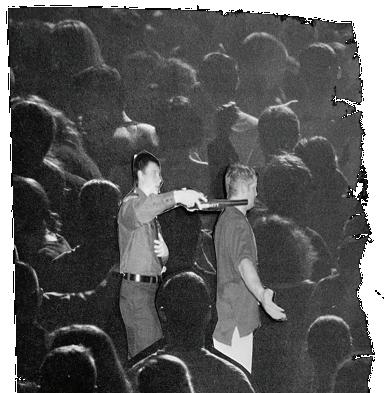

Connor Arakaki, pg 14: Black Panthers in New Haven, 1970

Connor Arakaki, pg 14: Black Panthers in New Haven, 1970

To all the bulldozer-using orchid studiers,

It’s April and we’re back. In the year 1912, on April 15, the Titanic sank. The sinking is said to have taken less than three hours and there was no dramatic love story, nor was there a beautiful Rose with whom to fall in love. The wreck was found 73 years after the sinking. No bodies were found. Those sea creatures are relentless. Last August, we (Rafi) got seasick while kayaking. This week, we’ve been hanging out in a blue room on the second floor of 305 Crown Street. The walls remind us of the ocean and of Kindergarten.

Editors-In-Chief

Arthur Delot-Vilain/ Rafaela Kottou

Managing Editors

Madeleine Cepeda-Hanley/ Lydia Kaup/Hannah Szabó

Creative Directors

Sara Offer/Etai Smotrich-Barr/ Iris Tsouris

Senior Writers

Madelyn Dawson/Nadira Novruzov/ Jack Reed

Columnists

Joshua Bolchover/Irene Colombo/ Hardy Eville/Lyle Griggs/James Han/ Maude Lechner/Judah Millen/ Joanna Ruiz/Lucy Santiago

Design

Alexa Druyanoff/Georgiana Grinstaff

Angela Huo/Helen Huynh/ Mela Johnson/Grace Kim/Kris Qiu/ Mia Rodriquez-Vars/Claire SooHoo/ Alina Susani/Tor Wettlaufer/ Vivian Wang/Silvia Wang/Miya Zhao

In this week’s issue, Connor Arakaki, MC ’26, brings to life the New Haven chapter of the Black Panthers and reconstructs their May Day 1970 rally. In Voices, Lydia Kaup, SM ’24, riffs wonderfully on Frank O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You.” In Culture, Molly Reinmann, BK ’26, uses Kim Kardashian’s skims Ultimate Bra Nipple Push-Up Bra to think about the history of bras.

By the time you read this, everyone will be done talking about the solar eclipse. We hope you will have worn those special little glasses. We hope you will have Googled ‘solar eclipse’ to see a little sun move across your computer screen. Read our issue and enjoy it under the (now-visible) sun. Come see us at 305 Crown Street, see the blue room, see Arthur’s yellow socks. They have horses on them!

Most Daringly, Rafi + Arthur

Reviews Editors

Theo Kubovy-Weiss/Natalie Semmel/ Aidan Thomas

Reflections Editors

Eva Kottou/Jack Rodriquez-Vars

Culture Editors

Emily Aikens/Isabella Panico/ Alex Sobrino

Features Editors

Connor Arakaki/ Madelyn Dawson/Jack Reed

Opinion Editors

Ariel Kirman/ Daviana Rodriguez Zamora

Arts Editors

Jess Liu/Eli Osei

Voices Editors

Ana Padilla Castellanos/Will Sussbauer

Inserts Editors

(this could be you! email!)

Copy Editors

Dayne Bolding/Zoe Frost/Jisu Oh/ Ece Serdaroglu/ Tessa Stewart/ Alina Susani

Staff Writers

Lillian Broeksmit/Kaylee Chen/ Elizabeth Chivers/Kate Choi/ Krishna Davis/Oscar Heller/ Helen Huynh/Cameron Jones/ Anna Kaloustian/Megan Kernis/ Sophie Lamb/Hannah Nashed/ Jisu Oh/William Orr/AJ Tapia-Wylie/ Amalia Tuchmann/Ellen Windels/ Ashley Wang/Avery Wayne

Web Editor

Kris Qiu

Business

Abby Fossati/Evan-Carlo Fowler/ Avery Lenihan Calendar

Jess Liu

Photography

Fareed Salmon

This Week's Cover

Iris Tsouris

This Week's Collages

Georgiana Grinstaff/Mia Rodriquez-Vars

REFLECTIONS

Wonders by Kaylee Chen Tadpoles and tandem bicycles.

Wearing Your Blue Jacket… by Lydia Kaup After Frank O’Hara.

How to Preserve Negatives by Madelyn Dawson

If you listen close enough, maybe you’ll hear its antiheartbeat.

what’s up with American tourists?

Evan Fowler, DC ’25

Published in 1965, Frank Herbert’s Dune is arguably one of the best science fiction novels of all time. So why has it languished without an effective or commercially successful adaptation for over 50 years? I finished Herbert’s novel only a few years before Villeneuve would announce his ambitious plans to adapt it; I was delighted with it but also heavily surprised. Raised on both contemporary sci-fi like the Star Wars prequel trilogy, as well as a healthy dose of sci-fi classics such as Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, I had a very clear vision of what I thought Herbert’s Dune was going to be before I read it. However, I was immediately shocked by Herbert’s focus on interiority and world building coupled with

Theo Kubovy-Weiss, BR ’26 and Aidan Thomas, DC ’25, Herald staff

Following the shiny, star-studded lineup that has comprised our previous beer reviews, we decided to write about something a little closer to home. This week, we try a beer from Hardy Eville who, in addition to being a loyal food columnist for the Herald, has embraced a side hustle of beer brewing. Over the past year, he has fine-tuned his process and recipe, which uses locally sourced hops to emulate, but ultimately transcend, the popular Guinness flavor. A full list of ingredients can be found below. Hardy brought a sample of his stout to the Herald office, and was immediately met with enthusiasm from our editorial board. Adjectives lobbed at him to try to explain the flavor include “mealy,” “soy sauce-like,” “syrupy,” and

his utter disregard for action and epic battles. At almost every point in the book, you know exactly what its main character Paul Atreides is thinking due to a running inner monologue, and the story lingers on locations and builds up physical conflicts, only to skip over most of the actual action and fighting. This dynamic has proven to be an incredible problem for adaptation.

I watched Villeneuve’s first Dune movie in a movie theater with a few friends, none of whom had read the book. While I wholeheartedly enjoyed it, I remember seeing one of my friends go on the Dune book’s Wikipedia page to follow the story while another fell asleep. Both of them did not have favorable things to say as we walked out the theater and I realized that by faithfully telling the first half of the book’s story, Villeneuve lost many viewers due to its glacial pace and complicated story. While the first movie was

“chocolate-esque.” It’s a dark beer with a coffee-like aftertaste that might feel alien to lager and pilsner loyalists. The stout has a delicate bite that is quickly soothed by a familiar, homey flavor—its plain glass bottle, lined with residue from a previously-attached sticker, helps to evoke this sense of coziness. The beer is fantastic, packed with a complex flavor and a subtle carbonation that makes sure not to drown out the brew’s nuances. But the bulk of the enjoyment comes from the knowledge that it was brewed carefully by hand, with love, by a man passionate about his craft.

Rating: 8.9/10

bogged down by its weighty, slowpaced subject matter, Dune: Part 2 has garnered far more critical and commercial success for its riskiness as an adaptation and its own merit. Villeneuve’s own touches to the film most notably include his spin on Chani (Zendaya) as more defiant of Paul’s (Timothée Chalamet) actions. These changes create a film that does justice to its source material not only by being visually stunning with scenes like the black and white Harkonnen gladiator fight, but also by telling its own story that, just like the book, is engrossing from start to finish with high-stakes dialogue, enthralling action choreography, and dramatic moments that keep viewers on the edge of their seat. I have no doubt Villeueve will continue paving his own narrative path in Herbert’s world with Dune Messiah, the presumed third film in the groundbreaking trilogy adaptation. ❧

RECIPE:

Grain: 10lb Pale

2 Row Barley, 1lb

Dark Chocolate

Malt, 1lb Roasted Barley, 1lb Caramel

Malt, 1lb English

Brown Malt

Hops: 1oz Columbus Hops, 1oz Amarillo Hops, 0.5oz Saaz Hops

Yeast: Omega Lutra Kviek

Hardy Eville, DC ’26 and James Han, PC ’24

The Luke is a little bit of everything. Located at the foot of the Taft Apartments on College Street, it was once a ballroom and now is home to bistro-style seating, ornate chandeliers and a sleek marble-topped bar. That bar, and its dollar oyster happy hour, drew us in from our Thursday classes.

Eager to dine on mollusks at bargain prices, we arrived at 4 p.m., only to discover that The Luke doesn’t open until 5. Undaunted, we ventured to a bar across the street to kill time, each slowly sipping a beer. At 5 p.m., The Luke opened its doors and we walked into a totally empty restaurant, with employees still setting up the dining room. There’s a strange gray area that exists when a restaurant is technically open, yet there are no customers and the staff is still preparing for the onslaught of dinner service. Sitting there, it feels as though you’re somewhere you shouldn’t be, but for those of us who have worked in the industry, perhaps it feels oddly comforting. The ritual of wiping down tables, organizing mise-en-place, and mentally preparing for the rush of service is a familiar ceremony.

