Crystal Grand Banquet Hall 2110 Dundas St E #4, Mississauga, ON L4X 1L9

Live Band!

Full-course dinner and wine!

Tickets $120 (up to 12Y/O $60)

General sponsor

tickets: Grisha 416-625-3527

Armen 647-839-7810

Sevak 416-878-0746

Crystal Grand Banquet Hall 2110 Dundas St E #4, Mississauga, ON L4X 1L9

Live Band!

Full-course dinner and wine!

Tickets $120 (up to 12Y/O $60)

General sponsor

tickets: Grisha 416-625-3527

Armen 647-839-7810

Sevak 416-878-0746

In a landmark moment for the Armenian Catholic community of Toronto, Deacon Haig Chahinian was ordained as a priest on August 18, 2024, marking the first time a Toronto-born individual has achieved this sacred milestone within the church. The ordination, which took place at St. Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Catholic Church during the High Mass of the Assumption of Our Lady, was celebrated by His Excellency Bishop Mikael Mouradian, Eparch of the Armenian Catholic Eparchy of Our Lady of Nareg in the United States and Canada.

The journey leading up to this historic event began on August 17, 2024, with the "Presentation of the Ordinand" ceremony, where Monsignor Yeghia Kirijian, a longstanding figure in the Toronto Armenian Catholic community, formally presented Deacon Chahinian to Bishop Mouradian. The significance of this moment was underscored by the presence of distinguished clergy, including Very Rev. F. Zareh Zargaryan, Vicar of the Armenian Apostolic Diocese of Canada, who offered early congratulations on behalf of the Holy Trinity Armenian Apostolic Church of Toronto.

The following day, Deacon Chahinian was officially ordained during the High Mass. The ceremony was both spiritually profound and deeply rooted in tradition. After the readings, Monsignor Kirijian welcomed the congregation and provided insight into the theology behind the ordination. The ordination itself saw Chahinian called to the priesthood, followed by the sacred rites of vesting and consecration, where his hands and forehead were anointed, sealing his commitment to a life of apostolic service. In his sermon, Bishop Mouradian praised the newly ordained Fr. Haig Chahinian, highlighting the culmination of decades of dedication within the Toronto Armenian Catholic community. He also acknowledged Monsignor Kirijian's 50 years of service,

community.”

The Mass concluded with the traditional Blessing of the Grapes, coinciding with the Feast of the Assumption. The congregation, including clergy from various Armenian and Roman Catholic churches, as well as representatives from Armenian inter-church and cultural organizations across Canada and the United States, gathered to receive the first blessings from the newly ordained priest.

Present at the High Mass and Ordination were members of clergy from sister Armenian Apostolic churches, including Very Rev. F. Vartan Tashjian, Pastor of St. Mary’s Armenian Apostolic Church of Toronto, accompanied by his reverend Deacons; Rev. F. Myuron Sarkissian, Pastor of St. Vartan Armenian Apostolic Church of Mississauga; Monsignor Thomas Crane of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Buffalo; and Pastor Ara Balekjian of the Armenian Evangelical Church. The event was also attended by representatives from various Armenian inter-church, relief, charitable, educational, benevolent, and cultural organizations, along with faithful from across Canada and the United States.

Following the Divine Liturgy, a reception was held in the Church Hall, where parishioners and clergy alike shared in the joy of this momentous occasion.

Fr. Haig Chahinian's journey to the priesthood is a testament to his deep-rooted faith and academic rigor. Born on January 23, 1995, in Toronto, he was raised in a family that instilled strong Armenian Catholic values. His academic path led him through prestigious institutions, culminating in degrees in Philosophy and Theology from the

After years of theological study and service, Chahinian was ordained as a Deacon in June 2024 in Glendale, California, before returning to Toronto for his priestly ordination. This milestone not only marks a personal achievement for Fr. Chahinian but also a historic moment for the Armenian Catholic Church in Toronto, symbolizing the growth and continuity of faith within the community.

Fr. Haig Chahinian now embarks on his journey as a priest, with a mission to serve God, the Church, and the Armenian Catholic faithful of Toronto. ֎

editor@torontohye.ca

Publisher Torontohye Communications Inc. info@torontohye.ca

Editor Rupen Janbazian editor@torontohye.ca

Graphic designer/Layout editor Ara Ter Haroutunian ara@torontohye.ca

Associate editor/Staff writer Diroug Markarian Garabedian diroug@torontohye.ca

Associate editor/Armenia correspondent Salpy Saghdejian salpy@torontohye.ca

Administrator Missak Kawlakian missak@torontohye.ca

Advisor Harout Manougian harout@torontohye.ca

Advertisements ads@torontohye.ca

Branding Proper Company proper.am

բռնենք,

եւ «Հատիկ» կատարումներէն,

աւարտին կը հասցնեն, հարսին (Անուշ Յարութիւնեան), փեսային (Մասիս Գրիգորեան) ու աքլորին (Կարօ Լիպարեան, շաբաթ, Յարութ Թիքճեան, կիրակի) առաջնորդութեամբ։

By Rupen Janbazian

On the evening of Aug. 16, the AGBU Toronto offices were filled to near capacity for a thought-provoking lecture titled 'Our Voices Reached the Sky: Sonic Memories of the Armenian Genocide,' presented by Dr. Gascia Ouzounian. Dr. Ouzounian, an Associate Professor of Music at the University of Oxford, captivated the audience with her exploration of how sound and auditory experiences have shaped the historical understanding and collective memory of the Armenian Genocide.

