix of renewable energy sources supported by battery storage is achievable. Despite the fact that nuclear power is utilized by many countries, it is not the right solution for this one. The lack of existing workforce expertise, a regulatory framework or infrastructure only exacerbates the immense cost of planning and construction. And though uranium is found in abundance in Australia, the fact remains that the necessity of this finite resource will always cost more than the energy sources of renewables. And with the rise of more capable batteries, the need for baseload power is nullified, completely liberating renewables to provide power

independently and reliably. The construction of wind and solar takes a fraction of the time needed to build a nuclear reactor. The rapid timescale of global warming does not lend itself to extended construction periods in which it would take many years before the positive effects of low carbon nuclear power would be tangible. Furthermore, nuclear waste disposal remains a highly debated topic in which no solution is fully ideal. Nuclear therefore is not a plausible reality for Australian energy and serves to distract from the expansion of renewable production.

References

Beck, U. (1998), Politics of Risk Society, Environmentalism: Critical Concepts, Volume 4, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, London

Bird, D., Haynes, K., van den Honert, R., McAneney, J., Poortinga, W. (2014), Nuclear power in Australia: A comparative analysis of public opinion regarding climate change and the Fukushima disaster, Energy Policy, 65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.09.047.

Bezdek, R. (1993), The environmental, health, and safety implications of solar energy in central station power production, Energy, 18(6), https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-5442(93)90046-G

Brook, B., Alonso, A., Meneley, D.A., Misak, J., Blees, T., van Erp, J.B. (2014), Why nuclear energy is sustainable and has to be part of the energy mix, Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 1(2), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susmat.2014.11.001

Brundtland, G.H. (1987) Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-Document A/42/427

CSIRO (2024), The question of nuclear in Australia’s energy sector, Australia, https://www.csiro.au/ en/news/all/articles/2023/december/nuclear-explainer

Datta, U., Kalam, A., Shi, J. (2020), A review of key functionalities of battery energy storage system in renewable energy integrated power system, Energy Storage, https://doi.org/10.1002/est2.224

Energy & Mining (2024), Leading the Green Economy, Government of South Australia, https:// www.energymining.sa.gov.au/industry/hydrogen-and-renewable-energy/leading-the-greeneconomy#:~:text=South%20Australia’s%20aspiration%20is%20to,on%20180%20days%20(49%’s National Science Agency, 25).

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee (2023), Environment and Other Legislation Amendment (Removing Nuclear Energy Prohibitions) Bill 2022, The Senate, Senate Printing Unit Canberra

Ferguson, C. (2011), Nuclear Energy; What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford University Press, New York

GenCost (2023), GenCost confirms renewables remain the cheapest form of energy, as the cost of nuclear reactors skyrocket, Department of Industry Sciences and Resources, https://www.minister. industry.gov.au/ministers/husic/media-releases/gencost-confirms-renewables-remain-cheapestform-energy-cost-nuclear-reactors-skyrocket

Hileman, B. (1982), Nuclear Waste Disposal, Environ. Sci. Technol., https://doi.org/10.1021/ es00099a721

Jacoby, M. (2020), As nuclear waste piles up, scientists seek the best long-term storage solutions, Chemical and Engineering News, 98(12), https://www.westvalleyctf.org/NewsRecent/2020-03-30_ Chemical&Engineering_News.pdf

Lindblom, U., Gnirk, P . (1982), Nuclear Waste Disposal; Can we Rely on Bedrock?, Pergamon Press, Exeter

Lyman, E. (2024), Five things the “nuclear bros” don’t want you to know about small modular reactors, Renew Economy; Clean Energy News and Analysis, https://reneweconomy.com.au/five-things-thenuclear-bros-dont-want-you-to-know-about-small-modular-reactors/

MacDonald, C. (2003), Uranium: Sustainable Resource or Limit to Growth?, World Nuclear Association Annual Symposium, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/ document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=3db625c0eb734001649cf1d1c3815447676e0032

