his native island

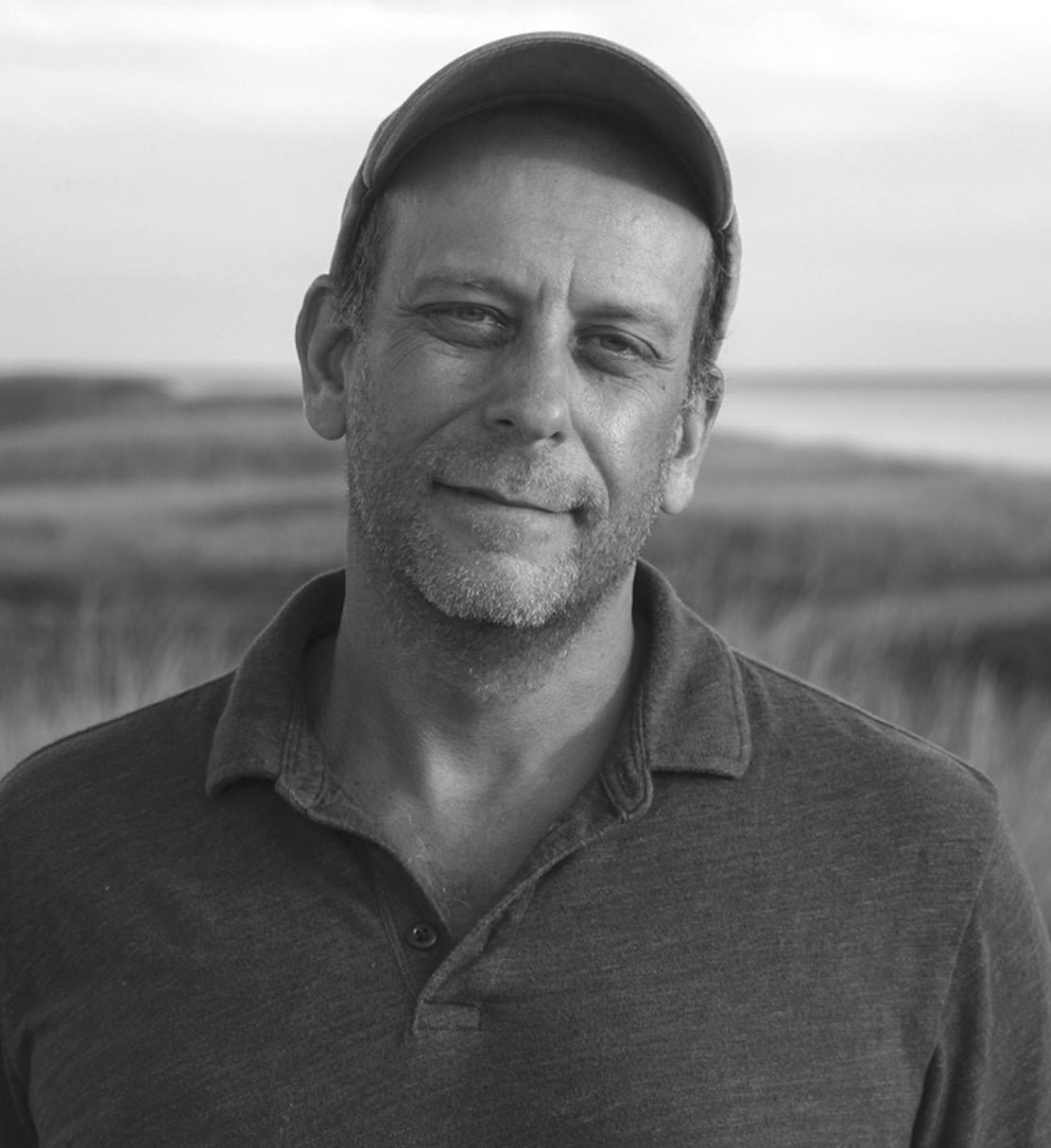

By Tom Groening Photos by Michele StapletonCampbell “Buzz” Scott has a sunny demeanor and friendly smile for the old friends he runs into as we tour Matinicus, the island some 20plus miles off Rockland where he grew up. Now 62, he reminisces with women he attended school with on the island, and has a warm exchange with an older couple who provided a second home for him and other kids when things weren’t great with Mom and Dad.

But from my perspective, the moment that anchors this visit is when Scott stands outside the home he grew up in and casually gestures to a peapod on the lawn, hemmed in by weeds, its planking looking like it would give way to a hard kick.

“This was my first boat,” he says. “My mother bought it for me for $50. She said, ‘From now on, if you want something, you’ve got to earn it.’” Another islander gave him 25 traps, he remembers, and at age 12, Scott began his working life.

A few minutes later, he is a bit wistful, looking at his childhood home, now a seasonal rental.

“The lighthouse would shine in my window every night,” he said.

They say you can never go home, but of course you can. It’s just that when it’s Matinicus, you can’t easily make a daytrip by ferry, but you can if you visit by airplane.

And on Sept. 29, that’s what we did, flying on Penobscot Island Air on a cloudless autumn day. Along with photographer Michele Stapleton, we

joined Scott with the idea of seeing the community through his eyes.

I first met Scott at a conference earlier this year, where he had a table showing his work through the nonprofit he launched called OceansWide, dedicated to removing “ghost” traps from the ocean bottom.