The event began with opening remarks by Dr. Araxie Altounian, a prominent Toronto-based pianist and lecturer and an active member of the Armenian community who emphasized the importance of preserving cultural memory. She warmly introduced Dr. Ouzounian, highlighting the significance of her research in expanding the discourse on genocide studies beyond visual evidence to include the often-overlooked dimension of sound.

In her introduction, Dr. Ouzounian expressed her deep connection to the Armenian community, emphasizing the importance of family and community in preserving cultural identity. She also took a moment to acknowledge one of her first Armenian teachers, who was present in the audience and expressed her gratitude to the AGBU Toronto chapter for their continued efforts in organizing events that foster cultural and historical awareness.

Dr. Ouzounian’s lecture drew from her chapter, 'Our Voices Reached the Sky: Sonic Memories of the Armenian Genocide,' in the book 'Soundwalking: Through Time, Space, and Technologies' (Focal Press, 2023). She meticulously examined the auditory experiences of Armenian Genocide survivors, known as earwitness testimonies, revealing how the sounds they remembered—ranging from the harrowing cries of those suffering to the profound silences imposed by fear—provide a richer, more complex understanding of the Genocide’s psychological and emotional impact. By focusing on what survivors heard during the Genocide—such as the distant echo of gunfire, the chilling silence of emptied villages, or the songs sung by perpetrators—Dr. Ouzounian demonstrated how these auditory memories carry a weight that extends beyond the visual, embedding deep within the psyches of the survivors and their descendants.

Dr. Ouzounian emphasized that while visual evidence often dominates genocide studies, the auditory dimension offers unique insights into the lived experiences of survivors, adding layers of understanding to both personal and collective memory. She illustrated how sounds, such as the ominous announcements of town criers demanding either conversion to Islam or exile, the celebratory songs of perpetrators rejoicing in their brutal acts, and the whispered prayers of the desperate, played a crucial role in both the trauma of the Genocide and its remembrance. These sounds, preserved in memory and transmitted through generations, serve not only as a record of suffering but also as a form of resistance and survival, enabling a communal sense of identity and continuity despite attempts at erasure.

Central to her research is the work of the late Armenian ethnographer Verjiné Svazlian, whose courageous efforts to collect and preserve over 700 memoir-testimonies and 315 song-testimonies during the Soviet era provided the foundational material for this study. Dr. Ouzounian paid homage to Svazlian’s act of 'counter listening,' a term she used to describe the act of listening against the official narrative of denial perpetuated by the Turkish state. Svazlian’s work, often conducted in secret and at great personal risk, ensured that the voices of those who lived through the Genocide could continue to resonate through time, allowing future generations to hear and learn from their experiences. Dr. Ouzounian highlighted the importance of these sonic memories as a form of historical documentation that challenges official narratives and offers a visceral connection to the past, enabling listeners to engage with the emotional and psychological realities of the Genocide in a profound and impactful way.

Another fascinating aspect of Dr. Ouzounian’s research, explored in her talk, is the phenomenon of sounds that continue to ‘resound in the ear’ of survivors long after the events have passed. These unwanted, persistent sounds, such as the cries of victims or the taunting songs of perpetrators, are not just memories but enduring auditory experiences that haunt the survivors. Dr. Ouzounian explained how these ‘in the ear’

sounds function as a form of psychological scar, a continuous reminder of the trauma endured. This concept illustrates the deep psychological impact of the Genocide, where even decades later, the auditory memories are so vivid and intense that they continue to affect the survivors’ daily lives. These sounds, she argued, are a testament to the lasting nature of trauma and the importance of acknowledging and understanding these experiences as part of the broader narrative of the Genocide.

The evening concluded with a lively question-and-answer session, during which attendees engaged Dr. Ouzounian with a range of insightful questions. The discussion further emphasized the importance of her work in ensuring that the voices of Genocide survivors continue to be heard and remembered.

Organized and hosted by AGBU Toronto, the lecture underscored the chapter’s commitment to preserving and promoting Armenian heritage through educational and cultural initiatives. Following the lecture, attendees gathered for a small reception, continuing the conversation sparked by Dr. Ouzounian’s compelling presentation. ֎

(1930-2024)

“My childhood was both Armenian and Canadian. I grew up with a dual heritage, and I have always been proud of and loyal to both,” reflects Isabel KaprielianChurchill, a distinguished Canadian scholar and the child of Armenian Genocide survivors, who has spent her career exploring the complexities of Armenian immigration and diaspora culture. Her deep connection to her heritage has fueled her research, resulting in significant contributions to the understanding of the Armenian experience in Canada. In this interview, Kaprielian-Churchill reflects on her upbringing in Hamilton's Armenian community, her academic journey, and the personal and professional motivations behind her extensive work on Armenian history and cultural preservation.