Martin, P . (2024), When it comes to power, solar could leave nuclear and everything else in the shade, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-07-03/energy-power-solar-leave-nuclear-in-theshade/104049276

McNeil, B. (2007), The costs of introducing nuclear power to Australia, The Journal of Australian Political Economy, (59), 5–29. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200804571

Mirkhusanov, U., Semenova1, D., Kharitonov, V. (2023), Forecasting the cost and volume of uranium mining for different world nuclear energy development scenarios, Nuclear Energy and Technology 10(2): 131–137 DOI 10.3897/nucet.10.130485

Moses, M. (2019), All you need to know about wind power, EDF Energy, https://www.edfenergy.com/ energywise/all-you-need-to-know-about-wind-power#:~:text=Wind%20farms%20can%20be%20 built,need%20replacing%20during%20this%20time

NCI (2022), Accidents at Nuclear Power Plants and Cancer Risk, National Cancer Institute, https:// www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation/nuclear-accidents-fact-shee t#:~:text=At%20high%20doses%2C%20ionizing%20radiation,cataracts%2C%20as%20well%20 as%20cancer

Parkinson, G. (2024), Blackouts, bankruptcy and “bugger off Bowen” posters: Ted O’Brien’s dystopian and error riddled energy vision, Renew Economy; Clean Energy News and Analysis, https:// reneweconomy.com.au/blackouts-bankruptcy-and-bugger-off-bowen-posters-ted-obriens-dystopianand-error-riddled-energy-vision/

Parkinson, G. (2024), “Prohibitive:” Australia’s biggest energy consumers and producers say no to nuclear, but is Coalition listening?, Renew Economy; Clean Energy News and Analysis, https:// reneweconomy.com.au/prohibitive-australias-biggest-energy-consumers-and-producers-say-no-tonuclear-but-is-coalition-listening/#google_vignette

Prakash, B.D. (2023), 75 Years of Indian Independence; The Changing Landscape, Angik Press, Ambari Guwahati

Ritchie, H. (2023), How long does it take to build a nuclear reactor?, Sustainability by Numbers, https://www.sustainabilitybynumbers.com/p/nuclear-construction-time

Wilkerson, J. (2016), Reconsidering the Risks of Nuclear, Science in the News; Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2016/reconsidering-risks-nuclearpower/

World Nuclear Association (2024), Nuclear Power in The World Today, World Nuclear Performance Report 2023, https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/nuclearpower-in-the-world-today

Nicholas

Kristof and Sheryl Wudunn’s

Approach to Exposing

How are the language features of non-fiction used in Half the Sky to give voice to women facing oppression in developing countries?

Lilias Smart

Franc Carse Essay Prize

Introduction

Language plays a central role in constructing and defining the meaning of the world but also has the power to inspire, provoke change and create awareness. Language can be used as a vehicle; a means to empower and can give a voice to the marginalised. Having a voice can provide women with agency and power and allow one to express their beliefs, hardships, and rights. When that voice is taken away, women often become powerless and more vulnerable to oppression. Those with a voice and power can promote change in society and speak for those who are vulnerable. Language in non-fiction texts has the ability to turn oppression into opportunity.

Language can share stories that empower women in a patriarchal society and can enable women to rise above oppression. The more knowledge in society regarding the issues females face in developing countries, the increased chance that actions will be made towards reducing gender-based discrimination and violence.

Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn draw on their skills as writers, through the composition of their non-fiction text, Half the Sky, to expose the oppression of women in developing countries.

Half the Sky is a non-fiction text that raises awareness through informing the reader about the status of women in developing countries. Throughout Half the Sky Kristof and WuDunn share testimonies and encounters with women who have been victims of rape, sex trafficking, forced prostitution, honour killings and gender-based violence. By sharing these stories, it provides insight into the oppression being faced in developing countries and creates the opportunity for change. Half the Sky shares the stories of women from all over the world, specifically those in patriarchal society who are victims of oppression. To reduce the effects of these global issues it is vital that these women who are being mistreated are given a voice and freedom through exposing their oppression, specifically in a patriarchal society. The purpose of Half the Sky is to spur readers to take action against acts of oppression and the text can be described by Kristof and WuDunn as “saving the world, one woman at a time” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009).

