November 14 - December 30, 2025

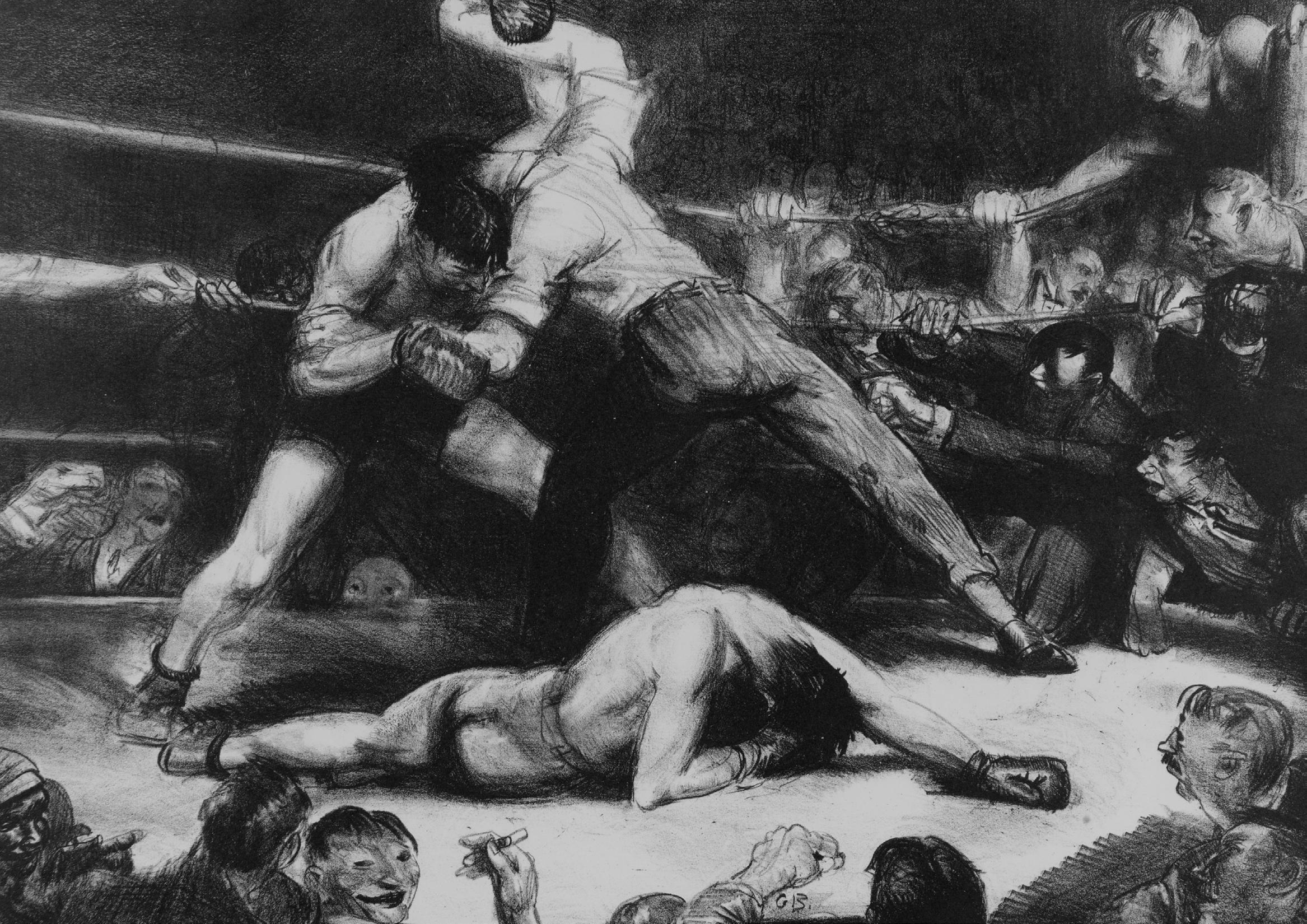

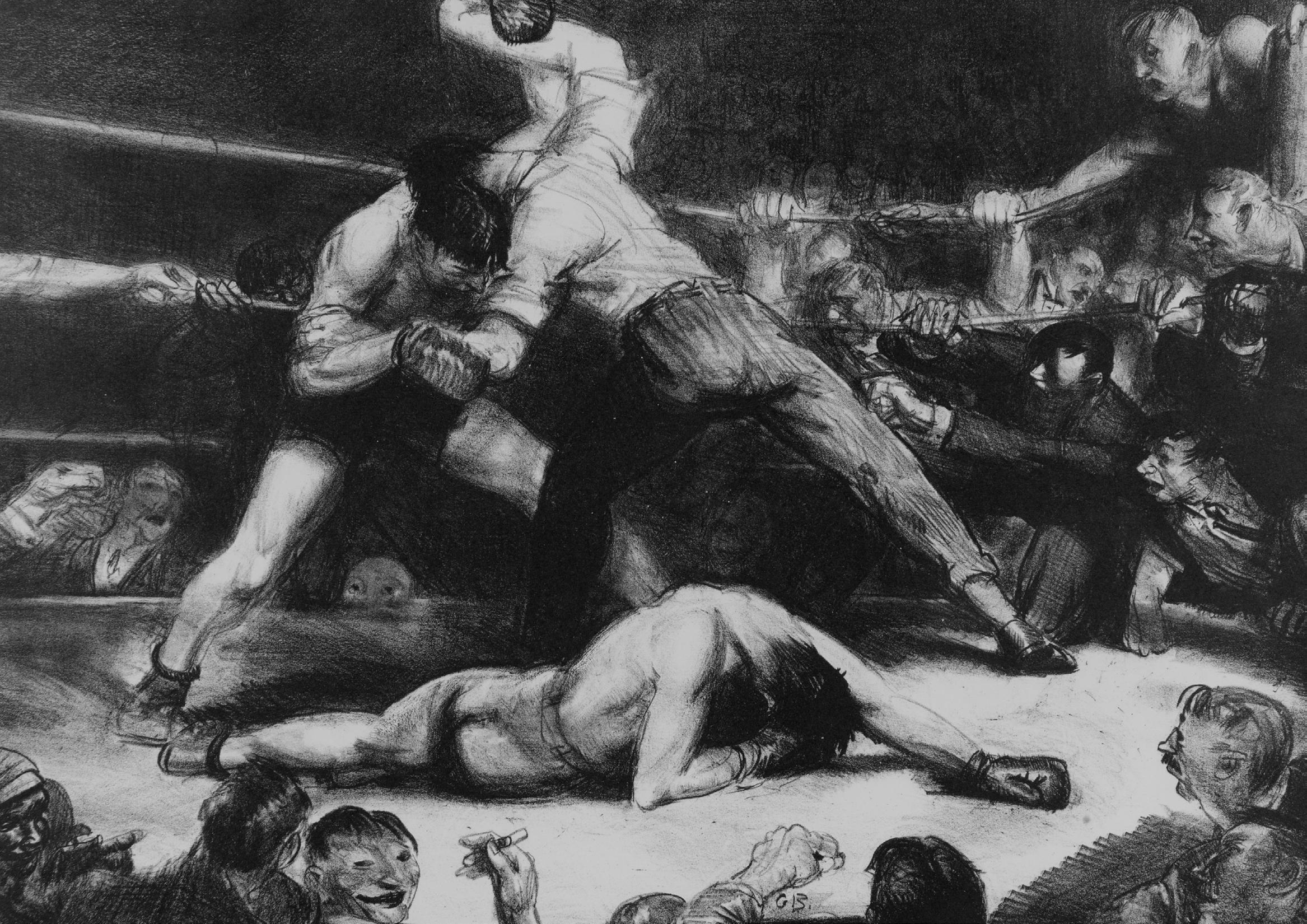

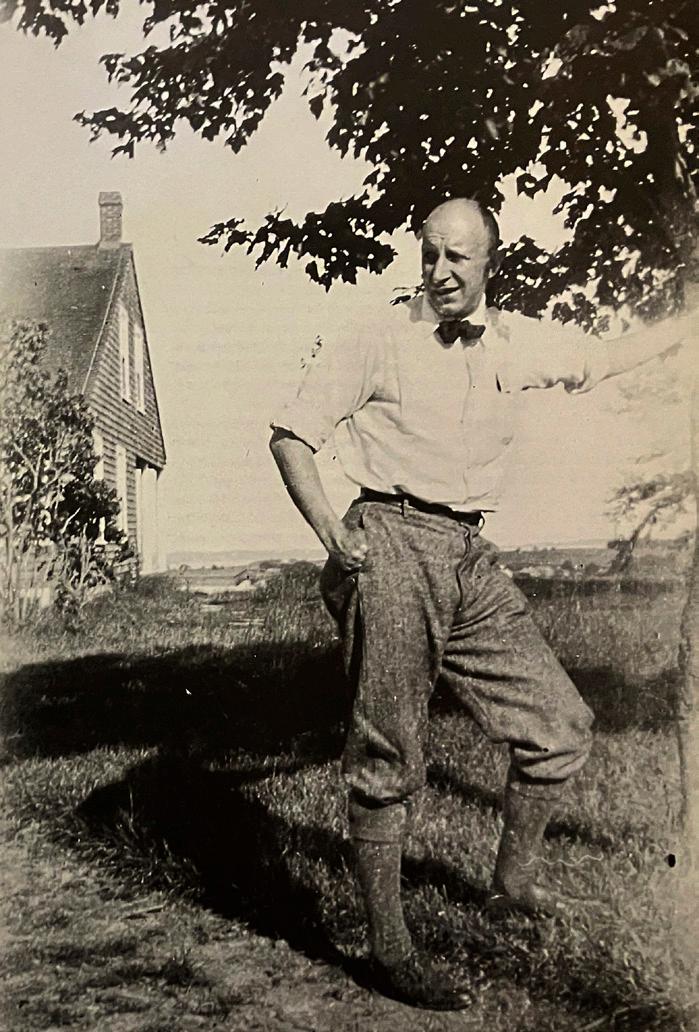

In 1925 the Metropolitan Museum of Art featured an exhibition lionizing the work of George Bellows, one of America’s finest artists and a leading figure in the art world of early 20th century New York. Tragically, the Columbus native died prematurely of peritonitis brought on by a burst appendix at the age of 42. Within six years of his arrival in New York in 1904, Bellows meteorically rose to the apex of the American art world. By 1910 he was recognized as the leading champion of realism in America. As such, he captured the raw underbelly of New York at a time when such visceral “ash can” subject matter was not in vogue. Always a keen observer, his blood soaked fight scenes, teeming images of tenements, vulnerable depictions of street urchins, and painterly snapshots of rugged working men braving the elements are iconic aspects in American art. Remarkably, Bellows concurrently produced many sensitive portraits of his family and friends and several seering indictments of social ills that also define his oeuvre.

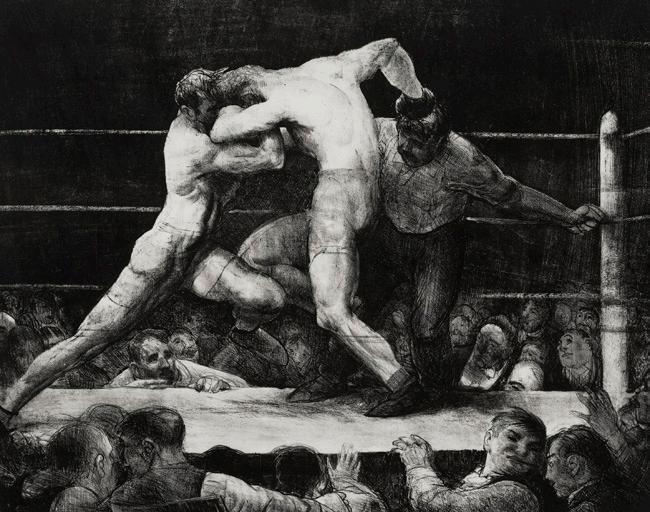

While widely known for his paintings, the artist also explored these subjects in a completely different medium. Betwween 1916 and 1924 he produced a series of over 200 lithographs which repositioned this largely commercial medium as a fine art form. To achieve this end, Bellows worked closely with the lithographers George Miller and Bolton Brown. His well-honed draftsmanship, photographic eye for detail, strong sense of design and deep empathy for his subjects are particularly evident in these objects.