Throughout the conversation, she shares insights into her early life, the influence of her father's storytelling, and her commitment to documenting the Armenian diaspora's rich history. KaprielianChurchill's passion for preserving Armenian identity and her dedication to educating future generations shine through, offering a glimpse into the life of a scholar who has profoundly impacted both her community and the broader field of diaspora studies.

Hrad Poladian: Tell us about your childhood and family origins.

Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill: I was very fortunate to grow up in the “Armenian village” in Hamilton. Most Armenians in the city lived around Gibson and Princess Streets in Hamilton’s north end. While the area wasn’t exclusively Armenian, we Armenians dominated it. The neighbourhood’s focal point was our “club,” what we would now call a community centre.

The community centre was crucial for us. It consisted of a large rented room where the men played cards and backgammon and where meetings were held for the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), the Armenian Relief Society (ARS), and the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF). The space also hosted community events like the April 24 commemorations, May 28 Armenian Independence Day celebrations, Easter and Christmas festivities, and other gatherings like plays and concerts.

Next to the large room was a much smaller space that served as our Armenian supplementary school. We attended Armenian school three evenings a week to learn to read and write our mother tongue. A small kitchen in the rear allowed the guardian of the “club” to prepare Armenian coffee for his male clients. A small confectionary in the big room also provided soft drinks, ice cream, liquorice, and chocolate bars for anyone interested.

Poladian: How did growing up in this Armenian neighbourhood shape your childhood experience?

Kaprielian-Churchill: We children felt safe and secure in the neighbourhood. It had a special warmth, where all the women were our “aunties” and we children were all “cousins.” The older children looked out for the younger ones. Saying we played is an understatement—we played constantly. There were few cars at the time, so the streets were ours. We played hide and seek, kick the can, kick the stick, relief-o, British bulldog, London Bridge, leapfrog, and blind man’s bluff. We played war, cowboys and Indians, and “house,” wearing our mother’s old high heels and pushing our “buggies” with our dolls bundled inside. We roller-skated, skipped rope, and played agates (marbles) and ball games. Often, on summer evenings, we would gather on someone’s veranda and stretch our imaginations by telling spooky and scary stories. The spookier, the more thrilling!

On Saturdays, our group headed for the Playhouse Theatre to watch a double movie feature, The News of the World, and cartoons—all for six cents! On Sunday afternoons, we joined Sunday School at St. Philip’s Anglican Church in our area.

Poladian: What was the significance of these activities and the neighbourhood for your sense of identity?

Kaprielian-Churchill: While these activities were enjoyable, the crucial issue was that they helped us bond with each other. We children were all Armenians. We played together, trusted one another, and cared for each other. Through these many facets of child and youth culture and by our camaraderie, we entrenched our Armenian identity.

All the Armenian children attended Gibson Street Public School. It was a little Europe. The children’s families were from all parts of Europe. In addition to us Armenians, we had Hungarians, Ukrainians, Poles, Dutch, Czechs, Jews, Russians, and Germans. We also had a good number of British children: English, Scots, and Irish, though most of the Irish, like the Italians, attended St. Ann’s Roman Catholic School, located in the same general area.

Poladian: Did you ever feel different or out of place at school because of your Armenian heritage?

Kaprielian-Churchill: I never felt that the teachers at Gibson looked down on us “foreigners.” Nor did Gibson interfere with our Armenian school. I presume Gibson treated the Ukrainian and Polish part-time schools in the same way. Our Christmas pageants reflected our multicultural society. The Irish danced their jigs; the Poles and Ukrainians, in their brightly coloured dresses and flowing ribbons, performed their cultural dances; a Ukrainian boy played traditional music on his piano accordion; a Czech boy sang songs in his home language; and a Hungarian boy

played some gypsy music on his violin. When I was in kindergarten, this little Armenian girl was selected to be Miss Canada! We all participated in this vibrant display of ethnic culture. From an early age, we learned to appreciate Canada’s ethnocultural society. Every morning, we pledged allegiance to the Union Jack, sang our national anthem, “God Save the King,” and said the Lord’s Prayer. We learned children’s hymns like “Jesus Loves Me” and “God Sees the Little Sparrow Fall.” Like the society we grew up in, our school was multicultural and had a British and Christian foundation. And yet we were Armenian. We spoke Armenian, learned Armenian history and cultural traditions, ate Armenian food, and felt Armenian.

You can see that my childhood was both Armenian and Canadian. I grew up with a dual heritage and have always been proud of and loyal to both.

Poladian: You’ve written extensively on Armenian history and immigration issues in Canada. You’ve authored articles such as “Armenians in Ontario” in Polyphony’s Fall/Winter 1982 issue and the book Like Our Mountains: A History of Armenians in Canada, among others. What motivated you to pursue this work?

