Jisu Oh on the new MENA suite at 305 Crown Street

Gabrielle Burrus-Bustamante on the new YUAG exhibition

Sara Cao and Oscar Heller on The Dare

Jisu Oh on the new MENA suite at 305 Crown Street

Gabrielle Burrus-Bustamante on the new YUAG exhibition

Sara Cao and Oscar Heller on The Dare

We began this school year on the steps of the New Haven Courthouse, in solidarity with a group of 44 of our peers, who appeared for their court hearing, following the arrests made by Yale Police last semester for their peaceful occupation and encampment of Beinecke Plaza.. We continue to call on Yale University to disclose and divest from the ongoing war in Gaza, and reinvest in New Haven.

We hope that the Yale Herald can serve as an alternative to the rigid stylistic restrictions that are placed on traditional journalism—not in opposition to the tenets of rigorous, thoughtful reporting, but in their service. To treat our communities with the care that arises from remembering that they, like us, are composed of people. People with voices. For this, the Herald is a magazine replete with stories

Editors-In-Chief

Connor Arakaki/ Madelyn Dawson

Managing Editors

Jack Reed/ Emily Aikens/Eva Kottou

Creative Directors

Tor Wettlaufer/Emily Cai/ Alexa Druyanoff

Columnists

Cameron Jones / Theo Kubovy-Weiss / Thea Robertson

Design

Michelle J Lee/Matthew Messaye/Alex Nelson/Malina Reber/Alina Susani/ Claire SooHoo/Sarah Sun/Nicole Tian

Reviews Editors

Sara Cao / Theo Kubovy-Weiss / Thea Robertson

that have voices.

Our inaugural issue of the 76th volume of the Herald is dedicated to embracing homecoming, in both its accelerating certainty and ruminatory unfinishedness. In their review of The Dare’s What’s Wrong With New York? Sara Cao ’26 and Oscar Heller ’26 unveil faux individualism and grasp for authenticity. Los Angeles-native Julian Raymond ’28 reflects on the slowness possible in a callous and clamoring hometown. In the cover story of this issue, Jisu Oh ’27 chronicles the six years of student advocacy that preceded the opening of the MENA suite at 305 Crown Street this semester. Finally, Gabrielle Burrus-Bustamante ’26 pulses through the rhythm of the Yale University Art Gallery’s new exhibition, The Dance of Life.

Thank you to the eyes, ears, hands, and voices that have embraced and generated this issue. We want to especially thank Yale’s

MENA community—specifically

MENA Assistant Director Lena Ginawi, Asian American Cultural Center Director & Assistant Dean of Yale College Joliana Yee, MENA peer liaisons, house staff, and members—for trusting us to report on and photograph the new space as the cover story of this issue.

The Herald is a place for incisive, assertive criticism, for experimental, creative narratives. For offbeat comic strips and intimate, relational profiling. It is a place that writers and editors can, together, shape into their own kind of home. We have a deep belief in the imaginative possibility of this publication. You, reader, are a part of this process. Together, we can begin creating an otherwise, our alternative homecoming.

Yours most daringly, Connor Arakaki & Madelyn Dawson

Reflections Editors

Amanda Cao/Jack Rodriquez-Vars

Culture Editors

Alex Sobrino/Will Sussbauer/ Sophie Lamb

Features Editors

Calista Oetama/ Amber Nobriga/ Jisu Oh

Opinion Editors

Richie George/Oscar Heller

Arts Editors

Ashley Wang/ Everett Yum/ Diego Del Aguila

Voices Editors

Gavin Guerrette/Lana Perice

Copy Editors

Lu Arie / Elizabeth Chivers / Diana Contreras Nino / Cameron Jones /

Irene Kim / Alina Susani/ Alina Vaidya Mahadevan / Nicole Viloria / Reese Weiden

Publisher Bella Panico

Social Media Manager

Jess Liu

Business Manager

Avery Lenihan

Calendar

Connor Arakaki/Madelyn Dawson

Photography Editor

Tashroom Ahsan/Natalie Leung

This Week's Cover

Tor Wettlaufer / Tashroom Ahsan

In

Reinventing

On the Asian American Cultural Center: A Morsel’s Perspective

What could be more than making a friend over free boba.

In the Wake of brat

Neon green paraphernalia and an ouroboros of self-subversion.

On Tap, Coors Banquet by Theo Kubovy-Weiss, Thea Robertson, Jack Reed You're cordially invited.

Sara Cao TD ’26, Herald staff

Design by Claire Soohoo

Ona late Thursday night in New York City, hedonists, nihilists, and fun-havers clumsily jumped up and down in frenzied euphoria. Kicking off his “I’m Coming” tour with a sold-out show at Webster Hall, The Dare debuted his latest album, What’s Wrong With New York, against a backdrop of flashing lights and rows of Marshall speakers. The Dare donned his uniform Gucci suit and Celine sunglasses. His signature IDGAF attitude dangled like a gleaming golden medallion around his neck. Two standalone soundboards flanked his left and right. Behind him, a single cymbal. A mic stand stood dead center. This was a one-man show.

The audience wore microscarves, baby tees with “I heart [insert noun]” text in American Typewriter, and an array of black

sequined items. The Dare kicked, screamed, clashed his cymbal midair, and danced in fits of hysteria. There was no shortage of lewd lyricism, obnoxious beat drops, strobing drum kicks, and distorted synth sounds. While he had yet to release eight of the fourteen songs on the setlist, the audience sang along to the ones they knew and screamed alongside the ones they didn’t. In his performance of “I Destroyed Disco,” arguably the best song on his new album, The Dare gritted out, “What’s a blogger to a rocker? What’s a rocker to The Dare?,” before the audience erupted into a cheer. None of The Dare’s new material felt innovative or unfamiliar, and he certainly did not beat the James Murphy impersonator allegations. Everything was raunchy and in your face— right where he wanted it to be.

Overloaded with obscenity, The Dare’s performance felt like the sonic counterpart to a particularly online brain rot. The concert was an addictive guilty pleasure, like any 2 a.m. descent down an Instagram Reels rabbit hole. Neither experience leaves me satisfied in the long run, but I cannot break free from the pattern of short-term dopamine fixes. After each song, I wanted more.

But at what point does The Dare’s commitment to the bit become too tacky or too much? The audience’s infectious energy never reached a climax. An inundation of flashy media and ostentatious production generates hollow grandiosity. This is the danger of extravagant maximalism under the guise of purported minimalism. The indie sleaze revival and electroclash aesthetics depend

on consumer culture and microtrends, rapidly growing with our shrinking attention spans.

Even if we try to grasp the problem of inauthenticity in indie sleaze revival by understanding who—or what—The Dare is, it doesn't get us very far. Behind The Dare is Harrison Patrick Smith, a twenty-eight-year-old former substitute teacher from Los Angeles. He is aware of his critics but shrugs them off. The Dare is both an enigma and entirely predictable. If Harrison Smith is an unbothered Bruce Wayne, The Dare is Batman. But instead of fighting crime in a bat mask, he’s in a Gucci fit shackling New York twenty-somethings within the confines of faux individualism.

Through all the artificial silliness, sleaziness, and fun that The Dare represented at his concert, I am tempted to keep my seat at the electroclash circus to see where the theatrical mess of it will lead. So when The Dare asks What’s Wrong With New York? perhaps it’s that all faux individualism will get you in the city is a plastic participation trophy engraved with “I was at The Dare show.” ❧

Oscar Heller ES ’26, Herald staff

Iamalone in my room. In front of me are two Sony speakers and an Aiyima power amp with wires intertwined like blood vessels. I find my phone, take a quick glance at the narrow black tie and white button-down on the album cover, and click play. Everything throbs. I listened to What’s Wrong With New York? for the first time a few days after going to the concert in New York last Thursday, so maybe I was already inclined to imagine the songs being played at

a club. But the point still stands, even if you hear the songs through cheap wire headphones on your way to class. It feels good. And not in the way that it feels good to be riveted by an exceptional writer or painter or sculptor or director. The Dare is primal, and there is an instinctual flavor to his album.

