45 years at 45 Hallcrown

14 յունիս 1979-ին։ Վերջին չորսուկէս դարերուն

Հայ կեդրոնը դարձած է թորոնթոհայ համայնքին բաբախող

Last month, we proudly celebrated the 45th anniversary of the Armenian Community Centre of Toronto’s official opening at 45 Hallcrown Place on June 14, 1979. This milestone marked 45 years of being the vibrant heart of the Armenian community of Toronto!

Before settling at its current home, the Armenian Community Centre was located on Dupont Street. Over the past four and a half decades, Hallcrown Place has become a cherished space where our community gathers to celebrate heritage, faith, and unity. Housing the ARS Armenian Private School, the St. Mary Armenian Apostolic Church, and the Armenian Community Centre (and don't forget the Armenian Youth Centre next door!), 45 Hallcrown Place stands as a testament to our shared commitment to cultural preservation and community spirit.

To mark this special occasion, we present

('The opening ceremonies of the Armenian Community Centre of Toronto'), published in the Hairenik Daily’s (now Hairenik Weekly) July 27, 1979 issue (in Armenian) and 'Toronto opens new centre: $250,000 raised at opening banquet' from the front page of the Armenian Weekly's June 23, 1979, issue.

CASSANDRA HEALTH CENTRE

ARMENIAN

MEDICAL CENTRE & PHARMACY

Dr. Rupert Abdalian Gastroenteology

Dr. Mari Marinosyan

Family Physician

Dr. Omayma Fouda

Family Physician

Dr. I. Manhas

Family Physician

Dr. Virgil Huang

Pediatrician

Dr. M. Seifollahi

Family Physician

Dr. M. Teitelbaum

Family Physician

Physioworx Physiotherapy

City of Markham to unveil monument celebrating Sara Corning’s humanitarian impact

Born in Nova Scotia in 1872, Sara Corning’s life was marked by extraordinary acts of bravery and humanitarianism. From her efforts in aiding the victims of the Halifax Explosion to rescuing Armenian and Greek orphans in the aftermath of World War I, Corning’s story is one of unwavering dedication to serving others in their most desperate times of need. Now, 55 years after the Canadian humanitarian’s death, a monument celebrating her life’s work and selfless accomplishments will be unveiled in Markham.

On Saturday, July 13, 2024, the City of Markham, in collaboration with the Armenian National Committee of Toronto (ANCT), the Armenian Community Centre of Toronto, and the Sara Corning Centre for Genocide Education, will unveil a monument in her honour at the Forest of Hope in Ashton Meadows Park. The ceremony, starting at 3 p.m., will celebrate Corning’s remarkable life and the enduring bond between the Armenian and Canadian communities. It will highlight the shared values of compassion, resilience, and mutual respect.

Sara Corning’s courage and compassion were most prominently displayed during the Armenian Genocide, where she played a crucial role in rescuing and caring for thousands of Armenian and Greek orphans. Her tireless efforts earned her international recognition, including the Silver Cross Medal of the Order of the Saviour, awarded by King George II of Greece in 1923. The new monument in Markham will stand as a lasting tribute to her invaluable contributions and the importance of humanitarian action in times of adversity.

The ongoing struggles faced by Armenians today highlight the relevance of Sara Corning’s legacy. The 2020 war in Artsakh and continued humanitarian challenges have underscored the resilience and strength of the Armenian community. Families have been torn apart, homes destroyed, and lives upended by conflict and violence. Yet, despite these trials, the spirit of compassion within the Armenian community remains unbroken.

Sara Corning’s legacy inspires action with empathy and solidarity in addressing modern challenges. Her life demonstrates that, even in the darkest times, individuals possess the power to make a difference. The monument symbolizes a commitment to fostering a world where compassion and understanding triumph over indifference and division.

“We extend our heartfelt gratitude to Mayor Frank Scarpitti, the Markham City Council, the Armenian Community Centre of Toronto, and all those who have worked tirelessly to bring this monument to fruition. We would also like to thank the artist and sculptor, Mr. Garen Bedrossian. Your efforts ensure that Sara Corning’s legacy will continue to inspire future generations,” the ANCT, Armenian Community Centre of Toronto, and the Sara Corning Centre for Genocide Education, an organization named in her honour, said in a statement.