Kaprielian-Churchill: I was blessed that my father was a spellbinding storyteller. He told me stories about life in his native village of Cherman in the Keghi region of the Erzerum province. He shared stories of Armenian heroes and of Armenian resistance to oppression. He recounted his journey to Canada in 1912—just missing sailing on the Titanic—and his early years in the new country. I loved hearing these stories. As a youngster, I devoured history books. My favourite was a series called Britain and Her Neighbours. As I grew older, I branched into American and Canadian history books. I was fascinated

by Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation. I pestered the local librarians with requests for books about the coureurs de bois and the French explorers, whose exploits fired my imagination.

In my teens, I promised myself that someday I would write the history of Armenians in Hamilton and asked my parents to keep any documents pertaining to Armenians. Luckily, they did. As I continued my education at the University of Toronto, I was fortunate to meet Professor Robert F. Harney, an ethnic historian. That meeting changed my life altogether. With his mentorship and supervision, I pursued immigration and ethnic studies, which eventually led to Like Our Mountains, published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in 2005. The book won the 2006 Clio Award for the best book on Ontario history, awarded by the Canadian Historical Association.

Poladian: Could you tell me about some of your other books and your latest work?

Kaprielian-Churchill: Sometimes, we come across interesting research material quite unexpectedly. One day, some years ago, I was working at the

Stanford University Archives and came across the name of Dr. Ruth Aznive Parmelee (1885-1973). Aznive? Immediately, I was drawn to this woman. After some research, I found that she was the daughter of American missionaries in the Ottoman Empire and had worked as an American-educated medical missionary in Kharpert, where she trained Armenian girls in nursing. I was quite excited about Dr. Parmelee, but I didn’t have much information about her work or the girls she trained. Then, at a dinner party in Fresno, I was telling the guests about Dr. Parmelee and Armenian nurses when one of the guests mentioned that his mother had studied nursing in Kharpert and had her diploma. I was at his house the next morning, bright and early, and he loaned me her diploma to copy. That was the beginning of my book about Armenian nurses, Sisters of Mercy and Survival: Armenian Nurses, 1900-1930.

My latest book is about the Georgetown Boys, titled The Georgetown Boys and Girls: Genocide, Orphans, and Canadian Humanitarianism.

Poladian: Are your children involved in Armenian issues?

Sunday, Sept. 29th, 1:30pm

Hamazkayin H. Manougian library

Armenian Community Center 45 Hallcrown Place

Kaprielian-Churchill: Yes, they are. All three of my children have visited Armenia with their spouses, and they continue to take a deep interest in developments in Armenia, Artsakh, and Canada’s role in Armenian affairs.

Poladian: What message do you have for the Armenian youth of Canada?

Kaprielian-Churchill: I would encourage them to bring their spouses into the Armenian community and send their children to our Armenian school— the ARS Armenian Private School. Non-Armenian spouses must appreciate more than just our delicious cuisine and understand more than just our tragic genocide. Even if they do not speak Armenian, they need to feel that they are part of a community—our community. They need to enjoy the warmth, support, and affection of our community members.

Poladian: You, Professor Lorne Shirinian, and Mrs. Sona Zeitlian have been great mentors and supporters as I began writing my book about the Georgetown Boys. I am forever grateful to the three of you. Thank you for this invaluable interview, Professor KaprielianChurchill, and good luck in your future endeavours. ֎

Known and Unknown

Dedicated to

The Armenian Community of iraq mesopotamia

Baghdad, Basrah, mosul, Kirkuk, Erbil, Dohuk, Baqubah, Zakho, Avzrog, Havresk

November 9, 2024 at 7։00 pm

Armenian Community Centre

45 Hallcrown Place, Toronto

Entertainment by ARSHAm BABERiAN, from Los Angeles

Requiem

in memory of the martyrs and deceased Armenians of iraq, at St. mary Armenian Apostolic Church Lecture at 2:00pm at The Armenian Community Centre Hall

For tickets contact:

∙ Arpi Salibian 416-838-5763

∙ Armig Safarian 416-493-7862

∙ Hroot Simonian 647-637-1155

∙ Lucie Gharibian 647-435-0065

45 Hallcrown Place, Toronto

By Sophia Alexanian

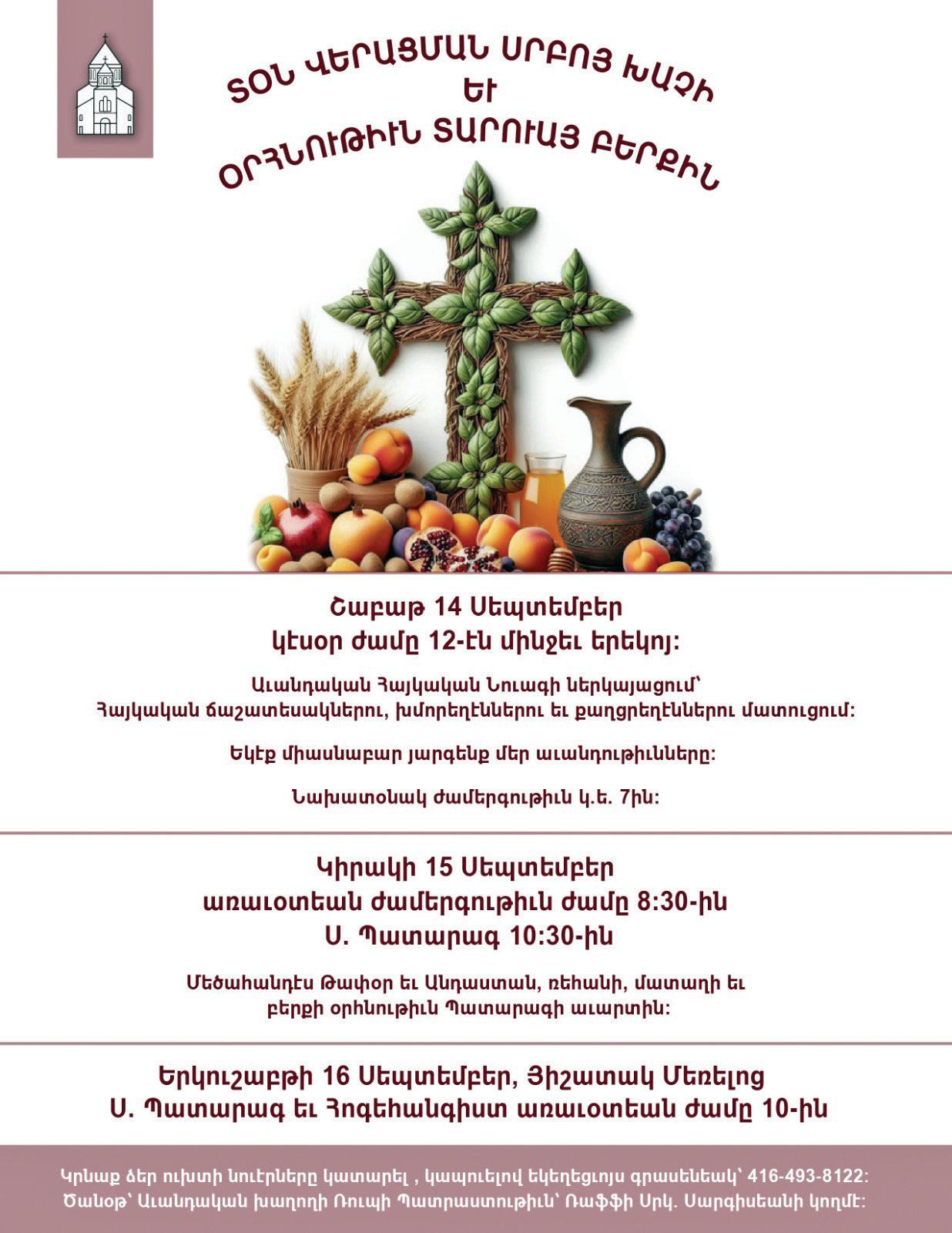

I didn’t know I was ugly until I visited Armenia as an adult woman.

That may sound dramatic. After all, beauty culture definitely exists in the Western world, but I somehow avoided the worst of it for most of my life. My fulltime occupation in Toronto as an engineering student is not exactly synonymous with following beauty trends. My discipline’s common room notoriously had posters on the walls reminding folks to shower and use deodorant. Suffice to say, the bar was low in terms of the level of personal upkeep expected. While nowadays there are many pretty girls in engineering, my own personal physical appearance felt irrelevant in my day-to-day life, which was packed to the brim with design projects, problem sets, and labs.

I should also note that as a preteen Armenian day school dropout, I was not only out of touch with beauty culture in the homeland but also no longer had daily interactions with diasporan Armenians outside my immediate family. I had limited exposure to models of Armenian femininity. I had spent the past eight months living in an engineering dorm, a predominantly male environment, where my indifference to beauty culture was the norm.

When I landed in Armenia to participate in an eightweek volunteer program, I was entering another planet. I suddenly exclusively interacted with Armenians outside my immediate family, most of them women. My daily, in-person interactions were with my fellow diasporan volunteers, my extended family, or the broader local populace. This environment is where I learned that I was ugly.

I should note here: Obviously, no one directly looked into my eyes and said, “Sophia, you are ugly.” The tactics were much more subtle than elementary school taunts. Instead of calling me ugly directly, my new-found social circle of Armenian women would suggest I consider various cosmetic procedures—everything from chemically straightening my curly hair through keratin or other means; getting lip fillers; getting ‘preventative’ Botox injections; and even considering more invasive procedures like breast augmentation and rhinoplasty as a normal part of working on one’s appearance. All this made it difficult to actively ‘call out’ harmful messaging, because to notice that there even is a message being said, you need to be able to read between the lines.

When cosmetic procedures are suggested to women, it implies that they should change their physical appearance. But why should anyone alter their appearance to another form? Perhaps it's because the altered appearance is perceived as more attractive.

Does this mean the unaltered appearance is unattractive?

