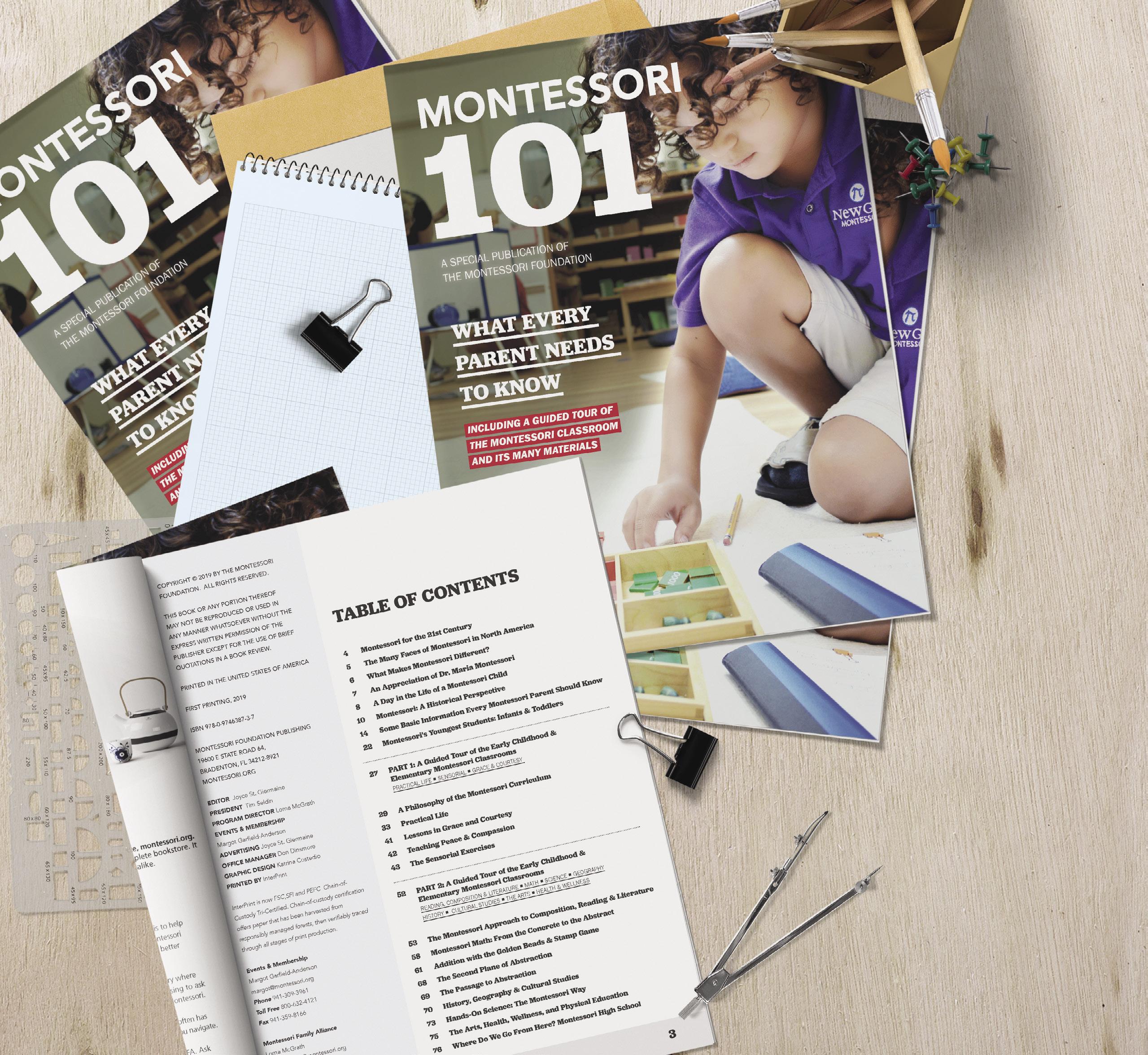

Montessori 101: What Every Parent Needs to Know

This 80-page full-color publication is a wonderful resource for anyone seeking to demystify Montessori. It addresses topics such as the history and philosophy of Montessori; offers a guided tour of the Montessori classroom; and serves as an illustrated guide to dozens of wonderful Montessori materials. This mini-encylopedia of Montessori is newly redesigned and contains new sections on Infant/Toddler and Montessori Secondary programs. It is a must-have resource for anyone interested in Montessori, and one that parents will surely refer to throughout their child’s Montessori experience.

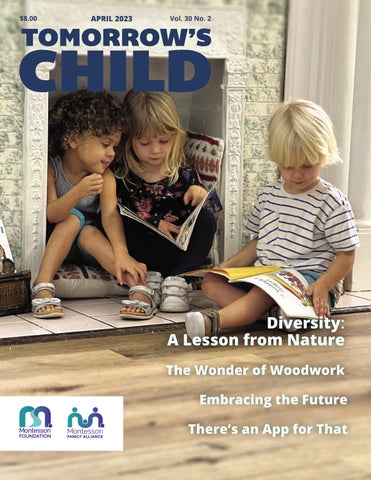

Tomorrow’s Child (ISSN 10716246), published four times a year, is the official magazine of The Montessori Foundation, a non-profit organization. The opinions expressed in Tomorrow’s Child editorials, columns, and features are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the magazine or The Montessori Foundation. Acceptance of advertising does not represent the Foundation’s endorsement of any product or service.

It is policy of The Montessori Foundation, a non-profit organization, to encourage support for the organization by discounting the sale of bulk order shipments of Tomorrow’s Child in order that schools may make the magazine available to their families. The Montessori Foundation does NOT grant permission to reprint material from Tomorrow’s Child in any other form (book, newsletter, journals). Copies of this issue or back issues are available for purchase through our online bookstore: montessori.org. For School Group Memberships, call 800-6555843 (toll free), or place your order at montessori.org. The Montessori Foundation does not provide refunds for canceled School Group Memberships.

Send all correspondence to:

The Montessori Foundation | 19600 E State Road 64, Bradenton, FL 34212-8921 MONTESSORI.ORG

EDITOR Joyce St. Giermaine

PRESIDENT Tim Seldin

PROGRAM DIRECTOR Lorna McGrath

EVENTS & MEMBERSHIP Kristi Antczak

DISPLAY ADVERTISING Joyce St. Giermaine

BOOKKEEPER Don Dinsmore

PRINTED BY InterPrint

Note: InterPrint is now FSC,SFI and PEFC Chain-of-Custody Tri-Certified. Chain-of-custody certification offers paper that has been harvested from responsibly managed forests, then verifiably traced through all stages of print production

Workshops, IMC Memberships, Past Issues & Orders or Questions about an Order

Phone: 941-309-3961/Toll Free: 800-632-4121 info@montessori.org

Conference Coordinator George Markham georgemarkham@montessori.org

Subscriptions, Bookkeeping, & Classified Ads

Don Dinsmore

Phone: 941-729-9565/800-655-5843

Fax: 941-745-3111 dondinsmore@montessori.org

Display Advertising Don Dinsmore

Phone: 941-729-9565/Fax: 941-745-3111 dondinsmore@montessori.org

Montessori Family Alliance Lorna McGrath Phone: 941-729-9565/800-655-5843 lornamcgrath@montessori.org

Executive Director of the IMC Kathy Leitch Phone: 941-729-9565/800-655-5843 kathyleitch@montessori.org

Director of Parenting Education Cheryl Allen cherylallen@montessori.org

Senior Consultant Tanya Ryskind, JD tanyaryskind@montessori.org

Senior Consultant Robin Howe, EdD robinhowe@montessori.org

“Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.”

