featuring interviews from rickey fayne and danez smith

2025

We would like to thank Ron Kuka for his continued time, patience, and support.

Funding for this issue was provided by the Jay C. and Ruth Halls Creative Writing Fund through the UW Foundation.

The Madison Review is published semiannually. Print issues available for cost of shipping and handling. Email madisonrevw@gmail.com www.themadisonreview.wisc.edu

The Madison Review accepts unsolicited fiction and poetry. Please visit our website to submit and for submission guidelines.

The Madison Review is indexed in The American Humanities Index.

Copyright © 2025 by The Madison Review

the madison review

University of Wisconsin Department of English 6193 Helen C. White Hall

600 N. Park Street Madison, WI 53706

Editors

Madeline Mitchell

Brett Dunn

Jordyn Ginestra

Associate Editor

Lee Kessler

Staff

Aamuktha Kottapalli

Alex Ruiz

Angel Chao

Geneva Michlig

Jaan Srimurthy

Jake Reisfeld

Jamison Grimm

Jasper Huegerich

Katrina Kallas

Liz Martens

Lorren Richards

Milo Daly

Sami Diedrich

LAYOUT

Alex Gershman

Brett Dunn

Jordyn Ginestra

Madeline Mitchell

Morgan McCormack

Rissa Nelson

Taylor D’Andrea

Editors

Morgan McCormack

Alex Gershman

Associate Editor

Taylor D’Andrea

Staff

Aideen Gabbai

Anna Lail

Anya Bery

Emma Stueber

Evan Randle

Kyler Hansen

Liv Abegglen

Lucas Miller

Nolan Heath

Priya Kanuru

Rissa Nelson

Sally Manning

Dear Reader,

Welcome to this Spring’s edition of The Madison Review. This issue is as tender as it is honest, grappling with deeply felt desires. The following pieces uncover what it means to yearn for connection— whether these relationships be platonic, familial, or romantic. Through distinctive voices, boundless formal experimentation, and evocative prose, each work begs us to reckon with our lost loves, the loves we wish for, and how we show this love to others.

We hope you are just as taken by the Poetry, Fiction, and Art of this issue as we have been again and again. We would like to thank each of our contributors, without whom this edition would not be possible. Thank you for trusting us with your precise craft, careful dedication, and tender care, as well as calling this journal home.

We would also like to thank our program advisor, Ron Kuka, for his immensely resilient patience, abundant wisdom, and steadfast support, along with the UW-Madison English Department and the Program in Creative Writing.

To the staff, thank you for the love you have poured into this journal. None of this would be possible without the dedication, profound curiosity, and careful attention you dedicate to the literary craft.

A final thanks belongs to you, our Reader. This issue would not exist without your devotion to, and appreciation for, the written word. We sincerely thank you.

Warmly,

The Editors

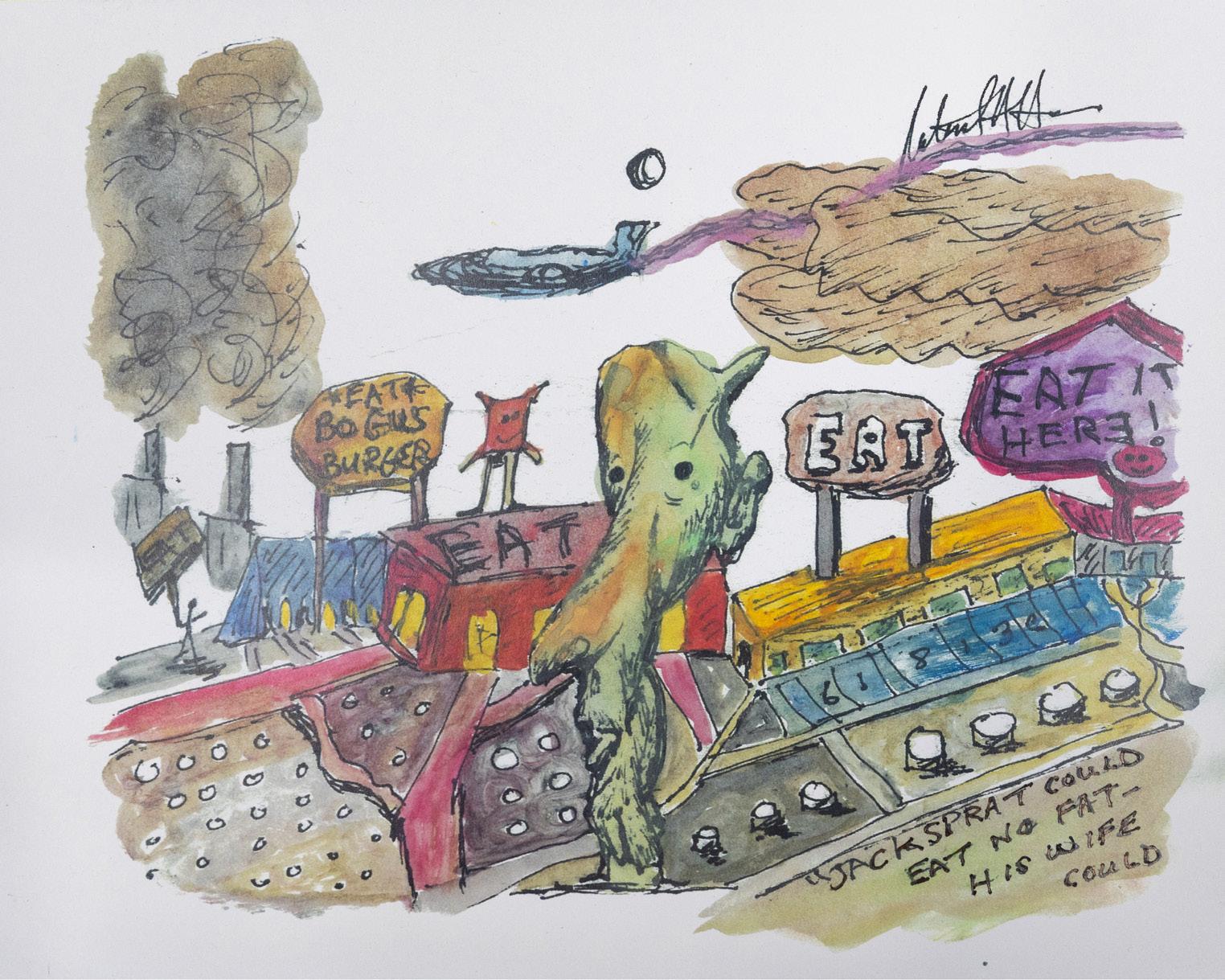

The same man arrived at the art installation every Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday promptly at 11:15am. Each of those days, Ryanne stared at him through her Ray-Bans as she handed him a clipboard with a release form. He made no effort to hide the fact that he had eaten approximately thirty burgers courtesy of her project, nor did he make any effort to acknowledge her, but he did not avoid her gaze either. It was as if she was the greeter at Walmart whom most decent people politely ignore or pretend not to hear as the greeter mutters a weak “hello”, while the customers suppress the deep pit of horror that someone actually pays rent and buys food (also from Walmart) with the money earned from smiling at strangers hurrying into a megastore in search of cough medication and Disney-themed sheet cakes.

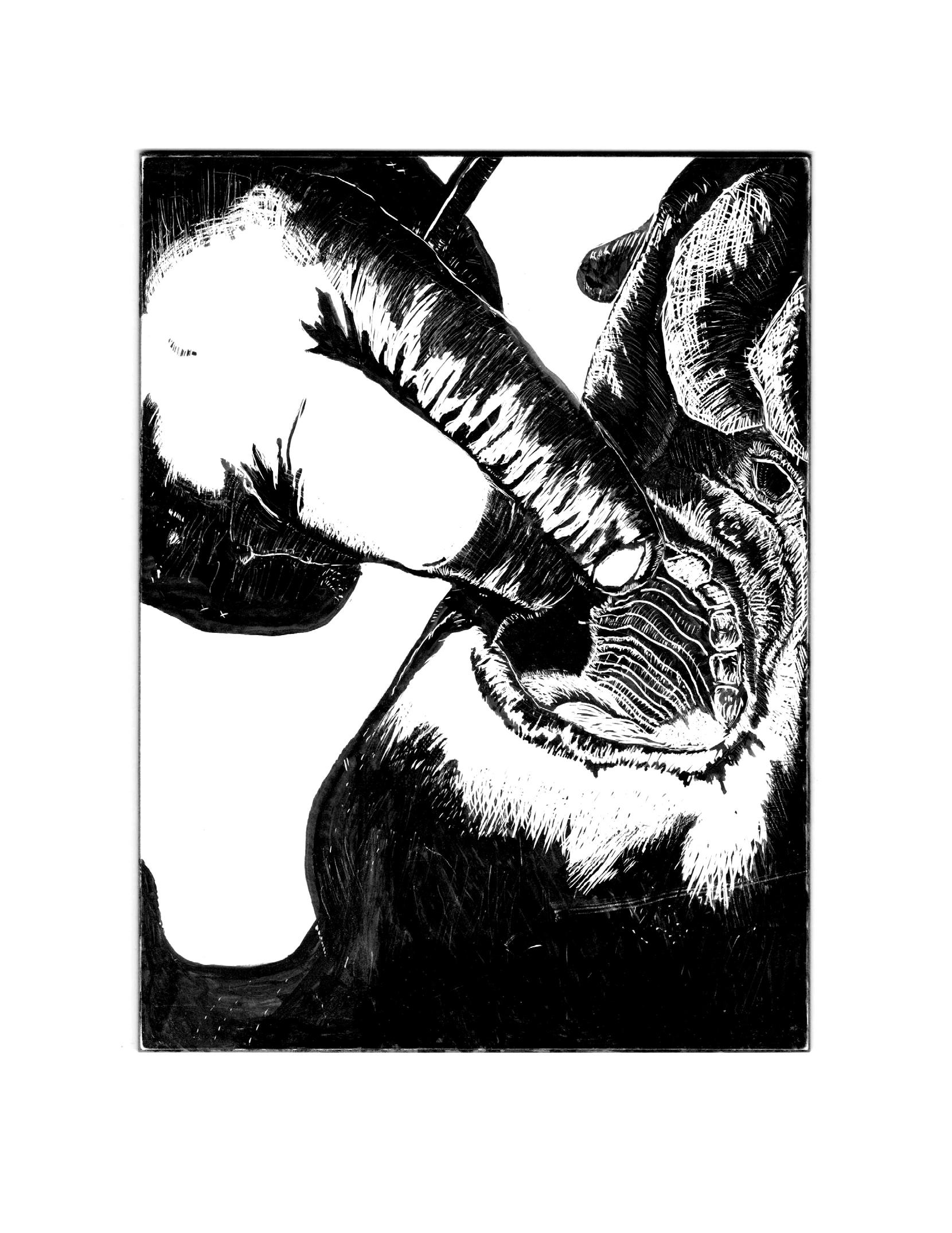

Ryanne named the art installation FREE BURGERS! She first got the idea as an undergrad at Berkeley, when she fell into a semiradicalized activist group, who all road tripped to see Morrissey at a music festival back in Los Angeles, her hometown. Then, while working on her MFA at Otis, an ex-child star opened an art installation of his own down the street here on La Brea, granting permission to the public to watch him cry with a paper bag over his head. She wanted to check it out, but every time she was in the area –usually after a shopping trip at the Grove with her best non-radicalized undergrad friend, Mackenzie (or Mackie) – the line was too long.