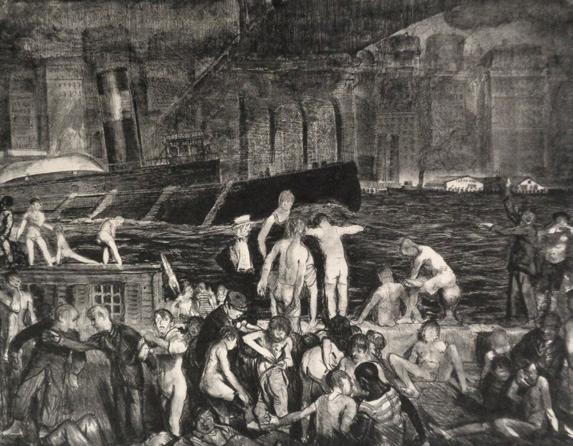

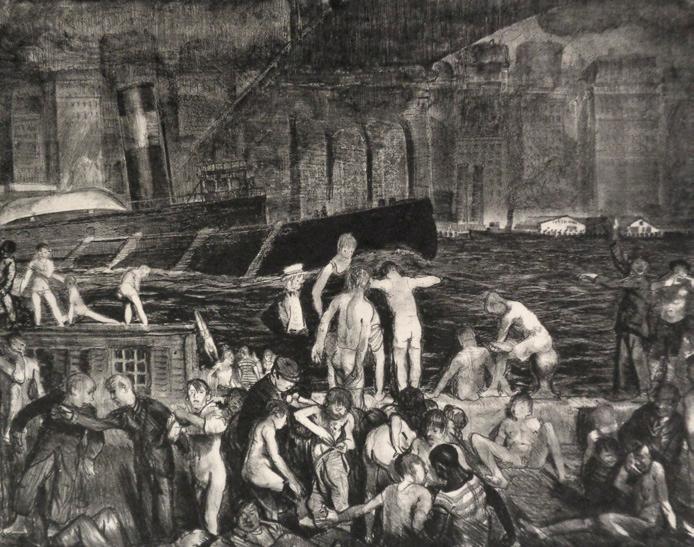

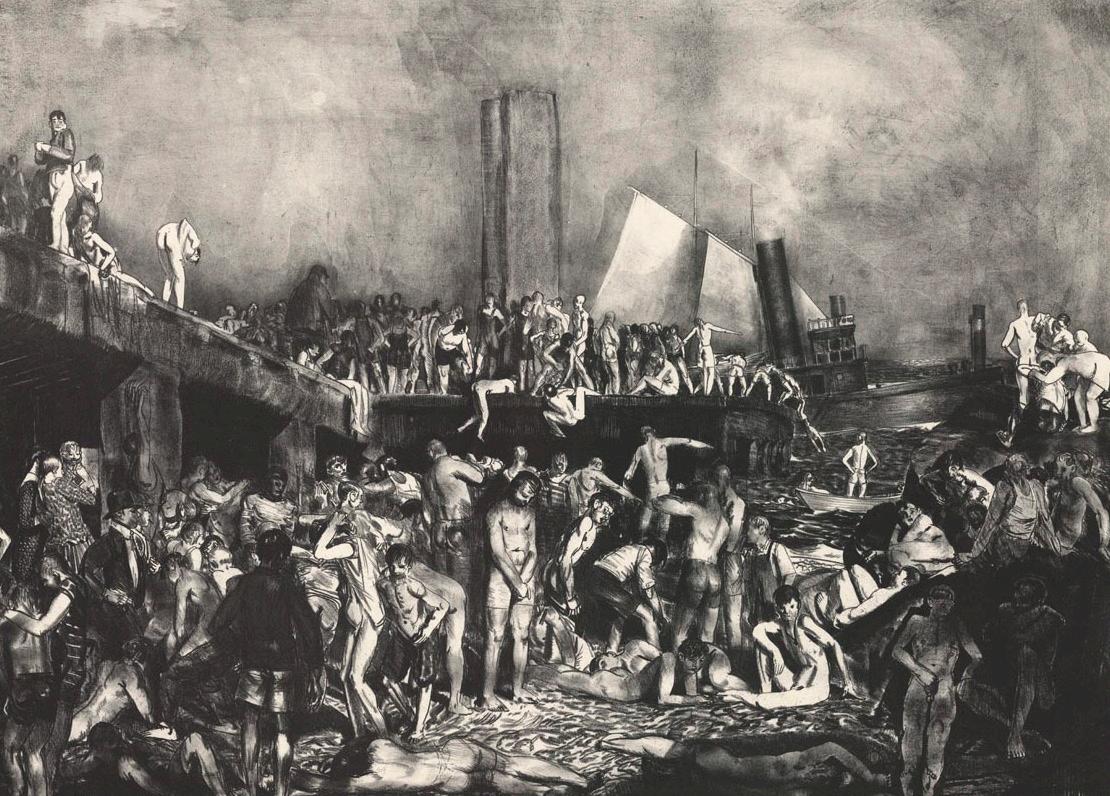

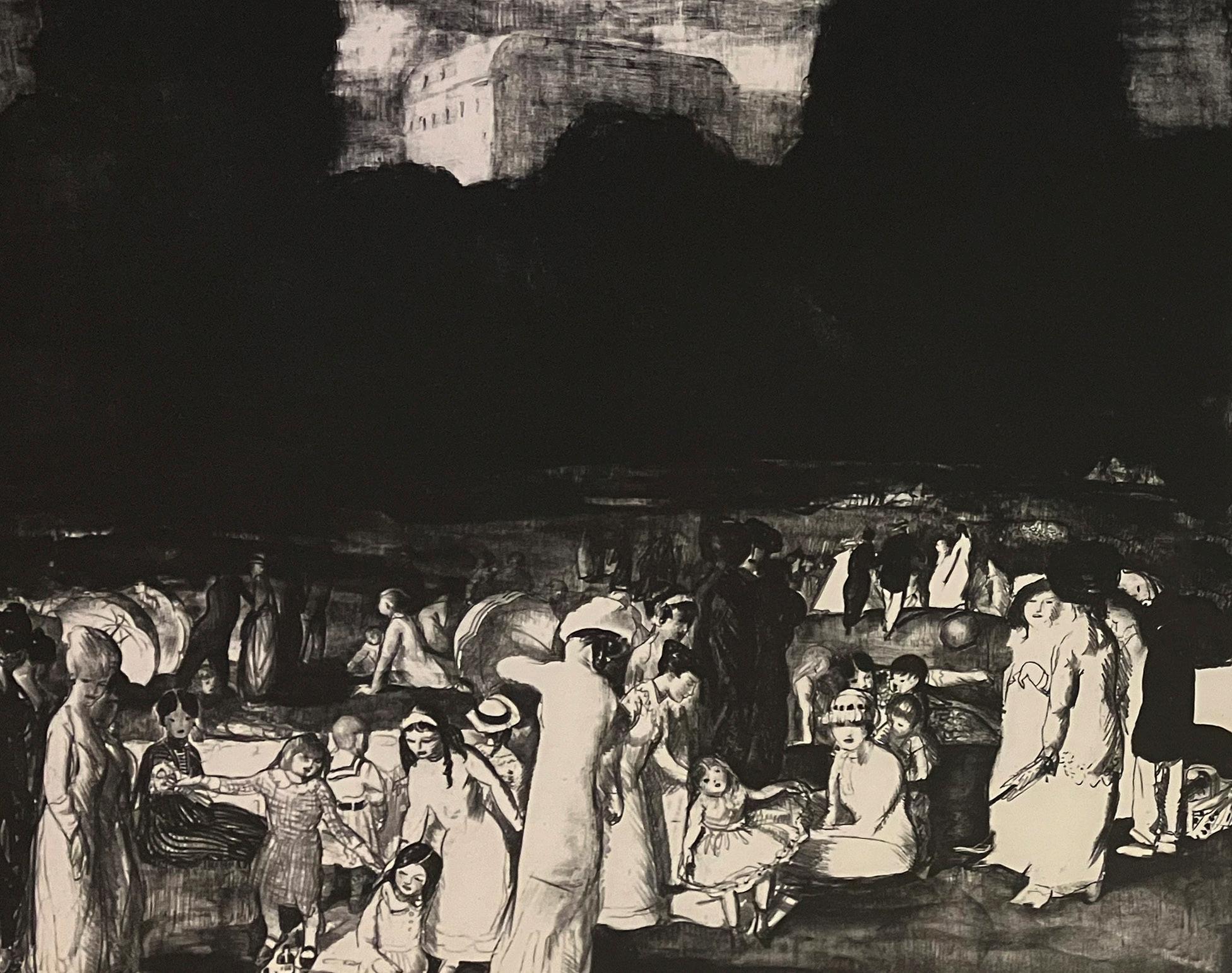

The lithographs were comprehensive in their scope. Most famous are the boxing images but he explored many other subjects. His elegant polo and tennis matches, unsparing indictments of the cruelty experienced in prisons and insane asylums, unforgetable images of children swimming in the filthy rivers surrounding New York and his amusing antics of the art scene are all engaging.