In 2016, the City of Markham designated a section of Ashton Meadows Park as the Forest of Hope in honour of the centenary of the Armenian Genocide. This area sym-

bolizes remembrance, resilience, and the enduring spirit of those affected by historical injustices. Designed by architect Mr. Haig Seferian, the Forest of Hope is a place of reflection and commemoration. Commemorating Sara Corning’s life and legacy calls for building upon her spirit of service and empathy, continuing her commitment to a more compassionate and just world.

Community members are invited to join the celebration of Sara Corning’s life and legacy. The event will take place on Saturday, July 13, 2024, beginning at 3 p.m. at the Forest of Hope in Ashton Meadows Park, located at 200 Calvert Drive in Markham. This gathering will honour Sara Corning’s remarkable contributions and reflect on her enduring impact. Standing together in solidarity honours her memory and carries forward her spirit of service in all aspects of life. ֎

մասին: Նուշիկ Փափազեան – Այո,

(The Hospital for Sick Children)

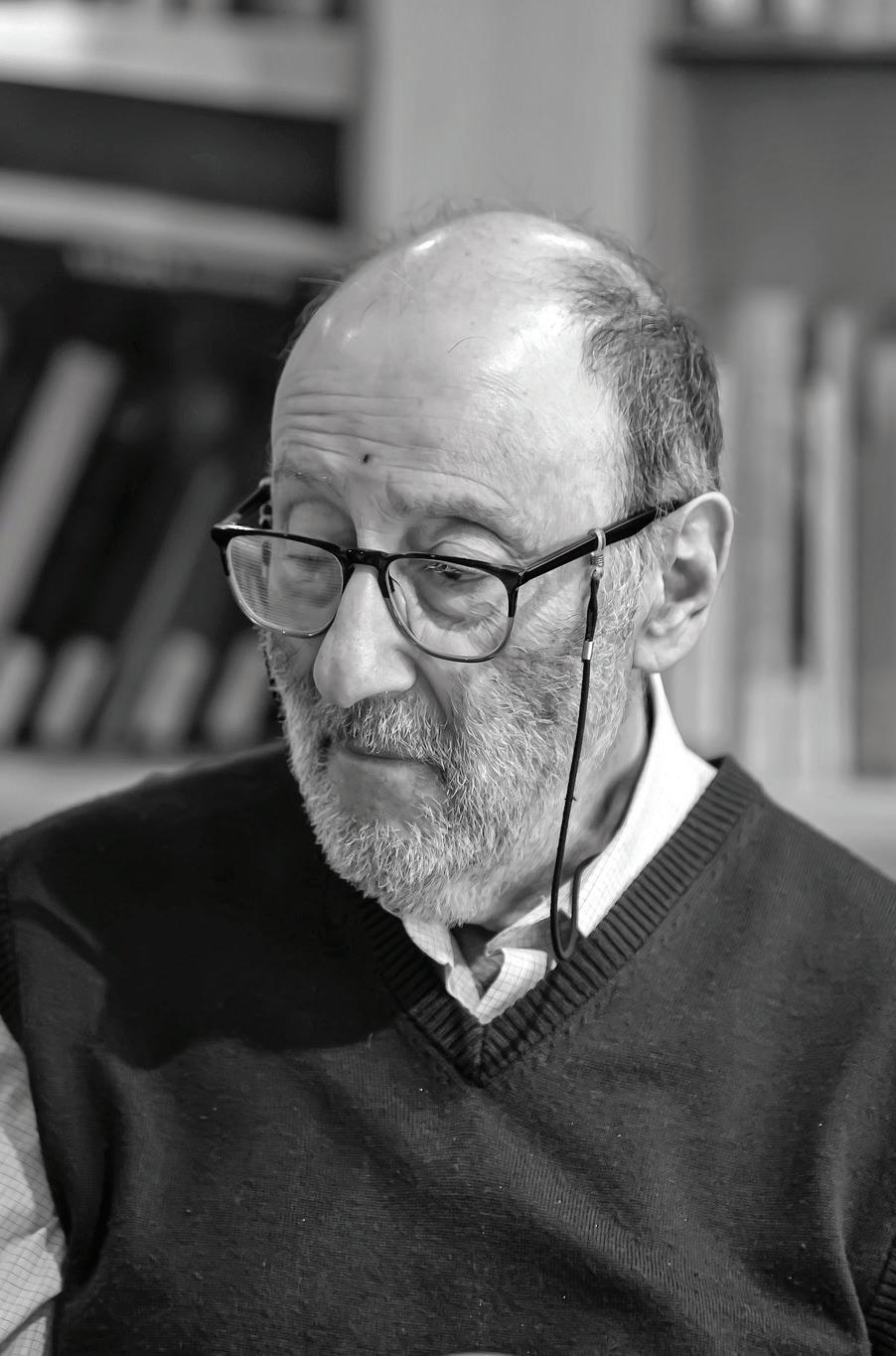

Reclaiming heritage: Professor Lorne Shirinian’s Armenian journey

By Hrad Poladian

"At first glance, it may appear that this young Armenian boy abandoned his heritage in order to better fit into a very English society. The issue is a lot more complex than it might seem," reflects Professor Lorne Shirinian. Born in Toronto in 1945 to orphan survivors of the Armenian Genocide, Shirinian's journey is a tapestry of cultural reclamation and literary activism. With an academic career spanning over three decades and a prolific output of over 30 books, he has become a key figure in Armenian diaspora literature.

Professor Shirinian completed an Honours BA in French language and literature at the University of Toronto, an MA in Comparative Literature at Carleton University, and a PhD in Comparative Literature at l’Université de Montréal. He founded and edited Manna: A Review of Contemporary Poetry (1971-1974) and lived, taught, and wrote in the Montreal area for 20 years. In 1994, he moved to Kingston, Ontario, where he became a Professor in the Department of English at the Royal Military College of Canada. He retired as Professor Emeritus of English and Comparative Literature in 2010 after 35 years in the profession, returning to Toronto in 2014 to continue writing full-time.

The son of Mampre Shirinian (Boy #73) and Mariam Mazmanian (Girl #16) of the Georgetown Boys and Girls, both orphan-survivors of the Armenian Genocide, Professor Shirinian has devoted much of his life to chronicling Armenian history and raising awareness about the Genocide. He also revised, edited, and wrote the introduction to the 2009 revised edition of Jack Apramian’s book, The Georgetown Boys, published by the Zoryan Institute. From his early reluctance to embrace his heritage to becoming a dedicated chronicler of Armenian history, Professor Shirinian's life is a testament to the enduring power of identity and memory. ***