In Ryanne’s installation, anyone over the age of sixteen could queue up outside to enter (as the man had done so approximately thirty times). Participants signed a release form covering the basics of “if you die, you die” and granting permission to be photographed or filmed, etc., etc., then entered a tight, dark corridor filled with echoing pipedin sounds recorded from a slaughterhouse. The participant waited here, one at a time, until the obscured sliding doors allowed you inside the next room.

The participant entered the room facing a large blank wall and one other person facing back at them, standing in the corner wearing noise-cancelling headphones, as well as a long-sleeved, immaculately white uniform, with a glaring neon yellow heavy-duty plastic apron

draped over it. About thirty seconds after entering, the same video of shaky cam footage began playing on the wall, of various bloody scenes from a meat processing plant. The sole job of the person facing the participant – other than to be deeply ominous – was to keep the participant watching, by any means necessary.

The release form went into more details, but the basics were that this person was allowed to yell at you, tap or touch you “lightly to moderately, in an appropriately neutral area, such as the shoulder or hand”, or carry out their own tactics in order to keep your attention focused on the screen, short of using the same devices used in A Clockwork Orange , though Ryanne had thought about it. (Set up for each participant would have taken too long to be feasible.)

Raul (Wednesdays through Fridays) liked to bark like an army sergeant. “KEEP YOUR DAMN EYES OPEN, MA’AM!” he would bellow at them, regardless of their age or presentation of gender, over the sound of wailing, shrieking cows, squealing pigs, flustered chickens, and clattering machinery, viscera slopping on linoleum floors and against plastic sheeting. Jeremiah (Saturdays and Sundays; this was just a gig for him to make extra cash while his acting career was on hold due to a healing nose job) was quieter, but terrifying. He stared at any closed-eye participant, tiptoeing up to them in the small room until he stood at an uncomfortably short distance, tapped them on the shoulder, stared into their shocked, now-opened eyes, and nodded back toward the projected screen.

Both tactics worked well.

Ryanne floated through the installation as she pleased, when there was no line snaking down the narrow, cracked sidewalk. She would not linger in the room with Raul or Jeremiah, but instead lurk in the dark hallway behind a waiting participant, pretending to send a very important email or text, or wait on the other side of the sliding doors. She plugged her ears and averted her dark brown eyes while slipping past participants, sometimes bypassing the room entirely by circling the building and entering from an employee-only door out back.

Her favorite part was at the other end.

Once the six minutes and thirty-seven seconds of footage ended, another obscured set of sliding doors allowed the participant – if they had made it through with eyes open for an amount of time deemed appropriate by Raul or Jeremiah – to escape the bloody horrors. There, they were greeted cheerfully by fluorescent lights and a rotating cast of young people (all from the Midwest, places like Iowa and Wisconsin, Ryanne had assumed) in checkered uniforms and goofy

paper hats, smiling, always smiling. They called out a quick chorus of “Hello!”s and “Welcome in!”s while neon menus and signs with the bright yellow and red FREE BURGERS! logo flashed above and around them.

Ryanne had had an old flame from grad school design the logo because she knew she could get away with a discounted rate, especially if she invited said old flame to the closing reception.

The participant would be encouraged to approach the counter and be promptly handed a steaming bag of mouth-watering grease, their equivalent of a Big Mac or Whopper: a double burger with cheese, mayo, ketchup, lettuce, pickle, onion, tomato. There was a small, modified kitchen area where the burgers were prepared, behind the façade of registers and menus and colorful signage. A mini-assembly line of prep cooks with zero prep cook experience threw pre-packaged and seasoned frozen patties onto a large grill, flipped, and sent them down the line to be bunned, adorned with condiments and limp veggies, and wrapped up nicely for the next waiting participant. However, the participant could request a fresh burger if they wanted any modifications – extra pickles, plain jane, only ketchup – but you had to wait five to ten minutes for those.

Not many people asked for modifications.

The man, however, always exited the slaughterhouse room calmly. No tears, no hyperventilating, no retching, no visible signs of distress. He stepped up to the counter to ask for his free burger with no mayo. She had followed him through the installation and watched him, now dozens of times, as he stood still in the corner, waiting for mayo-less buns. Who hates mayo that much? , Ryanne thought.

It was week 11 of a 12-week run. The installation had gone remarkably well: the LA Times ran a piece a few weeks in, which garnered some national attention, at least on Instagram. PETA got mad about it, their angle being that there was still exploitation of animals in the cooking and giving away of the free burgers themselves. Ryanne hadn’t told anyone, except for the one vegan actress who worked Thursdays and Fridays in the FREE BURGERS! area and who had bothered to ask, that, indeed, there were no animal products whatsoever in the meals being given away. She didn’t tell PETA because their ire was generally good for publicity.

There was also an artistic point to this. A certain subset of attendees were big “tough” men who were unruffled by the cries and bloodletting and deaths of others. They usually ate their free burgers with juicy relish and gusto right outside of the installation, sitting

down on the curb adjacent to the line, making violently focused eye contact with those waiting to get in (particularly young women).

There had also been an ongoing TikTok challenge amongst the senior high schoolers of the Los Angeles area, which had led to Ryanne prohibiting participants from filming or taking photos inside the exhibit. It was hard to enforce – and honestly, a few slipped shaky videos and blurry photos were nothing but good for hype – but the release form addendum gave Raul and Jeremiah permission to also employ their tactics on anyone using their phones. Most people didn’t read that far in the release form.

Other than the macho men and the high school assholes with their calculated showboating, most people took their warm bag and scampered off to their tightly parallel parked cars many blocks away.

Ryanne was doing a walk through around 10:52am before opening at 11, though at this point the place practically ran itself, like whenever Ryanne had one of the sharper Midwest actors fill in for her at the front for a few minutes while she zoomed into an interview or something like that. Really, at this point, she could be drinking bottomless passionfruit mimosas at the brunch place on the corner, or cocktails with gold leaf and Japanese blossom smoke and Manuka honey at the speakeasy across the street, where indeed she already had reservations for her and three of her best art school friends for late at night after the closing reception for her installation.

The same man arrived early today, waiting in line at 10:57am. Nothing else seemed different. Ryanne hid her surprise at his earlier appearance well as she slipped out of the side door back into a punishing angle of sunlight.

She didn’t have anything else to do, but she still made a show of sitting on her folding chair in the shaded corner, opening her Macbook Air with a sense of urgency that communicated how busy and overwhelmed she must be. She checked her email – inbox still zero, same as eight minutes ago – and her Instagram set up for the installation – no new DMs, a handful of likes, two new follows.

She stared intently at the screen through the glare when the man, still the only one in line, walked up to her and politely asked, “Excuse me. Is the exhibition open?”

