the madison review

Volume 49 No. 1 Fall 2022

We would like to thank Ron Kuka for his continued time, patience, and support.

Funding for this issue was provided by the Jay C. and Ruth Halls Creative Writing Fund through the UW Foundation.

The Madison Review is published semiannually. Spring print issues available for cost of shipping and handling. Email madisonrevw@gmail.com

www.themadisonrevw.com

The Madison Review accepts unsolicited fiction and poetry. Please visit our website to submit and for submission guidelines.

The Madison Review is indexed in The American Humanities Index.

Copyright © 2022 by The Madison Review

the madison review University of Wisconsin Department of English 6193 Helen C. White Hall 600 N. Park Street Madison, WI 53706

the

ii

madison review

POETRY

Editors

Aidan Aragon Milly Timm

Associate Editors Madeline Mitchell Staff Esmeralda Rios Esti Goldstein Ev Poehlman Matthew Rivard LAYOUT

Kora Quinn Madeline Mitchell Shailaja Singh

FICTION

Editors

Kora Quinn Matthew Bettencourt

Associate Editors Anna Watters Eleanor Bangs Nadia Tijan Staff Ava McNarney Jackson Baldus Lyn Golat Natalie Koepp Sam Downey Sarah Egan Shailaja Singh Sophia Halverson

the madison

iii

review

Editors’ Note

Dear Reader,

The Madison Review is proud to present our Fall 2022 issue, filled with stunning works of fiction, poetry, and visual art. These carefully selected pieces represent the craft, wit, and emotional candor we strive toward as a journal, and have impressed us forward and back. We are grateful to our contributors who have gifted us with such clever and evocative work. It is an honor to provide a home for your voices.

The quality of this issue also indicates the quality of our staff, a stellar group of thoughtful and compassionate individuals. We thank you deeply for your dedication to the journal. We would also like to thank our program advisor, Ron Kuka, for his unyielding support and kindness, along with the UW-Madison English department and the Program in Creative Writing.

And of course, we are grateful to you, reader, for your support of The Madison Review. We hope that when you read this issue, you find something that strikes you, makes you dance, or fills you with heart. Ideally, all three. Read on!

Warmly, The Editors

the madison

iv

review

Table of Contents

Fiction

Ben Porter | Scout Spirit 2

Caleb Kostechka | Canonized 20

Susan Hettinger | It’s a Wrap 32

Julie Ianonne | The Punk Out 48

Jessica Hollander | Anything You Watch For 56

Poetry

Jacob DeVoogd | Thumbsucker 16

Phil Keller | Aubade Before Surgery 18

Beth Suter | Maverick 30

Anthony Borruso | Like Bartleby’s 46

Ace Boggess | Before the Seasonal Change 54

Javier Sandoval | In the Name of Perfection 70

Art

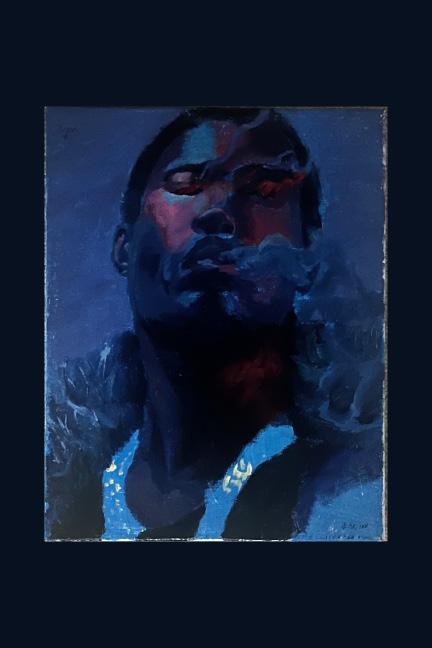

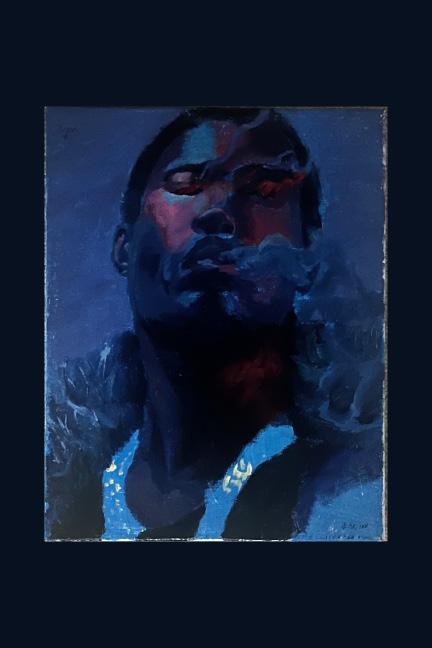

Elise Adams | Isolation 1 cover Isolation 2 77

Contributor Biographies 74

the madison review 1

Scout Spirit

Ben Porter

Content Warning: Neglect; child abuse

But for the Mormons, our town’d be up shit creek. A lot of us think so. Look at Wesleyton. You can tell the difference. The empty shops up there. The methhead’s dulies ripping up and down the trailer rows that by now sort of took over Main. Ain’t got no more open shops up there, shopkeepers leaving after the hatchery closed and the work quit. No work except to watch the gas station so to call the cops when it gets robbed.

Not us though. We got work, got the Walmart, got construction, too, and the lumber mill, and the Darigold farm. Got a good little downtown with shops working steady. All on account of the Mormons. They’ll show you the difference between a Mormon town and a Christian one.

But it’s funny because sometimes, no matter how Mormon a town is, the bullshit Christian side of it’ll still be there, ready to take over. Like in the Scouts for instance. Not the Boy Scouts you understand. Scouts now. That’s what I mean. They used to be boys only and now they are just Scouts on account of girls having to be involved. Not that there are any girls in our Troop, or in any Troop within 100 miles. But, if we want any Scout money or to use any Scout campground for our Jamborees, then we gotta adopt the moniker of Scout, which we don’t like much.

They say they been here since our town got founded. But Daddy says that’s bullshit, that he could remember when the Mormons came, that he didn’t know Mormon-one in highschool, that they showed when Davis bought the Finlayson spread and built those machine shops on it. Then they started coming, he says, and buying up land and getting elected, and that’s when the statue got built, he says, that’s when the museum showed up—used to be a fucking Woolsworth, he says. Not that he says much anyways.

In fact, he says almost nothing on his own. But I can get him talking when the VA in Constance has Wellbutrin™. It’s the real thing, that Wellbutrin™. Shit works. He took it the first time and a week later, at night, when we was watching the news, he got up! No bullshit. Got up and took a shower and came back and asked me if I wanted something

the madison review 2

from the Circle K! Just like that. Maybe first time he did in five years since Mamma left us. Which is why I couldn’t move, pinned to my recliner. I was shocked. And chatty! He wouldn’t shut up. Talking there with a towel wrapped around his waist and half a face of shaving cream and me silent as can be. Couldn’t move until the front door closed and the truck fired up and the headlights bounced off into the woods. Then I couldn’t help it. I hung my head and cried there by myself. I just couldn’t believe that joy had returned to my Daddy’s life. But it hadn’t. Not really. The VA ain’t always got the Wellbutrin™. They seem mostly to have the Bupropion which is spotty. Man handed it to me over the counter and told me to wait. Came back with a piece of paper had a big black box on it with a block of lettering filling up the whole page. Made me feel uneasy. So I waited to read it til on the bus back from Constance. It said a bunch a stuff like,

patient must be monitored appropriately and observed for clinical worsening, suicide, or unusual changes in behavior. Families and caregivers should be advised of the need for close observation with the prescriber.

Which didn’t make me feel too good. Right there on that cold bus I felt all the shit twisting in my guts. I wanted nothing but not to be there reading that bull. So I stared out the window and tried to wipe my mind clean and feel as little as possible, watched the rain roll down the window and, as the bus moved, all the strip malls running like a piece of many-colored tape, smoke shops and cell phone stores on the outskirts of Constance. But I couldn’t help it. Shit kept twisting up and twisting up, making me think. How the fuck was I supposed to be in close communication with a goddamned prescriber? The VA don’t grant no thirteen year old access to no information without accompanying the insured. But he can’t take a shower most days, let alone drive his own ass to the VA to pick up antidepressants which, apparently, would make him want to kill himself even if his son could sneak enough into his food. What’s the point?

So I stared out the window and I punched my palm and I tried not to think as much as I could. That’s why, when I saw the sign for Weslyton, I pulled the cord and got off and used our EBT to buy three King Sized Snickers, and ate them as I waited on a late 5:25 to cart my ass back home.