Due to the accuracy of nonfiction literature, the issues of oppression that are raised within the text can be confronting for the readers. This is most commonly presented through statistics and detailed facts throughout the text. Kristof and WuDunn strategically include numbers and figures to highlight logical importance regarding the issue, providing evidence that is difficult to refute. Statistics directly expose the oppression being faced which then allows for an argument to be discussed, creating a firm measurement for the readers to comprehend the oppression. In chapter four, the stigmatizing nature of rape is discussed, with reference to the increasing issue of rape in South Africa. The tricolon of three successive statistics “21 percent of Ghanian women reported… that their sexual initiation was by rape; 17 percent of Nigerian women

said that they had endured rape or attempted rape by the age of nineteen; and 21 percent of South African women reported that they had been raped by the age of fifteen” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.69) appeals to logos and establishes credibility with what the author’s are saying. Statistics demonstrate the authors’ perspective, and data is often manipulated in a way to exaggerate the issue, altering the reader’s view on oppression of women. In the opening chapter, the gender imbalance regarding education in Cambodia is discussed using statistics. For example, “Cambodian women averaged just 1.7 years [of education]” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.21) which conveys the complete lack of education that Cambodian women experience and allows the readers to grasp the education deprivation. The number of men with an education in Cambodia is intentionally not included as the data could be just as low and hence, not make the issue of oppression of women appear as significant. Statistics can convey the imbalanced gender dynamic found in developing countries. In chapter nine, the economic struggles faced by females in Yemen is voiced, using statistics such as “In Yemen, women make up only 6 percent of the non-agricultural labour force (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.177)” which highlights the mistreatment of women in the labour force in comparison to men, creating a dichotomy between males and females. Statistics can also expose the enormity of the issues women are facing. Throughout chapter five, the brutality spreading in the Congolese province of South Kivu is exemplified through the statistic “The UN estimates that there were twenty-seven thousand sexual assaults in 2006” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.95). Additionally, “between 600,000 to 800,000 people are trafficked across international borders each year, 80 percent of them women and girls, mostly for sexual exploitation

(Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.11). This conveys the vastness of the issue and the inclusion of figures referencing females only emphasise the gender specific problem. The excessive use of statistics and figures throughout Half the Sky make the oppression of women clear and illustrates the vast number of women affected by oppression globally, creating a firm visual measurement for the readers.

Another non-fiction literary device employed by Kristof and WuDunn is the inclusion of peritextual elements, suggesting that the information found in the text is factual and creates a sense of reliability (Martinez, Stier, and Falcon, 2016). Elements such as headings, headers and subheadings make the content within the novel accessible, creating clarity for the readers. Headings can support the reader in navigating each theme throughout the novel and can produce a preconceived notion about what the following chapter will be about. For example, “Rescuing Girls Is the Easy Part” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.38) alludes to the long lasting and farreaching complications that encompass these women facing various forms of oppression, suggesting that the following recounts of women being rescued from brothels is just the start of their struggles. Chapter seven discusses reproductive rights and female access to healthcare. The chapter’s title “Why Do Women Die in Childbirth?” is a rhetorical question that triggers an internal response within the reader and encourages them to think about the consequence that inadequate medical facilities have on women facing oppression in developing countries. The common epithet “maid of honour” is repurposed in the heading to become “The Shame of Honor” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.90) which draws attention towards the priorities of developing and developed