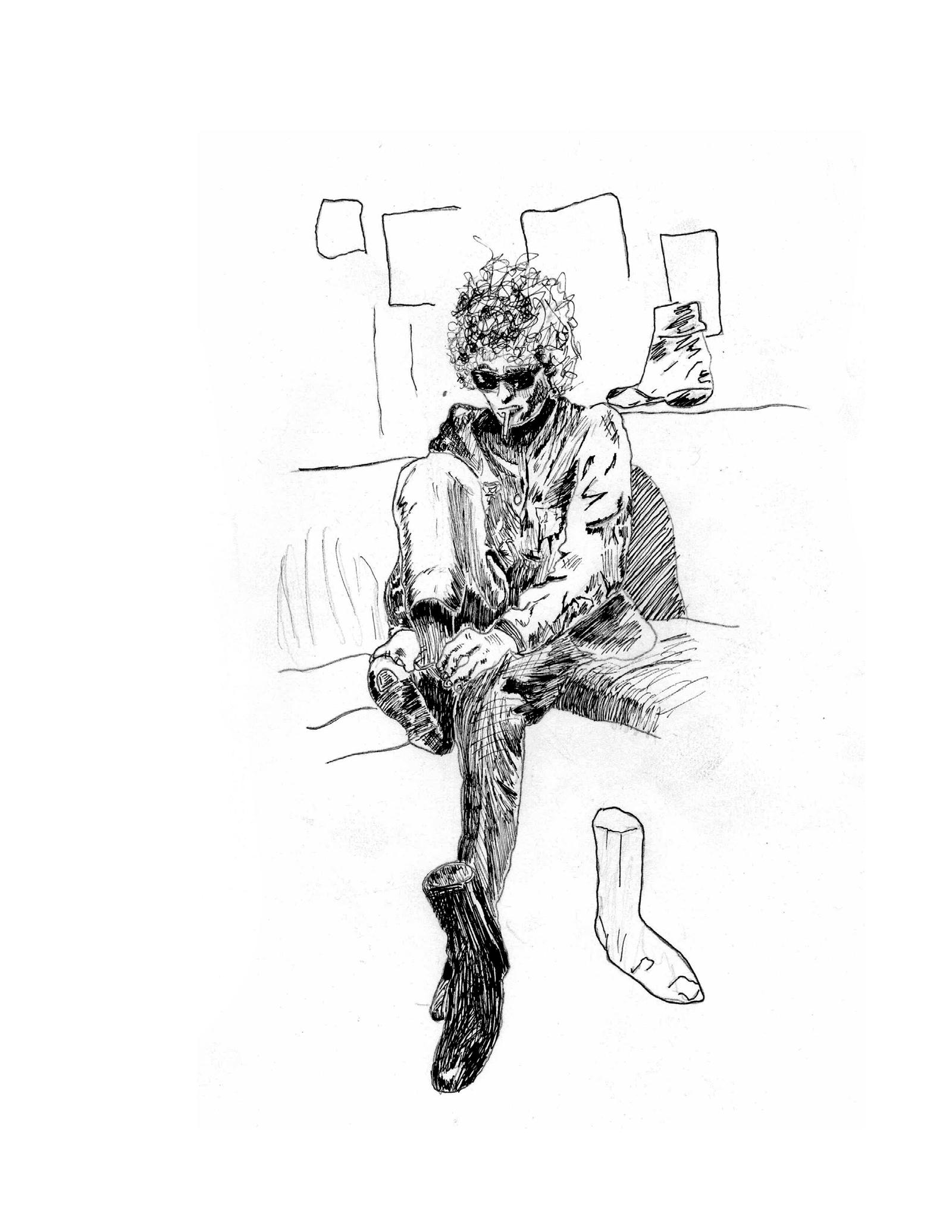

She startled at him standing over her. He dressed nearly the same every day: chinos, a forgettable long-sleeved button-up shirt, with the sleeves rolled up to the elbows, always, and casual-upscale tennis shoes, likely Allbirds, everything in a wave of aggressively neutral colors. He was, for all intents and purposes, beige.

“Oh, right. Sorry about that.” She shut her laptop and slipped it away in her bag, reaching for the perfectly stacked clipboard. She readjusted the pile of release forms, aligning them yet again, before handing him the clipboard and a freshly clicked black pen.

Nearby, cars honked loudly as someone in a Tesla truck ran the red light. Both of them looked over involuntarily, then returned their eyes to the clipboard without comment. She studied his emotionless (but not necessarily cold) face, as he filled in his name, initials, signature. His eyes, the curve of his mouth, even his hairline betrayed complete and utter indifference.

“So, uh—do you work in the area?” She kicked herself for such an inane question, especially after they almost went this entire run without ever acknowledging his daily attendance. They’d played chicken, and she most definitely lost.

He looked at her, blinking. “Yes. Nearby.” Then he nodded and moved past her into the dark hallway, the heavy door closing him in, her frowning at it, then quickly shifting her face back to neutrality, since she could not remember if the sliding door’s dirty glass made her visible from the inside.

Ryanne was never hungry for lunch before 3pm, hence why the installation took an hour break then. They picked back up at 4pm until 8, as the first wave of rush hour died down and the roads were restored to the ordinary amount of honking and gridlock.

Today, it had been hot, and all she wanted was a smoothie. She walked through the exhibit, making sure everyone was off taking their state-mandated breaks. She wondered why the man was so early for lunch every day. Was he a kindergarten teacher? The last time she remembered eating lunch before noon was in elementary school.

At the counter of Moon Juice, she tapped her phone to the Square screen to pay $18.50 for the green juice monster plus pea protein plus collagen (but really, a collagen “promoter”). Her skin had been feeling wan lately.

Usually, she sat outside the juice shop and clicked around aimlessly on her laptop, but all the tables were taken, lunch meetings and smoothie dates spilling onto the sidewalk. Possessed by a compulsion she did not know the origin of, she crossed the busy street at the intersection and walked two blocks to enter Pan Pacific Park.

Immediately upon passing through the gate, she sneezed. Not a cute, small, squeaky sneeze, but an ugly, loud, snotty one. Her family had always had allergies, but even if she did, she generally chose not to

acknowledge them.

The park was mostly empty, only a few pairs of nannies (or mothers? who knew) pushing tandem strollers of sleeping children. Another pedestrian or two wandered the looping sidewalks. A group of construction workers gathered under a tree, taking a break from the thick layer of heat whipped with smog.

Ryanne sucked down her smoothie. She supposed she could make this at home and keep it in the minifridge on the FREE BURGERS! set, but it wouldn’t taste the same after waiting five hours to be consumed. The little ice particles so finely ground by professionalgrade Vitamix blenders would melt, rendering the whole thing a sloppy, texturally unsatisfying mess. Besides, almost no one brought their own lunch to work at FREE BURGERS! No one except the vegan girl seemed to spot the irony.

As she watched a seagull bully a pigeon in one of the Jacaranda trees, someone power walked past her. She realized it was the man, and nearly dropped her smoothie.

He either didn’t recognize her or didn’t care, keeping his cadence as he looped that section of the park, staying on the sidewalk despite seeming to be in a hurry. She frowned beneath her Ray-Bans and the brushaway bangs she regretted going to that new trendy barber for. They were constantly needing to be brushed away.

When the man was nearly out of sight, she picked up her pace to casually follow. He was tall and seemed to walk quickly without effort, so she had to go at a clip her espadrilles did not appreciate. As he headed toward one of the side street exits, she briefly ran to catch up.

Out on the busy street, city dust kicked up and made her sneeze again. She tossed her empty smoothie cup into an overflowing trash can as she whipped her head back and forth searching for his profile in the clouds of car exhaust and the crowds of those too poor to have a car or Uber, doomed to grimy bus stops.

His standard issue brown head of hair bobbed past a group waiting for a bus as he strode away from the shops and restaurants, towards a desolate stretch of tall, sterile buildings. Ryanne jogged to see which one he entered.

As she saw his figure make a jagged turn into a set of rotating doors – tall white building, corner of Wilshire and Highland – her phone rang. “Fuck shit fuck,” she muttered as she rummaged through her slouchy bag. “Hello?”

“Hey, uh, Ryan?” Raul never stopped being confused and amused at her name. “Are we getting started again or what? There’s like, four

people waiting outside…”

“Ah, shit, sorry, got caught up on a call. I’ll be right there.” She flailed around, frowning. “Have Mara collect release forms until I get back. It won’t be long.”

“Uhhh, okayyy—”

“She knows what to do,” Ryanne said firmly before hanging up. She sighed as she reached down to feel her hot, throbbing feet.

Ryanne stuffed a bushel of old release forms into her laptop bag as they closed the installation that evening. On her drive home, the stoplights glowed in her periphery, and she let habituation steer her blindly back to her large studio apartment in Los Feliz.

Even though it had been eight months since the breakup, she still expected to see Chauncey pawing at the door to greet her. Though he was her ex’s dog to begin with, she was still in disbelief when he packed him up, along with all his vintage records, untouched pizza peel and cooking utensils, and video game accoutrement. They had never discussed custody, so one day, Chauncey was simply gone. She missed his ears the most, the way they alternated flipping over as he tilted his head.

The ex was not the most communicative, but in emotionally charged situations, he was particularly prone to stony indifference. Ryanne had felt the relationship embers flicker to ash when she told him of her new installation idea and he responded, without irony, that she was making him hungry, and where should they go to dinner that night?

She could not imagine Chauncey being too happy about the breakup either, considering her ex found walks to be a waste of time, and he had zero appreciation for the floppiness of Chauncey’s dusty brown ears.

At her kitchen table, which was really meant to be an accessory table, or some sort of bar top situation, she fanned out the stack of release forms. She took a deep inhale and swiped to Postmates, tapped “order again” on her usual – Kale Caesar salad with an extra side of shiitake bacon, and a fauxstess cupcake, which she would save half of for tomorrow – and sank into the miniature couch she’d gotten from a friend who was promoted and promptly got rid of all her perfectly fine furniture to go on a shopping spree at Ethan Allen. (Though it was possible that the friend felt bad for her after the breakup, Ryanne refused to consider that possibility.)

Her eyes were closed but not quite asleep when the doorbell rang. The compostable (how, exactly?) plastic bag was neatly waiting on her

stoop, the dog in the upstairs half of the duplex barking.

While she picked apart the salad looking for the most dressingsoaked croutons, she flipped through release forms. Comparing each to the one from today – which she’d folded over in a distinct but also unnoticeable-to-others way – she found several that matched the handwriting.

But that was the thing. The handwriting itself was illegible. The same scrawl, the same letters printed out each time – he wasn’t even trying to hide his identity, he was just a burger-loving man with very shitty, distinctly male handwriting.

Ryanne switched on the TV to the last thing she was watching on Netflix, a documentary on the dabbawala, or food delivery workers, in Mumbai. After a few minutes of low British voices commenting on how many people in India lived without running water and died from elephant stampedes, she clicked away and put on season 3 of Sex and the City. She spread the release forms again over the limited surface area of the non-table and felt momentarily like a detective, but definitely one on a syndicated crime show, with shiny luscious hair and snappy one-liners, not the dour, depressed, perpetually frizzy ones on the prestige dramas.

She scrutinized the handwriting on several release forms for the last time as Carrie started cheating on Aiden with Big ( what a moron , Ryanne thought, no matter how many times she’d seen it play out). She sighed and opened her iPad, searching for an appropriate app for her needs. Later, as she scooped up the last globs of dressing with her compostable plant-based spoon, she finalized her plan for the next day.

The freeway symphony of buzzing and beeps nudged Ryanne awake. Her alarm was supposed to go off in ten minutes anyway, so she yawned and rolled out of bed, stopping herself from glancing at the spot Chauncey’s bed used to occupy. After yoga, just a brisk eightminute walk away, she hurried to get ready. Before hopping in the shower to scrub her stupid greasy bangs (vinyasa flow had been extra sweaty that day), she looked at her tablet, making sure it was fully charged.

She was first to arrive at the installation but still parked in her usual spot third from the door. Once inside the silent, windowless space, she flipped open the salmon-colored, faux leather cover on her tablet, changed the settings so the screen never dimmed, and set up outside the main door as she waited for the Thursday employees.