In its entirety, What’s Wrong With New York? is an exercise in surrender through an erasure of all types of meaning: physical and metaphysical. The first track quite literally invites you to “Open Up” to the project—stop whatever you’re doing, grab the metaphorically present hand of The Dare, and join him on a trek through an album rife with jokes, sex, and synthesized bass lines. If the first song invites you into his world, the fifth dismantles yours. The first line on “I Destroyed Disco”—“I break records, glasses, faces, kick the whole world in the teeth with my untied laces”— seems like an enraged response (albeit, one laced with irony) to a condition The Dare ascribes to both the audience and himself on the second track: “We’re all on the brink of suicide.” Here, he points to a real sense of cultural desperation, a desire to feel something a little beyond whatever’s being shoved down your throat by advertisements and the televisual entertainment that dominates your day. “I’m in the club while you’re online,” he tells us. His solution, in one sentence, reads as follows: “I got no money, we got no money, we got a good time.” But the Dare doesn’t just present you with a good time. Yes, the music is intoxicatingly catchy and might even prompt you to turn up the volume dial a little bit and move around, but the most intriguing part of The Dare's whole shtick is irony. Here’s a hyper-individualist guy who, with his sunglasses and generic haircut, blends in public settings

and never actually tells us who or what The Dare is. He’s a one-man show, sure, but he’s also a faceless symbol (at least on the album cover) who likes “girls who give it up for lent” and “girls who so fuckin’ kinky that they’re bent.” He’s also someone who, on the last song on the project, remixes the beginning of ABBA’s “The Winner Takes It All,” turning Agnetha Fältskog’s lyrical dejection into euphoric transfixion.

Hell, even the album itself, which represents a never-ending night at the club full of desire and sex and drugs and ecstasy, is ironic—the joke being that it’s only 27 minutes in length. But the funniest and longest-running joke is that The Dare’s answer to individualized, mechanical consumption is to consume the album. To give into an explosion of immediate desire. So, if What’s Wrong With New York? is Fight Club, the Dare is Tyler Durden: comically unhinged, powerfully seductive, and just so fucking fun. ❧

Victor Attah, DC ’25

Design by Michelle Lee

JPEGMAFIA is one of the most boundary-pushing artists in hiphop. He consistently defies norms, and his latest album, I LAY DOWN MY LIFE FOR YOU, is no exception. The album follows up his 2023 project with Danny Brown, SCARING THE HOES. What sets this album apart from his earlier work is the way JPEGMAFIA leans into his rock influences more than ever. He blends rock seamlessly with his signature rap and soul influences to craft an eclectic sound, further elevated by his knack for incorporating unconventional samples. The album's list of samples includes soulful AI-generated sounds, Fortnite, NBA commentators, Brazilian funk music, and Logan Roy from the HBO Series Succession.

The album's genre-bending approach is evident from its opening

song, "i scream this in the mirror before i interact with anyone," a raprock piece that features a driving guitar melody and hard-hitting drums. The next track, "SIN MIEDO," pushes this rap-rock fusion even further. The song features a sample of the classic hip-hop group 2 Live Crew’s “Hoochie Mama,” with JPEGMAFIA rapping over the sample’s chopped vocals for the first 30 seconds. When the beat finally drops, it erupts into a stuttered drum pattern that amplifies the song’s chaotic energy. Then, a 30-second guitar riff shreds overtop vocals from 2 Live Crew. Blending guitar solos typical of rock with rap's sampling techniques, JPEGMAFIA creates a genre-defying track that showcases his ability to form a cohesive sound from distinct musical elements. Other rock-inspired songs on the album include "vulgar display

of power," which shares its name with the sixth album by the heavy metal band Pantera, and features riffs and breathy screamo vocals reminiscent of the genre.

My favorite track from the album, "either off or on the drugs," is a soulful song with impressive lyricism and flow, packed to the brim with references to pop culture icons, including Lionel Messi, Michael Jackson, and Scarface's Tony Montana. JPEGMAFIA raps about his musical triumphs, struggles with his mental health, and rocky romances. He takes us through his discography: “The first one was good with the beats / The second one put me up in the deep / The third one was sick, no disease / The fourth, I had to rush it to complete.” Instrumentally, the track opens with a 4-count start reminiscent of Pharrell Williams's signature beat tag, leading into a sample of "Turn on The Lights," an AI-generated cover of Future’s song of the same name reimagined to sound like a blues number from the early ’70s. While artists like Drake have received criticism for using AI in music in ways that disrespect the original artists or cut corners, JPEGMAFIA shows he can draw from any material to make a good song.

I LAY DOWN MY LIFE FOR YOU is a collision of rap, rock, and soul that highlights JPEGMAFIA's refusal to make cookie-cutter music. Putting his visionary artistry on full display, he’s cemented his status as a hip-hop trailblazer and innovative producer. ❧

Madelyn Dawson SM ’25, Herald staff

ThoughMJ Lenderman’s latest record gives one the sensation that he was born centuries ago, guitar in hand, and has been cranking out the indie-rock bangers for, well, ever, Manning Fireworks feels like it took ages to drop. Perhaps we’d been waiting since the appearance of “Rudolph” as a stand-alone Manning Fireworks single back in July 2023, before he’d even announced Live and Loose, a full-length live album he’d put out that November. In other ways, we’ve been waiting since Rat Saw God, the April 2023 release with his band Wednesday, on which he and ex-girlfriend Karly Hartzman made, of the many attempts that year, the closest thing to a satisfying slacker-rock-revival record.

But for all intents and purposes, let’s say we’ve only been waiting since he dropped the blisteringly cool “She’s Leaving You,” almost a full year post-“Rudolph,” and announced that he would put out his fourth fulllength solo project in the coming months. In the time between “She’s Leaving You” and the forthcoming Manning Fireworks (read: Jun. 24 until Sep. 6), approximately three years' worth of Lenderman press was published. If it wasn’t odd enough, Lenderman’s release cycle was made even stranger by a critical bottled lightning of sort: all everyone had to say was that the guy was fucking brilliant. Which, while likely true, made for a repetitive story. Couple this with the fact that Lenderman, a 25-year-old rock singer from North Carolina, is just as normal as you might imagine him to be, and suddenly you’ve got the everyman thinking he’s indie rock’s unlikely savior. Lenderman’s denial of this position only strength-

ens it. Of course, he doesn’t think he’s saving rock and roll, not in the jeansand-a-t-shirt uniform that every interviewer and their mother has felt compelled to include in their portrait.

If not a redeemer, then what is MJ Lenderman? He’s not country-rock revival á la Zach Bryan—he toes the line between earnestness and disaffect too adeptly. He’s got that David Berman-esque way of looking at the world like he’s watching it on a TV screen. He’s having a coke with you. He writes with his finger on the pulse as tight as I’ve seen since Isaac Woods was still writing for Black Country, New Road (Lenderman, though, is importantly all-American, though one can’t help but to read at least a touch of British sensibility into the blackness of his humo(u)r.). But perhaps the closest thing I can find to an MJ Lenderman lyric isn’t a Berman or Molina-ism, not even Neil Young or The Band’s approach to ordinariness, but something from a little 1994 album called Little Earthquakes. Tori Amos sings, “I want to smash the faces / of those beautiful boys / those Christian boys / so you can make me cum / That doesn’t make you Jesus.” I can hear her explaining the line with, please don’t laugh only half of what I said was a joke—a lyric from Lenderman single “Joker Lips,” maybe the album’s cleverest cut, and the container of already oft-invoked coupling “Kahlúa shooter/DUI scooter.” For what it’s worth, I prefer “Every Catholic knows he could’ve been Pope.”

Henri Lefebvre writes, in his The Everyday and Everydayness, “The everyday is the most universal and the most unique condition, the most

social and the most individuated, the most obvious and the best hidden” It’s impossible not to hear Manning Fireworks as some twisted celebration of the everyday: take the endlessly clever “On My Knees” that marshals Noah’s Ark against John Travolta’s bald head. It’s a rock song, no modifiers of indie or alternative or country necessary. It’s an everyday rock song, and one that lands on the everyday as its subject. Whether he’s sat in the pews or just waking from a wet dream, Lenderman is on his knees. He’s not afraid to admit that he’s begging.

Perhaps it is the everydayness of Lenderman’s lyrics that makes them feel so intimate, or maybe it’s the tightness—of both his wordplay and his songwriting. Lenderman can riff fast and hard, and I emphasize the double entendre there. See how many times you hear that dun-dun-dun-dun-dun opener to “She’s Leaving You” echo through the rest of the tracklist. I promise it will keep popping up in the most satisfying interstices.

Either way, Lefebvre seems to be right. Manning Fireworks becomes my own unique condition, my everyday. I am thirteen years old and in the car with my mom. It’s dark and warm and we should probably be driving to a hospital. My chest is black and blue from the pounding of my own fist. The car ends up in the parking lot of the Holy Child Church, and we sit silent for a long while before it drives home. I am in my apartment listening to the acoustic, The Band-inspired “You Don’t Know The Shape I’m In.” I’m under a half-mast McDonald’s flag. I’m half-mast under the open sky of time, and I don’t know whether to turn back or forward. “Some people

cry out against the acceleration of time,” Lefebvre writes, “Others cry out against stagnation. They’re both right.” Only half of what I said was a joke.