— ARISTOTLE

In crossing an immense stretch of desert in Arizona, if one was hunting and searching those very arid acres, attempting to quench a thirst for inspiration, answers, and enlightenment, the desert is not a place to find such an oasis, a fertile spot, or place to nourish your soul and bloom strong. At first glance, the desert might look hot, dry, and lifeless; nevertheless, on deeper inspection, one can see that within the seemingly endless desert there are numerous ecosystems and plant communities living and thriving together. Nature has a way of creating whole systems filled with abundance and diverse life. These systems are based on interdependent relationships, where resources are regularly exchanged because it is both more effective, and it allows them to contribute to the health of the whole system.

Nature is one of our greatest teachers. It teaches us that there is another way of living and working together, one that is not based on scarcity and fear but on abundance and generosity. It teaches us that we need each other to survive. As healthy ecosystems evolve in nature, they become more diverse. This diversity creates more resources, not less, in a community. So, what is it about differences that threatens us? Is it because being a part of a group identity meets our fundamental needs: safety (survival), as well as a sense of belonging? Nature finds ways to work together to help systems regenerate and create conditions for sustainable life. Nature counts on diversity and rewards cooperative, interdependent relationships, showing us that diverse systems are more resilient.

Conservationist Eleanor O’Hanlon has seen this theory in action repeatedly through her work. “The patterns of living relationships are always in motion as the animals test and are tested by the terrain, the weather, and each other,” she explains. “Through the generations, they refine their capac-

by Cassi Mackey, M.Ed.ity to innovate, adapt, and thrive together as one community, interdependent, and whole. To be what they truly are, to live ardently and fully, each one requires the other. This is what’s required of us as well — a willingness to observe the patterns of relationship that give shape to the systems we inhabit and perpetuate, alongside the courage to adjust our behavior accordingly in ways that will benefit the whole.”

the teacher, who is to help life, is something far more than the learning of ideas. It includes the training of character; it is a preparation of the spirit.”

We might truly believe ourselves to be open minded and accepting, but the fact remains that we all have biases. Montessori describes how adults must systematically study themselves to be able to see a child in their purest form. It is our responsibility as

One does not, of course, need to go on a hike in the Arizona desert to see these systems in action. Just peek into Montessori classrooms. Children are encouraged to be their authentic selves and learn in ways that connect to their minds and hearts. The Montessori prepared environments are supportive learning communities that honor all, built on mutual trust and care for one another across a wide spectrum of human diversity, so they can all thrive. Montessori works from an abundance mindset, opening spaces for everyone, which makes those spaces stronger, richer, innovative, dynamic, more engaging, and more fulfilling. In turn, Montessori children tend to honor and embrace people who are different from themselves and find ways to create space for them to find their place within the group. Yet, our children can still grow to become influenced by the world around them, so that biases form and negatively affect how they treat others who may be different from them. Our part in that influence is determined by our willingness to do the work of change.

We begin with ourselves. In The Absorbent Mind, Dr. Montessori extolled that “the real preparation for education is a study of oneself. The training of

adults to examine our biases and understand where they come from. The personal biases we carry significantly influence what we teach and what we don’t teach our children about valuing differences.

Recognizing our own bias is essential as we teach our children to love themselves and value diversity. Bias is often an unconscious belief that is developed in our own upbringing and experiences and reinforced by status quo systems. If we don’t recognize the biases that we hold ourselves, we may unintentionally pass them on to our children. We need to be vigilant about always asking ourselves why we have a bias. How might we create different learning experiences for our children if we open-heartedly and open-mindedly accept that we have biases and acknowledge our biases inherently embedded in how we parent? We are all called on to do this work, so we can be prepared to teach our children.

Biases are learned. Children begin to absorb both the attitudes and biases attached to aspects of identity by family members and other significant adults in their lives. Adults can convey negative biases through gestures, body language, and facial expression. Children pick up on these non-verbal cues to form their own biases. If we, as parents, guardians, and caregivers, want to pass on lessons

Recognizingourownbiasisessentialasweteachourchildren tolovethemselvesandvaluediversity.

that emphasize acceptance and inclusion, we must be willing to live those values, through our words and our actions. To do this, we must take on the critical work of examining and addressing our own personal biases: why we developed those biases; what contributed to us having those biases; and what we might do about that inevitability within the systems around us. This work never ends.

From Learning for Justice, explore your experiences with and attitudes about differences by considering these situations and questions:

• The first time I became aware of differences was when...

• As I was growing up, my parent(s) taught me that people who were different from us were...

• As I was growing up, my parent(s) taught me that people who were like us were...

• A time I was mistreated because of my own difference was when...

• A time I mistreated someone for being different was when...

• I feel most comfortable when I am around people who...

• I feel least comfortable when I am around people who...

• The memories I have of differences in people affect my parenting by...

• How do I create a space and teach in a way that invites and encourages difference?

• How do I reinforce acceptance and the value of difference in our home?

Giving children the opportunity to look for the value in difference helps them engage in their world with curiosity, confidence, and love. It helps them better understand themselves and those around them. They learn to empathize with people who are different from them. They gain a deeper understanding of subjects and issues when looked at from multiple perspectives.

Children are remarkably good at observing differences in the world. This ability is an important de-

velopmental learning strategy. Noticing differences between people helps children construct their own social identity. According to research, children begin to take note of differences in other people as early as age two. Early childhood provides children their first introduction to human characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, race, physical ability, etc. They marvel both at the differences and at the similarities they share with others in their world. They begin to use their observations to determine how they should treat others and how others should treat them. This factoring includes how the adults around them respond to differences. It is the time when parents, guardians, and caregivers have the greatest influence on a child’s perception and attitude about differences. If we don’t help our child process their observations, they will create their own understanding of what those differences mean.

Elementary-aged children start moving past simply noticing similarities and differences among people. They begin to experience how these differences and similarities are used to either include or exclude people. Although it is uncomfortable to think about, during these years your child will likely be excluded themselves, as well as exclude someone else because of differences. While a parent’s influence still plays a critical role in how children view and respond to differences, outside sources (social media, friends, TV/internet, video games, etc.) start to compete for influence.

Once your child reaches adolescence, your opinion and advice may not be the first they seek, if they seek it at all, because they rely heavily on those outside influences. It is important that you continue to find ways to communicate with them and provide a safe space for them to share their views and opinions. The lessons, advice, opinions, and experiences you have provided about embracing differences begin to have real-world impact and consequences during these years. Open, honest conversations with adolescents is essential, to provide messages that promote a healthy self-esteem, which will encourage them to embrace differences in themselves and others. Your words are very important, but your actions are what an adolescent will remember more. They are quick to point out the incongruence between what you say and what you do.

Whether you are the parent of a 3-year-old who is curious about why a friend’s skin is brown; the parent of a 9-year-old who has been called a slur because of his religion; or the parent of a 15-yearold who snubs those outside of her social clique at school, it is helpful to have strategies to navigate these situations and conversations.

The following tips are in a resource guide from Learning for Justice called “Beyond the Golden Rule: A Parent’s Guide to Preventing and Responding to Prejudice.” The tips are designed to help you teach your children to honor the differences in themselves and in others — and to reject prejudice and intolerance.

Primary (3-6 years old)

Be honest. Don’t encourage children “not to see color” or tell children “We are all the same.” Rather, discuss differences openly and highlight diversity by choosing picture books, toys, games, and videos that feature diverse characters in positive, non-stereotypical roles.

Embrace curiosity. Be careful not to ignore or discourage your youngster’s questions about differences among people, even if the questions make you uncomfortable. Not being open to such questions sends the message that difference is negative.

Broaden choices. Be careful not to promote stereotypical gender roles, suggesting that there are certain games, sports, or activities that only girls or boys can do.

Explore family history. Talk to your child about your family heritage to encourage self-knowledge and a positive self-concept.

Lead by example. Widen your circle of friends and acquaintances to include people from different backgrounds, cultures, and experiences.

Elementary (6-12 years old)

Model it. Talking to your child about the importance of embracing difference and treating others with respect is essential, but it’s not enough. Your actions, both subtle and overt, are what they will emulate.