There’s little acknowledgement of this underlying messaging when cosmetic procedures are suggested to young women. I think it’s time to have a serious discussion about the way cosmetic procedures are pitched to Armenian women, and the underlying beliefs about Armenian ethnic features that are being propagated, especially as a thriving plastic surgery industry is emerging in Armenia.

Beliefs about beauty do not exist in a vacuum. Physical features are physical manifestations of gender expression and ethnic heritage. The decision to elevate certain physical features as ‘beautiful’ often says more about our biases about the identities represented by those features than our personal aesthetic preferences.

When observing a beauty culture from the outside, without personal emotions clouding our judgment, it’s easy to read the subtext, make the connections, and confront internalized racism. East Asian blepharoplasty, or double eyelid surgery, is a popular procedure that adds an eyelid crease to those born with monolids (a type of eyelid seen in people who don't have a double eyelid or crease), making their eyes look wider and larger. The procedure was first performed in Japan during a period of increasing Western influence. While researching this piece, I read about the prevalence of double eyelid surgery among the people of Buryatia, in the far east of the Russian Federation. Natalya Badmayeva, a Buryat who underwent double eyelid surgery, shared her reasons with the Siberia-based outlet People of Baikal: “In my youth, Buryats were [considered] village people. Narrow-eyed, swarthy, uneducated, Buryat-speaking—this was the image I was trying to escape. I specifically didn’t learn to speak Buryat and had my eyelids done twice.”

From Badmayeva’s comments, we can easily observe that the idea that double eyelids are more desirable than monolids does not exist in a vacuum–the aesthetic preference comes from internalized racism. The monolids themselves are not ugly; it is the fact that they are associated with an ethnic group otherized by mainstream Russian society that makes them undesirable. The decision to get double eyelid surgery does not come from some innate preference but is influenced by the background noise around what (and who) is beautiful, desirable, and acceptable.

Armenians have lived as an ethnic minority under various empires for centuries. Currently, as a largely diasporic people, most Armenians live as ethnic minorities, including those in our community here in Toronto. While conditions for Armenians living as ethnic minorities have largely improved since the days of the Ottoman Empire and Soviet Union, the beliefs and beauty standards our community has internalized from oppressors remain. Now, when confronting antiArmenian beauty standards, we mostly push back against messaging from our community members, not external oppressors.

Which brings me back to my experiences confronting beauty culture in Armenia. You can’t escape advertisements

In 2012, medical student Tareq Hadhad’s family home and chocolate factory in Syria were destroyed. His family fled the country and became refugees in Lebanon. After three years, they arrived in Antigonish, Nova Scotia. Today, Hadhad is a successful entrepreneur and the owner of Peace by Chocolate, a company built on the bonds of family, community, and a desire to give back.

In a season three episode of Dispersion, the Zoryan Institute’s podcast about diaspora experiences in Canada, Hadhad recounts how he and his family settled in a new place vastly different from their hometown of Damascus, Syria. The episode, titled “Everybody Loves Chocolate,” describes Hadhad’s journey not only as a newcomer to Canada but also as someone navigating the process of finding support in community, embracing new opportunities, and overcoming challenges and uncertainty. His story mirrors many others featured on Dispersion stories of finding new beginnings and opportunities away from the homeland and as part of the diaspora. As Hadhad explains in the episode: “One of my favourite inspirations, since I came to Canada, is a friend of mine, a Canadian friend, who would tell me, ‘You know that we are born human beings with legs, not with roots like trees, for a reason.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because we have the opportunity to move. If we don’t find an opportunity, we can go and create one.’”

The podcast centres its episodes around important theories, topics, and diaspora experiences, navigating identity, home, and belonging while challenging stereotypes and discrimination. Shortly after the launch of its first season, Dispersion was ranked as one of the leading educational podcasts worldwide, with many professors incorporating it into their classrooms. One such professor is Dr. Sushan Karapetian, director of USC Dornsife Institute of Armenian Studies, who uses Dispersion as an educational tool. She says, “I used the episode [‘The Generational Cappuccino’] as required course material to jumpstart a conversation on the Armenian diaspora(s) and just how heterogeneous it is. The pairing of father and daughter, different generations, gender dynamics, upbringings, and so on, were just so ripe for discussion… My students had such visceral reactions, which sparked an excellent class conversation.”

Season one, episode two,‘The Generational Cappuccino,’ features Zoryan Institute’s president K.M. Greg Sarkissian, in conversation with his daughter, Talar Sarkissian, about the generational differences of growing up in the diaspora. The two discuss their identities as members of the Armenian diaspora, delving into the complexities of being multi-generational diasporans and their understanding of the concept of ‘home.’ Mr. Sarkissian explains in the

episode: “I am an Armenian by choice. At the end of the day, if my father was 100 percent Armenian, and I am 50 percent Armenian, maybe Talar is 25% Armenian... All of us are some sort of cappuccino, but the coffee and milk levels change.” The episode is emblematic of Dispersion, addressing the differences and similarities that unite diaspora groups globally.

