News from Maine’s Island and Coastal Communities

Short-term gain, long-term pain?

Ordinances seek to stem exodus of year-round housing

ANALYSIS BY JACK BEAUDOIN

Short-term rentals have a long and storied history in Maine’s coastal communities. On Mount Desert Island, for example, many families who “head up to camp” each summer rent their homes to seasonal visitors to earn extra income. In communities like Peaks Island and Deer Isle, families have long offered rustic cabins—without heat or insulation—to summer tourists seeking a few weeks on the seaside.

But planning officials say that since the COVID pandemic first struck, changes to both the nature and quantity of short-term rentals have become problematic. Today, houses historically used as year-round residences are being converted to short-term rentals, marketed on platforms like Airbnb and VRBO. Investors are buying properties, sight unseen and above asking prices, and in some cases, dislocating existing renters.

As a result, coastal towns that once absorbed the influx of tourists and seasonal residents without disruption now fear they could turn into clusters of vacation-only houses that go dark in the fall. Beyond empty neighborhoods, the trend may be making it harder and more expensive for workers to get to their jobs, undermining the local economy.

SPRING IN WINTER HARBOR —

“We saw a lot of year-round renters being kicked out, evicted continuously out of their properties,” Bar Harbor Planning Director Michele Gagnon says. “We also had testimony of a lot of people not being able to find housing and therefore living in situations that were less than ideal... People living in closets, to cars to a large number of people in one room just trying to figure it out.”

Beyond the impacts to individuals, some fear that growing numbers of short-term rentals may threaten the year-round sustainability of the communities themselves.

“What are we going to do here on MDI if you don’t have people here in the wintertime to go to the schools or shop at the local grocery store and keep

continued on page 5

Tourism research: Appeal to diverse visitors

Length of stay grew in 2023, but rain hurt

BY TOM GROENING

It’s not enough to put “Vacationland” on your license plate, have the world’s best supply of lobster, and host an island-based national park. The tourism marketplace is congested

and competitive, and for Maine to remain successful, it must respond to visitation trends.

The benefit of seeking and catering to a diverse population—including those who identify as Hispanic and LGBTQ—was one takeaway from the

CAR-RT SORT POSTAL CUSTOMER

Governor’s Tourism Conference in Portland on April 25.

Keynote speaker Danny Guerro, CEO and founder of The Culturist Group, described himself as gay and Hispanic and noted that “culture is king” among LGBTQ and brown/ black travelers. Some 93% of Hispanics travel with family, and 36% of Hispanic millennials travel with their parents.

“That’s what comes to mind now when I think of Nashville,” he said.

“ Tourism assets are also what make people want to live here.”

The size of this market should not be ignored, Guerro said, with 25% of Gen Z (born between thee late 1990s and early 2010s) identifying as Hispanic/ Latino, 14% identifying as black, and 6% identifying as Asian. He argued that “multi-cultural and inclusive marketing is mainstream marketing.”

DECD Commissioner

Heather Johnson

Maine’s tourism numbers from last year were good—visitation was down slightly, to 15.2 million from 15.3 million in 2022. But spending was up—$9 billion, up from $8.6 billion in 2022, probably tied to inflation. Individual visitor spending increased from $563 in 2022 to $593 in 2023. Spending in the tourism sector supports 131,000 jobs and $5.7 billion in wages, according to state contracted analysts, saving $2,400 in household taxes.

And an important indicator for Maine, the average number of night stays, also was up, from 4.5 to 4.8.

Guerro recounted a story from friends who, he said, were harassed in a bar in Nashville because they were gay.

Speakers acknowledged that the rainy summer last year dampened

continued on page 4

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID PORTLAND,

PERMIT

ME 04101

NO. 454

published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com published by island institute n workingwaterfront . com

free circulation: 50,000

volume 38, no. 4 n june 2024 n

A shaft of sunlight strikes a lobster boat in Winter Harbor in late April. PHOTO: TOM GROENING

Sea Meadow on firmer ground with funding

Federal grant strengthens Southern Maine working waterfront

BY CLARKE CANFIELD

Anonprofit that owns a waterfront property in Yarmouth serving multiple marine-related businesses has received $790,000 in federal funding that will allow it to make much-needed improvements and position itself for future growth.

The Sea Meadow Marine Foundation will use the grant to extend water and sewer lines to its property on the Cousins River. It will also replace the retaining wall, or bulkhead, for its wharf and rebuild its boat launch.

The property, simply called Sea Meadow, is used as a base for aquaculture businesses, boatbuilders, dock and boat storage, a marine construction company, and a rowing club. The improvements will help those establishments and make the property more appealing for other marine-related businesses that need waterfront access, said Chad Strater, president of the Sea Meadow board.

Casco Bay including aquaculture and electric boats, along with educational opportunities and scientific research projects.”

Sea Meadow is a 12-acre parcel along the tidal Cousins River, which flows into the Royal River and into Casco Bay. The property is located on a dirt road about a quarter mile from busy Route 1 and has been occupied by two boatbuilders for decades.

Working boatyards with multiple tenants are at a premium in Maine…”

With pricey waterfront property being bought up and developed in Southern Maine, it’s important to demonstrate that Sea Meadow cannot only be economically viable, but can also serve as an economic driver for the region, he said.

“We want to make this a model and say with these improvements, this is a source for the community for jobs, for connections to food sources, for connections to the water,” Strater said. “It’s something that a hotel or a condo development isn’t going to provide. We want to show it’s extremely valuable as a part of the way of life.”

In announcing the funding, Maine Congresswoman Chellie Pingree said it’s vital to protect waterfront properties for businesses that require ocean access. Pingree nominated Sea Meadow for what is known as community project funding, which was included in the federal appropriations bill approved by Congress in March.

“In the face of climate change and heavy development pressure, it is more important than ever that we work to protect our disappearing working waterfronts,” Pingree said in a statement. “The Sea Meadow Marine working waterfront supports a variety of businesses that require marine access to

Strater headed the effort to create the Sea Meadow nonprofit foundation, which bought the parcel for $1.2 million in December 2021. Strater and his business partner had been leasing land on the site for their marine construction company for a few years, but they were concerned that the region would lose a valuable working waterfront property if it was sold for development.

As a nonprofit, Sea Meadow is now used by a number of aquaculture companies to keep their equipment and launch their boats to tend to their kelp, oyster, and scallop farming operations. It’s also home to two boatbuilders, the Yarmouth Rowing Club, and Strater’s marine construction company, The Boat Yard, which also sells electric outboard motors, pumps, and other equipment.

The grant funding will be used to pay for water and sewer lines to be extended from Route 1 to the property. That will allow for sprinkler systems to be installed in buildings. Down the road, Strater envisions building bathroom facilities for tenants, instead of relying on a portable toilet and water that’s trucked in.

Money will also fund construction of a new bulkhead for the property’s wharf, where tenants load and unload their vessels and barges. Strater hopes to use what’s known as greenheart timber, a non-treated tropical wood commonly used for piers, docks, seawalls, and other marine uses.

The grant will also pay for the reconstruction of the boat launch, which is in bad shape and now can’t be used at high or low tides.

Pingree’s office said it typically takes a few months or longer for the funds to become available, but Strater is hoping that the water and sewer extensions and the wharf improvements can take place by fall. The permitting process is already complete for the wharf construction.

The boat launch, he said, will probably take longer because the Sea Meadow Marine Foundation still needs to get the appropriate permits.

When the foundation bought the property, it was financed through Coastal Enterprises Inc., a community development financial institution based in Brunswick whose goals include protecting waterfront-related jobs.

CEI liked that Sea Meadow would preserve a working waterfront property and help bolster marine-related businesses in Southern Maine. It was also impressed that Sea Meadow planned not only to preserve the property, but also upgrade and strengthen it for the future.

Nick Branchina, CEI’s director of fisheries and aquaculture, said the federal funding is vital for Sea Meadow’s long-term goals.

“CEI understood from the outset how critical it was to support the Sea Meadow project,” he said. “Working boatyards with multiple tenants are at a premium in Maine, and challenges in both gentrification and severe storm damage are making them become all the more endangered. We see in Sea Meadow the resident businesses and aquaculture operations that will be pivotal in sustaining a working waterfront amidst a rapidly changing commercial waterfront.”