At 5 p.m., we immediately ordered a dozen oysters without even looking at the menu—we knew what we were after; this trip had been on our calendar for a month. Usually happy hours make money by selling high-margin drinks and appetizers, so in an era of soaring food costs, dollar oysters are both a rare and exciting treat. We also ordered two of the seasonal martinis. Pear and warm spice might not be the most traditional flavors to accompany seafood, but at only $7 dollars any martini is pretty attractive.

Hitting an oyster and martini happy hour at 5 p.m. was our attempt to cosplay as adults—the kind of

Tambourine lycanthropic Thursday morning

Enlightened soap opera Wednesday afternoon

Foxtrot y’allternative Tuesday afternoon

Club house non-stop Tuesday morning

Nervous alternative pop Monday night

Sleepy weepy soul crushing Thursday morning

Art deco cinnamon Sunday afternoon

Monday music red dirt Friday morning

adults who wear navy sport jackets and have a drink immediately after work to take the edge off. Waiting for the oysters to be shucked, we soaked in the sounds of a kitchen prepping for service and the ornate space. As other patrons came in, we watched the restaurant transition from a hectic state of preparation to a calm, collected dinner service. The rock music blasting from the open kitchen faded into an easy listening dinner playlist. Floors wiped and tables set, The Luke was ready for the real adults to walk in.

Twelve oysters on a plate of cold, white navy beans appear in front of us, accompanied by a housemade sweet chili sauce. Far from the classic Tabasco or cocktail sauce, this thick, brick-red sauce lent the briny oysters a rounder sweetness and savory overtones. This choice of sauce is brilliant, highlighting the strengths of these particular oysters. All oysters have varying levels of sweetness, of brine—oyster liquor—and of chew. These oys-

ters weren’t sweet, but were clean and well seasoned by their brine. Reviewing a restaurant’s oysters is a bit unusual. After all, there’s no recipe or cooking technique to analyze and critique. With oysters, it’s all about sourcing and shucking— both of which The Luke does well. The inclusion of a somewhat more irregular and unique accompanying sauce elevated these oysters beyond their briny simplicity.

It quickly became clear that The Luke knows how to do hospitality right. Without us ordering it, a warm loaf of soft bread appeared. The bread was paired with a chestnut compound butter and was a needed detour of rich, decadent food after the lightness of the oysters. Later, we were treated to small salted caramel chocolates. Between drinks, oysters, and these surprises, it was hard not to feel pampered. The level of hospitality for a happy hour experience sets The Luke above others in a town flush with happy hours. ❧

In What We Like, Hardy Eville and James Han explore New Haven’s culinary scene with an emphasis on off the beaten track restaurants, unique cuisines, and the best hangover food.

Madison Butchko, JE ’25

In first grade, I had a secret. Whenever my teacher read books to the class, I’d memorize every word, repeating them in my head. Pretending my mind was a recorder, I’d replay each sentence to make sure it stuck. I played this game every day. Not for fun. For survival. I could not read until I was seven years old.

Anything with small print was my arch-nemesis. The chapter books along the back of our classroom were a death zone. I was stuck on reading picture books, a taxing quest in and of itself. I struggled to string the words into sentences. My only life of defense was my memory

“Madison, will you read the next part out loud? Starting at ‘The blue ball.’” My teacher’s request felt like she was asking me if I wanted to embarrass myself forever. As I braced myself for battle, I began to recall all of the words from the book. Whenever it was my turn to read in class, I would simply recite the book from memory. My secret was safe.

However, I forgot to calculate one important factor: for our reading comprehension test, my teacher changed all the books. I could only outsmart the system for so long before accepting that I continuously mixed up the order of letters. The game had changed, and I'd missed the software update.

At night when my parents thought I was asleep, I’d hear them in hushed voices, weighing my learning difficulties and their permanence. “What are we going to do with her?” My mom whispered, her words laced with a fraught apprehension. Rolling my eyes, I wanted to burst into my parents’ room and shout, “Jeez, it’s just reading! You guys sound like I’m dying of cancer.

What’s the big deal?” But my secret was out. All of the lines on the page looked like modern art and I felt like a simpleton trying to decode some hidden meaning. When my teacher asked to meet my parents after school, I knew it was not for my stellar doodles in the margins of my worksheets.

Thus, boot camp began. The summer between second and third grade, my parents bought children’s books from Costco. I did reading drills every morning and evening. I remember reading “Mad Dog.” Flipping begrudgingly through the pages, I thought to myself: “I bet he was a mad dog and not a happy dog because his parents were making him do summer school.” While I continued practicing to read, the letters felt like alphabet soup in my mind. As I tried to take in a spoonful of a sentence, the letters mixed around like noodles. That summer left me starving for anything fun.

To lighten my spirits, my parents decided to rent out the first Harry Potter movie from the library. I was enchanted, fully convinced my Hogwarts letter would come any day. “If you really liked the movie, there are books,” my dad suggested. “But I don’t think you can get through them yet.” My dad and I went to the library to check out the audiobook. On the way out, I stopped by the chapter book section, picking up the written edition as well. Every night, I’d slip a CD into my little Hello Kitty CD player. Listening to the audiobook, I’d follow along with the hardcover in my hand, tracing each little letter and word. The rewind button became my best friend. I replayed every word. I replayed every sentence. I replayed until the orderly black

lines became distinguishable into comprehensible words.

As a child, I was always quite stubborn and intense. I loved to compete. I refused to lose. And, I was most definitely not losing to little blobs of black squiggly lines. Black letters on the page formed an orderly infantry of soldiers marching into battle. And, it was war. To win was to read. To read was to win.

After countless hours next to my little CD player, I finally made it through “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.” I began my routine. Every time I wanted to read a book, I’d go to the library to check out both the audiobook and the physical copy to follow along with until I understood every single word. I learned each word, carefully repeating them out loud and pointing my finger to each corresponding letter. Although I didn’t know most of the words on the paper, the words “giving up” were not in my vocabulary. Either I finally learned to read because I was headstrong, or because I was just that obsessed with Harry Potter. By the fourth Harry Potter book, I didn’t need an audiobook, which felt like sorcery in itself. I could finally open a book, flip to the first page, and read on my own. Although the fourth book was 752 pages long, I wasn’t afraid. The journey to get here, to read independently, was longer. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the fourth book was both my favorite in the series and the first book I fully read by myself.

Graced with the newfound independence of reading, I discovered the freedom of imagination and the enchantment of living a thousand lives. Following my determination to read, reading determined my future: a future full of woven words, knitting a blanket of warmth around my soul. To read was not just to win. To read was the just start of my own story. I could not read until I was seven. But, I will continue to read until I die. ❧

Emily Aikens, TC ’26, Herald staff

As someone who has lived exclusively in the Northeast, I eagerly anticipate the changing seasons each year. I’ve spent winter mornings with my nose pressed up against the glass of my bedroom window, waiting for enough snow to accumulate for school to be canceled. I’ve spent spring afternoons walking my dog, basking in the first glimpse of warmth. I’ve spent fall nights curled up under my weighted blanket, listening to the wind blow against leaves that would soon fall from the trees in my backyard. I’ve spent summer days driving around Scranton, Pennsylvania with my windows down, indulging in country music that I would normally despise if the weather weren’t above 80 degrees. Living alongside the seasons has become a ritual for me. As soon as it gets cold enough to wear a sweater, a new autumn playlist appears on my Spotify. As soon as I can wear a sundress around campus without shivering, the spring playlist makes its return. There’s always a song on my seasonal playlists that becomes the background music to my daily life. This past winter, it was “Supercut” by Lorde. In the fall, it was “Vampire Empire” by Big Thief. The song of the spring is still up in the air, but strong contenders include “California” by Joni Mitchell, “Slide Tackle” by Japanese Breakfast, and “Octopus’s Garden” by The Beatles. When the season ends, the songs will disappear from my rotation until the next year. I like to think of them as notes to my future self. As I was crafting my spring playlist for this year, I looked back at

last year’s version for inspiration. I pressed shuffle, and the familiar sound of boygenius streamed through my AirPods. Walking along Yale’s uneven cobblestone, listening to the same music and stumbling over the same potholes as I did last year, I wondered how much I’ve actually changed during the past twelve months. On a macro-scale, nothing in my life is drastically different. I have the same friends, wear the same clothes, even order the same drink at Atticus.

But things have changed. Summer passed slowly; I walked around the streets of New Haven, learning to exist on campus without all of my friends here. Those were the days filled with rock climbing, solo East Rock hikes, and taking care of the two thousand high school students enrolled in the Yale Young Global Scholars

program. Autumn was a period of growth. After braving one too many situationships, I entered a period of reflection, working to shed my self-doubt with the falling leaves. Winter came all at once.