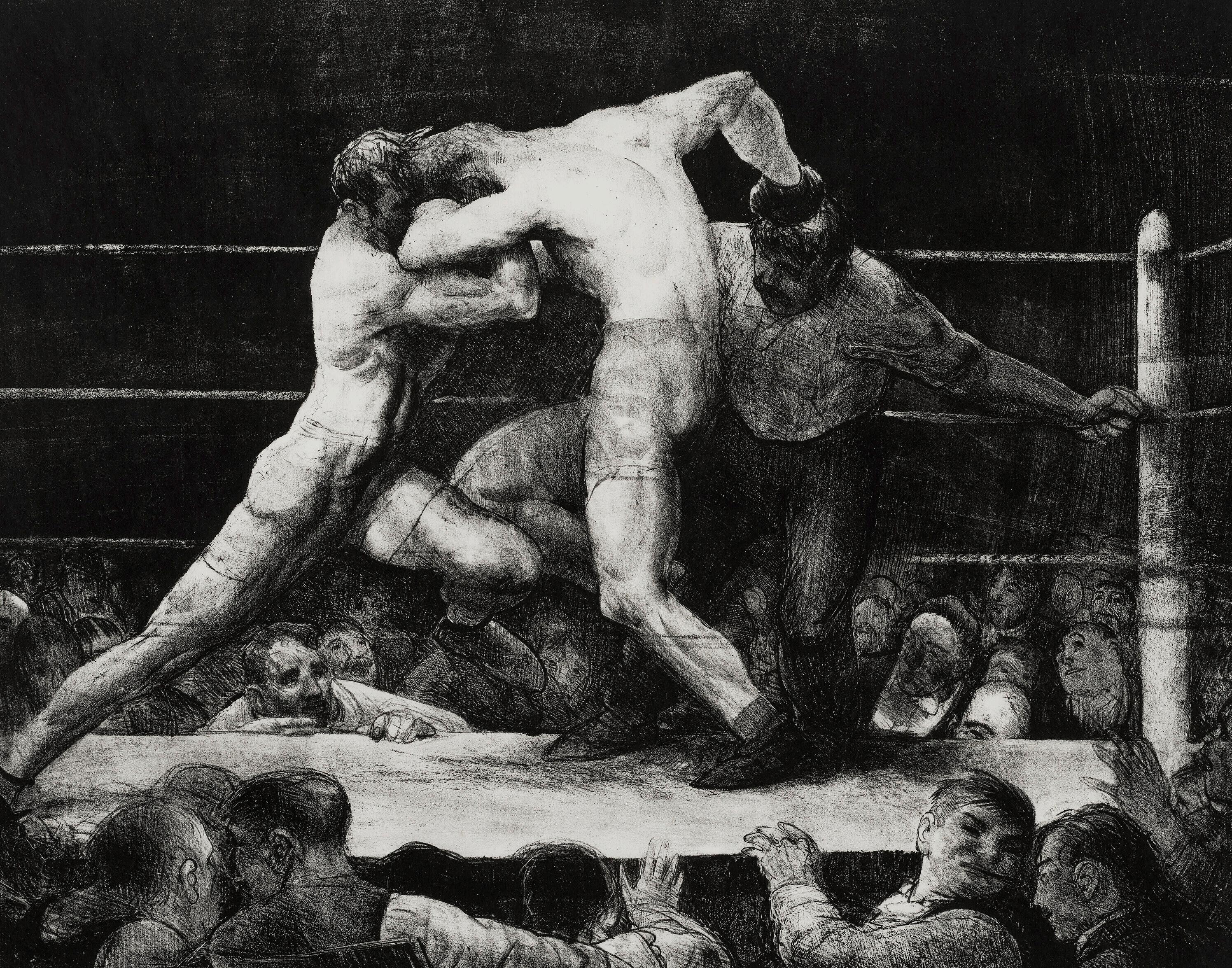

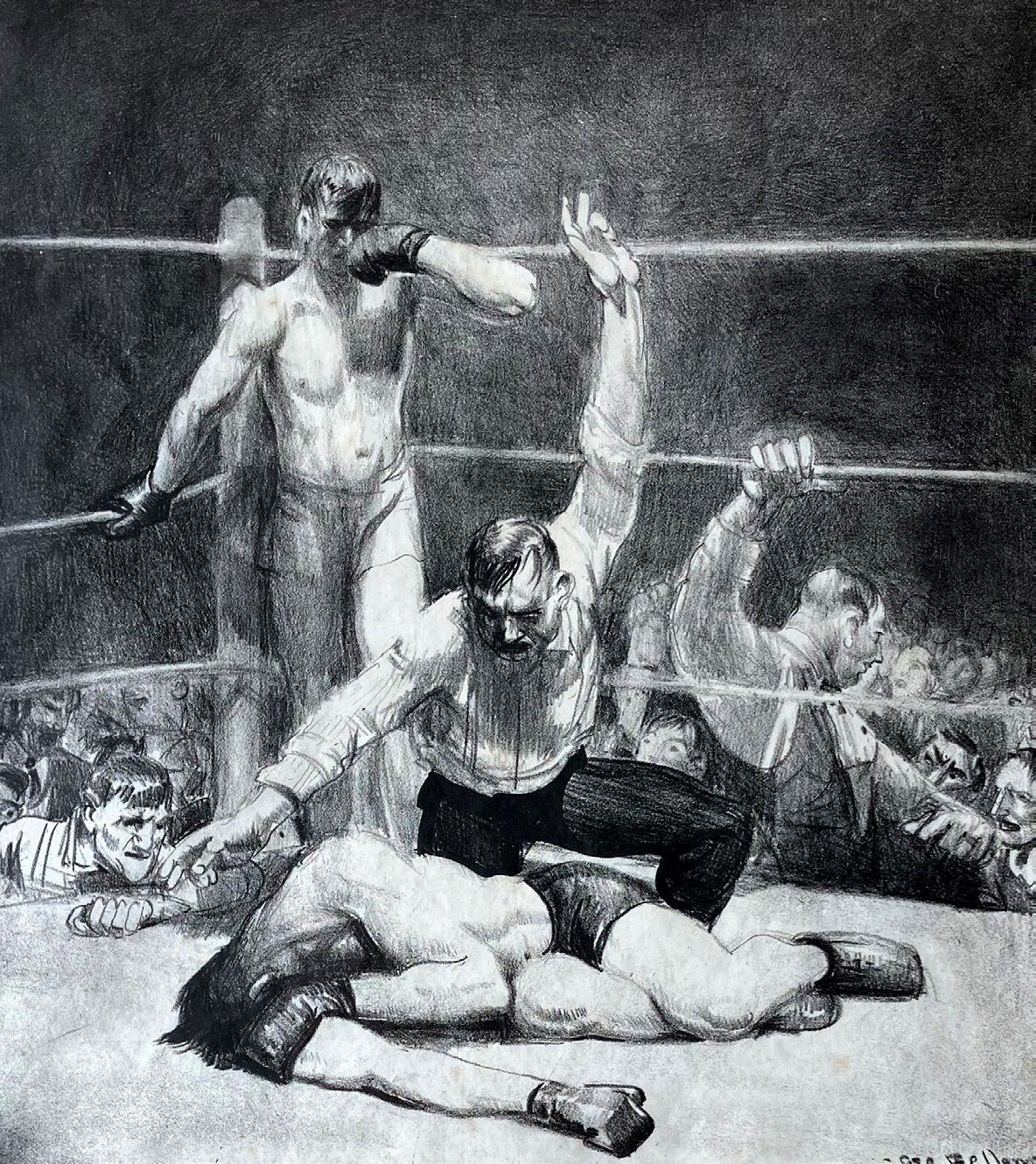

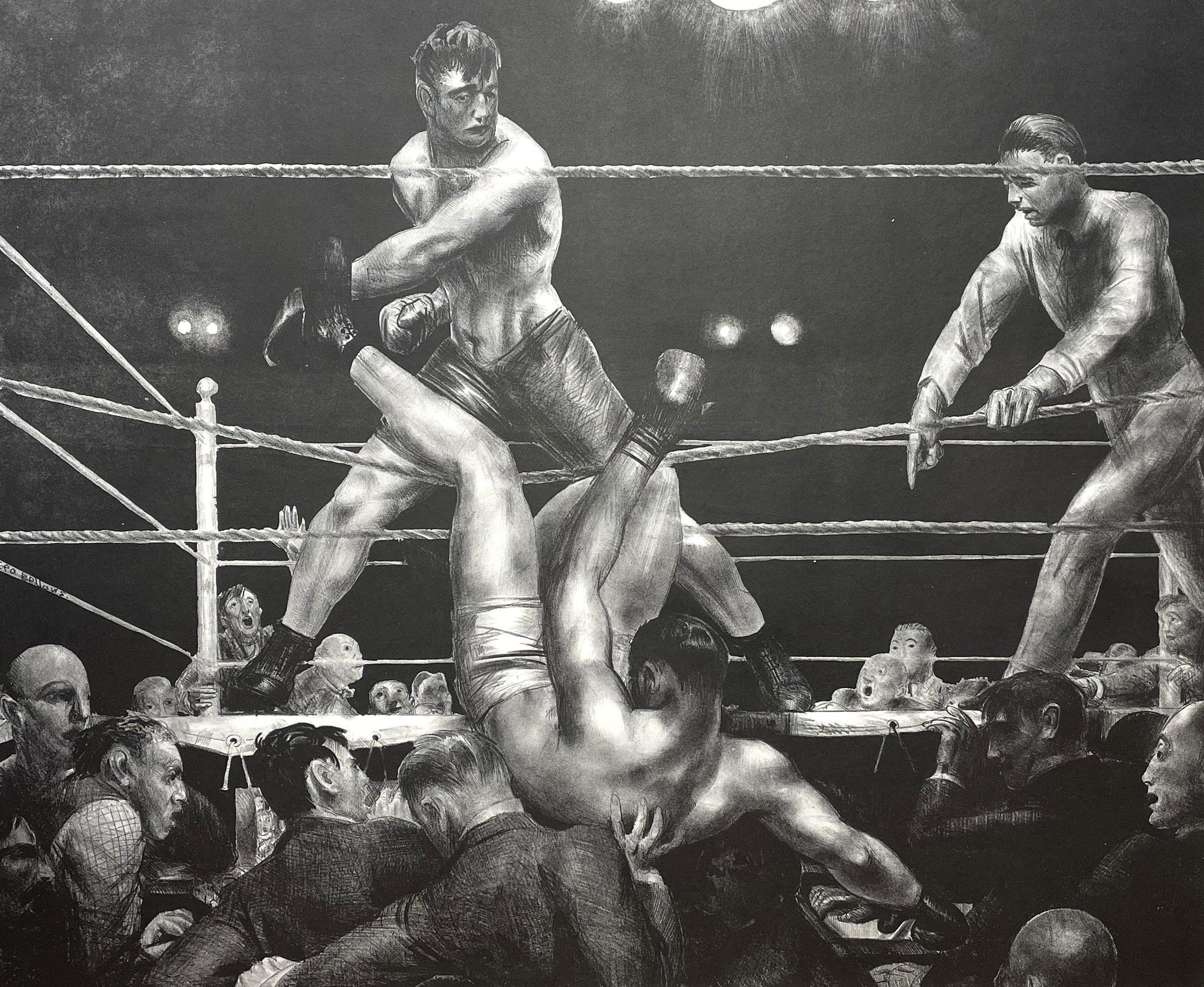

To underline his stature as a graphic artist, the lithograph, A Stag at Sharkey’s remains one of the most enduring images of American printmaking. Fortunately,the Columbus Museum of Art initiated a program to augment its modest holdings of these prints in 2002. Now it has arguably the fourth largest collection of these works in the country – including all 16 of the fight scenes. This collection is superceded only by those of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Ft. Worth, Texas, Boston Public Library and Cleveland Museum of Art.

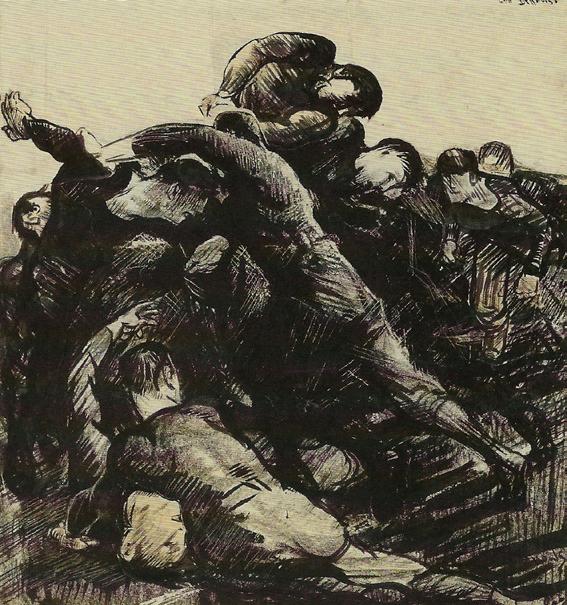

Before producing his lithographs Bellows created some of the most powerful drawings in the hostory of American art. These were exhibited in major institutions including Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Art Institute of Chicago, and the American Watercolor Society.

Watermelon Man is one of these drawings. Executed in 1906 it is a pioneering example of urban realism. Evoking the work of Francisco Goya, Bellows poignantly depicted the plight of New York’s “street urchins” gathering around a watermelon vendor in a flickering, forboding alleyway. It was purchased by an astute collector and close friend of the artist, Joseph B. Thomas, Jr. It then disappeared from public view for many years recently re-emerging in a New England collection. It is now one of two excellent drawings in Central Ohio. The other a football scene Hold ‘Em was acquired in 2021 by the Columbus Museum of Art with the support of the Shackelford family.

Since the opening of the gallery 45 years ago, Tim and I have researched, exhibited and sold dozens of Bellows’ most important prints, drawings and paintings. Several of these paintings were included in a major exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Art which were subsequently displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, London’s Royal Academy of Art and Columbus Museum of Art between 2012 and 2013.

Without the tremendous support of the Columbus community this exhibition could never have been possible. We are also deeply indebted to Nannette Maciejunes, Executive Director Emerita of the Columbus Museum of Art for her insightful essay highlighting the Columbus Museum of Art’s important role in securing George Bellows legacy. Thank you!

Tim and I hope you can join us for this exciting show highlighting the genius of Columbus’ native son.

Nannette Maciejunes

Executive

Director

Emerita, Columbus Museum of Art

On February 3, 1911, the Trustees of the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts (now the Columbus Museum of Art) voted to acquire George Bellows’ Polo at Lakewood for “a sum not to exceed $1000”. The bold work had been painted the previous year by a native son of the City, who had yet to celebrate his thirtieth birthday. The purchase was the beginning of a relationship between Bellows and the museum that has continued, unbroken for more than 100 years. When the journey began, few would have anticipated that that young painter would achieve renown as one of the most important American artists of his generation. The story of the museum’s enduring commitment to Bellows is both ordinary and remarkable. It is filled with strategy and intention, but also with serendipity and chance. The story features passionate collectors and curators, as well as an artist’s family who never stopped believing that an important part of the Bellows legacy needed to live in Columbus, Ohio.

Today the collection that Polo at Lakewood inaugurated is widely recognized as the largest and most significant public collection of Bellows’ art, and numbers nearly 250 works. It grew by both gift and purchase, and now represents the full breath of Bellows’s career with works ranging in date from 1905 to 1924. Many of the paintings entered the museum collection in the decades following Bellows’s death in 1925 at the age of 42. At the time of the artist’s death, Polo at Lakewood was still the only Bellows work in the collection. An early sign that the Bellows family intended to support the growth of the collection came in 1930 when George’s widow, Emma, donated Portrait of My Mother No.1. Another important gift from the family came in 1952 when the artist’s nephew, Howard B. Monett, donated two paintings, including Island in the Sea.

Columbus families found ways to support Bellows that ultimately benefitted the museum. The artist’s early career was given a boost by portrait commissions from Columbus citizens. Two of the most notable, Mrs. H. B. Arnold and Mrs. Albert M. Miller, were both painted in early 1913. Also known as The

White Dress, the portrait of Mrs. Miller was exhibited by Bellows the same year in the groundbreaking Armory Show, which introduced avant-garde art to many Americans. The portraits of the two women, whose children married each other, remained in the Arnold family for decades until they were donated to the museum. Other prominent families championed Bellows by collecting his work. Frederick W. Schumacher, a major arts patron who led the museum’s Board of Trustees for nearly twenty years, added Bellows to his wide-ranging collection. At his death in 1957 his collection, which included Summer Night, Riverside Drive, was bequeathed to the museum. The Edward Powell family, who owned Churn and Break, and the Everett D. Reese family also collected important works by Bellows, and then donated them to the museum.