2 The Working Waterfront june 2024

Chad Strater stands on a barge at Sea Meadow’s wharf. With the new federal grant, Sea Meadow will replace the wharf’s retaining wall. PHOTO: CLARKE CANFIELD

An aerial view of Sea Meadow waterfront marine center in Yarmouth. PHOTO: COURTESY TAYLOR APPOLONIO

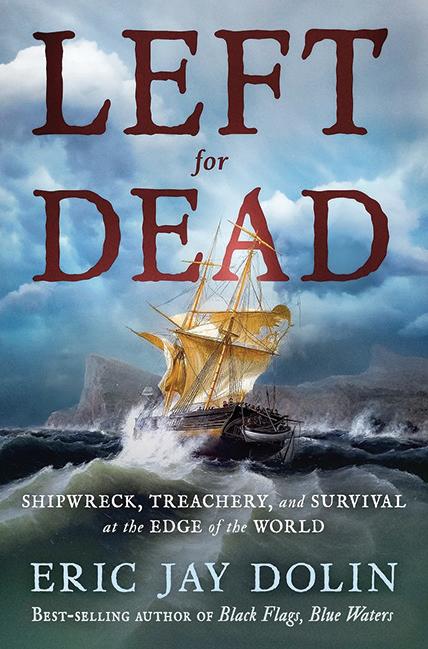

Left for Dead author Eric Jay Dolin

Forgotten maritime drama retrieved from history

BY STEPHANIE BOUCHARD

Eric Jay Dolin says he loves all the books he’s written, but his latest one, Left for Dead, is special, he says. “This may be a hard thing for an author to say, because why wouldn’t an author always say that their book is great?” he says. “But, this is definitely one of the most exciting, the most focused and the most novel-like of any of my books.”

Released on May 7, Left for Dead tells the kind of dramatic and emotional tale that stories about mariners and the sea are renowned for: adventure, near-death experiences, perfidy, courage, and wonder.

Set against the backdrop of the War of 1812, the book recounts the struggles of an American sealing crew and the wreck of a British ship carrying passengers home to England, including a pregnant woman who gives birth, on the deserted Falkland Islands, and the treacherous machinations that leave five of those people and one remarkable dog abandoned.

The Working Waterfront spoke to Dolin in April. What follows is an edited version of that conversation.

WW: You say in the book this story isn’t largely known today, even to historians. How did you find it?

A lot of these stories are the most dramatic because people die, people wreck, people get lost, people stay at sea for four or five, six years…

Dolin: The way that I come up with topics, oftentimes it’s when I’m working on a book and in working on that book, I stumble across some other topic. That’s not what happened here. There’s a book written in the 1970s by a professor in the Midwest. It was basically just an annotated list of maritime disasters and tales from the 1600s up through the early 1900s.

Dolin: The Americans viewed this as a humanitarian gesture, and of course as human beings, they had to reach out to these desperate individuals who had been wrecked on this desolate island. So, they came up with an agreement, which they thought was fair and the right thing to do, but then you get the British officer, D’Aranda, showing up, and he didn’t care at all about this agreement that was reached. Not only didn’t he honor the agreement, he viewed this as an opportunity to get a prize of war. And even worse than that, is when they left the five hunters on Beaver Island. It was a cold-hearted thing.

WW: Why are we so fascinated by people who go out to sea?

Dolin, the author of numerous books of maritime history, such as Leviathan and Rebels at Sea, will be in Maine in the coming months promoting Left for Dead, including a presentation with local maritime author James Nelson on May 15 at Maine Maritime Museum in Bath. Check his website, ericjaydolin. com, for events, and to read the first chapter of his new book.

When I looked through that book, I came upon this story of Charles Barnard and the Nanina going to the Falkland Islands. The paragraph was very brief. It didn’t have a lot of details, but it did mention that five men were marooned on the Falklands for about 18 months, and that got me really interested. He listed a couple of books, and one was written by Charles Barnard himself about his experience on the Falklands. I read his book and I said, “Oh, this is a great story.” It was dramatic, it was unknown, it involved maritime issues—which always excite me—and it had some really good characters in it.

WW: One of the most compelling things for me was the juxtaposition of the decisions the Americans made when offering help to the wrecked British passengers versus those of the rescuing British. On the record with…

UMaine funded for marine science program

SENS. SUSAN COLLINS and Angus King announced that the University of Maine has been awarded $2.4 million in funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF). This grant will create pathways for recruiting rural students and support the retention and graduation of high-achieving, lowincome marine science students with demonstrated financial need at UMaine.

“The University of Maine helps to inspire and prepare students to become the next generation of leaders in a variety of STEM fields and contribute to Maine’s blue economy,” Collins and King said in joint statement. “By supporting scholarships for students pursuing bachelor’s degrees in marine science, this federal funding will contribute to our state’s need for welltrained scientists, engineers, and technicians now and in the future.”

Specifically, this project will fund scholarships to 25 full-time students pursuing a bachelor’s degree in marine science. It will also support the advancement of scholars through the establishment of a scholar success mentoring network, along with optional participation in undergraduate research experiences, professional development workshops, networking opportunities, summer internships, and a variety of cohort-building activities.

The NSF supports research, innovation, and discovery to provide a foundation for economic growth in the U.S. Founded in 1950 by an act of Congress, the NSF is an independent federal agency that works to advance the frontiers of science and engineering so that our nation can develop the knowledge and cutting-edge technologies needed to address current and future challenges.

Dolin: I think there are a lot of reasons, one of which is the ocean and people going out in the ocean and doing their business in the great waters is such an important element of American history. We were for many years a maritime nation.

But another element is, for many people, it’s an alien part of our history. When we read stories about whaling, about sealing, about exploration like by Capt. Cook and other people, I think most people don’t have that as part of their daily experience. And it’s like being a voyeur on a totally different story of life.

And it’s fascinating because it’s dramatic. A lot of these stories, the ones that you hear about, are the most dramatic because people die, people wreck, people get lost, people stay at sea for four or five, six years and come back to a totally different family in some cases.

This has always puzzled me: for whatever reason, stories about the

ocean are viewed by us as romantic. It was not romantic at all. We marvel at the sheer courage that these people displayed in pursuing their livelihood. Unfortunately, in many instances, they were forced to do this for economic reasons. I mean, going out in the open ocean, especially as one of the crewmen, was not a particularly great way to make a living, but there weren’t a lot of great ways to make a living back then on land or at sea, and you did the best you could and you took the risks as they came.

Meet the Author: May 15, 1 to 2:15 p.m., Maine Maritime Museum, 243 Washington St., Bath. Event is free, but registration is required. Go to mainemaritimemuseum.org/event/ author-event-eric-jay-dolins-left-for-dead.

Washington County bilingual program funded

SEN. ANGUS KING has announced that Mano en Mano/Hand in Hand has been awarded $831,000 through the federal government’s appropriations package to expand affordable childcare services in Washington County. The funding will support Maine’s sizable farming and agriculture workforce and economy, by expanding the capacity of the non-profit Rayitos de Sol Bilingual Childcare center through the construction of a new, larger building.

The funding is part of the $454 million—for 185 projects — that the entire Maine delegation secured for state projects in the fiscal year 2024 appropriations package.

“Affordable and accessible childcare is one of the most pressing needs for working families in Maine,” said King. “This funding will be a critical investment in the Washington Country

community and ensure our hardworking farmers and seasonal agricultural workers can continue providing for their families. Access to childcare allows parents the opportunity to succeed in the workplace while having peace of mind that their children are well-cared for and safe.”

The funding allows the program to expand to serve 64 children, “connecting families from different backgrounds and celebrating language and culture to enrich our whole community,” said Sean Douglas, Mano en Mano/Hand in Hand Operations Director. “This support will help Rayitos de Sol Bilingual Childcare serve infants and develop after-school programming, as well as expand our culturally nourishing food pantry, and build outdoor spaces to encourage nature-based learning.”