The cold descended on New Haven one fateful day in November, and for months, I sped to classes to escape the biting chill.

But now it’s spring, and the sun shines down on Cross Campus once again. As I sat in the grass today—the same patch that I’ve sat on dozens of times before—I felt wholly myself. I don’t think I could have said the same a year ago. I still feel the ghosts of my old insecurities when I listen to the songs that I loved during my freshman year. But they’re subtle now, only floating in and out of my memory when I hear Phoebe Bridgers or Fiona Apple. ❧

Sara Cao, TD ’26

I met Chris Della Ragione on a snowy afternoon. It was a slow day at Elm City Sounds in Westville, and a comforting tranquility trailed the idle tempo of the record store’s background jazz music. 42-year-old Della Ragione, the owner and sole employee, was cleaning some vinyls behind the counter, nodding in brief acknowledgement at my entrance as he circled a rag around a disc. His hands moved with a soothing suaveness. His head of dark brown curls and a chin of light stubble dipped under a black baseball cap. A rhythmic intimacy blanketed the room. Bins and stacks overflowed with vintage records, but rather than overwhelming me, they invited curiosity and intentionality. In the age of instantaneous online music releases, the pace of the music industry follows the ever-changing track of trends. Interest in vinyl records has skyrocketed as obsessions with curating a musical identity have surfaced, leading to the mass production of Urban Outfitters “suitcase” record players, the oversaturation of Nirvana band tees at Target, and the availability of hit pressings at big box chain stores. As an avid record collector for over two decades, Della Ragione saw an opportunity in this development. In 2020, he decided to buy an empty space for his own record store, and he moved back to New Haven from New York City. “New York was already kind of saturated, and you could go open a shop and fight it out,” he explains. “But there’s an opportunity to go somewhere where the stores are already closed and open up a store and put the flag down.”

While this sudden vinyl boom opened doors for him, the digital accessibility of music and the romanticization of vintage records come at a cost. Della Ragione views this transition as a loss of authenticity. To him, listening to music is a craft. Like all things, it takes time and effort to get the full experience.

“People nowadays take things for granted to a degree,” he says with a hint of nostalgia. Growing up in Stamford, Della Ragione surrounded himself with hip-hop and jazz music, and embedded himself in the New Haven and nyc music scenes. He spent his early adulthood digging through records for samples, managing a record la-

bel called Sound of Dissent, and deejaying for local venues. “The mid-nineties was a very special time. I was just buying rap records, and it was the best time in hip-hop ever. There was a magic back then, and collecting records was like a discovery waiting to happen. It was very real.”

By now, the background record in the store has finished playing. Della Ragione wanders over to switch it to the B-side, and I ask him to elaborate on his opinions about accessibility. He explains that it comes at the risk of musical uniformity.

“It’s amazing to be able to hear all different types of music. But I think it’s really hurt local music

scenes and the way music styles are created over time. Back then, all music scenes were highly located in insulated little incubators, where for years, a sound could develop on its own and you wouldn’t hear stuff from other places. It wasn’t like today, where every night you’re just inundated with every different style and inevitably it influences you. And so everything just becomes very homogenous because of that.” Della Ragione believes that the loss of music’s regional identity has also taken sound quality with it, too.

“There’s no modern digital equipment—even if you spend as much money as you can—that’s better than a vinyl set,” he says with vehement confidence. “A real system is the best sounding thing in the world.” Not just any vinyl set, though. According to Della Ragione, the decline of sound quality has followed the rise of fast fashion and rapid trend cycles. Big vinyl pressing companies have shaved off quality for profits, catering to shareholders in order to create a brand identity. Now, it’s all about prioritizing quantity, and Elm City Sounds’ curated selection offers resistance to the culture of mass production.

I ask Della Ragione about the soundsystem he uses in his shop. He stops cleaning for a second to gesture at the record player a few feet away and talks about the various components of his soundsystem that he is currently building. He even graces me with a tangent about an IBM engineer who specializes in the production of diamond needles. Precision is key. New technology doesn’t mix with old. The best quality of sound is at a mid-range frequency. Amplifier design is a science in itself. His sheer dedication to his craft is evident, and his knowledge never once comes across as pretentious or alienating—traits that music fanatics are often branded with.

“I can’t disclose it,” Della Ragione half-jokingly responds when I ask how he obtains records to sell in the store. I expect him to stop at that, but he surprises me by continuing, “you have to earn trust. You have to have a good reputation because record collections are a very personal thing for a lot of people to pass on, because a lot of times the collections belong to a deceased relative, and it’s very personal. It’s a therapeutic thing— you have to sit down and listen to them. Let people tell you stories and they’ll feel good about passing on these records to you.”

The collection at Elm City Sounds is directly influenced by Della Ragione’s own music preferences. The conscious choice to include certain records in the store infuses the space with a deliberateness that also seems to influence the shopping experience there. Most customers do not come in to look for a specific album, preferring to browse through the store’s offerings with an open mind, sifting through bin after bin. Della Ragione supports exploring the identities of various record stores, saying that “shops should have character. I encourage people to go to other shops, because each one is different.”

The snow has dwindled to a leisurely flurry. In his black Supreme sweatshirt, laid-back khaki slacks, and brown loafers, Della Ragione peeks out in the back of a room filled to the brim with culture, history, value, and identity. But still, the thousands of records all boil down to one person’s passion for music. “I’m still a collector above everything,” he declares. His greatest pride isn’t his shop, his aptitude for communication, or his vast music knowledge. For Della Ragione, his connection with music always makes its return to his personal pride and joy: his own record collection. “Honestly, it all comes back to that.” ❧

203 562 6226

65 Howe St, New Haven, CT 11:30 AM-3 PM, 5-11 PM

Molly Reinmann, BK ’26

Climate change is real, and it’s getting worse. The ocean is warming, the ice sheets are shrinking, the sea level is rising, the glaciers are melting. I wore shorts in February! But don’t pull out your ultimate survival kits just yet. Lucky for the human race, Kim Kardashian might just have the solution to save us all: the skims Ultimate Bra Nipple Push-Up Bra. A recent addition to her $4 billion shapewear and undergarment brand, the Nipple Push-Up Bra is a padded bra with “a built-in raised nipple detail for a perky, braless look that makes a bold statement,” according to the skims website. The garment, priced at $62, comes in six colors, eight band sizes, and seven cup sizes, all of which are currently sold out. Our savior announced the news through an Instagram reel that, had it not been an advertisement for skims, could have been the trailer for a Keeping Up With the Kardashians spinoff called Kim Goes to Work. Donning a skin-tight beige bodysuit and rimless glasses, Kardashian sits behind a retro computer in a monochromatic office as she explains to her hundreds of millions of followers how her new Nipple Push-Up Bra can save them from imminent climate-change-induced peril, because 10 percent of its profits will go to an environmental nonprofit. “Some days are hard, but these nipples are harder,” Kim lectures, pointing to a “scientific illustration” on a beige chalkboard. “And unlike the icebergs, they aren’t going anywhere.” Now, no matter how hot it is, we can always look cold. Thanks, Kim!

While Kim may have pioneered the climate-change-reversing-faux-nipple push-up bra— though a 1970s advertisement suggests even that may be false— she is hardly the first savvy businesswoman to market the hell out of a bra. The story of iconic bras and bra advertisements begins long before Kim, long before global warming was even a part of the national conversation. Perhaps, then, in order to understand the Nipple Bra, we must look backward, point our nips to the past, and ask ourselves: what exactly is it we are selling when we sell bras?

The everyday bra came into existence at the start of the 20th century. Departing from the restrictiveness of the hard-wired corset upon which breasts depended theretofore, the earliest bras were sold as instruments of comfort rather than style. With level padding rather than separated cups, early bras—called brassieres—flattened, rather than lifted, boobs, promoting a “monobosom” look. They were more functional than stylish. As the 20th century progressed, styles of bras and breasts began to ebb and flow alongside larger fashion changes. In the flapper craze of the 20s, a lanky, boyish look was popular. Brassieres, as such, were tight-fitting and ribbed, designed to flatten breasts.

Certainly, then, the bra was making waves by the mid-20th century. But in order to achieve longevity, it needed support. It needed marketing, an angle, a creative vision. All of that came to fruition in the mind of Ida Rosenthal, who founded Maidenform, one of the country’s first

bra companies. Two decades after incorporating Maidenform, hoping to boost sales after the war, Rosenthal dreamt up one of the most iconic and longest-running print ad campaigns of all time. From 1949 to 1969, the more than 100 advertisements in Maidenform’s “Dream” campaign revolutionized how and to whom bras were marketed. The ads feature photographs of real women doing—or, rather, dreaming they can do—real things, topless but for their Maidenform bras. The Dreamers fantasize about going to work, swaying juries, traveling to Paris, winning elections, leading protests—all in their Maidenform bras!