The record’s final track is utter inversion, and it devastates in a way that no one could possibly have anticipated. Where Lenderman earlier reminded us that at least half of what he said was a joke, he begins “Bark At The Moon” letting us know “I’ve lost my sense of humor” (the next line, “I lost my driving range,” as if the two perhaps got misplaced in the back of the same SUV. Doing it in some cul-de-sac, even). Lenderman becomes the most earnest in this moment of self-recognition. He faces his ironic detachment almost head-on—“You’re in on my bit / you’re sick of the schtick / well, what did you expect?” He’s right: he’s lost his sense of humor, even despite the fact that the song’s conceit is at least slightly funny in its own right. He’s playing Ozzy Osbourne’s “Bark At The Moon” on Guitar Hero. It’s a simulacrum almost to parody. There’s no

guitar, no moon, no act of barking, in other words, no means of production, no object of desire, and no vocalization of that desire. Just hollowness. At last, Lenderman lets out perhaps the saddest-sounding wolf howl before the song, and therefore the album, nullifies itself into seven minutes of ambient guitar fuzz. Like he should’ve stopped the recording but he, just like his listener, became paralyzed with an ineffable vision of bleakness. The bit is over. Disaffect has been pushed to its absolute limit, and all it found was the auto-erasure of a distortion pedal. Oh MJ Lenderman we love you get up ❧

paranormal dark cabaret poetry thursday afternoon

tambourine dylanesque harmonica friday morning

bed rotting elevator music late monday night

family-friendly thespian power walk tuesday afternoon

coding ambient techno saturday night

Alina Susani ES ’26, Herald staff

Design by Nicole Tian

Your hands methodically rig the sleek, white, lightly damaged Laser. The motions you have built up over years and weeks and hours of setting up boats are now second nature; they have yet to fail you.

The wind is strong but bearable. You race across the sea like a speeding car, hair whipping around you. Droplets of water and salt cling to your skin. You feel godly, as if you are Poseidon. One with the power of the sea in this unbeatable moment of freedom. One subtle shift of the rudder or quick pull at the main sheet could transform your trajectory, could bring you to Greece. The nose of the Laser dips up and down into the unruly waves, splashing your arms and face. Your abs and thighs tense to keep the boat from leaning too far.

The ropes strain your hands as the wind brings you to the other side of the coast. Your old, green, fingerless gloves aren’t enough to protect your hands against the burns and aches from the ropes, but you don’t care enough to notice. The groan of the boat beneath you becomes your favorite sound, and the stinging eyes and horrid tan lines and scars littering your legs are all worth it for the fraction of freedom.

Your perfect moment is interrupted as your instructor calls you to the motorboat, asking if you want your friend to join. You love your friend and the experiences you’ve had sailing together, but you wish you could stay Poseidon. Nevertheless, you concede, and your friend carefully climbs over the side of her half-deflated motor-

boat, sitting on your sailboat’s nose.

Your arms ache from ceaselessly holding the coarse ropes, your cheeks hurt from grinning, and your friend is tired of getting splashed by the waves. You slowly release the main sheet. You must not be as strong as Poseidon. Your fingers stretch out, freeing themselves from the tension they carried. You and your friend lay back, comfortable on the uncomfortable plastic. You are grateful your instructor called you over.

You realize shortly into your break that the rope is slackening too much. Frowning, you reach to pull it a little, only to find that although you pull and pull and pull the main sheet won’t tighten. You see the end of the rope and suddenly you understand. It has untied itself and

escaped from its hook. Your knotting skills were not as flawless as you thought. You try to tie it back, but the end of the boom is too far. You cannot fix it from inside the comfort of the boat. The simplest solution is to jump into the cold water; the hook will be reachable from there. The sea is refreshing, cooling you down from the sun that stained your skin.

You swim a few short strokes to the end of the rope, now dangling from the central hook, finally within your reach. You begin to tie it the way you were taught, hoping that this time it will hold. It is not easy and your fingers fumble the slippery rope. You try to keep yourself afloat as you and the boat sway from the persistent waves. As you attempt knot after knot, your friend warns you that the boat is starting to move. Your grip on the rope has caused the wind to fill the sail.

“Can you make sure it’s not tangled on your end?” you ask, not letting go of the still untied rope afraid it will completely escape

the rest of the hooks. Your friend, making sure that it’s not tangled on her end, does not immediately notice how the wind fills the sail more than before, moving the boat quicker and quicker.

“We’re moving again!” you exclaim. It’s obvious you are moving. It would be impossible not to notice your movement with the speed you pick up. Still in fear of undoing the boat entirely, you hold tightly onto your end of the rope. You are dragged by the wind through the waves. You are like the sailboat you are so fond of, though gliding less gloriously. You wonder if Poseidon has to deal with saltwater in his eyes.

You understand, finally, that you won’t be able to solve this problem without letting go.

So you do, but the rope does not let go of you. Confused, you double-check, but there is no invisible fragment of rope knotted in your hands. It is wrapped around your ankle, instead, pulling you along

with the sailboat like a salmon going upstream. You do not understand how the rope has strangled your foot; perhaps it has learned to knot just as you have. The wind continues to drag you through the water. It is certainly saltwater, you think, as you catch wave after wave in your face. The sailboat does not seem to slow down; you do not know what your friend is doing.

The sailboat does not seem to slow down, and your friend is laughing, and perhaps she does not understand that you do not want to be dragged eternally through the sea, and perhaps she does not notice your head going under the water, and perhaps she does not see that the sea level must be lowering at the rate you are swallowing these waves, and they are filling your lungs, and the rope won’t detangle itself from you, and you cannot push against the wind because you are not Poseidon, and you cannot avoid the water in your face and your mouth and your eyes and your ears and you can’t tell if your friend is still laughing because you can’t hear her—

Somehow, you manage to unwrap your leg from the rope without losing your shoe or your life. The wind and the sea will always hold more power than you. ❧

Julian Raymond, TC ’28

Design by Natalie Leung

Ispent my last days of summer in Los Angeles as any Angeleno would: scouring overpriced thrift stores for fashionably distressed clothes. Packed between True Religion jeans and Affliction tees, I found a crumpled ball that was once a Blockbuster Video uniform.

Ten years ago, the last remnants of Blockbuster Video vanished from Los Angeles. Gone were the halls of Blu-ray discs and DVDs, the stores had been gutted and replaced with equally doomed frozen yogurt chains. It had been a decade since I’d seen that uniform, in all its crayon-yellow-collared glory, but I still knew it. I clawed through moth-ravaged “I Heart LA” shirts to reach that relic.

Time is fast and unforgiving in Los Angeles. It hurtles onward, breakneck and callous, flinging the city forward without a thought to whatever may be clutching at its palm tree-lined streets. It bulldozes and rebuilds before the dust has settled, would-be celebrities forgotten the moment their feet leave the desert sand. I’ve known this since childhood, since I learned skipping a day of school meant you vanished from the memory of your fifth-grade friends. Leaving was always out of the question. If I left Los Angeles, I’d be forgotten by my family, my friends, and the city. Any trace of my existence would be blown away in the Santa Ana winds and succeeded by an Erewhon.

When I found that uniform, I mourned my life, not yet gone. Blockbuster and I were cadavers, waiting for the hearses to arrive and bury our bodies, the last remnants of the life we once led. I took the uniform into the changing room with me and slid it over my sunburned shoulders—the skin left tight and red from my last walk along Venice Beach. I felt the fraying yellow threads rest against my throat. It didn’t fit. The sleeves barely reached my biceps and the hem hovered an inch above my underwear. The threads over my shoulder blades split with a muffled wail. I had to peel it off of me, tearing the seams below the armpit in the process. I threw it into the corner of the dingy stall, a mess of torn blue and yellow against the grime and dust.

Yet, in a mixture of affection, shame, and self-pity, I bought the uniform. Through a plastic garbage bag plopped in my passenger seat, it watched me the whole way home. I drove with it for 30 minutes, barely 20 miles in traffic, exchanging glances and stewing in

the pregnant silence. I wanted to ask questions. I wanted to know if it hurt to be forgotten, if it’d feared being abandoned, like I had. Instead, I looked out the window.

The waves wore the rocks down to dust. Rusted piers littered the shoreline, all black metal and barnacles. I saw the trail along the bluffs I skipped down with my family and the breeze that had blown dust over our footsteps. I saw the airplane that would take me from here, vanishing even in the cloudless sky.