Ferdinand Howald, the collector most closely identified with the museum in the first half of the twentieth century, however, is missing from the group of Bellows supporters in Columbus. Howald donated his superb European and American modernist collection to the museum in 1931 as part of a concerted effort to elevate the importance of his hometown museum. That collection perhaps surprisingly included no works by George Bellows. If Howald ever explained his disinterest in Bellows to anyone, that explanation has not survived, leaving us to wonder. It is likely though that Bellows’ paintings did not quite align with Howald’s own taste in modernism and that Howald did not feel compelled to acquire a Bellows since others in Columbus were already collecting the artist. He probably anticipated (rightfully it turns out) that those works would eventually join his collection at the museum. Indeed when Howald made his gift in 1931, the museum already owned two major Bellows paintings.

The museum also used its own acquisition funds to invest in its Bellows collection.

Several of the most significant paintings by the artist in the collection were purchases made over several decades by three different directors. These include: Snow Dumpers in 1941, Children on the Porch in 1947, Riverfront No. 1 in 1951, and Blue Snow, the Battery in 1958. All of these purchases were made with the museum’s primary acquisition fund - the Howald Fund, enabling Ferdinand Howald to posthumously make a singular contribution to the museum’s Bellows collection.

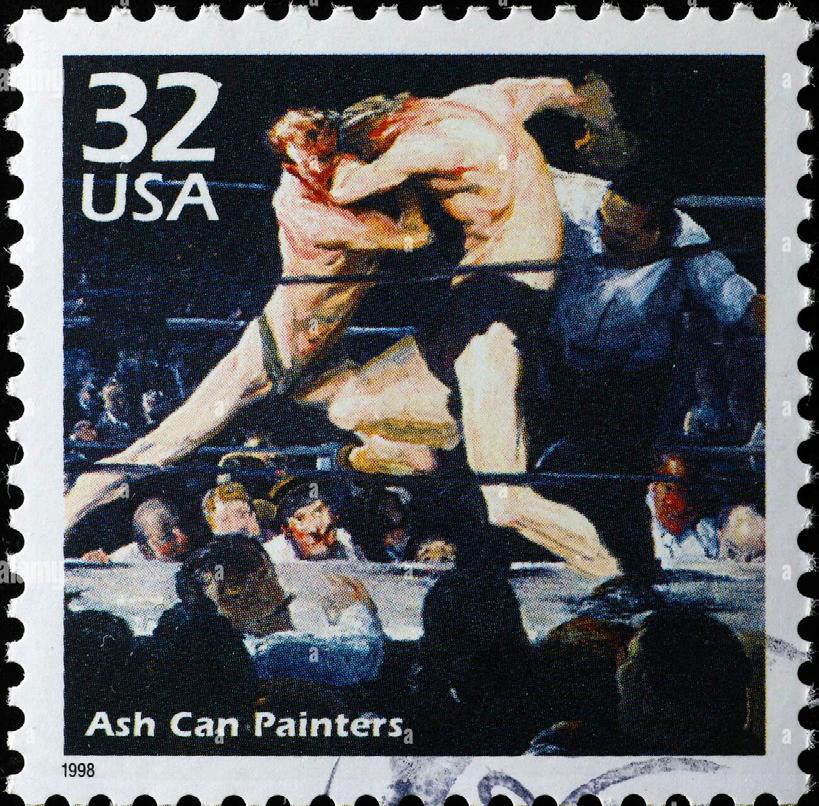

The steady hands that chose Bellows paintings for the collection rarely faltered. There is one notable exception however. The museum was offered the opportunity to buy Bellows’ A Stag at Sharkey’s, a painting now so widely acclaimed as an American icon that it was selected by the United States Postal Service in 1998 to be celebrated on a postage stamp. For reasons now lost to history, the museum declined to acquire the picture, which subsequently became part of the Cleveland Museum of Art collection in 1922. As the State Capital, Columbus has always taken some consolation from the fact that Stag is, at least, in an Ohio museum.

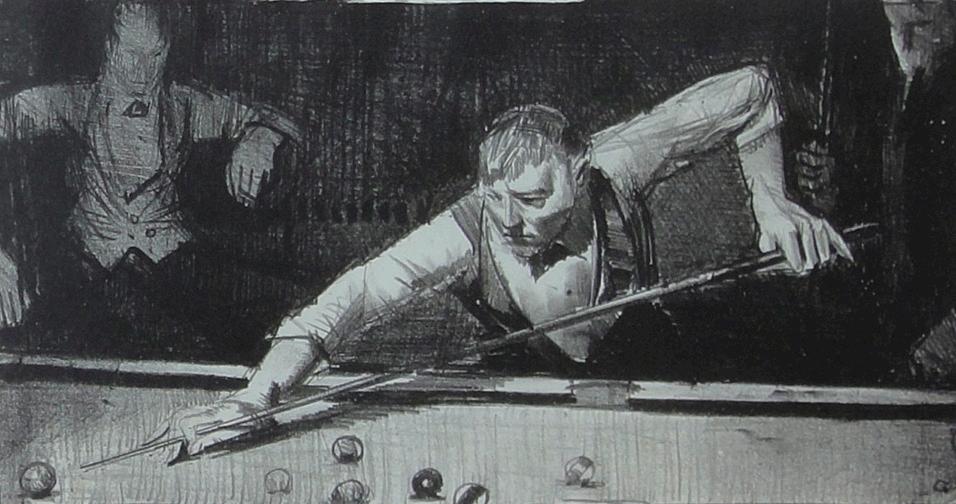

In addition to being an extraordinary painter, George Bellows was also an important printmaker. His commitment to lithography and his belief in its artistic potential are often credited with saving lithography from being abandoned as a fine art medium and becoming exclusively used for commercial art. Despite the significance of lithography to Bellows’s vision as an artist, the museum collection of his prints developed slowly. Only fairly recently did the museum make a commitment to building a top-tier Bellow lithography collection. Columbus did not acquire its first Bellows lithographs until 1930, five years after the artist’s death. Jean (second stone) and the Old Billiard Player were donated that year by Mrs. William Neil King. A steady drip of gifts followed over the next several years from different donors. Almost all of whom, interestingly, were women.

The museum did not purchase its first lithographs until 1955, acquiring Preliminaries to the Big Bout, The White Hope, and Sunday 1897 with monies from the Mrs. H. B. Arnold Memorial Fund. This is the same Mrs. Arnold whose portrait Bellows had painted four decades earlier and whose portrait was donated to the museum by her family that year. This was followed in 1959 by the acquisition of Artists Judging Works of Art, Prayer Meeting, and Portrait of John Carroll using the Howald Fund.

Though each of these was a wonderful addition to the collection, they seem to reflect the museum capitalizing upon opportunities as they arose rather than a specific strategy to build a significant Bellows lithography collection. This approach changed dramatically in 2002 when the museum decided to make building the Bellows lithograph collection

an institutional collecting priority. The museum’s new goal was to become one of the top five public collections. The new aspiration was launched that year with the purchase of the Rifkin Collection. Recognized as one of the finest private collections of Bellows lithographs, this New York collection of more than 30 superb impressions included, among its many treasures, all of Bellows’s boxing lithographs. It brought Columbus in a single acquisition the athletic pictures that the museum collection so desperately needed to fully represent Bellows as an artist.

Over the next twenty years, the museum added 124 lithographs to its holdings, which had numbered just 45 before 2002. The collection grew not just in size but in scope, increasing its capacity to tell the story of Bellows as a printmaker. The Bellows family became a strong ally in the project. The Bellows Trust still held many rare impressions that demonstrated the artist’s experimental approach to printmaking - the same subject created in multiple stones and states, and the use of different inks and papers. Acquisitions from the Trust would transform the texture of the collection. A perfect example is the early work, Hungry Dogs. The museum acquired seven distinctly different impressions of the lithograph from the Trust. Another important example is Electrocution from 1917. Thanks to the depth of the Trust’s holdings, the museum collection now includes all five versions of the lithograph, allowing an understanding of Bellows’s exploration of the subject in a way that seeing any one of the versions by itself does not. By 2023 the Columbus Museum of Art was able to claim that it housed one the top public collections in the country. Essay continues on page 42

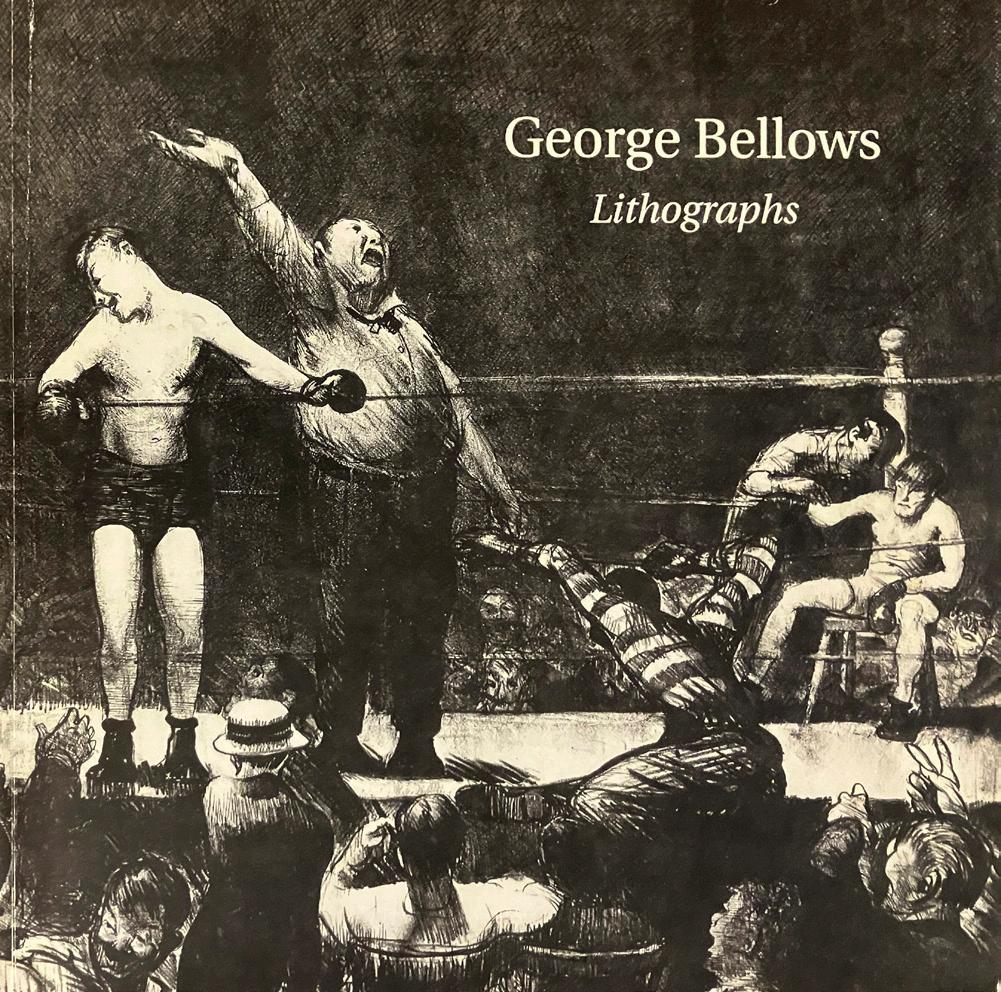

Clockwise from left: BetweenRounds,Large,FirstStone , 1916, Courtesy of Capital University’s Schumacher Gallery; CountedOut,FirstStone,1921; Introductions, 1921

Opposite Page: PreliminariestotheBigBout,1916

You would think that Bellows would have been appalled by Newport, but he seems to have enjoyed it. It really is the land of the rich. Even today, there’s nothing like the row of cottages along the sea, and the casino is right at the center of things. Maybe that’s the impression Bellows wanted to give. He made a lithograph with the same title, but it’s not at all the same. You’d think his friends at The Masses, where the artists were so much more important than the writers, would have kidded him about his adventures among the rich, but I guess you didn’t kid George Bellows.- MSY, p. 126

The Lithographs of George Bellows, A Catalogue Raisonné, 1977

Opposite Page: Evening Snow, 1921

Clockwise from top left: Splinter Beach, c. 1916; Figure Study for River Front – Boy on Sand, c. 1915; The Street, 1917; River Front, 1923-24