3 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2024

Eric Jay Dolin

Online from Peaks Island, it’s ‘Today in Tabs!’ New York Times touts Rusty Foster’s eclectic content

BY DORATHY MARTEL

From his Peaks Island home, Rusty Foster makes a living writing about other writers’ writing. And sometimes other writers write about him. And then maybe Foster writes about the things other writers write about him. His e-newsletter, “Today in Tabs,” is consistently meta and tongue in cheek.

For example, regarding a recent profile about him in the New York Times, Foster said, “I am glad that someone finally wrote that I’m ‘something of a Zelig-like figure in internet history.’ That’s not for me to say, of course, but it’s true and Steven Kurutz is right to say it.”

Available online for free at todayintabs.com, with additional content available to paying subscribers, “Tabs” is crammed with content about media, politics, and all manner of absurd happenings.

The April 29 offering references (among other things) renegade zebras and the rodeo professionals who recaptured them; Jerry Seinfeld’s grievance against “woke culture”; President Garfield’s least favorite day; and an un-stallable plane that stalled. There are also links to the source material, screenshots of tweets, and embedded videos.

TOURISM

continued from page 1

For a reader with a taste for eclecticism and irreverence, it’s easy to fall down a rabbit hole of content and come up wondering where the time went. Writing new posts for “Today in Tabs” four days a week, however, is more like putting a puzzle together, Foster says.

“I read broadly but usually not deeply,” he says. “I read whatever comes in and I think, ‘what is the shape of this?’”

Sometimes he does more research, looking for additional views. And if he still can’t find the shape around which to craft a piece of prose? “If not, I write a sonnet instead,” Foster says.

“Tabs” is Foster’s forum for commenting on the things he reads, most of which come his way through social networks. His circle includes people who have worked in media outlets such as “Buzzfeed” and similar New York-based blogs. “I have ties back to the community there— early blog writers and people building [tech] tools,” he explains.

“Tabs” is Foster’s forum for commenting on the things he reads, most of which come his way through social networks.

Stephen Colbert to support writers on his show “The Colbert Report.”

Foster started “Tabs” in 2013 and stopped in 2016.

“I thought it was finished,” he says.

He worked for a software company from 2016 to 2020, helping to develop a product called Scripto, which enables writers to develop scripts collaboratively. The company was cofounded by

In 2021 Foster resurrected “Tabs.” This was not a pandemic-driven decision. Foster didn’t want to stay in software, was already working remotely, and he wanted to get back to writing. Asked whether he currently sees “Tabs” as a lifelong endeavor, Foster says, “I can’t imagine that about anything. Historically I’m not good at doing something for more than seven years.”

Kurutz, the New York Times reporter, wrote that “a surprising thing” about “Today in Tabs,” “is that Mr. Foster

writes it from the bucolic setting of Peaks Island, Maine.” Foster, though, doesn’t see anything unusual about covering his diverse subject matter from Peaks.

“Peaks is a unique place. It’s an island; when the boat stops, you’re not getting off the island. There are 1,000 people in one square mile. In a lot of ways, it’s an urban neighborhood and in a lot of ways it’s a country village.”

“I feel like [the Times piece] presented a dichotomy,” he says. “It’s the weird parochialism of New Yorkers. And Mainers are the same way. I find all of us charming.”

the market, since travelers today are savvy enough to check forecasts before booking. A precipitation graph showed higher rates in May, June, July, August, and September in 2023 over 2022.

In her remarks, Heather Johnson, commissioner of the Department of Economic and Community Development, which includes the Maine Office of Tourism, speculated that the rainy weather may have driven visitors to restaurants, thereby increasing spending.

She also noted that what lures visitors to Maine for vacations might also boost population.

“Tourism assets are also what make people want to live here,” she said. One wrinkle whose impact will not be known until next year is the recent eclipse.

“The eclipse traveler,” coming to Maine because of it being in the path of totality, “was a really unique and different traveler,” Johnson said. Many were surprised at the lively and interesting towns they found, she said, citing anecdotal reporting.

Among the state’s strategic goals in 2022 was increasing off-season visitation; in 2023, fall and winter visitation increased from 6.2 million to 6.7 million. Still, 52% visited in spring and summer. One 2022 strategic goal for the state that was not met was growing the number of non-white visitors; the 2022 rate of 11% remained unchanged in 2023.

Sara Meaney of the Coraggio Group, a firm contracted by the state, emphasized that the industry must see itself as stewards of tourism assets, which include:

• Community well-being and inclusion

• Protection and respect for heritage and culture

• Environmental preservation and ecological balance

• Economic value and prosperity

She urged players in the industry to “amplify the essence of Maine” to attract the travelers who are best aligned with the state’s experiences and ethos, and to prioritize diversification of visitors.

Joseph St. Germain of the firm Downs & Germain Research explained the tourism marketing brand pillars:

• Escape to nature

• Small town spirit

• Food

• A place to pause

The culinary draw is especially appealing to millennials and Gen Z, he said. And nationwide research shows that 90% of travelers want to

DREAM

experience a destination “like a local.”

The Maine Office of Tourism includes just a handful of staff and so it relies on outside contractors for research and marketing. Jordan Kuglitsch of the firm Miles Partnership reported that New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, and Eastern Canada remain the primary markets, but efforts are expanding to Tampa, Orlando, Miami, and Jacksonville in Florida, as well as Raleigh-Durham in North Carolina, and Chicago.

Another wrinkle in Maine tourism is cruise ship visits. Steve Lyons, director of the tourism office, reported that 355 cruise ships visited Maine ports in 2023 resulting in 386,799 passenger days. Bar Harbor saw 129 ships, Portland 117, and Eastport 17.

For more information on the numbers, see MaineTourismConference.com.

4 The Working Waterfront june 2024 National Bank A Division of The First Bancorp • 800.564.3195 • TheFirst.com Member FDIC • Equal Housing Lender

FIRST

Rusty Foster

SHORT TERM RENTALS

continued from page 1

that open?” asks Noel Musson, a planner who is helping Tremont and Mount Desert look at options to regulate short-term rentals. “If you can’t go out to lunch in the wintertime when you want to have a business meeting because everything is closed— when places are only open here open in the tourism season—that changes the nature of a community.”

Gagnon is careful not to place all the blame for the town’s housing shortage—a recent study projected a need for more than 600 additional units through 2035—at the feet of short-term rentals. COVID also boosted the number of buyers looking for year-round homes on Maine’s coast, depleted the construction industry’s workforce, and drove up the cost of building materials, all of which inflated the cost of housing.

But she argues that with an already-tight housing market in place, the new investor-driven approach to short-term rentals, which now number about 700, acted like accelerant tossed onto a fire.

“There’s demonstrated evidence that there’s a relationship between the increasing number of vacation rentals and the increase of the cost of housing,” she observes. “It’s kind of like a perfect storm that happened.”

CLAMPING DOWN

In response, Bar Harbor voters approved new restrictions on short-term rentals in 2021. In addition to requiring registration and $250 annual permits, the rules distinguish two types of vacation rentals.

“A VR1 is someone’s primary residence. It’s the place that they can demonstrate that they are a registered voter at, or it’s the address on their driver’s license, their tax return,” explains Angie Chamberlain, Bar Harbor’s code enforcement officer. “Whereas VR2s are for property owners where it’s not their primary homestead.”

While all property owners with existing shortterm rentals were grandfathered in, a resident can apply for a new VR1 permit that allows up to two units on their property. VR2 permits have a hard cap, and Chamberlain said no new VR2 registrations have been issued since the rules went into effect.

Like Bar Harbor, Stonington residents passed a restrictive ordinance by a 2-1 margin in 2023. It also grandfathered in existing owners, if they renew registrations and pay fees annually but established a 1,000-foot setback for any new short-term rental.

“Our goal is to keep this a working waterfront community,” says Linda Nelson, the town’s economic and community development director, who adds that there are about 130 short-term rental units in town. About 50 percent of all homes in Stonington’s downtown are now owned by seasonal residents and is 80 percent of the town’s waterfront. “What this means is we no longer control our most valuable asset... While we have always had seasonal rentals, the pandemic shifted the balance. Everyone likes to say that the market will correct itself, but it takes policy to correct an imbalanced market.”