Acknowledge difference. Rather than teaching children that we are all the same, acknowledge the many ways people are different, and emphasize some of the positive aspects of our differences. Likewise, be honest about instances, historical and current, when people have been mistreated because of their differences. Celebrate victories of those people in overcoming this discrimination. Encourage your child to talk about what makes them different and discuss ways these differences may have helped or hurt them at times. After that, finding similarities becomes even more powerful, creating a sense of common ground.

Challenge intolerance. If your child says or does something indicating bias or prejudice, don’t meet the action with silence. Silence indicates acceptance, and a “don’t say that” is not enough. First, try to find the root of the action or comment. Then, explain why the action or comment was unacceptable.

Seize teachable moments. Look for everyday activities that can serve as springboards for discussions. Elementary children respond better to lessons that involve real-life examples than to artificially staged discussions about issues. For example, if you are watching TV together, talk about why certain groups are often portrayed in stereotypical roles and why this is a problem.

Emphasize the positive. Just as you should challenge your child’s actions if they indicate bias or prejudice, it is important to acknowledge them for behaviors that show respect and empathy for others. Catch your child treating people with kindness and dignity and let them know you noticed; also discuss why it is important.

Keep talking. Many believe that the last thing adolescents are interested in is having a conversation with parents, guardians, or caregivers; however, even if your adolescent doesn’t initiate conversation about issues of difference, find ways to bring those topics up with them. Use current issues from the news as an impetus for discussion. Ask your adolescent what they think about the issues.

Stay involved. Messages about differences exist all around your adolescent: the Internet; songs; music videos; reality shows; ads; commercials; social media; and social cliques at school. Know the social media in which your adolescent participates; take the time to listen to or watch the music and shows they enjoy; get to know their friends. Then, discuss the messages they send. Ask your adolescent about the group or groups they most identify with at school. Discuss the labels or stereotypes that are associated with such groups. When discussion is limited, some of this information can be garnered by careful observation and listening.

Live congruently. Discussing the importance of valuing difference is essential, but modeling this message is even more vital. Evaluate our own circle of friends or the beliefs you hold about certain groups of people. Do your actions match the values you discuss with your adolescent? Adolescents are more likely to be influenced by what you do rather than what you say, so it’s important that your words and actions be congruent, especially when

these actions take place at a time of great pressure or concern about the family’s well-being and the child’s future.

Broaden opportunities. It may be natural for adolescents to stick to groups they feel most comfortable with during the school day. These are often the people they identify as being most like themselves. Provide other opportunities for your teen to interact with peers from different backgrounds. Suggest volunteer, extracurricular, worship, and work opportunities that will broaden your adolescent’s social circle.

who is still creating [themselves] and therefore capable of affecting true change, perhaps even breaking out of our shared human heritage of strife and conflict, and building true peace,” she continued.

Dr. Maria Montessori believed that the path to peace, social change, and, ultimately, saving humanity is through children. The path, whether through a seemingly barren desert or any other of nature’s unexpectedly thriving biomes, can be found in the Montessori philosophy of how to educate children. The children move from respecting the materials (or resources) to respecting their classmates (or fellow denizens), from working as individuals to working with others, from voicing their opinions on peace and justice to taking action. They can become independent, self-actualized, empathetic, and compassionate members of the community (thriving elements of the natural abundance).

Encourage activism. Promote ways for your adolescent to get involved in causes they care about. No place for them to hang out with friends? Encourage them to get together with peers to lobby city officials for a teen social center or skate park. Upset about discriminatory treatment of teenagers by a storekeeper or business? Give your adolescent suggestions for writing a letter or planning a boycott. When young people know they have a voice in their community, they are empowered to help resolve issues of injustice.

Dr. Montessori was a humanitarian; her educational research and work with children are deeply rooted in serving and bettering humanity on individual, social, and global levels. She believed that the key to saving humanity lies within the child. She dreamed of a peaceful, harmonious world filled with kindness, respect, and dignity that is offered to each human being. She also knew that these beliefs and dreams mean little if the systems that hold all such ways of being are designed to actively work against providing those things for all, working for some but not others. She also knew that the only way to achieve her dream was through a new way of educating our children. “An education capable of saving humanity is no small undertaking; it involves the spiritual development of man, the enhancement of his value as an individual, and the preparation of young people to understand the times in which they live,” Dr. Montessori professed. “Our salvation is the child. For it is only the child

We are living in a time where there is a fundamental shift in how we must think about diversity. We need to let go of the notion that diversity is a threat, and we must shift to see the fundamental value and benefit of having difference, and thus abundance, in our system. Nature has proven that, to support a regenerative system, diversity is critical. It is time to learn from our 3.8-billion-year-old universe, to apply its lessons to our lives, and to model them for our children. For, only then will they be able to reap the rewards of diversity and to live in peace.

www.learningforjustice.org

Beyond the Golden Rule: A Parent’s Guide to Preventing and Responding to Prejudice

Cassi Mackey, M.Ed. is passionate about helping families create sacred spaces where love, joy, and honest connections are nurtured. Cassi has witnessed the transformational power when families engage in Montessori philosophy as an imputable practice. It is a promise of more meaningful relationships, greater depth of experience, and a broader, more compassionate view of oneself and the world. Cassi has lived, learned and taught the Montessori pedagogy for the last 30 years as a Montessori 9-12 teacher, a school principal, and consultant. She consults with and provides advice to Montessori communities and families that are intent on providing safe harbors for children. Contact Cassi via email at cassimackey11@gmail.com

Have you heard that you should use positive language with your child?

Positive language is often interpreted to mean just saying yes, yet really it means wording things in a way to offer specific guidance and tells children what to do. When we begin to consider it this way, we realize how often we tell what not to do, rather than what to do.

Positive language tells children why and how to do certain things. It is a communication strategy that avoids using the words no, don’t, and stop. When we implement this communication strategy with children, we offer specific guidance; reduce stress and fear; and boost confidence, understanding, and empowerment.

Positive language has some long-term positives:

• It respects the independence and the ability of children to manage themselves.

• It accepts the other person as an equal human being.

• It reduces triggering defiance or anxiety.

• It creates moments of collaboration, creativity, and stillness.

• It models the leadership principle that not one of us is as smart as all of us.

Consider “yes, and…” rather than simply yes or no. Find a connection with the issue: “You want the red ball your sister has. That is a fun toy.” Then help them understand your shared agreements: “In this family, we make choices from the toys that are available.” Offer a possible solution: “You could use the blue ball or play with another toy.”

Here are some “to do” phrases ready for when you need them:

Take a deep breath. Calm down.

I can see this is frustrating you. Stop crying.

It’s okay to feel sad. Don’t get upset.

Are you okay? You’re okay.

Please use a soft voice. Be quiet.

I can see you want to talk. Stop interrupting.

I can understand you better if you… Stop whining.

This article was based on a webinar titled “What Do You Want Me to Do? Telling Your Child What to Do Rather than What Not to Do,” presented in October 2022.

The Montessori Family Life Webinar series, a part of the Montessori Family Alliance and directed by Lorna McGrath, produces webinars focused on Montessori parenting topics. To join our team of Montessori experts and guests for webinars, visit news and announcements on montessori.org.

fruit of someone's imagination. In the study of history and geography, we are helpless without imagination, and when we propose to introduce the universe to the child, what but imagination can be of use to us? I consid er it a crime to present such subjects as may be noble and creative aids to the imaginative faculty in such a manner as to deny its use and, on the other hand, to require the child to memorize that which he has not been able to visualize. These subjects must be presented to touch the imagination of the child, make him enthusiastic, and then add fuel to the burning fire that has been lit." Maria Mon (p. 8)

Imagination becomes the driving force of learning. If we can spark an imaginative thought, Second-plane children can run with it. This isn't mere fantasy; it is imagin ing solutions to real problems, imagining the vastness of the universe, and imagining the past. We touch the imagination, and we open

sori, and it's the incredible power of imagination for elementary children, not younger ones. Imagination is something we often attribute to small children. During preschool years we might say, “Look at how much they pretend!” For the elementary years, society expects rote learning of concrete facts; however, as Montessori parents, we recognize that it’s quite the opposite. Young children live in a concrete world and elementary children have boundless imagination.