It was dark when the bus dropped me off downtown. And my stomach felt bad on account of the Snickers, and on account of the paper that come with the Bupropion. I walked for a spell, pushing my

the

3

madison review

bike under the glinty stars which cast over me as a great cage, and seemed to move in time as the earth twisted beneath it, the mountains, humping about me in the dark, round and black and slick looking, as whales beneath a boat.

Here I was crying again though I hated to. Don’t do no good. But no one was around on account of them being home with their families, so I did it, and before I knew, I was howling in the park by town square. My thoughts ran and I found myself wondering what depression was good for if it don’t kill you. Kid in school’s Mamma had leukemia that got her in six months. But that kinda sickness got a mercy to it built in on account of it having an end, a cycle. But depression is a parasite, like a baby, needs him alive for it to go on and I do hate it, my God. Something teased the edge of my sight. I looked up and saw it was the statue the Mormons built. I wiped my eyes and stared at it against the stars. It’s a family carved out one giant old growth stump. The Daddy, big and brawn, points out over our town, his eyes on the mountains and the big dipper over them. The Mamma clutches at her husband’s chest, and stares up at him. Made me think about something I heard, that Mormons marry forever, even into heaven, and Mammas have their babies in spirit after death, filling the planets their husbands earn with their very own righteousness. The babies are there, in the statue, huddled around Mamma and Daddy’s feet, their little faces everywhere, poking out from behind Mamma’s skirt, grouped as flowers around her feet, held in the crook of the Daddy’s arm. I sat back to lean against the statue, among the children, and looked up and thought about how the world is like a Mamma giving birth to death, and I surprised myself by the thought, and thought some more on it, and cried some more, and fell asleep there, at the hem of her skirt.

Next morning I sat up and the sun was high. I heard cars on the street. I glassed around and felt like a fish in a bowl. Wondered if anyone I knew had walked past and stood and pointed and laughed at me sleeping on the ground. I looked at my watch. 10:30! Not that I wanted to go to school, but weren’t no use to go now. So I put foot to pedal and got the fuck outta there.

On the way to the bus stop I saw the Circle K and pulled over and used the EBT to buy a Hot Dog and another Snickers. I got Daddy a frozen Big AZ Burger™. By the time I ate and the bus came and dropped me off and I biked down the road and up our long ass gravel driveway to the trailer, it was noon already.

4

the madison review

“Daddy!” I yelled, letting my bike drop in the middle of the gravel. “Daddy?” Could have been inside, could have been outside. His last couple Wellbutrin™ was gone but no telling how long the one he ate Tuesday would last. When he is on it, he is outside mostly, working on his vehicles. We have many vehicles, 47 of them, strewn everywhere in the field behind our trailer, like they fall from the sky. Some interesting ones. Got a red 57 Chevy. Got a Thing. Got a Gremlin. Got a VW Bus. Got a school bus. And you can tell the ones he worked on while on Wellbutrin™ because they got their hoods open. Some of them got chrome on the engine. Some of them have new seats. But he don’t finish them on account of me. Can’t keep Wellbutrin™ in the house long enough. So the cars are ripped open and left that way, some of them disemboweled, gear boxes and cylinder heads and screws all tumbled on the ground like vomit from their steely mouths.

“Daddy?”

He didn’t answer. I opened the screen door to the Single Wide and walked through the living room to his bedroom. He was lying there wrapped in blankets and looking at the door, looking straight at me.

“What you doin, here?” he asked.

His eyes were circled red and his face was pink and puffy. “I got you a hamburger,” I said.

Daddy blinked. He was in it. Not in the middle of it but on his way down. You could tell. Wellbutrin™ was petering out.

“Come on out and I’ll give you your food.”

He breathed heavy through his nose. He was waiting for it to drop, getting himself ready.

He blinked again and I turned to go.

“It’s school ain’t it?” he said as I closed the door.

I didn’t want to talk about that. Don’t like ignoring him. But what was I going to say? Figure he wouldn’t have the energy to ask again.

Went to the kitchen counter. Fucking mess. Paper plates and food and garbage I’d been ignoring. I swept them off and onto the floor and figured they’ll be easier to clean that way—just sweep them up after.

I took the Big AZ Burger™ out of my backpack. It was softening up and I tore the bun a little, getting it off the frozen patty. I took out the Bupropion from my backpack, then I grabbed the cast iron from the stove top, took a metal spoon and dumped two pills in the pan and started crushing. Pieces of shit came apart mealy, like sugar cubes. You can tell the difference. Wellbutrin™ comes apart nice, fine and white and powdery.

I sprinkled the mealy bits of pill on the cheese on the burger. And I

the

5

madison review

went to the fridge and got another slice and laid it over the top of that one. Paper plate. Microwave. Hoped that’d put some wind in his sails.

I heard him stir and went quick to wiping out the cast iron so there weren’t no trace.

“It’s school, Richie,” he said, standing in the bedroom doorway, leaning on it. Sun was bright and ran over his face, weird blocks of shadows on the wall.

I did not want to tell him about the park. I don’t tell him nothing never on account of his depression being catching. He wants me to. You can tell. Especially when he is on the upswing. His eyes get big and deep and he starts trying to talk, talk about how I’m feeling. Tries even to talk about Mamma which is never going to happen while I’m alive.

Fact is, you can feel it. Minute you open up—even about something small, just some little happiness—the darkness in him reaches up out of his mouth and goes down yours and grabs your heart and squeezes. So you are left cold, limp, and sad.

“Isn’t it school, Richie?”

I picked up the remote and turned on the TV and watched as he turned his head towards it. The microwave went off and he sat in his chair and dropped the blinds.

The Big AZ Burger™ was steaming and I lifted the bun to check on the cheese. All melted. I doused it with ketchup to cover the taste of the pill and walked it over to him. He was already into the Igloo full of Bud Light, which he ain’t supposed to be according to the paper that come with the meds. But I never stop him because one, I couldn’t, and two, who the fuck cares. It don’t seem to kill him and it takes the edge off and he gets quiet while plastered anyways.

I gave him the Big AZ Burger™ and he said, “sit down with me.”

“I got to do some—”

“Shit! Sit down.”

He looked up with a mouth full of burger and handed me a beer and I couldn’t find it in me to say no. So I sat.

Mauri was on with the sound off. He was talking with two ladies but one didn’t look like a lady much, and the one that didn’t was crying with her head in her hands.

“What you been up to?” he said.

The one that looked like a lady was up and around, pointing at the other one with her long ass fingernails. I took a sip of beer. It was warm.

“Just school, Daddy.”

6

the madison review

Daddy took another bite and nodded. “You come home last night?”

“Sure I did,” I said, taking a long sip.

“You sure about that?”

“Yep,” I said. “Woke up early is all.”

“And came home late?”

He was getting going. Thought maybe the Wellbutrin™ was still cooking.

“That’s right.”

He took another bite. The ladies were at it now and a security guard was splitting them up. Mauri was standing by watching with his hands in his pockets. I felt it. My stomach was tying up and I didn’t want to talk about the park but Daddy wasn’t leaving me alone.

“You getting into anything I should know about?”

“You’ll be the first to know.”

“I’m fucking serious.”

“Me too.”

“If I find out you’re on something or what-not.”

I felt my hot dog and snickers working at the base of my throat, felt warm and didn’t like it. So I tried something.

“How about you?” I said.

“How about me what?”

“You getting into anything?”

His face slackened and he smiled. I smiled too but still felt twisty. “Like what?”

“I’m serious,” I said.

“OK, like what then?”

He was off the scent, back looking at the TV. But I didn’t like how he was pushing me. So I gave him one.

“Like looking for work,” I said.

His face got hard and he shifted his weight and I felt cold and unfair like I went too far.

The ladies were wrestling and Mauri stepped in front of the camera and the show went to commercial.

“Once my back settles I’ll give Larry a call,” he said, turning to me. But we both knew it was bullshit. Then he said, “but until then, you all right?”

When I joined up I told people it was for to learn the woodcraft, the hiking and the camping and the fire making and the fishing and the so forth. But really I joined after I heard Phil Wilkerson talk about it in the bathroom after gym. But that’s not the real reason.

the

7

madison review

Truth is, it got so I couldn’t come home. Ashamed to say it. Spent another few nights at the statue. Started roaming town after dark, cops circling the block as I pedaled down Main. I finally put it together, realized that since I’d been bringing the pills home he’d been outside more, been trying to talk to me. Each time he did I felt weaker, like he was taking me from me. Got so I couldn’t look him in the eye.

That’s why when I heard Phil talking I knew it was a good excuse. Plus, Phil lives in a big house in the River Whispers, the new development outside of town. He wears And1 Basketball shorts you can only buy at the Everett mall. He has frosted tips in his golden hair. He knows lots of girls. He is Mormon. So I figured I’d be a Scout too.