Not everyone in Stonington thinks the ordinance is going to rebalance the ownership scales.

“It largely serves as a moratorium on short-term rentals,” says Morgan Eaton, owner of The Island

Agency, a Stonington real estate and rentals company. “We’re scapegoating SROs, but this approach will not lead to more affordable housing. The properties that are selling, especially on the water, will never be ‘affordable’ in that sense.”

Eaton, who served on a town committee charged with developing the ordinance, said instead of trying to manipulate the existing home market, Stonington should focus on creating more opportunities. She noted the town is moving in that direction but suggested that rental permit fees might be dedicated to a housing fund, encourage subdivisions, and plan for more growth.

CHALLENGES AHEAD

Other coastal towns such as Cape Elizabeth and Kennebunkport have also enacted similar rules, while Camden voters will have their say on an ordinance on June 11. In general, Maine’s short-term rental ordinances all require registration, safety rules, and permit fees at a minimum. The more restrictive have put a freeze on new units.

James Myall of the Maine Center for Economic Policy expects to see more towns experimenting with these ordinances, but he is hesitant to endorse highly restrictive approaches as the solution to more affordable and available housing.

“In general, short-term rentals and Airbnb are not the driving force in Maine’s statewide housing crisis,” he says, noting that a report in April called for the creation of 80,000 new housing units just to meet present demand. “Taking a registration approach, as opposed to banning them, is probably the right track.”

Myall said that there was no noticeable increase statewide in the number of seasonal homes between 2010 and 2020, and that of those, only a single-digit percentage could be repurposed for year-round occupancy.

But he acknowledged that existing data is obscured for two reasons—first, it doesn’t capture trends occurring over short periods of time, and second, statewide data can flatten out areas where activity is well-above, or well-below, the average.

“In Maine, housing policy is intensely local,” he adds, pointing out the impacts of comprehensive plans, zoning rules, setback requirements, and review processes. “It makes it hard not to push problems around.”

Gagnon, the Bar Harbor planning director, agrees.

“The fact that we took those decisions, that created a ripple effect,” she says. “So now you’re pushing the problem somewhere else—not that that’s what you intended to do, but you’re pushing the problem to other municipalities on the island and off island.”

Is a regional approach possible? Noel Musson thinks so.

“We say here on MDI, not every single town needs to solve the housing problem by itself. We are a larger community, and we all need to work together to figure out how to solve this problem in ways that are appropriate for the whole island, or even from Ellsworth to MDI,” he explains. “So that maybe some towns fill a different need, maybe a little less density. Whereas Bar Harbor or Southwest Harbor—towns with a village and public infrastructure—can create more density or tolerate more density. There’s a lot of tools in the toolkit. You just have to be proactively open to using those tools.”

5 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2024 156 SOUTH MAIN STREET ROCKLAND, MAINE 04841 TELEPHONE: 207-596-7476 FAX: 207-594-7244 www.primroseframing.com G eneral & M arine C ontraC tor D re DG in G & D o C ks 67 Front s treet, ro C klan D, M aine 04841 www pro C k M arine C o M pany C o M tel: (207) 594-9565 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro 43 N. Main St., Stonington (207) 367 6555 owlfurniture.com A patented and affordable solution for ergonomic comfort Made in Maine from recycled plastic and wood composite Available for direct, wholesale and volume sales The ErgoPro

Reliable transportation for all of your island needs 207-466-2636 www.midcoastbargeworks.com

Full Service Boat Yard, Repairs, Storage & Painting P.O. Box 443, Rockland, ME • knightmarineservice.com 207-594-4068

A rental property on Camden’s Bayview Street. FILE PHOTO: TOM GROENING

from the sea up

Pathways to possibility

Scholarships are critical for island, coastal students

BY KIM HAMILTON

AS SCHOOLS along the coast and on Maine’s islands prepare for the end of another academic year, many students are turning their thoughts to life after high school. Choosing between work or higher education—or choosing to pursue work and higher education— seems more complicated today.

For so many young people along the coast, finding the skills to provide a lifelong, sustainable livelihood has felt more like a game of Chutes and Ladders, with an unfair share of chutes and ladders that are far too short.

The pandemic further stacked the rules of the game against many students. It made transitions to careers and higher education even more difficult by exacerbating mental health challenges. It forced education to online platforms in communities where the technological underpinnings were not sufficient, and it isolated young people from each other, from mentors, and from important in-classroom socialization.

Knowing that rural, coastal communities face a disproportionate share of challenges, Island Institute has focused

on supporting pathways to education and careers for over a decade, helping open doors that might otherwise have remained closed.

In the past ten years, we’ve invested over $1.2 million in education and career development. More than half of these funds have gone to our Mentoring, Access, and Persistence (MAP) scholarship. This program supports high school juniors and seniors living on Maine’s year-round, unbridged islands, and scholarships are renewable for up to four years.

Through the support of generous donors who understand the special challenges facing island-based students, over 180 students have benefited from Island Institute support.

The costs of higher education are not limited to tuition, as we all know. Internships, summer experiences, and other forms of enrichment and travel programs help young people find their way and make them more competitive for financial support or a job.

To that end, our Geiger Scholarship program has helped over 186 students sharpen their skills and focus their interests.

rock bound

Noblesse oblige, Maine style

Benefactors like Linda Bean have left

BY TOM GROENING

ABOUT 15 YEARS ago, I had a most pleasant conversation with Linda Bean. I was covering the Maine Fishermen’s Forum for the Bangor Daily News and found myself sitting next to her at a session which had participants gathered in a circle.

A fellow journalist had recently told me something about Bean’s rival in the 1992 Republican primary for the 1st Congressional District seat, and I shared that with her. She spoke of her one-time rival with genuine concern and affection.

Several years later, early in my tenure with Island Institute, we decided to produce a lobster-themed issue and I wanted to include Bean, who established a buying station on Vinalhaven and who was operating as a lobster dealer. She had an office in Rockland about 200 feet from ours, and I visited a couple of times, trying to interview her. She wasn’t available, nor did the staff I was told to contact ever reply. Maine journalists know well what I learned then—Linda Bean was not a fan of our work.

Bean, who died in March, had been active in the Midcoast and beyond. In addition to the Vinalhaven lobster

Tim Farrelly, a Geiger scholar from Vinalhaven, is a great example. Tim turned an education abroad experience along the southern coast of France into skills applicable here in Maine by connecting the principles of social equity, sustainability, and environmental protection in the Mediterranean to kelp aquaculture in the Gulf of Maine. He’s bringing a global perspective to a critical local industry.

Fortunately, the broader context for developing career and work pathways has become more accessible. The Maine Community College System’s free community college scholarship program has allowed many students to consider the next steps in their education or applied training related to their job.

While the long-term sustainability of this bold approach needs to be worked out, this point-in-time experiment has offered hope for many students and families struggling to reconcile the value of education against the platinum price tag.

Fostering an interest in skillsbuilding and career aspirations is starting earlier, too. The award-winning partnership between the Mid-Coast School of Technology and the St.

George school system will expose all students beginning in kindergarten to trades, technology, and innovation.

The Makerspace, with its motto “hands-on/minds-on,” will use carpentry, boatbuilding, advanced technology, and other professions to build locally relevant expertise. This is the first of its kind K-12 career and technical education program in the nation, right here on the Maine coast. (Island Institute is fortunate to have Mike Felton, superintendent of the St. George MSU, serve on our board.)

Building a future should not be a game of chance. Our own experience at Island Institute with many extraordinary young people along with the positive changes afoot locally should give us all hope. The ladders are longer, the chutes are fewer, and the pathways to possibility are closer than they’ve ever been.

Kim Hamilton is president of Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. She may be contacted at khamilton@islandinstitute.org.

their mark

operation, she owned stores on the St. George peninsula and was developing a Wyeth art center. She also began purchasing houses in the area and renting them by the week and month.

Yes, she was the granddaughter of the founder of the L.L. Bean retail empire, but in her early life, according to a 1992 story in the Casco Bay Weekly, that didn’t bring wealth or clout. Her parents divorced when she was young. In her college years, she described herself as a “JFK Democrat,” and while living in Hallowell, helped establish Maine’s first downtown historic preservation district, which helped block a highway plan there.