Hrad Poladian: As a young boy, you shied away from everything Armenian, which is quite evident in your writings. I would now like to take you back a few years. In one of your essays on the occasion of the 50th-anniversary reunion of the Georgetown Boys, you wrote that you went unwillingly and stayed apart as an observer. But then something happened. What was it that made you affirm your Armenian identity and heritage?

Lorne Shirinian: Thank you for your question, Hrad. I grew up as an Armenian Canadian in the early fifties in Toronto. At first glance, it may appear that this young Armenian boy abandoned his heritage in order to better fit into a very English society. As I’m sure you are aware, the issue is a lot more complex than it might seem. I’m grateful for the opportunity to share with you and your readers

the twists and turns of my journey as the son of two orphan survivors of the Armenian Genocide, who, after losing everything, escaped with their lives to begin new ones first at the Georgetown Orphanage, then in Toronto. My maternal uncle arrived with the first group in 1923; my father landed in 1924; my mother came in 1927. I was born in 1945 and became the inheritor of a lot of history, much of which was tragic and dramatic.

Poladian: Can you tell us more about your childhood and the atmosphere in your home regarding your heritage?

Shirinian: As a young boy, I was certainly aware that there was something in our family background that continually weighed on everyone, something very heavy and sad. Whenever the Georgetown Boys and Girls visited us, there was always a lot of joy and laughter. Inevitably, when the coffee, tea, and cookies were served, the tone of the discussion would become sorrowful, and as personal stories of survival were retold, people would cry. I never knew the cause of this. I usually sat on the stairs where I could listen and observe everything. The language in our house was always Armenian, which I spoke until I began to go to public school at the age of six. Even as an adult, our parents spoke Armenian to each other and often to my brother George and me. After my first year of public school, I responded to them, to my regret, in English. My father taught Armenian to his friends and tried his best to teach me. I recall sitting at his desk and writing ayp, pen, kim . However, there were too many distractions and sports to play with my friends.

Poladian: Despite these distractions, how did your father's influence and the resources at home shape your understanding of Armenian culture and history?

Shirinian: To counterbalance this gap in my knowledge of the Armenian language, I had access to the large collection of books on Armenian history and literature my father had collected, as well as Armenian music. I still get emotional when I recall as a young boy playing the record of Armenag Shah Mouradian singing the songs of Gomidas, Kele Kele , in particular. As teenagers, we knew about the Armenian Genocide and felt there was something profoundly different about us that we shared with other Armenians around the world. The mother of one of my best friends always reminded me that when she was growing up, she remembered her mother telling her to eat all her food; “Remember the starving Armenians,” she was told.