Maria Montessori observed that small children in the First Plane of development were created to learn and absorb everything around them. From language to their culture, the littlest children are naturally drawn to the basic realities around them. They learn about these realities through their senses. Children in the First Plane manipulate the world around them to learn.

"Touching for the younger child is what imagining is for the older one. On the former

level of the imagination." Maria Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence (p. 20)

But, once the Second Plane of development hits, the world and its possibilities explode. No longer are children limited by the experiences that they can absorb. They move into abstraction because they can imagine. They can understand things that they cannot possibly hold. They crave big, new, and grand impressions. Maria Montessori goes so far as to call this a "sort of sensory period for the imagination." (From Childhood to Adolescence p. 22)

This is the age to give children more. It is the time to set their interests ablaze through supporting their imagination. It's not the time for just facts, just math problems, just history, or just rules. They are more than that. They are people capable of making connections, seeing the big picture, and the abstraction of all sorts of knowledge.

"Human consciousness comes into the world as a flaming ball of imagination. Everything invented by man, physical or mental, is the

for your elementary-aged child. We can't rely as much on modeling expectations we want to see; we can't hope they are going to observe us and want to follow along. No, we need to harness their imagination and use it to engage our child in their learning of both our family's expectations and academic subjects.

> Introduce more fantasy in media: The second plane of development is the time to introduce fables, myths, and other fantasybased works of fiction. They love it all: big stories, other worlds, and the unreal. It all opens with incredible interest. Find your child's love and go with it.

> Consider the Great Lessons: Even if your child isn't attending a Montessori school, opening the world to elementary-aged children through these incredible stories can help unlock a love of learning. The great lessons can spark the imagination and provide context for what they are learning in school.

> Use stories to teach: Even if you must make them up, there is incredible power

in helping your child make connections through a story. For the elementary-aged child, rules, morals, social manners, and values can be taught by engaging their imagination. When you’re able to do this, you spark a real interest and have a lasting impact on your child.

> Imagine with your child: Take time to imagine with your child. Things like, “What could the consequences be if XYZ happens?” or, “What could a solution to that problem look like?” Children can exercise their creative imaginative powers right alongside you.

> Ask for their help with issues: The imaginative power of elementary kids can lead to some very creative solutions and, some much happier participants, when they have a say in the solution to the problems that involve them.

> Give them time to play, imagine, and create: Playtime isn't just for small children. Don't rush your elementary kid away from open-ended toys, from creating, or from imagining. Don’t overschedule elementary children; make sure they still have time to play.

Montessori parenting is, at its core, about reaching, respecting, and responding to the developmental needs of our children and their unique paths. And, for children in the second plane of development, that is reaching them through the imagination.

Nicole Kavanaugh is the writer, parent educator, and most importantly, mom behind the Montessori website The Kavanaugh Report. For 11 years, she has shared her family’s Montessori journey with thousands of parents around the world in practical and real ways. She is mother to five Montessori kids, ranging from preteen to infant. Nicole is also the host of the popular Montessori podcast Shelf Help, hosts parenting courses, created a Montessori membership community, and can be found sharing daily Montessori inspiration on Instagram. In addition to sharing Montessori, Nicole loves gardening, children’s books, and a good museum gift shop!

15. Play-Doh™

16. Hula hoop

17. Hugg A Plant Earth

18. Uno + Playing Cards Holder

19. Potholder Loom Kit

20. Kids’ Garden Hand Tools

21. Egg Shaker

22. Jump Rope

23. Classic Rainbow Skwish

24. Wooden Bird Shaker

25. Bolt Block

26. Dynamo Dominoes

27. Playing Cards + Card Games for Kids

28. Tangram Puzzle

29. The Klutz Book of Paper Airplanes

30. MontiKids

And an extra copy of Montessori For Every Family!

(and a long, hot summer …)

Movement sits at the very core of Montessori education. Throughout her writings, we find Dr. Montessori advocating for schools to allow and encourage children of every age to move freely indoors and outside, refining the balance, coordination, concentration, strength, and fine- and gross-motor control of their hands and body.

Why the emphasis on physical activity? Montessori believed movement was an essential factor not only in terms of a child’s physical growth and well-being but also for their cognitive development.

The pioneering idea that led Montessori to advocate for bringing movement into the spotlight in education was that children need to move to learn, because learning happens through movement. In her view, mind and body are closely interrelated, and movement plays a vital role in this dynamic relationship.

On the one hand, we gain information from the environment through movement. When discussing the nervous system, Montessori points to the fact that the whole apparatus of the brain, senses, and muscles are often called the ‘system of relationships’ in that it puts us in touch with the outside world. Hence, when children walk across the room carrying the materials for a lesson, they add to their spatial awareness, i.e., the organized perception of the objects and environment around them, as well as of their body and its parts’ positions and orientations in that same space.

Movement helps turn thoughts into action and abstract ideas into concrete experiences, allowing children to learn by doing. Montessori wrote that the hand is the instrument that forms intelligence. She explained that when a child can trace the letters of the alphabet with their hand, the sensory impression that comes

from that movement helps them fix the symbol in their mind faster than if they were only using their sight.

As we often discover, Dr. Montessori was correct and far ahead of her time. Today, neuroscience confirms that movement and cognition are closely connected, with several research studies concluding that physical activity impacts brain development. Science likewise shows that exercise is good for us because it contributes to our physical, mental, and emotional well-being. Throughout life, physical activity is translated into many health benefits, such as a stronger heart, bones, and muscles, better posture, and coordination. Beyond physical health, exercise also boosts our emotional well-being, helping build confidence and positive self-esteem and reducing stress.

Staying active has likewise been argued to improve our mental health and even increase our immunity. How is this so? When we are physically active, our body releases what are known as ‘happiness neurochemicals.’ These include dopamine, oxytocin, serotonin, and endorphins. Dopamine is the reward hormone. It is released in the brain when we experience pleasurable moments, as well as when we anticipate or remember them. Music and spontaneous body movements, like dancing, increase our dopamine levels. Dopamine, in turn, helps with motivation and creativity. Oxytocin is the connection hormone released when we contact or bond with others, like when we play with a pet. Oxytocin promotes prosocial behaviors and helps maintain optimism. Serotonin, on its part, allows us to feel emotional happiness and calm.

Physical activity and exercise release serotonin. Serotonin, in turn, boosts our mood, helping prevent anxiety and depression, and it also

by Barbara Murphy, Ph.D.helps us regulate our sleep-wake cycles, improving sleep. Finally, endorphins are the pain-relief hormones the nervous system produces to cope with discomfort. Like dopamine, endorphins are also responsible for our feelings of pleasure. They are released by exercise, as well as by other activities like meditation.

Movement, then, supports child development and well-being across mind and body. As a form of self-care, it constitutes a foundation for wellness. Still, humanity is more sedentary than ever before in history. When discussing conventional schools in her time, Dr. Montessori spoke against traditional desks because she saw them as restricting child mobility. We are facing a much more significant challenge in terms of movement: an increasing worldwide trend towards sedentarism. That is why, today, more than ever, it is critical for children to develop and maintain the healthy habit of exercising and discover satisfying ways to keep moving when they reach adulthood.

This will become the backbone of their wellness for life. In this sense, Dr. Montessori’s emphasis on the importance of movement seems more relevant than ever.

How can we help children set the basis for an active lifestyle the Montessori way? The best way to approach Montessori's Movement and Physical Education curriculum is from the perspective of building physical literacy.