Before the Dream campaign, brassiere advertisements scarcely depicted real women at all. Early bra ads featured somewhat-realistic drawings of fictional women. Rather than at work, or in Paris, or on the town, these woman-sketches posed from the home, enacting domestic scenes like caring for children, cooking, or cleaning. Moreover, these pre-Dreamer bra ads appeared only in women’s publications and, as such, reached an almost entirely female audience. But the Dreamers were real, live women, photographed wearing real Maidenform bras, doing real things—not just stereotypically feminine things. These images of half-naked women outside of the domestic sphere were broadcast across most mainstream publications, in spaces as hyper-public as billboards.

The ads were doubtless a commercial success: in the campaign’s 20-year lifespan, Maidenform’s sales nearly quadrupled, increas-

ing from 14 million in 1949 to 43 million by 1963. But Maidenform’s Dreamers sold more than just bras. They sold a bra that could make you dream. They sold a new vision for femininity, a new definition of what it meant to dress and work and be as an American woman. They sold a fantasy.

Much like a conspiracy theory, a fantasy is only plausible when it contains an element of truth. The “I Dreamed” campaign arose in the 1940s postwar period, at a time when women were entering the workforce at higher rates than they ever had before. By 1949, a new generation of women spent much of their time outside of the home, working in offices and factories on tasks that exceeded domestic duties. For the first time in history, women and their fashions were perceived outside of the home, on a day-to-day basis. Rosenthal capitalized on this

shift in circumstance. A working woman needs to be supported, the Dream campaign proclaims—she needs a bra. But Maidenform also sold the inverse. A woman in a bra can aspire to do the things Maidenform’s Dreamers do; a woman in a bra can and should fantasize about independence and professionalism. Though its models are scantily clad, the advertisements exude empowerment more than sex. The sexiness of the Dreamers is the least interesting, least provocative thing about them.

The same can’t be said for Kim. Sure, kkw is also selling a fantasy, with her rimless glasses and antique computer and fake/real nipples that can reverse climate change if you just buy them. But her fantasy is markedly different than Maidenform’s. In the era of the Dreamers, the idea of a working woman was new and invigorating. Now it’s overdone. Women consistently graduate college at higher rates than men. Nearly half of U.S. workers are women. Women are doctors, lawyers, CEOs, and, in pretty much every first world country but America, presidents. In 2024, the working woman isn’t a fantasy at all. It’s a reality.

Perhaps the path towards the modern working woman begins in 2020, with the Covid pandemic and the rise of a workfrom-home ethos. With workers confined to their bedrooms and Zoom screens, we saw the rise of waist-up dressing. When they returned to in-person, their Gen-Z counterparts joining them for the first time, business casual became more casual. Fewer workers than ever before are getting dressed up for work. Before Covid, the workplace was somewhere we got ready for and mingled in, comfort only an afterthought. Now, it’s somewhere we go—less frequently than ever before—simply to do our jobs and go home.

Or perhaps the path towards the

2024 working woman begins even earlier in 2016, when pioneering journalists and courageous silence breakers popularized the #MeToo movement to crusade against sexual harassment in the workplace. For decades, workplace sex was something forced upon women, something in which they had no say. #MeToo sought to remedy that problem not by empowering women to have the office sex they want to have, but rather by making offices as sexless as possible.

No matter where we begin our story, we end up in the same place: a culture devoid of sex. Young people are having less sex now than at any other time in the recent past. As women, we’re putting less energy than ever before into making ourselves appear “sexy.” Workplace sex scandals went from the subject of hushed gossip to downright reprehensible career-enders. The working woman of 2024 is a sexless figure, but Kim, in her Instagram reel promoting the Nipple Bra, is oozing with sex. It’s emanating from her many curves, tightly hugged by her skims bodysuit, and glaring at us from each of her protruding fake nipples. Kim turns the modern-day taboo of wanting and performing sex and sexiness on its head. She’s practically a sex doll. And with her new bra, we can be too.

If, with their Dream campaign, Maidenform was selling the fantasy that women could be serious, powerful workers despite their sexiness, Kim, with her nipple bra, is selling the fantasy that women can be sexy despite their professionalism. If the skims Ultimate Bra Nipple Push-Up Bra teaches us anything, it’s that our sexiness not our skill, not our strength, not our brains—will solve the world’s problems. If you want our planet to survive long enough to see your children grow up, heed Kim’s advice, strap on a pair of Ultimate Push-Up Nipples and take your sexy ass to work. ❧

Wedemeyer, ES

The first “exhibit” in the new Yale Peabody Museum is a printed wall that showcases what has changed. The wall is a display of improvements from the past four years of the remodel. It details what quantitatively makes the museum better. Large Yale Blue text boasts technical additions: 10,000 square feet of new collection storage, 10 new classrooms, three floors of exhibits. What’s more, 27 additional brontosaurus vertebrae, 2,215 objects on display, and a 42-foot mosasaur. However, the new Peabody is not just an attempt to rehabilitate the physical space and showcase more, but to rehabilitate narratives around the items and their audience. The newfound focus on the museum’s contents as cultural, per-

sonal, and living is made clear when you engage with the exhibits and the changes that have been made. Interaction, engagement, and storytelling are the basis of the new Peabody, ultimately showcasing what is human and alive through inanimate objects and fossils.

Coming off Whitney Avenue on Tuesday, March 26th, I entered the lobby of the Peabody, a small rotunda with a matching circular desk inside two glass doors, angled 45 degrees away from one another. The skeleton of Pteranodons, a kind of ancient flying reptile, are secured to the ceilings on wires. The skull of the one above the desk is six feet long, and its wingspan is 24 feet. There are three other pteranodons, a female with an 11-

foot wingspan, and two babies, secured around the rotunda. The entrance is very ornate, unlike the open entrances and lobbies of the Yale University Art Gallery and the Center for British Art. After reading the wall text outlining the changes, I followed the crowd of kindergarten-age students and docents ahead of me into Burke Hall, where the dinosaurs are. I then remembered why I rarely make a point of visiting museums of natural history—the information they present is typically geared toward children. Plaques and posters explaining fossils and cast models hung just above my knee, eye level for the museum’s young visitors. An animated slideshow in one corner described species dispersal at a child’s reading level; the displayed teeth of a woolly mammoth were labeled “Please Touch!”; and a description next to recast ammonites and rubber isopods explained the importance of modeling specimens in place of real ones. I was reading things that I (a person who has not engaged much with biology, ecology, and paleontology) could glean, as a child would. I was learning a lot, and it was hard not to.

After completing two laps around Burke Hall, where brontosaurus vertebrates had been suspended above me for most of my walk, I entered the Central Gallery. It is a large empty atrium, and also the first new room on the first floor that has been added in renovation.The upper floors of the museum are rectangular walkways that keep this atrium open so that visitors can look down and see this central mezzanine from any gallery. The new Central Gallery is empty—with only a few couches, chairs, and prehistoric-looking palms—refusing to fulfill the assumption of eminence the title of central ascribes. Yale College senior Jasmine Gormley, TD ’24, who studies plant community ecology says, however, that the use

of this open space will be important for Yale students, especially undergraduates in the sciences. “It can be intimidating as a first-year student without a lot of experience in science to take up space in a scientific context,” she told me. “If there’s a place to be or work that isn’t just your lab or class, it makes it so much more comfortable and easy to approach.” For first-year students interested in the sciences unsure of their specific focus, and without much previous research or publication experience, a gathering space is key for making connections across disciplines and engaging with science outside of structured and intimidating educational spaces. Gormley started at Yale in the fall of 2019, before the Peabody’s closure, and remembers Science Hill as not having many spaces for students to work and meet between classes. Steep Café had yet to even open. The Central Gallery can now be a space for students and faculty to casually engage with the museum and collections or host events, engaging in their interests beyond labs and classrooms, which is important as these fields are often seen as requiring fewer “social” spaces compared to humanities fields.

Gormley also works in the entomology collection through the Peabody as a collections assistant and student tour guide. Entomology is one of ten collections managed by the museum, and singularly comprises “1.5 million curated specimens,” of which a tenth of a tenth of a percent are exhibited. The museum’s curators carefully select materials that are both relevant to viewers and representative of the greater reserve. As for entomology, right now that selection includes Harlequin and Hercules beetles, Jewel scarabs, leafcutter ants, and giant cicadas. Jasmine says that the Peabody has hired student collection guides, including herself, to lead tours of these

spaces and teach visitors about specimens that are not on display.

The Peabody Museum hopes to use its materials as educational resources: if visitors become interested after seeing curated presentations, there may be opportunities for them to see some of the millions of other pieces Peabody manages, collects, and uses for research. The role of the museum is not static, and as interests change and grow, the Peabody can foster engagement for those who want to see beyond the exhibition cabinets.

I thought that I had been to the Peabody before Tuesday, because I had been in both the Ornithology and Vertebrate Paleontology collections before. I associated this with the Peabody, having seen materials that would soon be on display at the times I visited. A caveat with viewing the collections though, is that in order to request any materials, you have to already know what you are looking for.