It’s rare for someone to save you a space in Los Angeles. Those flung from the speeding, reckless city find themselves torn to shreds, marred with road rash and broken fingernails from holding on too long. I choose to let go, to tumble through the dust, stumbling forward, clamoring up to my future. I'm not sure whether the space I filled will be there when I get back, or whether I'll be relegated to the shelves of a thrift store and forgotten, but I take a step. ❧

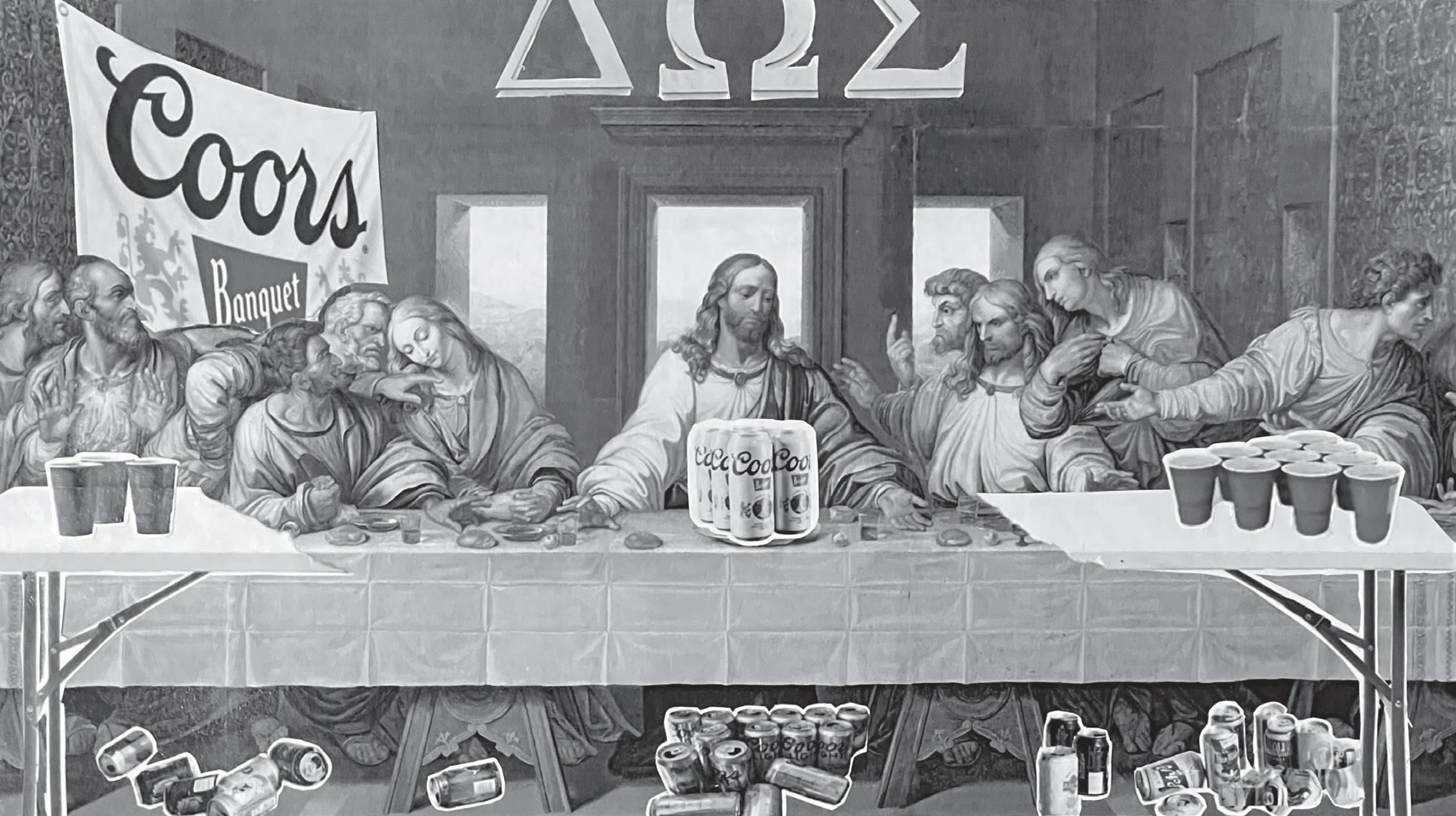

Theo Kubovy-Weiss BR ’26, Thea Robertson TK ’25,

Jack Reed BK ’25, Herald staff

Design by Matthew Messaye

This is the school year’s first installment of, On Tap the Yale Herald’s weekly beer column, written by Reviews Editors Theo Kubovy-Weiss and Thea Robertson. On Tap covers everything from Natty Lights to home-brewed stouts, aiming to expand Yale students’ tastes when it comes to the country’s most popular alcoholic beverage.

Banquet (n): an elaborate and formal meal for many people.

The Banquet’s name evokes grandeur, like this is the kind of beer you’d serve to a diplomat or a debutante while gorging on cavi-

ar. It positions itself as the beer of the aristocracy (Coors’s answer to Miller High Life’s “champagne of beers”), as if this would be an appropriate beverage to consume at the Metropolitan Opera or, like, the White House.

It is not. This is a frat beer, and no attempt by the Coors branding team can convince the public otherwise. It is cheap (a dollar a brew if you buy right), sold in units of 30, and its banana-yellow jacket can be seen littering the floors of Greek-lettered houses across the nation. Its flavor is subtle, but in more of an I’m-gonna-shotgun-

this-super-duper-fast way than in a tastefully delicate way. A muted echo of banana trails each sip, leaving you with a lingering sweetness that blunts the alcohol’s bite. And the centrally-emblazoned Coors logo makes it hard to see the can as anything but a mass-produced vessel for 19-year-olds’ favorite brand of bread-water.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. The Coors Banquet is an abundantly refreshing, impressively chuggable, and surprisingly inoffensive beer—one that can find its home at any party with people who prioritize intoxication over gustatory complexity.. And its cost-effectiveness makes this a great choice for the beer-averseturned-beer-curious. One of our editors, an outspoken beer hater, gave this beer the high praise of “tolerable.”

Overall: 6.9/10. ❧

Cameron Jones BF ’26, Herald staff

Design by Alex Nelson

Inside Voice is a new column by Cameron Jones, highlighting the eccentric decor choices of Yalies and the even more eccentric personalities behind them.

When I walk into my suite in Benjamin Franklin College, the overhead light is tragic. It manages to be dim while still drawing attention to every scuff on the wall and speck of dust on the floor. This is no way to come home after a long day.

“When you walk into a room, it’s

all about the first light you turn on,” James Ruskell, BF ’26, tells me, “My mom told me that— make sure you put that in there.”

Stepping into 916 Mansfield on a dark night, I know exactly what the place is about: the record playing through the stereo; the assemblages of second-hand prints, magazine covers, and Soviet movie posters along the walls; my friends in a new setting, smiling as I take the first step through the front door. Call it a wave, call it a bunch of particles, boil it down however you may, but light has preferences, attitudes, and moods beyond its atomic components. It knows when it's being honored, feels when it's in good company. Mansfield is a temple of light with many altars.

The centerpiece of the living room is a grand lamp with a pair of gilded cherubs twirling around its base. As the body of the lamp blooms upwards, it flares out to form a bowl. Its center rod continues, from which sprouts two stacked umbrella shades. Translucent faux crystals dangle from the first. The second shade, silk and haughty, sits like a hat in a royal wedding. A little switch at

the top of the umbrella turns on a light behind the crystals. Ruskell claims he bought it from a “traveling merchant.”

In a quiet corner, a rustic side lamp has found its home. The attached table is etched with the curlicues of cartoon flowers. Succulents sat on the table bathe in the warmth of two incandescent bulbs. Their tendrils stretch toward the twin suns. In a bedroom, lamps tower, perched like noble birds of prey. Their ceramic bodies are a deep blue speckled with gold. Inlaid, beneath a clear lacquer: crossstitched lilacs. The shade, navy velvet on the outside and gold paper on the inside, is perfectly cylindrical. These lamps don’t cast light across the room but direct their glow straight back onto themselves. They think they are the only thing worth seeing.

“I love the transition to the lamps when the sun is setting,” says Angela Chen, BF ’26. As the shadows lengthen across the floor and the glitter of the sun fades behind distant houses, the lamps come on. Lines soften. The walls blush. The furniture relaxes. As a warm fuzz washes over the whole apartment, Mansfield comes to know itself. ❧

Alyse Graham-Martinez, SY ’28

Design by Emily Cai

Nestled in the parking lot of Conte West Hills Middle School, the Wooster Square Farmers’ Market is the Saturday morning spot for anyone who loves fresh food. When I visited the market last weekend, Yale students, New Haven residents, and community members from neighboring towns walked through the lines of vendors, milling about with flowers and produce in hand.

The Wooster Square farmers’ market is one of three New Haven local farmers’ markets organized by the City Seed Organization, a New Haven based group committed to community-wide accessibility to fresh, nourishing food. Only a short southbound walk from campus, the Wooster Square market is particularly accessible for Yale students. Through City Seed, Connecticut food stamp recipients can use SNAP cards to pay for fresh produce at local farmers’ markets. City Seed participates in Fresh Match, a statewide program that allows food stamp recipients to double the value of their SNAP cards when used at participating local farmers markets on fresh produce. In addition, City Seed’s farmers’ market at the Dixwell Q-House is the first and only of the three markets where City Seed itself doubles Farmers Markets’ Nutritional Program purchases for WIC recipients.