countries. With the undertone suggesting that first world problems are fairly superficial when compared to the problems occurring within the text. Similarly, the use of epigraphs gives the reader an idea of the themes that will appear in the following chapter, whilst providing context. The opening epigraph “What would men be without women? Scarce, sir, mighty scarce.” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p. xi) sets the tone for the rest of the text, highlighting the importance of women in society through rhetorical questioning and reiterates the meaning through repetition. Then the following introduction provides a glimpse into the brutality inflicted on women globally. In the opening chapter, the epigraph “women might have something to contribute to civilization other than their vaginas” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.3) has a very satirical and patronising tone to reveal how archaic societal constructs are, and how unreasonable it is that women are still being treated this way. In chapter four, the culture of sexual predation is discussed, with reference to the stigmatizing nature of rape. The chapter’s epigraph “the mechanism of violence is what destroys women, controls women, diminishes women and keeps women in their so called place” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.68) uses antistrophe to emotively convey the continuous impact that rape can have on a woman, setting the initial tone regarding rape for the rest of the chapter. The foreword “Women hold up half the sky” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009) implies that females make up half the population and therefore should be represented equally, with the sky also acting as a metaphor for society. These peritextual elements that are present throughout the nonfiction text make the information accessible and clear for the reader to navigate.

A key feature used throughout Half the Sky to expose the various forms of oppression

is the use of anecdotes, giving a voice to these women. The anecdotes are told in a respectful and academic tone, providing insight into the women being oppressed, and inadvertently giving them a voice. The emotionally charged stories act as a vehicle for truth. Each chapter’s sole focus is around a strong female figure and different anecdotes are used to provide the reader with different voices and perspectives on the issues women face in developing countries. The opening chapter begins with an anecdote of a young Cambodian girl called Srey Rath who is described using imagery such as, “[her] black hair tumbles over a round, light brown face”. The description coming from the author allows the readers to picture an accurate and unmodified representation of her appearance and situation. Credibility and understanding of the oppression faced is created through the non-fiction element of an interview within an anecdote. A year later when the authors visited Srey Rath after rescuing her from the brothel, her dialogue “I never lie to people, but I lied to you… I said I would not come back, and I did. I didn’t want to return, but I did” (Kristof and Wudunn, 2009, p.43.) creates a disheartening and saddening tone through emotive language and repetition, exposing the hardships these women face as a consequence of oppression, through firsthand experiences. Dialogue is included to enhance the reader’s understanding of the environment. The man in charge of the girls in the brothel felt he was obliged to be repaid for his actions as seen through the dialogue “you must find money to pay off the debt, and then I will send you back home” (Kristof and Wudunn, 2009, p.xxi.) incorporating imperative language to give the offenders a voice and allow the reader to understand the brutality Srey experienced. Another anecdote of a young girl in Poipet demonstrates the physical and mental degradation that occurs due to

oppression. Srey Momm ran away from home and was sold into a brothel. She is described as “frail” and “anxious” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.40) which emphasizes her physical vulnerability as a result of forced prostitution. The use of anecdotes provides insight and exposes elements of oppression being faced that would otherwise have gone unnoticed, ultimately giving these women a voice.

Furthermore, emotive and confronting language is used throughout Half the Sky to evoke an emotional response within the reader by exposing the reality of oppression in developing countries. Kristof and WuDunn’s language is carefully chosen, with the purpose to expose these challenging and violent themes, immediately demanding the reader to face the issues (Besnier, 1990). This can be seen right from the opening chapter which takes the form of an autobiographical exposé to highlight the story of Meena Hasina, a young girl from India who was captured and “prostituted in a brothel” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.3). Meena states that many brothels in India “…[welcome] the pregnancy as a chance to breed a new generation of victims. Girls are raised to be prostitutes” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.7). This horrific statement confronts the readers, revealing how poorly these women are being treated and exposes the environment in which these women are being raised. The emotive language such as “fearing for her life” and emphatic language like “my life had been wasted” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.7) allows the readers to connect to these women and become aware of the difficulties being faced. The disheartening statement “We thought that even if we died, it would be better than staying behind” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.xiii) appeals to the readers through pathos and exposes the hardships these women face and the extent to which forced prostitution can impact a

