A life of language, learning, and legacy: A conversation with Order of Cananda inductee

Stacy Churchill

By Rupen Janbazian

“I never expected such an honour,” says Stacy Churchill, reflecting on his appointment as a Member of the Order of Canada. But for generations of minority Francophones in Canada, his decadeslong commitment to linguistic rights and education has been nothing short of transformative. From advising UNESCO and UNICEF to shaping policies that led to the creation of French-language universities in Ontario, Churchill’s career has been defined by a relentless pursuit of justice for linguistic minorities.

Beyond academia, Stacy’s deep ties to the Armenian community—fostered through his marriage to historian Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill—have given him a unique perspective on cultural preservation.

In this interview, he discusses his journey, his work, and his belief that preserving heritage is not about nostalgia but about ensuring communities continue to thrive in the future. ***

Rupen Janbazian: First off, congratulations are in order; being appointed a Member of the Order of Canada is a remarkable achievement. What does this honour mean to you personally and professionally? Looking back on your long career, which of your many contributions are you most proud of?

Stacy Churchill: Thanks for your kind words. I never expected such an honour. For me, the award is really a salute to generations of minority Francophones in Canada outside Quebec. They have struggled for more than a century to get their own French-language schools, colleges, and universities. They and their allies across Canada have used my research (and court testimony) in very successful political battles, administrative tussles, and court challenges. The most visible outcomes are, first, key court decisions that used my research and testimony to uphold minority constitutional rights and, second, the creation of French-language higher education institutions in Ontario–colleges La Cité and Collège Boréal with programs across the province and the very new Université de l’Ontario Français, based in Toronto. Less well-known are a host of policy and program changes at both federal and provincial levels. The goal was always to provide better

education and to help Francophone communities thrive. A career high point was to be called by the Canadian government as one of two expert witnesses in parliamentary hearings that led to the creation of the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Janbazian: Beyond your work in Canada, you’ve advised governments and collaborated with organizations like UNESCO and UNICEF on language policy and education. Where did your passion for linguistic and cultural rights first take root? And in your view, what are the most pressing challenges facing this field today?

Churchill: That’s a good question, you know. One that I ask myself sometimes. It started in my early childhood. I grew up in the United States during the Jim Crowe era. My mother had me, as a fiveyear-old, play with African American kids. This was in rural Texas in 1944–all to the horror of our neighbours and relatives. A few years later, Mother even got my grandfather to take me to a Baptist church with an all-Black congregation. He could not enter, but the pastor took me to sit in the front row. The fantastic experience of their singing was more powerful than any sermon. Then in high school in Denver, I got interested in learning Spanish, got to know some of the local Hispanic Americans, and was disgusted by segregation in the center of the city towards people whose ancestors lived in Colorado centuries before the US took over. I even published issues of a bilingual newspaper in my senior year.

As it turned out, my doctoral thesis and first book were about a minority, the East Karelians, in Russia during the period of the Soviet revolution. When I immigrated to Canada – officially bilingual Canada – in 1967, reality came as a shock. I read the volumes of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism to discover that minority French-speaking Canadians were still being denied basic educational rights. That lit my fuse. As a senior administrator of the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, I later helped organize a secret Canada-wide consultation meeting for the feds to give advice on how Trudeau should reply to the volume entitled The Cultural Contribution of the Other Ethnic Groups. The response was officially ‘a policy

of multiculturalism within a bilingual framework.’ “Although there are two official languages, there is no official culture,” Trudeau told the House of Commons.

Janbazian: Over the years, you’ve become a familiar face at Armenian events in Toronto, from gatherings at St. Mary’s Church to broader community celebrations. Many in the community see you as an ‘honorary Armenian,’ and of course, your wife, Professor Isabel Kaprielian-Churchill, has played a central role in shaping your connection to Armenian culture. What first drew you to the Armenian community, and what does being part of it mean to you on a personal level?

Churchill: Well it all started when crosses were placed on our heads and Srpazan Khajag Hagopian, then still vartabed Khajag, blessed the marriage between Isabel Kaprielian and myself. Decades later, being in an Armenian gathering or home has become an extension of our everyday life. All of the seven grandkids – yes, count them – have all grown up in homes where their parents validated their Armenian identity. As for me, it was a tough slog at first, learning the aip-pen-kim, attending classes taught by an ARS engerouhi Alice

Chitilian at a local high school here, later classes at the École des langues orientales in Paris, gradually building a vocabulary and studying grammar from a book by the late French linguist Feydit. Frankly, it’s all my wife’s doing, and now neither our marriage nor my identity would be complete without the Armenian community as an extension of our lives.