After her first marriage dissolved, she married a man almost 40 years her senior and seems to have converted to his conservative views. Beginning with that deeply held Maine value that a property owner ought to have free rein over his or her land, Bean’s politics expanded into the social realm, opposing women’s and gay rights.

When she inherited millions from her grandfather, she and her husband started The Maine Paper in 1979 to espouse their conservative views.

The Casco Bay Weekly story also chronicled her donations to national

conservative causes, even channeling her money to the Contras, the group trying to overthrow the Marxist government in Nicaragua during the Reagan years.

Her run for the 1st District seat had her describing herself as a single mother who had worked as a waitress. In those years, I worked at a paper that published another newspaper which included a “waitress of the week” photo feature—and yes, it was as sexist as it sounds. Some local wise guy wrote in saying Bean should be featured.

Bean’s activism continued, with the last big flap coming in 2017 when she gave $60,000 to a PAC supporting Donald Trump. Trump detractors called for a boycott of L.L. Bean.

Wealthy folks throwing their dollars behind political causes and candidates don’t sit well with we Americans. With Bean, I suspect there was an element of sexism, just as with Roxanne Quimby, whose efforts to establish a federal land preserve adjacent to Baxter State Park drew such passionate opposition. I imagine if Roxanne were instead Raymond, folks in Northern Maine might have argued that “he ought to be able to do what he wants with his land.”

Wealthy philanthropists often think about legacies. Credit-card lender

MBNA’s founder Charlie Cawley, with his company’s money and his own, put Midcoast YMCAs, libraries, schools, and parks on solid footing. Paul Coloumbe, the vodka magnate who has invested his wealth in Boothbay Harbor tourism infrastructure, also will leave a legacy. Both also had their detractors.

Years ago, I interviewed a retired businessman who was running Vinalhaven’s lobster coop and asked him why so many on the island were wary of Bean’s forays there. “She tends to lose interest in what she gets involved in,” he told me, and the fishermen who relied on her might be left high and dry.

The questions I’m left with are these: Does Linda Bean have a legacy? And do our big-impact philanthropists always invest with strings attached? George Dorr, John D. Rockefeller, and the others who created Acadia National Park had conditions for their donations, but do we care about them now?

Tom Groening is editor of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at tgroening@islandinstitute.org.

6 The Working Waterfront june 2024

A POET AND THE PEOPLE’S CAR—

Portland’s Longfelllow Square is captured in this photo from 1972, with a Volkswagen “bug” passing through the scene.

Bad habits revived again and again

Public

infrastructure problems need fresh thinking

BY DAVID D. PLATT

THE CHANGE OF seasons—spring being what’s on my mind—can call out old habits. Mine have to do with boats and the preparations they require at this time of year. The habits of others will be different, of course, depending on circumstances, priorities, and whose habits we’re talking about.

While my boat habit goes back a long way it’s important only to me, so except to say that I just got myself all tired and muddy setting out a mooring there’s no need to report further. The boat’s sitting out there right now.

A few other habits—not mine, I need to say—are on display for everyone to see, comment on, even complain about.

I’m referring to habits on display this spring, for better or for worse, at three different public entities: the state Department of Transportation, the Portland Jetport, and the Maine Turnpike Authority.

Let’s take these fine organizations and their habits one at a time. The DOT owns Sears Island, and after a long, official-looking process, it designated

Island Institute Board of Trustees

Kristin Howard, Chair

Doug Henderson, Vice-Chair

Shey Conover, Secretary, Chair of Governance Committee

Carol White, Chair of Programs Committee

Kate Vogt, Treasurer, Chair of Finance Committee

Bryan Lewis, Chair of Philanthropy Committee

Megan Dayton, Ad Hoc Marketing & Comms Committee

Mike Boyd, Clerk

Sebastian Belle

David Cousens

Mike Felton

Nathan Johnson

Emily Lane

Michael Sant

Mike Steinharter

Donna Wiegle

Tom Glenn (honorary)

Joe Higdon (honorary)

Bobbie Sweet (honorary)

John Bird (honorary)

Kimberly A. Hamilton, PhD (ex officio)

the island as the site for Maine’s new offshore wind port.

Nothing wrong with a wind port as we begin to de-carbonize our energy system, but the rationale for Sears Island looked too habitual to a lot of us: build it there because we already own it. Besides, the state has been looking for ways to justify its acquisition of Sears Island for the decades since proposals for cargo ports, refineries, and other developments have failed to fly or float. Some habits are getting old, and a change might be in order.

Next, let’s say a few less-thancomplimentary things about the Portland Jetport, which is running out of parking space. Proposed solution, really habitual if you ask me: fill in some swampy places, cut down some trees, and intrude on a neighborhood to expand the existing parking lot.

The result of this habitual thinking, which airports everywhere else abandoned years ago? Angry neighbors, likely lawsuits, delays—when getting beyond old habits and putting people on a bus to offsite parking lots at, say, the alreadypaved and declining Maine Mall, would be cheaper and less destructive to the

area next to the airport. (I know there is already offsite parking at a place called the Pink Lot, but why not head for the mall?

Lots of other folks aren’t these days.)

Candidate No. 3 for the skewer treatment is the great granddaddy of all habitual thinkers, the Maine Turnpike Authority.

Decades ago the Authority, which is less accountable to the public than it should be, decided to deal with the annual traffic jam at the tollgates at its southern end by a huge widening project. The resulting uproar actually got the legislature into the picture with the Sensible Transportation Act, diverting some of the Authority’s wealth (remember all those quarters we pitched into its toll baskets?) to uses other than the big road; that is, local road needs elsewhere.

Mass transit: The Amtrak Downeaster train comes to mind. Sure, the Turnpike got widened in the end, but with the help of non-habitual thinking we got a few other things done as well.

Now, of course, the Turnpike Authority has fallen back onto old habits by proposing to deal with traffic jams west of Portland with a toll-supported

THE WORKING WATERFRONT

Published by Island Institute, a non-profit organization that works to sustain Maine's island and coastal communities, and exchanges ideas and experiences to further the sustainability of communities here and elsewhere.

All members of Island Institute and residents of Maine island communities receive monthly mail delivery of The Working Waterfront. For home delivery: Join Island Institute by calling our office at (207) 594-9209

E-mail us: membership@islandinstitute.org • Visit us online: giving.islandinstitute.org

highway extension aimed at downtown. Forced to look at alternatives, it rejected things like buses and light rail in favor of—you guessed it—more road. It asked towns along the way for support and got it from local politicians responding to complaints about traffic jams but unwilling to entertain habit-free alternatives to more cars and roads.

Fortunately the project has run up against a big farm it wants people to drive through on their way to town. The battle is joined.

Old habits die hard, I know. A stateowned island connected to the mainland by a state-built causeway intended for a cargo port? Use it for a wind port! Airport parking got you down? Expand the parking lot as we’ve done in the past! Traffic jams between the existing Turnpike and downtown? Extend the highway, of course!

These examples of habitual thinking make my boat habits seem completely harmless—as they are.

David D. Platt is a former editor of The Working Waterfront and Island Journal. He lives in Scarborough.

Editor: Tom Groening tgroening@islandinstitute.org

Our advertisers reach 50,000+ readers who care about the coast of Maine. Free distribution from Kittery to Lubec and mailed directly to islanders and members of Island Institute, and distributed monthly to Portland Press Herald and Bangor Daily News subscribers.

To Advertise Contact: Dave Jackson djackson@islandinstitute.org (207) 542-5801

www.WorkingWaterfront.com

7 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2024

guest column

386 Main Street / P.O. Box 648 • Rockland, ME 04841

Working Waterfront is printed on recycled paper by Masthead Media. Customer Service: (207) 594-9209

The

guest columns

James Fitzgerald at Katahdin

Uncle Clarence recalled the Monhegan painter

BY DAVID ESTEY

MY UNCLE, Clarence Hilyard, bought and ran the Katahdin Lake Camps in the mid-1960s as a Maine guide. One of his most interesting visitors each fall was Monhegan painter James Fitzgerald, whose work is now well-known and highly regarded.