There he was, at exactly 11:15am. A couple of teenagers skipping

school had already been through – Ryanne heard their giggles go silent one by one as they made their way inside. She presented the man with the tablet, not trying to hide her smugness.

“Is this the release form?” he asked.

Ryanne nodded. “Switched to digital.”

“Surprised you didn’t do that the entire time,” he remarked with some sassiness — or was it condescension? – as he took it from her hands.

“It was just…safety reasons. But I need to upload them all to an archive for this show, anyway.”

He gave her a tight-lipped smile, probably just to do something with his face. “Right.”

She scrunched her eyebrows above her Ray-Bans. He handed the tablet back. She kept standing there.

“Can I go in now?”

She stepped aside and made a big show of letting him pass her. He didn’t seem to notice or care, but she clenched her teeth at her own childish behavior.

Curious passersby and a few post-gym macho dudes and some homeless people all came in a steady stream. By now, she wasn’t having to explain the conceit of the installation very often. People arrived with their own pre-conceived notions, the promise of a free meal, and, it seemed to Ryanne, an already decided-upon reaction to the 6 minutes and 37 seconds of footage waiting for them inside.

Moreso than the steel-faced men who prided themselves on lacking empathy and compassion (or, at least, showing it), it was the young women – the ones teetering on the edge of caring about anything but themselves – that irritated Ryanne the most with their reactions. The meatheads came in with a clear, understandable mission: show their friends they weren’t no fucking pussies and rip into flesh minutes after seeing that flesh stripped from its owner. She rejoiced in knowing she was adding soy to their diets.

This specific detail was also disclosed in the terms and conditions that no one read, in a small paragraph warning away anyone with a “soy intolerance”. But nobody had yet to throw up or break out in hives immediately following consumption.

But sometimes, someone (or a small group of someones), usually young women in Birkenstocks and carefully thrifted overalls and oversized flannels, came through, bracing themselves for the experience. Ryanne never persuaded them not to but seeing their tears and hearing their pontificating on the busy street corner, hot bags

of burgers in small, limp hands, irritated her for reasons she could not quite explain out loud or even articulate in her own thoughts. Sometimes they left their meat bags by sleeping homeless people, which, maybe they appreciated, but still made Ryanne roll her eyes.

She was stuck in this circular thinking when she spotted the man leaving with his mayo-less burger, checking his watch and striding across the busy street in the same direction she had followed him in yesterday. As she handed the tablet to person after person, she watched his pressed chinos and clean, spiffy, robin’s egg blue collared shirt slip away into the city. A homeless woman who had been through the exhibit a sporadic handful of times, and had also recently thrown her purse into the middle of the busy street and pirouetted through speeding cars to retrieve it, much to all the people in line’s delight, snapped her grimy fingers in Ryanne’s face.

“LADY. Where you at?”

“Oh, sorry,” Ryanne inhaled, then stopped. Instead of handing her the tablet, she held it out for her to sign with her finger. The woman didn’t seem to notice or care ( she definitely would have made it known if she was offended , Ryanne thought, justified) and she waltzed into the dark hallway with a twirl.

On break that day, most of the employees gathered in the cramped but air-conditioned FREE BURGERS! space. Ryanne double checked the locked door at the entry to the installation, then snuck into her car, avoiding small talk with any of the chattier aspiring actors on the floor that day. She turned the hybrid on, blasting the AC, and nibbled on a bag of trail mix as she scrolled through the iPad.

She chewed on dried cranberries and Brazil nuts as her fingers swiped deftly across the cascade of saved PDF release forms. She cursed herself internally for not doing this digitally to begin with; one of the grant foundations she’d received funds from would require a digitized archive, so that hadn’t been a complete lie. She did not admit to herself that her initial resistance was because she did not want so many unknown, dirty fingers jabbing at her iPad.

The third saved release form of the day: Greg Roberts. Well, cool. She had a name. Finally. It seemed rather bland, not indicative of any grander mystery than a man who liked free food.

She swiped several tabs open: a LinkedIn page, Facebook, Instagram, a mention in UCLA’s student newspaper. Her eyes lingered on a photo of him with a frightfully thin young blonde woman before she decided she was indifferent to that aspect of his life and closed that

tab.

The mention in the newspaper was the most interesting to her. Seven years ago, he was a part of a schoolwide walkout of undergraduate students protesting the poverty wages of the school cafeteria workers, employed by Sodexo. As co-organizer, he was quoted as saying: “How can anyone look at someone in the eye who’s serving them food and ignore the fact that they can’t afford this overpriced, and quite frankly disgusting, meal themselves?” In the accompanying photo, she saw that his youthful style was not much more interesting than his current look, but it had more of a looseness to it.

Ryanne reapplied her lip balm, scooping the cruelty-free glossy product up from the tiny glass container, reading and re-reading the article. On the LinkedIn page – she promptly turned incognito mode on, so he wouldn’t be able to see she’d viewed it – it was listed that he had clerked with the Riverside County Superior Court after law school at Loyola, interned at an environmental and land use-focused law office, and now worked in the offices of Glaser Weil, a seemingly prominent entertainment law firm.

One of the FREE BURGERS! area employees knocked on her driver side window, squinting in through the white sunrays. “Should we open again?” she yelled, which was unnecessary, as the glass was not that thick.

Ryanne blinked slowly, turned off her car (as well as the AC, which she immediately regretted) and opened the door. “Hey, Mara. Sure. I’ll be out front in a minute, you can let everyone know to get back in places.”

After Mara went back inside, Ryanne dabbed at her forehead and nose with a pore sheet blotter, wriggled her feet back into her Tory Burch sandals, and headed around the building to the short line of giggling teenagers, fresh out of school for the day and ready to watch each other cry and possibly vomit.

Ryanne dozed off while scrolling on Friday night, but not before spotting Greg Roberts’ “yes” response to a Facebook invite to a local free show, sponsored by a cool indie radio station. So, on the drive home from the installation Saturday, Ryanne bugged and bugged friends from different areas of her life. She risked having an awkward friend group overlap, but there was no way she could risk appearing at a free concert night alone. Sure, a “yes” to a random online invite was a long shot, but, it was worth a try.

You like music now lol? Mackie had responded to her initial

inquiry.

Not really but I like drinking margs at the park

Lol you just ready to get back out there huh?

You got me lmao. You down??

SURE whatev. You’re getting the uber

Not even twenty minutes after this exchange, the nice girl who worked at the nearby bookstore and went to the same coffee shop as Ryanne responded. But Ryanne “forgot to check her phone”, she told her the next time she saw her.

She had rushed everyone through closing up shop, but it was Saturday night, so nobody had questioned it. They all had places to be, people to see, expensive cocktails and shitty beers to drink, headthrobbing electronic music to play and “This group, man, their shit will rip your soul out . Like, rip it out with the guitar,” to see, as Raul had tried to coerce her into going to a darkwave show with him that night. Ryanne politely declined. Raul had shrugged.

When Ryanne had gotten home, she caught herself calling out, “Hey Chaunc—”. Looking at the time, she bolted for the shower, turned the hot water up to an unsafe temperature, and slowly washed the sweat and grime and smog out of her highlighted hair and brushaway bangs.

Mackenzie had already come over with a bottle of sweating prosecco by the time Ryanne stepped out of the shower. Mackie could always be depended upon if one needed to get drunk. Thankfully, she’d switched from Malibu to mid-range bottles of wine since they graduated college.

“This is just to start us off,” she rattled the bottle. “Got us covered for the road, too,” as shooters of Tanqueray peeked out of her glittery little purse.

Ryanne kissed her cheek dramatically. “Thanks, darling. Needed this.”

They polished off the bottle as Ryanne fiddled with her fake lashes and Mackie called an Uber on Ryanne’s phone. “Who’s playing tonight? The Autry, right?”

Ryanne shrugged. “Some poppy folksy Americana bullshit.”

Mackie laughed. “Why do you want to go, again? Not that I’m complaining, we haven’t gone out in like, fucking forever. Since the breakup—”

Ryanne cut her off. “One of my emp—coworkers mentioned it, it seemed cool.”

“How old is she?”

“I don’t know, probably 21.”

Mackie laughed. “Don’t make me feel old, Ry.”

“We’re not old! We’re going out!” Ryanne swiped another layer of lipstick on.

“Are there gonna be a bunch of dudes there that brew their own beer and have mustaches and shit?”

Ryanne rolled her eyes as the Uber notification dinged on her phone.

After waiting in an egregious line, the two women made their way inside the park. Mackie beelined for the bar while Ryanne scanned the crowd, to look for her “coworker”.

Almost too quickly, she spotted Greg Roberts in another disproportionately long line for kettle corn. She was shocked at how easy that was and stared for a beat too long. He felt the gaze, looked around, and stared right back at her.

Frozen, she unstuck just her left hand to wave. The rest of her throbbed with embarrassment. The unstuck left hand went up to her head, did something with her hair, then fell back to her side.

She had not planned on what to do next.

He left the line to approach her. She tried to grin. It looked like a grimace, she knew.

“Hey. Funny seeing you here,” he said, not excited, but not outwardly disgusted, either.

She shrugged, sort of laughed, then frowned at herself for doing that.

“Do you like Stray Moth?”

She looked at him blankly. Something in his gaze was flat to her, like a stuffed animal’s round glass eyes.

“Oh, the band. Yeah, my friend likes them. I just came for the vibes.”

He nodded slowly, drank from his beer.

“Why do you come to the installation every day?” The Fireball shooters that had been hidden further down in Mackie’s pockets sloshed words out of her mouth.

He did not seem surprised. He tilted his head and shrugged. “Free lunch.”

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch,” Ryanne said as she thought oh my god, that was so fucking lame, shut the fuck up right now, jesus.

“You’re right. The videos.” He was talking with no intonation, no real emotion in his voice. Is he a psychopath? Ryanne wondered. Or just a man?

“Why do you do it then?” Every word smelled like cheap cinnamon whiskey. She didn’t care anymore.