The closed, opaque, temperature cabinets in which the ornithology collections are kept cannot be perused, and I have rarely seen specimens I was not previously interested in. Curation and exhibition are what invite learning, rather than only seeing the things one already knows to look for. Some of the birds in the new Peabody are on the first floor’s Student Gallery and Richard Study Gallery. These two galleries break off to the left of the main Central Gallery and show collections curated by Yale students and professors—the content of their courses and research. Having walked through the rows of cold white cabinets holding

thousands of stuffed birds, I appreciated the curation of the small exhibitions more. The few materials on display at the Peabody reinforce the range of the collection, from hummingbirds to toucans to a dodo, while showing off unexpected connections between species. The selections highlight the innovation and work being done at Yale, aligning collections with what is relevant to the people at the university who engage with the collections, rather than just showing off rare physical elements of the Peabody catalog. The impact of the objects is what’s on view rather than the objects themselves just for the sake of spectacle.

All of the major exhibitions place their weight on the relationships between the objects and people. An entire room to the right of the rotunda when passing the stairs to the second floor is dedicated to what the museum calls the “human footprint.” It is a testament to human life on display in a gallery that would typically focus on plants, animals, and fossils. A row of early human skulls and skeletal systems stands across from the reconstructed skeletons of a wooly mammoth and a stag moose; two species that went extinct following the introduction of over-hunting and pollution into their environments. The progression of early human physiognomy to its modern state chronologically opposes the dates in which the animals displayed across the hall on the parallel wall went extinct. This narrative of human influence, though, continues through the room’s interactive components. Several large screens, positioned

low to the ground, mark the corners of the Human Footprint room. Their interfaces look like mobile games and they invite audiences to “play.” The first one I came across was immediately to my left upon entering and simply said “climate change.” When you touch the screen, the background shifts from the large text and a photo of snowy mountains, to a visual roadmap through “Earth’s climate history,” before showing the potential flood impacts that climate change has on New Haven. At another screen the viewer can understand species migration through the maps of the historical spread of tomatoes, horses, and humans. Humans are not usually shown alongside other animals or plants in these kinds of demonstrations. Relevance, whether focusing on humans or the location of the museum, is key. The gallery and the narrative approach focus on the anthropocene and how humans are a part of it like any other species, not a separate matter. Another exhibit, back in the Student Gallery, covers the wall with the words “Fakes and Fictions: Unraveling Museum Narratives.” The change in the museum’s focus from traditional history exhibitions to a more human-focused approach illustrates a thoughtfulness on behalf of the museum’s curators. This particular display remedies the difference between casts and models with what some museums would call “fake,” such as stuffed songbirds and a modeled Dodo in case in the center of the room. The new narrative is that these objects, “real” or not, are still useful for learning.

Acknowledging that people may not see displays as real, the museum considers how they “display, present, and discuss objects, shaping viewers’ knowledge and perspectives for generations.” How the viewer learns and what they learn about an exhibition, be it how an animal lived and survived,—be it how an animal lived and survived,

the importance of a certain medical device, or the utility of early lightbulbs—is brought back to the human experience.

The aim of “storytelling” in the new Peabody was refined by hoping to tailor the experience to visitors. Associate Director of Exhibitions, Kailen Rogers, tells me, “Students and visitors were at the fore of our minds while we were doing this work.” The larger group of administrators, exhibition leaders, and curators held focus groups while the museum was closed: “Over Zoom, sometimes at the farmers market or even on the sidewalk to get feedback from students, families, and people in New Haven.”

Successful techniques at other museums influenced the shorter text panels used in exhibits, the simplified explanations that I so enjoyed, and opportunities for curators to create displays that were exciting reflections of their own work.

The emphasis on the human ex-

perience of the museum gets even more specific, with one of the central “stories” the museum tells being about Yale itself and its people. Rogers says, “We are a university museum; we would not exist without this community, and we are here for this community. It has been a balance for us, making sure we find new ways to include this community and offer opportunities for people who are interested in museum work to be a part of it.” Some exhibits feature a short biography of a student or faculty member who was involved in curation or emphasize how students continue to work with the legacy of certain artifacts and events. Near the early computers exhibit on the second floor, a panel next to the descriptions reads “Boozhoo (Hello)!” from Madeline Gupta, MC ’25, an indigenous woman in computing who founded the chapter of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society at Yale. The blurb is titled “Women of Color in Technology” to

feature voices that have been historically excluded from displays such as this. Madeline states, “Creating products that serve all communities means including scientists and engineers from all communities,” bringing an indigenous woman’s experience into the historical context and how those early computers have led to contemporary usage. Work being done here, and the people driving that work, are part of the museum and the history it covers. What is contemporary and anthropological is not only just as important as, but is actually conveyed as, part of history.

Yale cannot be central to the museum narrative however, without attention to the university’s own historical action. Three new displays on the second floor discuss Yale and the American Eugenics Society, Yale and Slavery, and Hiram Bingham’s “discovery” of Machu Picchu in 1911. “We have these panels that focus on Yale and Peabody history that are not necessarily things we are celebrating, but want to acknowledge and explore,” says Rogers. The panels also bring to light what those specific collections mean today. Directors and curators like Rogers use the collections not only to educate, but also to generate conversations around Yale’s wrongs, and how individuals and the institution work to be cognizant of the persisting implications. This is part of Yale’s story, and the museum’s storytelling recognizes these histories, and calls upon viewers to heed them as warnings.

The narrative of humanity and liveliness in the Peabody’s reimagination is made concrete by rethinking what belongs in a natural history museum. In the case of the Peabody, the answer is art. Masters students in the Yale School of Art have created pieces that contribute to the broader narrative of the room they exhibit in. They work to reconcile the nature of a natural history museum, predicated on collection and classification. The Peabody makes space for art

as a tool to learn from, working to create a narrative that centers the animate side of its collections—how they were once used, and how these organisms once behaved. Grounding is a large installation that is lodged in the wall that divides the Central Hall and the Student Gallery. Created by Rafael Villares, art ’24, it is a reinterpretation of a diorama, with visible broken china below a layer of soil and plants growing on top. “I’ve been wanting to exhibit in a natural history museum for a while,” he says, “I am really interested in the historical representation of nature… and how we track the relation between humans and the concept of nature.” Villares was born and raised in Cuba, and his work is motivated by understanding landscape, shown through “inversion of familiar aspects of the surrounding environment from micro to macro scales.” He inspects the tie between art and science just as he does between human and nature.

Villares wanted to bring something to the museum that you wouldn’t typically see there— crushed China, the household objects. He started by thinking about cabinets as a way of displaying objects, in the museum or in our homes, and how we all have “collections” in some ways. We store items like dishes in cabinets and assign value to them. Villares begs the question: what is the difference between these galleries and a collection you have in a home? The household items he chose for the piece all had representations of nature, maybe just kitschy drawings of flowers or fruit, but still an artistic representation of scientific knowledge. The layer of live moss above the plates opens the possibility for life to exist there, while the bottom layer exemplifies Villares’ thoughts about what he calls the relationship between nature and the anthropocene. He calls the glassware “sediment we are creating in the world” while the life

above it is the future that builds on the sediment. The glass cabinet with life inside reflects back towards the gallery, full of glass cabinets containing taxidermied animals. Villares’ piece is a specimen itself. This raises a distinction: what is the difference between art and natural history? There are pieces from the Babylonian collection in both the Yale Art Gallery and the Peabody, so how do we decide what goes where? The inclusion of current artists in the Peabody reinforces that art and creativity are part of human history. “There is a proper balance in the museum,” he shares, believing human artifacts and art are both displays of knowledge, showing different ways of expressing agency in what one knows. Run your hand across the mammoth tooth so you can know what it feels like; it’s there for you to touch. Read the plaques, see the skeletons, and decide what you deem as “fake” or merely recreation. The new Peabody is for you. It is a place to learn about humanity through the conduit of objects, art, and artifacts. I’ve referred to it as a natural history museum, but the name was actually changed in the redesign from the “Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History” to the “Yale Peabody Museum.” The change in name is evidence that the Peabody is not yet finished—it is still a museum, but one that is shifting its focus beyond what it is known for. Yes, exhibitions will cycle through and new research will be presented, but even the third floor has yet to be opened to the public. Natural history has a lot of connotations,it could be a museum about sculpture, paintings, dinosaurs, plants, or whatever has been deemed natural. At the center of this experience, though, are the people who create the displays and the people who learn from them. People are back at the Peabody, and the museum is about them. ❧