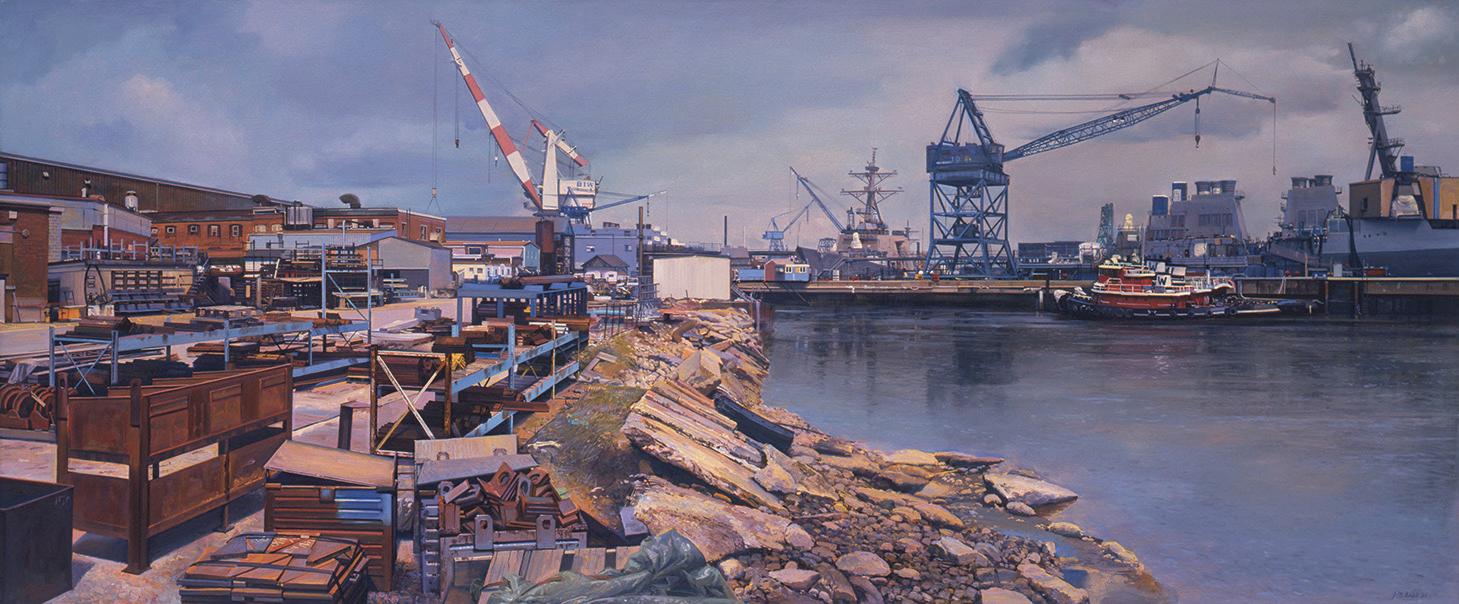

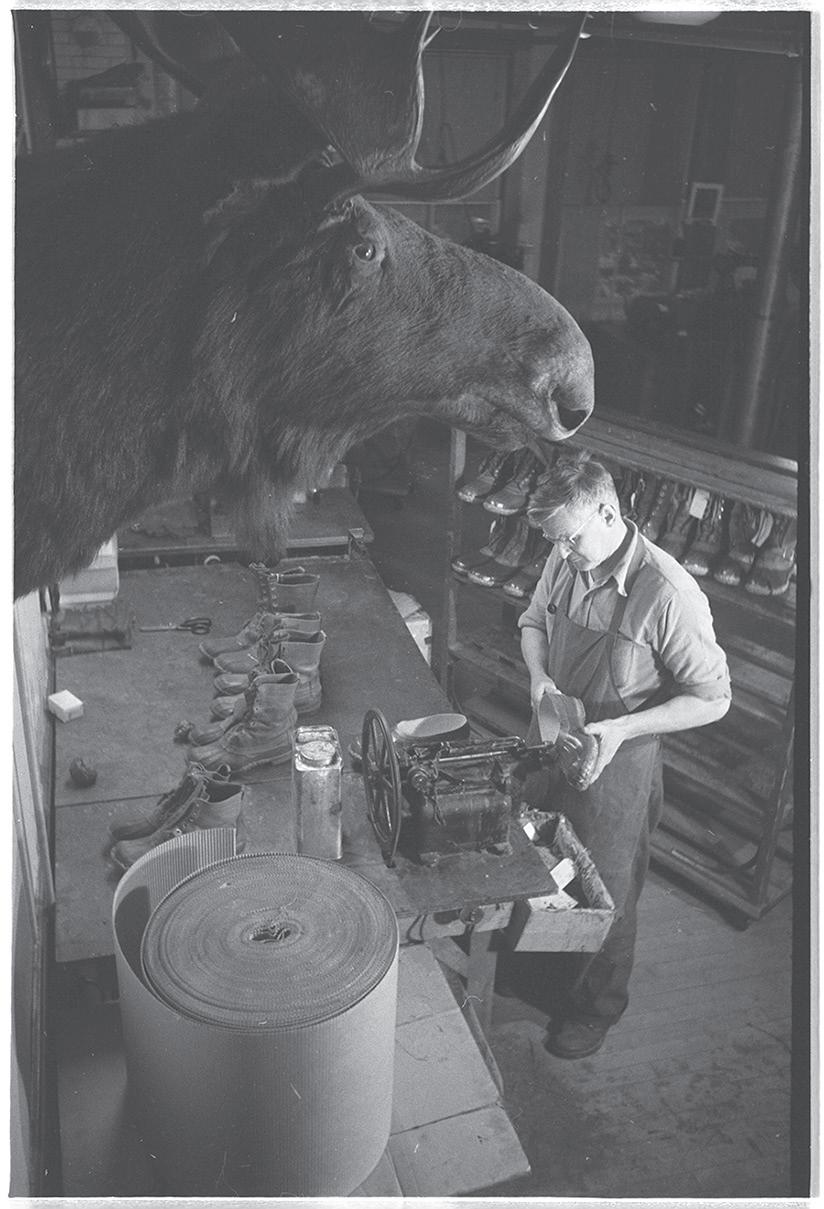

Maine boatbuilding: Busy, but fraught Diversified industry faces labor, supply shortages

By Stephen Rappaport

By Stephen Rappaport

Think of Maine and some classic images come to mind. The North Woods. Blueberry barrens. A rockbound coastline dotted with tiny communities where fishermen land

their harvest of Maine’s iconic lobster. The image likely includes lobster boats moored in a placid harbor, often among handsome sailboats or sleek powerboats. Most of those boats, both the rugged fishing boats that bring millions of dollars of lobsters and other sea creatures

ashore each year and the elegant yachts, were likely built by Maine boatbuilders, continuing a tradition that dates back a century or more.

Maine though primarily used for recre ation by 21st century “rusticators.”

CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

Historians name the 51-foot sailing vessel Virginia, launched by English settlers at the mouth of the Kennebec River in 1607, as the first ship built by Europeans in the New World, but even if one doesn’t look that far back Maine had a well-established boat building industry by the early 19th century. Shipyards along the coast built square-riggers and schooners that engaged in worldwide commerce—Bath Iron Works was founded in 1884—and countless boatyards built small fishing vessels, some, like the Friendship sloop and the peapod, still synonymous with

Boatbuilding

annual industrywide sales of more than $650 million and some 5,000 jobs.

According to the industry trade association Maine Built Boats, boat building in the state generates annual industrywide sales of more than $650 million and some 5,000 jobs. Many of those jobs are at the shipbuilder Bath Iron Works or larger yacht builders famous for their craftsmanship and technology, but there are also plenty of small boat shops where a few artisans—sometimes a single craftsman—hand build boats as elegant and technologically advanced as any.

Some builders craft boats that trace their lineage directly to the boats used a century or more ago for fishing in

in the state generates

“There’s 12 to 15 million traps in the ocean,” he says, most because their lines have been inadvertently cut by a boat’s propeller. To get an idea of the scope of the problem in Maine waters, Scott reports his group removed 3,000 from the inner region of Boothbay Harbor, all in 60-feet of water or less. Only about 20% were reusable, he said.

At one point during our visit, we stop and get out of a borrowed pickup near the harbor, and Scott gestures to a pile of traps—hundreds of them—tangled in a patch of what looks like wild raspberries.

“This island has thousands of traps on it,” he says. “When I was a kid, the island was pristine.”

A few minutes later, we walk to the working part of the harbor and see a lobster boat tied to the pier, traps being lowered aboard. Scott calls out to the men at work and confirms that they are taking decrepit traps to the mainland where they will be disposed of at a municipal trash center.

OceansWide has developed equipment to crush the traps, but recycling markets are elusive. The process begins with the wooden runners, hard plastic escape vents, and woven heads being removed.

“We’re working with Maine Sea Grant and Haystack,” the crafts school on Deer Isle, to find other uses for the escape vents, Scott said.

“They know they have a logistical issue that they haven’t dealt with in 30 years,” he said of Matinicus islanders, but now, the community agrees the gear must be removed, for which he is proud.

Scott is working with the owner of a pier on the harbor to purchase the property and set up a trap removal operation for OceansWide.

Not surprisingly, traps and boats and fishing have been a big part of Scott’s life, though that life took him far from the Gulf of Maine.

“My mother came out here when I was three,” then at about age ten, the family moved there perma nently. The house had no indoor plumbing and no electricity then.

“I basically learned to read like Abe Lincoln, with a candle burning,” he says with a smile.

“I fished with everybody out here and had boats of my own,” he said, and in his 20s, he flew a two-seater airplane, working as a spotter for an island herring fisherman.

But at age 27, an older man gave him some advice.

“I was good friends with Clayton Young, who owned the store,” Scott remem bers. Young took him aside and suggested he consider seeing the wider world.

The store burned to the ground in 2008. Scott remembers older men, World War II veterans, sitting around the stove in winter and telling stories about the island.

Despite the memories, Scott took Young’s advice and left, joining the Navy Seabees, a construction division, and served four years of active duty, including during Desert Storm in 1990-91.

“I’ve stood up and fallen into more things than I care to tell you about,” he jokes. He studied engineering, biology, and architecture at the University of Maine, then, “My first wife dragged me to Oklahoma.”

He met an old friend in Colorado who offered him the opportunity to work for a research project in Antarctica. That led to 34 trips over ten years to the region, working for Monterey Bay Aquarium’s research institute.

For a time, he worked for Bob Ballard, famed for having discovered the wreck of the Titanic, doing searches over other wrecks. He also worked on the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, five years after the oil leak there.

Scott lives in Newcastle now, but finds himself visiting Matinicus often. Walking and driving around the island, that familiarity is evident in waves and shouts of “Hey, Buzz!”

Islander Laurie Webber greeted us at the unpaved island airstrip, and we pile into her truck, drive to her house, and then she loans it to Scott.

“Back when we were kids, we all knew each other, we shared all our property,” she says. After leaving for the mainland for years, Webber now lives on the island from April to November. Her husband has fixed up the family homestead.

“My kids are fifth-generation owners,” she says.

At the harbor, we see the Island Transporter, a private ferry service, arrive with a septic pumping truck coming onto the island. Paul Murray assists the driver.

“He keeps everything running,” including the island’s electric grid, Scott says of Murray.

On our tour, we stop at Donna Rogers’ house and sit in her kitchen. She lobsters here during the warm months. Recently, she says, there has been a lot of activity in the real estate market.

“We had a big influx of homebuyers,” she says, with five or six new owners, probably related to the pandemic.

Reminiscing with the older couple who were at times surrogate parents, Scott tells a story about working on a herring seine and having two friends throw him into the net as a sort of initiation. He also recounts the time a humpback whale crashed through the net, eliciting a laconic response from one man: “Huh!”

The easy conversations Scott shares with these old friends speaks of a rare bond, maybe even intimacy, imparted by growing up on an island. It’s clear he relishes being here.

Growing up here in the 1960s, it was even harder to get to and from the mainland.

“That’s the big change,” he says. “No one went ashore in those days.”

The peapod he fished from as a boy, hauling traps by hand, is returning to the island soil. Scott hopes his plans for cleaning up the island’s derelict traps is a way to continue working here, and a way to give back to the community that he loves.

BOATBUILDING

continued from page 1

Casco Bay, around Vinalhaven, or Beals Island, with the modern lobster boat’s lines developed by designers such as Calvin Beal Jr., Ernest Libby, and the Lowell brothers—Royal and Carroll—among others. Some shops build sail or powerboats from the lines of such iconic yacht designers as Nathaniel Herreshoff or Maine’s own Joel White, or work with naval architects from around the world who draw boats at the leading edge of design.

Some boat shops are run by artisans who learned boatbuilding from their fathers or grandfathers. In Bass Harbor, Richard Stanley builds wooden lobster boats and sailboats using techniques he learned from his father, Ralph Stanley, famous for his Friendship sloops. In Yarmouth, the Lowell brothers are sixth-generation boatbuilders, descended from the legendary Will Frost, the “father” of the modern Maine lobster boat, who began building Maine’s first enginepowered fishing boats on Beals Island more than a century ago. And there are a great many small boat shops along the coast without the historical connec tions but still building classic wooden boats—sailing and power, working or recreational.

Some of Maine’s best-known yacht builders also have deep connections to Maine’s boatbuilding history.

Hodgdon Yachts, founded in 1816, is still family run and builds elegant custom sailing and power yachts, and high-speed tenders for megayachts, in East Boothbay. A few years ago, Hodgdon built an enormous oven at its boat yard to bake the carbonfiber hull and components for a record setting 100-foot sailing yacht.

Hinckley, synonymous with fine American yachts, builds its picnic boats, powerboats, and sailboats a few miles up the road from the Southwest Harbor boatyard where Henry R. Hinckley started the company in 1928 and built his first boat in 1933.