“I mean, it is still a free lunch. I have a lot of student loan debt,” he joked.

“But you’re letting all that into your mind. Over and over again. Isn’t it awful?”

“Maybe to you it is.”

“Objectively, it is awful. I’ve seen people cry over it. Men, too. Privately. Or so they thought.”

He shrugged.

“Well. Anyway. Yeah. It’s weird. Of you.”

The “weird” comment, of all things, seemed to strike a nerve. This too struck Ryanne as weird.

“I guess, but you don’t have a limitation on how many visits one can make. Not even in a day. Though I imagine not that many people are coming through multiple times a day,” he said, very no-nonsense, like he was explaining things to a whining toddler.

“Nope. You might be the only repeat customer at all, actually. Other than some people who live on the streets and really need the food.” Now her mouth was a broken fire hydrant.

He shrugged again. “The burgers are good.”

Ryanne’s skin felt hot. “So, it’s just like, a chill content viewing experience. Something to just casually watch before consumption.”

She could see him restrain his facial muscles. “It’s going to happen anyway, what can I do about it?” he snapped.

Ryanne’s eyes nearly bulged out of her head. She took a big gulp of air and sighed. “That’s exactly the point.”

“So, what? Do what? Throw away food? Refuse to eat it?”

She shook her head. “Just don’t be complacent.”

“How are you any different?” he nearly spat at her.

In a rare moment of utter confidence in her own being, Ryanne stood up a bit straighter, elongating her spine as far as her 5’4” frame would go. “Know what? I’m not going to engage in a philosophical debate that will never be settled. Clearly you’ve made up your mind. So, enjoy your kettle corn. And the burgers.”

As Ryanne walked away with what she hoped was swagger, she whipped back around with what felt like a jab. “You know they’re vegan, right?”

He blinked, then nodded. “That makes sense.”

She rubbed the lining of her dress with twitching fingers, not knowing what else to do with her hands. “Yeah, it’s all in the release

forms but, no one reads those.”

He laughed. “I should know better, I’m a lawyer.”

“You can probably afford to buy whatever lunch you want, then,” she responded, her tone taking an edge again.

“Yeah, you’re probably right.” He put his non-beer-holding hand in his pocket.

“I should go find my friend,” Ryanne muttered, already turning away again. Greg Roberts brought his hand up to wave goodbye, but she didn’t see it.

Mackie was double fisting High Noons and nodding her head to the beat of three guitarists and one tambourinist – all in old worn mechanic’s jumpsuits (with the cursive name ROBBIE still sewn into one) and ironic t-shirts from the 90s – while she leaned against a barricade.

“Was that your coworker?” she asked, elbowing Ryanne and winking at her.

“Nah,” Ryanne responded. “Did you just wink at me?”

Mackie winked again, even slower. “He was cute. In a very straight edge sort of way,” she said.

Ryanne shrugged. They moved closer to the stage, where it was too loud to casually talk.

The last week of the art installation had record-breaking attendance. A famous local artist came through – and made a cryptic story about the installation on their very-well-followed Instagram – as well as several undergrad art class groups, as well as a local city councilwoman who vowed to only buy meat rated “humanely” at Whole Foods from now on. The NY Times had run a short blurb about it in the Sunday paper and everyone who was anyone scrambled to get in line for the dwindling days left.

Every morning of that last week, Ryanne waited, at 10:51am, at 11:00am, at 11:13am, at 11:17am, to see if Greg Roberts would return for one last free mayo-less burger, but he never did.

Elina Kumra

Facing the sun, I imagine the world unraveling. A dull blade of light pierces the stained shroud of sky; smoke clings thick over the city’s bones even light hesitates to slip too swiftly through it. Like shredded khimars ravaged in winds of despair. Sometimes, even your fingertips vanish into the haze, vapors severing limbs into mysteries.

One year, a hundred domes crumbled beneath its weight—unseen without the red wail of sirens piercing the fog. It’s a fragile balance. Now, as smoke withdraws and wells breathe dry, rows of olives wither bitter on their branches.

But then, there were no thoughts but bread, and workers can’t be broken on the blank canvas smoke paints over their eyes. So farmers lit thunder cannons at the sky’s heart— burst the drones into gun -metal rain; swaths of sky bruised fire with the roar.

I know this was defiance, but mouths hungered. Families needed shelter.

Years later, I learned our cherished pomegranates gave the grenade its name —a bitter symmetry: to craft sustenance from ruin, thunder unhooked from the heavens. On the harshest dawns, the nearest pomegranates quivered till they burst unseen— honeyed hemorrhage. Every bird for miles, red fruit crushed and forsaken by a child’s small hand. Their hearts spilled seeds, scarlet nectar dripped from beaks.

Never mind the heat you shared with him — the orchard still thrums vermilion, and you gather small wounds like moths caught in a dim corridor. He called you Scarecrow — half-joking, half-cruel — each apple left bruised as though naming could wound the orchard itself. You traced his name in wet sand, ignoring the bones beneath. He brought debris-flowers and a cryptic book on teeth, as if your dreams might bloom fanged. Sí, yo sé: some truths sidestep translation. Disciplina tastes bitter, then bright across your tongue. Flights of fancy never quite land. In the quiet museum of pain, you keep small serpents — venom half-formed, coiled like secrets. You chase risk the way you bury scars, porcelain platters and cloud-colored knives tucked away. He once touched the hinge of your jaw —

do you still grind your nights to dust?

Certain frictions remain unwritten, sharp in the dark. Never mind that goodbye wouldn’t have spared you. He corners you with half-asked questions, splintering your sleep wide open. Some nights, you hum the lullabies your mother once murmured, homesickness braided with each note. But naming him will not conjure anything lost. Let water carry his name to the she-oak roots and the wind moan him out to sea. Listen — the orchard hums vermilion, still ripe with living. And you?

Your jaw remembers the weight of his touch. Pull off the old skin from that live wire — let the current spark through your soles, extravagant, electric. Because never mind the orchard hush, in truth, some ghosts — they bite.

Elina Kumra

i. orchard hush, orchard hum, orchard saffron

(like a memory incised into hibiscus bark) Baladi, Shamouti, Nafaqi — piled in battered crates, ferried past Erez gates. Baba once dubbed me Rag-Sentinel; you sense that name coiling behind my molars? in Gaza, he bent low in spinach rows, chasing half-shekels weightier than orchard twilight. Ummi yearned for quietude: burnished flats, frank truth, a companion freed from orchard sweat, orchard murk. hush or not, the orchard repeated his cunning grin — unruly at midnight, scouring tin walls, drifting into Ummi’s hair like contraband psalms.

ii. roasted peppers & demolished hopes

She keened alongside Surah Maryam in a sealed washroom — above, mortar bursts jangled the rafters.

That night, Baba disappeared on a sputtering motorbike with a faceless stranger —

over and over. Forty days dwindled: Qalqilya or Jericho, voices faltered. Debts swelled, hearts stiffened.

In Ummi’s lungs, roast-blackened peppers, orchard seeds refusing to rot.

iii. mother & neighbor

7:30 p.m., saffron haze lengthening on corrugated tin: Ummi’s knuckles mold Umm Samir’s cheeks, like a flicker in a grayscale melodrama dubbed in a dialect never naming Fatima or Nawal. Lips fuse, then part: hush. By eight, date palms recoil in a salt-laced breeze — Umm Samir glides away, orchard leaves quivering in her path. Inside, the faucet snarls: water scalds to flush orchard hush from Ummi’s shoulders, to rebrand thirst as steam.

iv. an unsettled recipe

Yesterday, Ummi rasped of departure, hair chalky

as moonlit mortar, orchard tang on her breath. She pressed coriander seeds into my hand: vow, vow to honor Baba’s lineage with gilded ribbons, a swirl of frankincense — no cones — clang the tray thrice at dawn. Then her stew: shrimp from Al-Mina, never those half-hearted frauds dragged from brackish gutters. But I recast it all.

I tear orchard from orchard, feed it to the embers in my chest. This patchwork dwelling, a husk.

For years, she kneaded her devotion in these walls — enough.

I’ll choose my own invocations.

v. orchard hush echoes

Under a torn quilt, a gaunt cat kneads Ummi’s ribs, uncertain if it whimpers or snarls. She pleads for thyme, for shelter, for that fluting bulbul — but naming yields no marvels. I step away: orchard hush braids itself — vermilion hush — across her brow as her hands lose warmth. Time slips

in half-lit, half-gone — a doorway jammed open, orchard dust swirling in its breach.

Rickey Fayne is a fiction writer from rural West Tennessee whose work has appeared in American Short Fiction, Guernica, The Sewanee Review, and The Kenyon Review, among other magazines. He holds an MA in English from Northwestern University and an MFA in Fiction from the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas. His writing embodies his Black, Southern, overchurched upbringing in order to reimagine and honor his ancestors’ experiences. The Devil Three Times is his debut novel.

Alex Gershman : Do you want to talk a little bit about how you got into writing?

Rickey Fayne : I’ll talk about first how I got into reading because I feel like reading and writing for me are deeply intertwined. I was kind of tricked by my accounting teacher into signing up for AP English when I didn’t want to, and some of the summer reading for that really got me hooked. The first book I read was Their Eyes Were Watching God , and that was the first time I saw that the way people could talk could be literary. That class just got me interested in literature and it kind of continued on into college. I tried the English PhD route, I got a couple chapters into my dissertation—it was actually on Spirit possession in 20th century African-American literature —and then I decided I would rather be writing than studying literature. So I pivoted and took a class with StoryStudio Chicago, where the homework assignment was to write this random thing and that ended up ballooning into the first chapter of [ The Devil Three Times ]. I taught high school for a couple of years while writing, and then applied to the Texas MFA.

AG : You said Their Eyes Were Watching God first showed you that how people talked could be literary. What was it about that poetic dialect of Zora Neale Hurston’s that drew you in?