woman. In chapter one, Meena Hasina abandons her children, fleeing the brothel in rural India where she was captivated for many years. Emotive language is used to describe the fragile woman such as “fearing for her life” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.8) and the emphatic language used by Meena like “my life had been wasted” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.7) allows the audience to connect to these women and become aware of the difficulties being faced. Confronting aspects of oppression in developing countries is exposed through language, allowing the audience to be aware of the societal norms around the mistreatment of women. The engrained attitude of male figures is seen through a conversation between a reporter and an officer, when the trafficking of girls was questioned, he replied by “[throwing] up his hands” and “laughed genially” then proceeds to say “prostitution is inevitable… What’s a young man going to do from the time when he turns eighteen until when he gets married at thirty” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.26). This conversation is included in the text to shock the audience, giving perspective and insight into the unacceptable treatment of women in these countries. Additionally, the threatening environment created by the owners of the brothels can be seen through the aggressive language used with the women, for example the dialogue between Meena Hasina and the owner of the brothel “if not, we will beat you to death. Do you want that?” Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.xii) replicates the terrifying environment and exposes the reader to the brutality occurring in developing countries. The descriptive and confronting language used throughout the text displays the hardships and exhibits the pain these women in developing countries are facing.

Throughout Half the Sky there is a continuum of authorial objectivity. The overarching

academic voice created by Kristof and WuDunn creates a sense of reliability, reassuring readers that the information gained is from a distinct and credible writer. Language is also used to engage and involve the readers with the information presented. Kristof and WuDunn use language that engages the audience, involving them in the process of uncovering female oppression (Trivedi, 2015). Call to actions are also made through the anecdotes, incorporating the use of firstperson pronouns and emotive language to engage and inspire the reader to create change. For example, in the first chapter after Meena Hasina and her children escape from a brothel she says “they may not speak to me, but I know what is right and I will stick to it. I will never accept prostitution of myself or my children as long as I breathe” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.17) which is a direct attempt to expose and encourage readers to make change. Similarly, rhetorical questions are used throughout the text to make the readers question their beliefs and understanding of female oppression. The tricolon of rhetorical questions “Why is acid thrown in women’s faces, but not men’s? Why are women so much more likely to be stripped naked and sexually humiliated than men? Why… are old women taken outside the village to die of thirst or to be eaten by wild animals?” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.75) demand the readers to question and reflect on the mistreatment of women in these developing countries. The difficult nature of the questions highlights the struggle to find an adequate solution to completely eliminate the oppression of women. Throughout the text Kristof and WuDunn adapt the language used by offenders to describe the women. As seen when using language such as “sale of virgins” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.36) which is objectifying and sexualising women based on their sexual experiences, similar to the way they are viewed in their own

communities. Additionally, the females in the brothels are referred to as a collective without any individual names, as seen in the narration “constantly had sex with the girls” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.44) which strips any originality and dehumanises them, only to be valued as sexual commodities. The way that Kristof and WuDunn present the information throughout Half the Sky instils authorial credibility and actively involves the readers in understanding the oppression of women in developing countries.

Subsequently, imagery used throughout Half the Sky allows the environment and information raised in the text to seem tangible to the reader. Imagery allows Kristof and WuDunn to evoke shocked and empathetic feelings towards the females, by making the atmosphere and experiences they encountered seem more tangible and understandable. Imagery allows the reader to absorb data through visuals and emotional descriptive terms helps the readers decode the complex facts which may be offered within the text (Chang, 2013). In the first chapter when Meena is sharing the inhumane scenarios that occurred within the brothel, phrases such as “girls would be summoned to watch as the recalcitrant one was tied up and savagely beaten” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.5) are included to provoke anger within the readers as they are informed of the extent to which these women are being poorly treated. The inclusion of the imagery “savagely beaten” allows the readers to clearly understand what is occurring, exposing the inhumane mistreatment being faced. The firsthand recount with excessive listing, from one of the victims of forced prostitution stating “and they beat me mercilessly, with a belt, with sticks, with iron rods… the beating was tremendous” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.5) uses confronting imagery to convey the violence being faced by these women. The use of “mercilessly” conveys the amount of

