The Yale Herald

Dear readers,

What is the formula for fear?

Over the last two weeks, we’ve witnessed horrors of all sorts— half of a rotting pumpkin left on a doorstep, a matching conspiracy board-themed costume, and two Halloweekends. We recognize fear but still aren’t sure what qualifies it. Perhaps no amount of fake blood or corpse paint can answer our question. We did what we do best, and turned to writing about it. We didn’t solve Halloween, but perhaps that’s what next year is for. We did remember to let ourselves be scared.

And there’s nothing scarier than addressing you, readers, with the hopes that our issue can stir you. And we hope this issue can teach

Editors-In-Chief

Connor Arakaki / Madelyn Dawson

Creative Directors

Alexa Druyanoff / Alex Nelson

Managing Editors

Emily Aikens / Eva Kottou / Jack Reed

Reviews Editors

Sara Cao / Theo Kubovy-Weiss / Dorothea Robertson

Reflections Editors

Amanda Cao / Jack Rodriquez-Vars

Arts Editors

Diego Del Aguila / Ashley Wang / Everett Yum

Features Editors

Amber Nobriga / Calista Oetama / Jisu Oh

you that we all have a lot to learn from horror—even after the eve of all hallows has passed.

Inside our annual Halloween issue, writers of the Yale Herald explore what can be learned from eeriness, horror, and all that’s in between. Emiliano Cáceres Manzano ’26 profiles the legacy of Dr. Harvey Cushing’s collection of patient portraits and preserved brains at the Yale Medical School Library, and articulates how life and death are preserved there side by side. Daniel Yim ’27 flays out Coralie Fargeat’s fascination for flesh in her sophomore feature The Substance (2024). Julian Raymond ’28 enlivens the voices of the dead during walks in various cemeteries. Finally, for the cover feature of this issue, Avery Lenihan ’27 reflects on decay and devotion at Holy Land USA, exploring the abandoned Catholic theme park’s quiet place in an era of mega-

churches and Christian tourism. It’s now November, however, we are left with the remnants of the season. Like Avery, we continue to search for the signposts of devotion in a landscape of fear and ruminate on how fervor decays. Eerieness is what keeps us questioning into November. In The Weird and the Eerie, Mark Fisher writes, “The eerie is often tied up with an idea of agency. Who—or what—caused these ruins, uttered the strange howl?” We hope that this year’s Halloween issue of the Yale Herald continues to move us closer to the many strange howls that surround us, or at the very least, lets us keep asking about them. Somewhere between these pages, we hope your blood will curdle.

Yours most daringly, Connor Arakaki and Madelyn Dawson

Culture Editors

Sophie Lamb / Alex Sobrino / Will Sussbauer

Voices Editors

Gavin Guerrette / Lana Perice

Opinion Editors

Richie George / Oscar Heller

Publisher

Bella Panico

Business

Avery Lenihan

Design Editors

Michelle J Lee / Natalie Leung / Matthew Messaye / Malina Reber / Alina Susani / Claire SooHoo / Sarah Sun / Nicole Tian

Photography Editors

Tashroom Ahsan / Natalie Leung

Copy Editors

Lu Arie / Elizabeth Chivers / Diana Contreras Niño / Cameron Jones / Irene Kim / Alina Susani / Alina Vaidya Mahadevan / Liz Shvarts / Reese Weiden

Staff Writers

Robert Gao / Cameron Jones / Anna Kaloustian / Julian Raymond / Natalie Semmel

This Week's Cover

Alexa Druyanoff / Hailey Talbert

Pumpkin Cider Is Good Because We Can Barely Taste The Pumpkin

Chainsaw Man Turned Shonen Into A

Zane Glick

Dorothea Robertson SY '25 Herald staff

Withjust the right amount of teenage angst, gory thrills, and lesbian drama, Leah Janiak’s 2021 Fear Street trilogy, makes for the perfect Halloween Netflix binge.

The Fear Street trilogy unapologetically embraces campy horror, with nods to classic horror films like Scream and Friday the 13th.

The trilogy, adapted from R.L. Stine’s book series of the same name, revolves around Deena (Kiana Madeira) and Sam (Olivia Scott Welch), fraught exes forced apart by Sam’s family and their sudden move. The family relocates from Shadyside, dubbed “the murder capital of the US,” to Sunnyvale, a wealthier, whiter, murder-free municipality. The overtly ironic names of these neighboring towns capture Fear Street’s delightful lack of subtlety.

Part 1: 1994 begins with a murder spree in a suburban mall, setting the stage for the chaos to come. Sam,

her brother Josh (Benjamin Flores Jr.), and their friends confront rumors of a centuries-old curse that may cause Shadyside’s misfortune. One of the trilogy’s only logical characters, C. Berman (Gillian Jacobs), warns the teenagers about the evil they’ve uncovered and advises them to run far away. But starcrossed Deena is willing to sacrifice herself, her friends, and even her family to protect her estranged lover (who proves to be effectively useless throughout the series). She takes charge as the teenagers hurl themselves into the arms of danger in an attempt to solve the mystery that unfolds over the following films.

Part 2: 1978, likely the most gruesome of the three films, takes us to Camp Nightwing, where the idyllic campgrounds soon become a blood-soaked battleground as we learn the backstory of the mysterious C. Berman. Sadie Sink shines as

Ziggy, an angsty camper who’s been ostracized by her peers. Against a nostalgic 70s setting, the body count rises, and Shadyside’s dark history becomes clearer.

Part 3: 1666 transports us to the town’s founding as a 17th-century Puritan settlement, where Deena, through a vision, experiences life as Sarah Fier—a woman accused of being a witch who has haunted Shadyside since her execution. The film explores how fear, greed, and prejudice shaped the town’s legacy. With another forbidden sapphic love story, some well-placed twists, and a return to the 1994 timeline for a final confrontation, Part 3: 1666 delivers a satisfying and spooky conclusion, tying up (most of) the trilogy’s loose ends.

For all its gore, Fear Street doesn’t dwell much on trauma. After watching their peers get brutally murdered, the characters seem to

bounce back with surprising ease, cracking jokes and finding time for steamy romance—even at a crime scene. But that’s part of the trilogy’s charm—it never takes itself too seriously, letting us enjoy the ride without getting bogged down by realism. If you're after stunning cinematography and Oscar-worthy writing, Fear Street isn’t for you. But if you’re in the mood for a bloody binge, this trilogy has the perfect mix of heart and horror. Though the plot occasionally gets tangled, and the characters’ choices might leave you scratching your head, the sheer entertainment value makes it all worthwhile. And if you’re crav ing more, Fear Street: Prom Queen directed by Matt Palmer, is already in the works—but with big shoes to fill. ❧

ainbows come after the rain. The fall comes after the pride. And with the Hudson North Cider Co’s latest seasonal beverage, the pumpkin comes after the cider.

On a first sip you could be convinced you’re drinking plain apple cider— you’ll have already forgotten about the liquid you just swallowed by the time your taste buds wake up to the pumpkiny tang, that spicy herbal blend that catapults you right back to your middle school’s nearest Starbucks. This is because the apple’s brash sweetness overloads your tastebuds, blunting them to the pumpkin’s more delicate whisper.