After hemming and hawing with myself, and pussying out, and saying that I could and should never do it, I drug my ass down to the VFW 1401 and presented myself for service. Mrs Dickerson who, being our Scout mother and wife to Scout Master Dickerson and real mother to Travis Dickerson, Scout Second Class, welcomed me and pulled me to her bosom. She called me honey and dished me up lasagna from a shiny tin tray. That’s when I knew I had made the right decision.

After I joined, they taught me things aside from the woodcraft which I enjoyed thoroughly. Two weeks after signing up, standing before the troop in a borrowed uniform and sweatpants, I repeated from memory the Scout Oath, and the Scout Law, and the Scout Motto, and delivered the Scout Slogan, and explained Scout Spirit and told Dickerson how I’ve shown Scout Spirit. I gave the Scout salute, and the Scout Sign, and the Scout Handshake, and I described the significance of the First Class Badge, and I explained the patrol method, and the types of patrols used in our troop, and I detailed the four steps of Scout advancement, and how the seven ranks of Scouting are earned, and that was it.

And if Scouts weren’t just what I needed. Gave my life some shape. Was not doing hot until I started coming to Troop meetings—started wondering if I caught some of daddy’s depression permanent, started splitting the Wellbutrin™, one for him, and one for me when he wasn’t looking—but then, when I was initiated, when I started working for merit badges—shit and goddamn.

It was Dickerson who pulled me aside a week after. We was outside, after troop meeting. I was pushing my bike across the parking lot. The sun was low and copper on the hills and gray clouds sat solid as pavement in the eastern sky. Dickerson was standing by his van, his family all loaded up, waiting on me.

the

8

madison review

“Yes, sir?”

“Richard, how you doing?”

“Doing real good.”

“Well all right. Headed home?”

“Yes sir,” I said, wondering why he asked.

“Well all right. Your Mamma’s not angry is she? That you’re missing dinner? You let her know that Mrs. Dickerson feeds you boys real good, ok? Pass that on.”

I felt funny and looked past Dickerson at the black windows of his van. I saw Travis playing his video games through it. “Yes, sir. I will,” I said without looking at him.

“Well all right,” he said, and a car drove by and the sound of it left too much silence between us. “Well, hey,” he said. “You never gave me your top ten.”

My mind raced through what I could remember of the Manual. The fuck was top ten, again? Too much to fucking remember. Fucking horse shit Boy Scout nonsense with their goddamn—was it the Ten Essentials?—no that ain’t it, dumb ass. What the fuck? Now you ain’t going to be a Scout. You is a stupid child who ain’t fucking nothing. You is—

“Sorry, did I tell you?” Dickerson said.

I blinked and rubbed my eye like I got something in it, but it was really to check for the wetness I felt coming on.

“It’s something we do special,” he said, putting his hands on his hips. “Stacey’s idea. You see, at the beginning, we have all the guys start on ten Merit Badges. We pick 5. You pick 5.”

No wetness. The sun glowed cold and copper against the Van window and I couldn’t see Travis no more. I put my hand over my eyes. Tried to make the stomach feeling go away.

“This here is the list,” he said and held out a green folder with the Scout logo on it.“You look this over and next week we’ll talk, ok?”

I took it like Moses taking tablets from God. Then he stuck out his hand and I shook it. My backpack fell to my wrist and ruined the shake.

Next week, after dinner, Mr. Dickerson prayed. Mormons don’t pray like folks pray on TV. Mormons pray with their arms folded and stand and look at their shoes. Dickerson usually has one of the guys pray. I try and pay attention in case he asks me, even though I don’t think you’re allowed if you ain’t Mormon.

This time Dickerson prayed. So he stood up and everybody stood up and folded their arms and I did too.

the madison review 9

“Father in heaven please bless this time we have here and be with us as we try and be better Scouts, in Jesus name, Amen.”

And we all said, “Amen.”

I walked over and handed him the folder with my merit badge choices. I picked Indian Lore, and Electronics, and Fingerprinting, and Wilderness Survival, and Rifle Shooting. And when Dickerson took the folder and opened it up and clicked his blue pen, he picked Family Life, and American Heritage, and Business, and Communication, and Golf. He gave me back the folder.

“We golf in this Troop,” he said. “You’ll see. The other guys love it. Twice a month. We got clubs for you. Your Dad golf? Get your long game together first. That’s the key. Long as you stay on the green. You’re playing. Yes sir. Does he?”

“No sir,” I said.

“Well let’s get him out there with us. We’ll show you guys a thing or two!”

I nodded.

“This Saturday morning. I can pick you fellas up. Tee time’s at 8:00.”

My guts tightened. “Where y’all live?”

I grabbed for a lie but had nothing so the truth came out.

“Up on Burn Road,” I said, picturing the Single Wide and the shed with all the garbage and Daddy’s VW bus on blocks.

Dickerson laughed to himself and shook his head. “That’s too far out of my way. Any chance I can meet you at the IGA in town? I’m picking up Jason and Derek, too.”

Buses wouldn’t be running so I’d have to ride my bike the whole way. But it didn’t matter. I’d drive twice the distance to keep him from coming to our place. “Great.”

“Alright. IGA. Downtown. 7:30.”

“Alright, thank you,” I said, looking at my shoes, feeling wetness coming, but a good kind. Almost happy.

That night, after roll call and the song, we had a fire building competition in the parking lot. It was awesome because it was after dark and our six fires were blazing hot and dancing sparks to the stars, all in a line. Dickerson stretched a twine between two car bumpers and the first one whose fire got tall enough to burn it won a pocket knife. And I won the pocket knife. I’m pretty good at starting fires.

And that was the start of a damn good week. Splitting the pills with

the

10

madison review

Daddy helped. And I started praying as the Mormons do, and that helped too. Every night before I went to bed I folded my arms and kneeled to the ground, always praying in the name of Jesus. I prayed for Wellbutrin™, prayed for good Troop meetings, prayed for Daddy’s back, that he’d retrieve his job at the transmission shop.

That Wednesday, I got a call from the VA and they said they got a whole shipment of Wellbutrin™. They told me to come and pick up the prescription. I got on my bike, prayed all the way down Burn Road, sun in my face, wind in my hair, thanking Mormon-Jesus for everything. And as I did, I thought about the statue downtown and about the planets each righteous man will receive. I started wondering whose spirit child I was, and about my spirit mother, and what she must have done with her husband to inherit a planet so full of green trees and blue water and animals. How good must she be? How kind and wise and gentle?

When in Constance I dropped by Value Village and was on the hunt for clubs and I found some! A whole mess. Fifteen, sixteen clubs in an old leather bag I could practice with. Balls too!

$12.00! No problem. I hoisted them upon my shoulder and toted them back to the bus stop.

When I got back Daddy was outside. He was working on the Gremlin. Sun showed light and golden on our field with the 47 cars and trucks, wild flowers sprouting up next to tires. Saw his boots poking out beneath the Gremlin’s hatchback. I let my bike fall and on a whim, set up my tee by the Gremlin. We was out there all day. Him fixing the rig and me teeing off into the woods. Didn’t say much but in a good way.

Friday night I made Hungry Man dinners, Salisbury steak. I ground up Daddy’s pill and mixed it into the gravy. I was looking forward to golf the next morning. Had my swing going a little bit, could get near the tree I was aiming for. Practiced in the morning but a rain storm rolled in and pushed us inside. Watched TV all day, prelims for the Cup Series. I liked Tony Stewart and Daddy liked Matt Kenseth. It was starting up just as I handed Daddy his Hungry Man. I was feeling good and hungry and wasn’t being careful.

That’s why he caught me popping the pill.

“The fuck you doing?”

“What?”

“What you just put in your mouth?”

“Candy.”

“Bullshit. Don’t lie to me. I’ll ask you again.”

the

11

madison review

He levered down the recliner and bent forward.

“Let me see your hands?” he said.

I showed him my hands quick and he looked at them, eyes darting across my lap.

“Don’t know what you’re talking about,” I said, feeling the pills work their way down my throat. I turned back to the TV, hoping he’d give up. I spooned a load of potatoes and watched the cars. But I felt his eyes on me.

“Get up,” he said. And I pushed the TV tray aside and got up, still watching, hoping I could stay cool and pretend like everything was normal and he’d just drop it and not ask me no more questions. I watched out of the corner of my eye as Daddy pulled the chair apart. And when he finished, he put the cushions back and sat and I felt his glare.

Tony Stewart passed on lap 14. The screen went dark.

Daddy set the remote down on the arm of the chair. “I saw you pop something in your mouth and you’re going to tell me what it is.”

“Candy, I told you.”