Clarence told several humorous stories about Fitzgerald, two of which appeared in Carl and David Little’s book Art of Katahdin, after I introduced them to Clarence.

My favorite is when Fitzgerald was standing lakeside studying “the moods of the mountain,” as he often did, when some hunters were walking in looking for the camps.

“Hey mister, which way to the camps?” they called, once in earshot. Fitzgerald ignored them. As they got closer, the called again, “Hey mister, which way to the camps?” No response. Once they were right next to him, one said, “Hey mister, didn’t you hear us calling you?” Fitzgerald turned slowly toward them and said, “Can’t you see I’m busy?”

Fitzgerald didn’t associate with the hunters and preferred to eat in the kitchen with Clarence and Aunt Glenda. Glenda used to watch TV painting episodes hosted by Bob Ross and fancied herself a painter also.

One day she asked Fitzgerald to repaint the faded colors on the lake trout mounted on the mantel. He declined. She kept pestering him until she finally enticed him with a promise to bake his favorite apple pie. He took his good ol’ time but finally delivered.

She told me, “It was an awful mess, all abstract and everything, so I had to repaint it myself.” When she asked Fitzgerald what he thought of her painting, he said, “Don’t give up your day job, Glenda.”

Clarence came upon Fitzgerald painting the mountain one day in his signature semi-abstract fashion and said to him, “Jim, the mountain doesn’t look anything like that!” Whereupon Fitzgerald replied, “No, but don’t you wish it did?”

One of Clarence’s predecessors, William Wingate Sewall, took on a sickly young Teddy Roosevelt at the camps and built him up to be a vigorous young man, later a Rough Rider and eventually president of the United States. They remained friends and Sewell visited him in the White House. When Clarence was repairing the dilapidated cabins, he found Roosevelt’s name carved into the one where he had stayed.

David Estey is a Belfast artist and president of the Union of Maine Visual Artists.

What’s lurking in the deep Gulf of Maine

Cooler water now holding sway after heatwave?

BY NICK RECORD

IT’S A FOGGY and rainy May. A little chilly. Today is a good day to talk about ocean temperatures.

Across most of the North Atlantic, sea surface temperatures have been absolutely shattering records recently. Yet when we look at the buoys in the Gulf of Maine, this winter and spring have been remarkably... average.

The surface temperature today (May 1 as I write) at the Penobscot Bay buoy is about 46 °F. That’s warmer than the 20-year average for May 1 (44 °F) but shy of the highest recorded for this date (47.68 °F, recorded in 2013).

If you check out the other buoys around the Gulf of Maine, you’ll see a similar pattern—surface temperatures running a hair above average through the winter and spring with some ups and downs, while some locations are even a little below average.

Twelve years ago, when the news was abuzz with the major ocean heatwave that struck the Gulf of Maine, many of us in Maine were scrambling to understand what it meant for lobsters, whales, cod, puffins, and people.

Maine was one of the first places to get an ocean climate shock like that. Much has been written about

that heat wave, but one of the take-home lessons for me as an oceanographer was that, if we had been watching the deep-water temperatures (600 feet or so), we would have seen the heatwave coming a year or two earlier. When big changes happen down there, they eventually overwhelm what happens at the surface.

So, as I’ve been perusing the buoy data, I decided to look deeper. The great thing about the NERACOOS buoys is that you can get up-to-date data all the way to the bottom of the Gulf of Maine.

So what’s going on down there, anyway?

To cut to the chase, the deep-water masses are colder and fresher than they’ve been in more than a decade. The pattern has been strengthening over the past few months. For an oceanographer, this suggests a shift in the Gulf’s primary water supply away from the warmer, saltier subtropics to the colder, fresher subarctic.

It’s hard to say how long this pattern will hold, but it has lasted long enough to catch my attention. We haven’t seen anything like this since before the 2012 heatwave.

If it does hold, we should keep an eye out this summer for the same biological patterns we saw before the heatwave. When deep waters are cold and fresh, it affects things like the timing of lobster molts, the production of forage fish, and the supply of food for North Atlantic right whales in eastern Maine.

Before the heat wave, shellfish closures were longer and more common. And I’ve been hearing from neighbors recently that the alewife timing is off. We’ll be checking in on these and other conditions. Stay tuned, and keep an eye on those buoys.

Nick Record is a senior research scientist at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay.

letter to the editor

THANK YOU for your piece on Communes in Maine. There is so much to say and so much to add. I too moved to Maine but not till 1978. We ended up in Liberty, Maine just down the road from Liberty Tool. There were people there from the Twitchell House Commune, people from Shelter Institute and people who had come to Maine because of the Cape Rossier couple. Each wave had its own inspiration, story,

history. I was hoping to do an interview with the Shelter people but the ones I know are too shy. (but they are friends with the gentleman in your article!) Thank you again for the piece.

It is sparking many conversations.

Gratefully, Nancy Dalrymple, Liberty

The Working Waterfront welcomes letters to the editor, which should be sent to Tom Groening at tgroening@islandinstitute.org with “LTE” in the subject line. Longer opinion pieces are also considered but should first be cleared with the editor.

8 The Working Waterfront june 2024

“Clarence Hilyard” by David Estey, 1988 oil on canvas, 10” x 8.”

The wonder and work of island schools

Despite idyllic settings, education faces familiar challenges

BY KEN STEVENSON

Teaching a handful of students, each in a different grade, in a quaint one- or two-room school overlooking the harbor on a remote Maine island accessible by ferry that runs intermittently in the winter might sound like complete nuttiness to one person, an interesting puzzle to figure out to another, and the perfect calling for a third. And, like most things in life, it’s more complicated than it might seem.

In general, teaching is hard work. I know this from first-hand experience; after 15 years as a school administrator I became a full time teacher at a Midcoast high school.

Start with lesson planning, grading papers, classroom management, parentteacher conferences, rampant technology use in the classroom, the needs of neurodivergent students, extracurricular opportunities and expectations of sports, arts, debate, etc. And then add the inherently messy process of adolescent identity development in an age of increasing polarization amidst an ongoing epidemic of mental health challenges with minimal societal esteem for teachers and you have your hands full. COVID exacerbated these dynamics and had an underappreciated, direct negative impact on anyone on teaching— and it’s a tougher challenge now than five years ago.

Island teachers take this stew and create something that nourishes all. I’ve been in a one-room school where an 8th grader and a 5th grader are reading the same book, each one answering different questions on a review sheet to prepare for a seminar type of discussion with the teacher, while a 3rd grade student is reading a different book and illustrating a short story intended to be a parallel construction to the book she is reading, while yet another younger student is sounding out letter combinations. All at the same time, all together in one very charming room, with one teacher.

There are almost no educational training programs to prepare a teacher for this kind of environment. The teachers who thrive in this setting rely on the formal training they have, blended with their instincts and talking to other teachers in similar settings.

To this latter point, 15 years ago, a group of teachers on Maine’s outer islands came together to create the Teaching and Learning Collaborative (TLC), a true partnership of teachers and students supported by Island Institute. In my work, I get to support the TLC via weekly Zoom calls and texts, and, my favorite part, visiting island schools to support them in person.

Isolation, particularly in the winter, on a remote island is hard to understand until you experience it. The news that the ferry isn’t running today, so

you can’t get off the island and no one can get on, is a dramatic illustration of the larger dynamic of social isolation.

Many island school children can’t participate in organized afterschool sports because there aren’t even enough kids on the island to have a three-onthree basketball game during recess.

But there are powerful positive dynamics at work as well. In an era where hands-on science and critical thinking skills are important educational principles, I’ve seen island students do all of the problem solving necessary to raise and release thousands of salmon fry and then do beautiful presentations that capture and communicate their project.

In support of the movement to introduce students to potential career pathways as early in their education as possible, I’ve seen 4th and 5th grade students collaborate across islands and with mainland-based scientists to build submersible robots, then design and perform experiments using these rovers in the waters around their schools.

The arts aren’t neglected either; a group of island students created a wickedly funny film capturing the ravages of the sun on an assortment of snow people, and I’ve been in the audience for a play performed on an outdoor stage with a view down the harbor to the hills of Acadia that rivaled any performance set in ancient Greece.