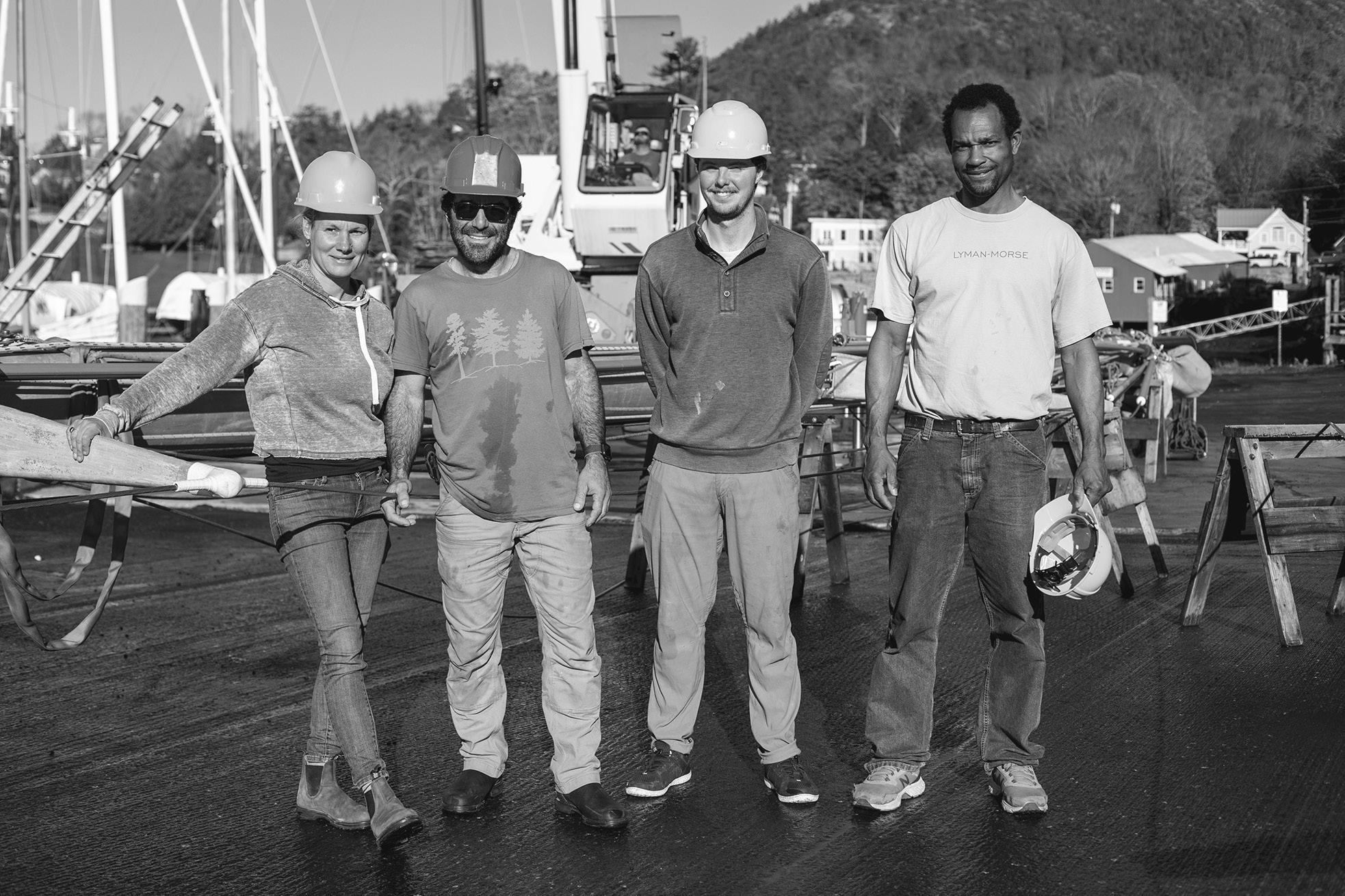

Lyman-Morse, a relative “newcomer” founded in 1978, builds custom yachts in Thomaston, continuing a tradition of boatbuilding in the former Morse family boatyard dating back more than a century.

Sabre Yachts, founded in 1970, and the younger, related Back Cove Yachts, may lack history but not pedigree. Virtually unique in Maine, Sabre and Back Cove sell their motor yachts through dealers, not directly to individual customers. The boats themselves allow relatively limited customization, but all feature a Downeast look and modern production techniques coupled with traditional Maine craftsmanship.

Large or small, Maine’s boat builders are a happy bunch, Phil Bennett, Hinckley’s longtime vice-president for sales and marketing and now a senior business advisor to the company, said recently.

“Stop in and ask for a cup of coffee in pretty much any boat shop and you’ll see smiling faces,” he said.

Because companies best known for their custom yachts—Hinkley, Lyman-Morse, Brooklin Boat Yard, Hodgdon, and a few others—“are not high-volume builders,” Bennett said, none of them has “a huge order book they have to build” to stay profitable. The compa nies he mentioned, and most smaller Maine boatbuilders too, build their boats, whether fiberglass lobster boats or custom wooden sailing yachts, to order rather than on spec. “Their order books are full,” Bennett said.

Wesmac Custom Boats builds large and expensive, fiberglass lobster boats, research and patrol boats

for state environmental and enforcement agencies, and “battlewagon” sportfishermen that venture far offshore hunting trophy-winning gamefish.

President Steve Wessel echoed Bennett’s take.

“Business is extremely strong, and it’s been strong for quite a while,” Wessel said recently. “We could build as many boats as we want.”

But Wesmac can’t really do that. Citing the wait time for a new boat of up to five years for potential customers, Wessel said “We’re turning a lot of work away.” The principal reason for the lengthy delay?

“We can’t get enough help.”

Wesmac is hardly the only Maine boatbuilder coping with a labor shortage. Hinckley, advertising jobs on Facebook recently, was offering a $2,000 sign-on bonus for experienced marine carpenters and was trying to fill several other production jobs.

Even Bath Iron Works is in a constant hunt for workers, currently advertising jobs ranging “from accounting to engineering to pipefitting to design and everything in between.”

“There’s not one boatbuilder that wouldn’t hire X number of people, if they could get them,” Bennett said.

Bennett attributed at least some of the labor shortage to the recent construction boom that sucked workers away from boatbuilding. And while he noted a recent shift by some young Mainers away from four-year colleges into technical education and traditional trades, he and Wessel both said there was some apparent reluctance among new workers to put in the long hours busy boatbuilders demand.

Assuming boatbuilders can find the help they need as construction slows, they still face plenty of issues. Wessel cited rapid and unpredictable increases in the cost of essential materials like fiberglass and resin. Bennett and other boatbuilders talked about supply chain problems that have rendered some parts and basic materials virtually unobtainable by manufac turers and suppliers Maine boatbuilders depend on.

Wesmac is hardly the only Maine boatbuilder coping with a labor shortage.Donnie Pierce of Lyman Morse stencils out custom carpentry for a customer’s yacht. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN A Lyman Morse employee hauls a boat stand as he prepares to remove a yacht from the facility. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN A Lyman Morse employee polishes a yacht’s trim while aloft in the boat yard’s largest storage shed. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN Darrin Low prepares a sail’s rod rigging for winter storage. PHOTO: JACK SULLIVAN

Also on the horizon, particularly for boat shops building lobster boats, is the uncertain impact of coming federal whale protection regulations on the lobster industry. That uncertainty is compounded by the extremely low boat price for lobster this summer coupled with the high costs—primarily for diesel fuel and bait—of fishing.

While the labor market always fluctuates and supply chain problems will abate eventually, Bennett said, boatbuilders, like fishermen, face diminishing access to the waterfront. As more people, many of them with substantial assets, move to Maine, boatyards and other shorefront owners are facing increased pressure to sell their property. Another concern: the cost of compliance with stricter environmental and workplace safety regulations, most acute for smaller boat shops.

Still, the outlook for Maine boatbuilders is hardly bleak. The industry has survived wars, depressions, a punitive luxury tax and is still going strong. The best evidence: several boatyards launched substan tial new projects—commercial and recreational—in recent months and have more big projects under construction or on order.

“I’m very optimistic,” Bennett said, “because we are different and people are starting to recognize that.”

Blue Hill’s wastewater blues

Nine towns depend on plant’s sea level rise fix

By Laurie SchreiberAtask force in Blue Hill is developing strategies to mitigate the impact of sea level rise on the town’s infrastructure and other resources. And it’s determined that the greatest risk is to the town’s wastewater treatment facility.

“It will be an expensive task to upgrade the current facility as well as to plan for a final disposition no later than the end of the century,” according to the task force’s 2020 report.

The task force is recommending that Blue Hill prepare for sea levels to rise 3 feet by 2050 and 8.8 feet by 2100. The situation impacts not only Blue Hill residents, but those of all nine towns on the Blue Hill peninsula.

“I would say the towns have an interest in being prepared and dealing with an issue before it becomes a real problem,” said Allen Kratz, convener of Peninsula Tomorrow, an ad hoc group that includes Blue Hill, Brooklin, Brooksville, Castine, Deer Isle, Penobscot, Sedgwick, Stonington, and Surry and tackles a variety of issues the towns have in common. Kratz credited the Island Institute as instrumental in getting the coalition started.

While the plant directly serves Blue Hill, there would be an impact to all nine towns if it were to shut down. That’s because Blue Hill is a regional service hub that includes a hospital, pharma cies, supermarkets, building supply stores, and other retailers and service providers—essentially, commu nity lifelines—used by residents of surrounding towns and would be affected by problems with the treatment plant.

it’s not just the hospital. It’s physicians and special ists. That’s why we were able to generate letters of support even though they’re not served by the plant directly.”

The plant dates back to 1975.

“After nearly a half century of wear-and-tear from the waters of the Blue Hill Harbor, Blue Hill’s waste water treatment facility is in need of upgrades and repairs to improve reliability for families and busi nesses in the area,” Rep. Jared Golden said in a press release. Golden noted the additional $1 million in federal funds would go toward repairs to the plant and upgrades that prevent further degradation from the rising water levels.