While chatting at the informa -

tion desk with market organizers, I got the chance to talk to mothers and their children, college students, and farmers market veterans coming to get their SNAP tokens. “Food is the second prayer…breathing is the first. Food is community, and that’s what you get here,” expressed Eben, a New Haven resident and farmers’ market regular. Eben exuded relaxation when he walked up with a reusable tote slung over his shoulder. When asked to be interviewed he enthusiastically told me not just about the market, but other community organizations like MakerSpace, a shop where members can be taught wood and metal working. He proudly showed me his membership card and encouraged me to come, his attitude emblematic of the inclusivity of the farmers’ market community.

Community was visible everywhere in the market. Farmers happily greeted their regular patrons and fellow farmers, kids ran in front of their parents with fruit juice dripping from their faces and hands, and friends walked by, catching up and picking out the perfect basket of apples to share. When I went to buy some massive peaches from Woodland farm, they happily helped me pick the best ones and encouraged me to try the apples and plums.

The Wooster Square market is the only year-round farmers’

market in New Haven, moving produce inside when the weather gets cold. When I asked Jenny, a farmer from Star Light Gardens, about attendance in the winter months, she described avid market goers waiting outside for the market to open to get a pick at the more limited winter produce.

“In the winter months, it’s more lettuce, spinach, and salads— green, nutrient-dense things,” Jenny explained to me. Many farms like Star Light focus on sustainable growing practices and food for health. The quality of freshly picked and locally grown products is unmatched; programs like Fresh Match help to make them accessible.. Having a year round market allows people to consistently reap the social, physical, and environmental benefits of fresh food. All markets are producer-only, meaning farmers grow everything they sell. One farmer’s stand, Root Life, attends the markets at the Dixwell Q-House and Edgewood with produce and herbs they grow in community plots here in New Haven.

As I left with a full stomach, a bag full of peaches, and a renewed appreciation for locally-grown food, I looked back at Eben. He was admiring the tomatoes he cradled, in conversation with the farmer selling them. ❧

The doors of 305 Crown Street open to a smooth expanse of olive green walls—a beautifully startling change from the faded yellow of only a couple of months earlier. The entire first floor is almost unrecognizable; uniform walls and floors illuminated by soft lights emphasize the empty, often grimy rooms and rusty door knobs of the past. A surprising change, but not unwelcome: as I open its doors on September 7, 2024, 305 Crown Street seems to stand up straighter, holding itself stiffly like a crisp new banknote— green and all.

The still-creaking door closes on me as I pause and wonder if I walked into the wrong building.

My eyes fall on a single chair with wheels by the right wall. It has one of those desks that flip out from the side of the chair— on it, a small sign reading YALE Middle Eastern and North African Cultural Community. I wouldn’t have known otherwise. I stand in front of the door by the sign and try in vain to swipe my ID before going back outside to wait for the person who has access: Koosha Maleknia, TD ’26, one of the six peer liaisons for the newly relocated Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) suite.

The suite extends across the right half of the first floor, containing a kitchen, a salon, and a connecting corridor. Koosha

lets us both into the kitchen, where he had offered to host our interview. “You can still kind of smell the paint everywhere,” he says. “It’s very new.” He opens the door, and I step in.

After more than six years of student-led activism, the MENA community finally acquired a dedicated Yale University campus space on the first floor of 305 Crown Street—an achievement so new that paint was still drying on the walls. In 2018, the Middle Eastern and North African Student Association was inaugurally led by co-pres -

idents Shady Qubaty ’20 and Yasmin Alamdeen ’21, after the emergence of MENA-identifying student groups such as the Arab Students Association, the Persian Students Association, and the Turkish Students Association. In the fall of 2019, the Middle Eastern and North African Student Association became a recognized undergraduate organization affiliated with the Asian American Cultural Center (AACC). In the same semester, the student association hosted welcome mixers and cultural events for MENA-identifying students to widen campus visibility of the existing MENA community and their ongoing work in solidifying their representation on campus.

Although the COVID pandemic had halted the momentum of community advocacy, MENA students swiftly returned to their goals once back in person on campus. In the fall of 2022, they asked Dean Joliana Yee, Asian American Cultural Center Director & Assistant Dean of Yale College, for a potential MENA space in the cultural house. On October 28, 2022, MENA opened its two small rooms in the third-floor attic of the Asian American Cultural Center: the first space established in institutional history to accommodate the formation of Yale’s MENA community.

Two years later, on August 19, 2024, the MENA suite officially moved from its original space in the Asian American Cultural Center to 305 Crown Street, under the supervision of Assistant Director Lena Ginawi. In my conversations with MENA community members, students spanning across grades and heritages have reflected upon their paths in the MENA suite and what it means to have their own space. This suite has

begun to plant its roots in the concrete strip of Crown Street, where La Casa, the Asian American Cultural Center, and the Native American Cultural Center line the sidewalk. However, the MENA suite differs from its neighbors: it is neither a house nor an independent building.

“We’re in our own space, which is very important, and

it’s the key distinction [for] being able to classify MENA as its own identity,” said Satia Hatami, SY ’25 and peer liaison for the MENA suite. “But it’s not even a cohesive space, and I think that’s…something we’re still working towards.”

The arduous and unfinished process of obtaining a communal campus space for students is just a microcosm of the global pursuit of defining MENA as a region and an ethnocultural community. The classification “MENA” dates back to usage

by the World Bank in 1994; yet three decades later, the MENA community still lacks a unified definition. Numerous global institutions have created their own classification: UNICEF defines the MENA region as 20 countries, spanning between Morocco and Iran, while the United Nations names only 18 of these countries. The intersectional, and often porous classifications of the MENA region crosshatch ethnicity, culture, language, religion, and history—creating challenges for an acceptance of a unified MENA cultural community, and often forcing MENA students to explain their own race category.

Although the United States Census Bureau reported that there are 3.5 million MENA-identifying people in the U.S., the Census does not name MENA as a distinct racial group. By extension, institutions that require racial identification such as the Common Application do not offer an option for MENA college applicants, forcing MENA students into the checkbox of “White/Caucasian.” Yale University was no exception to this limitation, resulting in a multitude of MENA students who had applied and matriculated to Yale under the “White/Caucasian” category. As a result, there is no administrative record of MENA-identifying undergraduates on campus.

When Noor Kareem, MY ’25, applied to Yale in the fall of 2020, there was neither a Common Application racial category nor university supplemental application racial category available to demarcate her MENA identity. “On the U.S. Census, we’ve historically just been white, and I also applied to Yale by checking the ‘White/ Caucasian’ box,” a blurry Noor tells me over Zoom on Septem -

ber 8.. “Obviously, coming from an Iraqi origin, I do not consider myself white or Caucasian in any way.”

For MENA students, the invisibility in demographics weighs upon one’s self-perception. What is irreversibly innate to an individual is disregarded and denied; one is forced to be seen as something they are not. Now a senior and the head peer liaison for the MENA suite, Noor has experienced firsthand the journey of advocacy for proper MENA representation. The absence of her MENA identity in university applications and federal records, the breadth of student advocacy steadily rising since her first year at Yale, catching the coattails of plans from upperclassmen to create a MENA space, to now leading monumental work in the creation of a new MENA cultur-

al center. “It’s hard to imagine how far we’ve come, and what it would’ve been for me four years ago, if I had the MENA space and community at Yale from the beginning—or the ability to identify as MENA.”

Sitting on the large couches in the corner of the kitchen, Koosha tells me that the MENA community’s long-standing relationship with the Asian American Cultural Center provided a sense of structure for creating a space to encompass the diversity of the MENA community. MENA-identifying students were hired at the Asian American Cultural Center as staff members, receiving organized support from a well-established, long-standing organization

and building. The center now approaches its 43rd year as a central space for Asian affinity groups, and carries a culture of activism since its founding in 1981.

Having spent much of his years at Yale in the third floor of the Asian American Cultural Center, Koosha noted his appreciation for the cultural center during this period. “Of course, our Assistant Director Ginawi is the main person that we look to, but [Dean Yee and Associate Director Sheraz Oki] did a phenomenal job of helping us adjust to the Asian American Cultural Center, and support recruitment or finding MENA PLees,” Koosha says. “We were part of the team—I never felt any separation.”

Since MENA student activism emerged in the fall of 2018, the

MENA community had been closely associated with the Asian American Cultural Center, constructing a relationship of financial, physical, and faculty support. After arriving at Yale in Spring 2018, Yee was heavily involved in the process of supporting Middle Eastern and North African Student Association events and initiatives to solidify their presence on campus as an official organization, such as pushing for round table discussions and contributing to outreach efforts for MENA-identifying students.