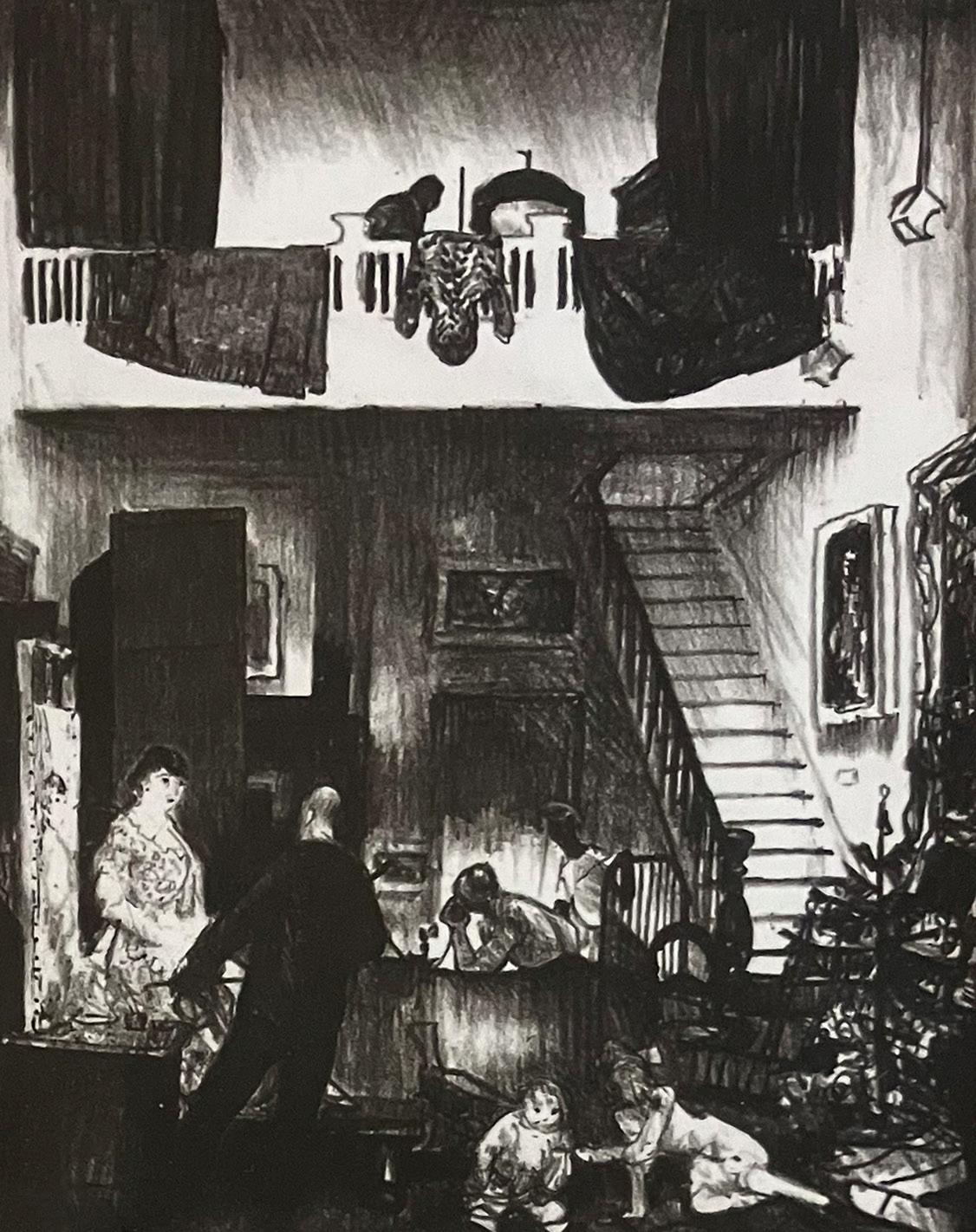

The scene is at “Petitpas,” a little French restaurant well over on West Twenty-ninth Street, New York. Here artists and writers liked to gather at the table of the old Irish portraitist John Butler Yeats, father of William B. Yeats, the poet, and Jack Yeats, Dublin artist. Mr. Yeats, although well on in the seventies, was a delightful conversationalist, a wit and a great lover of beauty. There was always the spirit of youth about his table.” -ESB. p.239

The Lithographs of George Bellows, A Catalogue Raisonné, 1977

Opposite page: Artists' Evening (At Petitpas'), 1916

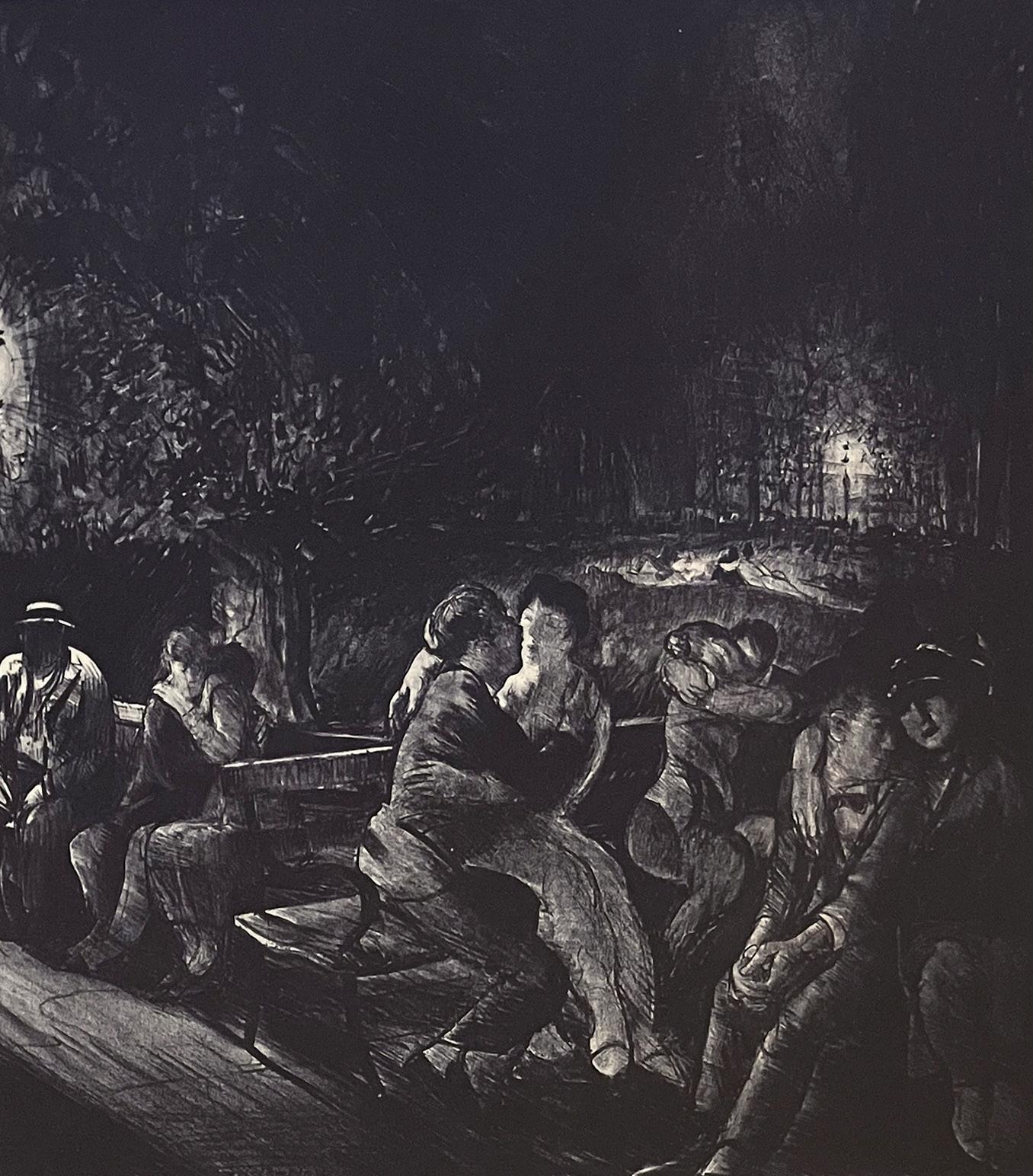

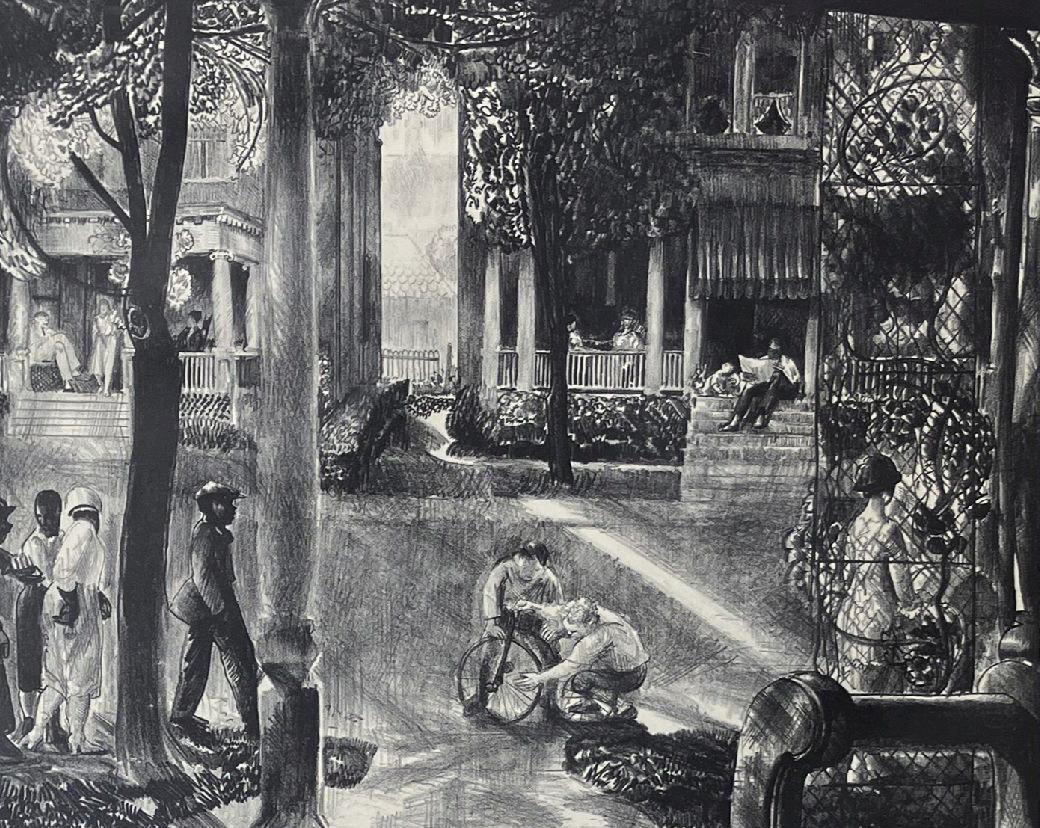

In the Park, Dark , 1916

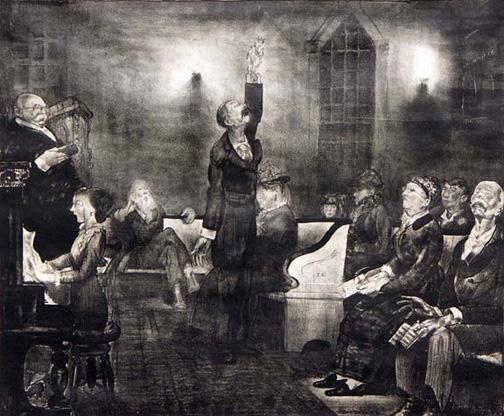

The artist as a young man was an intimate friend of the family of the superintendent of the great State Hospital at Columbus, Ohio. For years the amusement hall was a gloomy old brown vault where on Thursday nights the patients indulged in “Round Dances” interspersed with two-steps and waltzes by the visitors. Each of the characters in this print represents a definite individual. Happy Jack boasted of being able to crack hickory nuts with his gums. Joe Peachmyer was a constant borrower of a nickel or a chew. The gentleman in the center had succeeded with a number of perpetual motion machines. The lady in the middle center assured the artist by looking at his palm that he was a direct descendant of Christ. This is the happier side of a vast world which a more considerate and wiser society could reduce to a not inconsiderable degree. - GB