Poladian: Did you ever truly distance yourself

Shirinian at the Hamazkayin Toronto H. Manougian Library, 2024 (Photo: JH Kuzuian)

from your Armenian heritage, or was it always present in some form?

Shirinian: To answer your question honestly, I never abandoned my Armenian heritage. As a teenager, my attention focused on sports, then in university on my studies. My brother and I were still involved on the periphery of the Armenian community; for example, Father Tashjian, who was a family friend, listened to our idea of opening a bookstore at Holy Trinity Church on Woodlawn Avenue. The parish council agreed, and we brought in many Armenian books in English and records for community members, which we sold after the service on Sundays. At the end of the first year, we returned the money from sales to the church, five thousand dollars. Not bad for the early sixties. As I became friends with many Armenian poets who wrote in English, I organized a poetry reading at the church which over one hundred community members attended. There was a thirst for the arts in the community at that time. English was our outlet. The idea of hybridity was not understood nor accepted yet.

Poladian: How did the arrival of Armenians from the Middle East in the early 1970s impact the local community and your sense of identity?

Shirinian: In the early 1970s, the local community welcomed many Armenians from the Middle East, especially from Lebanon. They were part of Armenian communities in which their members could go to school in Armenian and live a good part of their lives in Armenian. That wasn’t possible here at that time. Being Armenian meant speaking Armenian. That’s understandable. Living in the North American diaspora back then was complex in a different way. For many years I wore a coin from

the era of Tigranes the Great around my neck. I was projecting my Armenianness. Nevertheless, not being able to communicate in Armenian undercut what I was trying to be.

Poladian: What academic and literary influences helped you reconcile your identity and focus your career on Armenian issues?

Shirinian: During my MA year at Carleton University in Ottawa (1971-72), I spent a lot of time reading the work of the Martiniquan poet Aimé Césaire (1913-2008), particularly his long poem cycle, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (1939), which was a major text of anti-colonial activism and a major force for pan-African culture. He and Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first president of Sénégal, were the major exponents of négritude, a movement which sought to reclaim the value of blackness and African culture. At the same time, I was reading as much Armenian history and Armenian literature in English and in translation as possible. There wasn’t much available at that time, and what came from Soviet Armenia was highly questionable. In 1972, my first book of poetry, Manuscript, Tom Sturgess, was published. I wanted to write. I wanted to express my Arménitude . Armenia was a colony of Russia. Armenians around the world wanted an independent Armenia that would represent us and be a home. The connection was clear. I decided that my writing career would focus on reclaiming Armenian

history. Because I was not able to work in Armenian, I wrote about what I knew, the Genocide, and the after-effects on those who survived and their sons and daughters.

Poladian: Was there a specific moment when you decided to dedicate your life to writing about Armenian issues?

Shirinian: That was the moment in 1972 when I thought that I could try to do the same for those of us in the North American diaspora that Césaire did for his people in 1939. Write. Not only to write but to take direct action. I marched many times on April 24 and spoke about Armenian diaspora literature written in English and the Genocide at many conferences in North America and Britain. My poems were translated into French and Armenian. In 1974, I contacted the Armenian American poets I knew who were mostly from the second generation as I was and edited and published Armenian North American Poetry: An Anthology (1974). It was the first such volume to gather our poems from the North American diaspora.

Poladian: Your activism played a significant role in the Canadian government's recognition of the Armenian Genocide. Can you share some details about this journey?

Shirinian: My activism continued. In 2001-02, I, along with my friend and colleague, Alan White -

horn, visited MPs and Senators in Ottawa to tell them the story of the Genocide and the Georgetown Boys and Girls. Through continued pressure from the entire community, the federal government finally recognized the Genocide on April 25, 2004. The key moment, Hrad, that changed my life and direction was understanding that I could dedicate myself through writing to Armenian subjects. Almost all my work since then has been to raise the consciousness of our fellow citizens and others about the Genocide, the ongoing trauma, and the depth of Armenian diaspora literature written in English. My doctoral thesis developed a theoretical and critical framework for understanding Armenian literary texts in English and French as Armenian diaspora literature. In addition, I had hoped that through my example as one who lives on the edge of the community and understands and speaks only a little Armenian, I can still claim that I am an Armenian writer whose works have resonance with Armenians.