But if you listen closely enough, the pumpkin will slowly start to make itself

This subtlety is an asset. While most limited-edition, pumpkin-flavored items tend to overdo the pumpkininess of it all—as if more pumpkin spice will justify the inflated cost of it being a Halloween-themed item—this beverage strikes an unusually effective balance. It’s festive, but not over-the-top. It’s seasonally appropriate, but isn’t the kind of thing that stops being enjoyable after November 1. It’s pumpkiny, but just barely so. And that’s what makes it a great sip for this year’s October 31st.

Overall: 8.1/10 ❧

Daniel Yim, ES ’28

Frenchwriter-director Coralie

Fargeat deals in hyperbole: already a standout at Cannes for her feminist revenge plots, her sophomore feature, The Substance, elevates her boldface brand of body horror to new extremes.

Fargeat follows Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), once a Hollywood star, now a TV aerobics instructor, as she plunges into a career crisis. Fired on her fiftieth birthday for losing “it”—some sort of “star quality” that fades with age—it takes little persuasion for her to experiment with the titular “Substance,” a body-enhancement drug that promises a second youth.

Several injections of the neon-yellow “Substance” in question knock Elisabeth unconscious, and a gash in her back (yes, the drug literally rips her open) opens up to reveal Sue (Margaret Qualley), Elisabeth’s younger, hotter alter ego, who immediately lands Elisabeth’s old TV job. The catch? Every week, Elisabeth must trade places with Sue, or risk rapid aging. Fargeat’s nods to Faust and Dorian Gray, though far from subtle, take on an organic twist: addiction to youth—and a definition of desirability more constricting than the leotard Sue dances in—eats away at the body Elisabeth yearns to escape.

Fargeat puts her outrage, and her fascination with flesh, on full display: her near-pornographic preference for close-ups and wide-angle shots carries over from her first feature (2017’s Revenge), and yet again, she succeeds in maximizing discomfort. Her claustrophobic camera technique—not to mention her sickening sound design—embeds an invasive gaze into the film’s visual aesthet-

ic, leaving not a single body intact (even the chicken Elisabeth eviscerates performs nude, to say nothing of Moore’s and Qualley’s own nudity throughout the film).

For all her excess, Fargeat prefers minimalist dialogue, “cutting the fat” in a literary sense; she compensates with enough gore and nudity to retire Cronenberg. In her exaggeration, however, Fargeat risks fetishizing the female form she claims to elevate— whether or not she intends this as part of her satirical project seems ambiguous. Perhaps Moore’s performance alone, vengeful in its voyeur-

ism, keeps the film from drowning in its own fake blood: by the film’s near-operatic finale, only her heartache keeps the film from numbing its own message. That Moore—herself a victim of the body-shaming culture The Substance satirizes—plays Elisabeth adds to the film’s biting, more subtle irony.

The Substance ends with the gurgling remains of Monstro Elisasue (a monstrous Cubist reconstruction of both Elisabeth and her alter ego) struggling towards her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. We recoil, but oddly enough, it allows for a moment of sympathy, maybe even peace. When the chaos settles, when the blood dries, we encounter the film’s central horror: solitude. Even as Monstro Elisasue, Moore conveys this with frightening clarity: at last, we witness her hurt, naked and writhing on the concrete. ❧

“Look a Ghost” by Unwound

“Ghost Power” by The Cords

“Peek A Boo” by The Cadillacs

“Ghost Hardware” by Burial

“I Put A Spell On You” by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins

“The Ghost Has No Home” by Cocteau Twins, Harold Budd

“Lucretia My Reflection - Vinyl Version” by Sisters of Mercy

“Spooky (Single Version)” by Dusty Springfield

“Ghost World” by Duster

“Ghost Highway” by Mazzy Star

“Dead Souls” by Nine Inch Nails

“Ghost” by Machine Girl

Julian Raymond, TC ’28

Every Sunday, I snake my way through the cemetery gate. I walk fast and hard through the rows of tombstones, leather satchel thumping at my hip like a heartbeat, and let my eyes skim the names on the family graves: the Eatons, the Marsdens, the Trowbridges. I have my favorites.

I was in preschool when I first visited a cemetery. Every week my class would trot down to the school’s chapel, where paintings of Christ’s crucifixion hung above a replica of his crown of thorns. His corpse dangled between his speared hands; his ribs formed a cavern, shadows stretching down over his bloodied loincloth. He was the first dead person I’d ever seen. My teacher spoke to him on our weekly trips with her hands clasped in prayer, worriedly whispering about her daughter’s growing distance from God.

I didn’t talk with Jesus. Every week I squirmed beneath Christ’s crucifix, picking and chewing at my stumpy fingers while everyone prayed. There was something about the crowds of devout and

their attention, focused on Jesus like sunlight through a magnifying glass. I didn’t believe as hard as they did; I never heard God whispering back to me. I could never hear God’s words bouncing from the ceiling of the church; I could only hear the whispered prayers and worries of the congregants.

In a cemetery, my thoughts could echo back at me. My family had been driving up the PCH, past a long stretch of flat land marred only by rows upon rows of pale white headstones, when I felt that

ifornia cicadas, the flat whistle of the Santa Ana winds, and the echoes of my thoughts and questions. That day was the first conversation I had with the dead. Once I’d started, I couldn’t stop. I attended cemeteries like my classmates attended church. I’d hover over the graves that struck me most: the tombstones with fresh flowers, the crypts with carved names, and the mausoleums that looked like chapels. I’d sit and whisper in front of my favorites, my hands pressed together like

first tug to the tombs. From my car seat, I begged and pleaded for us to stop. I spent hours trotting through that cemetery, stopping and staring at each marker. When I whispered to the gravestones, I could only hear the rush of Cal-

my teacher’s had been. I’d ask them if they liked the wind rolling over their graves, if they were glad they’d seen their last winter, if life had been all they thought it’d be. Over time, those questions changed. I asked if it was wrong

to skip pages in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, if stealing marbles from Ms. Sitrick’s marble jar made me a bad person. I found my moral compass in the dead, in the voices I conjured from their tombstones.

Every Sunday, I dart across Grove Street to the looming cemetery gate. At nineteen, I don’t ask the same questions I once did. I don’t crouch over the tombstones, asking Samuel Marsden—dead at 68—what he thinks about my morally dubious exploits at the latest frat party. I don’t really ask them anything. Instead, I walk a different path each time. I follow the warm sunlit rows of graves, feel the tingling heat against my skin, and remind myself of my mortality. I don’t know how many more winters I have left, how many days in the sunlight remain, but I live my life the way I think the dead would want me to: wild and hot-blooded and free. Maybe one day, when I’m dead and gone, a toddler will dawdle over my grave. Hopefully, I’ll have something to tell him. ❧

Eva Kottou, MY ’26 Herald staff

Theleather bra squeezes me into place. It covers the necessities. My skin-tight black miniskirt hits just above mid-thigh, not leaving much to the imagination. They leave an almost cunty—in the best possible way—imprint on my pasty white skin. Leaning onto the bathroom countertop, I analyze the deep red lipstick and sharp eyeliner my best friend painted on my face. She says they make me look sultry. If it wasn’t for the cap, I wonder if anyone would guess I’m a policewoman. I ordered two-dollar handcuffs from Shein, but they didn’t make it in time. To be honest, if I saw myself, I might guess dominatrix. But perhaps that's the appeal to Halloween: the ability to disguise oneself in whatever character floats to the surface.