The Lithographs of George Bellows, A Catalogue Raisonné, 1977

Page: Dance in a Madhouse, 1917

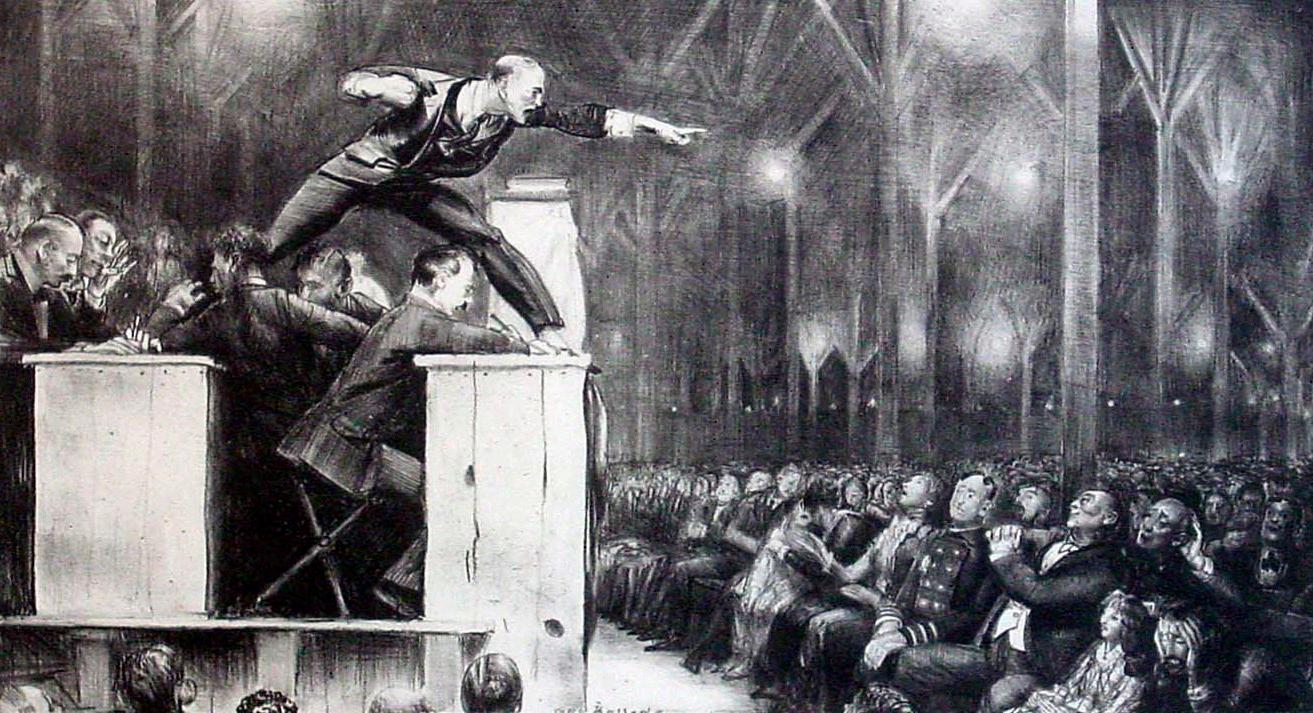

Billy Sunday, 1923

Prayer Meeting, Second Stone, 1916

George Bellows was a devoted family man, dedicated to his wife, Emma, and their two children. After an extended courtship he married Emma Story, an art student from Upper Montclair, New Jersey in 1910. Anne was born in 1911 and Jean in 1915. Bellows painted at least 140 portraits, over one third of them depicting family members, especially his wife and daughters. He also created 25 lithographs of his family.

Emma was a strong figure who steadfastly worked to augment George’s legacy after his death. She helped organize three major exhibitions of his work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1925), Art Institute of Chicago (1946), and National Gallery of Art (1957) prior to her passing in 1959. She also was actively involved with negotiating contracts with the estate’s dealers and the placement of paintings held by the estate. Her children and grandchildren have continued that tradition.

My Family, 1921

The result of a young artist’s first service on an official jury. For fear of offense none of the “likenesses” will be painted out. They are whoever they are. -GB

The setting is probably the National Arts Club. Bellows pictured himself as the observer in the upper right, in this satirical comment on the contemporary art world. Is that his friend Robert Henri seated in the shadow, right foreground?

Lauris Mason

The Lithographs of George Bellows, A Catalogue Raisonné, 1977

Sunday, 1897, 1921

Collection of Eric and Megan Vanderson

Sunday, 1897. Much against his will the artist, as a young man, being called to church in the family rig. The Reverend Purley A. Baker, first president of the Anti-saloon League, is saluted in passing. -GB, in FK

Memories of a Sunday morning in Columbus, Ohio, 1897. George, aged fifteen, is uncomfortably seated next to his father, who is driving. His mother is on the rear seat; two friends are being given a lift. - ESB, p. 250

Lauris Mason

The Lithographs of George Bellows, A Catalogue Raisonné, 1977

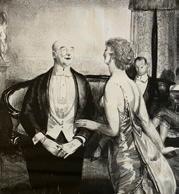

. . . the lady says to the at critic, “Oh, my dear Dr. Quince. I want you to meet my young artist, a word from you will mean so much!” -GB, in F.K.

The meaning of the print is best understood when the artist’s words are used as a caption for what he obviously intended as a cartoon. Although Bellows was sympathetic to the need of the young moderns for encouragement and was a founder of the New Society of American Artists, dedicated to this idea, he still saw the humor in the fact that no matter how social the situation, a professional critic was always considered to be on call.

Lauris Mason

The Lithographs of George Bellows, A Catalogue Raisonné, 1977

The museum has a relatively modest collection of Bellows drawings. The collection began in 1940 with the gift of I Remember Being Initiated into the Frat from the widow of Joseph R. Taylor, Bellows’s Ohio State English professor and lifelong friend. Taylor, who outlived Bellows by nearly a decade, wrote a tribute to the artist for The Ohio State University Monthly when he died. The large scale, conte crayon drawing was no doubt a gift from Bellows to Taylor, and is the final preparatory drawing for the 1917 lithograph of the same title. Over the next several decades, the museum acquired, through gift and purchase, a handful of drawings, particularly favoring studies and preparatory sketches for different paintings and lithographs. In the 1970s, Columbus’s Everett D. Reese family donated both the painting Boy and Calf, Coming Storm and a preparatory compositional study for it in pencil. In 1992, the Reeses also donated two preparatory figure studies for the painting Children on the Porch, which the museum had owned since 1947.

In 2010 the Bellows family doubled the size of the drawing collection with a rare, and wonderful group of ten “cartoons” that Bellows created for his young daughters. The amusing sketches are exemplified by I Want to See Anne and Jean, which depicts George and wife Emma, standing, bereft, in a bathtub, overflowing with the tears they are crying because they miss their children. The drawings not only capture Bellows’ wit and humor but also his love for his children. Bellows’ younger daughter, Jean, had always kept the sketches. After she and her husband died, her children wanted them to come to the museum.

Working with longtime donors and supporters Don and Teckie Shackelford in 2021, the museum was able to acquire a jewel for its drawing collection - Hold ‘Em. The large, finished master drawing is a first for the collection. The subject is a scrum of football players and was created by Bellows as the title illustration for Edward Lyell Fox’s article “Hold ‘em” in the November 1912 issue of Everybody’s Magazine. As one of his finest drawings, Hold ‘Em had been included in the National Gallery of Art’s major Bellows retrospective in 2012. The work captures the intensity of an athletic struggle, echoing the power of his iconic fight scenes. The museum’s choice of a football drawing is hardly surprising. Bellows was, after all, a Buckeye. Although George Bellows never lived in Columbus as an adult, he never forgot his hometown and was a regular visitor. His mother continued to live here and Bellows had many friends and supporters in the City. In many ways, the museum’s commitment to Bellows and his legacy is an extension of the City’s belief in Bellows - and perhaps Bellows’ belief in Columbus.

From the very beginning, the museum (known of course to Bellows as the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts) supported Bellows projects. Without its own building, the museum, in tandem with the Columbus Art Association, supported at least two early exhibitions at the Columbus Public Library,

In January 1911, in an effort to introduce the community to contemporary American art, Bellows and fellow artist Robert Henri organized an exhibition of more than a hundred works for the Library inspired by the earlier Independents exhibition in New York. The venture was not without its challenges. Some Columbus leaders objected to the inclusion of certain works they deemed improper, including Bellows own boxing drawing The Knock Out and Rockwell Kent’s Men and Mountains. In spite of the ruckus over the show, all was forgiven and two years later, the Library hosted a solo exhibition of Bellows’s work.

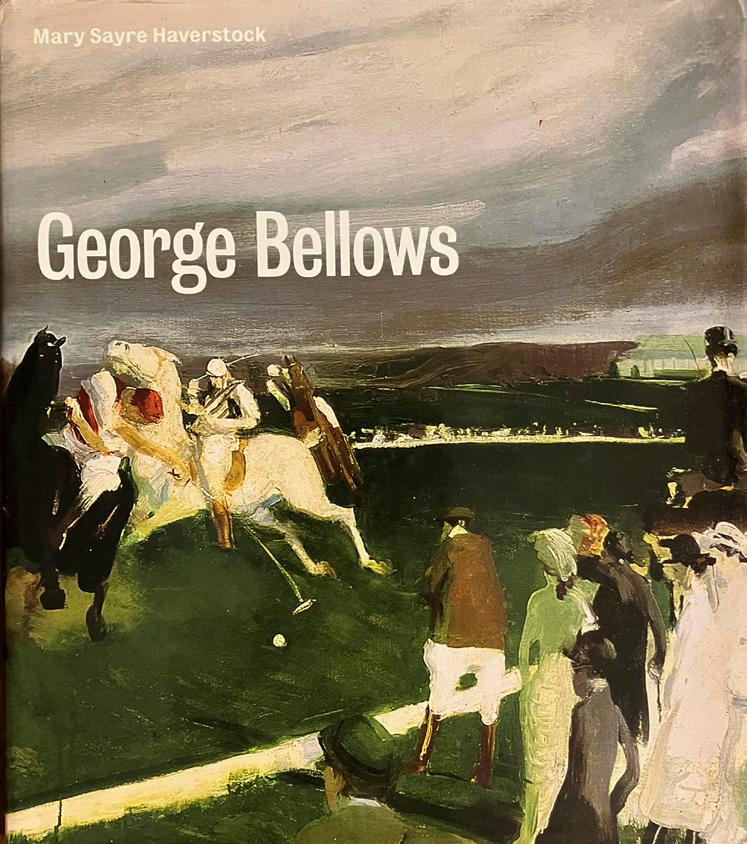

When the museum opened its new Broad Street home in 1931, unsurprisingly it celebrated with an exhibition of Bellows’ work. The walls of the new galleries going forward always included his paintings, lithographs and drawings. Whether originating Bellows projects of their own, like the 1979 retrospective that toured nationally and produced a book with new scholarship, the museum was steadfastly at the table if the subject was Bellows. It was always aware of its commitment and responsibility to its native son. The museum supported the research of scholars and lent generously to the exhibitions other museums organized, often participating in the tours. In 1998 the museum hosted the acclaimed George Bellows: The Love of Winter organized by the Norton Museum of Art. In 2007 the need for a new book on Bellows for the general public became apparent. Columbus stepped up again, partnering with Merrell Publishers, to commission a book from art historian Mary Sayre Haverstock, who had directed the Ohio Artists Project at Oberlin College.

What was best for Bellows, however, was not always easy for the museum and Columbus. A challenge came in 2012 when the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. organized the first major retrospective on Bellows in more than a generation.

The exhibition was to travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Royal Academy in London. A show on Bellows in Washington and New York showcasing new scholarship was important, but It would be the first time a Bellows exhibition would travel to Europe. The museum was asked to lend seven of its major paintings to the tour. Four of its pictures would travel to London. The paintings would be gone from Columbus for over a year.

The museum wanted to lend but it also wanted to bring the exhibition to Columbus; it wanted Columbus to be a part of this groundbreaking Bellows moment. What might have been possible in an ideal world was not practical in the real world. Works of art are fragile and loans for a four venue tour would be beyond challenging. If Columbus refused to lend, it would significantly impact the quality of the show. If the museum insisted it would lend only if it was on the tour, it threatened to diminish the power the exhibition could have at each of the venues. Columbus was faced with a difficult decision.