He breathed through his nose and his chest raised and lowered. And then, “you on drugs?”

I laughed and shook my head. “No.”

“Don’t laugh at me,” he said quick, leaning forward. “I’m not fucking stupid.”

“I don’t think you’re stupid,” I said, my guts tying up, my face getting hot.

“I’m going to ask you again, you popping pills?”

I felt too funny to sit, like scared and excited at the same time, so I stood.

“You standing up on me?” he said, and he stood up, halting half way, his face changing, confused.

I moved behind my chair. “No,” I said and froze.

The bottle of Wellbutrin™ rattled in my sweatpants pocket. The bottom of my stomach dropped out. Daddy’s eyes got big and my hand clapped against my pocket and made it rattle again. And there we stood before the black screen of the TV.

Both our Hungry Man dinners hit the floor when he lunged toward my pocket. I tried to get around the chair but he caught hold of my waistband with his finger, slowed me up, made the fabric tear, left my ass to hang out as I circled the recliner, wriggling to break free until he got hold of me. We went down in the Hungry Man mess on the floor. My eye got caught on the recliner’s chair lever. I felt the softness of

12

the madison review

my eyeball push into my skull and I saw stars and felt Daddy on top, grabbing for the Wellbutrin™, breathing hard. I heard a wail and it was me, touched my head and felt the grease of the Hungry Man. But it wasn’t. I opened my good eye and looked. My fingers were painted with blood.

I screamed again. Daddy’s hand shot round in my pocket. I couldn’t see. Touched my face. Felt around the eyehole, felt the gravy and the steak—a stab of white light.

“Lie to me? Huh?”

There was open skin around my eye.

Daddy shook the pill bottle like beans in a cup.

“Not my son,” he said. “I knew you was acting weird, gone all hours. Lie to me?”

I turned over and lamp light hit my eye like needles and Daddy went quiet and the pills hit the floor.

Both my eyes were shut and pain fell down my face like water. I dragged my arm across my brow and my sleeve caught something, piece of wood from the chair lever, stuck in my face. Made me pant it hurt so bad. I went to touch it.

“Don’t do that!” he said. “Hold on.”

I pulled myself up and leaned against the recliner, heard Daddy looking for something in his room. I thought about golf and tried to open my eye. It lit up, pain, like there was glass in it. Color fell in pieces like confetti and was gone, lost in the darkness to my left.

Daddy was back.

“Ok Ok. How we doing here?” He had a bunch of toilet paper and a bottle of water. He was looking at me close, peering into the black side of my face. His foot hit the bottle of Wellbutrin™ and I looked at it and screamed.

“Nononono,” he said. “Not that.”

He was squirting the water on my face and dabbing some with the TP. I couldn’t look to the left or the right. Just straight at him.

His lip was hanging low and shook. “Shit Richie,” he said. “You did a number. Sit tight.” He got up and left the trailer.

I was breathing hard. My face throbbed with my heart beat. I heard the Gremlin fire up outside. Headlights filled the trailer windows. Thought about golf again, thought about Dickerson. Touched my face—wet and soft. Fucking Daddy. They’d be waiting at the IGA in the morning. How was I supposed to get Rifle Shooting with one eye? How was I supposed to learn about American Heritage?

I heard Daddy skipping up the steps. He was at my side, helping me up.

the madison review 13

All his fault. No merit badges. Show up like this?

“Watch your foot.”

We was outside. Sky was black and the stars were small. It had stopped raining and a little wind pushed from the South. I saw the Gremlin. He had the door open, was helping me in but I stopped him.

“What’s the matter?”

“You ruined it,” I said.

“What?” he said, holding my arm.

“You ruined it,” I said again. Then I yelled it. “Ruined all of it!” Lightning strode across the darkness and my face caught fire.

He was quiet. I was panting for the pain. He didn’t move.

“Fucking golf. Fucking troop. Fucking Rifle shooting.”

I heard him breathing. He pushed a little on my arm but I pushed back.

“Fucking no job, crying all the time. Horse shit coward!!” I turned my head. Lightning and sweat. Needles. He pushed me harder. I pushed back.

“Fucking bed sleeping, tired all the time!”

Had my hand against the door frame. Face pulsed and he pushed.

“We’re going to fix you up Richie,” he said finally. “Get in the car.”

“You forced her out! No wonder she didn’t stay. You forced her out!”

He pushed. We scuffled. The darkness blazed.

“She’s gone because of you!”

I ripped my arm from his grip and slapped him, hard as I could on the head. He tripped on something in the dark and I took off running. Got round the corner of the trailer and into the field and among the cars, scattered as gravestones in the night.

Good-eye barely saw and my dark one exploded. Each step the veins in it pulsed blue and floating. Something was in there and I wanted to rub it out—tried, screamed in the dark— splinters, like pins, worked every which way. My head was cocked and I whimpered, stumbling among the metal shells.

It was all going, the whole thing. They’d be there at the IGA waiting for me, and I’d be gone, AWOL.

“Richie!” I heard him yell. Back there by the Gremlin. I pushed on toward the woods at the far end of the field. Bam! Stars. Head hit the side-view of the school bus and my eye lit up until I felt the pain in my teeth, until I moaned and stuffed it in my guts. Kept moving.

“Richie!”

He was out there with me. Roaming, looking for me. He never looked for her. Never once. Just let her go with a kiss on my forehead.

the

14

madison review

That’s what she gave me. Left me with a man to take care of, ten years old.

Something out there went bang, far off to the left, in the darkness of my eye and I heard him yell. I looked ahead at the woods. They stood black against the night, big trees sawing into the stars. There were cars in there, too. Old ones he’d pushed back there to make room for fresh ones, forgotten and mossy.

“Gotta get you to the hospital!” he said, far off, looking in the wrong direction.

I got to the woods, found a Studebaker behind a stump. Reached to open the door and my hands trembled. She’d left me alone with him. I had nobody. Alone with him, to be his Mamma.

“Richie!” I heard him call, thin and distant.

I crawled in and curled up on the seat. Felt the old moldy leather against me. No boy can be his own Mamma. I cried and folded my arms and prayed.

“Boy come back—don’t leave!” he said like a whisper out there, heading down the driveway, opposite of me.

I tightened my arms and the broke down seat held me too, curled up in it. I looked up. My good eye saw the stars, scattered like eyes among the cedar boughs.

I said the words, “Sweet Mama in heaven—” and dim, out of the fiery darkness, I saw her, and she was radiant.

the

15

madison review

Thumbsucker

Jacob DeVoogd

Sweat through sheets bouquet into days weeks that ride TV screens. Credits rattle: o n e m o r e hour. I cannot separate heartbeats from the dark gnawing eyelids shut. Do you smell blood

your father draws? Hammer held over mom’s hand.

Do you hear myths your uncle conjures? Couch you offer not enough for craving.

Do you feel breath? evaporated. Your brother, shared blanket, plays with untrimmed hair.

The winter I first sucked my thumb, virtuous. Not a fixation. a cure. simple.close. It felt foolish leaving it unnoticed.

Over time, teeth misplaced, thumb pruned, I will never run out of skin. I dream night will soon exhaust itself.

the madison review 16

17

the madison review

Aubade Before Surgery

Phil Keller

An ambulance grows louder in the street then fades in the distance. I cannot sleep: the night is full of memories and ghosts. In hours, as the streets begin to fill, and thoughts turn to the projects of the day, strangers will wheel my hospital gurney, hung with IV drips, into an antiseptic, brightly lit, tiled room where surgeons in protective masks and gowns will cut open my chest and gather round the heart that’s pumped in darkness my whole life. Beneath the operating lights they’ll cool its pulsing chambers, divert its blood supply, and wait until the years of beating quietly subside. I’ll be nowhere then, in the dreamless sleep of anesthesia, not knowing anything, even a scalpel’s deadly slip or something else gone wrong, heart listening for the blood’s return that starts it beating once again.

It is an errant gene; my aorta now the size of a tin can, symptomless but close to rupturing. A dacron implant will fix that, they say. There really is no choice, but still I want this waning night to linger like a lover by my side.

My children’s tiny hands, my wife’s gardens coaxed from the rocky soil each spring. A line of stately poplars standing watch over an empty green. Life passes like a Doppler shift, loudly approaching, dwindling to silence. I think of all the beauty I have seen and how much more I’ve missed.

the madison review 18

19

the madison review

Canonized Caleb Kostechka

Our obsession with the Russian revolution began when I was eight years old. We saw the film Anastasia on Saturday afternoon television. It’s the one in which Ingrid Bergman plays the Romanov princess, who at the time of the film’s making—1956—was rumored to have survived the 1918 slaughter in Yekaterinburg, living now incognito somewhere in Virginia.