The Asian American Cultural Center peer liaisons—like those of La Casa, the AfAm House, and the Native American Cultural Center—receive lists of first-year students who have specified their race on their applications to Yale. However, MENA peer liaisons never had similar resources due to the lack of a MENA term to identify such students. Yee acknowledged limitations in the assistance she could give in the lack of established MENA resources such as these lists—Asian American Cultural Center peer liaisons

worked with the MENA peer liaisons to spread word and recruit MENA-identifying firstyears. “I am not MENA-identifying, so there was definitely still a lack in that sort of expertise of finding people who identified [as MENA],” Yee said. “What we could do on our end was to say, here’s the dedicated space—how do you want to use it; if you want funding, you’re an affiliate organization [of the Asian American Cultural Center], so how can you get those; let’s just continue to create programming and not let the lack of a space stop you.”

Although the opening of the two MENA rooms in the Asian American Cultural Center contributed to the establishment of the new suite, MENA students such as Koosha did not fully identify and feel comfortable in a space nominally dedicated to Asian Americans. “The AACC is an amazing place, but some students might look at themselves, and be like, oh, why would I

waltz into the AACC and go up to the third floor, and just chill there?”

Echoing Koosha, Satia, who is Persian, explains her distance from an Asian American affiliation. “I never identified as Asian,” Satia tells me. “I’m Persian, so I would classify myself as specifically Middle Eastern. So to be associated with a space that is beautiful and so welcoming, and [where] I had such a positive experience in—despite all that, it was never my identity.”

Students such as Koosha and Satia have always had their goals firmly set for something more: a distinct cultural house. On November 30, 2023, they both participated in a community discussion at the AfAm House, uniting MENA students with members of the House, the Asian American Cultural Center, the Arab Students Association, the Persian Students Association, and Yalies4Palestine. Students emphasized the prevalence of the strong and diverse community of MENA-identifying students, who wanted a space to express their cultures and experiences.

Dean Pericles Lewis, Secretary and Vice President Kimberly Goff-Crews, and Assistant Vice President Pilar Montalvo all attended this discussion to hear and acknowledge students in their efforts to establish MENA-supporting resources.

The Asian American Cultural Center houses remnants of this community discussion. Colorful Post-it notes dot large sheets of paper taped to the wall: testimonial evidence of the hardships of being MENA, reflections on the lack of a communal space to celebrate culture, and—most strikingly—student notes imagining their ideal space: Persian rugs, a kitchen counter laden with spices, literature from all MENA countries and and in all MENA languages, MENA alumni panels, culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health resources, and tea on tap with mint. A space filled with specific, warm, binding purpose; a home to be accepted in.

In January 2024, Yale University officially launched a search and planning committee to prepare a new space for the MENA cultural community, as well as full-time staff to support the MENA students. The University opened a position for an assistant director of the new MENA space on January 18th, a process in which Yee invited MENA-identifying students to participate. Interviews for the position began around April of 2024 and were attended by peer liaisons and other members of the MENA community. Student coordinators were also sought for the new space; interviews starting in September 2024 were held similarly to those for the assistant director. Student en -

gagement in acquiring MENA staff has been a significant aspect of the establishment of the suite.

For Noor and other upperclassmen MENA students, the news came in disbelief: after more than six years of activism met with setbacks, the University was finally, and swiftly, constructing a designated place for the MENA community, releasing a statement in January of plans to complete the space by the fall of the same year. “We were collectively surprised at the speed in which Yale actually gave us the space and was able to build it,” Noor recalls. “I did not believe that I [was going] to see it throughout my time here at Yale. Halfway through the year, I was like ‘Oh I’m actually going to see a MENA space; it’s not this grand illusion that’s going to occur in a couple years from now.’ ”

While a sudden change, other students emphasize the long stretch of work contributing to the achievement finally coming into fruition. “It’s not true to display this MENA suite as a result of some newfound university effort,” Koosha says. “People have been pushing for this for-

ever—it’s been a thing.”

“There’s a lot of reasons factoring into why we’re starting to see real change for the MENA community,” Satia says. “Last year, the MENA community really did not have anywhere to go to congregate, to support each other during this really difficult time for so many members of our community. We could go to the MENA rooms [in the AACC], but those are just a few rooms within a space that honestly a lot of Middle Eastern and North African students don’t necessarily feel like is their space.” Unlike other cultural centers—which serve as central locations within the context of shared identity, and provide opportunities to discuss weighted issues—MENA students did not have a safe space for community and solidarity.

Noor and Satia note that the genocide in Gaza has emphasized the need for a communal space of support and belonging for MENA-identifying students. “I can’t really speak on why Yale decided to do it now, but this space spans all of MENA, and I don’t think that the decision to create a MENA suite should be for any other reason besides the

greater community at Yale,” says Koosha.

Even in September, the creation of a MENA house remains uncertain. MENA students prepare to fully decorate and establish the suite as something close to a home. It is a new process for all involved, historical for both the MENA community and other cultural centers standing firm on Crown St. “No one has ever been here at Yale to build a new cultural space—all of us inherited something that was already built,” says Dean Yee. She has been integral to the creation of both MENA spaces and for the continuing support in the growth and solidification of the community; her name peppers every conversation with the MENA peer liaisons in reverence and appreciation.

Yee also stresses the significance of cultural centers as a place for students to celebrate their present communities, as well as work towards a future of recognition. “It’s important to have cultural centers that understand and recognize the importance of having your racialized experience be identified and supported,” Dean Yee said. “Because it is different,

and it is [marginalized]. I think there’s always this sense of…solidarity, but also understanding that these advocacy pieces take time.”

The MENA suite opens into a room that feels barren despite the well-furnished kitchen: blank walls marked only with tape to reverse spaces for TVs; a multitude of counters and cabinets with nothing inside; a fridge free of smudge marks and stocked with just eight boxes of mango juice. Tucked against the windowsill—rows and rows of empty spice jars. The room feels

larger than it really is, particularly when standing in an awkwardly uninhabited spot with nothing but smooth floorboards and blank walls. In the salon stands a black podium, tracings on its surface scraping away the light coating of dust: two jubilant stick figures dancing amidst hearts and fireworks; I heart MENA written in the corner.

The MENA suite peer liaisons underscore the unfinished work of establishing an independent cultural house. “We’re being very intentional with the words used to describe the space we’re given,” Satia tells me. “So we’ve not been calling it a house, or even a center because it’s not a house or a center—it’s very much a MENA suite. We’re still pushing for something bigger, something more complete.”

There isn’t much that declares the space as the MENA suite other than that little slip of paper and the dust on the podium. But as bare and stark as it looks, there is nothing cold about each room. Light spills across the long kitchen counter, fracturing through each spice jar—still empty, each waiting to be filled with an unashamed, unrestrained declaration of their presence. The MENA suite is waiting. Quietly, eagerly.

Cameron Jones BF ’26, Herald staff

Design by Alex Nelson

Baby blue spooled out from the bag and snaked along the seat. It ran across her thigh. She pulled the yarn along. Small, insect-like movements turned the thin thread into the heap of blue in her lap. What it was, you couldn’t tell. Perhaps it would be a sweater like the one she was wearing: baggy and scratchy. Her wrists looked so small coming out those big sleeves. But there was no sleeve or neck or cuff in that pile, just blue ringlets spilling over her seat and swooping into the aisle. Still you decided it had to be a sweater.

You watched as she gave the yarn form and dimension. There was nothing else to look at on this long ride. The usual tricks—podcasts, books, the view out the window—had failed. This was it. She did not pause. She did not reach for food or drink or music. If she was breathing, you couldn’t tell. You imagined she took a sweater to be just one very complicated knot.

You wondered if you were heading for the same place, if you’d maybe see her in class one day. She’d be wearing that same furrowed expression she had now. You’d make a comment and she’d raise her hand

and she’d tell you, in a perfectly cordial fashion, that you were an idiot.

Both needles in one hand, the other reached for the bag. She grabbed a tube of grape chapstick. Grape? That wasn’t a flavor chapstick came in. You leaned forward. What brand was this? The seat creaked under you. She looked towards the sound.

You turned to the window until she popped the cap of the chapstick back on and the clack of the needles resumed. You couldn’t remember the color of her eyes. That seemed like an important detail. That seemed like something you should know about a stranger on a train you were going to give your number. Years later, you would say to people, “The first thing I noticed about her was her eyes.” Because that was romantic and because it sounded right. You didn’t want to have to lie about that. You hoped she caught the color of your eyes, even as they ran to the window. You got up. You went to the bathroom. She didn’t look when you passed. Returning to your seat, you spied a book inside her bag. It had bold text and bright colors on a white background. It was a pop-psychology self-help

book. The kind of book you could buy in a train station. She might have no intention to read it. You wondered if she bought it just to add weight to her bag. The heavier the bag, the more purposeful the journey, you reasoned. This was a stupid thought. She probably just liked to read. Maybe she read like she knit: inched steadily and without rest, stringing word after word into a chain of meaning. You planned an approach. It would be simple and quick. Any interruption could prove disastrous. You might interrupt at just the wrong time and the sweater would unravel. The needles would fly. She’d look up, crying and holding the tangled yarn like entrails. You decided to wait until she was done knitting. How long would it take? She would have to get tired soon. You closed your eyes. The mounting sound of rain on the window awoke you. You bolted up. A baby blue blanket slipped from your shoulder. You stared at it, looking for something hidden in its folds. Her seat was empty. You had a few more hours ahead of you and no one to approach. You pulled the blanket back over you and leaned into the window. Do you remember what you dreamt?