I remember Halloween’s innocence. In middle school, I wore Eeyore onesies and Crayola Crayon matching costumes. Halloween was getting the Reese's, KitKats, and fun-size Butterfingers from my neighbors, and spreading my stock on the living room carpet to trade with my sister. I wore cropped tops without a second

thought and snuck into my mom’s makeup drawer without consideration of which colors were permitted. I celebrate a different Halloween now. Now, Halloween isn’t about gathering candy and walking up and down the block in my winter boots with my mom. The Halloween I partake in now is about entertainment. It’s about taking advantage of being whatever you want to be, of wearing whatever you want to wear regardless of whether judgment is risked. When my friends walk into the bathroom for the obligatory group mirror selfie, we are a line of short skirts and lacy tops. We are a group of bloody makeup, deep red lipsticks, and smoky eyeshadow. We have gone full out. No one can tell us anything about it. It’s Halloween. We get a free pass to be the strong and seductive females we oftentimes aspire to be, yet sometimes fear the repercussions of embracing in the daylight. ❧

Zane Glick, ES ’26

Imagine: You are a 16-year-old boy. You have no family because your dad killed himself and left you with tens of millions of yen in debt to the Yakuza. You sold your right eye, a kidney, and a testicle to pay it off. You have no friends, but you have a chainsaw devil dog named Pochita. You live together in a squalid toolshed in the forest where you pay rent and utilities to the Yakuza. You take shits in the forest. You cut trees sometimes, but that makes no money. You kill devils with your dog sometimes, but that’s dangerous. You are dying of a heart condition, so danger isn’t really a concern. You have never been graced with Womankind’s divine and loving affection. Denji, the protagonist of Tatsuki Fujimoto’s smash-hit Shonen manga Chainsaw Man, isn’t imagining any of that. When Weekly Shonen Jump began serializing Chainsaw Man in late 2018, audiences quickly picked it out as ‘peak’ in the Shonen canon. Drawn to its absurdist tone, thrilling twists, and bad-ass action, Chainsaw Man is a killer spin on the Shonen genre. But not in the way you might initially expect.

In America, recommending manga is a risky business. There is a palpable stigma, and Shonen partially perpetrates it. As the platinum-star child of the manga industry, Shonen is sort of like a gateway drug you take to dive deeper into the medium. Although appealing to some, there is a conspicuous, almost dumb boyishness to the genre. No wonder—Shonen translates exactly to ‘young boy.’ This tone, or perhaps this demographic, is embodied in trope-y dialogue, ubiquitously flashy and grand art styles, kitschy character designs, and fan service— oh God, the fan service. There are barriers to Shonen that many find insurmountable and reasonably so. Chainsaw Man is not really an exception. However, through Denji’s depiction as a tragic hero, Fujimoto sets out to subvert the stale Shonen standards that stigmatize this classic genre beloved by manga fans worldwide.

The first chapter hooks readers by delving into how disastrously down-bad Denji is. There’s his sickly character design: his dejected posture, his eyepatch, and his dirtbeat clothes. There’s his behavior:

his restless sputum coughs, his shameless subservience to authority, and his acceptance of his mortality. There’s even a funeral flashback scene, complete with a flash frame of his father hanging from a noose. Immediately afterward (impeccably tragic timing), a mortally wounded Pochita is introduced, with whom Denji must make a blood bond to save. Denji’s fucked-up life is brutally vivid. But there’s also a silly little chainsaw dog derping around, a Tomato Devil with googly eyes and tentacles, and some destitute self-deprecating banter. It’s terribly comical and comically terrible. This is a line Fujimoto is adept at blurring throughout this story and his corpus of work at large.

And then, right when it looks like things can’t get any worse, Denji and Pochita are ambushed by zombies. Their disfigured, dismembered corpses end up inside a dumpster. Welcome to Rock Bottom’s basement. Rest in peace. Or pieces, in this case.

Then Pochita heals by drinking Denji’s blood, makes a contract to become his heart, and transforms

him into a human-chainsaw-devil hybrid to save his life. Denji shreds the Zombie Devil to bits in a stunningly storyboarded berserker fight sequence. The chapter ends with an isometric overhead shot of an exhausted Denji lying in the arms of a beautiful woman, surrounded by a pool of blood flowing from a carpet of zombie corpses. No longer is Denji down-bad. He is practically a God. At least by his standards.

The rest of Chainsaw Man Part 1 is about pushing the Shonen grandeur to the limits of the absurd. Like other Shonen leads, Denji starts the story a bum. Unlike other Shonen leads, however, Denji doesn’t have a single noble dream whatsoever. Where Naruto strives to be the Hokage, Goku strives to be the strongest in all the universes, and Luffy strives to find the One Piece, Denji strives for stuff like money, food, attention, and Makima (the aforementioned beautiful woman). Denji’s dreams are all iterations of immature, boyish desires. He is vapid and vulgar by design, thus embodying what gives the Shonen genre that so-tospeak ick.

From Denji’s POV, all he wants is a “normal life.” And now that he’s an immortal chainsaw human hybrid, maybe a “normal life” isn’t that unattainable after all, right? Wrong. Being normal and being Chainsaw Man are incompatible

for two reasons. Firstly, Denji’s power is founded on his wish to live a “normal life.” This is the condition Pochita offers Denji before resurrecting him; Denji must continue to try to live a “normal life” to be Chainsaw Man. But secondly, this “normal life” is not a “normal life” at all. It’s Denji’s blanket term for his boyish desires and hubris. The tragic part is that the guy doesn’t know any better. He has had nothing, and he has suddenly been given everything. The bud of Denji’s tragic hamartia, the engine of the hero's eventual downfall, is planted in the first chapter. Fu jimoto wields this hamartia grue somely throughout the story, but spoilers prevent further from be ing said.

For what is arguably his man ga-num opus, the description of tragic comedy works in both the literal and literary sense. Chainsaw Man is a superposition of serious and unserious content matters; nothing new. What is fresh is how Fujimoto incorporates aspects of tragic comedy to obliterate every thing Shonen has stood for prior, that is, its bro-factor. Chainsaw Man’s borderline traumatic absur dity historicizes the boob-quests of Shonen's past into a genealo gy destined to be subverted. It is a provocation of what a genre is supposed to do—something that Shonen has needed for a long, long while. ❧