Bergman got an Oscar for it.

Clearly, the Academy never saw my sister Claire’s performance, crumpled in gingham on the front lawn, amidst the mass murder of her entire family before a firing squad. Hollywood’s cameras never captured my brothers, Sebastian and Nathan, standing exactly twenty paces back—both chewing methodically on gum, the smack of Juicy Fruit sounding off and smelling more like gunpowder on August mornings. They held baseball bats tight to their shoulders to avoid kickback as we bravely donned our blindfolds.

That summer, almost ritualistically, my siblings and I would take turns reenacting the slaughter of the Czar’s family, Claire and I swapping lead roles. Directors missed viewing the sun-soaked choreography of t-shirts stuffed with water balloons, the bubble gum pop sound of the firing squad, and the strategically timed popping on our prepubescent breasts.

Our father watched one of our performances as he walked out to go to work, bleary eyed after a late bridge game, briefcase in hand, and took the time to single out my gaze. He gave a quick nod of approval at my supporting role of slain mother. I was tempted to bow but refused to break character.

Our mother, on the other hand, never watched our pageants with any consideration. There was the occasional questioning glance at a particularly sharpened tree branch duct taped to a bat, but I don’t think she ever saw it as the Bolshevik musket it was. We were outside and that’s where her concern ended. While we repeated the slaughter of the royal family, she tucked herself away in our suburban bunker.

I was dubious that Anna Anderson, on whom the character of Anna in the film is based, was truly the Princess Anastasia, alive after all these years. Still, I imagined there were other princesses out

the

20

madison review

there, suffering under the weight of oppressive regimes, that would inevitably be exiled or executed—clearing the path for me. When I read about a Danish royal family member my age in a magazine, I studied the picture and seized the opportunity. I cut my hair shorter and attempted to dye it golden blond with a tincture of lemon juice and sunlight to fit the description of the princess, hoping that a war would erupt over a fjord and she would be forced into hiding. I walked around smelling like a citrus grove. I insisted everyone begin calling me Anastasia. Even my grandmother.

“Who in God’s damn name do you think you are?” she fired back when I made my request, the five of us in our Sunday clothes sucking on mints in her living room during our weekly visits. My grandmother rolled her eyes at me and looked at my father who had brought her holy communion, her being bedridden and excused from proper mass. Our mother had stayed at home in bed but for different reasons.

“If you prefer, you may address me as Ana, seeing as you are a ‘familiar’,” I replied, extending my hand, and holding onto all the composure my eight-year-old frame could muster.

“Like hell I will,” my grandmother replied, striking me in the shin with an oak cane she kept beside her bed.

My three co-conspirators stood there staring at shined shoes, lips laced as tight as our loafers, refusing to come to my rescue. I shot them all a look that I hoped captured the anguish Anastasia would have flashed at the turncoats who betrayed her.

The confederacy did not end with my name. I rehearsed living life on the lamb that summer by sneaking out of my back window under the watchful eye of my brother Nathan and nestling myself under a sugar bush in the backyard where I would stack a nest of mildewed blankets my parents kept for moving things with our pickup. Through cool evenings, I would fold the blankets over my too skinny frame while the rest of them, my siblings, took turns keeping watch over the hidden royal princess. Knowing ousted royalty would need to think on their feet and fend for themselves, we also spent an ample amount of time stealing what we assumed were the basic necessities for staying alive in a safe house and hiding them in an old ammo can our grandpa had tucked away in his garage.

Any princess on the run surely needed Malto milk biscuits and a switchblade comb. Using my newly flaxen hair, I was emboldened to distract the clerk, a balding lecherous man, at Schultz Department store, as Sebastian shoved merchandise down the front of his pants. At one point he crotched a three-foot metal tube.

the

21

madison review

“We need a cannon,” he said matter-of-factly.

It had a circumference the size of a tennis ball, and he tucked it behind his belt, charged with the mission of bringing back something that could defend the sugar bush against Bolshevik secret police—need it come to that. And, as all this went on, I dreamed of the day I would be given my manilla identity envelope and truly begin living life anew as an Anastasia or whatever Danish equivalent existed.

These Romanavian exploits lasted about as long as the hair dye, although I still insisted on being called Anastasia. We quickly changed our script when we had a school performance of Shakespeare and learnt that Richard III—he of the beetle-black pageboy bob—was actually nearer to blond. This made me the likely choice in the shift of games, to go from Anastasia to Richard, and stage a frontal assault on all the rose bushes in our neighborhood. Claire was demoted to Buckingham. We tried to arouse our mother’s interest in our saga by bringing her the spoils, about two dozen roses and fistfuls of camellias. She gave a half smile and sighed before putting them in a bubbled glass vase without water. They died within hours.

By October, the wind had a bite and we were stealing the scissors from the drawer in our kitchen and playing Jack the Ripper. We rotated into the roles of cutting our dolls’ hair off and then brutally dismembering their bodies throughout the flower garden—our closest likeness to what we imagined was an approximation of Scotland Yard. The actual place we believed to be littered with murder victims; ours was a graveyard of plastic limbs and lawn clippings. Our mother sat in the kitchen, enveloped by a menthol fog and a phone cord coiled around her wrist, ignoring us as we pilfered white stuffing and Karo syrup mixed with food coloring from the pantry and sewing closet. This historical hopscotch of the macabre continued more or less until the Erebus incident.

Having found our grandfather’s cache of patch tires, we lashed them together one afternoon into a lumpy mass and christened them the HMS Erebus —the ship in which the British polar explorer Sir John Franklin was last seen entering Baffin Bay in 1845 in his attempt to navigate the Northwest Passage—and proceeded to terrorize our local swimming hole by maneuvering through the swim area on our vessel with a garden hoe, chopping into water while I shouted “iceberg ahead!” all the while repeatedly squeezing an old bicycle horn. Our racket and aquatic scythe, we assumed, cleared a path through arctic waters until our shovel made contact with buxom Ms. Greely, recently divorced and a member of our parent’s bridge club,who was

the

22

madison review

innocently swimming laps from shore to island. We left her with 17 stitches and a mild concussion before we decided to conclude, or at least put on hiatus, our historical reenactments.

“We gave warning. Anastasia foghorned,” Nathan pleaded. The four of us were lined up against the backdrop of the garage. “You only care because it’s Ms. Greely.”

“You could have killed Ms. Greely,” our father snapped back, “and I do care because she’s a friend of mine—and your sister’s name is Rebecca.” We all stared at the ground. My father’s glare rested on me.

“Ms. Greely’s death would not have been a tragedy worth a reenactment,” my mother muttered behind him. She spun on her heels. “Except for your father.”

“And what’s that supposed to mean?” our father said as she walked back into the house not looking back. We stood staring at her exit, the air colder. Our father left us standing there as he tailed after her. We heard the yelling inside and let out the air in our lungs, relieved we had avoided the worst of it.

We were wrong. Nathan was pulled aside the next morning by our father, him being the oldest and, decidedly by us, the most responsible for the maiming—although it had been Sebastian’s idea. My father and Nathan talked through most of breakfast behind the closed door of his room, much longer than a scolding would normally take. When Nathan emerged he looked ashen and neither my father or Nathan made eye contact with anyone in the room. Nathan beelined for the back door, slamming the screen. Our mother looked up toward our father with daggers.

As for the rest of us, our unruly marine performances sidelined our troupe to our grandmother’s house for the remainder of the summer where we sat, sticky with sweat, on her back porch for weeks, returning home only for dinner. There we’d find our mother in the kitchen booth with a full ashtray that spoke about how far she had moved that day. Dinner times stretched themselves out as our father began pulling into our driveway later and later. The sun’s rays, once a deep yellow on his car hood, shifted to the deep purples of old bruises, matching the bags under his eyes, and by the end of July we were eating without him.

That was the start of Nathan’s praying. He would perform silent incantations every morning, before meals, before bed—which were not atypical in our family if solicited by an adult—but he began saying little prayers at odd times. During TV time. After we had already said our bedtime prayers. We would be lying in the wave of the sprinkler, cooling down, and we would hear Nathan’s faint mumblings in time

the

23

madison review

with the tss, tss, tss of the spray.

Our mother also began deconstructing her recipes—eliminating an ingredient here, a side dish there—until the meal became “chicken” or “meatloaf”. The chicken being, quite literally a boiled chicken, and the loaf being the package of ground beef flipped over on an oven tray and baked at 350 degrees until the gray squiggled meat gelled into a brown rectangle. Nathan began taking his food and eating in his room. Seeing that this got no retribution, we tempted fate and began carrying our dinners to the TV room. Our mother would sometimes join us on the rare occasion but mostly she continued smoking, simmering in the kitchen booth.