Chloe Shiffman SM ’26

Katie is mad at me. I am sure of it this time. I am sure that Katie is mad at me because she did not stop at my locker this morning even though I saw her walk into the building with Jane and eat her cream cheese raisin bagel with Jane outside the art room and pretend not to see me when I crossed the courtyard to get to my locker—which had no Katie waiting at it—because Katie was talking with Jane by the art room with her cream cheese raisin bagel. I do not like cream cheese raisin bagels. I do like Katie. Katie blows her nose at the front of the classroom during quiet hour and knows the middle names of fourteen prime ministers and rescues mice from her stepdad’s glue traps. Katie is the closest thing I know to a saint, and I tell her so, not often but sometimes, in her trundle bed on Friday nights, both of us tuckered from soccer practice, red with sunburn and sharing nerds rope like the spaghetti dogs from Lady and the Tramp. The two dogs kiss at the end, but Katie and I don’t. Instead we keep our noses about a half an inch apart. We look at each other with watery wide eyes until I feel like I’m about ready to pass out. When I tell her I’m tired, she huffs and turns away. I can’t explain it, and neither can Katie, but maybe Jane can, Jane who is standing about a kiss apart from Katie by the art room with a little bit of cream cheese on her lip.

Three Poems by Daniella Sanchez, MC ’25

Believing myself a spirit-filled tabernacle holding inside potential architectures, unsuspecting of myself being under construction, I set out on building a grand cathedral so I would not die.

Once, I listened to women kneeling at pews sing about God needing a space to fill because God has no body. Iron being the only material I could afford, I started on the underlying framework. Cramps in the upper walls and tribunes, I attach with praise from the song of my clanging hammer. I aspire to bend this iron into spire ornaments, to finish off my pinnacles and decorate my desperation, to complete anything worthy of a prayer, or even just a thought. I fashion iron bars and wrap small rods around each other, iron supporting iron to support stained glass, because every great cathedral has stained glass windows to paint the light passing through the nave, which I outline with iron chains. And when I believe myself to be finished and imagine a liturgy echoing off the choir walls, I remove my hands and see a skeleton—armature holding erect a rusting body with no stone flesh.

I look down at my hands and see they are covered in rust, and my cathedral too lets rust color its bones.

Design by Tor Wettlaufer

who walks the same pace I do, isn’t it funny how we’ve gathered here today to wander alone?

I’ve come here (alone) to feel my aloneness. To praise my solitude in the presence of Apollo

sculpted from marble, the consecrated form we remember before the words that first gave him his existence. I come here in search of my origin for what utterances of love and beauty brought me here because I find myself only loving gods made of stone these days.

How difficult it is to admire flesh, flawed and unreliable.

When statues are always here, in these rooms, waiting for our gaze.

Do you see these matters the way I do?

As you walk beside me, a stranger, who wonders at her aloneness.

Do you wonder why I am alone? I question yours. Yet, we stay silent, pondering a representation of our being. Do you also wish the answer to our beginnings was that simple—a block of marble?

Black concrete cascades down a hill, pressed against a dark sky yellow lights illuminate the green of the palm trees, and the wall at the end of the street. The wall is light pink; it is all that he sees, staring from the top. The spiraling road feels invisible, and he feels invincible. Looking down, he imagines that when he releases his hands from the board, extends his legs upwards, and sits his butt back in a half-squat over the small pair of wheels supporting his weight, he is spiraling down the curves of the Guggenheim. He sees himself imagined as Frank Lloyd Wright, every round he makes, another floor of art. He skates like the easy stroke of Kandinsky’s paintbrush, even when he scrapes his knees, no artist can make red like he can. Not even Soutine dripping meat.

But he only ever rides on flat surfaces. Parking-lots. The sidewalks, the ones with no cracks. In his head, he has skated down staircases and skidded across the railings, burning the wood on the bottom of his board. His friends start to wonder why he hasn’t moved. Haven’t you done this before? He has. He says I have. So why does he wonder how to stop, before he gets to the pink wall and stains it with something a bit darker in shade. If he slams His leg into the pavement, will the color be the same As the walls of The Night Cafe? These are things only the artist thinks through, he tells himself. So he stays contemplating descent. Knowing, I am a skater.

23

Design by Sarah Sun

Gabrielle Burrus-Bustamante, BF ’26

Design by Tor Wettlaufer

Amassive, wall-spanning poster in vibrant blue sets a celestial tone, with Matisse-like figures floating, perhaps dancing, across the space. Superimposed over the scene is the title: The Dance of Life: Figure and Imagination in American Art, 1876-1914 , the newest exhibit of the Yale University Art Gallery, showing from Sept. 6, 2024 through Jan. 5, 2025. The Hours , a ceiling mural by Edwin Austin Abbey, depicts the passage of time through personified figures, is the focal study of The Dance of Life exhibition, which aims to portray the artistic land -

scape of post-Civil War America. By exhibiting the preliminary stages and preparatory materials for large-scale paintings of other American masters—including Edwin Blashfield, Daniel Chester French, Violet Oakley, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and John Singer Sargent— The Dance of Life grants renewed agency to artistic practices. According to the exhibition’s organizer, Holcombe T. Green Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture Mark D. Mitchell, The Dance of Life offers a fresh central subject: life itself. However, this curation of an American Renaissance doesn’t

always reflect the uplifting, modern vitality suggested by its official cover.

Upon reaching the fourth floor, a golden sculpture of a flying female figure appears in front of another vibrant blue wall. Though a striking setting, the sculpture, depicting the allegorical figure of Victory is too small for the grandeur it aims to convey. It’s an adaptation of Augustus Saint-Gaudens's General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument in New York.

The Dance of Life isn’t about pedestaling early modern American masterpieces; instead, it offers a behind-the-scenes visit to the interactive studios of post-Civil War American artists. The finished pieces are already revered public treasures, decorating prestigious institutions like Pennsylvania’s State Capitol, the Library of Congress, or the Boston Public Library, however, the exhibit’s interactive studios reveal the process beyond the display. The Dance of Life is the visual expression of a choreographic process, a more honest and faithful reflection of the intentions of artists.

As America attempted to reinvent itself, artists were reinventing their practice, returning to the fundamental question: how does one capture life in its most truthful form? Classicists would reply, through a deeper study of the human body . But this sensual subject was hardly something Puritanical America was eager to embrace, so artists like Kenyon Cox, Frederick Williams Macmonnies, and their peers took inspiration to Paris, embracing instead the Italian Renaissance’s legacy. I gazed at meticulous sketches of female nudes, standing male figures, contorted silhouettes, and floating limbs.

An elongated and contemplative male silhouette surges from different sketches, landscapes, and sculptural studies across the room. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Violet Oakley, and William Morris Hunt took their hand at depicting Abraham Lincoln, his commanding presence and the weight of his legacy essentialized to represent “America’s idea of a modern figure.”

The study panels of Violet Oak -

ley, the first American woman artist to receive a public mural commission, especially clarified this concept of an American Renaissance : establishing moral values to a nation both rebuilding identity and struggling to reconcile its own history. Lincoln at Gettysburg was created for the Senate Chamber of Pennsylvania State Capital and awkwardly inserts the 16th president in a historical scene with religious undertones. Depicting the moment of Lincoln’s oration at this pivotal moment of the war, the painting portrays the former president over a crowd of supplicants, giving him a priestly allure. The image is framed by a churchlike Roman arcade on which the words “it is for us the living rather to be dedicated to the unfinished work,” a line from Lincoln’s address, are inscribed.

Oakley’s other study, for her 1917, 44-foot-wide mural International Unity and Understanding features a central female figure with open arms. It is a rumination of the artist’s creative and intellectual processes, as she merges them with ideals and values America aspired to during this period. Formally, it reflects her intensive engagement with its subject, complete with an individual study of the figure’s face and movement. Conceptually, she seeks to represent a unified nation through the image of a female figure standing with open maternal arms, protecting, reuniting, and maybe dancing all at the same time.

Should we read all these figures belonging to a new collective imaginary as dancing through time? In an elevated spirit, the personified figures in Abbey’s Hours are defining a new rhythm, yet Abraham Lincoln’s solid stat -

ure conveys a sense of profound prudence.