Janbazian: And how has Professor Isabel’s heritage and work shaped your understanding of Armenianness? How do you both approach engaging with Armenian culture and traditions as a couple?

Churchill: Let’s start with the important. Working with Isabel has been a blast. We sit down one day with someone, and Isabel immediately begins discussing families, kids, ancestors, and what have you – sort of an encyclopedia of memories that only she still possesses about the Armenian communities in both Ontario and all of Canada. And I have been able to learn infinite amounts from reading her book drafts and discussing her research findings.

We are incredibly fortunate to have led lives as researchers that permitted us to see the Armenian presence in different environments. Isabel’s research has led us to many parts of the world, where

I sometimes help by photographing or copying archive items. I mean, really, to all parts of the world. Not just (just?)

London (Public Records Office) and Paris (Bibliothèque Nubar and Bibliothèque Nationale), but the Azkain Arkhiv in Yerevan, the library on the island in Venice, convents in Rome and the mountains of Lebanon, the League of Nations in Geneva, a personal library in Aleppo, and churches (now severely damaged) also in Aleppo or the Archives of the Catholicosate in Antelias, Lebanon. We have looked for Armenian graves in cemeteries in Bulgaria and Syria, visited churches in Italy, dined at community centres in Buenos Aires and California, stood in the beauty of ancient churches in Artsakh. A bus took us to Erzerum, Isabel’s mother’s birthplace, then up a long valley to see the village of Djerman (now Yedisu) in Anatolia where her father was born. We stopped to look at the field overlooking the Euphrates where his first family and a clan of 70 persons were driven over cliffs, leaving one survivor who later came to join him in Hamilton, Ontario.

But it’s all very personal. Once Isabel was invited to speak at a great conference in Yerevan. In the lobby of our hotel, we met a lady she did not know. With two questions Isabel located the lady’s home village in historic Armenia and was telling stories about her family ancestors and relatives, stories that the woman had never heard. A year later, while Isabel accompanied me on a mission for Unesco, we arrived in Damascus. A chat in the nearby souk and behold: That evening we were seated at a rooftop table for dinner with about 20 Armeniansministers, military and what have you. Our Armenian host drove us to the hotel in a car that had served a deposed president. But there is also the hallowed past. Only a few years ago, Srpazan Papken Tcharian allowed us and others to accompany him on a pilgrimage to ancient Armenian sites in Iran, learning about their rich history, meeting with Iranian Armenians and learning of their distinctive outlook.

So what does it all add up to? We have given every encouragement to the grandkids to understand their heritage. Both of us grew up in North America, so that we are fully part of that culture too. It is not a matter of trying to reject the environment of the New World as a means of respect for the old traditions. Rather it is honoring the old by participating in helping the community revive and remember the good, remember all the worthy parts of Armenianness that transcend the events of the genocide. The struggle for recognition is part of it, but

the strongest goal is preparation for the future of Armenianness in a diaspora that is a dynamic extension of Armenia, past and present, across the world.

After the Azeri blockades in the nineties, while Yerevan still shivered in the cold, Unesco invited me to visit and assist the country in creating its first national education policy. In a first visit, I worked with a team from an education research organization under the akademi nauk to help them define a program. Months later I returned for a national meeting with representatives of the government and all the country’s educational institutions. The team then presented their report, the first educational policy statement of the reborn Republic. At the request of UNICEF, I returned later for two visits to organize the first ever study of the effects of the crisis on the lives and education of the youngsters in school during the years of great privation. We did uncensored interviews of students, teachers, and parents, a first in Armenia. The title of my report, “A Generation At Risk,” summarizes our conclusions.

Janbazian: Finally, what do you see as the most important lessons from your work, and how can younger generations continue to preserve culture and contribute to their communities?

Churchill: For many years, I was an adviser and frequent contributor to the Unesco Associated Schools Project. One of the lessons I learned from visiting schools and talking with officials, teachers and students in different places – North Africa, sub-Sharan Africa, the Caribbean, Latin America, Philippines, Japan, China, Thailand, India and the Middle East – is the universality of young people’s passion for a better, more peaceful world. There is a reservoir of good will in all children and youngsters, including the hope for change from the quarrels of the past. The key is that willing adults – teachers, parents, community members – must stop, reflect, and decide to make the effort to look for ways of engaging children and youth in activities that relate their hopes to making positive changes in their communities. Throughout the Armenian community in Toronto, I regularly see many outstanding examples of such efforts by a wide range of volunteers, a living example of how to put in action such a spirit of service and positive change.