Perhaps not surprisingly after a hundred years of supporting its native son, the museum chose to do what was best for Bellows’s legacy. It stepped back from its request to be on the tour, lent all seven pictures, and chose to help introduce George Bellows to new audiences outside Columbus. The museum’s generosity did not go unnoticed. The National Gallery offered to help organize a coda to the retrospective for Columbus. Drawing on a handful of lenders, including the National Gallery, and showcasing the museum’s own Bellows collection, the 2013 show enabled the museum to bring the excitement of the retrospective to the artist’s hometown. The exhibition even included a rare visit of A Stag at Sharkey’s from the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Two events have occurred in the last several years that exemplify how deeply intertwined Bellows’ legacy and the museum have become. The first happened in 2011 when Bellows family approached the museum about becoming the permanent public home for the artist’s Record Books. Bellows had been a meticulous record keeper, maintaining a chronological list of his works illustrated with thumbnail sketches. He regularly annotated the list with notes on sales and exhibition history. After Bellows death, his family continued to update the Record Books until 1997. The Books comprise the single most important research resource on Bellows and provide an invaluable look at the American art world of the early twentieth century. The family’s goal in transferring the Record Books to a public collection was to make them more accessible to scholars, and ultimately make them widely available by digitizing them. To achieve this goal, as well as properly care for such fragile archival documents, the museum knew it needed a partner. The logical choice to be that partner was the Ohio State University Libraries. Working together, the museum and OSU became the joint owners and stewards of the Record Books. Over the next few years, they were digitized and are now accessible online through OSU Libraries to any student, scholar or Bellows lover.

The second event occurred in 2021 when longtime museum supporters, Don and Teckie Shackelford, decided to endow the museum’s position of Curator of American Art. In addition to ensuring that the museum would always have an American curator, Don and Teckie wondered if there was also something they could do to contribute to Bellows’s legacy at the museum. The decision was made to establish the George Bellows Center at the museum, with the new Shackelford Family Curator of American Art serving as its director. The new Center would be dedicated to supporting projects on Bellows and the generation of American artists he was a part of. It would include a gallery and study space for students and visiting scholars, host public programs, and serve as an incubator for exhibitions, research and publications. The George Bellows Center opened in November 2021 with a weekend celebration that brought the Columbus community together with scholars and Bellows admirers from around the country.

The relationship of George Bellows and the Columbus Museum of Art has now flourished for more than a hundred years. The chance the museum’s Board of Trustees took in 1911 on a young, Columbus born and raised, artist on the cusp of his thirtieth birthday remains both the most ordinary and extraordinary of decisions. It was ordinary because it was the purchase of a single painting, Polo at Lakewood, for a relatively modest amount of money, ordinary because museums buy art for their collections all the time. It was extraordinary too though because of the amazing journey it launched and the fact that the museum is still on that journey today.

Note: This essay draws primarily on the records of the Columbus Museum of Art. It also references material found in The Lithographs of George Bellows: A Catalogue Raisonne by Lauris Mason (Revised Edition, 1992); George Bellows: An Artist in Action by Mary Sayre Haverstock (2007), George Bellows (Exhibition Catalogue for the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C, 2012 Bellows Retrospective); Reflections: The American Collection of the Columbus Museum of Art (2019).

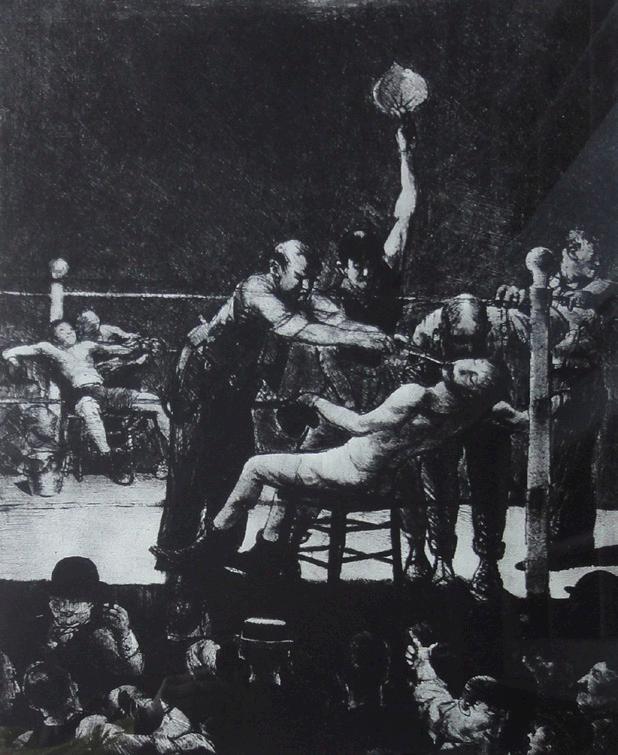

A Knockout Incident of the Ring (A Knock

Out) (Second state), 1921

Lithograph

15 ⅜ x 21 ⅝ inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Titled lower center: Incident of the Ring

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown-imp.

Edition of c. 6

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 92

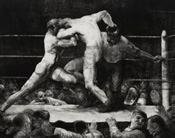

A Stag at Sharkey’s, 1917

Lithograph

18 7/16 x 23 13/16 inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center:A Stag at Sharkey’s

Numbered lower left: No. 26

Edition of 98

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 46

Anne in a Black Hat, 1923-24

Lithograph

14 ½ x 11 ¾ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Anne in a Black Hat

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp.

Edition of 40

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 185

Arrangement, Emma in a Room, 1921

Lithograph

9 ¼ x 7 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp

Edition of 43

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 112

Artists’ Evening (At Petitpas’), 1916

Lithograph

8 ⅞x 12 ⅛ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Artists Evening

Inscribed lower left: No 5

Edition of 65

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 19

ArtistsJudgingWorksofArt(Secondstate) , 1916

Lithograph

14 ½ x 19 ⅛ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows / J.B.B.

Numbered lower left: No 32

Edition of 52

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 18

ArtistsJudgingWorksofArt(Secondstate) , 1916

Lithograph

14 ½ x 19 ⅛ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Numbered lower left: No 35

Titled lower center:Artists Judging Works of Art

Edition of 52

Mason catalogue raisonne no. 18

Private Collection

BetweenRounds,Large,FirstStone , 1916

Lithograph

20 ¼ x 16 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Between Rounds

Numbered lower left: No 29

Edition of 58

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 25

Courtesy of Capital University’s Schumacher

Gallery

Billy Sunday, 1923

Lithograph

8 ¾ x 16 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Billy Sunday

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown Imp.

Edition of 60

Mason catalogue raisonné no.143

Counted Out, First Stone, 1921

Lithograph

12 ⅜ x 11 ⅛ inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Titled lower center: Counted Out

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp.

Edition of 11

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 94

Dance in a Madhouse, 1917

Lithograph on China wove paper

18 ½ x 24 ⅛ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Numbered lower left: No 46

Titled lower center: Dance in a Madhouse

Edition of 69

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 49

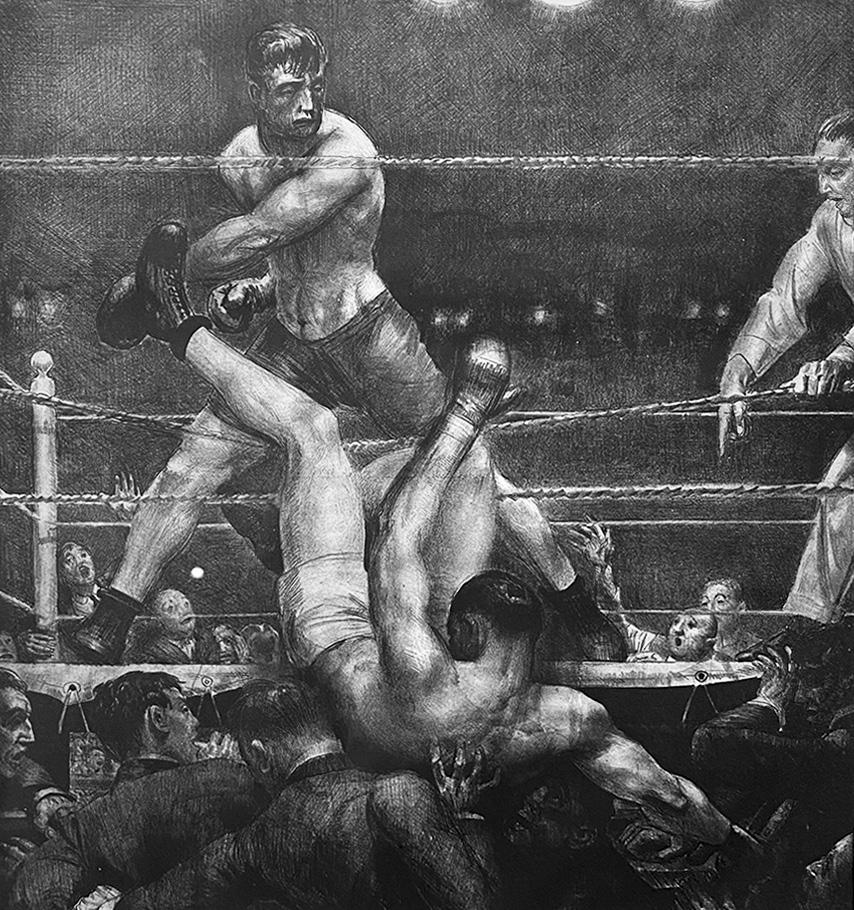

Dempsey and Firpo, 1923-24

Lithograph

18 ⅛ x 22 3/8 inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Dempsey and Firpo

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp.

Edition of 103

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 181

Dempsey Through the Ropes, 1923-24

Lithograph

17 ⅞ x 16 ½ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Dempsey Through the Ropes

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp.

Edition of 30

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 182

Elsie, Emma, and Marjorie (First Stone), 1921

Lithograph

9 ⅝ x 12 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown Imp.

Edition of 16

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 103

Elsie, Emma, and Marjorie (First Stone), 1921

Lithograph

9 ⅝ x 12 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Marjorie, Emma, and Elsie

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown Imp.

Edition of 16

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 103

Private Collection: Arizona

Evening Snow, 1921

Lithograph

7 ¼ x 9 ¾ inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Titled lower center: Evening Snow

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp

Edition of possibly 24

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 91

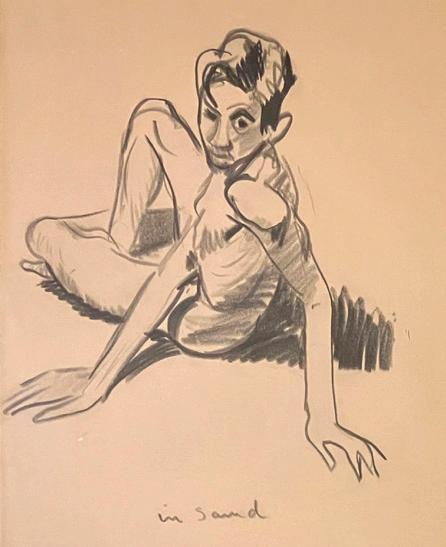

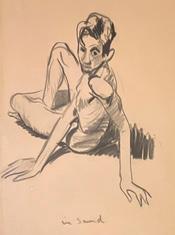

Figure Study for River Front – Boy on Sand, c.