The International Physical Literacy Association defines physical literacy as “the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life” (IPLA 2017). In Montessori, the goal is to help the child reach their full potential in all areas of life. Through the

concept of physical literacy, we are adopting a holistic perspective, approaching physical education as a preparation for life and building skills that are important for everyday activities. We are also rethinking exercise as a form of self-care, another critical component of Montessori education. By providing the child with opportunities to learn and master fundamental physical skills so they can move with competence and confidence, we are setting the foundation for healthy habits that will support them throughout life.

At the same time, we should ensure that we faithfully apply Montessori principles to support physical development. Hence, for example, in Montessori, we help the child learn independently by providing freedom of movement and choice within a carefully prepared environment, where materials are available for the child to use without us after the proper introduction. Also, to support self-directed learning, lessons need to offer control of error built into the activity whenever possible.

Likewise, in Montessori, we often say that the environment is the best teacher. This means that physical education or movement activities need a properly prepared environment,

organized around areas that offer a variety of engaging and purposeful movement experiences, such as working on balance and proprioception to walk on different surfaces

ibility, with different difficulty levels and possible progressions and variations, to adapt to each child’s unique situation. Along the same line, learning in Montessori takes place in a

without falling. This ‘gym’ environment, like the classroom, should also be balanced by beauty, with a prevalence of natural materials like wood, cork, and cotton, as these are more enticing for the child and enhance the sensory experience.

It is equally essential that the adult adopts a Montessori teaching approach and observation as the core method to identify a child’s needs and interests in different physical activities. Similarly, when preparing movement activities, we must always remember the sensitive periods in physical development to provide children with exercises that add the most value as they develop body awareness and control to master various physical skills. Montessori movement lessons must offer flex-

non-competitive atmosphere, where children develop at their own pace, and all children learn from collaboration and peer learning within a multi-age group. This fosters connection, social skills, and solidarity, which we should preserve and enhance by including, for instance, different community-building exercises.

As Dr. Montessori eagerly stressed, children need movement. They need movement for their cognitive development, to absorb the world around and learn by doing. They also need physical activity for their well-being, which is the backbone of a healthy lifestyle. The current trend towards sedentarism demands that we take a more proactive approach to movement, helping children build physical literacy as the basis for an active life. This means we need to intentionally bring movement back into the spotlight, just like Montessori intended. Physical activity is a cornerstone of learning, a must-have in education, and a form of self-care, a foundation for wellness. In essence, we are championing movement education the Montessori way.

Barbara Murphy is passionate about education. Barbara holds a Ph.D. from Northwestern University and a Montessori certificate from CGMS. As the mother of two, she fell in love with Montessori pedagogy while living in Milan, Italy. After moving to Miami, Florida, Barbara founded what is now Montessori Wellness, with the vision of promoting a deeper understanding of the connections among Montessori education and wellness practices, so as to support the physical, emotional, and mental well-being of children and adults alike. As a speaker, Barbara has presented on movement and other wellness topics at several international, national, and regional Montessori conferences.

barbara@montessoriwellness.com

www.montessoriwellness.com

The best way to approach Montessori's Movement and Physical Education curriculum is from the perspective of building physical literacy.

Millie (four) has a satisfied, radiant glow. She is admiring her work after spending two hours in the woodwork area, where she has been engrossed in constructing a bed for a princess. She used the hammer, hand drill, screwdriver, and a small pull-saw. It was a complex process, first designing, then making, adapting, and resolving problems as she went.

She had to adapt, and problem solve, using creative and critical thinking skills throughout; for example, cutting sections of wood so they would be the right size to fit. She joined the four legs but was disappointed to discover that the bed was wobbling. On closer examination, she realized this was because one leg was too long. The next problem was how to remove it, and then how to make it the right length … woodwork certainly throws up lots of problems! Millie finished by elaborately decorating the bed with beads and buttons, ensuring it was a bed fit for a princess.

Millie made a wonderful bed, but what was really ‘made’ was within Millie. Seeing her sense of agency flourish as she put her ideas into action and seeing her confidence grow as she mastered the tools were both clearly visible. We also know that by using the multitude of creative and critical thinking skills involved in the making, new neural connections and pathways will have been established. This is the wonder of woodwork. It can be truly transformational.

If you’re new to woodwork with young children, you may well have some initial concerns. But once some very basic health and safe -

ty measures are put in place, you’ll see that woodwork is low risk and makes a wonderful addition to early childhood programs. In this article, I’ll give some insight into the value of woodwork and provide some safety pointers for working with young children.

There is something special about woodwork. It is so different from other activities. The smell and feel of wood, using real tools, working with a natural material, the sounds of hammering and sawing, hands and minds working together to express their imagination and to solve problems, the use of strength and coordination all go together to captivate young children’s interest.

‘We observe children working with their hands, tinkering, constructing models, and working on projects but, in fact, the real transformation is inside the child – personal development is at the heart of woodwork.’

These are exciting times. Currently, around the world, we are seeing a surge of interest in woodwork within early childhood education, with examples from all corners of the globe. In some schools, this will be starting from scratch; in others, it’s a case of dusting down the workbench and digging out the tools after many years of neglect.

This is very welcome, as the benefits of woodwork run deep. Teachers who provide woodwork regularly observe exceptional levels of sustained engagement, with deep focus, concentration, and perseverance with challenging tasks — especially with complex problem solving. It is not unusual for children to spend all morning at the woodwork bench. Woodwork really engages hands, minds, and hearts.

When we analyze a woodworking session it is extraordinary to see just how much learning is involved. It’s truly holistic, encompassing all areas of learning and development and

invites connections between different aspects of learning. In this sense, woodwork really can be central to the curriculum. It incorporates mathematical thinking, scientific investigation, knowledge of technology, a deepening understanding of the world, as well as physical development, coordination, communication, language, and personal and social development. This is evidenced by research from ‘The Big Bang Research Project’ for which the interim research findings are now available.

Children are particularly drawn in as they explore possibilities, rise to challenges, and find solutions. Woodwork is really unrivalled in terms of providing children with problem-solving opportunities and challenges. With woodwork, children can develop their learning at their own pace and find their own challenges. Once they have mastered basic skills, they move into open-ended exploration — initially tinkering, exploring possibilities, and then starting to make unique creations, drawing on previous experiences and their emerging knowledge of tools.

“The child who concentrates is immensely happy; he ignores his neighbors or the visitors circulating about him. For the time being, his spirit is like that of a hermit in the desert; a new consciousness has been born in him — that of his own individuality.” (Montessori, 1949, p. 273)

In terms of sustainability, woodwork helps counteract the current culture of ‘consume and dispose’ by introducing an understanding of the value of making and repairing. Children also discover how they can re-purpose materials by making models from a selection of recycled wood and other materials. In addition, the understanding of where wood comes from and seeing the beauty of wood can develop respect for the value of wood and inspire us to take responsibility for our shared environment.

To ensure equal opportunities, introduce the tools to all children so they all feel comfortable in the woodwork area. In that way, they can make an informed decision as to whether they want to choose to do woodwork. It’s important to acknowledge that there is often gender stereotyping around woodwork and sometimes an assumption that only boys will be interested. However, after an initial introduction, we notice no gender difference in who chooses woodwork. It’s hard to become what you don’t see, so support equality by having books with positive role models of girls and women using tools.

Woodwork captures children’s curiosity, and it has been particularly successful in significantly engaging children who may be less confident and have more difficulty focusing. Giving children a high level of trust and responsibility is empowering, and woodwork so often has been key to unlocking certain children’s learning and really building their self-esteem and confidence.

Woodwork is perhaps one of the more difficult activities to offer. There is a fair bit of tools, wood, and other materials, such as: corks and bottle tops; nails and screws; sandpaper; safety glasses; and a workbench all need to be sourced. A sturdy workbench is essential as the wood being sawn must be clamped tight in a vice.

When it comes to your toolbox, only four tools are essential for children:

• Hammers

• Hand drills (manual, non-electric drills)

• Screwdrivers

• Pull saws

Having incremental progression is important in responding to each individual child’s stage of development and confidence. Avoid introducing too much challenge too soon.