In other ways, the very small, island school experience captures the imagination of a certain set of people who just can’t help but to come up to the doors and knock, or even just let themselves in, even when school is in session. Intriguingly, these are often current or retired teachers or librarians, who just want to “take a quick peek,” even though they must know they are disturbing the teacher’s carefully calibrated plans.

One school I get to visit often has to put a carefully worded sign on the door, once spring arrives and the ferry schedule picks up, imploring people—yes even you charming retired educators with nothing but the best intentions in your heart—to please not poke your head in to take a quick look around. Let the teachers do their magic with the kids.

Spending time with island teachers reminds me of this quote from Maya Angelou: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Ken Stevenson is a community development officer with Island Institute, publisher of The Working Waterfront. He may be contacted at kstevenson@islandinstitute.org.

What follows is a note from Bill Geary, director of Maine State Ferry Services, posted in several public venues. Geary has pledged to share the report he makes to the Maine State Ferry Advisory Board in online venues.

I WANT TO acknowledge that we have seen an unprecedented number of ferries go out of commission at the same time. The Margaret Chase Smith, which serves Islesboro, has been out since Jan. 9 due to misaligned and worn reduction gear. The Henry Lee, which serves Swan’s Island and Frenchboro, has been out since March 9 because of a leak in the hull.

We have been running the Everett Libby, our oldest ferry, which normally only serves Matinicus, daily to continue service, and that ferry had engine issues and is now out for repairs.

Additionally, we, like many other industries, are having staffing challenges, particularly at the Able-Bodied Seaman level. We are working tirelessly to fill in call-outs or gaps in coverage to keep the required staffing as directed by the U.S. Coast Guard.

If we have one crew member short, we cannot sail—period. I would like to thank all our crew members who have stepped up and volunteered to work extra shifts to cover these gaps to keep the ferries running. We have six vacant

AB positions, and we are interviewing and offering jobs for those and other positions as fast as possible when we get applicants.

Vinalhaven’s regular two-boat schedule and capacity has taken the brunt of cancellations related to the breakdowns and lingering staffing issues. These are difficult decisions. We appreciate our Vinalhaven customers for understanding that we cannot leave other islands without service.

For some positive news, the Henry Lee was returned to service in Swan’s Island and Frenchboro recently, and the Charles Philbrook was brought to Rockland Marine to finish up remaining repairs from her drydock.

The Margaret Chase Smith is expected to be back in service for Islesboro, and the Richard Spear will return to Rockland and serve as the “day boat” for Vinalhaven. The Charles Philbrook should finalize her drydock soon and will replace the Neal Burgess on the North Haven run as that ferry will go to Rockland Marine for a drydock inspection.

Also, new ferries are on their way— more details to come.

If you have any questions, reach out to your island advisory board member or email me at william.geary@maine.gov

9 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2024

Independent. Local. Focused on you. Boothbay New Harbor Vinalhaven Rockland Bath Wiscasset Auto Home Business Marine (800) 898-4423 jedwardknight.com

Ferry

woes tied to vessel breakdowns, staff shortages

A way forward for marine economy: Small-scale aquaculture

BY TOM GROENING

Near the end of an April 24 panel discussion in Stonington, a speaker described what he hoped the harbor would look like 50 years from now. Today, early mornings see fishermen heading out in skiffs to their boats, off to haul traps in this toplanding lobster port. But in the future, those skiffs might be heading for a variety of ocean-based farms.

The scenario was described by Mike Thalhauser of Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, a participant in the fourth and final “Talk of the Towns” panel discussion, this one on small-scale aquaculture.

“We want to keep our community on the water for generations to come,” moderator Linda Nelson said in introducing the discussion. Nelson serves as Stonington’s director economic and community development.

Key themes within the concept of aquaculture were the owner-operator nature of many of the businesses, the way growing seaweed and shellfish enhances water quality, and the opportunity for growth in this seafood sector.

Marsden Brewer, who now grows scallops on lantern nets in the water column, worked as a fisherman for many years. “I had every opportunity to fish,” he said, but his son would not have the same.

Brewer recounted traveling to Japan on a Maine Sea Grant-sponsored visit to learn about growing scallops, and he now has six years experience with the process.

“It’s a lot of learning,” he admitted, “but it’s working,” he said of his business, Pen Bay Farmed Scallops.

The scallops are suspended 10-15 fathoms (60-90 feet) deep linked to the surface by buoys.

Abby Barrows, who operates Deer Isle Oyster Company and also grows kelp, said her forays into aquaculture came with the future in mind.

“Growing up here, I recognized things were changing,” she said.

Her operation has the native Maine oysters in bags that hang from buoys. No feed is used.

“Tomorrow, we’re harvesting our kelp crop,” she said. The seaweed grows through the winter months.

Barrows said her lease site of about 3 acres and 25 years in duration. A scientist who has focused on microplastics in the ocean, she said her goal is to build a plastic-free oyster farm.

To a question about how small operations might be expanded, Barrows said it’s a variable environment.

“It’s farming, and stuff happens out there,” she said. She hopes to secure a few more acres to be successful financially.

Brewer said his operation, which he runs with his son, is about 12 acres, but he hopes to expand it to 40 acres. He also grows kelp along with the scallops.

Christian Brayden of the Maine Aquaculture Association also was on the panel, and said a study showed that seaweed-growing operations of 8 acres or more prove to be profitable. Generally, aquaculture businesses typically take 6-7 years in operation before revenue begins to come in, he said.

Brayden described how he helps would-be entrepreneurs, meeting oneon-one with the “aqua-curious,” as he described them.

Brewer described the lease process— through which permits are granted from the state for use of portions of the sea—as “slow, burdensome,” but added that it’s effective.

Panelist Kyle Pepperman of the Downeast Institute, a shellfish research center on Beals Island which operates a mussel hatchery that supplies seed to aquaculture farms, said the organization works to identify problems before they impact businesses.

Pepperman said lease applications, submitted to the Department of Marine Resources, are available for up to ten years for up to 100 acres.

DMR hosts “scoping sessions” at which

adjustments to location might be suggested. A formal hearing follows. Later in the discussion, former DMR Commissioner Robin Alden said from the audience that neighbors should engage in that scoping process.

“It’s important to attend the hearing if you have concerns,” she said, and added that the cumulative impact of operations in a small area can be considered by regulators.

Barrows urged those with concerns about a new farm to research the applicant’s track record, find out where they live, and learn what technologies they plan to use. A $5,000 bond must be filed with the host town to cover any repair costs to the operation.

Pepperman said asking about noise, and whether there would be lights on and boat traffic to the farm at night, also were advisable for land-side neighbors. Most applicants work to resolve concerns, he said, because “Angry neighbors are not good to have around.”

Jaclyn Robidoux, seaweed extension specialist with Maine Sea Grant, explained how some farmers use a checker-board arrangement with their kelp and mussel operations. She said in Maine, native kelp is used.

Asked about threats to these smallscale operations, Barrows pointed to land-side activities.

“I think there should be a lot more regulations on what we put on our lawns,” she said.

10 The Working Waterfront june 2024

G.F. Johnston & Associates Concept Through Construction 12 Apple Lane, Unit #3, PO Box 197, Southwest Harbor, ME 04679 Phone 207-244-1200— ww w. gfjcivilconsult.com — Consulting Civil Engineers • Regulatory permitting • Land evaluation • Project management • Site Planning • Sewer and water supply systems • Pier and wharf permitting and design

Owner-operated farms are responsible, panelists say

John Martin, Bud Staples, and Elsie Gillespie chat around the woodstove at the annual town meeting.

13 www.workingwaterfront.com April 2020 Brewer recounted traveling to Japan to learn about growing scallops on lines.

Gerald “Punkin” Lemoine Bud Staples

A panel discussion on small-scale aquaculture in Stonington on April 24 included, from left: Marsden Brewer, Mike Talhauser, Abby Barrows, Christian Brayden, Jaclyn Robidoux, and Kyle Pepperman.

Marsden Brewer grows scallops in lantern nets, seen here on his boat.

A scallop fresh from the sea.