disregard and lack of respect for these women. The emotive phrase “once a girl is broken and terrified, all hope of escape squeezed out of her” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.5) uses confronting language created by the tactile imagery and personification to amplify the effects oppression has on women. The use of “broken” and “terrified” are strong adjectives and paired with the verb “squeezed” is physically conveying her diminished state, exemplifying the impact forced prostitution can have on a female. The evocative imagery used to describe one of the females such as “she dissolve[d] into sobs and rage” uses passionate language to display the detrimental physical effects that these brothels can have on a young woman. Additionally, the physical and auditory imagery “cracking from the strain” (Kristof and WuDunn, 2009, p.40) incorporates onomatopoeia, stimulating the reader. This enhances their understanding of the physical degradation faced by these women, and the discomfort due to low standards of living in these developing countries. Imagery allows the mistreatment of women to be expressed through immersing the audience in the environment where the oppression is taking place.

Throughout Half the Sky, Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn use the form of a nonfiction text to expose the oppression of women in developing countries. Non-fiction is an accurate representation of the inequalities occurring to females and instills credibility through a continuum of authorial objectivity. The overarching voice of Kristof and WuDunn is deemed reliable through the selection of literary techniques found in non-fiction writing which assist to inform the readers about the far-reaching issues of oppression of females, enhancing one’s understanding throughout the text. Kristof and WuDunn enlighten the readers about the oppression of women that occurs globally, and the detrimental physical and emotional impact this can have on a female.

References

Besnier, N. (1990). Language and Affect. Annual Review of Anthropology, 19, 419–451. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/2155972

Chang, C. (2013). Imagery Fluency and Narrative Advertising Effects. Journal of Advertising, 42(1), 54–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23353249

Gerrig, R. J. (1989). Reexperiencing Fiction and Non-Fiction. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 47(3), 277–280. https://doi. org/10.2307/431007

Healy, J. (2019). Global Poverty and Wealth Inequality (Vol. 447). Thirroul: The Spinney Press.

Kristof, N., & WuDunn, S. (2009). Half the Sky. London: Virago Press.

Martinez, M., Stier, C., & Falcon, L. (2016). Judging a Book by Its Cover: An Investigation of Peritextual Features in Caldecott Award Books. Children’s Literature in Education, 47(3), 225–241.

Trivedi, S. (2015). Surplus, Authorial Intentions, and Hypothetical Intentionalism. College Literature, 42(4), 699–724. http://www.jstor. org/stable/24544207

Kauri Tree

A kauri tree stands strong dirt mountains decorate its prominent roots. Sun rays cleanly split by swords of algae green twirling in the wind around the tree

Hills of sand, soft lulls the skin of a young body smile lines crack their ebb and flow

The kauri has a straight back whirlpools of wooden spirals reach upwards, its arms in a joyous spread

The ocean grabs, grabs again.

Far behind long fingers the horizon stretches

Tūī rest on high branches, a superb vantage; up there they make friends with the sun and sky

All the while the sun watches, perched on the dunes.

Kauri filtered light.

Observing the brilliance of youth.

Breathing in endless air.

Letting go

The kauri tree is young much younger than its ancestors whose age enriches the land

Yawning, the sun puts its head down. With the remnants of its energy it splays fire over water

Sea Sand Air

Bark Skin a new kauri grows by:

Asher Goddard

Philip Sargent Prize

There Was A Blackbird In The Road

by: Evie Grace

Winner: Philip Sargent Prize

There was a blackbird in the road. Squashed flat, though its tail feathers Stuck up straight in a salute. Its head was bent right back, Plastered to its spine. Its beak tilted to the left, And its eye still open.

That blackbird will fly no more. But its scent, like death, lingers For days, under the baking sun.

Down another road, birds are bathing In a stream that runs from pipe to drain. And bird song fills the air above. It reminds me how the blackbird Will never bathe again, nor will he sing A note more.

Hours pass, weeks, And the blackbird is still playing On my mind. Its dark eye staring Straight through me. Animated, even in eternal quietude. Watching all the people who pass, And ignore its carcass. An eye that met the grim-reaper With grim curiosity.