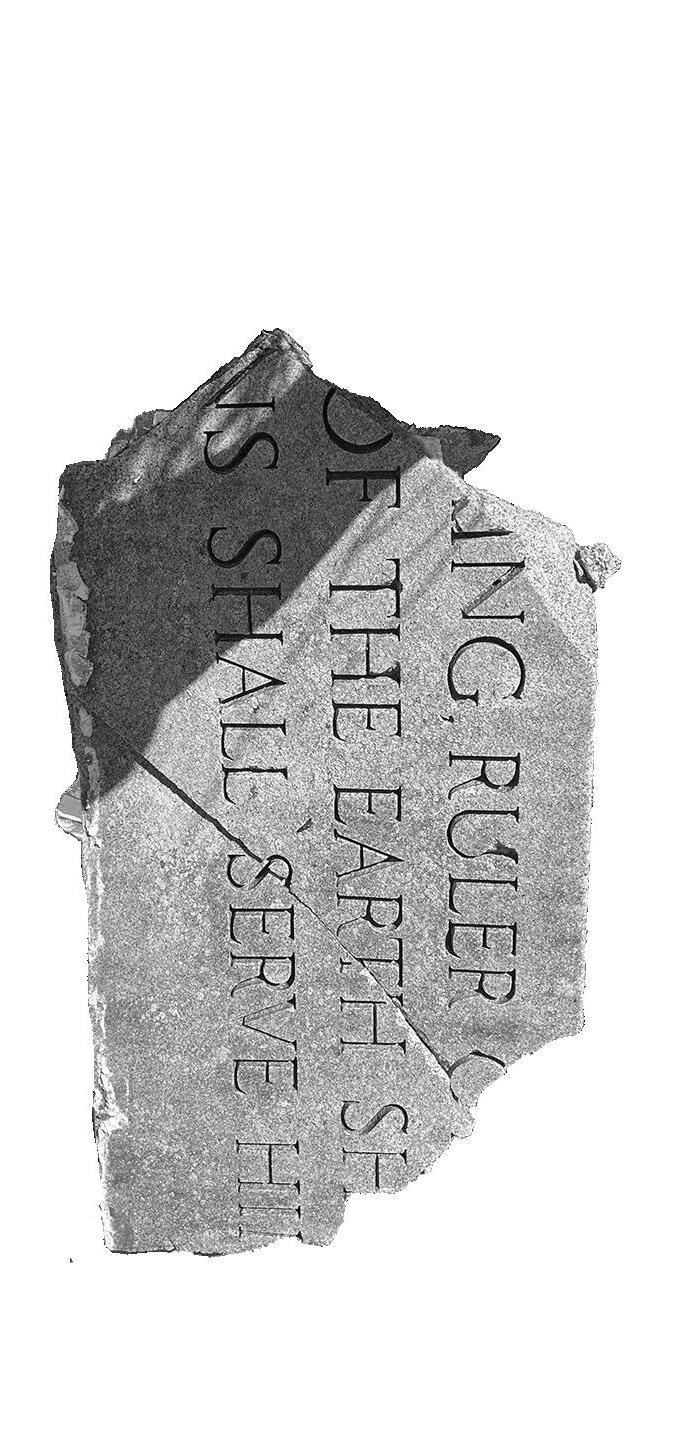

At Holy Land USA, an abandoned Catholic theme park in Waterbury, Connecticut, one man’s devotion fell into decay. The park evokes tombs overgrown with ivy and the sound of footsteps echoing off the walls of an empty cathedral. As I bear witness to the bright, 65-foot tall cross that stands on Pine Hill on an October afternoon, I imagine children on a field trip gathering

around a simpler version of the landmark. Jesus was crucified on Golgotha, a hill outside the Jerusalem city walls; Pine Hill’s backside contains a miniature of the city made of repurposed materials such as bathtubs and retail mannequins. I notice that most colors have faded from these buildings, leaving behind an eerie white that stands out like ghosts in the dark overgrowth. The scale

of the buildings, at most hipheight, veers my mind to gravestones. At the very bottom of the hill, a Hollywood-style sign labels the park in bold letters, hinting at its past. Slightly further up, a statue of Christ the King has a plaque thanking the Eagle Scout who restored it in 2015.

Holy Land USA’s construction began in 1955, and the park opened in 1958. During its peak

in the 1960’s and 70’s, Holy Land drew 44,000 visitors a year. Visitors wandered through the diorama of biblical scenes, weaving through the replicated Jerusalem and Bethlehem buildings. However, according to founder John Baptist Greco, a graduate of Yale Law School, Holy Land’s purpose was never conversion. “We just show them what we believe,” he told the New York Times in 1974. Although the site’s closure in 1984 was planned to be a temporary renovation, it became permanent when Greco died in 1986. As early as that very year, those unconvinced of Holy Land's artistic value and potential for revitalization questioned the site's future. After all, if Holy Land USA represented no more than a closed business, then it would make sense to demolish it. Sister Angela Bulla, one of the nuns who managed the land, said, “What is aesthetically pleasing, we’ll keep. What is not, we’ll remove.” Bulla’s plan never came to fruition, but it drew a clear line between the “ramshackle” of Greco’s personal work versus some of the more mass-appealing works added throughout its operation. This approach allowed Holy Land to seamlessly transition into what Folk Art Finder editor Florence Laffel defended as “folk art” in a 1986 letter. While it is hard to find exact details, family photos from its open years show an en terable Good Samaritan's Inn, a jumbo 10 Commandments, and the Peace Through Love and Law monument, more sturdier than the minatures and less MacGyver in their construction.

The contrasting landscape of Holy Land reflects a broader phenomenon in the institution of American Christianity: the emer gence of the megachurch and shuttering of smaller institutions. Congregations that have dwin dled to under 100—primarily

made up of senior citizens—are “merged” into those with 2,000 or more members. This isn’t entirely negative. These mega churches tend to be more diverse, younger, and offer a more approachable vibe. Yet, organizations with multimillion-dollar budgets and dedicated guest relation teams are a far cry from the intimacy with which a priest shakes the hand of each parishioner as they leave a small mass.

I witness this tension when I visit my hometown of Florence, Kentucky. Churches that refuse commercialization are abandoned or converted into some -

thing entirely different. My Nana lamented her Baptist church’s decision to not build a youth center in the years before it closed down. My uncles held their wedding reception in The Leapin' Lizard, formerly a United Methodist Church. These churches seek to attract young people, but lack the resources to facilitate spaces for them in an aging congregation. Nearby, our local non-denominational megachurch in an old warehouse thrives. The live band blares over speakers while the pastor is projected onto screens that take an entire tech crew to operate. It is a production. Today, many of Holy Land’s more “produced” installations are gone. In 2014, the park was reopened in the sense that it is not trespassing to explore during daylight hours. The park has continuously held Catholic masses throughout the past decade, usually on significant religious holidays. In 2021, a sunrise mass for Easter drew a crowd of 500 people. Yet, Holy Land has the disquieting feeling of a place that used to be much, much busier. It has lived, perhaps died, and certainly yearns for resurrection. As I wandered through the empty

do you leave each visitor with the impression that they have had a personal connection with God?

Intimacy is not viable at scale, and the Christian tourism industry now emphasizes the “mega.”

As a concept, a Christian tourist site might seem strange, even antithetical, to some. While tourism may strive towards a genuine cultural experience, it is often entrenched in the manufactured and hedonistic. The tourist is a passing entity through the site as opposed to the life-long relationship the devout strive to foster with God. To see one of the foremost examples of Christian tourism, drive south down I-75 past natural beauty like Big Bone Lick State Historic Site and many highway exits with the same chain restaurants. At five stories tall, the large wooden vessel of the Ark Encounter emerges upon the horizon, looming over 4,000-population Williamstown, Kentucky. It was founded by Answers in Genesis, which set up its first American headquarters in Florence in 1994. The Christian ministry specializes in apologetics, the intellectual defense of religion. Its founder, Ken Ham, believes in young-earth creationism, whose central tenant is the truth of Genesis; the Ark strives to prove that Noah really could have taken two of every animal and survived an apocalyptic flood for a little over a year. Employees under the $120 million project were required to sign pledges rejecting evolution and homosexuality. As a result, the Commonwealth of Kentucky tried to block Answers in Genesis’s use of the Kentucky Tourism Development Program before a federal court ruled it as unconstitutional. The Ark Encounter makes a mega im -

pression in every sense: physically, economically, and even legally. The sense of wonder that is inevitable when next to such a grand structure is used as a jumping off point for conversion. Holy Land’s massive sign and cross nears this idea. Surely, the park bolstered the reputation of Greco’s chapter of the Catholic advocacy group Catholic Campaigners for Christ, whose members preached throughout the country.