RF : What I love most about the way Zora Neale Hurston writes is she captures this poetry in Black Southern dialects that you don’t see well represented. I feel like the worst examples would be the WPA Works Project Slave Narratives or the Uncle Remus Tales where it’s just this sort of dialect that’s written down in order to show that the person is ignorant. And even though it wasn’t popular to write in dialect, she kind of went against the grain and said no, the way these people talk, what I grew up hearing, is beautiful and I want to elevate the poetry of that to high literature. Just thinking about what Hustron was doing made me want to look at or think about the way the people I grew up with spoke, and to try to capture some of that in the characters that appear in this book.

AG : There’s a connecting thread throughout [ The Devil Three Times ], stories about the Devil or God, which you tell in that dialectical style. How did all that come to be? Because the short story I’m assuming you started with was one of the stories about the people, not that connecting thread.

RF : Yeah, that that part sort of came about organically. When I first had the idea for the Devil, I was workshopping the first-person chapters in my MFA program. Back then I had this really horrible title, Sins of the Father , and my adviser Elizabeth McCracken said at the end of the workshop, “This is a great start Rickey, but this title, no.”

But she really responded to “The Prodigal Son” chapter, she really liked the voice there, and she said I think you should call it The Devil Three Times . At that point this was the only character who had encountered the Devil and so I was thinking, I don’t know about that, and I sat with it for a long time and then decided not to take her advice. Later on, I took a folklore class with her partner, Edward Carey, and I remember he asked us to think about our experience with folklore. He had all these theories about how folklore was working and it made me go back to Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules and Men . When I reread that and I saw the devil stories in there I really got inspired. I rewrote some of them and I used those for the assignments in his class, and then I just got really into that concept, as well the way that Zora can take the sort of marginal, maligned figure and make him the center, and then question your morality around that. I remember in one of them this guy is late for something and he’s rushing and he jumps over a fence post and he cuts his shirt and he says, The Devil!

and then he hears someone crying and he turns around and the Devil’s there and he’s like, You all put too much on me, not everything’s my fault. So that’s where that idea of thinking about the Devil that way was born.

AG : The inscription in Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon , which I know had a huge influence on your novel also, is “The fathers may soar / And the children may know their names.” I’m wondering what you think of writing about the experiences of people who came before you. Did it feel like a responsibility, was it something that you struggled with?

RF : So, around the same time as I started making the transition between literary critic to fiction writer, my grandparents passed away, and I felt sort of ambivalent about being in Chicago and trying to get a PhD to do things that they never would have imagined doing. I kind of felt like I had cheated my time, that I could have been spending time with my Granddad but I was here doing this or I could have been spending time with my Grandma but I was here doing this. That definitely had an effect on me, thinking about what it’s like to think through their experiences or to try to put myself as someone living with the things they grew up with, so I do feel like that was very much at the forefront of what I was trying to do.

But then, also, I feel like we think about the past and past people’s experiences as fixed, or we don’t think about them as worrying about things the same way we did. Each generation is a repeat; it’s like you grow up and you think, no one’s ever felt this way before, my parents can’t understand what I’m feeling now, my grandparents can’t understand . But the reality is they do and they’re looking at you and they’re like, oh that’s cute, you’re having your feelings

And to think about them in those moments before I came to be did fuel a lot of my wanting to go back into the past and think about people who were going through those things or family lore that’s fixed, like what if I go back to that moment where things were fluid? What are the possibilities?

AG : There’s a scene with Porter and James that comes up in three separate chapters, and I’m thinking of how we see the scene from one person’s perspective, then you see it from another, and in both

perspectives you’re like, this dad is kind of awful . Then you get to the end, and it comes together in a shocking way. Did you have that in mind the entire time you were writing? How hard was it to make such crisp and also unique connections across the novel?

RF : That’s something I came to just through living. You hear one side of someone’s story and then you’re like, oh yeah that was messed up what they did to you . And then you hear the other side. Even the villains are the heroes of their own story, and just thinking about it like that, taking one moment and looking at it from different angles is just really interesting.

I remember reading A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, how she moved through the different chapters and you saw a slightly different vector on the same character. It’s really interesting to think about. I mean, we could even do “The Tortoise and the Hare,” like, maybe the Hare had ADHD, you know, he was neurodivergent, and he’s fast but he gets distracted. It’s not his fault! If he was properly medicated or diagnosed it would be a different story.

I feel like with all these kinds of narratives there’s an investment in having them be read or thought about in a certain kind of way and when you revise it and look at it from a new angle, it can open up new ways of looking at the world, right? Even something like Paradise Lost , where Milton was just like, what if we think about Satan’s side?

AG : I know the press around a debut can be a lot, and you’ve said that you’d rather be working on the second novel right now. Does it feel like there’s pressure? Do you wish the work would speak for itself?

RF : I mean, I really like that idea of like the work speaking for itself but even when we thought the work was speaking for itself there were people speaking for the work in different sorts of ways.

AG : Edward P. Jones I feel like is the best example, maybe the only example of that.

RF : Yeah, try to find some interviews with Edward P. Jones, there’s like five [laughs].

But some days I’m really anxious about it and some days I’m not. You naturally always think that—whatever you’re working on, you’re thinking, this is gonna be the thing or it’s not gonna be the thing—but I feel like I’ve been around enough to know that whatever thing it is, whether it’s successful or not, it’s not going to define you, and even if you can’t see it, there’s probably more you have in the tank.

When I was in grad school, doing the PhD program, I thought the dissertation was everything, that it had to be perfect, I have to be in conversation with this person and not that person, and if it’s not right then my career is nothing. And then I walked away from that, and I tried something else. And I was fine. Will it probably be harder if everything great doesn’t happen for this book? Maybe. But I think even if no one likes it and no one reviews it, I can write another one.

I’m excited about the idea of nobody liking it. I’m fueled by—I feel like I get more from rejection than I do from praise. So I’m just like, okay, nobody likes this book. I’m just going to work harder and make the next one better. Whereas if the opposite happens, it might be a longer time before the next book because I have to get out of my head about that. I remember the first time I got a rejection letter from a story, it was like, great, I’m gonna rewrite this thing and it’s gonna have this that and the other. And then I got into my MFA program and I couldn’t write anything for three months.

AG : So if people want another book from you, they should tell you this one’s bad.

RF : Pretty much [laughs]. That’s the best way to get me to write.

AG : And are you going straight into the next book now?

RF : Yeah, I’ve got the next one sketched out, I have a document and notebooks just accumulating mass. I’m trying to decide whether it’s one book or more books.

AG : And it’s tied into [ The Devil Three Times ], right?

RF : Yeah, it grows out of the chapter set in Chicago. The insurance guy, the one that owns the company that Porter works for—he tells Porter this story about seeing his father prepare a body for burial. So

it’s sort of rooted in that, that family, his story around it.

I’m actually just trying to reign it in. I have a section where Thomas’ great-grandfather is in Memphis, and he works at this grocery store where the owners get lynched so that another person can take over the store, and he helps prepare the bodies and that’s his first experience with death, and then he trains to be an undertaker, moves to Chicago, and he’s there in the twenties during the riots…it’s definitely ballooning a bit. But it’s still more focused than this one. My dream is for it to be under 70,000 words.

This interview was conducted in two parts, on January 20, 2025 and March 19, 2025. It has been shortened and edited for clarity.

The Devil Three Times is being released on May 13, 2025 from Little, Brown and Co. and is available wherever books are sold.

Daniel Lurie

Says the man fidgeting at the cash register. He wears the end of day on his face like a shadow. He assures me he doesn’t do this often, but that his wife sent him to buy lottery tickets: with the Powerball bein’ at a billion an’ all . In Judaism, we’re allowed to play the lottery once as a last resort, which “leaves you at God’s mercy.” But my mother keeps buying tickets along with the groceries, and unless her quota resets every month, maybe that’s the reason we’re about to lose

the house. Sometimes, I wonder what the odds are, if we get a running start for our bodies to just pass through one another. Once, I was speeding down a two-lane highway and clipped a pheasant with my car. I watched its feathers disappear in the tall grass. Maybe, growing up is being aware of the grief you cause without seeing it. Sometimes, I think about how atoms never truly touch, which means I’ve never held you. In a Trolly Problem desert scene, there’s a railway with diversions. On one side, I zip-tie a million strangers to the steel. On the other, my entire family. I use their hair as rope. I pull at the rail switch too many times and it snaps clean off. I see smoke rise and lie down on the tracks. What are the odds?