Moonscape

by: Forrest Wilkes

Philip Sargent Prize

We drive further than needed to make sure we hear the song finish, avoid the awkward edges of lyrics cut by a car door slam The awkward edges of things we leave unfinished

I stay up later than I should and plot and ponder the past 4 months are torn, raw at the end threads loose and unravelling replaced inextricably with a new, odd fitting saffron fabric

I walk the streets of old misshapen days feet landing back on pavement stones I shed tears over relegated to these ghosts that litter the footpaths like garbage

The stink of old memories

And it is easier to fall into routine and it is easier to see why you left and why you had to but turning your back is still difficult regardless

All the familiar things and faces jeer at me, crying words of treason and I feel like a traitor to this place where I was born unwanted

My mother inextricably lost and lonely in the apartment that is too big for her only I never feel solidly on the same ground my thoughts always lingering above me those thoughts of flight

All those glories of past years collect in vibrant, amber reels in my mind

I do not wish to discredit them merely wish to put them in old shoe boxes there they can remain

Yet it is not some tortured hellscape far from it

The roots of trees cling to clumps of soil packed between cement, each rising to frame the golden lights of the harbour picturesque

But I do not feel like I am home, the days simply an interruption to my greater scheme Those roads I paved brick by brick in a city not too far from here, coming back to see what you left behind is a sensation I cannot describe whether you see palaces or smoked pitfalls it is sombre all the same, all the possible lives unlived stretch out to the horizon the memories you were not there to make with the people who gave you everything but whom you fled and the yearning for that destined place where the fruits of your labour have been finally rewarded

The days feel like an endless yellow eclipse a deeply pigmented ivory like the colour of that rare moon one that delights and bewilders but that is all too hard to come by The moon that gleams spools of silver light down on all of us no matter what place we find ourselves in

But the sky begins to darken crisp edges of gold seeping into deep grey and my footfalls become rapid and uneven drunk and stumbling my flurry my escape and I walk away

And it becomes so clear, the inevitability of these days that I was always designed to leave couldn’t have beared it to stay and the eclipse is never the permanent state only a distraction Go about your day.

But I still walk by it, that bus stop outside my apartment that one we all sat at waiting on that morning when 18 felt like a landslide to me and the year ahead had no technicolour, was only hazy and I felt the sunlight on my neck and it was all dazzling these moments these friends the present my only concern

What I would give to stand there waiting again I would wait there till the end of the earth don’t let the song finish slam the doors behind

And I would pray that the bus never arrives never glides up the hill that the day never dawns that the whims never pull and tug that I never leave that I have no eclipses to come home to that I stay

What if I had stayed? What if I had stayed?

Milk

By: Grace Koczkar

She looks down at him, his unfocused blue, milky eyes opened slightly, the top of his head so soft as she brushes her lips across his hair.

“What a perfect baby boy,” the nurse remarks, adjusting the black cuff on her arm.

“Yes,” she replies, feeling the strength of the tiny mouth on her chest.

When she was reading through her pile of pregnancy books she had thought it would feel funny. Like a tiny fish. And be sure not to stuff your nipple into your baby’s unwilling mouth – let your baby take the initiative. It might take a couple of attempts before your baby opens wide enough to latch on properly. But no, it shocks her how strong he is. Ben walks in, holding two cups of the shitty hospital coffee, he rests the steaming half full cup on her bedside table which is already littered with magazines, tulips resting in a plastic jug that the night nurse found when her parents visited, chocolates from her sister, and the plates left over from her cold, lumpy breakfast.

“How are you?” He sits down next to them and kisses them both.

“We’re doing good, still a bit sore though.” The top of the blanket slips down and the thick, white padding covering her stomach peeks through.

“You did such an amazing job,” he whispers softly into her hair, as if he only wants her to hear and not the nurse taking her blood pressure.

You did such an amazing job. That phrase fixes itself in her brain, and tears start to pool, dripping down her cheeks onto his soft head which only makes her cry more.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” she attempts to smile. She tries to wipe the tears away but he starts to greedily whimper around her chest. Ben runs to grab tissues from the tiny sink in the corner of her room and softly pats under her eyes.