Introduce the tools in small groups. For younger children, starting with a softer material such as balsa wood makes for a much

more positive initial experience. Gradually, increase the level of challenge; start with small nails, and thin wood to join to blocks before slowly introducing a wider selection of wood sizes and larger nails.

As children gain confidence, woodwork can become a continuous project or be made available to larger groups at specific times. Continuous access gives children more choice and autonomy, but it only works well if you have enough resources, and children can go through a lot of resources fast! What is important is that working with wood is a rich experience, with enough resources to allow complexity in thinking.

If you have not done woodwork before, it’s natural to feel a little apprehensive! It’s easy to conjure up images of accidents with children wielding saws around! But those who have embraced woodwork find that it’s surprisingly safe. Woodwork is low risk when introduced correctly and basic safety measures are put in place. I have been providing woodworking for young children for over 25 years with no significant incidents. I would advise introducing woodwork from three or four years old.

sponsibility as educators to ensure the physical and emotional care of our children. We need to put in measures to reduce risk, such as using the most appropriate tools and taking proper safety precautions.

• Safety glasses must be worn at all times to eliminate the risk of eye injury. Children are more comfortable and are safer in safety glasses than chunky goggles.

• Ensure children are given instruction on the correct use of all tools. Take time to discuss safety together and draw attention to hazards. Children need to understand why health and safety measures are put in place.

• Monitor sawing with a 1:1 ratio. Ensure no children are watching from in front of the sawing area. The teacher should stand in this area to prevent other children from getting close to the saw. Pull saws (held with both hands) are easier and safer for young children. After use, the saw is to be put out of reach. Wood is always to be clamped in a vice when being sawn. An adult must check that the vice is clamped tight.

• Hammering follows gentle taps to get the nail standing up. Then hold the wood well away from the nail before hammering hard. Embed this practice right from day one.

• Be sure to check wood for splinters. We need to limit exposure to splinters. Avoid rough splintery wood. Sand the edge after sawing if rough.

We are now seeing a more balanced attitude to risk. Health and safety measures should enable children to experience new opportunities safely, not deny them. It is important that children get to experience risk within controlled experiences, as they need to learn to understand and manage risk. This way they learn to self-manage and make decisions and judgments to better protect themselves in the future. Giving children a high level of trust and responsibility is also empowering, and woodwork so often has been key to unlocking certain children’s learning and building their self-esteem and confidence.

Of course, health and safety does need to be taken seriously. After all, it is our prime re-

• Children should be monitored at all times, initially with close supervision. When children are confident using tools, ratios can be relaxed and they can work independently, with the exception of sawing which is always done with a 1:1 ratio. A staff member should always remain within line of vision of the woodworking area.

Woodwork is a symbolic language of shape, form, and space. It encompasses a way of working that develops over time as children express their ideas with increasing fluency and complexity. As children tinker and experiment and then construct, create, and explore narratives, these experiences can combine to

build rich foundations for children’s healthy emotional, physical, and cognitive development. Woodwork can promote an experimental mindset, and, at the workbench, children ‘become’ innovators, makers, sculptors, tinkerers, engineers, and architects.

“As children make with wood, they will be learning skills that will empower them to shape their world.”

Woodwork is certainly a very popular activity and incorporates so much learning – a real win-win. It would be wonderful for all children to have this opportunity to flourish at the woodwork bench.

Irresistible Learning

irresistible-learning.co.uk/woodwork

The Big Bang Project

www.youtu.be/OZkr5X-CqRE

Learning Through Woodwork

by Pete MoorhouseContact: studio@petemoorhouse.co.uk

by Montessori Foundation Staff

by Montessori Foundation Staff

If no one has asked you how Montessori will benefit your child, or will Montessori benefit your child, they have probably thought of it. In fact, you may have asked yourself the very same question. Why choose an education that is an alternative to traditional education?

Let’s examine ten reasons we may choose Montessori for our family.

6. Free from predefined times for activities, Montessori children delve into subjects that inspire them and are able to feel the intrinsic reward of seeing a task through to completion, without being cut off because that class has ended.

Pete Moorhouse is an Early Year’s creative consultant and artist educator. As an artist, Pete is a professional sculptor, and he has worked in education for over 30 years. His work in schools is centered around nurturing children's creativity. Pete is an associate trainer for Early Education and deliverers training both nationally and overseas.

Pete was awarded an honorary Research Fellow at the Graduate School of Education, University of Bristol, and is currently researching the impact of woodwork in ‘The Big Bang Research Project’. Pete is the UK's leading authority on woodwork in Early Years education and has written several books and journal articles, including Learning through Woodwork (Routledge). Pete won the national award (2019) from the Creative Learning Guild for his work promoting creativity in education. He was awarded a Churchill Fellowship Award (2022) for his international research and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

1. Learning is child-centered and individualized. A similar curriculum to traditional schools is taught, often in a different order, and children move through the curriculum at their own pace. Teachers observe and guide students as needed to develop mastery, rather than following a timeline for learning set by others.

2. With the freedom and support to question deeply, they learn to think critically and act boldly, developing the ability to lead with respect and consideration.

3. By giving students a choice of activities, they develop their executive function skills, making choices on their own, learning to wait and take turns, and developing self-discipline and motivation.

4. The guided independent approach to learning allows Montessori students to become confident, enthusiastic selflearners. Teachers observe, monitor, and guide children to make good choices to progress their learning.

5. There is limited standardized testing, and it is most often used as a way to observe as well as a practical life skill. Children are motivated by and measured against their own achievements, not those of others.

7. As students are active contributors to the classroom and the teacher their guide, there are more opportunities for cooperation and collaborative working among students of all ages.

8. Montessori focuses on the whole child, with social and emotional development equal to the academic curriculum. Learning to work with others, take turns, lead with respect, speak up, and consider needs outside their own prepares children to be global citizens.

9. The focus is on the key developmental stages of the child, with learning activities and materials designed to further develop key milestones. Neither introducing subjects or skills their brain and body are not prepared for, nor requiring them to stay with information and skills they have already mastered, allows children to reach their own full potential.

10. Montessori is hands-on learning with materials that enable self-correction and self-assessment. Auto-correcting materials (the largest cylinder does not fit in the smallest space) allow children to develop confidence in their own learning and become the developer of their own knowledge rather than go to an adult and drink from their fountain of knowledge.

Reaching out to a friend who has children

a bit older than yours can be a very comfortable way to get advice about your own parenting. When you are a part of the Montessori Family Alliance, the people to reach out to have very helpful pieces of advice.

Christine Lowry

Christine Lowry

Being a parent is both the most challenging and rewarding thing we can do. My advice is to respect your child's sense of dignity. Children (especially young children) have a remarkable sense of self-worth, self-direction for their own growth, a sense of their value as people, and being worthy of honor and respect.

I had a sense of its importance as a parent but didn't have the right language for it until I partnered with parents in my school. We often underestimate our children's rich emotional life; their natural attunement to us, to their environment, and to the world; their need to explore, do it themselves; and struggle until they get it without our help. Their ‘inner guide’ is the motivation for everything they do. Sometimes, they ‘push back,’ and we feel that they are challenging us. Perhaps, if we could take just a moment to reflect on our child's intense sense of dignity, we could more easily let go of our need now and see their need in a different light.

simple frozen pizza and evolved into family-made pizza as the children got older and could cook. The games could have started out very short and simple and grown into more challenging games as the children grew. Initially, we could have included just our nuclear family, embracing their friends and other family members when they were tweens or teens. Perhaps this prediction would have carried over into their own families.

Other traditions might have included special breakfasts that we all helped plan, cook, and enjoyed on holidays, days off from school, snow days, etc. Remember, it only takes doing something twice for it to become a beloved family tradition. This could also have been true for something special after school on the last day of the school year or the first morning the family wakes up on summer vacation. I had a friend who said that weeks, months, and years needed to have "punctuation in the book of life." Looking forward to doing things together helps a family want to spend time together, which is so important.

answers. We eventually found what worked best for our family and what felt right for us. In addition, I also felt a responsibility to help our children live as themselves as much as possible.