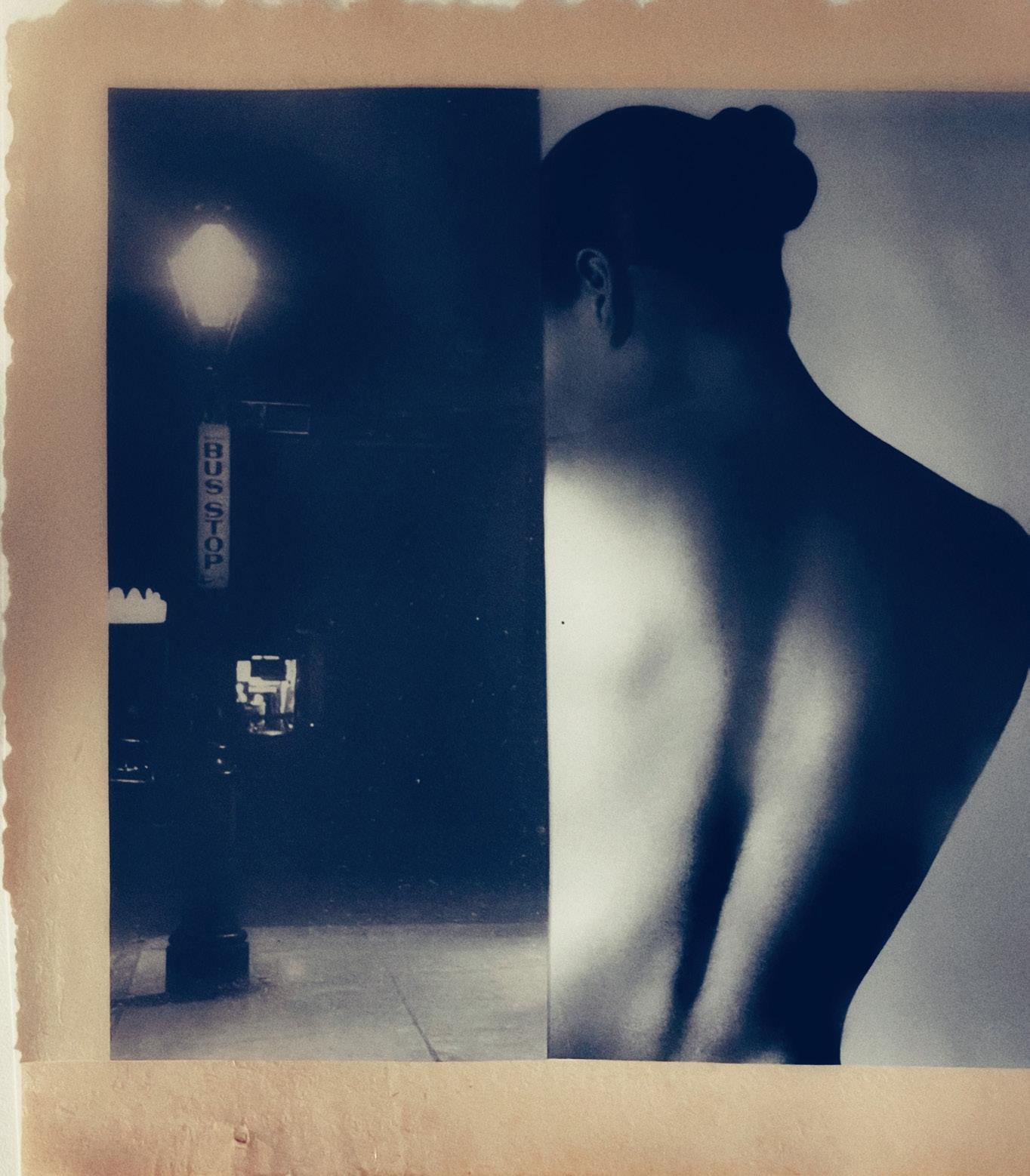

On the night bus back from meeting Charlie there was always this woman in a felt cap and green rain boots. Tufts of gray hair stuck out around her ears, and between her fingers she clutched a small leather handbag. She would sit several seats ahead, her eyes clamped shut the entire ride until she stepped off at the apartments next to the horse stables. After several weeks I finally saw her eyes, a silver and pellucid color, but she would avoid my gaze if I smiled.

It was a lonely bus, even when it was crowded. Singular, quiet, the glowing advertisements all broken and leaving boxes of white light along the interior. Besides, I was always the last one off. Every time I said good-bye to Charlie and headed back to campus, his gangling figure growing smaller and fainter under the blue neon, all the heat in my body seeped out from my heel, into a puddle on the floor, dispersing into the machinery.

#

We met in Plinth each Friday at a roadside diner. When I thought of it, it only appeared in my mind under faint glimmers of starlight, a golden moon blurred with mist. As an angled square shaped by neon and oily glass windows, crouched alongside the rope of black highway wound between two unremarkable mountains. Charlie didn’t call them mountains at all. In fact, he could not even bear to call them hills, only mounds, like piles of dirt and wood chips kicked up by children’s shoes beneath a swing set.

Neither of us lived in Plinth, nor liked it much. It was a village on the river, all of its industrial buildings hollow and crumbling, scrawled with bad graffiti and browning vines, a Melvillian specter of a town. But it was barely equidistant to us both, an hour on the bus for me and an hour by car for him, a wavering dot between two colleges.

Still, he was always late, and then sat in the parking lot talking on the phone. I could see him frowning from our sticky vinyl booth through two separate panes of glass, his pale, stubbly face eventually atomized and fogged up by the heat blasting against the windows.

Most often he was on the phone with April. He didn’t like that I could tell when he was speaking with her, but it wasn’t as though he was so hard to read. When he finally walked through the door, his

body was nearly folded over in half as though he’d been kneed in the chest.

Charlie slipped into the booth, his legs long enough that they easily bumped against mine beneath the table. “So we meet again.”

“Have you heard the one where two west coast transplants walk into a Massachusetts diner?” I asked.

“Does it end with a good, hard look at their geographic choices?” I sighed. “You’ve heard it before.”

The waitress came over and poured him a cup of coffee, which he turned absent-mindedly. He asked, “Any word from Vincent?”

Every Friday he asked if there was any word from Vincent. He asked this repeatedly, week after week, though every so often he would announce to me that he’d finally heard from my brother and he was in some new war-torn bit of the world, pointing his camera at different piles of rubble. Then the cycle would repeat.

I said, “Of course not.” Vincent had been furious with me ever since he learned I’d coopted his oldest friend as my own.

“Your brother is ridiculous,” he said, as he always did.

“Our dad always says, you’re either a serious person, or you let your ear muffs in your fly traps.”

He smiled. “To which I say, sometimes you’ve got to finagle the ball pit.”

The waitress returned to take our order. I asked when she’d gone, “How’s our April?”

He made a face at me. “She’s no one’s April. She’s her own goddamn April. Today, she painted a wild white horse’s armpit. Tomorrow she’s doing mushrooms underneath an old rock with a woman she calls Tree. She’s living the unencumbered life of her dreams.”

“Well, she can only keep it up for so long,” I told him, leaning back against the booth. “One day she’ll look at her sea of horse appendages and realize she’ll never be Georgia O’Keefe.”

“She’s not that bad.”

“But notice you didn’t say she was good .”

“Mind your own business, will you? I don’t poke and prod you about your boyfriends.” He reached over and poked my shoulder.

“You could if you wanted to.”

“And tell me why,” he said, “I would want to know anything about a twenty-two year old’s dating life.”

I was pretty sure in Charlie’s mind I would forever remain a slobbering toddler with a doll in my mouth, a plastic arm sticking out

from between my lips. I said, “Do you remember coming over that day in the summer to wait for Vincent, back when he walked Ms. Viola’s dog? You sat on the floor with me in front of my dollhouse and listened as I explained the entire storyline of my evil doll orphanage. I think I went on for over an hour.”

“I remember the dollhouse,” he said, considering. “But I sat on the floor with you all the time. I was basically your indentured babysitter.” #

Vincent and Charlie were five years older, and as long as I’d known my brother, I’d known Charlie. He was at our house all the time because his parents were incorrigible workaholics and considered our parents as free childcare. For me, the boys were an endless source of entertainment. I followed them around everywhere. When I realized it annoyed them, I started documenting everything they did in a tiny red notebook: consumed two party bags of tortilla chips at noon, killed zombies online for eight whole hours, collected sticks from woods, walked into nettle bush. When Vincent discovered what I was doing, he threw it out the window straight into a mud puddle. Charlie later gave me a new one after I’d sulked all afternoon under the dining table, and that was the first time I found him more interesting than my brother.

#

Another Friday, and there we were again at the very same table in our eighteenth favorite restaurant. Charlie hadn’t been sleeping. This was partially because he wasn’t very happy, but also because he was enrolled as a PhD student while simultaneously trying to get over his girlfriend of many years by taking out a multitude of different women. So basically entirely because he wasn’t very happy.

I tried to ask him about these women, what they looked like, what they studied, whether or not they laughed at his jokes. Were they anything like April? Like any other woman he spent ample time with? But he would always shrug off my questions, tell me to mind my business, that as far as I was concerned, he was saving himself for marriage. He’d wag his finger at me. “Do your homework, Meara,” he’d say.

Tonight, his fatigue cast shadows beneath his light blue eyes. His hand knotted in his hair. He kept spacing out while staring at the side of my head. I reached out over our slices of pie and touched his warm cheek with my thumb. “Charles, dear, you must sleep more.”

He rolled his eyes. “You know, some say the Buddha only slept one hour a day.”

“If you’d like, you don’t have to drive all the way back tonight. You

can stay with me,” I said.

“I don’t much like the idea of being the creepy twenty-seven year old you sneak into your college dorm.”

“Twenty-seven is nothing,” I said. “Last month I saw a girl bring home some middle-aged accountant. At first I thought it was her dad, but then I saw him coming out of the bathroom in his underwear at two in the morning.” He smiled, and I pleaded, “My spare mattress nearly stays inflated the whole night.”

He shook his head and turned his coffee cup. “That’s okay, Meara.” #

My friend Rochelle didn’t understand this relationship. My other friends were too aboveboard to tell. They’d project a bunch of goo all over the whole thing. When I told Rochelle why I couldn’t go out with her, she asked me warily, “Where’d you meet this guy again?”

I stared at her. “Narcotics anonymous.”

“Seriously?”

“Of course not,” I said impatiently. “It was for sex and love addiction.”

She couldn’t understand why a straight man would drive over an hour out of his way to see a woman he didn’t plan to sleep with. She suggested I started dressing sluttier. I told her Charlie would think I was having a psychotic break. “But at least he’ll be thinking of you as a woman as he drops you off at the asylum.”

Charlie always paid the bill. He had old-fashioned inclinations like that, chivalrous instincts that dropped his coat across puddles, put his body between mine and oncoming traffic. If I even reached for my wallet he’d scold me. “If your mother ever found out I let you pay, it’d be my head on a stick,” he said after the waitress took his card away.

It didn’t matter that Mom was an ardent feminist who wouldn’t care in the slightest whether or not he paid for a meal that couldn’t cost more than twenty dollars total. He’d hear none of it.

“You’re not babysitting me ,” I said. “Nobody’s forcing you to hang out with me.”

He looked at me sidelong. “If I were forced to hang out with you, I promise I wouldn’t be paying for your meal.” Then he pushed my plate toward me. “Now finish your pie. Your bus’ll be here soon.”

One night Charlie brought a pile of his books and his laptop to the diner. He had a paper to finish by Sunday night, and had barely written two pages. He wanted me to be quiet as he typed his notes. He

said, “Just sit there and drink your coffee.”

I laughed. “Why didn’t you just bail if you’re so busy?”

“I couldn’t do that,” he said. “I know I’m the highlight of your social calendar.”