No surprise: Bad weather causing outages

Twofold increase 2014-2023 compared to 2000-2009.

THE MAINE MONITOR

A NEW ANALYSIS shows that more major power outages across Maine, the Northeast, and the U.S. are happening as a result of bad weather.

The data from the nonprofit Climate Central shows an aging power grid under pressure as climate change brings more extreme storms in all seasons.

“Major outages are events that affect at least 50,000 customers (homes or businesses) or interrupt service of 300 megawatts or more,” Climate Central reports in a release about the analysis, based on federal data from utilities’ required reports of these large outages.

The analysis found that 80% of such events from 2000 to 2023 were weather-related, with a twofold increase from 2014 to 2023 compared to 2000 to 2009.

Severe storms (other than tropical cyclones) and winter weather accounted for nearly three-quarters of these outages. Hurricanes and tropical storms accounted for 14% of outages, though they marked some of the longest-lasting interruptions, Climate Central says.

Maine doesn’t make the top 10 when it comes to states with the most weather-related major outages, according to the Climate Central analysis. The top honor goes to Texas, with 210 major weather-related outages in the past 20-plus years.

But a quick breakdown of major outages affecting Maine (either alone or along with other New England states) in this same period shows a striking increase.

Maine also ranks high overall for outages of any size and cause.

Data from the federal Energy Information Administration put Maine in the top five for both the longest and most frequent outages in 2022:

“A higher average frequency of outages, unlike average duration,

tends to be associated more with nonmajor events,” the EIA says, noting that heavily forested states tend to see the most outages per customer.

“Power interruptions resulting from falling tree branches are common, especially because of winter ice and snowstorms that weigh down tree limbs and power lines.”

The federal data that Climate Central analyzed shows a range of non-weather causes for outages nationwide, from vandalism to technical glitches.

As Maine’s largest utility, Central Maine Power has taken its share of criticism for its response to outages in recent years. The storms in January and December, for example, left thousands in the dark and cold for days.

The utility is trying to invest in a more resilient grid. A $30 million federal grant announced last year could help the power system “selfheal” in outages, better containing disruptions before they can spread— part of efforts to “strengthen our state’s electrical system so it can handle increased threats from climate change,” CMP president Joseph Purington said at the time.

Grid modernization takes many forms, from circuit upgrades to better meters and new kinds of timeand technology-based rates, not to mention new poles, wires, and treetrimming approaches.

All of these changes are designed to make it easier to bring more variable, localized renewable energy online, while hardening that more flexible, variable grid to increasing weather extremes.

This story was originally published by The Maine Monitor. The Maine Monitor is a local journalism product published by The Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting, a nonpartisan and nonprofit civic news organization.

Over 100 Maine Craft Beers, Kombuchas, and Ciders

• Freshly made sandwiches & salads

• Hot entrees: soups, chili, and chowders

• Large selection of wine, craft mixers, and Naut-E botanical spirits

• We also now make pizza. Call to order: (207) 326-0781

• Free wine/beer tastings every 1st/3rd Friday at 4:30

We also have wonderful unique gifts, from finely crafted Japanese teacups, award-winning Folkmanis puppets, and our iconic coffee mugs and sweatshirts—this year’s line being in Pantone’s 2022 color of the year, Peri.

Open Daily 10-5

5 Castine Road • Castine, ME

windmillhillprovisions@gmail.com • https://windmillhillprovisions.store

INSTAGRAM: windmillhill.provisions FACEBOOK: Windmillhillprovisions

11 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2024 Sea Farm & Commercial Fisheries Loans FINANCING FOR MAINE’S MARINE BUSINESSES For more information contact: Nick Branchina | nick.branchina@ceimaine.org | (207) 292-1250 Hugh Cowperthwaite | hugh.cowperthwaite@ceimaine.org | (207) 292-1102 Funds can be utilized for boats, gear, equipment, infrastructure, land and/or operational capital.

CASTINE MAINE

provisions Garden & Market

Cheseapeake Bay in spring

Pound-netting and hand-tonging

PHOTO ESSAY BY JACK SULLIVAN

Ispent a week in Maryland in late March teaming up with my friend, the Annapolis-based photographer Jay Fleming, to get an inside look at the fishermen—or watermen as they’re called—of Chesapeake Bay.

Spring is a great time for pound-netting, and the end of March marks the close of the wild oyster harvest. Both are ancient fishing practices that date back to the region’s Native tribes.

Pound-netting requires preparation and patience but yields large catches of diverse species. A large net is erected perpendicular to the shore. Fish follow it out to deeper waters to navigate around it, but instead are corralled into a pen where they are extracted.

Some of the species we saw harvested from the net included perch, striped bass (known as rockfish in the Chesapeake), and invasive catfish.

The American oyster is found in waters all along the East Coast. Genetically, they are the same species as those found in Maine are harvested differently. Their flavor profile also differs.

A common method for oyster harvesting in the Chesapeake is hand-tonging, in which watermen use oversized tongs to scoop oysters from their beds in shallow rivers. Maryland oysters have a much milder flavor while Maine oysters are rich and briny.

The Chesapeake watermen have the same respect and stewardship for their waters as Mainers.

12 The Working Waterfront june 2024

High school student Hunter Mahoney pulls a rockfish out of the pound net while his dog Maverick observes expectantly.

Patrick Mahoney of Wild Country Seafood scoops the last of the fish out of his pound net.

The Neavitt fishing fleet hand-tongs for oysters in Broad Creek, a tributary of the Choptank River on March 29, the final day of oyster season in the Chesapeake.

13 www.workingwaterfront.com june 2024

While hand-tonging for oysters, piles of live oysters and shells are dumped on deck and culled by deckhands. The marketable shellfish are either sold live or canned.

Lewis Carter, captian of F/V Chelonte, has been fishing the Chesapeake 63 years.

F/V Stormbreaker dredges for oysters, similar to how draggers in Maine fish for urchins and scallops.

Many species of fish end up in the pound net. Some are freed, and others are harvested.

Predatory birds like ospreys and herons target the pound net for an easy breakfast.

Our Island Communities

Students contribute to ‘archipelago of knowledge’

Islesboro, Vinalhaven students sort spat with Hurricane Island

BY NATE HATHAWAY

PHOTOS AND

Students from Islesboro Central School (photos on opposite page) and Vinalhaven School (photos on this page) joined Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership educators for a boat ride to Deer Isle in mid-April as part of an ongoing collaborative marine research project.

The crew of high school students and Hurricane Island educators joined Dr. Carla Guenther, chief

scientist at the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, who is the principal investigator. The focus of this project is to understand where to find juvenile scallops along the Maine coast, and the method has been to deploy mesh spat bags in the fall and retrieve them throughout the spring.

The roster of researchers on this multi-year, NOAAfunded project include Dr. Caitlin Cleaver, former Hurricane Island Center for Science and Leadership Research Director and currently at Colby College,

and Phoebe Jekielek, another former Hurricane Island research director, currently a UMaine PhD candidate. They were joined by the organization’s current Research Director Dr. Anya Hopple. Assistant Education Director Kyle Amergian and year-round educator Claire Gabel joined in with students and teachers Haley Currie (Islesboro) and Ruth Brooker (Vinalhaven) to pick apart the bags, panning for the gold of hole-punch sized scallops amidst a slurry of marine growth from the past six months.

14 The Working Waterfront june 2024

STORY

The spat collection bags hosted arctic boring clams, mussels, and the often hilariously explosive sea squirts, or tunicates. This survey began as an Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission project which supported the survey in fall of 2022, and then the project received funding from NOAA’s SaltonstallKennedy for an additional two years, with spat bags being deployed again in fall of 2024.

The Vinalhaven students had a surprise during their sorting session with Eastern Maine Skippers Program founder Tom Duym on hand to help and boost morale with a mid-sort round of hot cocoa and glove replenishments from the nearby Harbor View store.

Many of the students have family connections to the working waterfront or fish from their own boats. Working with the spat bags introduced them to the fairly low-tech process by which would-be scallop farmers collect their stock. This is unique to scallop aquaculture as hatchery support is still being developed, so all farmed scallops start in the wild and need to be collected with spat bags every generation.