The Infrastructure Adaptation Fund grant was awarded by the Maine Department of Transportation. The $1 million was part of a total of $19.9 million awarded to 13 communities across Maine for municipal investments to protect vital infrastructure from effects of climate change such as flooding, rising sea levels, and extreme storms.

Other infrastructure likely to be impacted by sea level rise, storm surges, and flooding included the local fire department, town wharf, cemetery, town park…

Statewide, recipients will use the funds for projects to address flooding along ocean and river fronts, protect stormwater and wastewater systems, install culverts to reduce flooding, and ensure energy availability during extreme storms.

“The effects of climate change present significant challenges for our vulnerable infrastructure,” DOT Commissioner Bruce Van Note said in a press release.

According to the task force, the wastewater treat ment facility, at 48 Water St., is one of Blue Hill’s most vulnerable assets. It’s located less than one foot above the highest annual tide and has experienced trouble with outflow as pressure builds during high tides, necessitating the use of temporary measures.

“Rising sea levels and storm surge events have the potential to cause increasing harm,” the task force said.

The task force was convened in 2020 specifically to study the potential impacts of sea level rise, storm surges, and increased freshwater runoff from major rainstorm events on the town’s infrastructure, and to recommend adaptive strategies, a prioritization schedule, potential funding sources, and profes sional assistance.

In addition to the wastewater treatment plan, the task force determined that other infrastructure likely to be impacted by sea level rise, storm surges, and flooding included the local fire department, town wharf, cemetery, town park, and a variety of state and town roads.

Due to their low-lying locations, the fire station and town landing, like the treatment plant, have already experienced flooding as a result of high tides and storm surge events.

Northern Light Blue Hill Hospital and the Blue Hill Fire Department, both located near the waters of Mount Desert Narrows, cited a flood that was caused by an unusually high tide, which caused the outflow of a culvert, located behind the hospital, to back up.

Other areas, such as a cemetery and park, are on shoreline bluffs of soft gravel and dirt and are consid ered susceptible to sea level rise and storm surge.

Kratz helped coordinate support for a successful Infrastructure Adaptation Fund grant of $1 million, along with a request for an earmark for another $1 million federal grant pending before the Congressional appropriations committee.

“People come from Stonington to Blue Hill for medical care,” Kratz said by way of example. “The hospital has next to it a suite of medical offices, so

Most recently, the town was also approved for U.S. Department of Agriculture grant of $1.25 million and a loan for $2.75 million, with a 2.65 percent interest rate over 28 years, said Blue Hill Administrator Nicholas Nadeau.

The situation is growing urgent, he said.

“The sea level is rising, making it difficult for the current equipment to treat and pump out the treated material,” Nadeau said. “Additionally, the equip ment is outdated and on the smaller side for capacity compared to other municipalities with comparable size and influent.”

The task force identified potential strategies to mitigate the situation, including the placement of rip rap, a living shoreline, sea walls, breakwaters, and a lock—a dam-like structure that controls the amount of sea level allowed into a harbor.

Other coastal communities winning funding:

• Bath—$4 million

• Berwick—$1.425 million

• Boothbay Harbor—$4.15 million

• Eastport—$165,750

• Kennebunkport—$2.585 million

• Ogunquit—$2.85 million

• Rockland —$75,000

• Scarborough—$60,000

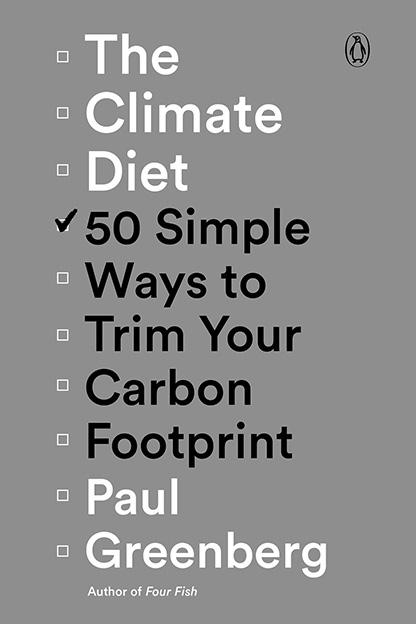

B ook R eviews

A well-deserved poetic tribute Women as lightkeepers inspired collection

Tending a lighthouse was usually a hardship posting, with deprivation of various sorts, social isolation, and serious occupational hazards. But might that life provide rewards as well as risks?

A Fixed White Light: Poems of Women Lighthouse Keepers

By Suellen Wedmore Down East Books, 2022

Review by Tina Cohen

By Suellen Wedmore Down East Books, 2022

Review by Tina Cohen

LIGHTHOUSES are often repurposed, becoming private residences, museums, or centerpieces of a park. There may be a historical charm to them, but their role in protecting and saving lives is often forgotten.

They’re a kind of benign relic now, maybe even disconnected from their raison d’etre, that sailors’ survival at sea could be completely dependent on their light, supplied by the hard work of that beacon’s keeper. And the keepers—those jobs are mostly rele gated to history, too.

Poet Suellen Wedmore, author of A Fixed White Light and poet laureate emeritus for the town of Rockport, Mass., has researched the lives of six East Coast female lightkeepers from the 19th century. She has taken their experiences and given them words in poems, as if written by them. The poems carry individualized voices, and yet themes are shared, shaped by common circumstances—where they lived and what they did.

Wedmore tells us in her introduction, “In the last half of the 19th century, more than one hundred women worked as primary keepers of our country’s lighthouses. Twice as many were assis tant keepers and many more worked without pay or recognition in their husband’s or in their father’s names...”

She reminds us that a “woman’s place” was seen as keeper of the hearth rather than keeper of a lighthouse, with its phys ical and emotional challenges of isolation and strenuous physical work. And she asks, “Were these women exceptional in their strength and endurance, or were they average women thrust into situa tions which nurtured heroism?”

The women she pays tribute to worked in places from Matinicus to Key West. Wedmore brings these women alive with vivid descrptions of their experi ences and their emotional underpin ning. Barbara Mabrity, who in 1832 succeeded her husband as keeper after his death from yellow fever, remem bers him—as Wedmore pictures it in this excerpt from the poem, “My Husband, Now I Climb”: “some clear day, will you approach and call my name? Nights, you know me: a fixed white light, keeper of the harbor.”

Catherine Moore, who took over in her adolescence after her father was injured as the keeper in Black Rock Harbor, Conn., describes her duties in “April 1820”: “I stumble toward the tower’s spiral stairs, to kindle the wicks, a signal to those uneasy in this uncaring sea.”

Abbie Burgess was 14 when she began to help her father at the Matinicus Rock Light Station off the coast of Rockland in 1853. Wedmore writes of her reality, in “Needle and Black Thread”: “...isn’t a lighthouse’s promise of smooth sailing presumptuous, when the sea prefers havoc over calm?”

Of Kate Walker, stationed with her husband off Staten Island, Wedmore imagines her disappointment with life on a sliver of rocky ledge: “The room reeks of coal and kerosene. I won’t unpack, I

think—what I want is geraniums, holly hocks, croquet on a plush lawn.”

Ida Lewis lived at Lime Rock Light off Newport, R.I., helping her mother tend the light after her father had a stroke. Then, with her mother ill after her father’s death, she maintained it alone.

Wedmore sees her keenly aware of gender discrimination. In “After Twenty Years Working Without a Contract, Ida Considers Addressing the Superintendent of Lighthouses,” she writes, “...A man would have a stipend and a contract, I serve, and yet, please do not confuse a sense of duty with weakness.”

With Maria Bray, who tended the Cape Ann Light Station off Rockport, Mass. with her spouse, Wedmore considers the Fresnel lens, a vast improvement in intensifying and focusing the light, installed there in 1864. In “Polishing the Fresnel Lens,” she pictures a mundane job maybe slightly enhanced: “Chamois in hand, I stretch toward the lens, a shimmering glass beehive taller than a man, melange of diamonds and stars, swirl away night’s soot...”.

Despite often marking frustration, fear, disappointment, longing, and sadness, the overall effect of these poems is oddly soothing. Perhaps it is because we can also feel something else those women likely felt—a sense of accomplishment. This book is a well-deserved tribute.

Girl from the hill country makes good An

originally and what she’d done in her early years. Intimidation aside, I was immediately fond of her, as were some of my newspaper colleagues. She had a calm confidence, a warm smile, and a natural beauty.

And so I eagerly read her recent memoir, Mountain Girl: From Barefoot to Boardroom. The assumptions I’d made about her name couldn’t have been more wrong. And that’s what makes her story so entertaining.

Rockefeller’s writing style is the right match for the sweep of the decades she covers. No flowery prose, no long contemplations, just a brisk account, lingering over moments that loom large, then and later, and teasing out their meaning in honest self-examination.

Review by Tom GroeningI HAVE A habit of “interviewing” people when I first meet them. Occupational quirk, I suppose. I find myself, in situations in which I am not reporting, asking people a lot of personal questions.

I met Marilyn Moss Rockefeller in the mid-1990s when she moved her busi ness, Moss Inc., to Belfast. I was editor of the weekly Republican Journal, and I remember being a little intimidated, probably because of her last name, and also because of her business success.

So, for once, I didn’t pepper her with questions about where she was from

Rockefeller (the surname came late, by marrying into the family) began life in rural West Virginia in the 1940s, living mostly with her grandparents in a setting that sounds like she could have been neighbors with TV’s The Waltons. Lots of family time, lots of gathering around food, and lots of love. Just not from her mother and father.

Her mother was an educator, and an ambitious one whose career gradually took her away from young MarilynRae (her father insisted on adding “Rae”) for longer and longer periods, coin ciding with a northerly migration from job to job.