1915

Crayon on paper

10 x 8 inches

Titled lower center: In Sand

Signed on the reverse: George Bellows, ESB

H.V. Allison & Co. Label verso

In the Park, Dark, 1916

Lithograph

16 ⅞ x 21 inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Numbered lower left: No. 14

Titled lower center: In the Park Edition of 81

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 30 (variant state) (related lithograph Amon Carter no. 135, 136)

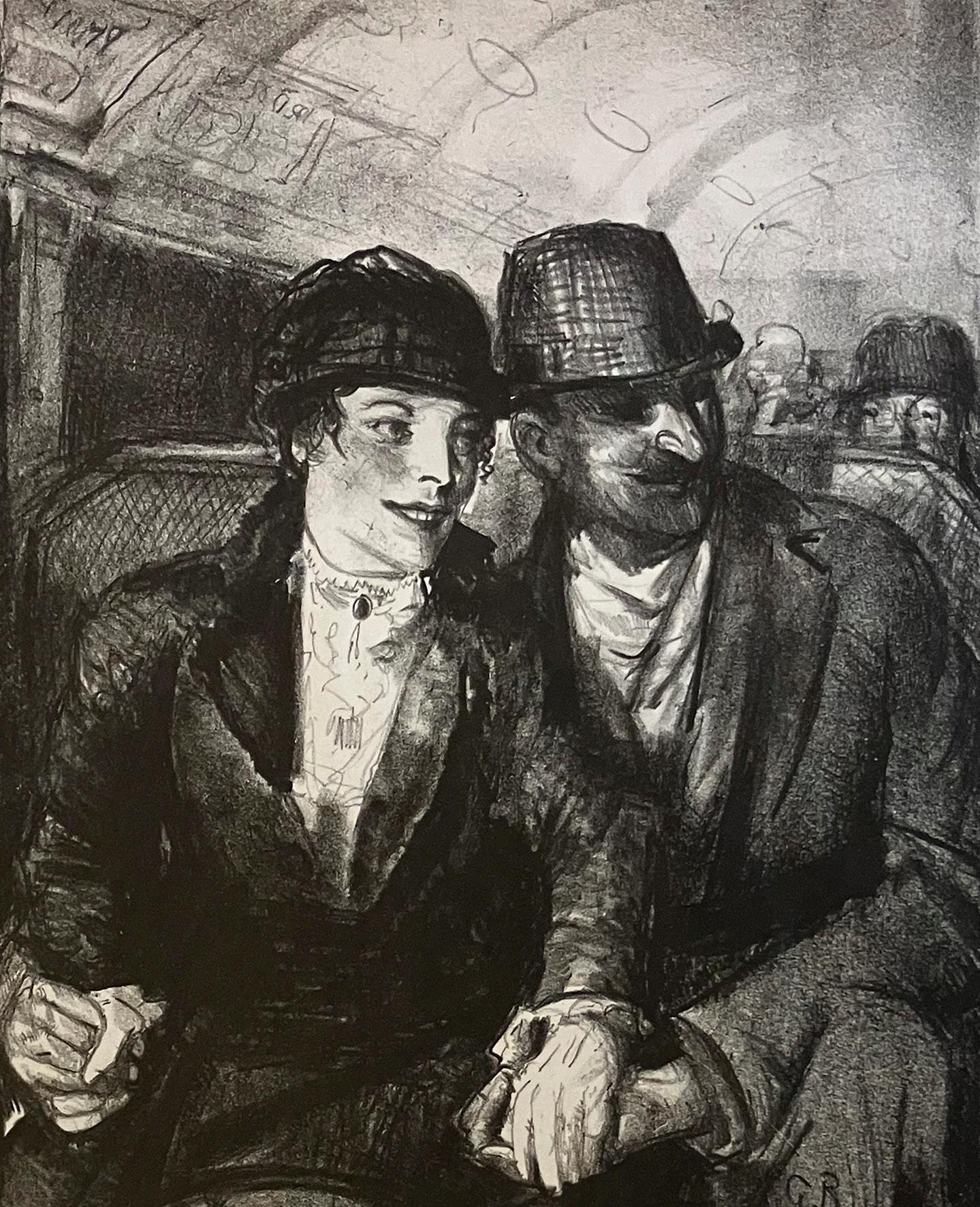

In the Subway, 1921

Lithograph

8 ½ x 7 inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp

Titled lower center: Subway

Edition of 16

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 88

Indoor Athlete, First Stone, 1921

Lithograph

6 ½ x 9 ¾ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp.

Edition of 21

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 81

Introductions, 1921

Lithograph

8 ⅜ x 6 ⅞ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Introductions

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp.

Edition of 57

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 97

Love of Winter, Christmas, 1917

Lithograph

4 ¾ x 5 ¾ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Love of Winter

Edition: unknown (small)

Second state of two

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 50

My Family (First stone), 1921

Lithograph

10 ¼ x 8 inches

Signed lower right: Bellows ESB

Titled and number lower left: My Family No. 1

Edition of 32

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 115

Polo Sketch, 1921

Lithograph

8 ½ x 10 ⅛ inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton S. Brown, imp.

Edition of 20

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 87

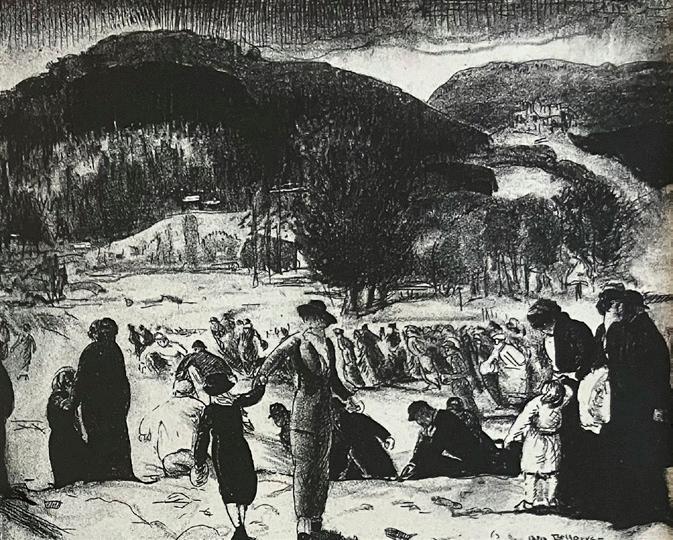

Prayer Meeting, First Stone, 1916

Lithograph

18 ¼ x 22 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Prayer Meeting

Inscribed lower left: No. 4

Edition of 77

Mason catalogue raisonné no.13

Prayer Meeting, Second Stone, 1916

Lithograph

18 ¼ x 22 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: Prayer Meeting

Inscribed lower left: No. 43

Edition of 47

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 14

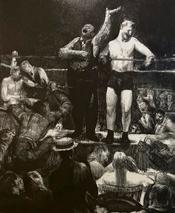

Preliminaries to the Big Bout, 1916

Lithograph

15 ¾ x 19 ½ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Ttitled lower center: Preliminaries to the Big Bout

Numbered lower left: No. 26

Edition of 67

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 24

River Front, 1923-24

Lithograph

15 x 20 ⅞ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: River Front

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp

Edition of 51

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 168

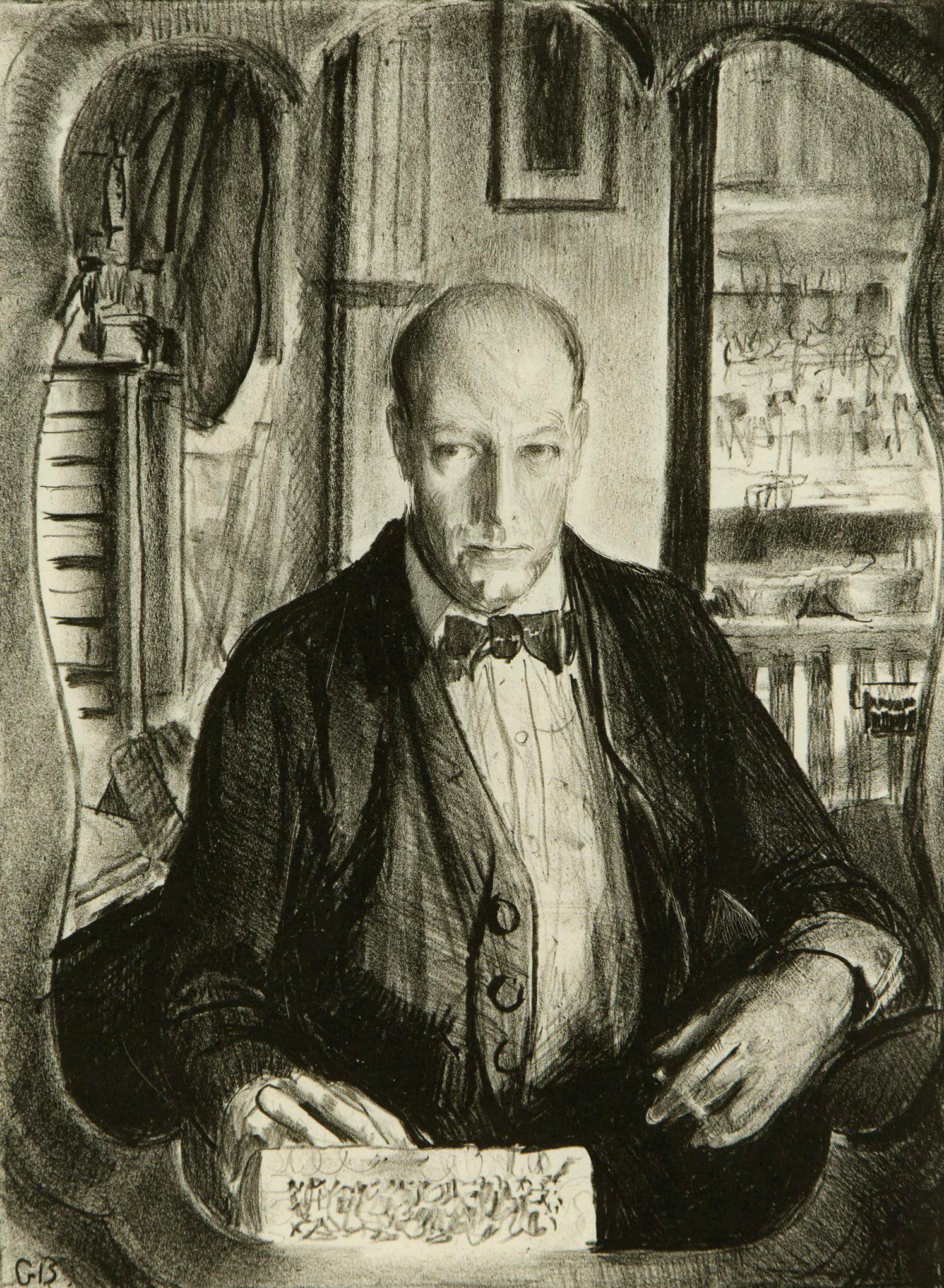

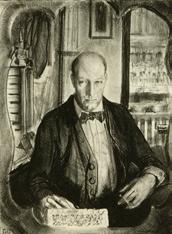

Self Portrait, 1921

Lithograph

10 ½ x 7 ⅞ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows / J.B.B.

Edition of 28

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 114

Courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art

Museum Purchase with funds provided by Lois Chope

Sixteen East Gay Street, 1923-24

Lithograph

9 ½ x 11 ¾ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower right: Bolton Brown-imp

Titled lower center: Sixteen East Gay St.

Edition of72

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 183

Sixteen East Gay Street, 1923-24

Lithograph

9 ½ x 11 ¾ inches

Signed lower right: George Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown - imp

Titled lower center: Sixteen East Gay Street

Edition of 72

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 183

Private Collection: Columbus, Ohio

Solitude, 1917

Lithograph

17 x 15 ⅜ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows / J.B.B

Inscibed lower left: No 52

Edition of 60

Mason catalogue raisonne no. 37

Splinter Beach, c. 1916

Lithograph

14 ⅞ x 19 ⅝ inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Inscribed lower left: No. 13

Titled lower center: Splinter Beach

Edition of 70

Mason catalogue raisonne no. 28

Spring, Central Park, 1921

Lithograph

8 ½ x 7 inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown

Edition of 10

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 90

Courtesy of Columbus Museum of Art.

Museum purchase with funds provided by Don and Thekla Shackelford

Sunday, 1897, 1921

Lithograph

12 ⅛ x 14 ⅞ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Edition of 54

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 73

Collection of Eric and Megan Vanderson

The Black Hat (Emma in a Black Hat), 1921

Lithograph

13⅛ x 9 ¼ inches

Signed lower left: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower right: Bolton Brown imp

Edition of 55

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 183

The Law is Too Slow, 1923

Lithograph

17 ⅞ x 14 ½ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: The Law is Too Slow

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown imp

Edition of 26

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 147

The Old Rascal, 1916

Lithograph

10 ⅛ x 9 inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows / J.B.B.

Numbered lower left: No. 13

Edition of 53

Mason catalogue raisonne no. 11

The Parlor Critic, 1921

Lithograph

8 ½ x 7 inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown - imp.

Edition of 38

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 80

The Pool Player, 1921

Lithograph

5 ½ x 10 inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Inscribed lower left: Bolton Brown, imp.

Edition of 40

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 83

The Sawdust Trail, 1917

Lithograph

25 ½ x 19 ⅞ inches

Signed lower right: Geo. Bellows

Numbered lower left: No 2

Titled lower center: The Sawdust Trail

Edition of 65

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 48

The Street, 1917

Lithograph

19 ⅛ x 15 ¼ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows / JBB

Numbered lower left: No. 45

Titled lower center: A Street

Edition of 54

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 47

The Studio, Christmas, 1916

Lithograph

5 ½ x 4 ¼ inches

Signed lower left: Geo Bellows

Inscribed lower right: Illegible

Edition: Unknown, scarce

Mason catalogue raisonné no. 35

The Tournament (Tennis at Newport), 1921

Lithograph

14 ¾ x 18 ⅞ inches

Signed lower right: Geo Bellows

Titled lower center: The Tournament

Inscribed and numbered lower left: 42 Bolton

Brown imp

Edition: c. 63

Mason catalogue raisonné no.72

Watermelon Man, 1906

Crayon, charcoal, pen and ink

14 x 17 inches

Signed lower left: Geo. Bellows