By trying to fabricate experiences, read books, and schedule playdates, I tried to force their development too much and redirect their personalities. It didn't happen at any moment in my parenting, but just gradually, over time, I realized that I had to trust what my wife and I were doing. Our children would be exactly who they were meant to be, and, to an extent, their personalities were hard-wired. I felt that I could breathe more and just trust my children's growth. It took about five or six years and a few children to learn that, but hey, who's counting?

Allowing children to make their own decisions and helping them to accept the natural consequences, positive or negative, of their decisions is my best parenting advice. As parents, we support our children by modeling decision making and helping them weigh the possible outcomes. Sometimes, allowing children to fail is what allows them to grow.

My wife gave birth to a beautiful baby girl and, instantly, we were parents. As a new parent, a new part of me seemed to come alive; a part of me that I didn't know even existed.

Lorna McGrath The Montessori Foundation Cathie Perolman Montessori Teacher Educator

Cathie Perolman Montessori Teacher Educator

If I had the chance to enhance my family, I would have created more family traditions during our younger years. We would have started with a weekly family pizza dinner and game night. This could have started with very

As a young parent, I began to feel that I needed to ‘know’ how to raise a child ‘the right way.’ I read countless books about raising girls. We tried so many things, and yet none of it felt natural because it wasn't us. We were just doing exactly what the books told us to do.

We spoke with friends and mentors who had older children (or were empty nesters) and asked for their advice/wisdom. Well, fast forward three more children (all boys), and we discovered there was not that one book, that one class, or that one person with all the

When your child seems to be struggling with something, it can become an ongoing struggle, weighing them down or weakening their self-confidence. Talk to them. Help them with their self-talk and assure them that everyone struggles with something. Most things can be overcome with practice, time, support from others, and determination.

Be empathetic without trying to make it all better. They must do that. Don’t pity them; instead, be confident when they are not. Show them your strength, patience, and willingness to receive help from others. Let them know, “You/we got this!”

My best advice to parents and grandparents is not to spoil anyone with things; instead, be invested and present when you have time with them. Bring them to places to show them there’s a world out there. Expose them to all the arts; take them on nature walks and teach them how to fix something when it’s broken or how to put something together. My favorite is to get them into the kitchen to cook— anything that helps them unplug from those devices. Help them learn to be of service in their communities.

I try to do this with my four granddaughters as well. We do art projects, listen to musicals, watch old movies, play board games, and do puzzles. We knit or crotchet, we paper mâché, we go to museums and science centers; we are going on a cave exploration this summer. I try to create times they will want to replicate and look back upon with the fondest of memories.

As we get the occasional texts from our college-aged kids that read, “Thanks for teaching me how to do my laundry and cook,” or “Thanks for teaching me how to do hard things,” we are grateful for the lessons learned as new parents. Letting go of perfection-oftask thinking to make way for independenthuman-in-development activities was the best decision we made as parents. And, once we understood that anything could be broken into smaller steps towards a larger goal, we created a home environment that allowed our children to become confident and selfsufficient. This worked for driving practice, talk practice, form-completion practice, and more. As James and I look towards retirement, we wonder what practical-life lessons lay in store for us, too. We are eager to learn and set practical-life goals for ourselves as well.

If I could go back to my children’s preschool years, I’d throw my expectations (and everyone else’s) out the window and watch my child show me their full potential. In schools, I hear many parents say, “He should be…” or “I wish she could…” or “When she does ….” My advice to parents is to eliminate should from your vocabulary and let your child blossom at their own unique pace.

The Montessori Foundation

Family meetings, held regularly, give every person in the family a chance to be a part of decisions and solutions. Knowing that your topic of concern or interest will be addressed goes a long way in helping to develop confidence. Having a voice in the family can make connections stronger and allow the family to work together.

One of the most revelatory experiences for me as a mom and as a person new to Montessori was just how wonderful the notion of Practical Life could be. As a new mom coming to Montessori twenty years ago, I was amazed as I observed what the children in the Primary classrooms could do by themselves. Not only did James (my husband) and I enroll the children in a Montessori school as fast as they would let us, but we left determined to see what else they could do for themselves at home, which turns out to be a lot! Adopting the motto “If you can do it for yourself, you should” has truly helped our children develop into the confident, capable young adults they have become.

Through my time as a parent and a Montessori educator, I’ve learned many things I wish I could have put into practice when my children were young. As a child, I was a Montessori student, and as an adult, I became a Montessori educator. Therefore, I was very knowledgeable of the “Montessori Method” and did my best to parent along a similar path. Now that my kids are teenagers and I have life experience and more training, I’ve learned a few things I wish I’d done when my kids were young.

Many parents think we know what’s best for our children. Although my heart was in the right place, I often forgot to listen to my child, both through their words and through their actions. Most parents think a three-year-old still needs a nap and a four-year-old needs to eat at each meal. We think a seven-year-old should know how to read, and a ten-year-old should know how to speak kindly to a friend. We often spend a great amount of time trying to control our child’s behaviors. What I encourage others to do is to observe, model, follow, and guide.

The Montessori Foundation

I would advise parents to be focused on a partnership with the school and the teachers, because we are all working for a common purpose: the child. Parents should attend as many school events as possible, even those that are not focused specifically on their child; it helps build school community.

Share expectations and goals for your child with the teacher and get affirmation that these are the right ones for your child. Learn from your child's teacher.

Share your family's culture, values, and parenting practices with your child's teacher. Attend PTA meetings and get involved, if you can, to support the school to be the best place for children. Actively help teachers and the school to recruit volunteer parents to help.

It was the Spring of 2007, and my husband, Bernard, and I were among the multitude of parents looking for a preschool for our eager learner, who was not quite three years yet.

I suspect that this was the year that the children in our city outnumbered the preschools. Lucky for me, I overheard a parent at the park recounting an amazing experience at a Montessori school in Sarasota, FL. I was determined to find this particular school and to explore what Montessori was.

On a beautiful morning in mid-May, our daughter Victoria, Bernard, and I had our first visit to the NewGate School. We met with its wonderful Director, Lorna McGrath. I believe at that time, they had two spots open in the Primary (age 3-6) classroom. We were chaperoned around the campus by one of the parents called an ambassador, who had raised all four of her children through the Montessori curriculum. The campus was small, but we felt it was the perfect size for our daughter.

Victoria and I spent the rest of the summer stopping by the school once a week to get a little preview in anticipation of our starting the new school year that fall.

August came around finally! Victoria’s assigned classroom teacher, affectionately known as Ms. Mini, came over to our home to visit and to get to know her before school commenced. I thought that was a nice process to break the ice, so to speak.

Then the first day arrived for Victoria to go to school! The students' assigned start dates were staggered to allow for a better, less stressful, more peaceful transition. Victoria couldn’t wait; she was (and still is) a keen learner.

After a few weeks had gone by, we knew that we had made the right choice. Victoria was having a great experience. She would come home bathed in sand from head to toe and with an orange rind in her fingernails from cutting oranges for snack time. It was awesome. We knew that she was fully immersed in exploring and learning.

Over the time that we spent at the NewGate School during our daughter's Elementary years, we saw her growth as an independent young lady; her ability to collaborate on projects as a team player; her insatiable curiosity to investigate and understand concepts; and her love of volunteering and contributing to her community.

While she left before middle school to attend a special program offered by the public schools, we were grateful for the Montessori formative learning that will continue to yield success throughout our daughter's life.

Iremember climbing the mango tree that grew behind my building as a child. I lived in a large metropolitan city and would beg my grandma to let me play behind the building with my friend. With the slightest nod of her head, I would squeal with excitement and fly down the stairs to the fourth floor where my best friend lived. I would ring and knock until I could, once again, beg whoever answered to let her play with me. Again, with the slightest nod, we both arrived at the ground floor, barely touching a step on the way down.