Her father, whom she credits with teaching her to ignore gender limita tions and with embracing a tenacity to succeed, was a drinker and a wayward husband. He died while she was a child.

One of those moments came in landing a job while in college in Michigan, working for Bill Moss. Moss was a fabric artist, designer, inventor, and a reluctant and unskilled entre preneur. He also was handsome, char ismatic, charming, and almost two decades older than Rockefeller. And a drinker and philanderer, she writes.

The 1960s in Ann Arbor is depicted as a fertile environment for creativity and experimentation—she writes about a night that the band Velvet Underground and Andy Warhol crashed in the couple’s house—but not without a dark side, as freedoms created relationship casualties.

Though Rockefeller’s life had ranged from West Virginia to Connecticut, where he mother had remarried, and then to Michigan, a twist brought her to Maine. At one point, her mother purchased a place on North Haven, and in the late 1960s, Rockefeller and Moss built an experimental house—a curvy dome, covered in a specially treated paper—on the island.

Though her husband’s innovations in the tent business matched a growing trend in hiking and camping, his busi ness sense kept Moss Tents perennially broke. The couple and the company set up shop in Rockport in 1970. It was there, after countless infidelities and selfish behavior, that Rockefeller ended her marriage to Moss.

One especially interesting section of her story is when a retired businessman offers to help Rockefeller rethink the company. Lots of tough love, delivered with a smile, changed the company from losing to making money. Good lessons here for any entrepreneurs.

And yes, she finds love with James “Pebble” Rockefeller, who is everything Moss was not—kind, attentive, loyal.

She confesses to having, for a time, to share his heart with his late fiancé, the writer Margaret Wise Brown, whose Vinalhaven cottage Pebble inherited and which served as a writing retreat for penning this memoir.

If I ever meet Rockefeller again, I think I still will have a question or two. But as with any good memoir, I now feel like we’re old friends.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront.

unlikely life has a happy ending

B ook R eview

A mammoth in Maine

Swan’s Island’s Gary Hoyle tells story of ‘Hairy-it’

clay in a muddy pool in Scarborough. A major news story of the day, the find would not be confirmed until the early 1990s when Hoyle and a team of experts, assisted by dedicated volun teers used modern methods, including radiocarbon dating and exhumed addi tional body parts—a mandible, a molar, some bones—to verify its origins.

Thought to be a female, the mammoth became known as Hairy-it, the author’s affectionate nickname.

Cameos by the likes of historian and journalist Herb Adams, meteorologist Lou McNally, and famed Natural History Museum diorama designer Fred Scherer (1915-2013) add to the storyline. The last-named mentored Hoyle when he joined the Maine State Museum staff as a research associate in 1973.

Mystery Tusk: Searching for Elephants in the Maine Woods

By Gart Hoyle North Country Press, 2022

Review by Carl Little

By Gart Hoyle North Country Press, 2022

Review by Carl Little

If you’re planning to start digging for Paleolithic remains in Maine, for heaven’s sake, first read Gary Hoyle’s Mystery Tusk: Searching for Elephants in the Maine Woods. With the enthusiasm and skill of a committed storyteller, Hoyle offers a step-by-step account of the “largest paleontological excavation in Maine history.”

The mammoth—its tusk—first appeared in August 1959 encased in

Hoyle takes us through the high and low points of the project, the bureau cratic hoops and funding barrels. His dedication to the project is perhaps exemplified by his volunteering for a dinosaur dig in Montana one summer in order to gain new sleuthing skills.

He also came up with an ingenious method for mapping out the excava tion site: an ice scriber, a tool once used by ice harvesters in Maine to mark off the frozen surface of ponds and lakes.

In the chapter titled “Goodbye, Hairy-it,” Hoyle imagines the course of the creature’s life. “Looking into deep time,” he writes, “is a bit like looking through a plate glass window at a shrub-studded meadow on a foggy day.” His account cuts through the fog in a loving manner.

A recent “Behind the Scenes” video from the museum relates the sad fate of some of their brilliant creations for the “Back to Nature” exhibit, which after 50 years is being dismantled due to deterioration.

About a third of the way through the book, Hoyle begins to inter weave a second story of research and revelation: the fate of “Old Bet,” said to be the first elephant to set foot in America (it arrived in New York City from India in 1796).

At the time of the initial tusk discovery, a reporter, Waldo Pray, ventured to wonder if the appendage might have belonged to Old Bet, shot to death by a crazed farmer in Alfred in 1816. In seeking to set the record straight, Hoyle branched off from Hairy-it to follow the life and times of an elephant that would eventually set P. T. Barnum on a journey that led to the greatest show on Earth.

Casco Bay data shows rapid warming

Friends group reviews 30 years of temperatures

Casco Bay is warming rapidly, according to a 30-year data set collected by Friends of Casco Bay. Temperatures in the bay have warmed 3 degrees Fahrenheit on average since 1993. At a rate of 1 degree Fahrenheit per decade, the warming trend suggests the nearshore environment in Maine’s most populated region will continue to see dramatic changes in the coming years.

“This rise in water temperature marks an enormous shift,” reports Mike Doan, staff scientist with Friends of Casco Bay. “It’s a stark reminder that climate change is altering the bay in a fundamental way. And not only is the temper ature increasing, but the rate of increase has continued to rise, too.”

Friends of Casco Bay completed its 30th year of collecting seasonal water tempera ture data in October. The full 30-year data set shows the bay’s three warmest years on record have all occurred in the past five years, between 2018 and 2022. These data confirm that warming conditions in Casco Bay align with those observed in the Gulf of Maine and that the region’s waters are warming faster than global averages.

Scientists have linked rising marine temperatures to shifts in species distri bution. Valuable cold-water fisheries like lobster are migrating north. Green crabs, well-known for decimating soft shell clam populations and ecologi cally critical eelgrass meadows, have grown in number in Casco Bay as waters have warmed.

“Rising water temperatures cause so many impacts,” says Ivy Frignoca, Casco Baykeeper. “A significant rise in temperature can lower the amount of oxygen in the water, cause ill health for cold water plants and animals, and signal an end to a species’ ability to live here. How do we help the bay adapt to these changes?”

Slowing the rate that Casco Bay is warming will require accelerated regional and national efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and turn to renewable energy. For many people living in the watershed however, changing energy policy to reduce carbon emissions can feel beyond their influence, says Will Everitt, Friends of

Casco Bay’s executive director.

“Locally, we have a limited ability to control carbon emissions across the nation or beyond our borders. But we can control the pollution we put into the Bay,” said Everitt. “Everything we do now to improve the health of marine ecosystems can help buy

Hoyle, who is a fine artist (see “’Creators in Arms’ on Swans Island,” Island Journal, 2019), provides most of the illustrations for the book, including drawings and paintings of the mammoth and Old Bet. His art reflects his dedication to natural science, but also our emotional attach ment to magnificent creatures.

Elephants are a constant source of fascination and empathy. Consider the case of Happy, the Bronx Zoo elephant whose right to selfhood was denied by the courts last June. The first-day ceremony for a new “Forever” elephant postage stamp designed by Rafael Lopez was held on Aug. 12, World Elephant Day, at the Elephant Discovery Center in Hohenwald, Tenn. The center is part of the Elephant Sanctuary, which provides refuge for elephants that have retired from zoos and circuses.

Hoyle’s stories reconfirm our deep feelings for all things pachydermic. Thanks to him, mammoth and elephant live on, in Maine and in our imagination.

Carl Little’s latest book is Mary Alice Treworgy: A Maine Painter.

us time in the face of the long-term impacts of climate change. Actions like limiting the use of pesticides and fertilizers, reducing stormwater pollu tion, and developing our towns in ways that do not harm water quality matter. Especially in highly populated areas like the shores of Casco Bay.”

The bay’s three warmest years on record have all occurred in the past five years…

Maine’s climate goals spur changes to grid

Utilities must now plan for new energy

Analysis by Stephen RappaportUntil recently, walking into a dark room and switching on a lamp rarely prompted thoughts about where the electricity energizing the light fixture came from or how it got to where it was needed. That’s changing.

Faced with threats that come with climate change, driven by green house gas emissions from fossil fuels burned to produce electricity, Maine is converting to cleaner, renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power. Part of that effort means restructuring the state’s electric power grid to accom modate those new sources.

In 2019, the legislature enacted three laws aimed at moving Maine onto a direct path to cleaner, greener energy. The legislation called for Maine to: • cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 45 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050

• increase the state’s “Renewable Portfolio Standard”— which requires increased production of energy from renewable energy sources such as solar and wind—from the present 40 percent to 80 percent by 2030 and sets a goal of 100 renewable energy by 2050

• established new incentives for the installation of energy-efficient heating systems and created new incentives for solar power programs.

sources

Earlier this year, the legislature passed another comprehensive bill, LD 1959, dealing with the regulation of the state’s electric utilities. Among its complex provisions, LD 1959 requires both Central Maine Power and Versant Power to begin an “inte grated grid planning” process aimed at maxi mizing the reliability and functionality of their distribution systems at the lowest possible cost to customers as those investor-owned utilities deal with the mandated switch away from fossil fuels to clean energy over the next 28 years.

growth in the number of heat pumps installed in homes and businesses to replace gas- or oil-fueled furnaces, as well as the ever-growing number of electric vehicles in Maine.

Until now, CMP and Versant have been able to plan expansion and invest ment strategies to realize purely corporate interests without any meaningful input from customers and without taking Maine’s commit ment to clean, renewable energy into account.

The move from fossil fuels to renewables will certainly have an enormous impact on Maine’s electric utility companies.