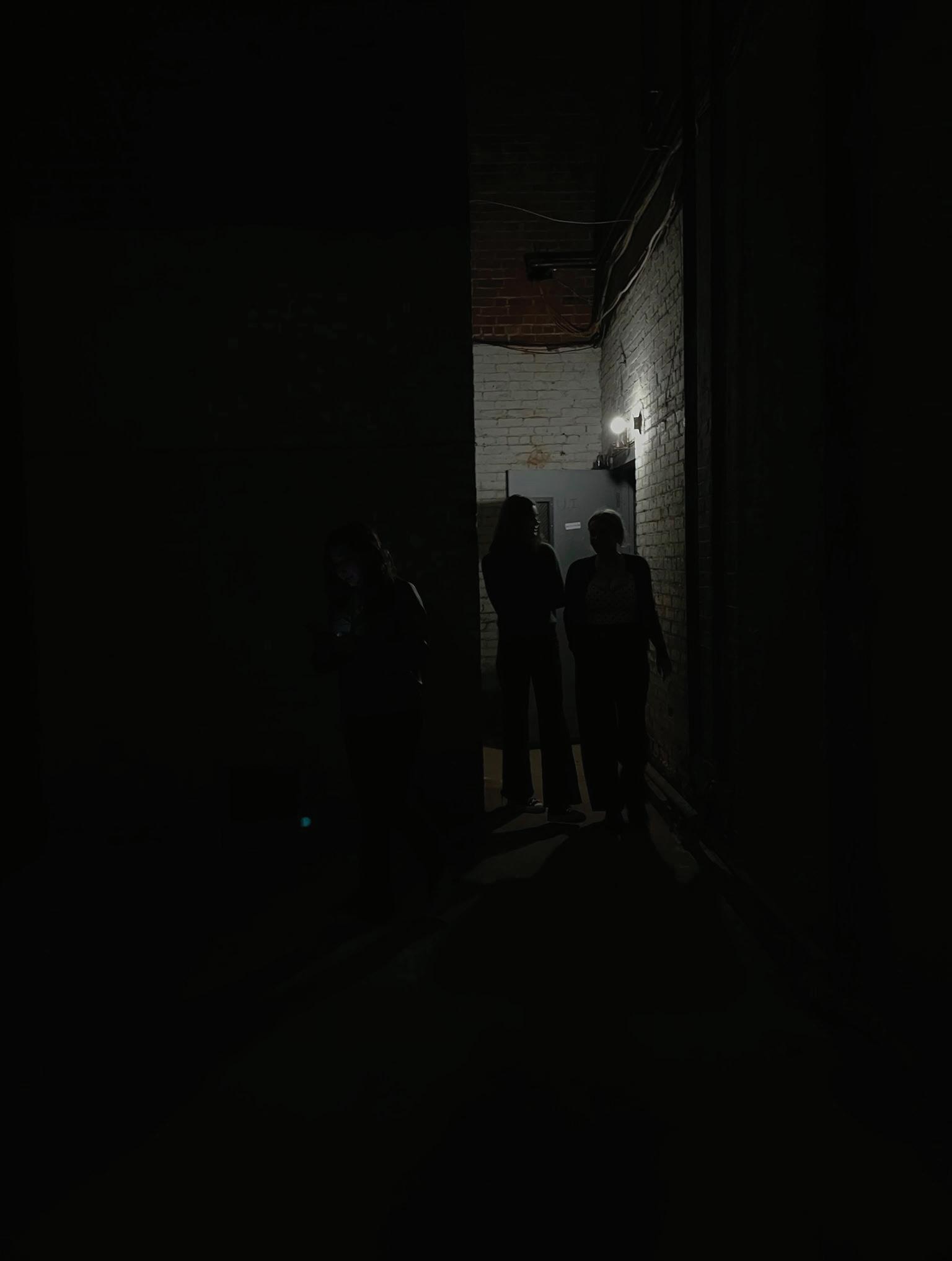

Connor Arakaki, MC ’26, Herald staff

On the morning of May 1, 1970, the black spray paint of a graffiti board on Cross Campus read: “If you really know what’s going on, then you don’t have to know what’s going on to know what’s going on.”

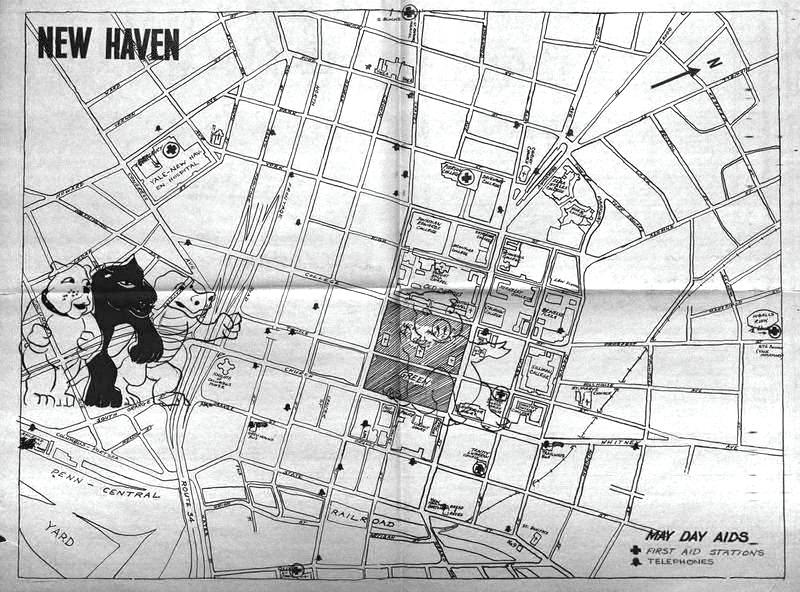

Two blocks north, J. Press, Cutler’s Record Shop, Broadway Wine Shoppe, Liggett’s, and Broadway Hiway Uniform boarded up their windows. Two blocks south, 15,000 people rallied together at the New Haven Green, listening to the press conference in front of the courthouse and dancing to emerging Black rock music from Elephant’s Memory, Polydor Records, and the Allnight Newsboys. The protesters overflowed into the then-gateless Old Campus. In a photo captured by Thomas Strong, art ’67, on Elm Street between Trumbull and Saybrook Colleges, a one-lane road and a lone bicyclist are all that separate Yale College undergraduate activ-

ists on strike from school from two single-file lines of National Guard soldiers, armed with rifles and tear gas. Strong’s photo would become one archival material of hundreds in the 17 accessions of the Yale University Library’s “May Day Rally and Yale collection,” documenting the responsive uproar after the arrest of the “Connecticut 14” Black Panther activists, including party leaders Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale.

Paul Bass and Douglas W. Rae’s 2006 reportorial book, Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, and the Redemption of a Killer, situates the May Day rally in the long tension between the New Haven government and the growing New Haven Black Panther Party. According to Bass and Rae, on January 23, 1969, New Haven played host to the funeral of native son John Huggins, once the leader of the Los Angeles chapter

of the Panthers. Huggins’s widow, Ericka, and their three-week-old daughter, Mai, traveled to Connecticut for the wake. Although Ericka Huggins and her colleague Warren Kimbrow had organized a chapter of the party in Bridgeport months prior, the chapter had fallen through. Huggins’s visit during the funeral catalyzed the creation of a new chapter in New Haven in the fall of 1969. The first Panther meetings were hosted in Kimbrow’s home on Orchard Street, where organizers taught political education classes and cooked free breakfast every school day for children attending neighboring elementary schools. The New Haven chapter’s “Basic Panther Platform” outlines in AIM Newsletter—the bulletin for the American Independent Movement—that Black communities are “unfree in much the same way as colonial subjects

are unfree,” underscoring that racial subjugation manifests in the community’s economic and political institutions and culminates in police brutality. The local platform agenda concludes: “Police control is only one way that the Panthers see Black people being denied self-determination.”

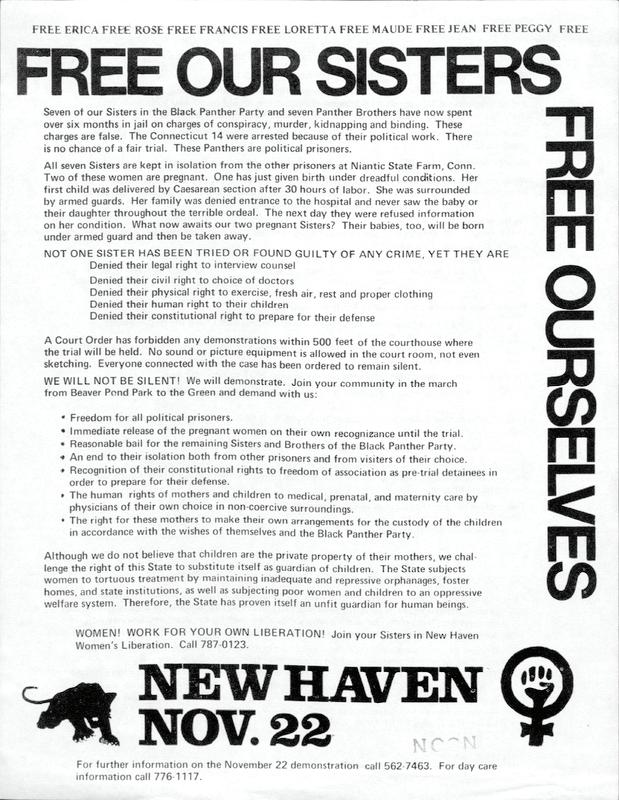

On May 20, 1969, the murder of suspected fbi informant and 19-year-old Panther Alex Rackley in New Haven precipitated the arrests of fourteen total Black Panthers, including party leaders Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale. Of the “Connecticut 14,” seven were women, two of whom were pregnant at the time of their arrest. Huggins and Seale were both denied counsel of their choice and, initially, the right to represent themselves in court. The Panthers saw this as the state and federal government’s concerted effort to rupture the Panthers’ agenda,

its growing print media presence, and its popularity. As Angela Davis wrote in a July 1971 retrospective for Ebony, “Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale would have to stand trial for their lives because they had been unyielding in their efforts to forge liberating actions for Black people. And there were innumerable other instances of frame-ups and similar political reprisals.” The arrests of Huggins and Seale, along with the other members of the Connecticut 14, inspired a new wave of print activism on both a national and local scale. In New Haven, protest flyers were rapidly disseminated across Yale’s campus and surrounding shops. A flyer demanding the effective counsel of the Connecticut 14 reads, “free our sisters free ourselves,” prefiguring the rhetoric of Black feminist grassroots groups that emerged in the 70’s. Most notably, the motto resonates

with the 1977 Combahee River Collective statement, which asserts, “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