I have the greatest memories of my childhood climbing that mango tree with just a salt shaker and my friend. We would sit and talk, play, and eat fresh mangos straight from the tree. Now, 30 years later, I can still recall and feel the pleasure of that time in the tree. I can still smell the sweet ripe fruit and recall unexplainable and seemingly unimportant details from those cherished experiences.

I know each of you has your own unique and special memories of playing as a child. You can recall an amazing time when you rode your bike on the street, rolled down a grassy hill, jumped into a pile of leaves, or built a sandcastle at the beach. I grew up in Caracas, Venezuela, and I spent countless hours and days playing with my friends in the street, climbing trees, and even walking every afternoon to the bakery with my grandma to buy bread for dinner. These memories are so precious to me, just as your unique childhood play experiences and memories are precious to you.

But we weren’t just playing, we were learning, and we were learning a lot! There is something amazing about play. When you expe-

rience pleasure, you become more driven to repeat that activity. And the more we repeat it, the more opportunities we must master it. With mastery of anything, from the most basic skill to the most complex, we experience self-accomplishment and the pride and individual confidence that result from it.

Playing is a critical part of our learning process. But play has to be fun. If something is not fun, it’s not play.

such as creativity, abstract thought, prosocial behavior, and expressive language”.

Let’s dive just a bit deeper and investigate what is really happening in the brain when a child is playing. Bruce Perry is a psychiatrist and Founder of the Child Trauma Academy, and through his research, he explains how kids develop through play.

Human brains are super organized, so let’s imagine a staircase in your brain. Our brains start developing on the bottom stair and systematically progress up the staircase. The bottom stair is the BRAINSTEM, which is the basic building block of the brain.

According to Perry, the Brainstem establishes (body) state regulation and is responsible for controlling body temperature, blood pressure, heart rates, sleep, and fear.

To develop the Brainstem and this critical first stair, Perry recommends playing games, such as peekaboo and frequently introducing new and different tactile and taste sensations.

Let’s look at why play is so critical to learning and cognitive development. Play serves as a crucial mechanism that enables the brain to develop neurological systems that play a key role in cognitive awareness, improved learning, and physical, social, and emotional well-being. Gaskill and Perry (2014), in their article “The Neurobiological Power of Play,” said that “Developmental theorists generally have viewed play as an essential experiential element of social, emotional, physical, intellectual, and psychological development. The ‘somatosensory’ experiences in some play activities have been viewed as the neurological foundations for later advanced mental skills,

The second stair is the MIDBRAIN, this part of the brain is responsible for the regulation of movement (motor skills) and the sensory integration of our brain. Play that involves gross- and fine-motor skills and music is well suited to help develop the Midbrain.

The third step in the brain staircase is the LIMBIC. The Limbic area is all about our emotions. I know many of you are thinking, “Yes, EMOTIONS, tell me more!” It is the Limbic portion of the brain that processes emotions, such as tolerance, belonging, and empathy, as well as how we react to a situa-

PLAYING IS A CRITICAL PART OF OUR LEARNING PROCESS. BUT PLAY HAS TO BE FUN. IF SOMETHING IS NOT FUN, IT’S NOT PLAY.

tion and regulate our feelings. It’s at this level of development that our brains start understanding and comprehending the complex dynamics of relationships and all those social-emotional skills that we need to live and function in society.

Once again, play is a critical component in the development of the brain’s Limbic system. Play that involves taking turns, sharing, winning, and losing will all work together to promote the development of this step in the brain staircase.

Our final level in the staircase is the CORTICAL area of the brain. As you might imagine, this is the most complex stage of development, where we see the child engaging in abstract thoughts, creativity, language, and morality. It’s at this stage that Perry notes that Cortical development is supported by playing complex games, humor, art, books, word games, etc.

So now we’ve reached the top of the brain staircase, and through play, our children have developed the ability to control their emotions and think in the abstract.

But what about executive functioning skills, and where do they come from?

Executive functioning is responsible for several skills that involve working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control. Basically, these skills act like our own internal ‘boss’ and tell us what to do. The ‘boss’ should be able to help us pay attention, keep and recall information, organize, regulate our emotions and internal clock, and keep track of what we are doing.

The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University says, “These skills are crucial for learning and development. They also enable positive behavior and allow us to make healthy choices for ourselves and our families.”

The important thing to remember is that we were not born with the ‘boss’; we must learn, practice, and develop these executive functioning skills throughout childhood.

These (executive function) boss’ skills live in the prefrontal cortex of the brain, and studies show that they begin to develop as early as age 3 and will normally continue to develop through the age of 21.

Perry and Baylor said in their research, "Curiosity, Pleasure, and Play: A Neurodevelopmental Perspective," that “while enjoying their play, children can acquire a wide range of interpersonal/social skills, ranging from communication to cooperation. When children argue about who stepped ‘out of bounds’ and agree upon a ‘do-over,’ they are learning how to negotiate, compromise, and work together.”

If play is so closely related to brain growth and development, and our prefrontal cortex (executive function) ‘boss’ skills are a result of all that playing, then we need to make sure our tiny humans are doing a lot more playing! It’s just that simple. Both in our education system and our own home, we need to implement and promote more playtime.

As Maria Montessori said, “Education is a natural process carried out by the child and is not acquired by listening to words but by experiences in the environment.” Let’s come together as parents and teachers and go out into the world to explore, be curious, and play more!

All the play that we engage in as children, even as a toddler, contributes to the development of strong executive functioning skills— or a really good ‘boss.’

With play being so important for our children, what are we waiting for? Why are we so laser-focused on rigid academic regimes and structured activities? Have we forgotten how to play?

More play time could better serve the academic and social development of our precious tiny humans. Since we now know the importance of play, let’s ask ourselves, as parents and teachers: How can we use play to better promote and foster childhood development? How can we make things more fun? How can we add more play time to our schedule? How can we remember how to play?

As Montessori educators and parents, we know and recognize the importance of playing, but sometimes we forget that play is such a critical part of the learning process and developing effective executive functioning skills.

Maria Montessori said that “play is the work of the child,” and by giving the child the opportunity to play and explore, we help the brain to grow. “Only through freedom and environmental experience is it practically possible for human development to occur” (Montessori, 1967).

So, what have we learned, and what is our takeaway?

Center on the Developing Child (2012). Executive Function (InBrief). Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

Montessori, M. (2016, originally 1949). The absorbent mind. Amsterdam: Montessori-Pierson Publishing.

Perry, B., & Baylor, S. (200-). “Curiosity, Pleasure, and Play: a Neurodevelopmental Perspective.” HAAEYC Advocate, 9-12.

Maria Eva Chaffin is the founder, owner, and director of Seeds of Life Montessori Academy, an inclusive school serving children from 18 months to 12 years old. Originally from Venezuela, she currently holds two master’s degrees in education and is currently completing her doctoral research on special needs and Montessori as well as a AMS Montessori Teacher Certification in early childhood. Her extensive teaching experience includes over 23 years working with neurodiverse children. She is a published co-author on the subject and has been invited to present at Montessori events around the country and host regular teacher education web sessions to help teachers and administrators around the world deliver the best Montessori experience possible. First and foremost, she loves being a Montessori educator and her passion for all children is endless. After years of experience teaching children, adults, and those with special needs, she remains convinced that the Montessori Method is the best way for children to learn.

It’s hard to believe that I began writing for Tomorrow’s Child thirteen years ago! While running a conference for the Montessori Foundation/IMC in California, my daughter went into labor ten days early up in Rochester, New York. Devastated that I was not in place and on time, the new parents Skyped me and (unknown to the joyous couple), several dozen conference attendees and exhibitors into the delivery room as the baby was swaddled and held up to the camera. There she was, my first grandchild, eyes wide open, looking at all these people crying and clapping and sharing in the miracle of her arrival.