The move from fossil fuels to renewables will certainly have an enor mous impact on Maine’s electric utility companies. They will have to reconfigure their distribution systems to receive power from new and less centralized generating facilities— called “distributed energy resources,” or DERs—including individual rooftop solar installations and multi-acre commercial solar farms, as well as land-based and eventually, offshore wind farms.

And the state’s “Maine Won’t Wait” climate action plan calls for an expo nential increase in the demand for electricity to power the anticipated

The only significant control on those activi ties comes through the rate-setting authority of the Maine Public Utilities Commission.

The new integrated grid plan ning process requires the utilities to consider the state’s commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions as they plan revisions to the electrical grid and to ensure that those revisions are consistent with Maine’s clean energy goals. Ideally, the process, which calls for substantial input from the public— technical and environment experts as well as customers—will make the utilities more accountable and save customers money through better use of the companies’ resources.

Southern Maine gets its own dredge

Gear will be used Kittery to Scarborough

By Clarke CanfieldCoastal communities in Southern Maine stand to benefit from a new dredge that will be used to improve navigational channels and replenish beaches from Kittery to Scarborough and possibly beyond.

The York County Commission has given the green light to purchase an 86-foot suction dredge using $1.54 million in federal funding made available through the American Rescue Plan Act. If all goes according to plan, the dredge should arrive in spring and be in operation for the 2024-25 dredging season, if not sooner.

The dredge would be managed through a newly created nonprofit organization called the Southern Maine Dredge Authority and would be rented on a “pay-as-you-go” system as dredging projects arise. In time, the goal is to have the dredge be self-sustaining from revenues generated from dredging projects for municipalities and possibly boatyards and other privately owned properties, said Al Sicard, chairman of the York County Commission.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Sicard said. “This is huge for communities up and down the coast.”

Ten federal navigational channels in the region have been dredged a total of 120 times between 1949 and 2018, generating nearly 3.5 million cubic yards of material, according to a 2018 study by the Southern Maine Planning and Development Commission that examined the feasibility of purchasing and operating hydraulic dredge equipment in southern Maine. Those navigational channels include places

such as York Harbor, Wells Harbor, the Josias River in Ogunquit, the Kennebunk River, and Pine Point Harbor in Scarborough.

But the driving force behind the initiative to buy a regional dredge was Save our Shores Saco Bay, an organization that has advocated for the need for ongoing beach replenishment at Camp Ellis, a small shoreside community in Saco whose beach has been decimated by shoreline erosion for more than a century.

A dredge is a critical tool for moving sand on a regular basis to reinforce the shoreline at Camp Ellis and other communities, much like places do in Cape Cod and Florida, said Kevin Roche, president of Save our Shores Saco Bay. Furthermore, he said, it’s also important to move beyond simply studying and discussing the impacts of climate change and take action in response to rising ocean waters.

“This is an important symbol that government is actually making an investment in infrastructure. I think it’s important that the county made the deci sion to get something physically here to help with that,” he said.

York County commissioners approved the purchase in October by a 3-2 vote. The dredge will be manufac tured by Ellicott Dredges LLC, of Baltimore, Md., and be equipped with a rotating cutter head that loosens and lifts sand and other materials from shallow chan nels to increase navigational depths and transfer the material to restore nearby shorelines.

The Southern Maine Dredge Authority will need to appoint an executive director, figure out who will serve as captain and crew of the dredge, and line up

The Natural Resource Council of Maine praises the laws requiring grid planning because it, for the first time, “holds utilities accountable for their responsibility to help Maine transi tion to a clean, affordable, and reli able electric grid quickly and cost effectively.”

Specifically, LD 1959 requires the utilities to develop plans every five years that incorporate a range of options for investments in expansion and reconfiguration of the grid. The process will, in theory, be transparent and, ultimately, will form the basis for the PUC’s work in rate cases and other regulatory matters.

Exactly how that process will work or how and to what extent the public will be able to participate are yet to be determined, but the PUC is charged with developing new rules and procedures.

Speaking at a recent seminar explaining some of the coming changes to Maine’s energy system, Jack Shapiro, NRCM’s climate and clean energy director, said the transition “requires a once in a century reimagining of the electric grid.”

The hope, and the governor’s and legislature’s expectation, is that the new integrated grid planning process will provide the framework for that reimagining.

Novel thought: time will tell.

orders for dredging jobs. Realistically, the dredge probably won’t be operating for another two years, beginning with the dredge season that runs from November 2024 through April 2025, Roche said.

State Sen. Donna Bailey of Saco has submitted legis lation to create the Southern Maine Coastal Waters Commission to oversee the Southern Maine Dredge Authority. Membership on the commission would be open to representatives from each coastal commu nity from Kittery to South Portland, and would also include representatives from the state departments of Environmental Protection, Transportation, and Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, and the Maine Geological Survey.

With rising ocean waters and climate change, coastal communities should have more control over their shorelines and not be at the mercy of the Army Corps of Engineers for dredging, Bailey said.

“Camp Ellis is a canary in the coal mine as to what can happen on the Maine coast,” Bailey said. “Although the Army Corps of Engineers periodically dredges the Saco River and dumps the sand on Camp Ellis Beach, local communities currently do not have control over the schedule or timing of the dredging. What happens when the Corps of Engineers isn’t available? What happens when there is a severe storm and a strong current that impacts not just Camp Ellis Beach, but any of the beaches along the coast of Southern Maine?

“Climate change has been increasing the severity of the storms which increases erosion and threatens the beaches. That’s why we need to have a dredge that we can call upon when it’s necessary.”

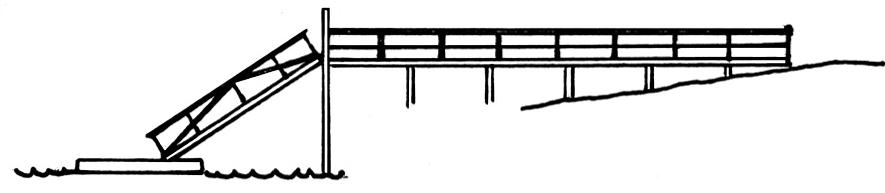

The Deer Isle causeway’s curvy history

Water flow should be part

By William A. HavilandTHE EXCELLENT ARTICLE on the vulnerability of the Deer Isle causeway (The Working Waterfront, November issue) prompts me to add some history, as well as some things to consider when planning future modifications.

Before the causeway was built, passage between Deer Isle and Little Deer, unless by boat, was at low tide across what was known as Scott’s Bar. This was not a true sand bar, but rather a sinewy line of hard clay that was slightly higher than the surrounding clam flats. Its snakelike pattern, retained by the present causeway, was the product of winds, waves, and currents.

As early as 1873, and again in 1875 and 1880, the town appropri ated the sums of $50 to fill a low spot in the bar near Little Deer. Not until the 1920s, however, was serious thought given to construc tion of a causeway. The thinking was that if ever a bridge was to connect Deer Isle to the mainland, it would have to be from Little Deer across the narrowest part of Eggemoggin Reach. But without an all-tide connection to Deer Isle across Scot’s Bar, raising money for a bridge would be difficult.

George E. Snowman of Little Deer, who was in the legislature, was able to get $15,000 from the state to begin construction of the causeway in 1927. Over the next ten years, further appropriations enabled work to continue. At first, stones were placed along the edges of the hard clay bar. As the years wore on, its height was built up until, in 1938, one could cross it at any tide. Because it followed the natural course of the hard clay, rather than crossing soft mud, it was based on a firm foundation

The causeway remained a town road until 1946, when the state was persuaded to take over full responsibility for its upkeep. At that time, the Little Deer approach was straightened and Pine Hill (on Little Deer) was quarried for stone to widen and raise the road’s height. This was perfectly adequate until the current era of over powered, bloated cars, SUVs, and monster trucks (not to mention increased traffic).

Up until the 1930s, the gap between Deer Isle and Little Deer was an important fish passage, which attracted the interest of Wabanaki Indians. Here, they built fish weirs, speared flounders, and dug clams. Interestingly, when the first colonial settlers arrived (in 1762), they did the same thing: built fish weirs, dug clams, and speared flounders. The importance of the place for the Wabanakis was reflected in two names for it: “Where the Fish Weirs Are” (the word Eggemoggin is a corruption of the Indian word) and “At the Great Fish Weir.” Also indicative is a concentration of ten known Wabanaki campsites nearby, some including

material as many as 3,000 years old to as recent as the early years of colonial activity.

A final reflection of the importance of this place is that it was chosen in 1626 for a meeting between Penobscots and colonists in an attempt to end one of several conflicts as Wabanakis defended their homeland from European incur sions. In exchange for the Penobscots laying down their arms, the colonists sent a sloop filled with trade goods as well as Indian captives for repatriation.

The gap where the causeway runs today was also an important trans portation route. An Indian canoe route ran through here, from the small cove in Brooksville known as the Punch Bowl, across the Reach and along the Deer Isle shore to a portage to Long Cove. From the Punch Bowl, a portage led to Walker’s Pond and the Bagaduce River and ultimately the Penobscot River. This canoe route remained in use from 3,000 years ago well into the 20th century. Once white settlers arrived, they also used this gap on the high water as a shortcut from the western bay to the Reach. One craft attempting this passage, in April 1859, was a whaleboat rigged as a sloop called bowcat (bow rhymes with oh). Enroute from Northwest Harbor to the Benjamin River loaded with hoop poles, it was crossing Scott’s Bar when the wind shifted, driving it on to the Little Deer Isle shore. From this inci dent, came the transfer of the vessel’s name to the body of water between Little Deer, the Causeway, Carney Island, and the facing shore of Deer Isle.

Given the historical and ecological importance of the causeway’s location, any alteration of this structure should restore the free flow of water between the Reach and Western Bay. When the causeway was completed, it blocked not only passage of watercraft, but of fish as well. Within a few years, the flounders were gone, and the last fish weir was built in 1950.