The New Haven Panthers’ fliers and newsletters moved community members to a series of protests, beginning in April 1970, which would finally culminate in protests on May Day. On April 14, 1970, New Haven high school students chanted in front of the courthouse and destroyed parts of Chapel Square Mall in protest. One day later, 1,500 protesters marched at Harvard University. By then, the Youth International Party leader and Chicago Seven defendant Abbie Hoffman had announced that the Panthers’ next rally would be at Yale—pressuring New Haven Panther leaders, undergraduate

student leaders at Yale, University administration and then-University President Kingman Brewster, to prepare and accommodate.

Five years before May Day, in 1964, the record number of fourteen Black men matriculated to Yale, according to the archives of the Afro-American Cultural Center, which hadn’t been founded yet. In 1967, the Black Student Alliance at Yale was founded with the policy agenda of increasing Black enrollment, developing Afro-American studies, forging a relationship with the Black New Haven community, and establishing an Afro-American Cultural Center. However, the founding political activism of the AfAm house did not extend their policymaking to women. It wasn’t until the rising momentum of the New Haven Panthers that the inaugural class of undergraduate women matriculated at Yale: Yale Corporation voted in favor of full coeducation in the College in the fall of 1969. The AfAm House was founded the same semester. Ultimately, after Huggins and Seale’s arrest, bsay wrote a statement to President Brewster, urging Yale to “take a vigorous stance on releasing these political prisoners” and called for a student strike from aca-

demic classes and activities and for a 500,000-dollar donation from Yale to the Panthers’ defense fund.

The uprising of the New Haven Panthers and their campus supporters met opposition. The Student Fair Trial Committee, a conservative student organization against the rally, disseminated fliers against the May Day events and wrote letters to President Brewster, arguing that “disruptions at Yale will also have the effect of further alienating the elements in the New Haven community— including, perhaps, the judge and the jury in the Panther case” and “the Yale community should not destroy its political efficacy merely to express ‘solidarity,’ when it might be needed much more desperately sometime in the very near future.”

Residential colleges were divided in supporting the May Day rally, however, Davenport College set forth a referendum to reallocate their budget for the Panthers’ Defense Fund, opened rooms to house visiting protestors, and transitioned their courtyard into a first aid station and a soup kitchen. In a photo captured by Strong in the archives, a white, tenfoot banner states in red text “child and family care center: Trained Personnel Present” hangs from the college entrance on York Street. In

above: New Haven Black Panthers flyer left: Map from the Yale Strike News Both documents courtesy of Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

another, taken by an unnamed student photographer, a young Black boy rides a tricycle above chalk that says “Liberate the Courtyard.” Finally, on April 24, 1970, Yale College faculty voted to allow class suspension for the week following the May Day rally, the nod of approval that the strike was still on. A day before at a faculty meeting, President Brewster said that he was “appalled and ashamed that things should have come to such a pass that [he is] skeptical of the ability of Black revolutionaries to achieve a fair trial anywhere in the United States.” The statement was controversial—it garnered national media attention and calls for his resignation. At a Florida fundraiser on April 28, then-U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew even called on Yale alumni to ask that Brewster be fired. In the same week, the Yale Strike News published their May Day issue featuring a spread mapping locations of telephones and first aid stations throughout campus, and includes a pocketlawyer for police confrontations. Another spread reprinted “Prison, Where is Thy Victory?,” an essay written by Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton after Huggins and Seale’s arrests. Newton’s essay concludes, “The prison

cannot gain a victory over the political prisoner because he has nothing to be rehabilitated from or to. He refuses to accept the legitimacy of the system and refuses to participate.”

By May Day, the Yale Strike News reports, 28 Panthers had been murdered by police force. Just the day prior, President Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger announced the United States’ assault on Cambodia during the Vietnam War—above the New Haven Green, where over 15,000 protestors gathered, a plane skywrote three peace signs. The May Day rally began with a press conference in front of the courthouse and featured speeches on the Green from participating organization members including Hoffman and fellow Chicago Seven defendant Dave Dellinger, political activist and French novelist Jean Genet, and Venceremos Brigade leader Carol Brightman. Thomas Strong’s photo collection at the Beinecke, alongside that of John T. Hill, art ’60, pulses the archival memory of the May Day crowds that the New Haven Green no longer remembers: in a photo of Hill’s, five Black boys stand next to the bordering gates of the park, the two in front with pinned papers to their shirt collars that read “ human rights not violence.”

In the afternoon, Black rock music reverberated through a crowd of thousands at Ingalls Rink and jazz music, featuring “Huey P. Newton Movement,” an original composition by trumpeter Cal Massey performed by the Ro-mas Orchestra. The sun had set, and the improvisation and dancing did not stop. Late that night, local New Haven police and National Guard troops used tear gas to “control demonstrations” that had involved bottle and rock throwing—several of these gas bombs exploded at the end of the rock concert. Despite the tear gassing, both immediate and longform coverage described the May

Despite the tear gassing, both immediate and longform coverage described the May Day rally as “peaceful” and “nonviolent”

Day rally as “peaceful” and “nonviolent,” neutralized by the news and eventually overshadowed by the Kent State University antiwar protests three days later, where Ohio National Guard troops opened fire at student protestors, killing four and injuring nine.

In the aftermath of May Day, the Yale Strike Steering Committee formed four demands for President Brewster, unveiled at a meeting in Dwight Hall on May 20, 1970: that the Yale Corporation demand that the State of Connecticut end the injustice of the trial of Bobby Seale and the New Haven Panthers; that Yale recognize its responsibility to provide daycare for children of the Yale community and establish facilities for that purpose; halt all development of the Institute of Social Science and the Social Science Center to establish at least an adult education and high school teacher training program; and pay unemployment compensation to its workers until January 1, 1972. Brewster did not meet any of the Committee’s demands.

Nearly 54 years later, on March 29, 2024, the Yale Daily News reported that approximately 100 Yale students and New Haven community members gathered on the New Haven Green, demanding city of-

ficials to call for a ceasefire for the war in Gaza. In 2021, the Black and Brown United in Action and Unidad Latina en Acción organized on the Green, celebrating Indigenous cultures and calling on Congress to welcome migrants. The Green remains to be animated by protest, albeit on a manifold smaller scale. With the exception of these ripples of protest, the Green is largely known today by Yale students as the stigmatized division between campus and city—where the university ends, and what’s left of New Haven begins. An afterlife of the Green also exists in the Yale University Library’s “May Day Rally and Yale collection.” The archives speak—and in doing so—survive the memories of the Green and the legacy of the May Day rally, but to know what is going on requires the living to gather. As Cappy Pinderhughes—New Haven Black Panther Party Lieutenant of Information—articulated to AIM Newsletter on behalf of the party, “We are saying that in order to defeat racism you have to fight racism with people solidarity. People getting together to define their own situation and act accordingly, and, if those people choose to come together, then so be it, we act on that basis.” Perhaps what has been going on is still going on. ❧

Tadpoles, and tandem bicycles, and other things I can’t see without smiling.

This show of scientific defiance, this forward tumble of progress, this must be the gift of spring: to make things feel lovely again, until the word begs back its vibrance

from the austere drapes of winter, which are not lovely but clean, and hollow, bones chilled to match the white of fallen snow, muted colors not allowed to scream—goodness, isn’t it lovely to wake from that dream?

I feel I could be the tadpole, growing

legs as the trees grow green, and a functioning head and heart and spleen. I feel I could ride one-half of the bicycle, becoming a fraction of the speed that sends us catapulting forward.

By God, the earth spins free, and so do I!

What a time this is, to be alive— this being our frantic flight, and the blooming seeds, and the shifting light, and the lifting breeze. Joy goes by a hundred names, but as long as there is a space between my hand and the brakes, I call it a welcome surprise:

The gift of spring.