Janbazian: Any parting words for our readers—perhaps a message of encouragement, advice, or thoughts on the importance of community and cultural heritage?

Churchill: One can take a page from our indigenous peoples, who rely upon their older members – the ‘elders’ – to teach the young. First Nations children learn beading, survival skills, and hunting from elders. What parts of the Armenian past should you/we teach? Tserakords from Marash or Aintab? Metalwork and jewelry? The music of Komidas, yes, but also the songs and dances of the many diasporas – from tangos of Argentinian Armenians to hillbilly imitations from Detroit or Fresno.

Positive change implies that young people should learn to view their own community – ethnic, religious, social class – as part of a larger whole. Service to the Armenian community in Canada should pursue two goals: Of course, projects are needed to help other Armenians, but that is not enough. Young Armenian-Canadians should be brought up to be leaders, examples of how a small group can make a difference not only for their friends, but also for the rest of our Canadian society.

As for their family life, young people should be taught reality: the likelihood of marrying a non-Armenian forces them, their families, and their community

to make a choice, even if the choice is to avoid a decision. One can pretend that there is nothing to do or to decide; ignoring it means accepting that the community will likely die or wither in two generations. OR they can imitate other families that welcome the nonArmenian groom or bride, bring him or her inside the Armenian tent, cover them with attention and help them to understand what history, culture and tradition means. We can make special efforts and designate volunteers – both older people and young students – to contact and help newcomer odars know they are always invited, to help them enjoy and feel always welcomed in community activities. My first lessons of Armenian with Alice Chitilian were crucial, and they involved her volunteering her time in addition to holding a job and being a wife and mother. But remember the children above all. Help them to learn Armenian, even just the rudiments, no matter what the usual excuses for not really bothering. Let’s keep Armenianness alive! ֎