Poladian: Professor, I thank you for this interview. In conclusion, do you have a message for the young Armenian youths of Canada?

Shirinian: We all live in history. Make your lives important and relevant, not only for yourselves and those around you, but for those who will follow you. Find your voice. Find your path. Remember the long and rich heritage of which you are a part. ֎

4. (անուն) բոյս՝

6. (գոյ.)

8.

11.

ան աշխարհի՝ քաղցրահամ ջուր ունեցող 2-րդ բարձրադիր լիճն է

12. (գոյ.) օդափոխութեան վայր

14. (գոյ.) սաւառնակ, ինքնաթիռ

15. (անուն) Այլակերպութեան կամ

17. (գոյ.)

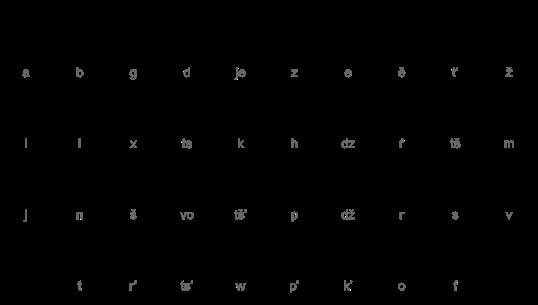

Խաչ-բառ

Crossword

1. (գոյ.)

2. (գոյ.) արտ, գետին,

3. (գոյ.) միրգ, բերք, արդիւնք

5. (գոյ.) լեռ մագլցող՝ մարզանքի

7. (գոյ.) սառնանուշ, սառած անուշ սերով՝ պտղահոյզով եւլն.

10. (գոյ.)սկաուտական Ճամբար, վրան լարելը

13. (գոյ.) մանր, փոշիացած խիճ

16. (գոյ.) երկնային աստղ, արեգակ , կեանք

18. (գոյ.) բարձունքէ վար թափող ջուր, հոսանք, քարավազ

Junior problem

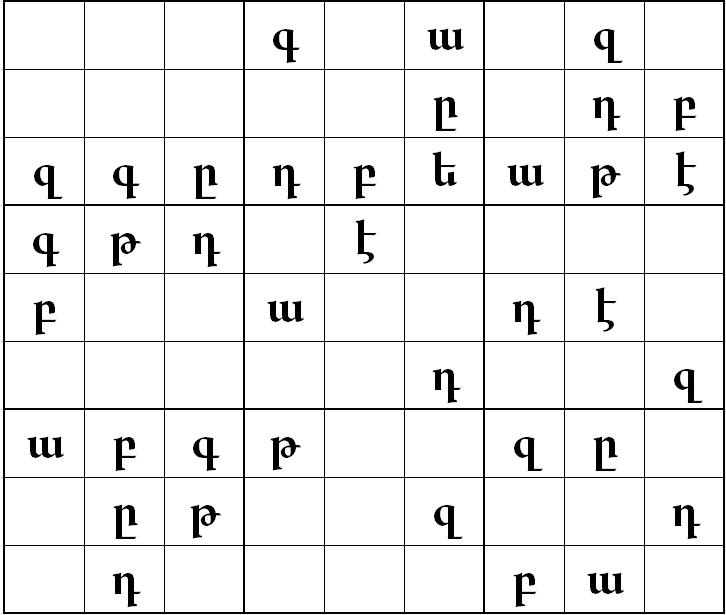

The Armenian alphabet was created around 405 AD by Mesrop Mashtots, an Armenian linguist and ecclesiastical leader. The alphabet consists of 38 letters, designed specifically to suit the phonetics of the Armenian language, with 31 consonants and seven vowels. This writing system has played a crucial role in preserving Armenian literature and culture over the centuries. Assume that the following pattern of Armenian letters continues.

Following this pattern, how many times does the letter

appear?

Across

Down

1. (գոյ.) օտար երկիր պտտող, օտարաշրջիկ, թուրիստ

2. (գոյ.) արտ, գետին, ցամաք, կալուած

3. (գոյ.) միրգ, բերք, արդիւնք

5. (գոյ.) լեռ մագլցող՝ մարզանքի համար

7. (գոյ.) սառնանուշ, սառած անուշ սերով՝ պտղահոյզով եւլն.

10. (գոյ.)սկաուտական Ճամբար,

Senior problem

If New Year's Day (January 1st) in a leap year is a Tuesday, on what day of the week does Canada Day (July 1st) fall?