Each episode of the podcast is grounded in an article from the Diaspora journal, providing a foundation for conversations that bridge the gap between academic and non-academic audiences alike. The Diaspora journal captures a world where borders are transgressed and elastic, boundaries are fractured and permeable, and identities are increasingly fluid and adaptable. Including literature from the social sciences strengthens the podcast's ability to make meaningful contributions to ongoing conversations about mobility, mobilization, and transnationalism, reorienting traditional accounts of home, homeland,

host state, and diaspora.

Despite the cultural, linguistic, religious, and geographical differences between various diasporic communities, Dispersion truly represents Canada’s cultural mosaic. It makes a brave foray into the changing and often complicated dialogue of diasporan experiences, offering Canadians from all manners of diaspora the opportunity to find commonalities and better understand their differences. The podcast allows the wider public to engage in diaspora studies through storytelling and documenting lived experiences. Dispersion serves as a platform for the kinds of conversations needed in today’s increasingly polarized world.

Dispersion is available for streaming on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, and Acast. ֎

for plastic surgery in Armenia: There are magazine articles about Botox, metro ads about filler, and if your Instagram algorithm figures out you’re in Armenia like mine did, you will be inundated with ads for local plastic surgeons. In my case, you also can’t escape the not-so-subtle suggestion to alter your appearance from friends and family. Probably the physical feature of mine that was targeted the most was my curly dark hair.

In Toronto, I was surrounded by odar (non-Armenian) classmates who complimented my hair often enough, especially when the ends of my hair were dyed a patchy ‘engineering purple.’ I had no insecurity about my hair texture or colour, so I was shocked when nearly every female companion in Armenia would insist that I needed to permanently straighten my hair and consider lightening the colour.

This was not an issue of one or two people having a personal preference; it was a broad cultural pattern of having one ‘look’ elevated as beautiful above another. Where does this cultural pattern come from? Who exactly would I be emulating if I changed my natural appearance? Why is this Eurocentric Slavic ‘look’ valued? These are important questions, but no one else was asking them.

It’s essential to question and reconsider the ‘need’ to alter the natural Armenian appearance because beauty culture does not exist without consequences. How we feel about one feature of our ethnicity impacts how we feel about others: We saw that Badmayeva’s shame around her monolids was also tied to shame around speaking her native tongue. As part of national pride, it’s important to elevate and preserve natural Armenian features so that Armenian children can grow up with healthy self-esteem (because just planning to eventually ‘fix’ their faces with plastic surgery is not a sustainable solution).

It’s difficult to have frank discussions about the negative consequences of plastic surgery. The decision of plastic surgery is often treated as an individual risk-benefit analysis of weighing the health risks of a procedure (of which there can be many) vs. the reward of becoming one step closer to conventionally pretty. Therefore, in my experience, any attempt to critique the pervasiveness of plastic surgery is taken as a personal attack by those choosing to undergo it. Which I find strange

since the mercenaries of beauty culture are the ones who are the most brutal in attacking individual people, creating a ‘problem’ out of ethnic features just to sell a ‘solution.’

The ‘solution’ to insecurity about one’s looks is not permanently altering them. Achieving beauty is fleeting; beauty trends come and go, our environment and society change over time. Only by improving our self-perception through a difficult unlearning process can we hope to build real confidence. The work cannot be done physically by a surgeon, but must be done mentally by the Armenian community as a whole.

I was lucky to learn the pointlessness of chasing after societally accepted ‘beauty’ at a young age. As an 11-year-old girl, I visited a museum dedicated to the Empress Elisabeth of Austria, or Sisi, as her fans know her. At her prime, Sisi was considered the most beautiful woman in Europe. I had known all the facts about Sisi going in: I knew that she was incredibly vain, moody, and obsessive about maintaining a waist measurement of 16 inches, to the point of disordered eating. Knowing the facts on paper was one thing, seeing it in person was another.

I remember feeling horrified when I saw a mannequin wearing Sisi’s coronation gown–a waist that was unnaturally small made her look so frail. The tour included viewings of the exercise equipment she used obsessively and the salon chair she reportedly sat in for hours each day so multiple hair stylists could style her floor-length hair. The tour allowed me to visualize how unglamorous Sisi’s daily life was since beauty rituals consumed all of her time.

Was Sisi happy as the most beautiful woman in Europe? I had known going in that she wasn’t, but the tour emphasized the extent of her misery. When the tour guide showed us the items she kept in her travel bag, they casually pointed out the many needles she carried with her. The needles were so that she could inject herself with cocaine syrup, the antidepressant prescribed for her deep depression. Seeing her needles packed next to a hairbrush and cosmetics made me sick to my stomach. I vowed I wouldn’t end up like her–accepted as beautiful by the world but deeply self-loathing.

Towards the end of her life, Sisi was so insecure that she spoke in a barely audible whisper to avoid showing her yellowed teeth, and wore veils in public to hide her middle-aged face. Her obsession with beauty culture literally silenced

Clever marketing or a reflection of deeper issues?