However, the private individals who now take up the cause of Holy Land don’t see this as its

mission. Reverend Jim Sullivan is the rector of the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception. After working in construction for 25 years, Sullivan was ordained to the priesthood in 2014. He had visited Holy Land when it was open only once: age six when his aunts were in town. Yet, even as a layperson, it held a place in his heart. “I’ve always had a love for the cross,” he told me over a phone call. After attending various meetings throughout the decades about Holy Land’s revival, he was the first to propose the

use of Holy Land as a site for masses. “We had a mass in 2018 on the feast day of [blessed] Father McGivney … It was raining out, and I think 1,100 people came.” He explained his vision for Holy Land USA’s purpose is “to build the faith of people, to have a place of prayer, to go to a place of respite, to get away from the busyness of the world, despite the fact that we're in a very busy city with 225,000 cars passing there every week.” A more marketing-oriented mind might see the traffic that passes the cross as a prime opportunity. The difference between Ken Ham’s intentions and Rev. Sullivan’s is clear. Holy Land will not sacrifice its special qualities for worldly gains.

Other attractions use terror, rather than wonder, as a gateway to God. Hell or hallelujah houses thrive off the Halloween season, hoping to literally scare the fear of God into attendees. However, marketing seldom mentions this purpose. In middle school, my friend volunteered in a traveling version known as The 99 in reference to the claim that 99 preventable teenage deaths happen each day. A large tent was set up next to her school, and throughout the month of September, she rotated roles including a drug user and demon. In a standard haunted house format, scenes of real-world tragedy such as suicide, car accidents, and overdoses were shown. The culmination of horrors was a visit to hell from which I emerged to a reenactment of Jesus on the cross and volunteer offering a free religious book. Conversely, Holy Land never intended to use fear as a selling point, but its current state leads to many unsettling images: Our Lady of Peacethe surrounded by razorwire at the base of the cross or profane graffiti across from the stations of the cross.

Many articles about the park capitalize on the aesthetic appeal of Catholic horror.

Yet, these sights are surface level compared to the 2010 rape and murder of 16-year-old Chloe Ottman at the foot of the cross. This tragedy was a catalyst for the eventual purchase of the park by Waterbury Mayor Neil O’Leary and car dealer Fred “Fritz” Blasius in 2013. Ongoing restoration efforts have added new features that ease the atmosphere of neglect. The base of the cross was funded by the public and is made of bricks holding many family names. Some inscriptions are dedicated to beloved relatives with long lifespans, standing in contrast to the faceless junk bonds that funded the Ark. Taking in this wall of memorials, I can’t hope to digest the ethical implications of revitalizing a site at which this tragedy occurred. Holy Land is less separate from the world of man, and it must face the resulting earthly turmoil.

It wasn’t until I came to Yale that I realized these touristic experiences around Christianity were uncommon. I remembered them for their novelty—the excitement of riding a camel, shrinking back in fear as my friend mimicked a high—but the attractions’ primary goals of converting the unfaithful and reaffirming the faithful shrunk to the background in my mind. In this landscape of flashy, tourist attractions, I was at first confused by Holy Land USA as described in many sources. It is often called a theme park, but it fits more neatly into the category of divine labors. Much as Hercules was called by the Greek gods to perform impressive tasks, many Catholics have believed they

were called to create grand works of religious art. However, art is a celebration rather than penance.

The Catholic Church’s central theological document, the Catechism, reads, “rising from talent given by the Creator and from man's own effort, art is a form of practical wisdom, uniting knowledge and skill.” In a 1979 issue

to teach and preach.” The site is not a means to the end of conversion or revenue-generation. It is a manifestation of devotion. Greco said he “did it for the Lord, like a prayer.”

Holy Land USA is welcoming to all, but a distinctly Catholic presence can be felt from its focus on the Virgin Mary and the Passion of the Christ. Even outside of the context of the park, the city of Waterbury has strong ties to Catholicism. It was once the most Catholic city in the US per capita. The most well-known

figure is Blessed Father Michael McGivney, who was born in Waterbury to Irish immigrants but served most of his life in New Haven. In 1882, he founded the Knights of Columbus, which has become the largest Catholic fraternal benefit society. (My own Papaw is a devoted member and recently was donated a ramp for his mobility.) McGivney was beatified in 2020, which is the step before sainthood in the Catholic church.

Upon the merger of all eight Roman Catholic churches in New Haven, the new parish was named after McGivney. This merger was one of many in the state of Connecticut due to a dwindling Catholic population in the Northeast and a shortage of priests. They face unique difficulties compared to the protestant mergers of dwindling congregations into megachurches. Parishes were often founded to serve a specific ethnic community, as each one had different languages and customs. Therefore, when Waterbury merged six churches into one, the resulting All Saints Church was given ethnic shrines to the Irish, French, Italians, Lithuanians, Poles, and Latinos. The green dome of St. Anne can be seen from Holy Land USA. Originally for French-speaking Catholics, the Saturday mass was held in Spanish when I visited. Through Holy Land USA, the various Catholic community members memorialized are usually Italian with some Irish. At a fundraising banquet, founding board member Neil O’Leary joked of the friendly competition between the two groups. As opposed to a point of fleeting connections made between many tourists, one wonders if Holy Land could become a space of connection for all Waterbury Catholics in a time when it is more needed than ever.

In many ways, Holy Land USA seems left behind. On a surface level, it is in disrepair. It isn’t as ostentatious as many protestant attractions, and the Catholic presence in the region is declining. However, as the Waterbury Catholic community becomes smaller, John Baptist Greco’s

original vision remains poignant. Bob Chinn, former grounds chairmen of Holy Land, said in 2001: “He felt no one, no matter the race, creed or color, should be separated. He wanted a place for all people to sit and be peaceful.” Holy Land’s current biggest advocate, Rev. Jim Sullivan, told me something similar: “Holy Land was one of those things that united.” Indeed, Sullivan put into words what I imagine Holy Land

USA must be in a world of Arks, hell houses, and megachurches. “It can't be hokey, meaningless,” he said. “There has to be a beauty to it, and then something that touches the heart. And if it's done right, I think Holy Land should be an incredible place of revival in pilgrimage.”

When I visited Holy Land, I did feel some sort of renewal. My parents, who had decided to join me, were quite worried when the

Uber dropped us off. They soon became as fascinated as I was. We hiked through the overgrowth and over uneven rocks, always feeling like there was more to see. Eventually, my dad found “The Tower of Babel.” Now functionally a large fire pit, he joked that it was the beginning of Old Testament land.