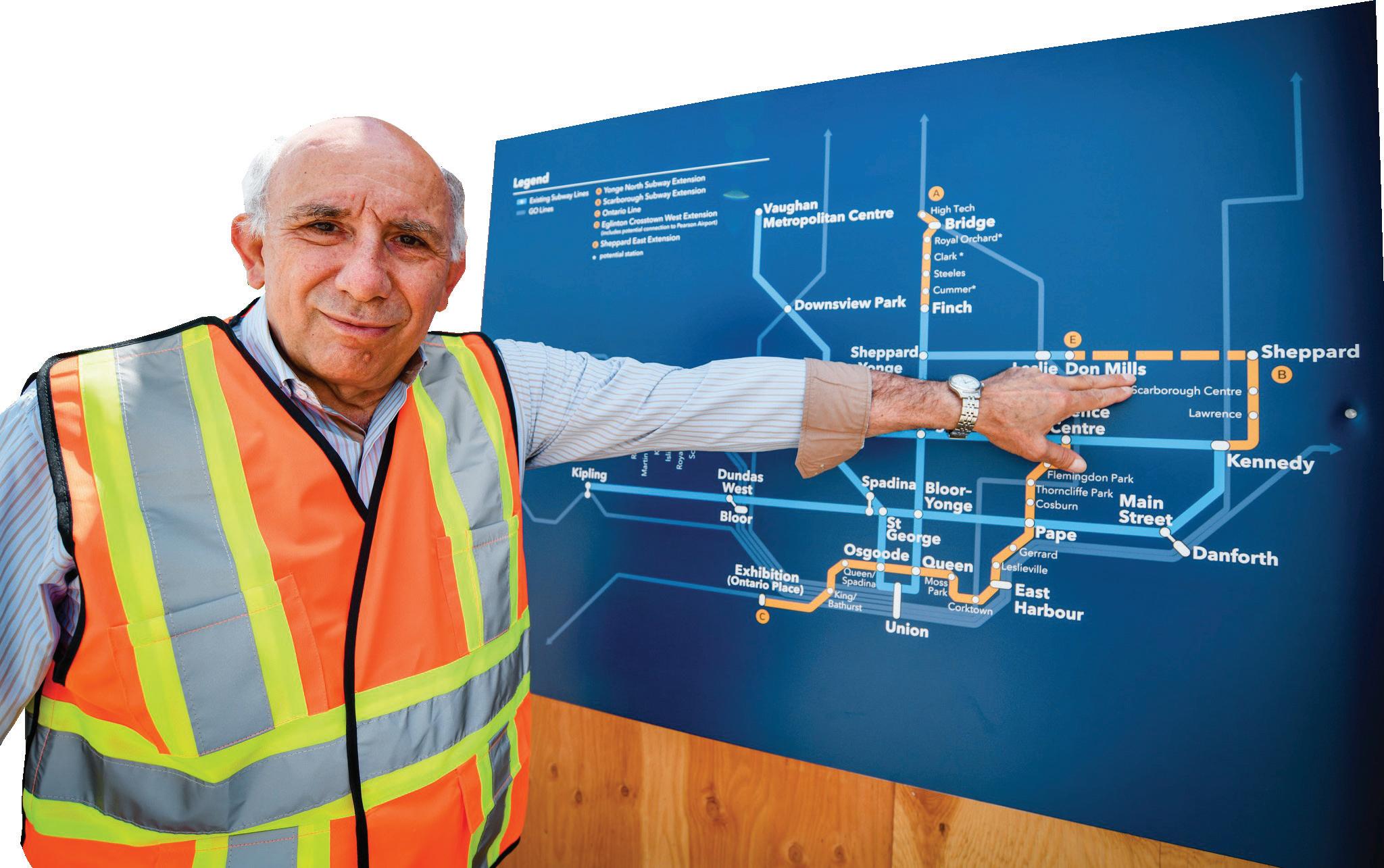

Photo: (opposite page) Stacy and Isabel at St. Stepanos monastery, northwest Iran, 2017.

գրչանունով Վահան Տէրեան, քնարերգու,

մանկութեան: Հաւատով լեցուն քու հոգին բարի,

We regret to inform you Rupen Khajag

This is not happening. This was never here.

No, you must be mistaken. We checked the records. Nothing was found.

A church bell does not ring.

A house does not burn.

A road does not vanish.

A name does not fade.

A mother does not carry her child across a border that does not exist.

A child does not drive seven souls through a war that does not happen.

A land that never was is now confirmed to be nothing at all.

We regret to inform you:

The past is no longer available. The present is under revision.

The future has been reassigned. For further inquiries, please contact no one. There is no one left to answer.

THE NAGHASH ENSEMBLE OF ARMENIA

March 29, 2025 • 8 pm

“Unmistakably Armenian, but out of this world.” – Armenisch-Deutsche Korrespondenz

The Museum’s Performing Arts programming is generously supported by the Nanji Family Foundation.

For tickets, scan the QR code or visit agakhanmuseum.org

1. (գոյ.) հունտ,

2. (գոյ.)

3. (գոյ.) մատղաշ

4. (գոյ.)

8. (գոյ., ածական) ոչ պահպանողական

10. (գոյ.) երեսփոխանական

13. (անուն) համոյթ, որ այս ամիս Թորոնթօ կը վերադառնայ (էջ՝ 10)

15. (գոյ.) ընտրող

17. (գոյ.) ընտրութեան

5. (գոյ.) ընտրութեան համար մղուած

6. (գոյ.) ընձիւղ, բողբոջ

7. (գոյ.) տարուան առաջին եղանակը, պատանութիւն

9. (գոյ.) երկրի վարչա-քաղաքական ստորաբաժանում, հողամաս

11. (գոյ.) արտ, գետին, ցամաք, կալուած

12. (գոյ.) բացուած կոկոն. (ածական) թարմ, մատաղ, երիտասարդ

14. (բայ) սերմանել, սփռել, սրսկել (ջուր)

16. (գոյ., ածական) աւանդապաշտ, հինի կողմնակից

18. (գոյ.) Ժողովուրդէն ընտրուած պետական

19. (գոյ.) քուէարկութեան

20th anniversary! (answers on pg. 18) Ուղղահայեաց

Junior problem

Anabel works for a financial company, where her current monthly salary for January is $2,026. Her employer has offered to increase her salary by $66 each month, with each raise applied to the previous month's salary. What will be Anabel's total earnings over exactly two years? a) $66,564 b) $65,184 c) $66,012 d) $67,392 e) $64,356 f) $66,840

(crossword)

Senior problem

Vaheh is thinking of two positive integers, A and B, which are in the ratio 4:7. If he subtracts 6 from both numbers, the resulting values are in the ratio 1:2. What is the sum of A + B?

Armen’s Math Corner