At the Sept. 20 meeting on the causeway, reported on by The Working Waterfront, Marsden Brewer of Stonington spoke of the potential benefit of restoring the flow of water for the scallop fishery. We know scallops were present on the bay side in the past, as there was a midden of scallop shells (now eroded away) on Carney Island.

And I recall in the 1950s someone hooking up significant numbers of scallops on the Reach side.

Clearly, something has to be done about the causeway in the face of climate change. We should take the opportunity to do it right!

William A. Haviland is a retired anthropologist and past president of the Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society. He lives on Deer Isle not far from the causeway.

Advertise in The Working Waterfront, which circulates 45,000 copies from Kittery to Eastport ten times a year.

Contact Dave Jackson: djackson@islandinstitute.org

Up until the 1930s, the gap between Deer Isle and Little Deer was an important fish passage…

of any repair

Be sure to feed the watchdogs

A robust press is a pillar of democracy

By Tom GroeningTHE IRONY wasn’t lost on the audience. Especially this audience.

I attended the Maine Press Association’s fall conference in Bar Harbor in late October—for the first time in over 20 years—and came away charged up and proud.

One of the presentations was by Steve Waldman, co-founder of Report For America, a nonprofit that places and helps pay for reporters across the country. Its mission is “to strengthen our communities and our democ racy through local journalism that is truthful, fearless, fair, and smart.”

At one point, Waldman was sharing his ongoing quest for donations and grants, and said one funding source told him, “We’re not going to fund reporters this year. We’re going to focus on democracy.”

With a slight raise of an eyebrow, the irony of that response was clear— because journalism is an essential part of keeping democracy functioning.

Nonprofit journalism—like that of The Working Waterfront—has been an anomaly for most of the last hundred years. But government has taken action to support newspapers, understanding its role.

Waldman said until the 1850s, news papers received a postal subsidy to allow them to mail their product. Later, political parties paid to distribute them, and then the “penny press” emerged, an affordable way for the masses to get news, with most papers at that time costing 6 cents.

Finally, advertising and reader purchases created the model we know today.

In the late 1990s, the rise of the internet changed everything, and newspapers failed to put a price on the content they shared online. And adver tising for real estate and cars, the staple of many papers, migrated online.

“I think it can go in a horrible direc tion,” Waldman said of the web, “or it can go in direction that’s better than ever.” One example of the horrible is the proliferation of what are known as “pink slime” websites which masquerade as new outlets by offering up the many press releases and calendar items that are readily available, while also including favorable content about a particular candidate or elected offi cial. Waldman asked if there were any operating in Maine, and journalists said there were at least two. Across the country, there are about 1,500, he said.

One of the most compelling arguments Waldman made for the importance of local journalism was that in small cities where papers had disappeared, bond ratings were lowered on those municipalities. In other words, without watchdogs, even bankers see how corruption can creep into government.

Since 2004, some 50,000 reporter positions have disappeared, Waldman said, which is why Report For America exists, though he admitted the 540 reporters it’s funded in the last five years are a drop in the bucket.

In the absence of local news, people turn to national TV news and social media, often skewed toward one polit ical view. From good information, to no information, to bad information is the sad progression, he said.

The Philadelphia Inquirer is now a nonprofit, Waldman said. Here in Maine, we have the Maine Monitor, a nonprofit news site.

In the evening, the press associa tion gave out awards and honored a few long-time journalists by inducting them into its hall of fame. Each had a moving story of dedication to what is a public service, just like being a teacher, nurse, and police officer.

The association’s incoming president, Courtney Spencer, an advertising vicepresident for the Portland Press Herald, succinctly captured our mission in her brief remarks:

“We are here tonight because we believe in the power of words. To inform. To illuminate. To provoke curiosity.

“We believe in the power of a photo graph. To tap emotion. To show the world as it is. To stimulate a memory.

“We believe in the power of an edit. To clarify. To deepen understanding. To expand perspective.”

This, the December-January issue, is our last of the calendar year. Please consider supporting the kind of community journalism we do by becoming a member of the Island Institute—which gets you a subscrip tion to The Working Waterfront. See: IslandInstitute.org/support.

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be reached at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

R efle C tions

Transitions and transformation on MDI

Reflections is written by Island Fellows, recent college grads who do community service work on Maine islands and in coastal communities through the Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront.

By Brianna Cunliffe

THE TIDE laps at the narrow road that joins Mount Desert Island to the mainland. Traffic jostles in the mist. All my life, I have lived in places heartbreakingly vulnerable to climate change.My new home in Tremont, on the island’s “quiet side,” is no different. Like my hometown of Wilmington, N.C., MDI’s coast is its lifeblood—a coast already battered by rising seas, worsening storms, and crumbling infrastructure. But as an Island Fellow working with A Climate to Thrive, I see this community rising to the call for transformation.

A Climate to Thrive (ACTT) came to be because neighbors at a potluck started talking about climate change. That gath ering gave rise to a nonprofit that has increased the island’s solar by seven times, pursuing energy independence for MDI

by 2030. But community-driven climate action is about more than just watts on the grid: ACTT also knows that how we transition off fossil fuels matters—tran sition can be an opportunity to build empowered, equitable, collaborative, and resilient communities. When neighbors talk to neighbors, focused on solutions, we build momentum by connecting based on what we value.

That idea is the heart of our Climate Ambassadors program, where on Wednesday evenings in the library, retirees, teenagers, business owners, church leaders, and others gather around a table, exploring their contri butions to climate action. We talk about the powerful spark of impact at the intersection of the climate’s needs, your skills, and your sources of joy. Climate Ambassadors shake off despair by cultivating and empowering that spark. The MDI pilot launched this fall, and starting Jan. 12th, we’ll take what we’ve learned statewide in a six-session training that’s free, virtual, and open to the public. Join us: www. aclimatetothrive.org/ambassadors.

This is our model: start at home,

then share as widely as possible. Our Local Leads the Way series exemplifies this. Launched in November 2021, the initiative brings together communitydriven climate action groups (and those interested in starting a group) from throughout Maine to build networks of collaboration and support, share resources, engage in trainings, and reduce duplication of effort.

Local Leads the Way meets virtually the first Monday of each month at 4 p.m.; anyone is welcome to join: www. aclimatetothrive.org/localleadstheway. Across Maine, we’re all grappling with different landfalls of the same big storm and we need all the help we can get.

The stakes are unspeakably high. But that’s never an excuse for steamrolling over our neighbors, or leaving the most vulnerable among us behind. It’s also never a reason to give in to despair.

It can be so tempting to try to reach people by talking about what will happen if we fail—the real but para lyzing realities of neighbors cut off from emergency services, lost jobs, a landscape of ecological loss. But that is not and cannot be the full story.

What does our island look like in 50 years, in a world where our choices have cut carbon emissions, re-centered equity, conservation, local food, and energy production? What precious things will we have saved, and what will we have created in the process? Thanks to my new neighbors, I live in hope of that possible future. I’m honored to work towards it every day.

Brianna Cunliffe works with ACTT on Mount Desert Island focusing on education and community-based climate action. She has worked with the National Parks Service, Appalachian Trail Conservancy, and Dogwood Alliance, and recently graduated from Bowdoin College with a degree in environmental studies and government.

STURGEON TALL—

This image from the collection of the Tides Institute & Arts Museum in Eastport shows a group of boys surrounding and holding up a sturgeon on the deck of a schooner docked at a wharf at Lubec. The photo dates to about 1910.

MDI housing crisis affects much more Community nonprofit focuses on Northeast Harbor

By Kathy MillerTHE TOWN of Mount Desert asserts in clear terms an underlying problem that radiates out into so many other issues.

“The high cost for housing is currently one of the primary driving forces behind many of the issues facing the town of Mount Desert,” the town’s comprehensive plan argues.

“An appropriate balance of housing should be sought after to support a healthy economy, and it should be kept affordable in order to avoid displacing community members to outlying areas,” the plan continues.

“Housing should be developed in a way that improves connections between and among community members to create vibrant year-round villages. It should not degrade or exhaust the natural resources that are integral to the success of this community, such as fragmenting or destroying important wildlife habitat, polluting or exhausting water supplies, or negatively impacting either natural or built scenic resources.”

These assertions are consistent with Mount Desert 365’s mission and purpose—to foster a sustainable

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kr istin Howard, Chair

Douglas Henderson, Vice Chair

Charles Owen Verrill, Jr. Secretary

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Finance Chair

Carol White, Programs Chair

Megan McGi nnis Dayton, Philanthropy & Communications Chair

Shey Conover, Governance Chair

Michael P. Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Michael Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Bryan Lewis Michael Sant

Barbara Kinney Sweet

Donna Wiegle

John Bird (honorary)

year-round community while preserving its natural environment. Our approach to achieving our mission runs along parallel tracks: supporting local businesses and creating afford able year-round housing opportunities to restore the year-round population.

The lack of housing affordable to the year-round residents who are essential to keeping our communities intact— municipal and public safety workers, medical staff, teachers, bank tellers, restaurant staff, tradespeople, and so many more—is an emerging crisis.

There are three compelling reasons we are focusing our efforts on creating housing in the village of Northeast Harbor, part of the town of Mount Desert:

• proximity to local businesses

• access to utilities

• preservation of natural areas and undeveloped land

Northeast Harbor is the commercial and municipal center of the town with the greatest concentration of storefront businesses. Having more people living here will support existing businesses in the quiet season and may make the difference in keeping them open. It may also make the difference in attracting

othe businesses many people have told us they want.

Access to utilities is the second reason. It will save money in devel oping the properties where water, sewer, and power are already in place, and most importantly eliminate the environmental disruption of digging wells and installing septic systems.