The real choreographers of life, nonetheless are these artists who, characterized by a great awareness of their time, were not afraid to start from scratch, crafting new anachronic conversations using myths, religion and modernity under one unifying spirit: life. ❧

Kelly Kong, MC ’28

Twenty-four hours before I moved into Yale, an email landed in my inbox with the subject line “Morse Asians!!!!!”

I was intrigued, partly due to the sheer abundance of exclamation points, but more so because I knew this wasn’t another mass message sent to the entire school about another Chipotle block party on Old Campus with finance bros. It was meant for me: an Asian living in Morse College.

I remember reading something about PLs earlier in the summer. The Peer Liaison program intends to provide additional mentorship to new minority students through culture-centered events and initiatives to help first-year students adjust to life at Yale. Among Yale’s cultural communities is the Asian American Cultural Center (AACC), to which my PL—the mastermind behind “Morse Asians!!!!”—belongs.

I paid my first visit to the AACC during Bulldog Days. I remember staring up at the center’s mural, on 305 Crown Street, decorated with murals of activists and ginkgo leaves bathing under the April sunlight. I remember walking into the kitchen’s scent of kimchi fried rice, trying to rub away the sticky residue of brown sugar boba off my fingers as Jay Chou blasted in the background. The space was packed, and I wondered if it was as well-attended on a reg -

ular day in college. The house wasn’t home, but it was the clos est replica I could find.

But I had my reservations. At the time, Yale’s cultural centers sounded like a more established version of something familiar to me: student-led affinity groups. I grew up attending predominantly white institutions in liberal Massachusetts towns where I watched the DEI work started by teachers of color get shut down by parents and administrations—with the occasional threat of a lawsuit. A few years later, the same admins posted the DEI program at the center of their website homepage in celebration of the multiculturalism at their still-seventy-percent-white-school. The affinity spaces themselves also reckoned with DEI’s paradoxical performance of inclusivity: after all, how do kids who never had a cultural community attempt to build one from the ground up? Many student leaders of these spaces knew how to facilitate collective vents about the hardships of being a minority in a PWI. We never realized, however, that complaints do not build community: solidarity does.

Can we find community and solidarity within Yale’s cultural houses? Following the email, I went to the AACC with the hope of something better than what I had in high school. I met up with my PL and picked up some free boba and chopsticks

souvenirs. I chatted among the Morse Asians and heard about the many retreats and free Chinese takeout being offered to us. Every room was packed with first-years shuffling in and out, trying to pull up another chair to join the circle. It felt, to put it simply, like an organized playdate for the Morse Asians. The matter of identity felt implicit: however divergent our life experiences or beliefs are, the undercurrent of a shared background ties us together. I haven’t seen most of those people for a while—I hope they didn’t shuffle off to the Chipotle block parties.

Many of the cultural houses didn’t come to find a home at this school without a fight. The AACC worked out from a oneroom office in Durfee serving 250 students for years. They made congressional records through petitioning against the McCarran Act in the 1970s—the ability for governments to place people in concentration camps for national security purposes. The Afro-American Cultural Center was founded as a response to mass civil unrest at Yale in the 1960s. They were a pivotal part of New Haven’s May Day Rally in 1970 and hosted members of the Black Panther Party during the murder trial of Bobby Seale. The list goes on. The presence of cultural centers, in this sense, is history in and of itself. We have a responsibility not to render these past efforts an afterthought. To realize our own role in this history. Or, at the very least, attempt to make a new friend over free boba. ❧

against our wallets.

Anna Kaloustian, TC ’26

Design by Tor Wettlaufer

In the middle of July, I received an unexpected text on my family’s WhatsApp. It’s Dad. What does brat mean? He texts again. Wow. Explanation gave me a headache. Thanks ChatGPT. The “explanation” read, “The brat trend is a vibrant cultural and fashion movement that emerged in 2024.” The words, “nonchalance,” “rebellion,” “messy,” and “luxury,” follow it. He calls me. I still don’t get it.

There was nothing to get. Maybe an energy of sorts, but brat’s ritual invocation eventually got to my head. Don’t get me wrong, I overused brat. Brat is that mean girl from middle school. We talk about her all the time, but we hate her. We act like we know every detail about her life, but she remains a mystery. This phenomenon isn’t limited to brat. Social media typification behaves like this. Think: “Barbenheimer,” “Demure,” and “Mindful.” These terms turned trends seem specific, but deep down, are vague: loaded with meaning yet meaningless. What is it about those words, so overused and oversaturated, that manage to trap us?

much of the appeal of these sorts of trends is the catchy term: the prospect of a label that applies to everyone, from your friend to the Vice President. From there, new forms of consumerism arise, mobilizing the word that we all recognize

Our digital communities are echo chambers, reverberating the dazzling word off into complete irrelevance. Like a flash flood, it inundates, is overwhelming, but recedes as quickly as it arrived. Because all of these words represent identities that people strive to embody. Brat is the party girl with the strappy black top with a cigarette. Yet in defining ourselves by these terms, we pull away from forming our desired, individuated identity. As we repeat the language of others, we move further away from the unique ness we seek to create and sub merge ourselves into a nebulous cultural dialogue. It becomes an ouroboros of self-subversion: as we constantly try to stand apart, we end up circling back to the mainstream.

This is where I believe my frustration came from. The overuse of brat provides a first hand view of a new type of con formity. Traditional social con formity is often driven by a fear of social failure—the pressure to align with societal expectations to avoid rejection or judgment. Usually, these pressures come from external forces, from our families or friends or social communities. With brat, confor mity feels different. It feels more self-imposed. It’s not about fit ting into some abstract socie tal mold, but about making the willing choice to capitulate our senses of self to a trend. It allows us to put our own identity on the back burner and experiment with a new, fleeting one. One that affords us a sense of accep tance within a group. Purchas ing all neon green paraphernalia is excused by the capitalist con sumerism so deeply entrenched within these trends. While this might be fun and empowering in the moment, it explains why

the phenomenon quickly loses its appeal as soon as it becomes too widespread. When everyone is playing the same role, the allure of uniqueness fades and the trend becomes irrelevant. Looking back, perhaps we can argue that brat gestures towards a more complex way of being in the world. The hyper-confidence displayed is a mask for hyper-vulnerability, a way to control how the world perceives us. However, it is only in hindsight, when the confident facade is cracked, that we can examine the layers of insecurity that fueled it. The nu

thu. 9/19 fri. 9/20

Zong! Reading. Listen to renowned Canadian poet and lawyer m. nourbeSe phlip read her seminal book-length poem, Zong! 12p.m. Cross Campus College Street Tent.

Tony Inzero Farmers Market. Buy homegrown fruits and vegetables and novelties from over 20 local Connecticut farmers and craftsmen. 10 a.m. until 2 p.m. Oak Street Beach parking lot, off Captain Thomas Boulevard.

In Praise of Black Performance. Attend the Windham Campbell Prize Festival panel, featuring Hanif Abdurraqib and Christina Sharpe and moderated by Yale William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of African American Studies, Daphne Brooks. 4 p.m. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, 121 Wall Street, Mezzanine.

Screening of VERA (2022). Watch the Venice Film Festival award-winning film, and attend a discussion panel with Directors Tizza Covi and Rainer Frimmel and Fatima Naqvi. 5 p.m. until 8 p.m. Humanities Quadrangle, L01.

The Tasting Series at The Well. A journey through Italy via a curated wine-tasting at none other than the Well. 5:30 p.m. until 7:30 p.m.

Mk.gee live at Toad’s Place. Attend the 26-year-old singer, songwriter, and producer’s New Haven installment of his 2024 world tour. Doors at 7 p.m.; show at 8 p.m.

Open Mic Surgery. Calling all poets (loosely defined) to an open mic reading. 6:30 p.m. at Never Ending Books. 810 State Street.

Artist Book Hour: New Acquisitions at Arts Library Special Collections. Take a look at some of the new artist books, of the thousands in Yale’s collections. 1:30 p.m. until 2:30 p.m.. Haas Arts Library.

Sewing Circle. No experience needed, and all supplies provided! 3 p.m. until 5 p.m. Yale LGBTQ Center. 135 Prospect St.

Hidden Treasures in Sterling Library. Join a library peer mentor for a tour inside the 16-story Sterling Library stack tower. 4 p.m. until 4:45 p.m. Sterling Memorial Library lobby.

Windham Campbell Prize Recipient Readings. Listen to the eight prize-winning authors, poets, scholars, and public intellectuals read excerpts from their seminal works. Yale University Art Gallery. 1111 Chapel Street. (Enter at 201 York Street, Robert L. McNeil Jr. Lecture Hall).

NFT Day. Send regards to your local crypto bro.