This ad campaign went viral for its witty approach— but it also raises questions about the growing normalization of cosmetic surgery in Armenia. (Ads: qit.am)

her and made her invisible. Do we want this fate for our Armenian girls?

I feel pain when looking at the bruised and bandaged face of yet another 18-year-old Armenian girl post-nose job. The constant stream of overfilled lips is disheartening; critics like myself are justified at feeling uneasy with this unnatural, over-replicated look. Something needs to be done to break this cycle of Armenian women wanting to butcher their natural faces. Until then, I return home to my odar environment in Toronto–an environment where, bizarrely, my Armenian face was never ugly. ֎ ***

Join the conversation! How has beauty culture impacted you or those around you? We invite you to share your thoughts, experiences, and reflections on the pressures of cosmetic procedures and beauty standards within the Armenian community. Write to our editor at rupen@ torontohye.ca, and your letter might be featured in an upcoming issue of Torontohye.

MEDICAL CENTRE & PHARMACY

Dr. Rupert Abdalian Gastroenteology

Dr. Mari Marinosyan

Family Physician

Dr. Omayma Fouda

Family Physician

Dr. I. Manhas

Family Physician

Dr. Virgil Huang

Pediatrician

Dr. M. Seifollahi

Family Physician

Dr. M. Teitelbaum

Family Physician

Physioworx Physiotherapy

Garen's bicycle tires have a radius of 35 cm. He rides his bicycle until the tires complete exactly eight full rotations. How many metres does Garen's bicycle travel? Round your answer to the nearest

Senior Problem: In a particular salad dressing, the ratio of oil to mayonnaise is 7:3. Rosita wants to make the dressing more acidic, so she doubles the amount of mayonnaise. What is the new ratio of mayonnaise to oil?

(answers on page 30!)

Հորիզոնական

3. (գոյ.) աղօթատեղի, տաճար, հաւատացեալներու

հաւաքականութիւն

5. (գոյ.) պատարագող եկեղեցական, տէր հայր

(ամուսնացած), վարդապետ (կուսակրօն, քարոզելու իրաւունքով)

6. (գոյ.) այս (9-րդ) ամիսը

8. (գոյ.) դպրոց

9. (գոյ.) hացաբեր բոյս, հացահատիկ

14. (բայ) մէկուն կամ բանի

15. (գոյ.) պատկեռասփիւռ, հեռուստացոյց

17. (գոյ.) միւռոնով նուիրագործում (եկեղեցիի, եկեղեցականի)

18. (գոյ.) թանկարժէք մետաղ մը (ընդհանրոապէս՝ դեղին), հարստութիւն, դրամ

19. (բայ) ջուրով մաքրել, սրբել

20. (բայ) ջուրին վրայ շարժելով յառաջանալ

1.

2.

4.

Across

3. (գոյ) աղօթատեղի, տաճար, հաւատացեալներու հաւաքականութիւն

5. (գոյ) պատարագող եկեղեցական, տէր հայր (ամուսնացած), վարդապետ (կուսակրօն, քարոզելու իրաւունքով)

քահանայ ________ (ազգանուն)

6. (գոյ) այս (9-րդ) ամիսը

7. (գոյ.) մեղուներու շինած նեկտարը

8. (գոյ.) դպրոցներու բացման շրջան

8. (գոյ) դպրոց

10. (բայ) ճաշակել, սնունդ առնել

11. (գոյ.) այս խաղը

9. (գոյ) hացաբեր բոյս, հացահատիկ

12. (գոյ.) փոքր ոտք (մանուկի, անասունի)

13. (գոյ.) մեղրագործ միջատ

14. (բայ) մէկուն կամ բանի մը մասին, չարախօսել, վատաբանել

16. (բայ) արցունք թափել, արտասուել

17. (գոյ) միւռոնով նուիրագործում

18. (գոյ) թանկարժէք

19. (բայ)

(հայերէն sudoku)

15. (գոյ) պատկեռասփիւռ, հեռուստացոյց

Down

1. (գոյ) որթատունկի

2. (բայ) սուրբ աստիճան

4. (յատուկ անուն) նորօծ վարդապետ՝

քահանայ ________ (ազգանուն)

7. (գոյ) մեղուներու շինած նեկտարը

8. (գոյ) դպրոցներու բացման շրջան

10. (բայ) ճաշակել, սնունդ առնել

11. (գոյ) այս խաղը

12. (գոյ) փոքր ոտք (մանուկի)

13. (գոյ) մեղրագործ միջատ

16. (բայ) արցունք թափել, արտասուել

Planning Ahead Is Simple Exclusively for The Armenian Community. Customized Options and Plans available to suit each Family’s Individual Needs.

In Tribute to Armenia, as symbolized by Holy Mt. Ararat, and to the Armenian people who were the first to embrace and adopt Christianity as a State religion in 301, and the first nation to be crucified in 19151923 falling victim to the first genocide of the 20th century. For the glory of a reborn free Armenia world-wide, whose generations of sons and daughters continue to believe in justice world-wide.

1T3 Contact: Tracy Burton Tel: 416-293-5211 Email: directors@ogdenfh.com