It was Claire who first discovered the Picture Book of Saints from our grandmother’s bathroom. She had found it buried beneath the leaning tower of Reader’s Digests . The pages were yellowed and curled from moisture. This only added to its air of solemnity and authenticity.

“Why are all their heads glowing?” Claire asked, pointing to a page with St. Christopher. His bulky frame towered over a raging river clutching an embryonic sized Jesus on his shoulder.

“It’s not fire,” said Nathan leaning over her shoulder. “Those are halos. That’s proof that they were the chosen.”

“Chosen for what?”

“Chosen to die for Christ Jesus and then they get to live the rest of the eternity doing the interceding,” Sebastian explained in his fifthgrade wisdom. “Don’t you pay attention?”

“What’s the interceding?”

Sebastian gave an exasperated sigh.

“It’s when they come down from heaven and work the miracles on His behalf for the downtrodden.’

I thought of my mother at the counter.

“Who can work miracles for us?” Claire asked.

We checked the glossary and quickly found the patron saint of children. Saint Agnes.

We flipped through to Saint Agnes. She glowed amidst an impressionist backdrop of blues, a lamb clutched in her arms.

“Saint Agnes. Patron saint of young girls, chastity, gardeners, engaged couples, the Girl Scouts of America, and rape survivors,” Claire read. “What’s rape?”

“The rapeture, dummy,” Sebastian said, “when all the souls come climbing out of their graves.”

Claire continued.

“Says she was dragged naked through the streets, taken to a house

the

24

madison review

of ill will and then they tried to burn her. But the fire wouldn’t light. So a guard chopped her head right off.”

We all looked around at each other for a quick moment before Claire ran to get her swimsuit and jump rope. Sebastian shuffled to the woods to get firewood. Nathan kept reading his book.

We made it through most of the saints that summer, at least the ones who died exceptional deaths, but our interest had waned by late August. Nathan had become more sullen and played less and less. There was once or twice, reluctantly, that we convinced him to crack the whip of a Roman guard but for the most part he read, prayed or stared off into space. No one wanted to don a makeshift lion costume in the kiddie pool coliseum or claim the name of Shadrach and withstand the garden-shed-turned-furnace with only God’s protection. Nathan would sometimes wander the roads back to our house where we imagined he hid out in our backyard avoiding both our squabbles over biblical roles and our parent’s fighting.

We had taken once again to fanning ourselves on the day porch, trading volumes of the encyclopedia set our grandmother kept in her living room. We would have probably ridden out the summer this way until Nathan came across the Shroud of Turin in a Life magazine. We all stared at the shroud in the pages when he showed us.

We could see its ghostly outline, and read that it was kept in the Royal Chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin , as it stared back at us from the glossy pages—like a negative in the back of photographs our parents picked up from Walgreens and saved in boxes in the basement. Only here, looking back at us, were the eyes of a man with holes in his wrists and his side. The blank holes seemed to possess sepia depth you could fall into, even at the age of eight. We dreamt of making a pilgrimage to northern Italy to encounter a miracle that could cure all our ills, the plantar warts on Claire’s feet and the stutter that sometimes overtook Sebastian when he read from the missal in church.

It was right around that time of discovery that someone deposited a whole deer carcass in our backyard.

The deer had obviously been hit by something. There were scrapes all along its torso. Its back legs rested above its hips like some tangled yogi from the East. I think it was Nathan, with his late middle school wisdom, that concluded that it had been hit probably somewhere in our neighborhood by a drunk high schooler on his way back from The Pit, a gravel pit on the outskirts of town where, Nathan told us, by the time one reached the age of reason, everyone knew was the place to

the

25

madison review

go for Wild Turkey stolen from parents’ desk drawers and possibly the loss of virginity.

“What’s virginity?” Claire asked.

“Like Mary,” was Nathan’s reply, which seemed to satisfy all of us.

Deer were not a rarity in our neighborhood as they ambled from vegetable garden to flower bed, much to the chagrin of the gardening society, but they were also not routine. We assumed the perpetrator was so afraid of being found out, drunk and dented, that he dragged the body to our fence line and heaved it over. We could see the place on the lawn where the carcass had been dragged from the road. A deep fault line created a miniature labyrinth where the antlers had dug in.

Our first instinct was to go straight to our mother, but something came over Nathan. He’d always been on the side of slightly cruel or careless in our games. He was the one who would not thoroughly check the dirt clods for rocks before hurling them across the battlements of our front hedges. Not a bad seed, necessarily, just not afraid of a little blood and tattling. Before he quit playing, he was always a member of the Gestapo, raiding our closets for the hidden refugees, or the Stasi listening in on our parents’ conversation, writing down shorthand notes we would later retire to our bedrooms to decode and record. We had never seen him soft.

But here, Nathan paused by the deer and knelt gingerly by its side. He rested its head on his lap, and, though the deer was clearly devoid of anything that resembled life, he leaned his ear over the mouth. We all watched in morbid fascination, half expecting, I suppose, to see the soft hair around his ears rustle with warm breath, maybe watch an earlobe get nicked by those huge yellowed teeth.

After a prolonged silence, Nathan set the head down like an infant and disappeared into the house. He emerged with our mother’s spare bed sheet. The good one she reserved for company.

He didn’t have to say anything.

We all took our places around the animal, dirt stained, Kool-aidlipped pallbearers, and lifted it onto the sheet—no small effort for our sizes. Nathan straightened its legs and wrapped the linen around the torso until it lay flat, save for the antlers which caused one side to look like the head of some huge cloth worm. A papier-mache Mardi Gras float ready for decoration. We hauled and heaved the body behind our garage—a place we were sure our father wouldn’t venture until the next summer when he lugged back another load of spring cuttings.

That night, our father returned and, surprising all of us, wandered

the

26

madison review

out to the backyard. We all listened, breathless in beds, for the discovery, but he just sat out there. We could smell the smoke from the rare cigarette he lit through our open window. We listened until the screen door slammed and braced ourselves for our bedroom door to swing open. All we heard, though, was the creak of the couch in the living room shuffling under his weight.

The next day when we sat for breakfast, Nathan wasn’t there. He wasn’t in his room and didn’t show up at our grandmother’s either. He had vanished. No one told our parents, who, in their adherence to feral parenting, didn’t notice. That first day we assumed he was planning something with the deer carcass. But it was untouched, the bedsheet bunched where we had left it. We looked for him as far as we could, tethered by the limits of the four block perimeter we had permission to explore. We went to our grandmother’s and waited.

He didn’t show up that night either. We listened at our window for the sound of him trying to climb back in but all we heard was our parents’ silence.

That next morning, as we were shuffling outside to head over to our grandmother’s, Nathan emerged with the cloth. He was different. None of us ever knew what he did with the carcass, how he had even moved it. He just emerged with the sheet after breakfast. No one spoke as he draped the sheet meticulously between the other laundry—out of our mother’s view—for it to dry.

When we finally had a chance to gaze upon it, that evening, the resemblance turned our backs to ice.

“It’s just like the book,” Sebastian said, mouth agape. Our heads silently nodded.

It’s remarkable how the shadows of all of God’s creatures can look the same on cloth. That the blood stains of hooves could match hands. The eye sockets stared back at us, calling us into their depth. And where antlers had been, a crown of thorns now appeared to rise above the visage like a halo. A transfiguration I felt radiate through my flesh and organs.

And it was this bed sheet, hanging on our clothesline, that caused Ms. Greely to collapse on her way in the back door to bridge night as we were bringing in the washing for the night. She met it in full view, a slight breeze licking the edge of the sheet.

In the bedlam that followed: my father holding her head and fanning her with his newspaper, insisting he would drive her to the hospital; my mother, unmoved, wrapping tin foil around poker sandwiches, left uneaten, that would now be our lunch for the rest of

the

27

madison review

the week—somewhere in the ruckus Nathan tore the sheet down from the line before any other adults saw it and rolled it tight, leaving it in the sarcophagus of his bedroom closet on the highest shelf, so far back that from the floor you couldn’t see it and the shelf looked bare.

Our father returned the next morning before the sun rose. We all woke and knew our mother was seated in the kitchen booth. We could hear, from our rooms, snippets of the conversation. Ms. Greely, upon awakening immediately spoke of a miracle she had witnessed, animated, tongue gaping, and desperate with divine fervor….that is until she saw the pitying looks of the nurse and our father glancing around the room at each other—and she locked away her secret as either her own blessed miracle or private delusion. My father had driven her home.

Our mother was silent.

Then she said something none of us could make out. We strained by our doorframes but no one could grasp anything but the cadence of her voice.

When we emerged, bleary eyed, our father sat in her place, in the kitchen booth. The morning light and the cigarette smoke formed a glowing haze around his hanging head.