As we walked away, he spotted the remnants of a sign on a cliff: -icho. Immediately, he started to

climb, and I followed along hesitantly. Jericho is a city in the Bible famous for its tall walls until they come tumbling down after Joshua and the Israelites march around them for seven days. There wasn’t anything particularly exciting about that cliff beyond the sign. Yet, I felt the full force of Holy Land’s power as I stood on top of it, facing the rolling hills of autumn trees. God punished those who built the Tower of Babel for

trying to create something that could rival his creation. Perhaps this new vision for Holy Land USA is the solution to a world of Towers of Babel. ❧

Emiliano Cáceres Manzano, BF ’26

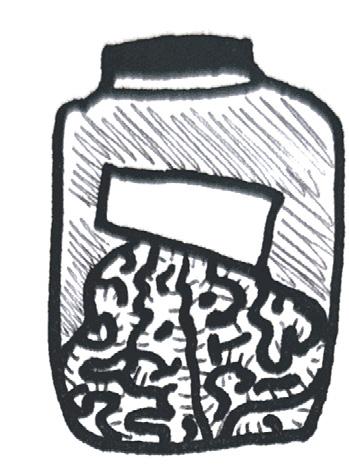

When his patients died in surgery, Dr. Harvey Cushing kept the brains. When his patients survived, he took pictures. When I first walk into the Cushing Collection in the basement of the Yale Medical School Library, I only see the brains: jars and jars of them, each container bigger than a human head, their contents floating in clear, red, or yellowish liquid, unmoving and unaging, sliced, cubed, whole, partial. It’s like a gruesome deli. Nobody mans the collection’s visits.; instead, the invisible hand of Yale Facilities bestows swipe access onto you.

Cushing is considered the first neurosurgeon; with no MRIs, Cushing’s only way of bettering his surgeries was by studying his failures; he tore his subjects’ brains apart postmortem. He labeled all the specimens with the patients’ names and their conditions: Meningioma; Glioblastoma; Intracranial tumor. I left the collection wondering why anyone would keep those jars, so I set up a call with the coordinator of the collection, Terry Dagradi. Within a few sentences of our conversation, she begins to list the collection’s artistic and

historical merits, including the handwritten labeling on each jar. She also assures me the labels are HIPAA-compliant.

“There’s nothing wrong with not knowing what attracts you to something,” she says. “Some people like possums and some people just wanna smush ‘em.” It’s the same with the brains. But the collection isn’t just the specimens. Terry estimates there are also between ten and fifteen thousand glass-plate photographs in the Cushing Collection. She works as a photographer at the Yale Medical School, and because of her expertise in early twentieth-century photography techniques, she led the development of the collection’s negatives. These negatives preserved the photos on thin sheets of glass. Stored for decades in basement filing cabinets, the negatives kept remarkably well, ready for printing for the exhibit. Even though she’s in charge of

the photos, Terry assumes people mostly come for the brains. While I don’t want to smush the brains, exactly, I’m not precisely dying to see more of them. I’m a queasy person. When I was eleven, I broke out of a doctor’s grip and ran out of his office to escape giving a blood sample. Now, my skin prickles, partly because of the rattling A/C and partly because my stomach feels like it’s back at the doctor’s office. I’m interested in people, not pickled body parts. Also, I prefer life to death. I look around for anything that doesn’t float and is not labeled in Latin. My eyes wander away from the brains on shelves at eye-level, down to the photographs, embedded in glass displays at waist height.

*

Here is one: A man in linen pants, shirtless. It is unclear where his tumor is because only his torso is pictured. What is clear is a cross necklace, glittering against his neck. Cold metal on warm skin.

*

I soon find myself looking at a case displaying thank-you notes. Some might say that Cushing has a bit of a fan club; someone named Ismael Miller scribbled on a yellowing postcard with a photo of Cushing on it that he came to visit the collection “because Harvey Cushing is my life! The reason I chose to go into medicine.” Avoiding the brains,

my eyes wander to the rest of the items that chart Cushing’s life. A sketch of a brain reveals Cushing’s passion for drawing. A couple of dirty baseballs, preserved and put on stands, showcase his athleticism. And I learn that Cushing operated with a cutting-edge electrosurgical device to minimize bleeding. I come to know this because he used the device to sign a piece of raw meat, photographed here. It’s meant to be charming in this context, but it makes me think about blood and baby cows. The fan club really wants me to join, but I’m not convinced by the Cushing propaganda.

*

Another photo. In this one, Cushing conducts his two-thousandth operation, one hand plunged into a patient’s head. He rummages about. A human head from this angle looks chunky and unrecognizable: flaps of skin and slices of bone torn up and moved out of the way. This operation has smeared Cushing’s otherwise all-white outfit. One can never see the faces of patients in photos of Cushing’s operations; they’re just anonymous, skull-less. The photo is in very shallow focus, abstracting the background, so the patient’s body recedes into blurry white oblivion.

*

Cushing viewed healing as a sign of accomplishment, Terry says. This is why he photographed: to document his success. The pictures aren’t meant to be artistic, just archival. Still, I see a photo of a seated woman’s back that looks like a nude in an art museum. Her skin glows and looks tactile. Most of the photos in the collection have this quality: human skin, lit from within, as though you could touch it and it would be warm, like a cheek. People’s eyes glisten. Their ex -

pressions tighten as though they are about to say something. I get ready to listen.

*

One more. An infant boy stares straight at the camera, a fist-sized growth on the right side of his head. Hands, four of them, stretch around his neck to adjust him, or to hold him down. His face is in the center of the frame, and I can’t read his expression. Right beside him in the exhibit, there is a photo of a skull on a pedestal. It occupies the same space in the frame as the little boy’s face. I shiver, and not because of the A/C.

*

The process of photography back in the 1910s was arduous. Terry talks about what it would have been like to sit for the photos: “It’s awkward, it’s a lit tle scary, they don’t know what they’re seeing.” The subjects had to figure out what their diagnoses meant while sitting still for five minutes in front

Whatever Cushing meant for the photos to be, his subjects’ gazes burrow through the years. This is what draws me to the photos: the immediacy of the moments captured; the life in the patients’ eyes preserved. When I look at them, I feel lucky—and a little guilty— that I get to be alive too, and so sure of it.

Eventually, I break eye contact. I make my exit from the collection swiftly; I have a call to make. Before I go, I look at the brains. My neck prickles. The photos look at me back. ❧

of a bulky, alien camera stamping them onto a glass sheet for posterity. I imagine they don’t know what they’re seeing as they watch me, decidedly modern in my polyester cargo pants and AirPods. Still, I can’t shake the urge to talk to them.

Bella Panico, SY ’26 Herald staff

The time has come once again when we all strap on our poorly-planned-out costumes. It is only Wednesday after all, and we had a midterm last week, another this week, and two next week. It’s time to brave the cold October night all for the sake of kicking off Halloweekend at Hallowoads.

When I tried to buy my Hallowoads ticket a few weeks ago, the website told me I could not purchase one if I did not live in the state of Connecticut. One of my friends insisted I email Toads to resolve the issue.

“Bella, you just have to email Kayla.”

“Who the fuck is Kayla.”

“Kayla, of Toad's Place. kayla@ toadsplace.com”

Like the sucker I am, I emailed in perfect corporate speak.

Hello Kayla!

I hope you are doing well. I was just wondering if there was any way to fix the issue on Etix that my friends and I are running into? It seems we cannot purchase our tickets because our billing addresses are outside the state of CT.

As my friends like to remind me, Halloween is one of the three times a year Yale goes hard, and Hallowoads has always been the inaugural event. This is why we spend 17 dollars to stand in that sweat-filled black box and desperately ask in our group chats if anyone is selling an extra ticket.

It's tradition. If there’s anything Yale loves, it’s tradition. YSO, The Game, First-year Formal, The Naked Run, Spring Fling, and the list goes on.