These housing issues have been a concern for decades, and Island Housing Trust continues to make real headway. But the need is still great, and the pandemic and the high financial returns of short-term rentals have only exacerbated the problem.

We know that businesses and orga nizations are experiencing hiring issues due to the year-round housing shortage. While we may not have homeless people sleeping on the streets, we do know of individuals and families pushed out of their rentals in the spring, living in their cars to finish the school year or until their rental becomes available in mid-fall.

We also know that MDI is not the only place experiencing these dire housing issues. A recent New York Times story, headlined “Whatever

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by the Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

All members of the Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront.

For home delivery: Join the Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209

E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841

The Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

Happened to the Starter Home?,” iden tified communities across the country with similar issues. It included this: “The starter home has always done a lot of work. It builds equity, creates stability, gives shelter from landlords and inflation. It has been an incubator of small businesses and community institutions like day care centers.”

What we are working to create may be starter homes or forever homes, but the outcomes of equity, stability, shelter, and incubation still apply.

Market forces will not fix our housing problem, which is reaching a crisis level. It needs an intervention and a commit ment to move forward with plans that will relieve the stress for the long haul while maintaining the character of the town we all love.

Kathy Miller is executive director of Mount Desert 365, a nonprofit, community-based organization dedicated to promoting long-term economic vitality of the town of Mount Desert, through expansion of year-round residential communities and economic revitalization of commercial districts.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine.

Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of the Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

JUST DUCKY—

Those people driving over Belfast’s Route 1 bridge or walking along the harbor on Saturday, Oct. 22 saw the Duck of Joy emerge from the fog. The duck had appeared on the waterfront last summer, then seemed to migrate south to Islesboro. Several days later, winds kicked up and the duck was again bound for Islesboro, with Belfast’s harbormaster boat in pursuit. The duck’s ownership remains in the fog.

A close working relationship with your insurance agent is worth a lot, too.

We’re talking about the long-term value that comes from a personalized approach to insurance coverage offering strategic risk reduction and potential premium savings.

Generations of Maine families have looked to Allen Insurance and Financial for a personal approach that brings peace of mind and the very best fit for their unique needs.

We do our best to take care of everything, including staying in touch and being there for you, no matter what. That’s the Allen Advantage.

Call today.

(800) 439-4311 | AllenIF.com

This holiday season, give the gift of comfort and hope with a donation to the American Red Cross. You can give a meaningful gift that helps people through some of life’s toughest moments.

Donate today at redcross.org

We are an independent, employee-owned

company with offices in Rockland, Camden, Belfast, Southwest Harbor and Waterville.

Owning a home or business on the coast of Maine has many rewards.PHOTOS: JOSH POVEC

UMaine study finds ‘tick clusters’ in Acadia Deciduous,

Acadia National Park is one of the most beautiful and popular places to visit in Maine, for tourists and residents alike. With so many visitors, Acadia is a hotspot for exposure to tick borne diseases, which are on the rise in the state. A new study from the University of Maine has found clusters of tick populations in the park, which could help inform prevention strategies for tick-borne illnesses like Lyme disease.

Former UMaine master’s student Sara McBride, now a medical entomologist for the Indiana Department of Health, and Allison Gardner, associate professor of arthropod vector biology at the University of Maine School of Biology and Ecology, led a team of researchers from UMaine, Cornell University, and the National Park Service in overlaying tick surveys with ecological habitat feature data to model the risk of exposure to tick-borne disease in Acadia.

The researchers collected black legged ticks at 114 sites across the park over two years and mapped that data

out on the park’s landscape features. The results showed that tick density varies significantly across the park, but is particularly high in areas with deciduous forest cover and relatively low elevation, especially the northeast area of Mount Desert Island.

“Understanding the spatial distribu tion of tick exposure risk in the park may ultimately inform practical environ mental and public health management strate gies,” says Gardner. “For example, the National Park Service could post informational signage in areas that have high tick densities, or build boardwalks in known tick habitat.”

The researchers then chose 19 of the sites and looked more deeply at the microclimate conditions, vegetation, and activity of tick host species like mice and deer to further explore the fine-scale patterns of tick distribution. They found significant differences in microclimate conditions and vegetation across the sites, but not in host activity. Mean temperature

SWANS ISLAND PRIME WATERFRONT

and mean humidity at the sites corre lated with tick nymph populations and may provide a link between landscape features and blacklegged tick densities.

“Sara [McBride]’s study is novel in her attempts to link broad associations between tick densities and landscape features with the fine-scale microhabitat conditions that are directly experienced by ticks and may influence their survival and host-seeking behavior,” says Gardner.

The researchers also tested ticks and

small mammals in the area for multiple tick-borne pathogens and found a variety of them, including the patho gens that cause Lyme disease, babesiosis and anaplasmosis. Therefore, the results could help inform the exposure risk for different areas of Acadia National Park.

The study was supported by Schoodic Institute at Acadia National Park through a Second Century Stewardship Fellowship. The study was published Oct. 22 in the Journal of Medical Entomology.

Panoramic ocean views at the Northwestern tip of Swans Island. Fabulous offering is one of the most unique & spectacular of its kind in the state. Incredible 151 +/- acre parcel with nearly two miles of ocean frontage. Covenants in place for a dock in Seal Cove. Seller has already acquired engineered plans and the dock itself. Privacy. Seclusion. Magnificent Views!

Offered at $1,200,000

The

Davis Agency Real Estate & Vacation Rentals 363 Main Street, SW Harbor 207-244-3891 www.DavisAgencyRealty.com Email: davco@daagy.com

The researchers collected blacklegged ticks at 114 sites across the park over two years…

low vegetation favored by arthropods

A rugged island outpost

Photographer Michele Stapleton visited Matinicus in the outer reaches of Penobscot Bay in late September (see front page story) and captured the rugged beauty of this island outpost.

Photographer Michele Stapleton visited Matinicus in the outer reaches of Penobscot Bay in late September (see front page story) and captured the rugged beauty of this island outpost.

Our Island Communities

Housing is top need, survey finds North Haven narrows focus on town issues

By Sophie HansenTHE TOWN of North Haven is taking steps to address three issues affecting the year-round community:

• access to housing

• economic diversification and workforce development

• environmental sustainability and climate change impacts.

The limits imposed on human, natural, and housing resources on an island intensify these issues drastically.

According to Mia Colloredo-Mansfeld, an Island Institute Island Fellow working with the town on the community vision process that started in late August 2021, the priorities were determined after a commu nity survey and focus group conversations. A vision statement was created from this research.

“A vision statement and some clear priorities around that statement would help us focus and make good choices,” observed Town Administrator Rick Lattimer.

According to a findings report, 137 out of 387 people who participated selected access to housing as their highest priority.

Rex Crockett, 84, who was born on North Haven and has lived here for the last 60 years, said the hot real estate interest is changing the island.

Calling island artists, writers, creative spirits The Island Reader seeks submissions for 2023

The Island Reader, a creative arts anthology published annually by the Island Outreach program of Maine Seacoast Mission, is accepting submissions for its 2023 edition. The theme for this, the 17th edition, is “Island Families.” Creative works can relate to the theme or express the unique and beautiful experience of living on one of Maine’s outer islands.

Submissions are open to everyone who lives or spends time on our islands. Please submit work to The Island Reader through Maine Seacoast Mission’s website via this link: https:// seacoastmission.org/sunbeam/island-outreach/ the-island-reader/

Submission guidelines are available on the website. The deadline for submitting is Dec. 31. Express your creative side and island experi ence in The Island Reader. We would love to include you!

“These houses that come up for sale are just bought by the summer people which takes a home out of the year-round community,” he said.

Davidson Realty currently lists just two available homes on the island, selling for $500,000 and $6.4 million.

Lattimer explained that along with price increases, it is a lot more lucrative to make one’s house available for short-term rentals than longer term year-round rentals. Colloredo-Mansfeld added that on the island there is very limited housing stock, and the housing options that do exist are often not winterized.

To combat the housing crisis, the town is trying to shrink minimum lot size requirements and is applying for state money to support the creation of up to 12 rentable living spaces.

“There needs to be more places to live, especially for young people,” Crockett said.

Economic diversification and workforce develop ment were rated as the second highest priority.

Workforce development priority involves trying to get people, especially young people, trained in the trades, such as plumbing and electrical work. Colloredo-Mansfeld said they are “recognizing that there is a lot of demand for different services that aren’t being met on the island.”

Environmental sustainability and climate change impacts were rated as the third highest priority.

According to Lattimer, the island is particularly vulnerable to climate change, especially the village which has buildings just feet from the water. The town hopes to receive state money to fund building improvements to help mitigate the effects of climate change.

One of their first action steps is to make townowned facilities more sustainable and eco-friendly as well as engaging young people in raising aware ness about climate change and helping to reduce its impacts.

Maddie Hallowell, 24, who grew up on the island said, “This work is really important because it shows that the town cares about the North Haven commu nity and wants to move forward, not fall behind the rest of the world.”

Lattimer explained that no one cares who solves these problems or who gets the credit; it is just impor tant that these issues start getting addressed.

Sophie Hansen is a student at North Haven Community School.

A belfry, a rope, and a Leatherman

Island church celebration saved by women

On Aug. 15, 1957, an article appeared in Stonington’s Island Ad-Vantages newspaper reporting on the Isle au Haut church centennial: “Sunday was a great day down on the Gem of the Penobscot. The occasion was the centennial of the Isle au Haut Congregational Church. As the entire community walked up the long boardwalk to the church, the codfish weather vane pointed proudly to the westerly as it has done so many times during the course of the century, for this church and its steeple has not only been a spiritual guide to the bay for the past 100 years, it has also been a landmark for many a mariner in time of doubt.”