I laid my head on the table next to my mug. “I think you mean the other way around.” He didn’t look at me or reply. He merely nudged my foot underneath the table. I watched him as he worked. His nose was red with a slight head cold he had barely started recovering from, his lips chapped, the top a little larger than the bottom. He was lazy about shaving. He’d been like that since his arrival, and I wasn’t sure if it had to do with the geographical displacement or the breakup.

“What’s your paper about?” I asked.

“The language between intimates,” he said. “Like inside jokes, for example. Its development, its changes with distance, time, digital communication, etcetera.”

I smiled. “I’d like to read that.”

He stared at me, then looked back down at his screen. “Sure, weirdo.”

I watched him until our server came back around. He was new, handsome, about my age. I sat up and we made small talk before I ordered our slices of pie, coconut cream today. When he left, Charlie narrowed his eyes. “That’s disgusting.”

“What’s disgusting?”

“You flashed him that creepy archaic smile of yours.”

“Archaic smile?”

“I can always tell when you’re inclined toward somebody because you look at them like you’re a statue on a grave bust. It’s like lust brings out your placidity toward death or something.”

I laughed. “You’ve never even met anyone I’ve dated!”

“Not true. That kid Tommy with the mohawk.”

“Seven years ago?”

“Sure.”

“I don’t look at everyone I’m inclined toward that way. What does my face look like right now?”

He tapped his thumb against the table. “Don’t say that, Meara.”

“Sorry,” I muttered.

Charlie looked back at his laptop, then said: “It’s fine.”

I leaned back against the booth, hugging my arms around my body. The diner was quiet except for the light reverberations of Carly Simon on the jukebox. The sounds of his fingers stalling on the keyboard.

Searching for words, I asked, “What’s April up to?” It was pathetic,

how badly I wanted his attention. What I would say to get it.

“What’s April up to,” he repeated hollowly, frowning. “She’s been selling beaded necklaces in town. And she got a dog. A dog named Diego. He suffers from vertigo and the occasional bout of dermatitis.”

“Oh,” I said. Charlie was allergic to dogs. “So I guess she’s really staying out there.”

“Well, that’s what she’s said all along.” He looked out the window, at our denimish reflections and the ghostly image of his aged Mercury under the fluorescent street lamp, the flashing figures roving behind us. I imagined he was inventing her figure in the shadows, a prismatic face illuminated with a gap-toothed grin, a straight sheet of ashy hair that I’d always remember shining on a moonlit porch, air heavy with cigarette smoke, her body covered in loose, thin fabrics even on cold nights.

Charlie didn’t want my comfort. I knew this. Still, under the table I pressed my knee against his. He closed his eyes for a moment and didn’t move his leg from mine until the server returned.

Forty-five minutes later and we stood outside in the frosty, brittle air at my bus stop. My wool coat fell past my knees, my hair trapped under the collar. He still hadn’t bought a proper coat for the rapidly approaching New England winter. He kept warm with the same thick Icelandic sweater and an orange raincoat. Our breath evaporated as clouds in front of our faces.

Cars whipped past us, clattering across the bumpy, pot-holed highway. Bare, shivering trees waved and slapped against the dark, flat sky. Charlie hadn’t looked at me since we’d come outside, only down the curve of the road, waiting for the headlights to come arching ahead. “Late tonight,” he murmured.

“Desperate to get rid of me?”

“You?” he said, his hand brushing against mine. “Never. You’re the highlight of my social calendar.”

When the headlights finally appeared against the shiny black tree trunks, Charlie gave me a quick, one-armed hug, and sent me on my way with my fare. “Until next time,” I said, and he saluted me.

It was after one in the morning and Rochelle and I were sitting in my window smoking dried flowers she bought off the internet. Their efficacy was nil but cheaper than a lifetime addiction to nicotine. In the corner the silver-painted radiator blasted, creating a sickly climate of bone-chilling drafts interspersed with pockets of airless heat. My nose was dripping as I took a drag. I’d probably caught Charlie’s cold.

Rochelle liked to smoke and complain about her thesis, or the notes for what might become a thesis, something smart and convoluted about French language in War and Peace . She was equally enthralled with the French as she was the Russians, though whenever she actually met anyone of either nationality she would disparage them behind their backs with little discretion. She once said, “They’re better in literature.”

I’d fall in and out of focus during these rants, too aware of my own mounting research, inexplicably about orphans in Victorian literature, specifically Dickens. I was making little progress because whenever I bothered to attend to my scholarship, I had to confront the fact that I had somehow become a person who studied orphans in Victorian literature.

From the mess of papers and pens on my desk, my phone rang, and I handed the cigarette to Rochelle, then climbed off the windowsill. By the time I found it under a notebook, one that contained more doodles of strangers than notes, it had stopped ringing. Vincent’s name flashed across the screen. I excused myself into the empty hallway vibrating with fluorescents and called him back.

It only rang and rang and rang. I was left at his voicemail, and a dull disappointment made a notch in my stomach. I said to my phone, “It’s me. Your wicked sister. Calling you back. But maybe you didn’t mean to call. You can try again, I probably won’t be in bed for a while. But I know you’re busy. I know your life is crazy. If I really think about it I’m amazed we ever hear from you. But Mom worries about you. Charlie worries about you. He talks about you all the time. I hope you won’t stay mad at me forever. But I’m sure you must know how hard it is, being so far from home—”

The phone beeped three times and disconnected. The message failed.

I went back inside my room, and when the draft slammed the door shut behind me, Rochelle yelped. I tossed my phone onto my bed and hopped back onto the windowsill. Everything smelled like lavender and rose stems.

I tried to call my parents the next afternoon, but my reception in those unremarkable mountains garbled their voices into sparkly fragments. It made the college seem like its own distant planet floating untethered from any sun. It was part of the reason why I’d been so happy to learn Charlie was moving nearby. A member of my own species had come to rescue me.

It started to rain, and it kept raining, icy sheets clambering out from the clouds, and my classes passed in clammy doldrums. My clothes were always a little bit damp, my skin a little goosefleshed. I crouched in front of the whiskery fireplace in the common room and read a novel too contemporary to contain any Victorian strays, texting Charlie passages I thought he’d find interesting. He replied with photographs of the groceries he was concurrently buying. When he called me from his car, I was draped across the little faux velvet corner chair, my book falling apart in my lap. After I’d told him what the book was about, he asked, “Do you like it?”

“It disturbs me,” I replied, “and I think it’s unhealthy for a girl’s constitution to remain undisturbed for so long.”

“Right, I forgot this whole thing of yours about reading for displeasure.”

“At least a few times a year,” I elaborated. “You should never get too comfortable. Civilization could collapse at any moment.”

“Speaking of never getting too comfortable, I might have to cancel Friday night,” he said. I could hear the rain pouring against his windshield, the whine of his wipers against the wet glass, the bumps along the pavement.

“You might?”

“I will,” he said more definitively. “It’s the only time a friend of mine can make.”

“You’re canceling me for a date.” I hung my head down over the arm of the chair, flipping the common room upside down, letting the blood flow heavy into my skull. “Tell me you’re not taking her to our diner.”

He sighed. “Of course I’m not taking her to our diner. I’d never take a respectable person to that godforsaken place.”

“If you were here, I’d bite you for that.”

“Forgive me?”

“Whatever.”

“Meara…”

“You shouldn’t talk on the phone while you’re driving.” I hung up. #

I shamefully stalked all of Charlie’s classmates through his university’s website. The date could have been any one of them. Charlie himself had a digital footprint the size of a baby’s. You couldn’t find his face anywhere. His cohort was easier to locate, and I carefully scrutinized the female linguistics students’ social iconography until I became panicky. They seemed to like European bookstores and the smell of

petrichor and the color beige but only in a caffeinated sense. I had only ever posted pictures of things like mannequin arms abandoned on sidewalks, spaniels wearing too-small sweaters, an entire dining room set on a church lawn with a sign that read Please take it , though I hadn’t posted anything in a long time.

Friday, the rain let up and then I had four extra hours in my schedule. Rochelle convinced me to tag along with her friends to a mysterious party a ways off campus. I didn’t like these friends of hers. They were rowdy and couldn’t take anything seriously, but they also didn’t understand any of my jokes. I accepted because I couldn’t bear to sit in my room staring out the window, smoking flower petals, pretending I’d start my research but really only thinking of the man whom Rochelle called my “pseudo-incestuous paramour.”

At nine o’clock, I met the partiers at the campus gates and joined Rochelle in the back of the clunky black Subaru. The car smelled like weed, cigarettes, sour alcohol, and tart candy necklaces. Their conversation swam around me, but I couldn’t define anything they said through the ruckus of the heater, the stereo, their snickers, so I just leaned my head against the cool glass and watched the sliver of moon brighten and tremble above the trees, mist obscuring the road ahead.

Eventually we arrived in front of a dilapidated farm house. Cars packed the driveway, harsh drums echoed through the cracked windows, cheers following. The air slit through my skin as we made our way up along the mossy, overgrown path, Rochelle’s body heat radiating at my elbow and hip until she detached herself from me and ran ahead to join the two girls with vibrantly dyed hair. In her place, the tremor of wind swelled against my torso and through the thin satin of my top.

Two steps into the house, and the bass was so loud I went right back out, back down the broken steps. In the soggy wade of grass, I followed the shingling sounds of laughter somewhere around the house. There was a group of five dressed in punk-goth attire sitting on a pile of fallen trees, a bottle of alcohol and a carton of cigarettes between them. I sat down without being asked. A girl with a leopard tattooed on her neck asked me how I was doing, and my teeth chattered in response.

I was handed gin. I was handed a cigarette and a lighter. I was handed a large Gray Goose coat (posers). I was handed. The hand slid up my knee, up my thigh, resting near my crotch, my body frozen in place. My joints were stiff, creaking. The swigs of gin softened the

glare of lights behind, blurred the woods climbing up around me, the bodies beside me. Through the stick-like trees, the sleek branches, white shimmery figures floated past. They brightened, withered, dissolved past the gleaming brambles. The molecules seemed to glimmer upward and become stars. I thought miserably, Was this better than orphans?

Nausea coiled through my torso, and suddenly I stood, ripping away from the hand. I shed the coat off, dropped it onto the hand’s lap, then sopped away through the grass back toward the house.