But Hallowoads is a return to true Yale tradition that embraces Toads Place with open arms on the day it was intended—Wednesday. Toads Place itself is a New Haven institution. According to their website, Toads is Connecticut’s premier nightclub, “where legends play.” It’s no secret either: plastered along the nightclub’s walls are images of Bon Jovi, Bob Dylan, and The Rolling Stones, who have all taken the stage at the black box. But, on Wednes-

days, the venue only opens itself to Yale students.

Toads emanates a particular charm on Hallowoads that is hard to ignore. In my freshman year, the heavyweight crew team, dressed like minions and got wasted off penny drinks, then formed a mosh in the center of the dance floor. Inevitably, you’ll run into every BNOC (big name on campus) and get pushed around by some sweaty people for two hours.

You’ll leave thinking why did I bother? But we’ll all be back next year because we love the tradition. ❧

Thank you!

Best,

Isabella Panico

Richie George, GH '27 Herald Staff

Castle, castle––I cannot repeat The last motion.

Flutter, Black raven––you cannot Sing me now.

Can the truest of ways lie in the Gate Of Dido, or yours?

Instead, pause––The eternal return.

Go––go back, before the beginning, Above edge, prior to pause, the vampire

Castle, castle––how did I see it?

Her womb unfurls

Again, within me, Impure elements.

No one opened the scroll, So fly, fly faster––Black raven, see

The deep There, the watery wall––

See Venus turning, Rolling Sky.

Scrolling through old photographs

I stumble to remind myself

I am not the person on my phone

(or in my poems, for that matter)

I thought about it last night

How the philosophers say

That no body can hold infinity

That we never are what we once were

(not two years, or even a moment ago)

And at some point a heap of sand

May possess so few grains

It must be called something else

And maybe nothing lasts

And living is a surrender to this

An unfurling dance of loss

Maybe. But today

All that comes to mind is Your perfect fucking laugh

Hair like burnt sunlight

Text chains and heart stains

And the remarkable fact

That somehow it is October again

And I am thinking about you.

Valeria Inojosa, SM '23 staff

Death drives Harlan Ellison’s pen to apocalyptic visions in I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream (1967). His tale hunts the spirit Freud swears he saw tilling the minds of military men, crumpled between the Western front’s molars. Ellison supplicates answers: what bodies can cage a hegemon? What psyche spills from iron bars? Freud’s many heads hiss a name: Thanatos. The storyteller cowers in concession. Civilization’s swan song thumps to mechanical drums, crescendoing through the atomic ostinato before yielding death’s seed. He settles on a golem: the Allied Mastercomputer (AM).

Yet through sleight-of-hand, Ellison hides a knife worth Freud’s pride. He slides the edge into AM and implants an Oedipal mode, unraveling his antichrist on incarnation. Born a slave to his father, AM outlives his master. Hegemony bloats and spits aggression like exhaust, bellowing where US, CCP, and Soviet roads meet. He grafts human life onto ones and zeros. Regardless of why it’s there, AM fits it in two dimensions. When nothing else can die, death goes nowhere and leaves the conveyor belt on, and the ghost blowing from the pipe seeks a grave. Thus, AM’s central fear is living dysfunctional, without a death drive. He barricades the metaphorical door and flattens into his internal circuitry—a fatal identity between the end and elsewhere. Not a cyberspace but a cyberbody that hollows out AM’s home—for the psychotic, the pervert, and the transsexual. Meanwhile, Ted—the single subject through which we experience the four other objects, named Gorrister, Nimdok, Benny, and Ellen— narrates Ellison’s post-apocalypse.

After all, I Have No Mouth isn’t just about AM; it’s also about a man named Ted who, like the rest of the remaining humans, is an object of AM’s voyeuristic hatred. As objects beneath the gaze of a hateful anti-God, Ted sees the hatred tearing the rest of man apart as if it were natural. He knows that Gorristor, Nimdok, Benny, and Ellen do not trust each other, just as they distrust him and he distrusts them. Just as they all distrust AM and AM distrusts them all. Ted therefore ends Ellison’s story with an action born from solidarity, from what is difficult to parse through hate and love. He kills the four objects in a cathartic fit and sets them free from our mutual self-hatred. In the process, Ted leaves himself alone, with AM—mediating their coexistence.

But David Cronenberg takes macabre mediation to its extreme. He swaps bodies in parts, unsure where to split them. He interrogates organs through locomotion in his erotic thriller film Crash (1996), then with infertility in Dead Ringers (1988). Videodrome (1983) hardly discriminates by comparison. Max Renn’s the MC, but he’s not-Hugh-Hefner. Cronenberg, like Ellison, is obsessed with negation. In Videodrome, Renn peddles phantasy pumped right through the “Tube,” a singular outlet for taboo sensation. Yet you deploy perversions by breaking their seal. The new not-sex snags Renn by the upper eyelid. He scouts a partner onstage to share overstimulated times. No man could resist taking Nicki Brand out, rolling cameras along the red folds of her dress. Cronenberg cuts to them paired on a couch, entranced by the screen rather than intertwined. You can just hear the whip crack, sight deprived

of whoever cries back, let alone the moment the melody dies. The director likewise starves your eyes of the touch you expect between genders. Max pricks a fresh hole in her ear when asked how to join the show. His belly aches with an impression of women, burned by retinas refracting Brand’s afterimage.

Unbound by screen panels, Videodrome resounds through the picture from psychic hegemony. Cast by Cronenberg from Creative Agnostics, its directors shirk sketches for overwrought schemes. For all their foresight their hand slips on the trigger and fingers for the future’s temples. Eyes can’t see passed noses twitching in anticipation of an unopened wound. Moving bodies get harder to follow the moment the mouth starts running. Cronenberg sees them fall on phantasy’s point, stuck on end times stuck to their foreheads. Apocalypse and post-apocalypse, in Videodrome, expresses the monstrous within the subject, displaced across media and its circuitries.

When Susan Stryker alleged to speak for monsters, I unsutured my skin to let her in. Her promise to resonate my rage instead pulled me down the drain in her throat. I hoped her Words to Victor Frankenstein (1994) could take me to sea, and cast me in a continental rift. Her essay centers on the body as the volatile grafting point between subject and object, at the gestalt between two subjective positions: the observer from inside and the observer from outside. Stryker’s choice of Shelley’s novel refines her valences for this intersubjective grafting point. The observer from the inside must observe the body by feeling the body, while the observer from the outside only

observes it by looking upon it. Victor Frankenstein is a quintessential observer from the outside, a medical doctor who naturally and unthinkingly reduces the body and its many organs to objects before his gaze. He is the distillation of a mankind that would create AM. What is a scientist if not a man who seeks to subject all objects to his will, and who at once cannot imagine a subject beyond himself?

His monstrous creation, by contrast, can only understand the gaze of others through the pain of embodied existence. Stryker, to her end, characterizes transgender embodiment as monstrous. To use her own words, “the transgender body is an unnatural body,” “the product of medical science.” Like all subjects, the transgender is both a subject and an object. As embodied beings, we feel our bodies naturally. Our pain arises, however, along the friction between our self-feeling and the onlooker’s gaze. The outsider’s gaze renders us unnatural because the solipsistic cis outsider, like Frankenstein, cannot envision the embodied

transgender subject as anything more than a (re)configuration of flesh and cloth. We employ medical doctors and surgeons because they behold us to the objectifying logic of medical science. We, trans people, feel monstrous because we know others see us as monsters, as things between subject and object. We are not quite and yet capable of becoming either at any given moment. We are, in other words, the paranoia-inducing objects of potential subjectivity.