Sh e pulled away that night, the engine revving in our driveway and the exhaust pipe firing away at each of us lying in our beds, pillows like blind folds. I like to think that one of us was able to slip away unnoticed, helped by some Czarist sympathizer in our mind. I don’t think that was the case. She was the only one who absconde d from this massacre.

Our father leaned on our grandparents even more after th at, never talking about the hole that had formed in our mother’s absence like a forgotten chapter of history. The stale air in that house held our silence and made it clear that we were not allowed to ask. We became year-round day residents of our grandparents’ house and our mother’s absence hung over our lives like a shroud, a stigmata no adult ever explained.

And I’m hoping the shroud stayed on that shelf when my father finally moved from that house on Beverly. I hope it still sits, tucked away where Nathan left it, someday to be unearthed and declared a miracle. Historians will try and fail at carbon dating it. A new mystery. A suburban ranch veneration. An act of divine providence that will be recognized by the Vatican. That the historical record will uncover our family…and myself, my sister and brothers will be called upon, years from now, in an illustrated book of saints. And someone will look up to the heavens and ask Saint Anastasia the Transformed for intercession.

the

28

madison review

29

the madison review

Maverick

Beth Suter

I dream him behind the wheel of his name-sake Ford, my rebel father, his dark mane flying—

the car named for an unbranded animal free to be captured by any who can. Like a feral horse, he was ropy and short,

raised on grass and moonshine. The trailer-park neighbors watched him like ranchers afraid for their mares—

I nightmare the Maverick leaping off the road, breaking against hard prairie, wheels spinning my insomnia.

The wreck he walked away from sure he would be put down.

the madison

30

review

31

the madison review

It’s a Wrap

Susan Hettinger

Saturday, February 27, 6:25 a.m.

While sitting in the duck blind where Colin goes to think—the hunters who built it won’t be back until fall—the day after ordering the wrap, he panics. He’s inexperienced with extravagant gifts, slow to realize that he’s left out an important part. You can’t just heave an object toward the recipient with an implied “Here, have this.” There must be a message, like a cover letter, answering the question “Why?” He’s neglected this in his haste to make an ingratiating gesture when he learned on Thursday of Prof. Miriam Gopen’s medical leave of absence for an indeterminate period.

His father suggested the gift. He’s expert at control, proficient in ingratiating oneself, skills for which Colin lacks aptitude and interest. He’s interested in creatures that fly; he has little use for mammals. His father doesn’t believe that knowledge of flying creatures will lead to a lucrative career. He’d thought Colin’s bachelor’s degree in Zoology would prepare him to manage a zoo. When Colin, now a senior at the University of Wisconsin, expressed a desire to attend graduate school to study ornithology, his father balked. “Frivolous,” he’d said. “Selfindulgent. Expensive.” This last objection proved Colin’s undoing. His father, after supporting his undergraduate work at a miserly level, insisted that future investment in Colin’s education be directed toward “income generation.”

Specifically, business.

A gift seemed a good way to remind the professor of who Colin was. But without a personal message, how could it prompt her to the desired action: a letter of recommendation?

He’s a few weeks early for ducklings but continues to gaze at the still surface of the lake, hoping to see them, but worried that it’s too cold for them to survive.

Maybe it’s not too late to add a message?

Monday, March 1, 9:10 a.m.

Nancy’s patients all die. That’s the nature of hospice work. Her

the madison

32

review

approach to caring for people is business-like. She has a low bullshit threshold and doesn’t get involved in their hopes and dreams of an afterlife. She’s all about clean and comfortable. She’s a large person, well-muscled, not fat, six feet tall. Most of her patients are bedridden and require lifting; she needs strength. She wears her brunette hair in a no-nonsense pixie not often seen on women in their fifties, announcing to the world that she doesn’t give a flying fart how she looks.

She likes the short-term nature of her patient relationships. She has favorites, and, on the flipside, unfavorites: the clingy, the self-pitying, the bossy. Miriam has earned favorite status because she’s practical and irreverent. Miriam doesn’t seem to have many people in her life—or need them. There’s a sister in Canada, but she won’t take the vaccine, and there are travel restrictions. Miriam is sixty-one, single, childless, and emotionally self-sufficient, like Nancy herself. Nancy has cared for Miriam for five months and never seen her cry.

She knocks and enters Miriam’s ground-floor apartment. It’s in an old house divided into apartments with no setback, opening directly onto the sidewalk. Nancy lugs her supplies and Miriam’s mail, which today includes a package found on the porch. Leaving things untended in this deteriorating neighborhood is risky. UPS, FedEx, Amazon— nothing’s safe these days. Though if a delivery person rang the doorbell, Miriam couldn’t rise to answer it.

Now Miriam sits up in bed, stroking Janet The Cat, a sleek creature with black and white tuxedo markings. Both gaze out a large window at Lake Mendota Park, formerly one of Madison’s nicest. They watch the park’s inhabitants.

Monday, March 1, 9:15 a.m.

Colin holds for ages. His cellphone reclines on the minuscule kitchen table in his nasty studio apartment, all he can afford on his father’s stingy stipend. He fusses with the message he’s composed, hoping it’s not too late.

A hummer flits by the small cloudy window above the sink. Apodiformes, he thinks, able to scoot or perch, but not walk.

After seventeen minutes, a customer service rep answers, identifying himself as “William.” He has a hard-to-place accent. India? Pakistan? Colin supplies his order number and explains his predicament. In the back of his mind, his father’s voice reminds him to treat such people with courtesy because if you’re nice, you’re likelier to get what you

the

33

madison review

want. These people have little power but can exercise it in nefarious ways, his father says. It occurs to Colin that if he doesn’t get into business school, he may become one of them, forced to take a menial position answering phones. Or even homeless.

Monday, March 1, 9:20 a.m.

The two women exchange greetings. Then Miriam, spying the stuff in Nancy’s arms, says, “Crap. At least email can be ignored. But this stuff, it’s so physical. So insistent. What must I do to avoid mail? I know—die!” Nancy wishes she wouldn’t make these little death jokes. She doesn’t know how to manage her face when Miriam talks this way.

Nancy pours tea. Miriam sluices down her pills, then says she’s tired, will open the package later, hopes it’s not another cancer cap. She says she’s beginning to enjoy baldness.

The trickle of cards, flowers and caps in cheerful colors has subsided in recent weeks. The chemo failed and neither surgery nor radiation are options, so now it’s a classic waiting game. Miriam will not return to her teaching job. Nancy has already disposed of the kindly meant head coverings—Mr. MaGoo-style beanies, a turban, a baseball cap with a creepy pre-attached ponytail of real human hair sticking out the back—by distributing them to the occupants of the homeless encampment in the park across the street. Miriam occasionally tells Nancy when she recognizes one of these hats on the head of an unhoused person she sees from her window. She gets a kick out of it, remarking once, “See, cancer is too good for people. Other people.”

Monday, March 1, 9:27 a.m.

The keyboard rattles as William types. He says that according to the infallible computer, Colin’s order has “perhaps shipped, perhaps not. It is unknown.”

Perhaps it hasn’t shipped? Perhaps a message can be added. A handwritten note would be better, but since that’s impossible, perhaps an elegant font, perhaps Colona? But William says this is not permitted; messages must be entered into the computer in ten-point Arial, all caps. Colin authorizes the addition of giftwrap for seven dollars and dictates his message. The total charged against his Visa is $317.11. Steep, Colin thinks, but worth it. The best quality, his father says, comes from the Classy Cashmere Catalog. He’s chosen peach for Prof. Gopen, to compliment her fair complexion and blond hair, which

the

34

madison review

she may or may not have at this stage. Colin is unclear on her exact condition. A teaching assistant who lacks discretion has taken over her online microbiology class and dropped heavy hints about her rapid decline. The TA, a silly young post doc, enjoys her insider knowledge. Colin worries that the professor may die before producing the letter of reference he needs.

Monday, March 1, 9:28 a.m.

Colin hasn’t left his apartment since Saturday. He’s skipping class today. He should be finishing a term paper, but final semester grades can’t affect his average much and won’t interfere with graduating on time.

He’s fretting about his application to business school, due April 1. He regrets his procrastination. The automated, impersonal nature of this process irritates him. He’s applying to only one, his father’s alma mater, the University of Wisconsin, the only school his father will bankroll. He’s allowed his father, the CFO of a mid-sized brewery in the mid-sized city of Milwaukee, in the middle of America, to push him in this direction. His father believes that if he’d earned an MBA instead of a CPA, he would now be CEO. He sees Colin as CEO material. Colin has doubts. He lacks what his father calls “fire in the belly.”