Fuck me, I can picture it if I told him.

He’d pale, frantically run his hands through his hair continuously, and talk about letting down his parents. That’s why I couldn’t tell him. He’d be bloody useless.

The paper gown crinkles as I shift in the seat, the plastic sticking to my bare legs.

I hear the door click open and the doctor comes in. The paper is rough and thin against my skin and it makes me feel on display.

“Just relax your legs a bit more, that’s good, okay we’re going to begin.”

The silver point of the needle flashes between my legs and – fucking hell it hurts, tears fill my eyes as I press the pads of my fingers into the sides of the chair. I feel numb, dulled, stretched open like an elastic as the doctor leans back down to pull it out of me.

The doctor appears in my blurry line of vision, “That’s all finished now.”

He leaves the room for me to pull my clothes back on, I put my t-shirt back on and wish I had brought a jumper, I’m shivering. My jeans rub uncomfortably against me and I wish I had my tracksuit pants.

I sit down gingerly in the waiting room, seeing all the other women around me who I now share a secret with. One of them looks as young as me, the lady beside her looks like my Mum’s age and she is silently reading a magazine.

A plastic cylinder vase is filled with the colourful packaging of pads, the sticky note stuck on it says they’re free to take for the bleeding. I look up at the clock. 17 minutes and it is all over. Relief washes over me, but with the strange feeling of loneliness. Whatever, thank fuck it’s over.

I walk out of the clinic, and a sweaty woman heaves herself into my face holding a sign with a bloodied mass of flesh on it.

“God hates you, murderer.” Her breath stinks with hate.

I stumble backwards and look for my car. I’m still clutching a pamphlet with a smiling blonde lady on it talking about getting help after your abortion. I unlock the car, it hurts to get it, my fingers are shaking on the steering wheel.

I’m lucky really, I read a story recently about a woman in Ireland who’d been refused an abortion and died of a blood infection.

I take a deep breath and start the car.

She had wanted to do it, she didn’t want a baby, she only had a few months left of Uni, and was about to start her placement. And last time she heard, her exboyfriend had gotten a job at his father’s company and married his old girlfriend from high school.

She thought about the girl from her high school who got pregnant when they were in year 11. She didn’t come back to school after the term two holidays, when you could start to see the outline of her stomach through her netball dress.

“Take a deep breath for me now.”

She inhales and feel a tug deep inside of her, discomfort floods her.

“Okay” – the nurse leans over to her – “your catheter is out now so we’ll change the pads more regularly to keep everything clean.”

Great, she thinks, not only am I bleeding, now I might wet myself.

I lie down under my doona, stretched awkwardly to stop the aching.

“Is everything okay? You’re acting really weird.”

As if I’d fucking tell him now.

She feels a warm hand softly shaking her shoulder, her eyes open to the glowing green light of the clock that blinks 5:42 am.

“We’re going to try and use the bathroom now,” the nurse softly speaks. She’s a different one to before she went to sleep, this one looks older with silver hairs slinking their way through her jet black hair. Her nametag says ‘Mary’.

She tries to sit up and winces at the shooting pains coming up her body. The nurse braces her arm – “that’s okay sweetie we can take it as slowly as you want.”

Sweat trickles down her back as she shuffles towards the small en-suite, her milkstained pyjama top sticks to her skin.

All of a sudden she looks back in panic searching for him, he is lying in his Perspex cot, only his tiny face peeking out like a little moon from his swaddled form. She tries to turn and grips the doorframe in pain as the movement stretches her skin. She yelps quietly, not wanting to wake him.

“What about him?” she asks, feeling the strangest urge to place her nose on the top of his head and smell him. She needs to be near him.

“Baby will still be there when you get back, he’s sleeping so nicely for his Mum.” Mary gently squeezes her arm.

She eases herself onto the ceramic bowl, clawing the metal handles next to the toilet seat.

“Well done, the hardest part is over now, you’re doing so well.”

She looks down at her body, her hot, hard chest filled with the warmth of his milk.