- Kaylee Chen, TC ’27

(After Frank O’Hara’s “Having a Coke with You”)

…feels more foreign than being a Midwesterner in Madrid, Morocco, Montmartre or trying on red skirts for flamenco-dancing lessons in Salamanca if I ignore your right sock and the hair gel on my bathroom counter if I ignore your allusions to my hometown restaurants or to my cousins if I ignore the familiarity my words assume when I address you, bracing for the October wind that will seep into my apartment after you leave for work, the cold exhale of some crafty mouse hiding in my drywall while I dress myself, and the chill that settles over my mirror like snow across a lawn

which heightens the strangeness of the blue cotton, as if it were something I was supposed to wear in another life but certainly not this one I smell your cologne on the collar and it’s like a cuisine I tasted somewhere that more or less can’t be explained by most ontological accounts of the universe though if you’ve read Leibniz we could laugh about a different reality where you’ve conversed in the language of some pretend country like Uqbar or even Wonderland and I’ll say I stumbled upon you like how people say that a monkey could type Macbeth if you let it at the typewriter long enough or how despite all of Zeno’s infinitesimals Diogenes walked away

which is exactly why I’m rolling up your oversized sleeves this morning because of some miracle that’s maybe just you walking but you knew that already

All of it strung, like popcorn through a hard, silver needle. Emulsion on acetate, backlit, in reverse. Inverse purple sycamore cardiovascular

branches, like the veins that carry breath. All that is there isn’t. Not really. All that isn’t really there hanging between the pads of my fingers. Careful, don’t touch!

Not yet. Lay it out, let it curl. Remember the orange gray, gray orange. Let it sit there and don’t touch. It has to dry, it has to come to a boil, simmer until it thickens.

You have to hang it from a clothesline and pin its feathery wings to the styrofoam so it sits straight. It might be hot! You don’t want the styrofoam to melt, so better yet

don’t touch it at all. Leave it in an editor’s inbox instead, just to make sure it’s never read. You don’t want to get fingerprints all over it, do you? Talk to it a little, but remember

to pitch your voice up. Everything sounds lower in the womb, and you want it to recognize your voice, right? Don’t worry about the blood, it has its own, and it’s pulsing

in the negative. If you listen close enough, maybe you’ll hear its antiheartbeat. The eyes, not the brain, will develop first, that way it knows how to render you in its gaze.

I bet if I touched it to my tongue, it would be salty, like two beady eyes glistening in the backlight. The body produces so much salt; it bleeds in technicolor and it weeps. Never sweet.

I’d let you touch it, but it has to scab up, send platelets to crust the open wound. You closed the shutter, therefore making it bleed. The least you can do is fire it,

put it in the kiln so it can find its shape, and as it hardens you better pray that it doesn’t bleed out, leaving you nothing but empty signifiers and tortoise shells.

- Madelyn Dawson, SM ’25, Herald staff

so far this year µ C ftp.I II bmafkir

Allwomen think they fear gets in the way of are different they all any kind of learning think there are some growth things that will never Kathryn Lofton in my happen to them and seminar today they are all wrong

MARCH 8 de Beauvoir TheWoman

You dream in a Destroyed language I can't

MARCH 18 understand my mom is Past Lives 2023 moving just here to tell you that the books

MARCH 12 Youkeep are who you are life is bestexpevienced zoefishman76ontwitte r whenlived.in thosedays we werelivingit

MARCH 26

MARCH 15 stopgooglingyourself Stopreadingthe reviews myupdated letterboxd review for cala land stopspendingmoney Stop talking to anyone everyone art reminds us we are ALIVE Dumpthe banker aboutyour new projects just bequiet and think datethe dreamer

Heti Alphabet Diaries

Read last week's feature: an interview with

Arthur Delot-Vilain, DC ’25, Herald staff

Becca Rothfeld’s official bio describes her as the nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, an editor at The Point, and a lapsed academic philosopher. She is also a staunch defender of the importance of all that is beautiful and erotic in life. Her debut essay collection, All Things Are Too Small, was officially released on April 2, 2024. I interviewed her over the course of two hours in an increasingly crowded café in Washington, DC, on March 18, 2024.

[ADV] I'm trying to figure out where to start. Which I'm realizing I should have figured out before. Um... Well, I guess one... So, you start here, which is... One thing

that's different about your... Or that you seem to insist on a lot in your practice is the idea of paying attention to aesthetic principles or paying attention to... or special attention to aesthetic principles and elaborating them and defending them. What do you consider your... First of all, actually, what are aesthetic principles? Whether that's examples or just a category definition, but...

[BR] So, I think that I would say that I'm a defender of the aesthetic.

A defender of the idea that aesthetic value matters, but I think that it's quite hard to articulate aesthetic principles and I think that that's not accidental.

I am somebody who is very influenced by Kant’s theory of aesthetic value and aesthetic judgment, and so I'm always positioning myself in relation to Kant. One of the things that Kant says that I think is true, although I think he says many that

are not true, is that there are no aesthetic concepts. He's famously obsessed with thinking of concepts as they pertain to metaphysics, but he thinks that there are basically no rules for when something is aesthetically good or bad.

He has a theory of what an aesthetic judgment is and the conditions under which you can make an aesthetic judgment and so on, but he doesn't have aesthetic principles. And I'm sort of still agnostic about this.

Interestingly, I think you can operate as a critic without having a clear idea of whether you think that there are aesthetic principles or not, but I'm inclined to think that there are not aesthetic principles. One can have a theory about what aesthetic judgment is and how it differs from other kinds, but I think that that's distinct from saying, “here are the qualities that all good works of art have.” →

Alina Vaidya Mahadevan, MC ’27

To reinstate standardized testing or not? That is the question that universities all over the US tackled at the onset of the pandemic—and one that has continued to plague them ever since. At the end of February, Yale University offered a response: a reinstatement of the standardized testing requirement. When I first started thinking about which colleges I wanted to apply to, I remember a college counselor telling me: “Alina, most of these places are still not up for discussion until you get a score higher than at least a 1530 on the SAT.” Even though I was applying during the pandemic, when most universities had test-optional policies, the choice to withhold my scores never seemed available to me. Growing up in the college-obsessed Bombay school system, I was constantly reminded that all of my immediate competitors would be submitting impressive scores. If I wanted to be taken seriously, I would have to match up.

As my first year at Yale comes to a close, my world is now far larger than the web of competitive Indian high schools that I grew up in. My one-track perspective on the

unquestionable value of testing has been colored with much-needed nuance through conversations with my peers, and my belief in the institution of standardized testing is no longer a product of blind faith. But even after exposure to opposing perspectives, I still find myself erring on the side of supporting Yale’s requirement for testing.

And I am not alone in this sentiment. Against the backdrop of Old Campus on a chilly March afternoon, I sat across from one of my best friends. She spent her childhood almost exclusively in Colombia; her family moved to the US halfway through the first semester of her sister’s junior year of high school. Her sister, now a student at MIT, aced the SAT and ACT—my friend maintains that submitting her test scores strengthened an application that she perhaps would not have made the cut without them. As a fellow international student, I, too, see this story as a testament to the positive attributes of standardized testing.

If universities make the decision to stay test-optional in a postCOVID world, citing commitment to diversity and inclusion,

I wonder whether they are in fact disadvantaging the same marginalized students that they claim to be protecting. A study published by Johns Hopkins found that schools that required testing experienced a similar uptick in diversity as those that adopted test-optional policies, dismissing the argument that Yale is abandoning its dedication to building a diverse class through this policy. In fact, Yale’s commitment to considering test scores in the context of each applicant’s background and high school might indicate the very opposite—a desire to prioritize inclusion rather than disregard it.

In conversations with friends at Yale who are FGLI, I learned that most of them were likewise in support of reinstating the testing requirement. They viewed these requirements as an opportunity to present their academic excellence in the context of their background and high school, rather than in comparison to all Yale applicants. Furthermore, they explained, other parts of the admissions process, like personal essays, recommendation letters, and extracurricular activities, have even greater disparities across race and class. These differences arise largely because these ‘qualitative’ measures can rely heavily on funding, such that these gaps far outstrip those that result from standardized testing.

Ultimately, the onus is on admissions officers, not only to build a diverse student body, but also to ensure that the students they recruit can keep up with the rigor of the institution. There is good reason for admissions officers to ensure that they admit students who show the potential that a Yale education demands. Research studies have found that test scores are better indicators of success in college than high school grades. In an interview with YaleNews, Jeremiah Quinlan, Dean of Yale Undergraduate Admissions, mentioned that

Iris Tsouris, DC ’25, Herald staff

“students with higher scores have been more likely to have higher Yale GPAs,” and that “test scores are the single greatest predictor of a student’s performance in Yale courses.”

I do not mean to suggest that the standardized testing system itself is flawless. The accessibility of fee waivers should be expanded, and providing more test dates and centers would make a world of difference. Even with those reforms slowly emerging, we are a long way from leveling the playing

field in terms of the education and resources available to low-income students, and my support of Yale’s policy in no way is meant to diminish my belief in the importance of efforts to bridge these gaps.

Conversations surrounding Yale’s efforts to prioritize diversity and inclusion are essential in order to create the academic and social landscape that Yale envisions for itself—an environment in which people from all walks of life can thrive. Standardized testing policies form a small part of