Colin logs onto the portal and reviews the checklist of items that constitute his application. Marked green for “complete” are most of the necessary components: transcript; resume; responses to a ridiculously detailed questionnaire; Statement of Learning Objectives; demographics, useful in discriminating against his white, male, heterosexuality in this brave new Diversity, Equity and Inclusion world (his father advised claiming Native American heritage, but Colin fears his red hair will give him away); and reference letters, red for “Incomplete.” Two of the three have submitted letters. The third, Prof. Gopen, has not.

Colin has taken mostly large survey courses during his undergrad days. He got decent grades but never cultivated faculty relationships; he now sees his mistake. He put her on his list because she’d commented that his paper on the bacterial infection wiping out songbirds of the Great Lakes was “interesting,” emboldening him to raise his hand more often in class. This might have distinguished him from the other fifty students in the room. She might remember him and be willing to say something positive about him in letter form.

35

the madison review

Or not.

Maybe Colin doesn’t matter to her. Or to any other instructor. Has she even received the automated request for the letter? No way to know.

Who else could he ask? It must be an academic. His other references are personal (his father’s dentist) and professional (his supervisor from a summer job selling tote bags for the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology at the farmers market).

The deadline for submitting the application is twenty-eight days away.

Friday, March 5, 9:20 a.m.

Nancy sits on the bedside chair, the package on her lap. No room for it on Miriam’s night table, which holds typical sickroom gear—water glass, straw, Kleenex, pill dispenser—depressing but necessary clutter. The room is tidy, almost barren. Pale blue walls, off-white duvet and curtains. Miriam herself is pale blue and off-white these days. Her circulatory system shows through her scalp, resembling a map of Madison’s bus routes. Her pale lavender lips match her nail beds. Nancy has noticed that as the end nears, people lose pigment, shrink, blend in with their surroundings. Miriam is no exception. She is fading away. Nancy expected this gig to end by Christmas but here it is, nearly Easter. Doctors and their time estimates—what do they know? Less than they pretend to.

As Nancy passes the package over, Miriam says, “Would you please do it?”

Nancy yanks the ripcord on the flat brown envelop revealing two shrink-wrapped rectangles. She peels away the plastic and hands them to Miriam, along with a shipping document.

“Well, what is it? There are two here.” She unfolds a vivid knit object and holds it up. Then another. “Hideously bright, whatever it is. I loathe neon colors.”

“Looks like blankets. About the size of baby blankets. But they’re usually pastel. Plus, there’s fringe.”

“Just what I need at this stage of my so-called life. Something dyed traffic-cone orange,” Miriam says. “Maybe it’s a throw? Like for the back of a sofa. You need matching throw pillows. Ugh, throw pillows. Over my dead body.” She barks a harsh laugh.

Nancy winces, then says, “But why two?”

“Who knows. Maybe they’re lap robes for invalids?” Janet The Cat

36

the madison review

jumps up to inspect. She sinks her claws in and kneads. “I like that word, ‘invalid.’ In-valid. Like if you get sick enough, you’re no longer valid.”

Nancy catches the attached tag. “Cashmere. Dry clean only. It comes from alpacas or llamas, not sheep, right? Impractical, but expensive. Who’s it from?”

Miriam consults the paper that came with it. “There’s no personalized message, just the computer thingie. ‘Colin White.’ A former student, maybe? So many Colins and Jasons and Jeremys over the years.”

“What should we do with them?”

“How about the Goodwill box?” Much sorting and discarding has taken place in this apartment. Miriam has shrunk her footprint so there’s less mess for her sister to clear up when she comes from Toronto, afterward.

Friday, March 5, 6:00 p.m.

An email notification lands in Colin’s mailbox. It shows the shipping date, delivery confirmation of today and—yes!—the message Colin dictated to William, the customer service representative. Relief floods his system. He decides to treat himself to an outing. He bundles up and heads for the Sandhill Crane Preserve.

Monday, March 8, 9:45 a.m.

“Janet The Cat is sleeping in the Goodwill box. She likes that orange woolly thing. I brought her some smoked salmon,” Nancy says. “Ready for your oatmeal?”

“Seems fair. Salmon for Janet. Mush and morphine for me.” Nancy knows Miriam works at cheerfulness. But, she wonders, at what cost?

“Not jealous, are you? Remember, she licks her own butt.”

“I’ll keep that in mind. She used to sleep here with me, but she knows something’s wrong. She wants nothing to do with me.” She runs a skeletal hand over her skull. “Oh well. At least someone’s enjoying the cashmere.”

“I could put it here on your bed, if you want.”

“Lure her here to keep me company? Thanks, but no. If she wanted to be here, she’d be here.” Miriam’s grumpy today. Tired of sickness. Tired of being tired. Tired of being.

the

37

madison review

Tuesday, March 9, 8:47 p.m.

Only after Colin entered the names of people he planned to ask for references, called “referees,” did he realize that the computer would send immediate demands that they create accounts, enter passwords, and upload letters. He should have asked first, personally, with reminders of who he is, what he wants them to say. The checklist shows that the computer nags “referees” weekly until the status cells turn green. He wishes he’d managed it with grace. Too late now.

If he doesn’t get in, the monthly deposits will stop. His father won’t pay for Colin to study birds. Then what? Some crummy minimum wage job, like at a call center? Re-apply next term? By then, everyone will have bonded. Biz school is for networking. Nope, this is a one-shot deal. He curses his introversion and passivity. He should have joined a fraternity. Sucked up to faculty members. Sought internships. Too late, too late, too late now.

He experiences more doubt as he contemplates his message to Prof. Gopen. Is it overly familiar? She’s a tenured professor, he a mere undergrad. Even before she received the wrap, the electronic portal had pestered her for a reference. Not good. The application process, about which he’d felt confident, given his solid GRE scores, now seems tenuous.

A computer “bing” interrupts his descent into the worry pit. His Visa bill. The balance, now in five figures, is worse than he expected. He pays the minimum each month. This practice, he assures himself, is temporary.

Wednesday, March 10, 9:15 a.m.

Nancy arrives to find Miriam in a fitful sleep. She decides to let her rest and begins to clean the bathroom. As she works, she listens to a podcast about allergies. Without Miriam’s knowledge she has taken home one of the orange throws. It’s not theft; Miriam didn’t want it. Nancy has never owned cashmere. Miriam seems well-off, accustomed to luxury goods, whereas Nancy has no experience with them. Now a bumpy purple rash has appeared on her hands and forearms. She attributes it to either a punishing universe or an allergic reaction to cashmere and toxic orange dye. After an hour, she hears a distress call and finds Miriam half out of bed, wet pajamas clinging to her legs. “I’m sorry,” Miriam gasps, “I thought I could make it.”

“No problem,” Nancy says, her voice calm. She grasps Miriam

the

38

madison review

under the arms and pulls her up, pretending not to notice the tears. “I’ve got you.”

Wednesday, March 10, 9:30 a.m.

Colin’s Visa account shows three new charges totaling nearly a thousand dollars. An obvious error. He must dispute the charges and get them reversed. Could he report the card stolen and get a replacement with a higher limit? The website offers neither of these options. It instructs him to call the tollfree number.

The Visa woman who answers interrogates him, alleges that the number he’s calling from is not associated with his card, puts him on hold twice to consult some higher power. When she returns, she says, “I’m sorry, sir, but a duplicate shipment is something you need to address with the vendor.” Really? No help from Visa? He’s surprised and peeved. These charges put him dangerously close to his limit. Rent is due April first; he’d planned to charge it.

Thursday, March 11, 9:15 a.m.

“More packages,” Nancy announces, entering Miriam’s bedroom. “Shall we?” And they discover three blazing orange cashmere stoles identical to the first two, one of which Janet The Cat has appropriated. Each is accompanied by a gift card reading:

SORRY TO HEAR OF YOUR ILLNESS. HERE’S A WRAP THAT WILL FEEL LIKE A WARM, FRIENDLY HUG TO SPEED YOUR RECOVERY. YOU’RE IN MY THOUGHTS AND PRAYERS. AFFECTION AND GOOD WISHES, COLIN

“One was enough. More than enough,” Miriam says. “And I’m still foggy on this guy Colin. Hundreds of faceless kids. Few memorable relationships. Maybe the nerdly, dandruffy redhead from fall quarter?”

“But Janet’s pleased.” Nancy likes Janet a great deal and will adopt her when the time comes. “What should I do with them?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Just dump them in the corner for now. I should be grateful. Sorry to whine but they’re so bright they cause pain.”

“Well,” says Nancy, “at least it’s not flowers. They just rot. Or live plants you have to take care of.”

“Think they’re compostable?”

the

39

madison review

Thursday, March 11, 10:10 a.m.