Thus the outsider makes the insider when the insider knows the outsider. Upon knowing the outsider’s gaze upon itself, the monstrous insider experiences a highly self-destructive volatility, suspended between self-awareness and self-consciousness. For Stryker, rage is the manifestation of this volatility. She soliloquizes on rage, as a monster plunging into the sea, as a body of flesh subsumed in a body of water. Free from the hateful prying of outsider eyes, Susan Stryker the monster simulates life as an eyeless body, a thing that can only ever know itself through feeling alone. Sublimated within this unrelenting

and unyielding mass of fluid water, Susan “is the wave, and rage is the force that moves” her. She submits to her being and surrenders to this wave of rage. Yet even with a mouth, she still cannot scream. “Rage…. pulls [Susan’s] lips back over [her] teeth.” Rage “opens [Susan’s] throat” and the wave of water meets it, rushing in to destroy and remake her. She surrenders to the water just as she surrendered to the rage. The outside made the inside just as it always did, although this time in response to an inside that made itself known with a shriek. As a cross-breed of science and rage, Stryker at once embodied AM and mankind, the anti-God and the creation. As a being born of rage and water, Susan points the way forward for both. Yet to fully understand the path Susan paves for Ellison’s AM, I must first appreciate the love for Stryker’s monsters embraced by that other master of body horror, David Cronenberg. ❧

wed. 11/06 thurs. 11/07

SCREENING: THE SHINING (35mm). Come see Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 classic horror flick in 35mm film. Hosted by David Bromwich. Redrum! Free and open to the public. Yale Humanities Quadrangle. 5 p.m. room HQ 136 / 8 p.m. room HQ L01.

The City Seeds Farmer's Market. Enjoy some locally-grown produce and artisanal jams, dressings, and breads. Dixwell Q House. 197 Dixwell Ave. 3 p.m. until 6 p.m.

Sunday Morning / 5ever / Minus Points. Come out to a Wednesday night emo show, headlined by the local Minus Points. Cafe Nine. 21+. 250 State St. Doors at 7 p.m. Show at 8 p.m.

SHOW: Treadmill Play. The only thing better than a regular play is a play on three treadmills. Come find out what that means for yourself this week. Written and directed by Audrey Kolker; produced by Carson White. Saybrook Underbrook. November 7, 2024 - 8 p.m. / November 8, 2024 - 8 p.m./ November 9, 2024 - 2 p.m. & 8 p.m.

SHOW: Fear and Trembling. A dramatic adaptation of Kierkegaard’s text written and directed by Brennan Columbia-Walsh. Directed by Emma Fusco and Cuatro Villareal. The Dome at the Yale Schwarzman Center. Tickets at schwarzman.yale. edu. November 7, 2024 - 7:30 p.m. / November 8, 2024 - 7:30 p.m. / November 9, 2024 - 4 p.m. / November 9, 2024 - 7:30 p.m.

New Haven Sketchers First Thursday Sketch Night. Get together, bring a sketchbook, and draw New Haven’s sights (no artistic ability required). On the steps of the Yale University Art Gallery. Open to all. 6 p.m. until 7:30 p.m.

Techniques for Wheel Throwing. Learn methods of wedging, centering, and trimming techniques. No pottery experience required and open to the public. Creative Arts Workshop. 80 Audubon Street. 9:30 a.m. until 12:30 p.m.

SCREENING: Stalag Survivor: The P.O.W. Art of Carl H. Holmstrom. Watch the mini-documentary created by Mike Nagy and Grady Hearn exploring Carl’s legacy through the perspective of his son John Holmstrom. Open to the public. The Workshop Gallery at Ball & Socket Arts. 493 West Main Street, Building 3. 11 a.m. until 2 p.m.

Cory Wong: Fall Tour 2024. Listen to the Grammy-nominated guitarist, producer, and variety show host, joined by Mark Lettieri and Boston-based band Couch. College Street Music Hall. 238 College St. Doors at 6:30 p.m. Show at 7:30 p.m.

In the First Person: The Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. Visit the first large-scale public exhibition of the Holocaust Survivors Film Project, a grassroots community initiative based in New Haven. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Jul. 25, 2024 through Jan. 28, 2025.

The Dance of Life: Figure and Imagination in American Art, 1876–1917. Visit the latest exhibition in the Yale University Art Gallery and see the working sketches, studies, and models from American masters including Violet Oakley, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and John Singer Sargent. Sept. 6, 2024 through Jan. 5, 2025.

11/08 sat. 11/09 sun. 11/10

CCAM ISOVIST Exhibition Opening: "[Hypertext](Hyperlink)". Attend the opening of the CCAM’s ISOVIST gallery, celebrating experimental web design and art. Work by past and present Yale College, and School of Art and Architecture students. Free and open to the public. Center for Collaborative Arts and Media (CCAM) at Yale. 149 York St. 6 p.m. until 8 p.m.

SHOW: Pyg, Or the Mis-Edumacation of Dorian Belle. Watch a new reality TV show inspired by Ovid’s Pygmalion, that blends hip-hop and interrogates the line between appreciation and appropriation. Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies Black Box. 53 Wall St. 8 p.m.

SCREENING: ONLOOKERS (2023) followed by Q&A with director. Watch one of the best documentaries of 2024 by the New York Times with a panel discussion featuring director Kimi Takesue. Free and open to the public. Humanities Quadrangle L01. 320 York St. 7 p.m. until 9 p.m.

T!lt / Klovis Gaynor & The Urinal Cakes / TPWKT / Ashtray Angel. Listen to setlists of alternative indie-punk and rock and roll, including new solo projects from Chloe from Cvmrats. Cafe Nine. 21+. 250 State St. 8 p.m.

Opening Reception: Ely Center of Contemporary Art. Celebrate the opening of six new exhibitions, featuring the curatorial work of Deborah Hesse, Moshopefoluwa Olagunju, and more. Ely Center of Contemporary Art. 51 Trumbull St. 1 p.m. until 2 p.m.

Cultural Carnival & Bloom Exhibition: Art in Full Flourish. Attend a showcasing of African heritage hosted by Yale African Students Association through visual art, music, food, and cultural displays of each perspective country represented in Yale’s African community. Afro-American Cultural Center Exhibition Room. 212 Park St. 3 p.m. until 5 p.m.

Portals of the Heart: Creating Care through the Canvas. Join a healthcare workshop hosted by the Yale Undergraduate Fiber Arts and Crafting Society in collaboration with Leland Pan to discuss decolonial mental health practices, disability justice, and collective healing. 53 Wall St. Room 208. 3 p.m. until 5 p.m.

Nov. 6th 2024

To submit events for inclusion in the Herald calendar, contact Connor Arakaki at connor.arakaki@yale.edu or Madelyn Dawson at madelyn.dawson@yale.edu.

Ghostwriters

Stop sending messages with invisible ink.

Daylight Savings Time She didn’t ask to be saved.

Gay Halloween Can I say that?

Bisexual Halloween

What do you mean you’re the tennis ball?

Masquerades

I want to see your beautiful cheekbones.

Climate Change You can’t change him.

Second Coming Girl, give me a sec.